CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

Proposed Five-Year

Financial Plan

Fiscal Years 2023-24 through 2027-28

JANUARY 13, 2023

Page intentionally left blank.

Page 1 of 106

Acknowledgements

Department

Staff

Mayor’s Budget Office

Anna Duning, Sally Ma, Radhika Mehlotra, Damon Daniels, Jack English,

Xang Hang, Matthew Puckett, Fisher Zhu

Controller’s Office

Ben Rosenfield, Ted Egan, Todd Rydstrom

Controller’s Office:

Budget and Analysis

Michelle Allersma, Mark Chen, Yuri Hardin, Ken Hinton, Sylvia Ho, Nicholas

Leo, Carol Lu, Michael Mitton, Calvin Quock, Risa Sandler, Jamie Whitaker

Board of Supervisors’ Budget and

Legislative Analyst

Severin Campbell, Dan Goncher, Christina Malamut

Office of Resilience and Capital

Planning

Brian Strong, Kate Faust, Nishad Joshi, Olivia Chen

Committee on Information

Technology

Jillian Johnson, Julia Chrusciel, Neil Dandavati, Danny Vang

Page 2 of 106

Page intentionally left blank.

Page 3 of 106

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 5

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW............................................................................................................................... 8

FIVE-YEAR BASE CASE PROJECTION ......................................................................................................... 20

FISCAL STRATEGIES ................................................................................................................................... 56

CITYWIDE STRATEGIC INITIATIVES ........................................................................................................... 65

APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................................. 83

OTHER LONG-RANGE FINANCIAL PLANNING ................................................................................... 84

MAJOR DEPARTMENT ISSUES & GOALS ............................................................................................ 89

Page 4 of 106

Page intentionally left blank.

Page 5 of 106

PURPOSE OF THE PLAN

The Five-Year Financial Plan is required under Proposition A, a charter amendment approved by voters in

November 2009. The City Charter requires the plan to forecast expenditures and revenues during the five-year

period, propose actions to balance revenues and expenditures during each year of the plan, and discuss

strategic goals and corresponding resources for City departments.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

Presented in this report is an overview of the economic context which informs the revenue projections in the

Five-Year Plan.

FIVE-YEAR OUTLOOK

Over the next five years, the plan projects the City will experience a slow-growth revenue outlook, due to

anticipated structural changes in San Francisco’s economy, and a loss in one-time sources in the first three years

of the plan. The Five-Year Financial Plan shows that the cost of City services significantly outpaces revenue

growth during the five-year period. If the City does not take corrective action, the gap between revenues and

expenditures will reach approximately $1,224.1 million by Fiscal Year (FY) 2027-28.

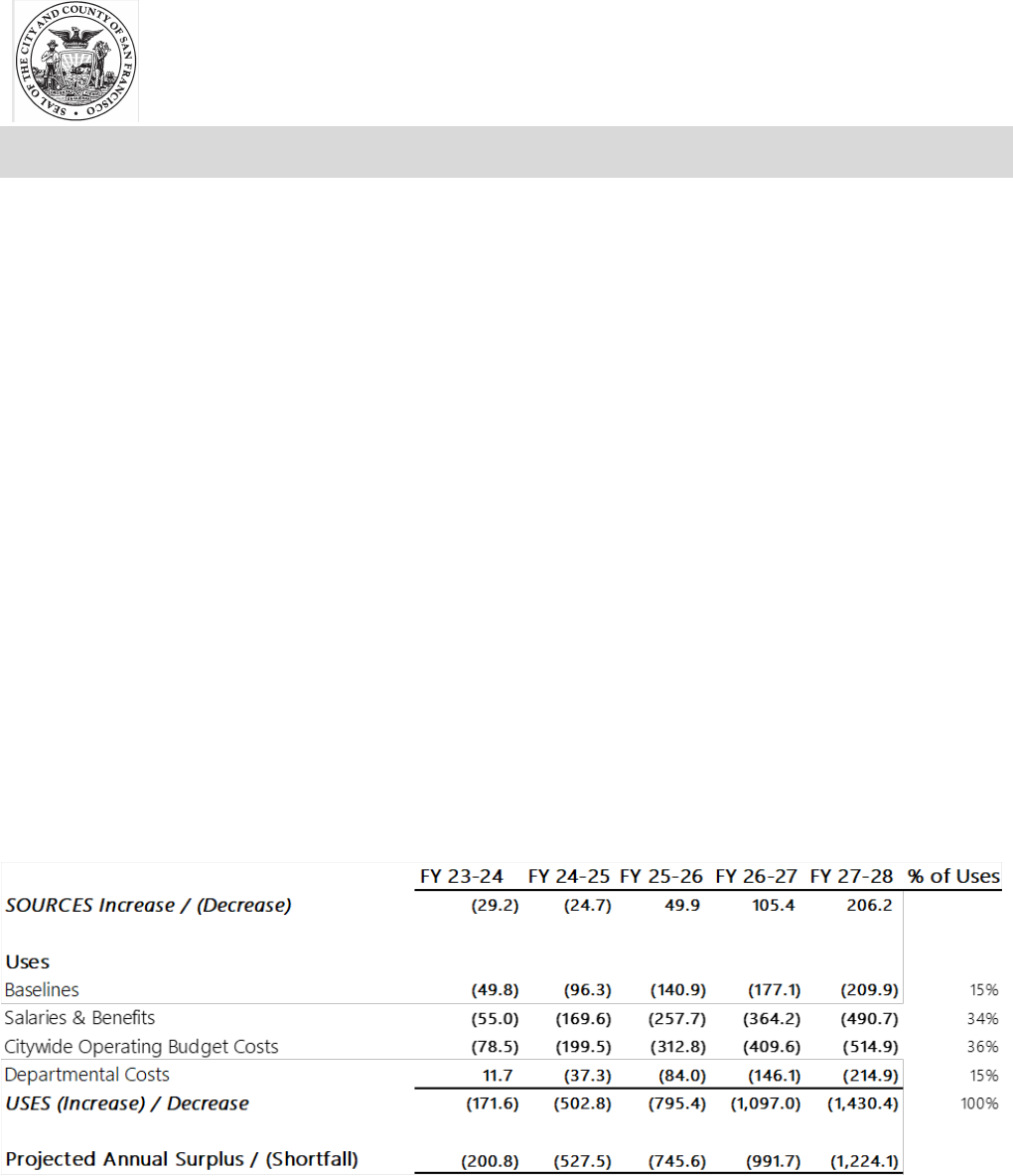

Table 1: Base Case - Summary of General Fund-Supported Projected Budgetary Surplus / (Shortfall)

($ Millions)

Total expenditures are projected to grow by approximately $1,430.4 million over the next five years, which

represents an increase of 21.1% from FY 2022-23. During the five years of the plan, baselines grow by $209.9

million (15% of total expenditure growth), employee salary, pension, and fringe benefit costs grow by $490.7

million (34% of total expenditure growth), citywide operating costs grow by $514.9 million (36% of total

expenditure growth), and departmental costs grow by $214.9 million (15% of total expenditure growth).

City and County of San Francisco

FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL PLAN

Executive Summary

Page 6 of 106

In contrast to expenditure growth, available General Fund sources are projected to increase by $206.2 million

over the same period, an overall growth of 3% from FY 2022-23.

As required by the Charter, the City will need to implement strategies to close the gap between sources and

uses over the five-year time period.

FISCAL STRATEGIES

The City projects budget deficits over the next five years if proactive steps are not taken to address the

imbalance between revenues and expenditures. Unlike the major budget shortfalls that followed the 2001 and

2008 recessions, the current projection reflects longer-term structural challenges, even absent another

recession. Given this economic reality and the major risks that could deepen the projected deficits, the fiscal

strategies discussed in this report propose implementing ongoing budget solutions while limiting the use of one-

time sources to close remaining gaps.

This approach aims to ensure the City is able to maintain services and respond to future economic challenges,

and acknowledges the need for planning for longer-term and more complex budget solutions in the coming

years. Detailed projections regarding the Base Case and fiscal strategies are included starting on page 20 of this

report.

CITYWIDE STRATEGIC INITIATIVES SECTION

The plan also includes an update to the Citywide Strategic Initiatives section. This section describes the long-

term strategy for City investments, under Mayor London N. Breed’s leadership, to achieve an equitable and

vibrant economic recovery through focusing on key areas: recovery that prioritizes Downtown and the

surrounding area, as well as neighborhood business corridors and small businesses; public safety and improved

street conditions for all communities to feel safe and welcomed in their neighborhoods; decreasing

homelessness through housing and shelter; building housing to make San Francisco more affordable; Improving

and building on systems of care that focus on the growing mental and behavioral health needs of the City; and

investing in the future of San Francisco.

Page 7 of 106

Page intentionally left blank.

