FI N A L REPORT

Effects of the Affordable Care Act on

Safety Net Hospitals

November 2016

Laurie Felland

Peter Cunningham*

Annie Doubleday

Cannon Warren

Submitted to:

The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

United States Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Avenue, SW

Washington, DC 20201

Project Officer: Andrew Sommers, PhD

Contract Number: HHSP23320095642WC/HHSP23337039T

Submitted by:

Mathematica Policy Research

1100 1st Street, NE

12th Floor

Washington, DC 20002-4221

Telephone: (202) 484-9220

Facsimile: (202) 863-1763

Project Director: Laurie Felland, MS

*Virginia Commonwealth University

iii

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION / EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 1

II. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND PROCESS ........................................................... 3

A. Policy context............................................................................................................................. 3

B. Project team............................................................................................................................... 3

C. Planning stage ........................................................................................................................... 4

D. Conceptual framework ............................................................................................................... 4

E. Study scope and methodology .................................................................................................. 5

F. Dissemination of findings ........................................................................................................... 6

III. KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................ 7

A. Summary ................................................................................................................................... 7

B. Changes in patient volumes and mix ........................................................................................ 7

C. Experiences with alternative payment models and value-based payment initiatives .............. 12

D. Financial impacts ..................................................................................................................... 17

E. Additional observations about differences between the 2014 and 2015 semi-

structured discussions ............................................................................................................. 23

1. Quantitative findings.......................................................................................................... 23

2. Qualitative findings ............................................................................................................ 24

F. Limitations and challenges ...................................................................................................... 24

IV. CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. 27

APPENDIX 1: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK .......................................................................................... 28

APPENDIX 2: TABLE OF HOSPITAL CHARACTERISTICS .................................................................... 32

APPENDIX 3: METHODOLOGY OVERVIEW ........................................................................................... 36

APPENDIX 4: FINANCIAL TABLE TEMPLATE......................................................................................... 45

APPENDIX 5: 10 SITE SUMMARIES ........................................................................................................ 49

