Information Note

Malaria

Allocation Period 2023-2025

Date published: 29 July 2022

Date updated: 2 December 2022

Page 1 of 34

Table of Contents

Introduction 2

Investment Approach 3

Prioritized Interventions to be Funded by the Global Fund 6

1. Evidence-based decision making 6

1.1. Sub-national Tailoring (SNT) of the malaria response 6

1.2. Malaria surveillance 7

2. Prevention 9

2.1. Vector control 9

2.2. Preventive therapies 15

3. Case management 18

3.1. Diagnosis 18

3.2. Treatment 19

3.3. Tailored service delivery across all sectors 21

4. Elimination 23

5. Cross-cutting Areas 24

5.1 Equity, human rights, and gender equality 24

5.2 Community leadership and engagement 25

5.3 Social and Behaviour Change (SBC) 26

5.4 Pandemic Preparedness and Response (PPR) 27

5.5 Environment and climate change 27

5.6. Urban malaria 28

5.7. Challenging Operating Environments (COE) 28

5.8 Malaria emergencies 29

5.9 Program management 29

5.10. Sustainability of malaria response 29

List of Abbreviations 31

Annex 1: Key Data 34

Page 2 of 34

Introduction

The Global Fund has developed a new Strategy for the period 2023-2028. The malaria

component of the Strategy aims to end the disease by funding the development,

implementation, and monitoring of national malaria programs that are tailored to local

contexts. It intends to ensure optimal and effective vector control coverage; make best use

of chemoprevention; expand equitable access to quality early diagnosis and treatment of

malaria; and drive towards malaria elimination and prevent the re-establishment of malaria.

This Information Note supplements the applicant guidance , provides information to prepare

a malaria funding request, makes recommendations on priority interventions and

encourages strategic investments to achieve impact. The document also adheres with and

complements normative technical guidance

1

from the World Health Organization (WHO) and

other partners.

To enable the Technical Review Panel (TRP) evaluation of the funding request within the

country-specific context, this note provides an outline of both the process and information

that are expected from applicants. Applicants are required to:

1. Hold a robust and inclusive country dialogue involving all relevant partners

engaged in the national malaria response and health system strengthening,

including communities, civil society, community-based organizations, and private

sector.

2. Ensure the program split and prioritization decisions are informed by a

comprehensive gap analysis to achieve value for money. Applicants may use the

RBM Country Regional Support Partnership Committee (CRSPC) gap analysis tool

2

to inform the Global Fund gap analysis.

3. Use WHO’s guidance on sub-national tailoring of malaria to inform the decisions

on intervention mixes and delivery strategies.

4. Include a brief overview of the national malaria response and the program

performance at national and sub-national level in the funding request. This includes

the epidemiology of malaria, relevant contextual factors, health system components,

health financing data and progress and challenges towards achievement of strategic

plan goals. Key data points should be included in the funding request (either in the

Essential Data Table or in the narrative) - for details, please see Annex 1.

1

World Health Organization Guidelines for malaria https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria

2

The RBM partnership CRSPC guidance note on malaria gap analysis tools

Page 3 of 34

Investment Approach

The Global Fund incorporates Program Essentials within all aspects of its investment. They

are derived from normative and technical guidance and are considered critical to meet the

Global Fund’s malaria strategy and the Global Technical Strategy (GTS) targets. Program

Essentials, which include criteria for services (Table-1) and a framework of processes,

standards and requirements that apply to pharmaceuticals and diagnostic products, should

be applied consistently for all interventions funded by the Global Fund.

Applicants are expected to consider the Program Essentials during the country dialogue,

funding request development, grant making, implementation and performance monitoring.

While not all national programs will be able to achieve every Program Essential, the funding

request should clearly demonstrate the program’s plans to achieve these standards,

progress, and challenges and how their achievement is prioritized with the available

resources. As for malaria, the Program Essentials are well aligned with the evolution of

malaria programs and may already be within the National Strategic Plans (NSPs) or other

standard documents which should be annexed as relevant.

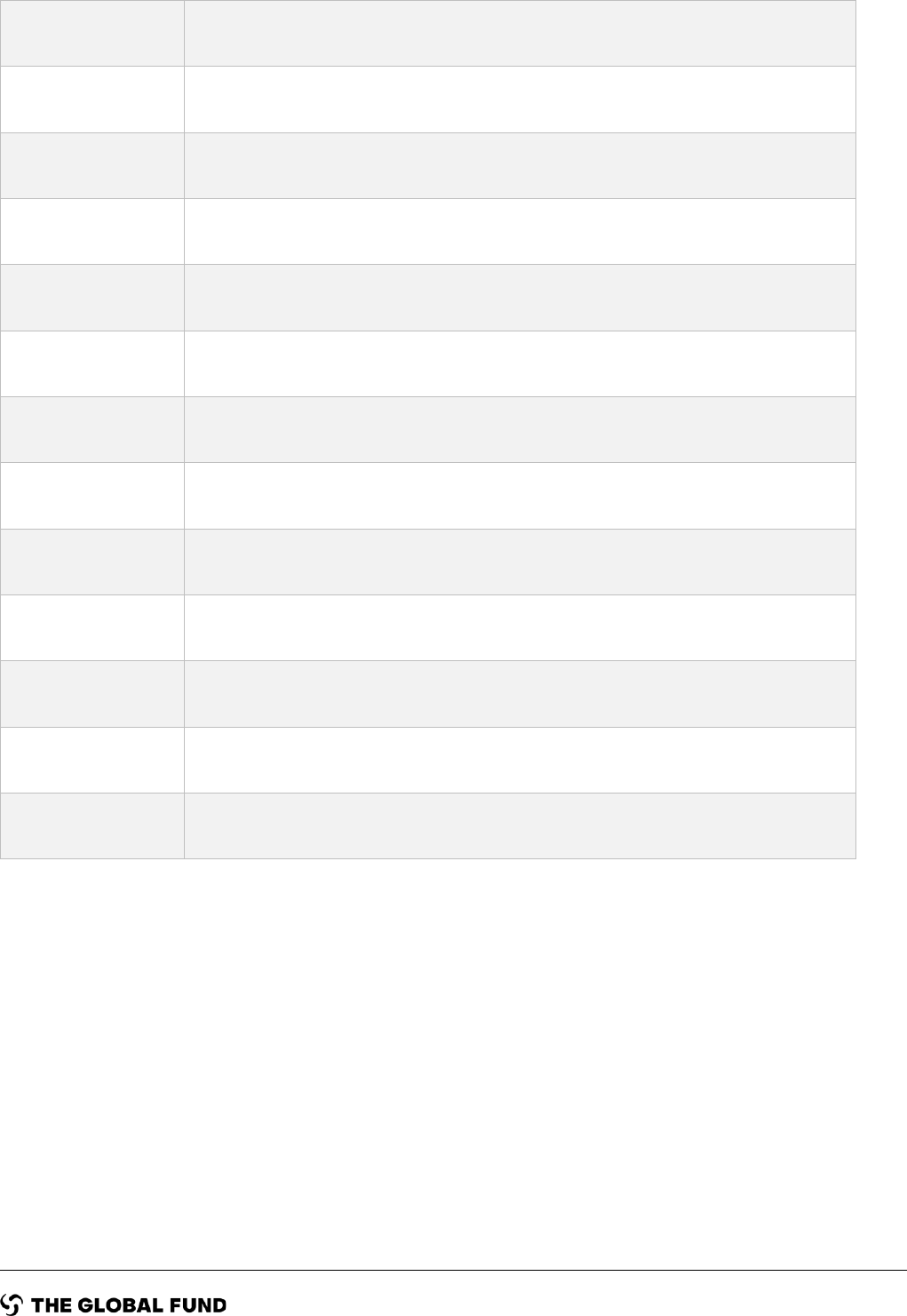

Table 1. Malaria program essentials

Objective

Program Essentials

(a) Implement malaria interventions,

tailored to sub-national level using granular

data and capacitating decision-making and

action.

