i

iii

Table of Contents

Abstract Page IV

1. Background and Model Overview Page 1

2. Scope of the Proposed APM Page 6

3. Quality and Cost Page 8

4. Payment Methodology Page 9

5. Value over volume Page 10

6. Flexibility Page 13

7. Ability to be evaluated Page 13

8. Integration and Care Coordination Page 15

9. Patient Choice Page 16

10. Patient Safety Page 17

11. Health Information Technology Page 18

12. Supplemental Information Page 20

Appendices

I. Abstract: Validation of American Gastroenterological Association’s Crohn’s

Disease Care Pathway

II. Abstract: Project Sonar: Improvement in Patient Engagement Rates Using a

Mobile Application Platform

III. Abstract: Project Sonar: Validating a Cost Normalization Methodology in a

Community-based Registry

IV. Project Sonar Abstract of Distinction: Digestive Disease Week 2016

V. Guide to the use of Crohn’s CDS Tool

VI. AGA Crohn’s Disease Care Pathway Risk Assessment

VII. SonarMD Nurse Care Manager Dashboard

VIII. SonarMD Patient Survey

IX. Examples of SonarMD Ping Reports

X. SonarMD Cost Report - Graphic

iv

Project Sonar Abstract

Project Sonar (PS) is a care management program developed by community-based physicians in

partnership with a major payer to improve the management of patients with chronic disease.

The key to the success of PS is the combined use of evidence based medicine coordinated with

proactive patient engagement. The goal of PS is to move physicians from a dependency on fee

for service medicine into value based practice. The initial chronic disease category chosen by

PS was Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), a family of disorders that are high cost and high risk

with a frequency that has been increasing over the past few decades.

In addition to high cost and high risk, CD is also associated with a high variability in outcome

and cost. We term this combination of factors as “High Beta”

and believe that chronic illnesses

can be stratified into high beta and low beta based upon an analogy from the financial industry.

The essential features of PS for the management of patients with chronic conditions, a PFPM,

are:

Evidence Based Guidelines are used to direct the course of care. These are embedded

into the EMR through use of CDS tools

All patients are risk assessed using a set of biopsychosocial measures

All patients are enrolled in a web-based communication platform; if not web- or smart-

phone enabled, they are engaged by phone calls from the NCM

Every patient is proactively ‘touched’ at least once a month; more frequently as needed

A team based care model has been incorporated into the practice

Clinical and financial data are analyzed

The care pathway is continually refined through the development of care management

algorithms

We intervene before patients even realize they need care

1

PTAC Proposal – Project Sonar

1. Background and Model Overview

In the United States, chronic diseases accounts for an estimated 83% of total U.S. health

spending and virtually all (99%) of Medicare’s expenditures are for beneficiaries with at least

one chronic condition.

12

Project Sonar (PS) is a care management program developed by community-based physicians to

improve the management of patients with chronic disease, using evidence based medicine

coordinated with proactive patient engagement. Project Sonar was initially deployed in 2012 by

the Illinois Gastroenterology Group (IGG), a 50-physician practice with locations in Cook, Lake,

Kane, and DuPage counties. IGG is the largest single-specialty, non-academic, Gastroenterology

practice in Illinois. As envisioned by the leadership of IGG, the goal of PS was to move

physicians from a dependency on fee for service medicine into value based practice. As part of

this exercise, IGG analyzed their practice demographics by conditions / diagnoses, procedures,

age, payor mix, etc. and confirmed that the most significant chronic disease in a community-

based Gastroenterology (GI) practice is Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), which includes

Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. When factoring in the costs of pharmaceuticals,

whether physician or patient administered, IBD is responsible for almost 25% of the services

generated by IGG and likely most other community-based GI Groups. IBD disorders are high

cost (due to hospitalizations for complications and use of biologic medications) and high risk

(loss of intestine, infections, development of cancers and extra-intestinal manifestations) with a

frequency that has been increasing over the past few decades. After evaluating other chronic

conditions managed by a community-based GI practice, such as GERD / Barrett’s esophagus,

celiac disease, and chronic pancreatitis, the group determined that Crohn’s Disease (CD) was

most appropriate for the development of a chronic care management program.

In addition to high cost and high risk, CD is also associated with a high variability in outcome

and cost. We term this combination of factors as “High Beta”

3

and believe that chronic illnesses

can be stratified into high beta and low beta based upon an analogy from the financial industry.

In finance, “beta” is a measure of a stock's volatility in relation to the market

4

. The market has a

beta of 1.0, and individual stocks are ranked according to how much they deviate from the

market. A stock that swings more than the market over time has a beta above 1.0. As beta is a

measure of risk, a beta greater than one generally means that the asset is volatile.

1

Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook. AHRQ Publications No, Q14-0038.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

2

Partnership for Solutions. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care (2010 Update). February 2010.

3

Kosinski L, Brill J. The Promise of Patient Self-Monitoring: An App a Day Won’t Necessarily Keep the Doctor Away.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, December 2016; 1751-1752

4

Sharpe W. Portfolio Theory and Capital Markets. June 1970, McGraw Hill, New York NY

2

This same analogy can be applied to most chronic illnesses. Examples of other high beta

illnesses include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, end-stage liver

disease, and type 1 diabetes, while examples of low beta illnesses include hypertension,

diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. There are high beta periods in low beta illnesses.

IGG is contracted with every major commercial payor operating in Northeast Illinois, including

Aetna, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois (BCBSIL), Cigna, Humana, and United. Based on their

own internal analysis of data, IGG met with all the payors, and BCBSIL was willing to work with

the group to analyze this issue. A review of commercial claims for 21,000 patients with a ICD-9

diagnosis consistent with CD for the years of 2010 and 2011 revealed:

The annual cost per patient with a diagnosis of CD was $11,000 (2011 data)

The overall hospitalization rate for patients with CD was 17%

Over 50% of the expenditures incurred were for inpatient care for the treatment of

complications of CD

Although 1/3 of the total spend was for physician services, only 3.5% of the total spend

was for gastroenterology care.

Over 2/3 of the patients who were admitted to a hospital for a complication related to

CD had no identifiable contact (based on claims data) with a provider in the 30 days

prior to the admission

Based on this data, we asked the following questions:

Is there a way to decrease the cost of care of patients with CD by decreasing the

complication rate through better medical management?

Is there a way to identify the high-risk patient with CD before complications ensue?

Is there a way to channel the care of these patients to those healthcare professionals

who have the most knowledge, experience and expertise?

Is there a better way to engage our patients so that their early warning signs can be

assessed even before they realize they need intervention?

While IGG was analyzing and researching these questions, the American Gastroenterological

Association developed and published a care pathway for the management of Crohn’s Disease.

AGACDCP

5

. The recommendations in the pathway are as follows:

5

Sandborn WJ. Crohn's Disease Evaluation and Treatment: Clinical Decision Tool. Gastroenterology 2014;147:702-

705.

3

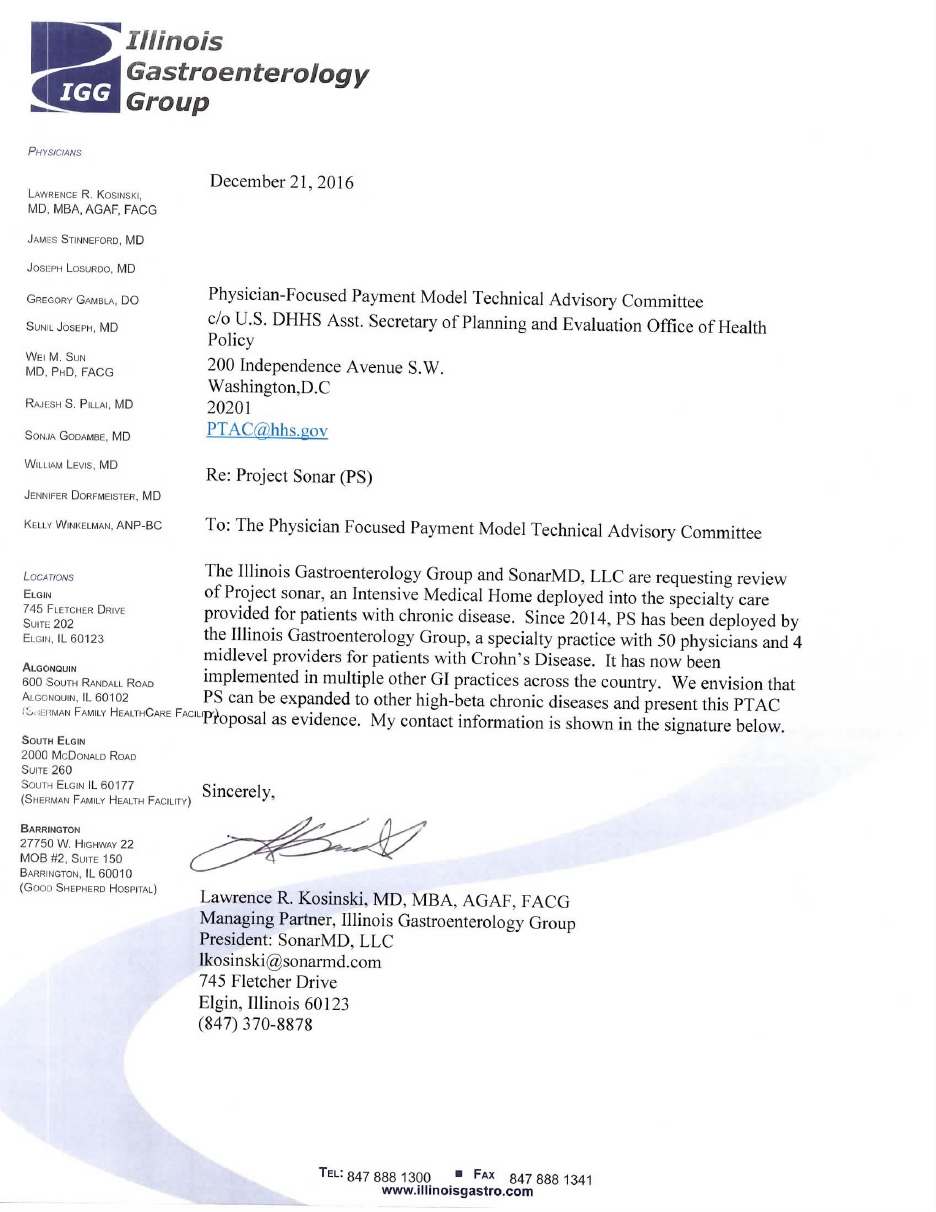

To reduce potentially avoidable hospitalizations and to control the expense of those who are

hospitalized, physicians must work with patients to control complications, which requires

physicians to identify the high-risk patient and control their inflammation. This includes a

biopsychosocial risk assessment that will identify the biological markers of risk and assess the

patient for anxiety/depression along with their social environment.

The ensuing management requires a team-based approach deploying Clinical Decision Support

(CDS) tools to guide healthcare professionals on optimal care, appropriate use of anti-tumor

necrosis factor (TNF) and other biologic medications, and incorporation of Nurse Care

Managers (NCMs) as the focal point in the team that was engaging with and managing the

patient. Importantly it requires the engagement of the patients with the use of “hovering

tools” to non-intrusively monitor the patient’s symptoms, in effect creating a “sonar system” to

ping them in their usual environment on a periodic basis. Collectively, the goal of PS was to

engage those patients who might otherwise minimize the severity of their disease, identify

patients who were depressed and/or at risk of decompensation, and optimize patients on

appropriate pharmaceutical treatment as early as possible, with the objectives of improving

patient quality of life and decreasing costs through reducing potentially avoidable

complications, emergency department (ED) visits, and inpatient (IP) admissions.

