Mike Swiger is a member and Megan

Grant is an associate of the law firm

Van Ness Feldman, P.C. Van Ness Feld-

man represents a number of hydroelec-

tric project owners currently in the Fed-

eral Energy Regulatory Commission

relicensing process.

implies, came first and was the default

licensing process. The traditional

process provides that the formal pro-

ceeding before FERC does not begin

until the application is filed, and FERC

staff generally do not participate in pre-

filing consultation. Then, after the

application is filed, the federal agencies

with responsibilities under the Federal

Power Act and other statutes, the states,

Indian tribes, and other participants

have opportunities to request additional

studies and provide comments and rec-

ommendations.

Although emphasizing extensive pre-

filing consultation, the traditional process

has come to be viewed as adversarial

and applicant-driven. Moreover, the ini-

tiation of National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA) scoping often provides a

“second bite” opportunity for resource

agencies to raise new issues and expand

the record.

The alternative process, on the other

hand, approaches licensing from a col-

laborative standpoint. The alternative

process allows pre-filing consultation

and environmental review procedures to

proceed concurrently. An applicant may

use the alternative process if it can

demonstrate that a consensus exists

among the applicant, resource agencies,

Indian tribes, and citizen groups that the

alternative procedures are appropriate

under the circumstances.

An applicant who has not yet filed its

statutory Notification of Intent to seek a

license has the option of choosing the

existing traditional process, alternative

process, or the new ILP. In 2005, the

ILP will become the default licensing

process, and FERC approval, based on a

“good cause” standard, will be required

to use the traditional process. The alter-

native process has always been and will

remain subject to FERC approval.

The ILP, according to FERC, “merges

pre-filing consultation and the NEPA

process, brings finality to pre-filing study

disputes, and maximizes the opportunity

for the federal and state agencies to coor-

dinate their respective processes.”

2

The

new process provides for:

— Increased public participation in

pre-filing consultation;

— Development by the applicant of a

commission-approved study plan;

— Better coordination between the

commission’s processes, including

NEPA document preparation, and those

of federal and state agencies with

authority to require conditions for com-

mission-issued licenses;

— Encouragement of informal reso-

lution of study disagreements, followed

by dispute resolution; and

— Schedules and deadlines.

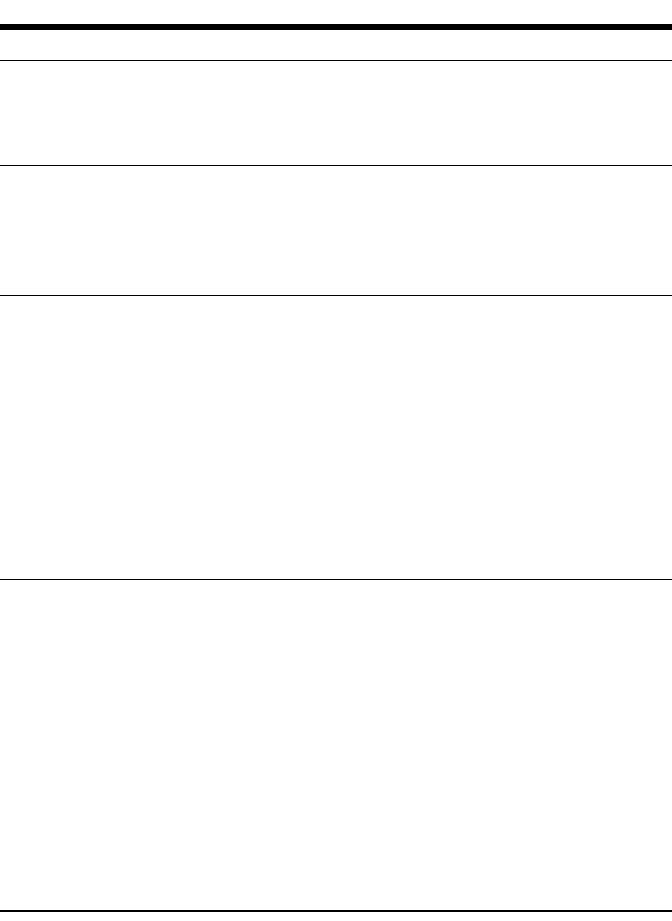

The practical benefit of the ILP for

applicants appears to be the substantial

shortening of the time between filing an

application for a license and a FERC

decision on the license application. This

is primarily due to the fact that under

the new ILP, NEPA scoping and the

applicant’s preparation of a draft NEPA

document will now be conducted as part

of the pre-filing process. (See Table 1

on page 2.) Also, study disputes will not

be as likely to carry over into the post-

filing period.

