J lltlth l!N 1

CANADIAN HEALTH

INSURANCE

Lessons for the

United States

Ill II 118 II II

144039

,

._------.-

‘!

CAO/EEKI)-w-!10

GAllIll ~$iz?t&z&Lwmf&

,

. .

Human Resources Division

B-244081

June 4,199l

The Honorable John Conyers, Jr.

Chairman, Committee on Government Operations

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

This report, prepared at the Committee’s request, reviews Canada’s universal, publicly

funded insurance system. The report describes the policies used in this system, consequences

for both health care spending and access, and implications for the United States.

We are sending copies of this report to interested congressional committees and are making

copies available to others on request.

This report was prepared under the direction of Mark V. Nadel, Associate Director, National

and Public Health Issues, who may be reached on (202) 276-6196 if you or your staff have

any questions. Other major contributors to this report are listed in appendix II.

Sincerely yours,

Lawrence H. Thompson

Assistant Comptroller General

Executive Summary

Purpose

Recent polls indicate widespread dissatisfaction with the way the

United States finances and controls the cost of health care. Health

spending consumes a steadily rising share of our national income-

almost 12 percent of gross national product in 1989, headed to 16 per-

cent by the end of the decade. Yet many Americans who lack health

insurance face severe difficulty gaining access to health care. This situa-

tion has revived national debate over the way we finance health care.

Meanwhile, other industrialized nations assure that everyone has access

to the health care system, have health status indicators that equal or

exceed those of the United States, and accomplish these goals while

spending less than the United States. This contrast between the U.S. and

foreign experience suggests that the way other nations finance health

B”J

services may contain useful ideas that might be adapted to the U.S.

system. Some have looked to Canada, where the health program has

broad popular support and all residents are covered by the program, but

per capita spending is significantly less than in the United States. Yet

the Canadian program has some features in common with the United

States. Canadians choose their own private physicians, those physicians

are compensated on a fee-for-service basis, and most hospitals are pri-

vate, nonprofit institutions.

The Chairman, House Committee on Government Operations, asked

GAO

to assess whether the Canadian health care system had useful lessons

for the United States. He asked

GAO

to review salient features of the

Canadian system and analyze the likely effects on cost and access of

adopting elements of a Canadian-style system.

Background

Canada’s publicly funded health care system consists of

10 separate

provincial plans sharing certain features. Health insurance is universal,

covering all medically necessary hospital and physician services. Thus

coverage does not change dramatically or disappear when a person

changes jobs, as can happen in the United States.

The Canadian system is administered in each province by a public

agency, which is responsible both for reimbursing providers and for

health planning. The provincial governments are the single payers of

physicians and hospitals and make the key decisions on health

financing. Those governments are thus responsible, both politically and

financially, for the health care system. In this role, provincial govern-

ments determine overall increases in hospital budgets and physician fees

and regulate the acquisition of expensive equipment and services. This

Page 2

GAO/HItDQl-90

Chnadhn Health Insurame

Executive Summaxy

contrasts with the U.S. system, in which hospitals and physicians are

reimbursed by numerous payers (federal and state governments, private

insurers, businesses, and individual consumers) using widely differing

procedures and coverage, and no one has responsibility for the condition

of the system as a whole.

An added feature of the Canadian system is that there are no deduct-

ibles or copayments for covered services, so Canadians spend out of

pocket (or purchase private insurance) only for services that are not

covered by their provincial plan-such as routine adult dental care, cos-

metic surgery, and hospital room amenities.

Results in Brief

If the universal coverage and single-payer features of the Canadian

system were applied in the United States, the savings in administrative

costs alone would be more than enough to finance insurance coverage

for the millions of Americans who are currently uninsured. There would

be enough left over to permit a reduction, or possibly even the elimina-

tion, of copayments and deductibles, if that were deemed appropriate.

If the single payer also had the authority and responsibility to oversee

the system as a whole, as in Canada, it could potentially constrain the

growth in long-run health care costs. Measured either on a per capita

basis or as a share of gross national product, health care costs have

risen at a dramatically slower pace in Canada than in the United States.

The difference reflects Canada’s low administrative costs, controls on

hospital budgets and on the acquisition of high-technology equipment,

and fee controls for physician services.

Canadians have few problems with access to primary care services.

There are more physicians per person in Canada than in the United

States, and Canadians use more physician services per person than do

US. citizens. Yet the cost of physician services per person in Canada

was one-third less than in the United States.

The Canadian method of controlling hospital costs has limited the use of

expensive, high-technology diagnostic and surgical procedures. As a

result, waiting lists or queues have developed for some specialty care

services, such as cardiac bypass surgery, lens implants, and magnetic

resonance imaging. Emergency cases, however, are treated immediately,

bypassing the waiting lists.

Page 3

GAO/HRBQl-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Executive Summaw

A reformed U.S. system is not likely to look exactly like the Canadian

system, in part because the institutions that deliver and finance health

care in the two countries have evolved quite differently. But particular

elements of the Canadian system are worthy of consideration, including

universal access, a uniform payment system, and expenditure controls,

Principal Findings

Universal Access, Single

Payer, and No Cost

Sharing Are Key Features

of the Canadian System

Coverage, administration, and the use of copayments and deductibles

are the principal areas in which the U.S. and Canadian systems differ. In

other respects, such as the general use of fee-for-service physician reim-

bursement and the predominance of private, nonprofit hospitals, the

two systems are quite similar.

. In Canada, the Canada Health Act covers all residents in all provinces

for necessary physician and hospital care. Private health insurance that

duplicates services covered by the provincial plans is prohibited. In the

United States, coverage depends primarily on whether health insurance

is provided by an employer or through public programs serving the poor

and the elderly. Since some U.S. employers do not provide health insur-

ance benefits, there is a potentially significant impediment to moving

from one job to another in the United States that is not found in Canada.

. In Canada, health insurance is administered in each province by a single

public agency. In the United States, insurance programs are adminis-

tered by numerous private companies and public agencies. The Cana-

dian arrangement of concentrating financial responsibility in a single

payer permits much more efficient administration and allows for

greater control over health expenditures. In 1989, Canadian spending on

health was $670 per person less than in the United States; the differ-

ences primarily reflected savings on administrative costs and on physi-

cian and hospital reimbursement.

9 In Canada, direct patient payments to providers for covered services are

banned, and there are no copayments or deductibles. In the United

States, copayments and deductibles are common, and it is not unusual

for health care providers to bill the patient for charges in excess of the

standard insurance reimbursement. The Canadian arrangement elimi-

nates any financial barrier to access.

Page 4

GAO/HRDQl-99 Canadian Health Insurance

Executive Summary

Canada More Effective at

Canada has been much more successful than the United States in con-

Cost Containment

taining health care expenditures. In 1971, when Canada fully imple-

mented its system for financing medical services, the two countries

spent about the same share of gross national product on health care. In

1989, the U.S. share was 11.6 percent, whereas Canada’s was 8.9 per-

cent. The differences reflect lower Canadian spending on insurance

administration and on physician and hospital reimbursement.

Spending on Insurance

Canada’s publicly financed single payer system eliminates the costs

associated with marketing competitive health insurance policies, billing

for and collecting premiums, and evaluating insurance risks. As a result,

in 1987, the latest year for which comparable data are available,

Canada’s per capita spending on insurance administration was only one-

fifth that of the United States.

Spending on Physicians

In 1987, Canada spent 34 percent less per capita on physician services

than did the United States, reflecting the use of negotiated fee schedules

and lower practice expenses.

l

In Canada, physician professional associations in each province set

reimbursement rates for each service. Increases in these rates are nego-

tiated annually with the provincial government, which can use its power

as the single payer to restrain growth in costs. Between 1971 and 1986,

after adjusting for inflation, Canadian physician fees decreased 18 per-

cent, while those of U.S. physicians were rising 22 percent.

