U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

National Institute of Justice

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

National Institute of Justice

Jeremy Travis, Director

continued…

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T

O

F

J

U

S

T

I

C

E

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

J

U

S

T

I

C

E

P

R

O

G

R

A

M

S

B

J

A

N

I

J

O

J

J

D

P

B

J

S

O

V

C

Impacts of the 1994 Assault

Weapons Ban: 1994–96

by Jeffrey A. Roth and Christopher S. Koper

March 1999

zines. The legislation required the Attor-

ney General to deliver to Congress within

30 months an evaluation of the effects of

the ban. To meet this requirement, the

National Institute of Justice (NIJ) funded

research from October 1995 to December

1996 to evaluate the impact of Subtitle A.

This Research in Brief summarizes the

results of that evaluation.

A number of factors—including the fact

that the banned weapons and magazines

were rarely used to commit murders in

this country, the limited availability of

data on the weapons, other components of

the Crime Control Act of 1994, and State

and local initiatives implemented at the

same time—posed challenges in discern-

ing the effects of the ban. The ban ap-

pears to have had clear short-term effects

on the gun market, some of which were

unintended consequences: production of

the banned weapons increased before the

law took effect, and prices fell afterward.

This suggests that the weapons became

more available generally, but they must

have become less accessible to criminals

because there was at least a short-term

decrease in criminal use of the banned

weapons.

Debated in a politically charged environ-

ment, the Public Safety and Recreational

Firearms Use Protection Act, as its title

On January 17, 1989, Patrick Edward

Purdy, armed with an AKS rifle—a

semiautomatic variant of the military

AK–47—returned to his childhood

elementary school in Stockton, California,

and opened fire, killing 5 children and

wounding 30 others. Purdy, a drifter,

squeezed off more than 100 rounds in

1 minute before turning the weapon on

himself.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, this

tragedy and other similar acts of seem-

ingly senseless violence, coupled with

escalating turf and drug wars waged by

urban gangs, sparked a national debate

over whether legislation was needed to

end, or at least restrict, the market for im-

ported and domestic “assault weapons.”

Beginning in 1989, a few States enacted

their own assault weapons bans, but it

was not until 1994 that a Federal law was

enacted.

On September 13, 1994, Title XI of the

Federal Violent Crime Control and Law

Enforcement Act of 1994—known as the

Crime Control Act of 1994—took effect.

Subtitle A (the Public Safety and Recre-

ational Firearms Use Protection Act) of

the act banned the manufacture, transfer,

and possession of certain semiautomatic

firearms designated as assault weapons

and “large capacity” ammunition maga-

Issues and Findings

Discussed in this Brief: This study

examines the short-term impact

(1994–96) of the assault weapons

ban on gun markets and gun-

related violence as contained in

Title XI of the Federal Violent Crime

Control and Law Enforcement Act

of 1994. Title XI prohibits the

manufacture, sale, and possession

of specific makes and models of

military-style semiautomatic fire-

arms and other semiautomatics

with multiple military-style features

(detachable magazines, flash sup-

pressors, folding rifle stocks, and

threaded barrels for attaching

silencers) and outlaws most large

capacity magazines (ammunition-

feeding devices) capable of holding

more than 10 rounds of ammuni-

tion. Weapons and magazines

manufactured prior to September

13, 1994, are exempt from the ban.

Key issues: Although the weapons

banned by this legislation were used

only rarely in gun crimes before

the ban, supporters felt that these

weapons posed a threat to public

safety because they are capable of

firing many shots rapidly. They

argued that these characteristics

enhance offenders’ ability to kill and

wound more persons and to inflict

multiple wounds on each victim, so

that a decrease in their use would

reduce the fatality rate of gun

attacks.

The ban’s impact on lethal gun

violence is unclear because the

short period since the enabling

legislation’s passage created

methodological difficulties for

2

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

suggests, attempted to balance two

competing policy goals. The first was to

respond to several mass shooting inci-

dents committed with military-style and

other semiautomatics equipped with

magazines holding large amounts of am-

munition. The second consideration was to

limit the impact of the ban on recreational

gun use by law-abiding owners, dealers,

and manufacturers. The ban specifically

prohibited only nine narrow categories of

pistols, rifles, and shotguns (see exhibit 1).

It also banned “features test” weapons, that

is, semiautomatics with multiple features

(e.g., detachable magazines, flash suppres-

sors, folding rifle stocks, and threaded bar-

rels for attaching silencers) that appeared

useful in military and criminal applications

but that were deemed unnecessary in

shooting sports (see exhibit 2). The law also

banned revolving cylinder shotguns (large

capacity shotguns) and “large capacity

magazines,” defined as ammunition-

feeding devices designed to hold more

than 10 rounds, far more than a hunter or

competitive shooter might reasonably need

(see exhibit 3).

Various provisions of the ban limited

its potential effects on criminal use. As

shown in exhibit 1, about half the banned

makes and models were rifles, which are

hard to conceal for criminal use. Imports

of the five foreign rifle categories on this

list had been banned in 1989. Further,

the banned guns are used in only a small

fraction of gun crimes; even before the

ban, most of them rarely turned up in

law enforcement agencies’ requests to the

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms

(BATF) to trace the sales histories of guns

recovered in criminal investigations.

As a matter of equity, the law exempted

“grandfathered” guns and magazines

manufactured before the ban took effect.

While it also banned “exact” or duplicate

copies of the prohibited makes and mod-

els, the emphasis was on “exact.” Short-

ening a gun’s barrel by a few millimeters

researchers. The National Institute

of Justice is funding a followup

study by the authors that is ex-

pected to be released in 2000. It

will assess the longer term impacts

of the ban and the effects of the

other firearms provisions of Title XI.

The long-term impacts of the ban

could differ substantially from the

short-term impacts.

Key findings: The authors, using

a variety of national and local data

sources, examined market trends—

prices, production, and thefts—for

the banned weapons and close

substitutes before estimating

potential ban effects and their

consequences.

● The research shows that the

ban triggered speculative price in-

creases and ramped-up production

of the banned firearms prior to the

law’s implementation, followed by

a substantial postban drop in prices

to levels of previous years.

● Criminal use of the banned guns

declined, at least temporarily, after

the law went into effect, which

suggests that the legal stock of

preban assault weapons was, at

least for the short term, largely in

the hands of collectors and dealers.

● Evidence suggests that the ban

may have contributed to a reduc-

tion in the gun murder rate and

murders of police officers by crimi-

nals armed with assault weapons.

● The ban has failed to reduce the

average number of victims per

gun murder incident or multiple

gunshot wound victims.

Target audience: Congressional

representatives and staff; State and

local legislators; Federal, State, and

local law enforcement officials;

criminal justice practitioners and

researchers; advocacy groups; State

and local government officials.

Issues and Findings

continued…

or “sporterizing” a rifle by removing

its pistol grip and replacing it with a

thumbhole in the stock, for example,

was sufficient to transform a banned

weapon into a legal substitute. On April

5, 1998, President Clinton signed an

Executive order banning the imports of

58 foreign-made substitutes.

Gun bans and gun crime

Evidence is mixed about the effectiveness

of previous gun bans. Federal restrictions

enacted in 1934 on the ownership of fully

automatic weapons (machine guns) ap-

pear to have been quite successful based

on the rarity with which such guns are

used in crime.

1

Washington, D.C.’s re-

strictive handgun licensing system, which

went into effect in 1976, produced a drop

in gun fatalities that lasted for several

years after its enactment.

2

Yet, State and

local bans on handguns have been found

to be ineffective in other research.

3

The inconsistency of previous findings

may reflect, in part, the interplay of sev-

eral effects that a ban may have on gun

markets. To reduce criminal use of guns

and the tragic consequences of such use,

a ban must make the existing stockpile

of guns less accessible to criminals (see

exhibit 4) by, for example, raising their

purchase prices.

