Saudi Arabian Handbook for

Healthcare Guideline Development

April 2014

The Saudi Center for

Evidence Based Health Care

Version 1.0

2

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Contents

1. Preamble ......................................................................................................................................... 5

2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6

Guideline definition ......................................................................................................................... 6

When is a guideline the right approach? ...................................................................................... 6

Context for guideline development in Saudi Arabia .................................................................. 6

Information reviewed for this handbook ..................................................................................... 7

3. Overview of the guideline enterprise ......................................................................................... 8

Guideline panel ................................................................................................................................ 9

Guideline panel chair .................................................................................................................... 11

Guideline support unit .................................................................................................................. 11

4. Topic proposal and selection ..................................................................................................... 13

By whom and how are topics proposed? ................................................................................... 13

What is the process for making a proposal? .............................................................................. 13

Who selects the topic? ................................................................................................................... 13

How is topic selection done? ........................................................................................................ 13

5. Defining the scope of the guideline .......................................................................................... 15

What is the scope of the GL? ........................................................................................................ 15

Who prepares the scope? .............................................................................................................. 15

Drafting the initial scope ............................................................................................................... 15

Informing other stakeholders about the initial scope ............................................................... 17

Formulating questions for the scope ........................................................................................... 17

Choosing and rating outcomes .................................................................................................... 19

Identifying resource implications ................................................................................................ 20

Finalising the scope ........................................................................................................................ 20

6. Panel meetings ............................................................................................................................. 21

Management of conflict of interests ............................................................................................ 21

7. Evidence retrieval ........................................................................................................................ 22

What is ‘evidence’ for guideline development? ........................................................................ 22

Evidence to decision tables ........................................................................................................... 23

Prioritizing evidence retrieval ...................................................................................................... 23

The process of evidence retrieval ................................................................................................. 24

Retrieving and assessing existing guidelines ............................................................................. 25

Retrieving existing systematic reviews ....................................................................................... 26

Adequacy of systematic reviews.................................................................................................. 26

8. Grading the quality of evidence ................................................................................................ 27

Limitations that can reduce the quality of the evidence: .......................................................... 30

Factors that can increase the quality of the evidence: ............................................................... 37

Presenting the evidence to the Guideline Panel ........................................................................ 38

9. Assessing cost implications ........................................................................................................ 38

10. Developing recommendations ................................................................................................... 40

How a panel decides on recommendations ............................................................................... 40

Grading recommendations ........................................................................................................... 40

Indicators for implementation ..................................................................................................... 43

3

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

11. Producing and disseminating the guideline ............................................................................ 44

12. Guideline authorship .................................................................................................................. 45

13. Updating a guideline................................................................................................................... 45

14. Glossary and references .............................................................................................................. 46

16. Appendices ................................................................................................................................... 63

Appendix 1: Template for topic proposal ................................................................................... 63

Appendix 2: The GRADE process in developing guidelines ................................................... 64

Appendix 3: WHO Conflict of Interest Form ............................................................................. 66

Appendix 4.1. Example of an evidence profile .......................................................................... 70

Appendix 4.2. Example of evidence to decision framework ................................................... 72

4

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Acronyms and Terms

A full glossary of terms and their definitions may be found at the end of this handbook.

AMSTAR Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews

AGREE

Appraisal

of

Guidelines for Research

and

Evaluation

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

CADTH Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

COI Conflict of interest

DOI Declaration of Interest

GAB Guideline Advisory Board

GRADE Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

GDT Guideline Development Tool

GIN Guideline International Network

GL Guideline

GP Guideline Panel

ICER Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

IOM Institute of Medicine

MeSH Medical Subject Headings

MoH Ministry of Health

NGC National Guideline Center

NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)

PICO Patient/Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome

QALY Quality-adjusted life years

WHO World Health Organization

5

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

1. Preamble

Guidelines, if based on the best available evidence for the decision criteria that determine the

direction and strength of a recommendation, are an ideal tool to support health care decision

makers. The handbook for guideline development in Saudi Arabia establishes a framework for

guideline development in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that addresses organizational and

practical issues to ensure practice is evidence based and addresses the need of the population.

The aim of Healthcare Guidelines is to reduce unnecessary variation in practice through

involvement of all relevant groups including health care professionals, such as nurses, physicians,

allied health workers and patients in the development of health care recommendations based on

the best available evidence. Such guidelines must provide support rather than dictate care; they

will not be cookbooks. For that reason, much of the suggested methodology focuses on

approaches, such as the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and

Recommendations (GRADE) approach with its rationale approach to decision determinants.

The handbook places emphasis on using existing evidence syntheses, sometimes from existing

guidelines, as a means to develop recommendations for Saudi Arabia. Emphasis is also placed on

using decision determinants (so called evidence to decision frameworks) to ensure that

information that is relevant for the target populations is sought for and integrated rather than

placing undue emphasis on existing guidelines that may be outdated or not considerate of the

context.

The approach and methodology are also based on the work done for the World Health

Organization in 2006, modelled on country specific advice given to the country of Estonia and

advice given to numerous professional societies and other organizations. It is based on research

in the field of evidence to decisions using existing highly credible systematic reviews rather than

de novo reviews and placing emphasis on transparency, including conflict of interest

management. Existing standards by the Guideline International Network and authorities such as

the Institute of Medicine are carefully integrated. Finally, the experience collected during a large

guideline development effort in Saudi Arabia in December 2013 helped fine tune the approach

described here.

This handbook has been developed by a team of researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton

Canada (headed by Dr. Holger Schünemann with collaboration from Drs. Reem Mustafa, Alonso

Carrasco, Romina Brignardello-Petersen, Jan Brozek and Wojtek wiercioch) with involvement of

key informants in Saudi Arabia who commented on an early draft and provided invaluable advice

during in-depth interviews. In particular the authors would like to thank Prof. Lubna Al-Ansary,

Dr. Noha Dashash, Dr. Sohail Bajammal, Prof. Hassan Baaqeel, Dr. Zulfa Al Rayess, Dr. Yaser Adi

and Dr. Rajaa Alraddadi who provided important insights.

The ministry of health welcomes the opportunity to introduce this new era of supporting care

providers in the Kingdom.

Preamble written by Holger Schünemann, Chair of the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and

Biostatistics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

6

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

2. Introduction

2.1 Guideline definition

A guideline (GL) is a product that contains recommendations about health interventions,

including interventions focusing on health care related tests and test strategies.

1-3

As defined by

the World Health Organization, the recommendation is a statement that assists health care

providers and recipients of health care in making the best possible health care decision. A

recommendation implies a choice between different interventions that may have an impact on

health and that have influence on resource use as well as other consequences. The direction and

strength of a health care recommendation depends not only on the magnitude of anticipated

benefits and harms or burden, but also on the certainty in the intervention effects, the value the

population places on these associated outcomes and interventions and the impact on resources,

including considerations around feasibility, acceptability and equity.

4,5

Such considerations may

be highly context or setting specific and may require local information or evidence.

The main difference between a guideline and a typical textbook is that a guideline provides

answers as actionable statements to foreground questions; advice about “what to do” rather

than background questions which deal with “how or why does it work“. There is broad

agreement that these statements should be based on systematic reviews.

6-8

Systematic reviews

are transparent syntheses of the available best evidence for a given question following

established methodology. Given the best available evidence should be used, the synthesis of

evidence may be derived from different types of studies, such as randomized trials and various

types of observational studies, depending on the type of questions and availability of evidence.

Detailed processes on guideline development are available through various resources, such as

the guideline development checklist on: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/guidecheck.html.

9

2.2 When is a guideline the right approach?

Before beginning the process of guideline development, prioritization should include

considerations if and what type of a guideline is the correct approach to solving the problem.

10,11

The need for rapid responses may lead to providing interim or preliminary advice or guidelines

that will later be supported by a fully developed guideline.

2.3 Context for guideline development in Saudi Arabia

Several groups have supported or carried out the development of guidelines in Saudi Arabia with

limited co-ordination. There has been no uniformly accepted approach to guideline development

and this has resulted in a wide array of different guideline formats and compilation processes.

The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia (MoH) has embarked on standardizing and coordinating

guideline development nationally.

This handbook has two main goals: 1) to summarize the internationally accepted methods and

approaches related to the health care guideline enterprise; and 2) to provide an approach on

how to successfully implement and sustain the guideline enterprise in Saudi Arabia. It intends to

7

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

cover all aspects of the guideline enterprise, starting with assessing the need for one

(prioritization) and finishing with the distribution and implementation covered in the following 18

topics found to be relevant for guideline development.

9

1. Organization, Budget, Planning and Training

2. Priority Setting

3. Guideline Group Membership

4. Establishing Guideline Group Processes

5. Identifying Target Audience and Topic Selection

6. Consumer and Stakeholder Involvement

7. Conflict of Interest Considerations

8. (PICO) Question Generation

9. Considering importance of outcomes and interventions, values, preferences and

utilities

10. Deciding what Evidence to Include and Searching for Evidence

11. Summarizing Evidence and Considering Additional Information

12. Judging Quality, Strength or Certainty of a Body of Evidence

13. Developing Recommendations and Determining their Strength

14. Wording of Recommendations and of Considerations of Implementation, Feasibility

and Equity

15. Reporting and Peer Review

16. Dissemination and Implementation

17. Evaluation and Use

18. Updating

Although the need for country-specific guidelines is envisaged in most areas of health care due to

the need to consider costs and values in addition to the health care evidence, the use of

international resources is encouraged.

2.4 Information reviewed for this handbook

Writing this handbook involved multiple steps and a mixed methods approach. First, critically

reviewing different sources to develop a first draft of this handbook. A list of these sources

include: A series of articles on “Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development

(16-article series)”,

12

another series entitled “Integrating and Coordinating Efforts in COPD

Guideline Development (14-article series)”,

13

articles published in Implementation Science on

developing CPGs (3-article series),

14

Estonian Handbook for guideline Development (work done

by Dr. Schünemann and colleagues on that handbook served as partial template for this

handbook),

11

AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health

care,

15

Conference on Guideline Standardization (COGS): Standardized Reporting of Clinical

Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine: Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust,

2

and

Guideline International Network (GIN): Toward International Standards for CPGs.

16

Additionally,

multiple manuals of guideline developers were reviewed. These manuals include: Argentina

National Academy of Medicine, Colombia Ministry of Health and Social Security, Peru Ministry of

Health, Spain Ministry of Health, American College of Cardiology-American Heart Association,

Cancer Care Ontario, Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care, Kaiser Permanente,

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), National Institute for Health and Clinical

Excellence (NICE), New Zealand Guidelines Group, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

8

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

(SIGN), United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC), and the World Health Organization (WHO). Second, using information from

interviews with key Saudi stakeholders to obtain feedback on local needs and requirements that

are relevant for the adaptation. Third, critical revision of initial draft based on comments, written

response, and development work based on the KSA context following a workshop in KSA.

