A Guide to Property Taxes:

An Overview

By

Mandy Rafool

NCSL Fiscal Affairs Program

National Conference of State Legislatures

William T. Pound, Executive Director

1560 Broadway, Suite 700

Denver, CO 80202-5140

444 North Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 515

Washington, DC 20001

http: //www.ncsl.org

May 2002

The National Conference of State Legislatures is the bipartisan organization that serves the legislators and

staffs of the states, commonwealths and territories.

• To improve the quality and effectiveness of state legislatures.

• To promote policy innovation and communication among state legislatures.

• To ensure state legislatures a strong, cohesive voice in the federal system.

NCSL provides research, technical assistance and opportunities for policymakers to exchange ideas on the

most pressing state issues and is an effective and respected advocate for the interests of the states in the

American federal system.

Printed on recycled paper

2002 by the National Conference of State Legislatures. All rights reserved.

ISBN 1-58024-235-9

National Conference of State Legislatures iii

CONTENTS

Preface and Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................iv

Participating Legislators and Legislative Staff ...................................................................................vi

Representatives of the Foundation Fiscal Partners ...........................................................................vii

About the Author....................................................................................................................................iv

Introduction.............................................................................................................................................1

The Property Tax.....................................................................................................................................2

History of the Property Tax .....................................................................................................................2

Types of Taxable Property........................................................................................................................2

Determining the Tax Base........................................................................................................................3

Who Levies Property Taxes?.....................................................................................................................4

How Property Taxes Work.......................................................................................................................5

Other Valuation Methods...............................................................................................................10

Equalization....................................................................................................................................10

Appeals ...........................................................................................................................................11

Property Tax Limits........................................................................................................................11

Reliance on the Property Tax ..........................................................................................................11

Property Tax Burdens ............................................................................................................................14

Appendices

A. Tax Treatment of Personal and Intangible Property, by State .......................................................17

B. Property Classification, by State ...................................................................................................20

C. Tax Treatment of Agricultural Property, by State .........................................................................27

D. Property Taxes as a Percent of Total State and Local Revenue ......................................................30

E. Total State and Local Taxes, FY 1999 ..........................................................................................31

Notes ....................................................................................................................................................32

iv National Conference of State Legislatures

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mandy Rafool is a senior policy specialist with the Fiscal Affairs Program at National

Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). She works on a wide variety of issues with special

emphasis on general state tax policy. She is the author of State Tax Actions 2001, State Tax

Actions 2000 and State Tax Actions 1999. In addition, she covers general fiscal issues such as

state tax and expenditure limits, death taxes, funding for arts and tourism, and funding for

sports facilities. She also wrote State Death Taxes and the updated version of Travel and

Tourism: A Legislator’s Guide, several reports and articles on other fiscal issues, including State

Tourism Taxes, State Tax and Expenditure Limits and Playing the Stadium Game: Financing

Professional Sports Facilities in the ‘90s.

An NCSL staff member since 1994, Ms. Rafool holds an undergraduate degree in business

administration from Colorado State University and a master’s degree in public

administration from the University of Colorado.

National Conference of State Legislatures v

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several members of the National Conference of State Legislatures’ (NCSL) Foundation for

State Legislatures convened in 1991 to discuss how they could assist in the development of

sound state fiscal policy. They concurred that they could pool their resources to examine

specific areas of state fiscal policy and then make recommendations on these state fiscal

policy issues. This group, known as the Foundation Fiscal Partners, supports the NCSL

Fiscal Affairs Program in an ongoing effort to improve the quality of fiscal information

available to state policymakers.

One of the continuing goals of the Foundation Fiscal Partners Project is to improve dialogue

among state legislators, business representatives, and other organizations that are interested in

and affected by state fiscal policy. Basic information is an important tool for state

policymakers who must make decisions about how best to generate revenue in this new

economic environment. This Foundation Fiscal Partners Project, A Guide to Property Taxes,

will provide solid comparative information to assist legislatures with those decisions.

Property taxes, which generally are not well understood, make up one of the most complex

revenue systems used at the state and local levels. This project consists of three stand-alone

reports that together provide a resource for policymakers and others. The three project

reports are listed below.

1. A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

The first product is an overview. This report examines the various types of taxable property

and explains the mechanics of how property taxes are levied. It also examines various types of

property and examines how states classify property and how they apply different assessment

ratios.

