FINAL REPORT OF THE TASK FORCE

ONEXTREMISM IN FRAGILE STATES

February 2019

PREVENTING

EXTREMISM IN

FRAGILE STATES

A New Approach

Members of the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

Cochairs

Governor Thomas Kean

Former Governor of New Jersey;

former 9/11 Commission Chair

Representative Lee Hamilton

Former Congressman from Indiana;

former 9/11 Commission Chair

Task Force Members

Secretary Madeleine Albright

Chair, Albright Stonebridge Group;

formerU.S.Secretary of State

Senator Kelly Ayotte

Board of Directors, BAE Systems, Inc.;

formerU.S. Senator from New Hampshire

Ambassador William Burns

President, Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace; former Deputy Secretary of State

Ambassador Johnnie Carson

Senior Advisor to the President, United States

Institute of Peace; former U.S. Assistant

Secretary of State for African Aairs

Ambassador Paula Dobriansky

Senior Fellow, The Future of Diplomacy Project,

Harvard University; former Under Secretary

ofState for Global Aairs

Ambassador Karl Eikenberry

Director of the U.S.-Asia Security Initiative,

Stanford University; former U.S. Ambassador

toAfghanistan

Dr. John Gannon

Adjunct Professor at the Center for Security

Studies, Georgetown University; former

Chairman, National Intelligence Council

The Honorable Stephen Hadley

Chair of the Board of Directors, United States

Institute of Peace; former U.S. National

SecurityAdvisor

Mr. Farooq Kathwari

Chairman, President and CEO,

EthanAllenInteriors Inc.

The Honorable Nancy Lindborg

President, United States Institute of Peace

The Honorable Dina Powell

Nonresident Senior Fellow, The Future

ofDiplomacy Project, Harvard University;

former U.S. Deputy National Security

AdvisorforStrategy

The Honorable Rajiv Shah

President, The Rockefeller Foundation;

formerAdministrator, U.S. Agency for

International Development

Mr. Michael Singh

Senior Fellow and Managing Director,

TheWashington Institute; former Senior Director

forMiddle East Aairs, National Security Council

Senior Advisors

Ambassador Reuben E. Brigety II

Adjunct Senior Fellow, Council on

ForeignRelations

Mr. Eric Brown

Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Dr. Susanna Campbell

Assistant Professor, School of International

Service, American University

Ms. Leanne Erdberg

Director of Countering Violent Extremism,

United States Institute of Peace

Mr. Steven Feldstein

Nonresident Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace; Frank and Bethine Church

Chair, Boise State University

Dr. Hillel Fradkin

Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Ms. Alice Friend

Senior Fellow, International Security Program,

Center for Strategic and International Studies

Dr. George Ingram

Senior Fellow, Global Economy and

Development, Brookings Institution

Dr. Seth G. Jones

Director of the Transnational Threats Project

and Senior Advisor to the International

SecurityProgram, Center for Strategic and

International Studies

Dr. Mara Karlin

Associate Professor of the Practice of Strategic

Studies, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced

International Studies

Dr. Homi Kharas

Interim Vice President and Director of the

GlobalEconomy and Development Program,

Brookings Institution

Mr. Adnan Kifayat

Senior Fellow, German Marshall Fund

andHead of Global Security Ventures,

GenNextFoundation

Dr. Rachel Kleinfeld

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment

forInternational Peace

Mr. Christopher A. Kojm

Visiting Professor of the Practice of International

Aairs, George Washington University

Mr. Michael Lumpkin

Vice President of Human Performance

andBehavioral Health, Leidos Health

Mr. Robert Malley

CEO, International Crisis Group

Dr. Bridget Moix

Senior U.S. Representative and Head

ofAdvocacy, Peace Direct

Mr. Jonathan Papoulidis

Executive Advisor on Fragile States, World Vision

Ms. Susan Reichle

CEO and President, International

YouthFoundation

Mr. Tommy Ross

Senior Associate, International Security Program,

Center for Strategic and International Studies

Dr. Lawrence Rubin

Associate Professor, Sam Nunn School

ofInternational Aairs, Georgia Institute

ofTechnology

Mr. Andrew Snow

Senior Fellow, United States Institute of Peace

Dr. Paul Stares

Senior Fellow for Conflict Prevention and

Director of the Center for Preventive Action,

Council on Foreign Relations

Ms. Susan Stigant

Director of Africa Programs, United States

Institute of Peace

Dr. Lauren Van Metre

Senior Advisor, National Democratic Institute

Ms. Anne Witkowsky

Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of

Defensefor Stability and Humanitarian Aairs,

U.S. Department of Defense

Ms. Mona Yacoubian

Senior Advisor for Syria, Middle East, and

NorthAfrica, United States Institute of Peace

Project Sta

Mr. Blaise Misztal

Executive Director

Mr. Michael Hurley

Advisor to the Cochairs

Dr. Corinne Gra

USIP Senior Advisor for Conflict Prevention

Dr. Daniel Calingaert

Lead Writer

Dr. Nathaniel Allen

Policy Advisor

Dr. Michael Marcusa

Policy Advisor

Mr. Philip McDaniel

Policy Advisor

Ms. Alyssa Jackson

Program Manager

Acknowledgments

The Task Force is grateful to the U.S. Congress, particularly Senator Lindsey Graham,

for entrusting it with this important mission. It is deeply appreciative of the support it has

received from the United States Institute of Peace and the Bipartisan Policy Center, on whose

earlier work this eort builds. The work of the Task Force would not have been possible

without the deep expertise, time commitment, and guidance that the Senior Advisors have

generously provided. Many experts at the United States Institute of Peace also contributed

their knowledge to guide our eorts. In addition, the Task Force wishes to acknowledge and

thank the many institutions and individuals who have provided valuable advice and feedback

throughout the course of the Task Force’s deliberations. These include U.S. government

representatives; foreign government ocials; international organizations; research

institutions; nonprofit organizations; and private sector organizations. In particular, the Task

Force is deeply grateful to the Secretariats of the g7+ and the International Dialogue on

Peacebuilding and Statebuilding, the Aspen Ministers Forum, the Alliance for Peacebuilding,

the Brookings Institution, InterAction, the International Republican Institute, the National

Democratic Institute, and The Prevention Project for allowing the Task Force to present its

thinking and for providing valuable feedback.

Disclaimer

This report represents the consensus of a bipartisan Task Force with diverse expertise and

aliations. No member may be satisfied with every formulation and argument in isolation.

The findings of this report are solely those of the Task Force. They do not necessarily

represent the views of the United States Institute of Peace or the Senior Advisors.

Contents

Letter from the Cochairs 1

I. Executive Summary 3

II. The Imperative of Prevention 6

The Unsustainable Costs of the Cycle of Crisis Response 9

Beyond the Homeland: The Evolving Threat of Extremism inFragile States 11

Changing the Paradigm: The Case for Prevention 13

A Dicult Road: Getting to Prevention 15

Recommendations for a New Approach 18

III. A Shared Framework for StrategicPrevention 19

The Conditions for Extremism: Political and Contextual 19

Addressing the Conditions for Extremism: Country-Led andInclusive Programs 21

Strategic Criteria for Prevention 22

Preventive Approaches in Fragile States: Partnerships, Opportunities, Risks 23

IV. U.S. Strategic Prevention Initiative 26

V. Partnership Development Fund 28

Demonstration Project 29

VI. Conclusion 30

Appendices 31

Appendix 1: Authorizing Legislation 31

Appendix 2: The Conditions for Extremism 32

Appendix 3: Principles for Preventing Violent Extremism 36

Appendix 4: A Global Fund for Prevention 43

Appendix 5: Prevention Program and Policy Priorities 46

Appendix 6: Aligning Security Sector Cooperation with Prevention 50

Appendix 7: Consultations 54

Notes 57

Letter from the Cochairs

Since September 11, 2001, the courage and skill of our military, intelligence, and law

enforcement professionals have prevented another mass-casualty terrorist attack on U.S.

soil. American diplomats and development professionals have also dedicated great eort

to improving conditions in the dangerous places that give rise to terrorism. Yet all of us

recognize that challenges remain. Our success in defeating terrorists has not been matched

by success in ending the spread of terrorism.

It is to address this shortcoming that Congress tasked the United States Institute of Peace

to “develop a comprehensive plan to prevent the underlying causes of extremism in fragile

states.” We have been honored to lead this eort—working with a bipartisan Task Force

comprising thirteen of America’s most talented foreign policy professionals. Each of us on

the Task Force understands the importance of the problem as well as the diculty of finding

asolution. We have endeavored to learn from previous administrations that have wrestled

withthis challenge.

Our principal recommendation is both simple and daunting: Prevention should be our policy.

Preventing the underlying causes of extremism is possible but requires us to adopt a new

way of thinking about, structuring, and executing U.S. foreign policy.

The challenge is not that we lack the tools for prevention. Rather, our prevention eorts are

fractured. The relevant capabilities and expertise are spread across the U.S. government,

with no shared criteria for when to use them, no policy guidance for how to use them, and

no mechanism for coordinating them. When tried, prevention eorts have been disjointed,

piecemeal, and intermittent.

What we need is a sense of urgency. We need a high-level political commitment to undertake

prevention. We need a coherent, coordinated, and committed focus to prevent the underlying

causes of extremism in fragile states. This will require all U.S. departments and agencies with

national security responsibilities to adopt a shared understanding of how to stop the spread

of extremism. It will require the Congress to grant U.S. diplomacy, development, and defense

professionals greater flexibility in the field, while faithfully executing its oversight role. Most

important, it will require the United States to convince otherinternational actors to join and

support prevention eorts.

1 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

We recognize that this is no easy task. It will take time. It will not succeed everywhere. There

will be failures. We will have to make adjustments along the way based on lessons learned.

But if we can do it right—engaging the energy, creativity, and resourcefulness of our foreign

service, development, and military professionals—our policy will be more aordable and

more sustainable. We also believe that this policy will save lives in the years ahead.

This is the right moment for a new approach. After 9/11, U.S. ocials rightly focused on

imminent threats to the homeland. There was little understanding of how to go about

preventing violent extremism. We have learned much since. The weakening of the Islamic

State in Iraq and Syria creates an opportunity to focus on prevention. The threat that

it could reestablish itself in another fragile state underscores prevention’s importance.

Manyinternational actors share our view; we should harness this emerging consensus.

A preventive strategy is neither passive nor naive. The United States always reserves the

right to use force and should do so to confront imminent terrorist threats. The broader

challenge before us is to prevent future threats from emerging. We want to foster resilient

societies in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel that are capable of resisting

thespread of extremism. We want not only to defeat today’s terrorists but also to alleviate

theconditions that spawn tomorrow’s.

