Authors:

Triona Fortune, Elaine O’ Connor and Barbara Donaldson

Guidance on Designing

Healthcare External

Evaluation Programmes

including Accreditation

2015

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

I

Table of contents

Acknowledgements iii

Foreword ISQua iv

Foreword World Bank & WHO vi

List of Tables vii

Glossary of Terms viii

Introduction 2

Chapter 1: Why develop an external evaluation programme? 4

1.1 The growing demand for external evaluation in health and social care 4

1.2 Models of external evaluation 5

1.3 Benefits of external evaluation 8

1.4 Challenges for external evaluation programmes 10

Chapter 2: Establishing the fundamentals 12

2.1 Defining the purpose of the external evaluation programme 12

2.2 Defining the scope of the external evaluation programme 15

2.3 Establishing the role of government 18

2.4 Determining incentives 21

2.5 Developing relationships with stakeholders 24

Chapter 3: Setting up the external evaluation organisation 27

3.1 Establishing a preliminary board or advisory committee 27

3.2 Proposing a governance board and framework 28

3.3 Funding of the programme 30

3.4 Setting up strategic, operational and financial management systems 33

3.5 Timeframes 35

Chapter 4: Developing the standards 37

4.1 The role of standards 37

4.2 Principles for standards 38

4.3 Referencing to quality dimensions 39

4.4 Developing the measurement system 40

Chapter 5: Developing assessment methodologies 43

5.1 Selection, training and evaluation of surveyors 43

5.2 Developing the survey management process 46

5.3 Establishing the accreditation / certification process 48

5.4 Quality Assurance 51

Chapter 6: Evaluating systems and achievements 52

6.1 Measuring performance internally 52

6.2 Evaluating independently 53

6.3 Monitoring by regulatory agencies 53

6.4 Accrediting the external evaluation bodies 53

II

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Table of contents

Conclusions 54

References 55

Bibliography 58

Useful web resources 62

Appendix 1: Case Studies 64

Appendix 1a. Danish Case Study 64

Appendix 1b: Jordanian Case Study 67

Appendix 1c. New Zealand Case Study 69

Appendix 1d: Practice Incentive Program (PIP) 72

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

© 2015 Publisher: The International Society for Quality in Health Care, Joyce House,

8-11 Lombard Street East, Dublin 2, D02 Y729, Ireland.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

III

Acknowledgements

This document is based on the Toolkit for Accreditation Programs, 2004 developed by Charles

Shaw. The International Society for Quality in Health Care would like to thank the following for

their contributions to the development of this document:

Reviewers

Mark Brandon, AACQA - Australia

Stephen Clark, AGPAL - Australia

Heleno Costa Junior, CBA - Brazil

Carsten Engel, IKAS - Denmark

Eric de Roodenbeke, International Hospital Federation

Carlos Goes de Souza, CHKS - UK

Helen Healey, DAP BC - Canada

Salma Jaouni, HCAC - Jordan

Thomas Leludec, HAS - France

Hung-Jung Lin, JCT - Taiwan

Lena Low, ACHS - Australia

Kadar Marikar, MSQH - Malaysia

Wendy Nicklin, Accreditation Canada

BK Rana, NABH - India

Charles Shaw, Independent Consultant

Paul van Ostenberg, JCI - USA

Kees van Dun, NIAZ - The Netherlands

Stuart Whittaker, COHSASA - South Africa

Hongwen Zhao, WHO

Nittita Prasopa-Plaizier, WHO

Akiko Maeda, World Bank

Dinesh Nair, World Bank

Rafael Cortez, World Bank

A special acknowledgement to Akiko Maeda and the World Bank for supporting this project.

IV

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Foreword

Accreditation is an important tool for improving the care delivered by healthcare systems, and

one of the key roles of the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) has been to

accredit the accreditors. However, accreditation has to evolve to be beneficial. An increase in

requests - especially from developing economies - for advice on establishing an accreditation

programme prompted ISQua to review two of its major tools: the Toolkit for Accreditation

Programs, 2004

1

, and Checklist for Development of New Healthcare Accreditation Programs,

2006

2

. The last decade has seen considerable changes, worldwide, to healthcare systems

and external evaluation programmes. To reflect these changes, a revision to the existing

guidance was deemed inadequate and this new Guidance manual was therefore developed. We

believe this document will be suitable for a much wider audience; it is designed for countries,

governments and policy makers within public or private, primary, secondary or tertiary

healthcare systems. It is also intended as an aid for funding and development agencies such as

the World Bank, international aid agencies, the World Health Organization (WHO), Ministries of

Health, other government agencies, groups and organisations who want to improve the quality

and safety of healthcare in their country, region or specialty area.

It has now been almost 100 years since the first external evaluation programme, known as

accreditation, was established. Nearly every country currently has some form of external

evaluation, whether voluntary or mandatory. There are both “aficionados” and critics of

healthcare accreditation. Anyone who has dealt with accreditors coming into their site has

likely felt that they were arbitrary, or focused on things that were less than important. However,

accreditation gets organisations to pay attention to things they might otherwise prefer to ignore

or put off. While it is sometimes voluntary, following a series of adverse events policymakers

then change it to mandatory in response. While traditionally accreditation was a programme

for developed economies, developing countries are now equally as interested. This document

has extended its scope beyond healthcare accreditation programmes to include other external

evaluation programmes such as certification and licensing as they apply to organisations, not

individual practitioners. These programmes have different scopes and organisational coverage

but are based on the same principle of evaluating and improving performance against a defined

set of standards, using external evaluators, to improve the safety and quality of health services

for the public.

Accreditation is not a panacea to address all quality improvement issues but it can provide

a systematic approach that identifies areas where improvements are necessary, and when

mandatory, can “lift all the boats”, including some of the less strong entities within our

healthcare systems. When used with tools such as checklists and supported by technology, it

can become a powerful instrument for healthcare reform.

Developing an external evaluation system is a process that should be designed according to

each countries’ profile. Firstly, the purpose should be clear and secondly, depending on the

desired outcome, a decision should be made as to whether a voluntary or mandatory system

is appropriate. This document is not designed as a rigid guideline, rather as a diverse range

of practices which should be discussed. It includes advice on best practices for governance,

developing standards and assessment methodologies. It also includes real case studies from

both developed and developing countries.

Healthcare continues to evolve; some of the key changes occurring today are that populations

are ageing, while technology is becoming smarter and the relationships between providers

and patients are tilting so that patients are much more empowered, and they are becoming

our partners. We all need to strive to reach country specific and global goals such as the World

Health Organization’s mandate on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2020.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

V

Governments will ultimately be responsible for providing UHC and they will be required to

demonstrate efficient use of limited public funds while providing safe quality healthcare.

External evaluation systems can provide this assurance.

ISQua believes that accreditation can continue to be a powerful force for improvement in the

quality of care that is delivered. However, like all quality improvement initiatives, it must evolve

with the times to reflect the needs of our healthcare systems.

Professor David W. Bates

President International Society for Quality in Health Care

August 2015

VI

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Foreword

World Bank and the World Health Organization

The public has a growing awareness of and expectation for their healthcare to be accountable,

safe, of high quality and responsive to their needs. Globally, healthcare costs are rising, putting

increasing burdens on both governments and healthcare organisations, as they try to meet

the growing challenges with limited resources. Governments are working towards Universal

Health Coverage (UHC) as a way to ensure that their populations have equitable access to safe,

high quality services, without suffering financial hardship. The critical question remains: how

can countries maximise access whilst maintaining safe and quality services within affordable

margins?

External evaluation programmes, which include accreditation, certification and licensing of

healthcare institutions, are among measures that can help improve organisational efficiency and

effectiveness as well as the safety and quality of services. However, implementation of these

programmes is not uniform. This may be due to a lack of resources or expertise or, importantly,

due to a lack of operational ‘know-how’ on the implementation of such programmes.

This report aims to provide a practical guide for setting up an external evaluation programme

at both a national and an organisational level. It will help governments and policy makers to

identify and determine health systems’ priorities and gaps, so they can re-orient healthcare

systems and policies to meet such growing challenges. The report offers a range of approaches

and practical steps on the setting up of external evaluation programmes, including creating an

enabling environment and developing human and system capacities.

Better implementation of external evaluation programmes can contribute to improved safety

by requiring services to meet standards, and by encouraging quality improvement through

organisational and individual professional development. Such programmes, if adopted

and implemented appropriately and consistently, will contribute to a more resilient, more

accountable, and more effective healthcare system in the long run.

It is hoped that this report will encourage governments and healthcare organisations to adopt

and implement external evaluation programmes in order to achieve safe, high quality, resilient

and sustainable health systems and services.