PS was deployed in IGG in 2013, initially in a pilot study population of 50 patients with CD. CDS

tools designed around the AGACDCP and a hovering tool using the Crohn’s Disease Activity

Index (CDAI) were deployed into IGG’s NextGen electronic medical record (EMR) system. Using

the EMR practice portal, patients were sent a subset of questions derived from the CDAI at the

beginning of each month. This subset of the CDAI returned a score (Sonar Score) that applied a

numeric value to the patient. At the end of the first year, the hospitalization rate for these

patients decreased from 17% to 5%.

4

IGG presented the data from this pilot to BCBSIL. Based on the findings from the pilot, BCBSIL

partnered with IGG to create its first specialty-based Intensive Medical Home (IMH). Using a

model similar to what it had deployed in its primary care PCMH, BCBSIL attributed 303 patients

with CD to IGG of which 185 were enrolled, and the IMH project, which went live on Dec. 1,

2014 was based on the clinical structure described above. The practice receives a supplemental

per member per month (PMPM) payment to cover the infrastructure for participating in PS.

The PMPM payment is additional to fee for service payment and varies on an annual basis,

adjusted based upon mutually agreed-upon goals for the clinical and financial performance of

the patients enrolled. The practice receives one year of historical claims data on its attributed

patients and quarterly medical and pharmacy claims data going forward. The practice is

responsible for calculating the performance of physicians at an individual, strategic business

unit (SBU), and practice level, including comparison of BCBSIL patients depending on their level

of engagement (‘pinger’ vs. ‘nonpinger’) and comparison to patients enrolled in other

commercial and government (Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare) programs.

Early on, it became clear that the EMR patient portal would not sustain the level of patient

engagement required for adequate care. It was replaced with a web and mobile-based

platform which includes interactive text messages to patients, and patient response data which

drops directly into the EMR using a HIPAA-compliant HL7 interface. Patient engagement

increased from 27% to 75-80% which has now been sustained for over 20 months.

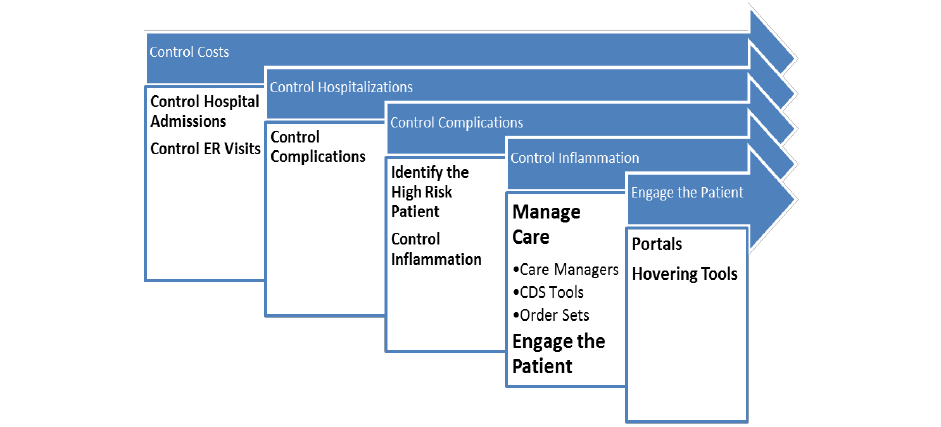

The initial first full year of clinical, financial, and patient engagement data for PS are shown in

the graphic below which was presented as a Distinguished Abstract at Digestive Disease Week

2016:

The data below are normalized to

Medicare payment to emphasize true

utilization rates. They show:

A net decrease in cost of 9.87%

even with an 8.97% increase in

infusible biologics and Net of

PMPM payments to the practices

A 57.14% decline in inpatient costs

driven by an equivalent decline in

admissions/complications

5

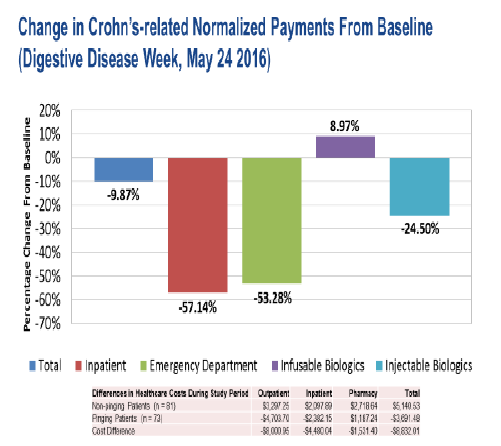

These financial results are highly dependent

upon the patient engagement. When we

filter our patient population by those who

respond to at least 50% of their monthly

surveys (pingers) vs. those who do not

respond (nonpingers), the cost differential of

care falls 18% in the Pinger group whereas it

rises 23% in the nonpinger group. This 41%

difference in cost is shown in the figure

below.

Thus, the cost savings is highly correlated to patient engagement, as it is derived from those

patients who respond. Patient engagement is key to the success of PS and for the care of

patients with chronic disease. Our results, which we believe are generalizable to other high-

beta chronic conditions and to high beta periods in low beta conditions, lead to a model that

must incorporate the use of evidence based medicine and, more importantly, must provide for

ongoing patient engagement which is integrated into the workflow of care.

Key to the success of a management program for a chronic condition must be the use of

appropriate risk measures. Every patient in PS is initially assessed using the risk assessment

tool embedded in the AGACDCP, which includes 26 biopsychosocial risk metrics in three

categories: Inflammation Risk, Disease Burden Risk and Comorbidity Risk. Multiple linear

regression analyses of each risk measure against the Crohn’s Related Cost of Care has helped us

to identify which measures hold predictive value. This has led to further refinement of the

processes within PS.

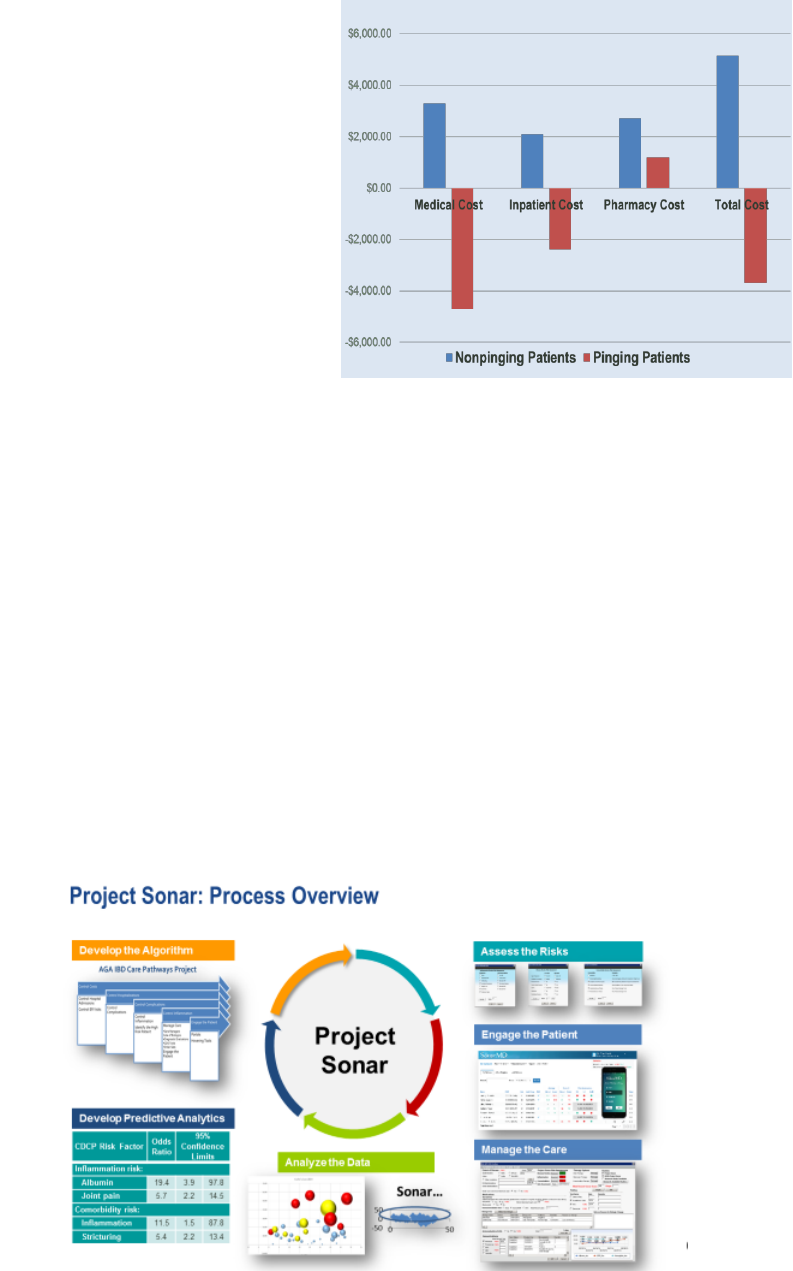

A process overview of PS is shown below:

6

The essential features of PS for the management of patients with chronic conditions, an APM,

are:

Evidence Based Guidelines are used to direct the course of care. These are embedded

into the EMR through use of CDS tools

All patients are risk assessed using a set of biopsychosocial measures

All patients are enrolled in a web-based communication platform; if not web- or smart-

phone enabled, they are engaged by phone calls from the NCM

Every patient is proactively ‘touched’ at least once a month; more frequently as needed

A team based care model has been incorporated into the practice

Clinical and financial data are analyzed

The care pathway is continually refined through the development of care management

algorithms

We intervene before patients even realize they need care

2. Scope of Proposed APM

This proposal to the PTAC will expand CMS’s APM Portfolio in the following ways:

It will move providers, especially specialists, from fee for service to reimbursement

based on value based payment methodologies. It is addressing an issue in payment

policy in several ways:

o Moves patient care from reactive to proactive.

o Focuses on early identification of potential problems and complications,

encouraging ‘preventive’ management

o Rewards physicians and other qualified healthcare professionals for ‘doing the

right thing’ in a team-based manner, as opposed to reimbursement solely on an

RVU-based methodology.

It will promote “cost sensitivity” in specialist providers who are currently almost

exclusively paid on a fee for service basis. This will promote the inclusion of APM

entities for specialists whose opportunities to participate in APMs has been limited.

It will link payment for specialist services to clinical, financial, and patient reported

outcomes.

It will allow specialists to participate in value based care outside of an ACO / MSSP /

CRC+ model.

It will allow physicians to participate in value based care for chronic conditions that are

not triggered by a surgical procedure on an inpatient or outpatient basis.

Specialists want to be part of the value based solution but have not been fully able to exert the

powerful force they have on cost containment and care improvement. The majority of CMS /

CMMI initiatives to date have focused on ACOs, primary care based models, or conditions

7

triggered by a hospital procedure (orthopedic, cardiac). This has left the specialist out of the

solution and kept them as part of the problem.