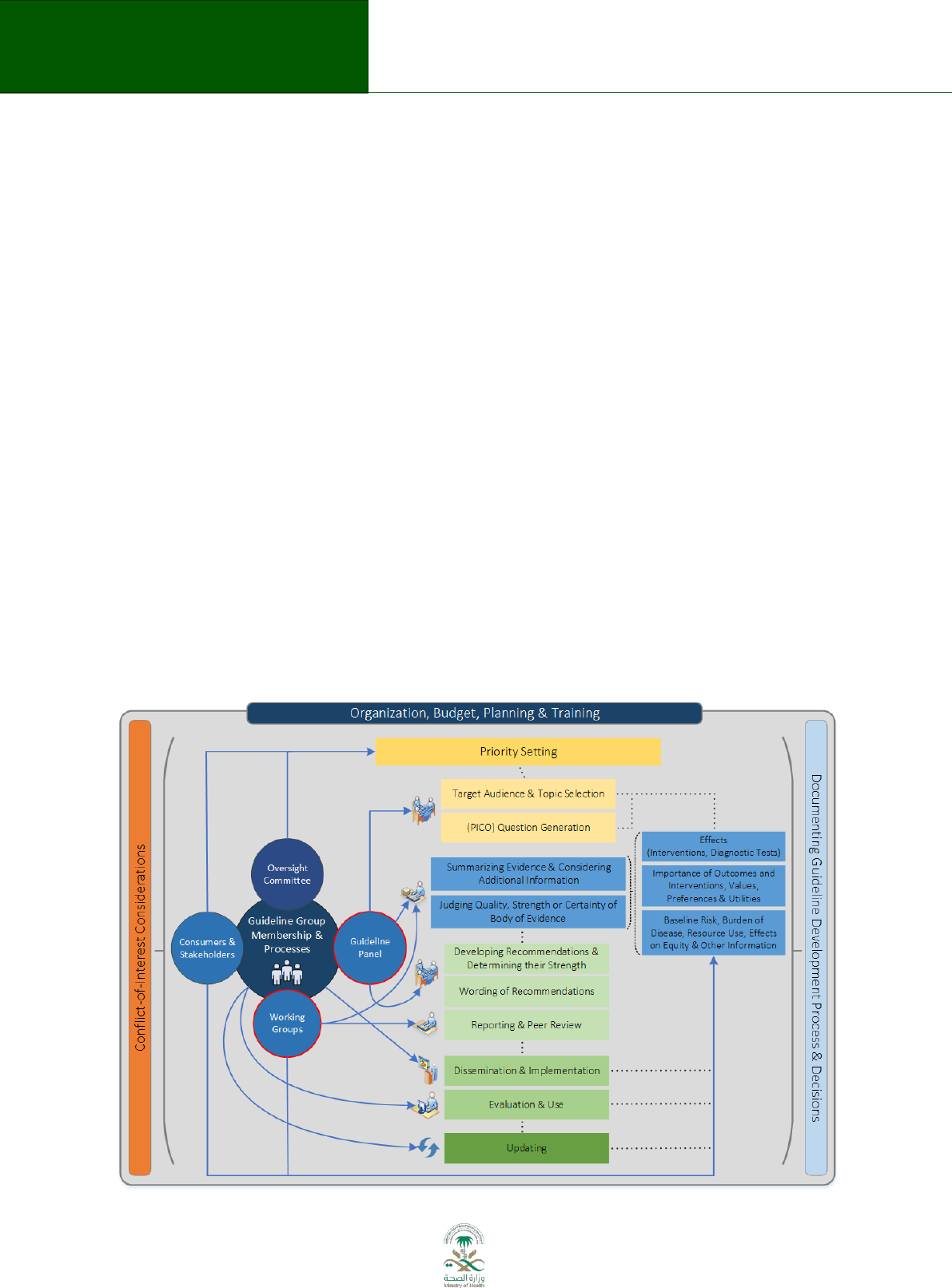

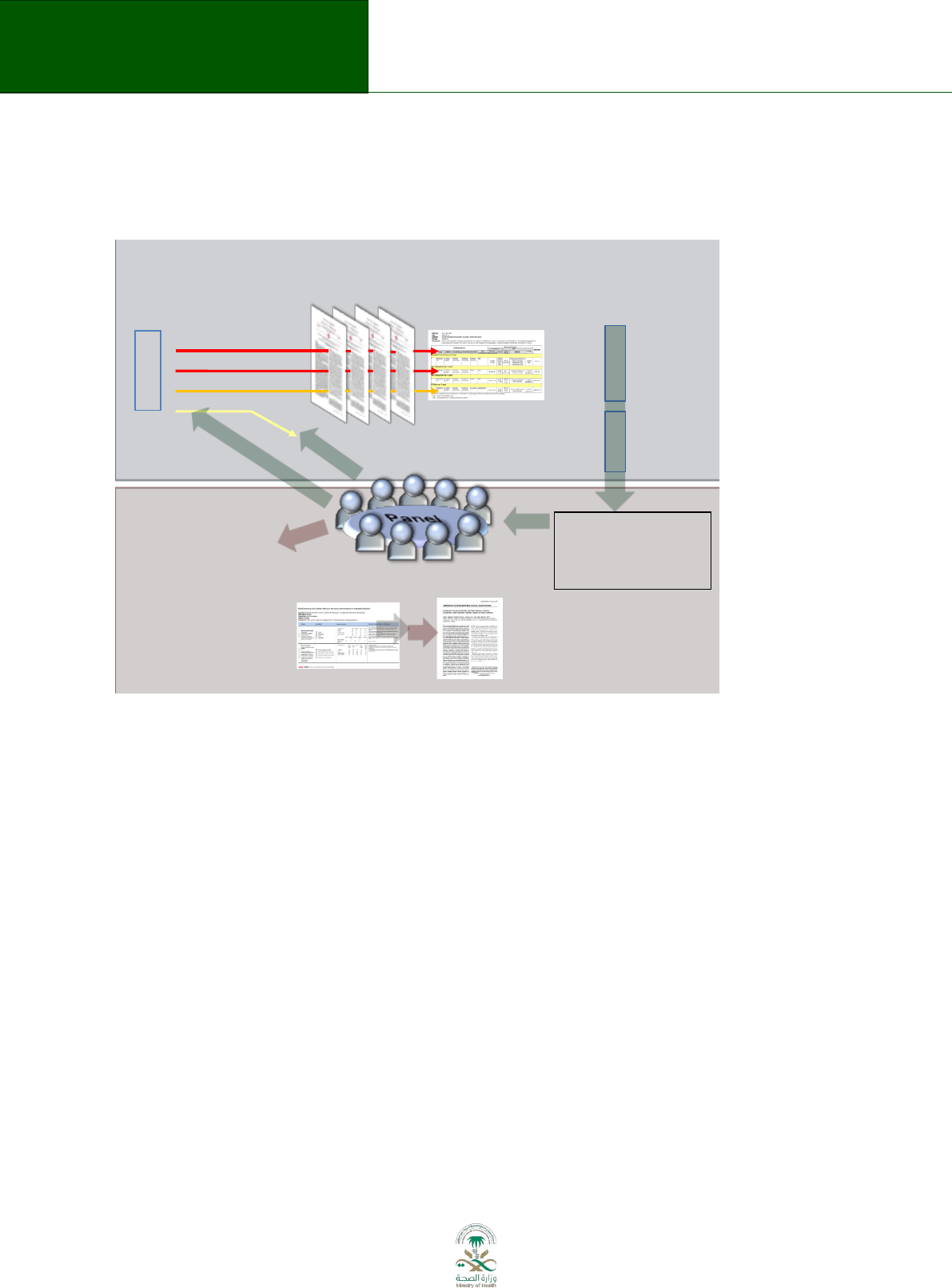

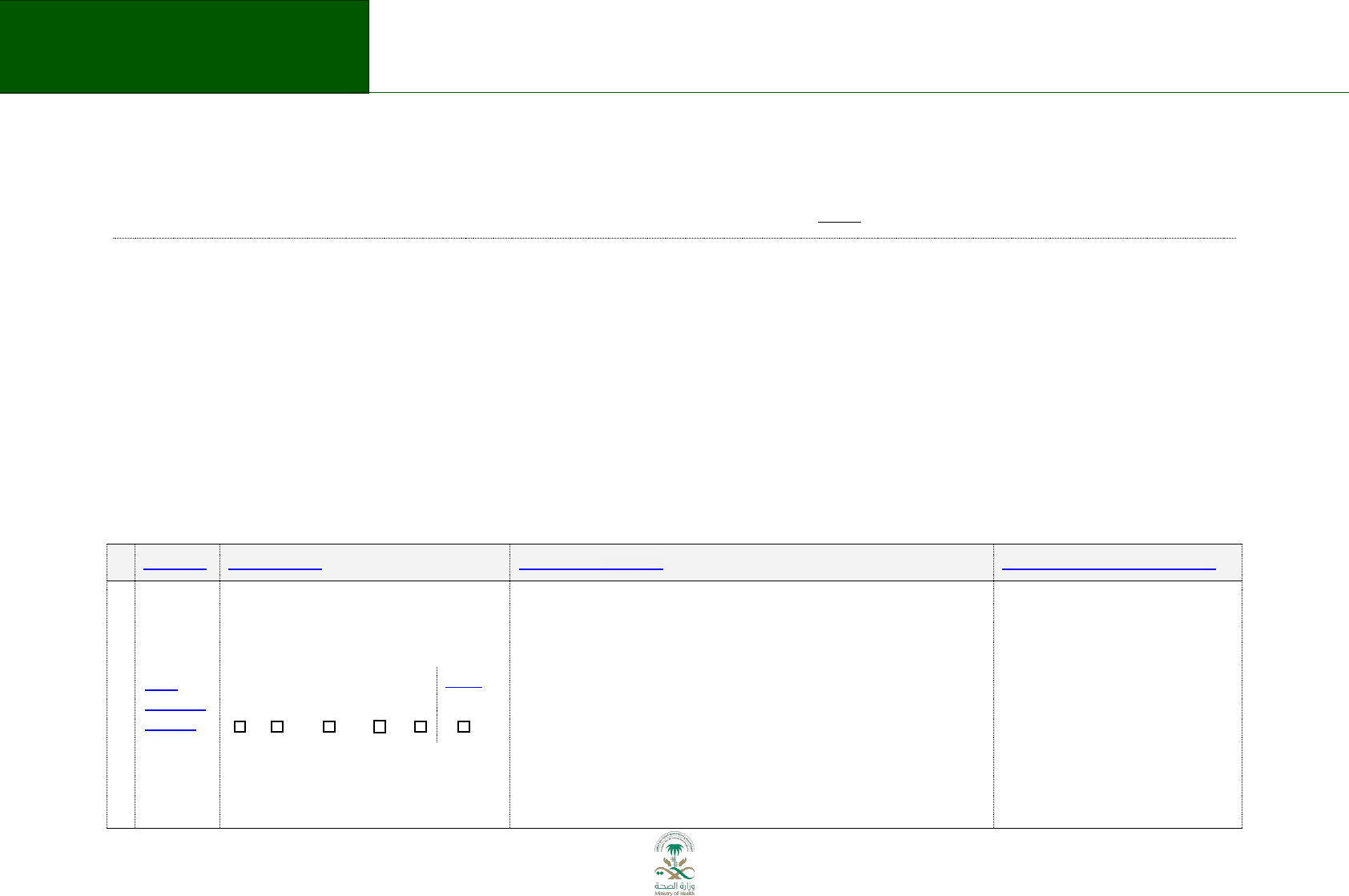

3. Overview of the guideline enterprise

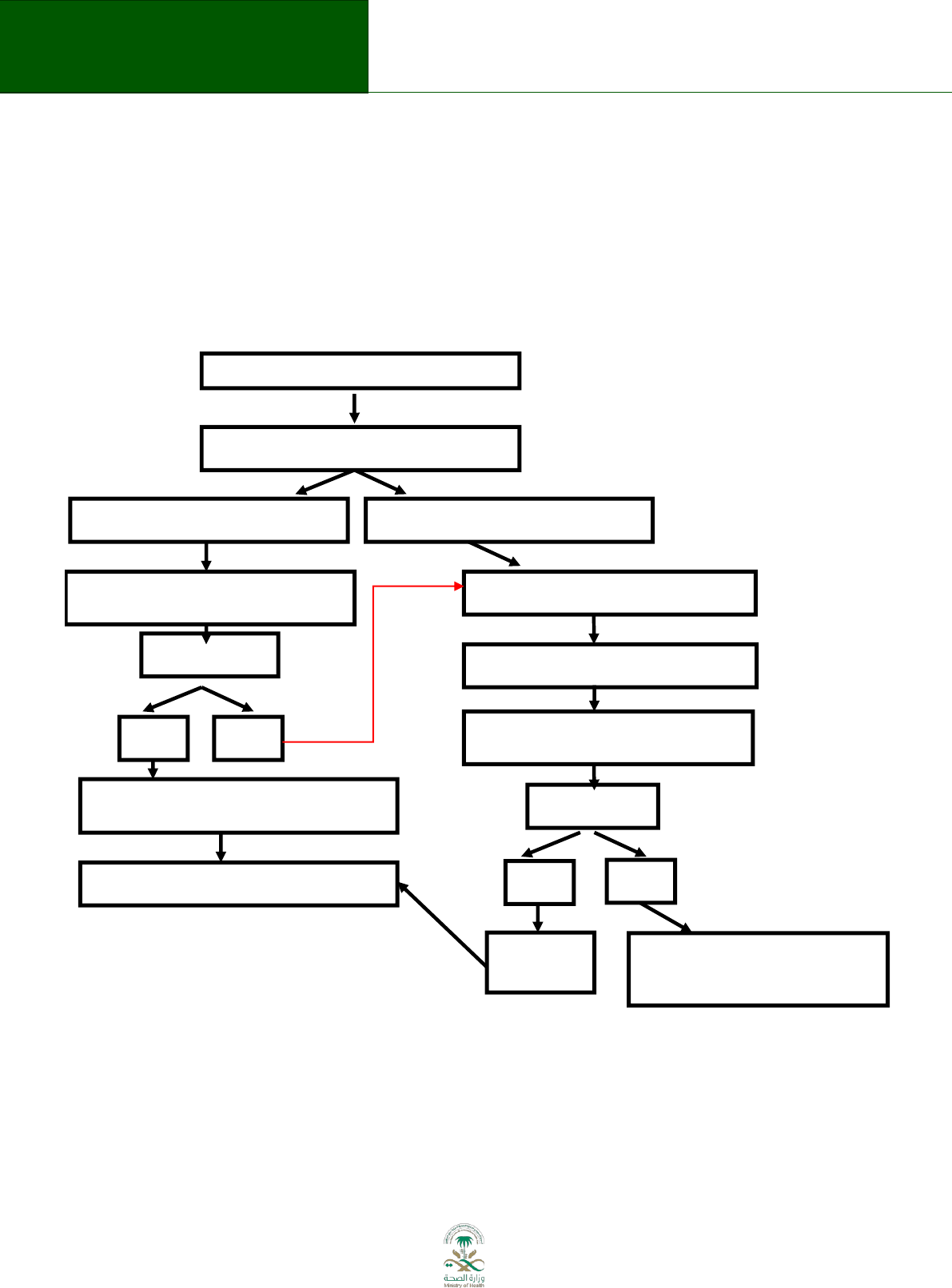

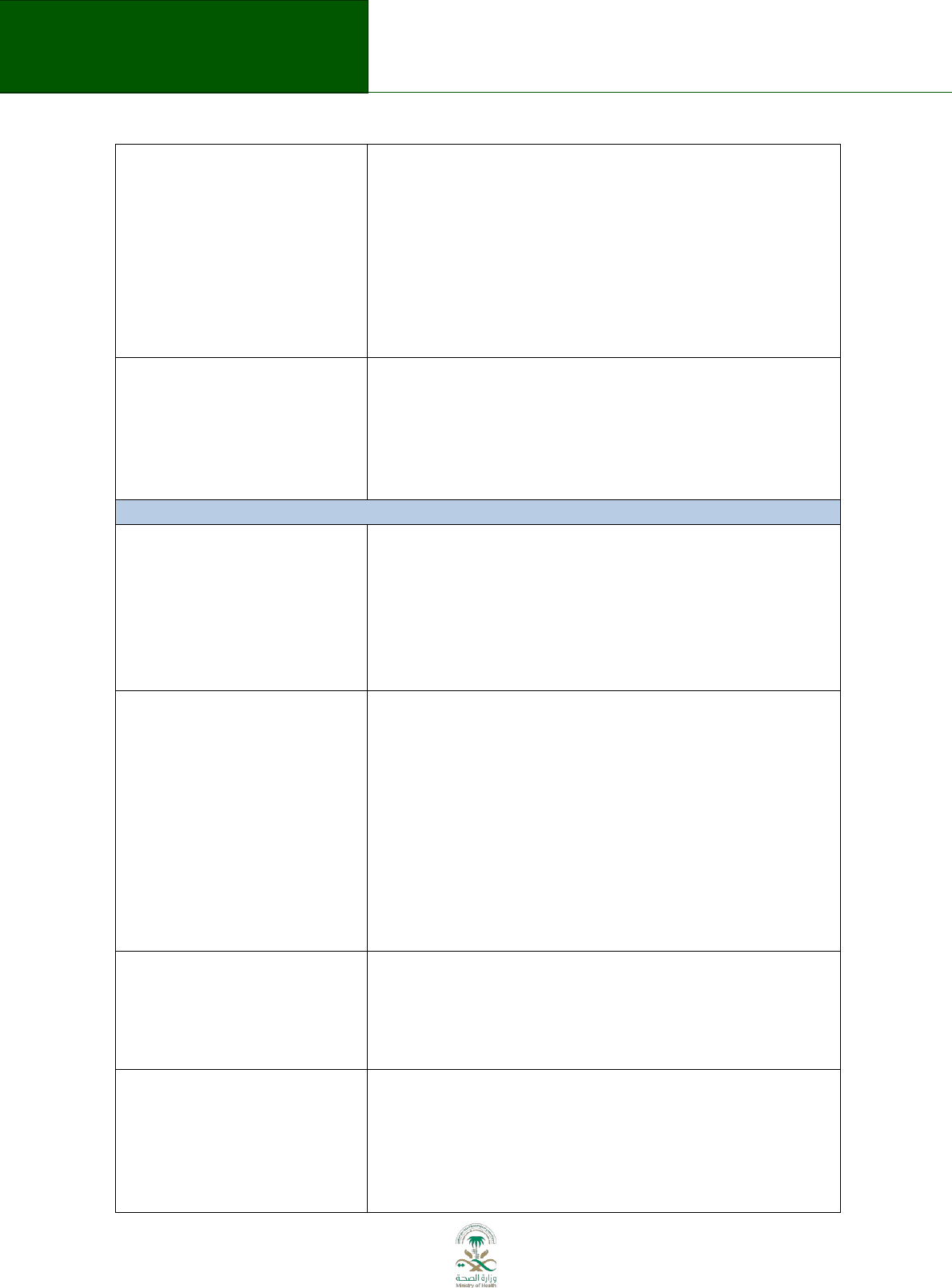

A formal process to support guideline development under the auspices of the MoH is a

prerequisite for consistent application of the guideline development process. Figure 3.1

describes this process (from reference

9

). A national guideline center (NGC) will be established. A

10 person advisory board to oversee organization, budget, planning and training will include

representation of various stakeholders (e.g. MoH, medical societies, care providers, National

Guard, Military hospitals) and act as advisory board to support organization, planning and

training. Members of the advisory board will be selected based on qualification and background.

The advisory board is chaired by an elected member. The NGC is chaired by a member who is

nominated by the MoH and approved by the advisory board. The NGC will nominate one or

more oversight committees with representation from various stakeholders for guideline projects

depending on the type of guidelines. Further roles of the NGC will be described below and are

represented by the blue circles in Figure 3.1.

9

Figure 3.1:

9

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Legend: Flow diagram of the guideline development process. The steps and involvement of

various members of the guideline development group are interrelated and not necessarily

sequential. The guideline panel and supporting groups (e.g. methodologist, health economist,

systematic review team, a secretariat for administrative support) work collaboratively, informed

through consumer and stakeholder involvement. They report to the oversight committee. While

deciding how to involve stakeholders early for priority setting and topic selection, the guideline

group must also consider how developing formal relationships with the stakeholders will enable

effective dissemination and implementation to support uptake of the guideline. Furthermore,

considerations for organization, planning and training encompass the entire guideline

development project, and steps such as documenting the methodology used and decisions made,

as well as considering conflict-of-interest occur throughout the entire process.

The need for a guideline can be identified by any body (e.g., professional medical society, patient

group, academic institution etc.), but requires coordination by the NCG. This need will be

described in a topic proposal (see Chapter 4) and a draft scope (see chapter 5), and a proposal for

the guideline panel membership needs to be made, bearing in mind the panel requirements for

multidisciplinary.

A guideline topic proposal is submitted to the NGC advisory board. Guidelines intended to be

financed by the MoH must be submitted to the NGC for approval. Despite the effort of

centralizing guideline development through the NGC, other entities in Saudi Arabia may wish to

develop guidelines independently. Such guideline developers using other financing mechanisms

and not developing guidelines as part of the activity of the NGC are encouraged to submit their

proposals as well to benefit from methodological advice of the NGC.

The roles of the NGC are:

developing an oversight committee for guideline topics

proposing and evaluating guideline topic(s) to be financed;

consulting on and approving the composition of guideline panel;

evaluating conflict of interests of panel members;

overseeing and acting as an advisory resource for the work of the guideline panel;

finalizing the initial scope with the panel;

signing off on the final scope;

being an arbiter in situations of lack of agreement on issues other than recommendations

(e.g. authorship issues);

approving the final guideline (note, this function is not to alter recommendations but to

ensure that the guidelines are methodologically sound).

3.1 Guideline panel

The guideline is drafted by a guideline panel. The panel should be multidisciplinary and should

incorporate representatives of specialities involved in the relevant guideline.

15,17-22

The panel

should include representatives of patient and/or consumer groups.

2,17,19,23,24

Patients may be

familiar with the topic and its treatments based on personal experience and may be able to

10

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

provide information and evidence relative to the guideline. Conflicts of interests of all panel

members must be managed appropriately as described below.

The initiator of the guideline presents the potential composition of the Panel and the name of

the proposed chair to the NGC for approval. The NGC may deliberate on the composition of the

Panel.

The Panel should include:

medical experts;

methodologists;

health economist;

representatives from key stakeholders and organizations involved in implementation,

including:

representatives from consumer or patient associations;

representatives from the medical faculty of a university;

representatives of organizations involved in the health-care process and who are likely to

be end-users of the guideline;

The size of the panel depends on the topic of the guideline, but is generally up to

20 persons. The size of a guidelines panel should be small enough for effective group interaction,

but large enough to ensure adequate representation of relevant views.

11,16,18,19,23,25-27

The roles of the Guideline Panel Members include:

11,16-18,25,28,29

Comment on the initial scope selected by the NGC and finalize it (including the

formulation of clinical questions and choosing outcomes), taking into account the views

of stakeholders. During the development of the questions for the guideline, the guideline

panel has to consider which clinical questions may require information from existing

guidelines or from systematic reviews.

Review draft recommendations based on the presented evidence, with explicit

consideration of the overall balance of risks and benefits. The assumption for the Panel is

that the research evidence to support a particular recommendation is global, whereas

costs, values and preferences, feasibility, acceptability and equity of recommendations

are local considerations, and therefore should be the basis of adaptation of international

recommendations for local situations.

Approve recommendations according to the GRADE approach, taking into account values

and preferences and resource implications.

Decide on consultation needed for the draft guideline.

Plan and agree on the primary methods for implementation and indicators for measuring

the use of the guideline.

After guideline finalization, facilitate the process of implementation (i.e. to act as opinion

leaders for and advocates of the guideline).

Work closely with the guideline support groups (see below).

11

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Specifically, the backgrounds of various panel members would be:

2,10,11,17,19,23,25,30,31

experts who should represent the perspective(s) of health-care professionals, as well as

social care and other professionals, where relevant.

involved in the care of patients affected by the guideline topic; detailed evidence

research expertise is not necessary, although an understanding of evidence-based

medicine is essential.

methodologists in assessing clinical evidence and developing guidelines, should be

included as appropriate, ideally as a panel co-chair. Inclusion of a methodologist in a

leading role, particularly one with experience in the guideline development process, is

recommended to explain to the panel the evidence retrieval process and to guide the

process of formulating recommendations.

patient representatives, e.g. from patient organizations (or a representative of the

patient with the relevant chronic condition) – they will represent the view of the

patient(s) with the relevant condition.

managers and other health professionals may represent the view of the health-care

services and provide expert opinion on the implementation of guidelines.

health economists and/or bio-statisticians can provide an analysis or explanation of the

costs of health services, cost-effectiveness, data on the provision of health care services

and medicines.

