The dierence that an eecve teacher can make in

the trajectory of a student's life is oen discussed and

well documented. Research indicates that teachers

are the most important school-based factor for

student growth and achievement. A single year with an

ineecve teacher can cost a student up to one and a

half years’ worth of achievement. On the other hand,

ve consecuve years with an eecve teacher could

nearly close the achievement gap.

In the 16 years since the inial passage of No Child Le

Behind (NCLB), the body of research around the impact

of teachers and state policy experimentaon on how

to measure eecveness have grown. This brief traces

the evoluon from the “Highly-Qualied Teacher”

provisions of NCLB to the teacher evaluaon systems

of the 2011 Elementary and Secondary Educaon Act

(ESEA) waivers to the present Every Student Succeeds

Act (ESSA), which refrains from being prescripve

on how states choose to address this queson, but

does oer several opportunies for innovaon and

experimentaon.

By Casey Wyant Remer,

Director of Policy & Research

ESSA

Educator

Policies & the

Every Student

Succeeds Act

Educator Policies & ESSA

1

In 2001, the Elementary and Secondary Educaon Act was reauthorized as No Child Le

Behind (NCLB). Among the general public, NCLB is probably best known for spurring the

implementaon of statewide standards and assessments and the reporng of the results

of those assessments annually. But the law also introduced a new term to the policy

discussion: highly-qualied teacher (HQT).

Highly-Qualied Teacher (n.) An educator who meets the following three

requirements: 1) Holds a bachelor’s degree; 2) Holds full state cercaon

or licensure; and 3) Demonstrates subject maer competency.

NCLB required that all core academic subjects be taught by teachers who were “highly

qualied,” but le it to states to individually dene the term. Evaluaons of NCLB

implementaon found that most teachers met the HQT requirement as determined by their

states—and also that those who did not were more likely to be found in special educaon,

science, and schools serving higher concentraons of low-income students. In addion,

because the specic criteria were set by the state, the denion varied widely, parcularly

when it came to the bar for subject-maer competency.

A 2007 survey conducted by the Center on Educaon Policy found that a majority of

state and district leaders reported that the HQT requirement had minimal or no impact

on student achievement. To explain this nding, crics would point to the focus on inputs

rather than outputs.

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, the Highly-Qualied Teacher requirements

are eliminated beginning in the 2016-17 school year.

ESSA does not set a minimum requirement for entry into the teaching profession.

States may set standards for cercaon and licensure as they see t.

2009-2015 | Priority: Eecveness

The conversaon began to change from the importance of inputs to outputs, and in 2009,

TNTP (then known as The New Teacher Project) released a report that added urgency to the

discussion around teacher qualicaons and eecveness: The Widget Eect.

For policymakers and educaon leaders who felt an urgent need to ensure that all students

were taught by an eecve teacher, the report rang an alarm bell: Under the exisng

evaluaon systems, more than 99 percent of teachers received a “sasfactory” rang under

the binary rang system that had been commonly used.

The conversaon changed again. No longer focused on inputs or binaries, stakeholders

began to explore how to dene and measure eecve teaching—in parcular the impact

that teachers have on their students’ achievement and growth.

These policies were pushed ahead by incenves from the U.S. Department of Educaon,

beginning with the Race to the Top compeon in 2009 and followed by ESEA exibility

waivers in 2011 (see box on next page).

2001-2017:

An Evoluon of Educator Policies

ESSA

Check

X

2001-2008 | Priority: Qualicaon

Educator Policies & ESSA

2

As a result, most states have moved towards evaluaon systems that:

» Include mulple levels of performance classicaon;

» Require more frequent evaluaon of all teachers; and

» Incorporate mulple measures, including student achievement.

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states are not required or incenvized to

implement educator evaluaon systems.

States that received waivers from ESEA are no longer required to adhere to the

systems they proposed.

