NATIONAL CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK FOR

ADULT EDUCATION

REPORT OF THE EXPERT COMMITTEE

March 2011

New Delhi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

PREFACE iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

CHAPTER-1: INTRODUCTION 13

Introduction 13

Context and Brief Review of existing Institutional Framework 14

CHAPTER-2: CHALLENGES 19

Provisioning of adult education-Perspective and Challenges 19

Role of Adult Educator 20

Rights Approach-National Commitment 20

CHAPTER-3: PRINCIPLES OF CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK 22

3.1 Principles 22

3.2 Pedagogy 23

3.3 Curriculum 23

CHAPTER-4: CONTINUOUS AND LIFELONG LEARNING-STRATEGIES 25

4.1 Adult education in the framework of Continuing and Lifelong learning 25

4.2 Profile of Adult Learners 26

4.3 Adolescents 27

4.4 Strategies for Imparting Literacy and Adult Learning Programmes 28

4.5 Adult Learning Classroom Processes 34

CHAPTER-5: TRAINING 36

5.1 Training for Lifelong Adult Education 36

5.2 Approach to training for Lifelong and Continuing Education 37

5.3 Structure of training mechanism for Lifelong and Continuing Education 38

5.4 Training of Basic Literacy facilitators 38

5.5 Training for running equivalency courses and Skill development programmes 39

5.6 Long Term Academic programmes in Adult Lifelong Education 40

5.7 Jan Shiksha Sansthans (JSSs) and the AE framework 41

5.8 Convergence of other development programmes and AE programmes 41

CHAPTER-6: ASSESSMENT, OUTCOMES AND EQUIVALENCEY 42

6.1 Assessment, Outcomes and Equivalency 42

6.2 Purpose of evaluation 42

6.3 Key issues to be covered by evaluation 43

6.4 Evaluation process 46

6.5 Equivalency 48

6.6 Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) 48

CHAPTER-7: PROPOSED SYSTEMIC FRAMEWORK 50

7.1 Introduction 50

7.2 Diversity in Stages of Adult Education Programme 50

7.3 Institutional Framework-From Gram Panchayat to National Level 51

7.4 Convergence 64

CHAPTER-8: CONCLUSION 69

Annexeure-I: NCFAE EXPERT COMMITTEE MEMBERS 71

Annexeure-II: GENDER 74

PREFACE

An Expert Committee was constituted by the MHRD, Govt., of India on 30

th

March 2010,

to draft the National Curriculum Framework for Adult Education in the context of

‘Saakshar Bharat’ the Central Scheme of National Literacy Mission Authority (List of

Members in Annexure-1).

The Expert Committee was to spell out the following issues in the curriculum

framework:

• The content and its comprehensiveness in respect of core academic areas and

locally relevant issues;

• Teaching-learning methods and processes for achieving the literacy and other

objectives;

• Reflecting on national values, and how to address the demands of the learners,

while taking into account the diversity of their socio-cultural background, life

experience, linguistic skills and motivational levels;

• Striking a balance between the larger social objectives of the Mission and

relevance to local contexts and to wider opportunities;

• Laying down guidelines for the syllabi, the T-L approaches, methods and

processes and spelling out the levels and norms of learning outcome, and

learning assessment system;

• Developing a Curriculum Framework that would serve as the basis for the States

to develop the curriculum and learning materials, with adequate reflection of

locally relevant issues and aspects.

In its first meeting on 2

nd

July, 2010, chaired by the Minister for Human Resource

Development (MHRD), Shri Kapil Sibal along with Smt. Purandareshwari Devi (MOS)

emphasized that the focus of the Expert Committee was to include not just a curriculum

framework for literacy but education that would lead to empowerment. He stated that

the curriculum should touch the needs of learners and the endeavor for literacy and adult

education should lead to true empowerment. The curriculum framework should embed

these as pre-requisites and, to that end, the Committee should also take the views of the

learners of how literacy could be helpful in their life context.

The Members felt that the curriculum framework should:

• Articulate the vision of adult education, not as literacy, narrowly defined as the 3

Rs, but as a vision of national values to encompass secularism, democracy, social

and gender equity and equality, women empowerment, etc.;

• Spell out the national needs, values and approaches rather than try to make

curriculum and syllabus;

• Highlight the basis and approach to learning in the context of adults that

respects their experiential knowledge and involves them in knowledge creation;

• Harnesses learners’ experiential knowledge and enable the processes of

empowerment to become an integral part of assessment of the learning

outcome, as intended by Saakshar Bharat;

• Livelihood-oriented skills to be considered as inseparable facets of the

education program, and to be seen as ongoing process and not as short-term

based intervention;

• The content while adhering to core principles such as secular democracy, equity

and justice and gender parity, as enshrined in the Constitution of India, must be

locally relevant and blend into geographic, cultural and economic diversities of

different regions;

As regards the modalities of its working, the Committee felt the need to enlarge the scope

of its consultations by also involving all stakeholders in the field. HRM fully endorsed this

view and suggested that the Committee visit different regions and States, form an

assessment of learning needs of learners through intensive dialogue with all stakeholders

and reflect on them for the proposed curriculum framework. Accordingly, the Expert

Committee held four Regional Consultations at (i) Hyderabad for Southern Region, (ii)

Pune for Western Region, (iii) Kolkata for Eastern and North-Eastern Regions, and (iv)

Delhi for Northern Region, with stakeholders such as representatives of civil society,

researchers, experts, members from women’s groups and officials from SLMAs, State

Directorate of Adult Education, SRCs, JSSs, PRIs , faculty of Adult Education of Colleges

and Universities, and so on (about 40-60 in each Region).

In respect of academic tasks, the Committee spelled out broad sub themes which related

to: (1) Literacy in India: Values, Approaches and Teaching and Learning Processes, (2)

Assessment, Outcomes and Equivalency, (3) Sectoral Approaches, (4) Systemic Reform: (i)

Government-Administration; (ii) Partnership and Collaboration; (iii) Involvement of PRIs,

CSOs, SHGs, etc., and (5) Orientation and Capacity Building. The Committee Members

prepared write ups on different sub-themes, which helped during the consultations to

gather stakeholders’ views, and also ultimately in preparing the document.

By the end of the consultation it was clear that all planning must begin on the premise

that it is possible to make India a fully literate and empowered nation. The adult

education program must develop institutional capacities to reach out to each and every

learner wholeheartedly. It must be a continuous and lifelong education with attainment of

basic literacy as a non-negotiable.

It is my privilege to present the Draft Report of the Expert Committee for your perusal.

The final report would be presented soon.

I thank the Members for their contribution in enriching the deliberations and their write

ups. I should also like to particularly thank Dr. A. Mathew, Senior Consultant (NLMA) for

extending his support to the Expert Committee in organizing the consultations and in

drafting the report.

Shantha Sinha

Chairperson,

Expert Committee on National Curriculum Framework for Adult Education

Executive Summary

Introduction

A nation that is literate is one where its citizens are empowered to ask questions, seek

information, take decisions, have equal access to education, health, livelihood, and all

public institutions, participate in shaping ones realities, create knowledge, participate in

the labour force with improved skills, exercise agency fearlessly and as a consequence,

deepen democracy.

Systems are to be in place to build a nation that builds citizenship which is truly

informed and literate and in the process the content of governance, development and

democracy is also vitalised.

It is only when there is a credible, whole hearted and institutionalized effort on a long

term basis that the learner would take the programme of adult education seriously.

The first step, therefore, is to understand Adult Education Programme as a continuous

and lifelong education programme. It must contain all structures and institutions from

national to habitation levels, on a permanent basis, as part of the education

department. The structures and processes should be receptive to the learners’ needs on

the ground.

Compared to the model in vogue, these imperatives represent a basic transformation in

the character of the programme, with pronounced permanency in learning centres for

adult and continuing education in the lifelong learning perspective. This will qualify for

the shift from Plan to Non-Plan phasing for planning and budgeting.