Panel members are asked to make a commitment to attend meetings for the guideline

development process, in order to ensure continuity and effective participation in the

process.

11,18,26,27,32

3.2 Guideline panel chair

The choice of the co-chairs (ideally one content expert and a methodologist) of the panel is

important to ensure that the panel will be able to work effectively. In most situations, groups

work most effectively if the chairs have knowledge of the content, but there must be particular

expertise in facilitating groups, interpreting evidence and developing guidelines. People who are

experts in the content area of the guideline and who have strong views about interventions or

aspects that may be included should not chair a guidelines panel. A panel would be chaired

jointly by a methodologist and a content expert with appropriate division of tasks and

labor.

2,16,17,26,32-36

3.3 Guideline support unit

The panel is supported in its work by a guideline support unit within the NGC, consisting of

experts in methodological aspects of guideline development, evidence retrieval and assessment

and health economics. If the guideline is financed by the MoH, the MoH provides the guideline

support unit for the panel

2,17,18,27,29,32,36

. The guideline support unit reports to the NGC advisory

board and works with the guideline oversight committee forming various working groups.

12

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

The roles of the guideline support unit are:

11,18,25,32,37,38

provide technical and administrative support for developing the guideline;

make panel members aware of items on the guideline checklist;

preparation of materials, evidence retrieval and summary for recommendations;

organizing the panel meetings;

use and manage the guideline development tool (www.guidelinedevelopment.org);

prepare draft records (minutes) of all panel meetings, taking special care to document

areas of controversy and dissent.

Once finalised by the panel, the guideline is endorsed by the NGC, making sure the appropriate

methodology has been followed while developing it.

The principles for the production and dissemination of the guideline are described in the chapter

on implementation and dissemination of this handbook.

13

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

4. Topic proposal and selection

4.1 By whom and how are topics proposed?

General topics for guideline development can be proposed by medical societies, the medical

faculty of a university or MoH (the proposer is subsequently called “the initiator”). Topics

together with initial scope must be presented by the initiator to NGC on October 31 of each year.

4.2 What is the process for making a proposal?

Topics can be triggered by many different inputs: regular audits, feedback from practitioners,

variations in care, guidelines being issued by other entities that need to be adapted, introduction

of new interventions, emerging health problems, etc.

10,18,21,23,36,39

Topic proposal will need an active communication between the initiator and other potential

stakeholders including the MoH and the guideline support unit to provide background

information and statistical data for the proposals.

4.3 Who selects the topic?

The selection of topics for guidelines intended to be financed by the MoH has to be made by the

NGC taking into account the initial scope (see Chapter 3). In process of choosing topic(s) to be

financed and approved applicability of further guideline should be taken into account (including

organisational and potential resource implications of a guideline). This would help to avoid

situation when the NGC chooses to finance a guideline topic which implementation is

organizationally not feasible and evidently not affordable to the health system.

4.4 How is topic selection done?

The NGC will assess the topics together with draft scope documents presented annually based

upon the criteria listed below. The NGC advisory board will evaluate all topics. A nine point Likert-

type scale will be used; were 9 is the score of the most important and useful topic and 1 is the

score of the topics that are not important or useful to address. Following resolution of possible

misunderstandings, the average will be used to determine priority topic. Raters (members of the

NGC) will be encouraged to use the whole range of the scale to allow for differentiation between

topics’ importance.

In general, the NGC will evaluate topics based on an assessment of:

Burden of disease

o the population suffering the disease/condition in Saudi Arabia (incidence,

prevalence, mortality,)

o the resource impact of the disease/condition in Saudi Arabia

14

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Variations

o practice variation and variations in health outcome by different

regions in Saudi Arabia

providers in Saudi Arabia

level of care (primary care, specialist services)

patient populations (here and after most critical subgroups under the

disease/condition can be identified if necessary)

international practice compared with Saudi Arabia

o variation in treatment costs (regions, providers, level of care, patient populations).

Treatment costs analyses can be conducted using data from databases.

service treatment (all treatment costs in certain period)

pharmaceuticals

hospitalization (rate, length of stay)

Potential

o potential for modernization of current practice

availability of new interventions (including diagnostic tests and strategies)

availability of new evidence that will likely change practice

availability of new service delivery

o potential result of successfully implemented guideline

measurable impact on health (indicators)

more cost-effective use of resources

Problem statement and the purpose of the guideline

o problem statement is completed by the initiator based on the information listed

above eg, “persons having condition X in the Riyadh area are hospitalized more

frequently and their average prescription cost for drug B is different from other

regions in Saudi Arabia.” and the purpose of the guideline: eg, “to guarantee up-to-

date treatment with equitable costs for persons with condition X irrespective of

region”

Initial scope prepared by initiator (See template below)

Relationship of topics and scope to health related government priorities.

The NGC may exclude proposed topics if the topics proposed are not potential subjects for

guidelines. The MoH may propose topics of special importance that receive financing through

purpose directed channels. Topics receiving directed financing should be prioritized.

15

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

5. Defining the scope of the guideline

5.1 What is the scope of the GL?

The scope of a guideline provides a framework within which to conduct the guideline

development work, that is the topics that should generally be addressed.

17-19,25,27,36

Proposing

topics and the scope of the guideline will be influenced by existing guidelines and systematic

reviews. The NGC will make a list of preferred topics available. These topics will result from

surveying existing systematic reviews and guidelines from international organizations to allow for

adaptation of guidelines.

Considering the resources for possible guideline topics, scoping should be conducted in stages:

1. Drafting the scope

2. Consulting with stakeholders about the draft scope

3. Finalizing the scope

5.2 Who prepares the scope?

The initial scope, with questions and preliminary outcomes, is prepared by the initiator of the

clinical guideline. The scope is finalized by the oversight committee for an approved topic, in

cooperation with the NGC, and signed off by NGC, e.g. the advisory board.

5.3 Drafting the initial scope

After the general topic is defined by the group proposing the topic, the aspects of care that the

guideline will cover should also be defined:

17-19,25,27,36

population to be included or excluded (e.g., specific age groups or people with certain

types of disease);

healthcare settings (primary or specialized care);

the different types of interventions and treatments to be included or excluded

(diagnostic tests, surgery, rehabilitation, lifestyle advice). Does the potential guideline

complement other programs or interventions in the particular therapeutic area?

information and support for patients and carers;

the preliminary outcomes that will be considered (benefits and potential harms to

patients, impact on health insurance, society perspective); this list will be completed by

the guideline panel;

links with other relevant guidance. Are there any similar guidelines available in Saudi

Arabia in this particular therapeutic area? If so, will the new guideline replace or

supplement the existing one(s)?

16

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

On the basis of these aspects, formulate two-page document with a scope that:

provides an overview of what the clinical guideline will include and what will not be

covered;

identifies the key questions (clinical, as well as organizational, regulatory, etc). It is useful

to formulate the questions using the PICO format (see below for formulating questions);

chooses and rates the outcomes in the PICO (see below for choosing and rating

outcomes)

sets the boundaries of the development and provides a clear framework to enable the

work to stay within the agreed priorities;

informs the development of the detailed review questions from the key clinical issues

and the search strategy;

provides information about the expected content of guideline;

ensures that a minimum set of essential aspects, questions and recommendations is

covered;

ensures that the guideline will be of reasonable size (no more than 20 key questions are

suggested) and can be developed within a specified time period.

evaluates, if:

- any existing guideline in Saudi Arabia covers this topic?

- up-to-date evidence is likely to be available on the topic (see list of preferred topics)?

finalizes:

- the title of guideline;

- who should be key stakeholders for implementation for further consultation on the

scope, if they have not already been involved in preparing it.