• Build in-country capacity for sub-national

tailoring and evidence-based prioritization of

tailored malaria interventions.

• Build capacity for quality data generation,

analysis & use at national and sub-national

levels.

• Ensure sub-nationally tailored planning

considers factors beyond malaria epidemiology

such as health systems, access to services,

equity, human rights, gender equality (EHRGE),

cultural, geographic, climatic, etc.

• Ensure quality of all commodities and monitor

effectiveness.

• Deliver all interventions in a timely, people-

centered manner

3

.

(b) Ensure optimal vector control coverage.

• Evidence-based prioritization for product

selection, implementation modality and timing,

and frequency of delivery with a focus on

ensuring sustained high coverage among the

highest risk populations.

• Expand entomological surveillance.

• Address barriers hampering the rapid scale-up

of new products.

• Evolve indicators to improve the tracking of

effective vector control coverage.

3

For example, in a migrant community, a community health worker from the migrant population targeted may be more appropriate;

adjusting service hours to address population/patient availability (SMC or ITN delivery early morning or in the evenings), etc.

Page 4 of 34

(c) Expand equitable access to quality,

early diagnosis, and treatment of malaria

through health facilities, at the public

sector and community level, and in the

private sector.

• Understand and address key barriers to access.

• Engage private sector providers to drive

parasitological testing before treatment.

• Expand community platforms where access is

low.

• Improve and evolve surveillance and data

collection tools and processes to enable

continuous quality improvement (CQI) and

accurate surveillance.

• Use of quality of care (QoC) stratification to

tailor support to case management across

sectors.

• Strengthening coordination and linkages

between public, private and community systems

for service provision.

(d) Optimize chemoprevention.

• Support data driven intervention selection and

implementation modality.

• Support flexibility on implementation strategies

including integration within primary healthcare

(PHC) as relevant.

(e) Drive toward elimination and facilitate

prevention of re-establishment.

• Enhance and optimize vector control and case

management.

• Increase the sensitivity and specificity of

surveillance.

• Accelerate transmission reduction.

One of the key program essentials is Sub-national Tailoring (SNT) of malaria

interventions, which is defined as the use of local data and contextual information

4

to

determine the appropriate intervention mixes, and in some cases deliver strategies for

optimum impact on transmission and burden of disease for a given area, such as a district,

health facility catchment or village. Funding requests are expected to demonstrate the use

of SNT strategies and plans where they have been conducted and/or future planning for

such efforts,

5

but also to be aligned with national priorities and normative guidance.

Applicants are strongly encouraged to prioritize interventions based on sub-national data to

the extent possible. Malaria funding requests should be strategically focused on delivering

optimal intervention mixes that are cost-effective and affordable in the context of a country's

own epidemiological, programmatic, financial, and health system contexts.

Value for money (VfM) aims to guide applicants to make sure investments maximize and

sustain equitable and quality health outputs, outcomes and impact for a given level of

resources. VfM is defined through five dimensions: economy, efficiency, effectiveness,

equity, and sustainability. For more information, please refer to the Value for Money

Technical Brief.

Grant implementation arrangements shall be bespoken on the needed capacities to

implement and coordinate the malaria interventions at sub-national level. Integrated risk

management is essential to achieve impact.

4

Contextual information includes health systems, access to service, EHRGE and climatic information,

5

At time of publication, the WHO manual on sub-national tailoring of interventions was not yet published. Please check the WHO

website for update. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme

Page 5 of 34

Applicants are also recommended to consider the Protection from Sexual Exploitation,

Abuse and Harassment (PSEAH), as well as child protection in the planning and design of

program interventions. Program related risks of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment

to beneficiaries, community workers and others (as relevant) need to be identified in the

proposed interventions, which should also include the necessary mitigation measures to

ensure that services are provided to, and accessed by, beneficiaries in a safe way. It is also

recommended to include PSEAH in community awareness activities like outreach

strategies, communication campaigns, trainings or other activities which target grant

beneficiaries.

Effective, integrated, quality, people-centered malaria services are dependent on functional

health system and primary health care (PHC). The required Resilient and Sustainable

Systems for Health (RSSH) interventions, including community systems strengthening,

designed to ensure achievement of malaria outcomes should be discussed during country

dialogue, and the identified priorities should be included for funding. It is critical that malaria

program managers participate in the country dialogue on RSSH investments and vice versa

to prioritize the key RSSH functions required for malaria service delivery. Key considerations

for investments in RSSH for national malaria control programs include:

1. Investments to identify and address quality gaps in key services at primary health

care level, such as quality improvement for acute febrile illness, community health

packages and antenatal care (ANC). Opportunities to integrate activities such as training,

referral networks and support supervision can be considered to improve quality and

efficiency of PHC, of which malaria is a part.

2. Investments to strengthen the health workforce, including both facility-based health

workers (public and private) and community health workers (CHWs). Applicants are

encouraged to prioritize support to workforce planning and optimize available skills mix

through improved deployment of the available personnel. This may include support to

analyses related to human resources for health (HRH), such as workload analyses;

governance and planning, such as data systems and strategic planning; and capacity for

HRH planning and management at national and/or sub-national level.

Applicants are also encouraged to develop context-specific interventions to improve

health worker performance. CHWs are an essential part of HRH and broader community

systems strengthening (CSS) and recruitment, training, supervision, and reimbursement

of CHWs could be included in any analyses, strategy, planning and performance

improvement efforts. Integrated supportive supervision or quality improvement activities

are evidence-based interventions that can be scaled up through RSSH investments

including CSS.

3. Investments to strengthen generation and use of data, strengthen national supply

chain management and improve routine primary care services.

4. Adaptations to foster people- and population-centered service delivery, including

equity, cultural and gender-relevant issues to improve access and uptake of services;

community-based service delivery; community-led monitoring; CHWs for service in

migrant/refugee/indigenous populations, where such populations are at risk of malaria.

Page 6 of 34

Prioritized Interventions to be Funded by the Global

Fund

1. Evidence-based decision making

1.1. Sub-national Tailoring (SNT) of the malaria response

A sub-national tailored response is based on the use of malaria-specific, health system,

geographic, equity, human rights, gender equality (EHRGE), climatic, political, and other

relevant data as well as intervention quality and performance data at the lowest level

possible. The aim is to provide quality, people-centered care that maximizes resources and

impact. An SNT response requires the gathering, storing and analysis of sub-national data,

the use of this data for decisions on mixes and delivery of interventions, as well as the

continual use of this information for sub-national planning. The Program Essentials outlined

in Table 1 are built around this framework: therefore, funding requests should be based on

an SNT analysis and plan and, when feasible, funding should be included to strengthen data

generation, quality, and use.

The Global Fund can support the different components needed to facilitate a sub nationally

tailored malaria response, which include:

1. Creation, maintenance, and use of malaria data repositories (MDRs) and required

staffing and equipment, in alignment with WHO guidance.

6

MDRs should draw from

routine surveillance (health management information system, surveys, etc.),

retrospective data on the malaria burden and response, as well as human resource

information, health workforce accounts, climate, commodities, etc. They should be

interoperable with existing information systems (laboratory and logistics management

information systems).

