Housing Finance Reform Plan

Pursuant to the Presidential Memorandum Issued

March 27, 2019

September 2019

i

Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1

Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4

A. FHA Background ..................................................................................................... 5

B. GNMA Background ................................................................................................. 6

I. Refocus FHA to its Core Mission ................................................................................... 8

A. Targeting Programs to Borrowers Not Served by Traditional Underwriting ........... 8

B. Define Roles for Government-Supported Programs Through Better Coordination12

C. Strengthening FHA Single-Family Default Servicing Processes ........................... 13

D. Ensure HUD’s Multifamily Programs are Appropriately Targeted ....................... 15

E. Provide Regulatory Certainty to FHA Lenders ...................................................... 16

II. Protect American Taxpayers ........................................................................................ 18

A. Strengthen FHA Risk Management Systems and Governance .............................. 18

B. Improve Financial Viability of the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage Program 19

C. Implement Tiered Pricing to Protect the MMIF ..................................................... 20

D. Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing Including Manufactured

Housing .................................................................................................................. 20

III. Provide FHA and GNMA the Tools to Appropriately Manage Risk ....................... 23

A. Establish FHA as an Autonomous Corporation within HUD ................................ 23

B. Hire and Retain the Right Talent to Mitigate Risks to Taxpayers ......................... 23

C. Align Contracting and Procurement Processes with Business Needs .................... 23

D. Modernize FHA Technology .................................................................................. 24

E. Realign Housing Assistance Programs into a New Office of Rental Subsidy and

Asset Oversight within HUD ................................................................................. 25

IV. Provide Liquidity to the Housing Finance System ..................................................... 27

A. Advance GNMA Counterparty Risk Management and Securitization Platform

Transformation ....................................................................................................... 28

B. Guaranty Fee-setting Flexibility ............................................................................. 29

C. Reforms to Maintain the Integrity of GNMA Securities ........................................ 30

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 31

Appendix A ................................................................................................................................... I

1

Executive Summary

1. Refocus FHA to its Core Mission

The financial crisis resulted in private capital receding from the housing finance system. As a

result of the crisis and subsequent policy decisions of the previous Administration, the market

share of the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA) increased dramatically from pre-crisis

levels. As the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) pursues

reforms, FHA should refocus on its mission of providing housing finance support to low- and

moderate-income families that cannot be fulfilled through traditional underwriting, including

targeting first-time and lower-wealth creditworthy homebuyers who benefit from FHA’s ability

to provide affordable mortgage credit at fixed rates with lower down payments.

Since the financial crisis, the risk profile of FHA’s portfolio has increased steadily, endangering

FHA’s ability to support access to affordable mortgage credit for first-time homebuyers

(FTHBs). Credit scores of borrowers have fallen, while loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income

(DTI) ratios have increased. The use of downpayment assistance (DPA) programs also has

grown significantly. Further, FHA’s activities have strayed away from its core mission—through

July of FY2019, 70 percent of FHA refinance endorsements are cash-out refinancing and FHA

remains the largest insurer of reverse mortgage products through its Home Equity Conversion

Mortgage (HECM) program. These activities create risks to the solvency of FHA and interfere

with its core mission of helping low- and moderate-income borrowers with good credit – yet

limited assets – afford a home and build wealth.

Through a formalized collaborative approach, FHA and the Federal Housing Finance Agency

(FHFA) must work together to ensure that government-supported mortgage programs are not

competing and do not crowd private capital out of the marketplace, both in their Single Family

and Multifamily programs. Further, FHA must ensure that borrowers are creditworthy and that

they have access to loans that meet their financial needs without creating undue risk. A mortgage

product that is inappropriate for a borrower may lead to default and foreclosure, destroy credit,

and exacerbate affordable housing need.

FHA must continue to have a strong enforcement regime that appropriately punishes bad actors

and those who willingly defraud taxpayers. However, its enforcement regime should not deter

reputable and well-regulated lenders from participating in FHA’s programs. Accordingly, it must

provide clarity and transparency in its regulatory expectations for participating lenders, including

addressing lender and loan-level certification standards and the defect taxonomy. In

collaboration with the Department of Justice (DOJ), FHA should continue to work to provide

more clarity on how the agencies will consult on the appropriate use of the False Claims Act

(FCA), which has driven away many lenders, including many depository institutions, from the

FHA program. FHA must ensure it continues to appropriately use all enforcement remedies and

mechanisms available. Doing so will provide lenders with transparency and a higher level of

certainty and promote the participation of a more diverse lender base in FHA’s programs.

2

2. Protect American Taxpayers

With mortgage insurance on loans of over $1.4 trillion in unpaid principal balance (UPB) and

more than $2.1 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) guaranteed by the full faith and

credit of the United States, FHA and the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA),

respectively, must ensure their business and operational practices protect American taxpayers.

Meeting this duty also is essential to FHA’s and GNMA’s respective missions and if either does

not operate in a fiscally responsible manner, HUD’s ability to provide affordable and sustainable

mortgage credit for borrowers is severely jeopardized. FHA must maintain an appropriate level

of capital reserves in the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMIF). It is unacceptable for FHA

to require a draw on taxpayer funds to sustain its book of business and so FHA should seek to

build its capital ratio well above the statutory two percent minimum to ensure that it is able to

weather stress events without requiring a taxpayer bailout.

FHA’s risk management capabilities must be improved in order to prudently serve its core

mission and to protect taxpayers. In particular, FHA must transform its data analytics and risk

management capabilities. FHA also must continue to develop policies that ensure its reverse

mortgage product – HECM, which has cost the MMIF billions of dollars in claims in recent

years – is fiscally sustainable. To ensure that HUD and taxpayers are properly compensated for

riskier loans, FHA should implement a “tiered pricing” framework to protect the MMIF.

FHA and GNMA must ensure that they can properly manage their counterparty risk exposure

and strengthen surveillance practices. To achieve this strategic aim, FHA and GNMA should

continue to work with FHFA and other federal entities to institute a framework that allows for

ongoing coordination and evaluation of housing finance policies to ensure proper alignment

across taxpayer-supported segments of the nation’s housing finance system. GNMA must also

evaluate its counterparties and their ability to withstand the stress inherent to changing

conditions in the financial markets.

3. Provide FHA and GNMA the Tools to Appropriately Manage Risk

FHA’s and GNMA’s respective footprints have increased significantly over the last decade—

FHA has become the world’s largest insurer of mortgages, insuring over $1.4 trillion of

mortgage loans on single-family homes, multifamily properties, and healthcare facilities. The

experience of the financial crisis exposed the importance of improving the operational

capabilities of FHA and GNMA and their critical need to have some autonomy and greater

flexibility in hiring and procurement.

Today, FHA relies upon 40-year-old technology requirements that inhibit responsiveness to

sudden market changes. To modernize FHA, Congress should re-charter it as an autonomous

government corporation within HUD, which would provide the agency tools and resources

necessary to make appropriate risk decisions to respond to changing markets. It is crucial FHA

and GNMA have the appropriate tools to manage risk and both agencies must be given resources

to hire and compensate talent with specialized expertise in the mortgage finance, risk

management, and MBS markets. These reforms will help FHA prevent foreclosures and

minimize risk of a taxpayer bailout in times of economic stress in the housing market.

3

4. Provide Liquidity to the Housing Finance System

GNMA securitization helps provide liquidity in the mortgage credit market to support the

objectives of FHA, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the United States

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mortgage insurance programs. During the last 10 years, the

size of the GNMA guaranty program has increased in size from less than $500 billion in 2008 to

almost $2.1 trillion today.

Currently, GNMA’s technology platform is secure and robust. As outlined in the U.S.

Department of the Treasury’s housing finance reform plan, if Congress should authorize it,

GNMA could provide an explicit, paid-for guaranty of the timely payment of principal and

interest on qualifying MBS that are guaranteed by the GSEs and any potential competitor

guarantors that might be chartered by FHFA. In recognition of its increased size and a potential

expansion of its role, GNMA must also ensure that program participation requirements mitigate

risk to the Federal Government. In support of this goal, GNMA must use its authorities to end

lender practices, such as loan “churning,” that increase the cost of mortgage credit for borrowers

utilizing FHA, USDA, and VA mortgage insurance.

4

Introduction

In the wake of the financial crisis, the dream of homeownership receded for many Americans.

Today, however, lower taxes and the elimination of unnecessary government regulations have

created an economic renaissance, making homeownership less of a dream and more of a

possibility. As a direct result of the Trump Administration’s pro-growth policies, unemployment

is at a 50-year low,

1

and American families are earning higher incomes and enjoying more

opportunities than seemed possible just a few years ago.

Yet, there is still one piece of unfinished business from the 2007-2008 financial crisis: housing

finance reform. Due to government policies that encouraged risky lending and created moral

hazard by building expectations that the Federal Government would bail out failing firms, the

housing finance system was a central cause of the financial crisis. This system must be reformed

and it is long overdue.

HUD plays a critical role in the nation’s housing finance system—FHA provides credit

enhancement and regulatory oversight for a portfolio exceeding $1.4 trillion and GNMA

guarantees more than $2 trillion in MBS, with the full faith and credit of the United States of

America. The symbiosis between the government-insured mortgage programs at FHA, the

USDA, and the VA – with GNMA-guaranteed MBS – contributes to lower-cost mortgage credit

and more affordable homeownership opportunities for creditworthy American borrowers.