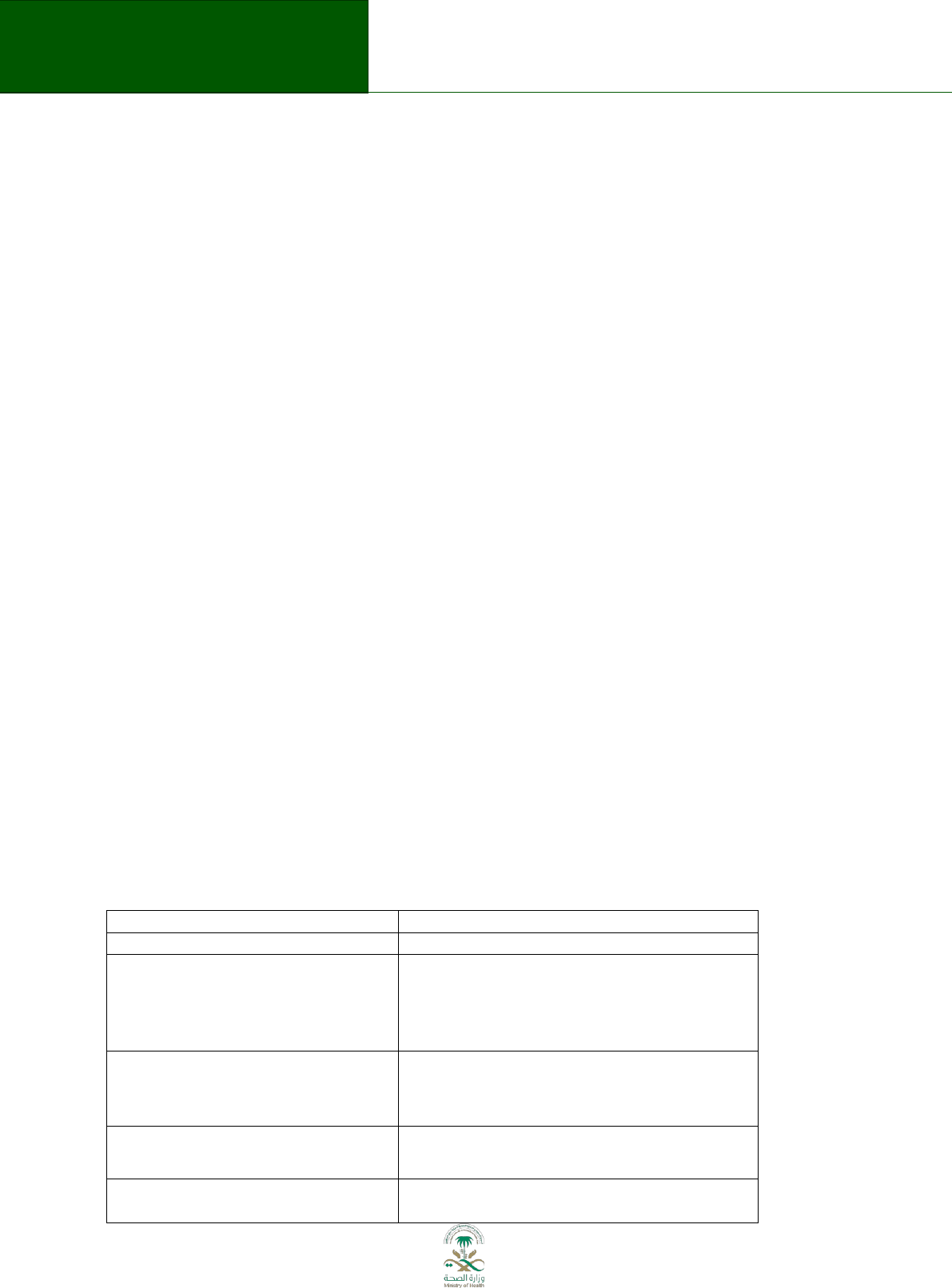

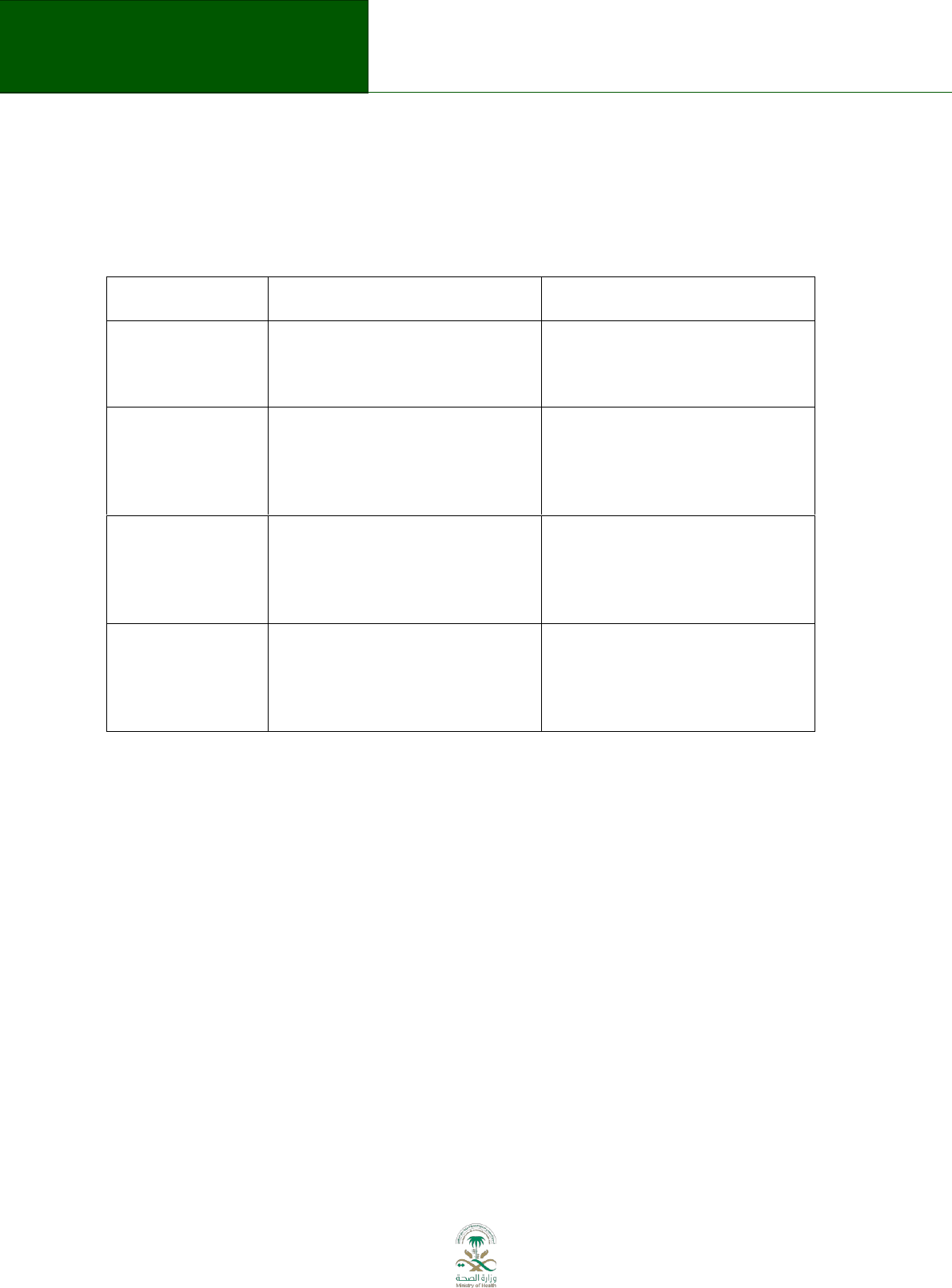

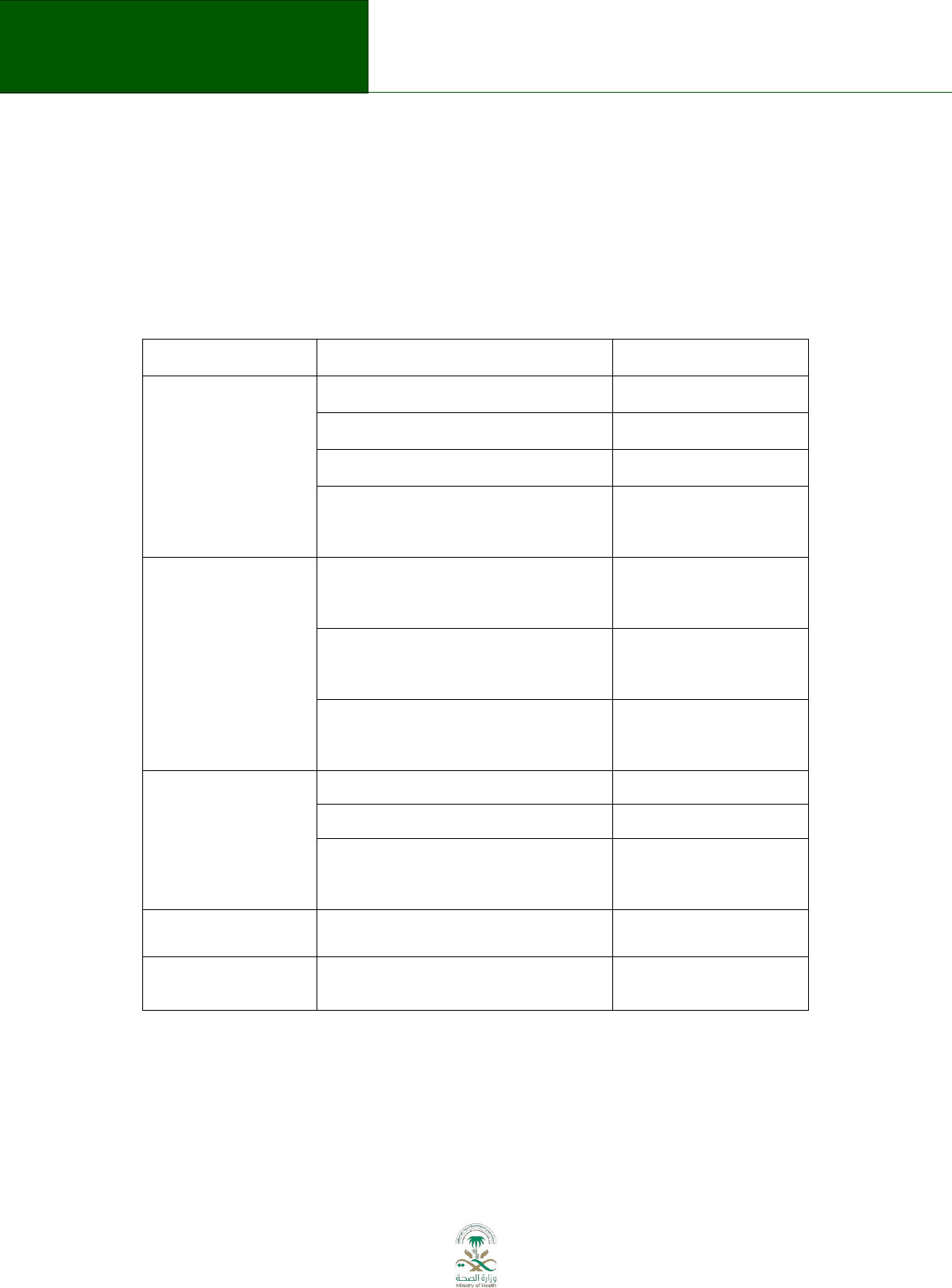

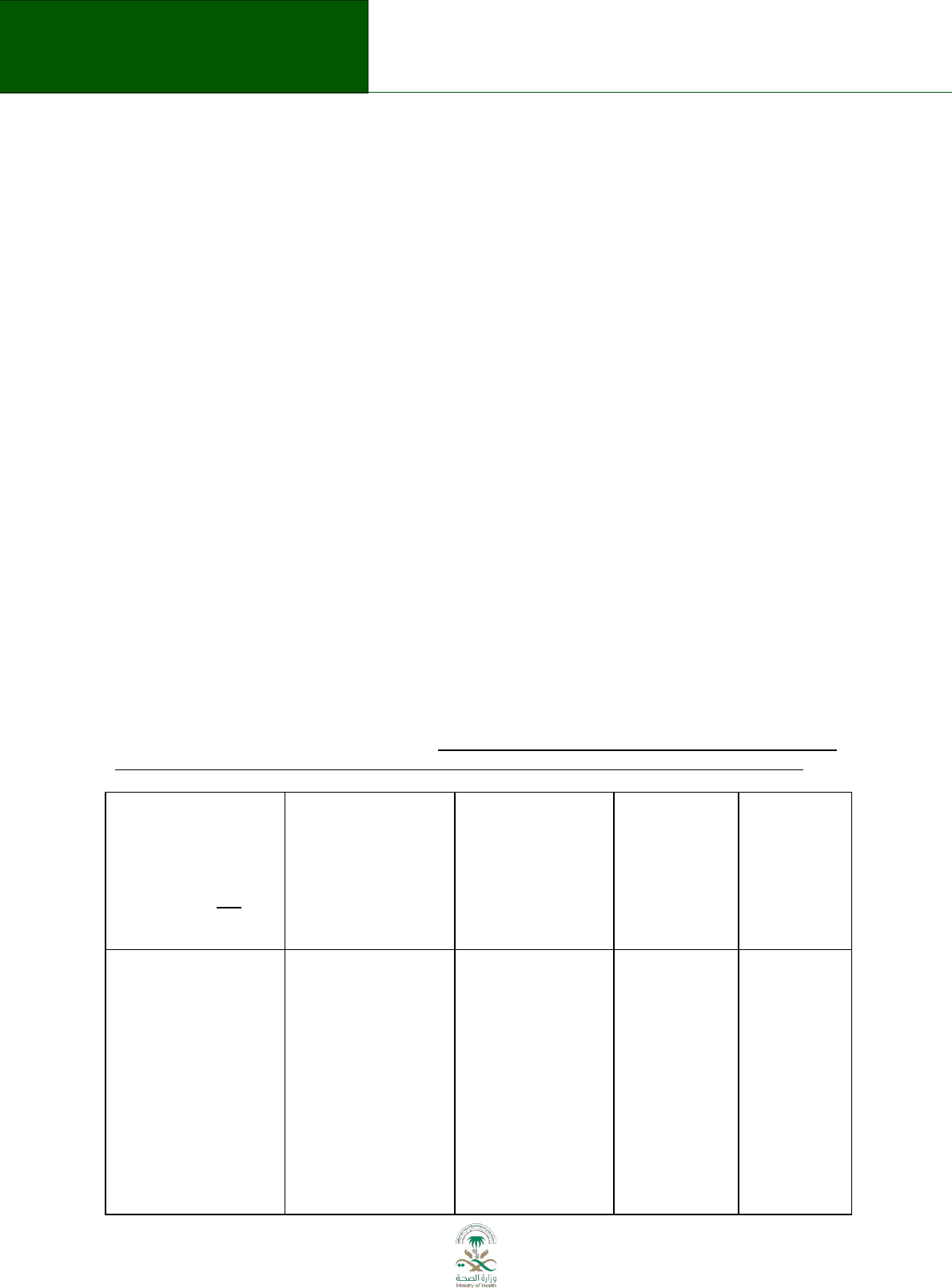

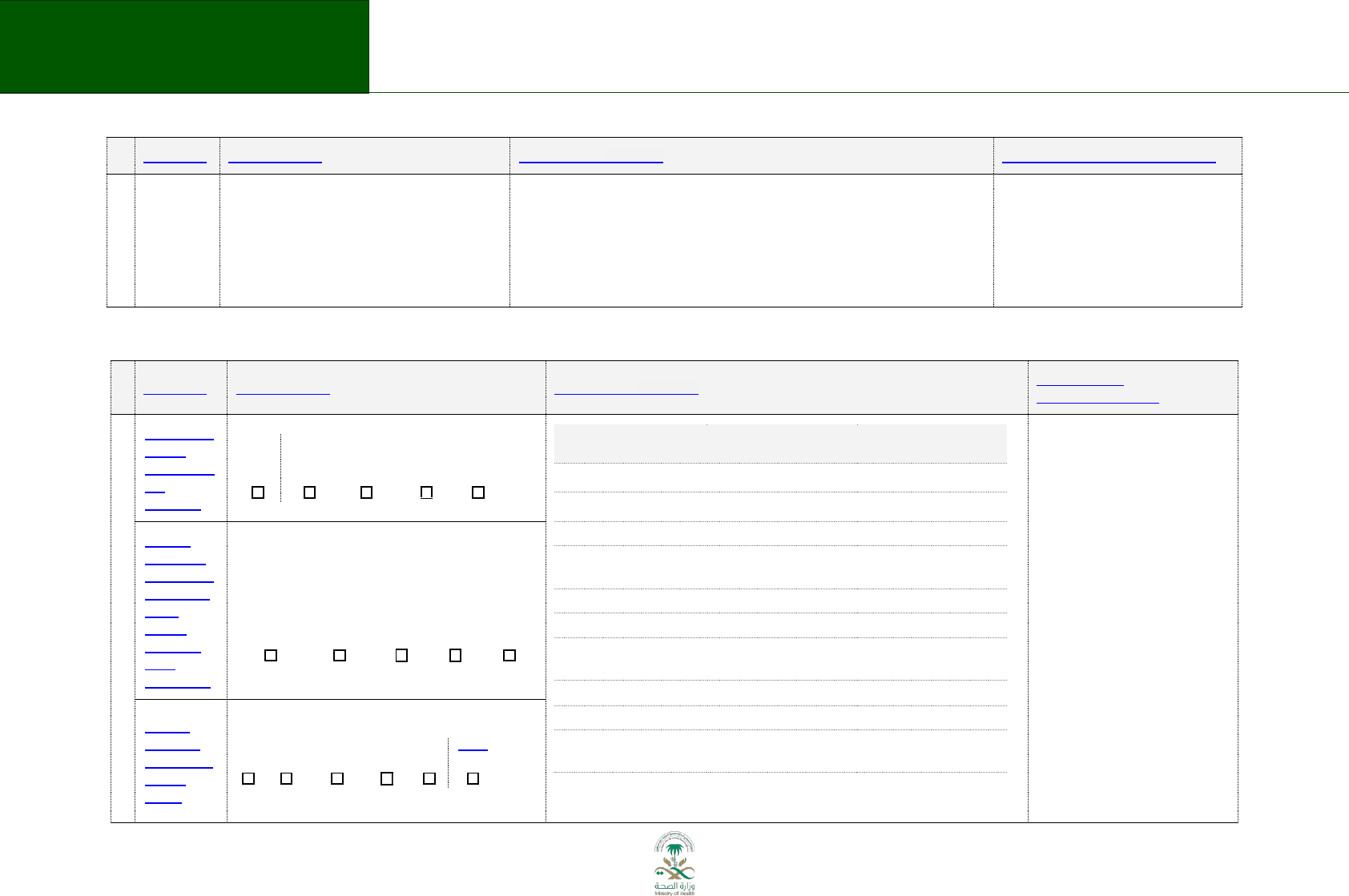

Table 5.1 Submission of topic and scope

Domain

Description

Describe the general topic:

Does the potential guideline

complement other programs or

interventions in the particular

therapeutic area?

Population to be included or excluded

(e.g., specific age groups or people

with certain types of disease):

Healthcare settings (e.g. primary or

specialized care):

The different types of interventions

and treatments to be included or

17

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

excluded (diagnostic tests, surgery,

rehabilitation, lifestyle advice).

Information and support for patients

and carers to be provided:

The preliminary outcomes that will be

considered (benefits and potential

harms to patients, impact on health

insurance, society perspective)

Links with other relevant guidance.

Are there any similar guidelines

available in Saudi Arabia in this

particular therapeutic area? If so, will

the new guideline replace or

supplement the existing one(s)?

Provide an overview of what the

clinical guideline will include and what

will not be covered:

Identify some of the key questions

(clinical, as well as organizational,

regulatory, etc) following PICO

format:

Describe the up-to-date evidence that

is available on the topic (see list of

preferred topics)?

Who are the key stakeholders for

implementation and for further

consultation on the scope, if they

have not already been involved in

preparing it.

5.4 Informing other stakeholders about the initial scope

When the initial scope is prepared the initiator must decide who else should be consulted and

involved

2,18,27,29,33

. This can be an informal process, the main purpose of which is to check that the

initial scope is clearly understood.

5.5 Formulating questions for the scope

The selection of questions (and their components) that are to be addressed in the guideline has

major consequences for the scope of the guideline. The questions will drive the direction

(inclusion and exclusion of data) and determine the type of information that will be searched for

and assessed. The questions are also the starting point for formulating the recommendations. It

is very important that the questions are clear and well defined, and that there is agreement

18

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

about them among panel members. The guideline development tool can be used to complete

this task.

10,19,23,26,35,38-40

Updating a guideline may include a change of scope; not only the questions but also the selection

of critical outcomes may differ from the original guideline.

It is helpful to start by dividing the types of information and questions into three main categories:

Definition/background questions

e.g., What is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)?

What are the causes of caries?

Facts/foreground questions

e.g. What is the effect of inhaled steroids in COPD?

What types of public health interventions reduce the incidence of caries?

Recommendation/decision

e.g. Should inhaled steroids in COPD be used?

Should regular dental hygiene visits be included in dental care?

Guidelines should focus on the recommendation and decision and minimize the description of

the definition and background to what is needed to put the recommendations in context.

The questions to be covered by the guideline should be identified on the basis of clinical, public

health or policy needs and input from clinicians and other experts. Input from consumer or

patient groups may also be helpful. Questions should focus on areas where changes in policy or

practice are needed and/or controversy may exist.

41,42

During the development of the questions for the guideline, the guideline panel should consider

which questions may need information from systematic reviews or from existing

guidelines.

7,11,18,19,23,27,33

Questions that may require new systematic reviews will have the

greatest impact on the time taken to complete the guideline. Thus, the preferred approach is

one in which existing, highly credible systematic reviews can be used.

The foreground questions are the most important ones for a guideline and they are used to

inform the recommendation/decision and they may require a systematic review and quality

assessment of the evidence about effects using the GRADE approach. Ideally systematic reviews

inform adaptation issues, values and preferences, clinical needs and baseline risks.

For priority setting and defining the scope, the initial list of types of question may be probably be

a long one. Some examples could be:

What is the frequency of the condition or issue of interest? (background)

What causes the condition or issue of interest? (etiology)

Who has the condition or issue of interest? (diagnosis)

What happens if someone gets the condition or issue of interest? (prognosis)

How can we treat the condition or issue of interest? (interventions)

19

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

What policies should we introduce to alleviate the condition or issue of interest? (policy

intervention)

To formulate these general questions in a way that they can be answered, the PICO framework is

useful:

10,19,23,43,44

Population (What factors are essential?)

In patients with cancer

Intervention (Specific intervention or class?)

what is the impact of blood

thinning with heparin

Comparator (Compared with nothing or with standard treatment)

compared with no heparin

Outcome (Patient-relevant outcomes, including both benefits

and potential side effects and burden and over what

time, e.g. mortality at 2 years)

This format can also be used, with slight modifications, for questions on prevalence and

incidence, etiology (exposure-outcome) and diagnosis. For instance:

In women in Saudi Arabia (P), what is the frequency of breast cancer (O)?

In men over 40 years of age (P), what is the rate of lung cancer (O) in smokers versus non-

smokers (C)?

In babies born (P), does screening with a new rapid diagnostic test

(I, C) accurately detect disease?

5.6 Choosing and rating outcomes

Once the clinical questions for the guideline have been defined, identify the key outcomes that

need to be considered in making the recommendations. Specially define the outcomes for

foreground questions and for the outcomes that will be critical for making decisions and

recommendations. These outcomes will also be used to guide the evidence retrieval and

synthesis. It is important to focus on the outcomes that are important to patients, and to avoid

the temptation to focus on those outcomes that are easy to measure and are often reported

(unless those are also the important outcomes).

11,44,45

Step 1. Create an initial, comprehensive list of possibly relevant outcomes for each question,

including both desirable and undesirable outcomes from the interventions that will be

considered in the recommendations.

45

Step 2. Score the relative importance of each outcome from 1–9. Rating an outcome 7–9

indicates that the outcome is critical for a decision to recommend or not recommend a particular

intervention or diagnostic test, 4–6 indicates that it is important, and 1–3 indicates that it is not

important. The average score for each outcome can be used to determine the relative

importance of each outcome, although it is helpful to provide the range of results as well.

Sometimes people with different perspectives (patients, physicians, researchers, policy-makers)

on…

20

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

have different opinions about which outcomes are important.

44,45

Therefore all these

stakeholders should have an opportunity to contribute to the discussion on the selection of

critical outcomes either by participation in the panel or by consultation.

Please note that meetings are not required to accomplish this task. These ratings can be

conveniently completed using electronic tools.

5.7 Identifying resource implications

Once the key questions are formulated, the initiator should list the resource implications for the

potential interventions that may be recommended. This might include for example, possible

costs of new medicines or diagnostic tests, or possible outcomes, such as admission time to

hospital, that might be associated with costs.

40,46

This step will inform any budget-impact

assessment that will be carried out by one of the working groups of the guideline support unit.

5.8 Finalising the scope

Topics together with initial scope must be presented to NGC according to template (see Table

5.1). The NGC will assess the topics together with initial scope documents and will approve topics

to be proper for guideline development. The NGC will consult and approve the composition of

the guideline panel.

The panel may revise the initial scope based on the clinical importance of some the questions and

outcomes, the potential evidence available or the potential for recommendations that will be

useful in the Saudi Arabian health care context.

11,18,29,43

It is critical to maintain the scope as

narrow as sensible to ensure feasibility of completing the guideline in a timely manner.

Final scope will be approved by NGC advisory board.

21

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

6. Panel meetings

The purpose of the meetings and expected tasks must be clearly laid out at the start,

including:

11,18,32

what is expected from meeting participants;

what needs to be achieved during the meeting;

what can be done afterwards;

what follow-up will take place with meeting participants;

what the ground rules and processes to be followed (there should be no discussion about

the process, i.e. members of the panel agree to the process when they agree to become

a member).

Decisions are made based on consensus and voting as a form of forced consensus is used only in

exceptional situations when consensus cannot be reached through discussion.

47

If voting takes

place, existing models can be used.

48

The panel will usually benefit from 2 to 3 face-to-face meetings with a minimum of one face-to-

face meeting (the meeting to agree on recommendations). The purpose of the first meeting is

generally to finalize the scope of the proposed guideline. At the (essential in person) meeting

when recommendations are formulated, the panel reviews recommendations based on evidence

prepared by guideline support unit. Another meeting might include finalizing plans for

dissemination and for assessment of implementation of the guideline. Additional consultations

(outside group meetings) may be held through electronic communication.

If the purpose of the meeting is to formulate recommendations:

distribute the evidence profiles (see Appendix 4.1 for an example based on the GDT)

prepared by the methodologist before the meeting, ideally two weeks before the

meeting;

distribute the evidence to decision tables (see Appendix 4.2 for an example based on

the GDT) prepared by the methodologist in consultation with the guideline panel

before the meeting, ideally two weeks before the meeting;

at the meeting, present draft recommendations that have been prepared by the

guideline support unit (meeting participants will comment on these and refine them).

6.1 Management of conflict of interests

Nominated Panel members should declare to the NGC their conflict of interests, for

example according to the declaration used by the World Health Organization.

22,41,49,50

The

NGC oversight committee will decide whether any declared interest are such that a

proposed panel member should not be included, for example due to significant financial

or personal ties with a company who has an interest in a product that is the subject of

the guideline; the NGC advisory board will resolve conflicts.

22

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Once the Guideline Panel is approved by the NGC, the guideline support unit collects

declarations of interest (can be done electronically with the GDT) before the first meeting

and later if there are any changes so that there is enough time to intervene if necessary

(e.g. if any invited participant needs to be excluded owing to major conflicts or to prevent

there being too many participants with potential conflicts of interest).