APPENDIX 6: HOSPITAL PERFORMANCE ON CMS QUALITY MEASURES ........................................ 94

v

FIGURES

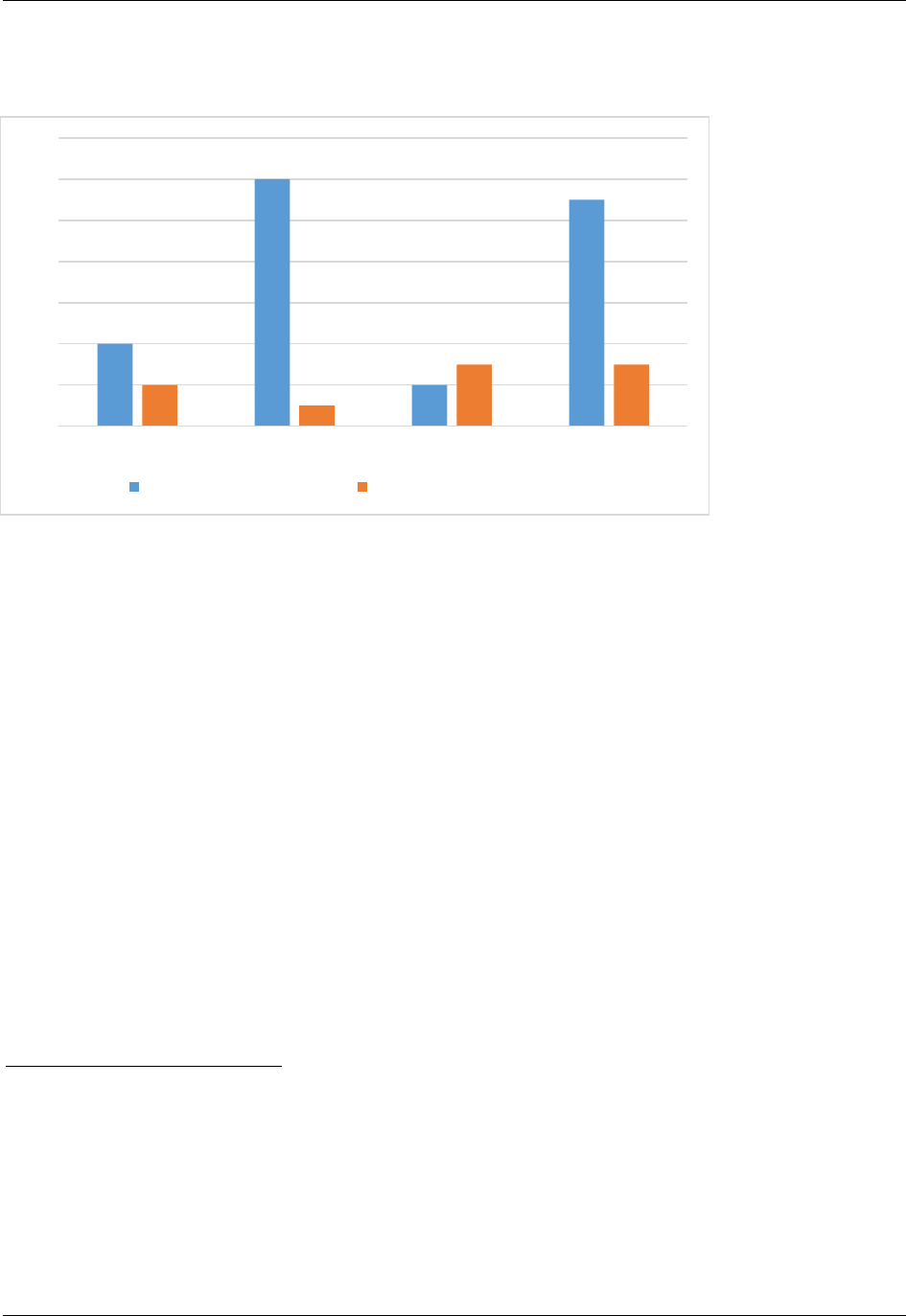

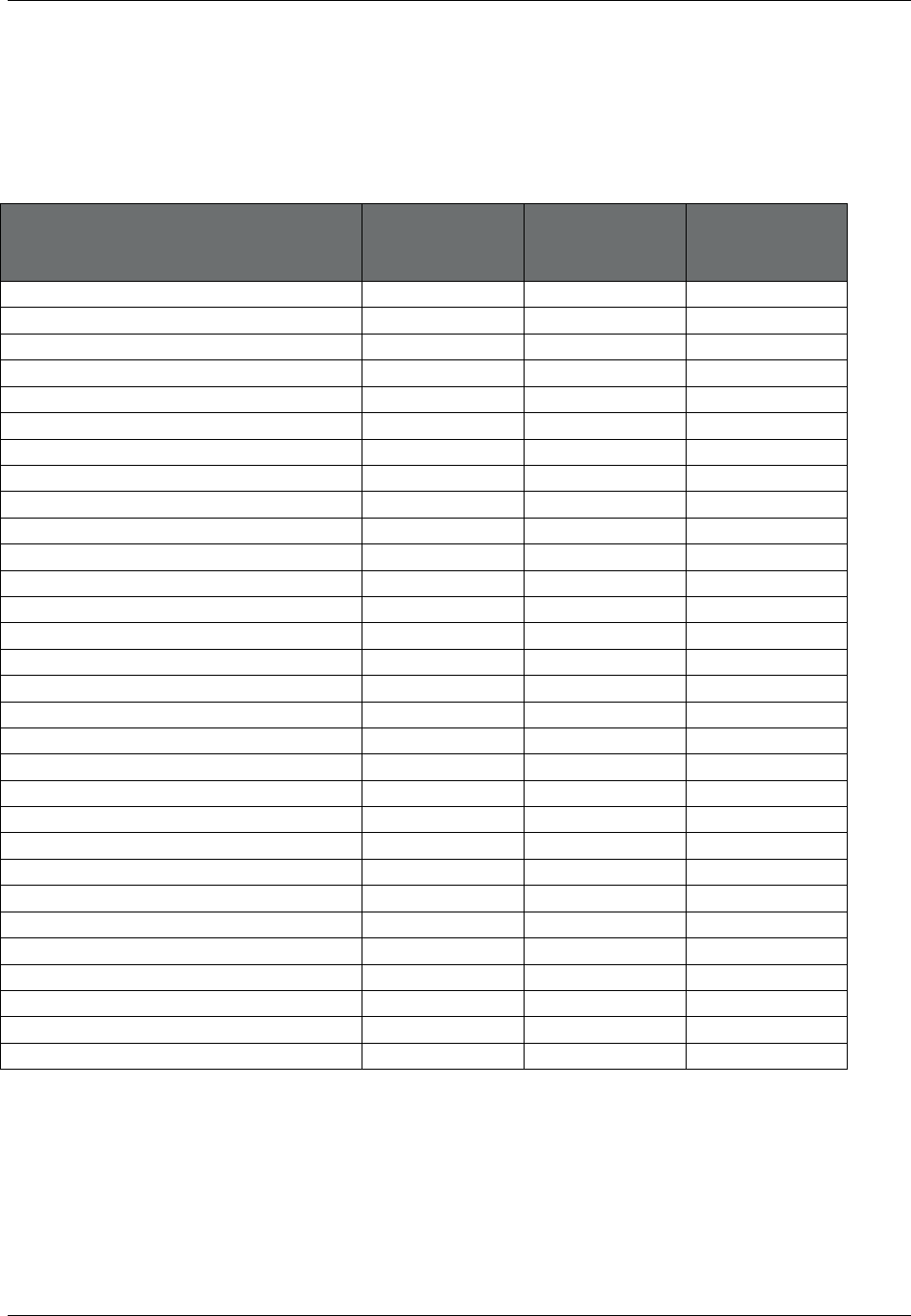

1 Average change in patient volumes by service between 2013 and 2015........................................ 8

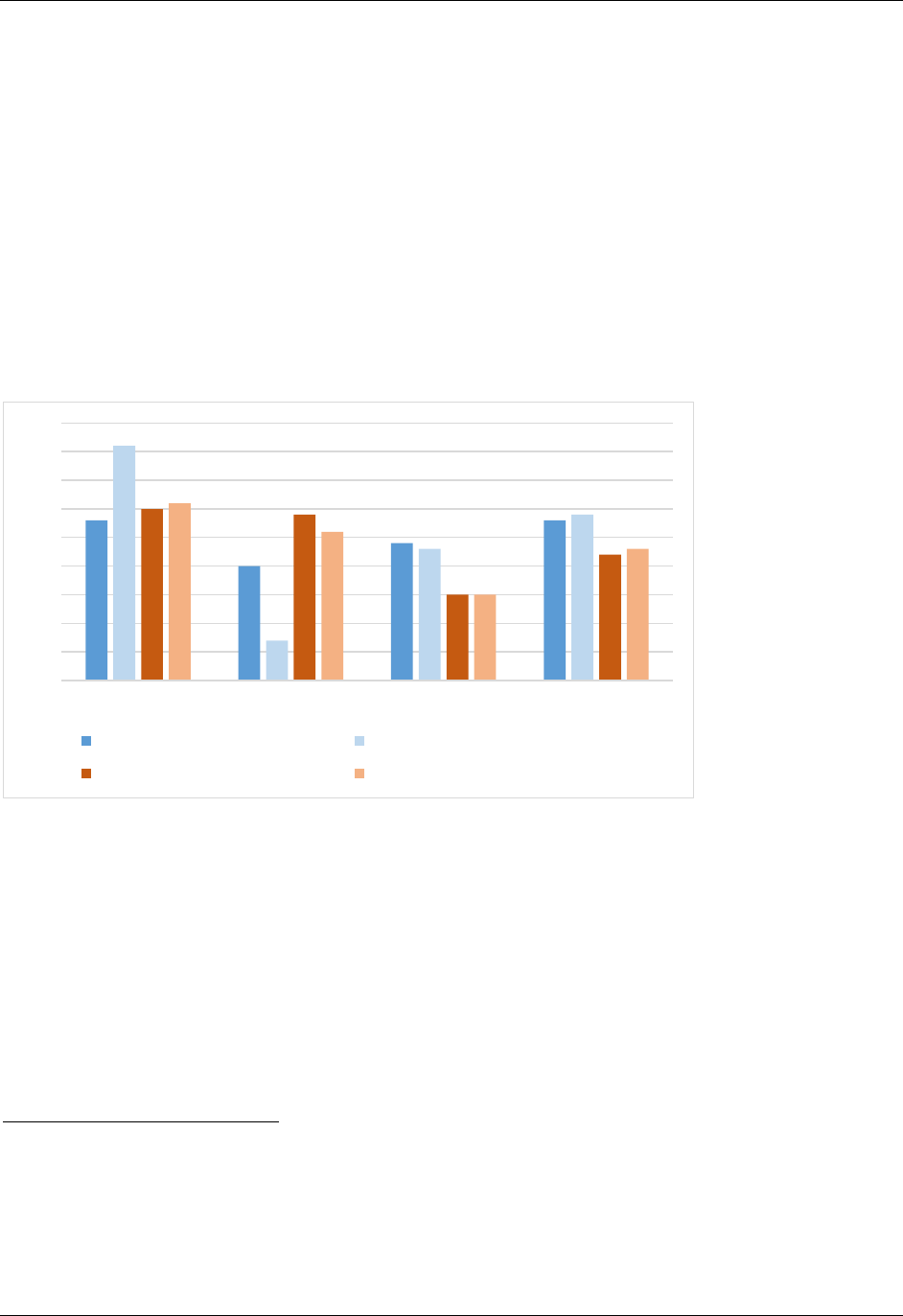

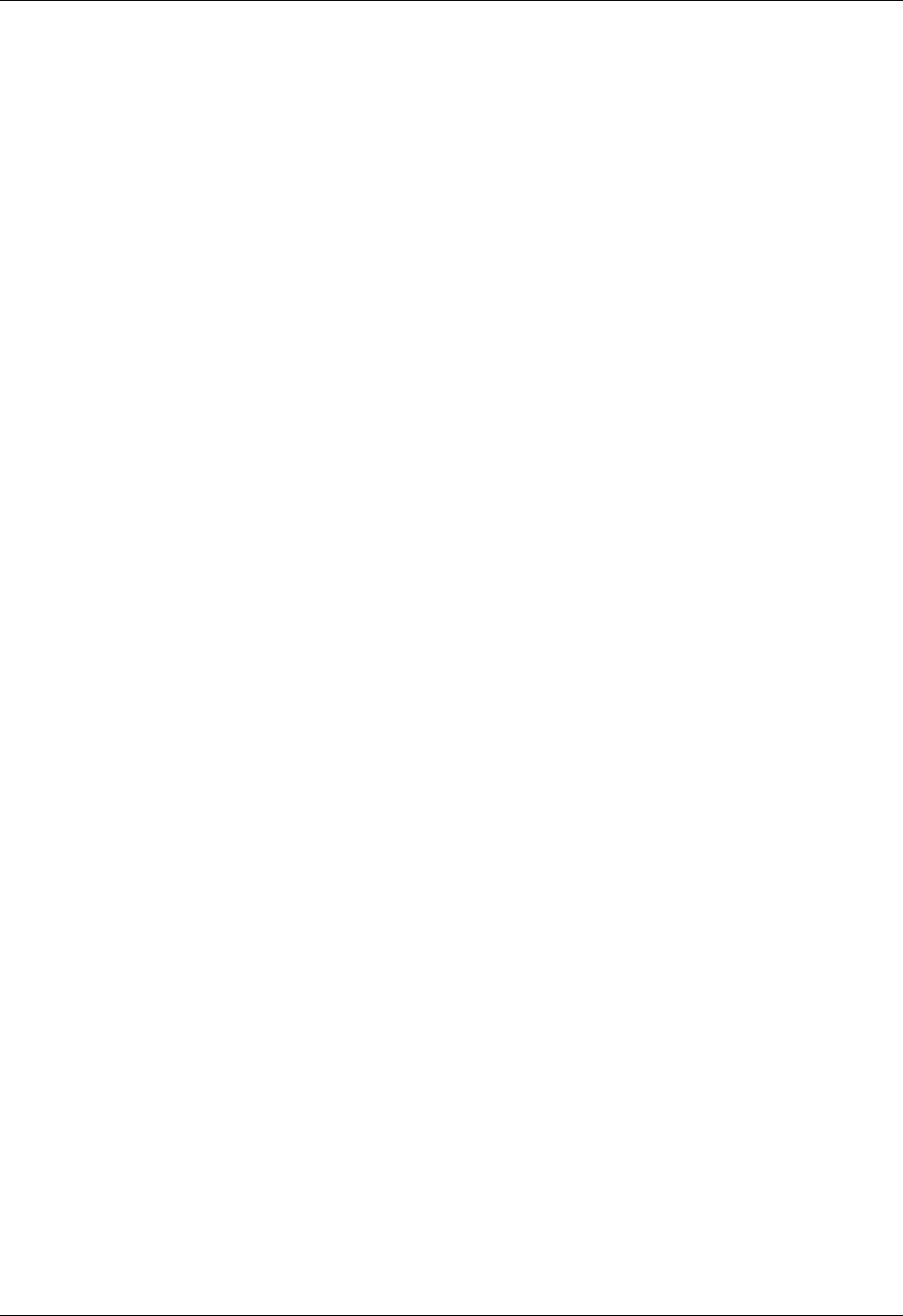

2 Average change in patient volume by payer source between 2013 and 2015 ................................ 9

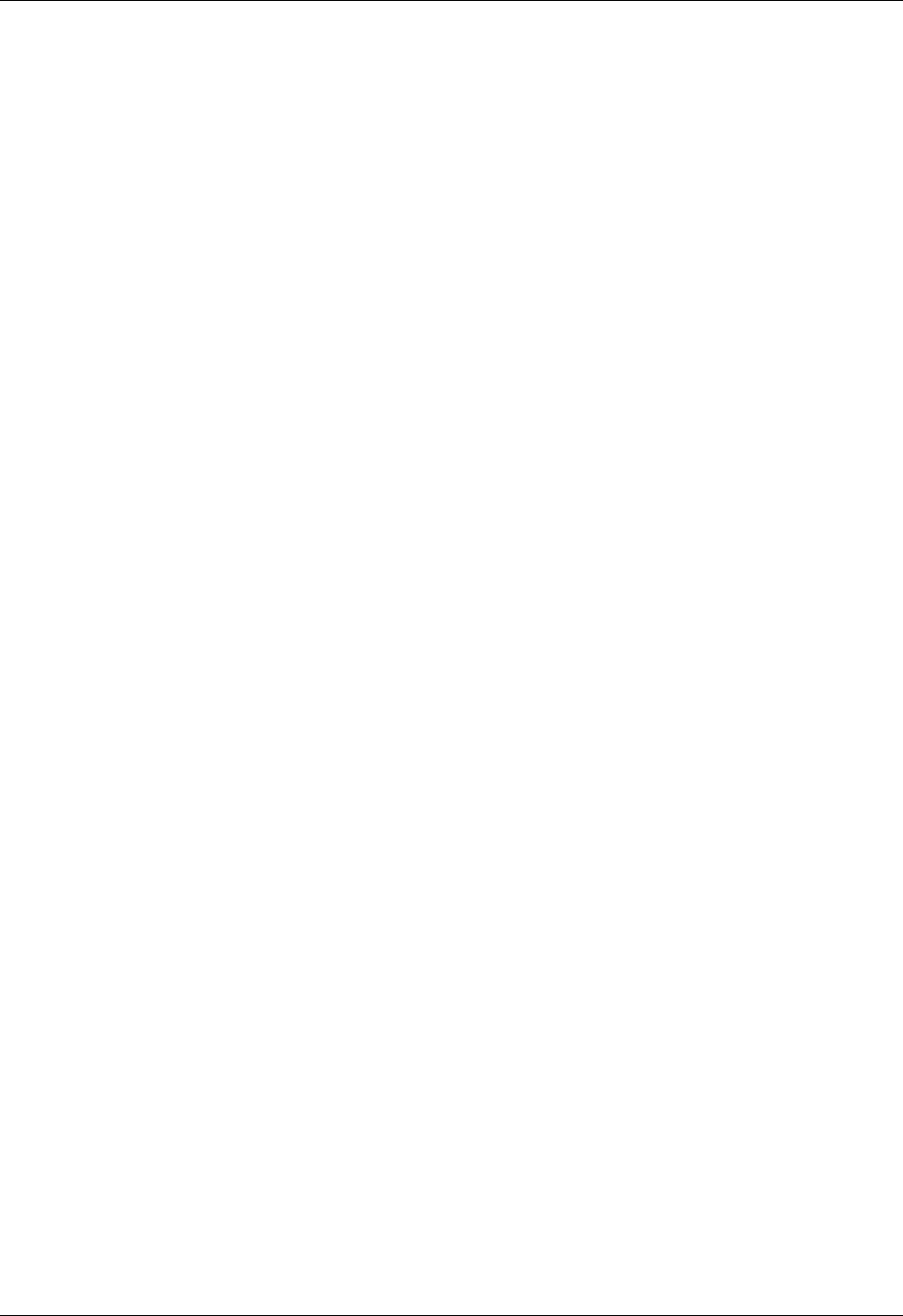

3 Average patient mix, 2013 and 2015 ............................................................................................. 10