4

However, the anticipa-

tion of higher prices may encourage gun

manufacturers to boost production just

before the ban takes effect in the hope of

generating large profits from the soon-to-

be collectors’ items. Immediately after the

ban, criminals may find it difficult to pur-

chase banned weapons if they remain in

dealers’ and speculators’ storage facili-

ties. Over the long term, however, the

stockpiled weapons might begin flowing

into criminals’ hands, through straw pur-

chases, thefts, or “off-the-books” sales

that dealers or speculators falsely report

to insurance companies and government

officials as thefts.

5

3

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

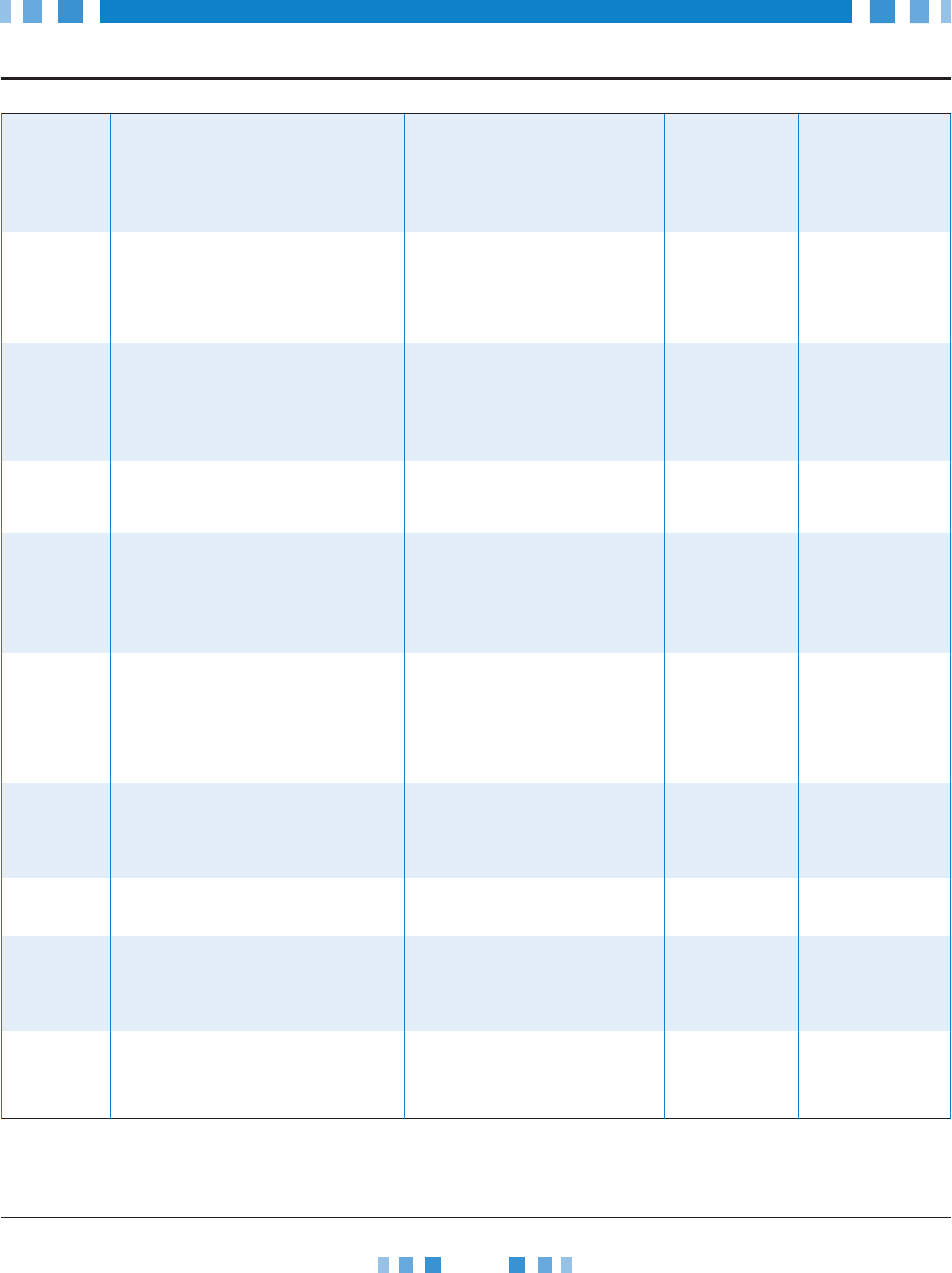

* Imports were halted in 1994 under the Federal embargo on the importation of firearms from China.

** Imports banned by Federal Executive order, April 1998.

*** Street Sweeper.

Source for firearm descriptions: Blue Book of Gun Values, 17

th

ed., by S.P. Fjestad, 1996.

Exhibit 1. Description of firearms banned in Title XI

Name of Description 1993 Blue Preban 1993 BATF Examples of

firearm Book price Federal legal trace request legal substitutes

status status count

Avtomat Chinese, Russian, other foreign, and $550 (plus Imports 87 Norinco NHM*

Kalashnikov domestic: 0.223 or 7.62x39mm caliber, 10–15% for banned in 90/91

(AK) semiautomatic Kalashnikov rifle, 5-, 10-, folding stock 1989

or 30-shot magazine, may be supplied models)

with bayonet.

Uzi, Galil Israeli: 9mm, 0.41, or 0.45 caliber $550–$1,050 Imports 281 Uzi; Uzi Sporter**

semiautomatic carbine, minicarbine, or (Uzi) banned in 12 Galil

pistol. Magazine capacity of 16, 20, or 25, $875–$1,150 1989

depending on model and type (10 or (Galil)

20 on pistols).

Beretta Italian: 0.222 or 0.223 caliber, semiauto- $1,050 Imports 1

AR–70 matic paramilitary design rifle, 5-, 8-, banned in

or 30-shot magazine. 1989

Colt AR–15 Domestic: Primarily 0.223 caliber $825–$1,325 Legal (civilian 581 Colt; Colt Sporter,

paramilitary rifle or carbine, 5-shot version of 99 other Match H–Bar,

magazine, often comes with two 5-shot military M–16) manufacturers Target; Olympic

detachable magazines. Exact copies by PCR Models.

DPMS, Eagle, Olympic, and others.

FN/FAL, Belgian design: 0.308 Winchester caliber, $1,100–$2,500 Imports 9 L1A1 Sporter**

FN/LAR, FNC semiautomatic rifle or 0.223 Remington banned in (FN, Century)

combat carbine with 30-shot magazine. 1989

Rifle comes with flash hider, 4-position

fire selector on automatic models.

Manufacturing discontinued in 1988.

SWD M–10 Domestic: 9mm paramilitary semiauto- $215 Legal 878 Cobray PM–11,

M–11, matic pistol, fires from closed bolt, PM–12; Kimel

M–11/9, 32-shot magazine. Also available in fully AP–9, Mini AP–9

M–12 automatic variation.

Steyr AUG Austrian: 0.223 Remington/5.56mm caliber, $2,500 Imports banned 4

semiautomatic paramilitary design rifle. in 1989

TEC–9 Domestic: 9mm semiautomatic paramilitary $145–$295 Legal 1202 Intratec; TEC–AB

TEC DC–9, design pistol, 10- or 32-shot magazine; 175 Exact

TEC–22 0.22 LR semiautomatic paramilitary copies

design pistol, 30-shot magazine.

Revolving Domestic: 12 gauge, 12-shot rotary $525*** Legal 64 SWD Street

Cylinder magazine, paramilitary configuration, Sweepers

Shotguns double action.

4

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

The timing and magnitudes of these

market effects cannot be known in ad-

vance. Therefore, the study examined

market trends—prices, production,

and thefts—for the banned weapons

and close substitutes before estimating

potential ban effects on their use and

the consequences of that use.