We urge Congress and the administration to take up the recommendations in this report,

andwe look forward to working to implement them.

Governor Tom H. Kean Representative Lee H. Hamilton

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 2

I. Executive Summary

We need a new strategy to prevent the spread of extremism, which threatens our homeland,

our strategic interests, and our values. Our current focus on counterterrorism is necessary,

but neither sucient nor cost-eective. Congress has charged this Task Force with

developing a new approach, one that will get ahead of the problem.

We need a new strategy because, despite our success protecting the homeland, terrorism

is spreading. Worldwide, annual terrorist attacks have increased fivefold since 2001.

Thenumber of self-professed Salafi-jihadist fighters has more than tripled and they are

nowpresent in nineteen countries in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Near East.

We need a new strategy because the costs of our current approach are unsustainable. Over

the last eighteen years, ten thousand Americans have lost their lives and fifty thousand have

been wounded fighting this threat, at an estimated cost of $5.9 trillion to U.S. taxpayers.

1

We need a new strategy because terrorism is not the only threat we face. Terrorism is a

symptom, but extremism—an ideology calling for the imposition of a totalitarian order intent on

destroying free societies like ours—is the disease. Extremism both preys on fragile states and

contributes to chaos, conflict, and coercion that kills innocents, drains U.S. resources, forecloses

future market opportunities, weakens our allies, and provides openings for our competitors.

To reduce our expenditure of blood and treasure, protect against future threats, and preserve

American leadership and values in contested parts of the world, we must not only respond

to terrorism but also strive to prevent extremism from taking root in the first place. This does

not mean seeking to stop all violence or to rebuild nations in vulnerable regions of the world.

Instead, it means recognizing that even modest preventive investments—if they are strategic,

coordinated, and well-timed—can reduce the risk that extremists will exploit fragile states.

The objective of a preventive approach should be to strengthen societies that are vulnerable

to extremism so they can become self-reliant, better able to resist this scourge, and protect

their hard-earned economic and security gains.

This imperative for prevention is not new. Back in 2004, the 9/11 Commission argued that

counterterrorism and homeland security must be coupled with “a preventive strategy that

is as much, or more, political as it is military.”

2

That call has not been answered. And so the

threat continues to rise, the costs mount, and the need for a preventive strategy grows

morecompelling.

Progress has undoubtedly been made since 9/11. The U.S. government has a better

understanding of what works. There is bipartisan agreement in Congress that a new

approach is needed. However, the United States cannot —nor should it—carry this burden

alone. U.S. leadership is needed to catalyze international donors to support preventing

extremism. And the international community—both donor countries and multilateral

organizations, such as the World Bank—are increasingly willing to engage these problems

withus, including through the Global Coalition to Defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

But challenges persist. There is still insucient prioritization, coordination, or agreement

onwhat to do, both within the U.S. government and across the international community.

3 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

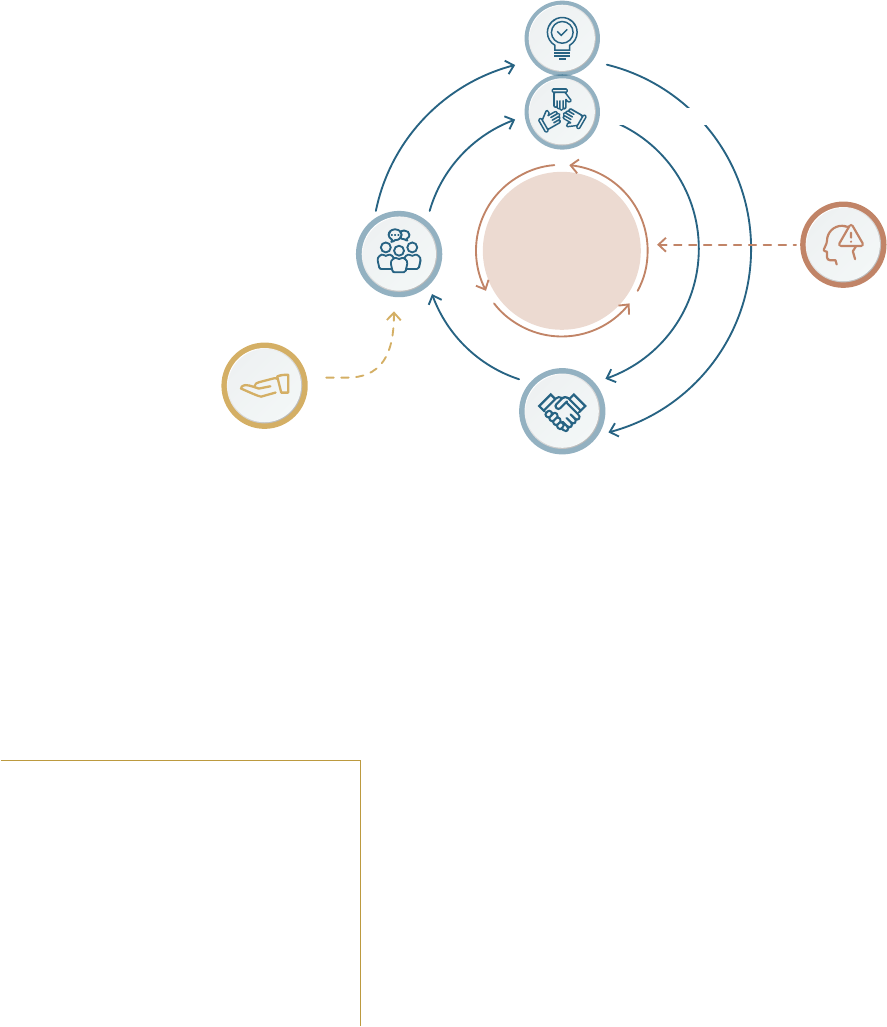

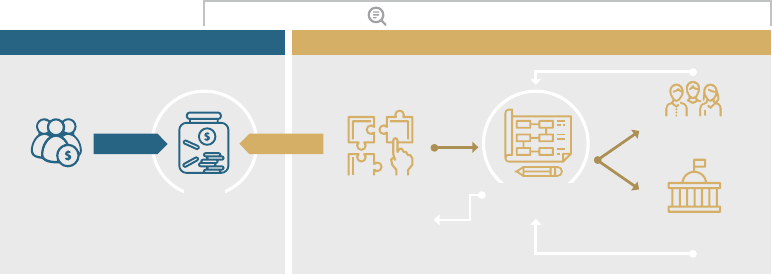

Our Task Force oers three recommendations to build on emerging opportunities and

overcome persistent hurdles to preventing extremism eectively (see figure 1, “Summary

ofTask Force Recommendations”).

First, there must be a new eort to unite around a joint strategy aimed at preventing the

underlying causes of extremism. The United States should adopt a shared framework for

strategic prevention that recognizes that extremism is a political and ideological problem.

The framework should also identify building partnerships with leaders, civil society, and

private sector actors in fragilestates who are committed to governing accountably as

the best approach to preventing extremism. Extremists’ attempts to, in the Middle East

and Africa, establish an absolutist state ruled by a rigid, twisted, and false interpretation of

Islam resonate only in societies where the existing state has failed its people. The antidote

to extremist ideology, therefore, must be political. But inclusive institutions, accountable

governments, and civic participation cannot be imposed from the outside. What the United

States can do is identify, encourage, and build partnerships with leaders in fragile states

including nationally and locally, in government and civil society with women, youth, and the

private sector who are committed to rebuilding trust in their states and societies. However,

bitter experience teaches that where such leaders are lacking, the United States stands little

chance of furthering its long-term interests. In such cases, it must seek to seize opportunities

where possible and always mitigate the risk that its engagement, or that of other actors,

could do more harm than good.

Second, to ensure that agencies have the resources, processes, and authorities they need

to operationalize this shared framework, the Congress and the Executive Branch should

launch a Strategic Prevention Initiative to align all U.S. policy instruments, from bilateral

assistance to diplomatic engagement, in support of prevention. TheInitiative should set

out the roles and responsibilities of each department for undertaking prevention. Its principal

objective should be to promote long-term coordination between agencies in fragile states.

Itshould grant policymakers new authorities to implement a preventive strategy. In particular,

because local conditions and needs dier widely, it is important that U.S. diplomats and

development professionals on the ground in fragile states be given direct responsibility,

flexibility, and funding to experiment with and develop eective and tailored solutions.

However, the United States neither can nor should prevent extremism by itself. It is not the only

country with a vested interest in doing so and can build more eective partnerships with fragile

states if other countries cooperate. Thus, our Task Force calls on the United States to establish

a Partnership Development Fund, a new international platform for donors and the private

sector to pool their resources and coordinate their activities in support of prevention.

This would ensure that the work being done by the United States as part of the Strategic

Prevention Initiative is matched by other international donors working jointly toward the same

goals. Itwould create a mechanism for other countries to share the burden and incentivize

an enterprise-driven approach. A single, unified source ofassistance might also entice fragile

states that would otherwise look elsewhere for help.

A preventive strategy will not stop every terrorist attack. It will take time to produce results. It

will require us to recognize the limits of our influence and work hard to leverage our resources

more eectively. And it is not something that we can implement alone—our international

partners should do their fair share. But it oers our best hope. Neither open-ended military

operations, nor indefinite foreign assistance, nor retrenchment oers a better alternative.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 4

Through targeted, evidence-based, strategic investments where the risks are the highest, our

interests the greatest, and our partners the most willing, prevention provides a cost-eective

means to slow, contain, and eventually roll back the spread of extremism. The United States

needs toenable fragile states and societies to take the lead in averting future extremist

threats. Ifwe succeed, our children and grandchildren will live in a more peaceful world.

