Using sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic

health records to assess for disparities in preventive health

screening services

Chris Grasso

a

, Hilary Goldhammer

a

, Russell J. Brown

b

, B.W. Furness

c,*

a

The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, 1340 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02215, United States

b

National Association of Community Health Centers, 7501 Wisconsin Ave., Suite 1100W,

Bethesda, MD 20814, United States

c

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of STD Prevention, 899 North Capitol

Street, NE, Fourth Floor, Washington, DC 20002, United States

Abstract

Background: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations have an

increased risk of multiple adverse health outcomes. Capturing patient data on sexual orientation

and gender identity (SOGI) in the electronic health record (EHR) can enable healthcare

organizations to identify inequities in the provision of preventive health screenings and other

quality of care services to their LGBTQ patients. However, organizations may not be familiar with

methods for analyzing and interpreting SOGI data to detect health disparities.

Purpose: To assess an approach for using SOGI EHR data to identify potential screening

disparities of LGBTQ patients within distinct healthcare organizations.

Methods: Five US federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) retrospectively extracted three

consecutive months of EHR patient data on SOGI and routine screening for cervical cancer,

tobacco use, and clinical depression. The screening data were stratified across SOGI categories.

Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact test were used to identify statistically significant differences in

screening compliance across SOGI categories within each FQHC.

Results: In all FQHCs, cervical cancer screening percentages were lower among lesbian/gay

patients than among bisexual and straight/heterosexual patients. In three FQHCs, cervical cancer

screening percentages were lower for transgender men than for cisgender (i.e., not transgender)

women. Within each FQHC, we observed statistically significant associations (P < 0.05) between

*

Corresponding author at: HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD & TB Administration, Strategic Information Division, 899 North Capitol Street,

NE, Fourth Floor, Washington, DC 20002 United States, [email protected]v (B.W. Furness).

Authors' contributions

CG and BWF conceived of the study design. CG conducted the analyses; HG and RJB helped to interpret the data analysis; HG wrote

the manuscript with input and revisions by CG, RJB, and BWF.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

We would like to thank Ashley Barrington and Kathleen McNamara of the National Association of Community Health Centers, and

Rodney VanDerWarker of Fenway Health for their guidance and support. We also wish to thank Corey Covell, Bridget Noe, and Dana

King of The Fenway Institute for their work on the data analysis.

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Published in final edited form as:

Int J Med Inform

. 2020 October ; 142: 104245. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104245.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

SOGI categories and at least one screening measure. The small number of transgender patients,

and limitations in EHR functionality, created challenges in interpretation of SOGI data.

Conclusions: To our knowledge, this is the first published report of using SOGI data from

EHRs to detect potential disparities in healthcare services to LGBTQ patients. Our finding that

lesbian/gay and transgender male patients had lower cervical cancer screening rates compared

to heterosexual, bisexual, and cisgender women, is consistent with the research literature and

suggests that using SOGI EHR data to detect preventive screening disparities has value. EHR

functionality should allow for cross-checking gender identity with sex assigned at birth to reduce

errors in data interpretation. Additional functionality, like clinical decision support based on

anatomical inventories rather than gender identity, is needed to more accurately identify services

that transgender patients need.

Keywords

sexual orientation; gender identity; SOGI data; electronic health record; LGBT; health disparities;

federally qualified health center

1. Introduction

i

Discrimination and stigma create conditions that increase health risks for people who

are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other gender and sexual minorities

(LGBTQ) [1-4]. In addition to having a higher prevalence of HIV, sexually transmitted

diseases (STDs), and substance use disorders, LGBTQ people have an increased likelihood

of cigarette smoking, depression, and anxiety [5-8]. LGBTQ people also experience

challenges in accessing appropriate health care For example, lesbian women and transgender

men have lower cervical cancer screening rates compared to heterosexual and cisgender

women [9-11], and transgender people report delaying medically necessary care due to

discrimination [12]. The routine collection of structured sexual orientation and gender

identity (SOGI) patient data in electronic health records (EHRs) has been recommended

as a key strategy for detecting, tracking, addressing, and ultimately reducing LGBTQ health

disparities [13-16]. Collection of SOGI data can also de-stigmatize sexual and gender

diversity, enable clinicians to offer more patient-centered care, and contribute to national and

global research on LGBTQ health [17-19].

A growing number of US healthcare organizations have begun to integrate SOGI data

collection into their EHR systems due in part to the enactment of new federal policies,

including a 2018 requirement that all EHR systems certified under the US Meaningful Use

Stage III incentive program have the capacity to record SOGI demographic data, and a 2016

mandate that all US federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) collect and report SOGI data

[20,21]. Organizations that capture SOGI data have an opportunity to stratify clinical health

indicators across SOGI categories in order to identify disparities in patient health outcomes

or in provision of clinical services within their own patient population [22].

i

LGBTQ: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other gender and sexual minorities; SOGI: sexual orientation and gender

identity

Grasso et al. Page 2

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

In 2017, we collaborated with five FQHCs to retrospectively extract and analyze patient

EHR data on SOGI and screening for cervical cancer, tobacco use, and clinical depression.

