The Mental Health Strategy

for Canada

:

A Youth Perspective

PAGE i

In March 2013, the Mental Health Commission

of Canada’s Youth Council (YC) came up with

the idea to rewrite or “translate,” from a youth

perspective, Changing Directions, Changing Lives:

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada. Although

every effort was made during the writing of the

Strategy to reach as many audiences as possible,

the YC decided to rewrite it to resonate better

among their friends and peers — or anyone else

interested in mental health discussions in Canada.

The main aim of their project was to develop

a supplemental document that highlights the

experiences and vision of young people working

toward system change, ultimately making the

original Strategy a more accessible document

to all.

Over the course of two years, the YC met in

person four times to work through the Strategy,

page by page. Using a critical youth lens, they

rewrote all six strategic directions, drawing on

personal experiences to make sense of a large

policy document and turn it into something

original. To our knowledge, never before has

a group of Canadian youth designed a project

of this scope or contributed to the eld of

knowledge exchange by translating a policy

document written largely for, and by, adults.

While the Strategy team consulted with hundreds

of youth and their families during the initial

writing process, the policy focus of the document

meant that many people could nd it challenging

to access. The YC hopes that the new version

helps to overcome this challenge.

The original Strategy is geared toward people of all ages and outlines a few specic recommendations for action

on child and youth mental health. For example, the Strategy recommends that we:

> Increase comprehensive school health and post-secondary mental health initiatives that promote mental

health for all students and include targeted prevention efforts for those at risk (from Strategic Direction 1).

> Remove barriers to full participation of people living with mental health problems or illnesses in

workplaces, schools (including post-secondary institutions), and other settings (from Strategic Direction 2).

> Remove nancial barriers for children and youth and their families to access psychotherapies and clinical

counselling (from Strategic Direction 3).

> Remove barriers to successful transitions between child, youth, adult, and senior mental health services

(from Strategic Direction 3).

FOREWORD

PAGE ii

This document builds on these recommendations and others in order to advance dialogue among mental

health advocates, activists, students, community mental health workers, policy makers, or anyone interested

in transforming Canada’s mental health system. We hope that you nd this document useful for becoming

even more engaged in policy discussions that directly impact people of all ages.

Despite being written by youth who highlight youth-specic examples, the report you are about to read is not a full

mental health strategy for youth, nor is it intended to take the place of the original Strategy. If you are interested in

more detailed policy recommendations on child and youth mental health, take a look at these other reports from the

MHCC: Evergreen: A Child and Youth Mental Health Framework for Canada, School-Based Mental Health in Canada:

A Final Report, Taking the Next Step Forward, and, of course, The Mental Health Strategy for Canada.

The YC also understands and appreciates the range of experiences people have with mental illness and do not

intend to use the term in any uniform way. For the purposes of this document, the YC chose “mental health issues”

as a way of encompassing the vast range of diagnoses and lived experiences with mental health problems and

illnesses. People living with schizophrenia, for example, may be at different stages of recovery than someone

living with depression or may require much more complex services than others. Some people may have so few

resources or support that conversations about recovery seem impossible. Either way, the YC acknowledges the

diversity of experiences and understands, through their own lived experience, the complexity of mental illness

and the range of services and supports our system needs in order to advance recovery for everyone.

FOREWORD

PAGE iii

On behalf of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), we are delighted to share

with you The Mental Health Strategy for Canada: A Youth Perspective.

The MHCC’s Youth Council worked tirelessly to adapt Changing Directions,

Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada into a highly accessible

format. Their enthusiastic effort saw the transformation of a 150-page – often

technical – document into an engaging, fresh, and relevant take on mental health

in this country.

Harnessing their keen minds, our Youth Council highlights issues and experiences

unique to young Canadians. Yet, their worldview is broad enough to encompass

the needs of ALL Canadians. Displaying an innate sensitivity to Canada’s diverse

population, they have created a resource that we believe will spur meaningful

dialogue from coast-to-coast-to-coast.

It isn’t enough to hear young people.

They have far too much to offer to simply be a voice at the table. They must be

active participants in setting the course for mental health policy and practice in

Canada. The MHCC is privileged to bene t from the wisdom and experience of

these thoughtful emerging leaders.

Now, our nation’s dialogue on mental health is richer for their contribution.

So please, read on.

Louise Bradley & the Hon. Michael Wilson, P.C., C.C.

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD AND THE PRESIDENT AND CEO

PAGE iv

.............................................................................................................. page i

................ page iii

................................................................................................. page iv

............................................................................................... page 1

......................................................................................................... page 2

1: ......................................................................... page 6

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2: RECOVERY ...................................................................... page 10

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3: ACCESS ........................................................................... page 13

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4: DIVERSITY ...................................................................... page 18

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 5: FIRST NATIONS, INUIT & MÉTIS ........................................ page 23

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 6: COORDINATION & COLLABORATION .................................. page 27

CALL TO ACTION .................................................................................................... page 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE 1

The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Youth Council (YC) has many people to thank for helping to make

this project a reality. When we decided to write a youth-translated version of the Mental Health Strategy for

Canada, we were not prepared for how much work that would actually entail. After almost two years since we

decided to do this project and after countless revisions, consultations, in-person meetings, brainstorming sessions,

more revisions, graphic design, knowledge exchange planning, we are nally able – and delighted – to share this

document with you.

The following people and organizations were instrumental in helping nish this project:

> The Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Youth Council, and

youth volunteers from the Métis Nation of British Columbia: thank you for helping us write certain sections

of this document from culturally relevant and safe perspectives.

> Sam Bradd, our image guy: thank you for bringing the Strategy to life with your amazing graphics.

> Former YC members: thank you for your ideas and help on the early parts of this project and for your

unconditional support from afar.

> Original developers and writers of the Strategy: thank you for helping us keep our messages in line with

Changing Directions, Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada.

Sincerely,

Kristen Zaun (YC Chair)

Amanee Elchehimi (YC Vice-Chair)

Ally Campbell

Dustin Garron

Aaron Goodwin

Patricia Laliberté

Simran Lehal

Don Mahleka

Katie Robinson

Jack Saddleback

Marta Sadkowski

Nancy Savoie

Vanessa Setter

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PAGE 2

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada

:

A Youth Perspective

DID YOU KNOW...

MORE THAN TWOTHIRDS OF YOUNG ADULTS LIVING WITH A MENTAL HEALTH

PROBLEM OR ILLNESS SAY THEIR SYMPTOMS FIRST APPEARED WHEN THEY

WERE CHILDREN?

That makes child and youth issues an especially important topic in mental health, one that the Mental Health

Commission of Canada (MHCC) recognized early on when it created the Youth Council in 2008.

WHO ARE WE?

The MHCC’s Youth Council (YC) represents young people with lived experience of mental health issues, whether

personally or through family or friends. YC members are selected from across Canada with consideration given to

the following: age and gender; province or territory of residence; cultural background; First Nations, Inuit, or Métis

background; linguistic background; siblings or family members of persons with mental illness; experience with the

child welfare system; sexual orientation and/or gender identities; or youth at risk with issues in housing, addictions,

and/or the justice system.

WHAT DO WE DO WITH THE MHCC?

>

Advocate for young people with mental health issues.

> Get involved with local, provincial, and national youth mental health networks.

> Bring a youth perspective to MHCC projects.

> Speak on behalf of youth at MHCC events.

> Promote recovery and inspire other youth at public events.

> Make sure youth have a voice in the decisions being made about Canada’s

mental health services and policies.

introduction

PAGE 3

in 2013, we got to thinking…

SO WHY MAKE A DIFFERENT VERSION OF THE STRATEGY?

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada was published in 2012. It took over ve years to research and write, with

thousands of Canadians being consulted in the process. It looks at a lot of issues and recommends ways to improve

the mental health system — but it’s over 150 pages long and can be technical sometimes.

We thought — let’s make sure these important messages reach as many people as possible. Young people, youth

advocates, service workers, and the general population need to equip themselves with the right knowledge so that

they can have an informed say in issues that affect Canadians now and in the future! We hope this document makes

mental health policy more accessible to anyone advocating for system or service level changes.

HOW DID WE DO IT?

It took us two years to write this version. We looked at every priority and recommendation in the Strategy and rewrote

them keeping our target audience in mind - Canadians who might not nd current mental health policy documents

accessible. We highlighted youth-specic examples to reect our own experiences, but certainly there are more that

could have been included to reect the needs of people of all ages. Before starting, we had to think about a number

of things:

> How can mental health policies be written to make better sense to Canadians directly

affected by the mental health system, services, and supports?

> What examples of best practices could make the Strategy more meaningful to

anyone engaged in mental health policy discussions across Canada?

> What parts of the Strategy’s recommendations are most relevant to youth?

> How can a youth perspective on the Strategy inspire mental health system

change and a sense of hope and optimism in young people?

In order to reect the histories of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (FNIM) in Canada, the YC also consulted with FNIM

youth groups who helped us write certain sections from culturally relevant and safe perspectives. We understand

that in order to truly transform Canada’s mental health system, the needs and challenges of Canada’s FNIM populations

must be recognized and reected in future mental health policies. We expand on what we mean by this in Strategic

Direction 5.

INTRODUCTION

PAGE 4

WHAT DO YOU NEED TO KNOW BEFORE READING OUR REPORT?

The priorities and recommendations in the Mental Health Strategy for Canada are grounded in mental health

and recovery terminology. That means you have to understand these terms in order to really “get” the rest of

this document.

GOOD MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

Mental health is a state of wellbeing in which you can realize your own potential, cope with the normal stresses of life,

work productively, and make a contribution to your community. Good mental health protects us from the stresses of

our lives and can even help reduce the risk of developing mental health issues.

It’s important to recognize that good mental health is not the same as “not having a mental health issue.” Even if you

develop a mental health issue, you can still experience good mental health and make progress along your personal

journey toward recovery.

