THE BENJAMIN A. GILMAN INTERNATIONAL

SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Evaluation Report

APRIL 2016

Evaluation Division

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

U.S. Department of State

Data collected by Research Solutions International, LLC

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Evaluation Division

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

United States Department of State

2200 C Street NW

Washington, DC 20037

Data collected by Research Solutions International, LLC

1142 Regal Oak Dr.

Rockville, MD 20852

Staff Contact: Dr. Izabella Zandberg

The Evaluation Division of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs thanks members of

the Research Solutions International team for their thoughtful approach to the evaluation design

and excellent data collection, as well as a thorough analysis of the data, and early drafts of the

report: Izabella Zandberg, Suzan Berkowitz, Colleen Ryan Leonard, Laura Johnson, Glenn Nyre,

Yalonda Lewis, Caroline Friedman, Beth Rabinovich, and Kim Standing.

We would also like to thank the Gilman Scholars, members of their families and communities,

and representatives of their home institutions, who provided the data upon which the report is

based.

To download a full copy of this report and its executive summary visit

http://eca.state.gov/impact/evaluation-eca

ii

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Prepared by RSI for the Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

CONTENTS ii

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

1 | INTRODUCTION 10

2 | GILMAN SCHOLARS: WHO ARE THEY? 14

3 | SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN PERSPECTIVES 18

4 | SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN ACADEMIC CHOICES 20

5 | FOREIGN LANGUAGE STUDY 25

6 | SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN PROFESSIONAL CHOICES 27

7 | EFFECTS ON U.S. HIGHER EDUCATION 32

8 | EFFECTS ON SCHOLARS’ FAMILY AND FRIENDS 37

CONCLUSIONS 41

DATA COLLECTION METHODS AND LIMITATIONS 43

Contents

iii

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Prepared by RSI for the Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

ECA – Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

ESL – English as a Second Language

HBCU – Historically Black Colleges and Universities

HSI – Hispanic Serving Institutions

IHI – Institutions of Higher Education

MBA – Masters of Business Administration

SES – Socioeconomic Status

STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering and Math

TEFL – Teaching English as a Foreign Language

TESOL – Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages

UNC – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Abbreviations and Acronyms

1

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Evaluation and Program Overview

Since 2001, the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA)

has administered the Congressionally-mandated Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship

Program (Gilman Scholarship, Scholarship) to offer grants for U.S. citizen, undergraduate

students of limited financial means to participate in study and internship programs abroad.

Gilman Scholarships are intended to help prepare these students to assume significant roles in an

increasingly global economy and interdependent world. In 2013, ECA commissioned an

evaluation by Research Solutions International, LLC to investigate whether the program’s goals

were being met. The evaluation studied the medium- and longer-term outcomes for recipients of

the Gilman Scholarship between the years 2003 and 2010, and also considered the impacts of the

scholarship on U.S. higher education institutions, and on the family and communities of

scholarship recipients. According to the data collected, representation of minorities among

Gilman Scholarship recipients well exceeds that of the U.S. study abroad population as a whole.

Participation in the Gilman Program from African-American, Latino and Asian communities is

two to three times greater than their participation in U.S. study abroad overall. Just under half of

Gilman Scholars (Scholars) in the cohort examined were part of the first generation in their

families to enroll in higher education.

The Evaluation data shows that the Gilman Scholarship is diversifying the kinds of students who

study and intern abroad and the countries and regions where they go by offering awards to U.S.

undergraduates who might otherwise not participate due to financial constraints. From changed

perspectives on the world and new interests in working on global issues to focusing academic

pursuits on international topics and deepening foreign language skills, the Gilman Scholarship

has enabled students of limited financial means to develop the knowledge and competencies

required to compete in a global economy. The evaluation also uncovered many ways in which

the Gilman Scholarship experience influences Scholars’ professional paths.

Executive Summary

2

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

KEY FINDINGS

SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN PERSPECTIVES

Two-thirds of Gilman Scholar survey respondents (66 percent) found opportunities to

serve as a bridge between Americans and people from different countries and cultures

when they returned to the United States.

While more than half of the survey respondents (52 percent) said they had had concerns

about living in a foreign culture prior to participation in the program, after the Gilman

Scholarship, seventy-nine percent of survey respondents continued to follow media

coverage on the country or geopolitical region where they studied and nearly three

quarters (74 percent) kept up an active interest in the culture of the country where they

studied.

SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN ACADEMIC CHOICES

Of the 1,441 survey respondents who returned to undergraduate studies after their Gilman

Scholarship, 87 percent (1,253) reported taking a greater interest in international or cross-

cultural topics, and more than one-third indicated that they had chosen an academic major

or minor field of concentration with an international or cross-cultural focus.

Seventy-nine percent of survey respondents studied a foreign language while on their

academic study program overseas. Among Scholars who had studied a language while

abroad, more than three-fourths (82 percent) sought opportunities to speak the language

they had studied when they returned home.

Of the 819 survey respondents who were attending or already completed graduate or

professional school at the time of the evaluation, almost half (48 percent) had chosen a

concentration with an international or cross-cultural focus, and more than one-third (36

percent) had studied abroad again or pursued international field research.

Eighty-three percent of survey respondents indicated that the Gilman Scholarship had

enabled them to undertake academic activities overseas that they could not have taken at

their home institutions.

SHIFTS AND EXPANSION IN PROFESSIONAL CHOICES

Eighty-three percent of survey respondents found jobs where they could interact with

people from different backgrounds or nationalities, and more than half (54 percent)

reported working in a field that includes an international or cross-cultural component.

Almost three-quarters (73 percent) of survey respondents reported that the Gilman

Scholarship experience caused them to broaden the geographic range of locations where

they were willing to work in the future.

EFFECTS ON U.S. HIGHER EDUCATION

One-third of university representatives interviewed, across all types of institutions,

credited the Gilman Scholarship directly for changes in their school’s study abroad

program offerings and for contributing to their internationalization efforts. Many stated

3

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

that the Gilman Scholarship had allowed them to expand their study abroad programs to

more diverse, non-traditional locations, including Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the

Middle East.

Several study abroad representatives, primarily at minority-serving institutions, reported

using the Gilman Scholarship parameters as a model for revising their study abroad

programs. Other effects included adaptation of campus study abroad programs to meet

Gilman Scholarship parameters, attracting new sources of funding for study abroad in

general, expanding course offerings to help students prepare for a wider array of study

abroad opportunities, and promoting professional development of study abroad

professionals.

Gilman Scholars on the Program’s Impact on their Academic and Career

Goals

Former Gilman Scholars:

My current employer told me that my international experience and the internship I held

while abroad was a deciding factor in my getting hired. —Scholar, 2010

I am a Naval officer and always focus on problems with global implications. I was able

to get a job in this field largely because of my study abroad. —Scholar, 2007

For the first time in my higher education experience, it allowed me to focus completely on

my academics and study abroad experience instead of worrying about [how] to pay for

school. It provided me with a stress-free environment to fully embrace the study abroad

experience. —Scholar, 2008

[The Gilman Scholarship experience was] crucial and definitely a pivotal [point] for

me… the first big step in figuring out how I wanted to contribute to the world. —Scholar,

2005

I have committed my life to helping U.S. citizens gain greater self-reliance so that we can

be positive contributors to globally shared resources…. —Scholar, 2008

(Now) when there is a problem of international concern, I try to think about it from a

comprehensive point of view knowing that the current state of a country, an event, or a

conflict is probably the result of years and years of different decisions and events…. —

Scholar, 2010

University Administrators on the Gilman Scholarships:

They’ve really had to fight hard to get where they are (just to pursue higher education).

[The Gilman Scholarship] makes something that seemed like an out-of-reach dream

become a reality for them.

[The Gilman Scholarship] allows some of our highest need students to think about their

[undergraduate] academic experience, their international experience in the same way as

other students do.

4

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

EVALUATION DESIGN

In designing this evaluation, the research team focused their inquiry on whether the Gilman

Scholarship addressed Department of State priorities, including increasing opportunities for

students of limited financial means, improving Americans’ understanding of other countries,

increasing U.S. global economic competitiveness, and supporting the internationalization of U.S.

institutions of higher education.

In order to assess medium and longer-term outcomes, the evaluation focused on collecting

information from Gilman Scholars who had studied abroad from the 2002-03 to 2009-10

academic years.

This evaluation gathered data from former Gilman Scholars and representatives from colleges

and universities. Data was also gathered from Scholars’ family or friends. In all, the research

team electronically surveyed 1,591 Scholars, conducted 17 focus groups with Scholars in six

cities, conducted phone interviews with 25 Scholars individually, and interviewed

representatives at 42 colleges. Thirty family or friends of Gilman Scholars were also

interviewed.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Gilman Scholars: Under-represented in Study Abroad

The Gilman Scholarship aims to support students who have been traditionally under-represented

in academic study abroad programs. The results from this evaluation confirm that the

Scholarship successfully targeted students in this population and provided additional insight into

how the program assists them in overcoming challenges to pursuing international opportunities.

Financial Obstacles: More than three-fourths of survey respondents (79 percent) reported that

financial considerations were a significant challenge in studying abroad. This included both the

cost of travel and lost income from leaving a position of employment.

Not the “Typical” Study Abroad Student: In focus groups and interviews, Scholars spoke

about seeing themselves differently from “typical” study abroad participants, primarily by virtue

of their lower socioeconomic status (SES). Other self-identified characteristics distinguishing

them from usual study abroad students included race/ethnicity, older age, having a physical

disability, and being a parent. Forty-four percent of survey respondents indicated they were part

of the first generation in their families to attend college.

New Academic Opportunities Overseas: In addition to giving recipients access to other

countries and cultures, Gilman Scholarships also supported their enrollment in a variety of

academic study abroad programs, providing experience with different academic structures,

students, activities, academic topics and extracurricular experiences than their home institutions.

Eighty-three percent of survey respondents indicated that the Gilman Scholarship had enabled

them to undertake academic activities overseas that they could not have taken at their home

institutions.

5

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Shifts in Perspectives

The evaluation results indicate that the Gilman Scholarship supported Scholars in expanding

their knowledge of other peoples, cultures and perspectives.

Shifts in Worldview and Perspective: More than half of the survey respondents (52 percent)

said they had concerns about living in a foreign culture prior to their study abroad experience.

After coming home, the majority (74 percent) kept up an active interest in the culture of the

country where they studied. Seventy-nine percent followed media coverage on the country or

geopolitical region where they studied. In focus groups, Scholars said that the Gilman

Scholarship provided an opportunity for them to develop an analytic framework through which

to observe the world and scrutinize information about it.