Market effects

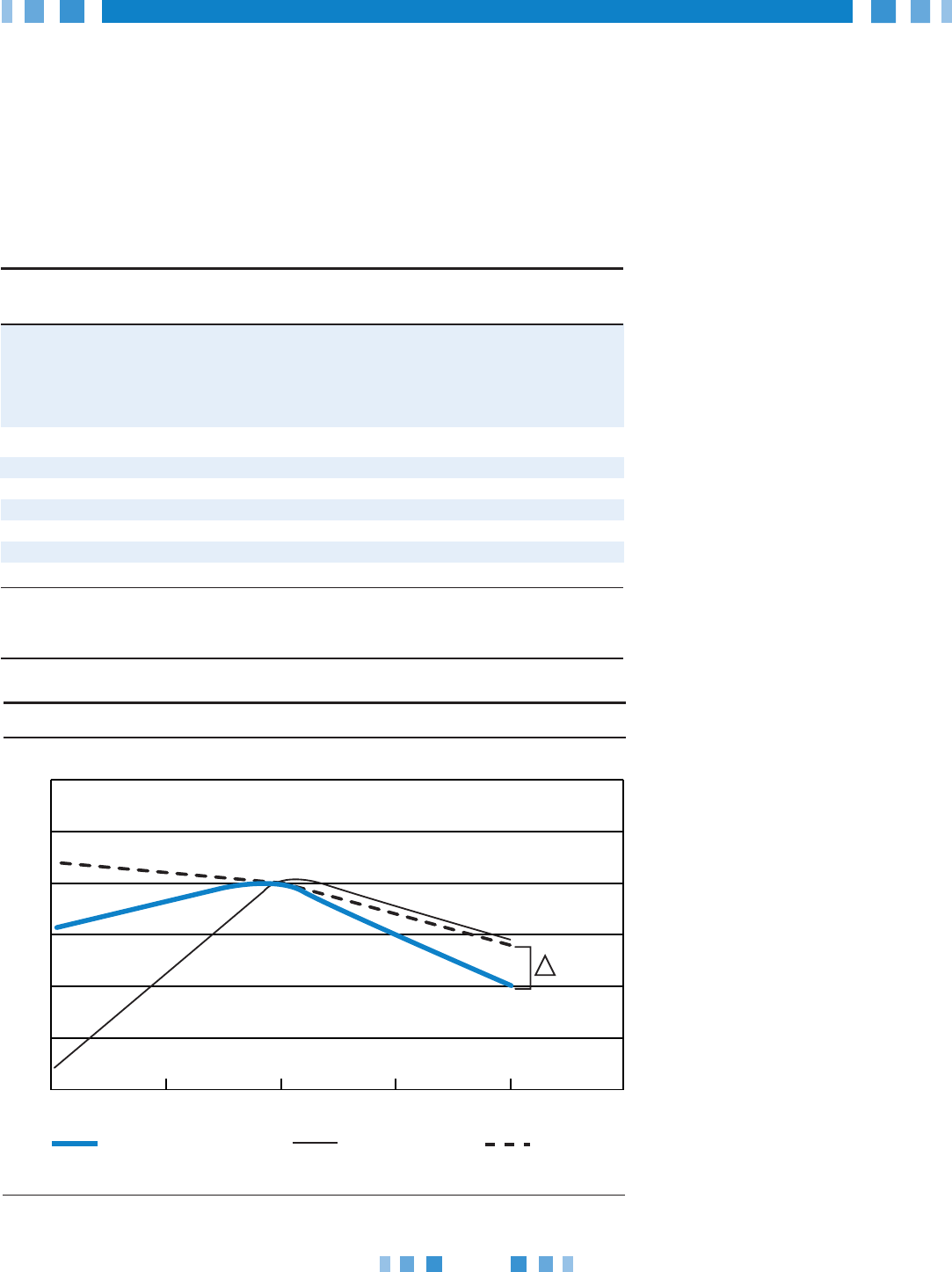

Primary market prices of the banned

guns and magazines rose by upwards

of 50 percent during 1993 and 1994,

while the ban was being debated in

Congress. Gun distributors, dealers,

and collectors speculated that the

banned weapons would become expen-

sive collectors’ items. However, prices

fell sharply after the ban was imple-

mented. Exhibit 4 shows price trends

for a number of firearms. Prices for

banned AR–15 rifles, exact copies,

and legal substitutes at least doubled

in the year preceding the ban, fell to

near 1992 levels once the ban took

effect, and remained at those levels

at least through mid-1996. Similarly,

prices of banned SWD semiautomatic

pistols rose by about 47␣ percent during

the year preceding the ban but fell by

about 20␣ percent the following year.

For comparison, exhibit 4 shows that

the prices of unbanned Davis and

Lorcin semiautomatic pistols (among

the crime guns police seize most fre-

quently) remained virtually constant

over the entire period.

6

Fueled by the preban speculative price

boom, production of assault weapons

surged in the months leading up to the

ban. Data limitations preclude precise

and comprehensive counts. However,

estimates based on BATF gun produc-

tion data suggest that the annual pro-

duction of five categories of assault

weapons—AR–15s, models by Intratec,

SWD, AA Arms, and Calico—and legal

substitutes rose by more than 120

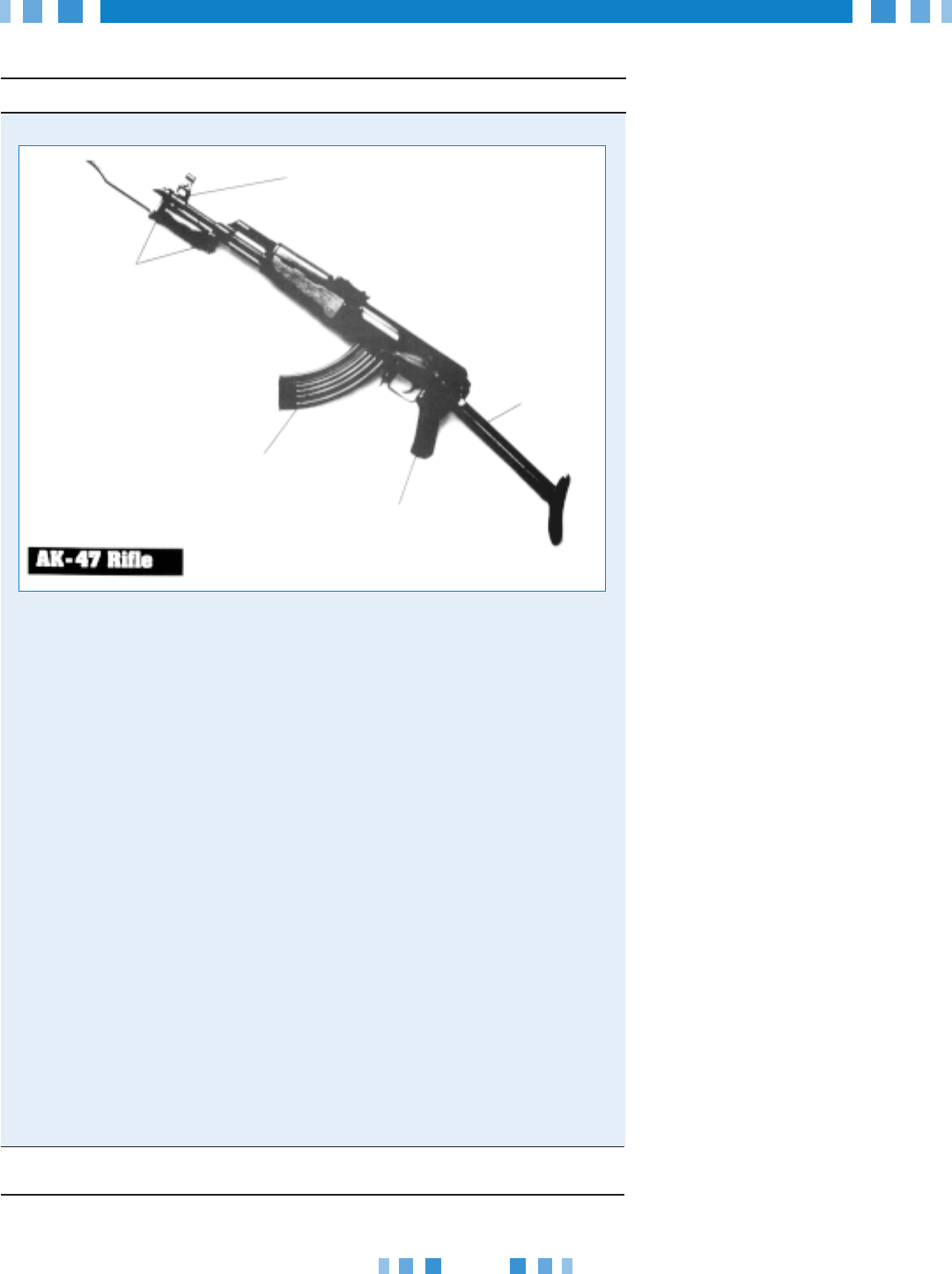

1. Semiautomatic rifles having the ability to accept a detachable ammunition magazine

and at least two of the following traits:

● A folding or telescoping stock.