Timothy Grant Evans

Senior Director

Health Nutrition and Population Global Practice

The World Bank Group

Marie-Paule Kieny

Assistant - Director General

Health Systems and Innovation

World Health Organization

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

VII

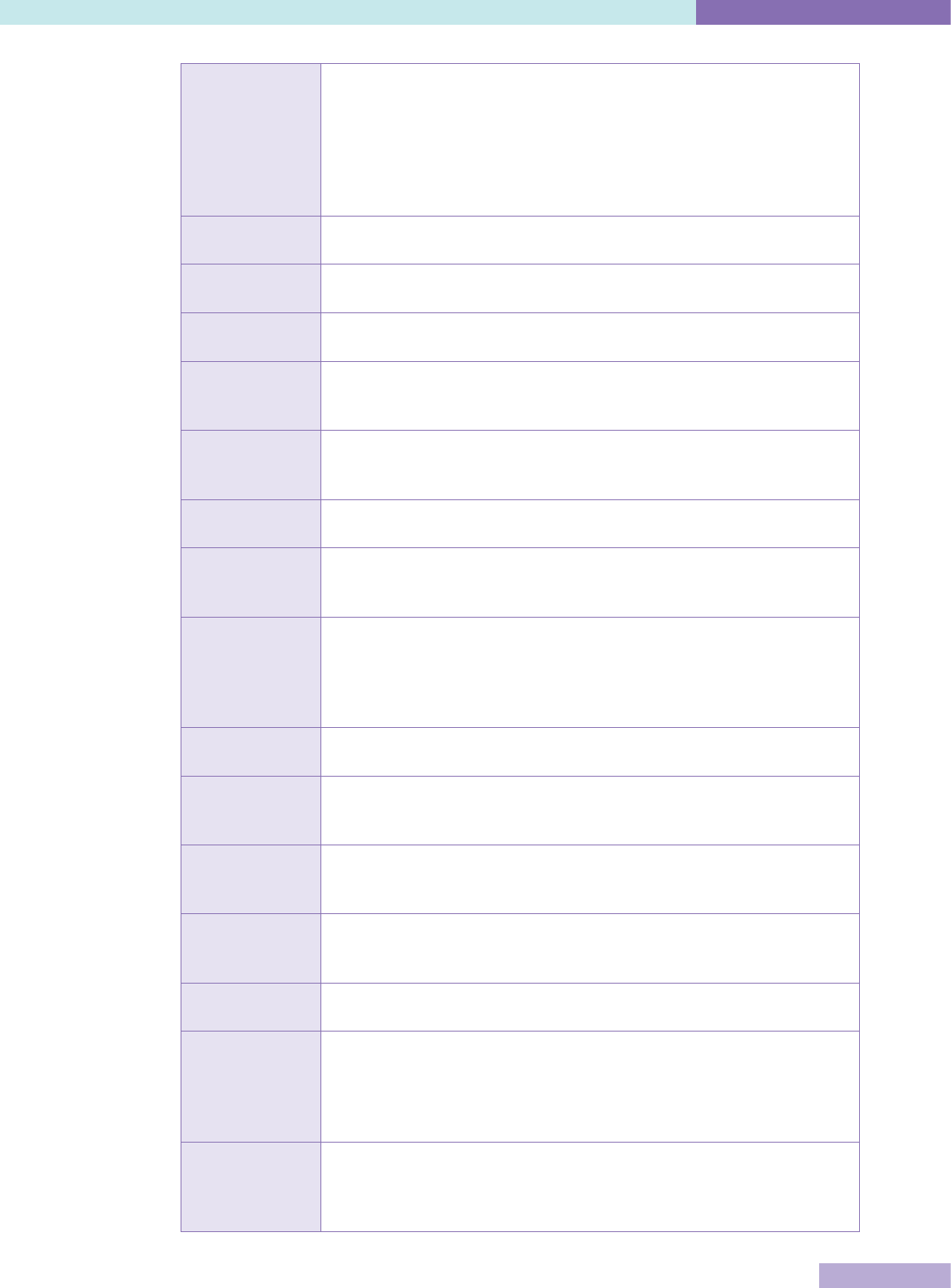

List of Tables

Table Page No.

Table 1: Definitions of accreditation, certification and licensing 8

Table 2: Comparison of capacity building and regulatory external evaluation 13

Table 3: Potential composition of a preliminary / interim board or advisory

committee

28

VIII

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Glossary of Terms

Accountability

Responsibility and requirement to answer for tasks or activities. This

responsibility may not be delegated and should be transparent to all

stakeholders.

Accreditation

A self-assessment and external peer review process used by health and

social care organisations to accurately assess their level of performance

in relation to established standards and to implement ways to

continuously improve the health or social care system.

Assessment

Process by which the characteristics and needs of patients, groups,

populations, communities, organisations or situations are evaluated or

determined so that they can be addressed. The assessment forms the

basis of a plan for services or action.

Assessor

Person who evaluates characteristics and needs. For external evaluation,

an assessor identifies and evaluates evidence that set criteria are being

met and makes recommendations for action to address any gaps. Also

auditor, surveyor, external evaluator.

Benchmarking

Comparing the results of services’ or organisations’ evaluations to

the results of other interventions, programmes or organisations, and

examining processes against those of others recognised as excellent, as a

means of making improvements. Also benchmark.

Certification

Process by which an authorised body, either a governmental or non-

governmental organisation (NGO), evaluates and recognises either an

individual, organisation, object or process as meeting pre-determined

requirements or criteria. The pre-determined requirements are set out in

standards which are developed specifically for the purpose of assessment.

The standards assess the performance of the organisation, object, process

or person, may focus on specific aspects of performance and may address

more than legal requirements.

Clients

Individuals or organisations being served or treated by the organisation.

Also patients, consumers, service users.

External

evaluation

Process in which an objective independent assessor gathers reliable

and valid information in a systematic way by making comparisons to

standards, guidelines or pathways for the purpose of enabling more

informed decisions and for assessing if pre-determined and published

requirements such as goals, objectives or standards have been met. An

organisation, object, process or individual may be assessed and evaluation

may be undertaken by peers, including organisations and professionals,

private professional auditors or consultants, purchasers / funders /

insurers, consumers / patients or governments.

Health Outcome

Health state or condition attributable to treatment, care or service

provided.

Leader

An individual who sets expectations, develops plans and implements

procedures to assess and improve the quality of the organisation’s

governance, management, clinical and support functions and processes.

Leadership

Ability to provide direction and cope with change. It usually involves

establishing a vision, developing strategies for producing the changes

needed to implement the vision, aligning people, motivating and inspiring

people to overcome obstacles.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

IX

Licensing

Process by which a governmental authority grants permission to an

individual practitioner or health and social care organisation to operate or

engage in an occupation or profession. Licensing regulations are generally

established to ensure that an organisation or individual meets minimum

standards to protect health and safety. The output of licensing is the

awarding of a document or licence allowing an organisation or person to

provide a service within a specified scope.

Medical tourism

Travel of people to another country for the purpose of obtaining medical

treatment in that country.

Organisational

peer assessment

A process whereby the performance of an organisation is evaluated by

members of similar organisations. Also peer review.

Outcome

standards

Standards which address the results, consequences or outcomes of the

performance and measurement of activities, systems and functions.

Patient

centredness

Focus on the experience of the patient / client from their perspective,

minimising vulnerability and maximising control and respect. Also patient

/ client focus.

Patient / Client

journey

The patient / client path through the care or treatment process – entry,

assessment, planning, delivery of care or treatment, evaluation, follow-up

and across services and providers. Also client continuum of care.

Process

standards

Standards which address the interrelated processes of different

organisational and clinical functions and activities.

Quality

improvement

Ongoing response to quality assessment data about a service, in ways

that improve the processes by which services are provided to clients. Also

continuous quality improvement (CQI).

Regulation

Is a form of external evaluation by which a body, who is authorised

by law, assesses an organisation or a person against pre-determined

requirements. The pre-determined requirements are derived from

legislation and therefore, the regulator may take a number of actions in

the event of non-compliance.

Risk mitigation

A systematic reduction in the extent of exposure to a risk and / or the

likelihood and consequences of its occurrence.

Self-assessment

A process by which an organisation evaluates its own performance against

set criteria or standards, identifies strengths and gaps, and plans actions

for improvement.

Standardisation

Process of developing and implementing technical, service or other

standards; that can help to maximize compatibility, interoperability, safety,

repeatability or quality.

Structure

standards

Standards which address the relatively stable characteristics of healthcare

providers, their staff, tools and resources, and physical and organisational

settings.

System

A set of interacting or interdependent processes forming an integrated,

whole function or activity.

Transparency

Operating in such a way that it is easy for others to see what actions

are performed; a principle that allows those affected by administrative

decisions, business transactions or charitable work to know not only the

basic facts and figures but also the mechanisms and processes. Usually

requires documented policies and procedures.

Universal health

coverage

The goal of all people having access to and obtaining health promotion,

preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need,

of sufficient quality to be effective, without suffering financial hardship to

avail of them.

2

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Introduction

The purpose of this document is to guide countries, agencies and other groups in the process of

setting up new health or social care external evaluation organisations or programmes. It is also

intended as an aid for funding and development agencies such as the World Bank, international

aid and technical cooperation agencies, World Health Organization, Ministries of Health, other

government agencies, groups and organisations who want to improve the quality and safety

of healthcare in their country, region or specialty area. It revises the International Society for

Quality in Health Care (ISQua) Toolkit for Accreditation Programs, 2004

1

, and ISQua Checklist for

Development of New Healthcare Accreditation Programs, 2006

2

. This document has extended

its scope beyond healthcare accreditation programmes to include other external evaluation

programmes such as certification and licensing as they apply to organisations, not individual

practitioners. These programmes have different scopes and organisational coverage but are

based on the same principle of evaluating and improving performance against a defined set

of standards or criteria, using external evaluators, to improve the safety and quality of health

services for the public.

Accreditation can be defined as a self-assessment and external peer review process used by

health and social care organisations to accurately assess their level of performance in relation

to established standards and to implement ways to continuously improve the health or social

care system. Certification is a process by which an authorised body, either a governmental or

non-governmental organisation, evaluates and recognises an organisation as meeting pre-

determined requirements or criteria. Licensing is a process by which a governmental authority

grants permission for a healthcare organisation to operate. Licensing regulations are generally

established to ensure that an organisation or individual meets minimum standards to protect

health and safety. For the purpose of this document we will refer to an accreditation body but

this includes any external evaluation programme as the principles remain the same.

The document refers mainly to healthcare organisations but is also applicable to social care

organisations. In it, the term external evaluation is used to cover accreditation, certification,

licensing and other standards based assessment programmes. The term survey is used to refer

to survey, assessment and audit. The term surveyor is used to include surveyors, assessors and

auditors.

Research and experience have identified the benefits of external evaluation programmes such

as improved organisational efficiency and effectiveness, improved safety and quality, better risk

mitigation, improved leadership, reduced liability costs, better communication and teamwork,

increased satisfaction of users and staff, and better patient care. However, there are challenges

in setting up these programmes. The principal threats to new external evaluation programmes

appear to be inconsistency of government policy, unstable politics, unrealistic expectations

and lack of professional / stakeholder support, continuing finance and / or incentives. The

effectiveness and sustainability of an external evaluation organisation or programme depends

ultimately on many variable factors in the particular healthcare environment of the country

or organisation involved. It also depends on the kind of programme concerned, and how it is

implemented.

To be sustainable, external evaluation programmes need ongoing government and / or private

support, a sufficiently large healthcare market size, stable programme funding, diverse

incentives to encourage participation, and continual refinement and improvement in the external

evaluation organisation’s operations and service delivery.

