Seed to Table

a secondary experiential education

agriculture and culinary arts curriculum

The Seed to Table Curriculum was developed by

Goodman Community Center is located in

Madison, WI. GCC strengthens the lives of the

people in its community by offering a diverse

array of programs and resources for people of

all ages. The center includes a teen run café, a

fitness center and gym, art rooms, a large food

pantry, community meals, preschool, and teen

center.

goodmancenter.org

Community GroundWorks is an educational

organization in Madison, WI. A 5-acre CSA

farm, award winning youth gardening

programs, a community garden and a natural

areas restoration program connect people to

nature and growing food.

communitygroundworks.org

East High School is a public school with a

diverse student body serving Madison, WI.

Students and teachers strive for excellence

while engaging in innovative curriculum.

eastweb.madison.k12.wi.us

Madison East High School

School

This product was funded by a grant awarded under the Workforce Innovation in Regional Development (WIRED)

Initiative as implemented by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration. The

information contained in this product was created by a grantee organization and does not necessarily reflect the

official position of the U.S. Department of Labor. All references to non-governmental companies or

organizations, their services, products or resources are offered for informational purposes and should not be

construed as an endorsement by the Department of Labor. The product is copyrighted by the institution that

created it and is intended as individual organizational non-governmental use only.

Seed to Table

Table of Contents

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………….…6

Part One: In the Field

Unit 1: History of Agriculture

Local Foods of Wisconsin ………………….……………………………………….…9

Geographic Origins of What You Eat …………………….…………..…………….…17

Historical Overview of Agriculture ……………..………….……………...……….…20

Organic vs. Conventional Farming ………………..………….…………..…….……..23

Grow Your Own Food……………………………………..…..………………………29

Who Grows Our Food? ……………………………….……………………………….31

So You Want to Be a Farmer? ………………….…………..…………..……………..35

Unit 2: Food Systems

From Farm To Table: Understanding Food Systems……..……………………………39

Ecosystems & Agroecosystems…….…………..………………………………………43

Organic Farming Business Structures – Case Study: Organic Valley…………………47

Unit 3: Local Foods

Eating with the Seasons………………………………………………………………...51

A Locavore Foodshed…………………………………………….…………………….56

Exploring Local Farms in WI.…….…… ………..…………………………………….60

Edible Plant Parts…………………….………………………………………..……….62

Exploring Your Local Grocery Store..…………….…………..……………………….67

Unit 4: Farm Planning

Designing Your Garden………………………………………………………………...73

How Are These Crops Planted? …………………..…………………………………...76

Creating a Planting Schedule………………....………….…………..…………………78

What is a Seed? …………..……………………………………………………………81

How to Start Seeds………………………..………….…………..…………………….84

Temperature Readings in Greenhouse……………………..…………………………..88

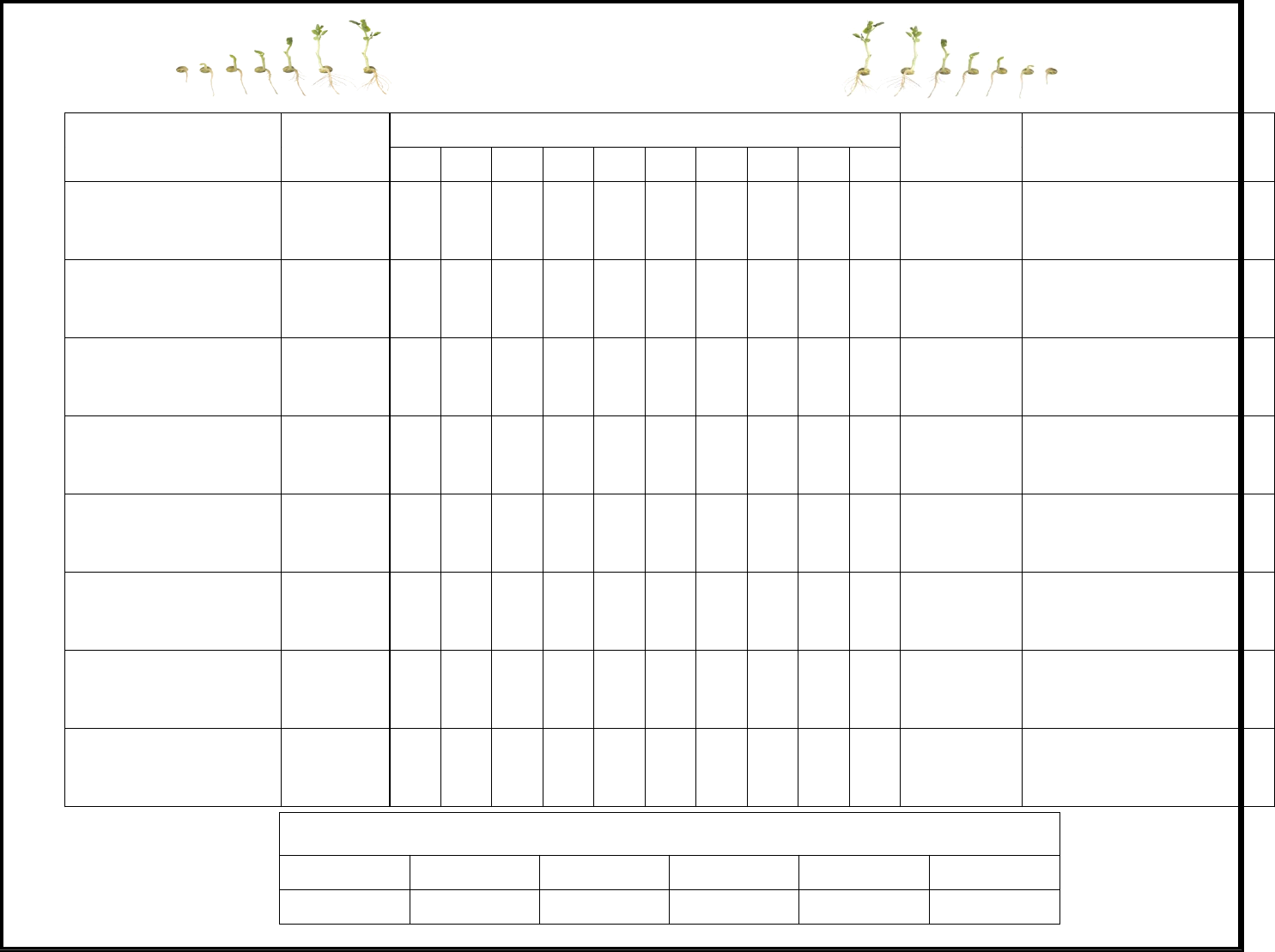

Tracking Germination……………………………………………..…..…………….…91

Unit 5: Planting and Harvesting

Spring Cultural Celebrations…………………..……………………………………….98

Fall Harvest Cultural Celebrations………………………..……….………………….102

Spring Gardening Topics ……………………..………….…………..……………….107

4

Direct Seeding and Transplanting…………………………..……………………….110

Harvesting Techniques….…………………………….…………..…………………114

Water Needs of Crops……………………………………....………………………..120

Nutrient Cycle: What Plants Need……………..…..………………………………...123

Compost MacroInvertebrates…………………………..…………………………….129

Compost, Recycling and Trash………………………………..……………………..132

Unit 6: Saving Food

Food Preservation………………………………………..…………………………..146

Growing Garlic………………………………………………………………………155

Unit 7: Veggie of the Month

Veggie of the Month: Beet…………………………………………………………..159

Veggie of the Month: Carrot……………..………….………….…..……..………...161

Veggie of the Month: Potato……………………….………..………………………163

Veggie of the Month: Rhubarb……………….………….…………..……………...165

Veggie of the Month: Pepper………………….…………..………….……………..167

Veggie of the Month: Winter Squash………………….…………..……………..…169

Veggie of the Month: Template……………………………………………………..171

Part Two: In the Kitchen

Unit 1: Introduction to ―In the Kitchen‖

Food Rules…………………………………………………………………………….181

Where to Find Food…………………………………………………………………...187

Omnivore's Dilemma………………………………………………………………….193

Food Security………………………………………………………………………….198

Fair Trade……………………………………………………………………………..202

Cultural Cooking……………………………………………………………………...207

Food Entertainment…………………………………………………………………...210

Food Allergies………………………………………………………………………...214

Vegetarianism…………………………………………………………………………221

Restaurant Review…………………………………………………………………….227

Unit 2: The Ins and Outs of Preparing Meals

Balanced Meal (protein, carbohydrate, vegetable)……………………………………233

Recipe (Read, Adapt, Create)…………………………………………………………239

Recipe Conversion…………………………………………………………………….253

Reading Ingredient Labels…………………………………………………………... 261

Safe Knife Handling Skills……………………………………………………………267

Salads………………………………………………………………………………….271

Soups………………………………………………………………………………….279

5

Entrées……………………………………………………………………………….290

Side Dishes…………………………………………………………………………..294

Rice…………………………………………………………………………………..297

Pasta………………………………………………………………………………….301

Desserts………………………………………………………………………………306

Iron Works Chef: Cooking Competition……………………………………………..310

Unit 3: Learning to Work as a Culinary Arts Professional

Meet a Chef ………………………………………………………………………….317

Dress for Success…………………………………………………………………….322

On Time to Work…………………………………………………………………….327

Customer Service…………………………………………………………………….332

Working with the Boss……………………………………………………………….336

Tips…………………………………………………………………………………...342

Dishwashing………………………………………………………………………….347

Catering………………………………………………………………………………352

Unit 4: Science of Cooking

Got Milk……………………………………………………………………………...362

Eggs…………………………………………………………………………………..372

Edible Parts of an Animal……………………………………………………………386

Salt……………………………………………………………………………………390

Fruits………………………………………………………………………………….397

Yeast and Other Leaveners…………………………………………………………...401

Sprouts………………………………………………………………………………..406

Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………..412

6

Introduction

The Seed to Table Curriculum

The Seed to Table curriculum is a collaborative project between three

organizations in Madison, WI - Community GroundWorks, East High

School and Goodman Community Center. This experiential

curriculum teaches youth valuable employment skills while they learn

the life cycle of plants, from seed to table.

By cultivating the natural connection between agriculture education

and culinary arts classes, this curriculum makes a clear link between

growing, cooking, and eating food. The lessons are multidisciplinary,

focusing on science concepts while incorporating English, social

studies, mathematics, and art. The lessons included in this curriculum

feature a range of hands-on activities, many of which take place in the

field and the kitchen. The classroom-based activities serve as

introductions, extensions, and reviews of material learned by working in the agricultural or culinary

settings.