l

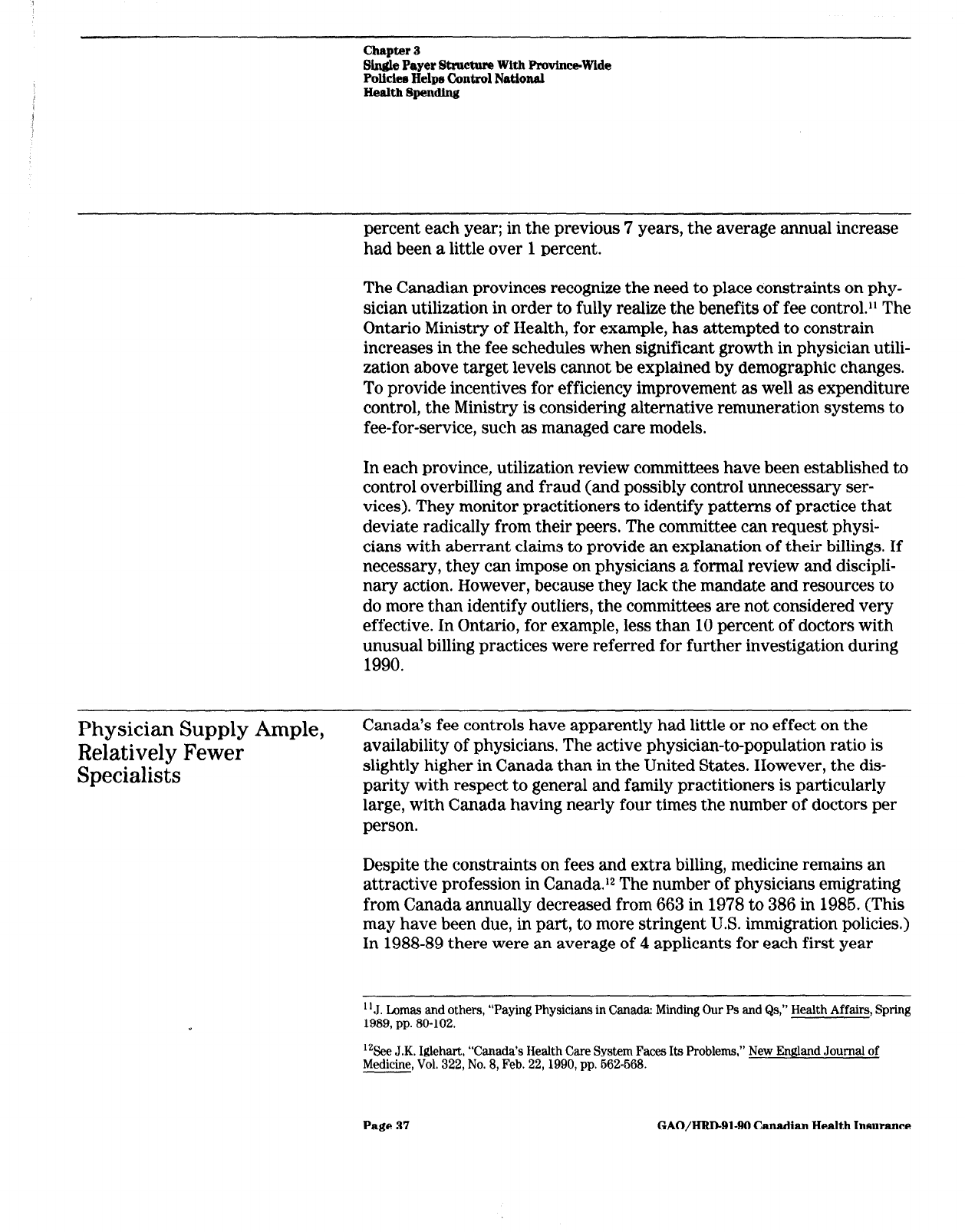

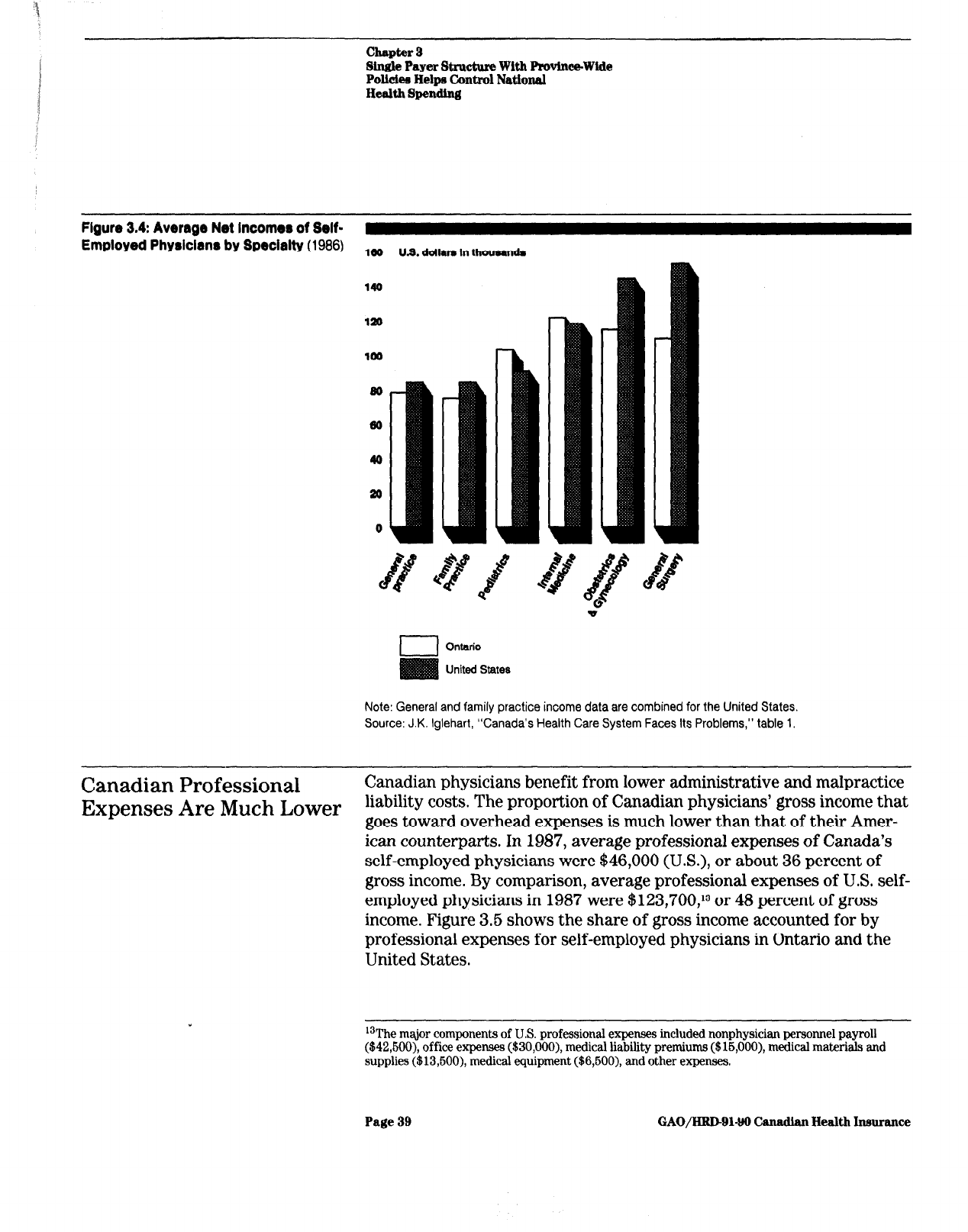

But lower physician fees do not necessarily mean substantially lower

net incomes under the single payer system. Canadian physicians need

not maintain an extensive office staff for insurance record keeping,

direct billing of patients, or collecting bad debts, as is needed by a U.S.

physician. In 1987, Canadian physicians spent an average of 36 percent

of their gross income on professional expenses, compared to 48 percent

for U.S. physicians. The Canadian system of negotiated fees permits

these savings to be captured for the taxpayer. In addition, malpractice

insurance premiums for U.S. physicians average 10 times those of their

Canadian counterparts, though this probably reflects differences in the

tort systems, rather than in the health insurance systems.

Spending on*Hospitals

The combination of lower hospital administrative costs and the use of

budget controls limiting equipment, facilities, and labor keeps Canadian

Page 6

GAO/HRD-91-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Executive Summary

hospital expenses down. In 1987, Canada spent 18 percent less per

person for hospital services than did the United States.

l

As with physicians, the single payer, universal coverage system permits

Canadian hospitals to have far lower administrative costs than do their

U.S. counterparts. A Canadian hospital has virtually no billing depart-

ment and a minimal accounting structure to assign costs and charges to

patients and physicians. This probably means, however, that Canadian

hospitals have substantially less detailed information on the cost of par-

ticular services than is available in a well-administered U.S. hospital.

. Canada’s chief means of controlling hospital expenditures are its system

of global (lump-sum) budgeting and its limits on the acquisition of high

technology. In Ontario, the Ministry of Health negotiates with individual

hospitals their annual operating budgets, which automatically capture

for the taxpayer the savings in administrative costs. The government

also decides which hospitals will acquire expensive high-technology

equipment and which will provide expensive specialized services.

Canadians Have Good

Access to Primary Care,

but May Wait for Some

High-Technology Services

In Canada, there are no financial barriers to health care, and there is an

ample supply of physicians. Residents of Canada make more physician

visits and have longer hospital stays than do their U.S. counterparts.

However, tight hospital operating budgets and restraints on the diffu-

sion of new medical technology mean that Canadians encounter limits on

access to some high-technology services.

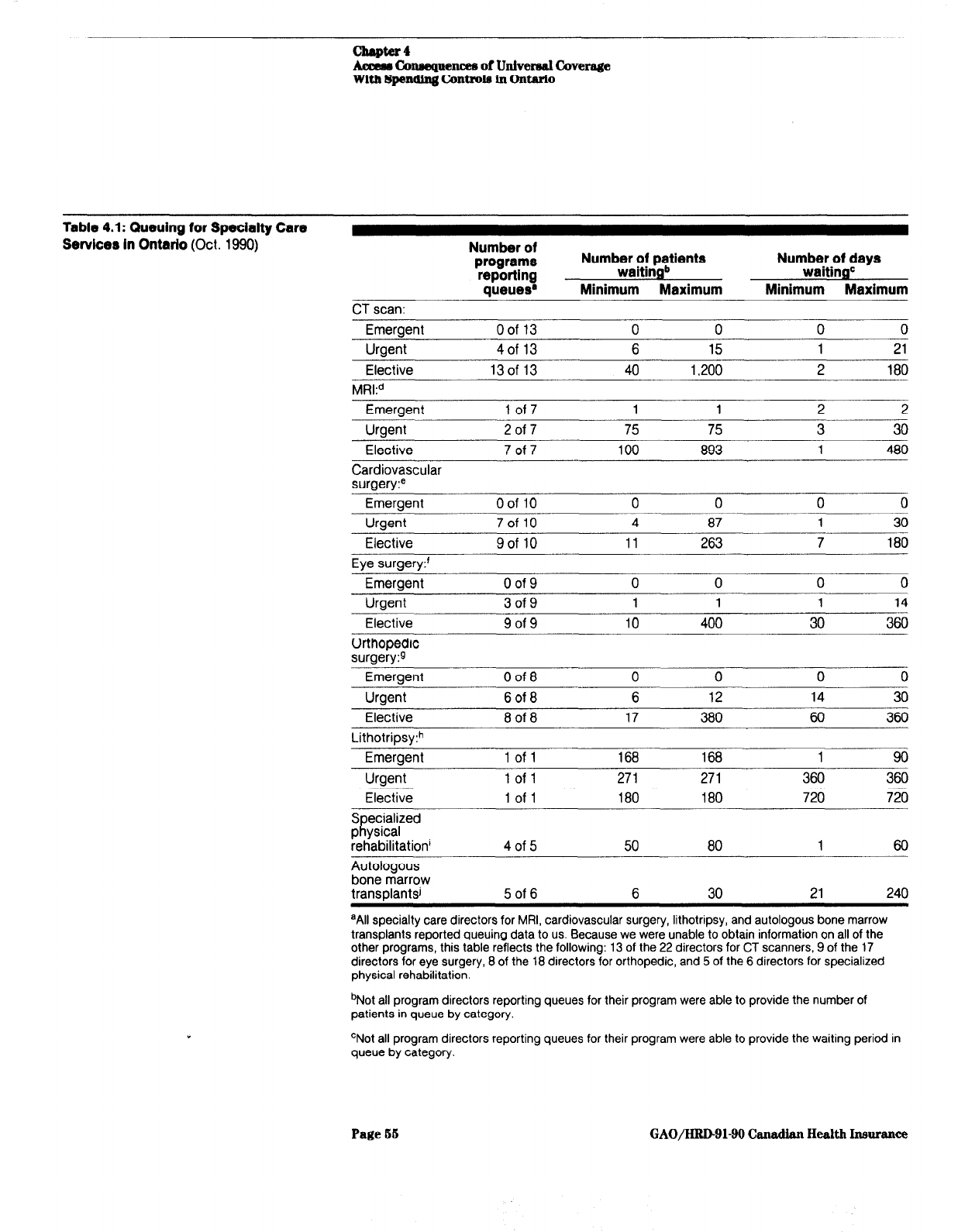

Patients with immediate or life-threatening needs rarely wait for ser-

vices, but waiting lists for elective surgery and diagnostic procedures

may be several months long. In October 1990, about 1,000 Ontario

patients were on waiting lists for cardiovascular surgery. There was no

wait for emergency patients, but “urgent” patients waited up to 1 month

while elective patients might wait up to 6 months. To some degree, hos-

pital capacity in the United States is a safety valve if Canadian waiting

lists become a problem, but such “border jumping,” at least in Ontario, is

not extensive.

