1

Global Fund

Prospective Country

Evaluation

2021 SYNTHESIS REPORT

19 February 2021

Myanmar

Knowledge

Management

CAMBODIA

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC OF THE

CONGO

GUATEMALA

MOZAMBIQUE

MYANMAR

SENEGAL

SUDAN

UGANDA

ii

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report are those of the author. The author has been commissioned by

the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) to conduct an assessment to provide input into

TERG’s recommendations or observations, where relevant and applicable, to the Global Fund.

This assessment does not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Fund or the TERG.

This report shall not be duplicated, used, or disclosed – in whole or in part without proper

attribution.

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report are those of the author. The author has been commissioned by

the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) to conduct an assessment to provide input into

TERG’s recommendations or observations, where relevant and applicable, to the Global Fund.

This assessment does not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Fund or the TERG.

This report shall not be duplicated, used, or disclosed – in whole or in part without proper

attribution.

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report are those of the author. The author has been commissioned by

the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) to conduct an assessment to provide input into

TERG’s recommendations or observations, where relevant and applicable, to the Global Fund.

This assessment does not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Fund or the TERG.

This report shall not be duplicated, used, or disclosed – in whole or in part without proper

attribution.

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report are those of the author. The author has been commissioned by

the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) to conduct an assessment to provide input into

TERG’s recommendations or observations, where relevant and applicable, to the Global Fund.

This assessment does not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Fund or the TERG.

This report shall not be duplicated, used, or disclosed – in whole or in part without proper

attribution.

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report are those of the author. The author has been commissioned by

the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) to conduct an assessment to provide input into

TERG’s recommendations or observations, where relevant and applicable, to the Global Fund.

This assessment does not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Fund or the TERG.

This report shall not be duplicated, used, or disclosed – in whole or in part without proper

attribution.

iii

Authorship

Alexander Marr

Allison Osterman

Audrey Batzel

Dr. Bernardo Hernandez Prado

Bethany Huntley

Casey Johanns

Christen Said

Emily Carnahan

Francisco Rios Casas

Dr. Herbert Duber

Dr. Juliann Moodley

Dr. Kate Macintyre

Dr. Katharine D. Shelley

Dr. Louisiana Lush

Matthew Cooper

Dr. Matthew Schneider

Dr. Nicole A. Salisbury

Patric Prado

Dr. Saira Nawaz

Thomas Glucksman

UCSF

PATH

IHME

IHME

IHME

IHME

UCSF

PATH

IHME

IHME

EHG

EHG

PATH

EHG

EHG

IHME

PATH

UCSF

PATH

IHME

iv

Contents

Authorship ................................................................................................................................................................................ iii

Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................................................... v

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ vii

Chapter 1 .................................................................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1

1.2 Grant cycle approach ............................................................................................................................................... 1

1.3 Focus topics .................................................................................................................................................................. 2

1.4 Methods .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3

Data ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3

Budget variance ............................................................................................................................................................ 3

Indicator performance tracking ............................................................................................................................ 4

Root cause analyses .................................................................................................................................................... 4

RSSH Support vs. Strengthening “2S” analysis .............................................................................................. 4

Analytical approach to synthesis .......................................................................................................................... 4

Chapter 2: NFM2 grant cycle ............................................................................................................................................ 5

2.1: NFM2 funding request to grant making ........................................................................................................ 5

2.2: NFM2 grant implementation .............................................................................................................................. 9

Implementation Progress ........................................................................................................................................ 9

The role of revisions during implementation .............................................................................................. 14

Chapter 3: Lessons learned NFM2 to NFM3 ............................................................................................................ 22

Chapter 4: Discussion and conclusions ..................................................................................................................... 35

Chapter 5: Strategic recommendations/considerations ................................................................................... 36

References ............................................................................................................................................................................... 39

Annexes .........................................................................................................................................................................................I

Annex 1. Summary of countries eligible for matching funds in NFM2 and NFM3 by type. .............I

Annex 2. Qualitative data collected by PCE countries .......................................................................................I

Annex 3. Approach to identification of human rights, gender, and other equity-related

investments .......................................................................................................................................................................... II

Annex 4. PCE 2020 Guidance on Operationalizing the 2S Framework ................................................... X

Annex 5. Supplemental figures of budget changes by disease and RSSH ........................................ XVII

Annex 6. Table of cumulative absorption by year for all modules, RSSH modules, and HRG-

Equity-related modules.............................................................................................................................................. XIX

Annex 7: Application of the Global Fund’s performance-based funding model ............................. XXI

v

Acronyms

ACT

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

APE

Agente Polivalente Elementars

AGYW

Adolescent girls and young women

ART

Antiretroviral therapy

C19RM

COVID-19 Response Mechanism

CCM

Country Coordinating Mechanism

CCS

Collaborating Centre for Health [Mozambique]

CEP

Country Evaluation Partner

CRG

Global Fund Communities, Rights, and Gender Team

COE

Challenging Operating Environment

CSO

Civil society organization

CSS

Community Systems strengthening

CT

Country Team

DGS/DAGE

Direction Générale de la Santé/Direction de l’Administration Générale et de

l’Equipement [Sénégal]

DHIS2

District Health Information System 2

DRC

Democratic Republic of the Congo

EDT

Essential Data Tables

EHG

Euro Health Group

FEW

Female Entertainment Worker

FSW

Female sex worker

GAC

Grant Approvals Committee

GEP

Global Evaluation Partner

HMIS

Health Management Information System

HRG-Equity

Human rights, gender, equity

IHME

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

ISD

Integrated service delivery

KII

Key informant interview

KVP

Key and vulnerable population

LFA

Local Fund Agent

LIC

Low-income country

LLIN

Long-lasting insecticide-treated net

LMIC

Lower-middle income country

M&E

Monitoring and evaluation

MDR-TB

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

MMT

Methadone maintenance treatment

MoH

Ministry of Health

MoHA

Ministry of Home Affairs [Myanmar]

MoU

Memorandum of Understanding

MSAS

Ministère de la Santé et des Affaires Sociales [Sénégal]

MSM

Men who have sex with men

NFM2

New Funding Model 2 (2017-2019 funding cycle)

NFM3

New Funding Model 3 (2020-2022 funding cycle)

NSP

National Strategic Plan

OBR

Official Budget Revision

OIG

Office of the Inspector General

vi

OPN

Operational Policy Note

PAAR

Prioritized Above Allocation Request

PCE

Prospective Country Evaluation

PLHIV

People living with HIV

PMTCT

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

PR

Principal Recipient

PSM

Procurement and supply chain management

PU/DR

Progress update and disbursement request

PWID

People who inject drugs

QA

Quality Assurance

RAI3E

Regional Artemisinin-resistance Initiative 2 Elimination Program

RCA

Root cause analysis

RSSH

Resilient and sustainable systems for health

SO

Strategic Objective

SR

Sub-recipient

STC

Sustainability, transition, and co-financing policy

TERG

Technical Evaluation Reference Group

TRP

Technical Review Panel

UCSF

University of California, San Francisco

UHC

Universal health coverage

UMIC

Upper middle income country

UNOPS

United Nations Office for Project Services

UQD

Register of Unfunded Quality Demand

VfM

Value for Money

WPTM

Work Plan Tracking Measures

vii

Executive Summary

Introduction

In 2020, the Prospective Country Evaluation (PCE) took a comprehensive look at the Global Fund

grant cycle, assessing how business model factors have facilitated or hindered the achievement

of objectives during implementation of grants approved through New Funding Model 2 (NFM2;

2017-2019 funding cycle), including around Resilient and Sustainable Systems for Health (RSSH),

sustainability and equity, and whether lessons learned during the current grant have informed

the next funding cycle. In this report, we present our synthesis of findings from eight PCE

countries: Cambodia, DRC, Guatemala, Mozambique, Myanmar, Senegal, Sudan and Uganda. The

objective of the grant cycle analysis was to understand what, when, why and how grant

investments change over time, including significant factors that influenced the implementation of

and changes to the original grant. In each country, this was assessed using focus topics as lenses

to evaluate the grant cycle and to better understand drivers of change. This report follows the

grant cycle, first presenting synthesis findings from NFM2, including the funding request and

grant making process and implementation, followed by how the NFM3 (2020-2022 funding cycle)

grant design process was informed by lessons from NFM2. Conclusions related to grant design

and implementation are discussed in Chapter 4, focusing primarily on RSSH and human rights,

gender and other equity-related investments (HRG-Equity), paralleling Global Fund Strategic

Objectives 2 and 3.

1

NFM2 funding request to grant making

The PCE found that grant design and budgets did not change significantly during the NFM2 grant

making process from the Global Fund’s Technical Review Panel (TRP)-approved funding

requests, although proportionally more changes were made to investments in HRG-Equity and

RSSH areas. In the majority of PCE countries, investments in reducing HRG-Equity barriers

declined during grant making, whereas RSSH budgets show large increases in some countries and

declines in others. Factors that influenced prioritization and changes during grant making

included Country Team support and input, catalytic matching funds investments and TRP review

and comments, among others.

NFM2 grant implementation

NFM2 grant implementation has been uneven, including start-up delays during Year 1, primarily

as a result of the lengthy selection and contracting processes for sub-recipient implementers.

After grant start-up, absorption performance increased in Year 2, although weak grant

coordination and issues with performance monitoring constrained ongoing implementation

progress. The PCE found that early implementation delays disproportionately affected RSSH and

HRG-Equity activities and absorption remained particularly low in some RSSH and HRG-Equity-

related investment areas. However, regular progress reviews and grant coordination meetings

among key stakeholders helped accelerate implementation of the grants. During Year 3, the onset

of the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruption, particularly for HRG-Equity

investments, which required agile adaptations. Grant revision processes introduced to support

1

Building from this 2021 PCE Synthesis Report, the TERG commissioned a three-month extension phase

(April-June 2021) to focus on deeper analysis. Key areas explored included: NFM2 grant revision issues

and lessons learnt from the Global Fund’s response to COVID-19; Health systems support and

strengthening; Reasons for the limited uptake of RSSH coverage indicators; and NFM3 grant making,

including drivers of budgetary shifts and transparency, country ownership and inclusion. Additional

findings and recommendations are being produced.

viii

the COVID-19 response were flexible and a reasonably ‘light lift’ for country stakeholders,

enabling rapid implementation adjustments in 2020.

In contrast, grant revisions are usually perceived as burdensome and administratively complex.

Additional funding revisions tended to occur earlier in the grant lifecycle, initiated by the

Secretariat and negotiated between the Country Teams (CTs), Country Coordination Mechanisms

(CCMs) and grant recipients, and were based on reviews of high-priority activities from the

register of unfunded quality demand (UQD). Program revisions (‘reprogramming’) to the scale or

scope of grants were uncommon, occurring in only four PCE countries. Evidence from some PCE

countries suggests that some potential program revisions (e.g., where new evidence became

available) were not undertaken during NFM2 and were instead shifted for inclusion in NFM3

funding requests—in part due to the burdensome program revision process and the short three-

year implementation cycle. PCE countries most frequently made budget revisions (‘reallocation’)

as a financial management tool to influence absorption. In most PCE countries, this resulted in a

cumulative shifting of unused resources to later in the grant cycle, rather than undertaking a more

substantial program revision, particularly for low absorbing RSSH and HRG-Equity interventions.

Using budget revisions systematically to shift unutilized resources from Year 1 to Years 2 and 3,

and subsequently from Year 2 to Year 3, has significant potential to reduce allocative efficiency.

The lack of sufficient programmatic performance data upon which to guide revision decisions

likely contributes to the emphasis on using budget revisions to influence absorption.

The annual funding decision does not appear to be working as intended to operationalize the

principle of performance-based funding. Specifically, disbursements often varied dramatically

from the total agreed budget for each reporting period and, even when performance against grant

targets and indicators was weak, disbursements were often above or a relatively high proportion

of the total grant budget. As such, it is unclear if or how disbursements are being used to

incentivize performance.

Lessons learned NFM2 to NFM3

Ensuring grants are well designed at the time of the grant award is critical. In most PCE countries,

the NFM3 funding request process was an improvement over NFM2. With some variation, it was

more streamlined, efficient and flexible, characterized by improved country ownership,

participation by a wider group of stakeholders and with a range of business model factors used

effectively to influence grant priorities. However, despite greater inclusivity, transparency and

country ownership during funding request development, this tended to decline during the grant

making stage, where key decisions were often taken. Nonetheless, KVP representatives reported

feeling more included in NFM3 funding request processes than in NFM2, in some cases helped by

having gained experience from previous processes and having received support to build their

capacity. The efficiency of the Matching Funds application process also improved for NFM3

compared to NFM2. TRP recommendations (made both on NFM2 and NFM3 funding requests)

informed NFM3 grant designs, often with implications for HRG-Equity and RSSH related

investments. However, across all application approaches, COVID-19 changed the way the funding

request and grant making processes were managed, with both positive and negative implications.

The Global Fund’s successful Sixth Replenishment, alongside a commitment to ‘do things

differently’ offered an important opportunity to ‘change the trajectory’ in NFM3. NFM3 funding

requests included significantly larger budgets and focus on some—but not all—of the areas

where a change in trajectory is needed to meet the Global Fund Strategic Objectives.

ix

HRG-Equity: PCE countries show evidence of NFM3 funding requests being designed with

explicitly more focus than in NFM2 on improving equitable access to health services and

allocating resources to intervention approaches that are known to contribute to greater

programmatic sustainability. However, in some cases, efficiency and/or effectiveness

considerations appear to have taken precedence over equity considerations in NFM3 grant

design. For instance, in response to concerns with efficiency, some countries adjusted NFM3 PR

and SR implementation arrangements with potentially negative consequences for equity. On the

other hand, several PCE countries used better-quality and/or more recent data on KVPs during

NFM3 compared to NFM2, which enabled grants to set up new interventions to target KVPs more

precisely or widen the geographical distribution of places that KVPs would receive services.

However, the quality of data (particularly the accuracy of KVP population size estimates)

continues to constrain these decisions and overall allocative efficiency.

