The Association of

Accountants and

Financial Professionals

in Business

ima

Statement on Management Accounting

Enterprise Risk Management:

Tools and Techniques for Eective Implementation

About IMA

®

IMA

®

, the association of accountants and nancial

professionals in business, is one of the largest and

most respected associations focused exclusively on

advancing the management accounting profession.

Globally, IMA supports the profession through research,

the CMA

®

(Certied Management Accountant) program,

continuing education,networking, and advocacy of the

highest ethical business practices. IMA has a global

network of more than 70,000 members in 120 countries

and 300 professional and student chapters. Headquartered

in Montvale, N.J., IMA provides localized services through

its four global regions: The Americas; Asia/Pacic, Europe

and Middle East/Africa. For more information about IMA,

please visit www.imanet.org.

© 2007

Institute of Management Accountants

10 Paragon Drive, Suite 1

Montvale, NJ, 07645

www.imanet.org

About the Author

IMA

®

would like to acknowledge the work of William

G. Shenkir, Ph.D., CPA, and Paul L. Walker, Ph.D., CPA,

both of the McIntire School of Commerce, University of

Virginia, who were the authors of this SMA. Thanks also

go to Tim Leech of Paisley Consulting and COSO board

member Jeff Thomson, CMA, CAE, of IMA, who served

as reviewers and Raef Lawson, Ph.D., CMA, CPA, of IMA,

who serves as series editor.

Transforming the Finance Function

IMA Research

This research area focuses on the various stakeholders

that play a role in directing and controlling organizations,

including governing and regulatory bodies, public

accounting rms, and organizations’ board of directors

and senior management. Beyond focusing on the rights

and responsibilities of these stakeholders, research in

this area includes additional topics such as executive

compensation and enterprise risk management (ERM).

Table of Contents

Executive Summary...............................................................................................................7

Introduction..........................................................................................................................7

Scope.....................................................................................................................................8

Risk Identication Techniques...............................................................................................9

Brainstorming.....................................................................................................................11

Event Inventories and Loss Event Data.......................................................................................12

Interviews and Self-Assessment...............................................................................................13

Facilitated Workshops...........................................................................................................14

SWOT Analysis...................................................................................................................14

Risk Questionnaires and Surveys...............................................................................................15

Scenario Analysis.................................................................................................................15

Using Technology................................................................................................................16

Other Techniques................................................................................................................17

Analysis of Risk by Drivers...................................................................................................17

Risk Assessment Tools.........................................................................................................19

Categories..........................................................................................................................20

Qualitative vs. Quantitative.....................................................................................................20

Risk Rankings......................................................................................................................21

Impact and Probability.........................................................................................................21

Keys to Risk Maps ................................................................................................................22

Link to Objectives at Risk or Divisions at Risk...............................................................................24

Residual Risk................................................................................................................................24

Validating the Impact and Probability.........................................................................................25

Gain/Loss Curves................................................................................................................25

Tornado Charts.................................................................................................................... 26

Enterprise Risk Management: Tools and Techniques for Eective Implementation

Table of Contents, Cont’d

Risk-Adjusted Revenues.........................................................................................................27

A Common Sense Approach to Risk Assessment..........................................................................29

Probabilistic Models..............................................................................................................29

Seemingly Nonquantiable Risks.............................................................................................32

Practical Implementation Considerations...........................................................................33

ERM Infrastructure ...............................................................................................................33

ERM Maturity Models............................................................................................................34

Staging ERM Adoption for Early Wins........................................................................................36

The Role of the Management Accountant.................................................................................36

ERM Education and Training....................................................................................................36

Technology.........................................................................................................................37

Aligning Corporate Culture..............................................................................................................37

Building a Case for ERM.........................................................................................................38

The ROI of ERM..................................................................................................................38

Conclusion..........................................................................................................................39

Glossary.............................................................................................................................40

Reference List......................................................................................................................40

Additional Resources.......................................................................................................... 41

Table of Exhibits

Exhibit 1: A Continuous Risk Management Process............................................................ 9

Exhibit 2: Industry Portfolio of Risks ..................................................................................12

Exhibit 3A-D: Risk Identication Template....................................................................13-14

Exhibit 4: Inuence Diagram..............................................................................................18

Exhibit 5: Quantifying Risk: Determine the Drivers............................................................19

Exhibit 6: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Risk Assessment..........................20

Exhibit 7: Risk Map.............................................................................................................22

Exhibit 8: Risk Map Model................................................................................................23

Exhibit 9: Gain/Loss Probability Curve.............................................................................. 26

Exhibit 10: Tornado Chart: Earnings Variability by Sample Risks...................................... 27

Exhibit 11: Actual Revenue vs. Risk-Corrected Revenue...................................................28

Exhibit 12: Goals of Risk Management..............................................................................28

Exhibit 13: Earnings at Risk by Risk Factor.......................................................................30

Exhibit 14: Earnings at Risk Hedge Effectiveness Comparisons........................................30

Exhibit 15: Expected Earnings and EaR............................................................................ 31

Exhibit 16: Probability Assessment of Earnings Outcome.................................................31

Exhibit 17: ERM Maturity Model......................................................................................35

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

7

Enterprise risk management (ERM) takes a broad perspective on identifying the risks that could cause an

organization to fail to meet its strategies and objectives. In this Statement on Management Accounting

(SMA), several techniques for identifying risks are discussed and illustrated with examples from company

experiences. Once risks are identied, the next issue is to determine the root causes or what drives the risks.

A suggested approach is described and followed by a discussion of several qualitative and quantitative

procedures for assessing risks. Some practical ERM implementation considerations are also explored, including

infrastructure and maturity models, staging adoption, the role of the management accountant, education

and training, technology, aligning corporate culture, building a case for ERM, and the return on investment

(ROI) of ERM. Any organization—large or small; public, private, or not-for-prot; U.S.-based or global—that

has a stakeholder with expectations for business success can benet from the tools and techniques provided

in this SMA.

Executive Summary

In the economic landscape of the 21st Century, an organization’s business model is challenged constantly by

competitors and events that could give rise to substantial risks. An organization must strive to nd creative

ways to continuously reinvent its business model in order to sustain growth and create value for stakeholders.

Companies make money and increase stakeholder value by engaging in activities that have some risk, yet

stakeholders also tend to appreciate and reward some level of stability in their expected returns. Failure

to identify, assess, and manage the major risks facing the organization’s business model, however, may

unexpectedly result in signicant loss of stakeholder value. Thus senior leadership must implement processes

to effectively manage any substantial risks confronting the organization. This dual responsibility of growing

the business and managing risk has been noted by Jeffrey Immelt, chairman and CEO of General Electric

Co., when he described his position at GE as follows: “My job is to gure out how to grow and manage risk

and volatility at the same time.”

1

While leaders of successful organizations have always had some focus on managing risks, it typically has

been from a reactive exposure-by-exposure standpoint or a silo approach rather than a proactive, integrated,

across-the-organization perspective. Under a silo approach, individual organizational units deal with their

own risks, and often no single group or person in the organization has a grasp of the entire exposure confronting

the company (especially the overall organization’s “reputation” risk). To correct such a situation, enterprise

risk management (ERM) has emerged in recent years and takes an integrated and holistic view of the risks

facing the organization.

Introduction

1

Diane Brady, “General Electric, the Immelt Way,” Business Week, September, 2006, p. 33.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

8

2

The authors acknowledge that the ideas in this paragraph about the changing role of nancial professionals were taken from a presentation heard

some years ago (uncertain as to the date and place) and given by Jim Smith of The Marmon Group, Inc. While the original remarks were not given in

the context of ERM, they have been adapted accordingly.

This SMA is the second one to address enterprise risk management. The rst, Enterprise Risk Management:

Frameworks, Elements, and Integration, serves as the foundation for understanding and implementing ERM.

It highlights the various risk frameworks and statements that professional organizations around the world

have published. In addition, it discusses and illustrates through company experiences the core components

of a generic ERM framework. It also points out some entrepreneurial opportunities for change within an

organization (with specic leadership roles for the management accountant articulated) when ERM is incorporated

in such ongoing management activities such as strategic planning, the balanced scorecard, budgeting,

business continuity planning, and corporate governance. Finally, it takes up the issue of transitioning from

compliance under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), where the focus is on risks related to nancial reporting,

to an enterprise-wide perspective on risks, including strategic risks.

This SMA is addressed to management accounting and nance professionals who serve as strategic business

partners with management in the implementation of ERM in their organization. Others within the organization

responsible for risk management, information technology, and internal audit will also nd this SMA useful.

Like many other change initiatives going on within dynamic organizations, ERM provides an opportunity

for management accounting and nance professionals to alter how they are perceived by others in

the organization. By becoming a strategic partner in ERM implementation, they can be seen as “bean

sprouters” of new management initiatives rather than merely “bean counters.” They also can move from

being the historians and custodians of accounts to futuristic thinkers. They can become coaches and

players in a new management initiative important to the future overall well-being of the company rather

than merely scorekeepers on what has or has not been accomplished.

2

The focus of this SMA is on core tools and techniques to facilitate successful ERM implementation. While

other tools and techniques can be found in the Additional Resources section, this document emphasizes

those that are critical for most ERM initiatives. Since all organizations have stakeholders with ever-increasing

expectations, the tools and techniques discussed here are generally relevant to:

• Large and small organizations,

• Enterprises in the manufacturing and services sectors,

• Public and private organizations, and

• For-prot and not-for-prot organizations.

