NATIONAL

ENVIRONMENTAL

POLICY ACT

Little Information

Exists on NEPA

Analyses

Report to Congressional Requesters

April 2014

GAO-14-369

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-14-369, a report to

congressional requesters

April 2014

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT

Little Information Exists On NEPA Analyses

Why GAO Did This Study

NEPA requires all federal agencies to

evaluate the potential environmental

effects of proposed projects—such as

roads or bridges—on the human

environment. Agencies prepare an EIS

when a project will have a potentially

significant impact on the environment.

They may prepare an EA to determine

whether a project will have a significant

potential impact. If a project fits within

a category of activities determined to

have no significant impact—a CE—

then an EA or an EIS is generally not

necessary. The adequacy of these

analyses has been a focus of litigation.

GAO was asked to review issues

related to costs, time frames, and

litigation associated with completing

NEPA analyses. This report describes

information on the (1) number and type

of NEPA analyses, (2) costs and

benefits of completing those analyses,

and (3) frequency and outcomes of

related litigation. GAO included

available information on both costs and

benefits to be consistent with standard

economic principles for evaluating

federal programs, and selected the

Departments of Defense, Energy, the

Interior, and Transportation, and the

USDA Forest Service for analysis

because they generally complete the

most NEPA analyses. GAO reviewed

documents and interviewed individuals

from federal agencies, academia, and

professional groups with expertise in

NEPA analyses and litigation. GAO’s

findings are not generalizeable to

agencies other than those selected.

This report has no recommendations.

GAO provided a draft to CEQ and

agency officials for review and

comment, and they generally agreed

with GAO’s findings.

What GAO Found

Governmentwide data on the number and type of most National Environmental

Policy Act (NEPA) analyses are not readily available, as data collection efforts

vary by agency. NEPA generally requires federal agencies to evaluate the

potential environmental effects of actions they propose to carry out, fund, or

approve (e.g., by permit) by preparing analyses of different comprehensiveness

depending on the significance of a proposed project’s effects on the

environment—from the most detailed Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) to

the less comprehensive Environmental Assessments (EA) and Categorical

Exclusions (CE). Agencies do not routinely track the number of EAs or CEs, but

the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)—the entity within the Executive

Office of the President that oversees NEPA implementation—estimates that

about 95 percent of NEPA analyses are CEs, less than 5 percent are EAs, and

less than 1 percent are EISs. Projects requiring an EIS are a small portion of all

projects but are likely to be high-profile, complex, and expensive. The

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains governmentwide information

on EISs. A 2011 Congressional Research Service report noted that determining

the total number of federal actions subject to NEPA is difficult, since most

agencies track only the number of actions requiring an EIS.

Little information exists on the costs and benefits of completing NEPA analyses.

Agencies do not routinely track the cost of completing NEPA analyses, and there

is no governmentwide mechanism to do so, according to officials from CEQ,

EPA, and other agencies GAO reviewed. However, the Department of Energy

(DOE) tracks limited cost data associated with NEPA analyses. DOE officials told

GAO that they track the money the agency pays to contractors to conduct NEPA

analyses. According to DOE data, its median EIS contractor cost for calendar

years 2003 through 2012 was $1.4 million. For context, a 2003 task force report

to CEQ—the only available source of governmentwide cost estimates—

estimated that a typical EIS cost from $250,000 to $2 million. EAs and CEs

generally cost less than EISs, according to CEQ and federal agencies.

Information on the benefits of completing NEPA analyses is largely qualitative.

According to studies and agency officials, some of the qualitative benefits of

NEPA include its role in encouraging public participation and in discovering and

addressing project design problems that could be more costly in the long run.

Complicating the determination of costs and benefits, agency activities under

NEPA are hard to separate from other required environmental analyses under

federal laws such as the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act;

executive orders; agency guidance; and state and local laws.

Some information is available on the frequency and outcome of NEPA litigation.

Agency data, interviews with agency officials, and available studies show that

most NEPA analyses do not result in litigation, although the impact of litigation

could be substantial if a single lawsuit affects numerous federal decisions or

actions in several states. In 2011, the most recent data available, CEQ reported

94 NEPA cases filed, down from the average of 129 cases filed per year from

calendar year 2001 through calendar year 2008. The federal government prevails

in most NEPA litigation, according to CEQ and legal studies.

View GAO-14-369. For more information,

contact Anne-Marie Fennell at (202) 512-3841

or

Page i GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Letter 1

Background 3

Data on the Number and Type of Most NEPA Analyses Are Not

Readily Available 6

Little Information Exists on the Costs and Benefits of Completing

NEPA Analyses 10

Some Information Is Available on the Frequency and Outcome of

NEPA Litigation 18

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 22

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 25

Appendix II Summary of Federal NEPA Data Collection Efforts 27

Appendix III CEQ NEPA Time Frame Guidelines 32

Appendix IV Sources of NEPA Litigation Data 33

Appendix V Comments from the Council on Environmental Quality 35

Appendix VI GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 37

Tables

Table 1: Number of Environmental Impact Statements from EPA,

CEQ, and NAEP, 2008 through 2012 8

Table 2: Number of Environmental Impact Statements by Agency

as Reported by National Association of Environmental

Professionals (NAEP), 2008 through 2012 10

Contents

Page ii GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Figure

Figure 1: Process for Implementing National Environmental Policy

Act Requirements 4

Abbreviations

BLM Bureau of Land Management

CE Categorical Exclusion

CEQ Council on Environmental Quality

CRS Congressional Research Service

DOD Department of Defense

DOE Department of Energy

DOT Department of Transportation

eMNEPA electronic Management of NEPA

EA Environmental Assessment

EIS Environmental Impact Statement

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

NAEP National Association of Environmental Professionals

NEPA National Environmental Policy Act

PAPAI Project and Program Action Information

PEPC Planning, Environment, and Public Comment

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

April 15, 2014

Congressional Requesters

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—the statute requiring

federal agencies to evaluate the potential environmental effects of

proposed projects on the human environment—has been identified by

critics as a cause of delay for projects because of time-consuming

requirements and praised by proponents for, among other things, bringing

public participation into government decision making.

1

Under NEPA, all

federal agencies generally are to evaluate the potential environmental

effects of actions they propose to carry out, fund, or approve (e.g., by

permit)—including the development of infrastructure projects, such as

roads and bridges. Enacted in 1970, NEPA, and the subsequent Council

on Environmental Quality Regulations Implementing the Procedural

Provisions of NEPA, set out an environmental review process that has

two principal purposes: (1) to ensure that an agency carefully considers

information concerning the potential environmental effects of proposed

development projects and (2) to ensure that this information is made

available to the public.

2

NEPA requires federal agencies to analyze the

nature and extent of a project’s potential environmental effects and, in

many cases, document these analyses.

3

1

NEPA applies to federal agency policies, programs, plans, and projects (40 C.F.R. §

1508.18(b)). The focus of this report is on development projects.

The documentation and

comprehensiveness of these analyses depends on the significance of a

project’s potential effects on the environment. The adequacy of NEPA

analyses has been a focus of litigation. You asked us to review various

2

Pub. L. No. 91-190 (1970), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 4321-4347. NEPA’s congressional

declaration of purpose states that the purposes of the act are “to declare a national policy

which will encourage productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his

environment; to promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment

and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man; to enrich the understanding of

the ecological systems and natural resources important to the Nation; and to establish a

Council on Environmental Quality.” 42 U.S.C. § 4321.

3

The CEQ “Regulations for Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National

Environmental Policy Act” (CEQ regulations), 40 C.F.R. Parts 1500-1508, set out the

levels of analysis and documentation for complying with NEPA. The level of analysis and

documentation can take the form of a Categorical Exclusion (CE), Environmental

Assessment (EA), or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Not all CEs are documented

at the time the CE is used for a specific proposed project.