Page 8 of 106

PROSPECTS FOR THE POST-COVID-19 SAN FRANCISCO ECONOMY

The nature, size, and direction of changes to the national economy wrought over the course of the pandemic

has no parallel. The COVID-19 pandemic shutdown ended the longest economic expansion in U.S. history and

caused the sharpest economic decline since the Great Depression. It was, however, also the shortest recession

in history. By the summer of 2020, the economy had started growing rapidly again. Supported by extremely

accommodative and pro-growth monetary and fiscal policy, the next two years saw an economic boom that led

to record-low unemployment rates, alongside the highest inflation in 40 years. As of December 2022, with

interest rates having rapidly risen in the second half of the year, the U.S. economy is preparing to turn yet

again—perhaps to a so-called “soft landing,” or perhaps to another recession.

In San Francisco, the economy is less diverse than it once was, rising interest rates spell trouble for two key

industries: tech and real estate. Tech start-ups flourished during the extremely low interest rate environment of

the 2010s, as investment flowed into risky areas. Higher rates have already caused venture capital investment to

sharply drop, and the stock prices of large tech companies suffered severe drops in 2022. Both are signs of an

impending slowdown in hiring. Construction and real estate both thrived when property prices were high, but a

combination of reduced demand and higher interest rates have weakened the local housing and commercial real

estate markets.

Cyclical issues aside, the pandemic appears to have brought about fewer permanent structural changes to the

U.S. economy than many feared in 2020. Entertainment, recreation, and travel industries have bounced back

rapidly with the end of COVID-19 restrictions, as people have been eager to socialize and have in-person

experiences again. Restaurants are struggling more with labor shortages than a lack of customers, and are not

being replaced by delivery services, as some predicted. Robots and automation have not eliminated routine jobs

in other industries either, like manufacturing, distribution, or accommodation. And while brick-and-mortar retail

lost ground during the pandemic to internet-based retailers, it has made a comeback; foot traffic in stores and

malls around the country is nearly back to pre-pandemic levels.

However, some structural changes adopted during the pandemic are persisting, namely, the high level of remote

work, which has significant economic implications for San Francisco. Office attendance in large metropolitan

areas is only 45% - 65% of pre-pandemic levels. The San Francisco area is trailing most other metro areas in

office attendance, and office industries produce approximately three-quarters of the City’s GDP. Remote work is

one of the major reasons why San Francisco’s economy has been slower to recover than other cities.

Over the next five years, the City’s financial planning will need to consider both cyclical and structural economic

risks. This section reviews the data of San Francisco’s economic recovery from the pandemic and considers how

the re-emergence of inflation and rising interest rates could affect the City during this five-year forecast period.

To begin with, the city’s employment recovery from COVID-19 has been relatively slow, though by the end of

2022, nearly all local jobs that were lost have been regained. Figure 1 below shows total employment in the San

Francisco Metro Division, which includes San Mateo and San Francisco counties, compared to the state and

nation, indexed to November 2019.

City and County of San Francisco

FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL PLAN

Economic Overview

Page 9 of 106

Figure 1

For most sectors of the local economy, the pandemic period was worse than the aggregate numbers imply. In

the three-year period from November 2019 to November 2022, twelve of sixteen industry sectors in the San

Francisco metro division showed declining employment

1

. The decline was led by the leisure and hospitality

sector which, despite some recovery throughout 2022, still employed 30,000 fewer people than in November

2019.

Growth was concentrated in the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services sector, and the Information

sector, which together added 51,300 jobs during the period. Most technology companies in San Francisco are

classified in these two sectors. Both 2020 and 2021 were record years for venture capital investment in the Bay

Area, and despite a slowdown and some notable layoffs at the end of 2022, the sector overall has experienced

very strong growth in the past three years.

1

The San Francisco Metro Division includes San Francisco and San Mateo counties. San Francisco makes up approximately

63% of employment in the metro division.

80

85

90

95

100

105

Nov-19

Jan-20

Mar-20

May-20

Jul-20

Sep-20

Nov-20

Jan-21

Mar-21

May-21

Jul-21

Sep-21

Nov-21

Jan-22

Mar-22

May-22

Jul-22

Sep-22

Nov-22

Monthly Total Employment November 2019-November 2022

(November 2019=100)

San Francisco Metro Division

California

U.S.

Page 10 of 106

Figure 2

These sectoral employment trends, with tech growing faster than other industries, represents a continuation of,

and not a break with, pre-pandemic economic trends in the city. In 2007, just before the Great Recession, the

information technology sector accounted for 4.0% of all private sector employment in San Francisco

2

. By 2019,

just before the pandemic, 15.5% of all private sector jobs in the city were tech jobs, and this number rose again,

to 18.7%, by 2021.

Despite the growth in employment in tech and other office-using industries, physical attendance in commercial

offices in San Francisco is far below levels seen before the pandemic. This is part of a national trend, made

necessary by public health controls early in the pandemic that limited in-person work by non-essential workers.

The remote work trend is the practice of employees doing their jobs from a location other than the central office

operated by their employer. Across the country, however, office attendance has been slow to recover even after

public health controls were no longer necessary.

San Francisco has led this trend. According to office attendance data published by Kastle Systems, metro San

Francisco’s office attendance was only 42% of pre-pandemic levels in mid-December 2022. This is lower than

most other comparable metro areas, although no area was above 65% of normal.

2

Data comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, “Information technology”

refers to NAICS codes 5112, 518, 51913, and 5415.

-40,000

-30,000

-20,000

-10,000

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

Leisure & Hospitality

Retail Trade

Administrative & Support & Waste Services

Management of Companies & Enterprises

Real Estate & Rental & Leasing

Manufacturing

Transportation, Warehousing & Utilities

Wholesale Trade

Other Services

Educational Services

Construction

Government

Finance & Insurance

Health Care & Social Assistance

Information

Professional, Scientific & Technical Services

Change in Employment by Industry Sector,

San Francisco Metro Division, November 2019-November 2022

Page 11 of 106

Figure 3

The fact that office attendance is less than half of normal, despite considerable employment growth in office-

using industries, is clear evidence that patterns of remote work have persisted after the pandemic and are

leading to reductions in office demand. San Francisco’s office vacancy rate reached 24% in the third quarter of

2022, up from less than 5% below the pandemic

3

.

This is also a national trend: office vacancies have risen in every major market, during a two-year period of

strong economic growth. But again, San Francisco is leading this trend, as no office market has seen a larger

increase in vacancy than San Francisco. To some extent, this is due to the importance of the tech industry in the

San Francisco office market, as tech has embraced remote work more than other office industries.

However, a comparison with the San Jose office market is instructive. Like San Francisco, the South Bay’s office

market is dominated by tenants in the tech industry; like San Francisco, its office attendance numbers have been

among the lowest in the country. But according to JLL, the office vacancy rate is much lower, indicating a greater

willingness among office tenants to hold on to office space for the future.

3

According to data in JLL’s report Pulse of the Market: San Francisco, 2022.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

04/01/20

05/01/20

06/01/20

07/01/20

08/01/20

09/01/20

10/01/20

11/01/20

12/01/20

01/01/21

02/01/21

03/01/21

04/01/21

05/01/21

06/01/21

07/01/21

08/01/21

09/01/21

10/01/21

11/01/21

12/01/21

01/01/22

02/01/22

03/01/22

04/01/22

05/01/22

06/01/22

07/01/22

08/01/22

09/01/22

10/01/22

11/01/22

12/01/22

Weekly Office Attendance Rate Vs. February 2020

Weekly Office Attendance in San Francisco and Other Selected Metros,

Through December 14, 2022

San Francisco

Austin

Los Angeles

San Jose

New York

Page 12 of 106

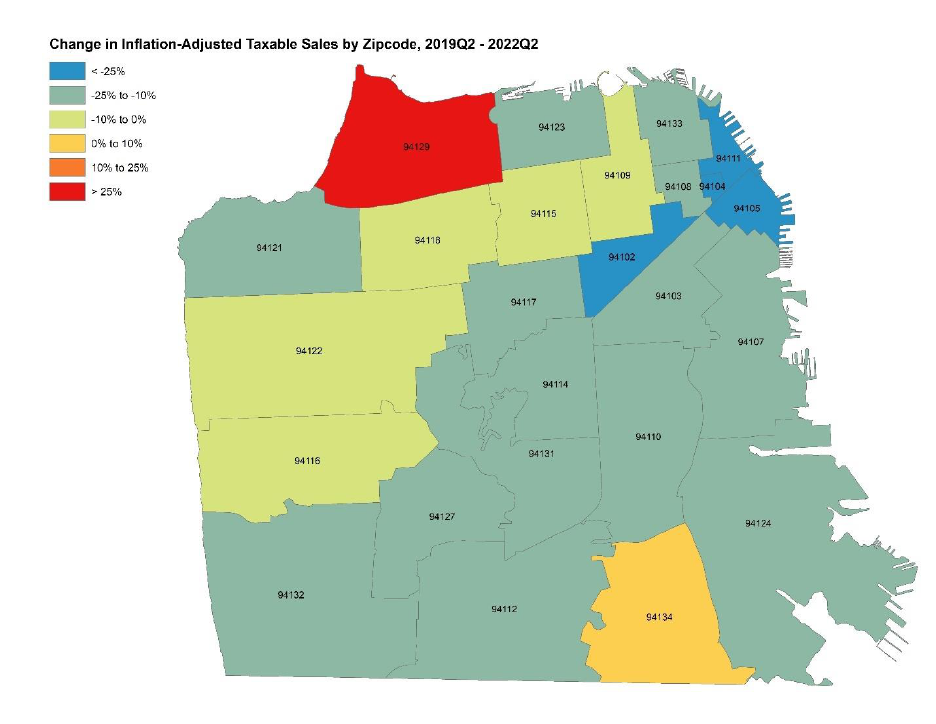

The trend towards remote work, and high office vacancy, has also weakened the economic linkages between the

tech and other office-using industries that largely drive the city’s economy, and the supporting industries that

have grown up to support them. This can clearly be seen in sales tax trends in the map below, which shows the

three-year change in taxable sales by zip code, after adjusting for inflation.

