Reverse Mortgages:

What Consumers and Lenders Should Know

T

he U.S. senior citizen population

is growing. Between 1990 and

2000, the number of individuals

at least 65 years of age increased from

31.2 million to nearly 35 million. Many

more are reaching the minimum social

security retirement age; by 2010, more

than 50 million people in this coun-

try will be at least 62 years old.

1

Life

expectancies are lengthening, creating

the need for retirement income to last

longer than in previous generations.

However, according to the U.S. Govern-

ment Accountability Office, “Efforts to

increase personal savings outside pension

arrangements seem to have had only

marginal success.”

2

As a result, older

people who need additional funds to

cover general living expenses are turning

to the reverse mortgage lending market

in greater numbers.

Historically, the largest investment of

the average American household is its

primary residence. A recent study by

the American Association of Retired

Persons (AARP) indicates that more

than 80 percent of households over the

age of 62 own their own home, with

an estimated value of $4 trillion.

3

Until

recently, equity in these homes has not

been tapped, but now it represents a

likely source of retirement income and

an opportunity for significant growth

in the reverse mortgage lending indus-

try. This article describes the features

of reverse mortgage loan products,

identifies key consumer concerns, and

provides an overview of potential safety-

and-soundness and consumer compliance

risks that lenders should be prepared to

manage when implementing a reverse

mortgage loan program.

What Is a Reverse Mortgage?

Reverse mortgage loans are designed

for people ages 62 years and older.

This product enables seniors to convert

untapped home equity into cash through

a lump sum disbursement or through a

series of payments from the lender to the

borrower, without any periodic repay-

ment of principal or interest. The arrange-

ment is attractive for some seniors who

are living on limited, fixed incomes but

want to remain in their homes. Repay-

ment is required when there is a “matu-

rity event”—that is, when the borrower

dies, sells the house, or no longer occu-

pies it as a principal residence.

Almost all reverse mortgage lending

products are nonrecourse loans: Borrow-

ers are not responsible for deficiency

balances if the collateral value is less than

the outstanding balance when the loan

is repaid. This situation, known as cross-

over risk, occurs when the amount of

debt increases beyond (crosses over) the

value of the collateral.

Reverse mortgages are fundamentally

different from traditional home equity

lines of credit (HELOCs), primar-

ily because no periodic payments are

required and funds flow from the lender

to the borrower. The servicing and

management of this loan product also

differ from those of a HELOC. (See

Table 1 for a comparison of reverse

mortgage loan products and HELOCs.)

Evolution of the Reverse

Mortgage

Reverse mortgages have been available

for more than 20 years, but consumer

1

U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census Population and Projections.

2

Retirement Income—Implications of Demographic Trends for Social Security and Pension Reform, United

States General Accounting Office, July 1997, p. 7.

3

Donald L. Redfoot, Ken Scholen, and S. Kathi Brown, “Reverse Mortgages: Niche Product or Mainstream Solu-

tion? Report on the 2006 AARP National Survey of Reverse Mortgage Shoppers” (AARP Public Policy Institute,

December 2007).