Page 2 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

issues related to costs, time frames, and litigation associated with

completing NEPA analyses. This report describes information on the (1)

number and type of NEPA analyses, (2) costs and benefits of completing

those analyses, and (3) frequency and outcomes of related litigation. We

included available information on both costs and benefits to be consistent

with standard economic principles for evaluating federal programs and

generally accepted government auditing standards.

To respond to these objectives, we reviewed relevant publications,

obtained documents and analyses from federal agencies, and interviewed

federal officials and individuals from academia and professional

associations with expertise in conducting NEPA analyses. Specifically, to

describe the number and type of NEPA analyses from calendar year 2008

through calendar year 2012 and what is known about the costs and

benefits of NEPA analyses, we reported information identified through the

literature review, interviews, and other sources. We selected the

Departments of Defense, Energy, the Interior, and Transportation; and

the Forest Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture for analysis

because they generally complete the most NEPA analyses. Our findings

for these agencies are not generalizeable to other federal agencies but

provide examples of NEPA implementation. To describe the frequency

and outcome of NEPA litigation, we reviewed (1) laws, regulations, and

agency guidance; (2) NEPA litigation data collected from federal entities

and the National Association of Environmental Professionals (NAEP), the

professional association for NEPA practitioners within and outside the

federal government; and (3) relevant studies. To assess the reliability of

data collected from the selected agencies, we reviewed existing

documentation when available and interviewed officials, including those

from the U.S. Department of Justice, knowledgeable about the data. We

found all data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. See

appendix I for additional details on our objectives, scope, and

methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2013 to April 2014 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Page 3 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

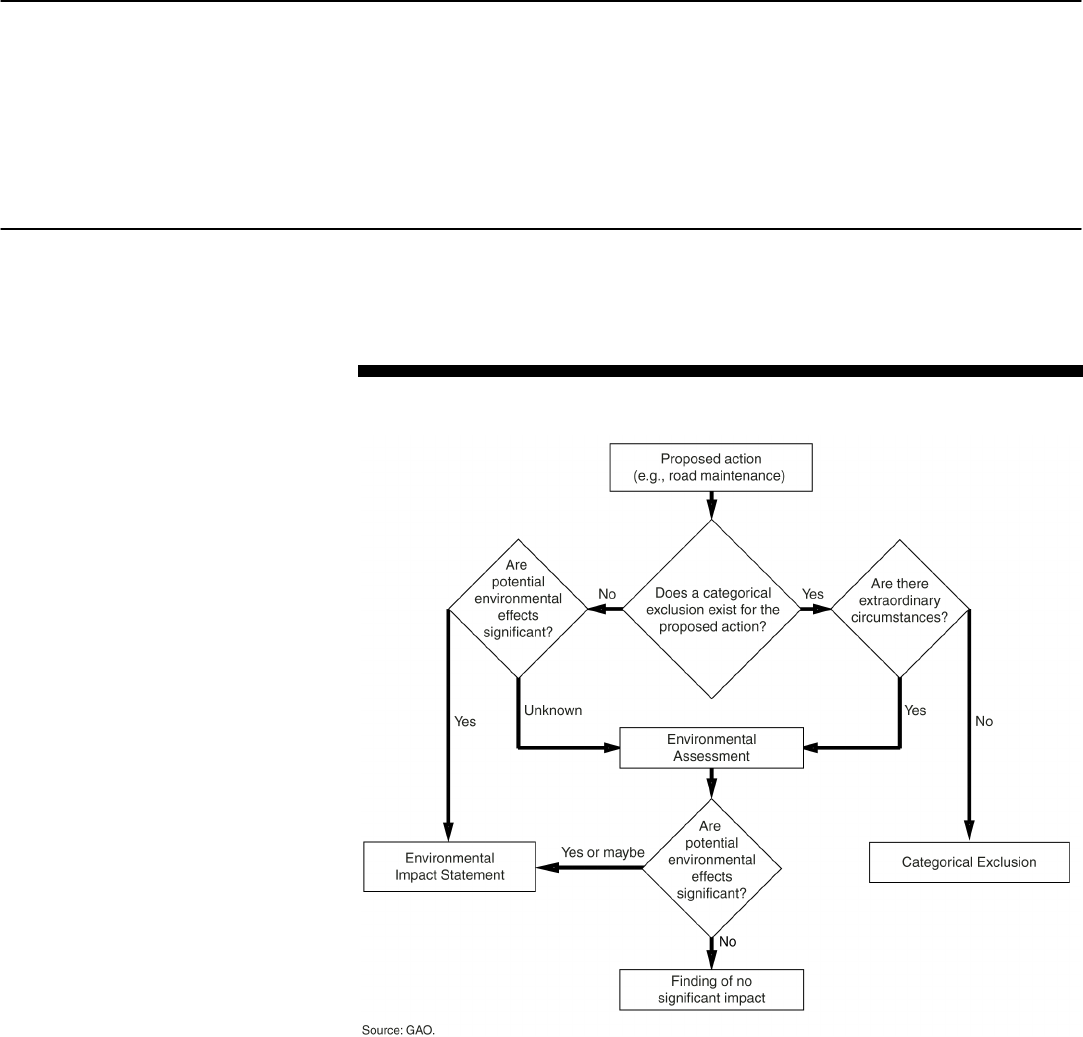

Under NEPA, federal agencies are to evaluate the potential

environmental effects of projects they are proposing by preparing either

an Environmental Assessment (EA) or a more detailed Environmental

Impact Statement (EIS), assuming no Categorical Exclusion (CE) applies.

Agencies may prepare an EA to determine whether a proposed project is

expected to have a potentially significant impact on the human

environment.

4

If prior to or during the development of an EA, the agency

determines that the project may cause significant environmental impacts,

an EIS should be prepared. However, if the agency, in its EA, determines

there are no significant impacts from the proposed project or action, then

it is to prepare a document—a Finding of No Significant Impact—that

presents the reasons why the agency has concluded that no significant

environmental impacts will occur if the project is implemented. An EIS is a

more detailed statement than an EA, and NEPA implementing regulations

specify requirements and procedures—such as providing the public with

an opportunity to comment on the draft document—applicable to the EIS

process that are not mandated for EAs.

5

If a proposed project fits within a category of activities that an agency has

already determined normally does not have the potential for significant

environmental impacts—a CE—and the agency has established that

category of activities in its NEPA implementing procedures, then it

generally need not prepare an EA or EIS.

6

4

The human environment is interpreted comprehensively to include the natural and

physical environment and the relationship of people to that environment (40 C.F.R. §

1508.14). The effects analyzed under NEPA include ecological, aesthetic, historic,

cultural, economic, social, or health (40 C.F.R. § 1508.8).

The agency may instead

approve projects that fit within the relevant category by using one of its

established CEs. For example, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

within the Department of the Interior (Interior) has CEs in place for

numerous types of activities, such as constructing nesting platforms for

wild birds and constructing snow fences for safety. For a project to be

5

An EIS must, among other things, (1) describe the environment that will be affected, (2)

identify alternatives to the proposed action and identify the agency’s preferred alternative,

(3) present the environmental impacts of the proposed action and alternatives, and (4)

identify any adverse environmental impacts that cannot be avoided should the proposed

action be implemented.

6

Some categorical exclusions are established by statute and therefore generally do not

require an agency determination that such actions do not have a significant environmental

impact.