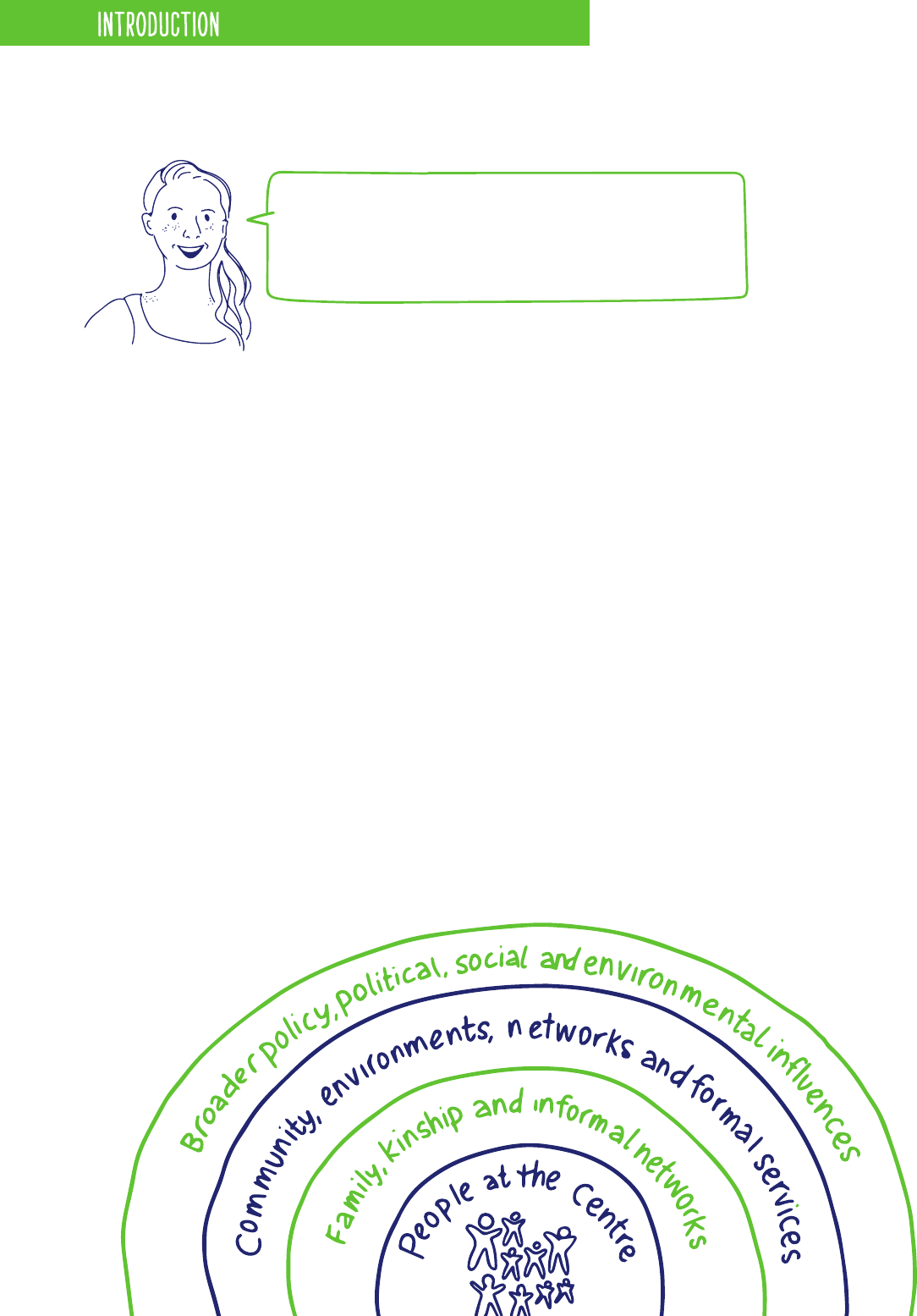

There is no single cause of any mental health issue. Whether a mild mental health problem or a severe mental illness,

mental health issues are the result of a complex mix of social, economic, psychological, biological, and genetic factors.

“THE YOUTH COUNCIL IS A BRIDGE BETWEEN THE MHCC AND

YOUTH EXPERIENCING MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES. WE MAKE

SURE YOUTH ARE REPRESENTED IN MHCC’S DECISION-MAKING

SO CHANGES IN THE MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEM WILL BENEFIT

YOUTH.” – MARTA S.

INTRODUCTION

PAGE 5

RECOVERY

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada denes recovery as living a satisfying, hopeful, and meaningful life, even

when there are ongoing limitations caused by mental health issues. With the right combination of services and supports,

many people who are living with even the most severe mental illnesses can experience signicant improvements in

their quality of life.

Recovery does not imply a “cure.” Yes, the full remission of symptoms may be possible for some. But for others, mental

health issues should be thought of in the same way as diabetes or other chronic health problems — something that has

to be managed over the course of your life but does not prevent you from leading a happy, fullling life.

At its core, the concept of recovery is about hope,

empowerment, self-determination, and responsibility.

Good mental health and wellbeing are important for all of us — no matter our age and whether or not we experience

mental health issues. The principles of recovery apply to everybody. With children and youth, for example, a key focus

should be on becoming resilient and attaining the best mental health possible as they grow. For seniors, it’s about

addressing the additional challenges that come with aging.

Our goal in doing this work was simple. We wanted to bring to life a document that is

accessible to everyone, including youth, with the hope of sparking the minds of Canadians

to want to be a part of changing the mental health policy landscape.

“I ALWAYS THOUGHT BEING MENTALLY ILL MADE ME A BAD PERSON, EVEN

BROKEN, BUT WHEN I REACHED RECOVERY I WAS ABLE TO SEE EVERYTHING

THAT MY ILLNESS TAUGHT ME: COMPASSION, EMPATHY, APPRECIATION, AND

RESILIENCY. WHEN I LEARNED TO LIVE AND THRIVE WITH IT, I REALIZED IT

MADE ME A BETTER AND STRONGER PERSON IN THE END.” NANCY S.

“THE YOUTH PERSPECTIVE ENRICHES THE WORK OF MHCC AND OTHER

MENTAL HEALTH GROUPS. BECAUSE THERE ARE GAPS IN SERVICE PROVISION

AND PROMOTION, THERE NEEDS TO BE MORE YOUTH LEADERSHIP,

COORDINATION, EVIDENCEINFORMED STRATEGIES, AND PARTICIPATION IN

THESE SERVICES. YOUTH WITH LIVED EXPERIENCE NEED TO BE ENCOURAGED

TO SPEAK OUT MORE ON VARIOUS ISSUES TO INSPIRE AND GIVE DIRECTION

FOR BETTER CHANGE.” DON M.

INTRODUCTION

PAGE 6

ENCOURAGE LIFELONG MENTAL HEALTH IN ALL SOCIAL ENVIRONMENTS

WHERE PEOPLE LIVE OR SPEND TIME AND PREVENT MENTAL HEALTH

ISSUES AND SUICIDE WHEREVER POSSIBLE.

Mental health issues can have many causes, ranging from the biological (such as chemical changes in the body) to

the environmental (such as stressful life events). No one can predict for sure who will experience them and who

won’t. What we do know is that efforts to promote mental health, and to treat and prevent mental health issues

and suicide, are more successful when they do the following:

When people live in a healthy and

supportive environment, they tend to

have better mental health and less risk

of mental illness.

STRENGTHEN PROTECTIVE FACTORS

& REDUCE RISK FACTORS

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 1

KNOW WHO TO REACH

Prevention efforts work better when

they’re designed for one specic group –

for example, people with the same age or

from the same community.

PAGE 7

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 1

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

The TAMI (Talking About Mental Illness) Coalition’s Stomping Out Stigma campaign in Durham, Ontario has been called a “best-in-class” example of mental

health awareness and prevention for middle and high school students. It uses contact-based education to decrease stigma about mental health issues and

promote help seeking. Speakers with lived experience go into schools giving teachers and students the opportunity to meet and interact with real people

who have experienced mental health challenges. The program’s website has helpful links for students, parents, and teachers, with separate curricu-

lum-based teaching guides and toolkits specically for middle school (Grades 7 and 8) and high school students. http://tamidurham.ca/

KEY WORDS

Risk factor: Any-

thing that makes

a person more

likely to suffer

from mental health

issues.

Protective factor:

Anything that

helps a person to

keep their mental

health.

Stigma: Negative

attitudes and

behaviours that

make people with

mental health

issues feel judged

and ashamed.

Ageism: Being

prejudiced against

someone because

of their age — old

or young.

Contact-based

education: Meeting

people who have

experienced mental

health issues and

are willing to share

their stories of

recovery.

SET CLEAR GOALS

Knowing in advance what the goals are

helps to measure success down the road.

Communities have the potential to take

care of people – as long as they have

the right tools and enough resources.

GIVE COMMUNITIES WHAT

THEY NEED TO TAKE ACTION

PLAN FOR THE LONGTERM

The best initiatives are those that last a

long time, giving them more of a chance

to be effective.

We all have a part to play in improving mental health. It isn’t just something for therapists

and clinics to deal with. Mental health must be addressed anywhere people spend their time —

including home, school, and work.

PAGE 8

PRIORITIES

1.1 HELP PEOPLE UNDERSTAND HOW TO ENCOURAGE MENTAL HEALTH,

REDUCE STIGMA, AND PREVENT MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AND SUICIDE.

Being mentally healthy helps us to do better at school, make a good living,

and be physically well.

As youth, we have a unique opportunity to be young leaders — lend a hand,

make a point to connect with others, take part in group recreation when

possible. In our various communities, having access to programs that foster

better mental health is a must.

Many people with mental health issues experience stigma.

One of the best ways to break down stigma is through contact-based education.

It’s important that people get support as soon as possible when experiencing mental health issues.

We all need to be educated to be able to recognize symptoms of mental health issues in ourselves

and others. For youth, for example, it’s especially important that front-line workers have this

expertise because people like teachers, coaches, and community workers are the ones young

people usually turn to rst.

1.2 HELP FAMILIES, CAREGIVERS, SCHOOLS, POSTSECONDARY INSTITUTIONS, AND

COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS ENCOURAGE CHILD AND YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH AND

INTERVENE EARLY WHEN SIGNS FIRST EMERGE.

70 per cent of young adults with mental illnesses report that their symptoms rst started

in childhood. It's kind of a no-brainer that encouraging good mental health early in life

is important.

The best places to reach youth are at home, school, community centres and in the places

where youth work.

We should have programs that take a very broad approach to mental health and more

targeted programs that specically address children and youth who have a high risk of

mental health issues —due to poverty, family violence, or a parent having a mental health

or substance use problem.

“DURING THE PROCESS OF MY RECOVERY, I HAVE COME TO REALIZE THAT

WE HAVE A RESPONSIBILITY AS INDIVIDUALS, COMMUNITIES, AND LEADERS

WITHIN COMMUNITIES TO ADVOCATE FOR THE PREVENTION, PROMOTION,

AND ACCESS TO QUALITY MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN, YOUTH,

AND ALL CANADIANS. TOGETHER, THROUGH THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVER

SITY AS CANADIANS, WE CAN CREATE A DIALOGUE THAT IS NECESSARY

TO FOSTER COLLABORATION AND INNOVATION FOR TANGIBLE, IMPACTFUL

CHANGES IN MENTAL HEALTH.” KRISTEN Z.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 1

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

The Thunder Bay Youth Suicide Prevention Task Force (TBYSPTF) is made up of 30 organizations working together to address the issues of youth suicide.

Their goals are to increase awareness of issues related to youth suicide, to work collaboratively to prevent suicides in our community, and to mobilize

services to respond quickly to a youth suicide or other tragic event. The Task Force has run public health campaigns for teachers, coaches, and parents,

with posters and quick-reference cards about spotting early warning signs of mental illness plus tips on what to say and where to get help. Check out

their web site at http://www.heresthedeal.ca

PAGE 9

1.3 CREATE MENTALLY HEALTHY WORKPLACES.

Just as mentally healthy schools are important for children and youth, mentally healthy

workplaces have a signicant inuence on the mental health of everyone who spends

time at work. We need to make sure workplaces inuence in a positive and not a negative

way, otherwise they can also contribute to the development of mental health issues like

depression and anxiety.

To encourage good mental health and ght stigma, workplaces need to:

> Have strong leaders and managers willing to make change happen

and to play their part in stopping bullying and harassment.

> Implement management training, employee assistance, and promotion

and prevention programs.

> Encourage a positive work-life balance.

> Support recovery for employees living with mental health issues.

1.4 ENCOURAGE GOOD MENTAL HEALTH IN SENIORS.

Many of you can probably remember a time when you or someone you know has been stereotyped or

discriminated against because of their age (ageism). This can affect people at all stages of life.

Take depression for example. Many people don’t take depression later in life

seriously (including seniors themselves) because they think it goes hand in hand

with the aging process. If we want to stop stereotypical attitudes based on age,

we need to challenge the idea that mental illness

is just a normal part of aging. We need to better

understand the difference between age and illness.