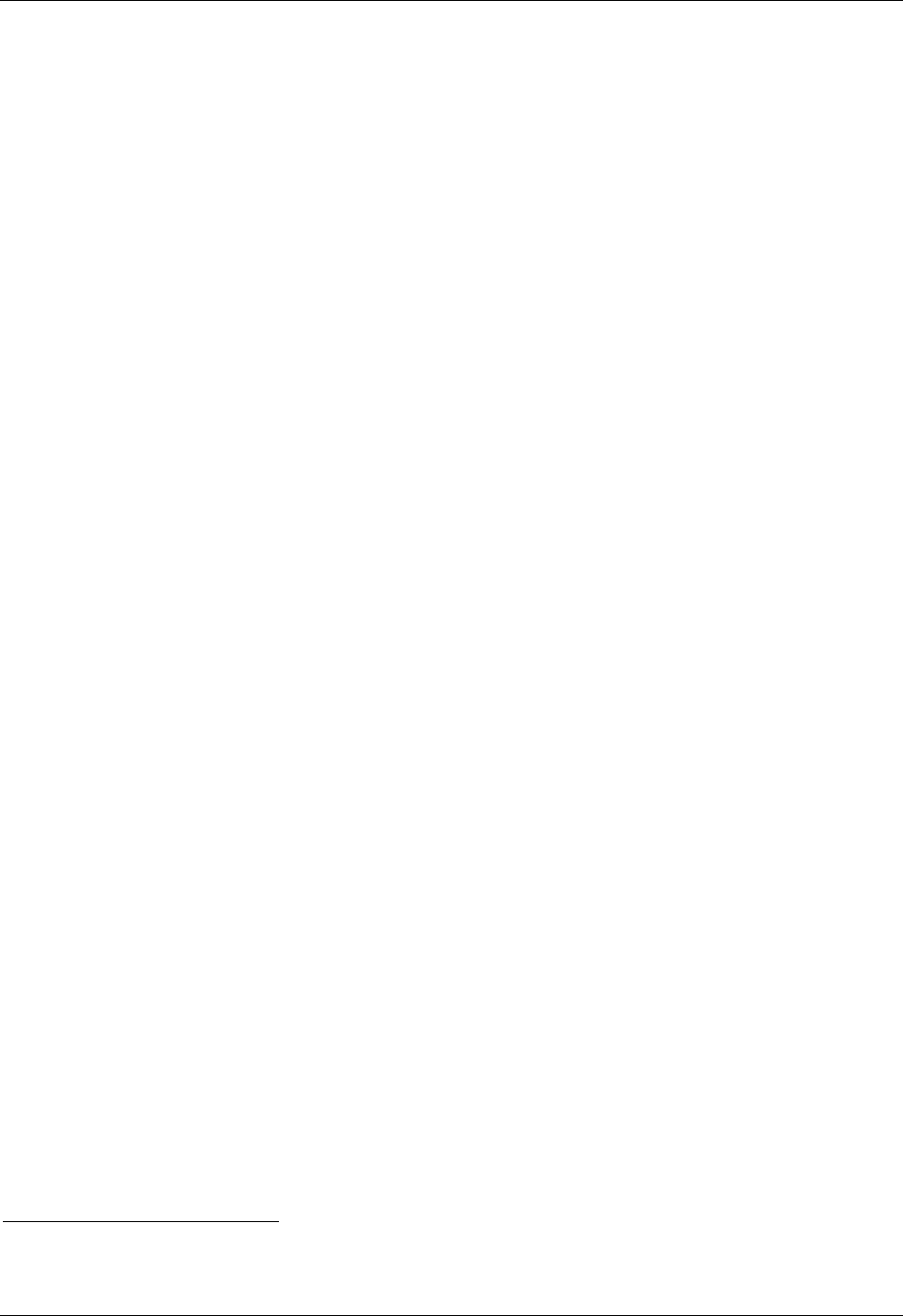

4 Average payer mix, 2013 and 2015 ............................................................................................... 18

5 Average financial margins, 2013 and 2015.................................................................................... 21

1

I. INTRODUCTION / EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is expected to have profound effects on the health care

system in the United States, including the safety net hospitals that care for many low-income

uninsured people, Medicaid enrollees, and other vulnerable populations. Given the important role

safety net hospitals play in their communities, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning

and Evaluation (ASPE) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) contracted with

researchers from Mathematica Policy Research and Virginia Commonwealth University to study

the early effects of the ACA on 10 safety net hospitals, both in states that expanded income

eligibility for Medicaid under the ACA and those that did not. This primarily qualitative research

study, conducted between September 2013 and March 2016, provides an on-the-ground

assessment of the extent and nature of early changes in patient demand for services; hospital

capacity; preparations for payment and delivery system reforms; and changes in hospital

revenues, costs, and overall financial status.

In this final report, we summarize the objectives and process for designing and conducting

this study; the key findings, challenges, and limitations faced; the ways in which the results have

been disseminated; and the major conclusions and policy implications of these findings. Overall,

our research found that, on average, safety net hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid under

the ACA are treating significantly more insured and fewer uninsured patients than in 2013, and

that this shift has helped the hospitals financially. In contrast, the hospitals in states that did not

expand Medicaid typically experienced little change in their patient mix and increased financial

challenges. Overall, hospitals in both types of states experienced little effect from new

Marketplace coverage, faced declining subsidies, and are bracing for additional cuts, although

experience varied within the study set. The study also identified a number of challenges that

safety net hospitals face in adapting to payment and delivery system reforms; several of the study

hospitals have made progress in developing integrated delivery systems capable of assuming

financial risk, but others lag behind. The future viability of safety net hospitals may hinge on

potential changes to financial supports, as well as strategies to reduce hospital costs and better

manage care.

3

II. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND PROCESS

A. Policy context

Policymakers, health care providers, researchers, and others have expected the ACA to have

profound effects on the U.S. health care system, including the safety net hospitals that provide

health services to many low-income uninsured people, Medicaid enrollees, and other vulnerable

populations. Based on the assumption that as more people gain insurance coverage, hospitals will

receive increased revenue from insured patients and reductions in uncompensated care, the ACA

reduces Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, although

these reductions have been delayed until 2018. To avoid a negative financial impact, safety net

hospitals likely will need to attain substantial changes in payer mix—that is, more insured

patients and fewer uninsured patients—to offset the loss of these subsidies. The degree to which

safety net hospitals fare well under health reform will also depend in part on whether they are

considered “essential community providers”

1

by health plans and the extent of competition with

other hospitals for newly insured patients.

The ACA also has called for major changes in the delivery and financing of health care.

These changes include a shift from paying for volume to paying for value and encouragement for

health care providers to accept greater financial risk for the care of patients. The ACA

encourages new forms of payment and care delivery—such as Accountable Care Organizations

(ACOs), value-based payment, bundled payments, and patient-centered medical homes (PCMH).

Given many of these new models are still in the relatively early stages of implementation,

limited evidence exists to date that alternative payment models can successfully improve quality

of care and lower health care costs on a national scale. In 2015, the Secretary of Health and

Human Services announced ambitious delivery system reform with the goals of tying 90 percent

of all Medicare fee-for-service payments to value-based payment programs by 2018, and making

50 percent of Medicare payments via alternative payment models in the same time frame.

2

Success under alternative payment models will require hospitals to function differently than

before, as payment is tied to performance on measures of quality and costs of care, and

accountability is shifted to the hospital for patient outcomes across the care continuum.

3

Safety

net hospitals in particular face a number of challenges to success under value-based payments

and alternative payment models, including more limited financial resources and a patient

population with more complex clinical and social needs.

B. Project team

The research team worked closely with Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation (ASPE) staff throughout all stages of the project. The principal investigators (Laurie

1

National Academy for State Health Policy. “Essential Community Providers: Tips to Connect with Marketplace

Plans.” April 2013. Available at http://www.nashp.org/sites/default/files/ecp.tips.connect.marketplace.plans.pdf.

2

Burwell, S.M. “Progress Towards Achieving Better Care, Smarter Spending, Healthier People.” Available at

http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html.

3

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “Better Care, Smarter Spending, Healthier People: Improving Our

Health Care Delivery System.” Available at https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-

sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26.html.

II. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

4

Felland from Mathematica and Peter Cunningham, formerly from Mathematica and now at

Virginia Commonwealth University)—collectively called the “project team” throughout this

report—discussed the project in regular biweekly calls with the project officer to provide updates

and seek guidance. The purpose of these calls was to report on progress, discuss issues that arose

over the course of the project, and seek input and comment from ASPE on key aspects of the

project and all deliverables. During the field period for the case studies, these calls also provided

an opportunity to share our early impressions with ASPE and report on any difficulties

encountered as we conducted our research. We also held several additional in-person meetings at

ASPE after the kickoff meeting, including one to discuss site selection, another to discuss the

earlier proposed quantitative study, and one on early findings from the qualitative data collection

effort.

