Rebalancing the

Criminal Justice System

in favour of the

law-abiding majority

Consultation on restricting the

use of backed for bail warrants

28 December 2006

Rebalancing the

Criminal Justice System

in favour of the

law-abiding majority

Consultation on restricting the

use of backed for bail warrants

28 December 2006

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 1

Aim and structure

1.1 The purpose of this paper is to consult on how to restrict the use of “warrants backed for bail” in

order to help speed the return to court of bailed defendants who fail to appear, in line with the

commitment in the Home Office’s review on

Rebalancing the criminal justice system in favour of the

law-abiding majority (July 2006).

“Once the police have found a bail breacher, it is critical that they can take effective action. At

present, courts can issue either a warrant with or a warrant without bail when someone fails to

attend. But warrants with bail just mean that the person who has not attended is served with

another piece of paper telling them to appear at some future date. So we will restrict the use of

warrants with bail, so that, except for the most minor of offenders, anyone failing to answer to bail

can expect to be taken into police custody as soon as they have been found until they can be

brought before the court.” Paragraph 2.4.1, page 20

1

1.2

The consultation paper is structured as follows:

●

Chapter 2 provides some background infor

mation relevant to the consultation exercise;

●

Chapter 3 analyses the problems posed by backed for bail warrants;

●

Chapter 4 sets out what action is already being taken to reduce the use of backed for bail

warrants, including good practice and planned legislation;

●

Chapter 5 seeks views on options for further legislative change aimed explicitly at restricting

the use of backed for bail warrants;

●

Annex A is the ACPO/OCJR Warrant Priority Matrix, providing guidance on how to prioritise

warrants into appropriate categories;

●

Annex B is the Schedule of qualifying offences for retrial of serious offences in the Criminal

Justice Act 2003;

●

Annex C offers an assessment of the potential impact of restricting the use of backed for bail

warrants on prison places and police cells;

●

Annex D is a list of those persons and bodies that have been consulted.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1 Rebalancing the criminal justice system in favour of the law abiding majority. Cutting crime, reducing re-offending and protecting the public Home Office, July 2006 Ref: 275921

How to respond to the consultation

1.3 Questions about the consultation and any responses should be directed to:

Aidan Wilkie

Justice and Enforcement Unit

Office for Criminal Justice Reform

Ground Floor Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London SW1P 4DF

020 7035 8459

Elizabeth Austin

Justice and Enforcement Unit

Office for Criminal Justice Reform

Ground Floor Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London SW1P 4DF

020 7035 8693

Deadline for responses

1.4 Responses are requested by 19th March 2007.

Responses and disclaimer

1.5 The information you send in may be sent to colleagues within the Office for Criminal Justice Reform,

the Government or related agencies. Furthermore, information provided in responses to this

consultation, including personal information, may be published or disclosed in accordance with the

access to information regimes (these are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA),

the Date Protection Act 1998 (DPA) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004).

1.6 If you want the information you provide to be treated as confidential, please be aware that, under

the FOIA, there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and

which deals with, among other things, obligations of confidence. In view of this it would be helpful

if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we

receive a request for disclosure of the information we will take full account of your explanation,

but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances.

1.7 An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded

as binding on the Department. Please ensure that your response is marked clearly if you wish

your response and name to be kept confidential. Confidential responses will be included in any

statistical summary of numbers of comments received and views expressed.

1.8 The Department will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act –

in the majority of circumstances this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to

third parties.

2 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 3

What is a backed for bail warrant?

This consultation relates to Fail To Appear (FTA) warrants, issued under the Bail Act 1976 s.7 or the

Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 (MCA 1980) s.13. Magistrates obtain their power to back a warrant for

bail under the MCA 1980 s.117. The Crown Court obtains its power to back a warrant for bail

under the Supreme Court Act 1981 s.81 (4).

When a defendant fails to appear at court in answer to a summons or to bail, the magistrate can

issue a warrant for his arrest. This can be “backed for bail” or “not backed for bail” (MCA 1980

s.117). If the magistrate issues a warrant backed for bail, the police will find the defendant and

produce the warrant which will contain a direction that the person arrested be released on bail

(with or without conditions) subject to a duty to appear before a particular court at a par

ticular

time. If the warrant is

not backed for bail the defendant will be arrested, detained and brought

bef

ore the court at the earliest possible opportunity. Depending on the time of day of the arrest,

the def

endant may spend a night in police custody – in some cases up to three nights if arrested on

late on a Friday and no Saturday court is available.

Any subsequent remand decision remains with the magistrates. The decision whether to issue a

warrant and whether to back it for bail is a judicial one based on law and the facts of the case.

A warrant cannot be issued unless the substantive offence to which the warrant relates is

punishable with imprisonment, or the Court, having convicted the accused, is proposing to impose a

disqualification on him (MCA 1980 s.13).

The judiciary have an unf

ettered discretion to issue backed for bail warrants. The prosecution can

oppose this if they feel a no-bail warrant is more appropriate. Soundings with practitioners suggest

that there are two main reasons for issuing a backed for bail warrant:

●

it is believed the defendant may have a justifiable reason for non-attendance (e.g. illness or doubt

over whether the def

endant was informed of the court date);

●

the alleged offence is relatively minor and a no-bail warrant, possibly resulting in custody (once

the warrant is executed), would be a disproportionate response.

Any failure to attend in response to a backed for bail warrant is an offence under the Bail Act 1976.

This is irrespective of whether the proceedings were initiated by arrest and charge or summons.

Failure to appear in answer to a summons itself is not a Bail Act offence.

FTA warrants backed for bail are only very rarely issued by the Crown Court. (As an indication of this,

only 8 out of the 8,500 unexecuted warrants held by the Metropolitan Police in July 2006 were Crown

Court backed for bail warrants). This consultation therefore concentrates on magistrates’ courts.

Chapter 2: Background

2.1 The Department for Constitutional Affairs report Delivering Speedy, Simple, Summary Justice

2

provides the context for restricting the use of backed for bail warrants:

“Police and courts working together have made major improvements in the enforcement of fail to

appear warrants, achieving a 43% reduction in the number outstanding over the past two years.

The challenge now is to sustain this momentum through more integrated approach to improving

compliance with the terms of bail, sharing information, and faster and more certain execution of

warrants for failure to appear at court.”

2.2 Since the launch of “Operation Turn Up” in September 2004 the number of outstanding failure

to appear (FTA) warrants has been driven down from 65,321 to 35,871 In September 2006. This

reduction (now 44%) is equivalent to a reduction from 4.7 to 2.8 months’ worth of warrants

issued.