2. A Guide to Property Taxes: Property Tax Relief

States provide property tax relief to citizens in a number of different ways, and the number

and type of relief has increased significantly in the past few years. The second report of the

Foundation Fiscal Partners Project will discuss state relief efforts, including homestead

exemptions, circuit breaker programs, tax deferrals and property tax freezes, among others.

vi A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures Legislatures

3. A Guide to Property Taxes: The Role of Property Taxes in State and Local

Finances

During the past decade, the relationship between property taxes and state and local

government services has changed significantly. Years of surplus revenue, coupled with voter

dislike of the property tax, has resulted in major property tax cuts and has forced states to

shoulder a growing share of education costs. In addition, a number of states rely heavily on

businesses and personal property to provide a large portion of property tax revenue.

Sometimes these taxes are not very straightforward or obvious. This report will begin to

examine some of these issues.

A Guide to Property Taxes is the sixth Foundation Fiscal Partners Project. Previous

Foundation Fiscal Partners Project publications include:

Principles of a High-Quality State Revenue System (November 1992)

Fundamentals of Sound State Budgeting Practices (May 1995)

State Strategies to Manage Budget Shortfalls (December 1996)

Critical Issues in State-Local Fiscal Policy, Part 1: Sorting Out State and Local Responsibilities

(July 1997) and

Part 2: A Guide to Local Option Taxes (November 1997)

The Appropriate Role of User Fees in State and Local Finance (June 1999)

Participating Legislators and Legislative Staff

Representative Macy Easley, Oklahoma

Senator John Fonfara, Connecticut

Senator Emmet Hanger, Virginia

Senator Beverly Hollingworth, New Hampshire

Senator Bob Jauch, Wisconsin

Representative Ann Kitchen, Texas

Senator Janis Lee, Kansas

Representative Steve May, Arizona

Senator Caroline McCarley, New Hampshire

Representative Jim Murphy, Missouri

Representative Alice Nitka, Vermont

Representative Lane Shetterly, Oregon

Senator Ron Teck, Colorado

Representative Peggy Welch, Indiana

Fred Baatz, South Dakota

Deborah Davison, Louisiana

Lee Derr, Pennsylvania

Joe Falzon, District of Columbia

Bob Keaton, Louisiana

George Kilpatrick, Nebraska

Stephen Klein, Vermont

Bill Lock, Nebraska

Bill Marx, Minnesota

Matt Massman, Minnesota

Rick Olin, Wisconsin

Preface and Acknowledgments vii

National Conference of State Legislatures

Martin Poethke, New Jersey

Dennis Prouty, Iowa

John Rappa, Connecticut

Bill Robinson, Texas

Sara Teachout, Vermont

Jean Vandal, Louisiana

Andrea Wilko, Utah

Jay Wortley, Michigan

Representatives of the Foundation Fiscal Partners

American Federation of Teachers: Ed Muir and Bill Tammelleo

International Council of Shopping Centers: Herbert Tyson

NCSL Foundation for State Legislatures: Caroline Carlson

National Education Association: Janis Hagey and Ed Hurley

Philip Morris Management Corporation: Pam Inmann and Michael Stojsavljevich

Mandy Rafool is the principal author of this report, with contributions by Judy Zelio.

Corina Eckl and Leann Stelzer provided valuable editing advice, Anabliss Design designed

the cover, and Lisa Houlihan prepared the report for publication.

The author also would like to acknowledge former NCSL staff member Scott Mackey, who

originally wrote some of the text. Special thanks go to the funding partners for their generous

support and the legislative partners for their insight and contributions.

This page intentionally left mostly blank viii

National Conference of State Legislatures 1

INTRODUCTION

The Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview is the first report in a three-part series of property

tax publications produced by the NCSL Foundation Fiscal Partners. The purpose of this

Foundation Fiscal Partners Project is to introduce policymakers to property taxes and the

associated policy issues. Even though the property tax is largely a local tax, state law provides

the power to impose it. In addition, state legislatures develop property tax policies that have

major effects on local governments’ ability to raise revenue and provide services.

This first report, a property tax overview, contains basic information about property taxes

and how they are administered. The other two project publications will focus on property tax

relief and the role of property taxes in state and local finances. The three project reports are

listed below.