C. Planning stage

Under Mathematica’s contract with ASPE, “Building Analytical Capacity for Policy

Analysis and Decision-Making,” the research team led a separate planning task in early 2013 for

conducting the case studies for this project. The planning phase consisted of four main

components: (1) an environmental scan to identify the key research questions and conceptual

framework for understanding the effects of health reform on safety net hospitals; (2) the metrics

and potential data sources that would be available for case studies; (3) a plan for conducting case

studies; and (4) convening an eight-member technical expert panel (TEP) meeting to provide

input to the plan. These activities informed the overall strategy as well as the specific

methodology for selecting the individual hospitals to study, identifying the types of organizations

and individuals with whom to speak, and specifying the content of the semi-structured

discussions and other information collected. In September 2013, Mathematica received the

contract to conduct the study and held a kickoff meeting with ASPE in November 2013.

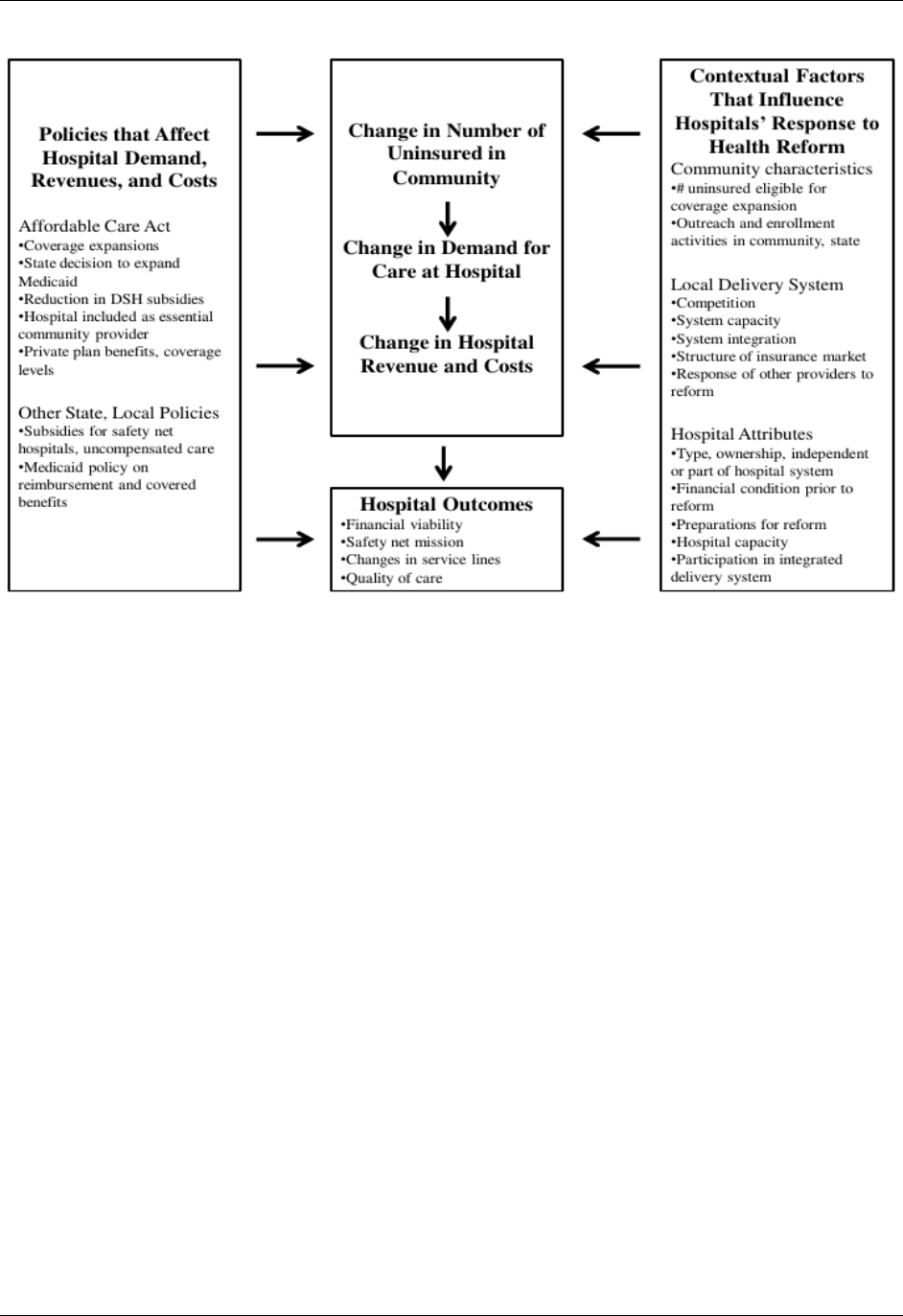

D. Conceptual framework

The project team developed a conceptual framework during the planning stage to guide the

project (see Appendix 1). The framework draws on other efforts to develop a monitoring strategy

for safety net hospitals, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ’s)

Safety Net Monitoring Initiative, and an initiative by the Health Resources and Services

Administration (HRSA) to monitor the effect of state health insurance expansions on safety net

organizations.

4

We used the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) definition of safety net providers:

“providers that organize and deliver a significant level of both health care and other health-

related services to the uninsured, Medicaid, and other vulnerable populations,” as well as

providers “who by mandate or mission offer access to care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay

and whose patient population includes a substantial share of uninsured, Medicaid, and other

vulnerable patients.”

5

4

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. “The Safety Net Monitoring Initiative: Fact Sheet.” August 2003.

Available at http://archive.ahrq.gov/data/safetynet/netfact.pdf; Harrington, Mary E., and Vivian L. Byrd.

“Monitoring the Impact of State Health Insurance Expansion on Safety Net Organizations. Final report submitted to

the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, July 2009.

5

Institute of Medicine. “America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered.” Washington, DC: National

Academies Press, 2000.

II. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

5

We adapted the conceptual frameworks used in these previous efforts to account for both

specific provisions of the ACA and recent changes in the health care delivery system, along with

issues specific to safety net hospitals. We also incorporated comments from the TEP. The

framework identified the key policies (other state and local policies and funding streams in

addition to the ACA provisions) that affect hospital demand, revenues, and costs, as well as the

types of contextual or “market” factors that influence hospitals’ responses to health reform, such

as community characteristics, the structure of the local health care delivery system, and

individual hospital attributes. Taken together, these policy and market factors contribute to

changes in the number of uninsured people in the community, which in turn affects demand for

care at safety net hospitals, and thus changes in these hospitals’ revenues and costs. These

changes, along with care delivery and payment reforms, affect a hospital’s “outcomes”; these

outcomes include its financial viability, ability to remain a safety net provider, array of service

offerings, and quality of care.

E. Study scope and methodology

ASPE and the research team purposively selected for study 10 safety net hospitals or

systems that range in size, role in their local safety net, ownership, and geographic location.

Some are single hospitals, some are hospital systems with several hospitals included in the

analysis (and other outpatient or other facilities), while others are part of larger hospital systems,

for which the other hospitals are separate from the analysis (either because they are in a different

community, focus on a limited set of services and/or are not deemed safety net hospitals).

Appendix 2 provides a table displaying key characteristics of these hospitals in more detail;

Appendix 3 provides details of our methodology.

Six hospitals are in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA:

LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California (flagship hospital of a four-hospital

county system)

Yale-New Haven Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut (part of the three-hospital Yale New

Haven Health System)

Denver Health in Denver, Colorado

University of Kentucky HealthCare (UK Health, three hospitals) in Lexington, Kentucky

Marcum and Wallace Memorial Hospital in Irvine, Kentucky

Lakewood Health System in Staples, Minnesota

Four hospitals are in states that have not expanded Medicaid:

Harris Health System (three hospitals) in Harris County (Houston), Texas

Regional One Health in Memphis, Tennessee

Froedtert Hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (part of a three-hospital Medical College of

Wisconsin system)

II. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

6

Homestead Hospital in Dade County, Florida (part of the Baptist Health South Florida

system)

The research team primarily used qualitative methods to understand the effects of the ACA

on these hospitals between early 2013 and 2015. Using a mix of in-person and telephone semi-

structured discussions, we spoke with the six hospitals from states that expanded Medicaid

(“Medicaid expansion states”) in both 2014 and 2015, and the other four hospitals in 2015 only.

The semi-structured discussions covered the following key topics: the hospitals’ role in the

local safety net; changes in their operational and financial well-being (including changes in

patient volumes for different service types, patient mix, system capacity, revenues and expenses,

and overall financial performance); factors contributing to these changes (ACA and other); and

the hospitals’ strategies, goals, and expectations for the future. The 2015 semi-structured

discussions also covered the hospitals’ experiences with Medicare value-based payment

initiatives—specifically, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Hospital-Acquired

Conditions (HAC) Reduction Program, and Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program

6

—and

involvement in alternative payment arrangements, in which hospitals take on more financial risk.

We also gathered quantitative indicators directly from each hospital on patient volumes and

financial performance for the same time period, which informed both the semi-structured

discussions and the analysis (see Appendix 5). We analyzed the findings in two main stages: by

individual site (see Appendix 5 for the 10 summaries) and across sites (see below).

F. Dissemination of findings

We presented study findings (see next section) to several important audiences during the last

year of the project. Laurie Felland presented early findings from the original 6 sites at the June

2015 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting. Peter Cunningham presented key findings

across the 10 sites at the Annual AHRQ Research Conference in October 2015. We also

conducted a final study briefing for ASPE staff in April 2016.

The project team also summarized the findings of the cross-cutting analyses in two research

briefs. One paper examines the early effects of the ACA on the study hospitals’ patient volumes

and finances, while the second brief explores how the study hospitals are preparing for payment

and delivery system reforms.

6

See the CMS website for more information on these programs at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare.html.

7

III. KEY FINDINGS

A. Summary

Study hospitals (Appendix 2) in states that expanded eligibility for the Medicaid program

experienced considerable patient volume increases from Medicaid enrollment expansions,

whereas they experienced little volume change from the ACA’s expansion of commercial

coverage through the federal and state Marketplaces. Despite concerns that they might lose many

newly insured patients to other providers, these study hospitals largely retained existing patients

and gained new ones. The growth in patient volume was especially notable for outpatient care,

and there were corresponding marked increases in the proportion of their patients with insurance

coverage. The growth in outpatient visits reflects in part safety net hospitals’ active efforts to

help uninsured patients enroll in coverage, expand primary care capacity, and improve their

facilities and systems to attract or retain patients as they gained coverage. Respondents (the

hospital executives and staff we spoke with for the study) reported that these changes both

supported their patients and the hospitals’ overall financial health. The words of one hospital

executive captured the sentiment of many: “The biggest success of the ACA is reducing our self-

pay [uninsured] patients and getting people the health care that they need. That to me has been a

great thing financially and a great thing for patients … we have anecdotal stories that people are

accessing care and identifying issues and getting better.”

