Patient Experience Journal Patient Experience Journal

Volume 8 Issue 3 Article 12

2021

The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers' The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers'

patient experience scores patient experience scores

Katelyn J. Cavanaugh

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Monica A. Johnson

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Courtney L. Holladay

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Follow this and additional works at: https://pxjournal.org/journal

Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Training and Development Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Cavanaugh KJ, Johnson MA, Holladay CL. The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers'

patient experience scores.

Patient Experience Journal

. 2021; 8(3):109-116. doi: 10.35680/

2372-0247.1564.

This Research is brought to you for free and open access by Patient Experience Journal. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Patient Experience Journal by an authorized editor of Patient Experience Journal.

The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers' patient experience The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers' patient experience

scores scores

Cover Page Footnote Cover Page Footnote

We would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Garcia and Dr. Randal Weber for reviewing this paper. This article

is associated with the Policy & Measurement lens of The Beryl Institute Experience Framework

(https://www.theberylinstitute.org/ExperienceFramework). You can access other resources related to this

lens including additional PXJ articles here: http://bit.ly/PX_PolicyMeasure

This research is available in Patient Experience Journal: https://pxjournal.org/journal/vol8/iss3/12

Patient Experience Journal

Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021, pp. 109-116

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3

© The Author(s), 2021. Published in association with The Beryl Institute.

Downloaded from www.pxjournal.org 109

Research

The effect of service excellence training: Examining providers' patient

experience scores

Katelyn J. Cavanaugh, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, kjcavanaugh@mdanderson.org

Monica A. Johnson, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, MAJohnson@mdanderson.org

Courtney L. Holladay, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, clhollada[email protected]

Abstract

Previous research and applied work has shown that communication-based training has the potential to impact important

outcomes for healthcare organizations. Our institution developed and deployed Service Excellence, a communications-

focused training, in our large academic cancer-focused healthcare system. In this study, we investigated whether patient

experience improved for those with care providers who completed Service Excellence, as measured by Press Ganey

Provider Experience surveys, and whether the effect of Service Excellence training depends on employee engagement.

Results indicated that participating in Service Excellence training positively impacts perceptions of patient experience,

and that the impact of the training is stronger for providers with low engagement as compared to providers with high

engagement. Findings suggest that communications-based training can be an effective mitigation strategy to assist even

those low engaged physicians with displaying the expected behaviors for positive patient interactions. Implications for

healthcare organizations are discussed, including the rationale for motivating providers to attend such training.

Keywords

Engagement, patient experience, patient-centered, provider communication, communication skills, Press Ganey

Introduction

Communication is the thread that pulls healthcare

providers together with their colleagues and patients. As

Gallup identified, employees want to make these

connections within their work environment. However, the

quality of these relationships and the communication

occurring within them can lack substance and purpose.

1

Training has been acknowledged for decades as an

effective and necessary tool for building communication

skills

2

within the medical community.

3,4

Communication is especially important and complex within

the healthcare environment. The National Cancer Institute

identifies the emotions, including denial, fear, and anger,

that can surface when patients are diagnosed with cancer.

5

Providers’ capability to communicate responsively and

empathetically toward patients is critical in this context.

Furthermore, providers’ ability to communicate directly

impacts patient safety. Some organizations have created

training to increase providers’ communication skills and

positively impact safety and the patient experience. For

example, TeamSTEPPS (Strategies and Tools to Enhance

Performance and Patient Safety) is a set of evidence-based

teamwork tools specifically developed as an approach to

increase patient safety as part of the patient experience.

The tools focus on leadership and communication among

team members.

6

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

requires that physicians report patient experience scores in

the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare

Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) for inpatient care and

in the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of

Healthcare Providers and Systems (CGCAHPS) for

outpatient care. A major driver of these scores is provider

communication. Both providers and hospitals have turned

to methods to increase these skills with an eye toward

impacting the patient experience. As one example, the

Cleveland Clinic implemented their REDE model

(Relationship Establishment, Development, and

Engagement) which focuses on improving the patient

experience through patient-physician communication

7

.

Other organizations have shown communications training

can have a positive impact on providers’ skill

demonstration. What is less clear is whether there are

boundary conditions for communications training

effectiveness. The purpose of this investigation is to

describe a communications-based training program and

report the results of our investigation into the potential

impact of this training on the patient experience.

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

110 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021

Service Excellence Program Purpose and

Development

Our organization, a cancer-focused academic healthcare

institution, developed a Service Excellence program to

provide employees with communication strategies and

decision-making tools to deliver an excellent experience to

patients. The content was based on research of best

practices, such as the service standard strategies of the

Disney Institute and findings published by Press Ganey in

the healthcare industry.

8,9

To customize the content to our

organization, we held workshops with more than 100 staff

and faculty to discuss stakeholder groups – their needs,

wants, stereotypes, and emotions – and to establish the

Service Standards needed in our organization. The service

standards and preliminary training content were evaluated

by a cross-sectional group of institutional leaders and

piloted within one division prior to organization-wide

implementation. The Service Standards identified were: 1.

Safety, 2. Courtesy, 3. Accountability, 4. Efficiency and 5.