By the middle of 2022, only two zip codes in the City have recovered to the real taxable sales level of mid-2019,

making San Francisco the slowest-recovering county in California in terms of taxable sales, according to the sales

tax consultant HDL. The contraction is greatest in zip codes in the downtown core, where the loss of office

commuters and other customers is most acutely felt.

Figure 4

A decline in office attendance is not the only factor behind the slow recovery in sales tax. San Francisco’s

tourism industry – also concentrated downtown - was also badly hit by the pandemic and has lagged other cities

in recovery. While competing tourism centers are at or above their 2019 hotel revenue levels, San Francisco’s

October revenue per available room (RevPAR) was only about 70% of October 2019 levels. Tourism in the City

was adversely affected by the loss of international tourists, particularly from China, as well as the postponement

of business conventions during the pandemic. While leisure tourism has recovered strongly in the first part of

2022, business and convention travel recovery has been much more modest.

Page 13 of 106

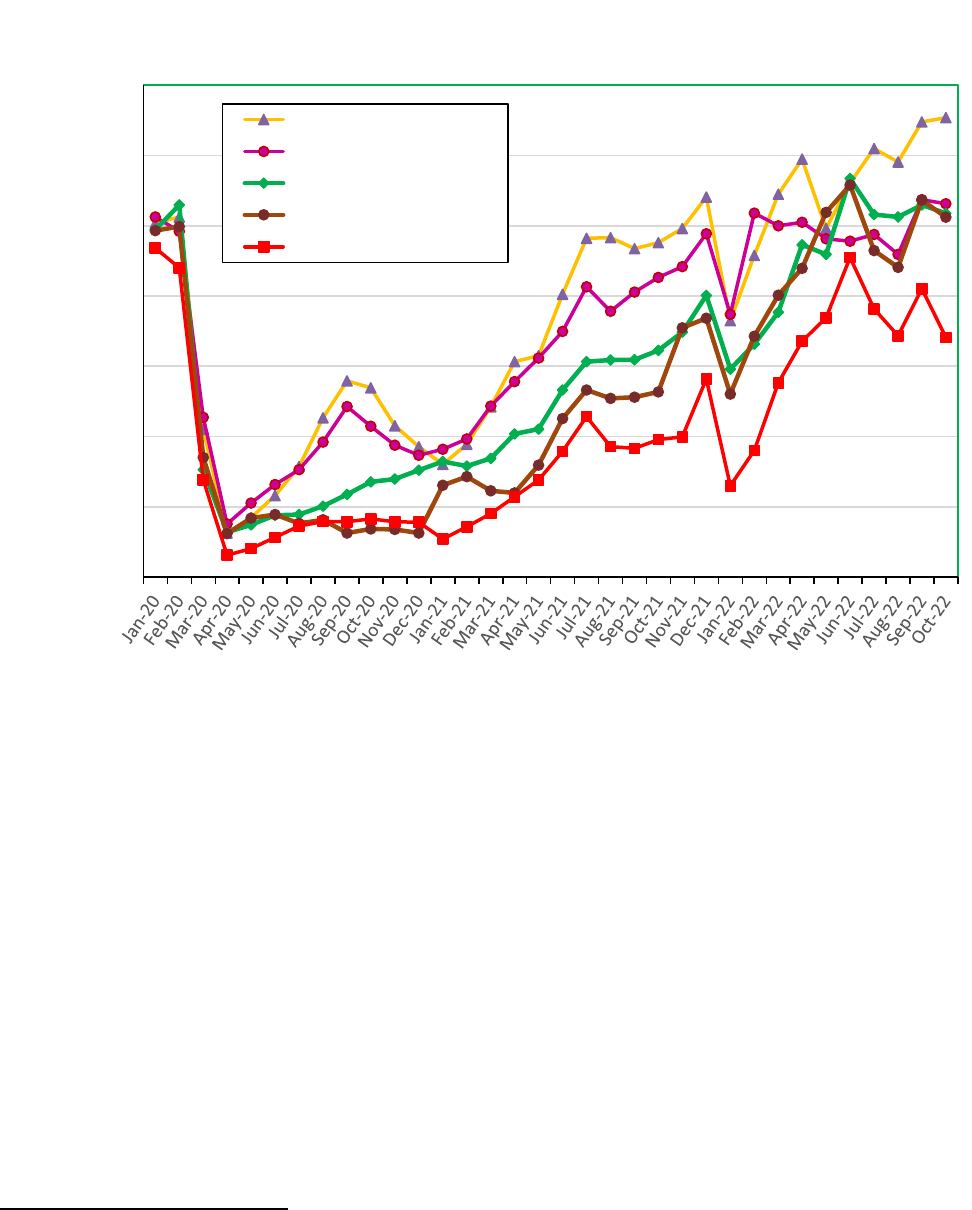

Figure 5

Aside from office workers and hotel guests, downtown and the city as a whole have also experienced a dramatic

loss in resident population since the start of the pandemic. According to Census data, San Francisco’s population

loss between July 2020 and July 2021 was the steepest of any city above 50,000 in population

4

, at 6.3%.

San Francisco’s population loss has been associated with softness in the city’s housing market. As the chart

below illustrates, both apartment rents and owner-occupied housing prices in San Francisco have widely

diverged from the U.S. average since the beginning of 2020. By November 2022, apartment asking rents in the

city were down more than 10% in the nearly 3 years since January 2020, compared to a more than 20% growth

nationally. For owner-occupied housing prices, the gap was even wider: a 43% growth for U.S. housing,

compared to only a 3% growth for San Francisco housing. As mortgage interest rates began to rise quickly during

2022, prices have begun to level off nationally by the middle of the year. In San Francisco, however, they had

already dropped 9% in the 6 months from May to November.

4

Census Bureau, “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1,

2021 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021”

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

120%

140%

Hotel Revenue as a % of the Same Month in 2019

Monthly Hotel Revenue Available per Room Night vs. 2019:

San Francisco and Selected Cities, Jan. 2020 - Oct. 2022

San Diego

Los Angeles

Seattle

New York

San Francisco/San Mateo

Page 14 of 106

Figure 6

This loss of population is clearly a contributing factor to declining taxable sales across the city, and the weakness

of its housing market, but it also constrains the ability of the city’s labor force to expand to meet the needs of

the office workers and tourists that have returned. Census data indicates the changing nature of the San

Francisco resident labor force. The table below shows the change in the number of residents of San Francisco,

and the five-county San Francisco metro area

5

, by occupation between 2019 and 2021.

Within the city, there was a small (1%) increase in the number of residents working in social services, education,

or legal services during this time period, however, the number of residents working in all other occupational

groups declined. In the metro area as a whole, which has also experienced an overall population drop since

2019, declines were also widespread, but generally smaller than in San Francisco proper.

5

San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and Marin counties.

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

Trends in Median Asking Rents and Typical Home Values in San Francisco and the U.S.

(January 2020 = 100)

SF Apartments

US Apartments

SF Housing Values

US Housing Values

Page 15 of 106

Figure 7

While there has been considerable concern that the prevalence of remote work in the technology sector would

lead to a loss of San Francisco’s talent pool in that industry, the evidence for that happening is rather weak. San

Francisco did lose 8% of its residents in computer, engineering, and science occupations, but the metro area lost

negligible amounts. Since residents in the metro area can still work in San Francisco offices as the need arises,

local tech companies have generally the same talent pool that was available to them before the pandemic.

By contrast, the city suffered severe population losses in occupations like food preparation and serving, personal

care and service, sales, building and maintenance, protective services, arts and design, production and

transportation, and construction. In these fields, two-year population declines ranged from 15% to over 50% of

the resident population in the city in 2019.

Given that San Francisco remains one of the most expensive cities in the country, notwithstanding the recent

decline in housing prices, the loss of so many low- and middle-income workers could lead to longer-term,

structural labor supply challenges for the local industries that rely on them. These include activities that are vital

to the city’s attractiveness to visitors and its quality of life, such as restaurants, art and entertainment venues,

neighborhood services, retail trade, and home renovation.