Potential Administrative

Sayings Would Offset

Costs of Universal

Coverage *

If the United States were to shift to a system of universal coverage and

a single payer, as in Canada, the savings in administrative costs would

be more than enough to offset the expense of universal coverage.

GAO

estimates that, in the short run:

Page 6

GAO/HRD-91-90

Canadian Health

Insurance

Executive Summary

Savings in insurance overhead would be $34 billion.

Savings in hospital and physician administrative costs could be another

$33 billion. However, the United States might deem it appropriate for

management purposes to retain some of the more detailed statistical and

financial data that are now collected in U.S. hospitals. This might reduce

the savings somewhat.

The cost of serving the newly insured would be about $18 billion.

The cost of providing additional services to those currently insured-

stemming from the elimination of copayments and deductibles-could

be about $46 billion.

However, the United States may want to retain some level of cost

sharing to control utilization and constrain total health expenditures.

In the long run, effective limitations on provider payments through

global budgeting and negotiated physician fees, as well as controls on

expensive technology, could significantly constrain the future growth of

U.S. health spending, leading to substantial further cost savings.

Conclusions

The situation in the United States today differs in several important

respects from that in Canada at the time its health insurance program

was implemented. The expansion of the private health insurance

industry, the diffusion of medical technology, and the development of

alternative service delivery arrangements make circumstances in the

United States today different from those in Canada when it adopted its

system.

Some elements of the Canadian system are worthy of consideration in a

reformed U.S. system, however, because they might solve recognized

problems. These might include Canada’s universal access, uniform pay-

ment system, and expenditure controls.

But a reformed U.S. system should also retain and build upon the unique

strengths of the existing structure of US. health care. The strong U.S.

research establishment, the continuing development of medical tech-

nology, and the capacity to evolve new and potentially more efficient

service delivery mechanisms, such as health maintenance organizations,

are characteristics of the U.S. system that should be preserved, even as

we search for models elsewhere that would help us overcome our recog-

nized problems.

Page 7

GAO/HBDQl-99 Canadian Health Insurmce

Contents

Executive Sumrnary

2

Chapter 1

12

Introduction

Canada May Be an Instructive Model for U.S. Reform

12

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

18

Chapter 2

20

Structure of the

Canadian Insurance Coverage Does Not Depend on

21

Canadian System

Income or Health Status

Canada’s System Is Administered by a Single Payer in

26

Creates Differences in

Each Province

Access and Cost

Control

Chapter 3

Single Payer Structure

Single Payer Lowers Insurance Overhead

With Province-Wide

Fee Controls and Other Policies Limit Physician

Policies Helps Control

Expenditures

Global Budgeting and Technology Management Constrain

National Health

Hospital Spending

Spending

28

29

33

42

Chapter 4

Access Consequences

Access to Primary Care Is Unconstrained

52

52

53

of Universal Coverage

Queues Have Developed for Specialized Services

With Spending

Controls in Ontario

Page 8

GAO/IiRIkQl-90 Canadian Health Insurance

contents

Chapter 5

Potential Savings in

Administrative

Administrative Savings Would Offset Costs in the Short

Run

62

63

Expenses Could offset

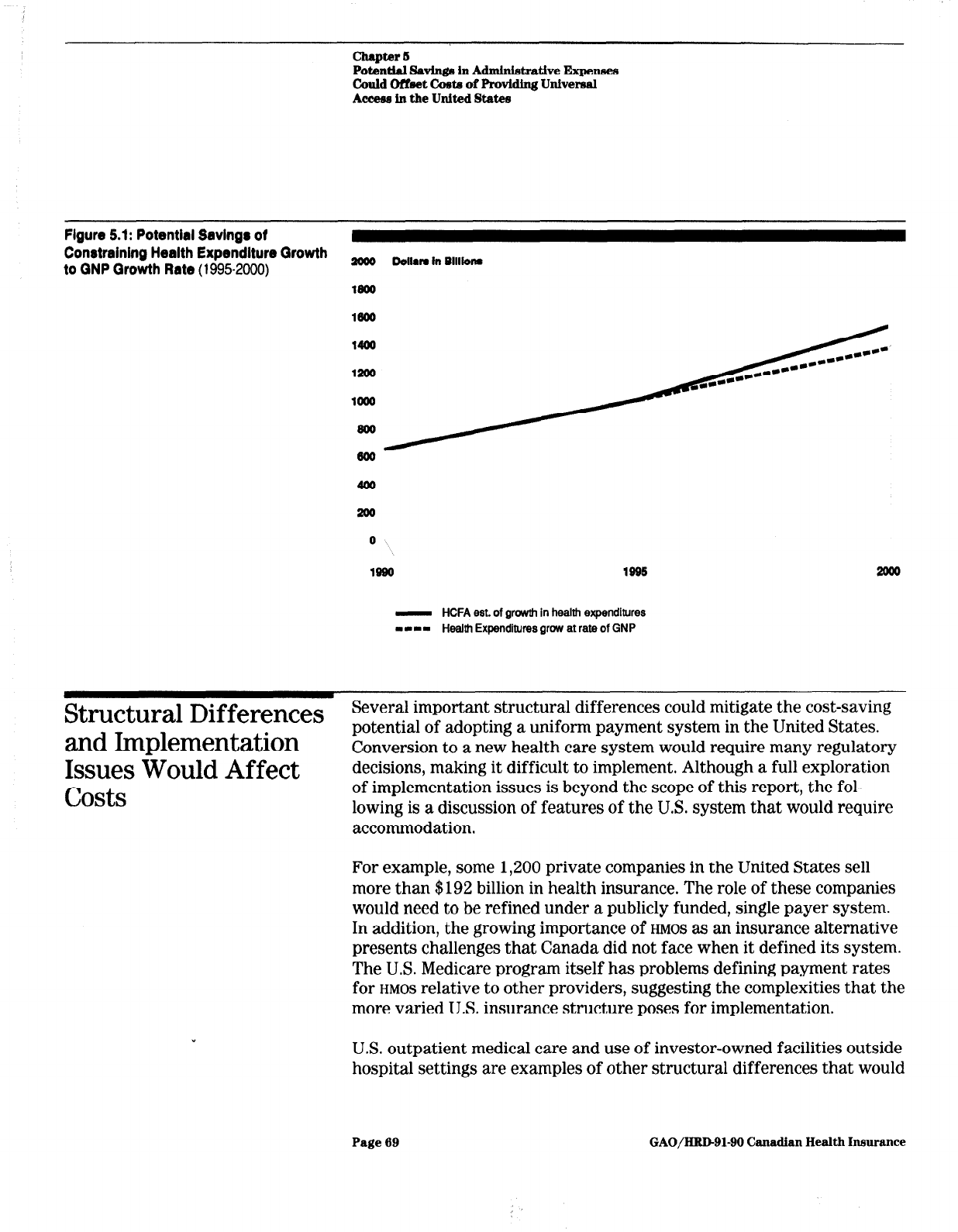

Substantial Savings Could Accrue in the Long Run

67

Structural Differences and Implementation Issues Would

69

Costs of Providing

Affect Costs

Universal Access in

the United States

Chapter 6

Conclusions

71

Appendixes

Appendix I: Health Implications of Expanding Access to

Care

74

Appendix II: Major Contributors to This Report

85

Tables

Table 3.1: Health Expenditures Per Capita, by Sector

(1987)

29

Table 3,2: Professional Liability Premiums for Self-

Employed Physicians (1987)

Table 4.1: Queuing for Specialty Care Services in Ontario

(Oct. 1990)

41

55

Table 5.1: Estimated Savings and Costs of Adopting a

Canadian-Style System in 1991

Table I. 1: Percent Increase in Annual Use of Medical

Services Under Free Care Over Use Under Cost-

Sharing Plans

63

78

Figures

Figure 1.1: Total Health Care: Real Expenditures Per

Capita (1971-89)

Figure 1.2: Total Health Expenditures as a Share of GNP

(1971-89)

15

Figure 2.1: Survey Respondents Who Did Not Receive

Needed Medical Care (1988)

22

Figure 2.2: Sources of Health Insurance for Individuals

Under Age 65 (1988)

24

Figure 3.1: Insurance Overhead: Real Expenditures Per

Capita (197 l-87)

32

Page 9

GAO/HRDBl-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Figure 3.2: Physicians’ Services: Real Expenditures Per

Capita (1971-87)

34

Figure 3.3: Indexes of Per Capita Utilization and

Inflation-Adjusted Physicians’ Fees in Canada

(1971-85)

36

Figure 3.4: Average Net Incomes of Self-Employed

Physicians by Specialty (1986)

Figure 3.5: Professional Expenses as a Percentage of

Gross Income for Selected Specialties (1986)

Figure 3.6: Hospital Care: Real Expenditures Per Capita

(1971-87)

39

40

43

Figure 3.7: Availability of Selected Medical Technologies

Figure 5.1: Potential Savings of Constraining Health

Expenditure Growth to GNP Growth Rate

(1995-2000)

50

69

Abbreviations

CT

computed tomography

DRG

diagnosis related group

GAO

General Accounting Office

GNP

gross national product

HIAA

Health Insurance Association of America

HMO

health maintenance organization

HMSA

Health Manpower Shortage Area

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

OHIP

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

PNHP

Physicians for a National Health Program

Page 10

GAO/HRDBl-BO Canadian Health Insurance

Page 11

GAO/HUDBl-BO

fhmdlan Health lnmuance

Chapter 1

Introduction

Concern over inadequate access to health care for many Americans and

continually rising costs for health care are generating renewed interest

in restructuring the U.S. health care system. Most other industrialized

countries provide universal health insurance while spending less per

capita on health services than the United States. The Congress is inter-

ested in whether the health care systems in these countries offer any

lessons that could help the United States expand access to care while

stemming the rate of growth in health care costs. The Chairman, House

Committee on Government Operations, requested that we compare the

organization of the Canadian and U.S. health care systems and assess

the implications for the United States of adopting a Canadian-style

program.

Canada May Be an

The Canadian system, really a network of 10 provincial and 2 territorial

Instructive Model for

systems, is frequently presented as a possible model in US. health care

reform. Provincial governments operate plans that provide universal

U.S. Reform

access, cover nearly all physician and hospital services, provide portable

benefits, and are publicly administered on a nonprofit basis. The federal

government funds about 40 percent of the provinces’ costs. For the

province to qualify for maximum federal support, providers must accept

the provincial plan reimbursement as payment in full. There are no

upper limits on the provision of care provided as long as it is deemed

medically necessary. Canada prohibits private health insurance, except

for items not covered by the provincial plans.