2. Introduction of additional relevant data sets into MDRs – such as geospatial mapping,

meteorologic data sets, EHRGE analyses, etc. This includes facilitation for the

required adaptations of data to align with the operational framework of a malaria

program’s MDR.

3. Mapping of sub-national Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) activities and results

to address quality issues in a targeted and timely manner.

4. Addressing data gaps such as understanding barriers to access, in order to adapt

intervention choice and implementation methodology.

5. Short- and long-term capacity building of national and district malaria programs to

use available data to develop (and update) sub- nationally tailored strategies and

plans (including the associated modelling) with the vision of programs being able to

conduct these exercises independently.

6

WHO guidance for evidence-informed decision-making

Page 7 of 34

1.2. Malaria surveillance

Malaria surveillance is a key intervention in all malaria-endemic countries. It is especially

important in areas approaching elimination or those which have eliminated malaria. A

malaria surveillance system comprises the people, procedures, tools, structures, and

processes necessary to gather and interpret information on when, where and at what level

malaria cases are occurring. An effective national surveillance system allows programs to

monitor and evaluate interventions and to make sub-national tailored, prioritized decisions

on investments.

Malaria programs need to work towards robust surveillance systems and build monitoring

and evaluation (M&E) staff capabilities to: (a) Identify sub-national areas and population

groups most affected by malaria; (b) Assess quality and effectiveness of necessary

interventions through a holistic review of surveillance information with sufficient granularity

to guide the response; (c) Review progress and decide whether adjustments to interventions

or combinations of interventions are required; (d) Detect and respond to epidemics in a

timely way; and (e) Perform case-based surveillance, provide relevant information for

certification and monitor whether the re-establishment of transmission has occurred in

elimination settings.

1.2.1. Health Management Information System (HMIS)

One important aspect of a malaria surveillance system is a strong routine Health

Management Information System (HMIS). Investment in HMIS will also contribute to building

the national SNT capacities. Applicants are strongly encouraged to consider interventions

that better link HMIS to broader national efforts (e.g., District Health Information Software-

2, (DHIS2) roll out) and surveillance, monitoring and evaluation plans. Applicants should

also consider interventions that support the digitization of HMIS and data collection and the

integration with National MIS (e.g., DHIS2) as they contribute to broader national plans and

systems. In countries nearing, elimination surveillance systems should support active case

detection and notification.

The Global Fund supports the people, procedures, tools, training and supervision for routine

data collection and analysis (HMIS). This includes the various components of the routine

data system (public, private, community) and different administrative levels. Robust, quality

assured HMIS data are critical to a sub-national tailored malaria response and should be

supported with quality assurance activities. Actions and decisions based on this data can

only be as strong as the data itself.

Register revisions need to be considered to align with disease categorization across the

case management cascade (for details, see WHO Surveillance Manual

7

), including reasons

for care seeking, test performed, test result, diagnosis and treatment. Activities to support

quality registration of cases can include training and supervision on recording, compilation

7

Malaria surveillance, monitoring & evaluation: a reference manual

Page 8 of 34

and record submission as well as data entry, quality assurance reviews and follow up.

Applicants are strongly encouraged to detail how interventions that support health

information systems will use/analyze data and assess/improve data quality.

The WHO malaria surveillance assessment toolkit

8

can be used to support countries in the

assessment of surveillance systems and data quality. Technical assistance needs in

strengthening the HMIS system and in using the surveillance assessment toolkit can be

budgeted in the funding request.

1.2.2. Other surveillance data collection

The Global Fund also supports the collection and analysis of data through household and

health facility surveys. Such surveys can provide robust estimates of intervention coverage

and access to services at the population level. These results are critical to ensure that

interventions are reaching the intended target population at desired levels. National

household surveys can be supported with appropriate justification of the timing and utility of

the modules. Other survey methodology, potentially useful for program management

evaluation such as lot quality assurance sampling (LQAS) and ANC surveillance, can be

considered when appropriate justification and methodology are presented.

Entomological surveillance, ITN durability studies (see Vector Control section below) and

therapeutic efficacy studies (see Case Management section on page 21) should be included

in the budget. In addition, targeted behavioural surveys, and specific, targeted operations

research to inform access and delivery bottlenecks can be considered. Please see the

respective sections of this Information Note for more information on funding for these data

collection activities.

Malaria programs should also strengthen financial data intelligence and management

system. Possible activities to be funded included to: (1) Assess the funding landscape

including program expenditure by key program areas and source; (2) Understand the unit

costs of key interventions, main cost drivers and variation across regions and delivery

platforms; (3) Compare what types of intervention may be more cost-effective for a given

area, taking into account service accessibility and program feasibility; and (4) Delineate

potential resource needs to implement sub-nationally tailored response or intervention

mixes given the disease burden and program reality.

8

Malaria Surveillance Assessment Toolkit

Page 9 of 34

2. Prevention

2.1. Vector control

All requests for vector control need to be grounded in a national vector control strategy

based on up-to-date entomologic and epidemiologic data and follow the WHO Guidelines

for Malaria

9

. Insecticide resistance management principles, as outlined in the WHO Global

Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management

10

, are expected to be followed. Intervention

choices should be guided by the manual

11

for monitoring insecticide resistance in mosquito

vectors and selecting appropriate interventions.

Applicants should describe:

1. Their target populations for vector control and planned Intervention mixes, as

appropriate; and

2. The rationale for the choice of vector control tools, such as Insecticide Treated

Nets (ITN) or Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS), epidemiological, entomological and

user behaviour context, alongside any other criteria considered relevant by the

program.

Please refer to the relevant Program Essentials in Table 1 to ensure the funding request

includes the relevant information on progress, challenges and plans to address any gaps

and to achieve optimal vector control coverage.

It is assumed populations at risk of malaria will be targeted with at least either ITNs or IRS

(where the main vectors and context make these tools appropriate). If scale back of vector

control is proposed, the chosen approach should be robustly justified: it should demonstrate

how it is part of a sub-nationally tailored malaria control plan that responds to the

epidemiological, entomological and user context, and include a detailed examination of the

potential for resurgence given malaria burden prior to any recent vector control. Any such

scale back should also be accompanied by sufficient surveillance and response capacity in

order to detect and respond to any potential resurgence and be initially moderate in scale

with a plan to assess impact.

2.1.1. Insecticide Treated Nets (ITN)

Expression of full need and rationale for request:

As with all interventions, it is important for the Global Fund and partners to understand the

full need for a country program. While the NSP and tools such as the RBM CRSPC gap

analysis tool

12

cover all interventions, the Global Fund is specifically asking for the full

9

WHO Guidelines on Vector Control

10

Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors

11

Manual for monitoring insecticide resistance

12

RBM Country/Regional Support Partner Committee (CRSPC) Gap Analysis

Page 10 of 34

expression of need for ITNs to ensure a clear understanding of a national program’s plans

based on the recent introduction of new ITN products, global reviews on attrition/durability

and widespread piloting of new distribution strategies.

It is expected that the ITNs program will be sub-nationally tailored, as appropriate to

variations in epidemiology, vector profile (including insecticide resistance), historical ITN

durability and/or attrition, population behaviors etc. Sub-national variations may include type

of ITN, ITN distribution approach, frequency of ITN distribution, social and behavior change

activities (SBC), or other relevant program areas.

Applicants should therefore:

1. Describe the ITN strategy (including ITN types, volumes, delivery approaches) as

an expression of the full need to maintain optimal effective ITN coverage of the target

populations. The full volume need should be based on local data on durability,

attrition, and coverage at different post-distribution time points; the rational for the

ITN strategy and the data sources should be described.