At each panel meeting each participant reports verbally potential conflicts of interest

(with actions taken if necessary); all panel members and any individuals who have direct

input into the guideline should update their declaration of interests form before each

panel meeting. Any changes to a panel member’s declaration of interests should be

recorded in the minutes of the panel meeting.

Declarations of interests will be published in the final full guideline.

10,11,19,22,41,49-52

Recusal or excusal from certain decisions or recommendations is appropriate. If guideline

panels involve members with (limited) conflict of interest, Chairs and group members on

a guideline group should ensure that committees are reminded of the specific COI before

discussion of individual conclusions or recommendations on which those COI bear. This

will allow recusal from recommendations of those with important COI. Group chairs can

play an active role and excuse group members from discussions or decision-making on

particular recommendations.

Procedures for handling disputes in conflict of interest resolution: Final decision about

inclusion and exclusion from a panel with rest with the NGC. Chairs of guideline panels

will have to review individuals’ conflicts before each panel meeting and evaluate if the

NGC should be involved based on new or changing conflict of interest. Once a member is

approved for participation in a guideline panel, the panel chair will determine if specific

panel members should be excused from individual recommendations or part of the

discussion.

7. Evidence retrieval

7.1 What is ‘evidence’ for guideline development?

A summary of all relevant research evidence is essential when developing a recommendation,

ideally based on systematic reviews.

49,53-56

In contrast to narrative reviews, systematic reviews

address a specific question and apply a rigorous scientific approach to the selection, appraisal

and synthesis of relevant studies. Systematic reviews, if conducted properly, reduce the risk of

selective citation (the 'my favourite study' approach) and improve decisions.

Many guideline organizations rely on groups such as the Cochrane Collaboration for systematic

reviews for use in guideline development. In countries or organizations with limited resources

(including staff and expertise), however, it may be more practical and efficient to use existing

systematic reviews including those used for already existing guidelines as the basis for local

guideline development or to adapt recommendations from existing guidelines, and only

occasionally develop recommendations de novo. The assumption here is that the research

evidence to support a particular recommendation is 'global' whereas costs, values and

23

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

preferences and the feasibility of recommendations are 'local' considerations, and therefore

should be the basis of adaptation of existing, sometimes international, recommendations.

Guidelines and recommendations will therefore be developed from a variety of sources, where

the emphasis in existing guidelines is on the possibility of extracting information from highly

credible systematic reviews from these guidelines:

1. recommendations and systematic reviews developed from published clinical guidelines

that were created by independent organizations or groups that meet specified criteria

(see “Retrieving and assessing existing guidelines”);

2. recommendations developed from existing systematic reviews;

3. recommendations developed from new systematic reviews;

Existing guidelines could be assessed for their credibility using validated tools such as the AGREE

tool.

15

However, the emphasis is on finding systematic reviews that include the information of

interest. If a guideline recommendation is required when there is truly little evidence to support

a decision, then the panel will need to document the reasons for developing the

recommendation based on little evidence and the basis for their judgement.

6,20,42,57,58

Such a

recommendation may also be the basis for a proposal for research.

7.2 Evidence to decision tables

Regardless of the source of a recommendation or a systematic review, evidence to decision

tables should be completed by a guideline panel, ideally for each recommendation or set of

related recommendations based on the obtained information (see appendix 6.2).

57,58

Existing

evidence to decision tables can be used and checked for relevance and possibility of adaptation.

7.3 Prioritizing evidence retrieval

Whatever the source of the evidence, retrieving evidence to support every recommendation in a

guideline may simply not be feasible. This is where it becomes important to identify priority

questions or issues that the guideline should address (see section on defining the scope).

11

To avoid duplication, the process outlined below starts by using existing guideline

recommendations, and checking the evidence that relates to the recommendations (i.e.

availability of systematic reviews supporting them), then describes the full process of developing

recommendations based on systematic reviews, and includes a process for undertaking

systematic reviews. This third option should be carried out only when there is no existing basis

for recommendations and when the question is a major issue for the guideline to cover.

2,10,11,16,18-

21,26,27,29,32,36

The methodology of development of systematic reviews is not covered in this

handbook. Preparation of systematic reviews should follow the Cochrane Handbook for

Systematic Reviews of Interventions (available at:

http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook).

24

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

7.4 The process of evidence retrieval

The process of evidence retrieval, assessment and synthesis is described in further detail below

and is summarized in the figure below (adapted from Estonian Handbook for guideline

development)

Figure 7.1

Guideline question formulated

Systematic search for existing guidelines

Current, relevant guidelines identified

No relevant guidelines identified

Assess quality, currency, and relevance of

systematic reviews in these guidelines

High credibility?

YES

NO

Create evidence to decision tables of

recommendations

Decide on need for additional evidence

Systematic search for systematic reviews

Relevant systematic reviews identified

High credibility?

YES

NO

Assess the

evidence

Decide whether to do systematic

reviews or wait to make

recommendation

Assess quality, currency, and relevance of

systematic reviews

25

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

7.5 Retrieving and assessing existing guidelines

Start by conducting a systematic search for existing guidelines (generally, those published in the

last 5 years to ensure currency) on the same topic(s).

11

Guidelines can be difficult to find through

electronic databases, so the following sources, in addition to Medline, may be helpful:

the National Guideline Clearinghouse - http://www.guideline.gov/

websites of guideline-producing agencies, such as NICE

the guidelines international network (GIN) database of guidelines

It is strongly recommended to consult with an expert in information retrieval to ensure the use of

a sound search strategy.

The search strategy should include key words for target population, intervention and

comparators if relevant, etc. MeSH terms could be used. See http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh.

The search strategy should be clearly documented and should specify:

19,23,36

the details of the sources (including web sites) searched, and the search used in each

database including the date when the search was performed;

If relevant guidelines are identified the following aspects should be assessed:

1) are the guidelines based on systematic reviews?

o if not, they should not be used.

o If they are evidence based, are evidence summaries provided and are evidence

to decision tables provided? (including GRADE evidence profiles, summary of

findings tables, or references to systematic reviews)

2) who funded the guideline development?

o what processes were used to manage conflicts of interest? If these are not

described, the guidelines should not be used further, but there may be relevant

systematic reviews or evidence profiles incorporated into them that can be

helpful.

For the assessment tool it is suggested to use AGREE instrument questions 8-11 and 22-23.

15

Once it is decided if the guidelines can be used as the basis for development of local

recommendations, one will need to identify the recommendations in them that are relevant to

the scope of the guideline. One approach that has been used is to make a table that includes all

similar recommendations from different guidelines on the same topic, compare their sources

(who produced them and if there are systematic reviews).

If the recommendations and the sources are the same, the main task is to develop or use

evidence to decision tables (see section on developing recommendations). It is also possible that

new evidence may be available that might need to be considered. Pragmatic decisions will have

to be made about how to supplement the evidence in existing guidelines with new evidence, if

26

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

necessary. Advice on this should also be obtained from the content experts on the guidelines

panel.

If an existing guideline has used GRADE evidence profiles as the basis for evidence presentation

(based on systematic reviews), it may be possible to update the evidence profile and then

reassess the recommendation, adding in considerations such as costs, local values and

preferences, feasibility and other factors in the evidence to decision tables.

7.6 Retrieving existing systematic reviews

Rationale

Systematic reviews, if conducted properly, reduce the risk of selective citation and improve the

reliability and accuracy of decisions. Systematic reviews should be assessed for their quality (see

below “Adequacy of systematic reviews”).

20,27,28,33,35,36

Each systematic review under consideration should have a protocol that describes:

11,55

the search strategy used to identify all relevant published – and unpublished – studies;

the eligibility criteria for the selection of studies;

how studies will be critically appraised for risk of bias;

an explicit method of synthesis of results and, if feasible, a quantitative synthesis of the

results of studies to estimate the overall effect of an intervention (meta-analysis).

The first step is to identify relevant systematic reviews for each of your questions. The most

readily accessible biomedical database is PubMed. The PubMed “Clinical Queries” or “Special

Queries” options permit specific searches to be set up to identify systematic reviews of different

types of studies identified with MeSH terms (see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh). This

includes searches of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. A expert in information

retrieval should be consulted through the NGC.

7.7 Adequacy of systematic reviews

Once the reviews are retrieved, they should be checked for:

11,18,23,59

relevance (to the questions to be addressed in the recommendations);

timeliness (assessed by date of last update);

quality (assessed by a standard critical appraisal instrument).

There are multiple checklists available for critical appraisal of systematic reviews, such as the one

developed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

(http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1157) or, better, the validated AMSTAR toolto assess the

credibility of a systematic review.

60,61

An update of the AMSTAR tool is being prepared (under

the leadership of one of the authors of this handbook) and table 7.1 shows the current draft

version which could be used for the assessment of systematic reviews.

27

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

If there are several relevant systematic reviews, use the most recent one that is of high quality. If

the review is of high quality but more than two years old, consider updating the review to include

more recent evidence and compare if other reviews include more or additional studies.