The two nations have certain common features that make Canada’s

experience relevant for the United States. Although it is not identical to

the United States, Canada probably comes closer to sharing certain U.S.

characteristics than any other industrialized country. First, it does not

have a socialized system of delivering medical care. Rather, most health

resources in Canada are in the private sector. It is a system whereby a

third party pays private providers. Second, most physicians are inde-

pendent and earn their incomes by fee-for-service. Ninety-five percent

of Canadian doctors work for themselves, not for the government.

Finally, 90 percent of hospitals are private, nonprofit corporations,

exceptions being federally owned and operated veterans’ hospitals and

provincial psychiatric hospitals.

Page 12 GAO/HRD-91-90 Canadian Health insurance

t

chapter

1

Introduction

Canada Constrains

A comparison of real health care expenditures in the two countries

Aggregate Health

shows that Canada spends less per capita and a smaller share of its eco-

Expenditures Better Than

nomic output on health care. Canada’s relative success in containing

the U.S.

costs is evidenced by its slower rate of growth in health care expendi-

tures since 197 1, the year publicly funded health insurance was imple-

mented in all provinces, As a result, health care expenditures per capita

and as a proportion of gross national product

(GNP)

remain significantly

less than in the United States. This gap is due to differences in how the

two countries finance and deliver health care as well as socio-

demographic differences.

Canada spent roughly one-fourth less per capita on health care in 1989

(the latest year for which comparable data are available). The average

per capita expenditure was $1,570 in Canada compared to $2,196 in the

United States (in 1987 dollars). Between 1971 and 1989, Canada’s

average annual growth rate in real per capita health expenditures was

lower than the comparable US. rate. Real per capita expenditures on

health care grew by 3.7 percent per year in Canada compared to 4.5

percent in the United States. As shown in figure 1.1, the difference in

spending, after adjusting for inflation, grew from $167 per person in

1971 to $626 in 1989.

Page 13 GAO/HRDBl-BO

Canadian Health Insurance

ChJlpteF

1

Intxoductlon

Figure 1 .l: Total Health Care: Real Expenditures Per Capita (1971-89)

2200 1a67U.s.ooll~n

197l lQ?2 1m

1974

1975 1978; lQ77 1978 1979 1980 1981 1882 1983

1984 lw5 1988

1987 1988 1989

- UnitedStates

---- Canada

Notes: Expenditures were converted to 1987 constant dollars by dividing health care spending by the

gross domestic product implicit price deflators for the United States and Canada. The Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development’s purchasing power parity for 1987, $1.24 CAN = $1.00 U.S.,

was used to convert Canadian to U.S. dollars.

In 1989, Canada’s health spending share of

GNP

was 2.7 percentage

points below that of the United States. In 1971, health care consumed

about the same share of economic output in both countries (7.4 percent

in Canada and 7.5 percent in the United States). However, between

1971

and 1989 the two shares diverged; health expenditures as a share of

GNP

grew at a l-l-percent annual average rate in Canada compared with a

2.5-percent rate in the United States. In 1989, Canada’s health spending

share of

GNP

was 8.9 percent compared to 11.6 percent in the United

States. (See fig. 1.2.)

Page 14 GAO/HRD-91-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Figure 1.2: Total Health Expendlturer a8

a

Share of QNP

(1971-89)

12 Pam.w

10

.I -------

-- ,

--.

---’

C.“.---....L...-

~.I------.........

. .- .,.

a

.’

/’

**-•

-. _

_ --

-------- ..lll,,,L. *

C............-----....-

**..----*

6

4

2

0

.- _

197l

lQ7Q lQ7Q

1974 1272

1076 lwr 1972

1979 1880

1981 1982 1989 1984 lQ85

1Qm 1987

1988 1989

- UnitedStates

-1-g Canada

This analysis of the Canadian and U.S. record of cost control has been

subject to criticism. A recent study by the Health Insurance Association

of America

(HIAA)

suggests that comparisons of the two nations’ health

spending as a proportion of

GNP

exaggerates Canada’s success in con-

taining health expenditures.’

HIAA

argues that faster

GNP

growth, not

slower health spending, explains why health’s share of

GNP

has stayed

lower in Canada. They contend that it is more appropriate to look at

changes in per capita spending as an indicator of the effectiveness of

health care cost controls.

Canada’s faster real economic growth provides better support for the

opposite conclusion to this argument.

HIAA’S

comparative analysis does

not consider the potential impact of faster

GNP

growth on health care

‘E. Neusehler, “Canadian Health Care: The Implications of public Health Insurance,” Health Incur-

ante Association of America Research Bulletin, June 1990.

Page 15 GAO/W&D-9180 Canadian Health Insurance

chaptm 1

Introduction

spending.2 If U.S. income had grown as fast as Canada’s, health spending

would have increased more and per capita spending would have been

even higher than the current U.S. levels. Indeed, a recent international

comparison of health expenditures indicates that for the United States,

health expenditures tend to grow at a faster rate than income. This sug-

gests that not only would per capita health spending increase, but the

share of

GNP

spent on health care would also rise. Canada’s ability to

restrain health care spending despite rapid economic growth may be

attributed to how it finances and allocates health care services3

Health Status Indicators

Are Comparable

Health indicators do not differ substantially between the United States

and Canada even though the proportions of

GNP

allocated to health in

both countries vary. The health of Canadians, as measured by standard

(if crude) indicators, is as good as or better than that of U.S. residents4

The average life expectancy of Canadian men and women is longer than

in the United States. In 1986, life expectancy at birth was 73.1 years for

a Canadian man compared to 71.3 years for an American man, and 79.9

years for a Canadian woman compared to 78.3 years for an American

woman. In both countries the leading causes of death were heart dis-

ease, malignant tumors, respiratory disorders, cerebrovascular diseases,

and accidents.

The infant mortality rate’in Canada also is lower than that of the United

States. In 1987, the infant mortality rate in Canada was 7.3 deaths per

1,000 live births, compared to the U.S. rate of 10.1. Another children’s

health status indicator is the proportion of infants born with low birth

weights; these infants are at greater risk of dying or developing long-

term disabilities. In the mid-1980s, in the United States, 6.8 percent of

all births were low birth weight, compared to 6.7 percent in Canada.

2Health expenditures tend to increase faster than income growth in the United States. Income growth

generates increased spending on health care in Canada, but health expenditures tend to grow at a

slower rate than income. See G.J. Schieber and J.P. Poullier. “Overview of International Comoarlsons

of Health Care Expenditures,” Health Care Financing Review, Annual Supplement 1989, pp. i-7.

3A.J. Culyer, Health Care Expenditures in Canada: Myth and Reality; Past and Future (Canadian Tax

Foundation Paper No. 82), 1988.

4Although aggregate data are comparable, there is a significant difference when comparing these

indicators for U.S. whites and blacks. Relative to all Canadians, U.S. whites have similar or low

mortality rates for several leading causes of death. However, U.S. whites have a shorter life P

tancy and higher infant mortality rate than all Canadians. At the same time, U.S. blacks bar

higher mortality rates for almost all leading causes of death, higher infant mortality rates.

shorter life expectancy than either U.S. whites or the average Canadian. Data from Canar

status indicators are not readily available by race.

Page 16

GAO/IIRD91-90 Canadian Hr

Life expectancy, cause-specific mortality, and infant mortality data may

be poor indicators of the relative quality of the two health delivery sys-

tems. A more discriminating measure of quality would be a comparison

of incidence rates for sentinel health events.6 Such data, however, were

not readily available on a comparable basis.

Health status is influenced by many other factors. A 1979 study by the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare estimated that only 10

percent of premature deaths in developed countries are attributable to

inadequate health services. The rest are due to unhealthy lifestyles (50

percent), environmental factors (20 percent), and human biological fac-

tors (20 percent). Thus, broadening access to health care may not be

enough to raise the health status of all Americans. It is likely, however,

to improve the health of those who currently lack access to health care

services.

Critics of Canada Cite

Rationing Problem

Health experts have identified a number of weaknesses in the way the

Canadian health care system is manageda US. critics of the Canadian

system widely cite rationing of medical technology as an unacceptable

weakness. For services that are in tight supply, such as cardiac bypass

surgery, lens implants, and magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI),

patients

are placed on waiting lists to receive care according to the urgency of

treatment. Such rationing of services results from government con-

straints on hospital budgets and the number of facilities used for

specified high-technology services. Some health experts argue that con-

straints on the availability of innovative technologies conflict with

quality-of-care concerns. (See ch. 4.)

Some Canadian patients who experience delays in obtaining specialized

medical services cross the border to seek care in the United States. In

this way, the United States acts as a “safety valve” for Canada. If the

United States implemented the Canadian-style system of stringent con-

trols on technology acquisition, there would be no similar backup system

for U.S. citizens.

“Sentinel health events are medical conditions or stages of conditions that indicate a lack of access to

quality primary care. These events include, for example, cases of measles, mumps, or polio in chil-

dren, and advanced breast cancer, uncontrolled diabetes, or uncontrolled hypertension in adults.

‘M. Rachlis and C. Kushner, Second Opiion: What’s Wrong With Canada’s Health Care System and

How To Fix It (Toronto: Harper and Collins), 1989.

Page 17

*

I

3 “,,@

GAO/HRD-91-90

Chnadim Health Insurance

Chnptm 1

Introduction

Objectives, Scope, and

At the request of the Chairman, House Committee on Government Oper-

Methodology

ations, we examined Canada’s two decades of experience under uni-

versal, publicly funded health insurance and sought implications of that

experience for U.S. health care reform. Specifically, we sought to

answer the following questions:

. What are the major similarities and differences between the health care

systems of the United States and Canada?

l

What policies has Canada used to control costs in the physician and hos-

pital sectors?

l

As a consequence of the structure and policies implemented in the Cana-

dian health care system, are there serious limitations on access to high-

technology and specialized services?

l

If the United States adopted certain features of a Canadian-style

system, how would national health spending change?

. What are the access and health implications for the United States of

adopting a system with universal, first-dollar coverage?

Scope

Our review includes data from Canada as a whole and from the province

of Ontario.7 Since each of the 10 provincial programs has some unique

features, we often found data available only at the provincial level. For

our analysis of access issues, we confined our data collection efforts to

Ontario, recognizing that there may be significant differences across

provinces. Our cost estimates assume the United States would imple-

ment a publicly funded system modeled after that in Ontario. We did not

review the financing and delivery of long-term care services provided at

institutions other than hospitals.

Methodology

To carry out our objectives, we:

l

Analyzed expenditure patterns in Canada, Ontario, and the United

States using data from Health and Welfare Canada, the Ontario Ministry

of Health, and the U.S. Health Care Financing Administration.

l

Reviewed literature over the last 10 years describing Canadian

approaches to regulating hospital and physician payments.