A range of efforts is needed to help promote physical and mental wellness in

seniors and to prevent mental illness, dementia, and suicide wherever possible.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 1

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace

Championed by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, and developed by the Canadian Standards Association and the Bureau de normalisation

du Québec, the Standard is a voluntary set of guidelines, tools and resources focused on promoting employees’ psychological health and

preventing psychological harm due to workplace factors.

HOW ARE YOU?

PAGE 10

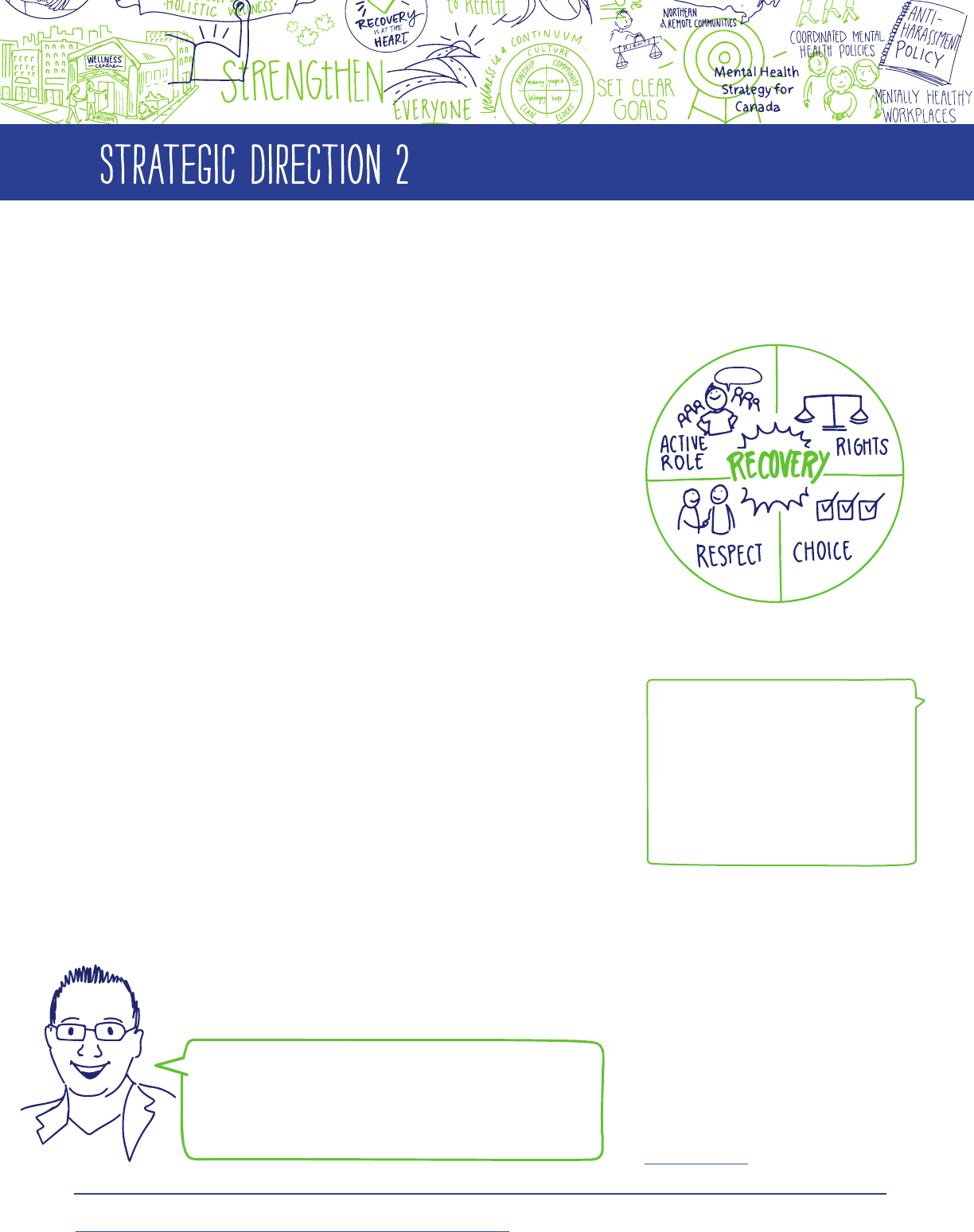

FOCUS THE MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEM ON RECOVERY AND

WELLBEING FOR PEOPLE OF ALL AGES AND PROTECT THE

RIGHTS OF PEOPLE WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES.

Recovery is an important concept in mental health, but it is

not always well understood. When a mental health system is

focused on recovery, it helps those with mental health issues

to live satisfying, hopeful, and meaningful lives (as dened by

each individual person).

Recovery and wellbeing are for everyone — people living with

mental health issues, their families and communities, and the

country as a whole. In 2006, the Out of the Shadows at Last

report

1

said recovery should be “at the centre of mental health

reform” in Canada. But even today, our mental health system is

still not focused enough on the full range of services, treatments,

and supports that promote recovery and wellbeing. That means

there’s still a lot of work to be done.

To truly put recovery at the centre of the system, we need to

make sure that:

> People with lived experience are able to play an

active role alongside mental health professionals.

> The rights of people with mental health issues

are protected.

> People with mental health issues are treated with

respect in every setting and situation.

> People can choose the service, treatment, and support

options that work for them.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2

1

The Out of the Shadows at Last report, produced by the Senate of Canada in 2006, can be viewed online at:

http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/391/soci/rep/rep02may06-e.htm.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Student-athletes can face incredible pressure

to perform in sport and in the classroom and,

like many youth, they can also be reluctant to

talk about their mental health. The Student-Athlete

Mental Health Initiative (SAMHI) was created

to protect and promote the mental health of

student-athletes and to support those struggling

with mental illness. Because one of the keys to

recovery is opening up and realizing other people

have been through the same journey, a highlight

of SAMHI’s work is the “SAMHI Champion Series.”

Student-athletes are invited to write about their

real-life experiences with recovery and mental

illness on the blog so others can learn from their

challenges and victories. The blog also provides

links to help connect student-athletes with

counselling resources and other mental

health services.

http://www.samhi.ca

“WHEN YOU RECOGNIZE THE IMPORTANCE OF YOUR MENTAL

HEALTH, YOU CAN DETERMINE THE BEST ROUTE TO ATTAINING

GOOD MENTAL HEALTH. FOR ME, THIS INCLUDED HOSPITALIZATION

AND SEEING A THERAPIST. FOR OTHERS, THIS MIGHT INVOLVE

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY OR MEDICATIONS. WE CAN GET TO THE SAME

DESTINATION BY TAKING DIFFERENT ROUTES.” DUSTIN G.

Recovery: The process through which a

person is able to live a satisfying, hopeful,

and meaningful life (as dened by that

individual), even when there are ongoing

limitations caused by mental health issues.

Wellbeing: The physical and emotional

state that comes from living a balanced,

fullling life. Wellbeing can mean different

things to different people and can even

change depending on where a person is in

his or her recovery journey.

KEY WORDS

PAGE 11

PRIORITIES

2.1 PUT RECOVERY AND WELLBEING AT THE HEART OF MENTAL

HEALTH POLICIES AND PRACTICES.

Canada’s mental healthcare system needs to shift its focus to

recovery and wellbeing. Guidelines, indicators, tools, standards, on-

going training, and leadership are all essential pieces in creating this

shift from the current policies and practices to recovery-oriented ones.

There also needs to be greater collaboration between those who provide services and those who use them. People

living with mental health issues must be actively involved in developing and managing their own care plans.

Families and friends need information, resources, and supports to be partners in the recovery journey, while

respecting people’s right to keep things condential. For youth, siblings and peer networks are often important

members of the circle of care and those siblings and friends need supports and services themselves.

2.2 ACTIVELY INVOLVE PEOPLE LIVING WITH MENTAL

HEALTH ISSUES AND THEIR FAMILIES.

Anyone who has experienced or been close to someone affected by mental

health issues has unique expertise and perspective that can help change the

mental health system.

People with lived experience should be actively involved on boards and advisory

bodies that make decisions about the system and welcomed into the mental

health workforce — not just as peer support workers but at all levels within an

organization. Who better to help guide the changes that need to be made to the

system than individuals who have gone through the process themselves and

know where the pitfalls lie?

“RECOVERY IS A JOURNEY.

THE ONLY THING I SEE ON THE

MAP IS WHERE I AM TODAY

AND THE DISTANCE FROM

MY STARTING POINT. IT’S

ALSO ABOUT GIVING MYSELF

PERMISSION TO STRUGGLE

AND HAVING THE SUPPORT

AND COPING RESOURCES TO

GET THROUGH THAT STRUGGLE

FOR A LITTLE LONGER EACH

DAY.” ALLY C.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Youth advocates are changing lives across Canada and around the world. Youth with lived experience can play a major role in the recovery process.

Consider Kevin Breel, a Vancouver stand-up comic whose TED talk on depression has received more than three million views — highlighting how

youth can give voice to their struggles with suicide in a way that resonates with others around the world.

http://www.ted.com/talks/kevin_breel_confessions_of_a_depressed_comic

PAGE 12

2.3 RESPECT AND PROTECT THE RIGHTS OF PEOPLE LIVING

WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES.

Canada signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons

with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2010. The CRPD is a commitment to making

sure our laws and regulations include and protect the human rights of

all people with disabilities, including those with mental health issues.

What exactly do we mean?

Here’s an example: When police are called in to respond to a mental

health crisis, information about the incident may be recorded and then

disclosed in police record checks, which can make it difcult for the

person to get a job or travel outside the country. Some police agencies

have already stopped this practice. Now we need to make sure they

all do.

When mental health issues cause people to be potentially harmful to

themselves or others, the CRPD says safety measures should be the least

“intrusive” and “restrictive” possible. That is, any decision to restrain the

individual, whether physically or through the use of medication, or to

isolate them, should be evaluated in terms of his or her human rights.

The caregiver needs to ask, “Are human rights being respected?”

2.4 REDUCE THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

LIVING WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AND PROVIDE PROPER SERVICES AND

SUPPORTS TO PEOPLE ALREADY IN THE SYSTEM.

Most people living with mental health issues have no involvement with the criminal

justice system. But those who do are “over-represented” — meaning there are more of

them in the system than the general average. Where youth are concerned, it’s hard to

know exactly how common mental health issues are because many young people are

not diagnosed until they leave jail and are placed in group homes or foster care.

Changing this trend will require:

> A focus on prevention and early intervention, which can help keep youth

out of the criminal justice system for their entire lives. How? By preventing

mental health issues from developing and by providing help quickly when

they do.

> Adequate access to professional mental health services in correctional settings.

> A “continuity” of services — from a person’s rst interaction with the justice

system all the way through to when he or she returns to life in the

community — that involves more than just a check-in with a parole ofcer.

> More training and resources for police and corrections workers,

teaching them how to interact with people living with mental health

issues, including youth.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Putting mental health at the front lines of police response: The Mental Health Emergency Services Program run by Vancouver Coastal Health features

a mobile response unit called Vancouver’s Car 87 which pairs police ofcers with registered psychiatric nurses to provide onsite interventions for

people experiencing mental health crises. The nurses and ofcers respond to calls together and then work as a team in assessing, managing, and

deciding the most appropriate action. Similar steps are taken by Toronto’s Mobile Crisis Intervention team, which has its own crisis line supported by

crisis workers, specially trained police ofcers, and mental health nurses who provide secondary responses to calls for people in crisis.

http://www.torontopolice.on.ca/community/mcit.php

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities:

Article 1 – Purpose

The purpose of the present Convention is to promote,

protect, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment

of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by

all persons with disabilities and to promote respect

for their inherent dignity. Persons with disabilities

include those who have long-term physical, mental,

intellectual, or sensory impairments which in

interaction with various barriers may hinder their

full and effective participation in society on an

equal basis with others.