International Engagement: After returning home from studying abroad, Scholars sustained

their international engagement through a wide range of activities. Eighty-four percent reported

maintaining relationships with people from the country where they studied. Seventy-four percent

remained actively interested in the culture of the host country. Two-thirds of survey respondents

found opportunities to serve as a bridge between Americans and people from different countries

and cultures when they returned to the United States.

In addition to influencing their peers at school, some Gilman Scholars targeted their educational

efforts on their communities back home, taking the time to share their experiences with people

who have less access to international opportunities.

Gaining a Greater Understanding of and Representing American Diversity: In focus group

discussions, several Scholars also described the study abroad experience as clarifying their own

American identity, and discussed how this understanding influenced their role as American

ambassadors. Scholars who were children of immigrants, raised in the United States but

identified with their parents’ cultural heritage, found themselves representing American diversity

in other countries.

Expanding Disciplines and Degrees of Study: The Gilman Scholarship influenced Scholars’

choices to pursue study of international topics that they might not have previously considered. In

some cases, the Scholarship catalyzed a desire to pursue graduate studies or professional degrees.

Enhancing Interest in International Study: Of the 1,441 survey respondents who returned to

undergraduate studies after their Gilman Scholarship, over 1,250 reported taking a greater

interest in international or cross-cultural topics, and more than one-third indicated that they had

chosen an academic major or minor field of concentration with an international or cross-cultural

focus.

A Decisive Factor in Graduate/Professional Study: Scholars who went on to pursue graduate

studies or professional degrees described the Gilman Scholarship experience as a decisive factor

in their choice of what to study.

6

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Of the 819 survey respondents who were attending or already completed graduate or professional

school at the time of the evaluation, almost half (48 percent) had chosen a concentration with an

international or cross-cultural focus, and more than one-third (36 percent) had studied abroad

again or pursued international field research. Almost one-third (31 percent) had written or were

writing a thesis/dissertation on an international or cross-cultural topic.

Fellowships, Scholarships, and Certificates: Thirty percent of all survey respondents reported

having pursued educational activities inspired by their Gilman Scholarship experience. Of these,

34 percent received fellowships or scholarships—the largest portion of that group going abroad

again as Fulbright Students (14 percent). Twenty-three percent reported having pursued

professional certificates, including Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) and

Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL).

Enabling Graduate Study: In addition to influencing their academic choices, some Scholars

believed that the Gilman Scholarship was the reason they were accepted to graduate school.

Whether through the coursework or the international experience—or both— the Gilman

Scholarship provided them with the qualifications to make them competitive and better prepared

graduate students.

Foreign Language Study

Foreign language skills are critical to improving Americans’ understanding of other countries

and increasing U.S. global economic competitiveness. Language learning gives young

Americans tools that will allow them to better engage with foreign counterparts in international

settings. The Gilman Scholarship affords recipients the opportunity to pursue language study

while abroad. However, in some cases where foreign language study was not the focus of the

international experience, Scholars returned home and participated in language study that was

inspired by their time in a foreign country.

Foreign Language Learning Overseas: Seventy-nine percent of survey respondents studied a

foreign language while on their academic study program overseas. They studied a diverse group

of languages, with forty-three percent studying romance languages and twenty-eight percent

studying Asian languages.

Foreign Language Study after Returning Home: Scholars were asked if they had undertaken

specific language-related activities during the period of time that they were undergraduates or

graduate or professional school students. A majority of the undergraduates (64 percent) had

either continued or started taking language courses. More than a quarter of graduate/professional

students (29 percent) had taken more foreign language courses. Among Scholars who had

studied a foreign language while abroad, more than three-fourths (82 percent) sought

opportunities to speak the language they had studied when they returned home.

Expanded Professional Choices

The Scholarship enabled U.S. undergraduates with limited financial resources to develop

competencies required to compete in a global economy, helped focus their academic pursuits on

7

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

international topics, and encouraged recipients to deepen their foreign language skills. In this

section we will see how the Gilman Scholarship experience influences Scholars’ professional

paths.

Gilman Scholars’ Professional Visions: Scholars found that the experience of studying abroad

gave them a new perspective on their career possibilities. For example, almost three-quarters (73

percent) of survey respondents reported that the international experience afforded by the Gilman

Scholarship caused them to broaden the geographic range of locations where they might work in

the future. Sixty-seven percent of survey respondents reported wanting to work in a cross-

cultural or international field. In addition, more than half (59 percent) reported having applied for

positions at companies that included an international or cross-cultural focus. For nearly half of

the survey respondents (48 percent), the Gilman Scholarship experience clarified their

professional direction. In some cases, Scholars were introduced to new academic fields, for

example, various science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, which

became their professional focus.

Seeking Diversity in the Workplace: As a result of their Gilman Scholarship experience, most

survey respondents (83 percent) found jobs where they could interact with people from different

backgrounds or nationalities, and more than half (54 percent) reported working in a field that

includes an international or cross-cultural component. In addition, 47 percent of survey

respondents said they had sought out a company or organization with a diverse workforce. In

focus groups, some Scholars elaborated on this preference and its connection to their Gilman

Scholarship experience. Further, nearly half (45 percent) reported working in an environment

where they could use a foreign language. Many reported that the Gilman Scholarship had

allowed them to acquire the language skills necessary for specific positions. Almost one-third of

Gilman Scholars (30 percent) reported taking a position where they could travel internationally.

Effects on Scholars’ Family and Friends

Survey responses from Scholars revealed that they are sharing their international experience with

family and friends. Interviews with family and friends provided evidence of how they are being

changed by their Scholars’ experiences.

How Scholars Shared Their Experience: The most frequently reported activity (over 80

percent) was offering a first-hand perspective on a country or an international issue; notable

numbers of Scholars encouraged their family and friends to directly participate in cross-cultural

activities.

Changes in Family and Community Members: Virtually all interviewed family and

community members believed that Scholars’ experiences had affected them in varying degrees.

Some family members responded to their Scholar’s desire to discuss international topics by

developing more of an interest in foreign news. A few interviewees who had only traveled

domestically in the United States reported a new eagerness to go to another country.

Community members testified to the educational opportunities offered by Gilman Scholars.

8

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

A small number of family members reported hosting international students, either because they

were interested in “giving back” the kind of experience that their Scholar had while abroad, or to

support their family member’s new interest in hosting foreign exchange participants.

Influencing Family and Friends to Study Abroad or Seek other International Experiences:

Just over half of the survey respondents (53 percent) reported influencing someone else to study

abroad or participate in an international exchange. Of those survey respondents, 40 percent said

they influenced friends, 34 percent said they had influenced fellow students, and 27 percent had

influenced either a sibling or other family member.

Other family members, especially siblings, observed the example set by Gilman Scholars and

became motivated to undertake study abroad themselves or to pursue other international

opportunities.

Encouraging Family and Friends to Apply for Gilman Scholarships: In focus groups and

interviews, some Scholars—especially those who identified themselves as atypical study abroad

students—recognized that study abroad is a less obvious option for their peers and felt a

particular responsibility to encourage others similar to themselves.

Effects on U.S. Higher Education

The Department of State also seeks to support the internationalization of American colleges and

universities through the Gilman Scholarship and other educational exchanges and related

programs. This evaluation probed effects of the Gilman Scholarship on higher education by

speaking with university representatives at 42 colleges and universities from a wide range of

school types and student populations.

Making Study Abroad Available to a Much Broader Range of Students: University

representatives who were interviewed regarding the impact of the Gilman Scholarship on their

institutions said that it had contributed to changing perceptions about the kind of student who can

study abroad.

Support for Short Term Programs and Flexible Approaches to Study Abroad for Working

Adults: For students who must work during their studies or have familial obligations year-

round—including many enrolled in community colleges, in particular—spending a semester or

academic year in another country is difficult or impossible. To allow more students to

participate, the Gilman Scholarship has instituted offerings for summer (and now also winter)

that are a minimum of four weeks in length (now two weeks for current community college

students.)

According to university representatives interviewed for this evaluation, STEM majors had

difficulty fitting study abroad into their schedules during the regular academic year because of

the high number of courses and labs that are required to complete their degree. For some STEM

majors, a shorter summer session is the only opportunity to study abroad. According to

interviews with university representatives, the Gilman Scholarship Summer Program awards

9

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

made it possible for low-income STEM majors to overcome both financial and curricular

obstacles.

Changes to Study Abroad Offerings: About one-third of university representatives, from all

types of institutions, credited the Gilman Scholarship directly for changes in their school’s study

abroad program offerings. Many stated that the Gilman Scholarship had allowed them to expand

their study abroad programs to more diverse, non-traditional locations, including Africa, Asia,

Latin America, and the Middle East.

Reorganizing Study Abroad Programs: Several study abroad representatives, primarily at

minority-serving institutions, reported using the Gilman Scholarship parameters as a model for

revising their study abroad programs.

Other effects on higher education included adapting study abroad programs to meet Gilman

Scholarship parameters, attracting new sources of funding for study abroad in general, expanding

course offerings to help students prepare for a wider array of study abroad opportunities, and

promoting professional development of study abroad professionals.

University representatives also featured Gilman Scholars prominently in study abroad

information sessions, particularly as a way to educate other “less traditional” potential study

abroad students about the possibilities available to them.

10

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

About the Evaluation

This evaluation seeks to understand the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship

Program’s (Gilman Scholarship) contribution to advancing U.S. Department of State priorities

and fulfilling Congressional objectives for the Program.

In designing this evaluation, the research team

developed the following overarching research questions

to guide their inquiry:

1. How did the Gilman Scholarship change and

enhance Scholars’ global perspectives and worldview

and prepare them for a more interdependent world?

2. How did the Gilman Scholarship influence

Scholars’ educational achievements and educational

choices?

3. How did the Gilman Scholarship influence

Scholars’ professional paths?

4. How did the Gilman Scholarship impact the

Scholars’ home institutions of higher education?

5. What was the impact of the Gilman Scholarship

on family members and friends?

The evaluation focused on collecting information from

Gilman Scholars (Scholars) who had studied abroad

from the 2002-03 through 2009-10 academic years.

Looking at this period of Gilman Scholarship experience allowed for the immediate effects of

studying abroad to develop and express themselves as deeper, lasting outcomes.