The purpose was to assess for disparities in provision of preventive health screening services

to LGBTQ patients within each FQHC in order to better understand the promise and

challenges of analyzing and interpreting SOGI data collected through EHRs in healthcare

practices.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Project background

This retrospective study was conducted subsequent to a quality improvement project called

“Transforming Primary Care for LGBT

ii

People” (

Transforming LGBT Care

), which

focused on enhancing provision of comprehensive, culturally-responsive primary care to

LGBTQ people seeking care at ten FQHCs [23]. These ten FQHCS, which were identified

through a competitive application process, were located in rural and urban areas of nine

geographically dispersed US states, and served 441,387 unique patients at 123 clinical sites

in 2016. More detail on the quality improvement project has been published previously [23].

Designed and organized by the National Association of Community Health Centers,

Washington, D.C., the Weitzman Institute, Middletown, CT, and Fenway Health, Boston,

MA, with direct assistance and funding by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Transforming LGBT Care

included a year-long intervention from March 2016 to March

2017 focused on: making care environments more culturally affirming, implementing SOGI

data collection and reporting, and increasing targeted STD and HIV screening of LGBTQ

patients. As part of the

Transforming LGBT Care

intervention, FQHCs received training

and technical assistance to improve SOGI data collection and documentation. FQHCs also

worked directly with their EHR vendors to make necessary modifications to accommodate

SOGI data fields. In addition, FQHC clinicians received didactic and case-based training

in primary care health topics, including cancer prevention, smoking prevention, and mental

health care for LGBTQ patients.

2.2. FQHC selection

At the completion of the

Transforming LGBT Care

quality improvement project, five of

the ten FQHCs that had participated in the project were selected to join an ancillary study

to detect potential LGBTQ disparities in preventive health services using SOGI EHR data.

To be selected for this ancillary study, an FQHC needed to have met the following criteria:

(a) participated in the

Transforming LGBT Care

intervention; (b) reported from their EHR

to the 2016 Uniform Data System (UDS), which is an annual reporting system of the

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for tracking patient demographics,

diagnoses, and services [20], and (c) received an EHR Reporter Quality Improvement Award

for Fiscal Year 2016, which is given by HRSA to FQHCs that employed EHRs to report on

all clinical quality measure data for all of their patients.

ii

LGBT was used for the project title because the federal government mostly uses LGBT in its communications and initiatives. For the

purposes of this manuscript, we use LGBTQ when referring to the population, and LGBT when referring to the project title.

Grasso et al. Page 3

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

2.3. Study design

In August 2017, the five selected FQHCs retrospectively extracted three months (January

1, 2017 to March 31, 2017) of data on SOGI and routine screening for cervical cancer,

tobacco use, and clinical depression. Data were de-identified and submitted in aggregate

from each FQHC for analysis. We estimated the prevalence of screening for cervical cancer,

tobacco use, and clinical depression stratified by SOGI category, and tested for significant

differences in screening across SOGI categories within each FQHC.

The Community Health Center, Inc. Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective

data analysis of the

Transforming LGBT Care

project. The FQHCs did not receive any

financial compensation for participating.

2.4. Data Measures

2.4.1. Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) measures—FQHCs

collected SOGI data and entered the data into EHRs as part of routine workflow processes.

Patients provided SOGI information during registration, during check-in with a nurse or

medical assistant, and/or during the medical visit with a primary care provider. SOGI

questions were answered by patients verbally, or were entered on paper forms, electronic

tablets, or through computer portals.

FQHCs were guided to use SOGI questions based on HRSA UDS 2017 instructions [24], as

follows:

Do you think of yourself as:

•

Lesbian, gay, or homosexual

•

Straight or heterosexual

•

Bisexual

•

Something else

•

Don’t know

•

Choose not to disclose

What is your gender identity?

•

Male

•

Female

•

Transgender male, female-to-male (FTM), trans man

•

Transgender female, male-to-female (MTF), trans woman

•

Other (genderqueer)

•

Choose not to disclose

What sex were you assigned at birth?

•

Male

Grasso et al.

Page 4

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

•

Female

The gender identity question has two steps: the first assesses a person’s self-reported gender

identity. The second assesses a person's assigned sex at birth. Cross-checking both data

points enables healthcare organizations to identify transgender people who currently identify

as simply male or female (rather than transgender male or transgender female). This method

has been recommended by authorities on transgender health, and is considered a best

practice [16]. For this study, the participating FQHCs were encouraged to use the two-step

method to identify and count transgender people. However, the FQHCs reported that their

EHRs did not have the functionality to use the two-step method to identify transgender

people while also reporting on screening measures. Therefore, the FQHCs submitted gender

identity data based only on the first step of the question (i.e.,

What is your current gender

identity?

).

FQHCs with large numbers of Spanish-speaking populations translated the SOGI questions

into Spanish. Patients who did not answer the SO or GI questions, or who checked “choose

not to disclose,” were grouped together in the analysis as “not disclosed/unknown.”

2.4.2. Preventive health screening measures—Preventive health screening data

were collected by clinicians as part of routine care. EHR functionality indicated the

screenings that patients were due for at their next visit. During or after patient visits,

clinicians recorded in the EHR the screenings given to the patients. The three screening

measures included in this analysis (Table 1) were defined and reported according to HRSA

UDS 2017 instructions (except as noted in Table 1) [

24].