PAGE 13

GIVE PEOPLE ACCESS TO THE RIGHT SERVICES, TREATMENTS, AND

SUPPORTS WHEN AND WHERE THEY NEED THEM.

Everybody should be able to access the full range of mental health services, treatments, and supports.

Yet for a lot of people, the mental health system often feels like a maze, one with lots of cracks that are

easy to fall through.

Because each person’s recovery journey is unique, there will never be a “one-size-ts-all” solution for mental

health services. Still, there’s much that can be done to ensure “every door is the right door” — meaning no

matter where a person enters the system, they can get the care they need.

In order to improve the ow and efciency of mental health services, it’s helpful to think of the system in

tiers (or as having levels). Each represents a cluster of services of similar intensity. In order for the system

to function in a way that makes sense, access to all services should be available to everyone with no barriers

to entry and exit.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3

INTEGRATING AND COORDINATING

Doctors, teachers, police ofcers, and social workers should all work together with mental health service

providers to help people along the journey to recovery — whether that means providing timely access to

medication, affordable housing, professional counselling, or peer support.

PAGE 14

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3

KEY WORDS

Barriers: Anything that

keeps people from access-

ing services or moving

through the system in

the way they want.

Primary Healthcare:

Healthcare provided by

family doctors, nurses, and

other health profession

-

als, often in collaborative

teams.

Peer Support: People

who have experience

with mental health issues

offering support, encour-

agement, and hope to each

other when facing similar

situations.

Recovery First: A recov

-

ery-oriented approach that

focuses on providing per-

manent, independent hous-

ing and additional supports

to homeless populations in

order to end homelessness.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Combining the skills and experiences of a wide range of professionals is key to delivering effective

services. This is especially true at the Nova Scotia Early Psychosis Program (NSEPP), a specialized,

community-focused outpatient program for youth experiencing a rst episode of psychosis. NSEPP

involves a team of psychiatrists, nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, people with lived

experience, and more, all working together to provide timely care in any form required. NSEPP also

provides art therapy programs as well as follow-up services and continuity of care for up to ve

years — along with courses that encourage family members to become more involved in the

recovery process. http://earlypsychosis.medicine.dal.ca/

PRIORITIES

3.1 GIVE PRIMARY HEALTHCARE A LARGER ROLE IN MENTAL HEALTH.

Mental and physical health are deeply connected and people are more likely to

talk to their family doctor about a mental health issue than any other healthcare

provider. Fortunately, many of the same approaches primary healthcare providers

use to deal with chronic illnesses like

heart disease and diabetes can be

applied to mental health. These include

working in multidisciplinary primary

healthcare teams (that is, teams of

people with different skills and training)

and giving people the tools they need to

better manage their own health.

Technology can also help in a big way.

Electronic health records and video chats

are all making it easier for doctors to provide people with the information they

need. New kinds of online and mobile services are also helping connect people to the care they need, with many

of them designed specically for youth.

What family doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals need now are stronger mental health skills and

training as well as a clear recovery approach in their work — all shaped by input from people with lived experience.

Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Distance Treatment Service for Families, Nova Scotia

Strongest Families is a program developed by the IWK Health Centre in Halifax and now run by the Strongest Family Institute. This program helps

parents and children in four Nova Scotia health districts, as well as in B.C., Alberta, and Ontario, to learn to deal with the challenge of common childhood

behaviour and anxiety problems. Families receive handbooks and skill-demonstration videos and work through step-by-step modules at home, supported

by telephone consultations with trained coaches. Research using randomized controlled trials found that Strongest Families was more effective than

usual care services. The treatment drop-out rate was less than 10 per cent and children in the Strongest Families program were signicantly less likely to

still have a diagnosable illness after eight and twelve months. In addition, positive treatment effects were sustained at a one year follow-up and parents

reported high satisfaction with the quality of services.

YOUTH COUNCIL TIPS: GETTING THE MOST FROM YOUR DOCTOR APPOINTMENTS

A family doctor is often the rst place people go

with a mental health issue — but given the short

amount of time you usually have with your doctor,

it’s important to be prepared. Here are some tips to

make the most of your appointment.

> Don’t be afraid to ask questions. It might

help to write your questions down in advance

so you don’t forget any of them.

> Don’t be intimidated by the doctor and

remember that you’re allowed to bring a

parent or friend into your appointment if it

will help you feel more comfortable.

> Keep in mind that medication is only one type

of treatment option. Be sure to ask about all

of the options that might be available to you.

> Don't lose your voice. If you don’t understand

the doctor’s technical jargon, be sure to ask

for a simpler explanation.

> Only you know what’s going on inside your

head. Be totally honest and explain things as

clearly as possible; otherwise, your doctor

will have a harder time helping you.

PAGE 15

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3

3.2 MAKE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES MORE READILY AVAILABLE IN THE COMMUNITY FOR PEOPLE OF ALL AGES.

When mental health services and treatments aren’t available in the community, people

living with mental health issues can end up homeless, in jail, or constantly going to the

emergency room for support. Unfortunately, many communities are stretched to the limit.

Some no longer keep waiting lists for mental health services because it might give false

hope to people in need that eventually their turn for support will come.

Everyone should have the same access to a full range of services and care, no matter

how old they are, where they live, or their income level. If people can’t afford to pay,

they shouldn’t be prevented from getting services like psychotherapy that are mostly not

covered by provincial health plans. Children and youth stand to benet the longest from

better access to services and better youth mental

health means lower costs over the long-run for

governments as well.

Community services must also be better

coordinated so people can “navigate” between

them easily as their needs change. One way to do

this is to have people with mental health issues

work with service providers on personal plans

tailored to their individual recovery journey.

3.3 GIVE PEOPLE LIVING WITH COMPLEX MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES BETTER ACCESS TO THE SPECIALIZED

SERVICES AND TREATMENTS THEY NEED.

The mental health system must be able to meet everybody’s

needs, including those with complex mental health issues

like schizophrenia and people with multiple diagnoses —

for example, youth with both autism and anxiety.

In some cases, people with complex mental health issues

need “acute” (short-term but intensive) hospital services.

Others may require specialized, long-term services. There

is a major need for better coordination between health,

education, justice, and social services and for improved

skills and knowledge among service providers.

Because of this poor coordination, youth with complex

mental health issues often “fall through the cracks” as they age, losing access to services that may be unavailable

or difcult to access in the adult system. They might also encounter gaps because their move to adult services is

not properly organized.

“MY RECOVERY BEGAN WHEN I WAS ABLE TO BE HONEST WITH MYSELF ABOUT

WHAT WAS GOING ON AND TO BE ABLE TO VERBALIZE IT. IT WAS IMPORTANT TO

IDENTIFY THAT THIS WAS REAL AND WAS NOT JUST ALL IN MY HEAD.” VANESSA S.

PAGE 16

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

MHCC Youth Transitioning to Adult Mental Health Services Project

Identifying gaps and best practices in the mental health system leads to better services and outcomes for all people living with mental illnesses. This project is an

initiative of the MHCC launched to guide policy and practice that will improve how youth make the shift to adult mental health programs as they grow older.

3.4 INCLUDE PEER SUPPORT AS AN ESSENTIAL PART OF MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES.

A peer is someone who has something in common with you, such as

age, background, or qualications.

Peer support works because people who have experience with mental

health issues can offer encouragement and hope to each other — often

reducing hospitalization, providing social support, and improving

quality of life. It can also connect families experiencing similar

situations, helping them better understand the mental health system

and improving their ability to take care of their loved one’s needs.

Despite its effectiveness, peer support gets very limited funding.

Continuing to develop standards and guidelines will help make peer

support more credible and seen as a key part of the mental health

system. Because peers have such a signicant inuence on youth, the

contributions of younger peer support workers, including high school

students, must also be taken more seriously.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Guidelines for the Practice and Training of Peer Support

Published in 2013, the guidelines were created to provide direction to policy makers, decision makers, program leaders, and the public about the practice of

peer support and to help enhance the credibility of peer support as an essential component of a transformed mental health system. The guidelines focus on a

structured form of peer support that fosters recovery. Peer support workers from across the ten provinces and three territories came together to develop the

guidelines in conjunction with the MHCC.

Another barrier relates to the accessibility of medication, which is usually not covered by public insurance outside of

hospitals. This is a problem especially for people transitioning back into the community, when uninterrupted access

to medication is often critical. From the youth perspective, many are unable to afford their medications once they

become adults.

Striking the right balance of intensive services in community and institutional settings requires “benchmarks” to guide

planning. In other words, it’s about knowing what different people — children, youth, adults, seniors — require by way

of care. It also requires everybody with a role to play — police, doctors, social workers, families — to contribute in a

coordinated community-based support system.

PAGE 17

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 3

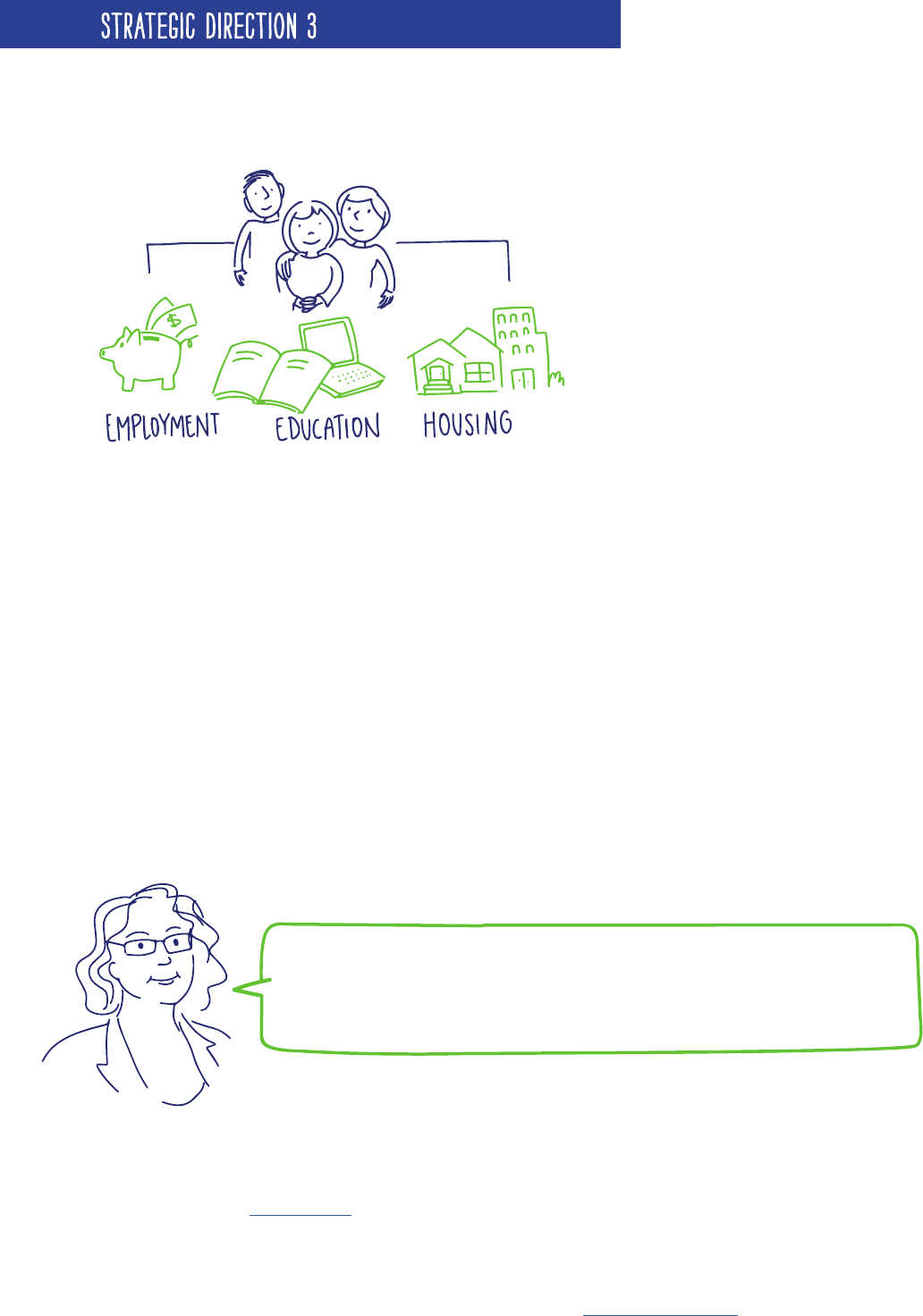

3.5 GIVE PEOPLE LIVING WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AND THEIR FAMILIES AND CAREGIVERS BETTER

ACCESS TO HOUSING, EMPLOYMENT, AND EDUCATION.

