Corrections

Policy, Practice and Research

ISSN: 2377-4657 (Print) 2377-4665 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ucor20

The Evolution of Correctional Program Assessment

in the Age of Evidence-Based Practices

Stephanie A. Duriez, Carrie Sullivan, Edward J. Latessa & Lori Brusman

Lovins

To cite this article: Stephanie A. Duriez, Carrie Sullivan, Edward J. Latessa & Lori Brusman

Lovins (2017): The Evolution of Correctional Program Assessment in the Age of Evidence-Based

Practices, Corrections, DOI: 10.1080/23774657.2017.1343104

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23774657.2017.1343104

Published online: 11 Oct 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ucor20

Download by: [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 05:44

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

https://doi.org/10.1080/23774657.2017.1343104

The Evolution of Correctional Program Assessment in the Age

of Evidence-Based Practices

Stephanie A. Duriez

a

, Carrie Sullivan

a

, Edward J. Latessa

a

and Lori Brusman Lovins

b

a

School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA;

b

University of Houston Downtown,

Houston, Texas, USA

ABSTRACT

As evidence-based practices becomes an increasingly popular term, it

is crucial that correctional programs are assessed to ensure that

research is being translated and implemented with fidelity. Too

often the corrections field is quick to treat different interventions as

a panacea, without truly understanding how the program does or

does not meet the literature on effective practices. Data is provided

based on decades of assessment using the Correctional Program

Assessment Inventory and the Evidence-Based Correctional Program

Checklist. Findings suggest program adherence to effective practices

has shown some improvement, but still has a way to go, particularly

in the area of treatment characteristics and quality assurance.

KEYWORDS

Correctional program

evaluation; evidence-based

practices; principles of

effective intervention;

Risk Need Responsivity

In 2015 the Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation released a joint brief on the increasing trend of state legislatures enacting

laws requiring the use of evidence-based programs and practices. The Pew–MacArthur

partnership led to the review of more than 100 state laws put in place between 2004 and

2014, many of which were geared toward criminal justice programs. The brief outlines

how policy makers and legislatures have been under increasing pressure to get the “biggest

bang for their buck,” when it comes to the efficacy and accountability of tax funded

programming (Pew Charitable Trust, 2015). In 2011, as many states were adopting

evidence-based policies and practices (Mears, Cochran, Greenman, Bhati, & Greenwald,

2011: Welsh, Rocque, & Greenwood, 2014) the federal government launched the website

crimesolutions.gov. The website was created as a resource for agencies and policy makers

to ensure that they had access to examples of what works in the criminal justice system,

including correctional programs that have been implemented in a variety of correctional

settings and varying correctional populations.

The website, initially launched with “150 justice-related programs” (Department of

Justice, 2011) and now includes more than 1,000 programs, containing 69 corrections and

reentry programs and 22 corrections practices. The website provides practitioners and

policy makers with a rating of each program: effective, promising, or no effects to inform

decision makers on what the evidence has indicated about a particular program. The

website has been especially helpful to practitioners because most federal grants related to

the criminal justice system now require proven methods in reducing recidivism for

CONTACT Stephanie A. Duriez [email protected] School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati,

Teachers Dyer Complex 560 O, PO Box 210389, Cincinnati, OH 45221 USA.

© 2017 Taylor & Francis

2

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

funding. Having funding tied to use of evidence-based or promising practices does limit

correctional quackery and the temptation to run programs based on the “way we’ve always

done it.” Programs can no longer overlook the research on what works in reducing

recidivism (Casey, Warren, & Elek, 2011; Latessa, Cullen, & Gendreau, 2002; Petersilia,

2004; Quay, 1977).

Understanding what makes a program effective and implementing those components

are key to ensuring that the quality of correctional interventions keeps improving, leading

to improved offender lives, reduced recidivism, and increased public safety. The key

elements to a program, or the elements that drive recidivism reduction, are known as

the “black box” of correctional programs (Latessa, 2004). By understanding the “black

box,” researchers are better able to provide a blueprint for effective interventions.

Understanding key program components has the added benefit of being able to support

program implementation in other locations. For example, though some program models

or offender rehabilitation strategies are developed with the best of intentions the field has a

history of treating interventions as a panacea prior to fully understanding the components

that lead to their effectiveness (Duriez, Cullen, & Manchak, 2014; Finckenauer, 1982). We

have seen this in the past when interventions have gained great popularity and been touted

as a cure for all that ails offenders. Whether it be boot camps, juvenile drug courts, Scared

Straight, or more recently, Honest Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE),

these programs have had significant investment and been expanded to multiple locations

all over the country only to find that, overall, they had little to no effect on recidivism or,

worse, resulted in offenders recidivating at a higher rate than no treatment comparison

groups (Duriez et al., 2014; Lattimore et al., 2016; Lipsey & Wilson, 1998 ; MacKenzie,

2006; MacKenzie, Wilson, & Kider, 2001; Petersilia, 2004; Petrosino, Turpin-Petrosino, &

Buehler, 2003; Sullivan, Blair, Latessa, & Sullivan, 2014). Programs have not always

undergone such strict scrutiny to ensure that they are effective at reducing recidivism.

In fact, program evaluation has evolved significantly over the years to assist the field with

program development and implementation.

The early years of program evaluation

Early program evaluations took one of two forms. First, the basic program audit. A

program audit, normally performed by a governing or state agency, determined whether

a program met the minimum specific requirements for continued funding (Latessa &

Holsinger, 1998). The second type of evaluation was based on a quantitative examination

or outcome measures (e.g., rearrest, reincarceration, new conviction, relapse, etc.). These

limited methods of program evaluation had far-reaching consequences. One such con-

sequence was the well-known Martinson (1974) survey of 231 correctional program

evaluations whereby Martinson declared that, save for a few isolated programs, offender

treatment programs were not effective at reducing recidivism (Cullen, 2013; Martinson,

1974; Smith, Gendreau, & Swartz, 2009).

Martinson’s(1974) pronouncement had far-r eaching con sequences, with the left and

right embracing the view that treatment does not work, and rehabilitation is ineffective

(Cullen, 2013; Cullen & Gilbert, 2013;Phelps, 2011;Smith et al., 20 09 ). Valuable

lessons wer e learned from Martinson’s critique of correctional treatment. Researchers

became painfully aware of what happens when restricting program evaluation to an

3

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

outcome measure, usually operationalized as a type of recidivism. Additionally, by

reducing evaluations to a single outcome measure, researchers and practitioners are

left without understanding what inside the “ black box” seems to be driving a recidivism

reduction(Latessa&Holsinger, 1998; Lowenkamp, M akarios, Latessa, Lemke, & Smith,

2010). In 1977, Quay noted that a program should not be evaluated solely on the basis

of design and outcome measures, but must also include some measures of program

integrity. Program integ rity,orprogram fidelity, refers ge nerally to a program that is

created, implemented, and conducted according to a theory and design, whatever that

may be (Andrews & Dowden, 20 05;Nesovic, 2003;Quay, 1977;Yeaton & Sechrest,

1981).

