The BACPR Standards and Core Components for

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

and Rehabilitation 2017

(3rd Edition)

The Six Core Components

for Cardiovascular Disease

Prevention and Rehabilitation

Supported by

The British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation is an affi liated group of the

The

Six Core Components

for Cardiovascular Disease

Prevention and Rehabilitation

Supported by

A

U

D

I

T

A

N

D

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

L

O

N

G

-

T

E

R

M

S

T

R

A

T

E

G

I

E

S

Health

behaviour

change and

education

P

s

y

c

h

o

s

o

c

i

a

l

h

e

a

l

t

h

L

i

f

e

s

t

y

l

e

r

i

s

k

f

a

c

t

o

r

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

M

e

d

i

c

a

l

r

i

s

k

Foreword

All health care professionals are motivated to provide the best care and achieve the optimal

outcomes for their patients. This has been a recurrent ambition I have heard from colleagues

working in the front line of the NHS. The 3rd edition of the BACPR Standards & Core

Components provide an excellent and essential guide to support cardiac rehabilitation and

prevention programmes across the UK.

Taking the findings of research and translating these into day to day practice is the starting point

of a chain of events that will achieve this ambition. The evidence-based standards allow us to

drive quality improvement and the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation allows us to know how

well we are doing. None of this however would be possible without the efforts of the healthcare

professionals providing cardiac rehabilitation across the UK.

Cardiovascular disease is a long term condition. Saving someone’s life following a heart condition

is vital, but giving them a fulfilling life that is worth living is equally important. The aims of cardiac

rehabilitation and prevention is to provide the patient and family with the skills and knowledge to

self-manage, facilitate recovery both physically and psychologically and educate to reduce the risk

of further CVD events, as well as achieving an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular mortality.

The NHS should provide and fund evidence-based care, but the reduction in hospital admissions

for patients who receive comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation, there exists an added financial

motive to invest in these essential services.

Leo was 47 when he had a heart attack followed by triple bypass surgery. While he was in

hospital he was offered a place on a cardiac rehabilitation programme. Following cardiac

rehabilitation, as he says, it is about being in control – “I definitely feel much better in myself. I’m

more in control of my own health than I ever was before.”

The BHF is delighted to be able to support the publication of these updated Standards and

Core Components, but more importantly work with the BACPR team and members, to promote

excellence in cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation.

Dr Mike Knapton, Associate Medical Director, BHF

Supported by

Contents

1

Introduction

1

1.1

Definition

1

1.2

Evidence

2

1.3

National and local factors for assuring quality

3

1.4

Cardiac rehabilitation pathway of care

3

1.5

Funding

4

2

The Standards

5

2.1

The delivery of six core components by a qualified and

competent multidisciplinary team, led by a clinical coordinator

6

2.2

Prompt identification, referral and recruitment of eligible

patient populations

7

2.3

Early initial assessment of individual patient needs, which

informs agreed personalised goals that are reviewed regularly

8

2.4

Early provision of a structured cardiovascular prevention

and rehabilitation programme (CPRP), with a defined

pathway of care, which meets the individual’s goals and is

aligned with patient preference and choice

9

2.5

Upon programme completion, a final assessment of

individual patient needs and demonstration of sustainable

health outcomes

10

2.6

Registration and submission of data to the National Audit

for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) and participation in the

National Certification Programme is desirable

10

3

The Core Components

11

3.1

Health behaviour change and education

12

3.1.1

Health behaviour change

12

3.1.2

Education

12

3.2

Lifestyle risk factor management

13

3.2.1

Physical activity and exercise

13

3.2.2

Healthy eating and body composition

14

3.2.3

Tobacco cessation and relapse prevention

14

3.3 Psychosocial health

15

3.4

Medical risk management

16

3.5

Long-term strategies

17

3.6

Audit and evaluation

18

4

Appendices

20

Appendix 1

References

20

Appendix 2

Acknowledgements

24

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 1

1. Introduction

This is an update (third edition) of the BACPR Standards & Core Components and represents

current evidence-based best practice and a pragmatic overview of the structure and function

of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Programmes (CPRPs) in the UK.

The previously described seven standards have now been reduced to six but without sacrificing any

of the key elements and with a greater emphasis placed on measurable clinical outcomes, audit and

certification. Similarly, the second edition provided an overview of seven core components felt to be

essential for the delivery of quality prevention and rehabilitation, and this too has been reduced to six.

The interplay between cardio-protective therapies and medical risk factors is almost impossible to

disentangle for the vast majority of patients and even if specific drug therapies are deployed exclusively

for risk factor modulation, the indirect effect will also be cardio-protective. Thus, these have been

combined into a single core component – medical risk management.

This updated and revised third edition is designed to build upon the success of the earlier publications

and to refocus the attention of commissioners, health-care professionals, politicians and the public

on the critical importance of robust, quality markers of service structure and content. However, the

overarching aim of these standards and core components remains unchanged – to provide a blueprint

upon which all effective prevention and rehabilitation services are designed and a template through

which any variation in quality of service delivery can be assessed.

It is recognised that cardiac rehabilitation (CR) has an established evidence-base and existing services

are in a strong position to evolve in order to provide care to include an ever-broadening spectrum of

in-scope patients, from those with established atherothrombotic vascular disease right through to those

asymptomatic individuals who have been deemed at high risk for the future development of adverse

cardiovascular events.

1-3

In addition, there is enormous overlap in terms of profile and potential benefits

for patients with other non-communicable diseases, particularly individuals with chronic respiratory

disease and certain forms of cancer.

4-5

Therefore, an opportunity exists to further expand the influence

of prevention and rehabilitation services which may, in turn, allow financial resources to be released and

a more cost-effective deployment of staff and facilities to take place.

All such potential developments will require innovative practice and close working between providers

and commissioners whilst also adhering to the principles set out within this BACPR Standards & Core

Components document.

1.1 Definition

There are many definitions of cardiac rehabilitation.

6-8

The following definition presents their combined

key elements:

“The coordinated sum of activities* required to influence favourably the

underlying cause of cardiovascular disease, as well as to provide the best possible

physical, mental and social conditions, so that the patients may, by their own

efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in their community and through

improved health behaviour, slow or reverse progression of disease”.

*The BACPR’s six core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation

constitute the coordinated sum of activities.

2 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

In meeting these defined goals, all CPRPs should aim to offer a service that takes a multidisciplinary

biopsychosocial approach in order to best influence uptake, adherence and long-term healthier living.

The involvement of partners, other family members and carers is also important.

9-11

1.2 Evidence

The evidence base that supports the merits of comprehensive CR is robust and consistently

demonstrates a favourable impact on cardiovascular mortality and hospital re-admissions in patients

with coronary heart disease

12

although there remains some uncertainty regarding the effect of CR on

all-cause mortality.

13-14

For patients who have experienced myocardial infarction (MI) and/or coronary

revascularisation, attending and completing a course of exercise-based CR is associated with an

absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular mortality from 10.4% to 7.6% when compared to those who

do not receive CR, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 37. In terms of recurrent MI and repeat

revascularisation, the effect of CR would appear to be neutral, however, there is a significant reduction

in acute hospital admissions (reduced from 30.7% to 26.1%, NNT 22) which is a key determinant of the

intervention’s overall cost-efficacy.

13

For individuals with a diagnosis of heart failure, CR may not reduce total mortality but does impact

favourably on hospitalisation, with a 25% relative risk reduction in overall hospital admissions and

a 39% reduction (NNT 18) in acute heart failure related episodes.

15

The consequences of relapse

and readmission are enormous in terms of quality of life, associated morbidity and financial impact

thus the more recent emphasis on the importance of CR for heart failure patients within national and

international guidelines. In terms of direct measures of anxiety, depression and quality of life, CR

demonstrates consistently favourable outcomes for all patient groups and for those with heart failure,

a clinically relevant (and highly statistically significant) change in the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure

questionnaire point score of 5.8.