7We agreed with the Committee that Ontario would serve as a “benchmark” province for such com-

parlaon~~. Ontario accounts for 37 percent of the Canadian population, 38 percent of national health

expenditures, and 38 percent of Canadian physicians.

Page 18 GAO/HRD-Bl-90

Canadian Health Insurance

chapter 1

lntrudu&on

l

Interviewed Canadian hospital administrators and physicians, provin-

cial officials, and professional health care groups and U.S. health policy

experts.

. Surveyed selected Ontario hospitals providing high-technology and spe-

cialized services.

. Consulted an advisory panel composed of U.S. and Canadian govern-

ment and academic health care experts.

We conducted our review from January through December 1990 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Page 19

GAO/HltD-91-W) caNuHanHealthInsurance

Chapter 2

Structure of the Canadiayl System Creates

; Differences in Access and Cost Control

The Canadian system provides health insurance coverage to all

residents regardless of financial or health status. Unlike in the United

States, where access is often limited by an individual’s insurance cov-

erage, access in Canada is limited province-wide by annual health care

budgets. By maintaining a single payer for all medical services, the

Canadian system has the leverage and institutional incentives to reduce

administrative costs and control overall expenditure growth. But as a

consequence of these controls, some health care services may not be

available or accessible due to limits on expensive technologies and ser-

vices. (See ch. 4.)

The Canadian approach to health insurance proceeds from a base of

national standards that are implemented through a network of provin-

cial plans. As a condition of federal funding, provincial plans must

implement

. universal coverage for all legal residents,

. comprehensive coverage of all medically required services,

. reasonable access to insured services with no deductibles, copayments,

or extra billing,’

l

portability between jobs and residences, and

. public administration on a nonprofit basis.

Provinces set their own plan policies and finance the plans according to

their budgets. For the most part, plan benefits are similar across

provinces.

Under this arrangement, most features of the Canadian health financing

system are different from those of the U.S. system. These include uni-

formity of benefits, streamlined administration of insurance plans, pro-

hibition against cost sharing, lump-sum budget reimbursement of

hospitals, and government’s active role in constraining health costs

across entire health sectors.

‘No extra billing means providers may not charge a fee in addition to that which is reimbursed by the

insurance plan. Canada further discourages private payment by requiring physicians who bill

patients directly to leave the provincial health plans altogether. A doctor can choose not to partici-

pate. However, few doctors could survive in full-time private practice since free care is always avail-

able. Thus, nearly all participate. A patient can patronize any doctor privately, but few are willing to

pay fees rather than go where care is free.

Page 20

GAO/HRD-91-99 Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 2

Strncture of the Cnnadb syetem create9

Dif’ferencee in Access and Coat Control

Canadian Insurance

In both Canada and the United States, health care is limited by financial

Coverage Does Not

resources. However, each country approaches access to health care ser-

vices in a different way. In Canada, financial constraints are applied to

Depend on Income or

the entire system, but not directly to an individual‘s utilization. In the

Health Status

United States, financial constraints are placed directly on individuals’

utilization-ability to pay is an important factor in obtaining access and

amount of care-not on the system as a whole.

Canadian health policy reflects the ideal that all citizens have equal

access to medical care regardless of their ability to pay. Under this ideal,

people who can afford to pay do not purchase medical care that is better

or more readily available than that obtained by people who are less well

off. Instead, financial constraints on health care in Canada are applied

through provincial budgets, for example, by limiting expenditures on

technology. (See ch. 4.) The effects of these constraints apply, in prin-

ciple, equally to all residents.

In the United States, access to health care is determined largely by indi-

vidual insurance status or ability to pay, which is usually determined by

whether and where people are employed. In addition, federal and state

programs help reduce the effect of individual financial constraints

through Medicaid, Medicare, and state assistance programs. Neverthe-

less, over 32 million Americans under age 66 lack either public or pri-

vate health insurance coverage. These uninsured Americans must either

pay out-of-pocket or rely on public hospitals, clinics offering free or sub-

sidized care, and other forms of charity care. Financial constraints on

health care in the United States are applied by the different payers for

health care, thus creating an ad hoc collection of cost-control policies

that vary by insurance carrier.

Barriers to health care are less evident in Canada than in the United

States. For many Americans, such financial barriers as lack of insur-

ance, inadequate coverage, and cost-sharing requirements limit their

access to health services. In a 1988 survey2 of US. and Canadian adults,

7.6 percent of Americans surveyed-representing about 18 million

people-reported that they failed to receive needed medical care for

financial reasons, compared to less than 1 percent of Canadians. The

proportion that did not receive needed medical care for nonfinancial

reasons (such as inability to get appointments or lack of transportation)

was also higher in the United States than in Canada. (See fig. 2.1.)

2R.J. Blendon, “Three Systems: A Comparative Survey,” Health Management Quarterly, First Quarter

1989, pp. 2-10.

Page 21

GAO/H&D91-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 2

StlUetureOftlli?cMdion

System Credfs

Diffemncm in Aamw and Cost control

Flgure 2.1: Survey Rerpondentr Who Did

Not Receive Needed Medlcal Care (1988) 8

I

United States

Canada

Source: Slendon, “Three Systems,” pp. 2-10, Exhibit 9.

Coverage in Canada Is

Universal

In Canada, universal health insurance covers the entire population.

Each provincial health plan must offer health coverage to all legal pro-

vincial residents. Thus, Canadians are not excluded on the basis of

income or health status3

Coverage in Canada is “portable.” It is not linked to employment,

patient residence, or provider location. A resident’s home province will

pay for health expenses incurred in other provinces and, to some extent,

outside the country. Portability enhances job mobility: since health

insurance coverage is not linked to employment, people need not stay in

a job simply because it offers a needed health benefits package.

3While all social classes use the same facilities and get similar care, wealthier patients are able to

afford more amenities, such aa private rooms instead of standard wards, and to seek care in the

United States.

Page 22

GAO/HRD-91-99 Canadian Health

Insurance

chapter 2

s-orthecsnadirn System Ckent.4~

Diilereneecl in Acceea and Coot control

Provincial health plans provide unlimited insurance coverage for all

medically necessary services. These include hospital inpatient care (at

standard ward level), hospital outpatient care, and physician services,

Hospital admissions are the prerogative of the physician and patient

without interference by the insurer (the government). There are no

restrictions placed on a patient’s choice of physician.4 Other covered

benefits vary by province and may include outpatient prescription

drugs for the elderly and poor, preventive services, and routine dental

care for children.

For both hospital and physician services, government reimbursement

represents payment in full. Individuals do not pay deductibles or copay-

ments for covered services. Provincial plans vary in the range of bene-

fits provided and the extent to which they reimburse charges. People

may still incur out-of-pocket expenses for services not included in the

provincial plans, such as routine adult dental care and cosmetic surgery,

and additional charges for a private or semiprivate hospital room. Indi-

viduals often obtain private health insurance coverage through their

employer to defray the cost of such services.

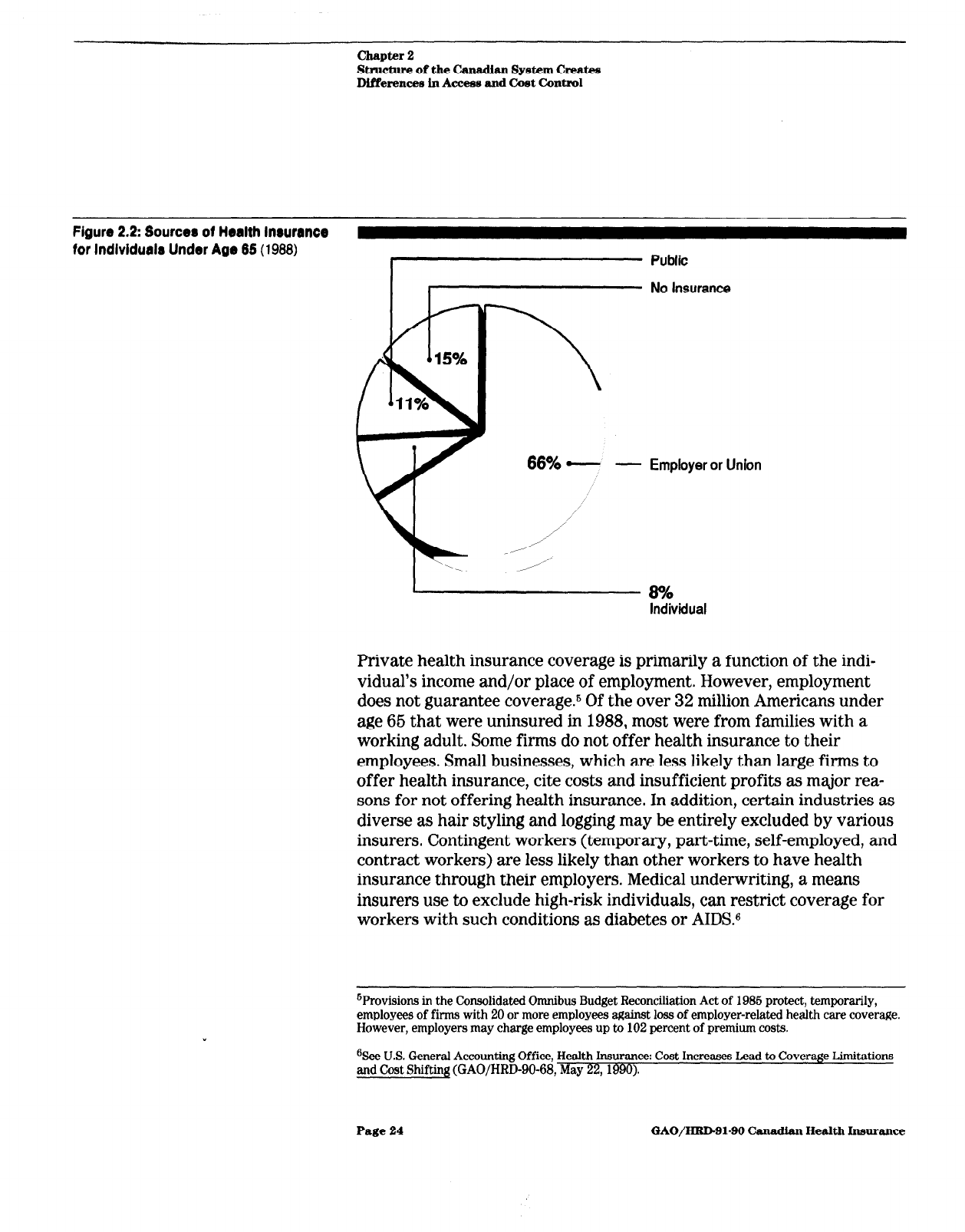

Coverage in the United

States Is Uneven

In the United States, residents have varying degrees of health insurance

coverage-from comprehensive to none at all. In 1988,86 percent of

Americans under age 66 had some health insurance, either public or pri-

vate. (See fig. 2.2.) Private health plans cover almost three-quarters of

the under 66 population. A variety of public programs provide health

insurance or direct health care to the elderly, the disabled, military per-

sonnel and their dependents, veterans, federal civilian employees, native

Americans, and the poor.

