The National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

TA

Cente

r

national

early childhood

IDEAs ★ partnerships ★ results

Explaining Rights and Safeguards

Joicey Hurth & Paula Goff

Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

June 2002, 2nd Edition

Assuring the

Familys Role on

the Early

Intervention Team

The National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center (NECTAC)

is a program of the

Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute of

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

with the

National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE)

and

Parent Advocacy Coalition for Educational Rights (PACER Center)

June 2002, second edition

This resource is produced and distributed by the National Early Childhood Technical As-

sistance Center (NECTAC), pursuant to contract ED-01-CO-0112 and no-cost extension of

cooperative agreement H024A60001-96 from the Office of Special Education Programs,

U.S. Department of Education (ED). Contractors undertaking projects under government

sponsorship are encouraged to express their judgment in professional and technical mat-

ters. Opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the Department of Educations po-

sition or policy.

Additional copies of this document are available at cost from NECTAC. A complete list of

NECTAC resources is available at our Web site or upon request.

For more information about NECTAC, please contact us at:

137 E Franklin Street, Suite 500

Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3628

919-962-2001 ★ phone

877-574-3194 ★ TDD

919-966-7463 ★ fax

Principal Investigator: Pascal Trohanis

Contracting Officers Representative at OSEP: Peggy Cvach

Contract Specialist at U.S.ED: Dorothy Hunter

Author: Joicey L. Hurth

Publications Coordinator: Caroline Armijo

Introduction

The procedural safeguards required by The In-

fants and Toddlers with Disabilities Program

(Part C) of the Individuals with Disabilities Edu-

cation Act (IDEA) are intended to protect the in-

terests of families with infants and toddlers with

special needs and of the early intervention sys-

tem. Procedural safeguards are the checks and

balances of the system, not a piece separate from

the system. For families, rights and safeguards

help ensure that an Individualized Family Service

Plan (IFSP) is developed that addresses their pri-

orities and concerns. For the early intervention

system, rights and safeguards assure quality and

equity. For families and for the system, proce-

dural safeguards provide the protection of an

impartial system for complaint resolution. Early

intervention system personnel are legally obli-

gated to explain procedural safeguards to fami-

lies and to support an active adherence to and

understanding of these safeguards throughout the

early intervention system.

In order for families to be fully informed of

their rights and safeguards, they also must un-

derstand the early intervention system and their

role as partners and decision-makers in the early

intervention process. They should be advised

that the intent of Part C of IDEA is to enhance

families’ abilities to meet the special needs of

their infants and toddlers by strengthening their

authority and encouraging their participation in

meeting those needs.

Assuring the Familys Role on the

Early Intervention Team

Explaining Rights and Safeguards

Joicey Hurth & Paula Goff

This paper is a synthesis of practices and ideas

for explaining procedural safeguards to families,

which assure that families are fully informed in

ways that support their role in the early interven-

tion process. The authors solicited information

about practices and ideas for explaining procedural

safeguards to families from early childhood

projects funded by the Office of Special Education

Programs of the U.S. Department of Education and

from the state lead agencies for Part C. The paper

includes a step-by-step model of explaining proce-

dural safeguards that parallels the early interven-

tion process. The authors intend to explore the

implications of procedural safeguards for families,

but not to analyze the Part C safeguards them-

selves. The paper has been developed for state Part

C leaders, service providers, families, family ad-

vocates, and especially for those people who are

involved in explaining procedural safeguards to

families.

2002 edition

The 1997 Amendments to the IDEA required

an update to the original 1996 edition of this

monograph. The most substantive change to the

rights and safeguards discussed in this monograph

was the requirement that states ensure that media-

tion services are available as part of complaint

resolution procedures. The revised 2002 edition

incorporates the new regulation (34 C.F.R.

303.419). At this time many excellent materials

have been developed to explain procedural safe-

2 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

guards in family-friendly ways. A new collection

of materials was not undertaken for the current

revision. However, the original examples cited

are still useful to illustrate principles of develop-

ing family-friendly materials, even if the cited

materials are no longer available. The reader is

encouraged to request the most current materials

for families from their state’s lead agency for

Part C. A complete contact list for all states lead

agencies is available on the NECTAC web site

at http://www.nectac.org/ .

Background and Issues

The primary safeguard provided for in Part C

is the clear acknowledgment of the family’s role

as a primary decision-maker in developing an

IFSP. Part C regulations strengthen and clarify a

family’s right to accept or reject any service

without jeopardizing other services that

they want (see 34 C.F.R. §303.405). The

family-centered spirit of early interven-

tion affords an opportunity to develop

new strategies for supporting families in

informed partnerships with the system

and to change practice that too often has

been perfunctory, adversarial, or cultur-

ally insensitive.

For example, a common method of in-

forming parents of the safeguards guaran-

teed them is to provide them with written

materials about these safeguards during

intake or entry into an early intervention

program. At that time, providers may re-

view the materials with families who then

are asked to sign all of the informed con-

sent forms and releases. Often, these

documents are nothing more than direct

citations of the law. Sometimes, the safe-

guards are listed in a “you have the right

to” format, reminiscent of being “Mirandized”

or being read your rights. Procedures such as

these assume that all families can read English,

can interpret legal rights, and feel free to assert

themselves and ask questions.

Such procedures are likely to produce unfor-

tunate consequences. Many families and service

providers come to view procedural safeguards as

administrative paperwork that only becomes im-

portant when a problem arises. This attitude is a

disservice to families and providers because it

belittles a hard-won legacy of respect for and

protection of families’ rights and safeguards that

strengthen service systems. Worse, families can

be overwhelmed by the legal jargon, by the

adversarial connotations, and by a lack of under-

standing of why these rights are necessary.

