The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

1

Playbook:

Enterprise Risk Management

for the U.S. Federal Government

(Fall, 2022 Update)

Developed and issued in collaboration with Federal Government organizations

to provide guidance and support for Enterprise Risk Management.

MEMORANDUM FROM: Chief Financial Officers Council (CFOC)

Performance Improvement Council (PIC)

DATE: November 28, 2022

SUBJECT: Update to Playbook: Enterprise Risk Management for the U.S. Federal

Government

As our experience these past two years responding to the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates, integrating

sound risk management approaches and practices at both the programmatic as well as enterprise level

into agency management routines is critical for effective operational and strategic planning. Thus, the

Chief Financial Officers Council (CFOC) and the Performance Improvement Council (PIC) are releasing

this update to the Playbook: Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) for the U.S. Federal Government

(Playbook) as an inter-council effort convened by the Office of Shared Solutions and Performance

Improvement of the General Services Administration. Led by agencies, the updated Playbook resulted

from the efforts of a Working Group of ERM practitioners who are members of the ERM Community of

Practice from over 50 federal agencies and included cross-functional representation.

The updated Playbook contains expanded sections on incorporating ERM into management practices,

risk appetite and tolerance, workforce, a new section on ERM and Cybersecurity, and updated

appendices, including a new ERM maturity model.

Because the Playbook was always intended to be updated as agencies’ ERM capabilities mature, future

revisions to the Playbook will be released as this critical management function evolves to provide

support to agency leadership decision-making. As part of these ongoing efforts, we will continue to

accept comments, suggestions, and examples for the Playbook through the CFO and PIO Councils and

ERM Community of Practice.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4

A. Using This Playbook ............................................................................................................................... 4

B. What is Risk Management? What is ERM? Why Do Government Agencies Need Them? ................. 5

C. Integrating ERM into Government Management Practices .................................................................. 6

II. Enterprise Risk Management Basics ........................................................................................................ 17

A. Outcomes and Attributes of Enterprise Risk Management ................................................................ 17

B. Common Risk Categories ..................................................................................................................... 17

C. Principles of Enterprise Risk Management .......................................................................................... 18

D. Maturity of ERM Implementation ....................................................................................................... 20

III. ERM Model ............................................................................................................................................. 20

IV. Developing an ERM Implementation Approach ..................................................................................... 25

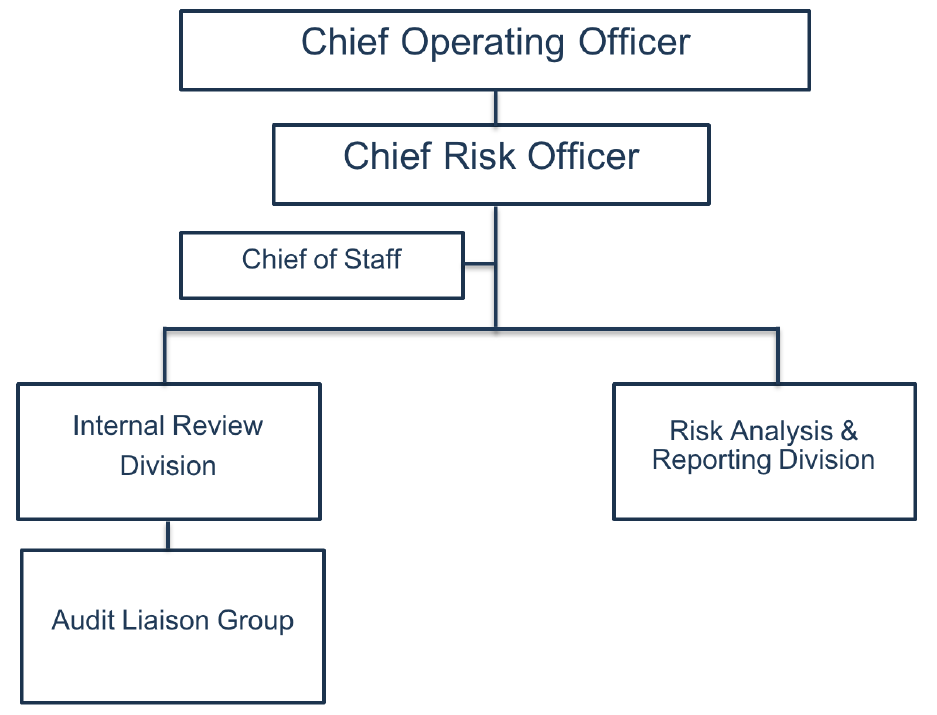

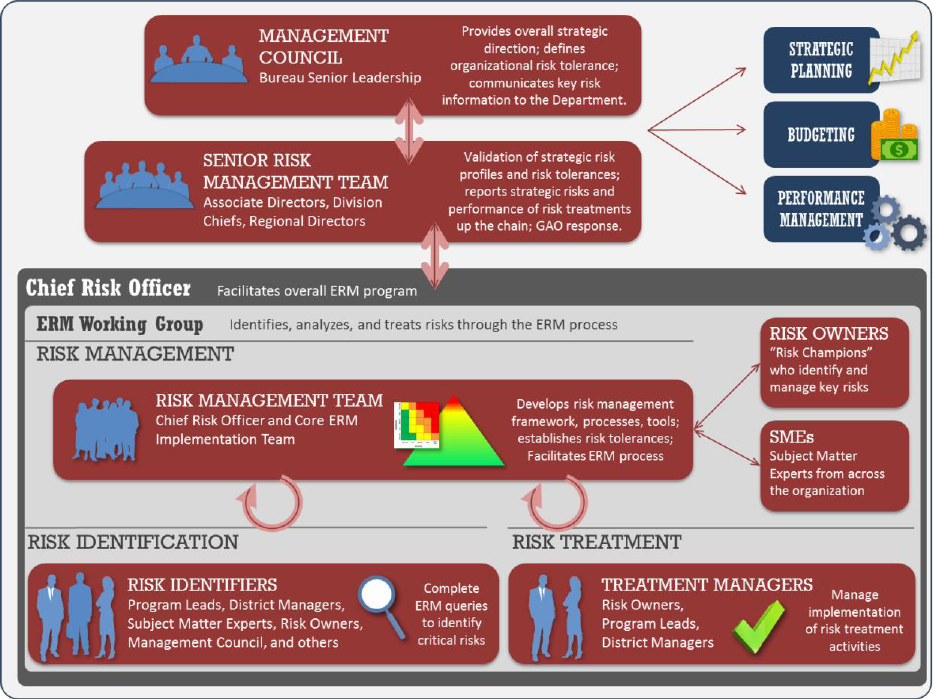

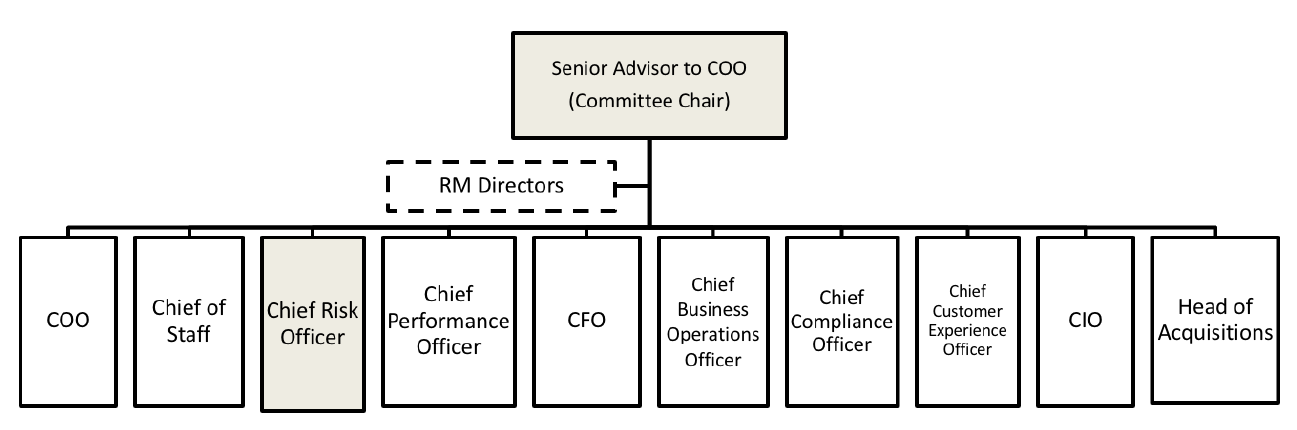

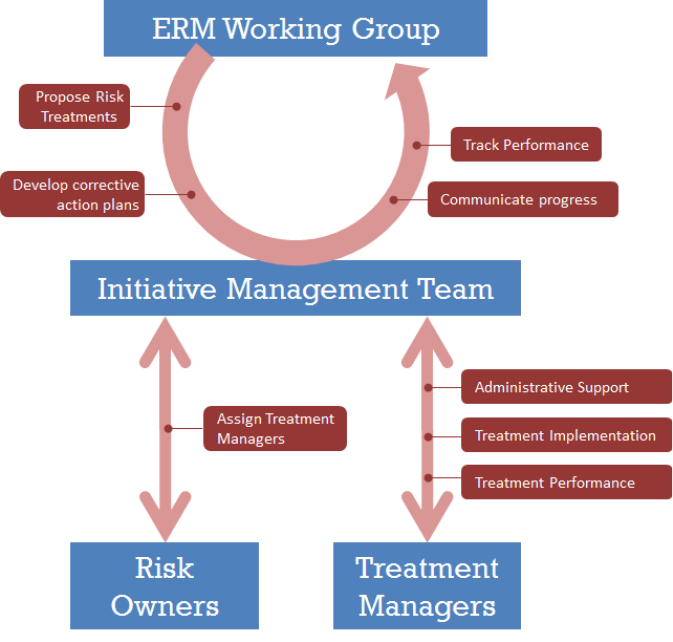

V. Risk Governance ...................................................................................................................................... 26

A. Culture and Governance .................................................................................................................. 26

B. Organizational Design, Alignment, Leadership and Staffing ........................................................... 27

VI. The Risk Appetite Statement .................................................................................................................. 28

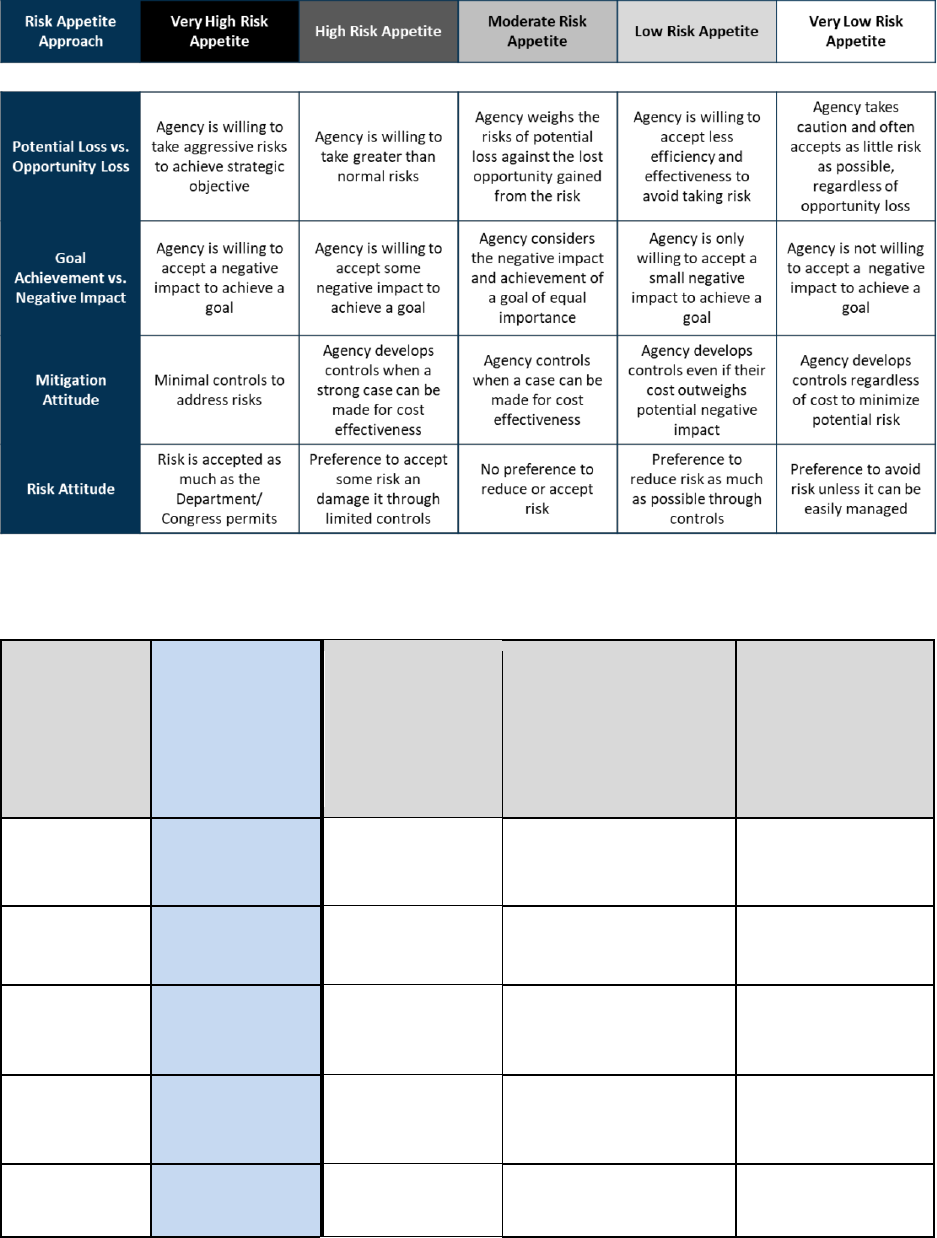

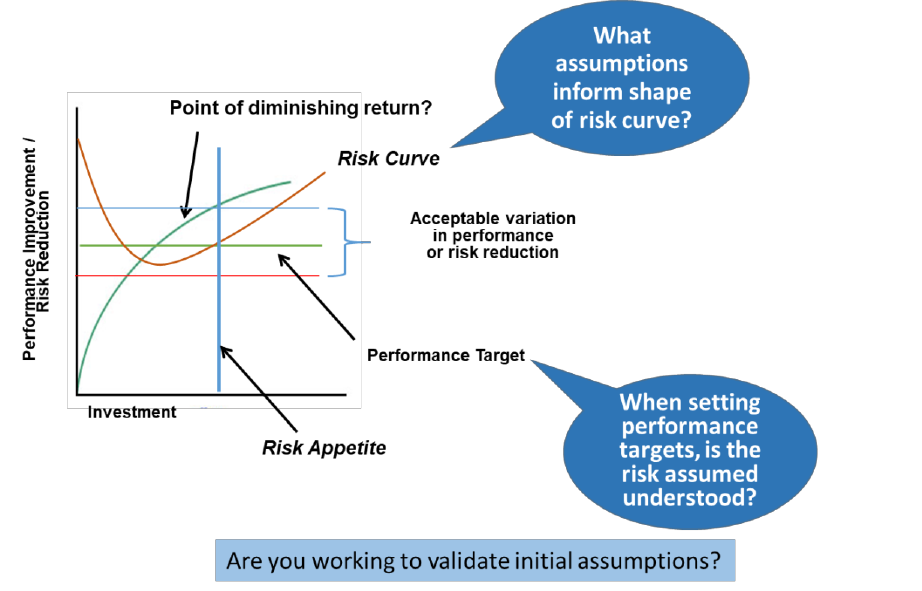

A. What is Risk Appetite and Risk Tolerance? ..................................................................................... 28

B. Methods for Assessing and Updating Risk Appetite........................................................................ 30

C. Methods for Establishing a Risk Appetite Statement ...................................................................... 33

D. Considerations When Developing Risk Appetite ............................................................................. 34

E. Examples of Risk Appetite being applied in an agency ................................................................... 35

VII. Developing a Risk Profile ....................................................................................................................... 38

A. Steps to Creating a Risk Profile ............................................................................................................ 38

B. Additional Considerations ................................................................................................................... 47

VIII. GAO/OIG Engagement .......................................................................................................................... 48

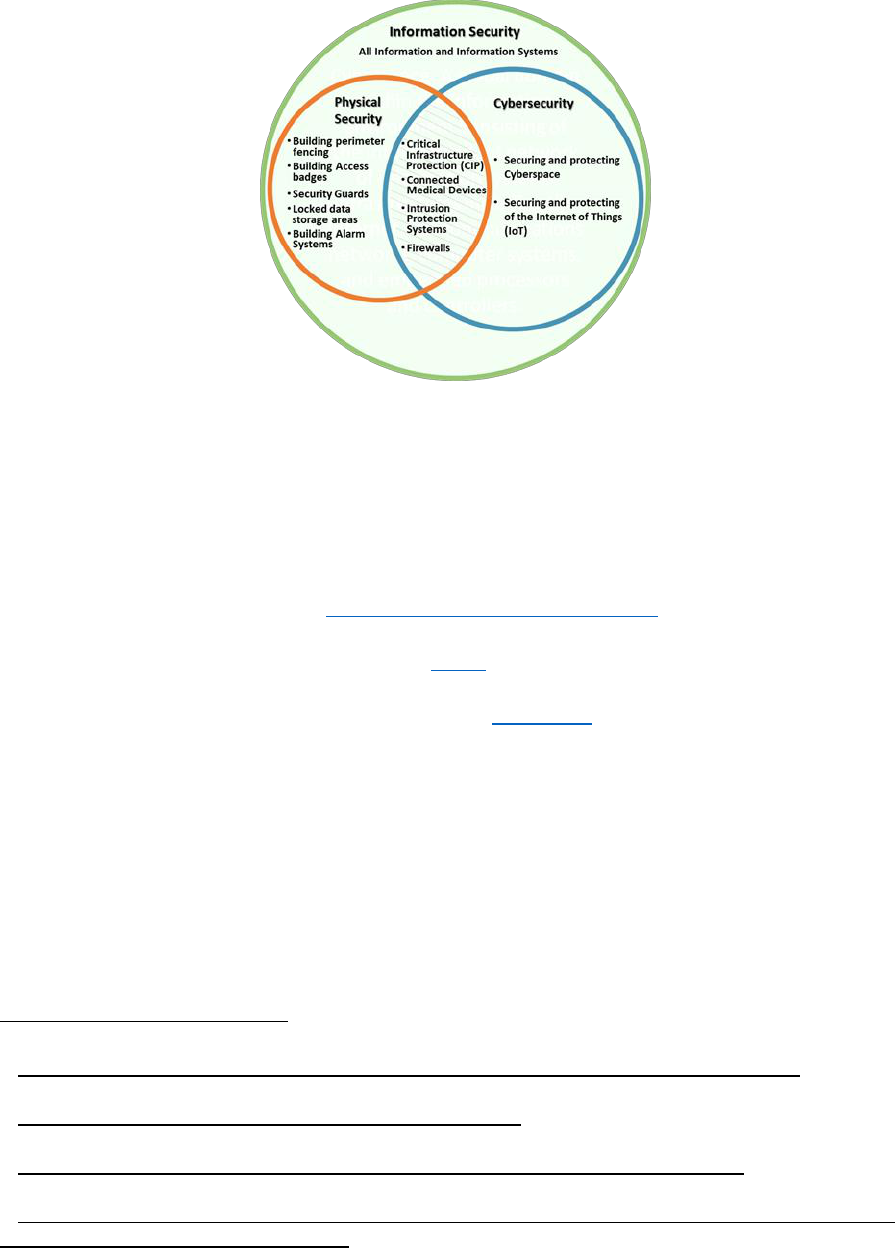

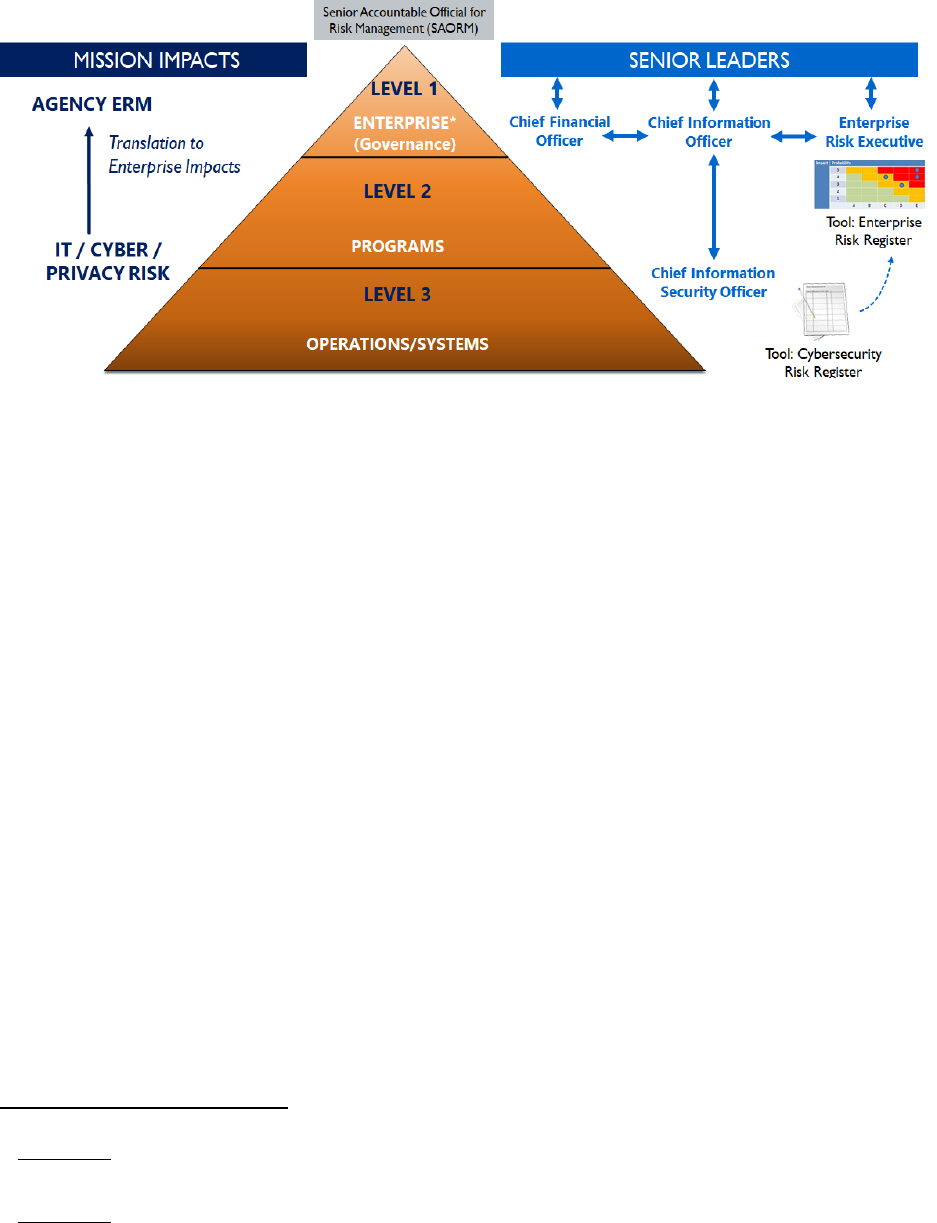

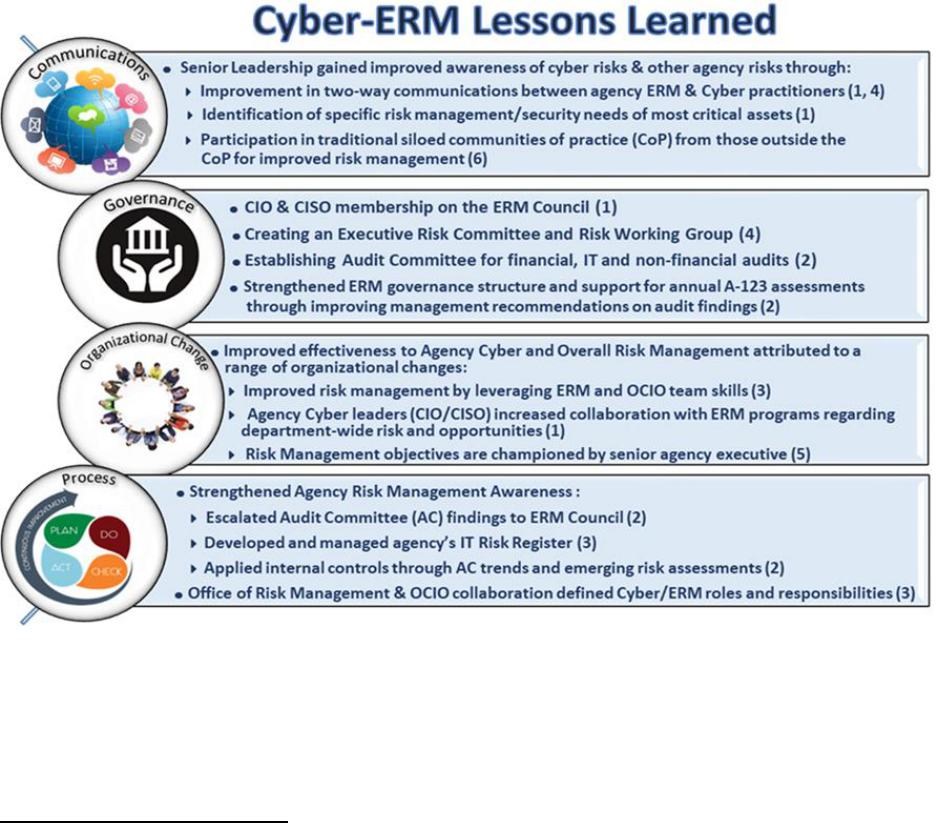

IX. Special Chapter: Integration of Agency ERM with Information Security and Cybersecurity Risk

Management................................................................................................................................................ 48

A. Foundations of Information Security and Cybersecurity ................................................................ 48

B. ERM Principles within Information Systems.................................................................................... 52

C. Approaches to ERM, Information Security, and Cybersecurity Risk Management Integration ...... 56

D. Addressing Confusion in FISMA Audits ............................................................................................ 59

X. Appendices .............................................................................................................................................. 61

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

4

I. Introduction

Playbook: Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) for the U.S. Federal Government (Playbook) is the

result of an interagency effort to gather, define, and illustrate practices in applying ERM in the federal

context. This Playbook and accompanying appendices are tools designed to help government

departments and agencies meet the requirements of the revised Office of Management and Budget

(OMB) Circular No. A-123 (OMB A-123). The appendices are designed to provide high-level key concepts

for consideration when establishing a comprehensive and effective ERM program. Nothing in this

Playbook should be considered prescriptive. All examples provided should be modified to fit the

circumstances, conditions, and structure of each agency (or other government organization). The goal

of the Playbook is to promote a common understanding of ERM practices in agencies. This shared

knowledge will support effective and efficient mission delivery and decision-making processes, such as

policy and program development and implementation, program performance reviews, strategic and

tactical planning, human capital planning, capital investment planning, and budget formulation. The

Playbook is intended as a useful tool for management. It is not intended to set the standard for audit or

other compliance reviews.

The material in this document is intended to be:

1. Useful to employees at all levels of an agency;

2. A useful statement of principles for senior staff, whose leadership is vital to a successful risk

management culture and ERM program implementation;

3. A useful tool for those throughout an organization to improve decision-making, strategy,

objective-setting, and daily operations;

4. Practical support for operational level staff who manage day-to-day risks in the delivery of the

organization’s objectives;

5. A reference for those who review risk management practices, such as those serving on Risk

Committees; and

6. Helpful for implementing the requirements of OMB Circulars A-11 and A-123.

1

To manage risk effectively, it is important to build strong communication flows and data reporting so

employees at all levels in the organization have the information necessary to evaluate and act on risks

and opportunities, to share recommendations on ways to improve performance while remaining within

acceptable risk thresholds, and to seek input and assistance from across the enterprise.

A. Using This Playbook

This Playbook is intended to assist Federal managers by identifying the objectives of a strong ERM

program, suggesting questions agencies should consider in establishing or reviewing their approaches to

ERM, and offering examples of best practices.

An agency-wide ERM program should enhance the decision-making processes involved in agency

planning, including strategic and tactical planning, human capital planning, capital investment planning,

program management, and budget formulation. It should build on the individual agency’s risk

1

Note that OMB Circulars A-11 and A-123 does not seek to describe a comprehensive ERM program, and the

requirements set forth are not required for all agencies but are required for CFO Act agencies.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

5

management activities already underway and encompass an agency’s key operations.

Responsibility for managing risks is shared throughout the agency from the highest levels of executive

leadership to the service delivery staff. Effective risk management, and especially effective ERM, is

everyone’s responsibility.

This Playbook was written by a group of agency risk practitioners and is not an authoritative part of

OMB Circulars A-11, A-123 or other guidance. While this Playbook provides the foundation for applying

ERM principles and meeting the requirements of the Circulars, it is not an exhaustive manual with

specific checklists for implementing ERM. Each agency should determine what tools and techniques

work best in its unique context. ERM is a process. As agencies' ERM capabilities mature, their

implementation of the recommendations in this Playbook should be modified to fit the circumstances,

conditions, and structure of each entity. This Playbook is intended to provide guidance to help agencies

make better-informed decisions based on a holistic view of risks and their interdependencies. The

appendices include examples of documents some agencies have found helpful.

This document is not intended to set standards for audit or other compliance reviews, nor is it intended

to be prescriptive.

B. What is Risk Management? What is Enterprise Risk

Management? Why Do Government Agencies Need Them?

Risk is unavoidable in carrying out an organization’s objectives. Government departments and agencies

exist to deliver services that are beneficial to the public interest, especially in areas where the private

sector is either unable or unwilling to do so. This work is surrounded by uncertainty, posing threats to

successfully achieving objectives while at the same time offering opportunities to increase value to the

American people through planning and mitigation.

While agencies cannot respond to all risks, one of the most salient lessons learned from past crises and

negative reputational incidents is that public and private sector organizations both benefit from

establishing or reviewing and strengthening their risk management practices. Agencies are well advised

to work to the greatest extent possible to identify, evaluate, and manage challenges and opportunities

related to mission delivery and manage risk within their established tolerances and appetites.

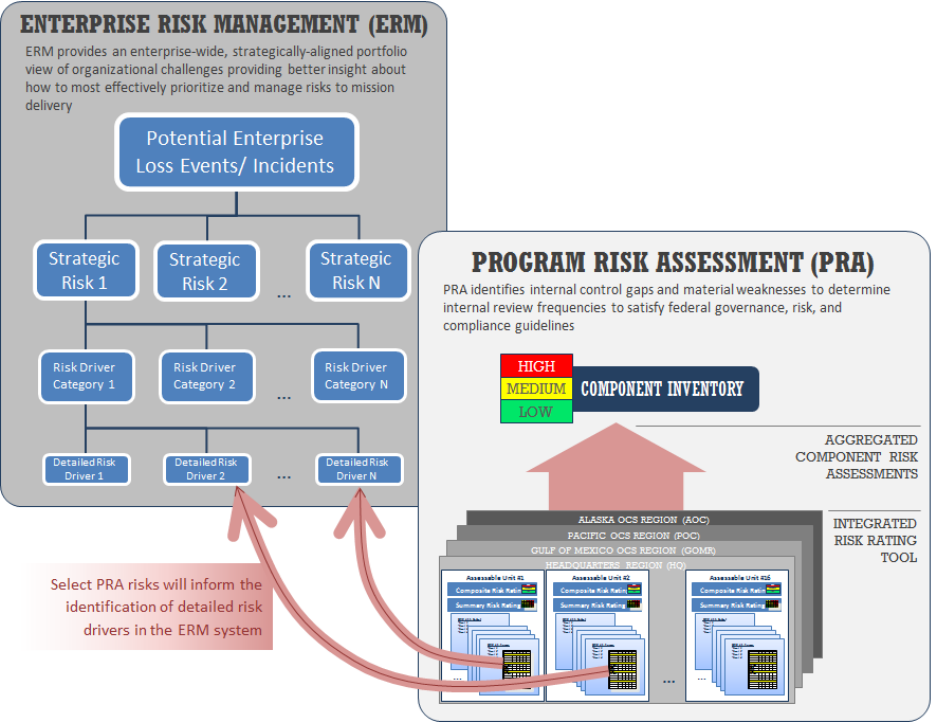

For the purposes of ERM, Risk is the effect of uncertainty on objectives. Risk management is a

coordinated activity to direct and control challenges or threats to achieving an organization’s goals and

objectives. Enterprise Risk Management is an effective agency-wide approach to addressing the full

spectrum of the organization’s significant risks by considering the combined array of risks and

opportunities as an interrelated portfolio, rather than addressing risks only within silos. ERM provides

an enterprise-wide, strategically-aligned portfolio view of organizational challenges and opportunities

that provide improved insight to more effectively prioritize and manage risks to mission delivery.

2

Effective ERM facilitates improved decision-making through a structured understanding of opportunities

and threats. Effective ERM also helps agencies implement strategies to use resources effectively,

optimize approaches to identify and remediate compliance issues, and promote reliable reporting and

monitoring across business units. It promotes a culture of better understanding, disclosure, and

2

OMB Circular No. A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, Section 260.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

6

management of agency risks and opportunities. The benefits of ERM integration include the ability to:

increase opportunities, increase positive outcomes and advantages, reduce negative surprises, identify

and manage entity-wide risks, reduce performance variability, and improve resource deployment.

3

ERM

helps agencies strengthen their ability to evaluate alternatives, set priorities, and develop approaches to

achieving strategic objectives. The adoption of consistent risk management processes and tools can help

ensure risks are managed effectively, efficiently, and coherently across an agency.

An ERM framework allows Federal departments and agencies to increase risk awareness and

transparency, improve risk management strategies, and align risk taking to each agency’s risk appetite

and risk tolerance. Risk Appetite is the amount of risk (on a broad, macro level) an organization is willing

to accept in pursuit of strategic objectives and the value to the enterprise.

4

Risk Tolerance is the

acceptable level of variance in performance relative to the achievement of objectives.

5

It is generally

established at the program, objective, or component level. In setting risk tolerance levels, management

considers the relative importance of the related objectives and aligns risk tolerance with risk appetite.

Federal agencies will be most successful in managing risks when there is a high level of awareness and

ownership of risk management at all levels of the agency.

C. Integrating ERM into Government Management Practices

Successful integration of ERM into agencies’ day-to-day decision-making and management practices

enables agencies to leverage opportunities for accepting, reducing, sharing, pursuing, or avoiding risk that

ultimately results in more resilient, effective, and efficient government programs. ERM can help to focus

and strengthen decisions by informing the development of goals and objectives and the strategies to

achieve them. This includes advocating for and aligning resources, monitoring progress, and ensuring

compliance with applicable laws, regulations, and controls.

ERM Pitfall

ERM not integrated

ERM should not be an isolated exercise, but instead, should be integrated into the

management of the organization and eventually into its culture.

Integrating ERM into agencies’ decision-making and management practices can be done successfully and

in various ways. It can be supported by co-locating the ERM function with other management functions

such as strategic planning, organizational performance, budget, or internal controls; through the ERM

function and other management functions reporting to the same management official; or through equal

organizations with strong collaboration across the offices. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to

organize an ERM program to achieve integration, it is imperative that the ERM function be tailored to the

function, characteristics, and culture of the agency.

3

The Committee of Sponsoring Organization of the Treadway Commission (COSO) Enterprise Risk Management-

Integrated Framework, pgs. 6-7.

4

The Committee of Sponsoring Organization of the Treadway Commission (COSO) Enterprise Risk Management-

Integrated Framework, p. 20.

5

Ibid.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

7

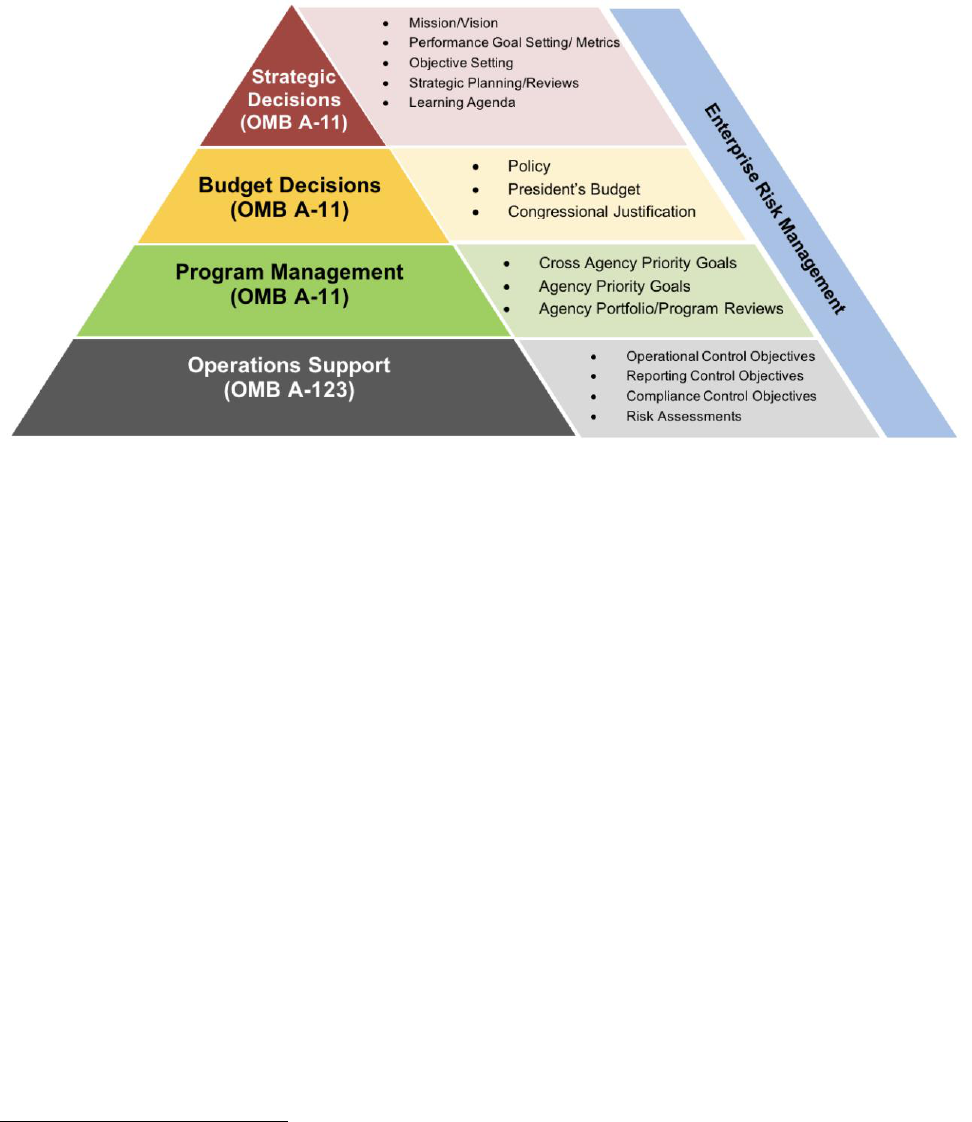

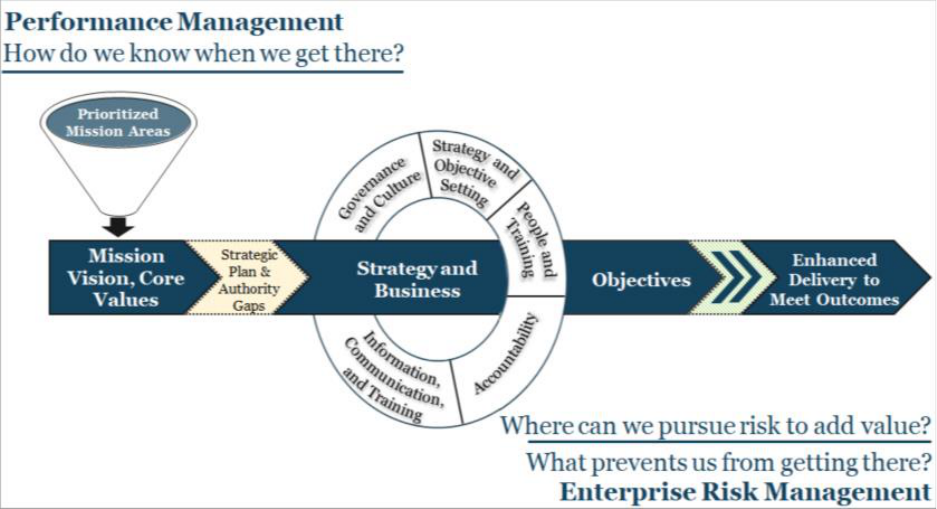

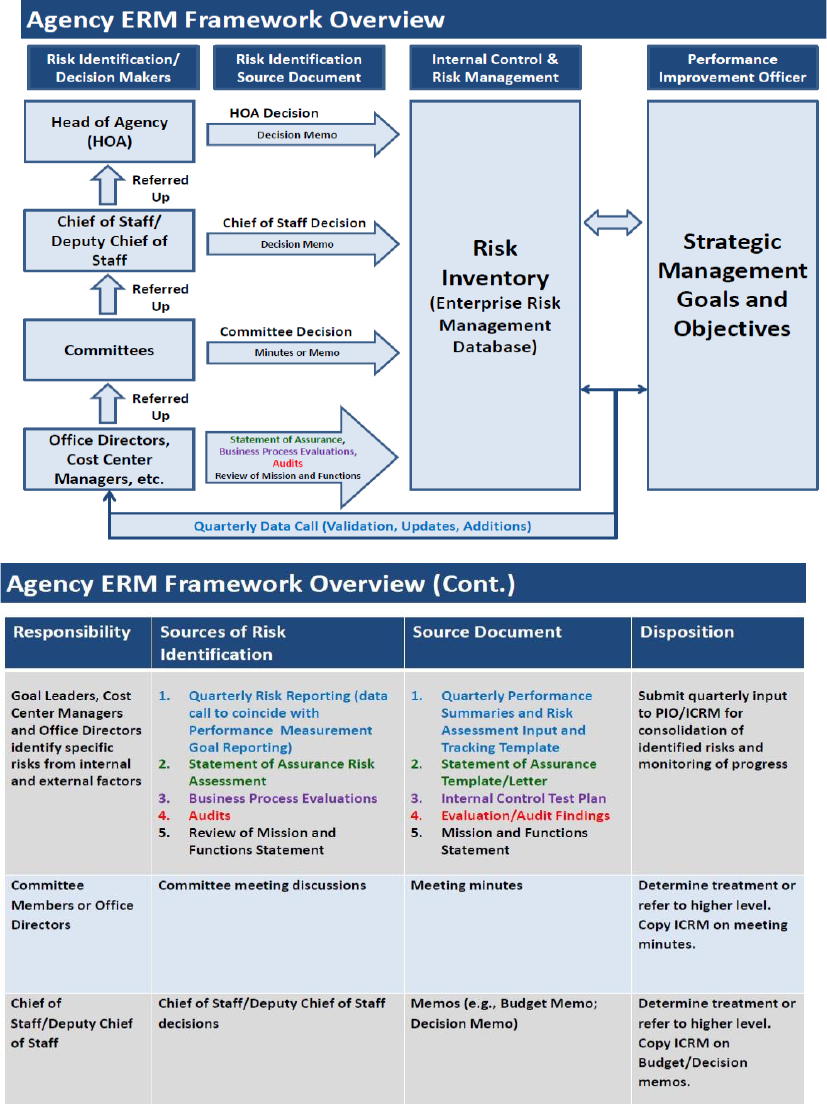

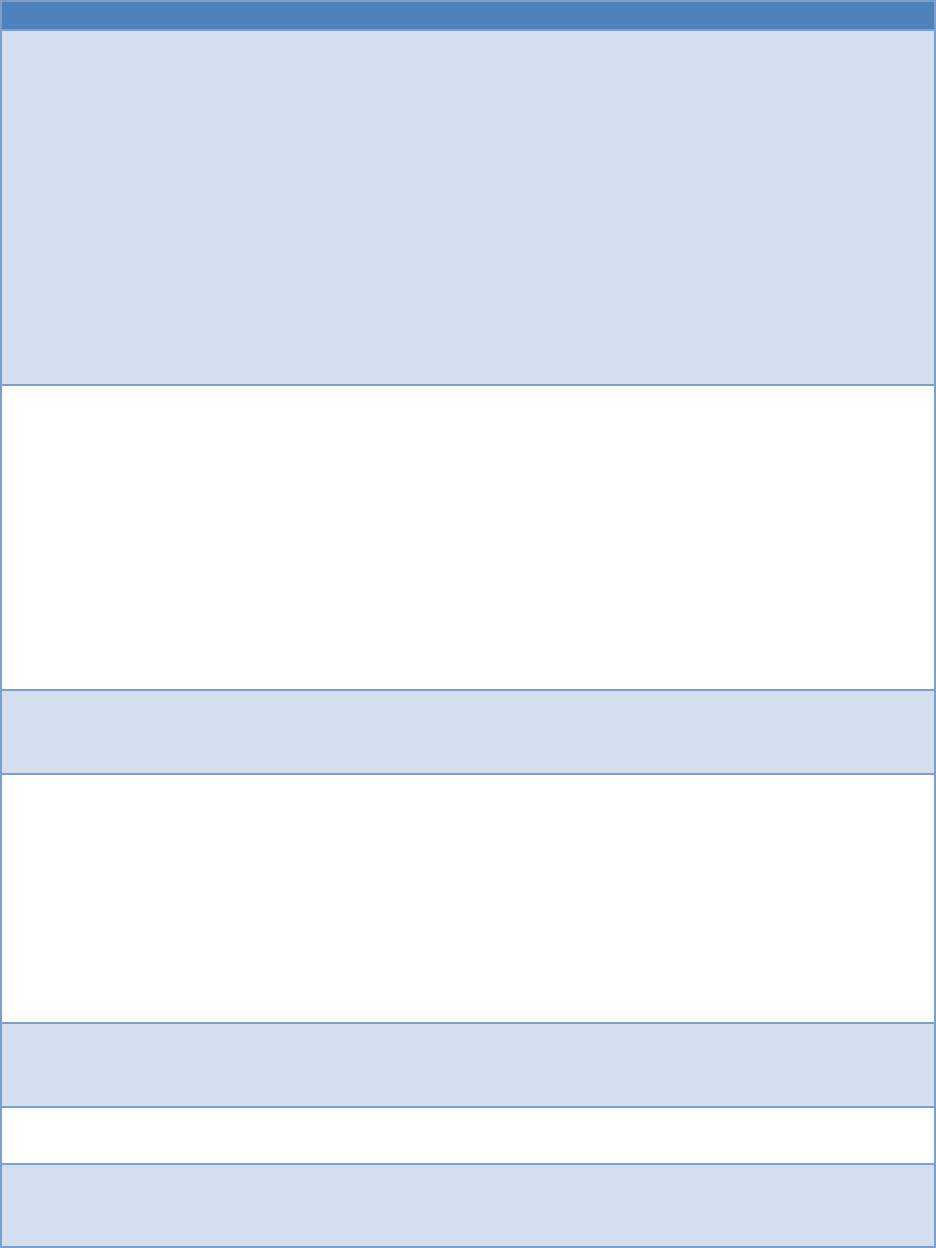

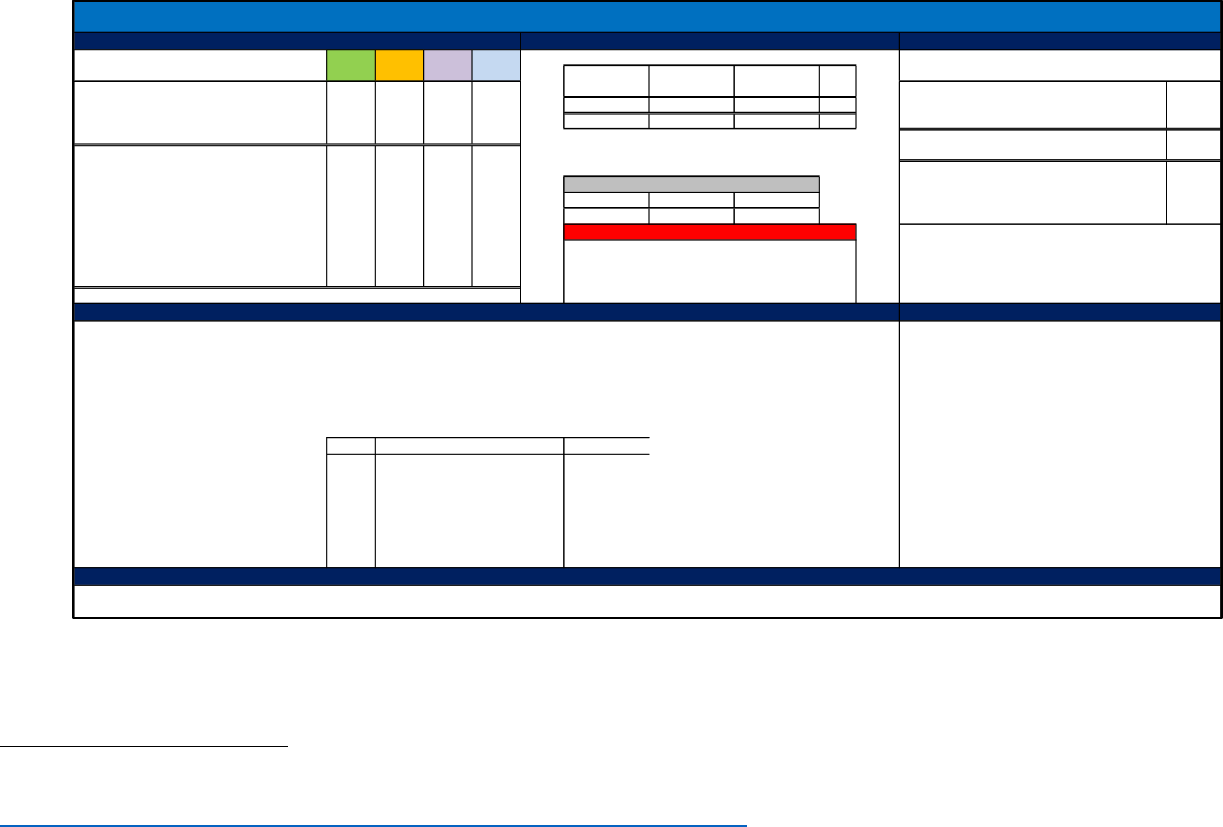

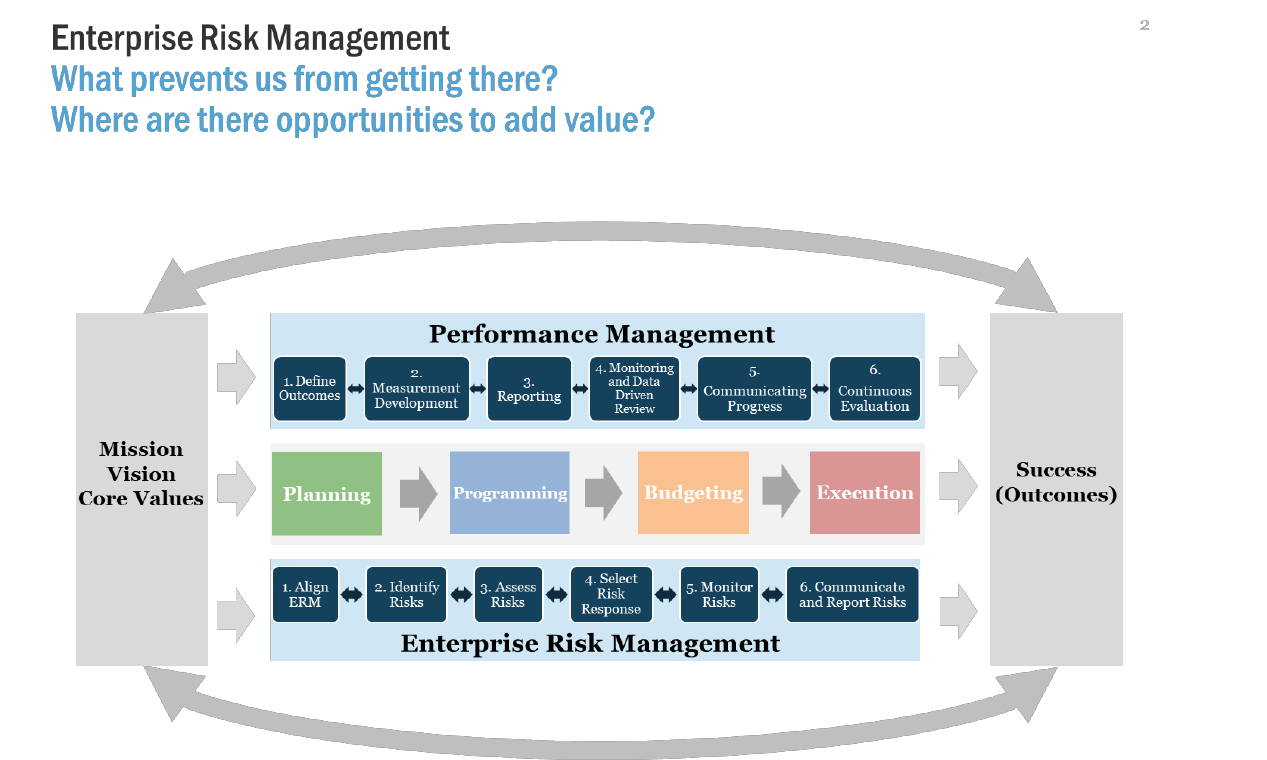

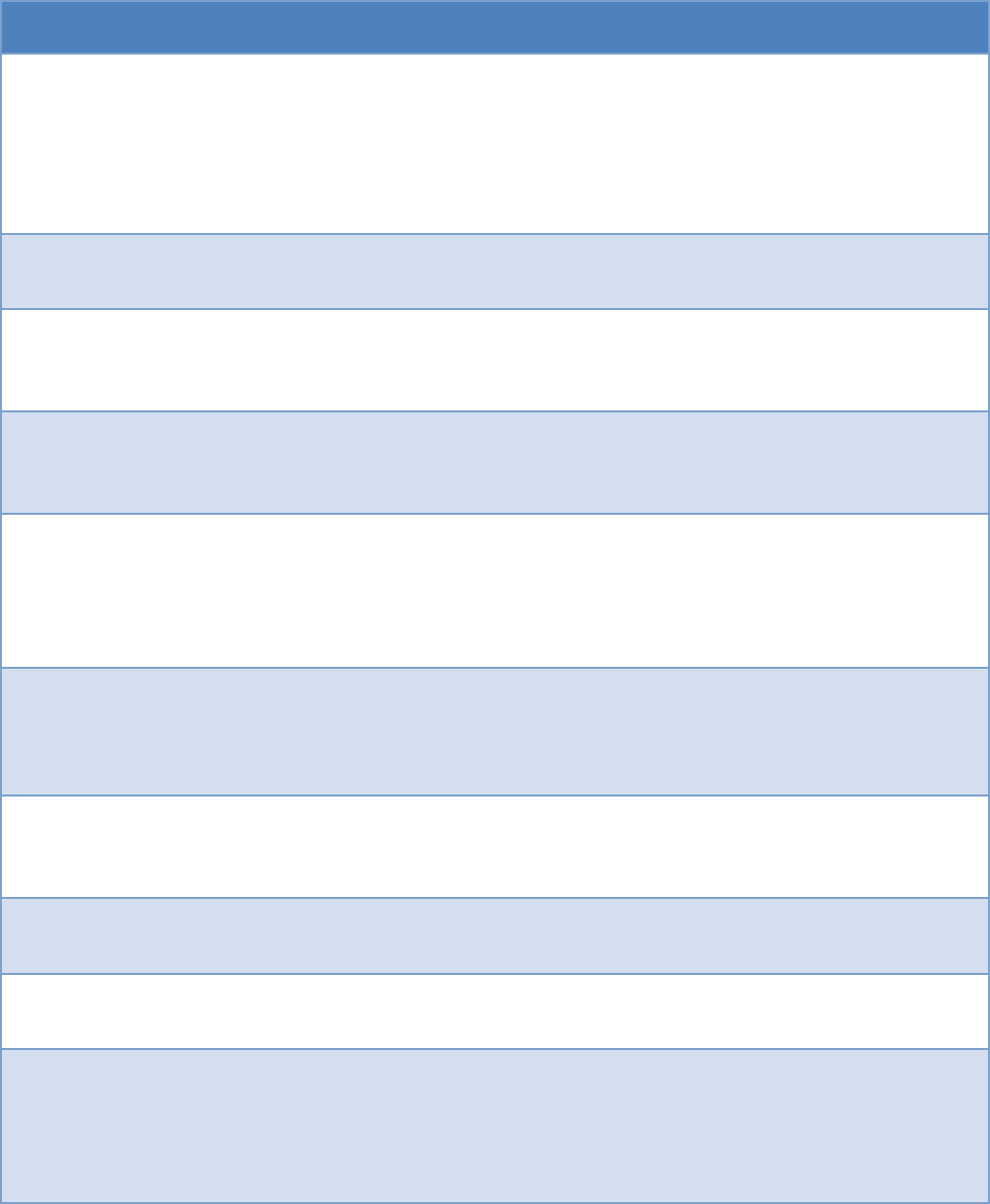

OMB issued several guidance documents that call for the integration of ERM into existing management

practices. For example, since the update to Circular A-123’s release in 2016, enterprise risk management

has been more fully incorporated into OMB Circular No. A-11 (OMB A-11). As shown in Figure 1, OMB A-

11 calls for agencies to consider and prioritize risks across the enterprise as part of program and service

delivery and implementation, operations support, organizational strategic and performance planning, and

budget decisions and resource alignment (including the workforce). The updated Section 260 of OMB A-

11 discusses agency responsibilities for identifying and managing strategic and programmatic risk as part

of agency strategic planning, performance management, and performance reporting practices. The

budget formulation sections of OMB A-11 state that agencies should include ERM as a basis for budget

proposals.

6

OMB instructs that agencies, when creating their budget proposals, should use a

comprehensive system that integrate analysis, performance management and strategic planning,

evaluation, ERM, and budgeting, as well as appropriately incorporate the analyses and assessments

resulting from the agency's annual strategic reviews.

Section II of OMB A-123 defines management’s responsibilities for ERM and includes requirements for

identifying and managing risks. It encourages agencies to establish a governance structure, including a

Risk Management Council or Committee (RMC) or similar body. It also requires agencies to develop “Risk

Profiles” that identify major risks arising from mission and mission-support operations and analyze how

those risks affect the agency’s achievement of its strategic objectives. Appendix A of OMB A-123 was

updated in 2018 and provides updated guidance to agencies that integrates internal control over

reporting with ERM processes, and assurances over internal control. Specifically, the update expanded

internal controls from financial reporting to all reporting objectives. By aligning the updated Appendix A

to the agency’s ERM processes, agency management should apply their analysis of risk in the agency’s

risk profiles across a portfolio view of the agency’s objectives. They should decide where internal

controls will be most effectively employed to those reporting objectives where inaccurate, unreliable, or

outstanding reporting would significantly impact the agency’s ability to accomplish its mission and

performance goals or objectives. More importantly, management decisions to apply internal controls

over reporting should not be done against the entire Annual Agency Performance Plan or Annual Agency

Performance Report, but only where there is significant risk that a material reporting error may impact

achievement of the agency’s mission objectives and internal controls are likely to cost effectively

mitigate the risk.

OMB A-123 and OMB A-11 constitute the core of the ERM policy framework for the Federal Government

with specific ERM activities integrated and operationalized by Federal agencies.

7

The following figure

shows the interplay among these two Circulars and controls, program management, budget, and

strategic decisions within the ERM framework.

6

See OMB Circular No. A-11, Section 51 and Part 6 (Sections 200-290).

7

Requirements set forth in OMB A-11 and OMB A-123 are necessary for CFO Act agencies and are optional for

others. Therefore, not everything discussed in this section may be relevant to all agencies.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

8

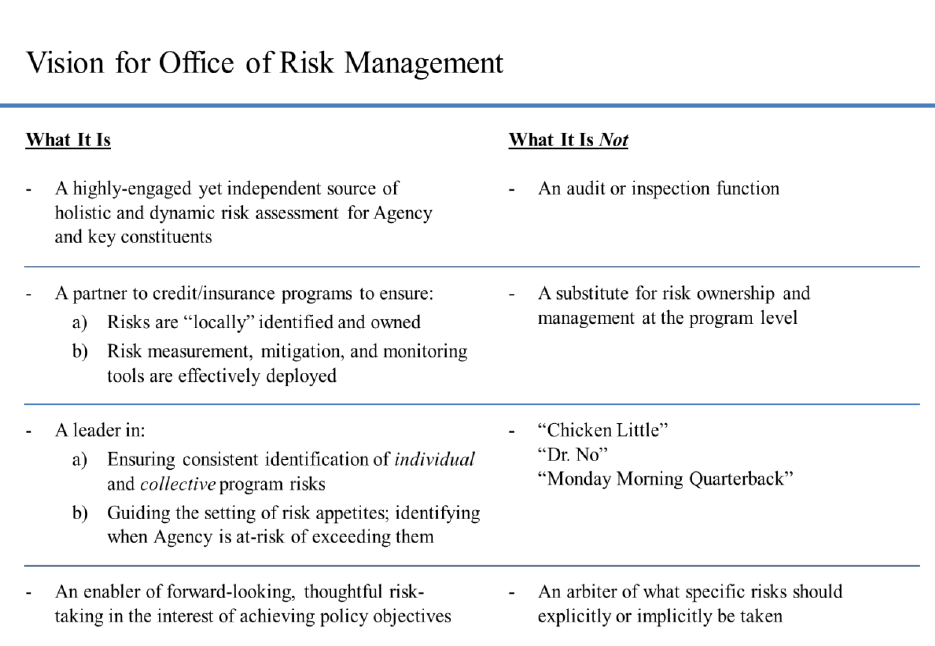

Figure 1: The ERM Policy Framework

As shown in Figure 1, an effective ERM program is an integral part of the agency’s decision-making

processes. Agencies should identify top risks to the goals and objectives laid out in their strategic plans.

Assessing and prioritizing risks is an important step in operationalizing the strategic plan through the

development of operational plans and implementation strategies, budgets, and the establishment of

performance goals and controls.

In addition to the ERM guidance laid out in OMB A-11 and OMB A-123, OMB provides guidance on

integrating risk management practices in the management of federal credit programs and non-tax

receivables in OMB Circular No. A-129 (OMB A-129). This includes guidance for risk management, data

reporting, and use of evidence to improve programs through regular program reviews as well as

establishing the Federal Credit Policy Council, an interagency collaborative forum for identifying and

implementing best practices.

Finally, in September 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released an updated

“Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government” or “Green Book.” This document sets the

standards for an effective internal control system for Federal agencies and provides the overall

framework for designing, implementing, and operating an effective internal control system. It includes

new sections on identifying, assessing, and responding to risks in the control environment.

In addition to issuing guidance on ERM, OMB demonstrated its commitment to ERM by establishing and

chairing the ERM Executive Steering Committee. Membership includes representatives from several

federal agencies.

8

Membership may change over time. Its mission is to promote and facilitate a risk-

aware culture across the Federal Government by developing a Federal ERM framework and strategies;

promote integrated strategy-setting with performance and cost management practices that are

8

These agencies include the Department of Defense, Department of Justice, Department of the Treasury,

Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Health and Human Services, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau,

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Small Business Administration.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

9

supported by quality data agencies can rely on to manage risk in creating, preserving, and realizing value;

and drive resource prioritization and allocation by leveraging risk-informed decisions across the Federal

Government.

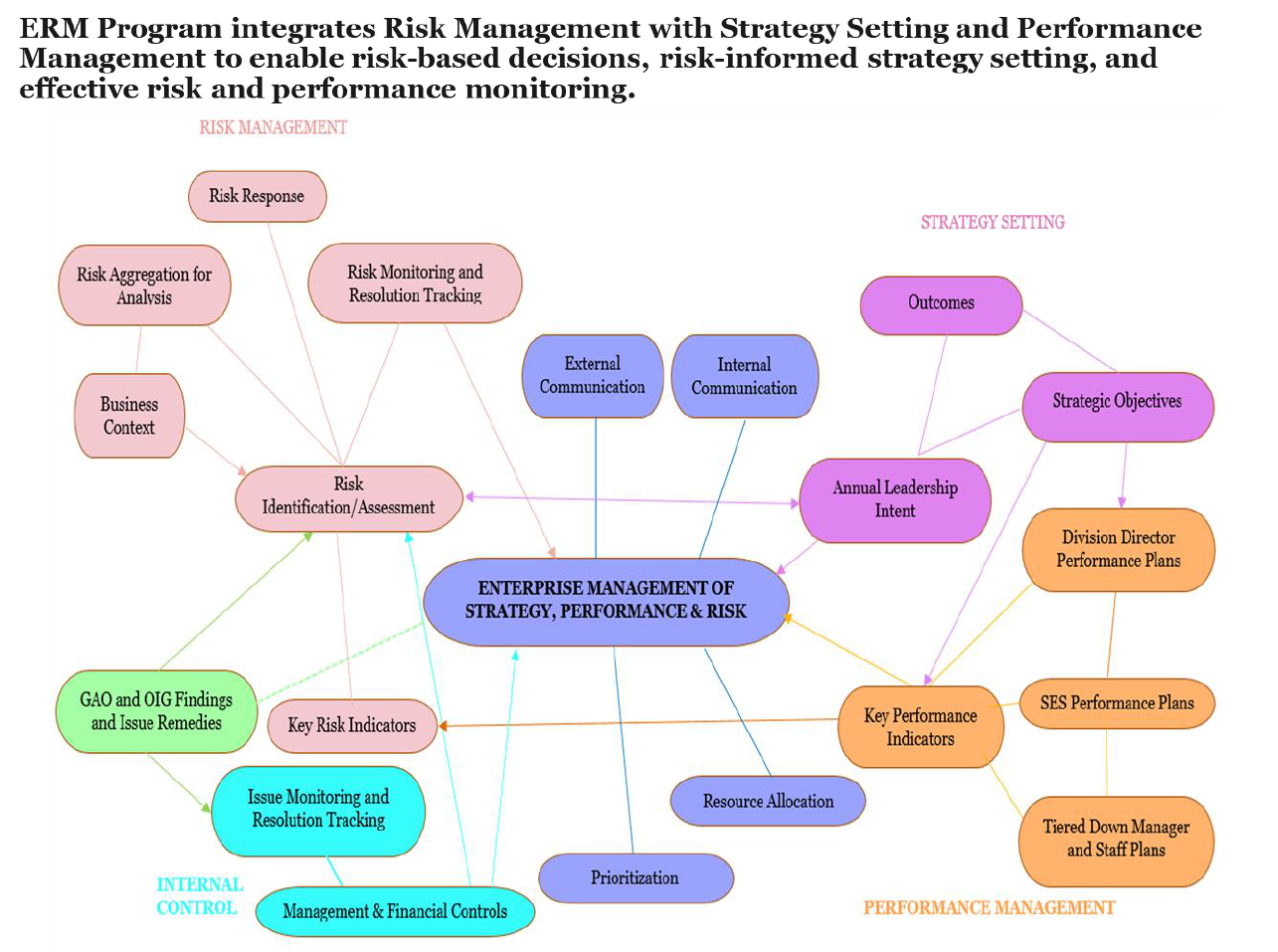

Integration with Strategic Planning and Performance Management

Aligning strategic planning and performance management with ERM helps the agency understand

possible risks to reaching its objectives and how to use risks to identify opportunities to meet those

objectives. A goal of ERM is to strengthen an organization’s capacity to manage risks by creating

internal management processes that facilitate the identification of risks, resource allocation and

alignment, and the proactive discussion of strategies and activities to manage negative risks and pursue

positive risks and opportunities.

During the development of a Strategic Plan, it is important for agencies to identify and consider both

negative and positive (opportunities) risks and articulate how they may evolve over time. Considering

the future environment and its associated risks in the early stages of the strategic planning process will

help the agency better align the management of risks with the organization’s overall mission, goals, and

objectives. When agencies develop their four-year Strategic Plans, they should leverage analytical

processes and data, such as findings from annual strategic objective reviews, that assess progress being

made against strategic objectives in the Agency Strategic Plan. Agencies should consider the top risks

and opportunities to pursue based on strategies and objectives. These practices will help the agency

identify the most effective long-term strategies.

As part of the strategic objective review process, agencies annually assess their progress toward

achieving strategic goals and objectives. Through the evaluation of key performance indicators (KPIs), as

well as other qualitative and quantitative success criteria, agencies can evaluate the effectiveness of

their implementation strategies as identified in the agency’s Strategic Plan and make changes

accordingly while also identifying areas of noteworthy progress and focus areas for improvement.

Through this lens, agency leadership can more effectively view the progress being made to improve

program outcomes and look at opportunities for efficiencies. The annual reviews should leverage

performance management, ERM, program management, and evaluation to determine where the agency

has been (backward looking) and where the agency is going (forward looking). The results of these

reviews, discussed with OMB during the Strategic Review meetings, helps inform decision-making

processes, including possible effects of programmatic and operational risks on achieving strategic goals,

objectives, and strategies. This organizational performance and management perspective facilitates the

development of a learning-focused organization that successfully manages enterprise risks and

opportunities.

Incorporating ERM into the strategic objective review process is critical and provides another lens by

which agencies can more effectively identify opportunities and manage risks to performance, especially

those risks related to achieving an agency’s strategic objectives. An organizational view of risk allows

the agency to look across silos, objectively gauge which risks are directly aligned to achieving strategic

objectives, and determine which risks have the greatest probability of impacting the mission. Risks that

are determined to be significant are prioritized, vetted and escalated appropriately to agency

leadership, where they can be regularly monitored, analyzed and considered as part of the agency’s

internal management routines. Opportunities and mitigation efforts are then incorporated into the

agency’s performance plan, an evolving document that is updated annually. With a shorter time horizon

(two-year) than the strategic plan, the agency’s performance plans are often more operationally and

programmatically focused. Aligning strategy and performance to develop appropriate risk responses

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

10

through the planning process is critical to mitigating the influence of risks on achieving agency goals and

objectives.

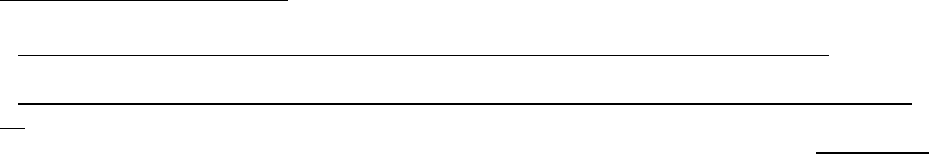

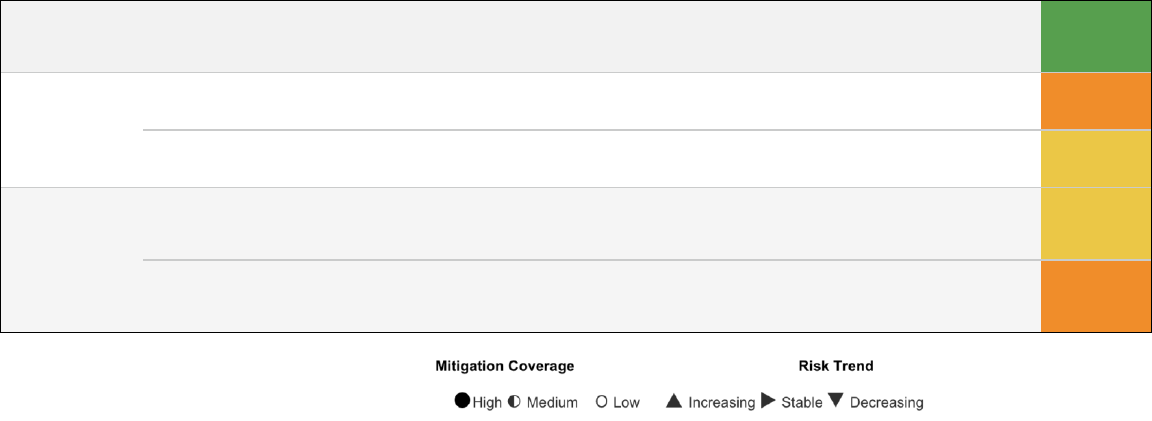

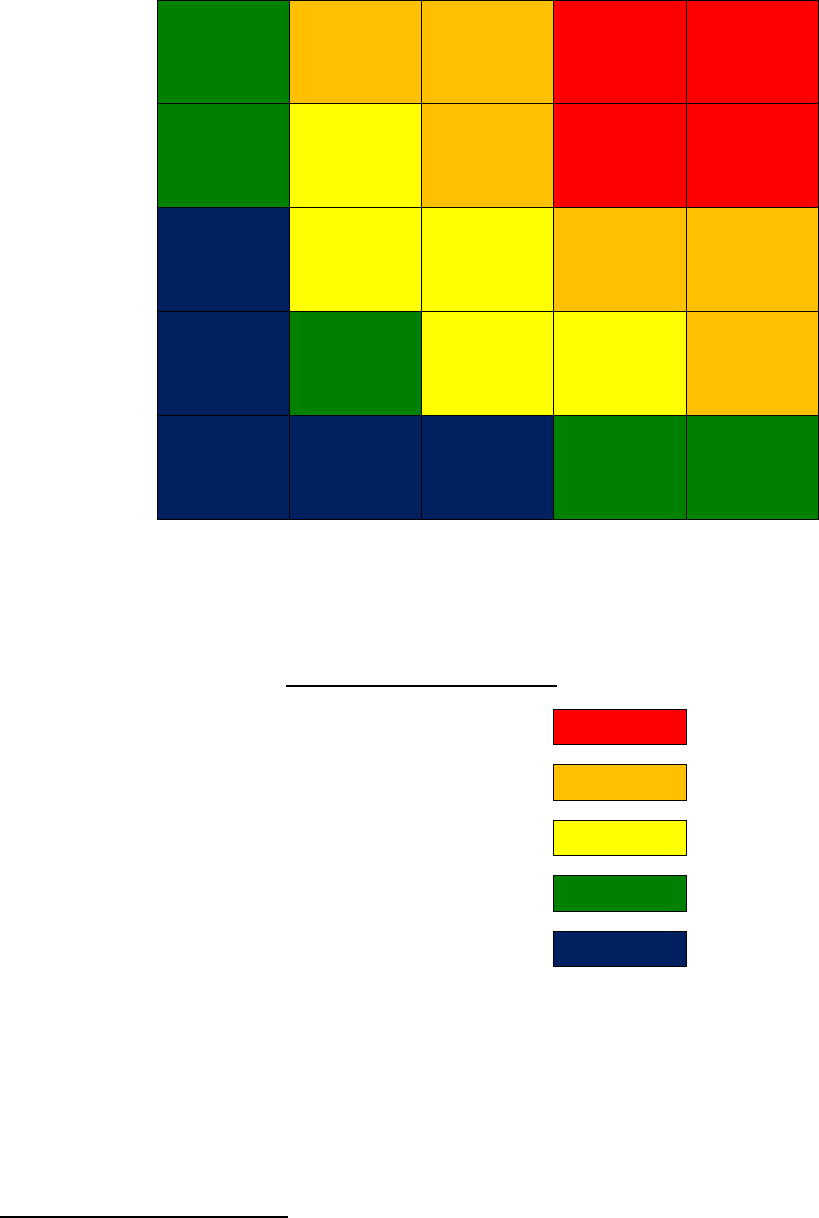

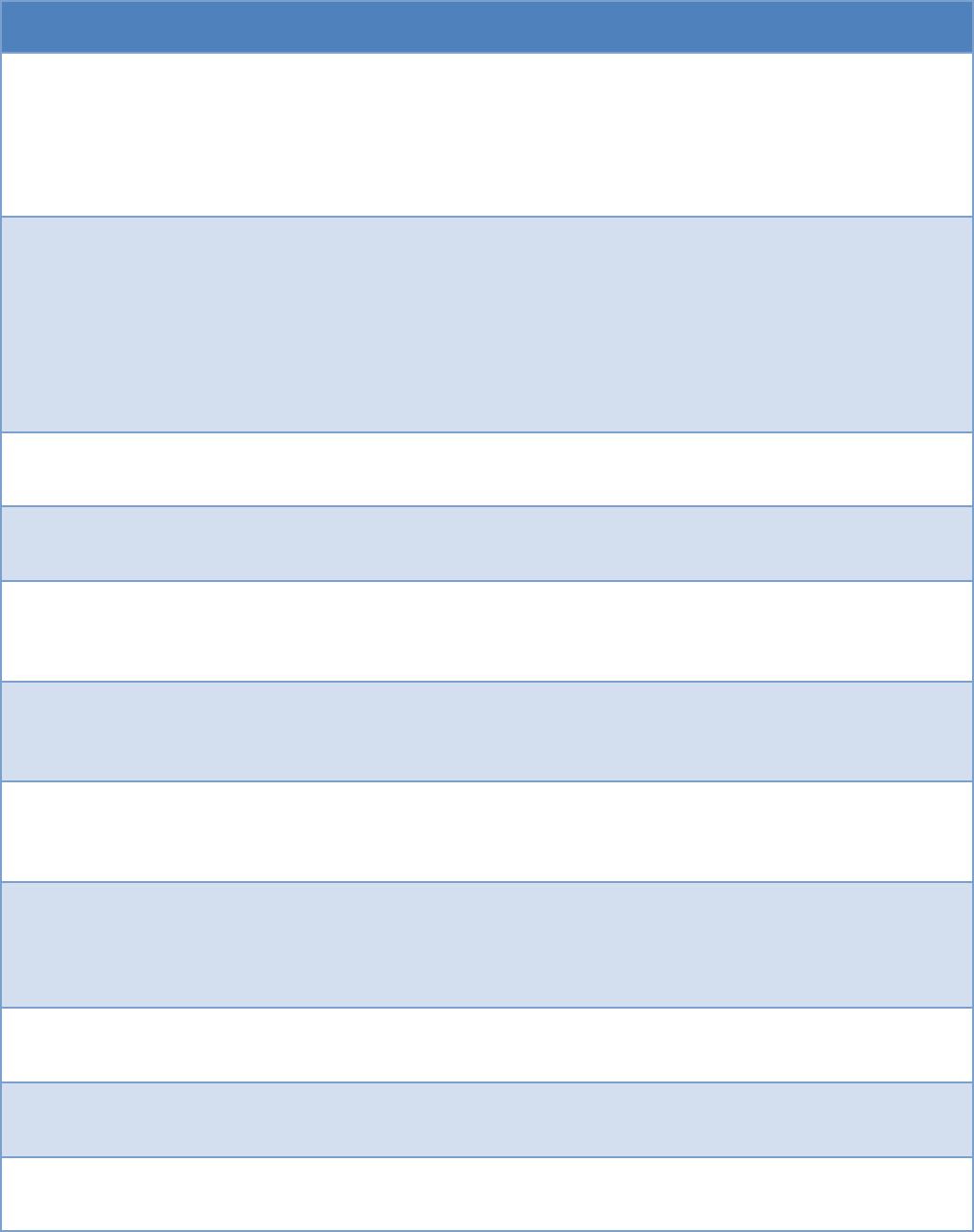

Figure 2: ERM Linkages to Strategy and Performance

Agencies should consider as a best practice coordinating the analysis of top risks with the strategic

review. This integration of complementary processes can support the identification, assessment and

prioritization of probable risks that may impact program delivery or outcomes and are likely to impact

the success of a given strategic objective. One approach is to integrate ERM into an existing

management process that can help agencies determine its strategic risks while mutually reinforcing the

comprehensiveness of the organizational analyses required by each process.

The agency’s strategic objective review process is an optimal time to coordinate an enterprise analysis

of risk and make informed decisions. This allows the agency to reflect the compiled results of the

analyses in proposals contained in the agency’s budget submission, annual planning, and priority-

setting. This includes identifying risks arising from mission and mission-support operations, providing a

thoughtful analysis of the risks an agency faces towards achieving its strategic objectives, and

developing responses that may be used to inform decision-making through existing management

processes.

As part of the strategic objective review process, agencies can include as part of the Summary of

Findings those risks considered by their agency leadership to be the top risks from their risk profile.

Discussing these risks during the OMB Strategic Review meeting can be an opportunity to increase

OMB’s and the agency’s shared understanding of the agency’s needs and strategies. The identification

of risks and risk management strategies around them may be used to inform changes to agency

implementation strategies and future strategic and performance planning efforts. Agencies will need to

coordinate the timing of the update to their agency risk profile to effectively inform the analyses and

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

11

assessment of strategic objectives being generated in the agency’s Summary of Findings and for

discussion with OMB.

Consistent with OMB Circular A-11, Part 6, agency Chief Operating Officers (often, the Deputy Secretary

or Deputy Administrator) should, with the agency’s Performance Improvement Officer, lead at least

quarterly data-driven reviews to assess progress toward meeting the organization’s priorities, including

Agency Priority Goals. In some agencies, these are referred to as Quarterly Performance Reviews.

These meetings are designed to review progress on the top priorities for the agency with agency

leaders. Some agencies base the meetings on Agency Priority Goals while others conduct meetings with

some or all of their bureaus and components. It is a good practice to incorporate in these meetings a

discussion of risks to achieving those priorities as well as opportunities of pursuing risk to meet a stretch

goal or objective. This helps focus leaders on the top risks to their priorities on a quarterly basis. These

meetings can also be used to discuss crosscutting risks or challenges that may affect the achievement of

objectives as discovered during the strategic objective review process. By incorporating risk in the

quarterly performance reviews, agencies are better positioned to know more quickly how risk is

affecting progress on priorities and adapt to changes in the operational environment in order to manage

possible changes to strategies. Having regular discussions of risk, integrated with performance, helps

evolve the organizational culture, build transparency, and inculcate risk terminology into strategic

discussions.

Integration with Budgeting

Aligning budgeting decisions and ERM assessments helps the agency understand possible risks and the

funding available to mitigate those risks. When well executed, ERM improves agency capacity to

prioritize efforts, optimize resources, and assess changes in the environment. ERM can help agency

leaders make risk-aware decisions that impact prioritization, performance, and resource allocation.

ERM offices should share the enterprise risk profile with the team developing the budget, so they

understand the agency’s top risks and the responses being proposed to address those risks, some of

which may have resourcing implications. In partnership with the budget teams, some agencies include

language on the consideration of risk into budget guidance.

Sample Risk Language for Budget Guidance

Identifying Risks and Opportunities for Improvement

Incorporating risk-based decision making into strategic planning, organizational

performance management, and budget processes allows business units (BUs) to better

allocate scarce resources to address the highest priority risks, enhance performance,

drive efficiencies, and promote cost savings. BUs should consider risk factors from

across their programs and use them as important inputs to these processes. In budget

submissions, BUs should identify major risks to their mission and to the strategic

objectives they support, then articulate existing risk response strategies and additional

resources necessary to address these risks. Transparency, business practices, reporting,

and governance help define the overall risk culture.

Clear, data-rich information on an agency’s significant risks can help agency leadership make better risk-

based decisions for internal budget allocation, especially when choosing where to pursue risks to add

value, determine whether to seek additional funds, weigh funding trade-offs, and better justify to OMB

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

12

budget examiners why specific funds are needed. In addition, ERM can demonstrate inter-relationships

between financial and programmatic risks to inform these decisions. Articulating or cross-walking ERM

risks to agency funding requests builds the business case for funding decisions and integrates the budget

process with the agency’s ERM program.

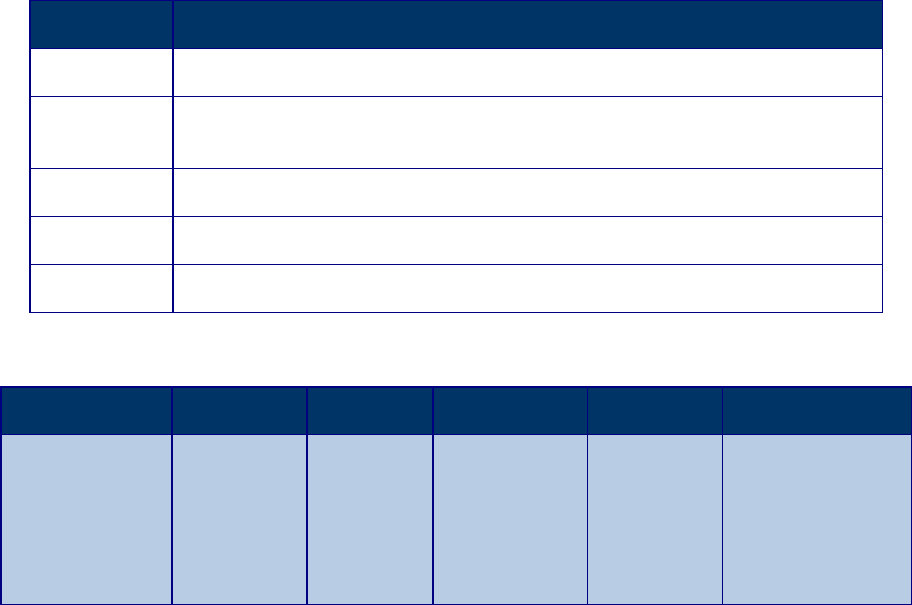

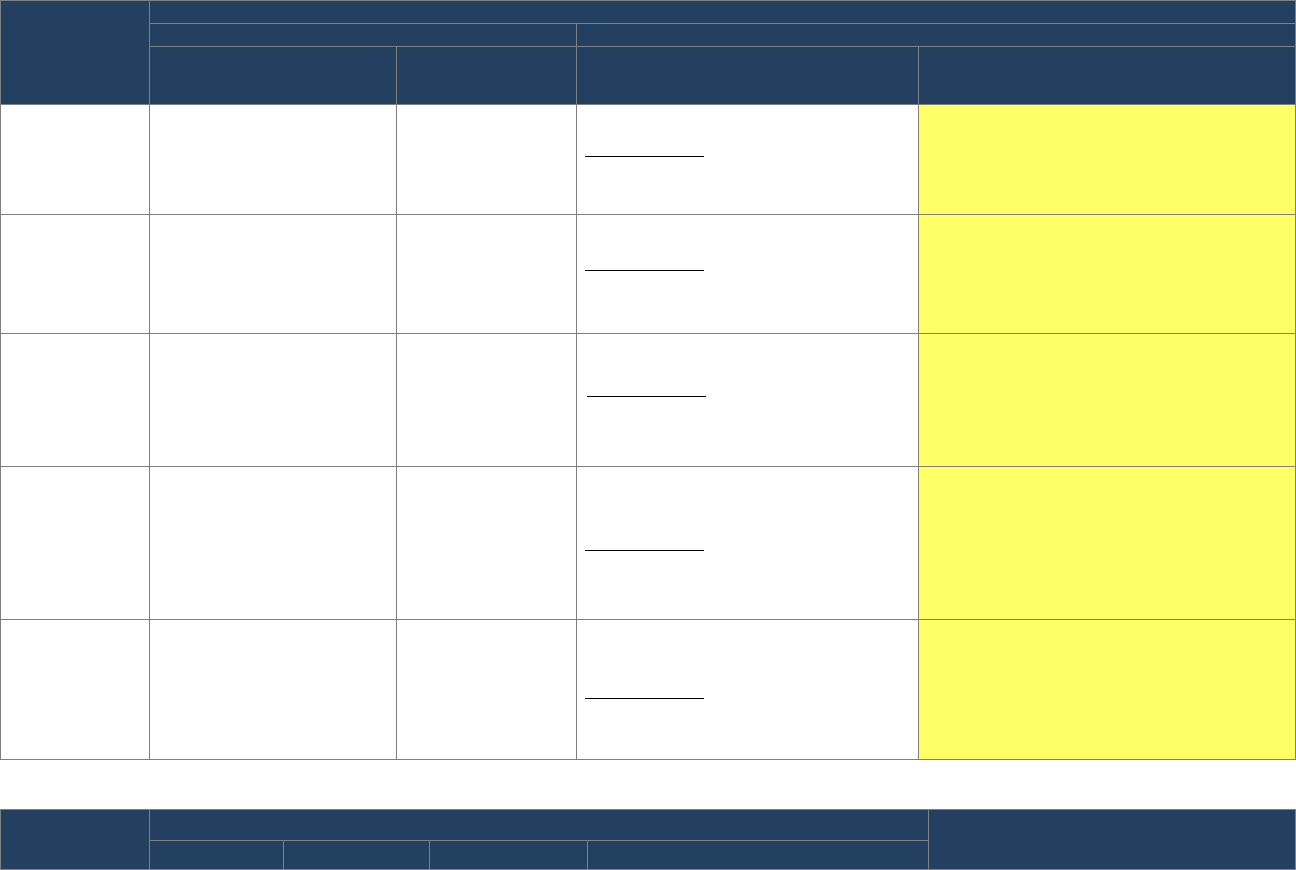

Table 1. Key questions for senior leadership conversations about risk, strategy, and budget

Strategic Context

Resources Needed

Impact and Timing

• What are the agency’s

top risks?

• What is the time

horizon to address the

risks (e.g., short-term:

1-2 years; mid-term: 2-4

years; long-term:

greater than 4 years)?

• Do the top risks address

all of the risks in the

agency’s programs and

operations?

• Is the agency already

responding to these

risks?

• What actions is the

agency taking to

mitigate, avoid, accept,

transfer, or purse this

risk? Do you agree with

the response?

• Are there non-financial

options, such as policy

changes or process

enhancements that

would have the same

effect?

• If non-financial options

are limited, how much

will it cost the agency to

address this risk?

• Can the risk be

addressed with current

funding levels?

• Does the agency have a

business case to

account for

requirements and gaps?

• Who is accountable?

• Is it a one-time

expenditure or

recurring? For how

long? When will it

start?

• Can resources be re-

allocated to address the

risk? If so, from which

areas?

• What agency actions

are important to take

this year? Next year?

Future years?

• Is there a foreseeable

return on investment or

improvement in

program performance

or agency operations?

• How did the analysis

generated by the

agency’s risk profile

inform the budget?

• Are the agency’s budget

line items aligned with

the agency’s analysis of

risks from the strategic

review summary of

findings and the risk

profile?

While an agency’s budget will never be solely based on a risk-based decision, it is a good practice to

incorporate a discussion of what risks an office/program is trying to manage by requesting additional

funds and the tradeoffs involved in those decisions.

Evidence-building Efforts: Evaluation Officer and Learning Agenda

9

The Evaluation Officer plays a leading role in overseeing the agency’s evaluation activities and capacity

9

The “Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018” required CFO Act agencies to create the

positions of Evaluation Officer and Chief Data Officer and required agencies to create multi-year learning agendas.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

13

assessments, learning agenda (or evidence-building plan), and information reported to OMB on

evidence. The Evaluation Officer also collaborates with, helps shape, and makes contributions to other

evidence-building functions within the agency.

One of the Evaluation Officer’s primary deliverables is a multiyear agency Learning Agenda. A Learning

Agenda is a systematic plan for identifying and addressing policy questions relevant to the programs,

policies, and regulations of the agency. The Learning Agenda, a stand-alone part of an agency’s Strategic

Plan, should align to the Strategic Plan and address priority questions across the entire agency.

Developing the Learning Agenda offers a systemic way to identify the data agencies intend to collect,

use, or acquire as well as the methods and analytical approaches to facilitate the use of evidence in

policymaking. Learning Agendas allow agencies to more strategically plan their evidence-building

activities, including how to prioritize limited resources and how to address potential information gaps

that may inhibit the agency’s effective management of risks identified through their ERM processes.

The Learning Agenda should consist of “priority questions” that are meaningful and specific to the

agency, including short- and long-term questions, as well as operational and mission-strategic questions.

The intent is that answering the question could help drive progress toward achieving the agency’s

mission and strategic goals and objectives. ERM officials should work closely with their agency

Evaluation Officer to develop priority questions to ensure an understanding of enterprise risks is built

into agency evaluations and policy analyses.

Integration with Internal Controls

Aligning internal control with ERM helps harness internal controls capabilities to create a more effective

risk response. OMB A-123 requires that internal control activities be integrated under a larger ERM

program; accordingly, internal control should be an integral part of risk management and ERM. ERM

and internal control should be components of an agency’s overall governance framework. ERM and

internal control activities provide risk management support to an agency in different but

complementary ways. ERM is a strategic business discipline that addresses a full spectrum of the

organization’s risks and opportunities and integrates that full spectrum into a portfolio view. This

encompasses all areas of organizational exposure to risk, as well as internal controls that focus on

operational effectiveness and efficiency, reporting, and compliance with applicable laws and

regulations. ERM modernizes internal control efforts by integrating risk management and internal

control activities into an ERM framework to improve mission delivery, reduce costs, and focus corrective

actions towards key risks. ERM allows agencies to view the portfolio of risks as interrelated, helping to

illuminate the relationship between key organizational risks and how and which controls can be used to

mitigate or reduce risk exposure.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

14

ERM Pitfall

Focusing too much on internal controls

ERM includes internal controls but also larger issues of the external environment, as

well as performance, transparency, business practices, reporting, and governance that

help define the overall risk culture.

Leaders should understand how their offices align with the risk management structure and how it

intersects across their agency’s internal controls, compliance activities, and oversight functions. Agencies

may find it useful to build an inventory that captures key oversight, compliance, and internal control

activities, even those that are not formalized. For agencies that choose to establish an RMC, the concept

should be communicated across the organization to help key leaders and staff understand the role of

both the ERM organization and the RMC in relation to existing oversight activities as well as those still

under development.

Coordinating ERM with other oversight activities in a complementary way will require both trust and

collaboration between risk personnel and various oversight groups across the organization to ensure a

proper understanding of their respective objectives and authority. It also requires a broad knowledge

and subject-matter expertise by the team inventorying these activities, as well as an ability to identify

and depict interdependencies among various groups. Table 2 highlights how traditional risk

management activities complement ERM.

Table 2: Comparison Between Traditional Risk Management and ERM

Traditional Risk Management

ERM

Risk Management

(Project or Program)

Internal Controls

Definition

Coordinated activity within a

component to proactively

identify, assess, and manage

risks to a specific project,

program, or function in an

organization.

10

A process affected by an

entity’s oversight body,

management, and other

personnel that provides

reasonable assurance that

the objectives of an entity

will be achieved.

11

An effective agency-wide

approach to addressing

the full spectrum of the

organization’s significant

risks by considering the

combined array of risks

as an interrelated

portfolio, rather than

addressing risks only

within silos.

Examples

in Federal

Guidance

• OMB A-133 Audits of

States, Local

Governments and Non-

Profit Organizations

• Standards for Internal

Control in the Federal

Government (GAO Green

Book)

• OMB A-123

Management's

Responsibility for

Internal Control and

10

Risk management – Guidelines, International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 31000:2018.

11

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (United States Government Accountability Office

(GAO) Green Book).

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

15

Traditional Risk Management

ERM

Risk Management

(Project or Program)

Internal Controls

• Risk Management

Requirements for the

Federal Acquisition

Certification for Program

and Project Managers

(FAC-P/PM)

• Federal Managers’

Financial Integrity Act of

1982 (FMFIA)

• OMB A-123

Management's

Responsibility for

Internal Control

• Chief Financial Officers

(CFO) Act of 1990

• Federal Financial

Management

Improvement Act of

1996 (FFMIA)

Enterprise Risk

Management (2016)

• OMB A-123, Appendix

A Management of

Reporting and Data

Integrity Risk

• OMB A-11 (Section

260) Preparation,

Submission, and

Execution of the

Budget

Additional

References

• Risk management –

Guidelines (ISO

31000:2018)

• Risk management- Risk

assessment techniques

(IEC 31010:2019)

• Internal Control –

Integrated Framework

(COSO 2013)

• GAO Internal Control

Management and

Evaluation Tool

• Enterprise Risk

Management –

Integrating with

Strategy and

Performance (COSO

2017)

• Management of Risk -

Principles and

Concepts, “Orange

Book” (Her Majesty’s

(HM) Treasury (United

Kingdom))

Focus

Selected risk areas and

processes focused on

effective program/project

implementation or fraud,

waste, and abuse within

Federal Programs (e.g.,

grants management,

program-specific risks).

Selected risk areas and

processes generally

governed under compliance

activities and assessments

(e.g., financial

management, information

technology).

Enterprise-wide and

across every level taking

an entity-level portfolio

view of risk.

Emphasis

and

Application

Compliance with planned

scope, time, and cost, as

well as identifying and

organizing risks for any

particular program.

Conforming to external

reporting requirements

(e.g., audit reports,

identified material

weaknesses). Focused on

assessing effective

operations, reliable

financial reporting, and

compliance.

The use and application

of risk information to

improve decisions

related to strategic

planning, budgeting, and

performance

management across

programs and activities.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

16

Traditional Risk Management

ERM

Risk Management

(Project or Program)

Internal Controls

Key

Attributes

• Risks are traditionally

based on program or

project operational

execution, with risk

tradeoffs made across

cost, schedule, and

performance.

• Focus on risks is more

forward looking than with

internal controls but does

not extend beyond scope

of program or project.

• Some risk integration can

occur but may not extend

past the program or

project level.

• Risk appetite and

tolerance is usually not

explicitly addressed.

• Requires domain and

technical program or

product expertise, in lieu

of functional experience.

• Risks primarily viewed in

a negative construct.

• Primarily addresses

traditional financial,

compliance,

transactional, and

operational risks, with a

focus on risk reduction

through the application

of discrete controls.

• Risk assessments

traditionally review past

performance and

activities and are

generally not forward

looking.

• Risks are identified and

managed on a siloed,

non-integrated basis

(e.g., financial reporting,

human resources,

physical security).

• Risk appetite and

tolerance is usually not

explicitly addressed.

• Requires specialized,

functional skillsets (e.g.,

financial accounting, IT

security).

• Addresses the full

spectrum of an

agency’s risk portfolio

across all

organizational (major

units, offices, and

lines of business) and

business (agency

mission, programs,

projects, etc.) aspects.

• Provides the potential

for a fully integrated,

prioritized, and

forward-looking view

of risk to drive

strategy and business

decisions.

• Allows for more risk

management options

through enterprise-

level tradeoffs, versus

a primary focus on

reducing risk through

controls.

• Risks can be viewed as

threats and

opportunities (positive

risks).

• Explicitly addresses

risk appetite and

tolerance.

• Requires more general

and interdisciplinary

skillsets, beyond

functional and domain

knowledge.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

17

II. Enterprise Risk Management Basics

A. Outcomes and Attributes of Enterprise Risk Management

ERM supports agencies’ ability to articulate risks, align and allocate resources, and proactively discuss

management and risk response strategies and activities to better equip agencies to deliver on their goals

and objectives and potentially improve stakeholder confidence and trust. ERM should operate with the

purpose of:

• Supporting the mission and vision of the agency.

• Integrating existing risk management practices across silos.

• Improving strategic planning and decision-making.

• Improving the flow of risk information to decision makers.

• Including diverse viewpoints while driving towards consensus.

• Establishing early warning systems and escalation policies.

• Identifying, prioritizing, and proactively managing risks.

• Identifying opportunities.

• Supporting budget decisions and performance management.

• Establishing forums to discuss risks across silos.

• Promoting accountability and integrity of the agency’s work.

• Using a common approach to evaluating risks within the agency.

ERM should:

• Help bring clarity to managing uncertainty.

• Facilitate continual improvement.

• Be fully integrated into agency decision making processes, with active leadership support and

engagement (i.e., setting the “tone at the top”).

• Be tailored to the needs of the agency and take human and cultural factors into account.

• Build upon and unite existing risk management processes, systems, and activities.

• Be systematic, structured, and timely as well as dynamic, interactive, and responsive to change.

• Be based on the best available information.

• Be responsive to the evolving risk profile of the agency.

B. Common Risk Categories

An effective ERM program promotes a common language to recognize and describe potential risks that

can impact the achievement of objectives. Such risks include, but are not limited to, strategic,

programmatic, compliance, credit, market, cyber, legal, reputational, political, model, and a broad range

of operational risks such as information security, human capital, business continuity, and related risks.

ERM addresses these risks as potentially interrelated and not confined to an agency’s silos. Also, some

risks may fall into multiple categories. A comprehensive list of common risk categories and their

definitions are included in Appendix A. This list is in no way complete but serves as an example of some

of the risks an agency may face. It is important to prevent the categorization of risk from becoming a

new silo for reviewing risk. Organizations should define risk categories in a way that supports their

business processes and should use these categories consistently. Agencies may also consider

developing a common risk language dictionary — a glossary of key risk terms to ensure all parties are

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

18

consistent in their understanding of key concepts, words, and ideas. Categories of risk evolve over time,

with new types of risk becoming salient and other risks becoming relatively less important.

D. Principles of Enterprise Risk Management

Part of developing an agency’s risk culture generally includes risk awareness, transparency, and the

agency’s attitude toward risk and how it is managed. Risk culture is a key indicator of how widely an

agency's risk management policies and practices have been adopted, and reflective of basic underlying

principles in approaching risk. These can be used as regular reference points to gauge the extent that an

agency is making progress. Moreover, these principles should be embedded in the approach of senior

management in setting the “tone from the top.”

1. Governance Framework is Important: ERM is built around a purposeful governance

framework supported by the most senior levels of the organization and embedded into the

day-to-day business operations and decision-making of the agency. Agencies may choose to

adopt a particular standard or framework (e.g., COSO Enterprise Risk Management–

Integrating Strategy and Performance, June 2017, (COSO 2017) or ISO 31000:2018), but it is

important that whatever framework is selected, the agency customizes it to meet the

mission, needs, structure, and culture of the organization. More important than compliance

with any ERM framework is the ability to demonstrate that risks are managed in a way that

supports good decision-making and meets its agency objectives. A framework should be

forward-looking with assessments concerning the maturity of the ERM program along the

way.

2. Managing Risk is Everyone’s Responsibility: Risk management enables understanding and

appropriate management of the risks inherent to agency activities. It does not eliminate

risk. While agencies cannot respond to all risks related to achieving goals and objectives,

they should work to the extent possible to identify, evaluate, manage, and where

appropriate, address challenges related to mission delivery. Risk management training

should be available to all staff, so they are equipped to manage risks associated with their

work. Managers at each level should be equipped with appropriate skills and resources to

manage risk appropriately. Further, agencies should put in place clear lines of

communication for employees at all levels to identify areas of concern/potential risk and

encourage open communication to escalate reports of risks and bring them to the attention

of the appropriate decision makers without repercussions.

3. Managers Own the Risk: Responsibility for success at each level of the organization means

responsibility for managing risk at that level. For example, agency executives are

responsible for the agency’s enterprise risk, program managers own risks to their programs,

and project managers are responsible for managing risks to their projects. The managers of

government programs and activities should understand and take ownership of risks to

achieving program outcomes, including both inherent risk and the tradeoffs of strategic

decisions. Making risk-informed decisions requires that program managers articulate these

risks and opportunities and, to the extent possible, manage risk in their portfolio across the

organization. If an agency creates a distinct ERM office, this is a second line of defense that

creates a partnership with agency leadership and program managers to help them

understand and manage their risk within acceptable levels, rather than taking responsibility

for managing risks directly.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

19

4. Transparency Supports Informed Decision Making: Informed decision-making requires the

flow of information regarding risks and clarity about uncertainties or ambiguities travel up

and down the hierarchy and across silos to the relevant decision makers so they can make

informed decisions. It is vital to create a culture where employees are comfortable raising

risk-related concerns to senior managers and discussing risk openly and constructively,

especially when parties disagree. Part of transparency is the need to report information so

that decision-makers have a clear view of risks within and across silos. The reporting of

“bad news” should become the way an agency does business rather than an act of courage

by a lower-level employee.

5. Forums for Discussing Risk are Important: Agencies need to establish forums or

committees to facilitate an open discussion of risk. Members should include policymakers,

program leaders, and risk management professionals within the agency, not just risk

executives speaking to each other. Discussions of risk should include those both within and

across silos in agencies. Forum structure will vary by agency. However, it is important that

there be a mechanism in place to funnel important risk information up to the senior

management of the agency or to the ultimate relevant policy maker.

6. Risk Management Should Be Integrated into Key Agency Processes: The risk management

process should be integrated within organizational processes such as strategic planning,

budgeting, and performance management. Agencies should consider risks from across the

agency and use them as important inputs to these processes.

7. Establishing Risk Appetite is Key: Risk is unavoidable and inherent in carrying out an

organization’s objectives. Agencies should evaluate, prioritize, and manage risks to an

acceptable level. It important to have clearly expressed and well communicated risk

appetite statements establishing thresholds for acceptable risk in the pursuit of objectives.

These statements help agencies make decisions about potential consequences or impacts to

other parts of the organization, limiting unexpected losses.

Defining risk appetite needs to be both a top-down and bottom-up exercise. The most

senior members of an organization should define overall acceptable levels in conjunction

with goals and objectives, and within the context of established laws, regulations, standards,

and rules. Risk appetite helps to align risks with rewards when making decisions. Agencies

can accept greater risks in some areas than in others. Each program establishes risk

appetite levels that, when consolidated, are within the risk appetite boundaries established

for the entire organization. Risk appetite can be implicitly established and communicated

when setting strategic or operational goals and objectives. These levels may be expressed

qualitatively or as quantitative metrics. They can also be explicitly set and communicated

through targets associated with performance measures and indicators.

8. Existing Risk Analysis Models are Important Within Limitations: Standard risk

management tools, including models and stress testing, can be important tools for

measuring risk. These tools can be used to show how the impact of an event could affect an

agency’s ability to achieve one or more of its objectives or performance goals. As helpful as

risk tools can be, they are supposed to help inform decisions, not make them outright.

Every model has simplifications that attempt to define reality and, thus, all have

imperfections. It is important to understand these imperfections and to use different

models and approaches where possible.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

20

9. Planning Fosters a Culture of Resilience: Risk management needs to be forward-looking,

while also considering lessons learned from past mistakes as well as current best practices.

This includes modeling severe downside scenarios and potential responses, as well as

foresight planning exercises that consider what could go wrong, external factors that could

impact mission achievement, gaps or shortcomings in current business processes and

resources, and other considerations. Developing strategies to respond to alternate future

scenarios facilitates a culture of resilience, where programs can continue to meet objectives

in the face of changing realities.

10. Diversity of People and Thought Aids Risk Management: The importance of bringing

together different views and perspectives to discuss issues across various departments and

programs (and not just within each program or department) is one of the lessons learned

from the 2008 financial crisis. Risk management is about getting the right people around a

table to discuss risk from various perspectives. This requires diversity of thought, which is

greatly enhanced by a diversity of people, opinions, and perspectives. Agencies can benefit

from diversity across all demographics in risk management discussions – including racial,

ethnic, religious, gender, disability, generational, geographic affiliation, educational,

occupational, and other factors.

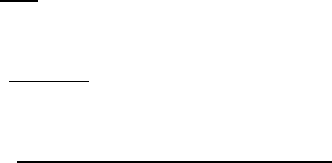

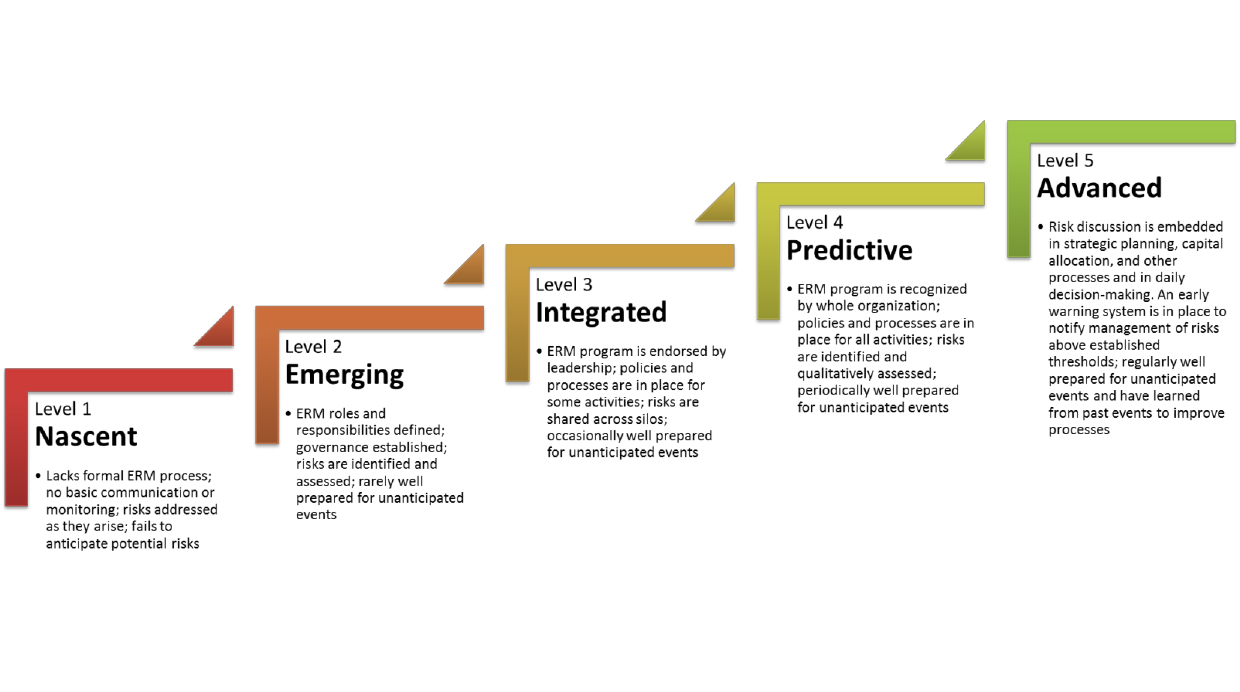

E. Maturity of Enterprise Risk Management Implementation

Implementing ERM throughout an agency requires careful thought and consideration about the best

structure for the ERM function and where it should be located within the organization. Every

organization has its own level of organizational and process maturity. These levels can be assessed

using capability maturity models. An organization matures as it progresses from having no structure or

doing ad-hoc work to an optimized leadership structure. A more mature risk organization will not only

react to issues that arise but will be able to articulate the risks it faces and have in place management

strategies to respond to those risks. It will look forward and try to predict what could happen and

develop strategies to meet those contingencies. It will have risk dialogue within and across silos. A

more mature risk organization will help create a culture that embodies the principles discussed in this

Playbook. Evaluating and improving the ERM of an organization is a long-term process that needs to

develop and change over time, and shaped by the unique needs, formal and informal decision-making

structures, culture, capacity, and mission of the organization. Examples of maturity models are available

in Appendix D.

ERM Pitfall

Too much too quickly

ERM is an iterative effort that develops over time. Management may consider an

incremental approach, initially focusing on the top two or three risks or a type of risk.

Success in a specific area can illustrate the benefits of ERM and build the foundation for

future efforts. Trying to change the fabric of an agency too much or too quickly could

result in defensive mechanisms within the agency hampering ERM efforts.

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

21

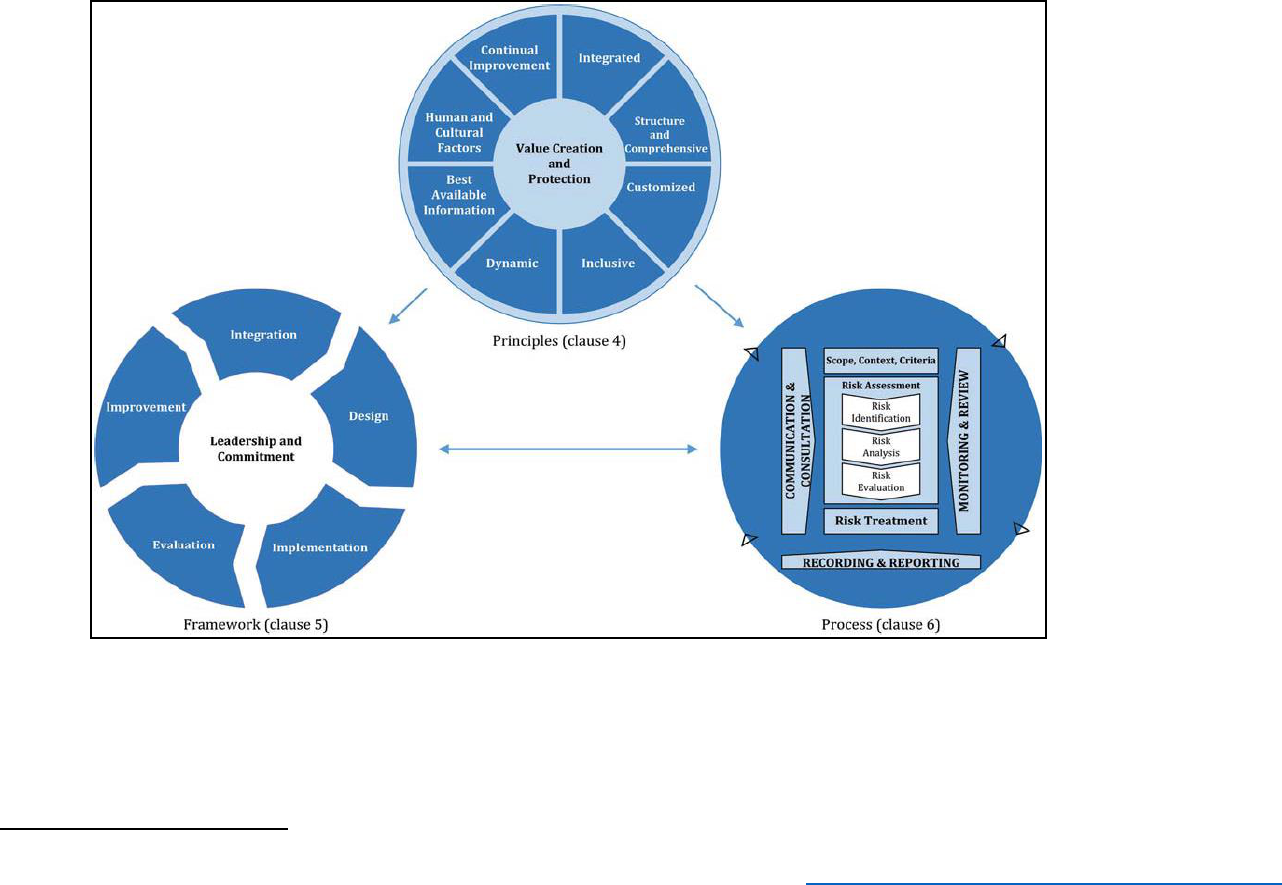

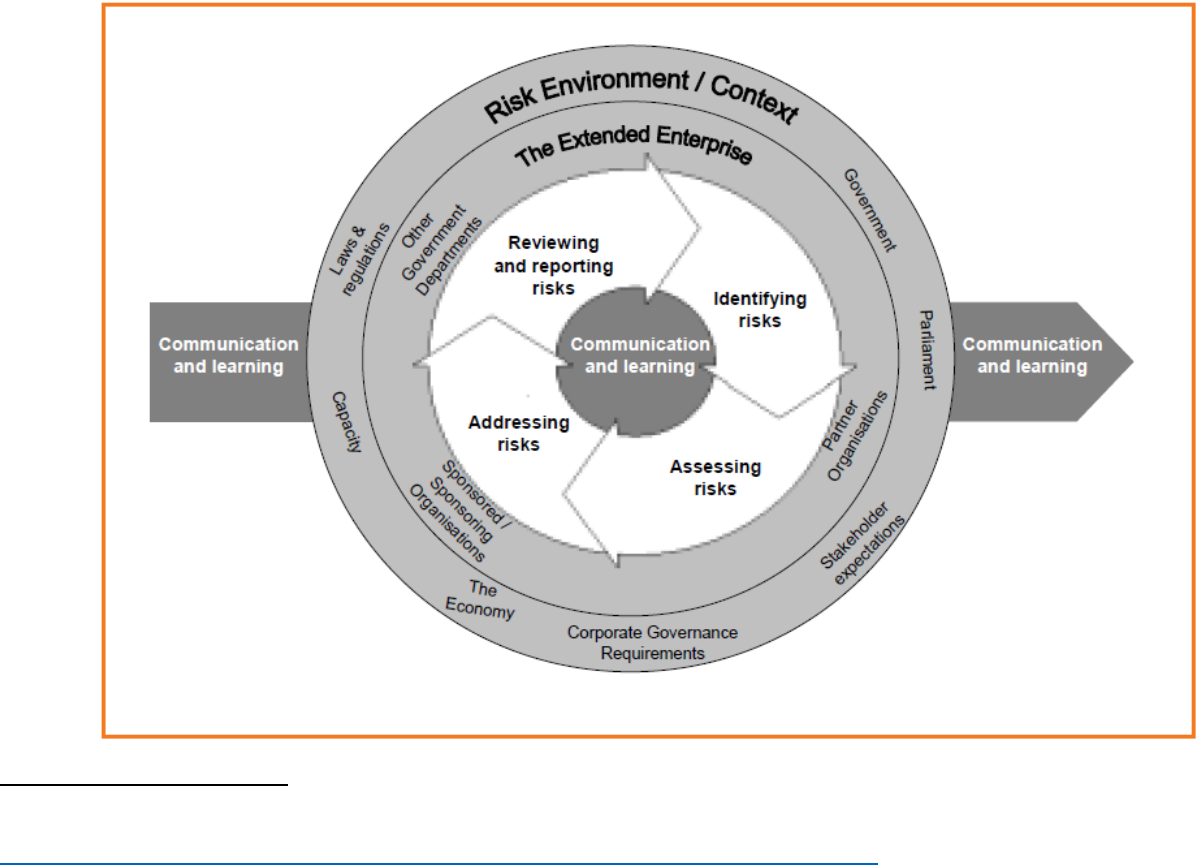

III. Enterprise Risk Management Model

Each agency will need to determine how it will implement a comprehensive ERM program. Various

frameworks may be considered as resources when making this determination including: 1) The

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission’s (COSO) Enterprise Risk

Management: Integrating with Strategy and Performance (June 2017); 2) ISO 31000:2018; and 3) The

United Kingdom’s Orange Book: Management of Risk – Principles and Concepts (July 2019). ERM

programs should be tailored to meet the individual needs of the agency or organization, and different

components of these frameworks may be considered where most appropriate. Examples of ERM

Frameworks are available in Appendix B.

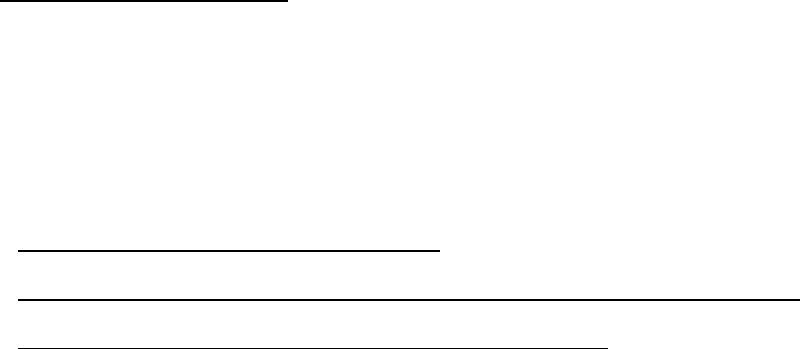

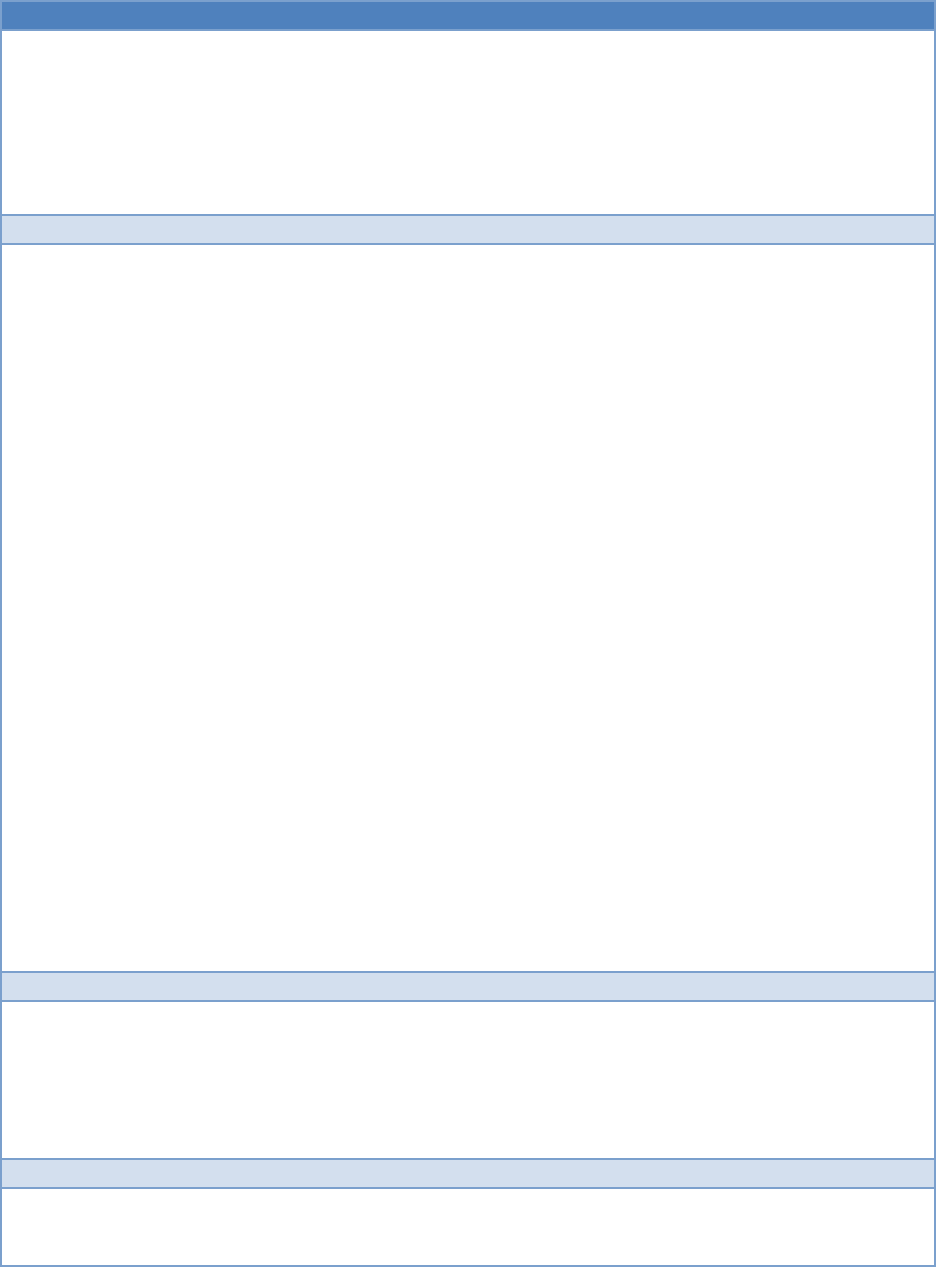

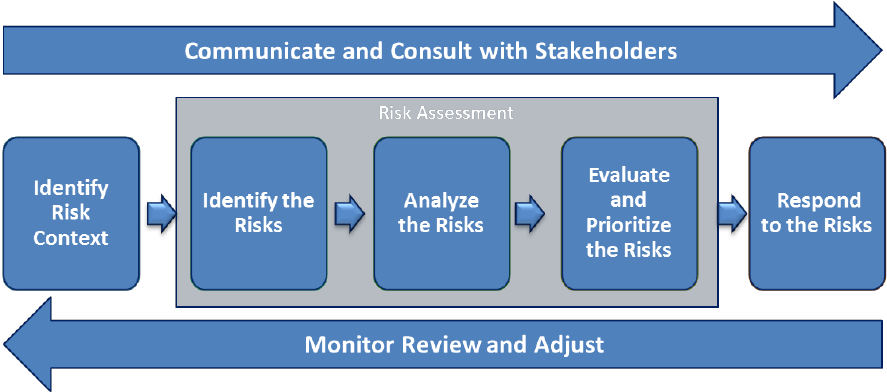

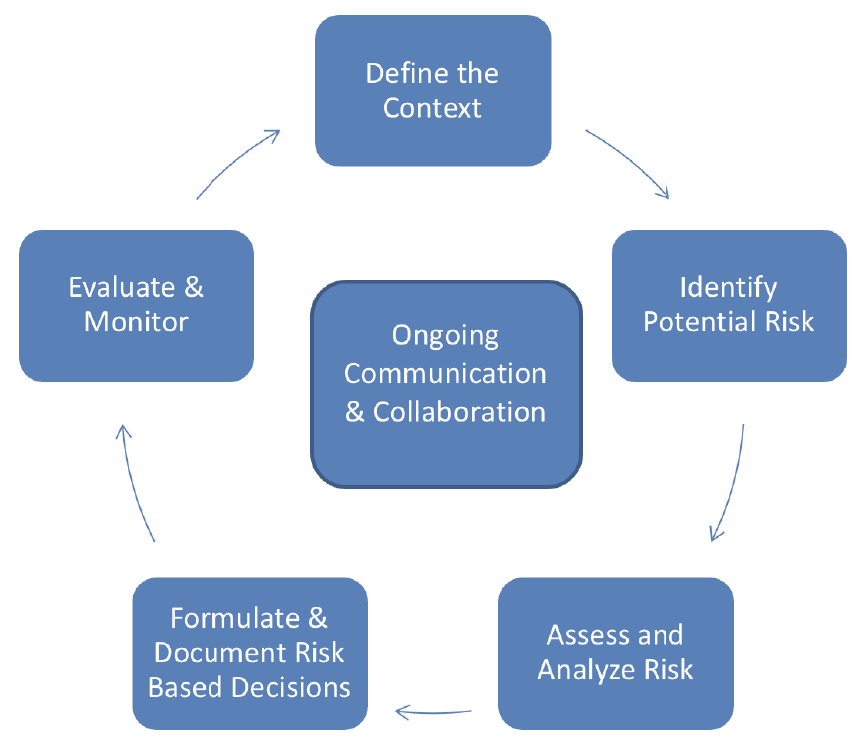

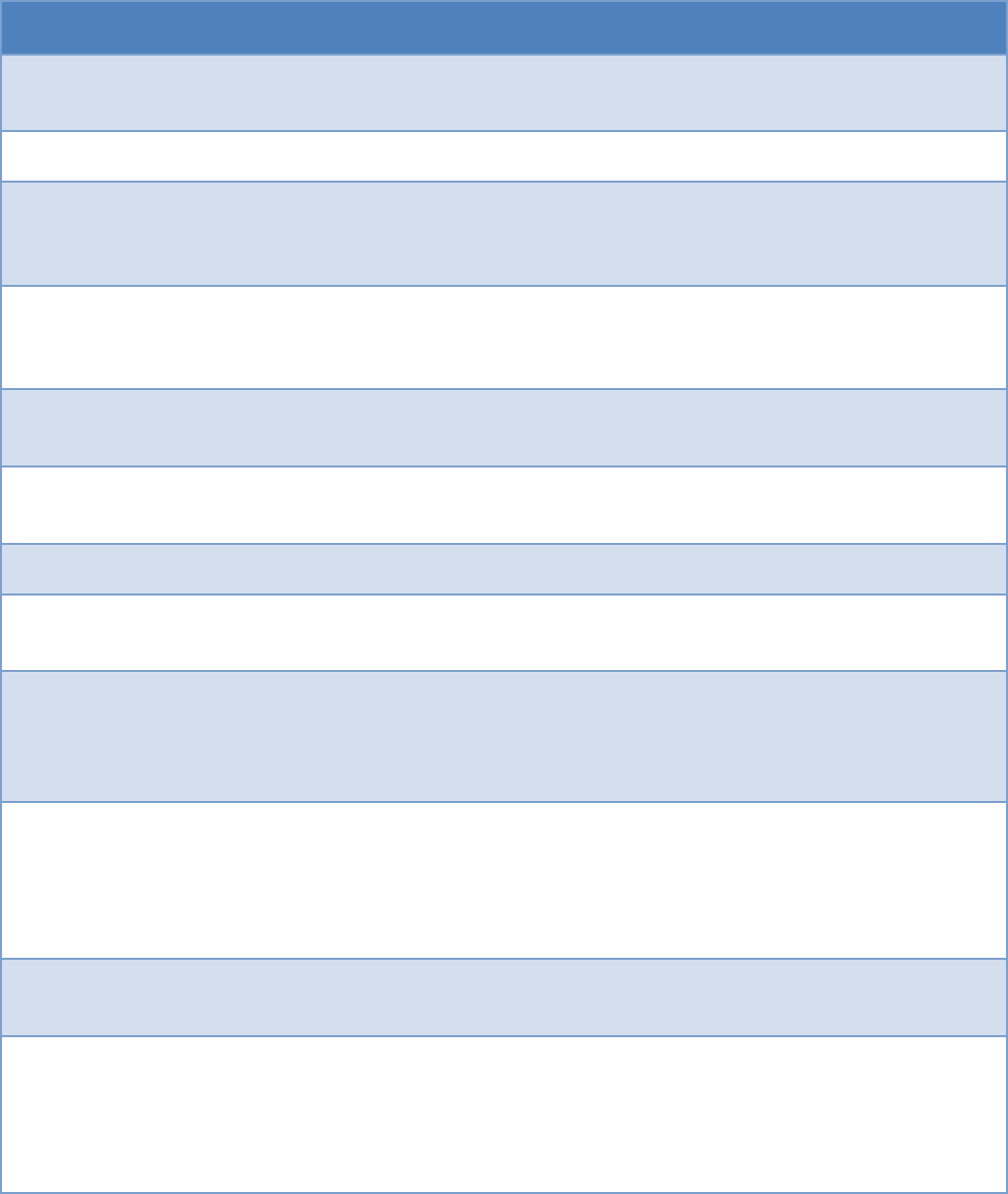

When considering these various frameworks, there are some common elements and phases of ERM that

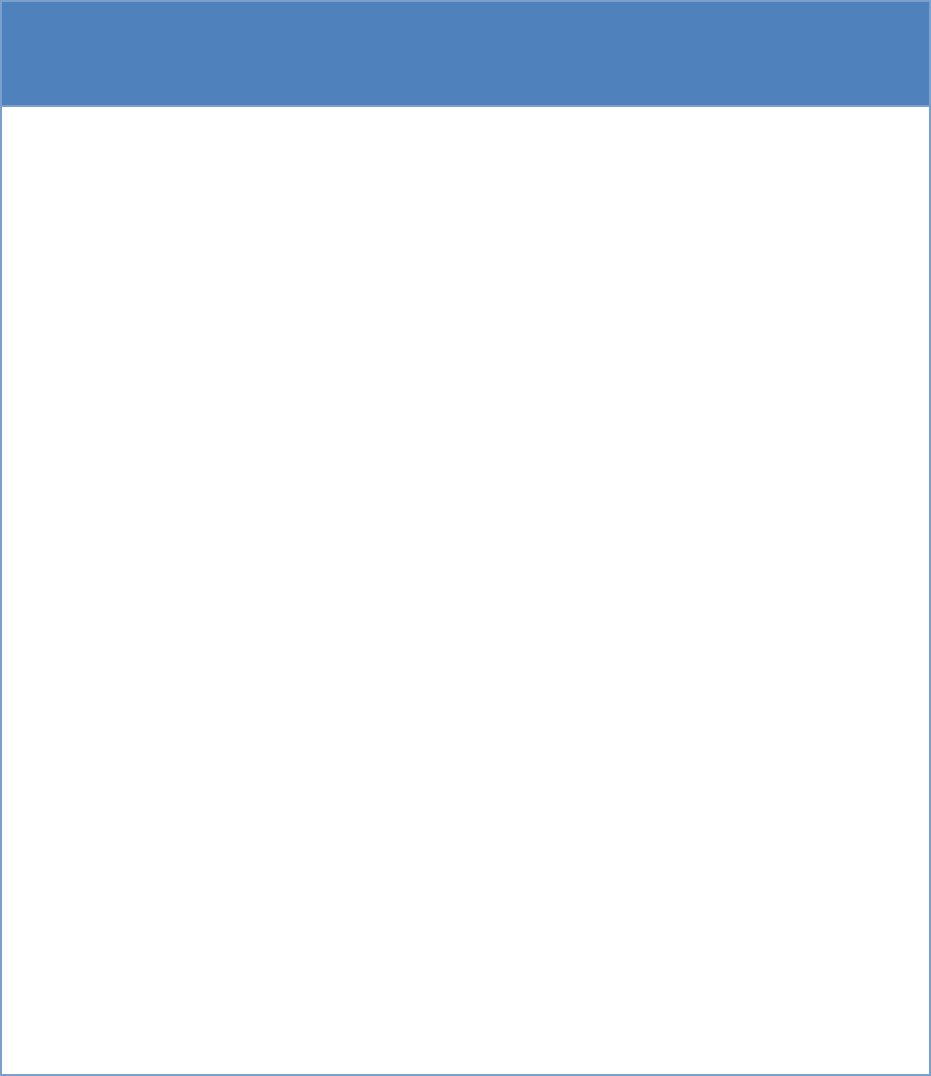

all approaches or models should include. These common elements are depicted in Figure 3 below.

COSO’s ERM 2017 highlights the value and role of integrating performance across an ERM framework,

notably in risk identification, assessment, and responses (COSO Principles 10-14).

It is important that whatever risk management approach is adopted, it be responsive to the unique

needs and culture of the organization. The purpose is to assist those responsible for efforts in

understanding, articulating, and managing risks. To complete this circle of risk management, the agency

should incorporate risk awareness into the agency’s culture and ways of doing business.

Figure 3: Illustrative Example of an ERM Model

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

22

Step 1: Establish Context

Every agency functions within an environment that both influences

the risks faced and provides the context in which risk has to be

managed. Further, every agency has partners that it depends on

for the delivery of its objectives. Effective risk management needs

to give full consideration to the context in which the organization

functions and to the risk aspects of partner organizations.

This broader risk context includes all factors that affect the ability

of an agency to achieve its mission and objectives, both internal

and external. This includes but is not limited to Congress, the

economy, the agency’s capacity, legal and compliance structures;

inter-dependencies with other agencies, partner organizations, and

individual taxpayers; and expectations placed on the agency by the

public.

The first step in establishing the context is to determine the requirements and constraints that will

influence the decision-making process, as well as key assumptions. This involves taking into

consideration policy concerns, mission needs, stakeholder interests and priorities, agency culture, and

the acceptable level for each risk, both for the agency in its entirety and for the specific program.

Program managers should consider the control environment, delineating the safeguards in place to

ensure compliance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies. Finally, agencies should consider how

relevant stakeholders -- from partner organizations, other departments and agencies, other levels of

government, industry associations, employee bargaining groups, Congress, the Judicial Branch, to

internal and external auditors, sovereign entities, vendors, and the public -- interact with the program.

Understanding and defining the context will inform and shape successive stages of ERM

implementation. Key components that should be considered, depending on the scope, timeline and

complexity involved, are described in Appendix C.

Step 2: Identify Risks

Agencies should use a structured and systematic approach to

recognize potential risks and strive to address all key risks

significant to the achievement of organizational objectives. As the

ERM process becomes more formal, agencies may want to develop

a risk register in which major risks are listed and their management

plans are documented. The identification of risk may be an

exercise conducted “top-down,” “bottom-up,” or both. In its most

basic form, developing an agency risk register is an exercise

through which managers and staff at each level of the organization

are asked to list and articulate their major risks (i.e., “What keeps

you up at night?”). Managers and subject matter experts, who are

closest to the programs and functions and most knowledgeable

about the risks faced, should serve as the primary source for identifying risks. The ERM office or

program can provide useful assistance throughout the risk management process, through its unique

background and view into the agency. After the listing of major risks is complete, agencies should

examine them and decide which are the most significant risks to the agency (e.g., prioritize the risks

based on likelihood and impact), and use the highest ranked risks to create the agency’s risk profile.

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

23

Some risks, such as disinvestment in systems, may take a long time to cause major harm while others,

such as a systems failure, can cause harm precipitously. For a list of key questions to help develop a risk

profile and examples of risk profile formats, refer to Appendix D.

Tips for Documenting Risks

1. Develop meaningful risk categories: When defining or categorizing risks,

agencies should consider categorization in ways that are most helpful and

relevant to agency mission. Agencies should recognize that any single risk

may be associated with more than one risk category and not limit risk

categories to silos.

2. Use common language: Risks should be described using a common

language that resonates within the agency regardless of program office or

individual expertise. Removing jargon whenever possible improves

communication.

3. Document risks regardless of control: Agencies should consider the risks

that are both within and outside of an agency’s direct control, including

third parties, vendors, or contractors, but present a genuine risk to an

agency’s mission. For major risks outside of the agency’s direct control, the

only response may be to prepare contingency plans.

4. Document action plans and outcomes: It is important for agencies to document

what was done to respond to possible risks and use these as lessons learned that

can be leveraged for future strategic planning and response plans for new risks

that may arise.

Step 3: Analyze and Evaluate

Once managers identify and categorize risks, agencies should

consider the root causes, sources, and probability of the risk

occurring, as well as the potential positive or negative outcomes,

and then prioritize the resulting identified risks.

As part of the evaluation of risks, it is essential for agencies to

reflect that risk can be an integral part of what agencies do. As an

example, Federal credit programs are designed to meet specific

social and public policy goals by providing financial assistance to

borrowers who may be too risky to obtain private sector credit

under reasonable terms and conditions from lenders. Perceived

risks can be a large factor in the private sector’s unwillingness to

participate in the transaction, but the government chooses to step

in with specific credit program objectives because the potential social benefits and objectives are

considered to outweigh the risks. Agencies should appreciate inherent risk within their programs or

operations and incorporate them into their analysis and assessment of overall risk.

Assessments of the likelihood and impact of risk events help agencies monitor whether risk remains

within acceptable levels and support efficient allocation of resources to addressing the highest-priority

risks. Agencies can be too risk-averse. It is important to assess risks of standing still and either missing

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

24

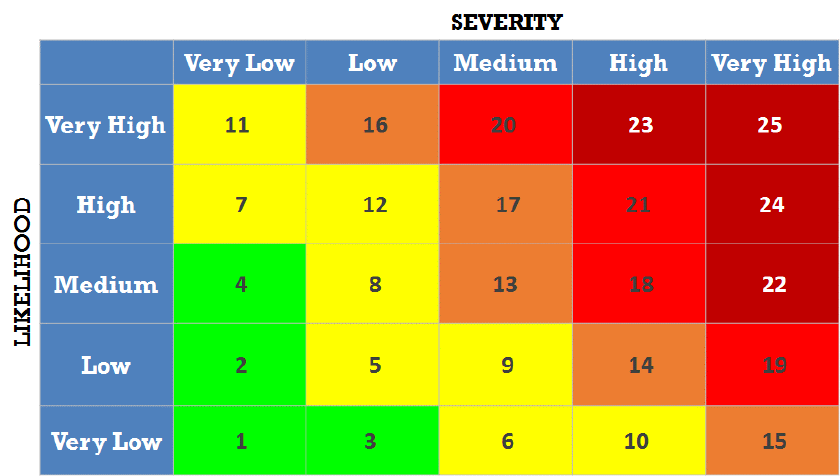

opportunities or becoming vulnerable to a changing environment. Examples of risk assessment tools

can be found in Appendix D.

Step 4: Develop Alternatives

Guided by risk appetite, agencies should (1) systematically identify

and assess a range of response options or strategies to accept,

avoid, pursue, reduce, transfer, or share major risks; (2) compare

the cost of addressing the risk with the risk of exposure, the value

of potential benefits and losses, and determine how to allocate

resources accordingly; (3) consider non-financial costs in terms of

the reputational or political capital at stake; and (4) evaluate

control options to respond to risk which may be preventative,

corrective, directive, or detective in design.

Step 5: Respond to Risks

After identifying and analyzing major risks, prioritizing them, and

developing appropriate strategies to address the highest priority

risks, the agency leadership must decide how to allocate scarce

resources, such as budget resources, analytical capabilities, and

management attention, to address them. While the risk officer or

risk office can help to facilitate the process, managing risk is the

responsibility of the unit heads where the risk resides. Once risks

are prioritized and risk responses are determined, milestones for

carrying out the risk management process should be documented.

The risk officer or office should then monitor implementation of

the risk management strategy to ensure that it is being carried out

effectively and in a timely manner. Agency leadership may need to

adjust its approach to managing particular risks if implementation

fails to bring the risk within the organization’s risk appetite.

Step 6: Monitor and Review

Agencies should regularly review, monitor, and update (as necessary) risk information in the enterprise-

level risk profile to identify any changes and determine whether risk responses and risk response

strategies are effectively mitigating risk. This review should occur semi-annually at a minimum. As part

of this ongoing process, risk personnel should work with senior leadership to determine if originally

identified risks still exist, identify any new or emerging risks, determine if likelihood or impact has

changed, and ascertain the effectiveness of controls or mitigants. It is a good practice to regularly

review and update risk data at all levels of the agency, as appropriate. Any significant changes to the

risk profile should be escalated to the appropriate senior leader and RMC, for discussion.

It is expected that this step will result in a risk register, dashboard, or other report to communicate the

status of risk response activities. This includes whether an action has been started, completed, or

delayed, and whether the action taken had the desired effect on the risk. It can also show what the

residual risk is and where additional response is required. Monitoring efforts may include assigning

responsibility for implementing risk responses (usually it lies with the manager where the risk resides),

setting milestones and criteria for success, and monitoring to ensure the intended actions are

completed. Examples of risk communication tools are available in Appendix E.

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

Communicate

and Learn

1. Establish

Context

4. Develop

Alternatives

2. Identify Risks

3. Analyze and

Evaluate

5. Respond To

Risks

6. Monitor and

Review

The material in this document should not be construed as audit guidance.

25

Progress in implementing risk response strategies provides a performance measure. The results can be

incorporated into the organization's overall performance management, measurement, and external and

internal reporting activities.

Step 7: Continuous Risk Identification and Assessment

Risk identification and assessment should be an iterative process,

occurring throughout the year, including surveillance of leading risk

indicators both internally and in the external environment. Once

ERM is built into the agency’s culture it is possible to learn from

managed risks, near misses when risks materialize, and adverse

events, and can be used to improve the process of risk

identification and analysis in future iterations. All aspects of ERM,

including formal tools such as risk profiles and statements of risk

appetite need to be regularly reviewed and evaluated to determine

whether the agency’s implemented risk management strategies are

achieving the stated goals and objectives, whether the identified

risks remain a threat, whether new risks have emerged, and how

ERM processes can be improved.

Integrating risk management into existing agency planning, performance management, and budget

processes is essential for ERM to be effective. Agency strategic plans, for example, should reflect an

assessment of current and future risks to mission achievement and plans for how the agency may

respond to such eventualities including risks of standing still while the context changes. The

Government Performance and Results Act Modernization Act (GPRAMA) requires agencies to revise

strategic plans every four years and assess progress toward strategic objectives annually. Incorporating

a review of the risk appetite and identified risks associated with each objective into this process

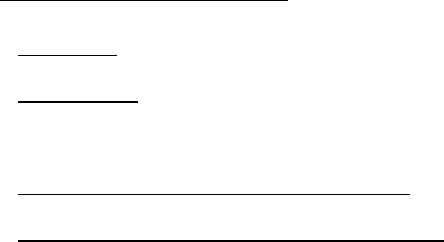

encourages an ongoing dialogue about risk and performance. Finally, integration with the budget