■

GENOCIDE

Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction is the most wide-ranging textbook on geno-

cide yet published. The book is designed as a text for upper-undergraduate and

graduate students, as well as a primer for non-specialists and general readers interested

in learning about one of humanity’s enduring blights.

Over the course of sixteen chapters, genocide scholar Adam Jones:

• Provides an introduction to genocide as both a historical phenomenon and an

analytical-legal concept.

• Discusses the role of imperalism, war, and social revolution in fueling genocide.

• Supplies no fewer than seven full-length case studies of genocides worldwide, each

with an accompanying box-text.

• Explores perspectives on genocide from the social sciences, including psychology,

sociology, anthropology, political science/international relations, and gender

studies.

• Considers “The Future of Genocide,” with attention to historical memory and

genocide denial; initiatives for truth, justice, and redress; and strategies of

intervention and prevention.

Written in clear and lively prose, liberally sprinkled with illustrations and personal

testimonies from genocide survivors, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction is

destined to become a core text of the new generation of genocide scholarship. An

accompanying website (www.genocidetext.net) features a broad selection of

supplementary materials, teaching aids, and Internet resources.

Adam Jones, Ph.D. is currently Associate Research Fellow in the Genocide Studies

Program at Yale University. His recent publications include the edited volumes

Gendercide and Genocide (2004) and Genocide, War Crimes and the West: History and

Complicity (2004). He is co-founder and executive director of Gendercide Watch

(www.gendercide.org).

GENOCIDE

A Comprehensive Introduction

Adam Jones

First published 2006

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2006 Adam Jones

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical,

or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including

photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Jones, Adam, 1963–

Genocide : a comprehensive introduction / Adam Jones.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0–415–35384–X (pbk. : alk. paper) – ISBN 0–415–35385–8 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. Genocide. 2. Genocide–Case studies. I. Title.

HV6322.7.J64 2006

304.6’63–dc22

2005030424

ISBN10: 0–415–35385–8 ISBN13: 978–0–415–35385–4 (hbk)

ISBN10: 0–415–35384–X ISBN13: 978–0–415–35384–7 (pbk)

ISBN10: 0–203–34744–7 ISBN13: 978–0–203–34744–7 (ebk)

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006.

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s

collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.”

For Jo and David Jones, givers of life,

and for Dr. Griselda Ramírez Reyes, saver of lives.

So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late.

Bob Dylan, “All Along the Watchtower”