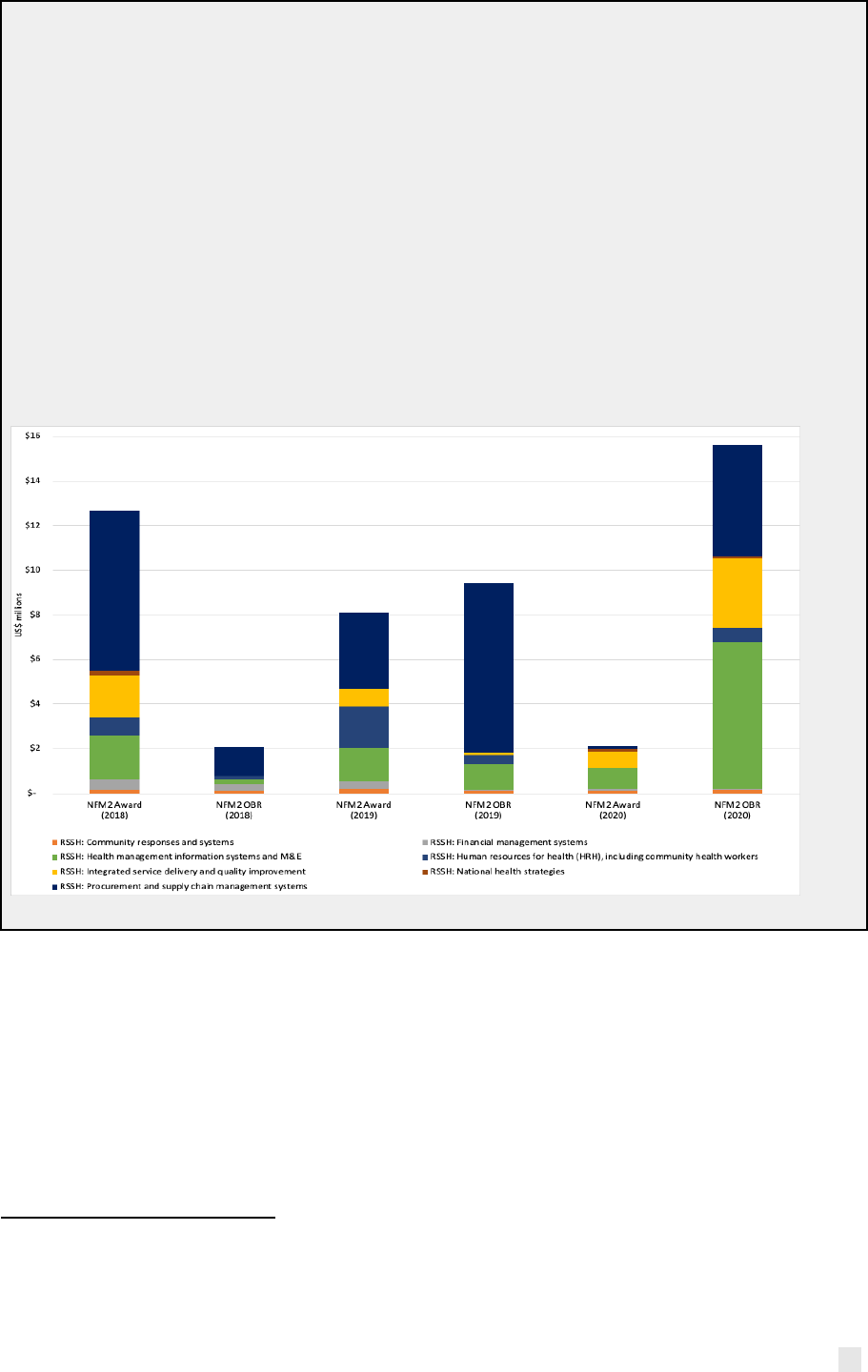

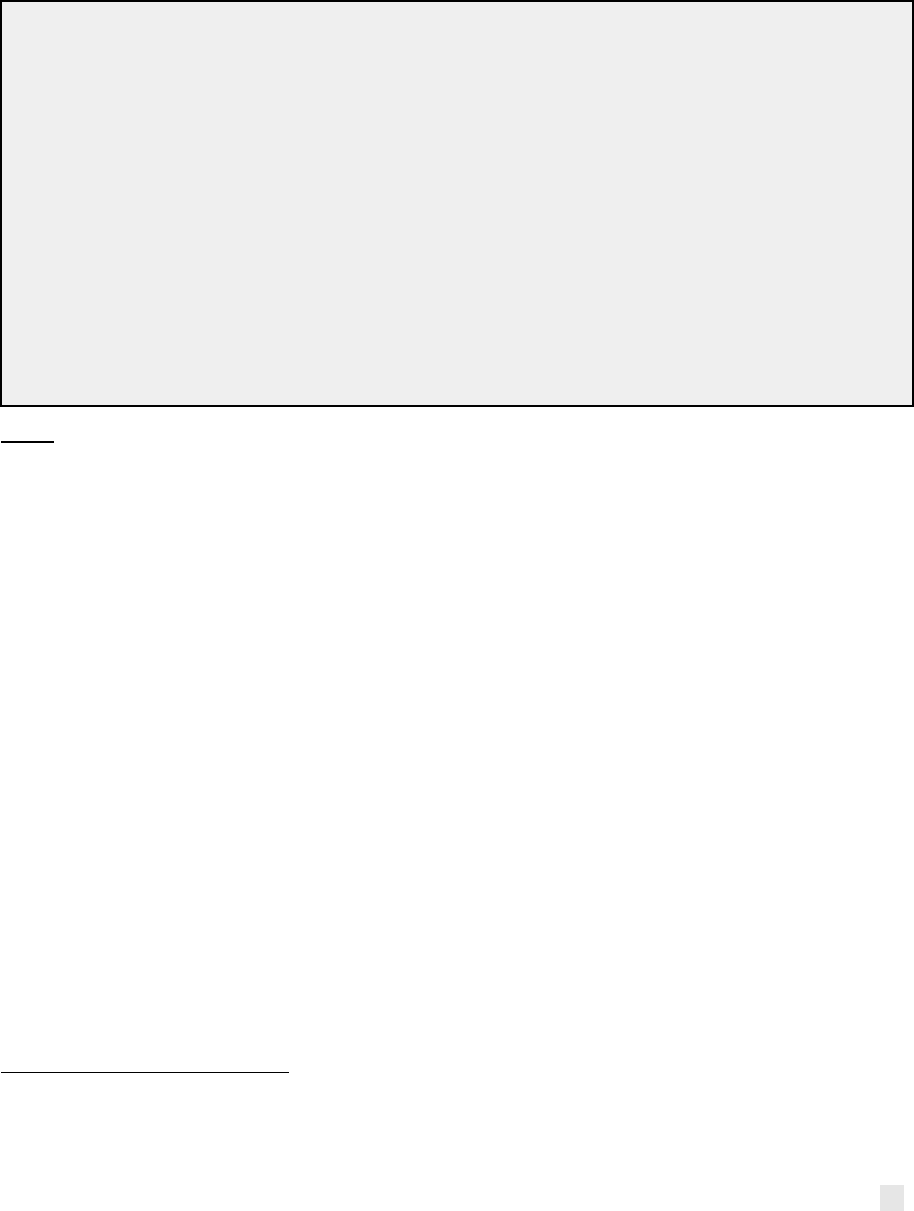

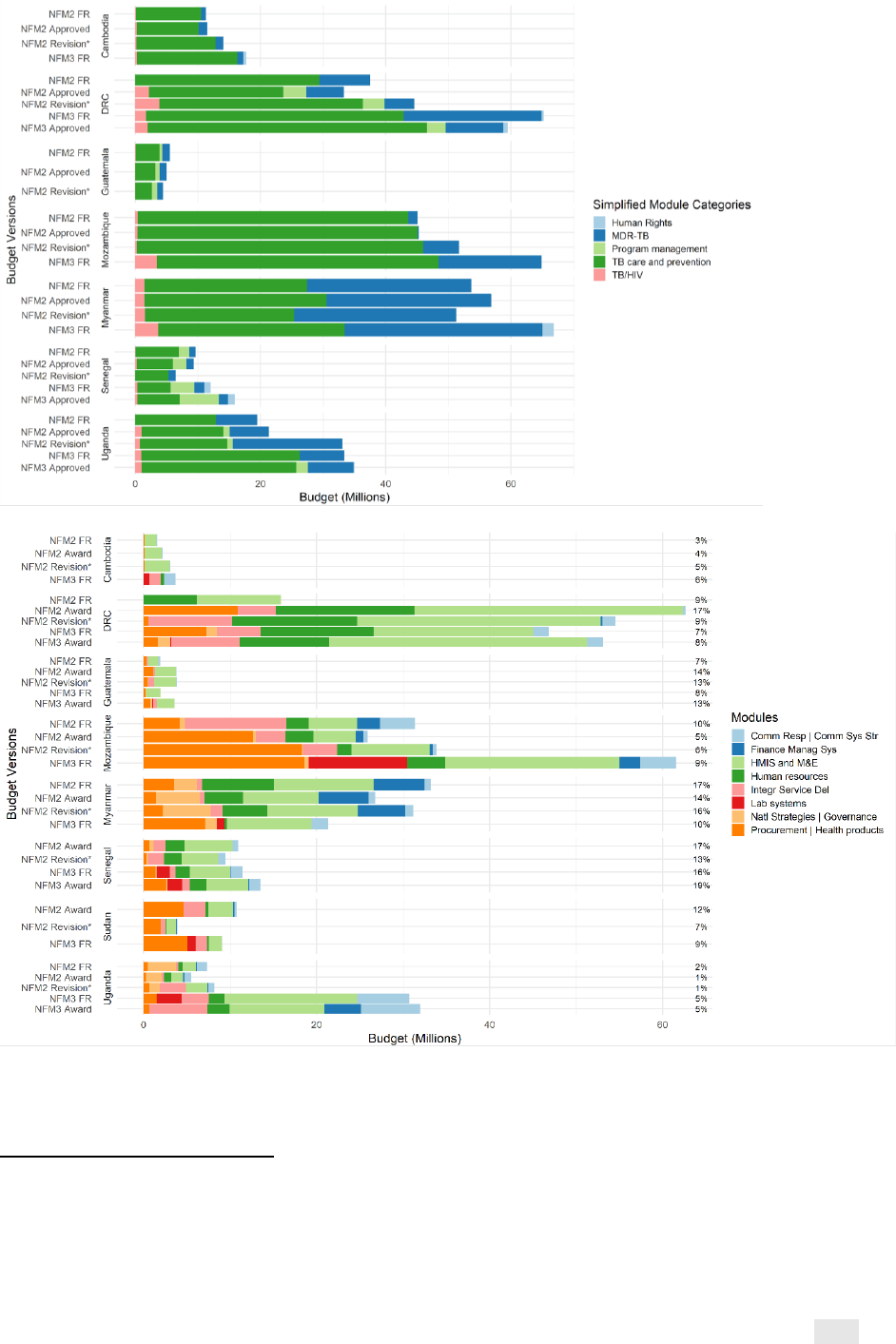

RSSH: Most PCE countries increased their allocation to RSSH in NFM3, although, compared to

NFM2, a greater proportion of these investments are designed to support rather than strengthen

health systems. As such, it is unclear how the NFM3 grants are intended to ‘change the trajectory’

for the achievement of SO2. Evidence suggests that the Global Fund’s RSSH guidance “to shift from

a focus on short-term, input-focused support...towards more strategic investments...that build

capacity and lead to sustainable results”(1) is not being systematically operationalized. In some

countries, NFM3 RSSH investment design builds upon progress made during NFM2, especially in

HMIS/M&E, but most PCE grants did not appear to use the NFM3 funding request process to link

RSSH investments more strategically with sustainability plans. In some countries, NFM3 grants

are shifting RSSH intervention approaches, with greater emphasis on community systems

strengthening for improving access to and quality of service delivery. Several countries show

governance adaptations to improve coordination and implementation of crosscutting RSSH

investments. Despite extensive new guidance, most NFM3 grant performance frameworks do not

appear to include many of the new RSSH coverage indicators, suggesting that monitoring RSSH

performance and progress toward meeting SO2 will remain a challenge. Coverage indicators

rarely capture aspects of system strengthening (such as data use for decision-making) and some

RSSH investment areas do not map well to available indicators.

Conclusions

Grant design

1. Improvements to the business model between NFM2 and NFM3 contributed to more

efficient and inclusive funding request processes. However, NFM3 saw limited adoption

of changes in the design of performance monitoring, particularly for HRG-equity and

RSSH.

2. In NFM3, both RSSH and HRG-Equity investments rose, in many cases as a result of

overall allocation increases. An increased proportion of RSSH investment is directed

toward activities that support rather than strengthen the health system.

Grant implementation

3. Implementation of NFM2 grants faced significant start-up delays and COVID-19

interruptions. Absorption was overall weaker for RSSH and HRG-Equity interventions.

4. Multiple barriers and challenges exist for undertaking revisions to the scope and/or

scale of grants mid-cycle, such as in response to new evidence or emerging performance

issues.

x

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Improve grant-specific performance monitoring to inform

implementation decisions.

• Establish routine grant review processes at the country level with a quality improvement

lens, emphasizing grant-specific performance data and drawing on emerging evidence

and data to better inform revisions that maximize impact. (PRs, Grant Management

Division including Country Teams)

• Implement proposed reforms of the grant rating system to reflect both grant-specific

performance and contribution of Global Fund grants to national program performance.

Additionally, this should draw upon qualitative inputs, including expertise of the CCM,

LFA, Country Team and wider Secretariat. (Grant Management Division, Strategy

Committee, Board)

• Based on the revised grant rating system, the Secretariat should also develop a set of

indicative options to demonstrate how good and poor performance could be responded

to, and a framework for deciding when and how to introduce these measures in different

contexts and circumstances (Grant Management Division, Strategy Committee, Board).

• Strengthen the use of revised RSSH indicators to address delayed implementation and

potential deprioritization throughout grant implementation. (PRs, Grant Management

Division including Country Teams)

Recommendation 2: Build in more flexibility and responsiveness in implementation by

simplifying grant revision processes to encourage their use throughout the grant cycle.

• Consider flexibilities and streamlining of material program revision process to

encourage/reward earlier introduction of innovative programming that maximizes

impact and limits non-strategic budgetary shifts to later in the 3-year grant cycle.

(Secretariat)

• Introduce flexibilities to PR and SR contractual arrangements and performance

frameworks that can be used to introduce mid-term changes as required. (PRs, Grant

Management Division)

• Through the Secretariat’s planned grant revision review (mid-2021), examine how

countries could strengthen data-driven revision decisions (thereby avoiding the over-

reliance on financial data to guide revision decisions), in line with establishing a more

streamlined, flexible process for program revision. (Secretariat)

Recommendation 3: In order to reduce gaps between policy guidance and grant design,

improve communication around how to invest more strategically in RSSH, including CSS.

• In the next Strategy, the Global Fund board in collaboration with the Secretariat should

clarify their position on whether the primary objective of RSSH is to support the three

disease programs or to invest more holistically in health systems strengthening. (Board,

Secretariat RSSH team)

• Clarify specific Global Fund RSSH priority areas and what strengthening as opposed to

supportive investment would look like for these, including specific purpose, indicators

and targets in performance frameworks. (Secretariat RSSH team, Country Teams)

• To facilitate integration and strengthening RSSH, ensure proper engagement and

ownership from health system planning experts and leaders to support health sector-

wide programming decisions, including alignment of grant design and sustainable

financing within wider national health, health system and UHC policy context, and the

timelines associated with broader strengthening efforts. (PRs, Country Teams)

xi

Recommendation 4: In order to improve grant contribution to equity and SO3, explicitly

promote grant investments in these areas, including through more direct measurement

of the drivers of inequity and of outcomes of human rights and gender investments.

• Invest more in data and data use, including up-to-date KVP surveys as well as other data

sources that shed light on socio-economic, gender, geographical and ethnic differences in

disease burden and access to services that grants are aiming to contribute to. (Country

Teams, national stakeholders)

• Ensure performance frameworks incorporate existing data including on human rights

and political commitment as well as disease burden and service access amongst different

population groups and use this data effectively to monitor grant contribution to both SO3

and SO1 or disease impact. (Country Teams, national stakeholders)

• Recognizing the success of strategic initiatives and/or matching funds in incentivizing

grant investments in reducing equity, human rights and gender related barriers to

accessing services, prioritize scaling up across the portfolio and incentivizing such

investments through mainstream grant management operations. This should include

explicit efforts to improve implementation and where necessary, timely revisions to

maximize grant contribution to reducing barriers to care and disease impact. (Grant

Management Division, Strategic Initiatives team)

1

Chapter 1

1.1 Introduction

The Prospective Country Evaluation (PCE) is an independent, multi-year prospective evaluation

of the Global Fund, commissioned by the Global Fund’s Technical Evaluation Reference Group

(TERG). The goal of the PCE is to evaluate how the Global Fund business model operates in eight

countries in order to generate evidence that will accelerate progress towards meeting the Global

Fund Strategic Objectives (SOs). The PCE is led by two Global Evaluation Partners (GEPs), in

collaboration with eight Country Evaluation Partners (CEPs). The Euro Health Group/University

of California San Francisco (EHG/UCSF) consortium supports Cambodia, Mozambique, Myanmar

and Sudan; the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)/PATH consortium supports

the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guatemala, Senegal and Uganda. These eight

countries, although not selected to be formally representative of the Global Fund portfolio overall,

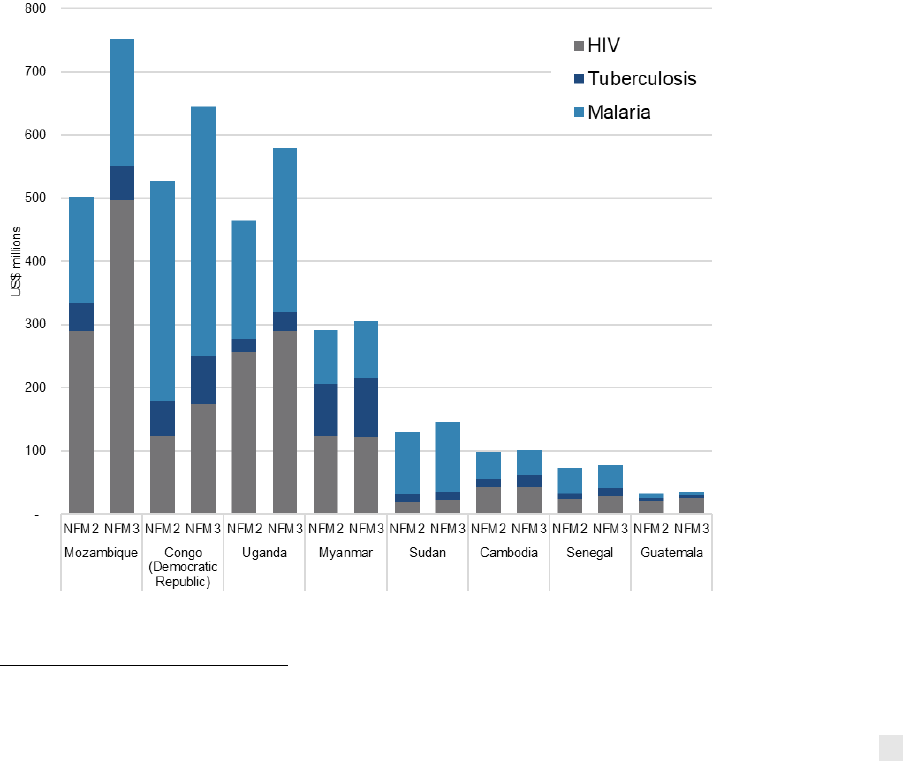

comprise approximately 20% of the investment during the 2017-2019 allocation period (US$2.2

billion) and 2020-2022 allocation period (US$2.5 billion), and present an array of disease

epidemics, geographies, development statuses and Global Fund support (Table 1, with additional

details available in Annex 1). Among the countries, only Guatemala is transition-eligible for

malaria and TB in the next funding cycle.