Scope

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

9

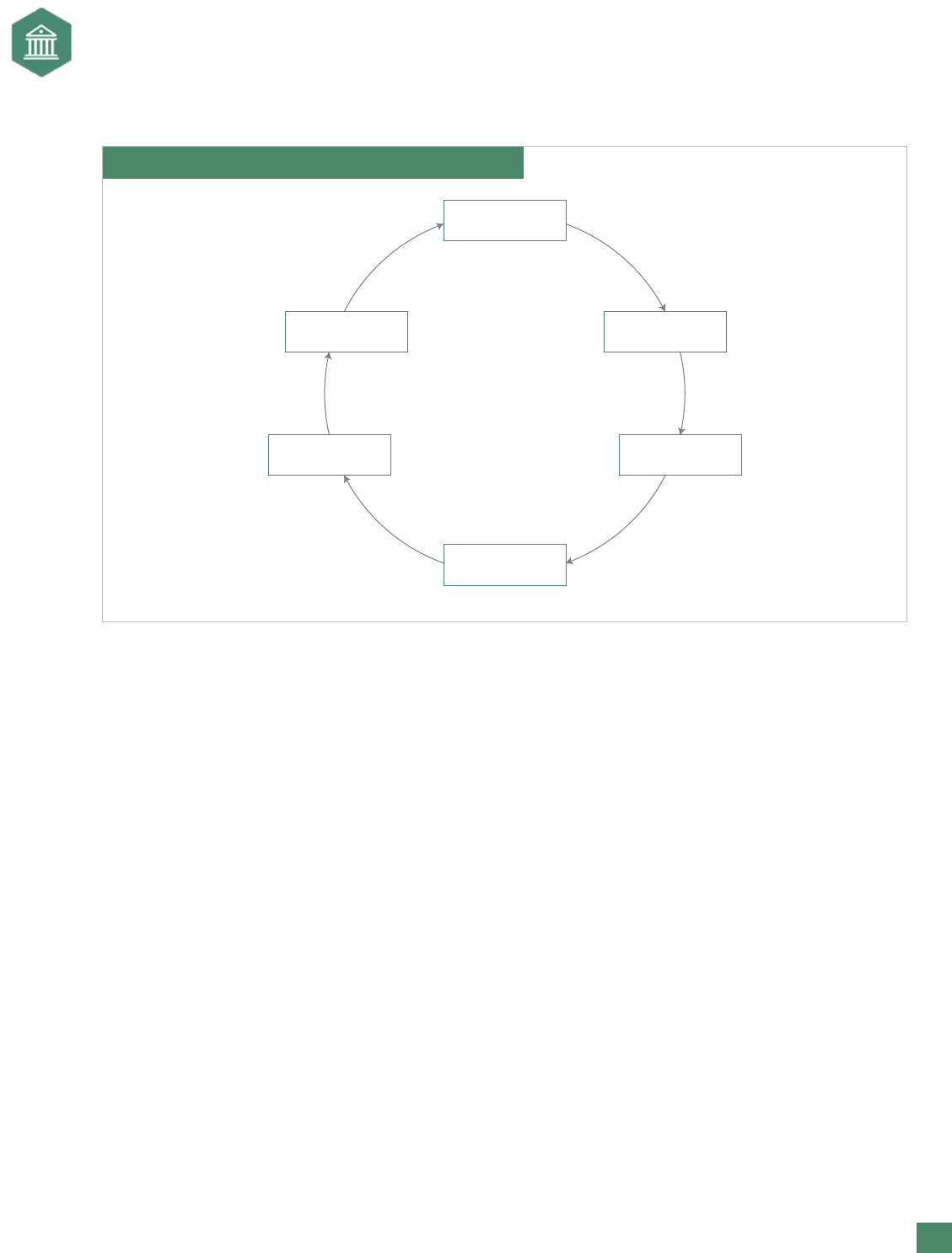

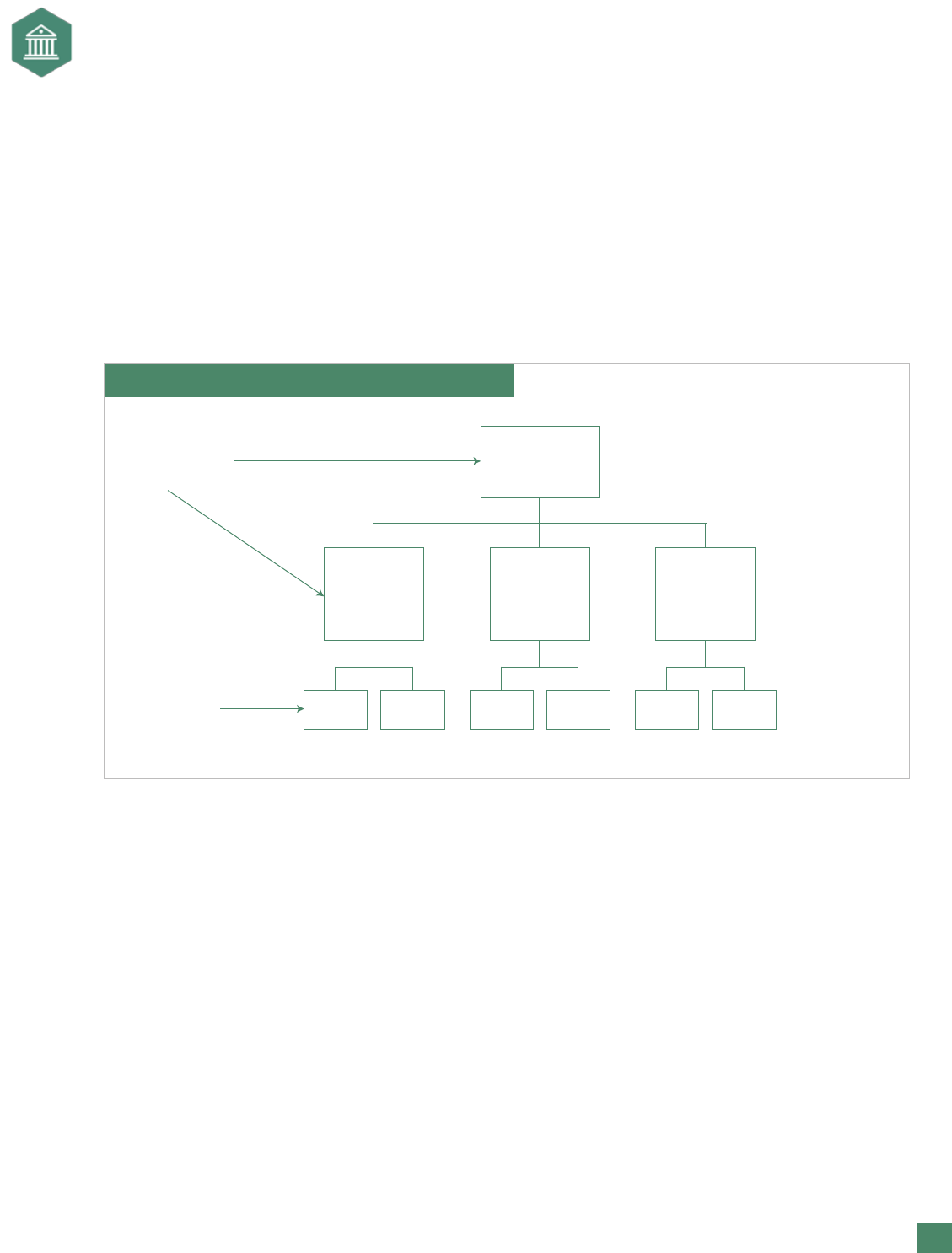

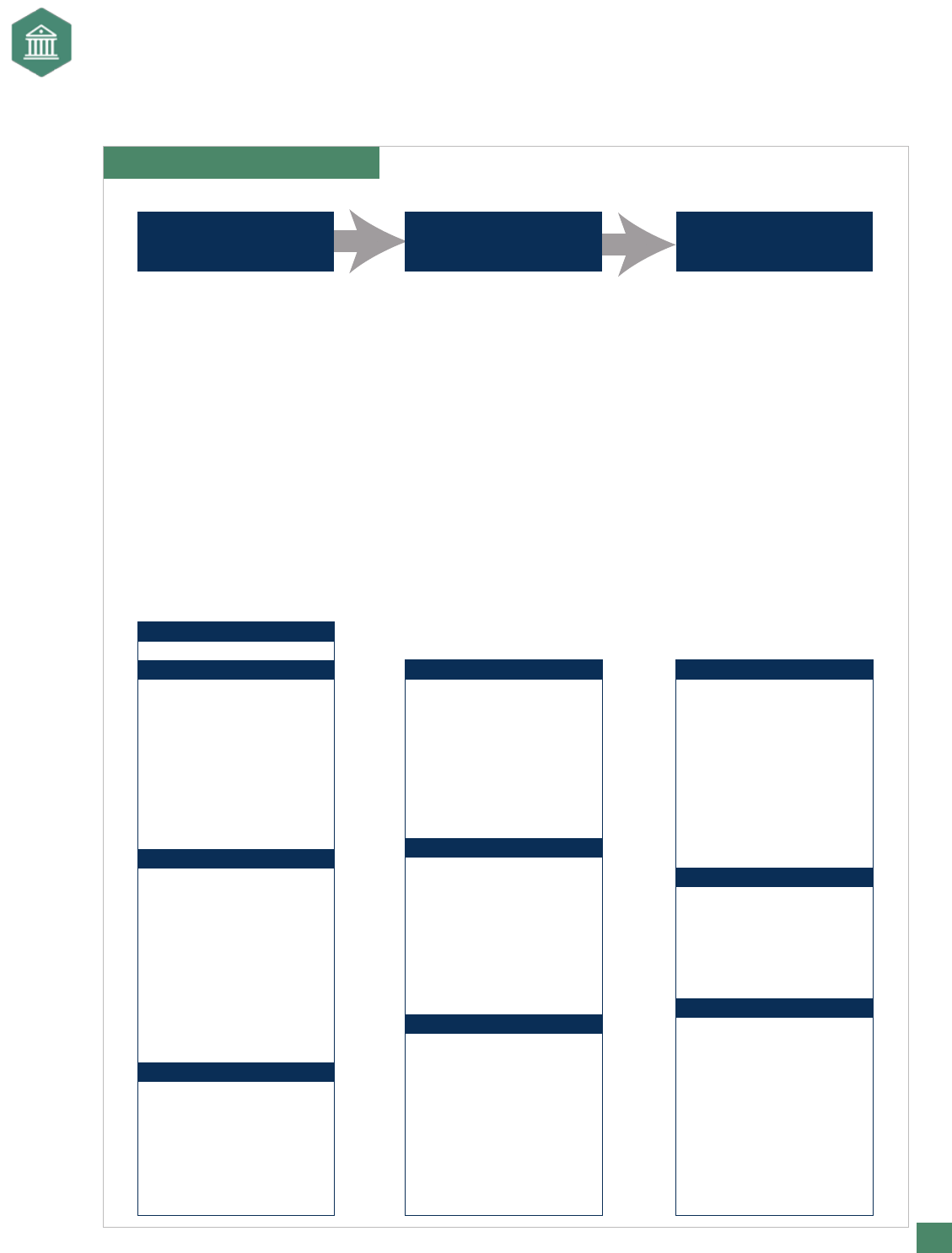

Exhibit 1 shows the generic ERM framework presented in Enterprise Risk Management: Frameworks,

Elements, and Integration. The initial focus is on clarity of strategies and objectives. The focal point for

risk identication may be at any level, such as the overall company, a strategic business unit, function,

project, process, or activity. Without clear objectives it is impossible to identify events that might give

rise to risks that could impede the accomplishment of a particular strategy or objective—regardless of

the scope of the inquiry. Assuming those involved in identifying risks have a clear understanding of the

strategies and objectives, the appropriate questions to ask, as suggested by one company’s senior

enterprise risk manager, are: “What could stop us from reaching our top goals and objectives?” and

“What would materially damage our ability to survive?” These questions can be modied for the

appropriate level of inquiry.

Risk Identication Techniques

Exhibit 1. A Continuous Risk Management Process

SET STRATEGY/

OBJECTIVES

TREAT

RISKS

IDENTIFY

RISKS

ASSESS

RISKS

COMMUNICATE

& MONITOR

CONTROL

RISKS

Source: Adapted from Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, No Surprises: The Case For Better Risk Reporting, ICAEW, London, U.K.,

1999, p. 47.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

10

Those involved in the risk identication process, should recognize that it is a misperception to think of a risk

“as a sudden event.”

3

Identifying an issue that is facing the organization and discussing it in advance can

potentially lead to the risk being mitigated. Two benets are possible:

“One, if you mitigate the risk and your peers do not—in a catastrophic, continuity-destroying event that

hits an industry—say a nancial scandal—you get what is called the survivor’s bonus. Two, if you survive

or survive better than others, then you have an upside after the fact, and this should be part of the

board’s strategic thinking.”

4

Before considering some of the specic techniques available for organizations to identify risks, several important

factors should be noted about this process:

• The end result of the process should be a risk language specic to the company or the unit, function,

activity, or process (whatever is the focal point).

• Using a combination of techniques may produce a more comprehensive list of risks than would

reliance on a single method.

• The techniques used should encourage open and frank discussion, and individuals should not fear

reprisal for expressing their concerns about potential events that would give rise to risks

resulting in major loss to the company.

• The process should involve a cross-functional and diverse team both for the perspectives that such

a group provides and to build commitment to ERM.

• Finally, the process will probably generate a lengthy list of risks, and the key is to focus on the

“vital few” rather than the “trivial many.”

Some techniques for identifying risk are:

• Brainstorming

• Event inventories and loss event data

• Interviews and self-assessment

• Facilitated workshops

• SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis

• Risk questionnaires and surveys

• Scenario analysis

• Using technology

• Other techniques

3

Corporate Board Member, 2006 Academic Council Supplement: Emerging Trends in Corporate Governance, Board Member, Inc., Brentwood, Tenn., p. 20.

4

Ibid.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

11

Brainstorming

When objectives are stated clearly and understood by the participants, a brainstorming session drawing

on the creativity of the participants can be used to generate a list of risks. In a well-facilitated brainstorming

session, the participants are collaborators, comprising a team that works together to articulate the risks

that may be known by some in the group. In the session, risks that are known unknowns may emerge,

and perhaps even some risks that were previously unknown unknowns may become known. Facilitating a

brainstorming session takes special leadership skills, and, in some organizations, members of the internal

audit and ERM staff have been trained and certied to conduct risk brainstorming sessions. In addition to

well-trained facilitators, the participants need to understand the ERM framework and how the brainstorming

session ts into the ERM process. The participants may very well be required to do some preparation prior

to the session.

In using this technique, one company familiar to the authors noted that because the objectives were unclear

to some of the participants, the process had to back up and clarify the objectives before proceeding.

Using a cross-functional team of employees greatly increases the value of the process because it sheds

light on how risks and objectives are correlated and how they can impact business units differently. Often in

brainstorming sessions focused on risk identication, a participant may mention a risk only to have another

person say: “Come to think of it, my area has that risk, and I have never thought of it before.” With the team

sharing experiences, coming from different backgrounds, and having different perspectives, brainstorming

can be successful in identifying risk. It is also powerful when used at the executive level or with the audit

committee and/or board of directors.

In a brainstorming session, the participants must have assurance that their ideas will not result in humiliation

or demotion. Otherwise, they may feel inhibited in expressing what they believe are major risks facing the

organization. As an example, a set of often overlooked risks are “people risks” vs. environmental risks, nancial

risks, and other more technical risks. People risks include succession planning (What if our very competent

leader departs the organization?) and competency and skills building (What if we continue with a team

that does not have the requisite skills for success?). Once a list of risks is generated, reducing the risks to

what the group considers the top few can be accomplished using group software to enable participants to

anonymously vote on the objectives and risks. Anonymity is believed to increase the veracity of the rankings.