1| Introduction

FOREIGN POLICY OBJECTIVES

UNDERPINNING THE

EVALUATION DESIGN

INCREASING OPPORTUNITIES

FOR STUDENTS OF LIMITED

FINANCIAL MEANS

IMPROVING AMERICANS’

UNDERSTANDING OF OTHER

COUNTRIES

INCREASING U.S. GLOBAL

ECONOMIC COMPETITIVENESS

GREATER

INTERNATIONALIZATION OF U.S.

INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER

EDUCATION

11

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Looked at Scholars who had

studied abroad 5 -10 years

ago (2002-03 to 2009-10

academic years)

Total survey respondents:

1,591

17 focus groups with

Scholars in DC, Chicago, New

York, San Francisco, LA, and

Seattle

25 telephone interviews with

Scholars residing in rural

areas

30 interviews with Scholars’

family and friends

Interviews with University

Representatives at a sample

of 42 colleges and

universities representing 4-

year institutions, 2-year

institutions, Historically Black

Colleges and Universities

(HBCU), and Hispanic-Serving

Institutions (HSI)

Exhaustive review of program

documentation and

electronic databases

Research conducted in 2012

and 2013

For in-depth details about the

evaluation methods, see the

last section of this report.

EVALUATION DESIGN

REPORT STRUCTURE

Any evaluation must start with an in-depth understanding of

the program. As such, this evaluation report opens with an

overview of the Gilman Scholarship, with a special focus on

facts and figures for the program during the research period

of academic years 2002-03 through 2009-10 (As shorthand in

this report, we will refer to the calendar year in which the

Scholar completed their experience abroad. For example,

academic year 2002-03 will appear as 2003 in this report).

Section two describes the Scholars, including their

motivations for applying to the Gilman Scholarship, their

experience studying abroad, and their role as international

ambassadors. The third section discusses Scholars’ shifts in

world perspectives as a result of studying abroad.

The report then follows Scholars on their academic and

professionals trajectories. In sections four, five, and six, the

report discusses how the Gilman Scholarship affected

Scholars’ educational choices and prepared them to join a

21

st

century global workforce.

Outcomes of the Gilman Scholarship extend beyond

individual students. In section seven, the report highlights

changes taking place on American college and university

campuses as a result of the Scholarship.

While overseas, Gilman Scholars serve as informal

ambassadors of the United States, and then as ambassadors

for increased international engagement when they return

home. In section eight, the report provides insight into the

influence of Scholars on their community members.

A note on charts contained in the report: All titles and

data within the charts refer only to the respondents of a

survey administered to Gilman Scholars from the 2002-03

through 2009-10 cohorts. The reader should also take note of

the N (N=1,591 total survey respondents) listed beneath each

table and note that the survey was administered in 2013 as a

part of this evaluation study.

12

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

69% female, 31% male

64% White

16% Asian/Pacific-Islander

14% Black/African-American

15% Hispanic/Latino

4% reported a having a physical

disability

97% attended 4-year school

(public or private)

3% attended a two-year public

school

11% attended a HBCU or HSI

73% studied abroad for a

semester

15% studied abroad for full year

9% studied abroad for one-quarter

or less time

Scholar cohorts from 2005 to

2010 made up the majority of

survey respondents. Earlier

scholars—who studied abroad

before 2005 still made up about

one-quarter (23%) of survey

respondents.

34% studied in Europe

27% studied in East Asia

21% in the Western Hemisphere

10% in Africa

2% in the Middle East & North

Africa

2% in South & Central Asia

PROFILE OF SURVEY

RESPONDENTS

ABOUT THE GILMAN SCHOLARSHIP

PROGRAM

1

The Gilman Scholarship offers grants for U.S. citizen,

undergraduate students of limited financial means to

pursue academic studies abroad. Such international

study is intended to better prepare U.S. students to

assume significant roles in an increasingly global

economy and interdependent world.

The Gilman Scholarship aims to support students who

have been traditionally under-represented in academic

study abroad, including but not limited to, students with

high financial need, community college students,

students in under-represented fields, such as the

sciences and engineering, students with diverse ethnic

backgrounds, and students with disabilities.

Gilman Scholarship applicants must be a recipient of a

U.S. Federal Pell Grant or provide proof that he/she

will receive a Pell Grant during the study abroad period.

The U.S. Federal Pell Grants program provides need-

based grants to low-income, undergraduate students, to

promote access to postsecondary education.

The Gilman Scholarship seeks to assist students from a

diverse range of public and private institutions from all

50 states, Washington, DC and Puerto Rico

2

.

Award recipients are chosen by a competitive selection

process and must use the award to defray eligible study

abroad costs. These costs include program tuition, room

and board, books, local transportation, insurance and

international airfare. Award amounts will vary

depending on the length of study and student need, with

the average award being approximately $4,000.

1

The following program description comes from the Institute of International Education website: “About the

Program,” Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship, Institute of International Education, accessed June 5,

2015, http://www.iie.org/en/Programs/Gilman-Scholarship-Program/About-the-Program.

2

It is important to note that the diversity of Gilman Scholarship recipients has increased over the life of the program.

During the 2014-15 academic year, the Gilman program awarded 2,799 scholarships to undergraduates from 623

colleges and universities. Sixty four percent of Gilman Scholars represented ethnic minority groups, including

African Americans and Blacks, Asian/Pacific Islander-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and Native Americans.

13

Evaluation of the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Awards for summer study abroad scholarships are $3,000.

Students who apply for and receive the Gilman Scholarship to study abroad are then eligible for

the Critical Need Language Supplement in selected countries, for an award total of up to $8,000.

The critical need languages include: Arabic (all dialects), Chinese (all dialects), Bahasa

Indonesia, Japanese, Turkic (Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgz, Turkish, Turkmen, Uzbek), Persian

(Farsi, Dari, Kurdish, Pashto, Tajiki), Indic (Hindi, Urdu, Nepali, Sinhala, Bengali, Punjabi,

Marathi, Gujarati, Sindhi), Korean, Russian, Swahili.

14

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

The Gilman Scholarship aims to support students who have been traditionally under-represented

in academic study abroad. The results from this evaluation confirm that the Gilman Scholarship

successfully targets students in this population and provides additional insight into the challenges

they faced in pursuing international opportunities. The research also reveals how the Scholarship

helps recipients overcome various barriers to study abroad.

Applicant Circumstances During Time of Application

When asked to reflect on the time leading up to their application for the Gilman Scholarship,

Scholars described a variety of challenges they faced while making the decision to study abroad.

As shown in Table 1, financial constraints predominated: most survey respondents (79 percent)

reported that financial considerations were a significant challenge. Very few said that finances

presented only a slight challenge (4 percent) or none at all (less than 1 percent).

The need to leave a job, and the income it provided, posed a challenge for 44 percent of survey

respondents.

Also notable is that more than half of survey

respondents (52 percent) described having had

concerns about living in a foreign culture prior to

participation in the program. Similarly, a majority

of survey respondents (62 percent) said they had

had concerns about academic challenges in their

study abroad programs.

2 | Gilman Scholars: Reaching Students who

Otherwise Would Not Study Abroad

FORTY-FOUR PERCENT OF

SURVEY RESPONDENTS

INDICATED THAT THEY WERE

PART OF THE FIRST

GENERATION IN THEIR FAMILIES

TO ATTEND COLLEGE.