When families are asked to sign a stack of con-

sent forms, the legal aspects of the relationship

with providers are emphasized.

Meeting legal requirements can be an oppor-

tunity for service providers to begin teaching

families about safeguards while conveying their

respect for the role of families in the early inter-

vention system. Unfortunately, this opportunity

frequently is missed, often because service coor-

dinators and/or service providers are not fully

trained in procedural safeguards, have a limited

understanding of them, and find them difficult to

explain when questioned. Although the method

of overwhelming families with paperwork dur-

ing their first contact with the system may com-

ply with the letter of the law, it does not assure

that families are fully informed. Families are not

fully informed until they understand the early in-

tervention system and their role in the system.

Rights and safeguards are an integral part of this

basic information.

Understanding Procedural

Safeguards: Implications for Families

A simple listing of rights and safeguards does

not adequately convey the meaning of these

protections.

Each right and safeguard has implications for

a family’s experience with the early intervention

system. Further, because Part C is family-ori-

ented legislation, the rights and safeguards con-

vey the law’s central principles of respect for

families’ privacy, diversity, and role as informed

members of the early intervention team.

Table 1, Understanding Procedural Safe-

guards: Examples of Explanations and Implica-

tions for Families (see page 4), lists some of the

central rights and safeguards under Part C that

must be addressed during the process of plan-

ning and providing services. The bold headings

Meeting legal

requirements can

be an opportunity

for service provid-

ers to begin teach-

ing families about

safeguards while

conveying their

respect for the

role of families

in the early

intervention

system.

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 3

in Table 1 are the section headings from the Part

C regulations (34 C.F.R. §303), followed by the

section citation in parentheses. The text below

each heading is not the actual regulatory lan-

guage but rather is an example of how a service

provider could explain to families the safeguard

and its implications. The regulatory text pertain-

ing to procedural safeguards under Part C of

IDEA (34 C.F.R. §§303.400–.460) is reproduced

in the Appendix.

Assuring That Families Are Fully Informed

Team Members: A Step-by-Step Model

Assuring that families are fully informed of

their rights and safeguards requires ongoing ex-

planations in the context of the early intervention

process. It would be impossible to fully under-

stand and appreciate the safeguards before

having had any experience with the procedures.

