DISASTER

ASSISTANCE

Additional Actions

Needed to Strengthen

FEMA’s Individuals

and Households

Program

Report to Congressional Requesters

September 2020

GAO-20-503

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-20-503, a report to

congressional requesters

September 2020

DISASTER ASSISTANCE

Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen FEMA’s

Individuals and Households Program

What GAO Found

From 2016 through 2018, 5.6 million people applied for disaster assistance from

the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and 4.4 million were

referred to the Individuals and Households Program (IHP) for assistance. For

eligible survivors, FEMA’s IHP can offer financial assistance—including money

for personal property losses and repair of certain home damages. The IHP may

also provide rental assistance or direct housing assistance, such as trailers,

when justified by the lack of available housing resources.

Individuals and Households Program (IHP) Assistance Awarded to Almost 2 Million Survivors

from 2016 through 2018

Type of Assistance

Amount of Assistance

Total Financial Assistance

$5.98 billion

Total Temporary Housing Assistance

12,805 housing units

Source: GAO analysis of IHP applicant data, as of February 24, 2020. | GAO-20-503

Of the 4.4 million referred to IHP, FEMA found almost 2 million eligible. On

average, FEMA awarded about $4,200 to homeowners and $1,700 to renters

during 2016 through 2018. FEMA determined roughly 1.7 million ineligible for IHP

assistance, and the most common reasons for ineligibility were insufficient

damage, failure to submit evidence to support disaster loses, and failure to make

contact with the FEMA inspector. The remaining applicants either withdrew from

IHP or received no determination due to missing insurance information. Program

outcomes also varied across demographic groups, such as age and income.

GAO found that survivors faced numerous challenges obtaining aid and

understanding the IHP, including the following:

• FEMA requires that certain survivors first be denied a Small Business

Administration (SBA) disaster loan before receiving certain types of IHP

assistance. FEMA, state, territory, and local officials said that survivors

did not understand and were frustrated by this requirement. GAO found

that FEMA did not fully explain the requirement to survivors and its

process for the requirement may have prevented many survivors from

being considered for certain types of assistance, including low-income

applicants who are less likely to qualify for an SBA loan. By fully

communicating the requirement and working with SBA to identify options

to simplify and streamline this step of the IHP process, FEMA could help

ensure that survivors receive all assistance for which they are eligible.

• Opportunities also exist to improve survivors’ understanding of FEMA’s

eligibility and award determinations for the IHP, for example, that an

ineligible determination is not always final, but may mean FEMA needs

more information to decide the award. By enhancing the clarity of its

determinations and providing more information to survivors about their

award, the agency could improve survivors’ understanding of the IHP,

better manage their expectations, build trust, and improve transparency.

Why GAO Did This Study

During the 2017 and 2018 disaster

seasons,

several sequential, large-

scale disasters created an

unprecedented demand for federal

disaster assistance. GAO was asked to

review issues related to the federal

response and recovery to the 2017

disaster season and

, specifically, the

effectiveness of the I

HP.

This report addresses (1) IHP

outcomes and challenges faced by

survivors from 2016 through 2018

; (2)

challenges FEMA faced implementing

the IHP during the same period

; and

(3)

FEMA efforts to assess and

improve the IHP,

among other things.

To answer th

ese objectives, GAO

analyzed data from all IHP applicants

from 2016 through 2018 and reviewed

relevant documentation and policies.

GAO also interviewed FEMA, state,

territory,

local, and nonprofit officials;

met with survivors; and visited

locations affected by hurricanes in

2017 and 2018 selected to include

multiple FEMA regions and other

characteristics.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 14 recommendations

,

and DHS concurred

.

To address challenges faced by

survivors, GAO recommends

improving the communication

of the

SBA loan requirement, identifying ways

to simplify the application process,

improve the IHP award determination

letters, and provide more information to

survivor

s about their award.

To address challenges FEMA faced

implementing the IHP, GAO

recommends improving the

communication of guidance changes,

ensure employee engagement to raise

morale, and improve training among

call center staff. GAO also

United States Government Accountability Office

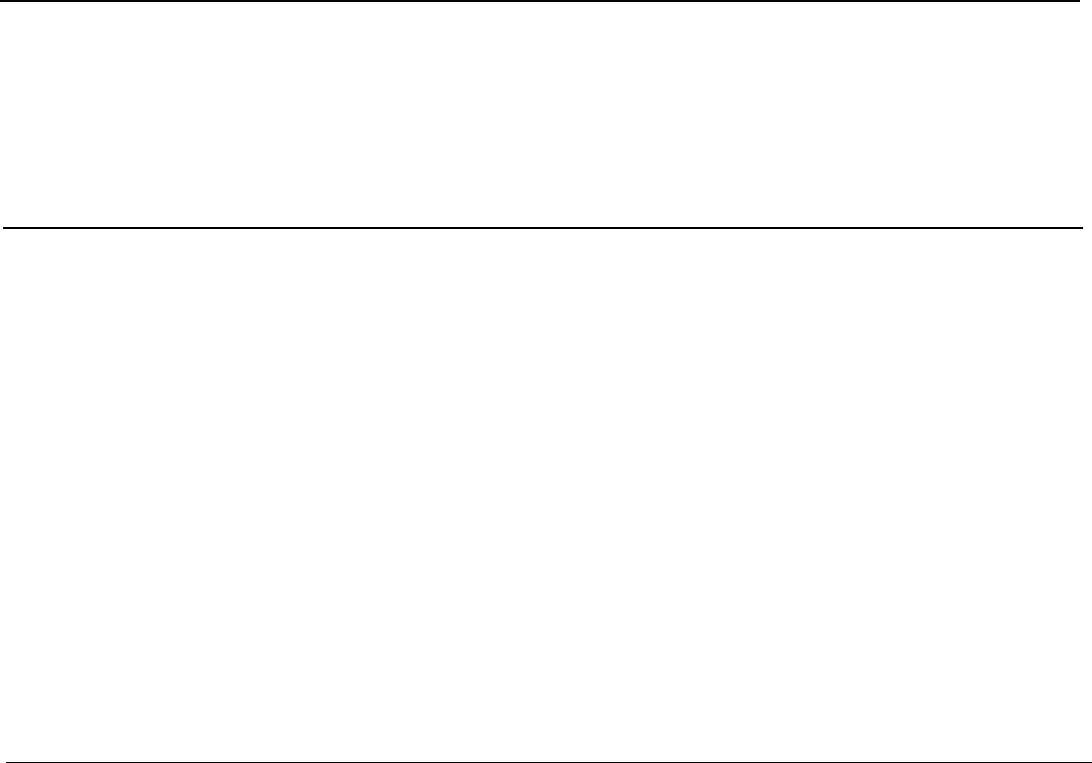

Disaster Survivors Sought Assistance from the Individuals and Households Program (IHP) to

Recover from Hurricane Michael in Panama City, Florida

Further, GAO found that since 2016, FEMA faced challenges implementing the

IHP through its call center and field workforce, as well as coordinating with state

and local officials, as noted below:

• Regarding workforce management, GAO found that FEMA has faced

challenges managing its call center and field staff. Specific to their call

center workforce—who help survivors apply for IHP and process

assistance—challenges using program guidance, low morale, and

inadequate training following the catastrophic 2017 hurricane season

affected their work supporting disaster survivors. For example, while

FEMA issues standard operating procedure updates for processing IHP

applications, staff we spoke to at all four call centers noted that they

could not maintain awareness of IHP guidance because of its large

volume and frequent changes, which made it difficult for staff to

appropriately address survivor needs. Identifying ways to improve the

accessibility and usability of program guidance would help staff better

assist survivors. Further, FEMA staff at disaster recovery centers (DRC)

lacked some skills and capabilities needed to support survivors, such as

knowledge to provide accurate guidance about required documents. By

identifying and implementing strategies, such as on-the-job training, to

ensure staff at its DRCs have the needed capabilities, FEMA could

improve support and streamline the survivor experience.

• Regarding coordination, GAO found that state and local officials

generally had trouble understanding the IHP. For example, these officials

said that FEMA did not provide sufficient training, support, and guidance

that was needed in order for them to be able to effectively work with

FEMA to facilitate IHP assistance. Further, local officials expressed

challenges coordinating with FEMA regarding temporary housing units,

such as recreational vehicles. By providing more information on the IHP

to local officials, and implementing best practices for information-sharing

with recovery partners, FEMA could help ensure that state and local

recovery partners are better able to help survivors navigate the IHP and

effectively deliver temporary housing units to survivors.

Lastly, FEMA has planned or implemented multiple efforts to improve assistance

to survivors since 2017, including a redesign of the Individual Assistance

Program, which includes the IHP. However, GAO found that FEMA did not

complete activities that are critical to the success of a process improvement

effort, according to GAO’s Business Process Reengineering Assessment Guide.

Specifically, the agency did not fully assess customer and stakeholder needs and

performance gaps in the program, or set improvement goals and priorities for the

redesign. By completing these process improvement activities, FEMA will be able

to further refine the redesigned Individual Assistance Program, and more

effectively direct and focus its implementation efforts.

recommends strategies to ensure

DRC staff have the skills to support

survivors. GAO also recommends

improving IHP information provided to

state, local, tribal, and territorial

recovery partners; and identifying and

implementing best practices for

informati

on sharing and coordination

on the delivery of temporary

transportable housing.

To further FEMA efforts to assess

and improve the IHP, GAO

recommends corrections to the

methodology used to survey

survivors; following key process

improvement activities

—including

engaging stakeholders, assessing

performance gaps, and prioritization

of process improvement

—during

program redesign activities; and

establishing time

frames for strategic

planning and implementation of

program improvement efforts.

To view the supplements online, click:

http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO

-20-

674SP

and

http://www.gao.gov

/products/GAO-20-

675SP

View GAO-20-503. For more

information, contact

Chris Currie at (404)

679

-1875 or [email protected].