Seed to Table can be used as a whole curriculum or as individual lessons. Even though this was created

for a class with a farm site and a commercial kitchen, many of the lessons can be adapted for use in

smaller gardens or kitchens with less specialized equipment. In addition, while the lessons are written

for high school-aged youth, the background information and activities can be easily modified for use

with younger students. We invite you to use and adapt the curriculum to best fit your needs.

In The Field

The East High Youth Farm serves as our Seed to Table field site.

The Youth Farm is an inclusive, collaborative project that

engages a diverse population of students in a hands-on science

and a vocational program focused on sustainable agriculture and

service learning. Youth are actively involved in the entire process

of running a small-scale organic urban farm - from raising

seedlings in the East High School greenhouse to harvesting

produce at the ¼ acre East High Youth Farm and packing the

food for delivery to the Goodman Community Center's Food

Pantry. Youth farmers strengthen food security in the community

by providing fresh vegetables and volunteer hours to the food pantry, thereby building relationships

with pantry consumers directly. During the school year, students work at the farm, in the greenhouse,

and in the classroom to explore a variety of topics focusing on small scale urban agriculture. In the

summer, youth farmers work three days a week planting, tending, harvesting, washing and packing the

produce for delivery. At the end of their experience at the farm, students have acquired the skills to

move into urban agriculture, landscaping, plant nursery, and environmental education jobs.

7

In the Kitchen

At the Goodman Community Center, youth workers

prepare food for community meals, as well as for the

Iron Works Café and Working Class Catering.

Students involved with these programs learn valuable

life and employment skills.

Students prepare over 200 meals each day for senior

citizens and preschoolers. Youth staff the Iron Works

Café—a coffee shop, bakery and lunch café that is

open to the public. The students also run the Working

Class Catering operation which provides meals to

conferences and weddings that are hosted at the

community center. These vocational opportunities

teach students safe sanitation skills, meal planning, culinary arts, and customer service.

In addition to on the job training, students are instructed in issues surrounding food. These include

food security, local and seasonal eating, and exploring different cultures‘ food choices. The students

are also able to earn credit towards a high school diploma while discovering the science involved with

cooking.

After six months of working in the culinary track at Goodman, students are prepared to move on to

other employers in the food service industry or to pursue further education in a culinary arts program.

8

Unit 1: History of Agriculture

In this section students discover where food comes from and how it is grown in a general sense.

Lessons compare different types of farming and enable students to meet different farmers.

Local Foods of Wisconsin

Geographic Origins of What You Eat

Historical Overview of Agriculture

Organic vs. Conventional Farming

Grow Your Own Food

Who Grows Our Food?

So You Want to Be a Farmer?

9

Lesson Plan: Local Foods of Wisconsin

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will learn the definition of local foods

Students will learn the health and environmental benefits of local food

Students will learn how to find and purchase local foods.

Students will compare locally grown food with foods produced in other parts of the

country/world.

Students will prepare a meal with locally based foods.

Modified Curriculum Objectives:

Materials: Map with scale, compass, internet access

Time: 45 minutes overview, 2 hours creation of local foods map, 45 minutes comparing eggs

Vocabulary: local, community supported agriculture, food processor

Background Information:

One hundred years ago almost all food was local. Much of the food people ate was grown on their own

property, that of the neighbors, or within 50 miles of their house. Local food includes vegetables

grown in a garden or nearby farm, animals raised for meat or dairy, animals hunted for meat, and foods

collected from native areas including berries, nuts, and mushrooms. Often the definition of local food

is food that is grown within a certain distance measured in concentric circles from the location where

the food will be eaten. The distance is often 50, 100 or 150 miles depending on how strict you want

your definition and the availability of food grown near your home. Another definition that is

sometimes used states if the food is grown in the same state as it is eaten, it is considered local.

There are certain foods/ingredients that cannot be grown in certain climates. While some local food

advocates encourage going without these foods, others recommend finding a local food processor that

purchases fair trade ingredients. These types of food include coffee, tea, chocolate, certain spices, nuts,

and fruits.

While it was originally less expensive to buy local produce, improvements in transportation, subsidies

of certain food crops and ignoring environmental costs associated with large scale farming operations

have created a price advantage for some non-local food producers. While locally grown food often

commands a higher price, it provides farmers who grow the food with additional income. When selling

processed foods the farmer only receives 20 percent of the revenue. However, when food is purchased

directly from farmers, they receive all of the profit.

10

There are several ways to find locally produced foods. The first is to grow it yourself in a backyard

garden or community garden plot. Another is to participate in a Community Supported Agriculture

farm where individuals pay for a share of a farm‘s produce. The customer pays for the food ahead of

time allowing the farmer access to money for seeds and other expenses. Then, depending on the

harvest the customer receives vegetables throughout the summer. Local farms also sell produce at

farmer‘s markets, roadside stands, or directly to grocery stores and restaurants.

In addition to vegetables there are also local food options for meat, eggs, milk, and cheese. There is

also local production of bread, beer, or liquor that may or may not use local ingredients. In addition,

local processors of products like chocolate and coffee, which cannot be grown in Wisconsin, allows

more revenue to stay in the community. In addition these processors have deeper background

knowledge in their products and are available to share that information with consumers.

Teacher Instruction:

1. Read ―High Cost of Cheap Food‖ by Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

2. Read ―Why Eat Locally and Sustainably Grown Food?‖ By REAP Food Group

Student Instruction:

1. Draw circles on a map that show what is included in 50 miles, 100 miles and 150 miles from

Madison or other city. Use a compass and different color pencil for each circle.

2. Place farms or other sources of food on this map.

3. Identify what ingredients from a favorite meal can be found locally.

4. Create a chart that compares and contrasts locally produced food with non-local food.

5. Go to this website to find local foods around Madison

http://www.chickmappers.com/100miledietmap/

6. Create a menu using foods found locally.

7. For other areas of the country try http://www.localharvest.org/.

8. Purchase, prepare and eat a meal made with all locally grown foods

9. Compare eggs. Conventional, Organic and Local. Determine the costs per egg. Make

observations about the color, size, and weight of each egg both inside and out. Using the same

method for each type of egg cook the egg and compare the taste. This can be done as a blind

taste test.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. What environmental costs are associated with non-local agriculture?

2. Local is not always organic, and what are the implications of local, nonorganic foods compared

to global organic foods?

3. What is the majority of corn/soybeans produced in Wisconsin used for?

11

4. Determine if conventional farmers are making enough money to continue farming? How much

does it cost to run a farm and a house? How much profit do they make? What is a subsidy?

Why do farmers not a lot of money by growing corn?

5. How can consumers find local foods?

6. What types of food can you not find produced locally?

7. What types of food are surprising to find produced locally?

8. Identify the benefits associated with local foods.

9. Should restaurants that use local foods market that to customers? Why and How?

Extensions:

Lesson Plan: Local Foodshed. Visit a Farmer‘s Market. Compare prices and taste of food purchased

locally versus commercially. Visit farms that produce a variety of food products. Compare duck eggs

and/or Ostrich eggs to chicken. Visit a cheese producer. Read Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara

Kingsolver, The Omnivore‘s Dilemma by Michael Pollan, or The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local

Eating (Canada & Australia Edition), Plenty: Eating Locally on the 100-Mile Diet (US Edition) by

Smith and MacKinnon. Watch films ―King Corn‖ or ―Food, Inc.‖

Resources:

http://wisconsinlocalfood.com/ Wisconsin local food resources.

http://www.localharvest.org/ Nationwide listing enter you zip code to find local food choices.

http://www.reapfoodgroup.org/ Research, Education, Action, and Policy on Food located in Madison

Wisconsin

http://www.chickmappers.com/100miledietmap/ GIS Map-Interactive with local food options listed for

Madison, Wisconsin.