■

CONTENTS

List of illustrations xiii

About the author xv

Introduction xviii

PART 1 OVERVIEW 1

1 The Origins of Genocide 3

Genocide in prehistory, antiquity, and early modernity 3

The Vendée uprising 6

Zulu genocide 7

Naming genocide: Raphael Lemkin 8

Defining genocide: The UN Convention 12

Bounding genocide: Comparative genocide studies 14

Discussion 19

Personal observations 22

Contested cases 23

Atlantic slavery 23

Area bombing and nuclear warfare 24

UN sanctions against Iraq 25

9/11 26

Structural and institutional violence 27

Is genocide ever justified? 28

Suggestions for further study 31

Notes 32

2 Imperialism, War, and Social Revolution 39

Imperialism and colonialism 39

Colonial and imperial genocides 40

Imperial famines 41

The Congo “rubber terror” 42

The Japanese in East and Southeast Asia 44

The US in Indochina 46

vii

The Soviets in Afghanistan 47

A note on genocide and imperial dissolution 48

Genocide and war 48

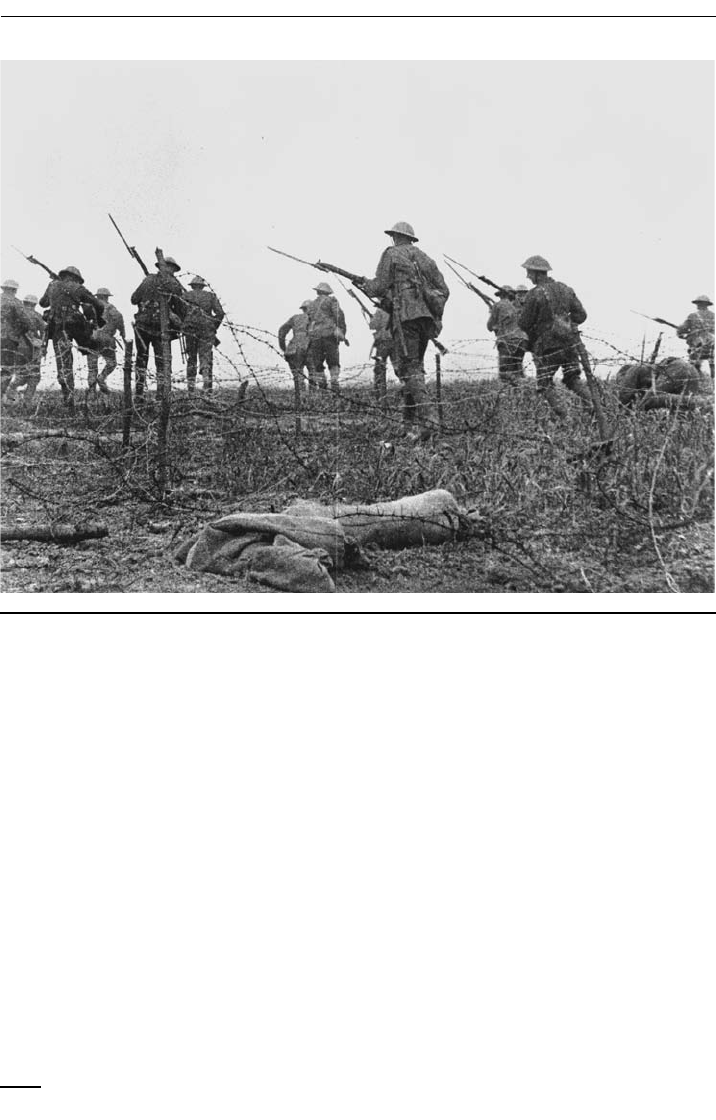

The First World War and the dawn of industrial death 51

The Second World War and the “barbarization of warfare” 53

Genocide and social revolution 55

The nuclear revolution and “omnicide” 56

Suggestions for further study 59

Notes 60

PART 2 CASES 65

3 Genocides of Indigenous Peoples 67

Introduction 67

Colonialism and the discourse of extinction 68

The conquest of the Americas 70

Spanish America 70

The United States and Canada 72

Other genocidal strategies 75

A contemporary case: The Maya of Guatemala 77

Australia’s Aborigines and the Namibian Herero 78

Genocide in Australia 78

The Herero genocide 80

Denying genocide, celebrating genocide 81

Complexities and caveats 83

Indigenous revival 85

Suggestions for further study 87

Notes 89

4 The Armenian Genocide 101

Introduction 101

Origins of the genocide 102

War, massacre, and deportation 105

The course of the Armenian genocide 106

The aftermath 112

The denial 113

Suggestions for further study 115

Notes 116

5 Stalin’s Terror 124

The Bolsheviks seize power 125

Collectivization and famine 127

The Gulag 128

CONTENTS

viii

The Great Purge of 1937–38 129

The war years 131

The destruction of national minorities 134

Stalin and genocide 135

Suggestions for further study 137

Notes 138

6 The Jewish Holocaust 147

Introduction 147

Origins 148

“Ordinary Germans” and the Nazis 150

The turn to mass murder 151

Debating the Holocaust 157

Intentionalists vs. functionalists 157

Jewish resistance 158

The Allies and the churches: Could the Jews have been saved? 159

Willing executioners? 160

Israel and the Jewish Holocaust 161

Is the Jewish Holocaust “uniquely unique”? 162

Suggestions for further study 163

Notes 165

7 Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge 185

Origins of the Khmer Rouge 185

War and revolution, 1970–75 188

A genocidal ideology 190

A policy of “urbicide”, 1975 192

“Base people” vs. “new people” 194

Cambodia’s holocaust, 1975–79 195

Genocide against Buddhists and ethnic minorities 199

Aftermath: Politics and the quest for justice 200

Suggestions for further study 202

Notes 202

8 Bosnia and Kosovo 212

Origins and onset 212

Gendercide and genocide in Bosnia 216

The international dimension 219

Kosovo, 1998–99 220

Aftermaths 222

Suggestions for further study 224

Notes 224

CONTENTS

ix

9 Holocaust in Rwanda 232

Introduction: Horror and shame 232

Background to genocide 233

Genocidal frenzy 238

Aftermath 245

Suggestions for further study 246

Notes 247

PART 3 SOCIAL SCIENCE PERSPECTIVES 259

10 Psychological Perspectives 261

Narcissism, greed, and fear 262

Narcissism 262

Greed 264

Fear 265

Genocide and humiliation 268

The psychology of perpetrators 270

The Zimbardo experiments 274

The psychology of rescuers 275

Suggestions for further study 281

Notes 282

11 The Sociology and Anthropology of Genocide 288

Introduction 288

Sociological perspectives 289

The sociology of modernity 289

Ethnicity and ethnic conflict 291

Ethnic conflict and violence “specialists” 293

“Middleman minorities” 294

Anthropological perspectives 296

Suggestions for further study 301

Notes 302

12 Political Science and International Relations 307

Empirical investigations 307

The changing face of war 311

Democracy, war, and genocide/democide 314

Norms and prohibition regimes 316

Suggestions for further study 320

Notes 321

CONTENTS

x

13 Gendering Genocide 325

Gendercide vs. root-and-branch genocide 326

Women and genocide 329

Gendercidal institutions 330

Genocide and violence against homosexuals 331

Are men more genocidal than women? 332

A note on gendered propaganda 334

Suggestions for further study 336

Notes 337

PART 4 THE FUTURE OF GENOCIDE 343

14 Memory, Forgetting, and Denial 345

The struggle over historical memory 345

Germany and “the search for a usable past” 349

The politics of forgetting 350

Genocide denial: Motives and strategies 351

Denial and free speech 354

Suggestions for further study 358

Notes 358

15 Justice, Truth, and Redress 362

Leipzig, Constantinople, Nuremberg, Tokyo 363

The international criminal tribunals: Yugoslavia and Rwanda 366

Jurisdictional issues 367

The concept of a victim group 367

Gender and genocide 367

National trials 368

The “mixed tribunals”: Cambodia and Sierra Leone 370

Another kind of justice: Rwanda’s gacaca experiment 370

The Pinochet case 371

The International Criminal Court (ICC) 373

International citizens’ tribunals 375

Truth and reconciliation 377

The challenge of redress 379

Suggestions for further study 381

Notes 382

16 Strategies of Intervention and Prevention 388

Warning signs 389

Humanitarian intervention 392

CONTENTS

xi

■

ILLUSTRATIONS

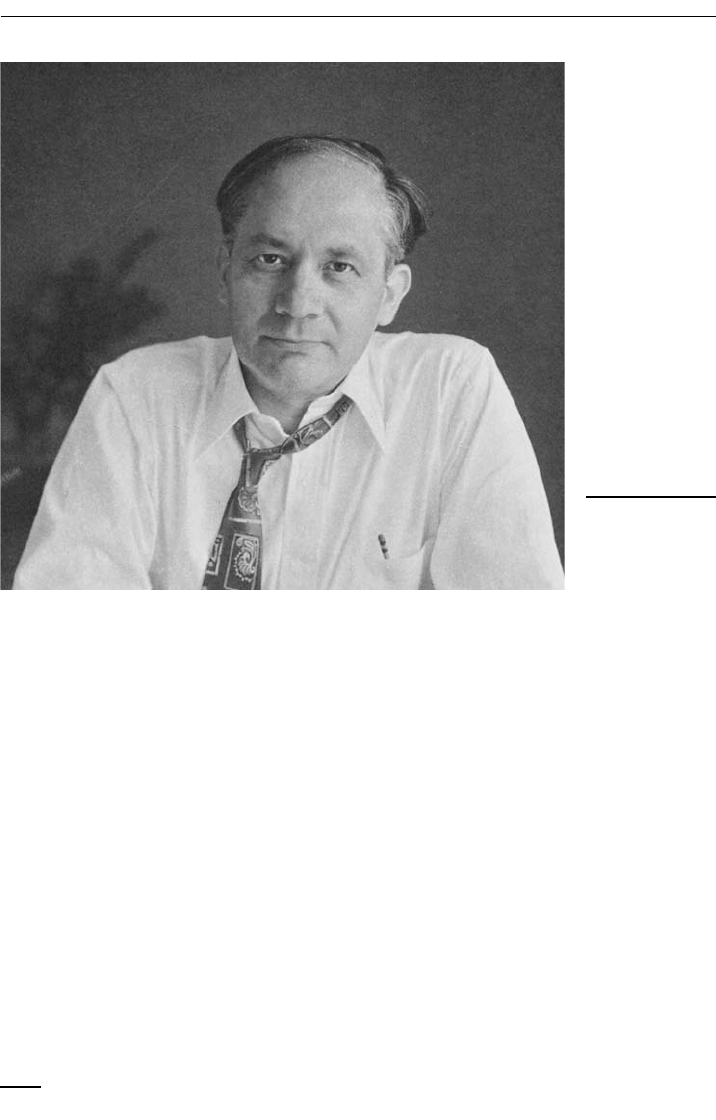

1.1 Raphael Lemkin 10

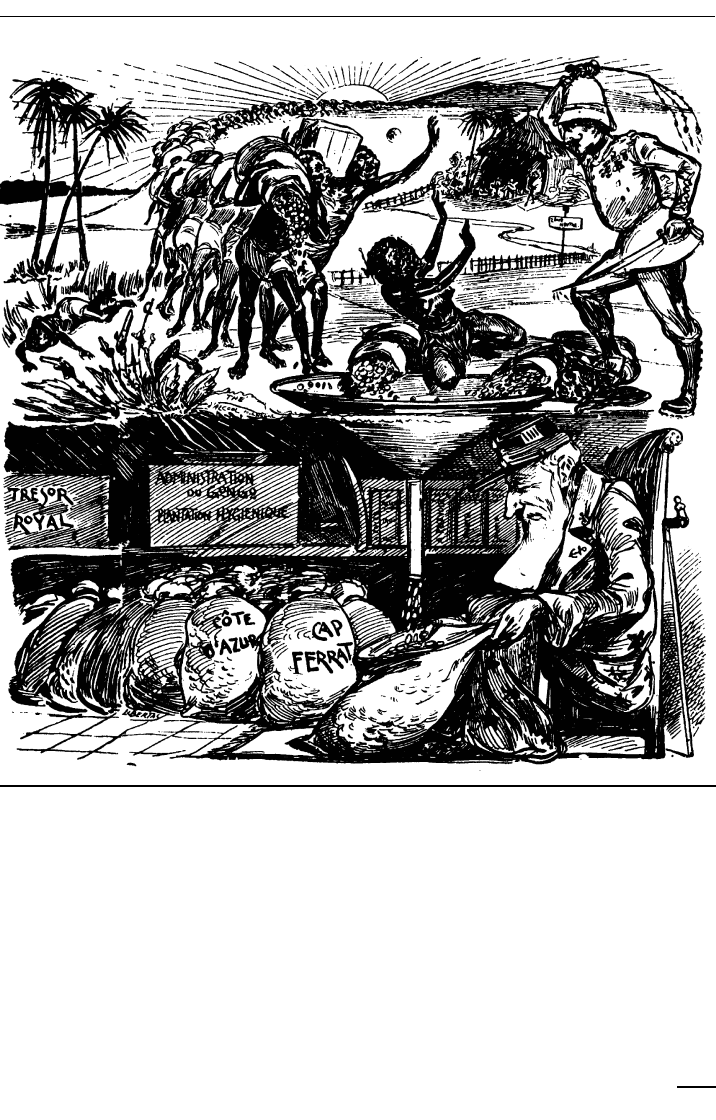

2.1 Imperial genocide: Belgian King Leopold and the Congo 43

2.2 British soldiers go “over the top” at the Battle of the Somme, 1916 52

2.3 Atomic bomb explosion at Nagasaki, 1945 57

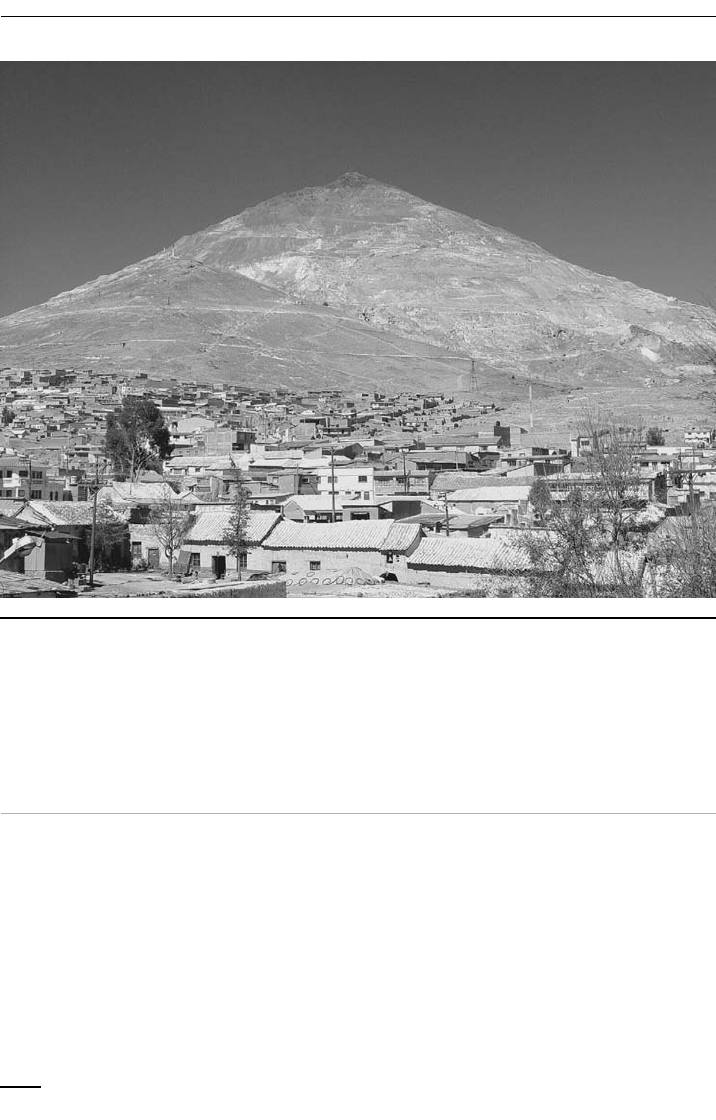

3.1 The Cerro Rico silver-mines in Potosí, Bolivia 72

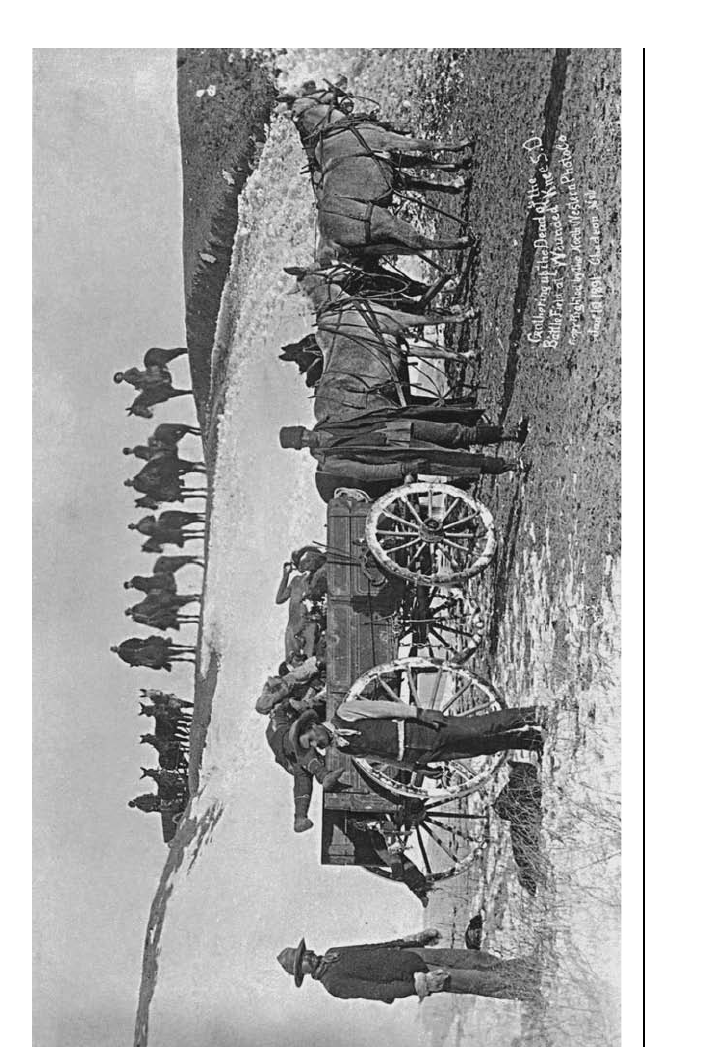

3.2 Loading Indian corpses from the Wounded Knee massacre, 1890 74

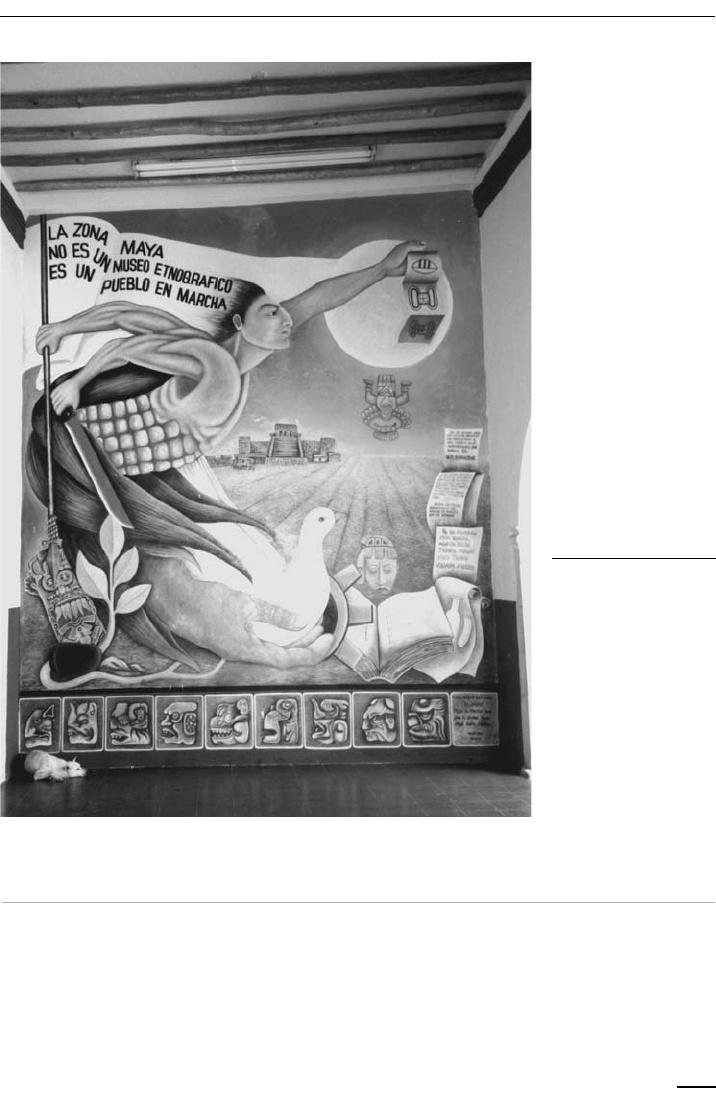

3.3 Mural of indigenous revival in Yucatán, Mexico 87

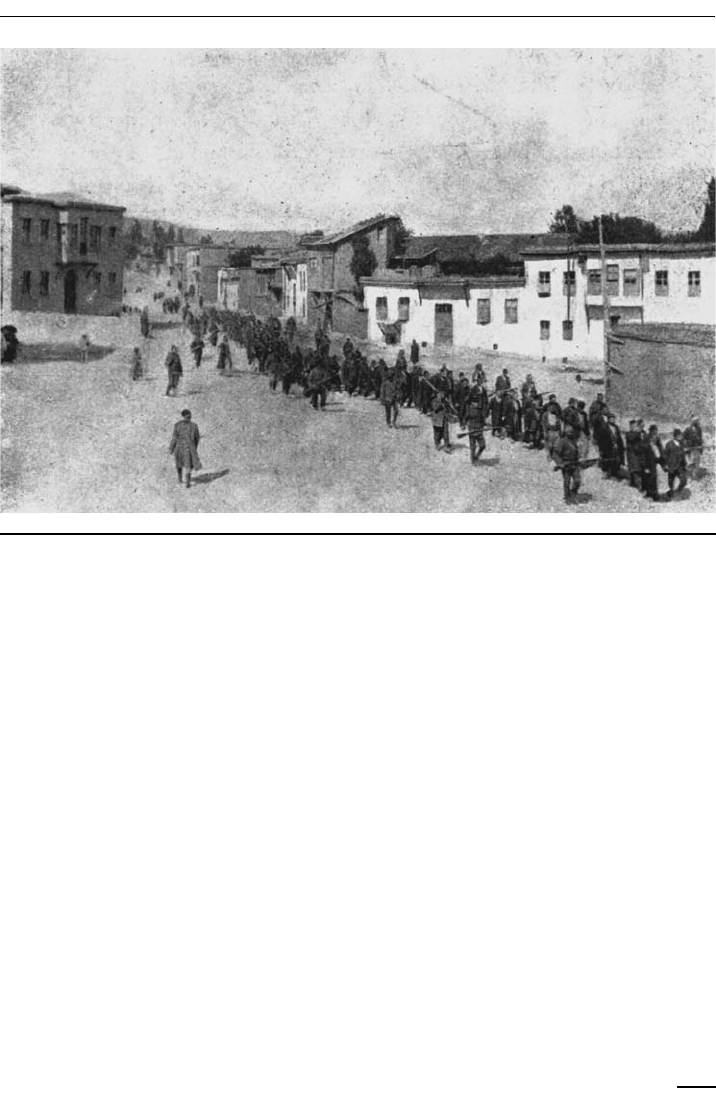

4.1 Armenian men being deported from Harput for mass killing, May 1915 107

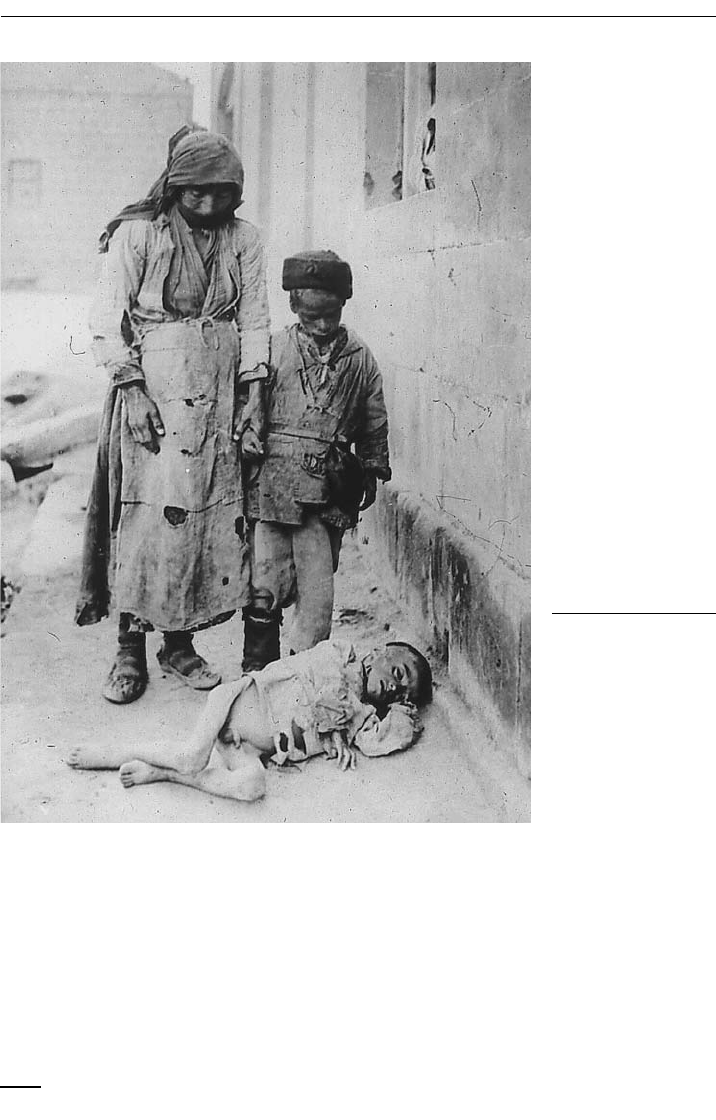

4.2 Armenian refugees, 1915 108

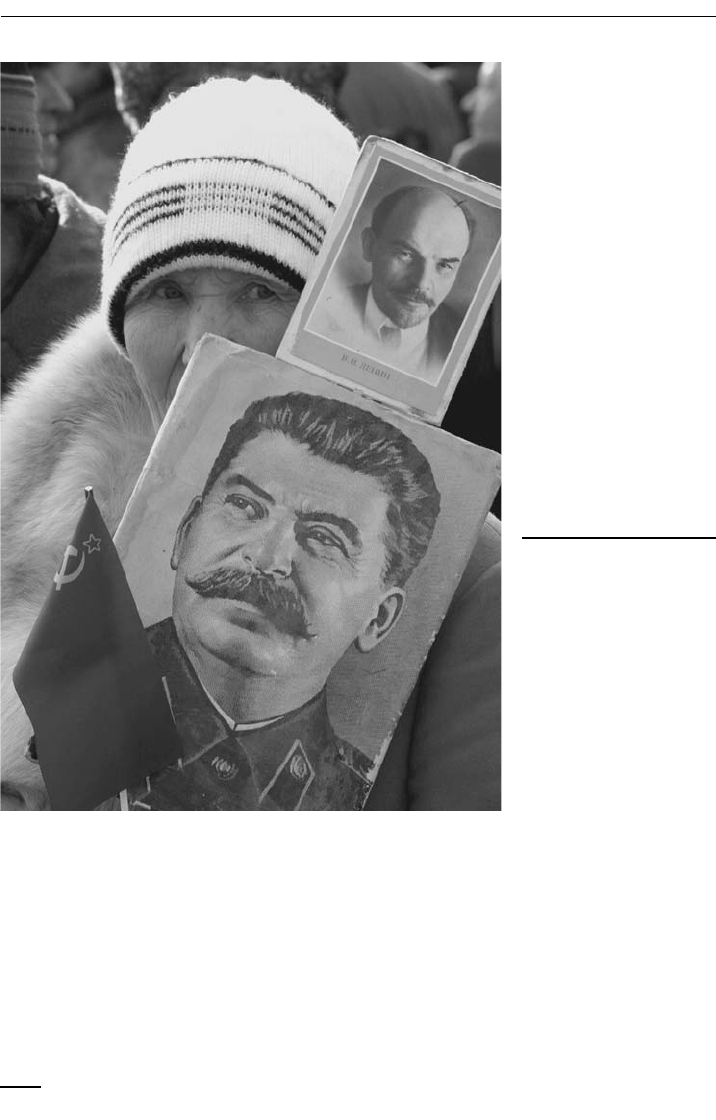

5.1 A supporter of Stalin and Lenin carries their portraits in Red Square 136

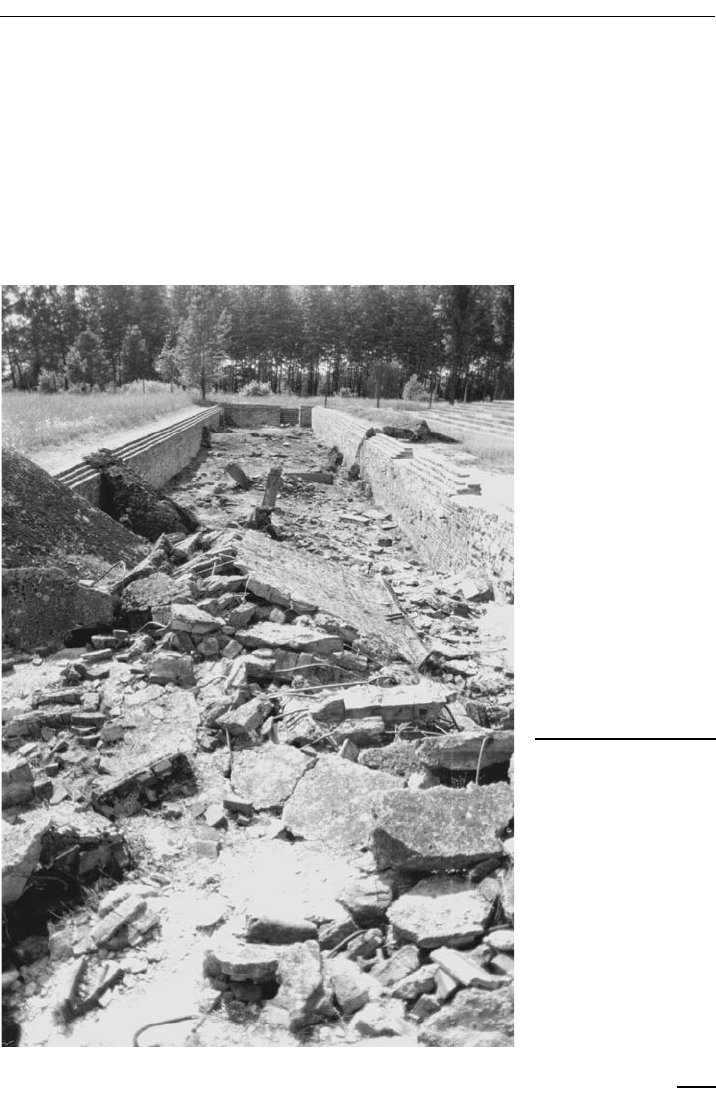

6.1 Ruins of a gas chamber and crematorium complex at Auschwitz-Birkenau 153

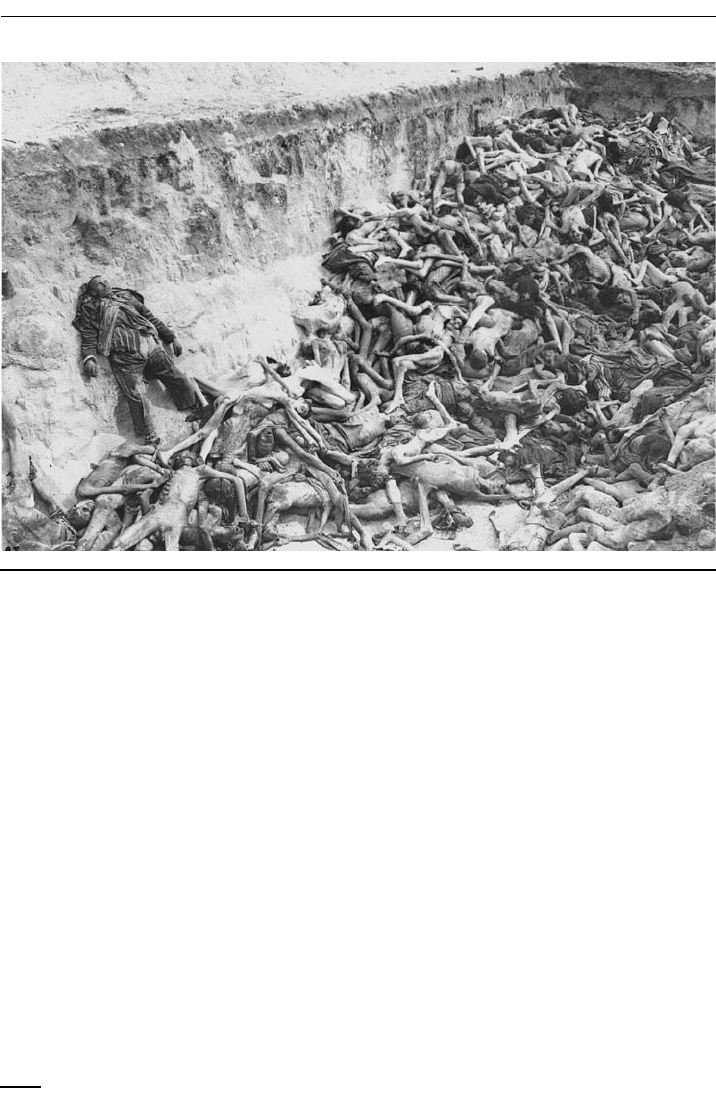

6.2 Mass burial of corpses at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, 1945 154

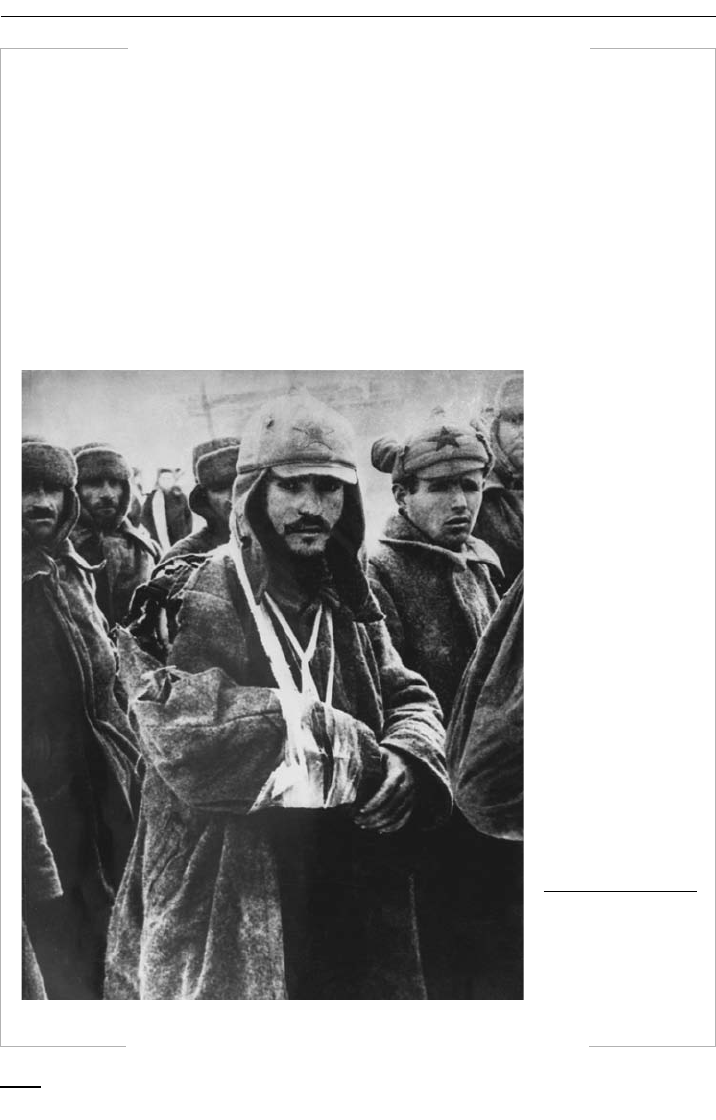

6a.1 A Soviet prisoner-of-war is dispatched “to the rear” 176

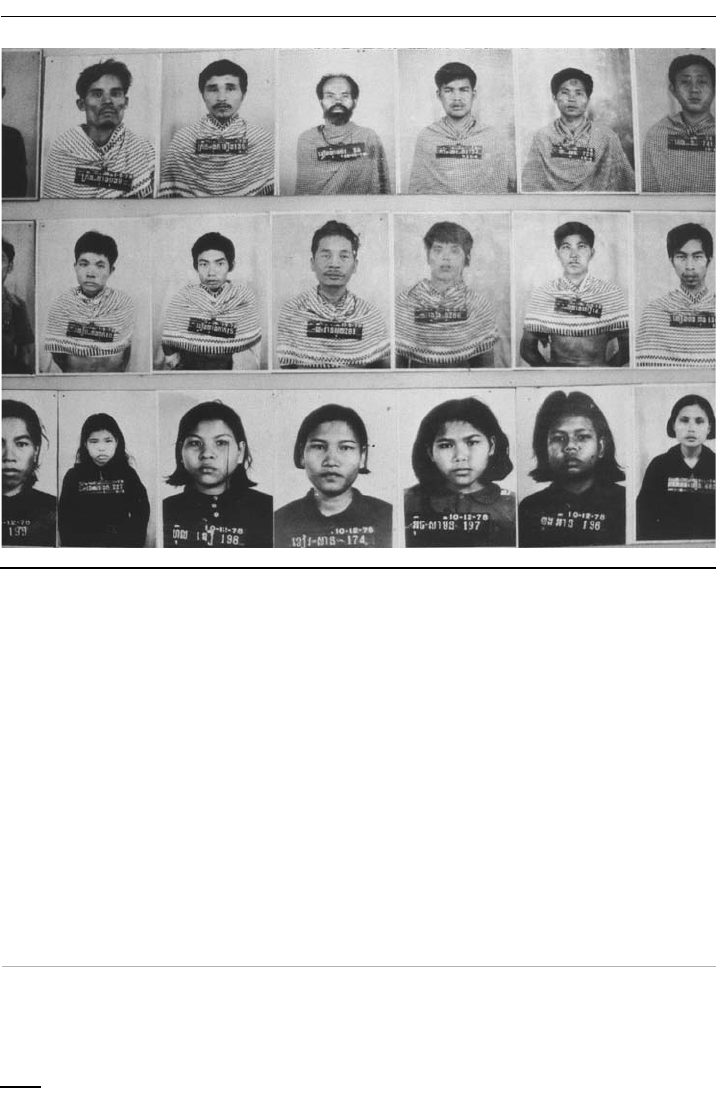

7.1 Photos of Cambodians incarcerated and killed at Tuol Sleng prison, Phnom Penh 200

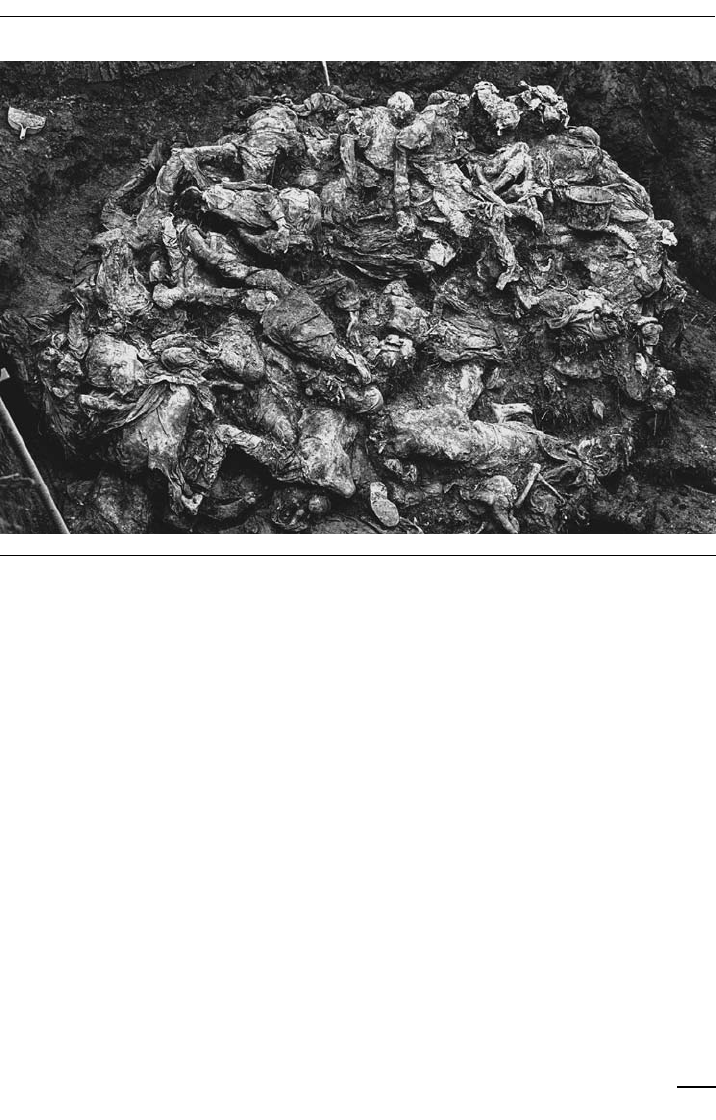

8.1 Mass grave at Pilice, near Srebrenica 217

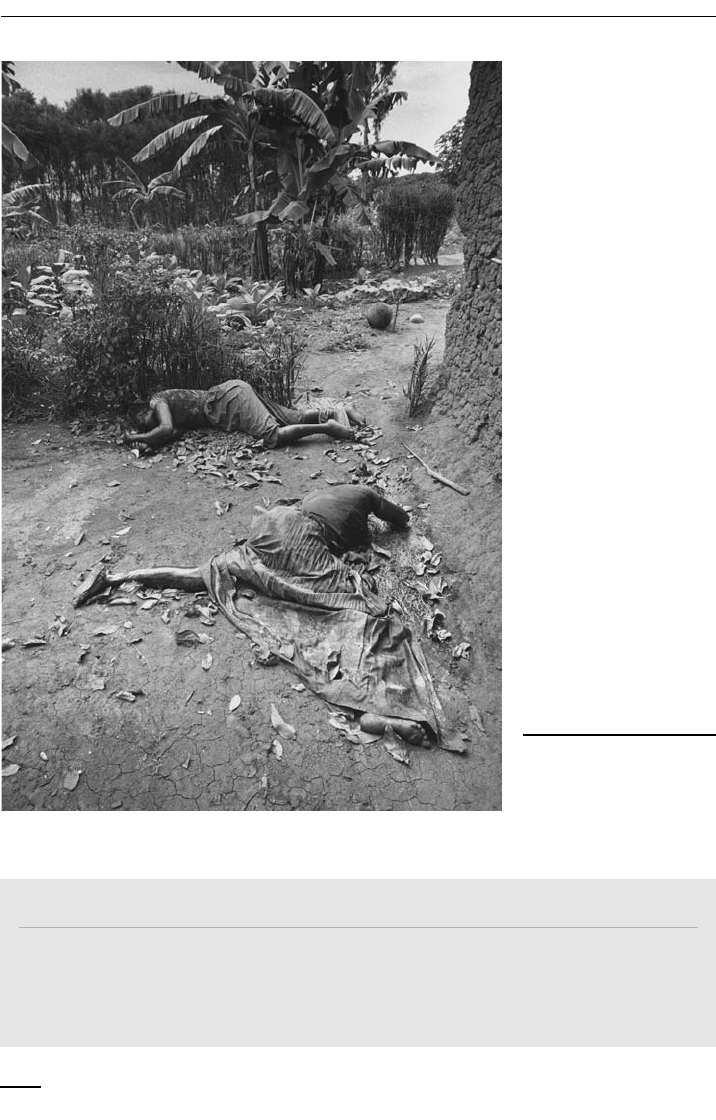

9.1 Tutsi women murdered in the Rwandan genocide of 1994 240

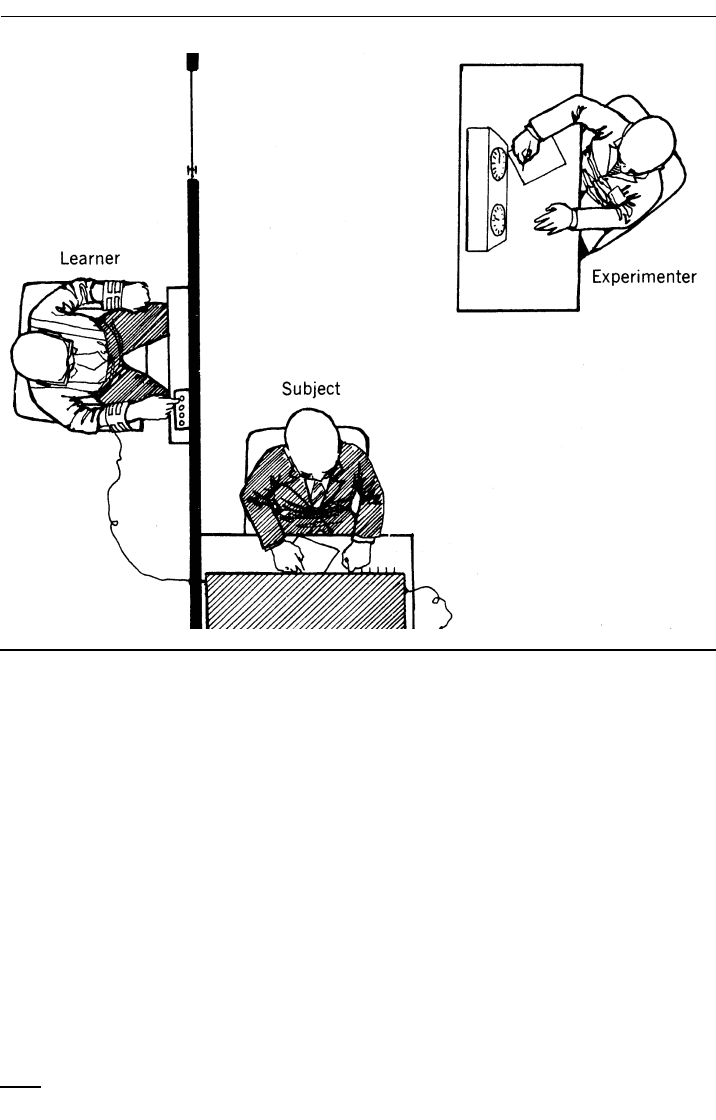

10.1 Core structure of the Milgram experiments 272

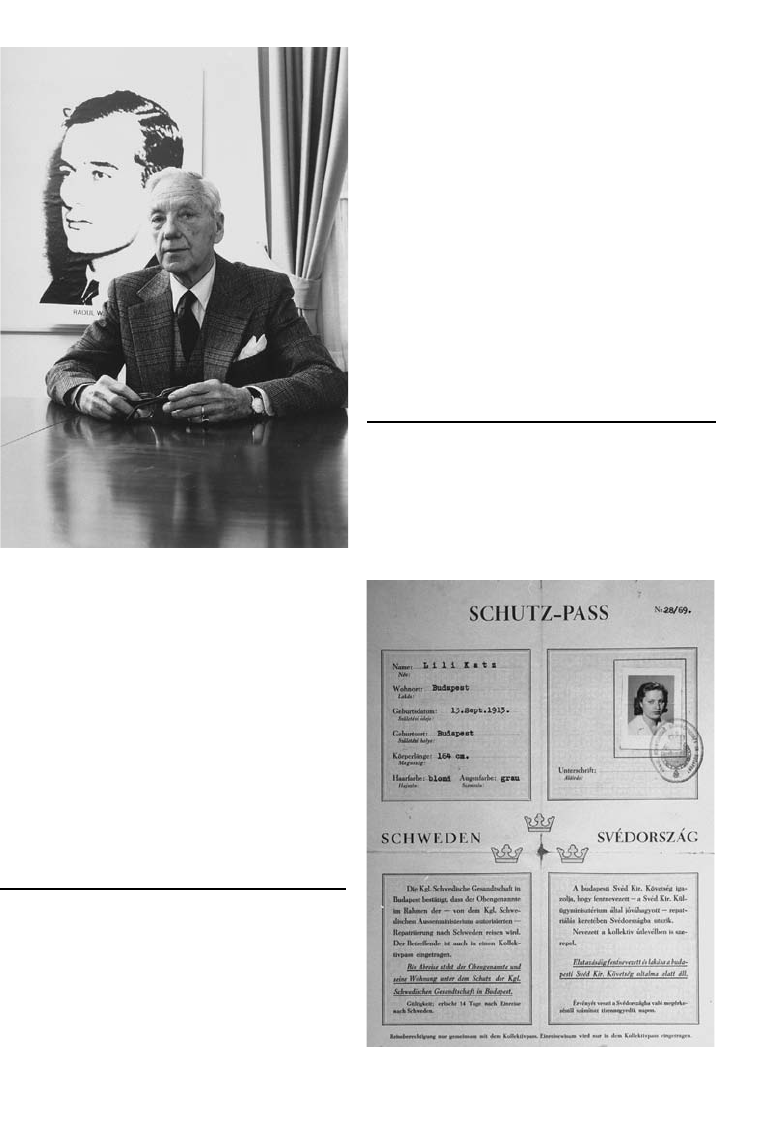

10.2 Per Anger with a portrait of Raoul Wallenberg 277

10.3 Pass issued to Lili Katz by the Swedish legation in Budapest, 1944 277

11.1 Forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow 300

12.1 Political scientist R.J. Rummel 308

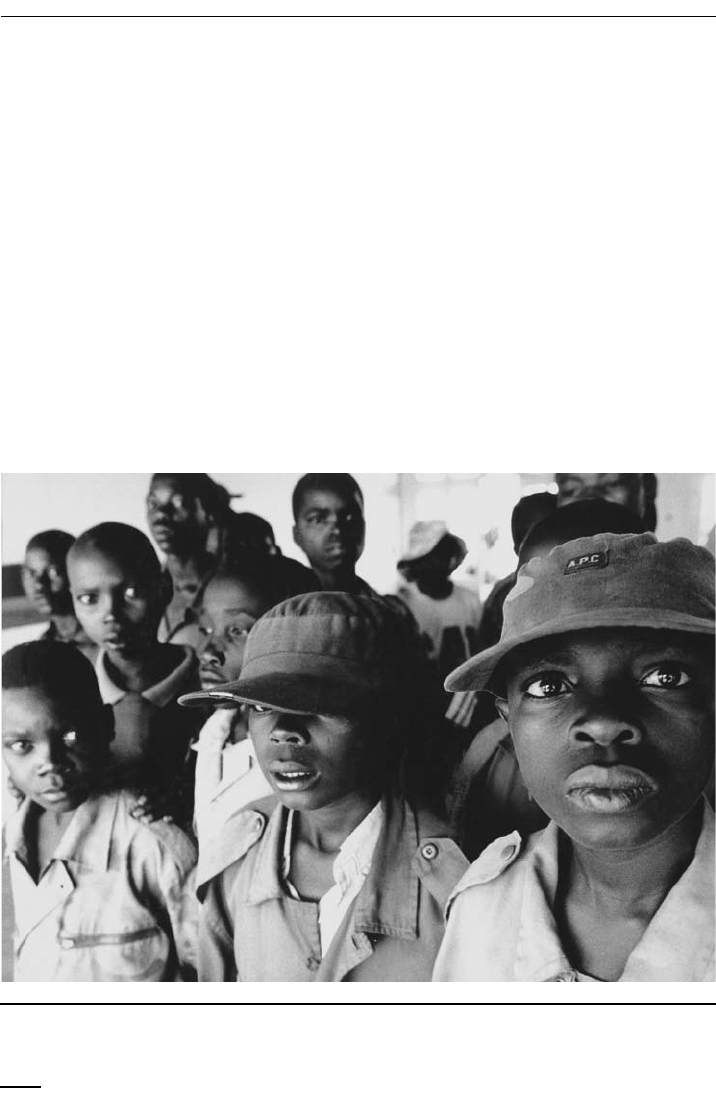

12.2 Demobilized child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2002 312

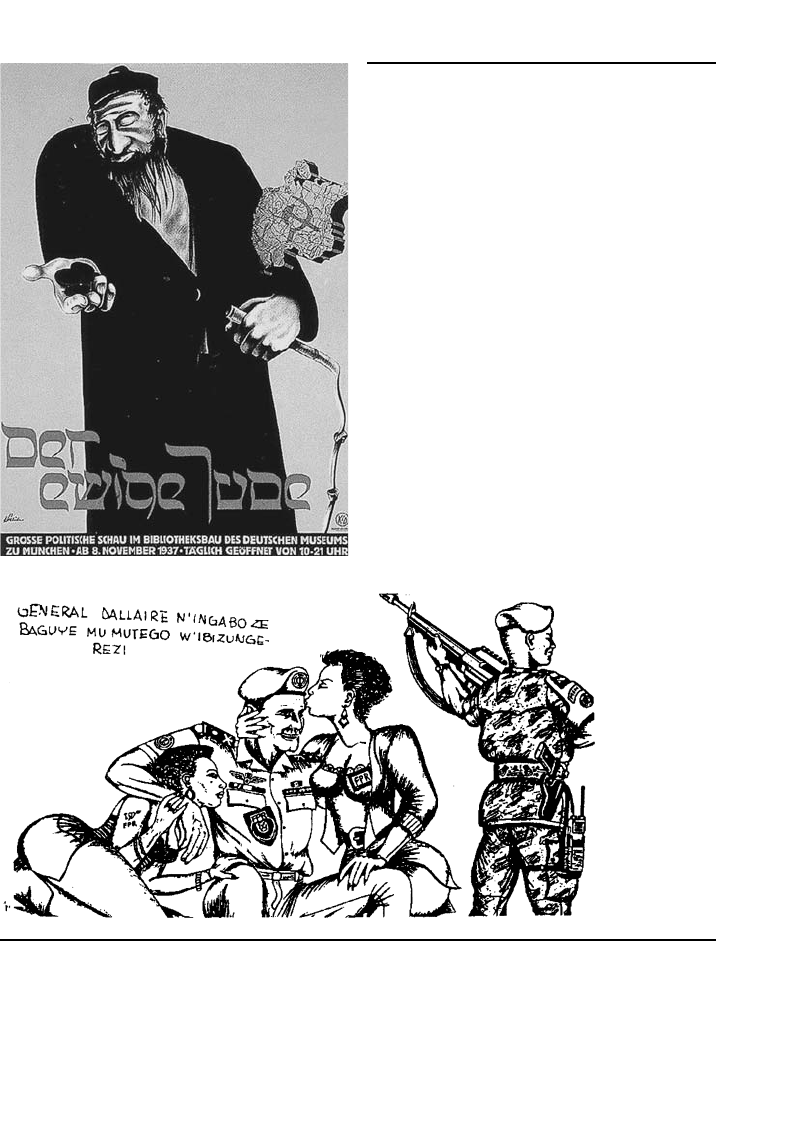

13.1 Nazi propaganda poster vilifying Jewish men 335

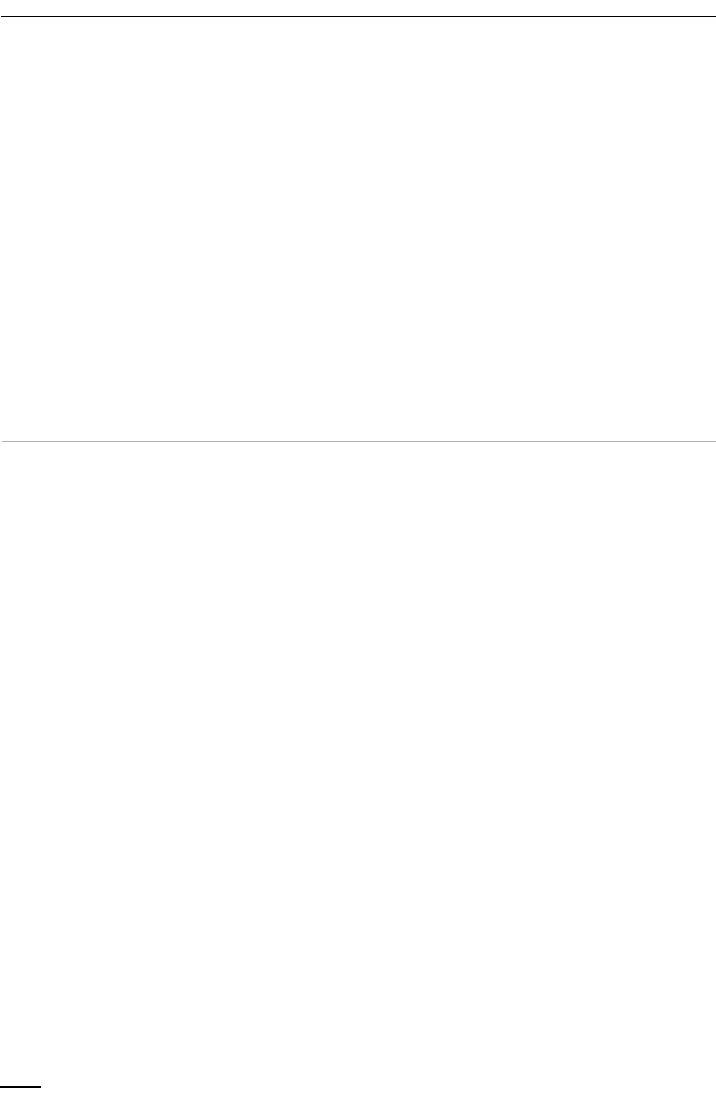

13.2 Tutsi women depicted seducing UN force commander General Roméo Dallaire 335

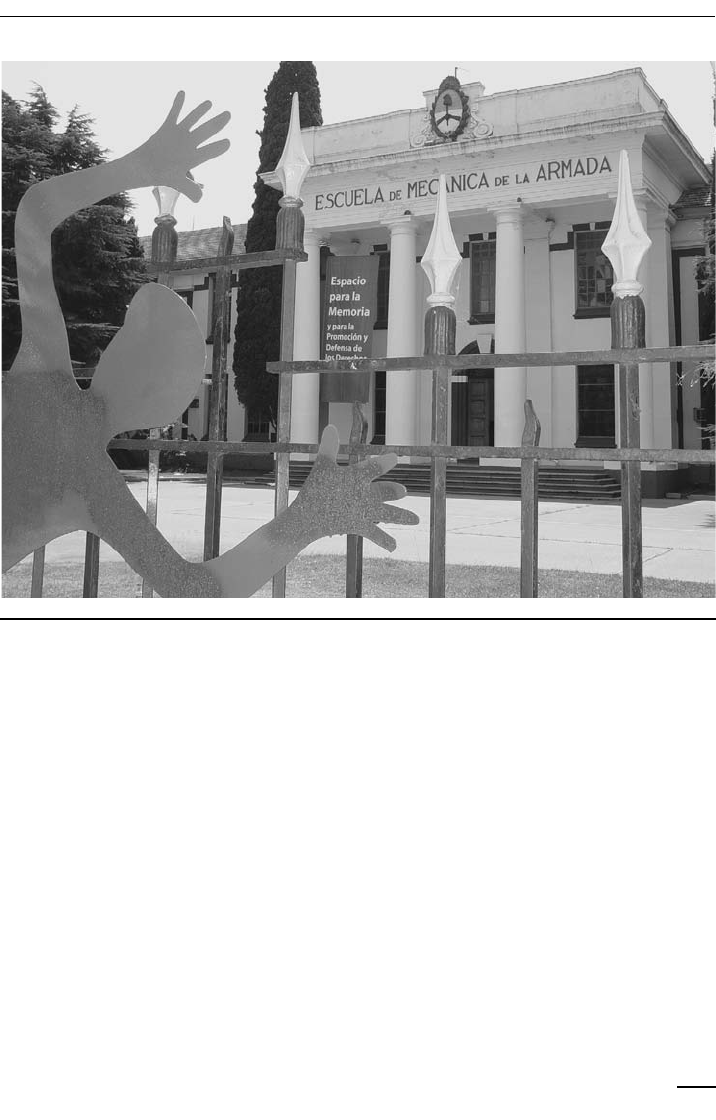

14.1 The Naval Mechanics School in the Buenos Aires suburb of Palermo 347

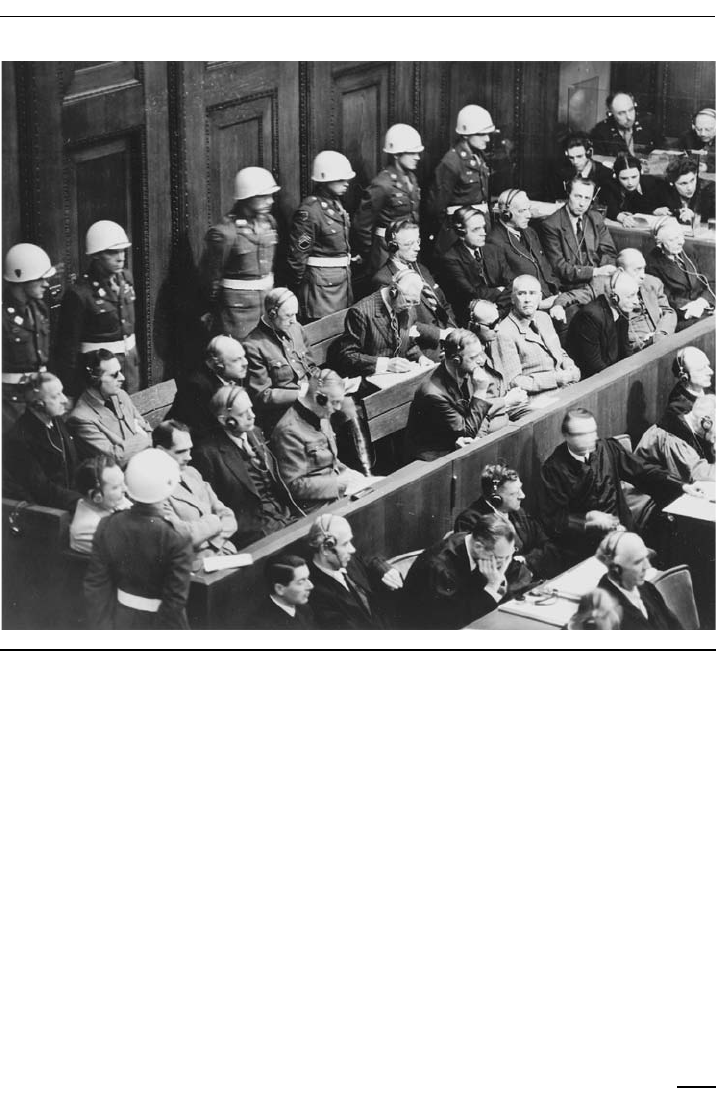

15.1 Judgment at Nuremberg, 1946 365

15.2 Luis Moreno Ocampo, the first prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) 374

■

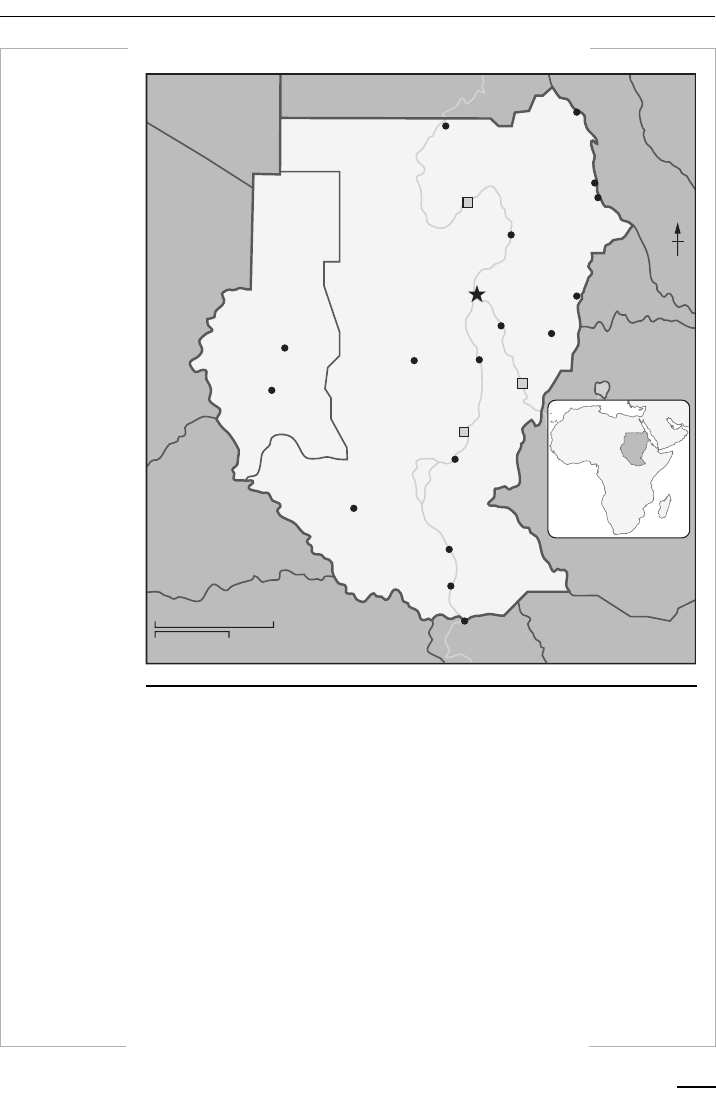

MAPS

World map xvi–xvii

5a.1 Chechnya 142

7.1 Cambodia 187

xiii

7a.1 East Timor 207

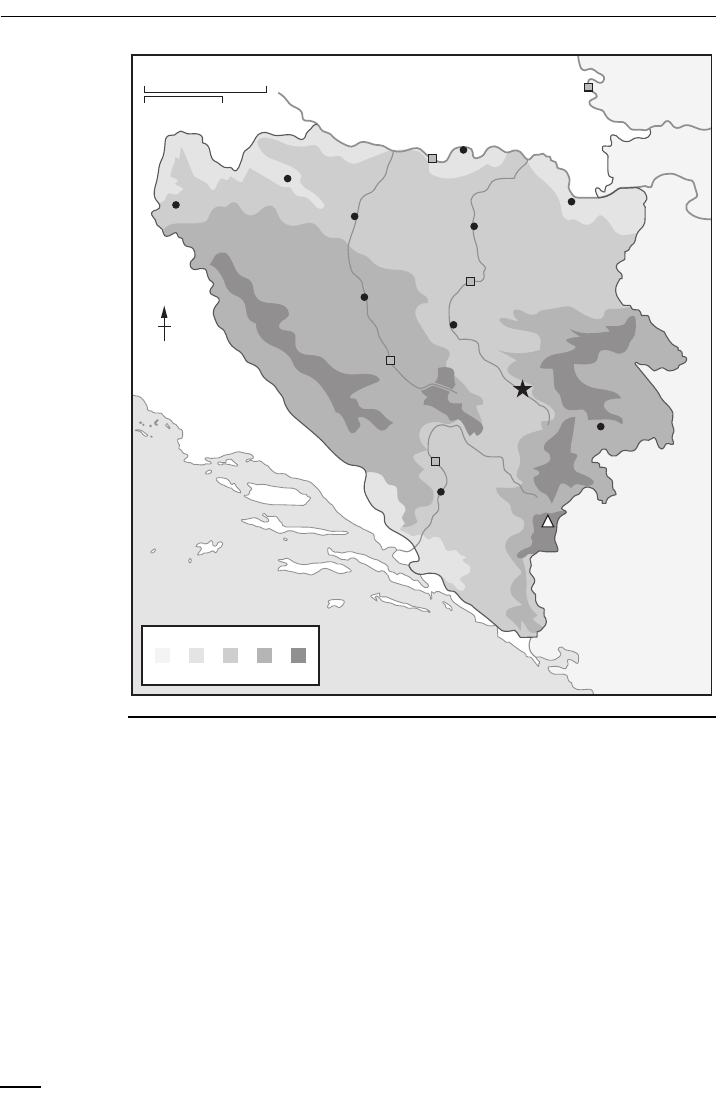

8.1 Bosnia 214

8a.1 Bangladesh 228

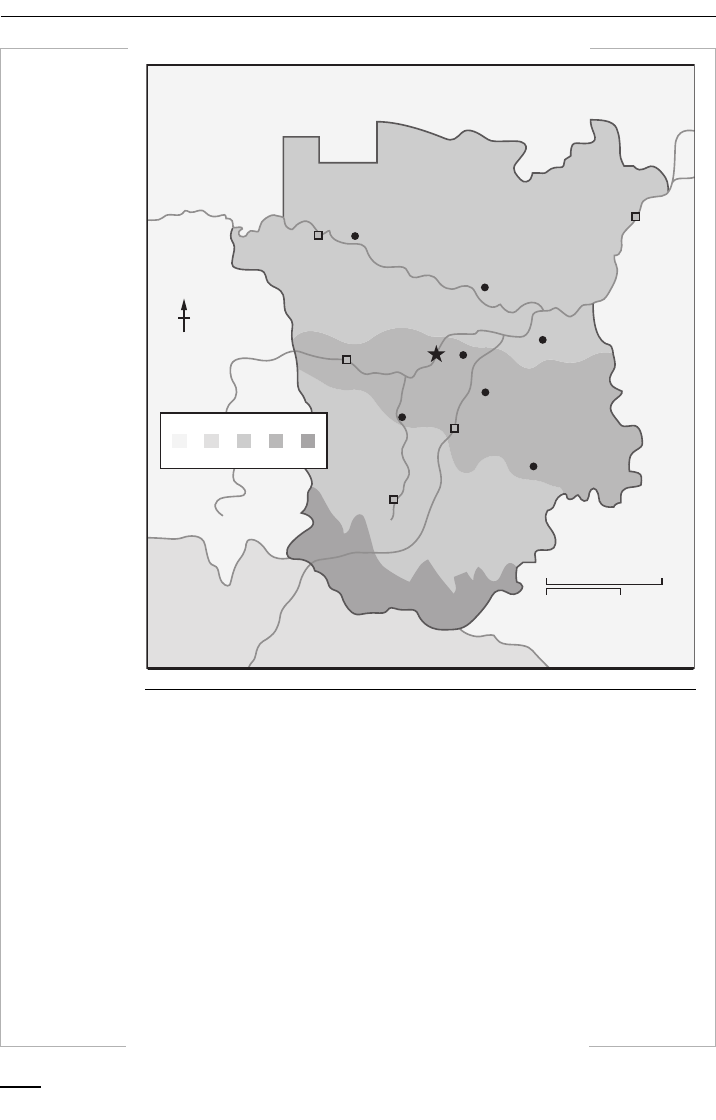

9.1 Rwanda 235

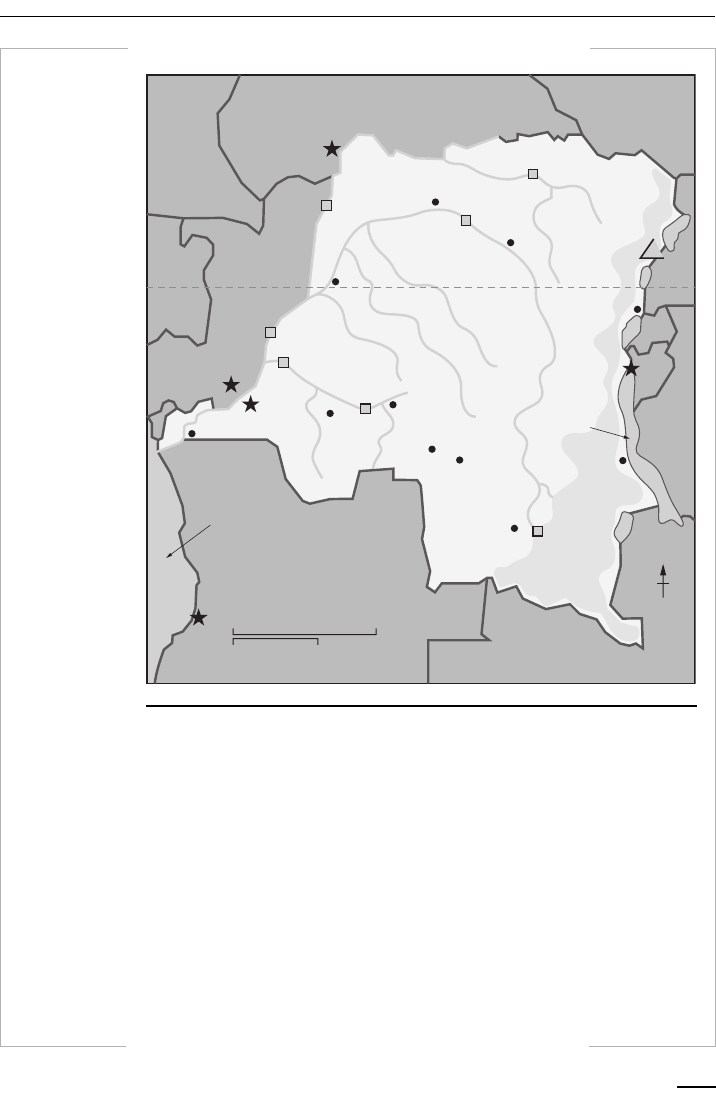

9a.1 Congo 251

9a.2 Darfur 253

■

BOXES

1.1 Genocide: scholarly definitions 15

3a Tibet under Chinese rule 94

4.1 One woman’s story: Vergeen 109

4a The Anfal Campaign against Iraqi Kurds, 1988 119

5.1 One man’s story: Janusz Bardach 131

5a Chechnya 141

6.1 One woman’s story: Nechama Epstein 155

6a The Nazis’ other victims 168

7.1 One girl’s story: Loung Ung 196

7a East Timor 206

8.1 One man’s story: Nezad Avdic 218

8a Genocide in Bangladesh, 1971 227

9.1 One woman’s story: Gloriose Mukakanimba 240

9a Congo and Darfur 250

ILLUSTRATIONS

xiv

■

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

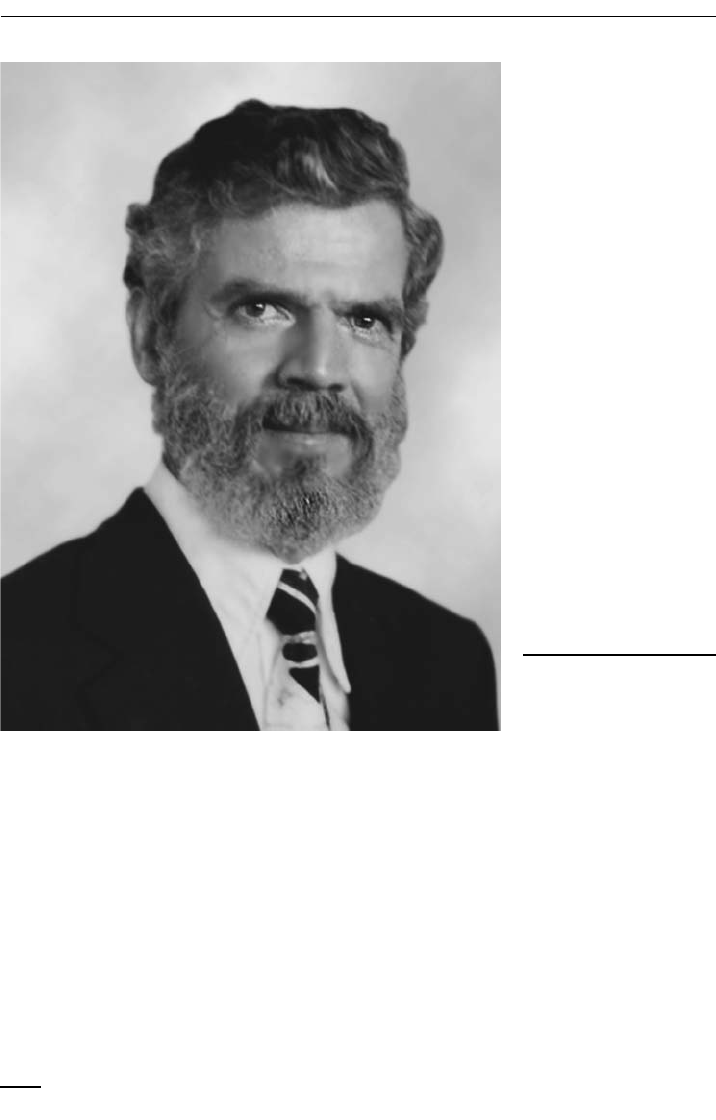

Adam Jones was born in Singapore in 1963, and grew up in England and Canada. He is currently

Associate Research Fellow in the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University. He holds an MA from

McGill University and a Ph.D. from the University of British Columbia, both in political science. He

has edited two volumes on genocide: Gendercide and Genocide (Vanderbilt University Press, 2004) and

Genocide, War Crimes and the West: History and Complicity (Zed Books, 2004). He has also published

two books on the media and political transition. His scholarly articles have appeared in Review of

International Studies, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Journal of Genocide Research, Journal of Human Rights,

and other publications. He is co-founder and executive director of Gendercide Watch (www.gendercide.

org), a Web-based educational initiative that confronts gender-selective atrocities worldwide. Jones has

lived and traveled in over sixty countries on every populated continent. His freelance journalism and

travel photography, along with a selection of scholarly writings, are available at http://adamjones.

freeservers.com. Email: [email protected].

xv

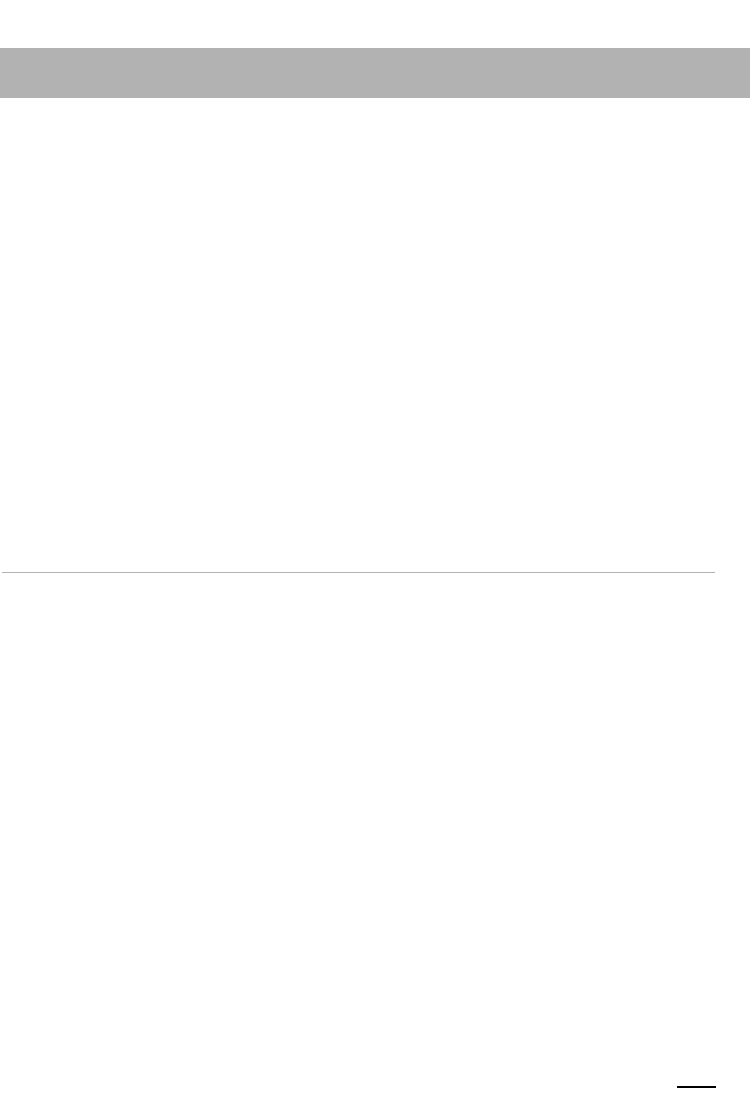

Canada

(Ch. 3)

United States

(Chs. 1, 2, 3, 12)

Guatemala

(Ch. 3)

Haiti

(Ch. 1)

Dominican

Republic

(Ch. 3)

Peru

(Ch. 3)

Bolivia

(Ch. 3)

Argentina

(Ch. 14)

Chile

(Ch. 15)

Brazil

(Ch. 1)

Sierra Leone

(Ch. 15)

France

(Ch. 1)

Germany

(Chs. 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 11, 13,

14, 15, 16, Box text 6a)

Mexico (Ch. 3)

World Map Cases of genocide and mass conflict referenced in this book

Source: Chartwell Illustrators

Rwanda

(Chs. 9, 10, 11, 13, 15)

Burundi

(Ch. 9)

Darfur

(Box text 9a)

Congo

(Ch. 2, Box text 9a)

Namibia

(Ch. 3)

Poland

(Ch. 6, Box text 6a)

Russia/former Soviet Union

(Chs. 2, 5, 16, Box texts 5a, 6a)

Chechnya

(Box text 5a)

Ukraine

(Ch. 5, Box text 6a)

Bosnia and Herzegovina

(Chs. 8, 13, 14, 15)

Croatia

(Chs. 1, 8)

Yugoslavia/Serbia

(Chs. 8, 13, 14, 15)

Kosovo

(Chs. 8, 16)

Turkey

(Chs. 4, 10,

11, 14, 15)

Iraq

(Ch. 1, Box

text 4a)

Kurdish region

of Iraq

(Box text 5a)

Kazakhstan

(Ch. 5)

China

(Chs. 2, 3, Box text 3a)

Tibet

(Box text 3a)

Japan

(Chs. 1, 2, 13, 15)

India

(Chs. 2, 13)

Bangladesh

(Box text 8a)

Pakistan

(Box text 8a)

Afghanistan

(Ch. 2)

Cambodia

(Chs. 7, 15)

Vietnam

(Ch. 2)

East Timor

(Box text 7a)

Australia

(Chs. 3, 15)

New Zealand

(Ch. 15)

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

Introduction

■

WHY STUDY GENOCIDE?

“Why would you want to study that?”

If you spend any time seriously investigating genocide, or even if you only leave

this book lying in plain view, it is likely you will have to deal with this question.

Underlying it is a tone of distaste and skepticism, perhaps tinged with suspicion.

There may be a hint that you are guided by a morbid fixation on the worst of human

horrors. How will you respond? Why, indeed, study genocide?

First and foremost, if you are concerned about issues such as peace, human

rights, and social justice, there is a sense that with genocide you are confronting the

“Big One,” what Joseph Conrad called the “heart of darkness.” That can be deeply

intimidating and disturbing. It can even make you feel trivial and powerless. But

genocide is the opposite of trivial. Whatever energy and commitment you invest in

understanding genocide will be directed towards comprehending and confronting

one of humanity’s greatest scourges.

Second, intellectually, to study genocide is to study our historical inheritance.

It is unfortunately the case that all stages of recorded human existence, and nearly

all parts of the world, have known genocide at one time or another, often repeatedly.

Furthermore, genocide may be as prevalent in the contemporary era as at any time

in history. Inevitably, there is something depressing about this: Will humanity ever

change? But there is also interest and personal enlightenment to be gained by delving

into the historical record, for which genocide serves as a point of entry. I well

remember the period, half a decade ago, that I devoted to voracious reading of the

genocide studies literature, and exploring the diverse themes this opened up to me.

xviii

For the first time, events as varied as the European witch-hunts, the War of the Triple

Alliance in South America (1864–70), the independence struggle in East

Pakistan/Bangladesh, the global plagues of maternal mortality and forced labor – all

were revealed to my bleary eyes. (I was researching case-studies for the Gendercide

Watch website (www.gendercide.org), which explains the eclectic choice of subject

matter.) The accounts were grim – sometimes relentlessly so. But they were also

spellbinding, and they gave me a better grounding not only in world history, but

also in sociology, psychology, anthropology, and a handful of other disciplines.

This raises a third reason to study genocide: it brings you into contact with some

of the most interesting and exciting debates in the social sciences and humanities.

To what extent should genocide be understood as reflecting epic social transfor-

mations such as modernity, the rise of the state, and globalization? How has warfare

been transformed in recent times, and how are the “degenerate” and decentralized

wars of the present age linked to genocidal outbreaks? How does gender shape

genocidal experiences and genocidal strategies? How is history “produced,” and what

role do memories or denial of genocide play in that production? These are only a

few of the themes to be examined in this book. I hope they will lead readers, as they

have led me, towards an engagement with cutting-edge debates that have a wider,

though not necessarily deeper, significance.

In writing this book, I am standing on the shoulders of giants: the genocide

scholars without whose trail-blazing efforts my own work would be inconceivable.

You may find their approach and humanity inspiring, as I do. One of my principal

concerns is to provide an overview of the core literature in genocide studies; thus

each chapter and box-text is accompanied by recommendations for further study.

Modern academic writing, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, is

often riddled with impenetrable jargon and not a little pomposity. It would be

pleasant to be able to report that genocide studies is free of such baggage. It isn’t; but

it is less burdened by it than most other fields of study. It seems this has to do with

the experience of looking into the abyss, and finding that the abyss looks back. One

is forced to ponder one’s own human frailty and vulnerability; one is even pressed

to confront one’s own capacity for hating others, for marginalizing them, for

supporting their oppression and annihilation. These realizations aren’t pretty, but they

are arguably necessary. And they can lead to a certain humility – a rare quality indeed

in academia. I once described to a friend why the Danish philosopher Søren

Kierkegaard (1813–55) moved me so deeply: “It’s like he’s grabbing you by the arm

and saying, ‘Look. We don’t have much time. There are important things we need

to talk about.’” You sense the same reading much of the genocide-studies literature:

that the issues are too vital, and time too limited, to beat around the bush. George

Orwell famously described political speech – he could have been referring to some

academic writing – as “a mass of words [that] falls upon the facts like soft snow,

blurring the outlines and covering up all the details.”

1

By contrast, the majority of

genocide scholars inhabit the literary equivalent of the Tropics. I hope to take up

residence there too.

Finally, some good news for the reader interested in understanding and con-

fronting genocide: your studies and actions may make a difference. To study genocide

is to study processes by which hundreds of millions of people met brutal ends. But

INTRODUCTION

xix

there are many, many people throughout history who have bravely resisted the

blind rush to hatred. They are the courageous and decent souls who gave refuge to

hunted Jews or desperate Tutsis. They are the religious believers of many faiths who

struggled against the tide of evil, and spread instead a message of love, tolerance, and

commonality. They are the non-governmental organizations that warned against

incipient genocides and carefully documented those they were unable to prevent.

They are the leaders and common soldiers – American, British, Soviet, Vietnamese,

Indian, Tanzanian, Rwandan, and others – who vanquished genocidal regimes in

modern times.

2

And yes, they are the scholars and intellectuals who have honed our

understanding of genocide, while at the same time working outside the ivory tower

to alleviate it. You will meet some of these individuals in this book. I hope their stories

and actions will inspire you to believe that a future free of genocide and other crimes

against humanity is possible.

But ...

Studying genocide, and trying to prevent it, is not to be entered into lightly.

A theme that has not been systematically addressed in the genocide studies literature

is the psychological and emotional impact such studies can have on the investigator.

How many genocide students, scholars, and activists suffer, as do their counterparts

in the human rights and social work fields?

3

How many experience depression,

insomnia, nightmares as a result of immersing themselves in the most atrocious

human conduct?

The trauma is especially intense for those who have actually witnessed genocide,

or its direct consequences, up close. During the Turkish genocide against Armenians

(Chapter 4), the US Ambassador to Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, received

a stream of American missionaries who had managed to make their way out of the

killing zone. “For hours they would sit in my office with tears streaming down their

faces,” Morgenthau recalled; many had been “broken in health” by the atrocities they

had witnessed.

4

My friend Christian Scherrer, who works at the Hiroshima Peace

Institute, arrived in Rwanda in November 1994 as part of a United Nations

investigation team, only a few months after the slaughter of a million people had been

terminated by forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) (see Chapter 9). Rotting

bodies were still strewn across the landscape. “For weeks,” Scherrer writes,

following directions given by witnesses, I carefully made my way, step by step, over

farmland and grassland. Under my feet, often only half covered with earth, lay

the remains of hundreds, indeed thousands, of unfortunate individuals betrayed

by their neighbors and slaughtered by specially enlisted bands of assassins . . . a

state-sponsored mass murder...carried out with a level of mass participation by

the majority population the like of which had never been seen before....Many

of those who came from outside shared the experience of hundreds of thousands

of Rwandans of continuing, for months on end, or even longer, to grieve, to weep

internally, and, night after night, to be unable to sleep longer than an hour or

two. When they returned to Europe, many of my colleagues felt paralyzed.

He describes the experience as “one of the most painful processes I have ever been

through,” and the writing of his fine book, Genocide and Crisis, as “part of a personal

INTRODUCTION

xx

process of grieving.” “Investigation into genocide,” he adds, “is something that

remains with one for life.”

5

Even as a latecomer to the Rwandan genocide – and as

someone who has never visited the country – I remember being so shaken by reading

a massive, agonizingly detailed human rights report on the genocide

6

that I dreamed

about Rwanda for many nights, feverish visions of encountering Hutu roadblocks,

of smuggling desperate Tutsis to Burundi. . . .

Now that interest in genocide is growing exponentially, and the field of

comparative genocide studies along with it, this may be a good time to undertake a

survey (say, of members of the International Association of Genocide Scholars) to

ascertain how common such symptoms are among those who devote their lives to

the theme. Meanwhile, I encourage you – especially if you are just beginning your

exploration – to be attentive to signs of personal stress. Talk about it with your fellow

students, your colleagues, or family and friends. Dwell on the positive examples of

bravery and love for others that the study of genocide regularly provides. If that doesn’t

work, seek counseling through the resources available on your campus or in your

community.

■

WHAT THIS BOOK TRIES TO DO, AND WHY

I see genocide as inseparable from the broad thrust of history, both ancient

and modern – indeed, it is among history’s defining features, overlapping a range of

central historical processes: war, imperialism, state-building, class struggle. I perceive

it as intimately linked to key institutions, in which state or broadly political

authorities are often but not always principal actors: forced labor, military conscrip-

tion, incarceration, female infanticide.

I adopt a comparative approach that does not elevate particular genocides over

others, except to the extent that scale and intensity warrant special attention. Virtually

all definable human groups – the ethnic, national, racial, and religious ones that

anchor the legal definition of genocide, and others besides – have been victims of

genocide in the past,

7

and are vulnerable in specific contexts today. Equally, most

human collectivities – even vulnerable and oppressed ones – have proved capable of

inflicting genocide. This can be a painful acknowledgment for genocide scholars to

make, and for that reason it is routinely avoided. But it will be confronted head-on

throughout this volume: there are no sacred cows here. Respect for taboos and tender

sensibilities takes a back seat to the imperative to get to grips with genocide –to

confront it in as clear-eyed a way as possible; to reduce the chances that mystification

and wishful thinking will cloud recognition, and thereby blunt effective opposition.

The subject of genocide has never been more prominent in the public and

academic debate than it is today. As one indication, consider the awarding of both the

Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award to Samantha Power for her 2002 work,

“A Problem From Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide, which criticized Western

passivity in the face of genocide.

8

Power’s book rapidly became a nucleus around

which a mainstream interest in genocide could coalesce.

“A Problem from Hell” was as much culmination as catalyst, however. The field of

comparative genocide studies has been developing for almost six decades. But it

INTRODUCTION

xxi

languished between the 1940s, when Raphael Lemkin coined the term “genocide”

and the UN Convention was propounded, and the early 1980s, when Leo Kuper

published his field-defining contribution, Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth

Century (1981).

9

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, the field blossomed, with the

formation of the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) in 1994, and

the publication of dozens of monographs and comparative studies – thousands, if

we include the literature focused on the Jewish catastrophe under Nazism.

Despite this proliferation, comparative genocide studies arguably has yet to find

its introductory textbook. Some important edited volumes have come closest to

establishing themselves as core texts (notably Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn’s

History and Sociology of Genocide, and Samuel Totten et al.’s Century of Genocide:

Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views).

10

As a single-authored work, the classic in

the field probably remains Kuper’s Genocide; but it is now well over two decades old,

and its author sadly deceased. Meanwhile, two fine encyclopedias and a couple of

specialized bibliographies have been published, but these are costly and unwieldy for

the student or general reader.

Excellent and accessible books on genocide have been published in recent years,

though the large majority adopt a specific disciplinary perspective. A partial exception

is probably the best of these texts, Alex Alvarez’s Governments, Citizens, and Genocide,

which approaches the subject from the angle of both political science and sociology.

11

Various scholars have explored psychological perspectives, including Roy Baumeister,

Ervin Staub, and James Waller.

12

Martin Shaw has added an important volume on

War and Genocide, from an international relations and conflict studies framework.

13

Meanwhile, highly stimulating work has begun to emanate from the discipline of

anthropology. Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Beatriz Manz, among others, have done

important work on genocide and crimes against humanity. Their work has been

bolstered by two anthologies of anthropological studies edited by Alexander Laban

Hinton.

14

Last but not least, a rich body of case studies and comparative-theoretical material

has accumulated – one this book leans on heavily, with appropriate citation. Thus it

now seems an opportune moment to offer a comprehensive introductory text: one

that samples the wealth of thinking and writing on genocide in an interdisciplinary

way, with a broad range of case studies, and with a unified authorial voice.

The first part of Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction seeks to ground readers

in the basic historical and conceptual contexts of genocide. It explores the process

by which the Polish-Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin first named and defined the

phenomenon, then mobilized a nascent United Nations to outlaw it. His story

constitutes a vivid and inspiring portrait of an individual who had a significant, largely

unsung impact on modern history. Examination of legal and scholarly definitions and

debates may help readers to clarify their own thinking, and situate themselves in the

discussion.

The case study section of the book (Part 2) is divided between longer case studies

of genocide and capsule studies that complement the detailed treatments. I hope this

structure will be conducive to discussion and comparative analysis.

The first three chapters of Part 3 explore social-scientific contributions to the

study of genocide – from psychology, sociology, anthropology, and political science/

INTRODUCTION

xxii

international relations. Let me indicate the ambit and limitations of this analysis.

I am a political scientist by training. As well as devoting a chapter to perspectives from

this discipline, I incorporate its insights elsewhere in the text (notably in Chapter 2

on “Imperialism, War, and Social Revolution,” and Chapter 16 on “Strategies of

Intervention and Prevention”). Likewise, Chapter 14 on “Memory, Forgetting, and

Denial” touches on a significant discussion among professional historians, while the

analysis of “Justice, Truth, and Redress” (Chapter 15), as well as parts of Chapter 1

on “The Origins of Genocide,” explore relevant developments and debates in inter-

national law.

Even if a synoptic examination of these disciplines’ insights were possible, given

space limitations, I would be unable to provide it. The massive proliferation of

academic production, of schools and subschools, has effectively obliterated the

“renaissance” man or woman, who once moved with facility among varied fields of

knowledge. Accordingly, throughout these chapters, my ambition is modest. I seek

only to introduce readers to some useful scholarly framings, together with insights

that I have found especially relevant and simulating.

This book at least engages with a field – genocide studies – that has been

profoundly interdisciplinary from the start. The development of strict disciplinary

boundaries is a modern invention, reflecting the growing scale and bureaucra-

tization of the university. In many ways, the barriers it establishes among disciplines

are artificial. Political scientists draw on insights from history, sociology, and

psychology, and their own work finds readers in those disciplines. Sociology and

anthropology are closely related: the former developed as a study of the societies of

the industrial West, while in the latter, Westerners studied “primitive” or preindustrial

societies. Other linkages and points of interpenetration could be cited. The point

is that consideration of a given theme under the rubric of a particular discipline

may be arbitrary. To take just one example, “ethnicity” can be approached from

sociological, anthropological, psychological, and political science perspectives. I

discuss it principally in its sociological context, but would not wish to see it fixed

there.

Part 4, “The Future of Genocide,” adopts a more forward-looking approach,

seeking to familiarize readers with contemporary debates over historical memory and

genocide denial, as well as mechanisms of justice and redress. The final chapter,

“Strategies of Intervention and Prevention,” allows readers to evaluate options for

suppressing the scourge.

“How does one handle this subject?” wrote Terrence Des Pres in the preface to

The Survivor, his study of life in the Nazi concentration camps. His answer: “One

doesn’t; not well, not finally. No degree of scope or care can equal the enormity of

such events or suffice for the sorrow they encompass. Not to betray it is as much as

I can hope for.”

15

His words resonate. In my heart, I know this book is an audacious

enterprise, but I have tried to expand the limits of my empathy and, through wide

reading, my interdisciplinary understanding. I have also benefited from the insights

and corrections of other scholars and general readers, whose names appear in the

acknowledgments.

While I must depict particular genocides (and the contributions of entire aca-

demic disciplines) in very broad strokes, I have tried throughout to find room for

INTRODUCTION

xxiii

individuals, whether as victims, perpetrators, or rescuers. I hope this serves to counter

some of the abstraction and depersonalization that is inevitable in a general survey.

A list of relevant internet sources, and a filmography-in-progress, may be found on

the Web page for this book at http://www.genocidetext.net.

16

■

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction was born over a lively dinner in Durban,

South Africa, at which I chanced to sit at the elbow of Taylor & Francis commis-

sioning editor Craig Fowlie. I understand that one of Craig’s tasks is to travel the

world marshalling promising-sounding book proposals. Not bad work if you can get

it. I am truly grateful for Craig’s early and enduring support. Thanks also to Nadia

Seemungul and Steve Thompson, and to Ann King for her sterling copy-editing.

Colleagues and administrators at the CIDE research institute in Mexico City

either encouraged my study of genocide or sought to divert me from it. I gained from

the positive and negative inspiration alike. For the former, thanks to Jorge Chabat,

Farid Kahhat, Jean Meyer, Susan Minushkin, and Jesús Velasco. The bulk of this book

was written while on contract as a project researcher at CIDE in 2004. My research

assistant, Pamela Huerta, compiled comprehensive briefs for the Cambodia case study

and the Tibet and Congo/Darfur box texts. Pamela, your skill and enthusiasm were

greatly appreciated.

Much of Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction was written during travels in

late 2004 through Córdoba province in central Argentina, and in vibrant Buenos

Aires. My thanks to the Argentine friends who welcomed me, especially Julieta Ayala;

to the hoteliers and apartment agents who put me up along the way, notably Jorge

Rodríguez; and the restaurant staff who kept me fueled with that awesome steak and

vino tinto.

The manuscript was completed in the Mexico City home of Jessica and Esperanza

Rodríguez; my warm thanks to both. In Puebla, Fabiola Martínez asked probing

questions, engaged in stimulating discussions, and supplied me with tender care

besides. Gracias, mi Fabi-losa. What one could call “post-production” took place at

Yale University, where I was fortunate to obtain a two-year postdoctoral fellowship

in the Genocide Studies Program for 2005–07. I will use this time to research a book

on genocide and communication. I am honored by the opportunity to conduct

research at one of the world’s leading universities. I am especially grateful to Ben

Kiernan, eminent Cambodia scholar and director of the Genocide Studies Program,

for his interest in my work and support of it over the past few years. Thanks also to

the Yale Center for International and Area Studies (YCIAS); its director Ian Shapiro;

and associate director Richard Kane.

Kenneth J. Campbell, Jo and David Jones, René Lemarchand, Benjamin Madley,

and Nicholas Robins generously read the entire manuscript. I benefited hugely from

their feedback. Jo and David’s meticulous proofreading of the typescript might have

landed them in the dedication to this volume even if they weren’t my parents. As for

Ben Madley, our weekly or biweekly lunches at Yale, when we went through his

insightful comments on individual chapters, were simply the most stimulating and

INTRODUCTION

xxiv

thought-provoking discussions I have ever had about genocide. As with Jo and David,

there are few pages of this book that do not bear Ben’s stamp.

Other scholars, professionals, and general readers who read and commented

upon various chapters include: Jennifer Archer, Peter Balakian, Donald Bloxham,

Peter Burns, Thea Halo, Alex Hinton, Kal Holsti, Craig Jones, Ben Kiernan, Mark

Levene, Evelin Lindner, Linda Melvern, Kathleen Morrow, A. Dirk Moses, Margaret

Power, Victoria Sanford, and Christian Scherrer. I also acknowledge the insights and

recommendations of two anonymous reviewers of the book proposal for Routledge.

Although I have not always heeded these individuals’ suggestions, their perspectives

have been absolutely crucial, and have rescued me from numerous mistakes and

misinterpretations. I accept full responsibility for the errors and oversights that

remain.

Friends and family have always buttressed me, and stoked my passion for studying

history and humanity. This book could not have been written without the nurture

and guidance provided by my parents and my brother, Craig. Warmest thanks also

to Atenea Acevedo, Carla Bergman, David Buchanan, Charli Carpenter, Mike

Charko, Ferrel Christensen, Terry and Meghan Evenson, Jay Forster, Andrea and

Steve Gunner, Henry Huttenbach, Luz María Johnson, David Liebe, John

Margesson, Eric Markusen, Peter Prontzos, Hamish Telford, and Miriam Tratt.

Dr. Griselda Ramírez Reyes shares the dedication of this work. Griselda is a

pediatric neurosurgeon in Mexico City. I have stood literally at her elbow as she

opened the head of a three-week-old girl, and extracted a cancerous tumour seemingly

half the size of the infant’s brain. I hope to open a few minds myself with this work,

but I would not pretend the task compares.

Adam Jones

New Haven, USA, March 2006

■

NOTES

1 George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language” (1946), in Inside the Whale and Other

Essays (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974). Available on the Web at http://www.resort.

com/~prime8/Orwell/patee.html.

2 The Second World War Allies against the Nazis and Japanese; Tanzanians against Idi

Amin’s Uganda; Vietnamese in Cambodia in 1979; Indians in Bangladesh in 1971;

soldiers of the Rwandan Patriotic Front in 1994. See also Chapter 16.

3 Writing the first in-depth study of the Soviet “terror-famine” in Ukraine in 1932–33 (see

Chapter 5), Robert Conquest confronted only indirectly the “inhuman, unimaginable

misery” of the famine; but he still found the task “so distressing that [I] sometimes hardly

felt able to proceed.” Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the

Terror-Famine (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 10. Donald Miller and

Lorna Touryan Miller, who interviewed a hundred survivors of the Armenian genocide,

wrote: “During this project our emotions have ranged from melancholy to anger, from

feeling guilty about our own privileged status to being overwhelmed by the continuing

suffering in our world.” They described experiencing “a permanent loss of innocence

about the human capacity for evil,” as well as “a recognition of the need to combat such

evil.” Miller and Miller, Survivors: An Oral History of the Armenian Genocide (Berkeley,

INTRODUCTION

xxv

CA: University of California Press, 1999), p. 4. After an immersion in the archive of S-

21 (Tuol Sleng), the Khmer Rouge killing center in Cambodia, David Chandler found

that “the terror lurking inside it has pushed me around, blunted my skills, and eroded

my self-assurance. The experience at times has been akin to drowning.” Chandler, Voices

from S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot’s Secret Prison (Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press, 1999), p. 145. Brandon Hamber notes that “many of the staff” working

with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa have experienced

“nightmares, paranoia, emotional bluntness, physical problems (e.g. headaches, ulcers,

exhaustion, etc.), high levels of anxiety, irritability and aggression, relationship difficulties

and substance abuse related problems.” Hamber, “The Burdens of Truth,” in David E.

Lorey and William H. Beezley, eds, Genocide, Collective Violence, and Popular Memory:

The Politics of Remembrance in the Twentieth Century (Wilmington, DL: Scholarly

Resources, Inc., 2002), p. 96.

4 Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response (New

York: HarperCollins, 2003), p. 278.

5 Christian P. Scherrer, Genocide and Crisis in Central Africa: Conflict Roots, Mass Violence,

and Regional War (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002), pp. 1, 7.

6 African Rights, Rwanda: Death, Despair and Defiance, rev. edn (London: African Rights,

1995). The reader who manages to make it through the 300-page chapter titled “A Policy

of Massacres” is then confronted with another 300-page chapter titled “Genocidal

Frenzy.”

7 “Genocide has been practiced throughout most of history in all parts of the world,

although it did not attract much attention because genocide was usually accepted as the

deserved fate of the vanquished.” Kurt Jonassohn with Karin Solveig Björnson, Genocide

and Gross Human Rights Violations in Comparative Perspective (New Brunswick, NJ:

Transaction Publishers, 1998), p. 50.

8 Samantha Power, “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide (New York:

Basic Books, 2002).

9 Leo Kuper, Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century (Harmondsworth:

Penguin, 1981).

10 Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case

Studies (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990); Samuel Totten, William S.

Parsons and Israel Charny, eds, Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical

Views (New York: Routledge, 2004) (2nd edn).

11 Alex Alvarez, Governments, Citizens, and Genocide: A Comparative and Interdisciplinary

Approach (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001).

12 Roy F. Baumeister, Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty (New York: W.H. Freeman,

1999); James Waller, Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass

Killing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002); Ervin Staub, Roots of Evil: The Origins

of Genocide and Other Group Violence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

13 Martin Shaw, War and Genocide: Organized Killing in Modern Society (Cambridge: Polity

Press, 2003).

14 Alexander Laban Hinton, ed., Genocide: An Anthropological Reader (Oxford: Blackwell

Publishers, 2002); Alexander Laban Hinton, ed., Annihilating Difference: The

Anthropology of Genocide (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002).

15 Terrence Des Pres, The Survivor: An Anatomy of Life in the Death Camps (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1976), pp. v–vi.

16 Readers who are interested in the background to my engagement with genocide studies

can consult the short essay, “Genocide: A Personal Journey,” at http://www.genocidetext.

net/personal_journey.htm.

INTRODUCTION

xxvi

PART ONE OVERVIEW

■

The Origins of Genocide

This chapter analyzes the origins of genocide as a global-historical phenomenon,

providing a sense, however fragmentary, of genocide’s frequency through history.

It then turns to examine the origin and evolution of the concept itself, and explore

some “contested cases” that test the boundaries of the genocide framework. No

chapter in the book tries to cover so much ground, and the discussion at points may

seem complicated and confusing, so please fasten your seatbelts.

■

GENOCIDE IN PREHISTORY, ANTIQUITY, AND EARLY MODERNITY

“The word is new, the concept is ancient,” wrote Leo Kuper in his seminal text of

genocide studies (1981).

1

* The roots of genocide are lost in distant millennia, and

will remain so unless an “archaeology of genocide” can be developed.

2

The difficulty,

as Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn pointed out in their early study, is that such

historical records as exist are ambiguous and undependable. While history today is

generally written with some fealty to “objective” facts, most previous accounts aimed

rather to praise the writer’s patron (normally the leader) and to emphasize the

superiority of one’s own gods and religious beliefs. They may also have been intended

3

CHAPTER 1

* Throughout this book, to reduce footnoting, I gather sequential quotations and citations from the same

source into an omnibus note at the end of the passage. Epigraphs for chapters and sections are not

footnoted.

as rattling good stories – so that when Homer quotes King Agamemnon’s quintes-

sential pronouncement of root-and-branch genocide, one cannot know what basis

it might have in fact:

We are not going to leave a single one of them alive, down to the babies in their

mothers’ wombs – not even they must live. The whole people must be wiped out

of existence, and none be left to think of them and shed a tear.

3

Factually reliable or not, Agamemnon’s chilling command encapsulates a fondly held

fantasy of kings and commoners alike. Humanity has always nurtured conceptions

of social difference that generate a primordial sense of in-group versus out-group, as

well as hierarchies of good and evil, superior and inferior, desirable and undesirable.

Chalk and Jonassohn again:

Historically and anthropologically peoples have always had a name for themselves.

In a great many cases, that name meant “the people” to set the owners of that name

off against all other people who were considered of lesser quality in some way. If

the differences between the people and some other society were particularly large

in terms of religion, language, manners, customs, and so on, then such others

were seen as less than fully human: pagans, savages, or even animals.

4

The fewer the shared values and standards, the more likely members of the out-group

were (and are) to find themselves beyond the “universe of obligation,” in sociologist

Helen Fein’s evocative phrase. Hence the advent of “religious traditions of contempt

and collective defamation, stereotypes, and derogatory metaphor indicating the victim

is inferior, sub-human (animals, insects, germs, viruses) or super-human (Satanic,

omnipotent).” If certain classes of people are “pre-defined as alien...subhuman or

dehumanized, or the enemy,” it follows that they must “be eliminated in order that

we may live (Them or Us).”

5

A vivid example of this mindset is the text that underpins the cultural tradition

common to most readers of this book: the biblical Old Testament. This frequently

depicts God, as one commentator put it, as “a despotic and capricious sadist,”

6

and

his followers as génocidaires (genocidal killers). The trend starts early on, in the Book

of Genesis (6: 17–19), where God decides “to destroy all flesh in which is the breath

of life from under heaven,” with the exception of Noah and a nucleus of human and

animal life. Elsewhere, “the principal biblical rationale for genocide is the danger

that God’s people will be infected (by intermarriage, for example) by the religious

practices of the people who surround them. They are to be a holy people – i.e., a

people kept apart, separated from their idolatrous neighbors. Sometimes, the only

sure means of accomplishing this is to destroy the neighbors.”

7

Thus, in 1 Samuel

15: 2–3, “the LORD of hosts” declares: “I will punish the Amalekites for what they

did in opposing the Israelites when they came up out of Egypt. Now go and attack

Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them, but kill both man

and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey.”

8

Sometimes, as in

Numbers 31, the genocide is more selective – too selective for God’s tastes. As Yehuda

Bauer summarizes this passage:

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

4

All Midianite men are killed by the Israelites in accordance with God’s command,

but his order, transmitted by Moses, to kill all the women as well is not carried

out, and God is angry. Moses berates the Israelites, whereupon they go out and

kill all the women and all the male children; only virgin girls are left alive, for

obvious reasons.

9

“Obvious reasons,” in that many genocides in prehistory and antiquity were designed

not just to eradicate enemy ethnicities, but to incorporate and exploit some of

their members. Usually, it was children (particularly girls) and women who

were spared murder. They were simultaneously seen as unable to offer physical

resistance, and as sources of future offspring for the dominant group (descent in

patrilineal society being traced through the bloodline of the male). We see here the

roots of gendercide against adult males and adolescent boys, discussed further in

Chapter 13.

A combination of gender-selective (gendercidal) mass killing and root-and-branch

genocide pervades accounts of the wars of antiquity. Chalk and Jonassohn provide a

wide-ranging selection of historical events such as the Assyrian Empire’s root-and-

branch depredations in the first half of the first millennium

BCE

,* and the destruction

of Melos by Athens during the Peloponnesian War (fifth century

BCE

), a gendercidal

rampage described by Thucydides in his “Melian Dialogue.”

Rome’s siege and eventual razing of Carthage at the close of the Third Punic

War (149–46

BCE

) has been labeled “The First Genocide” by Yale scholar Ben

Kiernan. The “first” designation is debatable; the label of genocide, less so. Fueled

by the documented ideological zealotry of the senator Cato, Rome sought to sup-

press the supposed threat posed by (disarmed, mercantile) Carthage. “Of a population

of 2–400,000, at least 150,000 Carthaginians perished,” writes Kiernan. The

“Carthaginian solution” found many echoes in the warfare of subsequent centuries.

10

Among Rome’s other victims during its imperial ascendancy were the followers

of Jesus Christ. After his death at Roman hands in 33

CE

, Christ’s growing legions

of followers were subjected to savage persecutions and mass murder. The scenes of

torture and public spectacle were duplicated by Christians themselves during Europe’s

medieval era (approximately the ninth to fourteenth centuries

CE

). This period

produced onslaughts such as the Crusades: religiously sanctified campaigns against

“unbelievers,” whether in France (the Albigensian crusade against heretic Cathars)

or in the Holy Land of the Middle East.

11

Further génocidaires arose on the other

side of the world. In the thirteenth century, a million or so Mongol horsemen under

their leader, Genghis Khan, surged out of the grasslands of East Asia to lay waste

to vast territories, extending to the gates of Western Europe; “entire nations were

exterminated, leaving behind nothing but rubble, fallow fields, and bones.”

12

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

5

*“

BCE

” means “Before the Common Era,” and replaces the more familiar but ethnocentric “

BC

” (Before

Christ). “

CE

” replaces “

AD

”(Anno Domini, Latin for “year of the Lord”). For discussion, see

ReligiousTolerance.org, “The Use of ‘

CE

’ and ‘

BCE

’ to Identify Dates,” http://www.religioustolerance.

org/ce.htm.

In addition to religious and cultural beliefs, what appears to have motivated

these genocides was the hunger for wealth, power, and fame. These factors combined

to fuel the genocides of the early modern era, dating from approximately 1492, the

year of Caribbean Indians’ fateful (and fatal) discovery of Christopher Columbus.

The encounter between expansionist European civilization and the indigenous

populations of the world is detailed in Chapter 3. The following section focuses

briefly on two cases from the early modern era: a European one that presages the

genocidal civil wars of the twentieth century, and an African one reminding us that

genocide knows no geographical or cultural boundaries.

The Vendée uprising

In 1789, French revolutionaries, inspired by the example of their American

counterparts, overthrew the despotic regime of King Louis XVI and established a

new order based on the “Rights of Man.” Their actions provoked immediate and

intractable opposition at home and abroad. European armies massed on French

borders, posing a mortal threat to the revolutionary government in Paris, and in

March 1793 – following the execution of King Louis and the imposition of a

levée en masse (mass conscription) – homegrown revolt sprouted in the Vendée.

The population of this isolated and conservative region of western France declared

itself unalterably opposed to the replacement of their priests by pro-revolutionary

designates, and the evisceration of the male population by the levée. Well trained and

led by royalist officers, Vendeans rose up against the central authority. That authority

was itself undergoing a rapid radicalization: the notorious “Terror” of the Jacobin

faction was instituted the same month as the rebellion in St.-Florent-le-Vieil. The

result was a ferocious civil war that, according to French author Reynald Secher

among others, constituted a genocide against the Vendean people.

13

Early rebel victories were achieved through the involvement of all demographic

sectors of the Vendée, and humiliated the central authority. Fueled by the ideological

fervor of the Terror, and by foreign and domestic counter-revolution, the revolution-

aries in Paris implemented a classic campaign of root-and-branch genocide. Under

Generals Jean-Baptiste Carrier and Louis Marie Turreau, the Republican authorities

launched a scorched-earth drive by the aptly named colonnes infernales (“hellish

columns”). On December 11, 1793, Carrier wrote to the Committee of Public

Safety in Paris, pledging to purge the Vendean peasantry “absolutely and totally.”

14

Similar edicts by General Turreau in early 1794 were enthusiastically approved

by the Committee, which declared that the “race of brigands” in the Vendée was to

be “exterminated to the last.” This included even children, who were “just as

dangerous [as adults], because they were or were in the process of becoming brigands.”

Root-and-branch extermination was “both sound and pure,” the Committee wrote,

and should “show great results.”

15

The resulting slaughter targeted all inhabitants of the Vendée – even those who

supported the Republicans (in today’s terminology, these victims were seen as

“collateral damage”). Specifically, none of the traditional gender-selective exemptions

was granted to adult females, who stood accused of fomenting the rebellion through

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

6

their defense of conservative religion, and their “goad[ing] . . . into martyrdom” of

Vendean men.

16

In the account of a Vendean abbé, perhaps self-interested but

buttressed by other testimony:

There were poor girls, completely naked, hanging from tree branches, hands tied

behind their backs, after having been raped. It was fortunate that, with the Blues

[Republicans] gone, some charitable passersby delivered them from this shameful

torment. Elsewhere, in a refinement of barbarism, perhaps without precedent,

pregnant women were stretched out and crushed beneath wine presses....Bloody

limbs and nursing infants were carried in triumph on the points of bayonets.

17

Possibly 150,000 people died in the carnage, though not all were civilians. The

generalized character of the killings was conveyed by post-genocide census figures,

which evidenced not the usual war-related disparity of male versus female victims, but

a rough – and rare – parity. Only after this “ferocious...expression of ideologically

charged avenging terror,”

18

and with the collapse of the Committee of Public Safety

in Paris, did the genocidal impetus wane, though scattered clashes with rebels

continued through 1796.

In the context of comparative genocide studies, the Vendée uprising stands as

a notable example of a mass-killing campaign that has only recently been concep-

tualized as “genocide.” This designation is not universally shared, but it seems

apt in light of the large-scale murder of a designated group (the Vendean civilian

population).

Zulu genocide

Between 1810 and 1828, the Zulu kingdom under its dictatorial leader, Shaka Zulu,

waged one of the most ambitious campaigns of expansion and annihilation the region

has ever known. Huge swathes of present-day South Africa and Zimbabwe were laid

waste by Zulu armies. The European invasion of these regions, which began shortly

after, was greatly assisted by the upheaval and depopulation caused by the Zulu

assault.

The scale of the destruction was such, and the obliteration or dispersal of victims

so intensive, that relatively little historical evidence was left to bear testimony to the

terror. But it remains alive in the oral traditions of peoples of the region whose

ancestors were subjugated, slaughtered, or put to flight by the Zulus.

19

“To this day,

peoples in Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda can trace their

descent back to the refugees who fled from Shaka’s warriors.”

20

At times, Shaka apparently implemented a gender-selective extermination

strategy that is all but unique in the historical record. In conquering the Butelezi

clan, Shaka “conceived the then [and still] quite novel idea of utterly demolishing

them as a separate tribal entity by incorporating all their manhood into his own clan

or following,” thereby bolstering his own military; but he “usually destroyed

women, infants, and old people,” who were deemed useless for his expansionist

purposes.

21

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

7

However, root-and-branch strategies reminiscent of the French rampage in the

Vendée seem also to have been common. According to Yale historian Michael

Mahoney, Zulu armies often aimed not only at defeating enemies but at “their total

destruction. Those exterminated included not only whole armies, but also prisoners

of war, women, children, and even dogs.”

22

Especially brutal means, including

impaling, were chosen to eliminate the targets. In exterminating the helpless followers

of Beje, a minor Kumalo chief, Shaka determined “not to leave alive even a child,

but [to] exterminate the whole tribe,” according to a foreign witness. When the

foreigners protested against the slaughter of women and children, claiming they

“could do no injury,” Shaka responded in language that would have been familiar

to the French revolutionaries: “Yes they could,” he declared. “They can propagate

and bring [bear] children, who may become my enemies . . . therefore I command

you to kill all.”

23

Mahoney characterizes these policies as genocidal. “If genocide is defined as a state-

mandated effort to annihilate whole peoples, then Shaka’s actions in this regard must

certainly qualify.” He points out that the term adopted by the Zulus to denote their

campaign of expansion and conquest, izwekufa, derives “from Zulu izwe (nation,

people, polity), and ukufa (death, dying, to die). The term is thus identical to

‘genocide’ in both meaning and etymology.”

24

■

NAMING GENOCIDE: RAPHAEL LEMKIN

Until the Second World War, the phenomenon of genocide was a “crime without a

name,” in the words of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

25

The man who

named the crime, placed it in a global-historical context, and demanded intervention

and remedial action was an obscure Polish-Jewish jurist, a refugee from Nazi-occupied

Europe, named Raphael Lemkin (1900–59). His personal story is one of the most

remarkable of the twentieth century.

Lemkin is an exceptional example of a “norm entrepreneur” (see Chapter 12). In

four short years, he succeeded in coining a term – genocide – that concisely captured

an age-old historical phenomenon. He supported it with a wealth of historical

documentation. He published a lengthy book (Axis Rule in Occupied Europe) that

applied the concept to campaigns of genocide underway in Lemkin’s native Poland

and elsewhere in the Nazi-occupied territories. He then waged a successful campaign

to persuade the new United Nations to draft a convention against genocide; another

successful campaign to obtain the required number of signatures; and another to

secure the necessary national ratifications. Yet Lemkin died in obscurity in 1959; his

funeral drew just seven people. Only in recent years has the promise of his concept,

and the UN convention that incorporated it, begun to be realized.

It is important not to romanticize Lemkin. He was an austere loner who

antagonized many of those with whom he came into contact.

26

His preoccupation

with genocide also drew him into bizarre opposition to other human rights initiatives,

such as the Declaration of Human Rights (which became the central rights document

of the contemporary age). Many have criticized the ambiguities of the genocide

framework, as well as its allegedly archaic elements. We will consider these criticisms

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

8

shortly. First, though, let us review the extraordinary course of Lemkin’s life. This is

examined at length in the first chapters of Samantha Power’s “A Problem from Hell,”

with access to Lemkin’s letters and papers; the following account is based on Power’s

study.

27

Growing up in a Jewish family in Wolkowysk, a town in eastern Poland, Lemkin

developed a talent for languages (he would end up mastering a dozen or more), and

a passionate curiosity about the national cultures that produced them. He was struck

by accounts of the suffering of Christians at Roman hands, and its parallel in the

pogroms then afflicting the Jews of eastern Poland. Thus began Lemkin’s lifelong

obsession with mass killing in history and the contemporary world. He “raced

through an unusually grim reading list”

28

that familiarized him with cases from

antiquity and the medieval era (including Carthage, discussed above, and the fate of

the Aztec and Inca empires, described in Chapter 3). “I was appalled by the frequency

of the evil,” he recalled later, “and, above all, by the impunity coldly relied upon by

the guilty.”

29

Why? was the question that began to consume Lemkin. Why did states

kill their own and other citizens on the basis of nationality, ethnicity, or religion? Why

did onlookers ignore the killing, or applaud it? Why didn’t someone intervene?

Lemkin determined to stage an intellectual and activist intervention in what he

at first called “barbarity” and “vandalism.” The former referred to “the premeditated

destruction of national, racial, religious and social collectivities,” while the latter he

described as the “destruction of works of art and culture, being the expression of the

particular genius of these collectivities.”

30

At a conference of European legal scholars

in Madrid in 1933, Lemkin’s framing was first presented (though not by its author;

the Polish government denied him a travel visa). Despite the post-First World War

prosecutions of Turks for “crimes against humanity” (Chapter 4), governments and

public opinion leaders were still wedded to the notion that state sovereignty trumped

atrocities against a state’s own citizens. It was this legal impunity that rankled and

galvanized Lemkin more than anything else. But the Madrid delegates did not share

his passionate concern. They refused to adopt a resolution against the crimes Lemkin

set before them; the matter was tabled.

Undeterred, Lemkin continued his campaign. He presented his arguments in

legal forums throughout Europe in the 1930s, and as far afield as Cairo, Egypt. The

outbreak of the Second World War found him at the heart of the inferno – in Poland,

with Nazi forces invading from the West, and Soviets from the East. As Polish

resistance crumbled, Lemkin took flight. He traveled first to eastern Poland, and then

to Vilnius, Lithuania. From that Baltic city he made use of connections in Sweden,

and succeeded in securing refuge there.

After a spell of teaching in Stockholm, the United States beckoned. Lemkin

believed the US would be both receptive to his framework, and in a position to

actualize it in a way that Europe under the Nazi yoke could not. An epic 14,000-

mile journey took him across the Soviet Union by train to Vladivostok, by boat to

Japan, and across the Pacific. In the US, he moonlighted at Yale University’s Law

School before moving to Durham, North Carolina, where he had been offered a

professorship at Duke University.

In his new American surroundings, Lemkin struggled with his concepts and

vocabulary. “Vandalism” and “barbarity” had not struck much of a chord with his

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

9

legal audiences. Inspired by, of all things, the Kodak camera,

31

Lemkin trolled

through his impressive linguistic resources for a term that was concise and

memorable. He settled on a neologism with both Greek and Latin roots: the Greek

“genos,” meaning race or tribe, and the Latin “cide,” or killing. “Genocide” was the

intentional destruction of national groups on the basis of their collective identity.

Physical killing was an important part of the picture, but it was only a part, as Lemkin

stressed repeatedly:

By “genocide” we mean the destruction of a nation or an ethnic group....

Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction

of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation.

It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at

the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the

aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would

be disintegration of the political and social institutions of culture, language,

national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and

the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the

lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against

the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against

individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

10

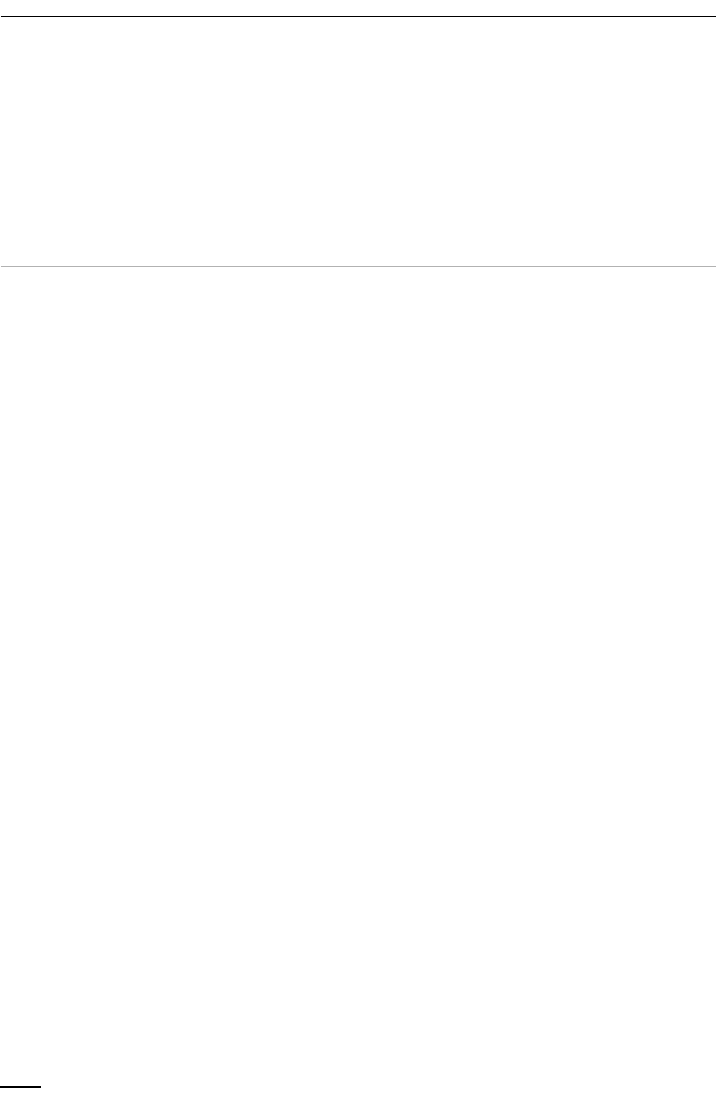

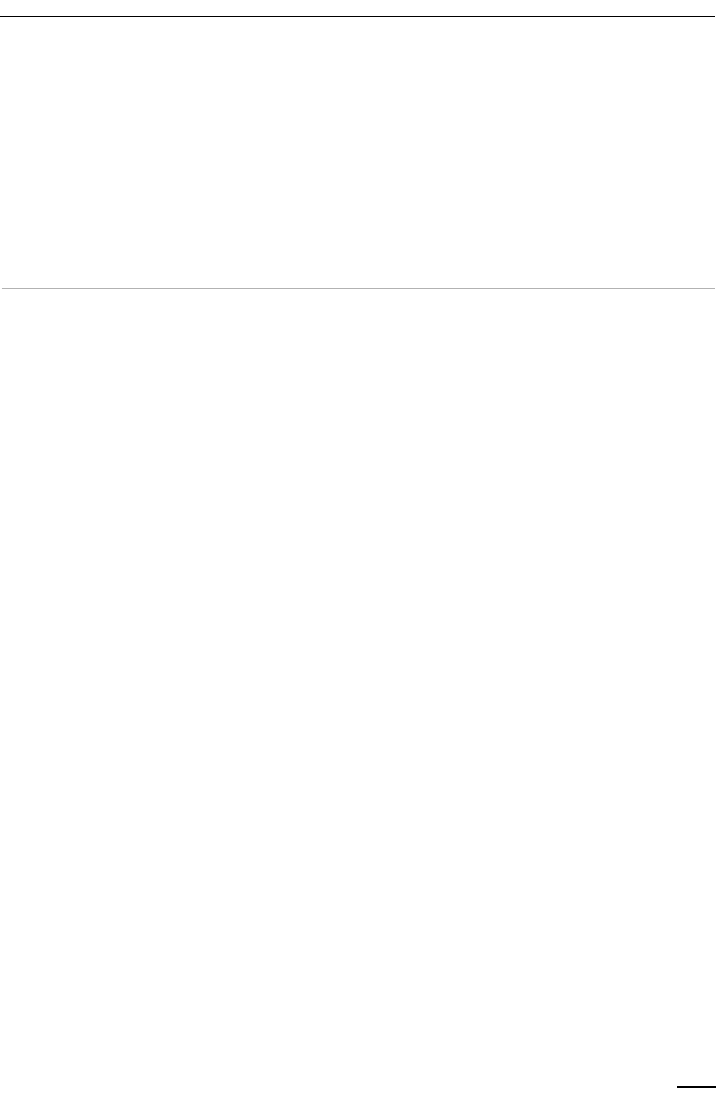

Figure 1.1 Raphael

Lemkin (1900–59)

Source: Hans Knopf/

Courtesy Jim Fussell/

preventgenocide.org.

...Genocide has two phases: one, destruction of the national pattern of the

oppressed group; the other the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor.

This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is

allowed to remain, or upon the territory alone, after removal of the population and

the colonization of the area by the oppressor’s own nationals.

32

The critical question, for Lemkin, was whether the multifaceted campaign proceeded

under the rubric of policy. To the extent that it did, it could be considered genocidal,

even if it did not result in the physical destruction of all (or any) members of the

group.

33

The issue of whether mass killing is definitional to genocide has been debated

ever since, by legal scholars, social scientists, and commentators. Equally vexing

for subsequent generations was the emphasis on ethnic and national groups. These

predominated as victims in the decades in which Lemkin developed his frame-

work (and in the historical examples he studied). But by the end of the 1940s,

and into the twilight of the Stalinist era in the 1950s, it was clear that political groups

would play a prominent if not dominant role as targets for destruction. Moreover,

the appellations applied to “communists,” or by communists to “kulaks” or “class

enemies” – when imposed by a totalitarian state – seemed every bit as difficult to shake

as ethnic identifications, if the Nazi and Stalinist onslaughts were anything to go by.

This does not even take into account the important but ambiguous areas of cross-over

among ethnic, political, and social categories.

But Lemkin would hear little of this. Although he did not exclude political groups

as genocide victims, he had a single-minded focus on nationality and ethnicity, for

their culture-carrying capacity as he perceived it. His attachment to these core

concerns was almost atavistic, and US law professor Stephen Holmes, for one, has

faulted him for it:

Lemkin himself seems to have believed that killing a hundred thousand people

of a single ethnicity was very different from killing a hundred thousand people of

mixed ethnicities. Like Oswald Spengler, he thought that each cultural group had

its own “genius” that should be preserved. To destroy, or attempt to destroy, a

culture is a special kind of crime because culture is the unit of collective memory,

whereby the legacies of the dead can be kept alive. To kill a culture is to cast its

individual members into individual oblivion, their memories buried with their

mortal remains. The idea that killing a culture is “irreversible” in a way that killing

an individual is not reveals the strangeness of Lemkin’s conception from a liberal-

individualist point of view.

This archaic-sounding conception has other illiberal implications as well. For one

thing, it means that the murder of a poet is morally worse than the murder of a janitor,

because the poet is the “brain” without which the “body” cannot function. This

revival of medieval organic imagery is central to Lemkin’s idea of genocide as a special

crime.

34

It is probably true that Lemkin’s formulation had its archaic elements. It is certainly

the case that subsequent scholarly and legal interpretations of “Lemkin’s word” have

tended to be more capacious in their framing. What can be defended, I think, is

ORIGINS OF GENOCIDE

11

Lemkin’s emphasis on the collective as a target. One can philosophize about the

relative weight ascribed to collectives over the individual, as Holmes does; but

the reality of modern times is that the vast majority of those murdered were killed

on the basis of a collective identity – even if only one imputed by the killers. The link

between collective and mass, then between mass and large-scale extermination, was

the defining dynamic of the twentieth century’s unprecedented violence. In his

historical studies, Lemkin appears to have read this correctly. Many or most of the

examples he cites would be uncontroversial among a majority of genocide scholars

today.

35

He saw the Nazis’ assaults on Jews, Poles, and Polish Jews for what they were,

and labeled the broader genre for the ages.

But for Lemkin’s word to resonate today, and into the future, two further devel-

opments were required. The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of

Genocide (1948), adopted in remarkably short order after Lemkin’s indefatigable

lobbying, entrenched genocide in international and domestic law. And beginning

in the 1970s, a coterie of “comparative genocide scholars,” drawing upon a gener-

ation’s work on the Jewish Holocaust,* began to discuss, debate, and refine Lemkin’s

concept – a trend that shows no sign of abating.

■

DEFINING GENOCIDE: THE UN CONVENTION

Lemkin’s extraordinary “norm entrepreneurship” around genocide is described in

Chapter 12. Suffice it to say for the present that “rarely has a neologism had such rapid

success” (William Schabas). Barely a year after Lemkin coined the term, it was

included in the Nuremberg indictments of Nazi war criminals (Chapter 15). To

Lemkin’s chagrin, genocide did not figure in the Nuremberg judgments. However,

“by the time the General Assembly completed its standard sitting, with the 1948

adoption of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of

Genocide, ‘genocide’ had a detailed and quite technical definition as a crime against

the law of nations.”

36

The “detailed and technical definition” is as follows:

Article I. The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in

time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they