Principles of Curriculum Framework

Assuming that the institutional structures would be transformed towards permanency,

it then becomes a challenge to define the pedagogy of Adult Education as a long term

ongoing process which would be implemented through such a structure. Minimally,

Adult Education is a literacy program that imparts rudiments of basic education. That is

more or less how it has been envisaged over the years. However, based on the theory

and practice of Adult Education internationally, it is much more than literacy and post-

literacy; it is the convergence of education, democracy, cultural practice, developmental

practices, gender empowerment and much more. Accordingly, it is useful to first outline

a set of principles that should inform policy and practice of Adult Education.

Some of the principles that should inform the Curriculum Framework for Adult

Education include:

- Developing learners’ critical consciousness, leading to their empowerment, and

informing pedagogy

- Empowerment that leads to participants becoming politically, socially and culturally

active, aware and confident

- Enabling democratic participation and inculcation of constitutional values

- Respecting the learner as a productive person with dignity, sense of well-being and

ability to realize his/her creative potential, removing social and other forms of

discrimination, and in particular, fostering gender equality.

Pedagogy

- Recognize that pedagogical approaches to adult learning are completely different

from that of children and need to be further differentiated for adolescents and

women

- Non-literate adults possess experiential skills, knowledge and wisdom. Adult-

pedagogy must be based on this fact and help expand their mental horizons. It

should be relevant to their learning needs, flexible and participatory, in order to

sustain their interest and motivation

Curriculum

- The context and principles of adult learning, as enunciated above, must inform the

contents and processes

- Contents must combine new skills, awareness and knowledge, learners’ lived

experiences and needs

- Structure the programme not as a short-term engagement but as beginning of

lifelong education, that includes avenues for equivalency

- Learning materials for adults need to be diverse and varied

- Curriculum must address skills and cognitive development as well as the affective

domain including values, self-confidence and dignity

- For curriculum and material development, Adult Education needs to be viewed as a

lifelong learning engagement, plural and flexible

Perspectives and Challenges in Provisioning Adult Education

Adult Education cannot and should not any longer be considered as a short-term project

for achieving a certain percentage of literacy. It should be conceived as a comprehensive

and life-long programme for providing a variety of learning programmes to all adults,

including basic literacy, life and livelihood skill development, citizenship development

and social and cultural learning programmes.

In a country like India, it should also not be seen as a program to benefit merely

individual learners. In addition to such individual benefit, the program should be so

conceived and delivered that it promotes and sustains communities of empowered

people – of women, farmers, workers and other sections of society. As the objectives of

the National Literacy Mission mentioned, literacy should make the learners understand

the causes of their deprivation and help them to unite to fight such deprivations. Since

the category of illiterates coincides with the deprived sections of the society – women,

minorities, low-castes, tribals and the poor, literacy programs should become a vehicle

for these sections of society to use knowledge, information and skills towards enhanced

opportunities leading to social justice and equality.

For this, there has to be an institutional framework both for delivering the learning

programme and also for capacity building, contents and material development at State,

District and Block levels as well as for planning and implementation of the programmes.

There has also to be a system and set up with clear cut administrative and personnel

hierarchy at State, District, Block and GP / Village levels. Given the cross-cutting nature

of adult education and the variety of learners in respect of their learning needs,

convergence between adult education and various line departments cannot be

underestimated.

The Adult and Continuing Education in the village, under well trained and motivated

Adult Educators and the programme under the control of the community is the base of

Adult and Continuing Education in lifelong learning perspective. Such a Centre and Adult

Educator would be able to mould the learning programmes as per the needs of different

categories of learners. The role of Adult Educator / Facilitator in hand-holding the Adult

Learners and guiding them through different levels / programmes is a vital component

of the programme.

The responsibility of provisioning for Adult and Continuing Education (CE) in the Lifelong

learning perspective at the national level must be backed with permanency of the

programme and adequate resources. The institutional framework and mechanism at

State, District, Block and Gram Panchayat/Village level must be envisioned and ensured

as part of the mandate upon the Central Government.

The State level must be endowed with dedicated staff and the State Govt. / SLMAs must

ensure creating of the institutional framework for provisioning adult education as well

as capacity building and administrative set ups. Convergence of Adult Education with all

Line Departments is a key to the success of adult and CE Programmes.

Existing Institutional Framework

Adult Education is a Concurrent Subject with both Central and State Governments being

required to contribute to its promotion and strengthening. At the national level,

National Literacy Mission Authority (NLMA), an autonomous wing of MHRD is the nodal

agency for overall planning and management and funding of Adult Education

programmes and institutions. Its inter-ministerial General Council and Executive

Committee are the two policy and executive bodies.

At the State Level, SLMAs have been reconstituted in 25 States and 1 UT which have

been covered under Saakshar Bharat Programme (SBP). The State Resource Centres

(SRCs, right now being 30), are engaged in development of learning materials, training

and capacity building, assessment, monitoring and evaluation.

The District level set up for Adult Education in respect of strength and priority, has been

on the decline over the years. The Zilla Saakshar Samiti (ZSS), a Registered Society,

generally under Chairpersonship of the DM, remained very effective wherever the

leadership was committed and involved people’s networks from civil societies. It

generated a great deal of community mobilization and energy that resulted in songs,

poetry, literature and wall newspapers. These witnessed a sharp decline by the end of

Tenth Five Year Plan.

The ZSS set up had a precarious existence as the programme itself was a Plan scheme.

These witnessed a sharp decline by the end of the Plan. At present, the Lok Shiksha

Samities (LSSs) have been constituted by a govt. order at District, Block and GP levels for

implementation of Saakshar Bharat Programme.

Continuing and Lifelong Learning Strategies

It is essential to re-conceptualize adult education in the lifelong education/ learning

perspective rather than as sequential and short-term.

This approach and strategy has implications for teaching-learning materials,

instructional methodology, institutional arrangements, and so on.

Adult learners must be provided with a multiplicity of options that relate to the interests

and needs with respect to their profile and work situation.

Learning Strategies: Literacy Centres: The centre-based model continues to be an

appropriate approach as it is in the neighborhood and easily accessible to women

learners.

It is amenable to suit the convenience of both learners and Instructor in respect of

timing, location, issues of local relevance for discussions, etc., and sustaining the learner

motivation. Ensuring effective T-L skills by the Instructors who are often Volunteers –

school or college students - are formidable challenge to the centre based approach.

Residential and non-Residential Camps of varying duration and age / work /

occupation-specific groups, exclusively for literacy as well as for connecting literacy with

other interests and needs specific-skills are some of the other approaches.

Each of these approaches has its own specific organizational, pedagogic, content and

design of learning materials, training and assessment needs and processes. The duration

would be governed by the load of learning content designed for the programme.

Especially for neo-literate adult learners, there should be a basket of short-term and

diploma courses either along the UNESCO classification of CE Programmes viz., (i)

Income Generation; (ii) Individual Interest Promotion; (iii) Future Oriented; (iv) Quality

of Life Improvement Programmes or other specific programmes for Socio-Cultural

Learning, and Citizenship Learning Programmes, etc. These certificate and diploma

programmes could also be of levels I, II, III with some approximation with the formal

education system.

Both govt. and non-govt. agencies could be engaged for developing and running such

courses and programmes under the overall supervision of NLMA, NIOS, IGNOU and such

other coordination, quality control, accreditation and certification bodies. The

underlying framework governing the programmes is Lifelong Education.

Training

Training for Adult and Continuing Education in the Lifelong learning perspective has

been the weakest link in the programme not only in India but also elsewhere. Some of

the elements characterizing the weaknesses include; (i) lack of a long term perspective

about adult education, short duration of training, lack of sufficient number of

professional training institutions, massive number and limited financial resources,

absence of local and cultural-specific training material, etc.

