Print Advisory – Document Pages: 72

Revised: 02/28/2022

A Guide to Fellowship Training Programs

in Surgical Critical Care and Acute Care Surgery

Third Edition

Developed by the

Surgical Critical Care Program Directors Society

EDITORS

William C. Chiu, MD, FACS, FCCM

Associate Professor of Surgery

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Director, Surgical Critical Care

Fellowship Program

R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center

University of Maryland Medical Center

Baltimore, Maryland

Samuel A. Tisherman, MD, FACS, FCCM

Professor of Surgery

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Director, Center for Critical Care

and Trauma Education

Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center

University of Maryland Medical Center

Baltimore, Maryland

Kimberly A. Davis, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCM

Professor of Surgery

Chief, Division of General Surgery, Trauma,

and Surgical Critical Care

Yale University School of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Yale-New Haven Hospital

New Haven, Connecticut

David A. Spain, MD, FACS

David L. Gregg, MD Professor

Chief of Acute Care Surgery

Associate Chief, Division of General Surgery

Department of Surgery

Stanford University School of Medicine

Stanford, California

Robert A. Maxwell, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

University of Tennessee College of Medicine

Director, Surgical Critical Care

Fellowship Program

University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Krista L. Kaups, MD, FACS

Professor of Clinical Surgery

University of California (San Francisco) / Fresno

Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

Community Regional Medical Center

Fresno, California

Charles A. Adams, Jr., MD, FACS, FCCM

Associate Professor of Surgery

Chief, Division of Trauma and Critical Care

Warren Alpert Medical School

Brown University

Providence, Rhode Island

Surgical Critical Care

Program Directors Society

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 2

Contributors

James E. Babowice, DO

Surgery Chief Resident

Allegheny General Hospital

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

16. Fellowship Interviews

Jacqueline J. Blank, MD

Surgical Critical Care Fellow

University of Pennsylvania Health System

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

17. Coaches, Advisors, Mentors, and Confidantes: What You Need and Why

Michelle R. Brownstein, MD, FACS

Associate Professor

Department of Surgery

Division of Acute Care Surgery

Associate Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

East Carolina University

Greenville, North Carolina

21. Re-entry Applicants

Clay Cothren Burlew, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Program Director, Trauma & Acute Care Surgery Fellowship

Denver Health Medical Center

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Denver, Colorado

1. Acute Care Surgery

Robert A. Cherry, MD, MS, FACS, FACHE

Adjunct Professor of Surgery

Chief Medical and Quality Officer

UCLA Health

Los Angeles, California

10. Geographic Considerations

William C. Chiu, MD, FACS, FCCM

Associate Professor of Surgery

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship Program

R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center

University of Maryland Medical Center

Baltimore, Maryland

Preface

Preface to Second Edition

Preface to First Edition

SAFAS Applicant Instructions

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

25. Web Sites of Interest

26. Acknowledgment

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 3

Daniel J. Cucher, MD

Dignity Health

Chandler Regional Medical Center

Chandler, Arizona

9. What Do Fellows Do, Day In, Day Out?

Kimberly A. Davis, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCM

Professor of Surgery

Chief, Division of General Surgery, Trauma, and Surgical Critical Care

Yale University School of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Yale-New Haven Hospital

New Haven, Connecticut

1. Acute Care Surgery

Matthew L. Davis, MD, FACS (posthumous)

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Scott & White Hospital and Healthcare

Temple, Texas

3. Surgical Critical Care or Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

4. Should I Do An Elective At An Institution That I Am Considering?

Therese M. Duane, MD, MBA, CPE, FACS, FCCM

Professor of Surgery

Texas Christian University

University of North Texas Health Science Center

Academic Chair and Program Director for General Surgery

Texas Health Resources

Fort Worth, Texas

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

Linda A. Dultz, MD, MPH, FACS

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Medical Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

Parkland Memorial Hospital

Dallas, Texas

16. Fellowship Interviews

Paula A. Ferrada, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Medical Director, Surgical and Trauma ICU

Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and Emergency Surgery

Virginia Commonwealth University Health System

Richmond, Virginia

3. Surgical Critical Care or Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 4

Laura N. Godat, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Clinical Surgery

Program Director

Surgical Critical Care and Acute Care Surgery Fellowship

Medical Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

Assistant Trauma Director

University of California San Diego Medical Center

San Diego, California

16. Fellowship Interviews

Shea C. Gregg, MD, FACS

Chief, Section of Trauma, Burns, and Surgical Critical Care

Yale New Haven Health – Bridgeport Hospital

Bridgeport, Connecticut

6. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

David A. Hampton, MD, Meng, FACS

Assistant Professor

Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

Department of Surgery

Associate Program Director, Adult Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Associate Clerkship Director, Surgery

University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

7. International / Overseas Surgical Rotations

16. Fellowship Interviews

Lewis J. Kaplan, MD, FACS, FCCM, FCCP

Professor of Surgery

Division of Trauma, Surgical Critical Care and Emergency Surgery

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Chief, Section of Surgical Critical Care

Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

17. Coaches, Advisors, Mentors, and Confidantes: What You Need and Why

Mansoor A. Khan, MBBS (Lond), PhD, FRCS(GenSurg), FEBS(GenSurg), FACS, AKC

Surgeon Commander, Royal Navy

Consultant Trauma Surgeon

Associate Professor in Military Surgery

Royal Naval Medical Services

St. Mary’s Hospital

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

London, United Kingdom

24. International Physicians

Uzer S. Khan, MBBS, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship Program

Associate Director, Trauma Intensive Care Unit

Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and Acute Care Surgery

Allegheny General Hospital

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

16. Fellowship Interviews

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 5

Jennifer C. Knight Davis, MD, FACS

Associate Professor

Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery and Surgical Critical Care

Department of Surgery

West Virginia University School of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Jon Michael Moore Trauma Center

Morgantown, West Virginia

11. Family Considerations

Stefan W. Leichtle, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Medical Director, Trauma Intensive Care Unit

Division of Acute Care Surgical Services

Virginia Commonwealth University

Richmond, Virginia

12. Applying to Fellowship Programs

16. Fellowship Interviews

Alexander L. Marinica, DO

Clinical Instructor

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Parkland Memorial Hospital

Dallas, Texas

16. Fellowship Interviews

Joshua A. Marks, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Division of Acute Care Surgery

Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Associate Program Director, General Surgery Residency

Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

13. Application Chronology

William A. Marshall, MD

Surgical Critical Care and Acute Care Surgery Fellow

University of California San Diego Medical Center

San Diego, California

16. Fellowship Interviews

Niels D. Martin, MD, FACS, FCCM

Associate Professor of Surgery

Vice Chair, Diversity & Inclusion

Chief, Section of Surgical Critical Care

Director, Traumatology & Surgical Critical Care Fellowship Programs

Perelman School of Medicine

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

12. Applying to Fellowship Programs

13. Application Chronology

16. Fellowship Interviews

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 6

Maureen McCunn, MD, MIPP, FASA, FCCM

Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Division of Trauma Anesthesiology

R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center

Baltimore, Maryland

23. Anesthesiologists

Benjamin J. Moran, MD, FACS

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University

Associate Director

Surgery Residency Program

Einstein Healthcare Network

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

8. What to Expect in a Fellowship Program

David S. Morris, MD, FACS

Associate Medical Director, General Surgery

Intermountain Healthcare

Salt Lake City, Utah

2. Acute Care Surgery Traits

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

6. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

14. Preparing Your Personal Statement

15. Letters of Recommendation

Chet A. Morrison, MD, FACS, FCCM

Associate Professor of Surgery

Central Michigan University College of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Attending Trauma and Critical Care Surgeon

Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital

Saginaw, Michigan

20. What is the Post-Fellowship Job Outlook?

Nathan T. Mowery, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Director, AAST Acute Care Surgery Fellowship

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

6. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

Catherine S. Nelson, MD

Arnot Medical Services, PLLC

Arnot Ogden Medical Center

Elmira, New York

12. Applying to Fellowship Programs

13. Application Chronology

14. Preparing Your Personal Statement

15. Letters of Recommendation

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 7

Mary Noory, MD

Surgery Chief Resident

State University of New York Downstate Medical Center

Brooklyn, New York

16. Fellowship Interviews

Samuel Osei, MD

Surgery Chief Resident

Beaumont Hospital

Royal Oak, Michigan

16. Fellowship Interviews

Jose L. Pascual, MD, PhD, FACS, FRCSC, FCCM

Professor of Surgery

Division of Trauma, Surgical Critical Care and Emergency Surgery

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

17. Coaches, Advisors, Mentors, and Confidantes: What You Need and Why

Susan E. Rowell, MD, MBA, MCR, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship Program