Innovation. They are prioritized in that order in instances

when employees need to make a service decision.

Employees should deliver on all service standards in every

interaction when possible, however, employees know

which standard takes priority if a choice must be made.

Figure 1 contains our Service Standards and their full

definitions.

Service Excellence Training Program

The curriculum is modular in nature to address the

multiple components of Service Excellence. The online

prerequisite showcases leaders from across the institution

voicing their support for a culture in which “we care while

we provide care.” The remaining six hours of training are

divided into two-hour sequential modules of experiential

learning, each containing both discussion and hands-on

activities. Module 1 evokes discussions around the

importance of engagement and walks through the service

standards. Module 2 focuses on communication tools to

enhance the patient experience and to enable

empowerment among employees. Module 3 encourages

employees to anticipate the needs of their stakeholders and

provides the tools for Service Recovery when expectations

are not met (see Table 1 for summary). The three modules

are designed for a facilitator and co-facilitator to lead the

sessions. This format allows for a wide variety of examples

to be shared with employees, helping them to connect to

the content and understand how to apply it in their roles.

Both facilitator roles participate in at least three hours of

train-the-trainer training prior to leading the sessions.

Our Study

We recognized that committing to the patient experience

through Service Excellence means committing to building

relationships in an environment of open communication.

One available method to measure our success of this

commitment is the Press Ganey survey, which measures

patient perceptions of their interactions with our care

providers.

10

Press Ganey is a company external to our

institution that develops and distributes patient satisfaction

surveys for the majority of US hospitals.

11

Patients

automatically receive and complete the Press Ganey survey

after their appointments. One portion of this survey asks

patients to rate their interaction with their care provider on

five dimensions.

12

We also recognize that important individual factors may

affect care providers’ ability to enact what they have

Figure 1. Service Excellence Standards

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021 111

learned in Service Excellence training. One factor that has

been shown to influence interactions and relationships,

including those between providers and patients, is

employee engagement.

13,14

Employee engagement has been

defined as “involvement and satisfaction with as well as

enthusiasm for work”.

15

We measure employee

engagement through our biennial employee engagement

survey which invites all employees to complete a

confidential online survey to gather their perspectives on

their work environment.

The purpose of this study was two-fold. First, we wanted

to investigate whether completing Service Excellence

training influences patients’ experiences with their

providers. To do so, we compared the Press Ganey Patient

Experience scores of our providers prior to and post

training. Second, we wanted to investigate whether the

impact of the training depends on the engagement levels

of the participating providers. Specifically, we sought to

identify the influence of Service Excellence training on

Press Ganey scores at different levels of provider

engagement. By doing so, we provide evidence to

determine whether communications training such as

Service Excellence (i.e., providing communication tools

and establishing cultural expectations) can help providers’

develop skills to better connect with their patients during

their interactions.

Method

Participants

Participants included 360 providers at a cancer-focused

academic research institution. Demographics including

provider type, gender, and ethnicity can be found in Table

2.

Measures

Service Excellence Course Completion.

During a two-

year time period from March 2017 through February 2019,

109 providers completed Service Excellence training.

During that same period, there were 251 providers that did

not complete Service Excellence.

Engagement

. All providers completed the biennial online

engagement survey sent to all employees in the institution

in February 2019. Three engagement items comprised the

mean composite engagement score; these items were

created specifically for this engagement survey by an

external consulting company for benchmarking purposes.

Responses were indicated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging

from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Thus, higher

scores indicate higher engagement (i.e., more positive

attitudes towards employees’ jobs and the organization).