12

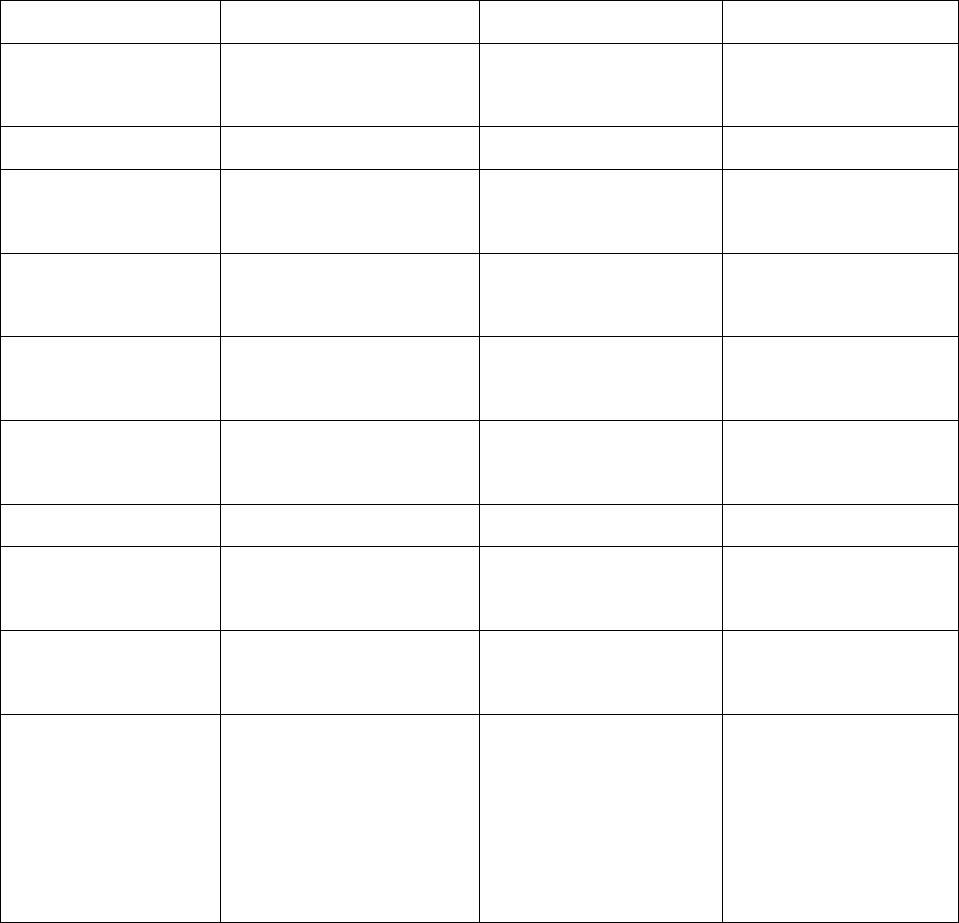

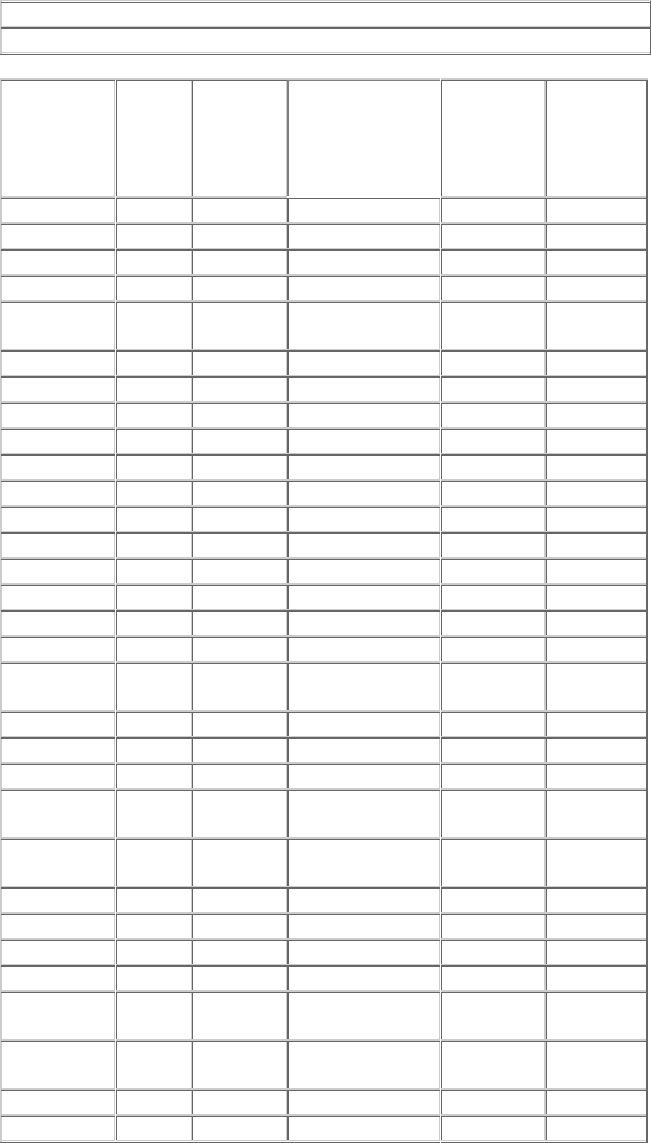

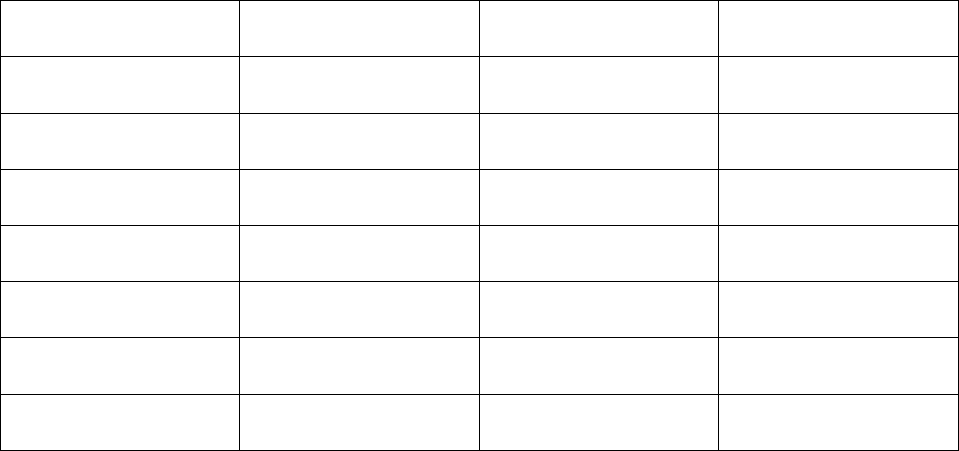

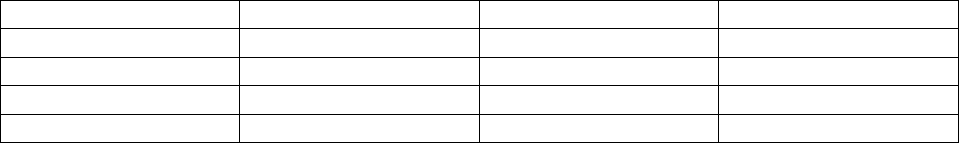

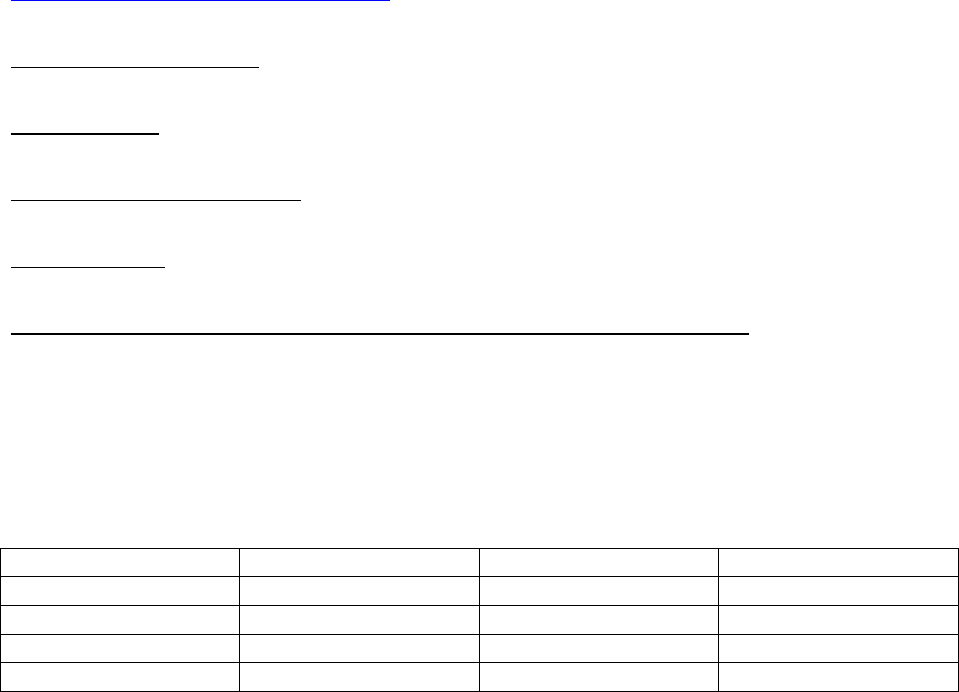

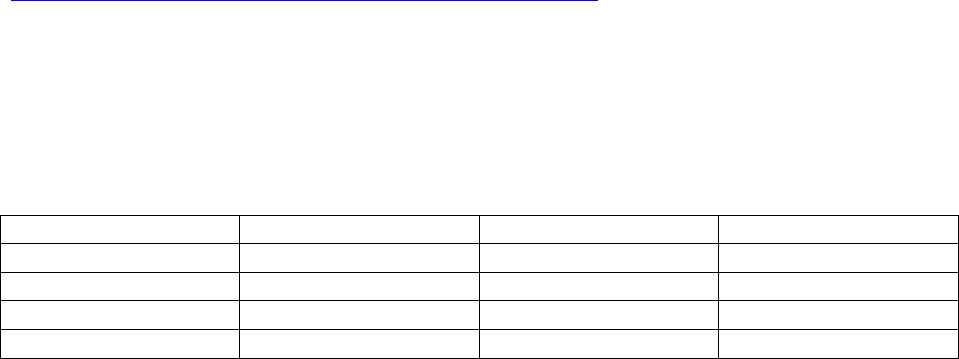

Eggs Comparison

Type

Conventional

Organic

Local

Cost per

Dozen

Cost per Egg

Color of

Shell

Weight of

Egg

Height of

Egg

Color of

Yolk

Size of Yolk

Nutritional

Content

Taste

Other

13

HIGH COST OF CHEAP FOOD (By: Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy)

This year American consumers will spend 10% of their household disposable income on food – a

lower percentage than any country in the world. As Americans, we are told that cheap and abundant

food is the backbone of a thriving economy. The fact is that cheap food often comes at a cost that is

often not reflected in the supermarket price tag. Farming communities struggle. The environment

suffers. And our overall public health gets compromised when price takes precedent over quality and

safety.

Why is U.S. food so cheap?

We can attribute much of our cheap food to the large expansion of industrial agriculture over the last

50 years – a system that substitutes fossil fuel energy, chemicals and capital for labor and management.

Larger farms operate on lower labor costs and are able to take advantage of large-scale economies that

produce more for less. The U.S. government offers many incentives, such as tax breaks and subsidies,

which favor large farms with little diversity. As large-scale agriculture has expanded, so has

concentration and consolidation within the food industry. In the Midwest, four firms now control the

processing of a variety of farm products (corn, soybeans, beef, etc) that thousands of farmers produce.

1

Because agribusiness and food retailers encourage farmers to produce a limited range of crops to

simplify their marketing and distribution operations, different regions of the U.S. specialize in a

limited number of crops and livestock. As a result, the majority of food sold in the typical grocery,

convenience and super-store must be shipped to reach market. A 2001 study found that the average

Midwestern meal travels 1,518 miles to get from producer to consumer.

2

The Social/Economic Costs

Every year the U.S. loses thousands of farmer jobs in a food system in which they are not paid an

adequate price for what they produce. Between 1993 and 1997 the number of mid-sized family farms

dropped by 74,440. Farmers have been urged to ―get big or get out.‖ Now just 2% of U.S. farms

produce 50% of agricultural product sales.

3

Although commodity prices (price paid to farmers) for

corn and soybeans, adjusting for inflation, are considerably lower than in the 1970s, the price of food

has continued to rise with inflation. From 1989 to 1999 consumer expenditures for farm foods rose by

$199 billion, 92% of which can be attributed to the marketing costs of agribusiness and food

companies. These expenses include transportation, packaging, labor and inputs used to sell food

products. Meanwhile, the farmer only gets 20 cents of each dollar spent on food, down from 41 cents

back in 1950.

