University of Kentucky University of Kentucky

UKnowledge UKnowledge

University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School

2003

THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING

Jennifer Sue Shank

University of Kentucky

Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document bene;ts you. Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document bene;ts you.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Shank, Jennifer Sue, "THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING" (2003).

University of Kentucky

Doctoral Dissertations

. 397.

https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/397

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been

accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of

UKnowledge. For more information, please contact UKnowledge@lsv.uky.edu.

ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION

Jennifer Sue Shank

The Graduate School

University of Kentucky

2003

THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING

_____________________________

ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION

_____________________________

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the

Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in the College of Fine Arts

at The University of Kentucky

By

Jennifer Sue Shank

Lexington, Kentucky

Director: Dr. Cecilia Wang, Associate Professor of Music

Lexington, Kentucky

2003

Copyright ©Jennifer Sue Shank 2003

ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION

THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of visual stimuli on music

listening skills in pre-service elementary teachers. “Visual Stimuli” in this study refers to

the presentation of arts elements in selected visually projected images of paintings.

Music listening skills are defined as those skills needed to identify and interpret musical

excerpts. A Pretest-Posttest Control-group Design was used in this study.

Subjects were pre-service elementary general educators enrolled in a large

southern university (N=93). Students from intact classes were randomly placed into

either the experimental group or the control group. The treatment consisted of six music

listening lessons over a two-week period with each group receiving the identical teaching

protocol with the exception of the use of paintings with the experimental group.

Listening instruction emphasized the identification of melodic contour, instrumentation,

texture, rhythm and expressive elements of the compositions.

The Teacher Music Listening Skills Test (TMLST) was constructed by the

investigator and administered before and after the treatment. The TMLST was designed

to assess music listening skills in adult non-musicians.

Results indicate that the group receiving visual stimuli in the form of paintings

scored significantly higher on listening skills (p<.01) than the control group which

received no visual stimuli in the form of visually projected images of paintings. There

was an instruction effect on both preference and familiarity of the musical pieces for both

the control group and the experimental group.

KEY WORDS: VISUAL STIMULI, MUSIC LISTENING SKILLS, PAINTINGS, NON-

MUSICIANS, INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC, GESTALT

Jennifer S. Shank

July, 20 2003

THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING

By

Jennifer Sue Shank

Dr. Cecilia C. Wang

Director of Dissertation

Dr. Lance W. Brunner

Director of Graduate Studies

RULES FOR USE OF DISSERTATION

Unpublished dissertation submitted for the Doctor’s degree and deposited in the

University of Kentucky Library are as a rule open for inspection, but are to be used with

due regard to the rights of the authors. Bibliographical references may be noted, but

quotations or summaries of parts may be published only with the permission of the

author, and with the usual scholarly acknowledgements.

Extensive copying or publication of the thesis in whole or in part requires also the

consent of the Dean of the Graduate School of the University of Kentucky.

A library which borrows this thesis for use by its patrons is expected to secure the

signature of each user.

DISSERTATION

Jennifer Sue Shank

The Graduate School

University of Kentucky

2003

THE EFFECT OF VISUAL ART ON MUSIC LISTENING

______________________________

DISSERTATION

_____________________________

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the

Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in the College of Fine Arts at

The University of Kentucky

By

Jennifer Sue Shank

Lexington, Kentucky

Director:

Dr. Cecilia Wang, Associate Professor of Music

Lexington, Kentucky

2003

Copyright © Jennifer Sue Shank, 2003

For my Parents

ACKNOWELDGMENTS

I would like to thank all the people that made the impossible possible. Thank you to Bill

and Lisa, for always being there. Thank you to my grandparents, Marge Jossi and August

Keyerleber, who have supported me and made sure there was food on the table and a

warm place to sleep. Thank you to Dr. Cecilia Wang, whose mentoring, guidance and

friendship were invaluable throughout my education. To Dr. David Sogin who has

helped me grow from a scared new student to a confident graduate. To Dr. Kate

Covington, Dr. Ron Pen and Dr. Skip Kifer for agreeing to sit on my committee. To my

colleagues, April McAllister and Donna Irwin, to whom I am eternally grateful for all of

the help, support and graded papers. And finally, thank you to my parents, Janet and Bill

Shank, for always encouraging me and allowing me to be anything in life.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………..………iii

LIST OF TABLES..………………………………………………………………………………vi

LIST OF FIGURES…..………………………………………………….………………………vii

LIST OF FILES………………………………………………………….……………………...viii

Chapter One: Introduction………………………...………………………………………………1

Chapter Two: Related Literature…....…………………………………………………………….3

Part One: On Listening……………………………………………………………………3

The Basis of Listening….…………………………………………………………3

Processing of Sound During Listening……………………………………………5

Listening for Understanding………………………………………………………7

Listening Lesson Approaches……………………………………………………..9

Aesthetic Education Through Listening…….……………………………..……..10

Listeners with Different Learning Styles….……………………………………..15

Differences Among Listeners...………………………………………………….17

Motivation for Listening…………………………………………………………18

Part Two: On Visual Stimuli…………………………………………………………….20

Visual Stimuli and Instruction…………………………………………………...20

Historical Connection Between Visual Art and Music…………….……………22

Art in Music Education…………………………………………………………..24

Applications of Gestalt Principles in Art and Music…………………………….24

Memory and Listening…...……………………………………………………...29

Statement of the Hypothesis……………………………………………………………..31

Chapter Three: Methodology and Introduction………..………………………………………...32

Selection of Subjects……………………………………………………………………..32

Research Design………………………………………………………………………….33

Instrumentation…………………………………………………………………………..35

Procedure………………………………………………………………………………...37

Treatment………………………………………………………………………………...39

Music and Art Used in the Study………………………………………………………...40

iv

Chapter Four: Results……………………………………………………………………………45

Results Related to Listening Skills………………………………………..……………..46

Results of Hypothesis Testing………………………………………………..…….……53

Secondary Results……………………………………………………………..…………53

Summary…………………………………………………………………………………57

Chapter Five: Discussion and Recommendations………………………………………………..57

Recommendations for Further Research….……………………………………….……..64

Implications for Educational Practice..…………………………………………………..65

Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………67

Appendix A- TMLST……………………………………………………………………67

Appendix B- Recall Test…………………………………………………………………77

Appendix C- Permission…………………………………………………………………83

Appendix D- IRB………………………………………………………………………...84

Appendix E- Sample Listening Lesson Scripts …….……..………………………….…85

Appendix F- Concepts Taught During Listening Lessons………………………….……87

Appendix G-Art Survey………………………………………………………………….90

Appendix H- Pilot Study…………………………………………………………………92

References………………………………………………………………………………………106

Vita……………………………………………………………………………………………...117

v

LIST OF TABLES

Table 4.1 Participant Demographic Information………………………………………………...45

Table 4.2 Table of Means for Pre-test TMLST for Subgroups 1-8……………….……………..46

Table 4.3 ANOVA Summary of TMLST for Pre-test Subgroups 1-8…...………………………47

Table 4.4 Table of Means for Pre-test Part B for Classes 1-4…..……………...………………..47

Table 4.5 ANOVA Summary of TMLST for Class Sections 1-4…...…………………………...48

Table 4.6 ANOVA Summary for Pre-test………...……….……………………………………..48

Table 4.7 Mean Values of TMLST Part A..……………………………………………………..49

Table 4.8 Mean Values of TMLST Part B…...…………………………………………………..49

Table 4.9 TMLST Means Showing Improvement from Pre-test to Post-test..…………………..50

Table 4.10 ANOVA Summary of TMLST Post-test for the Experimental and Control Groups..50

Table 4.11 Table of Means for TMLST Post-test for Subgroups 1-8…………………………...51

Table 4.12 Table of Means Shows Improvement from Pre-test to Post-test Divided by Subgroups

1-8………………………………………………………………………………………………..52

Table 4.13 Means of TMLST Post-test per Excerpt Score for Each Category…………………..54

Table 4.14 Mean Rating for Preference and Familiarity…………………….…………………..55

Table 4.15 Significant Correlations………………….…………………………………………..56

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 Common Decibel Ranges……………………………………………………………...4