Recovery isn’t just about having access to mental

health care. It’s also about having a place in a

supportive community with everything a person

needs to ensure their wellbeing.

At least 100,000 people living with mental health

issues and their families will need access to affordable,

adequate housing and related supports over the next

ten years, with options that suit each family’s needs.

Specic initiatives are also needed to assist people

who are homeless and have mental health issues. For

example, housing rst programs provide housing and

other recovery-oriented supports without requiring

people to accept treatment as a condition of housing. From a youth perspective, these and other models should be

further explored to prevent long-term homelessness in youth specically.

Action is needed on other fronts, too. Today, people with serious mental health issues have high rates of

unemployment and often lack opportunities to develop their talents. Barriers that keep people out of the workforce

must be removed. At the same time, supports that help them obtain employment should be increased.

Canada also needs to improve the ways it handles disability benets. The current system often discourages people

from returning to work, taking away benets — such as medication coverage — when they try to do so. Youth often

nd it quite difcult to access disability benets because they don’t know how to navigate the system or even where

to begin. Many simply give up trying, putting themselves at nancial risk.

Caregivers, including relatives and friends, who provide unpaid care for a person living with mental health issues can

also be held back from participating in the workforce. An estimated 27 per cent of caregivers lost income because

of the time they spent caring for a family member. For youth, providing care to a sibling, parent, or partner not only

makes it difcult to hold down a job, but it can also take away time from their studies. Caregivers need access to

nancial supports like tax credits and caregiver allowances, as well as the support of school and workplace policies

like caregiver leaves and exible hours to help ease their burden.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

In 2008, the Government of Canada allocated $110 million to the MHCC

to undertake a research demonstration project on mental health and

homelessness. The result? At Home/Chez Soi, a four-year project in ve

cities that aimed to provide practical, meaningful support to Canadians

experiencing homelessness and mental health problems. In doing so, the

MHCC is demonstrating, evaluating, and sharing knowledge about the

effectiveness of the "housing rst" approach, where people are provided

with a place to live and then offered recovery-oriented services and

supports that best meet their individual needs.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Halifax’s Laing House is a youth-driven, community-based organization

offering programs to help young people living with mental illnesses get

the support they need. Its Employment Program, for example, helps

with job searching, résumé writing and interview skills. Through its

Independent Living Program, Laing House helps youth develop the

skills to nd and maintain safe, affordable housing, with workshops on

apartment hunting, tenant rights and obligations, income assistance,

and more. Other programs include Creative Arts, Healthy Living, Family

Support Group, and Hospital and Community Outreach.

http://www.lainghouse.org/

“MY MENTAL HEALTH IS ABOUT BALANCE BETWEEN MY RELATIONSHIP

WITH OTHERS AND MY RELATIONSHIP WITH MYSELF. IT’S ABOUT BEING

ABLE TO EXPERIENCE A BROAD RANGE OF EMOTIONS AND STILL BEING

ABLE TO KEEP MY INDEPENDENCE.” PATRICIA L.

PAGE 18

ENSURE EVERYONE HAS ACCESS TO APPROPRIATE MENTAL HEALTH

SERVICES BASED ON THEIR NEEDS, ESPECIALLY IN DIVERSE AND

REMOTE COMMUNITIES.

Income, location, race, education, and many other factors have a profound inuence

on our physical and mental wellbeing. In general, people with higher incomes, more

education, and stronger relationships tend to be healthier than those who do not

have such advantages.

Because of these “social determinants of health,” different people face unique

realities and have different needs. Some groups in particular face more

discrimination and stigma, or require better access to services and supports.

These include:

> Immigrants and refugees

> Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, two-spirit and queer

(LGBTTQ) communities

> Faith groups

> People with differing abilities

> Those living in the North or in remote communities.

We need to recognize the strengths of diverse peoples. Because every community is

different, the way services are delivered to each needs to be different. In fact, every

individual is different — meaning that community-specic services should be tailored

even further to provide a truly “person-centered approach” to mental health.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4

KEY WORDS

Social determinants of

health: Factors like income,

education, housing, etc.,

that affect opportunities

for health and wellbeing.

Person-centered approach:

Making sure any mental

health service meets the

specic needs of an indi

-

vidual instead of using a

“one-size-ts-all” model.

Health equity: Ensuring

that every person can

access the healthcare

programs and services they

need.

Racialized groups: Group

about whom others make

assumptions based on race.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

The Positive Spaces Initiative (PSI) is a project of OCASI - Ontario Council

of Agencies Serving Immigrants. PSI supports the immigrant- and refugee-

serving sector in Ontario to work respectfully and effectively with LGBTQ+

(lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual, etc.) newcomers. They

provide consultations, four modules of online/ofine training for service

providers, a Positive Space Assessment Tool, and an online database of

resources. PSI also participates in regional networks, partnerships, and special

events around Ontario to connect LGBTQ+ newcomers, staff, volunteers, and

community members. http://www.positivespaces.ca

“MENTAL HEALTH IS MORE THAN THE

ABSENCE OF MENTAL ILLNESS. IT

MEANS STRIKING A BALANCE AMONG

BEING EMOTIONALLY, MENTALLY,

PHYSICALLY, AND SPIRITUALLY WELL.

AND JUST AS FINGERPRINTS DIFFER

FROM ONE PERSON TO ANOTHER, SO

TOO DOES MENTAL HEALTH.”

SIMRAN L.

PAGE 19

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4

PRIORITIES

4.1 IMPROVE MENTAL HEALTH BY IMPROVING PEOPLE’S LIVING CONDITIONS.

Poverty, a lack of affordable housing, underemployment, and other factors all affect people's risk of developing

mental health issues. Working towards better mental health goes hand in hand with working towards better

living conditions. For example, mental health can be improved through anti-poverty initiatives, which are often

collaborative efforts between public and private organizations and on-the-ground agencies.

Any new mental health policy or program should contribute to “health equity.“ A health equity approach makes sure

that all individuals are able to get the same degree of benets from a policy or program. Health equity is not about

giving everyone the same level of services. It's about making sure that everyone can get the services they need.

To know if vulnerable groups such as LGBTTQ or homeless youth are treated equitably, we need to gather more data.

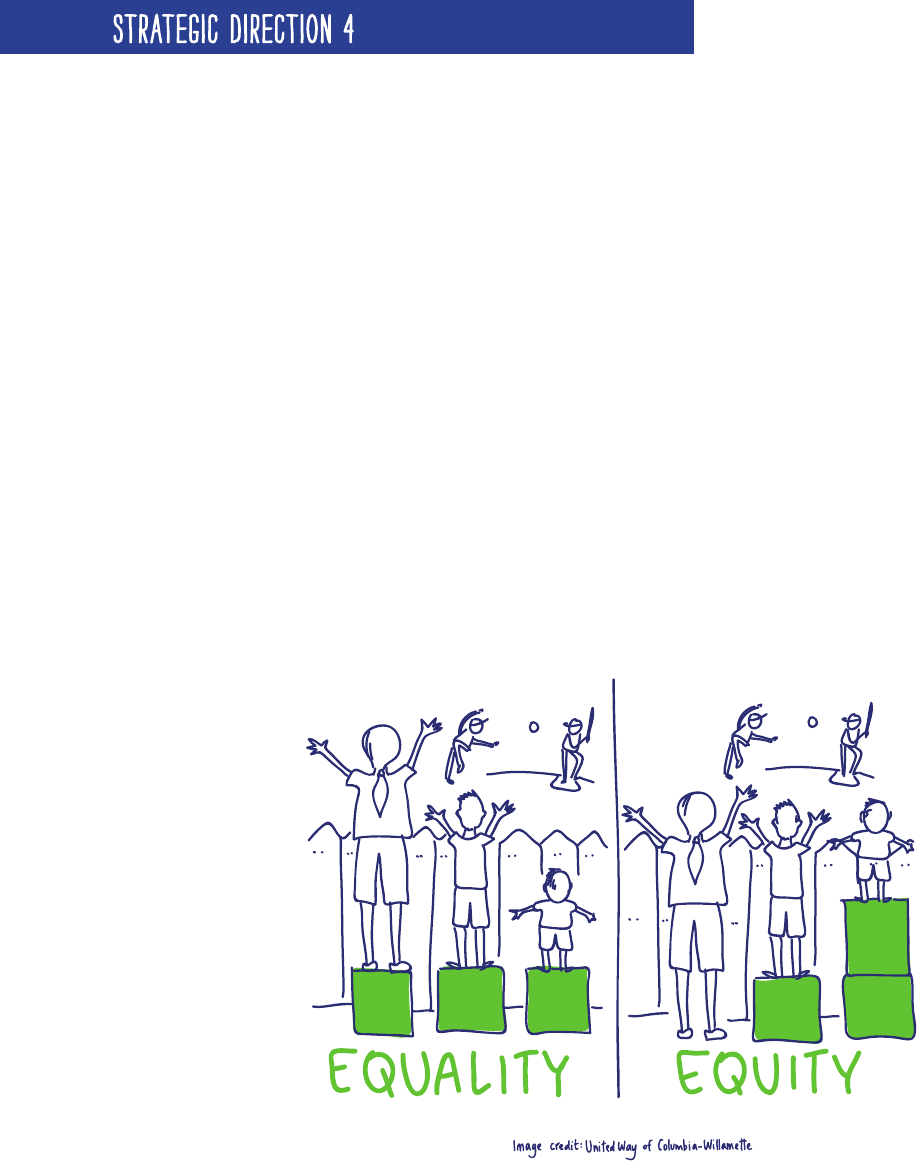

EQUALITY VS. EQUITY AND HEALTH EQUITY

Don’t understand what we mean by health equity? Take a look at the picture below to get a better understanding

of what equity is rst.

The same idea applies to "health equity" — it is not enough that the government provides equality (sameness)

in healthcare. There needs to be equity (fairness), meaning that barriers are removed that hinder people from

diverse or remote communities from getting the same care as the rest of the population.

Examples of these barriers include language, religion, culture, living conditions, and more.