2. After accounting for all partner contributions, if the funding request does not cover

the full need, applicants should explain the prioritization process that was followed to

balance the need across the three-years grant, cost, effectiveness, coverage, and

potential for impact.

ITN types: Applicants are required to align selection of ITN types with WHO

recommendations. ITN types effective against the local vector population are expected to

be proposed and sub-nationally varied as appropriate. Note that WHO has an updated

conditional recommendation for deployment of pyrethroid-PBO ITNs

13

advising:

• Deployment in areas of pyrethroid resistance should be based on a resource

prioritization exercise due to their higher cost; and

• Prioritization of areas for deployment could be based on data demonstrating

metabolically based resistance.

If additional ITN types are recommended by WHO for use in areas of pyrethroid resistance

by the time of the funding request submission, these will also be considered within a

resource prioritization exercise. Countries who have previously deployed non-pyrethroid-

only ITNs (i.e., pyrethroid-PBO ITNs or dual active ingredient ITNs under the Strategic

Initiative projects) should not revert to pyrethroid-only ITNs for these geographic areas in

their future funding requests.

13

WHO Guidelines for malaria Pyrethroid-PBO nets .

Page 11 of 34

Operational considerations. Distribution may be through:

1. Intermittent campaigns, which need to be accompanied (including during campaign

years) by continuous distribution through proven channels such as ANC, EPI, and/or

school- or community-based distribution; or

2. Higher through-put continuous distribution channels instead of campaigns (e.g.,

annual school distribution).

Sub-national variation in distribution approaches may be appropriate to target the specific

needs and vulnerabilities of the (sub)populations most affected. Applicants are encouraged

to demonstrate how the proposed distribution approaches are based on considerations of

cost per net delivered/used, equity of access, ability to maintain coverage or other

considerations. Using NetCalc can help with the assessment of different options

14

.

Evaluation plans will include assessment of these criteria to inform future planning.

The Alliance for Malaria Prevention (AMP) guidelines

15

for campaign planning should be

followed. It is essential that quantification for campaigns: (1) Assume no capping of ITNs by

household size; (2) Consider whether any quantification factors would be appropriately

tailored sub-nationally; and (3) Include a 10% contingency stock if the population data are

older than five years. A plan for sound waste management should be included in the funding

request, including efforts to limit waste. While retrieval of old nets from households is not

recommended (nor historically funded by the Global Fund), there are recycling pilots

underway for old ITNs. If successful, these could be considered for future fundings.

If a program requires technical assistance for ITN distribution planning, the Global Fund

strongly encourages prioritization of this assistance within the funding request (e.g., AMP

TA). Support for digitization of campaigns can also be included; the Global Fund encourages

an integrated, multi-purpose digital platform that can be used for malaria campaigns as well

as other campaigns and activities (e.g., vaccination campaigns).

ITN use and care: Applicants are required to include data on ITN use where there is access

(at national and sub-national level, if available) and describe how a high use given access

will be achieved/maintained. The scope and scale of social and behaviour change (SBC)

activities should be appropriate to the local profile of use given access (i.e., if a population

has high use given access, funding will focus on access rather than on additional SBC

activities around hang up and use). SBC activities to promote proper net care may be

warranted.

Exclusions: The Global Fund does not invest in ITN container storage, mop-up or hang-up

campaigns, or non-essential data collection required by other partners.

14

Choosing a continuous distribution channel

15

Alliance for Malaria Prevention resources

Page 12 of 34

ITN procurement: The Global Fund guidance on ITN specifications is available here. Only

WHO prequalified and recommended products can be procured. ITNs need to be

rectangular and one of the standard sizes listed here. Color (white, green, or blue) can be

specified as part of the product specifications. Material preference can be indicated, but

applicants cannot restrict their specifications to one single material.

If applicants request procurement of ITNs outside of the standard sizes, shapes or fabrics,

these requests need to be supported by local evidence of significant impact on differential

ITN use and/or durability. If necessary, funding for this evidence generation can be

supported. ITNs can be procured with or without hooks and strings, considering local

understanding of their importance, or otherwise, to encouraging hang-up. Applicants can

consider the unit cost savings on the size of ITN or included accessories (i.e., hooks and

strings) to support the procurement of more ITNs or more expensive, but more effective,

ITNs. When budgeting, applicants are required to use the appropriate Global Fund Standard

Reference Price. In line with WHO recommendations, the Global Fund does not allow

applicants to specify the type of pyrethroid on an ITN.

All products will undergo pre-shipment testing in accordance with Global Fund’s policy on

sourcing and procurement of health products. ITN durability monitoring, using standard

protocols, should be planned for, and are strongly encouraged to be included in the funding

request. Applicants are expected to explain how this data will be used to increase program

efficiency.

2.1.2. Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS)

Given its high cost, IRS in malaria endemic areas shall only be initiated if sustainable

financing is assured. If IRS is requested within the funding request for the 2023-2025

allocation period, applicants are strongly encouraged to include a description of long-term

IRS financing.

When a country maintains an existing IRS program, a sound insecticide-resistance

management strategy must be in place, in line with the Global Plan for Insecticide

Resistance Management

16

, and with the operational guidance in the IRS Operational

Manual

17

, as well as routine monitoring of the quality and coverage of IRS.

Comprehensive health and environmental compliance safeguards need to be implemented

for all IRS programs supported by the Global Fund. Applicants are strongly encouraged to

include and budget the following items/activities for every IRS program: appropriate

environmental contamination containment measures, waste management and disposal, and

personal protective equipment (PPE). A description of how these safety aspects will be

maintained must be included in the funding request if Global Fund resources are used to

support IRS.

16

Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors

17

Operational manual for IRS for malaria transmission, control and elimination

Page 13 of 34

2.1.3. Combining ITNs and IRS

The Global Fund supports deployment of ITNs and IRS in the same geographic area if all

the following points are true, which should be made explicit in the funding request:

1. The first method of vector control is funded at optimal coverage and delivered to a

high standard in the area of proposed co-deployment.

2. The combination is proposed for the management of insecticide resistance and as

part of a national insecticide resistance monitoring and management plan.

3. The proposal is part of a comprehensive malaria control plan which:

a. Is adapted at sub-national level.

b. Is supported by a prioritization process that includes cost-effectiveness

considerations, and

c. Leaves no gaps in other high or moderate burden areas.

2.1.4. Supplementary interventions

Larval source management

Larviciding can be supported as a supplementary intervention if applicants include the

following information in their funding request for the 2023-2025 allocation period:

i. Justification by the vector profile based on robust entomological data.

ii. Mapping of areas where optimal coverage with ITNs or IRS either has been achieved

or is inappropriate due to context such as vector or community behavior (justification

must be included); and

iii. Evidence that aquatic habitats are few, fixed and findable, and where its application

is both feasible and cost-effective

18

.

Habitat modification or manipulation is not recommended by WHO unless An. stephensi has

been detected and if this intervention is considered feasible as part of an appropriate,

multisectoral, An. stephensi response.

Larvivorous fish are not recommended by WHO and will not be funded.

House screening

House screening is conditionally recommended by WHO. Applicants proposing to include

this intervention should assess the feasibility, acceptability, impact on equity and resources

needed for screening houses within each context in order to determine whether such an

intervention would be appropriate for their setting. They are strongly advised to review the

18

WHO guidance on Larval source management

Page 14 of 34

detailed recommendation including rationale and practical guidance to determine if a strong

justification for inclusion can be provided. If prioritizing Global Fund resources for house

screening, applicants should detail how this intervention meets the following criteria:

1. Is part of an integrated vector management (IVM) approach.

2. Is proposed as a component of a wider strategy and follows the deployment of

interventions recommended for large-scale deployment (ITN or IRS); and

3. Is accompanied by an evaluation plan.

The proposed deployment approach should be well described and consider the practical

guidance included in the relevant section of the WHO Guidelines for Malaria

19

.