● A pistol grip that protrudes beneath the firing action.

● A bayonet mount.

● A flash hider or a threaded barrel designed to accommodate one.

● A grenade launcher.

2. Semiautomatic pistols having the ability to accept a detachable ammunition magazine

and at least two of the following traits:

● An ammunition magazine attaching outside the pistol grip.

● A threaded barrel capable of accepting a barrel extender, flash hider, forward

handgrip, or silencer.

● A heat shroud attached to or encircling the barrel (this permits the shooter to

hold the firearm with the nontrigger hand without being burned).

● A weight of more than 50 ounces unloaded.

● A semiautomatic version of a fully automatic firearm.

3. Semiautomatic shotguns having at least two of the following traits:

● A folding or telescoping stock.

● A pistol grip that protrudes beneath the firing action.

● A fixed magazine capacity of more than five rounds.

● Ability to accept a detachable ammunition magazine.

Note: A semiautomatic firearm discharges one shot for each pull of the trigger. After being fired,

a semiautomatic cocks itself for refiring and loads a new round (i.e., bullet) automatically.

Flash Suppressor

Barrel Mount

High Capacity

Detachable Magazine

Pistol Grip

Folding Stock

Exhibit 2. Features test of the assault weapons ban

Exhibit provided courtesy of Handgun Control, Inc.

5

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

percent, from an estimated average of

91,000 guns annually between 1989

and 1993 to about 204,000 in 1994—

more than 1 year’s extra supply (see

exhibit 5). In contrast, production of

unbanned Lorcin and Davis pistols fell

by about 35␣ percent, from an average of

283,000 annually between 1989 and

1993 to 184,000 in 1994.

These trends suggest that the preban

price and production increases re-

flected speculation that grandfathered

weapons and magazines in the banned

categories would become profitable

collectors’ items after the ban took

effect. Instead, assault weapons prices

fell sharply within months after the

ban was in place, apparently under the

combined weight of preban overpro-

duction of grandfathered guns and the

introduction of new legal substitute

guns at that time.

These findings resemble what hap-

pened in 1989, when imports of sev-

eral models of assault rifles surged

prior to the implementation of a Fed-

eral ban.

7

Shortly thereafter, while

California debated its own ban, crimi-

nal use of assault weapons declined,

8

suggesting that higher prices and

speculative stockpiling made the guns

less accessible to criminal users.

9

It was plausible that the price and pro-

duction trends related to the 1994 ban

would be followed by an increase in re-

ported thefts of assault weapons, for at

least two reasons. First, if short-term

price increases in primary markets tem-

porarily kept assault weapons from en-

tering illegal sales channels, criminals

might be tempted to steal them instead.

In addition, dealers and collectors

who paid high speculative prices for

grandfathered assault weapons around

the time of the ban, but then watched as

their investment depreciated after the

ban took effect, might be inclined to

sell the guns to ineligible purchasers

and then falsely report them as stolen to

insurance companies and regulatory

agencies.

10

By the spring of 1996, however, there

had been no such increase. Instead,

thefts of assault weapons declined

about 14 percent as a fraction of all

thefts of semiautomatics.

11

Therefore, it

appears that, at least in the short term,

the grandfathered assault weapons re-

mained largely in dealers’ and collec-

tors’ inventories instead of leaking into

the secondary markets through which

criminals tend to obtain guns.

Criminal use of assault

weapons

Because crime guns tend to be newly

purchased guns,

12

it was hypothesized

that speculative price increases would

tend to channel the flow of banned

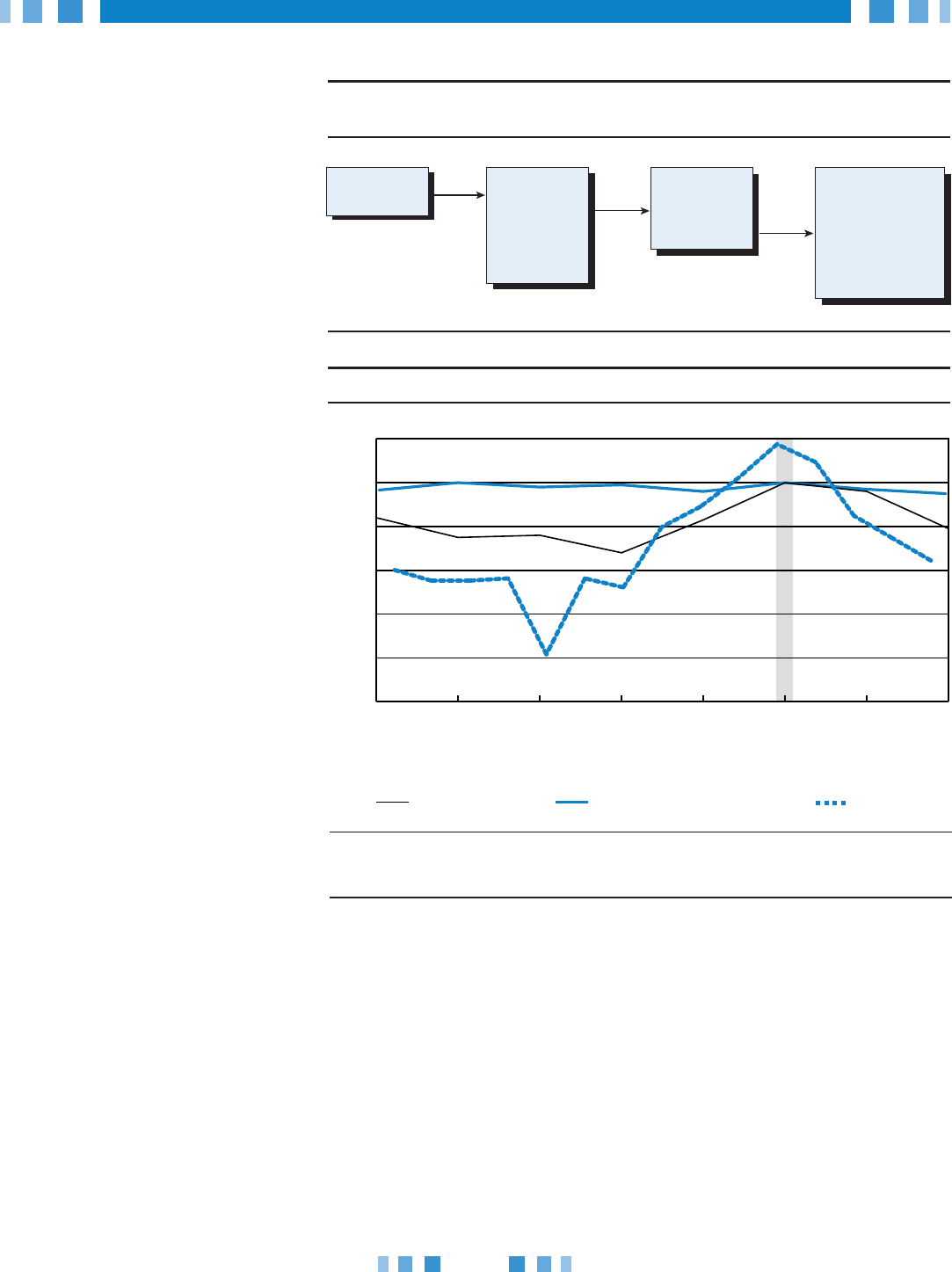

Exhibit 3. Logic model for Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use