PAGE 20

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4

4.2 IMPROVE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES FOR IMMIGRANTS, REFUGEES, ETHNOCULTURAL, AND

RACIALIZED GROUPS.

Different cultures often have unique ideas about mental health that can

sometimes make it difcult to start the conversation about mental health

issues. But, there are things we can do to make it easier.

Above all, stigma and stereotypes need to be eliminated. Mental health

professionals must have access to training in how to deliver culturally safe

and appropriate services and supports, so that their services are welcoming

to people from all backgrounds. This is especially helpful for youth who may

have to deal with family members who don’t understand the mental health

issues they face. These same youth may also feel that professionals are not

understanding them or their culture. People need to feel as though they can

get the help they need in a way that works for them. The value of traditional

knowledge and practices for healing and recovery must also be considered.

To be fully effective, this will require more than just service provider familiarity with cultural diversity. Service

providers must also acknowledge the inuence that social inequalities can have on a person’s wellbeing.

PAGE 21

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4

4.3 TACKLE THE MENTAL HEALTH CHALLENGES FACED IN

CANADA’S TERRITORIES AND IN NORTHERN AND REMOTE

COMMUNITIES.

People living in Canada’s territories and northern or remote

communities have tremendous strengths. However, they also experience

some of the toughest social challenges in the country, including

overcrowded housing, poor access to clean water and affordable food,

and high rates of suicide and disease. Services to address mental health

needs are scarce or not offered at all. Some places receive doctor visits

only a few times a year.

To meet the requirements of these communities, we have to attract

skilled service providers such as doctors, nurses, and community

support workers to live in Canada’s territories or in northern or remote

communities. We must also train local people to ll these roles.

Technology can help by overcoming the isolation of communities even when a service provider can’t physically be

there. Telehealth and online “e-health” services are both good options for reaching people remotely. Youth especially

would be likely to take advantage of technology-based services. What’s required is infrastructure, faster networks,

and more reliable applications to make sure these kinds of services are readily available.

4.4 RESPOND BETTER TO THE MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS OF MINORITY FRANCOPHONE AND ANGLOPHONE

COMMUNITIES.

People should have access to services and treatments in their

language of preference to ensure that they are understood in

a culturally relevant way. Yet francophones living outside of

Quebec and anglophones living in Quebec can nd it hard to

access services in their rst language, especially in smaller

communities.

We need to encourage initiatives that improve access to

information, services, treatments, and supports in a person’s

rst language. This means launching programs to identify,

recruit, and keep French-speaking mental health service

providers in minority francophone communities and English-

speaking providers in minority anglophone communities.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Nunavut Kamatsiaqtut Help Line

Kamatsiaqtut means "thoughtful people who care" in Inuktitut. The Nunavut Kamatsiaqtut Help Line provides anonymous and condential telephone counselling

for Northerners in crisis. Trained volunteers are available 365 days a year and come from many different walks of life — and all of them are ready to provide a

listening ear in English, French, or Inuktitut. 1-800-265-3333, http://www.nunavuthelpline.ca

PAGE 22

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 4

4.5 MEET MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS RELATED TO

GENDER AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION.

Men and women face different mental health risks at

different stages of life. For example, while women are

more likely to experience anxiety and depression, men

are more likely to develop schizophrenia at a younger age.

Our current system is especially difcult for trans-

identied people, as our society looks at gender as a

binary system (men/women) and not as a spectrum, which is inclusive of all peoples.

Sexuality and gender issues also affect a person’s risk for mental illness. LGBTTQ youth, for example, may be bullied

or assaulted. An accepting family and contact with other LGBTTQ youth can reduce risk for these young people; an

unaccepting family and no peer contact can increase risk. Stereotypes of all kinds can affect the way LGBTTQ people

living with mental health issues are treated by the mental health system.

Mental health service providers have to be careful not to stereotype or discriminate against LGBTTQ people. They

also need to better understand the impact discrimination and stigma can have on an LGBTTQ person’s mental health.

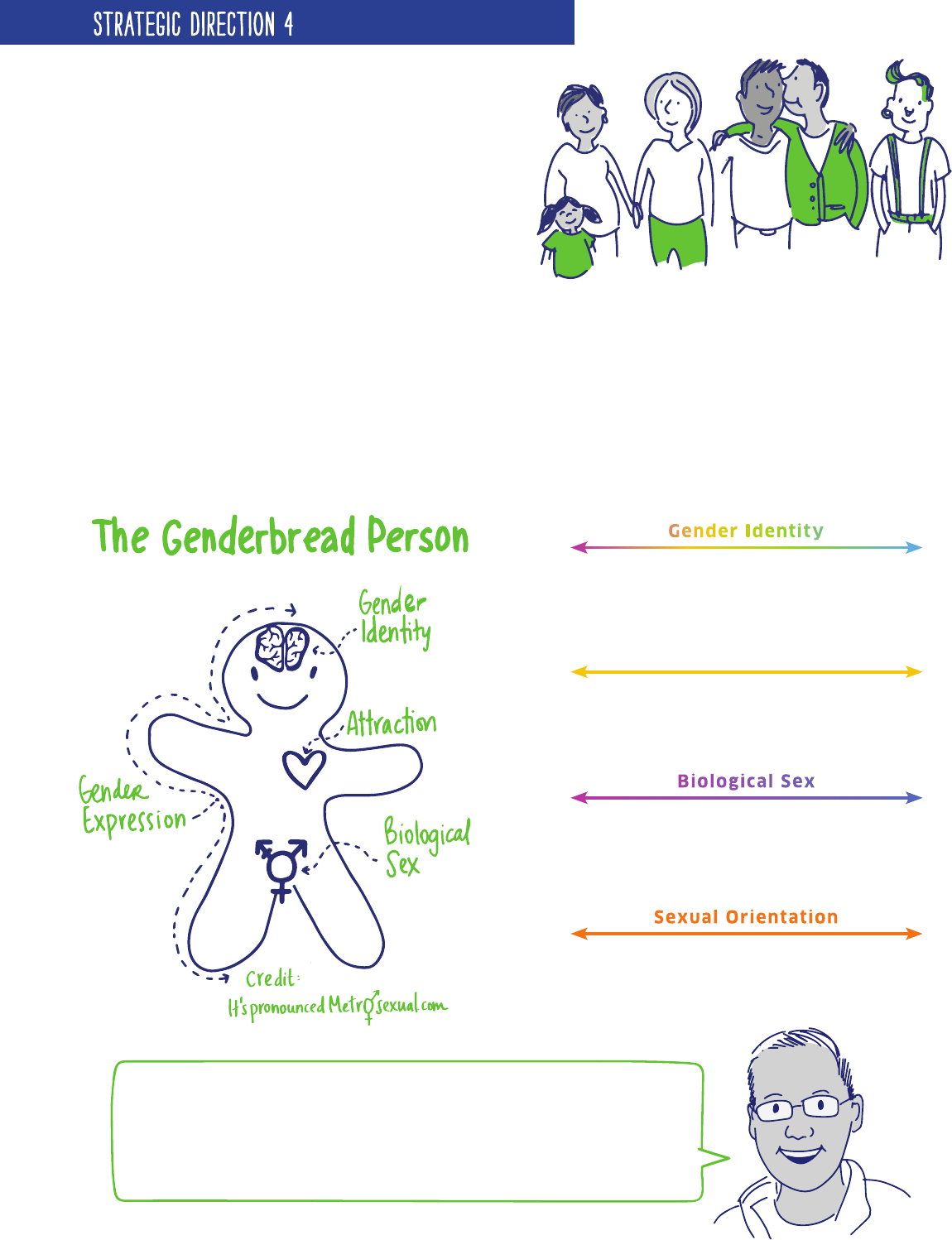

Woman

Gender Identity

Gender identity is how you, in your head, think about yourself. It's the

chemistry that composes you (e.g., hormonal levels) and how you interpret

what that means.

ManGenderqueer

Feminine

Gender Expression

Gender expression is how you demonstrate your gender (based on traditional

gender roles) through the ways you act, dress, behave, and interact.

Masculine

Androgynous

Female

Biological Sex

Biological sex refers to the objectively measurable organs, hormones, and

chromosomes. Female = vagina, ovaries, XX chromosomes; male = penis,

testes, XY chromosomes; intersex = a combination of the two.

Male

Intersex

Heterosexual

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation is who you are physically, spiritually, and emotionally

attracted to, based on their sex/gender in relation to your own.

Homosexual

Bisexual

“AT TIMES I FORGET THE FACES OF ALL THOSE WHO HELPED ME ALONG THE

WAY TO RECOVERY; IN THE NUMEROUS HOSPITALS, DOCTOR’S OFFICES,

COUNSELLING OFFICES, AND PSYCHIATRIC PRACTICES. BUT I WILL NEVER

FORGET THE FEELING OF BEING TREATED WITH KINDNESS, UNDERSTANDING,

AND COMPASSION. WHEN I GET ON THE EDGE OF RELAPSING BACK INTO

DEPRESSION AND SUICIDAL THOUGHTS, I REMEMBER THAT I AM NOT ALONE

AND THAT I DO HAVE PEOPLE TO TALK TO.” JACK S.

PAGE 23

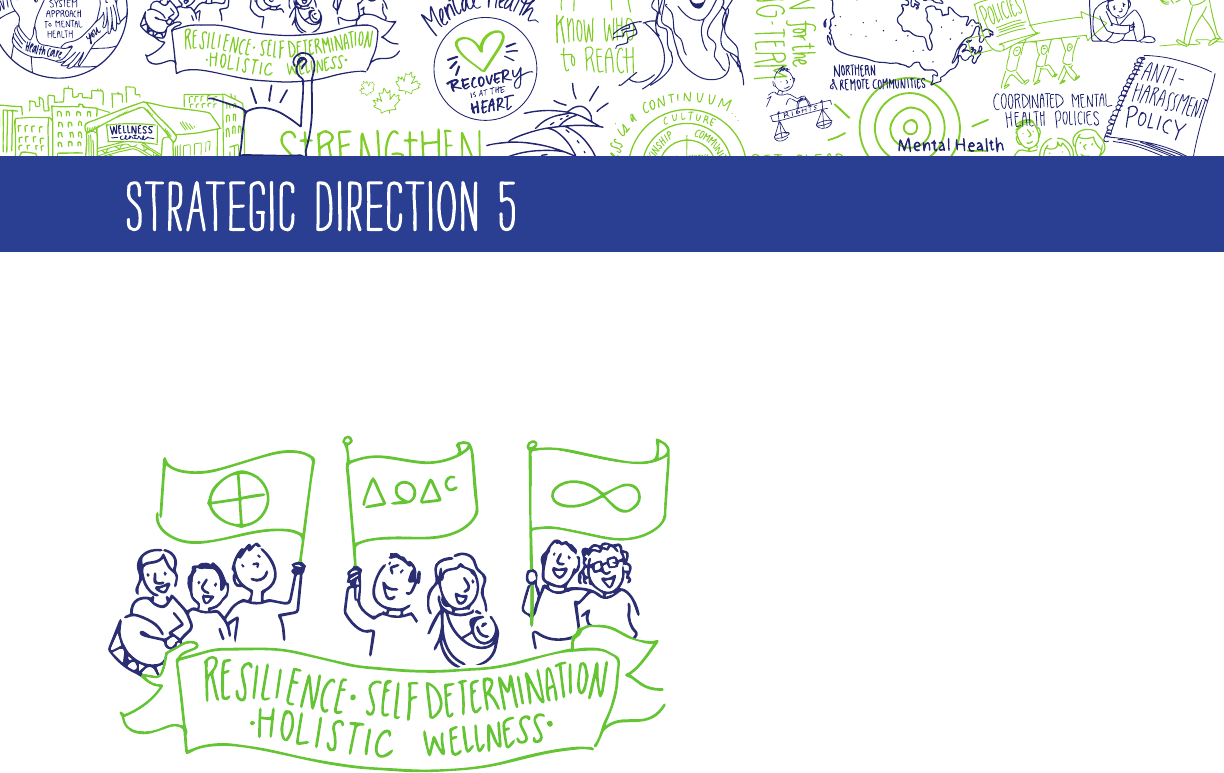

WORK WITH FIRST NATIONS, INUIT, AND MÉTIS TO MEET THEIR

DISTINCT MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS, WHILE RESPECTING THEIR UNIQUE

EXPERIENCES, RIGHTS, AND CULTURES.