Figure 2.2 The Ear………………………………………………………………………………...5

Figure 2.3 Wlodkoski’s Time Continuum Model for Motivation……………………………….18

Figure 2.4 Music and Association with Gestalt Laws…………………………………………...28

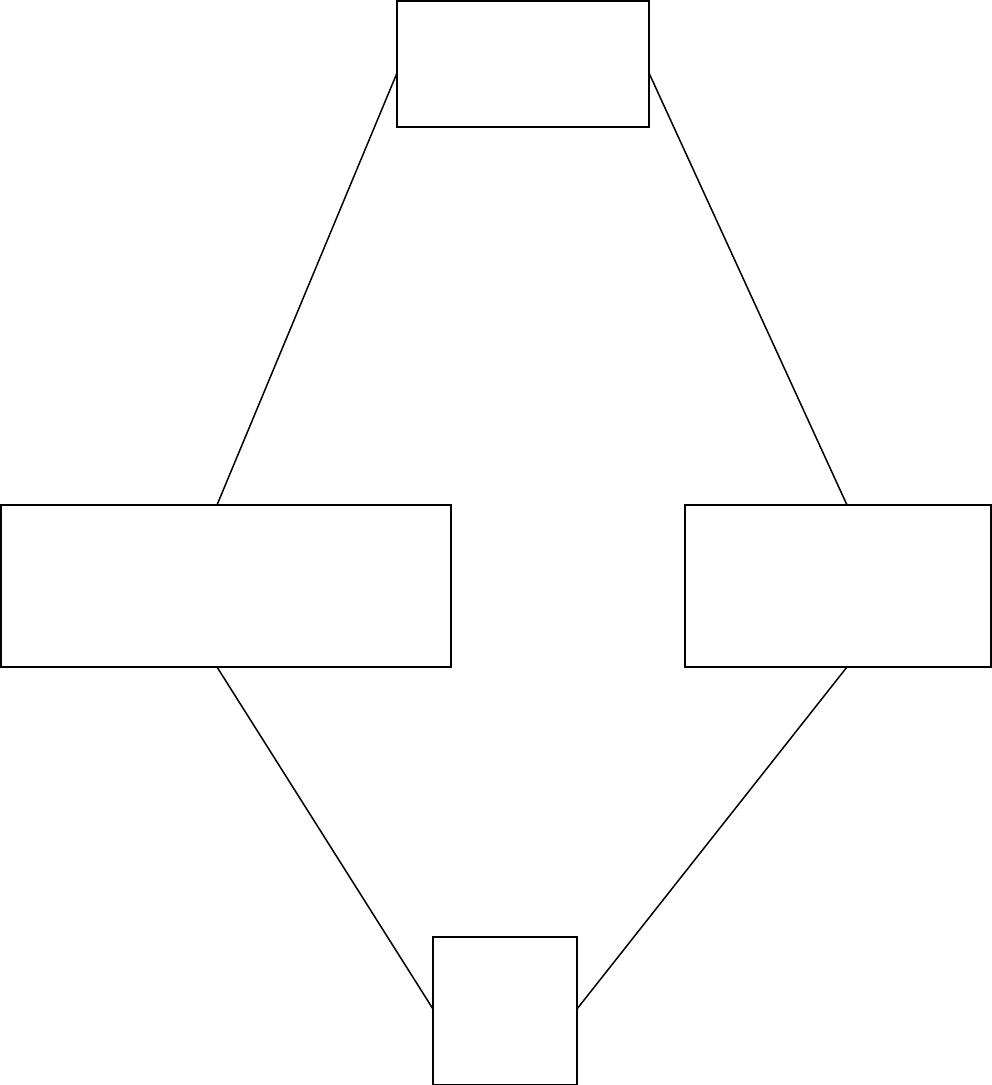

Figure 3.1 Research Study Design Model.…….…...……………………………………………34

Figure 3.2 Music Used in the Study……………………………………………………………...41

Figure 3.3 Paintings Used in this Study….……………………………………………………...42

Figure 3.4 Art and Music Combined, Direct and Indirect Relationships……………………..…42

vii

LIST OF FILES

Dissertation, Jennifer S. Shank, The Univerisity of Kentucky………………………………645kb

viii

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Listening to music is prerequisite to all other musical pursuits. Focus of attention

combined with developing a high level of aural discrimination seems to provide the basis

for meaningful music listening. Listening contributes to musical understanding and

enjoyment as well as increasing one’s aesthetic sensitivity (Madsen, C. & Geringer, J.M.

2000). The ability to listen is the first and most important skill that is needed for all

musical activities. Haack (1992) states,

Listening is the fundamental skill. Some aestheticians argue or imply that

until sounds are heard and perceived as music, there is no music. Clearly

this is the practical truth as concerns music listening. Music exists for

hearing and listening. Such listening is a skill in and of itself, as well as a

vital part of all other musical skills. Yet music listening is among the last

and least studied aspects of music (p. 451).

The National Standards for Arts Education (Consortium of National Arts Education

Associations, 1994) states that “proficient” students in grades 9-12 should be able to

“identify and explain compositional devices and techniques used to provide unity and

variety and tension and release in a musical work”(p. 61). “Advanced” students should

be able to “analyze and describe uses of the elements of music in a given work that make

it unique, interesting and expressive” (p.61). In order to accomplish these tasks students

must be able to hear the interaction between the elements of music that the composer has

used and be able to recall them.

People who are not musically trained approach listening differently than trained

musicians do. The non-trained person listens to features such as texture and melody

before other aspects of a musical piece. Previous research has indicated that adults learn

better when they are presented with materials in a multi-sensory way. This would

suggest that the use of paintings to reinforce musical knowledge would enhance the

listening skills of college students.

We compare the arts in order to discover similarities and common elements and to

draw parallels between them. Aristotle’s influential categorization in The Poetics of

2

painting, music and poetry as imitative arts was an element in his quest for a unified

theory of aesthetics. The need to compare also comes from the frequent inadequacy or

failure of the aesthetic language. Whenever critics and aestheticians have found

themselves struggling to describe something they have perceived in a work of poetry,

music or visual art, they have often fallen back on expressions such as the “poetry of

painting, the painting of poetry or the poetry of music,” attempting to characterize

something difficult to define by referring it to something else that is difficult to define.

The hope, presumably, is that some aspect of one art form will help to illuminate some

aspect of the other (Kagan, 1986). This hope fuels the idea of using art to help

understand music. Art and music are interrelated and influential upon each other for

inspiration, shared meaning and symbolic representation.

In the present school curriculum, we expect our classroom teachers to integrate

the arts into teaching different subjects and one or two courses in teaching music are

usually required college courses for teacher preparation programs. When teachers are

asked to integrate music into a general education classroom they are expected to make

listening an integral part of that, yet, there is very little research to indicate what method

is effective in training the listening skills of future teachers.

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether using the projected images of

paintings will enhance the ability of pre-service teaching candidates to identify and

recognize musical features of particular musical excerpts. If awareness of similarities in

the visual stimuli serves as a catalyst for awareness of similarities in the auditory stimuli,

this would indicate that visual art should be employed for pedagogical purposes in the

future.

3

CHAPTER TWO

RELATED LITERATURE

This chapter contains a review of literature on listening and visual stimuli. In

examining listening, it is important to look at how sound is created and internalized by

the ear and brain, how humans process sound, and how people understand that for which

they listen. Other important elements to consider are approaches in listening lessons,

aesthetic education and listening, listeners with different learning styles, and the

motivation for listening. The subject of visual stimuli is a broad topic that can be

examined in a multitude of ways. For this study, the aspects of visual stimuli that are

most important are those that directly affect how individuals process what they see and

how they process it in conjunction with other stimuli. Factors in this research include

visual stimuli and instruction, connecting visual art and music, applications of Gestalt

principles in art and music, and memory and learning.

Part One

On Listening

The Basis of Listening

The capacity to perceive music and respond at both a cognitive and an affective

level can be learned through particular listening experiences. One of the goals of music

education is to present strategies which will encourage attention to the music and enable

the listener to form cognitive and affective opinions on a piece. In order for these

activities to be effective, active engagement is necessary. To engage a listener, activities

and lessons must be developed that enhance understanding and allow the listener to

organize information in a meaningful way.

Even before examining how to approach active listening, one must consider how

one listens. It is the sensory experience of hearing that makes the perception of music

possible. The ability for individuals to use their hearing for the purpose of listening

varies. Good hearing does not necessarily insure skilled listening and, conversely, poor

4

hearing does not indicate an inability to listen. While good hearing is not completely

dependent on one’s ability to listen well, hearing does play a significant role in the

perception of music (Darrow, 1990). Listening is a mental process; the act of hearing is a

physical one. Understanding the physical act of hearing can offer insight into the human

potential for the capacity to listen and, ultimately, to understand. Examination of the

components of the aural process can provide general guidelines for structuring and

sequencing listening experiences. Sound consists of vibrations that travel in waves,

generally through air. Sound waves travel at different rates of speed; the faster the waves

travel the higher the pitch. Frequency is the measured number of vibrations per second

and is represented in hertz (Lipscomb & Hodges, 1996). Pitch is a subjective judgment,

while frequency is the physical reality of the speed of the sound wave. Normal hearing

range is 20-20,000 Hz. Intensity of sound is the amount of energy within a sound wave.

Intensity can be measured quantitatively in decibels, but loudness is a subjective

measurement of sound. Intensity is measured in decibels (dB). Zero decibels are the

quietest sound. Sound that exceeds 120 decibels can cause pain (Lipscomb & Hodges,

1996). Common decibel ranges are presented in the chart below.

Figure 2.1 Common Decibel Levels

Decibel Levels Sound Source Musical Level

0dB just audible sound

30dB soft whisper background music

50dB normal conversation mp

60dB loud conversation mf

80dB shouting f

90dB shouting marching band

5

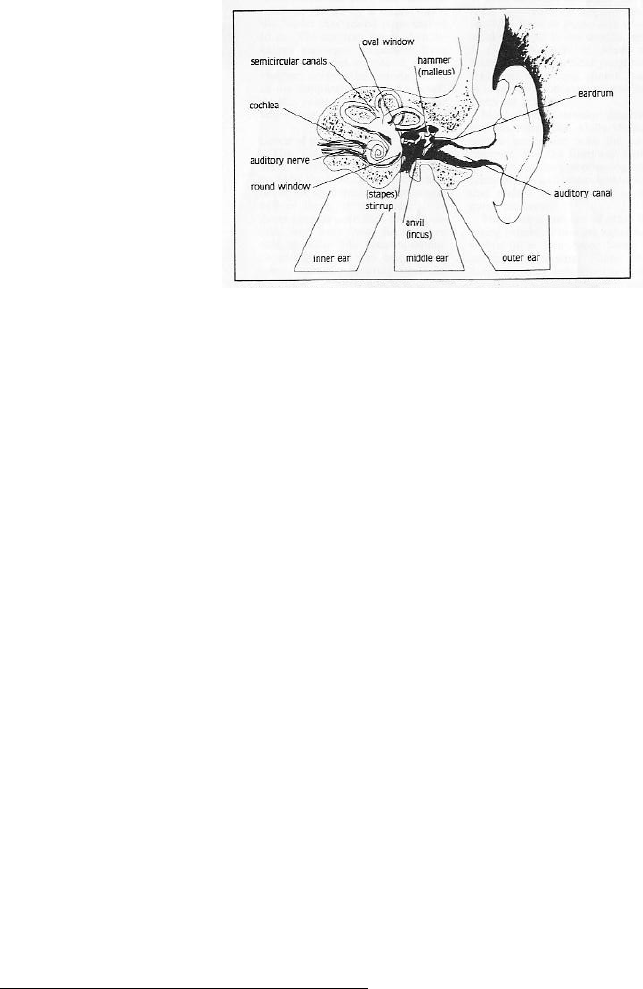

The ear is divided into three parts: outer, middle and inner ear. (See figure below)

Figure 2.2 The Ear

Sound waves enter the external canal of the outer ear, strike the eardrum and cause the

eardrum to vibrate. The vibrations from the eardrum reach the three bones of the middle

ear, the malleus, incus and stapes. These bones carry the sound waves across the middle

ear to the inner ear. Within the inner ear are the semicircular canals and the cochlea.

The semicircular canals are filled with fluid and lined with hairs and are responsible for

balance and equilibrium. The chochlea is involved in hearing. Within the cochlea lies

the Organ of Corti which is covered with many fine hairs. Sounds of different

frequencies affect hair cells at different locations. The thinner, shorter hairs, near the

opening of the Organ of Corti, respond to high sounds. The thicker, longer hairs, farthest

from the opening, pick up low sounds. Intensity is determined primarily by how many

hair cells are affected. The more hairs that are made to vibrate by a sound wave the

louder the sound is perceived. The auditory nerve then receives impulses from these

hairs and carries it to the hearing center (auditory cortex) within the brain. Once the

brain assumes control of the process, hearing becomes listening.

Processing of Sound During Listening

The brain is responsible for the levels of discrimination that we make during

listening. Training the brain to listen requires several elements: analysis of the desired

auditory task, the structuring of successive approximations to the desired goal, and

regular and systematic evaluation of auditory level. According to Norman P. Erber and

6

Ira J. Hirsh (1978), auditory tasks can be broken into four basic levels of aural

processing: (Erber & Hirsh, 1978).

1. Detection, in which the listener determines the presence or absence of

specified sound stimuli.

2. Discrimination, in which the listener perceives differences in sound stimuli

such as loud and soft or high and low.

3. Identification, in which the listener appropriately applies labels to the sounds

4. Comprehension, in which the listener makes critical judgments regarding the

sound stimuli.

There are a number of other listening behaviors that can be subsumed within the four

basic levels of the auditory processing mentioned above. In 1977, Derek Sanders

developed a hierarchy of auditory processing for speech. Since both speech and music

have similar properties, Sanders’ hierarchy can be applied to music. The following is that

hierarchy with reference to application in music:

1. Awareness of acoustic stimuli.

2. Localization: Can the listener identify the location of the sound source?

3. Attention: Can the listener attend to music over time?

4. Discrimination between speech and non speech or chant and melody.

5. Auditory discrimination: Can the listener discriminate between the timbres of

different instruments; can he or she locate the entrance and exit of specific

instruments within the total music context?

6. Suprasegmental discrimination: can the listener make discriminations about the

expressive qualities of the music?

7. Segmental discrimination: can the listener make discriminations about pitch?

8. Auditory memories: can the listener remember what instruments were heard?

9. Auditory sequential memory: can the listener remember in what order

instruments were heard?

10. Auditory syntheses: can the listener make critical judgments regarding form,

texture and harmony?

According to Sanders (1977), suprasegmental discrimination is defined as discrimination

on a large scale of such things as texture, form and expressive elements and segmental

7

discrimination is defined as discrimination of musical cues such as pitch. Sanders, along

with the other research, suggest that there are steps to listening and the process of

listening. This lends itself to what takes place during a listening activity in a music

education class such as the one used for this research. Students begin with an awareness

of acoustic stimuli and work their way through the hierarchy to achieve auditory memory.

Students are presented with a new musical piece to listen to and they are directed as to

what to listen for. Students make discriminations whether there are voices or

instrumental only, then different timbres, instrumentation and entrances and exits of

instruments. After students have made discriminations on timbre and instrumentation,

students then make critical decisions on expressive qualities.

Listening for Understanding

Once the hearing process involves mental processing, hearing becomes listening.

Successful listening is an active process that enhances understanding of the sound.

Listening is temporal because it involves making sense of information that is never all

presented at the same time. Understanding of aural events depends on what a listener

retains in a continuous moving stream of information (Elliott, D. J. 1995). Processes

involved in listening to music include sensory transduction, auditory grouping, analysis

of auditory properties and features, and matching immediate sonic events with an

auditory lexicon of previously experienced sounds (McAdams, S. 1993). For a listener

to deduce meaning and understanding from music, the music must create a meaningful

connection to that listener. Elliott (1995) points out that listening to music is analogous

to constructing a moving jigsaw puzzle. Listeners do not simply listen from wholes-to-

parts or parts-to-wholes because auditory parts and wholes coalesce (p.84). Green (1988)

describes the experience of listening to music as the result of the interaction between our

perceptions of the inherent meaning of sound (structural elements) and the degree to

which the sounds delineate themselves as sounds which are meaningful to us. This

would suggest that for listening to be active and successful, the musical sounds must be

familiar in some ways and must be associative with meaningful representation. In other

words, the sounds must have familiar timbres or instrument sounds and those sounds

must match our socially defined concepts about music.

8

A person who has experienced many ways of organizing particular types of

stimuli is at an advantage when confronted by unfamiliar materials that need organization

(Tait and Haack, 1984). The importance of segmentation in music cognition has been

emphasized in several models of music perception including that of Lerdahl &

Jackendoff (1983) and empirical studies by Krumhansl (1996). Listeners regularly

exploit melodic cues to recognize and to distinguish between different pieces of music

(Rosner & Meyer, 1986). It has also been suggested that anchoring can be effective for

the listening experience. Anchoring, as shown in research by Povel and Jansen (2001),

appears to be a powerful tool for tracing perceptual mechanisms at work in the on-line

processing of music. Anchoring, as was first described by Bharucha (1994), links

unstable tones to stable tones and gives the listener something to focus on within the

melodic structure. Musical experience is meaningful for the listener when the listener is

able to employ information that is familiar to glean understanding. Listening is not a

passive process; there is a difference between simple reception and active construction.