The patient has also been left out of the solution. Few value based models built around ACOs

maintain a focus on patient engagement as a value-added solution. This is exacerbated by

initiatives based on hospitalization triggers which do not have an outpatient focus on chronic

management.

Most serious chronic illnesses are managed by specialists who are still paid under fee for

service. PS shows how a specialty group in partnership with a major payer can move from FFS

to value-based care and demonstrate cost-savings with improved patient quality of life. We

believe this model, which has been proven in patients with IBD, is applicable to other

conditions.

Although PS focused on CD, this model can be applied to other chronic illnesses. As noted

earlier, we believe that chronic illnesses can be stratified into high beta and low beta. Some

chronic diseases, like diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, can be slow

and indolent in the expression of their symptoms and morbidities, which we term as “low-beta”

diseases. Other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are “high-beta”

conditions that are not as forgiving in their disease progression

67

. There are several high-beta

conditions including asthma, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, end-stage

liver disease, rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, cancers, malnutrition and other conditions

where patients are at risk for frequent, potentially avoidable, emergency department visits and

hospitalizations

8

. Even diseases like diabetes may have high beta periods, such as the period

following an admission for diabetic ketoacidosis or when patients have poor control of / high

fluctuations in blood sugar / hemoglobin A1c levels. Although most of the chronic care of

patients with low beta diseases can safely be provided by PCPs, the intervening high beta

periods most often require the care of a specialist. The PS platform can be applied to high beta

illnesses as well as the high beta periods embedded in the management of low beta chronic

diseases.

We believe that PS has applicability to many patients with chronic disease and would be

appropriate for use by primary care and specialist physicians and qualified healthcare

professionals, both cognitive and procedural.

6

Natarajan Y, Kanwal F. Pay for Performance in Chronic Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015

Nov;13(12):2042-7.

7

Fortune BE, Golus A, Barsky CL, et al. Linking a Hepatology Clinical Service Line to Quality Improvement. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Aug;13(8):1391-5

8

Kosinski L, Brill JV. The Promise of Patient Self-Monitoring: An App a Day Won’t Necessarily Keep the Doctor

Away. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016; 14: 1751 - 2

8

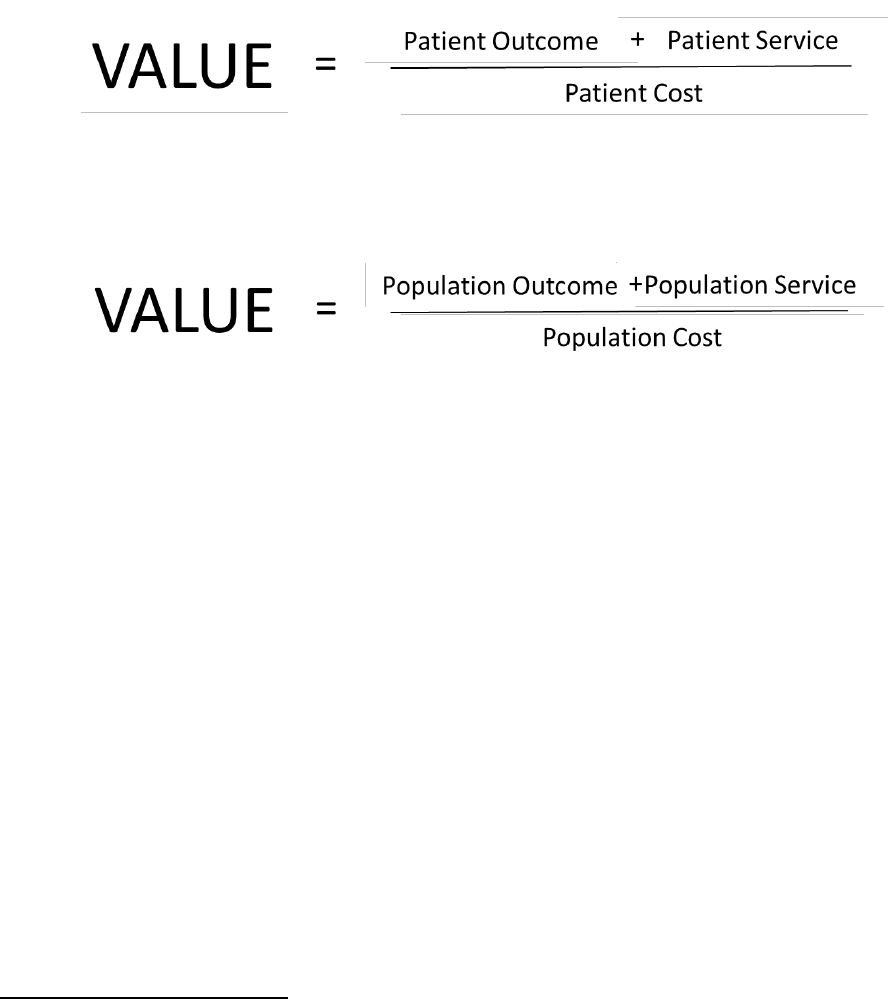

3. Quality and Cost

Value can be defined as Quality/Cost. Since Quality = Outcome, value can be further defined as

Outcome/Cost. The perception of care is essential to the measure of value, so the most

appropriate definition of value is: Value = (Patient Outcome + Patient Satisfaction)/ Patient

Cost.

The triple aim’s value today has refocused us on Population Health. So, the previous patient

based equation applied to a population would be:

PS applied to patients with chronic disease can provide this value through improving quality

and lowering cost. Quality can be improved through:

Use of Evidence Based Guidelines to support a focus on outcomes.

o PS has demonstrated a significant decrease in complications, hospital admissions

and emergency department visits using a model which is applicable to other

chronic conditions.

Improved Patient Satisfaction through targeted patient engagement.

o Patients engaged through PS maintain a very high level of satisfaction with the

program. They are benefitting from “Concierge Medicine” without the extra

expense.

Proactive Patient Engagement

Proactive patient engagement coupled with clinical surveillance and intervention is critical to

the successful management of patients with chronic disease. Patients with chronic disease

often surface only when they recognize they are in trouble and realize they cannot repair their

situation themselves. Patients with high-beta diseases can rapidly deteriorate, resulting in

hospitalization and complications

910

. Patients with CD frequently minimize their own

9

American Hospital Association. Examining the Drivers of Readmissions and Reducing Unnecessary Readmissions

for Better Patient Care. September 2011. Washington, DC

10

Hines AL, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ, et al. Conditions With the Largest Number of Adult Hospital Readmissions by

Payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #172. April 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

9

deteriorating symptoms; they may present too late at which time morbidity has occurred and

significant medical and/or surgical care must be provided. PS has demonstrated that patient

engagement is critical to avoiding these occurrences.

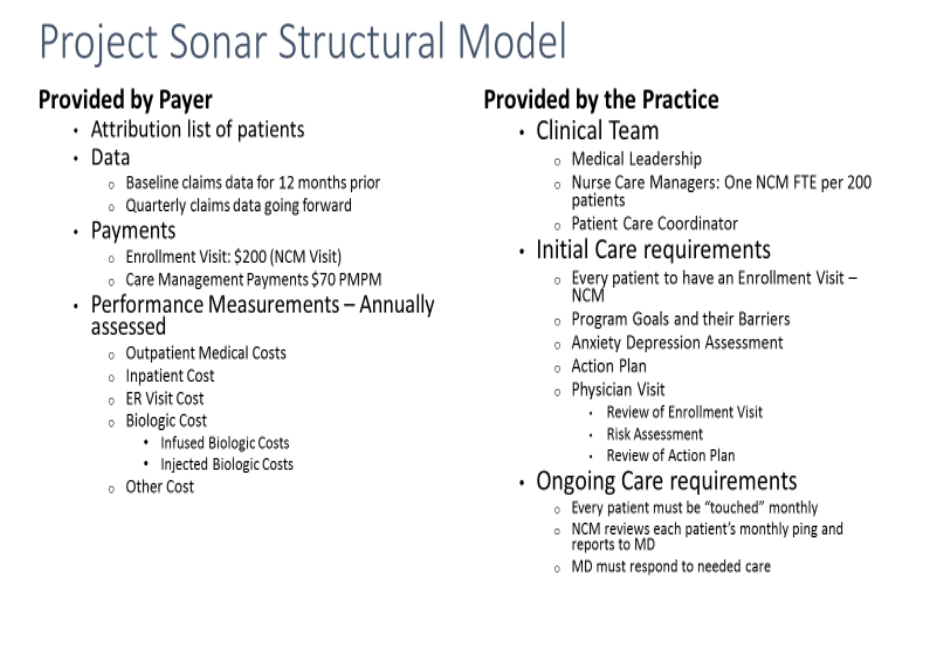

4. Payment Methodology

The payment model of PS represents negotiation of a transition from fee-for-service to fee-for-

value for physicians who may not ready or able to take on full risk, but are capable and should

be ready to accept accountability for the care they provide. PS will facilitate the development

of accountability for the care of the patient with chronic disease and will promote a decline in

the variability in the cost of care of these patients.

The Structural Model of PS is detailed below:

In the PS APM we are proposing a prospective payment model with retrospective

reconciliation. PS is based upon a chronic care management (CCM) model combined with

proactive patient engagement. Physicians who voluntarily choose to participate with the model

would continue to have their services reimbursed through the MPFS. Target prices are

compared to the actual cost of the care provided. Payment adjustments are based on quality

and financial performance. In the case of cost savings, the shared savings component of the

payment would be paid to the physician entity. In a situation where the physician’s attributed

10

costs overrun the expected target, the physician would be required to repay losses up to the

agreed upon limit in its contract with CMS. To protect against catastrophic losses, the model

will build in stop-loss provisions and outlier protections.

Participating providers would also be required to contribute based upon their agreement with

PS as the APM entity. A monthly payment for non ‘face-to-face’ services by clinical staff,

overseen by the physician, is essential for the successful deployment of the model to cover the

infrastructure costs required.

There are initial and ongoing costs for dedicated NCMs and ping coordinators (clinical staff), IT

expenses for incorporation of CDS tools into the EMR workflow and deployment of the patient

engagement platform and data management. These are detailed below:

NCM Cost: $25 PMPM

Ping Coordinator $12 PMPM

IT Platform $20 PMPM

Medical Director $2.50 PMPM

Total Cost $59.50 PMPM

The CCM payment is designed to cover the cost of deployment of the care management

infrastructure not to provide supplemental income to the practice. Incentives to the practice

will be generated by the sharing of cost savings derived from a retrospective adjust. A

Performance Based Adjustment (PBA) is made based upon this retrospective cost reconciliation.

If savings are favorable, the PBA will represent a supplemental payment to the practice. This

will be capped at 10%. If performance is poor and costs are excessive based on risk adjusted

norms, then the PBA would be negative up to a cap of 5%.

This payment structure should be viewed as one designed to promote a continuous process of

value generation over time. We anticipate that going forward many more value-based

initiatives will be necessary to continue to move the cost curve down. Episode and procedural

bundled payments will be necessary as well as consolidation in NCM functions. The goal will be

to gradually push cost down until a convergence to an ideal mean can be accomplished.

5. Value over Volume

Volume based drivers have dominated physician practices for the last 50 years. Since “every

system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets”

11

, medical practices are designed to “do

more”. In primary care practices this correlates to the metric: patients seen and RVU generated

per hour. The obvious challenge is to maintain quality of care when the physician or qualified

healthcare professional is seeing 4 or more patients per hour, especially if the patient has

multiple co-morbid conditions, complex medication regimens, psychosocial issues, etc. There is

11

Conway E, Bataiden P. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; August 21

st

, 2015

11

a limit to the productivity of a practice, whether primary care or specialist, which cannot be

solved through use of qualified healthcare professionals.

While specialists may be more procedural, they are equally as volume driven. Data from IGG

shows that over 54% of the revenue of a community-based GI practice comes from screening

(G0105, G0121), diagnostic (45378), and procedural colonoscopy (45380, 45384, 45385),

primarily related to colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, diagnosis, and surveillance. Many

Gastroenterologists have developed a very efficient focused-factory model for performing this

procedure.

Why should a GI move from this model to one based on value? Colonoscopy is a mature

service; CMS has adjusted procedure wRVU downwards in CY 2016 and 2017, revenue is

declining and costs are rising, compressing margins. Alternative methods for CRC screening are

available which, in a population based environment, might lead to a shift from procedural to

diagnostic colonoscopy with a corresponding decline in the volume of colonoscopy.

Anticipating this trend, Project Sonar was developed to provide GI physicians with an option to

improve care based on value based chronic disease management, rather than attempting to

perform more procedures.

In our initial review of commercial payer claim data from 2010 and 2011, the average

cost/patient with CD was $11,000, which includes professional, laboratory, imaging, hospital /

facility, and pharmaceutical costs. The average yearly reimbursement to a GI for managing

these patients was $385, which includes only professional fees for office visits, procedures, and

supervision of physician-administered infusions. Similar to oncology, physician administered

infusions represent an additional source of revenue to the practice, while prescribing a patient

self-administered drug would not generate any practice revenue.

The problems in today’s FFS model are obvious and include:

Physicians are compensated more to do more. Physicians are incented to perform more

procedures where the revenue per RVU is higher. By revising the 2017 fee schedule to

pay a facility more for colonoscopy procedures (e.g. 45380, 45385) and less for

screening / diagnostic procedures (e.g. G0105, G0121, 45378), CMS has potentially

created an incentive for physicians who own an ASC to perform more procedural

services.

As the per-minute compensation for cognitive services is less per RVU compared to

procedural services, many of these visits have been relegated to qualified healthcare

professionals (nurse practitioners, physician assistants) in the practice who might not

detect early signs of deterioration in a patient. This creates a paradoxical situation

where the most knowledgeable member of the healthcare team is busy performing the

most repetitive and least cognitive task (procedures) while the more complex cognitive

services are performed by less-trained professionals.

Prescribing infused biologics to increase practice revenue.

12

o The patient is seen every 6-8 weeks when they come in for their infusion. If that

infusion is performed in an office setting where the physician sees the patient,

our data suggests that the hospitalization rate is much lower than if the infusion

is performed in a setting (hospital outpatient or, for commercial patient, free-

standing infusion center) where the patient is not seen by their provider involved

in the ongoing management of their condition.

o Patients do not want to disrupt their lives every six to eight weeks to come in for

an infusion. This results in lost productivity at work, use of PTO days and time

away from family. For these and other reasons, patients may prefer self-

administered drugs, which creates a potential management issue as the patient

is not being monitored as they would if they were coming in for an infusion.

o On a total cost basis when looking at the cost of drug and infusion, the cost of

infusible biologics is higher than the cost of self-administered agent, which does

not consider the lost productivity cost. This must be balanced by the higher

hospitalization rate with self-administered agents due to a loss of ongoing

communication with the provider.

PS was developed to address these issues. How does PS move this to value?

The provider in PS is compensated a prospective payment fee in addition to their usual

FFS compensation. In our commercial model, this represents approximately $600 per

year to the provider, which is not significantly different from the approximately $490

per year were the physician to bill CPT code 99490 (chronic care management). The

physician is encouraged to continue office visits for the patient, and to provide

procedural services when clinically indicated, such as for CRC screening / surveillance.

The physician practice is responsible for paying the NCM and ping coordinator and data

management out of the monthly CCM payment.

Expenses for all procedures are paid under a bundled payment methodology.

Physicians are encouraged to utilize anti-TNF and other biologics based upon the most

efficacious agent, not the one that generates the most revenue to the practice. The PS

system facilitates patient engagement and communication regardless of the site of

service.

Performance data using PS in a commercial population has shown a “Net” 9.87% savings.

Based upon the $11,000 cost per patient, this amounts to a savings of over $1,000 per patient.

This is net of the monthly CCM payments and is a normalized savings based upon Medicare

Payment Rates. The combination of prospective CCM payments which support care

infrastructure of NCMs combined with the use of the Sonar Platform facilitate this overall

savings and its improvement in the quality of life of its patients.

13

6. Flexibility

PS represents a flexible and scalable platform upon which to expand its use to most all

practices. To date, we have installed the common PS platform in 20 GI practices across the

country representing approximately 600 physicians in 12 states, including community and

academic practices.

The “glue” that binds the PS practices is the use of the web and mobile-based platform, which

represents a single database of provider driven and patient driven metrics. A web-based

platform which is both EMR and smartphone device agnostic allows PS to apply changes

centrally and distribute automatically to all sites. The results of Sonar Scores are pushed into

EMRs as lab data using a HL7 interface.

The PS platform has been used for research on clinical and pharmacological outcomes and

effectiveness. For example, the network of PS practices has been leveraged to study the effects

of oral therapies for irritable bowel syndrome as well as IBD, and to assess whether assessment

of small bowel mucosa correlates with clinical and CDAI findings.

PS requires the practice to change its focus from ‘passive-reactive’ to proactive population

health. Instead of a “one patient at a time” passive focus, waiting for the patient to contact the

physician with new or intensifying symptoms, the PS practice is focused on the population of

patients. The practice, and the patients with a disease process, are actively engaged to improve

the care of the patient. This requires infrastructure changes such as the incorporation of NCMs

and the ping coordinator.

We believe that a similar care management infrastructure is applicable to other illnesses. We

further believe that PS is agnostic to the specialty and is applicable to other chronic illnesses,

and can be used by primary care and specialist physicians involved in the care of patients with

high beta chronic disease or the high beta periods in patients with low beta conditions.

7. Ability to be evaluated

Evaluation of any new care model is essential to validate its value. PS has been under

evaluation since its inception. The following financial metrics are monitored on a regular basis:

Average total cost/patient

Average inpatient cost/patient

Average Emergency Room cost/patient

Average biologic cost/patient – both infused vs injected

Total cost from a commercial plan is a misleading metric as it must be normalized to Medicare

Payment Rates to minimize the site of service differential. That is not to say the site of service

is not important, it must be minimized as well. By using a single payment methodology,

utilization can be better assessed.

14

Ultimately the most important outcome is the improvement in the quality of life of the patients

with the disease in question. Financial measures alone may not reveal the entire patient

benefit. We must always place higher value on the costs incurred for disease morbidity. An

example is the cost of inpatient care vs the cost of biologic therapy. Despite the expense of the

latter, it does not come with the suffering of the morbidity of disease.

Outcomes driven quality metrics, difficult to develop, have slowed the movement from volume

to value. Since PS has a unique access to both quality as well as claims data it has been able to

develop predictive models based on how changes in quality metrics effect cost. Utilizing the 26

risk assessment metrics in the AGACDCP, PS ran multiple linear regressions of each metric

against the Crohn’s Disease Cost of Care. This has allowed for the development of a

mathematical model which assigns a relative strength to each metric with respect to its ability

to control the cost of care.

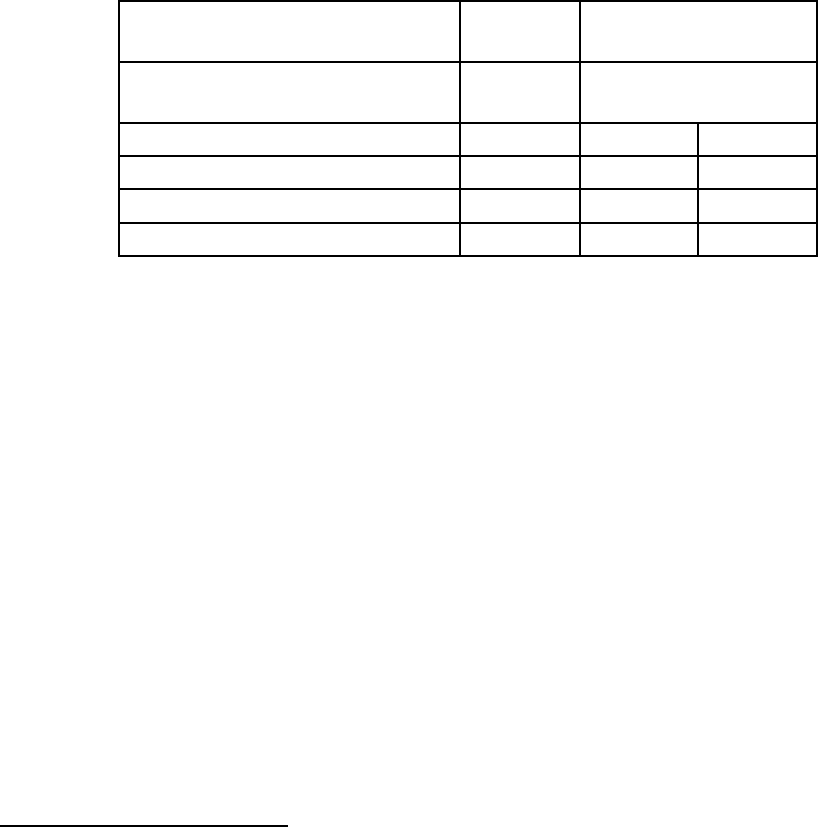

CDCP Risk Factor

Odds

Ratio

95% Confidence

Limits

Lower

Limit

Upper

Limit

Inflammation risk: Albumin

19.4

3.9

97.8

Inflammation risk: Joint pain

5.7

2.2

14.5

Comorbidity risk: Inflammation

11.5

1.5

87.8

Comorbidity Risk: Stricturing

5.4

2.2

13.4

Each risk assessment metric has a relative value. Patients can be profiled with this scoring

methodology and placed accurately in risk categories. An example would be the use of serum

albumin levels as a predictive value for risk. We have shown that changes in serum albumin are

predictive of 19.4% of the variation in cost of care for CD

12

. Patients are monitored quarterly

for serum albumin level changes.

We continue to refine this mathematical model, which will benefit from a larger “n” of patients.

This model enables rating of each physician and NCM performance on a risk adjusted basis.

Ping response rate is critical to the outcome of PS; provider and NCM specific ping response

rates can be used as a metric for performance.

We have developed an upside risk revenue share model which creates the proper incentives for

physician behavior. Working with physician groups in a variety of practice and geographic

settings, we have arrived at the following formula:

33%: based on number of patients followed

33%: based on the ping response rate

34%: based on the risk adjusted cost of care

12

Kosinski L, et al. Validation of AGA Crohn’s Disease Care Pathway Risk Assessment Metrics Against Crohn’s

Related Cost. Abstract. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 22 S23-24 March 2016

15

With additional data and additional participating practices, we believe this formula can and will

be adjusted in the future to promote optimal value-based behaviors.