Interventions currently not eligible for funding

Other interventions recently assessed by WHO, and not recommended due to limited

evidence for additional public health impact at the time of writing of this note, include topical

repellents, space spraying, insecticide treated clothing and plastic sheeting, and spatial

repellents. These will not be considered for funding unless a WHO recommendation is made

in the future.

2.1.5 Anopheles Stephensi

An. stephensi is an emerging threat to the control of malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Applicants are strongly encouraged to review the WHO GMP documents

20

advising on

surveillance and control approaches and include associated activities in their applications.

2.1.6. Entomologic surveillance

Applicants are strongly encouraged to put in place an insecticide resistance and

management plan, based on the WHO framework

21

and manual for monitoring insecticide

resistance

22

. Entomological surveillance should be prioritized in their funding request for the

2023-2025 allocation period if other sources of funding are not available. The surveillance

plan should cover data needs to inform planning and evaluation, including insecticide

susceptibility testing, at least annually. This data is important for supporting procurement

requests and shall therefore be prioritized.

2.1.7. Vector control capacity building

The Global Fund fully supports WHO’s recommendation in the Global Vector Control

Response that vector control needs assessments

23

be conducted via an inter-sectoral

process, to cover both vector control operational capacity and entomological surveillance

capacity. The funding request can include financial resources required to support the needs

assessment, as well as capacity building activities.

19

WHO guidelines for Supplementary interventions

20

WHO initiative to stop the spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa

21

Framework for a national plan for monitoring and management of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors

22

Manual for monitoring insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors and selecting appropriate interventions

23

Framework for a National Vector Control Needs Assessment

Page 15 of 34

2.2. Preventive therapies

2.2.1. Drug-based therapies

Decision-making on type of chemoprevention. With growing evidence on the impact of

different types of drug-based prevention tools, national programs can explore what needs

to be prioritized based on the local epidemiology, transmission intensity, seasonality, access

to services, and interaction of multiple chemoprevention strategies where applicable. Note

that people living with HIV and receiving Cotrimoxazole preventive treatment are not eligible

for malaria chemoprevention using Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP). In June 2022, WHO

updated a guidance on chemoprevention strategies

24

.

Refer to the relevant Program Essentials in Table 1 to ensure the funding request includes

the relevant information on progress, challenges and plans to address any gaps and meet

these standards.

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC)

25

WHO guidance has broadened the flexibility around targeting SMC to consider regions with

highly seasonal transmission outside of the Sahel region, different age groups, transmission

intensity and duration, and drug choice. Therefore, applicants should: (1) Provide the

relevant information and analysis on these factors when requesting resources for SMC (e.g.,

local age pattern of severe malaria admissions, duration of high transmission season, etc.);

(2) Provide an overview of the implementation plan containing a strong monitoring and

evaluation component that includes pharmacovigilance and drug resistance monitoring; (3)

Describe strategies to improve efficiency and quality of service delivery, including but not

limited to (nor required) digitalization and/or integration with other interventions (such as

malnutrition screening or Vitamin A supplementation); and (4) Consider the cost-

effectiveness of SMC i.e. accounting for the burden of disease in the targeted geographic

area as well as the age group(s).

Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy (IPTp)

26

Strategies to increase uptake of IPTp need to consider improving Antenatal Care (ANC)

attendance as well as improving quality of ANC, as low quality of service can affect

attendance. New methods of delivering IPTp such as community IPTp (cIPTp) require an

integrated systems approach in which the continuum of care for pregnant women is

reinforced. Intermittent screening and treatment of pregnant women is not supported by the

Global Fund as it has been found to be less effective than IPTp.

Integration of IPTp with other activities targeting pregnant women within reproductive,

maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCAH) services, sexual and

reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and activities such as HIV services for pregnant

24

WHO guidance on preventive chemotherapies

25

WHO guidance on SMC

26

WHO guidance on IPTp

Page 16 of 34

women will be encouraged as ANC is the usual entry point into the health care system for

women of reproductive age. Applicants are encouraged to think comprehensively about a

pregnant woman’s overall health and invest to strengthen antenatal and postnatal care

(ANC-PNC), including through training of CHWs who can deliver RMNCAH and malaria

interventions as part of a comprehensive package of care. Women, children and newborns

still have limited access to quality of care, and there are opportunities to invest in the health

system building blocks such as HRH, data systems, procurement and supply chain systems

and laboratory systems to strengthen IPTp as part of ANC-PNC. All Global Fund malaria

grants supporting Malaria in Pregnancy (MIP) services should include an indicator on IPTp3

and monitor ANC attendance.

Perennial Malaria Chemoprevention (PMC)

27

The Global Fund will continue to support Intermittent Preventive Treatment for infants (IPTi)

and its updated nomenclature with a broadened spectrum, PMC, to reach a larger number

of children with this preventive intervention. Countries introducing IPTi/PMC or modifying

the delivery mechanisms or target age groups need to closely monitor coverage and, where

possible, impact on malaria. PMC should be integrated with other strategies targeting the

same age group populations, such as EPI or deworming. Note that new evidence from the

several ongoing projects on IPTi will be generated in the coming years and may have

implications for the guidance. Where IPTi/PMC are implemented, monitoring of SP

resistance is advised.

Mass Drug Administration (MDA)

28

Mass drug administration (MDA) can be used with two different objectives: burden reduction

or transmission reduction. WHO recommends that MDA for burden reduction can be

considered in areas with moderate to high P. falciparum transmission for short-term burden

reduction (evidence of 1-3 months post-MDA). The Global Fund will support MDA for

emergency burden reduction (including malaria outbreaks and malaria control in emergency

settings, section 5.8) and will require strong justification given the short duration of the effect.

MDA for transmission reduction will continue to be supported by The Global Fund in the

context of intensified elimination efforts targeting all or specific vulnerable populations.

Plasmodium Vivax elimination is currently not included in the MDA elimination guidance.

Funding for MDA implementation needs to be balanced against funding for other

interventions with longer-term effects on malaria burden or transmission and on the overall

health system. Countries are expected to monitor susceptibility to the drug deployed, as well

as interaction with first line Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs).

27

WHO guidance on Perennial Malaria Chemoprevention

28

WHO MDA guidelines

Page 17 of 34

Other chemoprevention strategies

The funding request can include the two new chemoprevention strategies, Intermittent

Preventive Treatment for school children

29

(IPTsc) and Post Discharge Malaria

Chemoprevention

30

(PDMC). Introduction of IPTsc should not compromise

chemoprevention interventions for those carrying the highest burden of severe disease (e.g.,

children under 5 years old). PDMC provides a full therapeutic course of an antimalarial at

predetermined times following hospital discharge to reduce re-admission and death, and

targets children admitted with severe anaemia not due to blood loss following trauma,

surgery, malignancy, or a bleeding disorder. Applicants are requested to justify the selection

of the strategy at national or sub-national level and include methods to ensure equitable

access to preventive strategies.

2.2.2. Malaria vaccine

The Malaria Vaccine implementation program

31

will be funded until 2023 by the Global

Fund's Malaria Strategic Initiative, in collaboration with Gavi and Unitaid, in order to generate

more evidence on the vaccine's impact, safety, and feasibility.