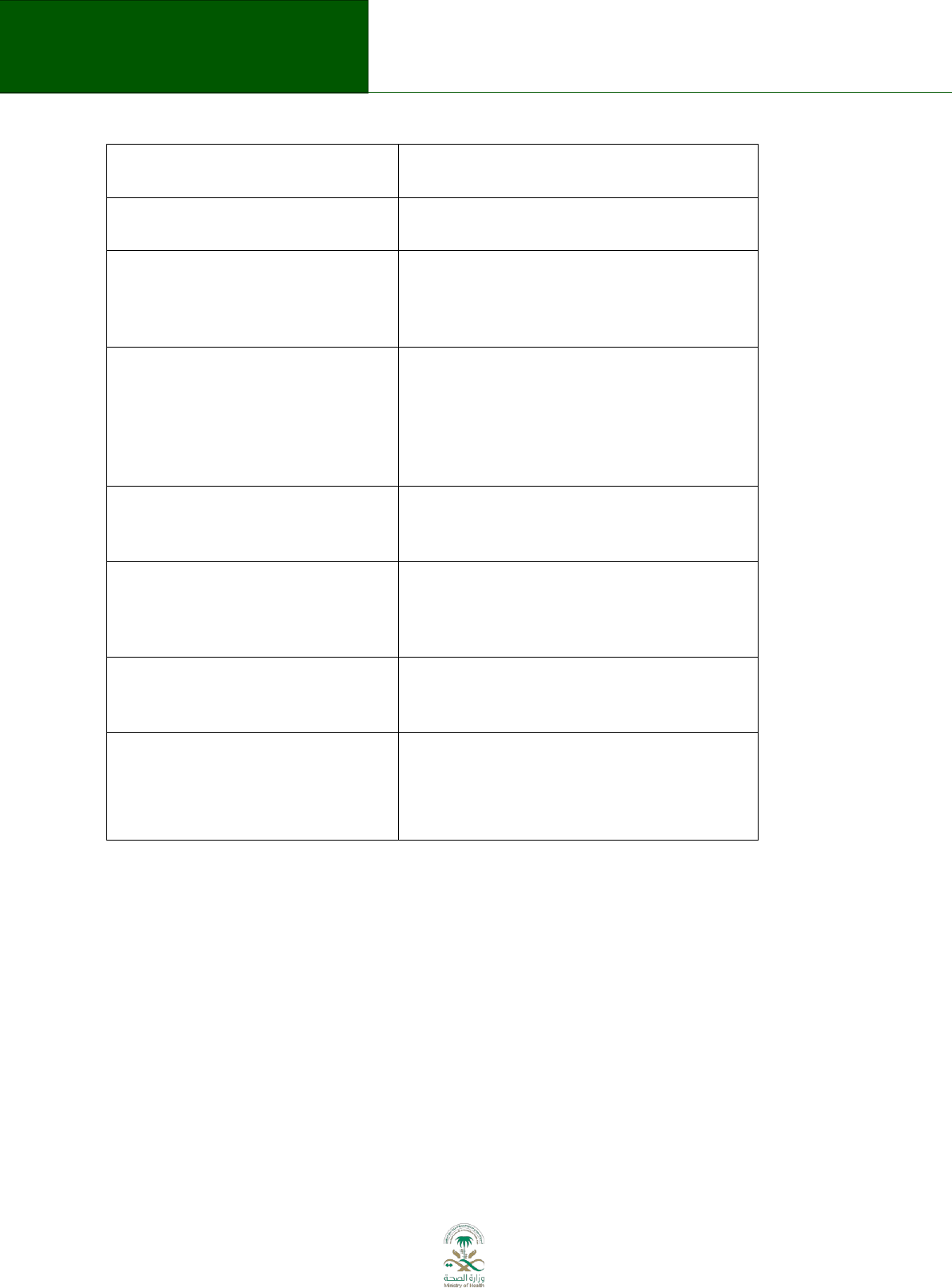

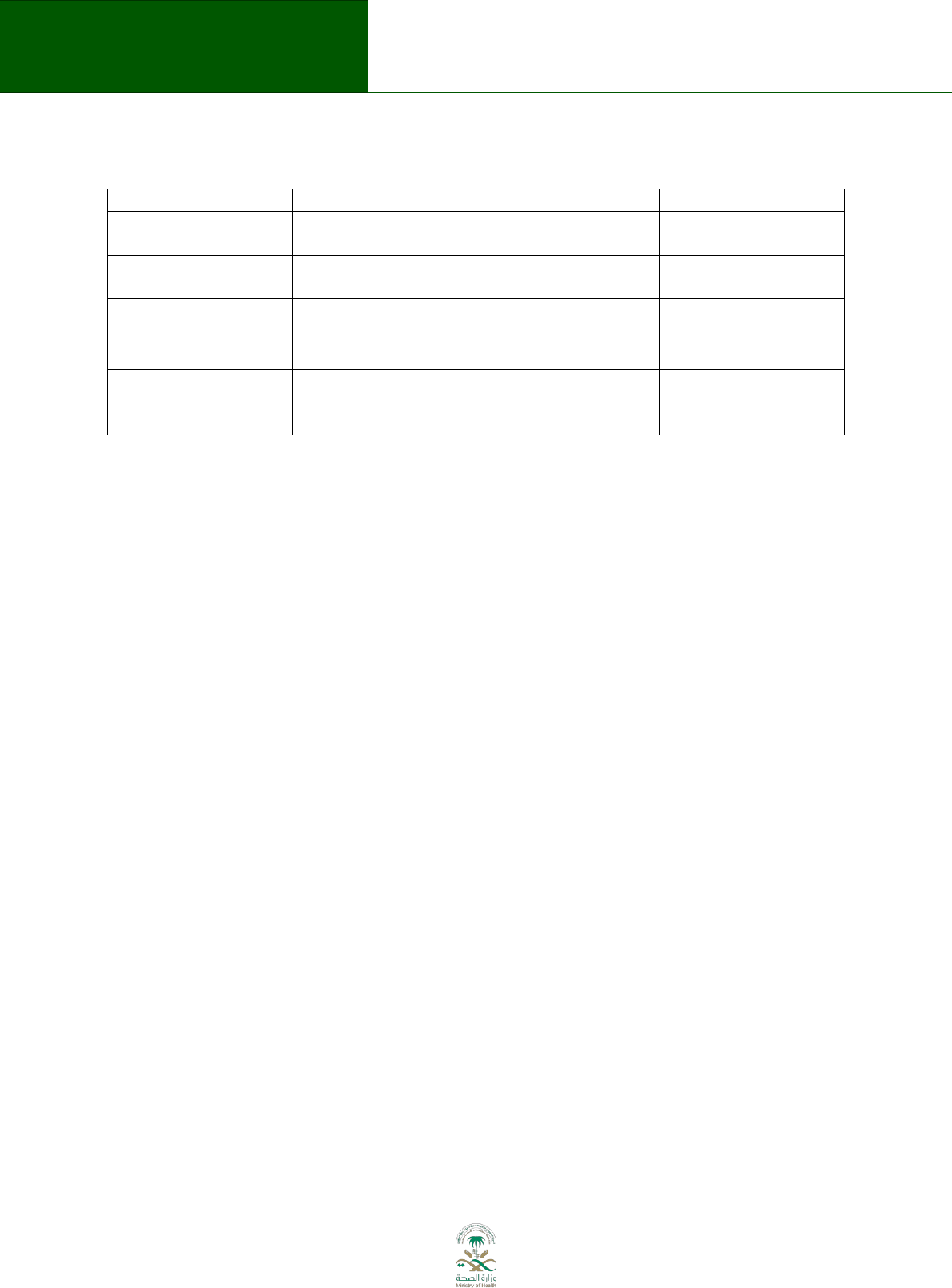

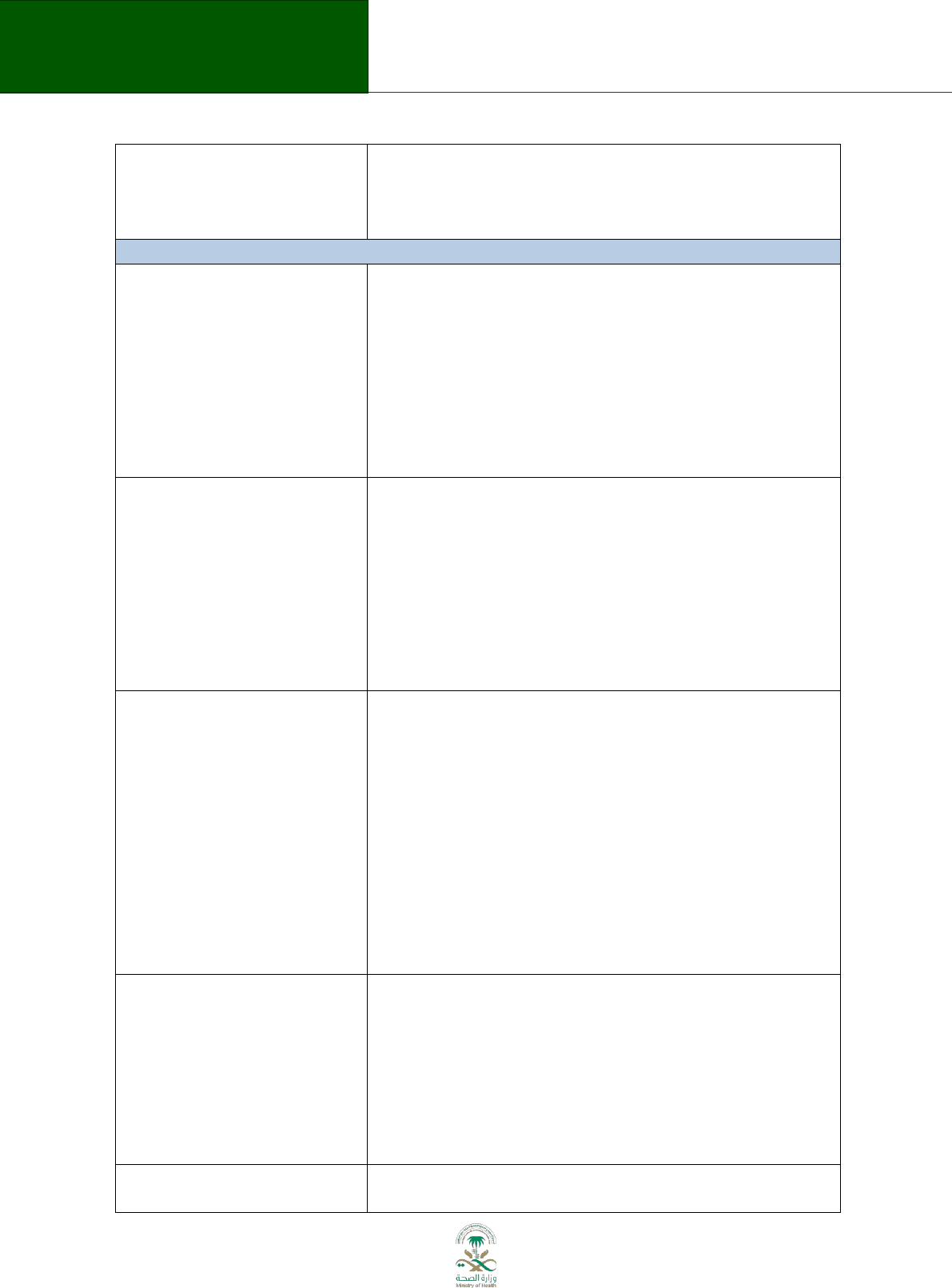

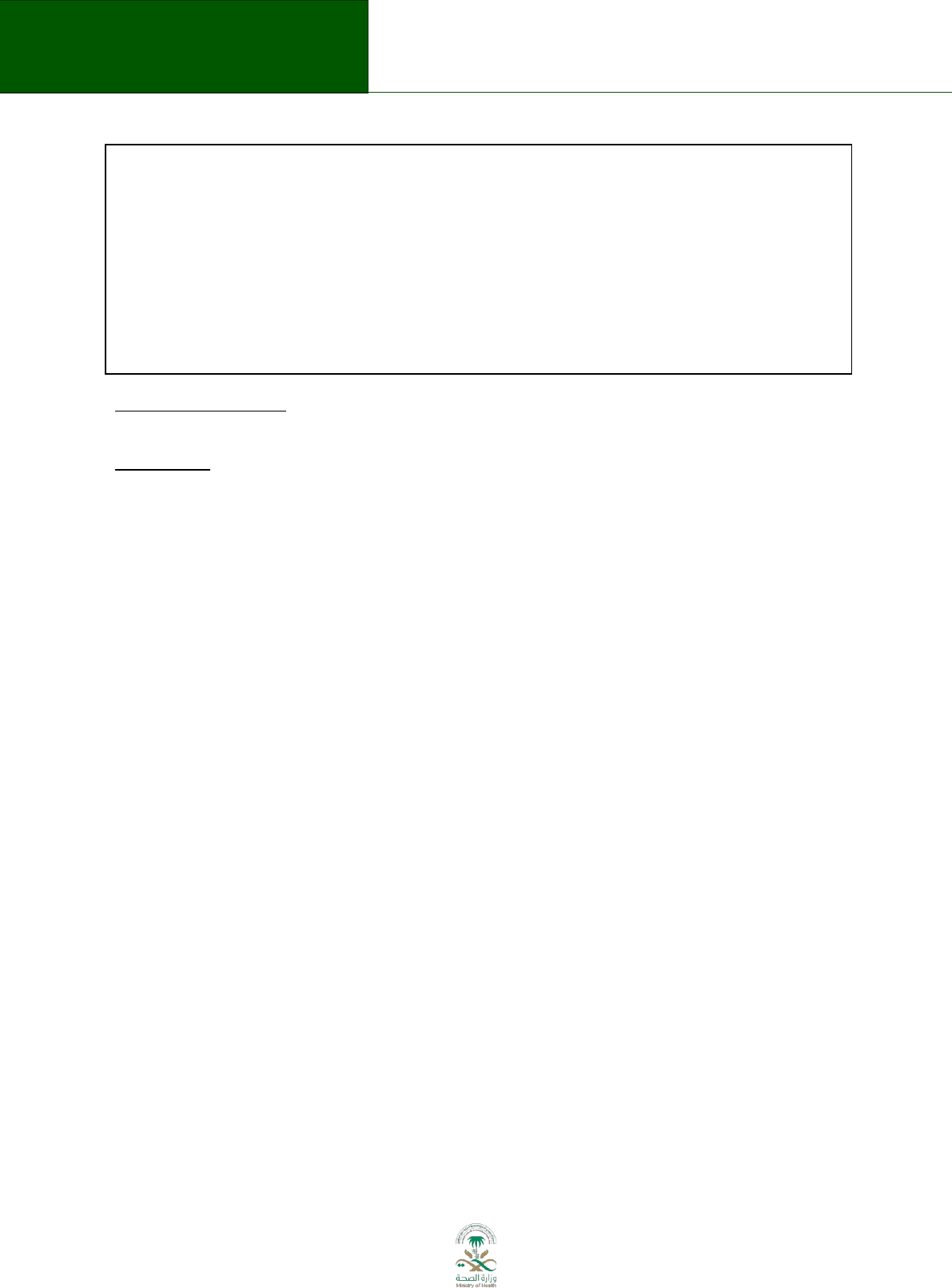

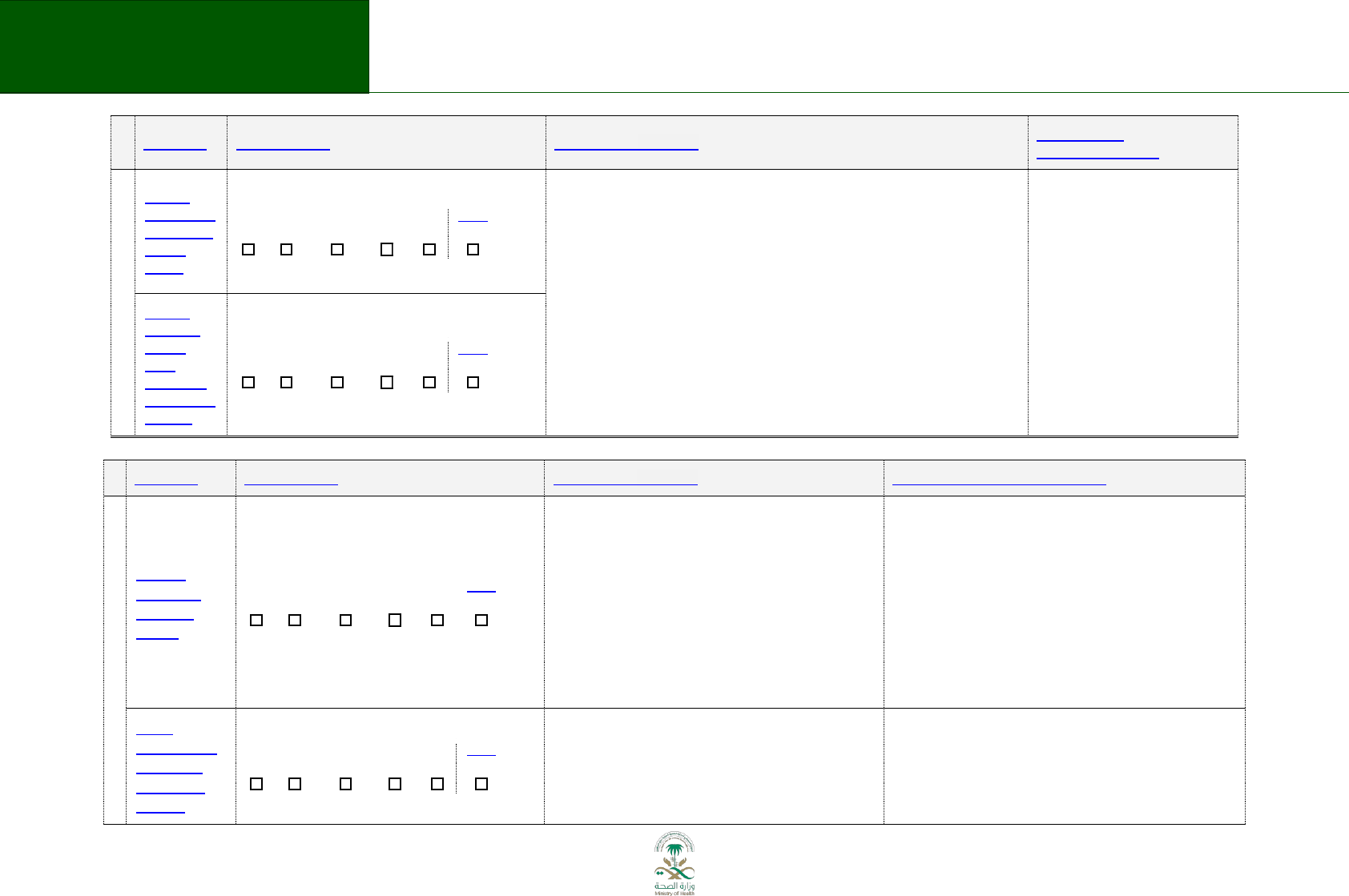

Table 7.1 Credibility of the Systematic Review Process

8. Grading the quality of evidence

Assessing the retrieved evidence is a crucial step that enables the guideline panel to formulate

recommendations.

62,63

The GRADE system for preparing evidence profiles, assessing quality of

evidence and developing recommendations should be used.

5,63,64

This approach allows for a

structured and transparent assessment of the quality of evidence for each outcome. For each

question, there should be relevant data (from the systematic review) for all the outcomes

(benefits and harms) that were rated as important.

If GRADE tables have already been prepared for the published guidelines they should be used as

the basis for formulating recommendations using the evidence to decision frameworks as

described above.

54,65

If there are no GRADE evidence summaries (evidence profiles or summary

of findings), the guideline panel will have to decide whether to retrieve the systematic reviews on

which the recommendations are based, and to prepare evidence summaries, or simply to use the

existing recommendations, and apply considerations of cost, local values and preferences and

feasibility. For potentially high-cost interventions it is strongly suggested that the systematic

review be retrieved and evidence summaries prepared.

The GRADE handbook contains (electronic help file in the GDT) all the instructions for developing

GRADE evidence profiles, and the software for the entire guideline development process can be

accessed on http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/.

In the GRADE system, the quality of evidence in the context of clinical practice guidelines reflects

“the extent to which confidence in an estimate of the effect is adequate to support

recommendations”.

63

It is implicit in the definition that guidelines panels have to judge the

quality of the evidence along with the specific context in which the evidence is being used.

Did the Review Explicitly Address a Sensible Clinical Question?

Was the Search for Relevant Studies Exhaustive?

Was the Risk of Bias of the Primary Studies Assessed?

Did the review address possible explanations of between-study

differences in results?

Did the review present results that are ready for clinical application?

Were Selection and Assessments of Studies Reproducible?

Did the Review Address Confidence in Effect Estimates (i.e, quality

of evidence)?

