IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

Duke Law Journal

VOLUME 70 DECEMBER 2020 NUMBER 3

THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP

JASON IULIANO†

A

BSTRACT

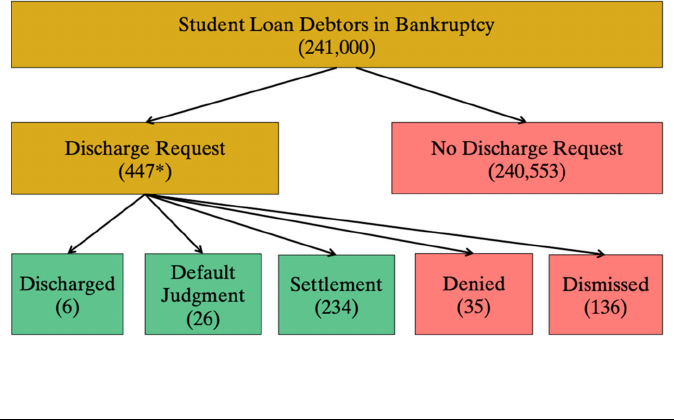

Each year, a quarter of a million student loan debtors file for

bankruptcy. Of those, fewer than three hundred discharge their

educational debt. That is a success rate of just 0.1 percent. This chasm

between success and failure is the titular “Student Loan Bankruptcy

Gap,” and it is a phenomenon that is unprecedented in the law.

Drawing upon an original dataset of nearly five hundred adversary

proceedings, this Article examines three key facets of the Student Loan

Bankruptcy Gap. First, it establishes the true breadth of the gap.

Second, it explores why the gap has persisted for more than two decades

and, in doing so, uncovers a creditor case-selection strategy designed to

deter debtors from bringing legitimate claims. And third, it identifies

solutions that have the potential to close the Student Loan Bankruptcy

Gap and bring debt relief to millions of individuals.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ............................................................................................ 498

I. The Student Loan Bankruptcy Framework .................................... 501

A. The Discharge Process ......................................................... 501

B. The Myth of Nondischargeability ....................................... 504

Copyright © 2020 Jason Iuliano.

† Assistant Professor of Law, Villanova University. Ph.D. in Politics, Princeton University;

J.D., Harvard Law School. Thanks to Laura Napoli Coordes, Seth Frotman, Jonah Gelbach,

Melissa Jacoby, Ted Janger, John Pottow, Austin Smith, Madeleine Wanslee, Jay Westbrook, and

the participants of the International Insolvency Institute’s Global Bankruptcy Workshop at

Brooklyn Law School for valuable comments and discussions relating to this Article. And thanks

to Greg Bailey, Alice Douglas, Andy Lee, Amy Phelps, and Callie Terris for exceptional research

assistance.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

498 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

II. The Two-Step Analysis.................................................................... 507

A. Is It an Educational Debt? .................................................. 507

1. Data .................................................................................... 513

2. Theory ................................................................................ 518

B. Is There Undue Hardship? ................................................. 521

1. Data .................................................................................... 523

2. Theory ................................................................................ 526

III. Closing the Gap .............................................................................. 529

A. Consequences of Inaction ................................................... 529

B. Solutions ................................................................................ 535

1. Educational Benefit: Class Action Litigation ................. 537

2. Undue Hardship: Increasing Attorney Awareness ........ 539

Conclusion ............................................................................................... 542

I

NTRODUCTION

This year, almost a quarter of a million student loan debtors will

file for bankruptcy.

1

Of those, about three hundred will discharge their

educational debt.

2

These statistics portend good news . . . for 0.1

percent of the student loan filers. For the other 99.9 percent, however,

the outcome is bleak. They will exit bankruptcy with their student loans

in tow, denied the fresh start that the system promises to every “honest

but unfortunate debtor.”

3

Take a moment to consider what those statistics mean. For every

one thousand student loan debtors in bankruptcy, only one will clear

the legal hurdles erected by Congress and obtain a discharge. This

chasm between success and failure is the titular “Student Loan

Bankruptcy Gap.”

4

And it is an unprecedented situation in the law.

Nowhere else have so many people sought legal relief while so few

have obtained it.

The most troubling aspect, though, is that the gap does not result

from existing law. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom, the student loan

1. See Jason Iuliano, An Empirical Assessment of Student Loan Discharges and the Undue

Hardship Standard, 86 A

M. BANKR. L.J. 495, 528 (2012) [hereinafter Iuliano, Empirical

Assessment] (calculating the number of student loan debtors who file bankruptcy).

2. See infra Part II.

3. Marrama v. Citizens Bank of Mass., 549 U.S. 365, 367 (2007) (“The principal purpose of

the Bankruptcy Code is to grant a ‘fresh start’ to the ‘honest but unfortunate debtor’” (quoting

Grogan v. Garner, 498 U.S. 279, 286, 287 (1991))).

4. Because referring to the situation as an access-to-justice problem is insufficient to

capture the scope of the crisis, this Article coins the term “Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap.”

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 499

discharge laws do not present an insurmountable hurdle. About half of

all bankrupt student loan debtors would obtain relief if they took the

appropriate legal steps.

5

Unfortunately, because nearly everyone has

bought into the myth that student loans are not dischargeable, most

debtors do not take those steps.

This failure has made the Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap the most

pressing issue in educational debt today. Given that student loan debt

now exceeds $1.7 trillion,

6

this is no small claim. But it is supported by

the evidence. The Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap has harmed millions

of members of Generation X, is harming millions of millennials, and

will harm millions in Generation Z—unless something changes.

7

Although scholars have been discussing failures in the student

loan discharge process for more than a decade,

8

they have neither

recognized the true extent of the Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap nor

understood the reason for its continued existence. This Article fills

both holes in the literature. First, by presenting original nationwide

data, this Article puts concrete numbers to the problem. And second,

by conducting an in-depth analysis of student loan bankruptcy

proceedings, it identifies the primary source of the Student Loan

Bankruptcy Gap: creditor manipulation.

Specifically, the data show that creditors have adopted a case-

selection strategy that distorts precedent and masks the true likelihood

of obtaining a student loan discharge. In particular, creditors are

engaging in strategic settlement—a process that involves settling

unfavorable cases to avoid adverse precedent and aggressively

litigating favorable cases to tilt the law in their favor. Ultimately,

through repeated interactions with the courts, creditors have

developed a body of precedent that supports their position,

5. See infra Part II.B.

6. See Student Loan Debt Clock, F

INAID, http://www.finaid.org/loans/studentloandebt

clock.phtml [https://perma.cc/X7R8-UCMM].

7. See infra Parts II.B, III.A, III.B.

8. See, e.g., Katherine Porter, College Lessons: The Financial Risks of Dropping Out, in

B

ROKE: HOW DEBT BANKRUPTS THE MIDDLE CLASS 85, 98 (Katherine Porter ed., 2012)

(advocating for bankruptcy courts to take into account the type of degree and whether the degree

was completed when assessing whether a debtor should have their student loan discharged);

Stephen G. Gilles, The Judgment-Proof Society, 63 W

ASH. & LEE L. REV. 603, 615 (2006) (arguing

that “federal law [makes] it extremely difficult for individuals to default on student loans”); John

A.E. Pottow, The Nondischargeability of Student Loans in Personal Bankruptcy Proceedings: The

Search for a Theory, 44 C

AN. BUS. L.J. 245, 265–76 (2006) (concluding that most policy

justifications do not support the “overly broad U.S. approach” to student loan

nondischargeability).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

500 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

notwithstanding the fact that debtors win the vast majority of cases. By

employing this strategy, creditors have successfully cultivated a myth

of nondischargeability—a myth that scholars,

9

bankruptcy attorneys,

10

and media commentators

11

all subscribe to.

12

This Article’s findings

dispel that myth and offer hope to the millions of borrowers burdened

by student loans they can never afford to pay back.

Although identifying the myth is a crucial first step, any

comprehensive solution must go further and encourage individuals to

assert their legal rights. This approach could take a variety of forms,

from providing bankrupt debtors with information about the discharge

process, to improving how attorneys evaluate student loan cases to

encouraging journalists to present a more data-driven—and less

sensationalistic—view of student loan bankruptcy. Despite their

modest nature, these debtor-focused reforms have two key virtues over

the sweeping legislative and judicial changes that scholars

13

and

9. See, e.g., Charles J. Tabb, Bankruptcy and Entrepreneurs: In Search of an Optimal

Failure Resolution System, 93 A

M. BANKR. L.J. 315, 334 (2019) (“[A] debtor is burdened by her

student loans forever unless she can prove an undue hardship, which is a very difficult standard

to satisfy under current interpretations.”); William Voegeli, The Higher Education Hustle:

Political Correctness and the Credentials-Industrial Complex, 13 C

LAREMONT REV. BOOKS 12, 14

(2013) (“Debts incurred by those . . . who will never finish school, are no more dischargeable than

degree recipients’ liabilities.”).

10. See, e.g., Do I Need an Attorney for Student Loan Discharges if There Is Evidence that

They Engaged in Predatory Student Loan Lending?, A

VVO, https://www.avvo.com/legal-answers/

do-i-need-an-attorney-for-student-loan-discharges—2252306.html [https://perma.cc/2A27-9HEE]

(responding to the question, bankruptcy attorneys uniformly gave discouraging answers,

describing the process as “very difficult,” if not impossible, with one attorney commenting that

he has “filed more than 6,000 cases and [is] yet to see student loans discharged”).

11. See, e.g., Jessica Dickler, Trump Administration May Make It Easier To Wipe Out

Student Debt in Bankruptcy, CNBC (Feb. 21, 2018, 1:37 PM), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/21/

trump-administration-may-make-it-easier-to-wipe-out-student-debt-in-bankruptcy.html [https://

perma.cc/3F8G-79QA] (quoting Mark Kantrowitz as noting that “[a]s of now, ‘it’s almost

impossible to discharge student loans in bankruptcy’”).

12. See Aaron N. Taylor & Daniel J. Sheffner, Oh, What a Relief It (Sometimes) Is: An

Analysis of Chapter 7 Bankruptcy Petitions To Discharge Student Loans, 27 S

TAN. L. & POL’Y

REV. 295, 297 (2016) (“Conventional wisdom dictates that it is all-but-impossible to discharge

student loans in bankruptcy.”).

13. See, e.g., Robert C. Cloud & Richard Fossey, Facing the Student-Debt Crisis: Restoring

the Integrity of the Federal Student Loan Program, 40 J.C.

& U.L. 467, 497 (2014) (arguing that

“the ‘undue hardship’ provision in the Bankruptcy Code should be repealed”); Rafael I. Pardo,

The Undue Hardship Thicket: On Access to Justice, Procedural Noncompliance, and Pollutive

Litigation in Bankruptcy, 66 F

LA. L. REV. 2101, 2177–78 (2014) (advocating for a system in which

judges “play a more robust monitoring role in undue hardship adversary proceedings and

thus . . . serve as a check against any attempts by creditors to run roughshod over student-loan

debtor’s procedural rights”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 501

politicians

14

have long advocated—namely, effectiveness and ease of

implementation.

This Article proceeds in three parts. Part I frames the student loan

bankruptcy debate. In doing so, it highlights the unique laws that

govern the student loan discharge process and explores the criticisms

that scholars and attorneys levy against those laws. Next, Part II

presents original data that challenge the veracity of these critiques.

Specifically, the data reveal two key findings: (1) that student loan

creditors have engaged in a case-selection strategy designed to deter

debtors from bringing legitimate claims, and (2) that, every year, tens

of thousands of bankrupt debtors miss out on obtaining a student loan

discharge simply because they fail to request one. Finally, Part III

explores the path forward. It begins by discussing the social and

economic consequences of inaction and concludes by offering solutions

that have the potential to close the Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap.

I.

THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY FRAMEWORK

A. The Discharge Process

Understanding the student loan discharge process requires a brief

dive into the Bankruptcy Code. The current iteration of the law

governing student loan discharges was enacted as part of the 2005

Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act.

15

The

relevant statutory language reads as follows:

(a) A discharge under section 727, 1141, 1228(a), 1228(b), or 1328(b)

of this title does not discharge an individual debtor from any

debt . . . .

(8) unless excepting such debt from discharge under this

paragraph would impose an undue hardship on the debtor and

the debtor’s dependents, for—

14. See, e.g., Zack Friedman, Bernie Sanders: I Will Cancel All $1.6 Trillion of Your Student

Loan Debt, F

ORBES (June 24, 2019, 7:18 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2019/

06/24/student-loans-bernie-sanders/#9623f33fc295 [https://perma.cc/E6X8-VALB] (comparing

Bernie Sanders’s plan to eliminate all student loan debt with Elizabeth Warren’s plan to cancel

$50,000 in student loan debt for individuals earning less than $100,000).

15. Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-

8, 119 Stat. 23 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 11 U.S.C.).

I

ULIANO IN

PRINTER

FINAL

(D

O

N

OT

D

ELETE

) 11/16/2020

7:37

PM

502 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

(A)

(i) an educational benefit overpayment or loan made,

insured, or guaranteed by a governmental unit, or

made under any program funded in whole or in part

by a governmental unit or nonprofit institution; or

(ii) an obligation to repay funds received as an

educational benefit, scholarship, or stipend; or

(B) any other educational loan that is a qualified education

loan, as defined in section 221(d)(1) of the Internal

Revenue Code of 1986, incurred by a debtor who is an

individual.

16

F

IGURE

1:

T

HE

S

TUDENT

L

OAN

B

ANKRUPTCY

P

ROCESS

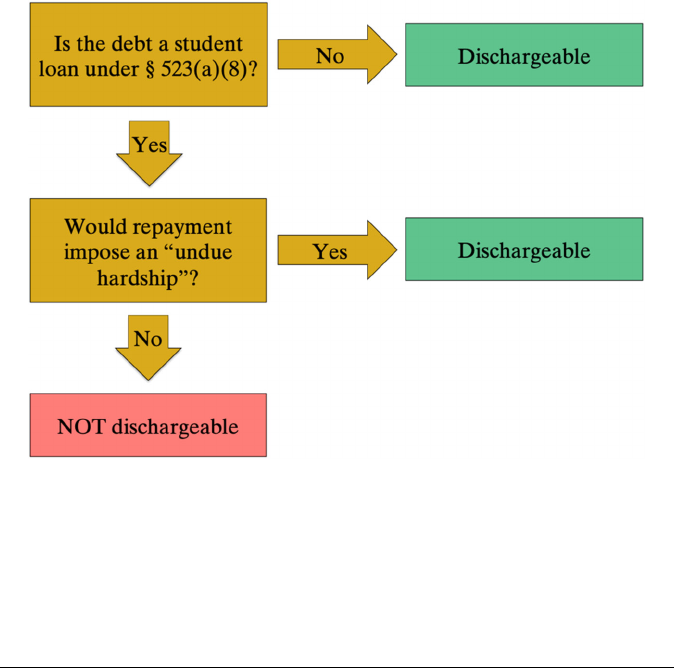

Although there is a lot to parse in this statutory excerpt, Figure 1

aims to provide a clear explanation of the text. As the flow chart

illustrates, judges must engage in a two-step analysis to determine

whether a student loan is dischargeable. At step one, the judge must

resolve whether the loan at issue is a qualifying educational debt under

16. 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(8) (2018).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 503

§ 523(a)(8) of the Bankruptcy Code. The precise contours of this

statutory provision will be important later.

17

For present purposes,

however, it is sufficient to know that the student loan discharge

exemption only applies to three categories of educational debt: (1)

government and nonprofit-backed loans and educational benefit

overpayments,

18

(2) obligations to repay funds received as an

educational benefit, scholarship, or stipend,

19

and (3) qualified

education loans.

20

If a student loan does not fall within at least one of

these categories,

21

the inquiry ends, and the debt is discharged through

the normal bankruptcy process. If, however, the student loan satisfies

the criteria for at least one of these categories, then it is a qualifying

educational debt under § 523(a)(8), and step two of the analysis is

triggered.

At this second stage of the inquiry, the judge must determine

whether repayment of the debt would “impose an undue hardship on

the debtor and the debtor’s dependents.”

22

Because Congress has

never defined “undue hardship,” the judiciary has been forced to flesh

out the meaning of the phrase. To that end, most courts have coalesced

around a test first set forth in Brunner v. New York State Higher

Education Services Corp.

23

To prove undue hardship under the

17. See infra Part II.A. See generally Jason Iuliano, Student Loan Bankruptcy and the

Meaning of Educational Benefit, 93 A

M. BANKR. L.J. 277 (2019) [hereinafter Iuliano, Student

Loan Bankruptcy] (arguing that courts have misinterpreted the statutory criteria for discharging

student loans in bankruptcy).

18. 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(8)(A)(i).

19. Id. § 523(a)(8)(A)(ii).

20. Id. § 523(a)(8)(B).

21. For a discussion of the scope of these categories, see infra Part II.A.

22. See § 523(a)(8); Brunner v. N.Y. State Higher Educ. Servs. Corp., 831 F.2d 395, 396 (2d

Cir. 1987) (per curiam) (citing § 523(a)(8)).

23. Brunner v. N.Y. State Higher Educ. Servs. Corp., 831 F.2d 395, 396 (2d Cir. 1987) (per

curiam). The Eighth Circuit and most bankruptcy courts in the First Circuit have adopted an

alternative test known as the “totality-of-the-circumstances test.” See, e.g., In re Long, 322 F.3d

549, 553–54 (8th Cir. 2003) (holding that the totality-of-the-circumstances test requires courts to

consider: “(1) the debtor’s past, present, and reasonably reliable future financial resources; (2) a

calculation of the debtor’s and her dependent’s reasonable necessary living expenses; and (3) any

other relevant facts and circumstances surrounding each particular bankruptcy case”); Bronsdon

v. Educ. Credit Mgmt. Corp. (In re Bronsdon), 435 B.R. 791, 797–98 (B.A.P. 1st Cir. 2010) (noting

that “[m]ost of the bankruptcy courts within the First Circuit have adopted the totality of the

circumstances test over the Brunner test”). Although bearing a distinct name and purporting to

undertake a more holistic analysis of the debtor’s situation, the totality-of-the-circumstances test

yields outcomes that mirror those in Brunner Circuits. See Iuliano, Empirical Assessment, supra

note 1, at 497 (“Identical debtors filing in a Brunner circuit and a totality of the circumstances

circuit should expect similar outcomes.”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

504 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

Brunner standard, a debtor must establish the following three

elements:

(1) that the debtor cannot maintain, based on current income and

expenses, a “minimal” standard of living for herself and her

dependents if forced to repay the loans;

(2) that additional circumstances exist indicating that this state of

affairs is likely to persist for a significant portion of the repayment

period of the student loans; and

(3) that the debtor has made good faith efforts to repay the loans.

24

This Article explores the meaning of these three elements in a

later Part.

25

For now, it is sufficient to know that proving undue

hardship requires the debtor to show (1) a current inability to repay

the loans, (2) a future inability to repay the loans, and (3) a good faith

effort to repay the loans.

26

If the debtor satisfies these three elements,

then the student loan is discharged. Otherwise, the debt is

nondischargeable and survives bankruptcy.

As this discussion highlights, there are two paths to discharge. The

debtor can either show that the student loan is not a qualifying debt

under § 523(a)(8) or prove that repayment would impose an undue

hardship. If the debtor clears either of these hurdles, then the student

loan is discharged.

B. The Myth of Nondischargeability

Despite the existence of these two discharge pathways, a myth of

nondischargeability pervades the discourse on student loan debt.

27

At

the extreme, many commentators fail to acknowledge either of these

pathways and, instead, assert that the law places a blanket prohibition

on the elimination of educational debt. As one journalist declares

without qualification, “[S]tudent loans are not dischargeable in

24. Brunner, 831 F.2d at 396.

25. See infra Part II.B.

26. I borrow this terminology from Rafael I. Pardo & Michelle R. Lacey, Undue Hardship

in the Bankruptcy Courts: An Empirical Assessment of the Discharge of Educational Debt, 74 U.

CIN. L. REV. 405, 496 (2005).

27. See, e.g., Mary Pilon, The Student Loan Effect, W

ALL ST. J. (Feb. 18, 2010, 9:00 AM),

https://blogs.wsj.com/juggle/2010/02/18/the-student-loan-effect [https://perma.cc/6UDE-RPKY]

(“[Student loan] debt is associated with a unique sense of hopelessness.”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 505

bankruptcy.”

28

And as another writes, “Since student loans are not

dischargeable in a bankruptcy, even the most financially distressed

former students cannot get out from under their debt.”

29

The media is,

unfortunately, not alone in advancing such claims. Even some scholars

make categorical statements about the impossibility of discharging

student loan debt.

30

Although these extreme positions anchor the myth,

more nuanced views are part of the discourse as well.

Unfortunately, the more measured claims are just as discouraging

to debtors.

31

They describe a system in which discharging student loans

is a theoretical possibility but a practical impossibility.

32

The following

quote from a consumer bankruptcy attorney is illustrative:

Student loans are not dischargeable in bankruptcy under almost any

circumstances. There is such a thing as a hardship discharge of student

loan debt, but to get one of those you need to be over the age of

eighty, have no hearing, and have a serious mental illness that

prevents you from ever being able to earn a dime or receive a social

security payment, and not have any family that can assist you.

33

28. Robert Jonathan, Student Loans: Paying Them Off Without Getting Schooled,

I

NQUISITR (July 8, 2012), https://www.inquisitr.com/271834/student-loans-paying-them-off-

without-getting-schooled [https://perma.cc/78CW-4G8D].

29. Rachel E. Dwyer, Student Loans and Graduation from American Universities, T

HIRD

WAY (June 18, 2015), https://www.thirdway.org/report/student-loans-and-graduation-from-

american-universities [https://perma.cc/4B98-JWRD]. Two authors went so far as to describe the

system as follows:

[Banks] wrote the student loan law, in which the fine-print says they aren’t

“dischargable [sic].” So even if you file for bankruptcy, the payments continue due . . . .

“You will be hounded for life . . . . They will garnish your wages. They will intercept

your tax refunds. You become ineligible for federal employment.”

Andrew Hacker & Claudia Dreifus, The Debt Crisis at American Colleges, A

TLANTIC (Aug. 17,

2011), https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/08/the-debt-crisis-at-american-colleges/243777

[https://perma.cc/NVG6-FY5Z].

30. See, e.g., Voegeli, supra note 9, at 14 (“[S]tudent loans are not dischargeable in

bankruptcy.”).

31. See, e.g., Kevin Carey, Lend with a Smile, Collect with a Fist, N.Y.

TIMES (Nov. 27, 2015),

https://nyti.ms/1NyckmI [https://perma.cc/YG7V-XEJE] (“[F]ederal law all but precludes

[bankruptcy as a] method of discharging student loans.”).

32. See, e.g., Mike Brown, Study: For Those Filing for Bankruptcy, Student Loan Debt Still

Lingers On, L

ENDEDU (June 11, 2019), https://lendedu.com/blog/student-loans-bankruptcy

[https://perma.cc/F54S-Y7SB] (“[S]tudent loan debt is one form of debt that is almost always

impossible to discharge in bankruptcy.”).

33. David R. Black, Successfully Guiding a Client Through the Chapter 13 Filing Process,

A

SPATORE, Jan. 2014, at *13, 2014 WL 10512.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

506 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

Although seemingly hyperbolic, this view represents how most

lawyers and scholars perceive the undue hardship standard.

34

Almost

to a one, they make bold statements regarding the herculean effort

required to prove undue hardship.

35

This myth is so pervasive and so frequently echoed that one could

fill multiple pages with quotes declaring that student loans “are almost

impossible to discharge in bankruptcy.”

36

To spare the reader that

undertaking, consider just one framing of the problem that conjures a

particularly striking image: “A student loan resembles a labyrinth; it’s

easy for you to enter, but once you get into trouble, it is difficult, maybe

impossible, to exit.”

37

This metaphor is apt, though not for the reasons

the scholars who drew the comparison believe. As the remainder of

34. See, e.g., Cloud & Fossey, supra note 13, at 479 (“[F]ederal courts have interpreted the

‘undue hardship’ requirement in such a way that makes it very difficult for student-loan debtors

to obtain bankruptcy relief.”); Jonathan M. Layman, Forgiven but Not Forgotten: Taxation of

Forgiven Student Loans Under the Income-Based-Repayment Plan, 39 C

AP. U. L. REV. 131, 136

(2011) (“[F]ederally backed student loans cannot be discharged in bankruptcy except in some

rare cases of extreme financial hardship.”); The Student Borrower Bankruptcy Relief Act of 2019,

38 A

M. BANKR. INST. J. 8, 70 (2019) (describing the undue hardship standard as “nearly

impossible to demonstrate”); Student Loans Difficult—But Not Impossible—To Discharge in

Bankruptcy, M

INILLO & JENKINS CO., LPA, https://www.mjbankruptcy.com/articles/student-

loans-difficult-but-not-impossible-to-discharge-in-bankruptcy [https://perma.cc/S6QA-Y2RE]

(“Discharging student loan debt in bankruptcy is exceedingly difficult and it occurs very rarely.”).

35. See, e.g., Victoria J. Haneman, A Timely Proposal To Eliminate the Student Loan Interest

Deduction, 14 N

EV. L.J. 156, 179 n.142 (2013) (“Student loans are nondischargeable absent a

showing of undue hardship, which is a standard that is seldom met.”). A small number of attorneys

have tried to chip away at the narrative of hopelessness. See, e.g., Austin Smith, Not All Student

Loans Are Non-Dischargeable in Bankruptcy and Creditors Know This, S

TUDENT BORROWER

PROT. CTR. (Mar. 18, 2019), https://protectborrowers.org/not-all-student-loans-are-non-dischargeable

-in-bankruptcy-and-creditors-know-this [https://perma.cc/NB3W-XQ2C] (“There is a great deal

of misinformation surrounding student loans in bankruptcy. Most people believe that anything

called a ‘student loan,’ or any debt made to a student, cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. This

notion is fundamentally untrue.”); Services I Provide,

STUDENT LOAN LAW., https://

thestudentloanlawyer.com/services [https://perma.cc/F9YR-VG5N] (offering legal help and

resources for managing student loan debt).

36. See Ryan Cooper, Opinion, The Case for Erasing Every Last Penny of Student Debt,

W

EEK (Feb. 8, 2018), https://theweek.com/articles/753769/case-erasing-every-last-penny-student-

debt [https://perma.cc/VAY9-NV2E]. A salient example involves the National Bankruptcy

Review Commission, which stated in its final report that “[a]lthough the drafters of the

nondischargeability provision may have intended that those who truly cannot pay should be

relieved of the debt under the undue hardship provision, in practice, nondischargeability has

become the broad rule with only a narrowly construed undue hardship discharge.” N

AT’L BANKR.

REV. COMM’N, BANKRUPTCY: THE NEXT TWENTY YEARS 211 (1997). The commission went on

to observe that “[i]t hardly is surprising that some courts see few requests for hardship discharges

of educational loans given the pitfalls of the undue hardship standard.” Id. at 212.

37. Doug Rendleman & Scott Weingart, Collection of Student Loans: A Critical

Examination, 20 W

ASH. & LEE J. CIV. RTS. & SOC. JUST. 215, 218 (2014).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 507

this Article will argue, the situation is dire, but the bankruptcy laws are

not to blame. Instead, it is the bleak perception of those laws that has

allowed the Student Loan Bankruptcy Gap to persist.

II.

THE TWO-STEP ANALYSIS

This Part analyzes the two discharge pathways in order. Each

analysis begins with a discussion of the key legal arguments that define

the inquiry. Next, original data are presented showing that both steps

of the analysis offer debtors a viable path to discharging their student

loans. One notable pattern in the data is revealing—namely, limited

precedent favoring creditors coupled with an overwhelming number of

settlements favoring debtors. Drawing on litigation theory, this Part

argues that the data pattern is best explained by strategic settlement.

In short, creditors are settling unfavorable cases to avoid adverse

precedent and litigating good cases to cultivate favorable precedent.

Ultimately, this litigation strategy has distorted the law and cultivated

the myth of nondischargeability.

A. Is It an Educational Debt?

In student loan bankruptcy cases, the first issue that a judge must

decide is whether the debt in question is a qualifying educational debt

under § 523(a)(8) of the Bankruptcy Code. As discussed above, if the

loan falls into any of three statutory categories, it is nondischargeable

absent a showing of undue hardship.

38

This section provides a brief

overview of two of the categories and then takes a deeper look at the

final statutory provision.

The first category is set forth in § 523(a)(8)(A)(i) and

encompasses any “educational benefit overpayment or loan made,

insured, or guaranteed by a governmental unit, or made under any

program funded in whole or in part by a governmental unit or

nonprofit institution.”

39

Courts have read this language to apply to “all

situations of student loans funded by the government or nonprofit

institutions.”

40

This category exists to protect American taxpayers and

nonprofit organizations from bearing the burden of student loan

defaults.

41

38. See supra notes 18–20 and accompanying text.

39. 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(8)(A)(i) (2018).

40. E.g., In re Rezendes, 324 B.R. 689, 692 (Bankr. N.D. Ind. 2004).

41. For a more detailed discussion of this provision, see Iuliano, Student Loan Bankruptcy,

supra note 17, at 283.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

508 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

The second category falls under § 523(a)(8)(B) and includes any

“educational loan that is a qualified education loan, as defined in

section 221(d)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, incurred by a

debtor who is an individual.”

42

As anyone who has opened the Tax

Code would guess, digging into this provision means wading through

more than a dozen technical terms. Completing that investigation,

though, would reveal that this category includes any debts that are

incurred for the purpose of paying approved costs of attendance at an

accredited educational institution.

43

The third category—and the one with which this Section is

primarily concerned—is found in § 523(a)(8)(A)(ii). This provision

excepts from discharge any “obligation to repay funds received as an

educational benefit, scholarship, or stipend.”

44

Most courts have

interpreted this clause as a broad catchall, reading it to include any

educational debts not covered by the other two provisions.

45

This sweeping analysis turns on the phrase “educational benefit.”

46

Specifically, judges have endorsed a colloquial reading of the phrase,

in which “benefit” means “an advantage or profit gained from

something.”

47

Understood this way, an “educational benefit” is

anything that facilitates or advances an individual’s education. In short,

if the debt is incurred to fund any educational expenses, then it is an

educational benefit. Given the breadth of this interpretation, I have

previously labeled it the “Broad Reading.”

48

In a prior article

49

and a number of amicus briefs,

50

I have proposed

an alternative interpretation of “educational benefit”—an

42. § 523(a)(8)(B).

43. For a more detailed discussion of this provision, see Iuliano, Student Loan Bankruptcy,

supra note 17, at 286–88.

44. § 523(a)(8)(A)(ii).

45. See, e.g., In re Corbin, 506 B.R. 287, 296 (Bankr. W.D. Wash. 2014) (observing that “a

majority of courts have held that a loan qualifies as an ‘educational benefit’ if the stated purpose

for the loan is to fund educational expenses.” (citing Maas v. Northstar Educ. Fin., Inc. (In re

Maas), 497 B.R. 863, 869–70 (Bankr. W.D. Mich. 2013))).

46. See, e.g., In re Beesley, No. 12-24194-CMB, 2013 WL 5134404, at *4 (Bankr. W.D. Pa.

Sept. 13, 2013) (“[C]ourts . . . have interpreted ‘funds received as an educational benefit’ to

include loans.”); In re Rumer, 469 B.R. 553, 561 (Bankr. M.D. Pa. 2012) (writing that “loans

received as an educational benefit, scholarship, or stipend” are excepted from discharge).

47. Benefit, O

XFORD ENG. DICTIONARY, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/benefit

[https://perma.cc/M4JB-K8YP].

48. See Iuliano, Student Loan Bankruptcy, supra note 17, at 291.

49. See id. at 288–313.

50. See generally Brief of Bankruptcy Scholars as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees and

Affirmance, McDaniel v. Navient Sols., LLC (In re McDaniel), No. 18-1445 (10th Cir. Apr. 18,

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 509

interpretation that I refer to as the “Narrow Reading.” The Narrow

Reading argues that “benefit” should be given the same meaning it has

when used in phrases such as “unemployment benefit,” “insurance

benefit,” and “retirement benefit.”

51

The defining feature of these

types of benefits is not that they promote an individual’s well-being but

rather that they provide monetary assistance that the beneficiary is

legally entitled to receive.

52

The payment can come from a variety of

sources—for example, the state, an employer, or an insurance

company—but in each instance, the payer is distributing guaranteed

benefits.

53

To draw out the distinction between the two readings of “benefit,”

consider the phrase “retirement benefit.” When asked what retirement

benefits are, people think of programs that provide defined payments

to retirees, such as pensions and social security. But consider another

example. Suppose someone offered a retiree one hundred dollars. Is

that a retirement benefit as well? In a strained sense, it may be. The

money does benefit the individual during her retirement. That said, the

money is clearly not a retirement benefit in any conventional sense of

the phrase. And notwithstanding the fact that the money benefits the

retiree, it would be very odd to say that the monetary gift provides a

retirement benefit.

Nonetheless, that situation is precisely analogous to what the

courts have done in the context of educational benefit. They have

defined each of the words by looking at them in isolation and have then

concluded that any monetary transfer benefiting an individual’s

education is an “educational benefit.” In doing so, courts have failed to

account for the way in which “educational” and “benefit” combine to

form a specialized term. If the courts were to read “benefit” in the same

2019) [hereinafter In re McDaniel Brief] (“The plain meaning of the statute, the legislative intent

behind the statutory exemption, and the Bankruptcy Code’s, fresh-start policy all support a

narrow reading of the student loan discharge exemption.”); Brief of Bankruptcy Scholars as

Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees, In re Crocker, 941 F.3d 206 (5th Cir. 2019) (No. 18-20254)

[hereinafter In re Crocker Brief] (same).

51. Benefit, D

ICTIONARY.COM, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/benefit?s=t [https://perma.cc/

4ZK3-CPZ2] (defining “benefit” as “a payment or gift . . . given by an employer, an insurance

company, or a public agency”).

52. See Benefit, O

XFORD ENG. DICTIONARY, supra note 47 (defining “benefit” as “[a]

payment made by the state or an insurance scheme to someone entitled to receive it”).

53. See Benefit, M

ERRIAM-WEBSTER DICTIONARY, https://www.merriam-webster.com/

dictionary/benefit [https://perma.cc/3ANF-DMS7] (defining “benefit” as “financial help in time

of sickness, old age, or unemployment . . . a payment or service provided for under an annuity,

pension plan, or insurance policy . . . a service (such as health insurance) or right (as to take

vacation time) provided by an employer in addition to wages”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

510 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

way they read the word in analogous contexts—such as “retirement

benefit” or “employment benefit”—“educational benefit” would refer

to a type of debt known as a conditional educational grant. These

debts, in short, include any educational funds that a student receives in

exchange for a promise to perform future services.

The Reserve Officer Training Corps is a notable example of an

educational benefit program. The fund pays college tuition for students

who meet certain qualifications and who agree to serve in the military

for a given number of years following graduation.

54

Another example

of an educational benefit is the federally funded National Health

Service Corps scholarship. Similar to its military counterpart, this

program pays the tuition of medical school students who agree to spend

several years working in underserved areas after graduation.

55

Importantly, these programs do not loan money but rather offer

conditional educational grants. The student must repay the money only

if she does not meet her obligations. This type of agreement is what the

statute means when it refers to an educational benefit.

A few key points illustrate the superiority of the Narrow

Reading.

56

First, if “educational benefit” is read broadly, then

§ 523(a)(8)(A)(i) and § 523(a)(8)(B) are rendered irrelevant. Recall

that these provisions cover loans backed by the federal government or

nonprofits and qualifying education loans. Both of these categories of

debts are undeniably educational benefits under the Broad Reading.

This interpretation, however, presents a significant problem. Giving

“educational benefit” a meaning that completely subsumes two other

statutory provisions violates the canon against surplusage.

57

Importantly, no such concern arises under the Narrow Reading. All

three subsections of § 523(a)(8) retain distinct, yet complementary,

meanings.

54. Angela Frisk, Get Money for College Through ROTC Programs, U.S. NEWS & WORLD

REP. (July 25, 2013, 10:00 AM), https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/the-scholarship-coach/

2013/07/25/get-money-for-college-through-rotc-programs [https://perma.cc/5FR8-L67M].

55. Scholarship Program Overview, N

AT’L HEALTH SERV. CORPS, https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/

scholarships/overview/index.html [https://perma.cc/C43E-2K33].

56. For a comprehensive discussion of the arguments in favor of the Narrow Reading, see

McDaniel Brief, supra note 50; In re Crocker Brief, supra note 50; Iuliano, Student Loan

Bankruptcy, supra note 17, at 288–313.

57. See, e.g., NLRB v. SW Gen., Inc., 137 S. Ct. 929, 941 (2017) (writing that courts must

“give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute” (quoting Williams v. Taylor, 529

U.S. 362, 404 (2000))); TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 31 (2001) (“[A] statute ought, upon

the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be

superfluous, void, or insignificant.” (quoting Duncan v. Walker, 533 U.S. 167, 174 (2001))).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 511

Second, the phrase “educational benefit” appears in another part

of the statute, and there, courts have interpreted the term in line with

the Narrow Reading.

58

The specific occurrence is in § 523(a)(8)(A)(i),

and the operant phrase is “educational benefit overpayment.”

59

An

opinion by a bankruptcy court in New Mexico provides a clear

explanation of how courts have interpreted the phrase in this context:

“Educational benefit overpayment occurs in programs like the GI Bill,

where students receive periodic payments upon their certification that

they are attending school. When a student receives funds but is not in

school, this is a[n] educational benefit overpayment.”

60

Interpreting

“educational benefit” in completely different ways in related sections

of a statute would make no sense. As the Supreme Court has affirmed

repeatedly, when identical words are used multiple times throughout a

statute, they must be given the same meaning each time, absent a

compelling reason otherwise.

61

And third, the only mention of “educational benefit” in the

legislative record strongly supports the Narrow Reading. As part of a

1990 congressional hearing, the chair of the Subcommittee on

Economic and Commercial Law asked the U.S. Attorney for the

Eastern District of Texas to explain “[t]he specific problem [the

provision] is designed to address.”

62

The U.S. Attorney responded as follows:

This section adds to the list of non-dischargeable debts, obligations

to repay educational funds received in the form of benefits (such as

VA benefits), scholarships (such as medical service corps

58. See, e.g., In re Moore, 407 B.R. 855, 859 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 2009) (describing “educational

benefit overpayment” as “an overpayment from a program like the GI Bill, where students

receive payments even though they are not attending school”).

59. 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(8)(A)(i) (2018).

60. In re Coole, 202 B.R. 518, 519 (Bankr. D. N.M. 1996). One court explained educational

benefit overpayments in further detail:

Clearly, Plaintiff’s failure to pay his student housing obligations cannot be deemed

debt for ‘an educational benefit overpayment.’ Defendant paid nothing to Plaintiff.

NYU merely allowed Plaintiff to live at school facilities in consideration for certain

charges which were not paid. No linguistic gyration can twist a no payment or

underpayment by Plaintiff to an overpayment by Defendant.

In re Alibatya, 178 B.R. 335, 338 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 1995).

61. See, e.g., Henson v. Santander Consumer USA Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1718, 1723 (2017)

(“‘[I]dentical words used in different parts of the same statute’ carry ‘the same meaning.’”

(quoting IBP, Inc. v. Alvarez, 546 U.S. 21, 34 (2005))).

62. Federal Debt Collection Procedures of 1990: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Econ. &

Com. L. of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 101st Cong. 42 (1990) (question for the record

submitted by Rep. Brooks, Chairman, H. Subcomm. on Econ. & Com. L.).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

512 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

scholarships) and stipends. These obligations are often very sizable

and should receive the same treatment as a “student loan” with regard

to restrictions on dischargeability in bankruptcy.’

63

This answer directly restates the Narrow Reading. The U.S.

Attorney clarified that educational benefits are not loans but rather

“educational funds received in the form of benefits.”

64

They are, in

other words, conditional educational grants.

Notably, within the last year, two courts of appeals have

considered this issue and both have endorsed the Narrow Reading.

65

Accordingly, this Article does not pursue these points further. Instead,

it focuses on an objection to the argument—namely, if the Narrow

Reading is so obviously correct, why did the Broad Reading prevail for

more than a decade in the overwhelming majority of bankruptcy

cases?

66

As I will show, the answer to that question lies in how student loan

creditors have litigated educational benefit cases. Specifically, they

have worked to ensure that courts only hear arguments in favor of the

Broad Reading. When debtors advance a narrow interpretation of the

statute, creditors entice them to drop the case by proposing

confidential settlement agreements. By contrast, when debtors

concede the accuracy of the Broad Reading, creditors pursue litigation

techniques designed to manufacture precedent supportive of their

preferred interpretation. This process is called strategic settlement.

67

And it is concerning because it exploits an access-to-justice gap in the

bankruptcy system.

Because student loan debtors often lack the ability to pay for

adequate counsel, most never learn they have strong legal claims in this

area and, therefore, acquiesce to their creditors’ demands. Moreover,

given that student loan debtors have no incentive to establish sound

63. Id. at 74–75 (response of Mr. Wortham, United States Attorney for the Eastern District

of Texas).

64. Id. at 74.

65. See McDaniel v. Navient Sols., LLC (In re McDaniel), No. 18-1445, 2020 WL 5104560,

at *7–10 (10th Cir. Aug. 31, 2020) (endorsing the Narrow Reading); Crocker v. Navient Sols.,

LLC (In re Crocker), 941 F.3d 206, 217–24 (5th Cir. 2019) (finding that the Broad Reading “is not

only unsupported by the text, it is unsupported by some of [the appellant’s] authorities” and

holding “that ‘educational benefit’ is limited to conditional payments with similarities to

scholarships and stipends”).

66. For a discussion of the case law endorsing the Broad Reading, see Iuliano, Student Loan

Bankruptcy, supra note 17, at 284–86.

67. See Frank B. Cross, Decisionmaking in the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, 91 C

ALIF. L.

REV. 1457, 1492–94 (2003) [hereinafter Cross, Decisionmaking] (discussing strategic settlement).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 513

precedent for future cases, those few individuals who do bring

challenges are eager to accept settlement offers. Because of this

incentive structure, creditors have been able to manufacture favorable

precedent, even in the absence of legally defensible arguments. This

strategy has been highly successful and has created a perception of

nondischargeability that has deterred many potential litigants.

68

The following two Subsections focus on the structural issues that

underlie much of the student loan bankruptcy litigation. The first

Section presents data showing the existence of a significant access-to-

justice gap. And the second discusses the litigation incentives that have

enabled this problem to persist.

1. Data. A majority of courts that ruled on the meaning of

educational benefit adopted the Broad Reading. That much is clear

from the case law. But what is not clear is why judges have endorsed

that interpretation. Is it because they believe the arguments in the

Broad Reading’s favor are more compelling, or is it simply because

they do not hear arguments against it? This Subsection presents data

that bear on this question and finds that the evidence points toward the

latter explanation. Judges have not had the opportunity to weigh the

Narrow Reading against the Broad Reading. And more troublingly,

student loan creditors have worked to prevent courts from having such

an opportunity. Uncovering this litigation strategy requires looking

beyond the judicial opinions to the parties’ briefs. This Subsection

accomplishes that by presenting data on those cases that addressed the

68. This perception of nondischargeability is widespread among consumer bankruptcy

attorneys. See, e.g., Rich Feinsilver, Education Department Reviewing Discharge of Student Loans

in Bankruptcy? – Not So Fast, F

EINLAWYER.COM (Feb. 22, 2018), https://feinlawyer.com/

education-department-reviewing-discharge-student-loans-bankruptcy-not-fast [https://perma.cc/

5H44-RGAW] (“As of now, it is almost impossible to discharge student loans in bankruptcy.”);

Refinancing Student Loans To Avoid Bankruptcy, S

IMON, RESNICK, HAYES LLP, https://

www.simonresnik.com/chapter-13/refinancing-student-loans-avoid-bankruptcy [https://perma.cc/

2WHH-DKEK] (“[P]rivate student loan debt [is] . . . almost completely (except for extreme

cases) nondischargeable in bankruptcy.”); John Rose, Are Student Loans Dischargeable in

Bankruptcy?, R

OSE L. OFF., https://www.johnwrose.com/Articles/Are-student-loans-dischargeable

-in-bankruptcy.shtml [https://perma.cc/DM3W-9ZV9] (“When the current bankruptcy law went

into effect in 2005, it became nearly impossible to discharge student loans in bankruptcy.”); Eric

M. Wilson, Tuscaloosa Student Loan and Tax Debt Relief Lawyer, E

RIC WILSON L., LLC, http://

www.ericwilsonlaw.com/Bankruptcy/Student-Loans-Tax-Debt.html [https://perma.cc/8BQL-HJ4J]

(“It is almost impossible to discharge student loans through bankruptcy.”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

514 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

meaning of educational benefit between October 2005 and December

2019.

69

To identify the relevant set of cases, I used the “Bankruptcy

Dockets Search” function on Bloomberg Law to run a “Dockets &

Documents” query for any docket materials that used the phrase

“educational benefit” at least three times and also referenced either

educational debt or student loans.

70

Because the term “educational

benefit” appears twice in § 523(a)(8), I required at least three mentions

to ensure that documents that quoted the statute but lacked any

additional discussion of the term were excluded from the search results.

To filter out irrelevant results, I read through the docket for each of

these cases. Many focused on the issue of undue hardship, not the

scope of the educational benefit exemption. And a number of others

involved issues unrelated to the dischargeability of student loan debt.

71

Through this filtering process, I narrowed the set of cases to those

that addressed the meaning of educational benefit. I counted a case as

addressing the issue if either party advanced an argument regarding

the scope of the educational benefit exemption in any court filing or if

the court discussed the meaning of the phrase in its opinion. To serve

as a partial check on Bloomberg Law, I also ran the same search query

on Westlaw. Between these two protocols, thirty-nine cases met the

criteria for inclusion in the dataset.

72

It bears noting that this search methodology is not comprehensive.

Because Westlaw only searches judicial opinions and because

Bloomberg Law does not run a full-text search on every document filed

in the bankruptcy courts, some relevant cases likely failed to turn up in

either set of results.

73

That said, the low number of cases is consistent

69. The start date was chosen to coincide with the effective date of the Bankruptcy Abuse

Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-8, 119 Stat. 23 (codified as

amended in scattered sections of 11 U.S.C.).

70. The precise query is as follows: (“student loan!” OR “educational debt!” OR

“educational loan!”) AND atleast3(“educational benefit”).

71. Many of these cases focused on the scope of 11 U.S.C. §§ 523(a)(8)(A)(i) or

§ 523(a)(8)(B) (2018), but did not discuss the meaning of § 523(a)(A)(ii). I excluded those cases

in which both debtors were individuals. There were very few of these cases, but generally, these

disputes involved two family members in a debtor–creditor relationship. See, e.g., In re Nypaver,

581 B.R. 431, 431–32 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 2018).

72. Several other cases are ongoing, but because they have not reached a resolution, they

are not included in the dataset.

73. Unfortunately, the only way to conduct a comprehensive search would be to manually

examine the PACER filings for every adversary proceeding. And given the large number of

adversary proceedings, that method would have increased the workload almost a hundredfold.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 515

both with prior research on student loan undue hardship proceedings

74

and with the data on student loan adversary proceedings presented

later in this Article.

75

Of these thirty-nine disputes, thirty-two were resolved by a

judicial ruling on the merits; one ended with a default judgment in

favor of the debtor; and another six concluded with settlement

agreements. In the cases where judges ruled on the merits, creditors

were highly successful, winning more than 80 percent of the time. In

light of the case law discussed in previous research, that win rate is

unsurprising.

76

But the question motivating this data collection is not

“Who wins?” but rather “Why do they win?” Digging deeper into the

cases reveals that the answer is not because creditors have the better

arguments but rather because most courts fail to hear debtors’ best

arguments.

Table 1 shows the strength of the link between the arguments

debtors raise and the discharge outcomes they receive. As the table

reveals, debtors won—or agreed to confidential settlements—in every

case in which they offered arguments in support of the Narrow

Reading. Conversely, they lost every case—except one—in which they

failed to propose the Narrow Reading. In the single outlier, the debtor

prevailed because the judge endorsed the Narrow Reading after

conducting his own examination of the issue.

77

74. See Iuliano, Empirical Assessment, supra note 1, at 505 (finding that only 0.1 percent of

student loan debtors in bankruptcy seek to discharge their educational debts).

75. See infra Part II.B. Between 2011 and 2019, there were an average of 573 student loan

adversary proceedings per year. See infra tbl.2. Educational benefit cases are, however, only a

small part of this total. More precisely, given the composition of all student loan debt, one would

expect approximately 2 percent of these adversary proceedings to address the meaning of

educational benefit—this approximation is derived from dividing the approximately $1.7 trillion

in total student loan debt by the roughly $50 billion that is subject to the educational benefit

discussion. See Teddy Nykiel, 2020 Student Loan Debt Statistics, N

ERDWALLET (Sept. 23, 2020),

https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/loans/student-loans/student-loan-debt [https://perma.cc/PL58-

H3YB] (noting that $1.67 trillion is owed in federal and private student loan debt as of June 2020);

Alexander Gladstone, Appeals Court Weakens Bankruptcy Protections for Private Student Loans,

W

ALL ST. J. (Sept. 1, 2020, 4:57 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/appeals-court-weakens-

bankruptcy-protections-for-private-student-loans-11598993841 [https://perma.cc/222G-RXCY]

(noting that “[r]oughly $50 billion of outstanding private student debt” is subject to the

“educational benefit” dispute).

76. See Iuliano, Student Loan Bankruptcy, supra note 17, at 289–301.

77. See Nunez v. Key Educ. Res./GLESI (In re Nunez), 527 B.R. 410, 413–15 (Bankr. D. Or.

2015) (discussing the merits of the Narrow Reading). Given the judge’s extensive treatment of

the issue in his opinion, it seems likely that the Narrow Reading was addressed during oral

argument.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

516 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

TABLE 1: DEBTORS’ ARGUMENTS AND DISCHARGE OUTCOMES

Did debtor propose Narrow Reading?

Discharge

Yes No

Yes 12

*

1

No 0 26

* This

f

igure includes five rulings on the merits, six stipulated

discharges, and one default judgment.

In contrast to the debtors, creditors won only those cases in which

debtors conceded the accuracy of the Broad Reading. For these cases,

the debtors’ strategies involved challenging the application of the

Broad Reading to the specific loans in dispute.

78

Most frequently, their

arguments focused on whether educational benefit referred to the

loan’s stated purpose or the loan’s actual use.

79

Many borrowers argued

for the latter interpretation, claiming that their educational loans were

dischargeable because they used them for noneducational purposes.

This argument is nothing short of bizarre. By its logic, if a debtor

took out an educational loan to pay for tuition but proceeded to use

the funds to purchase a car, the debt would be dischargeable. But if

that same debtor took out an educational loan to pay for tuition and

actually used it to pay for tuition, the debt would be nondischargeable.

For obvious reasons, courts have found this line of argument

unpersuasive.

80

Nonetheless, debtors keep raising claims like this, and that has

proven beneficial to student loan creditors. Each time they win,

78. See, e.g., Reply Brief for Appellant at 6–9, Desormes v. Charlotte Sch. of L. (In re

Desormes), 497 B.R. 390 (Bankr. D. Conn. 2012) (No. 10-50079) (conceding the Broad Reading

and focusing on the question of whether the funds were received).

79. See, e.g., Maas v. Northstar Educ. Fin., Inc. (In re Maas), 497 B.R. 863, 869 (Bankr. W.D.

Mich. 2013) (“Although the breadth of this term has been the subject of some debate, a majority

of courts determine whether a loan qualifies as an ‘educational benefit’ by focusing on the stated

purpose for the loan when it was obtained, rather than on how the loan proceeds were actually

used.”).

80. See Navient Sols., LLC v. Crocker (In re Crocker), 585 B.R. 830, 836 (Bankr. S.D. Tex.

2018), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 941 F.3d 206 (5th Cir. 2019). In Crocker, the court concluded that

“educational benefit” is to be read narrowly:

[The scope of educational benefit does] not include all loans that were in some way

used by a debtor for education. If such were the case, would not a loan for a car used

by a commuter student to travel to and from school every day be nondischargeable

under § 523(a)(8)(A)(ii)? The answer is obvious.

Id.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 517

creditors have another case they can point to in support of the Broad

Reading. As the list of supportive precedent expands, the perception

that the issue is settled grows stronger, and the argument itself becomes

more compelling. Creditors are aware of this fact and have worked to

ensure that the precedent weighs in their favor. They have done so not

only by litigating cases that are likely to bolster favorable precedent

but by settling cases that are likely to result in adverse precedent.

Indeed, in every single case that settled, the debtors advanced

arguments supporting the Narrow Reading.

81

As the data illustrate,

proposing the Narrow Reading is a virtual prerequisite for obtaining a

favorable outcome.

One point worth emphasizing is that the debtors who argued for

the Narrow Reading and those who failed to do so had similar student

loan obligations. In only 8 percent of the cases, borrowers had debts

that would be exempt from discharge under the Narrow Reading.

82

Despite this, borrowers lost 67 percent of the cases—more than eight

times the rate one would expect if the issues had been adequately

briefed. Although that disparity highlights a notable access-to-justice

gap, it is not the most significant problem. The far greater issue is the

small number of cases that are filed.

To put the extent of this shortfall into perspective, consider the

following: each year, several thousand debtors with student loans that

are not qualifying debts under § 523(a)(8) file for bankruptcy.

83

But

each year, fewer than five of those debtors bring forward cases to

request a discharge.

84

In percentage terms, fewer than 1 percent of the

educational benefit cases that should be filed are actually filed.

Regardless of the exact number, the key point is that few individuals

with dischargeable student loans recognize that those debts are, in fact,

dischargeable.

81. See, e.g., Plaintiff’s Notice of Hearing and Motion for Partial Summary Judgment at 7–

10, Ferguson v. Navient Sols., LLC (In re Ferguson), No. 17-04051 (Bankr. D. Minn. July 25, 2017)

(advocating a narrow construction of § 523(a)(8)).

82. See Chi. Patrolmen’s Fed. Credit Union v. Daymon (In re Daymon), 490 B.R. 331, 335–

37 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 2013) (finding that an employer-sponsored tuition assistance program—in

which the debtor received tuition reimbursement in exchange for agreeing to work for the

employer for a fixed period of time—conferred a nondischargeable educational benefit); Omaha

Joint Elec. Apprenticeship & Training Comm. v. Stephens (In re Stephens), No. 10-8056, 2011

WL 672000, at *3–4 (Bankr. D. Neb. Feb. 17, 2011) (same); Sensient Techs. Corp. v. Baiocchi (In

re Baiocchi), 389 B.R. 828, 830–32 (Bankr. E.D. Wis. 2008) (same).

83. This number is an estimate derived from the fact that approximately 2 percent of

outstanding student loan debt falls into this category. See supra note 75.

84. See supra notes 69–72 and accompanying text.

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

518 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

2. Theory. The existence of an access-to-justice gap in the student

loan bankruptcy system is unfortunate, but given the litigation

incentives, it is not surprising. This situation is a paradigmatic example

of the case-selection strategy that Marc Galanter identifies in his

landmark law and society article, “Why the ‘Haves’ Come out

Ahead.”

85

In that piece, Galanter divides litigants into two groups:

repeat players and one-shotters.

86

Repeat players are those who engage

in many similar cases over time.

87

One-shotters are those who have

isolated interactions with the judicial system.

88

Because one-shotters do

not expect to find themselves in court again, they are concerned only

with the outcome in the present case.

89

Repeat players, by contrast,

take a long-term view, which enables them to trade off immediate gains

to obtain greater gains in subsequent cases.

90

These incentives make it

such that repeat players care greatly about the establishment of

favorable precedent, and one-shotters do not care at all. By capitalizing

on these divergent interests, repeat players are able to engage in a case-

selection strategy designed to cultivate favorable precedent, even in

the absence of strong legal arguments.

91

As experience has proven, the repeat-player/one-shotter model is

more than an abstract theory. Its insights explain litigation strategy in

a large number of domains.

92

From plea negotiations between

85. See generally Marc Galanter, Why the “Haves” Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the

Limits of Legal Change, 9 L

AW & SOC’Y REV. 95 (1974) (explaining how litigants who expect to

be involved in many cases on a single issue have different incentives than litigants who expect to

be involved in only one case).

86. See id. at 97.

87. See id. (defining repeat players as those “who are engaged in many similar litigations

over time”).

88. See id. (defining one-shotters as “claimants who have only occasional recourse to the

courts”).

89. See Catherine Albiston, The Rule of Law and the Litigation Process: The Paradox of

Losing by Winning, 33 L

AW & SOC’Y REV. 869, 873 (1999) (“One-shot players who do not expect

to litigate again are more likely to . . . trad[e] the possibility of making ‘good law’ for tangible

gain—because they may not value a favorable legal opinion for future disputes.”).

90. See Galanter, supra note 85, at 100 (discussing repeat players’ incentives to “play for

rules in litigation itself”).

91. See Lynn M. LoPucki & Walter O. Weyrauch, A Theory of Legal Strategy, 49 D

UKE L.J.

1405, 1450–52 (2000) (discussing how repeat players can employ this case-selection strategy to

“pressur[e] judges into a favorable resolution of a case without entirely persuading them to it”).

92. See generally, e.g., Donald R. Songer, Reginald S. Sheehan & Susan Brodie Haire, Do

the ‘Haves’ Come Out Ahead over Time? Applying Galanter’s Framework to the Decisions of the

U.S. Courts of Appeals 1925–1988, 33 L

AW & SOC’Y REV. 811 (1999) (examining decisions in the

federal courts of appeals from 1925 through 1988 and finding support for Galanter’s hypothesis

that repeat players are more likely to win).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 519

prosecutors and defendants, to labor disputes between employers and

employees, to contract issues between businesses and consumers, the

model illustrates how repeat players are able to game the system to

their advantage.

93

The data in this study show that student loan bankruptcy litigation

is another area in which the theory has strong explanatory power.

94

As

the repeat players in this scenario, student loan creditors have taken a

long-term view with respect to their litigation strategy.

95

Because they

expect to be involved in similar disputes in the future, creditors quickly

settle cases that could yield adverse precedent and aggressively litigate

cases that are likely to yield beneficial precedent.

96

In fact, their

incentives are such that they are willing to devote substantial resources

to a single case when doing so will deter subsequent litigation or make

it easier to win the cases that are brought.

Student loan debtors, by contrast, follow the one-shotter playbook

and, accordingly, have no interest in the outcome of future litigation.

For them, everything turns on the disposition of just one case.

97

This

single-minded focus influences debtors’ strategic decisions in two

important respects. First, it promotes risk-averse behavior. Because

debtors are unable to average their wins and losses across a set of cases

and because the stakes are high relative to their net worth, debtors are

incentivized to accept settlement offers below their case’s expected

value.

98

Second, because debtors do not expect to be involved in similar

disputes in the future, they ignore the precedential effects that their

93. See, e.g., Albiston, supra note 89, at 898 (examining employment litigation involving the

Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 and finding support for Galanter’s hypothesis that repeat

players fare better).

94. See supra Part II.A.1.

95. Cf. Galanter, supra note 85, at 103 (noting “the superior opportunities of the [repeat

player] to trigger promising cases and prevent the triggering of unpromising ones”).

96. See id. at 101 (“We would then expect [repeat players] to ‘settle’ cases where they

expected unfavorable rule outcomes. Since they expect to litigate again, [repeat players] can select

to adjudicate (or appeal) those cases which they regard as most likely to produce favorable

rules.”).

97. See Janet Cooper Alexander, Do the Merits Matter? A Study of Settlements in Securities

Class Actions, 43 S

TAN. L. REV. 497, 534 (1991) (“One-shot players who expect to be involved in

only one litigation will not realize such benefits [from establishing favorable precedent]. For them,

there is no long run; there is only now.”).

98. Cf. id. at 533–34 (noting that, unlike one-shotters, “[r]epeat players can afford to ‘play

the averages’ and treat each case according to its expected value because gains will offset losses

over time”).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

520 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

cases will have on subsequent litigation.

99

This incentive structure

accrues to the benefit of creditors by skewing precedent in their favor

and by allowing them to settle unfavorable cases on favorable terms.

100

The unwarranted advantages of this repeat-player strategy are

even more salient when one considers that student loan creditors,

themselves, harbor doubts as to the veracity of the Broad Reading. In

disclosure statements for the Securities and Exchange Commission

(“SEC”), student loan creditors have repeatedly warned investors that

many types of private student loans may be dischargeable in

bankruptcy. For example, in its prospectus for a $1.5 billion student

loan securitization, Sallie Mae stated that the “risk of bankruptcy

discharge of private credit student loans” is a factor investors should

“carefully consider . . . in deciding whether to purchase any notes.”

101

Providing further details, Sallie Mae advised that

[p]rivate credit student loans made for qualified education expenses

are generally not dischargeable by a borrower in bankruptcy . . . [but]

direct-to-consumer loans are disbursed directly to the borrowers

based upon certifications and warranties contained in their

promissory notes . . . . This process does not involve school

certification as an additional control and, therefore, may be subject to

some additional risk that the loans are not used for qualified education

expenses. If you own any notes, you will bear any risk of loss resulting

from the discharge of any borrower of a private credit student loan to

the extent the amount of the default is not covered by the trust’s credit

enhancement.

102

According to Sallie Mae’s own financial disclosures, private student

loans that are not used for qualified education expenses may be

dischargeable in bankruptcy. Navient, a spin-off of Sallie Mae and

major student-loan servicing company in its own right, has issued

similar advisements in its SEC filings. In a 2014 offering memorandum,

for instance, the company warned investors that a key risk factor is the

99. See Galanter, supra note 85, at 102 (arguing that one-shotters “should be willing to trade

off the possibility of making ‘good law’ for tangible gain”).

100. See id. (“[W]e would expect the body of ‘precedent’ cases—that is, cases capable of

influencing the outcome of future cases—to be relatively skewed toward those favorable to

[repeat players].”).

101. SLM

STUDENT LOAN TRUST 2008-1, PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT TO BASE PROSPECTUS

DATED OCTOBER 16, 2007, at 20, 33 (2008), https://www.navient.com/assets/about/investors/

debtasset/SLM-Loan-Trusts/06-10/2008-1/20081.pdf [https://perma.cc/99GW-4JUU].

102. Id. at 33 (emphasis added).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

2020] THE STUDENT LOAN BANKRUPTCY GAP 521

“bankruptcy discharge of career training loans.”

103

As Navient

explained,

Career training loans are generally dischargeable by a borrower in

bankruptcy. If you own any notes, you will bear any risk of loss

resulting from the discharge of any borrower of a career training loan

to the extent the amount of the default is not covered by the trust’s

credit enhancement.

104

Interestingly, in its court briefs, Navient firmly claimed that loans not

used for qualified education expenses, such as career training loans, are

exempt from discharge and argued that reading the statute otherwise

“makes no sense” and “ignore[s] clear Congressional instruction.”

105

When faced with possible liability for issuing material misstatements to

investors,

106

Navient emphasizes the dischargeability of student loans.

But when making arguments in court, Navient wholly disclaims that

position, arguing that such loans are clearly nondischargeable.

With respect to educational benefit litigation, creditors have used

their status as repeat players to great advantage. Through careful case

selection, they have managed not only to develop favorable precedent

but to do so with such success that few debtors have been willing to

challenge the Broad Reading’s expansive interpretation. Despite

having the weaker legal arguments, student loan creditors have been

the clear victors.

B. Is There Undue Hardship?

In step two of the student loan discharge analysis, the court must

evaluate whether the student loan would “impose an undue hardship

on the debtor and the debtor’s dependents.”

107

As discussed in Part I,

most courts in the United States have adopted the Brunner test—a

standard that requires debtors to establish three elements to prove

undue hardship: (1) a current inability to repay the loans, (2) a future

103. NAVIENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM, at S-29 (2014), https://www.navient.com/assets/

NAVSL%202014-CT%20-%20Offering%20Memorandum%20-%20As%20Printed.pdf [https://

perma.cc/58Y6-ZPHD].

104. Id. (emphasis added).

105. See, e.g., Opening Brief of Appellants at 27–28, Crocker v. Navient Sols., LLC (In re

Crocker), 941 F.3d 206 (5th Cir. 2019) (No. 18-20254).

106. See 15 U.S.C. § 78j (2018).

107. 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(8) (2018).

IULIANO IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/16/2020 7:37 PM

522 DUKE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 70:497

inability to repay the loans, and (3) a good faith effort to repay the

loans.

108

These prongs are best thought of as three temporal dimensions—

present, future, and past, respectively—of a single analysis. The first