As recognized in the March 27, 2019 Presidential Memorandum on Federal Housing Finance

Reform (Presidential Memorandum), HUD plays an integral role in the nation’s housing finance

system. During the financial crisis, and after due to the policies of the previous Administration,

FHA’s and GNMA’s balance sheets swelled, growing by approximately 350 percent and 400

percent, respectively, between FY2007 and FY2018. While FHA and GNMA are designed to be

countercyclical, their balance sheets remain at substantially elevated levels and expose taxpayers

to significant risks. In the event of a potential downturn in the housing market, FHA and GNMA

may incur serious losses, inhibiting their ability to support the housing market and increasing the

likelihood of a taxpayer-funded bailout. When the mortgage market contracts and private capital

recedes, HUD must maintain stability in the nation’s housing finance system by continuing to

serve as a countercyclical buffer. When the economy is strong and markets are well-functioning,

HUD must avoid competing with other government-supported programs and private capital, and

take steps to provide housing finance support to low- and moderate-income families that cannot

be fulfilled through traditional underwriting.

Accordingly, now is the time to refocus FHA and GNMA to their core missions and make sure

they have the tools needed to manage their significant portfolios. Both organizations face

challenges, including FHA’s legacy information technology (IT) platforms and processes, the

need for enhanced data analytics to support enhanced risk management, and perhaps most

importantly, critical limitations on the ability to innovate and decisively react to changing market

conditions to prevent taxpayer losses.

1

Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2019 Household Survey (Apr. 2019),

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

5

Reform will reduce the Federal Government’s outsized role in housing finance and prevent its

activities from crowding out the private sector. Consistent with the goals set forth in the

Presidential Memorandum, this plan presents a unique opportunity to define an appropriate role

for HUD that refocuses FHA and GNMA on their core missions. By doing so, FHA and GNMA

will be better positioned to help low- and moderate-income families become sustainable

homeowners, build equity and wealth, and enable FHA and GNMA to act in a countercyclical

manner in the event there is an economic downturn without the risk of a taxpayer-funded bailout.

A. FHA Background

FHA’s origin traces back to the Great Depression when Congress authorized its creation under

the National Housing Act of 1934. The FHA of the 1930s served the same primary function as it

does today: providing insurance coverage against losses on mortgages originated by FHA-

approved lenders. Then, as in subsequent periods of market distress, FHA’s mortgage insurance

program has provided stability to the housing market and increased capital liquidity for home

buying and construction.

FHA mortgage insurance eliminates the need for lenders to charge additional risk premiums. The

reduction in risk allows lenders to offer affordable mortgage credit, expanding homeownership

to low- and moderate-income families that cannot be fulfilled through traditional underwriting.

FHA particularly benefits low- and moderate-income and FTHBs who may have good credit and

income sufficient to support a mortgage, but not the assets to cover more than FHA’s 3.5 percent

minimum down payment requirement. In return for the benefits of mortgage insurance coverage,

borrowers pay mortgage insurance premiums. FHA must generate enough premium revenue (and

interest thereon) to cover expected losses and maintain the minimum capital reserve ratio of two

percent required by statute.

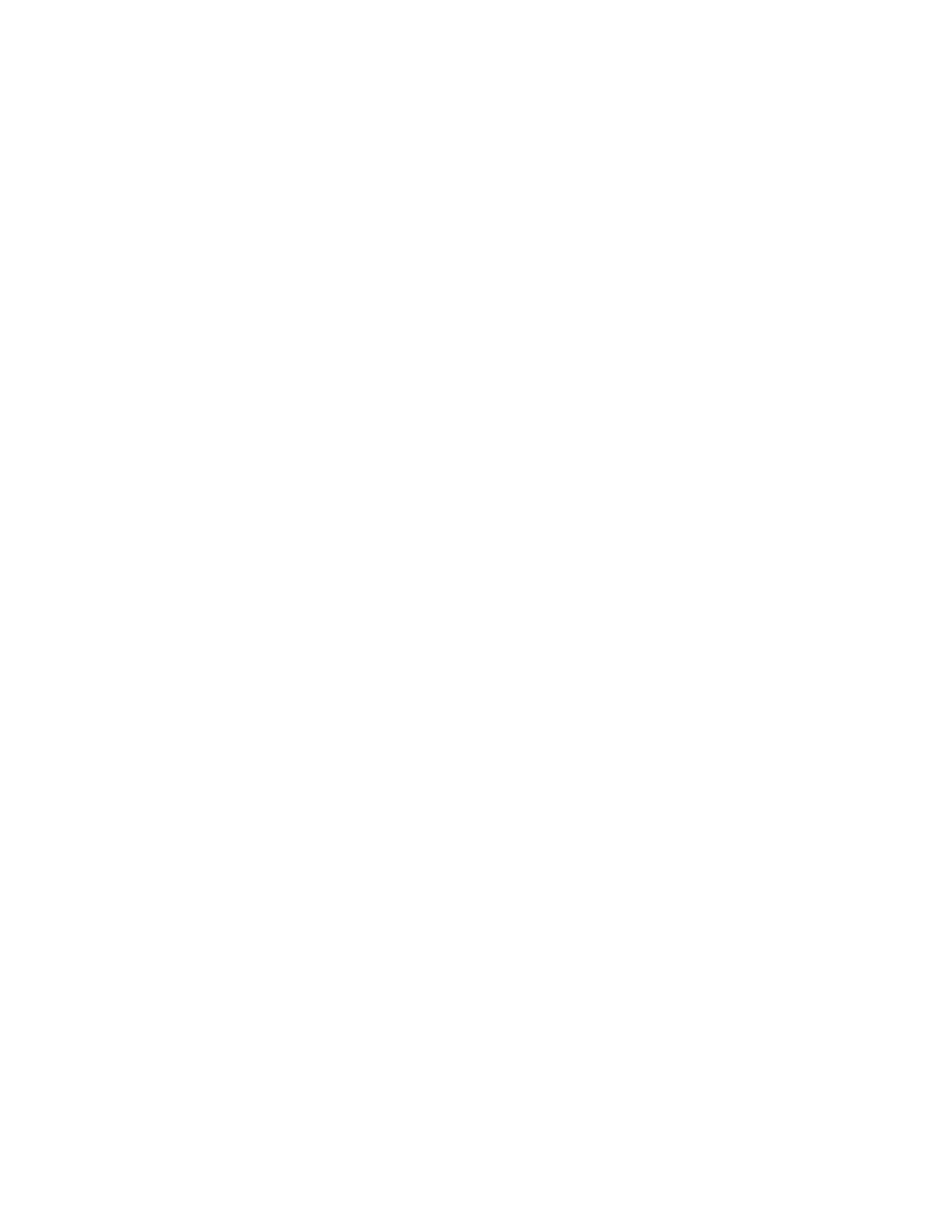

During the financial crisis, FHA served as a countercyclical buffer in the nation’s mortgage

finance system by expanding to support the stability of the housing market during and after the

financial crisis. When private capital largely withdrew from the housing finance system, FHA’s

share of mortgages for home purchase (as opposed to refinance mortgages) expanded to a peak

of nearly 30 percent. FHA’s single-family housing portfolio grew considerably in the wake of

the financial crisis, reaching a high of 1,831,234 endorsements in FY2009 and remains at an

elevated level. FHA endorsed 1,014,583 loans in FY2018. Today, FHA insures over 8.1 million

forward and nearly 500,000 reverse single-family mortgages with more than $1.2 trillion in UPB.

When FHA’s multifamily and healthcare programs are included, the total UPB is $1.425 trillion.

6

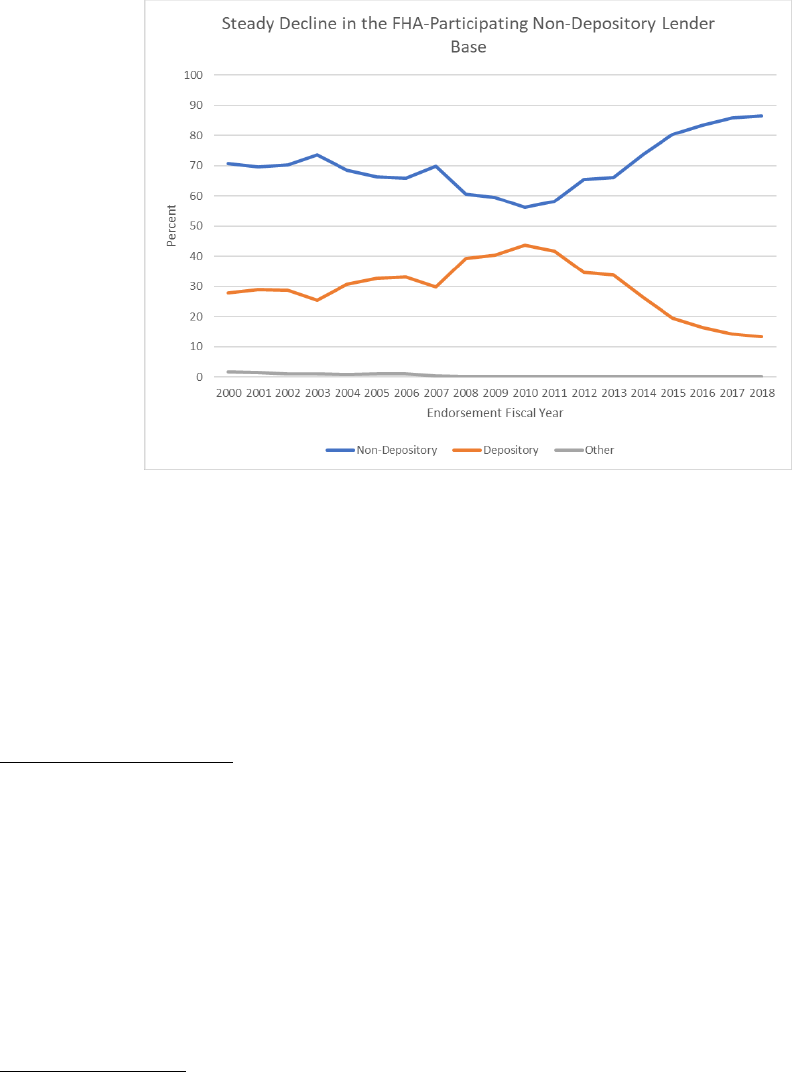

Figure 1

While FHA was created to counter the collapse of the housing finance market during the Great

Depression, its mission now includes the promotion of affordable housing opportunities and

homeownership, specifically for buyers not served by traditional underwriting. Then, as now,

FHA facilitated access to credit for borrowers from lenders and also increased investor

confidence to purchase mortgages.