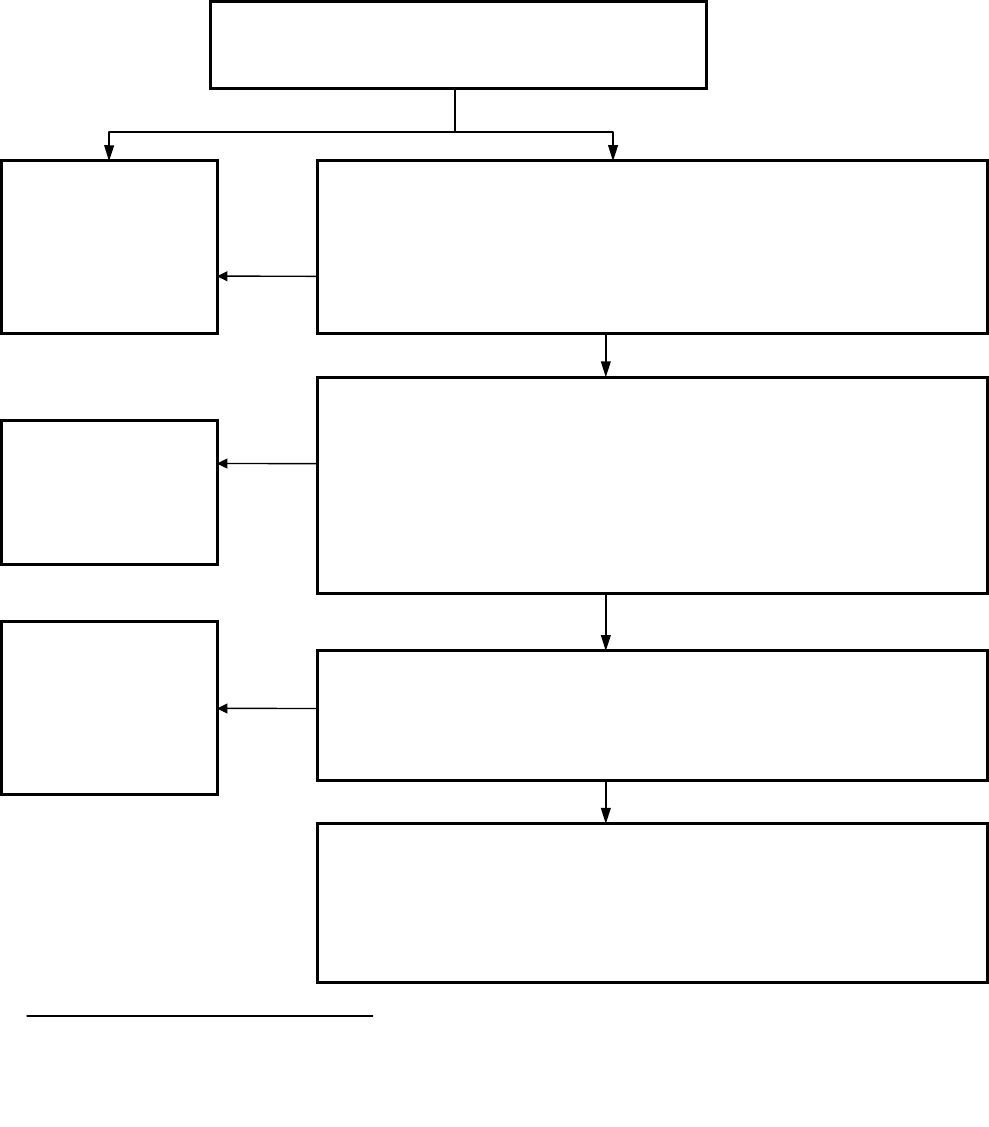

Figure 1, Explaining Part C Procedural Safe-

guards to Families: A Step-by-Step Model,

outlines the information that families need to un-

derstand at each step in the process, from referral

through IFSP development and service imple-

mentation. Each box in Figure 1 represents a ma-

jor step in the development of an IFSP. Citation

numbers in parentheses at the end of each sen-

tence refer to the relevant sections of Part C regu-

lations. Safeguards are intentionally repeated at

different steps (boxes) because of the numerous

times within the process that a safeguard may

apply. Italicized words indicate a recommended

practice, not one that is required by legislation.

Figure 1 is a generic model and should be

adapted to illustrate specific procedures used by

an early intervention program or agency.

The model suggests that families need infor-

mation to support their role as team members

throughout the IFSP process. At each step of the

IFSP process, important decisions must be made.

Only to the extent that families understand their

options can they fully exercise their decision-

making authority as part of the early intervention

team.

During early contacts, families should be in-

vited to participate as key members of the early

intervention team and should be oriented to the

early intervention system and services. This ori-

entation should include an introduction to rights

and safeguards. The introduction can be supple-

mented with a variety of easily accessible materi-

als about the early intervention system, as well as

about rights and safeguards, to which families can

refer over time (see the section “Prin-

ciples and Practices from States and

Projects for Creating and Using Family-

Friendly Materials” below). The Step-by-

Step Model does not suggest that all

rights and safeguards be presented in

detail at first contact unless a family

requests such information. Rather, an

explana- tion of each right and safeguard

is provided in the context of each proce-

dure to which it relates.

Explaining the safeguards and their

implications clarifies how the early inter-

vention system operates and exemplifies

the family’s role in the system. Each step

of planning with a child’s family provides

an opportunity to discuss the relevant

rights and safeguards and their meanings

or implications. For example, before

evaluation it is important to explain prior written

notice. It is also important to operationalize the

meaning of this safeguard by statements such as:

You will receive a letter explaining the evalua-

tion procedures we discussed and why we are

doing them. It will also remind you of the time

and location on which we agreed. This letter is

an example of prior written notice, a legal re-

quirement, which assures that the early inter-

vention program explains to parents what it

plans to do. You will receive other written no-

tices like this, before we initiate or change any

services for your child.

As suggested by the Step-by-Step Model (see

Figure 1, page 6), other safeguards that should be

explained before evaluation include consent,

native language or preferred mode of communica-

tion, and confidentiality of records. The implica-

tions of these procedural safeguards in the context

of evaluation include the family’s right and need to

fully understand suggested evaluation procedures

so that their consent is truly informed. Further,

these safeguards acknowledge that families are

from diverse backgrounds and that the early inter-

vention program will accommodate their commu-

Families are not

fully informed

until they under-

stand the early

intervention

system and their

role in the system.

Rights and safe-

guards are an

integral part

of this basic

information.

4 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

Table 1

Understanding Procedural Safeguards:

Examples of Explanations and Implications for Families

Rights and safeguards under 34 C.F.R. § §303. 400–.460.

Regulations for the Early Intervention Program for Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities, Part C of IDEA

Written prior notice (§.403)

The early intervention program must give you advance writ-

ten information about any evaluations, services, or other ac-

tions affecting your child. Parents know their children best.

The information you share with us will make sure that the

evaluations and services are right for you. The “paper work”

assures that you get all the details before any activity.

Use of parents native language or preferred mode of

communication (§§.401 and .403)

It is your right to thoroughly understand all activities and

written records about your child. If you prefer another lan-

guage or way of communicating [explain relevant option,

such as braille, sign language, etc.], we will get an interpreter

[use your mode of communicating], if at all possible. The

early intervention program wants you to understand so that

you can be an informed team member and decision-maker.

Parent consent (§.404)

The early intervention program needs your permission to

take any actions that affect your child. You will be asked to

give your consent in writing before we evaluate or provide

services. Be sure you completely understand the suggested

activities. By being involved, you can help the early inter-

vention program plan services that match your family’s pref-

erences and needs. The early intervention program needs to

explain what happens if you give your consent and if you do

not give your consent.

Confidentiality and release of information

(§§.401.404)

The early intervention program values the information you

and other service and health care providers have learned

about your child. We will ask others for this information, but

we need your written permission to do so. Just as the early

intervention program needs your permission to get your

child’s records from other providers, the records that the

early intervention program will develop will not be shared

with anyone unless you give your permission.

Examine records (§.402)

The early intervention record is your family’s record. You

can see anything in the early intervention program’s records

about your child and family. If you do not understand the

way records are written, the information in the child’s record

will be explained to you in a way you understand. You are a

team member and we want you to have the same information

as other team members.

Accept or decline services without jeopardy (§.405)

With the other members of your child’s early intervention

team, you will consider which services can best help you ac-

complish the outcomes that you want for your child and fam-

ily. You will be asked to give your consent for those services

that you want. You do not have to agree to all services rec-

ommended. You can say no to some services and still get the

services that you do want. If you decide to try other services

at a later date, you can give your consent then.