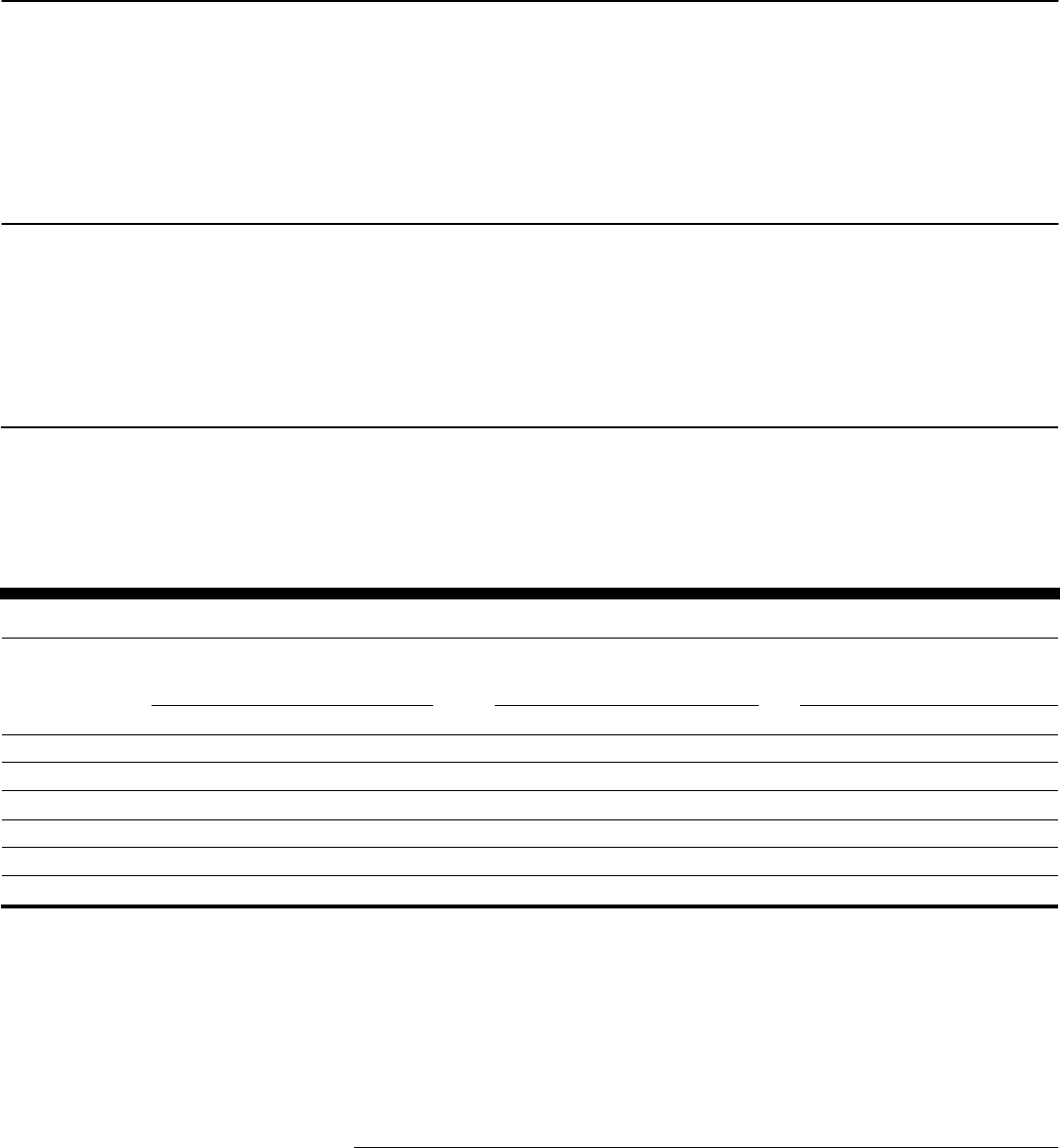

Background

Page 4 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

approved using a CE, the agency must determine whether any

extraordinary circumstances exist in which a normally excluded action

may have a significant effect. Figure 1 illustrates the general process for

implementing NEPA requirements.

Figure 1: Process for Implementing National Environmental Policy Act

Requirements

Private individuals or companies may become involved in the NEPA

process when a project they are developing needs a permit or other

authorization from a federal agency to proceed, such as when the project

involves federal land. For example, a company may apply for such a

permit in constructing a pipeline crossing federal lands; in that case, the

agency that is being asked to issue the permit must evaluate the potential

environmental effects of constructing the pipeline under NEPA. The

private company or developer may in some cases provide environmental

analyses and documentation or enter into an agreement with an agency

to pay a contractor for the preparation of environmental analyses and

Page 5 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

documents, but the agency remains ultimately responsible for the scope

and content of the analyses under NEPA.

7

CEQ within the Executive Office of the President oversees the

implementation of NEPA, reviews and approves federal agency NEPA

procedures, and issues regulations and guidance documents that govern

and guide federal agencies’ interpretation and implementation of NEPA.

8

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also plays two key roles in

other agencies’ NEPA processes. First, EPA reviews and publicly

comments on the adequacy of each draft EIS and the environmental

impacts of the proposed actions reviewed in the EIS. If EPA determines

that the action is environmentally unsatisfactory, it is required by law to

refer the matter to CEQ. Second, EPA maintains a national EIS filing

system. Federal entities must publish in the Federal Register a Notice of

Intent to prepare an EIS and file their draft and final EISs with EPA, which

publishes weekly notices in the Federal Register listing EISs available for

public review and comment.

9

CEQ’s regulations implementing NEPA require federal agencies to solicit

public comment on draft EISs.

10

When the public comment period is

finished, the agency proposing to carry out or permitting a project is to

analyze comments, conduct further analysis as necessary, and prepare

the final EIS. In the final EIS, the agency is to respond to the substantive

comments received from other government agencies and the public.

Sometimes a federal agency must prepare a supplemental analysis to

either a draft or final EIS if it makes substantial changes in the proposed

action that are relevant to environmental concerns, or if there are

significant new circumstances or information relevant to environmental

concerns.

11

7

40 C.F.R. § 1506.5.

Further, in certain circumstances, agencies may—through

8

40 C.F.R. Parts 1500-1508.

9

The EIS process begins with publication of a Notice of Intent stating an agency intends to

prepare an EIS for a proposed project. EPA publishes Notices of Availability in the Federal

Register notifying the public when a draft EIS is available for comment and when a final

EIS is has been issued.

10

While there is no corresponding requirement for an EA public comment period, agencies

may provide one. See, e.g., 40 C.F.R. § 1506.6 (Agencies shall make “diligent efforts to

involve the public in preparing and implementing their NEPA procedures.”)

11

40 CFR § 1502.9(c)(1).

Page 6 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

“incorporation by reference,” “adoption,” or “tiering”—use another analysis

to meet some or, in the case of adoption, all of the environmental review

requirements of NEPA.

12

Unlike other environmental statutes, such as the Clean Water Act or the

Clean Air Act, no individual agency has enforcement authority with regard

to NEPA’s implementation.

13

This absence of enforcement authority is

sometimes cited as the reason that litigation has been chosen as an

avenue by individuals and groups that disagree with how an agency

meets NEPA requirements for a given project.

14

For example, a group

may allege that an EIS is inadequate, or that the environmental impacts

of an action will in fact be significant when an agency has determined

they are not. Critics of NEPA have stated that those who disapprove of a

federal project will use NEPA as the basis for litigation to delay or halt that

project. Others argue that litigation only results when agencies do not

comply with NEPA’s procedural requirements.

Governmentwide data on the number and type of most NEPA analyses

are not readily available, as data collection efforts vary by agency (see

app. II for a summary of federal NEPA data collection efforts). Agencies

do not routinely track the number of EAs or CEs, but CEQ estimates that

EAs and CEs comprise most NEPA analyses. EPA publishes and

maintains governmentwide information on EISs.

12

See 40 C.F.R. §§ 1500.4, 1500.5, and regulations cited therein.

13

Also, unlike these other laws, while NEPA imposes procedural requirements, it does not

establish substantive standards.

14

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation,

RL33152 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 10, 2011). NEPA does not contain civil or criminal

enforcement provisions; litigation challenging an agency’s compliance is brought under

the Administrative Procedure Act.

Data on the Number

and Type of Most

NEPA Analyses Are

Not Readily Available

Page 7 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Many agencies do not routinely track the number of EAs or CEs.