We chose to use measures on screening for cervical cancer, tobacco use, and clinical

depression because: (a) FQHCs were already required by HRSA to report these as quality

of care performance data; (b) preventive screenings are good proxies for engagement in care

and positive health outcomes; and (c) there is consistent evidence of disparities of cervical

cancer screening, tobacco use, and depression in LGBTQ populations [6-8,10,11].

2.5. Data analysis

We calculated screening prevalence stratified by SOGI using SAS version 9.4. Chi-Square

and Fisher’s Exact tests were used to identify differences in compliance among SOGI

categories in each FQHC; statistical significance was determined at the

p

< 0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Health center characteristics

The participating FQHCs were located in Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, and

Pennsylvania. While the race/ethnicity proportions at each of the FQHCs differed, all

FQHCs had over 50% racial/ethnic minority patients, and all but one FQHC had over 50%

of unique patients who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino (Table 2). The majority

of patients at each FQHC were on Medicaid and/or Medicare and had a household income at

or below 100% of the federal poverty level.

Grasso et al.

Page 5

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Table 3 presents the SOGI distribution of all unduplicated FQHC patients with at least one

visit during the study period. The FQHCs, on average, saw 1.4% lesbian/gay patients (range:

0.8 to 1.8%), 1.0% bisexual (range: 0.7 to 1.5%) patients, 0.2% transgender male patients

(range: 0.0% to 0.4%) and .2% transgender female (range: 0.0% to 0.5%). About 32% of

patients (range: 17.6 to 46.8%) had not disclosed/unknown SO, and 27.8% (range: 5.1 to

46.7%) had not disclosed/unknown GI. The SOGI data include patients of all ages, including

the approximately 34% of patients who were under 18 years old. Because FQHCs are not

required by HRSA to ask the SOGI of patients younger than 18 years, the not disclosed/

unknown category is likely comprised primarily of patients under 18 years old.

3.2. Screening compliance across SOGI categories

3.2.1. Cervical cancer screening—In each of the five FQHCs, a lower percentage

of lesbian/gay and bisexual patients compared to straight/heterosexual patients received

cervical cancer screening (Table 4). Additionally, cervical cancer screening percentages

were lower for transgender men than for cisgender women in three FQHCs (FQHC2,

FQHC3, and FQHC4). FQHC5, however, had higher cervical cancer screening percentages

for transgender men than for cisgender women. The number of transgender men due for

cervical cancer screening in each FQHC was small, however (range: 3 to 70).

Unexpectedly, four FQHCs reported cervical cancer screening in cisgender men. Because

the FQHCs were unable to cross-check sex assigned at birth with gender identity, we could

not determine if these patients were assigned female at birth who identified as men (rather

than as transgender men) and were due for screening (assuming they retained a cervix); or,

if patients were misclassified as cisgender men, when in fact they were cisgender women or

transgender. It is also possible that these were simply data entry errors.

Three FQHCs reported cervical cancer screening in transgender women. There are no

current guidelines for cytology screening of transgender women who have undergone

genital surgeries. Although these FQHCs reported some transgender women as due for and

receiving cytology screening, we do not know if these data were a result of data entry error,

misclassification, or the clinicians’ decision to screen transgender women.

Among four of the five FQHCs, we observed a statistically significant relationship between

SO and cervical cancer screening. In all five FQHCs, we observed a statistically significant

relationship between GI and cervical cancer screening.

3.2.2. Tobacco and depression screening—We did not detect clear trends in

disparities for tobacco and depression screening for LGBTQ patients in any of the FQHCs

(Tables 4 and 5). However, in each of the five FQHCs, patients whose SOGI was not

disclosed/unknown had lower clinical depression screening percentages than patients in

all other SOGI categories. In addition, we observed statistically significant relationships

(P < 0.05) between depression screening and both SO and GI in four FQHCs; a

statistically significant relationship between SO and tobacco screening in three FQHCs, and

a statistically significant relationship between GI and tobacco screening in all five FQHCs.

Grasso et al.

Page 6

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

4. Discussion

This study provides an example of how healthcare organizations can extract and analyze

SOGI data from the EHR to detect possible disparities in preventive services for LGBTQ

patients. We believe this is the first publication that demonstrates such an approach.

Consistent with the research literature [9-11], our data showed that lesbian/gay patients

had lower cervical cancer screening percentages than straight/heterosexual and bisexual

patients, and that transgender men had lower screening percentages than cisgender women,

except in one of the FQHCs. Stratification of SOGI data across screening measures also

revealed statistically significant differences in distribution on at least one screening measure

for each of the FQHCs, although it does not tell us which categories accounted for those

differences. These findings suggest that using SOGI EHR data to detect screening disparities

in healthcare organizations is feasible and has value, although we did encounter some

challenges in analyzing and interpreting the data.

4.1. Challenges and limitations with EHRs and SOGI data

This study was completed as ancillary to a quality improvement project among a small

number of FQHCs; its findings, therefore, cannot be generalized to other FQHCs.

Nevertheless, the point of the study was not to perform generalizable research, but to present

an example of using SOGI data in the EHR in order to manage the population health of

LGBTQ patients within a healthcare organization. The limitations, therefore, are related to

making conclusions based on the data within each FQHC. Because the data for this study

were collected as part of standard of care, rather than as part of a research protocol, the

data reflect the current limitations and realities of capturing and analyzing data in healthcare

settings.