Certain cognitive abilities must be used in order to perceive the sound signals by the ear

and interpret them as music. Acoustical properties of music are organized by the mind

and then associations and connections are made (Mullee, 1996). This information would

suggest that carefully planned listening experiences may lead to a mode of attending that

is both different and more fulfilling than the free associational thinking that listening to

music so often involves. It is possible to increase the likelihood of people actually

engaging in works of art, moving inside of them through acts of imagination, and

perceiving them against their own personal histories as meaningful (Greene, 1986).

Choosing appropriate features for which to listen must be considered. When we

listen to music we actively select salient features from the stream of musical sounds,

focusing our attention one minute on one part of the sound environment and the next

moment on another. Attentional focus is guided by knowledge structures, or schemata,

developed through past experience (Dowling, W.J, & Harwood, D. W,1986. and Neisser

U. 1976). Listeners focus on what is recognizable first, relying on what they have

learned or developed in the past before moving to the new or unrecognizable. Because

listeners seek out salient features that are recognizable it is important to consider what

musical elements should be the focus in this study.

9

For this research the following musical elements will receive focus during

listening activities: melodic contour, texture, beat structure, articulation rhythm and

instrumentation. Research indicates that listeners’ mental representations of novel

melodies contain contour information but relatively little information about absolute pitch

or exact interval size (Dowling, W. J. 1994). Dowling also states that listeners make

errors about interval and absolute pitch of novel melodies soon after they are presented.

By contrast, listeners retain contour information for longer periods of time. This would

indicate that students would be more successful listening for melodic contour rather than

direct melodies. With regard to instrumentation, Rentz (1992) suggests that non-

musicians pay less attention to tone colors of strings while selecting the more obvious

tone color of brass, percussion and woodwind instruments. For this study, music was

chosen to reflect Rentz’s research. Beat structure, articulation and texture were chosen

based on the model by Sanders (1977). Sanders suggests that the use of suprasegmental

discrimination and segmental discrimination allows the listener to pick out global

concepts such as form and musical elements such as texture. He also suggests that the

highest level in his hierarchy would allow the listener to make critical judgments

regarding form and texture.

Listening Lesson Approaches

Carefully planned listening experiences may lead to a mode of attending that is

both different and more fulfilling than the reverie and free association thinking that

casual listening to music so often involves. Often, these planned listening experiences

are organized by following listening guides. The purpose of a listening guide is to focus

specifically on what to listen for in music. Strategies for planned listening experiences

include presenting a systematic method of music analysis, examining musical styles and

treatment of musical structure during different chronological periods, and exploring

different forms of music. Some of these approaches include The Experience of Music

(Reimer, 1972). The book explores the creative process of music, examining the

aesthetic sensibilities of the composer, the performer and the listener. Reimer also

discusses music by categorizing the structural elements: Rhythm, Harmony, Melody,

Tone Color, and Form. Reimer has also created a set of listening lessons to accompany

10

his 1972 text, Developing the Experience of Music: Listening Charts (1973). This text

lays out a concise plan for teaching students to listen by dividing lessons by musical

element. The listening charts are designed to focus on one musical element at a time.

For example, there are eight listening lessons that focus on form with different musical

examples for each. A Concise Introduction to Music Listening (Hoffer, 1979) suggests a

different approach that is more segmented into basic elements, musical form, and musical

types, western and nonwestern. Chapters are not laid out by musical element; instead the

text is laid out to follow an order of what students should know to be able to listen

effectively. Chapters include instruction on how music is written down, how to classify a

piece of music and instructions on how to listen.

Each text and listening guide is concerned with changing the listener’s perception

and origination of various elements in music. Both of these texts offer a great deal of

information, but for listeners who are not knowledgeable in music and who may not be

familiar with what they are listening for, these guides may be overwhelming or

discouraging to a listener. The approach favored by this researcher is to promote

listening skills by using materials familiar to the listeners in a multi-sensory setting.

Aesthetic Education Through Listening

The ability to detect aesthetic form (the arrangement of elements that attracts,

holds and directs the interest of the listener) is at the heart of music education (Broudy,

1958). This ability is needed to be successful at any musical skill, listening included.

Schwadron (1967) states that meaning in music is connected with the uniqueness of the

organization and control of sound, notated by symbols and characterized by the

relationships of music to the human senses and intellect. Music combines formal

elements such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and timbre into aesthetically patterned

sounds that have symbolic meaning in a culture of a society and its individuals (Mullee,

1996). The quality of a musical experience depends upon the type of connection that

occurs between the perception of musical stimuli and the responses to musical stimuli.

Sound emotion is a single musical concept and cultural associations are related in

listening to a performance (Masterson, 1994). Green (1988) describes musical

experience as a result of the interaction between our perception of the inherent meaning

11

of sound and the degree to which these sounds delineate themselves as sounds which are

meaningful to us. In other words, do they match our socially defined concepts about

music? This is particularly relevant in listening situations which present music to which

that the listener is unaccustomed.

In experiencing the combination of inherent and delineated meaning of an

unfamiliar musical experience, the capacity to actively engage in musical situations gains

insight into one’s self (musical or otherwise) and into the relationship of one’s self to

one’s own and other musical cultures. Accompanying all such risk-taking, disorientation

and eventual musical acculturation is self-examination and the personal reconstruction of

one’s relationships, assumptions and performances (Elliott, 1990).

The active contribution that listeners make in the aesthetic situation should not be

underestimated. Levinson (1990) states that we can feel emotion and recognize its

expression in the structure of tones in music. Both the emotion and musical structures

reference one another to heighten the expressiveness of the musical focus. Even strictly

formalist theories recognize that art, specifically music, is never self contained. Roger

Fry (1920) admits that art causes emotional responses based on our physical and

psychological traits. Although the basis for awareness in humans lies in the perception of

the senses, the scope of aesthetic experiences requires us to expand the definition of

perception to include the realms of imagination, fantasy, memory and dreams. This type

of inclusion of the perceptual experience is central to music and all of the arts. Dowling

and Harwood (1986) have found that listeners find it quite natural to attach general

emotional labels to pieces of music.

Dewey (1958) recognized the concept of total organic involvement in art - the

biological, the constant rhythm that marks the interaction of the live creature with his

surroundings (p. 15). This underlies his philosophy of experience including art:

It is proof that man uses the materials and energies of nature with intent to

expand his own life and he does so in accord with the structure of his own

organism- brain, sense-organs and muscular system. Art is the living and

concrete proof that man is capable of restoring consciously and thus on the

plane of meaning, the union of sense, need, impulse and action

12

characteristic of the live creature. The intervention of consciousness adds

regulation, power of selection and predisposition (p.25).

Suzanne Langer (1957) maintains that art possesses the form of living things and that

artistic forms are symbolic of human feeling. Art embodies the form of experience-what

life feels like. She makes the distinction between discursive forms of symbolization

which communicate meanings in an unambiguous manner and presentational symbols

such as those used in the arts which communicate metaphorically, where the symbol or

symbols must be seen “as a whole” rather than divided into individual meanings.

Berleant (1991), advocating a participatory aesthetic, emphasizes replacing

disinterestedness with engagement and contemplation with participation. He outlines the

four principal aspects of the aesthetic situation: the creative, the objective, the

appreciative and the performative. In his view, “music exemplifies the creative aspect of

perception; the composer’s activity in generating musical materials that is paralleled by

both the performer and the listener” (p.5). Music as a performing art is unique in that it

exists in time and needs to be recreated by both performers and listeners. Clarke (1989)

recognizes this, stating that musical events and the way in which they are performed,

perceived and created by performer and listeners give greater recognition to the natural

relationship that characterizes an organism and its environment.

All of these views of aesthetic experience share commonalties in that they reflect

an enlarging of aesthetic experience beyond a particular act of consciousness or

disinterested contemplation of a separate aesthetic object. It is the capacity to respond to

these properties that concerns us as educators. How does one change perception or

understanding of deeper intrinsic meaning? How does a teacher facilitate receptivity?

A place to start is with philosophers such as Langer and Goodman, who have both

written extensively on symbolization. Goodman (1968) continues Langer’s line of

thinking regarding the difference between discursive and presentational symbol systems.

He examines the psychological and educational implications of different kinds of

symbolic competencies:

“Once the arts and sciences are seen to involve working with- inventing,

applying, reading, transforming, manipulating, - symbol systems that

13

agree and differ in certain specific ways, we can perhaps undertake

pointed psychological investigations of how the pertinent skills inhibit or

enhance one another; and the outcome might well call for changes in

educational technology” (p.265).

Goodman (1968) calls attention to a range of symbolic codes such as language,

gesture, and musical notation. Human artistry is viewed as an activity of the mind, an

activity that involves the use and transformation of various symbols and symbol systems.

Individuals who wish to participate meaningfully in artistic perception must learn to

decode the various artistic symbols in their culture; individuals who wish to participate in

artistic creation must learn how to manipulate those symbols. Just as one cannot assume

that in the absence of help and support individuals will learn to read and write in their

natural language, one can assume that individuals can benefit from assistance in learning

to “read” and “write” in the various languages of the arts (Gardner, 1990, p.9). That

being said, a music program must address this and students must learn to understand the

symbols presented during a listening experience. Information is presented during the

performance of a piece of music and students should have the tools needed to participate

meaningfully.

The task in music education has been to discover truths about music, musical

behavior, and cognitive and affective links so that the aesthetic experience might be

identified, purused and developed in the proper educational setting (Schwadron, 1984,

p.17). Broudy (1958) maintains that the place of music in a specific curriculum should

be based on aesthetic considerations. Leonhard and House (1972) also write that the

primary purpose of music education is to develop the aesthetic potential possessed by

every person to its highest level. They believe aesthetic education satisfies our basic

need for symbolic experience and provides a means for self-realization and insight

(p.115). Reimer (1989) has constructed teaching models supporting his view that insights

from aesthetics, when incorporated with the expertise of musicians and educators, can

help articulate the values of the music experience and, specifically, listening.

Bowman (1969) calls for an aesthetic–based type of musical listening instruction.

He writes, “to engage in criticism as instructional method is to guide students away from

14

snap judgments, to direct them toward preferences grounded in closely scrutinized value

systems undergirded by the fullest possible musical awareness, to foster ultimate

sensitivity for the considered views of others and a willingness to entertain alternative

perspectives and to develop a tolerance for variousness and difficulty” (p.12). Reimer

(1993) states that “music education must concern itself with both the diversity and depth

of quality of the musical experience” (p.21). “Music is a universal, human phenomenon,

yet at the same time, is a manifestation of a particular cultural belief system about how

sound should properly be made into music” (p. 24).

The position of many music education theorists is consistent with the position set

forth by the Getty Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts: arts education

should include history, aesthetics and criticism, in addition to performance or production.

Unfortunately, emphasis in many music programs is almost entirely performance-based,

an emphasis that has generated support from parents and administrators (Leonhard,

1991p.203). Performance programs have done great things for both the profession and

the students involved in them. However, general music programs, despite the profession

recommendations, have not fared as well. “Many college students claim to have missed

out on having music available to them in elementary school and others regret not having

taken some music course beyond elementary school” (Drago, 1993 p. 40). Bresler (1993)

argues that the goals of music education are agreed upon, yet there exists a gap between

desired and actual outcomes. Although perception is the basis of musical experience

(Campbell, 1991, p35), the average listener receives no instruction in categorizing

musical phenomena. Most music is listened to and filtered through self-created and often

biased categories (Cutietta, 1993, p.52).

The literature regarding aesthetics in music education suggests that music

educators and administrators seem to agree that the development of listening skills should

rank highly as a concept in a music curriculum and that understanding what one listens to

is valuable to developing abilities for listening. Active listening is something most

people are capable of learning yet it does not receive the focus or attention due to a

variety of reasons, including time and budgetary constraints. Because of these

constraints, it is all the more important to teach general educators how to listen and how

to teach listening effectively.

15

Listeners with Different Learning Styles

People learn in different ways. In order to have a better understanding of how

people learn it is valuable to look at the process by which people learn and the mode

people use to learn most effectively. Learning style theory has its roots in the

psychoanalytic community (Silver, Strong and Perini, 1997). Carl Jung (1927) was the

father of learning style theory in that he noted the differences in the way students

perceived, made decisions and interacted, and how active or reflective they were while

interacting. Katherine Briggs and Isabel Meyers (1977) created the Myers-Briggs Type

Indicator, applied Jung’s work and influenced 25 years of research in this area.

Educators have become aware of the research of cognitive and educational psychologists

in the area of individual differences and learning styles. The research of these

psychologists in the area of learning styles, following the lead of Jung and Myers and

Briggs, includes that by Grasha and Reichmann, (1975); Hill, (1976); Dunn and Dunn,

(1978); Kolb, (1981); Gregorc, (1982); Silver and Hanson, (1995). Although theories in

learning style interpret the personality in different ways, nearly all models have two

things in common: a focus on process and an emphasis on personality (Silver, Strong &

Perini, 1997). Each of these theories provides educators with additional insights into how

to work with a diverse population of learners.

Learning styles are broadly described as cognitive, affective and physiological

traits that are relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with and

respond to the learning environment (Keefe, 1979). More specifically, style refers to a

pervasive quality in the learning strategies or the learning behavior of an individual, “a

quality that persists though content may change” (Fischer and Fischer, 1979, p. 245).

Learning style can also be defined as a biological developmental set of personal

characteristics that make the identical instruction effective for some students and

ineffective for others (Dunn and Dunn, 1993). Awareness of these different learning

strengths allows educators to customize lessons and presentations using multiple

modalities.

Research with secondary education students shows that teaching should address

all types of learning styles and use multi-sensory instructional materials, thus providing

16

resources and alternatives to assist students in gaining mastery of the curriculum (Park,

2000). This research would suggest that given how adults process learning, using a

multi-sensory approach to a concept would be more effective than using one mode of

teaching and one learning style.

Humans are typically visually oriented and the retention of information

presented in a visual form usually exceeds retention of information presented verbally

(Levie & Lentz, 1982). Being visually oriented however is typically not enough.

Students should have Visual Literacy, the ability to interpret visual messages accurately

along with the ability to create such messages (Rakes & Rakes, 1995). Research suggests

that the appropriate use of relevant visuals can enhance recall and understanding of

material, increase interest and motivation, and promote critical thinking (Blatnik, 1988,

Pressley and Miller, 1987 and Issing et al, 1989). Many studies demonstrate that visual

learning can positively affect cognitive process such as recall and problem solving

(Anglin, 1986; Ritchey, 1982; Yang and Wedman, 1993). Combining one or more

learning style also enhances learning. A breadth of processing occurs when identical

content is used in two different forms. This then can lead to better memory because

understanding of one form is likely to improve understanding through the other form

(Craik & Tulving, 1975). Using more than one sensory modality and instructional

materials with dual mode presentation, (e.g. visual diagram accompanied by an auditory

text) can be more efficient than the equivalent single modality formats (Kalyuga, S,

Chandler, P & Sweller, J, 2000). Also, the amount of information that can be processed

using both auditory and visual channels can be considerably larger than that using only a

single channel (Kalyuga, S, Chandler, P & Sweller, J, 2000). Therefore, it can be

assumed that a treatment that actively used both visual and auditory modes for learning a

concept would be effective for more learners. It also suggests that using two learning

modalities allows the learner to use a representation that may not directly explain a

concept but in some way enhances it. A picture that does not directly explain a concept

can provide a visual representation in memory to which the student can link supporting

ideas (McDaneil & Pressley, 1987). This would lend itself well to using visual art to

assist students in listening concepts of musical compositions. For this research, the

listening lessons will employ two modalities, the visual and the aural modalities.

17

Differences Among Listeners

Previous research findings indicate that listeners use different strategies in

listening. Since the subjects for this study are adults and musically untrained, it is

important to understand how they listen. In regard to the manner in which non-

musicians learn to listen, Madsen and Geringer (1990) indicated that musicians attend to

listening significantly differently than non-musicians. Musicians spend most of their

time attending to melody first, followed by rhythm, dynamics, and timbre, respectively.

Non-musicians spend the majority of their time focusing on dynamics, followed by

melody, timbre, and rhythm, respectively. Blocher (1990), however, found no significant

differences in the ability of musicians and non-musicians to attend to errors in

articulation, rhythm, phrasing, intonation, dynamics or note accuracy. Geringer and

Madsen (1995), in a study where the subjects were asked to note the prominence of

musical elements after they listened to a musical excerpt, found that musicians and non-

musicians had different listening patterns. Musicians listed timbre more frequently than

non-musicians did. A study by Wolpert (2000) showed that non-musicians did not hear

the difference in key or dissonance as well as musicians did. In that study, musicians

heard the difference in key 100% of the time whereas non-musicians heard it only 40% of

the time. Deutsch (1982) suggests that in recognizing a segment of music, we employ

global as well as specific cues, such as overall pitch range and distribution of interval

sizes, among others, so that melodies can be identified by their specific cues as a whole.

Earlier research results by Madsen (1987) and, Madsen and Wolf, (1979) suggest that

people attend to whatever they believe they should be attending to. This implies that non-

musicians can be directed to listen for specific ideas in sound.

Another consideration is the manner in which adults learn. The adult learner has

specific needs and expectations which differ greatly from elementary and secondary

school students. Lindeman introduced the pragmatic nature of adult learning in 1926

when he wrote that the approach to adult education should be focused on the situation

rather than the subject. Tough (1979) found that many adults start a learning project

because they anticipate using knowledge in a concrete way, strong motivation to gain and

retain knowledge that will produce some lasting change. Similarly, Scheckley (1983)

18

found that immediate knowledge was the reason most adults begin learning projects.

Literature on adult teaching strategies suggests the development of short, intensive

learning experiences with direct applications to the adult students’ lives (Wratcher and

Jones, 1988; Pomerance, 1991). Thus, lessons for adults should be interactive, well

managed with regard to time, and most of all, practical with regard to future use. This

would suggest that the present study should attend to adult’s learning needs. The lessons

should be relevant, intensive, and short in nature.

Motivation for Listening

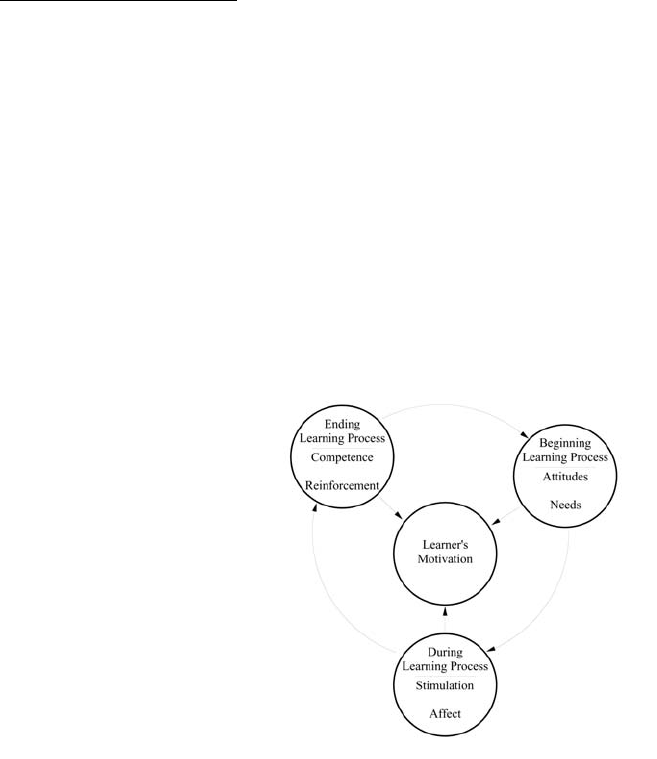

Wlodkoski’s (1985) Time Continuum Model of Motivation focuses on the

internal motivation of adults. Wlodkowski defines this as “a condition expressed by the

individual as an internal force that leads the person to move in the direction of the goal”

(p. 17). He believes that the motivation to learn is internal and depends on the students’

needs and expectations at a given time in the learning process. This model has been

applied successfully in research by Mullee (1996) and would serve well as a basis for the

present study.

Figure 2.3 Wlodkoski’s Time Continuum Model for Motivation

19

The model consists of three time frames in the learning process: beginning, duration and

end. For each time frame there are two major factors of motivation present. The

beginning motivation is mostly effected by the learners’ attitudes towards the general

learning environment, instructor subject matter, self, and the basic needs of the learner at

the onset of learning. During the learning process, motivation is influenced by the

stimulation and interest of the learner and the affective experience that learning provides.

At the end, the learner is able to apply new skills and become aware of new knowledge,

thereby feeling competent.

At the beginning of the process, the instructor needs to create a positive,

comfortable learning atmosphere to establish positive learner attitudes. Wodolkski goes

on to write that the beginning time frame is a critical period in determining the way

learners respond to and feel about what they are experiencing. At the same time that

attitude is being established and supported, the instructor should also attempt to maintain

learner attention and build learner interests. To insure a positive affective experience and

emotional climate, learners need from the instructor encouragement and assistance that

integrate their emotions within the learning process, methods and strategies that

emphasizes cooperation and maximize learner involvement, and sharing that contributes

to a supportive environment. Finally, the instructor should acknowledge the positive

changes that learning has produced and affirm and continue motivation for application

and future learning.

20

Part Two

On Visual Stimuli

Visual Stimuli and Instruction

Research in learning style shows that individuals utilize different types of stimuli,

auditory, visual, tactile and kinesthetic, to enhance learning. One of those stimuli is

visual, or using the sense of sight. Visual learning represents a particular form of human

achievement, one that includes the ability to notice what is visually subtle and use it in

ways that are personally meaningful (Eisner, E. 1998). Eisner also goes on to state that

visual learning pertains not only to our capacity to construe meaning from the visual

forms around us but to our capacity to create connections of visual stimuli with other

forms of stimuli including auditory stimuli. Apart from listening to auditory stimuli, in

the form of lecture and verbal instruction, visual stimuli are used extensively in

instruction in the form of charts, pictures, diagrams and video imaging. The visual

stimulus is then processed into a meaningful representation for the individual enhancing

what he or she is learning. Research indicates that the amount of information that can

be processed using both auditory and visual channels may be considerably larger than

information processed using a single channel (Kalyuga, Chandler, and Sweller, 2000).

Studies, including those by Anglin (1986), Ritchey (1982) and Yang & Weidman (1993),

demonstrate that visual learning can positively affect cognitive processes such as recall

and problem solving. The appropriate use of visuals can enhance recall and

understanding of material, increase motivation, and promote critical thinking (Blatnik,

1998; Levie and Lentz, 1982; Levie 1987; and Peeck 1987). The manner in which

information is presented visually can make a significant difference, especially for

students who have difficulty in one or more perception areas (Dickey, J.P. & Hendricks,

R.C 1991). It is noteworthy that the visual does not have to directly explain a concept in

order to provide a link for the memory process. In Imagery and Related Mnemonic

Devices by McDaniel and Pressley (1987), the authors point out numerous examples of

how visual stimuli do not have to be a complete one-to-one relationship with the

particular concept or event to be effective in creating a memory link.

21

Since the use of visual stimuli can affect memory and thus learning, the use of

visual stimuli should be made to enhance the music learning as well. The use of visual-

spatial stimuli to reinforce auditory discrimination has been incorporated in some popular

approaches to music teaching such as the Orff or Kodaly approaches. These approaches

make use of graphic representation of sound prior to learning musical notation and they

meet with strong endorsements from theorists and practitioners alike (Boardman, E.,

2001; Boardman & Andress, B., 1981, and Nye R.E. & Nye V.T., 1977). In fact,

research has been conducted using visual stimuli and music to indicate positive

relationships. Results of a study by Forsythe, J.C. & Kelly, M.M. (1989) suggest that the

use of visual cues paired with melodies is an effective aid to aural discrimination among

fourth grade subjects. In this study, 30 brief melodies were paired with visual cues in the

form of hand cues. There was a significant difference in identifying melodies between

those students who received visual cues and those students who did not. Other studies

have also shown positive results pairing visual and aural modalities. Olson (1978, 1981)

conducted several studies concerned with the perception of melodic contour in visual and

aural modes. Subjects were asked to determine whether visual and aural stimuli

presented matched and although research proved not to be significant it did suggest that

aural and visual stimuli could be paired temporally. Hair (1993) showed that children

were able to articulate descriptions of music when they were allowed to use drawn

representations or symbols and icons. Hair (1995) also showed that color was effective

when asking both adults and children to associate color to mood and a musical

composition.

While visual art is expressed in space and music is expressed through time, and

each is unique as an art form, music and art do have common linkage. Both evoke

human feelings and both rely on the concept of unity and contrast for expression.

Specifically, it is the structure that makes it possible to correlate art and musical stimuli.

Goldberg, and Schrack, (1986) stated that the correlation of musical and visual structures

is a theoretical discipline to be worked out creatively, similar to counterpoint or common

practice harmony. It involves studying the basic concepts common to both visual and

musical arts such as line, texture, rhythm and color and analyzing works of artists like

Kupka, Kandinsky and Klee who have developed ideas of correlation. Limbert and

22

Polzella (1998) showed that listening to matching music while viewing paintings

apparently intensified the listening experience. Haack (1970) showed that the use of

visual exemplars was found to enhance the development of the desired musical concepts

significantly and to bring about a definite improvement in related art viewing skills.

Stravinsky and Scriabin possessed skills of color hearing and their compositions express

richness in timbre. Scriabin assigned each pitch a direct color through chordal

complexities and according to some sources, he deduced the full cycle from his

spontaneous recognition of C=red, D=yellow and F#= Blue (Shaw-Miller, 2002).

Composers are not the only artistic individuals to have chromosthesis. It is documented

that Kandinsky also had this trait and painted to express colors in sound (Maur, 1999).

Not only did Kandinsky have chromosthesis but he related art to music in a direct way.

He wrote, “Color is the keyboard, the eye is the hammer, the soul the piano. The artist is

the hand that purposefully sets the vibrating by means of this or that key” (Lindsay &

Vergo, 1982).

Studies using music to enhance art skills have also been conducted. Limbert M.

and Polzella (1998) clearly showed that the music affects the artistically naive listeners

while viewing representational and abstract paintings in their perceptions of the paintings.

All of the above information gives validity to using visual stimuli in music instruction.

This research attempts to study the effects of paintings on a subject’s ability to listen and

recall musical elements.

Historical Connection Between Visual Art and Music

Music and art have been intertwined and compared since early times. In the early

17

th

century, in his Critical Reflections on Poetry and Painting (1715), the Abbe Dubos

claimed that “Just as paintings represent the forms and colors of nature, so does music

represent the tones, the accents, the sighs, the modulations of the voice, in short all of the

sounds through which nature itself expresses the feelings and passions…”. Another early

analogy between painting and music appeared in 1762 in Giovanni Berllori’s Lives of

Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Describing Lanfranco’s ceiling decoration at

St. Andrea dell Valle in Rome, Bellori wrote, “ This painting has been rightly compared

to full-bodied music, in which all the tones come together to form a harmony.” In 1849,

23

Thomas Purdie published a book entitled Form and Sound: Can their beauty be

dependent on the same physical laws? Purdie sought to demonstrate that visual artistic

beauty was universally based on mathematical ratios, manifested in music as the

harmonic rations of vibrating strings (Scheuller, H. M. 1953). From this comparison and

relationship, composers and painters alike have been influenced and created art based on

the other art form. Sometimes the connections can be loose and vague, other times more

intertwined.

Visual artists in the 1800’s explored expressing specific musical elements or

musical form. By the end of the nineteenth century, music and art were trading key ideas

back and forth. In 1853, John Ruskin stated, “We are to remember that the arrangement

of colors and lines is an art analogous to the composition of music.” (Kagan, 1986). A

prime instance is Claude Debussy’s seemingly impressionistic technique of “stippled

notes”. His suppression of the principle musical development through time in favor of

juxtaposed fields of contrasting tone color was also used in visual arts of the same time

period. By the 1890’s, musical elements in paintings often went hand in hand with an

allegorical symbolism. In Gustav Klimt’s Music, a sphinx stands for the infallible nature

of music (Maur, K. 1999). Klimt also translated the hymn from Beethoven’s 9

th

Symphony “Fruede Schoner Gotterfunken Diesen Kuss der gazen Welt” into visual

allegory (Willsdon, 1996). Another example of allegory and imagery used to cross the

visual and the music world is the work of Mendelssohn. Mendelsshon used visual

imagery to express his music, including Hebrides and his Symphony Number 2, the

Italian (Grey, T. 1997).

In addition to allegorical and imagery representation, composers and painters

alike have frequently gleaned ideas from or borrowed from procedures in sibling arts.

The reciprocal relationship runs like a thread throughout the 19

th

and 20

th

century. Using

similar symbolic information is one example of this. Leitmotif has the status of symbol,

which is often subjected to patternization, variation, development or metamorphoses.

With the concept of patterns as a basis, it is possible to employ a visual pattern that is

symbolic of meaning that works in the same manner as the leitmotif (Goldberg &

Schrack, 1986). The romantics envisaged breaking down the barriers between the

various genres to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total, comprehensive, or what today would

24

be termed a multimedia or interdisciplinary work of art. In this, music was granted a

leading role (Maur, K. 1999). Phillip Otto Runge saw in music the common primordial

source of all the arts and a guarantor of beauty. He discovered the possibility of a

figurative painting, his Lesson of the Nightingale, on the basis of the fugal principle of

imitation.

Art in Music Education

Art is found in education, both within and outside the music classroom. Outside

the music classroom art has been used in courses such as English and History. Erickson

(1995) found that students in history classes were able to incorporate knowledge of

individual artists and develop a historical perspective as they looked at artworks. In each

of these examples, art is used to enhance the learning in other disciplines either as

allegorical, symbolic or direct representation. As in music, art is used in history texts to

reinforce time periods as well as to depict historical scenes and events.

Music educators often advocate a multi-sensory approach to learning,

particularly as a way of accommodating individual differences among learners. Using

multi-sensory approach brings excitement in learning of all subjects for both teachers as

well as students (Wang & Sogin, 1998,1998,1991). Music curriculum text books use art

to reinforce musical elements, addressing the needs of visual learners. Examples of

integration of art in music lessons are found in the most recent and popular texts

including Making Music (2002), Share the Music (1995) and Music Connection (1995).

In all three of these text series, art works are used to reinforce music concepts including

timbre, theme and variation, and musical imagery. At the secondary and collegiate level,

music history texts such as History of Western Music by K M. Stolba use art works to

emphasize historical period and to reinforce the relationship between the art and music of

a given time period.

Application of Gestalt Principles in Art and Music

Gestalt theory is a broadly interdisciplinary general theory which provides a

framework for a wide variety of psychological phenomena, processes, and applications.

Human beings are viewed as open systems in active interaction with their environment.

25

It is especially suited for the understanding of order and structure in psychological events

and has its origins in some orientations of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Ernst Mach, and

particularly of Christian von Ehrenfels and the research work of Max Wertheimer,

Wolfgang Köhler, Kurt Koffka, and Kurt Lewin (Gordon 1989). According to Keith

Swanick, Gestalt psychology is “the organization of sensory information into meaningful

wholes based on prior experience” (1988). The sensory information is then grouped by

one of four ways: Proximity, Similarity, Common Direction or Simplicity. These four

make up the following four laws: 1.) The law of proximity: Elements are grouped

according to nearness in space or time; 2.) The law of similarity: Objects or events are

grouped with “same” attributes, such as timbre, color or shape; 3.) The law of common

direction: Elements are grouped according to their extrapolated completion; 4.) The law

of simplicity: Information is grouped with a preference for smoothness, symmetry and

regularity (Radocy, R & Boyle, J., 1988). The principles of Gestalt provide the basis for

learners to discover the underlying nature of a topic or problem (i.e., the relationship

among the elements). Gaps, incongruities or disturbances are an important stimulus for

learning and instruction should be based upon the laws of organization: proximity,

closure, similarity and simplicity.

These four laws and principles of Gestalt are often applied in the visual realm or

to separate theories of visual perception. The visual realm in and out of art has relied on

the principles of Gestalt to support its work. Visual perception is the bedrock on which

many ideas inevitably build their foundation (Kepes, G. 1965). The use of imagery and

visual thinking processes are primary ways of exploring, expressing and communicating

the known and imagined properties of a system, theory or general phenomenon

(Arnheim, 1954, 1974). Visual ways of thinking and learning move across, between and

through disciplinary commitments. This connection through vision creates a kind of

convergence that defines contemporary views of interdisciplinary areas. Vision is a

natural connecting force that can reestablish relationships that have been obscured by

arbitrary divisions (Klein, 1990). The Gestalt principles of similarity, continuity,

proximity and closure are the primary factors and forces that create and emphasize visual

units, groupings and organized wholes within a given perceptual setting. The degree of

visual order or disorder perceived within a setting is dependent to a large degree on the

26

recognition, interpretation and communication of these unifying principles (Wenger,

1997). Gestalt is part of a language of vision present in the simplest forms of mark

making as well as the complex configurations found in a work of art. In art, a unified

entity or whole can be a singular composition or individual graphic elements that make

up the totality of a creative work.

Since both art and music can be analyzed by studying the underlying structure, the

Gestalt principles can be applied to both visual and auditory stimuli. Musicians have not

researched extensively the use of the principles of Gestalt with auditory stimuli, however

some studies do exist. As early as 1890, Ehrenfels introduced the concept of

Gestaltqualitat. This concept was explained using a musical example. “When we hear a

tune, the experience of the tune itself (the gestaltqualitat) is something more than the

aggregate of the notes. It is not reducible to individual notes and is not an adding

together of simple sensations. For example, the last three notes of ‘God Save the Queen’

are the same as the first three notes of ‘Three Blind Mice’.” (Gordon, 1989, p.55). Even

Leonard Meyer, who subscribes to the theory of an emotional response to music, argues

that the work of Gestalt Psychologists has shown beyond a doubt that understanding is

not a matter of perceiving single stimuli, or simple sound combinations in isolation, but is

rather a matter of grouping stimuli into patterns and relating these patterns to one another.

(1956, p. 6). Meyer goes on to explain that the mind in its selection and organization of

discrete stimuli into figures and groupings appears to obey certain general laws, including

the Law of Good Continuation. He points out that the general laws that the mind follows

to group items operates within a socio-cultural context. It can be inferred from this that

listeners use this Gestalt Law to listen to music that has characteristics that are

identifiable within a particular socio-cultural context. This would help to support why

people listen for the familiar before moving on to the unfamiliar.

In support of Contour, Dowling (1994) explains the role of Gestalt Principles in

contour. He states that a melody is very much an integrated whole, a Gestalt. He points

out that the tonal context affects memory for contour and that contour interacts with both

tonality and rhythm in perception and memory. In his Auditory Scene Analysis,

Bregman (1990) describes a range of perceptual processes that enable us to construct an

auditory picture of the environment and form sensory data much the way Dowling

27

suggests the listener deals with contour. Bregman identified two types of processes: a.)

primitive, automatic process and b.) Schema driven or learnt processes. The cues used

by the primitive processes to group sound events together to construct patterns are akin to

the Gestalt Laws of grouping. It has been shown that Gestalt Laws operate in the

perception of visual arrays and it can be said that it is true in of music also. In the case of

vision, elements that are close together in space are more likely to belong to the same

objects than are elements that are spaced further apart.

The same line of reasoning holds for elements that are similar rather than those

that are dissimilar (Deutsch, D. 1999). In the case of hearing, similar sounds are likely to

have originated from a common source and dissimilar sounds from different sources. A

sequence that changes smoothly in frequency is likely to have originated from a single

source, whereas an abrupt frequency transition may reflect the presence of a new source.

Components of a complex spectrum that arise in synchrony are likely to have emanated

from the same source, and the sudden addition of a new component may signal the

emergence of a new source (Deutsch, D. 1999 pp. 300-301). A sequence of musical

tones tends to be heard as groupings of organized metrical, rhythmic, melodic and

harmonic units. Smaller units are joined together to form larger units in an embedded,

hierarchical fashion. The tones are then grouped together according to function, and

other attributes. These groupings are then perceived as similar based on such things as

similarity in frequency, spatial location, or having temporally synchronous onsets or

offsets (Krumhansl, C. 1990). Royal and Fiske (2000) took these identified processes

and their relationship to Gestalt and suggested grouping boundaries along various

dimensions of sound based on the four Gestalt Laws. They suggest that boundaries

between groups are likely to be apparent where these laws are broken. Royal and Fiske

suggest that for each Gestalt Principle the musical concepts of pitch, time, timbre

loudness and space have a relationship. Pitch and proximity are apparent when there is a

change in register. Time has a relationship in similarity when there is a change in

articulation. The example in the table below uses pitch, time and duration, timbre,

loudness, and space to illustrate the boundaries and their association with each of the

gestalt laws.

28

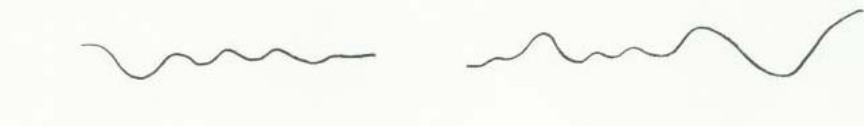

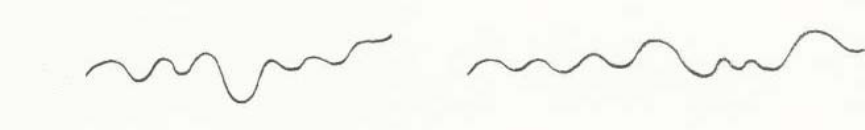

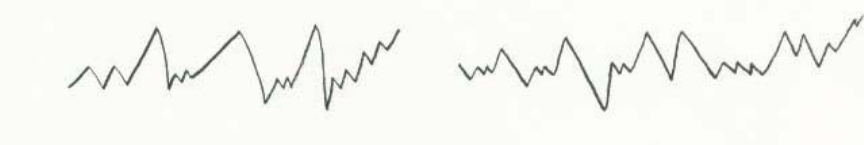

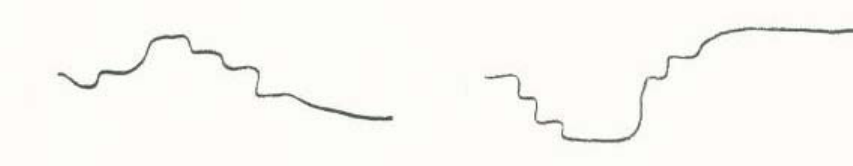

Figure 2.4 Music and Association with Gestalt Laws.

Grouping boundaries along various dimensions of sound * contrary to:

*Proximity *Similarity *Good Continuation *Common Fate

Pitch change in register change in melodic contrary or

direction oblique

Time rests and long notes articulation change in pulse onsets and

offsets

Timbre change in timbre evolution of evolving

timbre over components

time of timbre

Loudness Changes in loudness unpredictable change differing rates/

and stress in loudness directions of

of loudness

Space spatially separate unpredictable moving in

Sources movement in space different

Directions/

Along diff.

Trajectories in

space

Koniari, Predazzer and Melen ( 2001) suggest that listeners are able to build a mental

representation of a piece but that mental representation does not keep all of the details of

the actual piece; instead listeners pick up and focus on specific cues, or cue abstraction.

(Referred to as cue extraction in Deliege, 1987, 1989; Deliege & El Ahmadi, 1990).

While listening to a piece of music, listeners pick up from the musical surface small

entities that contrast sufficiently to attract listeners’ attention. The cues provide temporal

landmarks: the passages based on a given cue are approximated and localized by the

listener in the course of the musical piece. Listeners are then assumed to be able to

reorder the different segments along a mental line resulting in a mental schema. Neisser

(1976, p. 54) states “A schema… is internal to the perceiver, modifiable by experience

and somehow specific to what is being perceived. The schema accepts information as it

becomes available at sensory surfaces and is changed by that information.” The cues also

29

constitute the basis of a categorization process. This categorization process then relies on

the categories of Gestalt to help listeners place information in a useable, retrievable place

within memory. The abstracted cues are the bases on which different structures of a

piece are compared to each other. All of this would suggest that the law of similarity can

be very effective given that listeners use cue abstraction to obtain musical information. If

students are encouraged to listen for and view examples of similarity during listening

lessons it is suggested that it will help during recall.

Memory and Listening

While the Gestalt Principles enable people’s perceptions of visual and auditory

stimuli, learning takes place only when the new information can be stored as memory in

the brain. The listener does not initially remember exactly what was heard but

remembers certain global features of overall pattern such as contour and key (Dowling,

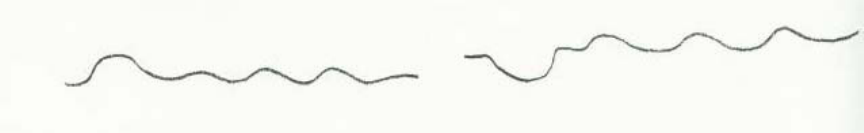

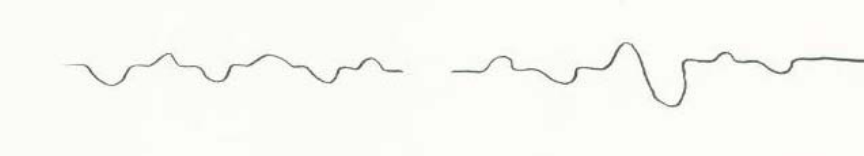

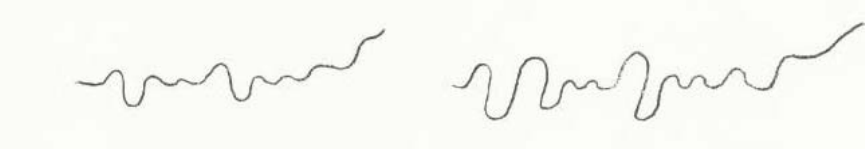

1978; Dowling & Barrlet, 1981; Dewit and Crowder, Dowling Et el, 1995/1998;