This guide addresses the variables of policy, organisation, methods and resources. It outlines

the reasons why an external evaluation programme might be developed, describes the different

models, and highlights the benefits and challenges associated with external evaluation.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

3

It then provides guidance on the steps that need to be taken in establishing a new external

evaluation organisation including:

Establishing the fundamentals of scope and purpose, and defining the important roles of

government and incentives in the external evaluation organisation / programme.

Setting up of the external evaluation organisational structure including: establishing an

advisory committee; developing relationships with stakeholders; designing a governance

framework; embedding the values of fairness and transparency; and getting outside

assistance and funding.

Establishing governance and management systems including: staffing; financial and

information systems; and risk management and performance improvement systems. It also

highlights the importance of allowing enough time for these stages.

Developing the standards to be used by the organisation and the system for measuring their

achievement.

Developing the surveyor and survey management systems including: the selection and

training of surveyors; the designing of processes and technology for managing surveys

and other events; developing and establishing education services; and determining and

establishing the process for awarding accreditation or certification status.

Integrating into all these systems and processes ways of measuring and evaluating

performance.

This document reflects the best practice guidelines and standards developed by the

International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) as part of its International Accreditation

Programme (IAP): ISQua Guidelines and Standards for External Evaluation Organisations, 4th

Edition Version 1.1, 2014

3

; ISQua Guidelines and Principles for the Development of Health and

Social Care Standards, 4th Edition Version 1.1, 2014

4

; and ISQua Surveyor Training Standards

Programme, 2nd Edition 2009

5

.

The appendices include case studies outlining how three different healthcare external

evaluation organisations were established. Two of the organisations featured are accreditation

organisations. The third featured organisation is an assessment organisation established

primarily to assess against government-mandated standards for compulsory certification.

Appendix 1d describes an Australian Practice Incentive Programme that demonstrates how

accreditation can be used as a lever to encourage quality improvement.

4

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Chapter 1: Why develop

an external evaluation

programme?

This chapter introduces what a healthcare external evaluation programme is; describes some

of the different models of external evaluation; outlines the benefits of such programmes; and

highlights the challenges which may be encountered in establishing such programmes.

1.1 The growing demand for external evaluation in health and

social care

There is growing worldwide demand, concern and focus on quality and safety in

healthcare. UUniversal Health Coverage (UHC) is now a key agenda item for the World

Bank and the World Health Organization and many countries have adopted or are about

to adopt this system of equal healthcare for all. The goal of universal health coverage is

to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial

hardship when paying for them. This requires:

A strong, efficient, well-run health system with good governance

A system for financing health services in an efficient and equitable way

Access to essential medicines and technologies and good health information

systems

A sufficient capacity of well-trained, motivated health workers

6

.

There is increasing support from governments, and from funding agencies, for

mechanisms, such as accreditation, to support UHC. Governments will ultimately be

responsible for providing UHC and they will be required to demonstrate efficient use

of limited public funds while providing safe quality healthcare. External evaluation

provides assurances that healthcare facilities have quality systems in place and

the data to demonstrate the required level of service provision. Depending on the

comprehensiveness of the standards against which health service performance is being

measured, external evaluation programmes such as accreditation and certification can

contribute to quality improvement, risk mitigation, patient safety, improved efficiency and

accountability, and can contribute to the sustainability of the healthcare system. They

can provide information on how well health services are being delivered, identify issues,

and assist the decision-making of funders, regulators, healthcare professionals and the

public. External evaluation supports transparency, benchmarking and accountability, so

that government funding is allocated in a fair and equitable way and supports a culture of

change and quality and an increased focus on risk.

Patients expect to receive safe care and are demanding quality services that meet their

needs. They expect to be treated with respect, to receive services of an appropriate and

consistent standard that are delivered with care and skill, that minimise risk and harm,

comply with legal, professional and ethical standards, and that facilitate continuity of

care. Patients need to receive information about their condition and treatment in a way

they can understand, to be able to make informed choices about their treatment and to

be communicated with openly and honestly. They want the right to complain if services do

not meet their needs and expect action to be taken to address the problem.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

5

They have a right to trust that their health provider or hospital has systems and

processes in place to provide such patient-centred, reliable, efficient, effective and

responsive care. An external evaluation programme based on best practice standards

will make a significant contribution to achieving this.

With preventable error rates estimated to be 83% in developing and transitional countries

and a 30% rate of adverse events associated with deaths, these countries require not only

more resources to improve the safety and quality of care, but a political environment,

policies and mechanisms that support quality initiatives. The contribution of external

evaluation organisations centred on promoting improvements, applying standards and

providing feedback is being increasingly recognised in these countries. Preventable

error rates of over 10% in developed countries are also unacceptable. A flourishing

accreditation programme is one element of the institutional basis for high quality

healthcare

7

.

1.2 Models of external evaluation

External evaluation

Is a process by which an objective independent assessor gathers reliable and valid

information in a systematic manner by making comparisons to standards, guidelines

or pathways for the purpose of enabling more informed decisions and for assessing

if pre-determined and published requirements such as goals, objectives or standards

have been met. An organisation, object, process or individual may be assessed and

evaluation may be undertaken by peers, including organisations and professionals,

private professional auditors or consultants, purchasers / funders / insurers, consumers

/ patients or governments.

The distinguishing features of external evaluation are as follows:

It is a formal process

The object being assessed is an organisation, object, process or individual person

Assessment is undertaken by an objective, independent assessor

Assessment is against pre-determined and published requirements / criteria

It is designed so that decisions are not influenced by those being assessed

The assessment results in a defined output

There are a number of models of external evaluation and it should be acknowledged

that there can be confusion regarding terminology due to the diverse applications of

the external evaluation models. Examples of external evaluation models include the

following:

Accreditation

Accreditation may be defined as a self-assessment and external peer review process

used by health and social care organisations to accurately assess their level of

performance in relation to established standards and to implement ways to continuously

improve the health or social care system. Although primarily applied in relation to

organisations, processes may also be accredited. Accreditation standards assess

the organisation’s or process’s ability to fulfil its core mission and may address more

than legal requirements. They are usually recognised as optimal, evidence-based and

achievable and are designed to encourage continuous improvement

8

. The output of

accreditation is a report summarising the findings of the assessment and a recognition

decision regarding the accreditation status.

6

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Accreditation is one of the longest established models of external evaluation. It is a

self-assessment and external peer review process that assesses the entire organisation

including both clinical and management processes and activities. Traditionally, health

and social care organisations engaged in accreditation on a voluntary basis and

accreditation schemes were provided by non-governmental agencies. However, there

has been a shift over time towards greater governmental involvement in accreditation

with the development of national government funded accreditation programmes and a

shift from voluntary to mandatory participation in such schemes. For example, in 2011

the Australian Health Ministers endorsed the National Safety and Quality Health Service

(NSQHS) Standards and a national accreditation scheme. As a result, all hospitals and

day procedure services and the majority of public dental services across Australia now

need to be accredited to the NSQHS Standards. Private health service organisations are

required to confirm their requirements for accreditation to any standards in addition to

the NSQHS Standards with the relevant

health department. Prior to 2011, participation in accreditation was voluntary for

Australian hospitals

9

.

Certification

Certification is a process by which an authorised body, either a governmental or non-

governmental organisation, evaluates and recognises either an individual, organisation,

object or process as meeting pre-determined requirements or criteria. The pre-

determined requirements are set out in standards which are developed specifically

for the purpose of assessment. The standards assess the performance of the

organisation, object, process or person, may focus on specific aspects of performance

and may address more than legal requirements. The output of certification is a report

summarising the findings of the assessment and a recognition decision regarding the

certification status.

Certification may be used by governments or other authorised agencies to assess the

compliance of healthcare facilities or specific departments / services within those

facilities with a set of standards. The focus is usually on essential elements being in

place rather than on continuous quality improvement. The standards and certification

may not be organisation-wide, but may apply to a particular service, e.g. physiotherapy.

Governments may authorise independent assessment organisations to assess health and

social care providers’ compliance with government-mandated standards.

An example of a certification scheme is ISO: the International Organization for

Standardization. ISO provides standards, e.g. ISO 9000 Quality Management, against

which organisations or functions may be certified by ISO accredited certification bodies or

organisations

10

. Although originally designed for the manufacturing industry, e.g. medical

devices, these have been primarily applied to radiology and laboratory systems in

healthcare, and more generally to quality systems in hospitals and clinical departments.

Conformance with ISO standards is assessed by professional quality auditors and any

non-conformance is followed up with a subsequent audit.

When applied to individuals, certification usually implies that the individual has received

additional education and training, and demonstrated competence in a specialty area

beyond the minimum requirements set for registration or licensing. For example, a

doctor may be certified by a professional specialty board in the practice of obstetrics

8

.

There can be confusion between the terms accreditation and certification and they are

often used interchangeably. However, accreditation usually applies only to organisations,

while certification may apply to individuals, as well as organisations.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

7

Regulation

Regulation is a form of external evaluation by which a body, authorised by law, assesses

an organisation or a person against pre-determined requirements. The pre-determined

requirements are derived from legislation and therefore, the regulator may take a

number of actions in the event of non-compliance.

Licensing

Licensing is a process by which a governmental authority grants permission to an

individual practitioner or health or social care organisation to operate or engage in an

occupation or profession. Licensing regulations are generally established to ensure that

an organisation or individual meets minimum standards to protect public health and

safety.

The output of licensing is the awarding of a document or licence allowing an organisation

or person to provide a service within a specified scope.

Organisational licensing or registration is granted following an on-site inspection

to determine if minimum health and safety standards have been met. Maintenance

of registration or licensure is an ongoing requirement for the health or social care

organisation to continue to operate and care for patients or clients.

Individual or professional licensing or registration is usually granted after some form of

examination or proof of education and may be renewed periodically through payment of a

fee and / or proof of continuing education or professional competence

8

.

Countries may have more than one model of external evaluation in operation in specific

sectors. For example, hospitals may be required to be licensed and meet specific

government-mandated standards in order to be able to provide health services in a

particular country, but may still engage voluntarily in organisational accreditation

or certification programmes for specific departments in the facility e.g. laboratory

certification programmes. Individual healthcare practitioners may need to be registered

with their professional body in order to be employed in a hospital but they may also

voluntarily undergo additional education in order to be certified in a respective field by a

professional specialty board.

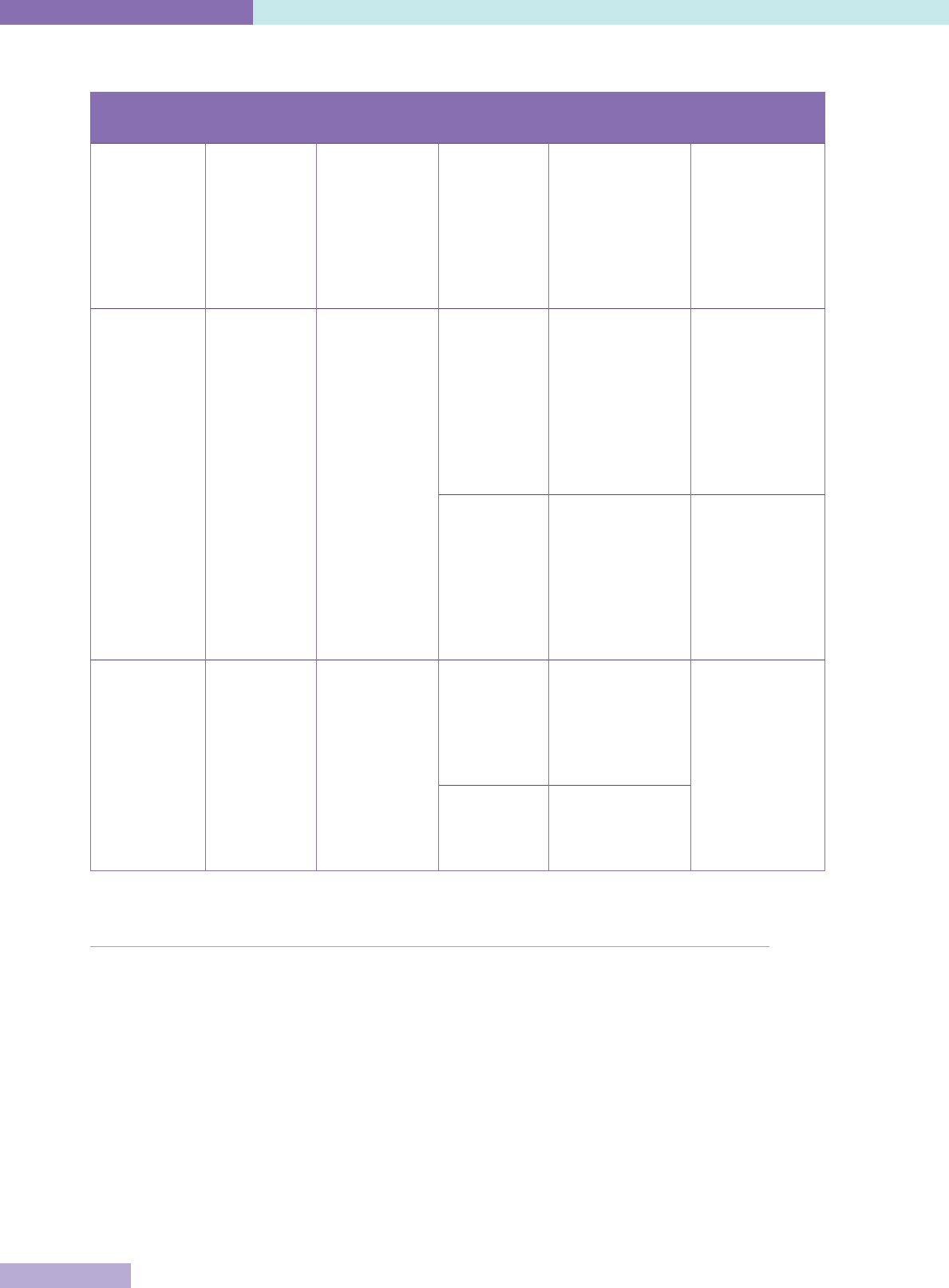

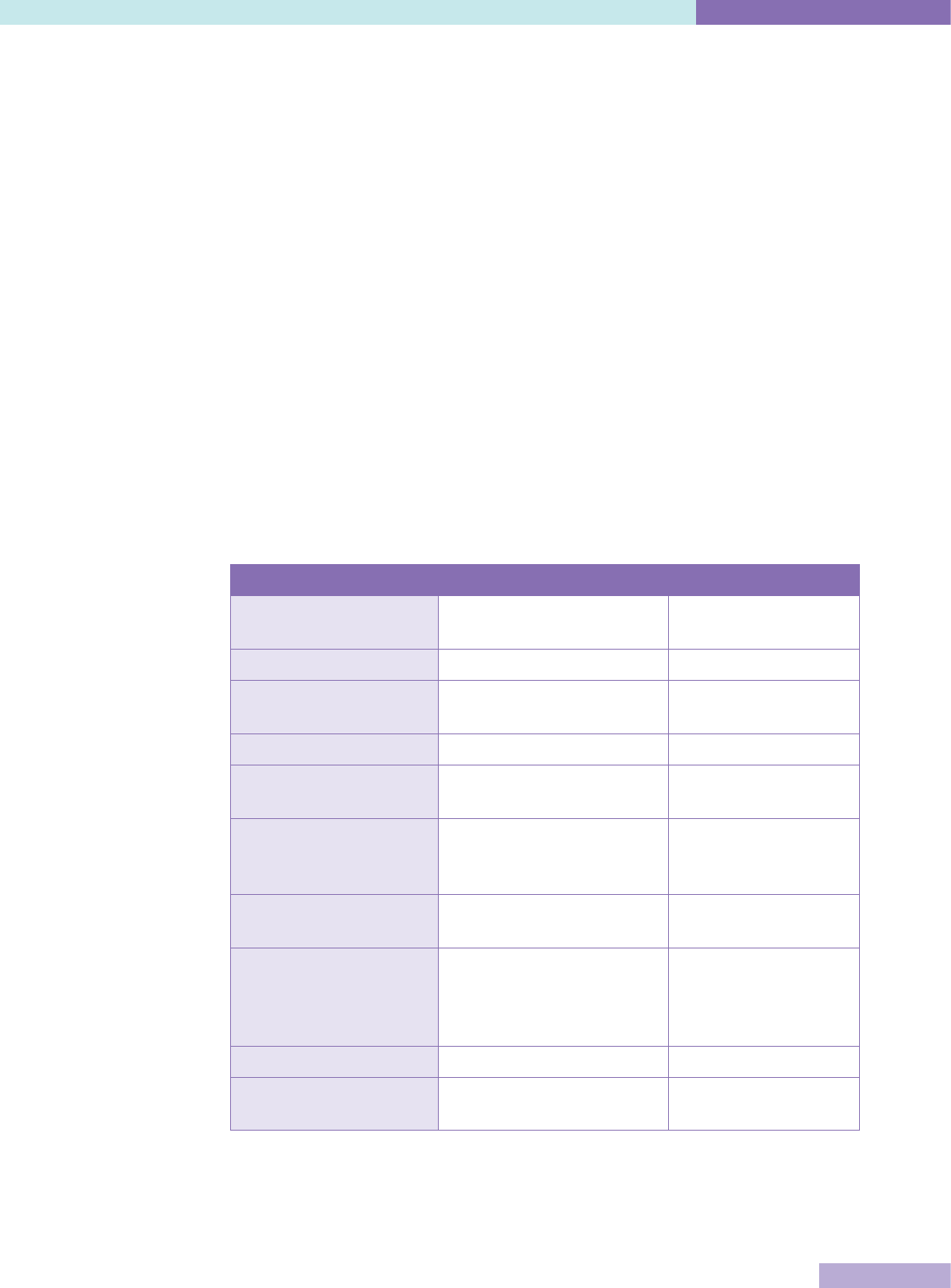

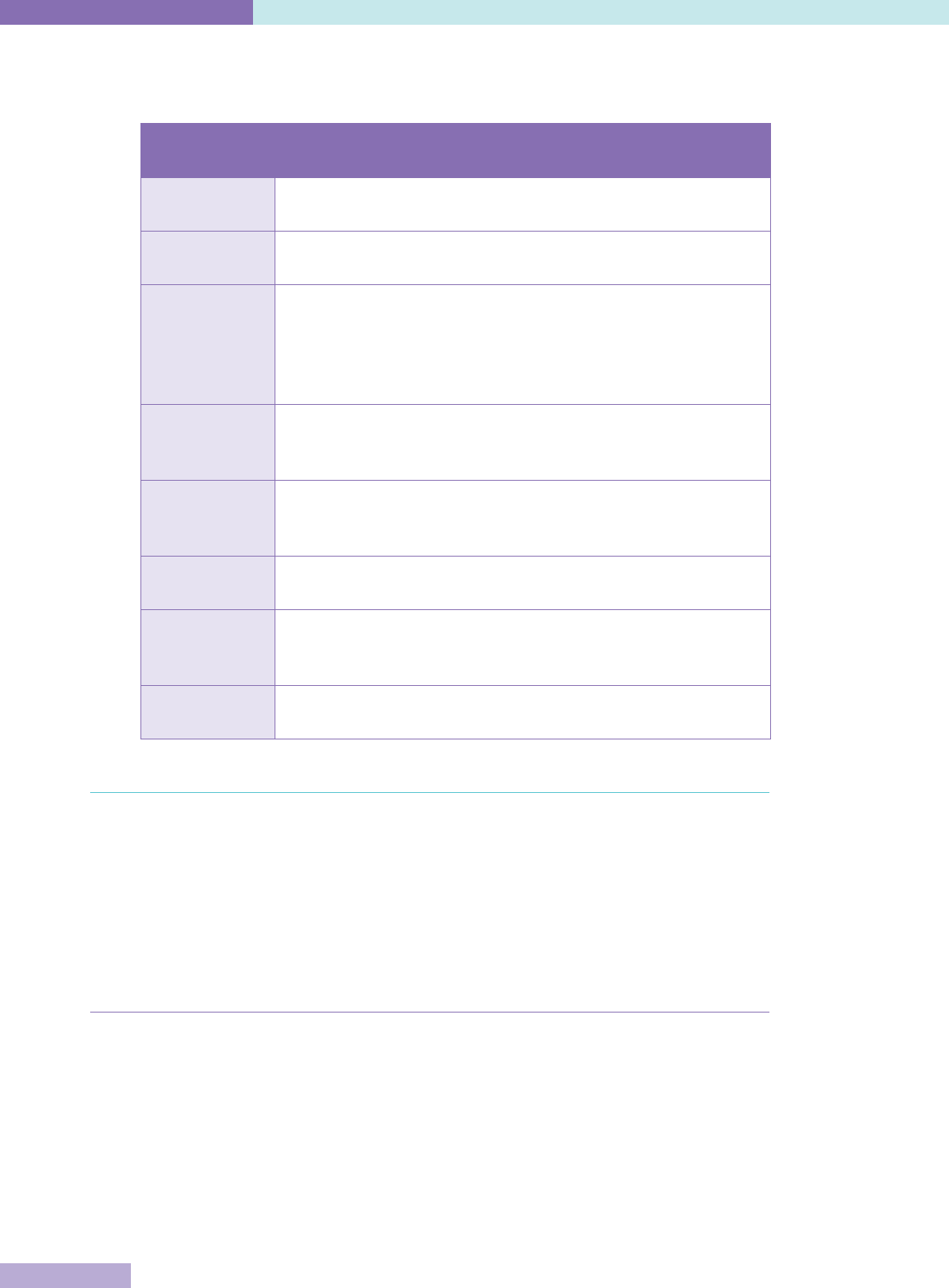

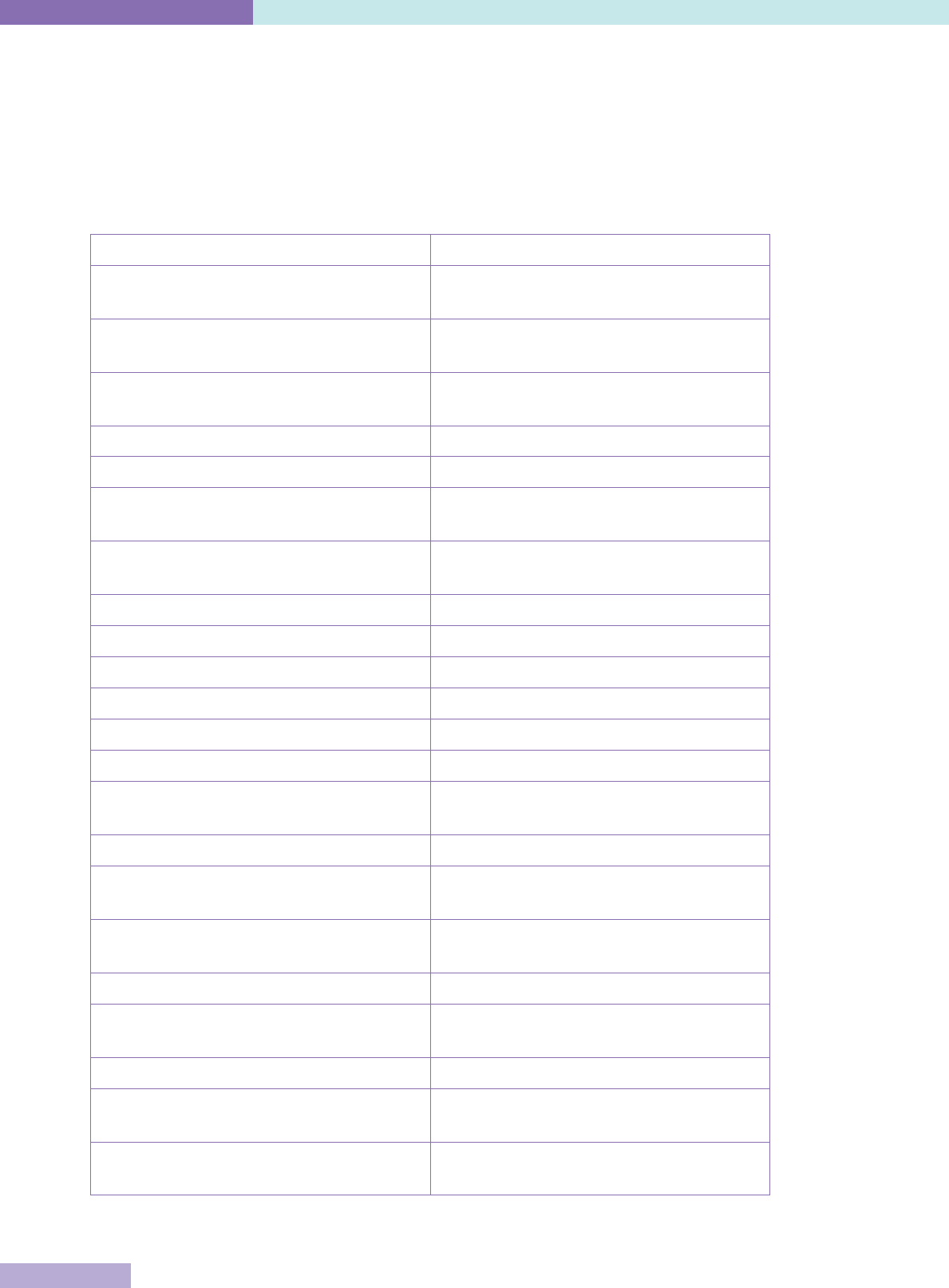

The key characteristics of accreditation, licensing and certification are set out in Table 1.

8

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Table 1: Definitions of accreditation, certification and licensing

Process Participation Issuing

organisation

Object of

evaluation

Components /

Requirements

Standards

Accreditation Voluntary or

mandatory

Non-

governmental

organisation

(NGO) or

government

authority

Organisation Compliance

with published

standards, on-

site evaluation;

compliance may

not be required

by law and / or

requlations

Set at a

maximum level

to stimulate

improvement

over time

Certification Voluntary or

mandatory

Authorised

body, either

government or

NGO

Individual Evaluation of

pre-determined

requirements,

additional

education

/ training,

demonstrated

competence in

speciality area

Set by national

professional or

speciality boards

Organisation

or component

Demonstration

that the

organisation

has additional

services,

technology or

capacity

Industry

standards

(e.g. ISO 9000

standards)

evaluate

conformance

to design

specifications

Licensing Mandatory Governmental

authority

Individual Regulations to

ensure minimum

standards,

exam, or proof

of education /

competence

Set at a

minimum level

to ensure an

environment

with minimum

risk to health

and safety

Organisation Regulations to

ensure minimum

standards, on-site

inspection

1.3 Benefits of external evaluation

External evaluation has contributed to improving the quality and safety of healthcare

for nearly 100 years and the majority of the published literature relates to accreditation.

Research on the benefits of certification, regulation and licensing is sparse. It must

be acknowledged that historically there has been limited evidence of the impact of

accreditation but in recent years more empirical research has been undertaken to

identify and quantify the benefits.

Some of the specific benefits of accreditation identified in the literature include impacts

on structural elements of quality improvement in healthcare organisations such as

leadership, governance and management, and process elements such as organisational

performance

11

.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

9

From a leadership, governance and management perspective, accreditation is

perceived as: providing a framework for helping to create and implement systems and

processes that improve operational effectiveness and advance positive health outcomes;

providing organisations with a well-defined vision for sustainable quality improvement

initiatives; and as a means of demonstrating credibility and a commitment to quality and