Mediation (§.419)

If you and the early intervention team do not agree on plans

or services, or if you have other complaints about your expe-

rience with the program, there are procedures for resolving

your concerns quickly. When informal ways of sharing your

concerns don’t work, you may submit a written request for a

due process hearing. Mediation will be offered as a voluntary

first step. A trained, impartial mediator will facilitate prob-

lem-solving between you and the early intervention program.

You may be able to reach an agreement that satisfies you

both. If not, you can go ahead with a due process hearing to

resolve your complaint. Mediation will not slow down the

hearing process. Some locations offer mediation before a

formal complaint is filed.

Due process procedures (§.420)

A due process hearing is a formal procedure that begins with

a written request for a due process hearing. The hearing will

assure that a knowledgeable and impartial person, from out-

side the program, hears your complaint and decides how to

best resolve it. The early intervention program recognizes

your right to make decisions about your child and will take

your concerns seriously. You are given a copy of regulations

that describe all these rights and procedures in detail, because

it is important that you understand. If you have questions,

call _____________________________.

Bold type: Section headings from regulations.

Narrative: Sample of language that might be used by an early intervention system to explain implications of regulations to families.

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 5

nication preferences. One implication of the con-

fidentiality safeguard is that, with the family’s

permission, the program will coordinate records

with other providers on behalf of the family. In

addition, families are reassured that information

they share will be treated confidentially, unless

they choose to release it.

The above examples illustrate rights and safe-

guards that should be explained in early contacts

with families, prior to evaluation and assess-

ment. These same safeguards and how they

apply to other procedures should be reiterated

at subsequent steps of the IFSP process, as sug-

gested by Figure 1. Such explanations of proce-

dures contain powerful messages about early

intervention’s operative principles, such as

respect for families’ privacy and diversity and

value as informed partners on the early interven-

tion team.

Explanations of rights and safeguards should

be a part of the service provider’s ongoing con-

versations with families. Rights and safeguards

are an integral part of the basic information

about how the system works. Reiterating rights

and safeguards and their implications for fami-

lies at each relevant step is a way to support a

family’s evolving understanding.

As equal team members, families need the

same information as the other team members.

When all team members are informed and fol-

low basic procedural safeguards, the process

goes more smoothly, the team can make more

appropriate plans and decisions, and the team

can work smarter, not harder.

Explaining Procedures for Complaint

Resolution

Although many rights and safeguards can be

explained when they occur in the early interven-

tion process, some need to be explained from the

beginning in case a family may need them. Due

process procedures for resolving complaints are

the most important example. Within the param-

eters of any relationship, disagreements arise; re-

lationships between family members and service

providers are no different. Disagreements are part

of the process of interaction and provide opportu-

nities for exploring options and solutions. When

family members and service providers disagree

about eligibility or IFSP issues, an opportunity

arises for an open discussion of interests, options

and alternatives. There is no single correct

method of early intervention. What is available is

a wide variety of options, ideas, and solutions

that can be tailored to fit the needs and values of

each individual child and family. Service provid-

ers and early intervention programs should have

many informal methods of hearing from families

that prevent or resolve concerns quickly (see be-

low). However, family members must also be in-

formed about their right to formal complaint

resolution procedures.

Under Part C regulations, states choose either

to develop due process procedures to meet the

requirements of the Part C regulations (34

C.F.R. §303.419 and §§303.420–.425), or to

adopt Part B child complaint process (34 C.F.R.

§§300.506–.512, and meet the requirements of

§303.425).

For families, an important difference between

these regulations is that Part C calls for a shorter

time period for resolving a complaint—30 days

as opposed to 45 days under Part B. While most

states have developed Part C procedures, some

states, particularly those in which the education

department is the Part C lead agency, have

adopted the Part B procedures. Recognizing that

infants’ needs change rapidly, several of these

states encourage service providers and hearing

officers to use the 30-day limit, instead of the

45-day limit under Part B, for complaint resolu-

tion. States are also required to provide parents

an appropriate means of filing a request for a

due process hearing. An impartial, knowledge-

able hearing officer listens to viewpoints about

the dispute, examines information, seeks a

timely resolution and provides a record of the

hearing, including a written decision. Parents

have many rights during these procedures, in-

cluding having an attorney or other knowledge-

able persons accompany them, presenting

evidence, cross-examining and compelling wit-

nesses, and having evidence disclosed to them

before the proceedings. They may obtain a ver-

batim transcription of the proceedings and writ-

6 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

Figure 1

Explaining Part C Procedural Safeguards to Families:

A Step-by-Step Model

Text in italics indicates practices that are recommended but are not required by legislation.

Referral (.321(d))

1

Distribute materials on availability of EI services (.320)

Explain referral information (name, address) will be shared (FERPA)

2

Parent Refuses

Evaluations

Explain right to decline

services (.405)

Assure awareness of

consequences of refusal

(.404)

Explain notice of override

(.404, Note 2)

Intake Procedures — First Contacts

Orient to EI services; overall procedures; rights Explain confidentiality of records (.401-.404)

and safeguards; parent’s role; IFSPs — examine records (.402)

Explain available advocacy and parent support — release of information (.401)

programs Implement surrogate parent if applicable (.406)

Explain prior notice (use of native language or usual Assign service coordinator (.343(a)(iv))

communication mode) (.403) Explore family concerns and priorities to plan

Explain consent (.404) evaluation

Ineligible

Explain procedures for

resolving child complaints

(.420) and mediation (.419)

Refer to other community

resources as appropriate

Evaluation and Assessment

Explain eligibility Explain nondiscriminatory procedures (.323)