However, based on information provided to CEQ by federal agencies,

CEQ estimates that about 95 percent of NEPA analyses are CEs, less

than 5 percent are EAs, and less than 1 percent are EISs. These

estimates were consistent with the information collected on projects

funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

(Recovery Act).

15

Projects requiring an EIS are a small portion of all

projects but are likely to be high-profile, complex, and expensive. As the

Congressional Research Service (CRS) noted in its 2011 report on

NEPA, determining the total number of federal actions subject to NEPA is

difficult, since most agencies track only the number of actions requiring

an EIS.

16

The percentages of EISs, EAs, and CEs vary by agency because of

differences in project type and agency mission. For example, the

Department of Energy (DOE) reported that 95 percent of its 9,060 NEPA

analyses from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2012 were CEs, 2.6 percent

were EAs, and 2.4 percent were EISs or supplement analyses. Further, in

June 2012, we reported that the vast majority of highway projects are

processed as CEs, noting that the Federal Highway Administration

(FHWA) within the Department of Transportation (DOT) estimated that

approximately 96 percent of highway projects were processed as CEs,

based on data collected in 2009.

17

Of the agencies we reviewed, DOE and the Forest Service officials told

us that CEs are likely underrepresented in their totals because agency

Representing the lowest proportion of

CEs in the data available to us, the Forest Service reported that 78

percent of its 14,574 NEPA analyses from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year

2012 were CEs, 20 percent were EAs, and 2 percent were EISs.

15

The Recovery Act required the President to report to the Senate Environment and Public

Works Committee and the House Natural Resources Committee every 90 days until

September 30, 2011 on the status and progress of projects and activities funded by this

Act with respect to compliance with National Environmental Policy Act requirements and

documentation. Pub. L. No. 111-5, § 1609(c), 123 Stat. 304 (2009). Recovery Act projects

may not be representative of ratios for all NEPA analyses. CEQ reports to Congress on

the status and progress of NEPA reviews under the Recovery Act can be accessed here.

16

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation,

RL33152 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 10, 2011).

17

GAO, Highway Projects: Some Federal and State Practices to Expedite Completion

Show Progress, GAO-12-593 (Washington, D.C.: June 6, 2012).

Many Agencies Do Not

Routinely Track the

Number of EAs or CEs,

but CEQ Estimates That

EAs and CEs Comprise

Most NEPA Analyses

Page 8 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

systems do not track certain categories of CEs considered “routine”

activities, such as emergency preparedness planning. For example, DOE

officials stated that the department has two types of CEs, those that (1)

are routine (e.g., administrative, financial, and personnel actions;

information gathering, analysis, and dissemination) and are not tracked

and (2) are documented as required by DOE regulations.

EPA publishes and maintains governmentwide information on EISs,

updated when Notices of Availability for draft and final EISs are published

in the Federal Register. CEQ and NAEP publish publicly available reports

on EISs using EPA data.

18

Table 1: Number of Environmental Impact Statements from EPA, CEQ, and NAEP, 2008 through 2012

As shown in table 1, the three compilations of

EIS data produce different totals.

Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA)

Council on Environmental

Quality (CEQ)

National Association of

Environmental Professionals

(NAEP)

Calendar year Draft Final Total Draft Final Total Draft Final Total

2008 270 277 547 270 277 547

a

272 276 548

b

2009 252 203 455 252 203 455

c

277 222 499

2010 242 240 482 241 246 487 243 231 474

2011 235 201 436 234 201 435 234 204 438

2012 200 197 397 199 198 397 194 210 404

Total 1,199 1,118 2,317 1,196 1,125 2,321 1,220 1,143 2,363

Sources: GAO analysis of EPA data, and CEQ and NAEP reports.

Notes:

NEPA calls for federal agencies to circulate a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for public

review and comment. When the public comment period is finished, the agency analyzes comments,

conducts further analysis as necessary, and prepares the final EIS. The final EIS is circulated for

review and may be made available for public review and comment.

The differences in EIS numbers are likely due to different assumptions used to count the number of

EISs and minor inconsistencies in the EPA data compiled for the CEQ and NAEP reports and GAO’s

18

NAEP’s annual NEPA reports generally include two sets of EIS data. The first set,

presented in tables 1 and 2, reflects NAEP’s analysis of the number of draft and final EIS

announcements published in the Federal Register. The second set of EIS data are used

by NAEP to analyze the time frames associated with completing EISs. The two sets of EIS

data within NAEP reports generally do not match, in part because the sample of EISs

used to evaluate time frames excludes certain projects, such as “adoptions” or EISs that

were subsequently supplemented.

Governmentwide Data Are

Available on EISs

Page 9 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

analysis of EPA’s database. EPA officials told us that the data it provides to others may differ

because EPA periodically corrects the manually entered data in their EIS database.

a

In 2008, two different CEQ documents listed 543 and 547 total EISs, respectively. We used the 547

value in this table because it matched the sum of the draft and final EIS reported by CEQ in 2008 and

also because it matched the total number we derived from the information supplied by EPA.

b

One section of NAEP’s Annual NEPA Report 2008 identified a total of 548 EISs for 2008, while

another section of the report identified a total of 547. We use 548 for this table to remain consistent

with NAEP’s summary of EIS data for 2008.

c

For 2009, the CEQ source document shows 450 for the total number of EISs, but this is a

computation error because the total from adding the “draft” and “final” entries is 455.

According to CEQ and EPA officials, the differences in EIS numbers

shown in table 1 are likely due to different assumptions used to count the

number of EISs and minor inconsistencies in the EPA data compiled for

the CEQ and NAEP reports and for our analysis of EPA’s data. CEQ

obtains the EIS data it reports based on summary totals provided by EPA.

Occasionally, CEQ also gathers some CE, EA, and EIS data through its

“data call” process, by which it aggregates information submitted by

agencies that use different data collection mechanisms of varying quality.

According to a January 2011 CRS report on NEPA, agencies track the

total draft, final, and supplemental EISs filed, not the total number of

individual federal actions requiring an EIS.

19

Four agencies—the Forest Service, BLM, FHWA, and the U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers within the Department of Defense (DOD)—are

generally the most frequent producers of EISs, accounting for 60 percent

of the EISs in 2012, according to data in NAEP’s April 2013 report.

In other words, agency data

generally reflect the number of EIS documents associated with a project,

not the number of projects.

20

As

shown in table 2, these agencies account for over half of total draft and

final EISs from 2008 through 2012, according to NAEP data.

19

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation,

RL33152 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 10, 2011).

20

NAEP, Annual NEPA Report 2012 of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

Practice (April 2013).

Page 10 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Table 2: Number of Environmental Impact Statements by Agency as Reported by National Association of Environmental

Professionals (NAEP), 2008 through 2012

Forest Service

Bureau of Land

Management

a

Federal Highway

Administration

Army Corps of

Engineers

All other agencies

b

Calendar

year Number

Percentage

of total Number

Percentage

of total Number

Percentage

of total Number

Percentage

of total Number

Percentage

of total Total

2008 123 22 49 9 65 12 43 8 268 49 548

c

2009 134 27 28 6 58 12 41 8 238 48 499

2010 104 22 55 12 56 12 39 8 220 46 474

2011 109 25 42 10 49 11 33 8 205 47 438

2012 102 25 56 14 44 11 41 10 161 40 404

Total 572 24 230 10 272 12 197 8 1,092 46 2,363

Source: GAO analysis of NAEP data.

Note: The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) calls for federal agencies to solicit input by

submitting a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for public comment. When the public

comment period is finished, the agency analyzes comments, conducts further analysis as necessary,

and prepares the final EIS.

a

According to BLM officials, BLM completed 53 NEPA analyses in 2010, 44 in 2011, and 20 in 2012.