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

14

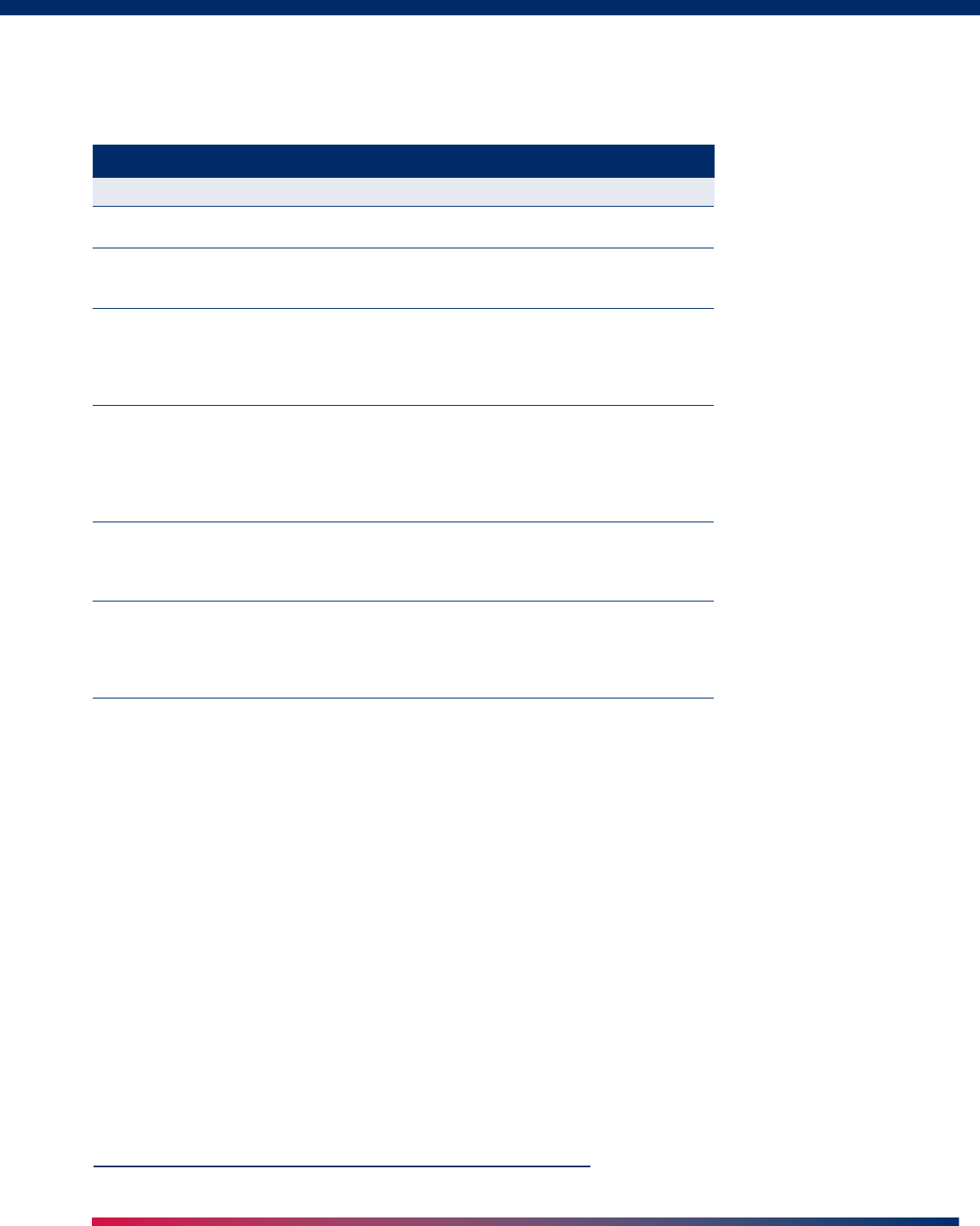

Table 1

Features of Reverse Mortgage and HELOC Products

Reverse Mortgage HELOC

Collateral /security

interest

Borrower remains owner of home;

lender takes security interest.

Borrower remains owner of home;

lender takes security interest.

Flow /access to

loan funds

Several options, including periodic

payments to borrower and draws on

the total available credit.

Borrower draws funds as necessary.

Interest, fees,

and charges

All up-front and periodic fees are

added to the loan balance. Interest

continues to accrue on the outstand-

ing balance until repayment at the

end of the loan.

Depending on the program, borrower

may pay fees outside closing or by

adding them to the unpaid balance.

Interest and fees are assessed on

outstanding balance until repaid.

Repayment No periodic payments of principal or

interest. One payment is due when

borrower dies, sells the house, or no

longer occupies it as a primary

residence.

Payments vary by program.

Generally, HELOCs feature monthly

interest-only payments for a set

period of time, followed by flexible

principal and interest payments until

the maturity date.

Maximum loan

amount

Some programs allow the maximum

loan amount to grow over time (see

description later in text of Home

Equity Conversion Mortgage).

May vary by program, but most

establish the maximum amount

based on combined loan-to-value

ratio at the time of origination.

Loan suspension Unused loan proceeds may not be

suspended by

the lender.

Subject to Regulation Z require-

ments, unused lines of credit may be

suspended in response to delinquent

payments or significant decline in

collateral value.

demand has been relatively weak because

of uncertainty about how this product

works. Consumers often ask the follow-

ing questions:

n Can I retain the title to my house?

n What happens if the loan balance

exceeds my home’s value?

n Will I be able to bequeath my home to

my heirs?

Financial institutions have been slow

to enter the reverse mortgage lending

market because of the unique servicing

and risk management challenges. For

example, when the reverse mortgage

was first introduced, banks were wary

of booking potentially long-term loans

that increase over time, do not have a

predefined, scheduled repayment stream,

and for which there was no established

secondary market. Lenders also faced

uninsured crossover risk.

However, the market changed in 1988

when the Federal Housing Administra-

tion (FHA) launched the Home Equity

Conversion Mortgage Insurance Demon-

stration, a pilot project that eventually

was adopted permanently by the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD).

4

The outcome was

the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage

(HECM), a commercially viable loan

product with strong consumer protec-

tions. For example, the HECM requires

prospective borrowers to complete a pre-

loan counseling program that explains

4

Redfoot, Scholen, and Brown, 2007, p. viii.

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

15

Reverse Mortgages

continued from pg. 15

the nature of reverse mortgages, includ-

ing the risks and costs.

5

In addition, the HECM is a nonre-

course credit that protects consumers

from crossover risk. HECMs carry FHA

insurance, which protects lenders from

this risk. HECMs have maximum loan

amounts based on the location of the

collateral (the house). (See Table 2 for

details.)

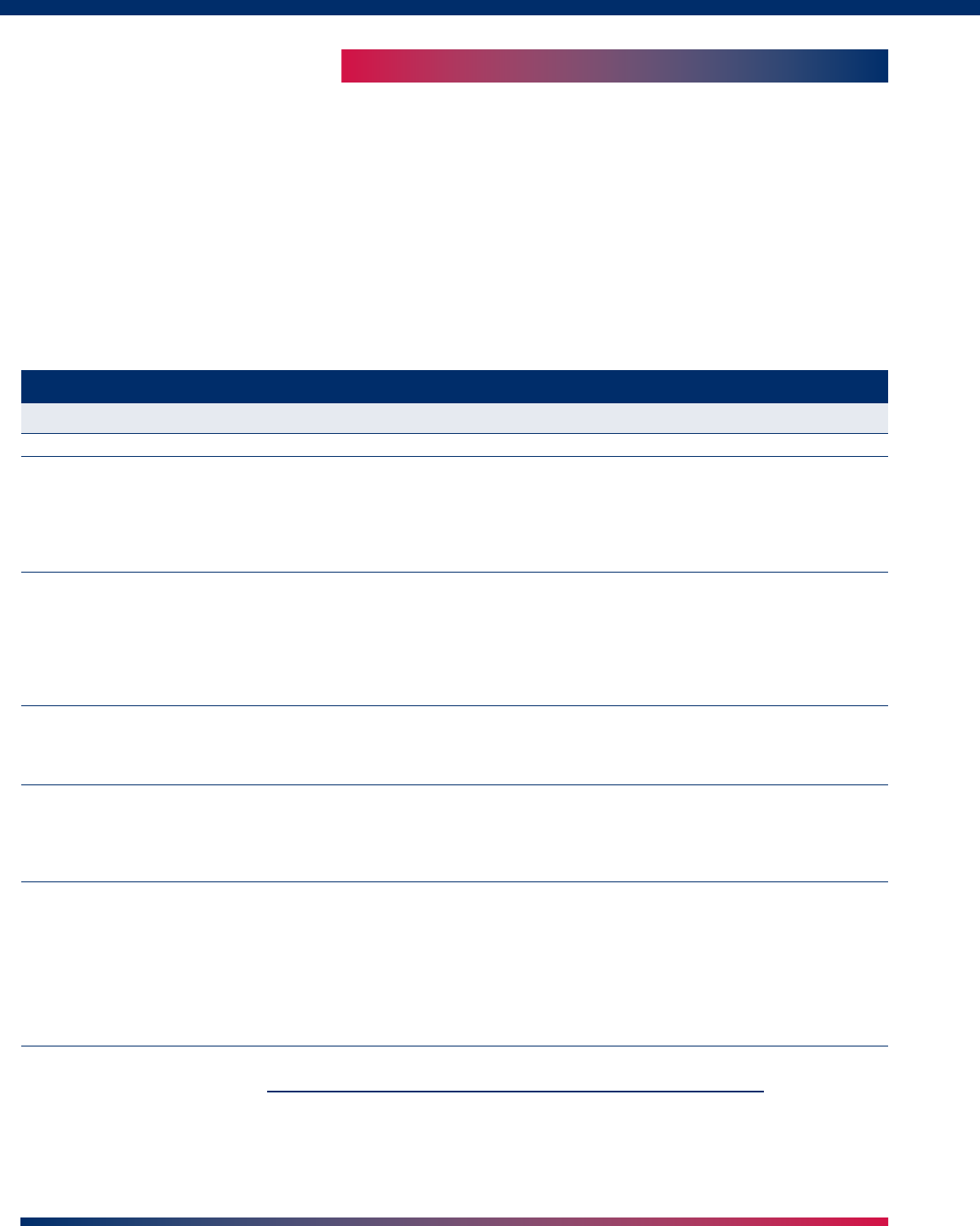

Table 2

In some cases, individuals with high

value homes desire loans that exceed

HECM maximums. This demand led to

the development of private, proprietary

programs through which consumers can

obtain alternative loan products if they

need access to higher equity amounts.

However, crossover risk is a concern

with these proprietary programs, as no

insurance is available to cover potential

collateral deficiencies. Generally, in these

Features of HECMs and Proprietary Programs

HECM

Proprietary Programs

Who grants the loan? FHA-approved lenders. Individual lenders.

What is the maximum Primarily based on the age of the youngest borrower. For all Lender’s discretion. Generally these are

loan amount? HECMs insured after November 5, 2008, the maximum loan jumbo loans designed to fill the market niche

amount is $417,000. The limit is higher in identified high cost areas for borrowers who want loans above the

in Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the Virgin Islands. In these areas, HECM limit.

loans may exceed the national limit up to 115 percent of the area

median price or $625,500, whichever is less.

6

How are funds Borrowers have five options:

Lender discretion—programs vary.

drawn?

1. Fixed monthly payments

2. Fixed monthly payments for a set period

3. Line of credit, drawn for any amount at any time

4. Combined fixed payments and a line of credit

5. Combined fixed payment term and a line of credit

Does overall loan cap Yes. HECM allows the loan to grow each year. For example, the

No.

grow over time? unused loan balance is increased by the same rate as the interest

charged on the loan. Therefore, for the unused portion of the loan,

the total loan amount continues to grow.

What happens if the

value of the house

becomes less than

the amount of the

loan?

FHA insures the difference. The borrower (or borrower’s heirs)

will not be responsible for shortages if the value falls below the

outstanding balance. The borrower pays FHA insurance premiums

during the term of the loan; these premiums are added to the loan

balance.

Anecdotal market data suggest that most

current programs are nonrecourse loans.

However, programs vary and may be subject

to limits under state laws. Lenders bear the

risk of collateral shortages.

What are the costs

and fees?

Origination fee: maximum of 2 percent of the first $200,000 plus

Lender discretion.

maximum of 1 percent of amounts over $200,000. The overall cap

is $6,000. The minimum is $2,500, but lenders may accept a lower

origination fee when appropriate.

Mortgage insurance (2 percent initial plus .5 percent annually).

Monthly servicing fee: $30.

Other traditional closing costs (appraisal, title, attorney, taxes,

inspections, etc.).

5

HUD partnered with the AARP Foundation’s Reverse Mortgage Education Project to develop consumer

education materials and train and accredit financial counselors. For additional resources, see

www.hecmresources.org/project/proje_project_goals.cfm.

6

“2009 FHA Maximum Mortgage Limits” (HUD Mortgagee Letter 2008-36, November 7, 2008),

https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/DOC_20412.doc.