accountability.

From an organisational performance perspective, some of the identified benefits include:

Increases healthcare organisations’ compliance with quality and safety standards

Stimulates sustainable quality improvement efforts and continuously raises the bar

with regard to quality improvement initiatives, policies and processes

Decreases variances in practice among healthcare providers and decision-makers

Highlights practices that are working well. Promotes the sharing of policies,

procedures and best practices among healthcare organisations

11

.

Accreditation has also been perceived as having an impact on team working by

strengthening interdisciplinary team effectiveness and promoting capacity building,

professional development and organisational learning

11

.

Similarly, a recent synthesis of 122 empirical studies that examined either the processes

or impacts of accreditation programmes concluded that research evidence generally

presents health service accreditation as a useful tool to stimulate improvement in

health service organisations and to promote high quality organisation processes.

Some of the cited studies found that accreditation promotes standardisation of care

processes; increased compliance with external programmes or guidelines; development

of organisational cultures conducive to quality and safety; implementation of continuous

quality improvement (CQI) activities; and superior leadership. There was limited evidence

showing positive associations between accreditation and patient outcome measures.

However, this was attributed to poor research design

12

.

A comparison of accreditation in low- and middle-income countries versus higher-

income countries showed all programmes promote improvements, apply standards

and provide feedback. Accreditation programmes are contributing to incremental

improvements in quality systems and clinical processes in health systems around the

world and are one element of the institutional basis for high-quality healthcare

7

.

A recent review examining the use of economic evaluation techniques in health services

accreditation research identified that no formal economic evaluation of health services

accreditation has been carried out to date. It also highlighted that the impact or

effectiveness of accreditation has been researched with a variety of foci and to differing

degrees. The research design of some studies, particularly those that are observational

or qualitative in nature, makes it difficult to provide statistically robust evidence for

the efficacy of accreditation or causality. The lack of a clear relationship between

accreditation and the outcomes measured in benefit studies makes it difficult to design

and conduct economic appraisal studies where a more robust understanding of the costs

and benefits involved is required. In turn, the absence of formal economic appraisal

means it is challenging to appraise accreditation in comparison to other methods to

improve patient safety and quality of care

13

.

While the evidence for the direct impact of accreditation on patient / client outcomes

is inconclusive, the available research suggests that accreditation may contribute to

improving health outcomes by strengthening interdisciplinary team effectiveness and

communication and by enhancing the use of indicators for evidence-based decision

making

14

. The challenge for mature external evaluation systems is to become more

outcome driven. This reduces the burden of audit but also helps to highlight its benefits.

10

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

1.4 Challenges for external evaluation programmes

The principal threats to new external evaluation programmes include: inconsistency of

government policy; unstable politics; unrealistic expectations; and lack of professional /

stakeholder support, continuing finance and / or incentives. To be sustainable, external

evaluation programmes need a number of elements to be in place, including some of

the following: ongoing government and / or private support; a sufficiently large health

or social care market size; stable programme funding; diverse incentives to encourage

participation; and continual refinement and improvement in the external evaluation

organisation’s operations and service delivery

15

(refer Chapter 2).

To be sustainable and credible, new programmes need sufficient numbers of trained

and skilled personnel and a realistic timeframe for the development of the programme.

They need to demonstrate objectivity and independence with transparent procedures for

the assessment of healthcare services and for decisions on accreditation or certification

awards. The expectations of governments and stakeholders about what the external

evaluation programme can achieve need to be realistic, in line with the purpose and

scope for which it has been designed and resourced, and in line with the government’s

broader strategy or policy for healthcare quality and safety. Within that strategy or policy

there needs to be a balance between the objectives of external control or regulation

and internal organisational development or improvement. Attempts to prescribe and

control every process of a complex system like a healthcare organisation or service,

which cannot be understood as simply a sum of a number of discrete and predictable

processes, will evoke resistance from staff, and can be counterproductive in terms of

quality and safety. Health and social care staff need to be motivated and committed to

improving quality rather than directed and sanctioned.

Expectations of accredited or certified health or social care services can be

unrealistically high. The external assessment of organisations for the purposes of

accreditation or certification is based on an on-site survey or assessment of compliance

with, or achievement of, standards. This is a snapshot in time and does not guarantee,

nor is it meant to guarantee, ongoing performance at the same level. However, external

evaluation organisations who themselves engage in an external evaluation process, such

as ISQua’s International Accreditation Programme (IAP) are expected, as part of this

process to monitor the continued maintenance of standards and quality improvements by

the organisations they have accredited or certified, e.g. submission of action plans and

reports of their implementation, periodic self-assessment or external reviews, random

reviews, follow-up of significant complaints or sentinel events.

Given the amount of effort and money invested worldwide in external evaluation and

regulation of healthcare delivery, and the common pursuit of valid standards and

reliable measurement, there are economic and technical reasons to share research and

experience more actively in the international community.

A study comparing European hospitals in terms of quality and safety was found to be

challenging because of the different hospital accreditation and licensing systems in each

country; the different indicators collected; different definitions of the same indicators;

different mandatory versus voluntary data collection requirements; different types of

organisations overseeing data collection; different levels of aggregation of data (country,

region, hospital); and different levels of public access to such data.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

11

This means that patients are unable to make informed choices about where they receive

their healthcare in different countries and some governments will remain in the dark

about the quality and safety of care available to their citizens as compared to that

available in neighbouring countries

16

.

Ongoing research is needed into the benefits and limitations of external evaluation

in healthcare. To measure the impact of any new programme, before and after

measurements are needed of the indicators that the programme is intended to address.

This chapter has introduced different external evaluation models and has outlined the

benefits of external evaluation and the challenges associated with establishing a new

programme. The following chapters will present the factors that need to be considered

when deciding which external evaluation model to adopt in a country and the steps to be

undertaken when setting up an external evaluation organisation and programme.

12

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Chapter 2: Establishing

the Fundamentals

This chapter outlines the initial decisions that need to be made when a new external

evaluation programme is being established: the purpose of the programme; its scope; the

role of government; and the incentives that may be needed to ensure health and social

care organisations participate. It also highlights the importance of identifying who the main

stakeholders may be and what external influences for the programme will look like.

2.1 Defining the purpose of the external evaluation programme

One of the first steps in the development of a new external evaluation programme is to

determine its purpose.

Factors to consider in determining the purpose of an external evaluation programme or

organisation include the following:

Developmental or regulatory

According to the World Bank

17

, governments regulate health services in order to guide

private activity and achieve national health objectives. Regulation can be used for control,

with instruments that use the force of law to ensure that services provided adhere to

legal requirements. Instruments that aim to control include: licensing, restrictions on

dangerous clinical practice and registration. Examples include: basic legislation on

health personnel such as registration and licensing requirements, which can also be

used to set minimum requirements for health services or facilities to operate. Regulation

can also use financial or non-financial incentives that change the behaviour of private

healthcare providers. The advantages of using incentive-based regulation is that it

avoids the informational, administrative and political constraints that control-based

interventions entail. Accreditation, certification and contracts are examples of incentive-

based regulation. However, in developing countries, regulation is often ineffective

because of the low level of enforcement and insufficient resources.

Standards-based external evaluation

Standards-based accreditation is a programme that contributes to developing an

organisation, and is designed to improve the quality as well as the safety of health

services.

Accreditation programmes monitor and promote, via self and external assessment,

healthcare organisation performance against pre-determined optimal standards

18

. They

also aim to contribute to the provision of high quality and safe healthcare services and to

improve patient health outcomes.

Certification may be similarly standards-based and use a rating system that encourages

improvement over time but its focus is usually more on continuing compliance with

criteria and the standards may be more limited. Licensing may be used when the priority

is ensuring basic health and safety requirements are met in order for a healthcare

organisation to operate and will usually be facility focused.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

13

Values and objectives underpinning a new programme

A survey of healthcare accreditation organisations revealed that quality improvement

was the reason healthcare organisations participated in accreditation. On the other hand,

the government agenda commonly focused more on the protection of public money and

public health as a priority, meaning reducing variation in practice to increase efficiency

and improve patient safety, consistent with WHO global initiatives

15

.

Values or principles may relate to features such as leadership, a system and process

approach, multidisciplinary teamwork, capacity building and training, patient

centredness, devolved decision-making and accountability, evidence-based decisions for

continuous improvement and performance-based incentives.

Objectives of external evaluation programmes identified in some developing countries

have included: improving leadership of a quality health system; improving resources and

capacity of the system and staff; improving performance by clearly defining the roles

and responsibilities of staff at all levels; developing the structures, systems and capacity

to support quality improvement; strengthening the focus and role of health service

consumers and other stakeholders; and improving health services through systematic

implementation of standards.