We present NAEP’s analysis of EPA data in this table.

b

In 2012, 31 other agencies completed at least 1 draft or final EIS. Five of them prepared 10 or more,

including the National Park Service (21 draft and final EISs) and the Fish and Wildlife Service (19),

both within the Department of the Interior; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

within the Department of Commerce (17); the Navy within the Department of Defense (14); and the

Federal Transit Administration within the Department of Transportation (10). The list of agencies

varied somewhat for each of the other fiscal years presented (2008 through 2011).

c

One section of NAEP’s Annual NEPA Report 2008 identified a total of 548 EISs for 2008, while

another section of the report identified a total of 547. We use 548 for this table to remain consistent

with NAEP’s summary of EIS data for 2008.

Little information exists at the agencies we reviewed on the costs and

benefits of completing NEPA analyses. We found that, with few

exceptions, the agencies did not routinely track data on the cost of

completing NEPA analyses, and that the cost associated with conducting

an EIS or EA can vary considerably, depending on the complexity and

scope of the project. Information on the benefits of completing NEPA

analyses is largely qualitative. Complicating matters, agency activities

under NEPA are hard to separate from other environmental review tasks

under federal laws, such as the Clean Water Act and the Endangered

Species Act; executive orders; agency guidance; and state and local

laws.

Little Information

Exists on the Costs

and Benefits of

Completing NEPA

Analyses

Page 11 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Little information exists on the cost of completing NEPA analyses. With

few exceptions, the agencies we reviewed do not track the cost of

completing NEPA analyses, although some of the agencies tracked

information on NEPA time frames, which can be an element of project

cost.

In general, we found that the agencies we reviewed do not routinely track

data on the cost of completing NEPA analyses. According to CEQ

officials, CEQ rarely collects data on projected or estimated costs related

to complying with NEPA. EPA officials also told us that there is no

governmentwide mechanism to track the costs of completing EISs.

Similarly, most of the agencies we reviewed do not track NEPA cost data.

For example, Forest Service officials said that tracking the cost of

completing NEPA analyses is not currently a feature of their NEPA data

collection system. Complicating efforts to record costs, applicants may, in

some cases, provide environmental analyses and documentation or enter

into an agreement with the agency to pay for the preparation of NEPA

analyses and documentation needed for permits issued by federal

agencies.

21

Two NEPA-related studies completed by federal agencies illustrate how it

is difficult to extract NEPA cost data from agency accounting systems. An

August 2007 Forest Service report on competitive sourcing for NEPA

compliance stated that it is “very difficult to track the actual cost of

performing NEPA. Positions that perform NEPA-related activities are

currently located within nearly every staff group, and are funded by a

large number of budget line items. There is no single budget line item or

budget object code to follow in attempting to calculate the costs of doing

NEPA.”

Agencies generally do not report costs that are “paid by the

applicant” because these costs reflect business transactions between

applicants and their contractors and are not available to agency officials.

22

21

The agency remains responsible for the scope and content of the analyses under NEPA

and the NEPA documentation. 40 C.F.R. § 1506.5.

Similarly, a 2003 study funded by FHWA evaluating the

22

U.S. Forest Service, Competitive Sourcing Program Office, Feasibility Study of Activities

Related to National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Compliance (Washington, D.C.:

Aug. 10, 2007).

Little Information Exists on

the Cost of Completing

NEPA Analyses

Most Agencies We Reviewed

Do Not Track the Cost of

Completing NEPA Analyses

Page 12 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

performance of environmental “streamlining” noted that NEPA cost data

would be difficult to segregate for analysis.

23

However, DOE tracks limited cost data associated with NEPA analyses.

DOE officials told us that they track the funds the agency pays to

contractors to prepare NEPA analyses and does not track other costs,

such as the time spent by DOE employees. According to DOE data, the

average payment to a contractor to prepare an EIS from calendar year

2003 through calendar year 2012 was $6.6 million, with the range being a

low of $60,000 and a high of $85 million.

24

DOE’s median EIS contractor

cost was $1.4 million over that time period. More recently, DOE’s March

2014 NEPA quarterly report stated that for the 12 months that ended

December 31, 2013, the median cost for the preparation of four EISs for

which cost data were available was $1.7 million, and the average cost

was $2.9 million. For context, a 2003 task force report to CEQ—the only

available source of governmentwide cost estimates—estimated that an

EIS typically cost from $250,000 to $2 million.

25

In comparison, DOE’s payments to contractors to produce an EA ranged

from $3,000 to $1.2 million with a median cost of $65,000 from calendar

year 2003 through calendar year 2012, according to DOE data. In its

March 2014 NEPA quarterly report, DOE stated that, for the 12 months

that ended December 31, 2013, the median cost for the preparation of 8

EAs was $73,000, and the average cost was $301,000. For

governmentwide context, the 2003 task force report to CEQ estimated

23

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Evaluating the

Performance of Environmental Streamlining: Phase II (Washington, D.C.: 2003). We have

ongoing work reviewing what is known about any duplication resulting from state and

federal environmental impact review requirements for federal highway projects, as

required by Section 1322 of the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, Pub.

L. No. 112-141, 126 Stat. 405, 553 (2012). We expect to issue a final report by the end of

October 2014.

24

According to DOE, the cost for the $85 million Hanford Tank Closure and Waste

Management EIS includes the costs for three major EISs—waste management, high-level

waste tank closure, and disposition of a nuclear reactor—that were started separately and

ultimately integrated into one document.

25

The NEPA Task Force Report to The Council on Environmental Quality, Modernizing

NEPA Implementation. (September 2003).

Page 13 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

that an EA typically costs from $5,000 to $200,000.

26

Some governmentwide information is available on time frames for

completing EISs—which can be one element of project cost—but few

estimates exist for EAs and CEs because most agencies do not collect

information on the number and type of NEPA analyses, and few

guidelines exist on time frames for completing environmental analyses

(see app. III for information on CEQ NEPA time frame guidelines). NAEP

annually reports information on EIS time frames by analyzing information

published by agencies in the Federal Register, with the Notice of Intent to

complete an EIS as the “start” date, and the Notice of Availability for the

final EIS as the “end” date.

Agencies provided

no cost data on CEs but stated that the cost of a CE—which, in many

cases, is for a “routine” activity, such as repainting a building—was

generally much lower than the cost of an EA.

27

Our review did not identify other

governmentwide sources of these data. Based on the information

published in the Federal Register, NAEP reported in April 2013 that the

197 final EISs in 2012 had an average preparation time of 1,675 days, or

4.6 years—the highest average EIS preparation time the organization had

recorded since 1997.

28

26

The NEPA Task Force Report to The Council on Environmental Quality, Modernizing

NEPA Implementation. (September 2003). This report estimated that a “small” EA typically

costs from $5,000 to $20,000 and a “large” EA costs from $50,000 to $200,000, but the

report did not define “small” and “large.”

From 2000 through 2012, according to NAEP, the

27

According to CEQ officials, time frame data do not reflect certain nuances in the NEPA

process. There could be a number of “non-NEPA” reasons for the “start,” “pause,” and

“stop” of a project, such as waiting for funding or a non-federal permit, authorization, or

other determination.

28

NAEP, Annual NEPA Report 2012 of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

Practice (April 2013). NAEP’s estimates are subject to sampling error and highlight the

considerable variability in the time frames associated with EISs across the federal

government. NAEP presented its time frame data along with margins of error at one

standard deviation. NAEP’s NEPA average preparation time of 1,675 days had a one

standard deviation confidence interval of plus or minus 1,247 days (plus or minus 3.4

years). Also, the number of final EISs included in this sample—197—does not match the

number of final EISs—210—presented for 2012 in table 1. NAEP’s annual reports use two

different sources of information on NEPA analyses, one for its count of NEPA analysis,

and another for analyzing time frames.

Some Information Is Available

on NEPA Time Frames

Page 14 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

total annual average governmentwide EIS preparation time increased at

an average rate of 34.2 days per year.