Quay’s essential program components

Quay (1977) outlined components in four domains that should be present for a correc-

tional program to successfully reduce recidivism among program participants. First, he

discusses treatment characteristics and empirical bases. Elements in these areas should

capture and measure the treatment being provided, evaluate how a treatment is concep-

tualized based on the theory used during the design stage, evaluate whether the treatment

is based in sound theory and prior research, and evaluate if the treatment was piloted in a

smaller setting before being released to the whole group.

The second domain, service delivery, should include indicators to assess whether the

program is achieving what it is meant to. This area would assess treatment-related

elements such as the duration and intensity of the services. Quay (1977) emphasizes

that the third domain, personnel, is especially important because the success rate for

treatment techniques are dependent upon those that are delivering the services. Concepts

such as the degree of expertise of program personnel, the amount of training provided to

staff, and the thoroughness of staff supervision were deemed by Quay to be vital to

program performance.

The fourth and final domain, responsivity, should at minimum evaluate how staff are

matched with treatment services they provide as well as clients on their caseload and/or

treatment group. The work of Quay (1977) outlined here led to a movement in correc-

tional treatment to understand the “black box” of treatment and outline strategies for

effective practices.

The “what works” movement

The “what works” movement has been growing over the last 25 years, much to the

satisfaction of those that never lost faith in the efficacy of correctional treatment post-

Martinson (Cullen, 2013; Taxman, 2012). The movement was a call by researchers, mainly

outside the field of corrections and outside the United States, to not give up on correc-

tional treatment and to let science guide decision making (Cullen & Gendreau, 2001 ).

Chief among the researchers advocating for continued correctional treatment were a

group of Canadian psychologists who developed a set of guidelines for researchers and

practitioners, known as the “principles of effective interventions” (Cullen, 2013; Latessa &

Holsinger, 1998). In numerous studies and across different correctional settings, programs

that adhere to these guidelines have been shown to produce meaningful reductions in

4

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

recidivism (Andrews & Dowden, 2005; Andrews et al., 1990; Dowden & Andrews, 1999;

Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005; Latessa et al., 2002; Lipsey, 2009; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007;

Petersilia, 2004; Taxman, 2012; Welsh et al., 2014).

The principles of effective

intervention

The principles of effective intervention, as outlined by Gendreau (1996), include eight

principles of effective interventions: (1) assess actuarial risk/needs, (2) enhance intrinsic

motivation, (3) target intervention, (4) skill train with directed practice, (5) increase positive

reinforcement, (6) engage ongoing support in natural communities, (7) measure relevant

processes/practices, and (8) provide measurement feedback. Many of these principles are

reflective of, or build on what Quay (1977) advocated for almost 40 years previously.

1

Rested within Gendreau’s(1996) broader guidelines are three specific principles that

have been shown to be effective at reducing recidivism if they are followed by correctional

treatment programs. These are known as risk, needs, and responsivity principles, or the

Risk Need Responsivity (RNR) model. First, the risk principle asserts the need for

offenders to be assessed using a validated risk assessment (Andrews & Bonta, 2010;

Smith et al., 2009), so that programs can target those at a higher risk to recidivate

(Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2005a; Smith et al., 2009). Just as it is imperative to ensure

programs are providing offenders who are higher risk with an adequate dosage of treat-

ment, it is equally important to safeguard against overdosing offenders who are low risk

with interventions. By placing offenders who are low risk in more intensive services, a

program increases the likelihood of association with offenders who are higher risk and

may also disrupt the positive and protective factors (e.g., employment, family, school, etc.)

in the life of an offender who is low risk (Andrews & Bonta, 2006; Latessa, Brusman-

Lovins, & Smith, 2010; Lovins, Lowenkamp, & Latessa, 2009; Lowenkamp & Latessa,

2005a; Sperber, Latessa, & Makarios, 2013a).

It is important to offer a qualifier for the assertion above regarding the concept of

“dosage.” The research into dosage is still in its infancy. Preliminary research has shown

support for the risk, in that offenders who are higher risk were found to require a

considerably higher dosage of treatment, and providing too much to offenders who are

lower risk results in increased failure rates. The early research suggests that 0 to 99 hours

of treatment targeting criminogenic needs is sufficient and associated with reduced

recidivism among offenders who are low risk; 100 to 199 hours for offenders who are

moderate risk; 200+ hours for those offenders assessed as a high risk to recidivate; and

finally, 300+ hours may be needed for offenders that have been assessed to be at a high risk

to recidivate and have multiple need areas to address in treatment (Bourgon & Armstrong,

2005). Research is ongoing to fine tune these guidelines around the appropriate level of

service (see Carter & Sankovitz, 2014; Lipsey, Landenberger, & Wilson, 2007; Sperber,

Latessa, & Makarios, 2013b). In a recent study of the impact of prison programming on

postrelease recidivism, there is preliminary evidence to show that it is not just the amount,

or the type, but the combination of services that can also play a role in reducing recidivism

among offenders (Latessa, Lugo, Pompoco, Sullivan, & Wooldredge, 2015). Hence, the

discussion of dosage should not be thought of as simply the number of hours of treatment

an offender

receives, but also what’s being targeted, the model being used, and the quality

of the interventions, discussed in further detail below.

5

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

Second, the need principle requires the targeting of dynamic risk factors, or crimino-

genic needs of offenders. These criminogenic needs, most effectively identified through a

risk/needs assessment, include antisocial attitudes, values, and beliefs; antisocial peer

associations; antisocial personality patterns; history of antisocial behavior; family and

marital factors; low levels of educational, vocational, or personal achievement; lack of

involvement in prosocial leisure activities; and substance abuse (Andrews & Bonta, 2010;

Latessa & Reitler, 2015). These criminogenic needs are those most strongly correlated with

recidivism, thereby the needs that should be targeted by correctional programs to decrease

likelihood of reo ffending. The need principle also emphasizes that needs should be

reassessed during and after treatment to monitor behavioral changes and/or to make

adjustments to treatment targets (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Smith et al., 2009).

The third and final principle, the responsivity principle, can be broken down into two

components. The first, general responsivity, asserts that cognitive, behavioral, and social

learning theories have shown to be the most effective at achieving behavioral change and

therefore should be the model that drives correctional interventions (Andrews & Bonta,

2010; Gendreau, Cullen, & Bonta, 1994; Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005; Lipsey & Wilson,

1993; Nesovic, 2003; Smith et al., 2009). The second component, specific responsivity,

recommends that offenders are matched with appropriate sta ff and interventions based on

their individual traits or barriers. For example, an offender who is highly anxious may not

perform well with staff that have a confrontational demeanor and/or may not do well in a

group environment (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Smith et al., 2009). The RNR model is

widely supported in recidivism reduction research (e.g., Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Andrews,

Bonta, & Hoge, 1990; Cullen, 2013 ; Dowden & Andrews, 1999; Latessa & Lovins, 2010;

Lipsey, 1989; Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2005a, 2005b; Lowenkamp, Latessa, & Holsinger,

2006; Polaschek, 2012) and has created the foundation and shaped the evolution of

program evaluation over the last 20 years.