15

Finally, there is persuasive data supporting the benefits of different modes of CR delivery with no

apparent difference in either clinical or quality of life outcomes when comparing supervised centre-based

CR with that undertaken in a domestic environment, nor any major variation in healthcare costs.

16

This

should allow CPRPs to be more flexible in their CR offer and to be more innovative when attempting to

attract either new or hitherto hard to reach “in-scope” groups.

In summary, CR reduces both cardiovascular mortality and episodes of acute hospitalisation whilst also

improving functional capacity and perceived quality of life. CPRPs support an early return to work and

the development of self-management skills,

17

and can be delivered effectively in a variety of formats,

including traditional supervised centres as well as domestic settings. Given that CR remains one of the

most clinically and cost-effective therapeutic interventions in cardiovascular disease management,

13 18

it is vital that systems are in place to maximise uptake and adherence. There is continued emphasis

(supported by these updated standards) placed upon the importance of early CR, commencing

within two weeks of either hospital discharge or confirmed diagnosis in the case of stable angina or

heart failure. Starting within this timeframe has been shown to be both safe and feasible, as well as

improving patient uptake and adherence.

19-22

In addition, there is evidence to suggest that if a member

of the CPRP to which a patient has been referred is able to make contact with the patient during the

in-hospital stay and begin the process of personalised goal-setting, then this may lead to greater uptake

of prevention/rehabilitation services.

23-24

1. Introduction

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 3

1.3 National and local factors for assuring quality

Quality assurance is facilitated through an alliance at both local (e.g. commissioners, service providers

and service users) and national level, together with participation in the National Audit for Cardiac

Rehabilitation (NACR) and ultimately attainment of national certification (Figure 1).

Figure 1: NCP_CR certification logo

The aim of this “alliance” is to deliver evidence-based and consistently high-quality CPRPs across all four

nations which can be accessed by all individuals deemed eligible. The National Certification Programme

(NCP_CR) has been designed in order to demonstrate that this is indeed the case and that programmes

are meeting (or working towards) a set of minimum quality standards adapted from those described

within this document, and which are reflective of the aggregated data submitted to the NACR.

25

The

NCP_CR is delivered via a BACPR/NACR collaborative and it is envisaged that all CPRPs will submit

complete data sets to NACR and register for certification.

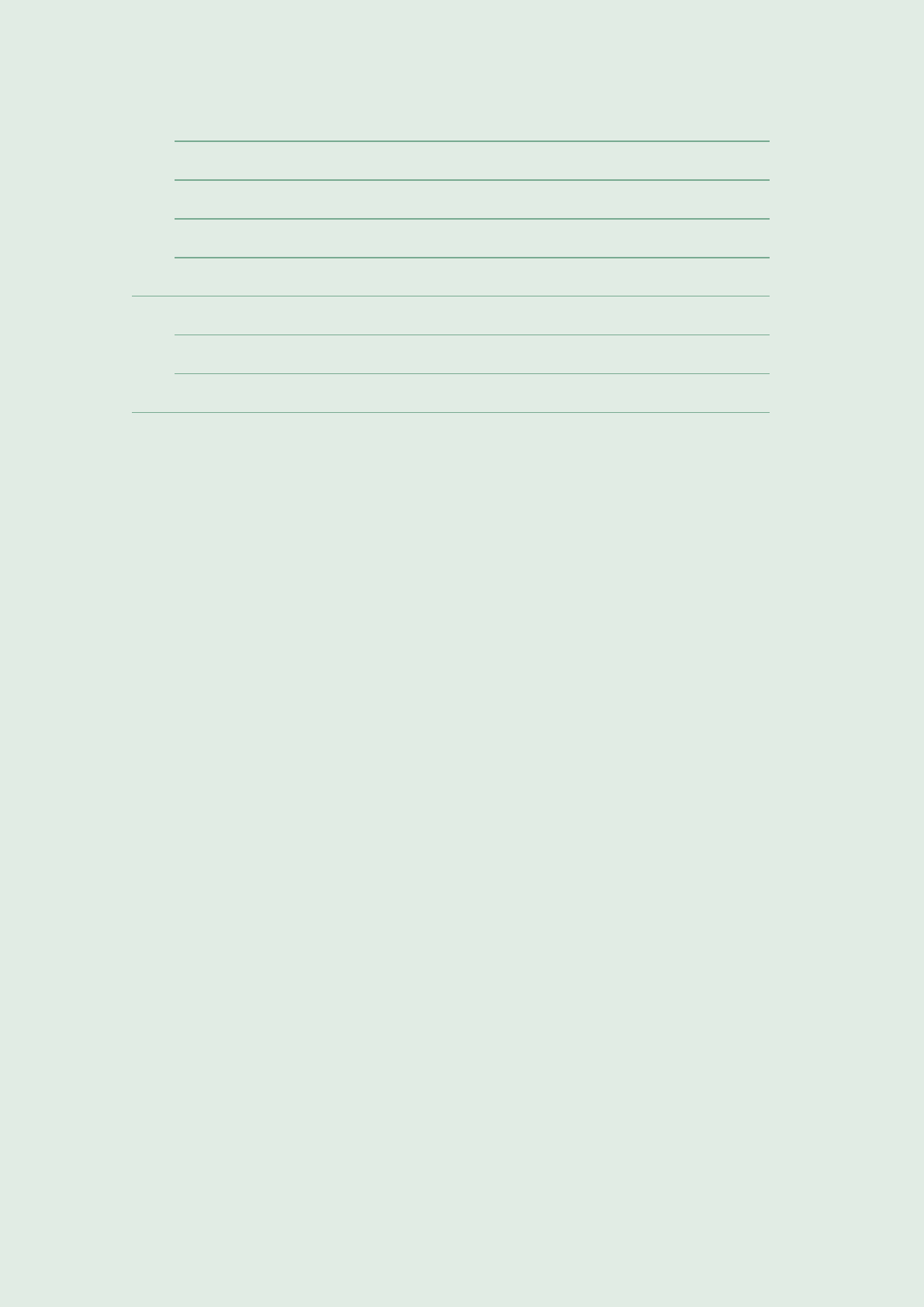

1.4 Cardiac rehabilitation pathway of care

The Department of Health Commissioning Guide for Cardiac Rehabilitation

18

summarises a

recommended six-stage pathway of care from patient presentation (e.g. diagnosis or cardiac event),

identification for eligibility, referral, and assessment through to long-term management (Figure 2). Whilst

intended for England, this pathway of care is relevant to all four nations. Each of these stages within

this process are vital for programme uptake and adherence, the achievement of meaningful clinical

outcomes and ensuring longer-term behaviour change and desired health outcomes. The assessed

information must also be managed in a manner to fulfil the need for audit and evaluation.

Figure 2: Department of Health Commissioning Guide Six-Stage Patient Pathway of Care

1. Introduction

4 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

1.5 Funding of CPRPs

Previously published guidance has suggested a minimum cost per patient for CR.

18 26-28

However,

the 2010 Department of Health Commissioning Pack has now been reviewed in 2016 by Monitor (an

organisational part of NHS Improvement) which recommends the CR costing tool.

29 30

This tool allows

CPRPs to work out the costs as per staff profile required to meet the needs of the population they serve.

This model only takes account of staff costs over 16 one-hour sessions which means that individual

CPRPs would need to add other capital and services costs and adjust in respect of the number of

sessions they run.

These revised standards and core components place equal emphasis on lifestyle risk factor

management, psychosocial health and medical risk factor management whilst placing health behaviour

change and education at the very centre of this model of care. Therefore, costings developed within

business cases and/or funding (commissioning) determined by local clinical commissioning groups or

health boards would need to reflect the corresponding mix of expertise and time allocation required for

qualified and competent practitioners to employ an evidence-based approach across the six stages of

CR (Figure 2).

1. Introduction

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 5

2. The Standards

The six standards for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation are:

Standard One The delivery of six core components by a qualified and competent multidisciplinary

team, led by a clinical coordinator.

Standard Two Prompt identification, referral and recruitment of eligible patient populations.

Standard Three

Early initial assessment of individual patient needs which informs the agreed

personalised goals that are reviewed regularly.

Standard Four Early provision of a structured cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programme

(CPRP), with a defined pathway of care, which meets the individual’s goals and is

aligned with patient preference and choice.

Standard Five Upon programme completion, a final assessment of individual patient needs and

demonstration of sustainable health outcomes.

Standard Six Registration and submission of data to the National Audit for Cardiac Rehabilitation

(NACR) and participation in the National Certification Programme (NCP_CR).

Important notes:

• Within the standards criteria the word shall is used to express a requirement that all programmes

are expected to comply with (Grade A/B recommendations based on the highest quality

evidence available and recognised as best practice). The word should is used to express a

recommendation that is recognised as desirable (Grade C/D recommendation).

• In some cases these recommendations may exceed the current minimum standards required for

the National Certification Programme, which sets annual targets based on national averages.

Performance indicators associated with meeting the minimum standards required for

programme certification can be found at: www.bacpr.com

6 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

STANDARD 1

The delivery of six core components by a qualified and competent

multidisciplinary team, led by a clinical coordinator

• Each programme shall deliver the six essential core components to ensure clinically effective care

and achieve sustainable health outcomes (as presented in Section 3).

• The team shall include a senior clinician who has responsibility for coordinating, managing and

evaluating the service. This also includes: resource and financial management for the service;

collaboration with NHS data analysts to successfully draw on all available funding and identify

any savings arising from reduced hospital admissions; and engagement with funding and

commissioning bodies.

• There shall be an appropriately qualified and competent named lead for each of the core

components. These practitioners who lead each of the core components should be able to

demonstrate that either they or their delivery team have appropriate training, professional

development, qualifications, skills and competency for the component(s) for which they are

responsible. Practitioners should use the BACPR Competences Frameworks, where available.

• The team shall include a physician who has sustained interest, commitment and knowledge in

cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation.

• The delivery of the core components requires expertise from a range of different professionals

working within their scope of practice. The composition of each team may differ but collectively

the team shall have the necessary knowledge, skills and competencies to meet the standards

and deliver all the core components. Patients benefit from access to a wide range of specialists,

which most typically may include:

• Dietitian

• Exercise specialist

• Nurse specialist

• Occupational therapist

• Pharmacist

• Physician with special interest in prevention and rehabilitation

• Physiotherapist

• Practitioner Psychologist

• There shall be dedicated administrative support.

• The cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation team shall actively engage and collaborate with

the patient’s/client’s wider care team (e.g. general practitioners, practice nurses, cardiovascular

disease specialist nurses, sports and leisure instructors, social workers and educationalists) to

create a truly comprehensive approach to long-term management.

• When designing, evaluating and developing programmes, service users should also be included

in this process.

2. The Standards

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 7

STANDARD 2

Prompt identification, referral and recruitment of eligible patient populations

a. Patient Identification:

• The following priority patient groups shall be offered a CPRP irrespective of age, sex, ethnic

group and clinical condition:

• acute coronary syndrome

• coronary revascularisation

• heart failure

• Programmes should also aim to offer this service to other patient groups known to benefit:

• stable angina, peripheral arterial disease, post-cerebrovascular event

• post-implantation of cardiac defibrillators and resynchronisation devices

• post-heart valve repair/replacement

• post-heart transplantation and ventricular assist devices

• Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD)

• It is recognised that asymptomatic individuals who have been identified as high cardiovascular

risk for CVD events are likely to benefit from the same professional lifestyle interventions and

risk factor management as those that currently qualify for CPRPs. In addition, risk factors

for cardiovascular disease are largely shared with the wider spectrum of non-communicable

diseases such as cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation.

4-5

Existing

cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation services, if appropriately resourced, are in a strong

position to provide high quality, cost-effective interventions to individuals both with and without

established CVD. CPRPs should demonstrate an ambition to broaden their offer and initiate

discussions with commissioners locally.

• It is recognised that local policy may be required to address priority groups in the first instance to

reduce variation, ensuring consistency and equity of access. These standards however advocate

investment in cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation services as to ensure all patient groups

ultimately benefit.

b. Patient Referral:

• An agreed and coordinated patient referral and/or recruitment process shall be in place so that

all eligible patients are identified and invited to participate.

•

CPRPs shall receive the referral of an eligible patient either during the in-patient stay or within 24 hrs

of discharge. Referrals sent within a community setting or following a day case intervention shall be

received by the CPRP within 72 hrs of the individual being identified as eligible.

• Prior to discharge, all eligible hospitalised patients should be encouraged by healthcare

professionals to attend and complete a CPRP

c. Recruitment:

• Upon receipt of referral, all patients deemed eligible shall be contacted within 3 working days to

review their progress and discuss enrolment.

• A mechanism of re-offer and re-entry should be put in place for patients who initially decline.

2. The Standards

8 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

STANDARD 3

Early initial assessment of individual patient needs, which informs the

agreed personalised goals that are reviewed regularly

• The initial assessment shall commence within 10 working days of receipt of referral.

•

The initial assessment is deemed complete when documentation of all the following has taken place:

• Demographic information and social determinants of health;

• Medical history, current health status and symptoms, together with a review of any relevant

investigations;

• Lifestyle risk factors (exposure to tobacco, adherence to a cardioprotective diet, body

composition, physical activity status and exercise capacity);

• Psychosocial health (anxiety, depression, illness perception, social support, psychological

stress, sexual wellbeing and quality of life);

• Medical risk management (control of blood pressure, lipids and glucose, use of

cardioprotective therapies and adherence to pharmacotherapies).

• Additional parameters should be assessed on an individual basis and may include psychosocial

factors such as anger, hostility, substance misuse, and occupational distress.

• Even if the initial assessment cannot be completed in its entirety (e.g. exercise capacity

assessment temporarily contraindicated) this shall not delay the assessment of the remaining

elements or the commencement of a formal CPRP.

• The initial assessment shall identify each individual’s needs using validated measures that are

culturally sensitive and also take account of associated co-morbidities.

• The assessment shall identify any physical, psychological or behavioural issues that have the

potential to impact on the patient’s ability to make the desired lifestyle changes.

• The assessment shall include formal risk stratification for exercise utilising all relevant patient

information (e.g. left ventricular ejection fraction, history of arrhythmia, symptoms, functional capacity).

• The written care plan should include a defined pathway of care which meets the individual patient

needs, participation preferences and choices.

• Patients shall receive on-going assessment throughout their CPRP and a regular review of their

goals with adjustments agreed and documented where required.

2. The Standards

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 9

STANDARD 4

Early provision of a structured Cardiovascular Prevention and

Rehabilitation Programme (CPRP) with a defined pathway of

care which meets the individual’s goals and is aligned with

patient preference and choice

• A CPRP shall be deemed underway once patient goal(s) have been identified and appropriate

interventions have begun. This should occur immediately following completion of the initial

assessment (Standard 3) and shall occur within 10 working days of receipt of referral.

• In instances where commencement of group-based exercise has to be postponed, such as a

patient presenting with a contraindication to exercise, this shall not delay initiating management

strategies in other relevant core components.

