Stte of Helth n the EU

Luxembour

Countr Helth Profle 2021

2

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

The Countr Helth Profle seres

The Stte of Helth n the EU’s Countr Helth Profles

provde concse nd polc-relevnt overvew of

helth nd helth sstems n the EU/Europen Economc

Are The emphsse the prtculr chrcterstcs nd

chllenes n ech countr nst bcdrop of cross-

countr comprsons The m s to support polcmers

nd nfluencers wth mens for mutul lernn nd

voluntr exchne

The profles re the ont wor of the OECD nd the

Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd Polces,

n cooperton wth the Europen Commsson The tem

s rteful for the vluble comments nd suestons

provded b the Helth Sstems nd Polc Montor

networ, the OECD Helth Commttee nd the EU Expert

Group on Helth Sstems Performnce Assessment (HSPA)

Contents

1 3

2 4

3 6

4 7

5 11

51 Effectveness 11

52 Accessblt 13

53 Reslence 16

6 22

Dt nd nformton sources

The dt nd nformton n the Countr Helth Profles

re bsed mnl on ntonl offcl sttstcs provded

to Eurostt nd the OECD, whch were vldted to

ensure the hhest stndrds of dt comprblt

The sources nd methods underln these dt re

vlble n the Eurostt dtbse nd the OECD helth

dtbse Some ddtonl dt lso come from the

Insttute for Helth Metrcs nd Evluton (IHME), the

Europen Centre for Dsese Preventon nd Control

(ECDC), the Helth Behvour n School-Aed Chldren

(HBSC) surves nd the World Helth Ornzton

(WHO), s well s other ntonl sources

The clculted EU veres re wehted veres of

the 27 Member Sttes unless otherwse noted These EU

veres do not nclude Icelnd nd Norw

Ths profle ws completed n September 2021, bsed on

dt vlble t the end of Auust 2021

Demographic factors Luxembourg EU

Populton sze (md-er estmtes) 626 108 447 319 916

Shre of populton over e 65 (%) 145 206

Fertlt rte (2019) 13 15

Socioeconomic factors

GDP per cpt (EUR PPP) 79 223 29 801

Reltve povert rte (%, 2019) 175 165

Unemploment rte (%) 68 71

1 Numbr of chldrn born pr womn gd 15-49 2 Purchsng powr prt (PPP) s dfnd s th rt of currnc convrson tht qulss th

purchsng powr of dffrnt currncs b lmntng th dffrncs n prc lvls btwn countrs 3 Prcntg of prsons lvng wth lss thn 60 %

of mdn quvlsd dsposbl ncom Sourc Eurostt dtbs

Dsclmer The opnons expressed nd ruments emploed heren re solel those of the uthors nd do not necessrl reflect the offcl vews of

the OECD or of ts member countres, or of the Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd Polces or n of ts Prtners The vews expressed heren

cn n no w be ten to reflect the offcl opnon of the Europen Unon

Ths document, s well s n dt nd mp ncluded heren, re wthout preudce to the sttus of or soverent over n terrtor, to the delmtton

of nterntonl fronters nd boundres nd to the nme of n terrtor, ct or re

Addtonl dsclmers for WHO ppl

© OECD nd World Helth Ornzton (ctn s the host ornston for, nd secretrt of, the Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd

Polces) 2021

Demographic and socioeconomic context in Luxembourg, 2020

3

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

1 Hhlhts

Luxembourg has seen a continuous increase in life expectancy up to 2019, but there was a significant fall in 2020

because of deaths due to COVID-19. Behavioural risk factors contribute to more than one third of all deaths, with

high alcohol consumption and growing obesity rates of particular concern. Luxembourg’s population enjoys good

access to health care, with a broad benefits package and low out-of-pocket payments. Luxembourg reacted rapidly

to the COVID-19 pandemic with implementation of a large-scale testing strategy, teleconsultations, a national

reserve of health professionals and a reorganisation of primary care.

Health Status

Life expectancy at birth in Luxembourg increased by nearly two years

between 2010 and 2019. Although it then fell by nearly one year in 2020

during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is still above the EU-wide average.

Despite reductions in ischaemic health disease and stroke rates, they

remain the leading causes of death, along with lung cancer.

Risk factors

Behavioural risk factors – especially poor nutrition, smoking, physical inactivity

and alcohol consumption – are major drivers of morbidity and mortality in

Luxembourg. One in three adults report binge drinking behaviour, which is

the third highest rate in the EU. Overweight and obesity levels and physical

inactivity among 15-year-olds are above the EU average. On a more positive

note, smoking levels have declined since 2001 for both adults and adolescents.

Health system

In 2019, Luxembourg spent EUR3742 per capita on health (adjusted for

purchasing power parity), which is relatively high compared to the EU

average of EUR3523. The public share of total health spending (85%) was

also above the EU average. In 2020, public spending on health increased

sharply in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Effectiveness

Preventable mortality is lower

than the EU average, reflecting

the effectiveness of prevention

policies. Treatable causes of

mortality are also low, indicating

that the health system provides

effective primary and acute care

for potentially fatal conditions.

Accessibility

Coverage of health services in

Luxembourg is generally good, and

unmet needs for care are among

the lowest in the EU. However,

during the first 12 months of

the COVID-19 pandemic, one

in five people reported forgoing

medical care – slightly lower

than the EU average. Growing use

of teleconsultations helped to

maintain access to care during the

various waves of the pandemic.

Resilience

Luxembourg responded rapidly

to the pandemic, and set up

various measures such as large-

scale testing and effective contact

tracing. The vaccination campaign

was rolled out in six phases. As of

the end of August 2021, 56% of

the population had received two

doses of COVID-19 vaccine (or

equivalent).

LU EU

Option 1: Life expectancy - trendline Select a country:

Option 2: Gains and losses in life expectancy

Luxembourg

80.8

82.4

82.7

81.8

79.8

80.5

81.3

80.6

2010 2015 2019 2020

Yea rs

Luxembourg

Life expectancy at birth

2.8

1.9

-0.9

2.5

1.5

-0.7

2010/2019

2019/2020

2000/2010

Lf xpctnc t brth, rs

Ag-stndrdsd mortlt rt

pr 100 000 populton, 2018

Preventble

mortlt

Tretble

mortlt

EEffffeeccttiivveenneessss -- PPrreevveennttaabbllee aanndd ttrreeaattaabbllee mmoorrttaalliittyy Select country

Country code Country Preventable Treatable

AT Austria 157 75

Treatable mortality

BE Belgium 146 71

Preventable mortality

BG Bulgaria 226 188

HR Croatia 239 133

CY Cyprus 104 79

FFoorr ttrraannssllaattoorrss OONNLLYY::

CZ Czechia 195 124

DK Denmark 152 73

EE Estonia 253 133

FI Finland 159 71

FR France 134 63

DE Germany 156 85

GR Greece 139 90

HU Hungary 326 176

IS Iceland 115 64

IE Ireland 132 76

IT Italy 104 65

LV Latvia 326 196

LT Lithuania 293 186

LU

Luxembourg

130 68

MT Malta 111 92

NL

Netherlands

129 65

NO Norway 120 59

PL Poland 222 133

PT Portugal 138 83

Original (don't change)

Austria

Belgium

Germany

Croatia

Cyprus

Bulgaria

Czechia

Denmark

Estonia

Finland

France

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Treatable mortality

Preventable mortality

Age-standardised mortality rate per 100 000 population, 2018

92

160

68

130

Treatable mortality

Preventable mortality

Luxembourg EU

Age-standardised mortality rate per 100 000

Shr of totl populton vccntd gnst

COVID-19 up to th nd of August 2021

SShhaarree ooff ttoottaall ppooppuullaattiioonn vvaacccciinnaatteedd aaggaaiinnsstt CCOOVVIIDD--1199

Note: Up to end of August 2021

Source: Our World in Data.

Note for authors: EU average is unweighted (the number of countries included in the average varies depending on the week). Data extracted on 06/09/2021.