Some of the interactive voting software that could be used in the risk identication process include Sharpe

Decisions, Resolver*Ballot, OptionFinder, and FacilitatePro. With the availability of interactive voting software

and Web polling, the brainstorming session might be conducted as a virtual meeting with participants working

from their ofce location, also enabling them to identify and rank the risks anonymously.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

12

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

12

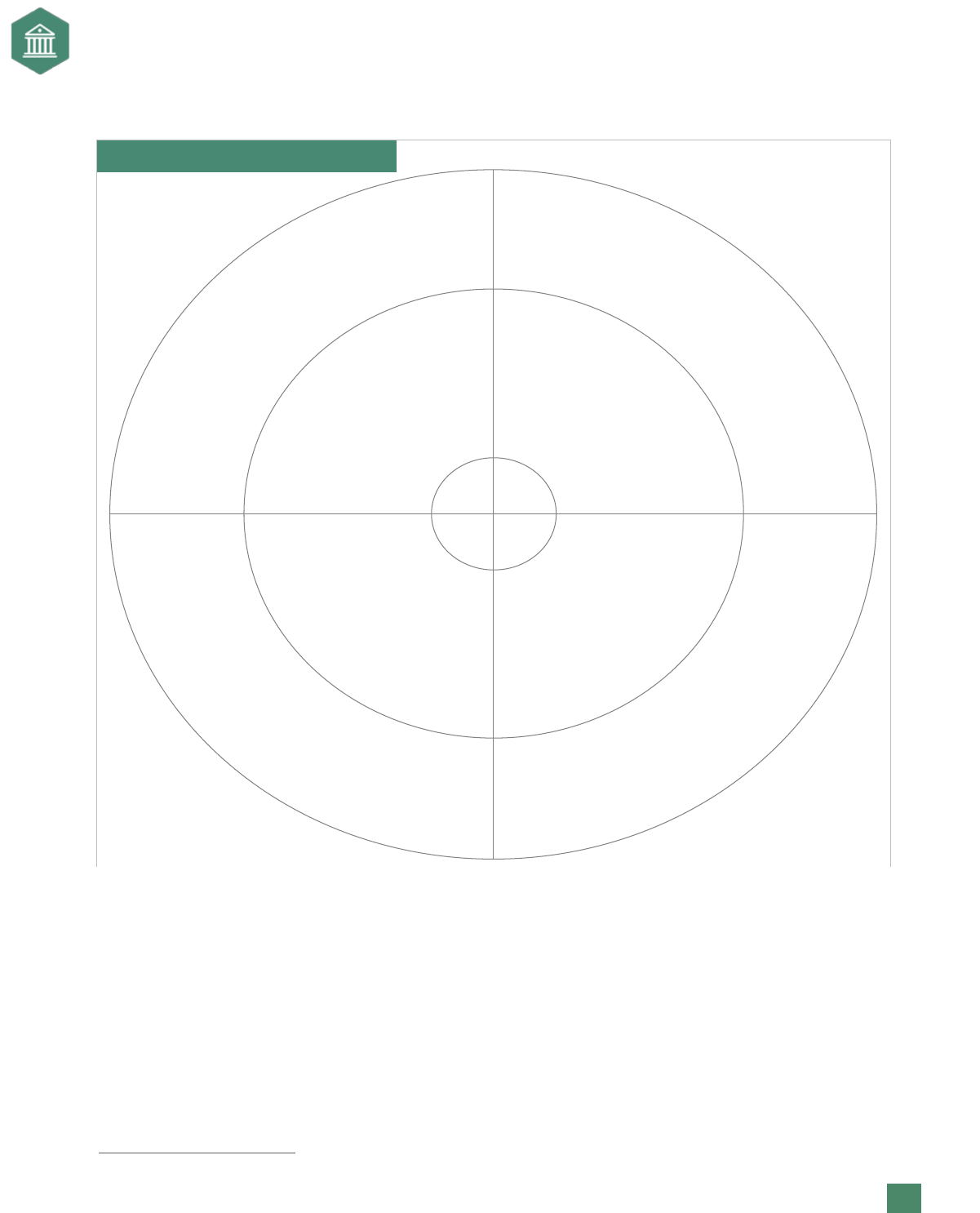

Exhibit 2. Industry Portfolio of Risks

ENTERPRISE

RISKS

FINANCIAL

RISKS

STRATEGIC

RISKS

HAZARD

RISKS

OPERATIONAL

RISKS

Credit

Default

Adverse

Changes

In Industry

Regulators

Shareholder

Activism

Fuel Prices

Counterparty

Risk

Interest Rate

Fluctuations

Currency & Foreign

Exchange Rate

Fluctuations

Financial

Markets

Instability

Economic

Recession

Currency

Inconvertability

Equip., Facilities, Business

Acquisitions & Divestitures

Asset Valuation

Asbestos Exposure

Accounting /

Tax Law

Changes

Uncompetitive

Cost Structure

Revenue

Management

Debt & Credit

Rating

Healthcare &

Pension Costs

Liquidity / Cash

Mold Exposure

Cargo Losses

Geopolitical Risks

Severe Hot /

Cold Weather

Hurricane /

Typhoon

Earthquake

Flooding

Terrorism / Sabotage

Wildfire

Disease / Epidemic

Animal / Insect Infestation

Blizzard / Ice Storm

Hail Damage

Tornados

Wind Damage

Tsunami

Volcano Eruption

Heavy Rain /

Thunderstorms

New or Foreign

Comepetitors

Transaction

Processing Errors

Adverse

Changes In

Environmental

Regulators

Inadequate /

Inaccurate

Financial Controls

& Reporting

3rd Party

Liability

General

Liability

Product

Liability

Directors &

Owners Liability

Property Damage

Bldg. or Equip. Fire

Loss of Key Facility

Workers Compensation

Boiler or Machinery

Explosion

Building

Collapse

Building

Subsidence &

Sinkholes

Land, Water,

Atmospheric

Pollution

Lightning Strikes

Public Boycott

& Condemnation

Offensive

Advertising

Corporate

Culture

Timing of Business

Decisions & Moves

Negative Media

Coverage

Market Share Battles

Loss of Intel.

Property

Pricing & Incentive Wars

Foreign Market Protectionism

Attacks on Brand Loyalty

Product-Market Alignment

Customer

Relations

Supplier Relations

Dealer Relations

“Gotta Have Products”

Program Launch

Mergers &

Industry Consolidation

Ineffective

Planning

Inadequate Mgmt. Oversight

Customer Demand

Seasonality & Variability

Technology Decisions

Budget Overruns /

Unplanned Expenses

Ethics Violations

Joint Venture / Alliance Relations

Perceived

Quality

Union Relations, Labor

Disagreements &

Contract Frustrations

Product Development Process

Product Design & Engineering

Restriction of

Access / Egress

Loss of Key

Equipment

Theft

Embezzlement

Vandalism

Arson

Dealer Distribution

Network Failures

Info. Mgmt. Problems

Kidnapping

Extortion

Logistics Provider Failures

Logistics Route or

Mode Disruptions

Loss of Key Personnel

Accounting or Internal

Controls Failures

Health & Safety

Violations

IT System Failure (Hardware,

Software, LAN, WAN)

Service Provider Failures

Computer Virus / Denial

of Service Attacks

Gov’t Inquiries

Workplace Violence

Supplier Bus.

Interruption

Tier 1, 2, 3...n

Supplier Problems

Financial Trouble,

Quality “Spills,”

Failure to Deliver

Materials, etc.

HR Risks - Key Skill Shortage, Personnel Turnovers

Harassment &

Discrimination

Warranty / Product

Recall Campaigns

Loss of Key Supplier

Operator Errors /

Accidental Damage

Utilities Failures

Communications,

Electricity, Water,

Power, etc.

Deductible

Limits

Source: Debra Elkins, “Managing Enterprise Risks in Global Automatic Manufacturing Operations,” presentation at the University of Virginia, January 23,

2006. Permission granted for use.

Event Inventories and Loss Event Data

Seeding or providing participants with some form of stimulation on risks is very important in a brainstorming

session. One possibility is to provide an event inventory for the industry (see Exhibit 2) or a generic inventory

of risks. Examples of the latter are readily available from various consulting rms and publications.

5

In the

rst SMA on ERM, a general risk classication scheme is given that could also be used to “seed” the discussion.

In a brainstorming session or facilitated workshop (discussed later), the goal is to reduce the event inventory

to those relevant to the company and dene each risk specic to the company. The risk identication process

can also be seeded by available loss-event data. A database on relevant loss events for a specic industry

can stimulate a “fact-based discussion.”

6

5

Economist Intelligence Unit, Managing Business Risks—An Integrated Approach, The Economist Intelligent Unit, New York, N.Y., 1995.

6

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework: Application

Techniques, AICPA, New York, N.Y., 2004, p. 28.

Source: Debra Elkins, “Managing Enterprise Risks in Global Automatic Manufacturing Operations,” presentation at the University of Virginia, January 23,

2006. Permission granted for use.

Event Inventories and Loss Event Data

Seeding or providing participants with some form of stimulation on risks is very important in a brainstorming

session. One possibility is to provide an event inventory for the industry (see Exhibit 2) or a generic inventory

of risks. Examples of the latter are readily available from various consulting rms and publications.

5

In the

rst SMA on ERM, a general risk classication scheme is given that could also be used to “seed” the discussion.

In a brainstorming session or facilitated workshop (discussed later), the goal is to reduce the event inventory

to those relevant to the company and dene each risk specic to the company. The risk identication process

can also be seeded by available loss-event data. A database on relevant loss events for a specic industry

can stimulate a “fact-based discussion.”

6

5

Economist Intelligence Unit, Managing Business Risks—An Integrated Approach, The Economist Intelligent Unit, New York, N.Y., 1995.

6

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework: Application

Techniques, AICPA, New York, N.Y., 2004, p. 28.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

13

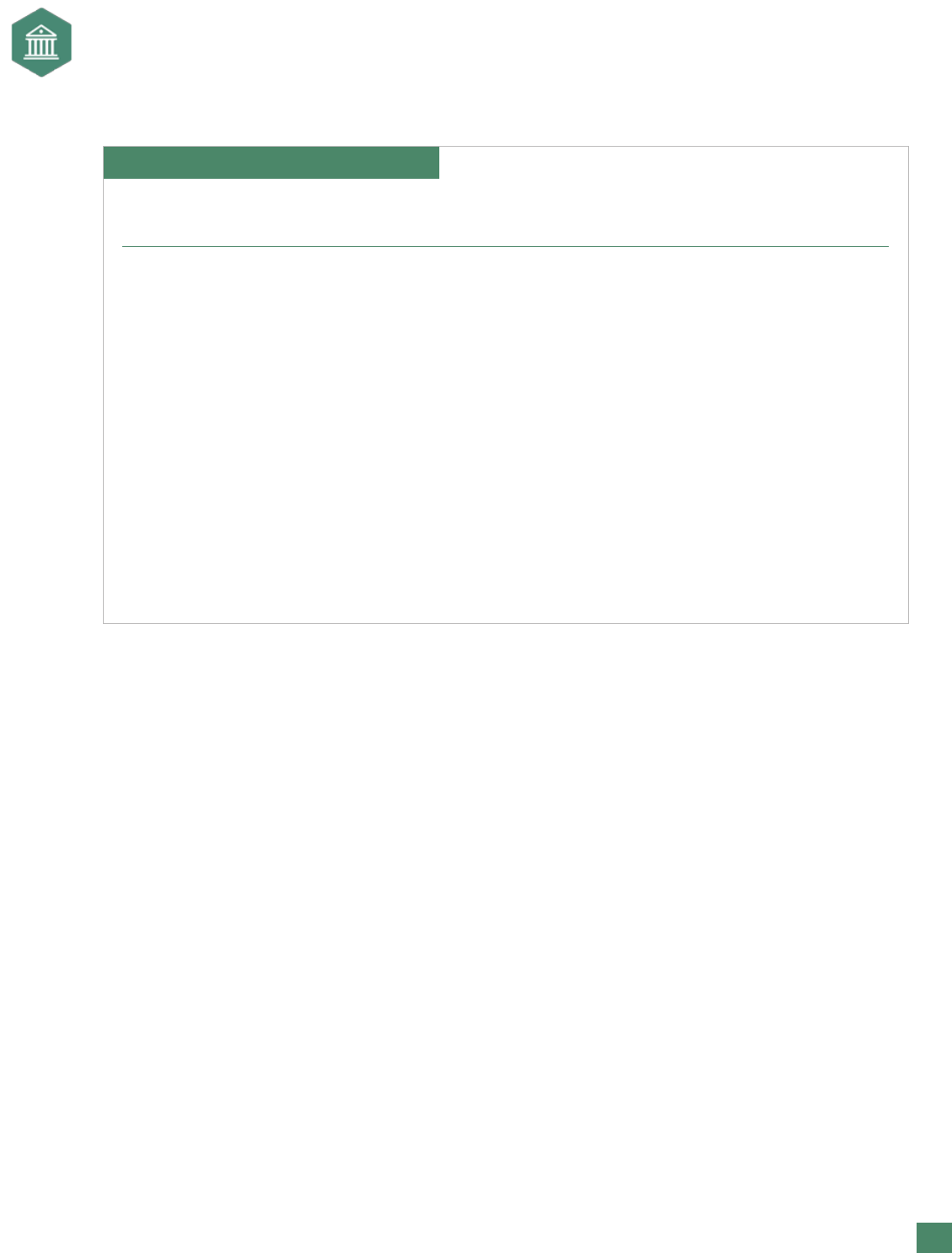

Exhibit 3A. Risk Identication Template

Please list the major strategies and/or objectives for your area of responsibility.