Page i GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Letter 1

Background 7

FEMA Expended at Least $11.8 Billion through the IHP and

Generally Used a Consistent Process to Provide Assistance to

About 3 Million Disaster Survivors from 2010 through 2019 12

Survivors Had Varying Program Outcomes and Faced Challenges

Understanding and Navigating the IHP 22

FEMA Faced Challenges in Managing its IHP Workforce and

Supporting and Coordinating with Local Officials from 2016

through 2018 49

FEMA Assesses IHP Performance and Has Ongoing Efforts to

Improve Program Delivery, but Opportunities Exist to Further

Enhance These Efforts 67

Conclusions 75

Recommendations for Executive Action 76

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 78

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 88

Appendix II Summary of Eligibility, Verification, and Delivery Considerations for

Individuals and Households Program Assistance 102

Appendix III Outcomes in the Individuals and Households Program by the Social

Vulnerability of an Applicant’s Community 110

Appendix IV The Small Business Administration’s Minimum Income Guidelines

for the Disaster Loan Program, Fiscal Year 2018 117

Appendix V Example of the Ineligible Determination Letter for the Individuals and

Households Program, 2019 118

Contents

Page ii GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Appendix VI The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Recent Efforts to

Improve the Individuals and Households Program 120

Appendix VII Comments from the Department of Homeland Security 124

Appendix VIII GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 139

Tables

Table 1: Referred Applicants Who Appealed a Determination on

Financial Assistance from the Individuals and Households

Program (IHP) and Appeal Approval Rates, 2016 – 2018 29

Table 2: Time between Key Events in the Financial Assistance

Process for the Individuals and Households Program

(IHP), 2016 – 2018 31

Table 3: Number of Potentially Low-Income Individuals and

Households Program (IHP) Applicants Who Did Not

Submit the Small Business Administration (SBA) Loan

Application and Had Personal Property Loss Verified by

the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA),

2016 – 2018 41

Table 4: General Eligibility Requirements, Verifications, and

Selected Adjusted Procedures to Meet Eligibility for the

Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA)

Individuals and Households Program Assistance 102

Table 5: Description of the Federal Emergency Management

Agency’s (FEMA) Eligibility Considerations for Types of

Direct Housing Assistance under the Individuals and

Households Program, according to March 2019 Guidance 104

Table 6: Description of the Federal Emergency Management

Agency’s (FEMA) Eligibility Considerations for Types of

Financial Housing Assistance under the Individuals and

Households Program (IHP), according to March 2019

Guidance 106

Table 7: Description of the Federal Emergency Management

Agency’s (FEMA) Eligibility Considerations for Types of

Other Needs Assistance under the Individuals and

Page iii GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Households Program (IHP), according to March 2019

Guidance 107

Table 8: Referred Applicants Who Appealed a Determination on

Financial Assistance from the Individuals and Households

Program (IHP), and Appeal Approval Rates, by Social

Vulnerability, for Major Disaster Declarations That

Included Individual Assistance in U.S. States and Puerto

Rico, 2016 – 2018 114

Table 9: Time between Key Events in the Individuals and

Households Program (IHP) Financial Assistance Process,

by Social Vulnerability, for Major Disaster Declarations

That Included Individual Assistance in U.S. States and

Puerto Rico, 2016 – 2018 115

Table 10: The Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Minimum

Annual Income Guidelines (in dollars) for the Disaster

Loan Program, Fiscal Year 2018 117

Table 11: Description of the Federal Emergency Management

Agency’s (FEMA) Recent Efforts to Improve the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP) 120

Figures

Figure 1: Types of Assistance Available under the Individuals and

Households Program 9

Figure 2: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

Regions, Four National Processing Service Centers, and

Field Locations for Hurricane Michael Recovery Efforts in

Florida 12

Figure 3: Expenditures for the Individuals and Households

Program and Number of Major Disaster Declarations

That Included Individual Assistance, 2010 – 2019 13

Figure 4: Percentage of Expenditures by Type of Financial

Assistance under the Individuals and Households

Program, 2010 – 2019 14

Figure 5: Number of Applicants Who Received Financial

Assistance from the Individuals and Households Program

(IHP) and Median and Average Award Amounts, 2010 –

2019 15

Figure 6: The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA)

Process for Financial Assistance under the Individuals

and Households Program (IHP) 16

Page iv GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 7: Eligibility Status Rates for Disaster Survivors Referred to

the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA)

Individuals and Households Program, from 2010 through

2019 18

Figure 8: Notional Case of Two Families with Similar Damage and

Different Awards Because of Individuals and Households

Program Eligibility Criteria and Circumstances 20

Figure 9: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

Process for Assessing Need and Providing Direct

Housing Assistance to Eligible Survivors 21

Figure 10: Referred Applicants and Approval Rates for the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018 24

Figure 11: Average Award Amounts and Number of Owners and

Renters Who Received Financial Assistance through the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018 26

Figure 12: Most Common Reasons Referred Applicants Were

Determined Ineligible for Assistance from the Individuals

and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018 28

Figure 13: Process for Determining a Survivor’s Eligibility for

Disaster Assistance from the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA) and the Small Business

Administration (SBA) 35

Figure 14: Small Business Administration (SBA) Loan Status of

Survivors Who Applied for Assistance from the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018 36

Figure 15: Selected Steps and Required Coordination to Deliver a

Transportable Temporary Housing Unit through the

Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA)

Individuals and Households Program (IHP) 64

Figure 16: Referred Applicants and Approval Rates for the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP), by Social

Vulnerability, for Major Disaster Declarations That

Included Individual Assistance in U.S. States and Puerto

Rico, 2016 – 2018 111

Figure 17: Average Award Amounts and Number of Owners and

Renters Who Received Financial Assistance through the

Individual and Households Program (IHP), by Social

Vulnerability, for Major Disaster Declarations That

Included Individual Assistance in U.S. States and Puerto

Rico, 2016 – 2018 112

Figure 18: Most Common Reasons Referred Applicants Were

Determined Ineligible for Assistance from the Individuals

Page v GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

and Households Program (IHP), by Social Vulnerability,

for Major Disaster Declarations That Included Individual

Assistance in U.S. States and Puerto Rico, 2016 – 2018 113

Abbreviations

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DRC Disaster Recovery Center

FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency

IHP Individuals and Households Program

NGO Nongovernmental organization

NPSC National Processing Service Center

ONA Other needs assistance

SBA Small Business Administration

SOP Standard Operating Procedures

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

September 30, 2020

Congressional Requesters

In 2017, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, along with devastating

wildfires in California, affected more than 47 million people in the United

States—about 15 percent of the national population—and Hurricanes

Florence and Michael caused significant damage in 2018.

1

The Federal

Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), a component of the

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), leads the nation’s efforts to

prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate

against the risk of disasters.

2

FEMA’s Individuals and Households

Program (IHP) provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible

individuals and households who have uninsured or underinsured

necessary expenses and serious needs as a result of a disaster.

3

For

example, the IHP provides various types of financial assistance for home

repairs, child care, and transportation and is intended to distribute this

assistance quickly.

In 2019, we reported on FEMA’s efforts to provide disaster assistance to

individuals who are older or have disabilities.

4

We recommended, among

other things, that FEMA implement new application questions that

improve FEMA’s ability to identify and address survivors’ disability-related

needs. FEMA concurred and implemented this recommendation in May

2019 by using a revised application that asked directly if survivors had a

disability. According to FEMA’s analysis, the percentage of survivors that

identified as having a disability-related need increased substantially after

implementing the revised application questions. However, FEMA did not

concur with our recommendation to improve communication of applicants’

disability-related information across FEMA programs. We continue to

1

Hurricane Harvey was in Texas; Hurricane Irma was in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North

Carolina, South Carolina, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; and Hurricane Maria

was in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Unless otherwise noted, the years

discussed in this report are calendar years because that is how the Federal Emergency

Management Agency accounts for disaster declarations.

2

See 6 U.S.C. § 313.

3

See 42 U.S.C. § 5174.

4

GAO, Disaster Assistance: FEMA Action Needed to Better Support Individuals Who Are

Older or Have Disabilities, GAO-19-318 (Washington, D.C.: May 14, 2019).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

believe that FEMA can improve this communication through cost-effective

ways, such as revising guidance to remind program officials to review

survivor case files for disability-related needs. In 2018, we reported our

initial observations on the federal response and key recovery challenges

for the 2017 hurricanes and wildfires.

5

Among other things, we reported

that federal, state, territory, and local officials faced challenges finding

temporary housing for disaster survivors. Further, state officials noted

challenges in managing housing programs, such as staffing shortfalls,

and challenges in coordinating with FEMA that led to delays in providing

assistance to survivors.

6

After a disaster, survivors are vulnerable. According to FEMA,

catastrophic disasters are difficult and life-changing events that disrupt

lives and hurt communities economically and socially. For example,

severe disasters may lead to the loss of life, render homes uninhabitable,

destroy important documents and possessions, and permanently displace

people from their communities. To help individuals and households deal

with the effects of disasters, FEMA established a strategic goal in its

2018-2022 Strategic Plan to reduce the complexity of FEMA to, among

other things, streamline disaster survivor experiences in dealing with the

agency.

You asked us to review a broad range of issues related to disaster

response and recovery following the 2017 disaster season. This report

addresses: (1) IHP expenditures from 2010 through 2019 and the

processes that FEMA used to deliver IHP assistance to disaster

survivors, (2) outcomes and challenges survivors experienced in

obtaining IHP assistance from 2016 through 2018, (3) challenges FEMA

experienced with implementing the IHP from 2016 through 2018, and (4)

the extent to which FEMA has assessed the IHP and initiated efforts to

improve the program in recent years.

5

GAO, 2017 Hurricanes and Wildfires: Initial Observations on the Federal Response and

Key Recovery Challenges, GAO-18-472 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 4, 2018). Also, see

Wildfire Disasters: FEMA Could Take Additional Actions to Address Unique Response and

Recovery Challenges, GAO-20-5 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 9, 2019); U.S. Virgin Islands

Recovery: Additional Actions Could Strengthen FEMA’s Key Disaster Recovery Efforts,

GAO-20-54 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 19, 2019);and Puerto Rico Disaster Recovery: FEMA

Actions Needed to Strengthen Project Cost Estimation and Awareness of Program

Guidance, GAO-20-221 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 5, 2020).

6

We are currently reviewing FEMA’s process for inspecting damaged property for its IHP.

Page 3 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

To address our first objective, we reviewed relevant laws and FEMA IHP

program guidance, including the March 2019 Individual Assistance

Program and Policy Guide,

7

to understand FEMA’s policies and

processes for providing assistance through the IHP, including how

disaster survivors apply for IHP assistance and how FEMA determines

applicants’ eligibility for assistance and the type and amount of assistance

to provide. We also analyzed IHP expenditure data from FEMA’s

Integrated Financial Management Information System, and application,

eligibility, award, and appeals data from the National Emergency

Management Information System for major disaster declarations that

included Individual Assistance during calendar years 2010 through 2019.

