Rowan University Rowan University

Rowan Digital Works Rowan Digital Works

Theses and Dissertations

6-4-2015

Using the Raz-Kids reading program to increase reading Using the Raz-Kids reading program to increase reading

comprehension and 7uency for students with LD comprehension and 7uency for students with LD

Angela Marchand

Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd

Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Marchand, Angela, "Using the Raz-Kids reading program to increase reading comprehension and 7uency

for students with LD" (2015).

Theses and Dissertations

. 556.

https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/556

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please

contact graduateresearch@rowan.edu.

USING THE RAZ-KIDS READING PROGRAM TO INCREASE READING

COMPREHENSION AND FLUENCY FOR STUDENTS WITH LD

by

Angela G. Marchand

A Thesis

Submitted to the

Department of Language, Literacy, and Special Education

College of Education

In partial fulfillment of the requirement

For the degree of

Master of Arts in Special Education

at

Rowan University

May 20, 2015

Thesis Chair: Joy Xin, Ph.D.

© 2015 Angela G. Marchand

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my daughter, Ella Sophia Marchand

iv

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Xin for advising me throughout my research seminar. I

would also like to thank my co-teacher Lauren Smith, as well as my classroom assistants

Linda Pino and Christina Ranson for helping to implement my research intervention as

part of our classroom routine.

v

Abstract

Angela G. Marchand

USING THE RAZ-KIDS READING PROGRAM TO INCREASE READING

COMPREHENSION AND FLUENCY FOR STUDENTS WITH LD

2015

Joy Xin, Ph.D.

Master of Arts in Special Education

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the computer program, Raz-

Kids will assist in supporting independent reading as well as increase a student’s guided

reading level, fluency, and comprehension. Four 1st graders with a learning disability in

an inclusive classroom participated in the study. The Raz-Kids online reading program

was provided individually for 15 minutes each session during the literacy intervention

period, 3 times a week for 16 weeks. The Developmental Reading Assessment was given

at the end of each month to evaluate student performance on a guided reading level,

fluency and comprehension. A single subject design with A B phases was used in this

study. The results showed participating students increased their guided reading levels and

fluency. It seems that the Raz-Kids program would be beneficial as a supplement to

reading instruction and small group guided reading for struggling readers.

vi

Table of Contents

Abstract ........................................................................................................................... v

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. viii

List of Tables.................................................................................................................. ix

Chapter I: Introduction.................................................................................................... 1

Statement of Problems ............................................................................................... 1

Significance of the Study ........................................................................................... 6

Statement of Purposes ................................................................................................ 6

Research Questions .................................................................................................... 6

Chapter II: Review of the Literature................................................................................ 8

Reading Strategies for students with LD .................................................................... 9

Shared Reading .................................................................................................. 10

Repeated Reading .............................................................................................. 12

Technology–Based Instruction ................................................................................. 13

Software Programs ............................................................................................. 14

CD-Roms and Electronic Talking Books ............................................................ 16

Summary ................................................................................................................. 20

Chapter III: Methods .................................................................................................... 21

Setting ..................................................................................................................... 21

Classroom .......................................................................................................... 21

School ................................................................................................................ 21

Participants .............................................................................................................. 21

Students ............................................................................................................. 21

vii

Table of Contents (Continued)

Teacher .............................................................................................................. 23

Materials .................................................................................................................. 23

Instructional Materials ....................................................................................... 23

Measurement Materials ...................................................................................... 24

Procedures ............................................................................................................... 26

Instructional Procedure ...................................................................................... 26

Measurement Procedure ..................................................................................... 26

Research Design ...................................................................................................... 27

Data Analysis .......................................................................................................... 27

Chapter IV: Results ...................................................................................................... 28

Chapter V: Discussion .................................................................................................. 35

Limitations .............................................................................................................. 37

Implications ............................................................................................................. 38

Conclusion and Recommendations........................................................................... 38

References ..................................................................................................................... 40

Appendix: Raz-Kids Reading Program ......................................................................... 46

viii

List of Figures

Figure Page

Figure 1. DRA Comprehension Rubric ......................................................................... 25

Figure 2. Reading performance of Student A ................................................................ 30

Figure 3. Reading performance of Student B................................................................. 31

Figure 4. Reading performance of Student C................................................................. 32

Figure 5. Reading performance of Student D ................................................................ 33

ix

List of Tables

Table Page

Table 1. General Information of Participants ................................................................. 22

Table 2. DRA Reading Levels ...................................................................................... 22

Table 3. Student reading performance by percentage .................................................... 28

Table 4. Student growth and average scores by percentages across phases .................... 29

Table 5. Activities Student Completed in Raz-Kids ...................................................... 29

1

Chapter I

Introduction

Statement of Problems

Reading is considered to be one of the most important academic skills in schools

(Gibson, Carledge, & Keyes, 2011). Being able to read is essential for students to learn

other subjects. For example, students are required to read directions, word problems, and

passages in textbooks when learning math, science and social studies (Gibson, Carledge,

& Keyes, 2011). Students who are not successful to become independent readers will

typically struggle in other academic areas, which will cause a wider achievement gap as

they progress through school (Melekoglu & Wilkerson, 2013). Further, the importance

of reading extends beyond schooling, literacy is necessary to function as a successful

independent adult in our society. As an adult, he/she needs to be able to read notes in

order to maintain a job, communicate with his/her family, and complete daily tasks.

Thus, reading is listed as a primary requirement in the state’s Common Core State

Standards to prepare all students to be ready for higher education and career. These

standards require students to retell stories with key details, read grade level texts with

sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension (CCCS, 2010).

Reading is a complex task which entails many skills including decoding unknown

words, recognizing sight words, understanding vocabulary as well as recalling facts and

events occurred in the story. According to Lacina (2006), there are five principles

deemed necessary for reading instruction, such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency,

vocabulary, and comprehension. Phonemic awareness begins at an early age. Most

students entering school are already expected to know most of the alphabet letters and

2

their corresponding sounds. Phonics instruction focuses on individual vowel and

consonant sound, and symbol correspondence to enable students to decode and encode

words. Students are required to transfer these phonics skills when reading an unknown

word. Fluency is the bridge between a student’s ability to decode words and comprehend

written text during reading. There are three elements of fluency: 1) accuracy which is

the ability to decode words correctly, 2) automaticity which is the speed or ability to read

words, and connected text automatically, and 3) prosody which is the rhythm and tone

exhibited when reading orally. A fluent reader uses voice inflections with various pitches

and tones, as well as reads through text in a fluid manner, free of errors (Thoermer &

Williams, 2012). As indicated by Biemiller (2001), vocabulary words specific to lessons

should be introduced to familiarize students with the subjects they are learning. As

required by the CCCS (2010), students should read fluently and comprehend the text they

are reading. Reading instruction should take place at a student’s independent reading

level (Allington, 2011).

According to the report of the National Assessment of Education Progress (2008),

only one-third of students in the United States read at or above the proficient level; which

means that two out of every three students are unable to read at a level proficient enough

to function independently at their grade level (Allington, 2011). Students without the

necessary reading skills cannot derive meaning from what they read, causing their

reduced motivation in reading. They become unmotivated towards all activities

involving reading and writing (Melekoglu & Wilkerson, 2013). Two thirds of children

entering kindergarten already know the names of the alphabet letters, and one third of

these children know the consonant sounds. The one third that does not know the letters

3

are most likely to become struggling readers (Allington, 2011). The expectations of

students entering school has increased over the years, making it increasingly difficult for

those not receiving literacy activities at home, as well as those that are developmentally

delayed or have learning disabilities.