28

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

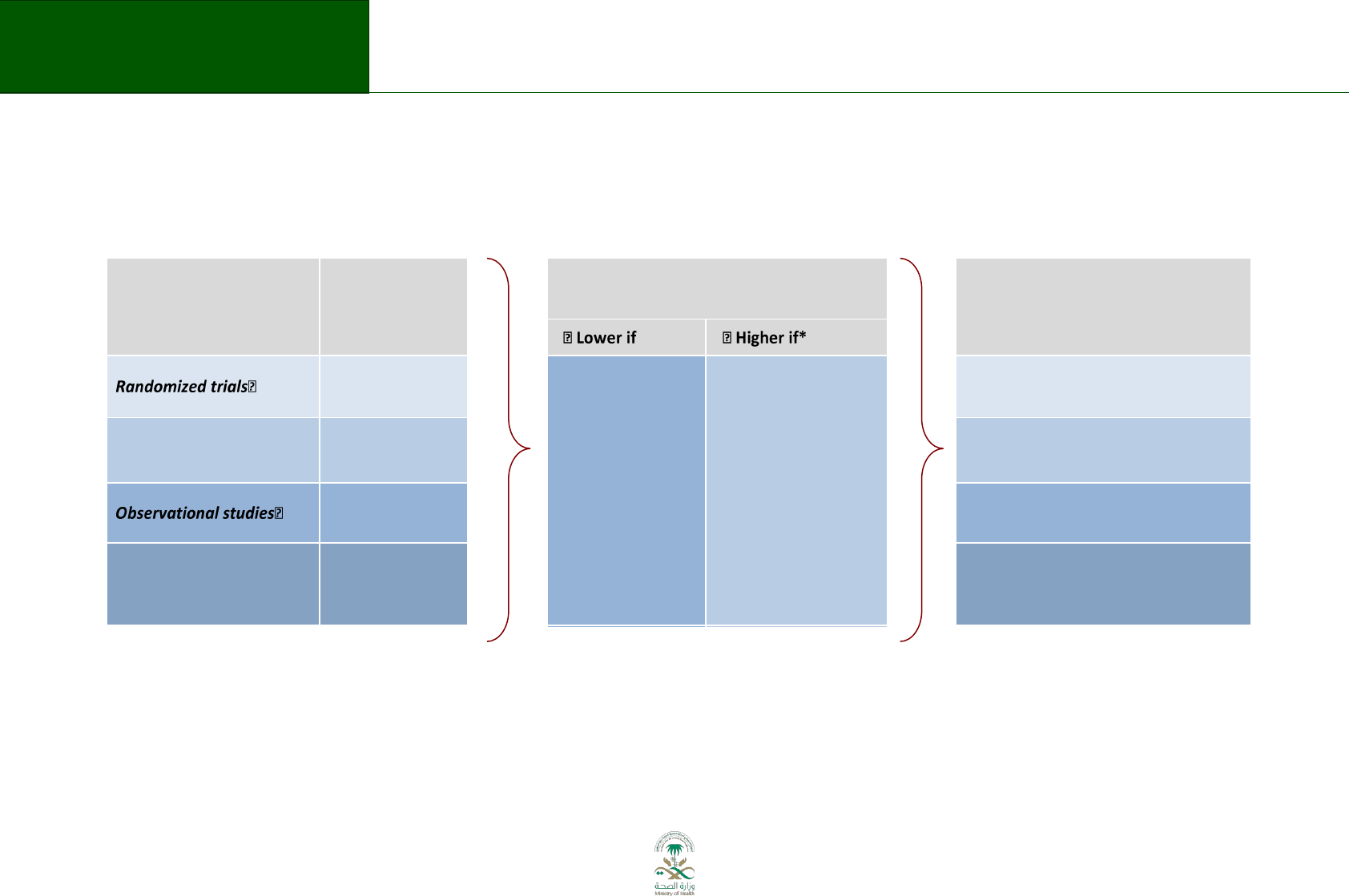

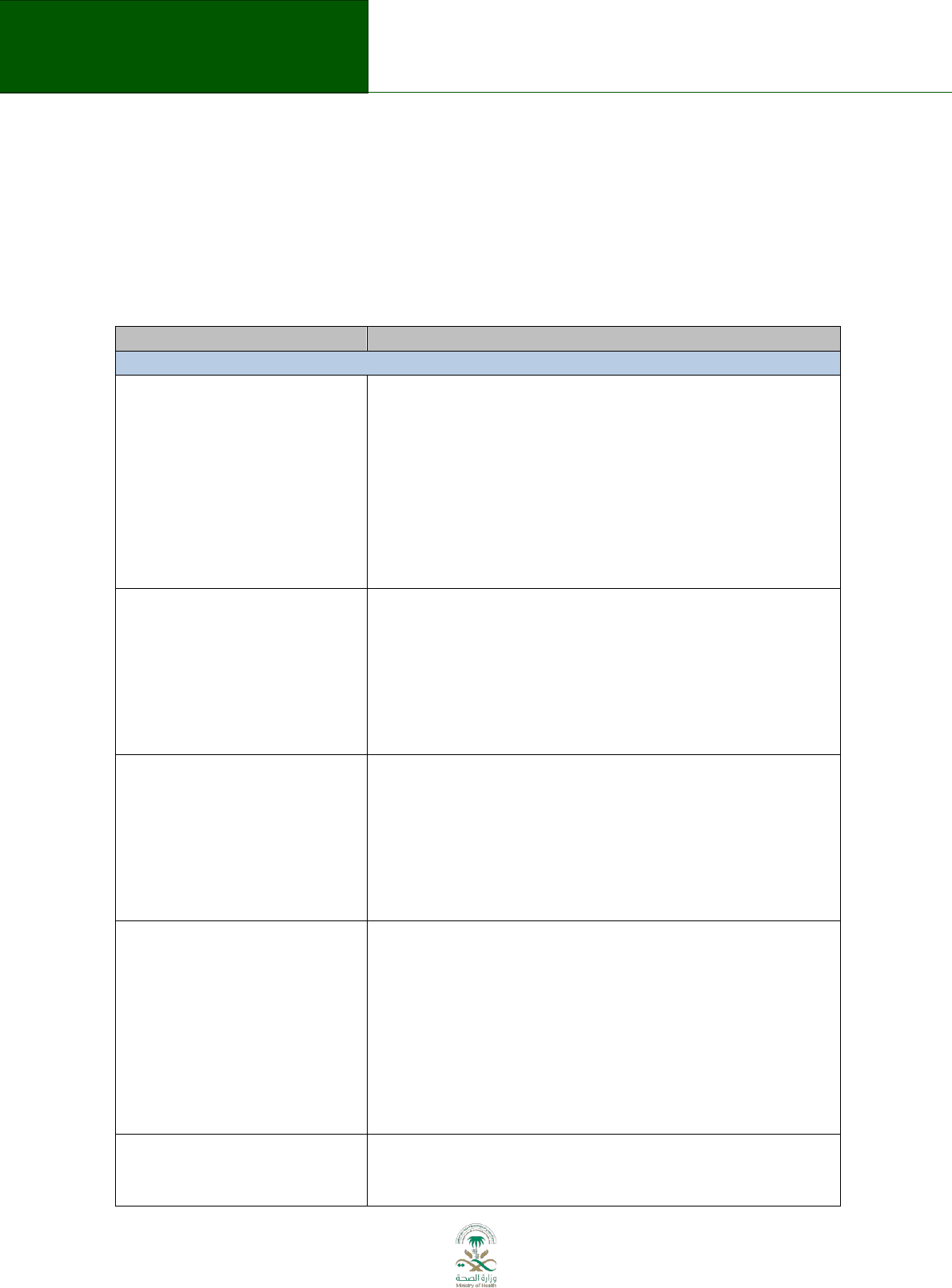

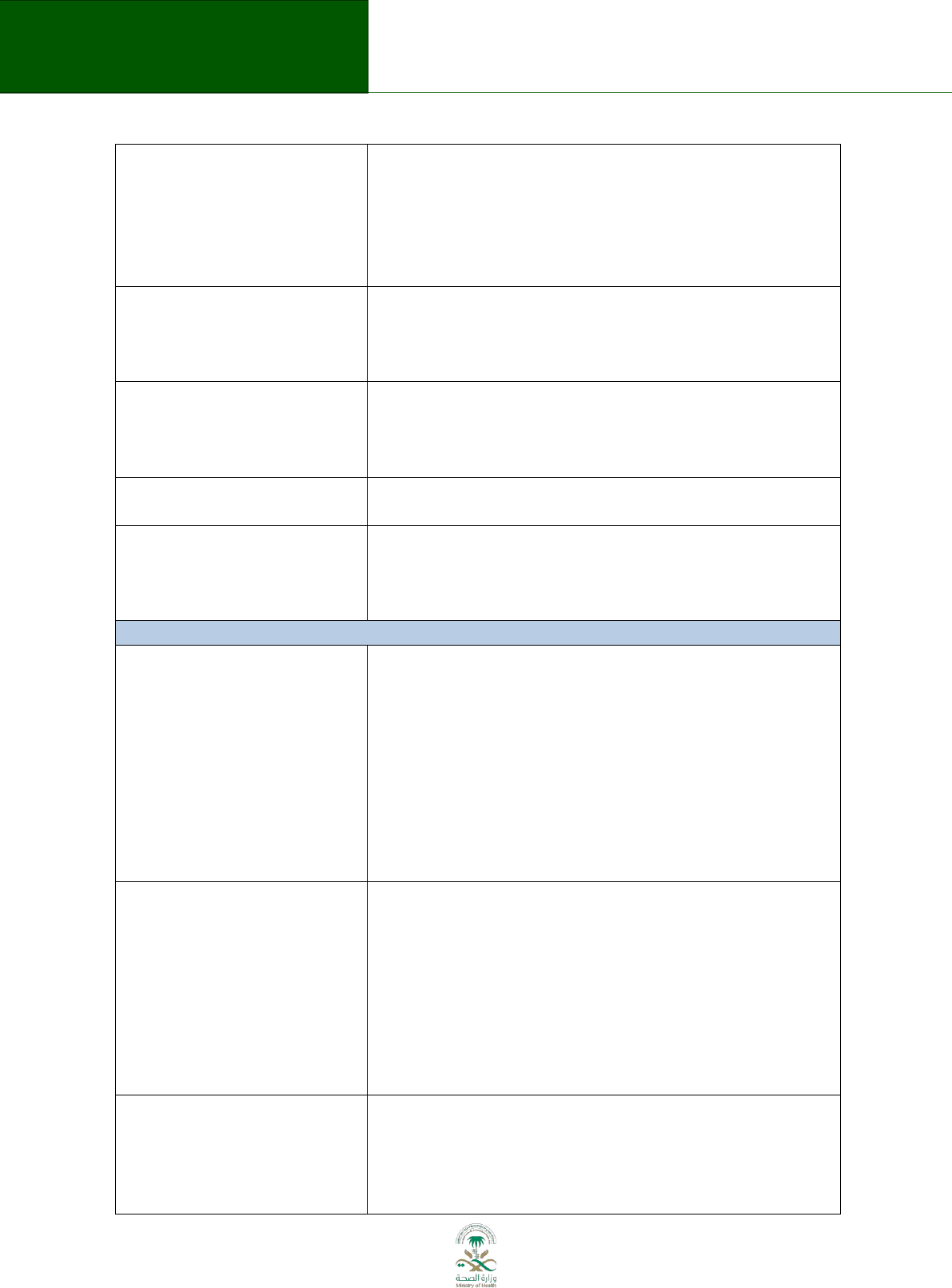

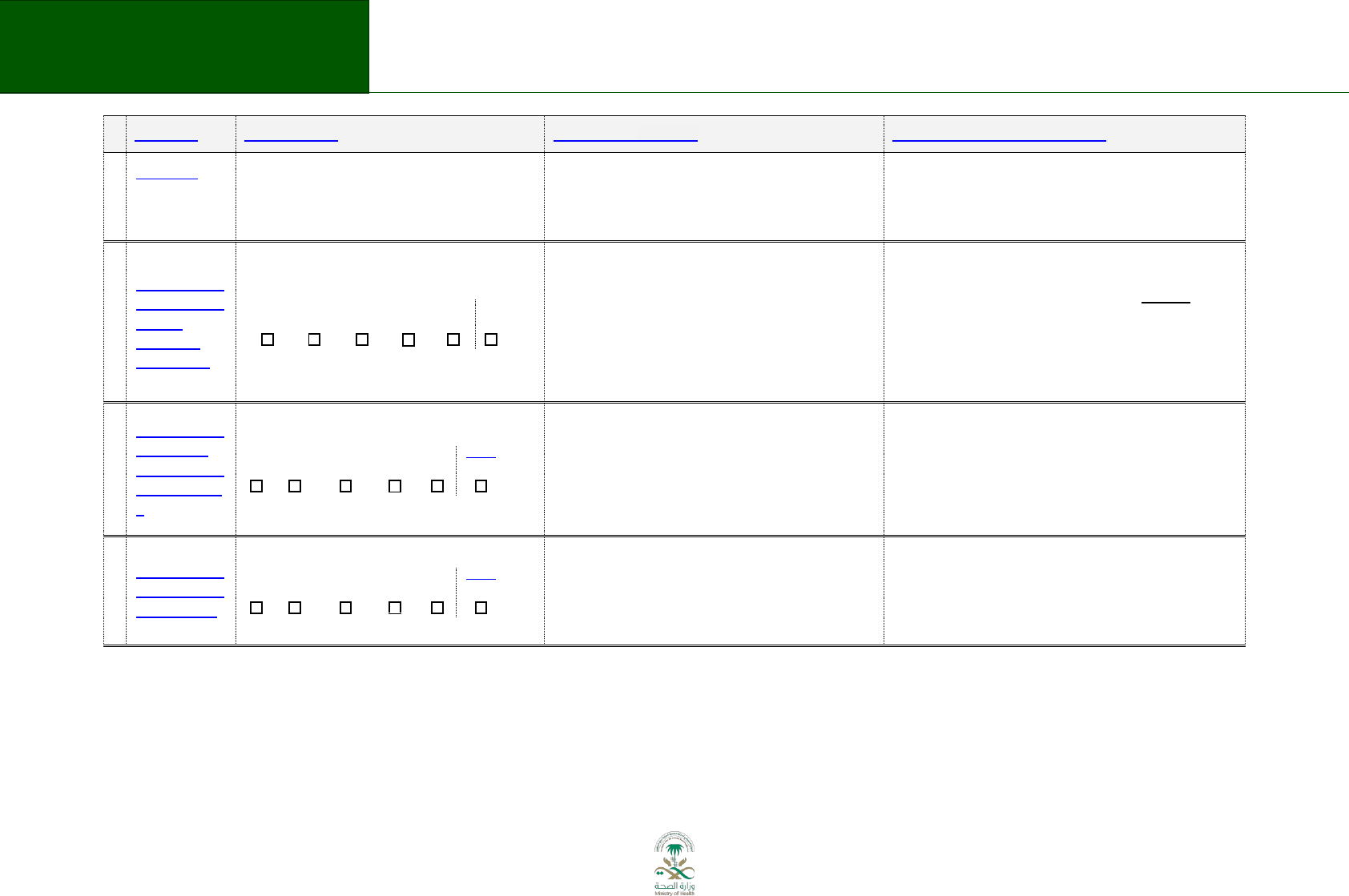

Table 8.1 explains the quality assessment according to GRADE. Although RCTs start as high quality

evidence, they can be downgraded depending on whether issues of risk of bias, indirectness,

imprecision, inconsistency, and publication bias are detected in the body of evidence. On the

other hand, observational studies start as low quality evidence; however, they can be upgraded

to moderate or high quality evidence if they are methodologically sound and evidence of a large

magnitude of effect, dose-response gradient or plausible confounding, which would reduce a

demonstrated effect, are identified. It is important to highlight that the assessment of the quality

of the evidence should be conducted at an outcome level, across studies.

This handbook will not provide details on grading as this is described in the GDT and in the series

of articles cited below. An overview is provided here.

29

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

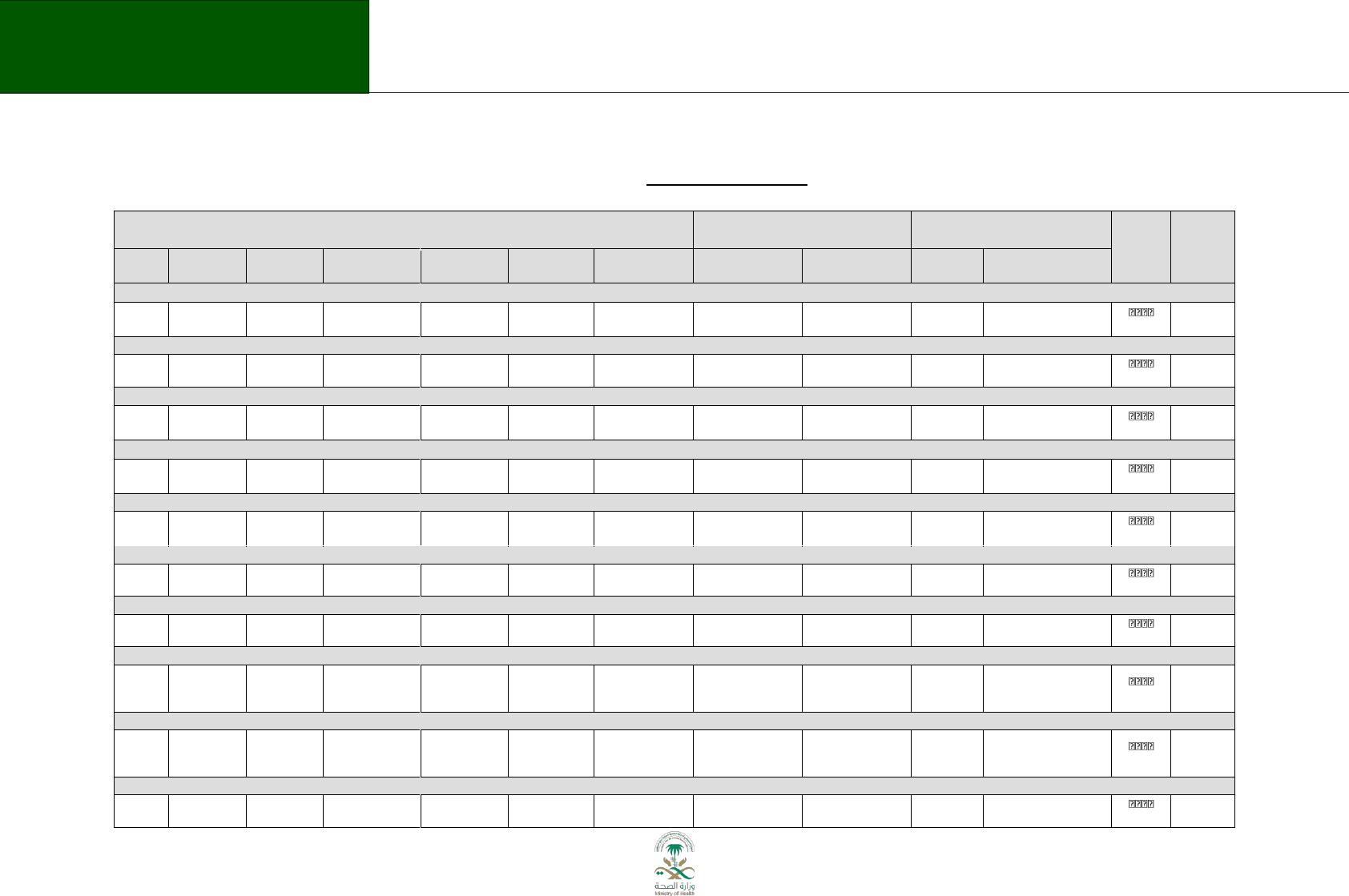

Table 8.1 GRADE's approach to rating quality of evidence (aka confidence in effect estimates)

For each outcome based on a systematic review and across outcomes (lowest quality across the outcomes critical for decision making)

1.

Establish initial

level of confidence

2.

Consider lowering or raising

level of confidence

3.

Final level of

confidence rating

Study design

Initial confidence

in an estimate of

effect

Reasons for considering lowering

or raising confidence

Confidence

in an estimate of effect

across those considerations

High

confidence

Risk of Bias

Inconsistency

Indirectness

Imprecision

Publication bias

Large effect

Dose response

All plausible

confounding & bias

would reduce a

demonstrated effect

or

would suggest a

spurious effect if no

effect was observed

High

Moderate

Low

confidence

Low

Very low

*upgrading criteria are usually applicable to observational studies only.

30

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

8.1 Limitations that can reduce the quality of the evidence:

1. Risk of bias or limitations in the detailed study design and execution: RCTs and observational

studies may suffer from limitations in the study design that could increase the risk of misleading

results. Although this assessment is conducted at a study level, the risk of bias can differ across

outcomes.

66

Some of the reasons for downgrading by one or two levels the quality of the evidence

of RCTs are:

• Lack of allocation concealment

• Lack of blinding (particularly if outcomes are subjective and their assessment highly

susceptible to bias)

• Large loss to follow-up

• Failure to adhere to an analysis according to intention-to-treat principle

• Selective reporting of events: investigators neglect to report outcomes that they have

measured (typically those for which they observed no effect).