The Global Fund will continue to support implementing countries' efforts to develop

evidence-based, costed national malaria plans and determine the best malaria intervention

mixes based on national context. Malaria vaccine RTS,S/AS01 (RTSS) introduction requires

a strong coordination between the national immunization program and the malaria control

program and has to consider several factors such as: levels of malaria transmission at sub-

national level, pattern of severe malaria, structure and function of the health system, use

and coverage of existing malaria control interventions, and the context where the vaccine

could best complement other tools as part of a package of interventions.

The WHO recommendation and position on the RTSS vaccine is now published in

an updated WHO position paper as well as in the WHO guidelines

32

for the prevention of P.

falciparum malaria for children living in regions with moderate to high transmission. Gavi has

approved an investment

33

to support the introduction, procurement and delivery of RTSS in

Gavi-eligible countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022-2025. To facilitate the distribution of

the limited supply, WHO has led the development of an “allocation framework”

34

that

provides guidance on the allocation of RTSS between countries, and priority criteria for

vaccination of certain countries’ areas until supply constraints are resolved.

A recent modelling analysis commissioned by the Global Fund in consultation with partners

showed that the optimal intervention mixes for a given country or subnational area is highly

dependent on its epidemiological and programmatic setting (e.g., parasite prevalence,

malaria seasonality, programmatic coverage achieved, cost of intervention including

29

WHO guidance IPTsc

30

WHO guidance PDMC

31

Malaria vaccine implementation program

32

WHO guidelines for the malaria vaccine

33

Gavi application window

34

Malaria Vaccine Allocation Framework

Page 18 of 34

products and service delivery, others). Countries are highly encouraged to carry out

intervention prioritization analysis with latest data, both epidemiological and financial, to

identify the optimal intervention mix given the resource envelope and considering

programmatic feasibility and other key factors.

While the Global Fund will not support the vaccine procurement and introduction, the funding

request can include technical support for SNT or for the National Strategic Plans (NSP)

update and Malaria Program Reviews (MPR) including the vaccine.

3. Case management

Effective diagnosis and treatment

Interventions included for malaria case management are required to support the expansion

and equitable access to quality, early diagnosis, and treatment of malaria, throughout the

continuum of care regardless of the sector, (e.g., public sector, community level and private

sector) and to address biologic threats such as drug resistance and parasite gene deletions

through generation of country-specific data and targeted implementation of mitigating

measures.

Refer to the relevant Program Essentials in Table1 to ensure the funding request includes

the relevant information on progress, challenges and plans to address any gaps in order to

meet these standards.

3.1. Diagnosis

The Global Fund supports early diagnosis of malaria through testing of suspected cases

with microscopy or Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs). Achieving universal coverage of testing

and confirmation of parasitological diagnosis of malaria before treatment requires availability

of testing capacity, reinforced by training, supervision, agile supply chain and quality

assurance at all levels of the health system. In the case of microscopy, consider efficiencies

across disease programs when funding external quality assurance (EQA), procurement and

lab technicians’ capacity.

Current evidence is still limited on the individual and public health cost-benefits of detecting

and treating low density malaria infections contribution to malaria transmission reduction.

As a result, for routine case management, the Global Fund does not support more sensitive

diagnostic tools targeting low density parasite infections such as polymerase chain reaction,

highly sensitive RDTs, and loop-mediated isothermal application (LAMP). If additional

evidence and related WHO policy guidance are developed, the Global Fund will reassess

support for these tools.

Key considerations for RDTs selection and procurement:

• Procurement of malaria RDTs needs to be in accordance with Global Fund’s Quality

Assurance Policy for Diagnostic Products and procurement policies.

Page 19 of 34

• Technical considerations for selection need to be based on plasmodium species

prevalence.

• RDTs within species categories are considered interchangeable, therefore brand

preference is not a criterion for selection. Continued supervision and training are

required to ensure quality of diagnosis, but brand-specific training is not necessary

based on RDT use and experience across many countries.

3.1.1. Addressing biologic threats: Pfhrp2/3 Gene Deletions

A critical biologic threat is the emergence of pfhrp2/3 gene deletions that evade detection of

the most used malaria RDTs. P. falciparum with deletions of pfhrp2/3 genes can cause false-

negative RDT results with standard Hrp2 based RDTs, resulting in patients going untreated

and potentially progressing to severe disease, while also perpetuating transmission.

First identified in Latin America, parasite gene deletions have been confirmed in the Horn of

Africa with signals of emergence in neighboring countries, posing a wider risk in all of Africa.

Depending on the country specific context, the Global Fund can support baseline and

periodic surveys

35

to determine whether local prevalence of mutations in the pfhrp2/3 genes

causing false negative RDTs has reached a threshold that might require a change in the

local or national diagnostic policy. Alternative RDTs appropriate for pfhrp2/3 gene deletion

settings can be procured with The Global Fund support in consultation with the technical

and sourcing operations teams and in accordance with product eligibility requirements.

3.2. Treatment

There are currently six WHO recommended and pre-qualified Artemisinin-based

combination therapies (ACTs)

36

which, in the absence of resistance, have all been shown

to be safe and result in parasitological cure rates above 95%. The selection

37

of first line

ACTs should be in line with country treatment guidelines, and informed by in-country drug

resistance surveillance, adherence, cost and usage in other settings, such as private sector

and chemoprevention interventions.

Quantification and forecasting for antimalarials are expected to consider trends on burden,

current access to care and any potential increases in access (e.g., scale-up of community

services), and/or removal of barriers to access to care (e.g., removal of user fees or inclusion

of people-centered care service delivery that improves access).

38

3.2.1. Management of severe malaria

At the health facility level, the Global Fund continues to support parenteral artesunate as

the first-line treatment for severe malaria in children and adults, including pregnant women

35

Protocol for surveillance surveys to monitor HRP2 gene deletion

36

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs)

37

For further details see WHO guidelines Artemisinin-based combination therapy

38

For further details please see the RBM CRSPC guidance note on malaria gap analysis tools

Page 20 of 34

in all trimesters. If artesunate is not available, then parenteral artemether is the second line

choice.

For community case management, the Global Fund supports pre-referral treatment with

rectal artesunate (RAS) for children under 6 years of age. However, recent implementation

evaluation results from CARAMAL project (Community Access to Rectal Artesunate for

Malaria), a three-year operational research project (2018–2020), highlighted significant

challenges to the effective delivery and expected impact of pre-referral treatment in part due

to weak or non-functional referrals systems and incomplete post-referral treatment. If the

funding request includes procurement of RAS, it has to elaborate on the ongoing and

planned activities in order to ensure effective training of CHWs and CHW supervisors,

education of caregivers, operation of the referral systems, 3-day treatment with ACTs

following initial parenteral treatment and other related aspects of the full continuum of care.

The funding request can include support for these activities.

3.2.2. Management of Plasmodium vivax

When requesting funding for primaquine (PQ) for radical cure, we recommend that countries

demonstrate having an adequate monitoring system for detecting and managing hemolysis

(irrespective of whether a country employs glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)

deficiency testing or not). This includes a pharmacovigilance system consisting of significant

patient education, appropriate follow-up and referrals. The Global Fund can support testing

for G6PD deficiency through diagnostics which are WHO pre-qualified or approved by

Expert Review Panel for Diagnostics (ERPD). This includes the laboratory-based

fluorescent spot tests and G6PD RDTs. Appropriate monitoring of relapses should also be

included in these contexts to follow up the efficacy of radical cure.

Single-dose treatment with tafenoquine for radical cure has received approval from two

stringent regulatory agencies with a follow-up label change: they state that tafenoquine

should be co-administered with chloroquine only and no other antimalarials (e.g., ACTs).