Explain evaluation procedures and instruments, including native language/usual

timelines, and parent’s role in process communication mode

Provide written prior notice (action, reasons, Explain interim IFSP (if applicable) and gain

available safeguards) (.403) consent (.345)

Provide written consent (for evaluation) (.403-.404) Introduce procedures for resolving individual child

Explain voluntary identification of family concerns, complaint (.420), including mediation (.419)

priorities, and resources (.322(d)) Explain informal, program-level complaint and

suggestion procedures

IFSP: Decline All

Services

Explain procedures for

resolving individual child

complaints (.420) including

mediation (.419)

Explain how to access services

If desired in the future

IFSP (.340-.346)

Plan IFSP meeting: written notice, timelines, Provide written consent required for services

(.342(e)) participants' convenience, accessibility, native Explain right to accept or decline services

without language (.342(d) jeopardizing services (.342(e)) and (.405)

Explain array of EI services and entitlements Explain procedures for resolving individual child

complaints (.420), including mediation (.419)

IFSP Acceptance and Implementation of IFSP

Explain periodic review, annual evaluation (.342) Explain termination of services: prior notice (.403);

Explain changes in provision of services, required child complaint procedures (.420); help families

notice, and possible consent (for newly initiated transition out of special services, if appropriate

services) (.403)

Transitions (.148 and .344(h): prior notice, timelines,

placement options, consent for record transfer

(.401—.404)

1

Numbers in parentheses reference 34 CFR Part 303, Regulations for the Early Intervention Program for Infants and Toddlers with

Disabilities (Part C) under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

2

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), enacted as Sec. 438 of the General Education Provisions Act (regulations at 34

CFR. Part 99).

Hurth and Goff © NECTAC 2002

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 7

ten findings of fact and decisions (Part C

§303.422 or Part B §300.509).

Because of the the 1997 reauthorization of

IDEA, a regulation (§303.419) was added requir-

ing states to offer mediation when a written re-

quest for a due process hearing is filed. Media-

tion services are provided at the state’s expense

and are voluntary for families. An impartial,

trained mediator will try to facilitate an agree-

ment between the family and the Early Interven-

tion program or provider. Mediators do not make

decisions; they facilitate problem-solving. Both

parties must be satisfied with the agreement they

reach or the dispute will continue to the due pro-

cess hearing. Mediation may not prolong the time

limit for due process procedures. Many see me-

diation as an opportunity for parents, service pro-

viders, and an impartial mediator to creatively

generate options for resolution of concerns, and

to avoid more formal procedures that tend to be

adversarial and costly for families and for early

intervention systems. In fact, many states are

making mediation services available to families

before they file a formal request for a hearing.

In order to develop truly family-centered

practices, early intervention programs, the com-

munity-based system, and the state lead agency

need to establish multiple avenues to encourage

family evaluation and feedback about their expe-

riences in early intervention. Adapting overall

program practice to meet families’ expressed

needs and preferences can create a service cul-

ture that is responsive to families and may pre-

vent formal complaints. Different families will

have different levels of comfort with and differ-

ent preferred means of voicing concerns and of-

fering evaluations.

Establishing a variety of opportunities for in-

put could include such strategies as:

• open-door policies that invite parents to talk

to administrators;

• ongoing program evaluations, using multiple

methods of information gathering (e.g.,

written evaluations, interviews, focus

groups, exit interviews, IFSP analyses, re-

views of progress towards outcomes);

• a policy that acknowledges the importance

of a good match between a service provider

and each family and that allows for parent

choice in assignments;

• a suggestion box or other avenues for submit-

ting comments anonymously;

• parent-to-parent support and/or parent group

opportunities;

• parent advisory board members;

• ongoing availability of interpreter or transla-

tor services;

• a designated contact person in the

state-level Part C system for parents

to call when they are concerned

about services or procedures; and

• mediation services offered before a

formal complaint is filed.

Principles and Practices from

States and Projects for Creat-

ing and Using Family-Friendly

Materials

As a part of a family-centered process

of explaining rights and safeguards, ser-

vice providers must recognize that each

family—indeed, each family member—

has a different approach to accessing and

using information. To accommodate these

unique approaches, providers must indi-

vidualize the timing and methods of shar-

ing information to match each family

member’s interests, needs, and prefer-

ences. The use of multiple methods of

sharing information and the use of a vari-

ety of family-friendly materials are key

approaches to respecting each family

member’s preferred learning mode. Be-

cause families have different levels of experience

and comfort with formal early intervention service

systems, a diverse group of experienced parents

and community representatives should be in-

formed about and available to explain services

and safeguards.

A review of materials and information submit-

ted by states and projects to the authors yielded

the following principles and examples of creating

and using family-friendly materials.

Many see media-

tion as an oppor-

tunity for parents,

service providers,

and an impartial

mediator to

creatively gener-

ate options for

resolution of

concerns, and to

avoid more formal

procedures that

tend to be

adversarial and

costly for families

and for early

intervention

systems.

8 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

★★

★★

★ Use family-friendly language and a clearly

stated philosophy of family-centered

services.

When procedural safeguards are fully

endorsed as a vital component of the early inter-

vention system, the philosophy of family-cen-

tered services is clearly stated throughout the

variety of materials used to explain family rights

and safeguards.

The language that is used should be free of

professional jargon and “legalese” (direct cita-

tions from the law without explanation). The

reading level of the materials should be similar

to that of popular newspapers and magazines

(about the fourth- to fifth-grade level). However,

care must be taken to assure that while the read-

ing level is simple, the content is not. Simple

sentences (as opposed to compound, complex

sentences), short, common words (e.g., “use”

instead of “utilize”), and active verb tenses

(e.g., “take” rather than “could be taken”) con-

vey important information without talking down

to families.

The language of materials can also carry mes-

sages about who is invited to use the information

and, perhaps unintentionally, who is excluded.

Today’s families are not always comprised of

mothers and fathers or parents and their chil-

dren. Materials portraying this concept of family

may exclude foster parents, grandparents, un-

married mates, or other people significant to a

child’s life. Except in instances when the legal

requirements specifically limit a right or safe-

guard to parents or legal guardians, the language

of materials should use inclusive terms like

“family,” “friends,” “people who are important

to you and your child,” and “caretakers.”

The following excerpts from print materials

exemplify the language and philosophy of fam-

ily-friendly materials:

Parents are decision makers on the team. . . .

You have many rights as the parent of a child

receiving early intervention services. These

rights are called procedural safeguards. All

early intervention service providers must

have written procedural safeguards. Because

your rights are so important, your service

coordinator must review them with you be-

fore the program of services begins and at

least once a year thereafter. Please be sure

you are given written information about your

rights (Garland, 1992, p. 31 ).

When I need early intervention services, the

Department of Health has 45 days to com-

plete my evaluation unless I get sick or my

family needs more time. . . . We can have

other members of our family, a friend, an ad-

vocate (supporter), or even an attorney

present during the IFSP meeting if we’d like.

. . . Should we disagree with any of the

recommendations being made or think we

are not receiving the services we need, we

have a right to voice our concerns (Hawai'i

Department of Health, n.d., pp. 2–5).

★★

★★

★ Present procedural safeguards in the con-

text of information about early intervention

services and the IFSP process.

The same rationale for explaining rights and

safeguards in the context of the early interven-

tion process applies to the content of print,

video, and other materials. Information on rights

and safeguards should be presented with infor-

mation on the early intervention system and ser-

vices, the IFSP process, and the family’s role on

the early intervention team. The following ex-

amples illustrate different approaches to embed-

ding rights and safeguards in information about

the Part C program.

Lengthy and complex information can be

broken apart conceptually and presented in brief,

attractive pamphlets that can be discussed with

families at the appropriate step of the early inter-

vention process. Project Vision at the University

of Idaho has created Parents as Partners in

Early Education (Project Vision, 1992b ), a

series of 16 booklets, each explaining an aspect

of early intervention services under Part C or

preschool services under Section 619 of Part B.

Titles in the series provide overviews to such

topics as protecting family rights or procedural

safeguards, IFSPs/IEPs, early intervention or

preschool services, IDEA, service coordination,

child assessment, gathering family information,

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 9

and transition issues. Each booklet is quickly

identified as one of a series by the consistent use

of title, format, and graphics. The language is

family-friendly and the text is concise and read-

able while conveying the necessary information.

Project Vision (1992a) also produced the Par-

ent Satisfaction Ratings series in a similar brief

format which asks families to evaluate key as-

pects of information received and their experience

relevant to the steps of the process outlined in the

Parents as Partners series. For example, Helping

Families Learn about Family Rights seeks family

members’ thoughts and feelings about questions

such as:

“I believe the people helping my child really

tried hard to explain my rights to me”;

“I know that I can read my child’s file when-

ever I want”; and

“I know that if I do not like the services my

child is getting I can request a meeting to talk

about my needs” (p. 3).

Another approach is to produce a family

manual or handbook that provides an overview

to the early intervention program, including

rights and safeguards, and refers to other materi-

als that address various topics in more detail.

The manual is useful for orientation and the

supplemental pieces can be used throughout the

process as families need and want more detail.

For example, the Maryland Infants and Toddlers

Program developed Dreams & Challenges:

A Family’s Guide to the Maryland Infants &

Toddlers Program (1992a), and three brochures:

Parents’ Rights in the Early Intervention System

(1992d); Mediation in the Early Intervention

System (1992c); and Impartial Procedures for

Resolving Individual Child Complaints (1992b).

★★

★★

★ Use a variety of media produced in multiple

languages to accommodate individual needs

and preferences for receiving and under-

standing information.

Although Part C requires that families receive

written information on their rights and safe-

guards, investment in multiple media presenta-

tions of information greatly expands options on

how, when, where, and who receives information

on rights and services. They also accommodate

different learning styles and preferences. Print

materials, even with multiple translations, are not

accessible by everyone. Some cultures have a tra-

dition of sharing information orally. Many people

have difficulty reading or learn better and more

quickly through listening. And most people better

understand information when it is presented in

more than one way.

When face-to-face contact may not be conve-

nient or appropriate, audiotapes and audio-video

cassettes can be loaned to parents, extended

family members, and concerned others. They

can be played in homes and in pediatricians’ of-

fices, placed in libraries, and used in training,

public awareness, and child find activities.

Alaska’s Part C program discovered that almost

all the remote frontier villages had at least one

video cassette player and that community view-

ing of informational tapes was a popular winter

pastime. The Alaska program is developing vid-

eos in a number of native dialects and languages

that can be maintained within each rural village.

The Colorado Department of Education has

produced videos on procedural safeguards, the

IFSP, and service coordination. Staying in

Charge: Information for Families and Service

Providers about Family Rights (M. Herlinger,

1993) presents comprehensive information about

procedural safeguards in the context of family

stories about their children and their involve-

ment with the early intervention process. The

presentation is family-friendly and safeguards

are explained through the families’ experiences.