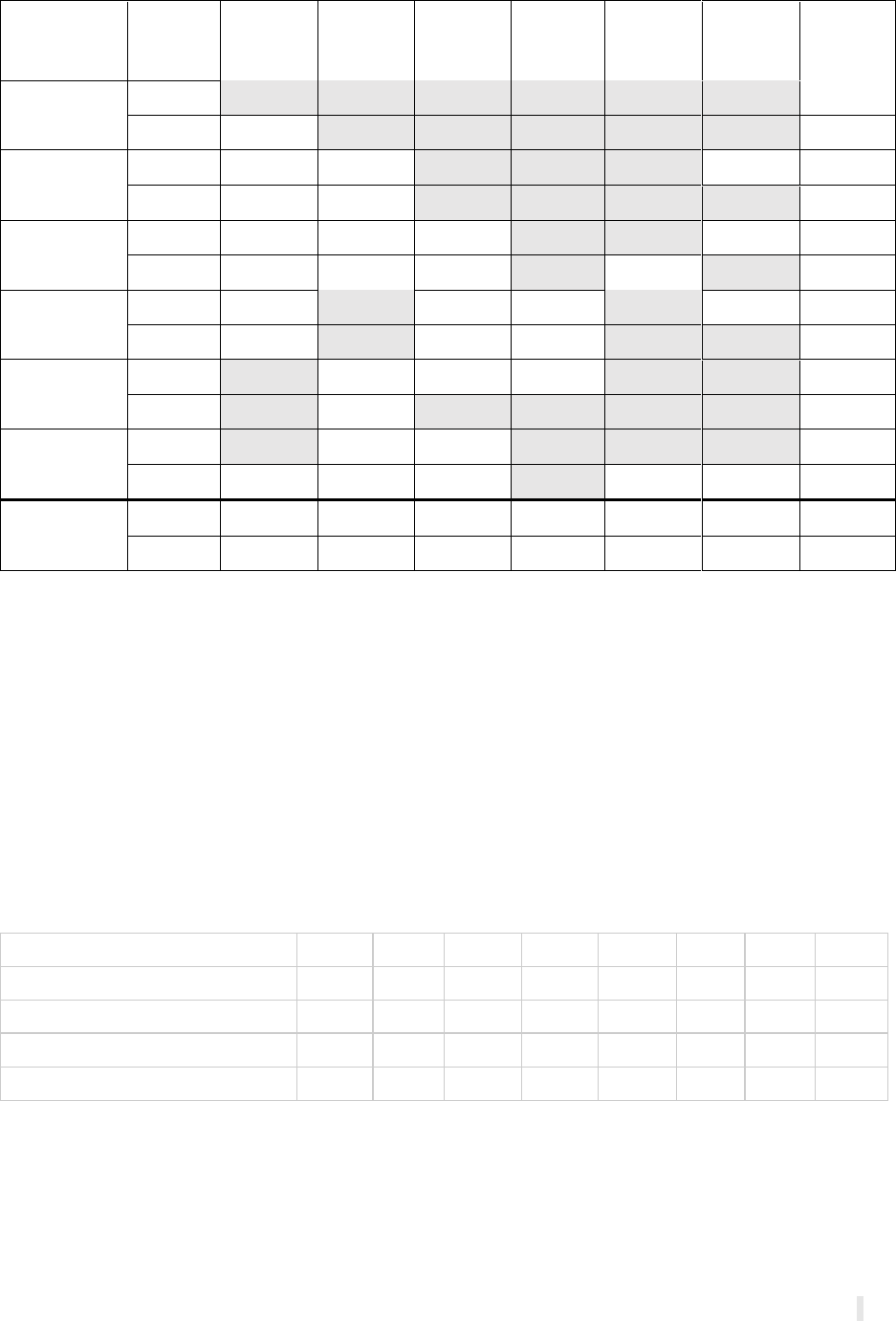

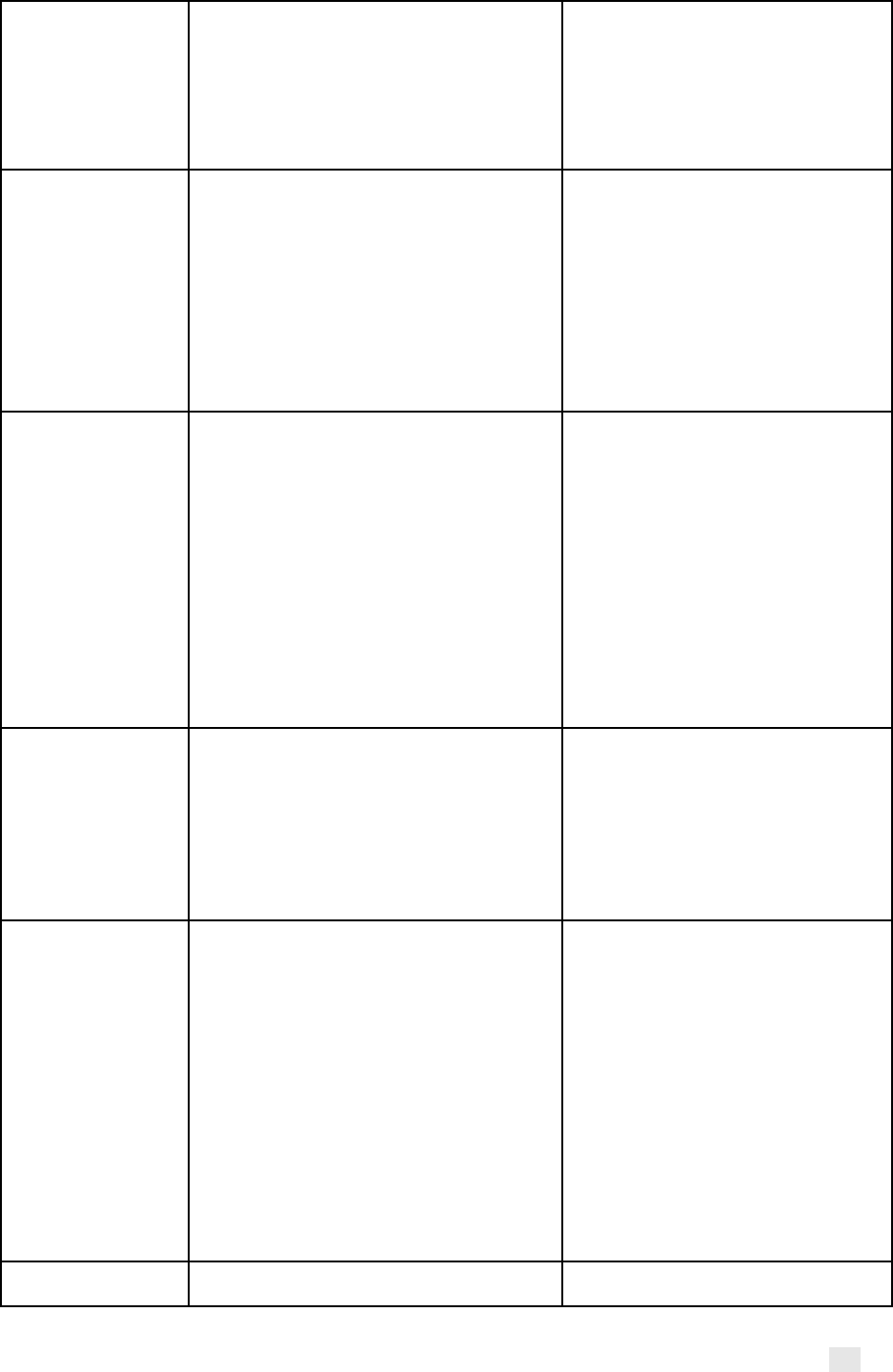

Table 1. PCE Portfolio Characteristics (US$)

Characteristic

CAM

DRC

GTM

MOZ

MYN

SEN

SDN

UGA

Total

World Bank Income Group

LMIC

LIC

UMIC

LIC

LMIC

LIC

LIC

LIC

High Impact Portfolio

X

X

X

X

X

5

Core Portfolio

X

X

X

3

Challenging Operating Environment (COE)

X

X

2

AGYW Priority Country

X

X

2

Matching funds eligible (NFM2, millions)

NA

$16.0

NA

$19.7

$19.3

$2.5

NA

$9.4

$66.9

Matching funds eligible (NFM3, millions)(2)

$6.0

$12.6

NA

$22.4

$12.3

$1.3

NA

$23.5

$77.9

Table Notes: LIC = low income country; LMIC = lower-middle income country, UMIC = upper middle income country

1.2 Grant cycle approach

Each year, the PCE synthesizes country findings to present a more comprehensive assessment of

the Global Fund business model. During the 2020 evaluation phase, the approach was informed

by the TERG’s interest in understanding how the Global Fund grant cycle has facilitated or

hindered the achievement of grant objectives during implementation within the New Funding

Model 2 (NFM2) grant cycle (2017-2019 funding cycle), including around Resilient and

sustainable systems for health (RSSH), sustainability and equity, and whether lessons learned

during the current grants have informed the New Funding Model 3 (NFM3) (2020-2022 funding

cycle). Applying a mixed-methods approach, information was collected from a variety of

quantitative and qualitative data sources; through analysis and data triangulation, the PCE

generated results that elucidate how the Global Fund business model plays out in-country.

The objective of the grant cycle analysis was to understand what, when, why and how grant

investments change over time, including significant factors that influenced the implementation of

and changes to the original grant. We examined aspects of grant design and implementation, and

specifically aimed to evaluate:

● how and why the NFM2 grants were modified along the grant cycle (during grant making,

implementation, and grant revision);

● how the Global Fund business model facilitated or hindered modifications along the grant

cycle; and

2

● whether and how grants contributed to achieving progress towards (or away from)

equity, sustainability and/or health systems strengthening objectives.

In addition, the PCE assessed the 2020 funding request and grant making process for NFM3 on

five themes, relative to the NFM2 process where relevant: (1) Differentiated applications: tailored

review, program continuation, and full review; (2) Transparency, inclusion, and country

ownership; (3) Moving beyond ‘business as usual’ to change in trajectory for achieving impact;

(4) Data use and target setting; and (5) Value for money.

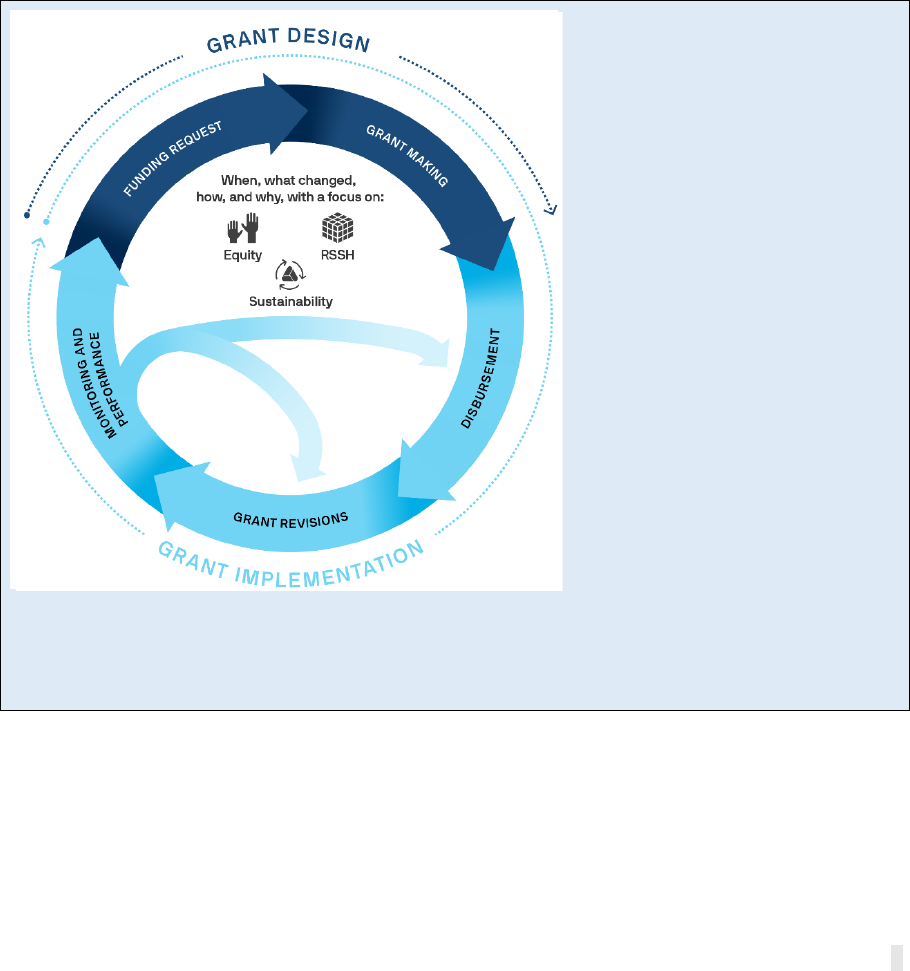

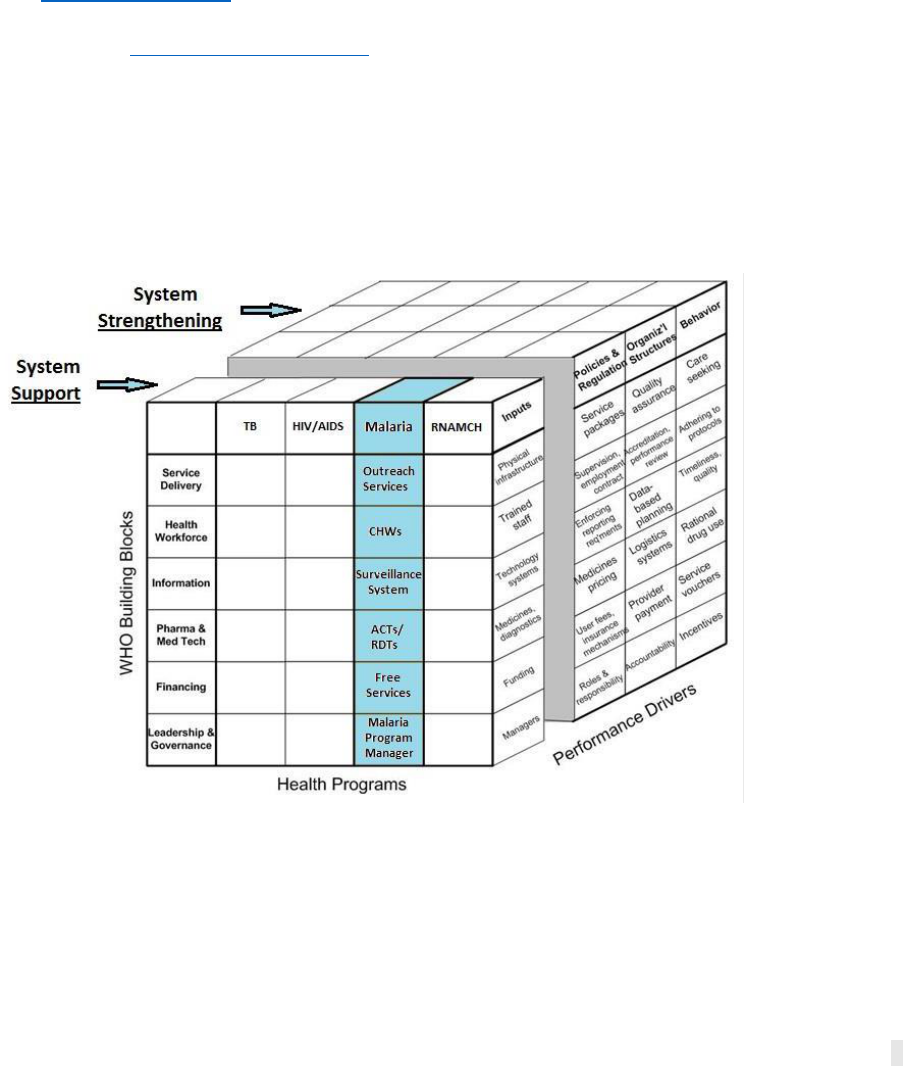

The PCE used a Grant Cycle framework (Figure 1) as the primary evaluation framework for

organizing 2020 data collection and analysis. The Global Fund grant cycle begins with the funding

request development leading to grant making, grant award, and grant signing. This process takes

eight to nine months and is followed by a three-year implementation period during which funds

are disbursed, activities are implemented, grants are modified through revision processes, and

progress is monitored. During the third and final year of implementation, the next funding

request development and grant making process begins for the upcoming grants and aims to be

informed by lessons learned from the current grants.

