Folic acid supplementation

49

Health Reports, Volume 15, No. 3, May 2004 Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003

In 1999, the rate of open neural tube defects, the

two most common of which are spina bifida and

anencephaly, was 5.6 for every 10,000 births.

1

These

defects occur in the first four weeks of pregnancy,

usually before most women know they are pregnant.

2

The prevalence of open neural tube defects tends

to be lower among children of women who have

taken folic acid supplements around the time of

conception.

3-5

Folic acid is a B-vitamin that facilitates nucleic

acid synthesis, which is

necessary for normal cell

replication. Naturally

occurring folates are found

in broccoli, spinach, Brussels

sprouts, corn, legumes, and

oranges.

If women relied only on

dietary intake, a substantial

proportion of the

childbearing population

would receive a lower level

of folic acid than is

recommended for

preventing neural tube

defects.

6

A diet that

conforms to Canada’s Food

Guide for Healthy Eating

would provide about 0.2

milligrams of folic acid a day.

The Society of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists of Canada recommends that

women who could become pregnant should take a

multivitamin containing 0.4 to 1.0 milligrams of folic

acid every day, in addition to the amount that would

be found in a healthy diet.

7

Health Canada advises

that daily folic acid supplementation be started at

least two to three months before conception and

continued throughout the first trimester.

8

FOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATIONFOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATION

FOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATIONFOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATION

FOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATION by Wayne J. Millar

Less than halfLess than half

Less than halfLess than half

Less than half

In 2000/01, as part of the Canadian Community

Health Survey, women aged 15 to 55 who had given

birth in the previous five years were asked questions

about their pregnancy, including, “Did you take a

vitamin supplement containing folic acid before your

(last) pregnancy, that is, before you found out that

you were pregnant?” Of the estimated 1.5 million

women in this age range who had given birth, 45%

reported that they had used

vitamin supplements

containing folic acid before

their last pregnancy.

The older the mother, the

more likely she was to have

used folic acid supplements.

The figure ranged from 33%

among women aged 15 to 24

to 48% at age 30 or older.

Although unplanned

pregnancies occur in all

marital status groups,

pregnancies among married

women are more likely to be

planned, and therefore, may

be more likely to involve the

use of folic acid supplements

before conception.

9

Close to

half (48%) of women who

were married had taken folic

acid supplements, compared

with 31% who were not married.

Folic acid supplementation was associated with

several socio-economic factors. Use tended to be

higher among urban than rural mothers, and among

those in higher-income households. Level of

education was also associated with use, which was

lowest among women with less than high school

*

34

39

48

56

Low Lower-middle Upper-middle High

Household income

*

*

*

Canada (45%)

*

Percentage of women aged 15 to 55 who took folic acid

supplements before pregnancy, by household income

Data source: 2000/01 Canadian Community Health Survey

* Significantly different from rate for Canada (p < 0.05)

Folic acid supplementation50

Health Reports, Volume 15, No. 3, May 2004 Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003

Use of folic acid supplements beforeUse of folic acid supplements before

Use of folic acid supplements beforeUse of folic acid supplements before

Use of folic acid supplements before

pregnancy among women who gave birthpregnancy among women who gave birth

pregnancy among women who gave birthpregnancy among women who gave birth

pregnancy among women who gave birth

in previous five years, 2000/01in previous five years, 2000/01

in previous five years, 2000/01in previous five years, 2000/01

in previous five years, 2000/01

Estimated Took folic acid

population

’000 ’000 %

Total 1,525 690 45

Age

15-24 191 63 33*

25-29 375 163 43

30-55 960 465 48*

Marital status

Married 1,296 620 48*

Not married 229 70 31*

Missing F F F

Province/Territory

Newfoundland 25 11 44

Prince Edward Island 7 3 43

Nova Scotia 43 22 50

New Brunswick 35 16 45

Québec 346 105 30*

Ontario 607 311 51*

Manitoba 55 25 46

Saskatchewan 51 22 43

Alberta 163 81 49*

British Columbia 184 91 49*

Yukon Territory 2 1 42

Northwest Territories 3 1 31*

Nunavut 3 1 41

Rural/Urban

Rural 271 110 41*

Urban 1,254 580 46*

Household Income

Low 229 78 34*

Lower-middle 367 145 39*

Upper-middle 505 242 48*

High 337 187 56*

Missing 88 38 43

Education

Less than high school graduation 202 67 33*

High school graduation 313 132 42*

Some postsecondary 138 49 35*

College/University graduation 860 439 51*

Missing F F F

Immigrant status

Immigrant 357 150 42

Non-immigrant 1,162 539 46*

Missing F F F

Data source: 2000/01 Canadian Community Health Survey

* Significantly different from value for Canada (p < 0.05)

F Coefficient of variation greater than 33.3%

graduation, and highest among postsecondary

graduates. The percentage of immigrant mothers

who had used folic acid supplements was lower than

the figure for those who were Canadian-born: 42%

versus 46%.

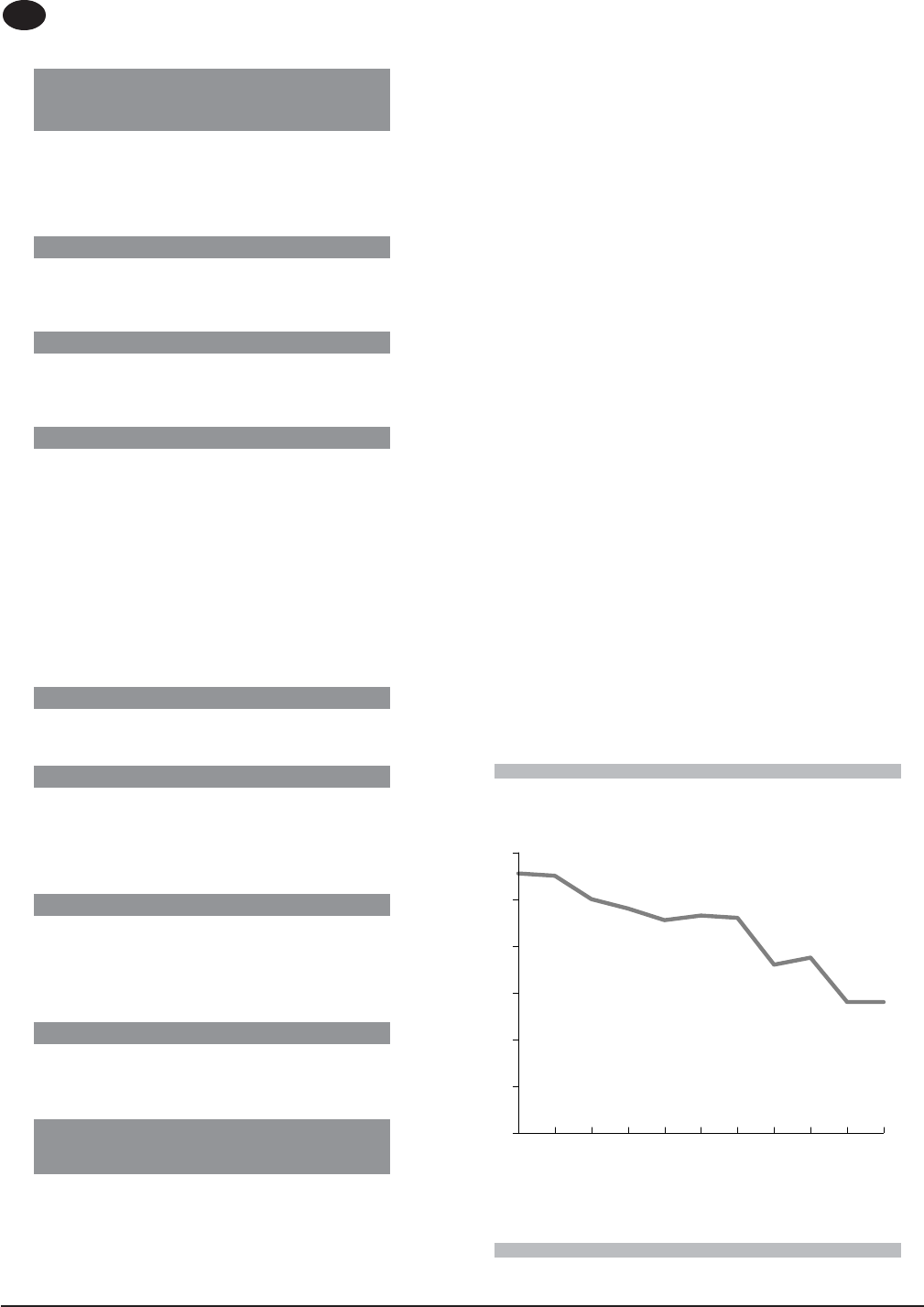

Declining rates of neural tubeDeclining rates of neural tube

Declining rates of neural tubeDeclining rates of neural tube

Declining rates of neural tube

defectsdefects

defectsdefects

defects

The 1999 level of open neural tube defects in

Canada—5.6 per 10,000 births—was substantially

lower than the rate of 11.1 per 10,000 in 1989.

1

Factors other than taking folic acid supplements

probably contributed to this decline. Food

fortification with folic acid is not likely involved, as

it was not mandated in Canada until 1998. However,

prenatal screening to detect congenital anomalies

may have resulted in some women opting for

therapeutic abortion.

10

For instance, in England and

Wales, the incidence of neural tube defects fell from

3.2 per 1,000 births in the early 1970s to 0.1 per

1,000 births in 1997. About 40% of this decline

was attributed to prenatal screening and termination

of pregnancy, with the remainder accounted for by

a decline in incidence, that coincided with an increase

in dietary folate.

11

Rate of neural tube defects, Canada, 1989 to 1999

1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Per 10,000 total births

†

Data source: Health Canada, Canadian Congenital Anomalies Surveillance System

Note: Excludes Nova Scotia

† Live births and stillbirths

Folic acid supplementation

51

Health Reports, Volume 15, No. 3, May 2004 Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003

Wayne J. Millar (613-951-1631; [email protected]) is

with the Health Statistics Division at Statistics Canada, Ottawa,

Ontario, K1A 0T6

References

3 Milunsky A, Jick H, Jick SS, et al. Multivitamin/folic acid

supplementation in early pregnancy reduces the prevalence

of neural tube defects. Journal of the American Medical

Association 1989; 262(20): 2847-52.

4 MIRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural

tube defects: results of the Medical Research Vitamin Council

Study. Lancet 1991; 338: 131-7.

5 Czeizel AE, Dudas I. Prevention of the first occurrence of

neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin

supplementation. New England Journal of Medicine 1992:

327(26): 1832-5.

1 Kohut R, Rusen ID, Lowrey RB, eds. Congenital Anomalies in

Canada - A Perinatal Health Report, 2002 (Catalogue H39-641/

2002E) Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government

Services Canada, 2002.

2 Elwood JM, Little J, Elwood JH. Epidemiology and Control of

Neural Tube Defects. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Data sourceData source

Data sourceData source

Data source

Use of vitamin supplements containing folic acid before

pregnancy was estimated using data from the first cycle of the

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), which was

conducted from September 2000 to October 2001.

12

The

survey covers the population aged 12 or older who were living

in private households at the time. It does not include residents

of Indian reserves, Canadian Forces Bases, or some remote

areas. The response rate for the first cycle was 85%; the total

sample size was 131,535.

All differences were tested to ensure statistical significance;

that is, they did not occur simply by chance. To account for

survey design effects, standard errors and coefficients of

variation were estimated using the bootstrap method.

13-15

A

significance level of p < 0.05 was applied in all cases.

The information about the use of folic acid supplements is

based on a sample of 7,875 women aged 15 to 55 who had

given birth in the previous five years, representing a population

of 1.5 million women. The survey did not ask the women if

they had planned their pregnancy or about their knowledge of

folic acid. No information is available about the dosage of

folic acid or the frequency of use. The percentage of women

taking folic acid may be underestimated, because some women

may not know that multivitamins contain it.

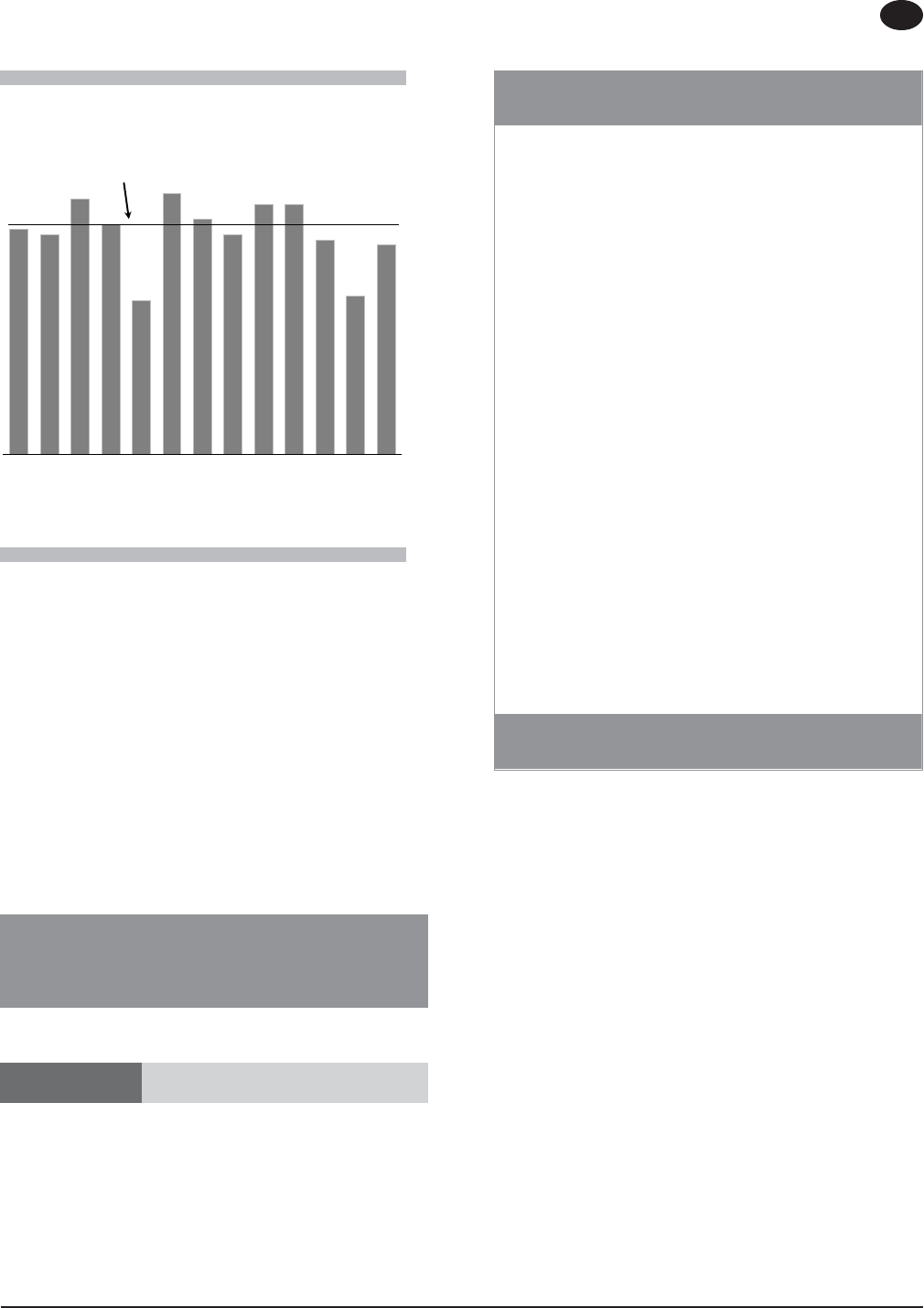

44

43

50

45

30

51

46

43

49 49

42

31

41

Nfld PEI NS NB Qué Ont Man Sask Alta BC Yukon NWT Nunavut

*

*

*

*

*

Canada (45%)

Percentage of women aged 15 to 55 who took folic acid

before pregnancy, by province/territory

Data source: 2000/01 Canadian Community Health Survey

* Significantly different from rate for Canada (p < 0.05)

Provincial and territorial rates of folic acid

supplementation varied from 30% in Québec and

31% in the Northwest Territories to 51% in Ontario.

Rates in Alberta and British Columbia were also

above the national level.

In Québec, where the reported use of folic acid

supplementation is low, the rate of neural tube

defects is relatively high.

7

However, in

Newfoundland, where the level of folic acid

supplementation matches the national figure, the rate

of neural tube defects is the same as in Québec.

7

Folic acid supplementation52

Health Reports, Volume 15, No. 3, May 2004 Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003

6 Werler MM, Louik C, Mitchell AA. Achieving a public health

recommendation for preventing neural tube defects with folic

acid. American Journal of Public Health 1999; 89(11): 1637-40.

7 Wilson RD. The use of folic acid for the prevention of

neural tube defects and other congenital anomalies. Journal

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2003; 138: 1-7.

8 Van Allen MI, McCourt C, Lee NS. Preconception Health: Folic

Acid for the Primary Prevention of Neural Tube Defects. A Research

Document for Health Professionals, 2002 (Catalogue H39-607/

2002E) Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government

Services Canada, 2002.

9 Morin P, De Wals P, St-Cyr-Tribble D, et al. Pregnancy

planning: a determinant of folic acid supplements for the

primary prevention of neural tube defects. Canadian Journal

of Public Health 2002; 93(4): 259-63.

10 Gucciardi E, Pietrusiak M, Reynolds DL, et al. Incidence

of neural tube defects in Ontario, 1986-1999. Canadian

Medical Association Journal 2002; 167(3): 237-40.

11 Morris JK, Wald NJ. Quantifying the decline in the birth

prevalence of neural tube defects in England and Wales.

Journal of Medical Screening 1999; 6(4): 182-5.

12 Béland Y. Canadian Community Health Survey—

Methodological overview. Health Reports (Statistics Canada,

Catalogue 82-003) 2002; 13(3): 9-14.

13 Rao JNK, Wu CFJ, Yue K. Some recent work on resampling

methods for complex surveys. Survey Methodology (Statistics

Canada, Catalogue 12-001) 1992; 18: 209-17.

14 Rust KF, Rao JNK. Variance estimation for complex surveys

using replication techniques. Statistical Methods in Medical

Research 1996; 5: 281-310.

15 Yeo D, Mantel H, Liu TP. Bootstrap variance estimation for

the National Population Health Survey. American Statistical

Association. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods

Section. Baltimore, Maryland: August, 1999.