University of North Dakota University of North Dakota

UND Scholarly Commons UND Scholarly Commons

Critically Appraised Topics Department of Occupational Therapy

2021

Critically Appraised Topic Paper: What is Motor Learning Theory? Critically Appraised Topic Paper: What is Motor Learning Theory?

How Can It Be Implemented into Occupational Therapy How Can It Be Implemented into Occupational Therapy

Interventions for Individuals with Cerebrovascular Accidents? Interventions for Individuals with Cerebrovascular Accidents?

Allyson Bourque

Alison O'Sadnick

Alexis Skogen

Callie Vold

How does access to this work bene=t you? Let us know!

Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/cat-papers

Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Bourque, Allyson; O'Sadnick, Alison; Skogen, Alexis; and Vold, Callie, "Critically Appraised Topic Paper:

What is Motor Learning Theory? How Can It Be Implemented into Occupational Therapy Interventions for

Individuals with Cerebrovascular Accidents?" (2021).

Critically Appraised Topics

. 21.

https://commons.und.edu/cat-papers/21

This Critically Appraised Topic is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Occupational

Therapy at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critically Appraised Topics by an

authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact

und.commons@library.und.edu.

Critically Appraised Topic Paper: What is Motor Learning Theory? How Can It Be

Implemented into Occupational Therapy Interventions for Individuals with

Cerebrovascular Accidents?

Allyson Bourque, OTS, Alison O’Sadnick, OTS, Alexis Skogen, OTS, & Callie Vold,

OTS

Department of Occupational Therapy, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, United

States

Please direct correspondence to Callie Vold at [email protected] or Allyson Bourque at

allyson.bourque@und.edu

***This resource was written by doctoral-level students in fulfillment of the requirements of the

Occupational Therapy course “OT 403 - Clinical Research Methods in Occupational Therapy” at the

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, under the advisement of

Professor/Course Director Anne Haskins, Ph.D., OTR/L, Assistant Professor Breann Lamborn, EdD, MPA,

Professor Emeritus Gail Bass Ph.D., OTR/L, and Research and Education Librarian Devon Olson Lambert,

MLIS.

Allyson Bourque, OTS, Alison O’Sadnick, OTS, Alexis Skogen,

OTS, & Callie Vold, OTS, 2021

©2021 by Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution International license (CC BY). To view a copy of this license, visit

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

2

Focused Question

Are motor learning theory-based interventions considered to be part of best practice in

occupational therapy rehabilitation for individuals with cerebrovascular accidents (CVA)? If so,

how might occupational therapists incorporate motor learning theory into intervention design

with maximum efficacy?

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this critically appraised topic (CAT) paper was to determine if motor

learning theory guides interventions that are considered to be best practice for individuals with

CVAs. We want to determine what is best practice for this population to provide practitioners

with synthesized research allowing practitioners to implement the most effective, client-centered,

evidence-based interventions possible.

Theory

The Ecology of Human Performance (EHP) was selected to understand the role of

context in occupational therapy intervention. A foundational postulate to the EHP framework is

that the interaction between person and environment affects human behavior and performance;

under this lens, performance cannot be understood outside of context (Dunn et al., 1994). The

contextual lens interacts with the person’s skills and abilities to enable them to perform certain

tasks; this interaction results in an individual’s performance range (Dunn et al., 1994). The

relationship between the person and their context presents an understanding of the extent to

which the person can perform specific tasks (Dunn et al., 1994). According to the motor learning

theory, occupational therapists develop therapeutic interventions by considering which task

requirements are most appropriate and which conditions of their environment may need to be

adapted to elicit optimal performance (Sabari, 1990). A person’s context is viewed as

fundamental to the understanding of human performance according to the motor learning theory

and EHP (Dunn et al., 1994; Sabari,1990). If an occupational therapist evaluates an individual’s

performance without considering the context of the performance, there is a great risk the

performance will be interpreted incorrectly (Dunn et al., 1994). The lack of consideration for the

contextual role in task performance when designing intervention may result in a poor

transference of the skills learned in the contrived setting to a person’s natural context.