Students with learning disabilities (LD) have difficulty in reading, due to their

poor cognitive skills, task avoidance, and lack of phonological awareness. It is found that

these students typically spend less time reading independently (Eklund, Torppa, &

Lyytinen, 2013). Limited time spent for reading books at their independent level will

hinder their growth to become successful readers. Students with LD often experience

social discomfort when struggling in reading contexts due to embarrassment, leading to a

reduced motivation in reading (Oakley & Jay, 2008). Their lack of motivation at times

causes them to avoid participation in class and small group activities in reading, while

this missing engagement in the learning process will hinder these students from the

instruction. It is found that acquisition of reading skills and comprehension has a direct

impact on one’s reading skills (Kotaman, 2013). Students with LD in upper elementary

and high school often read below the basic level, causing them to be challenged by the

demands of their grade levels (Melekoglu & Wilkerson, 2013). According to Hudson,

Lane, & Pullen (2005), reading texts at their independent level can benefit these students

enhancing fluency, comprehension, and positive attitudes toward reading. Incorporating

digital texts in reading instruction can increase students’ motivation to read and assist in

increased reading fluency (Thoermer & Williams, 2012). Shared reading provides

students with the opportunity to listen to different texts, which also can assist in

increasing reading motivation (Thoermer & Williams, 2012).

4

Learning to become a successful independent reader begins much earlier than the

time a child starts schooling. It is found that children that are read to regularly and have

access to books at an early age would become successful independent readers (Fox,

2013). Young children learn from adults because adults model fluent reading, show

expressions, make changes in their voice tones, and convey positive attitudes towards

reading. With these positive attitudes they learned from adults, children will spend more

time and enjoy their reading, eventually become better readers (Kotaman, 2013). It is

also found that children reading books at their independent level are making greater gains

in reading development than those instructed with classroom books only (Allington,

2011). It is expected that students should be reading books with 98% accuracy or better,

and 90% comprehension when reading independently (Allington, 2011). Therefore, early

exposure of books and practice of reading will benefit children to build their interests and

become a lifelong reader.

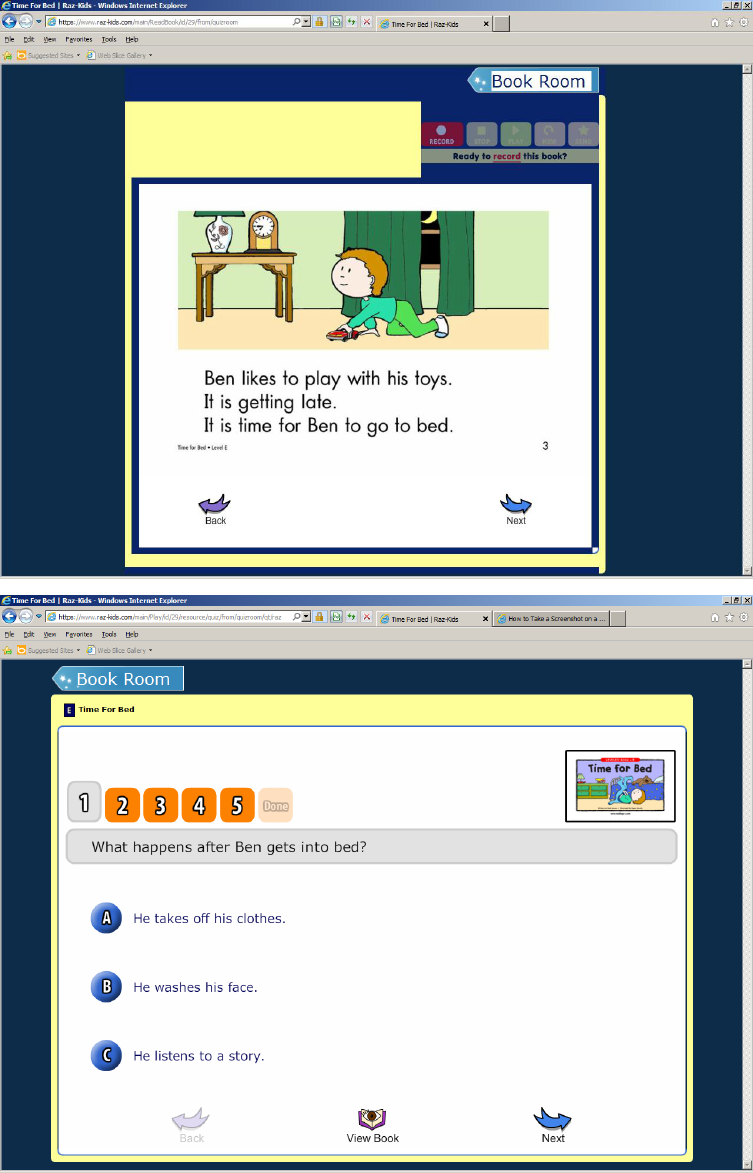

One of the early reading practices is to use technology as a tool to support young

children. There are many software packages available as well as websites developed for

reading. Raz-Kids is an internet-based computer program for young readers

(http://www.raz-kids.com). It was launched in 2004 as part of the Learning A-Z

resources. The mission of this program is to make reading easier and more fun for

children. The features of the program allow learners to listen to fluent reading, record

their own reading for practice, and take a quiz at the end of their reading. It also allows

teachers to set up individual accounts for each student, so that he/she is able to participate

in independent reading on his/her individual level. The teacher can input individual

students guided reading levels to ensure that they are reading at the most appropriate

5

level, with the flexibility to adjust levels at any time needed, and access to numerous

books. As a motivation, points were provided as an award for listening to the story,

reading the story, and taking the quiz. These points can be used to purchase items for

their individual Raz Rocket that is a game feature included in the program. Learners

work through each guided reading level, and their levels can be advanced as the books

are read completely.

To date, technology has been used to support reading instruction in early

elementary classrooms, such as electronic books, books on CD-ROM, and other software

program. For example, using a web-based computer program called Living Letters with

kindergarteners showed their increased phonological skills, invented spelling, and

decoding skills (Van der Kooy-Hofland, Bus, & Roskos, 2011). It seems that using

technology-based reading can improve students’ motivation (eg. Melekoglu &

Wilkerson, 2013), improve students’ reading proficiency and fluency, as well as allow for

independent practice of reading skills through repeated and silent reading while listening

and following along with the captions demonstrated in the digital texts (Thoermer &

Williams, 2012).

However, reviewing technology-assisted reading instruction, little has focused on

internet- based reading programs for students with LD. Some studies, (e.g. Doty et al.,

2001; Grimshaw et al., 2007; Matthew, 1997; Pearman, 2008) applied electronic books in

CD-ROM format which differ from the features of internet-based programs, such as Raz-

Kids, a particular reading program without animations. Schools are eager to provide

instruction, and today’s students are enthusiastic to use technology. Recently schools start

purchasing internet-based supplemental reading programs for their students to enhance

6

their reading and enrich their after school activities. Raz-Kids is one of the programs

used in school, while no data has been collected on learners’ learning outcomes to

evaluate such a program for reading instruction.

Significance of the Study

With the vast number of programs available, schools need to make a decision on

purchasing the best to meet their students’ needs. Unfortunately, many program reviews

available are provided by the companies selling the products, while no data on students’

learning outcomes to evidence the effect on their reading achievement. The purpose of

this study is to examine the Raz-Kids program used for the first graders in my school.

The main purpose of this study is to determine whether this program will assist in

increasing guided reading level, reading fluency and comprehension for students with

LD.

Statement of Purposes

The purpose of this study is to determine whether the computer program called

Raz-Kids will assist in supporting independent reading as well as increase a student’s

guided reading level, fluency, and comprehension by evaluating student scores obtained

using the Developmental Reading Assessment monthly.

Research Questions

1. Will the Raz-Kids computer program assist in the development of the

independent reading skills of children with LD?

2. Will the children with LD increase their guided reading level when the

Raz-Kids computer program is provided in reading instruction?