However, the quicker decision after

the application is filed comes at the ex-

pense of a heavily front-loaded proce-

dure that will require an applicant to in-

vest substantial resources in preparing

the application even before filing the

Notification of Intent. In this regard, an

applicant will have to begin preparation

for licensing much earlier than under

the previous regulations to fulfill the

comprehensive requirements of the Pre-

Application Document, which is filed

concurrently with the Notification of

Intent, 5 to 5 ½ years prior to license

expiration.

From Hydro Review, May 2004 - ©HCI Publications, www.hcipub.com

Reproduced with permission

Creating a New FERC Licensing Process

Using a stakeholder-based effort to reform the approach to

hydropower licensing, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commis-

sion created a new licensing process known as the ILP.

REGULATIONS

By Michael A. Swiger

and Megan M. Grant

T

he Federal Energy Regulatory Com-

mission’s (FERC’s) new process for

licensing a hydroelectric project —

the Integrated Licensing Process, or ILP

— is intended to improve process effi-

ciency, predictability, and timeliness;

balance stakeholder interests; and im-

prove the quality of decision-making on

hydropower licenses.

In addition to creating a new licens-

ing process, FERC’s recent licensing

reform efforts included making notable

changes to the existing “traditional” and

“alternative” licensing processes.

These reform efforts featured a num-

ber of stakeholder forums attended by a

wide range of individuals involved in

the hydro licensing process, including

project owners, state and federal natural

resource agencies, and environmental

groups. Many of the suggestions offered

at these forums were incorporated into

both the new licensing process and the

changes to the existing processes.

Now there are three

Prior to FERC’s action in 2003, there

were two licensing procedures avail-

able: the traditional licensing process

and the alternative licensing process.

1

The traditional process, as its name

tion of Intent. This requirement applies to

the traditional and alternative processes

as well, but does not take effect until

2005. FERC provides for the incorpora-

tion of ILP procedures in an ongoing tra-

ditional licensing process if the request is

made during first-stage consultation and

a consensus exists to incorporate the spe-

cific elements of the ILP.

FERC also extended the deadline for

filing an application for water quality

certification until after the Ready for

Environmental Analysis notice is issued.

Previously, the application for water

quality certification was required to be

filed no later than the date the license

application was submitted to FERC.

FERC also will now allow an applicant

in the traditional licensing process to

submit an applicant-prepared draft NEPA

Highlights of FERC’s reforms

Some of the licensing reforms apply to

all three processes, not just the ILP. For

example, one feature of the commis-

sion’s rule reforming hydro licensing is

that the formal proceeding before the

commission now begins when FERC

notices the applicant’s filing of the Noti-

fication of Intent and Pre-Application

Document. Previously, the formal pro-

ceeding did not begin until the license

application was filed. This triggers the

commission’s rules on ex parte commu-

nications much earlier in the process.

Another example is the requirement

that the applicant file a Pre-Applica-

tion Document, designed to provide all

available engineering, economic, and

environmental information relevant to

licensing the project, with the Notifica-

2 HYDRO REVIEW / MAY 2004

document with its application in lieu of

the Exhibit E currently required.

FERC was urged to amend its ex parte

rules to permit federal resource agencies

with mandatory conditioning authority to

be both cooperating agencies under

NEPA and intervenors for purposes of

challenging a FERC license. FERC

included this change in its Notice of Pro-

posed Rulemaking. After considering

many comments challenging this change,

particularly with respect to its legality,

FERC reversed course and ultimately

concluded that “precedent indicates that

allowing federal agencies to serve both

as cooperators and intervenors in the

same case would violate the [Administra-

tive Procedures Act].”