Protection Act impact study

Title XI:

Subtitle A

Primary &

Secondary

Markets

• Price

• Production

• Thefts

AW/Magazine

Use in Crime

• Total

• Violent

Consequences of

Criminal Use

• Gun murders

• Victims per event

• Wounds per victim

• Law enforcement

officers killed

Exhibit 4. Comparison of price trends for banned and unbanned weapons

Data were collected from display ads in randomly selected issues of the nationally distributed periodical

Shotgun News. Price indices are adjusted for the mix of products and distributors advertised during

each time period. SWD, Davis, and Lorcin handgun data are reported semiannually.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Jan–June ’92

July–Dec ’92

Jan–June ’93

SWD handguns (B)

July–Dec ’93

Jan–June ’94

July–Dec ’94

Jan–June ’95

July–Dec ’95

Davis, Lorcin Semiauto handgun

AR–15-type rifle

Percentage of price at ban

6

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

weapons from criminal purchasers to

law-abiding speculators, thereby poten-

tially decreasing their use in criminal

activities. (See “Study Design and

Method.”) However, the potential de-

crease in criminal uses of the banned

weapons might be offset by the produc-

tion increase and the postban fall in

prices. To estimate the net effect on

criminal use, the researchers measured

criminal use of assault weapons using

data on gun trace requests submitted by

law enforcement agencies to BATF,

whose tracing data provide the only

available national sample of the types

of guns used in crime.

13

These data are

limited because police agencies do not

submit a trace request on every gun they

confiscate. Many agencies submit very

few requests to BATF, particularly in

States that maintain gun sales databases

(such as California). Therefore, tracing

data are a biased sample of guns recov-

ered by police. Prior studies suggest that

assault weapons are more likely to be

submitted for tracing than are other

confiscated firearms.

14

As shown in exhibit 6, law enforce-

ment agency requests for BATF as-

sault weapons traces in the 1993–95

period declined 20 percent in the first

calendar year after the ban took effect,

dropping from 4,077 in 1994 to 3,268

in 1995. Some of this decrease may

reflect an overall decrease in gun

crimes; total trace requests dropped

11␣ percent from 1994 to 1995, and

gun murders declined 10␣ percent over

the same period. Nevertheless, these

trends suggest a 9- to 10-percent addi-

tional decrease (labeled with a triangle

in exhibit 6) due to substitution of

other guns for the banned assault

weapons in 1995 gun crimes.

15

In contrast, assault weapons trace re-

quests from States with their own assault

weapons bans declined by only an esti-

mated 6 to 8 percent in 1995—further

evidence that the national trends reflect

effects of the Federal ban. There were

fewer assault weapons traces in 1995

than in 1993 (3,748), suggesting that the

national decrease was not the result of a

surge of assault weapons tracing around

the effective date of the ban.

16

These national findings were sup-

ported by analyses of trends in assault

weapons recovered in crimes in St.

Louis and Boston, two cities that did

not have preexisting State assault

weapons bans in place. Although

Exhibit 5. Production trends estimates for banned assault weapons and

comparison guns*

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Firearm type 1994 1989–93 Ratio “Excess”

production average [(1)/(2)] production

production [(1)–(2)]

AR–15 group 66,042 38,511 1.714 27,531

Intratec 9mm, 22 102,682 33,578 3.058 69,104

SWD family (all) and MAC (all) 14,380 10,508 1.368 3,872

AA Arms 17,280 6,561 2.633 10,719

Calico 9mm, 22 3,194 1,979 1.613 1,215

Lorcin and Davis 184,139 282,603 0.652

Assault weapon total** 203,578 91,137 2.233 112,441

* Estimates are based on figures provided by gun manufacturers to BATF and compiled and

disseminated annually by the Violence Policy Center.

** Assault weapon total excludes Lorcin/Davis group.

Exhibit 6. Relative changes in total and assault weapons traces

1994=100

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

1993

Assault weapons traces

Total gun traces

Gun murders

1994 1995

Percentage of 1994 level

7

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

assault weapons recoveries were rare

in those cities both before and after

the ban, they declined 29 and 24

percent, respectively, as a share of all

gun recoveries during late 1995 and

into 1996. Because these cities’ trends

reflect all guns recovered in crime,

they are not subject to the potential

biases of trace request data.

S

ubtitle A of Title XI banned the

manufacture, transfer, and possession

of assault weapons and large capacity

magazines. Researchers hypothesized

that the ban would:

● Produce direct effects in the primary

markets for these weapons.

● Reduce, through related indirect

effects in the secondary markets, the use

of these weapons in criminal activities.

● Reduce the consequences of criminal

gun use as measured by gun homicides

and, especially, incidents of multiple vic-

tims, multiple wounds, and killings of law

enforcement officers.

Because the measures of available data

on these effects varied widely, the re-

search team decided to conduct several

small studies with different error sources

and integrate the findings. The strategy

was to test whether the assault weapons

and magazine bans interrupted these

trends over time. Researchers employed

various types of time series and multiple

regression analyses, simple before-and-

after comparisons, and graphical displays.

The analysis of market impacts included:

● Pricing trends in the primary markets

for banned semiautomatic weapons,

comparable legal firearms, and large ca-

pacity magazines using 1992–96 national

distributors’ price lists.

measured nationally from Supplementary

Homicide Reports.

● Descriptive analysis of the use of

assault weapons in mass murders in the

United States from 1992 to 1996.

● Comparison of data gathered between

1992 and 1996 from medical examiners,

one hospital emergency department, and

one police department in selected cities

regarding the number of wounds per

gunshot victim.

● Analysis of 1992–96 data of law

enforcement officers killed in action with

assault weapons.

For comparison purposes, researchers

examined trends of types of guns and

magazines that were affected differently

by the ban. Few available databases re-

late the consequences of assault weapon

use to the make and model of the

weapon, so most of the analyses of con-

sequences are based on treatment and

comparison jurisdictions defined by the

legal environments in which the incident

occurred. For instance, California, Con-

necticut, Hawaii, and New Jersey had

banned assault weapons before 1994.

Although interstate traffickers can cir-

cumvent State bans, researchers hypoth-

esized that the existence of these

State-level bans reduced the impact of

the Federal ban in those respective

jurisdictions.

● Comparison of gun production data

through 1994, the latest available year.

● Comparison and time series analyses

of “leakage” of guns to illegal markets as

measured by guns reported stolen to the

Federal Bureau of Investigation/National

Crime Information Center between 1992

and 1996.

The analysis of assault weapon use

included:

● Analysis of requests for BATF traces of

assault weapons (1992–96) recovered in

crime investigations, both in absolute

terms and as a percentage of all requests.

● Preban and postban comparisons and

analyses of gun counts recovered in crime

investigations by selected local law en-

forcement agencies.

The analyses of the consequences of us-

ing assault weapons and semiautomatics

with large capacity magazines in criminal

activities included:

● Examination of State time series data

on gun murders with controls for the po-

tential influence of legal, demographic,

and economic variables of criminological

importance.

● Comparisons and time series analyses

of trends between 1980 and 1995 in

victims per gun homicide incidents as

Study design and method

Consequences of assault

weapons use

A central argument for special regula-

tion of assault weapons and large ca-

pacity magazines is that they facilitate

the rapid firing of high numbers of

shots, which allows offenders to inflict

more wounds on more persons in a

short period of time, thereby increasing

the expected number of injuries and

deaths per criminal use. The study ex-

amined trends in the following conse-

quences of gun use: gun murders,

victims per gun homicide incident,

wounds per gunshot victim, and, to a

lesser extent, gun murders of police.