4

Unable to capture more of the food dollar, farmers are stuck in a vicious cycle to

produce high volumes of cheap commodities with a low profit margin. When we lose farmers and farm

families we also lose farmland. Encroaching urban areas drive up the real estate value of farms located

on the fringe. More than 6 million acres of rural land, an area the size of Maryland, were developed

between 1992 and 1997, often on the nation‘s best farmland.

5

With the loss of food/fiber producing

capabilities the country also loses wildlife habitat and the aesthetic qualities of America‘s rural

countryside – all costs that are unquantifiable and irreplaceable.

14

Environmental Costs

The corn and soybean crops that dominate the Midwest often cause soil loss and impair water quality

through the leaching and runoff of fertilizers and pesticides. The ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico is

ailing from a growing zone of low oxygen caused by excessive nitrogen from fertilizers on cropland

upstream. This phenomenon, a hypoxic zone the size of New Jersey, affects the communities and

fishermen that live by and work on the Gulf of Mexico.

6

Eighty percent of all the corn grown in the U.

S. goes to feed livestock, poultry and fish. Access to inexpensive corn and soybeans has facilitated the

rapid growth of large-scale confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) that feed a domestic and

international appetite for cheap meat. The U.S. protein industry (swine, poultry, beef and dairy)

generates an estimated 2 trillion pounds of manure a year

7

and can have significant impacts on the

environment; threatening neighboring waterways and air quality with potentially noxious

fumes.

8

2003E COSTS OF CHEAFOOD

INSTITUTE FOR AGRICULTURE & TRADE POLICY

Billions of gallons of petroleum fuel are required annually for the trucks that transport food across the

United States.

9

This does not include fuel used by trains, barges or planes that also transport food

products. U.S. taxpayers pay the price through subsidies to our roads and highways, more dependence

on imported oil and increased fossil fuel emissions that contribute to environmental problems like

smog and climate change.

Public Health Costs

A number of emerging public health concerns have resulted from the production and processing of

food that is increasingly concentrated and automated. Many of the country‘s CAFOs add antibiotics to

livestock feed. An estimated 70% of all antibiotics in the U.S. go into healthy pigs, poultry and cattle

to increase animal weight and to minimize disease risks associated with the large numbers of animals

within one complex.

10

A growing number of studies show that routine use of antibiotics can encourage

the growth of antibiotic resistant bacteria which can make treating human bacterial diseases more

difficult and potentially life threatening. Today‘s centralized systems for meat production and

processing are more susceptible to large-scale contamination by food borne pathogens. Food recalls are

increasing. The largest food recall in U.S. history took place in October 2002, when the country‘s

second largest poultry producer recalled 27.4 million pounds of fresh and frozen poultry products after

an outbreak of listeriosis killed 20 people and sickened 120 others.

11

While cheap food is plentiful, it is

not necessarily healthy – over half of U.S. citizens are considered overweight.

12

Currently, the United

States is plagued with an epidemic of chronic diseases associated with over-consumption (obesity,

diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers) that health professionals attribute to both a

decline in physical activity and an abundance of products high in animal fat and refined carbohydrates

and low in fiber. Additionally, cheap food has not eliminated hunger. Using U.S. Department of

Agriculture‘s conservative definitions, 5.6 million adults and 2.7 million children in the US are

hungry.

13

15

Winners and Losers in the Cheap Food Game

Cheap food, rather than fostering a food system that benefits the general American public, has

promoted an increasingly industrialized agriculture. Expanding national and multinational food

companies that purchase cheap commodities continue to increase their profits. Meanwhile, farmers and

rural communities in the United States do not benefit. A health care system, taxed with an epidemic of

diet related diseases, does not benefit. And the environment certainly does not benefit. But there are

other ways to fill America‘s dinner plate. Regional food systems that support the local production and

processing of farm products grown in environmentally sensible ways are emerging throughout the

country. These systems take out the ―middle men‖ and put the profits back into the pockets of the

farmers and communities they support. Farmers markets, Community Supported Agriculture farms,

restaurants featuring locally produced foods, and "Buy Local" campaigns give consumers the choice to

buy food that is not only affordable, but benefit farmers, the natural environment and local economies.

1 Hendrickson, M. and W. Heffernon (2002). ―Concentration of Agricultural Markets,‖ Department of

Rural Sociology - University of Missouri. February.

2 R. Pirog et al (2001).

3 USDA (1997). Census of Agriculture

4 USDA Economic Research Service

5 American Farmland Trust (2002). ―Farming on the Edge.‖ Online at:

http://www.farmland.org/farmingontheedge/major_pr_natl.htm

6 D.A. Goolsby and W.A. Battaglin (2000). ―Nitrogen in the Mississippi Basin-Estimating Sources and

Predicting Flux to the Gulf of Mexico,‖ USGS Fact Sheet, 135-00. December. Online at:

http://ks.water.usgs.gov/Kansas/pubs/fact-sheets/fs.135-00.html

7 Environmental Defense (2002). ―Scorecard - Animal Waste from Factory Farms.‖ Online at:

http://www.scorecard.org/

8 USEPA (2001). ―Environmental Assessment of Proposed Revisions to the National Pollutant

Discharge Elimination System Regulation and the Effluent Guidelines for Concentrated Animal

Feeding Operations,‖ EPA-81-B-01-001. January.

9 Ibid.

10 Mellon M. et al. (2001). ―Hogging It: Estimates of Antimicrobial Abuse in Livestock,‖ Union of

Concerned Scientists. Cambridge, MA.

11 Abboud, L. (2002). ―Fatal Strain of Bacteria Traced To Pilgrim‘s Pride Meat Plant,‖ Wall Street

Journal, October 16.

12 Center for Disease Control (2002). ―U.S. Obesity Trends from 1985 to 2000.‖ Online at:

www.cdc.gov/

13 http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/foodsecurity/

For more information on IATP’s work on cheap food and related topics, go to

www.agobservatory.org

Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy 2105 First Avenue S. Minneapolis, MN 55404 (612)

870-0453

16

Why Eat Locally and Sustainably Grown Food?

By REAP Food Group

Because What We Eat Matters. How our food is grown, processed, and packaged really does matter.

Our food choices influence our health, the quality of our environment, jobs in our community, and the

culture and diversity of our society.

Buying locally & sustainably grown food is good for YOU.

Food tastes better and is more nutritious when it's fresh. Foods grown using organic farming practices

come to your table with no harmful pesticides. And in these times, when obesity and diet related

illnesses are on the rise, replacing heavily processed foods with whole fresh produce will improve your

health.

Buying locally & sustainably grown food is good for our COMMUNITY.

Keeping our local farmers and producers in business supports our local economy. Dollars spent close

to home tend to stay close to home. Our local producers understand our community and work to

provide nutritious affordable food for all our citizens. The more we feel connected to the people who

produce what we eat, the better we preserve our regional food heritage. Rural and urban-- we're all

connected.

Buying locally & sustainably food is good for FARMERS

The current national food system is dominated by very few large corporations which are forcing

farmers to accept lower prices, grow only "travel-tolerant" varieties, grow bigger, use more chemical

inputs, or leave the farm altogether. When farmers sell directly to their neighbors, fewer middlemen

cut into their profits. Farmers can afford to stay on their land producing an abundance and variety of

food while being good stewards of the land.

Buying locally & sustainably food is good for the ENVIRONMENT.

Most of the food we eat travels an average of 1,500 miles from the farm to our table. By reducing the

travel distance our food takes, we save energy and reduce carbon dioxide emissions that likely

contribute to global warming. By buying whole local foods, we also reduce packaging, further saving

energy and resources. And sustainable farming practices protect the quality of our water and soil, while

preserving green space for healthy native habitats.

http://www.reapfoodgroup.org/Why-Buy-Local/why-buy-local.html

17

Lesson Plan: Geographic Origins of What You Eat

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will create a map of the world and label the countries and climate zones

Students will research the origins of fruits and vegetables then place them in specific

countries based on their research findings

Students will learn about the different climate zones and seasons around the world

Students will learn how food is transported over long distances

Materials: Map of world, overhead projector, large piece of white paper, magazines and catalogs,

colored paper, encyclopedia, Internet access

Time: 45min/day 3 days

Vocabulary: Origin, Fruit, Vegetable, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, fair trade, equator,

temperate, tropical

Background Information:

In our global economy food is grown everywhere. It is then transported to where it is sold and then

eaten. While 100 years ago a person would only eat food that was grown 50 miles from his/her house

we now have a far wider range of food available. However, there are costs associated with this global

food market.

One such cost is in transporting the food. Food can be shipped in boats, trains, trucks, planes or a

combination of these methods. Some foods need refrigeration during transit which requires extra

energy to keep the food cool during transport. Often food is picked before it is ripe so that it will not

spoil in transport. In many cases the food has had chemicals applied to it either to slow the aging

process or at a later point to speed the ripening process when it arrives at the grocery store.

In addition, labor laws in other parts of the world are often less strict than in the United States and

Western Europe. In some countries the minimum wage is very low and workers safety is not protected

by adequate regulations. Some other countries also have less stringent environmental laws allowing for

the use of more chemicals and more erosion of the soil in agricultural settings. There are organizations

fighting against these issues by labeling items as fair trade. Fair Trade brings more money to the

producer and insures that certain worker safety and environmental regulations are followed.

There are certain foods that can only be grown in more temperate or tropical climates so if you want to

eat those in Wisconsin you will need to import them. There are other foods that, while they will grow

in Wisconsin, they do not grow in Wisconsin year round. If you have not made preparations to save

these foods for the off season you will need to import them from other producers.

Because of the tilt of the Earth, the rotation of Earth, the Earth's orbit around the Sun and the thickness

of the atmosphere there are differing seasons on the Earth. The season will vary depending on whether

18

you are in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere. The closer a location is to the equator the less

variability in the seasonal temperatures there is. Simply put, the seasons are reversed in the Northern

and Southern Hemispheres: when it is winter in one, it is summer in the other.

Teacher Instruction:

1. Project the map of the world onto a large piece of paper. Group or pair students and assign them a

continent to trace. Have students trace the continents and countries.

2. Discuss with students where different foods come from and how those foods come to the local

grocery store.