Some signs of a labor shortage can be seen in local wage growth data. In a reversal of long-standing trends,

beginning in 2021, wage growth in the restaurant industry began to out-pace wage growth across all industries

-60% -50% -40% -30% -20% -10% 0% 10%

Management, business, financial

Computer, engineering, science

Social service, legal, educational

Arts, design, entertainment, sports, media

Healthcare practitioners

Healthcare support

Protective service

Food preparation and serving

Building and maintenance

Personal care and service

Sales and related

Office and administrative support

Construction

Production, transportation, material moving

Percent Change in Population by Occupation, 2019-2021:

City of San Francisco and the San Francisco MSA

San Francisco San Francisco MSA

Page 16 of 106

in San Francisco. While the 2021 second quarter data is likely an anomaly due to wage interruptions at the

beginning of the pandemic, annual wage growth in the second and third quarters of 2021 exceeded 20%.

Figure 8

Though this is good news for the food service and preparation workers who remained in San Francisco while

restaurants re-opened in 2021, this level of wage growth is likely not sustainable for the restaurant industry over

the long term. Higher wages can create an incentive for workers to move back to the San Francisco area. But

even a 10% drop in apartment asking rents, and a short-term boost in wages, may not be enough to provide a

large number of housing options for newly arriving workers for the restaurant industry and other lower-wage

industries. For this reason, alongside the remote-work phenomenon, labor shortage in low-wage industries has

the potential to remain a structural impediment to economic growth in the city for the next several years.

The structural changes in the city’s economy initiated by the pandemic mostly occurred during a favorable

macroeconomic environment for growth. The mandated shutdowns and stay-at-home orders of the pandemic

were faded within a year, and both the Federal Government and the Federal Reserve system provided

unprecedented levels of financial support and liquidity for the financial system.

Federal expenditures had spiked from an annual rate of $4.9 trillion in the first quarter of 2020 to $8.9 trillion in

the second, and again to $8.2 trillion in the first quarter of 2021.

-40%

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

2018-1 2018-3 2019-1 2019-3 2020-1 2020-3 2021-1 2021-3

Year-Over-Year Change in Quarterly Average Wages for Stable Employees in San

Francisco: Restaurant Industries and All Industries, 2018-2021

Restaurants

All Industries

Page 17 of 106

The Federal Reserve had expanded its balance sheet from $4 trillion at the start of the pandemic to close to $9

trillion by March 2022. This has had the effect of lowering short-term interest rates to near zero, and long-term

rates to record lows.

In the wake of these historically-accommodative policy conditions, growth soared. U.S. real GDP grew by 5.7% in

2021, the fastest rate since 1984. Unemployment, which had risen to 14.7% in April 2020, had dropped back to

3.5% by mid-2022, essentially the same rate as held before the pandemic.

However, inflation rose as well, and this prompted a change of course by the Federal Reserve. Inflation had not

exceeded 3% since 2011 but had risen to 8.6% by March of 2022. In that month, the Fed stopped its quantitative

easing program and began to raise the federal funds rate above zero. By the end of 2022, the federal funds rate

was approximately 4.25%, the highest it had been since before the Great Recession.

Fiscal policy changed significantly during 2022 as well. By the end of 2021, Federal expenditures had dropped

back to $6 trillion annualized, and remained at that rate throughout 2022. This effectively removed $2-3 trillion

of pandemic-era spending from the economy in 2022.

In the wake of these policy shifts, economic forecasts for 2023 have changed a great deal throughout 2022. The

chart below illustrates how the median forecast from the Blue Chip panel of professional forecasts have changed

throughout 2022, for the U.S. GDP growth rate, unemployment rate, and 10-year interest rates. By the

December 2022 forecast, the median forecast for the entire year of 2023 was below 0.5% - not necessarily a

recession, but a clear slowdown from 2021 and 2022 growth rates. Forecasts of interest rates and the

unemployment rate progressed higher throughout the year as well.

Figure 9

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

2023 Real GDP Growth 2023 10-year Treasury Rate 2023 Unemployment Rate

Changes in the Median Blue Chip Economic Forecasts for

U.S. Economic Indicators in 2023

Feb-22 Apr-22 Jun-22 Aug-22 Oct-22 Dec-22

Page 18 of 106

While the national economy was still resilient at the end of 2022, with unemployment only at 3.7% in

November, expectations are that rising rates will take a toll on growth, and the labor market, in at least the first

half of 2023.

For San Francisco, this means the macroeconomic tailwinds that have supported the recovery in employment

and commercial activity may wane in 2023. There are also reasons to believe that San Francisco could fare worse

in any recession than most other cities, because of the continuing importance of the tech industry to the City’s

economy and its post-COVID-19 recovery. Despite remote work, as noted above, tech has led the city’s

employment recovery, and the wealth effects of a booming stock market led San Francisco to have the fastest

GDP growth rates of any large county in the country, despite weak employment growth

6

.

Tech investment is highly sensitive to interest rates, however. In 2022, the stock market tumbled, and tech

stocks fared worse than most other parts of the market. Venture capital investment, which generally tracks tech

stocks, dropped as well. According to Pitchbook, U.S. venture capital dropped 52% between the third quarter of

2021 and the third quarter of 2022

7

. San Francisco’s tech industry has always relied on early-stage investment in

start-up companies to generate a sizable amount of its employment growth, and without that investment,

growth will most likely slow.

A slew of larger tech companies also announced layoffs, including DoorDash, SalesForce, Lyft, and Twitter. While

net employment in the tech sector was still rising through November 2022, it appears likely that tech will lead

any employment slowdown that San Francisco experiences in 2023. And, although remote work has weakened

the linkages between office commuters and downtown businesses, those workers still live in the city and near

the city, spend at local businesses, and invest in local real estate. An economic shock that adversely affects the

tech sector would inevitably ripple out to the rest of the local economy, notwithstanding the downtown office

vacancies.

In 2023 and beyond, the key macroeconomic question is how inflation responds to rising interest rates. The Fed

has remained committed to its 2% inflation target, and despite some recent softening of inflation, it remains

well above that target. If the Fed is required to maintain unusually high interest rates for an extended period of

time to curb inflation, that will continue to curtail the investment that drove San Francisco’s property values for

the past decade.

In summary, the cyclical and structural economic risks facing San Francisco in the next five years can be

summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Structural Economic Risks

6

Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product by County, 2021”.

7

Pitchbook, Venture Monitor Q3 2022.

Page 19 of 106

On the structural side, fundamental uncertainty is the return-to-office question. If remote work remains

significant for office-using industries, and their office demand does not recover during the next five years, then

the path to economic growth will be more challenging, regardless of cyclical factors. In this event, in time, the

office market will adjust and San Francisco offices could become more affordable and attractive to a wider array

of businesses. However, this process will likely be slow and not completed within the forecast period.

For as long as remote work is limiting office demand by the city’s leading industries – particularly the tech

industry – then the recovery office market, downtown commercial activity, business tourism, and housing

demand are will be dampened. Unless there are further substantial declines in housing prices, affordability is

likely to remain a barrier to population recovery, and the city could remain below its pre-pandemic peak

population for some time.

If, on the other hand, current trends around remote work reverse and normal levels of office demand is restored

during the forecast period, the challenges facing sectors like housing, tourism, and small business will be eased,

and a population recovery is more likely.

The extent and duration of an economic slowdown in 2023 could either exacerbate or ameliorate these

structural challenges. A soft landing, a quickly tamed inflation rate, and falling interest rates in late 2023 or early

2024 would be excellent news for the city’s economy, particularly if the slowdown encourages more office

attendance. On the other hand, if inflation remains stubbornly high, and the Fed continues to raise interest rates

and/or keep them high for longer, then macroeconomic headwinds can deepen the city’s economic problems.

Page 20 of 106

PURPOSE OF THE PLAN

The Five-Year Financial Plan is part of a comprehensive effort by the City to improve its long-range financial

management and planning. This section, the Base Case projection, is a joint effort by the Mayor’s Office, the

Controller’s Office, and the Board of Supervisors’ Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office to forecast the impact

of existing service levels and policies on revenues and expenditures over the next five years. The City is currently

implementing the following strategies as part of its long-range financial management and planning:

• The Five-Year Financial Plan: The City is forecasting revenues and expenses for the next five years on a

citywide basis, including departmental operations, facilities, debt management, capital, and technology.

• Two-Year Budgeting: The FY 2012-13 and FY 2013-14 budget was the first citywide two-year budget

adopted by the Mayor and the Board of Supervisors. The City has continued to utilize two-year rolling

budgets and most recently adopted the FY 2022-23 and FY 2023-24 budget.

• Citywide Capital and Technology Plans: These plans, which are released by March 1 every other year,

include detailed financial information and project descriptions outlining the City’s planned spending on

capital over the next ten years and technology over the next five years. This Five-Year Financial Plan

incorporates, to the extent possible, standards and assumptions that will be included in the upcoming

Capital and Technology Plans.

• Financial Policies: To date, the City has adopted a number of financial policies, including the creation of

an Economic Stabilization Reserve, modification of the General Reserve to increase deposits and make

withdrawals more flexible in a downturn, and restricting the use of one-time revenues. The forecast

assumes the City makes required deposits to the General Reserve. While preferable to the alternative,

these deposits will not be sufficient to return to pre-pandemic levels when the City had reached its goal

of 10% of General Fund revenue.

Multi-year budgeting and forecasting are best practices for all governments. The Five-Year Financial Plan is

designed to enhance the City’s ability to identify the key drivers of its revenues, expenditures, and needed public

services. The projected gap between revenues and expenditures is historically high due to sharp cost increases

at a time of very slow growth in tax revenues, including the loss of federal revenues and other one-time sources.

This five-year planning process will enable San Francisco to thoughtfully plan for the evolving fiscal picture and

adapt programs accordingly. Overall, the City will minimize volatility and risk by looking beyond the immediate

two-year budget horizon, resulting in more stable public service delivery that citizens can expect and rely on.

BUDGET OVERVIEW

The City and County of San Francisco’s budget for FY 2022-23 is $14.0 billion. Over half of the budget, $7.2

billion, is comprised of self-supporting activities at the City’s enterprise departments, which focus on City-

related business operations and include the Port, the Municipal Transportation Agency (MTA), the Airport, the

Public Utilities Commission (PUC), and others. The remaining 48%, or $6.8 billion, is comprised of General Fund

monies, which support public services such as public health, police and fire services, and public works. The City’s

budget can be broken down into six major service areas: Public Protection; Public Works, Transportation &

Commerce; Human Welfare & Neighborhood Development; Community Health; Culture & Recreation; and

General Administration & Finance.

City and County of San Francisco

FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL PLAN

Five-Year Base Case Projection

Page 21 of 106

Figure 10 shows the total $14.0 billion citywide budget by major service area. The Public Works, Transportation

& Commerce major service area has the largest overall budget, due primarily to the budgets of large enterprise

departments.

Total Budget by Major Service Area FY 2022-23

Figure 10

There are 33,207 full-time equivalent positions (FTEs) budgeted and funded between all six major service areas

in FY 2022-23. As shown in Figure 11, the Public Works, Transportation, and Commerce service area also has the

largest share of FTEs, which is largely driven by the MTA.

Full Time Equivalent Positions (FTEs) by Major Service Area FY 2022-23

Figure 11

Page 22 of 106

FIVE-YEAR OUTLOOK FOR GENERAL FUND-SUPPORTED OPERATIONS

San Francisco Administrative Code Section 3.6(b) requires that in each odd-numbered year, the City must submit

a Five-Year Financial Plan; in even-numbered years, a similar report, called the Joint Report, must be issued with

an update to the remaining four years of the previous year’s Five-Year Financial Plan. In both the Five-Year

Financial Plan and the Joint Report, the Mayor, the Controller, and the Board of Supervisors’ Budget and

Legislative Analyst must forecast expenditures and revenues during the projection period. In the Five-Year

Financial Plan, the Mayor’s Office must also propose actions to balance revenues and expenditures during each

year of the plan and discuss strategic goals and corresponding resources for City departments. This Five-Year

Financial Plan provides expenditure and revenue projections for FY 2023-24, FY 2024-25, FY 2025-26, FY 2026-

27, and FY 2027-28.

Summary of ‘Base Case’ Projections and Findings

This Five-Year Financial Plan describes the ‘Base Case’ – a forecast of revenues and expenditures that projects

revenue trends and the costs to support current service levels, adjusting for adopted or proposed policy changes

where noted. Significant changes include known revenue and expenditure changes in all areas where there is

reasonable information or basis for a projection. Key assumptions are also detailed below.

Table 3 summarizes the projected changes in General Fund-supported revenues and expenditures over the next

five years. As previously shown in Table 1, this report projects shortfalls of $200.8 million in FY 2023-24, $527.5

million in FY 2024-25, $745.6 million in FY 2025-26, $991.7 million in FY 2026-27, and $1,224.1 million in FY

2027-28.

Table 3: Base Case – Summary of FY 2023-28 General Fund-Supported

Projected Budgetary Annual Surplus/ (Shortfall) ($ Millions)

The projection demonstrates that revenue growth from FY 2022-23 to FY 2023-24 is offset by slow growth in tax

revenue and loss of one-time sources, leading to an overall decrease in FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25 sources

compared to the prior year. In all other fiscal years, revenues are projected to grow, but at a slow pace due to

anticipated structural changes in San Francisco’s economy that are easily outpaced by projected cost increases.

Page 23 of 106

The City currently projects revenue growth of $206.2 million, or 3% over the five-year period of this report, and

expenditure growth of $1,430.4 million, or 21.1%, as shown in Figure 12 below.

Projected Growth in General Fund Expenditures and Revenues

Figure 12

Total expenditure growth is shown below in Figure 13, which illustrates that citywide operating budget costs

represent the largest driver of the City’s deficit projection with 36% of the growth over the next five years, or an

increase of $514.9 million over the five-year period. Salaries and benefits represent the second largest area of

expenditure growth at 34%, or $490.7 million. The next largest drivers of expenditure growth are other

department-specific cost increases of $214.9 million (15%) and baselines cost growth of $209.9 million (15%).

General Fund-Supported Expenditure Increases by Expenditure Type FY 2024-28

Figure 13

While the projected shortfalls previously shown in Table 3 reflect the difference in projected revenues and

expenditures over the next five years if current service levels and policies continue, San Francisco’s Charter

Page 24 of 106

requires that each year’s budget be balanced. Balancing the budget will require some combination of

expenditure reductions and additional revenues. To the extent that budgets are balanced with new on-going

solutions, future shortfalls will decrease.

A key driver of projected shortfalls is increases in mandated costs. Many of the projected expenditure increases

are unavoidable, with limited ability to reduce spending to balance the budget. The City is required by law to

fund certain voter-mandated baselines and set-asides at specific levels. Additionally, assuming a constant City

workforce, non-discretionary health benefits will continue to rise. This limits the funding available for other uses

such as employee wage increases, cost-of-doing-business increases for non-profit service providers, capital and

technology investments, and other improvements to services to the public.

Key Assumptions Affecting the FY 2034-24 through FY 2027-28 Projections

• No major changes to service levels and number of employees: The projection assumes no major

changes to policies, service levels, or the number of employees from previously adopted FY 2022-23 and

FY 2023-24 budgeted levels unless specified below.

• Recovery continues, but high levels of remote work persist: San Francisco’s economic growth, and the

revenue derived from it, is heavily dependent on changes in employment, business activity, and tourism.

This report assumes changes in office use that occurred during the pandemic are long lasting, affecting

commercial and residential real estate and taxable gross receipts. While the recovery in travel and

tourism is stronger than prior forecasts, hotel tax revenues are not projected to reach their pre-

pandemic levels until FY 2026-27 and are subject to weakness in business travel and convention activity.

The Citywide Revenue Projections section of this report more fully details revenue assumptions.

• Implementation of measures adopted by voters in the November 2022 election: Projections assume a

net expenditure increase from these measures, including: costs to provide additional inflationary

increases to pre-1996 retiree pensions; savings from the elimination of the Department of Streets and

Sanitation and the consolidation of elections; creation of an oversight commission for the Department

of Homelessness and Housing; extension of General Fund transfers to the Library Preservation Fund; and

funding of a new baseline, the Student Success Fund.

• Previously negotiated wage increases and inflationary increases for open contracts in line with CPI:

This report assumes the additional salary and benefit costs for previously negotiated, closed labor

agreements. Police and Firefighters’ unions have closed memorandums of understanding (MOU)

through FY 2022-23 as a result of an amendment. Miscellaneous unions have closed MOUs through FY

2023-24. This report does not assume the recession trigger in these MOUs is met, which will be

revaluated for future projection updates. In open contract years, this report projects salary increases

equal to the change in CPI using the average projection of the California Department of Finance San

Francisco Area CPI and Moody’s SF Metropolitan Statistical Area CPI. This corresponds to 3.56% in FY

2023-24, 2.62% in FY 2024-25, 2.66% in FY 2025-26, 2.45% in FY 2026-27, and 2.51% in FY 2027-28.

Importantly, these assumptions do not indicate a willingness or ability to negotiate wage increases at

these levels, but rather are used for projection purposes.

• Pension investment returns meet expectations, but do not trigger a supplemental COLA: This report

assumes a return on San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System (SFERS) assets of 7.2%, the actuarially

Page 25 of 106

assumed rate of return. This projection does not assume that any on-going supplemental COLA payment

to certain retirees is triggered, which would require increased employer contributions.

• Health insurance cost increases: This projection assumes that the employer share of health insurance

costs for active employees will increase by 5.2% in FY 2023-24, 6.8% in FY 2024-25, 6.3% in FY 2025-26.

and then 6.0% in each of the remaining two years of the projection period, for an average of 6.0%

annually over the five years. Retiree health costs are assumed to grow by 5.3% in FY 2023-24, 6.8% in FY

2024-25, 6.3% in FY25-26, and then 6.0% in each of the remaining two years, an average of 6.1%

annually over the projection period.

• Inflationary increase on non-personnel operating costs: This projection assumes that the cost of

materials and supplies, professional services, contracts with community-based organizations, and other

non-personnel operating costs will increase by the rate of Consumer Price Index (CPI) starting in FY

2024-25 and thereafter. The projection reflects the adopted FY 2022-23 and FY 2023-24 budget, which

included a 4% cost-of-doing business increase for General Fund nonprofit contracts.

• Ten-Year Capital Plan, Five-Year ICT Plan, and inflationary increases on equipment: For capital, this

report assumes an increase to the adopted FY 2022-23 budget funding levels of $30 million in FY 2023-

24, with annual increases of $30 million thereafter, in line with the forthcoming recommendations in the

City’s upcoming FY 2024-33 Ten-Year Capital Plan. The IT investment projection assumes a $10 million

increase in FY 2023-24 funding of projects in the City’s Information and Communications Technology

(ICT) Plan with annual 10% increase in the following four years. For equipment, this report assumes the

budgeted level of funding in FY 2023-24, and annual growth based on CPI, which results in annual $0.3

million increases in the remaining four years of the forecast period.

• Deposits and withdrawals from reserves: Because General Fund revenue is generally forecasted to

grow slowly year-over-year, the City is not eligible to withdraw from or deposit to the City’s Rainy Day or

Budget Stabilization reserves. The projection only assumes reserve withdrawals that were previously

budgeted in FY 2023-24, primarily $90.2 million from the Fiscal Cliff Reserve, leaving an available

balance of $130.3 million. In accordance with Administrative Code Section 10.60(b), deposits to the

General Reserve are assumed in all years of the plan period, increasing from 2.0% of General Fund

revenue in FY 2023-24 to 3.0% in FY 2027-28. Furthermore, deposits to the Budget Stabilization Reserve

are expected in FY 2025-26, FY 2026-27, and FY 2027-28 as real property transfer tax begins to exceed

the prior five-year average as it begins to recover in the out-years.

• Property tax shifts: Beginning in FY 2018-19, the City’s General Fund received “Excess ERAF” property

tax allocations, after distributions from the Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) fulfilled all

other statutory distributions to other local taxing entities. This report assumes the City will continue to

receive Excess ERAF revenues in all years of the report according to current state law and assuming

enrollment increases in local schools. However, state budget shortfalls are very likely to result in

legislative proposals to alter ERAF allocations in a way that helps the state meet its Prop 98 school

funding requirements and reduces excess ERAF that reverts to the City.

• COVID-19 Response: The local cost of directly responding to the COVID-19 pandemic is projected to

decrease by $32.3 million in FY 2023-24 and will remain flat at $25 million during the remaining fiscal

years of the forecast period.

Page 26 of 106

• Non-General Fund revenue declines: This forecast only projects changes in General Fund revenues and

General Fund-funded expenditures. Other special purpose revenues, such as the November 2018

Proposition C Homeless Gross Receipts Tax and June 2018 Commercial Rents Tax, are also forecasted to

decline over the five-year period. However, because this report focuses on the General Fund’s position,

anticipated shortfalls in special revenue funds are not directly incorporated in the deficit.

Key Factors That Could Affect These Forecasts

As with all projections, uncertainties exist regarding key factors that could affect the City’s financial condition.

These include:

• Interest rate increases or other factors tip the nation into recession: This report assumes very modest

revenue growth over the forecast period given structural changes in office using sectors. It assumes

successive Fed interest rate increases slow growth without inducing a recession. However, there is

continuing discussion among economic forecasters of the likelihood of a mild recession beginning in the

first half of 2023. Assuming policymakers chose to completely deplete the City’s economic stabilization

reserves, the report estimates such a recession would increase the total shortfall amount by $339.0

million over the forecast period.

• Pending or proposed new programs or legislation: No pending or proposed legislative changes with a

fiscal impact are assumed in this projection. Legislation adopted by the Mayor and Board of Supervisors

with a fiscal impact would increase the projected shortfalls. Several appropriations for new program

initiatives are pending at the Board of Supervisors, and others may be proposed. Future projections will

include impacts from any subsequently adopted legislation.

• Revenue volatility from a highly progressive tax structure: The General Fund projection includes

revenue from the tax on executive compensation (November 2020 Proposition L) as well as revenue

from new transfer tax rates (November 2020 Proposition I). These sources add to the City’s already

progressive tax structure, increasing revenue volatility. In addition, both taxes will likely lead to a variety

of tax avoidance behaviors that are difficult to project in both form and timing, resulting in revenue that

could be higher or lower than projected.

• State fiscal shortfall: These projections assume excess ERAF property tax allocations continue under

current legal requirements. However, in its November 2022 fiscal outlook report, the state Legislative

Analyst Office projected a $24 billion shortfall in FY 2023-24 and ongoing deficits thereafter, increasing

the likelihood of legislative proposals to alter ERAF allocations in a way that reduces the draw on the

state’s general fund to meet its Prop 98 school funding requirements, which would reduce excess ERAF

that reverts to the City. In addition, discretionary state funding for housing, criminal justice, and other

local government grants will likely decline.

Tables 4 and 5 below, in addition to the subsequent narrative section, explain revenue and expenditure changes

in the citywide deficit in detail. First, revenue changes will be discussed, followed by expenditures changes,

including: changes to baselines and reserves; salary and benefit costs; citywide operating costs; and

department-specific changes.

Page 27 of 106

Table 4: Base Case – Key Changes to General Fund-Supported Sources & Uses – INCREMENTAL CHANGE

Sources & Uses FY 2024-28 ($ Millions)

Page 28 of 106

Table 5: Base Case – Key Changes to General Fund-Supported Sources & Uses – ANNUAL CHANGE

Sources & Uses FY 2024-28 ($ Millions)

Page 29 of 106

BASE CASE PROJECTION DETAIL

CITYWIDE REVENUE PROJECTIONS

The projections outlined in this section highlight changes in the City’s key revenues over the next five years,

building on both the trends outlined in the Economic Overview section and the most recent available data on

revenue collections. Detailed revenue assumptions are provided below.

General Fund Taxes, Revenues & Transfers

General Context Underlying Revenue Estimates

As detailed in the Economic Overview section, San Francisco faces the same macroeconomic and structural

pressures other cities face – high inflation, rising interest rates, and the persistence of work from home.

However, these trends are likely to have a larger impact on San Francisco than many other jurisdictions because

its economy is highly concentrated in sectors that are office-using and sensitive to interest rates. The Base Case

revenue forecast reflects the expectations of economic forecasters of very slow growth, and though the local

economy will need to contend with lasting structural change associated with remote work, the Federal Reserve

will be able to bring the economy into a “soft landing,” without triggering a recession. Should a recession occur,

revenues will be lower than forecasted in this report.

Overall growth rates of General Fund taxes, revenues, and transfers in are projected to be 2.9% in FY 2023-24, -

0.2% in FY 2024-25, and approximately 2.0% in FY 2025-26 through FY 2027-28. The City’s tepid revenue growth

is largely related to anticipated structural changes in the local economy, as office workers continue part- or full-

time remote work on a permanent basis, and in an elevated interest rate environment. These dynamics are

expected to result in sustained levels of office vacancies over the plan period and declining commercial and

residential real estate values, affecting property and transfer taxes. Increasing interest rates and sustained

remote work have a negative impact on the City’s business taxes. Rising interest rates change businesses’

investment decisions, and for some industries, businesses’ gross receipts taxes use payroll in San Francisco to

attribute business activity to San Francisco. In addition, the City is expected to receive its last reimbursement

from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for the COVID-19 public health emergency in FY 2023-

24, driving the overall decline in revenue in FY 2024-25.

Partially offsetting these reductions are the City’s tourism and hospitality sector, which expected to continue its

strong recovery through the plan period, benefitting hotel and sales taxes. In FY 2021-22, the City saw pent up

demand driving leisure travel, as well as the return of some conventions. Further bolstering the forecast, the

General Fund projection includes revenue from two new tax measures which the City has not yet begun

collecting: the tax on executive pay (November 2020 Proposition L) and the cannabis excise tax, which has been

delayed until FY 2026-27 (November 2018, Proposition D).

Below are details on key revenue streams included in the General Fund Taxes, Revenues, and Transfers line of

Table 4.

Property Tax

Overall General Fund property tax revenues are expected to grow slowly over the forecast period, from the

budgeted total of $2,379.5 million in FY 2022-23 to $2,449.6 million in FY 2027-28. General Fund property tax

revenue assumptions include:

Page 30 of 106

• Roll growth: The locally assessed secured property roll typically grows based upon an annual statewide

inflation factor (California CPI, capped at 2%) and new property value assessments triggered by changes

in ownership or newly constructed buildings. The unsecured property roll grows or shrinks based upon

the economic cycles and impacts on local businesses.