54%

56%

62%

64%

0%10%20%30%40%50%60%70%80%90%100%

EU

Luxe

Two doses (or equivalent) One dose

LU

EU

0% 50% 100%

Two doses (or equvlent) One dose

Overweight

and obesity

Smoking

Binge drinking

0 20 40

0 20 40

0 20 40

Smoking

% of adults

Overweight and

obesity

% 15-year-olds

Binge drinking

% of adults

1

LU EU Lowest Hhest

Pr cpt spndng (EUR PPP)

LU EU

Luxembourg EU

€ 4 500

€ 3 000

€ 1 500

€ 0

LU EU

Accessibility - Unmet needs and use of teleconsultations during COVID-19

Option 1:

Croatia

Option 2:

39%

42%

% using

teleconsultation

during first 12 months

of pandemic

21%

25%

Croatia EU

% reporting forgone

medical care during

first 12 months of

pandemic

0

10

20

30

Croatia

% reporting forgone medical

care during first 12 months

of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

39%

42%

% using

teleconsultation

during first 12 months

of pandemic

21%

25%

Croatia EU

% reporting forgone

medical care during

first 12 months of

pandemic

% reporting forgone

medical care during first

12 months of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

pandemic

% reporting forgone medical

care during first 12 months

of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

pandemic

0% 1% 2% 3% 4%

L

EU

High income

All

Low income

LU

EU

% rportng unmt mdcl cr nds, 2019

Hh ncome All Low ncome

4

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

2 Helth n Luxembour

1. Includes deaths with and from COVID-19 in all settings (hospitals, nursing homes and at home).

Life expectancy in Luxembourg is

relatively high, but COVID-19 had

an important impact in 2020

In 2020, life expectancy at birth in Luxembourg

stood at 81.8 years, over one year higher than the EU

average, but below other EU countries such as Ireland,

Malta and Italy (Figure 1). Life expectancy increased

from 80.8 to 82.7 years between 2010 and 2019, but

following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic,

it fell temporarily by 11 and a half months in 2020

compared to the average in the EU of nearly 8 months.

The gender gap in life expectancy was an estimated

4.8 years in 2020, which is smaller than the EU

average of 5.6 years.

Figure 1. Life expectancy in Luxembourg is still well above the EU average

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd Dt for Irlnd rfr to 2019

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs

Circulatory diseases and lung cancer are the

main causes of mortality, along with COVID-19

Circulatory diseases account for almost 30% of all

deaths in Luxembourg, followed by cancer (26%).

Looking at more specific diseases, ischaemic heart

disease was the leading cause of mortality in 2019,

accounting for 7% of all deaths, followed by lung

cancer (5.3%), which remained the most frequent

cause of death by cancer, and stroke (4.8%) (Figure 2).

Over the last decade, Luxembourg’s death rates have

been falling for nearly all causes. The increase in life

expectancy until 2019 resulted in particular from a

reduction in premature deaths from circulatory and

cerebrovascular diseases, as well as a decrease in

the number of suicides and road traffic accidents. In

contrast, mortality rates for breast cancer, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes and

Alzheimer’s and other dementias remained roughly at

the same level during this period.

In 2020, COVID-19 accounted for about 500 deaths

in Luxembourg (11% of all deaths). An additional

330 deaths were registered by the end of August

2021. Most deaths occurred among older people (see

Section 5.3). The mortality rate from COVID-19

1

up

to the end of August 2021 was about 17% lower in

Luxembourg than the average across EU countries

(about 1325 per million population compared with

about 1590).

LLiiffee eexxppeeccttaannccyy aatt bbiirrtthh,, 22000000,, 22001100 aanndd 22002200

Select a country:

GEO/TIME 2000 2010 2020

22000000 22001100 22002200

Norway 78.8 81.2 83.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Iceland 79.7 81.9 83.1 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Ireland 76.6 80.8 82.8 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Malta 78.5 81.5 82.6 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Italy 79.9 82.2 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Spain 79.3 82.4 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Sweden 79.8 81.6 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Cyprus 77.7 81.5 82.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

France 79.2 81.8 82.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Finland 77.8 80.2 82.2 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Luxembourg

83.3

83.1

82.8

82.6

82.4

82.4

82.4

82.3

82.3

82.2

81.8

81.6

81.5

81.3

81.2

81.1

81.1

80.9

80.6

80.6

78.6

78.3

77.8

76.9

76.6

75.7

75.7

75.1

74.2

73.6

65

70

75

80

85

90

2000 2010

Years

2020

Luxembourg

EU

80.8

82.4

82.7

81.8

2010 2015 2019 2020

Life expectancy at birth, years

5

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 2. In 2020, COVID-19 accounted for a significant share of deaths

Not Th numbr nd shr of COVID-19 dths rfr to 2020, whl th numbr nd shr of othr cuss rfr to 2019 Th sz of th COVID-19 box s

proportonl to th sz of th othr mn cuss of dth n 2019

Sourcs Eurostt (for cuss of dth n 2019) ECDC (for COVID-19 dths n 2020, up to w 53)

2. It should be noted that these estimates were made before the COVID-19 pandemic; this may have an effect on cancer incidence during 2020.

Prostate and breast cancers are the most

diagnosed cancers in Luxembourg

According to estimates from the Joint Research

Centre based on incidence trends from previous years,

around 3000 new cases of cancer were expected in

Luxembourg in 2020

2

. The age-standardised incidence

rates for all cancer types were expected to be lower

than the EU averages for both men and women.

Figure 3 shows that the main cancer sites among men

are prostate (24%), lung (15%) and colorectal (11%),

while among women breast cancer is the leading

cancer (37%), followed by colorectal (11%) and lung

cancer (8%).

Figure 3. Nearly 3000 people in Luxembourg were estimated to have cancer in 2020

Not Non-mlnom sn cncr s xcludd Utrus cncr dos not nclud cncr of th crvx

Sourc ECIS – Europn Cncr Informton Sstm

COVID-19

506 (108%)

Ischemc hert

dsese

287 (70%)

Lun cncer

219 (53%)

Chronc obstructve

pulmnr dsese

198 (48%)

Pneumon

111 (27%)

Pncretc

cncer

87 (21%)

Dbetes

83 (20%)

Brest

cncer

97 (24%)

Colorectl cncer

119 (29%)

Stroe

199 (48%)

Others

Non-Hodgkin

lymphoma

Pancreas

Skin melanoma

Bladder

Colorectal

Lung

Prostate

After new data, select all and change font to 7 pt.

Adjust right and left alignment on callouts.

Enter data in BOTH layers.

Others

Ovary

Uterus

Thyroid

Skin melanoma

Lung

Colorectal

Breast

31%

4%

4%

5%

6%

11%

15%

24%

27%

4%

4%

4%

5%

8%

11%

37%

Men

1 601 new cases

Age-standardised rate (all cancer)

LU 673 per 100 000 populton

EU 686 per 100 000 populton

Age-standardised rate (all cancer)

LU 474 per 100 000 populton

EU 484 per 100 000 populton

Women

1 356 new cases

6

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

3 Rs fctors

3. Binge drinking is defined as consuming six (five for Luxembourg) or more alcoholic drinks on a single occasion for adults.

Behavioural risk factors are a major driver

of mortality

More than one third of all deaths in Luxembourg in

2019 can be attributed to behavioural risk factors,

such as tobacco smoking, dietary risks, alcohol

consumption and low physical activity, while

environmental issues like air pollution also contribute

to a sizeable number of deaths from circulatory

diseases, respiratory diseases and some types of

cancer (Figure 4). About 17% of all deaths were due to

tobacco smoking (including direct and second-hand

smoking), a share similar to the EU average. Dietary

risks (including low fruit and vegetable intake, and

high sugar and salt consumption) are estimated to

account for about 13% of all deaths in Luxembourg.

About 7% of all deaths can be attributed to alcohol

consumption, while about 2% are related to low

physical activity. Air pollution in the form of fine

particulate matter (PM

2.5

) and ozone exposure alone

accounted for about 2% of all deaths in 2019.

Figure 4. Tobacco, dietary risks and alcohol are major contributors to mortality in Luxembourg

Not Th ovrll numbr of dths rltd to ths rs fctors s lowr thn th sum of ch on tn ndvdull, bcus th sm dth cn b

ttrbutd to mor thn on rs fctor Dtr rss nclud 14 componnts such s low frut nd vgtbls dt, hgh sugr-swtnd bvrgs

consumpton Ar polluton rfrs to xposur to PM

25

nd ozon

Sourcs IHME (2020), Globl Hlth Dt Exchng (stmts rfr to 2019)

Poor nutrition and low physical activity

contribute to rising obesity among adolescents

About one in six adults reported being obese in 2019

– a rate equal to the EU average. More than one in five

15-year-olds were overweight or obese in Luxembourg

in 2018 – a higher proportion than in most EU

countries, and a significant rise since 2006. Boys are

more likely to be overweight or obese than girls.

In Luxembourg, as in other countries, poor nutrition

is the main factor contributing to being overweight

or obese. Fruit and vegetable consumption is less

common than in most other EU countries, with only

about 40% of adults eating fruit or vegetables every

day. Altogether about 65% of 15-year-olds reported

in 2018 that they did not eat any fruit or vegetables

every day. Low physical activity also contributes to

weight problems. Regular physical activity among

adults is similar to the average among EU countries

(63% compared to a 64% EU average). Among

adolescents, only one in eight (12%) 15-year-olds

reported doing at least moderate physical activity

every day in 2018 – a lower proportion than the EU

average (14%).

Excessive alcohol consumption in adults

is among the highest in the EU

Limited progress has been achieved in tackling

excessive alcohol consumption, and it continues

to be a major public health problem. Although, in

general, alcohol consumption has declined slowly

over the last two decades, the percentage of adults

reporting heavy episodes of alcohol consumption

(“binge drinking”

3

) is the third highest in the EU after

Denmark and Romania, with more than one in three

adults reporting such behaviour on a regular basis in

2019 (see Section 5.1). On a more positive note, only

one in ten 15-year-olds reported having been drunk

at least twice in their life in 2018 – the second lowest

rate in the EU.

