RURAL COMMUNITY

COLLEGE EXCELLENCE:

A GUIDE TO DELIVERING STRONG

OPPORTUNITY FOR STUDENTS

AND COMMUNITIES

SPRING 2023

Rural Community College Excellence | ii

Authors

Ben Barrett, David Bevevino, Anne Larkin, Josh Wyner

Acknowledgments

The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program is grateful for Ascendium Education Philanthropy’s funding of and

partnership on the development of this guide. We would also like to especially thank Désirée Jones-Smith, Tania

LaViolet, Linda Perlstein, and Rachel Rush-Marlowe for their early research support and leadership on the project.

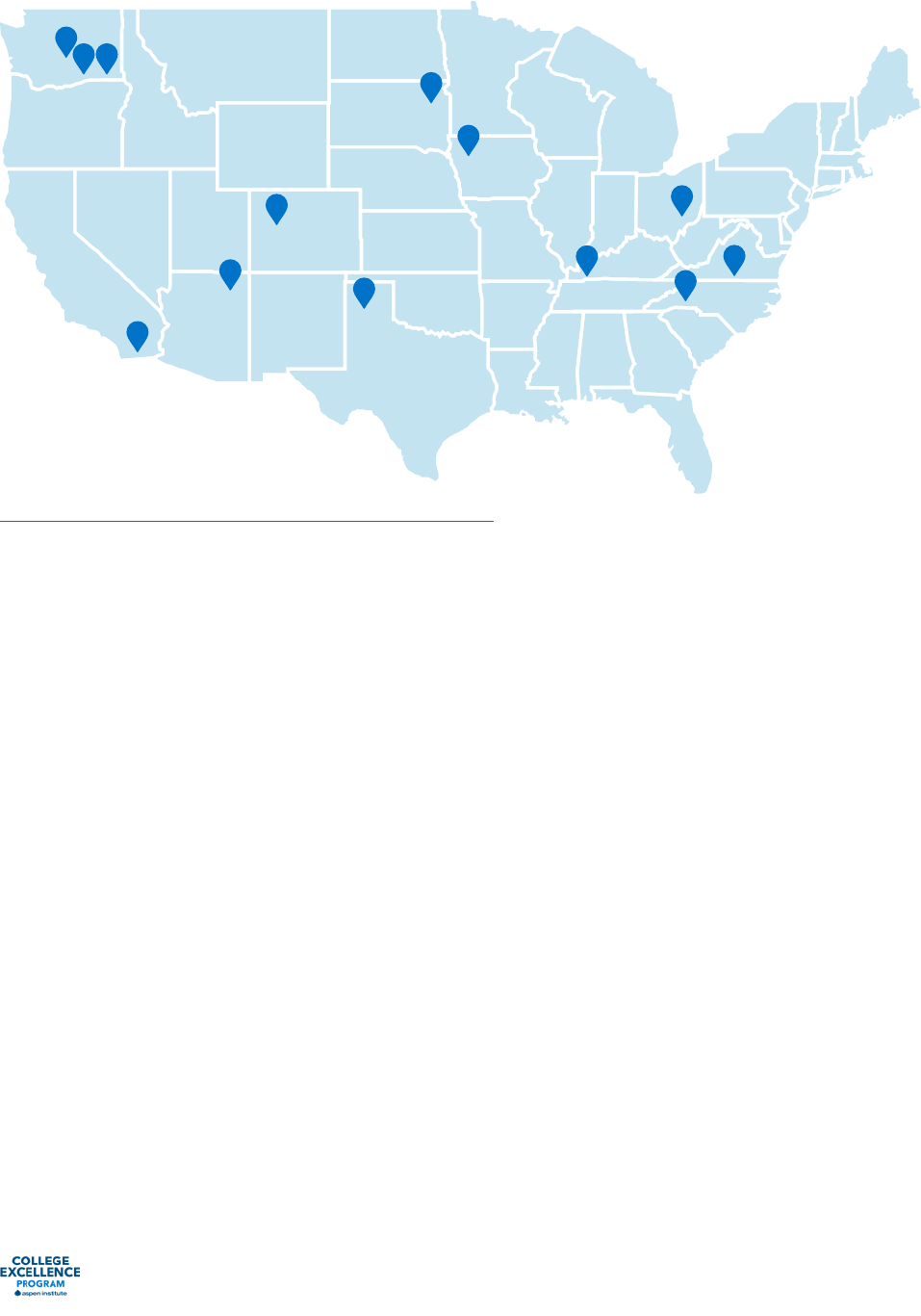

We appreciate the institutions that hosted our team for site visits to gain a deeper understanding of the particular

ways rural community colleges achieve success on behalf of students in their particular contexts. See a list of

colleges in the appendix.

We also would like to recognize all of our site visit research partners, who helped inform the practices highlighted

in this guide:

Cheryl Crazy Bull, American Indian College Fund

Devin Deaton, Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group

Galen DeHay, Tri-County Technical College, Pendleton, South Carolina

John Enamait, Stanly Community College, Albemarle, North Carolina

Rebecca Lavinson, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

Tania LaViolet, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

Konrad Mugglestone, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

Mary Rittling, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

Bonita Robertson-Hardy, Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group

Lenore Rodicio, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

Rachel Rush-Marlowe, ResearchED

Pamela Senegal, Piedmont Community College, Roxboro, North Carolina

The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program supports colleges and universities in their quest to achieve

a higher standard of excellence, delivering credentials that unlock life-changing careers and strengthen our

economy, society, and democracy.

We know it takes visionary college leaders to achieve this higher standard, and we make it our mission to equip

them with the knowledge, skills, and research-backed tools to inspire change, shift practice, and advance the

capacity of colleges to deliver excellent and equitable student outcomes.

Since our founding in 2010, we have used data to elevate excellence in practice; conducted extensive research

to deeply understand what improves student success and equity; equipped the eld with tools and guidance to

replicate what works; and developed diverse, transformational leaders advancing student success.

Cover Photo

Patrick & Henry Community College | Martinsville, Virginia

Rural Community College Excellence | iii

Contents

Introduction 1

Strengths and Challenges 3

Four Approaches to Promote Rural College Success 9

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility 10

Make Connections Between Programs and Existing Workforce Needs 10

Envision a Larger Service Area to Expand Opportunity 12

Combine Workforce and Transfer Pathways to Meet Regional Needs 12

Generate New Industries and Employment Opportunities for Students 13

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College 17

Overcome Misperceptions about Careers and Institutions 17

Evolve Outreach as Demographics Change 18

Start the College-Going Pathway in High School 19

Address K-12 School Resource Needs and Student Financial Barriers 21

Remove the Earn-or-Learn Dilemma for Low-Income Students 21

Advance Retention with Equity in Mind 22

Build Strategic Partnerships to Resource Student Success 24

Partner with Local Employers and Community Organizations

to Generate Mission-Aligned Resources 24

Leverage Institutional Consortia to Enhance Mission-Aligned Functions 26

Partner to Expand Bachelor’s Attainment 27

Utilize Small Size as a Strength 29

Combine Functions That Align Initiatives and Enhance Student Success Strategy 29

Strengthen Relationship-Driven Advising with Intentional Strategy 31

Conclusion 34

Research Design 35

Community Colleges Featured in this Guide 36

Rural Community College Excellence | 1

Introduction

Rural community colleges occupy a unique and important place in higher education. Of 332 million

Americans, 46 million live in rural communities, and more than 1.5 million attend one of 444 rural

community colleges. These institutions are more than education providers; they are essential hubs in

their regions, generating opportunities for economic mobility, driving talent development, and often

supporting their region’s health and education systems.

1

Successful rural colleges understand and lean into their unique strengths, including a deep

connection to place and the strong relationships among faculty, staff, and students that often

accompany small size. Leaders at great rural colleges describe an internal agility that allows people

at their institutions to think creatively about how to solve challenges, often by creating regional

connections: between new employers and members of the community who need jobs, between social

service agencies and people in need, between K-12 and higher education. These accomplishments

often happen notwithstanding substantial resource constraints: Nationally, rural community colleges

receive fewer nancial resources than other, often larger, community colleges.

2

1

For further discussion of the essential roles of community colleges, see, Koricich, Andrew, Vanessa Sansone, Alisa Hicklin

Fryar, Cecilia Orphan, and Kevin McClure. n.d. “Introducing Our Nation’s Rural-Serving Postsecondary Institutions

Moving toward Greater Visibility and Appreciation.” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://assets.website-les.

com/5fd3cd8b31d72c5133b17425/61f49f1f91e41a6effe3006f_ARRC_Introducing%20Our%20Nation%E2%80%99s%20

Rural-Serving%20Postsecondary%20Institutions_Jan2022.pdf.

2

Ibid.

|

Introduction

Catawba Valley Community College | Hickory, North Carolina

Rural Community College Excellence | 2

But while excellent rural community colleges offer many examples—and lessons—on how to improve

student success and strengthen communities, they tend to receive less attention than their urban

and suburban counterparts from policymakers, industry leaders, the media, and researchers. One

consequence: less information about how excellence in student outcomes can be achieved for

students in similar contexts. For this reason, the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program (Aspen),

supported by a grant from Ascendium, has developed this guide to share examples from high-

achieving rural colleges that, we hope, can help other community colleges deliver stronger and more

equitable results for the students and communities they serve.

The guide draws from several sources: data analyses of student outcomes, interviews with college

leaders, virtual site visits to high-performing rural colleges, in-person site visits to rural colleges as

part of the Aspen Prize process, and convenings of leaders of rural colleges.

3

Guiding our research is

Aspen’s framework for student success: strong learning and completion while in college; success in

transfer and employment after college; and equitable access and success for students of color and

students from lower-income backgrounds.

We are inspired by the examples of community colleges in this guide, and we hope other rural

colleges will use them to ensure that more of our nation’s diverse rural residents enjoy fullling careers

and develop their talents in ways that strengthen rural communities and economies.

|

Introduction

3

An explanation of the research methodology is at the end of the report, on page 35.

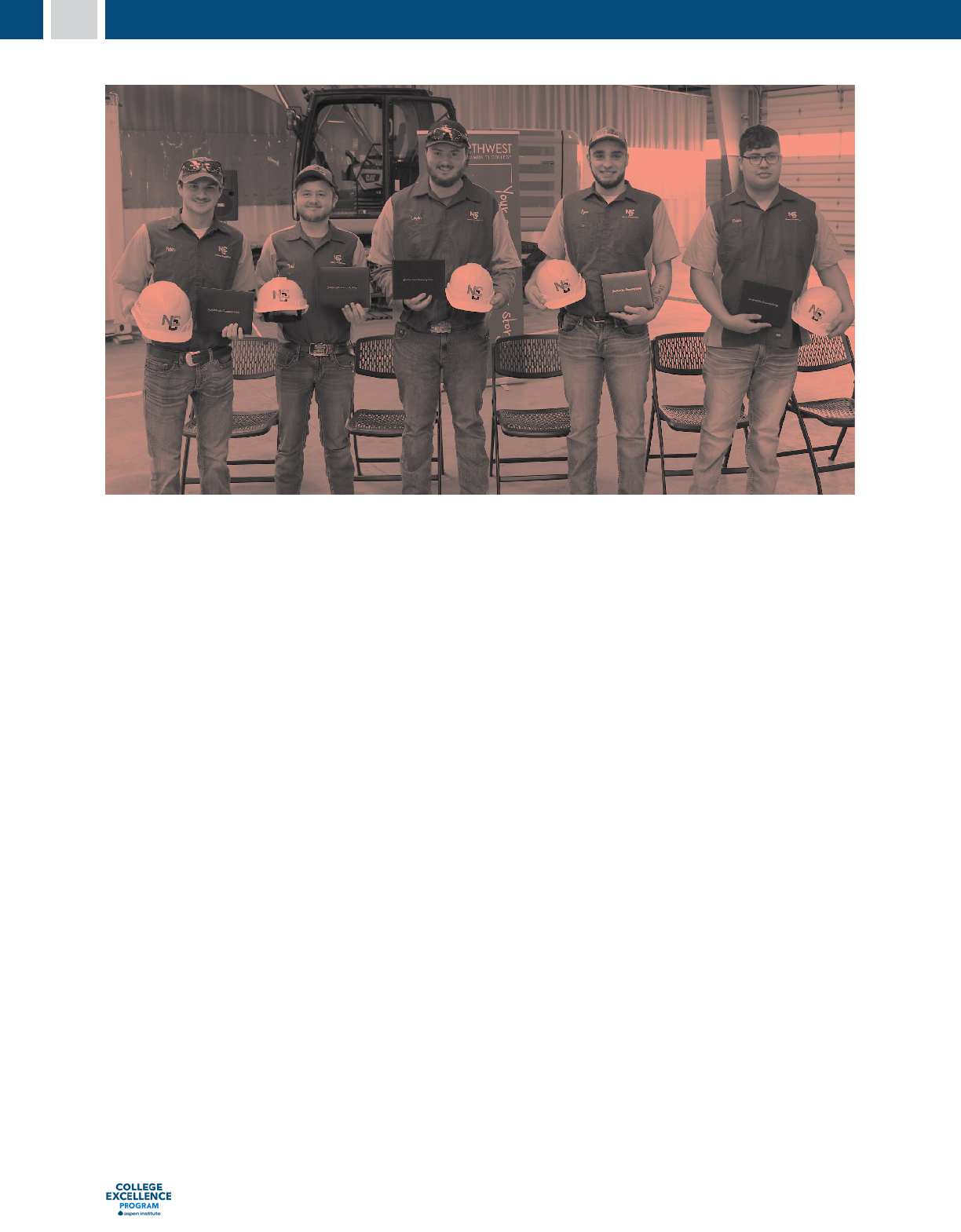

Northwest Iowa Community College | Sheldon, Iowa

Rural Community College Excellence | 3

Strengths and Challenges

To contextualize the strategies excellent rural colleges use to advance student success, we begin this

guide with a brief summary of the (often unique) strengths of and challenges within rural communities

and community colleges.

Common Strengths

Often, the conversation about rural communities and their colleges focuses on decits, with too little

attention paid to their strengths and assets. Excellent rural community colleges and their leaders

understand and build strategies around these strengths to expand opportunities for economic mobility

and to develop regional talent.

1. Economic Opportunity

Rural communities and their colleges benet from varied economic bases that include legacy and

emerging industries. While the economic drivers in rural areas differ signicantly across the country,

they generally fall into three categories. First are industries that relate to the large amount of available

open space: most notably agriculture, tourism/recreation (such as ski towns or areas around national

parks), and energy and mineral production.

4

Second are essential services, including jobs related to

public safety, teaching, accounting, and (especially in areas with a regional hospital) health care. Third,

community colleges in rural areas often sit at the forefront of new and evolving industries, including

advanced manufacturing, which often replaces legacy, traditional manufacturing industries.

5

Excellent

colleges strategically generate opportunity for graduates in each of these three areas.

2. Demographic Diversity

As is the case throughout the United States, rural communities are becoming more racially and

ethnically diverse. More than 30 percent of students at rural-serving public two-year colleges

nationally are people of color, with the number of Hispanic students growing fastest.

6

In many rural

communities, in-migration by people of color is resulting in overall population growth.

7

From 2016

to 2018, roughly half of rural counties grew in population, and some rural areas in every state have

seen population growth.

8

4

Kerlin, Mike, Neil O’Farrell, Rachel Riley, and Rachel Schaff. “Rural Economic Development Strategies for Local Leaders.”

McKinsey & Company. March 30, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/rural-

rising-economic-development-strategies-for-americas-heartland.

5

“Rural-Grown, Local-Owned Manufacturing.” Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/events/rural-manufacturing/

6

Koricich, Sansone, Fryar, Orphan, and McClure, “Introducing our Nation’s Rural-Serving Postsecondary Institutions”;

Hillman, Nicholas, Jared Colston, Joshua Bach-Hanson, and Audrey Peek. 2021. “Mapping Rural Colleges and Their

Communities.” https://mappingruralcolleges.wisc.edu/documents/sstar_mapping_rural_colleges_2021.pdf.

7

Pohl, Kelly. 2017. “Minority Populations Driving County Growth in the Rural West.” Headwaters Economics. August 1, 2017.

https://headwaterseconomics.org/economic-development/minority-populations-driving-county-growth/.

8

“A Few Things to Know about Rural America.” Aspen Institute. 2020. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/

uploads/2020/05/A-Few-Things-To-Know-CSG-Brief-Update.pdf.

|

Introduction

Rural Community College Excellence | 4

While college leaders interviewed for this guide often cited political challenges associated with

changing demographics, they viewed the inux of immigrants and diverse populations as a net

positive: an opportunity for their colleges to enroll and educate new residents, to provide them

paths to family-sustaining jobs, and to help develop talent needed by their communities.

3. Community Standing

Rural community colleges are often among the most important institutions in their communities,

serving not only as educators but as major regional employers, conveners, and economic

development engines.

9

As a result, rural community college leaders are often very inuential

community members, serving as a recruiters of prospective new industries and developers of

regional partnerships. Often these partnerships are with other educational institutions: universities

where rural college students transfer and K-12 systems from which students enroll, including through

dual enrollment programs. Because of the importance of these regional connections, rural college

leaders have an outsized opportunity to combine resources in ways that strengthen not just their

colleges but other institutions in the community, which can make the community more attractive to

new industries and residents.

10

4. Community Resilience

Leaders of excellent rural community colleges

often cited the resilient, innovative, and adaptive

spirit in their communities, which, at their

colleges, translates into a pervasive desire to

improve outcomes for both students and, more

broadly, residents of their communities. Many

rural communities have weathered changing

economic conditions, public health crises,

and population declines. As this research

demonstrates, excellent rural community colleges

have achieved success for students despite

having fewer and more dispersed resources

than most urban colleges. Through employer,

university, and other community partnerships, as

well as creative human capital strategies, these

colleges strategically utilize the resources of their

communities to advance their missions.

9

Miller, Michael T., and Daniel B. Kissinger. 2007. Connecting Rural Community Colleges to Their Communities.” New

Directions for Community Colleges 2007 (137): 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.267; Ajilore, Olugbenga and Caius Z.

Willingham, “Adversity and Assets: Identifying Rural Opportunities.” Center for American Progress. October 17, 2019.

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/adversity-assets-identifying-rural-opportunities/.

10

Peters, D.J. 2019, “Community Resiliency in Declining Small Towns: Impact of Population Loss on Quality of Life over 20

Years.” Rural Sociology, 84: 635-668. ht tps://doi.org/10.1111/r uso.12261; Ajilore and Willingham, “Adversity and Assets:

Identifying Rural Opportunities.”

|

Introduction

Northwest Iowa Community College | Sheldon, Iowa

Rural Community College Excellence | 5

Challenges

In addition to maximizing their strengths, leaders of excellent rural community colleges understand

the challenges their colleges and communities face and use that knowledge to develop strategies to

overcome them.

1. Limited Educational Opportunity

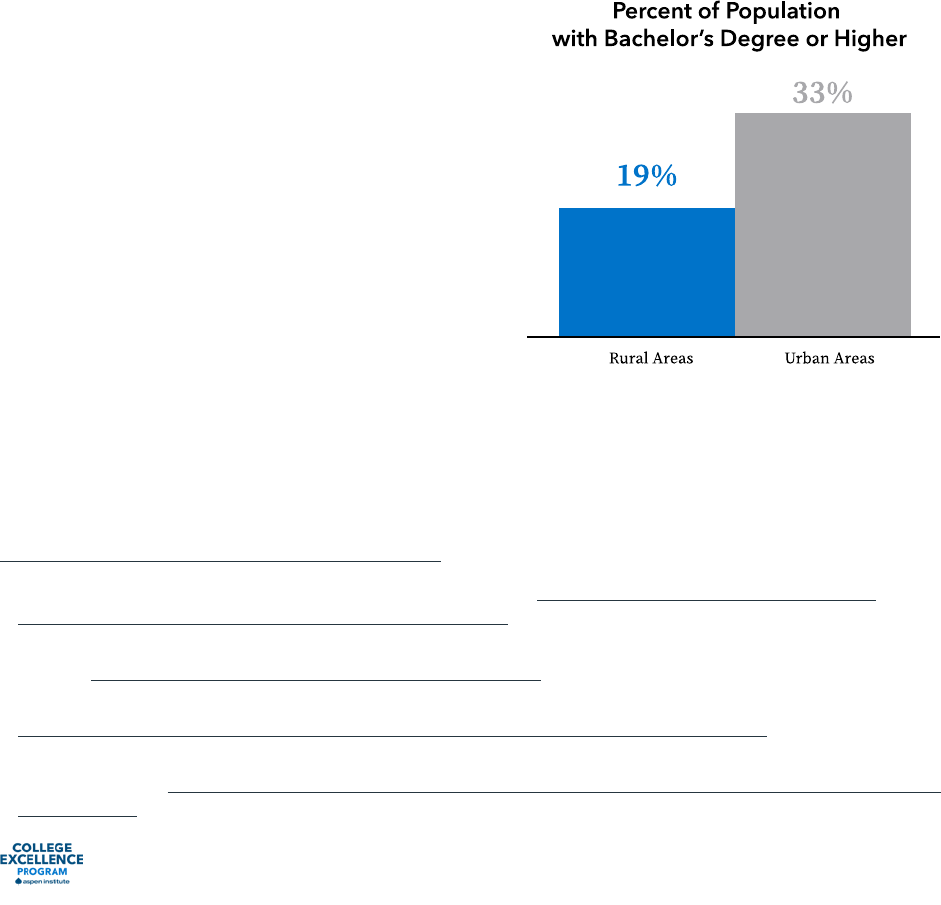

In rural communities, fewer adults hold a bachelor’s degree than in urban communities: 19 percent,

compared to 33 percent.

11

Part of the reason: Rural communities tend to have fewer nearby

postsecondary institutions and are more likely to rely on a community college as the entry point to

higher education.

12

With fewer university partners nearby, it’s harder for community college students

to transfer and attain a bachelor’s degree. And because many good jobs require a bachelor’s

degree, limited access to four-year colleges and universities translates into limited economic

opportunity for many rural residents.

13

On the other end of the education system, rural K-12 schools

are often under-resourced and spread over a large geographical area, making collaboration on dual

enrollment and college preparation more difcult.

14

Finally, with relatively few employers nearby,

community college students can struggle

to access internships and other work-based

learning opportunities that can help them apply

classroom learning. In response, leaders of

exceptional rural community colleges proled

in this report have developed innovative

partnerships and program delivery methods

to ensure that students have access to

comprehensive educational pathways with other

educational institutions and employers.

11

“A Few Things to Know about Rural America.” Aspen Institute. 2020. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/

uploads/2020/05/A-Few-Things-To-Know-CSG-Brief-Update.pdf.

12

“Unequal and Uneven: The Geography of Higher Education.” Jain Family Institute. December 2019. Accessed November

10, 2022. https://hef.jresearch.org/geography-of-higher-education/.

13

Carnevale, Anthony, Jeff Strohl, Neil Ridley, and Artem Gulish. 2018. “Three Educational Pathways to Good Jobs.”

https://1gyhoq479ufd3yna29x7ubjn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/3ways-FR.pdf.

14

Gutierrez, David. “Little School on the Prairie: The Overlooked Plight of Rural Education.” The Institute of Politics at

Harvard University. https://iop.harvard.edu/get-involved/harvard-political-review/little-school-prairie-overlooked-plight-

rural-education

|

Introduction

Rural Community College Excellence | 6

2. Geography-Driven Enrollment Challenges

Recruiting students is harder in less densely populated areas. With many prospective students

at a greater distance from campus, securing enrollment requires greater effort by recruiters and

advisors of rural community colleges. While about half of rural areas have seen some population

growth in recent years, other non-metro areas have lost population since 2010, and birth rate

declines suggest this trend will continue.

15

But the challenge goes beyond smaller potential

applicant pools. Prospective students in rural service areas—where college degree attainment rates

are low—are less likely to know someone with a college degree, someone who can inspire them or

guide them through the college application process.

16

Additionally, many rural areas lack critical

infrastructure for students to access information, including reliable broadband internet and public

transportation.

17

Excellent rural community colleges respond by directly lling these community

resource gaps where they can: building the needed infrastructure or bringing education to where

students are.

3. Skepticism About Higher Education

In rural communities where manufacturing, energy, and agriculture jobs were once prevalent, many

residents once earned good wages without a college degree. Many interviewed for this report noted

that, in their communities, the idea that a college education is unnecessary lingers, despite the

changing economy.

18

Another challenge is the recent political narrative questioning the value of higher

education.

19

Some rural community college leaders interviewed for this guide believe that as politicians

have increasingly voiced concerns about higher education, this view has had an outsized impact on

student recruitment in their relatively conservative communities.

20

Skepticism about the value of community college also likely comes from the calculations by prospective

students about the opportunity cost associated with enrolling. Multiple factors contribute to these

calculations: First, prospective rural community college students may not believe they can afford to lose

wages to come to college and complete a credential. Because a higher proportion of people in rural

15

Cromartie, John. “Rural Areas Show Overall Population Decline and Shifting Regional Patterns of Population Change”

Economic Research Service U.S. Department of Agriculture. September 5, 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-

waves/2017/september/rural-areas-show-overall-population-decline-and-shifting-regional-patterns-of-population-change/

16

S. Sowl, “View of a Systematic Review of Research on Rural College Access since 2000.” 2021. https://journals.library.

msstate.edu/index.php/ruraled/article/view/1239/921; Pappano, Laura. 2017. “Colleges Discover the Rural Student.”

The New York Times, January 31, 2017, sec. Education. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/education/edlife/colleges-

discover-rural-student.html.

17

Rush-Marlowe, Rachel. “Strengthening Rural Community Colleges.” Association of Community College Trustees. 2022.

https://www.acct.org/les/ACCT8169%20%28Strengthening%20Rural%20Community%20Colleges%20Update%29.pdf;

Hillman, Colston, Bach-Hanson, and Peek, “Mapping Rural Colleges and Their Communities.”

18

Carnevale, Strohl, Ridley, and Gulish, “Three Educational Pathways to Good Jobs.”

19

Parker, Kim. “The Growing Partisan Divide in Views of Higher Education.” Pew Research Center. August 2019. https://www.

pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/08/19/the-growing-partisan-divide-in-views-of-higher-education-2/

20

Keily, Tom and Meghan McCann. “Perceptions of Postsecondary Education and Training in Rural Areas.” Education

Commission of the States. June 2021. https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Perceptions-of-Postsecondary-Education-

and-Training-in-Rural-Areas.pdf

|

Introduction

Rural Community College Excellence | 7

areas live in poverty (over 14 percent, compared

to 11 percent in metropolitan areas), the pull to

choose employment over higher education may

affect a higher proportion of potential students

in rural communities.

21

Second, completing

a credential of value is far from certain. Most

community college starters (60 percent) do not

earn any credential in six years, and outcomes for

students of color are lower.

22

Finally, outcomes

for those who do complete may discourage

some prospective students. According to the

Community College Research Center (CCRC), only about a quarter (23 percent) of associate degree

graduates and a little more than a third (37 percent) of occupational certicate holders completed

programs associated with earnings of at least $35,000 two years after completion.

23

Rural colleges included in this guide strive to deliver better results, to improve completion rates,

and partner with employers and K-12 schools to build efcient pathways that result in good jobs

or efcient transfer to a four-year university. They then strategically tout those results to overcome

skepticism and enroll more students.

4. Constrained Resources

The higher rate of poverty in rural communities means many students struggle to afford tuition and

other costs associated with attaining a degree, such as transportation, childcare, and textbooks.

Rural community colleges tend to have fewer resources available to ll those gaps. They have, on

average, fewer students than other community colleges (about 2,500 versus a national average

of over 8,000) and receive thousands less in total revenue per student than the average for all

institutions.

24

Particularly in rural communities with declining populations and relatively low salaries,

social service providers have access to less tax revenue, compounding the effects of poverty.

25

21

Shrider, Emily, Melissa Kollar, Frances Chen, and Jessica Semega. “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 Current

Population Reports.” U.S. Census Bureau. September 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/

publications/2021/demo/p60-273.pdf.; https://journals.library.msstate.edu/index.php/ruraled/article/view/1239/921

22

Community College Research Center analysis of data from the National Student Clearinghouse’s Completing College

2020, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Completions_Report_2020.pdf

23

Fink, John and Davis Jenkins. “How Much Are Community College Graduates Earning Two Years Later?” Community

College Research Center. January 13, 2022. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/how-much-are-community-college-

graduates-earning.html; Carnevale, Anthony, Jeff Strohl, Ban Cheah, and Neil Ridley. “Good Jobs that Pay Without a BA.”

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. 2017. https://goodjobsdata.org/wp-content/uploads/

Good-Jobs-wo-BA-nal.pdf.

24

Hillman, Colston, Bach-Hanson, and Peek, “Mapping Rural Colleges and Their Communities”; McClure, Kevin, Cecilia

Orphan, Alisa Hicklin Fryar, and Andrew Koricich. “Strengthening Rural Anchor Institutions: Federal Policy Solutions for

Rural Public Colleges and the Communities They Serve.” Alliance for Research on Regional Colleges. January 2021. Page

8. https://assets.website-les.com/5fd3cd8b31d72c5133b17425/600f69daa492f04dedc7f691_ARRC_Strengthening%20

Rural%20Anchor%20Institutions_Full%20Report.pdf

25

Ajilore and Willingham, “Adversity and Assets.”

|

Introduction

Imperial Valley College | Imperial, California

Rural Community College Excellence | 8

Rural communities also generally have fewer regional actors with substantial assets with

which community colleges can partner to advance student success, such as large employers,

philanthropies, and sizable nonprot organizations. Finally, due largely to their remote locations,

rural colleges face relatively high costs for some services.

26

This means rural colleges have less

funding for support services, equipment for technical programs, and personnel critical to advancing

student success. To overcome funding limitations, strong community colleges work creatively

to identify and build mutually benecial partnerships with employers, universities, and other

organizations that can contribute resources to advance student success.

5. Faculty and Staff Hiring and Retention

Rural community colleges often have challenges recruiting and retaining staff and faculty. Many

community colleges researched for this guide cited particular challenges hiring for positions that

require technical skills in high demand, such as faculty and staff with information technology or

institutional research expertise. As noted earlier, part of the challenge is that rural colleges don’t have

equal nancial resources to compete with other colleges for essential personnel. Another factor:

Rural college leaders we interviewed reported hesitancy among candidates to move to a rural area

unless they have a prior connection to the place. Finally, limited housing availability—either because

of rising costs in rural communities with tourist attractions or low supply—makes faculty and staff

recruitment even more difcult. These recruitment challenges mean rural community colleges must

devise creative solutions, such as building housing for faculty and staff, sharing services with other

community colleges, and combining roles in ways that increase efciency and effectiveness.

26

Rush-Marlowe, Rachel. “Strengthening Rural Community Colleges.” In areas with fewer community resources, rural

colleges have both higher student services and instructional costs. They often provide more basic needs directly to

students, like transportation support and internet access, and without nearby hands-on learning opportunities provided

by industry, rural colleges must invest in expensive, high-tech equipment like medical simulation dummies to ensure

student learning when there is no neighboring partner hospital for nursing students.

|

Introduction

Catawba Valley Community College | Hickory, North Carolina

Rural Community College Excellence | 9

|

Four Approaches to Promote Rural College Success

Four Approaches to Promote

Rural College Success

In this report, we identify these four approaches that enable excellent rural community colleges to

capitalize on the strengths and overcome the challenges outlined in the previous section.

1.

2.

3.

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Convince Students to Enroll

and Stay in College

Build Strategic Partnerships to Resource

Student Success

4.

Utilize Small Size as a Strength

To enable these approaches to work, the rural community colleges proled in this publication are all

guided by a strong set of student success reform priorities. Presidents of these colleges put forth a

specic, actionable reform agenda rooted in a deep understanding of their community and aimed

at improving the success of students, advancing their economic mobility, and developing talent in

the region. With that reform agenda in place, the colleges and leaders proled in this guide used the

following four approaches to overcome doubts about higher education, attract new resources, and

deliver credentials that strengthen the lives of rural students and their communities.

Rural Community College Excellence | 10

1. Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

In a survey conducted by the Education Commission of the States, only half of rural respondents said

they believed additional education would advance their career, and only 40 percent saw enrolling in

higher education as a means to secure a stable job in times of economic uncertainty.

27

Data show that

this perception is inaccurate: Compared to rural residents with only a high school diploma, bachelor’s

degree holders in rural communities earn nearly $15,000 more a year,

and rural residents with some

college or an associate degree earn an additional $4,000 annually.

28

Despite these facts, the perception that higher education is not worth the investment creates enrollment

and student success challenges. Leaders of exceptional colleges understand that building trust with

potential students and community members starts with delivering programs with strong outcomes.

They work to understand their regional labor markets and ensure that programs of study align with real

opportunity, whether that means graduating directly into a good job or transferring and attaining a

bachelor’s degree that leads to a good job.

Excellent rural colleges also make the value of strong programs clear to students. They incorporate

hands-on learning that helps students see the value of their education while they are in college,

increasing the chances they will persist to graduation. They communicate that value to prospective

students and to others in the community who inuence them—including friends or family members who

might otherwise encourage prospective students to forgo college for a job.

29

Make Connections Between Programs

and Existing Workforce Needs

Part of delivering valuable credentials starts with

an understanding of where the best workforce

opportunities are (and are not). Leaders of

excellent community colleges do this through

a combination of data analysis on workforce

trends and conversations with employers about

future workforce needs.

At Lake Area Technical College in Watertown,

South Dakota, senior leaders and program

directors regularly conduct such analyses. New

programs are approved by senior leaders only

if there is enough labor market demand for

graduates to secure good jobs. Sometimes,

leaders must make the hard decision to turn

down potential partners if the payoff isn’t there

for students. For example, when the college

was approached by livestock farmers in need of

large-animal veterinary technicians, the college

declined to establish a program because labor

market data revealed that too few jobs with

strong wages would be available to graduates.

27

Keily and McCann, “Perceptions of Postsecondary Education and Training in Rural Areas.”

28

“Rural Education.” Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. April 23, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/

topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education

29

Schaidle, Allen. “Does Being Rural Matter? The Economic & Social Concerns of Rural Graduates,” The Evolllution. April

8, 2020. https://evolllution.com/revenue-streams/extending_lifelong_learning/does-being-rural-matter-the-economic-

social-concerns-of-rural-graduates/; Carr, Patrick J, and Maria Kefalas. 2011. Hollowing out the Middle the Rural Brain

Drain and What It Means for America. Boston, Mass. Beacon Press.

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 11

In contrast, when data suggested a dramatic

need for more nurses and diesel technicians

in their region, Lake Area leaders seized the

opportunity. The college partnered with a

healthcare provider to build the Prairie Lakes

Healthcare Center of Learning for their nursing

students (complete with a classrooms, medical

labs, and a state-of-the-art simulation lab). The

partnership enabled the college to hire more

faculty, support remote learning sites, and cover

costs associated with more clinical hours. These

strategic investments paid off: The college saw a

28 percent increase in program enrollment over

ve years, and the students who graduate from

these programs go on to provide much-needed

health care in the region.

In the eld of diesel technology, market demand

pushed college leaders to work within funding

constraints to expand their program by 7 percent

between 2018 and 2022. Recognizing that

this level of growth will still not meet growing

demand, college leaders are in discussion with an

industry leader to substantially expand training,

using the nursing partnership as a model.

In both programs, Lake Area struggled to hire

faculty away from industries that offered better

salaries, a challenge that has increased due

to recent worker shortages. So, the college

received state support to increase faculty

salaries, which are now competitive with

industry. Lake Area leaders believe they secured

those resources partly because of the college’s

track record of developing and implementing

clear plans to meet specic labor market needs.

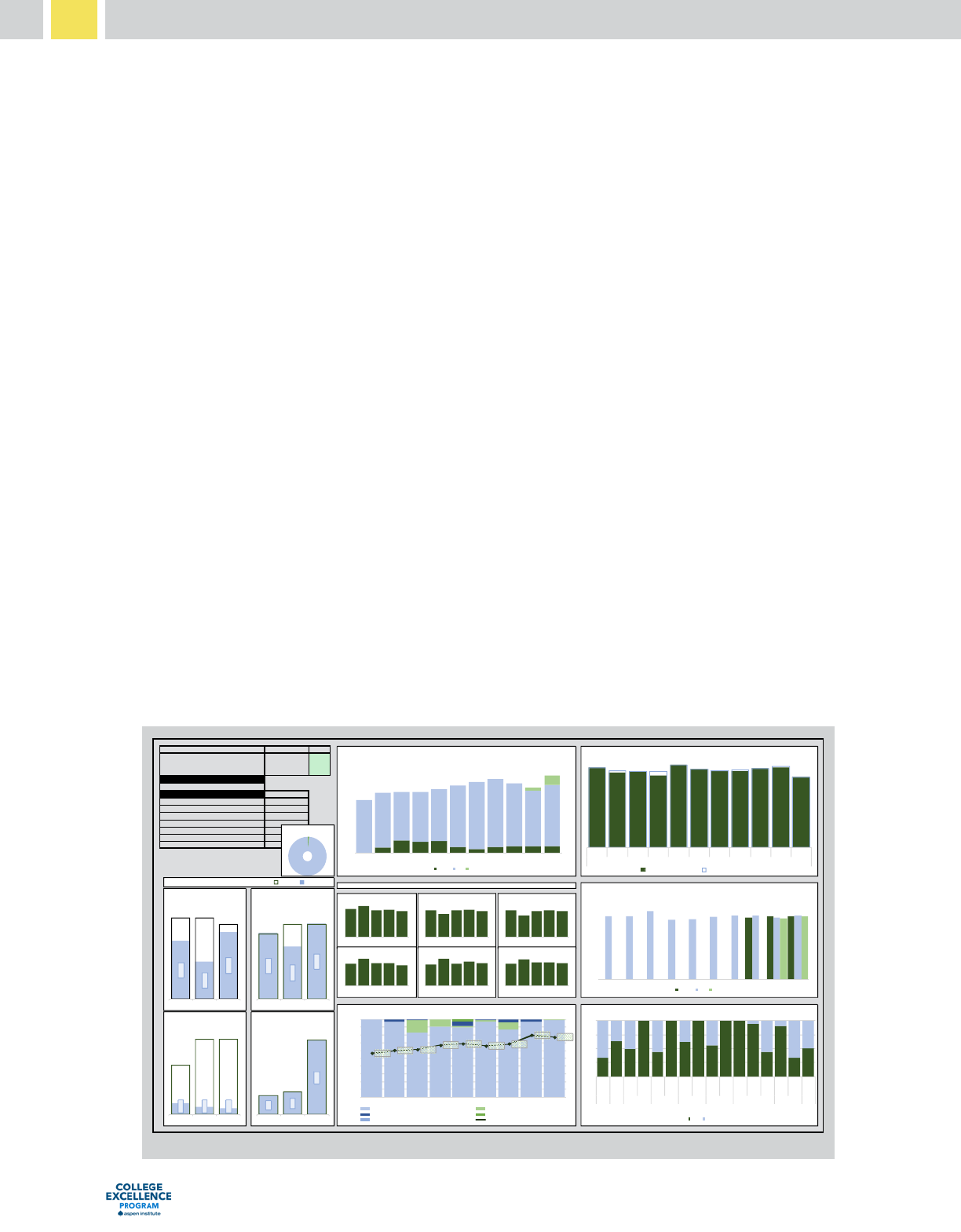

Once programs are built, Lake Area conducts

a rigorous annual program review process to

ensure that every program continues to deliver

value. Every year, program leaders assess data

on employer satisfaction, student satisfaction,

graduation rates, wages of college graduates,

and other information (see an example one

page data report below). These data reports

keep program leaders attuned to changes in the

labor markets so they can continue to deliver

strong outcomes and make adjustments when

weaknesses emerge.

KeyPerformanceIndicator sandTr endsAcademicYear2018‐2019

RowLabels C ap acity % Fu l l

DIESELTECHNOLOGY

(

DT&

DCAT)

155

113%

Accre d i tati on

NATEFthr oughOctober2020

Facu l ty an d Staf

f

Fu l l ‐ti m e Ins tru cto r 1 8

Part‐ti m e Ins tru cto r

Adjunct

Fu l l ‐ti m e Staff 1

Part‐ti m e Staff

Te m po rary Staff

Inte rn Staf

f

4.3

4.3 4.4

4.3 4.3

4.7

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4 4.4

4.2

4.4

4.2

4.3

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

StudentSatisfactionbyGradYear

(Averageofprogram‐relatedquestions. Scale1to5.Highisbetter)

D CA T DT D TB H

11

28

24

26

14

8

13 15 15 15

119

125

110

113

118

139 152

154

142

125

139

8

21

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Enrollment

DCAT DT DT BH

119

136

138

137

144

153

160

167

157

148

175

17

36

26

5

26

54

36

6

32

62 6

74

32

42

20

23

34

21

27

33

23

26

5

42

5

39

23

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

~T2Diesel

~T2Diesel

~T2Diesel

AE D

~T2Diesel

M ACS

~T2Diesel

AE D

~T2Diesel

M ACS

AE D

M ACS

T2 Diesel

M ACS

T2 Diesel

AE D

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2021

Pas s F ail

$6,033

$4,115

$3,336

$26K

$40K $40K

2019 2020 2021

Travel

$85,926

$67,808

$97,444

$85K

$97K $97 K

2019 2020 2021

Supplies

$25,060

$16,137

$29,013

$35K $35 K

$32K

2019 2020 2021

Services

$77K

$90K

$306K

$80K

$95K

$309K

2019 2020 2021

Equipment

Budget byFY

Budget Spent

3.6

4.0

3.4

3.5

3.3

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

Occupational

3.4

3.0

3.5

3.5

3.4

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

Work Ethic

3.6

3.0

3.6 3.6 3.6

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

Prof essionalism

3.2

4.0

3.3 3. 3

3.0

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

Problem Solving

3.1

4.0

3.2

3.6

3.3

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

Comm unicat ion

3.3

4.0

3.5 3. 5

3.4

2012 2015 2016 2018 2020

InfoHandling

EmployerSatisfaction

1YearafterGraduation(Scaleof1to4.High isbetter)

F

1%

M

99%

ByGenderthis

AY

94.5%

88.7%

89.8%

85.5%

97.8%

93.1%

90.8%

90.6%

93.3%

94.9%

83.7%

94.5%

90.9% 90.5% 90.5%

97.8%

93.1%

91.5% 91.8%

93.3%

96.2%

83.7%

20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 20 20 20 21

DT

Retention

%Retained inPrgm % R e tai n e d at L ATC

DieselCertifications (notincludingDCAT) byYear Tested

65

63

49

63

65

65

67

63

83

9

7

2

1

7

1

2

1

4

1

32

2

$16.86

$18.02

$18.38

$20.10

$20.58

$19.85

$20.45

$23.95

$23.15

$ ‐

$5.00

$10.00

$15.00

$20.00

$25.00

$30.00

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Placement &AverageWageafter6months

Jo b in fi e ld Co ntin ue E d /M il itar y

Job no ti nf i e ld Seeki ngJob

Not in L abor Mk t A verag e o fA vg wag e a f te r6 Mo nths

Lake Area Tech data report.

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 12

Envision a Larger Service Area to

Expand Opportunity

Many rural community colleges nd there are

simply not enough good jobs in their region

for graduates. Strong leaders look further

aeld, drawing concentric circles that extend

beyond their traditional service area, looking

for unmet labor market needs that can provide

opportunities for graduates.

Such an analysis led leaders at Walla Walla

Community College in southeastern

Washington to expand its nursing program.

The regional nursing shortage was clear

from communications with the local hospital,

but an economic analysis showed a large

shortage across the entire state. Leaders saw

an opportunity to help solve that problem and

serve their students. Walla Walla developed

a plan to dramatically expand its output of

nurses and made a strong case for investment

by the state, resulting in millions of state dollars

for facilities and equipment. The end result: a

tripling of graduates from the nursing program

and closure of a critical talent gap.

Combine Workforce and Transfer

Pathways to Meet Regional Needs

Invariably, analysis of a rural community’s labor

market reveals the need for more workers with

both workforce credentials and bachelor’s

degrees. Seeing that, leaders of strong rural

colleges work to not just strengthen workforce

programs but also pathways to bachelor’s

degrees that align with in-demand jobs and

long-term career opportunities.

A strong example comes from West Kentucky

Community and Technical College, located

on the banks of the Ohio River. Many in the

college’s service area, in and around Paducah,

nd employment in the river barge industry. But

most who took entry-level jobs as deckhands

failed to earn a family-sustaining wage and

had limited opportunity for promotion.

Meanwhile, riverboat operators needed

more people with technical skills for multiple

positions, including management. In response,

the college created a certicate in diesel

technology that fully articulates into associate

degrees in marine technology and engineering,

enabling deckhands to be promoted into boat

maintenance and captain roles. Those associate

degrees articulate to University of Kentucky

bachelor’s degrees in engineering, which

can be completed on the community college

campus. Deckhands with no formal training

can go to West Kentucky for a certicate, an

associate degree, and ultimately a bachelor’s

degree that leads to harbor management

roles, all without leaving Paducah. Designed in

collaboration with the river barge industry, this

degree path has effectively closed the talent

gaps the industry was experiencing.

In Northern California, leaders at Shasta

College recognized a similar need for talent

and opportunity to generate new career-

aligned pathways. The college and its university

partners—including California State University,

Simpson University, and Columbia College—

created a program called Bachelor’s Through

Online and Local Degrees that provides

accessible pathways from community college to

bachelor’s degrees in high-demand elds such

as business, criminal justice, early childhood

education, information technology, and social

work. After completing an associate degree at

Shasta, students stay on the community college

campus, taking both upper-division coursework

online from a partner university and a series

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 13

of four one-credit, in-person Shasta courses

(in university navigation, career development,

job readiness, and graduate education). This

arrangement gives students taking online

courses continued access to valuable services

on the community college campus and a local

cohort of bachelor’s-seeking students.

By designing program pathways with the end

in mind—good jobs for graduates in areas of

regional workforce need—West Kentucky and

Shasta deliver economic mobility for students

and needed talent for their communities.

Generate New Industries and

Employment Opportunities for

Students

The most forward-thinking rural college

leaders consider not just how to meet existing

workforce needs, but how to develop new job

opportunities. They look for trends in labor

market data, pay attention to existing and

emerging industries in similar areas, and talk to

industry leaders and workforce development

organizations to explore what might be possible

in their communities. Understanding that most

employers won’t show up in rural communities

uninvited, leaders take responsibility for

attracting them and even developing new

industry sectors.

30

This work is typically a team

effort, with community college leaders working

alongside local government ofcials, economic

development authorities, larger existing

employers, and sometimes state agencies

to develop a forward-looking economic

development agenda. Highly effective rural

community college leaders play a key role in

driving and supporting that collaboration.

Walla Walla Community College provides an

excellent example. In the late 1990s, 17 wineries

existed in its service area. College leaders

understood that fertile land was widely available

and that area winemakers were eager to see

the industry grow—and national market analysis

revealed both an increased national demand for

high-end wine and that tourists in wine country

typically spend more than twice the amount of

tourists elsewhere.

For more information on strengthening transfer in

rural communities, see Rural Transfer Pathways:

Balancing Individual and Community Needs

30

Baldwin, Chris, Joe Schaffer, and Gretchen Schmidt “Rural Community Colleges: Challenges, Context, and Commitment

to Students.” National Center for Inquiry and Improvement. July 2021, https://ncii-improve.com/wp-content/

uploads/2021/07/NCII-Rural-Leaders-Big-Picture-2021-1.pdf

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 14

The college initiated a collaboration with the

City of Walla Walla, the Port of Walla Walla,

Walla Walla County, and two major local

employers: Nelson Irrigation and ETS Labs

(which provided technical services to the

budding Washington State wine industry).

These partners helped the college raise

$5 million from investors to open the Center

for Enology and Viticulture in 2001.

Their strategy and hard work paid off. Within

a decade, Walla Walla had more than 170

wineries in operation and is now a wine-

tourist destination. That growth spurred

additional development in wine distribution

as well as the food and hospitality industries,

which led to new programs at the college and

new job opportunities for graduates.

Building on that success, Walla Walla College

looked for additional economic opportunities

to collaborate with regional partners, leading

to a partnership in water management

with local environmental groups, the

Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian

Reservation, and local farmers. This coalition

built the Water and Environmental Center,

where partners work together to solve

water shortage problems and students

earn degrees in watershed ecology, a eld

with growing demand in the region. Walla

Walla also started a wind energy program

to capitalize on the growing wind turbine

industry, collaborating with regional partners

to create new pathways to economic mobility

for students.

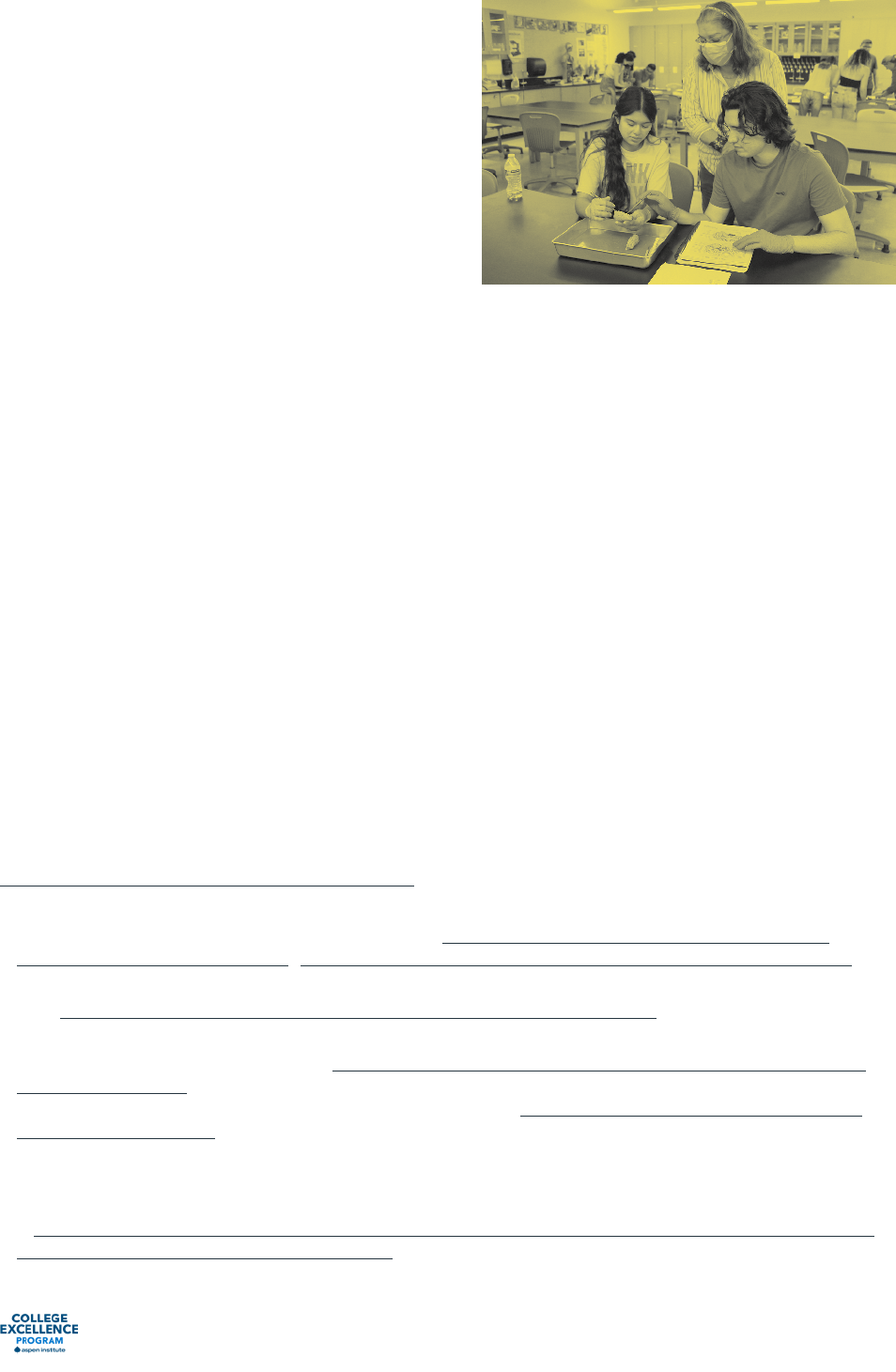

Sometimes, colleges step up to help ll a hole

left by employers who have relocated or shut

down. In Hickory, North Carolina, the once-

dominant furniture manufacturing industry

has all but disappeared. Understanding

that students needed new opportunities

for living-wage jobs, leaders at Catawba

Valley Community College set a bold goal:

to become a major auto mechanic hub for

the Southeastern United States. Leaders

started by raising funds to build a state-

of-the-art auto mechanic training facility in

partnership with local auto dealers, providing

an immediate path for students to good local

jobs. Next, college leaders worked with local

Toyota and Lexus dealerships— with whom

the college had already built trust and strong

partnerships by training employees—to lobby

Toyota’s national headquarters to appoint the

college as a certied Toyota training center.

Winning a bid to be the Southeastern United

States Toyota Technical Education College

Support Elite program provider, the college

now trains Toyota technicians from North

Carolina to Florida and Alabama. In this way,

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Northwest Iowa Community College

Rural Community College Excellence | 15

Catawba Valley’s efforts to deliver quality

technicians grew into a regional partnership

that benets students and the community.

When advancing these kinds of new pathways

and opportunities, leaders of excellent rural

colleges consider the historical context of the

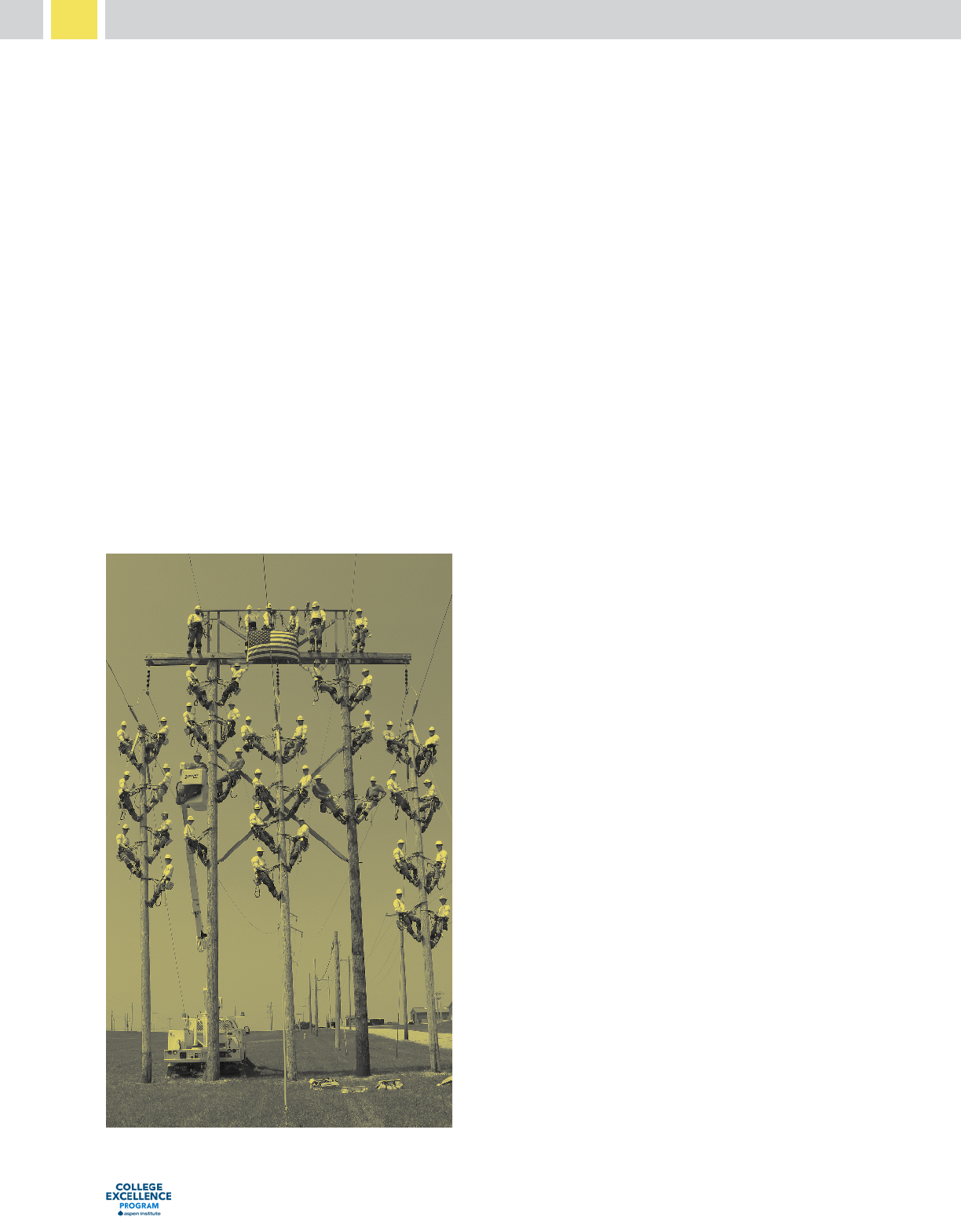

communities they serve. At Patrick & Henry

Community College in Martinsville, Virginia,

that included the legacy of a large textile

manufacturing industry, much of which shut

down in the early 2000s, creating substantial

economic hardship.

31

When considering how

to help the community rebuild, Patrick &

Henry leaders decided to focus on building a

strong network of smaller employers to avoid,

once again, a community over-reliant on a few

large ones.

As a rst step, the college partnered

with Festo Didactic, a leader in advanced

manufacturing training, to build a state-of-

the-art mechatronics training facility that was

recognized as a center of excellence by the

National Coalition of Certication Centers.

The strong program at this facility led to other

successes: attracting Schock Industries, a

German company, to the area for the rst time

and encouraging Ten Oaks, a local hardwood

ooring manufacturer, to expand existing

operations, creating additional opportunities

for Patrick & Henry graduates.

Since 2015, Patrick & Henry has also

partnered with the Chambers of Commerce

in Henry County and Martinsville on an

entrepreneurial incubation program and an

eight-week entrepreneurial bootcamp. Thirty

million dollars have been invested, resulting

in the creation of 45 small businesses, 85

percent of which remain open two years

after founding. And more than half of these

businesses are owned by people of color,

expanding economic opportunity in a place

where a third of residents are people of color.

As in other rural communities, tribal colleges

(most of which are rural or rural-serving insti-

tutions) often have a unique and leading role

in economic development in their regions.

Such is the case with Diné College, a tribal

college headquartered in Tsaile, Arizona.

The college serves the Navajo Nation, an area

that covers 27,000 square miles, larger than

the state of West Virginia. Diné President

Charles Roessel understands the college’s role

to be one of not just economic development

but “nation-building.” Roessel has advanced

an ambitious vision for his college, including

through the creation of sustainable businesses

that can retain graduates in the Nation and

generate income in a community with extreme

economic hardship: Nearly 43 percent of the

Navajo population lives in poverty, and only 7

percent of adults have a college degree.

32

Diné does not have many large nearby

industry partners. Attracting new ones is

hard because much of the region lacks

reliable services and road access, and about

90 percent of land is owned by the federal

government, which prevents the construction

of new permanent buildings.

33

31

Gettleman, Jeffrey. “In Martinsville, Va., Fleece Has Lost Its Luster.” March 3, 2002. Baltimore Sun. Accessed November 10,

2022. https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2002-03-03-0203030083-story.html.

32

“Employment by sectors of the Navajo Nation.” The Navajo Nation. Accessed November 10, 2022. http://navajobusiness.

com/fastFacts/EconomicSectors.htm

33

Wagner, Dennis and Craig Harris. “Why it’s so difcult to build homes on the Navajo Reservation.” The Arizona Republic.

December 14, 2016. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-investigations/2016/12/14/why-its-difcult-build-

homes-navajo-reservation/79541556/

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 16

Given the tribe’s history with uranium mining —

which led to contaminated water and other

widespread

health issues—there also remains

lingering skepticism of outside corporations.

34

In light of these challenges, the college chose

to start its own businesses, including a wool

business that will offer signicant employment

opportunities to graduates. In the Navajo

nation, sheep ranching has been a cultural and

economic staple for hundreds of years. Given

the long distances farmers often must travel

to sell the wool and insufcient infrastructure

to shear sheep and prepare wool in ways

that yield, Navajo people working in this area

earned only subsistence wages. In recent years,

economic development leaders and Navajo

elders have centralized the sale of wool and

attracted external buyers. For its part, Diné

College employs a grant-funded extension

agent who trains and educates ranchers on how

to efciently shear and process wool.

35

These

efforts have spurred growth in the wool market

and improved incomes for workers and the tribe.

President Roessel has strategically engaged

key community stakeholders, including local

business leaders, to ensure that programs the

college offers provide sustainable employment

opportunities to graduates while also

addressing the needs of the Navajo Nation.

The college has changed the composition

of the board from solely tribal elders to also

include local business leaders who can provide

the college with an expanded understanding

of employment trends. These new board

members help the college make employer

connections, provide mentorship and support

to students, and provide legal and accounting

expertise to the college. An example of a

program that serves Navajo needs and delivers

students to jobs: The college’s extension

programs offers a 10-week course to train

students to become water scientists so they can

identify contamination in wells from uranium

mining runoff.

36

No matter their region, colleges that deliver

excellent workforce outcomes for their

students and generate talent needed in

their communities make sure their programs

connect to existing workforce needs and

proactively cultivate new jobs and industries.

They pay close attention to their communities’

needs, building on community strengths

and learning from the past. And whenever

economic opportunities are limited, they build

new ones in partnership with others in their

region and beyond.

34

Morales, Laurel. “For The Navajo Nation, Uranium Mining’s Deadly Legacy Lingers.” NPR April 10, 2016. https://www.npr.

org/sections/health-shots/2016/04/10/473547227/for-the-navajo-nation-uranium-minings-deadly-legacy-lingers.

35

Petrovski, Leslie. “Wool on the Reservation?” https://www.interweave.com/article/knitting/navajo-wool-global-market/.

Interweave. August 9, 2018.

36

“UA, Diné College Receive $500K USDA Grant to Train Navajo Water Scientists.” Fronteras. June 4, 2021. https://

fronterasdesk.org/content/1689006/ua-din-college-receive-500k-usda-grant-train-navajo-water-scientists.

|

Create Pathways to Economic Mobility

Rural Community College Excellence | 17

2. Convince Students to Enroll and Stay

in College

Effective rural college leaders understand that they—and others at their colleges—must make the case to

community members about how higher education can lead to better lives for students and a stronger

community for everyone. Often, efforts to drive economic development and shape cultural perceptions

inform one another: Colleges that consistently demonstrate positive impact from their programs of

study can more readily strengthen a college-going culture.

Skepticism in rural communities about higher education’s value originates from multiple places,

according to the leaders interviewed for this guide. To some prospective students and families, higher

education is perceived as elitist or exclusionary—a view that can be especially prevalent among those

who have little exposure to college.

37

Others doubt the return on investment, especially in areas where,

historically, individuals could secure stable, family-sustaining employment in manufacturing, energy,

or agriculture with just a high school diploma. There is also a sense among potential students that they

cannot afford the opportunity cost of forgoing working hours to pursue a degree, especially when

college is far away from home or work. Regardless of what’s behind this skepticism, our research shows

that leaders at excellent rural colleges have found ways to effectively overcome it by thoughtfully

designing communications and outreach strategies that meet students where they are and, more

importantly, by providing strong, workforce-aligned educational programs that back their promises.

Overcome Misperceptions about

Careers and Institutions

Research suggests that students who feel they

belong in college and have a high degree

of trust in educational institutions and their

programs are more likely to enroll and persist

through their programs.

38

Patrick & Henry

Community College leaders realized that

if they were to meet the talent needs of new

manufacturing employers that had moved to

their area, they needed to convince students

that advanced manufacturing jobs are very

different from the unstable manufacturing jobs

that had left the community. “Manufacturing was

a dirty word in the community,” Patrick & Henry

President Greg Hodges said. “If you said it, you

had to go wash your mouth out with soap.”

In 2016, the college had only two or three

students enrolling in advanced manufacturing

courses. The college amped up outreach,

bringing students, families, and K-12 guidance

counselors onto campus to show them the

new facilities and explain potential career

pathways. The college’s messaging focused

heavily on the program’s connection to good

37

Pappano, Laura. 2017. “Voices from Rural America on Why (or Why Not) to Go to College.” The New York Times, January 31,

2017, sec. Education. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/education/edlife/voices-from-rural-america-on-why-or-why-

not-go-to-college.html?action=click&module=RelatedCoverage&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer.

38

“The Trust Gap Among College Students.” Evidence-Based Improvement in Higher Education. National Survey of Student

Engagement. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://nsse.indiana.edu/research/annual-results/trust/index.html.

|

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College

Rural Community College Excellence | 18

jobs. Students were repeatedly told they could

receive job offers—sometimes at as high as $36

an hour—and that some employers covered

tuition. After ve years of dedicated effort, the

college is seeing every course lled within two

days of registration opening.

At a time when other community colleges across

the U.S. have struggled to ll classes, Patrick &

Henry’s enrollment has remained steady. “We

haven’t had an enrollment decline so much as

we have an enrollment realignment,” Hodges

said. That comes from an understanding of what

students really want: “a J-O-B degree,” a term

Hodges uses frequently.

For tribal colleges, the work of convincing

students to enroll must be done against a

backdrop of long-standing inequities and

economic marginalization.

39

Recognizing this,

Diné College leaders focus on building trust.

The college embeds Navajo values, language,

and traditions into all its curriculum so students

can see the college’s connection to the

community, feel understood, and feel pride in

their culture. In an area where many homes lack

running water and electricity, the eight-story

building on the main college campus stands

in sharp contrast to what people are used to.

40

Understanding that this and other contextual

factors might cause residents of the Navajo

reservation to view a college as intimidating,

Diné leaders dedicate resources to making the

campus approachable.

41

The college’s main

building and its dorms are built to resemble

a hogon, the traditional home of the Navajo

people. The library is at the center of the

building and represents where the re would

be in the hogon. These design choices have

helped create a greater sense of belonging and

trust among the students and, more broadly,

the Navajo people. In an area where only 7

percent of adults have a college degree, these

strategies have contributed to an impressive

60 percent increase in degrees awarded by the

college annually since 2010.

Evolve Outreach

as Demographics Change

In communities with changing demographics,

efforts to build visibility and trust must also

evolve if they are to succeed. Leaders at

effective rural colleges pay attention to shifting

demographics in their area’s K-12 schools,

then use that information to identify what the

growing populations of students and families

value, who is best suited to reach them, and

how to convey the messages that will bring

them to campus.

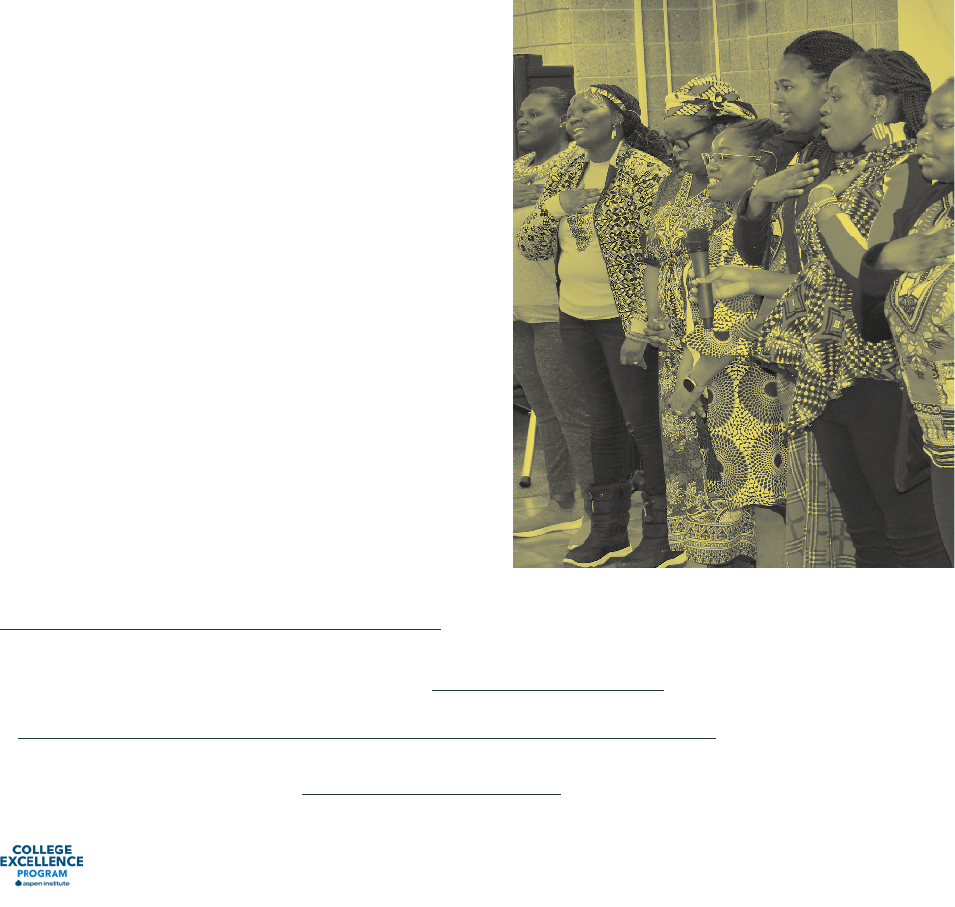

Northwest Iowa Community College is

in a region with a fast-growing Hispanic

population: Between 2010 and 2020, the

Hispanic population of Sheldon, Iowa, nearly

doubled.

42

Many immigrant parents with

children moving through the K-12 system have

limited prociency in English. The college has

long held campus visits for high school juniors

and seniors, but Northwest Iowa leaders saw

that in order to reach the growing Hispanic

39

Crazy Bull, Cheryl and Justin Guillory, “Revolution in Higher Education: Identity & Cultural Beliefs Inspire Tribal Colleges

& Universities,” 2018. Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/les/

publication/downloads/010_Crazy-Bull-Guillory-pp095-105.pdf

40

“Life in Rural America: Part II.” May 2019. NPR, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public

Health. https://media.npr.org/documents/2019/may/NPR-RWJF-HARVARD_Rural_Poll_Part_2.pdf.

41

Bogody, Candace. September 20, 2010. “Overcoming the Hurdles to College as a Navajo Student.” The Nation.

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/overcoming-hurdles-college-navajo-student/

42

Author’s calculation using data from U.S. Census Bureau

|

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College

Rural Community College Excellence | 19

population, the college would need to modify

its approach. The solution: A series of events

called “Latino Thunder Fridays,” (named after

the college’s mascot, “Thunder”) designed

to bring students and families to campus and

show them that the college understands their

needs. The events, conducted completely

in Spanish, include a sit-down meeting with

faculty members in students’ elds of interest.

The results have been outstanding: 75 percent

of students who participate in Latino Thunder

Fridays enroll at the college.

In addition to the growing Hispanic student

population, Northwest Iowa enrolls a sizable

number of students from Kenya, Egypt, and

Uganda. The college helps these students feel

welcomed, accepted, and supported by giving

them practical guidance on how to succeed in

the small town of Sheldon, population 5,178.

Advisors and other student support staff

proactively contact students in their programs

and provide information on how to navigate

Iowa winters (including buying winter clothing)

and life in rural America.

Northwest Iowa leaders view Hispanic and

African students not just as potential regional

workers but as assets to the college and

community. The college hosts monthly events

on campus, open to all students and Sheldon

residents, that showcase different cultures.

In one recent event, “A Taste of the World,”

23 students and 10 staff prepared food,

decorations, and presentations representing

21 different countries. Multicultural leader

Samson Nyambati and nursing student Daniel

Nyanchoga led everyone in Kenyan dances

and songs, and Mexican students showcased

the popular line dance Caballo Dorado.

Over 150 attended, including staff, students,

Northwest Iowa board members, and

representatives from the multicultural clubs

at nearby four-year partners, Dordt University

and Northwestern College.

Start the College-Going Pathway

in High School

Establishing a reliable presence in K-12 schools

is a central strategy used by strong rural

community colleges working to advance trust

and belonging among potential students. But

deep engagement with K-12 schools requires

an investment of resources. Dual enrollment

programs, for example, can require signicant

staff time and money from a college, and don’t

always generate the same revenue as enrollment

of students after high school. Even so, leaders

of excellent rural colleges understand that

increasing dual enrollment helps more students

start on the path to a college credential, which

benets both the community and the college.

In the small town of Zanesville, Ohio—where Zane

State College is located—community leaders

The Dual Enrollment Playbook

Learn more at as.pn/DualEnrollmentPlaybook

|

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College

Rural Community College Excellence | 20

knew they needed to tackle their region’s

social and economic challenges head-on.

“There is some pressure to not do better than

your parents,” Doug Baker, the superintendent of

Zanesville City School District, explained. “One

of my students went to a university in Cincinnati,

hit a snag with nancial aid and had to move back

home. Her mom then started telling her, ‘You’re

from Zanesville, you’ll get a job in Zanesville,

and you’ll marry a boy from Zanesville.’” In other

words, “College is not for you.”

To build and strengthen a college-going culture,

Zane State partnered with the school district

to establish a robust dual enrollment program.

While not all dual enrollment students come

to Zane State after high school, the college’s

leaders believe that broadening exposure and

access to college courses is important for the

community, as is the condence gained when

students succeed in them. When data analysis

revealed that some dually enrolled students

never continue to college, Zane State identied

nearly 1,000 students who earned college

credit in high school but never enrolled in any

postsecondary institution after graduating, and

is now actively recruiting them, showing them

pathways to economic mobility.

Guided by the idea that students who graduate

from high school already on a college degree

path are more likely to understand the value

of continuing in college, Zane State also works

directly with high school advisors to help dually

enrolled high school students take courses

tightly aligned to degree pathways. The

college has equipped local K-12 advisors with

information about which Zane State courses t

into certain pathways and access to documents

showing continuing students how close they

are to completing a degree.

Another rural community college that has

established strong dual enrollment pathways:

Imperial Valley College in a rural part

of Southern California near the Mexico

border. The college has developed a deep

relationship with its K-12 system, providing

students dual enrollment courses alongside

robust guidance on college. Instead of waiting

until students graduate, Imperial Valley

College advising staff go into high schools

to help students complete nancial aid

applications, choose a program of study, and

understand what preparatory work they need

to complete an associate degree. As a result of

the college’s efforts, many students leave high

school with an educational plan, developed

with the help of high school advisors (rather

than solely through staff on the community

college payroll). The percentage of high

school graduates who go on to enroll at

Imperial Valley is much higher than at other

community colleges, ranging from 60 percent

to 88 percent, depending on the high school.

And those students persist: The increases

in high school advising and nancial aid

support provided to high school students

have coincided with a steadily increasing

completion rate at Imperial Valley for the area’s

high school graduates.

|

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College

Imperial Valley College | Imperial, California

Rural Community College Excellence | 21

Address K-12 School Resource Needs

and Student Financial Barriers

Providing resources to struggling high schools

can also be a path to strong K-12 partnerships.

Colorado Mountain College leaders saw

an opportunity to do just that when, in 2012,

budget cuts forced local high schools in

Glenwood Springs, near one of the college’s

campuses, to move to a four-day week to

save $500,000 annually.

43

Recognizing the

difculties that no-school Fridays presented for

working parents, Colorado Mountain College

partnered with the school district to offer “career

academies” in programs ranging from certied

nursing assistance to welding to graphic design.

Through these programs, many high school

students have earned degrees; participating

high schools now host standing-room-only

graduation ceremonies for high school students

who also complete a college credential.

Large geographic distances and limited

transportation options often impede dual

enrollment access in rural communities. To

solve this problem, Wenatchee Valley College

strategically sited an education center to

increase access to geographically isolated

students and provides grant funding to rural

high schools to help rural and Native American

students take dual enrollment courses there.

Columbia Basin College, also in Washington,

provides gas cards for dual enrollment students

who live farther than 25 miles from the college

so they can visit the campus. The efforts of these

two colleges have helped increase college

access in their regions, especially among the

growing Hispanic population.

44

Remove the Earn-or-Learn Dilemma for

Low-Income Students

Leaders at effective community colleges

understand that students want, and often need,

to earn money right after high school. Rather

than forcing students to choose between college

and a job, effective rural colleges ensure that

students have simultaneous access to both.

There are multiple models that pay students as

they develop skills aligned to their ultimate goal:

a good job and fullling career.

In Zane State College’s Appalachian service

area, students often face pressure to earn full-time

wages after high school to support their families.

So, the college partners with regional employers

to create “earn-and-learn” opportunities. Students

attend class two days a week and, on the other

three, get on-the-job training directly related to

their coursework. Students receive wages while

progressing in a program that will benet them

after they graduate. The college started in an area

of community need, establishing partnerships

with local employers who needed bookkeepers

and accountants. Employers report beneting

immediately from the work the student-interns

provided. Due to the success of the program,

the college will soon spread this model to

engineering and medical laboratory technician

elds, where there are also regional shortages.

43

Stroud, John. March 12, 2012. “Gareld Re-2 Board OKs Four-Day Week.” Post Independent. Accessed November 10, 2022.

https://www.postindependent.com/news/gareld-re-2-board-oks-four-day-week/.

44

Mehl, Gelsey, Joshua Wyner, Elisabeth Barnett, John Fink, and Davis Jenkins. 2020. “The Dual Enrollment Playbook:

A Guide to Equitable Acceleration for Students.” The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/

uploads/2020/12/ASP-2020-Dual-Enrollment-Playbook.pdf

|

Convince Students to Enroll and Stay in College

Rural Community College Excellence | 22

Advance Retention with Equity in Mind

Nationally, community colleges have failed

to retain and graduate students of color and

those from low-income families at the same

rates as other students.

45

But the conversation

around, and the strategies for, advancing

equity in student retention and graduation can

look different in rural communities, especially

as political polarization has increased and

conversations about race have become more

charged in recent years.

46

While successful

rural community colleges often use similar

strategies as urban colleges to close equity

gaps, rural leaders at times communicate about

those strategies differently, using language that

resonates in their communities.

With a student population that is almost all

Navajo, the professional development center at

Diné College trains faculty on how to advance

equity with students’ Navajo culture at the center.

Building on the sacred Navajo concept of “Sa’ah

Naaghai Bik’eh Hozhoo,” which places Navajo

life in harmony with the natural world, Diné

emphasizes social responsibility and resilience.

Students’ pathways are grounded in familiar

cultural references like the cycle of seasons, or

night and day. From entry to post-graduation

success, students learn how Nitsáhákees

(Thinking), Nahat’á (Planning), Iiná (Living) and

Sihasin (Assuring) are the key “seasons.’’ Each

of these concepts maps to key junctures in a

student’s academic path: thinking about the right

major, planning nancial aid, following a degree

plan, and preparing for life after college.

This connection to Navajo culture and

philosophy not only guides how students

progress, but also how the college expects

faculty and staff to support students. The

college’s faculty development efforts

are based in storytelling, a fundamental

component of Navajo life. For instance,

Diné faculty explored how different equity

challenges appear in a majority Native

American population by sharing stories about

their own experiences. As a result, faculty and

staff have in recent years strategized about

how to better support LGBTQ+ students,

engage with students with different tribal

backgrounds, support students dealing with

mental health issues, and better support

students living with disabilities.

47

Successful colleges also pay attention to the

specic needs of students who come from low-

income backgrounds. Rural-serving Amarillo

College in the Texas Panhandle and Patrick

& Henry Community College in southern

Virginia have both centered anti-poverty in

their student success strategies. Amarillo

College President Russell Lowery-Hart knew

that low-income students and students of

color—who make up half of Amarillo students—

completed degrees at lower rates than other