2.3 In almost all areas FTA warrants – both backed for bail and not backed for bail – are executed by

a police officer. With the progressive introduction over the next 18 months of the Warrant

Handling Strategy, under the aegis of the National Enforcement Service, it will fall to Court

Enforcement Officers (CEOs) to execute most backed for bail warrants. This consultation

concentrates on police as warrant executors, but the same efficiency arguments apply to CEOs.

2.4 The evidence in this consultation comes from two main sources: the warrant management

systems developed by police over the past two years; and interviews with practitioners. The

analysis of this evidence (outlined in this paper) suggests that:

●

restricting the use of warrants backed for bail does not necessarily require increasing

the use of warrants not backed for bail (”no-bail” warrants) – there may be more effective

“non-warrant” alternatives;

●

replacing most backed for bail warrants with no-bail warrants would not necessarily result in a

more efficient redeployment of resources.

While the overall number of warrants issued might

be expected to fall, no-bail warrants require more police resources to execute than warrants

backed for bail; and police would still need to give priority to the execution of more serious

offence/defendant warrants; and

●

the key principles informing any new approach should be speed, certainty and proportionality.

Judicial independence

2.5 Decisions in relation to bail, including the issue of a warrant, are for the judiciary. None of the

following proposals on how to restrict the use of warrants backed for bail is intended to

undermine that discretion, but rather to enable the judiciary to make a major contribution to

achieving two important aims:

●

ensuring that more defendants are returned more quickly to court;

●

allowing police (and, increasingly, CEOs) to focus their resources where most needed.

4 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

2 Delivering Simple, Speedy, Summary Justice, DCA, July 2006, DCA 37/06

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 5

In many cases backed for bail warrants delay the defendant’s

return to court

3.1 The Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System Review focused on the need to return those who

breach bail back to court as quickly as possible. A swift response sends a message that breaches

of Court orders will be taken seriously (and thus should improve compliance), heightens the

likelihood of enforcement and limits the opportunity for re-offending.

3.2 Much effective work has gone into speeding up processes associated with failure to appear: for

example, in the period from April 2005 to August 2006 courts have improved the speed with

which they notify police of the issue of a warrant.

April 05 August 06

% notified to police in one working day 61% 95%

% notified to police in three working days 87% 100%

3.3 Data are now being collected on how quickly the warrants themselves are being executed, and

Local Criminal Justice Board timeliness of execution targets will be set from April 2007.

3.4 However, there is still work to be done in improving the speed of execution, including addressing

issues associated with backed for bail warrants, which have been identified as a blockage to the

quick return to court of defendants who fail to appear.

3.5 Based on a sample of 12 criminal justice areas, around 23% of all FTA warrants issued are backed

for bail (approximately 40,000 warrants a year). Around 30% of the current total of outstanding,

unexecuted warrants are backed for bail (approximately 11,000), although this ranges from 3% in

some areas to 47% in others. Backed for bail warrants therefore account for a disproportionate

amount of the outstanding warrants total, suggesting that they are not accorded a high priority by

the executing agencies.

3.6 On receiving an FT

A warrant, the police assign it a priority in line with the ACPO/OCJR Warrant

Priority Matrix (Category A, B or C in descending order) according to the seriousness of offence,

the offending history of the defendant, and other factors derived from the National Intelligence

Model (see annex A). The prioritisation aims to ensure that police resources are directed first at

those defendants posing the highest risk. As the new warrant handling strategy rolls out, an

increasing proportion of categor

y C warrants are being allocated to CEOs to execute.

Chapter 3: What problems are

posed by backed for bail

warrants?

National Enforcement Service – Warrant Handling Strategy

On 15 March 2005 Lord Falconer and the Attorney General announced the Government’s proposal

for a National Enforcement Service (NES). Building on the wide range of initiatives currently being

taken forward to improve performance across all aspects of enforcement. It will put in place a

framework for improved enforcement and sentence compliance, with enforcement professionals who

will focus on fine defaulters, those skipping bail, community penalty breaches and confiscation orders.

The warrant handling strategy divides responsibility for execution between Police and Court

Enforcement Officers (CEOs). The dividing line is set in accordance with the ACPO/OCJR warrant

matrix, with CEOs taking responsibility for the execution of category C warrants (subject to risk

assessment). As the vast majority of backed for bail warrants are classified as category C warrants,

this will free considerable police resource which will allow them, amongst other things, to return the

more serious offenders to court as quickly as possible.

The warrant handling strategy is currently being piloted in the North West of England, with plans

for staged roll-out across the rest of the country throughout 2007/2008.

3.7 Almost all backed for bail warrants are given priority C; and around half of priority C warrants

are backed for bail. Timeliness of execution is considerably worse for category C warrants than

for Category A or B warrants.

Priority % executed within Number of days

A6214

B 61 21

C 51 28

3.8 With only 51% of Category C war

rant currently being executed within 28 days, this does not

compare well with the post.With a letter, one might expect 100% delivery to the given address

within two days at a fraction of the cost of personal delivery. There is no centrally held data on

when, within those 28 days, most warrants are executed. Practitioners have suggested that some

may be executed on day one and others on day 27.

3.9 There are no separate data for timeliness of execution of backed for bail warrants, but police

practitioners have suggested that backed for bail warrants are regarded as lower priority than no-

bail warrants – in effect an unofficial category D. This is not just because the relevant defendants

are generally regarded as low risk. It is also because executing backed for bail warrants is often

seen as an inefficient use of police resources. The reason for this is that a backed for bail warrant

is view

ed as similar to an adjournment notice – albeit one which requires personal service by an

executing officer, and where failure to surrender is an offence. The warrant having been executed,

there is also no guarantee that the defendant will in fact subsequently attend court.

3

3.10 There are a number of other factors associated with backed for bail warrants which also

contribute to major delays in the process:

●

the time taken to execute the warrant, given its relative low priority;

●

the time lapse until a new court date can be set; and

6 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

There are, however, fundamental differences between a backed for bail warrant and an adjournment notice. If the defendant is not on bail (i.e. fails to appear in answer to a

summons) and then subsequently fails to appear in answer to an adjournment notice he/she will not have committed an offence under the Bail Act 1976. However, if a

backed for bail warrant is issued and the defendant fails to appear, then a Bail Act offence will have been committed.

●

possible further failure to appear on the new court date.

In certain situations a backed for bail warrant is not a sufficiently

robust response

3.11 Despite the inherent delays, a backed for bail warrant may be the most proportionate response

in certain situations, for example where the offence is minor and there is no evidence to suggest

the defendant will fail to appear again (although the Court may also choose to send a defendant

warning letter (see para 3.12) in this situation).