This Strategic Direction highlights three

distinct streams for First Nations, Inuit,

and Métis, an approach that respects the

important differences in the cultures and

histories of each group. The three streams

identify the unique needs of, and complex

social issues affecting, First Nations,

Inuit, and Métis, and also highlight a few

common priorities regarding the mental

health of all people.

Working with concepts such as resilience,

self-determination, and holistic

understandings of wellness, First Nations,

Inuit, and Métis cultures have much to contribute to the transformation of the mental health system in Canada.

At the same time, the problems they often face are serious.

For example, although suicide is not a universal problem in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities, it is a

signicant challenge in many communities across Canada. First Nations youth die by suicide ve to six times

more often than non-Aboriginal youth. The suicide rates for Inuit are among the highest in the world, at 11

times the national average. For young Inuit men, those rates are 28 times higher. Less is known about suicide

rates for Métis youth. Mental health and suicide need to be addressed together through the promotion of good

mental health for all.

There is no “one-size-ts-all” answer, because every community has unique strengths and challenges. But we

need to do something, especially about:

> The harms caused by colonization, the residential school system, and other policies that kept First

Nations, Inuit, and Métis parents from passing their culture and history on to their kids.

> How hard it is for people in Canada’s territories and northern or remote areas to get mental health

professionals to live and work in their communities.

> How hard it is to access basic mental health services in Canada’s territories and northern or remote

areas, which often results in having to travel outside of one’s own community for support.

> The ongoing impact of racism, poverty, and other systemic issues on mental and physical wellbeing.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 5

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

One of the keys to providing effective services to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (FNIM) is to take an approach that involves all aspects of mental, physical,

emotional, and spiritual health. In downtown Calgary, the Elbow River Healing Lodge provides a range of primary health care services such as health

assessments and examinations, specialized services, advocacy for social supports, street outreach, and spiritual and cultural supports for FNIM people. An

Adult Aboriginal Mental Health team is also on site and provides culturally appropriate mental health services (assessment, treatment, information, referral,

and outreach). As part of a broader primary health care framework to ensure a culturally appropriate and respectful approach to health service delivery

adaptable to individual and community needs, the clinic is implementing Integrated Primary Care Standards. These standards are based on a holistic model

of care and treatment characterized by the integration of physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental components of health and wellbeing identied in First

Nations, Inuit, and Métis cultures.

PAGE 24

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 5

PRIORITIES

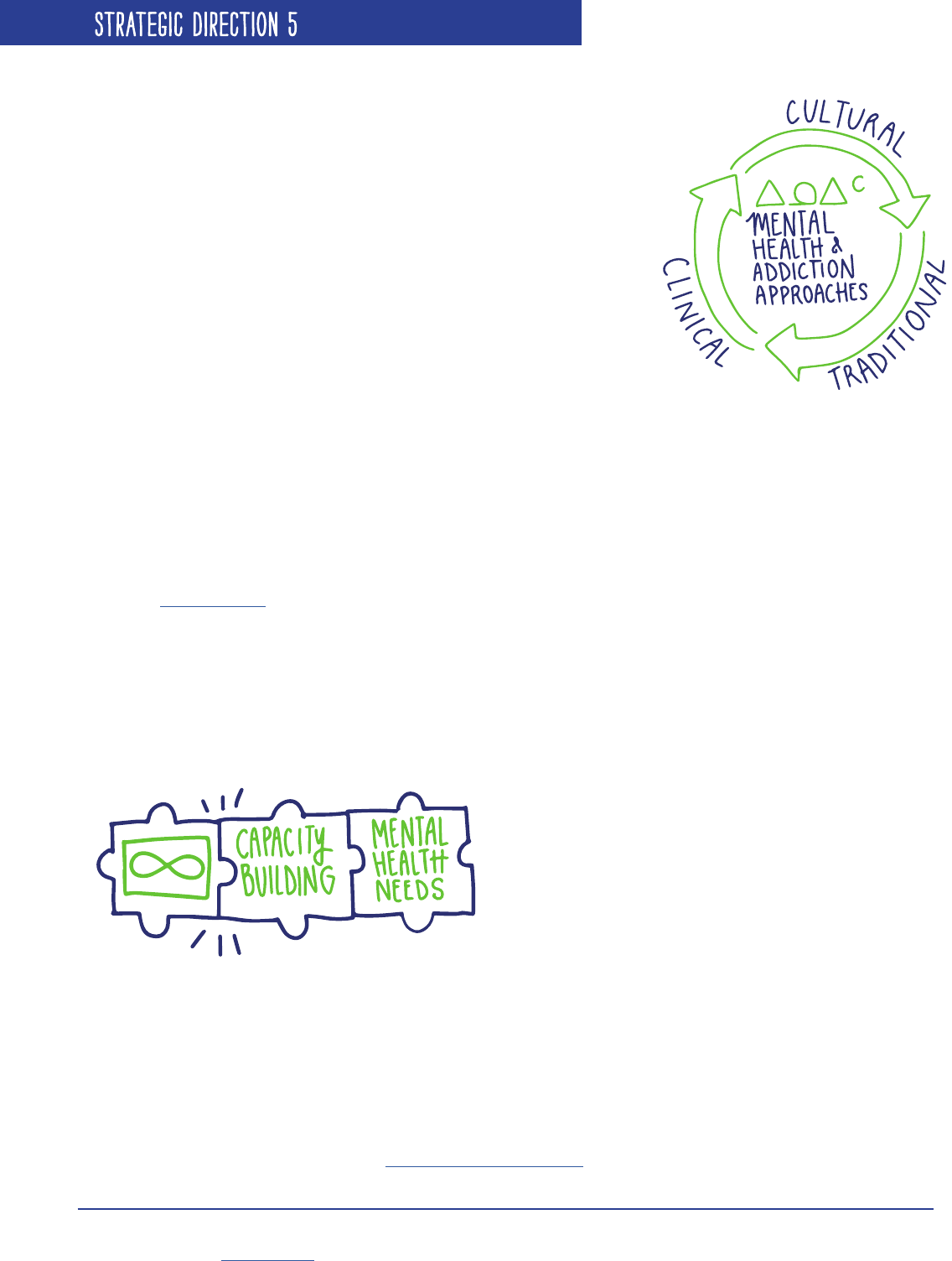

5.1 ADDRESS GAPS AND ENSURE GREATER COORDINATION BETWEEN MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIONS

SERVICES FOR AND BY FIRST NATIONS, INCLUDING TRADITIONAL, CULTURAL, AND MAINSTREAM APPROACHES.

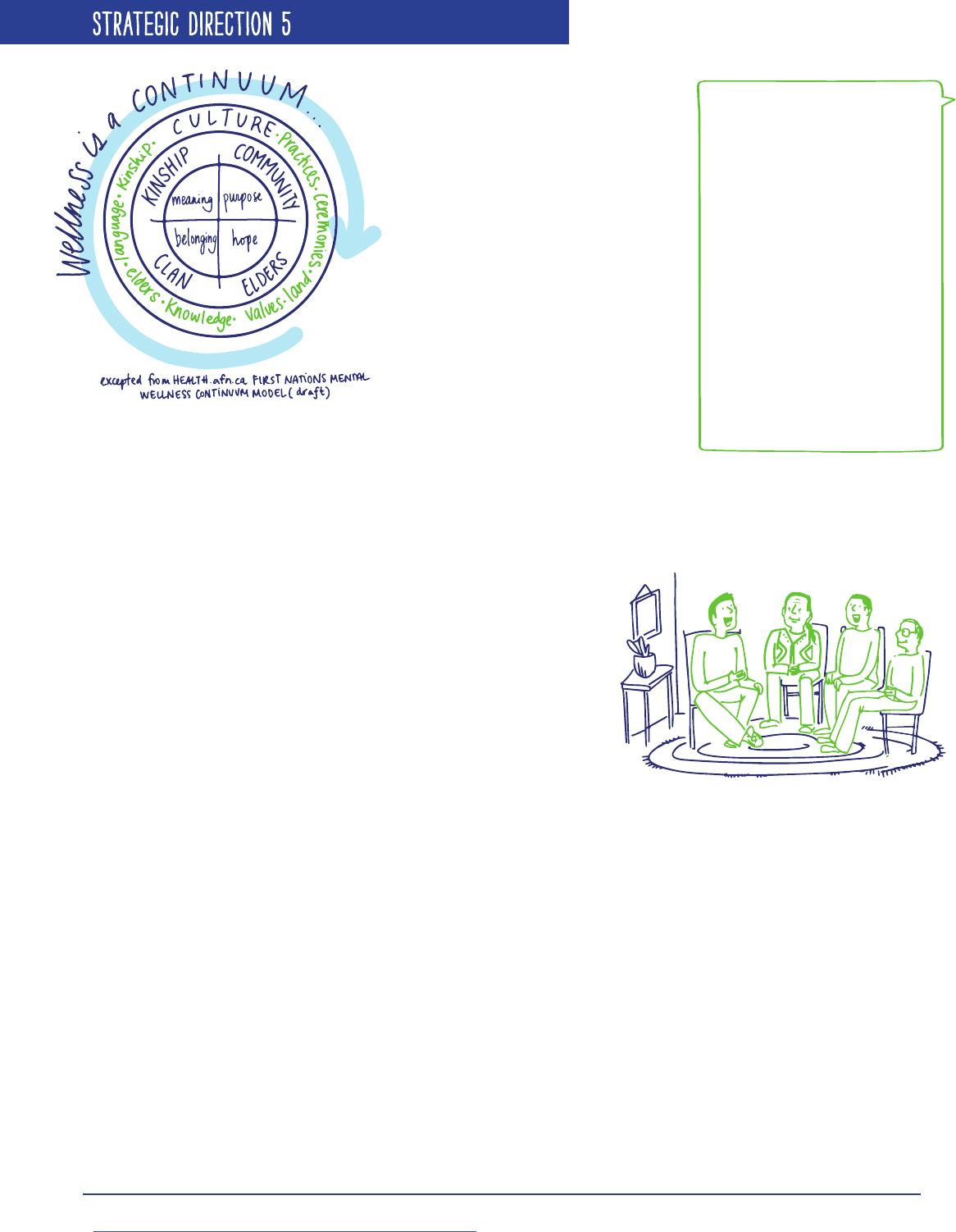

For First Nations, wellbeing is about balancing spiritual, mental,

emotional, and physical health. That way of life was nearly destroyed

by residential schools and the child welfare system. Combined with

poverty, poor housing, and a lack of educational opportunities, the

history of trauma suffered by First Nations has led to high rates of

mental health issues, substance use, suicide, and family violence in

many communities.