15

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

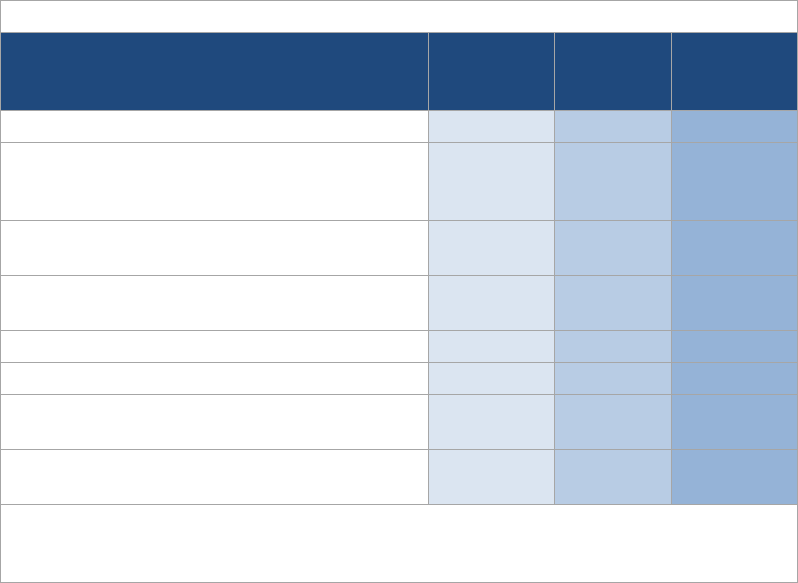

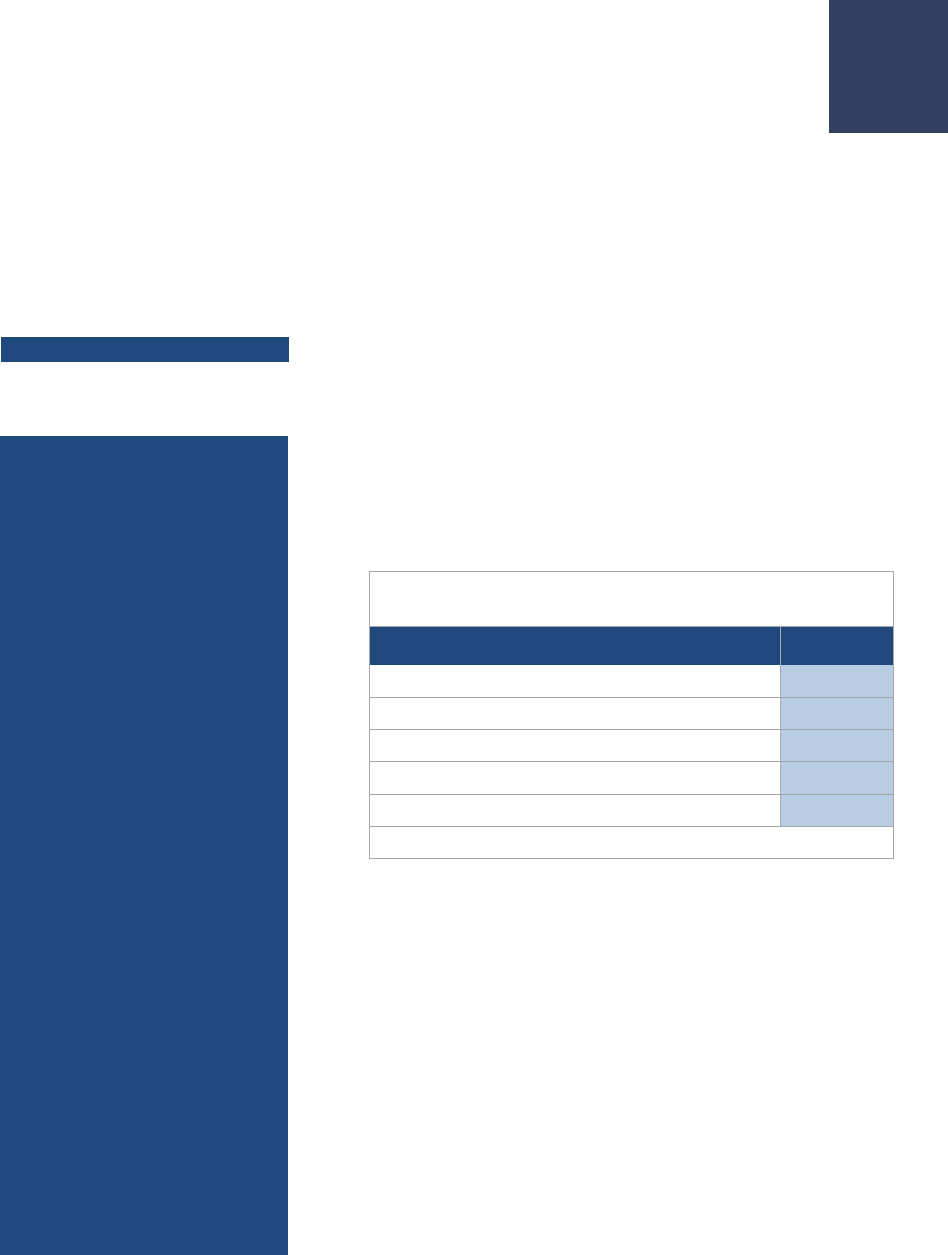

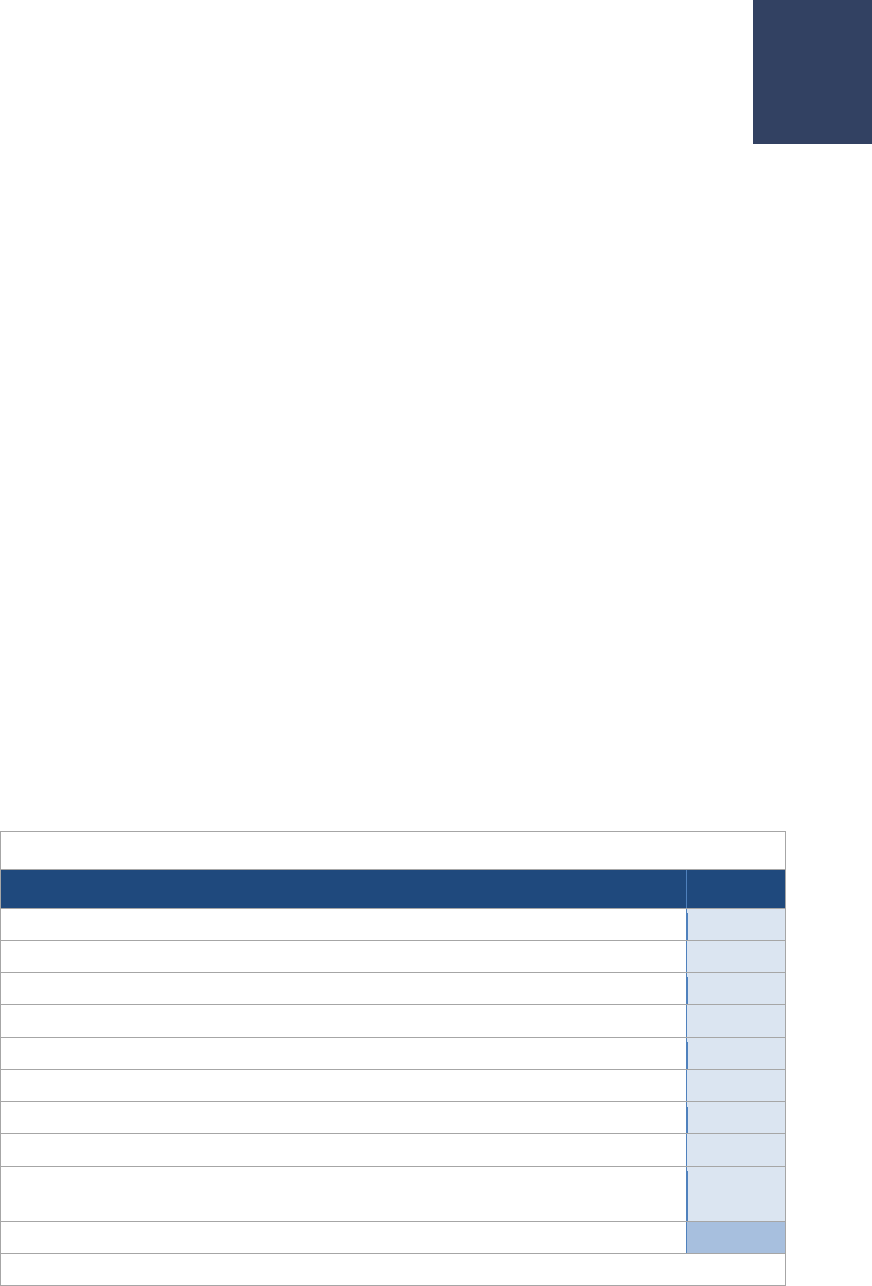

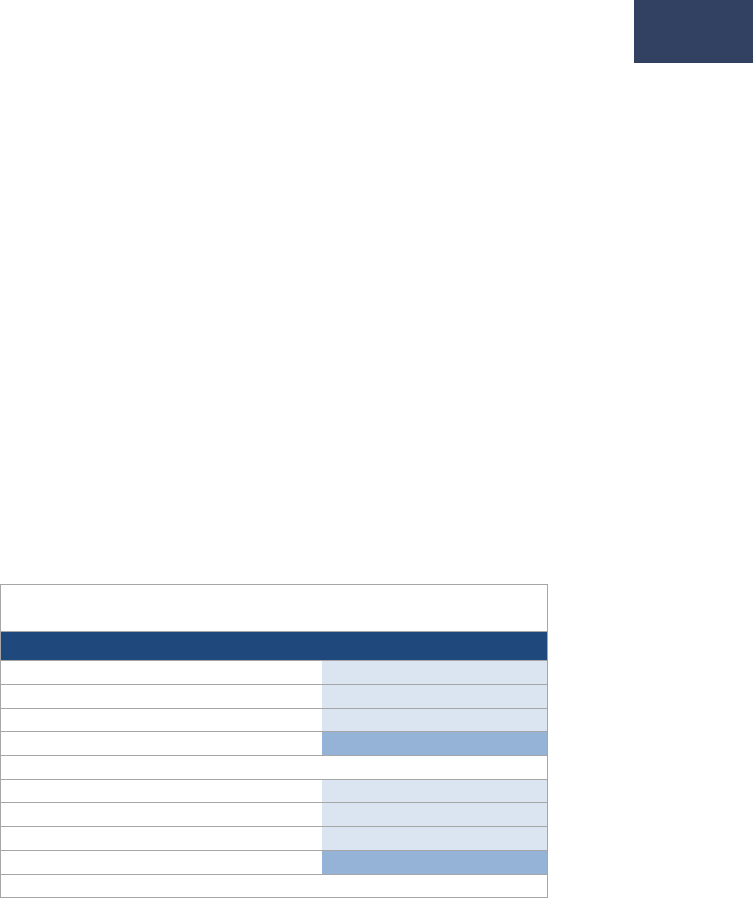

Table 1: Challenges to Studying Abroad at Time of Application

Challenges

Not at all a

challenge*

A slight/

moderate

challenge*

A significant

challenge*

Financial considerations

1

20

79

Difficulties meshing the study abroad program

with the academic schedule or requirements at

home institution

35

59

7

Concerns about the academic challenges to be

faced

39

58

4

Lack of support or encouragement to study

abroad from family members

63

31

6

The need to leave a job

56

39

5

Concerns about living in a foreign culture

48

49

3

Caregiving responsibilities for family members or

others

71

24

4

Lack of support or encouragement to study

abroad from friends or peers

79

20

1

N range=1,580–1,589

(Differences in total N are due to question non-response)

*Numbers displayed in percentages

How Gilman Scholars Define Themselves

Financial constraints made up a large part of how Scholars identified themselves. In focus groups

and interviews, Scholars spoke about seeing themselves differently from “typical” study abroad

participants, primarily by virtue of their lower socioeconomic status (SES). Scholars were aware

of their families’ specific economic status and how it had affected their educational paths.

Interviewed scholars made a point

of speaking about their family’s

financial circumstances and income,

often noting that they were the first

in their families to attend college.

At times they referred to themselves

as poor.

Forty-four percent of survey respondents indicated that they were part of the first generation in

their families to attend college. Along with their SES, these Scholars also identified their race or

ethnicity as other factors that made them “atypical” of U.S. study abroad participants.

In addition, Scholars who had a disability, were older students, or had children mentioned these

situations as factors that had made them “atypical” of the U.S. study abroad population.

…MY PARENTS ARE FROM GUATEMALA…MY DAD

WORKS IN A FACTORY, SO WHEN HE HEARS HIS

KID WANTS TO GO TO SWITZERLAND—HE

[LITERALLY SAID], “THAT’S WHAT RICH KIDS DO.