The full text items, along with descriptive statistics for the

participants’ responses, can be found in Table 3. Together,

the items exhibited acceptable internal consistency

reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

Press Ganey Scores

. Five items from the Care Provider

section of the Press Ganey survey comprised the mean

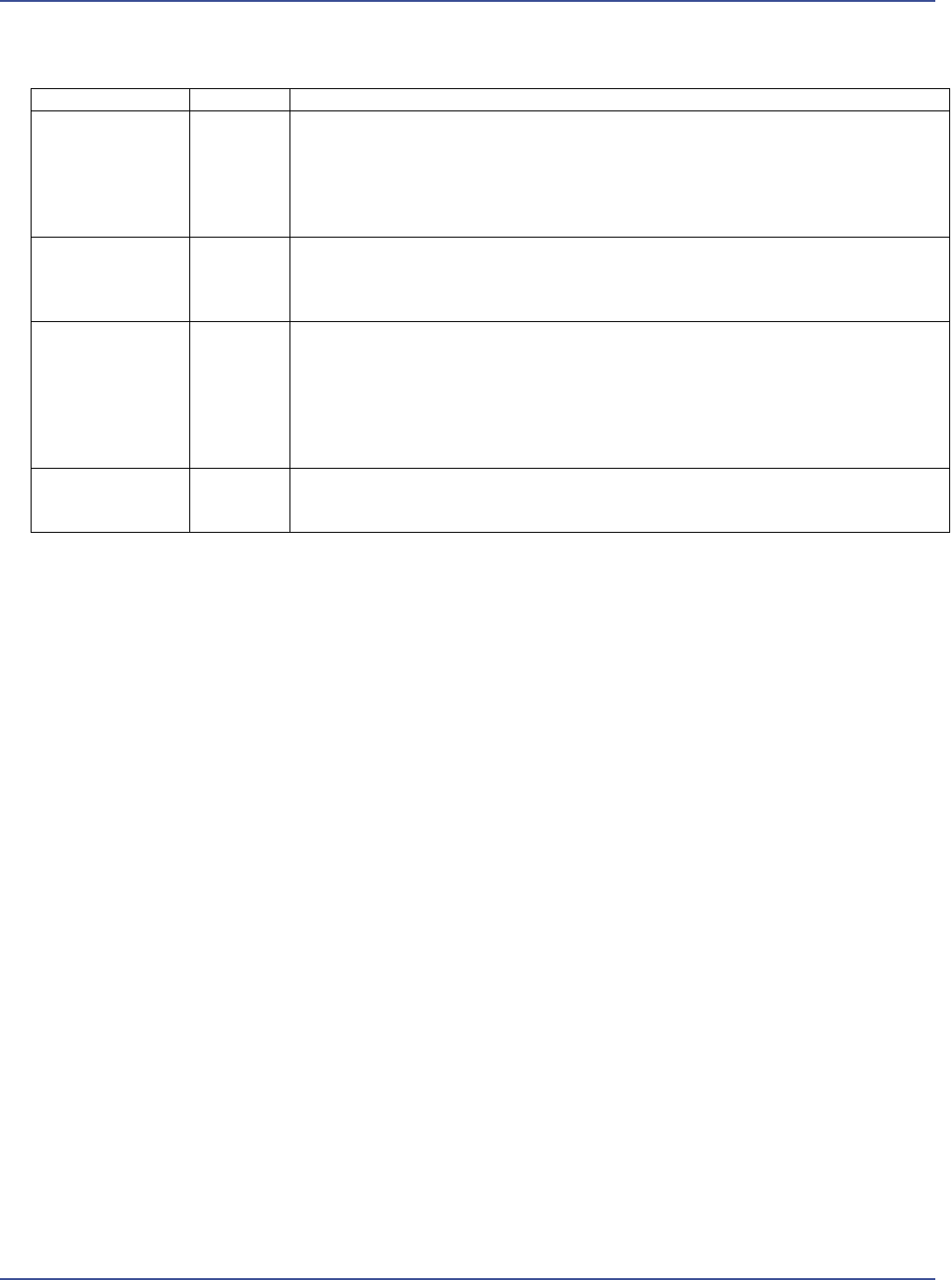

Table 1. Service Excellence Curriculum Overview

Course

Timing

Topics

Online

Prerequisite

45 minutes

History – Create an emotional connection to our organization’s purpose and how each

employee fits into our institution and its history

The Why – Understand why patients, caregivers, and colleagues choose to come to our

institution and the choice they have among competitors

Service Foundations – Recognize the Service Standards as a tool to empower each

employee to deliver on Service Excellence

Module 1

2 hours

Engagement – Create awareness of how engagement can impact the environment and

interactions with stakeholders

Service Standards – Establish the standards of service and use them as a decision-making

tool

Module 2

2 hours

Communication – Increase awareness of the need to convey feelings and rationale when

motivating others, and use communication tools, such as AIDET (Acknowledge,

Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank You), to improve interactions

Patient Experience – Understand the patient perspective and how direct and indirect

patient-facing positions affect the patient experience

Empowerment – Define the boundaries to allow each employee to deliver on their role

with purpose

Module 3

2 hours

Anticipating Needs – Promote behaviors that create moments of hope for stakeholders

Service Recovery – Build stakeholder loyalty and trust when service is less than what is

set by standards

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

112 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021

composite scores for patient experience. These items were

selected because they most directly asked patients about

their interaction with their care provider. Previous research

evaluating the psychometric properties of Press Ganey

items have found “acceptable” levels of internal

consistency reliability, factor structure, and convergent and

discriminant validity.

16

The Press Ganey surveys were

completed by patients during two time periods; pre Service

Excellence from December 2016-February 2017 (n =

15,002 patient respondents, with an average of 34

respondents per provider) and post Service Excellence

from March-May 2019 (n = 13,717 patient respondents,

with an average of 33 respondents per provider). Year-

over-year, the average patient response rate to the surveys

is 20%, and the response rate is mirrored within gender

and ethnic subpopulations, ranging from 15-20% response

rates year-over-year.

Patients rated their provider on a 5-point Likert scale

ranging from 1 (Very Poor) to 5 (Very Good), in which

higher scores indicate more positive perceptions of patient

experience. Press Ganey automatically converts all

responses to a score ranging from 0 to 100 in increments

of 25 because “most people find it easier to interpret

scores from 0-100.”

12

This is an automatic conversion and

the raw responses are not available at the individual level;

thus, Press Ganey item responses are reported on the 0-

100 scale, although the response scale is not continuous.

Together, the items exhibited acceptable internal

consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α for 2017 = 0.95;

Cronbach’s α for 2019 = 0.87). Full items and descriptive

statistics can be found in Table 4.