2015 & Beyond | Priority: State Control

With federal incenves for teacher evaluaon removed through the passage of ESSA, state

leaders now have greater control and exibility to decide how best to connue (or if to

connue) implemenng and improving their evaluaon systems. ESSA does, however, sll

contain a range of provisions that relate to teachers and school leaders. As states move

from plan development and into implementaon and renement, there are several key

opportunies to address teacher and school leader eecveness within the law.

Federal Incenves for Teacher Evaluaon Systems

Beginning in 2009, many states modied or created legislaon regarding the

evaluaon of teachers in response to federal iniaves like Race to the Top (RT) and

ESEA exibility waivers. Both the RT rubric and the guidelines for ESEA exibility

emphasized the signicance of linking annual teacher evaluaons with measures of

student growth.

As a result of these

incenves, states

have moved towards

systems that include

mulple levels

of performance

classicaon, require

more frequent

evaluaon of all

teachers, and

incorporate mulple

measures, including

student achievement.

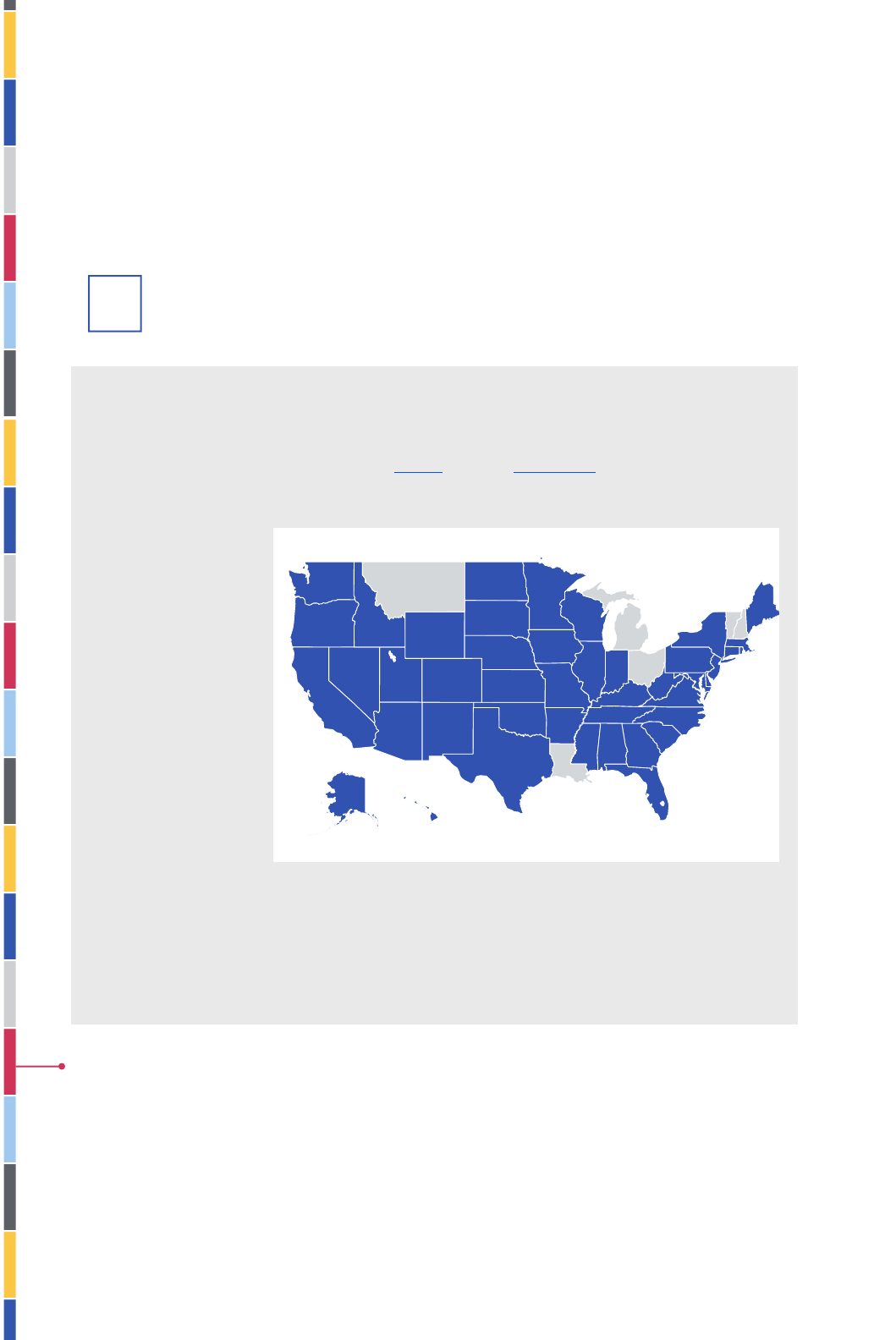

The number of states

requiring annual

evaluaons of all teachers increased from 15 states in 2009 to 26 states in 2015; 44

states require annual evaluaons of all new, probaonary teachers.

In the absence of these incenves for certain aspects of teacher evaluaon systems

under ESSA, some state legislatures are proposing bills that reduce the frequency

by which teachers are evaluated or eliminate student growth requirements for

determining eecveness.

ESSA

Check

X

Educator Policies & ESSA

3

48

States that Require Annual Evaluaons of New Teachers

Source: Naonal Council on Teacher Quality

While ESSA moves away from the “highly-qualied teachers” provisions in NCLB, the

new law draws aenon to an equity issue that has connued to stump states and

districts: the distribuon of teachers. Oen, one nds that the strongest teachers are

not necessarily in the schools that need them the most. ESSA requires states and districts

to report disparies that result in low-income students and minority students being taught by

ineecve, inexperienced, or out-of-eld teachers at higher rates than other students. This

requirement presents an opportunity for states to address any inequies in access to

eecve teaching and begin to address imbalances that have likely existed for years.

How does my state dene and measure teacher eecveness?

While there are no longer requirements for evaluaon systems linking teacher

