Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

Copyright 2013 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved.

March 2013

(volume 36 number 2)

In this issue:

Chapter News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Bulletin Board . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Holmgrens Honored by American

Society of Plant Taxonomists . . . 4

Unidentified Flowering Object . . 4

Hanging Gardens of Utah . . . . . . . . 5

Agropyron by any Other Name is

Still Wheatgrass . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Grow This: Short Shrubs . . . . . . . . 10

Funny Pages: Black-eyed Susan . 11

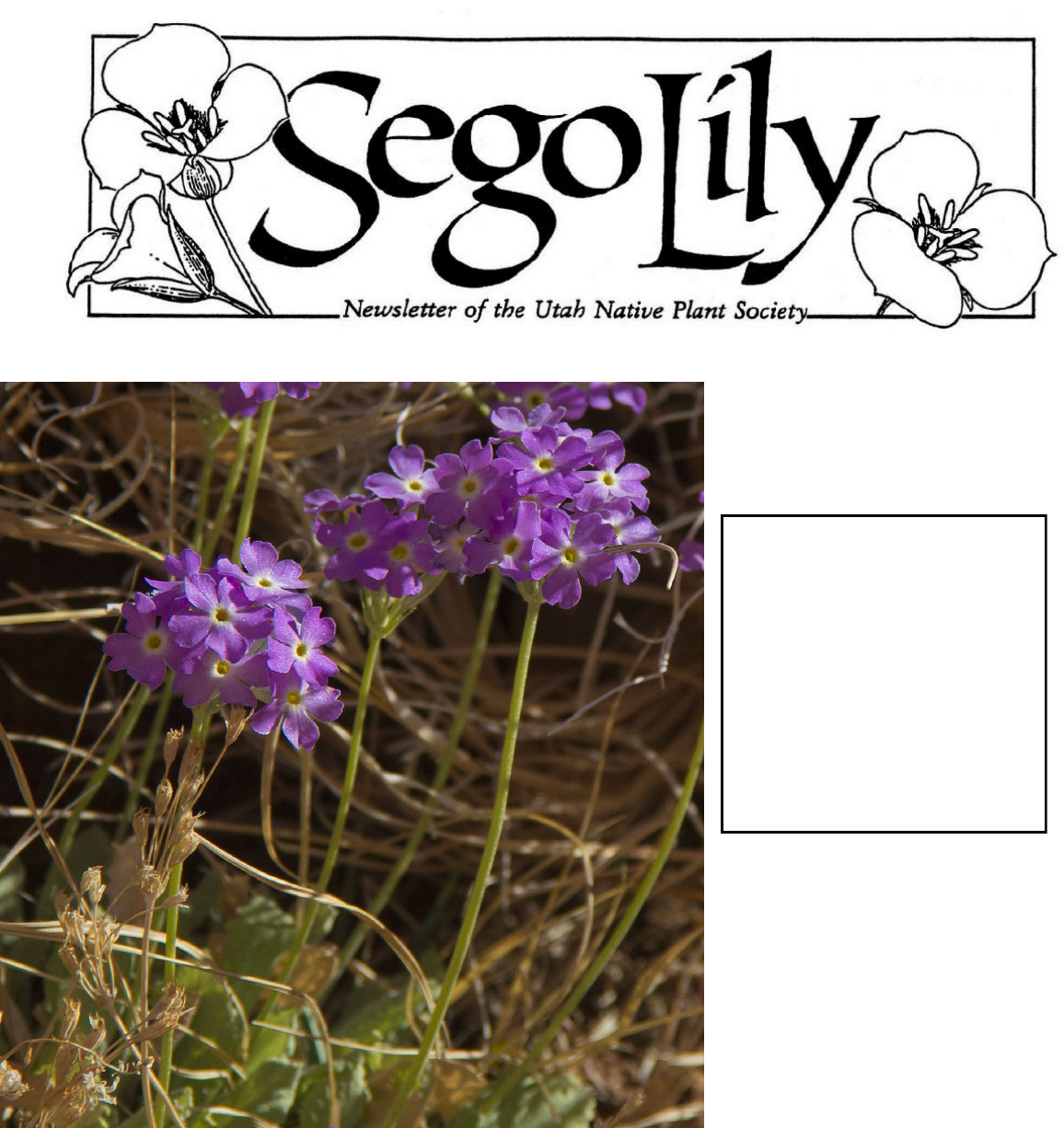

Cave primrose (Primula specuicola) is one of our earliest flowering plants in the spring, earning it

the alternative name of Easter-flower. This species is found primarily in hanging gardens and is re-

stricted to the Colorado River and its main tributaries in southeastern Utah and northern Arizona. Cave

primrose can be recognized by its erect, toothed leaves that are green above but covered by white mealy

(“farinose”) hairs on the margins and undersides. Sylvia Kelso has suggested that P. specuicola evolved

from populations of the wide-ranging boreal species P. mistassinica that became isolated on the Colo-

rado Plateau following the Pleistocene. Photo by Bill Gray.

2

Utah Native Plant Society

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sego Lily Editor: Walter Fertig

(walt@kanab.net). The deadline for the

May 2013 Sego Lily is 15 April 2013.

Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Soci-

ety. All Rights Reserved

The Sego Lily is a publication of the Utah

Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-

for-profit organization dedicated to

conserving and promoting stewardship

of our native plants.

Important Plant Areas: Mindy Wheeler

Invasive Weeds: Susan Fitts

Publications: Larry Meyer & W. Fertig

Rare Plants: Walter Fertig

Scholarship/Grants: Therese Meyer

Chapters and Chapter Presidents

Cache: Michael Piep

Cedar City:

Escalante: Toni Wassenberg

Fremont: Marianne Breeze Orton

Manzanita: Walter Fertig

Mountain: Mindy Wheeler

Salt Lake: Bill Gray

Southwestern/Bearclaw Poppy: Mar-

garet Malm

Utah Valley: Jason Alexander & Robert

Fitts

Website: For late-breaking news, the

UNPS store, the Sego Lily archives,

Chapter events, sources of native plants,

the digital Utah Rare Plant Field Guide,

and more, go to unps.org. Many thanks

to Xmission for sponsoring our web-

site.

For more information on UNPS:

Contact Bill King (801-582-0432) or

Susan Fitts (801-756-6177), or write to

UNPS, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake City,

UT, 84152-0041 or email

Officers

President: Kipp Lee (Salt Lake Co)

Vice President: Jason Alexander (Utah

Co)

Treasurer: Charlene Homan (Salt Lake

Co)

Secretary: Mindy Wheeler (Summit Co)

Board Chair: Robert Fitts (Utah Co)

UNPS Board: Walter Fertig (Kane Co),

Susan Fitts (Utah Co), Ty Harrison (Salt

Lake Co), Celeste Kennard (Utah Co),

Bill King (Salt Lake Co), Margaret Malm

(Washington Co), Larry Meyer (Salt

Lake Co), Therese Meyer (Salt Lake Co),

Leila Shultz (Cache Co), Dave Wallace

(Cache Co), Blake Wellard (Davis Co),

Maggie Wolf (Salt Lake Co).

