COUNCIL OF WAR

COUNCIL OF WAR

A HIstORy OF tHe JOINt CHIeFs OF stAFF

1942– 1991

By Steven L. Rearden

P J H O

O D, J S

J C S

W, D.C.

2012

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are

solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the

Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for

public release; distribution unlimited.

Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, pro-

vided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a

courtesy copy of reprints or reviews.

First printing, July 2012

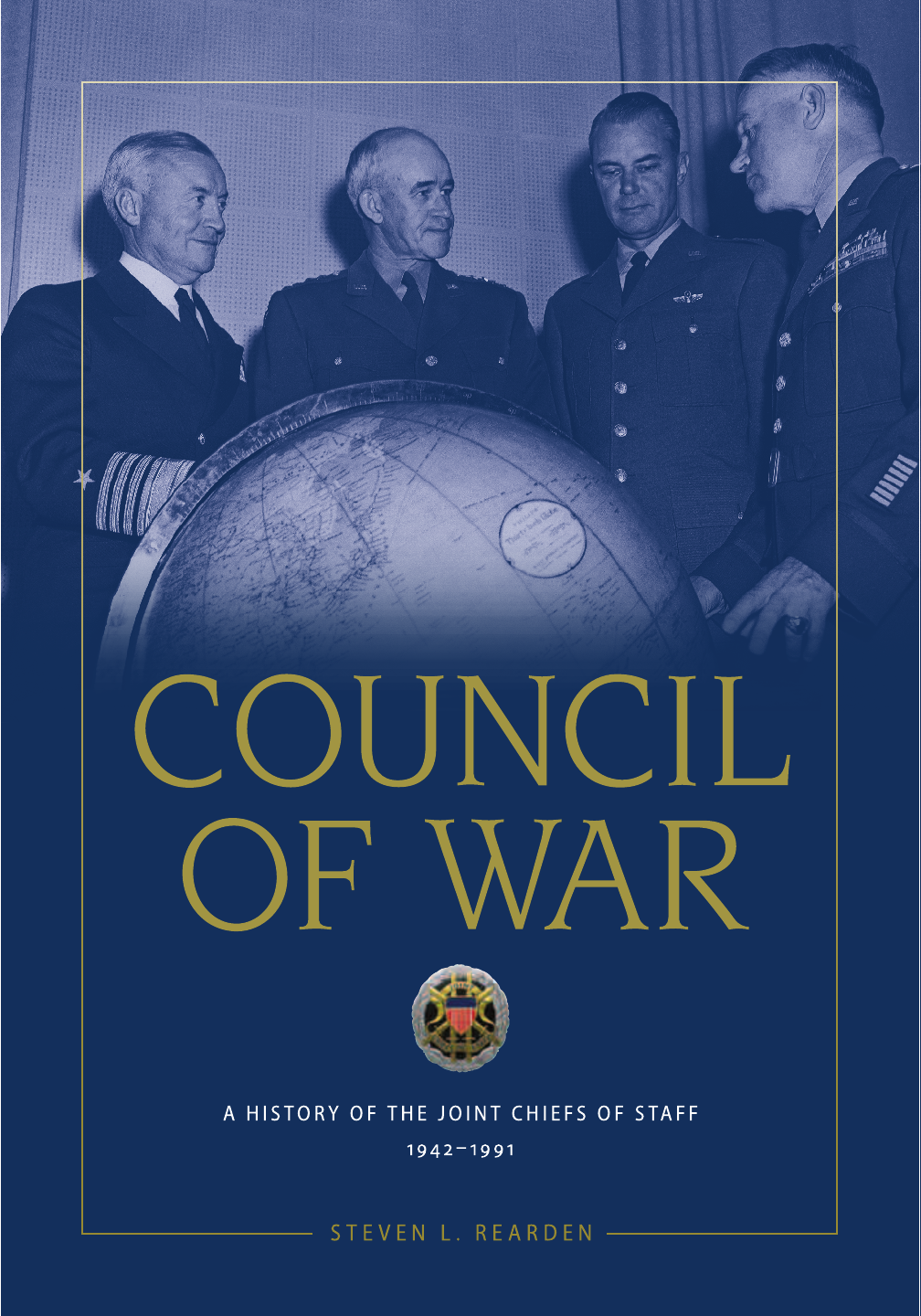

Cover image: Meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Sta on November , , in their

conference room at the Pentagon. From left to right: Admiral Forrest P. Sherman,

Chief of Naval Operations; General Omar N. Bradley, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Sta;

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, U.S. Air Force Chief of Sta; and General J. Lawton Col-

lins, U.S. Army Chief of Sta. Department of the Army photograph collection.

NDU Press publications are sold by the U.S. Government Printing Oce. For ordering

information, call (202) 512-1800 or write to the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Oce, Washington, D.C. 20402. For GPO publications on-line,

access its Web site at: http://bookstore.gpo.gov.

Cover image: Meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

on November 22, 1949, in their conference room

at the Pentagon. From left to right: Admiral Forrest

P. Sherman, Chief of Naval Operations; General

Omar N. Bradley, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff;

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, U.S. Air Force Chief

of Staff; and General J. Lawton Collins, U.S. Army

Chief of Staff. Department of the Army photograph

collection.

Contents

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ix

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi

Chapter 1. THE WAR IN EUROPE ...........................................

The Origins of Joint Planning .......................................

The North Africa Decision and Its Impact ..........................

The Second Front Debate and JCS Reorganization ................

Preparing for Overlord ...............................................

Wartime Collaboration with the Soviet Union .....................

Chapter 2. THE ASIA-PACIFIC WAR AND THE

BEGINNINGS OF POSTWAR PLANNING

....................

Strategy and Command in the Pacic

..............................

The China-Burma-India Theater ...................................

Postwar Planning Begins ............................................

Ending the War with Japan .........................................

Dawn of the Atomic Age ...........................................

Chapter 3. PEACETIME CHALLENGES ....................................

Defense Policy in Transition ........................................

Reorganization and Reform .......................................

War Plans, Budgets, and the March Crisis of ..................

The Defense Budget for FY ..................................

The Strategic Bombing Controversy ...............................

Chapter 4. MILITARIZING THE COLD WAR ..............................

Pressures for Change ................................................

The H-Bomb Decision and NSC ...............................

Onset of the Korean War ..........................................

The Inch’on Operation ............................................

Policy in Flux ......................................................

Impact of the Chinese Intervention ...............................

MacArthur’s Dismissal .............................................

Europe—First Again ...............................................

Chapter 5. EISENHOWER AND THE NEW LOOK .......................

The Reorganization

..........................................

Ending the Korean War ............................................

A New Strategy for the Cold War .................................

Testing the New Look: Indochina .................................

v

Cover image: Meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

on November 22, 1949, in their conference room

at the Pentagon. From left to right: Admiral Forrest

P. Sherman, Chief of Naval Operations; General

Omar N. Bradley, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff;

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, U.S. Air Force Chief

of Staff; and General J. Lawton Collins, U.S. Army

Chief of Staff. Department of the Army photograph

collection.

vi

Confrontation in the Taiwan Strait ................................

The “New Approach” in Europe ..................................

NATO’s Conventional Posture ....................................

Curbing the Arms Race ...........................................

Chapter 6. CHANGE AND CONTINUITY ................................

Evolution of the Missile Program ..................................

The Gaither Report ...............................................

The “Missile Gap” and BMD Controversies .......................

Reorganization and Reform, – ..........................

Defense of the Middle East ........................................

Cuba, Castro, and Communism ....................................

Berlin Dangers .....................................................

Chapter 7. KENNEDY AND THE CRISIS PRESIDENCY ................

The Bay of Pigs ....................................................

Berlin under Siege .................................................

Laos ................................................................

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis ...............................

Showdown over Cuba .............................................

Aftermath: The Nuclear Test Ban ..................................

Chapter 8. THE MCNAMARA ERA ........................................

The McNamara System ...........................................

Reconguring the Strategic Force Posture ........................

NATO and Flexible Response ....................................

The Skybolt Aair .................................................

Demise of the MLF ................................................

A New NATO Strategy: MC / ................................

The Damage Limitation Debate ...................................

Sentinel and the Seeds of SALT ...................................

Chapter 9. VIETNAM: GOING TO WAR ...................................

The Roots of American Involvement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Road to an American War ....................................

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident and Its Aftermath ....................

Into the Quagmire .................................................

Chapter 10. VIETNAM: RETREAT AND WITHDRAWAL .................

Stalemate ..........................................................

Tet and Its Aftermath ..............................................

Nixon, the JCS, and the Policy Process ............................

vii

Winding Down the War ...........................................

Back to Airpower ..................................................

The Christmas Bombing Campaign ...............................

The Balance Sheet .................................................

Chapter 11. DÉTENTE ........................................................

SALT I .............................................................

Shoring Up the Atlantic Alliance ..................................

China: The Quasi-Alliance ........................................

Deepening Involvement in the Middle East .......................

Chapter 12. THE SEARCH FOR STRATEGIC STABILITY ...............

The Peacetime “Total Force” ......................................

Modernizing the Strategic Deterrent ..............................

Targeting Doctrine Revised .......................................

SALT II Begins ....................................................

Vladivostok ........................................................

Marking Time .....................................................

Chapter 13. THE RETURN TO CONFRONTATION .....................

Carter and the Joint Chiefs ........................................

Strategic Forces and PD- ........................................

SALT II ............................................................

NATO and the INF Controversy ..................................

The Arc of Crisis ..................................................

Rise of the Sandinistas .............................................

Creation of the Rapid Deployment Force .........................

The Iran Hostage Rescue Mission .................................

Chapter 14. THE REAGAN BUILDUP .......................................

Reagan and the Military ...........................................

Forces and Budgets ................................................

Military Power and Foreign Policy ................................

The Promise of Technology: SDI ..................................

Arms Control: A New Agenda .....................................

Chapter 15. A NEW RAPPROCHEMENT ..................................

Debating JCS Reorganization .....................................

The Goldwater-Nichols Act of ..............................

NATO Resurgent .................................................

Gorbachev’s Impact ................................................

Terrorism and the Confrontation with Libya ......................

viii

Showdown in Central America ....................................

Tensions in the Persian Gulf .......................................

Operation Earnest Will .............................................

Chapter 16. ENDING THE COLD WAR .....................................

Policy in Transition ................................................

Powell’s Impact as Chairman ......................................

The Base Force Plan ...............................................

Operations in Panama .............................................

The CFE Agreement ..............................................

START I and Its Consequences ...................................

Chapter 17. STORM IN THE DESERT ......................................

Origins of the Kuwait Crisis .......................................

Framing the U.S. Response ........................................

Operational Planning Begins ......................................

The Road to War ..................................................

Final Plans and Preparations .......................................

Liberating Kuwait: The Air War ....................................

Phase IV: The Ground Campaign ..................................

The Post-hostilities Phase ..........................................

Chapter 18. CONCLUSION ...................................................

Glossary .........................................................................

Index ............................................................................

About the Author .................................................................

ix

Foreword

Established during World War II to advise the President on the strategic direction of

the Armed Forces of the United States, the Joint Chiefs of Sta (JCS) continued in

existence after the war and, as military advisers and planners, have played a signicant

role in the development of national policy. Knowledge of JCS relations with the

President, the Secretary of Defense, and the National Security Council is essential to

an understanding of the current work of the Chairman and the Joint Sta. A history

of their activities, both in war and peacetime, also provides important insights into

the military history of the United States. For these reasons, the Joint Chiefs of Sta

directed that an ocial history of their activities be kept for the record. Its value for

instructional purposes, for the orientation of ocers newly assigned to the JCS orga-

nization, and as a source of information for sta studies is self-apparent.

Council of War: A History of the Joint Chiefs of Sta, 1942–1991 follows in the

tradition of volumes previously prepared by the Joint History Oce dealing with

JCS involvement in national policy, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Adopt-

ing a broader view than earlier volumes, it surveys the JCS role and contributions

from the early days of World War II through the end of the Cold War. Written from

a combination of primary and secondary sources, it is a fresh work of scholarship,

looking at the problems of this era and their military implications. The main prism

is that of the Joint Chiefs of Sta, but in laying out the JCS perspective, it deals also

with the wider impact of key decisions and the ensuing policies.

Dr. Steven L. Rearden, the author of this volume, holds a bachelor's degree

from the University of Nebraska and a Ph.D. in history from Harvard University.

His association with the Joint History Oce dates from . He has written and

published widely on the history of the Joint Chiefs of Sta and the Oce of the

Secretary of Defense, and was co-collaborator on Ambassador Paul H. Nitze’s book

From Hiroshima to Glasnost: At the Center of Decision—A Memoir ().

This publication has been reviewed and approved for publication by the Depart-

ment of Defense. While the manuscript itself is unclassied, some parts of documents

cited in the source notes may remain classied. This is an ocial publication of the

Joint History Oce, but the views expressed are those of the author and do not

necessarily represent those of the Joint Chiefs of Sta or the Department of Defense.

—John F. Shortal

Brigadier General, USA (Ret.)

Director for Joint History

xi

Preface

Shortly after arriving at Fort McPherson, Georgia, in , to head the U.S. Army

Forces Command (FORSCOM), General Colin L. Powell put up a framed poster of

the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a present from Dr. King’s widow, in the

main conference room. On it were inscribed Dr. King’s words: “Freedom has always

been an expensive thing.” Dr. King had in mind the sacrices of the civil rights move-

ment, of which he had been a major catalyst, in the s and s. But to Powell, a

career Army ocer who would soon leave FORSCOM to become the

th

Chair-

man of the Joint Chiefs of Sta, Dr. King’s words had a broader, deeper meaning. Not

only did he nd them applicable to the civil rights struggle, but also he felt they spoke

directly to the entire American experience and the central role played by the Armed

Forces in preserving American values—freedom rst among them.

For the Joint Chiefs of Sta (JCS), the defense of freedom began with their

creation as a corporate body in January to deal with the growing emergency

arising from the recent Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Thrust suddenly into the

maelstrom of World War II, the United States found itself ill-prepared to coordinate

a global war eort with its allies or to develop comprehensive strategic and logisti-

cal plans for the deployment of its forces. To ll these voids, President Franklin D.

Roosevelt established the JCS, an ad hoc committee of the Nation’s senior military

ocers. Operating without a formal charter or written statement of duties, the Joint

Chiefs functioned under the immediate authority and direction of the President in

his capacity as Commander in Chief. A committee of coequals, the JCS came as

close as anything the country had yet seen to a military high command.

After the war the Joint Chiefs of Sta became a permanent xture of the country’s

defense establishment. Under the National Security Act of , Congress accorded

them statutory standing, with specic responsibilities. Two years later they acquired a

presiding ocer, the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Sta, a statutory position carrying statu-

tory authority that steadily increased over time. While often criticized as ponderous in

their deliberations and inecient in their methods, the JCS performed key advisory

and support functions that no other body could duplicate in high-level deliberations.

Sometimes, like during the Vietnam War in the s, their views and recommendations

carried less weight and had less impact than at other times. But as a rule their advice, rep-

resenting as it did a distillation of the Nation’s top military leaders’ thinking, was impos-

sible to ignore. Under legislation enacted in , the Joint Chiefs’ assigned duties and

responsibilities passed almost in toto to the Chairman, who became principal military

advisor to the President, the Secretary of Defense, and the National Security Council.

But even though their corporate advisory role was over, the Joint Chiefs retained their

statutory standing and continued to meet regularly as military advisors to the Chairman.

xii

The history of the Joint Chief of Sta parallels the emergence of the United States

in a great-power role and the growing demands that those responsibilities placed on

American policymakers and military planners. During World War II, the major chal-

lenge was to wage a global war successfully on two fronts, one in Europe, the other in

Asia and the Pacic. Afterwards, with the coming of an uneasy peace, the JCS faced

new, less well-dened dangers arising from the turbulent relationship between East and

West known as the Cold War. The product of long-festering political, economic, and

ideological antagonisms, the Cold War also saw the proliferation of nuclear weapons and

soon became an intense and expensive military competition between the United States

and the Soviet Union. Though the threat of nuclear war predominated, the continuing

existence of large conventional forces on both sides heightened the sense of urgency and

further fueled doomsday speculation that the next world war could be the last. A period

of recurring crises and tensions, the Cold War nally played out in the late s and

early s, not with the cataclysmic confrontation that some people expected, but with

the gradual reconciliation of key dierences between East and West and eventually the

collapse of Communism in Europe and the implosion of the Soviet Union.

The narrative that follows traces the role and inuence of the Joint Chiefs of

Sta from their creation in through the end of the Cold War in . It is,

rst and foremost, a history of events and their impact on national policy. It is also

a history of the Joint Chiefs of Sta themselves and their evolving organization, a

reection in many ways of the problems they faced and how they elected to ad-

dress them. Over the years, the Joint History Oce has produced and published

numerous detailed monographs on JCS participation in national security policy.

There has never been, however, a single-volume narrative summary of the JCS role.

This book, written from a combination of primary and secondary sources, seeks to

ll that void. An overview, it highlights the involvement of the Joint Chiefs of Sta

in the policy process and in key events and decisions. My hope is that students of

military history and national security aairs will nd it a useful tool and, for those

so inclined, a convenient reference point for further research and study.

Like most authors, I have numerous obligations to recognize. For their willing-

ness to read and comment on various aspects of the manuscript, I need to thank Dr.

Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., former Vice Chancellor and Professor of History Emeritus

of Sewanee University; Dr. Lawrence S. Kaplan, Professor of History Emeritus of

Kent State University; Dr. Donald R. Baucom, former Chief Historian of the Ballistic

Missile Defense Organization; Dr. Wayne W. Thompson of the Oce of Air Force

History; and Dr. Graham A. Cosmas of the Joint History Oce. I am also extremely

grateful to the people at the Information Management Division of the Joint Chiefs

of Sta, in particular Ms. Betty M. Goode and Mr. Joseph R. Cook, for their help in

xiii

the documentation and clearance process. I am especially indebted to Molly Bom-

pane and the Army Heritage and Education Center for their outstanding pictorial

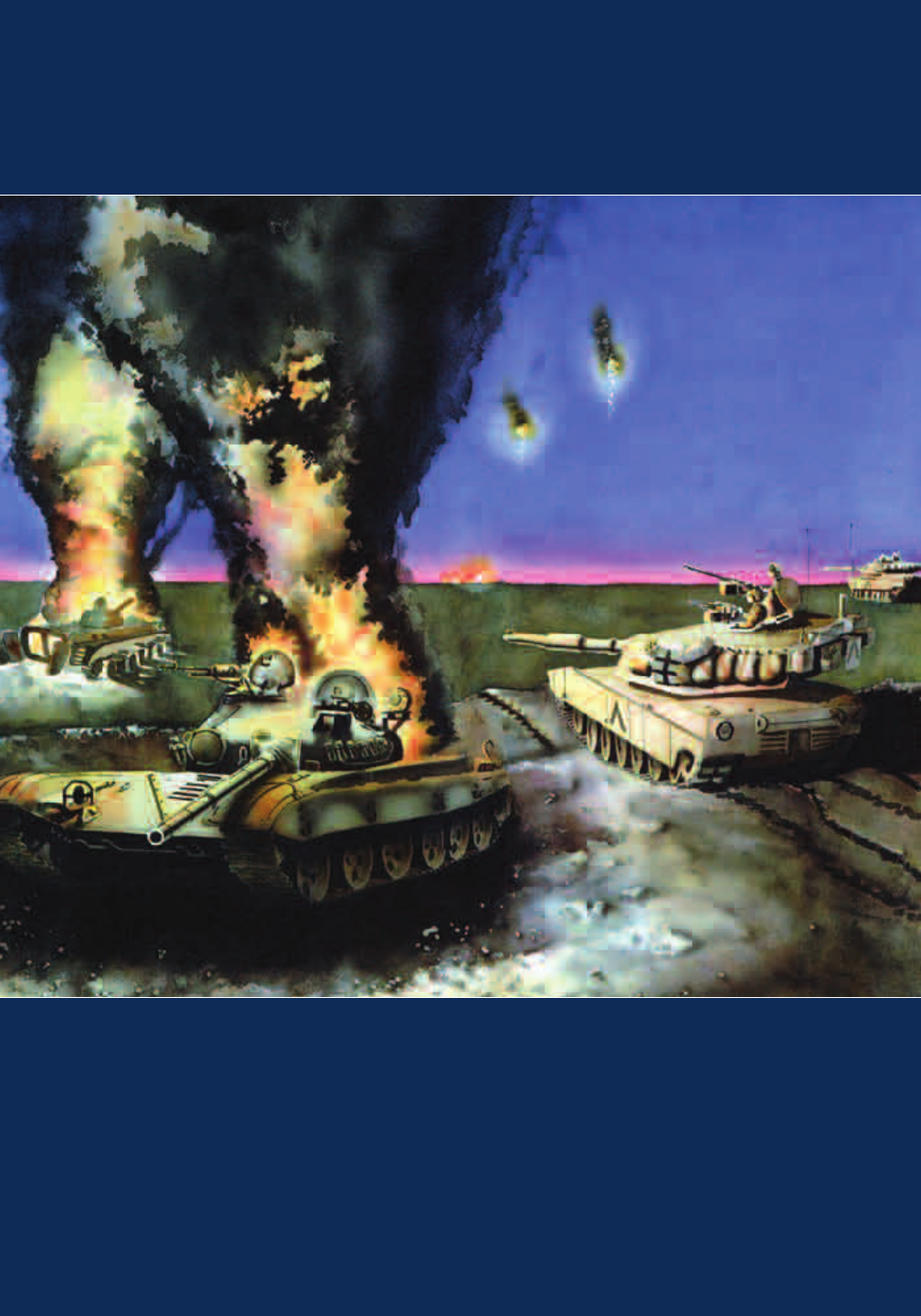

support. I would like to thank Richard Stewart of the Center of Military History for

the use of the Army’s art. The production of this book would not have been possible

without the able advice and assistance of NDU Press Executive Editor Dr. Jerey D.

Smotherman and Senior Copy Editor Mr. Calvin B. Kelley.

I am also deeply indebted to Dr. Edward J. Drea and Dr. Walter S. Poole who

contributed in more ways than I can begin to enumerate. Both are long-standing

friends and colleagues whose unrivaled knowledge, wisdom, and insights into mili-

tary history and national security aairs have been sources of inspiration for many

years. I want to thank Frank Homan of NDU Press for his faith in and support

of this project. My heaviest obligations are to the two Directors for Joint History

who made this book possible—Brigadier General David A. Armstrong, USA (Ret.),

who initiated the project, and his successor, Brigadier General John F. Shortal, USA

(Ret.), who saw it to completion. They were unstinting in their encouragement,

support, and human kindness.

Lastly, I need to thank my wife, Pamela, whose patience and love were indispensible.

—Steven L. Rearden

Washington, DC

March

Note

Colin L. Powell, with Joseph E. Persico, My American Journey (New York: Random House,

), -.

British and American Combined Chiefs of Sta with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill at the Second

Quebec Conference, September 1944. (front row, left to right) General George C. Marshall, Chief of Sta, U.S. Army;

Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Sta to the Commander in Chief; President Franklin D. Roosevelt; Prime Minister

Winston S. Churchill; Field Marshal Sir Alan F. Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Sta; Field Marshal Sir John Dill,

Chief of the British Joint Sta Mission to the United States; (back row, left to right) Major General Leslie C. Hollis,

Secretary of the Chiefs of Sta Committee; General Sir Hastings Ismay, Prime Minister Churchill’s Military Assistant

and Representative to the Chiefs of Sta Committee; Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations; Air Chief

Marshal Sir Charles Portal; General Henry H. Arnold, Commanding General, Army Air Forces; and Admiral Sir Andrew B.

Cunningham, First Sea Lord.

Chapter 1

The War in europe

During the anxious gray winter days immediately following the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt confronted the most serious crisis of his Presi-

dency. Now engaged in a rapidly expanding war on two major fronts—one against

Nazi Germany in Europe, the other against Imperial Japan in the Pacic—he wel-

comed British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill to Washington on December

22, 1941, for 3 weeks of intensive war-related discussions. Code-named ARCADIA,

the meeting’s purpose, as Churchill envisioned it, was to “review the whole war

plan in the light of reality and new facts, as well as the problems of production and

distribution.”

1

Overcoming recent setbacks, pooling resources, and regaining the

initiative against the enemy became the main themes. To turn their decisions into

concrete plans, Roosevelt and Churchill looked to their senior military advisors,

who held parallel discussions. From these deliberations emerged the broad outlines

of a common grand strategy and several new high-level organizations for coordinat-

ing the war eort. One of these was a U.S. inter-Service advisory committee called

the Joint Chiefs of Sta (JCS).

2

ARCADIA was the latest in a series of Anglo-American military sta discus-

sions dating from January 1941. Invariably well briefed and meticulously prepared

for these meetings, British defense planners operated under a closely knit organiza-

tion known as the Chiefs of Sta Committee, created in 1923. At the time of the

ARCADIA Conference, its membership consisted of the Chief of the Imperial

General Sta, General Sir Alan F. Brooke (later Viscount Alanbrooke), the First Sea

Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, and the Chief of the Air Sta, Air

Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal. They reported directly to the Prime Minister

and the War Cabinet and served as the government’s high command for conveying

directives to commanders in the eld.

3

Prior to ARCADIA nothing comparable to Britain’s Chiefs of Sta Com-

mittee existed in the United States. As Brigadier General (later General) Thomas

T. Handy recalled the situation: “We were more or less babes in the wood on the

planning and joint business with the British. They’d been doing it for years. They

were experts at it and we were just starting.”

4

The absence of any standing coordi-

nating mechanisms on the U.S. side forced the ARCADIA participants to improvise

if they were to assure future inter-Allied cooperation and collaboration. Just before

1

COUNCIL OF WAR

2

adjourning on January 14, 1942, they established a consultative body known as the

Combined Chiefs of Sta (CCS), composed of the British chiefs and their Ameri-

can “opposite numbers.” Since the British chiefs had their headquarters in London,

they designated the senior members of the British Joint Sta Mission (JSM) to the

United States, a tri-Service organization, as their day-to-day representatives to the

CCS in Washington. Thereafter, formal meetings of the Combined Chiefs (i.e., the

British chiefs and their American opposite numbers) took place only at summit

conferences attended by the President and the Prime Minister. Out of a total of 200

CCS meetings held during the war, 89 were held at these summit meetings.

5

U.S. membership on the CCS initially consisted of General George C. Mar-

shall, Chief of the War Department General Sta; Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief

of Naval Operations (CNO); Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S.

Fleet; and Lieutenant General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces and

Deputy Chief of Sta for Air. Though Arnold’s role was comparable to Portal’s, he

spoke only for the Army Air Forces since the Navy had its own separate air com-

ponent.

6

Shortly after the ARCADIA Conference adjourned, President Roosevelt

reassigned Stark to London as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe, a liaison

job, and made King both Chief of Naval Operations and Commander in Chief,

U.S. Fleet. In this dual capacity, King became the Navy’s senior ocer and its sole

representative to the CCS.

7

To avoid confusion, the British and American chiefs

designated collaboration between two or more of the nations at war with the Axis

powers as “combined” and called inter-Service cooperation by one nation “joint.”

The U.S. side designated itself as the “Joint United States Chiefs of Sta,” soon

shortened to “Joint Chiefs of Sta.”

The Origins Of JOinT Planning

Though clearly a prudent and necessary move, the creation of the Joint Chiefs of

Sta was a long time coming. By no means was it preordained. When the United

States declared war on the Axis powers in December 1941, its military establishment

consisted of autonomous War and Navy Departments, each with a subordinate air

arm. Command and control were unied only at the top, in the person of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt in his constitutional role as Commander in Chief. Politi-

cally astute and charismatic, Roosevelt dominated foreign and defense aairs and

insisted on exercising close personal control of the Armed Forces. The creation of

the Joint Chiefs of Sta eectively reinforced his authority. Often bypassing the

Service Secretaries, he preferred to work directly with the uniformed heads of the

military Services. From 1942 on, he used the JCS as an extension of his powers as

THE WAR IN EUROPE

3

Commander in Chief. The policy he laid down stipulated that “matters which were

purely military must be decided by the Joint Chiefs of Sta and himself, and that,

when the military conicted with civilian requirements, the decision would have

to rest with him.”

8

In keeping with his overall working style, his relations with the

chiefs were casual and informal, which allowed him to hold discussions in lieu of

debates and to seek consensus on key decisions.

9

Below the level of the President, inter-Service coordination at the outset of

World War II was haphazard. Ocers then serving in the Army and the Navy were

often deeply suspicious of one another, inclined by temperament, tradition, and

culture to remain separate and jealously guard their turf. Not without diculty,

Marshall and King reached a modus vivendi that tempered their dierences and

allowed them to work in reasonable harmony for most of the war.

10

Their subordi-

nates, however, were generally not so lucky. Issues such as the deployment of forces,

command arrangements, strategic plans, and (most important of all) the allocation

of resources invariably generated intense debate and friction. As the war progressed,

the increasing use of unied theater commands, bringing ground, sea, and air forces

under one umbrella organization, occasionally had the untoward side-eect of ag-

gravating these stresses and strains. According to Sir John Slessor, whose career in the

British Royal Air Force brought him into frequent contact with American ocers

during and after World War II, “The violence of inter-Service rivalry in the United

States in those days had to be seen to be believed and was an appreciable handicap

to their war eort.”

11

Inter-Service collaboration before the war rested either on informal arrange-

ments, painstakingly worked out through goodwill as the need arose, or on the

modest achievements of the Joint Army and Navy Board. Established in 1903 by

joint order of the Secretaries of War and Navy, the Joint Board was responsible for

“conferring upon, discussing, and reaching common conclusions regarding all mat-

ters calling for the co-operation of the two Services.”

12

By the eve of World War II,

the Board’s membership consisted of the Army Chief of Sta, Deputy Chief of Sta,

Chief of the War Plans Division, Chief of Naval Operations, Assistant Chief of Naval

Operations, and Director of the Naval War Plans Division.

13

The Joint Board’s main functions were to coordinate strategic planning be-

tween the War and Navy Departments and to assist in clarifying Service roles and

missions. Between 1920 and 1938, the board’s major achievement was the produc-

tion of the “color” plans, so called because each plan was designated by a particular

color. Plan Orange was for a war with Japan.

14

But after the Munich crisis in the au-

tumn of 1938, with tensions rising in both Europe and the Pacic, the board began

to consider a wider range of contingencies involving the possibility of a multifront

4

COUNCIL OF WAR

war simultaneously against Germany, Italy, and Japan. The result was a new series

of “Rainbow” plans. The plan in eect at the time of Pearl Harbor was Rainbow

5, which envisioned large-scale oensive operations against Germany and Italy and

a strategic defensive in the Pacic until success against the European Axis powers

allowed transfer of sucient assets to defeat the Japanese.

15

To help assure eective execution of these plans, the Joint Board also sought a

clearer delineation of Service roles and missions. A contentious issue in the best of

times, roles and missions became all the more divisive during the interwar period

owing to the limited funding available and the emergence of competing land- and

sea-based military aviation systems. The board addressed these issues in a manual,

Joint Action of the Army and Navy (JAAN), rst published in 1927 and revised in

1935, with minor changes from year to year thereafter. The doctrine incorpo-

rated into the JAAN called for voluntary cooperation between Army and Navy

commanders whenever practicable. Unity of command was permitted only when

ordered by the President, when specically provided for in joint agreements be-

tween the Secretaries of War and Navy, or by mutual agreement of the Army and

Navy commanders on the scene. For want of a better formula, the JAAN simply

accepted the status quo and left controversial issues like the control of airpower

divided between the Services, to be exploited as their respective needs dictated

and resources allowed.

16

After 1938, with the international situation deteriorating, the Joint Board be-

came increasingly active in conducting exploratory studies and drafting joint stra-

tegic plans (the Rainbow series) where the Army and the Navy had a common

interest. For support, the board relied on part-time inter-Service advisory and plan-

ning committees. The most prominent and active were the senior Joint Planning

Committee, consisting of the chiefs of the Army and Navy War Plans Divisions,

which oversaw the permanent Joint Strategic Committee and various ad hoc com-

mittees assigned to specialized technical problems, and the Joint Intelligence Com-

mittee, consisting of the intelligence chiefs of the two Services, which coordinated

intelligence activities. Despite its eorts, however, the Joint Board never acquired

the status or authority of a military command post and remained a purely advisory

organization to the military Services and, through them, to the President.

17

While the limitations of the Joint Board system were abundantly apparent, there

was little incentive prior to Pearl Harbor to make signicant changes. The most ambi-

tious reform proposal originated in the Navy General Board and called for the cre-

ation of a joint general sta headed by a single chief of sta to develop general plans

for major military campaigns and to issue directives for detailed supporting plans to

the War and Navy Departments. First broached in June 1941, this proposal was referred

5

THE WAR IN EUROPE

to the Army and Navy Plans Divisions where it remained until after the Japanese

attack. Public reaction to the Pearl Harbor catastrophe, allegedly the result of faulty

inter-Service communication, awed intelligence, and divided command, led Admiral

Stark in late January 1942, to rescue the joint general sta paper from the oblivion of

the Plans Divisions and to place it on the Joint Board’s agenda. Here it encountered

strong opposition from Navy representatives, its erstwhile sponsors. Upon further

reection, they declared it essentially unworkable. Their main objection was that such

a scheme would require a corps of sta ocers, which did not exist, who were thor-

oughly cognizant of all aspects of both Services. Army representatives favored the plan

but did not push it in light of the Navy’s strong opposition. Discussion of the matter

culminated at a Joint Board meeting on March 16, where the members, unable to

agree, left it “open for further study.”

18

By the time the Joint Board dropped the joint general sta proposal, the Joint

Chiefs of Sta were beginning to emerge as the country’s de facto high command.

This process resulted not from any directive issued by the President or emergency

legislation enacted by Congress, but from the paramount importance of forming

common cause with the British Chiefs of Sta on matters of mutual interest and

the strategic conduct of the war. As useful as the Joint Board may have been as a

peacetime planning mechanism, it had limited utility in wartime and was not set

up to function in a command capacity or to provide liaison with Allied planners.

Though still in its infancy, the Combined Chiefs of Sta system was already exercis-

ing a pervasive inuence on American military planning, thanks in large part to the

easy and close collaboration that quickly developed between General Marshall and

the senior British representative, Sir John Dill.

19

As the CCS system became more

entrenched, it demanded a more focused American response, which only the orga-

nizational structure of the Joint Chiefs of Sta could provide.

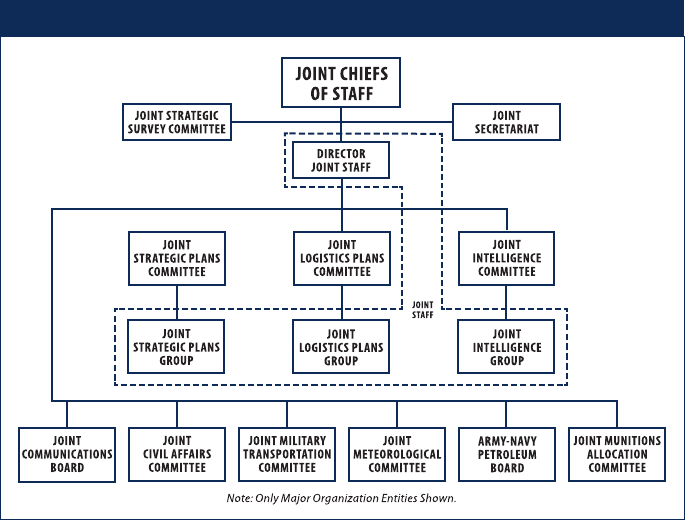

The Joint Chiefs held their rst formal meeting on February 9, 1942, and over

the next several months gradually absorbed the Joint Board’s role and functions.

20

To support their work, the Joint Chiefs established a joint sta that comprised a

network of inter-Service committees corresponding to the committees making up

the Combined Chiefs of Sta. Initially, only two JCS panels—the Joint Sta Plan-

ners (JPS) and the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC)—had full-time support sta,

provided by remnants of the Joint Board. Most of those on the other joint com-

mittees served in a part-time capacity and appeared on the duty roster as “associate

members,” splitting their time between their Service responsibilities and the JCS.

A few ocers, designated “primary duty associate members,” were considered to be

full-time. Owing to incomplete records, no one knows for sure how many ocers

served on the Joint Sta at any one time during the war. Committees varied in size,

6

COUNCIL OF WAR

from the Joint Strategic Survey Committee, which had only three members, on up

to the Joint Logistics Committee, which once had as many as two hundred associate

members.

21

Money to support the Joint Chiefs’ operations, including the salaries for

about 50 civilian clerical helpers, came from the War and Navy Departments and an

allocation from the President’s contingent fund.

22

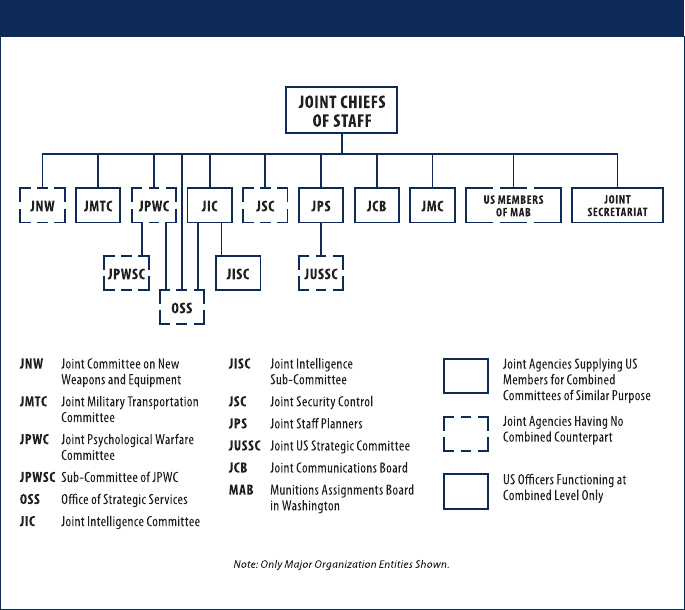

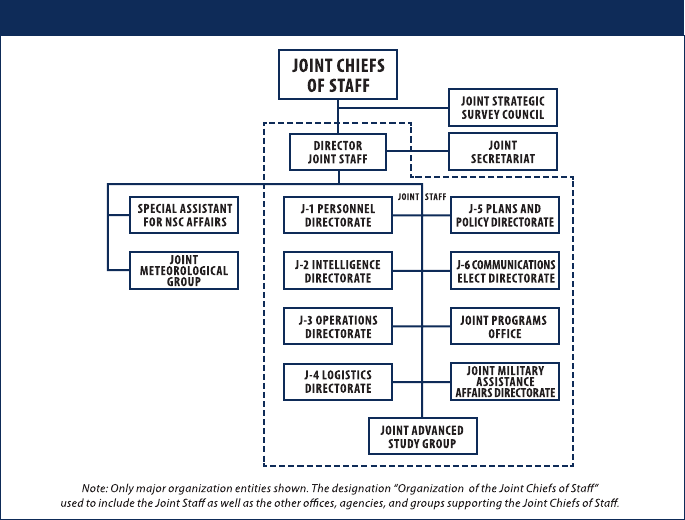

Figure 1–1.

JCS Organization Chart,

Initially modeled on the CCS system, the JCS organization gradually departed

from the CCS structure to meet the Joint Chiefs’ unique requirements. During

1942 the Joint Chiefs added three subordinate components without CCS counter-

parts—the Joint New Weapons Committee, the Joint Psychological Warfare Com-

mittee, and the Oce of Strategic Services (OSS). The rst two were part-time

bodies providing advisory support to the Joint Chiefs in the areas of weapons re-

search and wartime propaganda and subversion. The third was an operational and

research agency that specialized in espionage and clandestine missions behind en-

emy lines. Though the OSS fell under the jurisdiction of the Joint Chiefs of Sta, it

7

THE WAR IN EUROPE

had its own director, William J. Donovan, who reported directly to the President.

23

Between 1943 and March 1945, the JCS organization expanded further to include

the Army-Navy Petroleum Board and separate committees dealing with produc-

tion and supply matters, postwar political-military planning, and the coordination

of civil aairs in liberated and occupied areas.

Wartime membership of the Joint Chiefs was completed on July 18, 1942, when

President Roosevelt appointed Admiral William D. Leahy as Chief of Sta to the

Commander in Chief. The inspiration for Leahy’s appointment came from General

Marshall, who suggested to the President in February 1942 that there should be a

direct link between the White House and the JCS, an ocer to brief the President

on military matters, keep track of papers sent to the White House for approval, and

transmit the President’s decisions to the JCS. As the President’s designated represen-

tative, he could also preside at JCS meetings in an impartial capacity.

24

President Roosevelt initially saw no need for a Chief of Sta to the Com-

mander in Chief. Likewise, Admiral King, fearing adverse impact on Navy interests

if another ocer were interposed between himself and the President, opposed the

idea. It was not until General Marshall suggested appointing Admiral Leahy, an old

friend of the President’s and a trusted advisor, that Roosevelt came around.

25

The

Admiral, who had retired as Chief of Naval Operations in 1939, was just completing

an assignment as Ambassador to Vichy, France. The appointment of another senior

naval ocer was perhaps the only way of gaining Admiral King’s endorsement, since

it balanced the JCS with two members from the War Department and two from

theNavy.

A scrupulously impartial presiding ocer, Leahy never became the strong rep-

resentative of JCS interests that Marshall hoped he would be. In Marshall’s view,

Leahy limited himself too much to acting as a liaison between the JCS and the

White House. Still, he played an important role in conveying JCS recommenda-

tions and in brieng the President every morning.

26

In no way was his position

comparable to that later accorded to the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Sta. In meet-

ings with the President or with the Combined Chiefs of Sta, Leahy was rarely the

JCS spokesman. That role usually fell to either General Marshall, who served as the

leading voice on strategy in the European Theater, or Admiral King, who held sway

over matters aecting the Pacic.

Though considerable, the Joint Chiefs’ inuence over wartime strategy and

policy was never as great as some observers have argued. According to historian

Kent Roberts Greeneld, there are more than 20 documented instances in which

Roosevelt overruled the chiefs’ judgment on military situations.

27

While the chiefs

liked to present the President with unanimous recommendations, they were not

8

COUNCIL OF WAR

averse to oering a “split” position when their views diered and then thrashing

out a solution at their meetings with the President. During the rst year or so of the

war, the President’s special assistant, Harry Hopkins, also regularly attended these

meetings. Rarely invited to participate were the Service Secretaries (Secretary of

War Henry L. Stimson and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox) and Secretary of

State Cordell Hull, all of whom found themselves marginalized for much of the war.

But despite their close association, the President and the Joint Chiefs never devel-

oped the intimate, personal rapport Churchill had with his military chiefs. Between

Roosevelt and the JCS, there was little socializing. Comfortable and productive,

their relationship was above all professional and businesslike.

28

Even though the Joint Chiefs of Sta functioned as the equivalent of a na-

tional military high command, their status as such, throughout World War II, was

never established in law or by Executive order. Preoccupied with waging a global

war, they paid scant attention to the question of their status until mid-1943 when

they briey considered a charter dening their duties and responsibilities. The

only JCS member to evince strong interest in a charter was Admiral King, who

professed to be “shocked” that there was no basic denition of JCS duties and

responsibilities. In the existing circumstances, he doubted whether the JCS could

continue to function eectively. Admiral Leahy took exception. “The absence of

any xed charter of responsibility,” he insisted, “allowed greater exibility in the

JCS organization and enabled us to extend its activities to meet the changing

requirements of the war.” He pointed out that, since the JCS served at the Presi-

dent’s pleasure, they performed whatever duties he saw t; under a charter, they

would be limited to performing assigned functions. Initially, General Marshall sid-

ed with Admiral Leahy but nally became persuaded, in the interests of preserving

JCS harmony, to support issuance of a charter in the form of an Executive order.

29

The Joint Chiefs approved the text of such an order on June 15, 1943, and

submitted it to the President the next day. The proposed assignment of duties

was fairly routine and related to ongoing activities of advising the President,

formulating military plans and strategy, and representing the United States on

the Combined Chiefs of Sta.

30

Still, the overall impact would have been to

place the JCS within a conned frame of reference, and arguably restrict their

deliberations to a specic range of issues. Satised with the status quo, the Presi-

dent rejected putting the chiefs under written instructions. “It seems to me,” he

told them, “that such an order would provide no benets and might in some

way impair exibility of operations.”

31

As a result, the Joint Chiefs continued to

manage their aairs throughout the war without a written denition of their

9

THE WAR IN EUROPE

functions or authority, but with the tacit assurance that President Roosevelt

fully supported their activities.

The nOrTh africa DecisiOn anD iTs imPacT

While the ARCADIA Conference of December 1941–January 1942 conrmed that

Britain and the United States would integrate their eorts to defeat the Axis, it

left many details of their collaboration unsettled. The agreed strategic concept that

emerged from ARCADIA was to defeat Germany rst, while remaining on the

strategic defensive against Japan. Recognizing that limited resources would con-

strain their ability to mount oensive operations against either enemy for a year or

so, the Allied leaders endorsed the idea of “tightening the ring” around Germany

during this time by increasing lend-lease support to the Soviet Union, reinforcing

the Middle East, and securing control of the French North African coast.

32

To augment this broad strategy, the CCS in March 1942 adopted a working

understanding of the global strategic control of military operations that divided

the world into three major theaters of operations, each comparable to the relative

interests of the United States and Great Britain. As a direct concern to both parties,

the development and execution of strategy in the Atlantic-European area became a

combined responsibility and, as such, the region most immediately relevant to the

CCS. Elsewhere, the British Chiefs of Sta, working from London, would oversee

strategy and operations for the Middle East and South Asia, while the Joint Chiefs

of Sta in Washington would do the same for the Pacic and provide military coor-

dination with the government of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in China.

33

British and American planners agreed that the key to victory was the Soviet

Union, which engaged the bulk of Germany’s air and ground forces. “In the last

analysis,” predicted Admiral King, “Russia will do nine-tenths of the job of defeating

Germany.”

34

Keeping the Soviets actively and continuously engaged against Germany

thus became one of the Western Allies’ primary objectives, even before the United

States formally entered the war.

35

Within the JCS-CCS organization that emerged

following the ARCADIA Conference, developing a “second front” in Western Eu-

rope quickly emerged as a priority concern, both to relieve pressure on the Soviets

and to demonstrate the Western Allies’ sincerity and support. Unlike their American

counterparts, however, British defense planners were in no hurry to return to the

Continent. Averse to repeating the trench warfare of World War I, and with the Soviet

Union under a Communist regime that Churchill despised, British planners proved

far more cautious and realistic in entertaining plans for a second front.

10

COUNCIL OF WAR

The Joint Chiefs assumed that initially their main job would be to coordinate

the mobilization and deployment of a large army to Europe to confront the Ger-

mans directly, as the United States had done in World War I. As General Marshall

put it, “We should never lose sight of the eventual necessity of ghting the Germans

in Germany.”

36

By mid-March 1942, the consensus among the Joint Chiefs was that

they should press their British allies for a buildup of forces in the United Kingdom

for the earliest practicable landing on the Continent and restrict deployments in

the Pacic to current commitments. But they adopted no timetable for carrying

out these operations and deferred to the War Department General Sta to come up

with a concrete plan for invading Europe. At this stage, the Joint Chiefs of Sta were

a new and novel organization, composed of ocers from rival Services who were

still unfamiliar with one another and uneasy about working together. As a result, the

most eective and ecient strategic planning initially was that done by the Service

stas, with the Army taking the lead in shaping plans for Europe and the Navy do-

ing the same for the Pacic.

37

The impetus for shifting strategic planning from the Services to the corporate

oversight of the JCS was President Roosevelt’s decision in July 1942 to postpone a

Continental invasion and, at Churchill’s urging, to concentrate instead on the liber-

ation of North Africa. Personally, Roosevelt would have preferred a second front in

France, and in the spring of 1942 he had sent Marshall and Harry Hopkins to Lon-

don to explore the possibility of a landing either later in the year or in 1943. Though

the British initially seemed receptive to the idea and endorsed it in principle, they

raised one objection after another and insisted that the time was not ripe for a land-

ing on the Continent. Pushing an alternate strategy, they favored a combined opera-

tion in the Mediterranean.

38

Based on the production and supply data he received,

Roosevelt ruefully acknowledged that the United States would not be in a position

to have a “major impact” on the war much before the autumn of 1943.

39

Eager that

U.S. forces should see “useful action” against the Germans before then, he became

persuaded that North Africa would be more feasible than a landing in France. The

upshot in November 1942 was Operation Torch, the rst major oensive of the war

involving sizable numbers of U.S. forces.

40

While not wholly unexpected, the Torch decision had extensive ripple eects.

The most immediate was to nullify a promise Roosevelt made to the Soviets in May

1942 to open a second front in France before the end of the year.

41

A bitter disap-

pointment in Moscow, it was also a major rebu for Marshall and War Department

planners who had drawn up preliminary Continental invasion plans. One set, called

SLEDGEHAMMER, was for a limited “beachhead” landing in 1942; another, called

BOLERO-ROUNDUP, was for a full-scale assault on the northern coast of France

11

THE WAR IN EUROPE

in mid-1943.

42

Unable to contain his disappointment, Marshall told the President

that he was “particularly opposed to ‘dabbling’ in the Mediterranean in a wasteful

logistical way.”

43

In Churchill’s view, however, an invasion of France was too risky

and premature until the Allies brought the U-boat menace in the Atlantic under

control, had greater mastery of the air, and American forces were battle-tested. In

the interests of unity, Churchill continued to assure his Soviet and American allies

that he supported a cross-Channel invasion of Europe in 1943. But as a practical

matter, he seemed intent on using the invasion of North Africa to protect British

interests east of Suez and as a stepping stone toward further Anglo-American opera-

tions in the Mediterranean that would “knock Italy out of the war.”

44

Churchill’s preoccupation with North Africa and the Mediterranean reected

a time-honored British tradition that historians sometimes refer to as “war on the

periphery,” in contrast to the more direct American approach involving the massing

of forces, large-scale assaults, and decisive battles. Limited in manpower and indus-

trial capability, the British had historically preferred to avoid direct confrontations

and had pursued strategies that exploited their enemies’ weak spots, wearing them

down through naval action, attrition, and dispersion of forces. In World War I, the

British had departed from this strategy with disastrous results that gave them the

sense of having achieved a pyrrhic victory. Committed to avoiding a repetition of

the World War I experience, Churchill and his military advisors preferred to let the

Soviets do most of the ghting (and dying) against Germany, while Britain and

the United States concentrated on eviscerating Germany’s “soft underbelly” in the

Mediterranean. Although Churchill fully intended to undertake an Anglo-Ameri-

can invasion of Europe, he expected it to follow in due course, once Germany was

worn down and on the verge of defeat.

45

Following the planning setbacks they experienced in the summer of 1942, the

Joint Chiefs sought to regroup and regain the initiative, starting with a clarication

of overall strategy. Their initial response was the creation in late November 1942 of

the Joint Strategic Survey Committee (JSSC), an elite advisory body dedicated to

long-range planning. Composed of only three senior ocers, the JSSC resembled

a panel of “elder statesmen,” representing the ground, naval, and air forces, whose

job was to develop broad assessments on “the soundness of our basic strategic policy

in the light of the developing situation, and on the strategy which should be ad-

opted with respect to future operations.” In theory, Service aliations were not

to interfere with or prejudice their work. The three chosen to sit on the commit-

tee—retired Lieutenant General Stanley D. Embick of the Army, Major General

Muir S. Fairchild of the Army Air Corps, and Vice Admiral Russell Willson—served

without other duties and stayed at their posts throughout the war.

46

12

COUNCIL OF WAR

Early in December 1942, the JSSC submitted its rst set of recommendations,

a three-and-a-half-page overview of Allied strategy for the year ahead. In surveying

future options, the committee sought to keep the war focused on agreed objectives.

Assuming that the rst order of business remained the defeat of Germany, the JSSC

recommended freezing oensive operations in the Mediterranean and transferring

excess forces from North Africa to the United Kingdom as part of the buildup for

an invasion of Europe in 1943. The committee also urged continuing assistance

to the Soviet Union, a gradual shift from defensive to oensive operations in the

Pacic and Burma, and an integrated air bombardment campaign launched from

bases in England, North Africa, and the Middle East against German “production

and resources.”

47

Here in a nutshell was the rst joint concept for a global wartime strategy,

marshaling the eorts of land, sea, and air forces toward common goals. All the

same, it was a highly generalized treatment and, as such, it glossed over the impact of

conicting Service interests. At no point did it attempt to sort out the allocation of

resources, by far the most controversial issue of all, other than on the basis of broad

priorities. Challenging one of the paper’s core assumptions, Admiral King doubted

whether a landing in Europe continued to merit top priority. King maintained that,

with adoption of the Torch decision and the diversions that operation entailed, the

Anglo-American focus of the war had shifted from Europe to the Mediterranean

and Pacic. King wanted U.S. plans and preparations adjusted accordingly, with

more eort devoted to the Pacic and defeating the Japanese.

48

Meeting with the

President on January 7, 1943, the Joint Chiefs acknowledged that they were divided

along Service lines. As Marshall delicately put it, they “regarded an operation in the

north [of Europe] more favorably than one in the Mediterranean but the question

was still an open one.”

49

Despite nearly a year of intensied planning, the JCS had

yet to achieve a working consensus on overall strategic objectives.

The secOnD frOnT DebaTe anD Jcs

reOrganizaTiOn

Faced with indecision among his military advisors, Roosevelt gravitated to the Brit-

ish, who had worked out denite plans and knew precisely what they wanted to

accomplish. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, he gave in to Churchill’s

insistence that the Mediterranean be accorded “prime place” and that a move against

Sicily (Operation Husky) should follow promptly upon the successful completion of

Operation Torch in North Africa.

50

To placate the Americans, the British agreed to

establish a military planning cell in London to begin preliminary preparations for

13

THE WAR IN EUROPE

a cross-Channel attack. But with attention and resources centered on the Mediter-

ranean, a Continental invasion was now unlikely to materialize before 1944. Know-

ing that a further postponement would not go down well in Moscow, Roosevelt

proposed—and Churchill grudgingly agreed—that the United States and Britain

issue a combined public declaration of their intent to settle for nothing less than

“unconditional surrender” of the Axis powers.

51

A further result of the Casablanca Conference—one with signicant but unin-

tended consequences for the future of the Joint Chiefs—was the endorsement of an

intensive combined bombing campaign against Germany. This decision fell in line

with the recent recommendations of the Joint Strategic Survey Committee and was

widely regarded as an indispensable preliminary to a successful invasion of France.

Under the agreed directive, however, rst priority was not the destruction of the

enemy’s military-industrial complex, as some air power enthusiasts had advocated,

but the suppression of the German submarine threat, which was taking a horric

toll on Allied shipping.

52

Still, American and British air strategists had long sought

the opportunity to demonstrate the potential of airpower and greeted the decision

as a step forward, even as they disagreed among themselves over the relative mer-

its of daylight precision bombing (the American approach) versus nighttime area

bombing (the British strategy). The impact on the JCS was more long term and

subtle. Previously, as the senior Service chiefs, Marshall and King had dominated

JCS deliberations. Now, with strategic bombing an accepted and integral part of

wartime strategy, Arnold assumed a more prominent role of his own, becoming a

true coequal to the other JCS members in both rank and stature by the war’s end.

53

For the Joint Chiefs and the aides accompanying them, the Casablanca Confer-

ence was, above all, an educational experience that none wanted to repeat. Travel-

ing light, the JCS had kept their party small and had arrived with limited backup

materials. In contrast, the British chiefs had brought a very complete sta and reams

of plans and position papers. Admiral King found that whenever the CCS met and

he or one of his JCS colleagues brought up a subject, the British invariably had a

paper ready.

54

Brigadier General Albert C. Wedemeyer, the Army’s chief planner, had

a similar experience. At each and every turn he found the British better prepared

and able to outmaneuver the Americans with superior sta work. “We came, we

listened and we were conquered,” Wedemeyer told a colleague. “They had us on the

defensive practically all the time.”

55

The Joint Chiefs of Sta returned from the Casablanca Conference with less

to show for their eorts than they hoped and determined to apply the lessons

they learned there. In practice, that meant never again entering an international

conference so ill-prepared or understaed. To strengthen the JCS position, General

14

COUNCIL OF WAR

Marshall arranged for Lieutenant General Joseph T. McNarney, Deputy Army Chief

of Sta, to oversee a reorganization of the joint committee system, with special

attention to developing more eective joint-planning mechanisms. The main bot-

tleneck was in the Joint Sta Planners, a ve-member committee that had fallen

behind in its assigned task of providing timely, detailed studies on deployment and

future operations. The new system, introduced gradually during the spring of 1943,

reduced the range and number of issues coming before the Joint Sta Planners and

transferred logistical matters to the Joint Administrative Committee, later renamed

the Joint Logistics Committee.

56

Under McNarney’s reorganization, nearly all the detailed planning functions

previously assigned to the Joint Sta Planners became the responsibility of a new

body, the Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC), which functioned as a JPS working

subcommittee. Thenceforth, the JPS operated in more of an oversight capacity, re-

viewing, amending, and passing along the recommendations they received from the

Joint War Plans Committee. The JWPC drew its membership from the stas of the

chiefs of planning for the Army, the Navy, and the Air Sta. Under them was an inter-

Service “planning team” of approximately 15 ocers who served full time without

other assigned duties. The directive setting up the JWPC reminded those assigned to it

that they were now part of a joint organization and to conduct themselves accordingly

by going about their work and presenting their views “regardless of rank or service.”

57

The rst test of these new arrangements came at the TRIDENT Confer-

ence, held in Washington in May 1943 to develop plans and strategy for operations

after the invasion of Sicily during the coming summer. By then, King had grudg-

ingly resigned himself to the inevitability of a cross-Channel invasion and agreed

with Marshall that further operations in the Mediterranean should be curbed. King

viewed the British preoccupation there as a growing liability that had the potential

of preventing the Navy from stepping up the war against Japan. Based on naval

production gures, King estimated that by the end of 1943, the Navy would begin

to enjoy a signicant numerical superiority over the Japanese in aircraft carriers

and other key combatants. To take advantage of that situation, the CNO proposed

a major oensive in the Central Pacic and secured JCS endorsement just before

the TRIDENT Conference began. But with the British dithering in the Mediter-

ranean and a rm decision on the second front issue still pending, King could easily

nd his strategic initiative jeopardized.

58

At TRIDENT, for the rst time in the war, the Joint Chiefs obtained the use of

procedures that worked to their advantage. Namely, they insisted on an agenda and

some of the papers developed by the Joint War Plans Committee in lieu of those

oered by the British, who had controlled the “paper trail” at Casablanca.

59

As often

15

THE WAR IN EUROPE

as possible during TRIDENT, King tried to shift the discussion to the Pacic. But

the dominating topic was the choice between continuing operations in the Medi-

terranean or opening a second front in northern France. With President Roosevelt’s

concurrence and with Marshall doing most of the talking, the Joint Chiefs pressed

the British for a commitment to a cross-Channel attack no later than the spring of

1944. The deliberations were brisk and occasionally involved what historian Mark

A. Stoler describes as “some private and very direct exchanges.” Six months earlier

British views would probably have prevailed. But with improved sta support be-

hind them, the JCS were now more than able to hold their own.

60

A crucial factor in the Joint Chiefs’ eectiveness was a carefully researched fea-

sibility study by the JWPC showing that there would be enough landing craft to lift

ve divisions simultaneously (three in assault and two in backup), making the cross-

Channel operation feasible.

61

Forced to concede the point, the British agreed to be-

gin moving troops (seven divisions initially) from the Mediterranean to the United

Kingdom. While accepting a tentative target date of May 1, 1944, for the invasion,

the British sidestepped a full commitment by insisting on further study. The JCS also

wanted to limit additional operations in the Mediterranean to air and sea attacks. But

out of the ensuing give-and-take, the British prevailed in obtaining an extension of

currently planned operations against Sicily onto the Italian mainland, in Churchill’s

words, “to get Italy out of the war by whatever means might be best.”

62

A signicant improvement over the Joint Chiefs’ previous performance, TRI-

DENT demonstrated the utility and eectiveness of Joint Sta work over reliance

on separate and often uncoordinated Service inputs. From then on, preparations for

inter-Allied conferences became increasingly centralized around the Joint Sta, with

the Joint War Plans Committee the focal point for the development of the necessary

planning papers and inter-Service coordination.

63

The emerging dominance of the

JCS system was largely the product of necessity and rested on a growing recognition

as the war progressed that at the high command level as well as in the eld, joint

collaboration was more successful than each Service operating on its own.

PreParing fOr OverlOrd

Even though the Joint Chiefs secured provisional agreement at the TRIDENT

Conference to begin preparations for an invasion of France, it remained to be seen

whether the British would live up to their promise. Reports from London indi-

cated that Churchill was “rather apathetic and somewhat apprehensive” about a

rm commitment to invade Europe and that he would press next for an invasion of

Italy, followed by operations against the Balkans.

64

Even though a campaign on the

16

COUNCIL OF WAR

Italian mainland would delay moving troops and materiel to England for the inva-

sion, Churchill had made a convincing argument that Italy would fall quickly and

not pose much of a diversion. With U.S. and British forces currently concentrated

in Sicily and North Africa, the JCS acknowledged that it made sense to take advan-

tage of the opportunity before moving forces en masse to England. Still, they were

adamant that the operation be limited and not go beyond Rome, lest it jeopardize

plans for the invasion of northern France.

65

At the rst Quebec Conference (QUADRANT) in August 1943, Churchill,

Roosevelt, and the Combined Chiefs of Sta conrmed their intention to attack

Italy and attempted to reconcile continuing dierences over a landing on the north-

ern French coast, now code-named Operation Overlord. Despite pledges made at the

TRIDENT Conference, Churchill and the British chiefs procrastinated, prompting

several heated exchanges and some “very undiplomatic language” by Admiral King,

who considered the British to be acting in bad faith.

66

At one point the CCS cleared

the room of all subordinates and continued the discussion o the record. The sense

of trust and partnership appeared to be eroding on both sides. While professing their

commitment to Overlord, the British objected to an American proposal to give the

invasion of France “overriding priority” and wanted to delay the repositioning of

troops as agreed at TRIDENT so campaigns in the Mediterranean could proceed

without serious disruption. Working a compromise, the Combined Chiefs agreed to

make Overlord the “primary” Anglo-American objective in 1944, but couched the

decision in ambiguous language that left open the possibility of further operations

in the Mediterranean.

67

Once back in London, Churchill assured the War Cabinet

that the QUADRANT agreement on Overlord notwithstanding, he would continue

to insist on “nourishing the battle” in Italy as long as he remained in oce.

68

At that stage in the war, Churchill and the British Chiefs of Sta still viewed

themselves as the “predominant partner” in the Western alliance. Yet it was a role

they were less equipped to play with each passing day. By mid-1943, with the mo-

bilization and stepped-up industrial production initiated since 1940 beginning to

bear fruit, the United States was steadily overtaking Britain in manpower and ma-

teriel to become the preeminent military power within the Western alliance. One

consequence was to give the U.S. chiefs a larger voice and stronger leverage within

the CCS system, much to the consternation of the British.

69

Meetings of the Com-

bined Chiefs of Sta, as evidenced by the discussions at TRIDENT and QUAD-

RANT, were becoming more and more confrontational. Clearly frustrated, Sir

Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Sta, lamented that he and his British

colleagues were no longer able “to swing those American Chiefs of Sta and make

them see daylight.”

70

17

THE WAR IN EUROPE

With tensions mounting between the American and British military chiefs

over Overlord, a showdown was only a matter of time. It nally came at the Tehran

Conference in late November 1943, the rst “Big Three” summit of the war. Dur-

ing the trip over aboard the battleship Iowa, the Joint Chiefs had the opportunity

to discuss among themselves and with the President the issues they should raise and

the approach they should take, so when the conference got down to business, the

American position was unambiguous. Stopping in Cairo to meet with Generalis-

simo Chiang Kai-shek, the Chinese leader, Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Com-

bined Chiefs of Sta took time out to review the status of planning for the invasion

of France. Though Churchill again paid lip service to Overlord, calling it “top of the

bill,” he also outlined his vision for expanding military operations into northern

Italy, Rhodes, and the Balkans. Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs, feeling that now was

not the time to debate these issues, simply turned a collective deaf ear.

71

At Tehran, with the Soviets present, the Joint Chiefs left no doubt that launch-

ing Overlord was their rst concern, then sat back while the senior Soviet military

representative, Marshal Klementy Voroshilo, interrogated Brooke and his British

colleagues on why they wanted to devote precious time and resources on “auxiliary

operations” in the Mediterranean.

72

In the plenary sessions with Roosevelt and

Soviet leader Marshal Josef Stalin, Churchill fell under intense pressure to shelve his

plans for the Mediterranean and to throw unequivocal support behind the invasion.

To improve the prospects of success, Stalin oered to launch a major oensive on

the Eastern Front in conjunction with the landings in France. Outnumbered and

outmaneuvered, Churchill grudgingly acknowledged that it was “the stern duty” of

his country to proceed with the invasion. At long last, the British commitment to

Overlord had become irrevocable. Though the JCS were elated at the outcome, the

British chiefs were visibly distraught and immediately began picking away at the

invasion plan’s details as if they could make it disappear or change the decision.

73

Conrmation that Overlord would go forward signaled a major turning point

in the war. The beginning of the end in the West for Hitler’s Germany, it also af-

rmed the emergence of the United States as leader of the Western coalition, with

the Joint Chiefs of Sta rmly ensconced as the senior military partners. Even the

supreme commander of the operation was to be an American. Though General

Marshall had wanted the job, it went instead to a former subordinate and protégé,

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who presided over what became one of the most

truly integrated and successful international command structures in history. All the

same, with the United States contributing the larger share of the manpower and

much, if not most, of the materiel to the operation, British involvement took on a

diminished appearance. Except for a brief gathering in London in early June 1944

18

COUNCIL OF WAR

timed roughly to coincide with the D-Day invasion, the JCS had little need for

further full-dress meetings of the Combined Chiefs of Sta. In fact, they did not

see their British counterparts again until, at Churchill’s insistence, they reassembled

at a second Quebec Conference in September 1944. A year later, with the war over,

the CCS quietly became for the most part inactive. Though it met occasionally over

the next few years, its postwar contributions were never enough to make much dif-

ference, and on October 14, 1949, by mutual agreement, it was nally dissolved.

74

The decision to proceed with Overlord, giving it priority over all other Anglo-

American operations against Germany, marked the culmination of grand strategic

planning in the European theater. Once the troops landed in Normandy on June 6,

1944, it was up to Eisenhower and his British deputy, General Bernard Law Mont-

gomery, and their generals to wage the battles that would bring victory in the West.

Had it not been for the JCS and their determination to see the matter through, the

invasion might have been postponed indenitely, and the results of the war could

have been quite dierent. In a very real sense, the Tehran Conference and the Over-

lord decision marked the Joint Chiefs’ coming of age as a mature and reliable orga-

nization. Out of that experience emerged a decidedly improved and more eective

planning system within the JCS organization and a better appreciation among the

chiefs themselves of what they could accomplish by working together. A turning

point in the history of World War II, the Overlord decision was thus also a major

milestone in the progress and maturity of the Joint Chiefs of Sta.

WarTime cOllabOraTiOn WiTh The sOvieT UniOn

In contrast to the many contacts and close collaboration the Joint Chiefs enjoyed

with their British counterparts through the Combined Chiefs of Sta system, their

access to the Soviet high command remained limited throughout World War II. The

“Grand Alliance,” as Churchill called it, brought together countries—the United

States and Great Britain, on the one hand, the Soviet Union, on the other—which,

until recently, had viewed one another practically as enemies. Divided prior to the

war by politics and ideology, they found it expedient in wartime to concert their

eorts toward a common objective—the defeat of Nazi Germany—and little else.

While idealists like Roosevelt hoped a new postwar relationship would emerge

from the experience, promoting peaceful coexistence between capitalist and Com-

munist systems, realists like Churchill remained skeptical. All agreed that it was a

unique and uneasy partnership that was dicult to manage.

The bond holding the Grand Alliance together was, from its inception, the