For example, EHR reporting functionality prevented FQHCs from using the recommended

two-step method of cross-checking gender identity with sex assigned at birth [16]. As a

result, we could not verify that all people who identified as men or as women were cisgender

and not transgender. Notably, the inability to cross-check gender identity with sex assigned

at birth made it impossible to know whether the cisgender men reported as receiving cervical

cancer screening were assigned female at birth (and had a cervix), or were misclassified.

Another limitation of the data was the relatively high percentage of patients with “not

disclosed/unknown” or otherwise missing data in several FQHCs. In order to improve

data completeness and accuracy, healthcare organizations need to improve workflows and

prioritize staff training in asking SOGI questions. Patients may also need to be educated

in why these questions are being asked and how the data can benefit public and personal

health. Further, those responsible for data cleaning will want to run monthly reports of SOGI

data to identify problem areas and look for unexpected patterns and statistical outliers. They

can also select patient charts at random and cross-check forms with data entered in the EHR.

Another limitation of the data is the small number of patients identifying as transgender.

The average percentage of transgender patients (0.4%) in these FQHCs was similar to

the percentages found in an analysis of all FQHCs in 2016, and to other US population

estimates of transgender populations [25]. Therefore, most organizations will encounter a

Grasso et al.

Page 7

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

similar issue of having a low number of transgender people in a table cell, which can make

it difficult to interpret the data with confidence. Healthcare organizations with small or

average LGBTQ patient populations will likely need more than three months of data before

definitively characterizing disparities in services or health outcomes. Still, quarterly data can

offer insight on potential disparities and can allow FQHCs to make adjustments in real-time

rather than waiting for annual data.

4.2. Next steps

As increasing numbers of FQHCs and other healthcare organizations implement SOGI data

collection into their EHRs, they will look for ways to apply the data to improve quality

of care and health outcomes for LGBTQ patients. The methods described in this article

could be adapted in various healthcare settings, with some caveats and improvements, such

as determining how to cross-check sex assigned at birth with gender identity categories.

Three months of data provides only a snapshot of one point in time, but can be used as

a baseline. Organizations can continue to track data each quarter to look for trends. If

disparities continue, organizations can form quality improvement teams to begin uncovering

possible reasons for the disparities. For example, they can share the data with clinical teams

to receive feedback, hold focus groups of patients, and review other care and services

measures. Once the issue(s) are identified, the organization can offer targeted training,

develop materials, or make modifications to the workflow or EHR.

The Health Information Technology (HIT) staff of healthcare organizations will also need

to ensure their EHR is capturing SOGI data according to best practices, and that the data

can be extracted in a way that enables comparisons along clinical measures. To support

their customers, EHR vendors can work on improving the flexibility of their products to

accommodate SOGI data since many EHR systems still need modifications. In addition,

EHR vendors can expand clinical decision support tools to incorporate SOGI fields. For

example, the creation of an anatomical inventory form could more accurately identify

people due for cervical cancer screening than gender identity or assigned sex at birth [21].

Finally, it is critical for healthcare organizations to access training for their clinical and

front-line staff to help build understanding and confidence around talking to patients about

routine SOGI data collection and its relationship to health outcomes and equity. Free online

training materials are available from the National LGBTQIA + Health Education Center,

www.lgbthealtheducation.org.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant 6 NU38OT000223-05-03 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views

of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

[1]. Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH, Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority

individuals, J Behav Med. 38 (1) (2015) 1–8. [PubMed: 23864353]

[2]. Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health

among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications,

Pediatr Clin North Am. 63 (6) (2016) 985–997. [PubMed: 27865340]

Grasso et al.

Page 8

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

[3]. White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE, Transgender stigma and health: A critical review

of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions, Soc Sci Med. 147 (2015) 222–231.

[PubMed: 26599625]

[4]. Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, The impact of institutional

discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective

study, Am J Public Health. 100 (3) (2010) 452–459. [PubMed: 20075314]

[5]. Ross LE, Salway T, Tarasoff LA, MacKay JM, Hawkins BW, Fehr CP, Prevalence of depression

and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A

systematic review and meta-analysis, J Sex Res. 55 (4-5) (2018) 435–456. [PubMed: 29099625]

[6]. Gonzales G, Przedworski J, Henning-Smith C, Comparison of health and health risk factors

between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: results

from the National Health Interview Survey, JAMA Intern Med. 176 (9) (2016) 1344–1351.

[PubMed: 27367843]

[7]. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP, Health disparities among

lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study, Am J Public

Health. 103 (10) (2013) 1802–1809. [PubMed: 23763391]

[8]. HIV Surveillance Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, 2015, http://

www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

[9]. Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, et al. , Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening

behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women, Am J Public Health. 91 (4) (2001) 591–597.

[PubMed: 11291371]

[10]. Potter J, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein I, et al. , Cervical cancer screening for patients on the

female-to-male spectrum: A narrative review and guide for clinicians, J Gen Intern Med. 30 (12)

(2015) 1857–1864. [PubMed: 26160483]

[11]. Charkhchi P, Schabath MB, Carlos RC, Modifiers of cancer screening prevention among sexual

and gender minorities in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, J Am Coll Radiol. 16

(4 Pt B) (2019) 607–620. [PubMed: 30947895]

[12]. Grant JMML, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M, Injustice at every turn: A Report of

the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, Washington, DC (2011).