8

We selected the most recent 10-year period because we wanted to focus

on long-term trends. We assessed the reliability of data from these two

systems by reviewing existing information about these systems’

capabilities, interviewing data users and managers responsible for these

data from FEMA’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer and Recovery

Analytics Division, and cross-checking data across different sources to

ensure data consistency. Based on these steps, we determined these

data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing IHP applicant

and expenditure data. We also interviewed officials from FEMA’s

Individual Assistance Division and IHP Service Delivery Branch to discuss

IHP expenditures and processes.

To address our second objective, we analyzed FEMA’s IHP applicant

data from the National Emergency Management Information System for

all 5.6 million disaster survivors who applied for assistance for major

disaster declarations that included Individual Assistance from 2016

through 2018—the 3 most recent years for which complete application

data were available. We analyzed FEMA’s IHP applicant data to identify

and compare various outcomes, such as approval, award, and appeal

rates, overall and across different survivor groups, from 2016 through

2018. We assessed the reliability of FEMA’s IHP applicant data by

reviewing existing information about the National Emergency

Management Information System, including internal controls; interviewing

data users and managers responsible for these data from FEMA’s

7

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Individual Assistance Program and

Policy Guide (IAPPG), FP 104-009-03 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 4, 2019).

8

The Integrated Financial Management Information System is FEMA’s official accounting

and financial system that tracks all of the agency’s financial transactions. National

Emergency Management Information System is a database system used to track disaster

data for FEMA and grantees. Although the IHP may offer direct housing assistance, we

use “award” to refer to financial assistance throughout this report.

Page 4 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Recovery Analytics Division; and testing the data for missing data,

outliers, and obvious errors. Based on these steps, we determined these

data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting IHP outcomes

from 2016 through 2018.

We also conducted semistructured interviews with state emergency

management officials, local officials responsible for leading disaster

recovery efforts, and officials from nongovernmental organizations (NGO)

that help disaster survivors access and navigate the IHP from California,

Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Puerto Rico. We selected these four

states and Puerto Rico because they were among those states and U.S.

territories that experienced significant damage from disasters during

calendar years 2016 through 2018. For our interviews with local officials

responsible for disaster recovery efforts, we selected two counties in each

state and two municipalities in Puerto Rico that had higher numbers of

IHP applications.

9

For our interviews with NGO officials, we selected one

or two NGOs in each of our selected states and Puerto Rico, which we

identified through discussions with FEMA, state, and local officials, and

officials from other NGOs.

10

Further, we interviewed officials responsible

for implementing the IHP from FEMA’s headquarters and all four National

Processing Service Centers (NPSC), as well as FEMA’s Regions II, IV,

VI, and IX, which are the regions responsible for liaising with and

supporting our four selected states and Puerto Rico. The results of our

interviews cannot be generalized; however, they provide valuable

perspectives on particular challenges that disaster survivors faced in

obtaining IHP assistance.

In addition, we reviewed the requirement for certain IHP applicants to also

apply to the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Disaster Home Loan

Program, and FEMA’s communication of this requirement to survivors.

We compared FEMA’s process and communication efforts regarding this

requirement to the goals and objectives in FEMA’s 2018-2022 Strategic

Plan

11

and the federal government’s roles and responsibilities outlined in

9

We interviewed local officials from Harris County, TX; Jefferson County, TX; Bay County,

FL; Jackson County, FL; Craven County, NC; Pender County, NC; Butte County, CA;

Sonoma County, CA; Caguas, PR; and Bayamon, PR.

10

We interviewed officials from Lone Star Legal Aid (TX); The Facilitators: Camp Ironhorse

(PR); Endeavors (PR and NC); Rebuild Bay County (FL); SBP (FL); and Catholic Charities

(CA).

11

Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2018-2022 Strategic Plan, (Washington,

D.C.: Mar. 15, 2018).

Page 5 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

the National Disaster Recovery Framework.

12

We also analyzed previous

and current versions of FEMA’s IHP ineligible determination letters using

the Flesch Reading Ease score,

13

the Plain Writing Act of 2010,

14

and the

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s guidance on

disaster communications.

15

Lastly, we compared the amount of

information FEMA provides to IHP applicants about their case for

assistance to the federal government’s roles and responsibilities outlined

in the National Disaster Recovery Framework and the Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Administration’s key principles for serving individuals

suffering from trauma, such as those who experienced a disaster.

16

To address our third objective, we interviewed officials responsible for

implementing the IHP from FEMA’s headquarters and all four NPSCs, as

well as FEMA Regions II, IV, VI, and IX. We also interviewed state,

territory, local, and NGO officials in California, Florida, North Carolina,

Texas, and Puerto Rico, to understand their experiences, including any

challenges, working with FEMA to deliver the IHP. The results of our

interviews cannot be generalized; however, they provide valuable context

for any challenges FEMA experienced with implementing the IHP.

Further, we analyzed FEMA’s standard operating procedures for the IHP

and documentation on workforce capabilities, as well as information

provided to state and local officials, and compared them to Standards for

Internal Control in the Federal Government, a GAO human capital guide,

12

Department of Homeland Security. National Disaster Recovery Framework, 2nd ed.

(Washington, D.C.: June 2016).

13

Flesch Reading Ease scores fall on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 being nearly

impossible to read and 100 being simple enough for a fifth grader to read. The formula is

based on average sentence length and average word length. The version we used was

included in the Microsoft Word processing software. As we have previously reported, the

Flesch Reading Ease score is one of the most widely used, tested, and reliable formulas

for calculating readability. See GAO, Vehicle Data Privacy: Industry and Federal Efforts

Under Way, but NHTSA Needs to Define Its Role, GAO-17-656 (Washington, D.C.: July

28, 2017).

14

Pub. L. No. 111-274, 124 Stat. 2861 (codified at 5 U.S.C. § 301 note).

15

D

epartment of Homeland Security. National Disaster Recovery Framework; Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Communicating in a Crisis: Risk

Communication Guidelines for Public Officials, SAMHSA Publication No. PEP19-01-01-

005 (Rockville, MD, 2019).

16

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMHSA’s Concept of

Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-

4884 (Rockville, MD, 2014).

Page 6 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

FEMA’s 2018–2022 Strategic Plan, and the National Disaster Recovery

Framework.

17

To address our fourth objective, we analyzed documentation on FEMA

assessments and performance reports for the IHP, as well as data on

surveys that FEMA conducted with survivors who applied for the IHP. We

compared FEMA’s methodology for its IHP surveys to the Office of

Management and Budget’s Standards and Guidelines for Statistical

Surveys.

18

We also analyzed documentation on FEMA initiatives and

recommendations aimed at addressing challenges with the IHP, and

compared these efforts with key process improvement and program

management activities from GAO’s Business Process Reengineering

Assessment Guide and The Standard for Program Management.

19

We

also interviewed officials from FEMA’s Individual Assistance Division and

Recovery Analytics Division, which manages data and analytics for

Individual Assistance, and the IHP Service Delivery Branch, which

manages the IHP.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2018 to September

2020 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Further information on our scope and methodology can be found in

appendix I.

17

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: September 2014); and Human Capital: A Guide for Assessing

Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government, GAO-04-546G

(Washington, D.C.: March 2004); and Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2018–

2022 Strategic Plan; and Department of Homeland Security, National Disaster Recovery

Framework.

18

Office of Management and Budget, Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys

(Washington, D.C.: September 2006).

19

GAO, Business Process Reengineering Assessment Guide, Version 3,

GAO/AIMD-10.1.15 (Washington, D.C.: May 1997). Project Management Institute, Inc.,

The Standard for Program Management—Fourth Edition® (2017).

Page 7 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act

(Stafford Act) establishes the process for states, territories, and tribes to

request a presidential major disaster or emergency declaration, which, if

approved, triggers a variety of federal response and recovery programs

for government and nongovernmental entities, households, and

individuals. One of these programs is FEMA’s Individual Assistance

Program, which provides assistance to disaster survivors to cover

necessary expenses and serious needs such as housing assistance,

counseling, child care, unemployment compensation, or medical

expenses, that cannot be met through insurance or low-interest loans.

The Individual Assistance Program consists of six sub-programs:

• IHP. Provides financial assistance and direct services for housing and

other types of assistance to individuals and households who have

uninsured or underinsured necessary expenses and serious needs

due to a disaster;

• Mass Care and Emergency Assistance. Provides life-sustaining

services and resources to disaster survivors, such as shelter and

food;

• Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program. Assists

individuals and communities in recovering from psychological effects

of a disaster;

• Disaster Unemployment Assistance. Provides unemployment

benefits and reemployment services to individuals unemployed

because of a disaster;

• Disaster Legal Services. Provides free legal help to low-income

survivors of a disaster; and

• Disaster Case Management. Provides a survivor with a single point

of contact to facilitate access to a broad range of services.

Almost three-fourths of the expenditures under the Individual Assistance

Program were for the IHP from 2010 through 2019.

20

We discuss IHP

expenditures later in this report.

20

An expenditure is an amount paid by federal agencies, by cash or cash equivalent, to

liquidate government obligations.

Background

FEMA’s Role in Providing

Disaster Assistance to

Individuals and

Households

Page 8 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

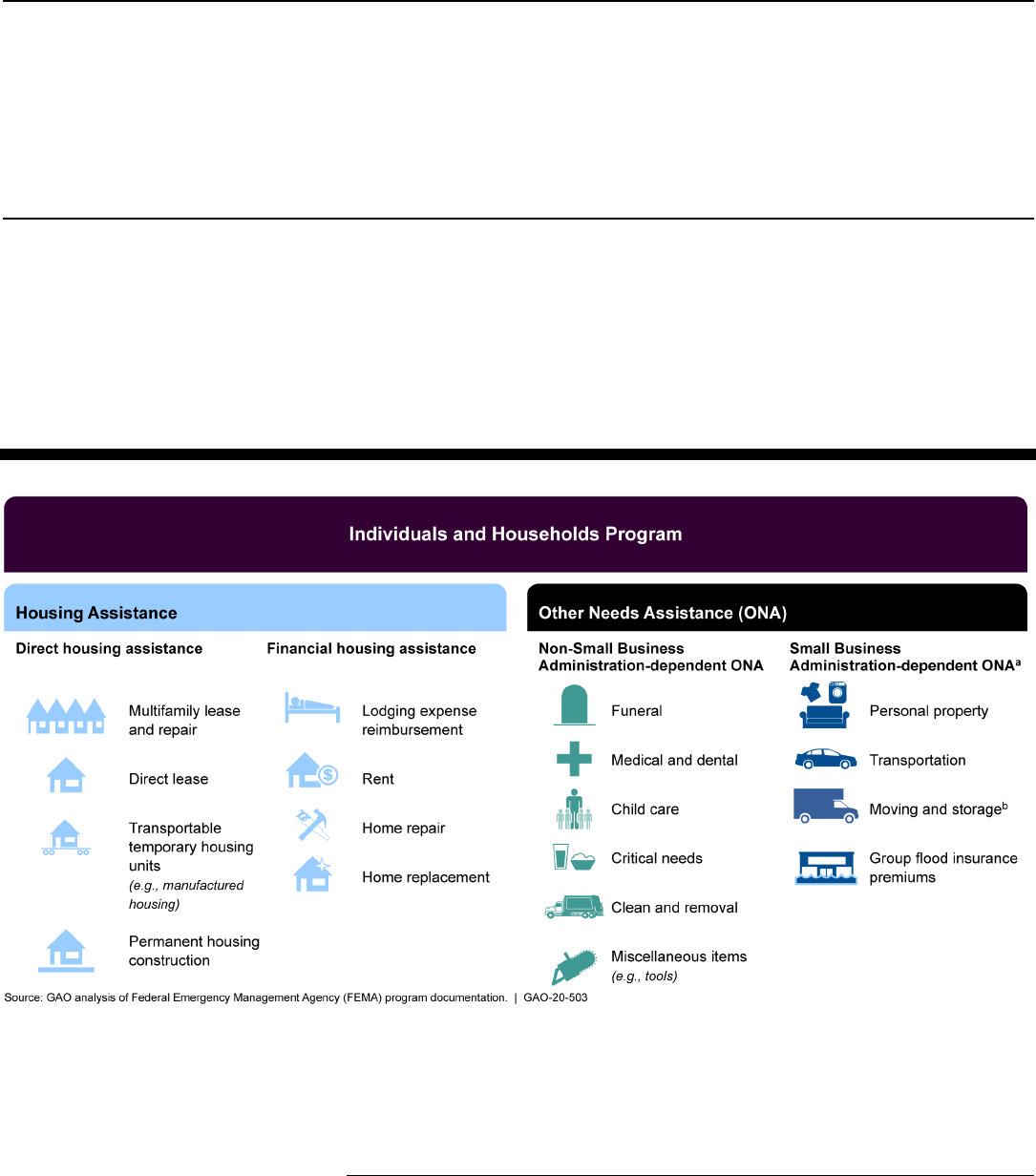

The IHP provides two categories of assistance: (1) housing assistance

and (2) other needs assistance (ONA).

Housing assistance. FEMA may provide financial and direct (i.e.,

nonfinancial) housing assistance to individuals and households, who are

displaced or whose residences are rendered uninhabitable as a result of

damage caused by a major disaster.

21

Financial assistance may include

lodging expense reimbursement for time spent at hotels or other

temporary lodging, rental assistance, and home repair or replacement

assistance.

Based on a request from the state, territory, or tribal government, FEMA

may provide direct housing assistance when eligible disaster survivors

are unable to use rental assistance. This type of assistance includes the

repair and lease of multifamily housing units—such as apartments—for

temporary use by survivors, direct lease assistance, and Transportable

Temporary Housing Units, such as recreational vehicles or manufactured

housing units. Transportable Temporary Housing Units can be placed on

private sites, commercial sites or on group sites. Commercial sites are

existing manufactured home sites with available pads that FEMA may

lease. Group sites require additional approval when housing needs

cannot be met by other direct temporary housing options. They may

include publicly-owned land with adequate available utilities. FEMA may

also provide assistance for permanent or semipermanent housing

construction when no alternative housing resources are available and the

types of temporary housing discussed above are unavailable, infeasible,

or not cost-effective.

22

ONA. This consists of financial assistance for other necessary expenses

and serious needs caused by the disaster. Some types of ONA are only

provided if an individual does not qualify for a disaster loan from the SBA;

this assistance includes personal property (e.g., furniture) and

transportation assistance, and group flood insurance policies (collectively

referred to as SBA-dependent ONA). However, FEMA requires

individuals with certain income levels based on family size to apply to the

SBA Disaster Loan Program and be denied or receive a partial loan

21

42 U.S.C. 5174(b)(1)). FEMA may provide such assistance to individuals with disabilities

whose residences are rendered inaccessible or uninhabitable as a result of damage

caused by a major disaster.

22

42 U.S.C. § 5174(c)(4).

IHP Assistance

Permanent Housing Construction Provided

through the Individuals and Households

Program

The Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) made repairs to the stairs, elevated

entrance (top), and interior (bottom) of the

home through the Permanent Housing

Construction program. This included new

appliances and cabinets in the kitchen, and

repairs to the doors, windows, walls, ceiling,

light fixtures, and floor.

Source: GAO; photos taken by GAO while on site in Puerto

Rico | GAO-20-503

Page 9 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

before FEMA will consider them for SBA-dependent ONA. Other types of

ONA can be provided regardless of SBA loan qualification, including

funeral, medical, dental, child care, critical needs, and clean and removal

assistance, and other miscellaneous items (e.g., tools).

23

Figure 1 illustrates the types of IHP housing assistance and ONA

available to individuals. However, not all types of assistance are

automatically available for every disaster declaration.

Figure 1: Types of Assistance Available under the Individuals and Households Program

a

FEMA requires individuals with certain incomes based on family size to apply to the Small Business

Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program and be denied or receive a partial loan before FEMA will

consider them for SBA-dependent ONA.

b

FEMA plans to implement moving and storage assistance as non-SBA dependent ONA in fall 2020,

according to agency officials.

23

Critical needs assistance may be provided to survivors with immediate or critical needs

because they are displaced from their primary dwelling. Immediate or critical needs are

life-saving and life-sustaining items, including: water, food, first aid, prescriptions, infant

formula, diapers, consumable medical supplies, durable medical equipment, personal

hygiene items, and fuel for transportation.

Page 10 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

According to FEMA officials, the IHP is intended to supplement

individuals’ recovery efforts and is not a substitute for insurance. Most

forms of IHP assistance are capped at a maximum amount an eligible

survivor can receive, which is adjusted annually based on changes in the

Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, as published by the

Department of Labor, and IHP assistance is generally limited to 18

months following the date of the disaster declaration. FEMA may extend

the period of assistance upon a determination, at the request of a state,

territorial, or tribal government, that due to extraordinary circumstances

an extension would be in the public interest.

24

In 2018, the Stafford Act was amended by the Disaster Recovery Reform

Act of 2018, and those amendments generally apply to each major

disaster and emergency declared by the President on or after August 1,

2017.

25

The act includes a provision that establishes separate maximum

amounts for financial housing assistance and ONA, thus doubling the

maximum amount an eligible survivor could receive.

26

For example, prior

to the enactment of the act, the maximum amount of financial assistance

an eligible survivor could receive in 2018 was $34,000. As a result of the

act, the maximum amount of financial assistance an eligible survivor

could receive in 2018 was $68,000 ($34,000 for financial housing

assistance plus $34,000 for ONA). The act also removed temporary

housing assistance and assistance for disability-related real and personal

property items from the financial assistance limits, so there is no limit for

those items.

27

The IHP is managed by FEMA’s IHP Service Delivery Branch, which is

decentralized and has staff at FEMA headquarters in Washington, D.C.,

and four NPSCs located in Winchester, Virginia; Hyattsville, Maryland;

Denton, Texas; and Caguas, Puerto Rico. According to FEMA officials,

the branch has approximately 1,300 staff and consists of three sections—

(1) Program Management, (2) Field Services, and (3) Applicant Services.

24

42 U.S.C. § 5174(h), (c)(1)(B)(iii); 44 C.F.R. § 206.110(b), (e). As discussed below,

temporary housing assistance and assistance for disability-related real and personal

property items are not subject to the financial assistance limits. 42 U.S.C. § 5174(h).

25

Pub. L. No. 115-254, div. D, § 1202(a), 132 Stat. 3186, 3438.

26

Id. at § 1212, 132 Stat. at 3448 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 5174(h)).

27

Id.

IHP Organization

Page 11 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

1. The Program Management Section develops and implements policies,

ensures coordination throughout the IHP, and manages direct housing

efforts.

2. The Field Services Section delivers services to disaster survivors and

coordinates the deployment of resources to the field. This section

includes the Housing Inspections Services Unit, Disaster Recovery

Center (DRC) Unit, and Disaster Survivor Assistance Unit.

3. The Applicant Services Section includes almost 1,000 call center and

case processing staff who help survivors apply for FEMA assistance,

answer their questions on the Disaster Helpline, and process cases

for IHP assistance.

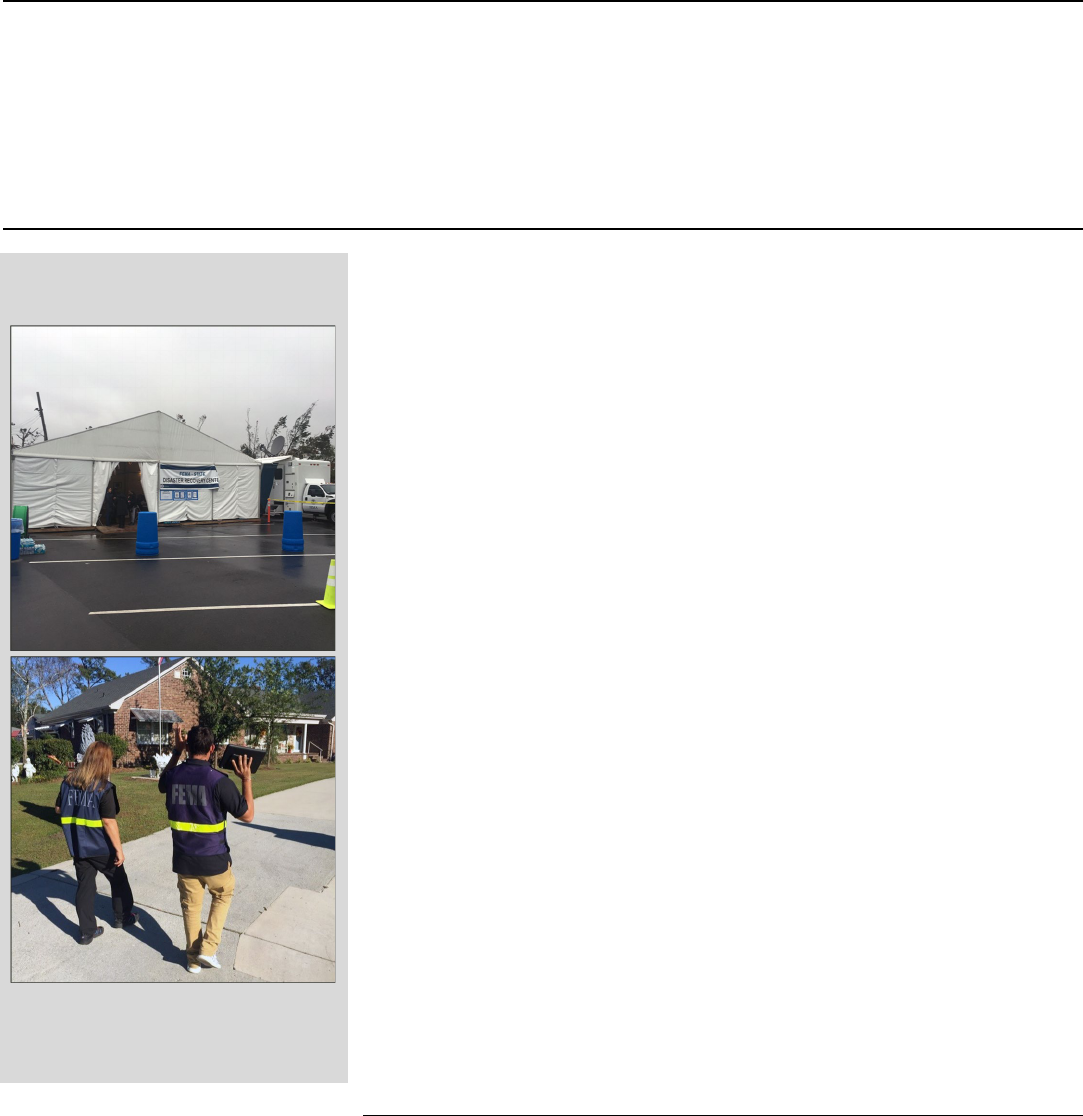

IHP operations are implemented in the field by staff from FEMA’s regions,

the Individual Assistance and Disaster Survivor Assistance cadres, FEMA

Corps, and the Housing Inspections Unit.

28

Staff from FEMA’s regions

manage and oversee the implementation of the IHP at Joint Field Offices

and Area Field Offices for disaster declarations in their region.

29

In areas

impacted by a disaster, FEMA establishes DRCs, which are facilities

where survivors may go to apply for the IHP and obtain information about

other FEMA programs, as well as other disaster assistance programs.

During 2016 through 2018, the daily average total staff from the Individual

Assistance and Disaster Survivor Assistance cadres and FEMA Corps

supporting Individual Assistance and IHP operations was over 3,000. To

provide an example of how IHP operations are organized, figure 2 shows

the FEMA regions and four NPSCs, as well as the field locations for

FEMA’s recovery efforts for Hurricane Michael in Florida.

28

A “cadre” is a group of FEMA employees organized by operational or programmatic

functions and FEMA Qualification System positions that perform disaster-related activities

during FEMA disaster operations. FEMA Corps are members of AmeriCorps National

Civilian Community Corps who work under supervision of FEMA staff.

29

A Joint Field Office is a temporary federal multiagency coordination center established

locally to facilitate field-level domestic incident management activities, and provides a

central location for coordination of federal, state, territory, local, tribal, nongovernmental,

and private-sector organizations with primary responsibility for activities associated with

threat response and incident support. An Area Field Office supports a Joint Field Office

and is its forward element responsible for a specific geographic area.

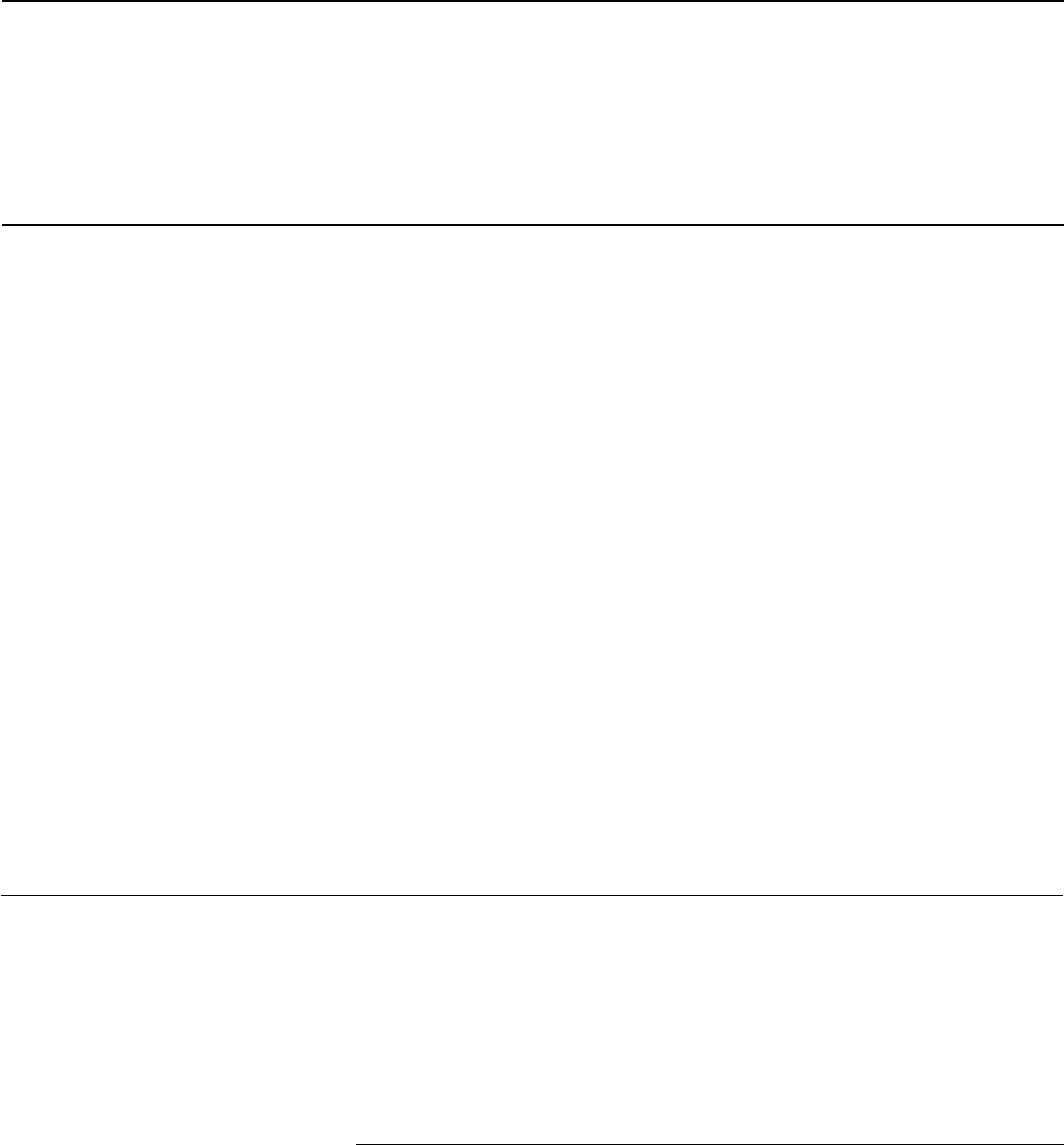

Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) Field Services Section Tent and

Staff

FEMA deploys staff to the field to assist

survivors at Disaster Recovery Centers and

conduct survivor outreach.

Source: GAO; photos taken by GAO while on site in Florida

and North Carolina. | GAO-20-503

Page 12 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 2: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Regions, Four National Processing Service Centers, and Field

Locations for Hurricane Michael Recovery Efforts in Florida

FEMA Expended at

Least $11.8 Billion

through the IHP and

Generally Used a

Consistent Process to

Provide Assistance to

About 3 Million

Disaster Survivors

from 2010 through

2019

Page 13 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

For the 161 major disaster declarations from calendar years 2010 through

2019 that included Individual Assistance, FEMA expended at least $11.8

billion in IHP assistance to eligible survivors—$10.4 billion in financial

assistance, including ONA, and at least $1.4 billion in direct housing

assistance (see fig.3). Approximately 40 percent of the $11.8 billion from

2010 through 2019 was expended in 2017 due to Hurricanes Harvey,

Irma, Maria, and the California wildfires. IHP financial assistance

expenditures ranged from a low of $235 million in 2014 to a high of $4.2

billion in 2017. IHP direct housing expenditures ranged from a low of at

least $4 million in 2010 to a high of at least $507 million in 2017.

Figure 3: Expenditures for the Individuals and Households Program and Number of Major Disaster Declarations That Included

Individual Assistance, 2010 – 2019

Notes: Expenditures have not been adjusted for inflation. Financial assistance includes other needs

assistance (ONA).

Three types of IHP financial assistance accounted for 89 percent of

expenditures from 2010 through 2019—home repair (48 percent), rental

assistance (26 percent), and personal property assistance under ONA (15

percent), as shown in figure 4.

FEMA Expended over $11

Billion through the IHP for

About 3 Million Eligible

Survivors from 2010

through 2019

Type of Assistance Awarded

Page 14 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 4: Percentage of Expenditures by Type of Financial Assistance under the

Individuals and Households Program, 2010 – 2019

From 2010 through 2019, FEMA determined that about 3 million survivors

were eligible for IHP assistance, and the number of survivors who

received IHP financial assistance ranged from a low of about 58,000 in

2015 to a high of about 1.7 million in 2017. The overall median and

average amounts of IHP financial assistance that FEMA provided per

eligible survivor were $1,332 and $3,522, respectively, for the 10-year

period from 2010 through 2019.

30

The average amount of IHP financial

assistance provided to eligible survivors ranged from a low of $2,508 in

2017 to a high of $6,916 in 2016. The median amount provided to eligible

survivors ranged from a low of $927 in 2017 to a high of $3,391 in 2012

(see fig. 5). From 2010 through 2019, approximately 1 percent of all IHP

30

In this report, “average” amount of IHP assistance refers to the mean amount. We

present the median in addition to the average (mean) assistance amount because the

distribution of IHP financial assistance is skewed toward larger amounts, as indicated by

the substantial difference between the average and median amounts of IHP assistance.

This is because some survivors received significantly higher amounts of IHP financial

assistance, which increases the mean value (because it is based on all values in the

distribution), but does not affect the median value, which is less sensitive to extreme

values (because it is based on the middle value of the data).

Amount of IHP Assistance per

Eligible Survivor

Page 15 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

applicants who received IHP financial assistance (33,051) received the

maximum award under the Stafford Act or the Stafford Act, as amended

by the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018. Regarding the amount of

IHP financial assistance that FEMA provided per eligible survivor during

this 10-year time period, FEMA stated that it encourages all disaster

survivors with damage to apply for the IHP, which leads to a larger pool of

eligible applicants and many of them have minimal damage, thus, driving

down the average award amount.

Figure 5: Number of Applicants Who Received Financial Assistance from the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP) and Median and Average Award

Amounts, 2010 – 2019

Note: Award amounts have not been adjusted for inflation.

Page 16 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

While FEMA adjusts the IHP to respond to disaster scenarios and

changes in technology—such as developing new forms of assistance and

developing smartphone applications to help disaster survivors register for

assistance—the IHP has generally followed a consistent process for

delivering assistance. This process includes the following four key steps:

(1) application, (2) referral, (3) verification of disaster-caused losses, and

(4) eligibility and award determination. In certain disasters, FEMA may

also offer direct housing assistance and use a separate process to

evaluate their eligibility and deliver assistance, when relevant. Throughout

this process, survivors have the opportunity to appeal certain IHP

decisions (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Process for Financial Assistance under the Individuals and

Households Program (IHP)

Note: The IHP generally limits applications for assistance to one per household. An applicant may

represent one person or multiple people.

FEMA processes the application information using its National

Emergency Management Information System—which collects and routes

applications through all decision points following rules defined in the

software—and refers disaster survivors to the IHP that meet certain

conditions, including that the survivor reported that they experienced

FEMA Generally Used a

Consistent Process for

Delivering Assistance and

Found Fewer than Half of

Applicants Eligible for

Assistance from 2010 to

2019

Page 17 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

home damages or personal losses because of the disaster.

31

Lastly,

FEMA must review documentation to verify that survivors meet the

general eligibility to receive assistance.

From 2010 through 2019, FEMA found that less than half (46.7 percent)

of disaster survivors referred to the program were eligible for assistance.

During this time, FEMA did not make an eligibility determination for

577,000 (9.1 percent) of disaster survivors referred to the program

because they did not submit insurance information. Over 416,000 (72.1

percent) of those who received no eligibility decision due to insurance

information were survivors from disasters in 2017 and 2018. In cases

where FEMA does not make an eligibility determination because of

missing insurance documentation, FEMA communicates this decision to

survivors as a denial of assistance, by mail or email. Applicants have 60

days to appeal the decision and up to a year to provide insurance

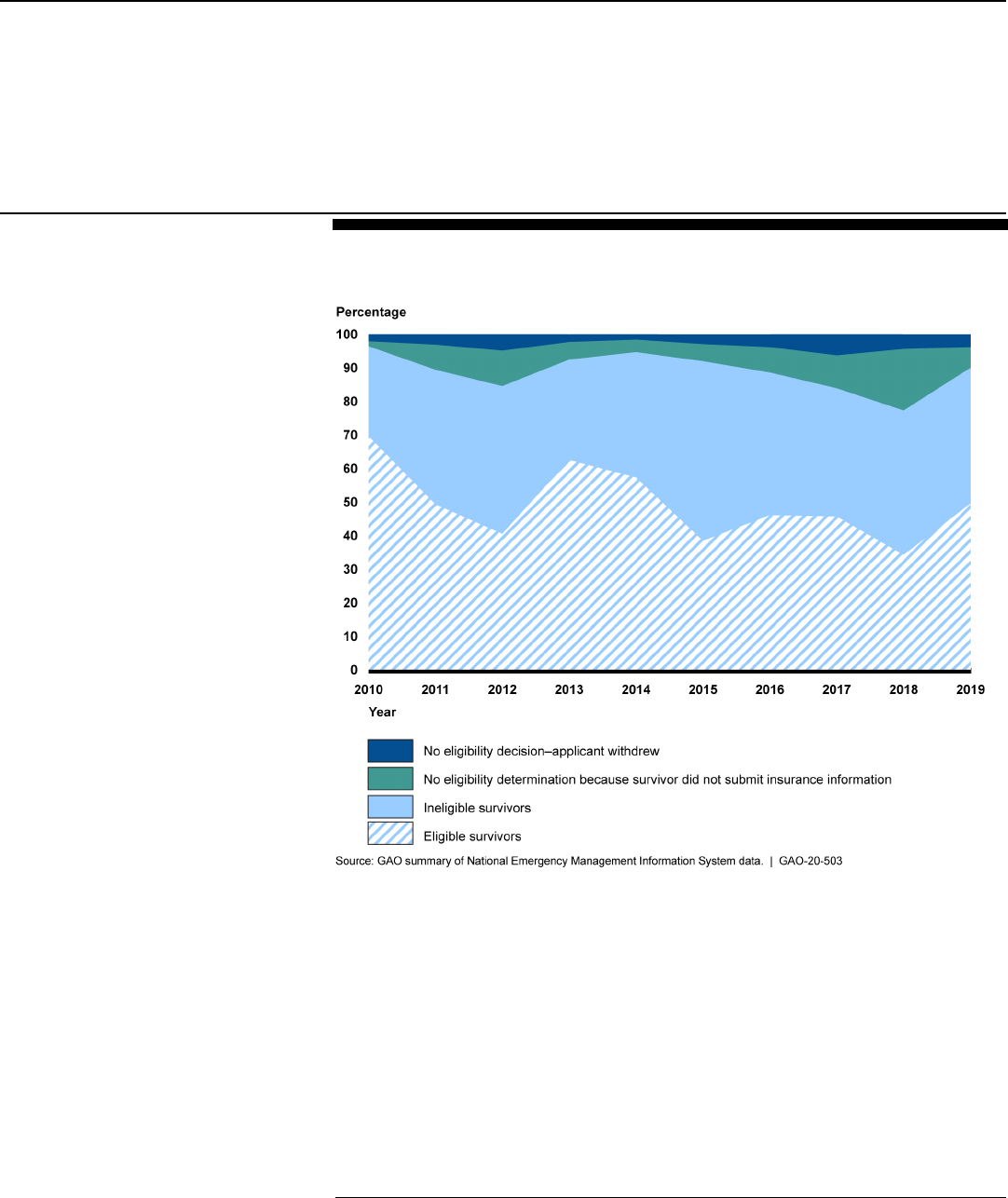

documentation. Figure 7 shows trends in eligibility rates.

31

IHP assistance is available for disaster-caused damages to the home, referred to as real

property, for applicants who own their home as their primary residence. Other assistance

is available, for both homeowners and renters, for items that were lost or damaged due to

the disaster, referred to as personal property. Throughout the report, we refer to disaster

damages, which may mean real property or personal property losses.

Page 18 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 7: Eligibility Status Rates for Disaster Survivors Referred to the Federal

Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Individuals and Households Program,

from 2010 through 2019

Note: From 2010 through 2019, FEMA also did not make eligibility determinations for 156 applicants

with a status that remained “pending.” This reflects less than .01 percent of referred survivors and is

not visible on the figure. According to FEMA, pending eligibility determinations reflect a processing

error that require manual corrections to ensure payment of any eligible assistance.

After the National Emergency Management Information System refers

disaster survivors to the IHP for assistance, FEMA may conduct a

housing inspection specifically to assess and verify that the IHP covered

disaster damages. The inspection does not collect information on all

damages because IHP assistance does not address all damages

resulting from a disaster; for example, home repair assistance provides

assistance only to restore the home to a safe and sanitary living or

functioning condition.

32

Inspectors record the cause of damage and

32

See 44 C.F.R. § 206.117(b)(2)(iii).

FEMA Considers Various

Factors to Determine

Type and

Amount of Assistance

Page 19 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

confirm the size of the home and number of people living there, among

other details. The inspector will also verify eligible transportation losses

caused by the disaster.

33

FEMA considers a variety of factors specific to the disaster survivor’s

unique circumstances when determining the type and amount of

assistance to award and may use alternative verifications to determine

eligibility based on disaster-specific circumstances, as was the case for

multiple disasters in 2017 and 2018. Further, each type of assistance may

have additional conditions of eligibility and verification requirements

beyond the general eligibility requirements noted above. For example, in

the case of multiple roommates who share a damaged residence, FEMA

follows different eligibility criteria and limitations when determining the

amount of personal property assistance but follows the standard criteria

for awarding transportation assistance, among others.

34

See appendix II

for a summary of adjusted verification procedures for general eligibility

requirements, as well as the additional eligibility requirements and

verification procedures specific to each type of assistance.

According to FEMA officials, considerations that frequently affect award

determination are availability of insurance, number of people in the

household, and whether the IHP allows assistance for the survivor’s

specific disaster damages and losses. For example, FEMA subtracts any

insurance settlements an applicant receives from their award. FEMA

considers household composition and provides assistance for personal

property damages in one bedroom when there is only one adult living in

the home, even if there were multiple bedrooms with damages. Figure 8

below demonstrates these considerations.

33

We plan to conduct a review in late 2020 on the challenges FEMA faced managing

housing inspections for the determination of IHP awards.

34

While transportation assistance is limited to one damaged vehicle per household, FEMA

may consider providing assistance for more than one vehicle in the case of roommates

when the survivor provides justification of their need.

Page 20 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 8: Notional Case of Two Families with Similar Damage and Different Awards Because of Individuals and Households

Program Eligibility Criteria and Circumstances

FEMA sends all IHP applicants an award determination letter explaining

the applicant’s eligibility for IHP assistance and, if eligible, the amount of

assistance awarded.

Page 21 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

FEMA monitors cases where the inspection finds over $17,000 or more in

eligible damages for homeowners or renters whose home received major

damage to determine the number of survivors who may need and be

eligible for temporary housing. FEMA can provide direct housing

assistance for up to 18 months, depending on their needs, which may be

extended due to extraordinary circumstances when the affected state,

territory, or tribe requests an extension in writing. Figure 9 shows this

process.

Figure 9: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Process for Assessing Need and Providing Direct Housing

Assistance to Eligible Survivors

Survivors may request a review of certain decisions within 60 days after

the date that FEMA notifies them of the award or denial of assistance,

and the request must be submitted in writing, explain the reason for

appealing, and include a signature.

35

FEMA reviews the survivor’s written

appeal and any documentation provided with the appeal. Upon review,

FEMA either provides a written decision or requests more information

from the survivor. FEMA must provide the survivor with a response within

90 days of when FEMA receives the appeal. From 2010 through 2019,

about 303,000 survivors (4.8 percent) submitted about 463,000 appeals

for FEMA decisions on their IHP applications. Of the approximately

35

44 C.F.R. § 206.115(a), (b).

FEMA May Provide Direct

Housing Assistance

Survivors Have the Right to

Appeal

Page 22 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

463,000 total appeals, FEMA approved over 115,000 (25 percent) and

denied over 336,000 appeals (about 73 percent).

36

From 2016 through 2018, survivors from 52 major disaster declarations

that included Individual Assistance applied for assistance from FEMA’s

IHP. Based on our analysis, survivors had varying program outcomes—

such as approval for and timeliness of financial assistance—depending

on their characteristics, such as age, gross annual income, and insurance

coverage, as well as the social vulnerability of the community in which

they lived. We also found that survivors faced challenges with

understanding and navigating the IHP, which may have prevented them

from receiving assistance for which they may have otherwise been

eligible. Specifically, survivors experienced challenges with the

requirement to apply for SBA’s disaster loan program, and understanding

FEMA’s eligibility and award decisions.

According to our analysis of FEMA’s IHP applicant data for 2016 through

2018, there were differences in approval rates, financial assistance

received, reasons for ineligibility, appeal rates, and time between key

36

The remaining approximately 2 percent of appeals were pending, withdrawn, or no

decision could be made.

Survivors Had

Varying Program

Outcomes and Faced

Challenges

Understanding and

Navigating the IHP

Identifying Vulnerable Communities Using

the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index

The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention created the Social Vulnerability

Index to help public health officials and

emergency response planners identify and

map the communities that will most likely

need continued support to recover following

an emergency or natural disaster. The index

indicates the relative social vulnerability of

census tracts in U.S. states and the District of

Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Census tracts are

subdivisions of counties for which the U.S.

Census Bureau collects statistical data

through the American Community Survey.

The index ranks tracts on 15 variables,

including unemployment, minority status, and

disability, and further groups them into the

following four themes—(1) socioeconomic

status, (2) household composition and

disability, (3) minority status and language, (4)

housing and transportation—as well as an

overall ranking. The index is a 0 to 1 scale,

with higher scores indicating greater

vulnerability.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

GAO-20-503

Program Outcomes Varied

across Survivor Groups

Page 23 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

events of the IHP financial assistance process for different groups of

survivors, including renters, older survivors, survivors with lower incomes,

survivors without property insurance, and survivors living in more socially

vulnerable communities. See appendix III for our analysis of IHP

outcomes by levels of social vulnerability in survivors’ communities. Also,

see our supplemental materials for our full analysis of program outcomes

for calendar years 2016, 2017, and 2018, and selected major disasters in

2016 through 2018.

37

Referred applicants’ characteristics and approval rates. Of the 5.6

million people who applied for FEMA assistance from 2016 through 2018,

4.4 million (78 percent) were referred to the IHP. We found that the

majority of referred applicants reported that they did not have flood

insurance coverage (92 percent) or property insurance coverage (63

percent); were from multiperson households (62 percent); owned their

homes (57 percent); or lived at or below 200 percent of the federal

poverty guideline (53 percent).

38

In addition, we found that 50 percent of

referred applicants were between the ages of 25 and 49, and roughly 40

percent of referred applicants reported a gross annual income below

$25,000, or lived in a community with the highest levels of social

vulnerability.

According to our analysis, 45 percent of all referred applicants were

approved for financial IHP assistance from 2016 through 2018. Of the

over 2.4 million referred applicants who were not approved, roughly 1.7

million were ineligible, almost 450,000 did not receive a decision from

FEMA because of missing insurance documentation, and over 260,000

had their applications withdrawn.

39

We found that approval rates varied

37

See GAO, Supplemental Material for GAO-20-503: Select Disaster Profiles for FEMA’s

Individuals and Households Program 2016-2018, GAO-20-674SP (Washington, D.C.;

September 2020); and Supplemental Material for GAO-20-503: FEMA Individuals and

Households Program Applicant Data 2016-2018, GAO-20-675SP (Washington, D.C.;

September 2020).

38

Federal poverty guidelines represent an annual household income for different

household sizes and locations. For example, the following families lived at 200 percent of

the federal poverty guideline in 2018: a family of two living in one of the 48 contiguous

states or the District of Columbia with a gross annual income of $32,920; a family of five

living in one of the 48 contiguous states or the District of Columbia with a gross annual

income of $58,840; and a family of five living in Hawaii with a gross annual income of

$67,680.

39

A survivor can voluntarily withdraw their application for IHP assistance. FEMA can

withdraw a survivor’s application for assistance if the applicant failed to provide a required

signature or could not be contacted.

Federal Poverty Guidelines

Each year, the Department of Health and

Human Services issues federal poverty

guidelines, which represent an annual

household income for different household

sizes and locations. For example, the 2018

poverty guideline for a family of four in any of

the 48 contiguous states and the District of

Columbia was $25,100. In comparison, the

2018 guidelines for a family of four in Alaska

and Hawaii were $31,380 and $28,870,

respectively. The guidelines are not defined

for U.S territories.

Federal poverty guidelines are used to

determine financial eligibility for certain federal

programs. For example, the Department of

Agriculture’s National School Lunch Program

provides lunches to children in schools for

free if their household income is below 130

percent of the poverty guidelines, and at a

reduced price if their household income is

between 130 percent and 185 percent of the

guidelines.

Source: Department of Health and Human Services and

Department of Agriculture. | GAO-20-503

Page 24 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

across survivor groups (see fig. 10). For example, from 2016 through

2018, we found that the following groups were approved for IHP

assistance at higher rates: renters (47 percent); applicants with reported

gross annual incomes less than $10,000 (52 percent); and those who

reported no insurance coverage on their real or personal property (50

percent).

Figure 10: Referred Applicants and Approval Rates for the Individuals and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018

Notes: The data used to create survivor groups were reported by the survivor in their FEMA

application. We found that less than 1 percent of referred applicants had missing age, household

size, or ownership status data, and 16 percent had missing gross annual income data, which also

Page 25 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

affects our federal poverty guideline analysis. We conducted an analysis of other socioeconomic

characteristics of applicants with missing income information and found that they are somewhat more

likely to have lived in communities characterized by lower levels of socioeconomic vulnerability than

those who provided income information. See appendix I for more details.

a

Federal poverty guidelines represent a household income for different household sizes and

locations. The guidelines are not defined for U.S territories. We calculated guidelines for relevant U.S.

territories by multiplying the federal poverty guideline for the 48 contiguous states and the District of

Columbia by the same factor that the Small Business Administration used to calculate its minimum

income guidelines for U.S. territories.

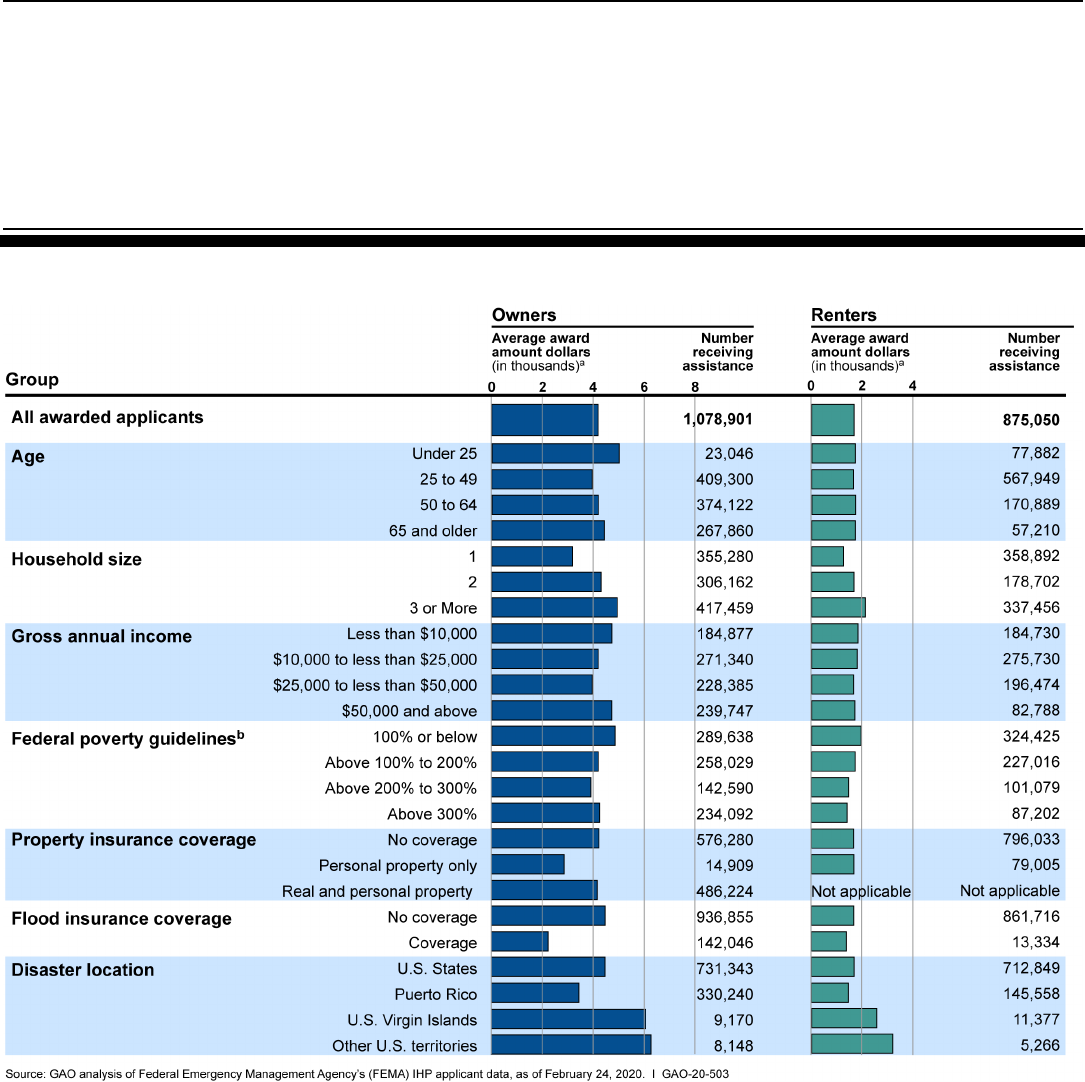

Financial IHP assistance received. According to our analysis, almost 2

million applicants received financial IHP assistance from FEMA from 2016

through 2018. The average amounts of financial assistance homeowners

and renters received from FEMA during this period were $4,184 and

$1,675, respectively.

40

We found that average award amounts varied

across survivor groups (see fig. 11). For example, from 2016 through

2018, we found that the following groups had the highest average award

amounts: homeowners under the age of 25 ($5,012); renters ages 65 and

older ($1,723); homeowners and renters from households with three

people or more ($4,940 and $2,116, respectively); and homeowners and

renters living at or below the federal poverty guideline ($4,852 and

$1,958, respectively).

40

For the purposes of this report, average refers to the mean. We did not include group

flood insurance in our analysis of average IHP award amounts because this type of

assistance is not a direct payment to the applicant. FEMA directly purchases group flood

insurance certificates—that cost $600 and provide 3 years of coverage—on behalf of

applicants who are required to obtain and maintain flood insurance. From 2016 through

2018, less than 3 percent of all awarded applicants received group flood insurance.

Page 26 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 11: Average Award Amounts and Number of Owners and Renters Who Received Financial Assistance through the

Individuals and Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018

Notes: The data used to create survivor groups were reported by the survivor in their FEMA

application. We found that less than 1 percent of awarded applicants had missing age, household

size, or ownership status data, and 15 percent had missing gross annual income data, which also

affects our federal poverty guideline analysis. We conducted an analysis of other socioeconomic

characteristics of applicants with missing income information and found that they are somewhat more

likely to have lived in communities characterized by lower levels of socioeconomic vulnerability than

those who provided income information. See appendix I for more details.

a

We did not include group flood insurance in our analysis of average IHP award amounts because

this type of assistance is not a direct payment to the applicant. FEMA directly purchases group flood

insurance certificates—that cost $600 and provide 3 years of coverage—on behalf of applicants who

are required to obtain and maintain flood insurance. From 2016 through 2018, less than 3 percent of

all awarded applicants received group flood insurance.

Page 27 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

b

Federal poverty guidelines represent a household income for different household sizes and

locations. The guidelines are not defined for U.S territories. We calculated guidelines for relevant U.S.

territories by multiplying the federal poverty guideline for the 48 contiguous states and the District of

Columbia by the same factor that the Small Business Administration used to calculate its minimum

income guidelines for U.S. territories.

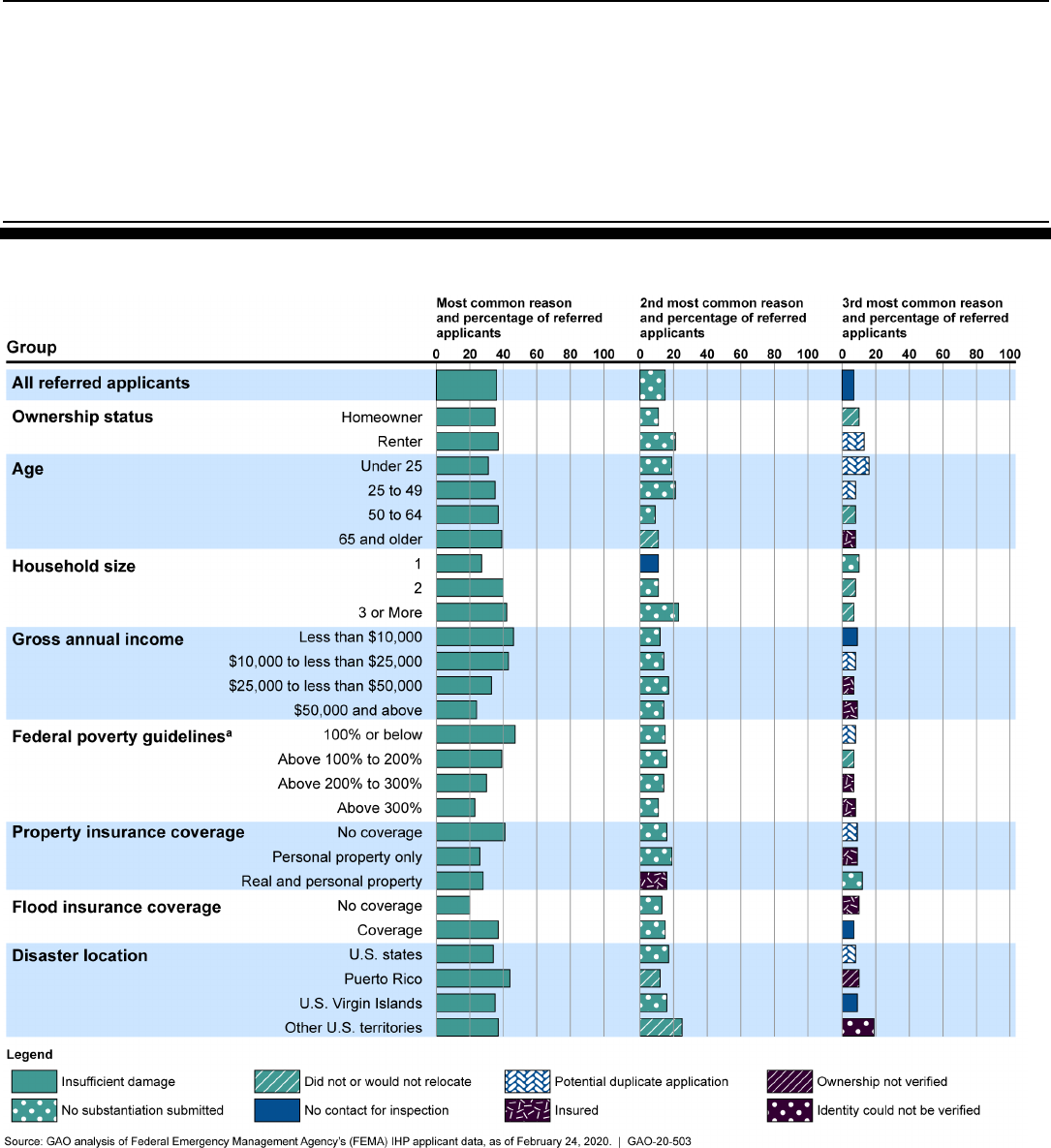

Most common reasons for an ineligible determination. According to

our analysis, from 2016 through 2018, the three most common reasons

FEMA determined that an applicant was ineligible for financial assistance

were (1) insufficient damage (36 percent of all referred applicants), (2)

failure to submit evidence to support disaster losses or needs (15 percent

of all referred applicants), and (3) failure to make contact with the FEMA

inspector (7 percent of all referred applicants). We also analyzed the most

common reasons for an ineligibility determination across survivor groups

and found differences in the rates at which certain applicants were

determined ineligible for IHP assistance because of insufficient

damages.

41

For example, lower-income applicants were determined

ineligible for financial assistance because of insufficient damage at higher

rates than higher-income applicants (see fig. 12).

41

FEMA will determine an applicant ineligible for IHP assistance if the agency does not

find enough damage to the applicant’s home or property to meet the IHP’s $50 minimum

threshold or the damages do not impact the habitability of the home.

Page 28 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

Figure 12: Most Common Reasons Referred Applicants Were Determined Ineligible for Assistance from the Individuals and

Households Program (IHP), 2016 – 2018

Notes: The data used to create survivor groups were reported by the survivor in their FEMA

application. We found that less than 1 percent of referred applicants had missing age, household

size, or ownership status data, and 16 percent had missing gross annual income data, which also

affects our federal poverty guideline analysis. We conducted an analysis of other socioeconomic

characteristics of applicants with missing income information and found that they are somewhat more

likely to have lived in communities characterized by lower levels of socioeconomic vulnerability than

those who provided income information. See appendix I for more details. Applicants may receive

multiple ineligible determinations.

Page 29 GAO-20-503 Disaster Assistance

a

Federal poverty guidelines represent a household income for different household sizes and

locations. The guidelines are not defined for U.S territories. We calculated guidelines for relevant U.S.

territories by multiplying the federal poverty guideline for the 48 contiguous states and the District of

Columbia by the same factor that the Small Business Administration used to calculate its minimum

income guidelines for U.S. territories.

Appeal rates. According to our analysis, roughly 153,000 applicants (less

than 4 percent of all referred applicants) submitted almost 223,000

appeals to FEMA from 2016 through 2018. Of the applicants who

appealed a FEMA determination, approximately 30 percent were

successful. We found that the percentage and success rate of applicants

who appealed a FEMA determination varied across survivor groups (see

table 1). For example, from 2016 through 2018, we found that the

following groups had among the highest percentage of applicants who

appealed a FEMA determination and appeal success rate: homeowners;

applicants ages 65 and older; and those who reported a gross annual

income of less than $10,000.

Table 1: Referred Applicants Who Appealed a Determination on Financial Assistance from the Individuals and Households

Program (IHP) and Appeal Approval Rates, 2016 – 2018

Group

Number and percent of referred

applicants who appealed

Percent who won

their appeal

All

153,114

3.5

30.2

Ownership status

Homeowner

125,086

5.0