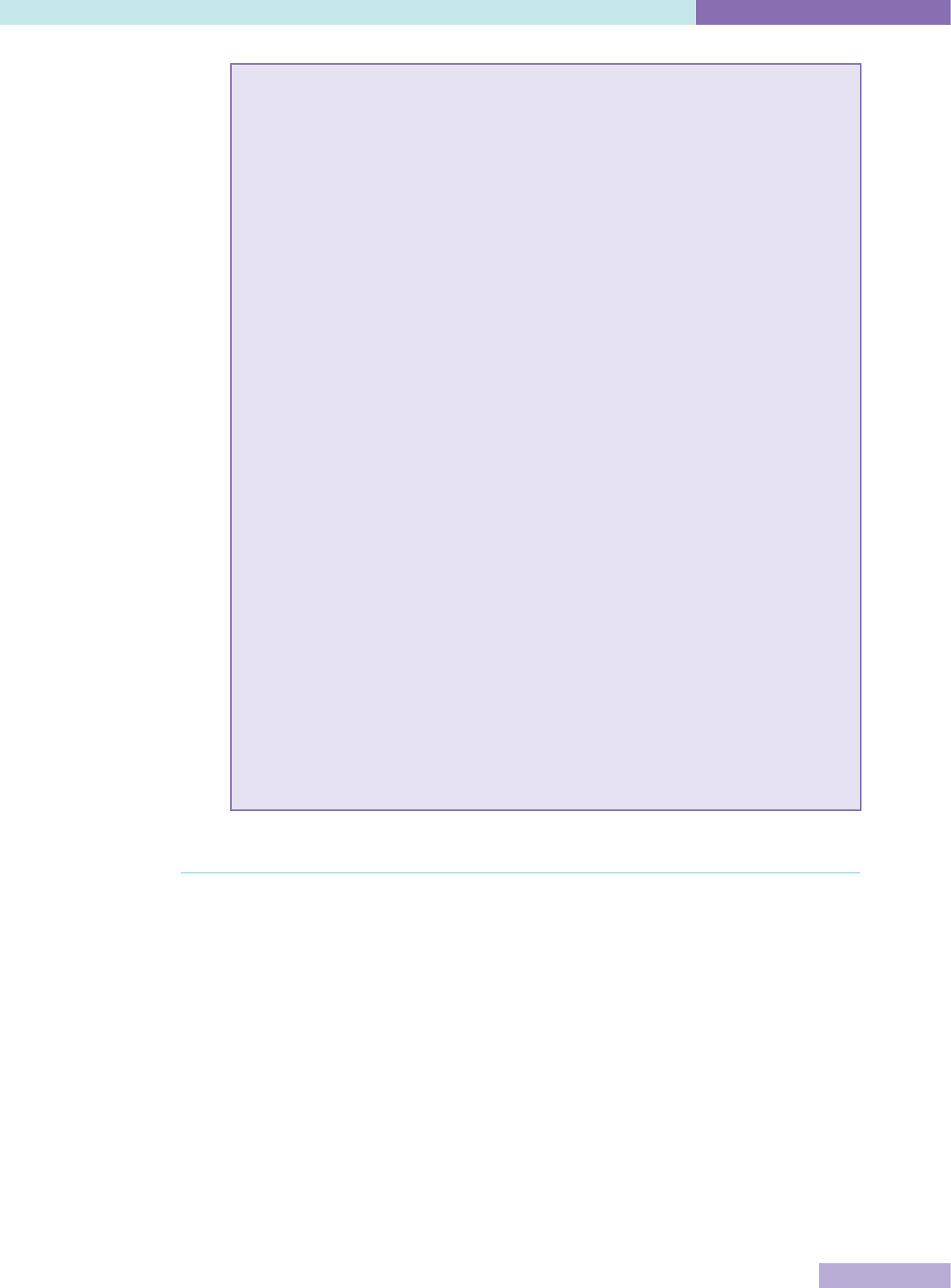

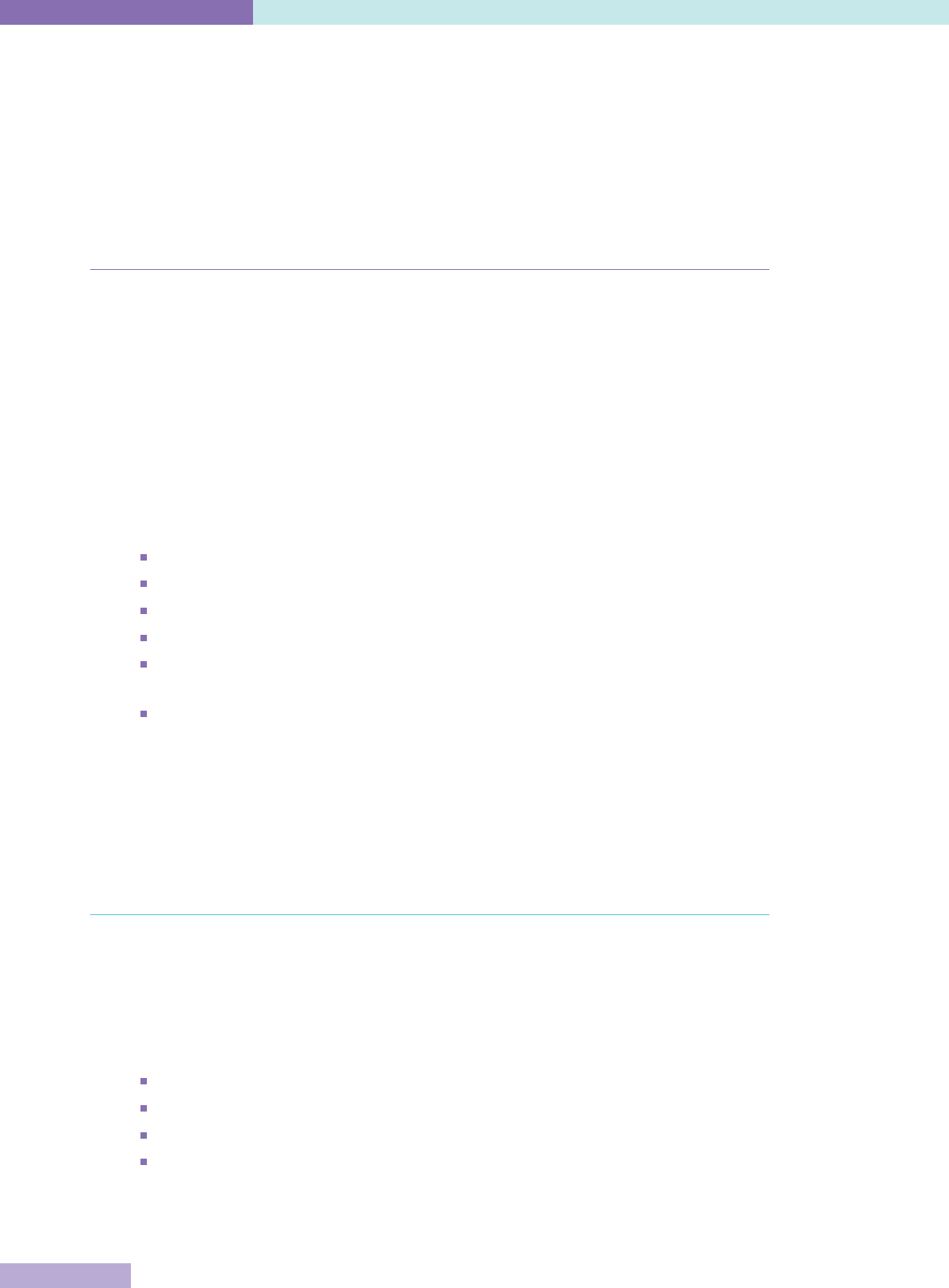

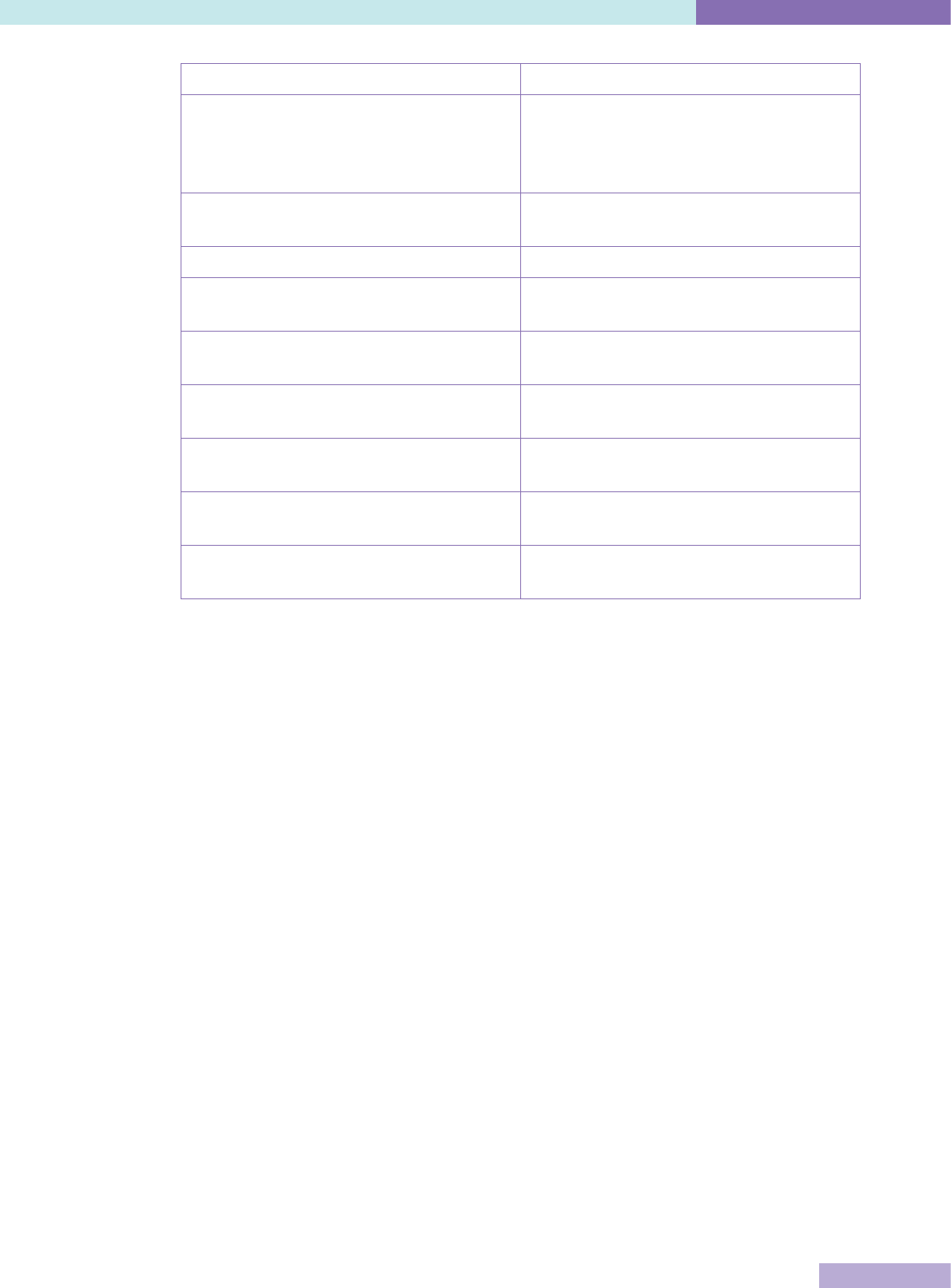

The following table compares capacity building and regulatory external evaluation

approaches

15

.

Table 2: Comparison of capacity building and regulatory external evaluation

Capacity building Regulatory

Purpose Dynamic, organisational

improvement

Static, control

Terminology Accreditation, certification Licensing, regulation

Governance Non-governmental

organisation, stakeholders

National / regional

government agency

Primary Customers Healthcare providers Government

Secondary customers Patients, professions,

healthcare insurers

Population, politicians,

public finance

Incentives for healthcare

organisations to

participate

Ethical, commercial Legal, mandatory

Uptake Voluntary self-selection to

available programs

All institutions in all

sectors

Standards Defined by non-governmental

organisation, optimal,

achievable, encourage quality

improvement

Defined by regulation,

minimal acceptable

Funding Self-financing State

Cross-border mobility Limited by language, culture Limited by political

borders

14

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Possible purposes or objectives of an external evaluation programme might be to:

Improve the performance of health services by setting and measuring the

achievement of standards

Increase public safety and reduce risks associated with injury and infections for

patients / clients and staff

Increase public confidence in the quality of healthcare services

Promote accountability of health services to funders and the public.

How do these values and objectives relate to plans for health reform in

general, and to the national quality strategy in particular?

The next important step is to identify if there are plans for health and / or social care

reform in the country or region and if there are any national or regional quality strategies

or plans in place. Reform plans outline the changes that a government intends to

make to a particular sector and outlines the specific actions that it will take to achieve

those reforms. For example, a government may outline in a reform plan that it intends

to establish an external evaluation organisation and what the role or purpose of this

organisation will be. A quality strategy provides an agreed direction and identifies the

most important activities for improving quality in the health and social care sector in the

country or region. It helps to identify the strengths of the system and also the constraints

that prevent the provision of a quality service. A quality strategy may outline the role

or will help to identify or clarify the role that external evaluation is expected to play in

achieving the country or region’s quality vision.

These factors will guide all further decisions - the role of the government, relationships

with stakeholders, the governance and management framework, the standards or

criteria to be used for assessment, the assessment process, and the outcome of

licensing, certification or accreditation.

The case study examples below provide further insight into the factors that influenced

the establishment of external evaluation agencies in different jurisdictions.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

15

Case Studies – Foundation of the programme

IKAS – Danish Institute for Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare

Country: Denmark

The Danish accreditation programme (DDKM) was established as part of the

“National Strategy for Quality Development in the Healthcare System – Joint Goals

and Action Plan 2002-2006”. The strategy was developed by the national, regional and

local political authorities in cooperation with stakeholder organisations, representing

professionals and consumers.

At that time, a number of hospitals already had positive experiences with

accreditation provided by international accreditors – one of the intentions of the

strategy was to spread this to the entire healthcare system, based on a Danish

model.

Health Care Accreditation Council (HCAC)

Country: Jordan

The HCAC is the national healthcare accreditation agency of Jordan. Several reasons

were stated for why the programme was developed including to improve the quality

of hospitals and to enhance medical tourism. In addition, it was a response to public

complaints of poor quality of care and a need to improve the entire healthcare system

in the country.

Health and Disability Auditing New Zealand Ltd (HDANZ)

Country: New Zealand

The commencement of the Health and Disability Services (Safety) Act on 1 July 2002

represented a significant change in the regulatory environment in the New Zealand

health and disability sector. This Act replaced several previous pieces of legislation

and changed the way in which residential and hospital services were licensed

or registered. In addition, the Act introduced health and disability standards for

hospitals, rest homes and residential disability services aimed at improving safety

levels and quality of care that became mandatory from 1 October 2004. The Act

required that designated audit agencies (DAAs) are approved by the Director General

of Health for the purpose of auditing these services to those standards.

2.2 Defining the scope of the external evaluation programme

Once the purpose is established it is important to define the initial scope of the

programme. The purpose of a new external evaluation programme may depend on

the government’s priorities, the national health reform or quality strategies, available

funding, the commitment of stakeholders and the problems or issues that need to be

addressed.

Factors to consider in defining the scope of the external evaluation programme include

the following:

Primary or hospital care?

Traditionally, accreditation has been developed for hospitals or aged care facilities and

then moved outwards towards home support, hospice and other community services and

then to regional networks or networks of preventive and curative services.

16

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

However, in developing countries the most urgent need may be for improved primary

and community care and the programme will initially be developed to cover primary

care clinics and outreach services, although there may be some resource advantages in

developing primary care and hospital programmes at the same time.

Often it is easier to develop facilities based programmes first, starting with core

standards and external evaluation for single institutions, e.g. acute hospitals, polyclinics

or health centres. Standards can then be developed for more specialised services, e.g.

rest homes or hospice care or mental health, followed by the linkages between them,

preventive health or health networks, and they can then be covered by the programme.

Assessment of single units, services or departments could offer large organisations a

gradual entry to a full programme but it does not carry the benefits of integration and

organisation consistency. It may hide the opportunities for improvement which frequently

lie in communication between services rather than within them. However, there are

many service specific external evaluation programmes which are operated either by a

larger generic programme, or by a provider or association which works only in that area,

e.g. palliative care, laboratory medicine, speech therapy, autism, general practice, aged

care, and community services.

Some programmes have started with tertiary hospitals and services, with the intention

of expanding to secondary care services later. Some programmes in North America (e.g.

Accreditation Canada) accredit entire health networks and regions and are applying

accreditation across the continuum of care. Some governmental programmes in Europe

address public health priorities (such as cardiac health, cancer services) by assessing

local performance of preventive to tertiary services against national service frameworks.

In such programmes, measures may include the application of evidence-based

medicine (process) and the measurement of population health gain (outcome) but many

health determinants, e.g. housing, education and poverty, remain outside the scope of

healthcare external evaluation programmes.

However, current best practice is to provide a programme that focuses on the patient or

client and their journey through the service, hospital, network or care programme and

the continuity of service or care for that individual or family across the entire continuum

of care.

Historically, external evaluation programmes have set their scope in a way which

compartmentalises care and service rather than optimising quality outcomes for the

patient or client.

Public or Private coverage?

Most external evaluation programmes offer services to both public and private sector

services, although some are restricted to either the public or private sector. Evaluating

across sectors has advantages to healthcare organisations in facilitating the focus on the

patient or client journey, providing a level playing field for comparing and benchmarking

potential competitors, to surveyors in learning from another sector and to self-financing

programmes in having a larger potential market. Sometimes either the private or

public sector has the size, resources and incentives such as funding incentives, medical

insurance and competitive advantage to adopt an external evaluation programme earlier.

Medical tourism is another large incentive. To attract patients who are crossing national

borders in search of affordable and timely healthcare, private and public health services

need accreditation or certification to demonstrate their competence and safety.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

17

Many medical tourism companies are now involved in organising cross-border health

services and it has been recommended that the care they arrange should only be at

accredited international health facilities. Other recommendations include the medical

tourism companies themselves having to undergo an accreditation review; standards to

ensure patients make informed choices; and continuity of care as an integral feature of

cross-border care

19

.

The case studies provide some further insights into how the scope of external evaluation

agencies in different jurisdictions was determined.

Case Studies – Scope of the programme

IKAS – Danish Institute for Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare

Country: Denmark

Public and private hospitals, pharmacies, municipalities (primary care services,

including long-term care), ambulance providers and General Practitioners (GPs) all

participate in DDKM.

Health Care Accreditation Council (HCAC)

Country: Jordan

The HCAC is the national healthcare accreditation agency of Jordan. The organisation

sets standards for hospitals, primary healthcare centres, family planning and

reproductive health, transport services (ambulances), cardiac care, and diabetes

mellitus. HCAC surveys against the standards and awards accreditation. HCAC also

provides consultation and education to prepare healthcare facilities for accreditation

and offers certification courses.

Health and Disability Auditing New Zealand Ltd (HDANZ)

Country: New Zealand

The commencement of the Health and Disability Services (Safety) Act on 1 July 2002

represented a significant change in the regulatory environment in the New Zealand

health and disability sector. This Act replaced several previous pieces of legislation

and changed the way in which residential and hospital services were licensed or

registered. HDANZ’s scope was determined by the Safety Act – the assessment of

standards is a legal requirement for public and private hospitals, rest homes and

residential disability services. Standards New Zealand (SNZ) is responsible for the

New Zealand standards and this includes others such as for home support, allied

health, and day surgery procedures.

Critical mass: economy, consistency, equity, objectivity

Larger countries can achieve economies of scale; smaller countries (perhaps with a

population of less than 5 million), or large ones which choose to devolve the process

to regional government, e.g. Italy, or ethnic groups, e.g. Aboriginal, have to share the

considerable costs of infrastructure and development among a smaller number of

healthcare organisations (giving higher unit costs). If the surveyor workforce is voluntary,

this may also mean having a smaller choice of surveyors (giving more potential for

conflict of interest). However, there are options such as contracting or employing a

smaller paid surveyor workforce or contracting surveyors from other countries for

surveys.

18

ISQua Accreditation International Accreditation Programme (IAP)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

Other options for enhancing the opportunities for smaller programmes include:

Sharing a programme with a neighbouring region or state which has similar culture

and language

Designing one national programme, rather than several regional ones

Providing national standards, guidelines or tools for regional agencies or

designated assessment organisations

Using a single organisation to provide multiple accreditation programmes

Using the same organisation or agency as a centre for research and development

of other quality methods, e.g. performance indicators, clinical guidelines, patient

surveys, technological assessment

Obtaining accreditation services from another region or state.

2.3 Establishing the role of government

The development of an external evaluation programme may be part of broader health

reforms, or part of an overall governmental strategy for quality improvement and a

transition from a centralised system to one which is more open and independent. It may

be necessary for the health ministry to re-define its own duties and responsibilities in the

context of a reformed organisational structure of the health system.

The relationships between departments of government which have a major impact on

quality may be unclear. The roles of agencies responsible for such areas as public health,

blood products, pharmaceuticals or medical devices and inspectorates responsible for

such aspects as control of the environment, safety, radiation at national or local level

need to be clarified as part of the overall quality plan. Dissemination of this structure and

plan would also provide an opportunity to develop a strategy for active communication of

the aims and operation of an integrated quality system.

Government controlled or not?

Specific to external evaluation is the question of whether the programme should

be organised and administered directly and solely within the ministry of health, like

licensing, or by an independent body totally unconnected to government, or by something

between these two extremes – which has become more common. The legitimate and

necessary role of government is the licensing of healthcare facilities, using basic safety

standards or criteria. Licensing of individual medical practitioners may be a government

function but is usually carried out by a medical council. However, there are challenges

for governmental external evaluation programmes which include:

Inconsistent policy and management with changes in government

Reviewing and updating standards consistently and in a timely way

Public perception of government that is too low to make them credible assessors of

healthcare

Conflict of interest between government roles as purchaser, regulator and insurer,

and lack of independence and continuity

Delegation of powers to local areas, which may result in multiple government

programmes duplicating development and ongoing costs of running the

programmes.

International Accreditation Programme (IAP) ISQua Accreditation

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation

19

Some countries, such as France and Saudi Arabia, have made participation in

accreditation by healthcare organisations legally compulsory, but most countries

merely authorise the functions of the external evaluation organisation. Two-thirds of

accreditation organisations surveyed in 2010 were supported by enabling legislation.

However, many independent programmes thrive without it. Five accreditation

organisations were struggling or inactive, despite being supported by a published

government strategy. If enabling legislation is not essential and national strategies often

change with ministers and governments, external evaluation organisations must choose

reliable partners for survival

15

.

Need for government support

To be successful, external evaluation programmes often need government support and

collaboration and to be recognised as an important part of the national health quality

strategy. The support may be through funding, providing incentives for participants

such as limiting other forms of inspection or audit, or recognising the programmes as a

legitimate and essential part of the overall health quality strategy.

Some functions, such as the definition of standards, the assessment of compliance

and the grading of awards may be totally independent or may be shared between

government and independent external evaluation organisations. Some governments,

for example, New Zealand, have developed or approved standards that they require

healthcare organisations to meet. However, the government have devolved the process

of assessment of compliance with the standards and follow-up to ensure the standards

are being maintained to independent designated auditing, accreditation or certification

organisations. These organisations in turn need to be internationally recognised by a

3rd party accreditor such as ISQua. In Australia, a similar system operates through

the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care which has developed

national quality and safety standards. The accreditation of healthcare organisations who

meet the national quality and safety standards has been devolved.