B. GNMA Background

Since 1968, when Congress authorized the creation of the agency, GNMA has played a central

role in the development of the U.S. mortgage securitization system. Then, as now, GNMA

effectuates its mission by providing a full faith and credit of the United States guaranty of the

timely payment of principal and interest to security holders of MBS backed by pools of

mortgages insured or guaranteed by federal agencies, including FHA, VA, and USDA. GNMA

does not originate mortgages and does not issue MBS—it relies on issuers that are approved

financial institutions to pool or securitize eligible mortgages, either originated or acquired by the

issuers to issue GNMA-guaranteed MBS. The GNMA MBS guaranty program supports single-

family forward residential mortgages, single-family reverse mortgages through the Home Equity

Conversion Mortgage MBS (HMBS) program, and mortgages secured by multifamily and

healthcare properties, and manufactured housing.

Following the financial crisis, GNMA’s outstanding MBS portfolio has increased nearly fourfold

to over $2.1 trillion concurrent with growth in the combined mortgage insurance and guaranty

programs of FHA and VA. The market was able to absorb this substantial growth, which has

been supported through investor demand for alternative full faith and credit instruments (i.e.,

U.S. Treasuries). The “last position” guaranty in mortgage securitization that GNMA covers in

7

its MBS guaranty program is an important element of potential reform of the broader housing

finance system. As described in the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s housing reform report

also required pursuant to the Presidential Memorandum, GNMA could – if authorized by

Congress – extend its explicit guaranty to MBS backed by conventional and multifamily

mortgage loans, as it already has experience in marketing and administering MBS guaranty

programs.

8

I. Refocus FHA to its Core Mission

A. Targeting Programs to Borrowers Not Served by Traditional Underwriting

Following the crisis, FHA’s market share increased dramatically while its risk profile has

degraded and activities beyond serving its mission borrowers expanded. FHA should refocus its

single-family housing mortgage insurance program on low- and moderate-income families,

including FTHBs, who cannot affordably access credit through traditional underwriting. Doing

so will strengthen FHA’s ability to help these borrowers build equity, avoid foreclosure, and

protect taxpayers.

Generally, FHA facilitates earlier entry points into homeownership for FTHBs than conventional

mortgage loans. This is FHA’s most important contribution to the American housing market. The

share of FHA-insured purchase mortgage activity for FTHBs has ranged between 75 percent in

FY2011 and 83 percent in FY2018. Without FHA insurance, many of FHA’s low- and moderate-

income, minority, and FTHBs would lack access to affordable mortgage credit. The benchmark

for success of FHA’s programs should be ensuring that borrowers are receiving financing that is

appropriate, sustainable, and optimized for long-term homeownership.

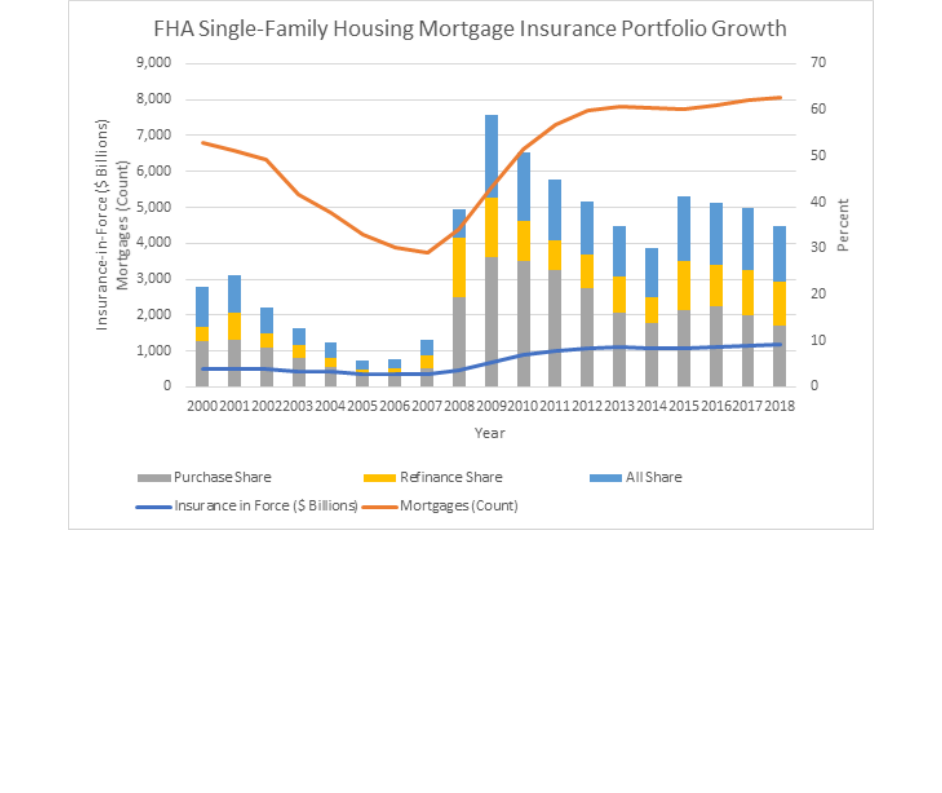

Despite the current strong economy, the credit risk profile of the average FHA FTHB has

deteriorated in recent years. Additionally, the average original loan amount for an FHA borrower

has increased steadily, from just over $140,000 in FY2011 to over $183,000 in FY2018, which

has led to an increase in DTI ratios, as home prices generally have increased faster than wages.

The average DTI for FHA purchase borrowers reached a post-crisis low in FY2013 of 40.02

percent, but has steadily increased, reaching 43.90 percent by FY2018. Moreover, nearly 24.80

percent of purchase loans in FY2018 had a DTI ratio greater than 50 percent, up from 13.54

percent in FY2013. In addition, average credit scores for FTHBs in the FHA program have

deteriorated, decreasing from 687 in FY2010 to 664 in FY 2018. Collectively, these borrower

attributes jeopardize the strength of FHA’s single-family portfolio.

9

Figure 2

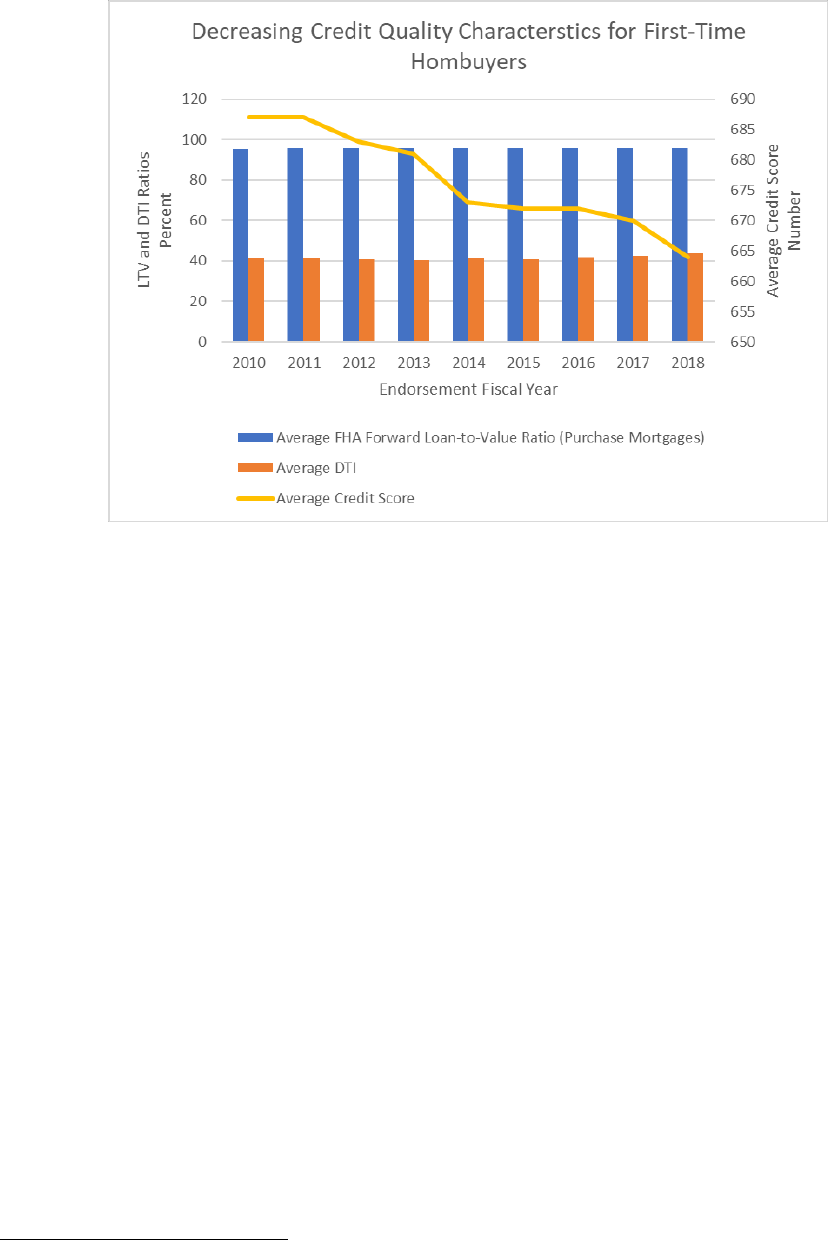

FHA has grown concerned as an increasing number of borrowers have used the FHA program to

extract equity from their homes. Some portion of FHA-insured mortgage loans are to borrowers

who currently have or previously had an FHA-insured mortgage loan. FHA should assess repeat

FHA borrowers to ensure these mortgage loans are consistent with FHA’s mission. The FY2018

cash-out refinance volume of 150,883 loans was the highest reported since 2009.