Please list the major risks your unit faces in achieving its objectives. List no more than 10 risks.

Please assess the overall risk management capability within your area of responsibility to seize opportunities

and manage the risks you have identied.

Exhibit 3B. Major Strategies/Objectives For Your Unit

Please list the major strategies/objectives for your unit.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Exhibit 3C. Major Risks For Your Unit

Please list the major risks your unit faces in achieving your objectives. List no more than 10 risks.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Interviews and Self-Assessment

This technique combines two different processes. First, each individual of the organizational or operating

unit is given a template with instructions to list the key strategies and/or objectives within his or her area of

responsibility and the risks that could impede the achievement of the objectives. Each unit is also asked to

assess its risk management capability using practical framework categories such as those contained in the

ERM framework from the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). A

sample template is presented in Exhibits 3A-D. The completed documents are submitted to the ERM staff or

coordinator, which could be the CFO, controller, COO, or CRO (chief risk ofcer). That group follows up with

interviews to clarify issues. Eventually, the risks for the unit are identied and dened, and a risk management

capability score can be determined from a ve-point scale, as used in Exhibit 3D. This technique might also

be used in conjunction with a facilitated workshop.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

14

Exhibit 3D. Risk Management Capability

Internal Environment

Objective Setting

Event Identification

Risk Assessment

Risk Response

Control Activities

Information/Communication

Monitoring

VL

VL

VL

VL

VL

VL

VL

VL

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

VH

VH

VH

VH

VH

VH

VH

VH

Use the following categories* to assess the overall risk management capability within your area of responsibility to seize

opportunities and manage risks using the scale at the bottom of the page.

What is your level of concern with respect to the overall risk management capability

of your area of responsibility to seize opportunities and manage risks?

Please circle the most appropriate response:

VL = Very Low L = Low M = Medium H = High VH = Very High

* The categories are taken from COSO, Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework:

Executive Summary, AICPA, New York, N.Y., 2004.

Facilitated Workshops

After the information is completed and collected, a cross-functional management team from the unit or several

units might participate in a facilitated workshop to discuss it. Again, by using voting software the various risks

can be ranked to arrive at a consensus of the top ve to 10, for example. As noted previously, using interactive

voting software allows the individuals to identify and rank the risks anonymously without fear of reprisal

should their superior be a member of the group.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis is a technique often used in the formulation

of strategy. The strengths and weaknesses are internal to the company and include the company’s culture,

structure, and nancial and human resources. The major strengths of the company combine to form the core

competencies that provide the basis for the company to achieve a competitive advantage. The opportunities

and threats consist of variables outside the company and typically are not under the control of senior management

in the short run, such as the broad spectrum of political, societal, environmental, and industry risks.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

15

For SWOT analysis to be effective in risk identication, the appropriate time and effort must be spent on

seriously thinking about the organization’s weaknesses and threats. The tendency is to devote more time to

strengths and opportunities and give the discussion of weaknesses and threats short shrift. Taking the latter

discussion further and developing a risk map based on consensus will ensure that this side of the discussion

gets a robust analysis. In a possible acquisition or merger consideration, a company familiar to the authors

uses a SWOT analysis that includes explicit identication of risks. The written business case presented to the

board for the proposed acquisition includes a discussion of the top risks together with a risk map.

Risk Questionnaires and Surveys

A risk questionnaire that includes a series of questions on both internal and external events can also be used

effectively to identify risks. For the external area, questions might be directed at political and social risk,

regulatory risks, industry risk, economic risk, environmental risk, competition risk, and so forth. Questions on

the internal perspective might address risks relating to customers, creditors/investors, suppliers, operations,

products, production processes, facilities, information systems, and so on. Questionnaires are valuable

because they can help a company think through its own risks by providing a list of questions around certain

risks. The disadvantage of questionnaires is that they usually are not linked to strategy.

Rather than a lengthy questionnaire, a risk survey can be used. In one company, surveys were sent to both

lower- and senior-level management. The survey for lower management asked respondents to “List the ve

most important risks to achieving your unit’s goals/objectives.” The survey to senior management asked

participants to “List the ve most important risks to achieving the company’s strategic objectives.” The survey

instruments included a column for respondents to rank the effectiveness of management for each of the ve

risks listed, using a range of one (ineffective) to 10 (highly effective).Whether using a questionnaire or survey,

the consolidated information can be used in conjunction with a facilitated workshop. In that session, the

risks are discussed and dened further. Then interactive voting software is used to narrow that risk list to the

vital few.

Scenario Analysis

Scenario analysis is a particularly useful technique in identifying strategic risks where the situation is less

dened and “what-if” questions should be explored. Essentially, this technique is one way to uncover risks

where the event is high impact/low probability.

7

In this process:

“Managers invent and then consider, in depth, several varied stories of equally plausible futures.

The stories are carefully researched, full of relevant detail, oriented toward real-life decisions, and

designed (one hopes) to bring forward surprises and unexpected leaps of understanding.”

8

7

Deloitte & Touche LLP, The Risk Intelligent Enterprise: ERM Done Right, Deloitte Development LLC, 2006, p. 4.

8

Peter Schwartz, The Art of the Long View, Currency Doubleday, New York, N.Y.,1991, p. xiii.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

16

Using this technique, a cross-functional team could consider the long-term effects resulting from a loss of

reputation or customers or from the lack of capability to meet demand. Another relevant question to ask is,

“What paradigm shifts in the industry could occur, and how would they impact the business?”

The risk management group of one company uses scenario analysis to identify some of its major business

risks.

9

One risk for this company is an earthquake. Its campus of more than 50 buildings is located in the

area of a geological fault. From a holistic perspective, the loss from an earthquake is not so much the loss

of the buildings but the business interruption in the product development cycle and the inability to serve

customers. The company’s risk management group analyzed this disaster scenario with its outside advisors

and attempted to quantify the real cost of such a disaster, taking into account how risks are correlated. In

the process, the group identied many risks in addition to property damage, including:

• “Director and ofcer liability if some people think management was not properly prepared,

• Key personnel risk,

• Capital market risk because of the rm’s inability to trade,

• Worker compensation or employee benet risk,

• Supplier risks for those in the area of the earthquake,

• Risk related to loss of market share because the business is interrupted,

• Research and development risks because those activities are interrupted and product delays occur, and

• Product support risks because the company cannot respond to customer inquiries.”

10

This example reveals the value of using scenario analysis: A number of risks are potentially present within a

single event, and the total impact could be very large. Another scenario that this company’s risk management

group analyzed was a stock market downturn (or bear market). The group also dened ve or six other scenarios.

Under each one, it identied as many material risks as could be related to the scenario and developed white

papers on each one for executive management and the board.

11

Using Technology

The risk identication process can also utilize the company’s existing technology infrastructure. For example,

most organizations utilize an intranet in their management processes. The group responsible for a company’s

ERM process can encourage units to place their best risk practices on the ERM site. Risk checklists, anecdotes,

and best practices on the intranet serve as stimulation and motivation for operating management to think

seriously about risks in their unit. Also, tools that have been found particularly useful to various units can be

catalogued. As new projects are launched, business managers are encouraged to consult the risk management

group’s intranet site.

9

Thomas L. Barton, William G. Shenkir, and Paul L. Walker, Making Enterprise Risk Management Pay Off, Financial Executives Research Foundation, Upper

Saddle River, N.J., 2001, pp. 132-135.

10

Ibid., p. 133.

11

Ibid., p. 133.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

17

Another use of technology is to recognize the company’s potential risk that resides with the Internet. For

example, a company’s products, services, and overall reputation are vulnerable to Internet-based new media

like blogs, message boards, e-mailing lists, chat rooms, and independent news websites. Some companies

devote information technology resources to scan the blogosphere continuously for risks related to the company’s

products, services, and reputation.

Other Techniques

Other possible approaches for identifying risks include value chain analysis, system design review, process

analysis, and benchmarking with other similar as well as dissimilar organizations. Also, external consultants

can add value in the risk identication process by bringing in knowledge from other companies and industries

and by challenging the company’s list of identied risks.

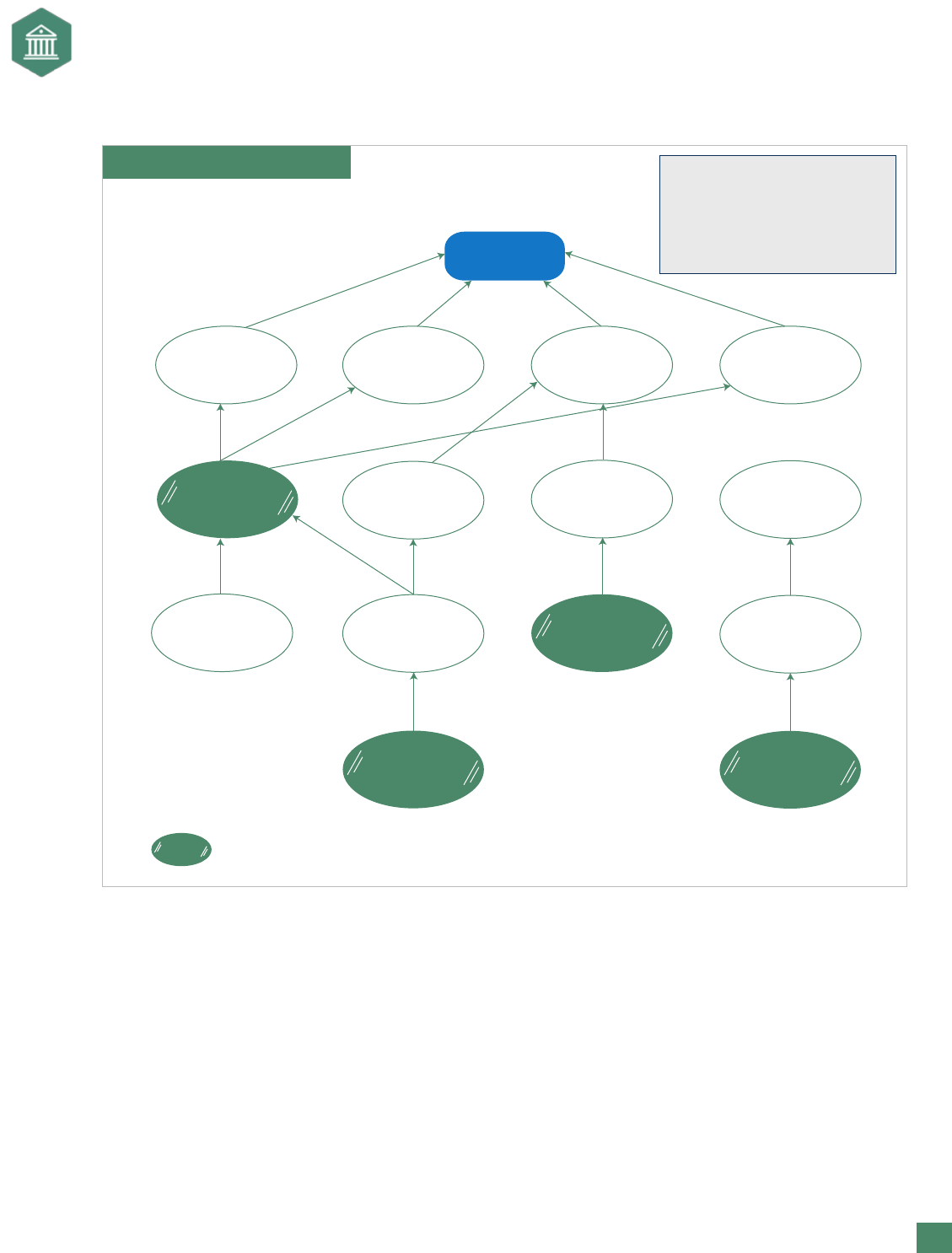

After a risk is identied, avoid the temptation to quantify it before further analysis is completed. Additional

understanding of the risk’s potential causes is required by the ERM team and management before its

impact can be quantied. Working with the various units of the organization that own parts of the risk,

the ERM team should drill into the risk to uncover what is beneath the surface and to get a better

understanding of the potential risk drivers. An inuence diagram or root cause analysis can be developed

using scenario analysis. This can be done by using supporting documentation and interviewing those

who own parts of the risk. Exhibit 4 presents an inuence diagram for a strategic risk provided by a senior

manager of ERM at a major company. In this exhibit, a chain of likely events within a given scenario is

spelled out where a strategic risk—revenue target not met—has been identied.