YOU’RE NOT A RICH KID.” —SCHOLAR, 2002

16

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Scholarship’s Role in Easing Financial Constraints

Several themes emerged from focus groups and survey responses about how the Gilman

Scholarship funds had helped survey respondents deal with financial constraints. Some Scholars

reported that they would not have been able to study abroad without the Gilman Scholarship:

I definitely couldn’t have afforded it. My family didn’t have a lot of money. I had to

support myself for school... I had to pay for everything on my own. There’s no way I

would have been able to go abroad without that. —Scholar, 2004

Gilman Scholarship funds also gave Scholars the opportunity to focus on their studies without

constantly worrying about money:

For the first time in my higher education experience, it allowed me to focus completely on

my academics and study abroad experience instead of worrying about [how] to pay for

school. It provided me with a stress-free environment to fully embrace the study abroad

experience. —Scholar, 2008

The Gilman Scholarship funds allowed Scholars to attend cultural events and travel to other

countries in the region:

The Gilman Scholarship allowed me to study abroad the way a curious student should—

with the ability to travel. Had I not received this scholarship, I would not have been able

to study abroad, and certainly would not have been able to leave the village where I lived

very often. I was able to travel to many different areas of Morocco, giving me greater

perspective into the range of experiences available there. This improved my knowledge of

the country, as well as my own savvy. —Scholar, 2008

New Academic Opportunities Overseas

In addition to giving recipients access to new countries and cultures, Gilman Scholarships also

supported their enrollment in a variety of academic study abroad programs offering different

structures, students, activities,

academic topics and extracurricular

experiences than their home

institutions. Some of these (such as

language study) are explored further

in this report. The vast majority (88

percent) took courses on the

history/culture of the host country; about half participated in service learning/volunteer project.

A smaller percentage had internships as part of their programs.

Eighty-three percent of survey respondents indicated that the Gilman Scholarship had enabled

them to undertake academic activities overseas that they could not have taken at their home

institutions.

83% OF RESPONDENTS INDICATED THAT THE

GILMAN SCHOLARSHIP HAD ENABLED THEM TO

UNDERTAKE ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OVERSEAS

THEY COULD NOT HAVE TAKEN AT THEIR HOME

INSTITUTIONS.

17

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

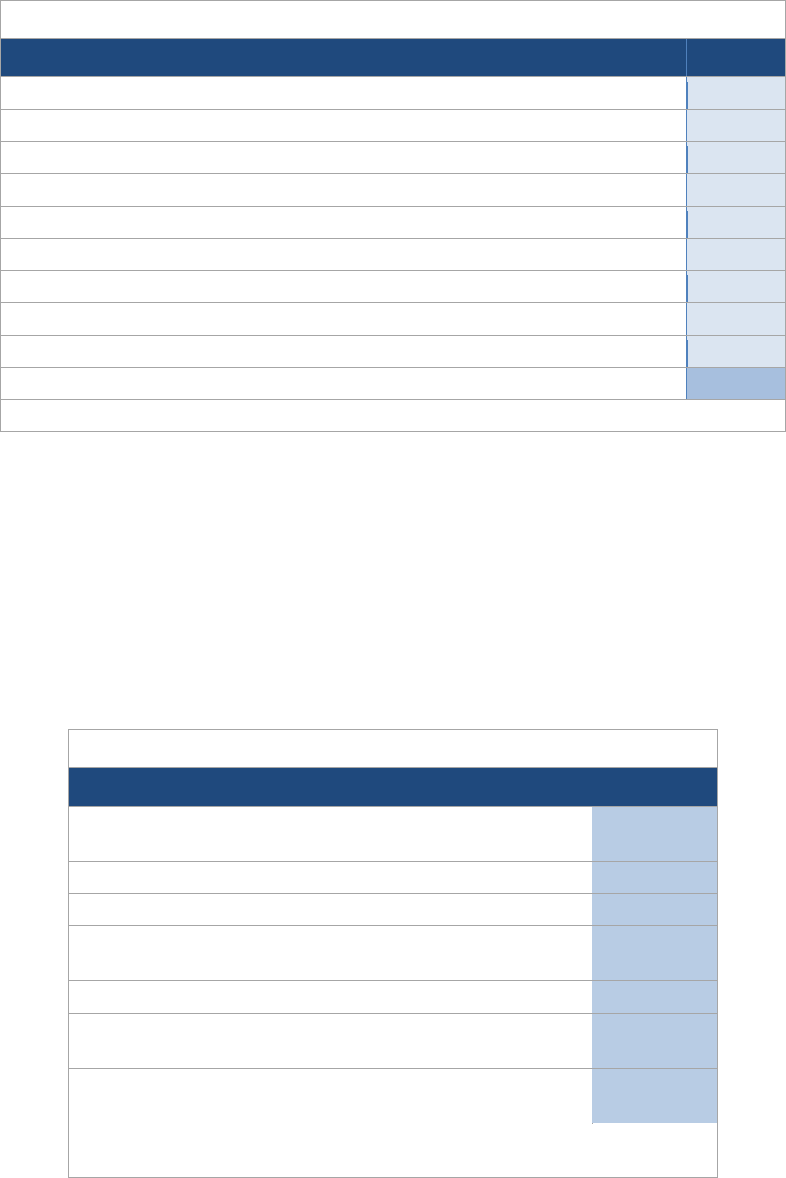

Table 2: Academic Activities while Studying Abroad

Academic and extracurricular activities

1

Percent

Took course(s) on history/culture of host country or region

88

Studied a foreign language

79

Participated in service learning/volunteer project

45

Carried out an internship

15

Participated in extracurricular activities sponsored by the host

institution

2

Took other academic courses

3

Conducted a research project or independent study

2

Other (e.g., student teaching, academic trip, thesis, video project)

4

N range=1,585–1,591

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

18

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

…[S]TUDY ABROAD CHANGES THE LENS

THROUGH WHICH YOU SEE THE WORLD…

WHEN THERE IS A PROBLEM OF

INTERNATIONAL CONCERN, I TRY TO

THINK ABOUT IT FROM A

COMPREHENSIVE POINT OF VIEW

KNOWING THAT THE CURRENT STATE OF A

COUNTRY, AN EVENT, OR A CONFLICT IS

PROBABLY THE RESULT OF YEARS AND

YEARS OF DIFFERENT DECISIONS AND

EVENTS… —SCHOLAR, 2010

The evaluation demonstrates how the Gilman Scholarship supported Scholars in expanding their

knowledge of other people, cultures and perspectives.

Shifts in Worldview and Perspective

As discussed in the previous section, more than half of the survey respondents (52 percent) said

they had concerns about living in a foreign culture. Yet after coming home, the majority (74

percent) kept an active interest in the country where they studied. In focus groups, when asked

how the Gilman Scholarship shifted their worldview, some Scholars said they came to see

themselves as members of a global community or described themselves as having a “global

perspective,” or being “citizens of the world.” Scholars developed a greater ability to analyze

world affairs and the international arena from a non-U.S. perspective. One Scholar described

seeing his community’s role differently: “[The Gilman experience] helped me be more active in

my immediate community and encouraged me to think about my community's place in the global

community.” —Scholar, 2002

Scholars also described feeling better

prepared to engage in the international

arena. Seventy-nine percent followed

media coverage on the country or

geopolitical region where they studied. In

focus groups, Scholars said that the

Scholarship provided an opportunity for

them to develop an analytic framework

through which to observe the world and

scrutinize information about it.

International Engagement

After returning home from studying abroad, Scholars sustained their international engagement

through a wide range of activities, as illustrated in Table 3. Eighty-four percent of Scholars

reported maintaining relationships with people from the country where they studied. Seventy-

four percent remained actively interested in the culture of the host country. More than half (66

percent) found opportunities to serve as a bridge between Americans and people from different

countries and cultures when they returned to the United States.

3 | Shifts and Expansion in Perspectives

19

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

[THE GILMAN SCHOLARSHIP EXPERIENCE

WAS] CRUCIAL AND DEFINITELY A

PIVOTAL [POINT] FOR ME… IT SORT OF

WAS THE FIRST BIG STEP IN FIGURING

OUT HOW I WANTED TO CONTRIBUTE TO

THE WORLD, DEFINITELY. —SCHOLAR, 2005

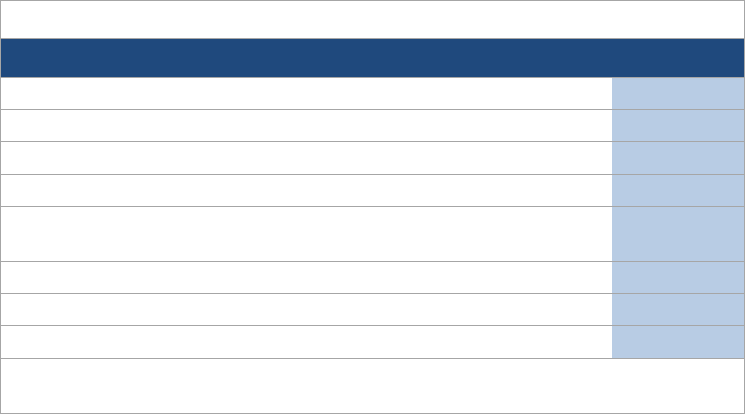

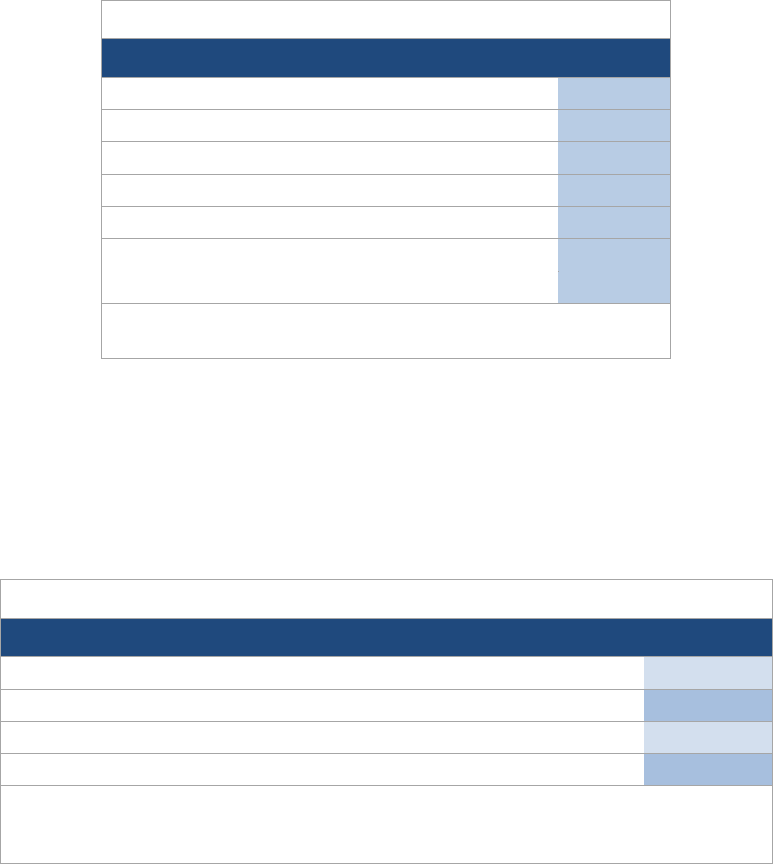

Table 3: International and Cross-cultural Personal Activities after

Studying Abroad

Activity

1

Percent

Maintained relationships with people from the country

where studied

84

Followed media coverage on the country or geopolitical

region where studied

79

Kept up active interest in culture of the country studied

74

Took on bridging roles between people from different

countries/cultures

66

Returned to the country where studied

36

Hosted someone from country

15

N=1,591

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

Diverse Ambassadors

In focus group discussions, several Scholars

also described the study abroad experience as

clarifying their own American identity, and

discussed how this influenced their role as

unofficial American ambassadors.

One African-American Scholar commented, “I would say that I didn’t think of myself as atypical

until I went to South Africa and [faced questions] like, ‘You’re not African? ….Black people

don’t come over here.’ Okay. So that started to [make me think about] why it was so important to

have this scholarship….”

The Gilman Scholarship helped to develop Scholars’ knowledge of specific areas of the world,

as well as broadened their perspective on global issues. Studying abroad also gave some

recipients an opportunity to see themselves—in some cases for the first time—as representatives

of American diversity in their host countries. These expansions and shifts in thinking were first

steps in helping Scholars consider how they want to contribute to the world.

20

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

At time of the survey

65% had a Bachelor’s

27% had a Master’s

21% degreed in STEM

field

23% in Humanities

33% in Social Sciences

10% Education/English

Language Instruction

When asked to project into

the future, 77% of survey

respondents envisioned

pursuing advanced degrees:

43% Master’s

25% Doctorate

9% Other professional

such as MD, JD or DDS

One-third were still enrolled

at full-time students. More

than half of these were

pursuing Master’s Degrees

and one-quarter were

pursuing a Doctoral Degree.

ACADEMIC PROFILE

The Gilman Scholarship gives participants access to a broader array of academic courses than

they would have at their home institutions. It also influences their choices to pursue international

topics that they might not have previously considered. In some cases, the Scholarship catalyzed a

desire to pursue graduate studies or professional degrees.

Ninety-two percent of survey respondents had obtained a

Bachelor’s or a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree since

studying abroad. Of particular note, of the 51 survey

respondents who had attended 2-year colleges at the time of

their applications, 35 percent had gone on to complete an

Associate’s degree and 43 percent had obtained Bachelor’s

degrees. A further 12 percent had gone on to attain a Master’s

degree.

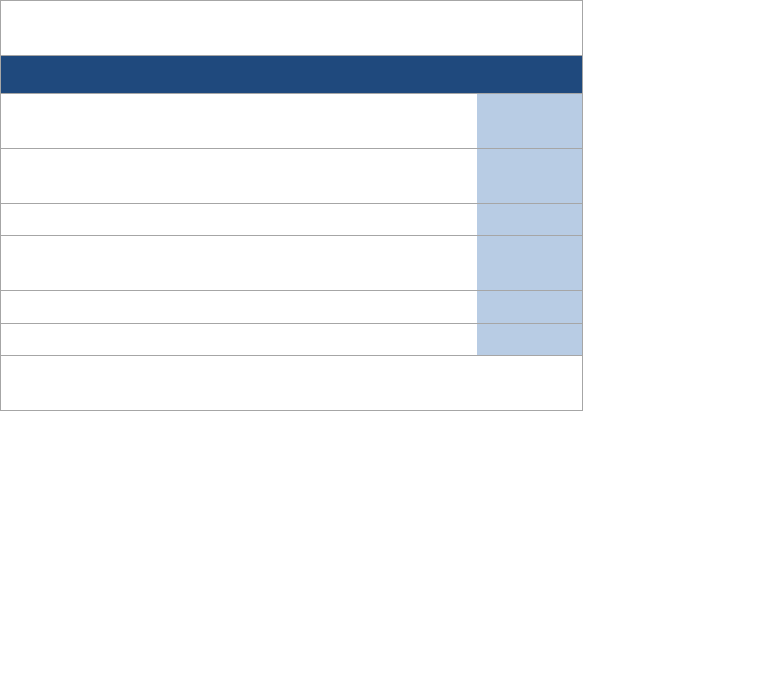

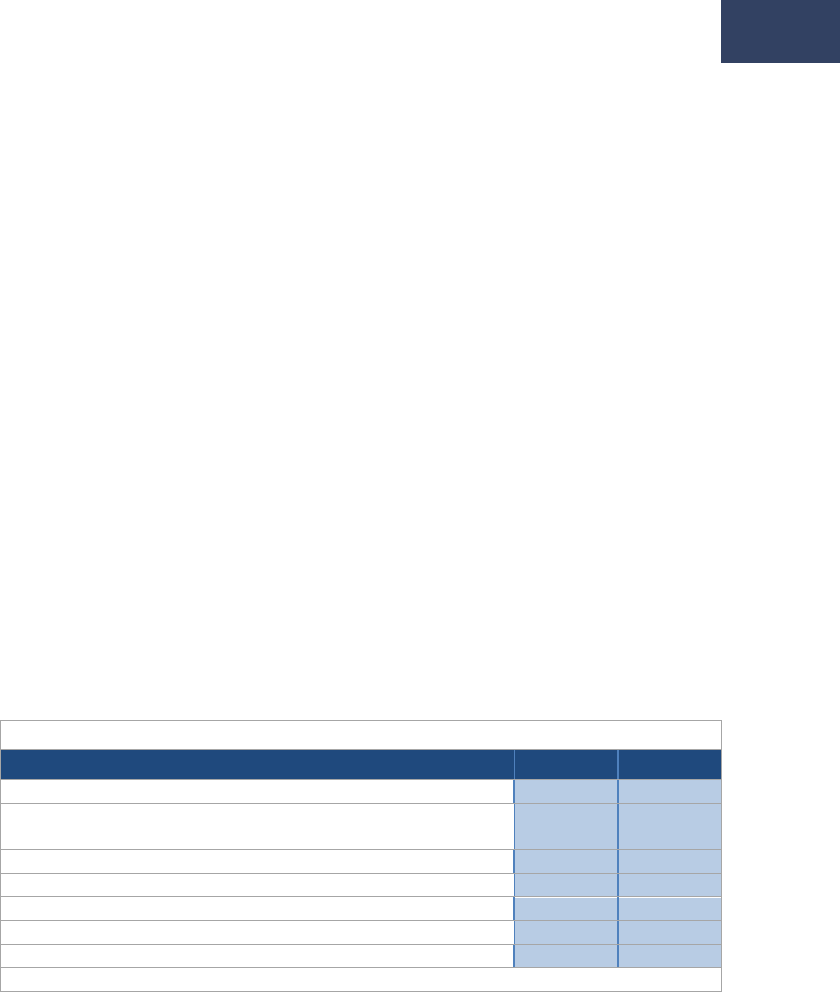

Table 4: Highest Degree Eventually Earned by Scholars who

Attended 2-year Colleges at Time of Gilman Application

Degree

Percent

High School degree or GED

10

Associate’s Degree

35

Bachelor’s Degree

43

Master’s Degree

12

Total

100

N=51

Keeping in mind that many of the surveyed Gilman Scholars

were the first in their families to attend undergraduate colleges

and universities (44 percent), it is notable that more than three-

fourths (77 percent) of survey respondents planned to pursue

advanced academic or professional degrees (Table 5). At the

time they were surveyed, 43 percent planned on pursuing a

Master’s degree, 25 percent a Doctorate and 9 percent some

other professional degree.

4 | Shifts and Expansion in Academic Choices

21

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

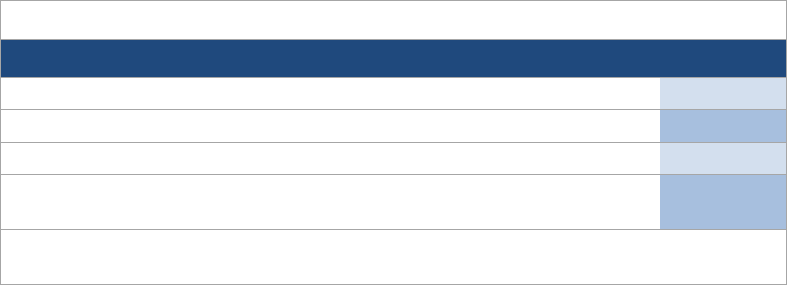

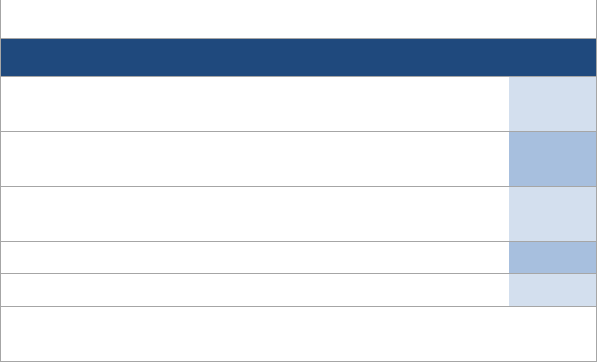

Table 5: Highest Academic Degree Planning to Pursue

Degree

Percent

1

Bachelor’s Degree

10

Master’s Degree

43

Doctorate

25

Other professional degree (MD, JD, DDS)

9

Not sure

13

Other (High School, Associate’s)

<1

Total

100

N=1,581

1

Column percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding

Effects on Undergraduate Study: Supplementing Core Studies with International Topics

Of the 1,441 survey respondents who returned to undergraduate studies after their Gilman

Scholarship experience, 87 percent (1,253 respondents) reported taking a greater interest in

international or cross-cultural topics, and more than one-third indicated that they had chosen an

academic major or minor field of concentration with an international or cross-cultural focus.

Table 6: Undergraduate Academic Study

Academic activities

1

Percent

Took a greater interest in international/ cross-cultural topics

87

Chose major and/or minor with international/cross-cultural focus

35

Undertook research project with international /cross-cultural focus

31

Pursued undergraduate thesis on an international/cross-cultural topic

2

25

N=1,441

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

2

Not all of respondents wrote, or had the option of writing, an undergraduate thesis.

In focus groups, Scholars reported taking on new academic courses, supplementing their major

core studies with international and cross-cultural topics. This approach enabled some to continue

exploring particular subjects in depth, while others studied new subject areas of interest on the

macro-level:

There was one class in particular that immediately sparked my interest in the social

sciences. I took a socio-politics class in Spain and when I was done with that course, I

knew I wanted to change my major to sociology. Upon returning to [my school], I

changed my major and fell in love with sociology. It expanded my mind and I now see the

world through a macro lens. —Scholar, 2009

Another approach these Scholars described was to select a minor field of concentration that

reflected their interest in the foreign language they had studied while abroad.

22

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Scholars also reported that they had taken an increased interest in specific sets of issues, as a

result of their experiences abroad. For example, one Scholar created her own undergraduate

major:

My experience in Ghana inspired me to pursue a degree in human rights and social

justice. —Scholar, 2008

For undergraduate study, the Gilman Scholarship experience was often the catalyst for a broader

interest in multiple international topics, or a more specific exploration of knowledge within a

particular undergraduate discipline.

Effects on Graduate/Professional Study: A Decisive Factor in Academic Choice

While undergraduates expanded their academic horizons upon returning home, Scholars who

went on to pursue graduate school or professional degrees described the Gilman Scholarship

experience as a decisive factor in their choice of academic field.

Of the 819 survey respondents who were attending or already completed graduate or professional

school at the time of the evaluation, almost half (48 percent) had chosen a concentration with an

international or cross-cultural focus, and more than one-third (36 percent) had studied abroad

again or pursued international field research. Almost one-third (31 percent) had written or were

writing a thesis or dissertation on an international or cross-cultural topic (Table 7).

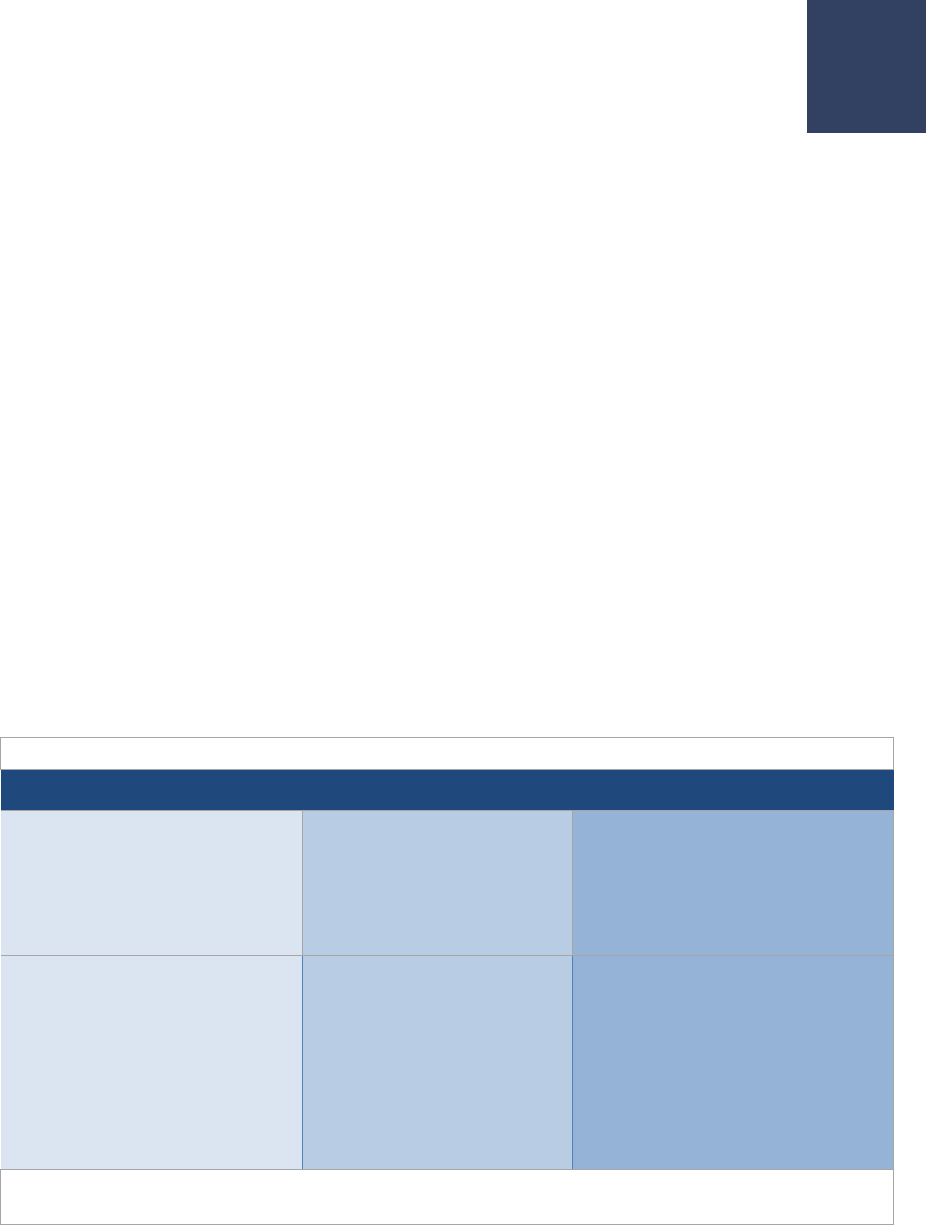

Table 7: Gilman Scholars’ Graduate or Professional Studies

Activities

1

Percent

Chose concentration or specialization with international /cross-cultural focus

48

Studied abroad and/or pursued international field research

36

Pursued an international /cross-cultural thesis or dissertation topic

31

Participated in internship or externship with international /cross-cultural

focus

27

N=819

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

Influence on Medical Studies

A number of Scholars who had gone on to study and practice medicine said that they had done so

because of the Gilman Scholarship experience. Of those in the medical profession, a small sub-

group described the experience as helping to affirm their commitment to serving low-income,

underserved populations, both in the United States and abroad.

For others in the medical field, the Gilman Scholarship had exposed them to new areas of

learning, such as medical ethics or national differences in health care delivery. This influenced

subsequent educational choices, adding international, political and socioeconomic dimensions to

their understanding of medicine and health care.

23

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Developing International Focuses

A number of Scholars said that their experiences had encouraged them to study international

fields or topics in graduate school. For example, one Scholar described how the Gilman

Scholarship experience inspired him to focus his interest in international relations on sustainable

agriculture:

I'd always wanted to pursue a graduate degree in international relations, but studying

abroad in a third world country showed me how interested I was in international

development and helping the impoverished of the world raise their quality of life. I'm now

more interested in pursuing a degree in international development with a focus in

sustainable agriculture and/or horticulture as opposed to security studies as I'd planned

before. —Scholar, 2008

International Education Studies

The Gilman Scholarship experience led some Scholars to study international education at the

graduate level, with the aim of eventually serving international students and Americans studying

abroad:

For my Master's thesis, I interviewed international students about their experiences

studying in the United States. My experience studying abroad as a Gilman Scholar

informed my research and let me connect with my research participants about their

intercultural experiences. —Scholar, 2006

Now, I am pursuing a Master's in higher education and hope to work with study abroad

offices to send students abroad as well as welcome international students to campus.

—Scholar, 2008

Other Scholars pursued teaching English and foreign language credentials:

I earned my ESL (English as a Second Language) program specialist certificate… after

graduation, inspired by my desire to continue working with Latinos after studying

abroad. —Scholar, 2003

Studying in Morocco pointed out to me the differences in how cultures approach the

teaching of second/foreign languages, and this is partly why I am pursuing my PhD on

the topic. —Scholar, 2010

Fellowships, Scholarships and Certificates

Thirty percent of all Gilman Scholars survey respondents reported having pursued educational

activities inspired by their Gilman Scholarship experience. Of these, 34 percent received

fellowships or scholarships—the largest portion of that group going abroad again as Fulbright

Students (14 percent). Twenty-three percent received certificates in specific professional fields—

the largest portion of that group obtained TEFL/TESOL certification (9 percent).

24

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Enabling Graduate Study

In addition to influencing their academic choices, some Scholars believed that the Gilman

Scholarship had been the reason for their acceptance to graduate school. Whether through the

coursework or the international experience—or both—Gilman provided these Scholars with the

qualifications to make them competitive, prepared graduate students:

I have recently been granted acceptance into an international executive MBA program

offered through UNC, Kenan-Flager Business School in conjunction with four other

premier universities, representing four other continents. [The universities] work together

to create a truly global executive MBA experience. I can trace my acceptance into this

prestigious program directly to the opportunities afforded me through the Gilman

[Scholarship]. —Scholar, 2007

Whatever their undergraduate field of study, Gilman Scholars reported that the opportunity to

study abroad expanded their academic horizons by cultivating their interest in international

topics. Some enriched their coursework through other classes or research projects with an

international focus. For those students who went on to pursue graduate or professional degrees, a

notable portion chose academic areas that would develop the skills needed to address global

challenges including food security, medical services for the poor, and the internationalization of

higher education.

In a later section, we will investigate how Scholars applied the skills they acquired as a result of

the Gilman Scholarship to the labor market.

25

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Foreign language skills are critical to improving Americans’ understanding of other countries

and increasing U.S. global economic competitiveness. Language learning gives young

Americans tools that will allow them to better engage with foreign counterparts in international

settings. The Gilman Scholarship affords recipients the opportunity to pursue language study

while abroad. However, in some cases where foreign language study was not the focus of the

international experience, Scholars returned home and participated in language study that was

inspired by their time in a foreign country.

Gilman Scholars are also eligible to receive a $3,000 Critical Need Language Supplement in

addition to their regular scholarship award. This scholarship, established by ECA as part of the

National Security Language Initiative of 2006, was designed to increase the number of U.S.

citizens learning high-priority languages, such as Arabic, Mandarin, and Russian.

Foreign Language Learning Overseas

Seventy-nine percent of survey respondents studied a foreign language while on their academic

study program overseas. They studied a diverse group of languages, with 43 percent studying

romance languages and 28 percent studying Asian languages.

Table 8: The breakdown of languages studied by Gilman Scholar survey respondents

Critical Need Languages are denoted by italics

Romance Languages: 43%

Spanish: 28%

French: 8%

Italian: 4%

Portuguese: 2%

Catalan: <1%

Asian Languages: 28%

Chinese: 12%

Japanese: 10%

Korean: 3%

Thai: 2%

Other: 1%

Semitic Languages: 7 %

Arabic: 7%

Other European Languages: 13%

German: 4%

Russian: 3%

Czech: 1%

Swedish: 1%

African Languages: 6%

Twi: 3%

Swahili/Kiswahili: <1%

Other: 3%

Other: 5%

Indic Languages: 1 %

Turkic Languages: 1 %

Native American Languages:

(Aymara, Tzotzil) <0.5 %

Oceanic/Polynesian Languages:

(Maori) <0.5 %

Other (not specified): <0.5 %

N= 1,251

Percentages may not add to 100 percent due to rounding

5 | Foreign Language Study

26

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Foreign Language Study After Returning Home

Survey results revealed that many respondents kept up their new foreign language skills upon

returning home. For a few who had not studied a foreign language while abroad, the Gilman

Scholarship experience led them to language studies after returning home. Scholars sought

continuing language opportunities through their academic studies or in their personal lives

outside of class.

Scholars were asked if they had undertaken specific language-related activities as undergraduates

or graduate or professional school students. A majority of the undergraduates (64 percent) had

either continued or started taking language courses. More than a quarter of graduate/professional

students (29 percent) had taken more foreign language courses. Among Scholars who had

studied a language while abroad, more than three-fourths (82 percent) sought opportunities to

speak the language they had studied upon returning home.

Table 9: Pursuit of foreign language activities after studying abroad

1

Activity

Percent

Sought opportunities to speak language studied

82

Took foreign language courses outside formal setting

28

N=1,251

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

Scholars also mentioned using strategies such as conversing with language partners, participating

in culture clubs, watching foreign dramas, reading foreign newspapers and novels, and taking

private language classes.

One Scholar used this multi-pronged approach to maintaining her French language skills:

I started a French circle at my college after I got back and went on to do the Peace

Corps in a French-speaking country and then... started a French circle at my [next]

employer. Then I’ve just kept working in places where you speak French. —Scholar,

2003

While foreign language study is not required under the Gilman Scholarship, it is a critical part of

many Gilman Scholars’ study abroad experiences. For some Scholars, it established a foundation

from which they continued language study during undergraduate and graduate studies. The next

section discusses some of the ways in which foreign language skills have influenced Scholar’s

professional paths.

27

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

As discussed in previous sections, the Gilman Scholarship can be a transformative experience for

award recipients. The Scholarship enabled U.S. undergraduates with limited financial resources

to develop competencies required to compete in a global economy, helped focus their academic

pursuits on international topics, and encouraged recipients to deepen their foreign language

skills. In this section we will see how the Gilman Scholarship experience influences Scholars’

professional paths. In this section we will see how the Gilman Scholarship experience influences

Scholars’ professional paths.

Employment Profile of the Gilman Scholars

Almost all survey respondents (97 percent) had worked in at least one job since returning home

from their Gilman Scholarship experience, and eight in 10 (79 percent) were working full-time at

the time of the survey. Scholars were working in a diverse set of professional fields. The most

common professional fields were in Education, Training, and Library (26 percent); Business,

Financial Operations and Sales (15 percent); STEM fields, such as Engineering, Computer

Science, and Life Sciences (13 percent); Healthcare (9 percent); and, Community and Social

Services (6 percent).

The most common employers of Gilman Scholars included Private Sector (39 percent), Colleges

and Universities (17 percent), and NGO/Non-Profit Organizations (16 percent). Thirteen percent

of Gilman Scholars were employed by the U.S. Federal Government or State or local

governments.

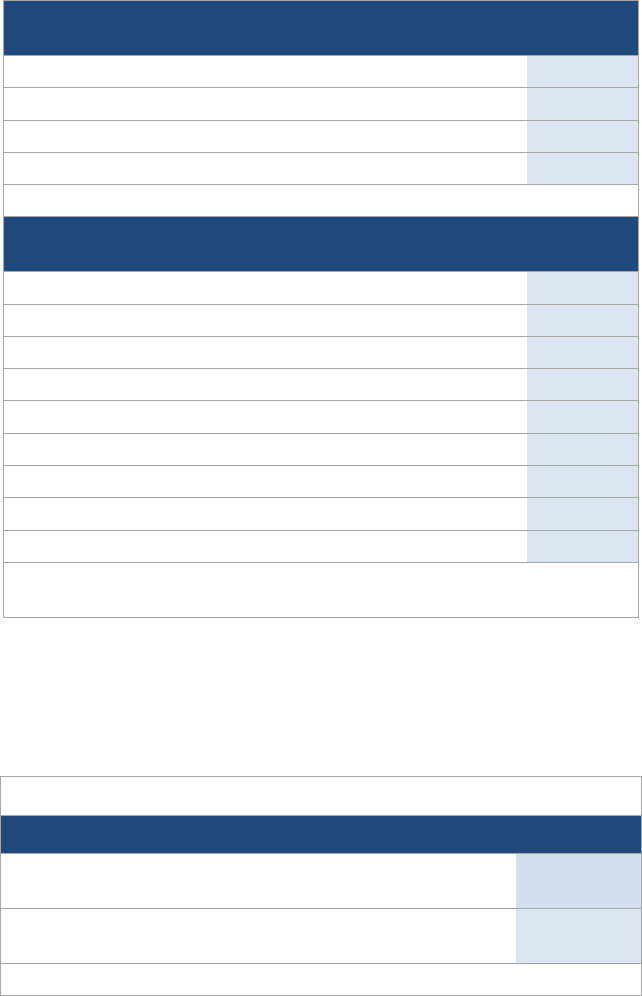

Table 10: Professional Fields of Gilman Scholars

Field

Percent

Education, Training, and Library

26

Business and Financial Operations

10

Healthcare

9

Community and Social Services

6

Engineering, Architecture, and Landscape Architecture

5

Sales and Related Occupations, including Marketing

5

Computer and Mathematical

4

Life, Physical, and Social Science

4

Other (e.g., Legal, Media, Arts, Design, and Entertainment, Military,

Management, Office and Administrative Support)

30

Total

100

N=1,257

6 | Shifts and Expansion in Professional Choices

28

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

Table 11: Current Employers of Gilman Scholars

Employment Type

Percent

Private Sector

39

College/University

17

NGO/Non-profit Organization

16

Elementary/Middle/High School

9

U.S. Federal Government

7

State or Local Government

6

Self-Employed

4

International Entity

1

Other

1

Total

100

N=1,238

Impact of Gilman on Career Perspective

Scholars found that the study abroad experience gave them a new perspective on the possibilities

for their careers. For example, almost three-quarters (73 percent) of survey respondents reported

that the international experience afforded by the Gilman Scholarship caused them to broaden the

geographic range of locations where they might work in the future. Sixty-seven percent of

survey respondents reported wanting to work in a cross-cultural or international field. In

addition, more than half (59 percent) reported having applied for positions at companies that

included an international or cross-cultural focus.

Table 12: Impact of Gilman Scholarships on Career Perspective

Professional Vision

1

Percent

Broadened the geographic locations where they are willing to

work

73

Promoted desire to work in cross-cultural/international field

67

Broadened range of employers they would consider

60

Led them to applied for positions at companies with

international/ cross-cultural focus

59

Clarified desired career

48

Led them to seek company/organization with diverse

workforce

47

Changed their career direction to more international/cross-

cultural focus

39

N=1,591

1

Respondents could give multiple answers

For nearly half of the survey respondents (48 percent), the Gilman Scholarship experience

clarified their professional direction. In some cases, the experience introduced Scholars to new

29

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

academic fields, for example, in various STEM fields, which became the focal point of their

professional lives:

[Studying in Spain] exposed me to a different world [neuroscience] that I didn’t know

existed as a field and as a career. And, after that it definitely changed how I was thinking

about myself and what I wanted to pursue for my professional career. —Scholar, 2010

Before the Gilman experience, I did not have a clear career focus. The Gilman began my

transition toward my current career path pursuing an advanced degree in Geography –

Scholar, 2003

Scholars gained awareness of issues such as global poverty and social inequality and this had an

impact on their professional choices:

I [had] never thought about a lot of social issues that were brought up when I was in

Cape Town, South Africa. They’re sort of in your face, and it really, I guess, really

sparked an interest in me in social justice and actually changed the course of my career

from there. —Scholar, 2009

Working with Disadvantaged Communities

For some Scholars, their Gilman Scholarship experience proved a catalyst for their desire to

work with underserved or disadvantaged communities, in a variety of fields, both internationally

and domestically:

The Gilman, along with my home university, gave me the much-needed encouragement to

pursue my passion of working within the realm of international higher education. My

ultimate goal is to help other low-income minority students explore all options to make it

possible for them to study abroad as well. —Scholar, 2009

Their desire to serve disadvantaged communities was evident in the pursuit of employment and

careers in medicine, public health, education, public service, the Peace Corps, domestic violence

prevention and services, involvement with migrant agricultural workers, immigrant communities

and related research and study:

It [Gilman] reinforced my commitment to work as a physician with the poorest and most

needy communities around the world. —Scholar, 2008

My experience as a Gilman Scholar inspired me to pursue a career in public health.

While abroad I interned for an organization that provides support services to pregnant

and parenting teens in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Upon returning to the United States, I

continued to work with this population. —Scholar, 2008

Gilman... gave me a taste for working internationally and working on the ground and

being involved in the community. I’ve since started working in global health, and I have

30

Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program, Evaluation Report

Evaluation Division, ECA, U.S. Department of State

used what I’ve learned when I was in Mali whenever I go on work trips and try to get

more involved with what’s going on in the community. —Scholar, 2003

Scholars described how their Gilman Scholarship experiences had committed them to work

locally within their own communities:

Actually, my Gilman experience influenced me more strongly with regard to the fact that

I am more committed to working locally, as opposed to internationally… I have

committed my life to helping U.S. citizens gain greater self-reliance so that we can be

positive contributors to globally shared resources… —Scholar, 2008

I loved my time abroad and hope to go back to Brazil someday, but studying abroad (and

subsequent international trips) actually made me realize that I'm just as passionate about

giving back to my community here at home. This means that I am currently inclined to

work domestically, but it doesn't rule out future work abroad. —Scholar, 2006

Seeking International Workplaces

As a result of their Gilman Scholarship experience, Scholars had taken positions in workplaces

where they could use their international and/or cross-cultural competencies. As shown in Table

13 below, most survey respondents (83 percent) found jobs where they could interact with

people from different backgrounds or nationalities, and more than half (54 percent) reported

working in a field that includes an international or cross-cultural component.

Table 13: Work Environments of Gilman Scholars

1

After returning home

Percent

Interacted with people of different

backgrounds/nationalities in the workplace

83

Worked in a field that includes an international/ cross-

cultural component

54