41n some provinces, there are financial disincentives to discourage patients from using specialists

without referrals. The disincentives are directed to physicians rather than patients.

Page 23

GAO/IiRDBl-99 C%nadlm Health Insurance

Chapter 2

Structure of the Canadb System Creates

DlfYerences in Access and Cost Control

Figure 2.2: Sourcer of Health Inwrance

for lndlvidualr Under Age 65 (1988)

- Employer or Union

Private health insurance coverage is primarily a function of the indi-

vidual’s income and/or place of employment. However, employment

does not guarantee coverage.6 Of the over 32 million Americans under

age 66 that were uninsured in 1988, most were from families with a

working adult. Some firms do not offer health insurance to their

employees. Small businesses, which are less likely than large firms to

offer health insurance, cite costs and insufficient profits as major rea-

sons for not offering health insurance. In addition, certain industries as

diverse as hair styling and logging may be entirely excluded by various

insurers. Contingent workers (temporary, part-time, self-employed, and

contract workers) are less likely than other workers to have health

insurance through their employers. Medical underwriting, a means

insurers use to exclude high-risk individuals, can restrict coverage for

workers with such conditions as diabetes or AIDS.6

6Provisions in the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 protect, temporarily,

employees of firms with 20 or more employees against loss of employer-related health care coverage.

However, employers may charge employees up to 102 percent of premium costs.

%ee U.S. General Accounting Office, Health Insurance: Cost Increases Lead to Coverage Limitations

and Cost Shifting (GAO/HRD-90-68, May 22,199O).

Page 24 GAO/HID-91-99 Canadian Health Insurance

chapter 2

S~ctinre of

the

cauuman System CreaW

Differencea in Access and Cost Control

The extent of benefits varies widely among insurers. Most insurance

sold by private companies is regulated primarily by the states, and thus

must provide state-mandated minimum benefits. Self-insured employer

plans, which do not fall under the jurisdiction of state insurance laws,

cover about half of insured workers.7 Medicare provides reimbursement

for a standard set of benefits for all beneficiaries. Medicaid, the joint

federal and state health insurance program, also has a federally man-

dated core package of benefits, to which the states may add benefits.

Most insurance plans require copayments, including coinsurance,

deductibles, or both. In addition, insurance companies may have limits

on their total liability. Medicare requires copayments or deductibles and

allows extra billing by providers.8

In addition to cost sharing, health insurers use other approaches

designed to control costs, which result in limits on access to care. Under

managed care, for example, insurers’ strategies for deterring unneces-

sary care have controlled the use of services.O The Medicaid program

also limits access by a variety of means. Some states, for example, limit

the number of inpatient hospital days they will cover or establish low

physician reimbursement rates, which can restrict recipients’ ability to

find participating providers.

The uninsured face financial barriers to health care and receive less

health care than other individualslO They generally use fewer services

and rely more on providers’ willingness to provide uncompensated care.

Some receive services for free or at reduced rates in various settings,

such as private hospital emergency rooms and government-run clinics

and hospitals.

‘Employers that self-insure assume the risk of paying for their employees’ health care costs instead

of purchasing insurance coverage.

‘However, the United States is moving to liiit these charges for Medicare services; in other pro-

grams, it liits which services or beneficiaries may be liable for copayments.

Q’f’echniques include gatekeeping by a primary care physician, prior authorization, second surgical

opinions, utilization review, and capitation payments to the provider with financial disincentives for

hospitalization or referral to specialists. Inconveniences, such as delays for service or required

preauthorizations before using an emergency department, are also barriers to access.

%ee J. Hadley, E. Steinberg, and J. Feder, “Comparison of Uninsured and Privately Insured Hospital

Patients: Condition on Admission, Resource Use, and Outcome,” Journal of the American Medical

Association, Vol. 266, No. 3. Jan. 16, 1991, pp. 374-379.

Page 26

GAO/HRDBl-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 2

Stracture of the Canadhn

System Create9

Dlfferacea ln Aeceen and Cwt Coniml

Canada’s System Is

Administered

by

a

In Canada, the same entity in each province is responsible for adminis-

tration, regulation, and financing. Thus a single entity is responsible, in

Single Payer in Each

fiscal as well as political terms, for the performance of the system. In

the United States, responsibility for administering, controlling, and

Province

funding the health care system is diffuse. The United States has a plu-

ralistic system of financing that involves private insurers, employers,

and federal, state, and local governments in reimbursing health care

services.

The Canadian government-

federal

and provincial-is almost the

exclusive source of payment for medical care covered under the provin-

cial health plans. In 1987, public payments accounted for 74 percent of

the nation’s total expenditure for health care services. Private insurance

and individuals made up the balance of the health expenditures for

purchase of services not covered by the plans. In contrast, U.S. private

payers-insurance companies and individuals-provided 67 percent of

the funds used to purchase health care services in 1987.

Provincial Management

With Shared Federal-

Provincial Financing

Each provincial plan is financed jointly by the provincial and federal

governments. To receive a federal subsidy, provinces “enroll” in the

national health program by enacting provincial health insurance plans

meeting the set of five conditions outlined on page 20. The provincial

governments receive block grants to administer their plans (the federal

share of public expenditures on health averages about 40 percent). The

provincial governments use various combinations of general revenue,

premiums, and taxes to finance the program.

Following federal guidelines, provincial health plans are administered

by public agencies on a nonprofit basis. Provincial authorities decide

(1) how much money will be spent on health, (2) whether to insure ser-

vices beyond those of the national policy, and (3) how it will finance the

provincial share of the plan’s costs.

The leading constraint on spending derives from the single funding

source structure of the Canadian system. The provincial government is

the sole source of funds for the hospital and physician budget sectors.

Providers have no other source of income if they are dissatisfied with

government reimbursements unless they opt completely out of the

system. This provincial monopoly over payments serves as the founda-

tion for cost control over these sectors of the Canadian health budget.

Page 26

GAO/HUD-9180 Canadian Health Insnrance

chapter 2

Strnctnre of the Cunadi~ System Creat4s

Dlffemncea in Acmw and Cost Control

With the government as payer, patients do not take part in the reim-

bursement of hospital and physician services. The government pays hos-

pitals with lump-sum payments, which account for most of hospitals’

operating revenues. It also approves expenditures for capital improve-

ments, new equipment, and expansion. The government reimburses

physicians according to a schedule of fixed rates that are set by the pro-

vincial medical association and are constrained by the total percentage

increase in the fee base negotiated between the government and the

association.

U.S. Health Care System

Lacks Central Control

In the United States, multiple entities-some federal, some state, and

some private-have a role in financing, administering, and reimbursing

the health care system. The lack of a single entity managing the system

results in piecemeal measures to control costs. On the other hand, the

decentralized competitive system offers the possibility of greater con-

sumer choice concerning the level and nature of health care benefits for

some Americans. It has also led to the development of innovative

approaches to health care delivery, like

HMOS

and managed care.

With a variety of reimbursement systems, U.S. providers are often paid

different amounts for the same services, depending on the consumer’s

insurance carrier.” Hospitals are paid prospectively on a fixed amount

per case by Medicare or on a fixed percentage of charges, on a per diem

rate, or in full by other insurers. Others, such as Department of Veterans

Affairs hospitals, are funded on a fixed budget. Reimbursement

methods for U.S. physicians include salary, fee-for-service, and a fixed,

per-patient amount (capitation).

Under the US. multiple payer system, reimbursement rates often vary

among payers, with some payers being more “generous” than others (in

some states, for example, Medicaid is regarded as having low reimburse-

ment rates). As a result, providers may increase charges to other

sources to compensate for low reimbursement. Individual insurers try to

limit their own costs, usually without coordination with other payers,

“Medicare influences private sector payers because of its size. Some policies it adopts have been

adopted by other payen, such as Blue Cross/Blue Shield.

Page 27

GAO/HRDQl-99 Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 3

Single Payer Structure With Province-Wide

Policies Helps Control National Heakh Spending

With its single payer arrangement for financing and administering its

health care system, Canada has been more successful than the United

States in constraining costs in the insurance, physician, and hospital

components of its health care budget. A single payer lowers the cost of

administering both private and public health insurance and helps reduce

the administrative costs borne by hospitals, physicians, and patients. It

also has the political incentives and ability to restrain overall health

expenditures.

Within the single payer framework, Canada has been partially suc-

cessful in limiting spending growth for physician services by controlling

physician fees. Canada has also contained hospital costs by allocating to

individual hospitals lump-sum budgets, called “global budgets,” and by

setting constraints on the acquisition and use of high-technology equip-

ment and services.

Most of the difference between U.S. and Canadian per capita health care

spending comes from the insurance, physician, and hospital sectors. In

1987 (the latest year for which comparable sectoral data are available),

Canada spent $448, or 23 percent, less per capita on health care. Insur-

ance overhead (the cost of administering public and private insurance

programs), payments for physician services, and payments to hospitals

accounted for 78 percent of the total per capita spending difference

between the two countries. Except for two sectors, public health and

drugs and appliances, Canadian per capita expenditures were below the

U.S. level. (See table 3.1.)

Page 28

GAO/HRlb91-99 Canadian Health Insurance

Single Payer Stmcture With Province-Wide

Pollciea Helps Control Natlonal

Health Spending

Table 3.1: Health Expenditures Per

Capita, by Sector (1987)

In 1987 U.S. dollars

Sector

U.S.

2’E%

Canada Difference difference

Hospitals and constructiona $802

$659

$144

32

Physicians’ services

369 241 128 29

Insurance overheadb

95 18 77 17

Other c)rofessionalsc

84 20 64 14

Dentists’ services 108 82

26 6

Research

36 13 23 5

Other health care

49 42 7 2

Other institutionsd

158 156 2 1

Public health

58 67 -9 -2

Drugs and appliances

Total0

196

209 -13 -3

$1,955

$1,507 $440 100

Y.J.S. data include new construction at hospitals and nursing homes; Canadian data include capital

expenditures on construction, repair, and machinery at hospitals, clinics, and homes for special care.

bRepresents the difference between premiums collected and benefits paid by insurers but does not

include provider billing and collection expenses.