In a meta-analysis testing the elements of program integrity among 273 treatment

programs, Andrews and Dowden ( 2005) identified a number of important program

integrity indicators from previous research: a program’s model is based off a theory of

criminal behavior; program staff

are selected for their skills as well as their support for

offender

change; program staff are given proper training in the program model as well as

the interventions employed by the program; program staff are provided clinical super-

vision; the program provides training material and manuals for each intervention; a

process is in place in which staff are assessed on the quality and fidelity of their service

delivery; the program is set up to provide an appropriate amount of dosage to offenders;

an assessment of the length of time a program has been in operation; and finally whether

the program has employed the services of an evaluator to assist with design, delivery, or

supervision. Many of these indicators are congruent with what Quay (1977) advocated for

and what Canadian researchers have popularized through the effective practices in correc-

tional intervention and the RNR principles.

The evolution of evaluation

The use of meta-analytic reviews that took place in the 1980s and 1990s played a

monumental role in the development of knowledge regarding what does and does not

work in corrections. This type of literature review could take into account methodological

6

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

issues that studies faced, any potential moderating variables that could have a ffected the

outcome, and control for them (Nesovic, 2003). The resulting statistic, the effect size,

allows for direct comparison of different studies, and therefore different types of correc-

tional treatments (Nesovic, 2003). Gendreau and Andrews (1989), capitalizing on the

increased use of meta-analytic reviews introduced the Correctional Program Evaluation

Inventory (CPEI) in 1990, renamed the Correctional Program Assessment Inventory

(CPAI) in 1996, answering the call of earlier researchers like Quay (1977) for a more

comprehensive measurement of program fidelity (Nesovic, 2003).

The CPAI was the first attempt to create an empirically sound psychometric instrument

that would include a sample of indicators, or items, that assess the effectiveness of

correctional programs (Blair, Sullivan, Lux, Thielo, & Gormsen, 2014; Latessa &

Holsinger, 1998; Nesovic, 2003; Sullivan et al., 2014). A defining feature of the CPAI is

that it was never meant to be a static tool. Rather, it was meant to be fluid, allowing for

updates and modifications to reflect the current knowledge and best practices in correc-

tional treatment (Nesovic, 2003). As the CPAI developed over the years, a number of

different subcomponents were added and/or refined. Nonetheless, key sections of the tool

have remained stable, including organizational culture, program implementation/main-

tenance, management staff/characteristics, client risk/need practices, program character-

istics, interagency communication, and evaluation (Andrews, 2006; Nesovic, 2003). Each

section of the CPAI has a different number of items (in the CPAI-2000 this range was

between six and 22 items), all designed to operationalize the concepts introduced by Quay

(1977) and the principles of effective intervention defined above. In the CPAI, the number

of items was representative of the section’s weight on the overall score, with each item

scoring a 1 or 0. The overall program score produced a percentage that would place the

program into one of four categories: very satisfactory (70% to 100%), satisfactory (60% to

69%), needs improvement (50% to 59%), or unsatisfactory (less than 50%). This allows

programs to determine their level of adherence to effective practices relative to other

correctional programs; moreover, the CPAI provides the program with thorough report of

how the program is and is not meeting the evidence of what works in reducing recidivism

(Matthews, Hubbard, & Latessa, 2001).

The CPAI ran into a number of unexpected obstacles when first being used particularly

that programs failed to adhere to many practices on the CPAI that had been found to be

important for correctional programs (Nesovic, 2003). In time, correctional programs were

meeting more of the indicators, possibly a sign of the emphasis of research-informed

programming. As the years went on and the “

what works” research

continued to develop,

the CPAI grew in the number of items assessed, starting with a total of 66 items and

currently having more than 130 indicators on the assessment (Gendreau & Andrews, 1989,

2001).

In the late 1990s researchers at the University of Cincinnati (UC) saw an opportunity to

test the items on the CPAI with different populations of offenders in the State of Ohio.

Initially, a study of 28 juvenile justice programs showed that 11 of the programs met less

than 50% of the items on the CPAI, and only three programs met 70% of the items on the

tool (Latessa, Jones, Fulton, Stichman, & Moon, 1999; Nesovic, 2003). In a second study

using the CPAI, nine secured and nonsecured residential juvenile offender programs were

evaluated. Researchers found that the greater the program score the lower the recidivism

rate of residents. Although these results were encouraging the small sample size (N =9)

7

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

and the short follow-up period (3 and 6 months) did warrant further investigation into the

use of the tool before its widespread adoption (Latessa, Holsinger, et al., 1999; Nesovic,

2003; Sullivan et al., 2014).

To further test these results, Holsinger (1999), using the same nine facilities, tested the

link between overall CPAI score and a number of different recidivism measures (e.g., any

new court contact, new adjudication, return to a facility, etc.). Using logistic regression to

predict recidivism measures, Holsinger found significant negative relationships with

nearly all of the outcome measures. Specifically, Holsinger found that programs with the

lowest CPAI scores had the highest recidivism rates, despite how recidivism was

measured.

Recognizing the potential of the CPAI to help identify effective programs, researchers

from UC saw an opportunity to complete a number of large-scale studies looking at

program indicators and the validity of evaluation tools in identifying programs that meet

effective practices and reduce recidivism. To accomplish this researchers used a modified

version of the CPAI.

2

The first of these opportunities came in 2002 when the Ohio

Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections contracted with UCCI to study the state’s

half-way houses (HWH) and Community-Based Correctional Facilities (CBCF). This

opportunity allowed researchers to assess the correctional programming at 15 CBCFs

and 37 HWHs, serving more than 7,000 offenders. Data on nearly 6,000 additional

offenders who had not resided in a CBCF or HWH was used as a comparison sample.

Researchers found that recidivism was reduced among offenders who were higher risk but

increased among offenders who were low risk exposed to the more intensive services

offered at HWHs and CBCFs. Additionally, those offenders that completed the programs

at their respective residential placement had more favorable outcomes than those that did

not. This highlights the importance of adherence to RNR, as well as considering termina-

tion status when measuring a program’seffectiveness (Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2002).

The second UC study parsed out data from the project described above, which used a

survey tool that contained many of the CPAI items to assess program quality. The sample

included all offenders that spent at least 30 days in a jail or a prison diversion program

funded through Ohio’s Community Corrections Act during fiscal year 1999. In total, there

were more than 6,000 offenders included in the treatment sample. The final sample of

programs, 91 in total, represented a myriad of different types of programs: day reporting,

domestic violence, intensive supervision probation, work release, substance abuse treat-

ment, and residential placement. The domains included on this new survey were signifi-

cantly related to program effectiveness. For example, programs that scored 60% or higher

on the survey were associated with a predicted reduction in recidivism of 24%

(Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2005a).

The third and final UC study evaluated the efficacy of select measures from the CPAI as

well as additional programmatic measures researchers wished to test. This study evaluated

the Ohio Reasoned and Equitable Community and Local Alternative to the Incarceration

of Minors (RECLAIM) initiative. The sample comprised youth terminated in fiscal year

2002 from RECLAIM funded programs, Community Correctional Facilities, Department

of Youth Services (DYS) institutions, or youth discharged from parole/aftercare. In total,

more than 14, 000 youth and 72 programs were included in the analyses. There were two

important findings related to program evaluation from this study. First, the average risk

level of youth and the score of the program on the modified evaluation tool were

8

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

significant predictors of the recidivism rate of a program. Second, when the average risk

level of youth is controlled, the program score is still a significant predictor of the

recidivism rate of the program (Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2005b).