An overhaul of the content, approach and process of training is required if it has to be in

sync with the paradigm shift in the proposed system of adult and continuing education

in the lifelong learning perspective.

One of the pre-requisites is to recognize the variety of literacy and continuing education

programmes as mentioned earlier with varying duration, levels of expected learning

proficiency, etc. This would be relevant for the purpose of training those engaged in the

T-L process - assuming that it would be the same person – Prerak / Facilitator / Adult

Educator, etc. Their training and capacity building is necessary to lead the learners at

different learning programme situations or leading them from basic literacy to other

levels or types of programmes.

There needs to be a dedicated institutional mechanism to impart professional training

to the vast numbers / types of personnel engaged in the T-L process of different

programmes. And considering the vast social, cultural, linguistic and other types of

diversities in our country and also given the volume of personnel to be trained, the

institutional mechanism has to function in a highly decentralized manner.

Considering the various types of programmes envisaged such as basic literacy and

different types and varieties of Continuing Education Programmes, there has to be a

specific dedicated institutional set up at the district level and its block level

counterparts. It could be a District Adult and Continuing Education Resource Centre

(DACERC) for training of the Resource Persons (RPs) and Master Trainers (MTs) for

various programmes.

The existing SRCs need to be upgraded and strengthened so as to enable them to

provide the academic, training and research support to the DACERCs and BACERCs.

There also needs to be a National Institute of Adult and Lifelong Education. In all these

institutes, there should be separate division for special programmes like Equivalency

and various skill development programmes leading to certificates and diplomas.

There may be a number of degree and diploma courses connected with on-going field

programmes of Adult Education, needed for developing the academic competencies of

Adult Educators. These courses may be designed and conducted at the National

Institute of Adult and Lifelong Education.

The Jan Shikshan Sansthans (JSSs) should be entrusted with skill development

programmes with clear functional linkages with District and Block Adult and Continuing

Education Resource Centres.

Assessment, Outcomes and Equivalency

The need for redesigning the evaluation framework arises from the focus of Saakshar

Bharat Programme which is an integrated continuum of basic literacy, post-literacy and

continuing education. Saakshar Bharat focuses on the need to use literacy to empower

women. The assessment would also need to go beyond literacy levels achieved, into

assessment of empowerment and its impact through the different programme

interventions.

Irrespective of the forms such as, formative and summative evaluation, the key areas or

aspects to covered by the evaluation should be: (i) Relevance from the standpoint of the

service providers and the participants; (ii) Effectiveness as measured in achieving

intended objectives of different programme components; (iii) Efficiency, in respect of

programme delivery; (iv) Impact, in broader context of stakeholders, organizations,

committees and policies; and (v) Sustainability – with evidence of the programme’s

continuance beyond its govt. funded duration.

Given the multi-dimensionality of the programme, in respect of programme

components, the evaluation process also needs to be a combination of quantitative and

qualitative methods. It would need to include various methods, including participatory

method.

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) needs to become a part of Equivalency and this will

give a great boost to sustain the learning interest among adults especially neo-literates.

Proposed Systemic Framework

The proposed systemic framework for adult and continuing education must have

permanent institutions at the Village, Cluster, Block and District levels with a clear

demarcation of roles and responsibilities at each level. All of them must ultimately offer

full support to the adult learner and take her/him along through different stages of

learning.

There is a need to establish vertical linkages with line authorities that have the capacity

to respond to the dynamic needs of the learners, and also have horizontal linkages to

share experiences and constantly learn from one another.

The contribution and participation of the learner to the provisioning of services and in

the process adding inputs to the education policy itself must be built into the system.

There is a need to have a process of consultation with learners and local youth who are

part of the adult education endeavour, and also the members of the Gram Panchayat

and the community who are reviewing the progress at all levels along with the

department functionaries.

Basic Postulates

Basic literacy, post literacy and continuing education need to be seen as forming a

coherent learning continuum. The Adult and Continuing Education programme is

intended to establish a responsive, alternative structure for lifelong learning. It should

be capable of responding to the needs of all sections of society.

Some of the stages in Lifelong Education Programme would need to include: Basic

Literacy; Secondary Literacy- i.e., post-basic literacy, such as post-literacy and continuing

education; Life-long education and learning; equivalency; and skill development

The sheer complexity and contextual specificity of the concept of Adult, Continuing and

Lifelong Education render any attempt to define it in strait-jacketed terms an extremely

difficult exercise.

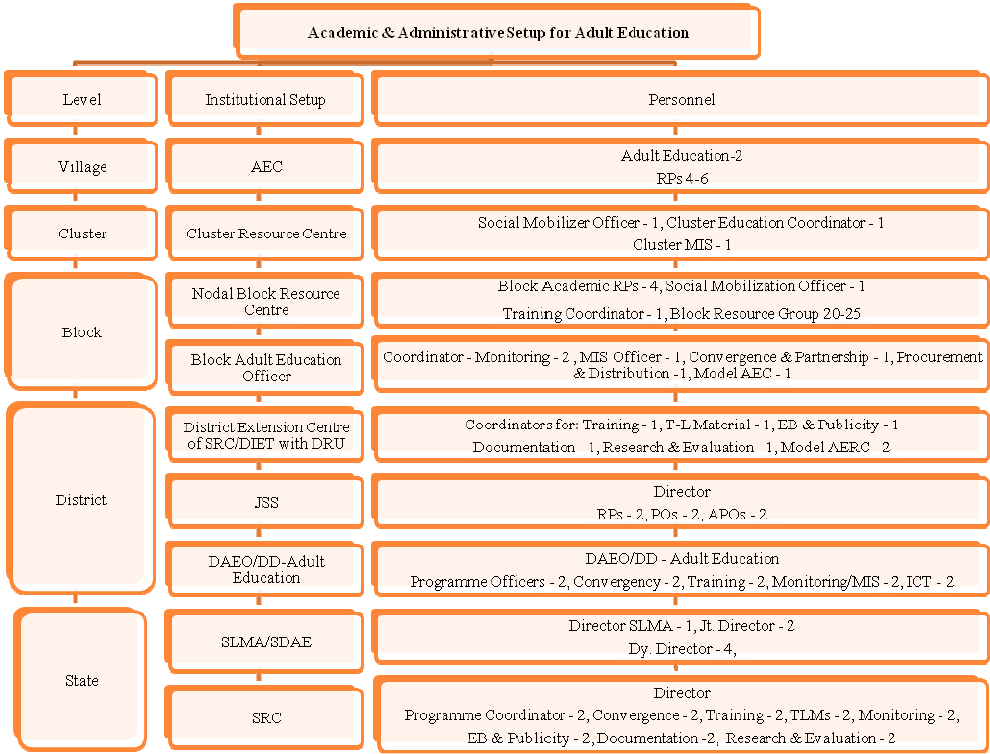

Institutional Framework from Gram Panchayat to National level

At every Gram Panchayat, there should be a Centre for Adult/Continuing

Education/Lifelong Learning, as part of the education department, and more than one if

the GP population is above 5,000. This permanent institutional framework should offer

full support to adult learners and take them along different stages in the lifelong

learning continuum.

The Adult and Continuing Education Centre (ACEC) is to have capacity to offer all the

range of services as Basic literacy, Continuing education, Computer technology and

internet, Multi Media Access, Village Library, Skill Development, Learning Support

Programme for school drop outs to re-join /pursue formal education through

equivalency, Residential Camps of flexible duration interspersed with Basic Literacy or

CE programmes including life and vocational skills.

The ACEC should have Adult Educators (2) on permanent basis, and Resource Persons

(4-6) - on a task based honorarium for assisting the ACEC in all its activities.