‘Represents all health care practitioners except physicians and dentists; includes private-duty nurses,

chiropractors, podiatrists, optometrists, osteopaths, and physiotherapists.

dU S data represent nursing home care: Canadian data include homes for the aged, institutions for the

handicapped, and nursing homes.

‘Sum of percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Source: Canadian data from Health and Welfare Canada; U.S. data from Health Care Financing Adminis-

tration, Office of the Actuary.

Single Payer Lowers

Insurance Overhead

The Canadian single payer system is much less costly to administer as a

result of the arrangements for paying benefits. Having a universal single

payer system lowers the costs of insurance administration by stream-

lining reimbursement and eliminating expenses associated with selling

multiple policies, billing and collecting premiums, and evaluating risk.

Having a single payer also lowers costs for providers by eliminating the

burden of completing numerous, complex claim forms and meeting other

administrative requirements.

Insurance administration was the source of nearly one-fifth of the dif-

ference between Canadian and US. health care spending in 1987. In the

United States, administrative costs for public insurance programs and

Page 29 GAO/HRD-91-w) Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 3

Single Payer Structure With Province-Wih

Polldee Helpa Control National

HeaIth Spending

the net cost of private health insurance amounted to $96 per person. In

contrast, Canada’s insurance administration cost was $18 per person.1

Payment System Trims

Canada’s single payer system simplifies the process of paying claims.

Insurance Administration

Each province issues a health plan “charge card” to each resident. Prov-

iders submit the card number with the claim to the provincial govern-

ment, which pays the provider in full. Because of universal coverage,

there are no costs to the system for determining eligibility. Nor are there

personnel or operational expenses for marketing, estimating risk to set

differential premiums or decide whom to cover, approving hospital

admissions, or allocating shareholder profits.

In Ontario, for example, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan

(OHIP)

administers payments to all health care practitioners for provincially

insured services. Physicians claim compensation for their services and

get paid according to an official schedule of benefits, which lists pay-

ment amounts for all services considered medically necessary.

In the United States, the large and complex private insurance system

accounts for the extra costs of administering the U.S. insurance pro-

grams. Multiple insurers marketing a range of plans differing in scope of

coverage require high overhead to cover claims processing and mar-

keting costs. The market mechanism creates greater consumer choice,

less bureaucratic decisionmaking, and greater responsiveness to con-

sumer needs. These advantages, however, are part of the reason for

higher administrative costs.

Insurance company administrative expenses include claims and general

administration, commissions, premium taxes, and other costs. As a per-

centage of claims, total administrative costs of private U.S. insurers

vary from 40 percent for plans with four or fewer employees to 6.6 per-

cent for groups with 10,000 or more employees.2

‘In 1987, Canadian insurance administration totaled $466 million (U.S. dollars). This expenditure was

made in three sectors: $246 million by provincial governments, $6 million by the federal government,

and $214 million in the private sector. In the United States, public program administration and the

net cost of private health insurance amounted to $23.9 billion in 1987. Of this amount, $6.6 billion

was for federal and state programs, and almost all the rest for private insurance carriers.

2Claims administration charges also vary by size of employer. For the smallest plans, charges average

9.3 percent of incurred claims; for the largest plans, they average 3.0 percent. This relatively low

share, however, is considered fixed since each claim has to be examined and a separate rate payment

made. See: Congressional Research Service, “Cost and Effects of Extending Health Insurance Cov-

erage” (Education and Labor Serial No. lOO-EE), Oct. 19%

Page 30 GAO/HRD91-99 Chnadhn Health Insurance

slngm Payer Stmwtum With ProvinwWide

PoUcha Helpa corrtrol National

Iiealdlspsndine

In both Canada and the United States, the overhead expense of health

insurance is far less for government programs than for private health

insurance. Public programs in both countries benefit from economies of

scale (public programs are generally much larger) and the absence of

marketing costs. For 1987, overhead expenses for Canada’s public

health insurance programs were about 1 percent of total program costs,

and for U.S. public programs, about 3 percent.3 These figures contrast

with about 11 to 12 percent for overhead costs of private insurance

plans in both countries.

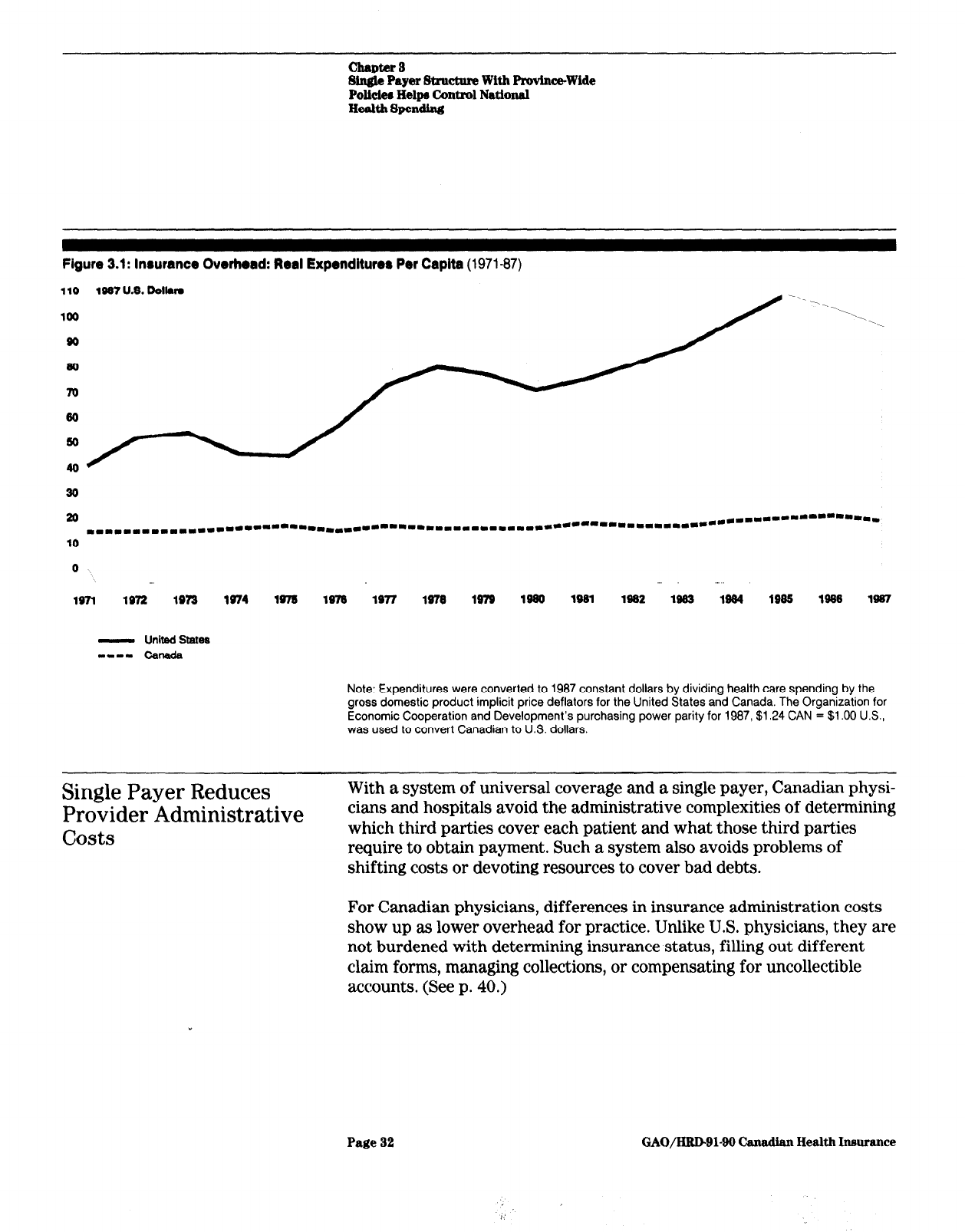

Insurance administration in Canada is a smaller component than in the

United States and has remained small since the introduction of

government-funded hospital and medical care insurance. In 1987, the

average administrative costs of public and private insurance programs

in the United States represented 4.9 percent of total health expendi-

tures. In Canada, the overhead share of public and private insurance

plans is only 1.2 percent. As shown in figure 3.1, real per capita expend-

itures for insurance administration in Canada have remained nearly

constant. Since 1971, this sector of the U.S. health economy has grown

at an average rate of 6.2 percent per year. By 1987, U.S. spending on

insurance overhead had increased to five times that of Canada.

3U.S. public programs incur more utilization review-type expenses and have higher eligibility deter-

mination costs that may help explain the higher U.S. percentage.

Page 31

GAO/HltD91-99 Canadian Health Insurance

chaptar 8

Single Payer Structure With ProvlneWide

Pollciem Help Control Natlonal

Health Spending

Figure 3.1: lnrurance Overhead: Real Expenditure8 Per Capita

(1971-87)

- Unitfd State8

m-1. c&la&

Note: Expenditures were converted to 1987 constant dollars by dividing health care spending by the

gross domestic product implicit price deflators for the United States and Canada. The Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development’s purchasing power parity for 1987, $1.24 CAN = $1 .OO U.S.,

was used to convert Canadian to US. dollars.

Single Payer Reduces

Provider Administrative

ll#.,&,

c/US

LS

With a system of universal coverage and a single payer, Canadian physi-

cians and hospitals avoid the administrative complexities of determining

which third parties cover each patient and what those third parties

require to obtain payment. Such a system also avoids problems of

shifting costs or devoting resources to cover bad debts.

For Canadian physicians, differences in insurance administration costs

show up as lower overhead for practice. Unlike U.S. physicians, they are

not burdened with determining insurance status, filling out different

claim forms, managing collections, or compensating for uncollectible

accounts. (See p. 40.)

Page 32

GAO/HRDBl-99 Canadian Health Inmrance

I’

chapter 3

Single Payer Structure With Province-Wide

Polici~ Help6 Control National

Health Spending

Hospital administration and accounting costs are also lower in Canada

because hospitals need fewer administrative personnel. A Canadian hos-

pital has virtually no billing department and a minimal accounting struc-

ture to attribute costs and charges to individual patients and physicians.

(see p. 47.)

In the United States, provider overhead includes the accounting costs of

complying with the requirements for many insurers’ documentation as

well as dealing with eligibility determinations, direct billing of patients,

and collections. One study estimated that, when provider overhead is

included, administration costs may account for more than half the dif-

ference in cost between the Canadian and U.S. systems.4

While Canada’s reduced administrative requirements may lower costs,

they also reduces the potential to manage costs as effectively. For

example, Canadian hospitals have been described by physicians as

having underdeveloped information systems. Unlike the U.S. reimburse-

ment system, the global budgeting approach provides hospitals fewer

incentives for careful tracking of costs per patient day or costs per case.

Fee Controls and

Other Policies Limit

Physician

Expenditures

Canada has more active physicians per person and uses more physician

services per capita than the United States, but it spends less for physi-

cian services per person. The difference in expenditure levels is attrib-

uted primarily to provincial governments’ control over fees.6 However,

Canada’s potential savings from constrained growth in fees are eroded

somewhat by increased use of physicians’ services. Physician supply

policies that affect the professional specialty mix also maintain rela-

tively lower spending for physician services. Finally, the universal cov-

erage, single payer structure lowers physicians’ expenses for

administration.

4S. Woolhandler and D.U. Himmelstein, “The Deteriorating Administrative Efficiency of the U.S.

Health Care System,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol.

324,

No. 18, May 2,1991, pp. 1263-

1268.

6V.R. Fuchs and J.S. Hahn, “How Does Canada Do It: A Comparison of Expenditures for Physicians’

Services in the United States and Canada,” New England

Journal

of Medicine, Vol. 323, No. 13, Sept.

27,1900,

pp. 884-890.

Page 33

GAO/HRD-91-90 t?amdan Health Insuran~

chapters

Single Payer Strum With Prmince-Wide

Polideo Helps Control National

Health Spending

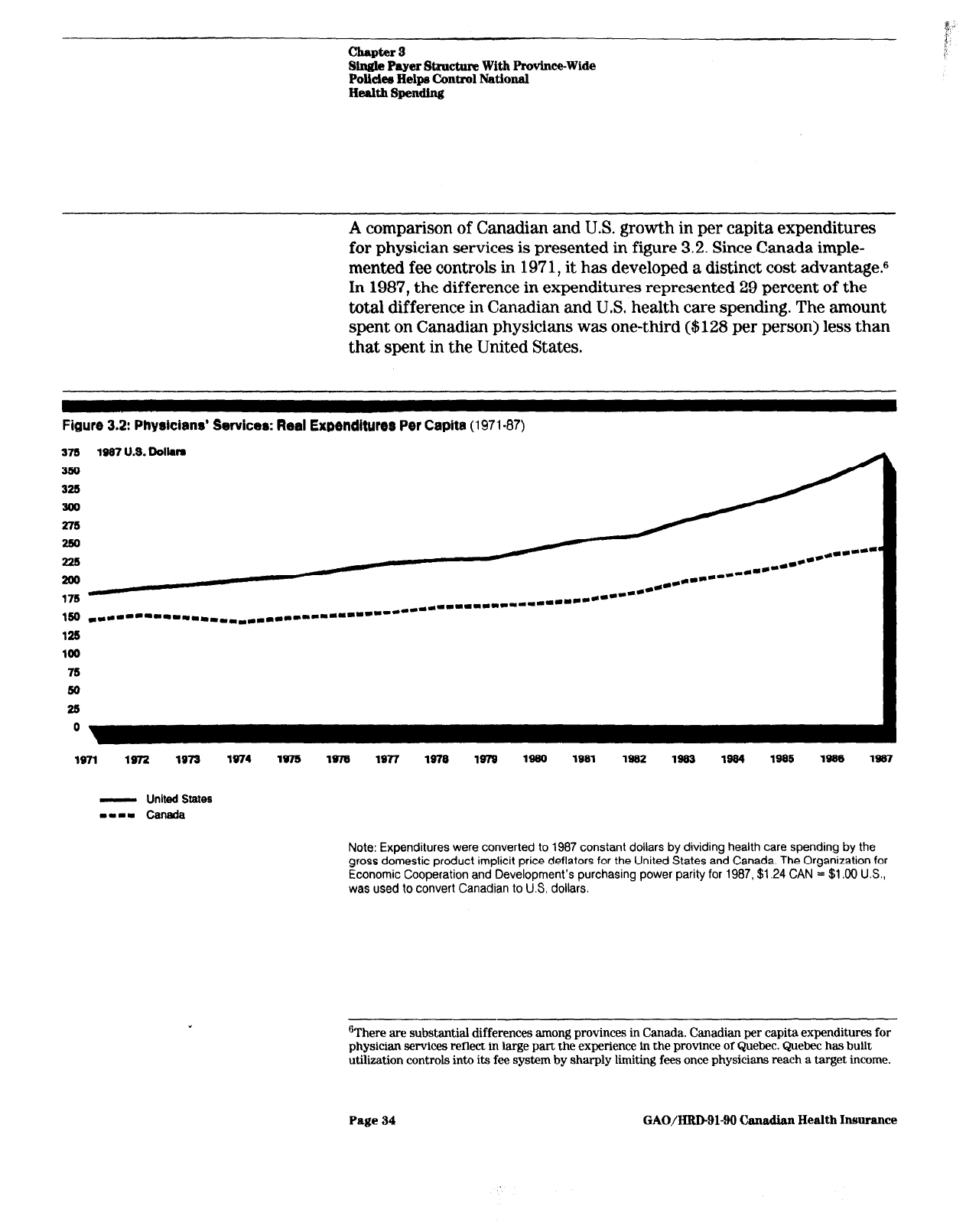

A comparison of Canadian and U.S. growth in per capita expenditures

for physician services is presented in figure 3.2. Since Canada imple-

mented fee controls in 197 1, it has developed a distinct cost advantagem6

In 1987, the difference in expenditures represented 29 percent of the

total difference in Canadian and U.S. health care spending. The amount

spent on Canadian physicians was one-third ($128 per person) less than

that spent in the United States.

Figure 3.2: Physicians’ Services: Real Expenditures Per Capita

(1971.87)

378 378

1997 U.S. Dolkm 1997 U.S. Dolkm

SW SW

325 325

300 300

375 375

250 250

238 238

**..----- *am-- **..----- *am--

.-- ****---* .-- ****---*

**.*.---- **.*.----

180 180

*L--*-----II.~~~*L*****~*~*~***- *L--*-----II.~~~*L*****~*~*~***-

******I.*I.*aL~~-*----- ******I.*I.*aL~~-*-----

12S 12S

100 100

76 76

80 80

28 28

0 0

1671 1972 1973

1974 1975 1975

1977 1970 1979 lseo

1991 1952 1933 1964

1995

1996 1997

- United States

-0-m Can&a

Note: Expenditures were converted to 1987 constant dollars by dividing health care spending by the

gross domestic product implicit price deflators for the United States and Canada. The Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development’s purchasing power parity for 1987, $1.24 CAN = $1.00 U.S.,

was used to convert Canadian to U.S. dollars.

gThere are substantial differences among provinces in Canada. Canadian per capita expenditures for

physician services reflect in large part the experience in the province of Quebec. Quebec has built

utilization controls into its fee system by sharply limiting fees once physicians reach a target income.

Page 34

GAO/H&D91-90 Canadian Health Insurance

chapter 8

Single Payer Stroctnre With ProvlnceWlde

Policiee Helps Control National

Health Spemding

Controlling Physician Fees

Canada’s ability to limit growth in per capita spending on physician ser-

Has Been Reasonably

vices is largely the result of constraints on physician fees. Through

Effective in Restraining

negotiations with provincial medical associations, provincial govern-

Overall Physician

ments use their power as the single buyer of medical services, called

Expenditures

monopsony power, to hold down prices paid to physicians. Since physi-

cians’ ability to bill patients directly was effectively eliminated in 1984,

government payment represents payment in full.

Fees for most specific physician services are much lower in Canada than

in the United States. A comparison7 of 1986 Ontario fees for selected

procedures with 1986 mean Medicare charges shows that Ontario fees

were consistently well below the average Medicare fee.g For example,

the Ontario fee for a coronary artery bypass was 25 percent of the Medi-

care charge. Similarly, the Ontario fee for cataract removal with inser-

tion of intraocular lens was 24 percent of the Medicare charge,

Fee schedule negotiations in Canada have succeeded not only in control-

ling physician fees but also in reducing them in real dollar terms.” A

comparative analysis of inflation-adjusted fees shows a decrease of 18

percent between 1971 and 1985 in Canada. (See fig. 3.3.) In contrast,

U.S. fees increased by 22 percent over the same period.

Utilization Increases

Reduce Some Gains From

Fee Controls

Although fee controls are crucial to containing physician expenditures,

they give physicians incentives to increase the volume of services they

provide. Physicians have responded, in both Canada and the United

States, to fixed and constrained fee schedules by increasing the volume

of services they provide. Provincial governments now recognize that the

method of reimbursing physicians must control both price and quantity

increases.

7W C Hsiao and others, “Results and Policy Implications of the Resource-Based Relative-Value

Study,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 319, No. 13, Sept. 29,19@3, pp. SSl-SSS.

*This does not reflect the fact that U.S. physicians can charge the patient fees above the Medicare fee

schedule, which is not permitted in Canada.

‘The fee schedule establishes a price for each medical service covered by public insurance. After the

medical association and the provincial government negotiate the overall increase in the fee schedule,

the association decides how to allocate the increase to different specialties and services.

Page 35

GAO/HID-91-90

Cam&an Health Insurance

Chapter 3

Single Payer Structure With Province-Wide

Polidee Helpa Control National

Health Spending

The ban on extra billing, an increase in physician supply (which has

lowered the number of patients per physician), and limitations on hos-

pital resources have put greater financial pressures on physicians.1o

Increasing utilization is the primary option left for physicians to raise

income levels beyond the rate of increase in fees, Figure 3.3 shows that

while inflation-adjusted fee levels declined during the 197Os, utilization

per capita steadily increased. These utilization increases were not

enough, however, to eradicate the constraining effects of fee limitations.

Figure 3.3: Indexes of Per Capita Utilization and Inflation-Adjusted Physicians’ Fees in Canada

(1971-85)

190 IndaodUlillzmtlon,Phploianm'hr(10FI .lW)

20

0 ._ ._ - ..-- - - - . ,. - ._ -

._- .

197-l 1972 lB73 1974 lw5 1976 1977 1978 1979 1960 1981 1902 1983 1984 1985

- Utilization

---- Physldans'Feea

Source: M.L. Barer. R.G. Evans, and R.J. Labelle, “Fee Controls as Cost Control: Tales From the Frozen

North,” Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. l-64, Table A3.

Canadian data indicate that the number of physician services has risen

more rapidly than the number of physicians. In the 2 years after

Ontario’s ban on extra billing, services per physician grew by nearly 2.5

‘%ontrols on hospital expenditures impinge on individual physicians by limiting the complementary

resources that are available to them. The number of hospital beds per physician has declined substan-

tially. This has resulted in more restrictions beiig placed on hospital admitting privileges, leading to a

commensurate reduction in physicians’ earning potential.

Page 36

GAO/HLuIsl-90 Canadian Health Insurance

Chapter 3

Single Payer Stmcture With Province-Wide

Polich Helps Control National

Health Spending

percent each year; in the previous 7 years, the average annual increase

had been a little over 1 percent.