Case Scenario

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021), in 2018, one in six

deaths from cardiovascular disease was due to CVA. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (2021) reported that every year more than 795,000 people in the United States have a

CVA, and about 610,000 of these are first or new CVAs. CVA is the leading cause of adult

disability in the United States, resulting in challenges such as weakness on one side of the body,

a decline in cognitive and emotional functioning, social disability, inability to walk, inability to

care for themselves, and a decrease in community participation (Nilsen et al., 2015). According

to the American Stroke Association (2018), women are at a higher risk of CVA compared to men

due to pregnancy, preeclampsia, birth control, hormone replacement, migraines, and atrial

fibrillation. The African American population has a higher chance of a CVA leading to death

compared to Caucasians due to higher blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity (The American

Stroke Association, 2018). People that are affected by CVAs experience deficits in muscle

power, balance, different sensations, and speech difficulties (Langhorne et al., 2011). These

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

3

implications may result in individuals having rehabilitation goals in areas of occupations such as

activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) to improve

their performance. There are multiple allied health disciplines that provide interventions

addressing functional outcomes for individuals with CVAs (Zahl et al., 2017). The rehabilitation

team may include, but is not limited to physical therapy, occupational therapy, recreational

therapy, and speech-language pathology (Zahl et al., 2017).

There is a large consensus in the literature that supports using motor learning theory for

CVA rehabilitation in occupational therapy. Motor learning refers to internal processes that are

associated with practice or experience and lead to relatively permanent changes in motor

behavior (Schmidt et al., 1988; as cited in Jarus, 1994). Motor learning theory approaches to

CVA therapy consist of addressing motor impairments post-CVA, high repetition of a

cumulative of 10,000 repetitions for optimal motor recovery (Kleim et al., 1998; Nudo et al.,

1996), positive feedback, and a motivating format (Birkenmeier et al., 2010). The goal of using a

motor learning approach in occupational therapy is to assist individuals with developing their

strategies for effective movement within their environment (Sabari, 1990). Occupational therapy

emphasizes the therapeutic use of purposeful activity allowing occupational therapists to

incorporate motor learning concepts into intervention (Sabari, 1990).

While there is large support for motor learning theory in the literature, there are

disparities for what is considered best practice for individuals with CVAs. New research has

started to show that a task-oriented approach may be better than motor learning theory-oriented

approach when providing occupational therapy interventions to individuals with CVAs

(Almhdawi et al., 2016). Almhdawi et al. (2016) defined task-oriented training as a “highly

individualized, client-centered, occupational therapy, functional-based intervention compatible

with motor learning and motor control principles such as intensive motor training, variable

practice and intermittent feedback” (p. 445). Scobbie et al. (2013) identified goal setting as best

practice for CVA rehabilitation, but there is no consensus regarding key components of goal

setting interventions or how they should be optimally delivered in practice. Major advances have

occurred in the last 20 years in the development and testing of interventions for CVA

rehabilitation, but there are many gaps in the evidence to inform clinical practice (Langhorne et

al., 2011). Thus, the purpose of this critically appraised topic paper is to determine if motor

learning theory-guided interventions are best practice for individuals with CVA, and how

occupational therapists can effectively implement motor learning theory into their intervention

design.

Key Terms

Best practice: interventions supported by the literature for the appropriate population. CVA:

commonly referred to as a stroke, cell death resulting from lack of oxygen and blood flow to the

brain (Shiel, 2017). Intervention: treatment for a specific diagnosis.

Summary of Search

Our initial literature search yielded 40 articles to review focusing on intervention, best

practice, current practice, motor learning theory, and frames of reference used in occupational

therapy for individuals with CVAs. Upon refining our focus question, we found that not all of

our initial articles were relevant to our topic resulting in 30 articles that met our criteria. Many of

our foundational articles were published decades ago, however, are still valid and relevant to our

topic and were therefore included in our literature synthesis. Databases searched for evidence to

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

4

our focus question include Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

(CINAHL), Pubmed, and the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT). These

databases were chosen given their plethora of evidence-based, occupational therapy literature.