2

In FY2018,

cash-out refinance transactions represented 63.31 percent of all FHA refinance transactions, a

substantial increase from the FY2017 level of 38.94 percent.

Particularly troubling is the number of FHA cash-out refinances of conventional loans. In

FY2018, 35.05 percent of all FHA refinances were conventional to FHA cash-out refinances up

from 23.38 percent in FY2017. On August 1, 2019, FHA took steps to curb the increase in cash-

out refinancing within its single-family portfolio by limiting refinances to 80 percent LTV,

matching the GSEs’ requirements. FHA should continue to monitor its cash-out refinance

business closely to determine whether further action is necessary.

2

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2018): Annual Report to Congress Regarding the Financial

Status of the FHA Mutual Insurance Fund.

10

Figure 3

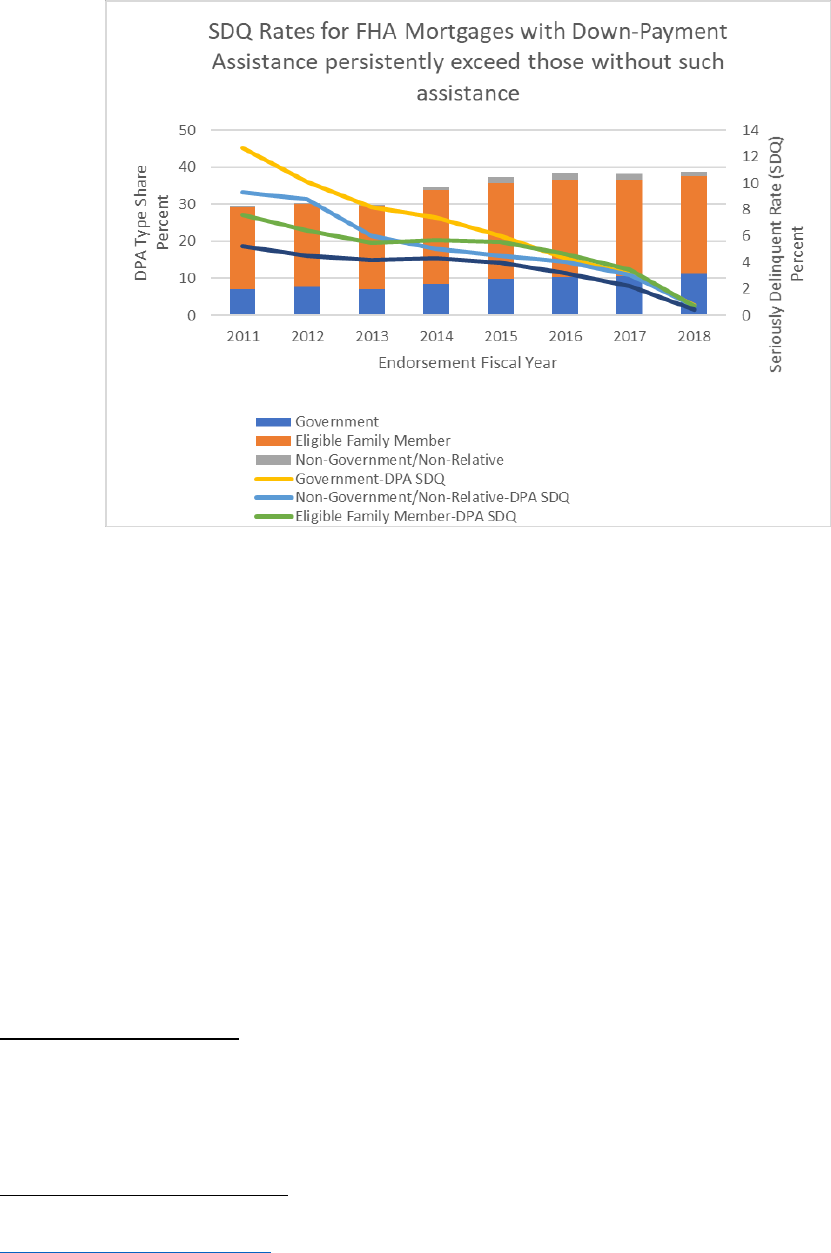

Also of significant concern is the increasing share of FTHBs relying on DPA to finance their

purchases. In FY2018, approximately 43 percent of FTHBs relied on some form of DPA. This is

the highest post-crisis share when only 34 percent in FY2010 used some form of DPA.

Moreover, the average amount of DPA has increased over this period from $6,667 in FY2010 to

$8,232 in FY2018.

FHA continues to monitor purchase mortgages with DPA given the additional risk in these loans.

FHA loan performance data indicate that mortgages with DPA have higher early payment default

(EPD) and serious delinquency (SDQ) rates than those without such assistance.

3

The SDQ rates

for FY2018 endorsements with government-funded DPA were nearly double those without any

form of DPA, and those with DPA covered either by a relative or other source performed only a

few basis points better than the government-financed DPA loans. Given the higher EPD and

SDQ rates associated with loans with government DPA, FHA will evaluate whether its current

premium structure for these loans is commensurate with the risk taxpayers are taking on. It also

is important that any DPA provided with respect to FHA loans complies with all legal

requirements.

3

Id. at 38.

11

Figure 4

FHA must consider reforms that maintain support of high initial LTV mortgages, as well as

alternative options that incent increasing borrower savings dedicated for repayment support in

addition to terms that accelerate equity accumulation, including 20-year mortgages. Faster

accumulation of equity benefits borrowers and provides additional protection to the MMIF in the

event of borrower default. Ultimately, homeownership must prove to be sustainable, which

requires FHA to have the proper incentives in place to ensure a reasonable probability of success

especially in the initial years of the loan when borrowers have accumulated limited equity.

4

In December of 2017, FHA issued a Mortgagee Letter making clear that properties encumbered

with Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) obligations will no longer be eligible for an FHA-

insured mortgage. However, FHA remains concerned with PACE assessments that are placed on

FHA loans after endorsement, and is monitoring this practice to determine if further action is

warranted. Taxpayers should never have another lien “jump ahead” of FHA and encumber the

collateral that makes FHA insurance viable and affordable.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should implement a Homebuyer Sustainability Scorecard to measure the

performance of loans to low- and moderate-income and FTHBs. The Scorecard will track

the percent of mission borrowers who default, return to renting, refinance out of an FHA

loan, remain in an original FHA-financed home, and monitor the risk associated with

4

American Enterprise Institute, Wealth Building Home Loan, American Enterprise Institute

https://www.aei.org/feature/wbhl/.

12

secondary financing (i.e. DPA). FHA should use the Scorecard to evaluate additional

underwriting criteria to ensure that new lending within its single-family portfolio is

consistent with FHA’s mission.

• FHA should conduct rulemaking to clarify the statutory prohibition on DPA providers

that financially benefit from a transaction.

• FHA should examine incentives to make shorter-term mortgages that accelerate equity

accumulation more attractive to FHA’s mission borrowers.

• FHA should ensure its programs and policies are consistent with its core mission of

serving families who cannot be served by traditional underwriting and that these

programs and policies do not incent negative borrower behavior such as equity stripping

via cash-out refinancing. FHA should continue to monitor its cash-out refinances closely

to determine whether further action is necessary.

• FHA should examine the impact of repeat borrowers on the MMIF and ensure these loans

are consistent with its mission.

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should establish statutory limitations on FHA cash-out refinances, or at least

ensure alignment (e.g., maximum allowed LTV levels) with such refinance transaction in

the conventional market (manages borrower adverse selection across agencies).

• Congress should authorize the subordination of any state or local authorized PACE liens

that jeopardizes the primary enforcement of FHA’s superior lien for its mortgage

insurance on existing loans.

B. Define Roles for Government-Supported Programs Through Better Coordination

A central principle of the Administration’s reform plan is that federal mortgage credit policies

should be better coordinated in order to allow qualified borrowers to access responsible and

affordable borrowing options and choices. Coordination ensures that there is not unhealthy and

irresponsible competition between government-supported programs, which can lead to lower

underwriting standards, increase risk to taxpayers, and threaten the long-term availability of

credit to qualified borrowers. The GSEs should not be able to selectively choose from the FHA

portfolio and leave taxpayers with the riskiest borrowers.

Due to the fundamental housing missions and mandates of both the GSEs and FHA, borrower

choice in selecting the mortgage product that best fits their needs will result in some overlaps in

the market. As discussed in this plan, the FHA program is primarily utilized by FTHBs who

cannot be served through traditional underwriting, as it generally accepts more risk and provides

low downpayment borrowers greater leverage than allowable in GSE programs while also

offering government-subsidized pricing.

13

Uncoordinated policies create incentives that encourage entities to work at cross-purposes,

resulting in little or no change in overall access to credit while increasing taxpayer exposure to

uncompensated risk. In recent years, the market overlaps might have increased to the extent that

the GSEs expanded credit guidelines to “stretch” into the FHA market. For example, DTIs on

GSE loans expanded significantly in 2018. Efforts are already underway to address these risk

trends and recent new originations indicate progress.