Figure 1. Grant cycle framework

NFM2 grant design: Little is known

about shifts between the Technical

Review Panel (TRP)-reviewed

funding request and grant making.

We examine shifts during the grant

making process as they relate to

Global Fund strategic objectives,

including prioritization of equity and

RSSH in funding requests and shifts in

equity and RSSH-related investments

during grant making.

NFM2 implementation: We examine

performance against grant and

national program indicators and

targets, Global Fund strategic

objectives, and implementation

progress, including the barriers and

facilitators to implementing RSSH

and equity-related investments. We

further examine budgetary shifts and

the role of grant revisions in

enhancing or detracting from RSSH

and equity investments.

NFM2 vs. NFM3: Global Fund’s 2019 replenishment set commitments to change the trajectory to meet

2030 disease goals. We compare NFM2 and NFM3 investments and interventions, exploring whether

lessons learned in NFM2 are informing the NFM3 funding request processes and grant design, with a

particular focus on equity, RSSH, and sustainability.

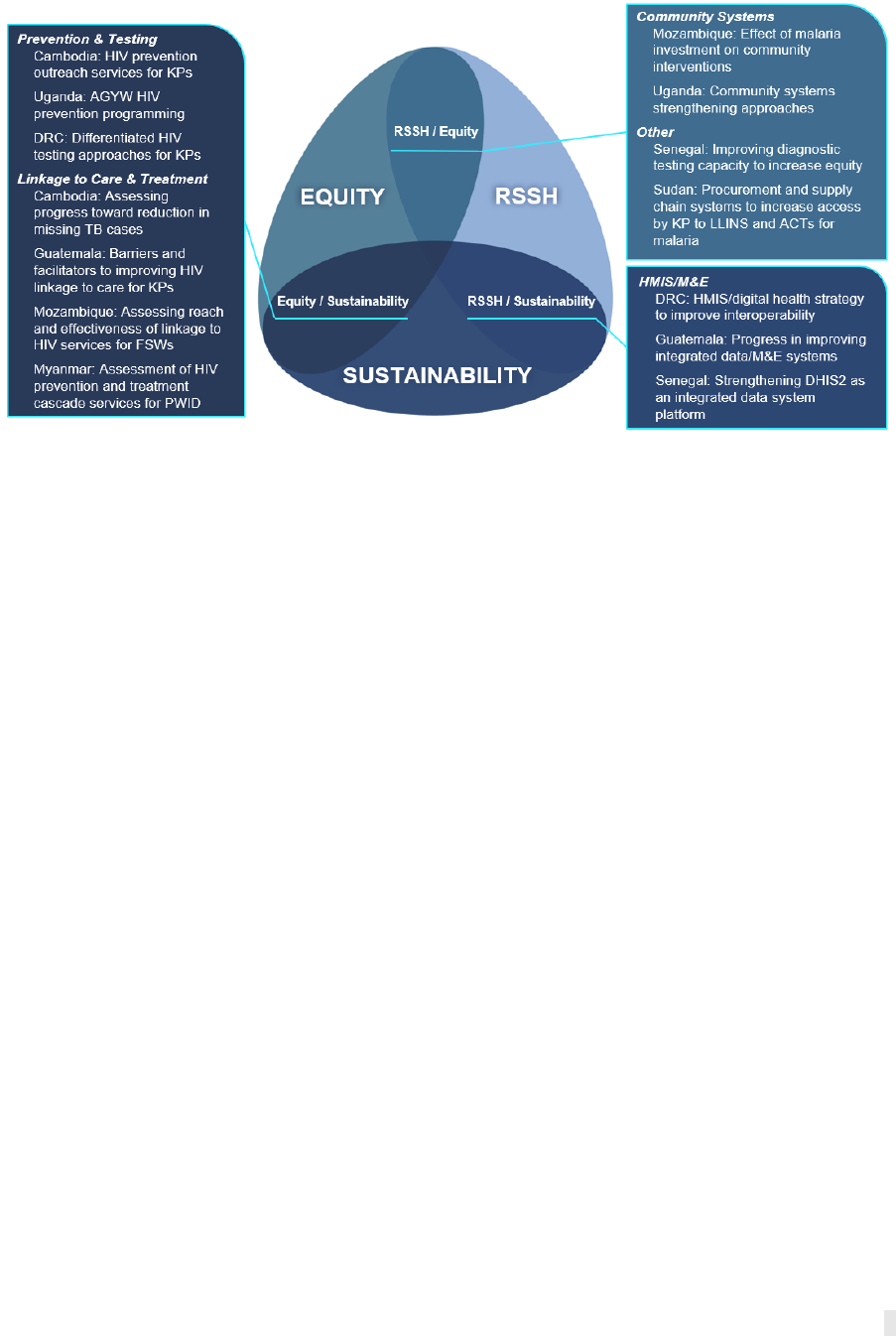

1.3 Focus topics

The PCE used a series of focus topics as lenses through which to evaluate the grant cycle and to

better understand drivers of change and results at the country level (figure 2). Focus topics were

selected with relevance to equity, RSSH and, in limited instances, sustainability considerations.

Through these focus areas, we examined how and why grants were modified along the grant cycle,

3

successes and bottlenecks to implementation, and results achievement against grant

performance targets.

Figure 2. Focus topics by country and theme

1.4 Methods

The PCE employed a mixed methods approach to assess how Global Fund business model factors

influence performance of grants throughout the stages of the grant cycle. Relying upon analyses

using both quantitative and qualitative data, the PCE examined and sought to explain changes in

planned resources and activities throughout the grant making process, revisions and

performance during grant implementation, as well as changes to the next grant window.

Triangulation of data across multiple sources and analytic approaches was used to ensure

robustness of findings, and interpretation of findings was commonly based on more than one

analysis. The EHG/UCSF consortium used contribution analysis to structure the interpretation of

findings against evaluation questions focused around the contribution of grant inputs (resources

and other inputs) to national disease program outcomes, as well as to assess the degree to which

this also enabled the achievement of Global Fund Strategic Objectives.

Data

Primary data were collected through meeting observations and key informant interviews (KIIs)

to explore issues in-depth; in addition, fact-checking interviews were conducted to fill

information gaps (Annex 2). KIIs elicited stakeholder perspectives on global and country-specific

evaluation questions and allowed the PCE to better understand grant cycle processes, including

barriers and facilitators. Interviews were also used to triangulate, interpret and validate results

generated through quantitative analyses and document review. Interview transcripts and

meeting notes were coded according to key themes.

The PCE obtained detailed budgets for all available active and planned grants from the Global

Fund Secretariat for funding requests, approved grants, awarded for grant making, and official

revisions (with corresponding Implementation Letters). In addition to detailed budgets, local

fund agent (LFA)-verified progress update/disbursement requests (PU/DRs) were obtained.

Budget variance

The PCE conducted detailed financial analyses of Global Fund budgets throughout the grant cycle

for NFM2 grants as well as available budgets from funding requests to grant making during NFM3.

4

Budgets were analyzed by recipient, disease, module, intervention, and focus topic.

2

Observed

changes in financial resources and prioritization between activities were triangulated using

qualitative data collected during KIIs, document review, and additional interviews. Using the

Global Fund’s modular framework, the PCE tracked resources for RSSH and human rights, gender,

and other equity (HRG-Equity) related interventions. HRG-Equity modules and interventions

were identified using Global Fund’s disease-specific technical briefs on gender, human rights, and

key populations; gender technical briefs; and validated through conversations with the Global

Fund Secretariat’s Community, Rights and Gender (CRG) team. Additional details can be found in

Annex 3, including a complete table of modules and interventions included in the PCE analysis of

HRG-Equity.

An analysis of financial absorption (expenditure as a percentage of budget) within and across

grants was conducted using PU/DRs, examining trends in absorption by semester, module, and

intervention. Similarly, absorption for RSSH- and HRG-Equity-related modules and interventions

were tracked throughout the grant cycle.

Indicator performance tracking

Indicator achievement against targets are reported within the LFA-verified PU/DRs during grant

implementation. These data were also compiled and tracked over the grant cycle to understand

changes in performance across grants, focus topics, and RSSH and HRG-Equity. Insights from

indicator trends over time were used to guide KIIs and fact checking interviews to triangulate

how the Global Fund business model facilitated or hindered performance.

Root cause analyses

The PCE used root cause analyses (RCA) to further explore, analyze and understand the root

causes underlying observed challenges or successes identified through a variety of triangulated

data sources (KIIs, secondary data analysis, document review).

RSSH Support vs. Strengthening “2S” analysis

The PCE analyzed RSSH activities in NFM2 and NFM3 according to whether they contributed to

“systems support” or “system strengthening,” drawing on definitions from Chee et al. (2013). (3)

We developed a coding methodology, aligned to Global Fund’s RSSH modules in the modular

framework, to designate each RSSH activity in the budget as either predominantly support or

strengthening. Three parameters—scope, longevity, and approach—were examined for each

RSSH intervention/activity pair, adapted from the methodology previously used by the TRP’s

examination of RSSH in the 2017-2019 funding cycle.(4) Two coders independently applied a

determination of support or strengthening after reviewing each intervention and activity

description, and any relevant text in the funding request narrative, and cost category. Details on

the methodology used are available in Annex 3.

Analytical approach to synthesis

Drawing from country analyses and annual reports, the GEPs compiled quantitative and

qualitative evidence into matrices organized by grant cycle stage and RSSH, equity, and

sustainability thematic areas. Evidence was drawn from focus topics as well as grant- and

country-level analyses. The evidence matrices helped identify patterns in the data across

countries and informed further discussion and analytical triangulation with cross-country budget

variance data. Due to the variation of focus topics, not all findings were able to be substantiated

across the eight countries; wherever possible, findings were supported by additional country

focus topics and portfolio-level analyses. Early synthesis findings were validated with CEP teams

for feedback and additional data interpretation.

2

Some budgets were not included in the synthesis as these grants were not subject to analysis at the country level

during the course of 2019-20, namely: Sudan HIV/TB, Cambodia malaria, and Myanmar malaria.

5

Chapter 2: NFM2 grant cycle

2.1: NFM2 funding request to grant making

This section presents findings on the changes that were made during 2017/2018 to NFM2 grant

designs between the country funding request submissions and the final approved grant award—

i.e., through the grant making process. This includes analysis of how and why changes were made,

who suggested that they be made, and whether these changes were in line with the Global Fund

guiding policies and priorities.

Key message 1: Overall grant designs and budgets did not change significantly during the

2017 grant making process (NFM2). More substantial changes were made to investments

supporting the achievement of SO2 (RSSH) and SO3 (HRG), although not necessarily to

prioritize these areas (despite being consistently highlighted through the PCE and other

analyses as requiring more attention).

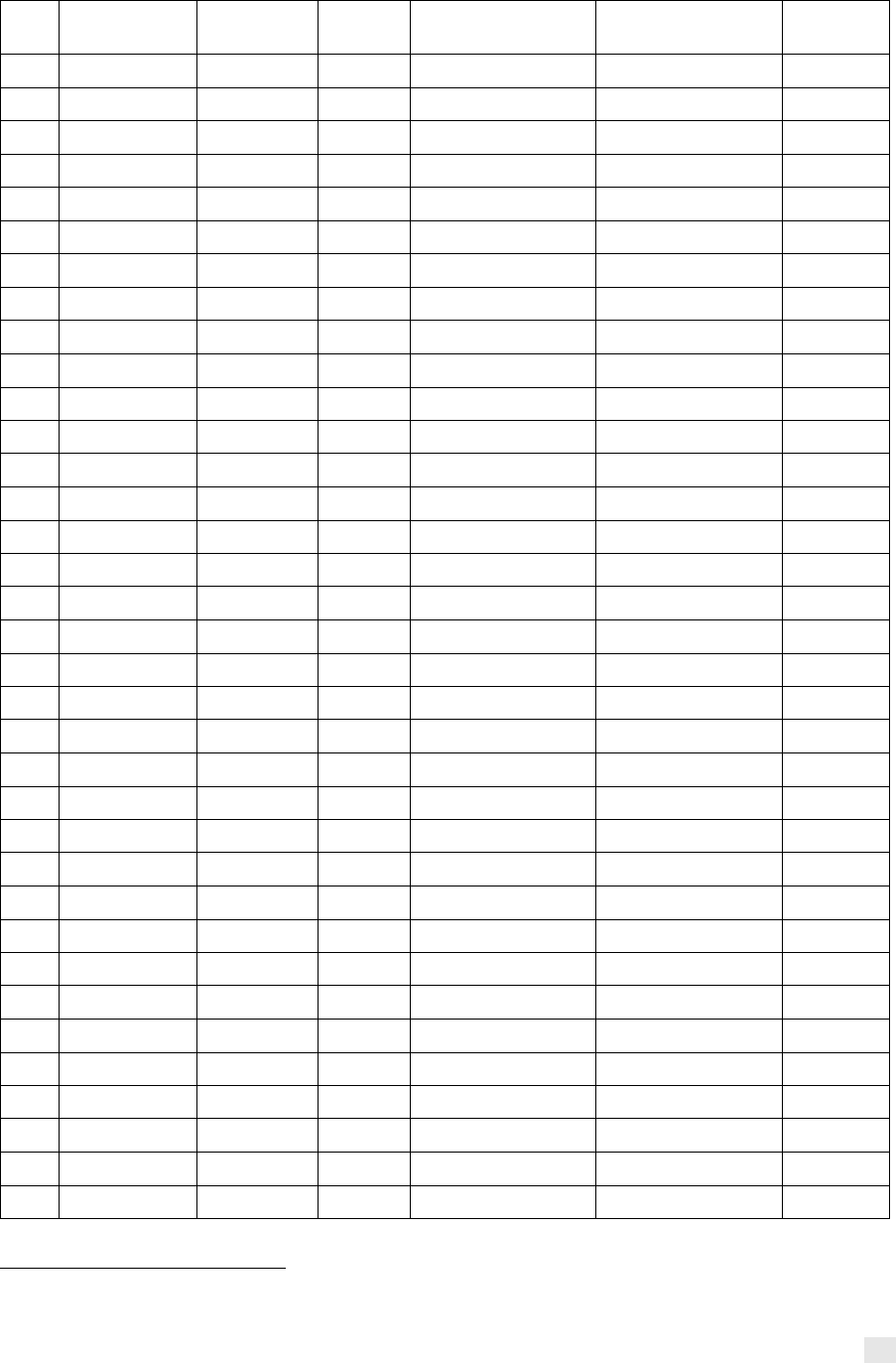

In general, during NFM2, relatively few major changes in overall grant design and budgets

occurred between funding requests and final approved grant awards for PCE countries (as seen