8

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

the power of the statistical analyses to

detect worthwhile ban effects that may

have occurred. Given the limited use

of the banned guns and magazines in

gun crimes, even the maximum theo-

retically achievable preventive effect

of the ban on outcomes such as the

gun murder rate is almost certainly

too small to detect statistically be-

cause the congressionally mandated

timeframe for the study effectively

limited postban data collection to, at

most, 24 months (and only 1 calendar

year for annual data series).

Nevertheless, to estimate the first-year

ban effect on gun murders, the analysis

compared actual 1995 State gun

murder rates with the rates that would

have been expected in the absence of

the assault weapons ban. Data from

1980 to 1995 of 42 States with ad-

equate annual murder statistics (as

reported to the Federal Bureau of In-

vestigation) were used to project 1995

gun murder rates adjusted for ongoing

trends and demographic and economic

changes. Tests were run to determine

whether the deviation from the projec-

tion could be explained by various

policy interventions other than the

assault weapons ban.

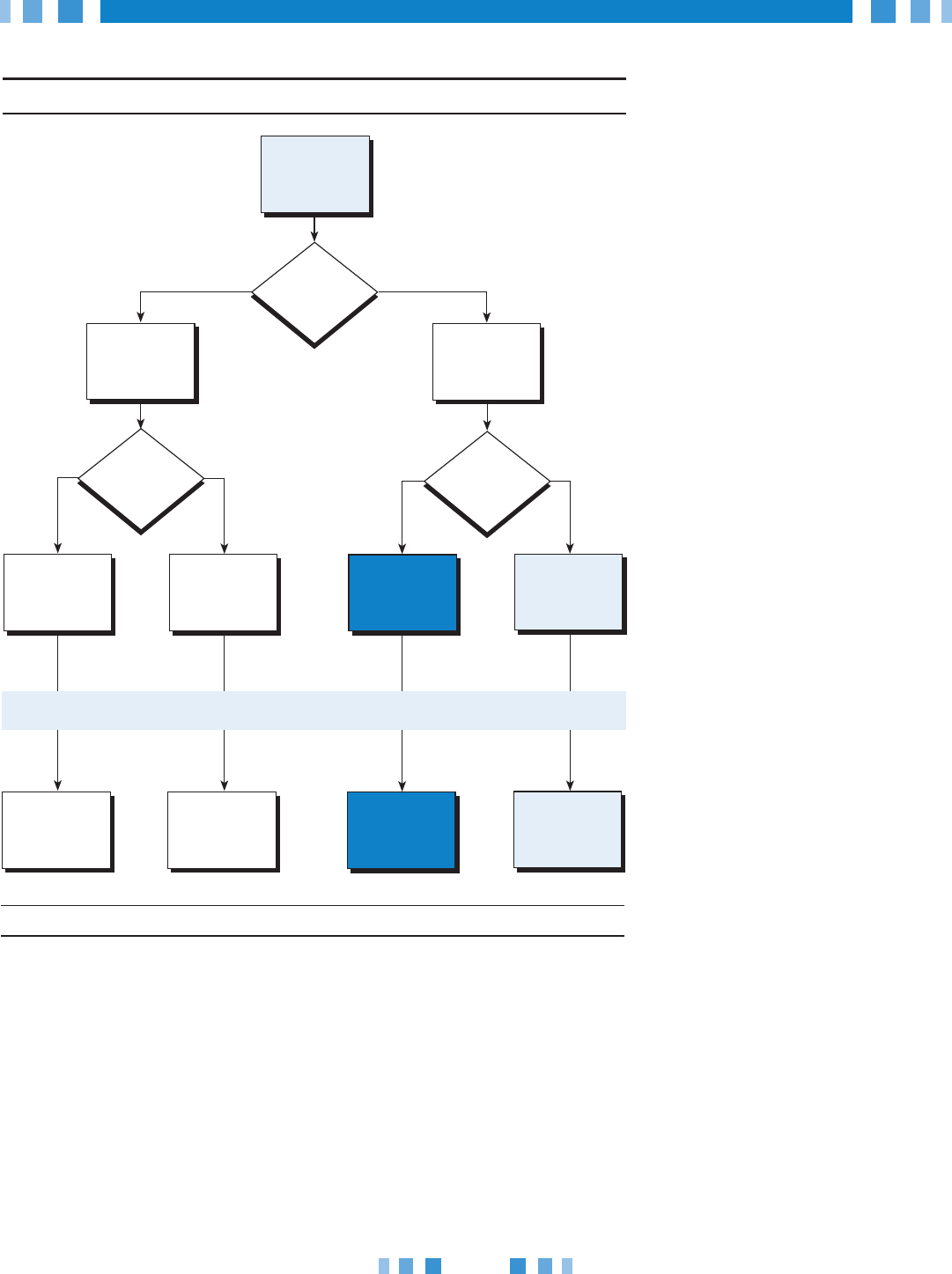

Exhibit 7 displays the steps in that

analysis. Overall, 1995 gun murder

rates were 9 percent lower than the

projection.

19

Gun murders declined

10.3 percent in States without preex-

isting assault weapons bans, but they

remained unchanged in States with

their own bans. After adjusting the

projection for possible effects of State

bans on juvenile handgun possession

and a similar Federal ban that took

effect simultaneously with the assault

weapons ban, the study found that

1995 gun murder rates were 10.9 per-

cent below the projected level. Finally,

statistical controls were added for

42 usable

States

-9.0%*

4 States

-0.1%

38 States

-10.3%*

State

juvenile

possession

ban?

State

juvenile

possession

ban?

State

assault

weapons

ban?

2 States

+4.5%

2 States

-7.3%

1 State

+5.8%

2 States

-7.6%

15 States

-6.7%

22 States

-9.8%

Drop California and New York

16 States

-10.9%

22 States

-9.7%

Yes

No

Yes No

Yes No

Exhibit 7. Estimated 1994–95 ban effects on total gun murder rate

* Statistically significant at 10-percent level.

There were several reasons to expect,

at best, a modest ban effect on crimi-

nal gun injuries and deaths. First,

studies before the ban generally found

that between less than 1 and 8 percent

of gun crimes involved assault weap-

ons, depending on the specific defini-

tion and data source used.

17

Although

limited evidence suggests that semiau-

tomatics equipped with large capacity

magazines are used in 20 to 25 per-

cent of these gun crimes, it is not clear

how often large capacity magazines

actually turn a gun attack into a gun

murder.

18

Second, offenders could

replace the banned guns with legal

substitutes or other unbanned semiau-

tomatic weapons to commit their

crimes. Third, the schedule for this

study set out in the legislation limited

9

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

postban drops in California and New

York to avoid confounding possible

effects of the assault weapons ban,

California’s “three strikes” law, and

New York City’s “quality of life” polic-

ing. Still, 1995 murder rates in the 15

remaining States with juvenile hand-

gun possession bans but no assault

weapons ban were 6.7 percent below

the projection—a difference that

could not be explained in terms of

murder trends, demographic and eco-

nomic changes, the Federal juvenile

handgun possession ban, or the

California and New York initiatives.

Random, year-to-year fluctuations

could not be ruled out as an explana-

tion of the 6.7-percent drop. With only

1 year of postban data available and

only 15 States meeting the screening

criteria for the final estimate, the model

lacks the statistical power to detect a

preventive effect of even 20 percent un-

der conventional standards of statistical

reliability.

20

Although it is highly im-

probable that the assault weapons ban

produced an effect this large, the ban

could have reduced murders by an

amount that would escape statistical

detection.

However, other analyses using a variety of

national and local data sources found no

clear ban effects on certain types of mur-

ders that were thought to be more closely

associated with the rapid-fire features of

assault weapons and other semiautomat-

ics equipped with large capacity maga-

zines. The ban did not produce declines

in the average number of victims per inci-

dent of gun murder or gun murder victims

with multiple wounds.