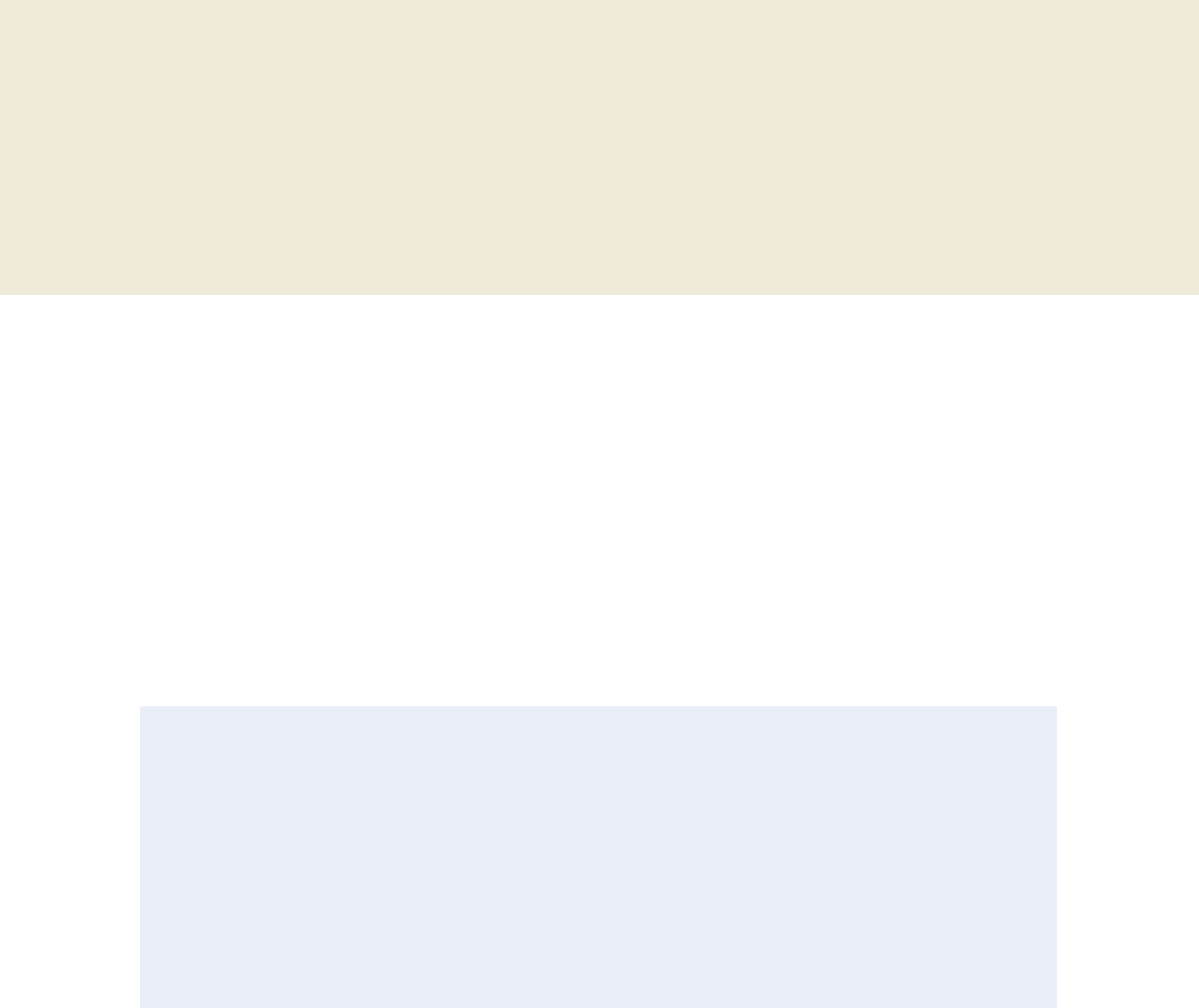

Figure 1. Summary of Task Force Recommendations

OBJECTIVESRESULTS RECOMMENDATIONS

Adopt a shared

understanding of how

to prevent violence

andextremism.

Operationalize

the prevention

frameworkwithin

theU.S. government.

Rally the international

community in support

of locally-led eorts

toprevent extremism.

Shared Framework for

StrategicPrevention

Strategic Prevention

Initiative

Partnership

Development Fund

• U.S. government (USG)

adopts a government-

wide understanding

of extremism

asapolitical and

ideologicalproblem.

• USG prioritizes

partnerships with

foreign leaders

committed to governing

accountably.

• Executive Branch

establishes clear roles

and responsibilities

for each department

undertaking prevention.

• Congress grants new

authorities for flexible,

long term funding for

field-based sta.

• Executive Branch aligns

security assistance with

prevention priorities.

• State Department

and USAID negotiate

with international

partners toestablish

new platform to

coordinate activities

and pool resources to

promoteprevention.

• Ensures other donors

and fragile states

contribute their

fairshare.

Ensures greater unity

ofeort around a joint

strategy for addressing

the underlying

conditions of extremism.

Provides the

authorities, procedures

and resources

needed by agencies

to align eorts and

empower committed

localpartners.

Leverages the

resources ofour

international partners

and promotes

coordination among

the U.S., international

donors, and

partnerstates.

5 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

II. The Imperative of Prevention

On September 11, 2001, nineteen young men from the Salafi-jihadist network of al-Qaeda

perpetrated the worst terrorist attack on American soil since Pearl Harbor. The attacks on the

World Trade Center and the Pentagon, which claimed the lives of nearly three thousand people,

have defined the course of U.S. national security policy for the better part of a generation.

That policy has focused on disrupting, degrading, dismantling, and decimating terrorist

networks overseas through a variety of means, but primarily militarily. Yet, despite U.S.

success on the battlefield, extremist groups, exploiting exclusionary governance, political

instability, and local conflicts, not merely persist but thrive. Since 9/11, jihadist groups have

participated in major insurgencies in Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Libya, Yemen, Nigeria, and Mali

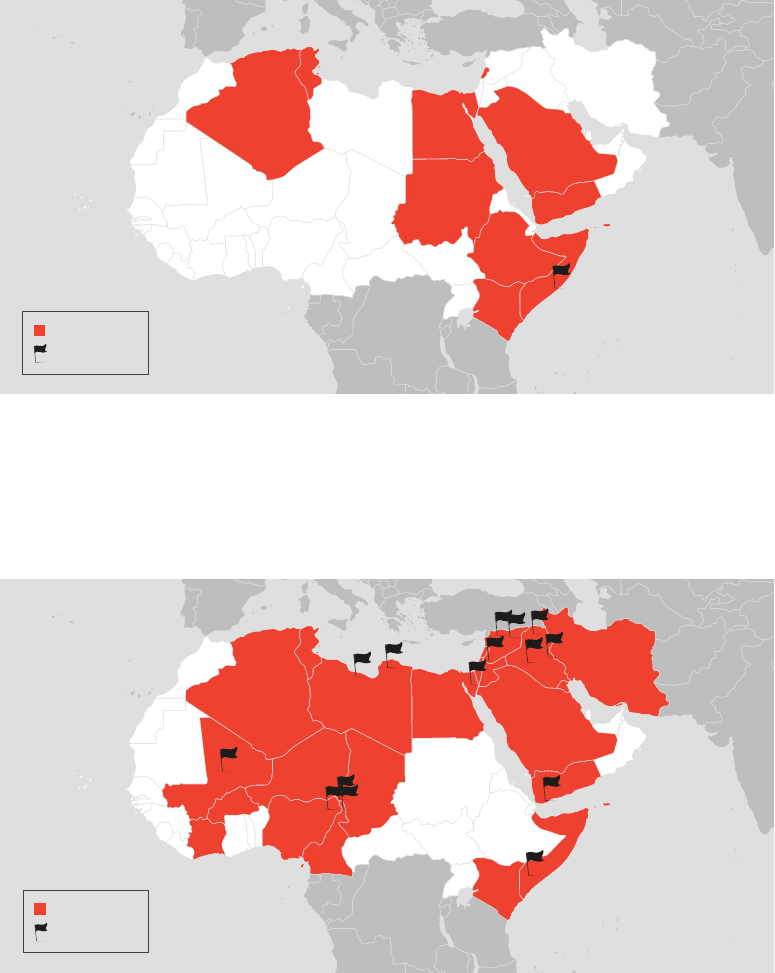

(see figure 2, “The Cycle of Crisis Response: Jihadist Insurgencies and U.S.-Supported

Interventions”). In none of these conflicts has the United States and its partners been able

to completely contain or mitigate the threat. Instead, after each supposed defeat, extremist

groups return having grown increasingly ambitious, innovative, and deadly.

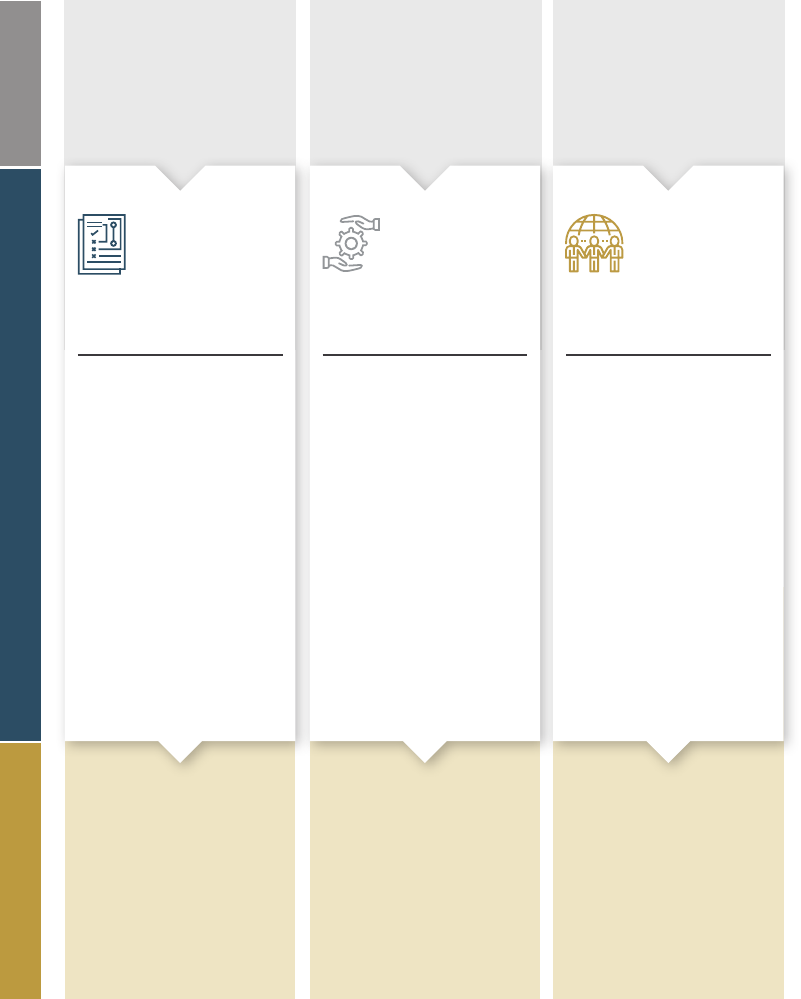

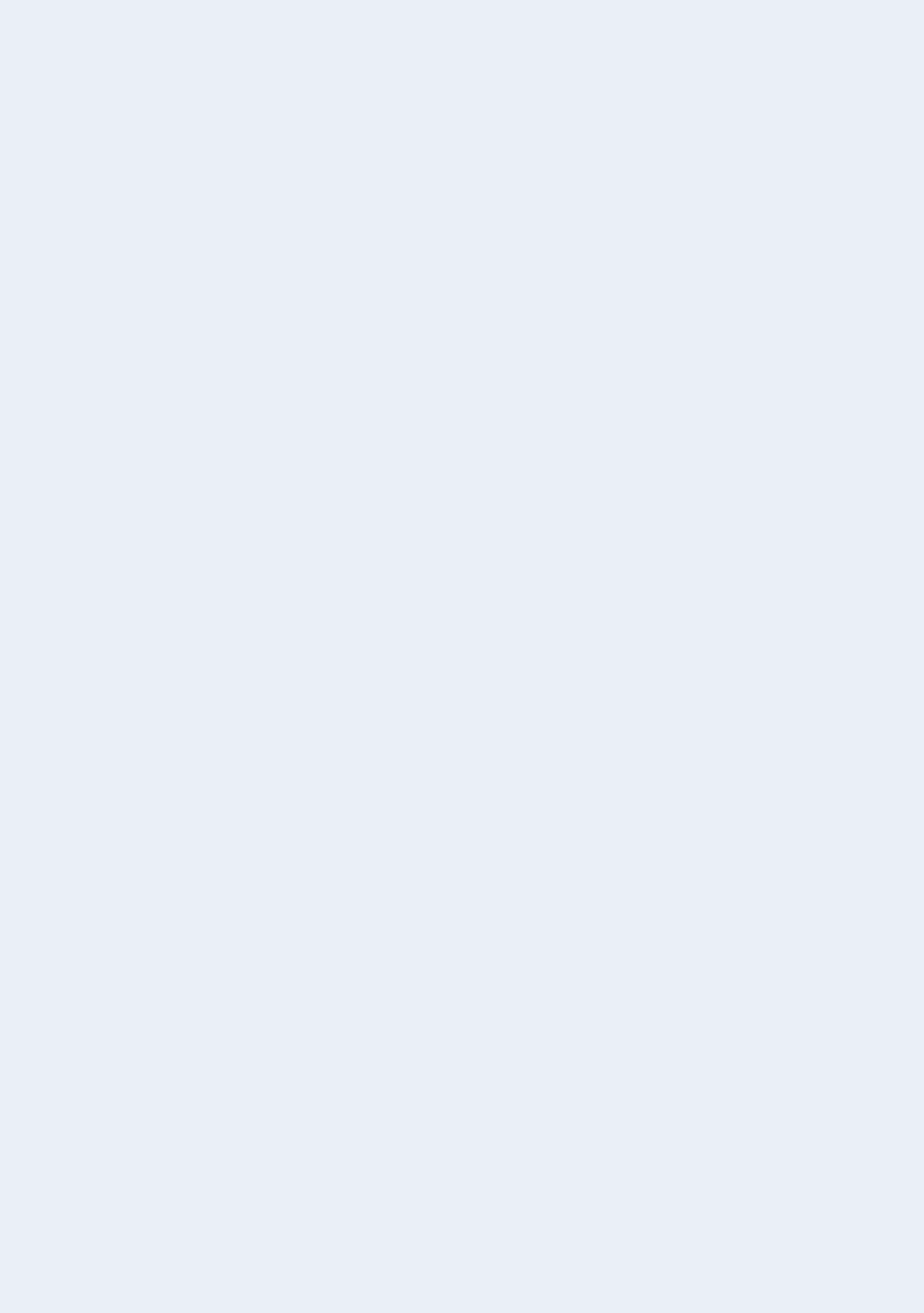

Figure 2. The Cycle of Crisis Response: Jihadist Insurgencies

and U.S.-Supported Interventions

This figure displays the conflict trajectories of major jihadist insurgencies where U.S.-led or supported interventions have

occurred. Major jihadist insurgencies are conflicts with the participation of an ISIS or al-Qaeda aliated group with at least ten

thousand battle deaths (as in the cases of Iraq, Syria, Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen), or where such groups have seized control

of major population centers (as in Mali and Libya). U.S.-led military interventions are those where the United States intervened

with ground forces, air strikes, drone strikes, or special forces during a conflict (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen).

U.S.-supported interventions are those where the United States provided military equipment, training, intelligence, or logistical

support to major combatants in confronting jihadist groups. Source on conflict-related deaths: UCDP / PRIO Armed Conflict

Dataset: http://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/#d8, Therése Patterson and Kristen Eck, “Organized Violence,” Journal of Peace Research

55, no.4 (2018), (accessed January 10, 2019). Data on U.S.-led or supported interventions compiled from secondary sources.

NIGERIA

5,000

0

LIBYA

2,500

0

SOMALIA

3,000

0

SYRIA

70,000

0

YEMEN

7,000

0

Yearly battle-related deaths

MAJOR JIHADIST INSURGENCIES

U.S.-LED OR -SUPPORTED MILITARY INTERVENTIONS

This gure displays the conict trajectories of major jihadist insurgencies where U.S.-led or supported interventions have occurred. Major jihadist insurgencies are

conicts with the participation of an Islamic State or Al-Qaeda aliated group with at least ten thousand battle deaths (as in the cases of Iraq, Syria, Nigeria,

Somalia, and Yemen), or where such groups have seized control of major population centers (as in Mali and Libya). U.S.-led military interventions are those where

the United States intervened with ground forces, air strikes, drone strikes, or special forces during a conict (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia and Yemen). U.S.-sup-

ported interventions are those where the United States provided military equipment, training, intelligence or logistical support to major combatants in confronting

jihadist groups. Source on conict-related deaths: UCDP / PRIO Armed Conict Dataset: http://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/#d8, Pettersson, Therése and Kristine Eck

(2018) Organized violence, 1989-2017 (accessed January 10, 2019). Data on U.S.-led or supported interventions compiled from secondary sources.

The Cycle of Crisis Response: Jihadist Insurgencies

and U.S.-Supported Interventions

IRAQ

15,000

0

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

MALI

1,000

0

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 6

Winning the Battles, Losing the Peace: The Case of Mosul, Iraq

Nine months, one hundred thousand troops, and some of the toughest urban combat since

World War II is what it took to capture Mosul in July 2017.

a

It was the third time in the past fifteen

years that the United States and its partners had “liberated” the city, Iraq’s second largest.

The first time the United States swept into Mosul was in April 2003. However, after the United

States overthrew Saddam Hussein’s regime, and a Shia-dominated government took power in

Baghdad, the predominantly Sunni Arab city resisted. In 2004, insurgents in Mosul declared

their allegiance to al-Qaeda and began attacking U.S. forces.

In 2008, the U.S. and Iraqi militaries launched another oensive into Mosul, this time against

these al-Qaeda linked groups. This “surge” of two thousand U.S. troops and twenty thousand

Iraqi soldiers,

b

succeeded in temporarily bringing calm.

c

But the U.S. military departed Iraq in

2011, leaving behind largely the same conditions that had sparked the first insurgency. The

Sunni population remained disenfranchised as Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a Shia, violently

crushed peaceful protests and stopped paying the salaries of Sunni tribal militias that had

helped push back al-Qaeda.

d

When, in June 2014, eight hundred ISIS insurgents marched on Mosul, the thirty thousand

soldiers of the U.S.-trained Iraqi army turned and ran. Worse, some of the city’s inhabitants

were willing to consider that their lives might be better under the extremists than under the

Iraqi government.

e

Mosul became the political and economic center of the caliphate of the

Islamic State of Iraq and Syria for nearly three years. American forces returned, for a third

time, to assist Iraqi troops in dislodging the extremists.

Already conditions are ripe for extremists to return to Mosul. One year after its liberation

from ISIS, much of the city still remained in ruins

f

and 80 percent of the youth population

was unemployed.

g

As it has been since the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, a Shia-dominated

government in Baghdad remains in charge of the country and is conducting a disturbing

campaign of revenge against the region’s Sunni population.

h

Bytheend of 2018, ISIS militants

in Mosul had staged a comeback, detonating a series of car bombs.

i

Notes

a

Rupert Jones, “Major General: Battle for Mosul is ‘Toughest since WWII’,” BBC News, June 26, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/

av/world-40409046/major-general-battle-for-mosul-is-toughest-since-wwii.

b

Drew Brown, “U.S. Troops Setting Down Roots in Mosul,” Stars and Stripes, February 23, 2008, https://www.stripes.com/news/

u-s-troops-setting-down-roots-in-mosul-1.75370.

c

Sam Dagher, “Fractures in Iraq City as Kurds and Baghdad Vie,” New York Times, October 27, 2008, https://www.nytimes.

com/2008/10/28/world/middleeast/28mosul.html?mtrref=www.google.com.

d

Anna Louise Strachan, “Factors behind the Fall of Mosul to ISIL (Daesh) in 2014,” K4D, January 17, 2017, https://assets.publishing.

service.gov.uk/media/59808750e5274a170700002c/K4D_HDR_Factors_behind_the_fall_of_Mosul_in_2014.pdf.

e

Martin Chulov, Fazel Hawramy, and Spencer Ackerman, “Iraq Army Capitulates to ISIS Militants in Four Cities,” Guardian, June

11, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/11/mosul-isis-gunmen-middle-east-states.

f

Mahmoud Al-Najjar, Gilgamech Nabell and Jacob Wirtschafter, “Smell of Death Fills Mosul Near a Year after Iraqi City Freed

from ISIS,” USAToday, May 2, 2018, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/05/02/mosul-iraq-smell-death-isis-

islamic-state/543030002/.

g

“Mosul Still a Pile of Rubble One Year On,” Norwegian Refugee Council, July 5, 2018, https://www.nrc.no/news/2018/july/mosul-

still-a-pile-of-rubble-one-year-on/.

h

Ben Taub, “Iraq’s Post-ISIS Campaign of Revenge,” New Yorker, December 24, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/

magazine/2018/12/24/iraqs-post-isis-campaign-of-revenge.

i

Salih Elias, John Davison and Kirsten Donovan, “Car Bomb Kills Several People in Iraq’s Mosul—Medical, Security Sources,”

Reuters, November 8, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/08/reuters-america-car-bomb-kills-several-people-in-iraqs-mosul--

medical-security-sources.html.

7 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

As a result, extremist groups continue to grow in number, size, lethality, and geographic

reach. Since 9/11, the number of people killed annually in terrorist attacks has increased

fivefold.

3

ISIS, al-Qaeda, and aliated groups boast more than thirty thousand foreign

fighters from more than one hundred countries, four times the number they had in 2001

(seefigure 3, “Estimated Number of Salafi-jihadist Fighters, 1980-2018”).

4

There are more

than twice as many Salafi-jihadist groups asthere were in 2001.