Tafenoquine does not currently have WHO prequalification pending development of

guidance around the use of tafenoquine in conjunction with approved G6PD point-of-care

quantitative tests. As confirming G6PD status is a critical safety component of tafenoquine

use, and has important operational challenges, procurement of tafenoquine through the

Global Fund will require consultations with the technical teams on a case-by-case basis until

such guidance is available.

Page 21 of 34

3.2.4 Addressing biologic threats: Antimalarial Drug Resistance

In addition to efforts to address drug resistance in the Great Mekong Subregion, the

emergence of artemisinin partial resistance and reduced efficacy of partner drugs in Africa

require a coordinated and proactive response

39

. The Global Fund supports routine

surveillance for drug resistance through Therapeutic Efficacy Studies (TES) which need to

be conducted at least once every two years. The U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI)

will provide funding and support implementation of TES to the countries they are supporting.

Therefore, these interventions do not need to be included in the funding request. If funding

is not available through other sources, TES will then need to be prioritized within the funding

request. The funding request can include surveillance for molecular markers of drug

resistance which can be integrated in ongoing TES, surveys or surveillance activities and

support for the in-country capacity to do so.

Transitions of first line ACTs are expected to be based on results from TESs, documented

signals of drug failure/delayed parasite clearance, evidence of low adherence to a current

treatment and need to consider cost implications. As further guidance on strategies to

address antimalarial drug resistance is developed in collaboration with WHO and other

partners, the Global Fund may support proactive mitigation measures including the

introduction of multiple first lines or rotation of ACTs. Programs that have already developed

antimalarial resistance mitigation strategies should elaborate their plans within the funding

request within a summary or as an annex. The Global Fund programmatic gap table includes

a request for information on the different ACTs planned for use (for first and second line

and/or alternative first line treatment). Applicants are encouraged to express any gaps, in

particular antimalarial molecules due to the significant differences in price between

molecules and prioritization of resources across all malaria interventions.

3.3. Tailored service delivery across all sectors

The Global Fund continues to support all channels of service delivery (public, private and

community level) and encourages people-centered approaches, with a focus on the

continuum of care, integration within PHC and other programs and levels of care. Service

delivery needs to be tailored according to the context in order to ensure that all suspected

malaria cases are tested, malaria infections are treated, timely referrals are done, and all

cases are reported. Stratification and programming should follow sub-national tailoring

guidance at the lowest sub-national level feasible and include a robust analysis of the

following: care seeking behaviors; community perception and values; provider adherence to

guidelines; EHRGE-related and other barriers to access and use of malaria case

management services; challenges and funding gaps to inform targeted, sector specific,

interventions. This will help justify any needs for prioritization and coordination of support

across sectors.

39

The Strategy to respond to antimalarial drug resistance in Africa

Page 22 of 34

3.4.1. Additional considerations: public sector health facilities

Interventions to strengthen service delivery of malaria case management should focus on

testing and confirmation of malaria prior to treatment, and accurate recording and reporting

of the clinical encounter. Stratification of key indicators for case management need to be

performed by districts on a routine basis to assess performance, to guide quality of care

interventions in low performing facilities and systematically document the root causes of

district challenges in meeting targets. In addition, as further elaborated in the RSSH

Information Note, the Global Fund strongly encourages applicants to invest in locally defined

intervention packages to improve the quality of people-centered, integrated care. These

packages, including supervision, training, and quality improvement approaches, can often

be combined across programs in an integrated manner.

3.4.2. Additional considerations: private sector

The Global Fund strongly encourages a costed strategy for the delivery of quality malaria

case management in countries where private sector care offers the potential to expand the

reach of services. Priorities include efforts to expand parasitological diagnosis for

confirmation of malaria prior to treatment, support regulatory framework to allow testing and

availability of quality drugs, to reduce cost barriers to quality diagnosis and treatment and to

ensure reporting of malaria cases to national systems.

Governments can use various pathways to engage systematically with the private sector,

such as: 1) Policy and strategic level dialogue, 2) Two-way information sharing, 3) Inclusive

balanced regulations (across service sectors), 4) Capacity building for the private sector;

and 5) Financing the private sector (e.g., performance-based contracting, subsidies, etc.).

The funding request can include supporting activities. The private sector technical brief and

RSSH Information Note elaborate further on private sector engagement strategies.

As part of setting and implementing standards for service delivery requirements, the Global

Fund will only support the ACT co-payment mechanism for the private sector in settings

offering the full test and treat pathway, including confirmation of malaria with a diagnostic

test before treatment, recording and reporting into national information systems.

3.4.3. Additional considerations: integrated community case management

As part of broader PHC, CHWs play a critical role in the fight against malaria. They make

malaria interventions closer and more accessible to populations at greatest risk and increase

access to malaria case management, typically as part of integrated community case

management (iCCM) for children under-five and increasingly as malaria case management

for older children and adults. They also play an essential role in the delivery and promotion

of vector control interventions (e.g., ITNs) and drug-based malaria prevention services (e.g.,

SMC, IPTp, PMC). Building effective, strong, resilient, and sustainable CHWs programs with

the capacity to surge and scale is necessary for expanding access to quality malaria case

Page 23 of 34

management whether within the malaria epidemic and pandemic preparedness at

community level, or the broader context of strengthening PHC services and community

systems.

The Global Fund will invest in the systems components of CHWs programs,

40

including

where CHWs provide malaria case management services (i.e., iCCM and case management

for malaria among older children and adults). Detailed information on the CHW investments

eligible for Global Fund support are provided in the table Investments in health policy and

systems support to optimize CHWs in Section 4.5 Human Resources for Health and Quality

of Care of the RSSH Information Note. Use the CHW programmatic gap table to facilitate

planning for funding requests. They can also refer to the Global Fund Budgeting Guidance

regarding remuneration (i.e., salaries, allowances, and benefits).

Strengthening community health systems also requires emphasis on improving bidirectional

referrals between community and facility care. A detailed intervention approach on referrals

is outlined in Annex 2 of the RSSH Information Note. Applicants should outline the needs

and sources of funding for CHW commodities not provided by the Global Fund. Funding of

non-malaria commodities for iCCM can be considered co-financing in most countries (please

consult the Global Fund Co-Financing Policy). Note that the Global Fund will now support

non-malaria medications for iCCM (e.g., for pneumonia and diarrhea) where CHWs provide

malaria case management, where iCCM is part of the package of services CHWs are

allowed to provide, and where the criteria in Annex 3 of the RSSH Information Note are met.

If resources and/or supplies for non-malaria illness included in the iCCM package are not

available simultaneously during implementation, the malaria component should continue as

planned, though efforts should be made to identify additional sources of funding to deliver

the complete package.

4. Elimination

Malaria elimination requires country ownership, with strong political commitment, reaching

hard-to-reach populations, robust surveillance systems including case-based surveillance

and case investigations-response, addressing cross-border issues and innovation in

products and service delivery. The transition from malaria control to elimination requires a

shift in strategy supported by evidence and the implementation of new activities tailored to

each country’s specific context. Please refer to the relevant Program Essentials in Table 1

to ensure the funding request includes the relevant information on progress, challenges and

plans to address any gaps to meet these standards.

Intervention packages

41

in countries approaching elimination are required to focus on: (1)

Enhancing and optimizing vector control and case management (component A); (2)

Increasing the sensitivity and specificity of surveillance to detect, characterize and monitor

40

WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes

41

WHO guidance on interventions in the final phase of elimination and prevention of reestablishment

Page 24 of 34

all cases (component B); (3) Accelerating transmission reduction (component C); and (4)

Investigating and clearing individual cases, managing foci, and following up (component D).