29

In addition, some agency officials told us that time frame measures for

EISs may not account for up-front work that occurs before the Notice of

Intent to produce an EIS—the “start” date typically used in EIS time frame

calculations. DOT officials told us that the “start” date is unclear in some

cases because of the large volume of project development and planning

work that occurs before a Notice of Intent is issued. DOE officials made a

similar point, noting that time frames are difficult to determine for many

NEPA analyses because there is a large volume of up-front work that is

not captured by standard time frame measures. According to technical

comments from CEQ and federal agencies, to ensure consistency in its

NEPA metrics, DOE measures EIS completion time from the date of

publication of the Notice of Intent to the date of publication of the notice of

availability of the final EIS. Further, according to a 2007 CRS report, a

project may stop and restart for any number of reasons that are unrelated

to NEPA or any other environmental requirement.

30

Less governmentwide information is available on the completion time for

EAs and CEs. According to DOE’s June 2013 quarterly NEPA report, for

the 12 months that ended March 31, 2013, the average completion time

for 16 EAs was 13 months (with a median of 11 months). For the past 10

calendar years (i.e., 2003 through 2012), DOE’s average EA completion

time was 13 months (with a median of 9 months). Interior’s Office of

Surface Mining estimated that its EAs take approximately 4 months on

average to complete, and the Forest Service reported that its 501 EAs in

fiscal year 2012 took an average of about 18 months to complete.

Further, officials from Bureau of Indian Affairs within Interior told us that

For example, a 10-

year time frame to complete a project may have been associated with

funding issues, engineering requirements, changes in agency priorities,

delays in obtaining nonfederal approvals, or community opposition to the

project, to name a few.

29

For more information on EIS time frames, see Piet deWitt and Carole A. deWitt, “How

Long Does It Take to Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement?” Environmental

Practice 10, no. 4 (December 2008) and Piet deWitt and Carole A. deWitt, “Preparation

Times for Final Environmental Impact Statements Made Available from 2007 through

2010,” Environmental Practice 15, no. 2 (June 2013).

30

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act: Streamlining NEPA, RL33267

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2007).

Page 15 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

their EAs are generally completed in about 1 month but that they may

take up to 6 months depending on their complexity. In addition, DOT

officials said that determining the start time of EAs and CEs is even more

difficult than for EISs. The time for completing these can depend in large

part on how much of the up-front work was done already as part of the

preliminary engineering process and how many other environmental

processes are involved (e.g., consultations under the Endangered

Species Act).

The little governmentwide information that is available on CEs shows that

they generally take less time to complete than EAs. DOE does not track

completion times for CEs, but agency officials stated that they usually

take 1 or 2 days. Similarly, officials at Interior’s Office of Surface Mining

reported that CEs take approximately 2 days to complete. In contrast,

Forest Service took an average of 177 days to complete CEs in fiscal

year 2012, shorter than its average of 565 days for EAs, according to

agency documents. The Forest Service documents its CEs with Decision

Memos, which are completed after all necessary consultations, reviews,

and other determinations associated with a decision to implement a

particular proposed project are completed.

According to agency officials, information on the benefits of completing

NEPA analyses is largely qualitative. We have previously reported that

assessing the benefits of federal environmental requirements, including

those associated with NEPA, is difficult because the monetization of

environmental benefits often requires making subjective decisions on key

assumptions.

31

Encouraging public participation. NEPA is intended to help government

make informed decisions, encourage the public to participate in those

decisions, and make the government accountable for its decisions. Public

According to studies and agency officials, some of the

qualitative benefits of NEPA include its role as a tool for encouraging

transparency and public participation and in discovering and addressing

the potential effects of a proposal in the early design stages to avoid

problems that could end up taking more time and being more costly in the

long run.

31

GAO, Federal-Aid Highways: Federal Requirements for Highways May Influence

Funding Decisions and Create Challenges, but Benefits and Costs Are Not Tracked,

GAO-09-36 (Washington, D.C.: December 12, 2008).

Information on the

Benefits of Completing

NEPA Analyses Is Largely

Qualitative

Page 16 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

participation is a central part of the NEPA process, allowing agencies to

obtain input directly from those individuals who may be affected by a

federal action. DOE officials referred to this public comment component of

NEPA as a piece of “good government architecture,” and DOD officials

similarly described NEPA as a forum for resolving organizational

differences by promoting interaction between interested parties inside and

outside the government. Likewise, the National Park Service within

Interior uses its Planning, Environment, and Public Comment (PEPC)

system as a comprehensive information and public comment site for

National Park Service projects, including those requiring NEPA

analyses.

32

Discovering and addressing design problems. One benefit of the

environmental review process, according to a 2012 CRS report, is that it

ultimately saves time and reduces overall project costs by identifying and

avoiding problems that may occur in later stages of project

development.

33

32

Click

Projects that make it through the NEPA process are

financially and environmentally improved, according to a senior NAEP

official, because the process helps planners avoid the multiyear cost of

mitigating a project’s potential adverse effects up front by identifying and

evaluating alternatives that would not otherwise have been identified.

Moreover, agency officials who oversee federal NEPA programs told us

that one of the benefits of NEPA analyses is that they lead to improved

projects. For example, DOT officials stated that the NEPA process allows

project decision makers to discover and solve design problems that could

end up being more costly in the long run. Similarly, Forest Service

officials said that NEPA leads to better decisions on projects because of

the environmental information considered in the process. Providing

examples to illustrate these points, CEQ published a document describing

time savings and improved outcomes on projects funded by the Recovery

Act. Similarly, NEPA Success Stories: Celebrating Forty Years of

Transparency and Open Government—published in August 2010 as a

joint effort by the Environmental Law Institute, the Grand Canyon Trust,

and the Partnership Project—described and highlighted improved

here for more information on PEPC.

33

CRS, The Role of the Environmental Review Process in Federally Funded Highway

Projects: Background and Issues for Congress, R42479, (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 11,

2012).

Page 17 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

environmental outcomes brought about through the NEPA process.

34

DOE has also published a document showing its NEPA “success

stories.”

35

In one example from this document, DOE cited the November

28, 2008, Final Programmatic EIS for the Designation of Energy Corridors

on Federal Lands in 11 Western States (DOE/EIS-0386), that it had

developed in cooperation with BLM. In this case, public comments

resulted in the consideration of alternative routes and operating

procedures for energy transmission corridors to avoid sensitive

environmental resources.

Agency activities under NEPA are hard to separate from other required

environmental analyses, further complicating the determination of costs

and benefits. CEQ’s NEPA regulations specify that, to the fullest extent

possible, agencies must prepare NEPA analyses concurrently with other

environmental requirements. CEQ’s March 6, 2012, memorandum on

Improving the Process for Preparing Efficient and Timely Environmental

Reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act states that

agencies “must integrate, to the fullest extent possible, their draft EIS with

environmental impact analyses and related surveys and studies required

by other statutes or executive orders, amplifying the requirement in the

CEQ regulations.

36

34

Click

The goal should be to conduct concurrent rather than

sequential processes whenever appropriate.” Different types of

environmental analyses may also be conducted in response to other

requirements under federal laws such as the Clean Water Act and the

Endangered Species Act; executive orders; agency guidance; and state

and local laws. As reported in 2011 by CRS, NEPA functions as an

“umbrella” statute; any study, review, or consultation required by any

here to see “NEPA Success Stories and Benefits.” As of February 26, 2014, CEQ’s

NEPA.gov website was down due to security issues.

35

DOE’s NEPA success stories can be found here.

36

40 C.F.R. Parts 1500-1508, at § 1502.25.

Activities under NEPA Are

Hard to Separate from

Other Required

Environmental Analyses,

Complicating the

Determination of Costs

and Benefits

Page 18 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

other law that is related to the environment should be conducted within

the framework of the NEPA process.