5

Across the Sahel, the Horn

ofAfrica, and the Near East, they have established apresence in nineteen countries and are

actively seeking to expand.

6

A new approach is needed. The current approach is unsustainable and ineective. But

withdrawal from the fight against extremism is not an option. At a time of global political

struggle between freedom and its adversaries, the United States faces real threats, not just

of terrorism against the homeland, but from the conflict, chaos, and coercive governance that

extremists spread in fragile states.

It is to address this challenge of extremism that Congress has

charged the United States Institute of Peace and this Task

Force. Section 7080 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act

of2017 (Public Law 115-31), signed into law on May 5, 2017,

calls for a “comprehensive plan to prevent the underlying

causes of extremism in fragile states in the Sahel, Horn of

Africa and the Near East.”

The Task Force finds that the United States should turn

to a third option by seeking toact early to prevent the

dangers of extremism. A new focus on strategic prevention,

recommended by this Task Force, would shift the paradigm

from reaction to prevention, fromjust stopping terrorist

attacks to also addressing the conditions that have led to the

growth of extremism, from focusing only on immediate threats

to building long-term partnerships.

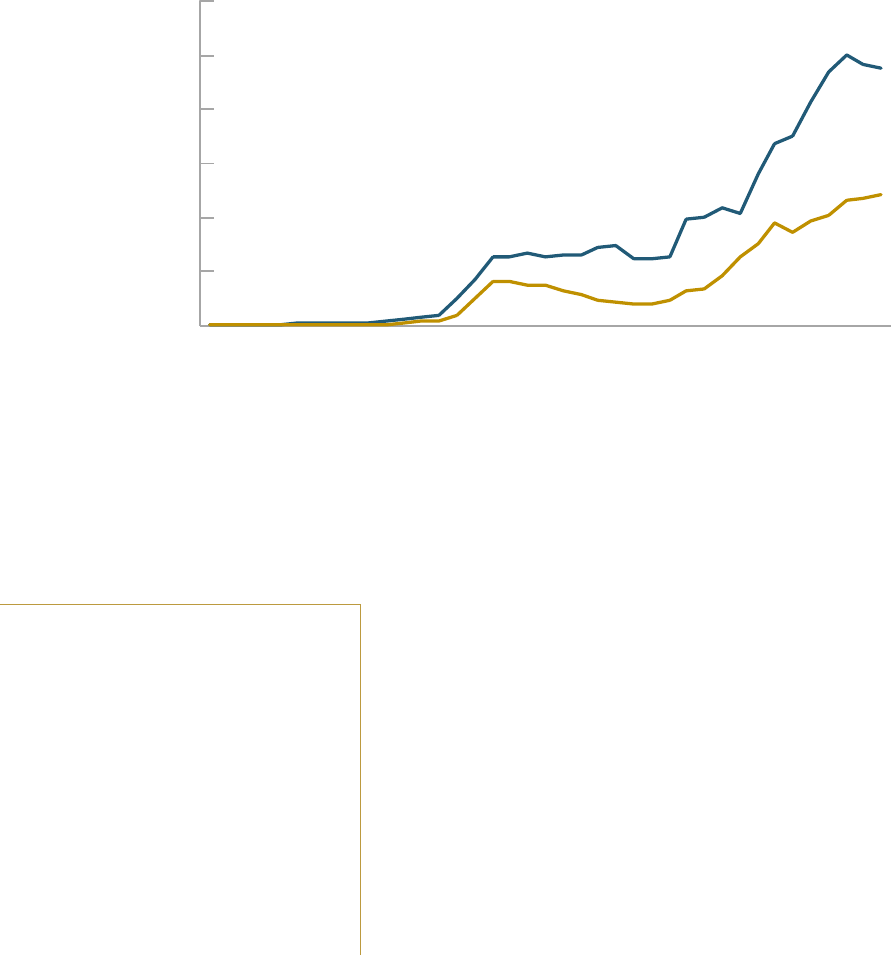

Figure 3. Estimated Number of Salafi-jihadist Fighters, 1980–2018

Source: Seth Jones et al., The Evolution of the Salafi-jihadist Threat (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International

Studies, 2018), 9, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/181221_EvolvingTerroristThreat.pdf.

Estimated Number of Jihadi-Salast Fighters, 1980–2018

Source: Seth Jones et al., The Evolution of the Sala-Jihadist Threat (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2018), p. 9,

https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/181221_EvolvingTerroristThreat.pdf.

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

LOW ESTIMATE

HIGH ESTIMATE

A new focus on strategic

prevention, recommended by

this Task Force, would shift

the paradigm from reaction

to prevention, from just

stopping terrorist attacks to

also addressingthe conditions

that have led to the growth of

extremism, from focusing only on

immediate threats to building

long-term partnerships.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 8

The Unsustainable Costs of the Cycle of Crisis Response

In the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, U.S. policymakers rightfully focused on

making sure that terrorists would never again strike America. In this respect, the strategy of

dismantling terrorist networks has been eective: there has been no mass-casualty terrorist

attack against the United States since 2001. If this were still the sole metric for success, the

current approach might suce.

But extremism persists, despite U.S. oensives, because it

adapts. Since 9/11, groups such as al-Qaeda and ISIS have

recognized that overseas wars of attrition are more likely

than attacks against the American homeland to precipitate

U.S. withdrawal from Muslim lands; that the existing political

order in many Muslim-majority states is already weak; and

that, therefore, inflaming already volatile societies, latching

onto existing conflicts, and instigating new ones is the best

strategy against an adversary such as the United States.

Yet, even when extremists threaten to seize territory, the U.S. response tends to be reactive,

and focused only on short-term objectives directly related to the immediate threat of violence.

Nearly all U.S. policy tools, both hard and soft, aim to dismantle terrorist networks, thwart

attacks, or stop individual radicalization. U.S. air strikes and special operations are used to

evict jihadist groups from the territory they seize; security partners in fragile states, supported

by U.S. military assistance, do much of the fighting. And even nonmilitary programs that aim to

“counter violent extremism” (CVE) focus primarily on “eorts by violent extremists to radicalize,

recruit, and mobilize followers to violence”—eorts that are typically the immediate precursor

of terrorist attacks.

7

These responses, even when successful, do little to prevent,

and at times even lay the groundwork for, further extremist

eruptions. The U.S. military interventions in Iraq and Libya,

for example, contributed to political vacuums that extremists

were able to fill. Substantial U.S. security cooperation

with regimes in Mali and Yemen may have inadvertently

contributed to systematic neglect and exclusion that

extremists exploited to gain support for their cause.

Toooften, U.S.-supplied weapons are diverted to, or U.S.-

trained fighters defect to, extremists.

With every major jihadist insurgency whose causes remain unaddressed, extremists seize

opportunities to move into neighboring countries. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, which has

established an ongoing presence in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Tunisia, was born from the

bitter fruits of a civil war that began in Algeria in 1991. After a decade of intermittent insurgency

in Iraq, extremists inserted themselves into the Syrian Civil War, leading to the rise of ISIS in

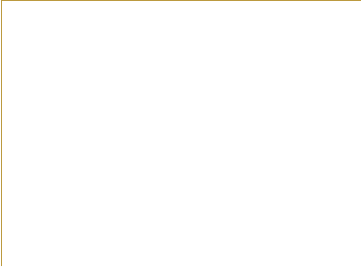

both countries (see figure 4, “Spillover from Major Jihadist Insurgencies, 2000–2017”).

Even when extremists threaten to

seize territory, the U.S. response

tends to be reactive, and focused

only on short-term objectives

directly related to the immediate

threat of violence.

These responses, even

when successful, do little

to prevent, and at times

even lay the groundwork for,

furtherextremist eruptions.

9 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

The United States thus finds itself trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of crisis response.

Since 2001, the fight against terrorism is estimated to have cost the United States between

$2.8 and $5.9 trillion dollars and sixty thousand killed or injured,

8

with no end in sight.

Inthewords of former National Security Advisor and Task Force member Stephen Hadley:

“When you have a series of crises and all you end up doing is crisis management, all you’re

going toget is more crises.”

9

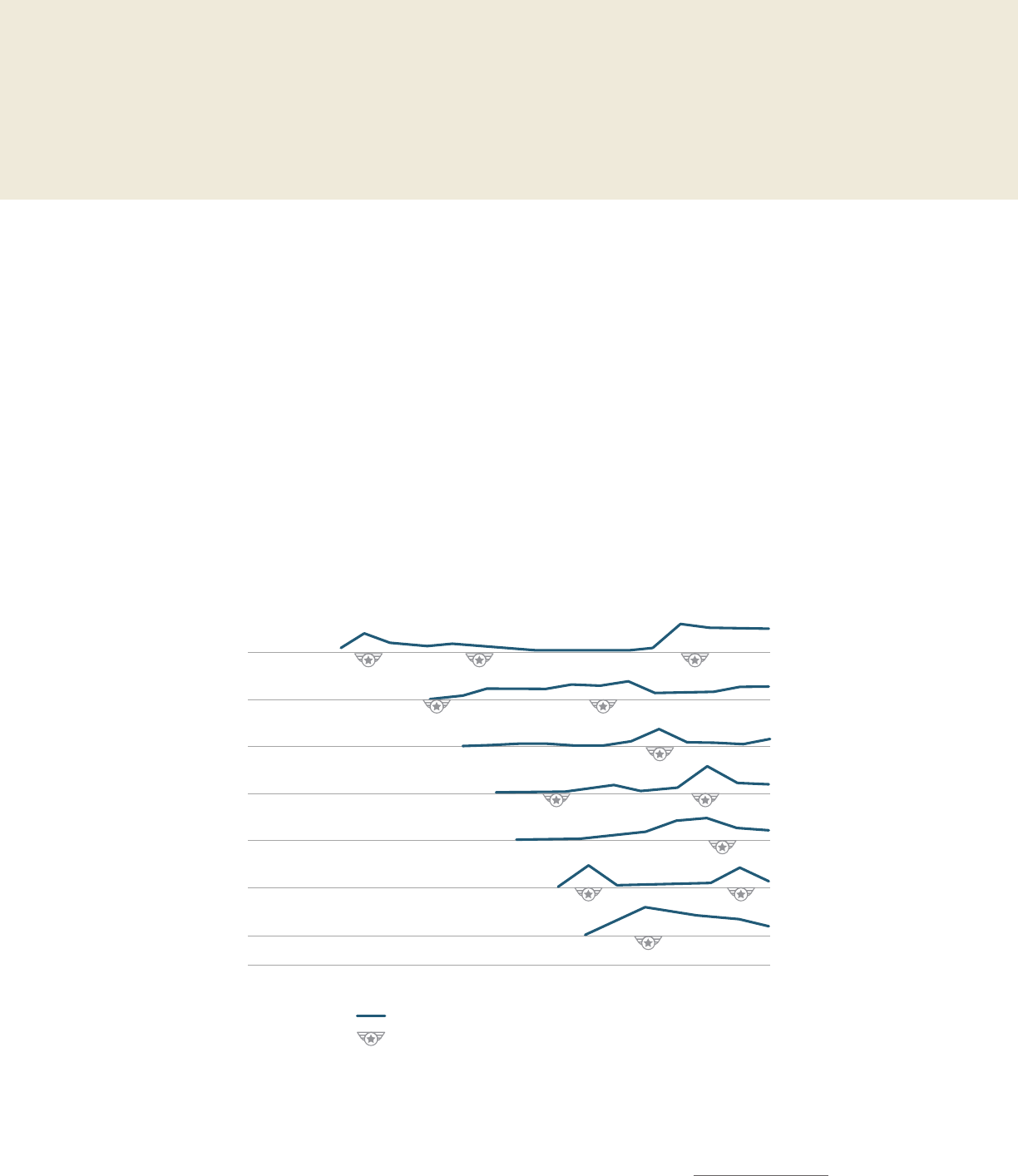

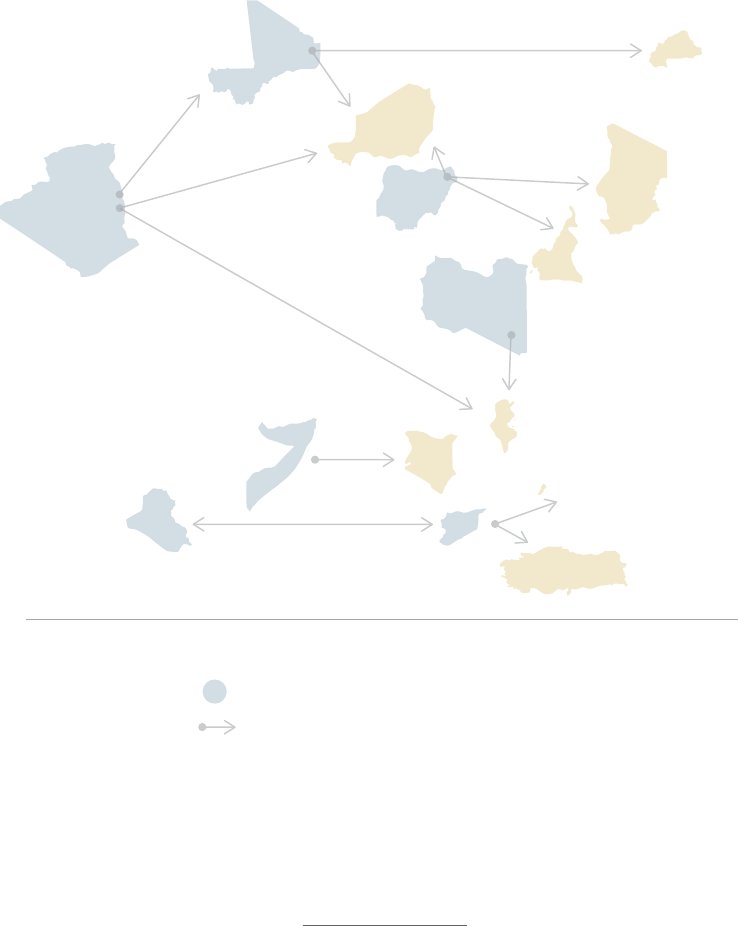

Figure 4. Spillover from MajorJihadist Insurgencies, 2000–2017

The above chart depicts instances where jihadists have used their presence in countries with major insurgencies to “spill

over,” establish themselves, and launch terrorist attacks in neighboring countries for a period of at least two years continuing

through the end of 2017. Countries are placed along the chart according to the year of the first terrorist attack or the start date

of the major insurgency with the exception of Algeria, whose insurgency against Islamist militant groups started in the 1990s.

Source used for establishing the start date and whether or not terrorist campaign was ongoing: Global Terrorism Database at

the website of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

(accessed January 10, 2019). Start date of major insurgencies derived from figure 2, which used the following source to chart

the course of major jihadist insurgencies: UCDP / PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset: http://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/#d8, Therése

Patterson and Kristen Eck, “Organized Violence,” Journal of Peace Research 55, no.4 (2018), (accessed January 10, 2019).

Ongoing Extremist Presence in Neighboring Countries Sparked

by Spillover from Major Jihadist Insurgencies, 2000–2017

IRAQ

ALGERIA

MALI

NIGERIA

LIBYA

SOMALIA

SYRIA

BURKINA FASO

LEBANON

TURKEY

KENYA

CHAD

CAMEROON

NIGER

TUNISIA

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

SPILLOVER INTO NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES

MAJOR JIHADIST INSURGENCIES

The above chart depicts instances where jihadists have used their presence in countries with major insurgencies to “spill over,” establish themselves and launch

terrorist attacks in neighboring countries, for a period of at least two years continuing through the end of 2017. Countries are placed along the chart according to the

year of the rst terrorist attack or the start date of the major insurgency with the exception of Algeria, whose insurgency against Islamist militant groups started in

the 1990s. Source used for establishing the start date and whether or not terrorist campaign was ongoing: Global Terrorism Database at the website of the National

Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/ (accessed January 10, 2019). Start date of major insurgencies

derived from Figure 2, which used the following source to chart the course of major jihadist insurgencies: UCDP / PRIO Armed Conict Dataset: http://uc-

dp.uu.se/downloads/#d8, Pettersson, Therése and Kristine Eck (2018) Organized violence, 1989-2017 (accessed January 10, 2019). Journal of Peace Research 55(4).

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 10

Yet, the United States can ill aord to be consumed by terrorist crises. The strategic

environment has grown more challenging and complicated in recent years. The United States

confronts, according to the 2017 National Security Strategy, “rivals [that] compete across

political, economic, and military arenas . . . to shift regional balances of power in their favor.

These are fundamentally political contests between those who favor repressive systems and

those who favor free societies.”

10

Yet, the continuous cycle of counterterrorist crisis response is

likely to impede any attempt to pivot U.S. foreign policy to address these new strategic realities.

Counterterrorism taxes the national security enterprise, consuming blood, treasure, political

will, and bureaucratic bandwidth, diminishing policymakers’ ability to focus on more important

priorities. “There is no doubt in my mind that the resource shift and focus on terrorism,”

former Acting Director of Central Intelligence Michael Morrell has warned, “were in part

responsible for our failure to more clearly foresee some key global developments such as

Russia’s renewed aggressive behavior with its neighbors.”

11

To compete eectively on the

global stage, the United States must get ahead of the extremist threat.

Beyond the Homeland: The Evolving Threat of Extremism

inFragile States

Although the current approach is costly, failure to address

the spread of extremism into fragile states would be

extremely dangerous. “Prominent terrorist organizations,

particularly ISIS and al-Qa’ida,” observes the 2018

National Strategy for Counterterrorism, “have repeatedly

demonstrated the intent and capability to attack the

homeland and United States interests and continue to plot

new attacks and inspire susceptible people to commit acts

of violence inside the United States.”

12

Such attacks, however, are not the only major extremist

threat confronting the United States. According to the U.S.

Department of Defense’s 2018 National Defense Strategy, “We

are facing increased global disorder, characterized by decline

in the long-standing rules-based international order—creating

a security environment more complex and volatile than any

we have experienced in recent memory.”

13

Terrorism—like the

unprecedented rise in nonstate armed groups over the past

two decades—is a symptom of this disorder.

One of the pathologies driving this assault on the rules, institutions, and values critical to

U.S. national security is extremism, specifically militant groups professing false Sunni and

Shia Islamist teachings. They seek to displace the existing, rules-based international order

and the states within it with a transnational, absolutist and totalitarian entity ruled by a rigid,

twisted, and distorted interpretation of sharia law. The extremists’ pursuit of this goal, and

the response it provokes from governments, often generates destructive cycles of violence.

Thesuccess of extremists’ experiments in governance in parts of Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya,

Mali, Nigeria, Afghanistan, pose a grave, long-term threat to U.S. interests (see figures 5

and6, “Extremist Attacks and Extremist Governance in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa,

and the Sahel”).

Yet, the United States can ill

aord to be consumed by terrorist

crises. The strategic environment

has grown more challenging and

complicated in recent years. The

United States confronts, according

to the 2017 National Security

Strategy, “rivals [that] compete

across political, economic, and

military arenas . . . to shift regional

balances of power in their favor.

These are fundamentally political

contests between those who favor

repressive systems and those who

favor free societies.”

11 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

The most conducive environments for extremist attempts at statebuilding, and therefore for

demonstrating the validity of the extremist ideological agenda, are fragile states. According

to the National Strategy for Counterterrorism, “These groups stoke and exploit weak

governance, conflict, instability, and longstanding political and religious grievances to pursue

their goal.”

14

It is no coincidence that 99 percent of all deaths from terrorist attacks over the

Figure 5. Extremist Attacks and Extremist Governance in the Middle East,

the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel, 1996–2001

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, Beyond the Homeland: Protecting America from Extremism in Fragile

States (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, September 2018), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Taskforce-

Extremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf.

Extremist Attacks and Extremist Governance in the Middle

East, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel, 1996–2001

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States (2018). Beyond the Homeland: Protecting American From Extremism in

Fragile States. Interim Report of the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, p. 18. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/sites/

default/les/Taskforce-Extremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf.

Governance

Attacks

Figure 6. Extremist Attacks and Extremist Governance in the Middle East,

the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel, 2013–18

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, Beyond the Homeland: Protecting America from Extremism in Fragile

States (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, September 2018), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Taskforce-

Extremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf.

Extremist Attacks and Governance in the Middle

East, Horn of Africa, and Sahel, 2013–18

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States (2018). Beyond the Homeland: Protecting American From Extremism in

Fragile States. Interim Report of the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, p. 18. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/sites/

default/les/Taskforce-Extremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf

Governance

Attacks

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 12

past seventeen years have occurred in countries that are in conflict.

15

Nor is it surprising

that, today, 77 percent of conflicts in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel have

aviolent extremist element, compared with 22 percent in 2001.

16

These same fragile states and conflicts are also the front lines of regional and global

competitions for power, influence, and resources. Russia, China, and Iran have preyed on the

weakness of fragile states to extend their spheres of influence. Fragile states in the Horn of

Africa and the Sahel are also increasingly arenas for regional rivalries, particularly between

Iranian-backed Shia and the Middle East’s looser Sunni bloc, but also the growing intra-Sunni

contest between Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, on the one side, and Turkey and

Qatar, on the other.

These twin dynamics of the extremist political project and

authoritarian influence set upself-sustaining conflicts,

making fragile states a vital battleground in the fight

against the adversaries of freedom. The more support that

extremists garner for their critique ofthe state, the more

inclined the state is to repress them harshly, which in turn

alienates citizens, who look to radical alternatives. Societies

trapped between fragility, predation, andextremism—with

no viable alternatives for just, inclusive, and competent

governance—will remain unstable, impoverished, and

susceptible to conflict and foreign interference.

Once a country is caught in this trap, there are few good options for the United States:

stay out of the fray and appear powerless; side with the rulers and compromise America’s

democratic principles while inviting potential extremist growth; or intervene to oust the

extremists and be held responsible if stability does not quickly return. The United States has

tried all three options and found that each one can be ineective and erode its standing in

the region and the wider world.

As long as extremism persists and extremist beliefs persuade and inspire more people than

does the hope for tolerant and inclusive governance, the United States will see its ability to

shape the prospects for peace and prosperity in the twenty-first century diminished.

Changing the Paradigm: The Case for Prevention

The United States needs to adopt a dierent approach. To break out of the costly cycle of

crisis response and push back against the growing threat of extremist political orders, U.S.

policymakers need to better balance eorts to respond to terrorist threats with eorts to

prevent these threats from arising in the first place. This means proactively and preemptively

identifying countries and regions that are vulnerable to future extremist penetration in fragile

states. It requires adopting a paradigm of prevention.

This Task Force finds that prevention should be understood as a pro-active and inherently

political endeavor that requires aligning U.S. government and international eorts—

diplomatic engagement, foreign assistance, and defense—to support local and national

leaders in seeking to strengthen state legitimacy.

17

Societies trapped between

fragility, predation, and

extremism—with no viable

alternatives for just, inclusive,

and competent governance—will

remain unstable, impoverished,

and susceptible to conflict

andforeign interference.

13 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

A preventive strategy should be a complement to, not a replacement, for counterterrorism.

But prevention is superior to a counterterrorism-only approach. While the 2018 National

Strategy for Counterterrorism aims to eliminate threats to the United States by pursuing

terrorists to their source,

18

a complementary preventive strategy should seek to avert the

emergence of extremism. Thus, prevention could, over time, supplant counterterrorism as

theprimary policy focus in fragile states.

A preventive approach is also superior to a policy of retrenchment. Strengthening the ability

of fragile states to withstand political assaults—whether from extremists or from authoritarian

state adversaries and insurgents—builds strategic depth for the United States. Prevention

must become an integral part of a broader strategy of political competition against the

adversaries of freedom.

The goal of a preventive approach cannot and should not be to avert individual terrorist

attacks; to eradicate every extremist group in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Near

East; or to prevent all violent conflict. Nor should it necessarily be to establish Western-

style democracies across the region. Instead, in targeted countries where conditions are

conducive and engagement can happen suciently early, preventive eorts should seek

to reduce the likelihood that extremists will turn local conflicts into transnational jihads,

hold territory, or establish governance. The success of such preventive eorts should

be determined by whether national and local leaders are becoming more widely trusted

within a given community or society.

Savings from Prevention

The costs of violent conflict, military expenditure, counterterror operations, and law

enforcement are extremely high. In 2017, the global economic impact of conflict was $14 trillion,

two-thirds of which was spent on internal security, incarceration, and military operations. The

costs of violent conflict were over $800 billion, $161 billion of which was from the economic

impact of terrorism.

a

Even though the cost of fighting the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has

declined, total counterterrorism spending by the United States amounted to $175 billion in 2017,

an elevenfold increase over 2001.

b

By contrast, activities aimed at preventing violence have been shown to save money compared

with the costs of responding to conflict.

c

The most pessimistic estimates place the cost-

eectiveness ratio of investments geared toward prevention at two dollars saved for every dollar

invested.

d

Two of the most recent estimates, conducted by the United Nations and the World

Bank (2017) and the Institute for Economics and Peace (2018), put the ratio at sixteen to one.

e

Notes

a

Conflict deaths, refugees and IDPs, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, and “terrorism” are included in the costs of violent conflict;

see Institute of Economics and Peace (IEP), The Economic Value of Peace, 2018: Measuring the Global Economic Impact of

Violence and Conflict (Sydney: IEP, October 2018), 9, http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Economic-

Value-of-Peace-2018.pdf.

b

Stimson Center, Counterterrorism Spending: Protecting America while Promoting Eciencies and Accountability (Washington,

DC: Stimson Center, May 2018), 5. https://www.stimson.org/content/counterterrorism-spending-protecting-america-while-

promoting-eciencies-and-accountability.

c

United Nations and World Bank, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict (Washington, DC:

World Bank, 2017), 4–5, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28337.

d

M. Chalmers, “Spending to Save? The Cost-Eectiveness of Conflict Prevention,” Defence and Peace Economics 18, no. 1

(2007): 2.

e

United Nations and World Bank, Pathways for Peace, 4; IEP, Global Peace Index, 2017, (Sydney: IEP; June 2017), 4.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 14

Yet a preventive approach need not be costly or ambitious; to the contrary, in the longer

term it will result in considerable cost savings. According to a recent analysis by the World

Bank and the United Nations, every dollar invested in eorts to prevent conflict saves sixteen

dollars in spending on reconstruction, crisis management, and the military.

19

This strategy should be undertaken humbly and with

realistic expectations. There are no simple prescriptions

foraddressing the challenge of extremism. Prevention is a

step-by-step process that happens within societies, one that

plays out on a generational timeline. The United States cannot

hope to fix the underlying drivers everywhere. Nor can it hope

to solve other countries’ problems from the outside, or by

acting alone. But with a new policy paradigm—supplementing

a short-term, reactive focus on terrorism with a longer-term

commitment to preventing extremism, aligning all its policy

tools behind a shared strategy, and leveraging its unique

convening power to encourage its international partners to do

their part—the United States will be able to make a dierence.

A Dicult Road: Getting to Prevention

The need for policies that do more than react to terrorist

threats and instead address the root causes of the problem

is hardly new. In 2004, the 9/11 Commission foresaw the

possibility for extremism to spread, mutate, and reemerge.

Thus, the Commission recommended a comprehensive

strategy that would not only “attack terrorists and their

organizations” and “protect against and prepare for terrorist

attacks,” but just as critically “prevent the continued growth

of Islamist terrorism.”

20

Since then, the U.S. government and the international

community have designed and implemented policies to

prevent extremism. Progress has undoubtedly been made.

21

Yet, serious challenges persist. More often than not, the

United States and its partners lose focus on prevention;

fail to work with and through communities; fail to integrate

development, diplomacy, and defense interventions; or fail

to follow up on hard-won gains.

But with a new policy paradigm—

supplementing a short-term,

reactive focus on terrorism with

a longer-term commitment to

preventing extremism, aligning all

its policy tools behind a shared

strategy, and leveraging its unique

convening power to encourage its

international partners to do their

part—the United States will be

ableto make a dierence.

There are no simple prescriptions

for addressing the challenge

of extremism. Prevention is

a step-by-step process that

happens within societies, one

that plays out on a generational

timeline. The United States

cannot hope to fix the underlying

driverseverywhere.

15 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

This Task Force’s analysis suggests that three key hurdles have hampered previous eorts

and need to be overcome to render eective eorts to prevent the underlying conditions

of extremism in fragile states: (1) the lack of a shared understanding of the conditions of

extremism, which has inhibited the development of a cohesive policy framework to guide

the activities of agencies in fragile states; (2) in contrast to measures taken to confront

terrorists, eorts to prevent extremism have not been a consistent, sustained priority

for policymakers, and; (3) U.S. diplomatic, development, and defense tools are not well

integrated with one another, nor are they coordinated with those of international partners.

Each of these hurdles merits elaboration.

First, policymakers for the most part still lack a shared understanding of the underlying

conditions that make fragile states vulnerable to extremism and strategies for addressing

those conditions. As the independent, nonpartisan Fragility Study Group convened by the

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Center for New American Security, and the

United States Institute of Peace concluded in 2016, “across the U.S. government there is no

clear or shared view of why, how, and when to engage fragile states.”

22

This problem is only

magnified at the international level and exacerbated by politically-motivated debates about

the origins and nature of terrorism.

The Persistence of Extremism amid Failure to Consolidate

Gains:Somalia

Iraq is not the only country where extremists have regrouped in the aftermath of U.S.-led

orsupported military operations, and where the international community has failed to follow up

on hard-won gains. In Somalia, between 2009 and 2011, the al-Qaeda linked group al-Shabaab

controlled most of the country, including significant portions of the capital of Mogadishu.

Al-Shabaab gained power following Ethiopia’s 2006 military invasion—aninvasion tacitly

supported by the United States—to rid Mogadishu of the Islamic Courts Union, anIslamist

group of warlords. Following the Courts’ removal, the group’s most radical members

reconstituted to become al-Shabaab and eventually seized most of the country. They were

pushed out ofMogadishu yetagain by U.S.-backed African Union peacekeepers between

2011 and 2013.

a

Yet al-Shabaab retains control of a substantial part of Somalia and has sought

apresence or mounted major attacks in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

b

Notes

a

“Somalia Profile–Timeline,” BBC News, January 4, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14094632; and “Al-Shabab in

Somalia,” Global Conflict Tracker, Council on Foreign Relations, (accessed January 15, 2019), https://www.cfr.org/interactives/

global-conflict-tracker#!/conflict/al-shabab-in-somalia. In fact, the roots of U.S. involvement in Somalia go back even further. The

regime of Siad Barre, a major patron of the United States during the Cold War, collapsed in 1991, leading to the collapse of the

Somali state and close to three decades of nearly continuous conflict. The Islamic Courts Union established itself in the early

2000s in the aftermath of a failed international eort to provide humanitarian aid, which included the 1993 “Black Hawk Down”

incident in which nineteen U.S. servicemembers killed and seventy-two wounded.

b

See International Crisis Group, Al-Shabaab Five Years After Westgate: Still a Menace in East Africa (Brussels: International

Crisis Group, 2018), https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/265-al-shabaab-five-years-after-westgate.pdf.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 16

Yet, over the past two decades, a series of studies has contributed to a growing evidence

base on the underlying causes of extremism and violence as well as the types of approaches

needed to mitigate their recurrence in fragile states.

23

These insights are known in some

parts of the U.S. government and increasingly across the international community. Within

the U.S. government, the Stabilization Assistance Review, a new shared policy framework

to guide stabilization activities, represents a step forward; it provides a shared definition of

stabilization and describes agencies’ respective roles. The Department of State and U.S.