The Adult Educators manning the ACEC should be trained to facilitate the processes,

such as the establishment of Village Education Committee as a sub-committee of the

Gram Panchayat; hold monthly meetings of adult learners; enable Gram Panchayats to

review the functioning of ACECs; and involve community and Gram Panchayat to

conduct periodic social audit of the ACEC.

Cluster Adult and Continuing Education Resource Centre (CACERC)

The CACERC could correspond with and be housed in the same place as the Cluster

Resource Centre in SSA, so as to ensure its physicality and permanence. It should have

permanent personnel like Social Mobiliser (1), Cluster Education Co-ordinator (1); and

Cluster MIS (1)

The CACERC will amalgamate all the plans of the ACEC through review meetings with all

the adult educators in the cluster, as well as with Members from SHG’s, Gram

Panchayats, community mobilisers, and local NGO’s.

Block Adult and Continuing Education Office (BACEO): The BACEO would have two

wings (i) administrative and (ii) academic and programme wing, viz., Block Adult and

Continuing Education Resource Centre (BACERC).

The BACEO is the lowest rung of the administrative set up of adult education, with its

vital link between the learners and the District level Adult and Continuing Education

Office (DACEO). The BACEO would have Coordinator/Officer for: MIS (1); Monitoring

and Supervision (1) Convergence and Partnership (1); Procurement and Distribution (1);

and Model ACEC (1)

Block Adult and Continuing Education Resource Centre (BACERC): The BACERC would

have Academic Resource Persons (4) for different aspects of the ACEC specialised

programmes; an RP for Social Mobilisation (1); Training Coordinator (1); and a panel of

Block Resource Group of 20-25 persons with expertise on curricular issues,

organisational skills and so on.

District Level: The DACEO would have two wings (i) administrative and (ii) academic and

programme wing, viz., District Adult and Continuing Education Resource Centre

(DACERC). In the case of Administration wing, it would have an administrative head

with a reach up to the Block level below and the State level, above.

The DACEO would deal with fund flow, implementation, including procurement and

distribution of learning materials, EB, Convergence, Monitoring, MIS, etc. The DACEO

would have District Adult Education Officer (1) Programme Officers (2); Convergence

Officers (2); Training Officers (2); MIS (2) and ICT (2)

The DACERC would deal with techno-pedagogy and academic support including Capacity

Building, EB, Assessment, Research and Evaluation. The academic support system would

be an institutional mode, much like the DIET, but specifically for the adult education

system.

Panchayat Raj Institutions: The Panchayat Raj Institutions (PRIs) at all levels shall have

their respective committees such as the village education committees, block and district

education committees, as well as standing committees on adult education at Block and

Zilla Panchayat levels. The PRI’s at each level, viz., Gram Panchayats, block or Mandal

Panchayats, Zilla Panchayats would need to review the programme enable its smooth

functioning and approve the new plans and proposals.

Jan Shikshan Sansthans: The brief of Jan Shiksha Sansthans is to provide vocational and

life skills as part of Adult and Continuing Education programme.

Krishi Vigyan Kendras: Considering that most agricultural activities are done by women

farmers and women workers, it is important that their skills are upgraded through the

institutions like Agricultural Universities, Research Institutes and NGOs, under the adult

education programme.

State Level (SDACE): There should be a full fledged Department of Adult and Continuing

Education at the State level. It should consolidate qualitative and quantitative data on

all the programs initiated by the District Adult Education Office down to the habitation

level, establish flexible procedures for fund release and ensure releases against district

plans, and periodically review with all other concerned departments on issues of

collaboration and convergence.

State Adult and Continuing Education Resource Centre (SACERC): The SACERC should

be visualized and strengthened in such a manner that it can lend institutional umbrella

to reach out to other institutional resources and draw upon expertise from other

agencies and institutions and civil society for its varied intellectual, organisational and

material resource requirement for literacy and adult education programmes. The

personnel for the SACERC must be drawn from those with abundance of field

experience.

National level: At the national level, there should be a National Authority on Adult and

Continuing Education, and in order to imbibe and radiate the paradigm shift in adult

education, the nodal agency should also be redesigned and re-designated as National

Authority on Adult and Continuing Education from its current restricted connotation

and ephemeral character, as National Literacy Mission Authority. The role at the

national level would be multifarious, including making resources available for

permanent structures and processes for adult and continuing education, enabling

sharing of experiences among state and district functionaries, recognising best practices

and showcasing them.

National Institute of Adult and Continuing Education: The need for a proper research

and resource centre at the national level with linkages with Universities and other

institutions of research cannot be underestimated.

National Open School System: The NIOS could provide Equivalency programme in the

context of neo-literate adults, and also lend the system of recognition, accreditation,

assessment and certification of prior learning.

Providing an equivalency dimension vis-à-vis the formal education system would help to

nurture further upgradation in the skill / knowledge area of prior learning.

Convergence

National Rural Health Mission (NRHM): ASHA:

Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), under NRHM, now at 8,09,637, is a huge force

of grass roots level women workers whose intervention could be harnessed for the

literacy and adult education programme. ASHA volunteers could also take part in

mobilization and awareness building programs. The VTs, Preraks, and Coordinators at

Block and District levels could be associated with ASHAs for health awareness creation

and such other tasks. The school dropouts among ASHA volunteers could be encouraged

to join the Equivalency programme. There has to be an interface and convergence

between Adult Education Department and the NRHM network.

MGNREGA: Under MGNREGA, millions of unskilled rural workers are being employed –

39 million during 2010-11, majority of whom belong to the socio-economically

disadvantaged sections like, the SCs, STs, Minorities and other disadvantaged sections

and a large number of them are women. They also constitute a large percentage of

country’s illiterate population.

Coordination with MGNREGA is necessary for getting a village wise list of job holders,

creation of material and information dissemination on entitlements. The programme of

adult education can be coupled with MNREGA for various purposes. Applying for the

job-card, seeking work, operating bank accounts and reading of the Job cards, etc., have

created an unprecedented demand among these workers for becoming literates. If

organized properly along their needs, the processes of learning to read and write could

be integrated with their daily life situations as workers in MNREGA. Work Supervisors

having necessary competence and qualification can be trained for imparting functional

literacy to these workers.

SABLA: The Ministry of Women and Child Development of Govt. of India launched “Rajiv

Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls – SABLA” initially in 200 districts

on a pilot basis. The Sabla scheme aims to address the multi-dimensional needs of

adolescent girls between 11 to 18 years, including their nutrition and health status,

upgrading their life skills, home-based skills and vocational skills, etc. The scheme which

will be implemented using the ICDS platform, through Aanganwadi Centres and its

functionaries, could be converged with functional literacy, equivalency, vocational skill

development and continuing education programmes for non-literate as well as literate

girls in 15-18 age group either through the Anganwadi centres or Adult and Continuing

Education Centres. The scope for convergence is enormous as there are 7075 ICDS

projects and 14 lakh Anganwadi Centres across the country.

Similar convergence must also be built into all forms of practice with the National Rural

Livelihood Mission, Panchayati Raj Institutions , particularly since there a millions of

elected women members in the these institutions, Right to Information and the Right to

Education that envisages School Management Committees to be mainly composed of

parents of children, half of them women. Properly linked literacy programs can be a

great way to prepare empowered and aware members (mostly women) of the PRI’s and

SMCs greatly benefiting governance and school education.

Role of NGO’s / Universities/Research Institutes

For Adult Education to be effectively implemented, the space for genuine long-term

partnerships between government and civil society organizations, based on appreciation

of their respective strengths and mutual respect, must be evolved. Critical to ensuring

this would be to legitimize and institutionalize the different roles of NGOs within the

institutional and other mechanisms.

The adult education system envisaged could also allow flexibility for implementation by

NGOs. Civil society organizations and NGO’s can also be associated in capacity building

of GPs, with funds from adult education department or the Panchayats.