Dietary risks

Luxembourg: 13%

EU: 17%

Tobacco

Luxembourg: 17%

EU: 17%

Alcohol

Luxembourg: 7%

EU: 6%

Air pollution

LU: 2%

EU: 4%

Low physical activity

LU: 2%

EU: 2%

7

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Smoking among adults and teenagers

has declined

The proportion of adults smoking on a daily basis

has decreased in Luxembourg compared to 20 years

ago. Only one in nine adults smoked daily in 2019,

compared with over one in four in 2001

4

. Similarly,

smoking rates among adolescents have decreased

over the last decade: 13% of 15-year-olds reported

smoking in the past month in 2018, down from 21%

in 2013-14, and a lower proportion than in most EU

4. The results from the Luxembourg Cancer Foundation Survey show higher rates of daily smokers among adults (around 17% in 2019 and 2020), with a slight

increase over the past five years.

countries (and the EU average of 18%) (Figure 5).

Some of this decrease could be attributed in part to

the anti-tobacco initiatives launched over the past

few decades, such as the smoking ban in public

places in 2006 (see Section 5.1). Although the smoking

ban contributed to a reduction in socioeconomic

inequalities in smoking (Tchicaya, Lorentz &

Demarest, 2016), the difference between the lowest

and highest income groups persists.

Figure 5. Rising child obesity and high alcohol consumption among adults are important public health issues

Not Th closr th dot s to th cntr, th bttr th countr prforms comprd to othr EU countrs No countr s n th wht “trgt r” s thr s

room for progrss n ll countrs n ll rs

Sourcs OECD clcultons bsd on HBSC surv 2017-18 for dolscnts ndctors EU-SILC 2017 nd EHIS 2019 for dults ndctors

4 The helth sstem

The social health insurance system is

administered by two ministries

Luxembourg operates a compulsory social health

insurance (SHI) system. The responsibility for

financing and purchasing of health services lies

with the National Health Insurance Fund – Caisse

Nationale de Santé (CNS) – which covers three

schemes: health care, sickness leave and long-term

care (LTC) insurance. Responsibility for health system

governance is highly centralised and split between

the Ministry of Social Security and the Ministry

of Health. The latter develops health policy and

oversees planning and regulatory functions, as well as

licensing of providers. Its Health Directorate oversees

public health issues. The Ministry of Social Security

supervises the public institutions funding health care,

sickness leave and LTC. The Ministry of Family Affairs

oversees LTC facilities, home care networks and care

services for disabled people. During the COVID-19

pandemic, governance mechanisms were put in place

to manage the crisis, with the Ministry of Health

primarily in charge of coordinating the health system

response (Box 1).

6

Vegetable consumption (adults)

Vegetable consumption (adolescents)

Fruit consumption (adults)

Fruit consumption (adolescents)

Physical activity (adults)

Physical activity (adolescents)

Obesity (adults)

Overweight and obesity (adolescents)

Binge drinking (adults)

Drunkenness (adolescents)

Smoking (adults)

Smoking (adolescents)

Select dots + Effect > Transform scale 130%

OR Select dots + 3 pt white outline (rounded corners)

8

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Luxembourg’s health system scheme

provides universal coverage

Luxembourg’s SHI scheme is compulsory for everyone

who is economically active or receiving social security

payments from the state. It covers family members,

including minors and students who have no other

5. A significant proportion of GDP in Luxembourg consist of profits from foreign-owned companies that are repatriated. Thus, gross national income may be a more

meaningful measure for the capacity to pay for health care, but even that is not a true measure of the productive capacity of the domestic economy.

health insurance coverage. The CNS’s large reserves

facilitate a broad benefits package (see Section 5.2).

People who only work occasionally in Luxembourg (i.e.

less than three months per calendar year) are exempt,

but may choose to pay voluntary contributions. People

working for European institutions or international

organisations, who represent an important share of

the population, are covered by their employers’ health

insurance schemes. Official data show that 100%

of the resident population are covered by health

insurance; however, a few people are without coverage

(see Section 5.2).

Health spending per capita is relatively high,

and the share of public funding is above

the EU average

Spending on health is high in Luxembourg. Health

expenditure per capita stood at EUR3742 in 2019

(adjusted for differences in purchasing power) –

about EUR220 higher than the EU average (Figure 6).

In contrast, Luxembourg spends only 5.4% of its

GDP on health, the lowest share in the EU (9.9%).

This statistic reflects Luxembourg’s strong overall

economic performance

5

. Public financing is based

on a system of shared contributions: 40% is paid by

the state, and the rest is shared between the insured

population and employers. Public expenditure

accounts for 85% of the total, a share that has

increased since 2012 (82.8%) and is above the EU

average (79.7%). Due to the very broad coverage

of the SHI scheme, out-of-pocket (OOP) spending

is low, at 9.6% compared to EU average of 15.4%.

Complementary voluntary health insurance (VHI)

represents only 4.1% of health expenditure, although

it is purchased by two thirds of the population.

Figure 6. Luxembourg is among the highest spenders on health in the EU

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 (dt rfr to 2019, xcpt for Mlt 2018)

Box 1. An inter-ministerial crisis unit was

established for the COVID-19 response

The Hh Commsson for Ntonl Protecton,

under the remt of the Prme Mnster nd

Mnster of Stte s responsble for coordntn

crss mnement nd plnnn the ntonl

protecton pln, whch stte mnstres, ences

nd deprtments re requred to mplement

In ddton, n nter-mnsterl crss unt ws

estblshed n md-Mrch 2020 under the Mnster

of Helth’s drecton to ssess the stuton

contnuousl, te necessr mesures nd

coordnte nttves cross mnstres Wthn

the Mnstr of Helth, n nternl crss unt

ws qucl set up to nlse the stuton n

the countr, set enerl response strtees

nd coordnte mplementton of ll mesures

relted to the crss The crss unt comprses 10

worn roups tht oversee nd mne dstnct

res (such s communcton, survellnce,

dnostcs nd trcn, testn nd prmr cre)

Ths unt coordntes ll efforts wthn hosptls,

lbortores, prmr cre, phrmces, nursn

homes nd cre networs, s well s mnn

lostcs, medcl equpment, helth worforce

suppl nd crss communcton

Sourc COVID-19 Hlth Sstms Rspons Montor

CCoouunnttrryy

GGoovveerrnnmmeenntt && ccoommppuullssoorryy iinnssuurraannccee sscchheemmeess VVoolluunnttaarryy iinnssuurraannccee && oouutt--ooff--ppoocckkeett ppaayymmeennttss TToottaall EExxpp.. SShhaarree ooff GGDDPP

Norway 4000 661 4661 10.5

Germany 3811 694 4505 11.7

Netherlands 3278 689 3967 10.2

Austria 2966 977 3943 10.4

Sweden 3257 580 3837 10.9

Denmark 3153 633 3786 10.0

Belgium 2898 875 3773 10.7

Luxembourg 3179 513 3742 5.4

France 3051 594 3645 11.1

EU27 22880099 771144 3521 9.9

Ireland 2620 893 3513 6.7

Finland 2454 699 3153 9.2

Iceland 2601 537 3138 8.5

Malta 1679 966 2646 8.8

Italy 1866 659 2525 8.7

Spain 1757 731 2488 9.1

Czechia 1932 430 2362 7.8

Portugal 1411 903 2314 9.5

Slovenia 1662 621 2283 8.5

Lithuania 1251 633 1885 7.0

Cyprus 1063 819 1881 7.0

2019

0.0

2.5

5.0

7.5

10.0

12.5

0

1 000

2 000

3 000

4 000

5 000

Government & compulsory insurance Voluntary insurance & out-of-pocket payments Share of GDP

% GDP

EUR PPP per capita

0.0

2.5

5.0

7.5

10.0

12.5

0

1 000

2 000

3 000

4 000

5 000

Government & compulsory insurance Voluntary insurance & out-of-pocket payments Share of GDP

% GDP

EUR PPP per capita

9

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Spending on outpatient care has decreased,

while spending on inpatient care has gone up

The largest category of health spending in

Luxembourg is outpatient care (including home care)

(Figure 7), which accounted for one third (32.9%)

of all health spending in 2019 and is above the EU

average (29.5%). Slightly less than one third (29.1%) is

spent on inpatient care, which is equal to the average

in the EU as a whole. Despite the 2010 health reform

law that aimed to contain rising health expenditure

in hospital care and to strengthen primary care, the

share of spending on inpatient care increased by 2.5

percentage points between 2010 and 2019, partly

as a result of collective labour agreements in the

hospital sector. Conversely, the share of outpatient

care spending fell by 5.1 percentage points during the

same period. Spending in the other categories has

remained fairly stable. Luxembourg spent slightly

more on LTC per capita than the EU average (EUR708

compared to EUR617). However, per capita spending

on pharmaceuticals, medical devices and prevention

is lower than the EU averages (Figure 7).

In 2020, additional financial allocations of

EUR194million were made to the health system

as part of the government’s COVID-19 fiscal

package. Resources were used to create outpatient

health centres for COVID-19 care, acquire medical

equipment, boost testing capacities and to cover

temporary accommodation expenses for cross-border

health and social care workers who needed to stay in

Luxembourg during the pandemic (see Sections 5.2

and 5.3).

Figure 7. Luxembourg spends more on outpatient, inpatient and long-term care than the EU averages

Not Th costs of hlth sstm dmnstrton r not ncludd 1 Includs hom cr nd ncllr srvcs (g ptnt trnsportton) 2 Includs

curtv-rhblttv cr n hosptl nd othr sttngs 3 Includs onl th hlth componnt 4 Includs onl th outptnt mrt 5 Includs onl

spndng for orgnsd prvnton progrmms Th EU vrg s wghtd

Sourcs OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021, Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019)

A substantial share of health services

are provided outside Luxembourg

About one third of those covered by the CNS (35%)

are cross-border employees (who make up nearly half

of Luxembourg’s workforce). As these non-residents

mostly seek health care in their country of residence,

many health services covered by the CNS are provided

outside Luxembourg – mainly in Germany, Belgium

and France. In 2019, 8677 patients (residents and

non-residents) requested authorisation by the CNS

for care outside Luxembourg, mainly for hospital

treatment (45%) and consultations and examinations

(33%). The costs for treatment in neighbouring

countries accounted for 20% of total health

expenditure in 2019 (IGSS, 2021; CNS, 2020).

Patients in Luxembourg enjoy a free choice of

providers and unrestricted access to all levels of care

(general practitioners (GPs), specialists and hospitals).

Hospital care is provided by four general and two

specialised hospitals, with 4.3 hospital beds (and 3.3

acute care beds) per 1000 population, which is below

the EU average of 5.3 per 1000 population. Hospital

bed rates have declined steadily by 34% since 2004,

mostly due to population growth. Meanwhile, the

average length of stay has increased by half a day

since 2011 – up to 9.3 days in 2019, which is well

above the European average (7.4 days). During the

COVID-19 pandemic, Luxembourg’s acute hospitals

were required to postpone or cancel procedures and

reorganise services to free up 270 acute beds and

about 100 intensive care unit (ICU) beds for COVID-19

1 022

1 010

617

630

102

0

0

0

0

0

1 231

1 088

708

495

92

Luxembour

Preventon Phrmceutcls

nd medcl devces

Lon-term cre Inptent cre Outptent cre

0

200

400

600

800

1 000

1 200

1 400

EU27EUR PPP per cpt

33%

of totl

spendn

29%

of totl

spendn

19%

of totl

spendn

13%

of totl

spendn

2.5%

of totl

spendn

10

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

patients, which represented 13% of Luxembourg’s

total acute bed capacity and two thirds of its intensive

care capacity (see Section 5.3).

The COVID-19 pandemic stressed the

challenge of Luxembourg’s dependency

on foreign health professionals

Luxembourg has the second lowest number of doctors

in the EU, with approximately 3 physicians per 1000

population in 2019 (compared to 3.9 across the EU;

Figure 8) despite an increase of 39% since 2000. The

low density of doctors mostly relates to the absence

of medical training in the country, which makes

it dependent on foreign-trained doctors. The first

national degree in general medicine started in 2021.

The share of doctors living outside the country but

practising in Luxembourg nearly doubled between

2008 and 2017 (from 15.6% to 26.4%), and only about

half of all practising doctors are national citizens

of Luxembourg (IGSS, 2021). GPs account for about

one third of physicians, which is higher than the EU

average (21%). The physician workforce is ageing:

more than half of practising GPs (54.4%) and nearly

two third of specialists (60%) were over the age of 50

in 2017 (Lair-Hillion, 2019) (see Section 5.2).

In contrast, the number of nurses in Luxembourg has

increased continually over the last few years, and its

density is one of the highest in the EU (approximately

11.7 compared to an EU average of 8.4 per 1000).

More than two thirds of practising nurses live in the

neighbouring countries of France (29%), Germany

(24%) and Belgium (12%) (Lair-Hillion, 2019), but are

attracted by higher remuneration and good working

conditions in Luxembourg. This made Luxembourg

particularly vulnerable to border closures during the

first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Figure 8. Luxembourg has sufficient nurses, owing to cross-border supply, but has very low numbers of

physicians

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd In Portugl nd Grc, dt rfr to ll doctors lcnsd to prcts, rsultng n lrg ovrstmton of th numbr

of prctsng doctors (g of round 30% n Portugl) In Grc, th numbr of nurss s undrstmtd s t onl ncluds thos worng n hosptls

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019 or th nrst r)

2 3 4 5 6 6.55.54.53.52.5

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Practicing nurses per 1 000 population

Practicing doctors per 1 000 population

EU average: 8.4

EU average: 3.9

Doctors High

Nurses Low

Doctors High

Nurses High

Doctors Low

Nurses Low

Doctors Low

Nurses High

NO

DK

BE

CZ

LT

LU

IE

SI

RO

PL

EE

SK

LV

IT

ES

CY

BG

SE

DE

IS

AT

PT

FI

HU

HR

EU

NL

MT

EL

FR

11

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

5 Performnce of the helth sstem

51 Effectiveness

Public health interventions in Luxembourg have

had a positive impact on preventable deaths

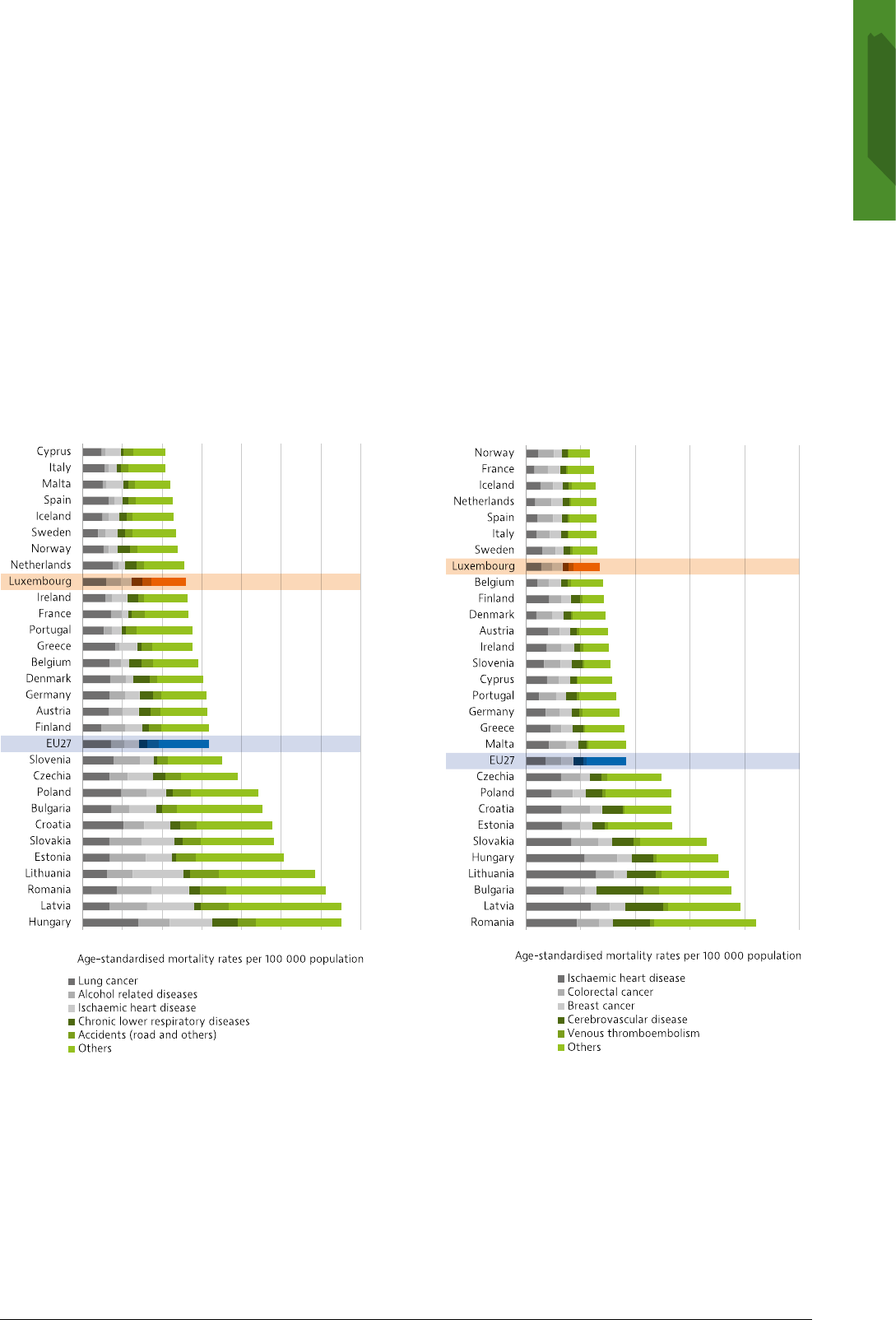

Luxembourg compares favourably with the EU as

a whole for mortality from both preventable and

treatable causes (Figure 9). In 2018, preventable

mortality accounted for 130 deaths per 100000

population, the main causes being lung cancer,

alcohol-related diseases, chronic lower respiratory

disease and ischaemic heart disease. To support

decreasing levels of preventable deaths, preventive

health policies remain a priority. In 2019, Luxembourg

launched its first National Plan against Cardio-

neuro-vascular Diseases (2020-24) to reduce related

preventable deaths. The main measures include

prevention of risk factors, screening and improvement

of patient pathways.

Figure 9. Mortality from preventable and treatable causes is among the lowest in the EU

Not Prvntbl mortlt s dfnd s dth tht cn b mnl vodd through publc hlth nd prmr prvnton ntrvntons Trtbl mortlt

s dfnd s dth tht cn b mnl vodd through hlth cr ntrvntons, ncludng scrnng nd trtmnt Hlf of ll dths for som dsss

(g schmc hrt dss nd crbrovsculr dss) r ttrbutd to prvntbl mortlt th othr hlf r ttrbutd to trtbl cuss Both

ndctors rfr to prmtur mortlt (undr g 75) Th dt r bsd on th rvsd OECD/Eurostt lsts

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2018, xcpt for Frnc 2016)

The comparatively low levels of preventable

deaths from causes such as lung cancer and road

traffic accidents registered in Luxembourg may be

explained in part by strong public health policies,

such as smoking bans in public places, bars and

cafés and awareness-raising campaigns for road

safety implemented in 2006 and 2014. The effect of

more recent anti-tobacco measures – such as public

104

104

111

113

115

118

120

129

130

132

134

138

139

146

152

156

157

159

160

175

195

222

226

239

241

253

293

306

326

326

59

63

64

65

65

65

66

68

71

71

73

75

76

77

79

83

85

90

92

92

124

133

133

133

165

176

186

188

196

210

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

0 50 100 150 200 250

Preventable causes of mortality Treatable causes of mortality

12

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

awareness campaigns under the Anti-Tobacco Plan

2016-20, the rise in the legal age for purchasing

tobacco products in 2017 and tax increases – have

helped to reduce smoking rates, particularly among

adolescents (see Section 3), but will take time to

translate into reduced preventable mortality. Despite

these early signs of improvement, the fight against

tobacco consumption remains a public health priority.

In 2008, the Ministry of Health and the CNS set up

a stop smoking programme that covers two doctor

consultations and half of the costs for substitutes

(capped at EUR100). Despite its long existence,

participation in the programme remains limited.

Frequent alcohol consumption continues to be a

public health issue, despite relatively low preventable

mortality specifically due to alcohol-related deaths.

Luxembourg has very high levels of binge drinking

(see Section 3), particularly among men. In 2020, the

National Alcohol Plan (2020-24) was finally adopted,

after being initiated in 2012, to reduce alcohol misuse

and harm and to create supportive environments

that enable people to adopt healthy and sensible

drinking behaviours at all ages. However, owing to

the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation had to be

postponed.

Cardiovascular disease and cancers play a

large role in mortality from treatable causes

Overall, mortality that can mainly be avoided through

health care interventions has decreased since 2011

and, at 68 deaths per 100000 in 2018 was below the

6. Other survey data from the European Health Information Survey (EHIS) indicate that 78% of women reported to have received breast cancer screening in 2019.

EU average of 92 deaths per 100000 (see Figure 9). The

main causes of treatable mortality in Luxembourg

were ischaemic heart disease, colorectal cancer,

breast cancer and stroke, and all rates were below the

EU averages.

Cancer screening is based on national

recommendations and has a central role in improving

survival outcomes and lower overall rates of mortality

from treatable causes. The rates of cervical cancer

screening across the country increased from 51%

to 70% between 2013 and 2019. However, the

participation rates in breast cancer screening, which

was introduced in 1992, have decreased over the last

decade from 64% in 2009 to 53% in 2019 – below

the EU average (Figure 10)

6

. While data on cancer

mortality and screening rates for most types of cancer

are available, evaluating the quality of cancer care

is more difficult, as data on five-year survival rates

are not systematically collected. Luxembourg has,

however, adopted a second National Cancer Plan for

the period 2020-24, which aims to improve prevention

and treatment (Box 2).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic many cancer

screenings, operations and non-essential

examinations were postponed in 2020. A recent survey

among cancer care providers revealed that during the

first lockdown the number of radiotherapy sessions

fell by almost one third and even after lockdown

(between July and October 2020) they remained below

usual levels (Backes et al., 2021).

Figure 10. Only about half the women in Luxembourg participate in recommended mammography screening

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd For most countrs, th dt s bsd on scrnng progrmms, not survs

Sourcs OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 nd Eurostt dtbs

Selected country

95

83

81

80

77

76

75

74

72

72

69

66

61

61

61

60

60

59

56

54

53

53

50

49

39

39

36

31

31

9

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2009 (or nearest year) 2019 (or nearest year)

% of women aged 50-69 screened in the last two years

13

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

The government ordered more influenza

vaccines in 2020 to increase vaccination rates

The COVID-19 pandemic raised the importance

of increasing vaccination rates against seasonal

influenza to avoid having another virus spreading

widely and to reduce pressures on hospitals. The

objective of the 2020/21 campaign was to vaccinate

30000 more people than in the previous year and

to avoid a shortage of influenza vaccine, which

Luxembourg experienced in 2018. To that end, up to

120000 shots in total were ordered by government

and the private sector. In the past, the influenza

vaccination rate among the population at highest risk

(over 65 years) has been low, despite health insurance

coverage and broad awareness-raising campaigns.

About 40% of the population over 65 received the

vaccination in 2019, which is slightly below the EU

average (42%). In contrast, high coverage is observed

for the universal childhood vaccination programme,

with centralised public procurement of vaccine

products and direct delivery to physician practices.

The low number of avoidable hospitalisations

points to effective primary care

Luxembourg’s rate of avoidable hospital admissions

for chronic conditions is lower than in many other

EU countries, suggesting that primary care and

outpatient secondary care are effective at managing

chronic diseases. Indeed, avoidable hospital

admissions for asthma and COPD, remained stable

7. The data from the Eurofound survey are not comparable to those from the EU-SILC survey because of differences in methodologies.

8. People on low incomes may apply for the benefit-in-kind model: local social welfare offices certify eligibility on an annual basis for medical and dental treatment

costs to be directly covered by the CNS. Patients’ co-payments are paid by local social welfare offices.

between 2007 and 2015 and are below the EU average.

Avoidable hospitalisations for diabetes decreased

in this period, although they are still above the EU

average. The outdated data on avoidable hospital

admissions and the data gaps on hospital quality

indicators such as 30-day in-hospital case fatality

rates, as well as cancer survival rates, point to gaps in

data collection. The new National Health Observatory

that Luxembourg is setting up aims to centralise

and harmonise health-related data, such as data on

health status and health provision (see Section 5.3).

52 Accessibility

Unmet needs for medical care have been low

but rose during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020

Since health coverage is universal and the benefits

package is fairly comprehensive, before the COVID-19

pandemic, very few residents in Luxembourg (0.2%)

reported having experienced unmet needs for medical

care due to cost, distance or waiting times – a share

well below the EU average, and with little difference

between income groups (Figure 11). The share of

people reporting unmet needs for dental care was

also among the lowest in the EU (0.4% compared to

2.8%). However, unmet needs for medical care may

have risen in 2020. According to the Eurofound (2021)

survey

7

, during the first 12 months of the COVID-19

pandemic, 19% of respondents reported having

forgone medical care compared to 21% across the

EU as a whole although due to the small sample size,

these results should be viewed with caution.

Despite universal coverage some gaps and

access barriers remain

Despite compulsory health insurance, some

population groups remain without coverage and

have very limited access to health care – namely,

homeless people, residents whose welfare benefits

are ending and undocumented migrants. At least 880

people were reported to be without health insurance

or faced financial difficulties obtaining it in 2019

(Médecins du Monde, 2019). In 2013, Luxembourg

introduced a “benefit-in-kind model”

8

for vulnerable

groups who encounter difficulties paying in advance

for outpatient services. A third-party payment system

is planned for the entire population from 2023, which

will mean that the CNS, rather than patients, will pay

the reimbursed tariff directly to providers for services

at the point of care.

Box 2. Luxembourg has adopted a second

National Cancer Plan for 2020-24

Luxembour’s second Ntonl Cncer Pln

(2020-24) contnues the efforts nd mesures of

the frst Ntonl Cncer Pln lunched n 2014

The mn prortes re dtlston of dt

exchne nd expnson of nformton sstems,

mplementton of modern enetcs nd moleculr

ptholo nd the structurn of ptent pthws

nto competence networs Bolstern the

pplcton of reserch nd the centrl role of the

Ntonl Cncer Insttute re lso e elements

The Ntonl Cncer Pln follows the

recommendtons of the Europen Prtnershp

for Acton Anst Cncer nd the pllrs of the

Europe’s Betn Cncer Pln, whch sets out new

EU pproch to tcle the entre dsese pthw,

from preventon nd screenn to tretment nd

qult of lfe of cncer ptents nd survvors

(Europen Commsson, 2021)

14

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 11. Before the pandemic, Luxembourg

recorded among the lowest levels of unmet needs,

with little variation by income

Not Dt rfr to unmt nds for mdcl xmnton or trtmnt

du to costs, dstnc to trvl or wtng tms Cuton s rqurd n

comprng th dt cross countrs s thr r som vrtons n th

surv nstrumnt usd

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs, bsd on EU-SILC (dt rfr to 2019, xcpt

Iclnd 2018)

The benefits package provides good

coverage for most health services

Individuals covered by the compulsory SHI scheme

enjoy a very broad benefits package, which goes

well beyond essential services and continues to

be extended gradually, especially for therapeutic

services. The SHI scheme covers most inpatient

treatments directly, with the exemption of a per

diem levied on all adults. Most outpatient services

are currently based on reimbursement: patients pay

providers in advance and are later reimbursed by the

CNS at different rates, ranging from 60% to 100%.

Usually, 88% of costs for medical and dental services

are reimbursed by the CNS, and the first EUR66.50 of

costs for dental care per year is also paid by health

insurance. Medicines included in the positive lists are

reimbursed at three different rates (100%, 80% and

40%). Cost-sharing exemptions apply for people with

disabilities or severe chronic conditions, children and

pregnant women, or if cost-sharing exceeds 2.5% of

annual gross income.

The shares financed by public spending for selected

health services and medical goods reflect the limited

cost-sharing requirements described above, and are

well above the EU averages (Figure 12). To cover OOP

payments or services not included in the benefits

package, such as acupuncture or single rooms in

hospitals, about 65.5% of the population purchases

VHI.

Figure 12. Extensive public coverage of services reflects comprehensive benefits coverage

Not Outptnt mdcl srvcs mnl rfr to srvcs provdd b gnrlsts nd spclsts n th outptnt sctor Phrmcutcls nclud prscrbd

nd ovr-th-countr mdcns s wll s mdcl non-durbls Thrputc pplncs rfr to vson products, hrng ds, whlchrs nd othr

mdcl dvcs

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 (dt rfr to 2019 or nrst r)

0 5 10 15 20

Estonia

Greece

Romania

Finland

Latvia

Poland

Iceland

Slovenia

Slovakia

Ireland

Belgium

Denmark

Italy

Portugal

EU 27

Bulgaria

Croatia

Lithuania

Sweden

France

Cyprus

Hungary

Norway

Czechia

Austria

Germany

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Spain

Malta

Low incomeTotal populationHigh income

% reporting unmet medical needs

Hh ncome Totl populton Low ncome

Unmet needs for medical care

LLuuxxeemmbboouurrgg

89%

93%

0% 50% 100%

EU

LU

Inpatient care

75%

88%

0% 50% 100%

Outpatient medical

31%

47%

0% 50% 100%

Dental care

57%

71%

0% 50% 100%

Pharmaceuticals

37%

43%

0% 50% 100%

Therapeutic

Inpatient care

Outpatient

medical care Dental care Pharmaceuticals

Therapeutic

appliances

Publc spendn s proporton of totl helth spendn b tpe of servce

15

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Luxembourg has very low out-of-pocket

spending, but pharmaceutical payments can

be substantial

The proportion of OOP payments in total health

spending is the second lowest among EU countries

(9.6%) after France, and well below the EU

9. The data from the Eurofound survey are not comparable to those from the EU-SILC survey because of differences in methodologies.

average (Figure 13). As a share of final household

consumption, it is one of the lowest in the EU (1.6%

compared to a 3.1% EU average). However, OOP

payments can still be substantial for pharmaceuticals,

LTC and dental care. About one third of OOP spending

is devoted to pharmaceuticals (29%), and about one

fifth each to LTC, outpatient and dental care.

Figure 13. Out-of-pocket spending in Luxembourg is well below the EU average

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd VHI lso ncluds othr voluntr prpmnt schms

Sourcs OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019)

Reorganisation of health care training aims

to increase the attractiveness of some health

professions

As noted in Section 4, Luxembourg has low

numbers of doctors; this has the greatest impact

on ambulatory care. To address potential scarcities

of health professionals in the longer term, various

initiatives have aimed to decrease dependence

on foreign health care professionals and improve

the attractiveness of the medical profession. For

example, specialised medical training for doctors

who have completed their studies has been expanded

in the areas of oncology and neurology, and a new

bachelor’s programme in general medicine starts in

2021. In the next few years, the government also plans

to offer new academic nurse training programmes to

enhance the profession, including bachelor’s degrees

in nursing care, midwifery and radiology medical

technical assistance and four specialised nursing

bachelor programmes. An advanced four-year nursing

degree is also being planned. The new professions

will allow more collaborative working environments,

in which care is provided by multidisciplinary teams,

and the opportunity to alleviate doctor shortages

through task-shifting. The creation of a digital registry

of health professionals is also planned; this will aid

creation of work placements in areas of need.

A newly created teleconsultation platform

has helped to maintain provision of services

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic,

Luxembourg acted quickly to ensure that health

services were maintained while preventing

transmission of the virus to vulnerable populations

and health professionals. In March 2020, the

Ministry of Health reorganised the model of primary

health care, establishing four different care patient

pathways: teleconsultations; medical visits within

residential care facilities and at patients’ homes;

advanced care centres for COVID-19 patients; and

emergency department visits (see Section 5.3).

Teleconsultations played a key role in maintaining

access to non-COVID-19 health services. In mid-March

2020, a teleconsultation platform was set up to allow

patients to consult their treating physicians, dentists

or midwives via telephone or teleconsultation,

as well as to obtain a certificate of incapacity for

work or medical prescription. By 9April, about 600

doctors and more than 4000 patients had registered

with the e-consult platform, and almost 3000

teleconsultations had been carried out. According to

the Eurofound (2021) survey, 44% of the population

reported having a medical teleconsultation (above

the EU average of 39%) in the first 12 months of the

pandemic

9

.

Government/compulsory schemes 85.0%

VHI 4.1%

Inpatient 0.6%

Outpatient medical

care 1.7%

Pharmaceuticals 2.8%

Dental care 1.7%

Long-term care 1.9%

Others 0.9%

Government/compulsory schemes 79.7%

VHI 4.9%

Inpatient 1.0%

Outpatient medical

care 3.4%

Pharmaceuticals 3.7%

Dental care 1.4%

Long-term care 3.7%

Others 2.2%

Luxembourg

Overall share of

health spending

Distribution of OOP

spending by function

OOP

9.6%

EU

Overall share of

health spending

Distribution of OOP

spending by function

OOP

15.4%

16

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Simultaneously, a remote monitoring tool for

COVID-19 patients was launched throughout

Luxembourg to follow up patients who had been

discharged and were in isolation at home. Monitoring

was carried out by a team of professionals from

the Health Directorate: within the first month of its

operation, 388 patients were recuperating at home

using this new tool (Ministry of Health, 2020a). As

part of Luxembourg’s ongoing consultation process

to develop a national health plan, initiated in 2020

and known as “Gesondheetsdësch”, the monitoring

tool will be expanded into a permanent telemedicine

solution, integrated into e-health services.

Draft legislation aims to improve patients’

access to pharmaceuticals

Luxembourg is currently the only EU country without

its own medicines authorisation agency. This leads

to challenges in pharmaceutical negotiations and a

lack of transparency in pricing and reimbursement

decisions. To ensure access to medicines, the

government adopted a draft bill in 2019 that provides

for the creation of a National Agency for Medicines

and Health Products, with comprehensive functions

such as monitoring the quality and safety of

10. Currently, marketing authorisations are issued by the Ministry of Health, and reimbursement pricing is determined by the Ministry of Social Security.

11. In this context, health system resilience has been defined as the ability to prepare for, manage (absorb, adapt and transform) and learn from shocks (EU Expert

Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment, 2020).

medicines, authorisation and control of activities of

biotech companies, administration of clinical trials

and price determination of medicines and medical

devices. The aim is to improve patient access to

medicines that have not yet been authorised in

Luxembourg

10

. Addressing medicines shortages

aligns with one of the key planks of the European

Commission’s pharmaceutical strategy for Europe,

which sets out enhanced co-operation between

national authorities on pricing, payment and

procurement policies, with a view to improving the

affordability and cost–effectiveness of medicines

(European Commission, 2020).

Use of generics as a means of widening access to

medicines is low in Luxembourg. In 2014, the country

introduced a system of generic substitution by

specifying two pharmacotherapeutic groups to be

eligible for mandatory substitution for the lowest

priced generic alternative, regardless of what the

doctor has indicated on the prescription. Even so, the

country has the lowest generic penetration in the EU

by volume (Figure 14) and by value: only 5.6% of the

publicly funded pharmaceuticals market consists of

generics.

Figure 14. Use of generics in Luxembourg continues to be low

Not Dt rfr to th shr of gnrcs b volum

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021

53 Resilience

This section on resilience focuses mainly on

the impacts of and responses to the COVID-19

pandemic

11

. As noted in Section 2, the COVID-19

pandemic had a major impact on population health

and mortality in Luxembourg, with just over 830

COVID-19 deaths recorded between January 2020 and

the end of August 2021. Measures taken to contain the

pandemic also had an impact on the economy, but

Luxembourg’s GDP fell by only 1.3% in 2020, which is

lower than the drop of 6.2% across the EU as a whole.

Various mitigation measures were implemented

throughout successive waves of the pandemic

After the first cases of COVID-19 were identified in

early March 2020, the government released several

recommendations and containment measures, such

as calling off large public events with more than

1000 people, restrictions on travel, suspension of

face-to-face teaching and restrictions on hospital

and care home visits (Figure 15). By mid-March, when

a state of emergency was declared, the parliament

endorsed a full lockdown, with shop closures and

restrictions on mobility. In April and May, these

Select a country Luxembourg

Select comparator

countries

Spain

Germany

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Luxembourg Spain Germany EU16

%

17

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

measures were lifted gradually, accompanied by

a large-scale testing and preventive measures

such as mask-wearing in public spaces and social

distancing. From summer 2020 onwards, Luxembourg

experienced a second wave of cases, although

numbers were less pronounced than in some other

European countries. In response, the government

implemented restrictions on gatherings, which were

further tightened in October 2020 when case numbers

again surged, followed by new mitigating measures

in November and a second lockdown in December

12. Since 2005, the IHR have provided an overarching legal framework that defines countries’ rights and obligations in handling public health events and

emergencies. Under the IHR, all Member States are required to develop public health capacities to prevent, detect, assess, notify and respond to public health risks.

The monitoring process of IHR implementation status involves assessing, through a self-evaluation questionnaire, 13 core capacities.

2020 (including a night curfew and non-essential

shops closures). Most of these restrictive measures

extended well into the new year and were gradually

lifted between January and May 2021. The government

also implemented the “CovidCheck” digital (or

paper) certificate, which is applicable for hospitality

establishments, events and a range of activities. The

certificate provides proof that the registered user

has been vaccinated against COVID-19, has received

a negative COVID-19 test or has recovered from the

disease.

Figure 15. Containment measures have brought down COVID-19 case numbers

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd (th numbr of countrs usd for th vrg vrs dpndng on th w)

Th numbr of COVID-19 css n EU countrs ws undrstmtd durng th frst wv n sprng 2020 du to mor lmtd tstng

Sourc ECDC for COVID-19 css nd uthors for contnmnt msurs

Luxembourg was relatively well prepared

for a public health emergency

Luxembourg had a very rapid initial response to

the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the country was

confronted with similar challenges to those seen

throughout Europe, such as shortages of personal

protective equipment (PPE) and health care workers,

public actors from various governance levels

(including communities and the fire and rescue corps)

rapidly joined the national effort to respond to the

crisis. Luxembourg’s small size helped it to put public

health measures in place quickly, and health system

actions (including mask-wearing, testing, contact

tracing, marshalling hospital infrastructure and

medical equipment, and organising COVID-19 care)

were centrally coordinated by the crisis unit at the

Ministry of Health (see Section 4).

According to the International Health Regulations

(IHR) framework

12

, Luxembourg recorded above-

average scores for indicators of self-reported capacity

to detect and manage public health risks (Figure 16).

This ample capacity was on display as the country

swiftly created ambulatory service points providing

testing and care for suspected COVID-19 cases, as well

as central procurement of laboratory equipment and

a centralised data monitoring system. At the Health

Directorate, a central contact tracing unit for early

detection of cases and clusters and notifications was

set up in March 2020. Laboratory capacities were

limited in the beginning but were quickly scaled

up with a large-scale testing strategy. Furthermore,

prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Luxembourg had

no national PPE emergency stockpile, which mostly

affected nursing homes and primary care providers.

However, the government procured material from Asia

and received stock from the EU.

Weekly cases per 100 000 population

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

Luxembourg European Union

1st locdown

16/03 Closure of ll non-essentl

shops, school closure, lmted trffc,

bnnn mss therns of 100

people, confnement

2nd locdown

30/10 Nht curfew t 11pm, contct restrctons

26/11 Closure of resturnts nd lesure fcltes

26/12 Nht tme curfew t 9pm nd closure of

non-essentl shops

Esn of locdown

11/01 Reopenn of shops, cnems, thetres,

ms under certn condtons

16/05 Re-openn of resturnts nd cfés

M Esn of locdown

11/05 Return of clsses on rotton

bss, ese of contct restrctons,

reopenn of culturl venues

29/05 Reopenn of resturnts

nd most busnesses

18

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 16. Prior to the pandemic, Luxembourg

reported better IHR public health emergency

capacities than the EU average

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd

Sourc WHO IHR (dt rfr to 2019)

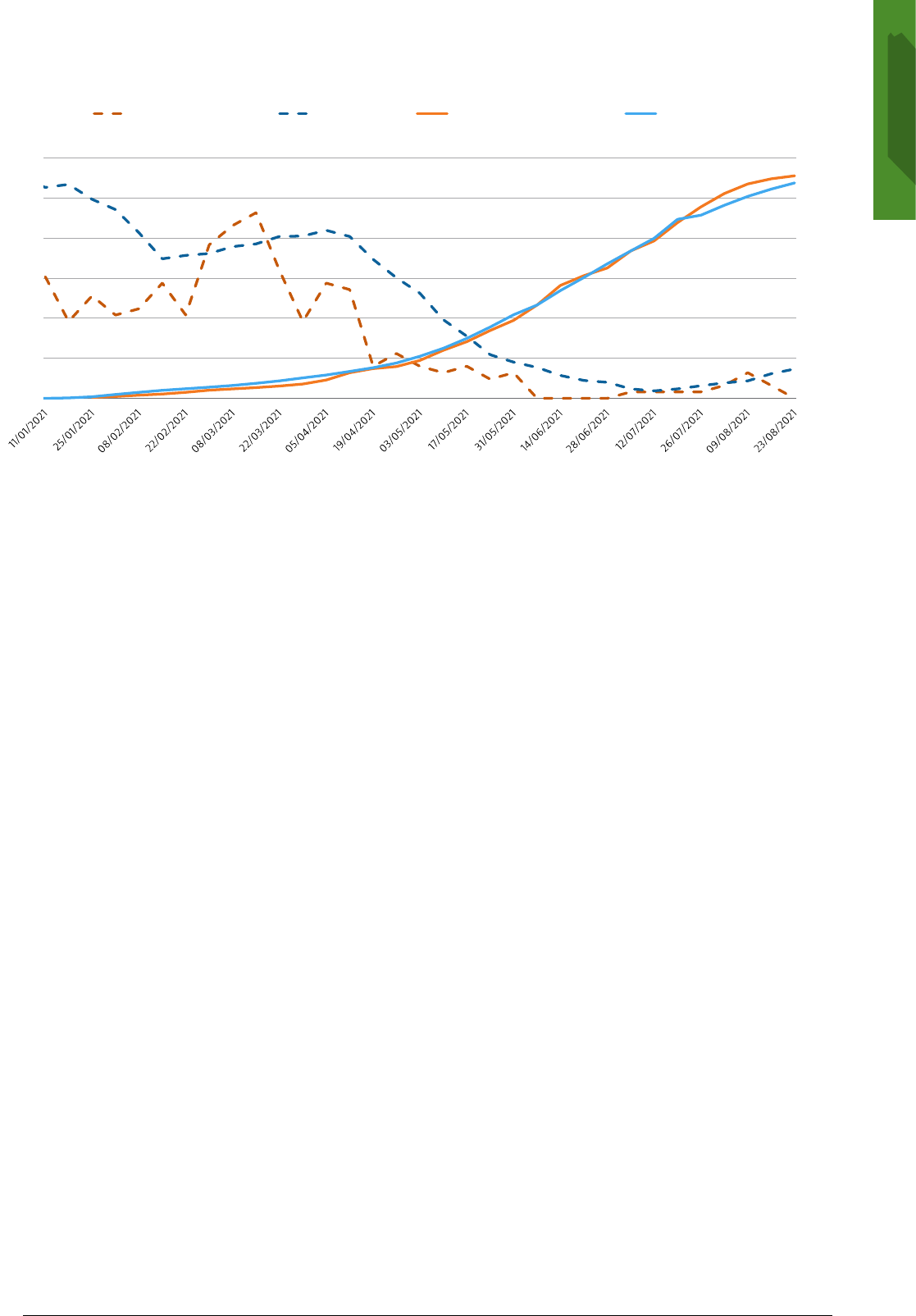

A long-term, large-scale testing strategy was

launched early on

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic,

Luxembourg pursued an ambitious large-scale testing

policy free of charge for everybody, resulting in a

very high testing rate (Figure 17). From May to July

2020, the entire population and cross-border workers

were invited for PCR testing, with the aim of lifting

lockdown restrictions based on reliable information,

and to gain a longitudinal perspective on household

transmission. The population was divided into three

categories depending on their risk of being exposed

to the virus, with each category invited at different

frequencies. Second and third testing phases were

rolled out in September 2020 to February 2021 and in

March to July 2021.

For this population-wide testing, Luxembourg had to

build the highest testing capacity in the EU, reaching

a weekly maximum of 23321 tests per 100000

population by mid-July 2020 – far above Denmark,

another country with a high testing rate (Figure 17).

All passengers entering the country from the end

of May 2020 were offered free COVID-19 testing

on arrival at Luxembourg’s airport. Until summer

2020, family gatherings made up a large part of

Luxembourg’s identified clusters, while cross-border

workers accounted for 16% of infections (ECDC, 2020).

When large-scale testing started in May and June 2020

and testing rates increased, positivity rates remained

stable and below 1%. During the second wave starting

in October 2020 testing declined somewhat and

positivity rates rose accordingly, peaking at between

6% and 8% (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Luxembourg achieved the highest testing rate in the EU early on, while positivity rates remained

lower

TTeessttiinngg aaccttiivviittyy

Note: The EU average is weighted (the number of countries included in the average varies depending on the week).

Source: ECDC.

Data extracted from ECDC on 15/03/2021 at 12:41 hrs.

CCoouunnttrryy 1100//0022//22002200 1177//0022//22002200 2244//0022//22002200 0022//0033//22002200 0099//0033//22002200 1166//0033//22002200 2233//0033//22002200 3300//0033//22002200 0066//0044//22002200

Austria #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A 139

Belgium #N/A #N/A 1 38 86 148 236 333 464

Bulgaria #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A

Croatia 0 0 4 3 13 48 103 158 218

Cyprus #N/A #N/A #N/A 7 2 26 43 40 43

Czechia 0 0 1 7 40 116 248 399 422

Denmark 0 0 6 14 85 126 172 485 478

Estonia 0 0 4 18 91 201 557 840 726

CCoouunnttrryy

Austria

Belgium

Bulgaria

Cyprus

Czechia

Denmark

European Union

Finland

France

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Italy

Latvia

Lithuania

Malta

Netherlands

Norway

Portugal

Romania

Slovakia

Spain

Sweden

0

5 000

10 000

15 000

20 000

25 000

Denmark European Union

Luxembourg

Weekly tests per 100 000 population

WWeeeekk

30-Dec-19

6-Jan-20

13-Jan-20

20-Jan-20

27-Jan-20

3-Feb-20

10-Feb-20

17-Feb-20

24-Feb-20

2-Mar-20

9-Mar-20

30-Mar-20

6-Apr-20

13-Apr-20

20-Apr-20

27-Apr-20

4-May-20

11-May-20

18-May-20

25-May-20

1-Jun-20

8-Jun-20

29-Jun-20

6-Jul-20

13-Jul-20

20-Jul-20

27-Jul-20

3-Aug-20

10-Aug-20

17-Aug-20

24-Aug-20

31-Aug-20

7-Sep-20

28-Sep-20

5-Oct-20

12-Oct-20

19-Oct-20

26-Oct-20

2-Nov-20

9-Nov-20

16-Nov-20

23-Nov-20

30-Nov-20

7-Dec-20

28-Dec-20

4-Jan-21

11-Jan-21

18-Jan-21

25-Jan-21

1-Feb-21

8-Feb-21

15-Feb-21

22-Feb-21

Select dots + Effect > Transform scale 130%

OR Select dots + 3 pt white outline (rounded corners)

Select dots + Effect > Transform scale 130%

OR Select dots + 3 pt white outline (rounded corners)

Points

of entry

Risk

communi-

cation

Health service

provision

Nationalhealth

emergencyframework

Human resources

availability

Surveillance

Laboratory

IHR Coordination

Legislation

and Financing

100

60

40

20

0

80

Luxembourg EU average

19

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd (th numbr of countrs ncludd n th vrg vrs dpndng on th w)

Sourc ECDC

The effective contact tracing system did

not necessitate an accompanying app

In March 2020, the Health Directorate set up a contact

tracing unit that identifies contacts, administers

quarantine and isolation and manages clusters of

infections. The contact tracing team comprised 220

people, including 68 employees from the national

airline, who were redeployed for this purpose. Owing

to rapidly rising positive cases in November 2020,

the Health Directorate simplified and sped up its

procedure by asking people who had tested positive

for COVID-19 to provide contact names through an

online form without having to wait to be contacted

by the contact tracing unit. People were also asked

to transfer a link and their reference number to their

high-risk contacts.

Luxembourg’s contact tracing system was very

effective: the time between identification of

laboratory-confirmed cases and notification was

generally 24-48 hours. Because of the effective contact

tracing system, Luxembourg did not set up a contact

tracing app, unlike most other EU countries. However,

from June 2020 residents could use other European

apps, such as Germany’s Corona-Warn-App.

Luxembourg had sufficient infrastructure and

workforce to manage COVID-19 patients

To meet the increased demand for health care due to

the COVID-19 pandemic, the government carried out a

mandatory census of all licensed health professionals

in March 2020, including residents, students, retirees

and people on unpaid leave. In parallel, it set up a

platform for medical and non-medical volunteers.

Based on these databases, Luxembourg started to

build up a medical reserve. Volunteers were also

deployed to other settings, such as hotlines, contact

tracing, sampling centres and COVID-19 consultation

centres.

Luxembourg is well equipped with acute and ICU

hospital beds, with rates above the EU averages (see

Section 4). The government asked hospitals to make

capacity available for COVID-19 patients, mostly by

delaying planned and elective procedures, as well

as by creating additional ICU beds. The operation

of hospital services was centrally coordinated and

defined by four phases according to the COVID-19

surge capacity plan in place. As a result, the available

capacities of acute and ICU beds were not exhausted

during the first and second wave of the COVID-19

pandemic (Figure 18). In fact, COVID-19 patients

from neighbouring countries such as France were

transferred to Luxembourg for treatment.

Four advanced ambulatory care centres

expanded capacity during the COVID-19

pandemic

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic (mid-March 2020),

the government and health professional organisations

set up four advanced care centres. These aimed to

provide specific care for COVID-19 patients, to reduce

pressure on hospitals and to keep patients away from

emergency departments and general practices. The

centres operated daily from 08:00 to 20:00, and had

two strictly separate channels of consultation: the

first for patients with signs of COVID-19 infection;

the second for those without (Ministry of Health,

2020b). Patients with a positive test result were either

sent home for isolation or transferred to a hospital

if necessary. The patient’s information was also

transferred to the Health Directorate’s contact tracing

unit to ensure appropriate contact tracing.

%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

Denmark European Union Luxembourg

ccoouunnttrryy

Austria

Cyprus

European Union

Greece

Italy

Malta

Portugal

Spain

Positivity rate

20

Stte of Helth n the EU Luxembour Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 18. Hospitals had sufficient intensive care unit capacity for COVID-19 patients

Not Onl ncluds ICU bds for lvl 3 n 2020 (th most ntnsv cr) othr ICU bds t lvls 1 nd 2 r not ncludd

Sourc Mnstr of Hlth

Consultations in advanced care centres were free of

charge, irrespective of a person’s health insurance

coverage. Outside these centres, COVID-19 tests

were carried out upon presentation of a medical

prescription, social security card and identity card.

With decreasing case numbers, the advanced care

centres were successively closed by early summer

2020 – and two consultation centres reopened

in October and November 2020 for patients with

COVID-19 symptoms or a COVID-19 diagnosis, with

the aim of relieving pressure on GPs and reducing the

risk of transmission.

Nursing homes were strongly affected

during the first wave, but the response

improved immediately afterwards

As in many countries, residential LTC facilities in

Luxembourg were particularly affected by the first

wave of COVID-19. Between March and the end of

May 2020, nearly half (46%) of all COVID-19 deaths

in Luxembourg were among LTC residents (OECD,

2021). A working group devoted to nursing homes set

up various safety and hygiene measures to prevent