In contrast, study hospitals in states that did not expand eligibility for Medicaid experienced,

on average, more modest increases in patient volumes and no overall change in patient mix, with

many of their patients remaining uninsured. On average, they experienced greater financial

challenges compared to the hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid (“expansion state

hospitals”); these challenges increased over the study period. Although hospitals in both types of

states experienced some declines in their subsidies to support care for the uninsured, all of them

are bracing for additional cuts.

B. Changes in patient volumes and mix

Patient volume grew overall but more so among expansion state hospitals. Most of the

study hospitals provided a higher volume of patient care in the first quarter of 2015 relative to

the first quarter of 2013. Respondents reported that this growth represents a mix of additional

services provided to existing patients who had previously been uninsured and services to new

patients. Overall, patient volumes increased more for expansion state hospitals than non-

expansion state hospitals, with the former reporting an average 11 percent increase and non-

expansion state hospitals reporting an average of 3 percent (Figure 1). The degree of increase

varied widely, from 2 percent to 22 percent, across all study hospitals. Outpatient volumes grew

more than other services (inpatient admissions and emergency department encounters) for

expansion state hospitals, by an average of 12 percent (the increases ranged from 4 percent to 24

percent across expansion state hospitals). In contrast, outpatient volumes did not change much at

non-expansion state hospitals: 1 percent on average (change across non-expansion state hospitals

ranged from -9 percent to 12 percent).

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

8

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

Inpatient Outpatient Emergency Dept. Total

Expansion-State Hospitals Non-Expansion-State Hospitals

Figure 1. Average change in patient volumes by service between Q1 2013

and Q1 2015

Expansion state hospitals’ outpatient growth reflects a variety of factors. Most of the

Medicaid expansion population receives care through managed care arrangements; the health

plans typically require new enrollees to choose a medical home (which provides primary care

and coordinates additional follow-up care) and encourage them to seek an appointment soon

after enrolling.

7

Also, many of the study hospitals had expanded outpatient capacity (see

Hospitals expanded ambulatory care section below) as they sought to redirect patients from their

emergency departments (EDs) and reduce or shift care away from inpatient facilities.

8

This

redirection occurred because of capacity constraints and the hospitals efforts to provide care in

less costly settings in preparation for new payment arrangements that reward value (better

outcomes at lower costs) over volume of services provided (see Experiences with Value-Based

Purchasing and Alternative Payment Models section.)

Overall, the study hospitals observed a 3 percent increase in ED volumes. Whereas changes

generally ranged from only small increases to small decreases, a couple of expansion state

hospitals saw larger (11–12 percent) increases in ED use. These increases are consistent with

studies that find that insured patients use EDs more than uninsured patients because EDs are

convenient and Medicaid patients typically face no cost sharing to use one;

9

access to primary

7

The extent to which Medicaid managed care plans use a strict gatekeeper model that authorizes referrals for

follow-up care varies by state/community, but the general concept is typically in place, whether the primary care

physician (PCP) has strict authorization authority or not.

8

Some apparent changes in volumes represent shifts among service categories. For Froedtert, part of the apparent

rise in outpatient cases is that the Medicare “two-midnight rule” shifted cases previously categorized as inpatient

into observation or outpatient cases.

9

Cunningham, Peter J., and Jessica H. May. “Insured Americans Drive Surge in Emergency Department Visits.”

Issue Brief No. 70, Washington, DC: The Center for Studying Health System Change, October 2003.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

9

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

Medicaid Uninsured Commercial Medicare

Expansion-State Hospitals Non-Expansion-State Hospitals All Study Hospitals

and specialty care in outpatient settings may be more difficult. Some respondents were surprised

that ED visits did not increase more as people gained coverage.

ED use among non-expansion state hospitals also increased slightly. In addition to the slight

Medicaid volume increases, each non-expansion state hospital provided additional reasons for

the increase, from growth in commercially insured patients (Homestead), to population growth

(Harris) and greater severity in patients’ conditions, possibly linked to delayed care (Froedtert).

Inpatient volumes and average length of inpatient stay also did not increase much for

expansion state or non-expansion state hospitals.

10

This finding suggests that new patients were

not significantly sicker than previous patients. Although hospital executives reported more

chronic conditions and pent-up demand among their newly insured patients, many of those needs

reportedly were addressed on an outpatient basis.

Medicaid growth outpaced Marketplace growth. Overall, the Medicaid expansion was a

more significant contributor to volume growth at the safety net hospitals than the new

Marketplace coverage options for low-income people. The growth in patient volumes stemmed

from different sources for expansion state hospitals and non-expansion state hospitals: for the

former, primarily from Medicaid patients; for the latter, primarily from commercially insured

patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average change in patient volume by payer source between Q1

2013 and Q1 2015

Medicaid volume grew more among expansion state hospitals in states that previously had

no or minimal Medicaid eligibility or other public coverage programs for childless adults

(California, Kentucky, and Colorado). A couple of the expansion state hospitals experienced

10

Only Marcum and Wallace had a significant increase (18 percent) in inpatient volumes, which mostly was

unrelated to the ACA or patient demand; rather, it reportedly represented a change in categorizing patients as

inpatients rather than observation stays.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

10

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

Medicaid Uninsured Commercial Medicare

Expansion-State Hospitals 2013 Expansion-State Hospitals 2015

Non-Expansion-State Hospitals 2013 Non-Expansion-State Hospitals 2015

dramatic increases in Medicaid encounters

11

and significant (but lesser) drops in encounters from

uninsured patients: for LAC+USC, Medicaid encounters jumped by 150 percent, whereas

uninsured encounters plummeted 85 percent; for UK Health, Medicaid encounters grew by 80

percent, whereas uninsured encounters fell 55 percent.

As a result of the shifts in volume, the patient mix changed markedly (Figure 3). Medicaid

encounters (inpatient, outpatient, and ED) became a much larger portion of the services provided

in some expansion state hospitals, whereas uninsured encounters as a portion of total encounters

dwindled. On average, Medicaid grew from 28 to 41 percent of total patient encounters (a 46

percent increase); the proportion of uninsured encounters fell from 20 percent to 7 percent (a 65

percent decrease).

Figure 3. Average patient mix, Q1 2013 and Q1 2015*

*Calculated based on average of inpatient, outpatient and emergency department patient mix.

Patient mix unavailable for Denver Health.

For non-expansion state hospitals, Medicaid volumes grew modestly for some hospitals, but

typically with little effect on Medicaid as a proportion of overall encounters (on average, non-

expansion state hospitals experienced little change in their overall patient mix between 2013 and

2015). Respondents attributed some of this growth to the ACA sparking more outreach activities

that led people already eligible for Medicaid to apply (often referred to as a “woodwork” or

“welcoming mat” effect). Reportedly, general population growth and increased capacity

contributed to Harris’s increase, whereas a change in Wisconsin’s Medicaid program that

brought people from a waiting list into the program led to growth at Froedtert.

12

However,

11

Total volume of inpatient admissions, outpatient, and ED visits.

12

Wisconsin allowed childless adults to enroll in Medicaid before the ACA but, with implementation of the ACA,

reduced income eligibility from 133 percent to 100 percent to align with the income level at which federal subsidies

for Marketplace coverage kick in; the state then opened its enrollment cap. Many people who had been on the

waiting list reportedly lived in the Milwaukee area, contributing to a net increase in Medicaid patients and a

reduction in uninsured patients for Froedtert.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

11

Medicaid volumes declined at Regional One, which executives attributed partially to Medicaid

patients aging into the Medicare program.

Although many study hospitals experienced some increase in commercially insured patients,

this source comprised more of non-expansion state hospitals’ volume growth than Medicaid (but

on average commercial as a percentage of overall patient mix remained stable and declined in

terms of overall revenue (Figure 4). Yet Marketplace coverage did not significantly affect either

expansion state or non-expansion state hospitals.

13

This finding is not especially surprising

because, in states that expanded Medicaid, enrollment typically far outpaced Marketplace

enrollment. Many of the study hospitals serve a very low-income population, so many existing

patients at expansion state hospitals qualified for Medicaid rather than Marketplace coverage,

and many non-expansion state hospitals’ patients live below the poverty line and are thus

ineligible for Marketplace subsidies. Also, a few hospitals reported challenges in obtaining

contracts with Marketplace health plans, either because they were not deemed “Essential

Community Providers” in their states and/or because they have historically lacked commercial

contracts as a basis for negotiation for inclusion in these plans’ provider networks.

Hospitals proactively worked to attract more patients. The growth in patient encounters

aligns with reported efforts by the study hospitals to retain and attract patients as they gained

coverage. Both expansion state and non-expansion state hospitals conducted in-reach (to existing

uninsured patients) and outreach (to find additional uninsured people in the community) to help

people apply for coverage. Some study hospitals gained ACA funding to assist in these efforts.

For example, UK Health participated in testing and implementing state outreach efforts in its

facilities, and a federally funded insurance navigator in Marcum and Wallace’s ED reportedly

helped many uninsured patients gain coverage.

The study hospitals made concerted efforts to improve their facilities, processes (for

example, appointment scheduling, wait times for appointments), and customer service so that

newly insured patients would select them over other providers. Many respondents referred to

these efforts as strategies to become “providers of choice, not last resort.” Also, some states

direct a large proportion of Medicaid enrollees who do not choose a health plan to those owned

by safety net providers; they also direct those who do not choose a medical home to safety net

providers. The study hospitals reported retaining many of their patients once they gained

coverage and also receiving new ones.

Hospitals expanded ambulatory care. Since many of these hospitals reportedly were

already operating close to or at capacity in their EDs and outpatient services before the ACA

coverage expansions, they needed to expand to treat more patients. With their focus on outpatient

services, most hospitals did not add inpatient beds; some even reduced staffed beds.

Whereas the study hospitals displayed a wide range in the extent of primary care they

provide, most had expanded primary care services between 2013 and 2015. As noted, primary

care capacity is vital if hospitals are to serve as medical homes in insurance networks; it also

helps them gain referrals for additional outpatient and inpatient services. In addition, primary

13

Many hospital executives noted difficulties in precisely parsing out Marketplace coverage from overall

commercial volumes to provide a percentage estimate of its total prevalence among commercial businesses.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

12

care is an important component of preparing for value-based payments (see next section). The

study hospitals mainly boosted primary care by adding physicians and other staff (for example,

nurse practitioners) on site; at least one hospital (Yale) acquired physician practices in the

community.

Some hospitals also added physical capacity on the hospital campus or at clinics in the

community, or extended their primary care reach by collaborating with other community clinics.

Homestead had not traditionally provided primary care but recently started a clinic that provides

comprehensive visits to patients after they leave the hospital so as to reduce their reliance on the

ED for follow-up care. Froedtert is developing more community clinics and partnering with a

federally qualified health center (FQHC). With many patients presenting in their EDs for

behavioral health issues, some of the study hospitals also have added social workers and

psychiatric staff (Denver) and/or are working to integrate behavioral health into primary care

(Lakewood).

A couple of non-expansion state hospitals substantially increased their primary care services

in anticipation of a Medicaid expansion, which then did not occur; Harris Health built two large

primary care clinics. With Texas opting out of the Medicaid expansion, the clinics serve many

more uninsured patients than before and identifies many specialty care needs; addressing these

needs has reportedly strained Harris’s capacity and financial status.

Given the costs of adding physical capacity and staff, some hospitals increasingly have

turned to other ways to extend primary care and other services outside of traditional patient-

provider visits. For example, Froedtert started a virtual urgent care clinic, using Facetime and

Skype Internet technology. Some of these efforts are not captured in the hospital volume data. In

a key example, LAC+USC makes greater use of telephonic medical advice as well as an

EConsult system, in which PCPs consult with specialists electronically to gain advice on how to

treat a patient’s condition or refer the patient to the specialist; this system reportedly has reduced

the need for face-to-face visits with specialists by one-third.

C. Experiences with alternative payment models and value-based payment

initiatives

Although adapting to changes in volume, patient mix, and service capacity, the study

hospitals (Appendix 2) also were responding to payment and delivery system reforms, both in

the ACA and through other federal and state initiatives. Unlike the changes in patient volume

and mix, we did not find clear distinctions between hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid

and those that did not regarding their participation in and readiness for these new payment

arrangements.

Varied participation in alternative payment models. The eight study hospitals (we did

not include the two rural hospitals in this analysis because of their small size and exemption from

Medicare value-based purchasing requirements) vary considerably in the extent to which they are

moving toward risk-based payments under managed care or alternative payment models. The

two county hospitals with a broad set of integrated services appeared more advanced in these

arrangements for the Medicaid population than the smaller hospitals and the academic medical

centers.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

13

LAC+USC and Denver Health are much further along the continuum of providing care

under risk-based payment arrangements than the other study hospitals. They already accept full

risk for their Medicaid patients (through capitation). Denver Health estimates that it currently

receives capitated payments for about 40 percent of patients (primarily through their Medicaid

and employee health plans). It is not pursuing ACO arrangements (typically involving sharing

risk with other providers) for any patient populations because “we think we are a bit ahead of

accountable care; we do full population health for the Medicaid population.” Crucially, both

hospitals exist in a state policy environment that is aggressively promoting payment and delivery

system reforms for Medicaid and public hospital systems. These reforms are Colorado’s

statewide Accountable Care Collaboratives for Medicaid beneficiaries and California’s Delivery

System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program targeting safety net hospitals, which

provides extra payments for these hospitals if they achieve quality improvement goals.

14

,

15

Also,

California provides the county hospitals with cost-based reimbursement for inpatient services for

new Medicaid enrollees, thus providing some protection from the risk-based arrangement.

Other study hospitals are participating in ACOs for their Medicare and/or commercially

insured patients but have yet to extend this approach to Medicaid patients. Froedtert in

Milwaukee is participating as a tertiary care provider in the Integrated Health Network of

Wisconsin, a “super ACO” comprising eight regional health systems and targeting Medicare and

commercially insured patients.

16

Northeast Medical Group, a physician practice owned by Yale-

New Haven Health System, is involved in a Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO.

Homestead has entered into an ACO with a major private insurance carrier (Florida Blue) for the

care of cancer patients. These hospitals tend to have higher volumes of Medicare and

commercially insured patients compared to the publicly operated systems described above.

The other study hospitals (UK HealthCare, Harris Health, and Regional One) are less

involved with alternative payment models for any payer type. They are more wary of accepting

greater financial risk for patients due to high uncompensated care levels and lack of Medicaid

expansion in their states (Harris Health and Regional One), or low Medicaid payment and lack of

integration with primary care and other services needed to manage and coordinate the care of

patients (UK HealthCare). These hospitals also cited a lack of political interest (both historically

and currently) at the state level in pursuing innovative Medicaid managed care programs and

payment models.

Patients’ social and clinical needs pose challenges. A major challenge for safety net

hospitals in value-based purchasing arrangements and new alternative payment models is that

many of the patients they serve are poor and low income, and have complex clinical and social

needs that require greater coordination with social services as well as other medical services.

These hospitals encounter greater difficulties with patients who are homeless or lack a permanent

address, lack social and family support in the community, have significant co-morbid mental

14

Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing. Accountable Care Collaborative. Available at

https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/accountable-care-collaborative.

15

California Department of Health Care Services. Delivery System Reform Incentive Payments (DSRIP). Available

at http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/provgovpart/Pages/DSRIP1.aspx.

16

Integrated Health Network of Wisconsin. Available at http://www.ihnwi.com/.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

14

health and substance abuse problems, or have inadequate transportation to get to medical

appointments.

The socioeconomic mix of patients they serve creates challenges for safety net providers to

perform well on measures of quality of care and hospital readmission rates, which can lead to

higher penalties on their Medicare payments.

17

,

18

Respondents across the study hospitals reported

that the lack of adjustment for socioeconomic status puts them at a disadvantage relative to other

hospitals with respect to the quality measures used for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s

(CMS’s) value-based purchasing programs. One specific example cited by multiple hospitals is

the relatively high rate of pressure ulcers in their facilities (included as a metric under the HAC

Reduction Program). Hospitals face more difficulty in preventing pressure ulcers among patients

who have been immobilized—for example, due to neurological injuries and wounds resulting

from violence, accidents, or other trauma; these hospitals care for many such patients.

Despite the hospitals’ concerns about the lack of adjustment for socioeconomic factors and

their perceived disadvantage, the study hospitals typically did not perform substantially worse on

the CMS quality measures compared to hospitals nationally (see Appendix 6). In cases in which

scores were relatively low, the penalties assessed tended to be modest and were of less concern

to these hospitals than other financial issues. In fact, some study hospitals have a low volume of

Medicare patients, which also limits the financial impact of these programs, either because these

hospitals are ineligible due to their small volume (the two rural hospitals in particular fall under

this category) or the amount of their penalty or bonus is modest.

In contrast, the challenges this set of safety net hospitals face tend to affect factors related to

patient satisfaction more than the quality of care provided. These hospitals tended to have

relatively low patient satisfaction scores based on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health

Plans (HCAHPS), which is administered to a sample of all patients, not just those under

Medicare.

19

Respondents believed that low HCAHPS scores reflected problems of access to care,

crowding in emergency and inpatient departments, and other resource constraints (for example,

inadequate staffing and customer service training, administrative and clinical information

systems) that affect patients’ experiences with the hospital. Initiatives were underway at a

number of hospitals to address these issues. In addition, many of them have been proactive in

improving interactions between clinicians and patients, including the use of outside consulting

groups that specialize in improving the patient experience.

Integrating primary care and addressing nonmedical needs are important. The

difficulty of transforming their delivery systems to improve integration and coordination with

other services and providers is a significant challenge for many of the study hospitals. Follow-up

for discharged patients who have no “medical home” was cited as particularly challenging,

17

Gilman, M., E.K. Adams, J.M. Hockenberry, A.S. Milstein, I.B. Wilson, and E.R. Becker. “Safety Net Hospitals

More Likely than Other Hospitals to Fare Poorly Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing.” Health Affairs, vol. 4,

no. 3, 2014, pp. 398–405.

18

Joynt, K.E., and A. Jha. “Characteristics of Hospitals Receiving Penalties Under the Hospital Readmissions

Reduction Program.” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 309, no. 4, 2013, pp. 342–343.

19

Chatterjee, P., K.E. Joynt, E.J. Orav, and A.K. Jha. “Patient Experience in Safety-Net Hospitals.” Archives of

Internal Medicine, vol. 172, no. 16, 2012, pp. 1204–1210.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

15

especially for a patient population with a high prevalence of mental and physical disabilities, low

health literacy, and inadequate transportation and housing.

Most study respondents felt that highly integrated delivery systems with a closed network of

providers was the optimal arrangement for managing the wide array of care needs for Medicaid

and uninsured populations. Among the study hospitals, the county-operated or supported systems

are more equipped for this approach. LAC+USC, Denver Health, Harris Health, and Regional

One typically employ their physicians (versus contracting with physicians in the community) to

align incentives. Also, they essentially “own the entire continuum of health care,” which helps

them achieve a high degree of integration between inpatient, primary care, and other outpatient

facilities. All of these hospitals believe that operating as an integrated system has allowed them

to keep 30-day inpatient readmission rates lower than they would be if the systems were more

fragmented—primarily because they facilitate greater communication and smoother handoffs

between different sectors within the system (see Appendix 6, which shows how the county-

operated hospitals tended to face lower readmission penalties than the private hospitals in the

study).

Denver Health, LAC+USC, and Harris Health have taken advantage of ACA-related grants

and programs to further increase the degree of integration and coordination of services they

provide. For example, Denver Health received a $19 million Center for Medicare and Medicaid

Innovation (CMMI) grant that supports patient navigators, programs to manage high utilizers,

co-location of primary and behavioral health services, and clinical pharmacists embedded in

primary care clinics. A major emphasis has been the use of patient navigators and dedicated staff

to proactively schedule primary care visits for patients with chronic illnesses who are at high risk

of readmission.

As part of reforms through California’s Medicaid waiver and DSRIP programs, LAC+USC

has focused on expanding access to primary care and assigning patients to medical homes in its

network, as well as greater integration of primary care and behavioral health. Also, LAC+USC

rented 600 units of supportive housing and opened 300 recuperative care beds for homeless

patients being discharged from the hospital. The estimated cost for the health system of

providing such housing, along with primary care and other supportive services ($1,200 per

patient per month), was less than the higher cost for inpatient readmissions and ED services that

could result without such support. However, capacity for these efforts remains limited,

reportedly leaving many patients with unmet primary care and behavioral health needs.

Harris Health has expanded primary care capacity and access within its system under

Texas’s DSRIP initiative, including the addition of nine primary care clinics. “Super-utilizers”

are being managed by sending medical teams out to patients’ homes to teach them how to

manage their chronic conditions. Care delivery reforms at the hospital also include identifying

patients at high risk for readmission and using case managers to follow up and encourage these

patients to see their primary care physician.

In contrast, the three academic medical centers in the study are much more limited in both

integration with primary care and other services used to address population health for their

Medicaid and/or uninsured populations. In general, their main strategy is to position themselves

as the tertiary and quaternary providers in ACO networks for Medicare and commercially

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

16

insured patients, rather than developing vertically integrated systems for these patients. These

systems have embraced ownership of physician practices in the community as a way to increase

their footprint for primary care and other specialties; however, these physicians primarily serve

Medicare and commercially insured patients. Instead of building primary care capacity within

their systems, they have focused on developing relationships with FQHCs to provide medical

homes for Medicaid and uninsured patients who use their EDs. For example, Froedtert recently

donated $15 million to a local FQHC to build an additional clinic site to expand access in the

community, and it has agreed to provide inpatient and specialty care for patients at the new

facility.

The Baptist Health Care System in South Florida (of which Homestead Hospital is a part)

also has little primary care capacity within its system. As a result, providing patients with follow-

up care after hospital discharge poses a major challenge for Homestead. In response, the hospital

has set up a “gap clinic”—a primary care center managed by a nurse practitioner and intended to

serve as a transitional center between inpatient and primary care for recently discharged patients.

Homestead has also tried to strengthen affiliations with local FQHCs to provide their patients

with a medical home for the longer term.

Electronic health record systems are essential for organizational and clinical

integration. All study hospitals agreed that having a system that maintains a single, integrated

electronic health record (EHR) for each patient throughout their system was essential for

coordinating patient care, documenting and analyzing the quality and costs of care, and

identifying operational changes that might be needed. Some hospitals were further along than

others in developing their EHR systems. With the exception of Regional One, all study hospitals

had (or had definite plans to implement) single EHRs linked to all providers in their system.

Some of the hospitals are also using outside consultants to develop systems for population health

management and patient engagement. Among the study hospitals, Regional One in Memphis

appears to lag furthest behind in adapting its information systems and enhancing its

administrative capabilities. It is the only study hospital that used different EHRs for different

departments, and still relies to some extent on paper records.

Despite system upgrades, the study hospitals appear to be limited in their understanding of

and ability to address cost drivers—both of which are key to long-term success under value-

based purchasing. For example, all facilities cited difficulties in attributing costs to patients,

service lines, or particular providers, which makes it challenging to understand the major cost

drivers in their health systems. The ability to hire staff devoted to collecting and analyzing data

on cost and quality performance varied across the hospitals; Harris Health and Regional One

identifying it as one of their major challenges, largely because of financial constraints.

For some hospitals, accurate documentation of patients’ condition(s) upon arrival and care

received can be as much of a challenge as implementing sophisticated EHR systems and

expanding analytical capabilities. For example, one hospital reported that it appeared to have a

high rate of accidental bowel lacerations during surgery (which factors into a CMS quality

indicator), which upon further investigation was a result of miscoding patients who arrived at the

hospital with that condition (for example, stabbing victims who arrived at the ED).

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

17

D. Financial impacts

Patient service revenue grew. Largely linked to the growth in patient volumes from

insured patients, operating revenues increased for expansion state hospitals (by an average of 17

percent) and, to a lesser extent, for non-expansion state hospitals (11 percent on average)

between 2013 and 2015. For expansion state hospitals, this increase came largely from Medicaid.

Revenue growth was especially large for the study hospitals that receive cost-based Medicaid

reimbursement (for at least some patients and/or services) from their states; these hospitals

include the rural critical access hospitals and LAC+USC (Appendix 2). For others, Medicaid

reimbursement is less than the costs of providing the services; however the hospitals previously

had been treating many of these patients as uninsured patients and so had received even less

reimbursement in the past.

Some hospital executives expressed concern that Marketplace products tend to reimburse

providers at rates considerably lower than traditional commercial coverage—at or closer to

Medicaid payment rates. One hospital detected lower payments as some patients switched from

employer-sponsored commercial coverage to Marketplace plans. Because Marketplace patient

volumes have been relatively low for these hospitals to date, however, the revenue impact has

been small overall.

Hospitals’ payer mix based on total patient revenues followed similar patterns to the shifts in

patient mix based on encounters (Figure 4). For both expansion state hospitals and non-

expansion state hospitals, commercial insurance revenues comprise a significantly larger

proportion of total revenues than commercial insurance encounters as a proportion of total

patient encounters, reflecting the higher payment rates for these services.

Hospital subsidies are on the decline. Longstanding federal, state, and local subsidies—for

example, from DSH programs, state provider taxes, or general county revenues—to safety net

hospitals began declining over the last few years, tempering their revenue growth. However, to

date some of these cuts have not been as large as the hospitals expected because of policymaker

decisions to phase them in more gradually, allowing hospitals to adjust to reform. Also payment

schedules typically lag behind the time frame during which the services are provided and shifts

in payer mix have occurred. That is, some safety net hospitals are temporarily benefiting from

stable subsidies based on a time frame during which they served more uninsured patients, even

as their uninsured numbers have since declined; in other words they are paid retroactively for

services provided. Some executives expect to have to repay some of these funds once the state

and/or federal government fully account for patient and payer mix changes.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

18

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

Medicaid Uninsured Commercial Medicare

Expansion-State Hospitals 2013 Expansion-State Hospitals 2015

Non-Expansion-State Hospitals 2013 Non-Expansion-State Hospitals 2015

Figure 4. Average payer mix, Q1 2013 and Q1 2015

In addition to direct patient revenues received from Medicaid programs and health plans,

safety net hospitals also typically receive additional Medicaid revenues through DSH. Most of

the study hospitals experienced either stable or declining Medicaid DSH payments between 2013

and 2015. Although the federal government has delayed the planned cuts to Medicaid DSH

several times (primarily because the initial schedule for reducing the payments preceded the

Supreme Court decision to allow states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion), states play a large

role in how these funds are allocated; some states changed their allocation formulas. Also, some

safety net hospitals’ allocations changed because their patient mix had changed.

Yet Medicaid DSH has not been a large funding source for some of the hospitals. Lakewood

and Homestead both receive less than $10,000 per year (less than 1 percent of revenues).

Marcum and Wallace reported the greatest decline in Medicaid DSH funds (55 percent between

2013 and 2015), but from a relatively small amount (from approximately $148,000 to $66,000).

Regardless of the amount, some of the study hospitals decided to no longer recognize DSH

payments as revenue; this strategy is intended to prepare for the upcoming cuts and out of

concern that they will need to repay much of the funds once their state assesses the change in

volumes and patient mix.

Medicare DSH payments to the study hospitals were either insignificant or did not change

substantially. However, Regional One’s Medicare DSH funds increased recently (amount not

available), reportedly related to the new allocation formula that distributes a portion of the 75

percent Medicare DSH fund reduction to hospitals with large numbers of uninsured patients.

20

Other common sources of Medicaid revenue for safety net hospitals are state programs that

redistribute funds generated by charging a fee to a broad set of providers; after receiving federal

20

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH). “The Medicare DSH Adjustment.” Accessed at:

https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/dsh.html.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

19

Medicaid matching funds, the state redistributes the funds to safety net hospitals. Denver

Health’s payments from such a fee program have been rising in the last few years. Homestead’s

$400,000 from Florida’s Low Income Pool has been stable over this period. After lengthy

negotiations over the future of the program, the state and federal governments came to an

agreement to continue this funding source, but at a lower level;

21

it is too early to know the

impact on Homestead’s funding levels. Yale’s experience with Connecticut’s provider fee

program differed, as the fee assessed on the hospital totaled more than the hospital received back

in enhanced Medicaid payments during the study period.

Federal Medicaid waivers are also important sources of funding for some safety net

hospitals. LAC+USC and Harris receive funds through the DSRIP component of their state’s

1115 Medicaid waivers, which has helped them to expand capacity in new ways, particularly for

primary care. The California waiver ended in October 2015, but a new waiver will extend the

DSRIP concept to 2020, with more expectations that hospitals will demonstrate that these funds

are helping them achieve better patient outcomes at lower costs. The Texas DSRIP program is

slated to end in 2016, unless the state’s Medicaid waiver (and the DSRIP program) is renewed.

The county-owned hospitals in the study appear more vulnerable than others because they

rely on additional state and local subsidies that also have started to decline. LAC+USC now

receives less funding through so-called realignment funds (sales tax and vehicle licensing fee

revenue that the state historically has provided to counties to provide health care to low-income

uninsured people); the state now directs more of these funds to social services.

Expansion state hospitals typically expected such funding reductions as their uninsured

populations declined, but the cuts are more painful for non-expansion state hospitals. County

funds (largely from property tax revenues) had made up almost half of Harris’s operating

revenue, but the county cut these funds by 13 percent (a reduction of $75 million annually)

starting in 2011. Reportedly, the county made this cut in anticipation of Texas expanding

Medicaid, which has not occurred. In contrast, Regional One’s county appropriation has been

steady over the last few years, and the hospital expects to receive an estimated 2 percent increase

this year. As a non-expansion state hospital executive suggested: “Medicaid expansion would

provide a better and more predictable funding stream” than the various subsidies on which the

hospital currently relies.

Uncompensated care expense fell. In line with reductions in uninsured patients,

uncompensated care (comprising both charity care and bad debt) declined by almost one-third

for expansion state hospitals.

22

Charity care tended to fall more than bad debt. In fact, some

study hospitals reported increases in bad debt, which hospital executives attributed to the

presence of more commercial insurance products with relatively high-cost sharing requirements

(deductibles and copayments) that patients cannot afford. The growth of such products started

before the ACA but has continued with the new Marketplace plans. Also, some of the newly

21

Associated Press. “Florida, Feds Agree to Extend Hospital Low-Income Pool Funds.” Modern Healthcare, June

24, 2015. Available at http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150624/NEWS/306249975.

22

Although we attempted to gather uncompensated care costs in a consistent way across the study hospitals—as the

sum of charity care and bad debt—Yale also uses Medicaid shortfalls in its uncompensated care calculation, which

reportedly led to an increase in the amount.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

20

insured patients might now be incurring bad debt for unpaid expenses that previously qualified

for charity care when the patient was uninsured.

The non-expansion state hospitals experienced mixed changes in uncompensated care. Both

Homestead and Harris experienced increases in uncompensated care—as much as 25 percent for

Harris—reflecting volume increases, general medical inflation, and the same bad debt issue.

However, Froedtert’s uncompensated care expense fell significantly (even as it increased the

upper-income limit for charity care eligibility) as more people gained coverage.

23

Overall

changes in uncompensated care at Regional One varied depending on time period (see Appendix

5).

Medicaid expansion helped financial performance. Most of the study hospitals started

with low or negative operating and total margins, and most of the expansion state hospitals saw

improved financial performance by 2015 (Figure 5). Reportedly, these improvements primarily

reflected gains in Medicaid patient revenue, but also some cost reductions (primarily through

staffing cutbacks). Between the first quarters of 2013 and 2015, average operating margins

across the six expansion state hospitals increased from -4 to 2 percent, and total margins

increased from 2 to 6 percent. Given their particularly large Medicaid enrollments in Kentucky,

UK Health and Marcum and Wallace stood out as experiencing significant gains, with margins

improving to more than 5 percent. LAC+USC’s margins improved but remained negative.

However, Yale faced declining margins, which executives attributed to reductions in the

hospital’s Medicaid reimbursement rates.

For most expansion state hospitals, much of the improvement in financial margins came

between 2013 and 2014; by 2015, margins typically had increased only slightly or even declined

from 2013. This fact likely reflects declining subsidies and increased costs, especially as

hospitals invested in more infrastructure to serve more patients and prepare for value-based

payments.

Non-expansion state hospitals’ average operating margins declined over the study period

and remained negative; total margins also fell but remained positive. The hospitals typically

attributed these losses to expenses (including investments in information technology, quality

improvement activities, and staff salaries) that outpaced relatively flat revenues. In contrast,

Froedtert had strong and improving operating margins, reflecting its relatively large growth (for

a non-expansion state hospital) in Medicaid volumes.

Financial constraints inhibited payment and delivery system reforms. Study hospitals in

states that expanded Medicaid have benefited financially from increased public insurance

revenue, which helped them address the new costs to develop infrastructure and implement other

needed changes to participate in value-based purchasing programs and alternative payment

models. As noted, participation in value-based purchasing programs has had little financial effect

23

Although Regional One’s uncompensated care appears to have increased in the quantitative data, the qualitative

information suggested an actual slight decline over the last few years (with the discrepancy attributed to the hospital

accounting for these expanses in batches throughout the year; also, the hospital first categorizes these accounts as

bad debt, then later determines what portion qualifies for charity care).

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

21

-50%

-40%

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

2013 2015 2013 2015

Expansion-State Hospitals Non-Expansion-State Hospitals

Operating Total

on the study hospitals; for the hospitals engaged in alternative payment models, it is too soon to

know the longer-term financial impact.

The financially weaker hospitals lacked the resources to make these new investments and

are more focused on remaining viable and avoiding reductions in services. Harris Health and

Regional One reported that the lack of Medicaid expansion in their states significantly

contributed to their inadequate staffing and inability to upgrade electronic medical records

(EMRs) to improve quality and efficiency of care. One respondent summed up the trade-off

between costs and quality improvement efforts as follows: “When you are a safety net hospital,

you put [full-time equivalents] FTEs where they have to be, which is the clinical and regulatory,

and when you are trying to work on safety and quality, that’s where the FTEs are soft and you

start knocking the proposed ones off the budget.”

Figure 5. Average financial margins, Q1 2013 and Q1 2015*

*Margins unavailable for Homestead Hospital

Medicaid expansion also affected the study hospitals’ ability to continue with quality

improvement and other delivery system reform activities after initial funding through grants or

pilot programs had ended. Aided by its increase in Medicaid revenues, Denver Health intends to

continue with most of the activities funded by its CMMI grant—which ends in 2016—because

hospital leaders think that many of these changes pay for themselves through reductions in

inpatient admissions, ED visits, and other services.

In contrast, the DSRIP program in Texas has had mixed effects for Harris Health. DSRIP

funds enabled the hospital to expand primary care capacity in 2011 (by leasing space to operate

nine additional community clinics), with the expectation that the state would expand Medicaid—

but this preceded the 2012 Supreme Court ruling that made Medicaid expansion optional.

Texas’s decision not to expand Medicaid has meant that the hospital must now absorb increased

uncompensated care costs associated with its expanded network of primary care clinics and the

increase in specialty care and other referrals generated from primary care visits. The state’s

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

22

current Medicaid waiver ends in September 2016; if it is not renewed, the funding to operate

these clinics also could cease.

The level of Medicaid payment to hospitals affects not only their financial viability, but also

their willingness to assume financial risk for Medicaid patients and transform their delivery

systems. LAC+USC and other major safety net hospitals in California receive cost-based

Medicaid reimbursement for the Medicaid expansion population, which helps them to make

changes to their delivery systems. By contrast, Yale-New Haven faced recent cuts to its

Medicaid reimbursement (to address state budget deficits), which it estimates has decreased

Medicaid payment from 59 percent of costs in 2013 to 39 percent in 2015.

Active preparations for the future. Overall, improved financial stability has helped

expansion state hospitals to prepare for the future. The hospitals with greater financial security

now have more resources to help them continue expanding outpatient capacity, invest in

strategies to improve care coordination, and develop better infrastructure to monitor costs. All of

these actions are important for new payment arrangements, under which hospitals expect to

assume more financial risk for patient care and outcomes.

All of the study hospitals are cautious about spending, however. Many hospital executives

expressed concern that their recently improved financial status might be fleeting as subsidies

decline, and because Medicaid enrollment and payments could decline after 2017, when the

federal government no longer covers the full cost of the expansion.

24

As one said, “We’re in the

sweet spot of health reform.” Many non-expansion state hospitals have less of a financial margin

to pursue such investments; their executives express less confidence about their future.

Indeed, both expansion and non-expansion state hospitals are focused on ways to raise

additional revenues, primarily by diversifying their payer mix. Most hospital executives did not

expect to see many more of their uninsured patients gain coverage. Instead, they are focused on

pursuing new Marketplace and other commercially insured patients and, to a lesser extent,

Medicare patients. The academic medical centers have focused on expanding inpatient and/or

outpatient specialty services (tertiary and quaternary care) that appeal to a broader population.

For example, UK Health has added a new ambulatory building and inpatient beds to support this

strategy. Better branding and marketing is also important, respondents reported. For instance,

Regional One previously was known as Regional Medical Center and referred to as “the Med” in

the community; it adopted its new name as part of a rebranding strategy to reflect the broader

system of services it now provides (for example, primary care, outpatient surgery, and

rehabilitation).

The study hospitals are also focused on ways to cut costs. Those in non-expansion states are

more likely consider more significant changes to policies that could affect access. For example,

24

Starting in 2017, states must take on a portion of the cost, which will increase to 10 percent by 2020.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

23

Harris Health has contemplated changing its charity care policy to reduce the number of people

eligible for free care.

25

E. Additional observations about differences between the 2014 and 2015

semi-structured discussions

Although the research team collected qualitative and quantitative information at two points

in time—2014 (reflecting back on 2013) and 2015 (reflecting back on both 2013 and 2014)—the

cross-site analyses discussed above generally focused on the overarching changes that the study

hospitals (Appendix 2) experienced between 2013 and 2015, rather than providing detail about

changes between 2014 and 2015. In response to ASPE’s request for more information about the

extent to which our findings differed between the 2014 and 2015 data collection periods, here we

summarize some common themes from both the quantitative and qualitative information (for the

qualitative piece, this summary represents only the six hospitals in the expansion states because

in 2014 we had not yet included the four hospitals in the non-expansion states).

1. Quantitative findings

The 2015 patient volume and financial indicators generally showed a continuation of what

had occurred in 2014. For hospitals in expansion states, Medicaid was a growing presence (in

patients and revenues); uninsured patients and uncompensated care costs were declining. Some

of those hospitals experienced more significant change between 2013 and 2014 than between

2014 and 2015. For others, the Medicaid expansion took more time to result in changes in

coverage and/or demand for care, and the degree of change between 2014 and 2015 exceeded

that of 2013 to 2014. However, these patterns often varied across service lines within an

individual hospital.

Still, many of the study hospitals in non-expansion states (and some in the expansion states)

experienced some fluctuation among the different time periods on different indicators. That is, in

a number of cases, patient volume in a certain category actually dipped a bit between the first

quarter of 2013 and 2014 but then showed more increase by 2015. Some respondents attributed

this development to more gradual coverage expansions in their states (especially if the state did

not expand Medicaid eligibility) but also to factors unrelated to the ACA. Such fluctuations

tended to be more prevalent among the Medicare and commercial volumes and payer/patient

mixes than in the Medicaid and uninsured categories.

Among hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, charity care steadily fell, but bad debt

fluctuated, in many cases rising between 2013 and 2014 and then falling to below 2013 levels in

2015. This finding could reflect initial increases in bad debt related to Marketplace and other

commercial insurance products that placed more cost-sharing requirements on consumers (for

example, through high-deductible products); whereas those products remained in place by 2015

and sometimes even grew more prevalent, coverage expansions may have caught up by 2015 to

reduce the number of people generating bad debt because they were uninsured (but did not

25

Hawryluk, Markian, “Harris Health considers cutting free care to close budget gap,” The Houston Chronicle, July

31, 2015. Available at http://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/health/article/Harris-Health-considers-cutting-free-

care-to-6416197.php.

III. KEY FINDINGS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

24

qualify for charity care). Indeed, respondents generally seemed more concerned about rising bad