Student Instruction:

1. On the map label the equator, tropics of cancer and Capricorn, hemispheres, countries, and climate

divides. Create a key for the map. See below.

Spring

(green)

Summer

(red)

Fall (yellow)

Winter

(blue)

Native Origin

(brown)

Northern

Hemisphere

March- June

June-August

September-

November

December-

February

Southern

Hemisphere

September-

November

December-

February

March-May

June-August

2. Find and cut out pictures of vegetables and fruits in catalogs and magazines.

3. Determine where these foods are grown and what time of year (resources listed below):

Based on the time of year the vegetable or fruit will be placed on a background color (green,

red, yellow, or blue)

Students will identify the native place for the fruit or vegetable to be grown and it will need a

brown backing and placed in that area of the world.

4. Tape the picture of these foods onto the map.

5. Continue to add to the map throughout the course of the class.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. What causes the different seasons?

2. Are there any foods grown in winter?

3. Why is there a difference in the months for each season based on hemispheres?

4. Why can some types of produce not grow in Wisconsin?

5. List several foods that cannot be grown in Wisconsin.

6. How does travel time/distance change harvest practices? If the food travels 16 hours to arrive in

Wisconsin is it harvested the same time or way if it were delivered one hour away?

7. How far does food travel to come to Wisconsin? What is a food that travels the longest distance?

19

8. How does the food stay fresh during transport?

9. What are some environmental costs of having food travel such a long distance?

Extensions:

Have a local meal. Create a meal in class using only local (100 miles) ingredients.

Compare the difference in taste between a local food and the same food that has traveled across

the world/country.

Take a field trip to a local grocery store and give each student a list of 5 vegetables or fruits to

identify. They will find the vegetable/fruit in the store, look at the tag, sticker, or container to

identify where it is from and write the location down. After the field trip the students discuss

what they found and pictures based on their findings can be created for the map of their

findings.

Resources:

http://www.foodtimeline.org/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_food_origins

http://www.nrdc.org/health/foodmiles/default.asp

http://online.sfsu.edu/~patters/culinary/pages/croporigins.html

http://marketnews.usda.gov/portal/fv USDA website listing where fresh fruits and vegetables are

produced. search able by food item.

http://www.leopold.iastate.edu/resources/fruitveg/fruitveg.php USDA site that allows students to

search specific fruits or vegetables and see the country, amount produced, and time of year.

20

Lesson Plan: Historical Overview of Agriculture

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will understand the role geography played in the establishment of agricultural regions

Students will understand what geographic and climatological factors create a favorable

environment for agriculture

Students will understand the regions in the United States devoted to farming and what they

produce

Modified Curriculum Objectives:

Students will understand that some regions are better than others for farming

Materials:

Picture books: By the Light of the Harvest Moon, by Harriet Ziefert

Time: 75 minutes

Vocabulary: Shaded relief map, topographic map, USDA, arable, citrus

Background Information on the Central Valley:

The world is not equal when it comes to arable agricultural land. How have cultures decided where to

farm? What climatological and geographic conditions made some areas better than others? This lesson

looks specifically at the United States, but certainly could be expanded globally. Conversely, the

lesson could zero in the conditions within a particular state or locality. The Central Valley in California

is used here due to its significance in US agricultural production.

General Background

http://geography.howstuffworks.com/united-states/geography-of-california2.htm

The Central Valley is a 400-mile stretch of fertile land bordered by California‘s coastal range in the

west and the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the east. It is home to many different regions each with its

own issues and needs. It takes approximately 8 hours to drive the entire stretch of the valley.

Fruits are grown in many parts of California. Hardy fruits, including apples, pears, plums, apricots,

cherries, and peaches, grow in the Central Valley and in the valleys of the coastal mountains. Most

widely grown are peaches, of which California is the country's leading producer. In grape production

as well, California is far ahead of the other states. By value, grapes are California's chief crop.

Near Los Angeles and in the southern part of the Central Valley, citrus orchards cover large areas.

California produces about 80 per cent of all the lemons grown in the United States and ranks high in

the production of oranges, grapefruit, and tangerines. Other semitropical fruits of southern California

include figs, olives, dates, and avocados. Great quantities of nuts, particularly almonds and English

walnuts, are grown in the Central Valley.

21

Many different kinds of winter and summer vegetables thrive in California. By tonnage the state

normally accounts for more than half of the commercial vegetables grown in the United States; by

value the state accounts for nearly half of the United States total. Among the chief vegetables are

broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, celery, lettuce, onions, and tomatoes. The Central Valley, the Imperial

Valley, and the Salinas Valley are major centers of production.

California was the first state to grow sugar beets successfully, and it remains a leading producer.

Cotton is grown mainly in the San Joaquin Valley; normally, production is second only to that of

Texas.

Wheat and barley are important California crops. Both are produced largely by dry-land methods,

although some irrigation is practiced. Rice, grown entirely by irrigation, comes largely from the

Sacramento Valley.

A Statistical Tour of California’s Great Central Valley

http://library.ca.gov/CRB/97/09/index.html

Teacher/Student Instruction:

Ask students:

1. Where does 25% of our nation‘s food come from? (The Central Valley in California)

2. Distribute/show topographic map of the Central Valley.

3. Ask students to ―read‖ the map explaining the geographic features included in and

surrounding the region.

4. Ask students to interpret the map. What features make the region particularly desirable for

agriculture?

5. Have students look at a shaded relief map of the United States. Ask which regions look like

they‘d be good agricultural regions. Have students explain why. Ask students to predict

which crops might grow well where and why? (Assess what they know about conditions for

specific crops.)

6. Distribute Farm Resource Regions handout. What is grown where in the United States?

7. (Optional) Google Earth (http://earth.google.com/) is a powerful (and free) software/web

tool that lets users see the earth‘s surface. Students are able to search for specific places and

see its physical characteristics (i.e. urban or rural, agricultural etc.)

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. Where is California‘s Central Valley? What is grown there? (Knowledge)

2. What conditions are necessary for specific crops to grow? (i.e. blueberries need acidic soil)

(Comprehension)

3. What conditions make a region favorable for crop productions and where are those regions

located in the United States? (Application and Synthesis)

22

Extensions:

Correlating topography with the world‘s climate zones adds the climatological basis for selecting

prime agriculture land.

1. Worldwide Climate Zones

http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/education/lesson_plans/index.html (Look for Module #9:

Earth's Climate System , in particular the lesson on World Climate Zones)

2. For more detailed zones, Worldwide Climate Classification Zones

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate

Looking at the broader issues surrounding California‘s Central valley gives students an understanding

of the pressures farmers and farm workers are facing in the region. NPR‘s report delves into

development issues, pesticide use, and immigration in a 3-part radio series.

California's Central Valley: NPR Series Profiles the State's 'Backstage' Rural Breadbasket

http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2002/nov/central_valley/

Resources:

1. Central Valley (CA) production data sheet. (http://www.library.ca.gov/CRB/97/09/index.html)

2. California Relief Map

(http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/cropmap/california/maps/CAgeo.jpg)

(http://education.usgs.gov/california/resources.html)

3. US Relief Map

(http://www.shadedrelief.com/physical/index.html)

4. US Farming Regions Map: Economic Research Service

(www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/aib760/aib-760.pdf)

23

Lesson Plan: Organic vs. Conventional Farming

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will learn the difference between organic and conventional foods.

Students will compare organic and conventional foods in terms of cost, taste, environmental

impacts, and social impacts.

Materials: Conventional and Organic foods to compare, prices of the foods, character cards.

Time: 45 minutes taste comparison, 30 minutes price comparison, 45-90 minutes character card

debate.

Vocabulary: Conventional, Sustainable, Organic, Industrial, Fertilizer, Pesticide, Herbicide

Background Information:

Food is classified in two main categories based on how it is grown. These categories are referred to as

conventional and organic. These terms are often misunderstood. Conventional farming methods refer

to most large scale farming operations that rely heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. While it

is true that all food is ―organic,‖ in terms of chemical makeup, the organic food movement focuses on

using natural forms of fertilizers and pest controls.

Conventional farming is also referred to as industrial agriculture or factory farming. This is how most

of the food is currently produced in the world. Food on conventional farms is typically one crop or

species of animal put into a small space to maximize output. Money is spent on expensive

manufactured equipment and costly chemical pesticides and fertilizers to increase yields. Conventional

farming is somewhat of a misnomer because this type of farming as only been around for the last 100

years and has only been prevalent since World War II.

Organic farming, also known as natural farming, or sustainable agriculture has been around since the

dawn of agriculture. It is typically, though not always, accomplished on smaller farms with more

diversity of crops. Organic farms put more resources into labor and strategies regarding about how best

to improve crops without using chemicals.

The main benefits of conventional farming include reduced cost, increased yield and a reduction in

workforce. However, conventional farming often is a monoculture or one group of plants grown over a

large area. This type of farming requires the use of fertilizers and pesticides to grow healthy crops. In

addition the end product typically has to be transported long distances before it reaches the end

consumer.

24

The main benefits of organic farming include less environmental degradation, higher pay for farmers,

better land use, more diversity, less erosion, healthier animals, lower cost for fertilizers and pesticides,

and cleaner water. While many organic farms are small farms that sell locally, there are also several

large global organic producers that use only organic fertilizers and pesticides. These farms take

advantage of economies of scale but typically do not have diverse crops, highly paid workers, or the

ability to market all of their products locally.

The laws regarding what makes an organic farm in the United States are set by the US Department of

Agriculture. These rules limit the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers, and require animals to have

some access to grazing. However, there is a fee for certification which is the same for both small and

large farms. This is one reason many small farmers selling at farmer‘s markets do not use the term

―organic‖ and instead substitute ―natural,‖ ―no chemicals used,‖ or ―herbicide free.‖

In addition to fruits and vegetables, meat can also be produced in either a conventional or an organic

manner. Animals in the conventional setting are typically confined to feedlots or buildings where they

are fed a diet consisting of corn. This setting usually causes more diseases than their organic

counterparts and these animals are often injected with hormones and antibiotics to fight the effects of

those diseases. In organic meat production, the animals can graze on land and find their own food at

least some of the time. This method is often more labor intensive but produces animals more likely to

be free of disease.

Teacher Instruction:

1. The first part of this lesson focuses on comparing organic to conventional produce. This

includes observing the look and feel of the foods as well as the taste. Give each student an

example of a conventional and an organic food to compare. In addition, students should

compare the cost of the two types of food.