8. Integration and Care Coordination

The success of PS rests on the deployment of a team-based care infrastructure. MD can no

longer stand for “My Decision”. To successfully manage the patient with a chronic condition,

physicians and qualified healthcare professionals, NCMs, Ping Coordinators and ancillary

personnel such as behavioral health and pharmacists are required.

At present, the current care management model for PS centers around the NCM, who is the

most important component of the team. Based on data from the Case Management Society of

America, each FTE NCM should be able to follow 150-200 patients

13

. Our data shows that using

PS’s web and mobile patient engagement platform, this number can be safely increased to 250

patients per FTE NCM. Practice management data indicates that one NCM can provide support

to multiple physicians and qualified healthcare professionals in the practice. For solo and

smaller practices that might not have the patient volume to support a dedicated NCM, we

believe that a shared-service model could support such practices.

The NCM relationship begins at enrollment when the patient comes in for a “Supervisit”. At

this visit, patients are introduced to the NCM and queried as to their personal goals for the

program. Barriers to accomplishing these goals are identified and an action plan generated.

Patients are rated with respect to depression/anxiety using a PHQ-2 tool as these components

affect all chronic diseases. Diet histories are generated with action plans for nutritional

support. At the conclusion of the initial visit, the patient is seen by the physician or qualified

healthcare professional who reviews the details of the Supervisit and all parties sign off on the

action plan.

After the initial Supervisit, ongoing management begins. The PS platform provides a desktop to

the NCMs where their patients can be monitored together as a population. The NCM follows

the Sonar scores of the patients and contacts all patients whose scores fall out of standards, or

who does not respond to their ‘ping’ within a predetermined amount of time. Based on the

patient responses, if required the NCM goes into the practice EMR and initiates a

communication with the physician or qualified healthcare professional. Patients whose scores

indicate that they are deteriorating are contacted and engaged with the physician or qualified

healthcare professional, either in-person or telephonically. Precision care is being managed

proactively and constantly. Patients are engaged and physician services are initiated as needed

by the NCM.

13

Case Management Society of America and National Association of Social Workers. Case Management Caseload

Concept Paper: Proceedings of the Caseload Work Group. October 30, 2008. Available at

http://www.cmsa.org/portals/0/pdf/CaseloadCalc.pdf

16

All care, from the Supervisit through the ongoing care, is contained in the same relational

database. Reports can be generated from queries developed by the PS leadership team.

Interactions between the members of the team can be monitored and rated. The platform

provides the ability to rate NCMs separately from providers.

Each practice should have a clinical staff member who functions as a “ping coordinator”,

monitoring the ping process on a regular basis. This person monitors who is entering and

exiting the program.

The issue of integration with PCPs and other specialists needs to be discussed. We see this

model as being integrated into the structure of the entire care team. In pure high beta illnesses

like CD, the specialist may be the only member of the team that receives the PMPM payment.

In high beta periods of low beta conditions, the specialist will receive the PMPM only during the

high beta period. The bottom line is that the provider managing the care of the chronic illness

in question receives the payment. When comorbidities exist which require management by

multiple specialists, then multiple management fees may be necessary.

9. Patient Choice

PS is focused around the needs of the patient. In fact, the focus of PS is the patient. Our data

and results have shown that the patients prefer the engaged infrastructure of PS - their NCM

functions as their own personal care coordinator, or “concierge care within a managed

environment.” Patient satisfaction is high; PS has maintained a 75-80% sustained patient ping

response rate over 2 years.

We learned this that hard way. In the first six months of PS, we used a patient portal for our

patient communication. This was not ideal and the patients did not like logging in to the portal

to obtain their surveys. The EMR portals are cumbersome, inflexible, and slow to align with

advancements in technology (e.g. new smartphones and devices used by consumers). In June

2015, we switched to a web and mobile-based platform developed by PS that utilizes smart

phone technology, which has been very well received by the patients and is clearly their choice

of communication.

For the 20-25% of the patients who either do not have a smart phone or choose not to use one,

we use more conventional means of communication. A small number of patients prefer the

portal. Telephone calls from the NCM asking the patients the questions in the survey are used

when other means are not possible. As we serve a population in whom English might not be

the primary language for some patients, PS is in process of translating the questions into

Spanish and using ATT Language Line for others. In the end, we “touch” every patient every

month.

Approximately 24% of patients are deemed depressed or anxious at enrollment. These patients

require a higher level of service which can be provided through PS. As our data shows that

17

patients with behavioral health issues is associated with a 13% higher cost of care, they are a

major focus for the NCM. These patients may receive multiple calls and touches during the

calendar month. In the end, PS is the patient’s choice. High levels of patient satisfaction exist.

10. Patient Safety

PS must be considered a Sonar System for patients with chronic disease. It is like looking out at

the ocean. Think of the patients as submarines, submerged and running silent and deep. They

only surface when they are in trouble which means two things will need to happen for them to

surface: they recognize they are in trouble, and realize they can’t get out of trouble on their

own. Unfortunately, patients make mistakes on both issues and their safety can be

compromised. In high beta diseases like Crohn’s Disease or end-stage liver disease, there is not

much room for error. They surface in deep trouble and must be brought in to port (the

emergency department) which usually results in hospitalization.

Our data shows a significant improvement in patient safety with implementation of PS, as

demonstrated by the significant decrease in emergency department use and hospitalization

rate. The close patient engagement built into PS minimizes patient safety issues.

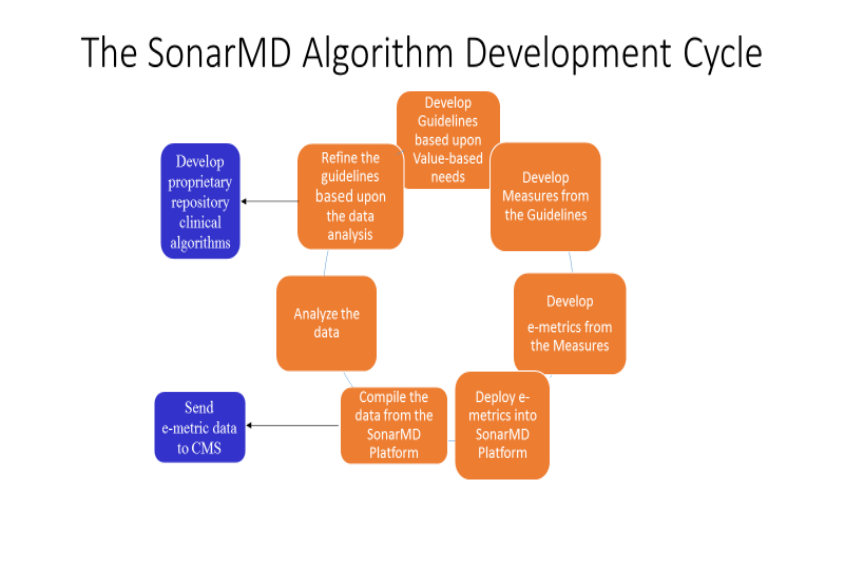

The algorithms which are built into PS are a key component of our success. The NCM desktop is

alerted when a patient’s Sonar Scores fall out of safety ranges. These ranges are based upon a

continuous process of refinement / development of algorithms:

18

11. Health Information Technology

PS is built on an HIT platform which utilizes both web and mobile-based technology to

communicate with providers, their staffs and their patients. It is cloud-based and agnostic to

the operating system of the handheld device as well as the practice EMR. Although not an

EMR, the PS platform integrates with all EMRs by pushing sonar scores through to the EMR as

lab data using an HL7 Interface.

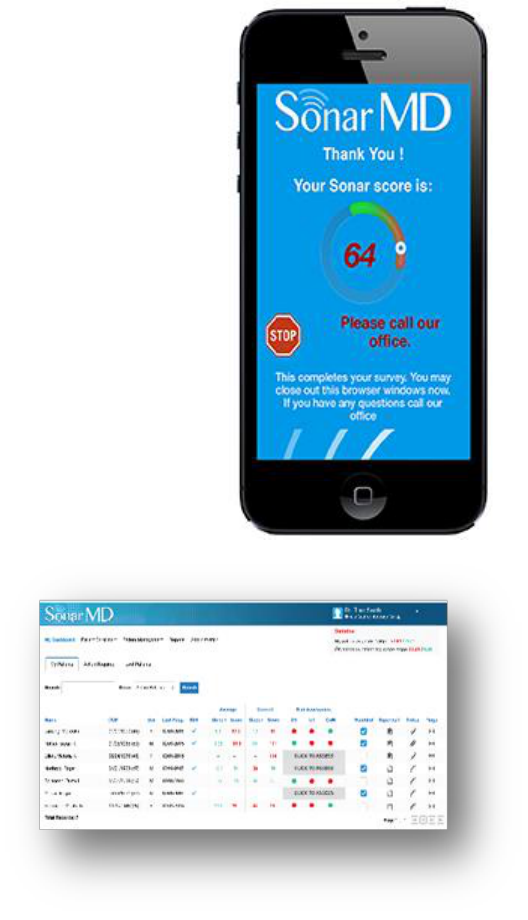

Patients using the PS platform receive monthly “pings” on the

device of their choice: smartphone, tablet, PC, etc. Some

patients who do not have access to this technology receive

their communication via telephone.

The strength of the mobile platform lies in its ability to provide

immediate feedback to the patient. Since it is a web-based

platform communicating to a SQL database, algorithmically

generated responses can provide patients with immediate

feedback. If the patient’s Sonar Score triggers one of the

algorithms, the patient is instructed to contact the office of the

practice. Concurrently, the NCM in the practice receives the

same notification and most often contacts the patient before

the patient does. This provides not only an excellent

communication tool, it provides the patient with a sense of

security that someone is constantly monitoring their condition.

On the practice side, the NCMs utilize a set of desktop

templates where they can monitor the

performance of each of their patients as

well as their assigned patients in

aggregate. Sonar Scores are color coded

based on algorithmic rules. See

Appendix VII for full images. Unlike an

EMR where patient charts are opened

one patient at a time, the Sonar

Platform is designed for population

health providing the NCM and the

physician with the ability to see all of

their PS patients in a user-friendly

interface.

Each practice participating in PS has its own sub-platform, thus they cannot comingle data from

other practices. At a central level, PS’s “Sonar Central” can pull data into a central repository

for query creation and reporting. The ability to aggregate and analyze data from practices

19

across the United States has in effect created a GI Registry for IBD. PS is able to monitor trends

across the population, study clinical factors related to outcomes, and provide guidance and

recommendations back to the practices. It is also our vision to use these capabilities to further

drive clinical decision support at the time of engagement and evidences based medicine across

the specific disease state(s).

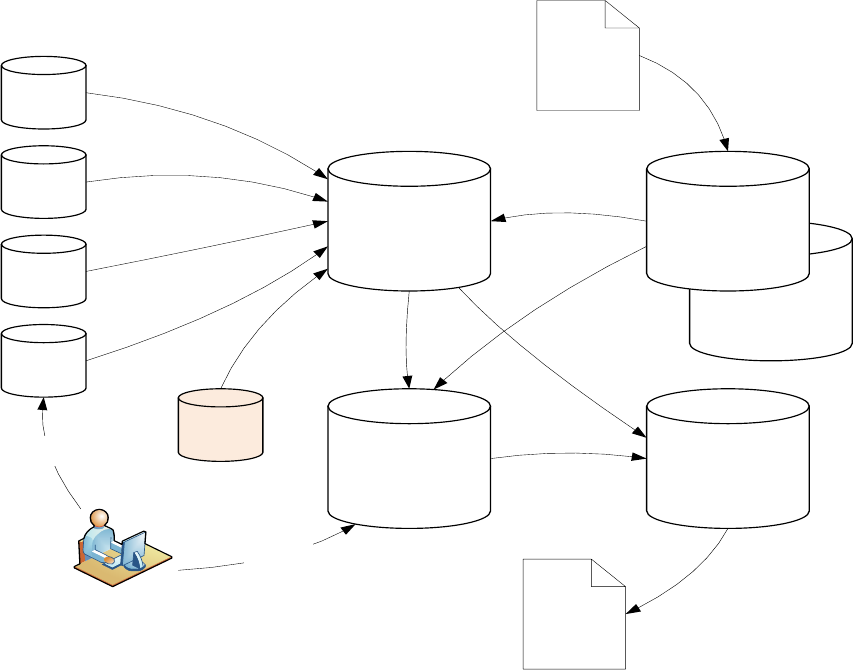

Safety and security are maintained through the appropriate use of encryption and use of

firewalls. This is shown in the diagram below.

Payer_XXX

Practice

Database

Practice

Database

Practice

Database

Practice

Database

Data Landing

Area

Claims Data

Practice Analytics

De-identified

Research

Analytics

Payer Database

Practice Users

(Nurses/Physicians/Administrators)

SonarMD

Application

Analytics &

Dashboards

Research

Extracts

Sonar

Central

The PS’ IT infrastructure lends itself to being expanded and scaled as necessary to

accommodate multiple practices and disorders. Safety and security are maintained through the

appropriate use of encryption and use of firewalls. Sonar has a full HIPAA compliance program

in place to safeguard access and use of the PS data.

There are currently over 600 in 20 large GI practices across the country who have implemented

the SonarMD platform. All of the data from these practices is contained in the above structure

in a safe/secure environment. This infrastructure is perfectly positioned to be expanded to

other disease processes and practices in other specialties.

20

12. Supplemental Information

The expansion of Project Sonar beyond the Illinois Gastroenterology Group necessitated the

formation of an entity to provide the necessary structure for a national project. SonarMD, LLC

is a Delaware LLC founded in 2014 by physicians dedicated to the development of chronic care

management tools. Through development of its provider focused CDS tools and its patient

engagement digital platform SonarMD provides medical practices with a patient friendly

infrastructure for population health.

The medical practices currently using the SonarMD digital platform constitute the SonarMD

Medical Group (SMG). Each practice is contracted with SonarMD under identical contractual

arrangements, and nominates a member to the SMG advisory board. We anticipate that as PS

grows, advisory groups will be organized around specialty and condition.

We have considered whether SonarMD, LLC could be the APM entity that contracts directly

with CMS. In this scenario, the risk arrangement for the APM entity including, total risk and

stop-loss provisions would be agreed upon in the APM entity’s contract with CMS.

Infrastructure expenses would include:

Development of a CCM payment designed to cover the infrastructure necessary to

implement the PS platform: NCMs, Ping coordination, IT Platform

Mechanisms for claims processing under prospective bundled vs. retrospective

payments.

Claims data reporting

Quality reporting based upon mutually agreed upon measures and metrics. These

measures will include MIPS measures as well as PS derived measures. An example for

IBD would be as follows:

Financial reporting measures as previously addressed

Category

Description

NQF 128

Preventive Care and Screening: Body Mass Index (BMI) Screening and Follow-Up Plan

NQF 226

Preventive Care and Screening: Tobacco Use: Screening and Cessation Intervention

NQF 271

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Preventive Care: Corticosteroid Related Iatrogenic Injury

– Bone Loss Assessment:

NQF 275

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Assessment of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Status Before

Initiating Anti-TNF (Tumor Necrosis Factor) Therapy

PHQ 2 Q1

Little Interest or Pleasure in doing things?

PHQ 2 Q2

Feeling Down Depressed or Hopeless

Lab

Serum Albumin

Lab

Serum Hb

Lab

Fecal Calprotectin

Lab

C-reactive protein

Lab

Endoscopic Assessment of Disease Activity

Sonar

Ping Response Rate

Sonar

Average Sonar Score

21

Appendices

I. Abstract: Validation of American Gastroenterological Association’s Crohn’s Disease Care

Pathway

Project Sonar: Validating Predictive Algorithms and Risk Scores for IBD Outcomes Using a

Community-Based Registry and Patient Engagement Data

Background

Project Sonar is a community-based registry and disease management program developed to

improve clinical and economic outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). This cloud-

based program integrates monthly patient-reported symptoms and health-related quality of life

(HRQoL) information with clinical data delivered through electronic medical record derived

Clinical Decision Support tools (CDS). These fields are then combined with payer provided-

claims data to provide comprehensive, real-time information to physicians and patients on

current symptoms and health status, as well as composite ‘Sonar’ scores. The CDS tools were

developed using the American Gastroenterological Association’s Crohn’s Disease Care

Pathway (CDCP), and Ulcerative Colitis Care Pathway, both of which determine treatment

guidelines for Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative colitis (UC), respectively. The objective of this

project was to verify and measure the variation of data within Project Sonar, validate the CDCP

and UCCP guidelines, and Sonar risk scores using the real world data collected via Project

Sonar and healthcare claims of a subset of patients. The objective of this presentation is to

detail the methods used in this process.

Methods

The verification and validation project consisted of three major steps: (1) verification and

comprehensive quality check of all Project Sonar data to assure its quality mirrors that of

commercially available patient databases; (2) creation of an analytic dataset that merges

disparate patient level data from electronic medical records, healthcare claims data, and patient

reported outcomes; and (3) validation of CD and UC algorithms and Sonar risk scores.

Assignment of patients into correct risk category was confirmed by verifying the elements of the

three sub-scores (i.e., burden categories) that were important to the treatment algorithm and

development of the overall risk score, and assuring that each element and sub-score were

weighted appropriately. Then, the drivers for risk categorization were identified (i.e. the variables

most commonly associated with patients moving to a higher risk category). Finally, convergent

validity was assessed for the three sub-scores, risk categories, and Sonar scores by assessing

the correlations between risk categories and other indicators of disease severity (e.g.,

healthcare resource use, health-related quality of life).

Results/Conclusions

Project Sonar provides a unique opportunity to combine electronic medical records, healthcare

claims/resource utilization data, and patient reported outcomes to predict treatment failure and

target appropriate therapy in a community-based setting. With the completion of this

22

comprehensive verification and validation process, the Project Sonar database provides a rich

source of IBD patient data for understanding the natural course of IBD, identifying practice

patterns, comparing treatment options and outcomes, and identifying potential therapeutic cost

savings.

II. Project Sonar: Improvement in Patient Engagement Rates Using a Mobile Application

Platform

Project Sonar: Improvement in Patient Engagement Rates Using a Cloud-based Platform

Background

Project Sonar (PS) is a community-based registry and disease management program

developed by the Illinois Gastroenterology Group (IGG) to improve clinical and economic

outcomes in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). PS integrates monthly patient-

reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) information using a subset of questions from the

Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) sent via a Patient Portal (PP) producing a monthly ‘Sonar

Score’. These scores are then joined by clinical data fields delivered through electronic medical

record derived Clinical Decision Support tools (CDS). This combined data is analyzed against

payer provided-claims data to provide comprehensive, real-time information to physicians and

patients on current symptoms and health status, as well as composite ‘Sonar’ scores. In an

effort to improve portal-based patient response rates PS deployed the SonarMD Platform

(SMDP), a cloud based platform developed by SonarMD, LLC which uses smartphone

technology to improve patient engagement instead of a PP.

Methods

Patient surveys were developed using five questions derived from the Crohn’s Disease Activity

Index in an effort to obtain HRQoL scores. The sum of the values on these questions results in

a Sonar Score (SS) which produces a quantifiable assessment of HRQoL. SSs are monitored

for individual scores as well as the slope of change over time, which allows for the development

of care management algorithms that drive interventions. The PP was used to send these

surveys from January 2014 through May 2015. Due to an unacceptable PP response rate, the

SMDP was deployed in June 2015. Patient response rates were compared for each of the two

methods.

Results

The patient response rate for the PP averaged 27.6% over the 17 months of its use. Due to the

structure of the PP, SSs needed to be individually calculated upon their receipt resulting in

significant staff expense and a delay in patient feedback. The patient response rate for the

SMDP was 66.27% for the three months it has been deployed, far exceeding the rate of the PP.

Since the SMDP platform automatically calculates the SS at the time the patient answers the

survey, patients receive immediate algorithm derived responses. Staff time is significantly

reduced as a result.

23

Conclusion

Project Sonar provides a unique opportunity to combine electronic medical records, healthcare

claims/resource utilization data, and patient reported outcomes to predict treatment failure and

target appropriate therapy in a community-based setting. Since patient participation is critical to

the success of PS, the cloud-based SMDP’s superior performance improved the patient

response rate over the patient portal from 27.6% to 60%. It also resulted in significant savings

in staff time. More time of deployment will be necessary to confirm that these findings will stand

the test of time.

III. Project Sonar: Validating a Cost Normalization Methodology in a Community-based

Registry

TITLE: Project Sonar: Validating a Cost Normalization Methodology in a Community-Based Registry

AUTHORS: Kosinski, Lawrence

1, 2

; Sorensen, Michael

2

; Brill, Joel

2, 3

; Landsman-Blumberg, Pamela

4

;

Turpin, Robin

5

; Baum, Charles

5

INSTITUTIONS (ALL):

1. Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Elgin, IL, United States.

2. SonarMD, LLC, Elgin, IL, United States.

3. Predictive Health, Paradise Valley, AZ, United States.

4. Xcenda, LLC, Palm Harbor, FL, United States.

5. Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc, Deerfield, IL, United States.

BACKGROUND

Project Sonar, a community-based registry and disease management program developed to

improve clinical and economic outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Project Sonar, uses a cloud-based platform combining health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

information with clinical data delivered through electronic medical record derived Clinical

Decision Support tools.

These data fields are then combined with payer provided-claims data obtained from the

Intensive Medical Home with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois (BCBS-IL) database.

OBJECTIVES

Develop and validate a normalization methodology to mitigate the variation of cost data

between actual payments made vs a normalized payment structure derived from Medicare

Payment information to allow for meaningful assessment of Project Sonar’s economic impact.

METHODS

Patient Sample

Patients participating in Project Sonar and continuously enrolled in BCBS-IL from January 1, 2014

through September 30, 2015.

Costing Method

24

Crohn’s related claims-based payments were identified for each patient in the BCBS-IL medical

claims with ICD-9-CM 555.X or select ICD-9-CM symptom codes.

Claims-based payments were calculated and presented as total Crohn’s-related payments and

by type of service (i.e., infusible injection, diagnostic services, inpatient services, and physician

services).

All claims-based payments were adjusted to 2015 US dollars using the medical component of

the Consumer Price Index

Normalization Method

Normalized Crohn’s-related payments were calculated using standardized provider payments as

displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Factors to Normalize

Service Type

Factors to Normalize

Physician Services

CPT Code Payment on 2015 Outpatient Prospective Payment System

Diagnostic Services

2015 Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory Fee Schedule

Infusible Biologics

2015 office based payment rates

Inpatient Hospital Payments

DRG Payment

To remove bias from site of service all infusible biologics were normalized to office based

infusion rate of $85/unit compared to $158/unit

For inpatient Hospital Payments:

o The DRG Payment was calculated using a base rate derived as the sum of the Operating

Base Payment and the Capital Base Payment.

o The base rate was then multiplied by the DRG Weight derived from the Medicare

Severity Diagnosis-Related Groups Relative Weighting Factors.

Analysis

We examined the absolute difference and percentage difference between actual and

standardized payments for total Crohn’s-related payments and by type of service.

RESULTS

Sample Description

185 patients participating in Project Sonar and continuously enrolled in BCBS-IL were included in

the analysis

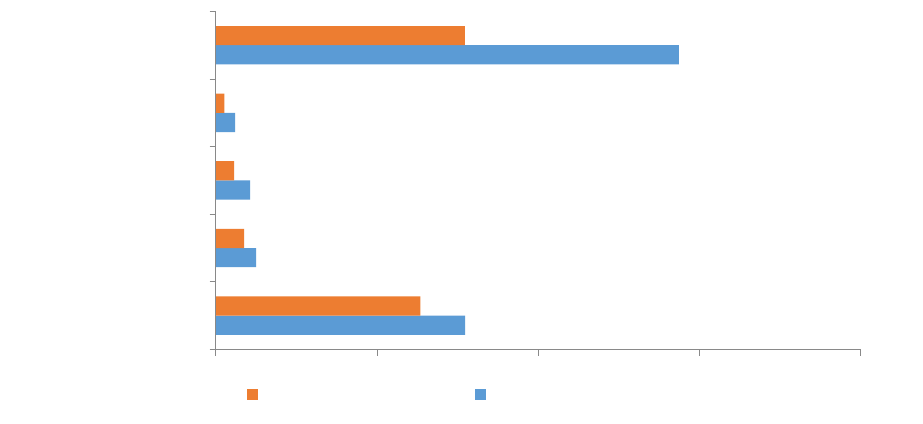

Figure 1. Crohn’s-Related Payments, Total and by Type of Service

25

Normalized Crohn’s –related payments are consistently lower than claims-based payments (see

Figure 1), although the percentage difference varies by service type

o Total: - 18%

o Physician services: - 30%

o Inpatient services: - 47%

o Diagnostic services: - 56%

o Infusible biologics: - 46%

Diagnostic

Inpatient

Physician

X% of infusions were administered in the hospital outpatient department which may contribute

to the large difference in normalized payments compared to claims based payments

LIMITATIONS

ICD-9-CM codes for Crohn’s related symptoms were selected based on clinical opinion after

review of a sample of medical claims for BCBS-IL Crohn's patients enrolled in Project Sonar and

the published literature. Therefore, costs could be underestimated if relevant ICD-9-CM codes

were omitted and overestimated if symptom claims included were related to alternative

diagnoses.

Claims data are collected for the purpose of billing, not research. Therefore, diagnoses may be

coded incorrectly or under-coded, possibly introducing measurement error.

CONCLUSIONS

Project Sonar represents a unique opportunity to manage care using the AGA Crohn’s Care

Pathway and analyze the results on payments.

For meaningful comparison, it is essential that payments are normalized against Medicare

Payments in order to mitigate the site of service differential in payment reporting.

The normalization methodology presented has broad applicability for those seeking to analyze

complex real-world clinical practice data and cost.

$1,546,899

$248,877

$210,967

$118,211

$2,872,914

$1,270,337

$173,776

$111,612

$52,028

$1,545,555

$0 $1,000,000 $2,000,000 $3,000,000 $4,000,000

Total Crohn's Payments

Physician Services

Inpatient Payments

Diagnostic Payments

Infusible Biologics

Normalized Payments Claims-Based Payments

26

IV. Project Sonar Abstract of Distinction: Digestive Disease Week 2016

Project Sonar: Reduction in Cost of Care in an attributed cohort of patients with Crohn’s

Disease.

Lawrence Kosinski,

1

Michael Sorensen,

1

Joel V. Brill,

2

Pamela B Landsman-Blumberg,

3

Robin Turpin,

4

Charles Baum

4

1. Sonar MD, LLC, Elgin, Illinois; 2. Predictive Health, LLC, Paradise Valley, Arizona; 3. Xcenda, LLC,

Palm Harbor, Florida; 4. Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., Deerfield, Illinois.

Background: Project Sonar (PS), a joint venture between Illinois Gastroenterology Group and Blue Cross

Blue Shield Illinois, is a community-based registry and disease management program developed to

improve clinical and economic outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). PS integrates patient-

reported symptoms and health-related quality of life information with clinical data delivered through

electronic medical record derived Clinical Decision Support tools (CDS) using a cloud-based program

developed by SonarMD, LLC. CDS tools are based on the American Gastroenterological Association’s

Crohn’s Disease Care Pathway (CDCP) to determine treatment guidelines for Crohn’s Disease (CD).

Clinical data is combined with payer claims data to provide comprehensive, real-time information to

physicians and patients on current symptoms and health status, as well as composite ‘Sonar’ scores.

This study reports performance of Project Sonar in a subset of continuously enrolled CD patients.

Methods: 152 attributed patients with CD were continuously enrolled in PS between Jan 1, 2014 and Sept

30, 2015. The baseline period was Jan 1 through Nov 30, 2014, and the study period was the PS go-live

of Dec 1, 2014 through Sept 30, 2015. Total Costs were corrected for the difference in time periods. CD -

based claims were identified using ICD-9 555 codes plus additional codes identified as Crohn’s-based

due to their relationship with CD. Payments for physician and diagnostic services were normalized using

a methodology based on Medicare payment rates; DRG payments for inpatient stays were adjusted to

eliminate site of service differentials in payment rates.

Results

Findings: Total payments for PS patients with CD declined by 11.03% driven by > 50% declines in

hospital and emergency room payments. Utilization of physician administered biologics rose 8.97% but

total biologic costs declined 3.95% driven by a 24.5% reduction in the use of injectable biologics.

Normalization of payments to eliminate site of service payment differentials resulted in a 9.87% savings

in payments.

Conclusions: PS demonstrates value-based improvement in care for CD patients in a community-based

setting through integration of clinical data, patient reported outcomes and healthcare claims/resource

utilization data. Over 50% declines in hospital admissions and emergency room visits were achieved

through CDS tools promoting adherence to AGA CDCP combined with intense patient engagement. PS

represents an innovative model of population health likely applicable to other chronic conditions.

Crohn's Payments

Total Crohn's

Payments

Average Per

Patient

Payment

Total Normalized

Crohn's

Payments

Normalization

Difference

Inpatient

Payments

Emergency

Room

Payments

Infusable

Biologics

Injectable

Biologics

Total Biologics

Pre-Period 2,118,308.65$ 13,936.24$ 1,932,069.37$ (186,239.28)$ 210,967.47$ 52,363.19$ 892,443.30$ 560,980.84$ 1,453,424.14$

Study Period 1,884,758.63$ 12,399.73$ 1,741,326.02$ (143,432.62)$ 90,410.85$ 24,465.00$ 972,485.87$ 423,561.72$ 1,396,047.59$

Difference (233,550.02)$ (1,536.51)$ (190,743.36)$ 42,806.66$ (120,556.62)$ (27,898.19)$ 80,042.57$ (137,419.12)$ (57,376.55)$

Percentage Difference -11.03% -11.03% -9.87% -22.98% -57.14% -53.28% 8.97% -24.50% -3.95%

27

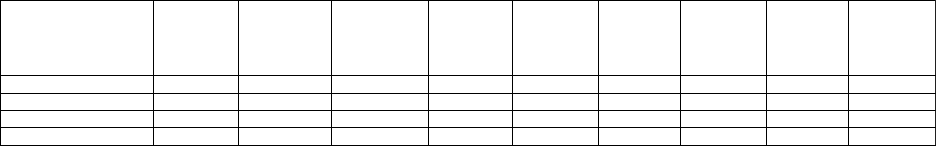

V. Guide to the Use of the Crohn’s Disease CDS Tool

The use of CDS tools is critical to our success in the management of our patients with chronic

disease. They also provide us an opportunity to bring together our PQRS requirements and

serve as a platform for participation in research studies. Accordingly, the Project Sonar

Physician Advisory Board, with the approval of the IGG Board of Managers, has decided to make

the use of these CDS tools mandatory. This document will provide you clarity in how to enter

data into this template.

The Crohn’s Disease CDS Tool is a “Demographic” template and therefore only has to be

populated only once. It will remain in its populated state from visit to visit and only requires

updates. It will be launched automatically when you enter a chief complaint of Crohn’s Disease.

The template has several sections as shown below:

28

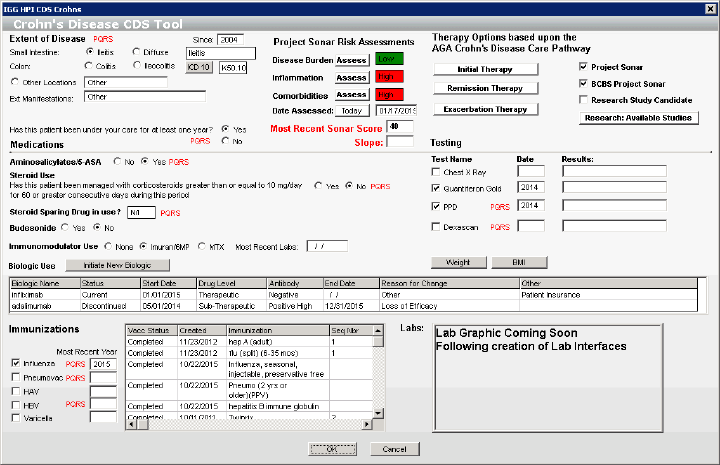

VI. AGA Crohn’s Disease Care Pathway Risk Assessment

25 metrics are captured in three categories: Disease Burden, Inflammation Burden, and

Comorbidity Burden. This assessment is updated annually on each patient. SonarMD is

developing a mathematical model behind the relative strengths of each metric.

Currently due to the size of our sample population, we are not able to reach statistical

significance. The implementation of this APM on a national basis would provide the

necessary patient population.

29

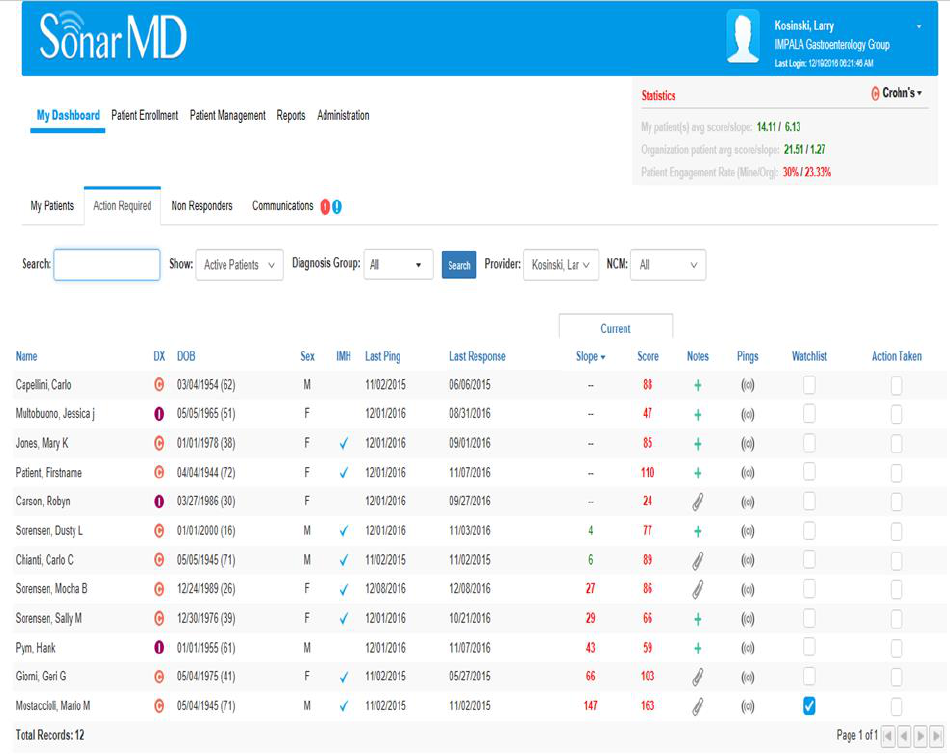

VII. SonarMD Nurse Care Manager Dashboard

The demo site shown below with fictitious patients demonstrates the user interface that the

NCMs and Physicians use each month to monitor their patients. Patients are listed according to

the assigned list of each NCM and Physician. Their raw Sonar Scores as well as the slope of

their scores over time are listed with color coordination based upon algorithmic rules. The

NCM or Physician can drill down on each one for further details. See VIII below.

30

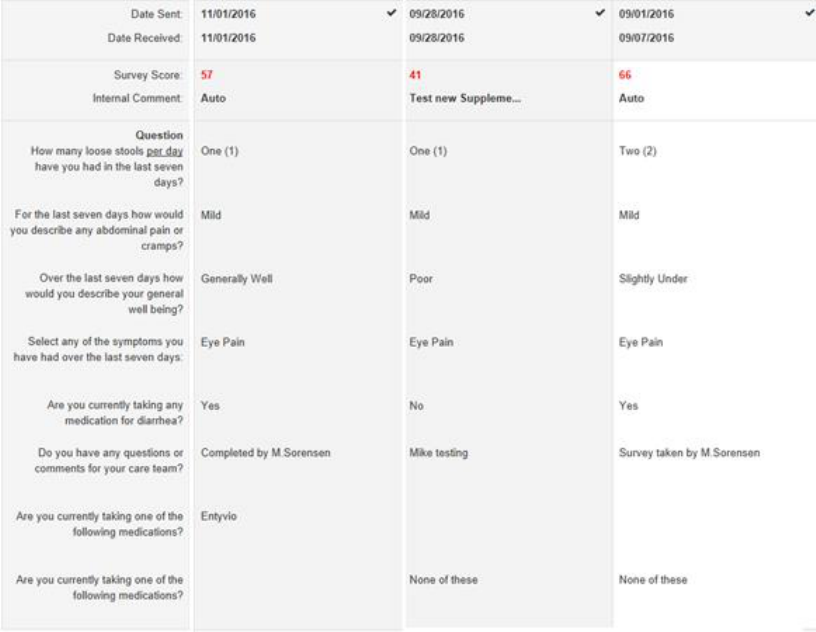

VIII. SonarMD Patient Survey

This template allows the reviewer to drill down on individual surveys. Each patient

receives the following questions every month via their device of choice. This template is

an example of what the NCMs utilize to monitor the answers and scores.

31

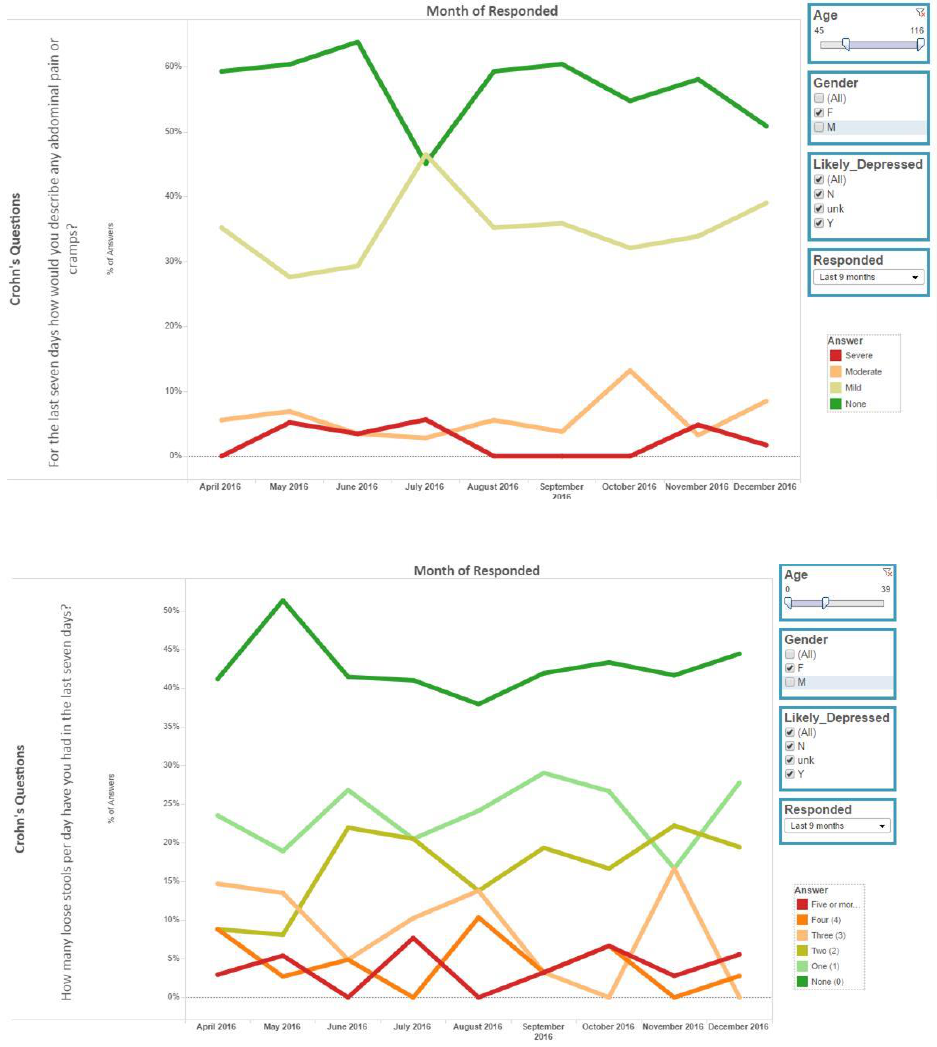

IX. Examples of SonarMD Ping Reports

The report corresponds to the answers for the first question in the survey shown in the

vertical axis. For the last seven days how would you describe any abdominal pain or

cramps? The figure can be filtered by the items shown on the right side: age, gender,

depression rating and by responder percentage.

The following figure demonstrates the same findings for the second question: “How

many loose stools per day have you had in the last seven days”

32

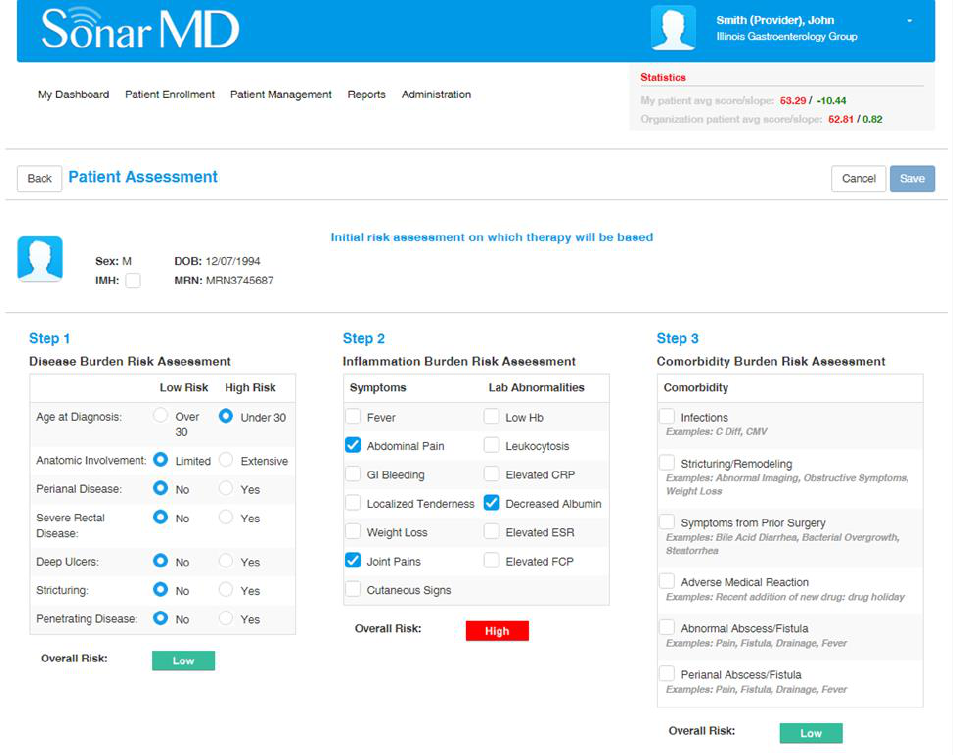

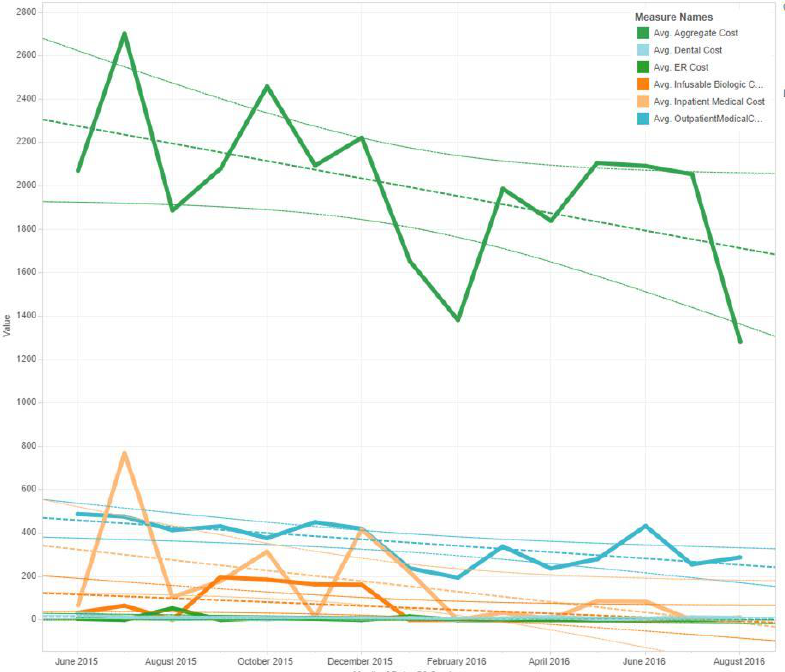

X. SonarMD Cost Report

The following figure shows a stead fall in average aggregate cost of care over the time

period of June 1

st

2015 through August 31

st

2016.