3

Some stakeholders also urged FERC

to use evidentiary hearings to resolve hy-

droelectric licensing matters, instead of

relying solely on the notice and com-

ment procedures currently employed. In

response, FERC included a provision

providing for such hearings. Although

FERC did not expressly address whether

it would liberalize its current practice of

granting a hearing only when the credi-

bility of a key witness is at stake, FERC

affirmed that “[r]esolving factual issues

before an [Administrative Law Judge] is

a time-tested means of decision making;

factual records developed in such hear-

ings are useful to courts which may be

called upon to review the final decision

on the license.”

4

Highlights of the ILP

Notable features of FERC’s final rule

applicable to the ILP include the spe-

cific study criteria against which the

commission will weigh study requests

in both approving the study plan and

resolving any disputes. The most prom-

inent criterion is a threshold determina-

tion that there is a nexus between proj-

ect operations and effects on the re-

source in question.

Another significant criterion is the

consideration of level of effort and cost,

and why proposed alternative studies

would not be sufficient to meet the

stated information needs. Under the new

process, any study requests made fol-

lowing the initial study report are sub-

ject to a good cause standard, and re-

quests made following the updated study

report are subject to an extraordinary

circumstances standard. Although speci-

fically applied to the ILP, these criteria

appear to reflect FERC’s thinking about

appropriate study criteria and thus pro-

vide guidance to parties engaged in the

Table 1: Steps in FERC’s New ILP Licensing Processes

Licensing Stage Integrated Licensing Process

Pre-Notice of Intent FERC provides notice approximately 1.5 years prior to Notice of

Intent deadline

Applicant prepares Pre-Application Document, contacts agencies and

Indian tribes, reviews relevant federal and state comprehensive plans

Notice of Intent Applicant files Pre-Application Document with Notice of Intent

(Filed 5-5½ years prior

to license expiration) Initiates formal FERC proceeding

Includes resource information and study needs

Pre-Application Document subject to due diligence standard

Pre-Application FERC issues Scoping Document 1 (SD1), then holds scoping

meeting and site visit; comments on Pre-Application Document

and SD1; receives study requests

Applicant files proposed study plan; FERC issues SD2, if necessary;

informally resolves study issues; comments on proposed study plan

Applicant files revised study plan for FERC approval; FERC issues

study plan determination; mandatory conditioning agencies may

invoke formal study dispute resolution process

Applicant conducts studies; issues initial study report and holds study

meeting; receives requests for study plan modifications

Applicant files Preliminary Licensing Proposal; receives comments,

additional information requests

Application Application filed with NEPA-like document as Exhibit E no later than

2 years before expiration; procedural notice by FERC

FERC decides any outstanding prefiling additional information

requests; Applicant responds to any application deficiencies

FERC issues Ready for Environmental Analysis notice

Applicant files application for water quality certification

Comments, interventions, preliminary terms and conditions received;

reply comments filed

FERC issues non-draft EA, draft EA, or EIA; comments received;

modified items and conditions received

FERC issues final NEPA document

License issued

traditional and alternative licensing

processes as well.

FERC provides in the ILP for study

dispute resolution that includes the con-

vening of an advisory panel aided by a

technical conference of the parties. The

binding study dispute resolution applies

only in the ILP. FERC acquiesced to

commenters and decided not to apply

binding dispute resolution in the tradi-

tional process.

FERC’s final rule regarding the ILP

took effect October 23, 2003. How-

ever, the commission made some clari-

fications in its Order No. 2002-A,

issued January 23, 2004, in response to

two requests for rehearing. The requests

for rehearing raised various issues, in-

cluding:

— The binding nature of the study

plan order on applicants, but not other

parties, without a clear right to rehear-

ing and judicial review of such orders;

— Lack of stakeholder recourse if

an applicant files an inadequate Pre-

Application Document;

— Allowing all interested parties, not

just the applicant, to submit written com-

ments to the technical conference; and

— Lack of explicit ability to request

additional information after the filing of

an application.

In Order No. 2002-A, FERC denied

the requests for rehearing, but made

some notable clarifications. For exam-

ple, the commission reiterated that the

study plans are binding, but clarified

that “once the Director makes a study

plan determination pursuant to the au-

thority delegated to the Director by the

Commission . . . that determination may

then be appealed to the Commission in a

request for rehearing . . . .”

5

The com-

mission added that “[w]hether judicial

review of the Commission’s decision on

rehearing is appropriate is a matter to be

determined by the court from which ju-

dicial review is sought.”