eecveness with student growth or performance, states will need to carefully design

measures and denions of eecveness (and ineecveness), as well as dene

“inexperienced” if they are truly to idenfy and address imbalances in teacher distribuon

across their states. NCTQ provides best pracces and state exemplars for states to

consider around these issues in their ESSA Educator Equity Best Pracces Guide.

How will my state use this data to balance the distribuon of teachers?

States should explore any exisng programs they may have, as well as programs instuted

by districts to recruit and retain eecve teachers in tradionally under-resourced schools

and areas of the state. In parcular, states should consider how the opportunies around

teacher preparaon and school leadership (below) can be targeted to increase equity.

School leadership has been found by researchers to be second only to teaching in

its impact on children’s learning outcomes. The successful transformaon of low-

performing schools will require a sucient supply of school leaders with the requisite

skills, knowledge, and disposions to eect meaningful change. Research has shown that

frequent turnover of principals in underperforming schools serves to create instability

and undermine improvement eorts. For that reason, it is not enough to simply prepare

and hire talented leaders; policy soluons must be developed to ensure that eecve

principals remain in high-need schools for the long term.

Under ESSA, states have the ability to priorize school leadership through Title II monies,

including a new opon that allows them to reserve addional money for state-level school

leadership support (see box on next page). A variety of acvies that serve to improve the

principal pipeline, including the development or expansion of preparaon academies and

residencies. States can also consider using Title I School Improvement Funds to support

acvies to include school leaders.

Key Opportunies for

Enhancing Educator Policies

Equity

School Leadership

Educator Policies & ESSA

4

Title II At a Glance

Title II provides grants to State Educaon

Agencies and subgrants to local educaonal

agencies to:

» Increase student achievement consistent

with challenging state academic standards;

» Improve the quality and eecveness

of teachers, principals, and other school

leaders;

» Increase the number of teachers,

principals, and other school leaders

who are eecve at improving student

academic achievement in schools; and

» Provide low-income and minority students

greater access to eecve teachers,

principals, and other school leaders.