• In order to maximise uptake, completion and outcomes, CPRPs shall deliver a menu-based

approach to meet a patient’s individual needs. This should include choice in terms of venue (e.g.

home, community, hospital) and scheduling of sessions (e.g. early mornings, evening & weekends).

• CPRPs can be delivered using a variety of modes (e.g. centre-based, home-based, manual-

based, web-based etc.). Irrespective of mode of programme delivery:

• Interventions provided are evidence-based and address the individual’s needs across all the

relevant core components.

• Patients shall have access to the multidisciplinary team as required.

• Patients shall be supported to participate in a personalised structured exercise programme

at least two to three times a week, designed specifically to increase physical fitness. This

requires documented evidence of regular review, goal setting and exercise progression.

• There shall be documented interaction between the patient and the multidisciplinary team

lasting a minimum of 8 weeks.

2. The Standards

10 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

STANDARD 5

Upon programme completion, a final assessment of individual

patient needs and demonstration of sustainable health outcomes

• In order to demonstrate effective health outcomes and ascertain the extent to which a patient’s

goals have been achieved, a formal assessment shall be performed at programme completion

which includes all the initially assessed components:

• Lifestyle related risk factors (exposure to tobacco, adherence to a cardioprotective diet, body

composition, physical activity status and exercise capacity);

• Psychosocial health (anxiety, depression, illness perception, social support, psychological

stress, sexual wellbeing and quality of life);

• Medical risk management (control of blood pressure, lipids and glucose, use of

cardioprotective therapies and adherence to pharmacotherapies).

• Any additional parameters assessed initially should be re-assessed formally upon programme

completion. For example, additional psychosocial factors such as anger, hostility, substance

misuse, and occupational distress.

• Data from the final assessment shall be formally recorded for evaluation of outcome measures

and audit.

• Final assessment shall be used to identify any unmet goals as well as any newly developed or

evolving clinical issues. This shall assist the formulation of long-term strategies.

• Within 10 working days of programme completion, the primary care provider (and the referral

source where relevant) shall be provided with a pre/post comparison of the patient’s risk factor

profile together with current medications and a summary of the long-term strategies proposed. A

copy shall also be provided to the patient.

STANDARD 6

Registration and submission of data to the National Audit for

Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) and participation in the National

Certification Programme

• Formal audit and evaluation shall include service level and patient level data at baseline and

following CR on clinical outcomes, patient experience and satisfaction.

• In order to monitor the quality of service delivery and to clearly demonstrate clinical outcomes

every service shall routinely submit the required audit data to NACR each year.

• Every cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation service should strive to meet requirements

for the National Certification Programme and submit their data to the certification panel. Once

achieved, CPRPs should maintain their certification status.

2. The Standards

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 11

3. The Core Components

A key aim of a CPRP, through the core components, is not only to improve physical health and quality

of life but also to equip and support people to develop the necessary skills to successfully self-manage.

Delivery should adopt a biopsychosocial evidence-based approach which is culturally appropriate and

sensitive to individual needs and preferences.

Figure 3 illustrates the six core components which include:

• Health behaviour change and education

• Lifestyle risk factor management

- Physical activity and exercise

- Healthy eating and body composition

- Tobacco cessation and relapse prevention

• Psychosocial health

• Medical risk management

• Long-term strategies

• Audit and evaluation

Practitioners who lead each of the core components must be able to demonstrate that they (or their

delivery team) have appropriate training, professional development, qualifi cations, skills and competency

for the component(s) for which they are responsible (Standard 1). BACPR aims to be a resource for

providing guidance on the knowledge, skills and competences required for each of the components.

Figure 3: The BACPR model for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Rehabilitation

A

U

D

I

T

A

N

D

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

L

O

N

G

-

T

E

R

M

S

T

R

A

T

E

G

I

E

S

Health

behaviour

change and

education

P

s

y

c

h

o

s

o

c

i

a

l

h

e

a

l

t

h

L

i

f

e

s

t

y

l

e

r

i

s

k

f

a

c

t

o

r

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

M

e

d

i

c

a

l

r

i

s

k

The Six Core Components

for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Rehabilitation

12 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

3.1. Health behaviour change and education

In meeting individual needs, health behaviour change and education are integral to all the other

components of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Adopting healthy behaviours is the

cornerstone of prevention and control of cardiovascular disease.

3.1.1 Health behaviour change

To facilitate effective behaviour change, cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation services should ensure:

• The use of health behaviour change interventions and key behavior change techniques underpinned

by an up-to-date psychological evidence-base.

31

• The provision of or access to, training in communication skills for all staff which may include

motivational interviewing techniques and relapse prevention strategies.

• The provision of information and education to support fully informed choice from a menu of evidence-

based locally available programme components. Offering choice may improve uptake and adherence

to cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation.

16-32

• They address any cardiac or other misconceptions (including any about cardiovascular prevention

and rehabilitation) and illness perceptions that lead to increased disability and distress.

33-35

• Support for patients (and significant supporting others) including goal-setting and pacing skills, and

exploring problem-solving skills in order to improve long-term self-management.

• Regular follow up to assess feedback and advise on further goal setting.

36

• Where possible, the patient identifies someone best placed to support him/her (e.g. a partner,

relative, close friend). The accompanying person should be encouraged to actively participate in

CPRP activities whenever possible, to maximise patient recovery and health behaviour change whilst

also addressing their own health behaviours.

37-39

3.1.2 Education

Education should be delivered not only to increase knowledge but importantly to restore confidence and

foster a greater sense of perceived personal control. As far as possible, education should be delivered

in a discursive rather than a didactic fashion. It is not enough to simply deliver information in designated

education sessions; health behaviour change needs to be achieved simultaneously and fully integrated

into the whole service.

Attention should be paid to establishing existing levels of knowledge and to assessing learning needs (of

individuals and groups), and subsequently tailoring information to suit assessed needs.

• Patients (and significant supporting others) should be encouraged to play an active role in the

educative process, sharing information in order to maximise uptake of knowledge.

• Education should be culturally sensitive and achieve two key aims:

- To increase knowledge and understanding of risk factor reduction

- To utilise evidence-based health behaviour change theory in its delivery. Incorporation of both

aspects of education increases the probability of successful long-term maintenance of change.

3. The Core Components

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 13

• The educational component should be delivered using high quality and varied teaching methods

which take account of different learning styles and uses the best available resources to enable

individuals to learn about their condition and management. Information should be presented in

different formats using plain language and clear design, and tailored to the learning needs identified

during initial assessment.

40

• The education component of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation should empower individuals

to better manage their condition. Topics may include:

• Pathophysiology and symptoms

• Physical activity, healthy eating and weight management

• Tobacco cessation and relapse prevention

• Self-management and behavioural management of other risk factors including blood pressure,

lipids and glucose

• Medical and pharmaceutical management of blood pressure, lipids and glucose

• Psychological and emotional self-management

• Social support and other contextual factors

• Activities of daily living

• Occupational/vocational factors

• Resuming and maintaining sexual relations and dealing with sexual dysfunction

• Surgical interventions and devices

• Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

• Additional information, as specified in other components.

3.2 Lifestyle risk factor management

Physical activity and exercise, together with a healthy diet and avoidance of obesity and exposure to all

forms of tobacco, represents a lifestyle that is strongly associated with good cardiovascular health. All

patients should have the opportunity to discuss their concerns across all of these lifestyle risk factors as

relevant. Achievement of the lifestyle targets, as defined by the most up to date Joint British Societies

Guidelines, should utilise evidence-based health behaviour change approaches led by specialists in

collaboration with the multidisciplinary team. Supporting individuals in developing self-management skills

is the cornerstone of long-term cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation.

3.2.1 Physical activity and exercise

• Staff leading the exercise component of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation should be

appropriately qualified, skilled and competent.