Agency for International Development have also launched a Strategic Prevention Project

to respond to the need for a new approach to fragile states.

24

However, their application

has been largely confined to development agencies and remains uneven, at best. But

when preventing extremism, much more needs to be done to harness lessons learned from

disparate fields and integrate them into a coherent and shared policy framework.

Second, the long-term goal of addressing the underlying

conditions that enable extremism still fails to rise to the top

of the list of U.S. and international strategic priorities. In

general, policymakers too often fail to act on early warning

analysis and to take the long-term perspective that is

needed to address root causes. Short-term imperatives

takeprecedence; donors lose focus and often fail to

provide the sustained support and assistance that partners

in fragile states need.

Prevention tends not to be a high priority in our bilateral

relationships with fragile states. Tosucceed, however,

prevention needs to be the primary modality and objective of U.S. andinternational

engagement in priority countries. A new level of political commitment will be needed

toelevate prevention as a strategic priority.

Third, despite some progress toward more coordinated approaches, security, development,

humanitarian, and diplomatic stovepipes persist within the U.S. government and among

donors. This inhibits their ability to prevent extremism through comprehensive and integrated

activities that cut across governance, peacebuilding, health, and other development sectors.

Across departments and agencies, U.S. activities in fragile states need to be better prioritized,

more closely integrated, or even discontinued to ensure

they do not work at cross-purposes. In addition, a lack of

coordination among donor governments and international

agencies leads to fragmented approaches within the same

target country and missed opportunities to pool resources

and join forces. New incentives and institutional structures

are needed to create greater cohesion and drive concerted

action across diplomatic, security, and development systems,

both internationally and within the U.S. government.

Across departments and

agencies, U.S. activities in

fragile states need to be

better prioritized, more closely

integrated, or even discontinued

to ensure they do not work

atcross-purposes.

To succeed, however, prevention

needs to be the primary modality

and objective of U.S. and

international engagement in

priority countries. A new level

of political commitment will be

needed to elevate prevention

asastrategic priority.

17 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

Recommendations for a New Approach

To get ahead of the threat of extremism in fragile states, this Task Force recommends that the

United States adopt a shared framework for prevention as a key U.S. national security priority,

and launch two new initiatives to facilitate its implementation:

Recommendation 1:

Adopt a Shared Framework for Strategic Prevention

To date, the United States has lacked strategic guidance, shared across all

government agencies, for engaging preventively to address the underlying

conditions of extremism in fragile states. For prevention to become a key tenet

of U.S. foreign policy and to better align the activities of agencies working in

fragile states, the United States government must adopt a shared framework

forstrategic prevention to create a common understanding among all

agenciesof the conditions of extremism and how to mitigate themeectively.

Recommendation 2:

Establish a Strategic Prevention Initiative

Second, to operationalize this shared framework and ensure that agencies have

the resources, processes, and authorities they need, the Task Force recommends

that the U.S. government establish a Strategic Prevention Initiative that creates

and codifies the capabilities, procedures, authorities, and resources to improve

and integrate U.S. eorts to prevent extremism. The Initiative’s principal objective

should be to promote long-term coordination between agencies in fragile states.

Recommendation 3:

Launch a Partnership Development Fund

Third, the United States cannot carry the burden of addressing extremism alone.

Togalvanize international support for country-led eorts to promote prevention, the

Task Force recommends that the United States initiate diplomatic eorts to launch

a Partnership Development Fund, a new mechanism that can coordinate donor

activities and pool donor funds in support of a shared approach to prevention.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 18

III. A Shared Framework for

StrategicPrevention

Informed by a review of research, existing programs and policies, and established best

practices, this Task Force recommends that the United States adopt a new, shared

framework for strategic prevention. Informed by lessons learned about what works, the

purpose of this framework should be to create acommon, government-wide understanding

of: (1) the underlying conditions for extremism; (2) how to address those underlying

conditions; (3) criteria for where and when the United States should engage preventively;

and(4) eective approaches for engaging fragile states preventively.

The Conditions for Extremism: Political and Contextual

First, the framework for strategic prevention should reflect the emerging consensus that

the conditions that enable extremism to spread across fragile states in the Sahel, the Horn

of Africa, and the Near East are both political and context-specific in nature.

25

The local conditions that fuel extremism vary widely by place and over time. At the same

time, despite the variance across contexts, a core pattern is evident across communities

where extremism has taken hold: a community tends to become vulnerable to extremism

when the compact between society and the state has broken down. When citizens blame

thegovernment for their plight and when the bonds across diverse population groups have

frayed, violent extremist groups can gain a foothold by exploiting political and economic

grievances, advancing a radical ideology, provoking violence, establishing a presence,

andoering a viable alternative to the state.

26

Fragile states are vulnerable to extremism precisely because a defining feature of fragility is a

breakdown in the relationship between the state and society. Communities already alienated by

an oppressive, corrupt, or unresponsive government are fertile ground for extremists’ attempts

to create alternative political orders. Boko Haram, for example, played on Nigeria’s extrajudicial

killings of civilians in 2011 to fan outrage into popular support for their cause: “Nobody is

persecuting us like this government. . . nobody is persecuting our religion and our Prophet like it.

They use their soldiers, their police, their system of unbelief. . . We are being persecuted. . .”

27

Extremism

As used by this Task Force, “extremism” refers to a wide range of absolutist and totalitarian

ideologies. “Extremists” believe in and advocate for replacing existing political institutions with

a new political order governed by a doctrine that denies individual liberty and equal rights to

citizens of dierent religious, ethnic, cultural, or economic backgrounds. “Violent extremists”

espouse, encourage, and perpetrate violence as they seek to create their extremist political

order. Extremism is not unique to any one culture, religion, or geographic region.

19 | Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States

The conditions that foster extremism in fragile states can be both internal and externally-

driven as well. Seeking influence or access to resources, global and regional powers

sometimes intentionally exploit them. At other times, external actors—including donors

themselves—unwittingly exacerbate the conditions that foster extremism. Civil wars sometimes

spill over borders, aecting neighboring countries and fueling extremism. Challenging as it

may be, a comprehensive preventive strategy must therefore assess, address, and, where

possible, mitigate the role of external actors in exacerbating these conditions (see figure 7,

“TheConditions for Extremism”).

Fragility

According to the Fragility Study Group, fragility can be defined as “the absence or breakdown

of a social contract between people and their government.” Fragile states suer from

deficits of institutional capacity and political legitimacy that increase the risk of instability and

violent conflict and sap the state of its resilience to disruptive shocks.

a

Fragility also enables

transnational crime, fuels humanitarian crises, and impedes trade and development.

Note

a

William J. Burns, Michele A. Flournoy, and Nancy E. Lindborg, “U.S. Leadership and the Challenge of State Fragility”

(Washington, DC: Fragility Study Group, September 2016), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/US-Leadership-and-the-

Challenge-of-State-Fragility.pdf.

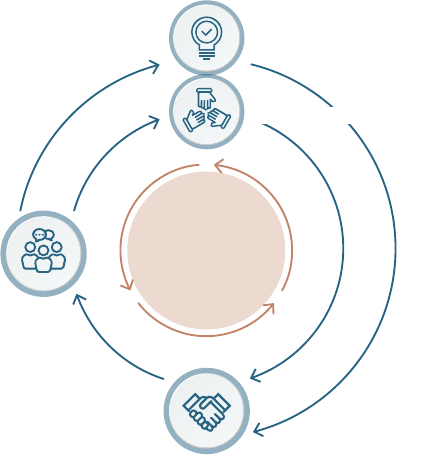

Figure 7. The Conditions for Extremism

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, Beyond the Homeland: Protecting America from Extremism in Fragile

States (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, September 2018), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Taskforce-

Extremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf.

The Conditions for Extremism

Source: Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States (2018). Beyond the Homeland: Protecting American From Extremism in Fragile States.

Interim Report of the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, p. 18. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/sites/default/les/Taskforce-Ex-

tremism-Fragile-States-Interim-Report.pdf.

SENSE OF

INJUSTICE

EXTREMISTS

FRAGILE

REGIMES

INTERNATIONAL

ACTORS

POLITICAL

EXCLUSION

ORGANIZATIONAL

PRESENCE

IDEOLOGICAL

SUPPORT

Cast secular

governments as

illegitimate, provoke

security forces abuse.

Threaten or intimidate

nonextremist activists.

Use mosques, schools,

and media to

proselytize extremism.

Smuggle operatives

and weapons into

territory.

Govern by patronage,

corruption, neglect,

and/or repression.

Close political space,

imprison nonextremist

activists.

Fail to provide schools,

leaving space for

extremists. Weaken

traditional religious

authority.

Preside over ineective

or abusive security

forces. Tolerate

extremists.

Give unconditional

security aid and

diplomatic cover

to abusive regimes.

Prioritize security

assistance over

political concerns and

conditions.

Propagate

fundamentalist religious

ideologies. Turn a blind

eye to citizens funding

extremism.

Pour arms into

territory. Back

unreliable proxies.

Preventing Extremism in Fragile States | 20

Addressing the Conditions for Extremism:

Country-Led andInclusive Programs

Second, the framework for strategic prevention should recognize that addressing the

political and contextual conditions for extremism will require adaptive programs that

empower leaders to strengthen state-society relations and better respond to their citizens’

needs. The success of such preventive eorts should be gauged by whether national and

local leaders are becoming more widely trusted within a given community or society.

Because the conditions that undermine the legitimacy of a state or spread mistrust in a

society are specific to individual contexts, a preventive strategy must be adapted to each

country in which it is applied, rather than oer general prescriptions for entire regions.

Rebuilding the social compact between a society and the state requires strengthening

inclusive, responsive, and accountable political and economic institutions at both the local

and the national levels

28

(see figure 8, “Building Resilience against Extremism”).

Accountability is important at the local level because, in the short term, it is the timely

demonstration of political will to listen and respond to citizens’ needs that gives societies

their best chance to withstand extremism. Over the longer term, such locally visible “quick

wins” need to translate into sustained results—unfulfilled promises could serve to exacerbate

grievances and alienation. More important, local accountability is not a viable long-term

substitute for national reforms. Local gains can quickly be undermined by a predatory central

government, whether through coopting local elites or by allowing security forces to commit

abuses (see appendix 5, “Prevention Program and Policy Priorities”).

29

Figure 8. Building Resilience against Extremism

Building Resilience Against Extremism

Inclusive governance

processes & community

consultations

Address and resolve grievances

Bolster social cohesion

Increase citizen

trust in the state

Exclusionary

governance &

injustice

undermining

resilience