[13]. Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Electronic Health Records: Workshop

Summary, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC, 2013.

[14]. The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-

and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A

field guide, IL: Joint Commission, Oak Brook, 2011.

[15]. Pinto AD, Glattstein-Young G, Mohamed A, Bloch G, Leung FH, Glazier RH, Building a

foundation to reduce health inequities: Routine collection of sociodemographic data in primary

care, J Am Board Fam Med. 29 (3) (2016) 348–355. [PubMed: 27170792]

[16]. Deutsch MB, Green J, Keatley J, et al. , Electronic medical records and the transgender

patient: recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR

Working Group, J Am Med Inform Assoc. 20 (4) (2013) 700–703. [PubMed: 23631835]

[17]. Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ, Demonstrating the importance and

feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific

Northwest, Am J Public Health. 100 (3) (2010) 460–467. [PubMed: 19696397]

[18]. Donald C, Ehrenfeld JM, The opportunity for medical systems to reduce health disparities

among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex patients, J Med Syst. 39 (11) (2015) 178.

[PubMed: 26411930]

[19]. Maragh-Bass Ac, Torain M, Adler R, et al. , Risks, benefits, and importance of collecting sexual

orientation and gender identity data in healthcare settings: a multi-method analysis of patient and

provider perspectives, LGBT Health 4 (2) (2017) 141–152. [PubMed: 28221820]

[20]. Cahill SR, Baker K, Deutsch MB, Keatley J, Makadon HJ, Inclusion of sexual orientation and

gender identity in stage 3 meaningful use guidelines: A huge step forward for LGBT health,

LGBT Health. 3 (2) (2016) 100–102. [PubMed: 26698386]

Grasso et al.

Page 9

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

[21]. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration.

Program Assistance Letter (PAL 2016-02). Approved Uniform Data System Changes for

Calendar Year 2016, Health Resources and Services Administration, Washington, DC, 2016.

[22]. Grasso C, McDowell MJ, Goldhammer H, Keuroghlian AS, Planning and implementing sexual

orientation and gender identity data collection in electronic health records, J Am Med Inform

Assoc. 26 (1) (2019) 66–70. [PubMed: 30445621]

[23]. Furness BW, Goldhammer H, Montalvo W, et al. , Transforming primary care for lesbian, gay,

bisexual, and transgender people: a collaborative quality improvement initiative, Ann Fam Med

18 (4) (2020) 292–302. [PubMed: 32661029]

[24]. Bureau of Primary Health Care, Health Resources and Services Administration, Uniform Data

System: Reporting Instructions for 2017 Health Center Data. OMB Number: 0915-0193.

[25]. Grasso C, Goldhammer H, Funk D, et al. , Required sexual orientation and gender identity

reporting by US health centers: first-year data, Am J Public Health. 109 (8) (2019) 1111–1118.

[PubMed: 31219717]

Grasso et al. Page 10

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

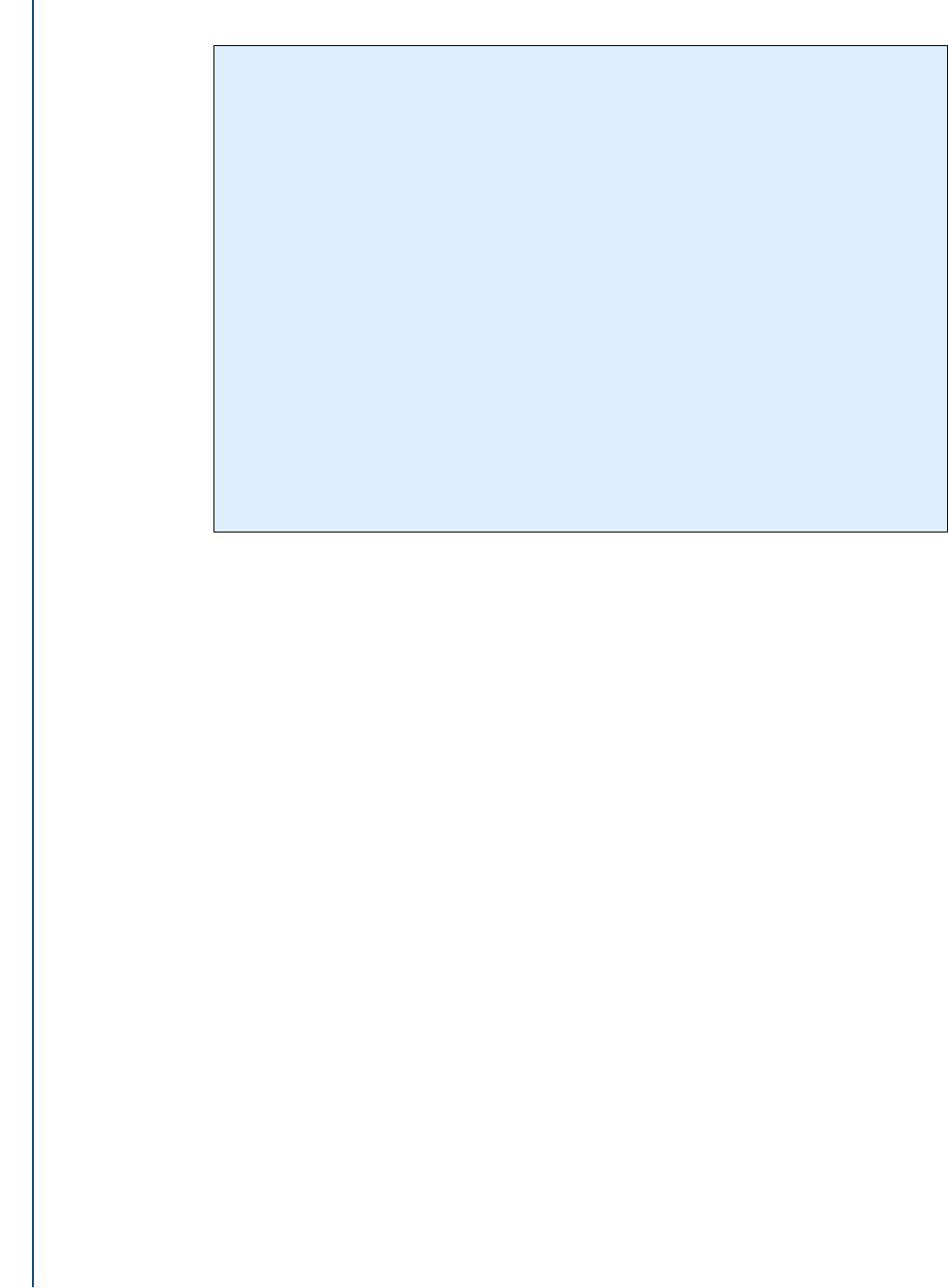

Summary Points

What was already known on the topic:

•

Capturing patient data on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in the

electronic health record (EHR) can enable healthcare organizations to identify

inequities in the provision of clinical services to LGBTQ patients.

•

An increasing number of healthcare organizations are collecting SOGI data;

however, organizations may not be familiar with methods for analyzing and

interpreting the data to detect disparities.

What this study added to our knowledge:

•

This first example of using SOGI data in the EHR to detect potential

disparities in healthcare services to LGBTQ patients shows potential for

adaptation in other healthcare settings, with some caveats due to EHR

functionality.

•

Expanded EHR functionality is needed to more accurately identify services

for transgender patients.

Grasso et al. Page 11

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 12

Table 1

Definitions of preventive health screening measures

Measure Definition

Cervical Cancer Screening Percentage of unduplicated patients 23–64 years of age with at least one medical visit during the measurement period who were due for cervical cytology based on

anatomy (a cervix)

+

and who received cervical cytology one or more times during the measurement period (or two years prior to the measurement period for patients who

are at least 21 years old at the time of the test)

++

.

Screening for Clinical

Depression and Follow-Up

Plan

Percentage of unduplicated patients age 12 years and older with at least one eligible medical visit during the measurement period who were screened for clinical

depression on the date of the visit using an age-appropriate standardized depression screening tool,

and

, if screened positive, who had a follow-up plan documented on the

date of the positive screen.

Tobacco Use: Screening

and Cessation Intervention

Percentage of unduplicated patients aged 18 years and older with at least one medical visit during the measurement period who were screened for tobacco use one or more

times within 24 months before the end of the measurement period

and

who received cessation counseling intervention if defined as a tobacco user.

Notes :

+

In the Reporting Instructions for 2017 Health Center Data, cervical cancer screening is written as “percentage of women 23–64 years of age.”

++

Measurement period was January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2017.

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 13

Table 2

Sociodemographic characteristics of the total unique patient populations served by the five participating federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in

2017

+

FQHC 1 FQHC 2 FQHC 3 FQHC 4 FQHC 5

Total patient population

15,548 96,204 101,536 25,003 53,842

Race and ethnicity (% of known)

Racial and/or ethnic minority 86.1 74.6 77.4 50.0 92.3

Non-Hispanic White 14.3 48.0 23.3 63.3 7.7

Hispanic/Latino 64.5 56.5 64.7 33.7 50.9

Black/African American

++

15.7 26.6 4.6 20.1 3.1

Asian

++

5.3 5.7 1.7 0.7 1.5

Native Hawaiian/ Other Pacific Islander

++

0.1 0.1 0.2 0.7 0.1

American Indian/Alaska Native

++

1.2 0.7 7.3 0.3 0.2

More than one race

++

2.5 0.6 0.8 0.8 Data unavailable

Insurance Status (% of total patients)

Uninsured 21.6 12.2 13.6 11.0 41.1

Medicaid/CHIP 70.4 67.3 54.3 65.7 49.8

Medicare 3.7 7.1 11.9 9.4 5.5

Dually Eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) 2.9 5.77 4.7 4.6 3.5

Other Third Party Insurance 4.3 13.5 20.2 13.9 3.6

Age (% of total patients)

<18 years old 23.3 41.1 33.9 40.9 32.3

18 - 64 years old 71.0 52.6 55.7 53.6 62.4

Age 65 and older 5.7 6.3 10.4 5.5 5.3

Income Status (% of known)

At or below 200% of federal poverty level 80.0 88.4 91.7 89.6 96.2

At or below 100% of federal poverty level 49.2 59.8 69.0 54.4 72.6

Notes :

+

Data are from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Health Center Program 2017 grantee data: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx.