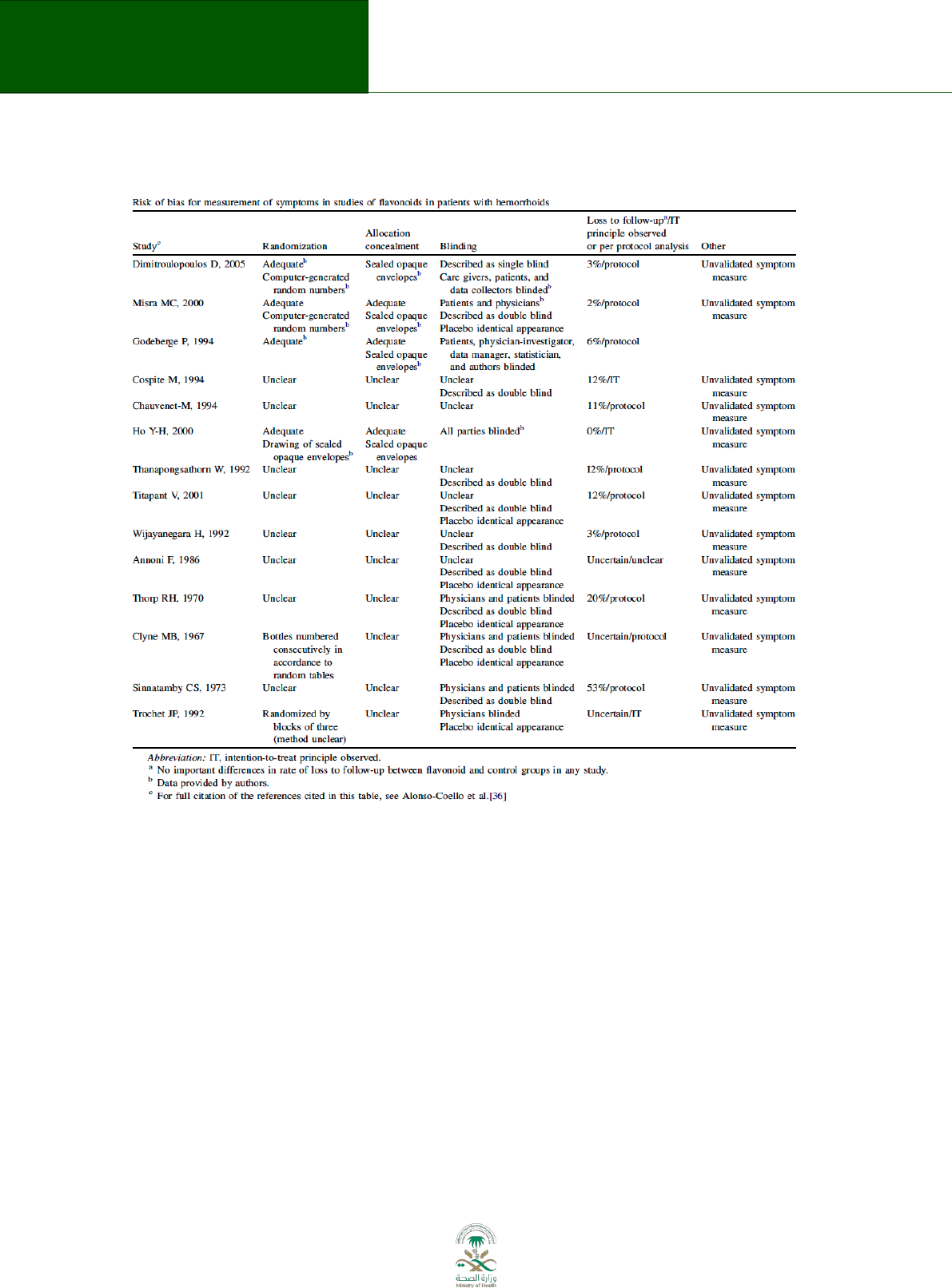

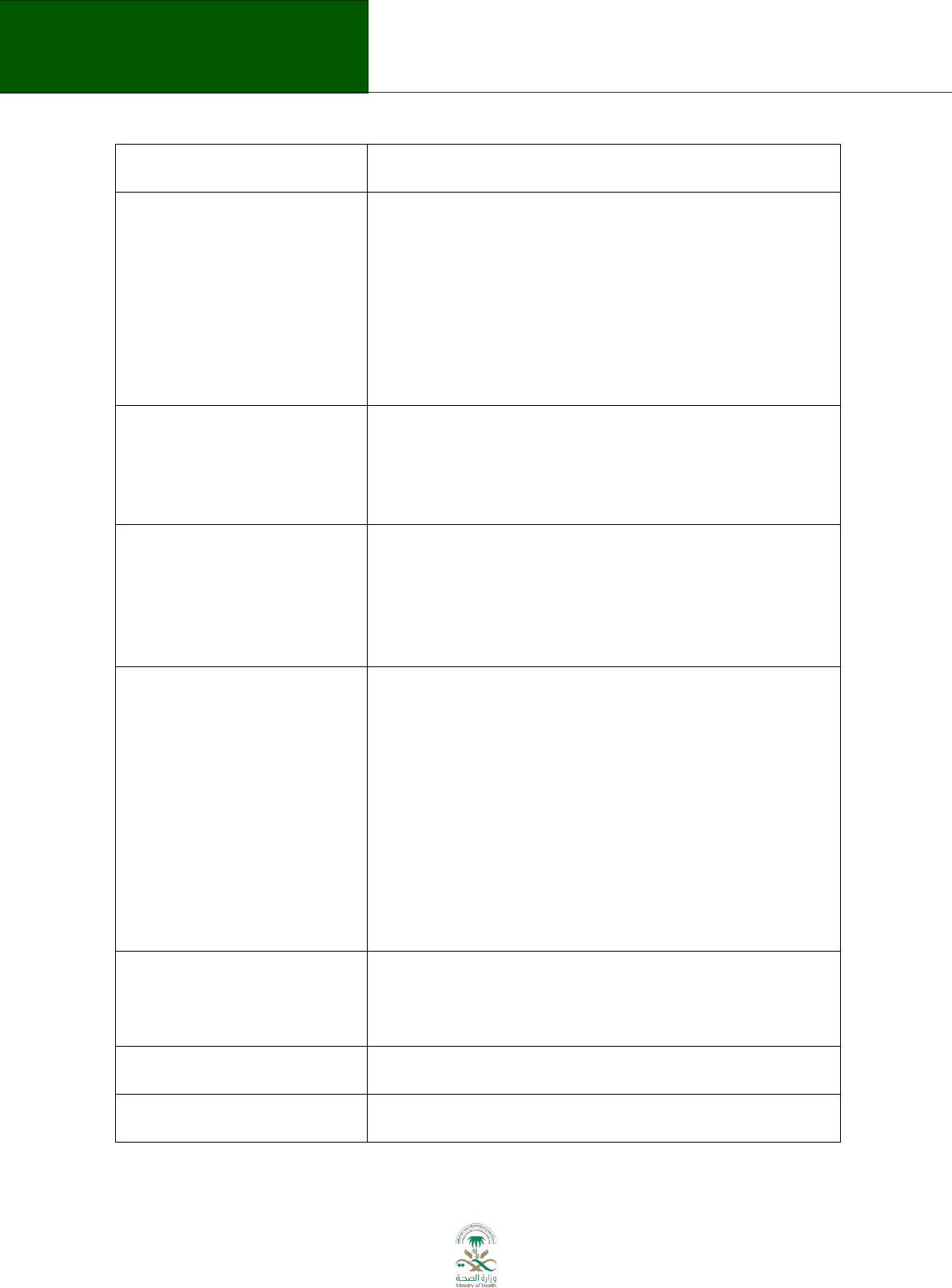

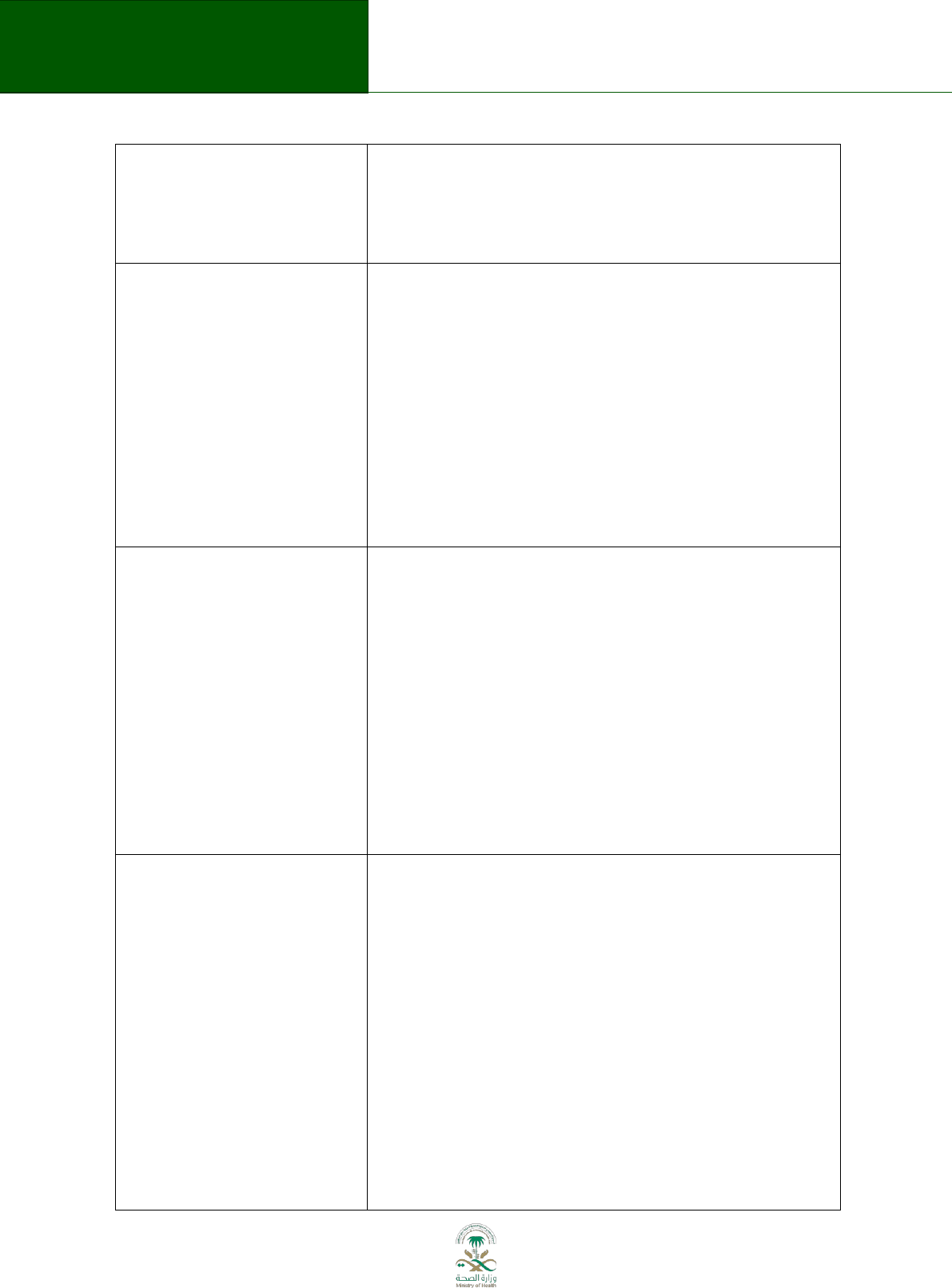

Consider the following example from the GRADE series in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.

The table below was extracted from a systematic review summarizing the evidence on the use of

flavonoids for treating haemorrhoids (Figure 8.1)

67

. The table describes the risk of bias

assessment of all the included studies providing evidence for the outcome of persisting

symptoms. Most of the trials did not provide enough information to determine which method

was used to generate the randomization sequence nor the appropriateness of the allocation

concealment. Most of the studies described blinding using the terms double blinding, with no

clear specification of who was blinded. Finally, the majority of the trials failed to conduct an

intention-to-treat analysis and did not report enough data to allow readers to conduct it.

After conducting an assessment of the risk of bias at a study level, it is necessary to obtain an

overall estimate of the risk of bias for the body of evidence informing a particular outcome.

Since we are using RCTs to inform this outcome, the quality of the evidence started as high

quality; however, due to issues of risk of bias it has to be downloaded at least one level going

from high to moderate.

31

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

Figure 8.1 Risk of bias example

2. Inconsistency: Widely differing estimates of the treatment effect (i.e. heterogeneity or variability

in results) across studies suggest true differences in underlying treatment effect. When evidence of

heterogeneity exists, but investigators fail to provide a plausible explanation, the quality of evidence

should be downgraded by one or two levels, depending on the magnitude of the inconsistency in the

results.

66

A systematic review provides a summary of the data from the results of a number of individual

studies. If the results of the individual studies are similar meta-analysis is used to combine the

results from the individual studies and an overall summary estimate is calculated. The meta-analysis

gives weighted values to each of the individual studies according to their size. The individual results

of the studies need to be expressed in a standard way, such as relative risk, odds ratio or mean

difference between the groups. Results are traditionally displayed in a figure (see Figure 8.2) called a

forest plot.

32

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

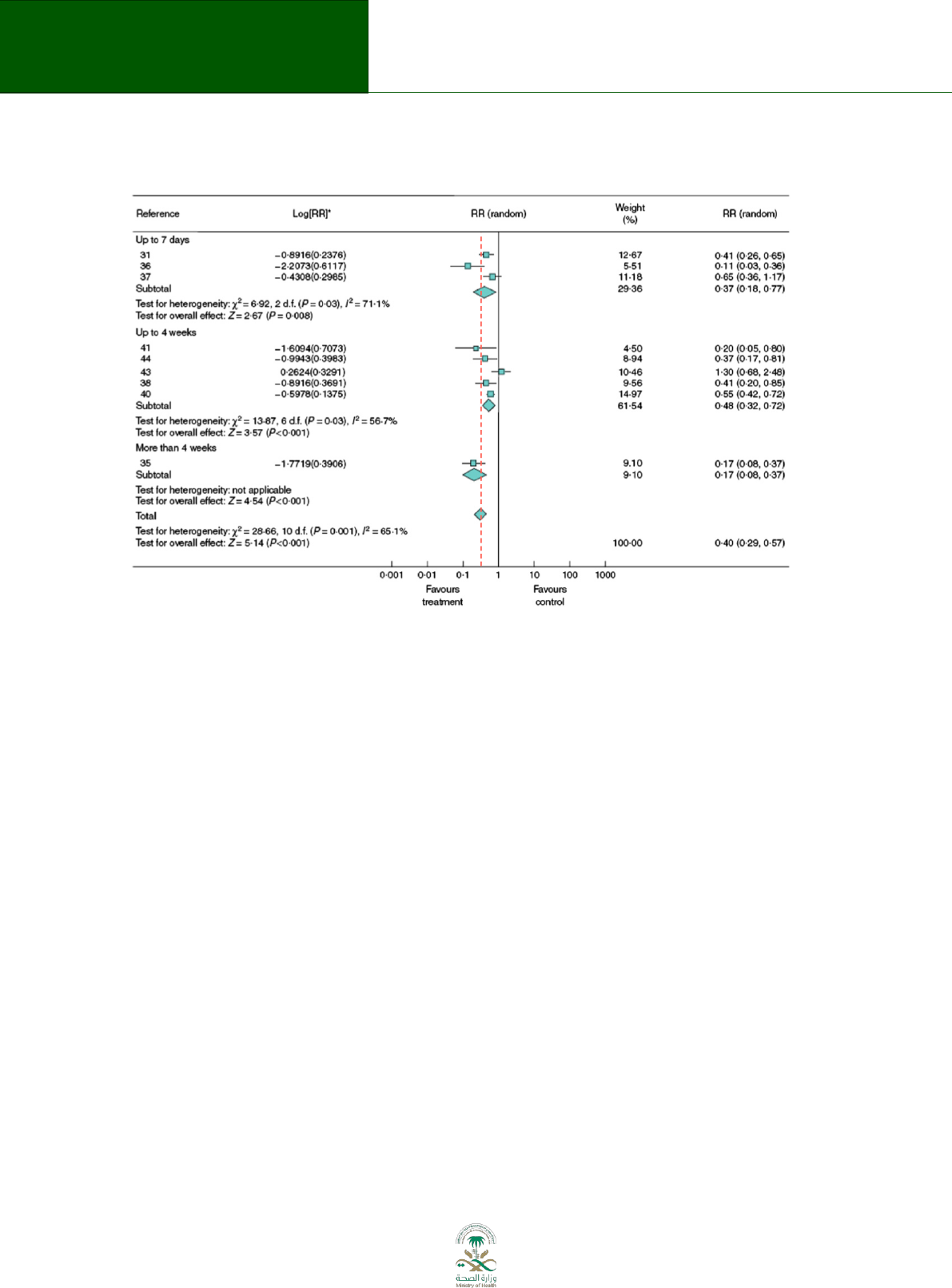

Figure 8.2 Forest plot

The forest plot depicted above represents a meta-analysis of 9 trials that assessed the effects of

flavonoids for the treatment of haemorrhoids

67

. Individual studies are represented by a square and

a horizontal line, which corresponds to the point estimate and 95% confidence interval of the

relative risk. The size of the square reflects the weight of the study in the meta-analysis. The solid

vertical line corresponds to ‘no effect’ of treatment – a relative risk of 1.0. When the confidence

interval includes 1 it indicates that the result is not significant at conventional levels (P > 0.05).

The diamond at the bottom represents the combined or pooled relative risk of all 9 trials with its

95% confidence interval. In this case, it shows that the treatment reduces persisting symptoms by

60% (RR 0.40 95% CI 0.29 to 0.57). Notice that the diamond does not overlap the ‘no effect’ line (the

confidence interval doesn’t include 1) so we can be assured that the pooled RR is statistically

significant. The test for overall effect also indicates statistical significance (p<0.001).

Heterogeneity can be assessed by eyeballing or more formally with statistical tests, such as the

Cochran Q test and the I

2

value. With the “eyeball” test one looks for the similarity of the point

estimates and the overlap of the confidence intervals of the trials with the summary estimate. In the

example above note that the dotted line running vertically through the combined relative risk does

not cross the horizontal lines of all the individual studies (3/9) indicating small to moderate degree

of heterogeneity among the included studies. If Cochran Q is statistically significant there is an

indication for heterogeneity. If Cochran Q is not statistically significant but the ratio of Cochran Q

and the degrees of freedom (Q/df) is > 1 there is possible heterogeneity. If Cochran Q is not

statistically significant and Q/df is < 1 then heterogeneity is very unlikely. In the example above Q/df

is >1 (28.66/10= 2.866) and the p-value is significant (0.001) indicating heterogeneity. Finally, the I

2

,

which quantifies the proportion of the variation in point estimates due to among-study differences is

large (65%). The higher the I

2

the greater the inconsistency (i.e. that differences between studies are

not likely due to chance).

33

Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare

Guideline Development

3. Indirectness: Two types of indirectness are relevant. First, a review of the evidence comparing the

effectiveness of alternative interventions (say A and B) may find that randomized trials are available,

but they have compared A with placebo and B with placebo. Thus, the evidence is restricted to

indirect comparisons between A and B.

Second, an evidence review may find randomized trials that meet eligibility criteria but which

address a restricted version of the main review question in terms of population, intervention,

comparator or outcomes. For example, suppose that in a review addressing an intervention for

secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, the majority of identified studies happened to be in

people who also had diabetes. Then the evidence may be regarded as indirect in relation to the

broader question of interest because the population is restricted to people with diabetes. The

opposite scenario can equally apply: a review addressing the effect of a preventative strategy for

coronary heart disease in people with diabetes may consider trials in people without diabetes to

provide relevant, albeit indirect, evidence. This would be particularly likely if investigators had

conducted few if any randomized trials in the target population (e.g. people with diabetes). Other

sources of indirectness may arise from interventions studied (e.g. if in all included studies a technical

intervention was implemented by expert, highly trained specialists in specialist centres, then

evidence on the effects of the intervention outside these centres may be indirect), comparators