37

As a result, the biggest challenge in determining the costs and benefits of

NEPA is separating activities under NEPA from activities under other

environmental laws. According to DOT officials, the dollar costs for

developing a NEPA analysis reported by agencies also includes costs for

developing analyses required by a number of other federal laws,

executive orders, and state and local laws, which potentially could be a

significant part of the cost estimate. Similarly, DOD officials stated that

NEPA is one piece of the larger environmental review process involving

many environmental requirements associated with a project. As noted by

officials from the Bureau of Reclamation within Interior, the NEPA process

by design incorporates a multitude of other compliance issues and

provides a framework and orderly process—akin to an assembly line—

which can help reduce delays. In some instances, a delay in NEPA is the

result of a delay in an ancillary effort to comply with another law,

according to these officials and a wide range of other sources.

Some information is available on the frequency and outcome of NEPA

litigation. Agency data, interviews with agency officials, and available

studies indicate that most NEPA analyses do not result in litigation,

although the impact of litigation could be substantial if a lawsuit affects

numerous federal decisions or actions in several states. The federal

government prevails in most NEPA litigation, according to CEQ and

NAEP data, and legal studies.

37

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation,

RL33152 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 10, 2011). According to technical comments from CEQ

and federal agencies, this statement is overbroad. Studies, reviews, or consultations

required by law and related to the environment may occur outside the NEPA process

when necessary, and in fact this routinely occurs in real practice. Thus, according to the

technical comments, it would be more accurate to track the language in the relevant CEQ

regulation, 40 CFR 1500.2(c).

Some Information Is

Available on the

Frequency and

Outcome of NEPA

Litigation

Page 19 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Agency data, interviews with agency officials, and available studies

indicate that most NEPA analyses do not result in litigation. While no

governmentwide system exists to track NEPA litigation or its associated

costs, NEPA litigation data are available from CEQ, the Department of

Justice, and NAEP. Appendix IV describes how these sources gather

information in different ways for different purposes.

The number of lawsuits filed under NEPA has generally remained stable

following a decline after the early years of implementation, according to

CEQ and other sources. NEPA litigation began to decline in the mid-

1970s and has remained relatively constant since the late 1980s, as

reported by CRS in 2007.

38

More specifically, 189 cases were filed in

1974, according to the twenty-fifth anniversary report of CEQ. In 1994,

106 NEPA lawsuits were filed. Since that time, according to CEQ data,

the number of NEPA lawsuits filed annually has consistently been just

above or below 100, with the exception of a period in the early- and mid-

2000s.

39

In 2011, the most recent data available, CEQ reported 94 NEPA

cases, down from the average of 129 cases filed per year from 2001

through 2008.

40

Although the number of NEPA lawsuits is relatively small when compared

with the total number of NEPA analyses, one lawsuit can affect numerous

federal decisions or actions in several states, having a far-reaching

impact. In addition to CEQ regulations and an agency’s own regulations,

according to a 2011 CRS report, preparers of NEPA analyses and

documentation may be mindful of previous judicial interpretation in an

In 2012, U.S. Courts of Appeals issued 28 decisions

involving implementation of NEPA by federal agencies, according to

NAEP data.

38

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act: Streamlining NEPA, RL33267

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2007).

39

As summarized by CEQ on its website, since 2001, fewer than 175 NEPA cases were

filed each year, with fewer than 100 filed each year in 2007, 2009, 2010, and 2011. A

2004 report by the Environmental Law Institute cited an increase in the number of NEPA

cases filed in 2001 and 2002. See Jay E. Austin, et al. Judging NEPA: A “Hard Look” at

Judicial Decision Making Under the National Environmental Policy Act (Washington, D.C.:

Environmental Law Institute, 2004).

40

Steven K. Imig, NEPA Case Law Update, Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Foundation

Special Institute on the National Environmental Policy Act, October 28-29, 2010, Paper

12.

Available Data Show That

Most NEPA Analyses Do

Not Result in Litigation,

but Individual Cases Can

Have Substantial Impacts

Page 20 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

attempt to prepare a “litigation-proof” EIS.

41

CEQ has observed that such

an effort may lead to an increase in the cost and time needed to complete

NEPA analyses but not necessarily to an improvement in the quality of

the documents ultimately produced.

The federal government prevails in most NEPA litigation, according to

CEQ and NAEP data and other legal studies. CEQ annually publishes

survey results on NEPA litigation that identify the number of cases

involving a NEPA-based cause of action; federal agencies that were

identified as a lead defendant; and general information on plaintiffs (i.e.,

grouped into categories, such as “public interest groups” and “business

groups”); reasons for litigation; and outcomes of the cases decided during

the year.

42

In general, according to CEQ data, NEPA case outcomes are

about evenly split between those involving challenges to EISs and those

involving other challenges to the adequacy of NEPA analyses (e.g., EAs

and CEs). The federal government successfully defended its decisions in

more than 50 percent of the cases from 2008 through 2011. For example,

in 2011, 99 of the 146 total NEPA case dispositions—68 percent—

reported by CEQ resulted in a judgment favorable to the federal agency

being sued or a dismissal of the case without settlement.

43

In 2011, that

rate increased to 80 percent if the 18 settlements reported by CEQ were

considered successes.

44

41

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation,

RL33152 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 10, 2011).

However, the CEQ data do not present enough

case-specific details to determine whether the settlements should be

considered as favorable dispositions. The plaintiffs, in most cases, were

public interest groups.

42

CEQ did not define the terms “public interest group” or “business group” in its published

survey results. According to CEQ officials, CEQ used the terms “public interest group” to

include citizen groups and environmental nongovernmental organizations and the term

“business group” to include business, industry, and development focused groups and

organizations.

43

The total number of dispositions does not relate directly to the 94 cases filed in 2011

because litigation may take multiple years to resolve and there may be more than one

disposition per case.

44

The CEQ surveys identify three types of nonadverse dispositions: (1) judgment for the

defendant; (2) dismissal without settlement; and (3) settlement.

The Federal Government

Prevails in Most NEPA

Litigation

Page 21 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Reporting litigation outcome data similar to CEQ’s, a January 2014 article

on Forest Service land management litigation found that the Forest

Service won nearly 54 percent of its cases and lost about 23 percent.

45

Other sources of information also show that the federal government

prevails in most NEPA litigation. For example, NAEP’s 2012 annual

NEPA report stated that the government prevailed in 24 of the 28 cases

(86 percent) decided by U.S. Courts of Appeals. A NEPA legal treatise

similarly reports that “government agencies almost always win their case

when the adequacy of an EIS is challenged, if the environmental analysis

is reasonably complete. Adequacy cases raise primarily factual issues on

which the courts normally defer to the agency. The success record in

litigation is more evenly divided when a NEPA case raises threshold

questions that determine whether the agency has complied with the

statute. An example is a challenge to an agency decision that an EIS was

not required. Some lower federal courts are especially sensitive to agency

attempts to avoid their NEPA responsibilities.”

About 23 percent of the cases were settled, which the study found to be

an important dispute resolution tool. Litigants generally challenged

logging projects, most frequently under the National Environmental Policy

Act and the National Forest Management Act. The article found that the

Forest Service had a lower success rate in cases where plaintiffs

advocated for less resource use (generally initiated by environmental

groups) compared to cases where greater resource use was advocated.

The report noted that environmental groups suing the Forest Service for

less resource use not only have more potential statutory bases for legal

challenges available to them than groups seeking more use of national

forest resources, but there are also more statutes that relate directly to

enhancing public participation and protecting natural resources.

46

NAEP also provides

detailed descriptions of cases decided by U.S. Courts of Appeals in its

annual reports.

47

45

Amanda M.A. Miner, Robert W. Mamsheimer, and Denise M. Keele, “Twenty Years of

Forest Service Land Management Litigation,” Journal of Forestry 112, no. 1 (January

2014).

46

Daniel R. Mandelker, with the assistance of Robert L. Glicksman, Arianne Michalek

Aughey, JD, and Donald McGillivray, NEPA Law and Litigation, 2

nd

ed. (Thomson

Reuters/West, Rel. 10, 2012).