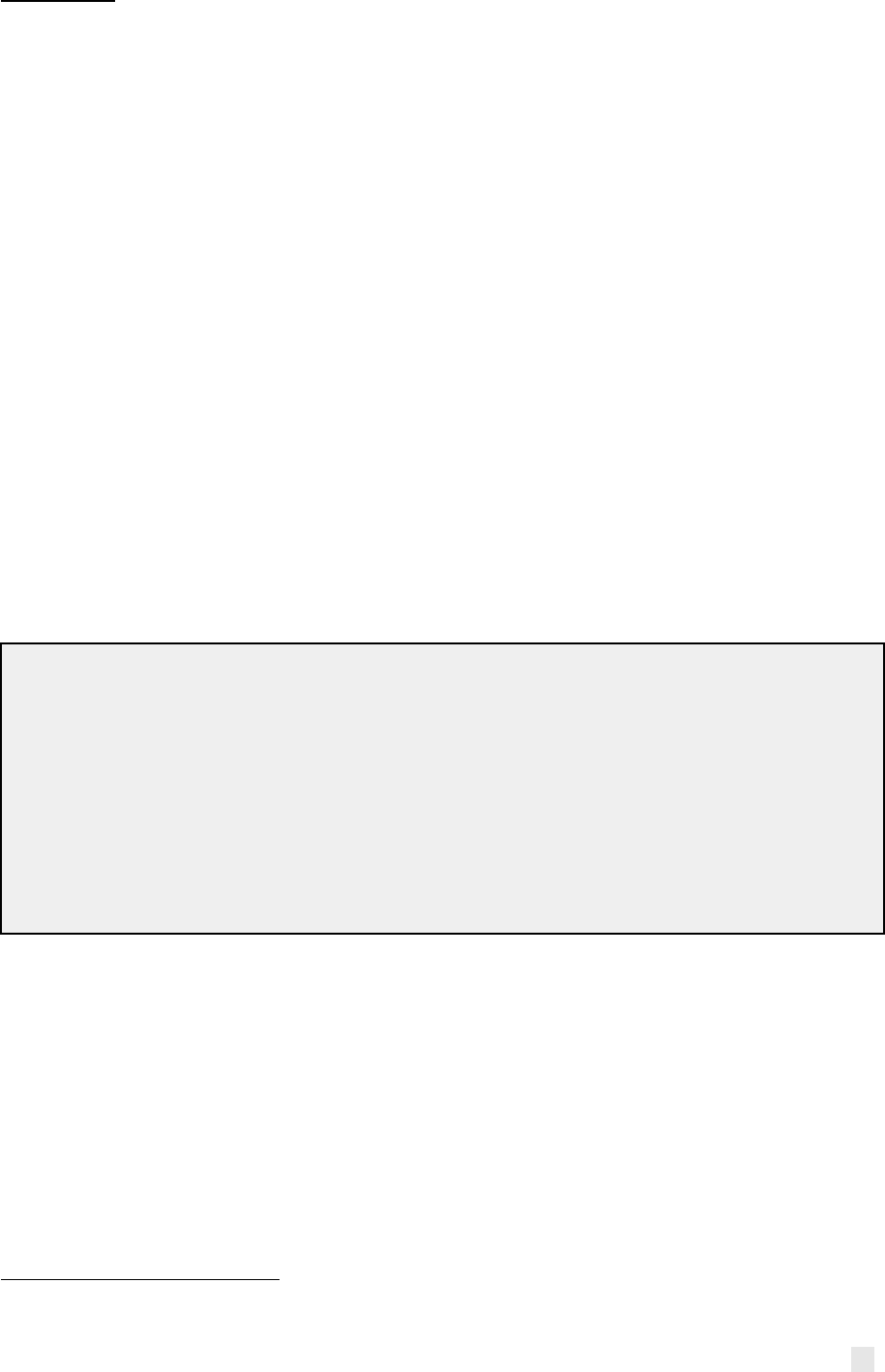

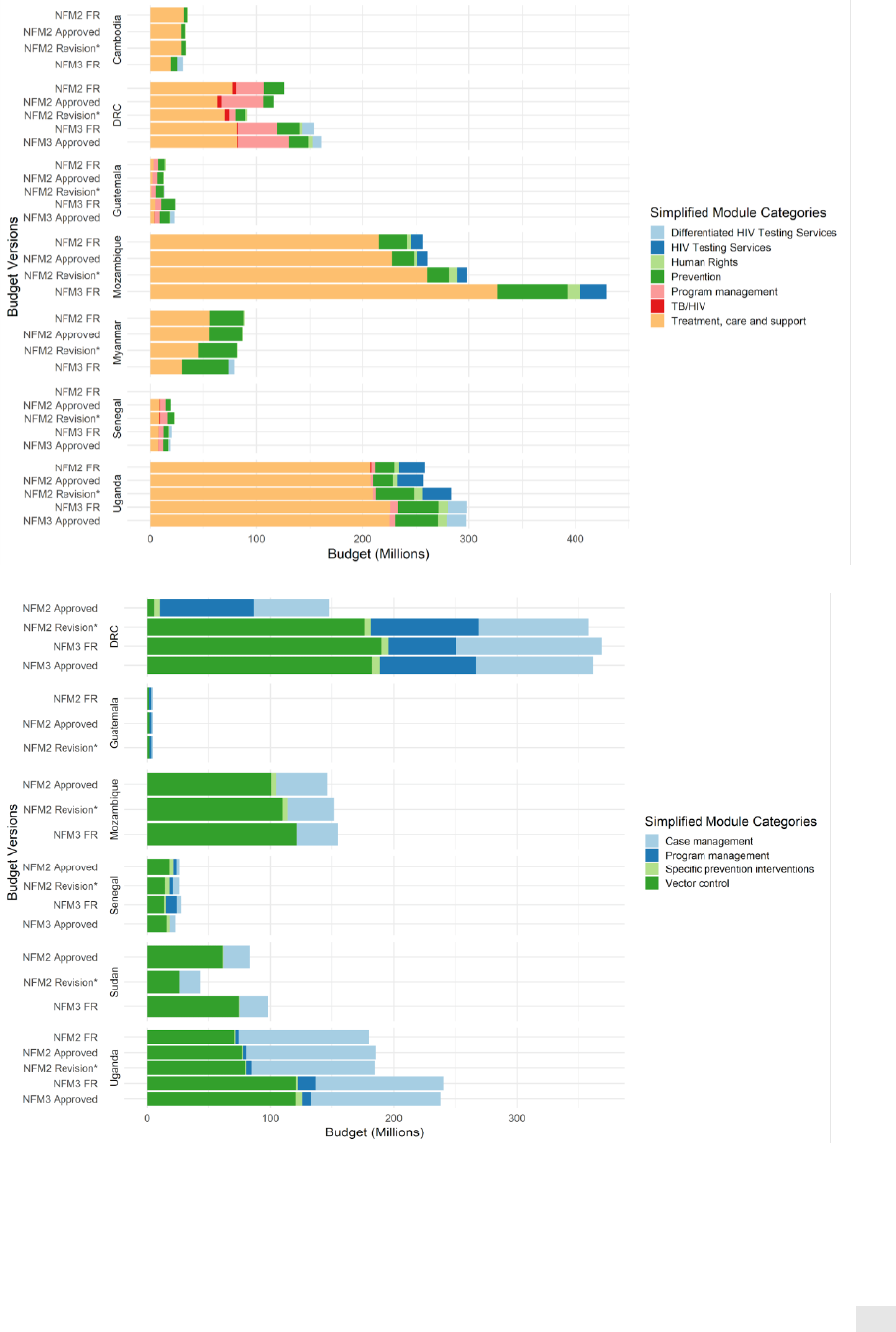

in Annex 5 figures 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3). Proportionally (given investments in these areas are relatively

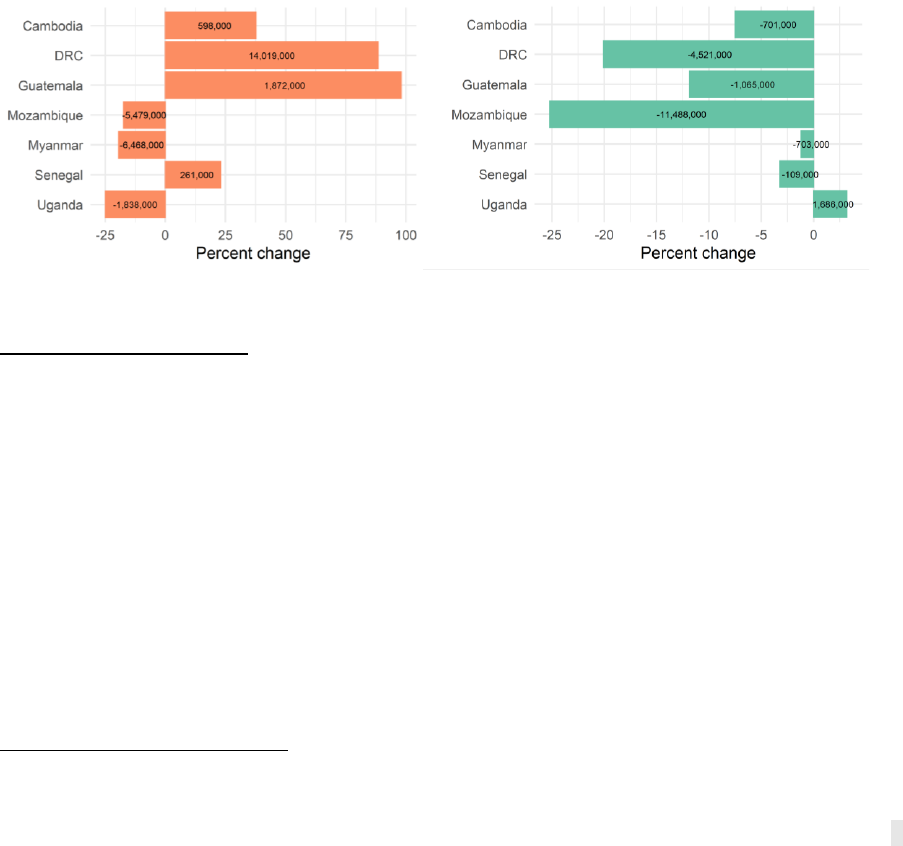

small compared to the overall grants), more significant changes were made to investments in

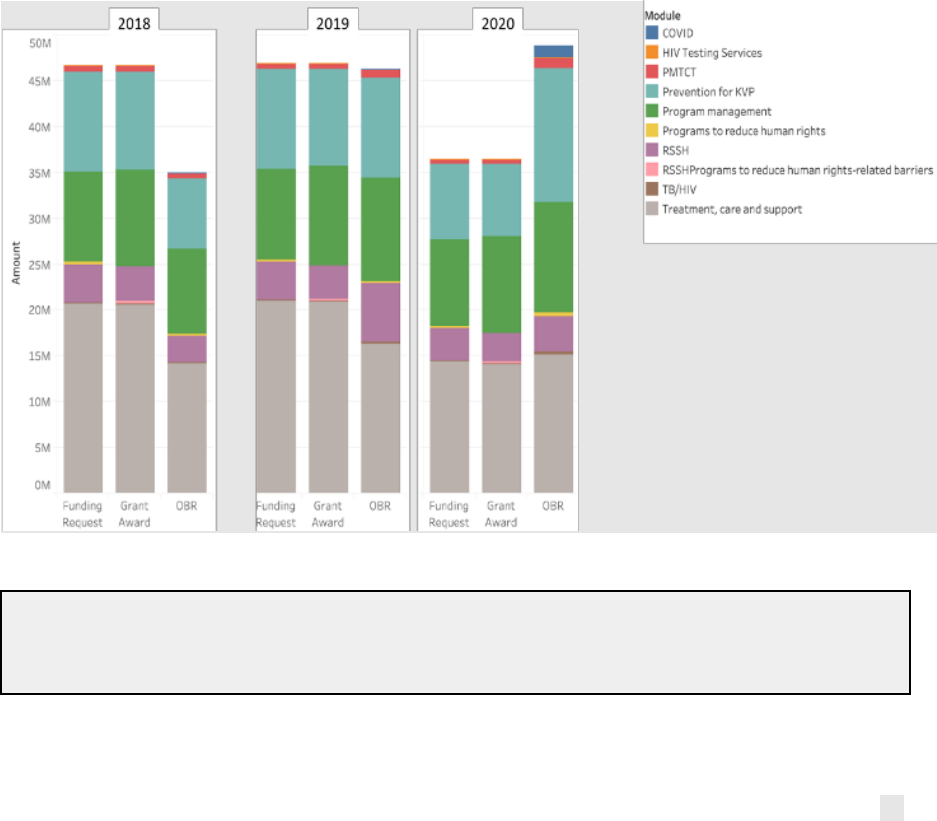

HRG-Equity and RSSH for most PCE countries during the NFM2 grant making process (Figure 3).

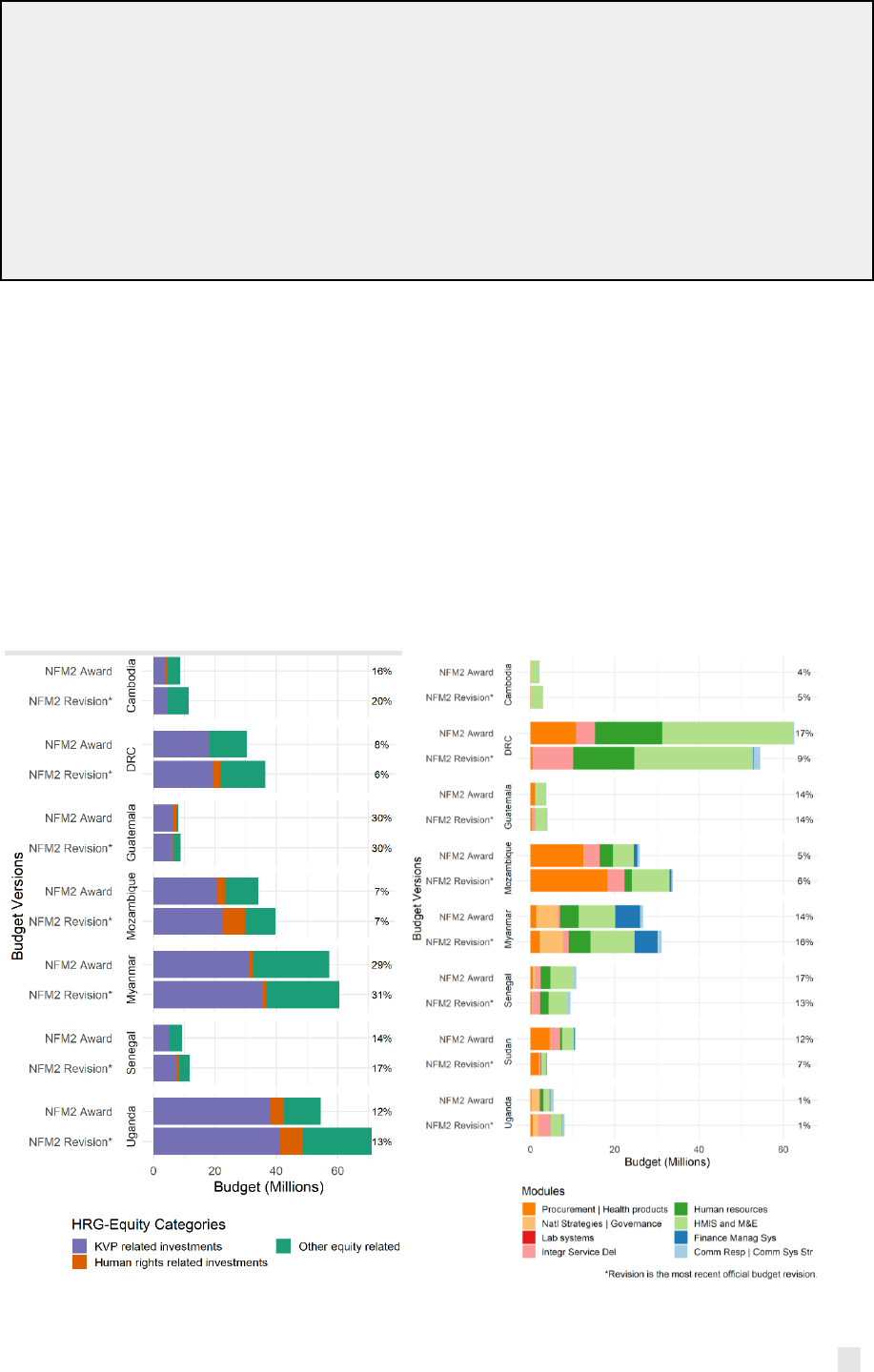

Figure 3. Percent change in RSSH (left) and HRG-Equity (right) investments from NFM2 funding

request to grant award

3

Source: Global Fund detailed budgets

HRG-Equity Investments

Analysis of all investments that seek to address HRG-Equity-related barriers to access and/or

health outcomes show that the budget for these areas declined in six of the eight PCE countries

during the grant making process. While no clear patterns emerged for TB and malaria (for which

these types of investments are small and difficult to track), HIV grant budgets mostly declined,

particularly for prevention among key and vulnerable populations (KVPs). Specifically, in all

countries that included some budget allocation for the following modules, the budget decreased

between the funding request and grant award:

● Prevention for Men who have sex with men (MSM): Substantial declines in

Mozambique, DRC and Guatemala.