This could be achieved through the following interventions:

i. Local stratification by malaria transmission intensity and other key

characteristics. This is essential for effective targeting of interventions and needs

be specific, ideally at the level of localities or health facility catchment areas. The

funding request would benefit from describing how intervention strategies have been

tailored to the different strata.

ii. Enhancing and optimizing vector control. Vector control is expected to target

remaining foci and areas of on-going transmission.

iii. Enhancing and optimizing case detection and case management including

support for quality assurance and reference laboratories. Case management

needs to focus on 100 percent parasite-based, quality-assured diagnosis, and

universal access to appropriate treatment including gametocytocidal primaquine

where deemed effective. The Global Fund will also continue to support approaches

to promptly investigate and respond to cases or foci detected such as case

investigations and focus investigation and responses (CIFIR) or Diagnostic,

Treatment, Investigation, Response (DTIR) and encourages applicants to

decentralize these wherever possible to shorten the time from detection to response.

iv. Strengthening surveillance systems to detect symptomatic and asymptomatic

cases; notify, report, and investigate all malaria infections. Routine surveillance,

active case detection and foci investigation are recommended, as well as response

planning and epidemic preparedness. Outbreak preparedness should include clear

alert mechanisms as well as systems to enable rapid access to malaria commodities.

v. Other activities aimed at accelerating malaria elimination (e.g., community

engagement and communication campaigns to promote awareness and avoid

reintroduction).

vi. Applicants are also asked to include a description of programs addressing

prevention of re-establishment of the disease.

5. Cross-cutting Areas

5.1 Equity, human rights, and gender equality

Equity, human rights, and gender equality considerations are essential for inclusion in the

sub-national tailoring analysis. Therefore, they should be incorporated into the

implementation approach to ensure people- and population-centred service delivery.

Page 25 of 34

While certain populations may have more health-related vulnerabilities than others,

prioritization on malaria prevention and control activities need to be based on malaria-

specific vulnerability. For example, children under five years of age and pregnant women in

areas with on-going malaria transmission are more at risk of suffering serious consequences

of and death from the disease. As such, malaria programs should focus interventions

accordingly. Migrants, internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees can also be more

vulnerable, particularly if coming from an area with limited/no transmission into an area with

high transmission. Disaggregation of data (e.g., gender, age, other equity-related variables)

should be considered when needed to guide decision-making. For example, gender and

socioeconomic variables collected through community-based surveys such as the Malaria

Indicators Survey and Demographic and Health Surveys should be analyzed to better

understand potential inequalities or barriers to access and uptake to guide appropriate

tailoring of interventions.

If not already in the National Strategic Plan (NSP) or other document, the funding request

should include an analysis of the data available to demonstrate any known barriers to access

and uptake of malaria services. Funding for implementation of the Malaria Matchbox or other

similar tools can be included where EHRGE analyses have not been undertaken and/or

information gaps exist, or to improve understanding of how to address identified issues.

Additional disaggregated information and analysis on workforce composition to deliver

malaria services may provide additional insights on increasing equity and access.

Interventions informed by such data, aimed at addressing EHRGE barriers, can be included

under the respective modules. RBM has developed an e-learning training

42

for national

programs for the assessment of human rights and gender-related barriers to equitable

access to malaria services. For further information please refer to the technical brief on

Equity, Human Rights and Gender Equality and Malaria.

5.2 Community leadership and engagement

Community Systems Strengthening (CSS) are useful to improve and monitor access to

malaria services for most affected, marginalized, and underserved populations in endemic

areas. This includes empowering and supporting communities, especially the most

vulnerable, to participate in national and local structures, platforms, and processes, including

in country coordination mechanisms (CCMs) and ensuring that communities and civil society

are key partners and play a meaningful role in the Global Fund grant application, decision-

making and implementation. Community leadership and engagement have been and

continue to be key to supporting strong responses to malaria: they should be at the heart of

future efforts to address novel health threats.

There is no “one size fits all” strategy; it is crucial for community-based and community-led

organizations to play a meaningful role in determining the elements of effective, equitable

and sustainable malaria responses.

42

Community, Human Rights and Gender in malaria programming for Malaria Program Managers

Page 26 of 34

Strengthening community participation may be especially important in elimination settings

43

.

Elimination strategies represent an opportunity for rights-based action to reach traditionally

excluded and geographically marginalized populations with malaria services.

Applicants are encouraged to explore the potential of community-led monitoring (CLM) as

part of efforts to improve availability, accessibility, responsiveness, and quality of services.

CLM can focus on general health, disease-specific or intervention-specific services (e.g.,

monitoring of correct usage of ITN, stock/workforce availability at health facilities or

geographic and other structural, and human rights and gender-related barriers).

The community also plays a role in improving services by identifying individuals or groups

of individuals who do not have appropriate access, or who do not understand the barriers

they face. Examples of CLM tools that applicants are expected to consider include

scorecards (like the ALMA community scorecards

44

), complaint mechanisms and monitoring

of human rights and gender-related barriers to services.

Additional information on CSS and CLM are available in the RSSH Information Note.

5.3 Social and Behaviour Change (SBC)

Investments in SBC need to be evidence-based, results-oriented, theory-informed and part

of the national malaria SBC strategy. The strategy and investments need to reflect the

relevant prevention, control and elimination objectives of the national malaria strategy and

include an M&E plan to guide and adapt approaches to improve access to and usage of

malaria interventions. SBC plans and activities should build on existing best-practice and

SBC efforts in other health sectors (e.g., maternal and child health, community systems).

While integration is encouraged, advocacy efforts, such as “Zero Malaria Starts with Me”

campaigns and activities, can also be considered.

SBC activities are required to:

• Account for differences amongst and within populations (e.g., cultural, socio-

economic, geographic, gender, occupational, literacy, race, ethnic and indigenous

backgrounds, and other considerations) that may affect equitable access and

utilization of interventions.

• Address identified barriers, including human rights and gender-related ones, to

uptake and use of malaria interventions (and health services more generally).

• Address issues related to provider behaviours, such as adherence to case

management guidelines, respect of fee policies and compassionate care.

• Address risk perception by communicating changes in the transmission dynamics

and associated risks.

43

The Malaria Free Mekong is an example of network platform of civil society organizations and communities.

44

ALMA Scorecard

Page 27 of 34

5.4 Pandemic Preparedness and Response (PPR)

In malaria endemic countries, components of the health system responding to malaria are

key in early identification of other conditions leading to pandemics. Investments in PPR can

build on already existing systems, including malaria control and surveillance systems for

acute febrile illness. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and response should

also be considered, as well as investments to ensure appropriate capacity and expertise,

recognizing that malaria program personnel at national and district level are often engaged

in investigation and response for acute febrile illness outbreaks. In addition, investments in

the PHC service delivery will strengthen the fight against malaria and preparedness for

future pandemics.

Malaria early warning systems (MEWS) are among the potential areas for integration, as

they can strengthen laboratory-based and community-based approaches. Exploring the

overlap between the 7-1-7 approach

45

recommended for PPR and malaria surveillance in

different transmission settings, notably the 1-3-7 approach in elimination contexts.

46

Synergies in HRH (training, remuneration, supportive supervision, and quality improvement)

at national, facility and community levels may exist. CHWs play important roles in PPR,

including risk communication and community engagement (RCCE), dispelling myths,

promoting, and supporting vaccination, behavioural interventions and other relevant

prevention tools, community-based testing and contact tracing, providing support to patients

on treatment, and surveillance.

47

When considering PPR efforts or integration of other activities into CHW’s terms of