5

The commission refused to add sanc-

tions for an inadequate Pre-Application

Document, noting that the due diligence

standard is sufficient. Furthermore, it is

not in the applicant’s best interests to

prepare a poor quality Pre-Application

Document.

The commission also explained that it

is unnecessary to provide an explicit

ability to request additional information

after the filing of an application because

the commission would continue to exer-

cise its authority to require additional

information in appropriate cases, on its

own initiative or in response to the

request of a party.

The commission further declined to

allow all interested parties to submit

written comments to the technical con-

ference, noting that although other par-

ticipants in the process may be inter-

ested in the outcome of the dispute, the

applicant has much more at stake be-

cause the applicant bears the expense

of implementing the study plan.

Which process to choose?

Each of the three licensing processes

presents different issues as to licensee

or applicant control, stakeholder in-

volvement, and coordination of envi-

ronmental reviews. It is also worth not-

ing that FERC is pushing applicants

toward the ILP process, making it the

default process within two years. If the

ILP works well, the other processes may

fall away.

As to the alternative process, some ap-

plicants may prefer the option of design-

ing their own process over the deadline-

driven ILP. This may be especially true

if the applicant believes a settlement

will be easily reached.

Applicants of small projects, or those

where it is not clear that a big, front-

loaded effort makes sense may prefer

the traditional process. It is unknown

how flexible FERC will be in granting

approval to use the traditional process.

In the final rule, FERC adopted five fac-

tors that are most likely to bear on

whether use of the traditional process is

appropriate:

1) Likelihood of timely license issu-

ance;

2) Complexity of the resource issues;

3) Level of anticipated controversy;

4) The amount of available informa-

tion and potential for significant dis-

putes over studies; and

5) The relative cost of the traditional

process compared to the integrated

process.

FERC stated in its final rulethat “the

more likely it appears from the partici-

pants’ filing that an application will have

relatively few issues, little controversy,

can be expeditiously processed, and can

be processed less expensively under the

traditional process, the more likely the

Commission is to approve such a re-

quest.”

6

Conclusions

FERC completed a massive reform of its

hydroelectric licensing process in a short

period of time in a rulemaking largely

heralded as successful by applicants and

the many other stakeholders who partici-

pated in the rewriting process. Whether

the new ILP process will, in fact, produce

more expeditious and balanced relicens-

ing outcomes is a story that will unfold

over the next several years as many of

the U.S.’s hydropower projects come up

for relicensing.

However, there is much optimism

that the new process is a step in the right

direction of maximizing licensing effi-

ciency without sacrificing consideration

of the key issues in hydropower licens-

ing decision-making.

Some of the initial concerns regard-

ing the ILP involve the amount of effort

required early on in the process, and the

tight time frames required. Indeed, some

applicants may experience difficulty

meeting all of the requirements in the 5-

to 5 ½-year period between the Notifi-

cation of Intent and the expiration of an

existing license. Practical experience

may dictate some future adjustments to

the process. ■

Mr. Swiger and Ms. Grant may be con-

tacted at Van Ness Feldman P.C., 1050

Thomas Jefferson Street, N.W. Seventh

Floor, Washington, DC 20007; (1) 202-

298-1891 (Swiger) or (1) 202-298-1913

(Grant); E-mail: [email protected] or

Notes

1

Swiger, Michael A., and Steven A.

Burns, “Cost-Effective Relicensing:

Choosing the Right Process” Hydro

Review, Volume 17, Number 4, Au-

gust 1998, pages 52-61.

2

Hydroelectric Licensing Under the Fed-

eral Power Act, 104 FERC ¶ 61,109,

Order No. 2002 (July 23, 2003) at P 39.

3

Order No. 2002 at P 300. Indeed, FERC

recently ordered a limited evidentiary

hearing in City of Tacoma, Washing-

ton, 104 FERC ¶ 61,324, (September

24, 2003).

4

Order No. 2002 at P 212.

5

Hydroelectric Licensing Under the Fed-

eral Power Act, Order on Rehearing

of Final Rule, 106 FERC ¶ 61,037,

Order No. 2002-A (January 23, 2004)

at P 17.

6

Order No. 2002 at P 48.

HYDRO REVIEW / MAY 2004 3