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

16

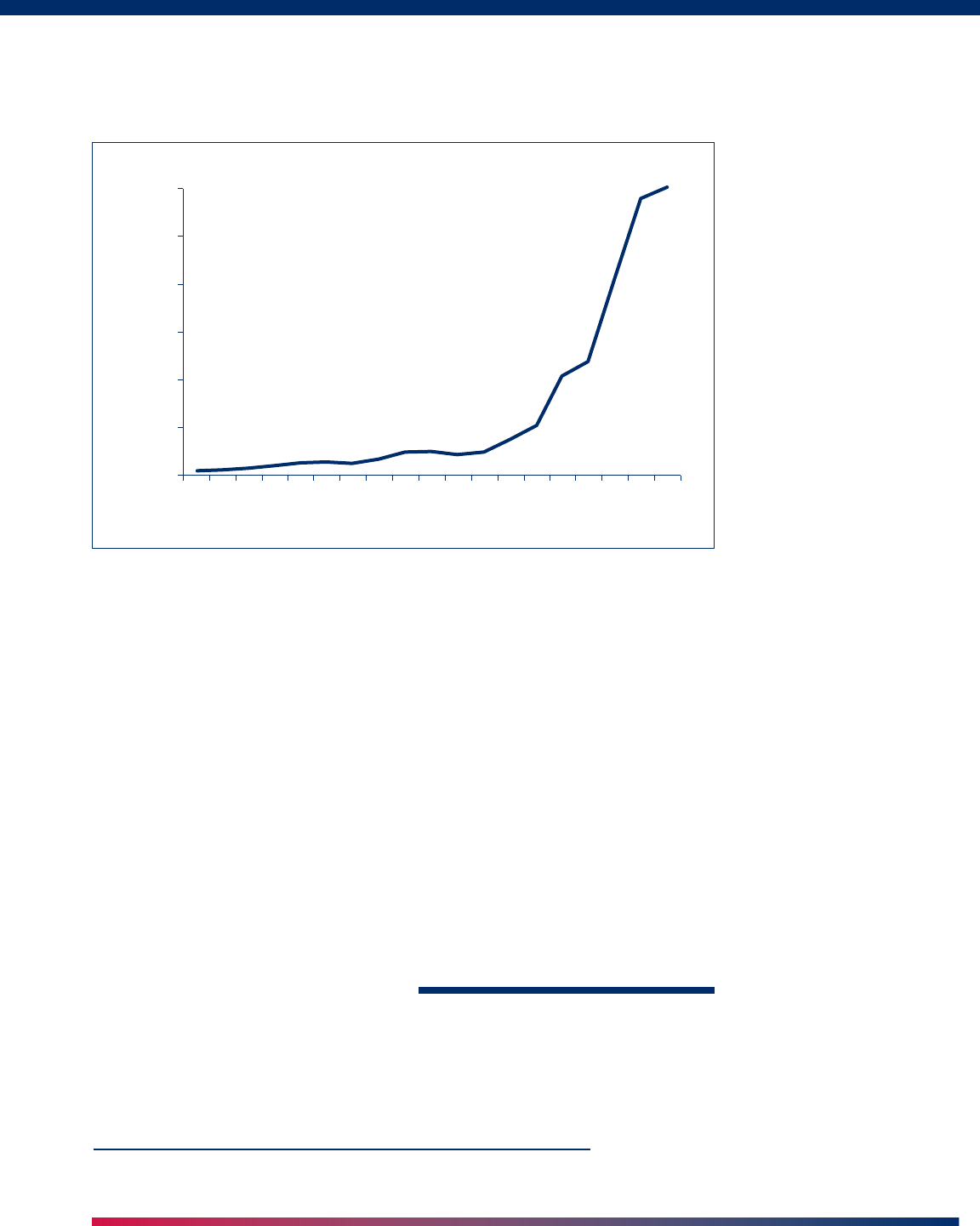

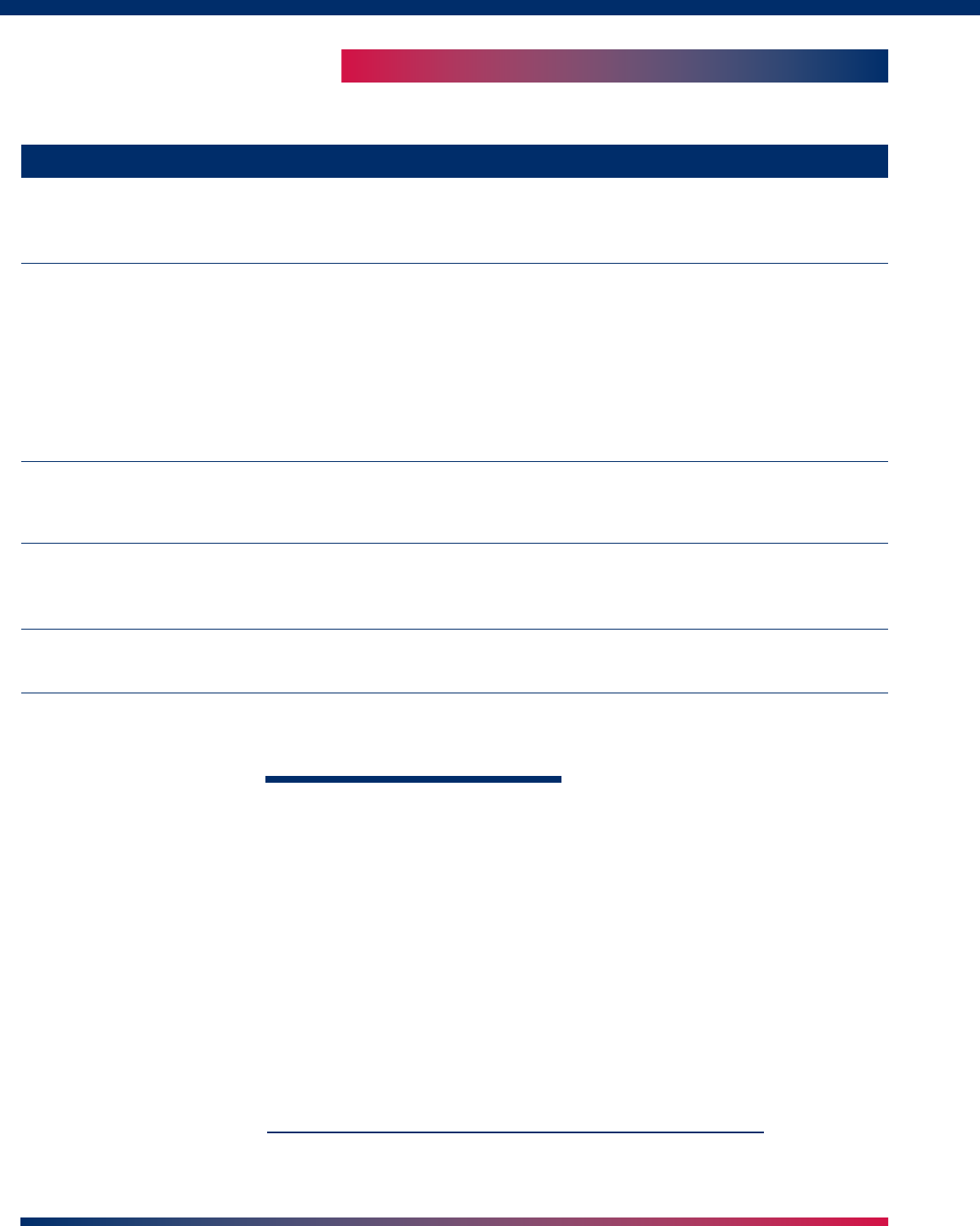

Chart 1: HECM Endorsements Have Increased Dramatically Since 2004

HECM Endorsements

112,154

120,000

107,558

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

6,640

4,165

389

0

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 Sep

2008

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (www.hud.gov).

private programs, greater risk translates

into higher costs for consumers—lenders

must price products to cover the risk of

repayment or loss. (See Table 2 for a

comparison of HECMs and proprietary

programs.)

The need for higher HECM loan limits

was addressed as part of the Housing

and Economic Recovery Act of 2008

(HERA), signed into law on July 30,

2008. The HERA effectively raised the

maximum HECM loan amount from a

range of $200,160–$362,790 to a new

nationwide ceiling of $417,000, by tying

the limit to the national conforming

limits for Freddie Mac. (Higher limits

are allowed in certain, designated high

cost areas, as noted in Table 2.) Given

that the maximum amounts were only

recently changed, the impact on the

demand for proprietary jumbo loans is

not yet known.

In addition to HECMs and proprietary

programs, Fannie Mae previously offered

the Home Keeper reverse mortgage loan

program. This product featured many

of the same consumer protections as

the HECM, including the counseling

requirement, as well as generally higher

maximum loan amounts. However, the

program did not capture a large segment

of the market, and Fannie Mae terminated

it in September 2008 subsequent to the

new loan limits allowed under the HERA.

Overall, even with the emergence of

proprietary programs, more than 90

percent of reverse mortgages are HECMs,

and the number of HECMs has increased

steadily since 2004. During HUD’s 2007

fiscal year, 107,558 HECMs were insured

by the FHA, an increase of more than

40 percent over the previous year.

7

As

of September 2008, more than 112,000

HECMs had been insured by the FHA

during the calendar year (see Chart 1).

Consumer Issues

Reverse mortgages benefit consum-

ers by providing a nontaxable source of

funds. This is particularly attractive to

seniors who have limited, fixed incomes

7

National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association, statistics as of July 2008. See

www.nrmlaonline.org/RMS/STATISTICS/DEFAULT.ASPX?article_id=601.

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

17

Reverse Mortgages

continued from pg. 17

but high amounts of home equity.

These loans can enable some people to

continue living in their homes, which

may not have been feasible without this

additional source of cash. However, this

loan product is not for everyone, and

potential borrowers should carefully

assess the pros and cons before taking on

a reverse mortgage.

The report Reverse Mortgages: Niche

Product or Mainstream Solution?

published by the AARP Public Policy

Institute in late 2007 presents informa-

tion about consumers who obtained

reverse mortgages, as well as those who

opted not to pursue them after complet-

ing the required pre-loan counseling.

8

Survey respondents cited many reasons

for deciding not to pursue a reverse mort-

gage. The following represent the three

most-cited reasons: the high cost (63

percent); respondents found another way

to meet financial needs (56 percent); or

respondents determined that the loan

was not necessary given the individual’s

financial position (54 percent).

9

The results of this study highlight key

consumer considerations, such as the

importance of pre-loan counseling, which

may provide information about other

programs better suited to a borrower’s

needs. For example, local lenders and

community organizations may offer

low-cost home improvement loans for

seniors. In some cases, consumers might

find they are better off financially if they

sell their property rather than refinance

an existing loan with a reverse mortgage.

Lenders also face risks associated with

the various consumer issues, including

those identified in the AARP survey.

For example, there is a potential for

reputation risk, and perhaps even legal

risks that could result from aggressive

cross-marketing of other financial prod-

ucts, such as long-term annuities. Some

financial service providers encourage

reverse mortgage borrowers to draw

funds to purchase an annuity or other

financial product. Interest begins to

accrue immediately on any funds drawn

from the reverse mortgage, and borrow-

ers may lose other valuable benefits, such

as Medicaid. For example, funds that are

drawn and placed in deposit accounts

or non-deposit investments would be

included in the calculation of the individ-

ual’s liquid assets for purposes of Medic-

aid eligibility.

Aggressive cross-selling is considered

predatory by many consumer advocates.

In fact, the HERA specifically prohibits

lenders from conditioning the extension

of a HECM loan on a requirement that

borrowers purchase insurance, annuities,

or other products, except those that are

usual and customary in mortgage lend-

ing, such as hazard or flood insurance.

These prohibitions apply to HECMs but

not to products in a proprietary lend-

ing program—a fact consumers should

consider when choosing a reverse mort-

gage product.

Another potentially predatory practice

is equity-sharing requirements, which

are contractual obligations for borrow-

ers to share a portion of any gain—or,

in some cases, equity—when the loan

is repaid. These provisions mean addi-

tional, sometimes substantial, charges

that the consumer or the consumer’s

estate is obligated to pay, thus reducing

the consumer’s share of his or her home

value. Such provisions are prohibited in

the HECM program but were a compo-

nent of early reverse mortgage programs

developed in the 1990s. A person who

chooses a proprietary program should

carefully review contracts for the exis-

tence of these provisions.

8

Redfoot, Scholen, and Brown, 2007.

9

Percentages total to more than 100 percent because survey respondents could select more than one reason for

not pursuing a reverse mortgage.

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

18

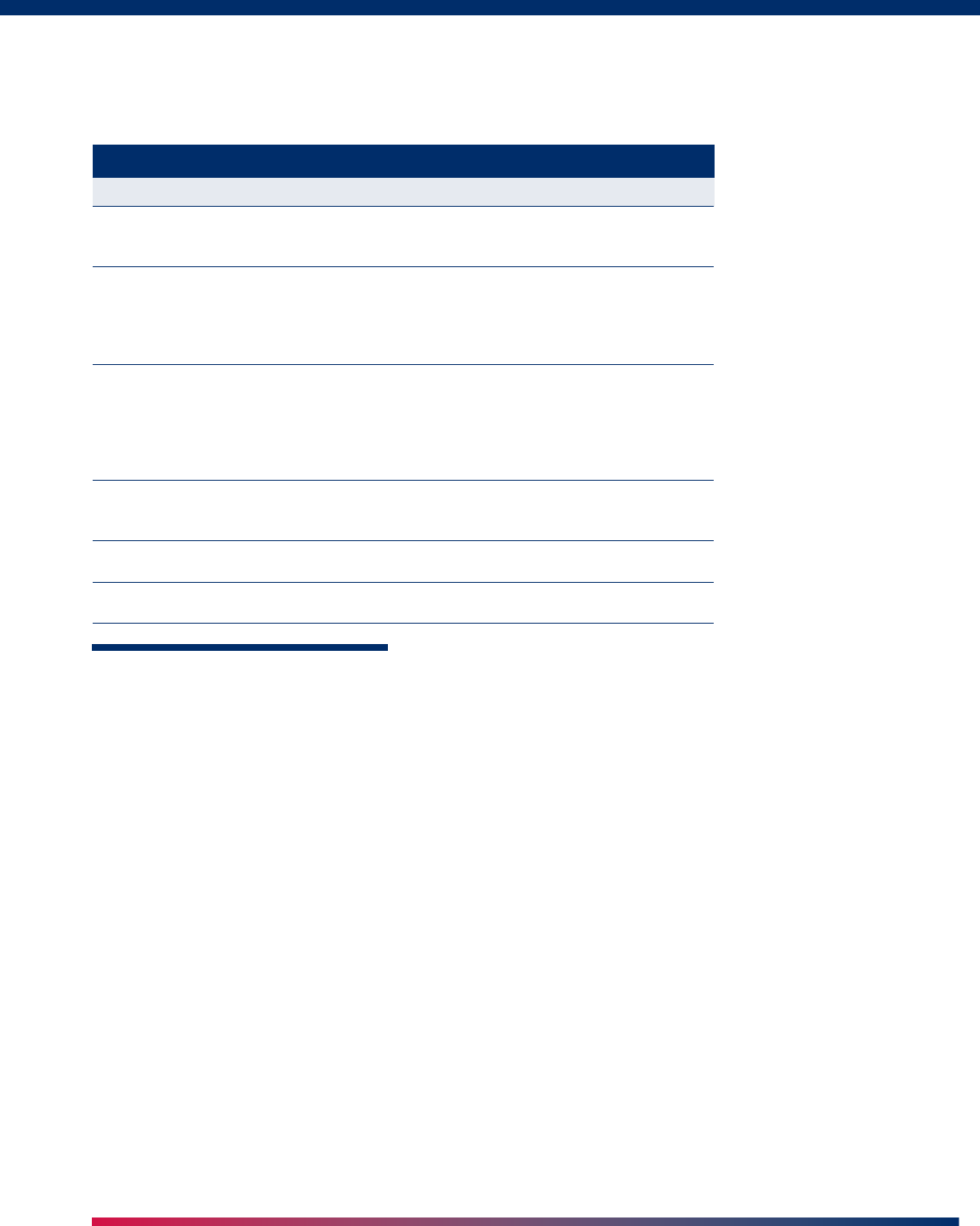

Table 3

Safety and Soundness Concerns in Reverse Mortgage Lending

Issue Description

Property appraisals Lenders must ensure that property appraisals are conducted in accordance

with the requirements of the appraisal regulations in Part 323 of the FDIC

Rules and Regulations.

Real estate lending Lenders must comply with Part 365 of the FDIC Rules and Regulations, which

standards requires insured state nonmember banks to adopt and maintain written poli-

cies that establish appropriate limits and standards for extensions of credit

that are secured by liens on or interests in real estate, or that are made for

the purpose of financing permanent improvements to real estate.

Third-party risks

Lenders must manage potential risks associated with third-party involve-

ment.

This is particularly relevant to situations in which lenders either

conduct wholesale activities or act as brokers or agents themselves.

For additional details, refer to “Guidance for Managing Third-Party Risk”

(FDIC Financial Institution Letter FIL-44-2008, June 6, 2008),

www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2008/fil08044.html.

Servicing complexity Specialized loan servicing functions must be implemented, including

processes for disbursing proceeds over extended periods of time and moni-

toring maturity events that will necessitate repayment.

Securitization and Although a secondary market for reverse mortgage lending exists, it is rela-

liquidity tively new, and financial institution expertise in this area may be limited.

Collateral Lenders/servicers must ensure that collateral condition is maintained during

the term of the loan.

Regulatory and Supervisory

Considerations

Given the downturn in traditional 1–4

family mortgage lending, reverse mort-

gages may become an attractive product

line for some institutions. However, these

loans can include complex terms, condi-

tions, and options that could heighten

consumer compliance and safety and

soundness risks.

Financial institutions participate in

the delivery of reverse mortgage loans

in a variety of ways. Generally, the

lender acts either as a direct lender or

a correspondent (or broker) that refers

applications to, or participates with,

other lenders. Rather than developing

the expertise in-house, small community

banks might establish referral arrange-

ments with other specialized lenders.

Regardless of the nature or extent of

the institution’s involvement in offering

reverse mortgage products, manage-

ment should be aware of the safety and

soundness and compliance risks associ-

ated with this type of lending. Reverse

mortgage lending is subject to many of

the same underwriting requirements

and consumer compliance regulations

as traditional mortgage lending. Table

3 gives an overview of key safety-and-

soundness issues, and Table 4 summa-

rizes provisions of some of the federal

consumer protection laws and regula-

tions that apply to reverse mortgage

lending.

In general, the same safety and sound-

ness and consumer compliance regula-

tions and requirements that apply to

traditional real estate lending apply to

reverse mortgage lending. However,

reverse mortgages often present unique

challenges and issues for institutions that

plan to offer this product line for the first

time. For example, management may

need to amend operating policies and

procedures to appropriately identify and

manage the inherent risks, regardless

of whether the institution offers reverse

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

19

Reverse Mortgages

continued from pg. 19

Table 4

Consumer Protection Laws and Regulations Applicable to Reverse Mortgage Products

Truth in Lending Act (TILA), 15 U.S.C. 1601 • Requires disclosure of overall costs of credit.

et seq. / Regulation Z, 12 CFR 226

• Contains provisions for reverse mortgages, because the traditional annual percentage rate

and total finance charge will vary depending on how the credit availability is used.

• Requires a disclosure of the “total annual cost” using three scenarios.

Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act

(RESPA), 12 U.S.C. 2601 et seq. / Regulation

X, 24 CFR 3500

• Requires disclosure of fees and charges in the real estate settlement process, including

fees not considered finance charges under Regulation Z.

• Prohibits kickbacks between settlement service providers in these transactions. These

provisions are particularly applicable to indirect lending situations in which banks make

referrals to other lenders.

• Effective October 1, 2008, only FHA-approved mortgagees may participate in and be

compensated for the origination of HECMs to be insured by FHA. Loan originations must be

performed by FHA-approved entities, including: (1) an FHA-approved loan correspondent

and sponsor; (2) an FHA-approved mortgagee through its retail channel; or (3) an FHA-

approved mortgagee working with another FHA-approved mortgagee.

10

Fair Lending

• Prohibits discrimination in all aspects of credit transactions on certain prohibited bases.

(Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. 1691

et seq. / Regulation B, 12 CFR 202, and Fair

Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq.)

Flood Insurance—National Flood Insurance • Requires lenders to determine whether property is located in a designated flood hazard

Program, 42 U.S.C. 4001 et seq. area prior to making the loan.

• Requires borrower notification if property is in a flood zone.

• Requires property to be covered by flood insurance during the entire loan term.

Unfair and Deceptive Acts or Practices • Generally prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices in all aspects of the transaction.

(UDAP)–Section 5(a) of the Federal Trade

• Provides legal parameters for determining whether a particular act or practice is unfair or

Commission (FTC) Act, 15 U.S.C. 45(a)

deceptive.

mortgages through direct lending or as a

correspondent for other institutions.

Conclusion

As the U.S. population continues to

age and life expectancies lengthen, more

people will be living longer in retire-

ment and undoubtedly will need addi-

tional sources of long-term income. This

scenario suggests that the demand for

reverse mortgages will increase. Poten-

tial borrowers should weigh the pros

and cons of this loan product for their

particular financial situation, and lenders

should take steps to ensure they under-

stand how to identify and manage the

risks associated with this product.

David P. Lafleur

Senior Examination Specialist

Division of Supervision and

Consumer Protection

10

“Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) Program—Requirements on Mortgage

Originators" (HUD Mortgage Letter 2008-24, September 16. 2008).

Supervisory Insights Winter 2008

20