Committees

Conservation: Bill King & Tony Frates

Education: Ty Harrison

Horticulture: Maggie Wolf

Chapter News

Cache: Plant Propagation Workshop,

Thursday, March 14 @ 6 PM and Sat-

urday, March 16 @ 9 AM. USU Teach-

ing Greenhouse (1390 North 800 East

Logan). Registration: $20 for UNPS

members of Cache Master Gardeners

(must state at time of registration);

$25 for all others. Cost includes

growing materials and selected seeds.

Other seeds or cuttings available for

additional purchase to cover cost. $5

for printed workbook (must be re-

quested at time of registration, other-

wise all printed materials will be

available online). To register, please

call 435- 752- 6263 or email taun.

beddes@usu.edu. For more informa-

tion, please contact Michael Piep at

Michael.piep@usu.edu. Co-sponsored

by the Cache Chapter and the Cache

Master Gardeners - Michael Piep.

Salt Lake: March 6, 7 PM at REI

(3300 S and 3300 E): Walter Fertig,

past president of UNPS and Sego Lily

Above: What is this funny thing? If you

have to ask, you probably are like me

and don’t have a smart phone and so

won’t be able to upload content from

this issue. So just enjoy the abstract

patterns. If you are tech-savvy, give

thanks to Bill Gray for making this QR

(“ Quick Response”) code for us.

Utah Valley: For anyone interested

in a morning hiking group in Utah

Valley contact me at 801-377-5918 or

and more details. First outing will be

Tuesday, April 9th at 9:30 AM,

weather permitting. Meet at the Rock

Canyon trailhead in Provo near the

restrooms. The next week (April

16th) will be a Shoreline Trail hike

starting at Slade Canyon in Provo.

This is not the Plants and Preschool-

ers Group, as we will be hiking fur-

ther and rougher terrain, but every-

one is welcome. We will try to make

this a regular event every Tuesday

morning. - Celeste Kennard

editor, will give a program on

“Wildflowers of Zion National Park”.

Southwestern: In response to par-

ticipants in our pruning workshop,

Rick Heflebower is planning a graft-

ing workshop for Saturday, March 2,

at 10 AM at the Canyon Community

Center in Springdale. Rick will also

talk briefly about fruits brought to

the area by early pioneers. - Marga-

ret Malm

3

Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

Bulletin Board

2013 Utah Rare Plant Meeting: The annual rare plant meeting sponsored by the Utah Native Plant Society and Red

Butte Garden is scheduled for Tuesday, March 5, 2013 from 9 AM to 4 PM in the conference room at Red Butte Garden.

The meeting will include more than a dozen 15-20 minute presentations by a variety of speakers studying plant conser-

vation biology in Utah. Some of the speakers and topics for this year’s meeting include: Jena Lewinsohn, USFWS

(Autumn buttercup); Tony Frates, UNPS (Wasatch fitweed pollination), Hope Hornbeck, SWCA (Demographic monitoring

of rare Uinta Basin cacti); Rita Reisor, Red Butte Garden (Gierisch’s globemallow and Uinta Basin hookless cactus); Blake

Wellard, University of Utah (Petalonyx parryi); Robert Fitts, UT Conservation Data Center (update on rare plant studies);

Juliette Baker, Utah State University (Shrubby reed-mustard); Jason Alexander, Utah Valley University (UVU projects);

Dorde Woodruff, cactophile (Sclerocactus blainei); Michael Piep, Utah State University (Utah fungi); Leigh Johnson, Brig-

ham Young University (Mussentuchit gilia); Loreen Allphin Rapier, Brigham Young University (Conservation of rare

Boechera); Jim Harris, Utah Valley University (Deep River Range Drabas); Mitch Power, University of Utah (role of muse-

ums and herbaria in global change research), Ron Bolander, UT BLM (BLM update), and Wayne Padgett, UT BLM (Rare

plant considerations in use of native plants for restoration in the Colorado Plateau).

Participants can register online at the Red Butte Garden website (www.redbuttegarden.org/conservation) or by call-

ing the Red Butte front desk (801-585-0556), A boxed lunch will be provided as part of the $15 registration fee, but only

for those who register before March 1. —W. Fertig

UNPS Scholarship: Students are encouraged to apply for the annual UNPS student research scholarship. The Society

will award $500-1000 for research proposals that address native plant taxonomy, ecology, or biology within the state of

Utah. See the UNPS website for more details and the application form. Applications are due by 1 April 2013.

Help Wanted: The Utah Conservation Data Center (natural heritage program) needs help with general office work,

mapping plant occurrences, and field work. This is a great opportunity to lean GIS. Please contact Robert Fitts in the bot-

any program for more information (801-538-4742).

Photos Needed: Bruce Barnes of Flora ID Northwest is revising his Interactive Plant Key for the flora of Utah and is in

need of a few photos. Of the 3418 species of flowering plants, gymnosperms, ferns, and lycophytes in his guide, he is

missing just the following 12 species! If you have a photograph of one of these plants and are willing to share it, Bruce

will include your name in the lower corner of the image, add you to the acknowledgements in the User’s Guide, and send

you a complimentary copy of the key (all while you retain copyright). The missing species (including their range in pa-

rentheses) are: Aquilegia desolaticola (NE Utah), Boechera pendulina (statewide), Eremogone loisiae (N Utah and Wasatch

Range), Erigeron higginsii (Washington Co.), Erigeron huberi (NE Utah), Eriogonum domitum (House Range in Millard

Co.), Lepidium moabense (SC and SE Utah), Navarretia furnissii (N Utah), Navarretia saximontana (Garfield Co.), Phacelia

argylensis (NE Utah), Potentilla holmgrenii (Juab Co.), and Suaeda linifolia (N Utah). Send images or questions to Bruce at

flora.id@wtechlink.us

Herbarium Days at Utah Valley University (Saturdays March 30, April 27, and May 25): The UVU Her-

barium is sponsoring another series of workshops to train volunteers how to use our digital imaging system and how to

mount plant specimens. Volunteers at these workshops greatly accelerate the herbarium's progress in processing our

backlog and will learn more about the plants in our region in the process. We will be going back to holding the event on

Saturdays and will now be located in the new UVU herbarium facilities. The herbarium, will also be hosting a Utah Valley

Chapter meeting toward the end of the volunteer session. Plant mounting will take place in SB 277 in the new Science

Building and run from 1 PM until 5 PM. The meeting will start around 4 PM. For the meeting I will be continuing my

seminar series titles “Pictorial Introduction to the Morphology of Utah’s Beardtongues”. Parking is not currently avail-

able in the Sorenson Visitor Lot due to construction, but is available at the Lakeside Visitor Lot (at the south entrance

past the traffic circle off University Avenue) and the student lots between the UCCU events center and the library. For

further information, contact me (801-863-6806; alexanja@uvu.edu) - Jason Alexander

New Life Member: Claire Crow of Tucson, AZ (formerly wildlife biologist for Zion NP) is our newest life member.

Thanks Claire. This just proves you can like that “other kingdom”, but still appreciate native plants!

Pocket Sagebrush Guide Available for Free Download: UNPS board member Leila Shultz has a new publication

on identifying the woody sagebrush species of western North America. This non-technical and fully illustrated field guide

is available to download from www.sagestep.org/pubs/pubs/sagebrush_pock_guide.pdf

4

Utah Native Plant Society

Unidentified Flowering Object: This month’s UFO is provided

by Bill Gray of the Salt Lake City Chapter. While perhaps not as

challenging as some of our recent UFOs, study the photo carefully

to notice the differences between each flower. Why does the flower

at lower left have an enlarged white 4-lobed stigma, but the others

do not? Why are the stamens full and pink in some flowers, but

withered and even greenish-blue in others?