41

• Baseline assessment of physical fitness shall be carried out to inform risk assessment, tailor the

exercise prescription and aid goal setting.

42-45

• Best practice standards and guidelines for physical activity and exercise prescription shall be used.

42-44

3. The Core Components

14 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

• Risk stratification, based upon clinical features and baseline exercise capacity shall be undertaken.

42

This will then determine the appropriate:

- Exercise prescription, activities of daily living (ADL) guidance and support

- Staffing levels and skills

41

- Resuscitation support and provision in line with current Resuscitation Council UK / BACPR

guidance

46

- Choice of venue (home/community/hospital).

• Patients should receive individual guidance and advice on ADLs together with a tailored activity

and exercise plan with the collective aim to increase physical fitness as well as overall daily energy

expenditure and decrease sedentary behaviour. The activity and exercise plan should be identified

with the patient, take account of their co-morbidities and should be sensitive to their physical,

psychosocial (cognitive and behavioural) capabilities and needs.

3.2.2 Healthy eating and body composition

• Staff leading the dietary component of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation should be

appropriately qualified, skilled and competent.

• All patients shall have a baseline assessment of their dietary habits, including adherence with a

cardioprotective diet and measurement of their weight, body mass index and waist circumference.

• The focus of advice should be on making healthy dietary choices to reduce total cardiovascular risk

and improve body composition.

• Misconceptions about nutrition, dieting and weight cycling should be addressed and corrected.

47-48

• Patients should receive personalised dietary advice that is sensitive to their culture, needs and

capabilities coupled with support to help them achieve and adhere to the components of a

cardioprotective diet as defined by the most up to date Joint British Societies and NICE guidelines.

49-51

• Patients with additional co-morbidities leading to more complex dietary requirements should be

assessed and managed individually by a registered dietitian.

• Weight management may form an important component in cardiovascular prevention and

rehabilitation and could include:

• weight gain (e.g. in debilitated patients)

• weight loss, which where appropriate and in relation to excess fat, is best achieved through a

combination of increased physical activity and reduced caloric intake

52

• weight maintenance (e.g. in those who have recently quit smoking

53

or those with heart failure).

• It may be appropriate to refer to the appropriate specialists for pharmacotherapy and/or bariatric

surgery in order to co-manage weight loss.

54

3.2.3 Tobacco cessation and relapse prevention

Staff delivering the tobacco cessation and relapse prevention component of cardiovascular prevention

and rehabilitation should be appropriately qualified, skilled and competent in keeping with the NHS

Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training Standard which is available for download from their website

– www.ncsct.co.uk.

55

3. The Core Components

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 15

• Current and past tobacco use should be assessed in all patients including whether they are a current user

or recent quitter, their history of tobacco use, past quit attempts and exposure to second hand smoke.

• In patients who are currently using tobacco, frequency and quantity of use should be quantified. In

addition, motivation to quit and a measure of nicotine dependence should be assessed, together with

identifying psychological co-morbidities like depression and tobacco use by others at home.

• At the first assessment, medical advice to quit should be reinforced and a quit plan discussed which

proposes the use of pharmacological support and follow up counselling within the prevention and

rehabilitation service. Every effort should be made to assist individuals to achieve complete cessation

of all forms of tobacco use, with repeat assessment of progress with cessation at every visit.

56-58

• Patient preference is a priority regarding the choice of aids to use in tobacco cessation. The use of

evidence-based therapies like Varenicline (Champix) and combination long- and short-acting nicotine

replacement therapy is considered the gold standard, however non-medical nicotine delivery devices

like e-cigarettes should also be considered as evidence is building for their efficacy. Guidance for

cessation advisers can be found in the NCSCT e-cigarette briefing.

59

• Preventing relapse is vital and may include prolonging the use of NRT and Varenicline (Champix)

beyond the usual duration, and/or e-cigarettes in cases where cessation has been problematic. Risk

of relapse is higher when an individual lives, socialises or works closely with others who use tobacco,

therefore encouraging quit attempts in partners/spouses/friends/children may be helpful.

3.3 Psychosocial health

People taking part in cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation may have many different emotional

issues, and a comprehensive, holistic assessment is crucial to achieving the desired outcomes.

Every patient should be screened for psychological, psychosocial and sexual health and wellbeing as

ineffective management can lead to poor health outcomes.

60-62

•

Staff leading the psychosocial health component should be appropriately qualified, skilled, and competent.

• All patients should undergo a valid assessment of:

- Psychological distress, for example, anxiety and depression (using an appropriate tool – Hospital

Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is available through the NACR)

-

Quality of life (using an appropriate tool - Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative (COOP) and Minnesota

Living With Heart Failure (MLWHF) are available through the NACR)

- Psychological stressors

- Illness perceptions and self-efficacy for health behaviour change

- Adequacy of social support (covered in Dartmouth COOP – available through NACR)

- Alcohol and substance misuse

• Services should help patients to increase awareness of ways in which psychological development,

including illness perceptions, stress awareness and improved stress management skills can affect

subsequent physical and emotional health.

• Attention should be paid to social support, as social isolation or lack of perceived social support

is associated with increased cardiac mortality.

63

Whereas appropriate social support is helpful,

overprotection may adversely affect quality of life.

64

3. The Core Components

16 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

• Levels of psychological intervention (for psychological distress):

- Cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation teams are best placed to deal with the normal range of

emotional distress associated with a patient’s precipitating cardiac event.

- Where appropriately trained psychological practitioners exist within the cardiovascular prevention

and rehabilitation team, individuals with clinical levels of anxiety or depression related to their

cardiac event can be managed within the service.

• In the absence of dedicated psychological practitioners in the team, individuals with clinical signs of

anxiety and depression, unrelated to their cardiac event, or with signs of severe and enduring mental

health problems, should have access to appropriately trained psychological practitioners and their GP

should be informed.

65-67

• Services should be aware of patients with problems related to alcohol misuse or substance misuse

and offer referral to an appropriate resource.

• It is also important to consider vocational advice and rehabilitation/financial implications and to

establish an agreed referral pathway to appropriate support and advice.

• Sexual health issues are also common with cardiovascular disease, and can negatively impact quality

of life and psychological wellbeing.

68-69

• Every patient should be provided with the opportunity to raise any concerns they may have

in relation to sexual activity and/or function. Assessment of patients’ sexual concerns can be

beneficial.

70

• Concerns or issues raised on assessment should be addressed through sexual counselling and

medical management where indicated.

70-72

• Patients dealing with longstanding or complex sexual health issues should be offered referral to an

appropriate resource.

70-72

3.4 Medical risk management

• Staff leading the medical risk management component of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation

services should be appropriately qualified, skilled and competent. Ideally an independent prescriber

should be part of the multidisciplinary team.

• Best practice standards and guidelines for medical risk factor management (blood pressure, lipids

and glucose),

49-51 73-75

optimisation of cardioprotective therapies and management of patients with

implantable devices

42 76-77

should be used.

• Assessment should include:

- Measurement of blood pressure, lipids, glucose, heart rate and rhythm.

- Current medication use (dose and adherence).

- Patients’ beliefs about medication as this affects adherence to drug regimens.

78

- A discussion regarding sexual activity / function (pending patient’s willingness to discuss).

- Implantable device settings where applicable.

• During the CPRP, blood pressure and glucose should be regularly monitored with the aim of helping

the individual to reach the targets defined in national guidelines by programme completion.

49-51 73-75

3. The Core Components

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 17

• Key cardioprotective medications are prescribed according to current guidance.

• Cardioprotective medications should be up-titrated during the programme so that evidence-based

dosages are achieved.

• Cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation staff should be involved with initiation and/or titration

of appropriate pharmacotherapy either directly through independent prescribing by a member of

the multidisciplinary team or agreed protocols / patient group directives or through liaison with an

appropriate healthcare professional (e.g. cardiologist, primary care physician).