7

3. Will the children with LD increase their fluency scores when the

Raz-Kids computer program is provided in reading instruction?

4. Will the children with LD increase their comprehension scores when the

Raz-Kids computer program is provided in reading instruction?

8

Chapter II

Review of the Literature

Reading is the most important academic skill in school to enable students to

acquire content knowledge of other subject areas. Students that do not become proficient

readers in the primary grades are often unlikely to be successful in later grades (Carnine

& Carnine, 2004; O’Reilly & McNamara, 2007; Roe et al. 1991; Visone, 2010). The

importance of reading extends beyond schooling into adulthood, because literacy is

necessary for an independent adult to function in the society.

Reading is a complex task consisting of many processes. The two areas focused

on reading instruction are fluency and comprehension. Fluency is the ability to read texts

with accuracy and proper expression. This is an important step to build skills for reading

comprehension (Speece & Ritchey, 2005; NRP, 2000), because reading is more than

simply saying the words on a page, but making connections from the text to the

information for understanding which is the comprehension of the reading.

The U.S. Department of Education (2002) reported that due to a developmental

delay in reading, the majority of school-aged children were identified as having learning

disabilities (LD). For example, 90% of students with LD have significant difficulties in

reading, especially combining the sounds of letters to decode words (Lyon, 1995;

Vaughn, Levy, Coleman, & Bos, 2002). They are struggling in reading fluency, which

makes difficult for them to understand the text they are reading (Manset-Williamson &

Nelson, 2005). Their poor cognitive and phonological awareness skills cause them to

spend more time to read, but less time to enjoy (Lyytinen et al., 2006). In addition, these

students often struggle with reading comprehension, and have difficulty with

9

understanding of word meanings, recalling specific details, making inferences, drawing

conclusions, and predicting outcomes (Denton & Vaughn, 2008; Newman, 2006). Many

of these students also lack general vocabulary knowledge, which makes difficult for them

to process phonological aspects of language, such as decoding unknown words and

understanding word tenses (Swanson, 1999).

Therefore, teaching reading to these students is important, especially providing

appropriate instructional strategies to meet their needs. It is found that shared reading,

repeated reading, and technology-based instruction can be used to promote their

comprehension and vocabulary development (Baker et al., 2004; Baker et al., 2006;

Santoro et al., 2008; Santoro et al., 2005). This chapter reviews research about these

reading strategies.

Reading Strategies for students with LD

According to the National Reading Panel (2000), instructional strategies for

literacy development should focus on phonological and phonics skills, as well as

encourage students to think about and understand their reading. Students should be

actively engaged in the learning and encouraged to connect prior knowledge, make

predictions and personal connections, and visualize before, during, and after reading

(NICHD, 2000). New information should be tied to what the learner already knows for

learning to occur, therefore appropriate text should be chosen according to students’

ability as well as supplemental vocabulary instruction (Sperling, 2006). Learning

outcomes should also be evaluated frequently to check for progress making and to drive

for follow-up instruction. In addition to these strategies, it is essential that teachers create

an environment in which students feel comfortable to overcome their reading difficulties

10

(Martin, Martin, & Carvalho, 2008). Educational success for students with LD is

dependent on their emotional and psychological needs being met (Martin, Martin, &

Carvalho, 2008).

Shared reading. According to the National Council of Teachers of English

(1992), students benefit from telling stories, as well as being active listeners. Listening to

stories enables students to be introduced to unfamiliar patterns of languages and practice

new vocabulary words. Using shared reading as a teaching technique where the teacher

models concepts and strategies is recommended for struggling readers (Allington, 2001).

Listening to someone’s fluent reading has been found to be beneficial for reading fluency

and vocabulary development (Cunningham, 2005).

Kotaman’s study (2013) focused on the impact of shared reading on a child’s

receptive vocabulary and reading attitude, including 40 preschool children and 40 parents

as participants. The children’s receptive vocabulary knowledge was measured using the

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) and their reading attitudes were measured by

the Preschool Reading Attitudes Scale as pre and posttests. These children and parents

were divided into a control and experimental group. Participating parents in the

experimental group received training on dialogical reading techniques for two hours, in

which they learned how to model and role play when reading to their children. These

parents were given prepared reading passages to their children, and a survey to record

how often they applied the techniques. After seven weeks, posttests were administered.

Results showed statistically significant increases of scores in the Reading Attitude Scale

and PPVT of the children in the experimental group comparing to those in the control.

11

Another study by Edwards, Santoro, Chard, Howard and Baker (2008) evaluated

the effectiveness of shared reading to introduce content and to teach comprehension and

vocabulary skills in a first grade classroom. A specific curriculum including text

structure, text focused discussions and vocabulary was used in a general education

classroom for shared reading which lasted 20 to 30 minutes per day for five days, for 15

units of study. The curriculum was designed to address the state standards including

specifically selected narrative and information texts. Students were assessed in the

experimental classroom and compared with students in another classroom in which the

teacher used her own shared reading procedures. Results of this study showed that

enhancing shared reading with comprehension strategies and text-based discussions made

a positive difference in student performance. Students in the experimental classroom

demonstrated higher levels of comprehension and vocabulary knowledge, and their

retelling of stories included more information.

Wiseman’s study (2011) focused on the implementation of interactive shared

reading in a kindergarten classroom to examine if student learning was supported. The

participants included 21 children, all of which were African American from low income

families. The teacher selected specific literature based on the culture of the students.

The shared reading was used to model oral reading, encourage discussion of texts, and to

connect to students’ individual reading and writing from 25 to 45 minutes each day for

nine months. Data was collected four times a week through observations for eight

months focusing on the teacher’s instruction, students’ interactions and responses to the

shared readings. In addition to the observations, students’ shared readings were audio-

taped and their journals were reviewed as well as an interview with teachers and students.

12

It was found that the shared reading led to a positive classroom environment in which the

students showed an increase in engagement in reading activities and academic

performance (Wiseman, 2011).

It seems that shared reading in an elementary classroom can have many benefits.

Students are able to experience different types of texts and learn how to become a better

reader through teacher modeling. Students in a classroom with shared reading tend to

have positive attitudes towards reading, as well as the knowledge of skills used to

comprehend texts they are reading independently.

Repeated reading. Repeated reading refers to reading text several times with

follow-up activities to assist students in reading concepts. It is noted that repeated

reading in the same passage may enable children to have a deeper understanding of the

story as well as vocabulary words (Philips & McNaughton, 1990).

In a case study by Ates (2013), the repeated reading technique was investigated

along with feedback practices to determine if these strategies would benefit a 10 year old

student with reading difficulty. In the beginning of the study, the student was tested and

found to be at the frustrate level for word recognition. Data was collected using a video

camera and computer software. The student’s reading level was assessed before and after

the intervention using narrative passages, and the teacher recorded the student’s word

recognition and reading miscues, as well as the number of correct words read in a minute.

This intervention lasted a total of 38 hours. The student worked one on one with a

researcher 2 to 3 times a week, and was given feedback on the prior session of reading

before a new session started. It was found that the student showed an increase in word

recognition and a decrease in miscues (Ates, 2013).

13

Another case study by Walker, Jolivette, and Lingo (2005) used the Great Leaps

Reading Program to implement repeated reading with a 10 year old boy in 3rd grade

diagnosed with a specific learning disability in reading. The students participated in this

program in the resource room setting, as well as in a community environment for 20 to 25

minutes. This case study lasted from the time the student was in 3rd through 5th grade.

Data was collected using the passages the student read aloud for one-minute timed

sessions. It was found that the repeated reading program was effective for increasing his

reading fluency. The student showed an increase in the number of correct words read in

one minute (Walker, Jolivette, & Lingo, 2005).