Murders of police by offenders armed

with assault weapons declined from an

estimated 16 percent of gun murders of

police in 1994 and early 1995 to 0 per-

cent in the latter half of 1995 and early

1996. However, such incidents are suf-

ficiently rare that the available data do

not permit a reliable assessment of

whether this contributed to a general

reduction in gun murders of police.

Implications and research

recommendations

It appears that the assault weapons ban

had clear short-term effects on the gun

market, some of which were unintended

consequences: production of the

banned weapons increased before the

law took effect and prices fell after-

ward. These effects suggest that the

weapons became more available gener-

ally, but they must have become less

accessible to criminals because there

was at least a short-term decrease in

criminal use of the banned weapons.

Evidently, the excess stock of grand-

fathered assault weapons manufactured

prior to the ban is, at least for now,

largely in the hands of dealers and col-

lectors. The ban’s short-term impact on

gun violence has been uncertain, due

perhaps to the continuing availability of

grandfathered assault weapons, close

substitute guns and large capacity

magazines, and the relative rarity with

which the banned weapons were used

in gun violence even before the ban.

To provide a more current and detailed

understanding of the assault weapons

ban and gun markets generally, we

recommend a variety of further steps:

● Update the impact analysis. This

study was conducted with data col-

lected within 24 months of the ban’s

passage; a number of the analyses

were conducted with only 1 calen-

dar year of postban data. This lim-

ited timeframe weakens the ability

of statistical tests␣ to discern im-

pacts that may be meaningful from

a policy perspective. Also, because

the ban’s effects on gun markets

and gun violence are still unfolding,

the long-term consequences may

differ substantially from the short-

term consequences reported here.

(A followup study of longer term

impacts of the ban and the effects

of other provisions of Title XI is

underway and is expected to be

released in 2000.)

● Develop new gun market data

sources and improve existing

ones. For example, NIJ and BATF

should consider cooperating to

establish and maintain time series

data on primary and secondary mar-

ket prices and production of assault

weapons, legal substitutes, other

guns commonly used in crime, and

the respective large and small ca-

pacity magazines. Like similar sta-

tistical series currently maintained

for illegal drugs, such a price and

production series would be a valu-

able instrument for monitoring

effects of policy changes and other

influences on markets for weapons

that are commonly used in crime.

● Examine potential substitution

effects. A key remaining question

is whether offenders who preferred

the banned assault weapons have

switched to the new legal substitute

models or to other legal guns, such

as semiautomatic handguns that

accept large capacity magazines.

● Study criminal use of large

capacity magazines. The lack of

knowledge about trends in the crimi-

nal use of large capacity magazines

is especially salient for three rea-

sons. The large capacity magazine is

perhaps the most functionally impor-

tant distinguishing feature of assault

weapons. The magazine ban also

affected more gun models and gun

crimes than did the bans on desig-

nated firearms. Finally, recent

anecdotal evidence suggests that

new and remanufactured preban,

10

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

high-capacity magazines are begin-

ning to reappear in the market for

use with legal semiautomatic pistols.

● Improve the recording of

magazines recovered with crime

guns. To better understand the role

large capacity magazines play in gun

crimes, BATF and State and local

law enforcement agencies should

encourage efforts to record the

magazines with which confiscated

firearms are equipped—information

that frequently goes unrecorded un-

der current practice. Further studies

are needed on trends in the criminal

use of guns equipped with large

capacity magazines.

● Conduct indepth, incident-

based research on the situ-

ational dynamics of fatal and

nonfatal gun assaults. Despite

the rhetoric that characterizes fire-

arms policy debates, there are still

questions regarding the impacts

that weaponry, actor, and situ-

ational characteristics have on the

outcomes of gun attacks. Therefore,

research is needed to gain a greater

understanding of the roles of

banned and other weapons in inten-

tional deaths and injuries. In what

percentage of gun attacks, for in-

stance, does the ability to fire more

than 10 rounds without reloading

influence the number of gunshot

wound victims or determine the dif-

ference between a fatal and nonfatal

attack? The study yielded some

weak evidence that victims killed

by guns having large capacity

magazines (including assault weap-

ons) tend to suffer more bullet

wounds than victims killed with

other firearms and that mass mur-

ders with assault weapons tend to

involve more victims than those

with other firearms. However,

research results were based on

simple comparisons; much more

comprehensive research that takes

into account important characteris-

tics of the actors and situations

should be pursued. Future research

on the dynamics of criminal

shootings, including various mea-

sures of the number of shots fired,

wounds inflicted, and victims killed

or wounded, would improve esti-

mates of the potential effects of the

assault weapons and magazine ban,

while yielding useful information on

violent gun crime generally.

Future directions

Gun control policies, and especially

gun bans, are highly controversial

crime control measures, and the debates

tend to be dominated by anecdotes and

emotion rather than empirical findings.

In the course of this study, the research-

ers attempted to develop a logical

framework for evaluating gun policies,

one that considers the workings of gun

markets and the variety of outcomes

such policies may have. The findings

suggest that the relatively modest gun

control measures that are politically

feasible in this country may affect gun

markets in ways that at least temporarily

reduce criminals’ access to the regu-

lated guns, with little impact on law-

abiding gun owners.

The public safety benefits of the 1994

ban have not yet been demonstrated.

This suggests that existing regulations

should be complemented by further tests

of enforcement tactics that focus on the

tiny minorities of gun dealers and owners

who are linked to gun violence. These in-

clude strategic targeting of problem gun

dealers,

21

crackdowns on “hot spots” for

gun crime,

22

and strategic crackdowns on

perpetrators of gun violence,

23

followed

by comprehensive efforts to involve com-

munities in maintaining the safety that

these tactics achieve.

24

These techniques

are still being refined, and none will ever

stop all gun violence. However, with dis-

passionate analyses of their effects and a

willingness to modify tactics in response

to evidence, these approaches may well

prove more immediately effective, and

certainly less controversial, than

regulatory approaches alone.

Notes

1. Kleck, Gary, Point Blank: Guns and

Violence in America, New York: Aldine De

Gruyter, 1991.

2. Loftin, Colin, David McDowall, Brian

Wiersema, and Talbert J. Cottey, “Effects of

Restrictive Licensing of Handguns on Homicide

and Suicide in the District of Columbia,” New

England Journal of Medicine, 325: 1625–1630.

3. Kleck, Point Blank: Guns and Violence in

America.

4. The ban exempted assault weapons manu-

factured before the effective date of the law.

Because significant deterioration or loss of

those guns occurs only over decades, any im-

mediate ban effects would have to reflect scar-

city of assault weapons to criminal purchasers,

rather than a dwindling of the stockpile.

5. A number of researchers and journalists

have commented on the weak state of Federal

firearms licensees (FFLs) regulation, particu-

larly before 1994 when Title XI strengthened

the screening process for obtaining and renew-

ing licenses. Empirical evidence suggests that

a small minority of gun dealers supply many of

the guns used by criminals. Analysis of Bureau

of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms tracing data

by Glenn Pierce and his colleagues in 1995

showed that while 92 percent of FFLs had no

confiscated guns traced back to them, 0.4 per-

cent of the dealers were linked to nearly 50

percent of the traced weapons. Although some

of this concentration could simply reflect the

proximity of some large law-abiding dealers to

high-crime areas, evidence suggests that illegal

practices by some dealers contribute to this

concentration. See Wachtel, Julius, “Sources of

Crime Guns in Los Angeles, California,” Polic-

ing: An International Journal of Police Strate-

gies and Management, 21(2) (1998): 220–239;

Larson, Erik, Lethal Passage: The Story of a

Gun, New York: Vintage Books, 1995; Pierce,

Glenn L., LeBaron Briggs, and David A.

11

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

Carlson, The Identification of Patterns in Fire-

arms Trafficking: Implications for Focused

Enforcement Strategy, Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol,

Tobacco and Firearms, 1995; and Violence

Policy Center, More Gun Dealers Than Gas Sta-

tions: A Study of Federally Licensed Firearms

Dealers in America, Washington, D.C.:

Violence Policy Center, 1992.

6. Like assault weapons prices, large capacity

magazine prices generally doubled in the year

preceding the ban. However, trends diverged

after the ban, depending on the gun for which

the magazine was made. See Chapter 4 in Roth,

Jeffrey A., and Christopher S. Koper, Impact

Evaluation of the Public Safety and Recre-

ational Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994,

Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, 1997.

7. American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs, “Assault Weapons as a

Public Health Hazard in the United States,”

Journal of the American Medical Association,

267 (1992): 3067–3070.

8. Mathews, J., “Unholstering the Gun Ban,”

The Washington Post, December 31, 1989.

9. Cook, Philip J., and James A. Leitzel,

“ ‘Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy’: An Economic

Analysis of the Attack on Gun Control,” Law

and Contemporary Problems, 59 (1996):

91–118.

10. Since enactment of the Gun Control Act of

1968, FFLs are required to retain records of all

gun sales and a running log of their gun acqui-

sitions and dispositions. Federal law has

various regulations governing sales by FFLs,

including the requirement that FFLs have po-

tential gun purchasers sign statements that they

are not legally ineligible to purchase firearms.

The 1993 Brady Act further requires FFLs to

obtain photo identification of potential handgun

purchasers, notify the chief local law enforce-

ment officer of each application for a handgun

purchase, and wait 5 business days before com-

pleting the sale, during which time the chief

law enforcement officer may check the

applicant’s eligibility.

FFLs who sell guns without following these re-

quirements may, if inspected by BATF, try to

cover up their illegal sales by claiming that the

guns were lost or stolen. To help prevent such

practices, Subtitle C of Title XI requires FFLs

to report all stolen and lost firearms to BATF

and local authorities within 48 hours.

Gun transfers made by nonlicensed citizens do

not require such recordkeeping. In some in-

stances, however, gun owners who knowingly

transfer guns to ineligible purchasers may

choose to falsely report the guns as stolen to

prevent themselves from being linked to any

crimes committed with the guns.

11. This finding is a revision of results reported

in Chapter 4 of Roth and Koper, Impact Evalu-

ation of the Public Safety and Recreational

Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994.

12. Zimring, Franklin E., “Street Crime and New

Guns: Some Implications for Firearms Control,”

Journal of Criminal Justice, 4 (1976): 95–107.

13. A gun trace usually tracks a gun to its

first point of sale by a licensed dealer. Upon

request, BATF traces guns suspected of being

used in crime as a service to Federal, State, and

local law enforcement agencies.

14. For additional discussions of the limits of

tracing data, see Chapter 5 in Roth and Koper,

Impact Evaluation of the Public Safety and Rec-

reational Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994;

Zawitz, Marianne W., Guns Used in Crime,

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice,

Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1995; and Kleck,

Gary, Targeting Guns: Firearms and Their

Control, New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1997.

15. Percentage decreases in assault weapon

traces related to violent and drug crimes were

similar to or greater than those for total assault

weapons, although these categories were quite

small in number. Separate analyses were con-

ducted for all assault weapons and for a select

group of domestically produced assault weap-

ons that were still in production when the ban

went into effect. Both analyses showed the same

drop in overall trace requests. See Chapter 5 in

Roth and Koper, Impact Evaluation of the Pub-

lic Safety and Recreational Firearms Use

Protection Act of 1994.

16. In general, our analysis of assault weapons

use did not include legal substitute versions of

the banned weapons. However, lack of preci-

sion in the data sources could have resulted

in some of these weapons being counted as

postban traces or recoveries of assault weapons.

17. For example, see Beck, Allen, Darrell

Gilliard, Lawrence Greenfeld, Caroline Harlow,

Thomas Hester, Louis Jankowski, Tracy Snell,

James Stephan, and Danielle Morton, Survey of

State Prison Inmates, 1991, Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice

Statistics, 1993; Hargarten, Stephen W., Trudy

A. Karlson, Mallory O’Brien, Jerry Hancock,

and Edward Quebbeman, “Characteristics of

Firearms Involved in Fatalities,” Journal of the

American Medical Association, 275 (1996):

42–45; Hutson, H. Range, Deirdre Anglin, and

Michael J. Pratts, Jr., “Adolescents and Chil-

dren Injured or Killed in Drive-by Shootings

in Los Angeles,” The New England Journal of

Medicine, 330 (1994): 324–327; Kleck, Gary,

Targeting Guns: Firearms and Their Control,

New York: Aldine De Gruyter 1997; Cox News-

papers, Firepower: Assault Weapons in America,

Washington, D.C.: Cox Newspapers, 1989;

McGonigal, Michael D., John Cole, C. William

Schwab, Donald R. Kauder, Michael F.

Rotondo, and Peter B. Angood, “Urban Firearm

Deaths: A Five-Year Perspective,” The Journal

of Trauma, 35 (1993): 532–536; New York

State Division of Criminal Justice Services,

Assault Weapons and Homicide in New York

City, Albany, New York: New York State Divi-

sion of Criminal Justice Services, 1994; Zawitz,

Marianne W., Guns Used in Crime; also see

review in Koper, Christopher S., Gun Lethality

and Homicide: Gun Types Used by Criminals

and the Lethality of Gun Violence in Kansas

City, Missouri, 1985–1993, Ann Arbor,

Michigan: University Microfilms, Inc., 1995.

18. See Chapter 6 in Roth and Koper, Impact

Evaluation of the Public Safety and Recre-

ational Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994;

and New York State Division of Criminal Jus-

tice Services, Assault Weapons and Homicide in

New York City.

19. In addition to the variables discussed in the

text, the models included an indicator variable

for each State, a polynomial time trend for the

national gun homicide trend, and annual State-

level controls for per capita income, employ-

ment rates, and age structure of the population.

20. By conventional standards, we mean statis-

tical power of 0.8 to detect a change, with 0.05

probability of a Type I error.

21. Pierce et al., The Identification of Patterns

in Firearms Trafficking: Implications for

Focused Enforcement Strategy.

22. Sherman, Lawrence W., James W. Shaw,

and Dennis P. Rogan, The Kansas City Gun Ex-

periment, Research in Brief, Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute

of Justice, 1995, NCJ 150855

Findings and conclusions of the research

reported here are those of the authors and do

not necessarily reflect the official position or

policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

NCJ 173405

This and other NIJ publications can be found at and downloaded from the

NIJ Web site (http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij).

Jeffrey A. Roth, Ph.D., is a principal research associate at the State Policy

Center of The Urban Institute, and Christopher S. Koper, Ph.D., is a research

associate at the State Policy Center of The Urban Institute. The views ex-

pressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban In-

stitute, its trustees, or its funders. The research for this study was supported by

NIJ grant 95–IJ–CX–0111.

The National Institute of Justice is a

component of the Office of Justice

Programs, which also includes the Bureau

of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice

Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for

Victims of Crime.

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

National Institute of Justice

Washington, DC 20531

Official Business

Penalty for Private Use $300

PRESORTED STANDARD

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

DOJ/NIJ

PERMIT NO. G–91

R e s e a r c h i n B r i e f

23. Kennedy, David, Anne M. Piehl, and

Anthony A. Braga, “Youth Violence in Boston:

Gun Markets, Serious Youth Offenders, and

a Use-Reduction Strategy,” Law and

Contemporary Problems, 59 (1996): 147–196.

24. Kelling, G.L., M.R. Hochberg, S.K.

Costello, A.M. Rocheleau, D.P. Rosenbaum,

J.A. Roth, and W.G. Skogan, The Bureau of

Justice Assistance Comprehensive Communities

Program: A Preliminary Report, Cambridge,

Massachusetts: Botec Analysis (forthcoming).