Co-Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit

University of Chicago Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

16. Fellowship Interviews

Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Associate Chief, Division of Acute Care Surgery

Director, Emergency General Surgery

Vice Chair of Clinical Operations

Department of Surgery

The Johns Hopkins Hospital

Baltimore, Maryland

2. Acute Care Surgery Traits

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

6. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

14. Preparing Your Personal Statement

15. Letters of Recommendation

Edgardo S. Salcedo, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Interim Vice Chair of Education

Program Director, General Surgery Residency

Program Director, Surgical Education and Simulation Fellowship

Division of Trauma, Acute Care Surgery, and Surgical Critical Care

University of California, Davis Medical Center

Sacramento, California

2. Acute Care Surgery Traits

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

6. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

14. Preparing Your Personal Statement

15. Letters of Recommendation

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 8

David A. Spain, MD, FACS

David L. Gregg, MD Professor

Chief of Acute Care Surgery

Associate Chief, Division of General Surgery

Department of Surgery

Stanford University School of Medicine

Trauma Medical Director

Stanford Health Care

Stanford, California

20. What is the Post-Fellowship Job Outlook?

Gary A. Vercruysse, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Director of Emergency General Surgery

Division of Acute Care Surgery

University of Michigan Medical School

University of Michigan Health System

Ann Arbor, Michigan

5. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

James F. Watkins, MD, MSc, FACS

Executive Director

Rocky Mountain Trauma Society

Snowmass Village, Colorado

19. How to Prepare for the SCC Board Certifying Examination

Julie Mayglothling Winkle, MD, FACEP, FCCM

Associate Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Critical Care

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Aurora, Colorado

22. Emergency Physicians

Salina M. Wydo, MD, FACS

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Cooper Medical School of Rowan University

Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship

Division of Trauma, Surgical Critical Care and Acute Care Surgery

Cooper University Hospital

Camden, New Jersey

18. Identifying and Developing Your Interests

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 9

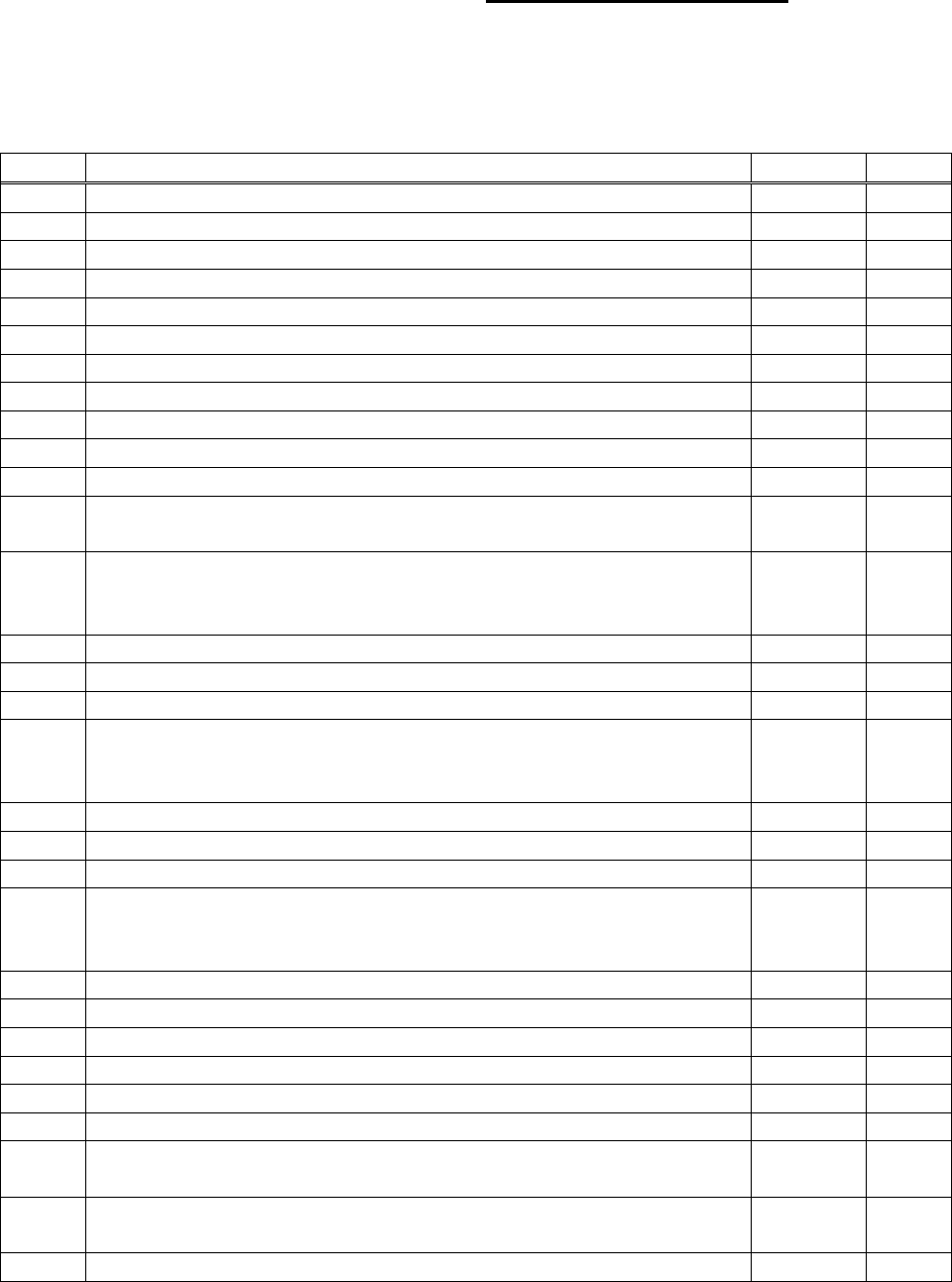

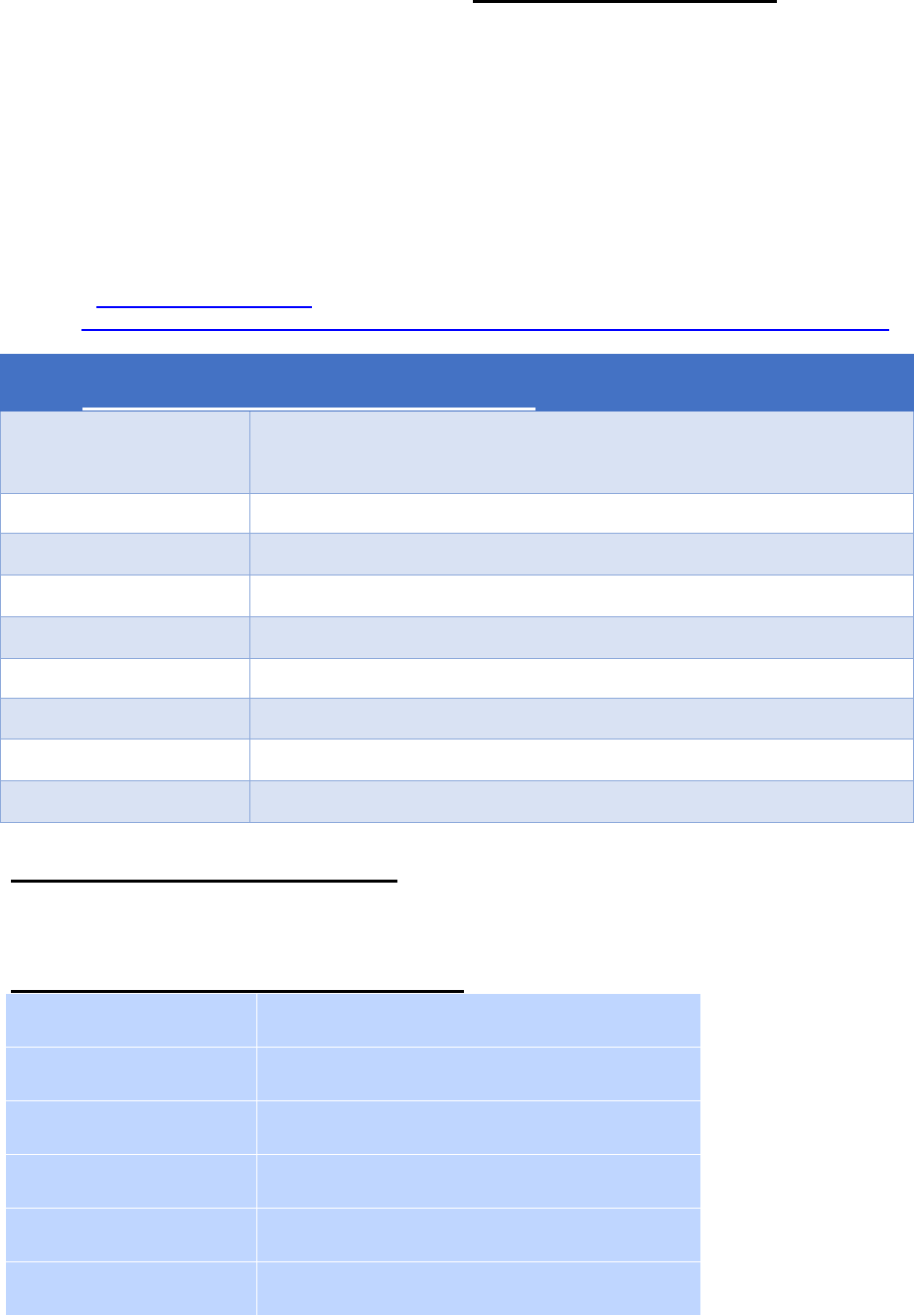

Table of Contents

Chapter

Title

Authors

Page

Cover

1

Contributors

2

Table of Contents

9

Preface

Chiu

11

Preface to Second Edition

Chiu

12

Preface to First Edition

Chiu

13

SAFAS Applicant Instructions

Chiu

14

1

Acute Care Surgery

K. Davis

Burlew

15

2

Acute Care Surgery Traits

Morris

Sakran

Salcedo

17

3

Surgical Critical Care or Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

Ferrada

18

M. Davis

19

4

Should I Do An Elective At An Institution That I Am Considering?

M. Davis

19

5

How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

Salcedo

Morris

Sakran

20

Duane

21

Vercruysse

22

Chiu

23

6

What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

Salcedo

Morris

Sakran

24

Gregg

26

Mowery

28

7

International / Overseas Surgical Rotations

Hampton

29

8

What to Expect in a Fellowship Program

Moran

30

9

What Do Fellows Do, Day In, Day Out?

Cucher

32

10

Geographic Considerations

Cherry

34

11

Family Considerations

J. Knight

Davis

35

12

Applying to Fellowship Programs

Leichtle

Martin

36

Nelson

37

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 10

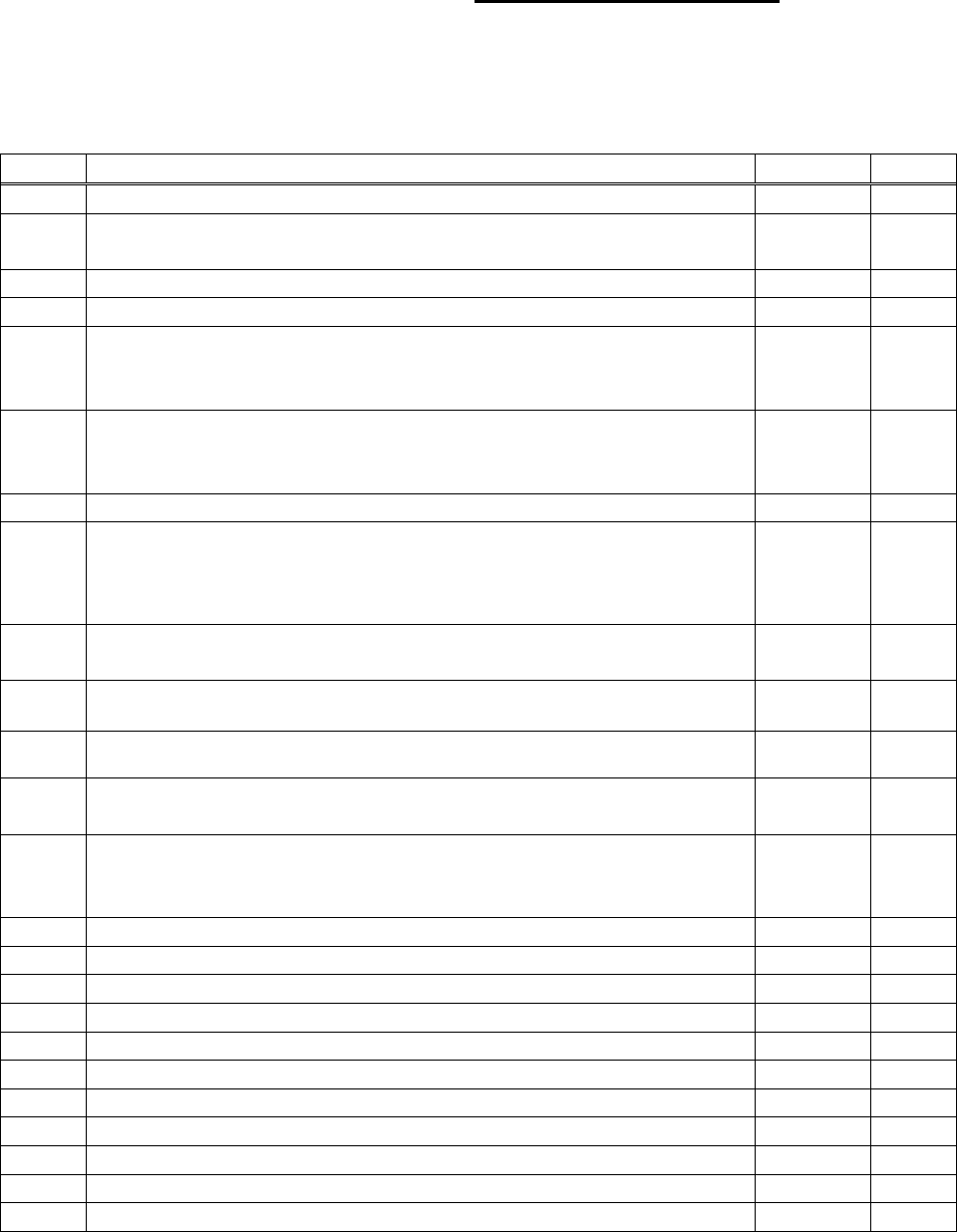

Table of Contents (continued)

Chapter

Title

Authors

Page

13

Application Chronology

Marks

Martin

39

Nelson

40

14

Preparing Your Personal Statement

Nelson

41

Sakran

Salcedo

Morris

42

15

Letters of Recommendation

Sakran

Salcedo

Morris

43

Nelson

43

16

Fellowship Interviews

Noory

Osei

Rowell

Hampton

44

Leichtle

Martin

46

Marinica

Dultz

48

Babowice

Khan

52

Marshall

Godat

54

17

Coaches, Advisors, Mentors, and Confidantes:

What You Need and Why

Blank

Pascual

Kaplan

56

18

Identifying and Developing Your Interests

Wydo

61

19

How to Prepare for the SCC Board Certifying Examination

Watkins

62

20

What is the Post-Fellowship Job Outlook?

Morrison

63

Spain

64

21

Re-entry Applicants

Brownstein

65

22

Emergency Physicians

Winkle

66

23

Anesthesiologists

McCunn

69

24

International Physicians

Khan

71

25

Web Sites of Interest

Chiu

72

26

Acknowledgment

Chiu

72

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 11

Preface

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Interview Process

and the New Application Chronology/Timeline

In the spring of 2020, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

resulted in widespread implementation of lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, and travel

restrictions for public health and safety. The pandemic also altered the process of

Residency and Fellowship applications, with the greatest impact being on the format of

interviews. Fellowship Programs had already started to convert traditional in-person

education and conferences to virtual and online teaching.

In April 2020, under the leadership of President Kimberly Davis, the Surgical

Critical Care Program Directors Society (SCCPDS) Board of Directors recommended

that all Fellowship interviews be conducted using a virtual format for that recruitment

cycle. We learned that there were many benefits for both Programs and applicants to

the virtual interview process. The following year, in 2021, we endured the Delta variant

surge that necessitated continuing virtual interviews for another recruitment year. In this

third edition, based upon these experiences, we have included a new chapter on

Fellowship Interviews. Several groups of SCCPDS members have contributed their

perspectives, focusing primarily on virtual interviews, what to expect, tips for preparation

and standing out, do’s and do not’s.

The Application Chronology and timeline for this year has changed compared to

the past six years. In March 2021, the SCCPDS Match Committee, under the direction

of Chair Niels Martin, embarked on an effort to optimize the Application to Match

timeline, with an initial objective of reducing the duration of the application period. The

proposal was made to open the Surgical critical care and Acute care surgery Fellowship

Application Service (SAFAS) on March 1. Furthermore, it was also proposed to move

the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) Surgical Critical Care (SCC) Match

Day approximately one month earlier.

The new shortened timeline proposal was distributed to the SCCPDS

membership for an open comment period, followed by approval with a majority vote

from SCC Fellowship Program Directors. In this third edition, the chapters on Applying

to Fellowship Programs and Application Chronology have been substantially revised to

reflect the new timeline. We hope that this Guide to Fellowship Training Programs will

continue to be a useful resource and provide essential information for applicants.

William C. Chiu, MD

President

Surgical Critical Care Program Directors Society

February 28, 2022

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 12

Preface to Second Edition

History of the Surgical critical care and Acute care surgery

Fellowship Application Service (SAFAS)

The first informal meetings of Surgical Critical Care (SCC) Fellowship Program Directors were held in

conjunction with the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) in 2003 and

2004, organized by William Cioffi, AAST Critical Care Committee Chair. The primary topics discussed were common

issues in training SCC Fellows, including curriculum updates, ACGME competencies, and possibly developing a

Fellowship Match program. After several meetings, it became clear that a concerted effort was needed from the

Program Directors. Independent meetings were held during the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress

starting in 2005. In 2008, the Surgical Critical Care Program Directors Society (SCCPDS) was formally incorporated

in the State of Rhode Island as a 501(c)(6) non-profit organization, with Dr. Cioffi as Founding President.

In those early years of SCCPDS, the Fellowship application process had not yet begun to evolve.

There were separate Fellowship listings on the Web sites for the Accreditation Council for Graduate

Medical Education (ACGME), Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST), AAST, and

SCCPDS. Back then, Residents with an interest in a SCC Fellowship were required to conduct their own

research on available programs. They were required to contact each Program individually, most often by

regular postal mail and occasionally by telephone. At the time, most Programs did not yet have a

significant Web presence, so Programs typically sent out application forms by mail. Since each

Program’s application forms were different, applicants were required to complete each one separately,

either in handwriting or rarely using a typewriter. Completed applications were sent by mail.

Recommenders were provided a list of Program addresses to send personalized letters of

recommendation by mail. Mail navigated through institutional channels, and arrived in Fellowship

Program offices without delay, only when lucky.

In 2010, David Spain, SCCPDS Treasurer, first introduced the idea of SCC Fellowship Programs

using the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS

®

). At the 2011 SCCPDS Annual Meeting,

under President Frederick Luchette, members discussed and endorsed the use of ERAS, with Secretary

Samuel Tisherman leading the implementation process. In 2013, many SCC Fellowship Programs

started using ERAS, but several major concerns became evident. SCC Fellowship Programs had

historically accepted applications beginning in the spring, but ERAS would not open until July annually.

This allowed for a short application season, with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP

®

) Rank

Order List deadline in September annually. Moreover, ERAS did not alert Programs to new application

submissions, forcing Programs to log in to ERAS daily to check for updates. These issues doomed ERAS

for SCC, and members unanimously voted to discontinue participation in ERAS after the one-year trial.

In November 2013, the SCCPDS Board of Directors began discussion on a combined SCC and

Acute Care Surgery (ACS) standard application service. In February 2014, with the assistance of our

freelance Web site developer, the Surgical critical care and Acute care surgery Fellowship Application

Service (SAFAS) was “under construction.” By May 2014, SAFAS underwent beta testing, but several

key issues (system glitches) could not be resolved. In February 2015, SCCPDS abandoned the project

with the freelancer, and contracted with a professional developer. FluidReview

®

, a subsidiary company of

SurveyMonkey

®

, was the leading online application management platform on the Web, powering the

application processes of organizations, educational institutions, and foundations around the world. With

the one-year development experience struggle behind us, customization and implementation of SAFAS

on FluidReview became an easy one-month process. SAFAS, sponsored by SCCPDS, launched on

March 2015, and has since been the application service utilized by all ACGME-accredited SCC

Fellowship Programs and AAST-approved ACS Fellowship Programs.

William C. Chiu, MD

President-Elect

Surgical Critical Care Program Directors Society

November 19, 2018

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 13

Preface to First Edition

On February 11, 2010, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST)

President Donald Jenkins extended a “thought for the EAST website” to Bruce Crookes

(EAST Information Management and Technology Committee Chair) and me. One of his

fourth-year Surgery Residents from the Mayo Clinic, Nicole Krumrei was an EAST

Oriens Award applicant, and had submitted a personal essay on “This is Why I Want a

Career in Trauma.” The story that President Jenkins related was that there seemed to

be a lack of clarity or central location of information for Residents applying for Trauma

Fellowships, and it was surprising that there wasn’t more information on the process.

The EAST Web site has emerged as the leading resource for Fellowship

information in our specialty. The EAST Fellowships Listing originated from the Trauma

Care Fellowships booklet, published by the Fellowship Task Force of the Careers in

Trauma Committee in 1996. In 1997, this booklet was converted to electronic format for

the EAST Web site. The EAST Fellowships Listing has represented a current database

of the most comprehensive descriptive information available on Fellowships in Trauma,

Critical Care, and Acute Care Surgery.

When I was a Surgery Resident, I had a copy of the “little red book,” a resource

to medical students who were applying for Residency Programs in Surgery, a guide to

finding and matching with the best possible Surgery Residency. This book was created

by Drs. Kaj Johansen and David Heimbach, both from the University of Washington.

The book has since been adapted to an electronic format with expanded content, and is

available on the American College of Surgeons Web site.

This current Fellowship guide will uniquely represent the only comprehensive

resource available offering subjective advice for prospective Fellows in our specialty,

and will have a staged development plan. The initial effort will be presented in Portable

Document Format (PDF), available on the EAST Web site. With the renovation of the

EAST Web site, we hope to eventually progress with a transition to an interactive

electronic resource.

On May 5, 2011, Michael Rotondo, EAST Past President and Past Careers in

Trauma Committee Chair offered me a “thought” on what he envisions as the future

development of a Fellowships guide (similar to TripAdvisor

®

,

“Read Reviews from Real

People. Get the Truth. Then Go.”) This initiative should continue to sustain the EAST

Web site as the definitive information resource for Residents interested in Fellowship

Training in Trauma, Critical Care, and Acute Care Surgery.

William C. Chiu, MD

Chair, Careers in Trauma Committee

Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma

May 30, 2011

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 14

Surgical critical care and Acute care surgery

Fellowship Application Service (SAFAS)

www.safas.smapply.io

APPLICANT INSTRUCTIONS

Please print and read all instructions prior to beginning application process.

REGISTER and CREATE ACCOUNT:

1. On the SAFAS Home page, go to “Register” for an Account.

2. Complete the Registration form.

3. You will receive a confirmation E-mail.

4. Click on the hyperlink in the E-mail to confirm Registration.

CREATE and EDIT APPLICATION:

5. Log In to SAFAS.

6. On Applicant Home Page, click on “View Programs”.

7. On Programs page, click on “MORE >” and then click on “APPLY”.

8. SAFAS Application Form: Complete all 4 sections.

9. You may Save, Log Out, and Continue Editing later.

UPLOAD SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS:

10. Upload your Photograph, Curriculum Vitae, and Personal Statement.

11. Upload a copy of your USMLE and ABSITE Scores (or equivalent).

12. The preferred image type is JPG and document type is PDF.

13. Extra Comments/Documents is optional.

REQUEST RECOMMENDATIONS:

14. Give your Recommenders advanced notice.

15. Recommendation Letters: Enter 3 Names and 3 different E-mail addresses for 3 Recommenders.

16. Each Recommender will receive an automated E-mail request.

17. Each Recommender will be requested to complete 2 tasks:

Separate and Standardized Letter of Recommendation.

18. You will receive an automated E-mail notification upon completion of the recommendation.

19. If Recommender’s institutional firewall blocks Web-generated E-mails, Contact SAFAS Administrator.

SELECT PROGRAMS and FEE:

20. Select the Programs you wish to receive your application materials.

21. Your Recommenders will have access to view:

All of your completed and uploaded documents in-progress.

Your Fellowship Programs Selection Form, if completed.

22. Programs selected will NOT have access to your Programs Selection Form.

23. The Application Fee is $10 for each Fellowship Program selected.

SUBMIT APPLICATION:

24. Submit your Application - Do NOT wait for Recommenders to complete Letters.

25. Upon Submitting your Application, it becomes Locked from Editing.

26. You will receive an automated E-mail confirmation.

27. Each Program selected will receive an automated E-mail notification.

28. You may “Download” Application as a PDF document.

29. To Edit/Withdraw Locked Application, Contact SAFAS Administrator.

SUBMIT APPLICATION TO ADDITIONAL PROGRAMS:

30. You may Create another Submission by returning to Applicant Home Page.

31. Your Application Form and most Supporting Documents are reusable.

32. You may edit your Application Form and Supporting Documents.

33. Do NOT re-enter Recommenders, unless you wish to edit them.

34. Select new Programs – Do NOT select Programs previously selected.

HELP and SUPPORT:

35. Resources, Links, and Contact information at the SAFAS Home page.

Revised: 02/24/2022

Surgical Critical Care

Program Directors Society

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 15

1. Acute Care Surgery

02/15/2022 Kimberly A. Davis, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCM (New Haven, CT),

Clay Cothren Burlew, MD, FACS (Denver, CO):

Although often used interchangeably, “emergency general surgery” and “acute

care surgery” have different meanings. Whereas emergency general surgery (EGS)

refers to acute general surgical disorders, acute care surgery (ACS) includes surgical

critical care and the surgical management of severely ill patients with a variety of

conditions including trauma, burns, surgical critical care or an acute general surgical

condition. The challenges in caring for these patients include around-the-clock

readiness for the provision of comprehensive care, the often-constrained time for

preoperative optimization of the patient, and the greater potential for intraoperative and

postoperative complications due to the emergency nature of care. Doubling as surgical

intensivists, acute care surgeons provide not only a much-needed service but a

continuity of care; the acute care surgeon combines both operative care of the acute

surgical disorder as well as postoperative management for the critically ill patient. This

combination of skill and breadth of care is not matched in any other field.

There are two routes of training for surgeons interested in a career in ACS.

Some will choose to participate in the RRC-accredited one-year training program in

surgical critical care. Others may choose a two-year fellowship, either under the

auspices of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) approved

fellowship programs, or other programs that may offer either additional trauma or burn

training. Which route of training often depends on the fellow’s prior training and career

goals. Graduating chief residents may feel ready to operate independently and thus

question the additional year of surgical training. Alternatively, they may acknowledge

the importance of added training to best position for a highly competitive faculty

appointment. These decisions are deeply personal and should be made in conjunction

with advice from trusted mentors.

The core components of ACS are trauma, surgical critical care and EGS; the

fellowship training paradigm designed by the AAST is designed to create a versatile

surgeon able to confront a host of acute surgical disease processes. Recent curricular

changes in the fellowship included the identification of a minimum number of operative

cases needed in specific body regions, similar to defined case volumes for general

surgery. These cases may be obtained either through defined rotations on subspecialty

services, through a more experientially based method, or a combination of both. Each

fellowship individualizes the fellows’ training components to capitalize on local expertise

and rotations to optimize the fellows’ educational experience both in and out of the

operating room. Additionally, there is a list of desired cases for the fellows; these

provide guidance to the fellows, program directors and subspecialty colleagues as to

the types of cases deemed important for the fellows' training. The fellowship is designed

to assure competence in the management of complex surgical disease in patients with

significant underlying comorbidities. The fellowship curriculum includes operative cases

and bedside procedures as well as nonoperative management of complex trauma and

EGS conditions.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 16

The AAST ensures that ACS fellowships will continue to build on the strong

foundation of process and structure that already exist. A comprehensive core curriculum

provides didactic information on trauma and EGS topics and state-of-the-art media

dedicated to complex surgical exposures. Additionally, key areas will have added

“pearls from the experts” with technical tricks for complex operative procedures; these

tips may be particularly advantageous for patients who, due to severity of illness, do not

have the luxury of preoperative physiologic restoration.

The goals of training acute care surgeons are to demonstrate mastery in the field

of ACS, expanding on the basics learned in a general surgery residency. Those trained

in ACS fellowships are eligible for board certification in surgical critical care through the

American Board of Surgery. Added certification in ACS following the 2 year fellowship is

currently offered through the AAST. Currently there are twenty-nine approved ACS

programs. Unlike most specialty training, this paradigm strives to create a broad-based

surgical specialist, specifically trained in the treatment of severely ill patients with acute

surgical disease across a wide array of anatomic regions.

Our most critically ill surgical patients have benefited from the evolution of ACS,

with improved outcomes, more efficient care, and decreased mortality. The training

paradigm for ACS fellows will continue to ensure that fully trained acute care surgeons

are comfortable with a wide variety of anatomic exposures across all body regions.

Acute care surgeons are uniquely positioned to decrease health care costs and improve

care in the United States as mandated by the Affordable Care Act of 2010. Cost savings

can be actualized, and the system for care delivery can be optimized by focusing on

efficiency and the use of standardized, evidence-based, consistent care. Acute care

surgeons stand at the front line of care delivery for the patients who are most critically ill

and injured. Getting the right patient to the right venue at the right time is the paramount

skill that the acute care surgeon, through training and experience, adds to the value

equation.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 17

2. Acute Care Surgery Traits

02/20/2022 David S. Morris, MD, FACS (Salt Lake City, UT),

Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS (Baltimore, MD),

Edgardo S. Salcedo, MD, FACS (Sacramento, CA):

Surgeons who choose Acute Care Surgery as a career come from a wide variety

of backgrounds with ultimate career goals that may be vastly different as well. Several

traits are common among those in the field. Chief among these is an interest in multi-

organ system physiology, a desire to operate in many areas of the body, and a love of

caring for the most acutely ill patients. In general, acute care surgeons are drawn to

managing the challenging or unexpected case and are accustomed to being called to

help when there’s no one left to call.

As a resident, did you find yourself thinking often about the complexities of

human physiology as you cared for your patients? Did you enjoy the time you spent in

the ICU? Did you ever find yourself wishing that you could really understand how to

manage a difficult ventilated patient, or balance the sometimes-competing requirements

of failing organ systems? Surgeons who choose to do a critical care fellowship

generally enjoy the medical aspects of surgical care. The acute care surgeon is a

further extension of this principle. Fellowship training in surgical critical care affords the

opportunity to maximize one’s knowledge of medical care and augments the surgical

skills one has worked hard to develop as a resident.

The acute physiology learned in the ICU portion of fellowship becomes the

foundation for trauma training. Trauma surgery involves many decisions that must be

made quickly, often without complete information. Unlike elective surgery, where

anatomy drives the decision-making, trauma surgery is driven by physiology. As a

trained trauma surgeon, one is qualified to use the knowledge of acute physiology to

intervene on behalf of very sick patients. This intervention knows no anatomic bounds –

if the physiology requires the opening of the chest, or exposure of peripheral

vasculature, the trauma surgeon will go there. The physiology dictates the extent and

timing of the operative repairs required.

In many cases, the trauma surgeon will wish to call for the assistance of

specialists. One key reason to pursue training in acute care surgery, however, is to

prepare oneself for the day (or more likely night) when such assistance is not available.

Trauma surgeons are trained to handle the middle of the night disaster and to put forth

the heroic effort to save a patient against all odds. Surgeons who require a fixed

schedule and predictable workday will do better in another field.

In summary, the work of the acute care surgeon is hard, with long, unpredictable

hours. The work is often thankless and definitely not glamorous in most cases. But the

satisfaction of saving the life of a patient in extremis makes the time and effort

worthwhile.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 18

3A. Surgical Critical Care or Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

08/22/2018 Paula A. Ferrada, MD, FACS (Richmond, VA):

Why do an extra year? Why Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

Acute Care Surgery (ACS) includes three specialties in one: Trauma, emergency

general surgery, and critical care. ACS is not a new concept, however, ACS fellowship

is relatively new. The AAST has several approved fellowships in ACS currently, each

one with different strengths and opportunities.

The concept of ACS was born many years before it was recognized as a

specialty because of the need to have further specialized training in general surgery.

There is a real necessity to train surgeons to take care of emergencies with proficiency,

and to recognize the immense and growing demand for emergency and critical care

surgical coverage that exists globally.

Having an extra year of ACS training will help you maintain an ample scope of

practice and make you more marketable. This is true if you want to go to the community

or stay in academics. In the community, the surgeon that takes care of trauma also

provides care to all the other surgical emergencies, and sometimes including critical

care. These surgeons are the backbone of rural hospitals and emergency general

surgery is an important source of revenue. In the academic setting, the extra year will

help you by offering you more technical exposure and time for research, as well as time

to reflect on your academic path after your training.

The extra year consists of 1-3 months rotations of different services with you

acting as the fellow (transplant, thoracic, vascular). This will enhance your technical

abilities. In some places, an added training or mentoring in research is also available for

ACS Fellows. This extra time makes you more comfortable as a technician and can help

when you join a group as junior faculty. You will feel the benefits of this extra time in the

OR within your first few months of junior faculty. This is true even if you had ample

cases during residency. Your role changes as you continue to grow in training.

Some fellowships offer the possibility of doing international rotations. If you can

take the opportunity to travel abroad, this is an amazing experience. Not only it gives

you exposure to different procedures and techniques, it allows you to understand

trauma systems differently, as well as to have a new appreciation for what we take for

granted in the United States. Some of these international rotations are trauma heavy,

some offer more experience in emergency general surgery or burns. You will learn to

take care of patients with different resource allocation. I believe this experience can

offer more than technical training, it can help you develop as a leader of a team that can

function in difficult circumstances.

In summary, the extra year that I spent as an ACS fellow can offer a vast

operative experience, time for research, but most important a different perspective to

help you build an academic career.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 19

3B. Surgical Critical Care or Acute Care Surgery Fellowship?

06/22/2011 Matthew L. Davis, MD, FACS (Temple, TX):

ACS vs Surgical critical care alone

In deciding whether a surgical critical care or an acute care surgery fellowship is

right for them, trainees also must consider their training background. Was their general

surgery residency completed in a place that had a large amount of emergency general

surgery, in addition to well-balanced specialty cases? How many cases did he/she

complete during their five years of clinical general surgery training? It is also important

that trainees be honest with themselves regarding their comfort level caring for complex

general surgical emergencies. In many residencies, trainees are mainly a spectator or

first assist during the vast majority of training. In others, a high level of operative

responsibility and autonomy is built in early. Those trainees who, after honest

introspection, feel that they need more experience to be comfortable with a wide variety

of surgical emergencies should definitely look at an acute care surgery fellowship.

4. Should I Do An Elective At An Institution That I Am Considering?

06/22/2011 Matthew L. Davis, MD, FACS (Temple, TX):

Elective at the prospective fellowship institution

Doing an elective rotation at an institution that you are really interested in can

have multiple advantages. First of all, you are able to see for yourself how the institution

functions on a day to day basis. You are able to watch the staff-staff, staff-fellow and

fellow-fellow interactions and get a feel for how you and your personality fit in at that

institution. Each training center has a distinct personality and it helps to know if that

personality meshes well with your own. Often, programs have developed a reputation or

have a name that, once you visit, you may feel is not deserved and that will lead you to

look elsewhere. Experiencing rounds, cases, management of trauma victims and sitting

in during didactic sessions can give you a real feel for an institution. If it is good for a

month, it is likely really good. Anything can be dressed up for interview day. Next, it

gives you the opportunity to show yourself off. When a program gets to know that you

are bright, willing to work hard and have a strong interest in their program, they will

remember that at match time. Be cautious though – if your performance is below

standard, they will remember that as well. I have seen several candidates lose their

chance of joining fellowships due to a lackluster performance. If your life is unsettled or

the rotation is closely following the birth of a child, near a board exam or other areas of

personal turmoil, it is best to either not do the rotation, or re-schedule for a better time.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 20

5A. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

02/20/2022 Edgardo S. Salcedo, MD, FACS (Sacramento, CA),

David S. Morris, MD, FACS (Salt Lake City, UT),

Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS (Baltimore, MD):

All ACGME-accredited fellowship training programs for Surgical Critical Care complete the

Surgical Critical Care portion of the training in one year. Many programs offer a second year of training.

The second year is not accredited by the ACGME and is not monitored by the RRC. The American

Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) approves programs for a two-year fellowship in Acute Care

Surgery (ACS) that incorporates the first year of Surgical Critical Care fellowship. In most cases, the

structure of that second year of fellowship is set up to emulate your first year of practice as a junior

attending.

The goal of the second year is to refine surgical skills and decision making in managing the

complex presentations of acute surgical disease, as seen in trauma, surgical critical care, and emergency

general surgery. The AAST ACS Fellowship aims to provide fellows with advanced operative

experiences in trauma and emergency surgery. Rotations in thoracic, vascular, and complex

hepatobiliary pancreatic procedures are expected clinical experiences for AAST ACS Fellowships with

experiences in neurosurgical injuries, orthopedic injuries and interventional radiology techniques

encouraged. Not all 2

nd

years of fellowship are AAST approved. Second year fellows at many programs

will function as attending surgeons, taking independent calls with admitting and OR privileges.

Choosing to proceed with a second year depends on the foundation you have built. General

Surgery residency programs will have widely variable emergency general surgery and trauma

experiences. If you trained at a place where penetrating trauma was rare, going to a program with a

second year where penetrating trauma is more common will help you gain experience and confidence in

managing those injuries. Even if you may not practice in a place where these injuries are common, the

principles employed when managing such cases are invaluable and applicable in many arenas. The

same is true if you trained at a place with minimal volume of trauma activations and resuscitations.

Practicing in a center where it is common to run multiple resuscitations simultaneously may be an

invaluable experience that helps polish off your training.

The second year of fellowship offers a tremendous career-development opportunity to practice at

a clinically busy, often Level 1 Trauma Center with a proven record of academic productivity. Such

programs allow fellows to tailor their second-year experience consistent with their ultimate career

aspirations. For those interested in pursuing an academic career, the additional year provides the time to

learn and hone the skills necessary to complete research projects and present them to the academic

community. The second year of training is also valuable for those destined for less traditionally academic

positions. Surgeons who wish to be trauma directors at regional centers, perhaps more community-

based, would do well to consider an extra year to finish off their training. The inner workings of what it

takes to run a trauma center smoothly can be learned from mature institutions that have been serving

their communities for decades. The details of these logistics may not be in place at non-trauma center

residency training programs, or if they were, adequate time was not available to help develop those skills

as you were focused on becoming a competent general surgeon. The second year offers the unique

opportunity to witness, “how the experts do it” both clinically and from a systems level viewpoint.

The decision to target programs with a second-year fellowship experience (and whether it is a

AAST ACS Fellowship) is a personal one. It requires applicants to consider their clinical and career

development experiences before embarking on fellowship training and their career aspirations after

completing training. As you weigh the various factors that will inform your decision, be sure to ask

questions about how each of these experiences you are considering is set up. Understanding the clinical

and career development opportunities each program offers will help you decide which ones are best

suited to your training history and your future plans.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 21

5B. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

01/03/2022 Therese M. Duane, MD, MBA, CPE, FACS, FCCM (Fort Worth, TX):

Careers in Trauma: Choosing 1 vs 2 years of fellowship.

My original contribution to this effort was almost 4.5 years ago and the focus was on whether 1 or

2 years of fellowship training was necessary for a successful career when looking at a strictly surgical

critical care fellowship, not an acute care surgery fellowship which includes the one year of surgical

critical care and is always two years. I think there are pros and cons to both the one and two year, and it

has to be based on the individual’s career goals. However, here is my general advice as someone who

was intending to do two years and changed my mind in the middle of my first year.

The fellows who benefit from two years are those who ultimately want to pursue an academic

career in which research and publishing will be an integral part, yet they have done very little during their

training. The extra year provides dedicated time to gain the skills necessary to learn how to execute

clinical trials, prepare IRB documents, develop research protocols as well as data collection and

manuscript preparation. All of these skills can only happen through practice, and once out in practice it is

difficult to find the time to learn all of these skills as well as gain the confidence necessary to get these

projects going. The time is even more important for fellows interested in bench science, as this absolutely

requires dedicated time in a lab to learn techniques and become facile with basic science research.

The fellows for whom a second year is not necessary, although still an option, are those who

have already taken research time during their training. This is true even if it was in fields other than

trauma, as the skill sets are similar. If the individual feels comfortable with the process of developing

study questions and seeing them answered to fruition, then an additional year may not be necessary.

This needs to be couched with the person’s goals, objectives, financial and family situation. The other

fellows who may not need a second year would be those whose intention is to work in a non-academic

setting in which he/she does not intend to continue a research focus.

Since I last offered the advice above in the previous edition, I have held more leadership roles in

departments as Chair and am now building a new academic department and general surgery program.

These experiences have provided me a new perspective and has somewhat changed my opinion on

duration of fellowship. The additional time for research as discussed is very important for those going into

academics if their experience during their general surgery program is limited. However, with the work hour

limitations and restructuring of training programs, I would highly encourage individuals who want to be

facile in trauma, especially those doing full acute care surgery with complex emergency general surgery,

to do a second year of an acute care surgery fellowship. In order to be comfortable with a wide variety of

cases and operative exposures, this second year provides an opportunity to work as junior faculty with

closer supervision than graduates receive once they are in their first position. Acute Care Surgery (ACS)

service lines are designed by nature to be a supportive team environment, so new recruits will always

have oversight and back-up by their more senior team members. However, in new ACS programs and

growing academic hospital systems unaccustomed to this model, having additional experience is

incredibly important to engender confidence in this “one stop shop” approach to handling all of the injuries

and issues which minimizes outside consultations, thereby streamlining care while optimizing resource

utilization. ACS is a high pressure environment, so having that extra year to build confidence and hone

skill sets will always be to the advantage of the trainee.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 22

5C. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

03/06/2018 Gary A. Vercruysse, MD, FACS (Ann Arbor, MI):

One vs. Two Year Fellowship Programs

This is some advice for the fellow candidate pondering a one year or two year

fellowship in trauma/surgical critical care (SCC). I am a graduate of a one year

fellowship with an optional second year (I did only the first year.) I now work at a

program that has a one or two year fellowship. Either a one or two year fellowship can

lead to a successfully trained Trauma/SCC surgeon. There are benefits and drawbacks

to both, and ultimately the choice is a personal one that should be made after some

serious consideration. What follows are simply one surgeon’s opinion.

For me, the great thing about a one year fellowship was that it was over in one year. As

a resident, I felt like I had adequate operative experience (but graduated before the

implementation of the 80 hour work week) and mostly needed to work on my critical

care skill set. An added benefit was that I could start making an attending salary after

only 6 years of post-graduate training. The downside of the one year fellowship for me

was that I did not have adequate time to accomplish any research whatsoever, not even

one case report. I have since built some skills in research and have accomplished

several successful projects that have led to grant funding etc., but it was not easy to

accomplish without early mentorship (that may have occurred during my second year of

fellowship). Having said all that, I still feel that my personal decision to pursue a one

year fellowship was a good one.

After working at several institutions that have mandatory two year programs, I

can definitely see some good things about the two year plan as well. Firstly, having a

whole year dedicated to trauma surgery, fellows get to do several hundred operations in

order to hone their skills at complex trauma surgery. In the post 80 hour work week

age, with less resident operative experience, this could be interpreted as a benefit.

Secondly, the fellows also get an extra year of critical care exposure as they co-manage

patients in the SICU with the SCC fellows their trauma year, and are primarily

responsible for the SICU patients in their SCC year. Thirdly, all fellows get ample

opportunities to begin to acquire the skills necessary to have a successful academic

career by becoming actively involved in research projects that stretch over both

fellowship years.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 23

5D. How Many Years of Fellowship Training?

02/28/2022 William C. Chiu, MD, FACS, FCCM (Baltimore, MD):

For many Fellowship applicants, the decision on a one- or two-year program is

frequently based upon the perceived extent of training and experience that is needed to

achieve independent competence and confidence. Many other applicants are burdened

by an overwhelming sense of educational debt, and are most influenced by the need to

begin earning a salary that will enable the start of loan repayment. I have had Fellows

who had initially committed to two years, and then changed minds mid-year, and found

jobs after one year. I have also had Fellows who were initially planning for just one

year, and then decided to pursue a second year. My advice to prospective applicants

would be to first choose the best program and institution as a priority, and then assess

the personal benefits and options for additional years.

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST)-approved Acute Care

Surgery (ACS) Fellowships are mandatory two-year programs. The minimum duration

required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

Surgery Residency Review Committee (RRC) for a Surgical Critical Care (SCC)

Fellowship is one year. The majority of SCC Fellowships are one-year programs, with

or without an optional second year. Some programs have separate tracks for one-year

and two-year curricula. Some programs may spread the ACGME required SCC one-

year experience into two years. There are some two-year mandatory SCC programs,

and some with an optional third year.

With the exception of AAST-approved ACS programs, those SCC Programs that

have a mandatory or optional second year have a variety of curricula, with no national

consistency or regulatory oversight. These second year curricula are not monitored by

the ACGME, and may include required clinical experience as a Fellow or a senior

Fellow, attending responsibilities, research, academics, and various formats and

arrangements. Some programs offer opportunities to pursue additional educational

degrees, such as a Master’s Degree in Public Health (MPH) or Business Administration

(MBA), or Certificate Programs.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 24

6A. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

02/20/2022 Edgardo S. Salcedo, MD, FACS (Sacramento, CA),

David S. Morris, MD, FACS (Salt Lake City, UT),

Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS (Baltimore, MD):

The Surgical Critical Care (SCC) year and the optional second year of training

can be evaluated separately. Only the SCC year is addressed here. The previous

section addresses second year fellowship programs in more detail. When assessing the

features of the SCC year at various programs it is important to understand what your

role will be within the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and ultimately, what you are looking to

gain at this stage of your training. At some programs you will be the first-call for all

patient care questions for anything from a missing Tylenol order to the coding patient.

At other programs you will be overseeing residents and advanced practitioners. One

might be expected to conduct teaching rounds, and mentor other trainees in bedside

procedures (e.g., central line placement, bronchoscopy). Some programs require in-

house call, while others take only home call. The calls themselves may be strictly

covering the ICU in one program and helping provide trauma and emergency general

surgery coverage in another.

The composition of the ICU attending staff is also important to consider. Some

institutions have units that are run solely by trauma surgeons while others have units

that are run by surgeons, anesthesiologists, and medical intensivists. It is our

perspective that it is valuable to see how different specialists manage critically ill

patients. While unifying literature exists for some conditions to direct practice patterns,

each practitioner brings a different perspective to the bedside and the more exposure

you have to different thought processes the more informed you will be when forming

your own management approach.

While fellowship programs are required to have clinical rotations for the entire

year, they are not required to rotate you in their SICU for all 12 months. Learning about

what other rotations each program offers besides the core time spent in the SICU is

important. Some institutions will have separate critical care teams for pediatric,

neurologic, cardiothoracic, burn and pulmonary / medical patients. The opportunity to

rotate with these other services is another way to gain new perspectives on critical care

issues. Learn about the different elective opportunities for each program you visit and

the flexibility of the various elective rotations within the schedule. For example, does

the institution have a strong practice in Burn Surgery and/or Burn ICU care, or is it a

busy liver transplant center. Details like these will provide you with an idea of the

clinical experience available at each respective program.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 25

The ICU’s place within the health system’s care paradigm may also be important.

Fundamentally, you want to know if the unit is closed or open, if the ICU team is primary

or consulting and the flow of the orders you write and the decisions you make for each

of the patients on your unit. That said, every ICU, wherever you practice, should always

adhere to principles of transparency and open communication between surgical and

ICU teams in the care of critical patients.

It’s important to know what patients are admitted to the SICU for the SCC

Service to manage. Are all the patients from the general surgery sub-specialties

(surgical oncology, colorectal, thoracic, vascular, transplant, etc.) being covered by the

SICU and the SCC Fellows? Similarly, are there clinical relationships with other

surgical specialties that routinely require critical care level services for their patients

(spine surgery, orthopedics, etc.)? Although trauma and emergency general surgery

patients will often provide enough clinical material for a rich and broad SCC Fellowship

experience, the opportunity to see patients with conditions related to other surgical

specialties is valuable.

The educational program for the SCC year will be mostly uniform at different

institutions because the training program is monitored by the ACGME and RRC. All

programs will provide educational opportunities at the bedside while caring for individual

patients and some places will have more established lectures and conferences

available to their trainees. If there are multiple critical care services in the system, the

programs may have varying degrees of inter-disciplinary educational activities as part of

their curriculum. Discuss these issues with current fellows during your interview

process. This is probably one of the best ways to really find out what takes place at the

program you might be interested in pursuing.

Finally, the size of the program is another feature that may be important to

consider. Fellowship programs will have anywhere from one fellow for the year up to

nearly ten in a class. Indeed, the size of the class will necessarily reflect the size of the

center where the fellowship is run to some degree. That said, it is worth reflecting on

the kinds of learning environments where you have thrived in the past and the kind of

environment you are seeking for your next level of training. On the one hand, as a

program’s only fellow you are, in a way, the collective project of the faculty. For a

program with multiple fellows, the camaraderie of shared intense experiences typical of

training in our field is both memorable and motivating.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 26

6B. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

02/21/2018 Shea C. Gregg, MD, FACS (Bridgeport, CT):

What is the specialty of Surgical Critical Care?

A Surgical Critical Care specialist receives additional training in the management of acute, life

threatening or potentially life threatening surgical conditions.

1

Specific knowledge that is gained during

fellowship will include the following: physiology of tissue injury from trauma, burns, operation, infections,

acute inflammation, or ischemia and their relation to other disease processes.

1

Additional topics that

fellows are typically exposed to include ICU administration, infection control, palliative care, organ

donation procedures, declaration of brain death, ICU billing and compliance and national quality

improvement guidelines.

Where to start: Residency considerations

Fellowship is meant to solidify your knowledge base in the physiology of critical illness, augment

your command of the technologies currently employed in management, and expand your appreciation of

outcomes among intensive care patients. With residents having varying degrees of exposure and comfort

managing critically ill patients, one should perform a self-evaluation of their previous residency training

prior to researching fellowship programs: What were the strengths and weaknesses of my residency

program in regards to the trauma, critical care, and/or emergency general surgery experiences? After you

define educational objectives, the following questions may be useful when evaluating individual fellowship

programs:

General considerations:

-Where is the program located?

-Will I be managing a diverse group of patients?

-Will I be rotating in academic and/or community-based hospitals?

-How well does the program adhere to work-hour regulations?

-How many fellows are in the program? Is there competition for educational experiences?

-How collegial are the faculty? Administrators? Nursing staff? Ancillary staff? Fellows? Residents?

-Are faculty engaged in the educational process?

-Do fellows find mentors/coaches during their fellowship training?

-Are the Program Director and/or Division Chief well-established? Are they active in the educational

process?

-Does the program participate in the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP)?

-How competitive is it to get accepted into the fellowship?

-Is the fellowship accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)?

-What is the regional, national, and international reputation of the fellowship?

-Are women and/or minorities comfortable in the fellowship?

Family considerations:

-How many years is the fellowship?

-Will the family be happy in the chosen fellowship location?

-Where do fellows live?

-How is the commute?

-Will the fellowship salary and benefit package adequately support your family over the course of the

fellowship training experience?

-Are there local job opportunities for your spouse?

Educational considerations:

-How formalized is the didactic curriculum?

-Is there protected time for lectures?

-How formalized are teaching rounds?

-What opportunities are there to participate in simulation-based education?

-What educational opportunities exist outside of the institutional curriculum (i.e. courses sponsored at

national meetings, Advanced Trauma Life Support, Advanced Trauma Operative Management, etc.)?

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 27

-What are the American Board of Surgery-Surgical Critical Care examination pass rates for previous

fellows?

-How does fellowship prepare you for the board examination?

-Are there international rotations/opportunities?

-Are there opportunities to work towards advanced degrees as part of the fellowship (i.e. Master’s in

Public Health, Master’s in Business Administration, etc.)

-Is there a curriculum dedicated to leadership training? ICU administration? Billing and compliance

issues? Critical incident stress debriefing? Quality improvement? Infection control? Palliative care?

Geriatrics?

Research considerations:

-What are the research expectations?

-Is there protected time to conduct research?

-Are there basic science and/or clinical research opportunities?

-What is the previous fellow experience with completing and presenting research at meetings?

-Is there support to attend conferences and/or national courses pertaining to surgical critical care?

Details of the critical care training:

-What technologies are being employed in the intensive care unit (i.e. Advanced airway management,

open-lung ventilation strategies, adjuncts to managing ARDS, damage control methods, renal

replacement therapies, ultrasound, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, bedside procedures, etc.)?

-Are subspecialists managing these technologies or do fellows manage them?

-Do simultaneous rotators (i.e. medical students, residents, other fellows, etc.) compromise the

educational experience?

-“Closed” versus “open” intensive care unit?

-What patients will you be caring for: Medical? Surgical? Trauma? Cardiac?

Details of the trauma experience:

-What is the patient volume?

-What is the operative experience?

-What are the call expectations?

-Will simultaneous rotators be competing for cases?

-What is the penetrating versus blunt trauma experience?

-Is there any experience managing severe burns?

Details of the emergency general surgery experience:

-What is the patient volume?

-What cases will I be performing?

-What are the call expectations?

-Is there an outpatient experience?

-Is there any experience managing necrotizing soft tissue infections?

Career considerations:

-Where do fellows find jobs?

-How difficult is it to get a job after completing fellowship?

-Is there an opportunity to become a faculty member at the institution where fellowship is being

completed?

Summary:

Finding the right fellowship in Surgical Critical Care can be intimidating given that everyone’s

circumstances and experiences are diverse. By using the above questions as a basis for evaluation, you

will hopefully find a fellowship that will maximize your educational experience and accommodate your

lifestyle outside the hospital.

Bibliography:

1. “Specialty of Surgical Critical Care Defined.” Absurgery.org. March, 2008. Web. Accessed: 2/20/2018.

http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?aboutsccdefined

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 28

6C. What Things Should I Look For At Each Program?

04/11/2018 Nathan T. Mowery, MD, FACS (Winston-Salem, NC):

Once you have made the decision to seek out additional training in Surgical Critical Care

you must sort through the abundance of well-qualified programs available. In the end your

focus must be on selecting the program that will make you the best possible attending physician

but also keeps all career options available to you. At the beginning of fellowship you may still

be struggling to decide between an academic career and a private practice job. You may not

have decided if you want to go to a place that requires significant research or one that would

allow you to focus solely on patient care. You may decide mid training that you want to switch

from one track to another. I would encourage you to pick a fellowship that can train you in all

those areas so that you will not limit your future employment choices. It is important to keep

focus on the fact that you are choosing a program that addresses not only your strengths but

potentially can make some of your weaknesses into strengths. Did you train at a residency

without a significant penetrating trauma experience? Now could be a time to seek out an urban

program that can round out that experience. Have you not gotten a chance to experience

research? Now would be a time to find a program that is familiar with mentoring inexperienced

fellows and that has multiple projects at various stages of development. Everyone wants to be

in an environment where our strengths are amplified but often a critical assessment of what you

need to improve in your weakest areas will lead you to be a better physician.

It is also important to consider what type of career you want after fellowship. Selecting a

fellowship that can train you for that job and has the networking connections to place you into it

is invaluable. If you plan to move to a geographic area with limited penetrating trauma and

practice surgical critical care you would be ill served to do a fellowship at a location that is heavy

in penetrating trauma and whose critical care experience consists mainly of the care of sick

trauma patients. Also, it is important to look at the track record of programs in placing fellows in

jobs they desire. You do not want your job search to be limited to jobs that are readily

advertised but instead to be able to pick your “dream location” and have a realistic chance of

them hiring you. If you do not know what type of practice you will want at the completion of your

fellowship I would encourage you to select a training program that will keep as many options

open to you as possible. It would stand to reason that programs that have sought out the

highest available designation from our parent organizations would be more likely to hire fellows

who had chosen to train at centers that also carried that designation.

Do not discount the advantages that a certain geographic location can afford you and

potentially your family outside of the hospital. You have no doubt worked hard to have options

available to you and should not feel bad in having the location of the training program factor into

your decision. There are fantastic programs available in all parts of the country that offer a

variety of activities outside the hospital. Surgeons often feel guilty about letting our

extracurricular activities influence our career paths, but with strong programs in a variety of

settings (urban vs. rural, warm vs. cold, beach vs. mountains) there is no reason to

compromise. Take advantage of the benefits your efforts to this point have netted you and

select a program that meets both your professional and personal needs.

[Table of Contents] SCCPDS Fellowship Guide 29

7. International / Overseas Surgical Rotations

01/24/2022 David A. Hampton, MD, MEng, FACS (Chicago, IL):

An international surgical rotation is an educational opportunity which can enhance your

Fellowship experience. Depending on the location, it has the potential to provide a high level of

independence, challenge your clinical and technical skills in a resource-limited environment, and

expose you to end-stage surgical pathology that may not be routinely seen at your home