In combination, the item-level analyses that were completed across the different studies

converged to confirm the predictive capability of a number of items included in the CPAI,

as well as a number of new items. Additionally, the studies showed that a number of items

included in the CPAI were not highly predictive of recidivism (e.g., a previous evaluation

appearing in a peer-reviewed journal, the utilization of an advisory board, and program-

matic changes in the last 2 years; Lowenkamp, 2004). These studies led to the development

of a new tool to evaluate program integrity, the next generation of program evaluation

tools, called the Evidence-Based Correctional Program Checklist (CPC).

The Evidence-Based Correctional Program Checklist

The CPC was created in 2005 after the conclusion of the three state-wide outcome studies

describe

above, by researchers at the University of Cincinnati Corrections Institute (UCCI.

The development of the tool included retaining items from the CPAI that were correlated

with reductions in recidivism. Further, items that did not appear on the CPAI but were

found to be correlated with program success were included in the CPC, whereas items not

correlated with recidivism were excluded from the new instrument. For example, an item

found on the original CPAI assessed whether a program had an advisory board. The

studies completed by UC, however, did not find a correlation between the existence of a

program advisory board and reductions in recidivism. Finally, select items found to be

strongly correlated with recidivism, such as targeting offenders who were higher risk, were

weighted so as to emphasize the importance of these program elements (Lowenkamp &

Latessa, 2002 , 2005a, 2005b).

The CPCs comprises five domains (compared to the CPAI’s six domains) and splits the

domains into two basic areas. The first area, capacity, measures the degree to which a program

has the ability to offer evidence-based interventions. The domains in this area are program

leadership and development, staff characteristics, and quality assurance. The second area of

the CPC, content, assesses the extent to which a program adheres to the RNR principles, and

consists of an offender assessment and a treatment characteristics domain.

The original CPC had 77 indicators, or items, worth a total of 83 points. Updated in

2015, the number of indicators was reduced to 73, worth a total of 79 points. The change

in items was based on patterned items being combined, as well as two new items being

added to the instrument. Although most items on the CPC are scored 1 or 0, the weighted

items are scored as 2 or 3. Finally, much like the CPAI, a program’s score places the

program in one of four categories

3

; very high adherence to evidence-based practices (EBP)

(65% to 100%), high adherence to EBP (55% to 64%), moderate adherence to EBP (46% to

54%), or low adherence to EBP (45% or less). The change in scoring categories is one of

the most notable changes from the CPAI to the CPC. Based on the work completed to

date using the CPAI and the CPC, it is evident that only a small number of programs meet

the requirements to be categorized as a top scoring category. However, programs can

make small number of program practice changes in the different domains to improve their

scoring, especially in the offender assessment and treatment characteristics domains where

there are weighted items.

9

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

The utility of using a program evaluation tool like the CPAI, or the more concise CPC,

is that it provides a program with a detailed report of the program’s status in respect to

adhering to EBPs and the report serves as a blueprint for program improvement. The

report documents for a program the areas where it is and is not adhering to EBP. Further,

the report provides an explanation of the areas that need improvement as well as program

specific recommendations that they are low cost and realistic.

The CPC, what works, and recidivism

The development and use of the CPAI and CPC has been described. In 2010, researchers

from

UC set out to further examine program characteristics associated with reductions in

recidivism. Researchers developed program-level data collection instruments which used

items from the CPC, the CPAI-2000 as well as additional, theoretically relevant items to

evaluate the association between the presence of those items in a program and reduced

recidivism among program participants. Researchers used data from 64 CBCFs and HWH,

with more than 12,000 people included in the analysis.

To determine program effectiveness, the average recidivism rate for the treatment

(program participants) and matched comparison groups was examined. The result was

an effect size that could be used to compare programs that had identified program

characteristics and those that did not. Finally, correlations were used to examine the

strength of the relationship between the presence of characteristics and program effect

size, or the reduction in recidivism.

Researchers found that a large number of items were significantly correlated with

reductions in recidivism.

4

Under the area of program leadership and development, for

example, having a qualified program director, stable funding, and completing a literature

review was associated with positive outcomes. The cumulative effect of meeting multiple

items in this area resulted in an overall correlation of .41, evidencing a modest relationship

with recidivism (Latessa et al., 2010). The same process was used to identify effective

program characteristics on the remaining areas of the CPC (i.e., staff characteristics,

offender assessment, treatment characteristics, and quality assurance). Although this

2010 study found a weaker relationship between the overall CPC score and outcomes

than the prior UC studies, the researchers hypothesize that the reduction in the strength of

the correlation between items in the CPC and recidivism can be attributed at least in part

to the reduction in the variation of the data due to programs’ ability to adapt to the

evaluation tool (Latessa et al., 2010).

Further evidence of the effectiveness of program evaluations came from a forthcoming

study of a parole board in a highly populated jurisdiction on the East Coast. Using the

CPC, researchers evaluated programs providing services to recent parolees living in semi-

custodial residential treatment centers. There were 2,615 offenders that received residen-

tial placement between 2009 and 2011. The parolees that were place in this type of

residential treatment center were overall at a higher risk to recidivate according to the

Level of Service inventory – Revised (LSI-R) (Andrews & Bonta, 1995). Overall, research-

ers found that after an 18-month follow-up period those offenders that were in programs

that scored highest on the CPC had lower rates of rearrest and reconviction. Although the

parolees who received services through residential placement had lower rates of recidivism

across the board when compared to the control group participants, who were returned

10

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

directly to the community, programs assessed to be more adherent to EBPs using the CPC,

saw even higher reductions in recidivism (Ostermann & Hyatt, 2017).

The CPC in action and further support for program evaluation

Since 2005, when the CPC was developed, the general CPC tool has been adapted to assess

specific

types of programs that have their own subset of research within the broader

context of correctional treatment programs. These adaptations include assessments for

Community Supervision Agencies (CPC-CSA), general correctional treatment groups

(CPC-GA), and Drug Court programs (CPC-DC). There were several motivating factors

that led to different versions of the tool being created. First, there has been an increase in

the popularity of different types of correctional programs. For example, there has been a

significant increase in the use of drug courts across the country over the last 10 years

(Blair et al., 2014). Second, as offenders are diverted from jails and prisons and placed on

community supervision in greater numbers, the role of probation and parole officers and

the services provided by their offices has expanded (Petersilia, 2004). Development of

specialty tools allowed assessors to evaluate the nuances of the specific areas. For example,

the group assessment incorporates a more detailed evaluation of core correctional prac-

tices, the drug court evaluation incorporates the role of the judge and community

providers in the program, and the community supervision tool includes items that assess

officer brokerage responsibilities and response to violations. Hence, based on studies

conducted by UCCI and other researchers, it is clear that some correctional interventions

have important features that may not be captured in the original CPC (Blair et al., 2014).

Within the last 10 years, UCCI has trained governmental staff in agencies across the

country and internationally, resulting in nearly 40 agencies being trained in the CPC (or

its variations). UCCI in conjunction with these trained agencies have assessed more than

700 treatment programs, community supervision agencies, treatment groups, and drug

courts.

The CPC has been used in 32 states; many of them started using the tool because policy

makers and legislatures were requiring that correctional programs be based on the

evidence of what works in reducing recidivism. For example, in 2005, Oregon’s legislature

passed Senate Bill 267, stipulating that 25% of state funding by the end of the year be

allocated to programs that could show they were evidence-based (O’Connor, Sawyer, &

Duncan, 2008 ). This percentage was to increase to 50% by 2007 and 75% by 2009. To

ensure that programs were meeting this requirement, the Oregon Department of

Corrections requested a number of staff members be trained in the CPC, and 47 programs

across the state were assessed using the CPC to establish a baseline of CPC scores for

future benchmarking. Six of the lowest performing programs were reassessed after 2 years,

allowing time for the program to implement changes based on the results of the first CPC

(O’Connor et al., 2008).

5

Initially the state found that their correctional programs were scoring above the

national average in overall score and in three of five domains (leadership and develop-

ment, staff characteristics, and treatment characteristics). The six programs that were

reassessed scored above average in overall score and across all five domains, once program

adjustments were made (O’Connor et al., 2008). The way in which Oregon utilized the

CPC, as a mechanism to help programs improve, is exactly how it was intended to be

used, and how many other agencies and programs are using the evaluation tool across the

11

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

country (e.g., Kansas, Minnesota, Maryland, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Ohio, Texas, West

Virginia, and Wisconsin), and now in Singapore as well.

Twenty years of program evaluation

One of the benefits of using an assessment tool like the CPAI or CPC is that different

components of a program can be evaluated and quantified as either meeting EBPs or not.

This allows programs to not only have a clear sense of where they can make improve-

ments, but also gives researchers the ability to track trends and progress in the field of

correctional programming. Given the scope of the assessment that we have conducted to

date, using the CPAI and the CPC, we can estimate averages for the different domains,

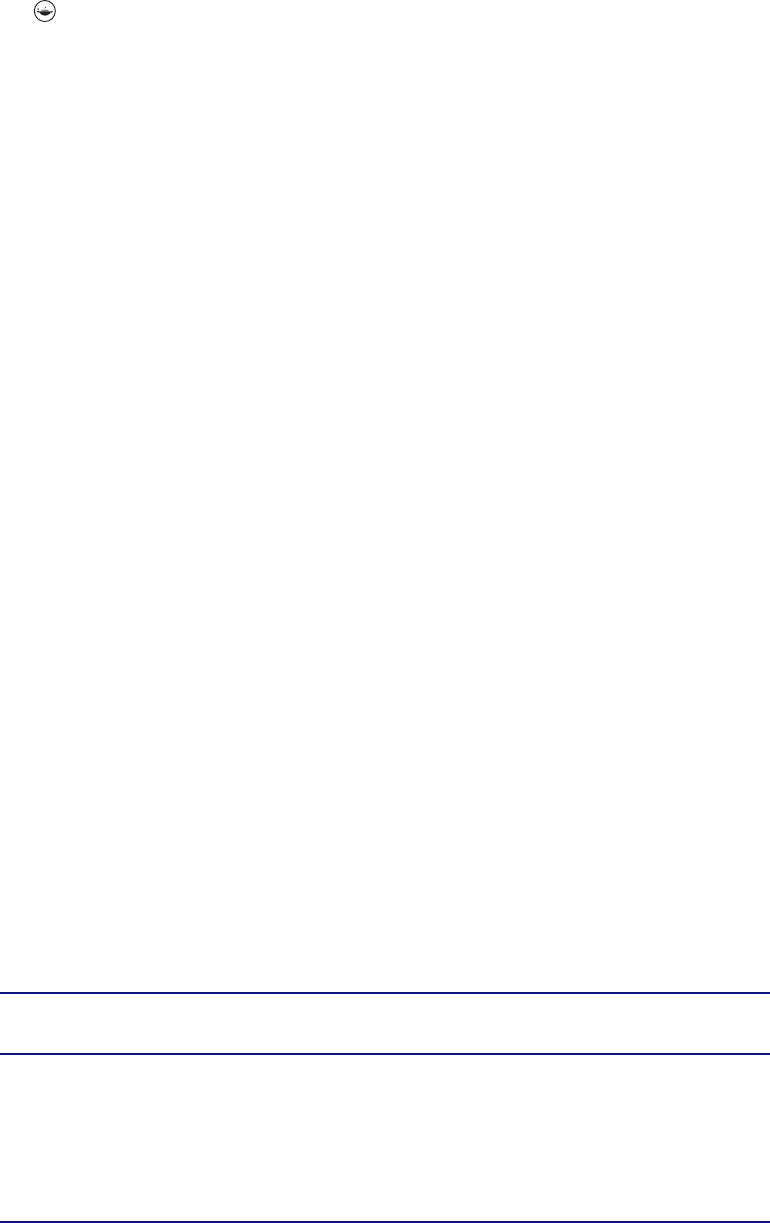

areas, and overall scores for programs assessed. Figure 1 presents a comparison of the

averages of 631 programs assessed using the CPAI between 1995 and 2005 to the 499

programs assessed using the CPC between 2005 and 2016. This presentation of the

averages over the course of the last two decades indicates that, overall, there have been

some very positive changes in corrections.

In the program leadership and development domain (the program implementation

domain of the CPAI),

6

we have seen the average hold steady at approximately 72%. The

program leadership and development domain consistently receives the highest scores. It is

encouraging that over the last 20 years, program leadership and development practices

have been consistent with the research on effective practices. The two most common

indicators that programs fail to meet in this domain is (1) whether there is evidence that a

comprehensive literature review was conducted during program development and at

regular intervals to keep up with the research on effective correctional practices, and (2)

whether the new initiatives have a structured pilot period in order to make adjustments

before widespread application.

The sta ff characteristics domain has shown an average increase of nearly 7% from

59.3% to 66%, pushing the mean of staff characteristics for all programs into the very high

adherence to EBP category. The indicators within this domain that have proven to be

challenging are around the training and clinical supervision that staff receive. Research

Program Staff Quality Capacity Offender Treatment Content Overall

Leadership & Characteristics Assurance Assessment Characteristics

Development

CPAI CPC

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Figure 1. A comparison of national average scores: Correctional Program Assessment Inventory versus

Correctional Program Checklist.

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

12 S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

shows that staff are critical to improved outcomes (Barnoski, 2002, 2004; Makarios,

Lovins, Latessa, & Smith, 2016). When an EBP is implemented with fidelity, in turn

reducing the rate of recidivism of participants, the idea that correctional programs can be

a tool to improve public safety is promoted (Duwe & Clark, 2015).

The average for the offender assessment category (client pre-service assessment on the

CPAI), improved by 4% from 50% to 54.4%. When looking at the assessments that have

been completed over the last 20 years, many programs fail to institute standardized instru-

ments to assess the risk, need, and responsivity needs of offenders. Most often, programs do

not assess for specific responsivity factors of their clientele, despite its importance in guiding

correctional programming (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Sperber et al., 2013a).

The treatment characteristics domain (program characteristics in the CPAI) is the

largest and most heavily weighted domain. This domain examines a range of program-

matic practices, such as the model used, the needs targeted, how the program responds to

participant behaviors, and the use of social learning and behavioral mechanisms to change

behavior. The CPAI national average was 36.2% indicating that the vast majority of

programs assessed were not meeting the guidelines prescribed by research. Although the

average has increased in the last 10 years (40.1%), the results using the CPC are not much

better. Consistent application of need and responsivity principles is clearly a challenge for

correctional programs.

Finally, the quality assurance domain (evaluation domain in the CPAI) was consistently

the weakest of the five domains. This domain had an average score of 31.9% under the

CPAI and dropped to just 30% in the last 10 years with the use of the CPC. Quality

assurance involves following up on strategies that have been implemented to ensure

continued fidelity to the program model; programs have historically struggled with

ensuring that adequate quality checks are in place in programs.

Tracking the progress of the field is important to ensure that programs are moving

toward adhering to what works in reducing recidivism. An additional benefit of using

program evaluation tools like the CPC and CPAI is the ability to assess the degree to

which different correctional settings are meeting the programmatic needs of offenders. In

Table 1, the national average of the different domains and areas of the CPC are displayed,

alongside the averages of three different types of correctional treatment settings: HWH,

institutions, and outpatient treatment programs. Although the average score varies for

each type of correctional setting, some trends are apparent. The highest scoring domain

Table 1. The average Correctional Program Checklist scores of the half-way houses, institutions, and

outpatient treatment centers.

Halfway

Average House Institutional Outpatient Most Common Scoring

Score (n = 24) (n = 97) (n = 136) Category

Program leadership & 71.7 69.1 69.7 76.4 Very high adherence to EBP

development

Staff characteristics 66.1 59.1 60.7 73.3 Very high adherence to EBP

Quality assurance 30.1 22.2 35.9 23.7 Low adherence to EBP

Capacity 58.9 53.6 57.6 61.9 High adherence to EBP

Offender assessment 54.7 43.0 62.4 47.6 Moderate adherence to EBP

Treatment characteristics 40.5 31.0 40.3 45.6 Low adherence to EBP

Content 44.8 35.6 47.3 46.2 Low adherence to EBP

Overall 50.5 42.8 51.4 52.4 Moderate adherence to EBP

EBP = evidence-based practice.

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

13 CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

for each program type is program leadership/development and staff characteristics,

whereas the lowest average domain is quality assurance. This result is consistent with

the overall CPC results. Some differences between program types were also noted.

Institutional programs score higher in quality assurance and offender assessment, than

either HWH or outpatient programs. The average score in staff characteristics was

approximately 13 percentage points higher for outpatient programs relative to institu-

tional or residential options. HWH programs consistently scored lower than either

institutional or outpatient programs, particularly in the program content area.

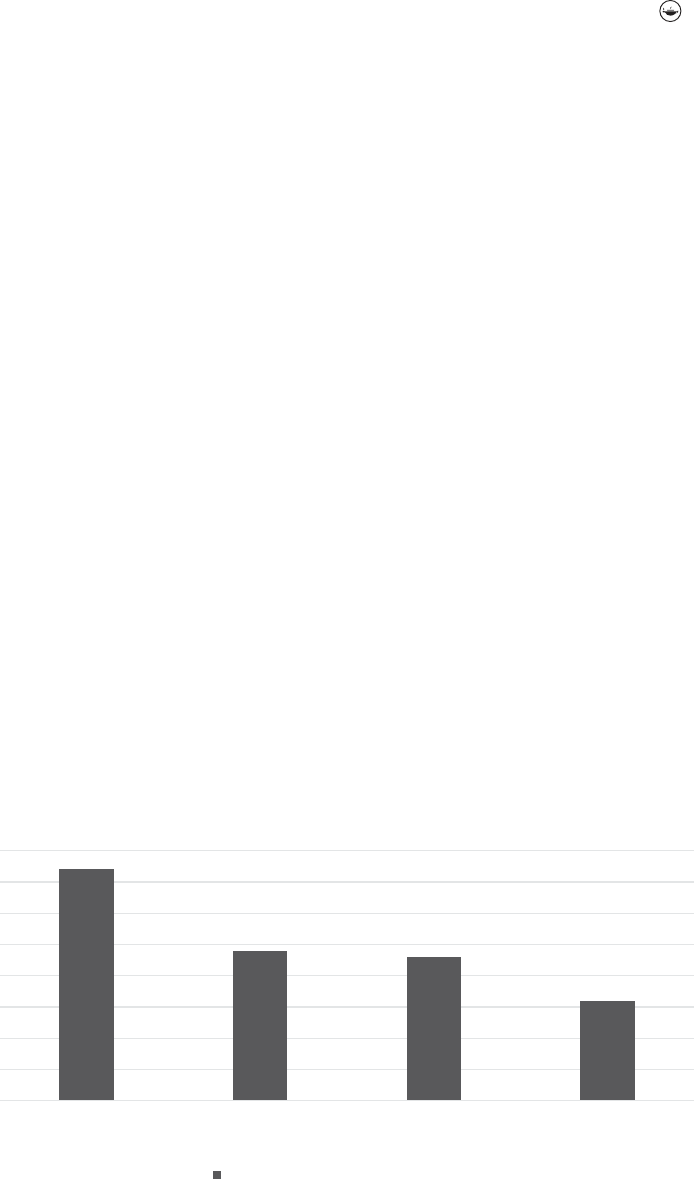

Figure 2 presents the distribution of programs assessed under each scoring category.

Unfortunately, most of the programs assessed fall under the “low adherence” category of

the CPC (36%). Although this suggests that there is clearly work to be done in enhancing

program adherence to EBPs, nearly 40% of programs did fall in the high or very high

adherence to EBP category. Given that the CPC and CPAI rate a program against what an

ideal correctional program would look like, classification in the upper two categories

represents programs that are clearly knowledgeable and conscientious about implement-

ing effective correctional programming. Moreover, research suggests that programs clas-

sified into these scoring categories have a greater impact on recidivism reduction.

Limitations and conclusions

With most states adopting policies requiring EBP, the need for program evaluation

and program integrity is crucial to ensuring that programs are not operatin g from a

foundation of false promises. EBPs dictate that research on effective correctional

strategies drive programmatic decisions. Instruments like the CPAI and CPC assist

programs in measuring the degr ee to which they are adhering to effective practices. It

is in the best interest of our field that we are off eri ng high-quality programs to secure

adequate funding and to help offenders suc cessfully reenter society (Duwe & Clark,

2015).

40%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Low Adherence to EBP Moderate Adherence to High Adherence to EBP Very High Adherence to

EBP EBP

Pro

g

rams Assessed usin

g

the CPC

Figure 2. Distribution of programs among the four scoring categories of the Correctional Program

Checklist (CPC).

14

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

When reviewing the results of the last 20 years of program evaluation it is important to

keep in mind that the differences that while the CPAI and CPC are very similar, changes

in the trends of program scores across time may in part be attributable to differences in

the tools. This is important because the CPAI is used for all of the earlier studies, and the

CPC for the more recent.

Although some of the data presented suggests there is much work to be done, we do

not want to paint a bleak picture of where we are. There are many agencies that are

getting it right. For example, in Pennsylvania there is a collaborative effort among

agencies within the state to measure the impact tha t programs who serve juvenile

justice involved clients are having on recidivism (EPISCenter, n.d.). Likewise, Ohio’s

Department of Youth Services and Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections

(adult system) have invested significant resources into redesigning their community

based programs to better conform to EBP and incentivizing use of effective interven-

tions in t he community. As correctional agencies continue to strive toward o ffering

EBP, it is important that funding sources and correctional programs explore the black

box of correctional treatmen t. This means no longer relying solely on the results of a

traditional audit, which histori cally provides l ittle informa tion about program prac tices

designed to change offender behavior, but rather t ha t they use a comprehensive

assessment of how programs are meeting the research on what works in reducing

recidivism.

Notes

1. For additional information regarding the principles of effective intervention, see National

Institute of Corrections (n.d.).

2. The staff and program director interviews were not detailed enough and/or complete enough to

include all indicators from the CPAI in the analysis.

3. These were also updated in 2015. Formerly, the categories were highly effective, effective, needs

improvement, and ineffective.

4. In the Latessa, Brusman-Lovins, and Smith (2010) study examining the relationship between

items on the CPC and reductions in recidivism, items that were not found to be positively

correlated with recidivism were removed from the analysis.

5. The remaining 41 programs were not reassessed by the state prior to the publication of this

article.

6. It should be noted that the indicators that make up the different domains of the CPC and CPAI

do not match item for item.

References

Andrews, D. A. (2006). Enhancing adherence to risk-need responsivity: Making quality a matter of

policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 5, 595–602.

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (1995). LSI–R: The level of service inventory-Revised. Toronto, ON:

Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2006). The psychology of criminal conduct (4th ed.). Newark, NJ:

LexisNexis/Matthew Bender References

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology,

Public Policy, and Law, 16(1), 39–55.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation:

Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 17,19–52.

15

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

Andrews, D. A., & Dowden, C. (2005). Managing correctional treatment for reduced recidivism: A

met-analytic review of programme integrity. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 10, 173–187.

Andrews, D. A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R. D., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F. T. (1990). Does

correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis.

Criminology, 8, 369–404.

Barnoski, R. (2002). Washington State’s implementation of functional family therapy for juvenile

offenders: Preliminary findings. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Barnoski, R. (2004). Outcome evaluation of Washington State’s research based programs for juvenile

offenders. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Blair, L., Sullivan, C. C., Lux, J., Thielo, A. J., & Gormsen, L. (2014). Measuring drug court

adherence to the what works literature: The creation of the evidence-based Correctional

Program Checklist–drug court. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative

Criminology, 60, 165–188.

Bourgon, G., & Armstrong, B. (2005). Transferring the principles of effective treatment into a “real

world” prison setting. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32,3–25.

Carter, M., & Sankovitz, R. J. (2014). Dosage probation: Rethinking the structure of probation

sentences. Silver Spring, MD: Center for Effective Public Policy.

Casey, P. M., Warren, R. K., & Elek, J. K. (2011). Using offender risk and needs assessment

information at sentencing: Guidance for courts from a national working group. Williamsburg,

VA: National Center for State Courts.

Cullen, F. T. (2013). Rehabilitation: Beyond nothing works. Crime and Justice, 42, 299–376.

Cullen, F. T., & Gendreau, P. (2001). From nothing works to what works: Changing professional

ideology in the 21st century. The Prison Journal, 8, 313–338.

Cullen, F. T., & Gilbert, K. E. (2013). Reaffirming rehabilitation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Department of Justice. (2011). Department of Justice launches crimesolutions.gov website [Press

Release]. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-launches-crimesolu

tionsgov-website.

Dowden, C., & Andrews, D. A. (1999). What works in young o

ffender

treatment: A meta-analysis.

Forum on Corrections Research, 11,21–24.

Duriez, S. A., Cullen, F. T., & Manchak, S. M. (2014). Is Project HOPE creating a false sense of

hope: A case study in correctional popularity? Federal. Probation, 78,57–70.

Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2015). Importance of program integrity: Outcome evaluation of a gender

responsive, cognitive-behavioral program for female offenders. Criminology & Public Policy, 14,

301–328.

EPISCenter. (n.d.). Standardized program evaluation protocol. Retrieved from http://www.episcen

ter.psu.edu/juvenile/spep.

Finckenauer, J. 0. (1982). Scared Straight! and the panacea phenomenon. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Gendreau, P. (1996). The principles of effective intervention with o ffenders. In A. T. Harland (Ed.),

Choosing correctional options that work: Defining the demand and evaluating the supply (pp. 117–

130). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gendreau, P., & Andrews, D. (1989). Correctional Program Assessment Inventory (CPAI). Saint

John, Canada: University of New Brunswick Press.

Gendreau, P., & Andrews, D. A. (2001). Correctional Program Assessment Inventory – 2000 (CPAI-

2000). Saint John, Canada: University of New Brunswick Press.

Gendreau, P., Cullen, F. T., & Bonta, J. (1994). Intensive rehabilitation supervision: The next

generation in community corrections? Federal Probation, 58,72–78.

Holsinger, A. M. (1999). Opening the ‘black box’: Assessing the relationship between program

integrity and recidivism (unpublished doctoral dissertation), The University of Cincinnati,

Cincinnati.

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. (2005). The positive effects of cognitive–behavioral programs

for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of

Experimental Criminology, 1, 451–476.

16

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

Latessa, E. J. (2004). The challenge of change: Correctional programs and evidence-based practices.

Criminology and Public Policy, 3, 547–560.

Latessa, E., Brusman-Lovins, L., & Smith, P. (2010). Follow-up evaluation of Ohio’s community based

correctional facility and halfway house programs—Outcome study. Cincinnati, OH: University of

Cincinnati, Cincinnati School of Criminal Justice. Retrieved from https://www.uc.edu/content/

dam/uc/ccjr/docs/reports/project_reports/2010%20HWH%20Executive%20Summary.pdf.

Latessa, E. J., Cullen, F. T., & Gendreau, P. (2002). Beyond correctional quackery-Professionalism

and the possibility of effective treatment. Federal Probation, 66,43–49.

Latessa, E. J., & Holsinger, A. (1998). The importance of evaluating correctional programs:

Assessing outcome and quality. Corrections Management Quarterly, 2,22–29.

Latessa, E. J., Holsinger, A. M., Jones, D., Fulton, B., Johnson, S., & Kadleck, C. (1999). Evaluation of

the Ohio Department of Youth Services community correctional facilities. Unpublished report.

School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Latessa, E. J., Jones, D., Fulton, B., Stichman, A., & Moon, M. M. (1999). An evaluation of selected

juvenile justice programs in Ohio using the Correctional Program Assessment Inventory.

Unpublished report. School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Latessa, E. J., & Lovins, B. (2010). The role of offender risk assessment: A policy maker guide.

Victims and Offenders, 5, 203–219.

Latessa, E. J., Lugo, M. A., Pompoco, A., Sullivan, C. & Wooldredge, J. (2015). Evaluation of Ohio’s

prison programs. Unpublished report. School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati,

Cincinnati, Ohio.

Latessa, E. J., & Reitler, A. K. (2015). What works in reducing recidivism and how does it relate to

drug courts? Ohio Northern University Law Review, 41, 757–789.

Lattimore, P. K., Dawes, D., Tueller, S., MacKenzie, D. L., Zajac, G., & Arsenault, E. (2016).

Outcome findings from the HOPE Demonstration Field Experiment: Is swift, certain, and fair

an effective supervision strategy? Criminology and Public Policy, 15, 1103–1141.

Lipsey, M. W. (1989, November). The efficacy of intervention for juvenile delinquency: Results from 400

studies. Paper presented at the 41

st

Annual Meeting o f the American Society of Criminology, Reno, NV.

Lipsey, M. W. (2009). The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile

offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims and Offenders, 4, 124–147.

Lipsey, M. W., & Cullen, F. T. (2007). The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of

systematic reviews. Annual. Review of Law and Social. Science, 3, 297–320.

Lipsey, M. W., Landenberger, N. A., & Wilson, S. J. (2007). Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs

for criminal offenders. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6,1–30.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1993). The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral

treatment: confirmation from meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 48, 1181–1209.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1998). Effective intervention for serious juvenile offenders: A

synthesis of research. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders:

Risk factors and successful interventions (pp. 313–345). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lovins, B., Lowenkamp, C. T., & Latessa, E. J. (2009). Applying the risk principle to sex offenders:

Can treatment make some sex offenders worse? The Prison Journal, 89, 344–357.

Lowenkamp, C. T. (2004). Correctional program integrity and treatment effectiveness: A multi-site,

program-level analysis (unpublished doctoral dissertation), The University of Cincinnati,

Cincinnati.

Lowenkamp, C. T., & Latessa, E. J. (2002). Evaluation of Ohio’s community based correctional

facilities and halfway house programs: Final report. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati,

Center for Criminal Justice Research, Division of Criminal Justice.

Lowenkamp, C. T., & Latessa, E. J. (2005a). Evaluation of Ohio’s CCA funded programs.

Unpublished report, University of Cincinnati, Division of Criminal Justice, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Lowenkamp, C. T., & Latessa, E. J. (2005b). Evaluation of Ohio’s RECLAIM funded programs,

community corrections facilities, and DYS facilities. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati,

Center for Criminal Justice Research, Division of Criminal Justice.

Lo

wenkamp, C., Latessa, E., & Holsinger, A. (2006). The risk principle in action: What we have learned

from 13,676 offenders and 97 correctional programs. Crime and Delinquency, 52,1–17.

17

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

CORRECTIONS: POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

Lowenkamp, C. T., Makarios, M. D., Latessa, E. J., Lemke, R., & Smith, P. (2010). Community

corrections facilities for juvenile offenders in Ohio: An examination of treatment integrity and

recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 695–708.

MacKenzie, D. L. (2006). What works in corrections: Reducing the criminal activities of offenders and

delinquents. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

MacKenzie, D. L., Wilson, D. B., & Kider, S. B. (2001). Effects of correctional boot camps on

offending. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 578, 126–143.

Makarios, M., Lovins, L., Latessa, E., & Smith, P. (2016). Staff quality and treatment effectiveness:

An examination of the relationship between staff factors and the effectiveness of correctional

programs. Justice Quarterly, 33, 348–367.

Martinson, R. (1974). What works? Questions and answers about prison reform. The Public Interest, 35,

22–54.

Matthews, B., Hubbard, D. J., & Latessa, E. J. (2001). Making the next step: Using evaluability

assessment to improve correctional programming. The Prison Journal, 81, 454–472.

Mears, D. P., Cochran, J. C., Greenman, S. J., Bhati, A. S., & Greenwald, M. A. (2011). Evidence on

the effectiveness of juvenile court sanctions. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39, 509–520.

National Institute of Corrections. (n.d.). The principles of effective intervention. Retrieved from

http://nicic.gov/theprinciplesofeffectiveinterventions.

Nesovic, A. (2003). Psychometric evaluation of the Correctional Program Assessment Inventory

(CPAI. (unpublished doctoral dissertation), Carleton University, Ottawa, ON.

O’Connor, T., Sawyer, B., & Duncan, J. (2008). A country-wide approach to increasing programme

effectiveness is possible: Oregon’s experience with the Correctional Program Checklist. Irish

Probation Journal, 5,36–48.

Ostermann, M., & Hyatt, J. M. (2017). When frontloading back

fires:

Exploring the impact of

outsourcing correctional interventions on mechanisms of social control. Law and Social

Inquiry,1–32.

Petersilia, J. (2004). What works in prisoner reentry? Reviewing and questioning the evidence.

Federal Probation, 68,4–8.

Petrosino, A., Turpin-Petrosino, C., & Buehler, J. (2003). Scared Straight and other juvenile awareness

programs for preventing juvenile delinquency: A systematic review of the randomized experimental

evidence. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 589,41–62.

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2014). State prison health care spending: An examination. Washington, DC:

Author.

Phelps, M. (2011). Rehabilitation in the punitive era: The gap between rhetoric and reality in U.S.

prison programs. Law and Society Review, 45,33–68.

Polaschek, D. L. (2012). An appraisal of the risk–need–responsivity (RNR) model of offender

rehabilitation and its application in correctional treatment. Legal and Criminological

Psychology, 17,1–17.

Quay, H. C. (1977). The three faces of evaluation: What can be expected to work? Criminal Justice

and Behavior, 4, 341–354.

Smith, P., Gendreau, P., & Swartz, K. (2009). Validating the principles of effective intervention: A

systematic review of the contributions of meta-analysis in the field of corrections. Victims and

Offenders, 4, 148–169.

Sperber, K. G., Latessa, E. J., & Makarios, M. D. (2013a). Establishing a risk-dosage research agenda:

Implications for policy and practice. Justice Research and Policy, 15, 123–141.

Sperber, K. G., Latessa, E. J., & Makarios, M. D. (2013b). Examining the interaction between level of

risk and dosage of treatment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40, 338–348.

Sullivan, C. J., Blair, L., Latessa, E., & Sullivan, C. C. (2014). Juvenile drug courts and recidivism:

Results from a multisite outcome study. Justice Quarterly, 33, 291–318.

Taxman, F. S. (2012). Probation, intermediate sanctions, and community-based corrections. In

Petersilia, J. & Reitz, K. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of sentencing and corrections, (pp. 363

–385).

New

York: Oxford University Press.

18

Downloaded by [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Carrie Sullivan] at 05:44 12 October 2017

S. A. DURIEZ ET AL.

Welsh, B. C., Rocque, M., & Greenwood, P. W. (2014). Translating research into evidence-based

practice in juvenile justice: Brand-name programs, meta-analysis, and key issues. Journal of

Experimental Criminology, 10, 207–225.

Yeaton, W. H., & Sechrest, L. (1981). Critical dimensions in the choice and maintenance of

successful treatments: strength, integrity, and e ffectiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 49(2), 156–167.