2. The second part of the lesson has students play the roles of different producers or consumers.

Student Instruction:

1. Make observations of the two fruits/vegetables in front of you. Compare the outside look and

feel. Cut open the items smell them, taste them and write down all of your observations.

2. Compare the price of organic and conventional produce. Be sure to compare like quantities and

similar items.

3. Read the character card you have been given. You need to formulate your position based on the

information found on this card.

4. In character, your class will have a debate discussing different viewpoints of the organic

farming debate.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. Create a list of reasons to use organic products in your cooking.

2. Create a list of reasons to use conventional products in your cooking.

25

3. Are there some products where you see more value in using organic versus conventional?

4. Compare the costs associated with organic and conventional foods. Be sure to include

environmental and social costs (not just monetary costs).

5. What marketing strategies would you use if you decided to serve organic foods in a restaurant?

Extensions: Visit both organic and conventional agriculture settings, visit different stores to compare

the prices and appearances of different food choices.

Resources:

http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/nop USDA-- National Organic Program

26

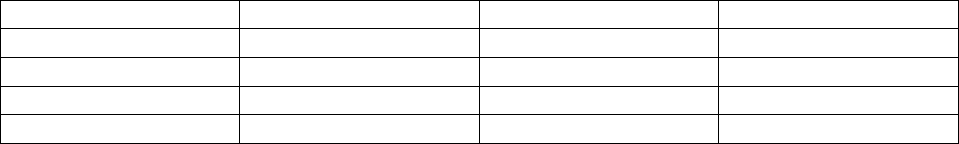

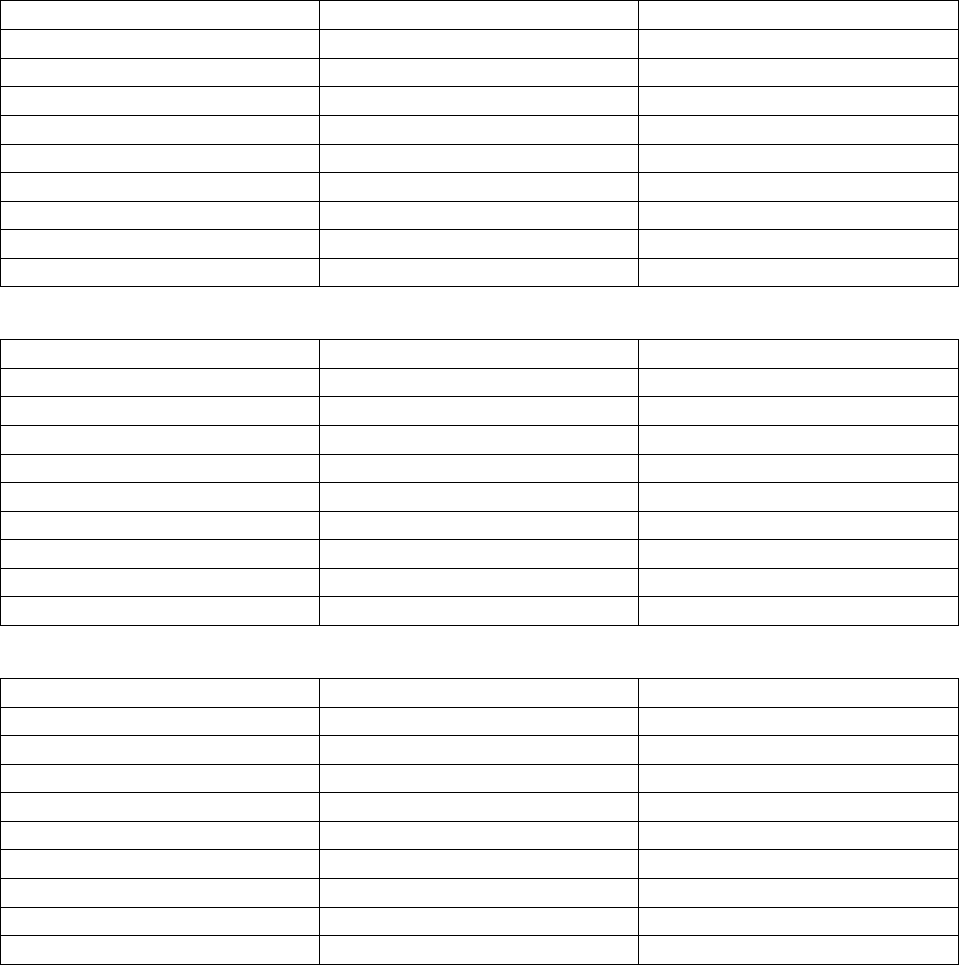

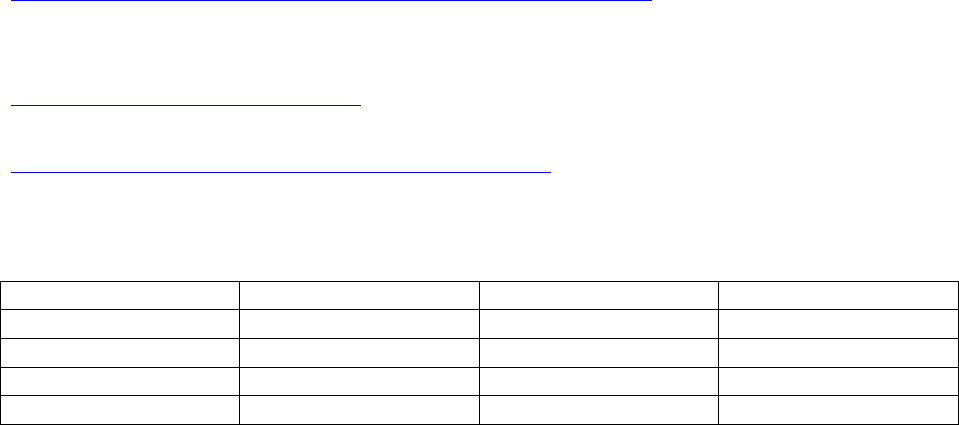

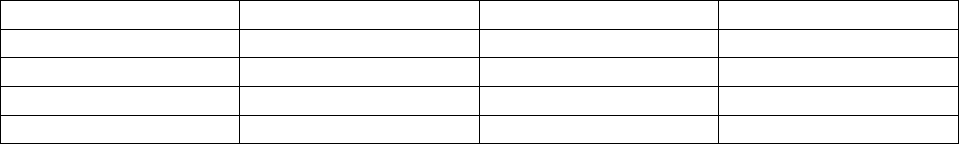

Conventional

Organic

Item

Size

Cost

Size

Cost

Apple

Banana

Orange

Avocado

Tomato

Potato

Onion

Garlic

Broccoli

Beef

Chicken

Which foods cost more?

Why do you think that these foods cost more?

Discuss whether this price differential is or is not worth the additional cost.

27

Character Cards (cut apart and give one to each student or group of students)

Organic Farmer

I am a farmer who grows vegetables on about ten acres of rolling hills just outside of Madison, WI. I

grow a wide diversity of vegetables for sale at local farmers‘ markets. During the season I spend 12

hours a day tending the land, weeding, harvesting, and selling my produce. I do not use any non-

organic pesticides or fertilizers on my crops; however the fee for organic certification is cost

prohibitive. I prefer to communicate my growing practices directly with the people who buy my food. I

love growing beautiful vegetables that taste great and are healthy for both the land and people who eat

them. Come and visit my farm.

Apple Producer

I run an apple orchard in the Baraboo Hills. I sell a wide variety of types of apples. A few years ago I

tried to produce some of my apples without pesticides. But the apples had black spots on them and

even though I spent more money on workers to care for the trees, very few people wanted to pay more

for apples with spots. I try to save money by limiting the about of fertilizer and pesticides I apply to

my crops, but I want to sell nice looking apples to my customers.

Produce Buyer Small Store

I buy produce for a cooperatively run grocery store in Madison, WI. My customers want to support

local farms. I try to find producers who have the food for a reasonable price. However, I often find that

while I need 200 pounds of carrots a week, the producer may only have 100 pounds. That means I have

to find another producer. Other times the farmer thought that an item would be ready but her field was

flooded. I am interested in supporting local agriculture but I also need to have good looking produce on

my shelves at all times of the year. It would be easier to just go to one company selling produce from

all over the world to provide all the produce but I know my customers want local foods.

Restaurant Chef

I am the chef at an upscale restaurant in Sun Prairie, WI. I prepare dishes using the most natural and

interesting ingredients I can find. I provide meals that are not found at a typical restaurant or that you

would not make for yourself at home. Because I buy all of the ingredients I use locally from small

producers. I often shop the farmers‘ market early in the morning; in addition I will drive directly to

different farms to find the food I want to serve my customers.

School Food Service Provider

I organize the preparation of over 20,000 meals a day. I am given very little money to prepare all these

meals and need meals that students will eat and can eat quickly. I do not have the time or the money to

run around in search of a specific ingredient. I buy all the food from one large food supplier. I receive a

discount because our purchase is so large each week.

28

Single Parent

I want to provide the best most nutritious food for my children. However, I do not have a lot of time

for shopping or food preparation. I want to go to one store that has everything I need that is

inexpensive and quick to prepare.

Produce Buyer Large Store

I buy all the produce for a large grocery store in Madison, WI. My customers are most concerned about

price and I buy 1000 pounds of carrots each week. The majority of these are from my food supplier

from a conventional farm; I also buy 100 pounds of organic carrots from the same provider and am

able to sell these for more money. The quantities I deal with prevent me from being able to deal with

local producers that may or may not have the produce I need on a given week. My company also has

an arrangement with the food supplier that provides the same food to similar stores all over the

country.

Conventional Farmer

I grow corn and soybeans. Just like my father before me. I am up early and late driving the large

tractors and combines that are worth more than my house. I care for my land and love being a farmer

but it is hard to make a living selling to the corn buyers. My corn is used for animal feed, producing

corn syrup for soft drinks and even making ethanol to run cars on. Every season I buy the newest

products that will produce the greatest yield but it always seems that the price changes so rapidly and I

do not know if I will be able to continue to farm this land. A developer just offered me a lot of money

to sell my farm. I am not ready to sell now but when I retire I think this land will become a housing

development.

CSA Buyer

I buy my vegetables from a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm. I pay for a share of

vegetables in February and every week from June through September I go to pick up a box of produce

from the local farm. My family and I enjoy the fresh produce and get to try vegetables we would

probably have never purchased at the store. We also get to visit the farm several times a year to pick

extra vegetables and to see where our food comes from and how it is grown.

29

Lesson Plan: Grow Your Own Food

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will understand their options for growing their own food in a range of scenarios from

containers to gardens to rooftops

Modified Curriculum Objectives:

To understand individual options for growing food

Materials:

Picture books: City Green, Dyanne DiSalvo-Ryan

Time: 75 minutes

Background Information:

Growing food can take place in a range of spaces from containers on a porch to rooftops to 100-acre

farms. Combining what grows in your region with what spaces are available, you and your students

can identify their options for growing food.

Simple web searches on Google Images or Flicker or your local Extension Office for ―growing food in

small spaces‖ or ―container gardening‖ or ―rooftop gardens‖ will yield a bounty of photographs to

share with your students. Contrast these with photos of larger farms

Other space options to consider: backyard plots, greenhouses, community gardens, leasing agricultural

land, hoop houses, urban farms, or traditional rural farms.

Teacher/Student Instruction:

Ask students:

1. Which plants do they like to eat? Encourage them to think about fruits, vegetables, nuts,

herbs, etc. Using background knowledge and teacher assistance identify which of those

crops are suitable for growing in your region.

2. Review the basics of what it takes for plants to grow: sun, air, soil, water

3. Ask students to brainstorm where could they grow food? At their home? In their

neighborhood? At their school? Some students may already know where food is being

grown nearby.

4. Review a slide show of photographs featuring different examples of where you can grow.

Such a slide show can be generated with web search results described above.

5. Have students create a map identifying both vertical and horizontal spaces where food

could be grown. Have them be zany. Have them color code it: 1. possible but not realistic;

30

2. doable with a little bit of work; or 3. ready to go right away (Or use a different coding

scheme.)The important part of the lesson is for students to understand they can grow their

own food in their own space with varying degrees of resources and effort.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. What plants do students like to eat? (Knowledge)

2. What conditions are necessary for various crops to grow? (Comprehension)

3. What different environments and spaces can food be grown in? (Application)

4. Where can food be grown in their own neighborhood? (Synthesis)

Extensions:

1. Have students identify how they would go about saving the seeds from food they eat. How

could other seeds be acquired?

2. Ask students to research where soil, compost, and containers could be gotten at low or no-cost

in their neighborhood. For example, in Dane County (WI) compost is available at several sites

throughout the county for a nominal fee:

(http://www.countyofdane.com/pwht/recycle/compost_sites.aspx)

Resources:

1. Fresh Food from Small Spaces: The Square-Inch Gardener's Guide to Year-Round Growing,

Fermenting, and Sprouting, by R. J. Ruppenthal

2. Square Foot Gardening, University of Wisconsin Extension:

http://www.uwex.edu/CES/cty/taylor/cnred/

31

Lesson Plan: Who Grows Our Food?

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will learn about several farmers from their foodshed

Students will identify several large and small scale production facilities in Wisconsin

Students will understand there is no one type of person who is a farmer

Modified Curriculum Objectives:

To learn who grows some of our food

Materials:

Farm Fresh Atlas (http://www.reapfoodgroup.org/atlas/index.htm)

Wisconsin Map (or other state)

Time: 75 minutes

Vocabulary: demographics

Background Information on Farming in the United States:

1. Structure of US farms:

USDA Economic Research Service

Economic Information Bulletin No. (EIB-24) 58 pp, June 2007

http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/eib24/eib24_reportsummary.html

U.S. farms are diverse, ranging from very small retirement and residential farms to enterprises

with annual sales in the millions of dollars. Farms are operated by individuals on a full- and

part-time basis, by multiple generations of a family, by multiple families, and by managers of

nonfamily corporations. Some specialize in a single product, while others produce a wide

variety of products. Some have full control over their farming processes while others produce

commodities under contract to strict specifications. But despite their diversity, most U.S. farms

are family farms.

Most U.S. farms—98 percent in 2004—are family farms, defined as operations organized as

proprietorships, partnerships, or family corporations that do not have hired managers.

Nonfamily corporations make up a small and stable share of farm numbers and sales,

accounting for less than 1 percent of farms and 6-7 percent of farm product sales in each

agricultural census since 1978.

Small family farms account for most U.S. farms and farm assets. Small family farms (sales

less than $250,000) accounted for 90 percent of U.S. farms in 2004. They also held about 68

32

percent of all farm assets, including 61 percent of the land owned by farms. As custodians of

the bulk of farm assets—including land—small farms have a large role in natural resource and

environmental policy. Small farms accounted for 82 percent of the land enrolled by farmers in

the Conservation Reserve and Wetlands Reserve Programs (CRP and WRP).

Large-scale family farms and nonfamily farms produce the largest share of agricultural

output. Large-scale family farms, plus nonfamily farms, made up only 10 percent of U.S.

farms in 2004, but accounted for 75 percent of the value of production. Nevertheless, small

farms made significant contributions to the production of specific commodities, including hay,

tobacco, wheat, corn,soybeans, and beef cattle.

The number of larger farms is growing. The number of farms with sales of $250,000 or more

grew steadily between the 1982 and 2002 Censuses of Agriculture, with sales measured in

constant 2002 dollars. The growth in the number of these larger farms was accompanied by a

shift in sales in the same direction. The most rapid growth was for farms with sales of $1

million or more. By 2002, million-dollar farms alone accounted for 48 percent of sales,

compared with 23 percent in 1982.

For the most part, large-scale farms are more viable businesses than small family farms.

The average operating profit margin and rates of return on assets and equity for large and very

large family farms were all positive in 2004, and most of these farms had a positive operating

profit margin. Small farms were less viable as businesses. Their average operating profit

margin and rates of return on assets and equity were negative. Nevertheless, some farms in

each small farm group had an operating margin of at least 20 percent. In addition, a majority of

each small farm type had a positive net farm income, although the average net income for each

small-farm type was low compared with large-scale farms.

Small farm households rely on off-farm income. Small farm operator households typically

receive substantial off-farm income and do not rely primarily on their farms for their

livelihood. Most of their off-farm income is from wage-and-salary jobs or self-employment.

Because of their off-farm work, small farm households are more affected by the nonfarm

economy.

Households operating retirement or limited-resource farms, however, receive well over half of

their income from such sources as Social Security, pensions, dividends, interest, and rent,

reflecting the ages of operators on such farms.

Payments from commodity-related programs and conservation programs go to different

types of farms. The distribution of commodity-related program payments is roughly

proportional to the harvested acres of program commodities. As a result, medium-sales

($100,000-$249,999) and large-scale farms received 78 percent of commodity-related

government payments in 2004. In contrast, CRP, which pays the bulk of environmental

payments, targets environmentally sensitive land rather than commodity production.

Retirement, residential/lifestyle, and low-sales small farms received 62 percent of conservation

33

program payments in 2004. However, most farms—61 percent in 2004—receive no

government payments and are not directly affected by farm program payments.

A growing number of farms operate under production and marketing contracts to

guarantee an outlet for their production. About two-fifths of U.S. agricultural production is

produced or marketed under contract, although the share varies by commodity and type of

farm. Relatively few small family farms use production and marketing contracts, while 64

percent of very large family farms use contracts and, as a group, produce 61 percent of the

value of production grown under contract.

2. Basic demographic data on farmers from USDA. The USDA has a myriad of demographic data

relating to US farmers, ranging from the amount of experience a principal farm operator has to the

gender, age, or race of the farmer. Find updated information at the Economic Research Service site:

http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WellBeing/demographics.htm

3. Specific Local Farm Data. Many states maintain a database or interactive map of operating farms.

In Wisconsin, the Farm Fresh Atlas Project (http://www.farmfreshatlas.org/) created originally by

REAP Food Group (http://reapfoodgroup.org/) maintains a publication and website called the Farm

Fresh Atlas. The Atlas profiles different farms, identifying what they grow, who their operator is, and

where they are located.

Teacher/Student Instruction:

Ask students:

1. Who grows our food? Who is a typical farmer in our state? What type of farm do they own?

Ask students if they know any farmers in their community. As students how types of farms and

farmers might be different in different parts of the country.

2. Share with students some of the demographic data from ERS.

http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WellBeing/demographics.htm

In particular students may be interested in the ―aging of farmers,‖ in other words the fact that

there aren‘t many young people going into farming.

3. For each of the graphs you share, ask students to both read and interpret the graph. First, ask

students to read the graph, simply making factual statements from the data. Second, ask

students to interpret the graphs. What are some of the implications of the data?

4. Next, give students access to a copy of the Farm Fresh Atlas, or access to it via the web site.

Have them browse the atlas and keep track of the types of farms they see. How can they

characterize the farms? Are there more of one type than the other? Have students make a list of

the farms they would like to visit or learn more about.

5. Give students the opportunity to explore farm web sites to collect more information. In small,

groups, have students share the farms they‘ve looked at. How are the farms they‘ve looked at

similar to one another? Different?

34

6. In the last part of the lesson, have students look at the structure of farms nationwide. Using the

background information provided above, have students contrast their local farms with national

trends.

7. If possible, invite a few farmers to class to have them talk about their experience as a farmer.

Students can use the Meet the Farmer handout available in the Appendix to track their notes.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

1. Who is a typical farmer in this country? (Knowledge)

2. Which farms do the students find interesting? Who are some of their local farmers?

(Application)

3. How similar are the farms in Wisconsin (or another state) to those found nationwide?

(Synthesis)

Extensions:

1. Interview a farmer one-on-one to discuss their background and current experience.

2. Do more in-depth analysis of farmer demographics and farm structures using the USDA ERS

website. Identify some key research questions that need to be addressed given current trends.

Resources: Meet the Farmer handout

35

Lesson Plan: So You Want to Be A Farmer?

Unit: History of Agriculture

Objectives:

Students will understand different options farmers have for selling their produce: farmer‘s

markets, grower cooperative, farm market stand, CSA, grocery store, wholesaler, restaurants,

institutions

Modified Curriculum Objectives:

To understand farmers have a choice for how they will sell their produce

Materials:

Internet Access

Butcher block paper or other large group brainstorming space

Children‘s Picture books (optional): Apple Farmer Annie, by Monica Wellington

Time: 75 minutes

Vocabulary: community supported agriculture, cooperative, corporation

Background Information on Distribution Networks:

Farmers have a range of options for selling their products. Each has its own advantages and

disadvantages, and several of them can be used simultaneously. A farmer first needs to decide what his

or her priorities are, have an accurate assessment of the farm‘s production capacity and schedule, and a

good handle on the amount of time the farmer wishes to devote to sales. Here are some examples of the

options a farmer might have:

Farmer‘s markets (producer only):

Dane County Farmers Market: http://www.dcfm.org/

Farm Fresh Markets (D.C. area): http://www.freshfarmmarket.org/markets.html

Grower Cooperatives:

Grower‘s Cooperative Grape Juice: http://www.concordgrapejuice.com/

Florida‘s Natural Orange Juice: http://www.floridasnatural.com/

Farm Market Stand/Sales from the Farm:

Massachusetts Roadside Stands: http://www.massfarmstands.com/

36

Community Supported Agriculture:

Madison Area Community Supported Agriculture Coalition: http://www.macsac.org/

Grocery Store:

Whole Foods: http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/

Roundy‘s: http://roundys.com/

Wegman‘s: http://www.wegmans.com/

Grocery Cooperative:

Willy Street Coop: http://www.willstreet.coop

The Wedge: http://www.wedge.coop/

Farm to Institution:

Farm to School: http://www.farmtoschool.org/

Farm to Hospital: http://departments.oxy.edu/uepi/cfj/f2h.htm

Teacher/Student Instruction:

1. Present students with a large bag of fruits and vegetables….the bigger the better. Tell them that

as a farmer, you are trying to figure out what your options are for selling your surplus crop.

2. Ask students to brainstorm a range of possible venues for selling your surplus. If they get stuck,

ask them to think about all the places they encounter fruits and vegetables for purchase. After

students have struggled a bit with brainstorming, fill in the gaps with options not yet discussed.

3. With the list the whole group generates, break students up into small groups and have them

discuss how the options differ. For groups needing more concrete direction, have them

brainstorm a list of advantages and disadvantages for each option. Have students identify some

examples of these structures within their own community. (Some examples are provided in the

Background section above. If available, students can look through some of these sites to get a

fell for the different options.)

4. Guide students into a discussion of variables that farmers need to consider in making these

decisions: time, location, volume, political goals, ecological goals, etc. (Be sure students have

an adequate understanding of the definition of each of these options.)

5. Ask students to write a reflection on which of the options they think would best fit their own

vision of farming. As an alternative, have students rank order the options they created, based on

their own personal criteria.

Questions: (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation)

37

1. What options do farmers have to sell their surplus produce? (Knowledge)

2. What are the variables that go into deciding which option is the most appropriate?

(Comprehension)

3. Which option does the student most see fitting themselves? (Application)

4. How do the different options influence society? (Synthesis)

Extensions:

1. Choosing a particular value (i.e. ecological, efficiency, price, etc.) rank order the options farmer

have for distributing produce.

2. For an added challenge, create a grid that identifies both particular values and distribution options.

Students can begin marking the boxes filling in the boxes with comments or a self-created ranking

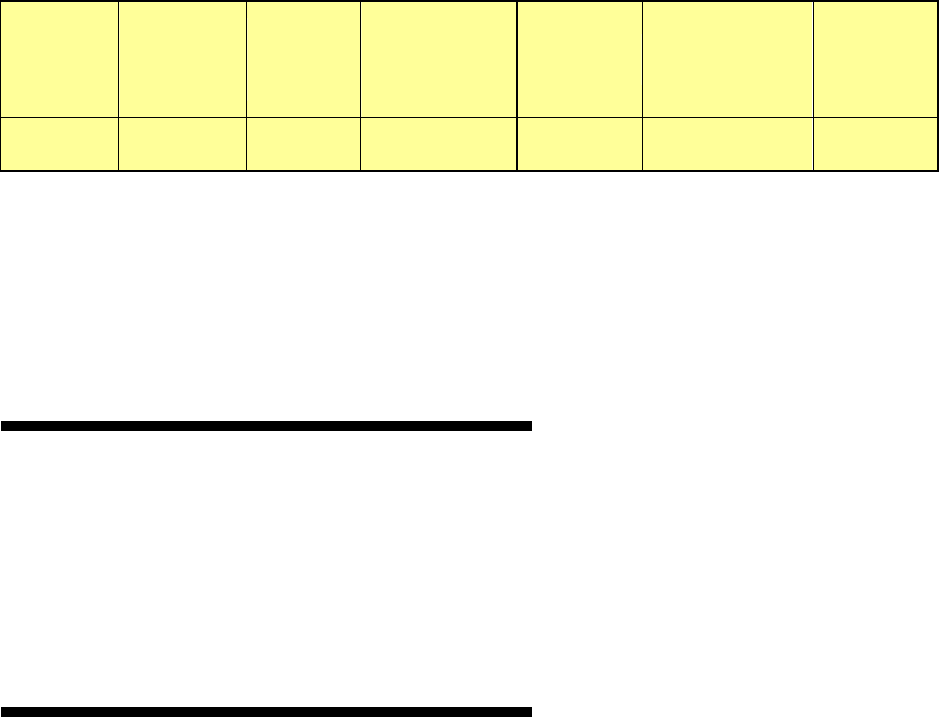

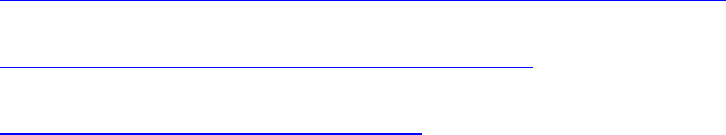

system. Something similar to this table would be a beginning.

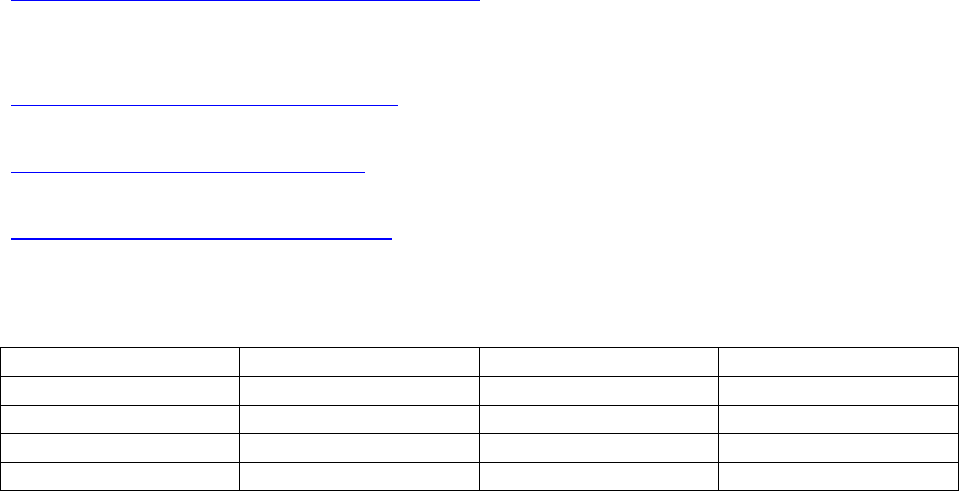

Ecological

Farmer Profit

Time Efficiency

CSA

Farmer‘s Market

3. Have students research the difference in business models these options represent: sole

proprietorship, limited partnership, cooperative, or corporation. The structure each represents will help

students better understand the legal implications of the options they choose.

Resources:

1. Farmer‘s Markets nationwide: http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/FARMERSMARKETS

2. Marketing your Produce, Tips from Cornell University Extension:

http://www.marketingschoolforgrowers.org/homepage.html

3. National Cooperative Grocer‘s Association: http://www.ncga.coop/

4. Local Harvest: http://www.localharvest.org/

38

Unit 2: Food Systems

In this section students explore the larger picture of how food moves from agriculture to the culinary

arts. In addition, lessons allow students to see how agriculture affects natural ecosystems.

From Farm To Table: Understanding Food Systems

Ecosystems & Agroecosystems

Organic Farming Business Structures – Case Study: Organic Valley

39

Lesson Plan: From Farm to Table: Understanding Food Systems

Unit: Food Systems

Objectives:

Students will define what a food system is.

Students will identify different parts of a food system.

Students will compare and contrast conventional and local food systems in the United States.

Students will compare and contrast large scale organic and local organic food systems in the

United States.

Students will learn what energy inputs are necessary for food systems to function.

Modified Curriculum Expectations:

Students will learn what a food system is.

Students will understand parts of a food system by tracing how milk and other dairy products

travel from farm to table.

Students will compare the path traveled by dairy products produced locally (in Wisconsin) with

those produced in California.

Students will identify one part of a food system that needs energy to work.

Materials Needed: Copies of Food System Flashcard Sets*, Scissors, Glue, Poster board or large

construction paper, Computer Access, Samples of Food Products (optional)

Illustrated cards to go along with terms below (excluding last two) are being completed and

then digitalized – lesson will include these to be reproduced and cut out by students.

Time: Minimum of 3 class periods.

Vocabulary:

Food system: the system that produces, processes, distributes, and consumes food from seed to table.

Organic Agriculture: a way of growing crops and raising animals that promotes and enhances

biodiversity, biological cycles and biological activity using very little, if any, synthetic chemical

fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and insecticides.

Conventional Agriculture: a way of growing crops and raising animals to maximize production by

including new technologies, mechanization, increased use of chemicals, and specialization, often

characterized by large scale production operations.

Vocabulary for Food System Flashcard Sets:

Farm Supplier: a company that produces farm inputs such as seeds, compost, fertilizer, pesticides,

herbicides, farm machinery, and fuel.

40

Producer: a farm that raises plants or animals, including fisheries, for food.

Processor: a company that takes raw product from a producer and turns it into a food product.

Distributor: a company that acts as a ―middle-man,‖ buying large amounts from producers and selling

them to a variety of retailers/stores.

Transporter: someone who uses trucks or other vehicles to move products from farms to other parts

of the food system.

Retailer: the grocery store or other food store that sells directly to the consumer.

Consumer: the person who buys and uses the food.

Background Information:

In order to create a map of your local food system, it is helpful to know who the main players are.

Identifying local grocery stores is easily done, but knowing who the local and regional distributors are

is more challenging. Calling a few local grocery stores, especially those that are not chain stores (they

often have their own distribution networks), and asking to talk with a Produce Purchaser is a great

place to start. They can tell you where the fresh vegetables, roots and frujt the store carries come from,

both in terms of local farm producers and local/regional distributors. Asking to talk with someone who