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 14

++

Includes Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic/Latino

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 15

Table 3

Sexual orientation and gender identity distribution of unduplicated FQHC patients with at least one visit during the study period (January 1, 2017 to

March 31, 2017)

Lesbian/Gay Bisexual Straight/Heterosexual Something Else Don't Know Not Disclosed/Unknown

% % % % % %

FQHC 1 (n = 7,691)

1.2 0.8 83.4 0.3 1.6 12.6

FQHC 2 (n = 38,462)

1.5 1.3 66.9 0.4 0.2 29.7

FQHC 3 (n = 46,095)

1.7 0.8 44.1 6.6 0.0 46.8

FQHC 4 (n = 8,868)

1.8 1.5 68.8 0.2 0.4 27.4

FQHC 5 (n = 26,326)

0.8 0.7 63.3 0.2 17.4 17.6

All FQHCs (n = 127,442)

1.4 1.0 59.1 2.6 3.8 32.2

Cisgender Women Cisgender Men Transgender Women Transgender Men Other Not Disclosed/Unknown

% % % % % %

FQHC 1 (n = 7,691)

58.1 36.6 0.1 0.1 0.1 5.1

FQHC 2 (n = 38,462)

42.1 27.9 0.5 0.4 0.1 29.0

FQHC 3 (n = 43,591)

34.7 18.3 0.0 0.2 0.1 46.7

FQHC 4 (n = 8,868)

45.6 27.0 0.1 0.1 0.0 27.1

FQHC 5 (n = 26,326)

47.8 30.7 0.1 0.0 15.7 5.7

All FQHCs (n = 124,938)

41.9 25.6 0.2 0.2 3.4 28.7

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 16

Table 4

Preventive health screenings stratified by sexual orientation categories

Cervical cancer screening

Lesbian/Gay n =

502

Bisexual n =

545

Straight/

Heterosexual n

= 30,888

Something Else n

= 679

Don't Know n

=

901

Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

6,733

X

2

(df)

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

2,614)

Screened n (%) 10 (34%) 23 (55%) 1,343 (54%) 5 (56%) 5 (63%) 110 (46%)

0.0993

+

Not Screened n 19 19 1154 4 3 127

FQHC 2 (n =

12,966)

Screened n (%) 116 (53%) 109 (55%) 6,647 (64%) 31 (70%) 6 (40%) 1,165 (55%) 71.2441 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 102 91 3754 13 9 938

FQHC 3 (n =

13,488)

Screened n (%) 76 (62%) 119 (74%) 7,341 (75%) 407 (67%) 0 (0%) 1986 (73%) 44.2673 (4)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 46 41 2446 200 0 826

FQHC 4 (n =

2,803)

Screened n (%) 17 (39%) 31 (57%) 1,402 (54%) 1 (20%) 6 (43%) 26 (34%) 18.8199 (5)

0.0021

++

Not Screened n 27 23 1207 4 8 51

FQHC 5 (n =

8,154)

Screened n (%) 48 (54%) 60 (67%) 3,349 (60%) 9 (64%) 460 (53%) 963 (64%) 30.1575(5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 41 29 2245 5 404 541

Tobacco use: screening and cessation intervention

Lesbian/Gay n =

1,560

Bisexual n =

804

Straight/

Heterosexual n

= 51,762

Something Else n

=

701

Don't Know n

=

2,912

Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

9,395

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

2,890)

Screened n (%) 34 (83%) 17 (81%) 2,475 (95%) 7 (88%) 8 (100%) 193 (93%)

0.0026

+

Not Screened n 7 4 130 1 0 14

FQHC 2 (n =

27,254)

Screened n (%) 422 (88%) 301 (84%) 20,287 (92%) 100 (94%) 46 (96%) 3,802 (89%) 102.7376 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 56 56 1682 6 2 494

FQHC 3 (n =

25,084)

Screened n (%) 561 (77%) 181 (70%) 14,346 (80%) 1 (100%) 1,779 (80%) 2,930 (86%) 3435.0775 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 164 79 3576 0 452 486

FQHC 4 (n =

4,360)

Screened n (%) 121 (100%) 79 (99%) 4,002 (99%) 9 (100%) 19 (100%) 82 (96%)

0.2623

+

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 17

Not Screened n 0 1 44 0 0 3

FQHC 5 (n =

8,137)

Screened n (%) 91 (88%) 73 (96%) 5,217 (90%) 17 (89%) 604 (90%) 1,324 (89%) 6.589 (5)

0.253

++

Not Screened n 104 13 3 560 2 67

Screening for clinical depression and follow-up plan

Lesbian/Gay n =

1,032

Bisexual n =

720

Straight/

Heterosexual

n=51,283

Something Else n

= 396

Don't Know n

=

314

Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

4,801

X

2

(df)

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

5,212)

Screened n (%) 52 (76%) 30 (70%) 3,687 (80%) 15 (88%) 10 (83%) 325 (67%) 54.4408 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened

n

16 13 897 2 2 163

FQHC 2 (n =

23,501)

Screened n (%) 296 (87%) 263 (89%) 15,282 (89%) 86 (83%) 54 (87%) 3,188 (62%) 2015.3671 (5)

