Hiroshi Nakaso

Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan

Monetary Policy Divergence and Global Financial Stability:

From the Perspective of Demand and Supply of Safe Assets

Speech at a Meeting Hosted by

the International Bankers Association of Japan

Bank of Japan

January 20, 2017

1

I. Introduction

In February 2008, the Financial Times ran an article describing the Bank of Japan as "Fortress

Japan." The article noted that the Bank was functioning as a fortress for Japan, shielding the

Japanese financial system from the turmoil in the global financial markets triggered by problems in

the U.S. subprime mortgage loan market. As you know, the Bank′s objective of maintaining

financial system stability is as important as that of maintaining price stability. In order to fulfill this

responsibility, not only is it important to uphold a microprudential perspective, which aims to

understand the risks faced by individual financial institutions and encourages management

responses thereto, but it also is important to formulate and implement policies from a

macroprudential perspective, which aims to analyze and evaluate risks to the financial system as a

whole.

Following the recent global financial crisis, the financial landscape is radically changing, with U.S.

and European banks shrinking their balance sheets and non-banks, such as investment funds,

increasing their significance. At the same time, in the sphere of monetary policy, we are now

experiencing monetary policy divergence, where interest rates have been kept low for long periods

in both Japan and Europe but the United States is entering a rate increase cycle. In order to

maintain financial system stability in such a changing global financial environment, it is necessary

to ensure that there are no hidden vulnerabilities from both the microprudential and

macroprudential perspectives. Today, I would like to approach this issue through the looking glass

of the demand and supply of safe assets.

II. Three Facts Regarding Global Financial Intermediation by Banks

Before going into my main thesis, let me point out three facts regarding global financial

intermediation by banks.

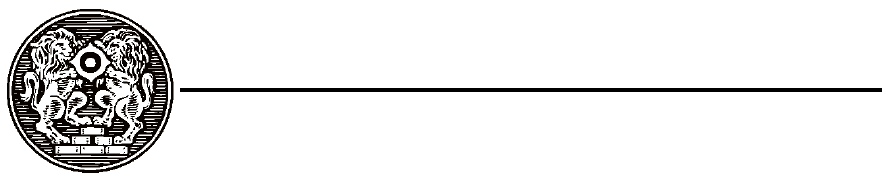

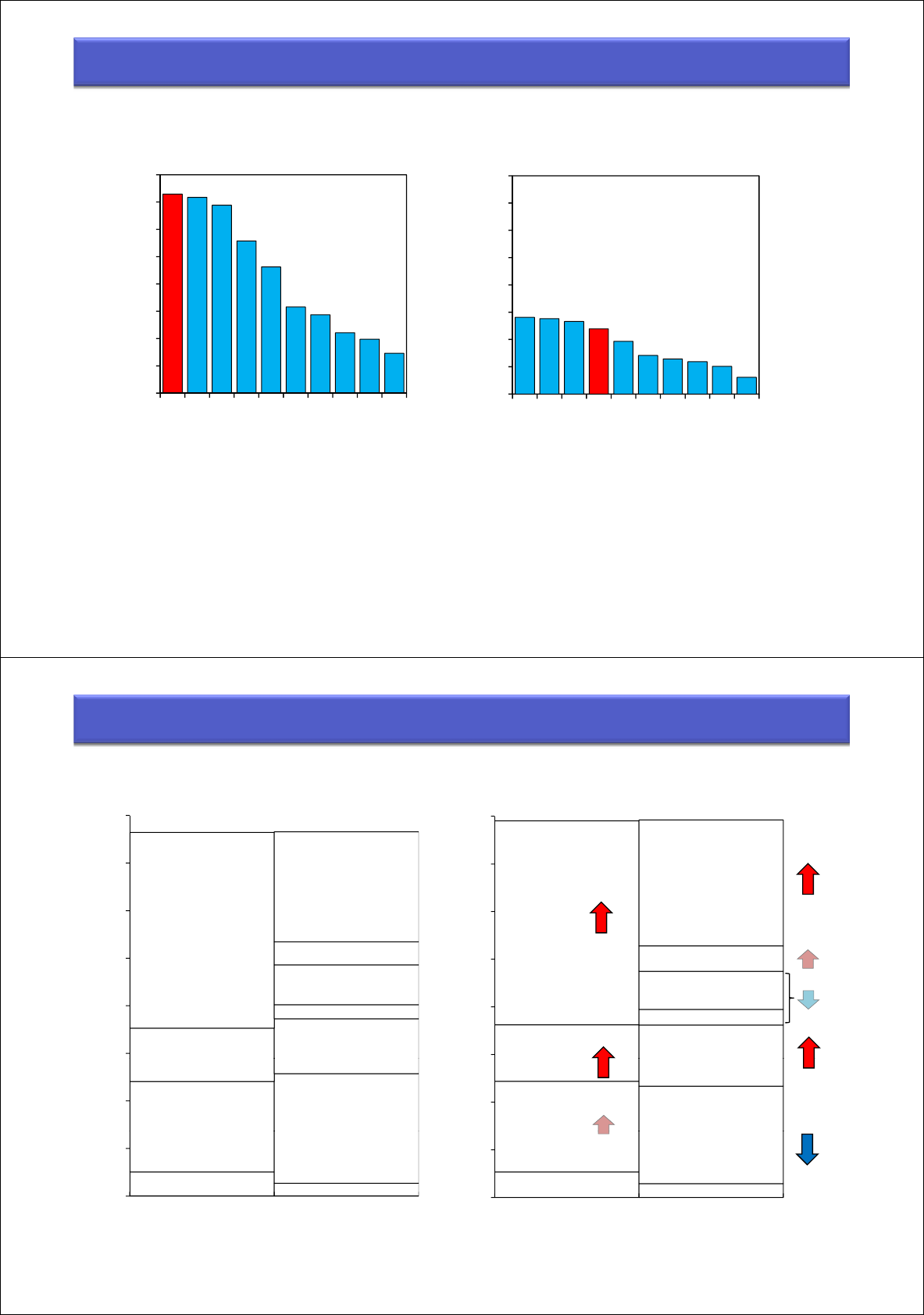

First of all, there is a close connection between fluctuations in banks' cross-border claims and

global economic activity. Looking at banks' cross-border claims by destination, financial cycles

have engulfed one region after another (Chart 1). In the early 1980s, there was the debt crisis

centered on Latin America. Later in the decade, we saw the bubble economy in Japan. In the late

1990s, we had the Asian currency crisis, and the 2000s started with a credit bubble in the United

States and Europe. Most recently, we are worried about debt expansion in emerging Asia. As these

examples show, the rise and fall of economic activity coincides with the rise and fall of banks'

2

cross-border claims.

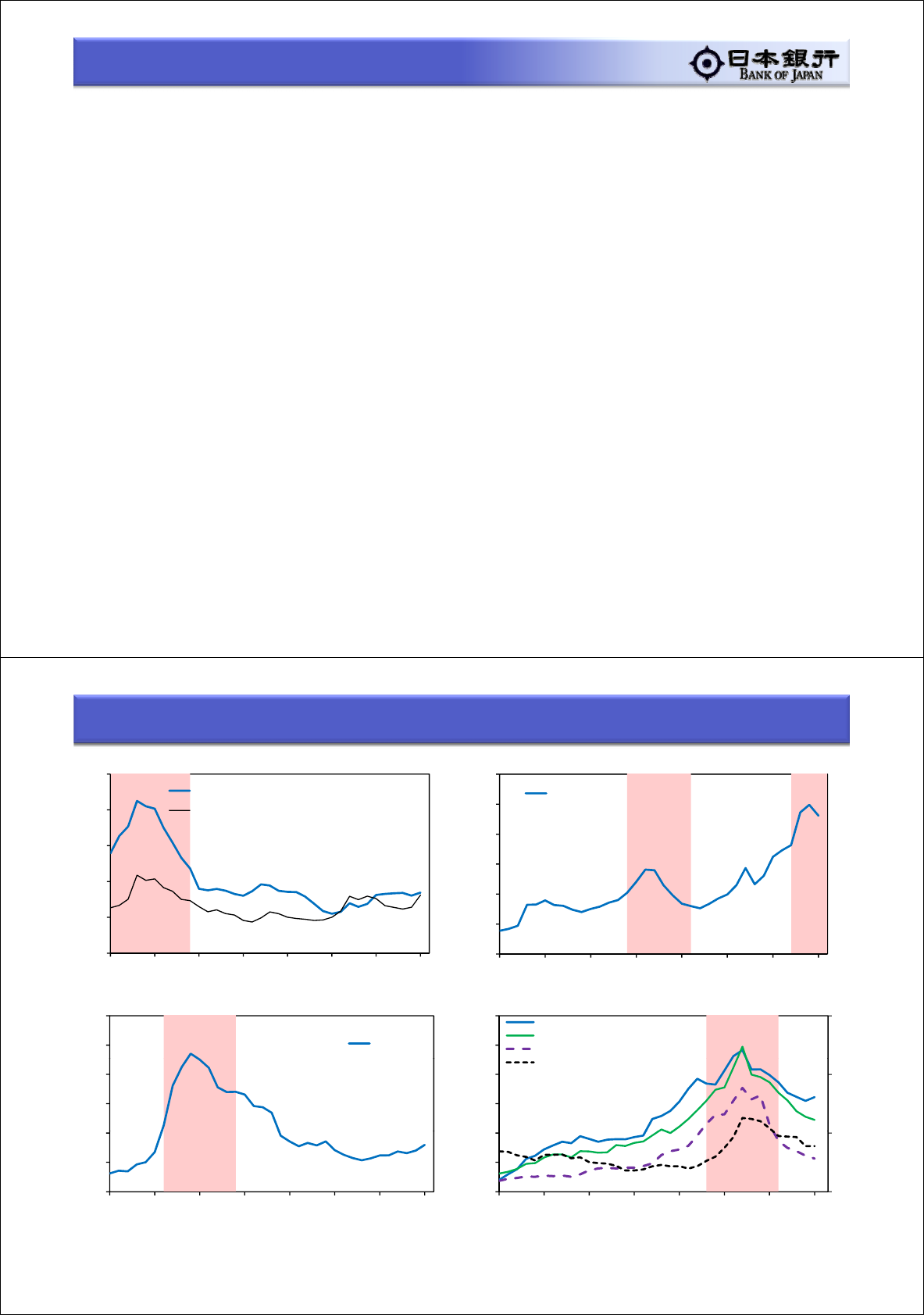

Secondly, looking at the nationality of banks extending U.S. dollar-denominated foreign claims,

non-U.S. banks overwhelm U.S. banks in terms of market share (Chart 2). Regarding the currency

composition of banks' foreign claims, with the exception of intra-European claims, more of which

are now in euros, a large part of the claims globally is denominated in dollars; yen use is still not

very common.

1

In one respect, this reflects the fact that, with much of global trade and financial

transactions being conducted in dollars, non-U.S. banks are financially supporting cross-border

activities, especially those of national firms.

Lastly, regarding the U.S. dollar funding of non-U.S. banks, the reliance on foreign exchange

swaps (FX swaps) is trending higher (Chart 2). When non-U.S. banks extend credit in dollars, they

have to fund themselves in dollars, and often their on-balance-sheet credit extensions exceed their

funding in dollars. This gap in funding is usually covered by FX swaps, which exchange domestic

currency with dollars. In an FX swap, the parties to the transaction simultaneously conclude the

purchase and sale of two different currencies of equal value on two separate delivery dates in the

opposing direction. For example, a Japanese bank would purchase some dollars against the yen in

the spot market and yen against the same amount of dollars in the forward market, which is in

effect obtaining dollars against yen collateral. The reliance on FX swaps can be approximated by

dividing the dollar funding gap by foreign claims. It can be seen that the ratio is trending higher in

the long term, with instances of sharp dips during periods of market stress.

Putting these facts together, one can conclude that it is important to monitor and analyze carefully

the dollar funding environment of non-U.S. banks as a window onto the stability and potential

vulnerability of the global economy and the international financial system. Looking also at the

foreign claims of non-U.S. banks by nationality, following the recent global financial crisis,

European banks are deleveraging while Japanese banks are enlarging their balance sheets (Chart 3).

This is one reason why I feel there is a need to be vigilant regarding the international financial

intermediation activities of Japanese banks.

III. The Foreign Exchange Swap Market and Monetary Policy Divergence

Let us now focus on the FX swap market, which offers important clues regarding developments in

1

For developments in bank lending by currency, see the following: Avdjiev, S. and E. Takáts, "Monetary

Policy Spillovers and Currency Networks in Cross-border Bank Lending," BIS Working Papers, No.549,

March 2016.

3

global financial markets.

In textbooks on finance, it is said that "covered interest rate parity" will hold. For example, the

effective interest rate when funding U.S. dollars through the FX swap market and the going rate in

the U.S. short-term money market (i.e., LIBOR) should be identical. The basis of this textbook

view is that, if the former is higher than the latter, there is an arbitrage opportunity, which will be

exploited by a bank lending dollars raised in the short-term money market to takers in the FX swap

market, until the opportunity is arbitraged away.

Increases in Dollar Funding Premia in the Foreign Exchange Swap Market

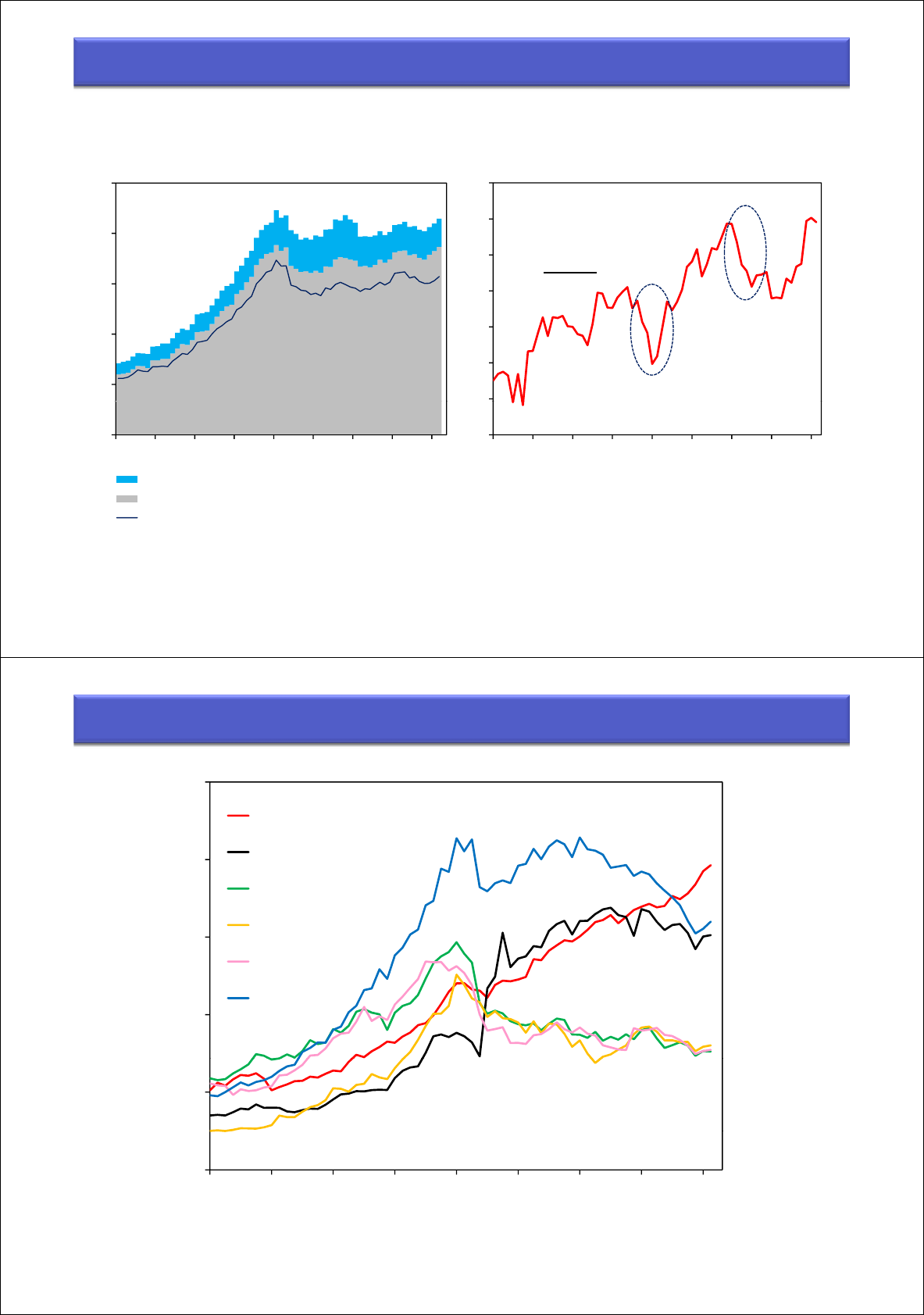

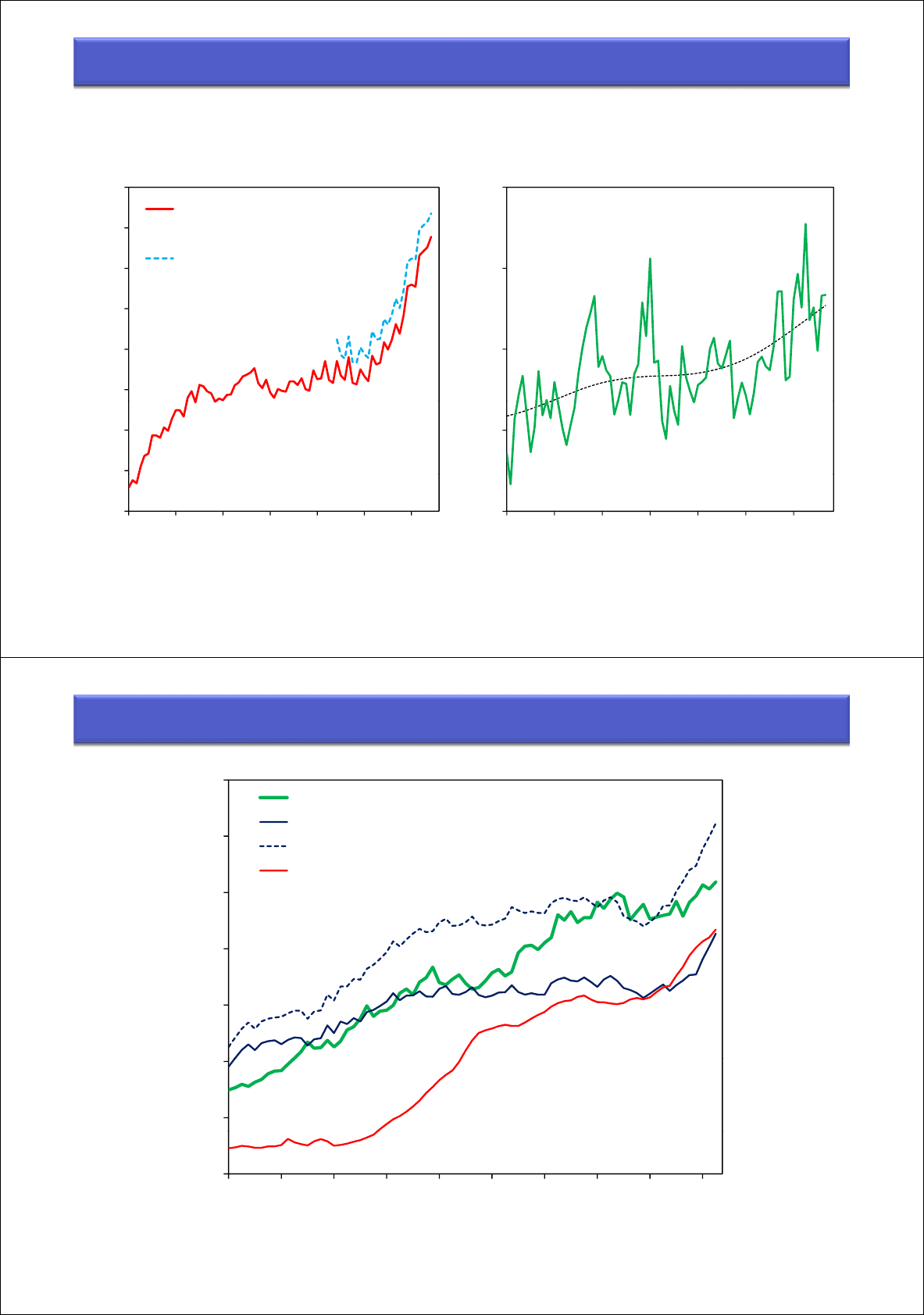

In real life, however, covered interest rate parity does not always hold, contrary to what the

textbooks say. We often see periods where U.S. dollar funding costs through the FX swap market

exceed the funding costs through the U.S. short-term money markets (Chart 4). Of these periods, in

cases like the Japanese financial crisis in the late 1990s, the recent global financial crisis from 2008

onwards, and the euro area debt crisis between 2011 and 2012, the increases in the spreads over

LIBOR, or the dollar funding premia in the FX swap market, seem to have been brought about by

the deterioration in the creditworthiness of banks trying to raise dollar funds. This happens when

(a) banks with shaky credit increasingly rely on funding dollars against home-currency collateral

through the FX swap market as they face growing difficulties in obtaining uncollateralized funding

in the U.S. short-term money market; (b) banks' counterparties, meanwhile, become increasingly

reluctant to lend dollars due to concerns over counterparty credit risk, because those counterparties

will incur replacement costs in case of banks' failure even if there was collateral; and (c) as a result,

tighter conditions prevail in the swap market and dollar funding premia for non-U.S. banks

increase.

Having said this, I should note that the recent increases in the U.S. dollar funding premia in the FX

swap market are occurring without any obvious problems regarding banks' creditworthiness (Chart

4). This should imply that the mechanism for current increases in the dollar funding premia is

different from that of past stress periods. Let me delve a little more into this issue.

Consequences of Monetary Policy Divergence and Regulatory Reforms

With the low interest rate environment persisting in Japan and Europe, the United States initiated

"tapering" and entered a rate increase cycle. Such a divergence in monetary policy outlook

influences the return-seeking behavior of financial institutions and investors. Against the

background of monetary policy divergence between Japan and Europe on the one hand and the

4

United States on the other, the nominal return on U.S. dollar assets is now higher than the return on

yen or euro assets, and financial institutions and investors in Japan and in Europe are increasing

their investments in dollar assets (Chart 5). When banks invest in foreign currency denominated

assets, they generally hedge foreign exchange risk in view of the high capital charges for such risk.

Such FX-hedged investments in dollar assets are economically equivalent to transactions that

purchase dollar assets with dollars obtained through FX swaps with yen or euros as collateral.

Investments in foreign currency bonds by life insurers are less likely to be hedged compared with

banks' investments, but slightly less than 70 percent of investments by Japanese life insurers seem

to be hedged in recent years. The pattern of behavior suggests that recent monetary policy

divergence is encouraging Japanese and European financial institutions to invest in dollar financial

assets and contributing to tighter market conditions in the FX swap market.

Meanwhile, this is not the first time that we have experienced monetary policy divergence between

Japan and the United States. For example, monetary policies also diverged in the middle of the

2000s, with the Bank of Japan continuing its quantitative easing while the Federal Reserve

gradually raised its policy rate, and during this period, Japanese financial institutions increased

their purchases of U.S. Treasury paper and agency securities. The U.S. dollar funding premia,

however, did not visibly increase during this period; i.e., broadly speaking, covered interest rate

parity held (Chart 4). One has to wonder why, in the FX swap market, reactions to monetary policy

divergence between Japan and the United States differ between then and now. Of the several likely

explanations, I would like to point out the effects of regulation on banks that are active in the

global financial market.

2

As I noted earlier, if the U.S. dollar funding rate in the FX swap market is higher than the going

rate in the U.S. short-term money market (i.e., LIBOR), there is an arbitrage opportunity where a

financial institution could definitely profit by swapping dollars obtained in the money market.

Nevertheless, when a financial institution wishes to conduct such a transaction, it would have to

enlarge its balance sheet. Recently introduced financial regulations, such as the leverage ratio,

which have the effect of increasing capital requirements for balance sheet expansion relative to the

more traditional risk-based capital ratio, seem to be dampening arbitrage trading. More specifically,

even when the swap market conditions tighten due to monetary policy divergence between the

Unites States and Japan, U.S. banks and others that used to provide dollars are not prepared to

2

The following paper by Bank of Japan staff analyzes the effects of monetary policy divergence and

regulatory reform on market conditions in the FX swap market from both theoretical and empirical

perspectives: Iida, T., T. Kimura, and N. Sudo, "Regulatory Reforms and the Dollar Funding of Global

Banks: Evidence from the Impact of Monetary Policy Divergence," Bank of Japan Working Paper, 16-E-14,

August 2016.

5

increase the supply of dollar funds because of higher costs for arbitrage trading. This is one of the

reasons why we now see dollar funding premia.

3

Meanwhile, up until the middle of the 2000s,

regulatory constraints were less acute than today, and it was easier for banks to conduct arbitrage

trading, which in turn seemed to result in a more ample supply of dollar funds and little or no

dollar funding premia.

IV. Bank Debt and Financial System Stability

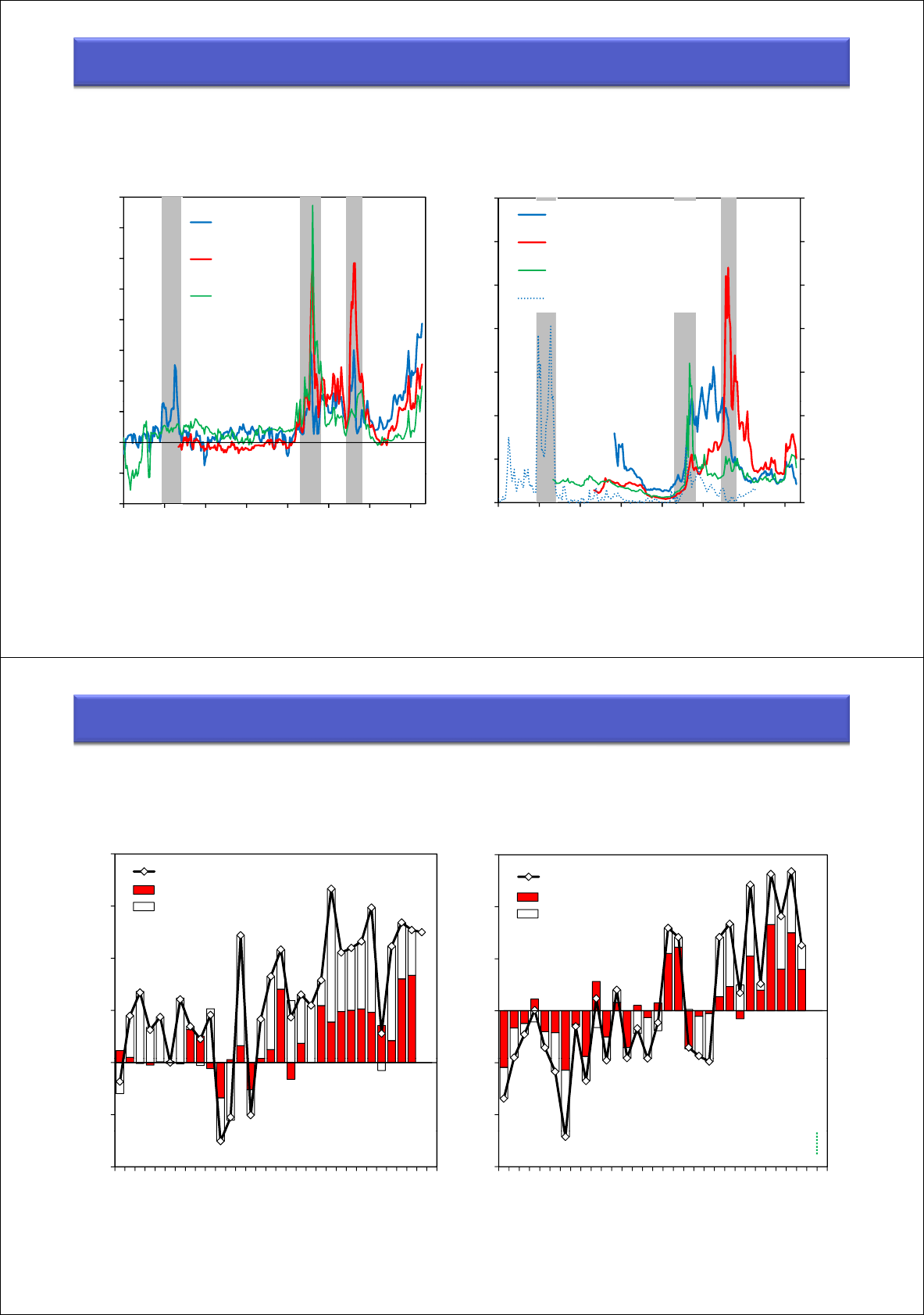

Recent financial regulation reforms are not only affecting the suppliers of U.S. dollars, as we have

just seen, but also the takers of dollars. For the next few minutes, I would like to touch upon U.S.

money market fund (MMF) reform, which affected the dollar funding of global financial

institutions, from the perspective of Japanese banks.

Changes in Debt Composition at Japanese Banks

Even in an environment where arbitrage trading by banks supplying U.S. dollars is constrained, the

dollar funding premia in the FX swap market may decline if non-U.S. financial institutions

(including Japanese banks) can shift their funding from the relatively expensive swap market to the

(uncollateralized) U.S. short-term money market. Considering that there are no serious concerns

regarding the creditworthiness of non-U.S. banks at this juncture, these banks should be able to

increase uncollateralized funding through commercial paper (CP) and certificates of deposit (CDs),

for example. This is not the case, however, because a substantial part of CP and CDs issued by

non-U.S. banks used to be purchased by "prime" MMFs, and their issue had to be compressed

considerably, following the U.S. MMF reform, which came into effect last October (Chart 6). The

reform, introduced under new U.S. SEC rules, requires the adoption of floating net asset value

(NAV) and imposition of redemption fees, and opens the possibility of restricting redemption. This

prompted a huge shift in funds from prime MMFs to "government" MMFs, which invest mostly in

U.S. government securities and are exempt from the new rules. This in turn significantly affected

3

The effects of financial regulation are typically observed in the quarter-end spikes of U.S. dollar funding

costs, as follows: (a) Since around 2013, U.S. banks have deleveraged, due partly to the stricter leverage

ratio in the United States (in which a higher ratio than international rules is required, and is calculated on the

basis of daily averaged assets); (b) non-U.S. banks, European banks in particular, which previously had

increased positions in the U.S. money market, have started to shrink their balance sheets at quarter-ends

since the middle of 2014, partly to hold down the leverage ratio at quarter-ends (in many countries, although

not in the United States, banks report only the leverage ratio at quarter-ends); (c) at quarter-ends, U.S. banks

increase market-making and arbitrage-trading activities in the money market at higher rates, inclusive of

higher costs posed by regulation.

6

the dollar funding of global banks.

The effects of the MMF reform were not small, but Japanese banks were able to cope, not by

compressing their assets, but by changing the composition of their funding (Chart 7). Looking at

the foreign currency denominated balance sheets of major Japanese banks, for approximately six

months preceding last October, they actually increased their assets, including an increase of 33

billion U.S. dollars in overseas loans.

4

On the liabilities side of the balance sheet, there was a

decrease of 62 billion dollars in CP and CD issues, which was more than compensated for by an

increase of 67 billion dollars in client-related deposits, reflecting banks' efforts to build up stable

funding sources, and an increase of 26 billion dollars in repo funding. These major banks were thus

able to avoid increasing their reliance on relatively expensive funding through the FX swap market.

Bank Debt and Safe Assets

One interesting question here is why major Japanese banks were able to pull off such a significant

change in their balance sheets in such short order. Let me reflect on this from the viewpoint of

balancing supply and demand of U.S. dollar-denominated financial assets at the macro level. The

key phrase is "safe assets."

Financial intermediaries perform an important function of investing in risky assets while issuing

safe debt. Debt issued by private financial institutions, along with securities issued by governments,

constitutes safe assets that are provided to the economy. A prime example of such a function is the

bank deposit. Through the results of recent research on safe assets, we are now aware of two

empirical regularities over long periods.

5

The first point is that the share of safe assets in the whole

universe of financial assets including equities is more or less constant. In other words, the demand

for safe debt has been relatively constant as a fraction of the total assets in the economy. The

second point is that safe debt issued by the government and safe debt issued by private financial

intermediaries are substitutes. These two regularities indicate that fluctuations in the stock or price

of government debt crowd in or crowd out safe debt issued by financial intermediaries so that the

share of safe assets as a whole may be kept constant.

When we attempt to assess the market conditions regarding safe assets in the U.S. financial system,

the rise and fall of the "yield spread," which is the difference between the stock yield and long-term

4

Given that foreign currency-denominated balance sheets of Japanese banks are predominantly based on

U.S. dollars, Chart 7 essentially shows the features of U.S. dollar-denominated balance sheets.

5

See Gorton, G., S. Lewellen, and A. Metrick, 2012 "The Safe-Asset Share." American Economic Review,

102(3): 101-06.

7

government bond yield, is quite illuminating (Chart 8). From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, the

stock yield and the Treasury yield moved almost in tandem and the yield spread remained mostly

around zero; after that, however, we find persistent and very large spreads. The size of the spread is

now beyond a level that can be explained by expected growth in corporate earnings or equity risk

premium.

6

Such persistently wide yield spreads indicate that the demand-supply balance of safe

assets has been much tighter than that of risky assets. An additional demand for safe debt issued by

the U.S. government has probably resulted from the need for emerging market authorities to invest

their foreign exchange reserves or from the need to comply with regulations that require financial

institutions to hold certain amounts of safe assets. With such increase in demand for U.S.

Treasuries, the price of Treasuries will rise (and their yields will fall), and following the recent

global financial crisis, the demand for safe assets from U.S. investors was fulfilled by debt

instruments substitutable for U.S. Treasuries and issued by financial institutions. In particular,

dollar-denominated highly rated paper issued by non-U.S. banks, mainly from Canada and

Australia, was preferred by U.S. investors.

7

In this environment, the U.S. MMF reform, which I mentioned a few minutes ago, had the effect of

further increasing demand for U.S. Treasuries.

8

As funds shifted from prime MMFs, which invest

in CP and CDs, to government MMFs, which invest in U.S. government securities, the yield on

U.S. government securities was pushed down (Chart 9). When Treasury Bill yields fall well below

LIBOR, which is the benchmark yield for debt instruments issued by private banks, the demand for

safe debt issued by banks will increase because substitutable Treasury Bills become relatively

expensive. That is, while prime MMFs have become less attractive as safe assets, an increase in

demand for U.S. government debt without a concomitant increase in supply could also lead to an

increase in safe debt issued by financial intermediaries so that the safe asset share may be kept

constant. Such overall rebalancing of the financial asset portfolio in the U.S. dollar financial

market enabled major Japanese banks to adjust the liability side of their balance sheets and focus

on increasing client-related deposits.

6

See Ichiue, H., T. Kimura, T. Nakamura, and H. Hasebe, "The Supply and Demand of Safe Assets and the

Scarcity Premium for Government Bonds," Bank of Japan Review, 12-J-1, January 2012 (in Japanese only).

7

See Bertaut, C., A. Tabova, and V. Wong, "The Replacement of Safe Assets: Evidence from the U.S. Bond

Portfolio," Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, International Finance Discussion Papers,

No.1123, October 2014.

8

The following paper reviews the shift of funds from prime MMFs to government MMFs from the

perspective of the supply and demand for safe assets: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, "Demand

and Supply of Safe Assets in the Economy," memo, March 2014.

8

Safe Assets and Financial Vulnerability

At this point, you might wonder why I am deploying as arcane a concept as safe assets in order to

explain the changes in the debt composition of Japanese banks. I have done so because the supply

and demand of safe assets is an important reference point for monitoring and assessing the stability

and potential vulnerabilities of the financial system.

Let us look back at the mid-2000s. At that time, as the yield spread suggests, the demand-supply

balance of U.S. dollar safe assets tightened. In response, U.S. and European investors searching for

yields bought large amounts of highly rated asset-backed securities issued by private financial

intermediaries with the perception that these financial instruments were safe but gave yields that

were only a little better than U.S. Treasuries. In turn, the issue of asset-backed securities, in

particular mortgage-backed securities, rose to meet increased demand from investors. We know

that not everybody lived happily thereafter: when problems surfaced in the U.S. subprime

mortgage sector followed by the global financial crisis, the asset-backed securities lost their status

as safe assets.

9

Furthermore, the increasingly noticeable outflow of wholesale deposits from

European banks, which aggressively invested in securitized instruments, could be explained at least

in part by doubts over the appropriateness of regarding certain bank deposits as safe assets. The

same mechanism seems to have been at work when U.S. MMFs reduced their exposure to CP

issued by European banks during the European debt crisis beginning in 2011.

10

To sum up, debt instruments issued by private financial intermediaries may be regarded as safe

assets substitutable for government securities in tranquil times, but it should be borne in mind that,

when the going gets rough, those instruments could lose their status as safe assets. With this in

mind, the Bank of Japan conducted stress tests on foreign currency liquidity risk at Japanese banks

and published the results thereof in the Financial System Report (most recently in October 2016).

According to those tests, even when the availability of foreign currency funding is impaired, in

addition to elevated funding premia for foreign currencies in times of stress, Japanese banks would

withstand the stress and remain viable. The Bank is also of the view that Japanese banks would be

able to maintain sufficient levels of capital, which is a sine qua non of their debt instruments being

9

In addition to securitized instruments backed by residential mortgages (RMBSs), the period saw

substantial increases in the issuance of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) backed by loans financing

leveraged buyouts (LBOs), and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBSs). In addition, it became

increasingly common to see "re-securitized" instruments called asset-backed securities collateralized debt

obligations (ABS CDOs), which were securitized instruments backed by (primary) securitized products such

as RMBSs. The price of these instruments, even of highly rated ones, fell significantly after the second half

of 2007.

10

See Ivashina, V., D. S. Scharfstein, and J. C. Stein, 2015 "Dollar Funding and the Lending Behaviour of

Global Banks," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 130, pp. 1241-1281.

9

regarded as safe assets, even under a tail-event scenario depicting the recent global financial crisis.

Of course, the Bank encourages individual Japanese banks not to be complacent and pursue

enhanced management of liquidity risk, under the assumption that their issued debt is more or less

"runnable."

11

V. Increasing Importance of Non-Banks in the International Financial System

Up until now, I have focused on global financial intermediation by banks, but after the global

financial crisis, we cannot ignore the increasing importance of non-banks in the international

financial system.

12

For the next few minutes, let me focus on this development and the effects on

and implications for Japan through the looking glass of the FX swap market.

Changes in the Market Structure of Foreign Exchange Swaps

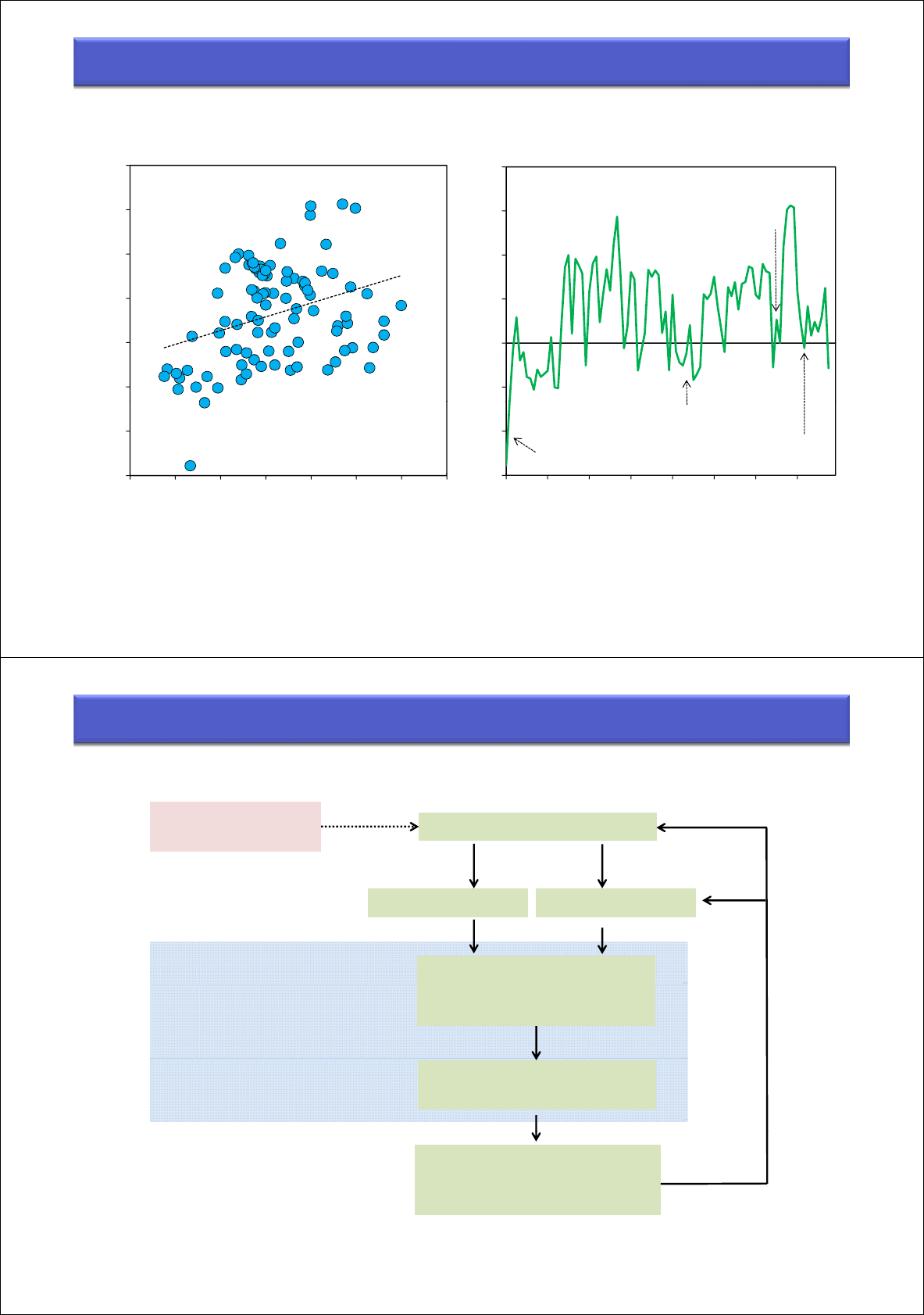

As described earlier, major Japanese banks, which can tap a relatively wide range of funding

markets, are currently refraining from heavily using the FX swap market for their U.S. dollar

funding (Chart 7). Having said that, statistics for Japanese financial institutions as a whole indicate

that there are large funding increases in that market (Chart 10). This reflects the increasing demand

for hedging dollar exposures from financial institutions that have limited funding options compared

with major banks. Looking at the statistics on outstanding external securities investments by

financial institutions, non-banks -- such as insurers, pension funds, and investment trusts -- are

increasing their investments as fast as banks (Chart 11). While pension funds are not expected to

hedge their exposures, life insurers seem to be hedging slightly less than 70 percent of their foreign

currency exposures in recent years. Investment trusts also seem to hedge their foreign exchange

risk in response to requests from investors, such as banks or households.

Against this increased hedging demand, as U.S. banks refrain from engaging in arbitrage trading in

response to regulatory requirements, we see increasing relative importance of non-banks -- such as

sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), reserve managers of emerging market economies, and private

investment funds -- as suppliers of U.S. dollars in the FX swap market. The existence of dollar

funding premia in the swap market signifies an opportunity for suppliers of U.S. dollars to obtain

yen funding at a very low rate. As a result, overseas non-banks that have dollars to spare can invest

11

As to runnable debt, see Bao, J., J. David, and S. Han, "The Runnables," FEDS Notes, September 3,

2015.

12

For example, see Financial Stability Board, "Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report," 2015.

10

in Japanese government securities (JGSs), even if the nominal yields on such paper are zero or

negative, and secure yields as good as or higher than U.S. government securities without taking on

foreign exchange risk. The fact that transaction volumes of FX swaps are positively correlated with

inward bond investments underscores the investment patterns of overseas non-banks regarding

FX-hedged investments in JGSs (Chart 12). In an environment where the demand-supply balance

of dollar safe assets is very tight, FX-hedged investments in JGSs may be viewed by investors as

safe assets substitutable for U.S. government securities.

The Swap Market and the Amplification of Procyclicality in Global Liquidity

One note of caution here is that FX-hedged Japanese government paper is not always a stable

substitute for U.S. government paper just as debt instruments issued by banks. In other words,

overseas non-banks cannot be regarded as stable sources of U.S. dollar funding. In fact, Japanese

inward bond investments statistics tend to decline sharply in times of market stress (Chart 12). That

means that, in times of stress, overseas non-banks have a tendency to reduce their FX-hedged

investments in JGSs and hence their dollar supply in the FX swap market. For example, when

currencies of emerging market economies started to slide after the Chinese stock market crashed in

the middle of 2015, market participants talked of emerging market reserve managers, aware of the

potential need to defend their currencies, refraining from offering dollars in the fixed-term FX

swap market and shifting their dollars into more liquid markets such as U.S. Treasury Bills.

13

Similar observations were heard when currencies of emerging market economies weakened

following the U.S. presidential election in November 2016. In short, while FX-hedged investments

in JGSs are regarded as substitutes for U.S. government securities in tranquil times, this could

easily break down in times of market stress.

Turning to SWFs of oil-producing economies, one often hears market talk that, when oil prices fall

and the country's fiscal position deteriorates, those SWFs tend to reduce their allocation of U.S.

dollars to the FX swap market, reflecting the reduced availability of investable funds. Staff analysis

at the Bank of Japan confirms that there is a positive correlation between fluctuations in oil prices

and transaction volumes in the FX swap market.

14

Such patterns, shown by overseas non-banks, of supplying dollar funds in the FX swap market

could exacerbate the procyclicality of international financial intermediation (Chart 13). For

13

For example, see Arai, F., Y. Makabe, Y. Okawara, and T. Nagano, "Recent Trends in Cross-currency

Basis," Bank of Japan Review, 16-E-7, September 2016.

14

See Iida et al. (2016) in footnote 2.

11

example, when emerging market economies are growing strongly, commodity demand would rise,

leading to increases in commodity prices including oil. Emerging market currencies would also

appreciate. In such an environment, increases in the assets of SWFs of oil-producing economies

would see those SWFs allocating some of the increases for investment in the FX swap market. At

emerging market economies, authorities would intervene to prevent the appreciation of their

currencies, and at least a part of U.S. dollars purchased in those interventions would be invested in

the FX swap market. Consequently, dollar funding premia in the FX swap market would decline

and encourage non-U.S. financial institutions to extend dollar credit. If this results in capital

inflows and increases in investment in emerging market economies, growth in those economies

would accelerate. On the other hand, if growth in emerging market economies were to decline for

one reason or another, the currencies of those economies would depreciate and commodity prices

would decline, reflecting weaker demand. Subsequently, the mechanism I have just described

would go into reverse gear. As SWFs of oil-producing economies and reserve managers of

emerging market economies restrain the supply of dollars in the FX swap market, dollar funding

premia would rise, non-U.S. financial institutions would cut back on their lending and securities

investments in emerging market economies, and growth of emerging market economies

consequently would be further adversely affected. An interest rate increase in the United States

could amplify such procyclicality in intermediation if such an action brings about rapid and

large-scale capital outflow from emerging market economies.

Interdependencies between Non-Banks and Banks

As I noted at the beginning today, fluctuations in external credit extended by non-U.S. banks

significantly affected the global economy (Charts 1 and 2). It also is a fact that, in the past,

non-banks such as SWFs and emerging market reserve managers had influenced the U.S. dollar

funding and credit activities of non-US banks.

15

For example, dollar deposits at European banks

were among the preferred destinations of investments by emerging market authorities, who have

increased their foreign exchange reserves in the 2000s, in view of the lessons learned during their

currency crises of the 1990s. Dollar deposits of European banks also enjoyed inflows of SWF

15

The Latin American Debt Crisis of the early 1980s was heavily influenced by international financial

intermediation stemming from abundant oil revenues. More specifically, following the two oil crises, a large

amount of oil revenues flowed into the oil-producing economies, and the money was lent to Latin American

economies via banks in the developed economies. Meanwhile, during the Japanese bubble economy of the

late 1980s, Japanese banks increased offshore funding and significantly increased lending through "impact

loans," which were outside the lending volume restrictions imposed by the Bank of Japan through "window

guidance." European banks, which were the main lenders to Japanese banks in the offshore market, were

sourcing a substantial part of their funding from the Middle East. As such, the impact loans were indirectly

supported by oil revenues.

12

money, which benefited from high oil prices until the summer of 2008. Subsequently, with the

global financial crisis and euro-area debt crisis, such deposits were withdrawn and contributed to

the deleveraging involving dollar assets at European banks.

16

The interdependencies between non-banks and banks have a history of procyclically amplifying

international financial intermediation in many forms. The developments in the FX swap market

represent only one manifestation of the interdependencies between overseas non-banks and

Japanese financial institutions. In order to maintain the stability of the international financial

system, it is important for the relevant authorities to always monitor and understand such

interdependencies.

VI. Final Words

Let me summarize my key points.

Non-U.S. financial institutions play a very important role in international financial intermediation,

which is dominantly U.S. dollar based. Monetary policy divergence between the U.S. and other

economies is likely to result in an increase of external claims of non-U.S. financial institutions and

hence they would be pressed for increased dollar funding. Given that there seems to be excess

demand for U.S. government securities, which are safe assets, the demand for debt instruments

issued by private financial intermediaries, which are substitutes of U.S. government securities,

would increase in tranquil times. Consequently, non-U.S. financial institutions would be able to

increase their dollar funding without difficulty. Meanwhile, from the viewpoint of investors

holding dollar funds, FX-hedged investments in non-U.S. sovereign securities arising from FX

swap transactions are substitutes of U.S. government securities. Here again, non-U.S. financial

institutions would be able to increase dollar funding through the FX swap market, although costs

could increase. Historically, however, there is evidence that the substitutability of debt instruments

issued by private financial intermediaries and FX-hedged investments in non-U.S. sovereign

securities might be compromised in times of stress, and this could negatively impact dollar funding

liquidity at non-U.S. financial institutions. Considering that the dollar funding of non-U.S.

financial institutions could be influenced by the investment behavior of non-banks -- including

SWFs, emerging market reserve managers, and investment funds -- we need to be mindful of the

16

For more detail, see Nakaso, H., "Financial Crises and Central Banks′ Lender of Last Resort Function,"

Remarks at the Executive Forum Hosted by the World Bank "Impact of the financial crises on central bank

functions," April 2013.

13

possibility of the behavior of banks and non-banks echoing each other under monetary policy

divergence and thus amplifying fluctuations in international financial intermediation and real

economic activity.

In addition, it is important to closely monitor risk-taking activities of non-U.S. financial institutions.

Under monetary policy divergence, U.S. dollar funding premia in the FX swap market could easily

spike higher. As such, the Bank of Japan would continue to monitor the activities of Japanese

banks so as to ensure that they would not, in response to increased funding costs for their dollar

investments, embark on excessive risk taking in terms of both credit risk and liquidity risk.

As much as monetary policy divergence itself is a product of central bank policy actions in each

economy aiming at price stability, it also is the responsibility of central banks to ensure that such

monetary policy actions would not destabilize the international financial system through the

behaviors of financial institutions. Today, the Japanese financial system remains stable. The Bank

of Japan will continue to encourage financial institutions to maintain a strong financial footing,

which prevents risks from materializing, and also strengthen its monitoring and analysis of

developments in the international financial system. The Bank, in coordination with other central

banks, will also enhance schemes to provide foreign currency liquidity to act as a backstop in case

of financial crises. I would like to conclude my observations today by promising you that,

consistent with what is in the Bank of Japan Act, the Bank will continue to discharge its

responsibilities as "Fortress Japan" and maintain financial intermediation functions in Japan.

Thank you very much for your attention.

MonetaryPolicyDiver

g

enceandGlobalFinancialStability:

g

FromthePerspectiveofDemandandSupplyofSafeAssets

January20,2017

Speech at a Meeting Hosted by

Speech

at

a

Meeting

Hosted

by

theInternationalBankersAssociationofJapan

HiroshiNakaso

DeputyGovernoroftheBankofJapan

Cross‐BorderClaimsofBanksintheWorldbyResidenceofCounterparty

Chart1

ratio to

world GDP %

ratio to

world GDP %

2.0

2.5

toDevelopingLatinAmericaandCaribbean

toDevelopingAfricaandMiddleEast

ratio

to

world

GDP

,

%

2.0

2.5

3.0

toDevelopingAsiaandPacific

ratio

to

world

GDP

,

%

1.0

1.5

1.0

1.5

0.0

0.5

1980 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15

CY

0.0

0.5

1980 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15

CY

3

10

12

toUnitedStates(lhs)

toUnitedKingdom(lhs)

toIreland,Italy,Greece,Portugal,Spain(lhs)

l (h)

ratiotoworldGDP,% ratiotoworldGDP,%

5

6

toJapan

ratiotoworldGDP,%

1

2

4

6

8

toDeve

l

opingEurope

(

r

h

s

)

2

3

4

0

1

0

2

4

1980

85

90

95

2000

05

10

15

0

1

2

1980

85

90

95

2000

05

10

15

Notes:1. Latest data as at end-December 2015.

2. Shaded areas indicate major credit cycle phases.

Sources: BIS; IMF.

1980

85

90

95

2000

05

10

15

CY

1980

85

90

95

2000

05

10

15

CY

USD‐DenominatedForeignPositionsofBanks

Chart2

U.S.andnon‐U.S.banks'

USD‐denominatedforeignclaims

Non‐U.S.banks'

cross‐currencyfundingratio

20

USDtrillions

18

%

16

20

14

16

18

A

B

12

10

12

14

Eurozonesovereign

debt crisis

A

‐

B

A

4

8

6

8

10

Global financialcrisis

debt

crisis

0

2000 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

CY

4

6

2000 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

CY

U.S.banks’USD‐denominatedforeignclaims

Non‐U.S.banks’USD‐denominatedforeignclaims(A)

Non‐U.S.banks’USD‐denominatedforeignliabilities(B)

Notes: 1. Latest data as at en

d

-June 2016.

2. "Non-U.S. banks' USD-denominated foreign claims" and "Non-U.S. banks' USD-denominated foreign liabilities" are calculated as USD-denominated foreign claims and

liabilities of all reporting countries after excluding those of U.S. banks, respectively.

3. "Non-U.S. banks' cross-currency funding ratio" is calculated as "Non-U.S. banks' USD-denominated foreign claims" less "Non-U.S. banks' USD-denominated foreign

liabilities," divided by "Non-U.S. banks' USD-denominated foreign claims."

Source: BIS.

ForeignClaimsbyBankNationality

Chart3

USD

t illi

5

Japanesebanks

USD

t

r

illi

ons

4

U.S.banks

Germanbanks

3

Frenchbanks

Swissbanks

2

U.K.banks

1

0

2000 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data as at end-June 2016.

2. Euro area claims for German and French banks are excluded.

Source: BIS.

CY

FXSwapImpliedUSDFundingRatesandBanks'Creditworthiness

Chart4

FXswap impliedUSDfundingrates

(DeviationfromUSDLIBOR)

Non‐U.S.banks'defaultprobability

(ExpectedDefault Frequency)

%

%

%

1.2

1.4

6

7

Japanesebanks(lhs)

Euroareabanks(lhs)

%

%

12

1.4

1.6

USD/JPY

EUR/USD

%

08

1.0

4

5

U.K.banks(lhs)

Japanpremium(rhs)

0.8

1.0

1

.

2

EUR/USD

GBP/USD

0.6

0

.

8

3

4

0.4

0.6

0.2

0.4

1

2

‐

02

0.0

0.2

0.00

1995 98 2001 04 07 10 13 16

CY

‐0.4

0

.

2

1995 98 2001 04 07 10 13 16

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data as at November 2016.

2. The shaded areas correspond to Japan's financial crisis (November 1997 through March 1999), the global financial crisis (December 2007 through June 2009), and the Eurozone

sovereign debt crisis (May 2011 through June 2012).

3. Non-U.S. banks' default probability is the average of the EDF (Expected Default Frequency) of G-SIBs that are headquartered in each jurisdiction. "Japan Premium" is calculated

as 3-month USD TIBOR less 3-month USD LIBOR.

Sources: Bloomberg; Moody's; BOJ.

OutwardPortfolioInvestment(EuroAreaandJapan)

Chart5

Euroarea Japan

ll

10

15

Outwardportfolioinvestment

JPY tri

ll

ions

toUnitedStates

to other countries

150

200

Outwardportfolioinvestment

EURbillions

toUnitedStates

toothercountries

5

to

other

countries

100

5

0

FRB

rate hike

▲▲

0

50

‐10

‐

5

FRB

tapering

▲

QQEwithYCC

‐50

0

FRB

tapering

FRB

rate hike

▲▲▲

‐15

2009 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

BOJmonetary easing

▼

▼▼

CY

▼▼

‐100

2009 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

▼

▼▼

▼

▼

▼

▼

ECB monetaryeasing

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data for euro area as at end-September 2016, data for Japan as at end-June 2016.

2. In each chart, ▲/▼ indicates the timing and direction of monetary policy changes since 2013.

Sources: ECB; Ministry of Finance; BOJ.

PrimeMMFHoldingsofBankRelatedSecurities

Chart6

Asatend‐June2016

Asatend‐October2016

160

USDbillions

160

USDbillions

100

120

140

100

120

140

60

80

100

60

80

100

0

20

40

0

20

40

Japan

n

itedStates

Canada

France

Sweden

Australia

e

dKingdom

Germany

N

etherlands

S

witzerland

k

nationality)

Canada

n

itedStates

France

Japan

Sweden

Australia

e

dKingdom

Germany

N

etherlands

S

witzerland

k n ationality)

U

n

Unit

e

N

S

(Ban

k

U

n

Unit

e

N

S

(Ban

Note: Prime MMF holdings of bank related securities are aggregated by country based on the location of banks' global headquarters. "Australia" includes New Zealand.

Source: SEC.

JapaneseMajorBanks'ForeignCurrencyDenominatedBalanceSheet

Chart7

Asatend‐March2016

Asatend‐October2016

1,600

USDbillions

1,600

USDbillions

463

1,200

1,400

Loans

Client‐relateddeposits

530

1200

1,400

Loans

Client‐relateddeposits

+67

823

168

97

1,000

1,200

Loans

Corporate bonds,etc.

Medium‐ to long‐term

856

106

1,000

1

,

200

Corporate bonds,etc.

Mdi

t

l

t

+9

+33

224

231

59

168

600

800

Interbank investments

FXandcurrencyswaps

Repos

Short‐termFXandcurrencyswaps

237

257

66

160

600

800

Interbankinvestments

M

e

di

um‐

t

o

l

ong‐

t

erm

FXandcurrencyswaps

Repos

Short‐term FXandcurrencyswaps

+26

‐1

380

461

224

400

Securities

Interbankfunding

38

1

09

257

400

Securities

Interbankfunding

+26

+1

+13

101

54

380

461

0

200

Others

Others

(ofwhich:CD・CP268)

107

58

38

4

09

0

200

Others

(ofwhich:CD・CP206)

Others

‐62

+1

Note: The charts include major banks classified as internationally active banks.

Source: BOJ.

Assets Liabilities

Assets Liabilities

U.S.YieldSpreads

Chart8

16

18

Stockyield(basedonexpectedearnings)

Stockyield(basedonactualearnings)

Long‐termgovernmentbondyield

%

6

8

Yieldspread(basedonexpectedearnings)

Yieldspread(basedonactualearnings)

%

12

14

4

6

10

12

2

6

8

‐2

0

2

4

‐4

0

1960 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15

CY

‐6

1960 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data as at end-November 2016.

2. Stock yield = EPS / stock price. "Stock yield (based on expected earnings)" is calculated using EPS (forward twelve months), "Stock yield (based on actual earnings)" is calculated

using EPS (trailing twelve months). Yield spread = Stock yield - Long-term government bond yield.

3. S&P 500 for stock price; U.S. 10-year government bond for long-term government bond yield.

Source: Bloomberg.

TheImpactofU.S.MMFReform

Chart9

MMFassets U.S.short‐termrates

3

USD trillions

0.5

OISspreads,%

GovernmentMMF

PrimeMMF

0.3

0.4

T‐Bill(3M)

LIBOR(3M)

2

0.1

0.2

1

‐0.1

0.0

0

1

3

14 1

5

1

6

20

‐0.3

‐0.2

13

14

15

16

20

Note: Latest data as at end-November 2016.

Source: Bloomberg.

3

5

6

CY

20

13

14

15

16

20

CY

AmountofForeignCurrencyFundingand FXSwapTransactionVolume

Amountofforei

g

ncurrenc

y

fundin

g

Transactionvolume

Chart10

g y

g

viaFXswapsandcurrencyswaps

byJapanesefinancialinstitutions

intheFXswapmarket(USD/JPY)

viaTokyoFXmarketbrokers

1300

USD billions

70

USDbillions

1,200

1

,

300

Majorbanksand

institutionalinvestors,etc.

Including regional financial

70

1,000

1,100

Including

regional

financial

institutions

60

800

900

50

600

700

40

500

600

2010 11 12 13 14 15 16

FY

30

2010 11 12 13 14 15 16

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data as at September 2016.

2.Average transaction volume for each business day (includes outright forwards).

3.Trends are calculated using the two-sided HP filter.

Source: BOJ.

Notes: 1. Estimates by the BOJ. Latest data as at end-September 2016.

2. "Major banks and institutional investors, etc." includes major banks, depository

institutions with a particular focus on market investment, and life insurance

companies.

Sources: Bloomberg; The Life Insurance Association of Japan; Published accounts of

each company; BOJ.

JapaneseFinancialInstitutions'OutwardInvestmentsinForeignSecuritiesChart11

JPY

t illi

120

140

Banks(depositorycorporations)

Insuranceandpensionfunds

JPY

t

r

illi

ons

100

120

Insuranceandpensionfunds(includingpublicpensions)

Securitiesinvestmenttrusts

80

40

60

20

40

0

1998 2000 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

CY

Notes: 1. Latest data as at end-September 2016.

2. The amounts are calculated by adding the flow during each period to the stock as at end-December 1997, to adjust for the impact of exchange rate fluctuations.

Source: BOJ.

CY

TransactionVolumeintheFXSwapMarketandBondInvestmentFlows

Chart12

Scatterplot(CY2009‐ CY2016) BondinvestmentflowsintoJapan

4

JPYtrillions

4

2

3

China's stockmarketcrash

Greekdebtissues

2

3

PYtrillions)

1

2

1

2

sintoJapan (J

‐1

0

‐1

0

v

estmentflow

3

‐2

Globalfinancialcrisis

Tapertantrum

Highvolatilityin

globalfinancialmarkets

3

‐2

Bondin

v

‐

3

2009 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

CY

‐

3

30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65

TransactionvolumeintheFX swap market

(USD/JPY,USDbillions)

Notes: 1. Latest data as at October 2016.

2. Figures are 3-month backward moving averages.

3. The transaction volume in the FX swap market (USD/JPY) is the average (via Tokyo FX market brokers) for each business day and includes outright forwards.

Sources: Ministry of Finance; BOJ.

Chart13

GlobalLiquidityAmplificationMechanismthroughtheFXSwapMarket

USmonetarypolicy

(Interest rate hike)

SlowdowninEMeconomies

?

spillover

(Interest

rate

hike)

Declineinoilprices EMCapitaloutflows

spillover

Whilearbitragetradingby

SWFsandFXreservemanagers

d h l f USD i h

bankshasdeclineddueto

regulations,realmoney

investorshaveenlarged

re

d

ucet

h

esupp

l

yo

f

USD

i

nt

h

e

FXswapmarket

theirfootprintintheFX

swapmarket

RiseinFXswapimpliedUSD

fundingrate

Globalbanks(non‐USbanks)

curtailUSD‐denominated

lending to EMs

lending

to

EMs