IRB approval was received for the analysis of these data

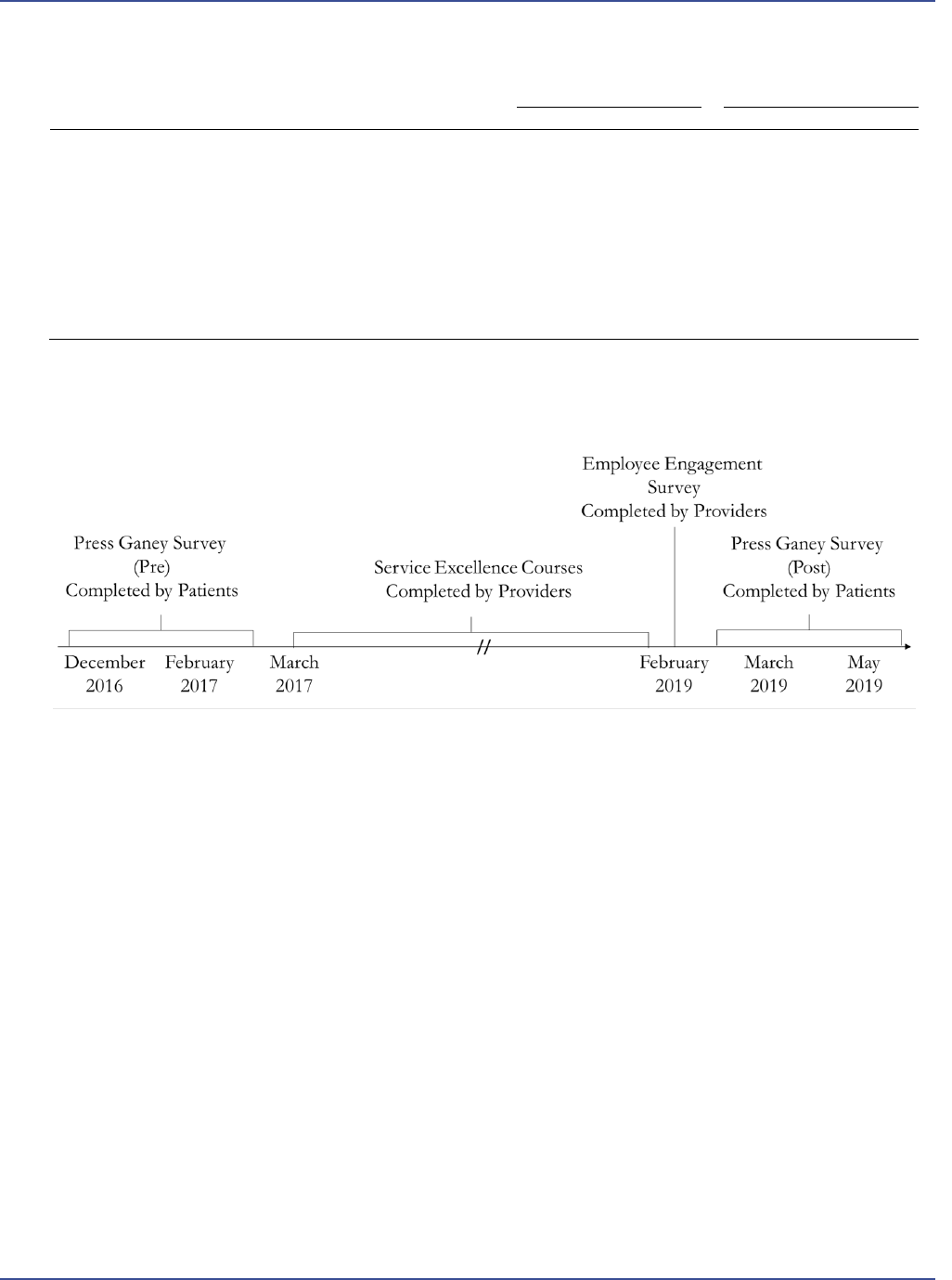

(IRB Protocol number # 2020-1323). Figure 2 depicts the

timing of the Service Excellence training, the employee

engagement survey, and Press Ganey survey completion.

Data Analysis

The engagement composite appeared bimodal based on

visual inspection of the data, indicating the existence of

two groups of providers based on their responses to

engagement items. Thus, engagement was split into two

groups; 142 providers with low engagement (ranging from

1.33 to 4.00) and 141 providers with high engagement

(ranging from 4.33 to 5.00).

In order to investigate the effects of Service Excellence

training, as well as the role of engagement, two ANOVA

models were conducted. First, a Repeated Measures

ANOVA was conducted to investigate the effects of

Service Excellence training on Press Ganey Care Provider

Table 2. Participant Demographic Characteristics

N

%

Provider Type

Doctor of Medicine (MD)

290

80.6

Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN)

47

13.1

Certified Physician Assistant (PA-C)

14

3.9

Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO)

1

0.3

Gender

Male

185

51.4

Female

175

48.6

Ethnicity

Caucasian

210

58.3

Asian

96

26.7

Hispanic

27

7.5

African American

21

5.8

Two or more races

3

0.8

Native American

2

0.6

Pacific Islander

1

0.3

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for Employee Engagement Items

Item

N

Mean

SD

1. My job provides me with a sense of personal accomplishment

283

4.35

0.69

2. I feel like I really belong in this institution

283

4.06

0.91

3. I would recommend [this institution] to others as a great place

to work

283

4.15

0.83

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021 113

scores in 2017 and 2019. Second, a two-way ANOVA was

conducted to investigate the effects of engagement and

Service Excellence training on 2019 Press Ganey Care

Provider scores. We had no theoretical reason to believe

that sociodemographic factors would impact these

relationships, thus no specific hypotheses were made

regarding the effects of group membership (provider type,

gender, and ethnicity). However, we tested for the

presence of effects by adding three dichotomous

covariates to the analyses. Dichotomous variables were

used due to sample size constraints (M.D. provider type

versus all others, male versus female, and Caucasian

ethnicity versus all others).

Results

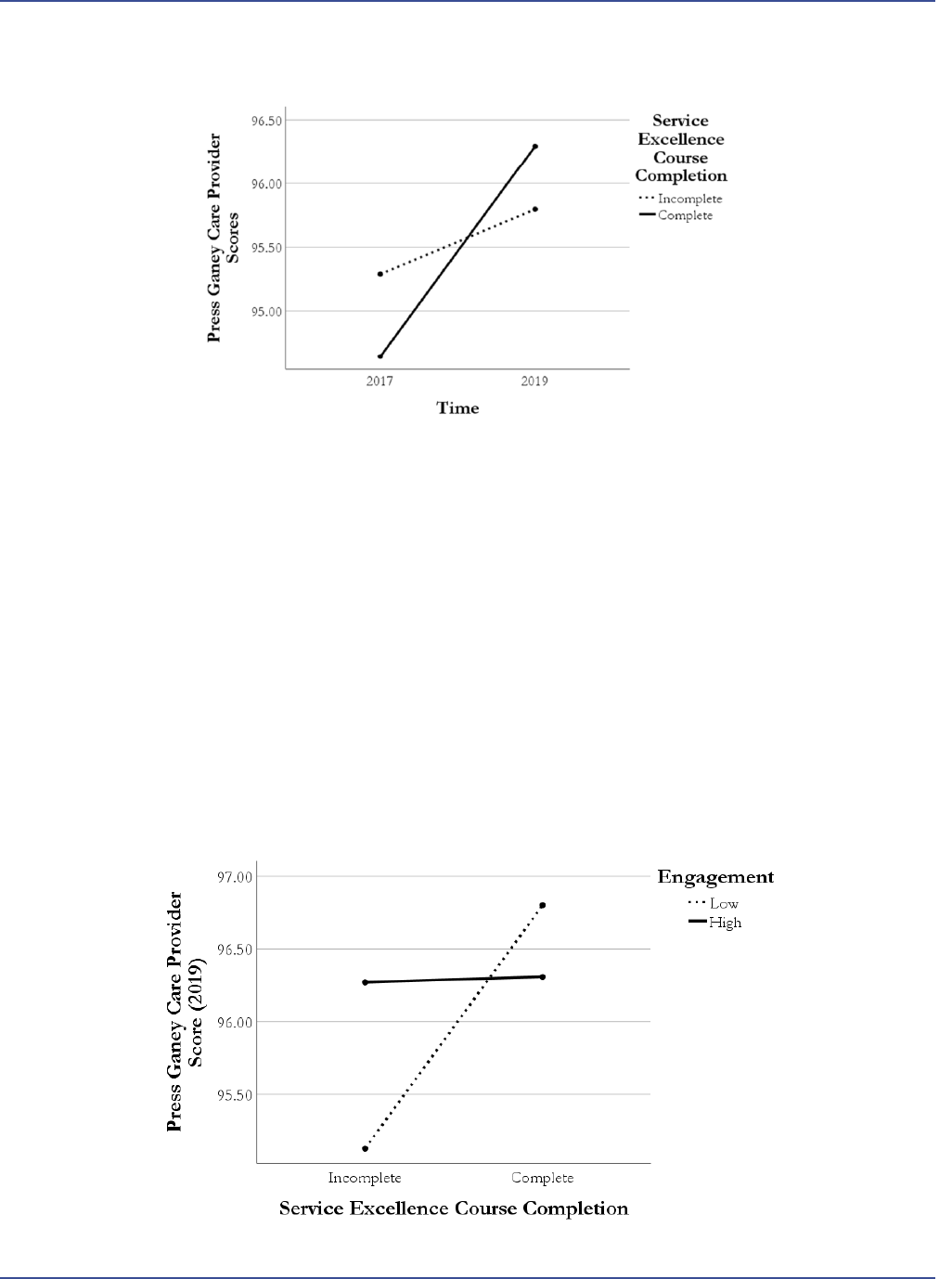

2017-2019 Press Ganey Care Provider Scores

Holding Service Excellence constant, ANOVA results

revealed that providers received higher Press Ganey Care

Provider scores in 2019 than in 2017. This difference was

statistically significant, F(1, 177.038) = 16.28, p < 0.001,

partial η

2

= 0.044. The interaction between time and

Service Excellence training was statistically significant,

indicating that providers who completed Service

Excellence training increased Press Ganey scores to a

greater extent than those who did not, F(1, 49.673) = 4.57,

p = 0.033, partial η

2

= 0.013. A graph of these effects can

be found in Figure 3. No sociodemographic factors were

statistically significant and were removed from the analyses

reported here for ease of interpretation.

2019 Press Ganey Care Provider Scores

The ANOVA revealed that the main effect of engagement

was not significant, F(1, 279) = 0.63, p = 0.428, partial η

2

= 0.002, but the main effect of Service Excellence training

was statistically significant F(1, 279) = 4.37, p = 0.037,

partial η

2

= 0.015. The interaction between engagement

and training was statistically significant, indicating that the

effect of Service Excellence on Press Ganey Care Provider

scores depends upon the level of employee engagement,

F(1, 279) = 4.01, p = 0.046, partial η

2

= 0.014.

For low engagement employees, the simple effect of

Service Excellence indicated that Press Ganey Care

provider scores were significantly higher for those that

completed training, F(1, 279) = 5.89, p = 0.016, partial η

2

= 0.021. For high engagement employees, the simple

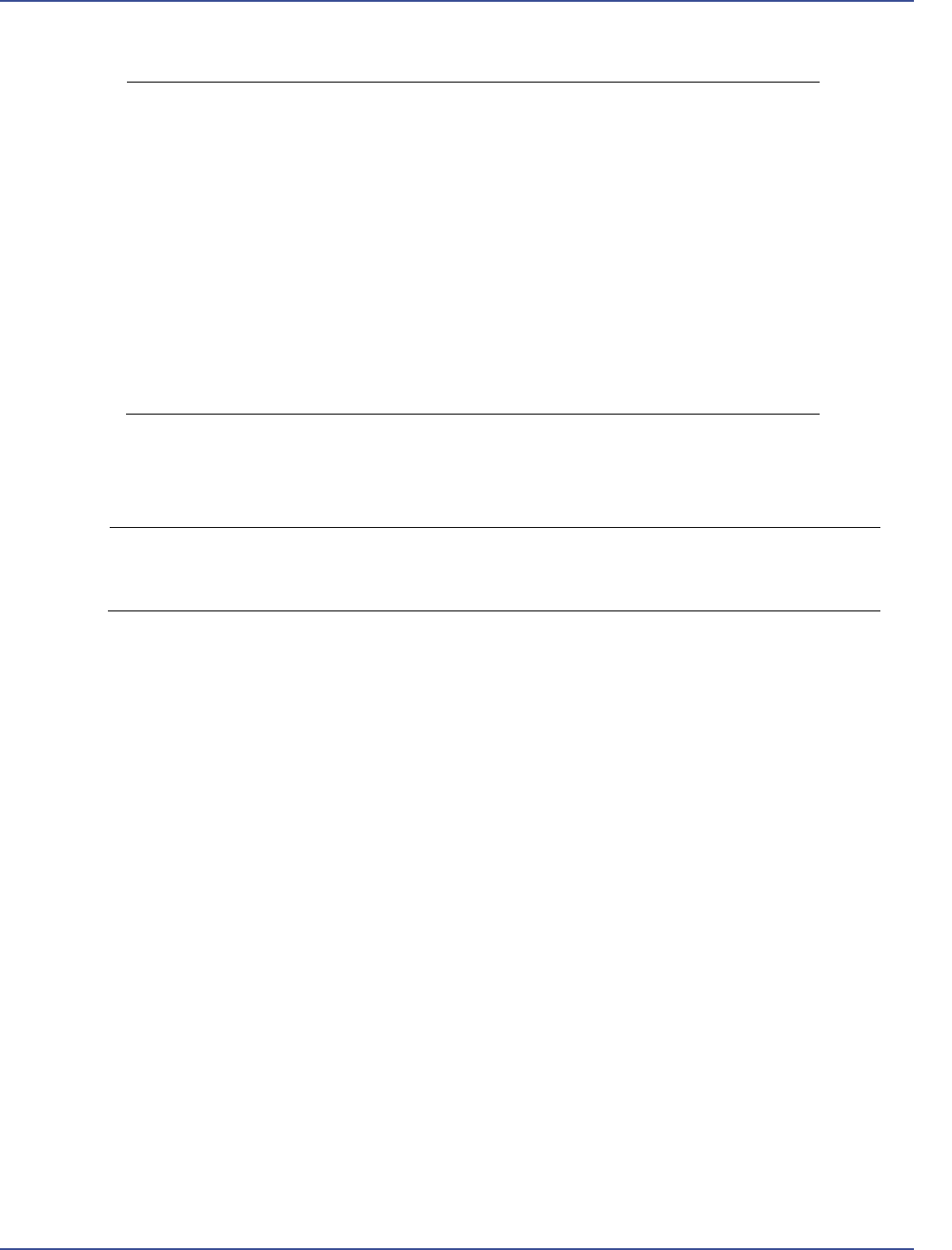

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for 2017 and 2019 Care Provider Press Ganey Items

2017 (pre)

2019 (post)

Item

N

Mean

SD

N

Mean

SD

1. Concern the care provider showed for your

questions or worries

360

95.19

5.48

360

96.21

3.50

2. Explanations the care provider gave you about your

problem or condition

360

95.44

4.47

360

95.96

3.85

3. Care provider’s efforts to include you in decisions

about your care

360

94.80

4.85

360

95.99

3.57

4. Likelihood of your recommending this care provider

to others

360

95.35

5.80

360

96.18

4.32

5. Extent to which your care provider talked with you

about your pain (if any)

358

94.71

5.04

356

95.35

4.23

Figure 2. Timeline of Press Ganey survey, Service Excellence courses, and Employee Engagement Survey

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

114 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021

effect of Service Excellence indicated Press Ganey Care

Provider scores was also higher for those that completed

training, though the effect was much weaker, F(1, 279) =

0.55, p = 0.461, partial η

2

= 0.002. Together, these results

indicate that Press Ganey Care Provider scores were

greater for providers that completed Service Excellence

training, and the effect of the training was stronger for low

engagement providers. A graph of these simple effects can

be found in Figure 4. No sociodemographic factors were

statistically significant and were removed from the analyses

reported here for ease of interpretation.

Discussion

Our results showed that providers who completed Service

Excellence training showed a greater improvement over

time in their patient experience scores compared to those

providers who did not complete the training. This finding

helps to establish the efficacy of training as an intervention

to support providers in growing in their communication

skills.

Employee engagement has been touted and repeatedly

reported to be related to patient experience; organizations

with lower employee engagement scores tend to have

lower patient satisfaction.

17, 18

Our results show that

Figure 4. Simple Effects of Service Excellence Training and Engagement on Press Ganey Care Provider Scores

Figure 3. 2017-2019 Press Ganey Care Provider Scores by Service Excellence Training

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021 115

training can potentially have a mitigating effect, such that

providers with low engagement are better able to increase

their patient experience scores following completion of

training. This finding shows that providers can learn new

communication skills and improve their interactions with

patients, and that training may be especially impactful for

providers or organizations with lower levels of

engagement.

The finding further shows that training can be an effective

intervention for organizations seeking to counter the

effects that low engagement can have. Those who are

already actively engaged may already behave in ways that

are aligned with a service culture. Those with low

engagement may benefit from communications training by

applying their new skills, awareness, and tools to foster

more effective and positive communication with their

patients. While this result may appear counterintuitive, the

effect could be due to contrasting behavior, where the

same behavior appears as marked improvement based on

comparison.

19

Patients could be perceiving the interactions

with less engaged physicians following training more

favorably when contextualizing them against their prior

interactions. Overall, this tie to engagement aligns with

recent efforts proposed to improve burnout by focusing

on communication and relationships

20,21

and provides

initial evidence showing the positive effects these efforts

can have on the patient experience.

Implications

Research shows that patients are likely to recommend or

not recommend care providers to others based on their

experiences; in fact, they are more likely to share their

negative reviews.

22

A positive patient experience is

necessary for organizations to not only do the right thing

but also stay competitive with their peer organizations.

Patient experience scores are becoming increasingly

transparent and are being used for decision-making; for

example, payers can now access such scores to determine

reimbursement (e.g., the National Research Corporation

Health Transparency StarCard rating system). While this

could serve as a motivator to attend training, it could also

explain why in our own organization we saw an increase in

scores across both trained and untrained providers. That

is, providers may already have been working to improve

their patient interactions to ensure positive feedback from

patients because of its visibility and its impact on

reimbursement. Supplying providers with resources and

tools to help improve these interactions is ultimately the

responsibility of organizations. These reasons together

provide healthcare organizations with the rationale to

support such training.

Finally, we want to note that less engaged providers are

more likely to cite time away from patient care as a reason

to not attend training, and in fact, time is a precious

resource in their patient interactions.

23

Our findings

provide evidence for rationale at the individual provider

level; training could help improve provider-patient

interactions and improve the quality of provider time

spent with patients. Showing providers the results other

providers achieved following training could serve to

minimize resistance, even from low engaged providers.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study described here took place within a single

organization. Future research could explore these same

effects across organizations and across different healthcare

providers to ensure the generalizability. While the findings

show promise for the impact of training on providers’

behaviors in their interactions with patients, more research

is needed to unpack the effects of communication-focused

training on provider behaviors and patient outcomes.

Specifically, research is needed to identify which aspects of

the training are most effective in transferring to patient

interactions and what organizations can do to support

providers in transferring their training to patient

interactions. Additionally, the effects we found on Press

Ganey scores were small. However, given the many factors

that contribute to these scores, even small effects are quite

notable. Examining more detailed information about

provider training beyond completion or participation (e.g.,

knowledge gained or engagement in the training program)

may provide deeper insights into the effects of training.

Conclusion

Healthcare is an especially important setting in which

effective communication facilitates relationships and leads

to a better patient experience. With training, providers may

raise their awareness and skills to positively impact how

they build relationships through more effective

communication, and this impact can be observed for less

engaged providers. The results presented here provide

much-needed evidence that providers can apply what they

learn in training to positively impact the patient

experience.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Garcia

and Dr. Randal Weber for reviewing this paper.

References

1. State of the American Workplace Report. Gallup,

2017. Retrieved July 07, 2021 from

https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238085/state-

american-workplace-report-2017.aspx

2. Nestel D, Woodward-Kron R, Keating JL. Learning

outcomes for communication skills across the health

Service excellence training and the patient experience, Cavanaugh et al.

116 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 – 2021

professions: a systematic literature review and

qualitative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014570.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014570

3. O’Keefe M, Henderson A, Pitt R. Health, medicine

and veterinary science: Learning and teaching

academic standards statement. New South Wales,

Australia: Australian Government Department of

Education, Employment and Workplace Relations,

2011.

4. CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework—

Communicator. Royal College of Physicians and

Surgeons of Canada, 2015.

http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/ca

nmeds/framework/communicator

5. National Cancer Institute. Feelings and Cancer.

Published 2018. Retrieved July 07. 2021 from

https://www.cancer.gov/about-

cancer/coping/feelings

6. Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality. TeamSTEPPS: National Implementation.

2013 http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/about-2cl_3.htm.

7. Windover AK, Boissy A, Rice TW, Gilligan T, Velez

VJ, Merlino J. The REDE model of healthcare

communication: optimizing relationship as a

therapeutic agent. Journal of patient experience.

2014;1(1):8-13.

8. Press Ganey. Will Your Patients Return? The

Foundation for Success. Published 2017. Retrieved

July 7. 2021 from

https://helpandtraining.pressganey.com/Documents

_secure/Medical%20Practices/White%20Papers/med

ical-practice_4.pdf

9. Jones B. How Disney Empowers Its Employees to

Deliver Exceptional Customer Service. Harvard

Business Review; 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2021 from

https://hbr.org/sponsored/2018/02/how-disney-

empowers-its-employees-to-deliver-exceptional-

customer-service

10. Press Ganey. Hospital Consumer Assessment of

Healthcare Providers and Systems. Published 2015.

Retrieved December 09, 2020

from https://www.pressganey.com/resources/progr

am-summary/hospital-consumer-assessment-of-

healthcare-providers-and-systems

11. Graham B, Green A, James M, Katz J, Swiontkowski

M. Measuring Patient Satisfaction in Orthopaedic

Surgery. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2015;97(1):

80-84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00811.

12. Press Ganey. Guide to Interpreting. Published 2014.

Retrieved July 7, 2021 from

https://helpandtraining.pressganey.com/lib-

docs/default-source/ip-training-resources/guide-to-

interpreting---part-2.pdf?sfvrsn=2

13. Khan A, Spector ND, Baird JD, Ashland

M, Starmer AJ, Rosenbluth G, et al. Patient safety

after implementation of a coproduced family centered

communication programme: multicenter before and

after intervention study. BMJ 2018;5;363:k4764. doi:

10.1136/bmj.k4764

14. Heath S. Employee Engagement Tied to Higher

Patient Satisfaction Levels. Published 2019. Retrieved

December 12, 2020

from https://patientengagementhit.com/news/emplo

yee-engagement-tied-to-higher-patient-satisfaction-

levels

15. Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Hayes TL. Business-unit-level

relationship between employee satisfaction, employee

engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis.

Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(2); 268-279. doi:

10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

16. Presson AP, Zhang C, Abtahi AM, Kean J, Hung M,

Tyser AR. Psychometric properties of the Press

Ganey® Outpatient Medical Practice Survey. Health

Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12955-

017-0610-3

17. Buhlman NW, Lee TH. When Patient Experience and

Employee Engagement Both Improve, Hospitals’

Ratings and Profits Climb. Harvard Business Review,

2019. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from

https://hbr.org/2019/05/when-patient-experience-

and-employee-engagement-both-improve-hospitals-

ratings-and-profits-climb

18. Heath S. Employee Engagement Tied to Higher

Patient Satisfaction Levels. Published 2019. Retrieved

December 12, 2020,

from https://patientengagementhit.com/news/emplo

yee-engagement-tied-to-higher-patient-satisfaction-

levels

19. Sumer, H C & Knight, P A. Assimilation and contrast

effects in performance ratings: Effects of rating the

previous performance on rating subsequent

performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1996; 81.4:

436.

20. Maslach C, Leiter MP. New insights into burnout and

health care: Strategies for improving civility and

alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):160-163.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918

21. Parks T. Cleveland Clinic’s approach to burnout

focuses on relationships. AMA. 2016. Retrieved July

07, 2021 from https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-

care/patient-support-advocacy/cleveland-clinic-s-

approach-burnout-focuses-relationships

22. 75 Customer Service Facts, Quotes & Statistics.

Retrieved December 12, 2020 from

https://www.helpscout.com/75-customer-service-

facts-quotes-statistics/

23. Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the

patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med.

1999;14 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S34-S40.

doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00263.x