Lo, Cooke, and Starling’s study (2011) investigated repeated reading to determine

the effects on participants’ oral reading rates. The study included three 2

nd

graders for 15

to 20 minutes daily four times a week. The intervention included repeated readings of

independent level passages four to five times with a preview of difficult words, unison

reading, error correction, and performance feedback. Results showed improved fluency

rates of all the participants (Lo, Cooke, & Starling, 2011).

It appears that repeated reading is another strategy that can be beneficial to

students with LD. Students instructed with this technique have shown increases in

reading fluency, as well as vocabulary development (e.g., Ates, 2013; Philips &

McNaughton, 1990; Walker, Jolivette, & Lingo, 2005; Lo, Cooke, & Starling, 2011).

Technology-Based Instruction

The U.S. Census Bureau report (2009) stated that 77% of children between the

ages of 3 and 17 use the Internet at home. The use of technology at home and in school is

getting popular for today’s children. There are many internet-based websites found to be

14

available for supplement materials in reading instruction. According to Leu (2002), the

internet offers new tools for effective early reading instruction. It is found that young

children are becoming increasingly exposed to, and interested in reading via online

electronic storybooks (e-books), and this type of digital text can promote language and

literacy skills such as phonological awareness, word recognition, and reading fluency

(Plowman & Stephen, 2003; Valmont, 2000; Van Kleeck, 2008). Technology becomes

an important part of literacy for educators to prepare their lessons and instruction for their

students beyond a paperbound book (Lacina, 2006). In school, students are expected to

navigate texts on a computer for their standardized assessments such as the Partnership

for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC). Teachers are expected

to expose their students to the different types of text media for these technology-based

assessments. For example, an increase in the use of technology in elementary schools

with computer programs for supplemental instruction, often found at a literacy center for

students while the teacher is instructing a small group (Gibson, Cartledge, & Keyes,

2011). Thus, computer-assisted instruction in reading has become a new pathway to

benefit students with reading difficulties, such as software programs, CD-Roms and e-

books (e.g., Elbro, 1996; Jimenez et al., 2007; Saine, Lerkkanen, Ahonen, Tolvanen, &

Lyytinen, 2011; val Daal & Reitsma, 2000; Wise, Ring & Olson, 1999).

Software programs. There are some software programs used in reading

instruction as supplemental materials. These include Read Naturally, Living Letters,

Omega-IS, and COMPHOT. A study by Gibson, Cartledge, and Keyes (2011) examined

the effects of a computerized supplemental program on students’ reading fluency, growth

rates, and comprehension. The study included eight 1st graders that were determined to

15

have a potential risk for reading failure. The students participated in treatment sessions

on the computer three to four times a week, for 14 to 16 weeks using the Read Naturally

software program. The results showed an increase in reading fluency and comprehension

for all the students. Of these, five reduced their risk status, and seven increased their

reading rate (Gibson, Cartledge, & Keyes, 2011). These results appear to support the use

of supplemental computer-based reading programs.

Another study by Van der Kooy-Hofland, Bus, and Roskos (2012) used the

Living Letters software program with 110 at risk kindergarteners to determine the

instructional effects of the program. The participants were divided into three groups.

The first group received instruction using the Living Letters program, the second group

used Living Books, and the final group used both programs. The kindergarteners in the

first and second groups spent 10 to 15 minutes a week on the program, while those in the

combined intervention group spent 15 to 30 minutes a week. All children were tested on

letter knowledge, phonological skills, invented spelling, word recognition, and decoding

prior to the start of the program. After 18 months of the implementation, the same test

was given as a posttest to compare the difference. Results showed positive learning

outcomes of participants in the Living Letters program. The kindergarteners

outperformed the others in the area of decoding related skills and these gains were

sustained beyond the kindergarten year.

In Falth, Gustafson, Tjus, Heimann, and Svensson’s study (2013), the Omega-IS

comprehension training program and the COMPHOT phonological training were used

with 130, 2

nd

graders with reading disabilities. The participants were divided into four

groups: phonological training, comprehension training, combined training, and special

16

instruction. They received 25 one to one sessions with a special education teacher in

their specific program for 15 to 25 minutes per day. Participants in the phonological

training group worked through four different activities involving word position, addition,

rhyme, and segmentation. The focus of the training was on phonemes, letters, words

segments, and words, and immediate feedback was provided after each activity. The

participants in the comprehension training group focused on word and sentence

processing. Their immediate feedback was given through speech and animations.

Participants in the combined training group received both phonological and

comprehension training. Those in the special instruction group received instruction with

the teacher and focused on activities such as reading aloud, discussing stories, and

spelling rules. At the end of the study, the participants were tested on sight word reading,

word recognition, non-word reading, segment subtraction, reading comprehension, rapid

automatized naming, processing speed, verbal fluency, short-term memory and working

memory. The results showed that the group receiving the comprehension training

improved in reading comprehension and working memory. The group receiving the

phonological training showed improvement in reading comprehension and verbal

fluency. The group that received both types of training showed gains in decoding,

reading comprehension, and non-word reading that lasted even after a one year follow up,

and was found to be the most effective.

CD-ROMs and electronic talking books. In addition to supplemental software

reading programs, Electronic talking books (ETBs) are available to children. ETBs have

support features, such as narrations, feedback, and sound effects. These features not only

make reading easier but also attracting children to read (Glasgow, 1996; Passey, Rogers,

17

Machell, & McHugh, 2004). ETBs allow students to access the higher level of texts that

they would not be able to read successfully on their own, because they can concentrate on

meaning while listening to ETBs, instead of struggling to decode unknown words

(McKenna, 2002). In Oakley and Jay’s study (2008), the use of ETBs was provided as

part of a home reading program. The participants included 41 students between the ages

of 8 and 11 defined as reluctant readers. Students brought home one ETB per week for

their reading activity for a total of 10 weeks. Interviews and surveys were completed at

the end of the study to evaluate their satisfaction. The results showed that overall students

enjoyed the ETBs and their reading time at home was increased.

However, research by de Jong & Bus (2002) found evidence that listening to

ETBs was not as beneficial as listening to stories read by adults. Often times, children

chose to use the play features included with ETBs instead of listening to the story for a

repeated time. This study included 55 Kindergarteners assigned to four groups: a regular

book group, restricted computer book group, unrestricted computer book group, and

control group. Participants in the regular book group listened to a paper version of a

book read by an adult examiner. The unrestricted computer book group explored the

electronic version of the same book including games. Participants in the restricted

computer group explored the same electronic version but were not allowed to play the

games. There were six, 15 minute training sessions for two and a half weeks. All

sessions took place in room free of interruptions with only the participant and examiner

present. The participants were pre and post tested on letter knowledge, rhyming, name

writing, word writing, and word recognition. The focus of the study was to compare

book formats and its effects on attention for meaning, phrasing, and text features. It was

18

found that in the unrestricted computer book group, the children played games almost

half the time. Only the children in the regular book group heard the entire story each

session, and could retell the story content. Results of the post tests showed that

participants in the regular book group and restricted computer group made progress in

word recognition.

It appears that E-books can be utilized in a manner that would provide students an

opportunity to listen to stories when a fluent model of reading, such as the teacher,

parent, or another adult is not available. Ciampa’s study (2012) utilized a researcher-

developed online e-book guided reading program for six, 1

st

graders. The participants

were involved in 12 e-book reading sessions for 3 months. They were able to access the

program at home. Results showed that the participants showed a favorable rating when

they were given the freedom to choose their reading selection, as well as an increase in

the time they spent reading online at home and listening comprehension. This study

differs from others on e-books involving in listening to texts on participants’ guided

reading level. It has been found that students make the most progress and increase their

reading fluency and comprehension when they are given the opportunity to choose their

reading material at their appropriate level.