University departments/Research Institutes must be engaged in research-related

activities (particularly action research and participatory research), undertaking

documentation, developing suitable academic programmes for field level functionaries.

The Use of ICTs

Even though the penetration of hardware and support systems is still fairly thin across

the country, Information and Communication Technologies never the less provide an

avenue that could be effectively combined with person to person contact to add

tremendous value to adult education efforts, particularly in bringing knowledge and

information resources from all over the World to the doorstep of the learner. In order to

prepare the pedagogical value of these technologies, efforts could be weaved into the

programmes where ever feasible to use these technologies appropriately, keeping

linguistic and cultural diversities in mind. In particular, using and training local resource

persons in free software opens avenues for creating a unlimited applications by the

locals,for the locals. Many innovative efforts underway in this direction, for example in

Kerala, need to be studied for further expansion in other states of the country. In

particular, making each Adult Education Center of the country into an e-kiosk could be

seriously explored.

Women’s Groups

There are a large number of women’s self-help groups already in existence which have

an urge to be literate as well as to be informed about issues concerning their lives, the

community, village and the country as a whole. A government account gives the number

of SHGs, as on 2008, coming under SGSRY of the Ministry of Rural Development, as

28,35,772, of which 23,29,528 were women SHGs (82%). With 15-20 members for each

SHG, there would be at least 5 crore membership, most of whom would be the target

group for literacy and adult education programmes. Not only the SHG issue could itself

become a theme for literacy, but it could also provide the basis for an entire range of

capacity building including leadership, entrepreneurship, as well as organization building

and development of social capital as well as financial capital.

Many other women’s groups, not necessarily self-help, exist in large numbers all over

the country, like that of Mahila Samakhya. Linking all these to the literacy effort would

be of immense mutual benefit.

CHAPTER-1: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

A nation that is literate is one where its citizens are empowered to ask questions, seek

information, take decisions, have equal access to education, health, livelihood, and all

public institutions, participate in shaping their realities , create knowledge, participate in

the labour force with improved skills, exercise agency fearlessly and as a consequence

deepen democracy. Systems are to be in place to build a nation that builds citizenship

which is truly informed and literate and in the process, the content of governance,

development and democracy is also vitalised.

At the time of country’s independence in 1947, the literacy rate was a mere 21%. With

the expansion of the elementary education structure, this rate was gradually improved,

but with increasing population, the gross number of adult illiterates kept on increasing,

so much so that the country has an unacceptable population of about 280 million who

are termed illiterate today. The first major attempt to address uneducated adults

directly was the launch of the National Adult Education Program (NAEP) in 1978. Using a

centre-based approach, the program had some limited success till the motivation of the

learners and that of the paid centre volunteers flagged in a few years. The next

important step came with the launching of the National Literacy Mission in 1989 that

initiated nation wide mass literacy campaigns during the decade of the 90s in nearly all

the districts of the country. Based on the voluntary mode by involving the community

and the Zilla Saksharta Samiti structure, the mass literacy campaign was fairly

spectacular initially, but gradually lost steam as volunteer fatigue set in. The campaign

mode saw the addition of post-literacy, continuing education and equivalency modes to

the adult education program, the remnants of which still exist. The Sakshar Bharat

Program is the next step in this process of addressing the needs of adult education of

the country. It is vitally important that the challenge that the SBP is to face benefits

from an analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the previous two major programs

that were practised in the country. The learning from these past programs is a basis for

the analysis and recommendations of this document.

One such learning is that to meet the challenging task of adult education in India the

practice and policy must always be informed by the voices of the learners themselves

and the challenges they face in accessing literacy, information and knowledge. This

would necessarily entail respecting the poor, their capacity to think for themselves and

providing for local institutions and structures that facilitates their participation in a

genuine fashion and not as tokenism. Such an institutional framework would

undoubtedly throw up new ideas and this would have to be supported by availability of

resources and greater investment in education.

It is only when there is a credible, whole hearted and institutionalised effort on a long

term basis that the learner would take the programme of adult education seriously.

The first step is to understand the adult education programme as a life- long continuous

education programme and not as a literacy mission or even a scheme. It must contain all

structures and institutions from the national to the state, district, block, cluster and

habitation levels on a permanent basis as part of the education department; and a

system in place for reviewing the existing institutions at the national, state and district

level and their capabilities for provisioning of education services to the adult learner.

Further, it has to identify structures and processes that listen to the voices on the

ground and is constantly addressing the new needs of the diverse section of learners.

These, in effect, mark a basic transformation of the programme for proposed planning

and budgeting. It will no longer be seen just as a transient activity of turning illiterates

into literates. It can no longer be expected to fold-up even as the illiterates fade away.

There has to be pronounced and prominent permanency about the centres, their

relevance and their utility. Once it is recognised thus, like any other programme, this

programme too should qualify for the plan/non-plan phasing. And with just this change

in character, the Adult Education Programme which is a lifelong continuous education

programme will gain in status, develop roots and, provide scope for embellishments to

become a major trigger of developments.

Envisaged in such a perspective, there is need for a paradigm shift in respect of adult

education. It should be a regular and permanent system of education of adults, and

encompass basic literacy, further higher levels of learning, as well as the learning

avenues to meet the needs of life and livelihood skills as a lifelong and continuous

endeavour.

Finally provision of adult education must be deemed as a right that has to be

guaranteed by the State to each and every individual above 15 years of age who has

missed the opportunity of completion of school education.

In order to understand better the transformed structure that is being suggested in this

report, we briefly present first the existing structure under which adult education is

practised in the country

1.2 Context and Brief Review of Existing Institutional Framework

Despite national and international commitments to achieve a 50% reduction in illiteracy

rate by 2015, India still has the largest population of illiterate adults (270 millions)

according to EFA monitoring report. Majority of them are poor.

There has been considerable improvement in literacy rates for all populations since

1991.

There are considerable disparities in literacy attainment across region, gender, ethnicity,

caste and linguistic minorities.

1. National Level

Presently, the provision of adult education is through the Saakshar Bharat Programme

(SBP) which is a centrally sponsored scheme. The programme is to be implemented in

mission mode. The National Literacy Mission Authority (NLMA), an autonomous wing of

the Ministry of Human Resource Development, is the Nodal Agency at the national level.

The Joint Secretary (Adult Education) is the ex-officio Director General of NLMA. It is

responsible for the overall planning and management of the scheme, including release

of funds to States/Voluntary Agencies, mobilization of resources, procurement, mass

campaigns, maintenance of national database on illiteracy and adult education,

publicity, facilitating techno-pedagogical support, research, monitoring and evaluation,

etc. The NLM is to achieve the goals by way of Total Literacy Programmes, Post Literacy

and Continuing Education programmes.

The NLMA has a Governing Body, Executive Committee and a Grants-in-Aid Committee.

The Governing Body is headed by the HRM, with MOS (HRD) as Vice Chairperson and

Ministers of I&B, Health & Family Welfare, Youth Welfare & Sports, Social Justice and

Empowerment, Women & Child Development, Rural Development, Panchayatyi Raj,

Minority Affairs and representatives of different line departments and the NGOs as

Members. The Executive Committee and Grants-in-Aid Committee are headed by the

Secretary (School Education & Literacy). At the National level there exists the Saakshar

Bharat Mission (National Literacy Mission Authority). The Adult Education Bureau is

organised in 6 Divisions, headed by Directors, along with support staff. They manage

the SBP, the SRCs (28) and JSSs (271), besides other tasks relating to NGOs, international

cooperation, etc.

2. State Level

The State Literacy Mission Authorities (SLMAs) have been re-constituted in 25 states

and 1 UT (which have the 365 districts with female literacy rate of 50% or less) which

are being covered under SBP. After winding up the Post-Literacy and Continuing

Education Programmes on 30

th

September, 2009, there has been no insistence or

instruction for reconstitution of SLMAs in those states not covered under SBP. It has

been envisaged that the reconstituted SLMA’s would include the Panchayati Raj

Institutions (PRIs) , as the implementing agencies of SBP.

State Resource Centres

The State Resource Centres (SRCs) have been established to play a critical role in the

implementation of Adult Education programmes. They are located mostly in the

voluntary organisations, and in a couple of universities. In some States the SRCs are

directly established as part of the education department.

The current role of the SRC’s includes the following:

-Development of primers, other learning materials for Basic Literacy, Equivalency, Life

and Vocational Skills and Continuing Education Programmes and Training Manuals.

-Assist the SLMAs in undertaking capacity building of the literacy personnel, including

the VT-MT-RP chain, the Preraks, and the Coordinators at Block and District level as well

as the orientation of other stakeholders such as the PRI representatives.

-Monitoring and review of Basic Literacy programmes (BLPs) including the ICT-based

literacy camps and the activities of Continuing and Lifelong Education Centres (L/CECs).

- Setting up and managing L/CECs as well as basic literacy classes, and literacy camps,

and orientation of GP & BP Presidents so as to enable their involvement in adult

education programmes.

-Assessment and Evaluation;

-Advocacy and Environment Building;

-Research and Documentation

-Setting up and running of Model L/CECs, Literacy Centres and Literacy Camp, including

ICT-based literacy camps.

-Involvement in the nation-wide literacy assessment, undertaken by NIOS.

3. District level

There is a district level set up for Adult Education in every state/UT although the

nomenclature varies by the designation of the department under which adult education

is implemented, such as Adult Education, Mass Education, Literacy and Continuing

Education, etc. But over the years, with the decline in the priority and scale of Adult

Education programmes, the size, in terms of personnel strength has also witnessed

acute reduction.

Zilla Saaksharta Samiti (ZSS)

In the early 90’s the Adult Education Programme was implemented under the aegis of

ZSS in the districts. The ZSSs were required to be a Registered Society, usually under the

Chairmanship of the DM / DC. It had a General Body, a policy organ, composed of

educationists, elected peoples’ representatives, NGOs, social activists connected with

literacy as well as officials of different line departments to allow for a non-bureaucratic

set up. The ZSS also had an Executive Committee, a smaller body, usually of 8-10

people, to take vital decisions regarding implementation, subject to ratification by the

GB later.

The design of ZSS as a Registered Society was a conscious choice to allow flexibility,

reflecting urgency in implementation of the programmes and to also take up a campaign

mode.

The ZSS functioned through different sub-committees, viz., Environment Building,

Training, Materials, Finance, Monitoring, etc., with full time Coordinators. Primarily

because the district did not have a district level counterpart of the SRC, the ZSS and its

different Sub-Committees, also took care of pedagogic and administrative support to

the programme by making use of the institutional resources and experts in DIETs and

other institutions which had training facility.

The system of ZSS, with its Sub Committees, functioned well wherever there was a

leadership provided by the concerned DM or DC involving administration and peoples’

networks from civil society. This set up, was replicated at the Block and village levels. In

most cases, however, they remained notional just like any other routine government

programme having no scope for flexibility or permanence of the committees.

By the end of the 10

th

Five Year Plan, NLM programmes of TLC, PLP, CE as well as the

centre-based adult education programme were covered by 597 districts out of the total

of the then 610 districts. In most of the cases, the programmes were implemented

under the aegis of ZSS.

District Resource Units (DRUs)

The District Resource Unit (DRU) planned as an integral part of District Institute of

Education & Training (DIET), was placed under the Vice-Principal of DIET and another

faculty, one in charge of non-formal, and another, for adult education. There were also

DRU’s sanctioned to NGO’s. In reality just one programme officer was appointed for the

DRU. In a multi-disciplinary DIET set up and under the weight of the formal education

system, the adult education officer(s) were overshadowed. Currently, DRUs in most

cases, are empty or the survivors have been diverted to the service of formal education.

As of now the DRU’s are nearly starved out of existence.

Lok Shiksha Samities

Lok Shiksha Samities (LSSs) at District, Block and GP levels have been constituted by

Government Order, for the implementation of Saakshar Bharat Programme. The Lok

Shiksha Samities are bodies or committees, with a President/Chairperson, Member

Secretary, and Members, much like the ZSSs earlier, as Registered Societies. The Lok

Shiksha Samities are decision-making bodies in respect of provisioning, planning,

management, implementation, coordination, monitoring, etc., of SBP.

Their duration is co-terminus with the particular Five Year Plan period just as the ZSSs

were under earlier NLM programmes. In this sense they are precarious and not

institutionalised.

Jan Shikshan Sansthan Scheme (JSS)

Some districts have been sanctioned the Jan Shiksha Sansthans-271 as on date, to take

up vocational and life skill up-gradation programmes. They impart skills from candle

making to computer skills and have covered hundreds and thousands of neo-literates.

Community Mobilisation and Empowerment

Starting from 1989-90, with the Ernakulum TLC, its model has been replicated in quick

succession, covering more than 150 districts before the end of the 8

th

Five Year Plan in

1991-92. The mass campaign approach for eradication of illiteracy was undertaken

through massive mass mobilization and environment building. The model of NLM’s

direct approach with the Districts, through the ZSS set up generated energy to create

songs, literature, poetry, wall newspapers at the local level along with empowered

learners with critical consciousness and power to question.

This massive mobilisation and campaign petered down in all the districts.

Village level

Under the SBP, there is a provision for an AEC in a GP with 5000 population, and an

additional AEC if the population is more than 5000. In respect of states in the North-

East, where the Village Councils are the prevalent administrative units, an AEC provision

is allowed even if the population is less than 5,000.

The entire task of running a literacy centre in a village is dependent on a volunteer, who

is unpaid and doubles up as a mobiliser, teacher and a trainer imparting literacy for 8-10

learners. S/he is expected to give 300 hours of instruction for basic literacy. Although

there is need for educators for higher levels, there has not been a provision of training

such practitioners. Their link with the department has been minimal if not non-existent.

The old system of Continuing Education as a cent percent Centrally funded programme

for initial three years, and the 50:50 sharing basis for next two years, and the state take

over after 5 years, exists in Kerala. In that state, the entire set up and personnel have

been taken over by the govt., and implemented through SLMA, and at ground level, by

the Panchayats.

CHAPTER–2: CHALLENGES

2.1 Provisioning of Adult Education: Perspective and Challenges

Adult Education cannot and should not any more be considered as a short term project

for achieving a certain percentage of literacy. Instead it should be conceived as a

comprehensive and Lifelong programme for providing a variety of learning opportunities

to all Adults (in the age group 15-50) in the country. In this, Basic Literacy will have to

be, certainly considered as an important and indispensable first step/stage in the

programme of Adult Education. But it should not be restricted to that alone. These

learning programmes will include life skill development programmes, livelihood skills

development programmes, citizenship development programmes, social and cultural

learning programmes and so on and will depend upon the learning needs of the adult

learner communities. Therefore, henceforth the nomenclature of the programme and

the institutional framework should be Continuing and Life-Long Education programme.

There is a need to demarcate areas of duties and responsibilities in terms of institutional

support that are required for the layers and stages of continuing and lifelong education

considering the complexity of the adult learners and the diversity of their needs. This

has to be an ongoing process and of a long term nature especially if continuing and life-

long education is seen as a major input. It must go beyond being just a scheme.

Thus it shall go beyond the scope of Adult education programmes which were conceived

as short term projects to achieve fixed ‘targets’ in terms of literacy percentages and thus

missed the crucial continuity. Each of the bodies or organisational set ups like ZSSs and

LSSs and institutions such as, SRCs, DRU/DIET, JSS, etc., have been of temporary in

nature. At the district level there are just no permanent structures. There is still no

permanent structure either as an institutional set up like the DIET or an agency like the

DRDA for adult education at the district level or below in any State with exceptions such

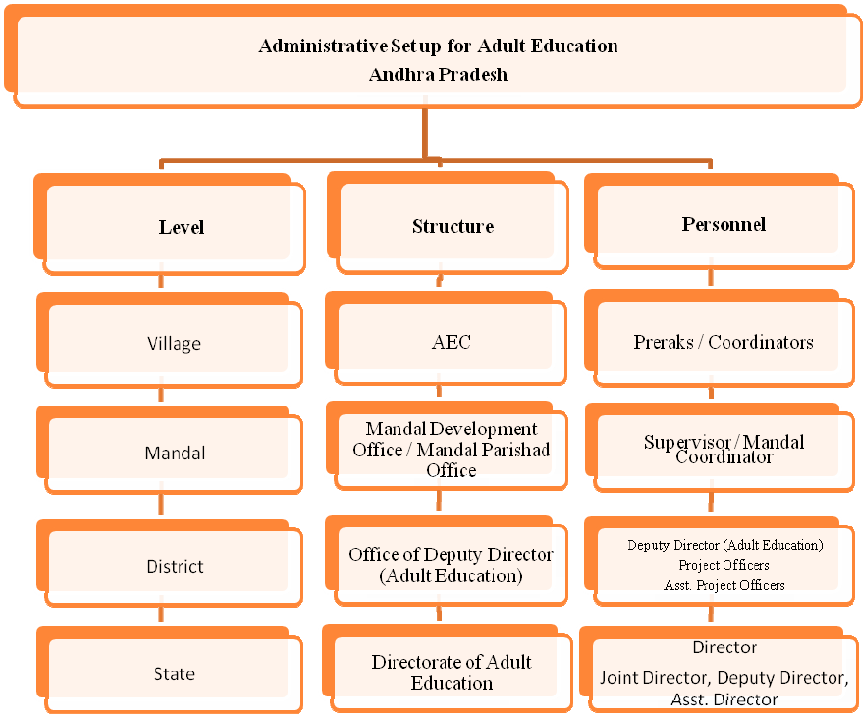

as in the State of Andhra Pradesh.

Further, there has not been any organic link among them and the department of adult

education. It is important that just as in the case of school education, adult education

too must have institutionalised structures at the district, block, cluster and Panchayat

level. The need for convergence and collaboration between institutions and agencies in

the government and private sectors cannot be understated. Further the institutional,

personnel resources and expertise in the formal education system at District, Block,

Cluster and GP levels, should also be available, if required.

As we have seen, any continuing education programme has to cater to a larger variety

of learner groups in an integrated and sustainable way relevant to the learners’ actual

living concerns. Secondly, continuing education programmes need to be designed within

the contextual peculiarities of the learner. This would mean cross-support to the

programme at the grassroots level from the formal, non-formal and informal sub-

sectors of education, as well as various other development schemes. In particular these

programmes would have to be dovetailed with the related programmes of training,

farmer’s centres, self-help thrift groups, other common interest groups and so on. It

would also entail strong local participation and socio-economic data collection to make

the programme effective and responsive to actual requirements.

The Continuing and Lifelong Education Center’s functioning under the control of the

community and operated by well trained and motivated adult education facilitators will

form the base for the entire programme. As a result, a lot of effort has to be made in

stabilizing the Continuing and Lifelong Education Centre and as envisaged in the GOI

concept paper, would be incorporated in stages. The mix of components would be

decided by the composition of the CEC members. Thus for instance, if most of them are

women farmers, then the centre would have a strong bias towards issues relating to

agriculture. If on the other hand the members are mostly drawn from among youth,

then it would function with a greater focus on training. Issues relating to quality of life

would invariably form a component of any CEC. Wherever possible, this would be linked

to the setting up of an information centre for the entire village. Once again the

emphasis has to be on training the adult education facilitators and developing a cadre of

well-trained cadre.

2.2 Role of Adult Educator

Once this basic approach to Adult Education is understood, the present notion about

the Adult Educator/Voluntary Instructor/Facilitator also will have to be changed. The

new Adult Educator will not be a literacy instructor but an expert facilitator hand-

holding the Adult learner to move ahead continuously along the lifelong path of

education. In concrete terms she/he will be a person with in-depth understanding about

the implications of the long term comprehensive lifelong education process, beginning

with basic literacy. She/ he must also have a clear understanding about the intricacies of

adult learning processes as different from the child’s learning processes. The Adult

Educator must be able to constantly link the vast life experience of the Adult Learner

with all the learning processes including the literacy learning processes.

2.3 Rights Approach-National Commitment

The responsibility for provisioning of Continuing and Lifelong Education at the national

level is to ensure that resources are available in a rights based perspective. It requires

establishment of institutions for providing services in all the districts and in both rural

and urban contexts. It has to cater to every individual/all groups that are vulnerable and

have all stages of adult education fully covered. It is in doing so that the message of

indispensability of continuing/lifelong education for the country’s development and

democracy is sent and the programme is taken with the seriousness it deserves.

1. State Support

At the State level, the Continuing and Lifelong/ Education department has to be fully

equipped with staff and personnel from the State to the level of the Continuing and

Lifelong Education Centre at the level of the Gram Panchayat. It needs to have the

flexibility to meet the demands of the adult learner and yet deliver the services through

a well-oiled institutional framework within the education department. There is need to

build mechanisms of knowing the strengths and challenges of the programme and

introducing systemic reforms/correctional devices so the adult learner accesses the

various components of the programme with comfort and ease.

Decentralisation is the Key

2. Convergence with other National Flagship Programmes

Since continuing and lifelong education is cross cutting in intent and purposes, it must

be equipped to meet all the learning needs of adults, outside formal education set up.

The learning needs can span from basic literacy to a vast array of learning interests and

needs including equivalency, skills development and short duration thematic

programmes in areas as diverse as NREGS, NRHM, SHG, PRIs, etc. It must also have the

ability to coordinate with all other departments viz., Panchayat Raj, Rural Development,

Health, Women and Child Development and insist on integrating adult education in their

core responsibilities.

The lessons learnt are that while there is a need to create an atmosphere that gives

confidence to the non-literates to access adult education, there has to be a process of

institutionalising the programme. This would include preparedness of education

department to provide for services through its systems and structures on a permanent

basis and involve the local bodies, adult learners as well as local NGO’S (if any) in giving

support to the programme at the local level.

CHAPTER-3: PRINCIPLES OF CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK

3.1 Principles

Some of the basic principles that should embed the curriculum framework are as

follows:

- Developing critical consciousness of the learner leading to a continuous process of

empowerment and informing the pedagogy. This entails the achievement of a

certain degree of autonomy, for empowerment that entails being “given” the power

to perform certain actions is but another form of subservience. Thus adult literacy

and continuous and lifelong education centrally involves the fostering of a critical

consciousness that can empower a learner to liberate herself and her society from

unequal and oppressive power relations.

- Empowerment of the learner resulting in exercising one’s agency to become

politically, socially and culturally active, as also self-aware, confident and with

dignity and a sense of personal well being – political as well as self empowerment.

- Building the capabilities of the learner to access and analyze knowledge and make

informed choices.

- Enabling democratic participation of the learner in negotiating diversity, demanding

accountability, equipping her with skills for critical analysis of democratic institutions

and accepting the ‘other’ as equal.

- Respecting the learner as a productive person, a person with dignity and a sense of

well being, with an ability to realize her creative potential - to realize and contribute

to a body of knowledge.

- Promoting values guaranteed by the Constitution such as, peace, justice, equity,

secularism.

- Responding to the reality of illiteracy that coincides with deprivation, dispossession,

poverty and discrimination. The pedagogy, curriculum, content and institutional

mechanisms must respond to this reality. The learning process must promote and

sustain community bonds that unite the deprived to fight the processes of

deprivation.

