2

DISCLAIMER AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not necessarily reect the views of the International Organization

for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or

concerning its frontiers or boundaries.

IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benets migrants and society. As an intergovernmental

organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in the meeting of operational challenges of migration;

advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human

dignity and well-being of migrants.

AUTHOR: Regional Data Hub

PUBLISHERS: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Regional Oce for Central America, North

America and the Caribbean

Sabana Business Centre, Boulevard Ernesto Rohrmoser

San José Costa Rica

Telephone: +(506) 2212-5300

Website: www.rosanjose.iom.int

International Organization for Migration (IOM)

Regional Coordination Oce for the Caribbean - Barbados

c/o UN House Marine Gardens Hastings

Christ Church Barbados

Website: www.rosanjose.iom.int

MAPS: Sofía Arce, Data and Reporting Specialist

LAYOUT AND DESIGN: Pamela Marín

COVER PHOTO: "Leaving the camp to evacuation shelter"

© 2023 International Organization for Migration.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of

the publisher.

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................................

2

KEY BACKGROUND DATA – ALL CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES .......................

5

1. OVERVIEW .....................................................................................................................................................................

6

1.1 MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE CARIBBEAN ................................................................................................

6

1.2 Scope and objectives of the report ......................................................................................................................

7

1.3 Geographic coverage ...................................................................................................................................................

8

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS .......................................................................................................

9

2.1 Regional emigrant stocks ...........................................................................................................................................

9

2.2 Breakdown of emigrants .........................................................................................................................................

10

2.3 Migrant Flows ..............................................................................................................................................................

10

3. PROFILE OF CARIBBEAN EMIGRANTS ..................................................................................................

20

3.1. OECD ............................................................................................................................................................................

20

3.2. United States ..............................................................................................................................................................

25

4. CUBAN AND HAITIAN MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES .................................................................

25

4.1 Data on migrants and migration from Haiti and Cuba .............................................................................

25

5. REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM ELSEHWERE IN THE CARIBBEAN ........

29

6. INTRAREGIONAL MOBILITY AND MIGRATION............................................................................

30

7. RETURN MIGRATION ........................................................................................................................................

32

7.1 Exploring trends in return migration through desination-side-data sources ...................................

32

8. IMMIGRATION TO CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES ..................................................................................

34

9. VENEZUELAN MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES ......................................................................................

35

10. IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON MOBILITY AND TOURISM ..........................................................

36

10.1. Data and trends on arrivals in the region ....................................................................................................

36

11. REMITTANCES.......................................................................................................................................................

38

11.1 Remittances as a percentage of GDP ............................................................................................................

38

11.2 Absolute volume of remittances ......................................................................................................................

39

11.3 Remittances compared with other forms of capital ows. ..................................................................

40

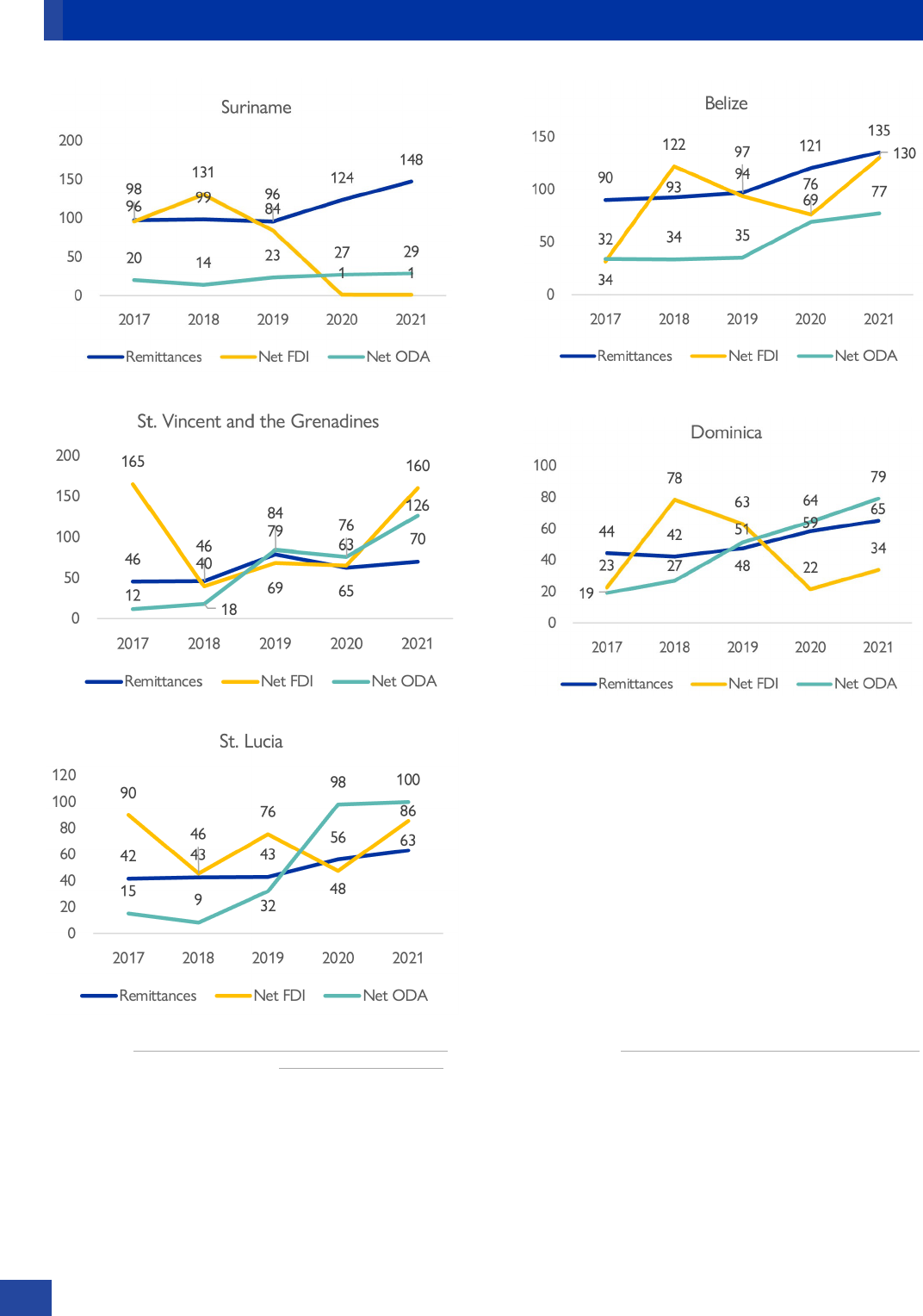

11.4 Remittance transaction costs.............................................................................................................................

42

12. NATURAL HAZARDS AND DISPLACEMENT .................................................................................

47

12.1 Key data on natural hazards and displacement in the Caribbean ......................................................

47

12.2 Risk models for natural hazards, disasters, and displacement .............................................................

48

13. SLOW-ONSET ENVIRONMENTAL PROCESSES RELATED TO CLIMATE

CHANGE, MOBILITY AND MIGRATION ....................................................................................................

62

13.1 The nexus between climate change, mobility, and migration in the Caribbean ..........................

62

13.2 Exploring sea-level rise and human mobility scenarios in the Caribbean .......................................

62

13.3 The impacts of other slow-onset processes on migration and human mobility – lessons

from sixth IPCC Assessment Report .......................................................................................................................

64

14. MISSING MIGRANTS .........................................................................................................................................

65

15. CONCLUSSIONS ..................................................................................................................................................

67

16. REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................................................

68

4

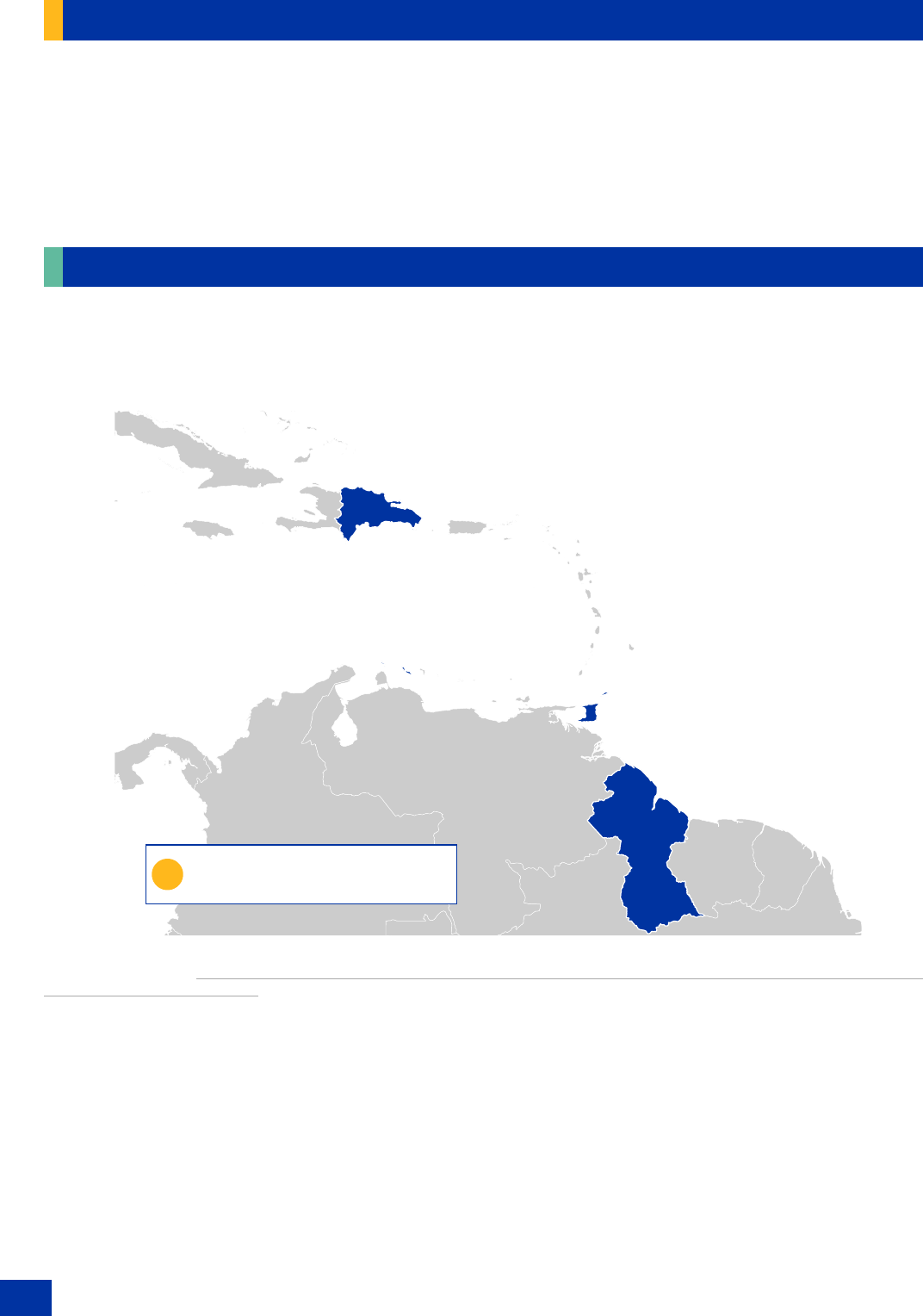

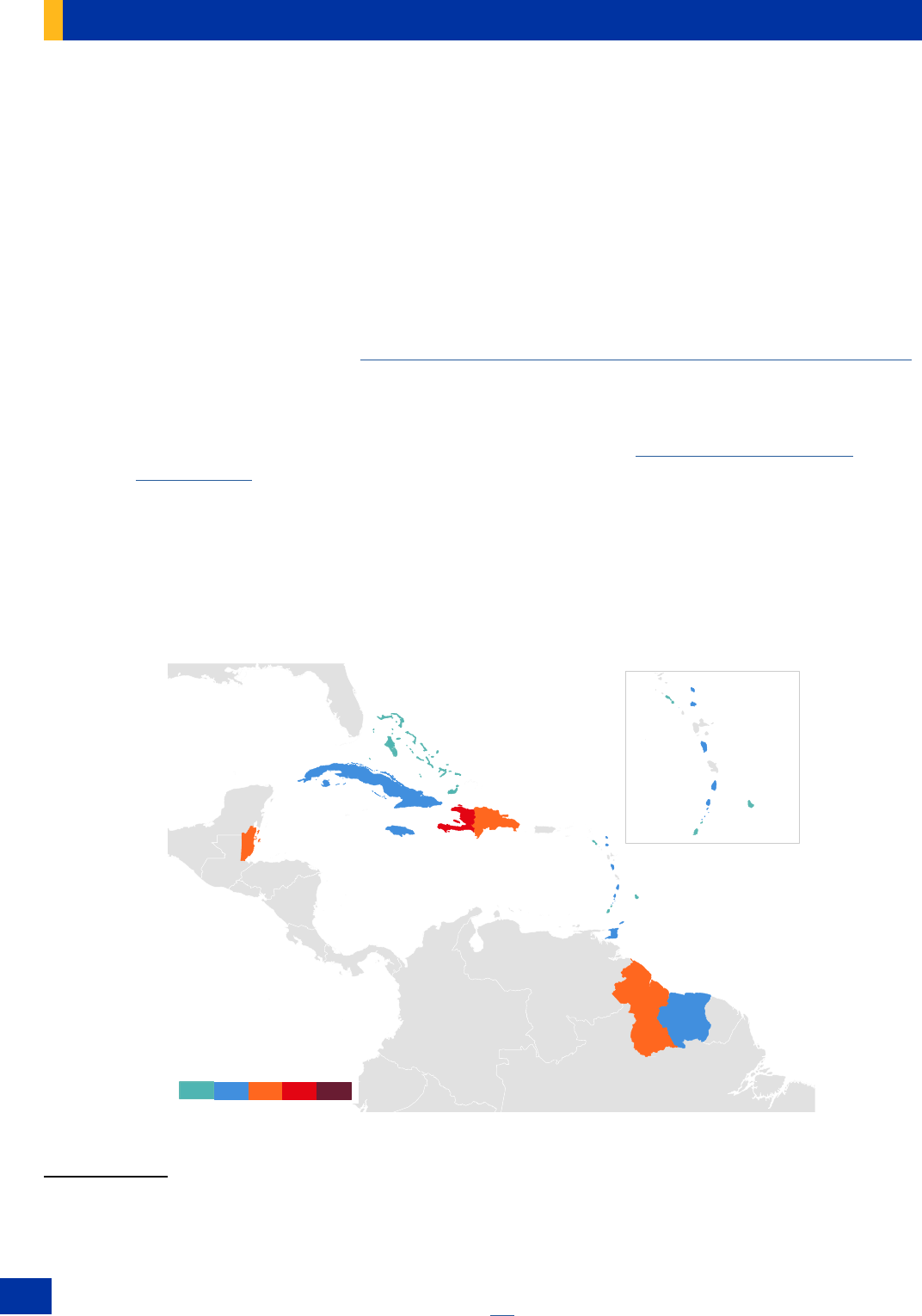

Map 1.1: Countries and territories which make up the Caribbean region in this report. ......................................8

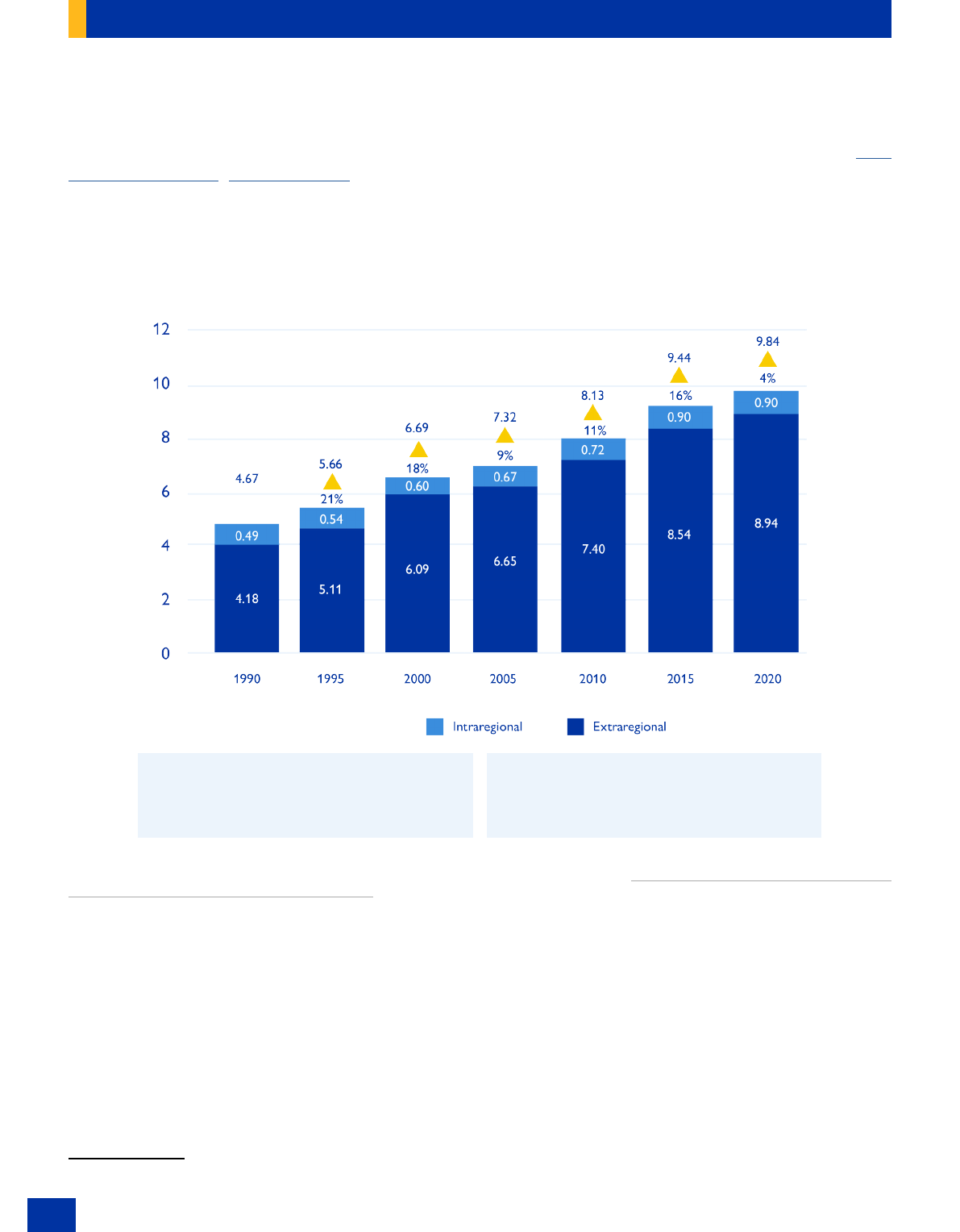

Figure 1: Stock of Caribbean nationals living abroad, and percentage

(%) change between reference years, 1990 – 2020 (millions)...............................................................................................9

Figure 2: Percentage (%) of nationals living abroad, by region

(overall) and by individual Caribbean UN Member Countries, 2020 ............................................................................. 15

Figure 3: Top destination regions of Caribbean migrants, 2020 ...................................................................................... 16

Figure 4: Sex composition of Caribbean nationals residing abroad, 2020 .................................................................. 17

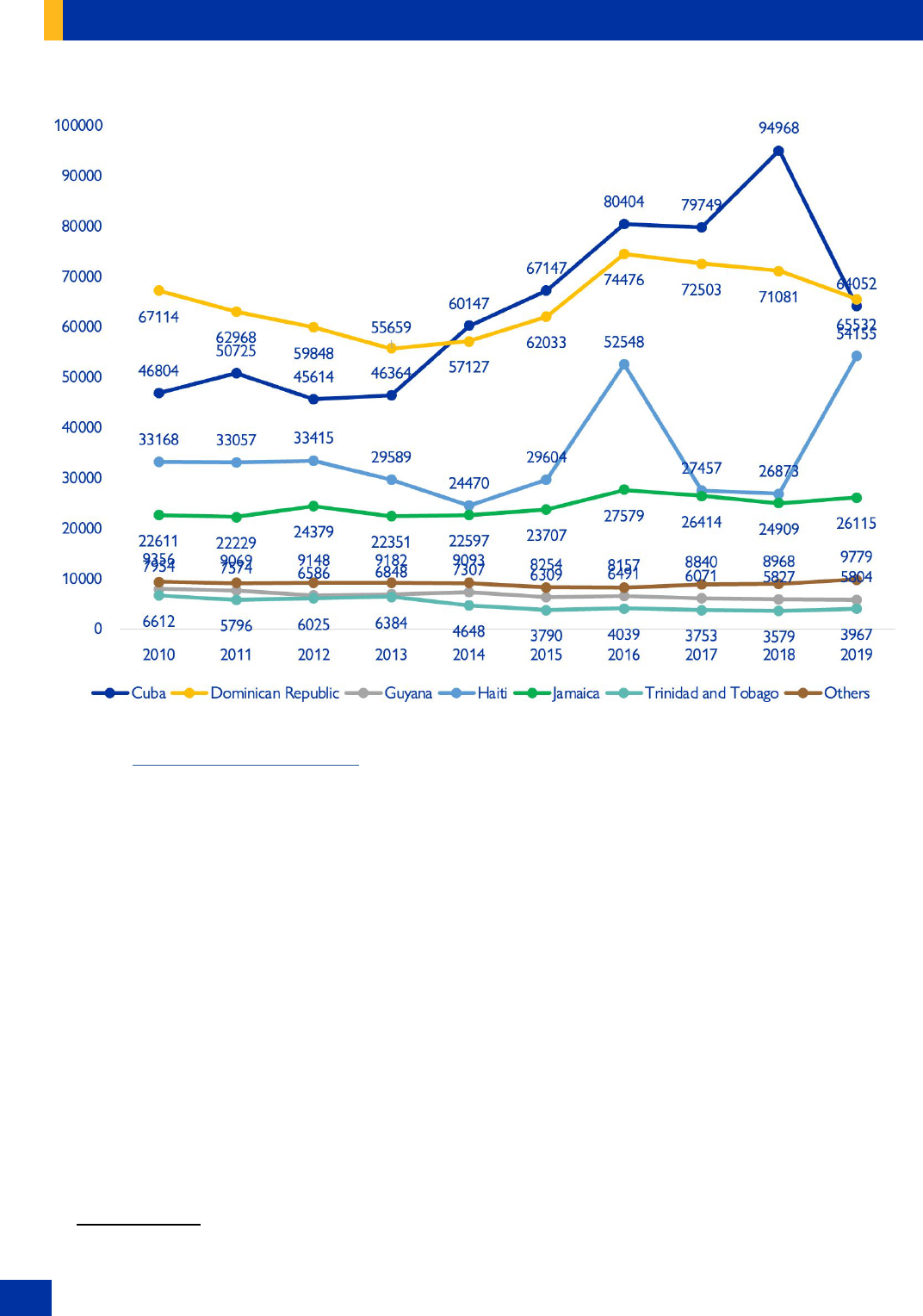

Figure 5: Inows of Caribbean nationals (by selected nationalities) into OECD Member

Countries, 2010 – 2019 ...................................................................................................................................................................... 19

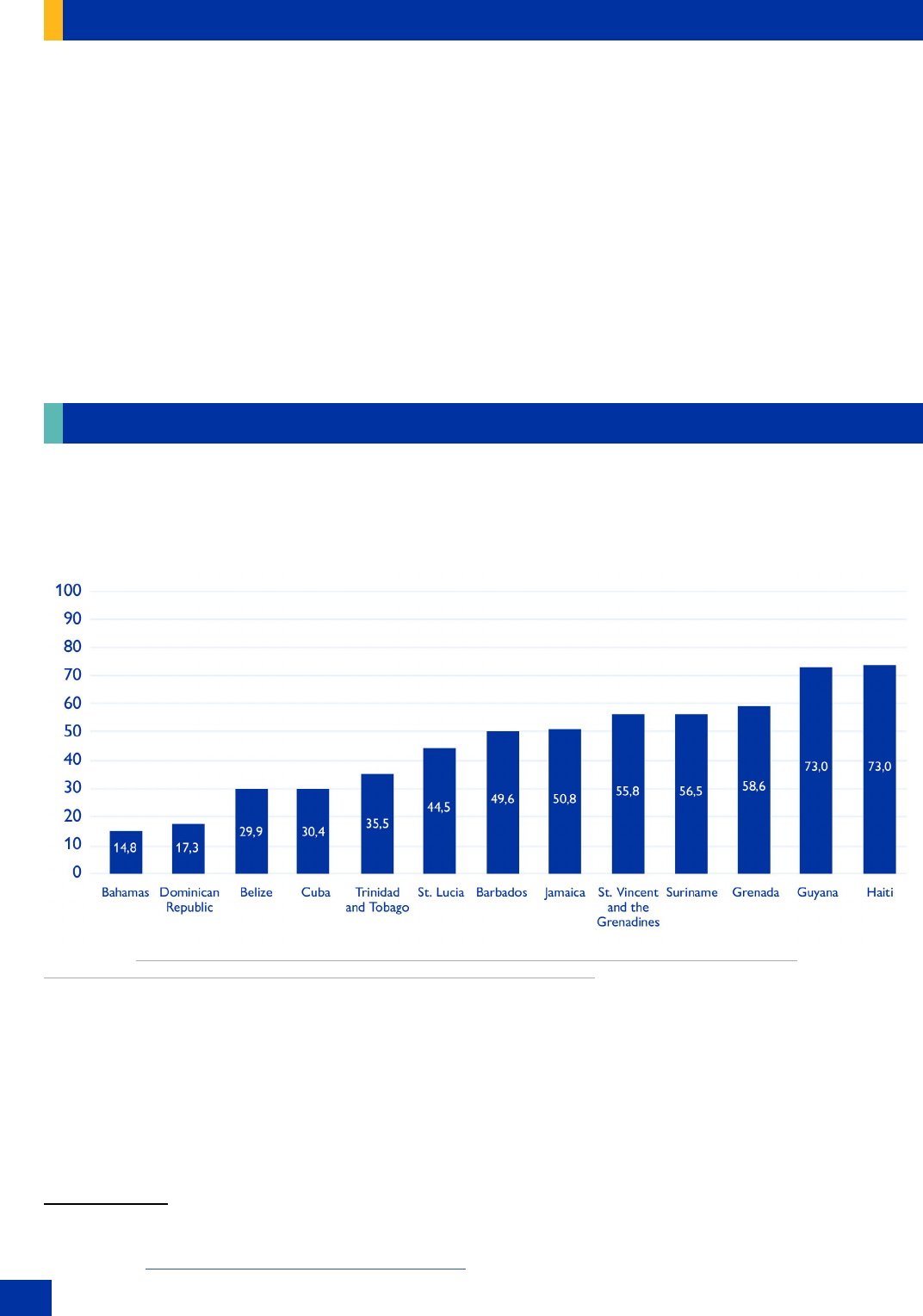

Figure 6: Highly educated population emigration rates of the highly educated population to

the OECD area, by country of birth, selected Caribbean countries of origin, as of 2015/16 ............................ 20

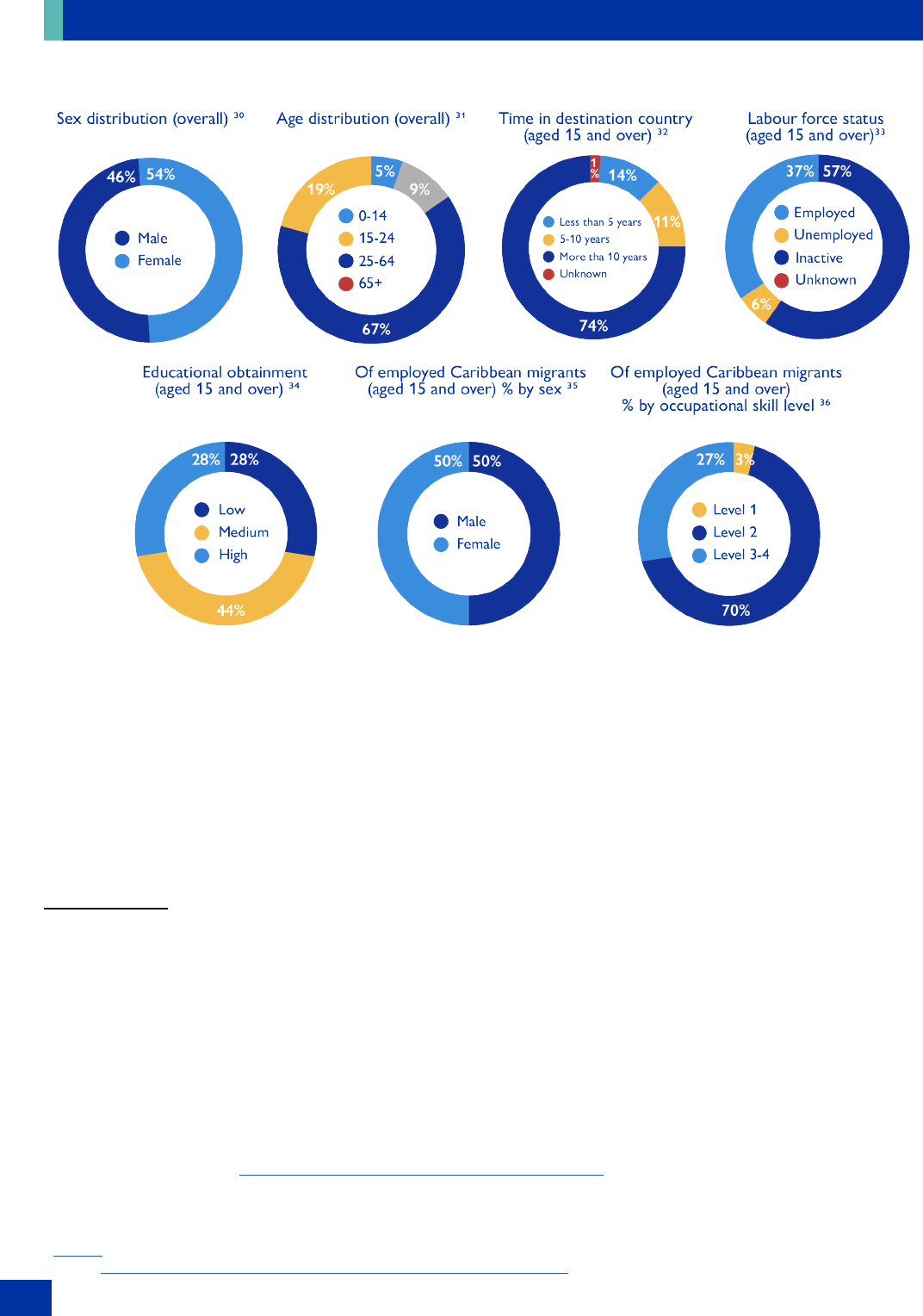

Figure 7: Key demographic and socioeconomic characteristics –

Caribbean migrants in OECD countries, as of 2015/16 ....................................................................................................... 22

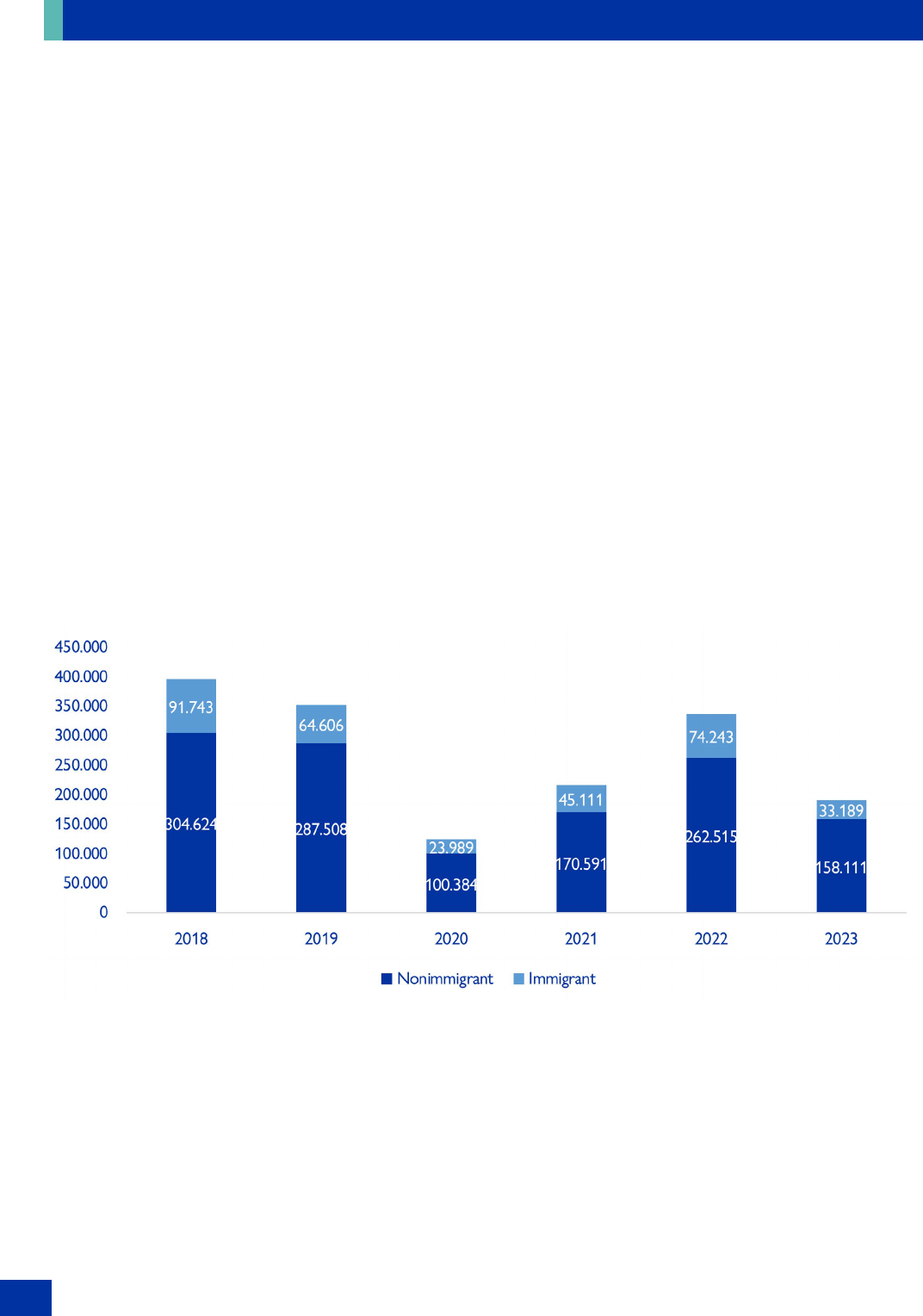

Figure 8: Nonimmigrant and immigrant visas issued to Caribbean nationals in the United

States, 2018 – May 2023 .................................................................................................................................................................... 23

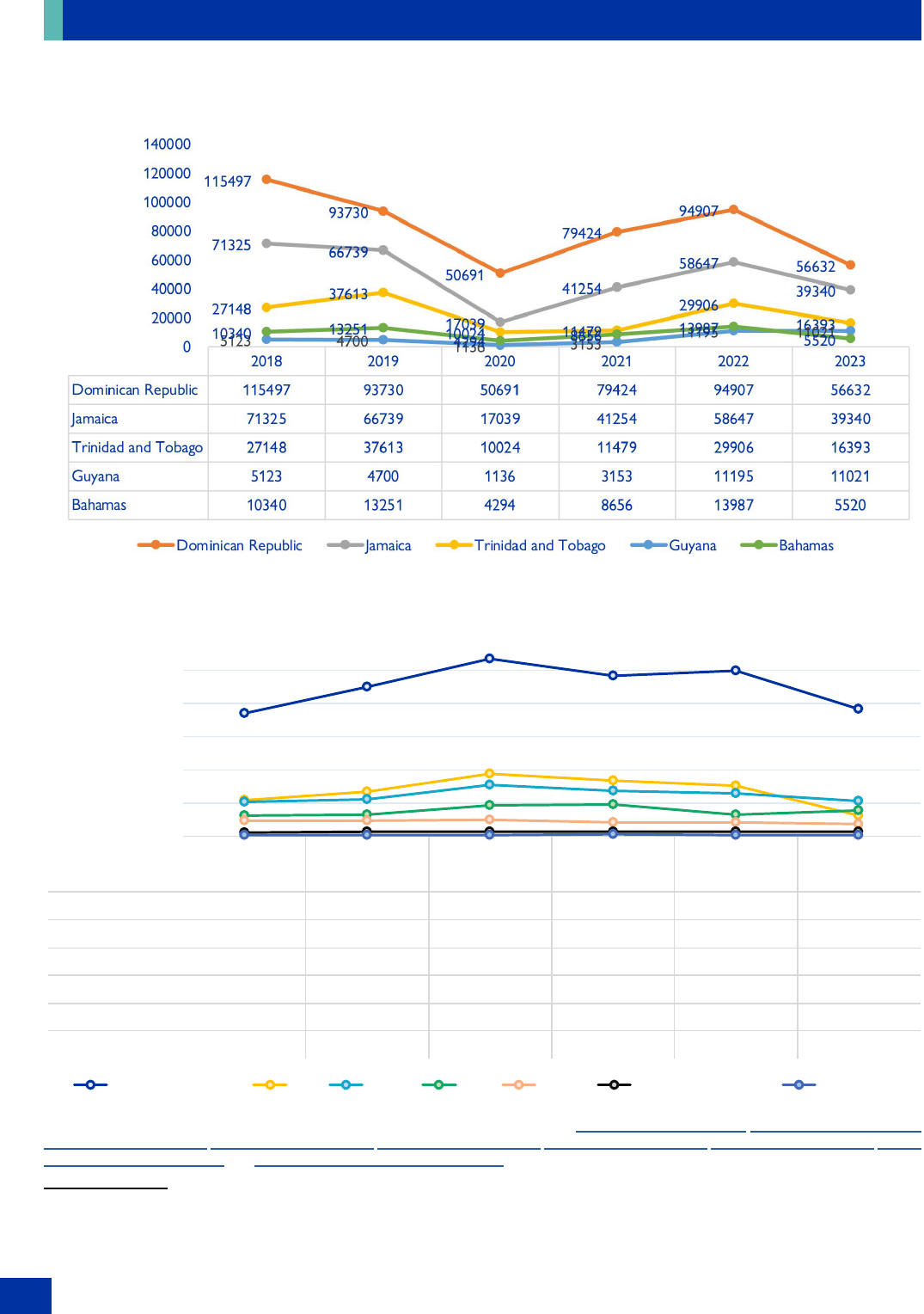

Figure 9: Nonimmigrant visas issued to Caribbean nationals in the United States, by top ve

Caribbean nationalities, 2018 – May 2023 ................................................................................................................................ 24

Figure 10: Immigrant visas issued to Caribbean nationals in the United States, by top seven

Caribbean nationalities, FY 2014 – 2019 .................................................................................................................................... 24

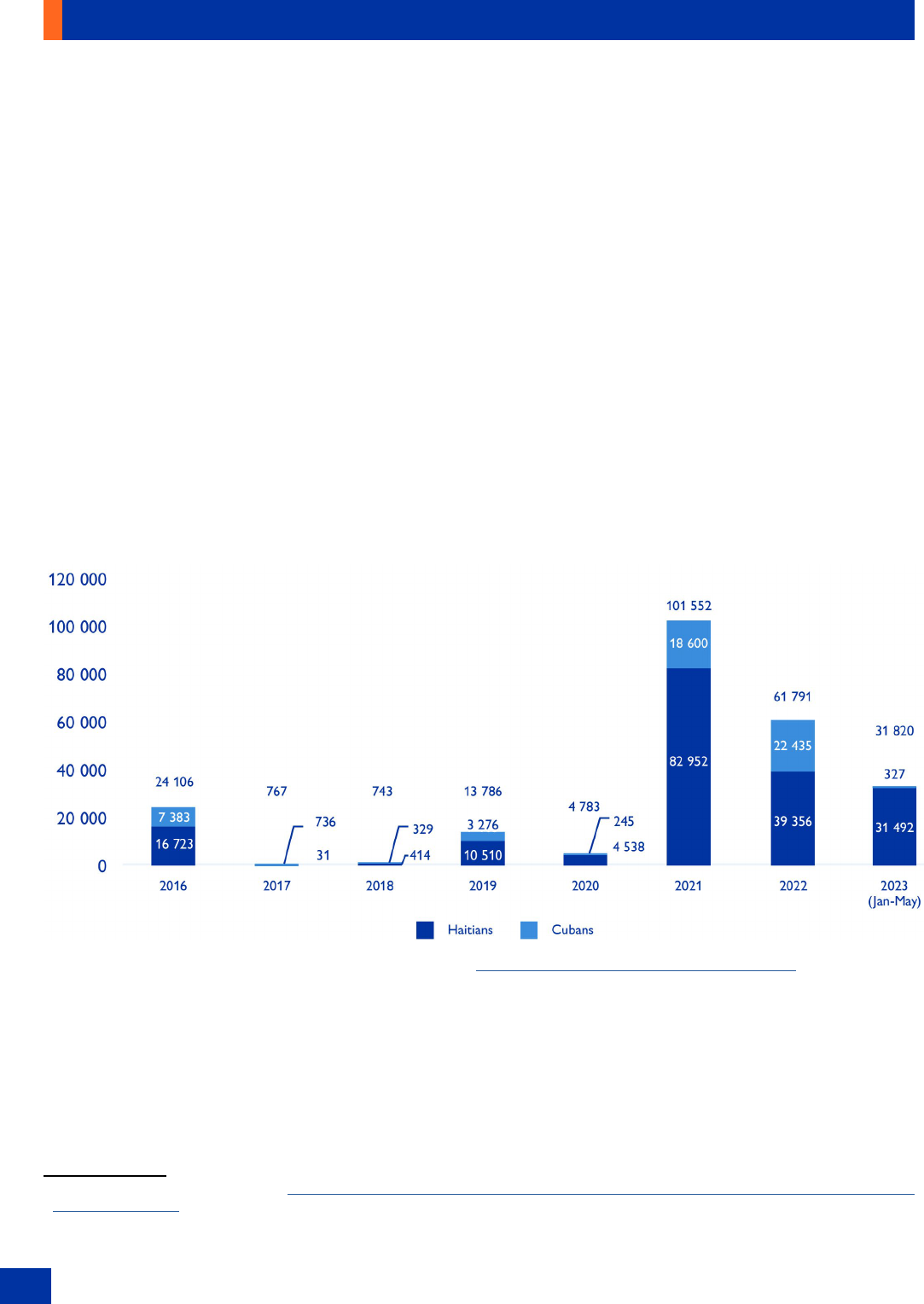

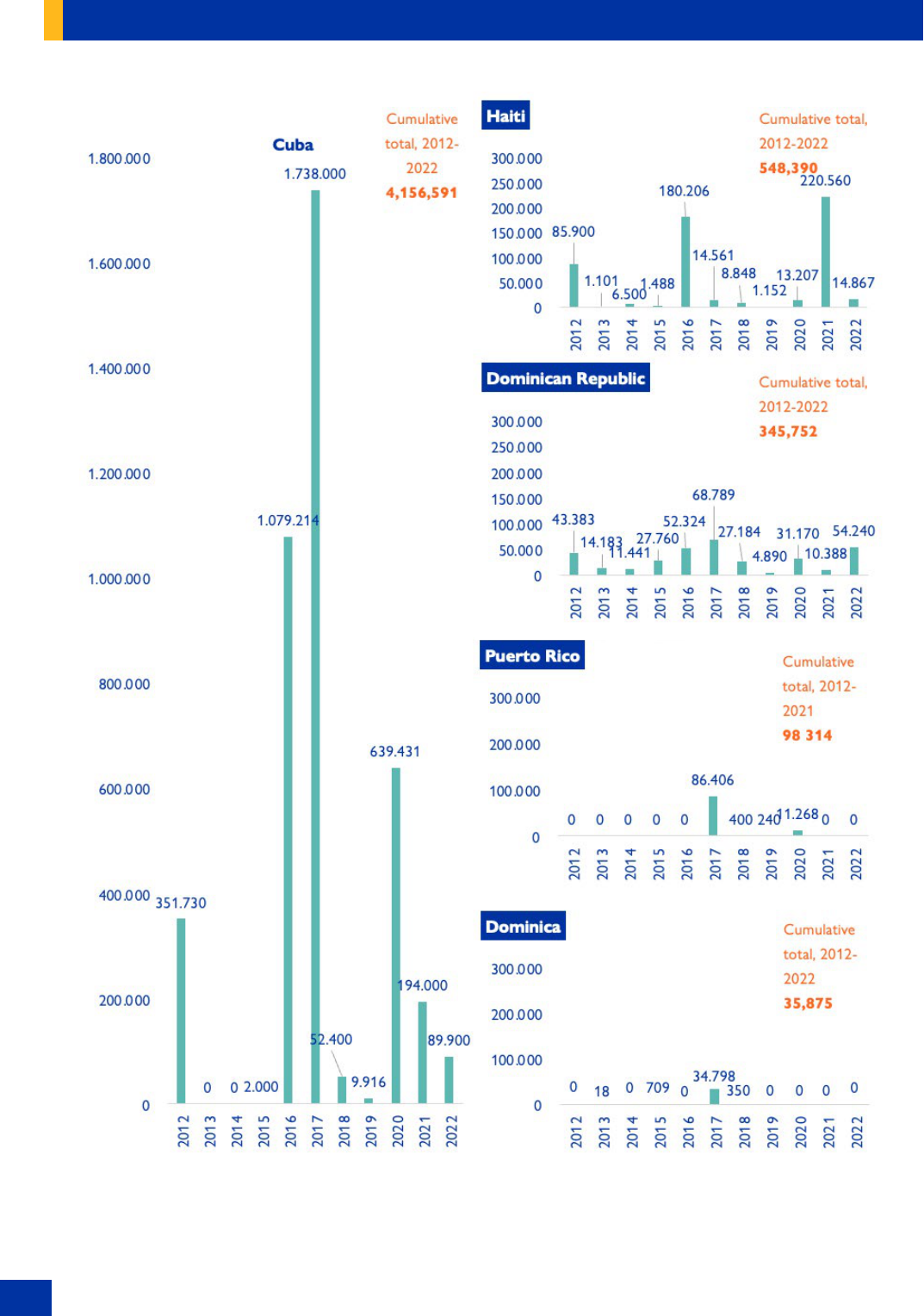

Figure 11: Cuban and Haitian migrants identied in irregular transit in the southern zone of

Panama (Darien Province), 2016 – 2023 (Jan – May). ........................................................................................................... 26

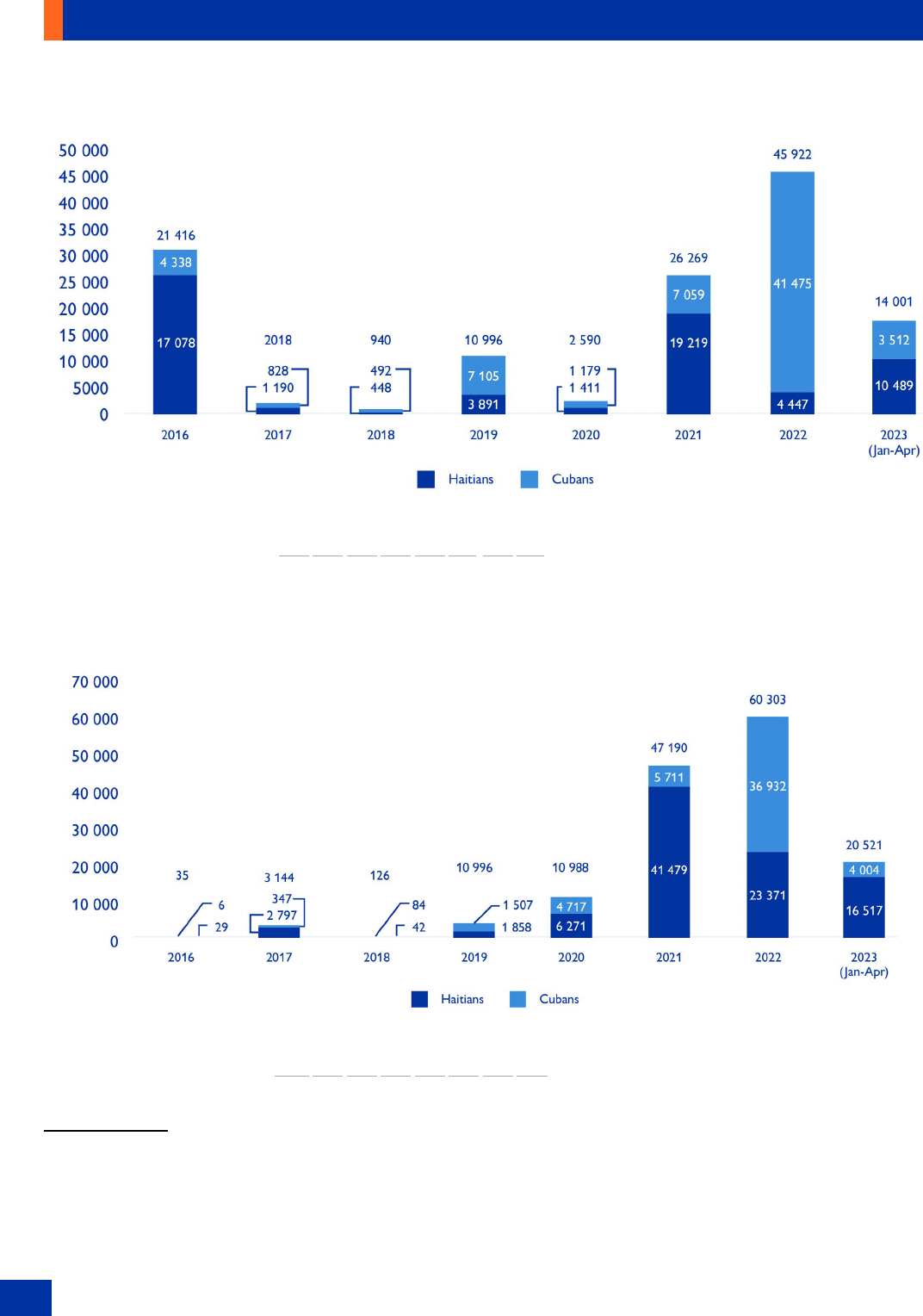

Figure 12: Cuban and Haitian migrants apprehended by Mexican immigration authorities,

2016 – 2023 (January – May) ......................................................................................................................................................... 27

Figure 13: Visitor cards for humanitarian reasons (TVRH) issued to Cuban and Haitian

migrants in Mexico, 2016-2023 (January -April)...................................................................................................................... 27

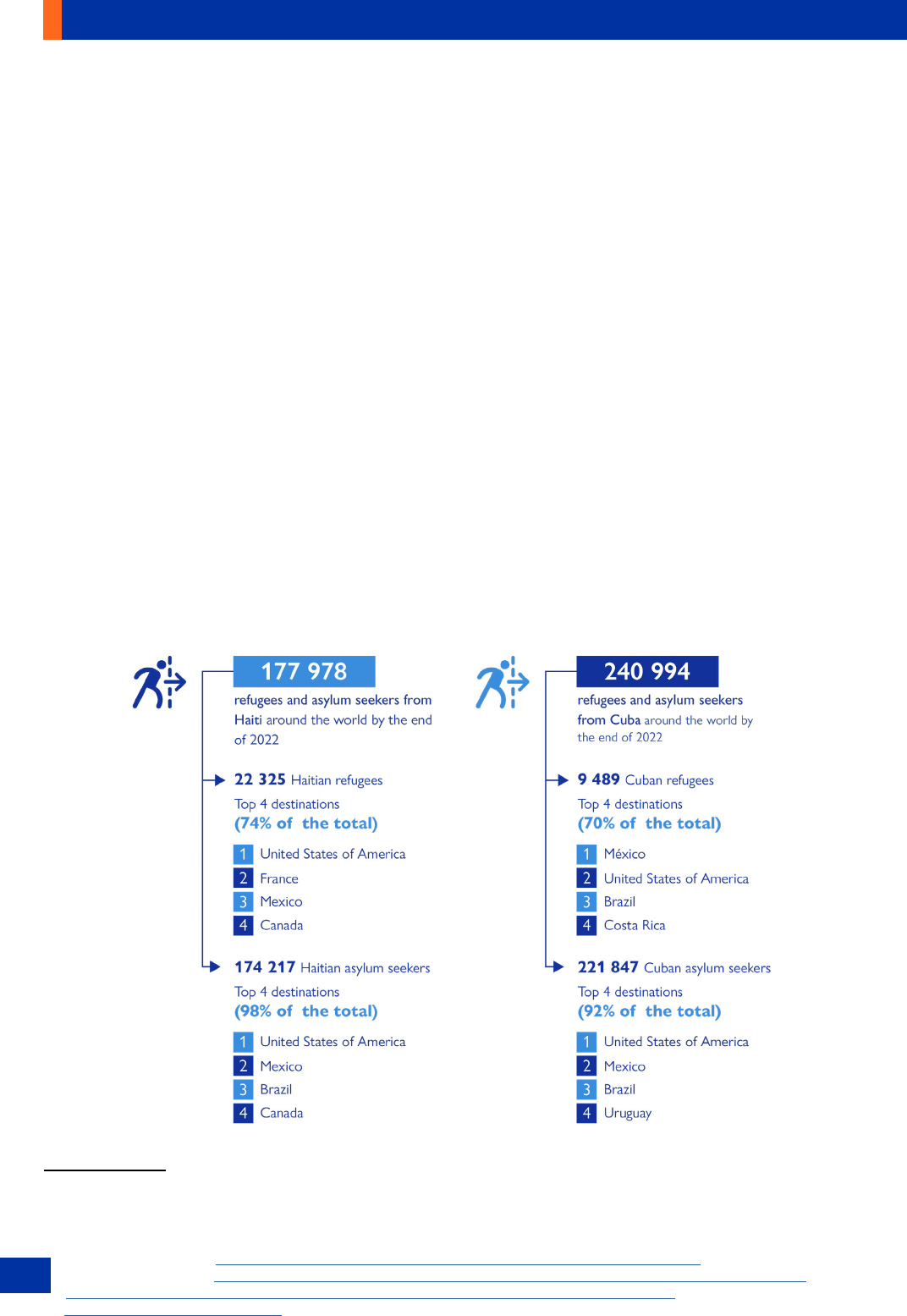

Figure 14: Cumulative global stock of refugees and asylum seekers originating from Haiti and Cuba under

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHRC) mandate as of the end of 2022 .......................... 28

Figure 15: Skills Certicates issued to CARICOM nationals from 2013-2017, by category............................... 31

Figure 16: Venezuelan migrants and refugees in the Caribbean countries as of May 2023 ................................36

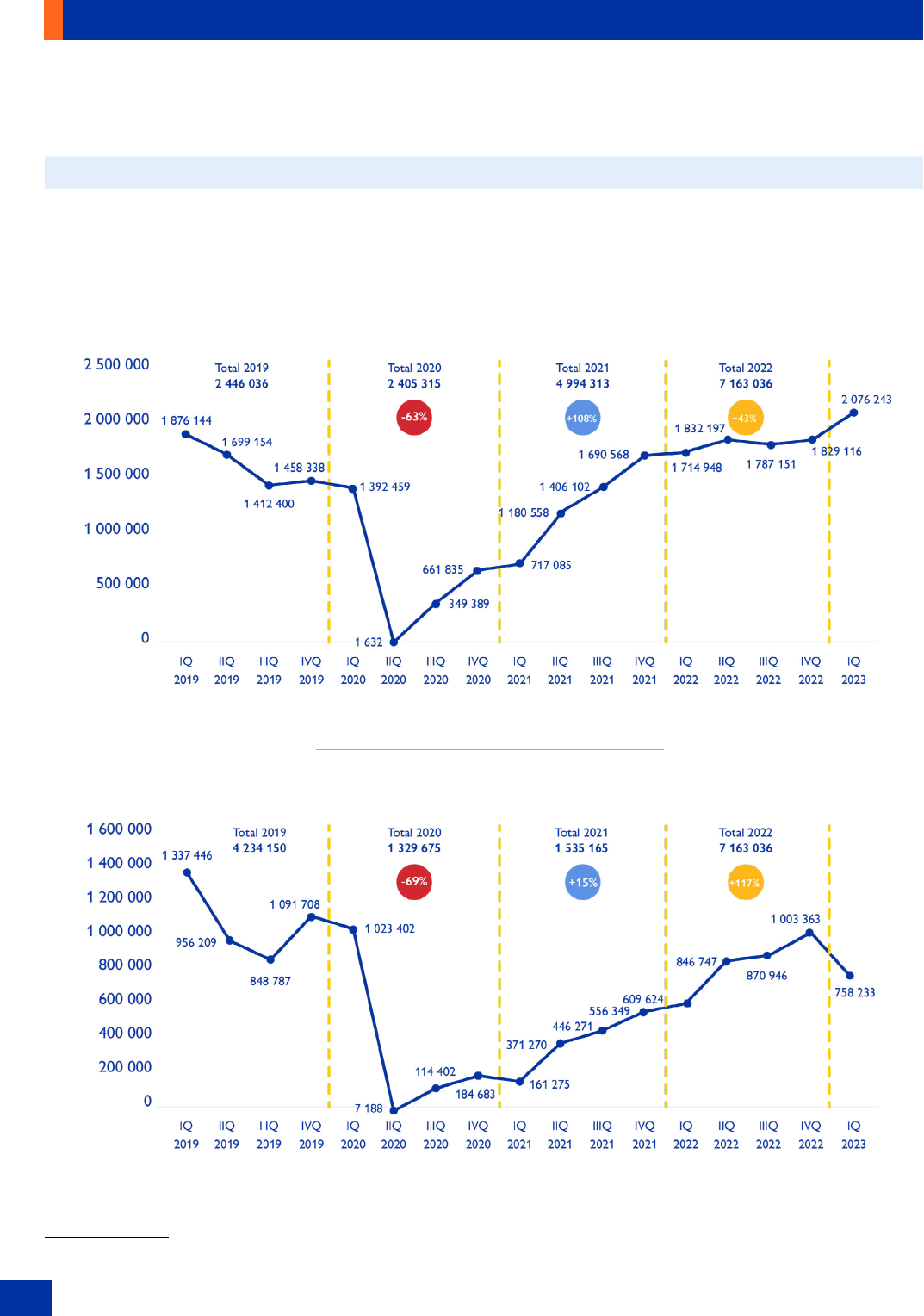

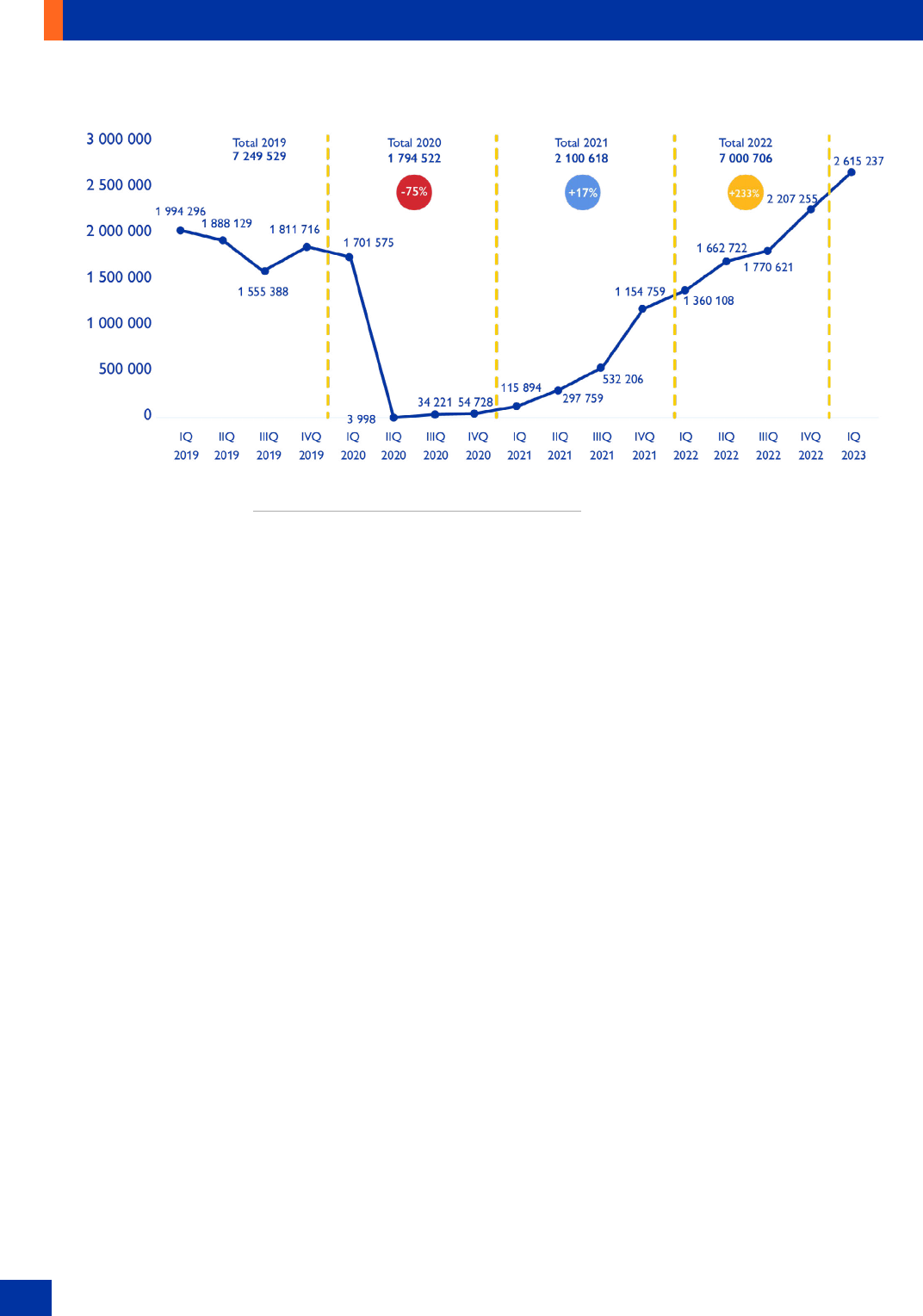

Figure 17: Quarterly entries of foreigners and/or nationals in Caribbean countries, 2019 –

2023 (rst quarter). .............................................................................................................................................................................. 36

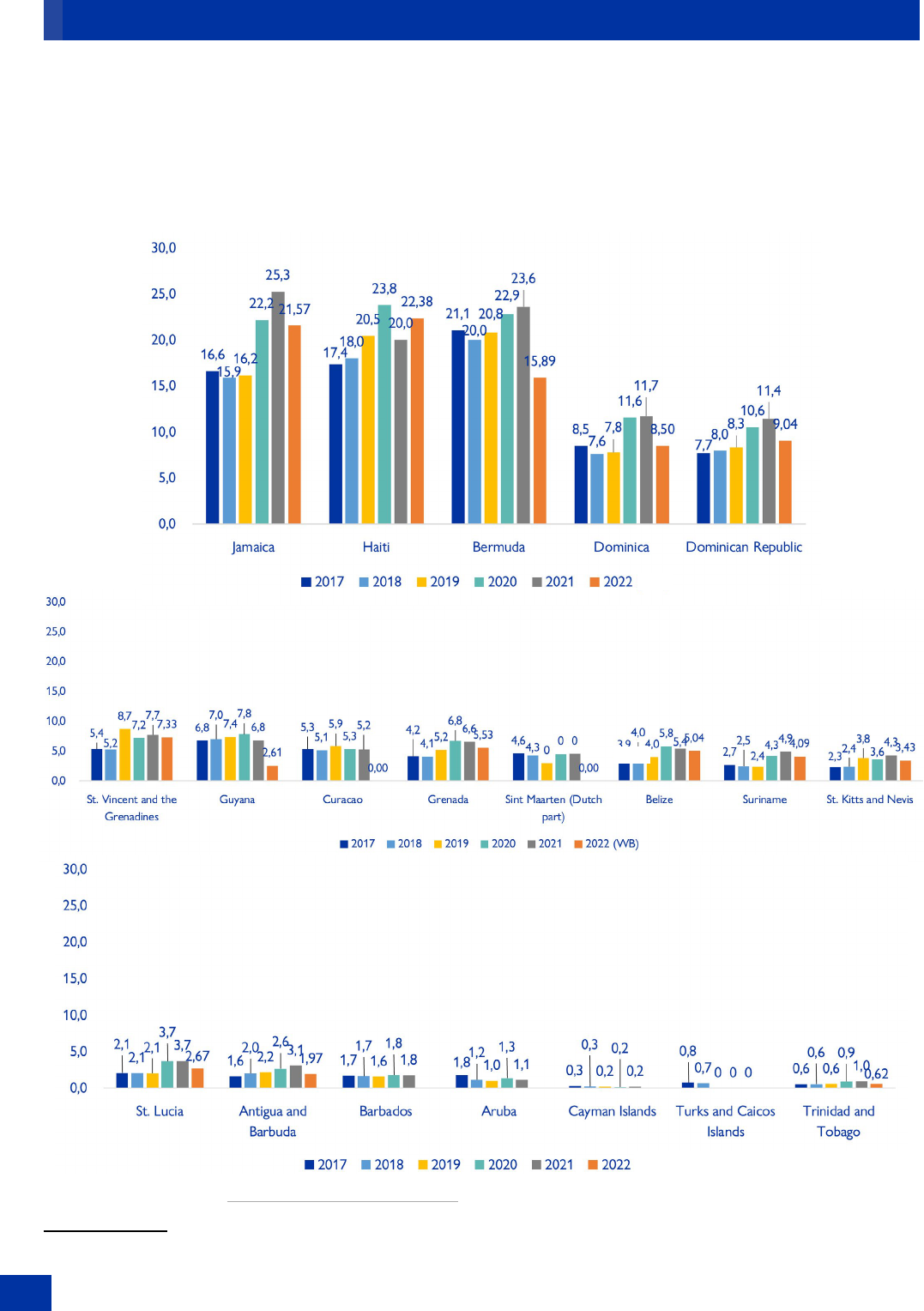

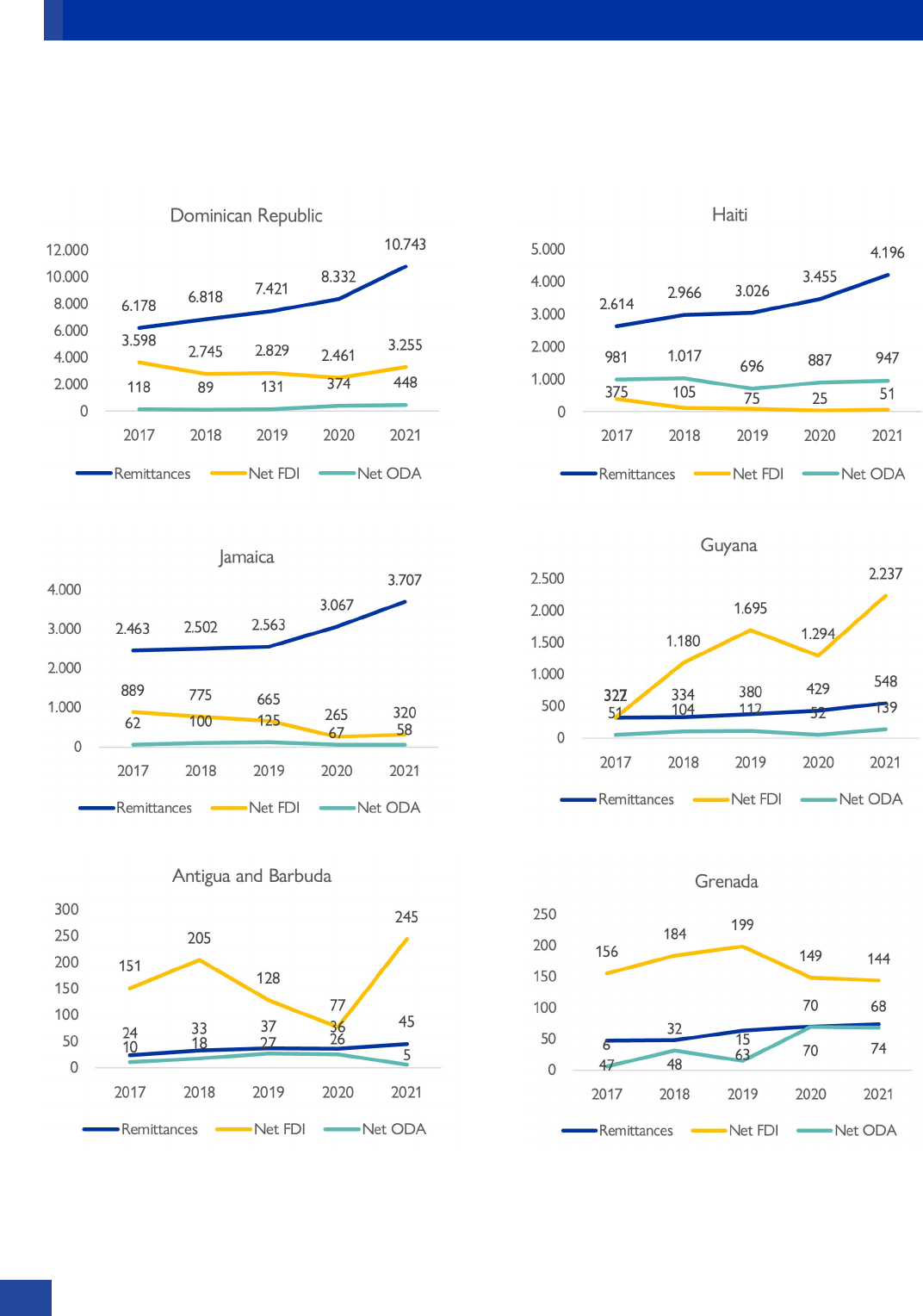

Figure 11.1: Migrant remittances received as a proportion (%) of total GDP, selected Caribbean

countries / territories, 2017-2022 .................................................................................................................................................. 39

Figure 11.2: Migrant remittances received, absolute value in current U.S. Dollar (USD)

thousands of millions, Caribbean countries / territories for which data were available,

2017-2022. ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 41

Figure 11.3: Migrant remittances received, vs. total net Ocial Development Assistance

(ODA) disbursements, vs. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) net inows (Balance of Payments,

BoP), current USD millions, selected Caribbean countries, 2017-2021. ...................................................................... 43

Figure 11.4: Average transaction cost (as % of transfer) of sending remittances to selected

countries in the Caribbean, Quarter 4 2019 – Quarter 3 2020 ...................................................................................... 46

Figure 12.1: Map of new internal displacements caused by natural hazards in the Caribbean

in 2021 by country / territory .......................................................................................................................................................... 47

Figure 12.2: Characteristics of new internal displacements caused by natural hazards in the Caribbean,

2012-2022 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 48

Figure 12.3: Map of INFORM Index for Risk Management in UN Member Countries in the

Caribbean, mid-2022 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 57

Figure 13.1: Map of one-meter sea level rise projections in the Caribbean .............................................................. 62

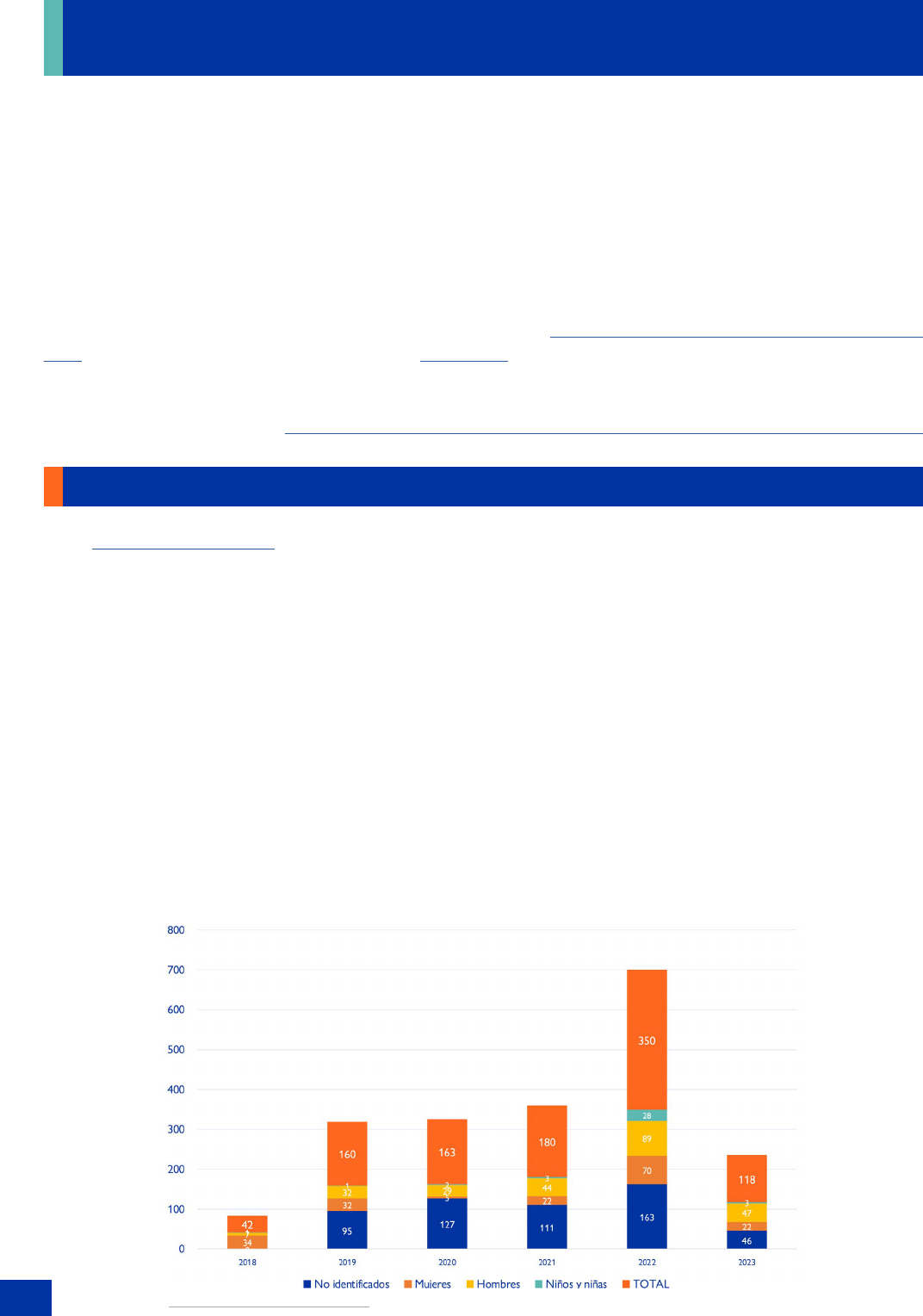

Figure 14.1: Migrant deaths and disappearances identied in the Caribbean region, 2016 – June 2023 ......65

INDEX OF FIGURES

5

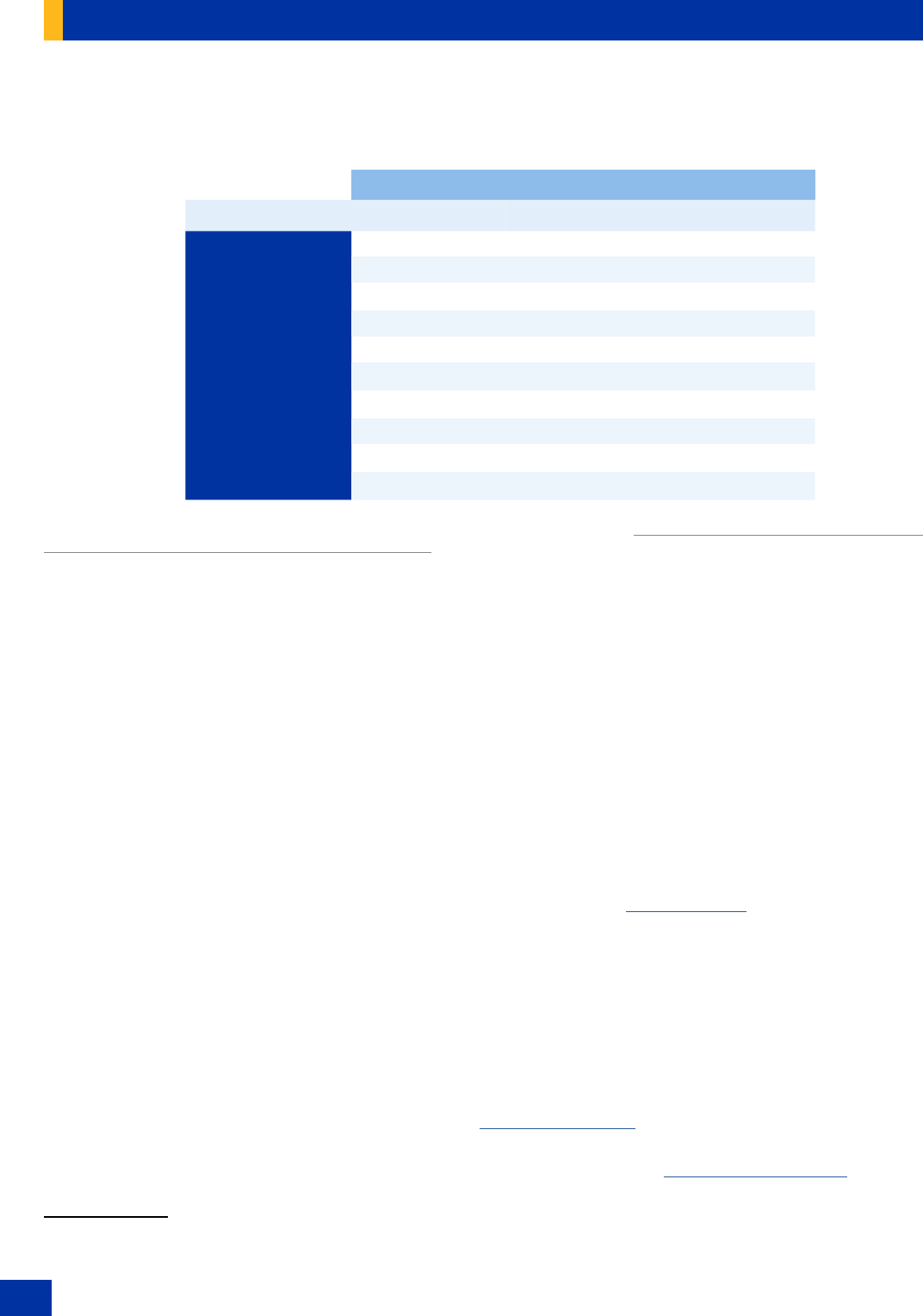

Table 1: Top 10 origin countries / territories of Caribbean nationals residing abroad in absolute terms,

and percentage (%) increase between 1990 and 2020 ......................................................................................................... 10

Table 2: Top 10 destination countries, territories or areas of Caribbean migrants, total and by gender,

2020 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 18

Table 3: Acquisition of nationality in OECD countries, by country of former nationality, selected

Caribbean nationalities, cumulative totals, 2010 – 2020 ...................................................................................................... 21

Table 4: Cuban and Haitian emigrants, total and by top 5 countries / territories of destination, 2020,

Haitians-Cubans ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 25

Table 5: Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Haitian migrants in the United States as of May 2023 ...... 29

Table 6: Cumulative global stock of refugees and asylum seekers originating from selected other

Caribbean origin countries reported by UNHCR as of end of 2020 .............................................................................29

Table 7: Flows of CARICOM nationals under the “Facilitation of Travel” framework, principal origin and

destination countries, based on cumulative totals of annual free movement data, 2013 - 2017 ....................... 31

Table 8: Returns of persons from the U.S. by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), by country

of citizenship, scal years (FY) 2014 – FY 2019, selected Caribbean nationalities ................................................... 32

Table 9: Caribbean nationals returned by Mexican authorities, by country of citizenship, 2015 - 2020 .......32

Table 10: Caribbean nationals returned from the European Union (E.U.) and the United Kingdom

(U.K.) after being issued an order to leave, by country of citizenship, 2014-2019 ................................................... 33

Table 11: Top 10 destination countries / territories of immigrants in the Caribbean region, 2020 ................34

Table 12: Monthly international tourist arrivals in 2020, Caribbean, % change over 2019 ................................. 36

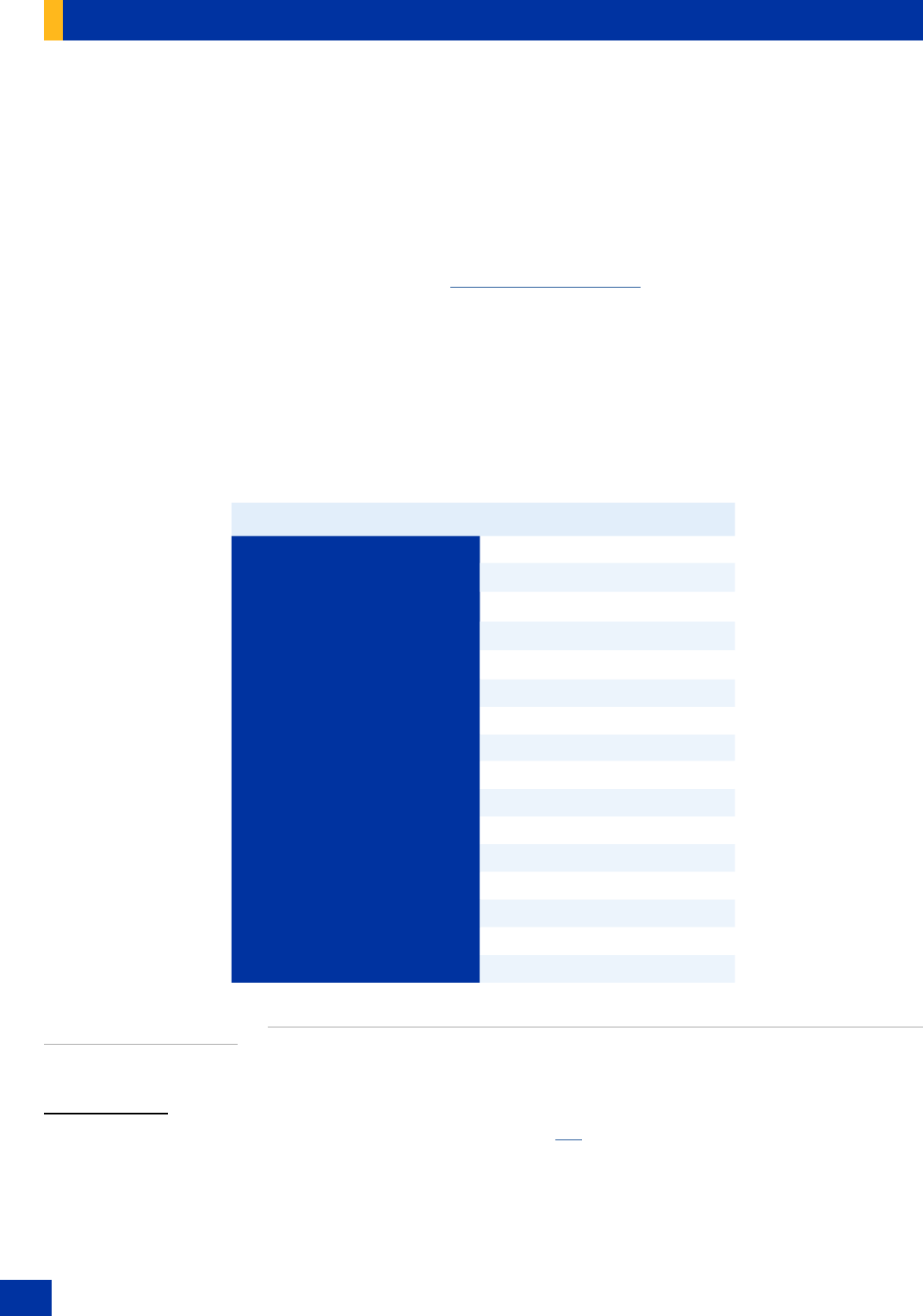

Table 12.1: Largest percentage (%) of the entire population displaced due to natural hazards in any

given year between 2012-2022, selected Caribbean countries and territories. ........................................................ 53

Table 12.2: Stock of internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to natural hazards estimated in the

Caribbean as of the end of 2022. ................................................................................................................................................... 54

Table 12.3: Average expected number of new displacements per year due to sudden-onset hazards,

selected Caribbean countries/territories. .................................................................................................................................... 55

Table 12.4: Climate Risk Index score and global ranking (out of 180) for selected Caribbean countries

and territories for the period 2000-2019 ...................................................................................................................................56

Table 12.5: INFORM Index for Risk Management in UN Member Countries in the Caribbean by

country, mid 2023. ................................................................................................................................................................................ 58

Table 13.1: Predicted impacts of a one-meter sea-level-rise in CARICOM Member States, by site /

category and percentage (%) at-risk* ........................................................................................................................................... 63

INDEX OF TABLES

1

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

(ACS) American Community Survey

CMC Caribbean Migration Consultations

CARICOM Caribbean Community

CBP United States Customs and

Border Protection

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

CReSIS Center for Remote Sensing

of Ice Sheets

CSME Caribbean Single Market and Economy

CTO Caribbean Tourism Organization

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DIOC Database on Immigrants in

OECD Countries

ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin

America and the Caribbean

ECUE Eastern Caribbean Economic Union

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FY Fiscal year

GCM Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and

Regular Migration

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GMDAC Global Migration Data Analysis Centre

GNI Gross National Income

HDI Human Development Index

IDMC Internal Displacement

Monitoring Centre

IDP Internally Displaced Person

ILO International Labour Organization

ISCO International Standard Classication

of Occupations

IMF International Monetary Fund

INFORM Index For Risk Management

IOM International Organization for Migration

ICE Immigration and Customs Enforcement

IRCC Immigration, Refugees and

Citizenship Canada

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change

LAC Latin America and Caribbean

LDC Least Developed Country

LPR Lawful permanent residence

MMP Missing Migrants Project

MPI The Migration Policy Institute

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NTMI Northern Triangle Migration

Information Management Initiative

ODA Ocial Development Assistance

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development

OECS Organization of Eastern

Caribbean States

R4V Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for

Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela

RMDU Regional Migration Data Unit, IOM

SDG Sustainable Development Goals

SIDS Small Island Development States

SLR Sea-level rise

TPS Temporary Protected Status

UASC Unaccompanied and separated children

UPMRIP Unidad de Política Migratoria,

Registro e Identidad de Personas,

Secretaría de Gobernación, México

UN United Nations

UNDESA United Nations Department of

Economic and Social Aairs

UNDP

United Nations

Development Programme

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner

for Refugees

UNSD United Nations Statistics Division

US United States

USCB United States Census Bureau

USCBP United States Customs and

Border Protection

USCIS United States Citizenship and

Immigration Services

USCRS United States Congressional

Research Service

USDHS United States Department of

Homeland Security

USDOS United States Department of State

USD United States dollar

WTTC World Travel and tourism Council

2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

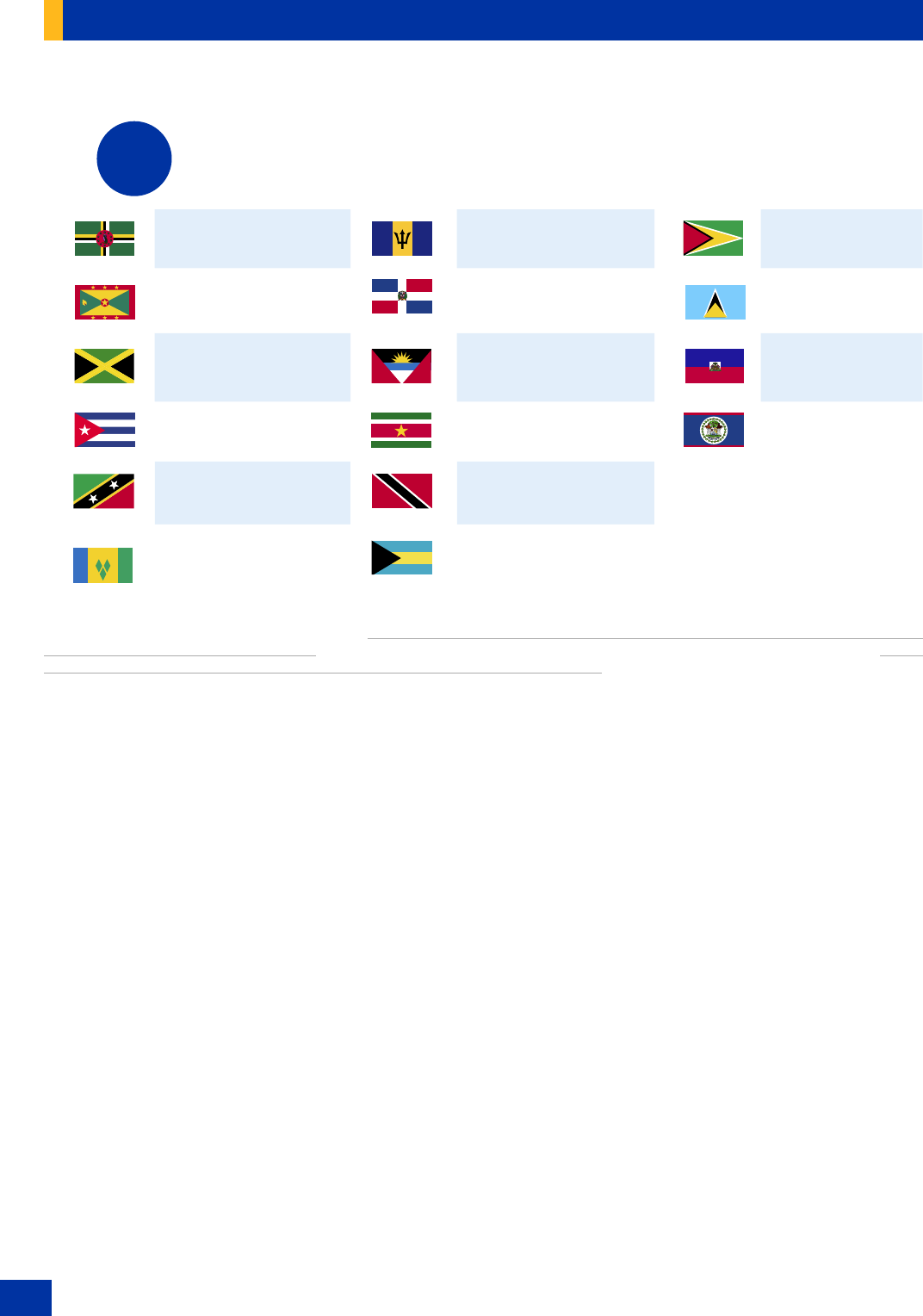

Comprised of a total of 29 countries and territories,

3

the Caribbean is an immensely diverse region of States

with populations ranging from just tens of thousands of people to those with more than 10 million. Between these countries

and territories are a range of income levels, development outcomes, language proles, ethnic groups, economic

structures and political systems. Despite this diversity, the region is interconnected through common historical ties,

while also sharing a number of shared challenges and opportunities. Twenty-ve (25) of the 29 countries and territories

in the Caribbean are designated as Small Island Developing States (SIDS) – a distinct group of United Nations and Non-

United Nations Members/Associate Members that face “unique social, economic and environmental vulnerabilities”

(United Nations, n.d.a). These vulnerabilities include, amongst others, small sizes, remoteness, climate change impacts,

biodiversity loss, dependence on external markets, high costs and narrow resource bases which together can hinder

broader socioeconomic development (ibid.).

Existing research shows that the above realities, as well as colonial ties and other historic and present push- and pull-

factors, have had a signicant impact on shaping migration trajectories in the Caribbean (ILO, 2014; Williams et al.,

2013; Cassin et al., 2022; IOM, 2020a; IOM, 2017a). Migration often serves as an important adaptation strategy for

millions of people in the region while also carrying an immense potential for regional development. Migration in the

Caribbean can also bring challenges, both due to the loss of specialized human capital (often known as “brain drain”),

and to the obstacles that arise in assisting and ensuring access to temporary and durable solutions for diverse ows of

vulnerable migrants, refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and other populations moving into, within and out

of the region.

In the area of migration, three key United Nations Programs of Action — the Barbados Programme of Action (1994)

(United Nations, n.d.a.), the Mauritius Strategy (2005) (United Nations, n.d.b.) and the SIDS Accelerated Modalities

of Action Pathway (also known as SAMOA Pathway, 2014) (United Nations, 2019) — highlight the vulnerability of

SIDS to external shocks and recognize the role of migration and migrants in the development of their communities through

nancial remittances, as well as the transfer of skills and knowledge. Recently, a number of Caribbean countries, alongside

other countries in the Americas, signed the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, reiterating the

will to “strengthen national, regional and hemispheric eorts to create conditions for safe, orderly, humane and regular

migration and to strengthen frameworks for international protection and cooperation” (The White House, 2022).

Many Caribbean countries also made pledges related to advancing the implementation of the Global Compact on

Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) during the International Migration Review Forum in 2022. While there

is political will to address the myriad challenges that migration poses in the region and to maximize the benets that

migration and migrants can bring to origin, transit and destination societies, there is a persistent lack of information

and data on migration trends or comprehensive reports that can be used to inform evidence-based policymaking

and programming.

Within this context, and in line with the GCM (particularly its objectives 1, 3 and 17 on data and information), and the

2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (particularly Objective 10.7 on orderly, safe, regular and responsible

migration and mobility of people, and Target 17.18 on disaggregation of data by characteristics including migration

status), the International Organization for Migration (IOM)’s Regional Oce for Central America, North America

and the Caribbean in San José, Costa Rica, presents this data report in order to highlight several key historical

and recent developments and trends in mobility and migration in the Caribbean region. The report focuses on ocial

statistics published by international agencies as well as records published and maintained by governments. While the

depth of migration dynamics across the entire region is far too complex to understand in a single report, this p

ublication

serves as an important starting point for technocrats, policymakers, researchers, practitioners and other actors across

governments, United Nations agencies, civil society, and academia to better understand complex phenomena of

migration and mobility in the Caribbean region, in combination with other national and regional resources.

3 For the purposes of this report, the Caribbean refers to all countries/territories under the UN Statistics Division (UNSD) regional grouping as well as Belize,

Guyana and Suriname. See Map A for further information.

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Caribbean is a region of emigration. Nearly one-fth of the region’s nationals lived outside of their countries / territories

of origin as of 2020, among them a signicant number of women (UNDESA, 2020, 2021a). In proportional terms,

10 of the top 20 countries of emigration in the world in 2019 (in countries where the combined population

of residents and emigrants residing abroad exceeded 100,000) were located in the Caribbean (IOM, 2019b). Cuban

and Haitian nationals constituted most of all refugees and asylum seekers originating from the Caribbean by the end

of 2022. These two nationalities have also been the most frequently detected among Caribbean migrants travelling

irregularly through key transit points in the Americas in recent years, underpinning the precarious and vulnerable

journeys that Cuban and Haitian migrants often embark on to seek better lives abroad.

Return migration is a prominent trend in the Caribbean, including of individuals who were removed involuntarily

by authorities in key destination and transit countries; young, economically active migrants returning

voluntarily to the region to work; older retirees returning voluntarily who had originally left the Caribbean mainly

in the 1950s and 60s; and family units, often returning to the region in order to aord private education and other

benets for their children (IOM, 2017a; Fraser and Uche, 2010; Reynolds, 2008). Administrative data available from

key countries of destination would indicate that tens of thousands of Caribbean migrants are removed or involuntary/

voluntarily returned by the United States, Mexico, European Union, and United Kingdom each year, with returns/

removals continuing in notable quantities during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

While the Caribbean region is mainly characterized by emigration, there is also a sizable population of immigrants

in the region – reaching 1.63 million as of 2020 (UNDESA, 2021a). The region’s immigrant population was relatively evenly-

distributed between immigrants originating from within and outside of the Caribbean. The top three destination countries/

territories in 2020 were the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Guadeloupe while the top three origin countries were

Haiti, the United States and the Dominican Republic (ibid.). Migrants from the United States included retirees as well as

second-generation children born of Caribbean parents in the United States who subsequently returned to the region.

In recent years, the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean have been facing one of the largest exoduses

of refugees and migrants in the history of the region. Through May 2023 more than 7.3 million refugees and

migrants from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela resided outside of their home country, an estimated 6.1 million

of whom were residing in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (UNHCR and IOM, 2022b). While

only a small proportion of these have arrived in the Caribbean, Venezuelan refugees and migrants constitute a

measurable proportion of the total population in some Caribbean small island States, representing a challenge to reception

and integration capacities.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, the Caribbean region is the most reliant in the world on travel

and tourism (in terms of proportion of GDP) (WTTC, 2022). The sector’s contribution to GDP reached 14 per cent

for the region and constituted 15 per cent of all jobs in 2019 (ibid.). However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic

led to signicant reductions in travel and mobility in the Caribbean and contributed to a nine per

cent decrease in

GDP in 2020 compared with 2019, as well as the loss of millions of jobs (ibid.). Changes in mobility from March 2020

onward are evident in the decreases in arrivals registered at ocial points of entry in selected countries and territories

of the region until 2021.

Aside from the fall-out generated on travel and tourism sectors, the pandemic also had a strong impact on

migrants themselves, as many became stranded and were unable to return home or reach their nal intended

destination (IOM, 2020c; Reuters, 2021). In light of mobility restrictions, those migrants who did choose to move were

often forced to embark on more dangerous or circuitous routes with added COVID-19 health risks (Collins, 2021;

IOM, 2021c). Migrants living in the region faced interruptions to education, job losses, lack of access to health care and

other services and rising incidents of racism and xenophobia, amongst other challenges (USAID and UNICEF, 2020;

IOM, 2020d; Bolivar Duerto, 2021; UNHCR and IOM, 2021).

4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Remittances are by far the most important source of external nancing for the Caribbean, far outnumbering

foreign direct investment (FDI) and ocial development assistance (ODA). The region has seen an increase in

absolute remittance inows year over year since 2013 (CEMLA, 2021). Remittances represent a considerable proportion

of GDP in several countries and territories and often form a fundamental support and insurance mechanism for

families and communities back home. While the COVID-19 pandemic generated concerns, both regionally and

globally, regarding the capacities of migrants to send remittances home, remittances to the Caribbean increased

18.2 per cent in 2020 compared with levels seen in 2019, a constant trend until 2021, in 2022 the economic recovery

has caused remittances to slightly lower their participation in comparison with the other income of the GDP in the

Caribbean countries or territories (ibid.).

Each year, in addition to signicant eects on economies, livelihoods, habitats, food security systems, key infrastructure

and other fundamental sectors, thousands of people are displaced due to the impact of rapid-onset natural hazards

in the Caribbean. In per capita terms, many Caribbean SIDS are amongst the most vulnerable countries/territories

in the world to disaster-related displacement in the context of rapid-onset natural hazards (Lemay, 2016.). There is

also broad consensus that extreme weather events such as tropical storms, oods, droughts and other phenomena

which occur in the region will likely increase in frequency and intensity in the coming decades (ibid.).

While data on sudden-onset disasters (notably, hurricanes) and their impact on human mobility in the Caribbean are

more widely available, displacement and migration related to other slow-onset processes which aect the region –

including sea-level rise (SLR), coastal erosion, droughts, rainfall variability, environmental degradation and more – are

more dicult to capture. However, slow onset environmental drivers are expected to play an increasingly prominent role

in generating migration in the region, particularly internally within countries and particularly from rural areas to cities.

Each year, hundreds of deaths and disappearances are registered by IOM’s Missing Migrants Project (MMP) in the

Caribbean, with countless more unregistered. Since the beginning of 2016 and through June 2023, a total of 1,298 migrant

deaths and disappearances were recorded by IOM MMP in the Caribbean region (IOM, n.d.a.). In the Caribbean region,

some of the main routes where migrant deaths and disappearances are known to occur are along maritime routes

between Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico (sometimes referred to as the “Mona passage”), Caribbean countries

and territories to the United States, and from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela to dierent locations within the region.

These routes are considered particularly risky not only due to weather and environmental conditions on the high seas

but also because many movements take place in non-seaworthy vessels (ibid.). It is suspected that many deaths and

disappearances taking place in the Caribbean go unregistered, as many shipwrecks are never identied (a phenomenon

often termed “Yola shipwrecks”).

5

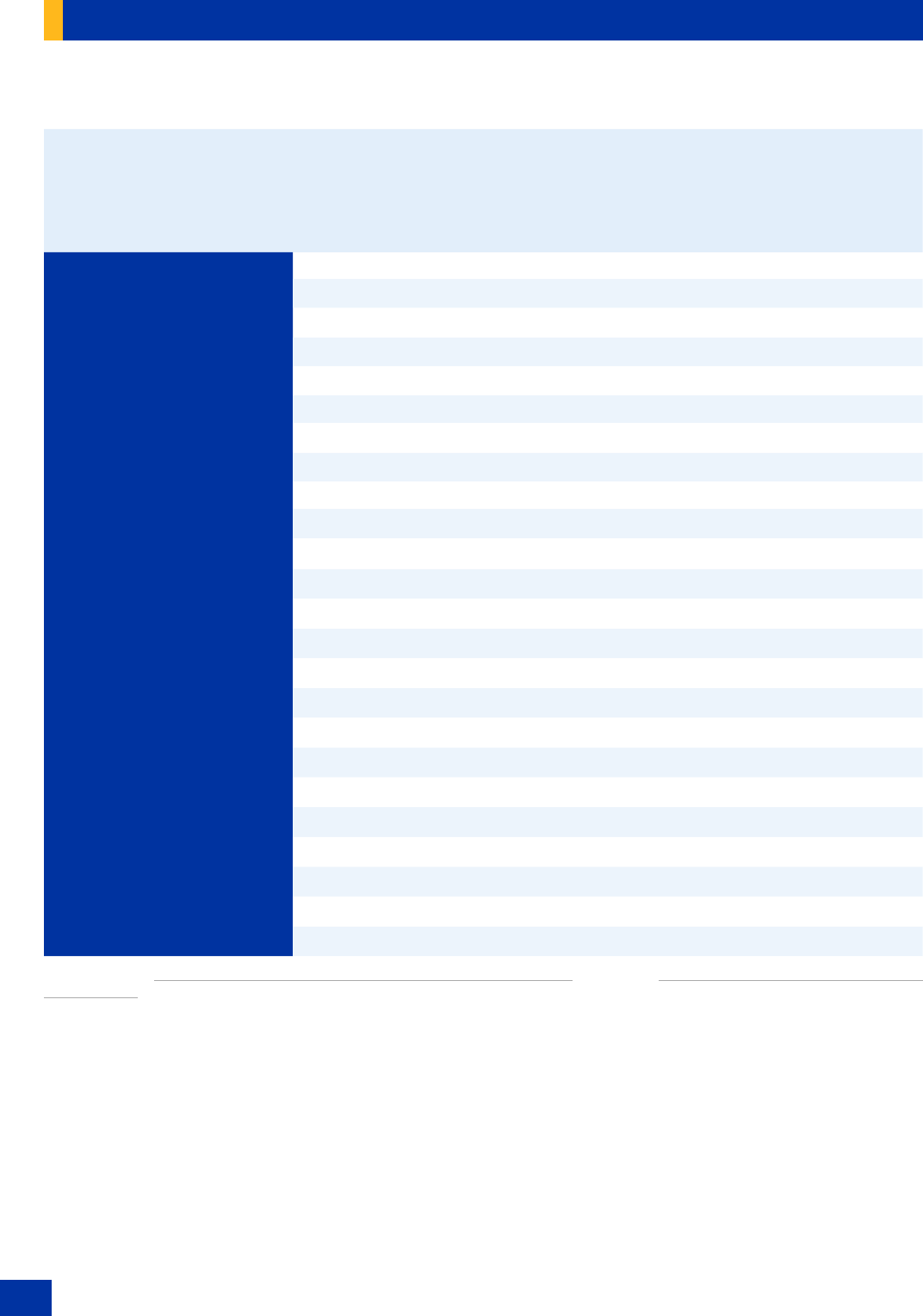

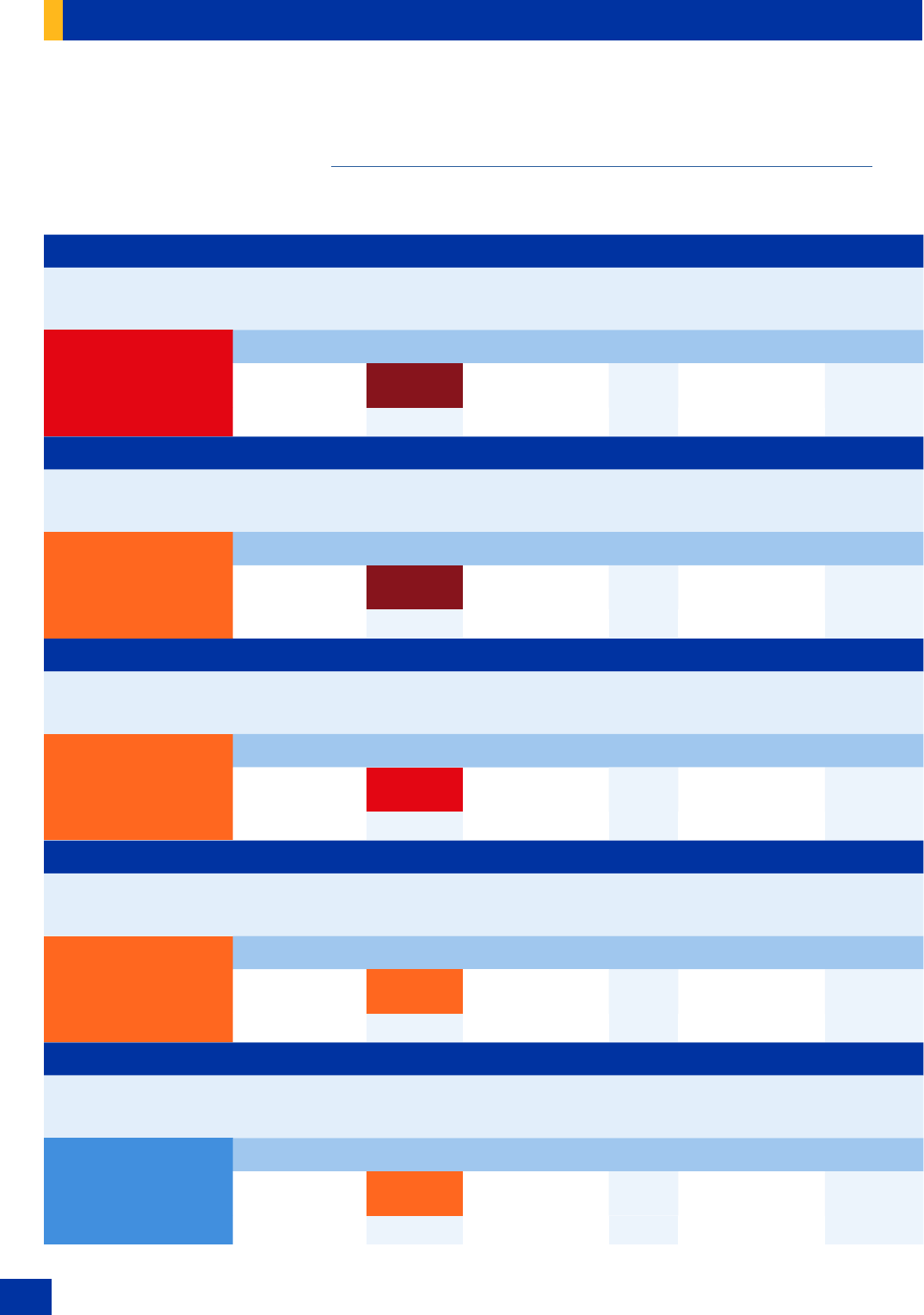

KEY BACKGROUND DATA – ALL CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES

3

Sources: a World Bank, “GDP (current US$)”, n.d. [04 Jan. 2022], *when 2022 is not available, most recent data is used (2020 or 2021); b World Bank, “GDP per capita (current US$)”,

n.d. [04 Jan 2022] *when 2022 is not available, most recent data is used (2020 or 2021); c United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Human Development Report 2020, 2020; d

World Bank, “Country and Lending Groups”, n.d. [04 Jan. 2022]; e United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA), World Population Prospects Revision 2019 –

Total Population – Both Sexes, 2019; f UNDESA, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and origin: Table 1”, 2021; g World Bank, “Personal remittances, received (% of GDP)”,

n.d. [04 Jan 2022]. Note: The spaces with a dash (“-“) indicate that no data were available.

Country

GDP, total, 2022,

billions (current

USD)

a

GDP per capita,

2022, thousands

(current USD)

b

Human

Development

Index (2021)

c

Income Status

2021-2022

d

Total population

(2020 projections)

e

Stock of

emigrants

(2020)

f

Stock of

immigrants

(2020)

g

Remittances

(% GDP, 2022)

h

Anguilla

- - - - 15,002 2,505 5,715 -

Antigua and

Barbuda

1.8 18,745 0.79 High 97,928 66,561 29,386 2.0

Aruba

3.1* 29,342* - - 106,766 21,456 53,593 -

Bahamas

12.9 31,458 0.81 High 393,248 53,793 63,583 -

Barbados

5.6 20,019 0.79 High 287,371 99,611 34,869 -

Belize

2.8 6,968 0.68 Lower middle 397,621 52,756 62,043 5.0

Bonaire, Sint

Eustatius and

Saba

- - - - 26,221 8,148 26,221 -

British Virgin

Islands

- - - - 30,237 5,355 22,164 -

Cayman

Islands

6.0* 88,475* - - 65,720 1,908 29,242 -

Cuba

107.4* 9,478* 0.76 Upper Middle 11,326,616 1,757,300 3,024 -

Curaçao

2.7* 17,717* - - 164,100 7,611 57,210 -

Dominica

0.6 8,415 0.72 Upper Middle 71,991 78,191 8,284 8.5

Dominican

Republic

113.6 10,121 0.77 Upper Middle 10,847,904 1,608,567 603,794 9.0

Grenada

1.3 10,016 0.80 Upper Middle 112 519 62,204 7,213 5.5

Guadeloupe

- - - - 400,127 12,542 90,206 -

Guyana

15.4 18,990 0.71 Upper Middle 786,559 438,413 31,169 2.6

Haití

20.3 1,748 0.54 Lower Middle 11,402,533 1,769,671 18,884 22.4

Jamaica

17.1 6,047 0.71 Upper Middle 2,961,161 1,118,931 23,629 21.6

Martinique

- - - - 375,265 12,963 68,624 -

Montserrat

- - - - 4,999 24,582 1,379 -

Puerto Rico

113.4 35,209 - - 2,860,840 1,850,529 247,132 -

Saint

Barthélemy

- - - - 9,885 - - -

Saint Kitts

and Nevis

1.0 20,177 0.78 High 53,192 50,285 7,725 3.4

Saint Lucia

2.1 11,481 0.72 Upper Middle 183,629 71,227 8,338 2.7

Saint Martin

(French part)

- - - - 38,659 - - -

Saint Vincent

and the

Grenadines

0.9 9,125 0.738* Upper Middle 110,947 55,525 4,738 7.3

Sint Maarten

(Dutch part)

1.6 36,220 - - 42,882 2,191 - -

Suriname

3.6 5,858 0.73 Upper Middle 586,634 273,209 47,801 4.1

Trinidad and

Tobago

27.9 18,222 0.81 High 1,399,491 330,519 78,849 0.6

Turks and

Caicos

Islands

1.1 24,918 - - 38,718 2,689 - -

United

States Virgin

Islands

4.2* 39,552* - - 104,423 3,908 - -

TOTAL STOCK OF EMIGRANTS FROM THE REGION 9,843,150

TOTAL STOCK OF IMMIGRANTS IN THE REGION 1,634,815

6

1. OVERVIEW

1.1 MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE CARIBBEAN

Comprised of a total of 29 countries and territories

2

, the Caribbean is an immensely diverse region comprised

of states with populations ranging from just tens of thousands of people to those with more than 10 million.

Between these countries and territories are a range of income levels, development outcomes, language proles

4

, ethnic

groups, economic structures and political systems. Despite this diversity, the region is interconnected through common

historical ties, while also sharing several shared challenges and opportunities.

Twenty-ve (25) of the 29 countries and territories in the Caribbean are designated as Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) – a distinct group of United Nations (UN) and Non-UN Members/Associate Members that face “unique social,

economic and environmental vulnerabilities” (UN, n.d.a). These vulnerabilities include, amongst others, small sizes,

remoteness, climate change impacts, biodiversity loss, dependence on external markets, high costs and narrow resource

bases which together can hinder broader socioeconomic development (Ibid).

Existing research shows that the above realities, as well as colonial ties and other historic and present push- and pull-

factors have had a signicant impact in shaping migration trajectories into, within and out of the region (ILO, 2014;

Williams, 2013; Cassin et al., 2022; IOM, 2020; IOM, 2017). Migration poses as an important adaptation strategy to

deal with the above-mentioned challenges for millions of people in the region while also serving as a potential tool

for development, both by way of migrant remittances sent to families and communities back home, and by way of

social remittances and the transfer of new knowledge, technology and skills. Migration in the Caribbean can also

bring challenges, both due to the loss of specialized human capital (often known as “brain drain”) as many Caribbean

workers seek better opportunities abroad, but also in the assistance and integration of diverse ows of vulnerable

migrants migrating both within the region and from countries outside of the region.

The Caribbean is a region of emigrants. Many countries in the region – including Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic

and Jamaica – had more than 1.1 million and even up to 1.7 million nationals living abroad as 2020 (UNDESA, 2021).

With an estimated 9.84 million Caribbean migrants living abroad in 2020, the majority of which (8.94 million)

resided outside of the region

5

, migration connects Caribbean countries, communities as well as migrants and their

families through strong and lasting transnational ties.

Recently, migration has risen on the agenda of many countries confronting disaster and displacement caused

by recurring and perhaps intensifying natural hazards, particularly hurricanes. In addition to sudden-onset disasters,

many Caribbean countries are increasingly susceptible to slow onset climate and environmental change, which

is expected to play an increasingly prominent role as a driver of migration in the region, particularly internally

within countries from rural areas to cities, but also across international borders

6

.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to generate a tremendous impact on mobility in Caribbean countries as of

2022, reducing regional cross-border movement and international tourist arrivals and jeopardizing tourist revenues

and economic livelihoods.

7

As one of the regions of origin most dependent on remittances, the pandemic’s impacts

have also generated concerns over Caribbean migrants’ capacities to send money to families in countries of origin

8

.

However, data through the end of 2020 show that remittances to the region have remained relatively resilient.

9

Mainly, Spanish, French, English, Dutch, Haitian Creole and Papiament (a Spanish and Portuguese-based creole language spoken in the Dutch Caribbean, mainly

Aruba, Bonaire and Curacao).

Data derived from UNDESA, International migrant stock 2019, and refer to all migrants originating from Caribbean countries and overseas territories as classified

by UNDESA (including Puerto Rico), as well as Guyana and Suriname (classified as South America) and Belize (classified as Central America).

Caribbean Migration Consultations, Migration Governance: An Adaptation Strategy for Environmental Change, n.d. (IOM, San José) [3 Feb. 2021].

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), The impact of the COVID- pandemic on the tourism sector in Latin America and the

Caribbean, and options for a sustainable and resilient recover, 2020.

World Bank, COVID-19 crisis through a migration lens, 2020.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “Stand by me: COVID-19 and the resilience of remittances ows to LAC”, 2 December 2020 [3 Feb. 2021].

OVERVIE W

7

Intraregional migration in the Caribbean, a foundational provision for broader regional integration across both

Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

10

and Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS)

11

Member States, is also

a notable trend and is playing an increasing role in the region’s economic and social development

12

.

Data also show that Cuban and Haitian migrants continue to leave their countries of origin, whether for family reunication,

in search of work, in need of international protection or for other reasons. The arrival of Venezuelan refugees

and migrants to the region in recent years has also added to complex migration dynamics and has had a strong

impact particularly (although not exclusively) on many small islands, states and territories

13

. Many of these vulnerable

migrants embark on dangerous and potentially life-threatening journeys in order to reach countries of destination, and

many have lost their lives while in transit through maritime and land routes

14

.

Finally, although data are limited, return migration – both voluntary and forced – of Caribbean migrants is

a prominent trend, bringing with them a wide variety of resources, skills, experiences and knowledge with the potential to

benet local economic development, while highlighting the importance of developing innovative policy responses

in countries and territories of origin in order to maximize return and reintegration and foster entrepreneurship and

innovation amongst returnee populations.

1.2 SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE REPORT

The importance of having accessible, disaggregated, reliable, timely, public, free and high-quality data is well recognized

and highlighted in various international frameworks.

• Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Target 17.18 “… increase signicantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated

by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status…”

• Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM)

Objective 1 Collect and utilize accurate and disaggregated data as a basis for evidence-based policies.

Objective 3 Provide accurate and timely information at all stages of migration.

Objective 17 Eliminate all forms of discrimination and promote evidence-based public discourse to

shape perceptions of migration.

As coordinator and secretariat of the United Nations Network on Migration, IOM is in a unique position to contribute to the

achievement of regional objectives with regard to improving the collection, management and dissemination of migration

data. For this reason, IOM has also established its own institutional migration data strategy. This report responds

in particular to the Objective 1 of this strategy.

• IOM Migration Data Strategy

Objective 1 Strengthen the global evidence base on migration;

Objective 2 Develop capacity of States and other relevant partners to enhance the national, regional

and global migration evidence base;

Objective 3 Ensure more evidence-based IOM- and United Nations system-wide programming,

operations, policy advice and communications.

CARICOM is made up of 15 Member States and ve Associate Members and was founded in 1973. More information available here.

OECD is made up of seven Protocol Member States and four Associate Members and was founded in 1981. More information available here.

IOM, Free movement in the Caribbean: Economic and security dimensions, 2019.

Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan – January – December 2021, 2020.

IOM, Missing Migrants Project – Americas, n.d. [3 Feb. 2021].

1. OVERVIEW

OVERVIE W

8

1. OVERVIEW

• Regional Strategy for Central America, North America and the Caribbean – The information available in the Report

also responds to the IOM Vision established for the region for the period of 2020-2024:

Pillar C

Governance – “Serving as a trusted and eective leader and partner in relevant bilateral,

regional and global initiatives and processes”

iv “Enhance the capacity of governments to collect, analyse and use migration and internal displacement

data for evidence-based policymaking.”

Despite the importance of migration in the Caribbean region, there exist very few resources which highlight

migration trends in the region, and even fewer that are focused on data. Data are a critical element of evidence-

based policy making.

Within this context, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Regional Oce for Central America, North

America and the Caribbean in San José, Costa Rica, presents this brief in order to highlight several key historical and recent

developments and trends in mobility and migration in the Caribbean region, focusing on ocial statistics published by

international agencies as well as records published and maintained by governments.

1.3 GEOGRAPHIC COVERAGE

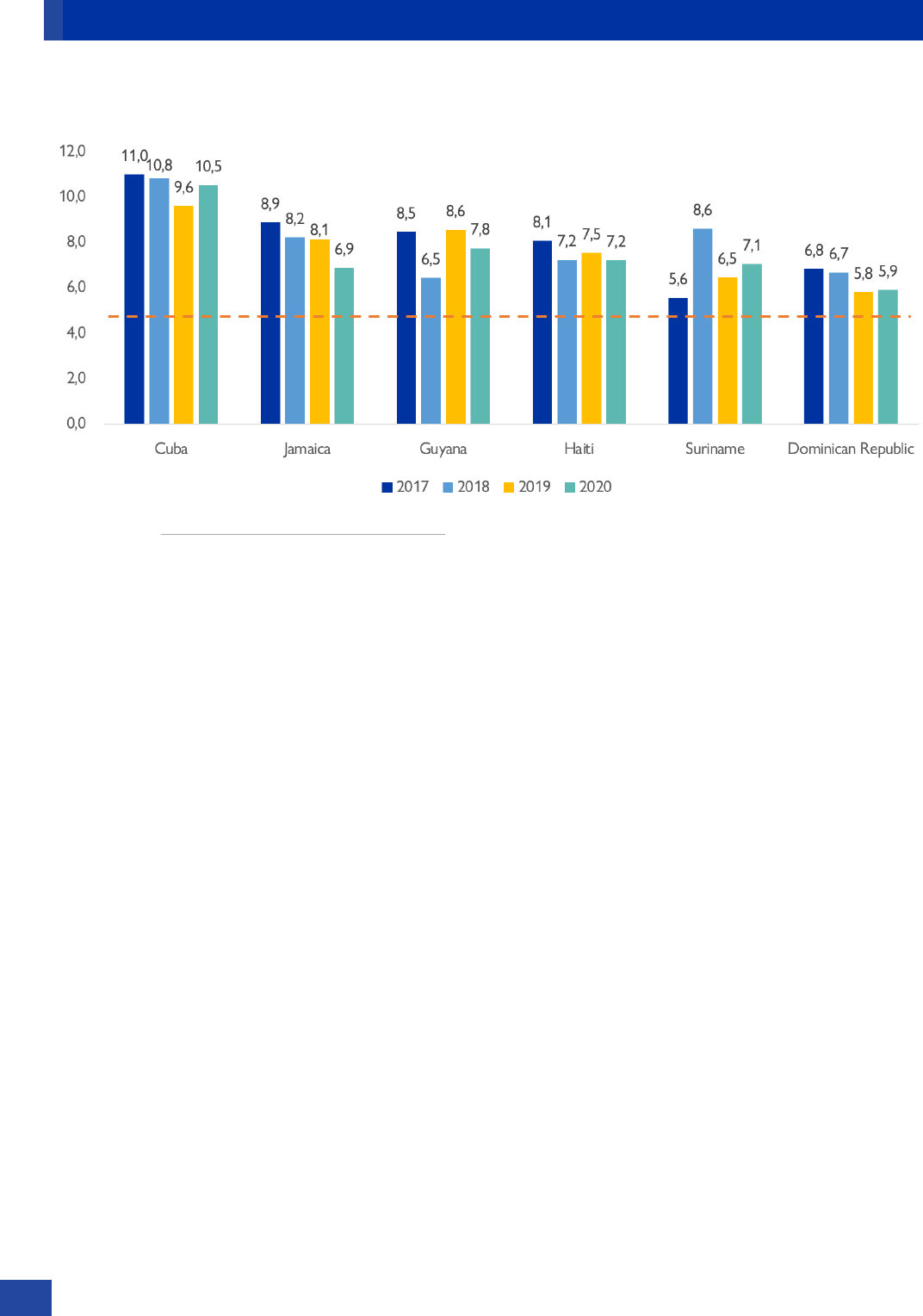

Map 1.1: Countries and territories which make up the Caribbean region in this report.

Note: This map is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown, and designations used on this map do not imply ocial endorsement or

acceptance by IOM.

Belize

Cuba

Jamaica

The Bahamas

Haiti

Dominican

Republic

Trinidad and

Tobago

Barbados

Guyana

Suriname

Aruba

Curaçao

Bonaire

Puerto Rico

Grenada

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent and

The Grenadines

Antigua and Barbuda

Martinique

Guadaloupe

Dominica

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Montserrat

Turks and

Caicos Islands

British Virgin Islands

United States

Virgin Islands

Anguilla

Sint Maarten

Saint Martin

Saint

Barthelemy

Saba

Sint Eustatius

Country

Territory

Cayman Islands

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

9

This section provides key data on emigration from the region, mainly sourced from estimates of the number (or

“stock”) of international migrants generated by UNDESA, with information disaggregated by sex and country of

origin/destination when possible. This section also highlights key changes in Caribbean emigration over time. For

additional information on how UNDESA generates its estimates on the international migrant stock, see the 2020

Methodological Note (UNDESA, 2021b).

2.1 REGIONAL EMIGRANT STOCKS

Figure 1: Stock of Caribbean nationals living abroad, and percentage (%) change between reference years, 1990 –

2020 (millions)

15

Source: Own calculations; based on United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA), Table 1: International migrant stock at mid-year by

sex and by region, country or area of destination and origin, 1990-2020, 2021 [05 May 2022].

• The stock of Caribbean emigrants more than doubled in three decades between 1990 and 2020, by

approximately 5.17 million. The size of the emigrant population grew on average by 13 per cent every ve

years in this 30-year period.

•

While it appears that net emigration rates have decreased in recent years, the Caribbean nevertheless remains

an area of signicant net emigration. The lion’s share of Caribbean emigration is extrarregional. While the

absolute number of intraregional migrants continues to grow, intraregional migrants as a proportion of all

Caribbean emigrants have remained relatively constant during the past three decades, hovering between 8.8

and 10.5 per cent. Of the stock of 900,462 intraregional Caribbean emigrants as of 2020, 63 per cent (567,956)

were Haitians.

Totals include migrants originating from all countries and territories signaled in section 1.3 / map 1.1.

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

91% of Caribbean migrants resided

outside of the region in 2020

9% of Caribbean

migrants resided in another country /

territory within the region in 2020

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

10

2.2 BREAKDOWN OF EMIGRANTS

Table 1: Top 10 origin countries / territories of Caribbean nationals residing abroad in absolute terms, and percentage

(%) increase between 1990 and 2020

Source: Own calculations; based on United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA), Table 1: International migrant stock at mid-year

by sex and by region, country or area of destination and origin,

1990-2020, 2021 [05 May 2022].

Note: migrants originating from Puerto Rico are United States citizens and thus may not be considered immigrants by certain entities in the United States

and elsewhere. However, for statistical purposes, Puerto Ricans born in Puerto Rico who move to the 50 states of the United States are considered migrants by

UNDESA. The * symbol indicates a dependent area or overseas territory.

• Migrants from the top ve origin countries / territories in the region - Puerto Rico, Haiti, Cuba,

the Dominican Republic and Jamaica - represented 82 per cent (8,104,9998) of the total stock

of emigrants from the region in 2020. The top 10 countries above amounted to 94 per cent (9,284,927)

of the regions’ total number of emigrants in 2020.

While the size of the emigrant population grew signicantly across all of the above countries and territories in the

specied 30-year period, these outows tended to occur at dierent times, and are linked to dierent trends occurring

both during this timeframe and prior to 1990:

Puerto Rico: The rate of emigration from Puerto Rico showed a decline through the 1990s and early

2000s before registering a marked increase beginning in 2010 onward (UNDESA, 2021).

Top 3 destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States (mainland)

16

: 1,829,251 (98.9%)

• Dominican Republic: 4,780 (<1%)

• Guam:

17

4,176 (<1%)

Although emigration from Puerto Rico to the continental United States took place long before World War II, the largest

waves occurred after the war ended from 1945 onward (Lehman College, n.d.). Immigration to the mainland United

States was at its peak in the 1950s (in a period often termed “the Great Migration”) both due to the precarious economic

situation on the island as well as active recruitment of workers from Puerto Rico (Library of Congress, n.d.).

A change of usual residence to reside in one of the 50 states of the United States would be considered internal migration.

A change of usual residence to reside in Guam would be considered internal migration, given that Guam is also an overseas dependent territory of the United States.

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

Emigrant stock

Country / Territory 1990 2020 % Increase

1

Puerto Rico* 1,200,245 1,850,529 54%

2

Haiti 524,711 1,769,671 237%

3

Cuba 835,175 1,757,300 110%

4

Dominican Republic 458,021 1,608,567 251%

5

Jamaica 588,450 1,118,931 90%

6

Guyana 233,318 438,413 88%

7

Suriname 177,857 330,519 86%

8

Barbados 84,766 273,209 222%

9

Dominica 40,563 99,611 146%

10

Saint Lucia 21,999 78,191 255%

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

11

Migration to the continental United States decreased slightly after the 1950s but remained steady through the next

few decades as the Puerto Rican economy obtained relative stability. However, particularly from 2006 onward,

renewed economic woes led to large outuxes at levels not seen since the 1950s (Cohn et al., 2014). The population

of the island peaked in 2004 and has declined since, mainly due to emigration as well as low birthrates (Ibid). The

socioeconomic impacts of Hurricane Maria, a category 4 storm which struck the island in September 2017, added to the

diculties stemming from the territory’s decade-long nancial crisis and has since generated further migrant outows

(United States Census Bureau, 2019).

Haiti: Rates of Haitian emigration remained sustained during the entire 30-year period, reaching their

highest levels after 2010. On average, the emigrant population from Haiti increased by 22 per cent every

ve years between 1990 and 2020, peaking at an increase of 31 per cent between 2010 and 2015

(UNDESA, 2021).

Top 3 destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States: 705,361 (39.9%)

• Dominican Republic: 496,112 (28.0%)

• Chile: 236,912 (13.4%)

The main drivers of Haitian emigration have included the collapse of a three-decade long dictatorship in 1986 (which

led to a political and economic crisis) as well as sustained endemic poverty and political instability through the

1990s and early 2000s (Olsen-Medina and Batalova, 2020). The large exodus of Haitian migrants witnessed after

2010 is mainly attributed to displacement and the socioeconomic fall-out resulting from the country’s devastating

2010 earthquake (Ibid). Continued insecurity and economic and political turmoil, as well as Hurricane Matthew in

2016, have also served as further drivers (Ya tes, 2021).

Cuba: The rate of emigration from Cuba remained virtually constant during the three decades spanning

1990-2020. On average, the size of the emigrant population increased by 13 per cent every ve years. The

highest growth rates in this period were seen between 2015 and 2020, when the emigrant population

increased by 17 per cent (UNDESA, 2021).

Top 3 destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States: 1,376,211 (78.3%)

• Spain: 162,368 (9.2%)

• Italy: 38,532 (2.2%)

Large-scale emigration from Cuba in modern times was spurred by the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and the resulting political

and economic challenges in the country (Duany, 2017). On the destination side, policy mechanisms in the United

States facilitated entry of Cuban refugees and migrants, particularly from 1966 onward with the signing of the

Cuban Adjustment Act, which allowed Cuban citizens living in the United States for at least one year to apply to

be lawful permanent residents (Nodarse Venancio and Oliver, 2022). From the mid-1990s the “wet-food, dry-foot”

policy in the United States (under which Cubans arriving to United States land border points without a visa would be

admitted to the country) continued to serve as a pull factor (Blizzard and Batalova, 2020). Despite the end of “wet-food,

dry-foot” in 2017, Cuban emigration has continued in recent years in the midst of deteriorating standards of living and

social unrest, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Nodarse Venancio and Oliver, 2022; Sherwood and Acosta,

2022). Emigration to Spain has long been a common trend amongst Cuban migrants in light of common colonial,

historic and linguistic ties – many Cuban migrants in Spain can claim Spanish ancestry (Sosa and Perez-Diaz, 2018).

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

12

Dominican Republic: Emigration from the Dominican Republic has slowed in recent decades but

still remains high. The largest outows from the Dominican Republic in the aforementioned 30-year period

occurred between 1990 and 2000, when the emigrant population grew by 94 per cent. After 2000

and through 2020, the size of the Dominican emigrant population grew at an average of 16 per cent every

ve years. The period spanning 2015-2020 saw the slowest rate of growth within the three-decade period,

at 11 per cent (UNDESA, 2021).

Top 3 destinations and % of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States: 1,376,211 (85.6%)

• Spain: 162,368 (10.1%)

• Italy: 38,532 (2.4%)

The large emigration rates from the Dominican Republic in the nineties came on the tail-end of three decades of

signicant outows (mainly toward the United States) of Dominicans eeing violence and political crises since the 1960s

as well as the eects of the Latin American economic and debt crisis of the 1980s (Babich and Batalova, 2021b). Many

Dominican nationals now emigrate through family reunication ties, particularly to the United States and Spain (Ibid).

Jamaica: The stock of Jamaican nationals living abroad increased by 46 per cent between 1990 and

2000. The rate of emigration decreased markedly after 2000, on average by seven per cent every ve

years through 2020 (UNDESA, 2021).

Top 3 destinations and % of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States: 792,370 (70.8%)

• Canada: 148,982 (13.3%)

• United Kingdom: 128,772 (11.5%)

Emigration from Jamaica occurred with increasing momentum by the mid-twentieth century as the United States and the

United Kingdom recruited large numbers of Jamaican workers during and after World War II (IOM, 2018; Zong and

Batalova, 2019). In the 1960s, various policy changes led to a shift in the direction of ows away from Western Europe

and mainly toward the United States and in smaller part to Canada (IOM, 2018). High levels of emigration of Jamaicans to

Northern America, including of highly skilled workers, continued into the 1970s. While persistent economic woes tied

in particular to declines in the agricultural sector (among other factors) would lead to sustained emigration in the

1980s and 90s, rates of emigration began to decline during this period and continued to do so into the 2000s (Ibid).

Guyana: In the period spanning 1990 – 2020, the largest rates of emigration from Guyana took place

between 1990 and 2000, when the size of the emigrant population increased by 55 per cent. However,

the growth rate of the emigrant population decreased signicantly between 2000 and 2015, and between

2015 and 2020 the size of the emigrant population actually shrunk by nine per cent, from 481,000 in

2015 to 438,000 in 2020, in light of return migration.

To p three destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• United States: 241,573 (55%)

• Canada: 94,421 (22%)

• United Kingdom: 28,074 (6%)

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

13

Sustained outows of Guyanese migrants have occurred since its independence from the United Kingdom in 1966,

particularly in the 1970s (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2020). Many of those migrating in the decades

after independence possessed tertiary-level education or had at least completed secondary education, leaving the country

in the backdrop of a persistent lack of economic opportunities as well as ethnic and political tensions, and facilitated

by favorable immigration laws particularly for skilled workers in key destination countries, like the United Kingdom,

Canada and the United States (ibid.). As the size of the Guyanese diaspora grew signicantly in recent decades,

family reunication has also become an important channel of emigration (ibid.).

• Trinidad and Tobago: Between 1990-2020, the largest growth in the emigrant population occurred

in the 1990s at an average of 25 per cent every ve years. However, from 2000 onward the growth

in the emigrant population slowed signicantly, and, between 2015 and 2020, the overall emigrant population

decreased by approximately 38,000 from 369,000 to 331,000.

To p three destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020

• United States: 208,075 (63%)

• Canada: 70,035 (21%)

• United Kingdom: 29,508 (9%)

Recent emigration from Trinidad and Tobago has mainly been of highly-skilled workers, including nurses and

other professionals migrating to the United States and Canada (IOM, n.d.). Otherwise, Trinidad and Tobago is one

of the most prosperous islands in the Caribbean and has signicant natural gas resources, an expanding tourist

industry, foreign direct investment and agriculture, serving as a key destination of Caribbean migrants in recent years

(Ibid.). This prosperity in part has led to a decrease in emigration from the island.

• Suriname: Between 1990-2020, the largest growth in the emigrant population occurred between

2005 and 2010 (increasing by 18%). However, from 2010 onwards the growth in the emigrant population

slowed, with the total stock increasing by a more modest six per cent between 2010 and 2020.

To p three destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020:

• Netherlands: 182,922 (67%)

• France: 27,892 (10%)

• French Guiana: 26,064 (10%)

From 1945 through the 1960s emigration from Suriname was dominated by high- and middle-income students

going to the Netherlands to study and settle to work (IOM, 2015). In the 1950s, Dutch industrial and shipping rms as

well as hospitals and care institutions began recruiting Surinamese workers (both male and female) to ll critical labour

market gaps in the Netherlands (ibid.). Migration from the mid-1960s onward shifted to include a far higher number of

women (whereas prior outows were predominated by adult males) as more nurses were recruited from the country

and as family reunication became a growing trend (ibid.). The highest rates of emigration from the county began in the

1970s onward, mainly due to weak economic prospects in Suriname and ethnic and political strife. Outows peaked

in 1975, mainly toward the Netherlands, in the same year that the country gained independence (ibid.). Favorable

visa policies in the Netherlands in the immediate years following and political turmoil in the wake of independence

would driver further sustained outows through the 1990s (ibid.). Throughout this period, certain ethnic groups

in Suriname – in particular Surinamese Maroons – have migrated to French Guiana and continue to do so to this

day (ibid.).

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

14

• Barbados: The emigrant population from Barbados grew modestly on average by six per cent every

ve years between 1990 and 2000. However, since 2000 the size of the emigrant population has remained

static growing on an average of just one per cent every ve years through 2020. Between 2015 and

2020 the size of the emigrant population decreased by approximately 2,300, from 101,900 to 99,600.

To p three destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020

• United States: 51,738 (52%)

• United Kingdom: 26,622 (27%)

• Canada: 15,177 (19%)

The bulk of emigration from Barbados occurred earlier in the 20th century. In the early 1900s many Barbadian

workers went to work on the Panama Canal (Barrow, 2010). Later, many Barbadians migrated in search of better

labour opportunities in the United Kingdom from the 1940s through the 1960s. However, upon the introduction

of more restrictive immigration policies in the 1960s in the United Kingdom, combined with the liberalization of

immigration policies in the United States / growing economic opportunities in both the United States and Canada, outows

shifted largely toward Northern America (ibid.). After independence in 1966, the country’s economy transformed from

being primarily agrarian to a more diverse service-based economy with strong earnings from tourism, manufacturing

and the nancial sector (Callaghan, 2018). With the exception of a strong recession in the early 1990s, the

improved economic performance and living conditions in the country have reduced pressures to emigrate, particularly

after the 1990s.

• Dominica: Between 1990 and 2000 the emigrant stock from Dominica increased by 19 per cent.

The highest rates of growth in the emigrant population took place between 2000 and 2005 (+33%) and

2005 and 2010 (+15%). However, since then the rate of growth has slowed signicantly, with the size

of the emigrant population increasing by six per cent between 2010 and 2020.

To p three destinations and percentage (%) of total emigrant stock as of 2020

• United States: 32,379 (41%)

• United Kingdom: 8,625 (11%)

• France: 7,368 (9%)

Emigration from Dominica has been primarily economic in nature, to surrounding Caribbean islands, the United States

and Europe. The country is highly volcanic and has very few beaches, meaning that tourism to the island developed

slower than other Caribbean islands (US Department of State, 2018a). Dominica has experienced challenges diversifying

its economy and still relies heavily on agriculture, which can be vulnerable to external global commodity price shocks

(in the case of bananas, for example), as well as weather (ibid.). The island has struggled to recover from numerous

devastating Hurricanes (for example Hurricane Dean in 2007 and Hurricane Maria in 2017) which have spurred

further economic diculties, displacement and international migration.

While Figure 1 and Table 1 have highlighted trends in Caribbean emigration in absolute terms, calculating emigration

from the region in proportional terms (that is, the percentage of each country / territory’s nationals living abroad)

portrays a more nuanced reality of emigration in the region. In fact, based on 2019 gures, IOM estimated that:

• In proportional terms, ten of the top 20 countries of emigration in the world in 2019 (In countries

where the combined population of residents and emigrants residing abroad exceeded 100,000) were

located in the Caribbean, including Saint Kitts and Nevis, Dominica and Suriname (which lled the top three

spots, respectively), Grenada (5th), Guyana (6th), Antigua and Barbuda (8th), Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines (9th), Barbados (13th), Jamaica (14th) and Saint Lucia (16th) (). IOM, 2020.

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

15

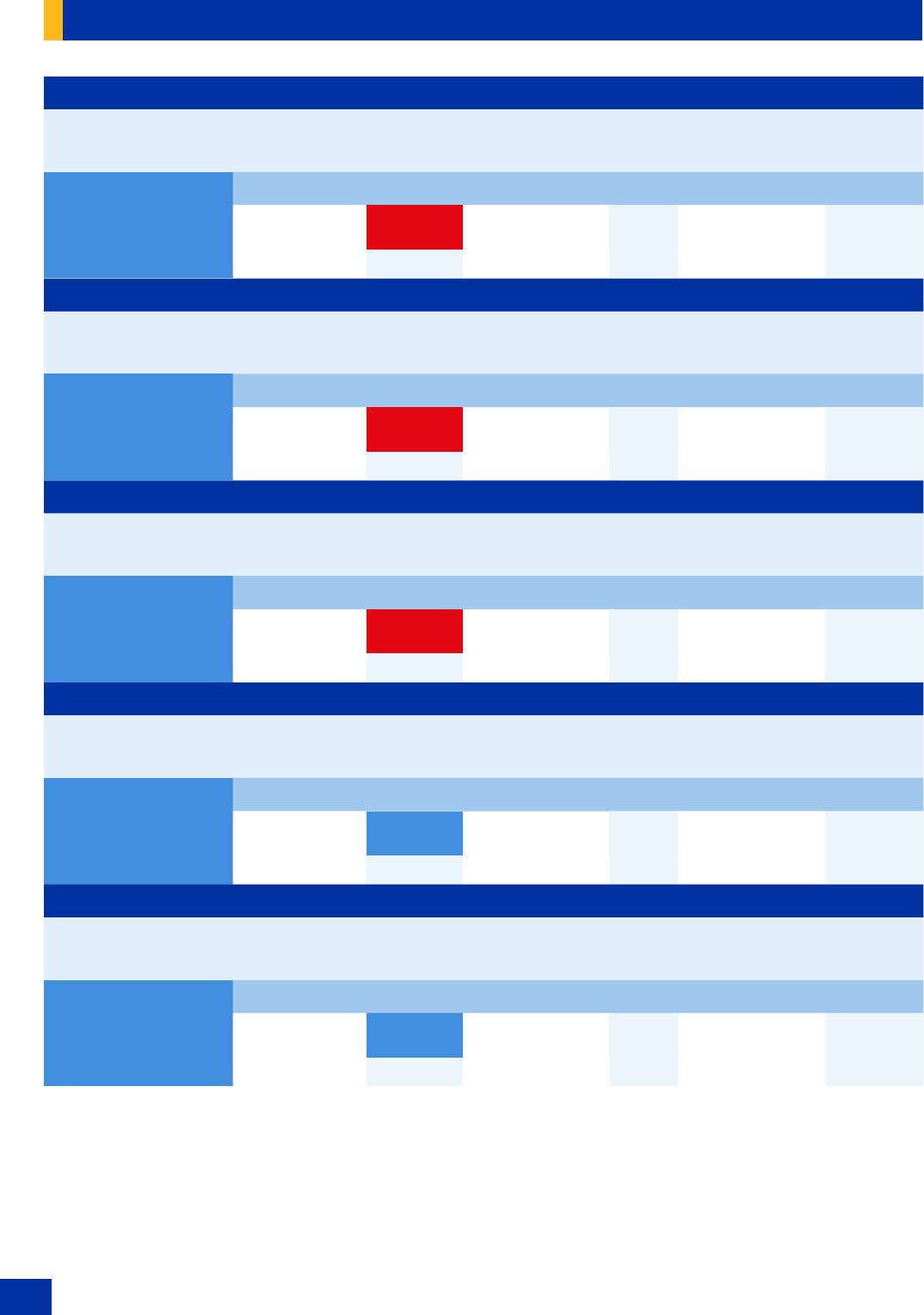

Figure 2: Percentage (%) of nationals living abroad, by region (overall) and by individual Caribbean UN Member

Countries, 2020.

Source: Own calculations, based on data from: UNDESA, World Population Prospects 2019: 1-1 Total population (both sexes combined) by region, subregion

and country, annually for 1950-2100 (thousands), n.d. [01 May. 2022]; Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA), Table 1:

International migrant stock at mid-year by sex and by region, country or area of destination and origin, 1990-2020, 2021 [05 May 2022].

A review of Figure 2 above reveals that various countries that did not appear among the top 10 origin countries

of migrants in the Caribbean in absolute terms featured prominently in the list of top 10 origin countries

in proportional terms, mainly: Saint Kitts and Nevis (ranked 2

nd

amongst UN Member Countries in the region),

Antigua and Barbuda (third), Grenada (fth) and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (sixth):

• Nearly one-fth of the region’s nationals were estimated to be living outside of their countries /

territories of origin as of 2020, reecting immense degrees of emigration in proportional terms.

• 7 of the 16 UN Member Countries in the Caribbean had one-third or higher of their population residing

abroad as of 2020, and the proportion of nationals living abroad did not fall below one-tenth in any

UN Member Country.

• Most emigrants from Saint Kitts and Nevis migrate to the United States – the destination of 27,765,

or 55.2 per cent of the total 50,285 emigrants from the country living abroad as of 2020. The United

Kingdom is the second-most destination of migrants from Saint Kitts and Nevis (7,998, or 16%)

followed by the United States Virgin Islands (7,103, or 14%).

• Emigration trends from Antigua and Barbuda are like Saint Kitts and Nevis, with the United States

serving as the main country of destination (46,037, or 69% of the total 66,561)

Below are some observations for specic countries included in Figure 2 above that did not appear in the top

10 countries of origin (in absolute terms) featured in Table 2:

• For each country in Figure 2 that did not fall within the top 10 countries of origin in absolute terms

(Table 2 – specically, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines, Bahamas and Belize – the top three countries of destination were the United States and

its territories, the United Kingdom and Canada.

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

18%

of all Caribbean nationals (from all countries and territories) were estimated to live

abroad as of 2020

Dominica

52%

Barbados

26%

Guyana

36%

Grenade

36%

Dominican Republic

13%

Saint Lucia

28%

Jamaica

27%

Antigua and Barbuda

40%

Haiti

13%

Cuba

13%

Suriname

32%

Belize

12%

Saint Kitts and Nevis

49%

Trinidad and Tobago

19%

Saint Vincent

and the Grenadines

33%

Bahamas

12%

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

16

• Fifty-ve per cent (55%) of the 27,765 migrants from Saint Kitts and Nevis in 2020 lived in the United

States, followed by 29 per cent in the United States Virgin Islands.

• Nearly 70 per cent of the total 46,037 migrants from Antigua and Barbuda were residing in the United

States as of 2020.

• Of the 62,204 total migrants from Grenada around the world in 2020, 41 per cent were living in the

United States, 20 per cent in the United Kingdom and 18 per cent in Canada.

• Over 27 per cent of the 55,525 migrants from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines as of 2020 were living

in the United States, followed by Canada (25%) and the United Kingdom (17%).

• Nearly nine in ten (87%) of the 53,793 migrants from the Bahamas in 2020 were living in the

United States.

• For Belize, 81 per cent or the total 52,756 migrants globally were estimated to be living in the United

States as of 2020.

Similar trends of signicant proportions of all nationals can be seen amongst Caribbean overseas dependent territories.

Aside from Puerto Rico (previously discussed) this include Montserrat, Bonaire, Aruba, the British Virgin Islands

and Anguilla:

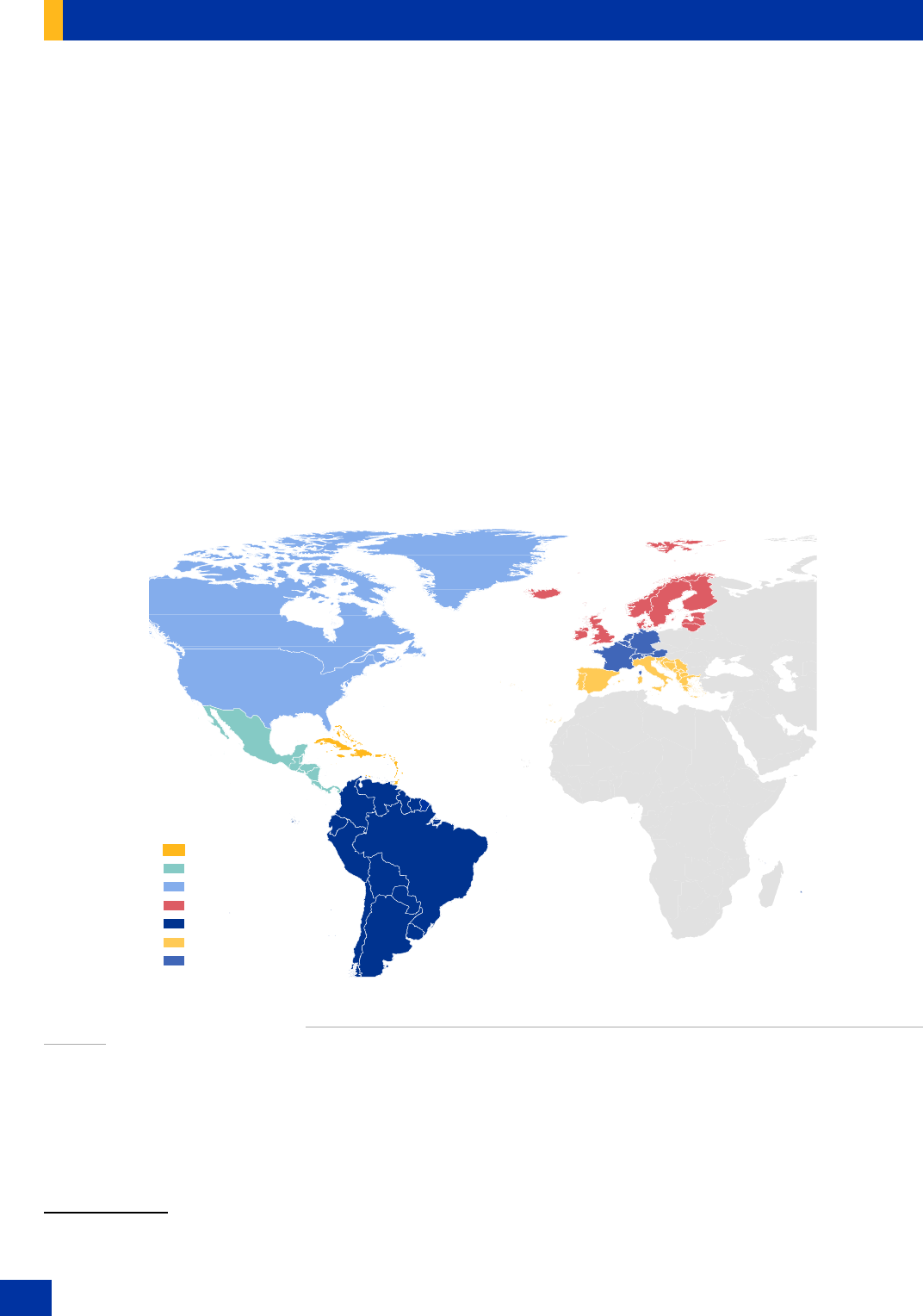

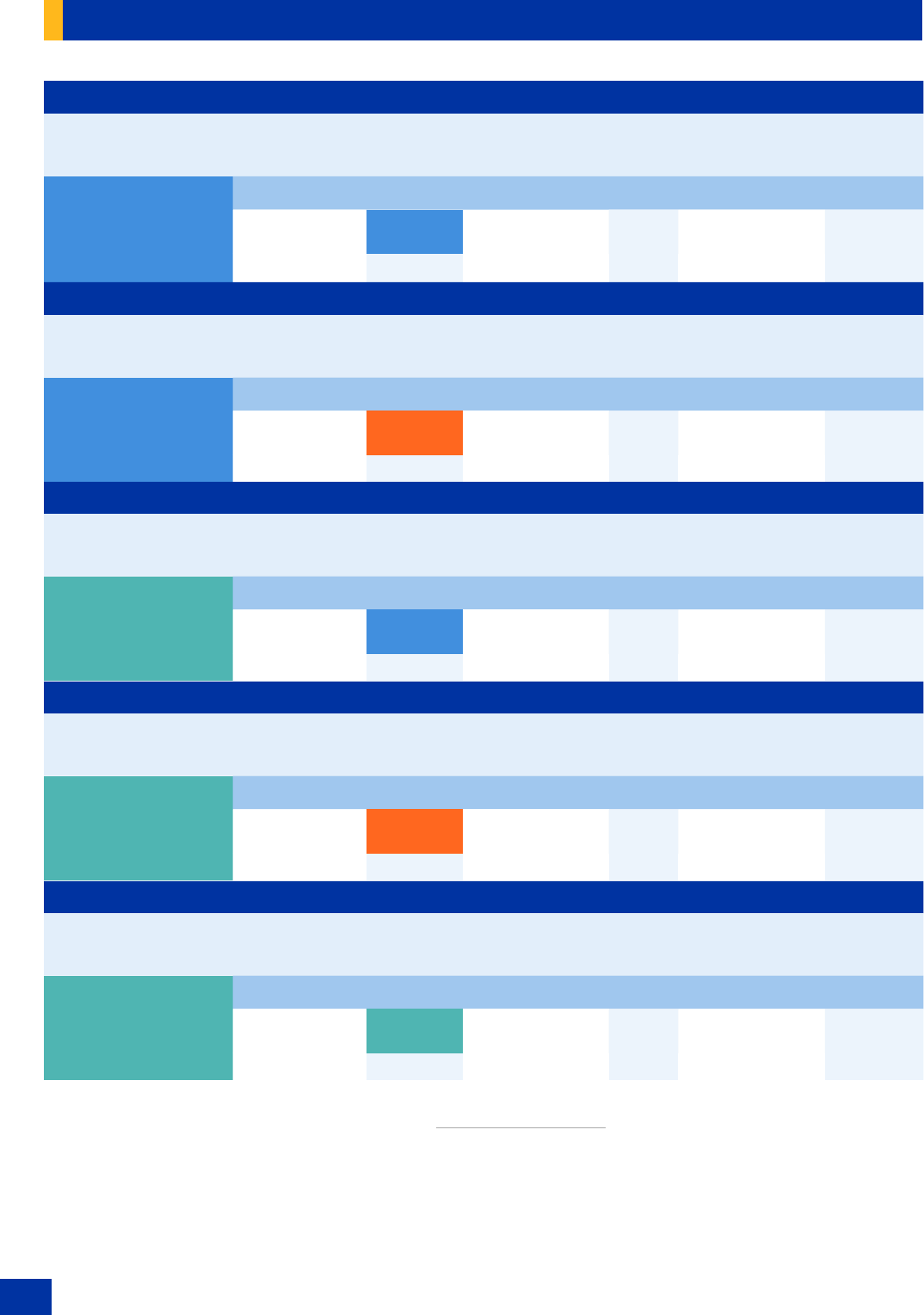

Figure 3: Top destination regions of Caribbean migrants, 2020

18

Source: Own calculations; based on UNDESA, Table 1: International migrant stock at mid-year by sex and by region, country or area of destination and origin,

1990-2020, 2020 [21 Jul. 2023].

Note: This map is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown, and designations used on this map do not imply ocial endorsement or

acceptance by IOM.

Analysis includes nationals originating from all sovereign countries, overseas territories and dependent areas included under UNDESA classications for the

Caribbean, as well as Belize, Guyana and Suriname. This map is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown, and designations used on this

map do not imply ocial endorsement or acceptance by IOM. Regions are based on UNDESA classications with the exception of Guyana, Suriname and Belize,

which have been included under the Caribbean for the purposes of the present analysis.

2. CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

Destination region

Caribbean

Central America

Northern America

Northern Europe

South America

Southern Europe

Western Europe

73.2%

7.20 million

9.1%

900,462

4.9%

483,243

0.6%

56,078

4.5%

443,848

4.3%

421,762

3.1%

302,763

CARIBBEAN EMIGRATION - STOCKS

17

The vast majority of Caribbean emigrants are concentrated in just seven global regions. As of 2019, 99.3 per cent of

Caribbean emigrants were residing in Northern America, elsewhere in the Caribbean, Western Europe, Southern

Europe, Northern Europe, South America and Central America

19

, corridors which, aside from intraregional

migration, largely reect post-colonial ties as well as the geographic proximity and growing popularity of the

United States and Canada as principal destinations within the last 40 – 50 years.

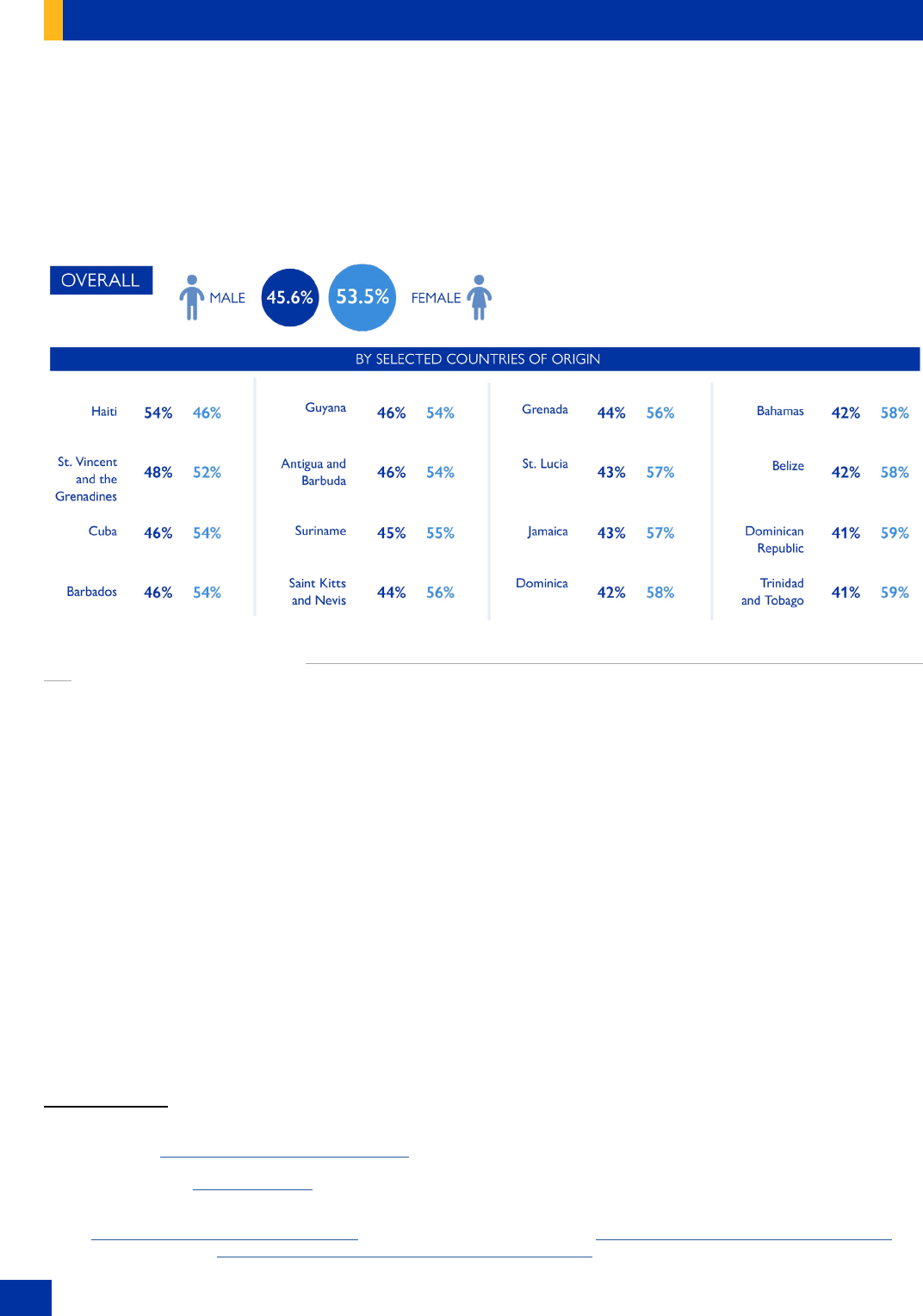

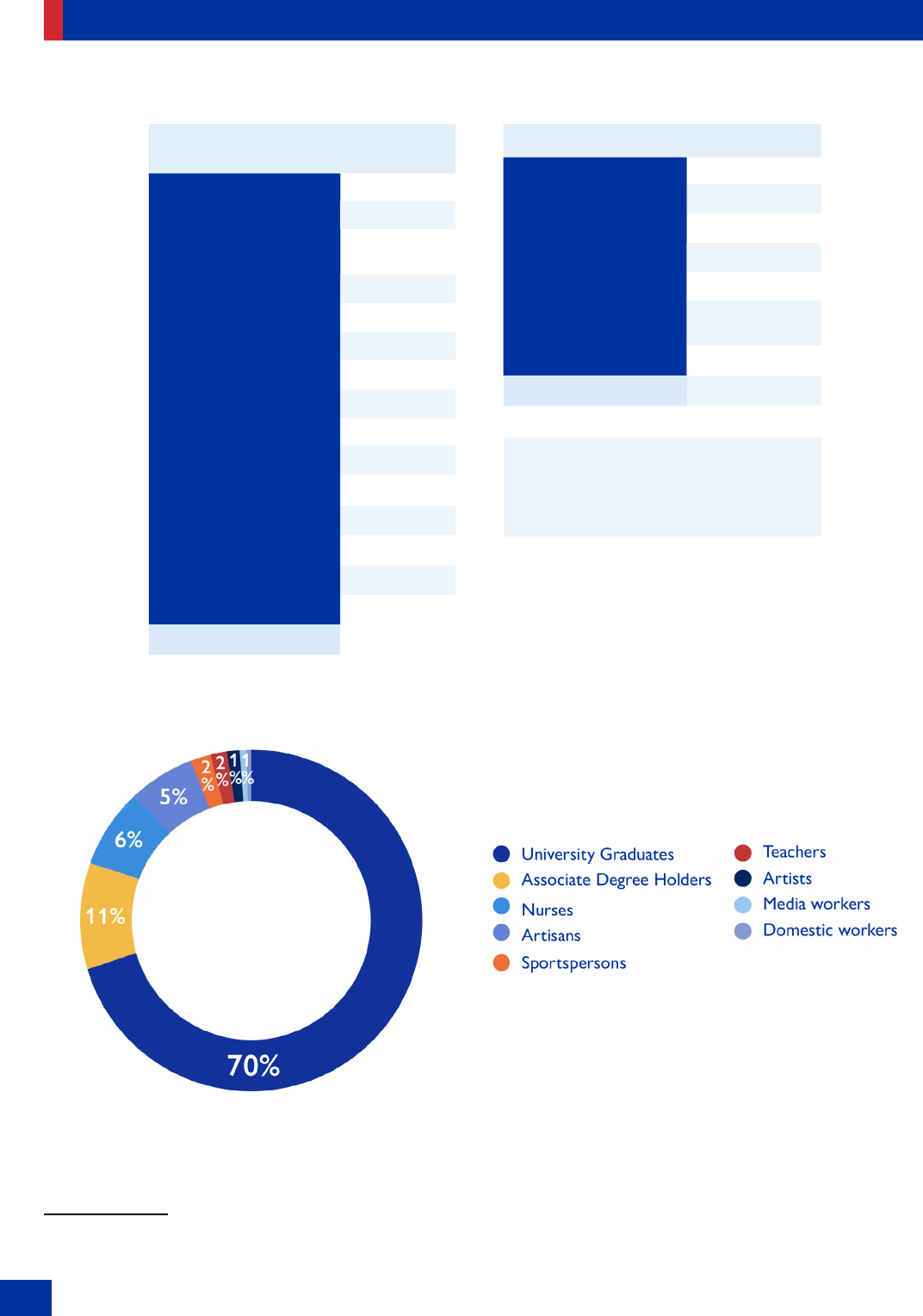

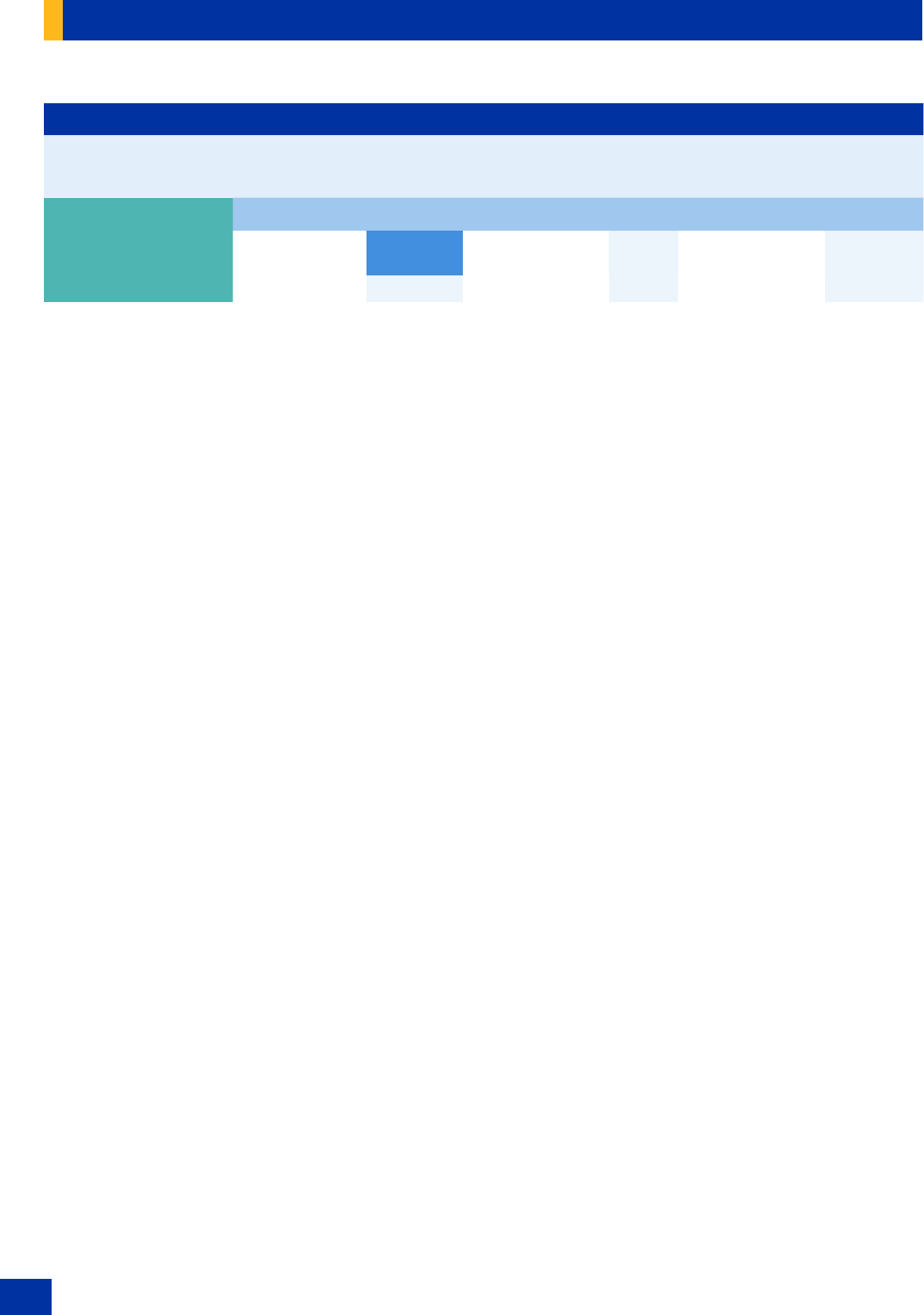

Figure 4: Sex composition of Caribbean nationals residing abroad, 2020

20

Source: Own calculations; based on UNDESA, Table 1: Total migrant stock at mid-year by origin and major area, region or country of destination, 1990-2019,

2019 [01 Dec. 2020].

Global data from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA) indicate that

48 per cent of migrants globally are women. This proportion is higher for the Caribbean region, where

53.2 per cent of all nationals living abroad were women as of 2020. This proportion has grown slightly over time,

given that in 1990 women migrants constituted 52 per cent of all Caribbean nationals living abroad. Data above

indicate that there is measurable variation between countries. However, amongst sovereign Caribbean countries,

only Haiti possesses an emigrant population that is majority male. The feminization of Caribbean emigration

in recent decades has been driven by large demand for highly-skilled female health and education workers in

key destination countries, gendered labour market segmentation and wage gaps in origin countries, increased

female labour force participation and changes in social norms regarding women’s work outside of the home and

women’s mobility, amongst other factors.

21

UNDESA regions are grouped based on seven Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) regions and 22 geographic subregions as dened by the United Nations

Statistics Division and used for the Sustainable Development Goals Report and do not imply ocial endorsement or acceptance by IOM. For more information