•

Erectile dysfunction in cardiovascular patients is typically multifactorial with vascular disease, psychogenic

factors and medication all acting as potential contributors. Individuals with erectile dysfunction should be

considered for medication review and appropriate referral made where indicated.

• In people with Implantable devices, such as implantable cardiac defibrillators and/or cardiac

resynchronisation therapy:

• Devices can have an impact on psychological and physical function, exercise ability, which should

be considered within the individualised programme and may require additional expertise.

42 79-80

• Liaison with specialist cardiac services is important (e.g. arrhythmia nurse specialist,

electrophysiologist and cardiac physiologist).

• Cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation services also provide an opportunity to identify patients

who may benefit from an implantable device.

76

3.5 Long-term strategies

By the end of the CPRP the patient should have:

• undergone assessment and reassessment as identified in Standards 3 and 5

• participated in a tailored programme that encompasses the Core Components

• identified their long-term management goals.

3.5.1 Patient responsibilities

• By the end of the programme patients will have been encouraged to develop full biopsychosocial

self-management skills and so be empowered and prepared to take ownership of their own

responsibility to pursue a healthy lifestyle. Carers, spouses and family should also be equipped to

contribute to long-term adherence by helping and encouraging the individual to achieve their goals.

• Patients and their families should be signposted and encouraged, where appropriate, to join:

- local heart support groups

- community exercise and activity groups

- community dietetic and weight management services

- tobacco and smoking cessation services.

• Promoting ongoing self-management strategies could also include online applications or tools and

self-monitoring resources.

3. The Core Components

18 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

3.5.2 Service responsibilities

•

Patients should be supported to plan and implement self-management strategies to help them transition

from the CPRP and continue to work towards minimising their risk of cardiovascular disease progression

following programme completion.

•

Upon programme completion there should be a formal assessment of lifestyle risk factors (physical

activity, diet and tobacco use as relevant), psychological and psychosocial health status, medical risk

factors (blood pressure, lipids and glucose) and use of cardioprotective therapies together with long-term

management goals. This should be communicated by discharge letter to the referrer and the patient as

well as those directly involved in the continuation of healthcare provision.

•

There should be communication and collaboration between primary and secondary care services to

achieve the long-term management plan.

•

Patients should be registered onto GP Practice CHD/CVD registers.

3.6 Audit and Evaluation

The NHS and its services are required, through NICE Guidance, to offer CR to all eligible patients and

in doing so they are duty bound to audit their performance locally and supply data to ensure equity of

service delivery nationally. Although uptake to CR is improving the quality of the services delivered is not

unified across the UK.

81

The BACPR recommends that every CPRP should formally audit and evaluate their service which can

be achieved through using the NACR directly or through upload of data if collected on local provider

software. The BACPR include the contribution of data to the National Audit for Cardiac Rehabilitation

(NACR) as a standard as this plays a key role in monitoring the quality of service delivery and influencing

and informing national policy. Data entered directly or uploaded to NHS Digital (the organisation that

hosts NACR data) should include both individual and service level data based on assessment and

including outcomes.

Service level audit should therefore include the collection of data to meet the following aims:

• Monitor and manage patient progress

• Monitor cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation service resources

• Evaluate programmes in terms of clinical and patient-reported outcomes

• Benchmarking against local, regional and national standards

• Provide measures of performance and quality for commissioners and providers of cardiovascular

prevention and rehabilitation services

• Contribute to the national audit functions

• Present and share cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation outcomes in both clinical and

patient formats

Where service resources and service design permits, the BACPR encourages cardiovascular prevention

and rehabilitation teams to provide one-year follow-up data as part of audit. NHS Digital-NACR has

the capability and capacity to capture this data within their online software. The ability to report at 12

months requires a high level of integration and communication between secondary and primary care

which can be achieved without duplication of work if carried out within the NHS Digital-NACR software

which is integrated along the patient journey.

3. The Core Components

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 19

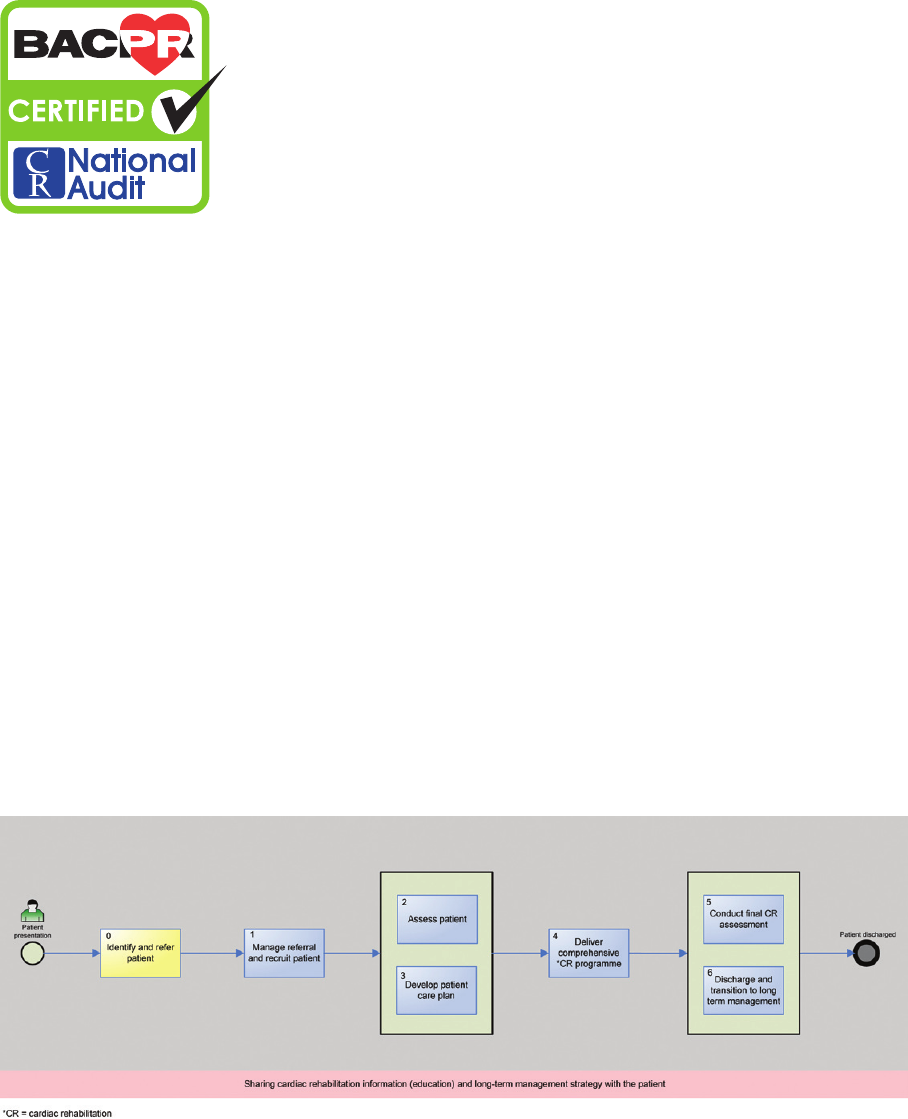

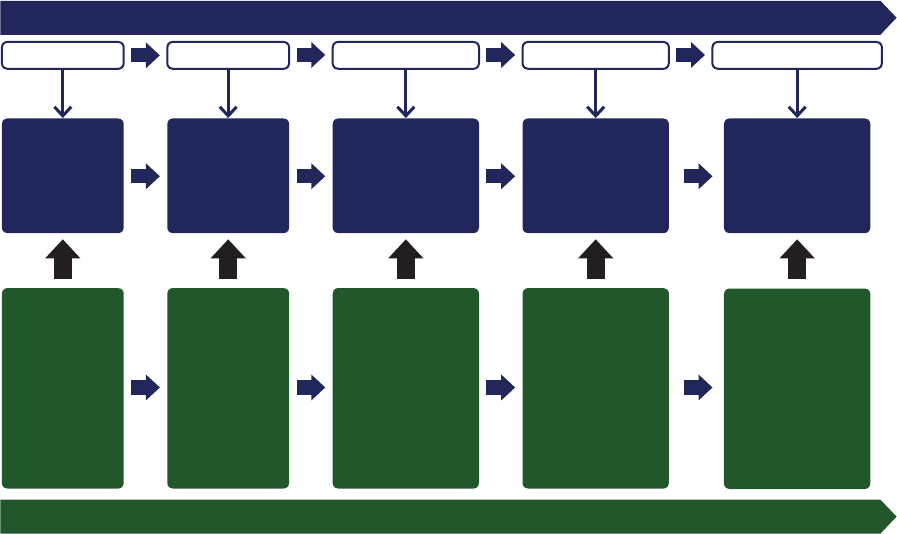

Figure 4. CR patient journey aligned with NACR data entry pathway

3.6.1 National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NCP_CR)

The BACPR and the NACR launched a joint National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation

(NCP_CR) in 2016 with an aim to ensure that all programmes are working to agreed clinical standards.

The new 2017 Standards and Core Components are aligned with data requirements for the NCP_CR.

25

The BACPR encourages all programmes to submit data and register for the NCP_CR so that patients,

wherever they live, can be confident that the services on offer meet agreed minimum standards.

The ultimate goal is for all CR programmes to deliver services in line with the Standards and Core

Components in this document, however at present most programmes are working towards the minimum

standards as outlined in the NCP_CR.

81

Future NACR reports will incorporate the extent by which

programmes are meeting NCP_CR criteria.

3. The Core Components

CR patient journey aligned with NACR data entry pathway

National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation

GP / Acute

Identify and refer

patient

Reason for referral

recorded in Initiating

Event. Source of

referral, and referral

date recorded

Referral dates and

start dates for all

early and core rehab

Risk Assessment

Previous events and

comorbidities

Manage referral

and recruit patient

Acute / Outpatient

Assessment 1, baseline

before core rehab

delivery:

From patient

self assessment

questionnaire, and clinical

appointment

Measures physical /

activity / fitness / anxiety

and depression / drugs

Tailored rehab based on

assessment

Assess Patient

Develop patient care

plan

Outpatient / Community

Duration and number

of sessions measured:

type of rehab delivered

recorded. Core

components listed

Deliver

comprehensive

CR Programme

Outpatient / Community

Assessment 2 end

of rehab. Repeat of

measurements at Ass 1

for outcomes

Onward referral

recorded

Ass 3 at 12 month follow

up if resourced to do so

Conduct final CR

Assessment

Discharge and

transition to long term

management

Outpatient / Community / GP

20 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

4. Appendices

Appendix 1: References

1. Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Vascular protection in people with

diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2013;37(Suppl 1):S100-4.

2. Dasgupta K, Quinn RR, Zarnke KB, et. al. for the Canadian Hypertension Education Program. The 2014 Canadian

Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk,

prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2014;30:485-501.

3. Schuler G, Adams V, Goto Y. Role of exercise in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: results, mechanisms, and

new perspectives. European Heart Journal. 2013;34:1790-9.

4. Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, Konety SH. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation.

2016;133(11):1104-14.

5. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, colleagues. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable

to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224-60. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/

article/pii/S0140673612617668

6. The World Health Organisation (WHO). Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention: long term care for patients

with ischaemic heart disease. Briefing letter. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional office for Europe, 1993.

7. Feigenbaum E. Cardiac rehabilitation services [microform] / [E. Feigenbaum, E. Carter]. Rockville, MD U.S. Dept. of

Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Center for Health Services Research and Health Care

Technology Assessment; Available from National Technical Information Service, 1987.

8. Goble AJ, Worcester MU. Best practice guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention. Melbourne,

Australia: The Heart Research Centre, on behalf of Department of Human Services Victoria, 1999.

9. DiMatteo MR, Haskard KB, Williams SL. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis.

Medical Care. 2007;45(6):521-8.

10. Gatchel RJ, Oordt MS. Clinical health psychology and primary care: Practical advice and clinical guidance for

successful collaboration. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003.

11. Carlson JJ, Norman GJ, Feltz DL, Franklin BA, Johnson JA, Locke SK. Self-efficacy, psychosocial factors, and

exercise behavior in traditional versus modified cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation.

2001;21(6):363-73.

12. Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, Zwisler A, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation

of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;Issue 1(Art. No.: CD001800.) Available at:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub3/abstract

13. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ. 2015;351 Available at: http://www.bmj.com/content/

bmj/351/bmj.h5000.full.pdf

14. Rauch B, Davos CH, Doherty P, Saure D, Metzendorf M-I, Salzwedel A, Voller H, Jensen K, Schmid J-P, on

behalf of the Cardiac Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). The prognostic

effect of cardiac rehabilitation in the era of acute revascularisation and statin therapy: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies – The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS).

European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2016;23(18):1914-39. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/

abs/10.1177/2047487316671181

15. Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJS, Dalal HM, Lough F, Rees K, Singh S, Taylor RS. Exercise-based

rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2015;2(1) Available at:

http://openheart.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000163

16. Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, Zawada A, Dean SG, Cowie A, Norton RJ. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac

rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(8) Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

CD007130.pub3

17. Yohannes AM, Doherty P, Bundy C, Yalfani A. The long-term benefits of cardiac rehabilitation on depression, anxiety,

physical activity and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(19-20):2806-13.

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiac rehabilitation services: commissioning guide. London: NICE,

2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs9/resources/cardiac-rehabilitation-services-commissioning-

guide-304110253

19. Eder B, Hofmann P, von Duvillard SP, Brandt D, Schmid J, Pokan R, Wonisch M. Early 4-Week cardiac rehabilitation

exercise training in elderly patients after heart surgery. Journal of Cardiopulmary Rehabilitation and Prevention.

2010;30(2):85-92.

20. Maachi C, Fattirolli F, Molino Lova R, Conti AA, Luisi MLE, Intini R, Zipoli R, Burgisser C, Guarducci L, Masotti G,

Gensini GF. Early and late rehabilitation and physical training in elderly patients after cardiac surgery. American Journal

of Physical and Medical Rehabilitation. 2007;86:826-34.

Standards and Core Components 2017 (3rd Edition) 21

21. Aamot I, Moholdt T, Amundsen B, Solberg HS, Mørkved S, Støylen A. Onset of exercise training 14 days after

uncomplicated MI: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation.

2010;17(14):387-92.

22. Haykowsky M, Scott J, Esch B, Schopflocher D, Myers J, Paterson I, Warburton D, Jones L, Clark AM. A meta-

analysis of the effects of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: start early and

go longer for greatest exercise benefits on remodeling. Trials. 2011;12(92): DOI: 10.1186/745-6215-12-92.

23. Davies P, Taylor F, Beswick A, Wise F, Moxham T, Rees K, Ebrahim S. Promoting patient uptake and adherence

in cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010; Issue 7.(Art. No.: CD007131.):

DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007131.pub2.

24. Cossette S, Frasure-Smith N, Dupuis J, Juneau M, Guertin M. Randomized controlled trial of tailored nursing

interventions to improve cardiac rehabilitation enrolment. Nursing Research. 2012;61(2):111-20.

25. Furze G, Doherty P, Grant-Pearce C. Development of a UK National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation

(NCP_CR). British Journal of Cardiology. 2016;23:102-5.

26. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Annual reports 2007 to 2016. University of York: British Heart Foundation

Available at: http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/reports.htm

27. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic heart failure: Costing report for CG 108. Implementing NICE

Guidance. London: NICE, 2010. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg108/resources

28. Department of Health. Commissioning pack for cardiac rehabilitation. London: Department of Health, 2010.

Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/

PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/DH_117504

29. Monitor. 2016/2017 National tariff payment system. London: NHS England Publications, 2016. Available at: https://

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/509697/2016-17_National_Tariff_Payment_

System.pdf

30. Department of Health. Cardiac rehabilitation: Costing tool guidance. London: Department of Health, 2010. Available at:

http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/docs/Cardiac%20Rehabilitation%20Costing%20Tool%20Guidance.pdf

31. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Behaviour change: Individual approaches. PH49. London: NICE,

2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49

32. Dalal HM, Wingham J, Evans P, Taylor R, Campbell J. Home based cardiac rehabilitation could improve outcomes.

BMJ. 2009;338(12, 1):1921.

33. Stafford L, Berk M, Jackson HJ. Are illness perceptions about coronary artery disease predictive of depression and

quality of life outcomes? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;66(3):211-20.

34. French DP, Cooper A, Weinman J. Illness perceptions predict attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute

myocardial infarction: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:757-67.

35. Furze G, Lewin R, Murberg TA, Bull P, Thompson D. Does it matter what patients think? The relationship between

changes in patients’ beliefs about angina and their psychological and functional status. Journal of Psychosomatic

Research. 2005;59:323-9.

36. Institute of Medicine. Priority areas for national action: Transforming healthcare quality. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press, 2003:52.

37. Moser DK, Dracup K. Role of spousal anxiety and depression in patients’ psychosocial recovery after a cardiac event.

Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:527-32.

38. Franks M, Stephens MAP, Rook KS, Franklin BA, Keteyian SJ, Artinian NT. Spouses’ provision of health-related

support and control to patients participating in cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):311-8.

39. Wood DA, Kotseva K, Connolly S, Jennings C, Mead A, Jones J, Holden A, De Bacquer D, Collier T, De Backer

G, Faergeman O, on behalf of EUROACTION Study Group. Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based

cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and

asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet.

2008;371:1999-2012.

40. Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human

resource development (8th ed.). Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 2015.

41. British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Exercise Professionals Group (BACPR-EPG).

Position statement: Essential competences and minimum qualifications required to lead the exercise component in

early cardiac rehabilitation. 2011. Available at http://www.bacpr.com.

42. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Cardiac Rehabilitation (ACPICR). ACPICR standards for physical activity

and exercise in the cardiac population. 2015. Available at: http://acpicr.com/publications

43. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR). Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation

and Secondary Prevention Programs. 5th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2013.

4. Appendices

22 British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

44. Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, Bittner V, Comoss P, Foody JM, Franklin B, Sanderson B, Southard D. Core

components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the

American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical

Cardiology; the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity,

and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation.

2007;115(20):2675-82.

45. Piepoli MF, Corrà U, Adamopoulos S, et al., on behalf of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European

Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR). Secondary prevention in the clinical

management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for

referral and delivery: A Policy Statement from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the EACPR. Endorsed by the

Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

2014;21(6):664-81.

46. Resuscitation Council (UK). Requirements for resuscitation training and facilities for supervised cardiac rehabilitation

programmes. 2013. Available at: https://www.resus.org.uk/cpr/requirements-for-resuscitation-training/

47. British Nutrition Foundation. Obesity: The report of the British Nutrition Foundation Task Force. London: Blackwell

Science, 1999.

48. Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, Daníelsdóttir S, Shuman E, Davis C, Caolgero RM. Weight-inclusive versus

weight-normative approach to health: evaluation the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. Journal of

Obesity. 2014;Article ID 983495. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/983495

49. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further

cardiovascular disease. CG172. London: NICE, 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg172

50. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Unstable Angina and NSTEMI: the early management of unstable

angina and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. CG94, Updated 2013. London: NICE, 2010. Available at:

www.nice.org.uk/CG94

51. JBS3 Board. Joint British Societies’ consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (JBS3).

Heart. 2014;100(Suppl 2):ii1-ii67. Available at: http://heart.bmj.com/content/100/Suppl_2/ii1.short

52. Shaw K, Gennat H, O’Rourke P, Del Mar C. Exercise for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews. 2006;Oct 18(4):CD003817.

53. Aubin H-J, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis.

BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4439

54. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Obesity guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and

management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. CG43. London: NICE, 2006, updated 2013. Available

at: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG43NICE

55. NHS Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT). NCSCT training. Available at: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/

training

56. Rice VH, Stead LF. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

2008(1):Art. No.: CD001188. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub3

57. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation: guidance.

PH1. London: NICE, 2006. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH1

58. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local

authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities.

PH10. London: NICE, 2008, Updated 2013. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH10

59. McEwen A, McRobbie H, on behalf of the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) and Public

Health England. Electronic cigarettes: A briefing for stop smoking services. Dorchester: NCSCT, 2016. Available at:

http://www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_electronic_cigarette_briefing.php

60. Shibeshi WA, Young-Xu Y, Blatt CM. Anxiety worsens prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of

the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49:2021-7.

61. Dickens C, McGowan L, Percival C, Tomenson B, Cotter L, Heagerty A, Creed F. New onset depression following

myocardial infarction predicts cardiac mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:450-5.

62. Kronish IM. Persistent depression affects adherence to secondary prevention behaviors after acute coronary

syndromes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:1178-83.

63. Mookadam F, Arthur H. Systematic overview: social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute

myocardial infarction. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(14):1514-8.

64. Joekes K, Maes S, Warrens M. Predicting quality of life and self-management from dyadic support and overprotection

after myocardial infarction. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:473-89.

65. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults with a chronic condition. CG 91. London: NICE,

2009. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG91

4. Appendices

66. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Common mental health problems: Identification and pathways to

care. CG123. London: NICE, 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123

67. Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Ebrahim S, Lui Z, West R, Moxham T, Thompson DR, Taylor

RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

2011;10(8):CD002902. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub3/full

68. Træen B, Olsen S. Sexual dysfunction and sexual well-being in people with heart disease. Sexual and Relationship

Therapy. 2007;22:193-208.

69. Günzler C, Kriston L, Harms A, Berner MM. Association of sexual functioning and quality of partnership in patients in

cardiovascular rehabilitation-a gender perspective. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(1):164-74.

70. Steinke EE, Jaarsma T, Barnason SA, Byrne M, Doherty S, Dougherty CM, Bengt F, Kautz DD, Mårtensson J,

Mosack V, Moser DK, 2013;128:2075–96 C. Sexual counselling for individuals with cardiovascular disease and their

partners: a consensus document from the American Heart Association and the ESC Council on Cardiovascular

Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP). Circulation. 2013;128(18):2075-96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1161/

CIR.0b013e31829c2e53

71. Tra Levine GN, Steinke EE, Bakaeen FG, Bozkurt B, Cheitlin MD, Conti JB, Foster E, Jaarsma T, Kloner RA, Lange

RA, Lindau ST, Maron BJ, Moser DK, Ohman EM, Seftel AD, Stewart WJ. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease:

a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(8):1058-72. Available at: https://doi.

org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182447787

72. Steinke EE, Swan JH. Effectiveness of a videotape for sexual counseling after myocardial infarction. Research in

Nursing and Health. 2004;27:269-80.

73. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension. CG127. London: NICE, 2011, Updated 2016.

Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG127

74. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including

lipid modification: CG181. London: NICE, 2014, Updated 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

75. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NG28. London: NICE,

2015, Updated 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

76. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators and cardiac resynchronisation