Projections for FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25 assume 2.5% annual increases in the secured property roll

and no changes in the unsecured property roll compared to the July 1, 2022, valuations for FY 2022-23

(reflected on the 2022 Certificate of Assessed Valuation, or CAV). The rapid increase in interest rates

during calendar year 2022 dampened demand for commercial and residential purchases and new

construction, and the valuation of office properties is expected to be affected by a permanent increase

in remote work affecting office leasing demand and rents as existing leases come up for renewal. FY

2025-26 through FY 2027-28 projections assume the maximum annual Prop 13 allowable increase of 2%,

and all projections assume interest rates remain at levels similar to current rates throughout the

forecast period. The unsecured property roll is projected to remain unchanged through FY 2027-28.

• Supplemental and escape assessments: Supplemental assessments capture changes in value for the

portion of the tax year remaining after a trigger date that results in a change in the base year assessed

value of a property. The escape assessment captures a full year’s increase in assessed value up to four

years after the trigger date. This report assumes supplemental assessment revenue of $29.8 million in

FY 2023-24, $44.7 million in FY 2024-25, and $39.7 million per year in FY 2025-26 through FY 2027-28. FY

2023-24 projected revenues are dampened by the expectation that the mid-year go live date of the

Assessor’s new property assessment system will pause enrollments for a period of time. Escape

assessment revenue of $12.7 million per year is assumed in all years, as the Assessor's Office is largely

up to date with assessments and there is currently a dearth of transactions.

• Assessment Appeals Board reserve requirements: General Fund property tax revenue required to fund

Assessment Appeals Board (AAB) decisions is assumed at $70.8 million for FY 2023-24, $109.1 million for

FY 2024-25, $122.1 million for FY 2025-26, $133.9 million for FY 2026-27, and $137.6 million for FY 2027-

28. These projections include estimates derived from a model developed by the Controller’s Office of

Economic Analysis to gauge assessed value of office properties at risk given existing lease expiration

data and assumptions about vacancy, rental, and capitalization rates during the forecast period. The

model assumes office vacancy rates peak at 28.8% in 2023 and decline to 22.6% in 2026 and forward;

gross rent per square foot bottoms out at $151 in 2023 and increases to $165 by 2026; and cap rates of

just over 8% in 2023 and 7.5% in 2026. These assumptions yield a total office value at risk of $5.6 billion

in FY 2023-24, $10.4 billion in FY 2024-25, $11.1 billion in FY 2025-26, $13.3 billion in FY 2026-27, and

$14.9 billion in FY 2027-28. A separate model for residential properties assumes market values of some

detached single-family homes and other single-family dwellings (townhomes, condominiums) fall below

taxable values, starting with FY 2024-25 (FY 2023-24 value at risk of $1.7 billion is estimated). The

model’s output indicates assessed value at risk of refund of $4.3 billion in FY2024-25, $6.4 billion in FY

2025-26, $6.8 billion in FY 2026-27, and $5.6 billion in FY 2027-28.

In general, properties that were most recently built or traded are the most likely to receive temporary

reductions in assessed valuations, resulting in property tax refunds when applied to prior tax years.

Properties that have not changed ownership in recent years or were built many years ago are likely

already taxed at below current market value, making it less likely such properties will receive temporary

decreases. Timing of refund payments is dependent upon the appeals hearing schedule, which is

currently calendared with 2021 cases. Appellants often waive the statutory deadline for hearings so that

Page 31 of 106

multiple years’ appeals can be heard at the same time, increasing uncertainty and revenue volatility

projections as several years' tax refunds and statutory interest might get triggered in one future year.

• Excess Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF): Excess ERAF represents the portion of

California county, city, and special district property tax revenues that revert to taxing entities once a

county’s educational entities reach the level of funding stipulated in state Proposition 98. In the City and

County of San Francisco, the only taxing entity contributing to ERAF, and therefore receiving excess

ERAF, is the City and County itself. Projections assume student attendance numbers and Proposition 98

funding levels along with property tax revenues for the City to arrive at excess ERAF estimates. This

report currently assumes excess ERAF revenue of $326.7 million in FY 2023-24, $292.8 million in FY

2024-25, $274.5 million in FY 2025-26, $261.2 million in FY 2026-27, and $254.6 million in FY 2027-28.

Business Taxes

General Fund business tax revenue is projected to grow from $881.7 million in FY 2023-24 to $1,025.0 million in

FY 2027-28. Business taxes include gross receipts taxes, business registration fees, and the administrative office

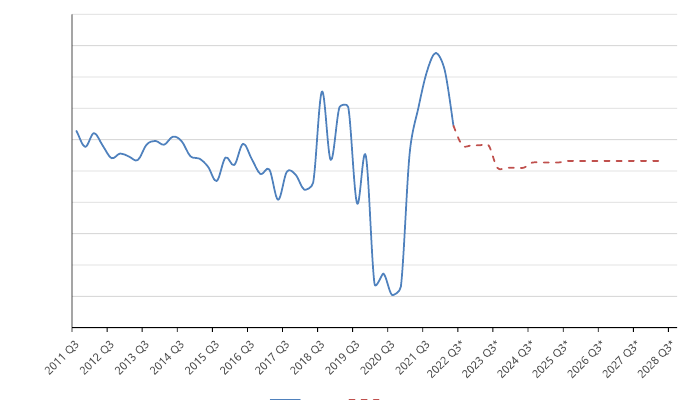

tax. Revenue from business taxes historically has followed economic conditions in the City. Figure 14 shows

actual and projected unemployment and wage growth from FY 2011-12 through FY 2027-28. Projected

unemployment remains low through the forecast period, as does projected wage growth.

However, in recent years, especially since the passage of Proposition F (discussed below), the gross receipts tax

has become dependent on fewer taxpayers. The top 10 taxpayers accounted for 19% of gross receipts tax

revenue in 2019 and 25% in 2021. Similarly, the top 50 taxpayers accounted for 34% of gross receipts tax

revenue in 2019 and 43% in 2021. Increasingly, circumstances specific to the largest companies could result in

large swings in gross receipt tax revenue, making it harder to project. This projection anticipates no economic

growth in the gross receipts tax base in 2023, 1% in 2024, and 3% in each of the remaining years of the forecast.

San Francisco Unemployment and Wage Growth

FY 2011-12 to FY 2027-28 Actuals and Projected

Figure 14

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Moody’s Analytics Forecast

Telecommuting and the Gross Receipts Tax Base

Since the pandemic began, there has been a fundamental shift in where office employees work. Originally,

telecommuting began as a public safety response to the pandemic, when offices were closed and on-site work

Page 32 of 106

was limited to essential employees. But over time, the severity of COVID-19 has lessened, in part due to

increased immunity from vaccines and from exposure to the virus. As it has lessened, the reasons for

telecommuting have shifted away from safety concerns to employee job satisfaction and productivity. This

suggests that there is no longer an expected increase in office work tied to the severity of the pandemic. Now,

returning to the office depends on negotiations between employers and employees. According to polling data

from WFH Research, soon after the pandemic began, employers planned on just over 1.5 days per week at home

on average when the pandemic ended but employees wanted more than 2.5 days at home. In polling data from

October 2022, employees’ desired amount of telecommuting had increased slightly to approximately 2.75 days

per week at home while employers’ plans have increased to about 2.25 days worked from home. This narrowing

gap suggests that employers and employees are coming closer to an agreement on how much work can be done

at home. While the degree of telecommuting in the long-term is still uncertain, it may be that the level of in-

office work has begun to stabilize.

In addition to the decline of the workforce in the City due to telecommuting, the population has declined as

well. From April 2020 to July 2021, the population of San Francisco declined by 6.7% according to the Census

Bureau. The population decline reduces payroll and thus reduces the gross receipts tax base in most industries.

Both telecommuting and population are important for the gross receipts tax base. For some business sectors,

such as information and financial services, the gross receipts tax depends in part on the share of a company’s

payroll that physically works within San Francisco. For example, if an employee works two days per week in the

office and three days per week at home from outside the City, then only 40% of that employee’s compensation

is included when determining the share of a company’s payroll generated in the City for gross receipts tax

purposes. This would then reduce the gross receipts tax generated by this employee by 40% in office-based

sectors, except information, where it would be reduced by half that amount, or 20%.

Telecommuting does have a smaller mitigating factor that supports the gross receipts tax base. Some San

Francisco residents previously commuted out of the City for work. To the extent that these out-commuters

telecommute from within the City, their payroll would now be included when calculating the gross receipts tax.

This report assumes that changes in telecommuting and population will reduce San Francisco payroll in office-

using industries by 40% from what it would have been without these changes. This assumption includes the net

effect of telecommuting from both in-commuters and out-commuters. There remains significant uncertainty

about this assumption. Currently, employers want more office work than employees do, which could lead to

further increases in office work. But this may change over time as office leases come up for renewal and

telecommuting allows employers to reduce their office space. In addition, in the past few months, layoffs have

been announced by some large San Francisco employers, such as Twitter, Meta, and Salesforce, which could also

decrease the gross receipts tax base.

Proposition F (2020)

In November 2020, voters adopted the Business Tax Overhaul measure (Proposition F) that altered the structure

of the City’s business tax to eliminate the payroll tax and increase the gross receipts tax over a period of four to

five years, beginning with tax year 2021. For certain business sectors, including information and financial

services, tax rate increases for tax year 2023 would be delayed to 2024 if citywide gross receipts in 2021 are less

than 90% of gross receipts in 2019 and increases for 2024 would be delayed to 2025 if gross receipts in 2022 are

less than 95% of gross receipts in 2019. The 90% threshold was not met. This report assumes that the 95%

threshold will be met and the tax increases on these sectors will be implemented in 2024. Should the 95%

threshold not be met in tax year 2024, business tax revenues will be approximately $20 million less in tax year

2024 than this report assumes, with the loss divided between FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25.

Page 33 of 106

Sales Tax

Sales tax revenues are expected to grow from $205.8 million in FY 2023-24 to $232.2 million by FY 2027-28,

exceeding pre-pandemic levels by the end of the forecast period. Sales tax experienced significant losses in FY

2019-20 and FY 2020-21 because of the COVID-19 public health emergency. The City has seen lower daytime

populations from the lack of travelers and in-commuters shopping and eating in restaurants. In addition, the

Census Bureau estimates that San Francisco’s resident population declined 6.7% between April 2020 and July

2021. During this time, sales taxes declined by 15.7% year-over-year from a peak of $213.6 million in FY 2018-19

to $180.2 million in FY 2019-2020 and by 18.5% year-over-year in FY 2020-21 to $146.9 million. As businesses

reopened and restrictions on restaurants, hospitality, and travel eased in mid-2021, sales taxes in San Francisco

and in the state have rebounded. Sales taxes grew to $188.3 million in FY 2021-22, an annual improvement of

$41.5 million or 28.2%. The recovery was attributable to growth in restaurants and hotels, business and

industry, general consumer goods, and fuel and service stations. Higher prices due to inflation also contributed

to higher sales tax revenues. Sales taxes from restaurants and hotels grew by $18.0 million (76.2%), the business

and industry sector grew by $9.5 million (93.4%), general consumer goods grew by $7.5 million (25.1%), and

sales tax from fuel and service stations grew by $5.4 million (118.4%). Figure 15 shows the changes in local sales

tax.

Change in Local Sales Tax Revenues from Same Quarter Prior Year, FY 2011-12 through FY 2027-28

Figure 15

*Projected. Data adjusted for corrections by the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

Projected growth in FY 2023-24 is driven by continued but slowing recovery in the restaurant and hotel industry,

largely due to improved tourism and conventions, as well as elevated prices due to inflation. Sales taxes from

the statewide pool, fuel and service stations, and general consumer goods are all forecasted to grow, although

at a lesser pace. However, revenue growth in other industries is expected slow as consumer spending shifts due

to rising interest rates and recession concerns. In FY 2024-25 and beyond, the projection assumes growth

between 2.7% and 3.2% annually.

Hotel Tax

Hotel tax revenue for all funds is expected to grow from $302.6 million in FY 2023-24 to $412.7 million by FY

2027-28. The forecast assumes the hospitality industry recovers to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the plan

-50%

-40%

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Percent Change from Same Quarter Prior Year

Actual Projected

Page 34 of 106

period. During the pandemic, a large portion of the City’s hotels were closed as a result of global travel

restrictions, public health policies, and cancellation of conventions and events. Hotel tax revenues in FY 2019-20

and in FY 2020-21 declined 35.7% and 86.8% year-over-year. FY 2020-21 revenues were 91.5% below the FY

2018-19 peak, the last full pre-pandemic fiscal year. As COVID-19 restrictions eased and vaccines became more

widely available in FY 2021-22, the City’s hotel taxes began to recover and totaled $158.2 million, an

improvement of 376.7% over the prior year.

Visitors to the City, and resulting hotel tax revenues, are primarily derived from three groups of travelers -

leisure domestic and international tourists, individual business travelers, and from group events such as

conferences and conventions. Most visitors travel to San Francisco by air, with combined enplaned and

deplaned passengers shown in Figure 16. By July 2022, total domestic and international airline passengers at San

Francisco International Airport (SFO) hit a pre-pandemic peak of 4.2 million passengers. The total number of

passengers traveling through SFO was 155% greater in FY 2021-22 than the prior year, with growth of 137% in

domestic visitors and 281% in international visitors. The improvement in the international sector is primarily due

to easing of travel restrictions to most international regions. Passenger activity is projected to continue to

improve from pandemic related service reductions in both the domestic and international sectors.

San Francisco International Airport Passengers, July 2014 through November 2022

Figure 16

Hotel tax revenue is strongly correlated with revenue per available room (RevPAR), which is influenced by

average daily room rates (ADR) and occupancy rates. RevPAR declined to an all-time low of $14.40 in April 2020.

As a result of low occupancy rates and hotel closures, the “Total Room Inventory” (TRI) methodology is used

when calculating RevPAR to provide a consistent comparison to pre-pandemic RevPAR. The industry gradually

recovered in FY 2020-21 because of eased restrictions and vaccines. FY 2020-21 annual average TRI RevPAR was

$28 and hit a peak of $61 in June 2021. The recovery continued in FY 2021-22 largely due to the return of

conferences and conventions. In FY 2021-22, a total of 23 conferences with over 126,000 attendees took place in

Moscone Center, primarily in the third (24.0%) and fourth (62.7%) quarters of the fiscal year. This is compared to

zero events in FY 2020-21 and 54 events with over 723,000 attendees in FY 2018-19. Though nowhere near the

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

Total Airport Passengers Domestic (Enplaned+Deplaned) International (Enplaned+Deplaned)

Page 35 of 106

FY 2018-19 peak, the effects of compression pricing on RevPAR as a result of conventions is clear; RevPAR spikes

with each convention and as a result drives up hotel tax collections. The average TRI RevPAR was $100 and

peaked at $191 in June 2022. We project annual average RevPAR will continue to improve as tourists and

conventions return to San Francisco. Figure 17 provides actual and projected RevPAR levels from January 2018

through July 2028.

Actual Monthly and Projected Annual Average San Francisco Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR),

FY 2017-18 through FY 2027-28

Figure 17

November 2018 Proposition E allocates 1.5% of the 14% hotel tax rate (or approximately 10.7% of revenue) to

arts programming outside of the General Fund. Due to the unprecedented drop off in revenue, this allocation

declined to $4.5 million in FY 2020-21 and $19.2 million in FY 2021-22. As hotel tax revenue recovers, we

project the allocation will increase to $34.5 million in FY 2023-24 and $44.7 million by FY 2027-28.

Real Property Transfer Tax

Real property transfer tax (RPTT) revenue is projected to increase from $277.5 million in FY 2023-24 to $365.0

million in FY 2025-26 and thereafter. While increasing year over year, these figures represent reductions of

$145.8 million (34.4%) and $91.2 million (20.0%) from prior projections, reflecting the current decade-long low

in large commercial transactions. RPTT is one of the most volatile of all revenue sources and is highly sensitive to

economic cycles, interest rates, and other factors affecting global real estate investment decisions. The forecast

assumes that office and residential values are threatened by the persistent trend to work from home during the

plan period, resulting in fewer transfers and revenue compared to rate-adjusted historical average.

Due to the tiered structure of the tax, a small number of transactions (primarily high-value, commercial real

estate transactions) generates a disproportionate amount of revenue. For example, in FY 2021-22 transactions

$0

$50

$100

$150

$200

$250

$300

RevPAR Total Room Inventory (TRI) RevPAR Projected Annual Average RevPAR

Page 36 of 106

over $10.0 million accounted for 1.0% of the number of total transactions but generated 69.6% of the revenue.

Compounding this source’s revenue volatility is November 2020 Proposition I, which doubled the transfer tax

rate on real estate transactions over $10.0 million. Prop I is projected to generate $119.3 million in FY 2023-24

and $156.9 million in FY 2027-28.

Tax on Executive Pay

In November 2020, voters approved Proposition L, which imposed a new general tax on businesses in the City

tied to the ratio of the total compensation of the highest-paid managerial employee to the total compensation

of the median employee in San Francisco. If this ratio is greater than 100:1, businesses will pay a tax that is a

percentage of their total San Francisco gross receipts. In this report, the measure is expected generate revenue

of $60 million in FY 2023-24, $80 million in FY 2024-25, and $100 million thereafter. This source is expected to

be highly volatile given the narrow base of expected payers, annual fluctuations in the value and form of

executive compensation, and potential relocation risk associated with tax increases.

Federal Emergency Management Agency Reimbursements

The plan assumes the City’s General Fund will receive $199.8 million of FEMA reimbursements for COVID-19-

related expenditures (incurred in prior years) in FY 2023-24, the last year of a five-year process. No FEMA

reimbursement revenue is anticipated after FY 2023-24.

Page 37 of 106

Table 6: Summary of General Fund Operating Revenues and Transfers in

FY 2021-28 ($ Millions)

FY 2021-22 FY 2022-23 FY 2022-23 FY 2023-24 FY 2024-25 FY 2025-26 FY 2026-27 FY 2027-28

Year-End

Original

Budget

Projection Projection Projection Projection Projection Projection