<. 0001

++

Not Screened

n

44 34 1929 18 8 1959

FQHC 3 (n =

24,394)

Screened n (%) 353 (85%) 174 (82%) 13,697 (86%) 1,142 (83%) 9 (100%) 4,849 (74%) 469.6665 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened

n

64 39 2152 242 0 1663

FQHC 4 (n =

4,333)

Screened n (%) 71 (97%) 60 (95%) 3,676 (97%) 9 (100%) 16 (84%) 334 (90%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened

n

2 3 121 0 3 38

FQHC 5 (n =

14,471)

Screened

n (%)

128 (96%) 91 (88%) 8,748 (89%) 22 (92%) 1,433 (87%) 2,403 (88%) 11.3849 (5)

0.0443

++

Not Screened

n

6 13 1094 2 212 319

+

Fisher’s Exact Test

++

Chi-square Test; FQHC = federally qualified health center

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 18

Table 5

Preventive health screenings stratified by gender identity categories

Cervical cancer screening

Cisgender

Women n =

34,027

Cisgender Men n

=

114

Transgender

Women n =

13

Transgender Men n

= 99

Other n = 763 Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

4,959

X

2

(df)

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

2,822)

Screened n (%) 1,461 (54%) 1 (33%) 1 (25%) – 1 (100%) 32 (35%)

0.0009

+

Not Screened n 1262 2 3 – 0 59

FQHC 2 (n =

12,977)

Screened n (%) 6,933 (64%) – 0 (0%) 41 (59%) 7 (47%) 1,094 (55%) 57.0991 (4)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 3979 – 4 29 8 885

FQHC 3 (n =

13,488)

Screened n (%) 8,112 (75%) 22 (54%) – 5 (28%) 4 (44%) 1,786 (70%) 50.1116 (4)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 2771 19 – 13 5 751

FQHC 4 (n =

2,803)

Screened n (%) 1,446 (53%) 8 (62%) – 1 (33%) 0 (0%) 28 (35%)

0.005

+

Not Screened n 1260 5 – 2 1 52

FQHC 5 (n =

8,154)

Screened n (%) 4,164 (61%) 26 (46%) 2 (40%) 7 (88%) 376 (51%) 157 (58%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened n 2639 31 3 1 361 115

Tobacco use: screening and cessation intervention

Cisgender

Women n =

34,548

Cisgender Men n

=

23,000

Transgender

Women n =

173

Transgender Men n

=

176

Other n =

677

Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

9,871

X

2

(df)

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

2,890)

Screened n (%) 1,847 (97%) 833 (90%) 0 (0%) 1 (100%) – 53 (88%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened n 54 94 1 0 – 7

FQHC 2 (n =

27,254)

Screened n (%) 13,050 (94%) 8,022 (90%) 138 (91%) 105 (95%) 32 (97%) 3,611 (88%) 161.0507 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 903 890 14 5 1 483

FQHC 3 (n =

25,084)

Screened n (%) 11,509 (84%) 4,965 (72%) – 38 (73%) 16 (80%) 4,257 (84%) 498.8324 (4)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 2184 1977 – 14 4 840

FQHC 4 (n =

4,360)

Screened n (%) 2,753 (99%) 1,462 (98%) 6 (100%) 7 (100%) 1 (100%) 83 (97%)

0.0245

+

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Grasso et al. Page 19

Not Screened n 21 24 0 0 0 3

FQHC 5 (n =

8,137)

Screened n (%) 1,955 (88%) 4,329 (91%) 12 (86%) 5 (83%) 552 (89%) 473 (89%) 26.6029 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 272 404 2 1 71 61

Screening for clinical depression and follow-up plan

Cisgender

Women n =

31,662

Cisgender Men n

=

25,027

Transgender

Women n =

164

Transgender Men n

=

155

Other n =

1,486

Not Disclosed/

Unknown n =

13,077

X

2

(df)

P-value

FQHC 1 (n =

5,212)

Screened n (%) 2,536 (81%) 1,451 (79%) 6 (75%) 4 (100%) 1 (50%) 121 (57%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened n 602 397 2 0 1 91

FQHC 2 (n =

23,161)

Screened n (%) 8,887 (88%) 7,009 (89%) 125 (93%) 78 (87%) 33 (89%) 3,037 (61%) 2146.8855 (5)

< .0001

++

Not Screened n 1177 835 10 12 4 1954

FQHC 3 (n =

24,394)

Screened n (%) 9,999 (87%) 5,329 (86%) 3 (100%) 37 (73%) 9 (64%) 4,847 (73%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened n 1529 863 0 14 5 1759

FQHC 4 (n =

4,333)

Screened n (%) 2,273 (97%) 1,570 (96%) 3 (100%) 1 (50%) 1 (100%) 318 (89%)

< .0001

+

Not Screened n 67 59 0 1 0 40

FQHC 5 (14,471)

Screened n (%) 4,048 (88%) 6,680 (89%) 14 (93%) 8 (100%) 1,260 (88%) 816 (90%) 4.4998 (5)

0.4799

++

Not Screened n 544 834 1 0 172 94

+

Fisher’s Exact Test

++

Chi-square Test; FQHC = federally qualified health center; – = No patients reported

Int J Med Inform

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2022 December 04.