First Nations also have a hard time accessing mental health services

in all areas and regions of Canada, with rural and remote communities

nding it especially difcult to recruit and keep healthcare workers.

To promote their own healing, First Nations are using traditional, cultural, and mainstream approaches, including

recognizing the key role of Elders. At the same time, all mental health professionals who serve First Nations

communities must be trained in culturally safe practices.

First Nations collectively continue to pursue self-determination and strive to strengthen their relationships with

federal, provincial, and territorial governments. First Nations have long advocated for improved mental wellness

services, but progress has been slow. To create more meaningful change, a continuum of services that is coordinated

across jurisdictions is needed.

5.2 ADDRESS GAPS AND ENSURE GREATER COORDINATION OF MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIONS SERVICES

FOR AND BY INUIT, INCLUDING TRADITIONAL, CULTURAL, AND CLINICAL APPROACHES.

Inuit dene mental wellness as “self-esteem and personal dignity owing from the presence of harmonious physical,

emotional, mental and spiritual wellness, and cultural identity.”

2

Because their traditional way of life centres on

working together to survive in the North, individual strengths — and those of the community — are very important.

Inuit experienced colonization recently and rapidly; many who are now adults grew up living off the land year-round.

Traumatic experiences, such as seeing children sent away to residential schools and being forcefully made to relocate

communities, have disrupted Inuit culture and language, resulting in high levels of depression, suicide, and addiction.

Just like all other Canadians, First

Nations, Inuit, and Métis need

equitable access to mental health

services, treatments, and supports,

wherever they live. They also

need access to services that are

appropriate to their distinct cultures

and traditions, no matter what

agency they go to.

All levels of government have to

work together to make this happen—

federal, provincial, territorial, and

Aboriginal, including the Assembly

of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit

Kanatami, the Métis National Council, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, and the

Native Women’s Association of Canada.

KEY WORDS

Colonization: Settling among and

setting up political control over

the indigenous people of an area.

Residential schools: Church-run,

government-funded boarding

schools that separated Aboriginal

children from their families to

have them learn English, embrace

Christianity and adopt Canadian

customs. The rst school opened

in the 1840s; the last closed in

1996. Physical and sexual abuse

were widespread.

Cultural safety: When services

recognize Aboriginal experience,

power imbalances between

service providers and service

users, and systemic issues such as

racism and poverty.

2

Alianait Inuit-Specic Mental Wellness Task Group (2007). Alianait Mental Wellness Action Plan. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

https://www.itk.ca/publication/alianait-inuit-mental-wellness-action-plan.

PAGE 25

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 5

Inuit mental wellness has to promote resilience as well as productive,

sustainable communities, based on traditional and cultural practices with

the support of clinical approaches. Yet many Inuit have to travel outside

their communities to receive even basic mental health services. More

Inuit need education and training so they can provide services to their

own people in their own language. Non-Inuit mental health workers also

require more training in cultural safety so they can deliver services in a

way that respects and understands Inuit culture.

Despite the challenges faced by Inuit communities, Inuit youth are

working towards raising awareness about mental health. The Inuit Tapiriit

Kanatami

3

(ITK) National Inuit Youth Council, for example, is developing

a strategy aimed at the following priority areas affecting Inuit youth in

all areas of Canada: suicide prevention; health and substance use; culture and language; youth political involvement;

youth facilities and resources; housing and poverty reduction; and education and research. These priority areas

build on ITK’s commitment to advancing Inuit knowledge in research and policy development within national and

international contexts.

3

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), formerly Inuit Tapirisat of Canada, is the national voice of 55,000 Inuit living in 53 communities across the Inuvialuit

Settlement Region (Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (Northern Labrador), land claims regions.

More information here: http://www.itk.ca.

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

Ilisaqsivik Family Resource Centre

Located in Clyde River, Nunavut, this centre focuses on family healing and has a range of programs for people of all ages provided by Elders as well as family,

addictions and youth counsellors. The centre’s hip-hop program helps reduce self-harm and drug use among youth and is contributing to an overall decrease in

crime rates and suicidal thoughts. Programs are also offered that integrate mainstream and traditional approaches to help youth learn and experience traditional

ways of life. http://ilisaqsivik.ca/

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada in Action

MCFCS High Risk/At Risk Support Program

The Metis Child family and Community Services High Risk/At Risk Support Program focuses on helping Métis youth at risk because of gang involvement,

addiction, violence, sexual exploitation, and mental health issues. Taking a culturally based approach, the program focuses on working with the youth’s social

workers, caregivers, and supportive circle to provide stabilization, prevention, and safety oriented services and supports. The program is relationship and

strength-based and focuses on working closely with the youth and their supportive circle of caregivers, family, and peers to develop and implement strategies

to reduce the youth’s risk and enhance their potential. http://www.metiscfs.mb.ca/index.php

5.3 BUILD MÉTIS CAPACITY TO BETTER UNDERSTAND AND ADDRESS THEIR MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS.

The descendants of European fur traders and First Nations women, Métis people have a unique culture with their

own traditions, language, and way of life. For a number of reasons — such as the aftermath of the Métis uprisings

and the execution of Louis Riel — Métis people have tended not to acknowledge their ancestry openly. As well, it took

until 1982 for the federal government to recognize Métis as

one of the three distinct Aboriginal groups in Canada.

Even today, Métis have limited access to federally funded

mental health and addictions programs. Instead, they

continue to fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction,

resulting in gaps in the availability and quality of Métis-

specic services.

More research is needed to understand how colonization has

affected the mental health of Métis people. What we do know

is that Métis people have many risk factors for mental health issues, including overcrowded housing, substance abuse,

and family violence. Fortunately, Canadian courts are increasingly recognizing Métis rights — and more and more

Métis are reconnecting with their culture and history, working together to improve their mental health and wellbeing.

PAGE 26

STRATEGIC DIRECTION 5

5.4 ADDRESS THE MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS OF FIRST NATIONS, INUIT, AND MÉTIS LIVING IN URBAN AND RURAL

CENTRES AND THE COMPLEX SOCIAL ISSUES THAT AFFECT MENTAL HEALTH.

More than 50 per cent of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis live in urban and rural centres, with considerable movement

to and from their home communities (typically these include First Nations reserves, remote Inuit communities, and

smaller Métis communities). The reasons for moving from smaller communities to larger cities and towns might be

better access to economic opportunities and employment, better access to health care, and the appeal of urban living.

For many, this choice does lead to improvements in key protective factors of mental health, such as better access to

education and employment.

Unfortunately, a signicant number of First Nations,

Inuit, and Métis continue to live in poverty. Even within

larger urban centres, there are problems with access to

services, such as long waiting lists, lack of transportation,

as well as lack of awareness and understanding of the

differences in cultures between service providers and

those receiving services.

Efforts to address factors like poverty and inadequate

housing in urban and rural centres have to be

coordinated across all levels of government. Better

support is also needed to deliver specialized mental

health services that integrate traditional, cultural, and mainstream approaches. Finally, more research is required

to deepen our understanding of the mental health issues faced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis living in urban and

rural settings so that we can develop more effective mental health and substance use strategies.

At the same time, there are complex social issues that affect the mental health of First Nations, Inuit, and

Métis whether they reside in urban or rural centres, on First Nations reserves, in remote Inuit, or smaller Métis

communities. Three priorities are addressed here:

> Violence against women and girls: In some communities, up to 90 per cent of women are victims of violence.

With the causes of violence including poverty, racism, and discrimination, services must focus on community

and family healing.

> Over-representation in the child welfare system: While First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children represent

less than ve per cent of all children in Canada, they make up between 30 and 40 per cent of those living

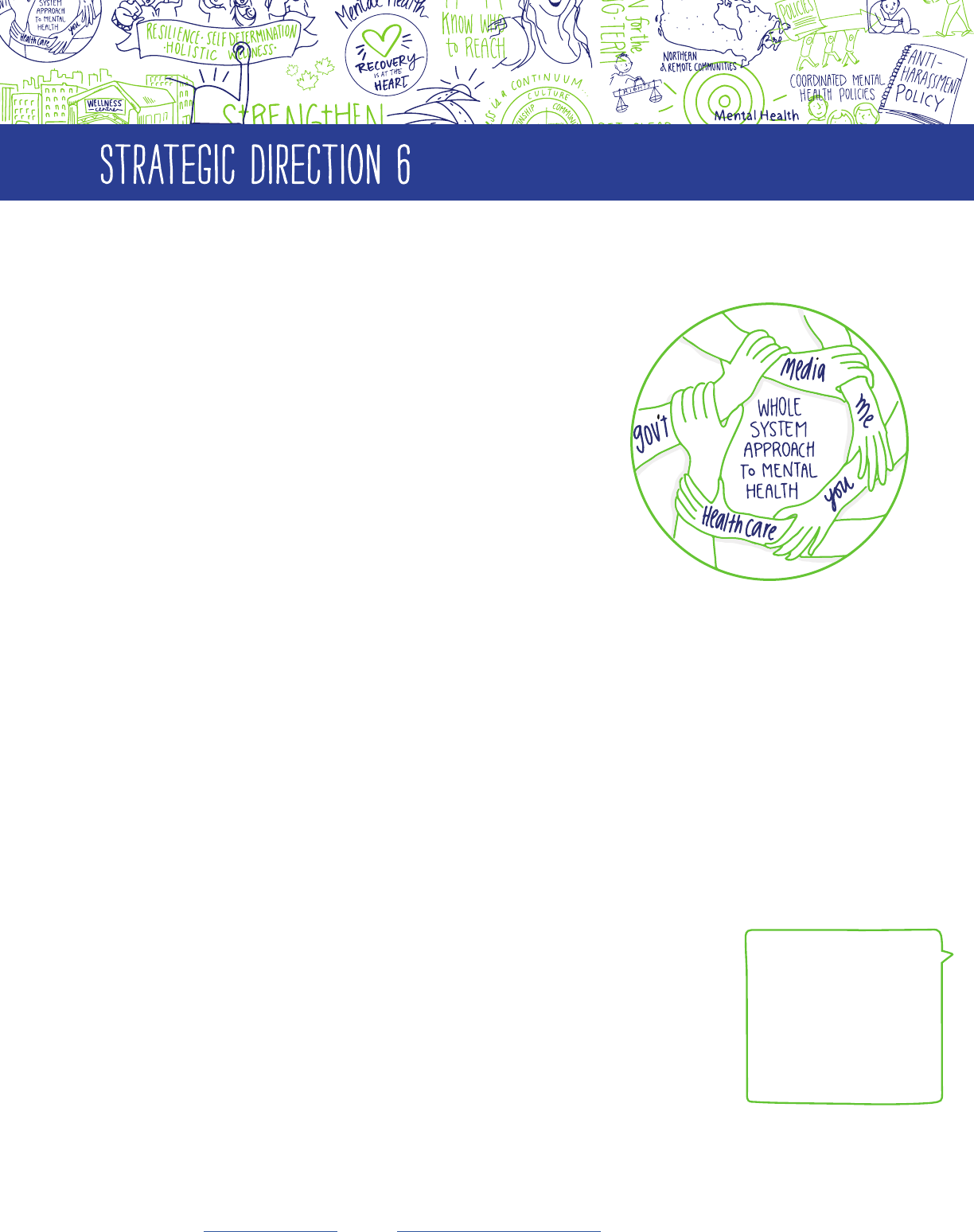

in out-of-home care. Changing this requires First Nations, Inuit, and Métis families to be more involved in