3.12 However there are certain situations where a more robust response (no-bail warrant) is

required, specifically:

●

where the substantive offence is ‘serious’;

●

where the defendant has a ‘poor’ bail history and there is real concern over their future

attendance at court;

●

where a backed for bail warrant has already been issued in the proceedings but the defendant

has failed to appear in answer to it.

3.13 Anecdotal evidence suggests that in some cases backed for bail warrants are being issued in these

circumstances, although there is limited evidence to support this.

3.14 The aim should be to restrict the use of backed for bail warrants in such circumstances. In these

situations the issue of a no-bail warrant will result in the defendant returning to court more

quickly. This sends a strong message that the orders of the Court should be complied with,

reduces the chances of further failure to appear and limits the opportunity for re-offending.

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 7

8 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

4.1 This chapter sets out what is already being done in terms of good practice to reduce the number of

backed for bail warrants, and the planned legislative changes which should also help in this respect.

Good Practice

4.2 Some criminal justice areas have already succeeded in restricting the use of backed for bail

warrants. Nottinghamshire in particular has implemented a number of measures with this aim in

mind, resulting in a very significant reduction in the number of backed for bail warrants issued.

Nottinghamshir

e case study

The use of FTA war

rants with bail is rare in Nottinghamshire, with Courts in Nottinghamshire

issuing only 125 (out of 3,708) in total during the past twelve months. In recent months, bail

warrants have averaged less than 1% of the domestic FTA warrant volume received by

Nottinghamshire Police. Currently, there are just 10 outstanding backed for bail warrants in the area

(<2% of total outstanding).

A cross-agency FTA Warrants Working Group was set up following Operation Turn-Up under the

auspices of the Nottinghamshire Criminal Justice Board, which identified that backed for bail

warrants were a blockage to swift return of defendants to court. While the action taken when a

defendant fails to appear remains a judicial decision, legal advisers now remind magistrates of the

potential impact of issuing a backed for bail warrant and remind magistrates of the other options

available to them.

The Courts have confirmed that they found the use of backed for bail warrants ineffective and,

while they are used in some cases, enlarging bail is often found to be a preferable alternative – bail

is enlarged f

or between 14 and 21 days whereas a backed for bail warrant always sets a hearing

date over 28 days ahead (and may require subsequent re-dating should the warrant not be

executed within the timeframe). This has significantly improved the speed at which defendants are

returned to court.

Notification of enlarged bail is made both in writing and through the defence solicitor, and there is a

clear message that further failure to appear will result in the issue of a warrant for arrest.

4.3 The Office f

or Criminal Justice Reform (OCJR) has initiated a project aimed at identifying and

disseminating good practice more widely as a means of restricting the use of backed for bail

warrants. The project will build on some of the examples of existing good practice set out below

in relation to bail, trials and sentencing in absence, and providing better information on bail

Chapter 4: What is currently being

done to restrict the use of backed

for bail warrants?

history. Many of these examples focus on alternatives to warrants, rather than on upgrading

backed for bail warrants to no-bail status.

4.4 This project will also explore how any such changes in process can be agreed and adopted locally.

One possible avenue is the local inter-agency bail agreements which already have wide cross-CJS

buy-in and are currently being rolled out across the country, under the auspices of Local Criminal

Justice Boards. The Justices’ Clerks Society and Magistrates’ Association will play a crucial role in

promulgating any findings from the project.

(i) Bail in Absence

4.5 One of the main reasons for issuing a backed for bail warrant (rather than a no-bail warrant) is

that the defendant appears to have a justifiable excuse for non-attendance (e.g. illness or lack of

knowledge of the court date). However, in some criminal justice areas, Courts will simply ‘enlarge

bail’ (also known as ‘extend’ bail and ‘bail in absence’) under the MCA 1980 s.129(3)

(supplemented by s.43(1)), by informing the defendant by letter (known as an adjournment

notice) of the new court date. This course of action is only possible if the defendant has been

bailed previously.

4.6 Where an adjournment notice is sent to the defendant, there is no requirement in the Criminal

Procedure Rules to show that it came to his or her knowledge or, alternatively, that it was sent by

recorded delivery or registered letter to his or her last known address. It is merely necessary to

satisfy the Court that the defendant had ‘adequate notice’ of the adjournment date (MCA 1980,

s.10(2). Most Courts require service of an adjournment notice to be proved as strictly as service

of a summons

4

, but some are willing to proceed on less full evidence.

4.7 That said, if delivered by post, there is no guarantee that the adjournment notice will be received

by the defendant. By contrast, an executed backed for bail warrant does offer the certainty that

the defendant was made aware of the new court date.

4.8 One of the advantages of an adjournment notice is that an earlier new court date can be set

than would be the case if a backed for bail warrant were issued, because of the expectation of

earlier delivery with the postal system. If the defendant answers the ‘enlarged bail’ then he or she

will generally be back in court more quickly than if a backed for bail warrant had been issued. Bail

in absence negates the need to issue a warrant thus saving on executing agency resources, while

still essentially resulting in the same outcome as a backed for bail warrant.

4.9 A variant on the practice described above of enlarging bail is for the Court to issue a defendant

warning letter. OCJR issued guidance in March 2006 (ref GDC 18) aimed at encouraging Courts

to consider sending letters instead of issuing backed for bail warrants, particularly where a

defendant fails to appear in answer to a summons (and the Court decides not to proceed in

absence). The Senior Presiding Judge, Lord Justice Thomas, wrote to colleagues in May 2006 in

support of this approach, highlighting the need to deal robustly with the defendant if they failed

to appear in answer to the letter, either by proceeding in absence or issuing a warrant not backed

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 9

4

A summons ma

y be ser

v

ed on a person by:

(a) personally delivering it to him;

(b) leaving it for him with another person at his last known or usual place of abode;

(c) posting it to his last known address or usual abode (CrimPR, r. 4.1(1))

for bail

5

. Such letters are already being used by a number of areas and, although there is a dearth

of evaluative evidence, some areas report the results have been positive.

(ii) Trials and Sentencing in Absence

4.10 One way of reducing the number of warrants issued, whether backed for bail or otherwise, is, in

appropriate cases to try and sentence the defendant in their absence. If the defendant does fail to

appear, the Court is within its right to proceed in his or her absence under the MCA 1980

s.11(1), as highlighted in the then Lord Chief Justice’s Practice Direction of February 2004.

The Practice Direction has 3 key strands:

●

the Court should seek to deal with the Bail Act offence, even if the “main” offence cannot be

dealt with at that time, and a separate sentence should be imposed for the Bail Act offence;

●

when the Court cannot deal with the main offence at the same time as the Bail Act offence, it

should carefully consider whether to revoke bail or to impose more stringent bail conditions;

●

the Court should consider trying a defendant in his or her absence in appropriate cases.

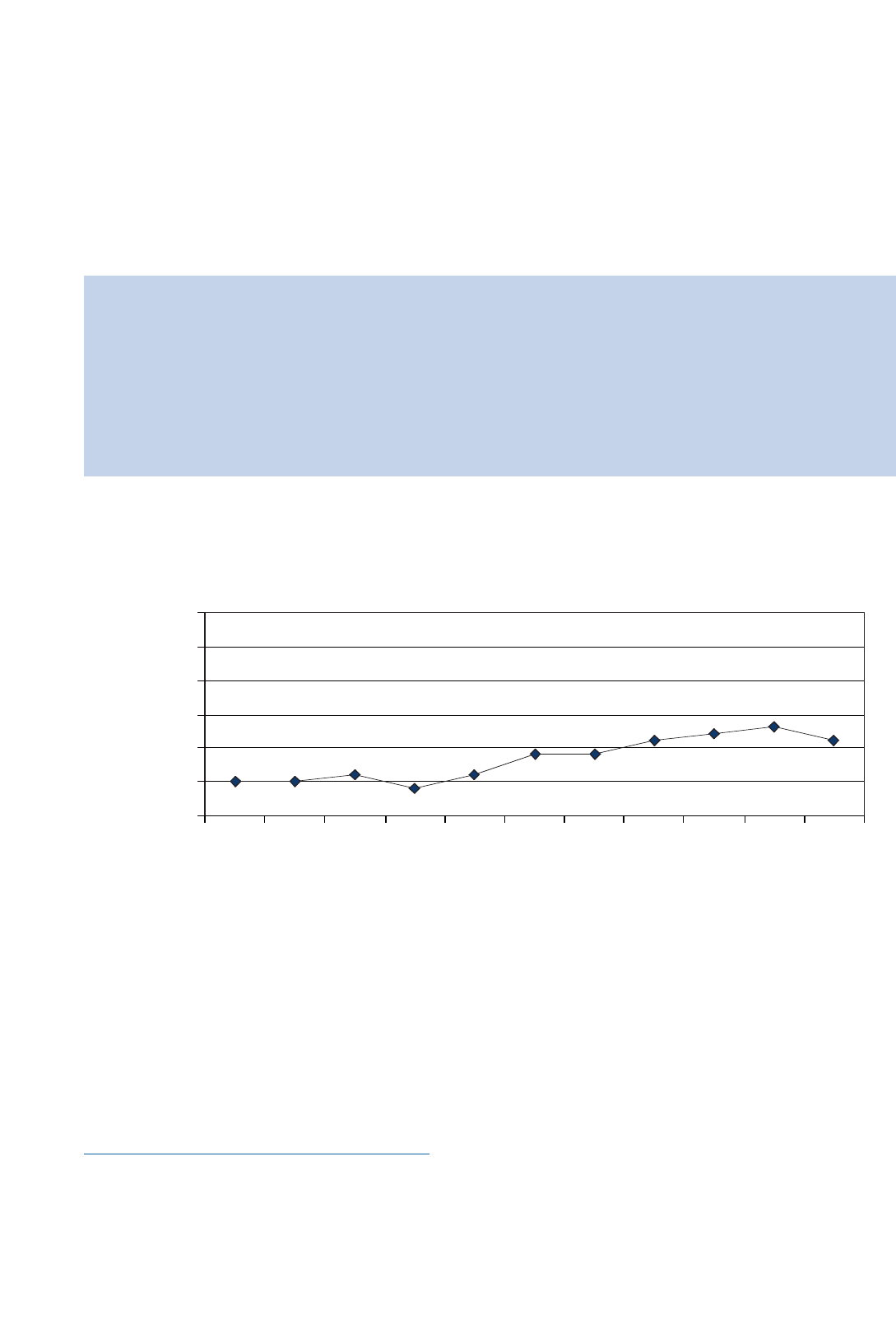

4.11 Data are now being collated from each criminal justice area on the proportion of trials

proceeding in absence in magistrates’ courts. This shows an overall increasing trend in trials in

absence at a national level, although there are regional variations.

4.12 As well as trying the case in absence, the Court may, if it finds the defendant guilty, sentence in

absence.

6

This also helps reduce the need to issue a warrant; a warrant may still need to be

issued after a conviction or sentence in absence, but the numbers issued are reduced as they

relate to the end of a process, not the beginning.

4.13 The project will investigate areas with a high proportion of trials in absence and identify the

drivers for this. If replicable and appropriate, these approaches can then be promoted in other

areas directly and through promulgation of the overall findings of the project.

60%

65%

70%

75%

80%

85%

90%

Sep-

05

Oct-

05

Nov-

05

Dec-

05

Jan-

06

Feb-

06

Mar-

06

Apr-

06

May-

06

Jun-

06

Jul-

06

Month

10 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

5 “there may be little to be gained by the issue of a warrant backed for bail in such circumstances (In cases where (1) a defendant does not attend, (2) the court decides not to proceed

in absence and (3) the court is considering issue of a warrant backed for bail). Furthermore its execution is not accorded the highest priority; such warrants are, I understand, sometimes

vie

wed as consuming a dispropor

tionate amount of police resource.

If the def

endant does not attend the rear

r

anged hear

ing without good reason, the court should then consider proceeding in absence or issuing a warrant not backed for bail. Unless

there were unusual circumstances, any other course of action would undermine the process. The letter to the defendant should make it clear that, if the defendant did not attend the

rearranged hearing, a court might well proceed in absence or issue a warrant not backed for bail.”

6

There are different approaches to this in different Courts, particularly as regards disqualification for driving.

(iii) Bail history

4.14 Consultation with practitioners suggests that some defendants with a poor bail history are being

issued with backed for bail warrants. There is no evidence that the Court is ignoring bail history,

rather this points to a lack of information being available to the Court at the time they make the

decision to issue the warrant.

4.15 OCJR is currently working on a separate project aimed at ensuring that sufficient information is

presented to the Court to ensure they can make an informed bail/remand decision in the first

instance. The two issues are clearly linked and so the project will be widened to focus also on

improving the information available to the Court in relation to the issuing of warrants.

4.16 The development of the

Criminal Justice – Simple, Speedy, Summary programme

7

and various IT

projects (Libra, NES IT) are also likely to have a positive impact on improving information flows

to the Court.

IT developments

LIBRA

LIBRA is the new magistrates’ courts’ IT system. It has the potential to improve bail information,

including the provision of information on the breakdown of conditional bail, a defendant’s non

attendance at court and a defendant’s attendance record. Roll-out is due to re-commence in

January 2007 in pockets of areas. At present there is no end date.

NATIONAL ENFORCEMENT SERVICE (NES) IT

The NES warrant management tool that is currently under development will allow a much clearer

view of a defendant’s bail history as well as other outstanding enforcement issues. It is anticipated

that the NES tool will be progressively rolled out from April 2007 but full functionality may take

until 2008.

Legislation

4.17 In addition to the good practice project (and linked to trials and sentencing in absence), the

Government has also announced an intention to legislate:

(i) to create a statutory presumption that, where a defendant fails to attend for trial at a

magistrates’ court without good reason, the Court should try (and, if convicted, sentence) him

in his absence, unless to do so would be contrary to the interests of justice; and

(ii) to remove the prohibition (MCA 1980 s.11(3)) on magistrates’ courts imposing a custodial

sentence on an offender who has been tried in absence and convicted, except where the

proceedings were commenced by summons or written charge.

4.18 Once enacted any such legislation should encourage the increasing trend in trials and sentencing

in absence, in tandem with the approach identified in paragraph 4.13.

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 11

7 “Deliver

ing Simple

,

Speedy

, Summary Justice”

Depar

tment f

or Constitutional

Affair

s, July, DCA 37/06

One of the main pieces of work under CJSSS is streamlining magistrates’ court proceedings. An important aspect of this is to ensure that all the necessary and relevant

information is collected in time for the first hearing, to enable cases to be resolved at the earliest possible opportunity. New processes aimed at achieving this are currently

being tested in various pilot areas, prior to national roll-out.

12 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

5.1 The identification and dissemination of good practice, and legislation on trials and sentencing in

absence as set out in Chapter 4 of this paper, are two ways of reducing the use of backed for bail

warrants. This chapter seeks views on another potential approach, of introducing further

legislation explicitly aimed at restricting the use of such warrants.

5.2 Five potential legislative options are set out below. In considering which might be the most

appropriate option, it is important to ensure that it requires a response from the Court that is

not disproportionate to the actions of the defendant.

(i) Remove entirely the Court’s power to issue a warrant backed for bail

5.3 Removing the Court’s power to issue a backed for bail warrant would restrict their use completely.

However, it could result in disproportionate responses from the Court. If a defendant failed to

appear and the Court decided against proceeding in absence, they would be left with two choices,

namely bailing in absence (possibly through a defendant warning letter) or issuing a no-bail

warrant. In the case of a minor offence, but one where there is no reason to believe the defendant

has a reasonable excuse for not appearing, neither response is desirable. Bailing in absence may not

be sufficiently robust, whereas a no-bail warrant might be disproportionately severe.

5.4 Backed for bail warrants may be the correct response in certain circumstances and this approach

would seem to be a step too far.

(ii)

Restrict the Cour

t’s po

wer to issue backed for bail warrants when the

substantiv

e offence is ‘serious’

5.5 Another option would be to restrict the power to issue backed for bail warrants on the basis of

the seriousness of the substantive off

ence.

5.6 Around 5% of warrants subsequently prioritised by the police as Category A or B were backed

for bail when issued by the Court. (This represents about 4500 warrants a year). This appears

inconsistent with ensuring that the more serious cases are prioritised by returning the defendant

to court as quickly as possible. However the majority (approximately two thirds) of these

category A and B warrants are so prioritised by the police not because of the seriousness of the

offence but because of the defendant’s past offending behaviour or considerations under the

National Intelligence Model, of which the Court may not be a

ware.

5.7 It is also likely that, in many cases, backed for bail warrants are issued in relation to defendants

charged with serious offences because the Court believes the defendant may have a legitimate

reason for absence. The good practice model project, outlined in Chapter 3, looks to encourage

the use of bail in absence in such cases.

Chapter 5: What more could be

done to further restrict the use

of backed for bail warrants?

5.8 In order to legislate in this way, there would need be a statutory definition of seriousness in this

context. To implement on the basis of seriousness of offences requires a clear objective basis for

the selection of offences. There are a number of options:

(a) Defining seriousness on the basis of the ACPO/OCJR Warrant Priority Matrix, which is used

subsequently by the police to prioritise the warrant. This is an operational tool agreed by CJS

partners, with no legal status, and it would be problematic to replicate it in statute. In addition, it

does not provide the robust objective basis which would be required. This option is unlikely to

have a significant impact, in that only 1,500 backed for bail warrants per year are currently

categorised as A or B.

(b) Defining seriousness in terms of ‘indictable only’ offences. This would ensure the focus was on the

top end of the range of serious offences but would not catch some that can be tried either way,

such as certain drugs or sexual offences. As with the first option, the impact is likely to be limited, as

it is arguable that these defendants would already attract no-bail warrants if they failed to appear.

(c) Defining seriousness in terms of the maximum sentence which the substantive offence attracts

(over ‘x’ years). This would ensure more offences were covered than under option (b) but would

mean that some offences would be captured even when, on the facts, they were not particularly

serious. The impact of such a provision would depend on the threshold that was set: the lower

the threshold, the greater the impact but the greater the chances of disproportionate outcomes.

(d) Specifying the relevant substantive offences on the face of legislation, as in the schedule of Qualifying

Offences for Retrial of Serious Offences in the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (see annex B). This would

help avoid some of the disadvantages of the other options, but would not remove all risk of

anomalies. Careful consideration would have to be given as to which offences should be included.

5.9 There is little evidence on which to base a robust impact assessment of these various options.

Significant further work would be required to gather this evidence, including data captures from

warrant management systems and considerable trawling, cleansing, organising and analysis of

information. This will be undertaken as part of the good practice project, with a view to

informing future consideration of legislative options.

(iii)

Restrict the Court’

s power to issue backed for bail warrants when the

defendant is deemed ‘serious’ (although the substantive offence may be

minor)

5.10 Another option is to restrict the use of backed for bail warrants by reference to the defendant,

rather than to the substantive offence.

5.11 Where a warrant is categorised as A or B but the substantive offence is not deemed serious, it is

almost invariably because of the previous offending nature of the defendant, for example, they

have been identified by the agencies as a Prolific and Priority Offender (PPO). However, PPOs are

not defined in statute, and indeed, the definition varies across the country according to local

priorities and problems. Moreover, at present the Court will generally not be made aware of an

individual’s offender status as it could be prejudicial.

5.12 Furthermore, it is arguable that a backed for bail warrant is a proportionate response to a minor

offence, irrespective of the defendant’s previous offending behaviour. In short, the defendant is

being bailed in relation to the current offence, not previous offences.

5.13 For these reasons, this is not considered to be a viable option.

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 13

(iv) Restrict the Court’s power to issue backed for bail warrants when the

defendant has a poor bail history

5.14 A stronger argument can be made that a defendant with a history of failing to attend should not

be given a warrant backed for bail. Prosecutors currently have the opportunity to oppose the

issuing of a backed for bail warrant if they believe the defendant’s bail history suggests that a no-

bail warrant would be more appropriate.

5.15 Defining what constitutes poor bail history may be problematic, particularly as the circumstances

of each case will be different. It might be possible to introduce a provision which stated that the

likelihood of absconding should be taken into account before issuing a backed for bail warrant (in

a similar manner to the provisions in the Bail Act 1976 which govern the decision whether to

grant bail). This would ensure that the Court consciously took bail history into account in

deciding what kind of warrant to issue.

5.16 However, anecdotal evidence suggests that although backed for bail warrants are on occasion

issued in relation to defendants with a history of non-attendance, this generally occurs because

the Court is not made aware of the defendant’s bail history rather than because the Court

knowingly fails to take that history into account.

5.17 This suggests that legislation alone would not be the best way of addressing the problem, without

first tackling the root cause by ensuring that the appropriate information is available at the time

the warrant is issued.

(v)

Remove the Court’s power to issue repeat backed for bail warrants in the

same proceedings

5.18 This is a more tightly defined variant of the option described in (iv) above, removing the power

to issue a back

ed for bail warrant specifically where a previous backed for bail warrant had been

issued and executed in the same proceedings.

5.19 Such an approach would seem logical, and there would seem to be no practical problems in

legislating in this way. However, it is unlikely that this would have a very significant impact in

practical terms. There is no quantitative evidence to suggest that Courts are issuing repeat

backed for bail warrants in relation to the same proceedings, although the issue has been raised

occasionally by police practitioners.

5.20 Again, further work would be needed to gather the necessary evidence to project the potential

impact of this legislative option. This would take some time to complete as this information is not

readily available from electronic systems, and a dip-sampling exercise would need to be

undertaken.

Consultation questions

5.21 As indicated above, there is very limited existing evidence to project the impact of any of these

legislative options.What little there is suggests that the changes would have only a limited impact

on restricting the use of backed for bail warrants. Further evidence will be gathered as part of the

ongoing good practice project.

14 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

5.22 Based on the analysis in earlier chapters and the legislative options highlighted in this chapter, this

consultation seeks views from respondents on:

Question 1: Would further legislation, along the lines outlined at options (i) to (v)

above, help in further restricting the use of backed for bail warrants?

Question 2: If so, which of the five legislative options outlined above is likely to be

most effective in further restricting the use of backed for bail

warrants, and why?

Question 3: Should the decision whether to legislate and, if so, which option to

choose, be postponed until further evidence of likely impact is

available as a result of the good practice work currently being

undertaken?

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 15

16 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

The warrant priority matrix offers clarity on the timescales within which warrants should be

executed as well as guidance on which agency should be responsible for the execution. The

categorisation of warrants (A, B or C) only applies to Fail To Appear (FTA) warrants as does their

associated timescales.

Whilst it is LCJBs that are held responsible for the achievement of targets rather than individual

agencies – it is right that any LCJB may approach warrants execution differently and therefore might

have their own local arrangements. One of the key principles of the National Enforcement Service is

that the right agency should execute the right warrant and although we should aim for consistency as

per the matrix, execution might differ according to local needs.

In cases where HMCS are deemed to be the lead executing agency, it is always the case that risk to the

executor may cause that warrant to be handed to the police for their execution. Local arrangements

will determine how that risk assessment would operate.

Inspector Gail Spruce Inspector Kevin Keen

ACPO (Disposal and Enforcement portfolio) National Enforcement Service

0161 856 1338 0207 2100561

gail.spr[email protected].uk Kevin.keen@HMCourts-Service.gsi.gov.uk

Annex A: Warrant Priority Matrix

– ACPO/OCJR

●

For execution by CEO subject to risk assessment

CEOCAny FTA warrant issued with bail

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCEONon Payment of Fine

CEOCFTA – Non Crime matters

●

See appendix A for guidance on executionCEOsCommunity Penalty Breach Warrants

(Magistrates Court)

●

See appendix A for guidance on execution

PoliceCommunity Penalty Breach Warrants

(Crown Court)

PoliceBFTA – Other crime matters

●

This information should be found on PNC or local

intelligence systems

PoliceAFTA – Registered Sex Offenders – Probation

defined “Dangerous Offender”

●

See appendix C for ACPO definitionPoliceAFTA – Hate Crime

●

As per national definition (see appendix C for list of

definitions)

PoliceAFTA – Persistent Young Offender

●

As defined by local PPO Strategy (see appendix C for list

of definitions)

PoliceAFTA – Prolific or Priority Offender

●

See attached appendix C for list of offencesPoliceAFTA – Serious Offence

●

This is intended for the most serious offences or those

other offences that have the greatest priority for the

Force

PoliceAFTA – Any offender involved in criminality

defined in the Forces NIM control strategy

●

This is intended for the most serious offences or those

other offences that have the greatest priority for the

Force

PoliceAFTA – Any Offender subject of the Forces

National Intelligence Model (NIM) control

Strategy*

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 17

Warrant Type Category Enforcement Comments

Lead Owner

18 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCEOWarrant of Arrest and Commitment –

Community Charges

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCEOWarrant of Arrest and Commitment –

Non Domestic Rates

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelines

CEOWarrant of Arrest and Commitment –

Council Tax

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCEOWarrant of Commitment – Child Support

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCEOWarrant of Commitment

●

Execution timescale as defined by current CEO guidelinesCertified BailiffWarrant of Distress

Warrant Type Category Enforcement Comments

Lead Owner

Appendix A

Execution Timescales for FTA warrants

Enforcement Officers (Police, Police CEO, Court CEO) should execute the warrant as soon as

practicable but should as an absolute minimum make every effort to execute in the timescales below.

Category A – within 14 total days.

Category B – within 21 total days.

Category C – within 28 total days.

Any FTA warrant that covers more than one category should retain the higher status ie a category C

warrant for a PYO should become a category ‘A’ and be executed in the 14 day timescale.

Relevant timescales for Community Penalty Breach Warrants (CPBW)

Community Penalty Breach warrants differ to FTAs in that the target measured is not the execution

timescale for the warrant.

The targets relating to Community Penalty Breach Warrants are:

●

Proceedings should take an average of 35 working days from second unacceptable failure to comply

to resolution of the case and

●

50% of all breach proceedings to be resolved within 25 working days of the second failure to

comply

Resolution’ includes the time taken to initiate breach proceedings, obtain and execute the warrant, hear

the case at court, adjourn where necessary and then finalise.

Although the timeframe for execution of the warrant is not the target there are

recommended

timescales from warrant issue to execution in order to enable the overall resolution target to be

achieved.

CBPW are either fast tracked (timescales roughly equivalent to an FTA category A) or standard

(timescales equating roughly to a category C FTA).

Adults Youths

Standard 20 working days (28 total) 10 working days (14 total)

Fast track 10 working days (14 total) 5 working days (7 total)

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 19

Appendix B

Categorisation of warrants

Categorisation of a warrant is the process that determines the executing agency and the timescales

that it should be executed in. Some of the factors to be considered are the risk to the public and the

intelligence value. Where an offender has committed a serious offence they should be monitored and

managed by the police. When a targeted offender comes to light, the police should control the warrant

as there is intelligence that can be gathered by which to manage that case and the offender’s behaviour.

If the offence or the offender is low level then the warrant should be managed by HMCS

CPBW that are fast tracked need not automatically default to the police for execution hence HMCS

remain as the lead agency. To ensure the principle of ‘the right agency executing the right warrant’ any

CPBW should only be handed to the police where there is a risk of danger to the executor or where

specifically requested because the offender or offence is identified as a target by the relevant police

area (as identified using NIM).

Health and Safety Risk Assessment

Each agency should undertake generic health and safety risk assessments of operational business to

ensure that staff are properly trained equipped and briefed.

In the case of category C warrants managed by HMCS, in addition to generic assessment of the

business the health and safety risk assessment is likely to be dynamic or situational (ie the circumstances

faced on the doorstep) rather than individual intelligence packages.

The health and safety risk assessment undertaken prior to execution of the warrant is intended to

identify extenuating circumstances that may be present and to inform the tactics that can be

appropriately employed.

Any warrant initially issued to HMCS staff that is deemed to present an unmanageable health and safety

risk should transfer to the police. Grade A or B warrants with a low health and safety risk can be

undertaken by CEOs (though this is only likely to be in exceptional circumstances).

Where a cross border warrant is being sent to another force it is essential that a health and safety risk

assessment is completed prior to the warrant being sent and details recorded on the proforma (see

GDC 20, or email FTAwarr[email protected].uk for a copy of the form). There may be local intelligence

or issues that might not be known to the receiving force and for the safety of our colleagues we must

ensure that this information is communicated to them. If there are no known risks then similarly this

must be indicated otherwise it will not be clear to the receiving force if a health and safety risk

assessment has been done.

A risk assessment/intelligence package should include the following:

●

Identification of any warning signs using the PNC

●

Scanning of local intelligence to identify potential warning signs and other useful information

●

For breach warrants – an evaluation of the offender should have been done by the Probation

Service (OAIS – ‘offender additional information sheet’) and provided to the issuing court for

onward transmission to whoever seeks to execute the warrant-check the availability of this with the

probation area associated with the court issuing the warrant .You may be able to negotiate a local

protocol to ensure that probation will automatically provide this information to you.

20 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

Although a risk assessment will be done by the sending force (and risk/warning detail

recorded on the proforma) the receiving force MUST still check its own intelligence

systems and PNC for any additional risk information.

It is the responsibility of the individual executing the warrant to ensure that it is still

live before an arrest is made.

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 21

Appendix C

Definitions

Serious Offences

The term ‘serious arrestable offence’ no longer exists within the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984

as amended (PACE). The matrix has now been revised to include as category A offences, those

deemed ‘

serious’. These are largely the same as before but with some additions.

The following offences should be categorised as ‘A’

●

Treason

●

Murder

●

Manslaughter

●

Rape

●

Other serious sexual assault

●

Kidnapping

●

An offence under section 3, 50(2), 68(2) or170 of the Customs and excise Management Act 1979

●

Cause explosion likely to endanger life or property

●

Possession of firearms with intent to injure

●

Use of firearm/imitation firearm to resist arrest

●

Carrying firearms with criminal intent

●

Hostage taking

●

Hijacking

●

Torture

●

Cause death by dangerous driving

●

Cause death by careless driving under influence of drink/drugs

●

Offences under the Aviation and Maritime security act 1990

●

Offences under the Channel Tunnel Security Order 1994

●

Protection of Children Act 1978 – indecent photographs of children

●

Publication of obscene matter

●

Offences under Sexual Offences Act 2003

●

Production, Supply and Possession for supply of controlled drugs

●

Offences under the Criminal Justice Inter

national Co-operation Act 1990

●

Terrorism offences

We should also include as ‘serious offences’ any conspiracy to commit, attempt, aid, abet, counsel or

procure any of the above.

Other offences may also be classed as serious if their consequences are as per the following list. Such

cases will be rare and it is possible that the individual grading the warrant will not have this information.

22 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

If this information is not clearly known to the person grading the warrant then the warrant would be

graded B or C as appropriate.

●

serious harm to the security of the state or public order

●

serious interference with the administration of justice or investigation of an offence,

●

the death or serious injury of a person

●

substantial financial gain or loss to a person

As an example, a traffic offence that would otherwise have been minor and classed as a category C

should be graded as an A where the consequences have led to the death or serious injury of a person.

Prolific or priority offender

There is no national definition but guidance states;

Individuals to be targeted should be selected locally, using the National Intelligence Model (NIM), to

identify those who are causing the most harm to their communities based on local priorities. These are

likely to be NIM level 1 type offenders.

The general criteria to be used in selecting the individuals should be:

●

the nature and volume of the crimes they are committing;

●

the nature and volume of other harm they are causing (e.g. as a consequence of their gang

leadership or anti-social behaviour);

●

other local criteria, based on the impact of the individuals concerned on their local communities.

Persistent Young Offender

A Young person aged 10-17 years, sentenced by a criminal court in the UK, on 3 or more separate

occasions, for 1 or more recordable offence and within 3 years of the last sentencing occasion has been

arrested (or information laid) for another. recordable offence.

Hate Crime

A hate crime is defined as any hate incident that constitutes a criminal offence, perceived by the victim

or any other person, as being motivated by prejudice or hatred.

National Intelligence Model

This model allows information to be categorised and policing activity to be planned based on

intelligence. Intelligence is gathered from different sources including partner agencies, crime reports and

stop and account/search forms and is then used to identify current and future problem areas and to

target persistent offenders.

Areas will have in place strategic (force or local) priorities identified by using the ‘NIM’ (this may be

referred to as a control strategy).

By applying this model your local area will ha

ve identified either specific individuals who are targets for

the police or certain offences that are a priority to your area.

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 23

24 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

List of offences for England and Wales

Offences Against the Person

Murder

1 Murder.

Attempted murder

2 An offence under section 1 of the Criminal Attempts Act 1981 (c. 47) of attempting to commit

murder.

Soliciting murder

3 An offence under section 4 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 (c. 100).

Manslaughter

4 Manslaughter.

Kidnapping

5 Kidnapping

Sexual Offences

Rape

6 An offence under section 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (c. 69) or section 1 of the Sexual

Offences Act 2003 (c. 42).

Attempted rape

7 An offence under section 1 of the Criminal Attempts Act 1981 of attempting to commit

an offence under section 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 or section 1 of the Sexual Offences

Act 2003.

Intercourse with a girl under thirteen

8 An offence under section 5 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956.

Incest by a man with a girl under thirteen

9 An offence under section 10 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 alleged to have been committed

with a girl under thirteen.

Annex B: Schedule of Qualifying

Offences for Retrial of Serious

Offences in the Criminal Justice

Act 2003

Assault by penetration

10 An offence under section 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (c. 42).

Causing a person to engage in sexual activity without consent

11 An offence under section 4 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 where it is alleged that the activity

caused involved penetration within subsection (4)(a) to (d) of that section.

Rape of a child under thirteen

12 An offence under section 5 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

Attempted rape of a child under thirteen

13 An offence under section 1 of the Criminal Attempts Act 1981 (c. 47) of attempting to commit

an offence under section 5 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

Assault of a child under thirteen by penetration

14 An offence under section 6 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

Causing a child under thirteen to engage in sexual activity

15 An offence under section 8 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 where it is alleged that an activity

involving penetration within subsection (2)(a) to (d) of that section was caused.

Sexual activity with a per

son with a mental disorder impeding choice

16 An offence under section 30 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 where it is alleged that the

touching involved penetration within subsection (3)(a) to (d) of that section.

Causing a person with a mental disorder impeding choice to engage in sexual activity

17 An offence under section 31 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 where it is alleged that an activity

involving penetration within subsection (3)(a) to (d) of that section was caused.

Drugs Offences

Unlawful importation of Class A drug

18 An offence under section 50(2) of the Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 (c. 2) alleged

to have been committed in respect of a Class A drug (as defined by section 2 of the Misuse of

Drugs Act 1971 (c. 38)).

Unlawful exportation of Class A drug

19 An offence under section 68(2) of the Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 alleged to

have been committed in respect of a Class A drug (as defined by section 2 of the Misuse of

Drugs Act 1971).

Fraudulent evasion in respect of Class A drug

20 An offence under section 170(1) or (2) of the Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 (c. 2)

alleged to have been committed in respect of a Class A drug (as defined by section 2 of the

Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (c. 38)).

Producing or being concerned in production of Class A drug

21 An offence under section 4(2) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 alleged to have been committed

in relation to a Class

A drug (as defined by section 2 of that Act).

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 25

Criminal Damage Offences

Arson endangering life

22 An offence under section 1(2) of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 (c. 48) alleged to have been

committed by destroying or damaging property by fire.

Causing explosion likely to endanger life or property

23 An offence under section 2 of the Explosive Substances Act 1883 (c. 3).

Intent or conspiracy to cause explosion likely to endanger life or property

24 An offence under section 3(1)(a) of the Explosive Substances Act 1883.

War Crimes and Terrorism

Genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes

25 An offence under section 51 or 52 of the International Criminal Court Act 2001 (c. 17).

Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions

26 An offence under section 1 of the Geneva Conventions Act 1957 (c. 52).

Directing terrorist organisation

27 An offence under section 56 of the Terrorism Act 2000 (c. 11).

Hostage-taking

28 An offence under section 1 of the Taking of Hostages Act 1982 (c. 28).

Conspiracy

Conspiracy

29 An offence under section 1 of the Criminal Law Act 1977 (c. 45) of conspiracy to commit an

offence listed in this Part of this Schedule.

26 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation 27

Prison population

There is no evidence to suggest that restricting the use of backed for bail warrants will have a direct

impact upon prison places. It is possible that the proposals will both reduce the number of warrants

issued (through use of bail in absence, trials in absence) and also increase the number of no-bail

warrants.

When an individual appears in court following the execution of a warrant, the Court may not be able

to proceed immediately and may adjourn to a future date. There is no evidence to suggest that an

individual produced from police custody (following the execution of a no-bail warrant) is more likely to

be remanded in custody for a subsequent hearing than an individual who has been bailed to attend

court (following the execution of a backed for bail warrant).

Police custody suites

Restricting the use of backed for bail warrants will have an impact on police custody suites if the

alter

native is to issue more no-bail warrants. However, the impact would be lessened if the use of bail

in absence and defendant warning letters were encouraged as an alternative.

Although there is a lack of sufficient evidence to model the impact accurately, the following set of

assumptions gives an idea of how man

y extra custody places may be needed.

It is assumed that no more than 5,000 of the 40,000 backed for bail warrants will become no-bail

warrants (it is assumed that a number will result in no warrant outcomes). Of these, it is assumed that

4,750 (95%) will be executed within 12 months of issue. Of these, it is reasonable to assume that no

more than 50% of defendants will be required to spend a significant time in police custody which they

would otherwise not have done (taking into account that many warrants are executed when an

individual is arrested on other matters). Assuming each defendant spends one night in custody, this

means that approximately 2,375 extra custody places a year will be required throughout England and

Wales. This works out, on average, as 6.5 extra cell places per night.

There are over 6,000 police custody places in England and Wales, which suggests that the system

should be able to bear the extra pressure.

Annex C: Impact assessment:

prison places and police cells

28 Rebalancing the Criminal Justice System in favour of the law-abiding majority: Consultation

Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

Sir Igor Judge, President of the Queen’s Bench

Senior Presiding Judge

Council of Her Majesty’s Circuit Judges

Senior District Judge

Magistrates’ Association

Criminal Bar Association

General Council of the Bar

Whitehall Prosecutors Group

Institute of Legal Executives

Her Majesty’s Courts Service

Crown Prosecution Service

Association of Chief Police Officers

Association of Police Authorities

Justices’ Clerks’ Society

National Offender Management Service

National Enforcement Service

Local Criminal Justice Board representatives

Law Society

Legal Services Commission

Annex D: List of persons and

bodies consulted