- Continuing and Lifelong education to be crucial in negotiating and realigning unequal

power relations based on gender, caste, religion, and ethnicity. It is not only a means

to access information but also enables creation of knowledge, especially gives tools

to engage with knowledge generation.

3.2 Pedagogy

- Adult learners’ pedagogy is different from that of children. Pedagogical approaches to

adolescents and women also need to be differentiated.

- Adult learners may be unable to read and write, but they possess a huge amount of

experiential skill, knowledge and wisdom. Adult pedagogy must be based on this fact.

- Adult teaching- learning processes and materials must be based, therefore, on their

existing knowledge base, rather than ignoring it.

- Pedagogy must also expand the mental and productive horizons of the learners to

knowledge outside their experiential base.

- Sustaining motivation amongst learners is a major challenge of adult education

pedagogy – one of the approaches must be to relate the teaching learning process to

their life situations.

- Adult pedagogy must be flexible and participatory to respond to the learner curiosities

and demands. This requires mapping learning needs before fashioning learning

materials and programmes.

- Adult pedagogy must also assess the learners’ views whether the programme is making

a change in their lives.

3.3 Curriculum

The curriculum needs to be based on the context and the principles outlined above.

- The content and process must begin from the life situations of the learners.

- This implies that the curricular process has to be participatory. The teaching learning

material must also be developed through a participatory process, which includes a

needs assessment of the learners.

- This does not imply that whatever the learners say must be accepted – the implication

is that professionals must combine their skills with the needs of the people to produce

contents that are academically sound, which also reflect the aspirations and needs of

the learners.

- The beginning of the programme must be structured as the beginning of Lifelong

Education, rather than as the first stage of Basic Literacy, Post Literacy and Continuing

Education. The learner must know from the very beginning that the learning

opportunity is not casual and short term, but will lead to a lifelong engagement.

Institutional mechanisms will have to be crafted accordingly. The question of

equivalency must be seen from this perspective, rather than as a mechanical way of

giving class 3, 5 or 8 certificates of school education.

- In terms of the choice of language for the curricular transaction, if the language

demanded by the learners is different (including English) from their mother tongue, well

known pedagogical methods that accommodate and bridge both the languages should

be used in the creation and transaction of materials.

- It is assumed that mathematics, numeracy in particular, has universal methods of

learning. This contrasts with the evidence that illiterate adults transact mathematics in

their everyday life in market and productive situations with ease, but use different

algorithms, that can change from place to place. Therefore just like language, teaching

of mathematics, including shapes and geometry, must bridge the ethno-mathematical

algorithms with standard methods.

Following on the foregoing, it should be obvious that these curricular pedagogies

demand to give up the notion of a single primer and move towards a variety of TL

materials.

- The above principles imply that to bring in knowledge, language and skill diversity that

exists in our country into the preparation and transaction of TL materials, the

institutional process of preparing and transacting these materials needs to be

decentralized, even below a district level, to bridge between the local and standard

knowledge systems.

- Learning takes place not only in learning centres, but in an overall learning

environment. This implies that the literacy programmes must also have larger learning

initiatives (libraries, web connected computer kiosks, newspapers etc) as part of the

programme, and not as add-ons.

- TL materials should not only address skill and cognitive development, but also address

the affective domain that includes values, self-confidence, caring and dignity.

The sheer complexity and contextual specificity of the concept of Continuing and

Lifelong Education make any attempt to define it in strait-jacket terms an extremely

difficult exercise. Even if a definition is attempted, the results are not uniform. Within a

single country, various programmers, academicians and literacy activists have their own

understanding of continuing education. Also, each country understands the concept

based on its own vision and indigenous requirements. There are two primary reasons

for this multiplicity of views. The first can be called normative, in as much as the area of

continuing education is inchoate. Thinking in this relatively new field is flexible and open

to several interpretations. The second is formal, in the sense that the content and style

of the programme is determined by the context of its implementation.

CHAPTER-4: CONTINUING AND LIFELONG LEARNING-

STRATEGIES

4.1 Adult Education in the Framework of Continuing and Lifelong

Learning

In order to fulfill the principles of the curriculum framework, it is essential to re-

conceptualize what constitutes an adult education/literacy programme. An adult learner

would need Lifelong Education (now Lifelong Learning) with an understanding that

learning and education are not short term processes that can be completed during a

particular period or course. Thus the programmes of Literacy, Post Literacy and

Continuing Education as they exist now are not to be considered as separate

compartments. Consequently, the piecemeal or compartmental approach to literacy

and allied programmes has led to massive regression to illiteracy in many parts of the

country. Many districts that had declared to be “totally literate” in the nineties are now

facing massive illiteracy levels and have to launch fresh programmes.

This happened basically because of a lack of continuity in the programme which in turn

is due to the absence of a comprehensive framework that relates and links literacy and

education with all other aspects of life on a long term basis. This shift in paradigm

implies the following:

First of all, the piecemeal, compartmental approach to literacy programme will have to

be abandoned. In its place we should adopt a long term, continuum approach. Every

learner who enrolls at the basic literacy centre should have the opportunity to continue

learning Lifelong. Actually the learner should be entering the basic literacy centre with

this understanding. This approach will have its implications on various aspects of adult

education including teaching learning materials, instructional methodology, institutional

arrangements and so on.

Secondly, the learner should be provided with a multiplicity of options to continue her

learning. Formal, non formal or even informal methods and also combinations of these

could be employed for this purpose. The most important consideration in deciding the

mode and method of continued learning should be the actual learning need of each

learner which would depend upon the socio, economic and cultural situation in which

she is living. One of the main objectives of the basic adult education programme should

be to help and facilitate the learner to identify her actual learning need and choose

appropriate learning programmes. It is important to provide a wide variety of options

from which the learner can choose.

4.2 Profile of Adult Learners

There is a huge back-log of non-literate population in the country numbering 260 million

in the 15+ age group (Census 2001). The five states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Andhra

Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan alone account for 50% of population of adult

non-literates. Adult learners fall into different groups depending upon their age,

experience, occupations, socio cultural situation, aspirations and so on. These

differences will naturally affect their learning needs and in turn their choice of learning

programmes.

They could be categorised under the following heads although there could be an overlap

in this regard:

- Members of 2,65,000 Gram Panchayats, especially women sarpanches and ward

members.

- 3.9 crore population of rural labour under NREGA

- Migrant Labourers- 53.6 million non-literates among Scheduled Castes and 30.2

millions Scheduled Tribes 15+ age group

- Non-literates among adolescent girls and boys in the 15 -18 years age group.

- 168 million non-literate adult women.

- Self-help groups

- Joint Forest Management Groups

- Adults who are non-literates requiring basic literacy

- Adults who can read and write but are school dropouts requiring post literacy and

continuing education

- Adult learners of younger age group who would like to pursue their learning in the

formal stream.

- Adult learners who are motivated to learn further, but at a more informal, leisurely

pace

- Adult learners who are willing to take up specific learning programmes relating to

specific learning need that they have identified

- Adult learners of older age group who would like to continue learning for recreational

purposes.

There may be adult neo-literate learners who have very specific learning needs and

would want to join learning programmes that matches their requirements. For example

a farmer wishing to learn more about improving his/ her yield using modern agricultural

techniques or a group of tribal women wanting to learn more about tribal rights or a

neo-literate Gram Panchayat member wanting to learn more about her duties and

responsibilities. There may be even composite learning needs. We recommend that a

chain of resource agencies capable of developing tailor- made learning programmes

may be established for formulating such learning programmes.

4.3 Adolescents

It is estimated that the number of adolescents in India (11-20) is 30 crores out of which

almost 10 corers are illiterates, though some of them could have attended a school for a

short while. They are all from families living in extreme poverty. Many of them face