Search terms used were: cerebrovascular accident, CVA, motor learning theory, stroke,

intervention, occupational therapy, OT, occupational performance, Ecology of Human

Performance, best practice, current practice, and frames of reference. Articles were excluded if

they did not closely fit the population, did not provide good information pertaining to specific

interventions used in practice and their efficacy, did not include information related to gaps in

practice, or did not contain current evidence.

Synthesis of Evidence Review

Included in this critical analysis portion of this project was one qualitative study (Jaber et

al., 2018), one systematic review (Langhorne et al., 2018), and one randomized control trial

(Waddell et al., 2015) that all describe the impacts on occupational performance post CVA.

These studies found that the top daily activities affected in people post-CVA included challenges

in driving, seeking employment, self-care activities, home management, community and

functional mobility, leisure activities, and perceptual problems (Jaber et al., 2018; Langhorne et

al., 2011., Waddell et al., 2015). Individuals with CVA reported adverse changes in vision,

cognition, memory, temperament, personality, energy, sleep, attention, psychomotor and

perceptual skills, mobility and stability of joints, muscle power, tone, reflexes, and endurance

(Langhorne et al., 2011). Affected body structures that contribute to these impairments include

the brain, cardiovascular system, legs, arms, and shoulders (Langhorne et al., 2011).

In a self-survey completed by individuals with CVAs, it has been found that CVAs affect

individual’s performance in different instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and activities

of daily living (ADL) (Waddell et al., 2015). In IADLs specifically, individuals had difficulties

with meal preparation, outdoor maintenance, managing doors around their homes, and driving

(Waddell et al., 2015; Jaber et al., 2018). The top reported ADL that is impacted by CVAs was

dressing and the top reported IADL was communication (Waddell et al., 2015). Waddell et al.,

(2015) also reported that some of the challenges noticed with their individuals were in the leisure

and work areas of occupation. These occupations may become difficult, as a CVA can cause

individuals to have affected brain trauma, leg, or arm challenges and may affect their

communication and problem-solving skills (Langhorne et al., 2011).

CVA rehabilitation is a multistep process involving the assessment and identification of

the patient’s needs, goal setting to define realistic and attainable goals, intervention to assist in

the achievement of set goals, and reassessment to assess progress made toward set goals

(Langhorne et al., 2011). Motor learning theory, task-specific training, and goal setting are

deemed as “best practices” in the evidence base (Almhdawi et al., 2016; Jarus, 1994; Sabari,

1990; Scobbie et al., 2013). The following paragraphs will compare motor learning theory, task-

specific training, and goal setting as interventions for individuals with CVAs.

Motor learning theory is affected by three major factors such as environmental

conditions, cognitive processes, and movement organization (Sabari, 1990). Environmental

demands determine how people organize purposeful movement and influence a person’s choice

of motor strategies (Sabari, 1990). Ultimately a person’s environment impacts the mental and

motor processes required to complete the task at hand. A person’s environment influences their

motor learning, therefore the therapist must consider the nature of the environment because

different environmental factors elicit different motor reactions (Gentile 1972, 1987 as cited in

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

5

Sabari, 1990). The occupational therapist must present activities to the client in a manner that

will elicit the retention and transfer of the specified skill in a functional setting (Jarus, 1994).

There are many strategies supported by the literature to increase retention and transference of

learned skills. Strategies such as increasing the difficulty of the learning context during practice,

using an open environment, and having limited knowledge of the task response facilitate

cognitive-motor functioning during the acquisition stage which enhances the retention and

transference of learned skills (Jarus, 1994). Selecting activities that include these strategies

further facilitates retention and transference because clients are forced to draw on prior

knowledge and develop a new movement plan for each practice trial (Jarus, 1994). Therapists

should utilize these strategies when designing interventions based on motor learning theory for

individuals with CVAs.

New research has started to show that a task-orientated approach may be better than

motor learning theory when it comes to the treatment of individuals with CVAs in occupational

therapy (Almhdawi et al., 2016). A task-oriented approach can be broken down into two main

aspects, task orientation, and training. Task orientation consists of the client engaging in

important behavioral experiences, which replicate the sensorimotor skills needed to successfully

complete the task (Lang & Birkenmeier, 2014 as cited in Rowe & Neville, 2018). Training

includes behavioral experiences consisting not only of the use of the same sensorimotor skills,

but also incorporating meaningful activity and progressive challenges to the client’s abilities

(Lang & Birkenmeier, 2014 as cited in Rowe & Neville, 2018). Therapeutic activities often focus

on sensorimotor control domains such as strength, endurance, active range of motion, degrees of

freedom, and postural control (Almhdawi et al., 2016). Therapeutic activities consist of open and

closed tasks. Open tasks involve unstable contextual factors during task performance and maybe

unpredictable during therapeutic practice (Gentile 1972, 1987 as cited in Sabari, 1990). Open

tasks require appropriate timing, sequencing, and spatial anticipation, such as being able to

maintain balance when a surface moves unpredictably (Sabari, 1990). Research supports open-

task training in a contextually variant environment to produce motor schemata that are versatile

enough to adapt to the conditions clients will encounter in their daily lives (Higgins & Spaeth,

1972; Sabari, 1990). Closed tasks are contextually stable and do not vary over time (Sabari,

1990). Closed-task training is not optimal in a task-oriented approach due to the absence of

varying contextual conditions. Many daily activities such as dressing and feeding require the

client to adapt to varying contextual conditions which cannot be achieved through closed-task

training (Sabari, 1990). Contextual conditions are a determining factor in effective sensorimotor

learning for individuals with CVAs; intervention should place a strong emphasis on the context

to be most successful with a task-oriented approach.

Goal setting is viewed as a necessary and effective component of stroke rehabilitation

(Scobbie et al., 2013). Goal setting provides the opportunity for client-centered care which

increases the client’s adherence to their therapy program and optimizes their goal-related

behaviors (Scobbie et al., 2013). Scobbie et al. (2013) designed a goal-action planning

framework to guide health professionals through a systematic goal-setting process, which

consists of four main stages: goal negotiation, goal setting, action planning and coping planning,

and appraisal and feedback. The primary goal of this framework is to optimize client goal-

attainment and client involvement (Scobbie et al., 2013). Research has shown that clients that are

more involved in the goal-setting process set goals with a stronger personal relevance and are

more satisfied with their therapy experience (Scobbie et al., 2013). Recommendations for

effective goal setting in practice include five main criteria: goals should be specific, measurable,

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

6

achievable, realistic or relevant, and timed (Scobbie et al., 2013). In order to implement optimal

goal-setting strategies in practice, therapists should include the client in the goal-setting process

and ensure that the set goals include the five recommended criteria.

Conclusion

There are multiple claims of what is considered best practice intervention for individuals

with CVAs. In this literature synthesis, we explored the evidence in the literature claiming motor

learning theory, task-oriented training, and goal setting as best practice interventions. While

there is large support for motor learning theory in the literature, there is not a claim that this is

the gold standard of practice for this population. Our synthesis of motor learning literature

suggests a shift from neurofacilitation techniques towards motor learning theory approaches, as

clients achieve greater improvement when therapy is guided by the principles of motor learning

theory (Latham et al., 2006; Jarus, 1994). There is confusion in the literature as to if task-

oriented training is a component of motor learning theory or if it is a stand-alone intervention

approach. Langhorne et al. (2011) stated that “task-specific and context-specific training are well

accepted principles in motor learning” (p. 1695). On the contrary, Almhadawi et al. (2016)

concluded that a task-oriented approach is similar to motor learning, but task-oriented has a more

client-centered approach. While task-oriented training has similar concepts to motor learning

theory, it is only supported by a handful of case studies (Flinn, 1995; Gillen, 2000, 2002). Goal

setting is claimed to be best-practice in stroke rehabilitation, but according to the literature, there

is no consensus regarding how to optimally deliver the goal-setting intervention in practice or

what the key components of goal-setting interventions consist of (Scobbie et al., 2013). Our

literature synthesis provided the strongest support for motor learning theory as best practice

intervention for individuals with CVAs.

Clinical Bottom Line

Are motor learning theory-based interventions considered to be part of best practice in

occupational therapy rehabilitation for individuals with CVAs? If so, how might occupational

therapists incorporate motor learning theory into intervention design with maximum efficacy?

Based on the literature, a best practice intervention for individuals with CVAs is motor learning

theory (Jarus, 1994; Gentile 1972, 1987 as cited in Sabari, 1990; Sabari, 1990). The three main

components of motor learning theory are environmental conditions, cognitive processes, and

movement organization (Sabari, 1990). These components should all be identified and evaluated

when designing interventions. The EHP framework supports that the interaction between person

and environment affects human behavior and performance; clearly aligning with motor learning

theory, which states that a person’s environmental demands determine how they are able to

organize purposeful movement and influences their choice of motor strategies (Dunn et al., 1994;

Sabari, 1990). Context is a fundamental component to both EHP and motor learning theory and

should be considered when designing interventions for individuals with CVAs. When a client

receives occupational therapy due to a CVA, it is often because of a need to learn or relearn

motor skills and a desire to be able to perform them in many contexts (Jarus, 1994). Individuals

with CVAs experience daily challenges completing occupations such as driving, self-care, home

management, community mobility and leisure activities due to adverse changes in vision,

cognition, memory, temperament, personality, energy, sleep, attention, psychomotor and

perceptual skills, mobility and stability of joints, muscle power, tone, reflexes and endurance

(Jaber et al., 2018; Langhorne et al., 2011; Waddell et al., 2015).The occupational therapist

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

7

should seek acquisition conditions that will produce the greatest retention and transfer of the

learned motor skills for successful completion of their desired occupations (Jarus, 1994).

Occupational therapy places a large emphasis on purposeful activity. The use of purposeful

activity provides the therapist with an opportunity to incorporate motor learning theory concepts

into goals that are occupation-based and client-centered (Sabari, 1990). The occupational

therapist should consider the client's cognitive processes and desired motor skills when designing

intervention to ensure the tasks or activities are challenging yet attainable (Sabari, 1990).

Research also supports the administration of motor training in the client’s natural context to most

closely align with common, everyday occurrences (Jarus, 1994; Langhorne et al., 2011).

Occupational therapists understand that motor skills also need to be applicable and transferable

to contexts outside of the client’s most common or contrived contexts. In order to produce the

greatest retention and transference of learned motor skills across a variety of contexts, the

therapists should utilize progressive difficulty, randomization, and variant contexts during the

learning period (Jarus, 1994). It is important for occupational therapists to have a clear

understanding of the components of motor learning theory, in order to provide interventions with

the largest support from the current evidence base (See Table 2).

Motor learning theory and occupational therapy are both focused on the learning of new

skills, but each emphasizes different aspects of the learning process. Occupational therapy

focuses primarily on the rehabilitation aspect of how the skill contributes to the client’s

independence and is less concerned with how the skill is learned (Gliner, 1985). In opposition,

motor learning theory is primarily focused on how the skill is learned, controlled, and retained

(Gliner, 1985). By implementing motor learning theory into occupational therapy intervention,

learning processes supported by research designed to increase transference and retention are

utilized, which overall increases the client’s independence in daily activities, catering to the

primary focus of occupational therapy. Clients who receive care in a stroke unit were most likely

to be alive, independent, and at home within one-year post-CVA (Latham et al., 2006). Multiple

health disciplines such as physical therapy, recreational therapy and speech language pathology

may also use motor learning theory to address functional implications of CVAs (Zahl et al.,

2017). Barriers to the implementation of these interventions in a clinical setting need to be better

understood because many effective interventions are not present in the clinic (Langhorne et al.,

2011). Studies have found a 17-year time lag between scientific discoveries in health care and

the implementation of them into practice, and that of these discoveries, only 14% of them are

implemented (Balas & Boren, 2000; Green et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2011). Understanding the

barriers behind why there is such a gap between what is done in practice, and what is supported

by the literature is fundamental to ensuring that most therapists are providing evidence-based

practice. Some barriers present in the literature include lack of evidence-based practice experts

amongst staff, increased cost associated with selecting evidence-based practice, time constraints,

logistical challenges, inadequate equipment, limited ability to trial and observe evidence-based

practice in entry-level education and practice (See Table 1) (Bayley et al., 2012; Levac et al.,

2016; McCluskey et al., 2013; Petzold et al., 2014; Scobbie et al., 2013; Scott et al.,

2020). Through our literature search, it was discovered that there is not a document that clearly

defines best practice interventions for individuals with CVAs. The presence of a document with

clear guidelines for best practice in the literature would make best practice guidelines more

accessible for practitioners to follow and implement. Other opportunities that would be

beneficial to reducing barriers of evidence-based practice implementation include experiential

learning opportunities in entry level education and professional development, along with

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

8

independent research. These strategies are supported by the literature to increase consumer

access to evidence-based practice and improve occupational outcomes (Scott et al., 2020). As a

practitioner, schedules are often filled, and interventions are often habitual. It is important to

continue researching evidence-based practice after leaving an educational program. This can be

achieved through independent research, attending conferences, panels, or workshops, or by

enrolling in a program with mastery in the field of interest.

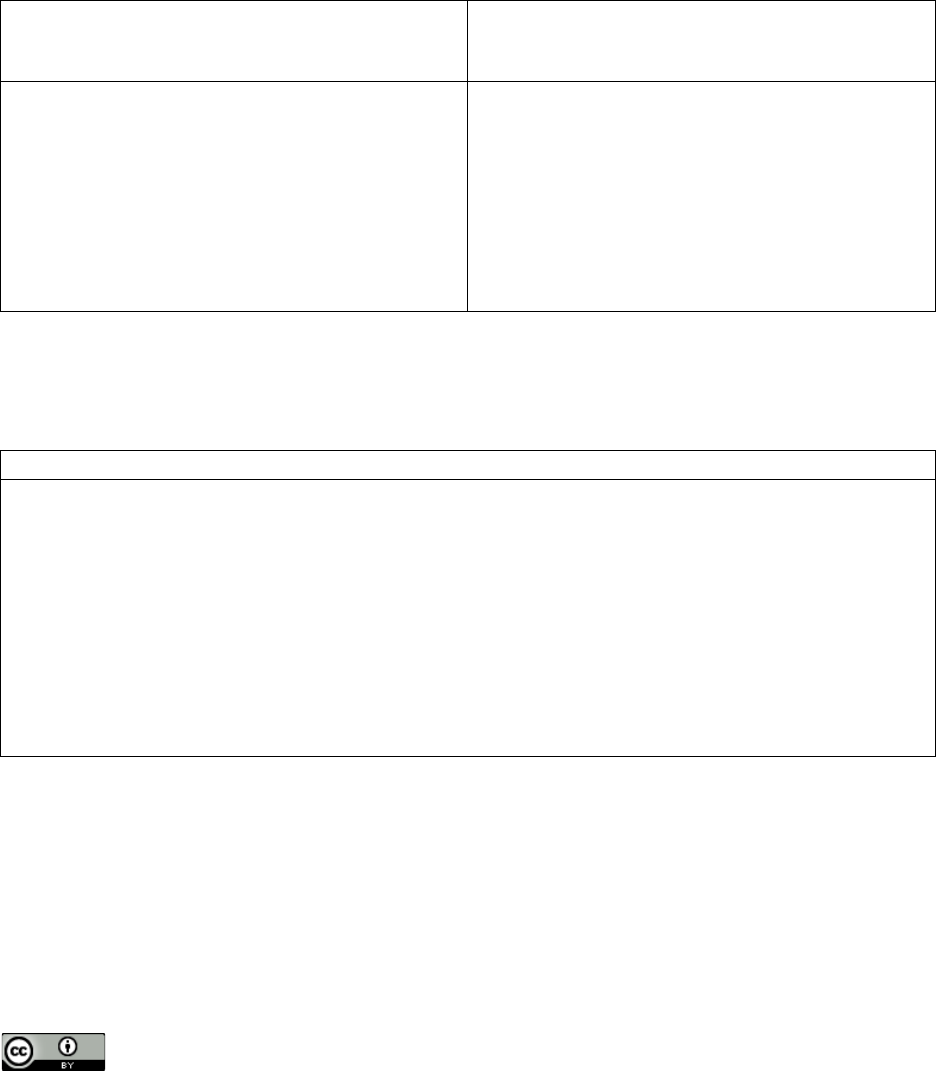

Table 1

Barriers to Evidence-Based Practice Implementation and How to Overcome Them

Barriers to Implementing Evidence-Based

Practice (EBP)

Methods to Overcome Barriers to EBP

Implementation

• Lack of EBP experts among staff

• Increased cost associated with

selecting EBP

• Time constraints

• Logistical challenges

• Limited ability to trial and observe

EBP in entry-level education and

practice

• Independent research

• Attending conferences, panels, or

workshops

• Enrolling in a program with mastery

in field of interest

Table References: Bayley et al., 2012; Levac et al., 2016; McCluskey et al., 2013; Petzold et al.,

2014; Scobbie et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2020

Table 2

How to Implement Motor Learning Theory into OT Intervention Design with Maximum Efficacy

Components for Intervention

• High repetition (Kleim et al., 1998; Nudo et al., 1996)

• Positive feedback (Birkenmeier et al., 2010)

• Environmental conditions (Sabari, 1990)

• Randomization (Jarus, 1994)

• Cognitive processes of client (Sabari, 1990)

• Movement organization (Sabari, 1990)

• Utilization of an open environment (Jarus, 1994)

• Increased difficulty of learning context during practice of motor skills (Jarus, 1994)

• Inclusion of client in goal-setting process (Scobbie et al., 2013)

• Purposeful Activity (Sabari, 1990)

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

9

References

Almhdawi, K. A., Mathiowetz, V. G., White, M. & delMas, R. C. (2016). Efficacy of

occupational therapy task-oriented approach in upper extremity post-stroke rehabilitation.

Occupational Therapy International, 23(4), 444-456. https://doi-

org.ezproxylr.med.und.edu/10.1002/oti.1447

American Stroke Association. (2018). Women have a higher risk of stroke. American Stroke

Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-risk-factors/women-have-a-

higher-risk-of-stroke.

American Stroke Association. (2018). Stroke risk factors not within your control. American

Stroke Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-risk-factors/stroke-

risk-factors-not-within-your-control

Balas, E. A., & Boren, S. A. (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement.

Yearbook of Medical Informatics. http://hdl.handle.net/10675.2/617990

Bayley, M. T., Hurdowar, A., Richards, C. L., Korner-Bitensky, N., Wood-Dauphinee, S., Eng,

J. J., ... & Graham, I. D. (2012). Barriers to implementation of stroke rehabilitation

evidence: findings from a multi-site pilot project. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(19),

1633-1638. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.656790

Birkenmeier, R., Prager, E., & Lang, C. (2010). Translating animal doses of task-specific

training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: A proof-of-concept

study. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 24(7), 620–635.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968310361957

Dunn, W., Brown, C., & McGuigan, A. (1994). The ecology of human performance: A

framework for considering the effect of context. American Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 48(7), 595-607. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.48.7.595

Flinn, N. (1995). A task-oriented approach to the treatment of a client with hemiplegia.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(6), 560–569.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.49.6.560

Gillen, G. (2000). Improving activities of daily living performance in an adult with ataxia.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy 54(1), 89–96.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.54.1.89

Gillen, G. (2002), Improving mobility and community access in an adult with ataxia. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(4), 462–466. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.56.4.462

Gliner, J. A. (1985). Purposeful activity in motor learning theory: An event approach to motor

skill acquisition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39(1), 28-34.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.39.1.28

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

10

Green, L. W., Ottoson, J. M., García, C., & Hiatt, R. A. (2009). Diffusion theory and knowledge

dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public

Health, 30, 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049

Higgins, J. R., & Spaeth, R. K. (1972). Relationship between consistency of movement and

environmental condition. Quest, 17(1), 61-69.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1972.10519724

Jaber, A. F., Sabata, D., & Radel, J. D. (2018). Self-perceived occupational performance of

community-dwelling adults living with stroke. Canadian Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 85(5), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417418821704

Jarus, T. (1994). Motor learning and occupational therapy: the organization of practice.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48(9), 810-816.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.48.9.810

Kleim, J. A., Barbay, S. & Nudo, R. J. (1998) Functional reorganization of the rat motor cortex

following motor skill learning. Journal of Neurophysiology 80(6), 3321–3325.

https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3321

Latham, N. K., Jette, D. U., Coster, W., Richards, L., Smout, R. J., James, R. A., ... & Horn, S.

D. (2006). Occupational therapy activities and intervention techniques for clients with

stroke in six rehabilitation hospitals. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60(4),

369-378. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.60.4.369

Langhorne, P., Bernhardt, J., & Kwakkel, G. (2011). Stroke rehabilitation. The Lancet,

377(9778), 1693–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5

Levac, D., Glegg, S. M., Sveistrup, H., Colquhoun, H., Miller, P. A., Finestone, H., ... &

Velikonja, D. (2016). A knowledge translation intervention to enhance clinical

application of a virtual reality system in stroke rehabilitation. BMC health services

research, 16(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

McCluskey, A., Vratsistas-Curto, A., & Schurr, K. (2013). Barriers and enablers to

implementing multiple stroke guideline recommendations: A qualitative study. BMC

Health services research, 13(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-323

Morris, Z. S., Wooding, S., & Grant, J. (2011). The answer is 17 years, what is the question:

Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of

Medicine, 104, 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180

Nilsen, D., & Geller, D. (2015). The role of occupational therapy in stroke rehabilitation.

American Occupational Therapy Association. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-

Therapy/Professionals/RDP/stroke.aspx

Bourque, O’Sadnick, Skogen & Vold, 2021

11

Nudo, R., Milliken, G., Jenkins, W., & Merzenich, M. (1996). Use-dependent alterations of

movement representations in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. The

Journal of Neuroscience, 16(2), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-

00785.1996

Petzold, A., Korner-Bitensky, N., Salbach, N. M., Ahmed, S., Menon, A., & Ogourtsova, T.

(2014). Determining the barriers and facilitators to adopting best practices in the

management of poststroke unilateral spatial neglect: Results of a qualitative study. Topics

in Stroke Rehabilitation, 21(3), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr2103-228

Rowe, V. T., & Neville, M. (2018). Task oriented training and evaluation at home. OTJR:

Occupation, Participation and Health, 38(1), 46-55.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449217727120

Sabari, J. (1990). Motor learning concepts applied to activity-based intervention with adults with

hemiplegia. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(6), 523–530.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.6.523

Shiel, W. (26, January 2017). Definition of cerebrovascular

accident. MedicineNet. https://www.medicinenet.com/cerebrovascular_accident/definitio

n.htm.

Scobbie, L., McLean, D., Dixon, D., Duncan, E., & Wyke, S. (2013). Implementing a framework

for goal setting in community based stroke rehabilitation: A process evaluation. BMC

Health Services Research, 13(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-190

Scott, S., Shade, H., Crowell, M., Lynch, M., Arpadi, L., Levine, A., ... & Harenberg, S. (2020).

Use it or lose it? The diffusion of constraint-induced and modified constraint-induced

movement therapy into OT practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(5),

7405347010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.039339

Waddell, K. J., Birkenmeier, R. L., Bland, M. D., & Lang, C. E. (2015). An exploratory analysis

of the self-reported goals of individuals with chronic upper-extremity paresis following

stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(9), 853–857.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1062926

Zahl, M. L., Horneber, G., Piatt, J. A., & Mwavita, M. (2017). The role of recreational therapy in

the treatment of a stroke population. Annual in Therapeutic Recreation, 24, 26–37.

http://ezproxylr.med.und.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tr

ue&db=ccm&AN=136972406&site=ehost-live&custid=s9002706