Studying Exhibit 4, the inquiry to determine the likely drivers in a scenario for the risk of not meeting the

revenue target could include:

• Failure to sell a new product.

• The new machinery and equipment purchased for making the new product was not selected properly

because of a process breakdown in the acquisition. This led to manufacturing failures attributed to

product design problems, which led to a high rate of product defect.

• Failure in the supply chain impacted the ability to meet the revenue target. A catastrophic event

occurred at a major supplier, and the business continuity plan recognized this event too late to nd

alternative suppliers.

• Together, the above events would result in losing some top customers because high-quality products

could not be delivered when required. Furthermore, in digging deeper, some misalignment of specic

goals might exist in the silos involved. For example, manufacturing might have a goal of cutting

cost, customer service naturally will want low defects in the products, the pricing function will be

seeking high margins for the products, and the sales force is motivated to generate revenue.

Analysis of Risk by Drivers

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

18

Exhibit 4. Influence Diagram

Revenue target

not met

Failure to

sell new

product

Supply

chain

failure

Loss of top

customer(s)

Capital

expense

Catastrophic

event

Decrease in

inventory

Mfg. failure

Error in product

planning or

design

Misalignment

of BUs

Mfg.

selection

mistake

Failure to have

BCP plan

Breakdown in

goal process

Process

breakdown

High defect

rate

= a key risk driver

Develop Influence Diagram and

Quantify the Risk Drivers:

Define root causes and main drivers

of the risks. Define the chain of

events in likely scenario. Drivers

should be small enough in scope

that they can be quantified.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

19

Risk Assessment Tools

Risks must be identied correctly before an organization can take the next step. Assessing the wrong list of

risks or an incomplete list of risks is futile. Organizations should make every possible effort to ensure they have

identied their risks correctly using some or all of the approaches discussed. The act of identifying risks is itself

a step on the risk assessment road. Any risks identied, almost by default, have some probability of inuencing

the organization.

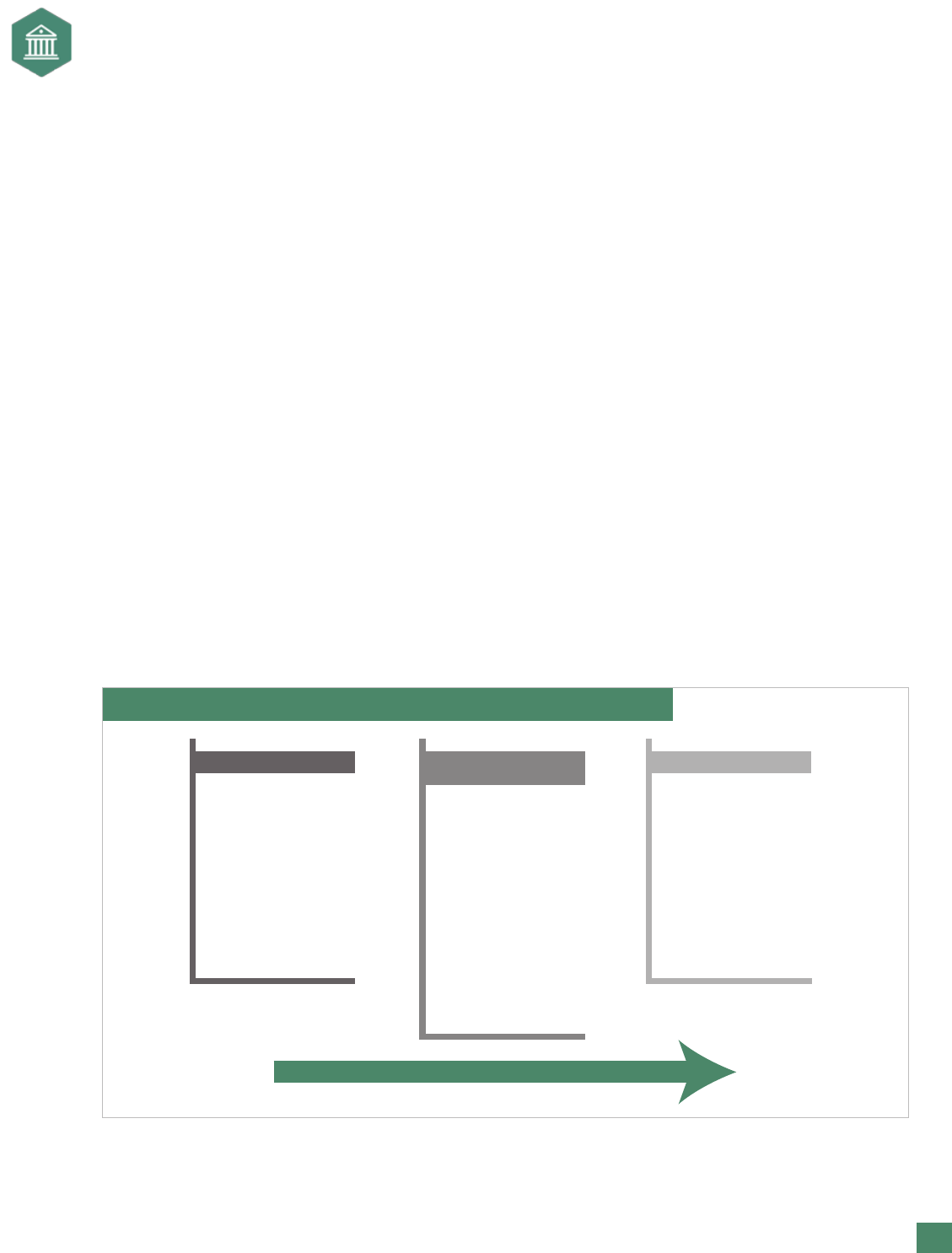

Exhibit 5. Quantifying Risk: Determine the Drivers

Do NOT try

to quantify at

these levels

Quantify risks

at this level

or below

Driver of

Risk #1

Driver of

Risk #1

Main Goals and

Objectives

(revenue missed)

Driver of

Risk #2

Driver of

Risk #2

Driver of

Risk #3

Driver of

Risk #3

Risk #2

to acheiving

goals and

objectives

Risk #1

to acheiving

goals and

objectives

(failure to sell)

Risk #3

to acheiving

goals and

objectives

With an in-depth understanding of how the strategic risk could occur, more information is now available to

assist in quantifying the risk. This information can be framed as noted in Exhibit 5 in order to begin estimating

the impact. The point of this analysis is to understand the level at which quantication can best occur. If the

risk is quantied at too high a level, it could end to be too broad or not actionable. Using a building block

approach around risk drivers facilitates the quantication process. At the end of the process, however,

quantication is still an estimate and should be viewed as merely providing an “order of magnitude” of

the impact.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

20

Categories

Once risks are identied, some organizations nd it helpful to categorize them. This may be a necessity if

the risk identication process produces hundreds of risks, which can be overwhelming and seem unmanageable.

Risk categories include hazard, operational, nancial, and strategic. Other categories are controllable or

noncontrollable and external or internal. Categorizing risk requires an internal risk language or vocabulary

that is common or unique to the organization in total, not just to a particular subunit or silo. Studies have

shown that an inconsistent language dening risks across an organization is an impediment to an effective

ERM strategy. Risk terms would certainly vary between a pharmaceutical company and a technology company

or between a nonprot and an energy company. Several risks could be grouped around a broader risk,

such as reputation risk. Other methods for categorizing risk can be nancial or nonnancial and insurable

or noninsurable. Some companies also categorize risks as quantiable or nonquantiable.

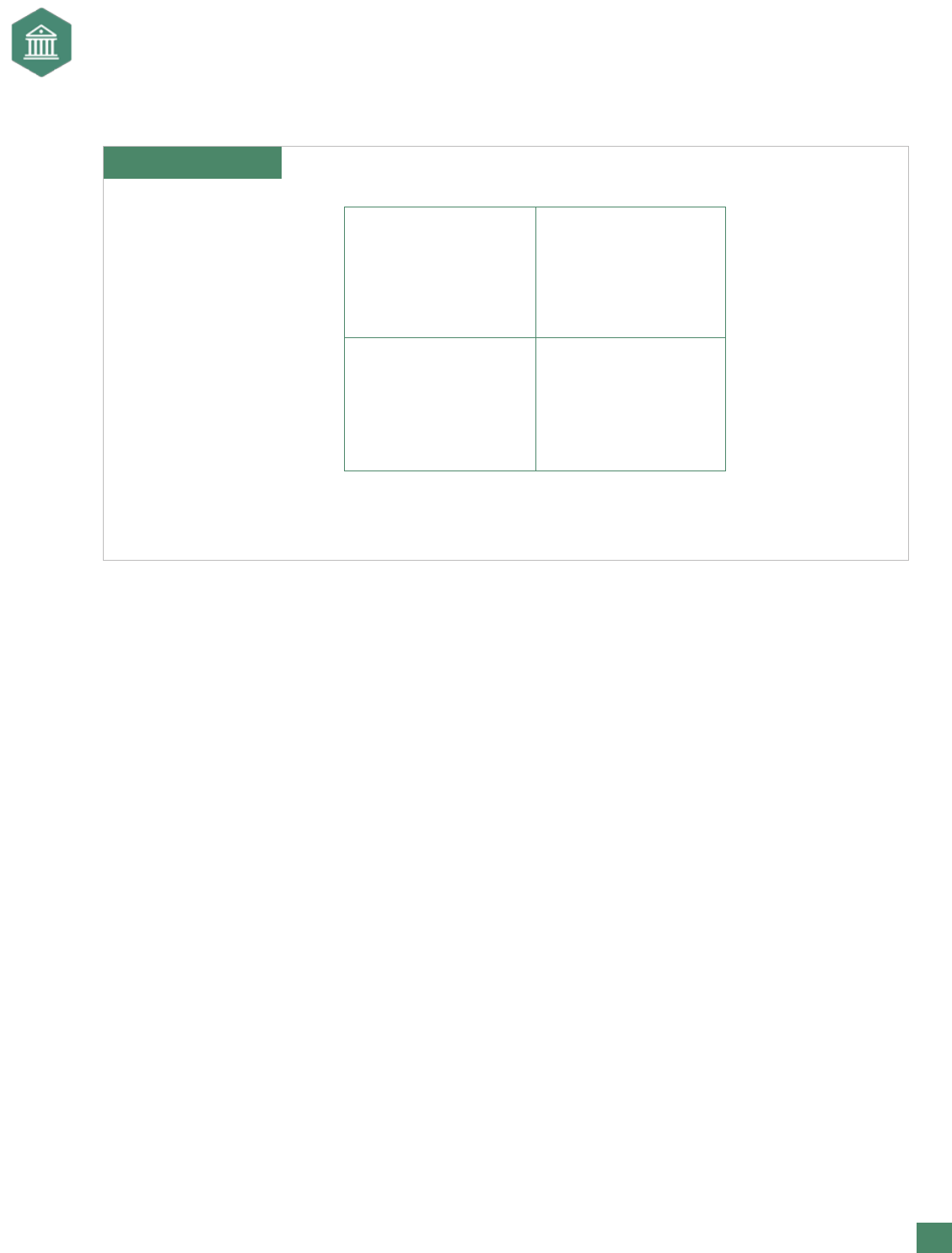

Qualitative vs. Quantitative

As Exhibit 6 shows, risk assessment techniques can vary from qualitative to quantitative. The qualitative

techniques can be a simple list of all risks, risk rankings, or risk maps. A list of risks is a good starting point.

Even though no quantitative analysis or formal assessment has been applied to the initial list of risks, the list

and accompanying knowledge is valuable. Some risks on the list may not be quantiable. For these risks,

identifying them and adding them to a priority list may be the only quantication possible. Organizations

should not be concerned that they cannot apply sophisticated modeling to every risk.

Exhibit 6. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Risk Assessment

• Risk identification

• Risk rankings

• Risk maps

• Risk maps with

impact and likelihood

• Risks mapped to

objectives or divisions

• Identification of risk

correlations

• Validation of risk

impact

• Validation of risk

likelihood

• Validation of

correlations

• Risk-corrected

revenues

• Gain/loss curves

• Tornado charts

• Scenario analysis

• Benchmarking

• Net present value

• Traditional measures

Probablistic techniques

• Cash flow at risk

• Earnings at risk

• Earnings distributions

• EPS distributions

Qualitative Qualitative /

Quantitative

Quantitative

Level of difficulty and amount of data required

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

21

Risk Rankings

Once an organization has created its list of risks, it can begin to rank them. Ranking requires the ERM team

to prioritize the risks on a scale of importance, such as low, moderate, and high. Although this seems

unsophisticated, the results can be dramatic. Organizations nd considerable value in having conversations

about the importance of a risk. The conversations usually lead to questions about why one group believes

the risk is important and why others disagree. Again, this process should use a cross-functional risk team

so that perspectives from across the entire organization are factored into the rankings. This is a critical task

requiring open debate, candid discussion, and data (e.g., tracking, recording, and analysis of historical error

rates on a business process) where possible.

Impact and Probability

The importance of an event considers not just its impact but also its likelihood of occurring. Therefore, many

ERM organizations generate risk maps using impact and probability. In ERM implementation, companies not

only generate risk maps to capture impact and likelihood but also to demonstrate how risks look when put

together in one place. The value of the map is that it reects the collective wisdom of the parties involved.

Furthermore, risk maps capture considerable risk information in one place that is easily reviewed. A basic

risk map, such as in Exhibit 7, captures both impact and likelihood.

When assessing likelihood or probability, the ERM team can use a variety of scales:

• Low, medium, or high;

• Improbable, possible, probably, or near certainty; and

• Slight, not likely, likely, highly likely, or expected.

The same is true for assessing impact:

• Low, medium, or high impact;

• Minor, moderate, critical, or survival; and

• Dollar levels, such as $1 million, $5 million, etc.

When qualitatively assessing these risks, it is also possible to estimate ranges. For example, a company

might determine that there is a low probability of a customer-related risk having an impact of $100 million, a

moderate probability (or best guess) of a $50 million impact, and a high probability of a $10 million impact.

For example, when Apple announced its entrance into the cell phone market, other cell phone makers likely

began making calculations to gauge the risk of the new entrant into their market.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

22

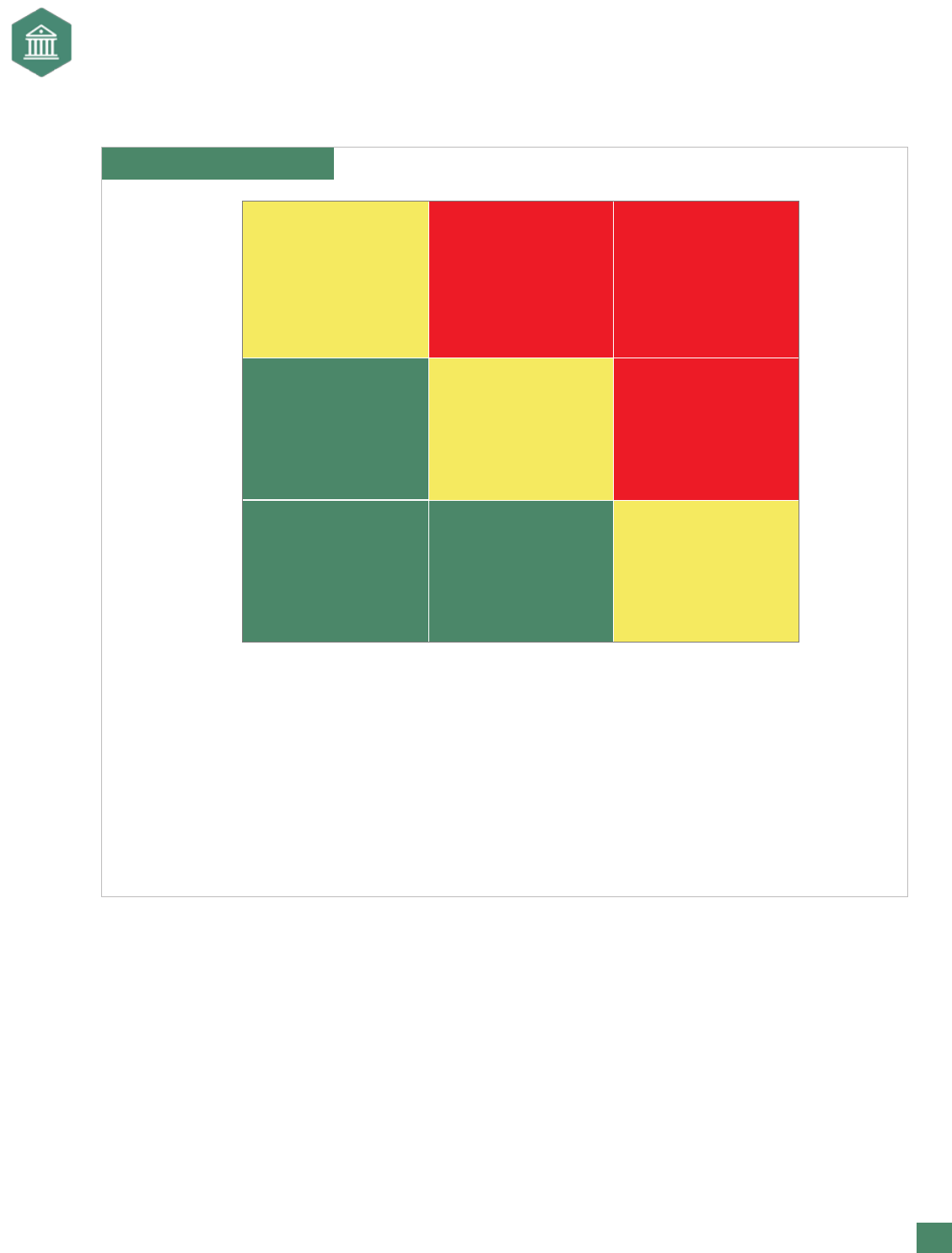

Risk maps can help an organization determine how to respond to a risk. As organizations see the greater

risks, they can plan a response. For example, one risk map approach used by a company is shown in Exhibit

8. For risks that are in the lower levels of impact and probability—the green zone on the map—a company

should respond with high-level monitoring. For risks with higher levels of impact and probability—the

red zone on the map—a company should take a stronger response and a higher level of commitment to

managing them.

Keys to Risk Maps

Several keys need to be considered when generating risk maps: condentiality, denitions, timeframe,

direction, and correlations. Organizations may want to consider doing impact and probability in a condential

manner. As noted previously, software tools are available to facilitate condential sharing. On the other

hand, some companies nd that openly sharing assessments within the group is acceptable. Even with

condentiality, good risk facilitators can bring out the risk source and root problems.

Denitions used during the risk map generation are critical. What is “important” to one work unit or individual

may not seem “important” to another. If organizations measure impact in dollars, the dollars must be without

ambiguity. Does the risk inuence dollars on one product, dollars for a certain division, or earnings per share?

Similarly, “improbable” might be interpreted by some to be 1% while others could think it means 15%. These

denitions and terms should be clearly established before the risk map sessions are conducted.

Exhibit 7. Risk Map

High

High Impact

Low Likelihood

Low Impact

Low Likelihood

Impact

HighLow

Likelihood of Occurrence

Low Impact

High Likelihood

High Impact

High Likelihood

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

23

Exhibit 8. Risk Map Model

Criticality of Achievement

Actual/Potential Performance Variability Around Targets

Process/Business

Level Impact

Segment/Intersegment

Level Impact

Level Impact

Low

(Consistently

within tolerable

variance in key

metric improvement

or target)

Moderate

(Sometimes

within tolerable

variance in key

metric improvement

or target)

High

(Mostly outside of

tolerable

variance in key

metric improvement

or target)

Achievement of Objective/Execution of Process/

Implementation of Change/Management of Risk

6 Yellow (Level III)

Close monitoring

for increased

impact and/or

variability

3 Green (Level II)

High-level

monitoring for

increased impact

and/or variablity

5 Yellow (Level III)

Close monitoring

for increased

impact and/or

variability

1 Green (Level I)

High-level

monitoring for

increased impact

and/or variablity

4 Yellow (Level III)

Close monitoring

for increased

impact and/or

variability

2 Green (Level II)

High-level

monitoring for

increased impact

and/or variablity

• Segment

Commitment

• Reported to

Segment

Leadership

• Close monitoring

of risk action plan

8 Red (Level IV)

• Segment

Commitment

• Reported to Audit

Committee

• Reported to

Segment Leadership

• Close monitoring of

risk action plan

9 Red (Level V)

• Segment

Commitment

• Reported to Segment

Leadership

• Close monitoring

of risk action plan

7 Red (Level IV)

Closely related to denitions are timeframes, which need to be established up front so that any understanding

of the risk and its impact is clear as to when it will affect the organization. An assessment of risk at one point

in time has the same failings as strategic plans and objectives, which do not take a longer-term perspective

on market trends, customer needs, competitors, etc. What seems important today or this week may not seem

important in ve years. Similarly, although some longer-range risks may not seem important today, these risks

could threaten the organization’s survival if left unmanaged.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

24

Some organizations nd it valuable to capture the direction of the risk. This can be labeled on the risk map

or communicated separately. Direction of risk can be captured using terms such as “increasing,” “stable,” or

“decreasing.” Related to the risk direction is the risk trend. Knowing the direction and trend of a risk as well

as its dollar impact and likelihood can be crucial to managing that risk. For example, risk trends can reveal

that the risk was decreasing over the last several years but has increased recently.

One weakness in risk maps (and in silo risk management) is that maps do not capture any risk correlations.

Ignoring risk correlations can lead to ineffective and inefcient risk management. Risk correlations can

be considered for nancial risks or nonnancial risks. Clearly, how some companies manage one foreign

currency exposure should be considered with how they manage another foreign currency exposure. Managing

these in silos (without an enterprise-wide approach) can be inefcient because dollar exposures to only the

yen or euro ignore that the yen and euro are correlated. Similarly, silo risk management would ignore the

fact that the movement of interest rates could inuence an organization’s pension obligations and debt

obligations differently. As another example, how an organization manages commodity exposure today

should be factored in with how it plans to change its long-term strategy to manage that same exposure.

Short-term solutions of foreign currency risk management are different from long-term solutions of building

plants in other countries. As is evident, correlations among risks and an enterprise-wide approach is critical.

Link to Objectives at Risk or Divisions at Risk

Identifying risks by objective gives an organization the option to map risks by objectives. For nonprot

organizations, this may be more important because earnings per share is not the biggest concern. A risk

map by objective captures all the risks related to a single objective, helping the organization understand

the broad spectrum of risks facing that objective. For example, the objective of maintaining the corporate

reputation at a certain level could have many risks to be mapped. Using such a map, the organization can

see the biggest risks to reputation. Similarly, risks can also be identied by division, which may be more

informative for division managers. Organizations can generate risk maps for each division and for the

organization overall.

Residual Risk

After organizations assess risks, they should also consider any related controls so that the residual risk is

known. A residual risk is the remaining risk after mitigation efforts and controls are in place to address the

initially identied inherent risks that threaten the achievement of objectives. Risk maps can show overall

risks, or they can be shown with just residual risks. Understanding residual risk can provide major benets

because companies do not want to over- or under-manage a risk that may be deemed by management and

stakeholders to be “tolerable” or acceptable relative to stated business objectives. This is a major reason

why some companies adopt ERM and try to understand, even qualitatively, the return on investment (ROI)

of an ERM program. In the process of identifying risks and controls, the management team/process owners

clearly play a leadership role, but there is a system of “checks and balances” in the control environment. For

example, the control environment for internal controls over nancial reporting includes the audit committee

as well as internal and external auditors.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

25

Validating the Impact and Probability

Organizations can validate the qualitative assessments of initial impact and probability by examining historical

data to determine the frequency of events or the impact such events have had in the past. Events that have

happened to other organizations can be used to understand how a similar event might impact your own

organization. Gathering such data can be time consuming, but it has certain advantages. Knowing the real

frequency or likelihood of a major drop in sales, for example, can provide an organization with the information

necessary to make informed cost-benet decisions about potential solutions.

Gain/Loss Curves

Gain/loss curves are useful tools because they help an organization see how a risk can inuence its nancial

statements and result in a gain or a loss. Furthermore, gain/loss curves also reveal the distribution of potential

gains and losses. Gain/loss curves do not show correlations between risks, however, and they do not show all

the risks in one place. A gain/loss curve is presented in Exhibit 9. The curve shows how much money the company

loses or gains from a specic risk. The horizontal axis represents dollars, and the vertical axis represents prob-

ability. The sample curve in Exhibit 9 shows that the organization loses $1.15 million dollars on average (at

50% probability in this illustration) as a result of this risk. Moving along the probability scale shows that, 90% of

the time, this organization loses $300,000 because of this risk. The organization believes it loses $4.28 million

about 10% of the time. Knowing how big of an impact a risk causes over a distribution of probabilities provides

management with the information necessary to decide how much money to spend managing the risk. Gain/

loss curves can also reveal that some risks occasionally generate gains instead of losses. Developing gain/loss

curves can require substantial data collection, and a company has to balance the data collection efforts with

the benets obtained.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

26

Exhibit 9. Gain/Loss Probabillity Curve

Probability

that Annual

Loss will

Exceed Amount

Shown

$0.00

Annual Loss Amount

$6.18

1.10

1.00

0.90

0.80

0.70

0.60

0.50

0.40

0.30

0.20

0.10

0.00

Note: All loss amounts are in millions of dollars.

90% - $0.30

80% - $0.48

70% - $0.68

60% - $1.13

50% - $1.15

40% - $1.50

30% - $1.98

20% - $2.73

10% - $4.28

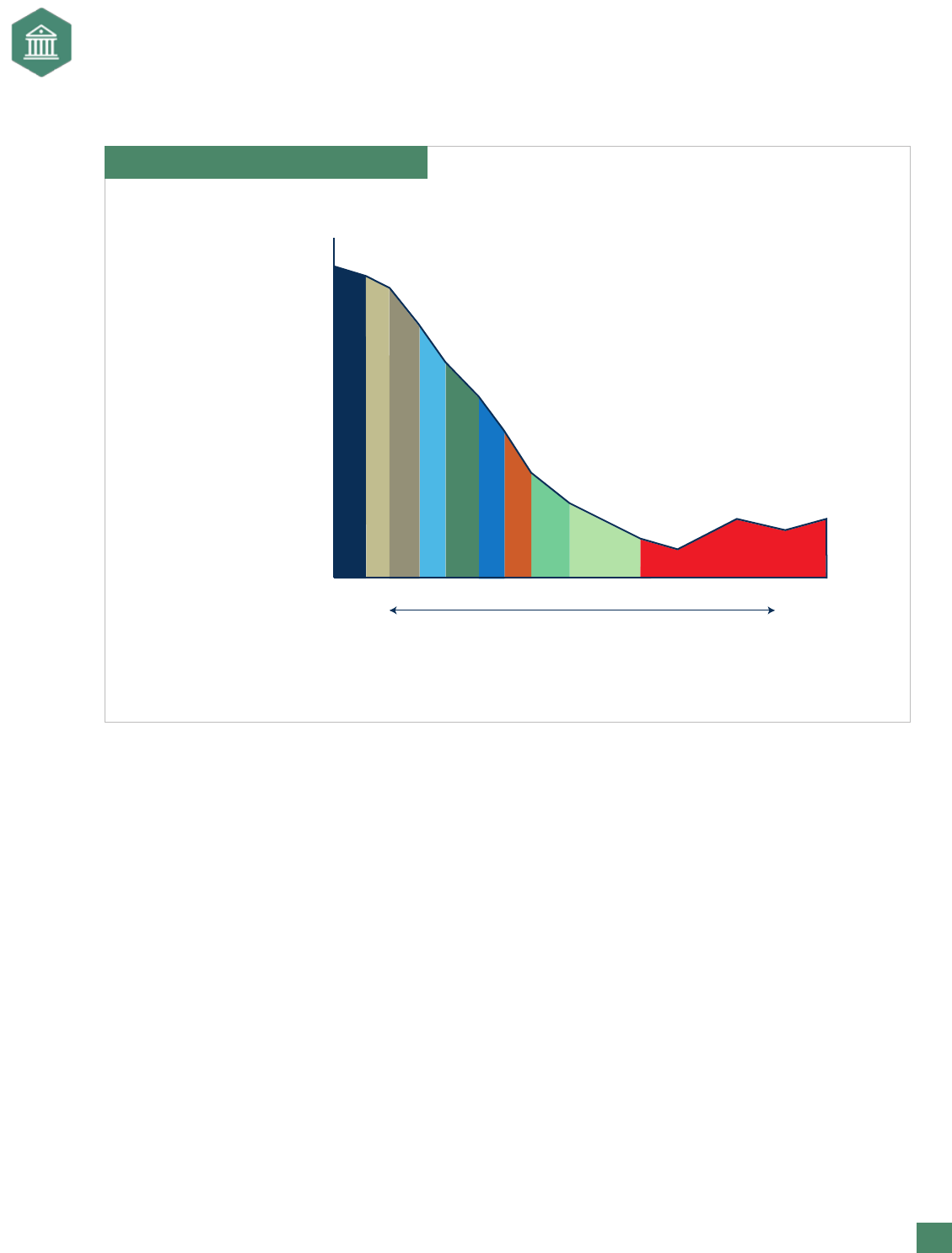

Tornado Charts

Similar to gain/loss curves, tornado charts attempt to capture how much of an impact a risk has on a particular

metric such as revenue, net income, or earnings per share. Exhibit 10 shows an example of a tornado chart.

Tornado charts do not show correlations or distributions, but they are valuable because executives can see, in

one place, the biggest risks in terms of a single performance metric.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

27

Exhibit 10. Tornado Chart: Earnings Variability by Sample Risks

Risk 1

(Cents per share)

Risk 2

Risk 3

Risk 4

Risk 5

Risk 6

Risk 7

Risk 8

Risk 9

-0.90

-0.70 -0.50 -0.30 -0.10

0.00

0.900.700.500.300.10

1.00

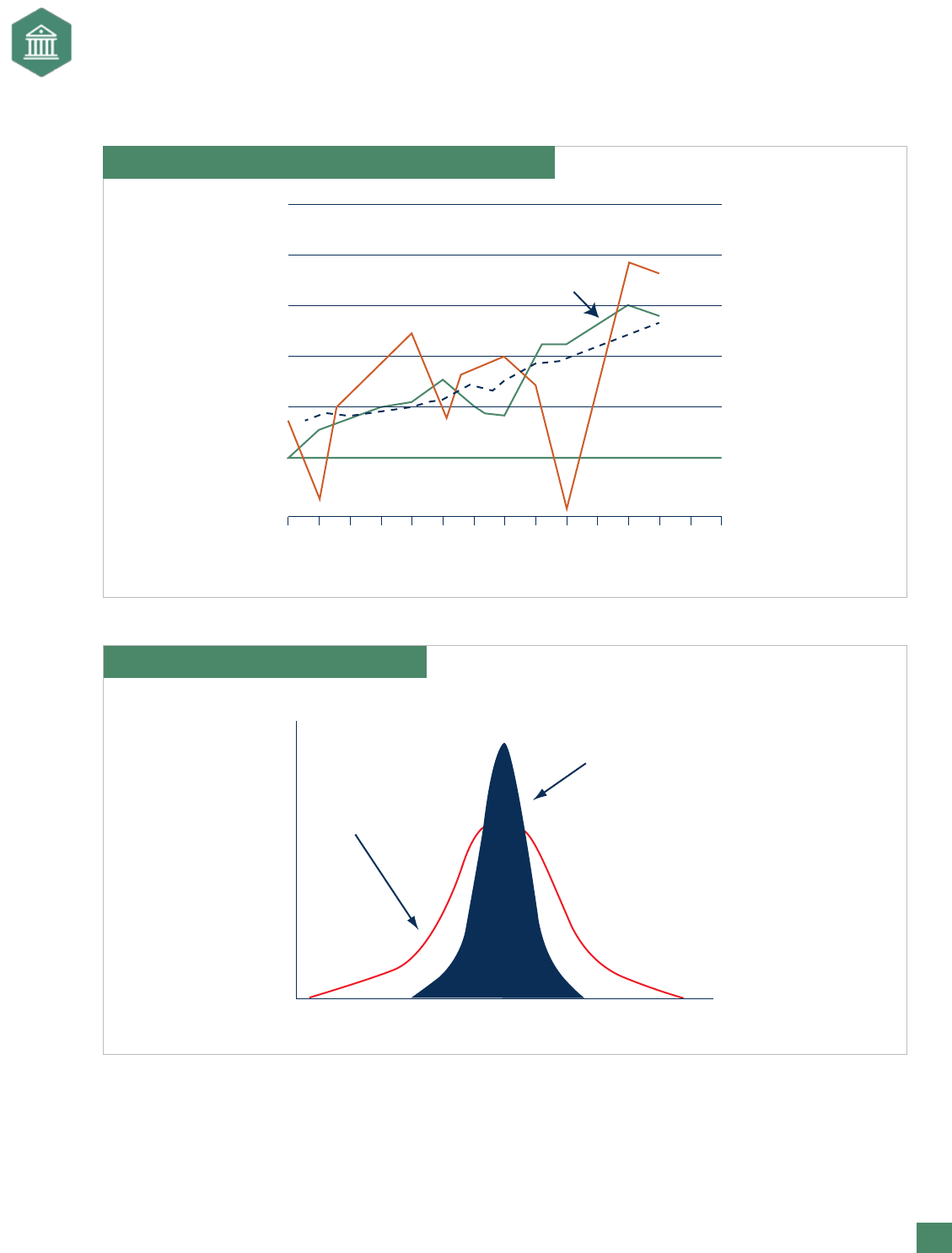

Risk-Adjusted Revenues

Risk-adjusted (or risk-corrected) revenues allow management to see how revenues could look if risks were

managed better. As Exhibit 11 shows, risk-corrected revenues are smoother and more controllable. On a

broader scale, Exhibit 12 shows one company’s view of how better risk management affects the distributions

of earnings. A tighter distribution of earnings could potentially lead to improved performance of its stock

price. The two types of analysis shown in Exhibits 11 and 12 are why some companies want to implement

ERM. While stakeholders (e.g., investors) appreciate growth in earnings, they also appreciate some level of

stability and predictability and are often willing to pay a premium for these attributes.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

28

Exhibit 11. Actual Revenue vs. Risk-Corrected Revenue

Risk-Corrected

Revenues

Actual

Revenues

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

2001

2000

2002

2003

1999

2004

Exhibit 12. Goals of Risk Management

Inherent

Distribution

Distribution

after Risk

Management

Earnings

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

29

A Common Sense Approach to Risk Assessment

While some of these risk metrics and tools may seem difcult, a simple approach can yield equally good

results. One approach is to measure where the company stands today on a risk issue. After implementing

risk mitigation techniques, the company can reassess the risk issue. Of course, not all of the improvement

related to a risk can be traced to the risk mitigation techniques, but improvement is still valuable. One major

retailer uses this approach to gauge the value added from their ERM efforts in addition to other value-added

metrics. This retailer identied inventory in-stock rates as a risk. Measuring in-stock rates over time gave

the company a good feel for the historical levels of in-stock rates. Next, after implementing risk mitigation

efforts, current inventory in-stock rates were captured. Improvements in in-stock rates are traced to improvements

in sales and, ultimately, to value added from the ERM process.

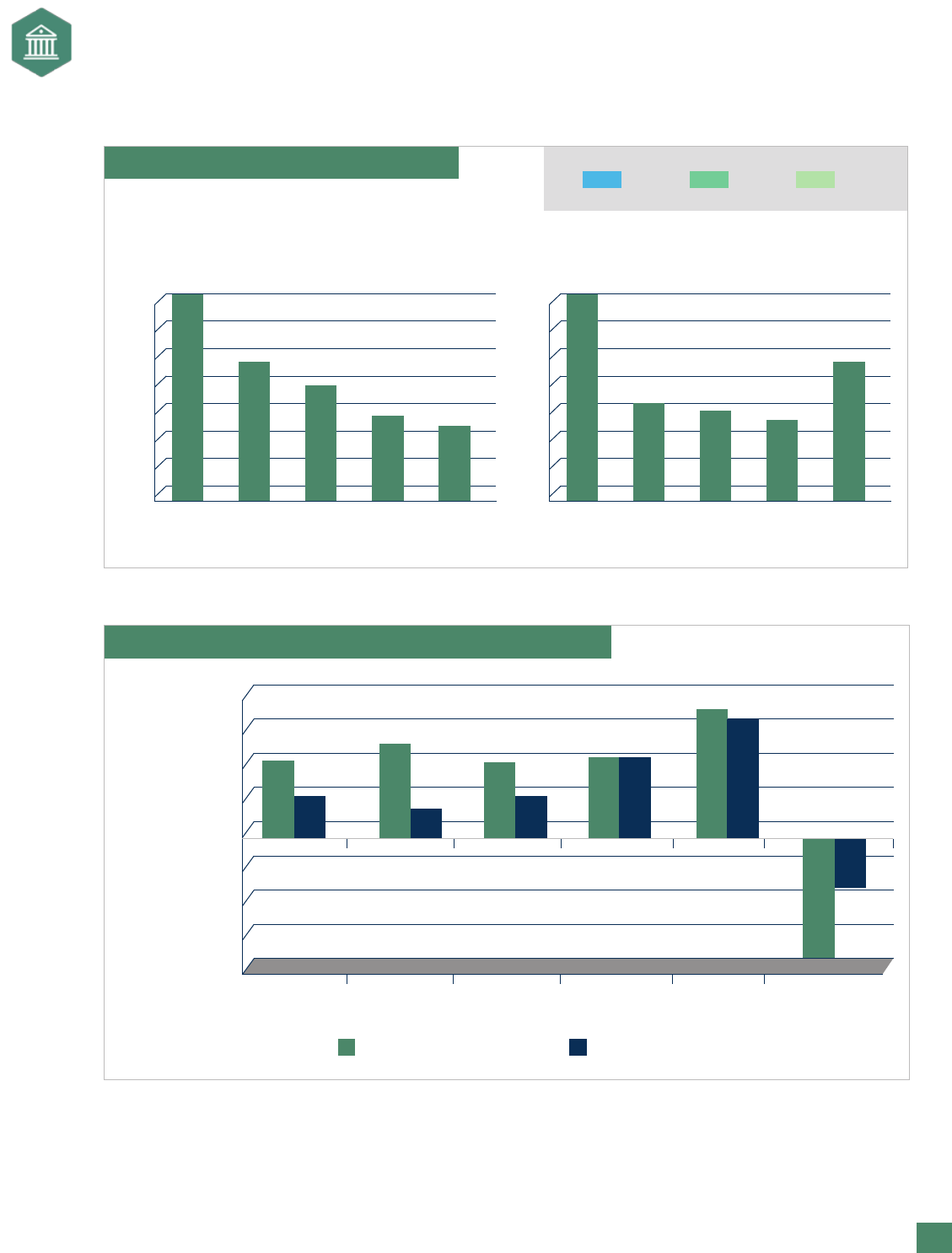

Probabilistic Models

Some organizations use quantitative approaches in ERM that are built on traditional statistical and probabilistic

models and techniques. The disadvantage to these approaches is that they require more time, data, and analysis

and are built on assumptions. Furthermore, using the past to predict the future has limitations even before

other “explanatory” variables are included in the statistical prediction process. But some organizations still nd

these models very useful as a tool in their solutions toolkit when approaching risk.

One technique focuses on earnings at risk, which are determined by examining how earnings vary around

expected earnings. In this approach, variables are examined to see how they inuence earnings, such as

determining the inuence that a one-point movement in interest rates would have on earnings. Similarly,

expected or budgeted cash ows can be determined and then tested for sensitivity to certain risks, yielding

a cash-ow-at-risk number. As Exhibit 13 shows, some companies trace the earnings-at-risk to individual risk

sources. Knowing the actual root cause or source of the risk helps manage it more efciently. Companies

can also trace the earnings at risk to business units to help gauge the hedge effectiveness of each business

unit (see Exhibit 14). Knowing which business units have the greatest risk is valuable information. With this

knowledge, a company could compare a business unit’s earnings level to the earnings at risk. Those units

that generate low earnings and high levels of risk may not be desirable business units. Having earnings at

risk in the aggregate allows an organization to see which months have the greatest risk (see Exhibit 15).

Also, distributions can be created that estimate the probability of meeting earnings targets (see Exhibit 16).

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

30

Exhibit 13. Earnings at Risk by Risk Factor

Commodity Contribution to

EaR by Major Commodity

(100% = $16 million)

Foreign Exchange Contribution to

EaR for Major Currency

(100% = $26 million)

Total EaR by Risk Category (100% = $35 million)

Interest Rates

17%

Commodity Prices

32%

Foreign Exchange

51%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Chemicals Precious

Metals

Natural

Gas

Agriculture Other

Commodities

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Euro Yen Mexican

Peso

Canadian

$

Other

Currencies

Exhibit 14. Earnings at Risk Hedge Effectiveness Comparisons

Earnings

at Risk

Contribution

(millions of

dollars)

“Natural” Earnings at Risk

-$30

-$20

-$10

0$

$10

$20

$30

$40

Business

Unit 1

-$40

Business

Unit 2

Business

Unit 3

Business

Unit 4

TOTAL Diversification

Benefit

With Hedging Earnings at Risk

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

31

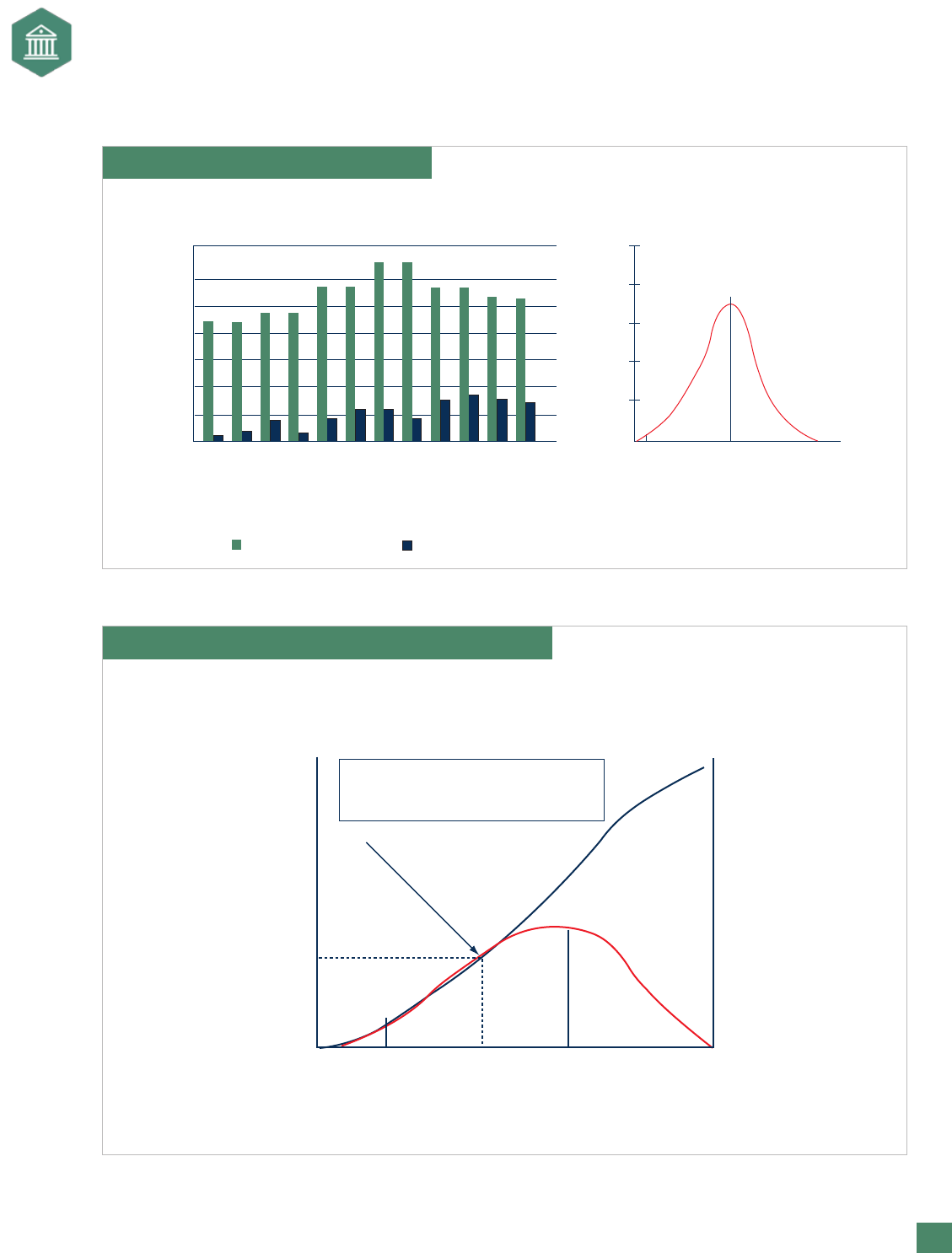

Exhibit 15. Expected Earnings and EaR

Expected Earnings Earnings at Risk

Summary By Month

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

$ Millions

$70

$60

$50

$40

$30

$20

$10

$0

Distribution or Annualized

Earnings Outcomes

$125

EaR

equals the

difference

$545

Equals the

earnings

corresponding

to the 95% CI

$670

Equals

the expected

or budgeted

earnings

Earnings

($ millions)

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

Exhibit 16. Probability Assessment of Earning Outcome

Interpretation: There is a 30% chance

that due to all risks earnings will

fall below $640 million for the year.

Probability

of a Specific

Outcome

Cumulative

Probability

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

$545

Level of

earnings

corresponding

with EaR

$640 Earnings

($ millions)

80%

90%

100%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

$670

Expected or

budgeted

earnings

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

32

Seemingly Nonquantiable Risks

Some risks seem to defy acceptable quantication, but a deeper look can reveal valuable information.

Reputation is a risk that has become increasingly important in today’s business environment, and it must be

managed. At rst glance, some executives would say you cannot quantify it, but it can be in some ways. In

academia, for example, a university’s reputation is a prodigious risk. Tracking a drop in contributions after a

scandal can provide preliminary data that could lead to the ability to quantify reputation risk. Ranges of

decreases in contributions could also be developed, with the maximum risk being a major decrease in donations.

Gathering data from universities or other nonprot organizations that have experienced a drop in contributions

can provide valuable external data that could assist in quantifying this risk. For public companies, the impact

of reputation risk could be examined by studying decreases in stock prices surrounding an event that damaged

an organization’s reputation. It is important to note that while this might capture and provide a quantiable

risk, it still partially ignores the damage that reputation events have on supplier or vendor relations. It also

ignores how future customers might be inuenced by the reputation event. Although these related risks

might not be quantiable, they highlight the importance of having an ERM team study and analyze risks very

closely so that conversations about the risks are focused on managing the risk and not just on identication

and measurement.

Another example of a risk that appears nonquantiable is a breach in IT security. Examining the movement

in stock price around the event, however, can help a company gather a preliminary estimate of how share-

holders view the event. Additionally, talking to other companies that have experienced IT security breaches

can help the company understand the potential impact. Finally, understanding the organization’s unique

method of creating value for its customers can also offer critical insights regarding the impact of the breach.

Companies that have customers who value trust and condentiality, such as nancial institutions, should

estimate a greater impact from a potential IT security breach.

A major electronic retailer may determine that a key risk to sales is a change in gas prices. The retailer relies

on consumers having discretionary income, and higher gas prices lower discretionary income and decrease

the retailer’s sales. The effect of gas prices on sales can be calculated and potentially planned for in advance.

Another example is the risk of weather related to a snow machine company’s sales. Guaranteeing a rebate

to customers if the amount of snowfall is below a certain level can increase sales in years with low snow

fall.

12

These examples show that while not all risks can be quantied with a sophisticated technique, valuable

risk assessment and management can still be applied.

12

Stephen W. Bodine, Anthony Pugliese, and Paul L. Walker, “A Road Map to Risk Management,” Journal of Accountancy, December 2001, pp. 65-70.

GOVERNANCE

SYSTEMS

Enterprise Risk Mamagement:

Tools and Techniques for Effective Implementation

33

Practical Implementation Considerations