FHFA and FHA should coordinate to ensure that the GSEs and FHA serve defined roles within

the marketplace. Ideally, coordinated policies would bring out the best that each has to offer.

Consistent with their charters, each GSE’s role should be to perform “activities relating to

mortgages on housing for low- and moderate-income families involving a reasonable economic

return that may be less than the return earned on other activities.”

5

Similarly, and consistent with

the Presidential Memorandum, FHA should focus on low- and moderate-income families that

cannot be fulfilled through traditional underwriting.

Administrative Reforms:

• HUD and FHFA should develop and implement a specific understanding as to the

appropriate roles and overlap between the GSEs and FHA, for example, with respect to

the GSEs’ acquisitions of high-LTV and high-DTI loans and FHA’s underwriting of

cash-out refinances, conventional-to-FHA refinances, and loans to FHA repeat

borrowers.

• Critically important to these overlaps is care by FHA that its government-subsidized

premiums, combined with the advantages of the GNMA full faith and credit MBS

guaranty, do not undercut private sector pricing for large segments of mortgage loans that

can be well served by private capital.

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should establish FHA, VA, and USDA – the government-insured mortgage

loan programs – as the sole source of low downpayment financing for borrowers not

served by the conventional mortgage market.

C. Strengthening FHA Single-Family Default Servicing Processes

A key part of FHA’s modernization effort is to significantly improve FHA’s outdated servicing

policies, processes, and technology. FHA servicing must focus on the critical outcomes of

ensuring sustainable homeownership and protecting taxpayers. Over the past decade, the costs

associated with servicing both performing and non-performing mortgages throughout the

industry have increased significantly. Between 2008 and 2014, the average cost of servicing

performing loans increased from $59 to $158 per loan per year. Over the same period, the

average cost of servicing non-performing loans increased from $482 to $1,949 per loan per year,

peaking at $2,357 in 2013.

6

5

12 U.S.C. § 1716(3).

6

Laurie Goodman, Servicing Is an Underappreciated Constraint on Credit Access, URBAN INSTITUTE (Dec. 15,

2014), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/servicing-underappreciated-constraint-credit-access

14

While servicing costs have increased across the mortgage finance market since the financial

crisis, independent estimates indicate that the FHA’s servicing costs for non-performing loans

are now multiples above the costs of servicing conventional mortgage loans.

7

A recent working

paper by the Federal Reserve Board suggests that the cost of servicing FHA loans in foreclosure

is 50 times the cost of servicing non-delinquent loans, whereas that ratio is 17 for the GSEs.

8

The increase in the cost to service loans within FHA’s mortgage insurance programs has likely

translated into a higher cost of borrowing. FHA proposes the following recommendations to

improve its servicing processes in order to promote sustainable homeownership and protect

taxpayers.

Administrative Reforms:

• To better protect taxpayers, FHA should enhance its ability to better manage borrower

defaults, have more flexibility to work out loans, and make timely changes that will

reduce costs to the MMIF during stressed economic environments.

• FHA should clarify rules around conveyance and enhance consistency on what is

considered “conveyance condition” while incentivizing timely conveyance of properties.

• FHA should enhance its ability to more effectively and efficiently utilize alternatives to

conveyance using a “best execution model” that would reduce cost to the MMIF and

improve outcomes.

• FHA should create more flexible loss mitigation processes, allowing for increased take-

up in such programs, and eliminate unnecessary paperwork and process steps that will

streamline borrower qualification in case of hardship.

• FHA should streamline its default milestone timeline that currently adds to management

costs, providing greater flexibility to servicers and more appropriately incentivizing them

to work toward more efficient resolutions, with consideration given to market conditions.

• FHA should reduce uncertainty and business risk of participation in FHA loan programs

produced by penalties that do not match the severity of missed deadlines.

• FHA should establish a paperless data-driven claims process to replace the current

inefficient and paper-intensive process. The new claims process will ensure that claims

are validated before they are paid in order to better protect taxpayers.

7

Karen Kaul, Laurie Goodman, Alanna McCargo, and Todd M. Hill-Jones, Reforming the FHA’s Foreclosure and

Conveyance Processes, URBAN INSTITUTE (Mar. 1, 2018)

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/reforming-fhas-foreclosure-and-conveyance-processes

8

You Suk Kim, Steven M. Laufer, Karen Pence, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, Liquidity Crises in the

Mortgage Market, WASHINGTON: BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

(2018), https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2018.016r1.

15

• The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), FHA, and FHFA should jointly

study how to reduce the costs of default mortgage servicing.

D. Ensure HUD’s Multifamily Programs are Appropriately Targeted

FHA’s multifamily mortgage insurance products play a critical role in ensuring that credit for

multifamily development is available in many mid-size and smaller markets with a focus on low-

and moderate-income families that are not traditionally served by private sector lenders. By

financing affordable and market-rate housing, FHA’s multifamily program ensures access to safe

and affordable housing for our nation’s workforce and vulnerable populations.

However, FHA’s multifamily lending policies should not discourage private capital from

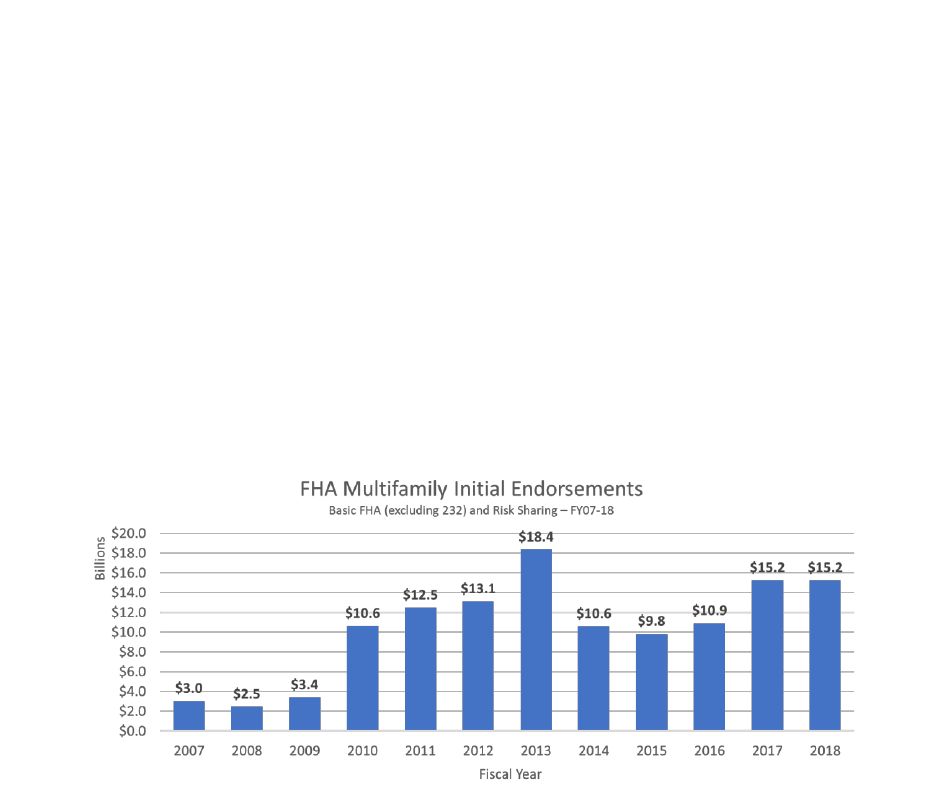

supporting preservation and development of affordable housing. Over the last decade, FHA’s

multifamily program grew substantially, and its market share remains far above pre-crisis levels.

FHA multifamily production volume peaked in 2013 with $18.4 billion in new originations. In

FY2018, FHA’s multifamily program closed 908 FHA-insured multifamily transactions worth

$15.2 billion with an asset management portfolio composed of 11,549 FHA-insured assets with a

UPB of $97 billion. In addition, FHA manages a portfolio of non-insured assets that support low-

income housing through rental assistance subsidies.

Figure 5

FHA maintains a successful program, the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD), allowing

public housing agencies (PHAs) and owners to leverage the private market to make capital

improvements and preserve the properties for long-term affordability. Using one of two

components, RAD facilitates the conversion of properties to project-based Section 8 contracts by

allowing public housing projects to convert to long-term Section 8 rental assistance contracts; or

allowing properties currently operating under HUD’s legacy programs to convert tenant-based

vouchers to project-based assistance. Launched in 2012, it has proven to be a successful model

for preserving HUD-assisted affordable rental housing that might otherwise be lost to disrepair

or neglect.

16

The following administrative and legislative reform recommendations are designed to reduce

barriers to development of affordable rental housing for lower-income, workforce, and

vulnerable populations in the nation’s most underserved markets.

Administrative Reforms:

• Similar to the planned collaboration on single-family housing mortgage insurance

programs, FHA and GNMA should establish proper coordination and information

exchange processes with FHFA to ensure that government-supported multifamily

programs do not overlap and compete with private capital.

• HUD should modify current noise regulations to permit development on property sites

with noise levels above 75 decibels, which would likely encourage development in

walkable, urban areas (including Opportunity Zones) close to transit and jobs and

aligning with FHA’s Multifamily Housing goals of more affordable housing.

• HUD should modify its current environmental review policy to increase the 200-unit

threshold to 300 units which would allow for the completion of multifamily projects in

more reasonable timelines, aligning with HUD’s goals of more affordable rental housing

to better meet the demand.

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should eliminate the 455,000-unit statutory cap in the RAD program, which

will expand its reach and impact.

• Congress should provide funding for investment in a strategic modernization plan which

will holistically overhaul and integrate FHA’s Multifamily IT systems. These systems

will likely face unsustainable operating and management costs in the near future, and not

leveraging the proposed IT road map, and retaining antiquated IT systems, is likely to

make new future interconnections across HUD difficult, if not impossible.

E. Provide Regulatory Certainty to FHA Lenders

FHA’s lender base has shifted substantially in the last decade. Today, depository institutions

represent less than 15 percent of lenders originating FHA-insured mortgages, down significantly

from approximately 45 percent of the lender base in 2010.

9

Depositories have cited potential

legal liability related to enforcement actions under the FCA as a leading reason for their limited

participation, although increased regulatory burdens after 2010 have contributed to the

decreasing share of depositories in mortgage lending, including participation with FHA.

10

Lenders have expressed concerns with the past discrepancy between the severity of the infraction

and the potential penalties that were sought under the FCA—minor errors leading to exposure to

severe financial penalties.

9

You Suk Kim, Steven M. Laufer, Karen Pence, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, Liquidity Crises in the

Mortgage Market, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION (2018), https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2018.016r1.

10

Greg Buchak, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, Amit Seru, Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of

Shadow Banks, JOURNAL OF FINANCIAL ECONOMICS 130 (3) (2018)

17

Figure 6

FHA strives to be clear in its guidance on compliance and legal enforcement matters and will not

tolerate bad actors—those who seek to defraud borrowers and taxpayers, as well as those who

make routine (and often material) errors that put strain on the agency’s resources. FHA makes it

a top priority to adhere to the rule of law, and this means the agency’s view of materiality should

be clearly communicated. FHA participants and advocacy groups have called for clarification of

the process by which HUD and DOJ consider whether to pursue FCA remedies.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should continue to work with the DOJ to provide more clarity on how the agencies

will consult on the appropriate use of the FCA.

• FHA should revise and expand its defect taxonomy in order to clearly align the severity of

loan underwriting defects with proposed remedies.

• FHA should continue prioritizing the revision of certifications, which lenders attest for

each FHA-insured loan, as well as lenders’ annual certifications. These revisions will

provide lenders additional certainty and clarity on FHA’s requirements.

Legislative Reform:

• Congress should make a statutory change to permit shorter suspension periods and

eliminate the annual cap on civil money penalties for program participants to provide FHA

more flexibility when assessing penalties.

18

II. Protect American Taxpayers

A. Strengthen FHA Risk Management Systems and Governance

To ensure protection of the American taxpayer, a modernized FHA risk management

organization is critical. As the size of FHA’s portfolio has not returned to pre-crisis levels and

taxpayers continue to bear increased risk, now is an appropriate time to develop and implement a

framework that will better allow the agency to monitor current, emerging, and future

countercyclical risks. The operational tools to build an exceptional risk management framework

should include establishing appropriate risk tolerances and scorecards to monitor risk, updating

risk model governance, and establishing credit risk transfer (CRT) program(s) which would

introduce private sector investment, reducing risk to the overall FHA portfolio and the American

taxpayer.

The lack of flexibility when addressing egregious underwriting errors or servicing breakdowns

has become particularly detrimental as counterparty risk escalates throughout the mortgage

system. For example, FHA is not allowed to force repurchases – as the GSEs are able – to

enforce underwriting guidelines. FHA instead is limited to an indemnification alternative,

essentially a “promise to pay,” to be applied regardless of the financial wherewithal of the

offending counterparty. An ability to unwind the FHA insurance policy would insulate FHA

from counterparty risk as it enforces its underwriting guidelines. Doing so will reduce the risk

that the taxpayer will have to bear the cost of a counterparty’s failure to perform.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should adopt a sound risk-based capital regime for the MMIF, well above the

statutorily mandated two percent capital ratio, which will manage risk exposure to

defined stress scenarios and ensure that FHA does not inappropriately compete with the

GSEs or private capital.

• FHA should adopt a sound risk-based capital standard to manage exposure in the current

insured portfolio for the General Insurance/Special Risk Insurance (GI/SRI) Fund and for

future stress cycles and ensure that FHA does not inappropriately compete with the GSEs

or private capital mortgage financing.

• FHA should pursue an inter-agency agreement with other government agencies

(including GNMA and FHFA) involved in mortgage insurance and mortgage

securitization on counterparty risks.

• FHA should pursue an inter-agency agreement on credit policy coordination with other

government mortgage insurance agencies and FHFA which will help ensure a more

efficient targeting and reducing overlap as FHA (and GNMA) achieve the policy goal of

assuming primary responsibility for providing housing finance support to low- and

moderate-income families that cannot be fulfilled through traditional underwriting.

• FHA should revise its risk-modeling governance, which will include a decreased reliance

on contractors for technical and modeling expertise.

19

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should direct HUD to evaluate the options, feasibility, and economics of a CRT

program similar to those recently implemented by the GSEs, with the purpose of

exploring options to reduce the overall risk to taxpayers while still serving HUD’s

mission borrowers.

• Congress should direct FHA to more effectively manage lender counterparty risk in

future books by authorizing such additional remedies as appropriate.

B. Improve Financial Viability of the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage Program

At the end of FY2018, FHA’s HECM portfolio had an economic net worth of negative $13.63

billion and a standalone capital ratio of negative 18.83 percent. Changes made to the principal

limit factors and insurance premiums in 2017, as well as the implementation of an appraisal

inflation risk mitigation policy in 2018, have been directionally positive, but financial volatility

within the HECM program remains a challenge for FHA.

The risks in the HECM portfolio have been shaped by the following features:

• HECMs accrue loan balances over time as opposed to forward mortgages where loans

generally amortize as they mature.

• Unique mobility risks generally dependent on the longevity of borrowers (and eligible

non-borrowing spouses that remain in homes secured by HECMs).

11

• HECMs are non-recourse loans, meaning FHA has limited ability to recover financial

losses on loan terminations beyond the value of the property.

12

• HECMs can carry fixed or adjustable rates, although since FY2014, new HECM

endorsements have predominantly been Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs).

• HECMs remain subject to front-end appraisal bias risks and extreme fluctuations in home

valuations. Several analyses have shown the prevalence of appraisal inflation in HECM

transactions—reaching as high as 29 percent in 2009—which ultimately increased losses

to the MMIF.

• Programmatic and capital/fund management challenges dealing with distantly-valued

collateral (based on long-term forecasts of interest rates and home price changes).

• Mortgagee risks in having to fund borrower draws over time with loan balance repayment

only demanded upon termination of HECMs. This puts cash-flow/liquidity risks on

financial institutions originating and servicing HECMs that must fund borrower draws

(that are not always neatly mapped out) prior to receiving any actual repayment from

borrowers.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should assess and revise its monitoring protocols of front- and back-end appraisal

bias.

11

Adam W. Shao, Katja Hanewald, Michael Sherris, Reverse Mortgage Pricing and Risk Analysis Allowing for

Idiosyncratic House Price Risk and Longevity Risk, INSURANCE: MATHEMATICS AND ECONOMICS Vol. 63

12

Reverse mortgages, which tend to limit household mobility correlate to discounted property values over time.

20

• FHA should develop servicing standards for HECM products that will result in reduced

operational and financial burdens on servicers and FHA.

• FHA should eliminate HECM-to-HECM refinancing, as these loan transactions result in

greater appraisal inflation, increasing lending against properties that go up in value while

being left with existing portfolio exposure on properties that have minimal (even

decreasing) change in value. These transactions also negatively impact GNMA-

guaranteed HMBS by influencing quick churn in pool participations.

Legislative Reforms:

• Similar to the forward mortgage product, Congress should revise the loan limit structure

in the HECM program to reflect variation in local housing markets and regional

economies across the United States instead of the current national limit set to the level of

high-cost markets in the forward program. Currently, the HECM program utilizes one

nationwide loan limit of $726,525 (for 2019).

• Congress should set a separate HECM capital reserve ratio and remove HECMs as

obligations to the MMIF. This would provide for more transparent accounting of program

costs and decrease cross-subsidization that occurs with mission borrowers in the forward

mortgage portfolio.

C. Implement Tiered Pricing to Protect the MMIF

To ensure that FHA and taxpayers are properly compensated for riskier loans, FHA should

implement a tiered pricing framework to protect the MMIF from excessive exposure to riskier

loans, especially loans with higher risk DPA. Tiered pricing would allow FHA to diminish the

drain of FHA’s higher risk loans on the MMIF. It would not open new markets already served by

private mortgage providers, since FHA would not lower premiums on its 30-year fixed rate

product through this effort.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should develop and implement a tiered pricing system in order to protect the MMIF

and ensure it is pricing appropriately for higher-risk loans.

D. Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing Including Manufactured

Housing

For many American families, ownership of a single-family home represents a key facet of the

American Dream. It is through single-family homeownership that many families put down roots,

become active in their communities, and build wealth for future generations. However,

overregulation of housing construction has been a key factor in supply failing to meet growing

demand, particularly for entry-level housing in high-cost urban markets. As a result, even with

low unemployment and strong wage and job growth, many creditworthy FTHBs are unable to

afford the purchase of entry-level housing.

21

Research indicates that more than 24 percent of the cost of a new single-family home is the

direct result of federal, state, and local regulations.

13

For multifamily, the figure is over 30

percent.

14

This has been a factor in the failure of new multifamily and single-family construction

to keep pace with the formation of new households. Census Bureau data indicates that from 2010

to 2016, only seven homes were built for every ten households formed. This shortage in housing

supply contributes to an unsustainably high financial burden borne by low- and middle-income

Americans.

The Trump Administration is committed to reducing the red tape that is stifling housing choice

for far too many American families. On June 25, the President continued his historic

deregulation campaign by signing an Executive Order establishing the White House Council on

Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing. The Council, led by HUD Secretary Ben

Carson, will build on the President’s commitment to hardworking Americans by reducing overly

burdensome regulations that artificially raise the cost of housing development that directly lead

to the undersupply of affordable housing, and engaging with state, local, and tribal partners to

help them do the same.

For many American families, entry-level housing options, including starter homes,

condominiums and manufactured housing, serve as important steppingstones to achieving their

ultimate dream of purchasing a single-family home in which to raise their children and build

wealth for the long term. HUD plays a critical role in helping creditworthy first-time and low-

and moderate-income borrowers achieve their goals, through FHA’s insurance of entry-level

housing, from which borrowers can successfully graduate to non-government-supported

mortgages of future homes.

Manufactured housing

15

plays a vital role in meeting the nation’s affordable housing needs,

providing 9.5 percent of the total single-family housing stock. More than 22 million Americans

reside in manufactured housing with a median annual household income of less than $30,000.

Manufactured homes are particularly important in rural communities, where they are

approximately 16.2 percent of occupied housing units. The manufactured housing industry also

plays an important part in the economy, accounting for approximately 40,000 jobs nationwide.

16

HUD regulation of manufactured housing fulfills a critical role of both protecting consumers and

ensuring a fair and efficient market.

Policies that exclude or disincentivize the utilization of manufactured homes can exacerbate

housing affordability challenges because manufactured housing potentially offers a more

13

Paul Emrath, Ph.D., Government Regulation in the Price of a New Home, HOUSINGECONOMICS.COM (May

2, 2016), http://www.nahbclassic.org/generic.aspx?genericContentID=250611&channelID=311

14

Paul Emrath and Caitlin Walter, Regulation: Over 30 Percent of the Cost of a Multifamily Development,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF HOME BUILDERS (June 12, 2018),

http://www.nahbclassic.org/generic.aspx?genericContentID=262391

15

A manufactured home is built to the Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards (HUD Code) and

displays a red certification label on the exterior of each transportable section. Manufactured homes are built in the

controlled environment of a manufacturing plant and are transported in one or more sections on a permanent chassis.

16

Manufactured Housing Institute, 2018 Manufactured Housing Facts: Industry Overview, MANUFACTURED

HOUSING INSTITUTE (June 2018), https://www.manufacturedhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2018-

MHI-Quick-Facts-updated-6-2018.pdf

22

affordable alternative to traditional site-built housing without compromising building safety and

quality. The failure to periodically update the Construction and Safety Standards, for example,

has hindered the manufactured housing industry’s ability to economize and leverage current

construction techniques and materials that require special HUD approvals. In the previous

Administration, updating the Construction and Safety Standards was not a priority, and the

current requirements have not been updated in any significant way since 2009. HUD should take

action to address barriers to the greater adoption of manufactured housing.

Administrative Reforms:

• Pursuant to the Executive Order of June 25, 2019, the HUD-led White House Council on

Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing will identify and recommend

actions and policies to mitigate regulations that unnecessarily increase the cost of creating

and preserving housing that is affordable and work with state, local, and tribal partners to

do the same.

• FHA should consider innovative proposals to modify single-family housing mortgage

finance underwriting to further encourage and promote additional supply of entry-level

housing, particularly manufactured housing.

• To encourage innovation in manufactured housing, HUD should create a formal

framework for identifying and evaluating new building, construction, and design

developments and ensuring that HUD’s regulations do not unnecessarily impede their

adoption. This framework would help gather the evidence necessary to update HUD’s

regulations on a regular cadence, thereby better keeping up with evolving technology.

• HUD should devote resources to ensure the HUD-Code is modernized to incorporate the

standards recommended by the MHCC, to minimize overly burdensome regulatory and

compliance requirements, and to encourage innovation. Once revised, HUD should also

move to a regular cadence of updating its code to ensure that it is keeping pace with

evolving technologies and best practices.

• HUD should publish updated Title I standards that address regulatory burdens of

participating in the program as part of its Single Family Housing Policy

Handbook 4000.1 (SF Handbook), which is intended to serve as the consolidated,

consistent, and comprehensive source of FHA Single Family Housing policy.

• HUD should elevate the Office of Manufactured Housing Programs within HUD and

appoint a Deputy Assistant Secretary to lead it.

23

III. Provide FHA and GNMA the Tools to Appropriately Manage

Risk

A. Establish FHA as an Autonomous Corporation within HUD

FHA was established as an independent agency in 1934, but was incorporated into HUD when

the Department was created in 1965. Unlike other offices within HUD, which generally support

very low- and extremely low-income individuals and families, FHA offers mortgage insurance

products to enhance access to homeownership, rental housing, and healthcare facilities. FHA

needs autonomy within HUD to ensure it is able to keep pace with evolving portfolios and a

dynamic, ever-changing marketplace. More independence would provide FHA greater control

over staffing and procurement, including technology. It is vital that FHA be given increased

authority to better address risk management functions that can suffer from being part of a larger

organization.

Legislative Reform:

• Congress should enact legislation to restructure FHA as an autonomous government

corporation within HUD.

B. Hire and Retain the Right Talent to Mitigate Risks to Taxpayers

FHA and GNMA face challenges in hiring and retaining sufficient staff with expertise in

mortgage finance and asset management. FHA and GNMA need the appropriate staff to manage

their current large portfolios and ensure future books of business are appropriately mission-

focused. Despite a significant increase in volume in both the forward and reverse mortgage

programs, FHA’s Office of Single Family Housing staff has decreased from 1,007 full-time

employees (FTEs) in 2010 to 751 FTEs as of August 2019, a decline of 25 percent. Furthermore,

28.7 percent of the current workforce is eligible for retirement and 45.76 percent will be eligible

within 5 years. By addressing these human capital challenges, FHA and GNMA can improve the

management and oversight of their guaranteed loan and MBS portfolios.

Administrative Reforms:

• Like GNMA, FHA should explore the targeted use of pay flexibilities available under

current law (e.g., Critical Pay) to improve hiring and retention of key positions requiring

specialized technical skills related to the mortgage and securitization markets.

C. Align Contracting and Procurement Processes with Business Needs

FHA is limited in its ability to engage qualified and capable contractors in a timely manner

because HUD’s contracting process is burdensome and protracted. The material deficiencies in

the agency’s operational processes, risk management guidelines, and technologies have

contributed to losses to the MMIF and a failure to capably protect HUD’s security interests,

respond to customer and borrower inquiries, monitor loans for program compliance, and process

property disposition requests. GNMA has made broad use of its authority as a government

corporation to contract for services as it conducts commercial activities. Its ability to do this

24

effectively has been a major contributor to its record of achieving its mission on a large scale

with a notably smaller base of government staff.

Legislative Reform:

• To the extent administrative reforms are insufficient to address procurement challenges at

FHA and GNMA, Congress should propose new statutory acquisition authorities for

HUD, particularly to address instances where material underperformance of contracting

vendors results in substantial quality deficiencies and costs.

D. Modernize FHA Technology

FHA has operated for decades on antiquated technology platforms that inhibit its ability to

appropriately manage risk. FHA’s over-reliance on outdated IT platforms ultimately increases

the cost of mortgage credit by increasing business operating costs of originators and loan

servicers. Currently, FHA’s platform is built on a more than 40-year-old mainframe system that

runs an obsolete programming language. The risk that this presents to FHA and, by extension, to

the American taxpayer, is significant. Not only is FHA’s current IT system outdated—it is

unreliable. In FY2018 alone, there were 174 outages of Single Family’s core systems.

To support the broad goal of greater standardization between FHA and industry business

practices and processes, FHA has developed a detailed technology roadmap that will guide the

development of a single platform and baseline architecture. The new IT system will cover all

aspects of the mortgage process, from loan origination, through endorsement, servicing, claims,

and, as required, disposition.

The investment in the new single platform structure will allow FHA to better adapt to changing

industry, regulatory, and statutory requirements. The modernized systems will be data-driven,

and ultimately allow FHA to fully digitize the mortgage process, opening doors to significantly

more intensified risk analysis and management. The completion of this effort will permit FHA to

increase compliance and reduce costly operational burdens, such as heavily paper-based

processes currently in place. Importantly, it will also protect taxpayers from losses that result

from fraud, in addition to reducing costs associated with maintaining and operating inefficient

legacy systems and business processes.

By grounding the development of the new architecture in reducing operational risk, FHA can

focus on delivering much-needed clarity and efficiency in its programs. This approach also lays

the foundation for the incremental phase-out of FHA’s legacy mainframe systems. By

modernizing now, FHA has an opportunity to move generations ahead to a state-of-the-art

system that leverages industry advancements including fast-feedback mortgage applications,

upfront certainty, appraisal scoring, revised Mortgage Industry Standards Maintenance

Organization (MISMO) data standards, integration of independent verification services, an

application programming interface (API) driven ecosystem, and active loss mitigation guidance.

Administrative Reforms:

• FHA should explore agreements to share technology with GNMA and other government-

supported mortgage programs when feasible.

25

• FHA should develop a mortgage origination risk tool integrating an automated

underwriting system (AUS) platform, appraisal scorecard, risk assessment tool, and third-

party verification services.

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should appropriate sufficient funds for FHA to complete its multi-year single-

family IT modernization effort.

E. Realign Housing Assistance Programs into a New Office of Rental Subsidy and Asset

Oversight within HUD

The Federal Housing Commissioner oversees and administers mortgage insurance on FHA’s

single-family forward and reverse, multifamily, and healthcare programs. Concurrently, that

same person serves as the Assistant Secretary for Housing, overseeing and administering

programs that provide rental assistance and subsidy to low-income, very low-income, and

extremely low-income Americans including: Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA), Section

202 Housing for the Elderly, Section 811 Housing for the Disabled; the Rental Assistance

Demonstration (RAD) program; federal regulation of manufactured housing, and housing

counseling.