Title II, Part A Funds are distributed to states

using a formula that weights both students in

poverty and total student populaon.

» Under ESSA, the formula will transion

to weight poverty more and overall

populaon less.

» Of a State’s Allocaon:

» 95% is directed for district acvies.

» Up to 5% may be used for state

acvies.

» ESSA will allow states to set aside an

oponal 3% for statewide leadership

acvies. (92% local, 8% state)

Key to improving student outcomes is

establishing a professionalized teaching

workforce that is supported at every stage of

their career. ESSA authorizes states to use Title

II funds in ways that can create sustainable

frameworks for excellent teaching, including:

» Establishing or expanding teacher and

principal preparaon academies, including

teacher residency programs and school

leader residency programs.

» Assisng local educaon agencies in developing human capital management strategies,

including career ladders, mentor and inducon programs, and/or redesigned roles.

» Providing professional development for all teachers (previously funds could only used

for core academic subjects).

What are preparaon academies and what would one look like in my state?

Teacher preparaon academies operate with more autonomy than tradional teacher

preparaon programs and would be freed from having to sasfy certain state requirements.

Nevertheless, academies would sll be held accountable for producing candidates with

demonstrated records of improving student achievement. A signicant part of an academy’s

curriculum is hands-on clinical preparaon, also known as a “residency.” States may use

up to 2 percent of their Title II dollars to establish or enhance preparaon academies. The

Naonal Center for Teacher Residencies has created a toolkit with policy recommendaons

for states looking to bolster teacher residences through ESSA.

Recruing, Preparing, and

Retaining Excellent Teachers

How can my state priorize school leadership?

If your state has not used Title II dollars for

school leadership improvement in the past,

you are not alone—historically less than four

percent of Title II funds have been spent on

development for school leaders. Allong state

Title II dollars to culvang your principal

pipeline is a wise investment, parcularly for

regions that have had a historically hard me

nding and retaining eecve principals in

high-needs schools. New Leaders idenes

potenal paths for improving school leadership,

along with exemplars and key quesons

for policy leaders in Priorizing Leadership:

Opportunies in ESSA for Chief State

School Ocers. Looking for more? RAND, in

partnership with the Wallace Foundaon, oers

guidance on how to ulize ESSA in School

Leadership Intervenons Under the Every

Student Succeeds Act.

Educator Policies & ESSA

5

Looking Ahead

The eecveness and distribuon of teachers will connue to be an issue

that states and districts grapple with, parcularly for states with higher

numbers of rural and/or low-income students. Compounding this issue is the

supply of school leaders with the requisite skills, knowledge, and disposions

to eect meaningful change. As states move from ESSA plan development

into implementaon, and eventually renement, they must connue to push

for equity in access to highly eecve educators and school leaders.

As state and local-level policymakers search for ways to improve the

lowest-performing schools, they should consider strategies like those

above to ensure that eorts to redistribute eecve teachers and leaders

are sustained in such a way as to facilitate instuonal stability and lasng

improvement.

How can my state redesign incenves and structures

to keep great teachers in every classroom?

In most states and districts, systems are designed such that high-performing teachers are

incenvized to:

1) teach in high-performing schools and/or

2) leave the classroom to take administrave roles.

This is because the current step-and-lane salary schedule rewards teachers for degree

and experience but fails to compensate for a teacher taking on addional challenges and

responsibilies. States can use their Title II funds to support the development of career

ladders like Opportunity Culture and create incenves to teacher in high-needs schools.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR.

Foundation Board Chairman

Governor of NC

(

1977-1985

|

1993-2001

)

JAVAID E. SIDDIQI, Ph.D.

Executive Director and CEO

© 2017. The Hunt Institute. All rights reserved.

The Hunt Institute

Twitter

Facebook

YouTube

The Hunt Institute is an affiliate of the Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy.