Electronic Health Record Usability

Vendor Practices and Perspectives

Prepared for:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

540 Gaither Road

Rockville, Maryland 20850

http://www.ahrq.gov

Prepared by:

James Bell Associates

The Altarum Institute

Writers:

Cheryl McDonnell

Kristen Werner

Lauren Wendel

AHRQ Publication No. 09(10)-0091-3-EF

May 2010

HEALTH IT

ii

This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special

permission. Citation of the source is appreciated.

Suggested Citation:

McDonnell C, Werner K, Wendel L. Electronic Health Record Usability: Vendor Practices and

Perspectives. AHRQ Publication No. 09(10)-0091-3-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality. May 2010.

This project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. The opinions expressed in this document are those

of the authors and do not reflect the official position of AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services.

iii

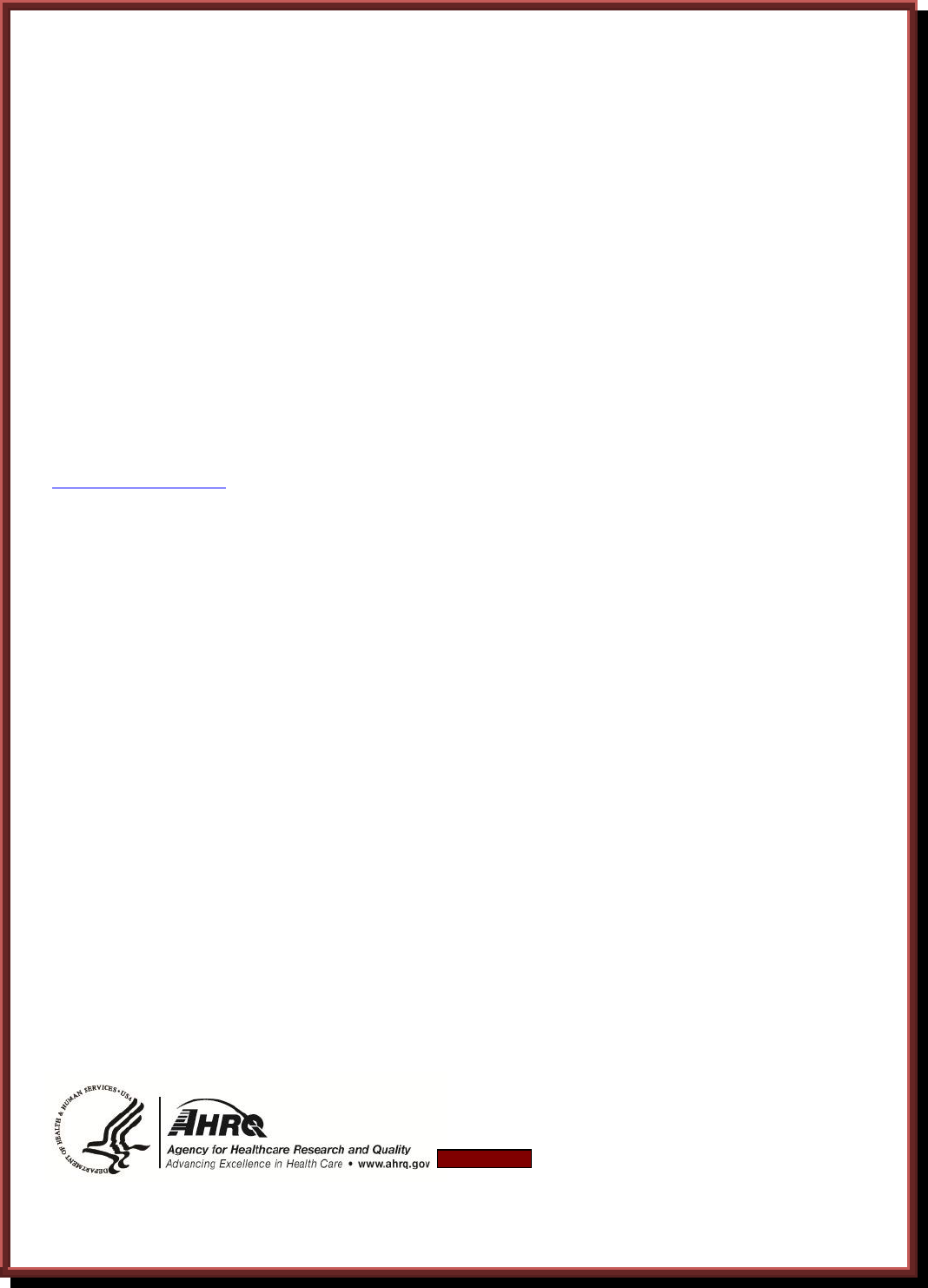

Expert Panel Members

Name

Affiliation

Mark Ackerman, PhD

Associate Professor, School of Information; Associate Professor,

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science,

University of Michigan

Daniel Armijo, MHSA

Practice Area Leader, Information & Technology Strategies,

Altarum Institute

Clifford Goldsmith, MD

Health Plan Strategist, Microsoft, Eastern U.S.

Lee Green, MD, MPH

Professor & Associate Chair of Information Management,

Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan; Director,

Great Lakes Research Into Practice Network; Co-Director,

Clinical Translation Science Program in the Michigan Institute for

Clinical and Health Research (MICHR)

Michael Klinkman, MD, MS

Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University

of Michigan; Director of Primary Care Programs, University of

Michigan Depression Center

Ross Koppel, PhD

Professor, University of Pennsylvania Sociology Department;

Affiliate Faculty Member, University of Pennsylvania School of

Medicine; President, Social Research Corporation

David Kreda

Independent Computer Software Consultant

Svetlana Lowry

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Donald T. Mon, PhD

Vice President of Practice Leadership, American Health

Information Management Association; Co-Chair, Health Level

Seven (HL7) EHR Technical Committee

Catherine Plaisant, PhD

University of Maryland, Human Computer Interaction Laboratory,

Institute for Advanced Computer Studies, Associate Director

Ben Shneiderman, PhD

Professor, Department of Computer Science; Founding Director,

Human-Computer Interaction Laboratory, Institute for Advanced

Computer Studies, University of Maryland

Andrew Ury, MD

Chief Medical Officer, McKesson Provider Technologies

James Walker, MD

Chief Health Information Officer, Geisinger Health System

Andrew M. Wiesenthal, MD, SM

Associate Executive Director for Clinical Information Support,

Kaiser Permanente Federation

Kai Zheng, PhD

Assistant Professor, University of Michigan School of Public

Health; Assistant Professor, University of Michigan School of

Information; Medical School’s Center for Computational Medicine

and Biology (CCMB); Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health

Research (MICHR)

Michael Zaroukian MD, PhD

Professor and Chief Medical Information Officer, Michigan State

University; Director of Clinical Informatics and Care

Transformation, Sparrow Health System; Medical Director, EMR

Project

iv

Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1

Background ................................................................................................................................ 3

Vendor Profiles .......................................................................................................................... 4

Standards in Design and Development ...................................................................................... 4

End-User Involvement ................................................................................................... 4

Design Standards and Best Practices ............................................................................. 4

Industry Collaboration ................................................................................................... 5

Customization ................................................................................................................ 5

Usability Testing and Evaluation ............................................................................................... 6

Informal Usability Assessments .................................................................................... 6

Measurement .................................................................................................................. 6

Observation .................................................................................................................... 7

Changing Landscape ...................................................................................................... 7

Postdeployment Monitoring and Patient Safety ........................................................................ 7

Feedback Solicitation ..................................................................................................... 7

Review and Response .................................................................................................... 8

Patient Safety ................................................................................................................. 8

Role of Certification in Evaluating Usability ............................................................................ 9

Current Certification Strategies ..................................................................................... 9

Subjectivity .................................................................................................................... 9

Innovation ...................................................................................................................... 9

Recognized Need ........................................................................................................... 10

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. 10

Implications................................................................................................................................ 11

Standards in Design and Development .......................................................................... 11

Usability Testing and Evaluation ................................................................................... 12

Postdeployment Monitoring and Patient Safety ............................................................ 12

Role of Certification in Evaluating Usability ................................................................ 13

References .................................................................................................................................. 14

Appendixes

Appendix I: Summary of Interviewed Vendors ......................................................................... A-1

Appendix II: Description of Electronic Health Record Products .............................................. B-1

1

Executive Summary

One of the key factors driving the adoption and appropriate utilization of electronic

health record (EHR) systems is their usability.

1

However, a recent study funded by the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) identified information about current EHR vendor

usability processes and practices during the different phases of product development and

deployment as a key research gap.

2

To address this gap and identify actionable recommendations to move the field forward,

AHRQ contracted with James Bell Associates and the Altarum Institute to conduct a series of

structured discussions with selected certified EHR vendors and to solicit recommendations based

on these findings from a panel of multidisciplinary experts in this area.

The objectives of the project were to understand processes and practices by these vendors

with regard to:

The existence and use of standards and “best practices” in designing, developing, and

deploying products.

Testing and evaluating usability throughout the product life cycle.

Supporting postdeployment monitoring to ensure patient safety and effective use.

In addition, the project solicited the perspectives of certified EHR vendors with regard to the role

of certification in evaluating and improving usability.

The key findings from the interviews are summarized below.

All vendors expressed a deep commitment to the development and provision of usable

EHR product(s) to the market.

Although vendors described an array of usability engineering processes and the use of

end users throughout the product life cycle, practices such as formal usability testing, the

use of user-centered design processes, and specific resource personnel with expertise in

usability engineering are not common.

Specific best practices and standards of design, testing, and monitoring of the usability of

EHR products are not readily available. Vendors reported use of general (software) and

proprietary industry guidelines and best practices to support usability. Reported

perspectives on critical issues such as allowable level of customization by customers

varied dramatically.

Many vendors did not initially address potential negative impacts of their products as a

priority design issue. Vendors reported a variety of formal and informal processes for

2

identifying, tracking, and addressing patient safety issues related to the usability of their

products.

Most vendors reported that they collect, but do not share, lists of incidents related to

usability as a subset of user-reported “bugs” and product-enhancement requests. While all

vendors described a process, procedures to classify and report usability issues of EHR

products are not standardized across the industry.

No vendors reported placing specific contractual restrictions on disclosures by system

users of patient safety incidents that were potentially related to their products.

Disagreement exists among vendors as to the ideal method for ensuring usability

standards, and best practices are evaluated and communicated across the industry as well

as to customers. Many view the inclusion of usability as part of product certification as

part of a larger “game” for staying competitive, but also as potentially too complex or

something that will “stifle innovation” in this area.

Because nearly all vendors view usability as their chief competitive differentiator,

collaboration among vendors with regard to usability is almost nonexistent.

To overcome competitive pressures, many vendors expressed interest in an independent

body guiding the development of voluntary usability standards for EHRs. This body

could build on existing models of vendor collaboration, which are currently focused

predominantly on issues of interoperability.

Based on the feedback gained from the interviews and from their experience with

usability best practices in health care and other industries, the project expert panel made the

following recommendations:

Encourage vendors to address key shortcomings that exist in current processes and

practices related to the usability of their products. Most critical among these are lack of

adherence to formal user-design processes and a lack of diversity in end users involved in

the testing and evaluation process.

Include in the design and testing process, and collect feedback from, a variety of end-user

contingents throughout the product life cycle. Potentially undersampled populations

include end users from nonacademic backgrounds with limited past experience with

health information technology and those with disabilities.

Support an independent body for vendor collaboration and standards development to

overcome market forces that discourage collaboration, development of best practices, and

standards harmonization in this area.

Develop standards and best practices in use of customization during EHR deployment.

Encourage formal usability testing early in the design and development phase as a best

practice, and discourage dependence on postdeployment review supporting usability

assessments.

3

Support research and development of tools that evaluate and report EHR ease of learning,

effectiveness, and satisfaction both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Increase research and development of best practices supporting designing for patient

safety.

Design certification programs for EHR usability in a way that focuses on objective and

important aspects of system usability.

Background

Encouraged by Federal leadership, significant investments in health information

technology (IT) are being made across the country. While the influx of capital into the electronic

health record (EHR)/health information exchange (HIE) market will undoubtedly stimulate

innovation, there is the corresponding recognition that this may present an exceptional

opportunity to guide that innovation in ways that benefit a significant majority of potential health

IT users.

One of the key factors driving the adoption and appropriate utilization of EHR systems is

their usability.

1

While recognized as critical, usability has not historically received the same level

of attention as software features, functions, and technical standards. A recent analysis funded by

the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that very little systematic

evidence has been gathered on the usability of EHRs in practice. Further review established a

foundation of EHR user-interface design considerations, and an action agenda was proposed for

the application of information design principles to the use of health IT in primary care settings.

2,3

In response to these recommendations, AHRQ contracted with James Bell Associates and

the Altarum Institute to evaluate current vendor-based practices for integrating usability during

the entire life cycle of the product, including the design, testing, and postdeployment phases of

EHR development. A selected group of EHR vendors, identified through the support of the

Certification Commission for Health Information Technology (CCHIT) and AHRQ, participated

in semistructured interviews. The discussions explored current standards and practices for

ensuring the usability and safety of EHR products and assessed the vendors’ perspectives on how

EHR usability and information design should be certified, measured, and addressed by the

government, the EHR industry, and its customers. Summary interview findings were then

distributed to experts in the field to gather implications and recommendations resulting from

these discussions.

Vendor Profiles

The vendors interviewed were specifically chosen to represent a wide distribution of

providers of ambulatory EHR products. There was a representation of small-sized businesses

(less than 100 employees), medium-sized businesses (100-500 employees), and large-sized

businesses (greater than 500 employees). The number of clinician users per company varied from

1,000 to over 7,000, and revenue ranged from $1 million to over $10 billion per year. The EHR

products discussed came on the market in some form in the time period from the mid-1990s to

2007. All vendors except one had developed their EHR internally from the ground up, with the

4

remaining one internally developing major enhancements for an acquired product. Many of these

products were initially designed and developed based on a founding physician’s practice and/or

established clinical processes. All companies reported that they are currently engaged in ground-

up development of new products and/or enhancements of their existing ambulatory products.

Many enhancements of ambulatory products center on updates or improvements in usability.

Examples of new developments include changes in products from client-based to Web-based

EHRs; general changes to improve the overall usability and look and feel of the product; and the

integration of new technologies such as patient portals, personal health records, and tablet

devices.

The full list of vendors interviewed and a description of their key ambulatory EHR

products are provided in Appendixes I and II. The following discussion provides a summary of

the themes encountered in these interviews.

Standards in Design and Development

End-User Involvement

All vendors reported actively involving their intended end users throughout the entire

design and development process. Many vendors also have a staff member with clinical

experience involved in the design and development process; for some companies the clinician

was a founding member of the organization.

Workgroups and advisory panels are the most

common sources of feedback, with some vendors

utilizing a more comprehensive participatory

design approach, incorporating feedback from all

stakeholders throughout the design process. Vendors seek this information to develop initial

product requirements, as well as to define workflows, evaluate wireframes and prototypes, and

participate in initial beta testing. When identifying users for workgroups, advisory panels, or beta

sites, vendors look for clinicians who have a strong interest in technology, the ability to evaluate

usability, and the patience to provide regular feedback. Clinicians meeting these requirements are

most often found in academic medical centers. When the design concerns an enhancement to the

current product, vendors often look toward users familiar with the existing EHR to provide this

feedback.

Design Standards and Best Practices

A reliance on end-user input and observation for ground-up development is seen as a

requirement in the area of EHR design, where specific design standards and best practices are not

yet well defined. Vendors indicated that appropriate

and comprehensive standards were lacking for EHR-

specific functionalities, and therefore they rely on

general software design best practices to inform

design, development, and usability. While these

software design principles help to guide their

processes, they must be adjusted to fit specific end-

“We want to engage with leadership-level

partners as well as end users from all venues

that may be impacted by our product.”

“There are no standards most of the time,

and when there are standards, there is no

enforcement of them. The software

industry has plenty of guidelines and good

best practices, but in health IT, there are

none.”

5

user needs within a health care setting. In addition to following existing general design

guidelines such as Microsoft Common User Access, Windows User Interface, Nielsen Norman

Group, human factors best practices, and releases from user interface (UI) and usability

professional organizations, many vendors consult with Web sites, blogs, and professional

organizations related to health IT to keep up to date with specific industry trends. Supplementing

these outside resources, many vendors are actively developing internal documentation as their

products grow and mature, with several reporting organized efforts to create internal

documentation supporting product-specific standards and best practices that can be applied

through future product updates and releases.

Industry Collaboration

As these standards and best practices are being developed, they are not being

disseminated throughout the industry. Vendors receive some information through professional

organizations and conferences, but they would like to see a stronger push toward an independent

body, either governmental or research based, to establish some of these standards. The

independent body would be required, as all

vendors reported usability as a key

competitive differentiator for their product;

this creates a strong disincentive for industry-

wide collaboration. While all were eager to

take advantage of any resources commonly

applied across the industry, few were

comfortable with sharing their internally developed designs or best practices for fear of losing a

major component of their product’s competitiveness. Some vendors did report they collaborate

informally within the health IT industry, particularly through professional societies, trade

conferences, and serving on committees. For example, several vendors mentioned participation

in the Electronic Health Record Association (EHRA), sponsored by the Healthcare Information

and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), but noted that the focus of this group is on clinical

vocabulary modeling rather than the usability of EHRs. Some interviewees expressed a desire to

collaborate on standards issues that impact usability and patient safety through independent

venues such as government or research agencies.

Customization

In addition to the initial design and development process, vendors commonly work with

end users to customize or configure specific parts of the EHR. Vendors differed in the extent to

which they allowed and facilitated customization and noted the potential for introducing errors

when customization is pursued. Most customizations involve setting security rules based on roles

within a clinic and the creation of document

templates that fit a clinic’s specific workflow. Many

vendors view this process as a critical step toward a

successful implementation and try to assist users to

an extent in developing these items. While some

vendors track these customizations as insight for

future product design, they do not view the customizations as something that can be generalized

to their entire user base, as so many are context specific. The level of customization varies

“The field is competitive so there is little sharing of

best practices in the community. The industry

should not look toward vendors to create these best

practices. Other entities must step up and define

[them] and let the industry adapt.”

“You cannot possibly adapt technology to

everyone’s workflow. You must provide the

most optimum way of doing something

which [users] can adapt.”

6

according to vendor since vendors have different views about the extent to which their product

can or should be customized. Vendors do not routinely make changes to the code or underlying

interface based on a user request; however, the level to which end users can modify templates,

workflows, and other interface-related characteristics varies greatly by vendor offering.

Usability Testing and Evaluation

Informal Usability Assessments

Formal usability assessments, such as task-centered user tests, heuristic evaluations,

cognitive walkthroughs, and card sorts, are not a common activity during the design and

development process for the majority of vendors. Lack of time, personnel, and budget resources

were cited as reasons for this absence; however, the

majority expressed a desire to increase these types of

formal assessments. There was a common perception

among the vendors that usability assessments are

expensive and time consuming to implement during the

design and development phase. The level of formal

usability testing appeared to vary by vendor size, with larger companies having more staff and

resources dedicated to usability testing while smaller vendors relied heavily on informal methods

(e.g., observations, interviews), which were more integrated into the general development

process. Although some reported that they conduct a full gamut of both formal and informal

usability assessments for some parts of the design process, most reported restricting their use of

formal methods to key points in the process (e.g., during the final design phase or for evaluation

of specific critical features during development).

Measurement

Functions are selected for usability testing according to several criteria: frequency of use,

task criticality and complexity, customer feedback, difficult design areas, risk and liability,

effects on revenue, compliance issues (e.g., Military Health

System HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act], and the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act) and potential impacts on patient safety.

The most common or frequent tasks and tasks identified as

inherently complex are specifically prioritized for usability testing. Neither benchmarks and

standards for performance nor formalized measurements of these tasks are common in the

industry. While some vendors do measure number of clicks and amount of time to complete a

task, as well as error rates, most do not collect data on factors directly related to the usability of

the product, such as ease of learning, effectiveness, and satisfaction. Many vendors reported that

the amount of data collected does not allow for quantitative analysis, so instead they rely on

more anecdotal and informal methods to ensure that their product works more effectively than

paper-based methods and to inform their continuous improvements with upgrades and releases.

“Due to time and resource constraints,

we do not do as much as we would like

to do. It is an area in which we are

looking to do more.”

“Testing is focused more on

functionality rather than

usability.”

7

Observation

Observation is the “gold standard” among all vendors for learning how users interact with

their EHR. These observations usually take place within the user’s own medical practice, either

in person or with software such as TechSmith’s

Morae.

4

Vendors will occasionally solicit feedback on

prototypes from user conferences in an informal lab-

like setting. These observations are typically used to

gather information on clinical workflows or process

flows, which are incorporated into the product design,

particularly if the vendor is developing a new

enhancement or entire product.

Changing Landscape

While informal methods of usability testing seem to be common across most vendors, the

landscape appears to be changing toward increasing the importance of usability as a design

necessity. Multiple vendors reported the current or recent development of formal in-house

observation laboratories where usability testing could be more effectively conducted. Others

reported the recent completion of policies and standards directly related to integrating usability

more formally into the design process, and one reported a current contract with a third-party

vendor to improve usability practices. While it is yet to be seen if these changes will materialize,

it appeared that most respondents recognized the value of usability testing in the design process

and were taking active steps to improve their practices.

Postdeployment Monitoring and Patient Safety

Feedback Solicitation

Vendors are beginning to incorporate more user feedback into earlier stages of product

design and development; however, most of this feedback comes during the postdeployment

phase. As all vendors interviewed are currently engaged in either the development of

enhancements of current products or the creation of new products, the focus on incorporating

feedback from intended end users at all stages of

development has increased. Many of the EHRs have

been on the market for over 10 years; as a result,

many vendors rely heavily on this postdeployment

feedback to evaluate product use and inform future

product enhancements and designs. Maintaining contact with current users is of high priority to

all EHR vendors interviewed and in many ways appeared to represent the most important source

of product evaluation and improvement. Feedback is gathered through a variety of sources,

including informal comments received by product staff, help desk support calls, training and

implementation staff, sales personnel, online user communities, beta clients, advisory panels, and

user conferences. With all of these avenues established, vendors appear to attempt to make it as

easy as possible for current users to report potential issues as well as seek guidance from other

users and the vendor alike.

“[Methods with] low time and resource

efforts are the best [to gather feedback];

wherever users are present, we will gather

data.”

“A lot of feedback and questions are often

turned into enhancements, as they speak to

the user experience of the product.”

8

Review and Response

Once the vendors receive both internal and external feedback, they organize it through a

formal escalation process that ranks the severity of the issue based on factors such as number of

users impacted, type of functionality involved, patient

safety implications, effects on workflow, financial

impact to client, regulation compliance, and the

source of the problem, either implementation based or

product based. In general, safety issues are given a

high-priority tag. Based on this escalation process, priorities are set, resources within the

organization are assigned, and timelines are created for directly addressing the reported issue.

Multiple responses are possible depending on the problem. Responses can include additional

user training, software updates included in the next product release, or the creation and release of

immediate software patches to correct high-priority issues throughout the customer base.

Patient Safety

Adoption of health IT has the potential for introducing beneficial outcomes along many

dimensions. It is well recognized, however, that the actual results achieved vary from setting to

setting,

5

and numerous studies have reported health IT implementations that introduced

unintended adverse consequences detrimental to patient care practice.

6

Surprisingly, in many

interviews patient safety was not initially verbalized as a priority issue. Initial comments focused

on creating a useful, usable EHR product, not one that addresses potential negative impacts on

patient safety. Vendors rely heavily on physicians to notice

potential hazards and report these hazards to them through their

initial design and development advisory panels and

postdeployment feedback mechanisms. After further questioning

specific to adverse events, however, most vendors did describe

having processes in place for monitoring potential safety issues

on a variety of fronts. Some vendors become aware of patient safety issues through user

feedback collected from patient safety offices and field visits; others educate support staff as well

as users on how to identify potential patient safety risks and properly notify those who can

address the issue. Once patient safety issues are identified, vendors address them in various

ways, including tracking and reporting potential issues online, using patient safety review boards

to quantify risk, and engaging cognitive engineers to uncover root causes.

When asked about client contracts, no vendors reported placing specific contractual

restrictions on disclosures by system users of patient safety incidents that were potentially related

to the EHR products, sharing patient safety incidents with other customers or other clinicians, or

publishing research on how the EHR system affects patient safety or their clinical operations.

“Every suggestion is not a good suggestion;

some things do not help all users because

not all workflows are the same.”

“Physicians are very acutely

aware of how technology is

going to impact patient safety;

that’s their focus and

motivation.”

9

Role of Certification in Evaluating Usability

Current Certification Strategies

The issue of certification is one that elicited strong opinions from most vendors.

Certification of any type represents an investment of time and money to meet standards

originating outside the organization. For many vendors, particularly the smaller ones, this

investment was seen as burdensome. Vendors commonly described the current CCHIT

certification process as part of a larger “game” they

must play in order to remain viable in the

marketplace, not as a way to improve their

product(s). Accounts of functions added

specifically for certification but not used by

customers were common, as well as specific

instances where vendors felt meeting certification guidelines actually reduced aspects of their

product’s quality. As one vendor noted, sometimes providing the functionality for “checking the

box” to meet a certification requirement involves a backward step and a lowering of a potentially

innovative internal standard. As meaningful use has entered the picture, however, vendors are

striving to provide their customers with products that will comply with this definition and plan to

participate in any associated certifications.

Subjectivity

Interviewees held mixed opinions on whether the certification process can effectively

evaluate the usability aspect of EHR performance. Without exception, participating vendors had

concerns about the inherent subjectivity of

evaluation of usability, which can be strongly

affected by the past EHR experience of the user,

the context in which the product is used, and even

the education and background of the evaluator.

Methods for overcoming these types of bias issues

included suggestions such as certifying workflows

rather than attempting to measure usability, comparing objective product performance (time and

error rates) for specific tasks, or measuring usability based on end-user surveys instead of juror

analysis.

Innovation

Several interviewees also expressed

concern about the effect of usability certification

on innovation within the EHR marketplace. This

seemed to stem from experience with CCHIT’s

feature- and function-based criteria. It was noted

that in the developing EHR marketplace, current

systems are striving to make significant changes

in the way physicians practice care, which has inherent negative implications for perceived

“We don’t want to get dinged for an

innovative standard that we’ve developed

and [that] tested well with users because it

doesn’t fit the criteria.”

“Some products may be strong, but due to the

familiarity of jurors of a product or technology,

some products may be overrated or

underrated.”

“Products are picked on the amount of

things they do, not how well they do them.

CCHIT perpetuates this cycle; if a product

contains certain functions, it is placed among

the elite. That has nothing to do with

usability.”

10

usability early in the product’s release. Guidelines or ratings that are too prescriptive may have

the effect of forcing vendors to create technologies that more directly mirror current practices, a

strategy that could limit innovation and the overall effectiveness of EHRs.

Recognized Need

Despite these concerns, vendors recognized the role certification could play both as an

indicator to support customers in selecting EHRs and as a method through which established

standards could be disseminated across the industry.

While there is unease about the details of the conduct

of certification, many vendors thought that some form

of certification or evaluation had the potential to serve

as a complement to what is now a predominantly

market-driven issue. While each vendor viewed itself as a leader in the development of usable

EHR systems and supported the role of consumer demand in continuing to improve product

usability, vendors recognized that there could be utility to more standardized testing that could

be evenly applied throughout the industry.

Conclusion

All vendors interviewed expressed a deep commitment to the continued development and

provision of usable EHR product(s) to the market. Vendors believe that as features and functions

become more standardized across the industry, industry leaders will begin to differentiate

themselves from the rest of the market based on usability. Current best practices and standards of

design, testing, and monitoring EHR product(s), particularly for usability, are varied and not well

disseminated. While models for vendor collaboration for issues such as interoperability currently

exist through EHRA and IHE (Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise), collaboration among

vendors with regard to usability is almost nonexistent. Given the current move toward the

adoption and meaningful use of health IT, and the role usability plays in realizing intended

benefits, a transition from the current environment seems likely. This could be driven by many

sources, including standards developed by academic research, certification required by

government entities, collaboration through a nonprofit association such as EHRA or IHE, or

simply market pressures demanding more usable offerings.

Vendors recognize these pressures and the importance of usability to the continued

success of their products. Disagreement exists as to the ideal method for ensuring that usability is

evaluated and communicated across the industry as well as to customers. This disagreement

exists even within companies, as well as across vendors. Regardless of this uncertainty, there is

agreement that end users need to remain a central component within the development process,

innovation needs to be encouraged, and usability needs to be a critical driver of efficient,

effective, and safe EHRs.

“Being aware of standards and guidelines is

very important, but we also want to make

sure we are not hamstrung by them.”

11

Implications and Recommendations

The summary interview findings were distributed to selected experts in the field, who

provided additional thoughts on the implications of these discussions and developed

recommendations based on the discussions. A summary of these suggestions follows.

Standards in Design and Development

Increase diversity of users surveyed for pre-deployment feedback. While the use of

subject-matter experts and inclusion of end-user feedback in the design and development process

are beneficial and important approaches, the end-user selection process currently in use has a

potential for bias. Vendors noted extensive use of volunteered feedback. Clinicians with a strong

interest in technology, the ability to evaluate usability, and the patience to provide regular

feedback are not indicative of the typical end user. Additionally, as these types of clinicians are

commonly found in academic medical centers, they may rely on residents or other trainees to do

most of the work involving the EHR. Similar issues exist when soliciting input from users

familiar with the existing EHR; these users have potentially learned, sometimes unconsciously,

to work around or ignore many of the usability problems of the current system. To some extent,

vendors must utilize this “coalition of the willing” to gather feedback, given the extremely busy

schedules of most practicing clinicians. However, steps must be taken both in the vendor

community and by independent bodies to encourage inclusion of a more diverse range of users in

all stages of the design process. This more inclusive approach will ultimately support a more

usable end product.

Support an independent body for vendor collaboration and standards development.

Lack of vendor collaboration resulting from attempts to protect intellectual property and uphold

a competitive edge is understandable. However, with the accelerated adoption timeframe

encouraged by recent legislation and increasing demand, letting the market act as a primary

driver to dictate usability standards may not ensure that appropriate standards are adopted. The

user base currently has relatively limited abilities to accurately determine product usability

before purchase and, if dissatisfied after purchase, may incur significant expense to explore more

usable products. Simply deeming an EHR usable or not usable does not create or disseminate

standards and best practices for design. The market can provide direction, but more must be done

to document trends and best practices, create new standards for design, and regulate

implementation across the industry.

Develop standards and best practices in use of customization during EHR deployment.

Customization is often a key to successful implementation within a site, as it can enable users to

document the clinical visit in a way that accommodates their usual methods and existing

workflow. However, customization may also serve to hide existing usability issues within an

EHR, prevent users from interacting with advanced functions, or even create unintended

consequences that negatively impact patient safety. There is an additional concern that

customization may negatively impact future interoperability and consistency in design across the

industry. Customer demand for customization exists and some level of customization can be

beneficial to supporting individual workflows; however, more work must be done to evaluate the

level of customization that maximizes the EHR’s benefits and limits its risks.

12

Usability Testing and Evaluation

Encourage formal usability testing early in the design and development phase as a best

practice. Usability assessments can be resource intensive; however, it has been demonstrated that

including them in the design and development phase is more effective and less expensive than

responding to and correcting items after market release.

7

Identifying and correcting issues before

release also reduce help desk support and training costs. Vendors indicated an awareness of this

tradeoff and a move toward investment in usability assessment up front. Further monitoring will

be required to evaluate how the vendor community incorporates formal usability testing within

future design and development practices.

Evaluate ease of learning, effectiveness, and satisfaction qualitatively and

quantitatively. Observations are an important component of usability testing but are insufficient

for assessment of the root cause of usability issues. Alternatively, quantitative data such as

number of clicks, time to complete tasks, and error rates can help the vendor identify tasks that

may present usability issues but must be further explored to identify underlying issues. A mix of

structured qualitative and quantitative approaches, incorporating at minimum an assessment of

the three basic factors directly contributing to product usability—ease of learning, effectiveness,

and satisfaction—will serve to broaden the impact of usability assessments beyond the informal

methods commonly employed today.

Postdeployment Monitoring and Patient Safety

Decrease dependence on postdeployment review supporting usability assessments.

Usability issues are usually not simple, one-function problems, but tend to be pervasive

throughout the EHR. So while small-scale issues are often reported and corrected after

deployment, the identified issue may not be the primary determinant of a product’s usability. It

is chiefly within the main displays of information that are omnipresent, such as menu listings,

use of pop-up boxes, and the interaction between screens, that the EHR’s usability is determined.

Even with the best of intentions, it is unlikely that vendors will be able to resolve major usability

issues after release. By not identifying critical usability issues through a wide range of user

testing during design and development, vendors are opening the door to potential patient safety

incidents and costly postrelease fixes.

Increase research and development of best practices supporting designing for patient

safety. Monitoring and designing for patient safety, like usability testing, appear to be most

prevalent late in the design of the product or during its release cycle. Vendors’ heavy reliance on

end users or advisory panels to point out patient safety issues in many ways mirrors the informal

methods used to advance usability of their products. While patient safety similarly lacks specific

standards for vendors to follow, vendors are currently collaborating on patient safety issues.

These collaborations appear to be in their early stages, but they provide an opportunity to

enhance vendor awareness and vendor response to potential patient safety issues within their

products and improve their ability to incorporate patient safety much earlier in the design

process. Further work must be done to directly connect design to patient safety and ensure that

standards are created and disseminated throughout the industry.

13

Role of Certification in Evaluating Usability

Certification programs should be carefully designed and valid. Any certification or

outside evaluation will be initially approached with questions as to its validity, and the concept

of usability certification is no exception. Usability is a complex multifaceted system

characteristic, and usability certification must reflect that complexity. Further complicating this

issue is the fact that vendors have already participated in a certification process that most did not

find particularly valuable in enhancing their product. Driving the EHR market toward creation of

usable products requires development of a process that accurately identifies usable products,

establishes and disseminates standards, and encourages innovation.

14

References

1. Belden J, Grayson R, Barnes J. Defining and

Testing EMR Usability: Principles and

Proposed Methods of EMR Usability

Evaluation and Rating. Healthcare

Information Management and Systems

Society Electronic Health Record Usability

Task Force. Available at:

http://www.himss.org/content/files/HIMSS_

DefiningandTestingEMRUsability.pdf.

Accessed June 2009.

2. Armijo D, McDonnell C, Werner K.

Electronic Health Record Usability:

Interface Design Considerations. AHRQ

Publication No. 09(10)-0091-2-EF.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality. October 2009.

3. Armijo D, McDonnell C, Werner K.

Electronic Health Record Usability:

Evaluation and Use Case Framework.

AHRQ Publication No. 09(10)-0091-1-EF.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality. October 2009.

4. TechSmith. Morae: usability testing and

market research software. Available at:

http://www.techsmith.com/morae.asp.

5. Ammenwerth E, Talmon J, Ash JS, et al.

Impact of CPOE on mortality rates—

contradictory findings, important messages.

Methods Inf Med 2006;45:586-93.

6. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role

of computerized physician order entry

systems in facilitating medication errors.

JAMA 2005;293:1197-203.

7. Gilb T, Finzi S. Principles of software

engineering management. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.; 1988.

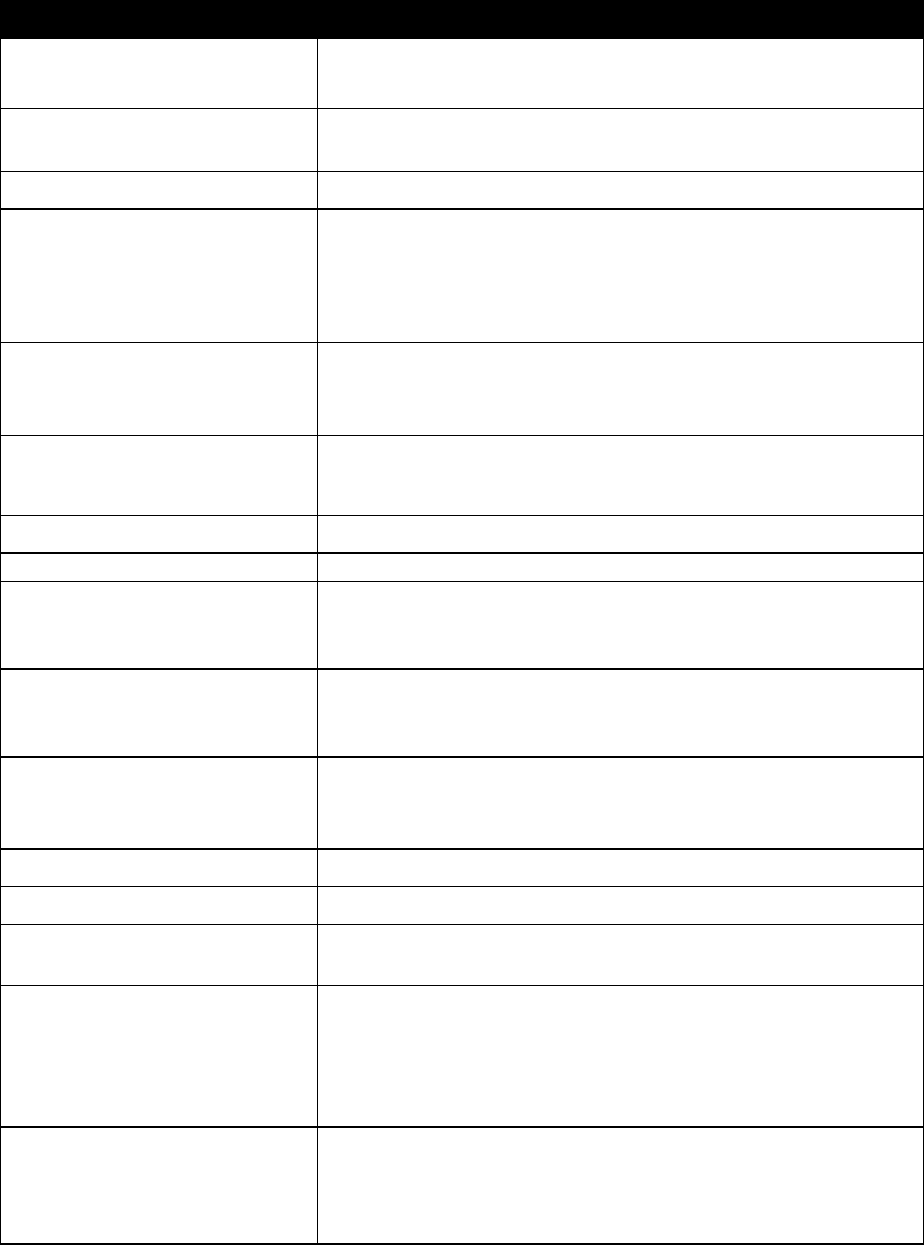

A-1

Appendix I: Summary of Interviewed

Vendors

Interviewed companies with disclosed company information that had CCHIT-certified

ambulatory electronic health records: 2008

Company

Product(s)

Core

markets

No.

employees

No. live

sites (all

versions)

No. users

Years in

business

Company Web site

athenahealth, Inc.

athenaClinicals 9.15.1

Multiple

101– 1,000

101-500

1,001–5,000

>10

http://www.athenahealth.com/

Cerner

Corporation

Cerner Millennium

Powerchart/PowerWorks EMR

2007.19

Multiple

101–1,000

>500

>5,000

>10

http://www.cerner.com

Criterions, LLC

Criterions 1.0.0

Multiple

11-100

>500

>5,000

>10

http://www.criterions.com

e-MDs

e-MDs Solution Series 6.3

Multiple

101–1,000

>500

>5,000

>10

http://www.e-MDs.com

EHS

CareRevolution 5.3

Multiple

101-1,000

> 500

>5,000

>10

http://www.ehsmed.com

GE Healthcare

Centricity Electronic Medical

Record 9.2

Multiple

101–1,000

>500

>5,000

>10

http://www.gehealthcare.com

NextGen

NextGen EMR 5.5

http://www.nextgen.com

Veterans

Administration

VISTA

Federal

Govt.

http://www4.va.gov/VISTA_MONOGRAPH/

B-1

Appendix II: Description of Electronic Health Record

Products

This appendix gives background information on select ambulatory electronic health

record (EHR) systems. Selected system characteristics are shown in Table 1.

A. athenahealth, Inc.: athenaClinicals

SM

9.15.1

athenaHealth, Inc., produces four integrated software systems for ambulatory

clinics/practices: (1) athenaClinicals, an EHR system; (2) athenaCollector, a physician billing

and practice management system; (3) athenaCommunicator, an automated patient

communications system; and (4) PayerView, a system that contains payer rankings and identifies

payers that provide high or low percentages of billed fees and charges. athenaClinicals is a Web-

based EHR system that requires only a computer with Internet access on the part of the

physician.

athenaClinicals incorporates tools such as Clinical Inbox, Workflow Dashboard, and

Intuitive Reporting Wizard that allow the physician to have visibility into practice management

processes and performance, including comparative benchmarks and metrics for compliance,

preventive guidelines, workflow lag times, and followthrough on clinical tasks. The system

receives incoming electronic documents and scans faxes, which are then matched to existing

patients and patient orders, routed to appropriate staff members, and stored for later access.

Through Clinical Inbox, physicians automatically see the documents that require attention, such

as lab results and prescription renewal requests.

The system’s advanced features are based on the athenaHealth Rules Database, which

brings together a compilation of industry data sources, including a real-time database of

insurance company rules and regulations, a list of billing codes, drug formulary rules, Pay for

Performance (P4P) quality program rules, and clinical guidelines and protocols. The information

in the Rules Database gets updated continuously by athenaHealth staff and embedded into the

patient encounters, providing drug interaction alerts, drug allergy alerts, and information required

for reporting. If the practice also has the athenaCollector software, the clinical information then

generates billing information for the patient’s visit.

The system’s updated database and reporting functions support compliance with

government mandates, such as P4P, the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), and the

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, making it

easier for smaller practices to participate. Data required for participation in these incentive

programs are presented at the time of the patient’s visit.

athenaHealth offers a Federal Stimulus Bonus Payment Guarantee Program to its

athenaClinicals clients. The company guarantees that physicians using their software will

receive their HITECH Act payment from Medicare for “meaningful use” of an EHR. Under the

guarantee program, practices’ total liabilities are capped at 6 months of their revenue.

B-2

B. Cerner Corporation: PowerWorks EMR

Cerner Corporation provides a comprehensive set of clinical and business application

systems to ambulatory care practices, small hospitals, and surgery centers encompassing more

than 3,300 clients and 30,000 physicians. Cerner’s Center Millennium system provides

comprehensive clinical and management systems for small hospitals, while their PowerWorks

Surgery Center system suite is tailored to the data needs of ambulatory surgery centers and

outpatient surgical hospitals. Cerner’s products for ambulatory clinics/practices are contained in

their PowerWorks EMR suite, which includes the following three options:

1. PowerWorks EMR—The full-function system that contains all of the suite’s features.

2. PowerWorks EMR Lite—A scaled-down version of the full-function system for practices

that want a user-friendly and affordable entry into EHR systems without comprehensive

physician documentation, E&M (evaluation and management) coding, and clinical

reporting capabilities.

3. PowerWorks ePrescribe—A stand-alone electronic prescription system without

comprehensive health records and reporting capabilities.

PowerWorks EMR is a Web-based system. Cerner hosts the data, and a computer with a

high-speed Internet connection is all that is required by the practitioner. The system’s EMR

functions include: Since Last Time, which offers a concise picture of any updates with the

patient; This Visit, which gives a quick summary of why the patient is there; Sticky Notes, which

incorporates personal patient information on the chart; and Key Notifications, which triages

results and orders by critical, abnormal, and due. In addition to basic electronic medical record

(EMR) functions, PowerWorks EMR includes electronic prescription, intra-office messaging,

staff/task management, diagnosis lists, decision support, immunization schedules, health

maintenance, nursing and physician documentation, E&M coding assistance, and clinical

reporting capabilities. Two additional modules are available for the PowerWorks EMR system:

(1) Patient Education provides the latest medical findings on disease management, procedures,

and aftercare instructions and (2) PowerWorks Advanced Reporting increases reporting

flexibility.

The system’s PowerWorks ePrescribe function allows the physician to electronically

order prescriptions and automate renewals. Functionalities include electronic decision support at

the time of order entry (the Multum® expert database checks against patient allergies and current

medication list) and the support of regulatory compliance. PowerWorks ePrescribe partners with

SuperScripts®, a third-party provider with access to 95 percent of the pharmacies throughout the

country. If the pharmacy is not a SuperScripts® partner, the system converts the prescription to a

fax.

PowerWorks EMR does not include a practice management function. The clinical practice

system does, however, interface with other PowerWorks business systems from Cerner,

including PowerWorks PM and PowerWorks Business Office Services.

B-3

C. Criterions LLC: The Criterions Medical Suite (TCMS) 1.0.0

Criterions provides a single product system that integrates medical practice management

and EHR functionalities for over 2,000 providers. TCMS is a client-server-based system.

Criterions’ system runs on a client-provided server and internal practice computing

communication system.

TCMS is an open-architecture system that employs a Health Level Seven (HL7) standard

communications interface. The system is HIPAA ready, and it supports real-time, live data

backups. The system’s clinical functions include:

Medical charting.

EHR HandRight, which captures handwritten progress notes.

e-Prescriptions, including formulary checking, drug-diagnosis warnings, and patient

pharmacy suggestions.

Total Recall, which offers physician-specific learning of problem treatment.

Validation reports.

Electronic remittance notification.

User tracking and auditing.

Electronic superbill.

Automated payment posting.

Workflow management.

Online system updates.

The TCMS system includes integrated practice management capabilities. The system’s

business functions include:

Accounts receivable management.

Automated collections.

Recall procedures.

Customized coding.

Eligibility checking.

Automated payment processing.

Recall procedures.

The system supports communication between mobile devices, including TCMS Mobile

and most PDAs (personal digital assistants). TCMS also has a number of document-management

functions, including scanning and imaging.

D. e-MDs: e-MDs Solution Series 6.3

The e-MDs Solution Series is a client-server-based system (Web-based version under

development) with an integrated suite of clinical and practice management modules that are

purchased separately in order to customize the system to the needs of the practice. The e-MDs

Solution Series is currently in use by over 1,350 ambulatory practices in the United States and

contains the following modules:

B-4

e-MDs Chart for electronic medical records.

e-MDs Bill for billing and filing claims.

e-MDs Schedule for staff scheduling.

e-MDs Tracking Board for enterprise workflow management.

e-MDs Rounds for mobile scheduling and charge capture.

e-MDS Patient Portal for scheduling and other patient communication.

e-MDs DocMan for electronic document management.

e-MDs Search ICD-9 for billing codes.

Medicapaedia for sharing data across providers and care settings.

The e-MDs Chart module facilitates point-of-care electronic documentation of clinical

data. The module’s features include:

Customizable point-and-click templates.

Automated E&M coding for calculating optimal codes.

Lab tracking for overdue tests and procedures.

Coding database that includes all ICD-9 (Ninth Revision International Classification of

Diseases) and HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) codes.

ScriptWriter, a database of over 35,000 drugs with informative consults.

Rules engine that tracks overdue preventive care.

Best-practice guidelines to guide optimal clinical treatment.

Immunization function that retains and reuses lot numbers and expiration date.

Customizable patient education handouts.

The e-MDs Bill module incorporates a number of integrated practice management

functions. The module’s features include:

Automated charge entry from e-MDs Chart.

Automated billing, including secondary and tertiary insurance billing.

In-office e-mail and task management to assign and track work.

On-screen work lists to schedule routine tasks.

Indepth and flexible reporting.

Referral management that creates a history of inbound and outbound referrals.

Electronic remittance for accounts receivable management.

Recall reporting that generates letters, envelopes, and other reminders for patient

followup.

The e-MDs DocMan module produces, stores, and retrieves electronic documents. The

module supports scanning of paper documents and then categorizing in customizable patient

and/or specialty folders. e-DocMan supports multiple document formats, including lab results,

color images, referral letters, images of insurance cards, and video with sound for reference

purposes.

B-5

E. GE Healthcare: Centricity Electronic Medical Record 9.2

GE Centricity represents a brand of 31 software systems from GE Healthcare. Introduced

in 1994 as Logician, Centricity Electronic Medical Record (EMR) is GE Healthcare’s clinical

data system designed for ambulatory clinics/practices and in use by over 30,000 clinicians.

Centricity EMR is a client-server-based system by GE Healthcare that can exchange data with

Centricity Enterprise, the company’s clinical data system for hospitals. In addition, Centricity®

Practice Solution from GE Healthcare is a completely integrated clinical and financial

management system that helps take care of the whole patient from first visit to final

reimbursement and every point in between. It is a singular approach to a more efficient, high-

quality practice.

Centricity EMR includes workflow, order management, electronic prescribing, and

clinical decision support functionalities. The system brings nationally accepted, evidence-based

guidelines to the patient encounter. Through the GE Medical Quality Improvement Consortium,

patient outcomes can be benchmarked by comparisons with those of other practices and/or

against nationally published standards by the American Medical Association, the American

Diabetes Association, and other professional organizations. Automatic reminders can alert the

clinician to needed tests or procedures required to proactively manage potential problems. The

system also includes an E&M advisor that assists with coding accuracy and reporting capabilities

that facilitate application for pay-for-performance and other incentives.

Centricity EMR’s e-Prescribing function can connect to over 95 percent of the country’s

pharmacies through its partnership with SuperScripts®. Centricity EMR has a formulary

eligibility-checking capability to ascertain patients’ eligibility status through their insurer.

Patients’ medication fill history can also be obtained. e-Prescribe communications are

bidirectional, allowing the pharmacy to submit renewal requests electronically.

Centricity EMR does not include billing or other practice management functions. The

system does, however, integrate with all of GE Centricity’s five practice management systems:

Centricity Business.

Centricity Group Management.

Centricity Practice Management.

Centricity Practice Solution.

Centricity Solutions.

All of the Centricity practice management systems provide patient and financial

management, document management, decision support, and connectivity capabilities. The

functional specifics of each system are tailored to best suit the business needs of different

practice types.

F. EHS Inc.: EHS CareRevolution 5.3

EHS CareRevolution is an integrated practice management and EHR system for

ambulatory clinics/practices. EHS is a single-product firm. EHS provides the system in three

configurations:

B-6

Application Service Provider (ASP) is a Web-based system that is completely hosted by

the EHS DataCenter. The clinic/practice is responsible only for the computer and Internet

connection. The ASP system includes the software license, servers, backup, maintenance,

and upgrades for a monthly fee.

Turnkey is a client-server-based system in which the clinic/practice purchases the

software license and hardware from EHS and the system is installed by EHS at the

clinic/practice. After installation, EHS provides only system support.

Hosted Turnkey combines the service advantages of the hosted ASP system with the

potential tax advantages for business equipment expenditure of the Turnkey system. The

clinic/practice purchases the hardware and software license. The software is installed,

operated, and maintained by EHS in their data center. The clinician then accesses the

system through a computer with an Internet connection.

EHS CareRevolution is designed around the clinical encounter. The system has a number

of customizable features that support the clinician before, during, and after the encounter to

facilitate optimal health outcomes for patients. The system’s clinical features include:

The option of using SpeechMagic® voice recognition by Phillips to populate data and

note fields in the chart through dictation.

Use of the Medcin® knowledge database for intelligent prompting, differential diagnoses,

and an E&M code advisor.

Interoffice communication to review orders, lab results, or phone messages.

Patient tracking to know where patients are located, how long they have been waiting, or

the next steps in the patient encounter.

e-RX to send prescriptions to the pharmacy and refill prescriptions electronically.

Order tracking and management for an order audit trail that automatically queues orders

for patient followup.

Patient portal to provide a two-way communication with the patient for appointment

requests, updating of demographic information, prescription refill requests, questions for

nursing staff, and automated forms and other correspondence.

Protocol management that employs a clinical event manager to aid the clinician in

monitoring best-practice guidelines and clinical protocols.

EHS CareRevolution includes integrated practice management capabilities. The system’s

business functions include:

Management of accounts receivable, billing, and collections with customizable

procedures and policies.

Insurance followup on delinquent claims that includes the ability to identify and address

the errors that cause payer rejections.

Alpha II CodeWizard, embedded to scrutinize the data from each encounter like a payer

and ensure accurate E&M coding.

Ad hoc query capability and customizable standard reporting formats.

Management of work queues and task assignments.

EHS also offers complete back-office business process outsourcing for clinics/practices.

EHS employees handle billing, claim submission, statement inquiries, collections, delinquent

B-7

claims, errors and rejections, and claim scrubbing based on the client’s data and practice business

preferences.

G. NextGen Healthcare Information Systems, Inc.: NextGen

Ambulatory Electronic Health Records (EHR) 5.6

NextGen Ambulatory Electronic Health Records (EHR) is NextGen’s EHR system for

clinics and practices, with over 1,800 installations nationwide. The system is available in either

client-server or Web-based formats. NextGen EHR is a patient charting and clinical data system.

For business and patient communication functions, NextGen EHR must be combined with one or

both of the following additional systems available from NextGen:

NextGen Enterprise Practice Management provides claims management, denial

management, eligibility verification, billing, collections, appointment scheduling,

accounts receivable, reporting, and workflow management capabilities.

NextMD Patient Portal provides online consulting, downloading and filing of patient

forms, patient messaging, communication of test results, and customized disease and

health management plan capabilities.

In addition to electronic charting, NextGen EHR provides reporting and document

management functions. The system’s specific features include:

Electronic data connectivity through interfaces to a number of lab devices.

Clinical content templates for over 25 specialties with built-in workflow management

capabilities.

E&M calculator for coding optimization and compliance.

Disease management templates for diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic diseases.

Image management to capture and import images into the patient chart.

Referral management to automatically populate treatment forms with authorization and

provider information.

Reporting capabilities that allow patient data to be collected, stored, and reported for

business analysis, outcomes analysis, medication recalls, and filing of P4P and other

incentives.

Health maintenance management that allows providers to create orders, customize

schedules, and determine overdue patient exams, screenings, immunizations, and tests.

e-prescribing that electronically transmits prescriptions to the pharmacy, manages refill

requests, checks formulary eligibility, and checks allergy, drug-to-drug, and disease

interaction alerts.

B-8

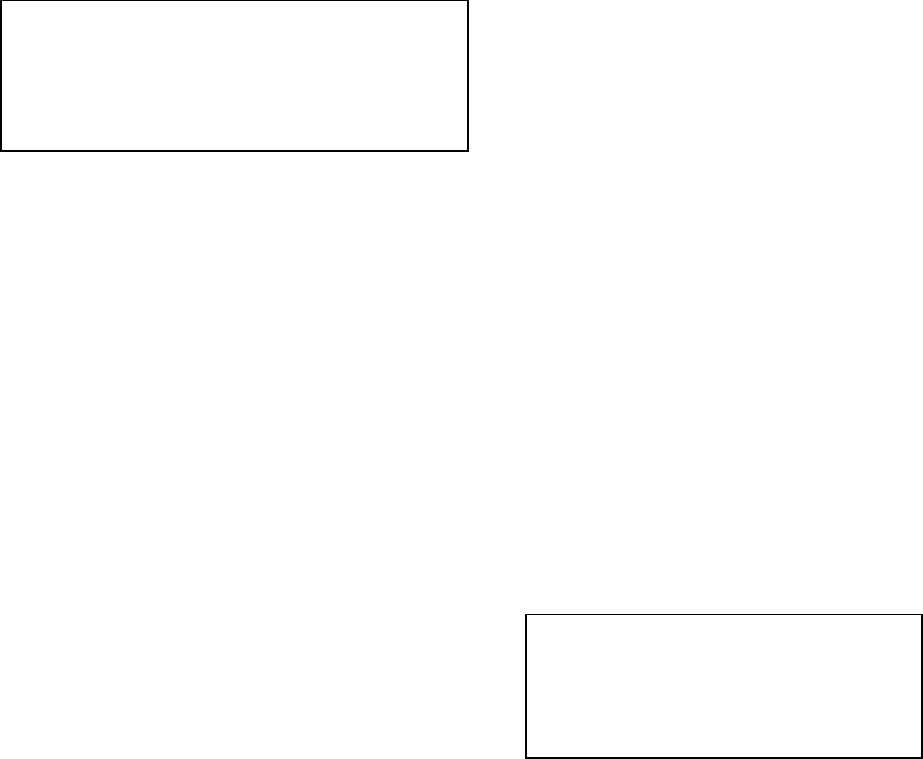

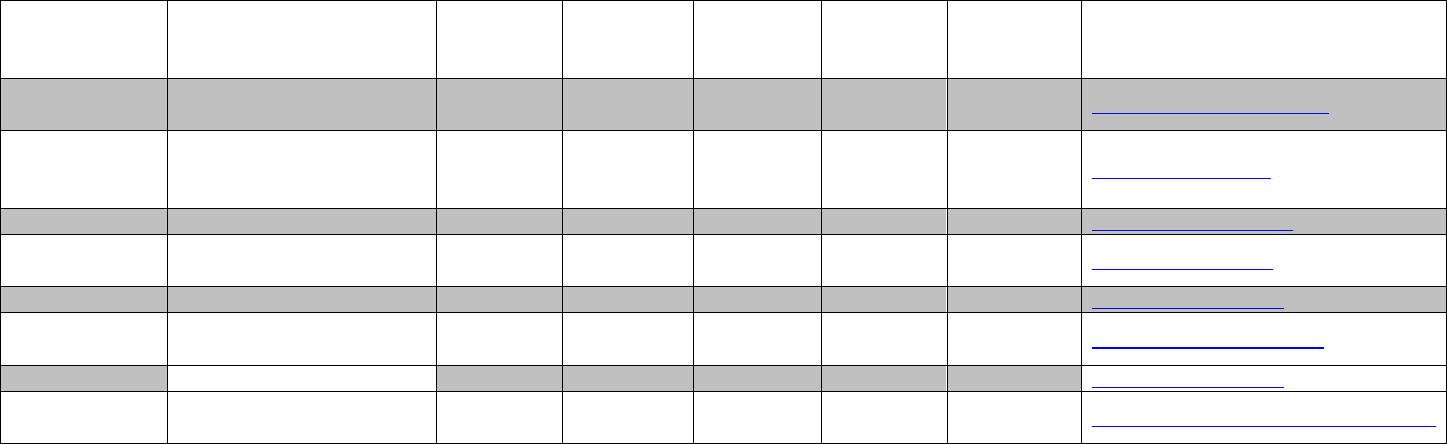

Table 1. Selected system characteristics

EHR system

Practice

management

Patient

comm.

Hardware

format

athenaClinicals

SM

9.15.1

S

S

W

PowerWorks EMR

S

S

W

The Criterions Medical Suite (TCMS) 1.0.0

I

N

C

e-MDs Solution Series 6.3

I/S

I/S

C

Centricity Electronic Medical Record 9.2

S

S

W

EHS CareRevolution 5.3

I

I

W/C

NextGen Ambulatory EHR 5.6

S

S

W/C

EHR=electronic health record.

Practice management and patient communication abbreviations:

I=integrated function within EHR system. I/S=separately purchased module within an integrated EHR system series. N=not

available. S =separately purchased system that integrates with EHR system.

Hardware format abbreviations: C=client server based. W=Web based. W/C=both formats offered.