Review of the introduction of fees

in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

January 2017

Review of the introduction of fees in the

Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

Presented to Parliament

by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice

by Command of Her Majesty

January 2017

Cm 9373

© Crown copyright 2017

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where

otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-

licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London

TW9 4DU, or email: psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission

from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Courts and Tribunals Fees Policy,

Ministry of Justice, Post Point 3.32, 102 Petty France, London, SW1H 9AJ.

Print ISBN 9781474140416

Web ISBN 9781474140423

ID 25011711 01/17

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum.

Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of

the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

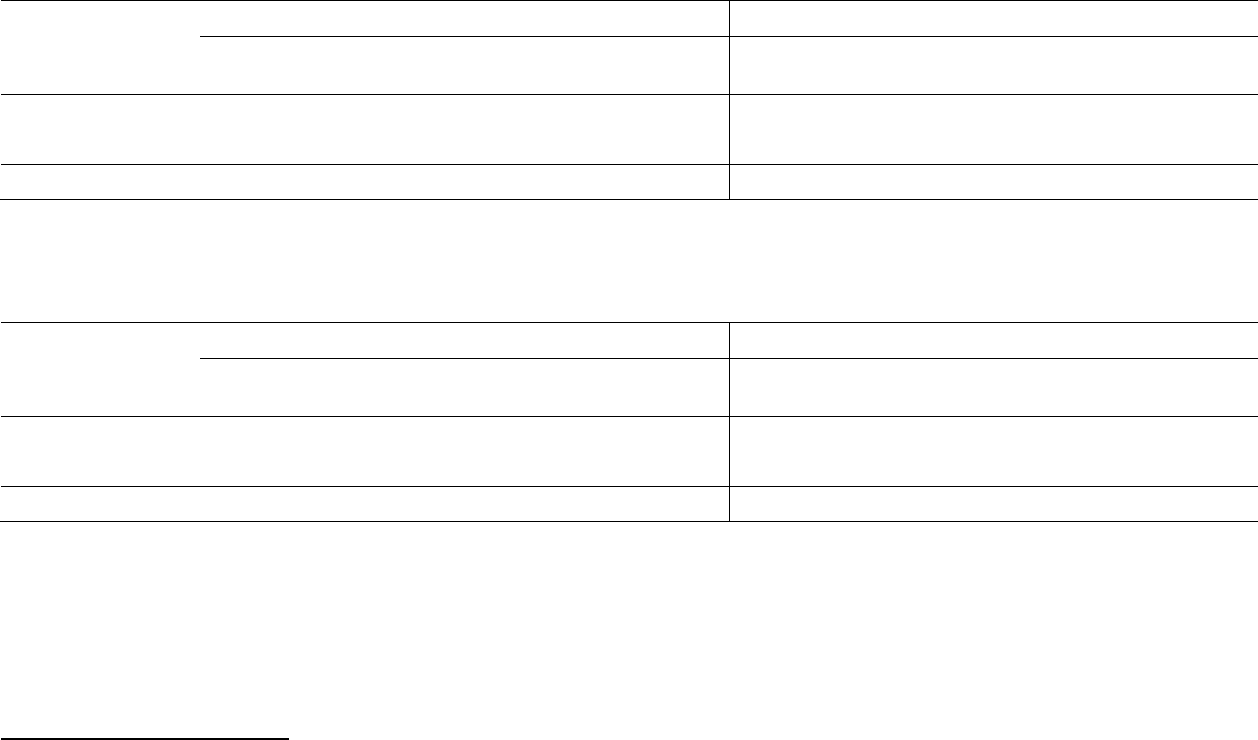

About this consultation

To:

This consultation is aimed at those who use the Employment

Tribunals, including legal professionals and members of the

public.

Duration:

From 31 January 2017 to 14 March 2017

Enquiries (including

requests for the paper in

an alternative format) to:

Michael Odulaja

Ministry of Justice

102 Petty France

London SW1H 9AJ

Tel: 020 3334 4417

Email: mojfeespol[email protected].uk

How to respond:

Please send your response by 14 March 2017 to:

Michael Odulaja

Ministry of Justice

102 Petty France

London SW1H 9AJ

Tel: 020 3334 4417

Email: mojfeespol[email protected].uk

Additional ways to feed in

your views:

There is an online version of this consultation at:

https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/review-of-

fees-in-employment-tribunals

Response paper:

A response to this consultation exercise will be published in due

course.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

1

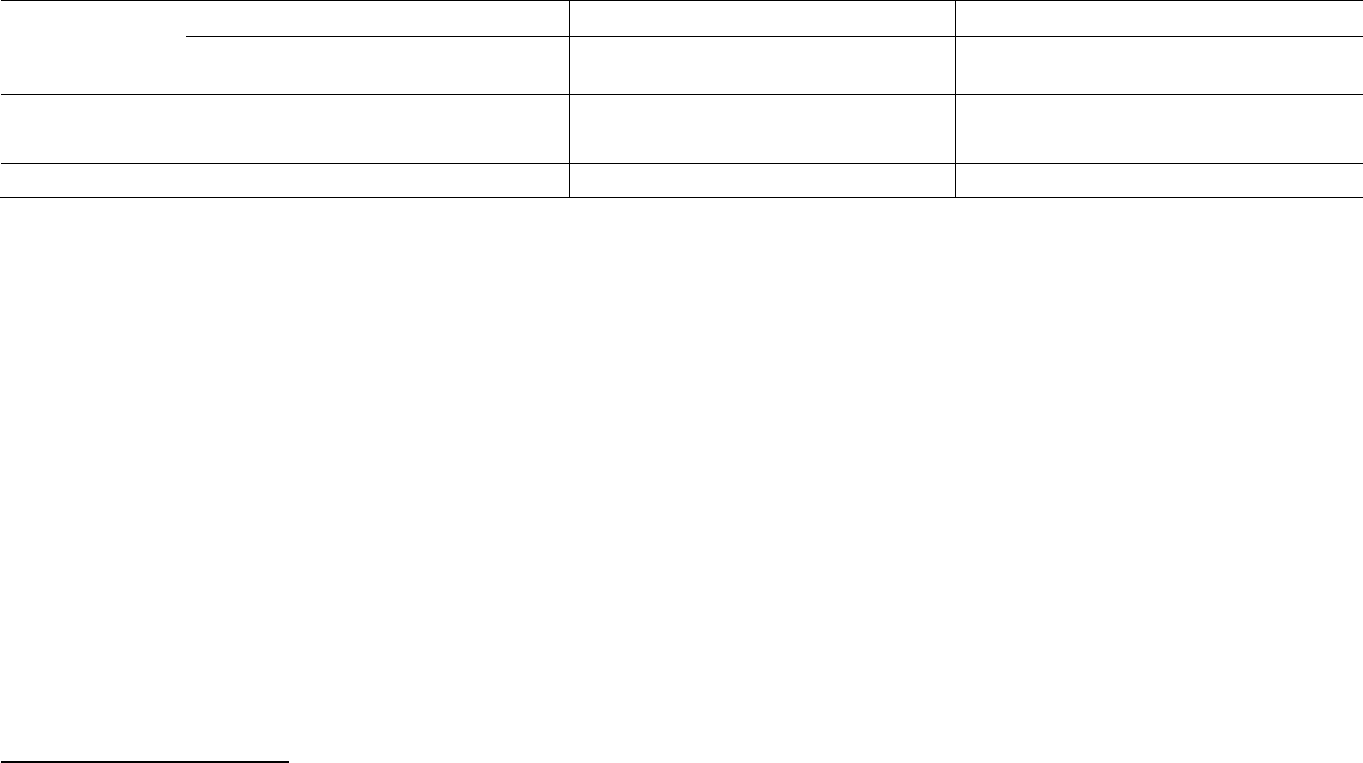

Contents

Foreword 3

Executive summary 5

1. Introduction 14

2. Evidence 20

3. Financial Objective 27

4. Behavioural Objective: Encouraging alternative ways of resolving disputes 29

5. Protecting access to justice 31

6. Other factors to be considered in accordance with the Terms of Reference 37

7. Public Sector Equality Duty 41

8. Consultation: proposals for adjustments to the fee remissions scheme 64

About you 69

Contact details/How to respond 70

Annex A: Terms of Reference for the Review 72

Annex B: Contributions to the review 73

Annex C: Fee remissions financial criteria 74

Annex D: Employment Tribunals financial information 76

Annex E: Employment Tribunals and Employment Appeal Tribunal caseload 77

Annex F: Information on Acas’s early conciliation service 82

Annex G: Fee Remissions Statistics 84

Annex H: Data on characteristics protected under the Equality Act 2010 90

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

2

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

3

Foreword

Fees were introduced for proceedings in the Employment

Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal in 2013. Most

people would agree that it is better for parties to try to resolve

disputes without going to the tribunal. Equally, few would

argue with the principle that those who use the Employment

Tribunals should make some contribution to the costs of the

service, where they can afford to do so.

These, alongside the need to protect access to the tribunal,

were the objectives that were set when we introduced fees.

There has been a significant fall in Employment Tribunal claims since then, but it is hardly

surprising that charging for something that was previously free would reduce demand. We

have consistently said that what was needed was a thorough assessment of the impact of

these fees, based on evidence. That is what this review has sought to do.

What this review shows is that the introduction of fees has broadly met its objectives:

users are contributing between £8.5 million and £9 million a year in fee income, in line

with what we expected, transferring a proportion of the cost from the taxpayer to those

who use the tribunal;

more people are now using Acas’s free conciliation service than were previously using

voluntary conciliation and bringing claims to the ETs combined; and

Acas’s conciliation service is effective in helping people who refer disputes to them

avoid the need to go to the tribunal, and where conciliation has not worked, many

people go on to issue proceedings in the ETs.

There are, of course, some lessons we can learn. It has become clear that there was a

general lack of awareness of the fee remission scheme, and those who did apply found

the guidance and procedures difficult to follow. We have taken steps to address these

concerns by relaunching the scheme as Help with Fees with improved guidance and

simplified application procedure, which has led to a marked increase in the numbers of fee

remissions granted. More recently, we have introduced the facility to apply for Help with

Fees online, and we have also published revised guidance on the Lord Chancellor’s

power to remit fees in exceptional circumstances, so that those who are entitled to help

receive it.

There is no doubt that fees, alongside the introduction of the early conciliation service,

have brought about a dramatic change in the way that people now seek to resolve

workplace disputes. That is a positive outcome, and while it is clear that many people

have chosen not to bring claims to the Employment Tribunals, there is nothing to suggest

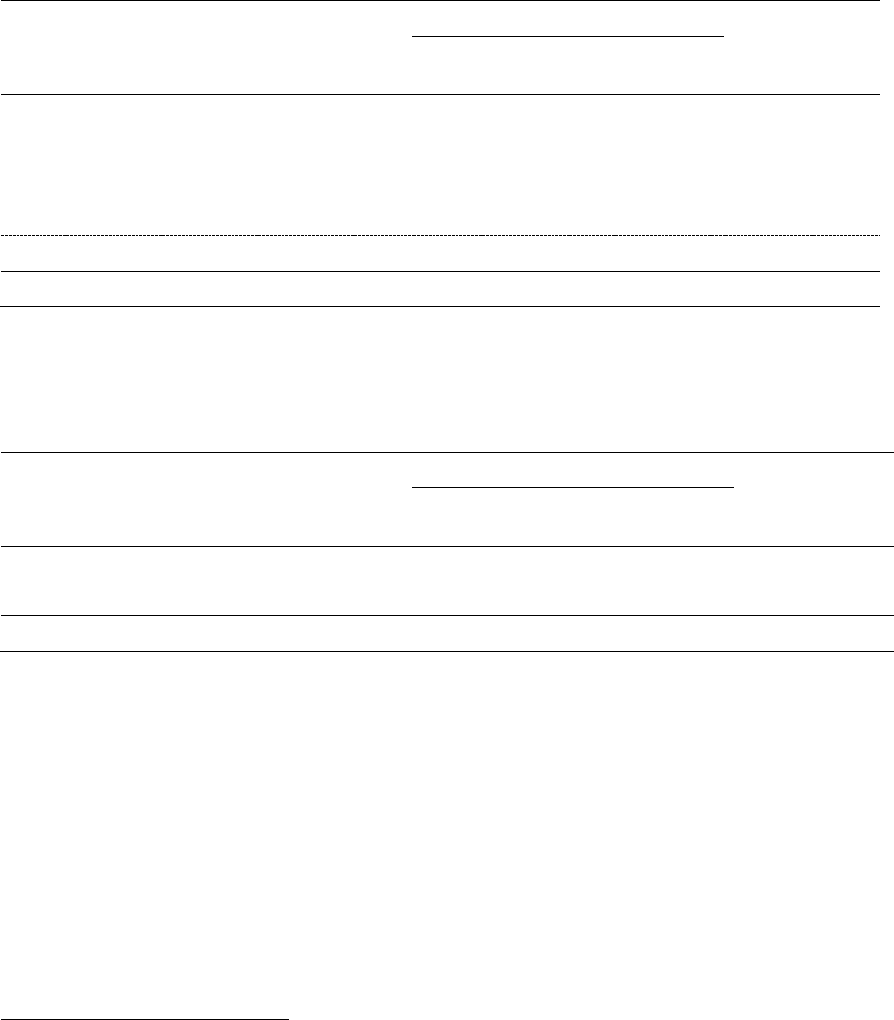

they have been prevented from doing so.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

4

This does not mean that there is no room for improvement, and where we have identified

issues, we have not been afraid to address them. In particular, the substantial fall in

claims, and the evidence that some people have found fees off-putting, has persuaded us

that some action is necessary. I believe that the best way to alleviate these impacts is to

widen access to the Help with Fees scheme and my proposals are set out in Chapter 8. I

have also decided that it is not appropriate to charge fees for certain ET proceedings

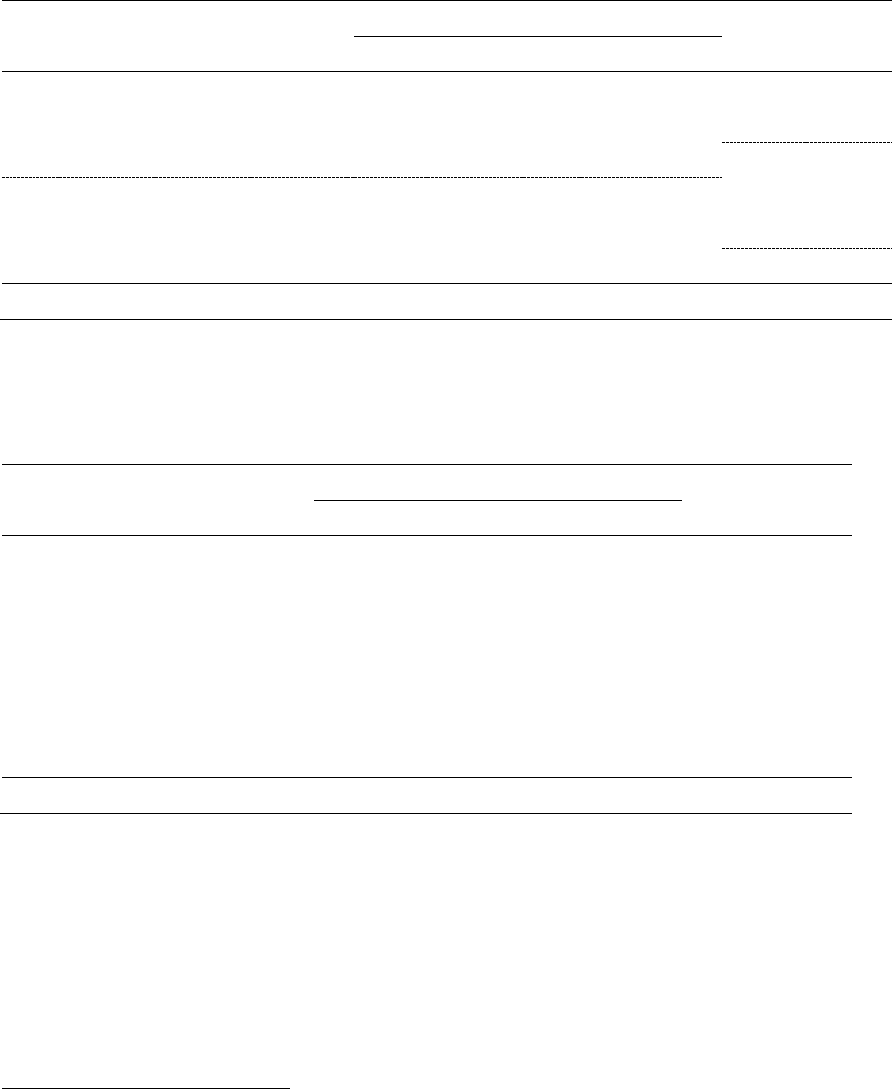

which are related to payments for the National Insurance Fund and they will, in future be

exempt from fees. Full details are set out in the review.

Employment Tribunals are also in the forefront of our vision for a modernised and

reformed justice system, which we have developed in partnership with the Lord Chief

Justice and the Senior President of Tribunals. The Government is committed to investing

more than £700 million to modernise courts and tribunals, and over £270 million more in

the criminal justice system.

Our specific proposals for reform of the Employment Tribunals were recently set out in the

consultation, published by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial

Strategy on 5 December. The Government will be considering the responses to

consultation carefully and we will bring forward our detailed plans in due course.

Sir Oliver Heald

Minister of State for Justice

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

5

Executive summary

1. This document sets out the Government’s review of the introduction of fees in the

Employment Tribunals (ETs).

2. Our review has assessed the impact of fees in relation to the three objectives set out

in the Terms of Reference (see Annex A). These objectives were:

(i) Financial: to transfer a proportion of the costs of the ETs to users (where they

can afford to pay);

(ii) Behavioural: to encourage people to use alternative services to help resolve

their disputes; and

(iii) Justice: to protect access to justice.

3. This review has considered a wide range of evidence on the income and cost of the

ETs; data on case volumes, complaint types and case progression; data on the

protected characteristics of people who use the ETs; and published information

about Acas’s conciliation service, including the evaluation of the introduction of the

early conciliation service.

4. Having considered this evidence against the objectives, the Government has

concluded that the original objectives have broadly been met:

(i) the financial objective: those who use the ETs are contributing around £9

million per annum in fees (which is in line with estimates at the time),

transferring a proportion of the cost of the ETs from taxpayers to those who

use the Employment Tribunals. Chapter 3 provides full details;

(ii) the behavioural objective: while there has been a sharp, significant and

sustained fall in ET claims following the introduction of fees, there has been a

significant increase in the number of people who have turned to Acas’s

conciliation service. There were over 80,000 notifications to Acas in the first

year of the new early conciliation service, and more than 92,000 in 2015/16.

This suggests that more people are now using conciliation than were

previously using voluntary pre-claim conciliation and the ETs combined. Our

detailed assessment is set out in Chapter 4; and

(iii) access to justice: our assessment suggests that conciliation is effective in

helping up to a little under half of the people who refer disputes to them (48%)

avoid the need to go to the ETs, and where it has not worked, many (up to a

further 34%) went on to issue proceedings. Chapter 5 provides further details.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

6

5. We acknowledge that the Acas evaluation of the early conciliation service has

identified a group (which we estimate to be between 3,000 and 8,000 people) who

were unable to resolve their disputes through conciliation, but who did not go on to

issue proceedings because they said that they could not afford to pay. We do not

believe, however, that this necessarily means that those people could not

realistically afford to pay the fee. It may mean, for example,

that paying the fee might involve having to reduce other areas of non-essential

spending; or

that they were not aware of the help available, or thought they might not qualify

for help, under the Help with Fees scheme; or

they may have been unaware of the Lord Chancellor’s exceptional power to

remit fees.

6. Furthermore, we have taken steps to raise awareness of the fee remissions

scheme, and to make it simpler to apply, which has led to a marked improvement in

the proportion of applications for a fee remission that are granted. Additionally, in

July 2016 we introduced the facility to apply for Help with Fees online to further

simplify the procedure.

7. Further help is also available, for those who do not meet the financial criteria for help

under the standard fee remissions scheme, under the Lord Chancellor’s power to

remit fees in exceptional circumstances. We have recently published revised

guidance on how this power should be applied to clarify the circumstances under

which help is available.

8. While there is clear evidence that ET fees have discouraged people from bringing

claims, there is no conclusive evidence that they have been prevented from doing

so. We have concluded on this basis that the system of ET fees combined with the

standard Help with Fees scheme, and underpinned by the exceptional power to

remit fees, means that no one should be prevented from bringing a claim to the ETs

because they cannot afford to pay.

9. Nevertheless, the review highlights some matters of concern that cannot be ignored.

The fall in ET claims has been significant and much greater than originally

estimated. In many cases, we consider this to be a positive outcome: more people

have referred their disputes to Acas’s conciliation service. Nevertheless, there is

also some evidence that some people who have been unable to resolve their

disputes through conciliation have been discouraged from bringing a formal ET

claim because of the requirement to pay a fee. This assessment is reinforced by the

consideration given to the particular impact that fees have had on the volumes of

workplace discrimination claims, in accordance with the duties under section 149 (1)

of the Equality Act 2010 (the detailed assessment is set out in Chapter 7).

10. The Government has decided to take action to address these concerns.

11. We believe that the best way to do so is to extend access to the support available

under the Help with Fees scheme. Our proposals would, if implemented, set the

gross monthly income threshold for a fee remission at broadly the level of someone

earning the National Living Wage. Additional allowances for people living as couples

and for those with children, would be maintained under our proposals.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

7

12. These proposals are designed to help those on low incomes and who are therefore

more likely to struggle to pay the fees (i.e. those people whose income is just above

the current gross monthly income threshold for a full fee remission). Although they

have been designed to alleviate the impact of fees on ET claims, HMCTS operates

a standard fee remissions scheme for all of its fee charging regimes, with the

exception of the First-tier Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum chamber). These

proposals would, if implemented, also benefit people on low incomes bringing

proceedings in the civil and family courts and in the tribunals where the standard

Help with Fees scheme applies.

13. Our proposals also maintain the financial discipline that fees bring to these

proceedings, providing people with an incentive to consider alternatives such as

Acas’s conciliation service, and to weigh the strength of their case against the

financial outlay required.

14. We have also concluded that it is not appropriate to charge a fee for three types of

proceedings in the ETs which relate to payments from the National Insurance Fund,

because conciliation is rarely a realistic option in these types of case, and they often

involve employers who are insolvent and are therefore unlikely to be able to satisfy

an order for the fee to be reimbursed. The specific proceedings are:

references to the ETs related to a redundancy payment from the National

Insurance Fund, under section 170 of the Employment Rights Act;

complaints that the Secretary of State has failed to make any, or insufficient,

payment out of the National Insurance Fund, under section 188 of that Act; and

complaints under section 128 of the Pension Schemes Act 1993.

15. From today these proceedings will be exempt from fees.

Public Sector Equality Duty

16. We have also considered the impact of fees in relation to the protected

characteristics under the Equality Act 2010 as part of the ongoing Public Sector

Equality Duty. There is only limited data available on the protected characteristics of

people who bring ET claims other than for gender and the results must therefore be

treated with some caution.

17. Having considered the impact of ET fees in relation to the obligations under the

Equality Act, we have concluded that:

ET fees are not directly discriminatory.

There has been no unlawful indirect discrimination from the introduction of ET

fees. Any differential impact which may have arisen indirectly from ET fees is

justified when considered against the success in transferring a proportion of the

cost of the tribunals to users and in promoting conciliation as an alternative

means of resolving workplace disputes.

It is clear that fees have discouraged some people from bringing ET claims,

including discrimination claims, but we have concluded that this has been

broadly a positive outcome to the extent that it has helped a significant

proportion of people to avoid the ETs by resolving their disputes through

conciliation. There is no conclusive evidence that ET fees have prevented

people from bringing claims.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

8

We have also, having regard to the duties under section 149 of the Equality Act

2010, given particularly careful consideration to the fall in the volumes of

discrimination claims, and the evidence that some people have been unable to

resolve their disputes through conciliation but have been discouraged from

bringing an ET claim. This assessment has reinforced our conclusion that some

adjustment to the scheme is justified to alleviate the effect that fees have had in

discouraging people from bringing claims. For the reasons set out above (see

paragraph 11), we consider that an adjustment to the Help with Fees scheme

would be the best way to alleviate the impact on those most likely to struggle to

pay fees.

18. We have also reviewed the concerns of those who have argued that ET fees have

had a particular impact on pregnancy and maternity discrimination, including the

Justice Committee and the Women and Equalities Committee. Our assessment of

the evidence is that the fall in these types of complaint has been consistently much

lower compared to other types of discrimination complaint, and compared to the

overall fall in complaints. There is, therefore, no evidence that these types of cases

should be treated more favourably in relation to the fees charged.

19. We will continue to monitor ET fees in relation to protected characteristics in

accordance with the Public Sector Equality Duty.

House of Commons Justice and Women and Equalities Committees

20. In the Justice Committee’s report

1

on their inquiry into Courts and Tribunals Fees

and Charges, the Committee made a series of recommendations about fees in the

ETs. Specifically, they recommended that:

(i) the overall quantum of fees charged for bringing cases to employment

tribunals should be substantially reduced;

(ii) the binary Type A/Type B distinction should be replaced: acceptable

alternatives could be by a single fee; by a three-tier fee structure, as

suggested by the Senior President of Tribunals; or by a level of fee set as a

proportion of the amount claimed, with the fee waived if the amount claimed is

below a determined level;

(iii) disposable capital and monthly income thresholds for fee remission should be

increased, and no more than one fee remission application should be

required, covering both the issue fee and the prospective hearing fee and with

the threshold for exemption calculated on the assumption that both fees will be

paid;

(iv) further special consideration should be given to the position of women alleging

maternity or pregnancy discrimination, for whom, at the least, the time limit of

three months for bringing a claim should be reviewed.

1

Courts and tribunals fees, House of Commons Justice Committee, HC 167, Second Report

Session 2016-17, 20 June 2016.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

9

21. The recommendation on pregnancy and maternity discrimination claims was also

included in the report of the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee.

2

22. As set out earlier in this report, the Government has decided to take action to

address the concerns about the scale of the fall in ET claims, and the evidence that

some people have been put off bringing claims because of fees.

23. We have concluded that the fairest and most effective solution is to widen access to

the Help with Fees scheme. Our proposals (see Chapter 8) would raise the income

threshold at which a full remission was available (subject to meeting the capital test)

to broadly the level of a single person working full time on the National Living Wage.

It would therefore benefit, if implemented, those people of relatively low means but

who may receive only limited help under the current scheme.

24. We therefore accept the Committee’s third recommendation. Our response to their

specific recommendations is set out in the following sections.

(i) The quantum of fee income

25. The Committee recommended that the overall quantum of ET fees should be

substantially reduced. We do not agree with this recommendation.

26. Chapter 4 of this review considers the impact of fees in relation to the financial

objective. This confirms that ET fees are generating the level of income that was

originally estimated: between £8 million and £10 million per year. Furthermore, fee

income of just under £4 million was remitted in 2015/16, so that overall just under

20% of the cost of the ETs is recovered through fees, after taking account of fee

remissions.

27. The Government’s view is that it is reasonable to expect people to contribute this

level of fee income towards the costs of the tribunals, where they can afford to pay.

Additionally, the requirement to pay a fee provides a financial discipline, encouraging

people to give serious consideration to the alternative sources of help available,

such as Acas’s free conciliation service, and to weigh carefully the strength and

merits of the claim against the financial outlay required.

28. Although the Government has concluded that an adjustment to the scheme is

required, we believe that widening access to the support available under the Help

with Fees scheme is a better way to do so.

(ii) Fee structure

29. The Justice Committee also recommended that the binary distinction between Type

A and B fees should be replaced by either a single fee regime, a three-tier regime or

by fees which were based on the value of the claim. We do not accept this

recommendation.

2

Pregnancy and maternity discrimination, House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee,

HC 90, First Report of Session 2016-17, 31 August 2016.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

10

30. During the original consultation on introducing fees in the ETs,

3

the Government set

out two options for the structure of fees which sought to balance four criteria:

recover a contribution from users towards the costs of the ETs where they could

afford to do so;

develop a simple, easy to understand and cost effective fees system;

maintain access to justice; and

contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of the system.

31. Having considered the consultation responses carefully, the Government decided to

implement a modified version of Option 1 (see paragraph 34 below) which was

considered to achieve the best balance of these criteria.

32. We continue to believe that the current structure best meets these criteria. In

particular, we believe that it is fair that those who make greater use of the ETs

should pay more as a contribution to the overall costs of the system, so that those

who bring more complex claims, which consume more tribunal time and resource,

should pay more than those who bring simpler claims. The current fees structure

also provides an opportunity and incentive for parties, once proceedings have

commenced, to continue to negotiate to seek to reach a settlement before the

hearing fee is due.

33. For these reasons, we do not believe that it would be reasonable to charge a single

flat fee to all types of claim.

34. The three-tier fee structure suggested by the Committee was the basis for Option 1

in the original consultation proposals. Option 1 proposed three separate fees for

cases allocated to:

the fast track: claims such as a claim for unpaid wages, paid leave and work

breaks;

the standard track: for example, claims for unfair dismissal; and

the open track: all discrimination claims.

35. Having considered the responses to the consultation, the Government decided to

proceed with a modified version of this option. In view of specific concerns about

charging the highest fees for discrimination claims, the Government decided to

implement a two-tier system of fees, under which claims allocated to the fast track

attracted Type A fees, and those allocated to the standard and open tracks attracted

Type B fees.

36. The current fee structure does therefore broadly reflect the categorisation of ET

claims, although modified so that discrimination claims do not attract higher fees

than all other types of claim.

3

Charging fees in the Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal, CP 22/2011,

Ministry of Justice, December 2011. https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/et-fee-

charging-regime-cp22-2011/supporting_documents/chargingfeesinetandeat1.pdf

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

11

37. We can see the attractiveness of an approach under which fees are charged as a

percentage of the value of the claim. In the original consultation, Option 2 was

based on a fee structure which, although it did not propose a fee calculated as a

percentage of the value of the claim, proposed that a higher fee would be payable

where the claimant sought an award over £30,000.

38. Few respondents to the consultation were in favour of that approach. They pointed

out the difficulties in assessing and quantifying the value of a claim at the outset of a

case, particularly in an ET case where the claimant may not have legal

representation. We believe that the difficulties faced by claimants would be greater

under a structure which charged a fee calculated as a percentage of the value of the

claim.

39. Neither do we agree that some types of claim, below a certain financial value,

should not attract a fee. We believe that the requirement to pay a fee provides the

right financial incentive for people to give serious consideration to the strength of the

claim and alternative ways of resolving dispute, such as Acas’s conciliation service.

40. A further complication is that many ET claims do not seek a financial award (for

example, the right to regular work breaks or a written contract of employment) and

these types of claim would therefore require a separate fee structure.

41. Overall, we consider that the current fee structure achieves the best balance

between the original criteria while maintaining access to justice.

(iii) Fee remissions

42. The Committee recommended that we should increase the capital and income

thresholds for a fee remission and simplify the procedure for applying so that only

one application for a remission is required.

43. As set out earlier, we agree that an adjustment to the Help with Fees scheme is the

fairest and most effective way to alleviate the impact of fees on volumes of claims.

44. We do not believe that it is necessary to increase the disposable capital threshold

for a fee remission. In principle, people with savings or other capital assets have

access to funding to pay the fee and can therefore afford to pay. If the claim is

successful, the tribunal has the power to order the respondent to reimburse the fee.

Furthermore, if the claimant has disposable capital, but cannot realistically afford to

pay the fee because the capital is required to meet other essential spending, he or

she is entitled to help under the Lord Chancellor’s exceptional power to remit fees.

The revised guidance

4

on the application of the Lord Chancellor’s exceptional power

makes clear that in those circumstances a remission must be granted.

45. We agree with the Committee that the gross monthly income threshold should be

increased: we believe that this is the fairest and most effective way of targeting

those who are most likely to find fees off-putting. Under our proposals, the gross

monthly income threshold for a fee remission would be increased from £1,085 to

£1,250: broadly the level of earnings for a single person working full time on the

4

How to apply for help with fees, EX 160A, HMCTS. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/508766/ex160a-eng-20160212.pdf

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

12

National Living Wage. We also propose to maintain the additional allowances for

people living as couples and for those with children.

46. Although these proposals have been designed to alleviate the impact of fees in ET

proceedings, Help with Fees applies a standard scheme across all of HMCTS’s fee

charging jurisdictions, with the exception of proceedings in the First-tier Tribunal

(Immigration and Asylum chamber) where a separate fee remissions, waivers and

exemption policy applies. These proposals would therefore also benefit people on

low incomes bringing proceedings in the civil and family courts and in the other fee

charging tribunals to which the Help with Fees scheme applies. Further details of

our proposed reforms are set out at Chapter 8.

47. We have separately taken steps to simplify and streamline the Help with Fees

scheme, including clearer guidance and a simplified application procedure; and the

introduction of the facility to apply for Help with Fees online. We have also updated

our guidance to the public and HMCTS staff on the Lord Chancellor’s exceptional

power to remit fees.

48. We have no current plans to remove the requirement to apply for Help with Fees

at each fee payment point but we are considering, in the context of the Court and

Tribunals reform programme, opportunities to further simplify and streamline our

procedures, and we will consider the Committee’s recommendation as part of that

programme of work.

(iv) Maternity and pregnancy related claims

49. The Committee recommended that special consideration should be given to the

position of women alleging maternity or pregnancy discrimination. Chapter 7

includes an analysis of the impact of fees in relation to discrimination claims, and in

particular on claims alleging pregnancy and maternity related discrimination. We

found that the fall in pregnancy and maternity related claims was much lower

compared with the fall in other types of discrimination claim, and compared with the

overall fall in claims more generally.

50. There is no evidence that maternity and pregnancy discrimination claims have been

particularly affected by the introduction of fees, and there is therefore no reason that

they should be treated more favourably as far as fees are concerned than other

types of claim. We do not therefore agree that fees for these types of claim should

be reduced. Instead, we believe that any concerns about the impact of fees on these

types of claim are better addressed through the proposed adjustment to the Help

with Fees scheme, under which support would be targeted to those most likely to

struggle to pay the fees.

51. The Government’s response to the recommendation on extending the time limit

for these types of claim from three to six months was included in the Government

response to the report of the Women and Equalities Select Committee, which was

published on 26 January 2017.

5

5

Government response to the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee report on

pregnancy and maternity discrimination, Cm 9401, January 2017.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

13

Other factors set out in the Terms of Reference

52. Although not a formal objective of the review, it was also hoped that the introduction

of fees would improve the efficiency of the tribunal, for example, by giving claimants

a financial stake in proceedings which might discourage people from bringing

weaker or speculative claims.

53. We have found that there has been little change in the outcomes of cases which

progress to a hearing in the ETs, which might have indicated a change in the

strength of cases. However, more generally, we believe that the introduction of fees,

combined with the introduction of Acas’s early conciliation service, has helped to

improve the efficiency of system for resolving workplace disputes by focusing the

ETs’ resources on those claims which require a litigated approach.

Conclusions and proposals for reform

54. Based on the analysis in this review, we have concluded that the three objectives for

ET fees have broadly been met, and while it is clear that fees have discouraged

people from bringing claims, there is no evidence that they have prevented them

from doing so.

55. Nevertheless, the Government recognises that the review has identified some

matters which raise concerns about the impact that fees have had. We have

therefore decided to take action to address them. In Chapter 8 we set out our

proposals to do so by widening access to Help with Fees. We have also decided to

exempt from fees certain proceedings in relation to payments from the National

Insurance Fund.

Consultation questions

Question 1: Do you have any specific proposals for reforms to the Help with Fees

scheme that would help to raise awareness of remissions, or make it simpler to

use? Please provide details.

Question 2: Do you agree that raising the lower gross monthly income threshold is

the fairest way to widen access to help under Help with Fees scheme and to

alleviate the impact of fees for ET proceedings? Please give reasons.

Question 3: Do you agree with the proposal to raise the gross monthly income

threshold for a fee remission from £1,085 to £1,250? Please give reasons.

Question 4: Are there any other types of proceedings, in addition to those specified

in paragraph 355, which are also connected to applications for payments made

from the National Insurance Fund, where similar considerations apply, and where

there may be a case for exempting them from fees? Please give reasons.

Question 5: Do you agree with our assessment of the impacts of our proposed

reforms to the fee remissions scheme on people with protected characteristics?

Are there other factors we should take into account, or other groups likely to be

affected by these proposals? Please give reasons.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

14

1. Introduction

56. The right of access to a tribunal to determine employment related rights was

established under the Industrial Training Act 1964. When first established, these

were known as Industrial Tribunals but in 1998 they were renamed Employment

Tribunals (ETs).

57. Section 42 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 provides the Lord

Chancellor with the power to prescribe fees for Tribunals both in the unified tribunal

structure, and also (under section 42 (1) (d)) for “added tribunals”. Under the current

arrangements, Her Majesty’s Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) is responsible for

the administration of the ETs in England and Wales, and in Scotland.

58. In November 2014, the Smith Commission Report recommended that responsibility

for the management and operation of reserved tribunals, including the ETs, should

transfer to the Scottish Government. The Government has accepted those

recommendations and the arrangements for implementing them are being agreed.

The introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

59. From their inception, access to the Industrial/Employment Tribunals was provided

free of charge.

60. In January 2011, the Government announced that they considered that it was right

in principle that those who wished to bring a claim to the ETs and the Employment

Appeal Tribunal (EAT) should, where they could afford to do so, pay a fee.

61. Detailed proposals for fees were set out in a consultation exercise published in

December 2011.

6

The consultation ran until 6 March 2012 and a response to

consultation was published in July 2012.

7

This confirmed the Government’s intention

to introduce fees but with some modifications to the original plans. In particular, it

confirmed that the Government had decided to introduce a two-fee structure in the

ETs, rather than a three-fee structure as originally proposed in the consultation.

It also confirmed that HMCTS’s standard fee remission scheme would apply to

proceedings in the ETs, so that those who qualified would be entitled to have the

fee remitted either in part or in full.

6

See footnote 3 above

7

Charging Fees in Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal, Response to

Consultation CP22/2011, Ministry of Justice, July 2012. https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-

communications/et-fee-charging-regime-cp22-2011/results/employment-tribunal-fees-

consultation-response.pdf

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

15

62. An Impact Assessment was published alongside the Government Response.

8

This

estimated that the introduction of fees would lead to a reduction in claims of around

0.01% to 0.05% for every £1 in fees, and generate income of between £8 million

and £10 million per annum in a steady state.

63. On 25 April 2013 a draft of the Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal

Tribunal Fees Order (the Fees Order) was laid before Parliament. It was approved

by both Houses under the affirmative resolution procedure, and came into force on

29 July 2013.

9

64. Under these rules, the person bringing proceedings is required to pay the fees

although the fee for judicial mediation in the ETs (£600) is paid by the employer. At

the same time rules came into effect that provided the Tribunal with the power to

order a respondent to reimburse a claimant any fees incurred.

Fees in the Employment Tribunals

65. The Fees Order provided for a two-tier structure for fees:

Type A fees for simpler and more straightforward disputes, and which consume

less Tribunal resource on average. Claims attracting Type A fees include:

seeking a written contract of employment; payment of unpaid wages; and

applications under the Working Time Directive (for example, entitlement to

regular working breaks). For this type of claim, the fees are £160 to lodge the

claim and £230 for a hearing;

Type B fees apply to cases which are more complex and consume more

Tribunal resource on average. Type B claims include: unfair dismissal;

discrimination; and equal pay. The fees for Type B claims are £250 to lodge a

claim and £950 for a hearing.

66. The types of case attracting a Type A fee were broadly those which are allocated to

the short track of the allocations system used in the ETs. As set out in the

Government response to consultation,

10

typically these claims require very little or

no case management work and are listed for a hearing lasting 1 hour. They

consume less tribunal resource than other types of case and therefore cost less.

67. Cases allocated to the open and standard tracks attract the higher Type B fees

because they consume more Tribunal resource, and therefore cost more.

68. Claims which include two or more complaints pay one fee. Where a claim includes

both a Type A and a Type B complaint, the claim attracts a Type B fee.

69. Many claims received in the ETs are lodged as part of a multiple claim: i.e. claims

brought by two or more people against the same employer based on the same, or

similar, facts. The Government response to consultation confirmed that these cases

are more expensive to administer, but there are efficiencies of scale, so that, for

8

See: https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/et-fee-charging-regime-cp22-

2011/results/et-fees-response-ia.pdf

9

The Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal Fees Order 2013, 2013 No

1892 (the “ET Fees Order”).

10

See footnote 7 above.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

16

example, it is cheaper to administer twenty claims as part of a multiple claim, than

twenty single claims. There is therefore a separate fee structure for multiple claims,

under which a person bringing a claim as part of a multiple claim will not pay more,

and will typically pay less, than the fee for a single claim.

70. Other fees introduced at the same time were:

an application for a reconsideration of a default judgment: £100;

an application for a reconsideration of a judgment following a final hearing: £100

(Type A) and £350 (Type B);

an application for a dismissal following a withdrawal of the claim: £60;

an employer’s contract claim: £160.

71. Fees also apply to appeals to the EAT: £400 to lodge an appeal, and £1,200 for a

hearing. There are no separate fees arrangements for multiple claims in appeals to

the EAT.

Fee remissions

72. When the ET Fees Order came into effect, it provided that the HMCTS’s standard

fee remissions scheme would be available for proceedings in the ETs. At the time, a

consultation on proposed changes to the fee remission scheme was underway, and

in September 2013, the Government Response to consultation was published. It

confirmed that the Government intended to:

establish a single fee remissions scheme operating across all court and tribunal

businesses of HMCTS (except proceedings in the Immigration and Asylum

Tribunal) and the UK Supreme Court;

introduce for the first time a disposable capital test; and

simplify the gross income test by introducing a single tapered income

assessment, replacing the three alternative bases of remission which existed

under the previous scheme.

73. The new fee remissions scheme came into effect on 1 October 2013.

74. Access to fee remissions is based on an assessment of financial eligibility and the

applicant must meet tests of both disposable capital and gross monthly income.

Applications are made using the form EX 160

11

and guidance is available to help to

complete the application (see form EX 160A: Court and Tribunal fees – Do I have to

pay them?).

12

75. Further details of the fee remission scheme are set out at Annex C.

11

Form EX 160. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/508760/ex160-eng-20160212.pdf

12

See footnote 4 above.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

17

The Lord Chancellor’s power to remit fees in exceptional circumstances

76. The Lord Chancellor has a power to remit any fee specified in a fees order where

she is satisfied that there are exceptional circumstances which justify doing so.

13

This power is exercised on the Lord Chancellor’s behalf by HMCTS staff.

77. On 10

th

October 2016 we published updated guidance on the exercise of the

exceptional power to remit to clarify the circumstances under which help is available;

in particular, that a fee must be remitted in circumstances where the applicant

demonstrates that they cannot realistically afford to pay the fee in question.

Fee remission improvement project

78. Following the introduction of fees, there were a number of complaints that the

system of fee remissions was complex and overly bureaucratic, which many people

said that they found off-putting. A project has been undertaken to explore whether

the scheme could be made simpler for the public to understand and use.

79. In October 2015, the fee remissions scheme was relaunched as Help with Fees.

This included:

a revised, simpler, version of the EX 160A guidance and a simplified application

form;

a simplified procedure, under which applicants no longer routinely need to

provide evidence of income; and

the introduction of a digital link to the Department for Work and Pensions with an

eligibility calculator to help court staff determine quickly the fee remission to

which the applicant is entitled.

80. Since the relaunch of Help with Fees, there has been a marked increase in the

numbers of fee remissions granted. Further details are set out in Chapter 2 (see

paragraphs 126 to 129). In July 2016, the facility to apply for Help with Fees online

was introduced.

Acas’s early conciliation service

81. In 2014, as a way of encouraging people to consider conciliation to resolve their

dispute, a requirement was introduced for most employment matters that anyone

considering bringing a claim to the ETs must first notify Acas to consider whether

Acas’s conciliation service might help to resolve the dispute. The service, known as

Acas’s early conciliation service, was introduced in April 2014 and became

mandatory in May 2014.

13

See, for example, paragraph 16 of schedule 3 to the ET Fees Order.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

18

Justice Committee

82. On 15 July, the House of Commons Justice Committee announced an inquiry into

Court and Tribunal Fees are charges. Details of the terms of reference for the

review are available on the Committee’s page of the Parliament website.

14

83. On 20 June 2016, the Committee reported on its inquiry.

15

Among its

recommendations, were recommendations to reduce substantially the fees for ET

proceedings, the introduction of fees for respondents and an expansion of the fee

remissions scheme. The Government responded to the Committee’s report on 9

November 2016 in which we said that we would provide a substantive response to

their recommendations on ET fees in this review.

16

Our substantive response to

those recommendations is set out at paragraphs 24 to 51 above.

Women and Equalities Committee

84. On 30 August the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee published

a report on their inquiry into Pregnancy and Maternity Discrimination.

17

This also

included a recommendation that ET fees for proceedings for pregnancy and

maternity discrimination should be substantially reduced. The Government

responded to the Committee’s report on 26 January 2017 indicating that we would

be responding to this specific recommendation in this review.

18

As set out in

paragraphs 49 and 50 above, there is no evidence to suggest that pregnancy and

maternity related discrimination claims have been more adversely affected by ET

fees, and therefore there is no reasons to treat them more favourably for fees than

other types of discrimination claim, or other ET claims generally.

The Review

85. On 11 June 2015, the Justice Secretary made a statement announcing the start of

the review of ET fees

19

and setting out the Terms of Reference for the review, which

are attached at Annex A.

86. The purpose of the review is to consider the impact of the introduction of fees and

how successful they have been in meeting the original objectives. In summary,

these were:

(i) to transfer a proportion of the cost of the tribunals from the taxpayer to those

who use them;

14

See: https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/justice-

committee/inquiries/parliament-2015/courts-and-tribunals-fees-and-charges/

15

See footnote 1 above.

16

Government Response to the Justice Committee’s Second Report of session 2016/17, Courts

and Tribunals Fees, Ministry of Justice, November 2016.

https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/Justice/governments-response-to-

the-justice-committees-second-report-of-session-2016-17-web.pdf

17

See footnote 2 above.

18

See footnote 5 above.

19

See: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/employment-tribunal-fees-post-

implementation-review.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

19

(ii) to encourage parties to use alternative mechanisms for dispute resolution,

which can often be simpler, cheaper and deliver better outcomes than formal

litigation; and

(iii) to ensure that access to justice is protected.

87. Although it was not a formal objective, it was also hoped that the introduction of fees

would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the ETs by, for example, giving

claimants a financial interest in proceedings and discouraging them from bringing

claims with little or no merit.

88. The review did not seek submissions, but a number of stakeholders have

contributed written evidence to the review. A list of those who have done so is at

Annex B, as well as a summary of the wider evidence we have considered.

89. This review sets out the work that the Government has undertaken, the evidence we

have taken into consideration, the assessments we have made on the delivery of

the key objectives, and the overall conclusions we have made.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

20

2. Evidence

Introduction

90. This section provides information on the evidence we have considered in this

review. The principle sources of evidence we have used are:

financial information on HMCTS’s costs and income from published accounts

and internal management information;

official Tribunal statistics, published by MoJ each quarter, which include statistics

the number of Employment Tribunal claims received (including a breakdown of

claims by jurisdictional complaint), the numbers disposed of, analyses of case

outcomes, and statistics on fee remissions;

20

and

Acas’s evaluation of the early conciliation service, published in April 2015.

21

91. This has been supplemented by:

management information from HMCTS and Acas’s published statistics; and

information on the protected characteristics of those who have brought claims to

the ETs, collected by HMCTS on the ET1 form.

92. A number of people and organisations wrote submitting views on the impact of the

introduction of fees. These have been useful in confirming the general and specific

concerns of people and organisations with an interest in the ETs and the review.

93. A summary of the people and organisations who contributed to the review, and the

evidence they submitted, is set out at Annex B.

Financial information

94. High level financial information on fee income collected, the value of fee remissions

granted and the costs of the ETs is published annually in HMCTS’s Annual Report

and Accounts. This is reproduced at Table 5 at Annex D.

95. We have supplemented this with information taken from HMCTS’s management

information systems on costs incurred on the project to implement fees in the ETs:

see Table 6 of Annex D.

20

See: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/tribunals-statistics

21

Evaluation of Acas Early Conciliation 2015, Acas, 04/15.

http://www.acas.org.uk/media/pdf/5/4/Evaluation-of-Acas-Early-Conciliation-2015.pdf.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

21

Employment Tribunals caseload

96. Data on the ET caseload, including volumes of receipts, jurisdictional complaints,

case progress and case outcomes, is set out at Annex E.

97. The broad approach we have taken in the review has been to compare data for the

years preceding and following the introduction of fees. In most cases, where the

data are available, we have looked at the year from July 2012 to June 2013 and

compared it with the years from October 2013 to September 2014 and October 2014

to September 2015.

98. Data on ET proceedings is collected for claims made either as:

a single claim: a claim brought by an individual;

a multiple claim case: these are cases which involve claims brought by two or

more claimants against the same employer based on the same, or similar facts.

In a small number of cases, a single multiple claim case can involve hundreds or

thousands of claims;

in both cases the claim may allege one or more jurisdictional complaint.

99. The analysis in this review has generally focussed on what has happened in single

claims. Multiple claims involving more than two people should generally attract lower

fees per claimant than those which apply to single claims because the fees are fixed

depending on the number of claimants. As the burden of paying fees is normally

shared between those parties, people involved in larger multiple claims should,

therefore, be less likely to have been affected by the requirement to pay a fee. It

would have been helpful to have been able to include analysis of fees within the

multiple claim fee groups (for example, to look at the effect of claims involving 2–10

people, 11–200 people and over 200 people) in order to see whether the effect of

fees differed depending on the number of multiple claimants. However, this

information is not collected and has not therefore been available to the review.

100. Furthermore, while the number of cases involving multiple claims is relatively stable

and has followed the same general trends on volumes of claims, the number of

multiple claims within those cases has been more variable. Some multiple cases

can involve a very large number of claimants, so that the numbers of people

involved in these types of case, and the types and number of jurisdictional complaint

they bring, are likely to be subject to greater normal variations over time compared

to single claims. Isolating the impact that the introduction of fees has had on the

volumes of claims made in multiple claims is therefore more difficult than for

single claims.

101. For these reasons, we believe that the impact of the introduction of fees on multiple

claims has been no greater than, but is likely to have been less than, the impact on

single claims. We have therefore preferred in most cases to concentrate the

analysis on single claims which are, we believe, a better measure of the workload of

the tribunal.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

22

Case receipts

102. Table 7 of Annex E sets out the number of claims received in the ETs in the years

preceding and following the introduction of fees.

103. The comparison shows that over that period:

the total number of claims (i.e. the number of single and multiple claims) fell by

78% (from around 196,000 in the year to June 2013 to around 44,000 in the year

to September 2014) but rose to 75,000 in the year to September 2015 so that

they were 62% lower in that year compared with the year to June 2013;

the total number of cases fell by 66% (from around 60,000 in the year to June

2013 to around 20,000 in the year to September 2014) and by 68% (from around

60,000 in the year to June 2013 to around 19,000 in the year to September

2015);

the total number of single claims fell by 66% (from around 54,000 in the year to

June 2013 to around 18,000 in the year to September 2014) and by 68% (from

around 54,000 in the year to June 2013 to around 17,000 in the year to

September 2015); and

the total number of multiple claims fell by 82% (from around 142,000 in the year

to June 2013 to around 25,000 in the year to September 2014). In the following

year, to September 2015, the number of multiple claims rose to around 58,000,

a fall of 60% compared with the year to June 2013.

104. Our analysis of the counterfactual trend in ET receipts (i.e. the number of claims that

we would have expected to have received in the ETs had fees not been introduced)

concluded that the volume of single claims would have fallen by around eight

percent by June 2014 as a result of the improving economy. Further details are

considered in Chapter 6 below.

105. The actual fall since fees were introduced has been much greater and we have

therefore concluded that it is clear that there has been a sharp, substantial and

sustained fall in the volume of case receipts as a result of the introduction of fees.

Type A and Type B claims

106. We have also looked at whether there had been any difference in the impact

between jurisdictional complaints classified as either Type A or Type B. These data

do not correspond to the number of individuals paying a Type A or Type B fee, as

claims can involve more than one complaint. If a claim includes both a Type A and B

complaint, the Type B fee is payable.

107. The data on complaint types comparing volumes of Type A and Type B complaints

in the year to June 2013 (pre-fees) and the years to September 2014 and

September 2015 (the first and second years after fees) are set out in Table 9 of

Annex E. These indicate that there was a small difference in the fall in Type A

complaints, which fell by 69%, and Type B complaints, which fell by 61% when

comparing the year before fees with the year after fees. This difference has

continued when comparing the year before fees with the year two years after fees:

in the year to September 2015, Type A complaints were 72% lower and Type B

complaints 64% lower when compared with the year to June 2013.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

23

Regional impacts

108. The review also considered whether there had been any regional differences in the

impact of fees. We looked at single claims received in the seven English regions

and Scotland and Wales, and compared the volumes of claims over time. We also

compared the fall in a selection of jurisdictional complaints.

109. All regions saw falls in the volumes of claims and complaints similar to the overall

fall in England Wales and Scotland over this period: 66% in the first year following

fees and 68% in the second year. There have been regional variations, but all were

within five percentage points of the overall trend. In both years, London, the South

East and Scotland saw falls in claims volumes lower than the national average while

the Midlands, North East, South West and Wales saw above average falls in claims.

110. Further details are set out in Tables 10 and 11 of Annex E.

Employment Appeal Tribunal

111. Table 7 of Annex E also provides details of the number of appeals to the

Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT).

112. In the year before fees were introduced (July 2012 to June 2013) there were around

2,200 appeals lodged with the EAT. In the year following the introduction of fees

(October 2013 to September 2014) there were 1,400 appeals, a fall of 39%. In the

following year there were 1,100 appeals to the EAT, a fall of 53% compared to the

year before fees were introduced.

Acas’s early conciliation service

113. Annex F sets out published information on Acas’s early conciliation service. This

review has considered two main sources of information.

114. The first is information on the number of notifications they receive, which is

published in Acas’s regular statistical bulletins. In the first year of the early

conciliation service, Acas received over 83,000 notifications,

22

and of these, around

8,500 employees and 9,000 employers refused conciliation. In 2015/16, the second

year of operation, Acas received around 92,000 notifications, around 100

notifications more a week than in 2014/15.

23

The 2015/16 bulletin does not provide

information on the number of employees or employers refusing conciliation.

115. The other main source of evidence is Acas’s evaluation of the early conciliation

service.

24

Acas’s evaluation is based on a survey of claimants, employers and

representatives whose early conciliation cases were concluded between September

and November 2014, involving over 2,500 interviews.

22

Early Conciliation Update 4: April 2014 – March 2015, Acas, 7 July 2015.

http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=5352

23

Early Conciliation Update 7: April 2015 – March 2016, 23 May 2016.

http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=5741

24

See footnote 21.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

24

116. Acas’s evaluation found that the introduction of the early conciliation service had

been broadly successful. Based on the responses of claimants, the evaluation found

that for those who had undertaken early conciliation :

31% obtained formal settlement (either through Acas or privately);

a further 17% did not obtain a formal settlement but decided not to submit a

claim about their dispute, and reported that Acas was a factor in helping them

reach this conclusion.

117. Combined, these are described as the Acas “avoidance rate”: i.e. in these disputes,

Acas has been effective in helping people to avoid the need to issue formal

proceedings in the ETs.

118. In the remaining cases (52% of cases that went through early conciliation) Acas was

unable to help people avoid formal proceedings. In these cases, the review found

that 34% of respondents issued formal proceedings in the ETs, and the other 19%

of respondents did not.

119. Of the 19% of respondents who did not issue ET proceedings, a quarter (or around

5% of all respondents) said that fees were a factor in the decision not to litigate.

Just under two thirds of those who said that fees were a factor (or around 3% of

all respondents to the evaluation) said it was because they could not afford the fee

(full details are set out in Table 13 in Annex F).

120. The findings in the review do not match Acas’s management information in certain

respects. In particular, the evaluation suggests that 31% of people using conciliation

obtained a settlement through Acas or privately, whilst the management information

shows this is closer to 15%. The review also suggests that around 34% of claimants

issue proceedings in the ETs, but the management information shows the

percentage is around 22%.

121. There are likely to be a number of reasons for these differences which are

considered in paragraphs 163 to 165 below. The effect of both of these differences

is to underestimate the proportion of people who did not, or were unable to,

conciliate and did not go on to issue proceedings in the ETs.

122. In this review, we have used the findings from the evaluation as this provides a

greater level of detail on the outcomes for those individuals who did not resolve their

dispute but did not issue proceedings in the ETs. However, our estimate based on

this information represents a best case scenario, and we have gone on to consider

the effect of using the management information findings, applying the findings from

the review about the reasons why people did not settle and did not go on to submit a

claim in the ETs to this larger pool of cases: see paragraph 164 and Table 14

(Annex F) for further details.

123. On 23 May 2016, Acas published a further independent study on the early

conciliation service.

25

This broadly confirmed some of the results of the 2015 study,

including that:

25

Evaluation of Acas conciliation in Employment Tribunal applications 2016, Research Paper

04/16, May 2016.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

25

seven out of ten (71%) claimants avoided going to court after receiving help from

Acas;

Acas’s post-claim conciliation has also been highly successful with eight out of

ten users being satisfied with the service; and

over nine out of ten employers (92%) and a similar percentage of claimants

(87%) said that they would use Acas conciliation again.

124. The study also confirmed that some found fees off-putting: around a fifth of people

who withdrew their claims gave that as their reason for doing so.

125. As set out earlier, Acas’s more recent published statistics show that conciliation

continues to be popular and effective, dealing with over 92,000 notifications in the

year to March 2016.

Fee remissions

126. Statistics on fee remissions have been collected since fees were introduced in July

2013, and included in the quarterly statistical bulletin. These data are summarised in

Tables 15 to 20 of Annex G.

127. Since fees were introduced, the proportion of claims for which a fee remission was

granted has increased steadily. For the issue fee:

the proportion of all claims (both single and multiple) for which a fee remission

was granted increased from 15% in the quarter to July – September 2013 to

29% in the quarter January – March 2016.

the proportion of single claims in which a fee remission was granted (either in

part or in full) increased from 13% of all Type A single claims between July –

September 2013 to 27% in the quarter January – March 2016. The percentage

of successful applications for a fee remission in this category of claims improved

from 24% to 64% over the same time period;

for Type B cases (in single claims) the proportion granted a fee remission

increased from 16% to 30% between July – September 2013 and January –

March 2016.The proportion of applications for a remission which were

successful increased from 29% to 67%;

128. Relatively few claims that are issued progress to a hearing, and the volumes of

hearing fees requested is significantly lower than the number of issue fees. The

trends over time are therefore liable to greater variation. For those cases which

progressed to a hearing, the number of fee remissions granted as a proportion of all

claims has increased from 8% in the quarter July – September 2013 to 24% in the

quarter January – March 2016 and the number of fee remissions granted as a

proportion of applications has improved from 57% to 89%.

129. There has been a marked improvement in the proportion of fee remissions granted

since the relaunch of the scheme as Help with Fees in October 2015. In the quarter

from January to March 2016, the statistics indicate that there has been an overall

improvement of eight percentage points in the number of remissions granted for an

issue fee, compared with the same quarter in the previous year (January to March

2015). The improvement has been particularly high for individuals bringing Type A

single claims, where the number of applications granted has increased from 182

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

26

(January to March 2015) to 291 (in the same period in 2016), and the proportion of

claims in which the issue fee is remitted has increased by 11 percentage points

(from 16% to 27%).

Protected characteristics

130. Annex H sets out information we have on those who use the ETs about the

characteristics protected under the Equality Act 2010. This has been taken from

information provided by applicants when completing the ET1 form to issue an ET

claim. This is not a mandatory part of the form, and in practice this section is only

completed in around a third of cases. For multiple claims, it is only completed by the

lead claimant.

131. We have only invited claimants to provide this information since fees were

introduced in July 2013, and comparative data is not therefore available for the

pre-fees period. To provide a reasonable comparison, we have used data from the

Survey of Employment Tribunal Applicants 2013 (the SETA)

26

and complemented

this with information on characteristics of employees from the Labour Force Survey

(the LFS).

27

SETA is a periodical survey undertaken by the Department for Business

and Skills (as it was when the SETA was last published) of people who bring ET

claims, including the types of claim they bring and their characteristics.

132. We have further supplemented this analysis with a study of jurisdictional complaints

alleging discrimination and other related complaints (for example, equal pay claims).

Our analyses of these data are set out in Chapter 7 of this report.

26

Findings of the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applicants 2013, Research Series 177, Dep’t for

Business Innovation and Skills, June 2014.

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/316704/bis-14-

708-survey-of-employment-tribunal-applications-2013.pdf

27

See: http://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentand

employeetypes/datasets/employmentbyoccupationemp04

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

27

3. Financial Objective

Introduction

133. The first objective in introducing fees was to transfer some of the cost of the ETs

from taxpayers to those who use the ETs. It remains the Government’s view that it is

reasonable for those who use the ETs to make a contribution to their cost where

they can afford to do so.

134. A scheme of fee remissions, known as Help with Fees, is available under which

those who qualify for help are entitled to have their fees waived either in part or in

full. The Impact Assessment

28

published alongside the Government Response to

consultation, estimated that the introduction of fees would generate fee income of

around £8 million to £10 million per annum in a steady state.

135. Overall, we estimated that introducing the planned fees as set out in the

Government Response would recover around a third of the cost of the tribunal

taking into account fee remissions.

Analysis

136. Table 5 of Annex D summarises the information on fee income taken from HMCTS’s

Annual Report and Accounts. In 2013/14,

29

HMCTS recovered £4.5 million in fee

income and remitted fees worth a further £0.7 million in the eight months of the year

during which fees were charged. The full cost of the Employment Tribunals for the

full year, including the costs of the Employment Appeal Tribunal, was £76.3 million.

137. In 2014/15,

30

the first full year of ET fees, £9 million was collected in fee income, a

further £3.3 million in income was remitted under the fee remission scheme. The

overall cost of the Employment Tribunals, including the Employment Appeal

Tribunal, was a little over £71 million.

138. In 2015/16, the amount collected in fee income reduced to around £8.6 million, with

a further £3.9 million remitted. The overall cost of the Employment Tribunals also

reduced to £66 million.

139. The introduction of fees required some capital investment in IT systems of around

£4.5 million. It also incurred project costs of £0.6 million, and ongoing additional

operational costs to process claims, determine applications for fee remissions and

account for income, of £0.7 million per annum. These costs are included in the

overall costs of the ETs (see Table 5 of Annex D).

28

See footnote 8.

29

See: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/

323112/hmcts-annual-report-2013-14.PDF

30

See: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/433948/hmcts-annual-report-accounts-2014-15.pdf, and I particular section 5.2.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

28

140. Our original Impact Assessment estimated that the introduction of fees would

achieve a cost recovery rate of around a third, taking into account fee remissions.

The actual recovery rate achieved has been much lower: 17% in 2014/15 and 19%

in 2015/16. The main reasons for the difference are a combination of two factors:

the fall in the volume of claims was greater than we had estimated in the Impact

Assessment but the fall in Type A claims has been greater than for Type B

claims; and

the value of fees remitted has been lower than were estimated in the Impact

Assessment.

Conclusion

141. Overall, our conclusion is that the introduction of fees has broadly met the main

financial objectives set. The level of income generated by fees has been broadly in

line with estimates, transferring a proportion of the cost from the taxpayer to users.

The cost recovery rate, which takes into account the value of fees remitted, has

however been lower than we originally estimated.

Review of the introduction of fees in the Employment Tribunals

Consultation on proposals for reform

29

4. Behavioural Objective: Encouraging alternative ways of

resolving disputes

Introduction

142. The second objective for fees in the Employment Tribunals (ETs) was to encourage

people to consider alternatives to the ETs to resolve their disputes. The Government

believes that using alternative services, such as conciliation, can be a better way of

resolving disputes because they can avoid the stress and cost often associated with

adversarial litigation.

143. The Government believed that introducing a requirement to pay a fee would give

people a financial interest in proceedings that would encourage them to give serious

consideration to alternatives, such as Acas’s conciliation service, which is provided

free of charge to those who wish to use it. Subsequently, the Government

underpinned this objective by also introducing a requirement that anyone

considering bringing an ET claim must (with some exceptions) first refer the dispute

to Acas to consider whether it would be suitable for conciliation.

144. The service, which is known as Acas’s early conciliation service, was introduced in

April 2014, and it became mandatory from May 2014.

Analysis

145. To consider how effective these policies have been in encouraging the use of

alternative dispute resolution services, we have compared the total number of

employment disputes referred to Acas or the ETs before and after the introduction of

fees. Specifically we have compared: