Vol. 79 Friday,

No. 100 May 23, 2014

Part II

Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

42 CFR Parts 417, 422, 423, et al.

Medicare Program; Contract Year 2015 Policy and Technical Changes to

the Medicare Advantage and the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Programs; Final Rule

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29844

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND

HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services

42 CFR Parts 417, 422, 423, and 424

[CMS–4159–F]

RIN 0938–AR37

Medicare Program; Contract Year 2015

Policy and Technical Changes to the

Medicare Advantage and the Medicare

Prescription Drug Benefit Programs

AGENCY

: Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

ACTION

: Final rule.

SUMMARY

: The final rule will revise the

Medicare Advantage (MA) program (Part

C) regulations and prescription drug

benefit program (Part D) regulations to

implement statutory requirements;

improve program efficiencies; and

clarify program requirements. The final

rule also includes several provisions

designed to improve payment accuracy.

DATES

: Effective Dates: These

regulations are effective on July 22, 2014

except for the amendment in instruction

27 to § 423.100, the amendment in

instruction 30 to § 423.501, and the

amendment in instruction 34 to

§ 423.505, which are effective on

January 1, 2016.

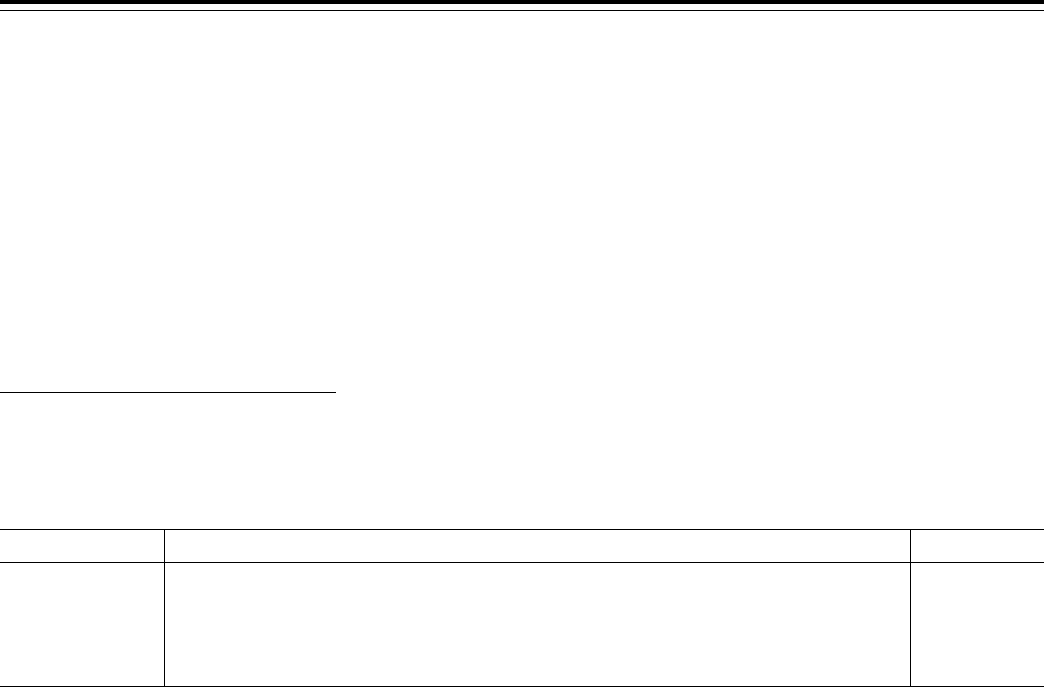

Applicability Dates: In the

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

section of

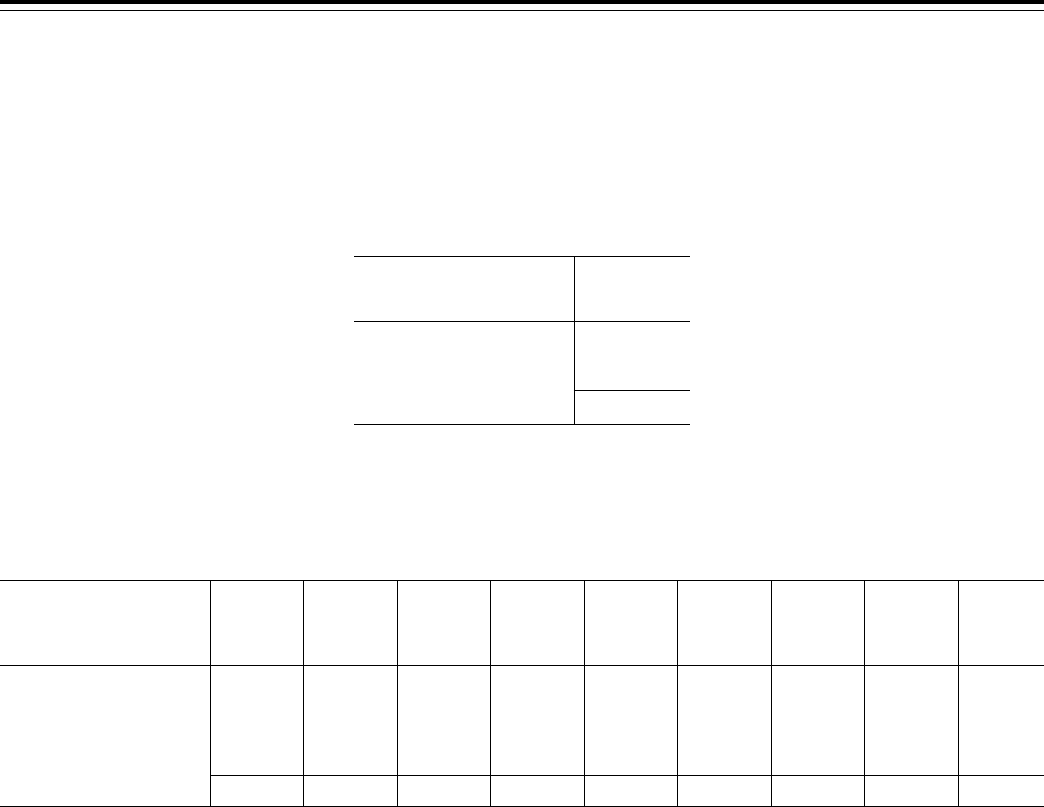

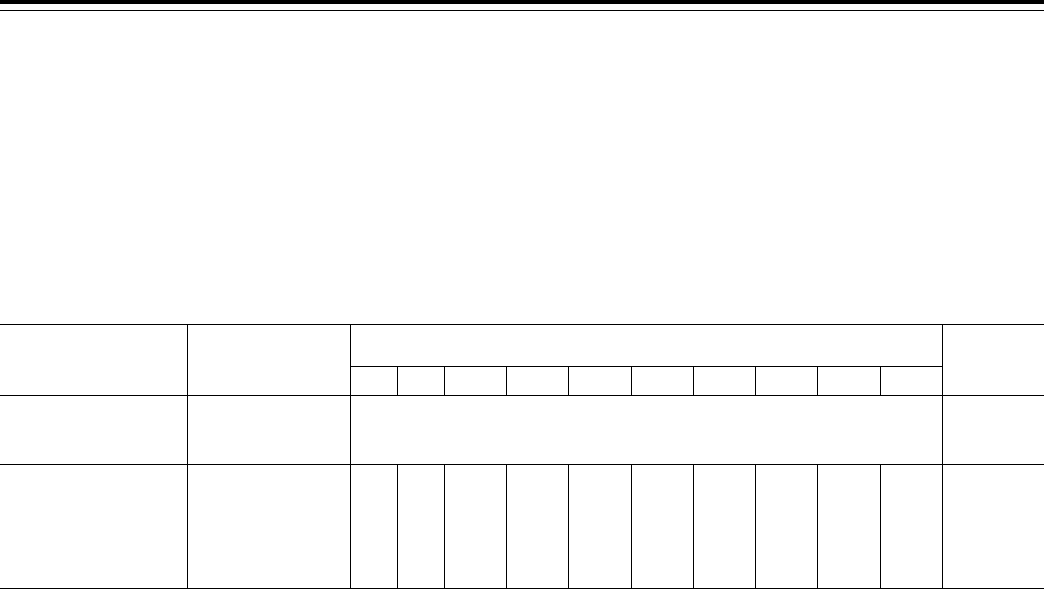

this final rule, we provide a table (Table

1) which lists key changes in this final

rule that have an applicability date

other than the effective date of this final

rule.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT

:

Christopher McClintick, (410) 786–

4682, Part C issues.

Marie Manteuffel, (410) 786–3447, Part

D issues.

Kristy Nishimoto, (206) 615–2367, Part

C and D enrollment and appeals

issues.

Whitney Johnson, (410) 786–0490, Part

C and D payment issues.

Joscelyn Lissone, (410) 786–5116, Part C

and D compliance issues.

Frank Whelan, (410) 786 1302, Part D

improper prescribing issues.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

: Table 1

lists key changes that have an

applicability date other than 60 days

after the date of publication of this final

rule. The applicability dates are

discussed in the preamble for each of

these items.

T

ABLE

1—A

PPLICABILITY

D

ATE OF

K

EY

P

ROVISIONS

O

THER

T

HAN

60 D

AYS

A

FTER THE

D

ATE OF

P

UBLICATION OF THE

F

INAL

R

ULE

Preamble section Section title Applicability date

III.A.4 ........................ Reducing the Burden of the Compliance Program Training Requirements (§§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(C) and

§ 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(C)).

01/01/2016

III.A.7 ........................ Agent/Broker Compensation Requirements (§§ 422.2274 and 423.2274) ............................................... 01/01/2015

III.A.20 ...................... Enrollment Requirements for the Prescribers of Part D Covered Drugs (§ 423.120(c)(6)) ..................... 06/01/2015

III.A.24 ...................... Eligibility of Enrollment for Incarcerated Individuals (§§ 417.1, 417.460(b)(2)(i), 417.460(f)(1)(i)(A)

through (C), 422.74(d)(4)(i)(A), 422.74(d)(4)(v), 423.44(d)(5)(iii) and (iv)).

01/01/2015

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

B. Summary of the Major Provisions

1. Modifying the Agent/Broker

Requirements, Specifically Agent/Broker

Compensation

2. Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical

Concern

3. Improving Payment Accuracy—

Implementing Overpayment Provisions

of Section 1128J (d) of the Social

Security Act (§§ 422.326 and 423.360).

4. Risk Adjustment Data Requirements

(§ 422.310)

C. Summary of Costs and Benefits

II. Background

A. General Overview and Regulatory

History

B. Issuance of a Notice of Proposed

Rulemaking

C. Public Comments Received in Response

to the CY 2015 Policy and Technical

Changes to the Medicare Advantage and

the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Programs Proposed Rule

D. Provisions Not Finalized in this Final

Rule

III. Provisions of the Proposed Regulations

A. Clarifying Various Program

Participation Requirements

1. Closing Cost Contract Plans to New

Enrollment (§§ 422.2 and 22.503)

2. Authority to Impose Intermediate

Sanctions and Civil Money Penalties

(§§ 422.752, 423.752, 422.760 and

423.760)

3. Contract Termination Notification

Requirements and Contract Termination

Basis (§§ 422.510 and 423.509)

4. Reducing the Burden of the Compliance

Program Training Requirements

(§§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(C) and

423.504(b)(4)(vi)(C))

5. Procedures for Imposing Intermediate

Sanctions and Civil Money Penalties

Under Parts C and D (§§ 422.756 and

423.756)

6. Timely Access to Mail Order Services

(§ 423.120)

7. Agent/Broker Requirements, Particularly

Compensation (§§ 422.2274 and

423.2274)

8. Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical

Concern (§ 423.120(b)(2)(v))

9. Medication Therapy Management

Program (MTMP) under Part D

(§ 423.153(d))

a. Multiple Chronic Diseases

b. Multiple Part D Drugs

c. Annual Cost Threshold

10. Requirement for Applicants or their

Contracted First Tier, Downstream, or

Related Entities to Have Experience in

the Part D Program Providing Key Part D

Functions (§ 423.504(b))

11. Requirement for Applicants for Stand

Alone Part D Plan Sponsor Contracts to

Be Actively Engaged in the Business of

the Administration of Health Insurance

Benefits (§ 423.504(b)(9))

12. Limit Parent Organizations to One

Prescription Drug Plan (PDP) Sponsor

Contract Per PDP Region (§ 423.503)

13. Limit Stand-Alone Prescription Drug

Plan Sponsors to Offering No More Than

Two Plans Per PDP Region (§ 423.265)

14. Applicable Cost-Sharing for Transition

Supplies: Transition Process Under Part

D (§ 423.120(b)(3))

15. Interpreting the Non Interference

Provision (§ 423.10)

16. Pharmacy Price Concessions in

Negotiated Prices (§ 423.100)

17. Preferred Cost Sharing (§§ 423.100 and

423.120)

18. Prescription Drug Pricing Standards

and Maximum Allowable Cost

(§ 423.505(b)(21))

19. Any Willing Pharmacy Standard Terms

& Conditions (§ 423.120(a)(8))

20. Enrollment Requirements for

Prescribers of Part D Covered Drugs

(§ 423.120(c)(5) and (6))

21. Improper Prescribing Practices

(§§ 424.530 and 424.535)

a. Background and Program Integrity

Concerns

b. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

Certification of Registration

c. Patterns or Practices of Prescribing

22. Broadening the Release of Part D Data

(§ 423.505)

23. Establish Authority to Directly Request

Information From First Tier,

Downstream, and Related Entities

(§§ 422.504(i)(2)(i) and 423.505(i)(2)(i))

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29845

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

24. Eligibility of Enrollment for

Incarcerated Individuals (§§ 417.1,

417.422, 417.460, 422.74, and 423.44)

a. Changes in Definition of Service Area for

Cost Plans (§§ 417.1 and 417.422(b))

b. Involuntary Disenrollment for

Incarcerated Individuals Enrolled in MA,

PDP and cost plans (§§ 417.460, 422.74,

and 423.44)

25. Rewards and Incentives Program

Regulations for Part C Enrollees

(§ 422.134)

B. Improving Payment Accuracy

1. Implementing Overpayment Provisions

of Section 1128J(d) of the Social Security

Act (§§ 422.326 and 423.360)

a. Terminology (§§ 422.326(a) and

423.360(a))

b. General Rules for Overpayments

(§ 422.326(b) through (c); § 423.360(b)

through (c))

c. Look-back Period for Reporting and

Returning Overpayments

2. Risk Adjustment Data Requirements

(§ 422.310)

3. RADV Appeals

a. Background

b. RADV Definitions

c. Publication of RADV Methodology

d. Proposal to Update RADV Appeals

Terminology (§ 422.311)

e. Proposal to Simplify the RADV Appeals

Process

(1) Issues Eligible for RADV Appeal

(2) Issues Not Eligible for RADV Appeals

(3) Manner and Timing of a Request for

RADV Appeal

(4) Reconsideration Stage

(5) Hearing Stage

(6) CMS Administrator Review Stage

f. Proposal to Expand Scope of RADV

Audits

g. Proposal to Clarify the RADV Medical

Record Review Determination Appeal

Burden of Proof Standard

h. Proposal to Change RADV Audit

Compliance Date

4. Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC)

Determination Appeals (Proposed Part

422 Subpart Z and Part 423 Subpart Z)

a. Background

b. Proposed RAC Appeals Process

(1) Reconsiderations (§§ 422.2605 and

423.2605)

(2) Hearing Official Determinations

(§§ 422.2610 and 423.2610)

(3) Administrator Review (§§ 422.2615 and

423.2615)

C. Implementing Other Technical Changes

1. Definition of a Part D Drug (§ 423.100)

a. Combination Products

b. Barbiturates and Benzodiazepines

c. Medical Foods

2. Special Part D Access Rules During

Disasters or Emergencies (§ 423.126)

3. Termination of a Contract Under Parts C

and D (§§ 422.510 and 423.509)

a. Cross-reference Change (§ 423.509(d))

b. Terminology Changes (§§ 422.510 and

423.509)

c. Technical Change to Align Paragraph

Headings (§ 422.510(b)(2))

d. Terminology Change

(§ 423.509(b)(2)(C)(ii))

4. Technical Changes Regarding

Intermediate Sanctions and Civil Money

Penalties (§§ 422.756 and 423.756)

a. Technical Changes to Intermediate

Sanctions Notice Receipt Provisions

(§§ 422.756(a)(2) and 423.756(a)(2))

b. Cross-reference Changes

(§§ 422.756(b)(4) and 423.756(b)(4))

c. Technical Changes (§§ 422.756(d) and

423.756(d))

d. Technical Changes to Align the Civil

Money Penalty Provision with the

Authorizing Statute (§§ 422.760(a)(3) and

423.760(a)(3))

e. Technical Changes to Align the Civil

Money Penalty Notice Receipt Provisions

(§§ 422.1020(a)(2), 423.1020(a)(2),

422.1016(b)(1), and 423.1016(b)(1))

IV. Collection of Information Requirements

A. ICRs Related to Improper Prescribing

Practices and Patterns (§ 424.535(a)(13)

and (14))

B. ICRs Related to Applicants or their

Contracted First Tier, Downstream, or

Related Entities to Have Experience in

the Part D Program Providing Key Part D

Functions (§ 423.504(b)(8)(i) through

(iii))

C. ICRs Related to Eligibility of Enrollment

for Incarcerated Individuals (§§ 417.460,

422.74, and 423.44)

D. ICRs Related to Rewards and Incentives

Program Regulations for Part C Enrollees

(§ 422.134)

E. ICR Related to Recovery Audit

Contractor Determinations (Part 422,

Subpart Z and Part 423, Subpart Z)

V. Regulatory Impact Analysis

A. Statement of Need

B. Overall Impact

C. Anticipated Effects

1. Effects of Closing Cost Contract Plans to

New Enrollment

2. Effects of the Authority to Impose

Intermediate Sanctions and Civil Money

Penalties

3. Effects of Contract Termination

Notification Requirements and Contract

Termination Basis

4. Effects of Reducing the Burden of the

Compliance Program Training

Requirements

5. Effects of the Procedures for Imposing

Intermediate Sanctions and Civil Money

Penalties under Parts C and D

6. Effects of Timely Access to Mail Order

Services

7. Effects of the Modification of the Agent/

Broker Compensation Requirements

8. Effects of Drug Categories or Classes of

Clinical Concern

9. Effects of the Medication Therapy

Management Program (MTMP) under

Part D

10. Effects of the Requirement for

Applicants or their Contracted First Tier,

Downstream, or Related Entities to Have

Experience in the Part D Program

Providing Key Part D Functions

11. Effects of Requirement for Applicants

for Stand Alone Part D Plan Sponsor

Contracts to Be Actively Engaged in the

Business of the Administration of Health

Insurance Benefits

12. Effects of Limit Parent Organizations to

One Prescription Drug Plan (PDP)

Sponsor Contract per PDP Region

13. Effects of Limit Stand-Alone

Prescription Drug Plan Sponsors to

Offering No More Than Two Plans per

PDP Region

14. Effects of Applicable Cost-Sharing for

Transition Supplies: Transition Process

Under Part D

15. Effects of Interpreting the Non-

Interference Provision

16. Effects of Pharmacy Price Concessions

in Negotiated Prices

17. Effects of Preferred Cost Sharing

18. Effects of Maximum Allowable Cost

Pricing Standard

19. Effects of Any Willing Pharmacy

Standard Terms & Conditions

20. Effects of Enrollment Requirements for

Prescribers of Part D Covered Drugs

21. Effects of Improper Prescribing

Practices and Patterns

22. Effects of Broadening the Release of

Part D Data

23. Effects of Establish Authority to

Directly Request Information From First

Tier, Downstream, and Related Entities

24. Effects of Eligibility of Enrollment for

Incarcerated Individuals

25. Effects of Rewards and Incentives

Program Regulations for Part C Enrollees

26. Effects of Improving Payment

Accuracy: Reporting Overpayments,

RADV Appeals, and LIS Cost Sharing

27. Effects of Part C and Part D RAC

Determination Appeals

28. Effects of the Technical Changes to the

Definition of a Part D Drug

29. Effects of the Special Part D Access

Rules During Disasters

30. Effects of Termination of a Contract

under Parts C and D

31. Effects of Technical Changes Regarding

Intermediate Sanctions and Civil Money

Penalties

D. Expected Benefits

1. Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical

Concern

2. Medication Therapy Management

Program under Part D

E. Alternatives Considered

1. Modifying the Agent/Broker

Compensation Requirements

2. Any Willing Pharmacy Standard Terms

and Conditions

3. Pharmacy Price Concessions in

Negotiated Prices

4. Special Part D Access Rules During

Disasters or Emergencies

5. Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical

Concern

6. Medication Therapy Management

Program (MTM) Under Part D

7. Requirement for Applicants or their

Contracted First Tier, Downstream, or

Related Entities to have Experience in

the Part D Program Providing Key Part D

Functions

F. Accounting Statement and Table

G. Conclusion

Regulations Text

Acronyms

ADS Automatic Dispensing System

AEP Annual Enrollment Period

AHFS American Hospital Formulary

Service

AHFS–DI American Hospital Formulary

Service–Drug Information

AHRQ Agency for Health Care Research

and Quality

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29846

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

ALJ Administrative Law Judge

ANOC Annual Notice of Change

AO Accrediting Organization

AOR Appointment of Representative

BBA Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (Pub. L.

105–33)

BBRA [Medicare, Medicaid and State Child

Health Insurance Program] Balanced

Budget Refinement Act of 1999 (Pub. L.

106–113)

BIPA [Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP]

Benefits Improvement Protection Act of

2000 (Pub. L. 106–554)

BLA Biologics License Application

CAHPS Consumer Assessment Health

Providers Survey

CAP Corrective Action Plan

CCIP Chronic Care Improvement Program

CC/MCC Complication/Comorbidity and

Major Complication/Comorbidity

CCS Certified Coding Specialist

CDC Centers for Disease Control

CHIP Children’s Health Insurance Programs

CMP Civil Money Penalty

CMR Comprehensive Medical Review

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services

CMS–HCC CMS Hierarchal Condition

Category

CTM Complaints Tracking Module

COB Coordination of Benefits

CORF Comprehensive Outpatient

Rehabilitation Facility

CPC Certified Professional Coder

CY Calendar year

DAB Departmental Appeals Board

DEA Drug Enforcement Administration

DIR Direct and Indirect Remuneration

DME Durable Medical Equipment

DMEPOS Durable Medical Equipment,

Prosthetic, Orthotics, and Supplies

D–SNPs Dual Eligible SNPs

DOL U.S. Department of Labor

DUA Data Use Agreement

DUM Drug Utilization Management

EAJR Expedited Access to Judicial Review

EGWP Employer Group/Union-Sponsored

Waiver Plan

EOB Explanation of Benefits

EOC Evidence of Coverage

ESRD End-Stage Renal Disease

FACA Federal Advisory Committee Act

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FEHBP Federal Employees Health Benefits

Plan

FFS Fee-For-Service

FIDE Fully-integrated Dual Eligible

FIDE SNPs Fully-integrated Dual Eligible

Special Needs Plans

FMV Fair Market Value

FY Fiscal year

GAO Government Accountability Office

HAC Hospital-Acquired Conditions

HCPP Health Care Prepayment Plans

HEDIS HealthCare Effectiveness Data and

Information Set

HHS [U.S. Department of] Health and

Human Services

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act of 1996 (Pub. L. 104–

191)

HMO Health Maintenance Organization

HOS Health Outcome Survey

HPMS Health Plan Management System

ICL Initial Coverage Limit

ICR Information Collection Requirement

ID Identification

IVC Initial Validation Contractor

LCD Local Coverage Determination

LEP Late Enrollment Penalty

LIS Low Income Subsidy

LPPO Local Preferred Provider

Organization

LTC Long Term Care

MA Medicare Advantage

MAAA Member of the American Academy

of Actuaries

MA–PD Medicare Advantage–Prescription

Drug Plan

MIPPA Medicare Improvements for Patients

and Providers Act of 2008 (Pub. L. 110–

275)

MOC Medicare Options Compare

MOOP Maximum Out-of-Pocket

MPDPF Medicare Prescription Drug Plan

Finder

MMA Medicare Prescription Drug,

Improvement, and Modernization Act of

2003 (Pub. L. 108–173)

MS–DRG Medicare Severity Diagnosis

Related Group

MSA Metropolitan Statistical Area

MSAs Medical Savings Accounts

MSP Medicare Secondary Payer

MTM Medication Therapy Management

MTMP Medication Therapy Management

Program

NAIC National Association of Insurance

Commissioners

NCD National Coverage Determination

NCPDP National Council for Prescription

Drug Programs

NCQA National Committee for Quality

Assurance

NDA New Drug Application

NDC National Drug Code

NGC National Guideline Clearinghouse

NIH National Institutes of Health

NOMNC Notice of Medicare Non-Coverage

NPI National Provider Identifier

NWS National Weather Service

OIG Office of Inspector General

OMB Office of Management and Budget

OPM Office of Personnel Management

OTC Over the Counter

Part C Medicare Advantage

Part D Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Program

PBM Pharmacy Benefit Manager

PDE Prescription Drug Event

PDP Prescription Drug Plan

PFFS Private Fee For Service Plan

POA Present on Admission (Indicator)

POS Point-of-Sale

PPO Preferred Provider Organization

PPS Prospective Payment System

P&T Pharmacy & Therapeutics

QIC Qualified Independent Contractor

QIO Quality Improvement Organization

QRS Quality Review Study

PACE Programs of All Inclusive Care for the

Elderly

RADV Risk Adjustment Data Validation

RAPS Risk Adjustment Payment System

RPPO Regional Preferred Provider

Organization

SCORM Sharable Content Object Reference

Model

SEP Special Election Period

SHIP State Health Insurance Assistance

Programs

SNF Skilled Nursing Facility

SNP Special Needs Plan

SPAP State Pharmaceutical Assistance

Programs

SSA Social Security Administration

SSI Supplemental Security Income

T&C Terms and Conditions

TPA Third Party Administrator

TrOOP True Out-Of-Pocket

U&C Usual and Customary

UPIN Uniform Provider Identification

Number

USP U.S. Pharmacopoeia

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

The purpose of this final rule is to

make revisions to the Medicare

Advantage (MA) program (Part C) and

Prescription Drug Benefit Program (Part

D) regulations based on our continued

experience in the administration of the

Part C and Part D programs and to

implement certain provisions of the

Affordable Care Act. This final rule is

necessary to—(1) clarify various

program participation requirements; (2)

improve payment accuracy; and (3)

make other clarifications and technical

changes.

B. Summary of the Major Provisions

1. Modifying the Agent/Broker

Requirements, Specifically Agent/

Broker Compensation

The former regulatory compensation

structure was comprised of a 6-year

cycle that ended December 31, 2013.

Under that structure, MA organizations

and Part D sponsors provided an initial

compensation payment to independent

agents for new enrollees (Year 1), and

paid a renewal rate (equal to 50 percent

of the initial year compensation) for

Years 2 through 6. MA organizations

and Part D sponsors had the option to

pay the 50 percent renewal rate for

CY2014 (year 1). This compensation

structure proved to be complicated to

implement and monitor, and also

created an incentive for agents to move

beneficiaries as long as the fair market

value (FMV) continued to increase each

year. To resolve these issues, we

proposed to revise the compensation

structure. Under our proposal, MA

organizations and Part D sponsors

would continue to have the discretion to

decide, on an annual basis, whether or

not to use independent agents. Also, for

new enrollments, MA organizations and

Part D sponsors could determine what

their initial rate would be, up to the

CMS designated FMV amount. For

renewals in Year 2 and subsequent

years, with no end date, the MA

organization or Part D sponsor could

pay up to 35 percent of the current FMV

amount for that year. We believed that

revising the existing compensation

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29847

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

structure to allow MA organizations or

Part D sponsors to pay up to 35 percent

of the FMV for year 2 and subsequent

years was appropriate based on a couple

of factors. First, we believed that a 2

tiered payment system (that is, initial

and renewal) would be significantly less

complicated than a 3-tiered system (that

is, initial, 50 percent renewal for years

2 through 6, and 25 percent residual for

years 7 and subsequent years), and

would reduce administrative burden

and confusion for plan sponsors.

Second, our analysis determined that 35

percent was the renewal compensation

level at which the present value of

overall payments under a 2-tiered

system would be relatively equal to the

present value of overall payments under

a 3-tiered system (taking into account

the estimated life expectancy for several

beneficiary age cohorts). In addition to

revising the agent and broker

compensation structures, we proposed

to amend the training and testing

requirements as well as setting limits on

referral fees ($100) for agents and

brokers.

We received more than 140 comments

from agents, health plans, and trade

associations opposing the 35 percent

renewal rate, and instead suggesting that

CMS maintain the 50 percent renewal

rate. A number of commenters

expressed concerns that the proposed

reduction in compensation would

represent a significant decrease from the

current compensation limit, and a rate

set at 50 percent of FMV would be in

line with industry standard. They noted

that the higher compensation amount

would be particularly important for

stand-alone prescription drug plans, as

35 percent would be insufficient to

cover an agent’s costs associated with

the renewal transaction and could

discourage agents from assisting in the

annual evaluation of a Medicare

beneficiary’s options. Commenters also

stated that, compared to current

practice, the proposed 35 percent

renewal rate is a reduction since a

number of MA plans began offering a

renewal rate of 50 percent for 10 years

or more at the end of the 6-year cycle

(2013). The majority of commenters also

stated that agents play an important role

in educating beneficiaries about

Medicare and the proposed reduction in

the renewal rate could reduce the level

and quality of services provided to

beneficiaries, thereby resulting in less

information sharing and poorer plan

choices by beneficiaries. Many

commenters also stated that agents

spend a significant amount of time in

training, preparing, and educating

beneficiaries and that the compensation

is already low relative to the hours

spent. Some commenters also expressed

concern that the lower compensation

rate would discourage new agents from

entering the MA market. Many agents

stated they would have to stop selling

MA products and instead sell other

more profitable products. No plans

strongly supported the 35 percent

renewal rate. Therefore, we are

modifying the compensation renewal

rate from up to 35 percent to up to 50

percent. These changes will be

applicable for enrollments effective

January 2015. Because the proposed rate

is similar to previous regulatory

requirements, present CMS guidance,

and industry practice, we believe this

implementation timeframe is reasonable

and appropriate. We are not finalizing

the proposed changes to agent and

broker training and testing at this time.

We are finalizing limits on referral fees

for agents as proposed.

2. Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical

Concern

We are not finalizing any new criteria

and will maintain the existing six

protected classes.

3. Improving Payment Accuracy—

Implementing Overpayment Provisions

of Section 1128J(d) of the Social

Security Act (§§ 422.326 and 423.360)

These proposed regulatory provisions

codify the Affordable Care Act

requirement establishing section

1128J(d) of the Act that MA

organizations and Part D sponsors report

and return identified Medicare

overpayments.

We proposed to adopt the statutory

definition of overpayment for both Part

C and Part D, which means any funds

that an MA organization or Part D

sponsor has received or retained under

Title XVIII of the Act to which the MA

organization or Part D sponsor, after

applicable reconciliation, is not entitled

under such title. To reflect the unique

structure of Part C and Part D payments

to plan sponsors, we also propose to

define two terms included in the

statutory definition of overpayments:

‘‘funds’’ and ‘‘applicable

reconciliation.’’ We proposed to define

funds as payments an MA organization

or Part D sponsor has received that are

based on data that these organizations

submitted to CMS for payment

purposes. For Part C we proposed that

applicable reconciliation occurs on the

annual final risk adjustment data

submission deadline. For Part D, we

proposed that applicable reconciliation

occurs on the date that is the later of

either the annual deadline for

submitting prescription drug event

(PDE) data for the annual Part D

payment reconciliations referred to in

§ 423.343(c) and (d) or the annual

deadline for submitting DIR data.

In addition, we proposed to state in

regulation that an MA organization or

Part D sponsor has identified an

overpayment if it has actual knowledge

of the existence of the overpayment or

acts in reckless disregard or deliberate

ignorance of the existence of the

overpayment. An MA organization or

Part D sponsor must report and return

any identified overpayment it received

no later than 60 days after the date on

which it identified it received an

overpayment. The MA organization or

Part D sponsor must notify CMS, using

a notification process determined by

CMS, of the amount and reason for the

overpayment. Finally, we proposed a

look-back period with an exception for

overpayments resulting from fraud,

whereby MA organizations and Part D

sponsors would be held accountable for

reporting overpayments within the 6

most recent completed payment years

for which the applicable reconciliation

has been completed.

We received approximately 30

comments from organizations and

individuals. Generally, commenters

supported establishing separate

applicable reconciliation dates for Part

C and Part D. Many commenters

questioned when the 60-day period for

reporting and returning begins, and

what activities constitute reporting and

returning an overpayment to CMS,

including questions about estimating an

amount of overpayment. A number of

commenters also requested to clarify the

standards for ‘‘identifying’’ an

overpayment, including questions about

the meaning of reasonable diligence.

Finally, a few commenters

recommended that we impose the same

limitation on the look-back period for

all overpayments, even those relating to

fraud.

We are finalizing the provisions at

§§ 422.326 and 423.360, with the

following modifications. First, we add at

the end of paragraph § 422.326(d) the

phrase ‘‘unless otherwise directed by

CMS for the purpose of § 422.311.’’

Also, to increase clarity we revise

§§ 422.326(c) and 423.360(c) regarding

identified overpayments. Finally, we

strike the following sentence in the

proposed paragraphs on the 6-year look-

back period: ‘‘Overpayments resulting

from fraud are not subject to this

limitation of the lookback period.’’

4. Risk Adjustment Data Requirements

We proposed several amendments to

§ 422.310 to strengthen existing

regulations related to the accuracy of

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29848

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

risk adjustment data, including: (1) A

requirement that medical record

reviews, if used, be designed to

determine the accuracy of diagnoses

submitted under §§ 422.308(c)(1) and

422.310(g)(2); (2) a revision in the

deadlines for submission of risk

adjustment data; and (3) a limitation on

the type and purpose of late data

submissions. We also proposed a

restructuring of subparagraph (g)(2) as

part of the revisions. We received

approximately 25 comments from

organizations and individuals regarding

these proposals; many of the comments

were concerned and critical of the

proposals, highlighting vagueness and

the potential for operational instability.

For reasons discussed in more detail

below in section III.B.2 of the preamble,

we are not finalizing the proposed

amendment regarding the scope of

medical reviews and we are not

finalizing at this time the proposal to

change the date for final risk adjustment

data submission. We are finalizing as

proposed the restructuring of

§§ 422.310(g)(2) and the 422.310(g)(2)(ii)

provision to prohibit submission of

diagnoses for additional payment after

the final risk adjustment data

submission deadline.

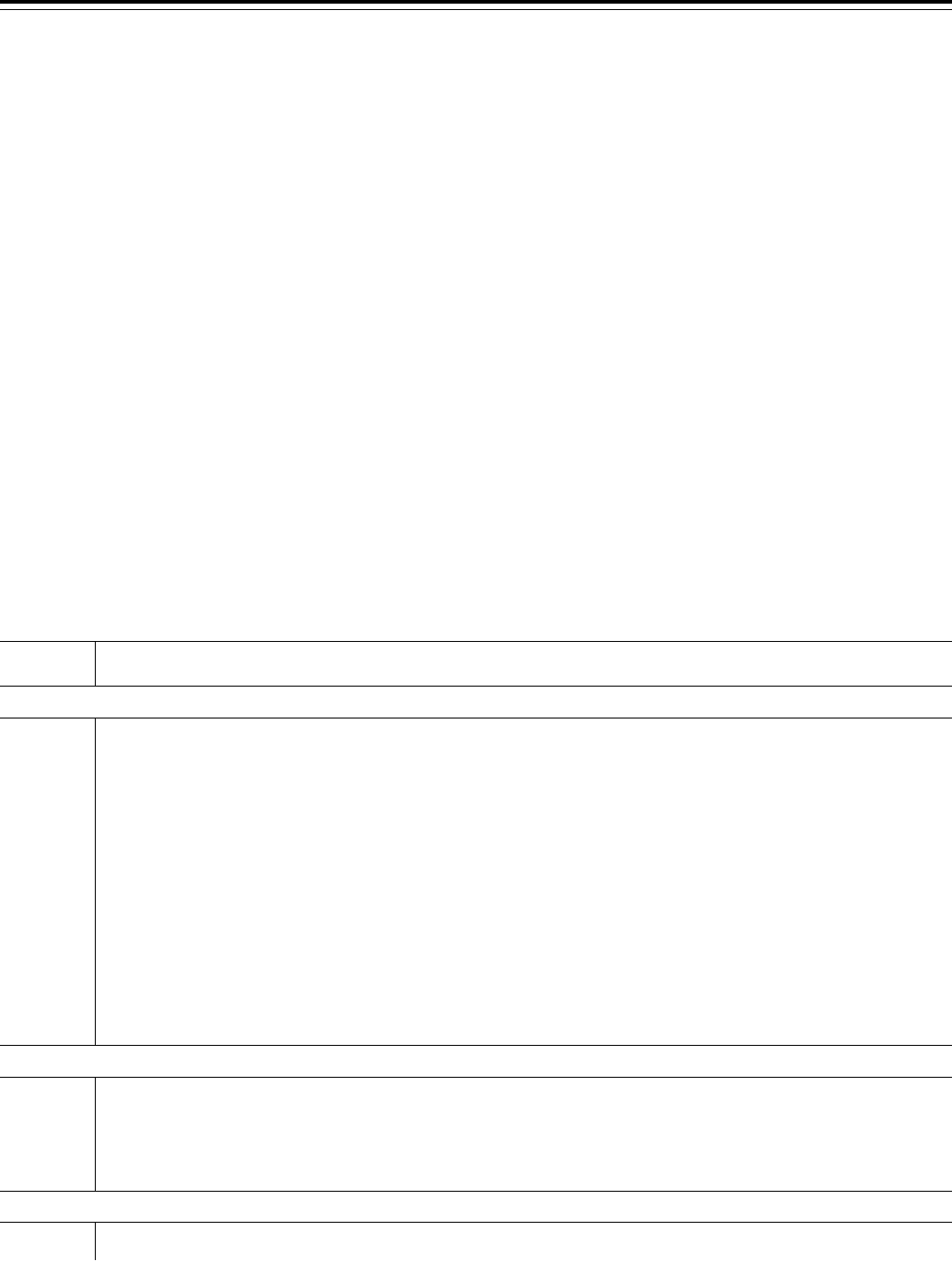

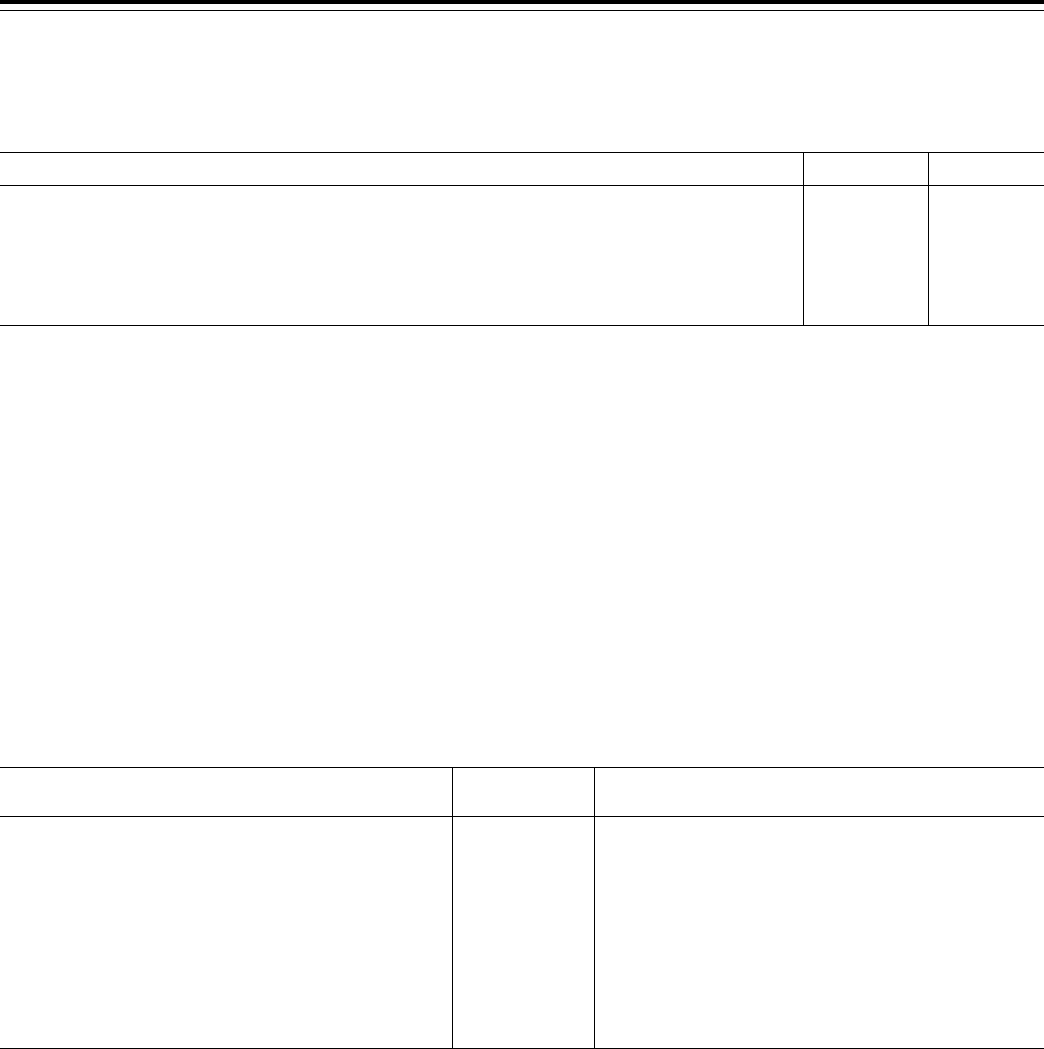

C. Summary of Costs and Benefits

T

ABLE

2—S

UMMARY OF

C

OSTS AND

B

ENEFITS

Provision description Total costs Transfers

Modifying the agent/broker require-

ments, specifically agent/broker

compensation.

N/A ............... N/A

Improving Payment Accuracy ........... N/A ............... N/A

Eligibility of Enrollment for Incarcer-

ated Individuals.

................. We estimate that this change could save the MA program up to $27 million in 2015, in-

creasing to $103 million in 2024 (total of $650 million over this period), and could save

the Part D program (includes the Part D portion of MA PD plans) up to $46 million in

2015, increasing to $153 million in 2024 (total of $965 million over this period).

II. Background

A. General Overview and Regulatory

History

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997

(BBA) (Pub. L. 105–33) created a new

‘‘Part C’’ in the Medicare statute

(sections 1851 through 1859 of the

Social Security Act (the Act)) which

established what is now known as the

Medicare Advantage (MA) program. The

Medicare Prescription Drug,

Improvement, and Modernization Act of

2003 (MMA) (Pub. L. 108–173), enacted

on December 8, 2003, added a new ‘‘Part

D’’ to the Medicare statute (sections

1860D–1 through 42 of the Act) entitled

the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Program (PDP), and made significant

changes to the existing Part C program,

which it named the Medicare Advantage

(MA) Program. The MMA directed that

important aspects of the Part D program

be similar to, and coordinated with,

regulations for the MA program.

Generally, the provisions enacted in the

MMA took effect January 1, 2006. The

final rules implementing the MMA for

the MA and Part D prescription drug

programs appeared in the Federal

Register on January 28, 2005 (70 FR

4588 through 4741 and 70 FR 4194

through 4585, respectively).

Since the inception of both Parts C

and D, we have periodically revised our

regulations either to implement

statutory directives or to incorporate

knowledge obtained through experience

with both programs. For instance, in the

September 18, 2008 and January 12,

2009 Federal Register (73 FR 54226 and

74 FR 1494, respectively), we issued

Part C and D regulations to implement

provisions in the Medicare

Improvement for Patients and Providers

Act (MIPPA) (Pub. L. 110–275). We

promulgated a separate interim final

rule in January 16, 2009 (74 FR 2881) to

address MIPPA provisions related to

Part D plan formularies. In the final rule

that appeared in the April 15, 2010

Federal Register (75 FR 19678), we

made changes to the Part C and D

regulations which strengthened various

program participation and exit

requirements; strengthened beneficiary

protections; ensured that plan offerings

to beneficiaries included meaningful

differences; improved plan payment

rules and processes; improved data

collection for oversight and quality

assessment; implemented new policies;

and clarified existing program policy.

In a final rule that appeared in the

April 15, 2011 Federal Register (76 FR

21432), we continued our process of

implementing improvements in policy

consistent with those included in the

April 2010 final rule, and also

implemented changes to the Part C and

Part D programs made by recent

legislative changes. The Patient

Protection and Affordable Care Act

(Pub. L. 111–148) was enacted on March

23, 2010, as passed by the Senate on

December 24, 2009, and the House on

March 21, 2010. The Health Care and

Education Reconciliation Act (Pub. L.

111–152), which was enacted on March

30, 2010, modified a number of

Medicare provisions in Pub. L. 111–148

and added several new provisions. The

Patient Protection and Affordable Care

Act (Pub. L. 111–148) and the Health

Care and Education Reconciliation Act

(Pub. L. 111–152) are collectively

referred to as the Affordable Care Act.

The Affordable Care Act included

significant reforms to both the private

health insurance industry and the

Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Provisions in the Affordable Care Act

concerning the Part C and D programs

largely focused on beneficiary

protections, MA payments, and

simplification of MA and Part D

program processes. These provisions

affected implementation of our policies

regarding beneficiary cost-sharing,

assessing bids for meaningful

differences, and ensuring that cost-

sharing structures in a plan are

transparent to beneficiaries and not

excessive. In the April 2011 final rule,

we revised regulations on a variety of

issues based on the Affordable Care Act

and our experience in administering the

MA and Part D programs. The rule

covered areas such as marketing,

including agent/broker training;

payments to MA organizations based on

quality ratings; standards for

determining if organizations are fiscally

sound; low income subsidy policy

under the Part D program; payment

rules for non-contract health care

providers; extending current network

adequacy standards to Medicare

medical savings account (MSA) plans

that employ a network of providers;

establishing limits on out-of-pocket

expenses for MA enrollees; and several

revisions to the special needs plan

requirements, including changes

concerning SNP approvals.

In a final rule that appeared in the

April 12, 2012 Federal Register (77 FR

22072 through 22175), we made several

changes to the Part C and Part D

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29849

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

programs required by statute, including

the Affordable Care Act, as well as made

improvements to both programs through

modifications reflecting experience we

have obtained administering the Part C

and Part D programs. Key provisions of

that final rule implemented changes

closing the Part D coverage gap, or

‘‘donut hole,’’ for Medicare beneficiaries

who do not already receive low-income

subsidies from us by establishing the

Medicare Coverage Gap Discount

Program. We also included provisions

providing new benefit flexibility for

fully-integrated dual eligible special

needs plans, clarifying coverage of

durable medical equipment, and

combatting possible fraudulent activity

by requiring Part D sponsors to include

an active and valid prescriber National

Provider Identifier on prescription drug

event records.

B. Issuance of a Notice of Proposed

Rulemaking

In the proposed rule titled ‘‘Contract

Year 2015 Policy and Technical

Changes to the Medicare Advantage and

the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Programs,’’ which appeared in the

January 10, 2014 Federal Register (79

FR 1918), we proposed to revise the

Medicare Advantage (MA) program (Part

C) regulations and prescription drug

benefit program (Part D) regulations to

implement statutory requirements;

strengthen beneficiary protections;

exclude plans that perform poorly;

improve program efficiencies; and

clarify program requirements. The

proposed rule also included several

provisions designed to improve

payment accuracy.

C. Public Comments Received in

Response to the CY 2015 Policy and

Technical Changes to the Medicare

Advantage and the Medicare

Prescription Drug Benefit Programs

Proposed Rule

We received approximately 7,600

timely pieces of correspondence

containing multiple comments on the

CY 2014 proposed rule. While we are

finalizing several of the provisions from

the proposed rule, there are a number of

provisions from the proposed rule (for

example, enrollment eligibility criteria

for individuals not lawfully present in

the United States) that we intend to

address later and a few which we do not

intend to finalize. We also note that

some of the public comments were

outside of the scope of the proposed

rule. These out-of-scope public

comments are not addressed in this final

rule. Summaries of the public comments

that are within the scope of the

proposed rule and our responses to

those public comments are set forth in

the various sections of this final rule

under the appropriate heading.

However, we note that in this final rule

we are not addressing comments

received with respect to the provisions

of the proposed rule that we are not

finalizing at this time. Rather, we will

address them at a later time, in a

subsequent rulemaking document, as

appropriate.

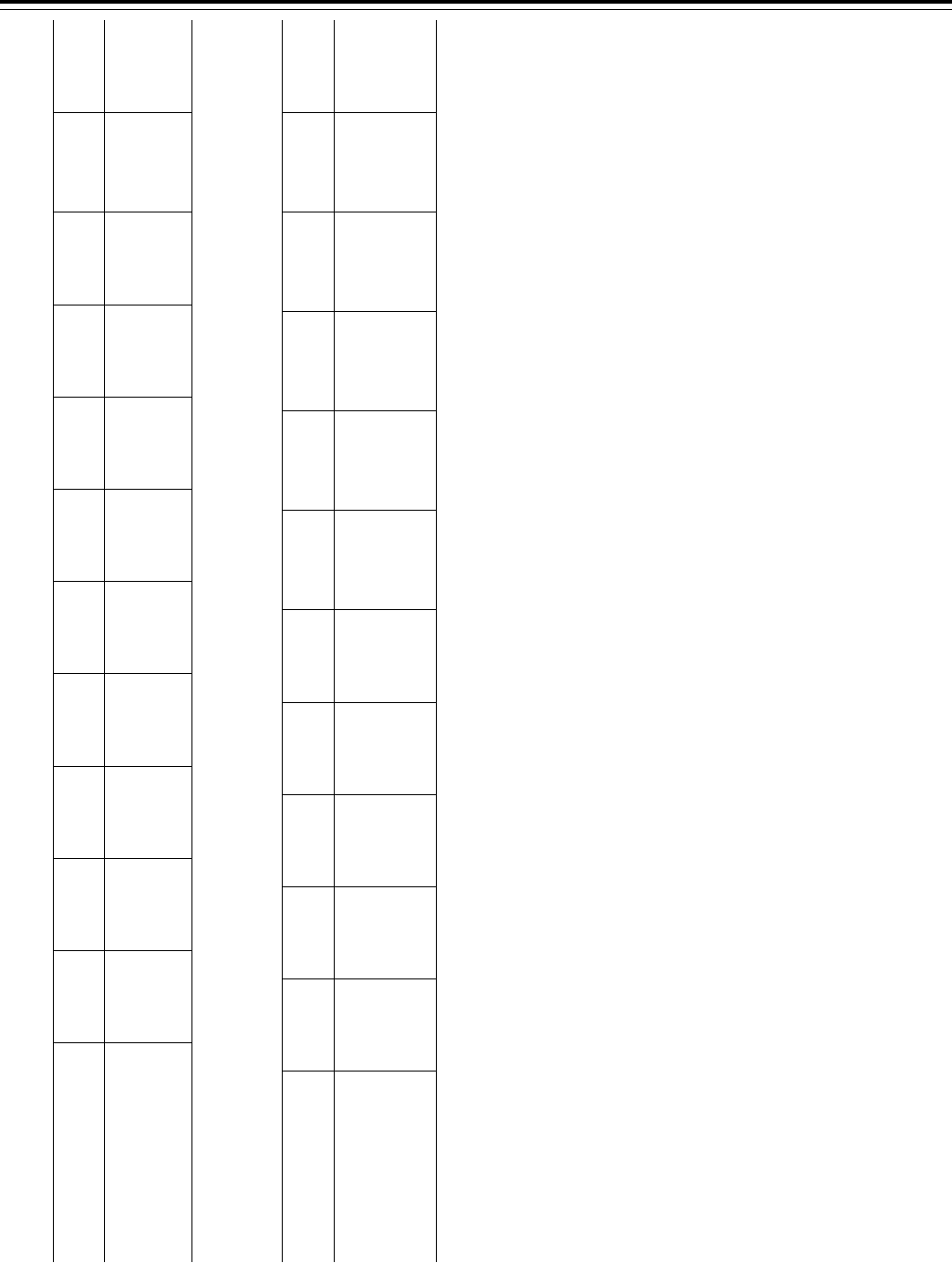

D. Provisions Not Finalized in This

Final Rule

As noted previously, some of the

provisions of the proposed rule will be

addressed later and, therefore, are not

being finalized in this rule. Table 3 lists

the provisions that were proposed but

are not addressed at this time. We note

that several provisions that were

proposed are not being finalized in this

rule and are effectively being

withdrawn; those provisions are not

listed in Table 3.

T

ABLE

3—P

ROVISIONS

N

OT

F

INALIZED AT

T

HIS

T

IME

Proposed

rule section

Topic

Clarifying Various Program Participation Requirements

III.A.2 .......... Two-year Limitation on Submitting a New Bid in an Area Where an MA has been Required to Terminate a Low-enrollment MA

Plan (§ 422.504(a)(19)).

III.A.6 .......... Changes to Audit and Inspection Authority (§ 422.503(d)(2) and § 423.504(d)(2)).

III.A.9 .......... Collections of Premiums and Cost Sharing (§ 423.294).

III.A.10 ........ Enrollment Eligibility for Individuals Not Lawfully Present in the United States (§§ 417.2, 417.420, 417.422, 417.460, 422.1,

422.50, 422.74, 423.1, 423.30, and 423.44).

III.A.11 ........ Part D Notice of Changes (§ 423.128(g)).

III.A.12 ........ Separating the Annual Notice of Change (ANOC) from the Evidence of Coverage (EOC) (§ 422.111(a)(3) and § 423.128(a)(3)).

III.A.14 ........ Exceptions to Drug Categories or Classes of Clinical Concern (§ 423.120(b)(2)(vi)).

III.A.15 ........ Medication Therapy Management Program (MTMP) under Part D (§ 423.153(d)(1)(v)(A))—outreach strategies.

III.A.16 ........ Business Continuity for MA Organizations and PDP Sponsors (§ 422.504(o) and § 423.505(p)).

III.A.21 ........ Efficient Dispensing in Long Term Care Facilities and Other Changes (§ 423.154).

III.A.23 ........ Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program and Employer Group Waiver Plans (§ 423.2325).

III.A.26 ........ Payments to PDP Plan Sponsors For Qualified Prescription Drug Coverage (§ 423.308) and Payments to Sponsors of Retiree

Prescription Drug Plans (§ 423.882).

III.A.32 ........ Transfer of TrOOP Between PDP Sponsors Due to Enrollment Changes during the Coverage Year (§ 423.464).

III.A.37 ........ Expand Quality Improvement Program Regulations (§ 422.152).

III.A.38 ........ Authorization of Expansion of Automatic or Passive Enrollment Non-Renewing Dual Eligible SNPs (D-SNPs) to another D-SNP to

Support Alignment Procedures (§ 422.60).

Improving Payment Accuracy

III.B.2 .......... Determination of Payments (§ 423.329).

III.B.3 .......... Reopening (§ 423.346).

III.B.4 .......... Payment Appeals (§ 423.350).

III.B.5 .......... Payment Processes for Part D Sponsors (§ 423.2320).

III.B.6 .......... Risk adjustment data requirements—proposal regarding annual deadline for MAO submission of final risk adjustment data

(§ 422.310(g)(2)(ii)).

Strengthening Beneficiary Protections

III.C.1 .......... Providing High Quality Health Care (§ 422.504(a)(3) and § 423.505(b)(27)).

III.C.2 .......... MA-PD Coordination Requirements for Drugs Covered Under Parts A, B, and D (§ 422.112).

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00007 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29850

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

T

ABLE

3—P

ROVISIONS

N

OT

F

INALIZED AT

T

HIS

T

IME

—Continued

Proposed

rule section

Topic

III.C.3 .......... Good Cause Processes (§ 417.460, § 422.74 and § 423.44).

III.C.4 .......... Definition of Organization Determination (§ 422.566).

III.C.5 .......... MA Organizations May Extend Adjudication Timeframes for Organization Determinations and Reconsiderations (§ 422.568,

§ 422.572, § 422.590, § 422.618, and § 422.619).

Strengthening Our Ability to Distinguish Stronger Applicants for Part C and D Program Participation and to Remove Consistently Poor

Performers

III.D.1 .......... Two-Year Prohibition When Organizations Terminate Their Contracts (§§ 422.502, 422.503, 422.506, 422.508, and 422.512).

III.D.2 .......... Withdrawal of Stand-Alone Prescription Drug Plan Bid Prior to Contract Execution (§ 423.503).

III.D.3 .......... Essential Operations Test Requirement for Part D (§§ 423.503(a) and (c), 423.504(b)(10), 423.505(b)(28), and 423.509).

III.D.4. ......... Termination of the Contracts of Medicare Advantage Organizations Offering PDP for Failure for 3 Consecutive Years to Achieve

3 Stars on Both Part C and Part D Summary Star Ratings in the Same Contract Year (§ 422.510).

Implementing Other Technical Changes

III.E.1 .......... Requirements for Urgently Needed Services (§ 422.113).

III.E.2 .......... Skilled Nursing Facility Stays (§§ 422.101 and 422.102).

III.E.3 .......... Agent and Broker Training and Testing Requirements (§§ 422.2274 and 423.2274).

III.E.4 .......... Deemed Approval of Marketing Materials (§ 422.2266 and § 423.2266).

III.E.5 .......... Cross-Reference Change in the Part C Disclosure Requirements (§ 422.111).

III.E.6 .......... Managing Disclosure and Recusal in P&T Conflicts of Interest: [Formulary] Development and Revision by a Pharmacy and Thera-

peutics Committee under PDP (§ 423.120(b)(1)).

III.E.8 .......... Thirty-Six-Month Coordination of Benefits (COB) Limit (§ 423.466(b)).

III.E.9 .......... Application and Calculation of Daily Cost-Sharing Rates (§ 423.153).

III.E.10 ........ Technical Change to Align Regulatory Requirements for Delivery of the Standardized Pharmacy Notice (§ 423.562).

III.E.12 ........ MA Organization Responsibilities in Disasters and Emergencies (§ 422.100).

III.E.14 ........ Technical Changes to Align Part C and Part D Contract Determination Appeal Provisions (§§ 422.641 and 422.644).

III.E.15 ........ Technical Changes to Align Parts C and D Appeal Provisions (§§ 422.660 and 423.650).

III.E.17 ........ Technical Change to the Restrictions on use of Information under Part D (§ 423.322).

III. Provisions of the Proposed

Regulations and Analysis of and

Responses to Public Comments

A. Clarifying Various Program

Participation Requirements

1. Closing Cost Contract Plans to New

Enrollment (§ 422.503(b)(4))

To ensure that our original intent is

realized and to eliminate the potential

for organizations to move enrollees from

one of their plans to another based on

financial or some other interest, we

proposed to revise paragraph

§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(G)(5) so that an

‘‘entity seeking to contract as an MA

organization must [n]ot accept, or share,

a corporate parent organization with an

entity that accepts, new enrollees under

a section 1876 reasonable cost contract

in any area in which it seeks to offer an

MA plan.’’

In making the proposed revision to

paragraph § 422.503(b), we also

proposed to add the definition of

‘‘parent organization’’ to § 422.2 of the

MA program definitions, specifying

that, ‘‘Parent organization means a legal

entity that owns one or more other

subsidiary legal entities.’’ Although the

MA program regulations do not

currently define the term ‘‘parent

organization,’’ our proposed definition

is consistent with the way the term is

currently used in the context of the MA

program, for example, when assessing

an organization’s business structure. We

requested comments on whether a

parent organization with less than a 100

percent interest in a subsidiary legal

entity should trigger the prohibition we

proposed with the amendment at

§ 422.503(b)(4).

During the public notice and

comment process, a handful of

commenters provided their input on our

proposal. Some of the respondents

included multiple comments. The

comments and our responses follow.

Comment: A commenter supported

the proposal, stating that it would

prevent possible shifting of sicker

enrollees to cost plans and should result

in Medicare savings.

Response: We thank the commenter

for the support.

Comment: A commenter stated that

there is no evidence of complaints about

the current situation and thus no change

in current policy is necessary.

Response: The intention of our initial

rule was to ensure that situations not

arise in which an entity was able to

move an enrollee from one of its plans

to another plan in the same area based

on financial or other reasons that may

not be in the enrollee’s best interest. The

current regulations limit this possibility

to some extent, but, without the

proposed changes, would leave open the

possibility that legal entities controlled

by a shared parent organization could

move enrollees from one plan to

another, based on something other than

the enrollee’s best interest.

Comment: A commenter stated that

risk-adjusted payments for MA plans

eliminate any incentive for an entity to

move sicker enrollees from an MA plan

to a cost plan.

Response: While risk adjusted

payments do help to account for costs

associated with sicker enrollees, it may

still be advantageous for an organization

to move an enrollee from an MA plan

to a cost plan. Even with risk

adjustment, there are other reasons an

organization might want to move

enrollees from one plan to another to

include enrollment and other interests

based on the organization’s business

model.

Comment: A commenter stated that,

because cost plan cost-sharing and

premiums must be equal to the actuarial

value of Medicare fee-for-service cost-

sharing, cost plan enrollees with high

health care needs would have high

relative costs resulting in higher

premiums for the cost plan, thus

removing any incentive for moving

sicker enrollees from an entity’s MA

plan to the cost plan.

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00008 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29851

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

Response: MA plans also have

constraints with respect to cost-sharing

that affect premiums, and out-of-pocket

payments by enrollees. We believe, as a

result, that any difference in cost plan

and MA premiums or cost-sharing is

negligible and does little to remove the

incentives for organizations to move

enrollees from one of their plans to

another.

Comment: A couple of commenters

requested that, at minimum, the

provision not be applied to entities that

have both a cost plan and dual eligible

special needs plan (D–SNP). One of the

commenters states that: (1) cost plans

would likely have a premium and cost

sharing that would make it unattractive

for dual eligibles; and (2) the regulation

could eliminate D–SNPs that

‘‘participate in longstanding dual

eligible integrated plans,’’ and thus the

proposal ‘‘could have the effect of

hurting a major initiative of the

Administration.’’

Response: As we have addressed

elsewhere in the comments on this

issue, we do not believe that any

premium and cost-sharing differences in

cost plans and MA plans necessarily

reduce the incentives an organization

may have for moving an individual from

one of its plans to another. We believe

this is also the case for D–SNPs and,

that in the case of D–SNPs, which are

frequently made up of enrollees that are

sicker and frailer than the general

Medicare population, there may be even

greater incentive to move these

enrollees to a cost contract plan.

Comment: A commenter requested

that we not finalize the proposal

because cost plan enrollees will already

be subject to dwindling cost plan

enrollment options as a result of the cost

plan competition statute. The

commenter stated that if we do finalize

the proposal, we should grant an

exception and not require cost plans

affected by the cost plan competition

requirements to close to new

enrollment.

Response: It isn’t clear at this point

what kind of overlap there might be

between cost plans affected by the cost

plan competition requirements and

those cost plans that would have to stop

accepting enrollment because of sharing

a parent organization with an MA plan.

However, we do not believe that a

significant number of cost plans will be

affected by expanding the requirement

to include a shared parent organization,

as the requirement is largely prospective

and designed to prevent a situation that

we did not originally account for, but

which we believe could lead to

potential harm for enrollees.

Comment: A commenter stated that

‘‘the test should not only be whether

entities have the same parent but also

whether the two entities are affiliated,

including if one entity is the parent of

the other (rather than shares a parent).’’

Response: We agree with the

commenter with respect to the specific

example cited and have included

language in the final rule that will also

trigger a prohibition on new enrollment

in a cost plan in situations in which a

parent organization and its subsidiary

have a cost contract and MA plan in the

same service area. In addition to the

proposed language that MA

organizations ‘‘Not accept, or share a

corporate parent organization with an

entity that accepts, new enrollees under

a section 1876 reasonable cost contract

in any area in which it seeks to offer an

MA plan,’’ we are adding to § 422.503

(b)(4)(vi)(G)(5)(ii) that MA organizations

‘‘Not accept, as either the parent

organization owning a controlling

interest of or subsidiary of an entity that

accepts, new enrollees under a section

1876 reasonable cost contract in any

area in which it seeks to offer an MA

plan.’’ The language from the initial

proposal along with the additional

language will now be contained in

§ 422.503 (b)(4)(vi)(G)(5)(i) and (ii).

Comment: A few commenters stated

that CMS should define a parent

organization as an entity that ‘‘exercises

a controlling interest in the applicant.’’

Other commenters stated that we should

limit the definition of ‘‘parent

organization’’ to the context of this

provision only as our proposed

definition could create inconsistencies

in the Part C and D polices and

guidance or have ‘‘unanticipated

implications that are difficult to identify

at this time.’’ One of the commenters,

who asked us to limit the application of

the ‘‘parent organization’’ definition to

this provision only, stated that it would

support our proposal if we clarified that

the parent organization must have a

‘‘controlling interest’’ in the subsidiary

legal entities in question.

Response: In the proposed rule, we

specifically solicited comments on

whether the requirement should be

applied to a parent organization with

less than 100 percent interest in the

affected cost contract and MA plan. We

agree that a controlling interest is a

reasonable standard that is consistent

with our intention to prevent an

organization from having control over

both a cost contract and MA plan in the

same service area. We also agree that the

threshold for determining when the

prohibition should be applied is best

established in the context of this

provision and thus are not finalizing the

definition of ‘‘parent organization’’ in

§ 422.2 . Instead, we are including the

threshold for the prohibition in

modifications in

§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(G)(5)(i) and (ii).

These sections will now state that any

entity seeking to contract as an MA

organization—

• Not accept, or share a corporate

parent organization owning a

controlling interest in an entity that

accepts, new enrollees under a section

1876 reasonable cost contract in any

area in which it seeks to offer an MA

plan.

• Not accept, as either the parent

organization owning a controlling

interest of, or subsidiary of, an entity

that accepts, new enrollees under a

section 1876 reasonable cost contract in

any area in which it seeks to offer an

MA plan.

We are finalizing the provisions of the

proposed rule with the revisions and

additions discussed in this section

III.A.1 of this final rule.

2. Authority To Impose Intermediate

Sanctions and Civil Money Penalties

(§§ 422.752, 423.752, 422.760 and

423.760)

Sections 1857(a) and 1860D–12(b)(1)

of the Act provided the Secretary with

the authority to enter into contracts with

MA organizations, and Part D sponsors

(respectively). Section 1857(g)(1) of the

Act provided a list of contract violations

and the corresponding enforcement

responses (intermediate sanctions

(sanctions) and/or civil money penalties

(CMPs)) are listed under section

1857(g)(2) of the Act (section 1860D–

12(b)(3)(E) applied these provisions to

Part D contracts).

We proposed two changes to our

existing authority to impose sanctions

and CMPs based on section 6408 of the

Affordable Care Act (Pub. L. 111–148).

The provisions of section 6408 provided

CMS with the authority to impose

intermediate sanctions or CMPs for

violations of the Part C and D marketing

and enrollment requirements. As well

as, an organization that enrolls an

individual without prior consent

(except in certain limited

circumstances) or transfers an

individual to a new plan without prior

consent. Additionally, we proposed to

revise the language of these provisions

to clarify that either CMS or the OIG

may impose CMPs for the violations

listed at §§ 422.752(a) and 423.752(a),

except 422.752(a)(5) and 423.752(a)(5).

Comment: A commenter expressed

concern and stated that MA

organizations and Part D sponsors

should be given the opportunity to

refute marketing or other allegations of

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00009 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29852

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

non-compliance prior to sanctions and/

or CMPs being imposed.

Response: Enforcement actions are

only typically taken based on

substantiated, well documented

instances of non-compliance and in the

case of both a sanction and a CMP, even

after they are issued, MA organizations

and Part D sponsors are given an

opportunity to rebut or appeal CMS’

determination through a formal appeals

process.

Comment: A few commenters

requested clarification regarding the

new sanction authority, specifically the

language that would allow CMS to

impose intermediate sanctions on an

organization that enrolls an individual

without prior consent (except in certain

limited circumstances) or transfers an

individual to a new plan without prior

consent. The commenters requested that

CMS clarify that this would not apply

to organizations that perform facilitated

or auto-enrollment, passive enrollment,

seamless enrollment or requests from

Employer Group Waiver Plans (EGWPs).

Response: In the proposed rule, we

proposed to amend the regulation text at

§§ 422.752 and 423.752 by adding (a)(9),

and (a)(7), respectively, which read:

‘‘. . . Except as provided under § 423.34

of this chapter, enrolls an individual in

any plan under this part without the

prior consent of the individual or the

designee of the individual.’’ Section

423.34 specifically refers to enrollment

of individuals who receive the low

income subsidy (LIS) and are therefore

subject to facilitated or auto-enrollment.

Therefore, we believe that the proposed

regulation text already makes clear that

this provision would not apply to those

organizations that are performing

facilitated enrollment of LIS

beneficiaries. Additionally, passive

enrollment and use of the seamless

enrollment option are initiated or

approved by CMS, respectively.

Therefore, an organization who is

contacted by CMS to receive passive

enrollment would not be considered to

have performed enrollment without

prior consent. As for the seamless

enrollment option, as these proposals

must be submitted to and approved by

CMS, as long as organizations are

following CMS’ enrollment guidance in

Chapter 2, § 40.1.4, an organization,

again, would not be considered as

enrolling without prior consent and

would, therefore, not be considered for

a possible sanction. Finally, an

organization who is accepting group or

individual enrollment requests from

EGWPs must follow CMS’ enrollment

guidance in Chapter 2, § 40.1.6. As long

as CMS enrollment guidance is being

followed with respect to processing

these enrollments, CMS would not

consider MA and Part D organizations

in violation of the new requirement.

Comment: One commenter stated that

only one organization, either CMS or

OIG should have CMP authority and

that there should be no overlapping

authority. They went on to state that if

CMS proposed to allow overlapping

CMP authority that CMS agree that the

total amount of the CMPs issued not

exceed what either CMS or OIG could

impose separately.

Response: It is not CMS’ intent to

create overlapping CMP authority,

simply to clarify our existing CMP

authority. However, to the extent CMS

or OIG were planning on pursuing a

CMP, we have internal mechanisms in

place to ensure that the other entity

within the department is not

simultaneously pursuing a CMP for the

same or similar conduct. If we were to

determine that OIG was pursuing a CMP

for similar conduct, we would

coordinate with the OIG so that only

one CMP action would move forward.

Comment: One commenter requested

that CMS not finalize this provision

because they believe the current

division of authority to impose CMPs

should remain unchanged, with the

authority to CMP for certain violations

remaining with OIG, instead of adding

to CMS’ existing CMP authority, as this

approach ensures a natural division of

power and oversight expected from

government agencies.

Response: CMS has always had the

statutory authority to impose CMPs for

the violations currently designated as

belonging solely to the OIG in the

regulation. However, CMS agrees that

there are certain violations that should

be retained solely by OIG for purposes

of imposing CMPs, which is why the

proposed rule states that the authority to

impose CMPs for violations listed at

§§ 422.752(a)(5) and 423.752(a)(5),

involving misrepresentation or

falsification of information furnished to

CMS, an individual, or other entity, will

continue to reside solely with the OIG.

Comment: One commenter, in

addition to expressing support for our

proposal, stated that CMS should

authorize use of monies collected from

CMPs to allow states to contract with, or

grant funds to entities, provided that the

funds are used for CMS approved

projects to protect or improve SNF

services for residents.

Response: We thank the commenter

for their support and we will explore in

the future if such arrangements are

allowed within our current statutory

authority.

Comment: We received several

comments that supported the new

proposed sanction authority for

marketing and enrollment violations.

Response: We thank the commenters

for their support.

After careful consideration of all of

the comments we received, we are

finalizing these proposals without

modification.

3. Contract Termination Notification

Requirements and Contract Termination

Basis (§§ 422.510 and 423.509)

Sections 1857(c) and 1860D–

12(b)(3)(B) of the Act provided us with

the authority to terminate a Part C or D

sponsoring organization’s contract.

Sections 1857(h)(1)(B) and 1860D–

12(b)(3)(F) of the Act provided us with

the procedures necessary to facilitate

the termination of those contracts. We

proposed three revisions to our existing

regulations that relate to contract

termination.

First, we proposed to clarify the scope

of our authority to terminate Part C and

D contracts under §§ 422.510(a) and

423.509(a) by modifying the language at

§§ 422.510(a) and 423.509(a) to separate

the statutory bases for termination from

our examples of specific violations

which meet the standard for termination

established by the statute. We proposed

to effectuate this change by renumbering

the list of bases contained in

§§ 422.510(a) and 423.509(a).

Second, we proposed revisions to our

contract termination notification

procedures contained at §§ 422.510(b)(1)

and 423.509(b)(1). Current regulations

state that if CMS decides to terminate a

Part C or Part D sponsoring

organization’s contract, we must notify

the organization in writing 90 days

before the intended date of termination.

We proposed to shorten the notification

timeframe from 90 days to 45 days.

Additionally, in an effort to respond to

changes in the media and information

technology landscape, we proposed a

slight modification to the termination

notification provision for the general

public at §§ 422.510(b)(1)(iii) and

423.509(b)(1)(iii) which includes the

contracting organizations releasing a

press statement to news media serving

the affected community or county and

posting the press statement prominently

on the organization’s Web site instead of

publishing the notice in applicable

newspapers.

Finally, we proposed minor revisions

to the wording of our regulations at

§§ 422.510 and 423.509 to reflect the

authorizing language contained in

sections 1857(c)(2) and 1860D–12 of the

Act. Specifically, we proposed to

replace the word ‘‘fails’’ with ‘‘failed’’

so that it reads consistently throughout

§§ 422.510 and 423.509.

VerDate Mar<15>2010 19:14 May 22, 2014 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00010 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\23MYR2.SGM 23MYR2

TKELLEY on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2

29853

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Rules and Regulations

Comment: Several commenters

opposed our proposal to shorten the

notification period for contract

termination from 90 days to 45 days.

Commenters made several arguments

supporting their opposition to the

shortened notification timeframe, but

most stated that it is not enough time to

ensure members’ needs are adequately

addressed, specifically noting the

difficulty in effectively communicating

the change with their members and

ensuring their members were effectively

transitioned to a new plan. Other

commenters stated that the timeframe

was too short to provide adequate notice

to affected providers and vendors. Yet

another commenter stated that the

shortened timeframe did not allow

enough time for a plan to appeal the

termination. A final commenter noted

that the shortened timeframe would

increase costs to the contracting

organization if the termination period is

reduced.

Response: After carefully considering

the commenters’ concerns, we

respectfully disagree that these concerns

outweigh the need to protect

beneficiaries and have them moved

from a plan that is in such substantial

non-compliance with our regulations

that CMS would proceed with

termination. Plans that receive a notice

of termination from CMS are instructed

that they must provide notice to their

affected beneficiaries at least 30 days

prior to the effective date of the

termination. If CMS provides their

notice of termination to contracting

organizations 45 days before the

effective date of the termination, this

affords plans 15 days to issue their

notice to enrollees while still complying

with the existing 30-day beneficiary

notification requirements. While we do

request that terminated plans work with

the receiving plan to transition enrollee

data and records, it is not expected that

these tasks would be completed by the

effective date of the termination, but

would instead begin upon transfer of the

enrollees once the termination was

actually effective.

As for adequate notification to

affected vendors and providers, it is the

responsibility of the contracting

organization to design their contracts

with their providers and vendors in a

manner that recognizes possible

contract actions, such as termination,

that could be taken by CMS. For

example, all plans that have a contract

with CMS could ultimately be subject to

immediate termination if they are found

in such substantial non-compliance by

CMS that it poses an imminent and

serious risk to Medicare enrollees.

Therefore, most, if not all plans, likely

have clauses in their provider and

vendor contracts that allow them to

terminate these contracts expeditiously

with the affected entities in the event of

a contract termination by CMS.

We also do not agree that the

shortened timeframe in any way affects

a contracting organization’s ability to

appeal. Contracting organizations who

are subject to a contract termination in

§§ 422.510(b) or 423.509(b) must file

their request for a hearing within 15

days from the date of receipt of the

notice of termination. A timely filed

request for hearing effectively stays the

termination proceeding until a hearing

decision is reached. Consequently,

shortening the notice of termination

from 90 to 45 days should have no

impact on a contracting organization’s

ability to file an appeal of the contract

termination.

Finally, we do not agree that the

shortened notice timeframe to effectuate

a termination would result in increased

costs to an organization. We already

have the ability to prorate its payment

to an organization for terminations that

are effective in the middle of a month;

consequently we do not agree that

shortening the notification timeframe

would in any way change the CMS’s

current approach to payment or

recoupment of capitated payments in

these circumstances.

Comment: One commenter suggested

that CMS should have different

notification timeframes for termination.

They recommended that 90 day notice

be provided to all post-acute care (PAC)

providers as well as to beneficiaries in

PAC. They stated that 45 days for notice

may be sufficient for non-post-acute

care beneficiaries, but not for people in

a short stay setting. They also suggested

that MA plans that are serving full dual

eligible beneficiaries should be required

to provide 180 day notice to individuals

and providers.

Response: CMS’ proposal to shorten

the notification of termination from 90

days to 45 days affects the amount of

notice that CMS must give to an MA or

Part D organization prior to moving

forward with a termination action. The

timeframe in which that organization

must then notify their beneficiaries,

which is currently 30 days, is not being

changed in this proposal. While we

appreciate the commenter’s suggestion,

we believe that it would be incredibly