The January UFO was Evolvulus nuttallianus, a member of the

morning-glory family (Convolvulaceae).

Have a UFO to share? Send it in! - W. Fertig

Above: Noel

(kneeling) and Pat

Holmgren in their

natural habitat,

pressing a collection

of Silene petersonii

var. petersonii (left)

for the New York

Botanical Garden

herbarium outside

of Cedar Breaks

National Monu-

ment, Utah, in 2009.

Photos by W. Fertig.

Holmgrens Honored by

American Society of Plant

Taxonomists

Citing their many contributions to

botany, the American Society of Plant

Taxonomists conferred the 2012 Asa

Gray Award to Drs. Patricia and Noel

Holmgren of the New York Botanical

Garden. The award honors Asa Gray

(1810-1888), the most prominent

American plant taxonomist of the

second half of the 19th Century.

Among their many accomplishments,

the Holmgrens recently completed

the 8 volume Intermountain Flora

series (1972-2012) and edited the

Index Herbariorum and Illustrated

Companion to Gleason and Cronquist’s

Manual of Vascular Plants. Pat was

Director of the New York Botanical

Garden from 1981-1990 and a past

president of the American Society of

Plant Taxonomists and the Botanical

Society of America. Noel was for-

merly editor-in-chief of the New Tork

Botanical Garden’s journal Brittonia.

Although both Holmgrens are now

retired to Logan, Utah (where Noel’s

father, Arthur was a curator of the

Intermountain Herbarium at Utah

State University), they remain active

in western botany. Noel is currently

working on the treatment of his be-

loved genus Penstemon for the Flora

of Oregon project.

In Quotes: “If you want to walk fast, walk alone. If you want to walk far,

walk with others. Unless you are on a plant walk, in which case you will be

lucky to get 100 feet from the cars in two hours” - modified African

proverb

5

Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

Hanging Gardens of Utah

By Walter Fertig

Although best known for his explo-

ration of the Grand Canyon and con-

tributions to geology and linguistics,

Major John Wesley Powell was also

an astute ecologist. In late July 1869,

Powell’s small fleet of wooden boats

paused in the deep canyon of the

Colorado River near modern-day

Page, Arizona, for a brief side trip to

explore an unusual vegetation fea-

ture. “Sometimes the rocks are over-

hanging” Powell noted in his book

Canyons of the Colorado, “in other

curves curious narrow glens are

found. Through these we climb, by a

narrow stairway, perhaps several

hundred feet, to where a spring

bursts out from under an overhang-

ing cliff and where cottonwoods and

willows stand, while along the curves

of the brooklet oaks grow, and other

rich vegetation is seen, in marked

contrast to the general appearance of

naked rock”. Powell named these

features oak glens, and the canyon in

which they occurred Glen Canyon.

Powell was the first scientist to

recognize what we now call “hanging

gardens”. Not unlike their namesake

from ancient Babylon, hanging gar-

dens consist of plants clinging to

steep cliffs, rubble fields, or alcoves

associated with small seeps in other-

wise barren settings. Hanging gar-

dens are only found in the Colorado

Plateau area of Utah, Arizona, and

Colorado along the main stem of the

Colorado River and its tributaries.

Although small in size, hanging gar-

dens are important oases of cool

shade, water, and cover in a sea of

aridity and thus attract dispropor-

tionate attention from wildlife and

humans.

Three ingredients are necessary

for a hanging garden: a reliable water

source, the proper geology, and

plants. Water is the most limiting

ingredient in the desert, and the main

reason that hanging gardens are nei-

ther larger nor occur more widely.

Certain sandstone formations on the

summer rainstorm. Plants may grow

on the back wall of the alcove along

the seep or dripline, on the overhang-

ing roof of the alcove (such plants

truly are “hanging on”), or among the

colluvial debris at the base of the gar-

den.

Hanging gardens form in a variety

of geologic layers. Most often, gar-

dens occur in thick, cross-bedded

sandstones derived from ancient

sand dunes, such as the Navajo and

Entrada formations. One notable ex-

ception, however, is the Wingate For-

mation. This massive sandstone is

not underlain by impervious clays,

Colorado Plateau have sufficient

pore space between the sand grains

or cracks and faults to act as giant

rocky sponges that can accumulate

and transport water from rain or

melting snow. Water moves slowly

through the sandstone (sometimes

taking many years) until it hits an

impervious layer of shale or heavy

clay. When blocked by such an

“aquitard” water flows laterally un-

til it either bypasses the barrier or

reaches the surface to emerge as a

seep. Often the seep is long and

linear, forming a dripline. If the

seep is sufficiently shaded within a

deep canyon or by an overhanging

ledge the wall will remain moist

enough to allow plants to become

established. These first plants must

literally cling for their lives on the

slickrock walls.

Over time, erosion caused by

dripping water and the plants them-

selves helps sculpt the shape of the

hanging garden. Saturated rock at

the seep face becomes weak and

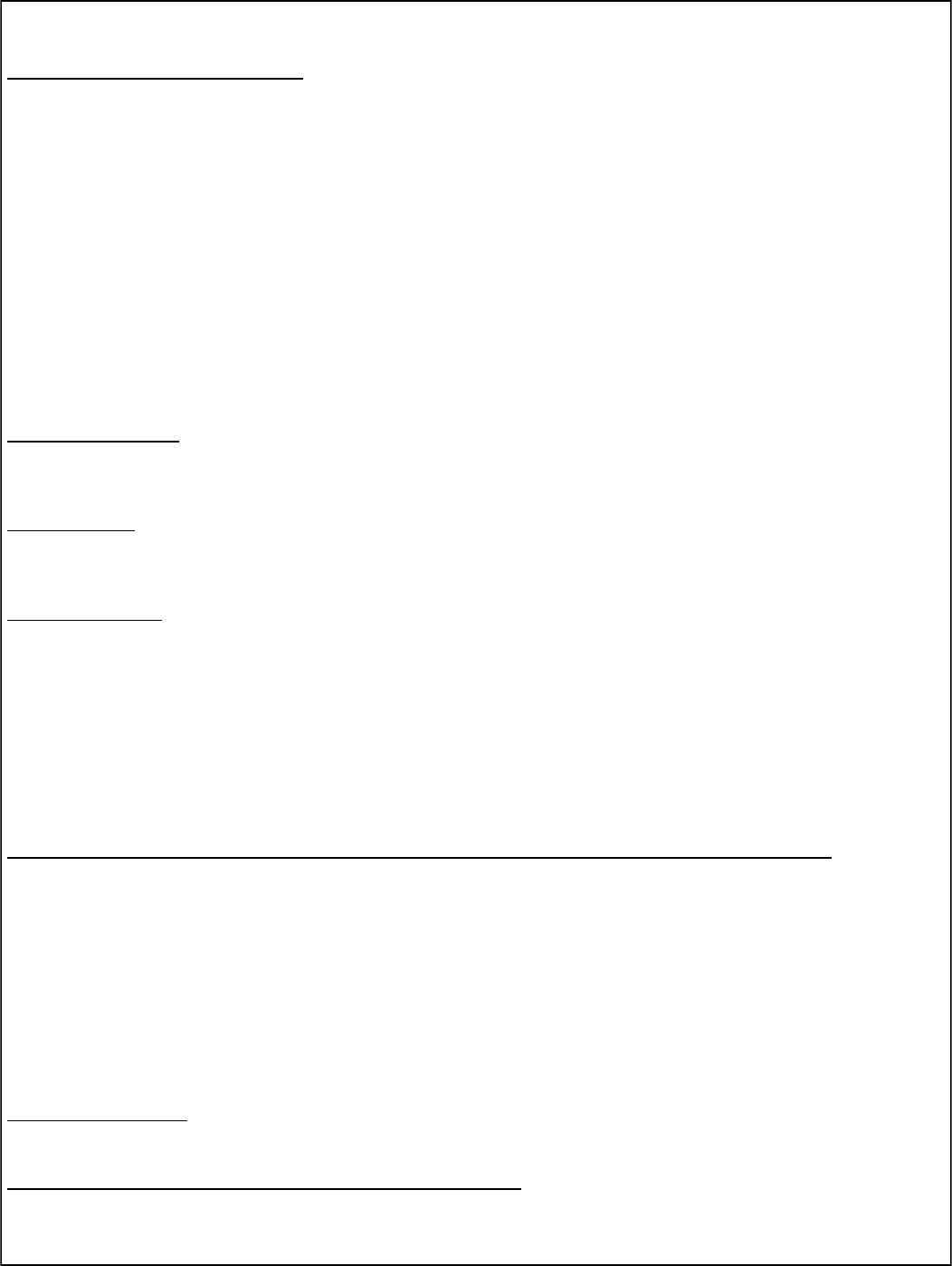

Above: A complex hanging garden in Zion National Park consisting of a series of driplines

wetting a shady back wall and a set of terraces. The vegetation consists of common riparian

species such as Calamagrostis scopulorum and Rhus trilobata interspersed with hanging

garden endemics like Viola clauseniana, Dodecathenon pulchellum var. zionense, Aquilegia

fosteri, and A. chrysantha. Photo by W. Fertig.

sloughs off, creating a colluvial slope

below and excising an alcove into the

cliff face. Plant roots secrete mild

acids that help weather the soft sand-

stone walls, further enhancing ero-

sion. Rock spalled off the cliff face

creates a steep talus slope of broken

sandstone below. Some gardens may

also have a deep plunge pool at their

base formed by water pouring off

smooth cliff faces after a torrential

6

Utah Native Plant Society

and thus allows water to flow right

through, rather than emerging in

seeps. Hanging gardens have been

documented in other formations,

ranging from the Pennsylvanian age

Hermosa Formation in Cataract Can-

yon to the Cretaceous Wahweap and

Straight Cliffs formations in the Kai-

parowits Plateau. Most of these for-

mations are thinner or have less wa-

ter-holding capacity than the Navajo

or Entrada sandstones and tend to

produce smaller seeps and less com-

plex gardens.

Not all hanging gardens have the

classic alcove-like morphology. In

Zion National Park, many gardens

occur on weeping walls, in which an

entire cliff face may be wet from a

parallel series of seeps, rather than a

single seep or dripline. Also known

as a window blind garden, this type

often lacks a deeply eroded alcove

roof. Sometimes they are associated

with chimney-like deposits of dried

carbonates called tufa. A less com-

mon hanging garden type consists of

a series of terraces or stair steps.

These form where the bedrock does

not erode to form an alcove, but in-

stead water flows over short ledges

representing different sandstone or

shale bands (Welsh and Toft 1981).

Many variations occur, and some

complex gardens may combine ele-

ments of two or more geomorphic

types.

Until recently, hanging garden

vegetation was often treated as a sin-

gle, homogeneous ecological commu-

nity. Studies by George Malanson

(1980) in the Zion Narrows demon-

strated that the species composition

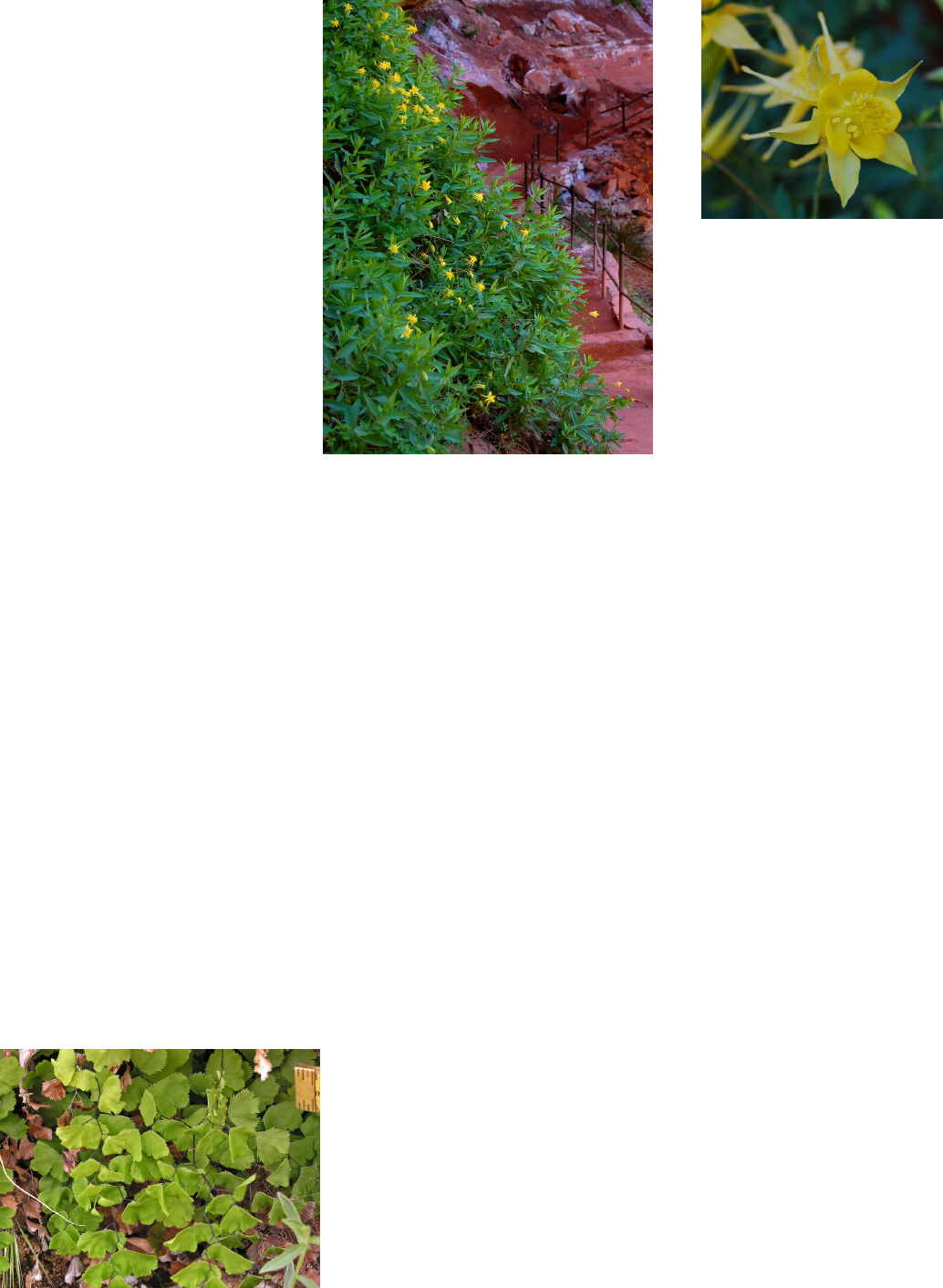

Below: Southern maidenhair fern (Adian-

tum capillus-veneris), a common hanging

garden species in Utah. Photo by Al Schnei-

der (www.swcoloradowildflowers.com)

Other hanging gardens, such as many

from Zion National Park, don’t easily

fit into Fowler’s categories and may

be dominated by Zion shooting-star

(Dodecatheon pulchellum var. zi-

onense), Welsh’s aster (Aster welshii),

or Blueleaf aster (Aster glaucodes).