Earlier studies also focused on comparisons of traditional books and computer or

e-books. For example, Leong’s study (1995) compared students’ comprehension when

computers were used in reading. The participants included 192 students categorized as

poor, below average, and above average readers. Participants were placed into two

groups, one group read from the computer either silently or aloud while the second group

listened as the computer read to them. The Canadian Tests of Basic Skills was used to

19

measure their reading comprehension. Results showed that no advantage to using

computer controlled reading could be concluded. The students did not show an increase

in reading comprehension when the computer read to them in comparison to reading on

their own. Greenlee-Moore and Smith (1996) completed a similar study in which 31, 4th

graders were given either a book or an electronic version of a book to read for a period of

eight weeks. The children were asked to complete comprehension questions at the end of

the study. It was found that the longer and more difficult the text, the on-line reading

made a positive difference on comprehension scores. Medwell (1996) also compared

electronic books with paper books, to evaluate 16 student’s performance. It was found

that students reading from the electronic books showed a greater degree of increase in

accuracy comparing to reading the paper book on their own. The result was supported by

Matthew’s study (1997) to evidence that reading comprehension increased when using an

electronic book over a paper version. It is reported that the embedded hotspots in the e-

books may encourage passive participation and distract learners from the printed text,

hindering comprehension (Labbo and Kuhn, 2000; Lefever-Davis & Pearman, 2005). In

addition, combining electronic books and printed books provided was found to be the

most benefit to students (Sharp, 1996). The e-book allowed children to get immediate

feedback on word meanings and pronunciations, and repeated readings of CD-ROM

storybooks resulted in substantial gains in sight word acquisition by using the read aloud

features (McKenna, 1994).

E-books for young children using Internet-based sites have become increasingly

available and popular, however, the effectiveness of these new literacy tools have not

been explored. In the past, research was focused on supplemental reading programs, CD-

20

ROM books, and electronic books, while learners with special needs, especially LD was

not included, and most participating students were in third grade or above in the report

(NICHD, 2000). Early elementary students at the beginning of their reading should be

included, as well as diverse learners including those with LD.

Summary

The definition of reading has changed drastically due to advancements in

technology. Reading includes texts in a variety of forms, such as the traditional printed

text, CD-ROM versions, e-books, and internet-based reading. Studies have shown the

benefits of utilizing alternate versions of books, such as e-books for students to improve

reading comprehension, vocabulary, and word recognition (e.g., Gibson, Cartledge, &

Keyes, 2011; Van der Kooy-Hofland, Bus,& Roskos, 2011; Falth, Gustafson, Tjus,

Heimann, & Svensson, 2013; Oakley & Jay, 2008; de Jong & Bus, 2002; Ciampa, 2012).

E-books should be provided for students in conjunction with printed text as part of the

elementary curriculum in reading. As the needs of learners in a classroom continue to

vary, e-books may become another way to differentiate instruction, which only need little

planning and training on the part of the teachers and students. This present study will

continue to use an e-book program to evaluate its effect for elementary children with

learning disabilities in learning to read with fluency and develop comprehension.

21

Chapter III

Methods

Setting

Classroom. The study took place in a 1st grade inclusive classroom consisting of

18 students, one general education teacher, one special education teacher, and one

assistant designated for two students with special needs. Of these students, 4 are

classified with a learning disability.

School. This classroom is one of five first grade settings in an elementary school

located in a middle class suburban area in southern New Jersey. There are 462 students

from 1

st

to 5th grades in the school. Students with disabilities are placed in inclusion,

resource, or self-contained classrooms based on their individual needs.

Participants

Students. Four 1st graders, classified with a learning disability in an inclusive

classroom participated in the study. They were taught together with 14 general education

students following the general education curriculum with additional support from a

special education teacher. Each of these students has an IEP addressed in learning

language with specific goals and objectives in reading fluency and comprehension. Table

1 presents the general information about participants. Table 2 presents different reading

levels across grades.

22

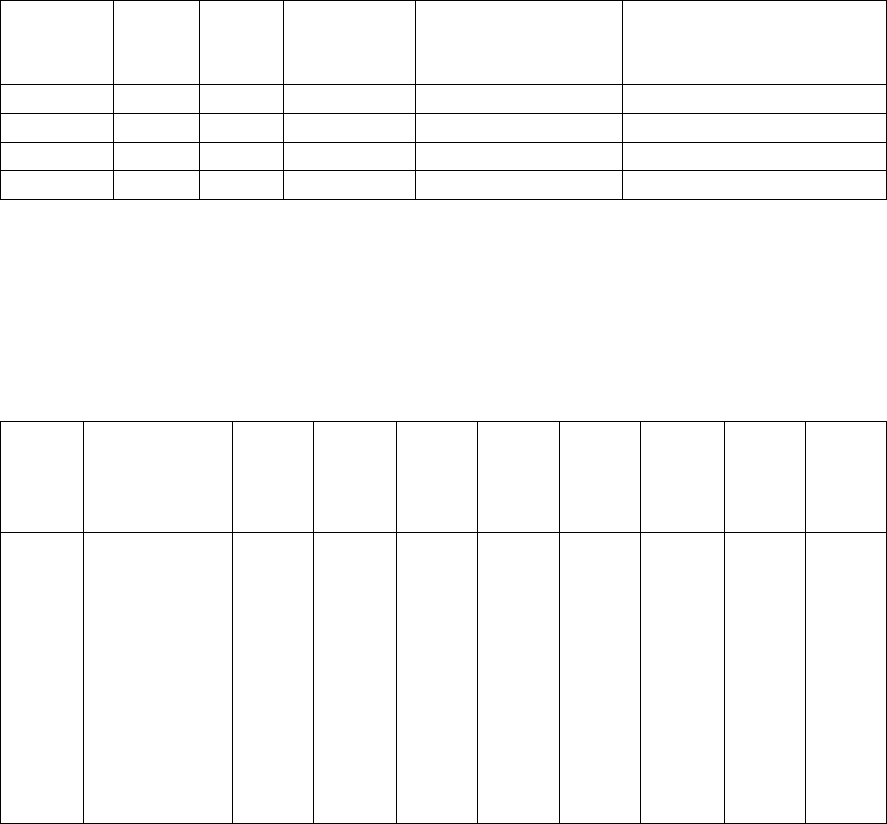

Table 1

General Information of Participants

Student

Age

Grade

Gender

Special Education

Service

DRA*

Reading Level

(Fall, 2014)

A

6

1

M

Since preschool

4C

B

7

1

M

Since preschool

3C

C

6

1

F

Since preschool

3C

D

7

1

M

Since preschool

8E

*Note: DRA: Developmental Reading Assessment (2001)

Table 2

DRA Reading Levels

Grade

Level

Kindergarten

1

st

2

nd

3

rd

4

th

5

th

6

th

7

th

8

th

DRA

Level

1A

2B

3C

4C

6D

8E

10F

12G

14H

16I

18J

20K

24L

28M

30N

34O

38P

40Q

40R

44S

44T

50U

60V

60W

60X

70Y

80Z

Student A is a six year old boy classified as LD with a teacher assistant to

support. This student has difficulty in discussing stories read or answering questions,

though he is able to read fluently. He often shuts down and refuses to speak, even when

working with the teacher one to one which makes it difficult to assess his level of

comprehension.

23

Student B is a seven year old boy classified as being Autistic. He is reading

below the grade level, and needs support for reading fluency and comprehension. He

struggles with sounding out sight words, and reads with a monotone voice without paying

attention to the punctuations. When prompted by the teacher he is able to answer

questions about a story but lacks details.

Student C is a six year old girl diagnosed as ADD, with reading problems. Her

reading is below the grade level. She has difficulty recognizing sight words and needs

many prompts when asked to recall the story. During reading, she often needs a teacher

assistant to support.

Student D is a seven year old boy classified with LD. His reading is at grade level

with fluency, but lacks comprehension skills. He is able to answer questions when

prompted by the teacher with some detail, but generally is unable to recall what he reads.

Teacher. All lessons were taught by a teacher who has 15 years of teaching

experience, 6 years in an inclusion classroom.

Materials

Instructional materials.

Raz-Kids online reading program. This program was purchased by the school

for the 1

st

graders in learning reading. It is an internet-based computer program for

young readers (http://www.raz-kids.com) launched in 2004 as part of the Learning A-Z

resources. The features of the program allow learners to listen to fluent reading, record

their own reading for practice, and take a quiz at the end of the reading. It also allows

teachers to set up individual accounts for each student, so that an individual student is

able to participate in independent reading on his/her own level. The teacher can input

24

individual students guided reading levels to ensure that they are reading at the most

appropriate level with the flexibility to adjust levels at any time needed, and access to

numerous books. As reinforcement, points were provided as an award for listening to

and reading the story, and taking the quiz. These points can be used to purchase items for

a learner’s Raz Rocket that is a game feature included in the program. Learners work

through each guided reading level, and their levels can be advanced as the books are read

completely. A timer will be used to monitor and signal the students when they have

completed 15 minutes on the program. This program was used as a supplemental activity

to the general education curriculum.

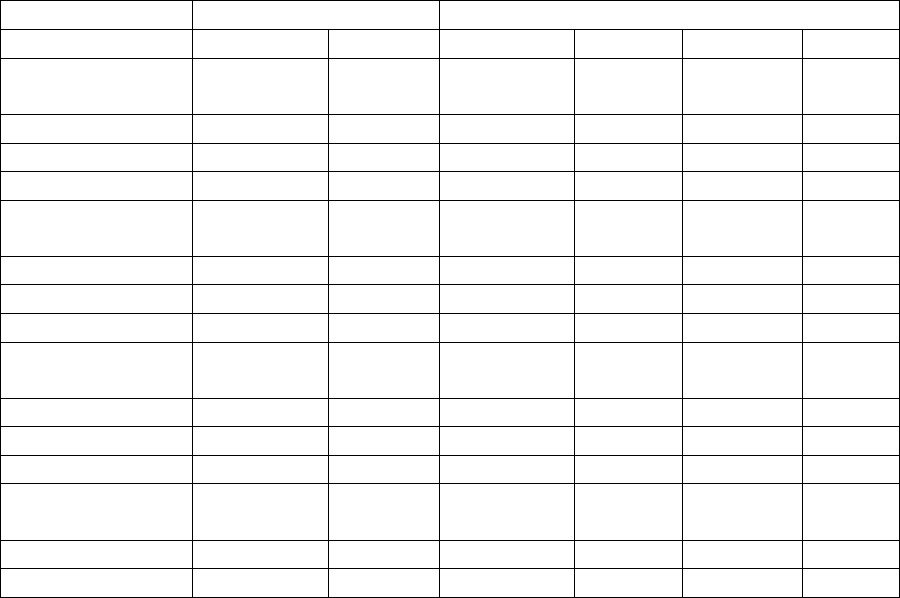

Measurement materials.

Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA). This assessment was used to

evaluate students’ learning outcomes. DRA provides a guided reading level, scores of

fluency and reading comprehension. It is a standardized reading test administered

individually by a teacher or reading specialist. The assessment consists of a collection of

leveled books starting with level 1A, and ending with 80Z. The teacher begins by

introducing the text, the student then reads the leveled book and the teacher makes notes

of oral reading behaviors; such as omitting words, adding words, reading words

incorrectly, self-correcting after a miscue, and repeating words. After the reading,

questions were provided and story retelling was requested. “Independent” level is

considered when a student reads with 95 – 100% accuracy, and comprehension scores of

75 – 100%; 90 – 94% accuracy, and scores of 67 – 71% as “Instructional “ level, and

lower than 90% accuracy and less than 67% is the “Frustrational” level. A rubric with 4

points was used to evaluate reading comprehension with 4 points indicating very good

25

comprehension and 1 for very poor comprehension, (See an example in Figure 1). A

fluency table was included to calculate percentages for reading fluency, while this table is

different in each DRA book on the number of words in the selected story.

Very Little Comprehension

6 7 8 9

Some Comprehension

10 11 12 13 14 1 5

Adequate Comprehension

16 17 18 19 20 21

Very Good

Comprehension

22 23 24

1 Tells 1 or 2 events

or key facts

2 Tells some of the

events or key facts

3 Tells many events

in sequence for the most

part, or tells many key

facts

4 Tells most events in

sequence or tells most

key facts

1 Includes few or no

important details from

text

2 Includes some

important details from

the text

3 Includes many

important details from

the text

4 Includes most

important details and

key language or

vocabulary from text

1 Refers to 1 or 2

characters or topics

using pronouns (he, she,

it, they)

2 Refers to 1 or 2

characters or topics by

generic name or label

(boy, girl, dog)

3 Refers to many

characters or topics by

name in text (Ben,

Giant, Monkey, Otter)

4 Refers to all

characters or topics by

specific name (Old Ben

Bailey, green turtle,

Sammy Sosa)

1 Responds with

incorrect information

2 Responds with some

misinterpretation

3 Responds with

literal interpretation

4 Responds with

interpretation that

reflects higher-level

thinking

1 Provides limited or

no response to teacher

questions and prompts

2 Provides some

response to teacher

questions and prompts

3 Provides adequate

response to teacher

questions and prompts

4 Provides insightful

response to teacher

questions and prompts

1 Requires many

questions or prompts

2 Requires 4 or 5

questions or prompts

3 Requires 2 or 3

questions or prompts

4 Requires 1 or no

questions or prompts

Figure 1. DRA Comprehension Rubric

26

Procedures

Instructional procedure. The Raz-Kids online reading program was provided

individually for fifteen minutes each session during the literacy intervention period, 3

times a week for 16 weeks. During each session, two students were required to log on

the program. Each child had his/her individual login name and password, and the

program was set to his/her independent reading level. The timer was set to fifteen

minutes during which students listened to, read, and took quizzes on the books designated

for their level. They were not allowed to access the play features during these sessions.

In addition, students were instructed in small groups for guided reading focused on

improving reading fluency and comprehension skills. Fiction and non-fiction stories

were selected to teach specific skills such as: a) asking and answering questions about

key details in text, b) retelling a story, c) describing characters, settings, and major events

in a story using key details, and d) using illustrations and details in a story to describe its

characters, settings, and events.

Measurement procedure. DRA was given at the end of each month to obtain a

guided reading level, comprehension, and fluency scores. It is administered by a teacher

to test an individual student. An estimated level of book from the DRA leveled books

was selected, and the teacher read the title with an introduction. The student was

required to read the story and his/her reading behaviors were recorded. After reading, the

student was asked to recall the characters, setting, and main events with details. If

needed, the teacher may prompt the student in order to attain more information to assess

comprehension. All prompts must be documented on the scoring sheet, and the rubric

was used for recording the comprehension scores. The teacher circled the number to the

27

left of one statement in each row that best described the student’s retelling of the story

read. The circled numbers were then added together to obtain a total score and level of

comprehension. The fluency table for oral reading percentages was used to record

student’s performance. The teacher circled the number of miscues and looked at the

corresponding percentage for the fluency score.

Research Design

A single subject design across students with A B phases was used in this study.

During phase A, the baseline, each student was tested by DRA monthly, their guided

reading level and comprehension and fluency scores were recorded. During phase B, the

intervention, students were instructed using the Raz-Kids reading program 15 minute

sessions, 3 times a week for 16 weeks. The same DRA assessment was administered

monthly to record student performance scores and reading level.

Data Analysis

Each student’s guided reading levels; fluency and comprehension scores were

plotted on a line graph to demonstrate individual student’s reading progress, as well as

tables to present student’s learning outcomes to compare their performance in the

baseline and intervention, in order to evaluate the effects of the Raz-Kids program.

28

Chapter IV

Results

Each student was tested monthly using the Developmental Reading Assessment

(DRA) to attain scores of guided reading level, fluency, and comprehension during the

baseline and intervention. Growth in guided reading level was reported, as well as

average fluency and comprehension scores. Data are also included on items of Raz-Kids,

specifically the number of books listened to, read, and quizzes completed. The total

amount of time spent was also recorded. Each student’s performance is presented in

Tables 3, 4, and 5 respectively.

Table 3

Student reading performance by percentage

Baseline

Intervention

September

October

November

January

February

March

Student A

Reading Level

4C

4C

8E

12G

18J

20K

Fluency

94

96

100

99

99

99

Comprehension

0

63

42

75

71

33

Student B

Reading Level

3C

3C

6D

8E

12G

14H

Fluency

96

100

96

97

96

99

Comprehension

67

79

50

75

63

50

Student C

Reading Level

3C

3C

4C

4C

8E

8E

Fluency

96

100

96

96

95

100

Comprehension

79

79

63

67

42

63

Student D

Reading Level

8E

8E

12G

16I

18J

20K

Fluency

100

100

100

99

100

100

Comprehension

46

58

54

50

63

46

29

Table 4

Student growth and average scores by percentages across phases

Baseline

(phase A)

Intervention

(phase B)

Reading

Level

Growth

Fluency

Comprehension

Reading

Level

Growth

Fluency

Comprehension

Student

A

+ 0

95

31.5

+ 8

99.25

55.25

Student

B

+ 0

98

73

+ 6

97

59.25

Student

C

+ 0

98

79

+ 3

96.75

58.75

Student

D

+ 0

100

52

+ 6

99.75

53.25

Table 5

Activities Student Completed in Raz-Kids

Books

(listened)

Books (read)

Quizzes taken

Total Time

Student A

161

31

86

12 hours

25 minutes

Student B

129

63

164

11 hours

53 minutes

Student C

126

52

78

11 hours

30 minutes

Student D

107

18

67

10 hours

44 minutes

Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 present each student’s reading performance in fluency and

comprehension.

30

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

4C 4C 8E 12G 18J 20K

Fluency

Comprehension

Intervention

Baseline

Figure 2. Reading performance of Student A.

At the reading level C, this student’s performance scores were 63% for

comprehension and 96% for fluency during the baseline. When using the Raz-Kids

program, the student’s reading level was increased 2 levels to 8E with scores of 42% for

comprehension and 100% for fluency. The student continued to show growth in reading

levels throughout the intervention. At level 12G, the scores were 75% for comprehension

and 99% for fluency. At level 18J, the scores were 71% for comprehension and 99% for

fluency. At level 20K, the scores were 33% for comprehension and 99% for fluency.

31

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

3C 3C 6D 8E 12G 14H

Fluency

Comprehension

Baseline

Intervention

Figure 3. Reading performance of Student B.

At the reading level C, this student’s performance scores were 79% for

comprehension and 100% for fluency during the baseline. When using the Raz-Kids

program, the student’s reading level was increased 1 level to 6D with scores of 50% for

comprehension and 96% for fluency. The student continued to show growth in reading

levels throughout the intervention. At level 8E, the scores were 75% for comprehension

and 97% for fluency. At level 12G, the scores were 63% for comprehension and 96% for

fluency. At level 14H, the scores were 50% for comprehension and 99% for fluency.

32

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

3C 3C 4C 4C 8E 8E

Fluency

Comprehension

Baseline

Intervention

Figure 4. Reading performance of Student C.

At the reading level C, this student’s performance scores were 79% for

comprehension and 100% for fluency during the baseline. When using the Raz-Kids

program, the student’s reading level did not increase at first. At level 4C the scores were

63% for comprehension and 96% for fluency. The student continued on the same level

with scores of 67% for comprehension and 96% for fluency. At level 8E, the scores were

42% for comprehension and 95% for fluency. The student continued at the same level

with scores of 63% for comprehension and 100% for fluenc

33

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

8E 8E 12G 16I 18J 20K

Fluency

Comprehension

Baseline

Intervention

Figure 5. Reading performance of Student D.

At the reading level E, this student’s performance scores were 58% for

comprehension and 100% for fluency during the baseline. When using the Raz-Kids

program, the student’s reading level was increased 2 levels to 12G with scores of 54% for

comprehension and 100% for fluency. The student continued to show growth in reading

levels throughout the intervention. At level 16I, the scores were 50% for comprehension

and 99% for fluency. At level 18J, the scores were 63% for comprehension and 100% for

fluency. At level 20K, the scores were 46% for comprehension and 100% for fluency.

At the end of the study, all participating students were asked the following 5

questions: 1. Did you like using Raz-Kids? 2. Did you like listening to books on Raz-

Kids? 3. Did you like reading books on Raz-Kids? 4. Did you like taking quizzes on

Raz-Kids? 5. Do you prefer reading traditional books or books on Raz-Kids? Three out

of the four students (75%) reported that they enjoyed using Raz-Kids. The same three

34

students also stated that they preferred reading books on Raz-Kids in comparison to

traditional books. One student reported that she did not like using the program because

the time spent on the program seemed too long for each session. The same student also

stated that she did not like to read, but that she preferred reading traditional books over

those on Raz-Kids. All four students (100%) reported that they liked listening to books,

reading books, and taking quizzes on Raz-Kids. Overall, the students seemed satisfied

with the Raz-Kids program.

35

Chapter V

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if the Raz-Kids program would be a

successful reading intervention for students with learning disabilities. The program

enabled students to listen to, read, and take quizzes on stories at their individual reading

level, as well as increased the amount of time for students involved in reading in their

school day. Student scores obtained using the Developmental Reading Assessment

(DRA) evaluated their learning growth in reading level, fluency, and comprehension.

The first research question focused on the development of the independent

reading skills of children with LD when the Raz-Kids program was provided. Results

showed that all students gained reading levels throughout the study. For example,

Student A made the most growth with 8 reading levels from 4C to 20K, but struggled

with comprehension as the stories increased with difficulty. Student B grew 6 reading

levels from 3C to 14H, and Student D grew 6 reading levels from 8E to 20 K, but still

had the same difficulty with comprehension as the stories increased with the difficulty

level. Student C made the least amount of growth, from 3C to 8E, only 3 reading levels.

Overall, all students gained their scores, though each gained at different levels. It seems

that the Raz-Kids program helped these students develop reading fluency by listening to

the stories, as well as the repeated reading of the stories. The Raz-Kids program did not

seem to help students develop their comprehension, because all participants had overall

low comprehension scores.

The second research question focused on guided reading levels to evaluate student

performance. All students showed growth in reading levels once the Raz-Kids program

36

was introduced as part of the intervention. For example, prior to the intervention, the

students had not made any growth in reading levels, while during the intervention,

Student A made the most growth, increasing 8 guided reading levels. Students B and D

increased 6 guided reading levels, and Student C increased 3 guided reading levels.

These results are similar to the findings in Gibson, Carledge, and Keyes’ study (2011) in

which students showed an increase in fluency when using the Read Naturally, another

computer program. This may mean that computer programs that allow students to listen

to stories being read increase the amount of time spent on reading. It may also improve

student’s sight word vocabulary through exposure to the many stories available on the

programs.

The third research question was addressed to evaluate students’ reading fluency.

Students’ scores varied due to the increasing difficulty of the books being read to

determine reading level. Overall, their scores were 95% or higher, which showed that the

students were reading with sufficient accuracy. According to the DRA, “Independent”

level is considered when a student reads with 95 – 100% accuracy, and comprehension

scores of 75 – 100%; 90 – 94% accuracy, and scores of 67 – 71% as “Instructional “

level, and lower than 90% accuracy and less than 67% is the “Frustrational” level.

During the intervention, all students gained their scores to reach the “independent” level,

for example, Student A had an average score of 99.25%, Student B, 97%, Student C,

96.75%, and Student D, 99.75%.

The fourth research question was asking about reading comprehension. Results

showed that the Raz-Kids program did not improve student progress in this area. The

average comprehension scores of all students during the intervention phase were below

37

67% that could represent “Frustrational” level according to the DRA. For example,

Student A had an average score of 55.25%, Student B, 59.25%, Student C, 58.75%, and

Student D, 53.25%. Comparing to fluency, the lower scores in comprehension can be

explained due to the increasing difficulty of the books being read as reading levels

increased. Lower scores can also be explained due to other circumstances, for example,

Student A often has difficulty in testing situations, which accounted for lower scores for

refusing to discuss the story. These results were similar to Leong’s study (1995) which

also found limited increase in comprehension when computers were used for reading. It

seems that the Raz-Kids program did not assist in the increase of student comprehension

when used as part of reading instruction. This may mean that comprehension skills need

to be trained in a longer time by guided practice with a teacher. Listening to and reading

stories may not result in immediate improvement in comprehension.

Limitations

Despite the positive results, there were some limitations in this study. The small

sample size of four limited the amount of data that could be collected to determine if the

Raz-Kids program was successful as a reading intervention for students with learning

disabilities. Second, the study took place over sixteen weeks; however, there were some

inconsistencies between the students and the amount of time spent on the program. Some

students were absent from school due to illnesses and were not able to complete all of the

sessions. Interruptions in the school calendar were also a factor, for example, schedule

changes due to snow day closings and delayed openings, holidays, and school assemblies.

Another concern is that the classroom setting with other students’ noise might affect

individual student’s concentration. It was noted that when students used the program on

38

the iPad they seemed to be more engaged and focused comparing to the use of the

desktop computer in the classroom. Because of the limited number of iPads available,

most of the sessions of the reading instruction were completed on desktop computers.

Implications

The results showed an increase in guided reading levels for all participating

students in reading fluency, though comprehension was an area of weakness. The Raz-

Kids program would be beneficial as a supplement to reading instruction and small group

guided reading. Teachers may encourage students to utilize the Raz-Kids program in a

structured way, for example requiring students to listen to, read, and then take a quiz on

each book in the designated level. Teachers should encourage school administrators to

support technology application in the classroom. In the study, it is found that students

benefited from an increased amount of time involved in reading when Raz-Kids on both

desktop computers and iPads was provided. If schools could provide a designated room

where students could read using technology, this would definitely increase their

concentration and motivate their reading interests resulting in enhanced reading of books.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The results of this study showed an increase in guided reading levels of the

students with learning disabilities by their growth in reading fluency. It seems that the

Raz-Kids program would be beneficial as a supplement to reading instruction and small

group guided reading for struggling readers. Future studies should include a larger

sample size to validate the finding. It would also be beneficial if the sessions could be

completed in a setting free of distractions. Future studies should also include groups in

which the subjects are instructed with paper copies of the Raz-Kids books during small

39

group instruction. These books could be given to students for additional practice at

home. Reading can be taught in various ways to encourage readers to be motivated in

reading activities. Using technology for reading enables students to be engaged in their

learning, increase time reading, and assist with fluency when listening to stories on the

computer. The use of technology in reading can also provide the teacher with

information about each individual student’s progress in reading instruction.

40

References

Allington, R.L. (2001). What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-

based programs. New York: Addison.-Wesley.

Allington, R.L. (2011). What At-Risk Readers Need. Educational Leadership, 68(6),

40–45.

Ates, S. (2013). The effect of repeated reading exercises with performance-based

feedback on fluent reading skills. Reading Improvement, 50(4), 158-165.

Baker, S., Chard, D.J., & Edwards, L. (2004). Teaching first grade students to listen

attentively to narrative and expository text: Results from an experimental study.

Paper presented at the 11

th

annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of

Reading, Amsterdam.

Baker, S., Chard, D.J., Santoro, L.E., Otterstedt, J., & Gau, J. (2006). Reading aloud to

students: The development of an intervention to improve comprehension and

vocabulary of first graders. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Biemiller, A. (2001). Teaching vocabulary: Early, direct, and sequential. American

Educator, 25, 24-28, 47.

Carnine, L., & Carnine, D. (2004). The interaction of reading skills and science content

knowledge when teaching struggling secondary students. Reading and Writing

Quarterly, 20(2), 203-218.

Ciampa, K. (2012). ICANREAD: The effects of an online reading program on grade 1

students' engagement and comprehension strategy use. Journal of Research on

Technology in Education, 45(1), 27-59.

Cunningham, P. (2005). “If they don’t read much, how they ever gonna get good?” The

Reading Teacher, 59(1), 88-90.

de Jong, M. T., & Bus, A. G. (2002). Quality of book-reading matters for emergent

readers: An experiment with the same book in regular or electronic format. Journal

of Educational Psychology, 94(1), 145-55.

de Jong, M. T., & Bus, A. G. (2004). The efficacy of electronic books in fostering

kindergarten children's emergent story understanding. Reading Research Quarterly,

39(4), 378-393.

Denton, C. A. & Vaughn, S. (2008). Reading and writing intervention for older students

with disabilities: Possibilities and challenges. Learning Disabilities Research and

Practice, 23, 61-62.

41

Doty, D. E., Popplewell, S. R., & Byers, G. O. (2001). Interactive CD-ROM storybooks

and young readers’ reading comprehension. Journal of Research on Computing in

Education, 33(1), 374-384.

Eklund, K. M., Torppa, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2013). Predicting Reading Disability:

Early Cognitive Risk and Protective Factors. Dyslexia 19, 1-10.

Elbro, C. (1996). Early linguistic abilities and reading development: A review and a

hypothesis about distinctness of phonological representations, Reading and Writing:

An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 505-5.

Falth, L., Gustafson, S., Tjus, T., Heimann, M., & Svensson, I. (2013). Computer-assisted

interventions targeting reading skills of children with reading disabilities--A

longitudinal study. Dyslexia, 19(1), 37-53.

Fox, M. (2013). What next in the read-aloud battle?: Win or lose? Reading Teacher,

67(1), 4-8.

Gibson, L., Carledge, G., & Keyes, S. E. (2011). A Preliminary Investigation of

Supplemental Computer-Assisted Reading Instruction on the Oral Reading Fluency

and Comprehension of First-Grade African American Urban Student. Journal of

Behavioral Education, (20), 260-282

Glasgow, J. N. (1996). It’s my turn! Part II: Motivating young readers using CD-ROM

storybooks. Learning and Leading with Technology, 24(4), 18-22.

Greenlee-Moore, M.E. & Smith, L.L. (1996). Interactive computer software: the effect

on young children’s reading achievement. Reading Psychology: An International

Quarterly, 18, 43-64.

Grimshaw, S., Dungworth, N., McKnight, C., & Morris, A. (2007). Electronic books:

Children’s reading and comprehension. British Journal of Educational Technology,

38(4), 583-599.

Hudson, R. F., Lane, H. B., & Pullen, P. C. (2005). Reading fluency assessment and

instruction: What, why, and how? The Reading Teacher, 58(8), 702-714.

Jimenez, J. E., Hernandez-Valle, M., Ramirez, G., del Rossario Ortiz, M., Rodrigo, M.,

Estevez, A. (2007). Computer speech-based remediation for reading disabilities:

The size of spelling-to-sound unit in a transparent orthography. Spanish Journal of

Psychology, 10, 52-67.

Kotaman, H. (2013). Impacts of dialogical storybook reading on young Children's

reading attitudes and vocabulary development. Reading Improvement, 50(4), 199-

204.

42