47

NAEP, Annual NEPA Report 2012 of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

Practice (April 2013).

Page 22 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

We provided a draft of this product to the Council on Environmental

Quality (CEQ) for governmentwide comments in coordination with the

Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Interior, Justice, and

Transportation, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In

written comments, reproduced in appendix V, CEQ generally agreed with

our findings. CEQ and federal agencies also provided technical

comments that we incorporated, as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional

committees; Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality; Secretaries of

Defense, Energy, the Interior, and Transportation; Attorney General;

Chief of the Forest Service within the Department of Agriculture;

Administrator of EPA; and other interested parties. In addition, the report

is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please

and (202) 512-4523 or [email protected]. Contact points for our Offices

of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last

Agency Comments

and Our Evaluation

Page 23 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report

are listed in appendix VI.

Anne-Marie Fennell

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Alfredo Gomez

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Brian Lepore

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Page 24 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

List of Requesters

The Honorable David Vitter

Ranking Member

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Howard P. “Buck” McKeon

Chairman

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Fred Upton

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Doc Hastings

Chairman

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bill Shuster

Chairman

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Honorable Rob Bishop

Chairman

Subcommittee on Public Lands and Environmental Regulation

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 25 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

This appendix provides information on the scope of work and the

methodology used to collect information on how we described the (1)

number and type of National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) analyses,

(2) costs and benefits of completing those analyses, and (3) frequency

and outcomes of related litigation. We included available information on

both costs and benefits to be consistent with standard economic

principles for evaluating federal programs and generally accepted

government auditing standards.

To respond to these objectives, we reviewed relevant publications,

obtained documents and analyses from federal agencies, and interviewed

federal officials and individuals from academia and a professional

association with expertise in conducting NEPA analyses. Specifically, to

describe the number and type of NEPA analyses and what is known

about the costs and benefits of NEPA analyses, we reported information

identified through the literature review, interviews, and other sources. We

selected the Departments of Defense, Energy, the Interior, and

Transportation and the Forest Service within the U.S. Department of

Agriculture for analysis because they generally complete the most NEPA

analyses. Our findings for these agencies are not generalizeable to other

federal agencies.

To assess the availability of information to respond to these objectives,

we (1) conducted a literature search and review with the assistance of a

technical librarian; (2) reviewed our past work on NEPA and studies from

the Congressional Research Service; (3) obtained documents and

analyses from federal agencies; and (4) interviewed officials who oversee

federal NEPA programs from the Departments of Defense, Energy, the

Interior, Justice, and Transportation; the Forest Service within the

Department of Agriculture; the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA);

the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) within the Executive Office of

the President; and individuals with expertise from academia and the

National Association of Environmental Professionals (NAEP)—a

professional association representing private and government NEPA

practitioners.

Specifically, to describe the number and type of NEPA analyses from

calendar year 2008 through calendar year 2012, we analyzed data

identified through the literature review and interviews. We focused on

data and documents maintained by CEQ, EPA, and NAEP. CEQ and

NAEP periodically report data on the number of certain types of NEPA

analyses, and EPA maintains a database of Environmental Impact

Statements, one of its roles in implementing NEPA. To generate

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 26 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

information on the number of Environmental Impact Statements from

EPA’s database, we sorted the data by calendar year and counted the

number of analyses for each year. We did not conduct an extensive

evaluation of this database, although a high-level analysis discovered

potential inconsistencies. For example, EPA’s database contained entries

with the same unique identifier, making it difficult to identify the exact

number of NEPA analyses. We discussed these inconsistencies with EPA

officials, who told us that they were aware of certain errors due to manual

data entry and the use of different analysis methods. These officials said

that EPA EIS data provided to others may differ because EPA periodically

corrects the manually entered data. We did not count duplicate records in

our analysis of EPA’s data. We believe these data are sufficiently reliable

for the purposes of this report.

To describe what is known about the costs and benefits of NEPA

analysis, we reported the available information on the subject identified

through the literature review and interviews. To describe the frequency

and outcome of NEPA litigation we (1) reviewed laws, regulations, and

agency guidance; (2) reviewed NEPA litigation data generated by CEQ

and NAEP; (3) interviewed Department of Justice officials; and (4)

reviewed relevant legal studies.

Information from these sources is cited in footnotes throughout this report.

To answer the various objectives, we relied on data from several sources.

To assess the reliability of data collected by agencies and NAEP, we

reviewed existing documentation, when available, and interviewed

officials knowledgeable about the data. We found all data sufficiently

reliable for the purposes of this report.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2013 to April 2014 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Summary of Federal NEPA Data

Collection Efforts

Page 27 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) data collection efforts

vary by agency. The Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) NEPA

implementing regulations set forth requirements that federal agencies

must adhere to, and require federal agencies to adopt their own

procedures, as necessary, that conform with NEPA and CEQ’s

regulations.

1

Federal agencies decide how to apply CEQ regulations in

the NEPA process. According to a 2007 Congressional Research Service

(CRS) report, the CEQ regulations were meant to be generic in nature,

with individual agencies formulating procedures applicable to their own

projects.

2

As stated by a CEQ official, “there is no master NEPA spreadsheet, and

there are many gaps in NEPA-related data collected across the federal

government.” To obtain information on agency NEPA activities, the official

said that CEQ works closely with its federal agency NEPA contact group,

composed of key officials responsible for implementing NEPA in each

agency. CEQ meets regularly with these officials and uses this network to

collect NEPA-related information through requests for information,

whereby CEQ distributes a list of questions to relevant agencies and then

collects and reports the answers. According to CEQ officials, NEPA data

reported by CEQ are generated through these requests, which have

quality assurance limitations because related activities at federal

departments are themselves diffused throughout various offices and

bureaus.

The report states that this approach was taken because of the

diverse nature of projects and environmental impacts managed by federal

agencies with unique mandates and missions. Consequently, NEPA

procedures vary to some extent from agency to agency, and

comprehensive governmentwide data on NEPA analyses are generally

not centrally collected.

Of the agencies we reviewed, the Departments of Defense, the Interior,

and Transportation do not centrally collect information on NEPA analyses,

allowing component agencies to collect the information, whereas the

Department of Energy and the Forest Service within the Department of

Agriculture aggregate certain data.

1

40 C.F.R. § 1507.3.

2

CRS, The National Environmental Policy Act: Streamlining NEPA, RL33267

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2007).

Appendix II: Summary of Federal NEPA Data

Collection Efforts

Appendix II: Summary of Federal NEPA Data

Collection Efforts

Page 28 GAO-14-369 National Environmental Policy Act

Department of Defense (DOD). Each of the military services and defense

agencies collects data on NEPA analyses, but DOD does not aggregate

information that is collected on the number and type of NEPA analyses at

the departmentwide level. Data collection within the military services and

agencies is decentralized, according to DOD officials. For example, the

Army collects Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) data at the

Armywide level, and responsibility for Environmental Assessments (EA)

and Categorical Exclusions (CE) are delegated to the lowest possible

command level. DOD officials said that each of the services and defense

agencies works to maintain a balance between the work that needs to be

completed and the management effort needed to accomplish that work.

While the level of information collected may vary by service or defense

agency, each collects the information that it has determined necessary to

manage its NEPA workload. According to these officials, every new

information system and data call must generally come from existing

funding, taking resources from other tasks.

Department of the Interior (Interior). Data are not collected at the

department level, according to Interior officials, and Interior conducts its

own departmentwide data calls to component bureaus and entities

whenever CEQ asks for NEPA-related information. The data collection

efforts of its individual bureaus vary considerably. For example, the

National Park Service uses its Planning, Environment, and Public

Comment (PEPC) system as a comprehensive information and public

comment site for National Park Service projects. Other Interior bureaus

are beginning to track information or rely on less formal systems and not

formalized databases. For example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs uses its

internal NEPA Tracker system—started in September 2012—which the

bureau states is to collect information on NEPA analyses to create a