● Prevention for People who inject drugs (PWID): Almost complete removal in

Mozambique and heavy cuts in DRC.

3

To ensure comparability, we restricted the grants to only those with full and tailored review (excludes continuation

grants for malaria in DRC, Mozambique, Senegal and Sudan, as well as HIV in Senegal and Sudan, and TB in Sudan).

6

● Prevention among prisoners: Complete removal in Mozambique and heavy cuts in

Cambodia and Guatemala.

The budget for prevention for female sex workers (FSW) also reduced or stayed the same in three

out of five countries, only increasing in Cambodia, where there was focused effort to increase

targeted programming to this group (and other KVPs) via improved management and support for

outreach workers.

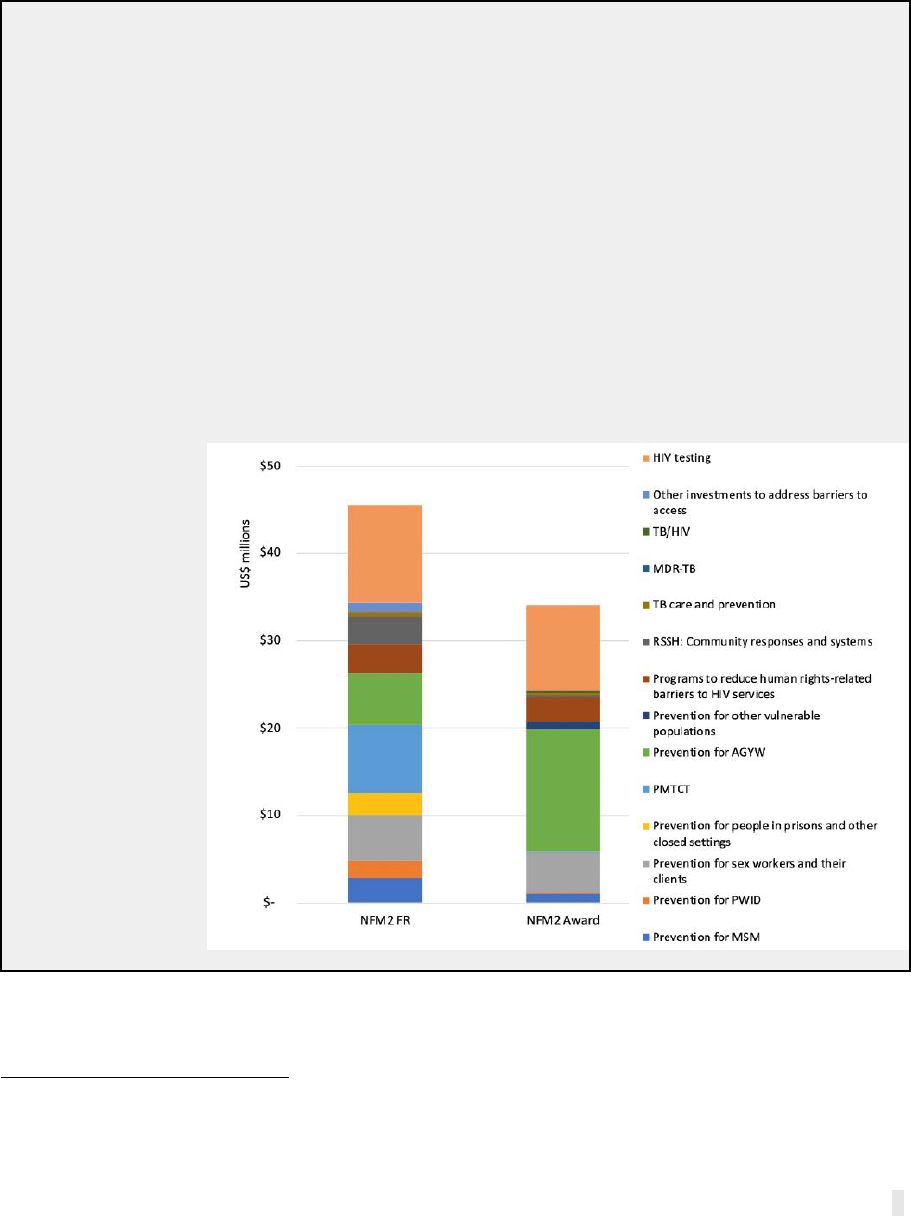

Box 2.1: Mozambique HIV/TB investments to address equity-related barriers.

The NFM2 grant making process reduced investments to address HRG-Equity-related barriers

in Mozambique by 25% (from US$46m to US$34m), mainly driven by a US$6m (68%) reduction

in HR-related investments and a US$3m (30%) reduction in wider KVP investments.

4

These

reductions were partly offset by a substantial increase in funding for prevention among

adolescent girls and young women (AGYW), from US$6m to US$14m, in response to emergent

evidence of increasing incidence among this group. Of note, anticipated matching funds for

human rights (US$4.7m) were added after the grant award, so appear in the first

implementation letter. For human rights, it was felt the strategy was not complete and the

implementation therefore was also not ready, so the Grant Approvals Committee (GAC) agreed

to delay the start and reduce the budget from the core allocation without jeopardizing eligibility

for matching funds. For AGYW, the budget from the core allocation was increased to support

more activities for this group.

Figure 4. NFM2 HIV/TB funding request and grant award budget variance analysis of investments

designed to address HRG-Equity or other barriers to accessing health services and/or achieving

health outcomes:

Source: Global Fund

detailed budgets

4

There was also a US$8m (98%) reduction in funding for Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) —

reflecting the shift from Option B+ to test and start. The related increases in testing and treatment costs were included

in other budget lines, notably treatment care and support, which is not included in our estimates of equity-related

investments at grant award.

7

RSSH Investments

Analysis of RSSH budget changes during grant making shows large increases in some countries

and significant declines in others, as well as substantial shifts between modules/program areas

in many countries. Three PCE countries increased the overall RSSH allocation from funding

request to grant award (Cambodia, DRC, Guatemala) and three countries decreased the overall

RSSH allocation (Mozambique, Myanmar, Uganda). In all countries, the final agreed level of RSSH

investment was below what was recommended by the Secretariat (which varied from 5% to 11%

of total grant value across countries) and the vast majority of the agreed NFM2 RSSH investments

were designed to support rather than strengthen the health system.(4)

RSSH module budgets shifted in different ways during grant making. Four out of seven PCE

countries with available data (excluding Sudan) increased resources for the Health Management

Information System and Monitoring and evaluation (HMIS/M&E) module and three countries

increased resources for Procurement and supply chain management (PSM)—two areas critical to

supporting core disease grant implementation. Guatemala introduced a substantial increase in

HMIS and M&E in response to TRP comments (discussed further below). In Mozambique,

investments for integrated service delivery (ISD) and quality improvement, which were relatively

limited in most PCE countries, declined significantly during grant making. Three countries

reduced resources allocated to community responses and systems between the funding request

and grant award, with negative implications for equity, given the role of these systems in reaching

the most vulnerable, and for achieving sustainability objectives. Value for Money (VfM)

considerations sometimes drove reductions. In Uganda, for example, per diem allocations for

community systems strengthening (CSS) outreach were reduced in alignment with the

government’s policy on rates.

Key message 2: Several business model factors, including the role of the Secretariat

Country Teams (CT), matching funds and the TRP review process, influenced prioritization

during grant making.

A range of country-specific and Global Fund business model factors affected prioritization

decision making during the grant making process. As compared to the relatively open and

transparent funding request development process, grant making was difficult to observe from an

evaluation perspective, with many discussions taking place in private between senior Secretariat

staff and country stakeholders. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that the most significant business

model factors influencing the design of grants were:

Role of the Secretariat: Across all PCE countries, qualitative evidence suggests that the

Secretariat played an important role in working alongside country stakeholders to guide

prioritization decision making. This included working with country stakeholders to revise initial

funding request submissions prior to TRP review, and in interpreting the recommendations made

by the TRP and GAC to finalize grant designs and budgets. In some countries, the Secretariat has

a ‘hands on’ role, such as in the DRC, where the budget for HIV testing among KVPs was reduced

during grant making to accommodate a Secretariat request to partake in the Supply Chain

Transformation Project, and the CT asked Principal Recipients (PRs) to identify budget cuts

across various modules to make US$10m available.

Matching funds: Five out of eight PCE countries received catalytic matching funds that served to

increase total investment in HRG-Equity-related areas. However, evidence is mixed on whether

these funds had the desired effect of increasing the level of investment to these areas made from

the core country allocations. Although in Mozambique, the human rights budget reduced (Box

1.1), for most countries receiving human rights matching funds (DRC, Senegal, Uganda), the total

budget from the core allocation increased for this priority area during grant making. By contrast,

of the three PCE countries that received matching funds for RSSH/data systems, the related

8

budget from the core allocation decreased in Mozambique, while in DRC it increased. In Myanmar,

although the allocation to RSSH from the HIV budget increased, the overall allocation to RSSH

declined due to TB grant reductions.

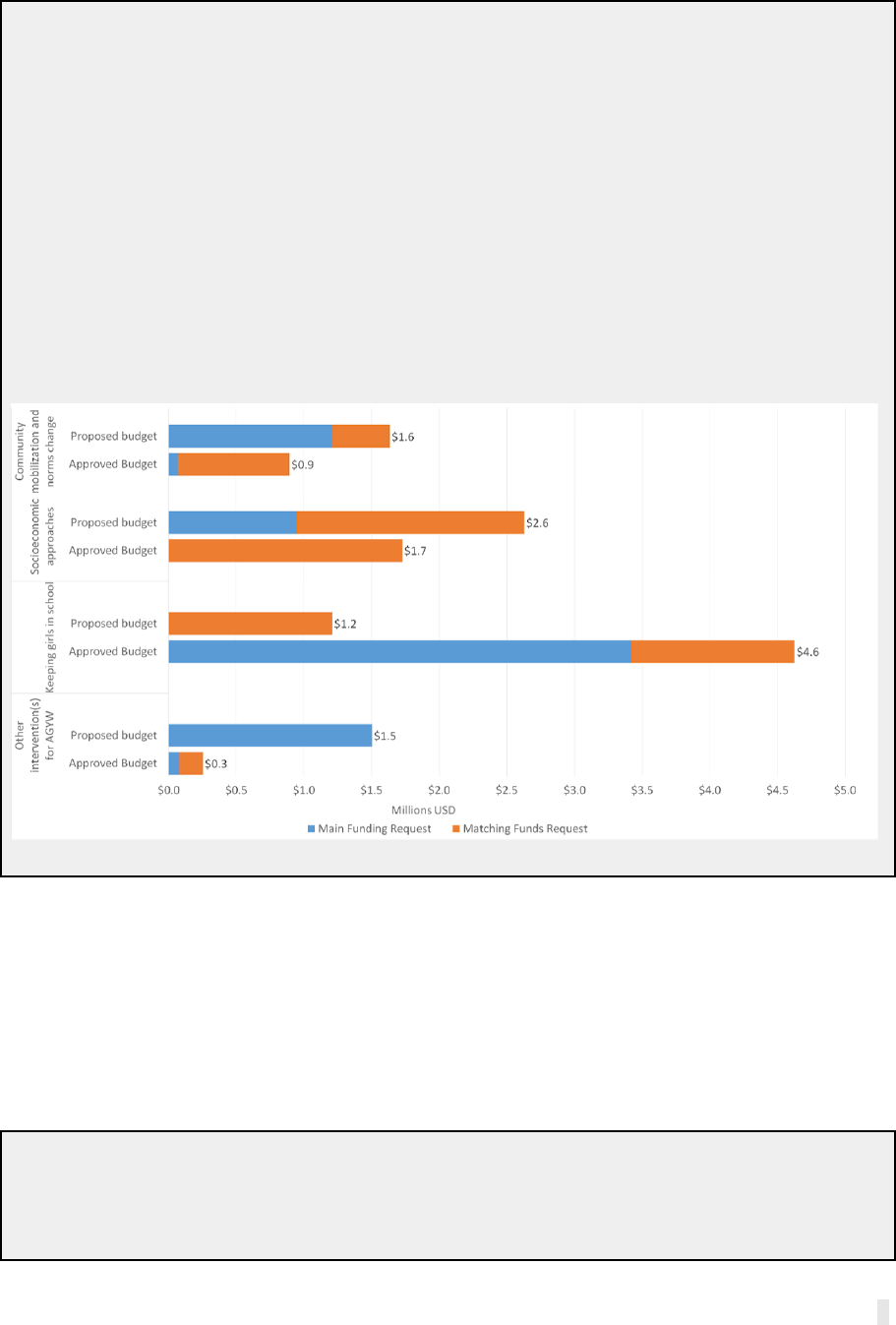

Box 2.2: Drivers of AGYW intervention shifts during grant making in Uganda.

The total investment in interventions within the AGYW module remained relatively unchanged

after grant making, decreasing 1% from US$5.0m to US$4.96m. However, there were substantial

shifts across four of the seven AGYW intervention areas budgeted, mainly in response to TRP

comments on the matching funds application requiring iteration. Per the TRP comments, the

proposed matching funds were spread across too many interventions and geographies, and

some interventions were unrelated to the proposed outcomes. During grant making, the PRs

and CCM adjusted the AGYW interventions in the HIV grant’s main allocation and revised the

matching funds submission to remove activities that did not contribute directly to accelerating

progress and enhancing outcomes among vulnerable AGYW. The reductions in the

socioeconomic approaches, community mobilization, and other AGYW interventions created

room for an increase of US$3.4m in the main HIV grant activities focusing on keeping girls in

school interventions, which had no allocation in the original funding request.

Figure 5. NFM2 funding request to grant making budget variance for select AGYW interventions:

Source: Global Fund detailed budgets in Uganda

TRP review process: TRP comments and recommendations influenced the grant design and

budget in several countries. For instance, following the TRP comments in Mozambique, during

grant making the PR placed significant emphasis on prevention among AGYW and reduced

budgets for prevention among other KVPs. TRP comments in Uganda contributed to narrowing

the focus of AGYW intervention areas during grant making with the aim of maximizing investment

into interventions with a strong evidence base, that would significantly reduce the HIV risk

among AGYW. Another example from Myanmar is provided in Box 2.3.

Box 2.3: Effect of TRP comments on equity investments during grant making in Myanmar.

One of the TRP comments on the NFM2 funding request was a request to expand service

coverage for HIV testing and methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) for PWID. Following

grant negotiations with the Secretariat, the two PRs increased targets for reaching PWID with

9

HIV prevention, testing and MMT for the NFM2 grant period through cost efficiencies in

prevention activities: PWID HIV prevention targets increased by 16%; the PWID tested target

increased by 32%; and the PWID on MMT target increased by 38%. The revised targets were

confirmed by the GAC for the grant award.

Box 2.4: Effect of TRP comments on RSSH design during grant making in Guatemala.

During grant making, the HMIS budget more than doubled in direct response to comments from

the TRP. Noting persistent weaknesses in the ability of the national HMIS to track program

indicators and monitor progress, the TRP requested a detailed plan to strengthen HMIS and

better monitor progress toward epidemic control and recommended consideration of DHIS2 as

a platform. As a result, the PR INCAP added US$500,000 to the program and data quality

intervention, to support the strengthening of the national HMIS and develop a system to enable

to PR to track relevant community level indicators. This targeted investment for the PR was

aligned with a national HMIS strengthening plan that had identified DHIS2 as an option for wider

HMIS strengthening endeavors and was presented by the CCM and PR as the response to the

TRP comments. Despite the increased investment in HMIS, no additional relevant indicators

were added to the performance framework.

2.2: NFM2 grant implementation

Implementation Progress

Key message 3: A number of Global Fund business model factors influenced grant start-up

and early implementation, especially: lengthy selection and contracting processes for

implementers and CT support. Early implementation delays disproportionately affected

RSSH and HRG-Equity activities.

NFM2 grant implementation was significantly disrupted, both by delays to start-up in Year

1 and by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Year 3. Across PCE countries, a number of

Global Fund business model factors resulted in initial start-up delays in Year 1 of NFM2 grant

implementation, discussed further below. Overall Year 1 absorption for all modules across all

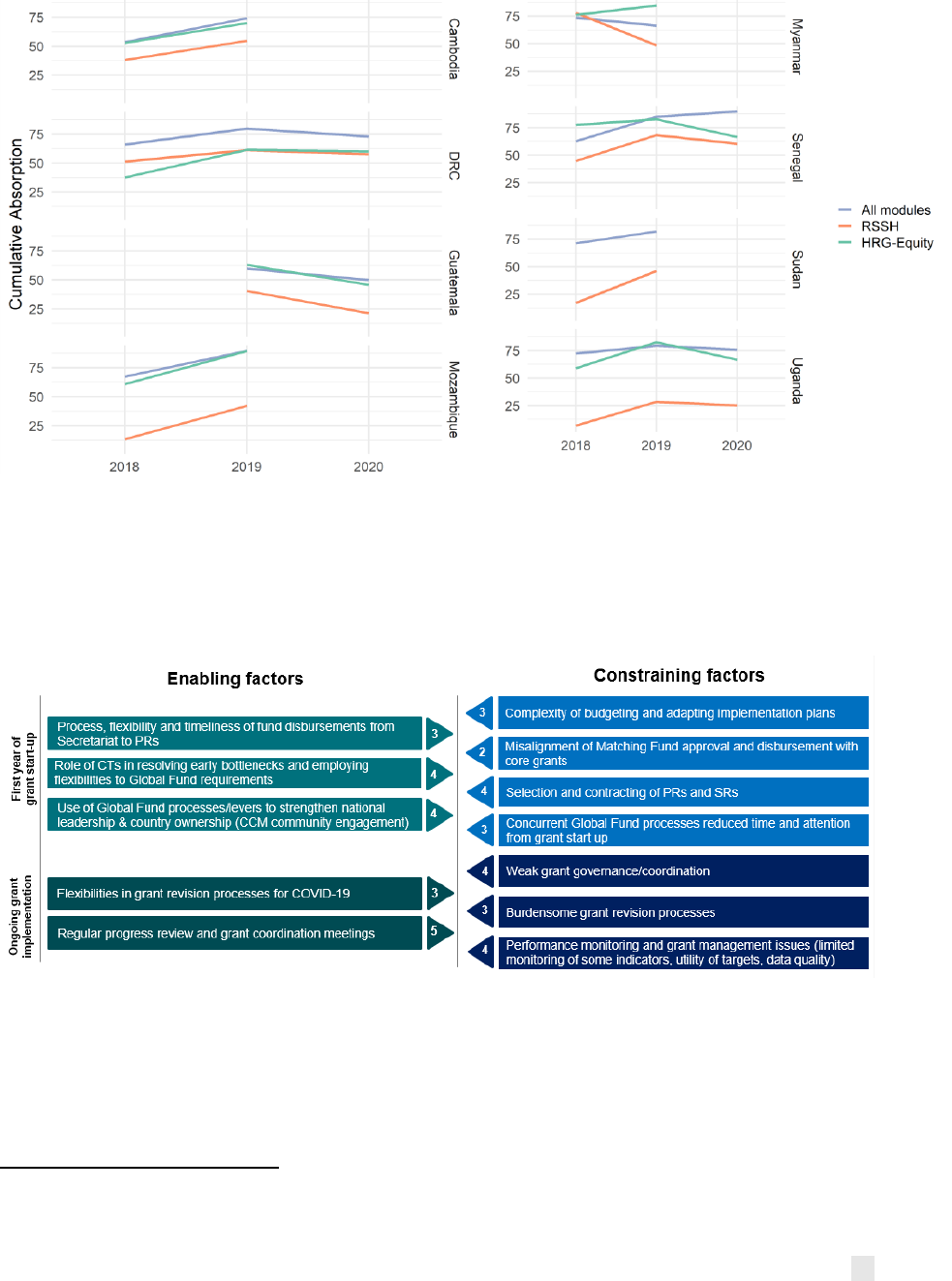

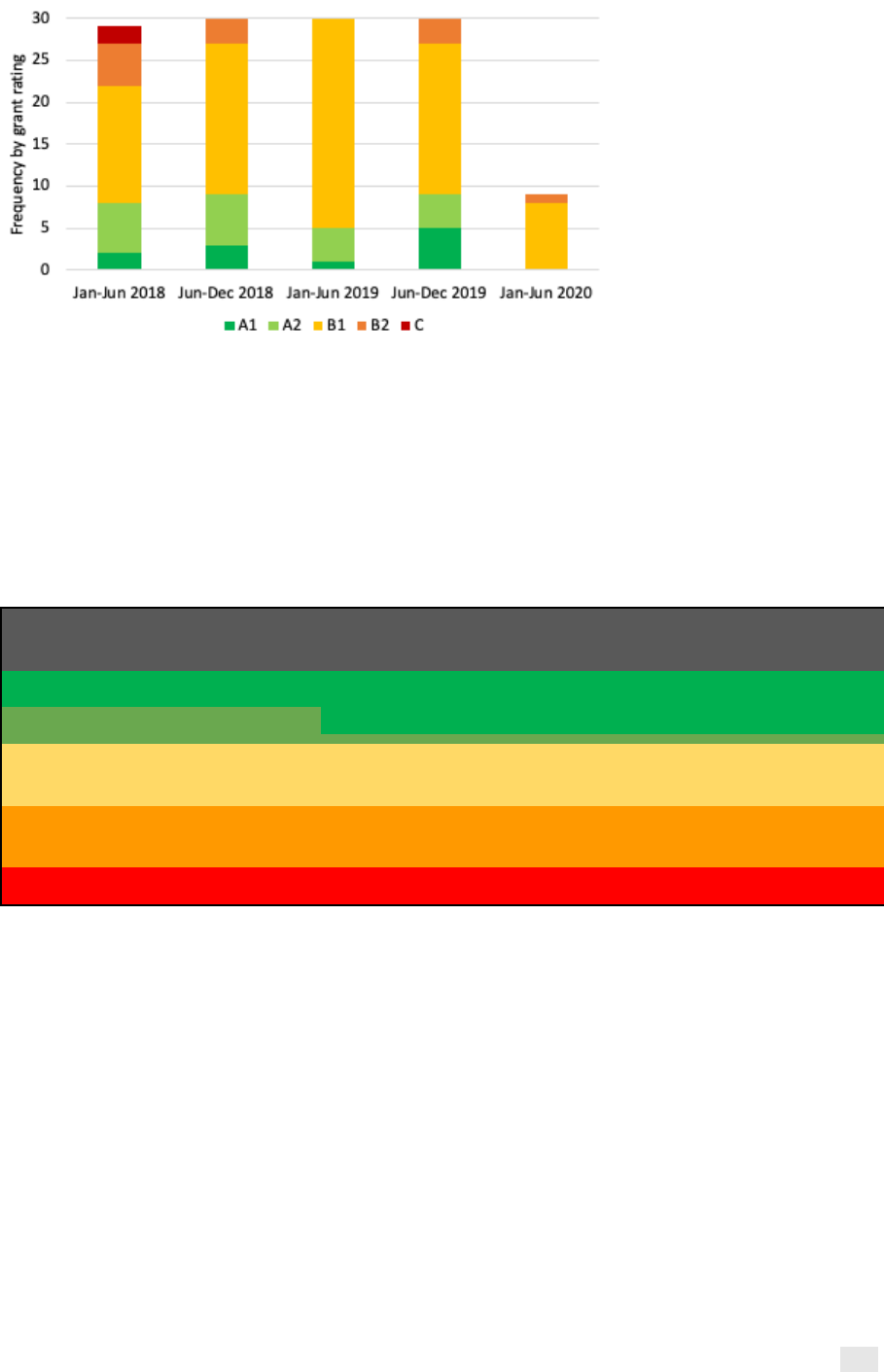

grants ranged from a low of 54% in Cambodia to a high of 74% in Myanmar, with an average of

68% (Figure 6). Implementation progress accelerated in Year 2 in nearly all PCE countries as

implementers overcame start-up delays and in some cases put in place accelerated or ‘catch-up’

implementation plans. Average absorption across PCE countries was 81% (see Figure 6 and

Annex 6). Based on available data for the first half of Year 3 (2020) in a subset of countries (DRC,

Senegal, Uganda), we observed lower absorption compared to Year 2. Evidence suggests that this

is partly due to challenges in implementation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. However,

the cumulative effect of budget revisions resulting in unutilized budgets from earlier years being

shifted to the final year of grant implementation also contributed to low absorption in Year 3.

Compared to the grants’ overall average progress, implementation remained particularly

slow in some RSSH and HRG-Equity-related investment areas. At the most recent time point

where data are available (2019 S2 or 2020 S1, depending on the country), seven of eight PCE

countries had lower cumulative absorption for HRG-Equity investment areas compared to the

overall grants, and all eight PCE countries had significantly lower cumulative absorption for RSSH

investments compared to the overall grants (see Figure 6).

5

Financial absorption is defined as the

percentage of the budget that was spent within a given time period. However, as noted in previous

PCE reports, absorption is an imperfect measure of implementation progress as it does not

5

RSSH absorption was 15 or more percentage points below total absorption in all countries, and in half of the PCE

countries (Mozambique, Senegal, Sudan, Uganda) it was 30 or more percentage points lower.

10

capture the quality of implementation and may incentivize implementers to focus on activities

that are more quickly absorbed.

Figure 6. NFM2 cumulative absorption over time for all modules, HRG-Equity-related

investments, and RSSH investments

Figure note: 2020 absorption only includes S1; Guatemala grants began NFM2 implementation later.

Source: PU/DRs

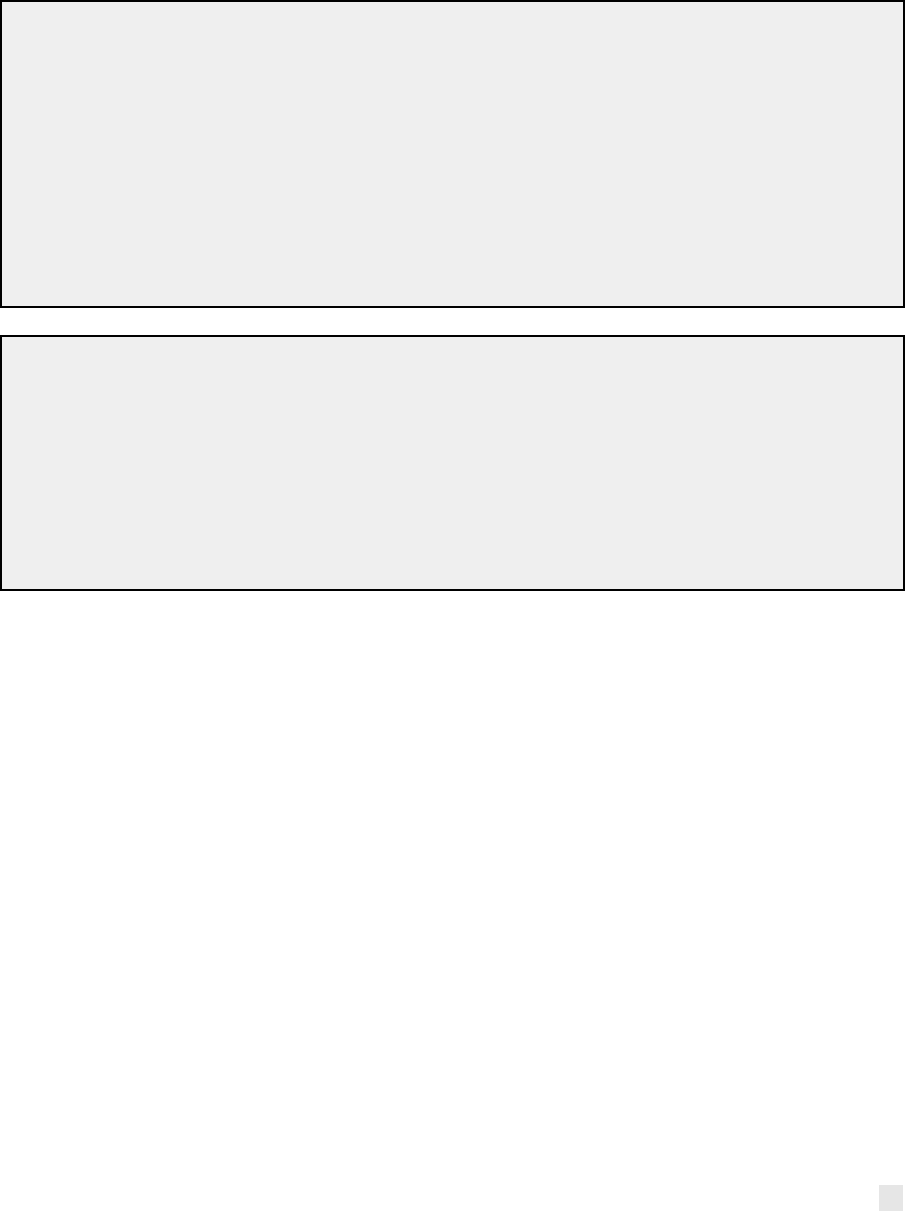

As summarized in Figure 7, and explored in more detail below, a number of Global Fund business

model factors influenced implementation progress during NFM2, with some particularly affecting

the grant start-up phase in Year 1.

Figure 7. Global Fund business model factors influencing implementation progress

6

Lengthy selection and contracting of implementers, particularly SRs by PRs, delayed

implementation of activities in the majority of PCE countries. In Sudan, the new PR undertook

capacity assessments with 14 new SRs and Implementing Units but not sufficiently in advance of

grant implementation, causing significant delays. In Cambodia, DRC, Mozambique, Senegal and

Uganda, disbursements to SRs did not occur until the second or in some cases third quarter of

2018 as a result of SR contracting delays due to weak capacity. SR contracting delays during grant

6

Each of the factors have been weighted in the form of a score based on their relative level of influence over grant

implementation, where five (5) is the most important and one (1) the least (noting that the least important factors are

not included to aid readability).

11

start-up particularly affected the implementation of HRG-Equity activities as PRs often rely on

SRs with community experience to deliver KVP, HR and gender interventions and these

organizations have less experience with Global Fund management systems. In other cases, new

government PRs, appointed to enhance sustainability, had relatively little experience with Global

Fund processes, resulting in early implementation delays. For example, Cambodia appointed the

Ministry of Finance as PR for NFM2 to promote national ownership and sustainability, which led

to a slow grant start-up in year 1 due to disbursement delays, but subsequently implementation

picked up pace (see also Senegal example in Box 2.5).

Box 2.5: Senegal new government PR lack of familiarity with Global Fund processes.

For NFM2, Senegal moved to consolidate and centralize responsibility for grant management

within the Ministry of Health to create efficiencies and streamline ownership. As recommended

by the CCM, the Secretariat awarded PR-ship of the TB/RSSH grant to the Direction Générale

de la Santé/Direction de l’Administration Générale et de l’Equipement (DGS/DAGE), while the

national TB program, the former PR, became a sub-recipient. These implementation

arrangement changes affected roles and responsibilities across different Ministry of Health

actors, and, along with the DAGE’s relative inexperience with Global Fund procedures as a new

government PR, caused implementation delays, which stakeholders attributed to the absence

of a transition phase between allocation cycles and inadequate consideration of onboarding

needs to support new PRs.

Box 2.6: Sudan new PR lack of familiarity with Global Fund processes inhibited malaria

grant implementation.

Under NFM2, the PR for the malaria grant transitioned to the Ministry of Health (MoH),

although government financial and management systems did not fully meet standard Global

Fund requirements. Throughout NFM2, extreme political and economic upheaval severely

impacted on the delivery of the malaria program, partly due to PR lack of familiarity with the

Global Fund business model. Together, these factors limited disbursement and delayed

implementation and absorption, particularly for routine LLIN distribution. Despite these

problems, in 2019 the GAC approved a budget of $25 million for LLIN mass distribution.

Concurrent Global Fund processes were a barrier to implementation progress. Most PCE

countries spent the first six months of NFM2 grant start-up simultaneously closing NFM1 grants.

These concurrent processes were reported as time-consuming in several PCE countries (Sudan,

Myanmar, Uganda) and reduced time and attention from grant start-up activities, even in the case

of program continuation grants.

Aligning budgets and implementation plans for Global Fund grants was a highly complex

process. As observed across all PCE countries, the advantages of input-based budgeting in terms

of risk management did not outweigh the complexity of subsequent changes to implementation

plans. In Myanmar, budgetary management tools inhibited implementation in a number of ways.

For instance, the managed cash flow system, introduced as a financial risk mitigation measure,

contributed to low budget absorption, alongside high program management costs. Intensive

reporting and data verification processes also took significant time for PRs to deal with,

detracting their focus from implementation.

Finally, some countries did not approve Matching Funds and related disbursements until well

into the NFM2 grant implementation period. This misalignment with the main grant approvals

negatively affected the implementation of those activities and had a significant effect on RSSH and

HRG-Equity activities, as they rely more on matching funds and take significant time to plan. In

DRC for example, the Secretariat processed matching funds for RSSH/data systems separately

from the main grant and they did not go through GAC approval until eight months into NFM2

12

implementation. Similarly, in Uganda, misalignment of timing of matching funds for AGYW and

Human Rights, due to the matching funds request sent back from TRP for iteration, delayed

signing of MoUs with public sector SRs, causing further implementation delays. Senegal also

experienced significant delays in the incorporation of matching funds.

Influential enablers of early implementation progress during NFM2 included the role of CTs in

resolving early bottlenecks and employing flexibilities to Global Fund requirements and the

process, flexibility and timeliness of fund disbursements from the Global Fund Secretariat to

PRs—most PCE countries received initial disbursements on time. In Uganda, DRC, Cambodia and

Senegal, the CTs played an important role in allowing for flexibility in the disbursement of funds

to avoid disruption to grant implementation. In Myanmar, stakeholders reported that alignment

with the National Strategic Plan (NSP) and the CCM coordinating partners also supported

implementation.

Key message 4: After grant start-up, weak grant coordination as well as issues with

performance monitoring constrained ongoing implementation progress. Again, these

factors particularly affected RSSH and HRG-Equity-related activities. Conversely,

stakeholders’ engagement in regular progress reviews and grant coordination meetings

facilitated implementation.

As summarized in Figure 7 above, a number of Global Fund business model factors influenced

implementation progress in Years 2 and 3. Most notably:

Weak coordination within and between grants, with other program teams and between donors,

constrained implementation in multiple PCE countries (Cambodia, DRC, Guatemala, Senegal and

Sudan). Coordination challenges particularly affected RSSH investments, in part due to resources

for RSSH activities being spread across grants, and because responsibility for the aspects of health

systems being targeted often lies outside of the disease programs. As a result, a diverse set of

stakeholders needed to be involved in grant design and implementation, which evidence suggests

was lacking in many countries. Where RSSH funds and activities were provided through the

disease-specific grants, stakeholders found it challenging to implement activities that were

intended to be integrated across diseases (see Box 2.7). In DRC, governance and coordination

challenges stymied implementation of digital health interventions following the government’s

creation of a new digital health agency with responsibilities overlapping those of the national

health information systems agency. In Senegal (Box 2.7), the Secretariat lacked an accountability

mechanism for ensuring follow-through and/or intervention, although between NFM2 and NFM3,

a strategic shift centralized management of TB and Malaria grants under a single unit within the

MoH, which may help address both coordination and leadership issues in the future. These

examples highlight that coordination and leadership are needed to implement activities with

objectives beyond the disease grants.

Box 2.7: Senegal RSSH coordination challenges. In Senegal, each disease program grant was

expected to contribute 10% of its RSSH budget to support the multi-sectoral RSSH platform,

created to improve coordination and harmonization of crosscutting RSSH activities under the

Ministère de la Santé et des Affaires Sociales (MSAS) Direction Générale de la Santé (DGS),

which was selected as the PR of the TB/RSSH grant. However, only the TB program allocated a

portion of their funds, while the HIV and Malaria programs did not because they were unclear

how the funds would be used. This contributed to the platform’s already weak financial and

logistical management capacity, and undermined efforts to integrate RSSH investments across

all three disease programs.

Some PCE countries have examples of successful approaches to overcoming coordination

challenges. In Mozambique, initial delays in recruitment of an RSSH lead delayed implementation

of critical RSSH investments. However, once that position was filled, their leadership facilitated

13

RSSH implementation progress. In other countries (DRC, Guatemala), support and/or persistent

follow-up from the CT supported RSSH implementation progress.

While weak grant coordination was identified as a common implementation constraint, a number

of other mechanisms strengthened these functions and leveraged national leadership and

country ownership over grant implementation. In some cases, the CCM ensured broad and

diverse engagement of stakeholders in a number of countries, particularly in Myanmar.

Regular progress reviews and grant coordination meetings, supported by CTs, also enabled

progress. In DRC, Uganda and Senegal, these reviews and meetings at national and/or subnational

levels facilitated coordinated implementation progress. In Mozambique, coordination of the grant

with the wider MoH program similarly facilitated implementation. Conversely, where there are

examples of lack of political support and the above levers were not suitable and/or used to good

effect, this negatively affected implementation—for instance, with a lack of progress made in

implementing activities to strengthen DHIS2 in Senegal.

Issues with performance monitoring and grant management inhibited implementation

across PCE countries. The Global Fund has designed performance frameworks to include

indicators that are helpful for tracking overall country progress but less useful as indicators to

measure grant implementation progress or results. Moreover, NFM2 performance frameworks

lacked specificity on key RSSH and HRG-Equity investments. Where indicators were proposed,

poor data quality often hampered their use (see Box 2.10 and 2.11).

The grant revision process, discussed in more detail in the section below, was also a barrier to

implementation progress. While the Global Fund intended grant revisions processes to enable

implementation adjustments to maximize impact, in practice, stakeholders found the process

burdensome and have sought to avoid undergoing significant changes that would trigger a TRP

review. In contrast, the grant revision processes for COVID-19 revisions were perceived as more

flexible and a lighter lift for country stakeholders, which has enabled rapid implementation

adjustments in 2020 (see Box 2.8), and may be a source for lessons learned in addressing some

limitations of the standard revision processes.

Box 2.8: Grant implementation and COVID-19 disruptions. Evidence from the PCE countries

underscores how COVID-19 particularly affected HRG-Equity investments in NFM2. For

example, the social distancing measures in Uganda as part of the COVID-19 response included a

ban on social gatherings and movement, as well as school closures, which affected activities like

dialogues, sports campaigns, outreach, and in-school activities that targeted AGYW to reduce

gender barriers to HIV prevention, care, and treatment. COVID-19 also affected HIV services for

KVPs in Cambodia, as described further below.

14

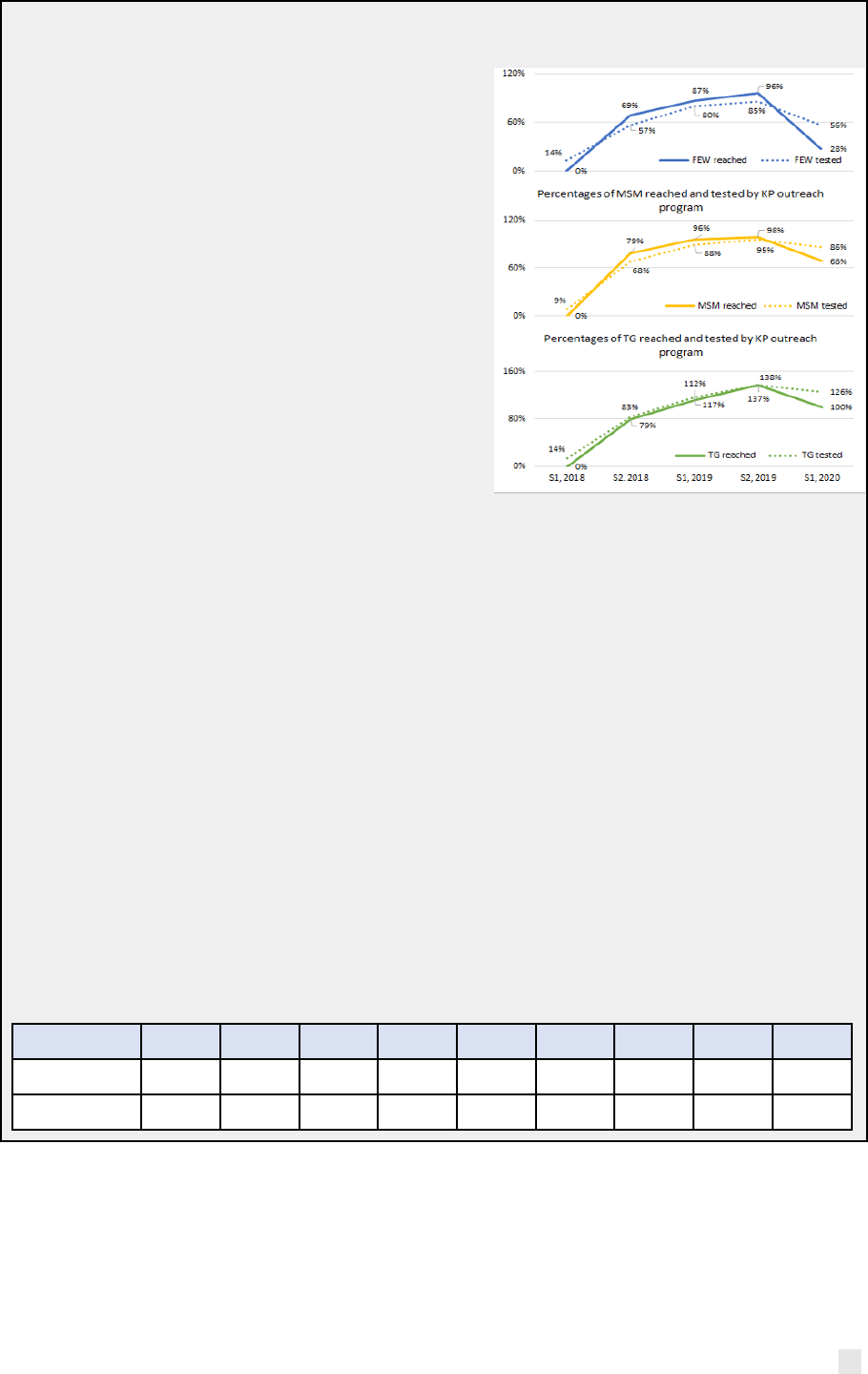

Equity implications of COVID-19 on delivery of HIV

services for key populations in Cambodia. By the

end of 2019, KVP outreach targets had largely been

met and/or exceeded, with the exception of PWID

(not shown). As a result, in 2019, the grant increased

resources for these services through portfolio

optimization and revisions, shifting funds to the

stronger performing interventions targeting Female

Entertainment Workers (FEW), MSM and

transgender people. However, during 2020, COVID-

19 restricted achievement of targets for all key

populations, especially FEW and PWID (not shown).

Entertainment venue closures triggered FEW to

migrate, which disrupted outreach contact. Some

stakeholders expressed concern around the capacity

of implementers to deliver on additional services

under COVID-19 and its effect on absorption.

Global Fund business model flexibilities were

critical in channeling additional resources to the COVID-19 national response through

grant savings and the COVID-19 Response Mechanism (C19RM). Countries used flexibilities

within the NFM2 grants through a mix of ‘true’ savings (e.g., delayed implementation over Year

1-2, lower unit costs, over-budgeting, etc.) and savings from activities that could not be

implemented during lockdowns (e.g., outreach, training, meetings, supervision, school-based

activities), revising US$26m from current grants. An additional US$209m was approved

through C19RM. PRs and SRs undertook various implementation adaptations in responding to

COVID-19 disruptions. For example:

● Cambodia: COVID-19 was predicted to affect antiretroviral therapy (ART) attendance, so

implementation shifted to providing multi-month scripting for all stable ART patients to

ensure maintenance.

● Guatemala: To limit face-to-face outreach interactions, a SR switched to online outreach for

KVPs, with early evidence of improved performance.

● Myanmar: Additional procurement for ARV buffer stock through October 2021, treatment

for opportunistic infections and methadone maintenance, rapid test kits.

● Senegal: Strengthen procurement and supply of laboratory equipment and reagents in

reference labs and potentially increasing use of GeneXpert for COVID-19 testing.

● Uganda: Innovations that leverage Global Fund investments, such as using the bed net

campaign database to guide distribution of facemasks to households, or utilizing community

health volunteers to support medication refill and distribution.

Table 2. Approved grant flexibilities and C19RM ($US millions).(5)

Mechanism

CAM

DRC

GTM

MOZ

MYN

SEN

SDN

UGA

Total

Flexibilities

$0.52

$0

$2.3

$2.6

$6.3

$2.2

$1.6

$10.5

$26.1

C19RM

$0

$55.1

$1.1

$60.5

$27.3

$4.9

$8.7

$51.9

$209.5

The role of revisions during implementation

As per the Operational Policy Manual: “The goal of a grant revision is to allow Global Fund

investments to adjust to programmatic requirements during grant implementation, in order to

ensure the continued effective and efficient use of Global Fund resources invested to achieve

Figure 8. Percentages of FEW reached and

tested by KVP outreach program

15

maximum impact in line with the Global Fund’s 2017-2022 Strategy. A grant revision may also occur

due to other changed circumstances and arrangements.”(6) Grant revisions include:

7

● Additional funding revisions: When the total approved funding is adjusted, including

through ‘portfolio optimization’ and additional donor pledges.

● Program revisions: When programmatic changes in the scope (changing goals,

objectives, or key interventions) and/or scale (increasing or decreasing targets) are

applied to the grant (formerly referred to as “reprogramming”).

● Budget revisions: When the budget is adjusted but the total approved funding does not

change, nor is there any effect on the performance framework.

In addition, subject to its review of grant performance, the Secretariat makes an annual funding

decision that determines the proportion of the grant budget that will be disbursed in the following

period. This is in effect how the Global Fund’s performance-based funding model is

operationalized—i.e., the full budget is disbursed where grant performance is strong, but a

proportion of the budget is withheld where grant performance is weak (see Annex 7). As such, in

theory these decisions also influence whether and how grant revisions are made. The cumulative

effect of these various processes is a grant budget that is frequently subject to change and highly

complex. We explore the implications of these processes for grant management and

implementation in the findings below.

Key message 5. The burdensome revisions process, alongside management incentives on

PRs and CTs to maximize absorption, resulted in revisions being used predominantly as a

financial management tool, rather than necessarily to maximize impact. The cumulative

effect was that grants shifted resources to later in the cycle rather than undergoing

significant restructuring to the scope and/or scale of grants, having the potential to reduce

allocative efficiency.

PCE countries made frequent budget revisions (N=38) and additional funding revisions

(N=37), but program revisions (N=17) to scale or scope were uncommon (Table 3).

Table 3. Number and type of grant revisions during NFM2

`

CAM

DRC

GTM

MOZ

MYN

SEN

SDN

UGA

Total

Additional Funding

Revision

1

11

2

11

0

3

4

5

37

Budget Revision

3