Due to its isolation, the Virgin

River has a suite of hanging garden

species that are not found on the

main stem of the Colorado River.

Even more interesting, is the pres-

ence of “congener pairs” (closely re-

lated members of the same genus) in

which one species is in the Virgin

drainage and the other in the Colo-

rado. Perhaps the most notable such

pair is Cardinal monkey-flower

(Mimulus cardinalis) and Eastwood’s

monkey-flower (M. eastwoodiae).

Both species have large, two-lipped,

reddish-orange corollas and sharply

toothed, opposite leaves. Cardinal

monkey-flower ranges widely across

western North America, though it

only occurs in Zion National Park in

Utah. Eastwood’s monkey-flower is

endemic to the canyons of the Colo-

rado River in the Four Corners Re-

gion, but is absent from Zion. Mimu-

lus eastwoodiae probably evolved

from populations of M. cardinalis that

became isolated in relatively recent

times.

In other cases, the less common

member of a congener pair is re-

stricted to the Virgin River, while

Above and left: Golden columbine

(Aquilegia chrysantha) is a common

hanging garden species in Zion Na-

tional Park. It can hybridize with the

red-flowered A. fosteri to form orang-

ish-yellow hybrids, which often co-

occur with one or both parents. Else-

where on the Colorado Plateau, this

species is replaced by another yellow

flowered species, A. micrantha. Photos

by Steve Hegji.

of hanging gardens is actually quite

diverse. Malanson found that gar-

dens varied widely in species rich-

ness (ranging from 2 to 20 species)

and representation of both common

riparian species and hanging garden

specialists. No single species oc-

curred in all 29 gardens that he ex-

amined.

Fowler et al. (2007) reported

similar results in a study of 73 gar-

dens across the Colorado and Virgin

River watersheds. The authors

used cluster analysis to organize the

hanging gardens into four main as-

sociations and a fifth, garbage-can

group for sites that were sufficiently

unique to defy classification. Each

association was named for its most

abundant species.

In Fowler’s system, Southern

maidenhair fern (Adi-antum cap-

illus-veneris) tends to be the domi-

nant species in relatively simple

gardens with a single dripline in

Navajo or Entrada Sandstone. Al-

cove columbine (Aquilegia micran-

tha) is often the most abundant

species in gardens on Cedar Mesa or

Weber Sandstone with moist collu-

vial slopes (such as those at Natural

Bridges and Dinosaur National

Monuments). Larger, wetter, or

more complex gardens tend to be

dominated by Jones’ reedgrass

(Calamagrostis scopulorum) or Ryd-

bergs’s thistle (Cirsium rydbergii).

7

Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

mediates between A. chrysantha

and A. fosteri, recognized by their

orangish flowers, are common at

the Weeping Rock hanging garden

in Zion National Park.

In all, more than 200 plant spe-

cies have been documented from

hanging gardens in Utah. These

species fall into four main catego-

ries: hanging garden endemics,

widespread wetland species, upland

species, and disjuncts. Only about a

dozen species are strict hanging

garden endemics (occurring no-

where else) and another dozen or

so can also be found along stream-

sides or in upland habitats. Besides

the endemics mentioned previously

are such species as Kachina daisy

(Erigeron kachinensis), Alcove prim-

rose (Primula specuicola), Zion

jamesia (Jamesia americana var.

zionis), Toft’s yucca (Yucca toftiae),

Alcove bog orchid (Platanthera

zothecina), Alcove rock-daisy

(Perityle specuicola), and Alcove

death camas (Zigadenus or Anticlea

vaginata).

Disjuncts found in hanging gar-

dens are often species more typical

of cool, northerly climates that be-

came isolated in the canyon country

after the Pleistocene, or have ar-

rived more recently via long-

distance dispersal. A number of

Great Plains grasses also re-occur in

hanging gardens, including Bushy

bluestem (Andropogon glomeratus),

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans),

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) and

Little bluestem (Schizachyrium sco-

parium).

Many of the largest and most inter-

esting hanging gardens in Utah are

found in National Parks and Monu-

ments. Despite their legal protection,

these gardens are still vulnerable to a

number of threats. Hanging garden

soils are fragile and easily disturbed

by visitors or livestock going off trail.

Invasive weeds are becoming a prob-

lem in many parks, particularly tama-

risk. In Zion, introduced Tall fescue

(Festuca arundinacea) is becoming

increasingly common in some hang-

ing garden sites and may be crowding

out rare species, such as Clausen’s

violet at Weeping Rock.

Perhaps the greatest threat comes

from drought and water develop-

ment. The potential effects of climate

change on hanging gardens are

poorly understood, as models predict

both hotter temperatures and wetter

conditions in the southwest. Diver-

sion of water from seeps for stock

tanks or human use has dewatered

many hanging gardens. Dam con-

struction and reservoirs in the Colo-

rado River have flooded some sites. It

is sadly ironic that formation of Lake

Powell destroyed many of the “oak

glens” that were originally discovered

by John Wesley Powell.

References

Fowler, J.F., N.L. Stanton, and R.L. Hart-

man. 2007. Distribution of hanging gar-

den vegetation associations on the Colo-

rado Plateau, USA. Journal Botanical

Research Institute Texas 1:585-607.

Malanson, G.P. 1980. Habitat and plant

distributions in hanging gardens of the

Narrows, Zion National Park. Great Ba-

sin Naturalist 40:178-182.

May, C.L. 1997. Geoecology of the hanging

gardens: Endemic resources in the

GSENM. Learning from the Land, Grand

Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Science Symposium Proceedings, Pp.

245-258.

Welsh, S. L. 1989. On the distribution of

Utah’s hanging gardens. Great Basin

Naturalist 49(1):1-30.

Welsh, S.L. and C.A. Toft. 1981. Biotic

communities of hanging gardens in

southeastern Utah. National Geographic

Society Research Reports 13:663-681.

the more widespread species occu-

pies the main stem of the Colorado.

Hays’ sedge (Carex haysii) of Zion

National Park closely resembles Can-

yonlands sedge (C. curatorum) of the

Colorado River, but has larger and

more narrowly lance-shaped perigy-

nia. Clausen’s violet (Viola clausen-

iana) is a blue-flowered Zion endemic

replaced by Northern bog violet (V.

nephrophylla) in Colorado River gar-

dens. The recently discovered Jo-

anna’s thistle (Cirsium joannae) is

restricted to Zion, while the compara-

ble Rydberg’s thistle is more wide-

spread. Both are remarkable in hav-

ing stems up to 6 feet tall and basal

leaves over a foot long.

Nearly half a dozen species and

varieties of columbine are found in

hanging garden sites across Utah.

These can be divided into two groups

depending on flower color (whitish/

yellow vs. red/orange). White or

cream-flowered Alcove columbine (A.

micrantha) is replaced by Golden col-

umbine (A. chrysantha) in Zion and A.

desolaticola in Desolation Canyon on

the Green River. Among reddish

flowered species, A. formosa is wide-

ranging but gives way to A. fosteri in

Zion NP, A. micrantha var. loriae in

the Grand Staircase area, and bicol-

ored A. micrantha var. grahamii near

Dinosaur National Monument. Hy-

brids may occur wherever yellow and

red species come in contact. Inter-

Above: Eastwood’s monkey-flower (Mimulus eastwoodiae), a Colorado River endemic

named for pioneer botanist Alice Eastwood, who was one of the first collectors of the

hanging garden flora of southeastern Utah, especially in the Bluff area. Photo by Al

Schneider ( www.swcoloradowildflowers.com).

8

Utah Native Plant Society

It seems that every few months

now we are confronted with the un-

wanted news that members of our

flora have “new” scientific names.

“Which of the several scientific names

should I be using” is a refrain often

heard. Actually, it is often the case

that many of these new names were

proposed decades ago. Regardless, it

wasn’t easy learning all those Lin-

naean binomials, and few appreciate

having to repeat the effort. In our

first plant taxonomy courses we were

told that scientific names were essen-

tial because they were stable and uni-

versal, while common names varied

depending on region and generation.

These days it seems that the common

names are more stable; Elymus spica-

tus, Agropyron spicatum, and Pseu-

doroegneria spicata are all currently

used scientific names for bluebunch

wheatgrass. So why are we burdened

with all this nomenclatural instabil-

ity?

To explore this question we must

recall the history of biological nam-

ing. Our modern system was devel-

oped by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish bi-

ologist in the middle 18th Century.

He proposed the binomial system in

which each species is identified by a

unique Latinized epithet and a ge-

neric epithet shared by other similar

species. Linnaeus primarily used sta-

men characters to assign degree of

similarity. He developed this system

before Darwin and Wallace intro-

duced the ideas of natural selection

and the evolution of species. Once it

was accepted that newer species

evolved from older species, taxono-

mists strove to construct classifica-

tions based on principles of Darwin-

ian evolution. Thus, taxonomic no-

menclature came to serve two func-

tions: (1) providing standardized

names to facilitate communication

and (2) reflecting evolutionary rela-

tionships. Unfortunately, serving two

functions often causes conflict.

Above: Quackgrass, a.k.a. Agropyron repens, Elymus repens, or Elytrigia repens is a use-

ful forage grass but tends to spread aggressively by subterranean stems (rhizomes) and

infest fields of cultivated crops and wildlands. The species was originally named by Lin-

naeus as Triticum repens in Species Plantarum (1753) but transferred to Agropyron by

Beauvois in 1812, Elytrigia by Desvaux (1895), and Elymus by Gould in 1947. Each name

change was prompted by a revision of the generic concepts of the Triticeae, one of the

more complex tribes of Poaceae. Adapting to new names is not a burden unique to the

current generation of botanists. Illustration from Hitchcock and Chase (1950).

Agropyron by any Other Name is Still a Wheatgrass

By Peter Lesica and Matt Lavin

(adapted from Kelseya, the newsletter of the Montana Native Plant Society, Winter 2004)

Reasons for the current round of

scientific name changes relate to

one of the other of taxonomy’s func-

tions. A perennial cause of nomen-

clatural instability centers around

the debate over what delineates a

species. In plant taxonomy the is-

sue has turned as much on opinion

as data. “Splitters” believe there is

merit in recognizing small but consis-

tent variation at the species level,

while “lumpers” prefer to empha-

size the close relationship among

variants. In the first half of the last

century Kenneth Mackenzie and oth-

ers recognized many different species

9

Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

Indeed, hybrids between meadow

fescue and other ryegrasses are of-

ten used in lawn seed mixes. So

these former fescue grasses have

been transferred to Lolium.* There

is good evidence that some mem-

bers of the goldenweed genus

(Haplopappus) are more closely

related to goldenrods (Solidago),

while others are closer to rabbit-

brush (Chrysothamnus).

Some of these insights come from

new analytical methods made possi-

ble by computers. Others can be

traced to recent advances in mo-

lecular biology. Up until 50 years

ago, plant taxonomy relied entirely

on morphological characters such

as fruit shape, number of stamens,

type of hairs, etc. Shared traits can

be an unreliable indication of close

relationship because they can also

evolve in unrelated groups as a re-

sult of convergent natural selection.

For example, many species of cush-

ion plants occur on windswept al-

pine ridges. They superficially re-

semble each other because they

suffer the same harsh conditions,

but they come from many different

and unrelated plant families. Mod-

ern plant systematists are using

portions of DNA and computers that

can analyze lots of data to uncover

past misunderstandings in evolu-

tionary relationships made using

earlier morphological methods.

Although molecular characters and

analytical methods have advanced

the field of biological taxonomy,

these approaches may not always

yield a definitive answer. Analyzing

two different regions of DNA some-

times fails to give congruent classifi-

cations, and phylogenetic analysis

yields only the most likely classifi-

cation. Nonetheless, plant systema-

tists are constructing classifications

that better reflect the course of past

evolution, and they are changing the

nomenclature to reflect their new

understanding.

Unfortunately for users of scien-

tific names, many recently proposed

name changes are based more on

* But since transferred to their own

genus, Schedonorus, in Volume 24 of

Flora of North America (2007)

of similar-appearing sedges. Then

Arthur Cronquist, who authored flo-

ras for much of North America in the

latter part of the century, lumped

many of these sedge species together.

Now sedge experts are more inclined

to be splitters, and many of the spe-

cies recognized during Mackenzie’s

time have been resurrected in the

Flora of North America treatment.

What’s old is new again, and those of

us who cut our teeth on Cronquist’s

treatments will be learning a lot of

new old names. This seems like the

most arbitrary reason for nomencla-

tural instability, but it will probably

continue as long as taxonomists re-

main human.

The most understandable reason

for nomenclatural revisions has to do

with standardization. A great many

botanical names were generated dur-

ing the latter part of the 19th and

early part of the 20th centuries.

These names were published in jour-

nals and books that had limited geo-

graphic distribution at the time. Presl

described Poa secunda as new to sci-

ence in an obscure European publica-

tion in 1830 based on a collection

from Chile. More than 60 years later

Vasey described the same species as

Poa sandbergii in the Contributions

from the U.S. National Herbarium, ap-

parently unaware of Presl’s descrip-

tion. All this began to change when

communication and travel increased

dramatically following World War II.

Museum specimens and literature

were exchanged freely, and Elizabeth

Kellogg, working at Harvard, realized

that these two bluegrass species were

the same. International rules of nom-

enclature specify that the earliest

published name takes precedence, so

the correct scientific name for

Sandberg bluegrass became Poa

secunda, both in South America and

here. It’s the globalization of botany.

Many recent name changes at the

level of genus and family are due to

new insights on evolutionary rela-

tionships, For example, there is now

unequivocal evidence that tall fescue

(Festuca arundinacea) and meadow

fescue (F. pratensis), two tame hay

meadow grasses, are more closely

related to species of ryegrass (Lolium

spp.) than they are to other fescues.

opinion than sound scientific evi-

dence. There may be preliminary

evidence suggesting that the tradi-

tional scientific names don’t accu-

rately reflect evolutionary relation-

ships. However, there is often not

enough genetic or morphological evi-

dence yet available to determine how

the names should be changed to rem-

edy the problem. New Linnaean bi-

nomials derived from inadequate,

preliminary evidence will often prove

no better than the names in current

use. In many cases it would be a good

idea to continue using traditional

names until enough solid evidence

compels us to change.

There are often several synonyms

for a particular species, but few of us

have the time or skill to evaluate all

the evidence buried in the scientific

literature. How should we choose the

name to use? There are several good

websites that provide synonyms for

scientific names. These include

Tropicos at the Missouri Botanical

Garden website (http://mobot.org/

W3T/Search/vast.html) and the In-

ternational Plant Names Index

(www.ipni.org/index.html). The US

Department of Agriculture PLANTS

website (http://plants.usda.gov/

index.html) even suggests which

names to accept. However, there is

no such thing as a botanical nomen-

clature arbitration committee to de-

cide which name should be in use.

We agree with Wayne Ferren and

Robert Haller, former editors for the

California Botanical Society. Confu-

sion can be minimized by adopting

the nomenclature presented on a

credible regional or local flora and

reporting that source when you use

scientific names.

Most plant systematists are stu-

dents of evolution, and having classi-

fications that reflect evolutionary

processes is, in the long run, a valu-

able goal. Unfortunately, in the short

term this goal is at odds with the

other function of taxonomic nomen-

clature—stability and standardiza-

tion. Like it or not, we’re in for a pe-

riod of nomenclatural revolution, but

we hope to know more about the

workings of nature in the process.

We just wish our memories were as

good as when we were twenty.

10

Utah Native Plant Society

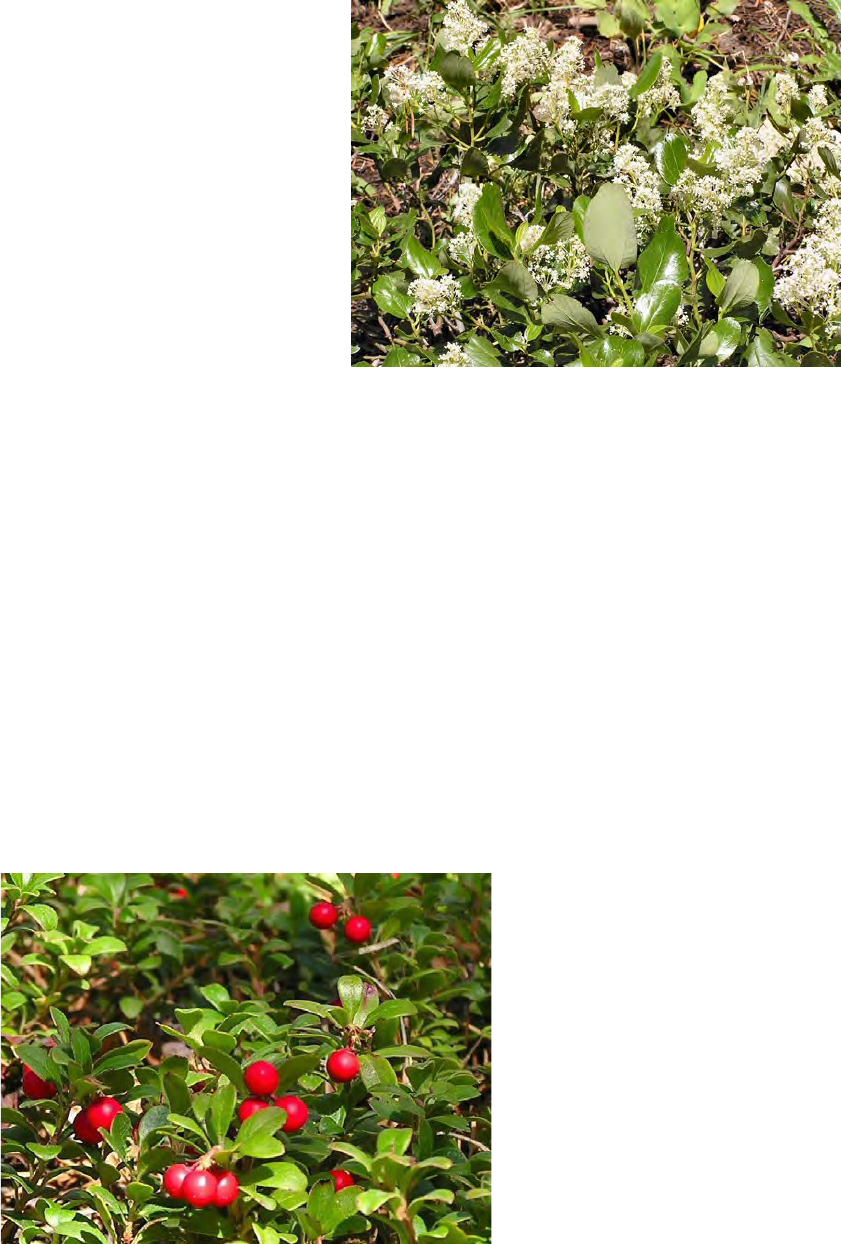

Short shrubs are used mostly

for cover, but some have attrac-

tive foliage, flowers, or fruits. A

sampling follows:

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, Bear-

berry, is a slow growing, ever-

green, mat forming shrub which

can reach about 1 foot high but is

usually only a few inches tall. The

leaves are dark green and shiny

and often turn bronze or occasion-

ally reddish in fall and winter.

The inconspicuous white to pink-

ish flowers are only about 1/4

inch long. The fruits are berry-

like and bright red and remain on

the plant until the birds get them.

The plant occurs naturally in

moist woods and thickets in the

mountains and foothills. It prefers

moist but well-drained soil and is

tolerant of heat, wind, and salt. It

does best in shade or part shade.

Small plants are easy to transplant

and it is easy to propagate from 6

inch stem cuttings in late summer.

Trim the leaves from the lower

third, dip ends in rooting hor-

mone, and plant the ends 2 inches

deep in peat moss and sand in

equal parts. Mist regularly. Keep-

ing them in a mostly closed clear

plastic container or covering will

varnished. The white flowers are

tiny but are aggregated into large,

showy clusters at the ends of the

branches. It occurs naturally in

moist to dry open woods or open

areas in the mountains. It re-

quires good drainage in full sun

and does not tolerate overwater-

ing nor highly alkaline soils. It can

be propagated from 2 or 3 inch

branch tip cuttings in late summer

dipped in rooting hormone. Pro-

vide bottom heat to the pots or

flats (70-80° F). Growing from

seed is a little tricky. Collect the

seed just before the capsules

open. Put the capsules into a pa-

per bag immediately. The seeds

fly out when the capsule splits.

Bring some water to a near boil,

turn off the heat, put in the seeds,

and leave until the water cools.

Then cold stratify for 60 days or

more and surface sow. It may

take 100 days or more for germi-

nation.

help retain humidity. Once

rooted (generally 6-8 weeks),

put in pots of equal parts sand

and loamy soil, mulch heavily,

and store in a cold area for the

winter. Plant out in the spring

minimizing disturbance to the

roots. It is also available in the

nursery trade.

Ceanothus velutinus, Big buck-

brush, is an evergreen shrub to 3

feet (rarely 6 feet) high and of-

ten forms large dense colonies.

The leaves are fragrant and the

upper surface appears like it is

Grow This:

Short Shrubs

By Robert Dorn (adapted from Castilleja, the publication of the Wyoming Native Plant Society)

Above: Ceanothus velutinus from Carbon County, Wyoming. Below: Arctostaphylos uva-

ursi, from Albany County, Wyoming. Photos by Robert Dorn.

11

Sego Lily March 2013 36 (2)

The Funny Pages:

Black-eyed Susan by Anne Garde [for best results, read out loud]

I rose early, at four o'clock, the morning glory still iris

away. I was worried. Anemone of mine, Johnny Jump Up,

was looking for me, and I'd heard he was carrying a pistil,

a 357 magnolia. I ironed a periwinkled blouse, got

dressed, and took a sprig of a dusty Miller's beer. Johnny

Jump Up. He was one of several rhizomes who'd gone to

seed in Forsythia, Montana. He was convicted of graft in

1984, arrested again in '85 for digging up coreopsis. Then

he drifted on the wind up to my neighborhood, the corner

of Hollyhock and Vine. He was a petal pusher in a phlox-

house nearby.

I knew he was trouble when he rhododendron to my

house and said, "Hey, little Black-eyed Susan, wanna come

over to my place and take a look at my vetches?" I didn't

want to te1l him that in all the cosmos, there was no one

for me but Sweet William, so I said no, I was taking care of

a pet dogwood that'd had a litter of poppies, which was

weird cause she'd just been spaded. But Johnny had no

sense of humus. He stamped his foot with impatiens.

"You'll rue the day you turned me down" he snapped.

Then he spit a wad of salvia into the petunia on my portu-

laca and stalked away. “Forget me not, Sue, cause I'll be

zinnia."

Ever since then, he'd cultivated a relationship with Lily

of the Valley, a self-sowing biennial. One day, I aster what

she seed in him. "Mum's the word on this" she said, "He's

got a trillium dollars in the bank. "

"A trillium?" I snorted. "He's lime to you. Besides, what

about love?”

"Alyssum" she said. "You bleeding hearts are all alike.

Kid, you can go for a guy who'll azalea with affection. Or-

chid, you can be like me and try to marigold. Now bego-

nia. "

Now I was in my kitchen, mullein over these past

events. But it was thyme to quit dilly-dahlia-ing. The ca-

lendula read August 3rd, and Johnny had sworn to propa-

gate vengeance before the snowdrop.

I hopped into my auto-lobelia and drove over to Daisy's

for help. Daisy was a pretty little transplant from Florida,

who'd wilted in the humidity there, but was rooted in the

well-drained soil of Bloom County. She mostly took care

of her babies breath, but lately she'd branched out and

was columbining work with home life. "We're all sick to-

day, I think it's gaillardia" she said. "Even the cat’s got

harebells. If we could take a knapweed be OK." Her face

was a bright yellow. She'd be no help.

I beetled feet over to Sweet William's. "Will, am I

gladiolus to see you." "And Blackeyed Sue. I been praying-

mantis see you. Let's lilac in the snow on the mountain

before it all melts down the geranium. Let's ride a sage to

Tansy-nia. It's only a chamomile away. "

"Don't be fritillary, honeysuckle " I said, clinging to him.

"Look. Here comes the clematis of the story."

Uh oh. Johnny had hired Pete Moss, a bearded iris-man

to do me in. He was wearing a blue nectar and larkspurs.

He had a larva men with him. The pests. They began to

charge. In all the con-fuschia, I said to Will , "Stem still and

give me some ground cover." I ran down the primrose

path in my ladyslippers, right towards Pete. "Don't gimme

any flax, bud or I’ll slug ya," I said. "You'11 look dandelion

in the alley." "Don't gimme any flax bud, "--Pete quoted

me verbena. It nettled me. I clovered him with a 2x4.

"Sound the tim-pansy" we sang. "We won.” “Curses, "

moaned Pete, "foliaged again. "

"I noticed Johnny Jump Up planted on the border. "I've

sunk pretty loam, Sue, but now I'm turning over a new

leaf."

"Bouquet, " I said. And he did. And Will and I lived

pearly everlasting.

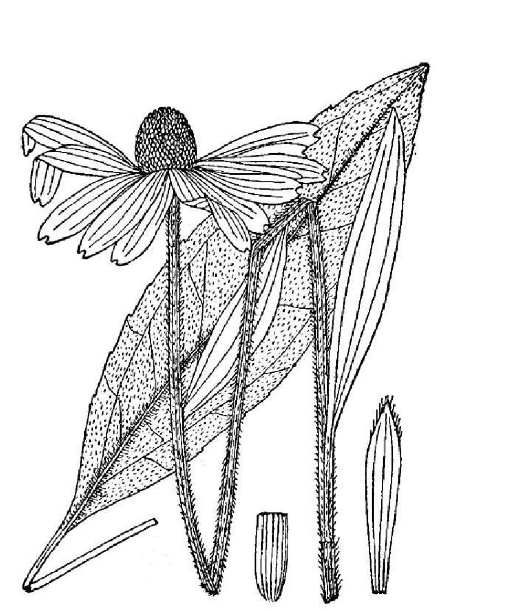

Above: Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) is native to the Great

Plains and eastern North America, but is introduced in Utah.

Three native species occur in the state. Cutleaf coneflower (R.

laciniata) has showy yellow ray flowers and deeply lobed leaves

and is known from the La Sals. Western coneflower (R. occiden-

talis) and Mountain coneflower (R. montana) lack ray flowers but

are characterized by raised cones of black disk flowers. These

two species differ in leaf shape, pubescence, and distribution, with

Western coneflower being common throughout the mountains of

Utah but Mountain coneflower only found in SW Utah. Illustra-

tion from Britton and Brown (1913) An Illustrated Flora of the

Northern United States, Canada, and the British Possessions.

12

Utah Native Plant Society

Utah Native Plant Society

PO Box 520041

Salt Lake City, UT 84152-0041

Return Service Requested

Utah Native Plant Society Membership

__ New Member

__ Renewal

__ Gift Membership

Membership Category

__ Student $9.00

__ Senior $12.00

__ Individual $15.00

__ Household $25.00

__ Sustaining $40.00

__ Supporting Organization $55.00

__ Corporate $500.00

__ Lifetime $250.00

Mailing

___ US Mail

___ Electronic

Contribution to UNPS scholarship fund ____ $

Name ______________________________________________________

Street ______________________________________________________

City _________________________________________ State ________

Zip __________________________

Email _______________________

Chapter _____________________________ (see map on pg 2)

__ Please send a complimentary copy of the Sego Lily to

the above individual.

Please enclose a check, payable to Utah Native Plant So-

ciety and send to:

Utah Native Plant Society

PO Box 520041

Salt Lake City, UT 84152-0041

Want to download this and previous issues of Sego Lily in color? Or read late breaking UNPS news

and find links to other botanical websites? Or buy wildflower posters, cds, and other neat stuff at the

UNPS store? This is a limited time offer (available just 365 days a year) so go to unps.org now!