As it considers restructuring FHA as an autonomous corporation within HUD, Congress also

should consolidate the PBRA, Public Housing, and Housing Choice Voucher subsidy programs

(Sections 8 and 9), along with the RAD and Real Estate Assessment Center (REAC) functions,

into a newly created Office of Rental Subsidy and Asset Oversight within HUD. In doing so,

Congress should separate the dual roles of Federal Housing Commissioner and Assistant

Secretary for Housing, as the Federal Housing Commissioner’s duties should focus solely on

managing the FHA insurance programs. The realignment will achieve greater efficiencies,

reduce regulatory and administrative burdens, increase self-sufficiency opportunities for

residents receiving federal rental assistance or supportive services, and promote greater cost

efficiency and asset management of the subsidized portfolio.

Administrative Reform:

• Absent legislation, the Department should pursue a reorganization that separates its

mortgage insurance and rental assistance programs into separate offices.

Legislative Reforms:

• Congress should enact legislation to separate the position and responsibilities of the

Federal Housing Commissioner from the position and responsibilities of the Assistant

Secretary for Housing.

• Congress should enact legislation to create a new Office of Rental Subsidy and Asset

Oversight overseen by the Assistant Secretary for Housing which would consolidate

multifamily housing subsidy programs, Public Housing and Housing Choice Voucher

programs, together with RAD and REAC.

26

• As part of this reorganization, Congress should establish the Office of Native American

Programs as a separate office, led by a Presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed

Assistant Secretary and separate the Native American programs from the other programs

within HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing.

27

IV. Provide Liquidity to the Housing Finance System

Issuers participating in GNMA’s MBS guaranty program pay the agency an on-going guaranty

fee, as well as other incidental fees, predominantly for provision of the guaranty on pass-through

income to securities investors. The guaranty fees charged by GNMA are fixed and set in statute.

Interest income from borrowers in excess of the pass-through rate payable to security holders and

GNMA’s guaranty fee is retained by the issuer as mortgage servicing fees. GNMA’s program

requires the retention of certain minimum servicing fees to ensure servicing of the loans for the

life of the GNMA MBS guaranty. Servicing fees, along with other cash flows associated with the

on-going servicing of the mortgage loan (and net of the costs to service the mortgage loan),

constitute an asset of the issuer called mortgage servicing rights (MSRs).

GNMA has prioritized risk management and the ongoing need for programmatic and

organizational change to reduce the risk of issuer failures, thus minimizing the possibility of

utilizing taxpayer funds in the operationalizing of the GNMA guaranty. In this regard, the agency

faces a wide spectrum of risks stemming from the risk of a single large issuer failure (today, for

example, nearly 40 percent of the securities outstanding are serviced by five non-banks) to

multiple issuer failures, which would be operationally challenging to manage simultaneously (at

present, one percent of the securities outstanding are serviced by 125 non-bank issuers).

Overall, there are five key areas where GNMA will continue to focus its efforts and implement

reforms:

• Strengthening the internal framework and operational structure to best manage

counterparty risk by re-aligning internal responsibilities and creating new position and

processes to monitor and address sources of risk that have increased as the housing

financing industry has evolved.

• Increasing reliance on data and modeling to uncover and illuminate trends and risks that

are not apparent from traditional compliance activities – a prime example is leading the

industry toward widespread use of stress testing modeling.

• Increasing the enforcement, recovery and resolution capabilities in the event of issuer

stress, with the objective that GNMA would be address adverse circumstances, including

a large-scale issuer failure, without the occurrence of severe market or consumer

disruption.

• Continuing focus on facilitating sufficient system liquidity (and liquidity management

practices), given the now non-bank-dominated industry’s increased reliance on steady

flows of external capital.

• Continuing refinement of program standards and requirements relating to all of the

above.

28

A. Advance GNMA Counterparty Risk Management and Securitization Platform

Transformation

GNMA should increase its counterparty risk management ability. GNMA continues to rely on

existing staff resources, the ability to update policies and requirements through All Participants

Memorandums (APMs), and the authority to take enforcement action if required. Critical to

GNMA’s success in such reform is support and coordination with those that oversee GNMA,

such as HUD and OMB.

The following details the areas where GNMA should continue to strengthen and modernize its

internal approach to risk, program guidelines and securitization platform transformation to better

serve and protect borrowers, investors, issuers and taxpayers.

Administrative Reforms:

• GNMA should transition the MBS platform from pool-level to loan-level functionality,

including the ability to transfer servicing of individual loans within a pool. This reform will

enhance the desirability and value of the MSR asset and reduce the cost of loans insured or

guaranteed by Federal agencies relative to conventional loans.

• GNMA should continue to facilitate adequate liquidity in the housing finance system,

including the implementation of reforms for the financing of and investment in MSRs, and

oversight of the development of industry-level liquidity management methods, as outlined in

the GNMA 2020 reform agenda.

17

• GNMA should continue to maximize the value of its servicing portfolios, such as through

establishing servicing fee standards and enhanced monitoring of servicing transfers to ensure

that both parties maintain adequate MSR values.

• GNMA should enhance issuer standards through strengthened risk management

requirements, including updated liquidity, leverage, and capital standards, with particular

focus on very large issuers and sub-servicers.

• GNMA should strengthen its risk management analytics and predictive capabilities to

mitigate risks, given the growing share of the agency’s portfolio comprised of very large,

non-bank counterparties. This should include GNMAs ongoing development of stress test

modeling capability and the imposition of a stress testing regimen for non-bank institutions

to evaluate performance under a range of economic scenarios.

• GNMA should implement enforcement, recovery and resolution reforms to protect taxpayers,

which should include building the capability for the agency to move quickly, effectively and

fairly to sanction firms who are failing to abide by program terms, and to address issuers who

are vulnerable to failure, or otherwise threatens the sound administration of the MBS

program.

17

https://www.ginniemae.gov/newsroom/publications/Documents/ginniemae_2020_progress_update.pdf

29

• GNMA should fully modernize platform access, data standards, collection, and storage,

which will transform the user interaction with the securitization and data analytical

architecture into a highly secure, single gateway. This reform would increase GNMA’s

ability to monitor its issuers, enforce its rules and requirements, and manage the overall

safety and soundness of the program, as well as efficacy and validity of data collected and

reported through the Mortgage Banker’s Financial Reporting Form.

• GNMA should develop and implement the policies, technology and operational capabilities

necessary to accept digital promissory notes (eNotes) and other digitized loan files as

acceptable collateral for its securities, which will enable issuers to enhance efficiency, risk

management and customer experience by moving to digital collateral and a fully electronic

“eClosing” process.

B. Guaranty Fee-setting Flexibility

GNMA’s single-family guaranty fee of six basis points (bps) was set by statute 1987. This

guaranty fee provides the funds from which losses would be paid if GNMA needed to step in to

remit funds to security-holders as the result of an issuer’s failure to do so. This six bps guaranty

fee is also the source of funds for payments relating to loans that were in pools seized in the past

by GNMA in cases of issuer failure.

GNMA believes that the authority to administratively adjust its guaranty fee within a narrow,

permissible range, would ensure that such fees are adequate for the risks in the program and

sufficient for GNMA to meets its statutory obligations under extreme circumstances. Under this

proposal, GNMA would be required to justify and seek approval for any proposed adjustments

from the HUD Secretary, but the change would require no further passage of law.

GNMA currently possesses a level of reserves the agency deems adequate to meet foreseeable

needs to exercise and fulfill its guaranty. Thus, GNMA is not at this time proposing a specific

increase in the fee. GNMA’s financial requirements have increased, however, and are likely to

continue to do so, notably due to the increasing share of non-bank responsibility for residential

mortgage servicing which has increased both the likelihood and the potential size of a call on

GNMA’s guaranty. This reform recommendation is not be intended to change the purpose of the

guaranty fee, which is to provide funds for financial obligations resulting from GNMA having

exercised the guaranty. Rather, the reform would provide flexibility to the agency to seek

adjustments needed to ensure efficiency and operational effectiveness as the secondary mortgage

market continues to evolve, and ultimately ensure its MBS guaranty program maintains fiscal

soundness.

18

18

For reference, this item was highlighted in Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) May 2019 audit, “GNMA:

Risk Management and Staffing-Related Challenges Need to be Addressed.” Specifically, GAO recommended that

“The Chief Risk Officer of GNMA should periodically conduct an actuarial or similar analysis that includes a stress

test to evaluate the extent to which the current level of the guaranty fee for single-family MBS provides GNMA with

sufficient reserves to cover potential losses under different economic scenarios.”

30

Legislative Reform:

• Congress should pass legislation granting GNMA the authority to administratively adjust

its guaranty fee within a narrow, permissible range.

C. Reforms to Maintain the Integrity of GNMA Securities

Over the past two years, GNMA has identified unsound loan origination and servicing practices,

broadly referenced as churning, that has elevated risks to the integrity of the MBS security as

investors attempt to account for such prepayment risks. This churning can increase the cost of

mortgage credit for borrowers utilizing FHA, USDA, and VA mortgage insurance.

Starting in 2016, GNMA instituted a six-month “seasoning” requirement for VA streamline

loans, and then in 2017 the agency extended the requirement to include cash-out refinances.

Additionally, in May 2018, federal legislation was enacted that placed additional requirements

for VA streamline loans and, in accordance with the law, the VA published a final rule placing

certain requirements for cash-out refinances, which have ultimately helped to protect Veteran