When developing and translating materials, it

is important to assure accurate and understand-

able translations. Materials should be reviewed

by several members of the community for which

the materials are intended. Special care should

be taken with legal concepts that may not have

direct translations into another language. English

words may need to be used and fully defined

and explained. Also, print and video materials

should include visual depictions of people of di-

verse cultures and people with disabilities.

10 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

★★

★★

★ Assure accessibility of information by en-

hancing materials appeal, availability in

multiple community locations, readability,

and inclusion of interpretive supports.

Appeal and attractiveness enhances the use of

the materials by families and service providers.

Pictures and graphics break up blocks of

text. Several parent handbooks (see for

example, Fortune, Dietrich, Blough, &

Hartman, 1993; Maryland Infants and

Toddlers Program, 1992a; Texas Early

Childhood Intervention Program, 1991)

have graphics such as headings, boxes,

and pictures, placed between small

amounts of text. This breaks up the narra-

tive and allows readers to view small

pieces of information at a time. Some

parent handbooks are written in an easy-

to-read, question-and-answer format with

very little professional jargon or legalese.

The questions also are typical of those

that parents ask and the answers provide

simple yet thorough explanations of the

issues. For example,

What information will I be asked to share

about my family?

You can share whatever family information

you choose. It’s up to you. Providers will

give you a chance to discuss family needs.

They should only ask for information about

your family which is important to the evalu-

ation of your child (Gilmer, 1992, p. 9).

One handbook submitted to the au-

thors included tips for families inter-

spersed throughout the handbook. Parents

assisted in writing the tips, which gave a

first-hand perspective. Some handbooks

include glossaries of terms and acronyms

to help readers understand the early intervention

system’s language.

Early On, the parents’ handbook produced

by Michigan’s Part C system, advises families:

“If anyone uses any initials you do not under-

stand, ask what they mean” (Fortune et al., 1993,

p. 26).

Another approach is to develop a handbook

that is designed to be a personal record of the

child and family as well as a record-keeping

tool for the early intervention system. The book

may be used more frequently by the family and

service providers if it is introduced to the family

at the beginning of their relationship with the sys-

tem, and if the format encourages the family to

personalize the handbook with pictures and anec-

dotes and contains space for copies of early inter-

vention records, medical records, IFSPs, and other

notes. When the book is used more, more oppor-

tunities occur to read information about the sys-

tem of early intervention services.

Any format used to provide information to par-

ents needs to use language that supports partner-

ship. For example, language such as “with your

direction and agreement,” “you know your child

like no one else,” and “you are part of a team” in-

dicates the expectation that families and service

providers work together. Terms like “due process”

connote an adversarial relationship, whereas de-

scribing the “procedures to resolve a complaint”

connotes negotiation and communication. Some

pamphlets have been developed with wording

such as “impartial ways to resolve concerns” or

“ways we can problem-solve.”

A few materials described mediation in a man-

ner that recognizes that disagreements occur and

are part of the process. “Sometimes families of in-

fants and toddlers with special needs disagree

with their service providers. Most often these situ-

ations are worked out but when that honest effort

falls short, families and service providers can find

agreement through mediation. With the help of a

neutral third party, cooperation, agreement and so-

lutions can become reality” (Hawai'i Department

of Health, 1991, p. 1).

When information is provided by many meth-

ods and in many formats, the information is ac-

cessible to more families. The law requires that

families receive information in the families’ pre-

ferred mode of communication. Therefore, early

intervention systems need to develop materials

and procedures that are available in a variety of

languages and formats. Audio and video products

make information available to nonreaders and oth-

ers who prefer these formats.

Because family-

centered early

intervention

services are inter-

agency, commu-

nity-based efforts,

service providers

from a variety

of disciplines and

agencies, family

members, and

other community

members will

need to become

comfortable with

a working knowl-

edge of procedural

safeguards which

can be applied in

daily experience

in the early

intervention

process.

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 11

´ Involve a diverse cadre of informed service

providers, experienced parents, and commu-

nity representatives in explaining early in-

tervention services and procedural safe-

guards to families.

Another method being explored is to train key

community leaders in the early intervention sys-

tem so that they can be a resource for families.

In keeping with the Part C requirement to reach

traditionally underserved families, informing and

involving leaders of their communities can be an

effective strategy. The use of community people

as interpreters to provide information to families

about the system and procedural safeguards also

is being piloted by some states and projects.

This appears especially helpful for families with

a tradition of communicating orally. Some states

are supporting local programs to recruit and

train a cadre of people from diverse communi-

ties and languages to serve as service coordina-

tors on a consulting or fee-for-service basis. The

Navajo Nation developed an interim service co-

ordination program, called Growing in Beauty,

to help Navajo families access services from the

three state systems which overlap the Nation’s

boundaries and have responsibilities for provid-

ing early intervention services.

Experienced family members, who are well

informed about the early intervention system,

are being connected with families who are new

to the system. Parents are being hired and

trained as service coordinators, trainers, guides,

and interpreters through the IFSP process. Some

states have funded parent programs to provide

these services (for example, Community Re-

source Parents in Vermont, Project LINC in

Colorado, Parents as Partners in Early Interven-

tion in Florida, and New Visions in Maryland).

In other programs, parents and other community

people volunteer to provide support and answer

questions for the new family as they go through

each step of the process.

Access to information also is improved by the

use of several outlets for dissemination. Al-

though state and local agency offices frequently

are used as dissemination points, other outlets

can include local physician offices, grocery

stores, public libraries, churches, public health

clinics, laundromats, and community programs.

Many video rental stores stock public service

tapes that are loaned free of charge. Public

service announcements can be played on radio

and television, and included in community

newspapers.

Conclusions

Part C provides the opportunity to enhance re-

lationships between families and service provid-

ers. Early intervention can prepare families for a

lifetime of productive interaction with service

systems. For this reason, investing the time and

resources to thoroughly explain rights and proce-

dural safeguards is an important service for all

involved. Assuring families a role as partners and

decision-makers in the early intervention system

is an evolutionary process. Technical support and

training is necessary to facilitate program level

change to truly family-centered practice.

The Part C system is enhanced when a person

or persons with expertise in procedural safe-

guards is (are) available for consultation with

families and service providers. It is probably not

feasible for every local service program to have

someone on staff with specialized knowledge

about all pertinent state and federal legislation

and judicial decisions. Some states have desig-

nated a staff person whose responsibilities in-

clude being available to discuss questions and

concerns from families and service providers. In

one state’s experience, this designated staff per-

son has been able to resolve most concerns. In

fact, most concerns were a result of inadequate

understanding of the rights, safeguards, and poli-

cies of the system (L. Bluth, personal communi-

cation, 1994).

The interagency approach to implementing

infant and toddler services means that many ser-

vice providers from multiple agencies will need

to be trained in Part C procedural safeguards.

These rights and safeguards may be different

than current policy and experience of non-educa-

tion agencies.

As states are developing training and techni-

cal assistance activities, care should be taken to

12 National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

involve many relevant stakeholders (such as

families, multiple agency providers, advocates,

parent groups, and community leaders) as col-

laborative planners and participants in training.

The benefits of multiple perspectives in discus-

sions include learning together, developing true

partnerships, and understanding one another’s

experience and point of view.

Family-friendly, culturally appropriate ap-

proaches for explaining procedural safeguards

need to be an integral part of program practice.

Because family-centered early intervention ser-

vices are interagency, community-based efforts,

service providers from a variety of disciplines

and agencies, family members, and other com-

munity members will need to become comfort-

able with a working knowledge of procedural

safeguards which can be applied in daily experi-

ence in the early intervention process.

References

Assistance to States for the Education of Chil-

dren with Disabilities Program Rule, 34

C.F.R. § 300 (2001).

Early Intervention Program for Infants and Tod-

dlers with Disabilities Rule, 34 C.F.R. § 303

(2001).

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Rule, 34

C.F.R. § 99 (2001).

Fortune, L.B., Dietrich, S., Blough, J., &

Hartman, A. (1993). Early on: Michigan’s fam-

ily guidebook for early intervention services.

Lansing: Michigan Department of Education.

Garland, C. (Ed.). (1992). A guide to early inter-

vention. Lightfoot, VA: Williamsburg Area

Child Development Resources, Inc.

Gilmer, V. (1992). A parent handbook: The New

Mexico Family Infant Toddler Program. Santa

Fe: New Mexico Department of Health.

Growing in Beauty Program. (1998). Building

bridges for Navajo families and children:

Policies, procedures and recommended prac-

tices. Window Rock, AZ: Navajo Office of

Special Education and Rehabilitation Services.

Hawai'i Department of Health. (1991). Once

upon a time. Honolulu: Zero-to-Three Hawai'i

Project.

Hawai'i Department of Health. (n.d.). Dear

family, on behalf of infants and toddlers with

special needs [Brochure]. Honolulu: Zero-to-

Three Hawai'i Project.

Herlinger, M. (Producer). (1993). Staying in

charge: Information for families and service

providers about family rights [Videotape].

Denver: Colorado Department of Education.

Hurth, J. (1998) Mediation in early untervention:

Results of a national survey of the Early Inter-

vention Program for Infants and Toddlers with

Disabilities in 50 states. (Reprinted from Part

C Updates, pp. 41-42, by the National Early

Childhood Technical Assistance System, 1998,

Chapel Hill, NC: Author)

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20

U.S.C. § 1400 (2000).

Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program,

Governor’s Office for Children, Youth, and

Families. (1992a). Dreams & challenges. A

family’s guide to the Maryland Infants & Tod-

dlers Program [Brochure]. Baltimore: Author.

Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program,

Governor’s Office for Children, Youth, and

Families. (1992b). Impartial procedures for re-

solving individual child complaints [Bro-

chure]. Baltimore: Author.

Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program,

Governor’s Office for Children, Youth, and

Families. (1992c). Mediation in the early in-

tervention system [Brochure]. Baltimore:

Author.

Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program,

Governor’s Office for Children, Youth, and

Families. (1992d). Parents’ rights in the early

intervention system [Brochure]. Baltimore:

Author.

Project Vision, University of Idaho. (1992a). Par-

ent satisfaction ratings [Booklet series]. Mos-

cow, ID: Author.

Assuring the Familys Role on the Early Intervention Team 13

Project Vision, University of Idaho. (1992b). Par-

ents as partners [Booklet series]. Moscow, ID:

Author.

The Texas Early Childhood Intervention Pro-

gram. (1991). Setting your course in ECI: A

rights handbook for families with children in

the Texas Early Childhood Intervention Pro-

gram. Austin: Author.

Citation

Please cite as

Hurth, J.L. & Goff, P. (2002). Assuring the

family's role on the early intervention team:

Explaining rights and safeguards (2

nd

ed.).

Chapel Hill, NC: National Early Childhood

Technical Assistance Center.

This document appears at http://www.nectac.org/

pubs/pdfs/assuring.pdf and updates to the data

herein will be announced at

http://www.nectac.org/pubs/.