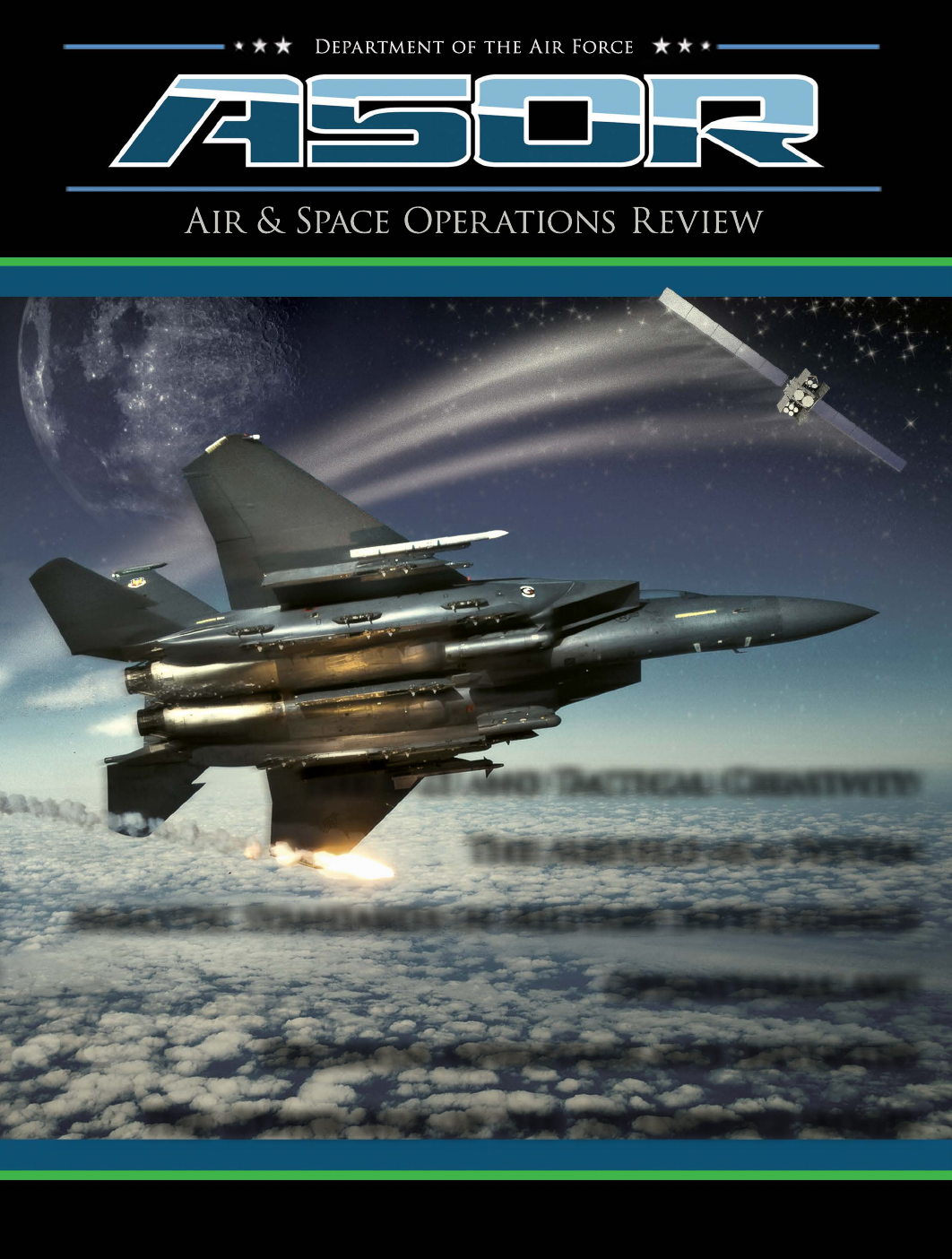

Air & Space Operations Review

Department of the Air Force

Vol. 3, No. 1 - S 2024

T B-21 T C

T A S

A S M I

O A

D A I

T O S D M

T B-21 T C

T A S

A S M I

O A

D A I

T O S D M

Chief of Staff, US Air Force

Gen David W. Allvin, USAF

Chief of Space Operations, US Space Force

Gen B. Chance Saltzman, USSF

Commander, Air Education and Training Command

Lt Gen Brian S. Robinson, USAF

Commander and President, Air University

Lt Gen Andrea D. Tullos

Chief Academic Officer, Air University

Dr. Mark J. Conversino

Director, Air University Press

Dr. Paul Hoffman

Journal Team

Editor in Chief

Dr. Laura M. urston Goodroe

Advisory Editorial Board

https://www.af.mil/ https://www.spaceforce.mil/ https://www.aetc.af.mil/ https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/

Mark J. Conversino, PhD

James W. Forsyth Jr., PhD

Kelly S. Grieco, PhD

John Andreas Olsen, PhD

Nicholas M. Sambaluk, PhD

Evelyn D. Watkins-Bean, PhD

John M. Curatola, PhD

Christina L.M. Goulter, PhD

Michael R. Kraig, PhD

David D. Palkki, PhD

Heather P. Venable, PhD

Wendy Whitman Cobb, PhD

Senior Editor

Dr. Lynn Chun Ink

Print Specialist

Cheryl Ferrell

Illustrator

Catherine Smith

Web Specialist

Gail White

Book Review Editor

Col Cory Hollon, USAF, PhD

Air & Space Operations Review

SPRING 2024 VOL. 3, NO. 1

3 From the Editor

AIR OPERATIONS

4 e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

Shane Praiswater

Paula G. Thornhill

19 e Airfield as a System

Mark D. Callan

35 Analytic Standards in the Context of Military Intelligence

Jack Duffield

PLANNING AND STRATEGY

50 Operational Art

A Necessary Framework for Modern Military Planning

Jonathan K. Corrado

60 Decision Advantage and Initiative

Completing Joint All-Domain Command and Control

Brian R. Price

77 e Other Side of the Deterrence Moon

Elevating “Deterrence from Space” in Strategic Competition

Timothy Georgetti

MULTIMEDIA REVIEWS

88 Masters of the Air, season 1, episodes 1 and 2

Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, Written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Dr. Stephen L. Renner, Colonel, USAF, Retired

90 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 3

Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Heather P. Venable, PhD

MULTIMEDIA REVIEWS, CONTINUED

93 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 4

Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Dr. John G. Terino, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF, Retired

96 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 5

Directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Dr. John G. Terino, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF, Retired

99 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 6

Directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Richard R. Muller, PhD

102 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 7

Directed by Dee Rees, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Richard R. Muller, PhD

105 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 8

Directed by Dee Rees, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Ziemann, USAF

108 Masters of the Air, season 1, episode 9

Directed by Tim Van Patten, written by John Orloff

Reviewed by Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Ziemann, USAF

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 3

FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader,

As conflict between Israel and Iran threatens to expand, and Russia continues its war

of attrition against Ukraine, air operations are persistently at the forefront of national

security discourse. Military planners and strategists are absorbing real- world lessons regard-

ing applications of and advances in contemporary air operations that have profound im-

plications for future battles and wars in which the United States will undoubtedly engage.

Our Spring 2024 issue of Air & Space Operations Review explores some key aspects of air

operations, planning, and strategy.

e first forum, Air Operations, opens with an analysis of the B-21 Raider. Retired

Brigadier General Paula ornhill, USAF, and Shane Praiswater argue that in the move

to pulsed operations, a rift has emerged between standoff and stand- in tactical philosophies

in the combat air forces. e Raider has the capabilities to bridge this divide and help

transcend long- standing parochial proclivities that have stalled the creative application of

airpower. In the second article in the forum, Mark Callan proposes that airfields are

centers of gravity in their own right. Accordingly, the Air Force needs to reorganize its

airfields into maneuverable rhizomatic teams, mitigating the shortfalls posed by the tra-

ditional root-tree organization of service airfields.

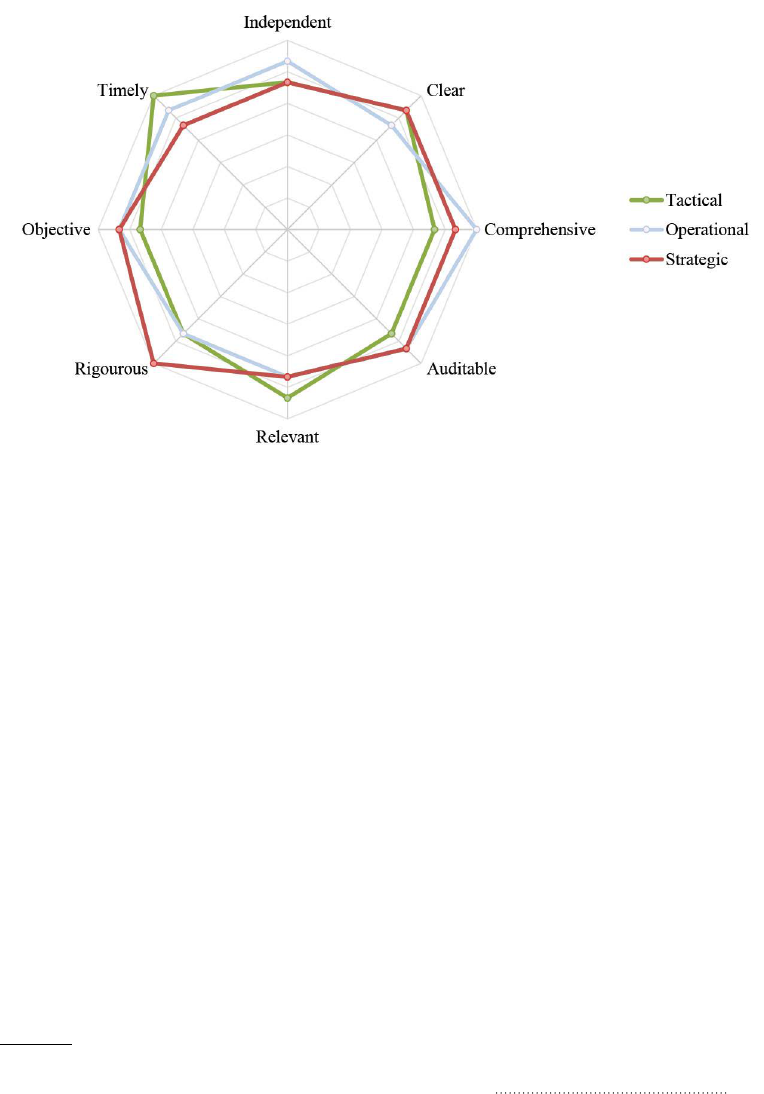

e forum concludes with an examination of analytic standards in military intelligence.

Jack Duffield finds that existing US and UK analytic standards’ focus on rigor, while ap-

propriate for the production of strategic intelligence, is less effective in producing timely,

relevant analysis at the tactical and operational levels of war. e US Air Force’s imple-

mentation of analytic standards provides an example of how to more effectively apply such

standards at these levels.

e second forum, Planning and Strategy, leads with a discussion about operational

art. John Corrado explores the history of operational art over the centuries and assesses

its importance in contemporary military planning and strategy, against state and nonstate

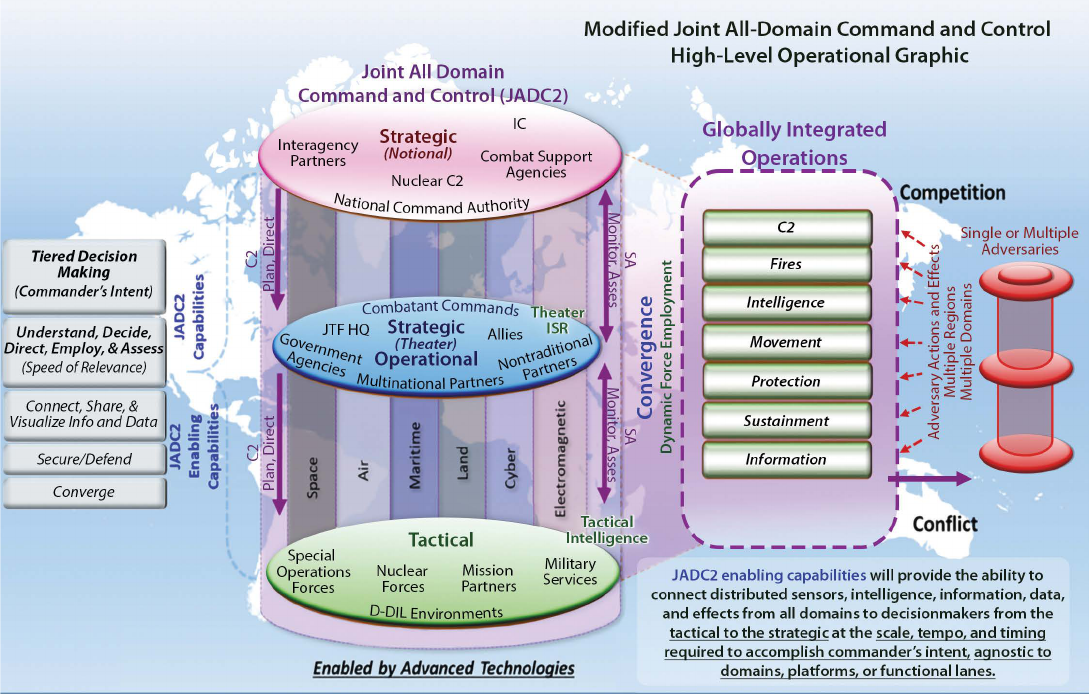

actors alike. In the second article in the forum, Brian Price defines decision advantage and

the concept of initiative against the backdrop of John Boyd’s observe, orient, decide, act

(OODA) loop, finding that decision advantage is necessary to operationalizing initiative.

In the final article of the forum and the issue, Tim Georgetti argues for the notion of

deterrence from space, reframing space capabilities—such as orbital- class rocket resupply

and space- based solar power—as both powerful deterrents and liabilities in need of defense.

As always, we welcome thoughtful, well- researched responses to our articles, with a po-

tential for publication in a future issue. ank you for your continued support of the journal.

~e Editor

4 AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW

AIR OPERATIONS

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

Shane PraiSwater

Paula G. thornhill

Combat air forces tacticians and operational planners have yet to understand the B-21 Raider’s

potential capability. Leadership’s vision is clear, but service- level parochial interests, insular

platform cultures, and competition for resources are creating unhealthy tensions within the

combat air forces, Department of the Air Force, and across the Joint force. Such tensions could

severely hamper tactical creativity, operational planning, and strategic competition, ultimately

undermining the US Air Force’s effectiveness against a peer adversary. Amid the move toward

pulsed operations, a rift has emerged between standoff and stand- in tactical philosophies. Yet

the B-21 Raider’s family of systems at a minimum operates in both areas, likely demanding a

reconsideration of these concepts. Such a reconsideration can also help the Air Force transcend

stealth/nonstealth and fighter/bomber debates to embrace new levels of tactical creativity.

S

ecretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall III established operational imperatives for

the US Air Force in recognition that adversaries have “capabilities designed to defeat

the United States’ ability to project power.”

1

ese imperatives state that diverse

capabilities are necessary, but translating Secretary Kendall’s vision to the tactical level

may prove difficult. Amid the combat air forces’ (CAF) move toward pulsed operations, a

rift has emerged between standoff and stand- in tactical philosophies.

2

Additionally, as the

B-21 Raider’s family of systems has capabilities in both areas, the service will soon need

to reconsider these concepts.

As a unique, sixth- generation platform, the B-21 can help the Air Force transcend the

stealth- versus- nonstealth and fighter- versus- bomber debates and embrace new levels of

tactical creativity. Cultural shifts are necessary for the CAF to accept the idea of a bomber

leading—and providing persistence—during pulsed operations. e B-21 and its family

of systems would not just be a lead striker; it would be a platform enabling pulsed opera-

tions or even utilizing pulsed strike packages as dynamic employment options.

Lieutenant Colonel Shane Praiswater, USAF, PhD, is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins University Strategic Thinkers Program

and is the director of operations, 31st Test and Evaluation Squadron, B-21 Initial Cadre, at Edwards AFB, California.

Dr. Paula Thornhill, Brigadier General, USAF, Retired, is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of

Advanced International Studies and an adjunct senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation. She is the author of De-

mystifying the American Military: Institutions, Evolutions, and Challenges since 1789 (Naval Institute Press, 2019).

1. Frank Kendall III, “Department of the Air Force Operational Imperatives,” infographic, US Air Force

(USAF), March 31, 2022, https://www.af.mil/.

2. “Air Force Future Operating Concept Executive Summary” (Washington, DC: USAF, March 6, 2023),

https://www.af.mil/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 5

is article is not about one aircraft being more important than another; rather, it argues

a shift in perspective is necessary due to the cultural problems surrounding aircraft spe-

cialization, which can lead to a narrowed focus regarding other platforms. Because of the

smaller bomber community, without a cultural shift that recalibrates CAF operations in

great power competition, the service might not employ the B-21 to a level sufficient to

achieve Secretary Kendall’s vision. Even worse, absent a proper and persistent demand

signal from the CAF, the B-21, like any burgeoning acquisition program, might be vulner-

able to budget cuts and risk becoming a redux of the reduced B-2 Spirit fleet.

3

Combat air forces tacticians and operational planners tend to reduce the operational

imperatives and the concept of pulsed operations to embrace standoff tactics while largely

ignoring stand- in advantages, thus leaving holes in operational plans. e B-21 Raider

family of systems addresses these challenges by unlocking the Joint force with stand- in

capabilities and addressing current Indo- Pacific region shortfalls. rough a reconsideration

of the standoff and stand- in concepts, the CAF can move past current debates and miscon-

ceptions to materialize unprecedented levels of tactical creativity and operational planning.

e authors draw from considerable experience in the Pentagon, with Congress, and

in all levels of war. e B-21’s initial cadre have returned to the combat air forces after

staff tours that revealed the propensity for budget advocacy to split along platform lines.

While Secretary Kendall’s initiatives are encouraging, and despite the fascinating and

potentially revolutionary aspects of the B-21, CAF planners and tacticians are not prepared

to think differently, given immediate challenges and parochial attitudes. is article thus

analyzes the key issues afflicting combat air forces—most notably, the ongoing lack of

tactical creativity and an adherence to rigid operational maneuver—and offers recom-

mendations to mitigate them.

Stando versus Stand- in Debate

Secretary Kendall’s operational imperatives emphasize that resilient and redundant op-

erations are necessary to compete with peer adversaries.

4

In light of aggressive statements

from China and the enduring risk of escalation in Ukraine, the US Air Force faces a sig-

nificant challenge in preparing to fight now while simultaneously planning for future op-

erations.

5

By focusing on the most immediate threats at the expense of future considerations,

combat air forces resist tactical creativity—the ability to consider novel solutions based on

emerging capabilities potentially dissimilar to established techniques and procedures.

3. Sebastien Roblin, “e U.S. Air Force’s Biggest Mistake: Only 20 B-2 Stealth Bombers in the Force,”

National Interest, February 23, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/.

4. Charles Pope, “Kendall Details ‘Seven Operational Imperatives’ & How ey Forge the Future Force,”

USAF, March 3, 2022, https://www.af.mil/.

5. Dave Lawler, “Xi Vows China and Taiwan Will ‘Surely Be Reunified’ in New Year’s Speech,” Axios,

January 1, 2024, https://www.axios.com/.

6 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

e most recent effort focused on near- term conflicts revolves around the concept of

pulsed operations. e Air Force Future Operating Concept argues winning “six critical

and concurrent fights” requires “ ‘pulsed airpower’,” or concentrating of airpower in time

and space to create windows of opportunity for the rest of the force.”

6

Pulsed operations

are a significant shift within CAF culture. Previously, establishing a relative level of endur-

ing air superiority was an assumed objective.

7

e shift is, of course, a sober reaction to

realities: US adversaries, having observed the Air Force’s dominance and ability to unlock

Joint force capabilities, have invested incredible resources into making air supremacy

impossible and even temporary air superiority as difficult as possible for the United States

and its Allies and partners near hostile territories.

8

Pulsed operations might be wise under certain constraints, but the fact remains that

embracing such a mindset de facto cedes control over a given area to the enemy for the

majority of a conflict. Pulsing is a concept driven primarily by geography, not threats.

Given more forgiving distances, the CAF might entertain more traditional methods to

continually contest airspace control: the lack of a persistence- capable platform denies

comprehensive takedowns of adversary defenses that require constant pressure to suppress.

Furthermore, an inclination to employ standoff tactics in the execution of pulsed operations

risks treating potential conflicts as anti- access/area denial (A2/AD) problems in which

more sustainable tactics are not possible.

Evidence from wargames and acquisitions suggests pulsed operations are evolving into

standoff- dependent tactics. Most recently, an unclassified wargame found standoff weap-

ons were “war- winning” weapons, although the United States won—at a great cost—only

a “Pyrrhic victory” in 2026.

9

e same wargame also found that China would continue to

evolve and target bombers employing standoff weapons, if not the weapons themselves.

10

Regarding acquisitions, weapons priorities in the president’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget,

approximately $15.1 billion worth, were all standoff munitions—Standard Missile (SM)-6,

Air Intercept Missile (AIM)-120D Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AM-

RAAM), Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), and Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff

Missile (JASSM)-ER.

11

Furthermore, to counter the decades- long effort to “install

6. Future Operating Concept.”

7. Elliot M. Bucki, “Flexible, Smart, and Lethal,” Air & Space Power Journal 30, no. 2 (Summer 2016).

8. Jeff Hagen et al., e Foundations of Operational Resilience—Assessing the Ability to Operate in an Anti- Access/

Area Denial (A2/AD) Environment: e Analytical Framework, Lexicon, and Characteristics of the Operational Resil-

ience Analysis Model (ORAM) (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, July 7, 2016), https://doi.org/.

9. David Axe, “3,600 American Cruise Missiles versus the Chinese Fleet: How One U.S. Munition Could

Decide Taiwan’s Fate,” Forbes, January 9, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/; and Mark F. Cancian and Eric Hegin-

botham, “e First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” CSIS: Center for

Strategic & International Studies, January 9, 2023, 4, https://www.csis.org/.

10. Cancian and Heginbotham, 140.

11. Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System: US Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Request

(Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense [Comptroller]/Chief Financial Officer, March

2023), iii, https://comptroller.defense.gov/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 7

thickets of surface- to- air missiles” posing a “wicked problem for U.S. forces,” the Pentagon

is ramping up standoff acquisitions.

12

e change in acquisition strategies reflects threats in which the “defense is inherently

the stronger form of air warfare, and new and emerging technologies and tactics are only

strengthening the defender’s advantage.”

13

Whether or not this argument is valid, the

combination of unclassified wargames and acquisitions reflects how planners and tacticians

prioritize standoff tactics during pulsed operations. ey are not necessarily proclaiming

a standoff dependency; they are just planning based on the understanding of the threat

and weapons provided during ongoing acquisition debates.

is planning methodology creates artificial tactical limits and critical dependencies.

As Israel and Russia are learning today, standoff weapons cannot achieve full military

objectives, which then limits national leaders’ decision space and cedes the adversary

significant advantages.

14

e further back the combat air forces launch weapons, the more

complicated the kill chain required. Forces must locate, destroy, and verify targets that

might be mobile or fleetingly observable while defeating systems finely tuned toward the

destruction of standoff munitions and platforms. Correlating pulsed operations with

standoff tactics makes those tactical problems inherently more complicated by removing

pressure and playing to the adversary’s strengths; namely, that by 2030, “stronger Chinese

conventional capabilities and a survivable nuclear deterrent” complicate potential US

theories of victory.

15

Furthermore, the move toward pulsed operations might be feeding a dangerous

perspective within the CAF, where it is believed a large- scale peer conflict will likely be

short. To be clear, the “wish- casting” associated with a short war is hardly the pre-

dominant view in the Pentagon or literature, but behind the scenes, this viewpoint is

surprisingly common within the CAF. is belief contravenes most expert opinions and

belies an ignorance of the “fragmented authoritarianism” within China, which persists

under President Xi Jinping. Considering the consensus necessary within China to make

12. Christopher Woody, “e US Air Force Is Training to Take Down Chinese Warships, but China’s

Military Has Built a ‘Wicked’ Problem for It to Overcome,” Business Insider, November 13, 2023, https://

www.businessinsider.com/; and Inder Singh Bisht, “Pentagon Wants to Ramp- Up Ship- Killing Missile Pro-

curement,” Defense Post, April 7, 2023, https://www.thedefensepost.com/.

13. Maximillian Bremer and Kelly Grieco, “Assumption Testing: Airpower Is Inherently Offensive, As-

sumption #5,” Policy Paper, Stimson, January 25, 2023), https://www.stimson.org/.

14. Ron Tira, e Limitations of Standoff Firepower- Based Operations: On Standoff Warfare, Maneuver, and

Decision (Tel Aviv: Institute for National Security Studies, 2007), https://www.jstor.org/; Gregory Weaver,

“e Role of Nuclear Weapons in a Taiwan Crisis,” Atlantic Council (blog), November 22, 2023, https://

www.atlanticcouncil.org/; and Alex Vershinin, “e Challenge of Dis- integrating A2/AD Zone: How

Emerging Technologies Are Shifting the Balance Back to the Defense,” Joint Force Quarterly 97 (2nd Quar-

ter, 2020), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/.

15. Jacob L. Heim, Zachary Burdette, and Nathan Beauchamp- Mustafaga, U.S. Military eories of Vic-

tory for a War with the People’s Republic of China (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, February 21, 2024),

5, https://doi.org/.

8 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

critical state decisions, it is highly unlikely a war would be started on such a whim that

initial failure would lower national resolve.

16

Completing long- range kill chains to meet pulsed operation objectives in a short series

of battles seems feasible, but doing so in a long, potentially escalating war will likely prove

much more difficult. If operators base their training on winning a short- term fight, pain-

ful—or even catastrophic—lessons might ensue.

Pulsed operations are a rational response to peer threats. Yet the implicit correlation of

this concept with standoff tactics in a short conflict reduces the capacity for tactical creativ-

ity and fails to meet the higher- level guidance provided by Secretary Kendall’s operational

imperatives or the tough operational problems any ensuing service leader would face. Even

worse, the defensive advantage—nothing new in modern warfare—has not made peer

adversary defenses invulnerable, but it has made, in most cases, the term standoff inac-

curate for many threats. e CAF will likely be employing weapons within threat rings,

and the weapons themselves are possible to target.

17

In other words, standoff implies a

level of safety or lower risk, combined with mission success, that is misleading. Moreover,

the logic of perpetual standoff is unsustainable; at some point, a platform or weapon must

enter a threat area.

Meanwhile, while the CAF uses the term stand- in for penetrating assets, the truth is

more nuanced. e B-21’s capabilities allow it to be much closer to targets but still outside

threat capabilities. e shorter distance makes weapons considerably more survivable and

the process of striking fleeting or mobile targets more realistic. e reduced distances

necessary for future weapons allow for acquisitional strategies favoring smaller, faster

systems with advanced seekers that provide the mass and persistence lacking with large,

exquisite—and expensive—hypersonics.

A stand- in capability, including a platform such as the B-21, could enable the long- range

kill chain standoff tactics currently favored by the CAF or act as an organic firing solu-

tion—thus not requiring offboard support—for critical threats in GPS and space- denied

environments.

18

e organic targeting aspect is important, as the combination of limited

penetrative assets and rapidly improving adversary threats is pushing the CAF into long-

range kill chain tactics that are inherently inorganic.

ese kill chains require players both in and outside of the Department of Defense to

strike highly contested targets. e Joint force has made laudable efforts to acquire the

resources necessary to implement long- range kill chain tactics. Yet an inescapable issue

remains: each link is a vulnerability, and the more links required for mission success, the

16. Andrew Mertha, “ ‘Fragmented Authoritarianism 2.0’: Political Pluralization in the Chinese Policy

Process,” China Quarterly 200 (December 2009), https://doi.org/.

17. Susie Blann, “Russia Fires 30 Cruise Missiles at Ukrainian Targets; Ukraine Says 29 Were Shot

Down,” AP, May 19, 2023, https://apnews.com/.

18. Eric Heginbotham et al., e U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Bal-

ance of Power, 1996–2017 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, September 14, 2015), 241, https://www

.rand.org/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 9

more opportunities an adversary has to disrupt or delay the targeting process.

19

e CAF

can compensate for those vulnerabilities by creating contingency solutions or lobbying for

redundancies, but the latter are not free and require acquisition resources in a contentious

spending environment.

e B-21 and its stand- in capabilities can fill operational shortfalls and address the

tenuous assumptions on which pulsed operations with standoff tactics depend. As adver-

sary systems improve, the B-21 and its family of systems can enable legacy standoff

platforms by eliminating the most critical threats to fifth- generation platforms and

weapons. Most importantly, the B-21 can help address significant hurdles facing the CAF

in theaters requiring pulsed operations. Given the standoff, fighter-centric approaches

currently preferred or required, planners must reckon with four specific challenges.

Limited Fuel

e first assumption Indo- Pacific- region plans rely on is that air and ground refueling

will be available. Given China’s A2/AD capabilities and the so- called tyranny of distance,

the idea that refueling tankers will be able to support fighters even in pulsed operations

is tenuous at best. Tankers will require levels of escort that detract from difficult targeting

operations and depend on accessible basing, not to mention willing Allies and partners

and vulnerable supply chains.

20

Vulnerable Bases

If adversaries choose to employ the full weight of their ballistic arsenal against US

regional bases, those operational headquarters are unlikely to survive. Dispersed ops are a

potential answer, but those tactics have limitations and are still vulnerable to follow- on

strikes.

21

It is telling that wargames in the last decade have focused on whether the United

States will target mainland China in a conflict over Taiwan.

22

Notwithstanding this welcome dose of political realism into planning assumptions,

a decision not to target China seems to be driven by the recognition that if China uses

its substantial missile arsenals to attack US bases in the Indo- Pacific—if not the US

mainland—the Air Force will struggle mightily to counter an invasion of Taiwan. e

combat air forces are not declining to target the Chinese mainland due to potential

19. Heather Penney, “Scale, Scope, Speed & Survivability: Winning the Kill Chain Competition,” Mitchell

Institute Policy Paper 40 (May 2023), https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/.

20. Andrew Tilghman, Guam: Defense Infrastructure and Readiness, R47643 (Washington, DC: Congres-

sional Research Service, August 3, 2023), https://crsreports.congress.gov/.

21. Patrick Mills et al., Building Agile Combat Support Competencies to Enable Evolving Adaptive Basing

Concepts (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, April 16, 2020), https://doi.org/.

22. John Speed Meyers, Mainland Strikes and U.S. Military Strategy towards China: Historical Cases, In-

terviews, and a Scenario- Based Survey of American National Security Elites (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Cor-

poration, December 20, 2019), https://doi.org/.

10 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

political realities. Instead, planners hope China will reciprocate by declining to target

Guam, Japan, or other nations due to Xi’s concerns “about the PLA’s ability to fight and

win wars” and the risk of undermining Chinese Communist Party control.

23

Especially since an invasion of Taiwan will already be occurring under devastating po-

litical and economic conditions, it seems beyond fanciful to hope China will cede its great-

est advantage in what would already be a war with the highest stakes imaginable.

24

Even the

assumption that there is a meaningful distinction between the First and Second Island Chains

might be problematic: it is unlikely China would be content to eliminate only Okinawa if

the United States could continue meaningful operations from Guam.

25

Given the fallout

from an invasion of Taiwan, it is logical to assume a Chinese Communist Party leader who

orders such a drastic action would face regime- threatening implications upon failure.

26

Assuming an inherently limited conflict disfavoring the enemy—to enable a preferred

set of tactics—is dangerous. Agile combat employment might mitigate risks to short- range

aircraft, but unless such efforts are flawless, fighters—and tankers, to an extent—cannot

reach the fight or seriously affect it without convenient basing. e 2022 National Defense

Strategy explicitly states that regional base protection, specifically Guam, is a priority, but

the Air Force has largely assumed that the missile defense emphasis and expeditionary

constructs will somehow ensure base viability.

27

Unpredictable Precision Navigational Timing

Despite years of acknowledgment that GPS may not be available or effective before or

during a war, the Joint force remains critically reliant on GPS to employ weapons, especially

against standoff targets. JASSM, for example, requires GPS to reach a final point where

an infrared seeker combined with anti- GPS jamming is effective.

28

is assumption is

dangerous because US adversaries continue to invest heavily in GPS- jamming technology,

not to mention the ability to shoot down the satellites themselves.

29

23. Mark Cozad et al., Gaining Victory in Systems Warfare: China’s Perspective on the U.S.-China Military

Balance (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023), 113, vi, https://doi.org/.

24. “Invading Taiwan Would Be a Logistical Minefield for China,” Economist, November 6, 2023, https://

www.economist.com/.

25. Derek Grossman, “America Is Betting Big on the Second Island Chain,” RAND Blog, September 8,

2020, https://www.rand.org/.

26. Andrew Mertha, “ ‘Stressing Out’: Cadre Calibration and Affective Proximity to the CCP in Reform-

era China,” China Quarterly 229 (March 2017), https://doi.org/.

27. Anthony H. Cordesman, “e New U.S. National Defense Strategy for 2022,” CSIS, October 28,

2022, https://www.csis.org/.

28. John Keller, “Lockheed Martin to Test and Integrate Extreme- Range Air- to- Ground Missile with GPS

and Infrared Guidance,” Military + Aerospace Electronics, June 5, 2023, https://www.militaryaerospace.com/.

29. Sandra Erwin, “U.S. Military Doubles Down on GPS despite Vulnerabilities,” SpaceNews, August 9,

2021, https://spacenews.com/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 11

Contested Space Domain

e threat to GPS satellites is clearly not restricted to navigation.

30

e previously

mentioned tactical problem of targeting would be virtually impossible without the space

layer and tactics that allow for target identification and actual weapon targeting—thus the

intricacies and inherent vulnerabilities of long- range kill chains. Difficult enough as a

standoff tactic, these kill chains, without the space layer, which includes much more than

GPS, might prove impractical, at best.

31

e electromagnetic spectrum is also necessary to

complete kill chains, even with a pristine space capability.

32

e recent concern over the

possible Russian deployment of nuclear weapons in space highlights this vulnerability.

33

Given the reality of these four challenges and the nuances of standoff versus stand- in,

embracing the B-21 and discovering how to unlock its tactical creativity can unleash a

devasting physical and psychological weapon. e B-21 does not solve every tactical

problem, but it counters multiple airpower weaknesses and the investments adversaries

have made to defeat the United States.

Unique Capabilities of the B-21

e US Air Force will soon possess an unparalleled and novel asset capable of creating

effects that manipulate the enemy and shape its reactions before or during pulsed opera-

tions. Despite its appearance, the B-21 is not, as some derisively refer to it, a B-2.1. While

both platforms are highly survivable in contested environments, the B-21 earns its sixth-

generation moniker by representing an evolutionary leap in stealth technology.

34

As

Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III stated, “Fifty years of advances in low- observable

technology have gone into this aircraft . . . Even the most sophisticated air- defense systems

will struggle to detect a B-21 in the sky.”

35

e CAF must wisely integrate the B-21 into

tactical and operational plans to engender the best possible combat outcomes.

30. Kevin L. Pollpeter, Michael S. Chase, and Eric Heginbotham, e Creation of the PLA Strategic Sup-

port Force and Its Implications for Chinese Military Space Operations (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation,

November 10, 2017), 9, https://doi.org/.

31. Courtney Albon, “Space Force Seeking $1.2B for ‘Long Range Kill Chains’ Target Tracking,” De-

fense News, March 20, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/.

32. Raj Agrawal and Christopher Fernengel, “e Kill Chain in Space: Developing a Warfighting Mind-

set,” War on the Rocks, October 24, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/.

33. David Sanger and Julian Barnes, “US Fears Russia Might Put a Nuclear Weapon in Space,” New York

Times, February 17, 2024.

34. Mark Gunzinger, Understanding the B-21 Raider: America’s Deterrence Bomber (Arlington, VA:

Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, March 2023), https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/.

35. C. Todd Lopez, “World Gets First Look at B-21 Raider,” Department of Defense (DoD) News,

December 3, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/.

12 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

Furthermore, the B-21 is far more flexible, adaptable, and dynamic than the B-2.

36

Organic

firing capabilities allow the B-21 to operate, if necessary, without significant preplanning,

and switching targets or missions airborne is no more difficult than what the CAF became

accustomed to in decades of close air support and dynamic targeting. erefore, the B-21

can enable the long- range kill chain standoff tactics preferred by the CAF or be an organic

firing solution for critical targets in GPS- and space- denied environments.

37

e B-21’s organic capabilities will not make long- range kill chain tactics obsolete;

indeed, the bomber’s sixth- generation characteristics, combined with its unique payload,

offer the ultimate defense against adversary defensive efforts to deplete these kill chains.

A fully resourced B-21 fleet will be able to operate in areas previously considered A2/AD

protected. Stopping the Raider would significantly drain adversary resources and require

an incredible degree of focus in the chaos of battle, both factors that enable current and

future long- range kill chain efforts.

Even if an adversary did discover a way to counter the platform, the Raider’s most

important feature is its modularity. Specifically designed with the space and capability to

integrate emerging systems rapidly, the B-21 is not only a response to current adversary

decisions but also an inherent counter to future enemy plans.

38

Even among the Joint

force, the B-21’s modularity and organic firing capabilities make it the most efficient form

of adapting to a war’s unknowns and adjustments while acting as a backstop for long- range

kill chain effectiveness.

Additionally, just as the B-21 directly contradicts adversary decisions and capabilities

in the electromagnetic spectrum, this sixth- generation jet addresses the CAF’s four major

challenges mentioned in the previous section. A B-21’s inherent fuel efficiency and range

drastically reduce the fuel bill, enabling a contiguous US strike capability and lowering

the dependency on forward bases. e Raider’s nuclear- hardened nature mitigates any

loss of GPS because nuclear- hardened jets are inherently resilient against GPS jamming,

and its full suite of sensors only strengthens its redundancy.

39

Similarly, due to its dynamic

and organic firing capabilities, the B-21 is not dependent on the space layer usually

necessary to execute kill chains against fleeting targets.

40

36. Tara Copp, “Pentagon Debuts Its New Stealth Bomber, the B-21 Raider,” AP, December 3, 2022,

https://apnews.com/.

37. Cameron Hunter, “e Forgotten First Iteration of the ‘Chinese Space reat’ to US National Secu-

rity,” Space Policy 47 (February 2019), https://doi.org/.

38. Stefano D’Urso, “New Photo and Details about B-21 Raider Program and Progress Released,” Avia-

tionist, September 18, 2023, https://theaviationist.com/.

39. Inder Singh Bisht, “USAF Tests B-2 Bomber System for GPS- Denied Environments,” Defense Post,

July 13, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost.com/; and Greg Hadley, “What Happens If GPS Goes Dark? e

Pentagon Is Working on It, Space Force General Says,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, May 12, 2022, https://

www.airandspaceforces.com/.

40. Albon, “Space Force.”

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 13

Stand- in with the B-21 also addresses the issues of available weapons rails and the

rising costs of hypersonics and associated upgrades.

41

e Air Force obtains the best strike

efficiencies when prioritizing mass at the lowest possible costs, but depending on fight-

ers—with their limited payloads—carrying standoff weapons results in poor costs per

effect.

42

Again, with limited B-2s and aging legacy bomber fleets undergoing difficult

upgrades, poor strike efficiencies have been prerequisite costs. Yet the B-21 can start a

commitment toward reversing the decades- long trend away from better strike efficiencies.

43

Unless the combat air forces embrace tactical creativity or at least understand the B-21’s

capabilities, however, it will be difficult to inform national leadership how the B-21 could

impact the battlefield and adversary decision- making. It is one thing to threaten the full

force of US conventional capabilities in a manner the enemy has been preparing for; it is

quite another to employ an aircraft capable of operating efficiently at the time and place

of its choosing. While hardly a silver bullet, fully realized, the B-21 could unlock Joint

capabilities and make more palatable solutions possible in a peer conflict if the CAF can

embrace tactical creativity through cultural changes.

44

Beyond the Debates: Tactical Creativity

e key to translating Secretary Kendall’s operational imperatives to the tactical

level—or, at a deeper level, increasing national- leader decision space beyond its current

tactical limits against a peer adversary—is finding a way for the combat air forces to move

beyond the stealth versus non- stealth, fighter versus bomber, and stand- in versus standoff

debates. Cultural adjustments are foundational to such an effort. For decades, the Air Force

has integrated with varying degrees of success against varying levels of opponents. Lever

-

aging the unique capabilities that fifth- and sixth- generation aircraft bring, however, will

require stand- in bombers and their family of systems to play a dynamic and leading role

to which fighter- led combat air forces are unaccustomed.

45

e current emphasis on standoff tactics undergirding pulsed operations is at least some

recognition that the Air Force has moved past the alleged successes of the first Gulf War,

in which even sympathetic accounts, such as those written by former President George

41. Mikayla Easley, “Physics and Cost Are Shaping Pentagon’s Hypersonics Paths,” DefenseScoop, April

11, 2023, https://defensescoop.com/.

42. David Deptula and Douglas A. Birkey, “Resolving America’s Defense Strategy- Resource Mismatch:

e Case for Cost- Per- Effect Analysis,” Mitchell Institute Policy Paper 23 (July 2020), https://mitchellaerospace

power.org/.

43. Mark Gunzinger, “Stand In, Standoff,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, July 1, 2020, https://www.airand

spaceforces.com/.

44. Daniel L. Haulman, “Fighter Escorts for Bombers: Defensive or Offensive Weapons,” Air Power

History 66, no. 1 (2019).

45. S. Rebecca Zimmerman et al., Movement and Maneuver: Culture and the Competition for Influence among

the U.S. Military Services (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, February 25, 2019), https://doi.org/.

14 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

Bush, make it clear that the United States was operating against a vastly inferior opponent.

46

Yet the transition to pulsed operations supporting standoff tactics has not—at least

yet—produced a version of the combat air forces radically dissimilar from the forces that

swamped Saddam Hussein in different decades. Furthermore, as numerous pundits and

leaders have pointed out, twenty years of close air support has not prepared the CAF for

a large- scale conflict against a peer adversary.

47

Embracing the B-21’s full capabilities would not mean rejecting pulsed operations or

standoff capabilities. Instead, combat air forces could start to engage the tactical creativity

that a persistent stand- in capability permits, whether as an enabler for pulsed operations,

a roaming threat that distracts the enemy, or—most tantalizingly—a mission- command

platform that dynamically directs pulsed operations against emerging targets. In some

respects, the F-35 Lightning II and F-15EX Eagle II communities have already started

these conversations by examining how a fourth- generation platform can complement

fifth- generation stealth.

48

is integrated vision might seem an obvious goal, but the idea of dynamic stand- in

bombers leading pulsed operations does not exist in current doctrine. is doctrinal

proclivity is not inimical. Rather, it is the natural progression of thought given the Air

Force’s evolution toward fighters in the 1970s. Today, however, the Air Force faces more

existential adversaries.

49

Parochial fights within the service are not unusual, but there is

also an ongoing debate over stealth due to the “threat” that stealth platforms present to

traditional, nonstealth platforms.

50

Unfortunately, the combat air forces are starting from a disadvantageous position regard-

ing stealth. e F-117 Nighthawk’s “retirement” in 2008 left the service with a de facto

niche capability in the B-2 due to its limited numbers, maintenance complications, and

nuclear commitments—that is, tacticians must assume that in any peer- to- peer conflict,

the B-2 might not be readily available due to nuclear alerts.

51

As a result, even with the

46. George Bush and Brent Scowcroft, A World Transformed (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).

47. omas Greenwood, Terry Heuring, and Alec Wahlman, “e ‘Next Training Revolution’: Readying

the Joint Force for Great Power Competition and Conflict,” Joint Force Quarterly 100, 1st Quarter (2021),

https://ndupress.ndu.edu/.

48. John A. Tirpak, “Joining Up on the F-15EX,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, November 1, 2020,

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/.

49. Zimmerman et al., Movement and Maneuver.

50. Mike Worden, Rise of the Fighter Generals: e Problem of Air Force Leadership 1945–1982 (Maxwell

AFB, AL: Air University Press [AUP], 1998); Mike Pietrucha, “Low- Altitude Penetration and Electronic

Warfare: Stuck On Denial, Part III,” War on the Rocks, April 25, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/; Pietrucha,

“Rediscovering Low Altitude: Getting Past the Air Force’s Overcommitment to Stealth,” War on the Rocks,

April 7, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/; and Pietrucha, “e U.S. Air Force and Stealth: Stuck On Denial

Part I,” War on the Rocks, March 24, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/

51. “Special Report: Nuclear Posture Review - 2018,” DoD, accessed January 6, 2024, https://dod

.defense.gov/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 15

introduction of fifth- generation fighters, planners and tacticians do not appreciate the

B-2’s penetration capabilities and how many targets the stealth fleet can service.

Ironically, the current B-2 community has enabled tacticians’ misperceptions regarding

advanced stealth tactics by embracing an insular culture in line with its highly classified

programs. Air Force leadership has wisely adopted a more open stance with the B-21: its

initial testing has been in broad daylight, and the B-21’s special access classifications

could—in theory—be downgraded, at least in part.

52

Unlike the B-2, this would allow

more tacticians to understand the B-21’s full capabilities and present creative options to

operational and strategic leaders.

Yet reducing classifications is no small task. e Air Force has struggled for decades

with “keeping a high fence around a small yard” to protect innovation advantages while

increasing platform crosstalk.

53

e service should consider the lessons of the F-117 and

General W. L. “Bill” Creech, whose support of the stealth aircraft was contentious. War-

fighters initially could not accept that the F-117 could act “as an enabler of the defense-

rollback strategy as well as a means to strike deep targets of high value.”

54

Above all, the Air Force as a whole must avoid categorical statements such as “stealth

is dead” or “stealth is the price of admission.”

55

e latter statement has been taken out of

context: it never meant that nonstealth platforms were unimportant. Additionally, while

former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Paul Selva acknowledged the constant

race between stealth and counterstealth, he also couched those comments with the as-

sertation that training—and by extension, packaging and planning—were what allowed

stealth to provide an “advantage over your adversary’s detection and targeting systems, not

dissimilar to quieting in submarines.”

56

While sixth- generation stealth assets can still reach stand- in ranges with reduced risk,

they are not white knights single- handedly capable of winning a war. Moreover, the stealth

of fifth- generation aircraft will struggle outside of pulsed scenarios if the CAF refuses to

embrace an integrated approach. Likewise, sixth- generation stealth is only “dead” if

unsupported B-21s are expected to behave as invisible platforms, not platforms utilizing

a family of systems and classified capabilities to achieve persistent stand- in ranges.

57

52. John A. Tirpak, “12 ings We Learned from the New B-21’s Taxi Tests and First Flight,” Air &

Space Forces Magazine, November 22, 2023, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/.

53. Laskai Lorand and Samm Sacks, “e Right Way to Protect America’s Innovation Advantage,” For-

eign Affairs, October 23, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/.

54. James Slife, Creech Blue: Gen Bill Creech and the Reformation of the Tactical Air Forces (Maxwell AFB,

AL: AUP, in collaboration with College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education, 2004), 59, https://

www.airuniversity.af.edu/.

55. Pietrucha, “Stuck on Denial”; and Josh Wiitala, “e Price of Admission: Understanding the Value

of Stealth,” War on the Rocks, June 2, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/.

56. Adam Twardowski, “e Future of US Defense Strategy: A Conversation with General Paul J. Selva,”

Brookings, July 2, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/.

57. Joe Pappalardo, “PM Interview: Air Force Gen. Mark A. Welsh III,” Popular Mechanics, April 15,

2014, https://www.popularmechanics.com/.

16 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

A combat air force culture that embraces an integrated approach should recognize the

nuances of stealth, reexamine the roles of traditional bombers versus the B-21, and recap-

ture the ability to balance immediately necessary standoff tactics with an earnest desire

for tactical creativity and stand- in capabilities. Part of this cultural change must include

the Joint force, namely US Strategic Command, and the recognition that a fully capable

B-21 fleet will enable conventional escalation options so influential as to replace tactical

nuclear options.

is is not to imply nuclear certification of the platform should be delayed, although

if it were to impede conventional capabilities, slightly delaying nuclear capabilities should

be acceptable. Rather, agreements should be made now to prevent the type of Strategic

Air Command conflicts that bedeviled planners in Vietnam desperate to maximize the

B-52’s conventional effects when the bombers were committed foremost to the nuclear

Single Integrated Operational Plan.

58

Overall, parochial fights are inevitable given restricted resources and Beltway politics,

but arguably, the most significant issue facing CAF warfighters is the rifts that have seeped

down to the tactical level. ese rivalries are not a luxury the service can afford in a large-

scale conflict against a determined peer adversary. While the comparison might be hyper

-

bole, on its current path—embracing standoff/fighter- based tactics at the expense of a

platform such as the B-21—the CAF could be replicating the disastrous mistakes plagu-

ing past militaries as they chose precious cultural attitudes over necessary evolutions.

59

Conclusion and Recommendations

If the B-21 program—which is still in early testing—remains on track, the Air Force

has a game- changing asset coming sooner rather than later. To that end, there are three

general steps leadership might consider to improve its chances in a near- term conflict.

Expedite Production and Prioritize Testing

History proves accelerating a successful program is a matter of motivation, faith, and

money. e United States famously produced one B-24 per hour at Willow Run during

World War II; less effort is probably necessary to embrace a breakout mindset with the

B-21.

60

Leadership can ameliorate developmental testing—a notoriously complicated

bureaucratic maneuver in Air Force circles—by prioritizing the B-21 over legacy platforms

and the new jet trainer. If testing and funding remain on track, these efforts should yield

58. Gregory Daddis, Westmoreland’s War: Reassessing American Strategy in Vietnam (Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press, 2014).

59. Jonathan B. A. Bailey, “Military History and the Pathology of Lessons Learned: e Russo- Japanese

War, a Case Study,” in e Past As Prologue, ed. Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich, 1st ed.

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 170–94, https://doi.org/.

60. Tim Trainor, “How Ford’s Willow Run Assembly Plant Helped Win World War II,” Assembly,

January 3, 2019, https://www.assemblymag.com/.

Praiswater & ornhill

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 17

operational B-21s able to employ weapons on practice ranges and potentially be conflict-

ready in three to five years, or sooner. In short, the B-21 would be impactful before 2030

and dominant no later than 2035.

Reduce Cost per Kill

Critically, the Department of Defense and Congress should continue their laudable

acquisition efforts with some relatively inexpensive modifications, but the primary focus

must be reducing the target cost per kill. Fully funding next- generation weapons for even

a fledgling B-21 force will unlock more strike efficiency than comparable platforms. And

part of this equation is the right weapons- to- platform matching. For example, taking full

advantage of the B-2 as a stopgap—perhaps by funding GBU-62 integration as soon as

possible—would offer planners an area- targeting option and stimulate tactical creativity.

61

e hypersonic attack cruise missile and other specialized efforts can remain a priority,

but not at the cost of more affordable capabilities or slowing B-21 investment. Numerous

studies have proven that a mostly standoff arsenal is unaffordable, even if the previously

mentioned limitations inherent to such a force did not exist.

62

Concerns expressed in a

RAND Corporation 2011 report that “adversaries may make calculations based on the

size of the US missile inventory”—especially given the cost increases associated with

building increasingly long- range weapons—must still be taken seriously.

63

Recalibrate the Combat Air Forces

If the combat air forces are to embrace the unique capabilities of the B-21 in the future,

they must destroy the “stealth is dead” mindset, of which the insular B-2 community is

partially responsible. Stealth and stand- in platforms are necessary to unlock strike efficiency

and affordable mass, and stealth bombers have capabilities their fighter brethren do not.

Often when planners think stealth, they typically conflate the B-2 and B-21 with more

widely understood fighter characteristics. e remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) community,

largely through the RQ-170, has proven the importance of stand- in stealth, but the fighter

community is approximately three times larger than the bomber and RPA communities

combined.

64

It is only natural that a fighter- led force coerced into standoff preferences

might struggle to embrace a new tool such as the B-21.

61. David Axe, “A Symphony of Bomb Blasts: One after Another, Four Ukrainian JDAMs Apparently

Strike Russian Positions in Bakhmut,” Forbes, April 23, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/.

62. Gunzinger, “Stand In, Standoff.”

63. omas Hamilton, “Comparing the Cost of Penetrating Bombers to Expendable Missiles over irty

Years: An Initial Look,” RAND Working Papers WR-778-AF, March 4, 2011, https://www.rand.org/.

64. Johnny Franks, “Famous Stealthy RQ-170 ‘Sentinel’ Drone Teams for Combat with B-2 & F-35,”

Warrior Maven: Center for Military Modernization, December 15, 2023, https://warriormaven.com/; and

“2021 USAF & USSF Almanac: Specialty Codes,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, June 30, 2021, https://www

.airandspaceforces.com/.

18 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e B-21 and Tactical Creativity

e Air Force must work now to enable its smart investments in fifth- and sixth-

generation stealth fully. Reducing the special accesses required—or easing the read- in

process for most tacticians—for current stealth platforms would be an excellent first step.

Additionally, directing exercises that require dynamic area targeting in heavily defended

airspace is an efficient way to breed tactical creativity and introduce the true level of mis-

sion command envisioned by Air Force leadership.

True strategic processes do not begin until combat starts, and history implies wars will

not happen where or how leaders expect.

65

e B-21, thanks to its generational leap in

stealth technology and modularity, firmly acknowledges that flexibility and adaption are

key to victory. Unfortunately, the realities of treating China and its A2/AD efforts as the

pacing threat have led the combat air forces to minimize operational challenges that will

be critical should a war ignite against any capable opponent: gas is limited, basing is as-

sailable, GPS might not be available, and the space layer is vulnerable. e B-21 offers a

chance to reconsider the relationships between stand- in and standoff and embrace a

movement toward tactical creativity. Q

65. Shane Praiswater, “Reconsidering the Relationship between War and Strategy,” RUSI Journal 168, no.

5 (July 29, 2023), https://doi.org/; and Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History (New York: Oxford Univer-

sity Press, 2013).

19 AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW

AIR OPERATIONS

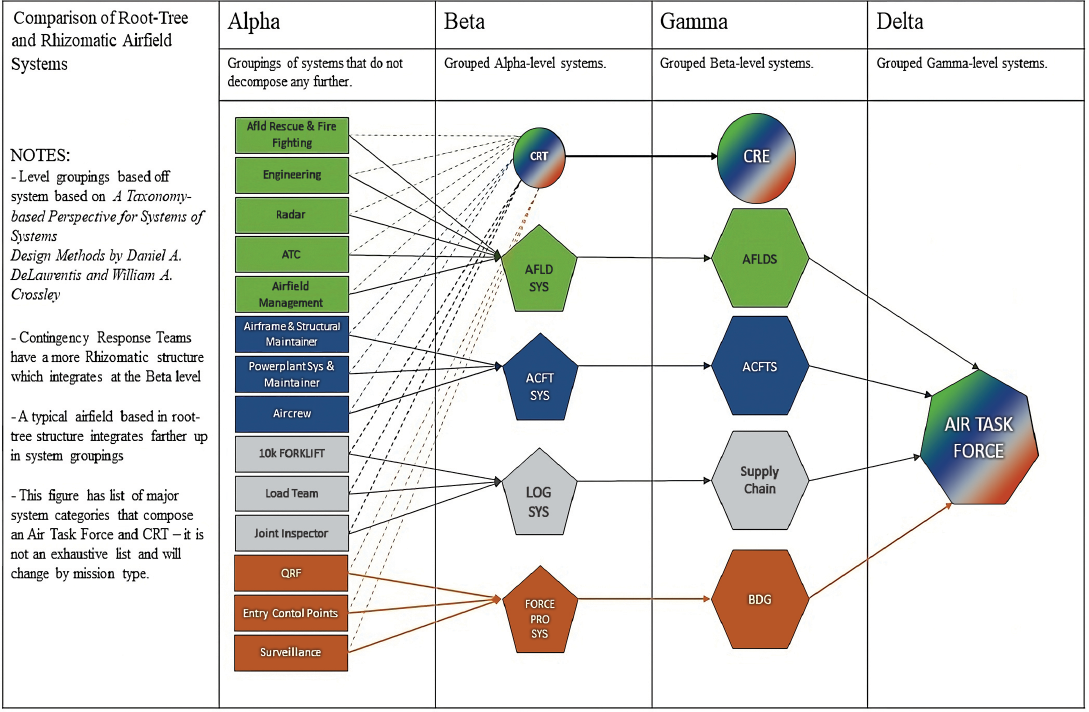

e Aireld as a System

Mark D. Callan

US Air Force airfields are partners in airpower with aircraft, but they are also centers of gravity

that cannot maneuver at tempo, making them a potential weakness for adversaries to exploit. If

the Air Force is to prevail in great power competition, it needs to rethink airfield organization.

Systems thinking can help the Air Force reorganize its airfields into maneuverable rhizomatic

teams, mitigating the shortfalls of traditionally organized airfields. is study aims to help Air

Force decisionmakers guide the development of airfield systems whose potential has remained

relatively unexplored.

W

hen one is asked to visualize American airpower, airfields rarely come to

mind. Instead, one would likely conjure the image of a flight of F-100s

menacing the skies over North Vietnam, unending streams of C-54 Skytrains

breaking Stalin’s blockade of West Berlin, or perhaps B-29s lifting off from Tinian to

usher in the atomic age of history. Few would consider the outnumbered airfield defend-

ers of Tan Son Nhut airfield repelling waves of North Vietnamese sappers during the

Tet Offensive; the constant guiding hand of Tempelhof approach controllers bringing

in the endless airflow of the Berlin Airlift; or the resourceful Seabee combat engineers

on Tinian island blasting coral to build B-29-capable runways.

1

Airfields are perhaps a

less sleek and more subtle reminder of American airpower, but airfields and the service

members who defend them, operate them, and build them have always been partners

in airpower right alongside aircraft.

Former Chief of Staff of the Air Force General Charles Q. Brown’s Accelerate Change

or Lose action orders are now over three years old.

2

In that time, airfields played critical

roles in the Afghanistan retrograde of 2021, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022,

Major Mark Callan, USAF, is an airfield operations officer and chief of the Mobility Operations Support Management

Branch, Mobility Support Operations Division (AMC/A34), Air Mobility Command, and holds a master of arts in emergency

and disaster management from American Military University.

1. Scott Wakefield, “A Look Back at the 377th Security Police Squadron’s Defense of Tan Son Nhut,” Air

Force Global Strike Command – AFSTRAT AIR, September 22, 2022, https://www.afgsc.af.mil/; “MISSIONS:

Tinian,” 6th Bomb Group, accessed August 20, 2023, https://6thbombgroup.com/; and Stewart M. Powell, “e

Berlin Airlift,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, June 1, 1998, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/.

2. Charles Q. Brown Jr., Accelerate Change or Lose (Washington, DC: United States Air Force [USAF],

August 2020).

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 19

20 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) expansionism in the South China Sea in 2023.

3

Yet, airfields are still not organized to best maximize agile combat employment (ACE),

as they remain siloed and parochial.

e US Air Force needs to operate and maneuver airfields at tempo to execute ACE

successfully, but the service is finding that often it cannot do so fast enough to execute the

hub- and- spoke schemes of maneuver. As a result, airfields are putting ACE at risk, and

in turn, the nation’s ability to prevail in great power competition.

is article argues for a change to this status quo: airfields must be reframed, redefined,

and reorganized. First, Air Force leaders must reframe the airfield by acknowledging it is a

center of gravity (CoG)—a strategic focal point—with inherent strengths and weaknesses.

Secondly, leaders must use a system- of- systems framework to redefine airfields and shape

them into systems that mitigate the weakness inherent in CoGs. Finally, the Air Force must

reorganize airfields into smaller, rhizomatic weapon systems equipped with a pioneering,

mission- driven ethos agile enough to keep pace in great power competition.

Centers of Gravity

Many people think of the airfield as infrastructure that supports operations—a minia-

ture city bustling with the activities of combat airpower generation. Yet consider the

distant floating relative of the airfield, the aircraft carrier. Despite its benign name, the

aircraft carrier is instantly recognized around the world as a symbol of American naval

power. When aircraft carriers sail somewhere, it can be a reassuring gesture for Allies and

a not- so- subtle threat to would- be adversaries.

When the Air Force maneuvers an airfield into place, it is an equivalent gesture. Like

aircraft carriers, airfields represent a gateway through which forces many time zones away

suddenly appear in the local environment, shifting the regional balance of power with

little warning. is maneuver and concentration of forces gives air component command-

ers enormous power and makes the airfield into a natural focal point of airpower. is

concentration phenomenon makes an airfield a center of gravity.

Air forces around the world have long understood airfields as CoGs. Early airpower

theorist Italian General Giulio Douhet wrote in 1927 about both the unparalleled of-

fensive potential of aircraft as well as the relative vulnerability of aircraft when they returned

3. Clayton omas et al., U.S. Military Withdrawal and Taliban Takeover in Afghanistan: Frequently Asked

Questions, R46879 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Services, updated September 17, 2021),

https://crsreports.congress.gov/; Bradley Martin, D. Sean Barnett, and Devin McCarthy, Russian Logistics

and Sustainment Failures in the Ukraine Conflict (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023), https://doi

.org/; Liam Collins, Michael Kofman, and John Spencer, “e Battle of Hostomel Airport: A Key Moment

in Russia’s Defeat in Kyiv,” War on the Rocks, August 10, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/; and “China Ap-

pears to Be Building an Airstrip on a Disputed South China Sea Island,” AP, August 17, 2023, https://

apnews.com/.

21 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

to land at the “nest.”

4

ough the vulnerability of airfields has been implicitly understood

for decades, a deeper discussion on what explicitly makes airfields a center of gravity is

warranted, because there is little contemporary literature or Air Force doctrine that explains

why. Reframing airfields as CoGs sets the stage for redefining airfields as systems- of- systems

before reorganizing them into something more rhizomatic and pioneering.

Classical Application to Airelds

e term center of gravity translates from the German ein Zentrum der Kraft und Be-

wegung.

5

e term was borrowed from physics by Carl von Clausewitz in the early- nineteenth

century and describes a point of cohesion in an enemy where a striking blow would prove

most effective. e intent of the Newtonian metaphor was to echo the effect of a physical

blow against an object’s literal center of gravity.

6

Clausewitz’s center-of-gravity metaphor

has endured from the Napoleonic era and still finds use among military theorists and

practitioners today. It remains a central concept in Joint warfighting doctrine.

7

Using this classic notion as discussed by Clausewitz reveals four reasons why airfields

are centers of gravity: (1) airfields contain the mass of Air Force forces and act as a hub,

(2) airfields are central to the maneuver of Air Force forces and ground forces, (3) the

geographical location of airfields determines how air campaigns are waged, and (4) airfields

can exert economic and political influence during peacetime as well as wartime.

Mass. Tactically and operationally speaking, airfields contain the mass of Air Force

forces and serve as a hub of activity. Aerial ports, air traffic control towers, aircraft main-

tenance hangars, fuel farms, runways, taxiways, aprons, navigational aid facilities, and the

airfield’s airspace maintain the highest concentration of forces at the point at which aircraft

and personnel are at their most vulnerable for the longest period of time—sitting ducks,

in other words.

8

Maneuver. In terms of logistics, airfields can send and receive inter- and intra- theater

logistics airflow. e ability to maneuver forces from one part of the world to another at

the speed of airlift is what gives the US military a global versus regional influence. Joint

forceable entry operations such as airfield seizures have been used throughout the history

4. Giulio Douhet, e Command of the Air, trans. Dino Ferrari (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press

[AUP], 2019), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/.

5. Joseph L. Strange and Richard Iron, “Center of Gravity: What Clausewitz Really Meant,” Joint Force

Quarterly 35 (2004).

6. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1989).

7. Joint Planning, Joint Publication (JP) 5-0 (Washington DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,

December 1, 2020).

8. Alan J. Vick, Snakes in the Eagle’s Nest: A History of Ground Attacks on Air Bases (Santa Monica, CA:

RAND Corporation, January 1, 1995), https://doi.org/.

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 21

22 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

of airpower.

9

Some examples include Russia’s attempted seizure of Hostomel Airport in

the opening days of its invasion of Ukraine (2022), the US seizure of Rio Hato Airfield

during its invasion of Panama (1989), and the Nazi Airborne jump operations on Maleme

airfield in Malta during World War II (1941).

10

Geography. e Air Force needs an airfield, airspace, aircraft, and many other systems

to project airpower. Airfields are the keystone support system that make airpower work.

e location of the airfield changes how airpower is employed. Airfields that are close to

the adversary pose different risks to mission and force than airfields that are distant. Each

has its own advantages and disadvantages. During World War II, Soviets favored airfields

close to the front lines of their advance because proximity gave their air forces the agility

they required to execute combined arms against the Germans.

11

During Operation Odys-

sey Dawn, however, the US Air Force used B-1Bs from Ellsworth Air Force Base, South

Dakota, to strike targets in Libya by flying sorties from the continental United States to

North Africa.

12

Influence. Airfields exert economic and political influence, and they can do so outside

of war. Unlike fighters and bombers which can only kill enemies, practice killing enemies,

or fly near adversaries to remind them that they can kill enemies, airfields controlled or

operated by the military can also be used for a range of operations that are below the

continuum of armed conflict. Examples include humanitarian assistance airlift operations

following the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan, which tangibly and positively affected the

state’s short- term opinion of the United States, and China’s construction of a ring of

airfields in the South China Sea to exert greater control over territorial claims.

13

Contemporary Application to Airelds

Contemporary center- of- gravity theory focuses on thinking of CoGs as systems that

can be broken down into subsystems, analyzed for weaknesses and then targeted. e Air

Force associates systems- based CoG thinking with Colonel John Warden, who applied his

five- rings targeting methodology while planning air campaigns against Iraq. After the

9. R. F. M. Williams, “e Development of Airfield Seizure Operations in the United States Army,”

Military Review, November 2021, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/.

10. Collins, Kofman, and Spencer, “Hostomel Airport.”

11. Martin van Creveld, Steven L. Canby, and Kenneth S. Brower, Air Power and Maneuver Warfare

(North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012).

12. Steven J. Merrill, “Ellsworth Airmen Recall Historic Mission 10 Years Later,” Ellsworth Air Force

Base, March 27, 2021, https://www.ellsworth.af.mil/.

13. Competition Continuum, Joint Doctrine Note 1-19 (Washington, DC: CJCS, June 3, 2019); Kali

Gradishar, “CRE Airmen in Pakistan Relate 2005 Earthquake to 2010 Flood Operations,” Air Mobility

Command, October 12, 2010, https://www.amc.af.mil/; and Jennifer D. P. Moroney, Lessons from Department

of Defense Disaster Relief Efforts in the Asia- Pacific Region (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2013).

23 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

success of Operation Desert Storm, contemporary thinking about CoGs grew conceptually

from culminating battles against focal points to include systems- based warfare.

14

Another scholar highlights seven common but not universal systems around which

contemporary CoG literature tends to coalesce: fielded military, leadership, industry,

infrastructure, population, public opinion, and ideology.

15

e Air Force and Western

military thinkers understand the weaknesses of CoGs—as do potential adversaries. e

PRC has grown a systems- based framework of warfare directly in response to the West-

ern use of systems- based targeting frameworks such as Warden’s rings or other contem-

porary CoG analyses.

16

Essentially, centers of gravity like the airfield can be broken down

into subsystems, analyzed for weaknesses, targeted, and neutralized.

17

On a practical level, Air Force planners understand the threat adversaries pose. ey

know that wrestling for air superiority often requires maneuvering their aircraft and ground

forces against an adversary. Allies in World War II, notably the American Air Forces of

the South Pacific, maneuvered in conjunction with Australian ground forces from airbase

to airbase, fighting against Imperial Japanese forces setting up decisive engagements like

the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

18

Ample Gain, a Cold War series of Allied aircraft cross-

servicing events and forerunner of agile combat employment, used the robust network of

NATO airbases to maneuver combat aircraft around what would be recognized today as

a base cluster.

19

Ample Gain worked because of robust airfield infrastructure, a large

network of NATO bases, and interoperable combat support functions.

e Air Force’s current strategy of agile combat employment, “a proactive and reactive

operational scheme of maneuver executed within threat timelines to increase survivability

while generating combat power,” relies on the dispersion of airpower from a main operat-

ing base into basing clusters to complicate enemy targeting.

20

Unlike Ample Gain, ACE

maneuvers both aircraft and airfields to complicate targeting while generating opportunity.

In terms of airfields and CoGs, the Air Force uses ACE to hedge against the inher-

ent vulnerabilities of large, static airfields by relying on the speed and surprise of ma-

neuverable airfields. ACE requires both Air Force aircraft and ground forces to simultaneously

14. Jeffrey Engstrom, Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare: How the Chinese People’s Lib-

eration Army Seeks to Wage Modern Warfare (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), https://doi.org/.

15. Miha Šlebir, “Re- Examining the Center of Gravity: eoretical and Structural Analysis of the Con-

cept,” Revista Científica General José María Córdova 20, no. 40 (December 2022), https://doi.org/.

16. Engstrom, Systems Confrontation; John Warden, “e Enemy as a System,” Airpower Journal 9, no. 1

(1995); Joe Strange, Centers of Gravity & Critical Vulnerabilities: Building on the Clausewitzian Foundation So

at We Can All Speak the Same Language, 2nd ed. (Darby, PA: Diane Publishing, 1996); and JP 5-0.

17. Warden; and Strange.

18. omas E. Griffith Jr., MacArthur’s Airman: General George C. Kenney and the War in the Southwest

Pacific, 1st ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998).

19. Joint Air Power following the 2016 Warsaw Summit: Urgent Priorities (Kalkar, Germany: Joint Air

Power Competence Centre, October 27, 2017), 98, https://www.japcc.org/.

20. Agile Combat Employment, Air Force Doctrine Note 1-21 (Washington, DC: Department of the Air

Force [DAF], August 23, 2022), 1, https://www.doctrine.af.mil/.

AIR & SPACE OPERATIONS REVIEW 23

24 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

maneuver in response to emergent threats. Maneuver of aircraft via flush—a type of

launch- for- survival—is a skillset that aircraft had before ACE and one that aircraft still

practice. Yet, Air Force ground forces cannot keep pace because rapid reactive or proac-

tive maneuver of ground forces in response to emergent threats is still not a cultural

norm in the Air Force.

Reframing airfields as CoGs in the classical sense and in the contemporary sense provides

two key insights. First, in the classical sense, airfields have a cohesive identity as a system

that military commanders can employ to achieve effects. Second, in the contemporary sense,

airfields can be dissected into subsystems and targeted by adversaries. e Air Force under-

stands this and actively tries to mitigate this via schemes of maneuver such as ACE.

Systems- of- Systems

Contemporary Wardian CoG analysis hints at the systems- based thinking paradigm

used to define many of society’s and nature’s complex systems. e Air Force needs to

think of airfields as systems so the service can reorganize them into systems that mitigate

their historical vulnerability. e system- of- systems framework breaks down complex

systems such as airfields, allowing the Air Force to understand and reshape them.

Airfield systems possess five characteristics appropriate for the system- of- systems

designation: operational independence, managerial independence, geographic distribution,

emergent behavior, and evolutionary development.

21

Operational Independence

is characteristic is straightforward when looking at airfields. A system is made of

separate component systems that are capable of independent operation. Military airfields

are meta systems with component systems, and they themselves are component systems

in a larger system. As meta systems, they contain component systems such as radar systems,

air traffic control facilities, pavement systems, and lighting systems. Each of these provides

use independent of the others.

22

Airfields are also component systems of larger systems

like the National Airspace System (NAS), within which an airfield operates independently

of the others.

23

Managerial Independence

Component systems are acquired and integrated into a meta system to achieve a specific

purpose. At first glance, military airfields can seem like integrated monolithic entities

21. Andrew Sage and Christopher Cuppan, “On the System Engineering and Management of Systems

of Systems and Federations of Systems,” Information- Knowledge Systems Management 2 (December 1, 2001).

22. Sage and Cuppan.

23. “National Airspace System,” Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), last updated April 20, 2023,

https://www.faa.gov/.

25 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

e Airfield as a System

under the control of a commander; however, airfields are managerially independent of the

systems they are administratively grouped with. An apt example comes from comparing

Chicago O’Hare International Airport to Travis Air Force Base (AFB). e more feder-

ated civil airfield of O’Hare has a diverse and loosely affiliated ecosystem of agencies that

interact for the common goal of generating economic activity.

O’Hare’s airfield, aircraft, logistics operations, housing communities, and security func-

tions are all distinct component systems required for the airport to function. As noted,

the airfield’s systems are run by a loose, federated mix of government, commercial, and