A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

A Guide to Property Taxes: Property Tax Relief

A Guide to Property Taxes: The Role of Property Taxes in State and Local Finances

2 National Conference of State Legislatures

THE PROPERTY TAX

History of the Property Tax

The property tax carries the weight of a long and honored tradition. Even before the

existence of money, early leaders received payments from their subjects in the form of

property. Over time, this practice evolved into the concept of taxation based on value, what

is now termed an ad valorum or property tax.

The property tax, which began in the United States as a national tax on land parcels,

provided a way for a fledgling country to fund its fight for freedom. As the young nation

expanded, state governments also grew and assumed more responsibilities. Taxes on property

provided the means to fund new state services while the federal government started to rely

more heavily on tariffs for revenue.

In the mid-1800s, local governments grew rapidly, surpassing state governments in number

and taking over investment in transportation, infrastructure and schools. Again, property

taxes supplied the revenue in a pattern that became the foundation for the current system of

fiscal federalism. Property taxes continued to be the primary source of local revenue in the

early 20th century, while the states turned to new revenue sources such as taxes on

automobiles. Later, during the great depression of the 1930s, states began levying

consumption taxes on general sales as their primary revenue source—a trend that remained.

Eventually, states began to impose taxes on income. Today, sales and income taxes are the

major revenue sources for states. As a result, the property tax remains almost exclusively a

local tax.

Types of Taxable Property

What exactly does it mean to tax property? Public finance textbooks describe property taxes

as levies on wealth, in contrast to two other categories of broad-based taxes: levies on income

(income taxes) and levies on consumption (sales taxes).

The Property Tax 3

National Conference of State Legislatures

As the property tax system developed in the United States, it adhered to the concept that all

property was taxable. New categories of property were taxed as they evolved, with new names

to fit. Now, for property tax purposes, three general categories of wealth are real property,

personal property and intangible property. The type of property taxed varies by state, but

most states use these general categories. Furthermore, other types of business property—such

as inventories, equipment and utility property—are beyond the scope of this report and are

not discussed here.

Real property. Real property, simply defined, is land and any permanent improvements to

the land, such as a building or other structure. It is generally labeled as residential,

commercial or agricultural. Real property is taxed in every state unless it is specifically

exempt.

Personal property. Personal property is defined as everything subject to ownership that is not

real property. In other words, it is property that can be seen, touched or moved around, such

as a vehicle or boat. At least some tangible personal property is taxable in most states,

although household goods and personal effects usually are exempt. Delaware, Hawaii,

Illinois, Iowa, New York and Pennsylvania exempt all personal property from property taxes.

Intangible property. Intangible property includes intangible financial assets, such as

investments in stocks and bonds. Only a few states tax intangible personal property.

Appendix A illustrates the tax treatment of personal and intangible property by state. As

mentioned earlier, real property is taxed in all states.

Determining the Tax Base

State lawmakers establish the tax base by determining what type of property is taxable. In

addition, they frequently reduce the tax base through property tax exemptions and

abatements.

Exemptions, which exclude certain types of property from taxation, vary tremendously from

state to state. Government-owned property and property owned by nonprofit organizations,

schools, religious institutions and other special categories of property almost always are

exempt. The list of exemptions is quite extensive in some states, which may cause financial

hardship for local governments that rely heavily on property tax revenues to provide services.

Some states reimburse local governments for lost property tax revenue. For example,

Minnesota makes payments to local governments for state wildlife lands used for hunting.

Wisconsin provides a reimbursement payment to local governments for state parks, forests

and other natural areas purchased by the Department of Natural Resources, based on the tax

that otherwise would be paid on that property.

A number of states also provide property tax abatements. Abatements differ from

exemptions in that the property in question is subject to taxation, but it is taxed at a reduced

rate. Abatements frequently are used as a tool to promote new development in designated

areas. For example, a community that wants to promote new development in a run-down or

4 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

“blighted” area may offer private developers a property tax abatement as an incentive to build

in the desired location.

In addition, property tax abatements may be court ordered. For example, if a taxpayer

challenges his property tax bill and wins, the courts may order a reduction in property value

after property taxes have been levied and before they are paid, resulting in a property tax

abatement.

Who Levies Property Taxes?

States and a variety of local government entities may levy property taxes. Depending on the

state, taxing authority may be granted to counties, municipalities, townships, school districts

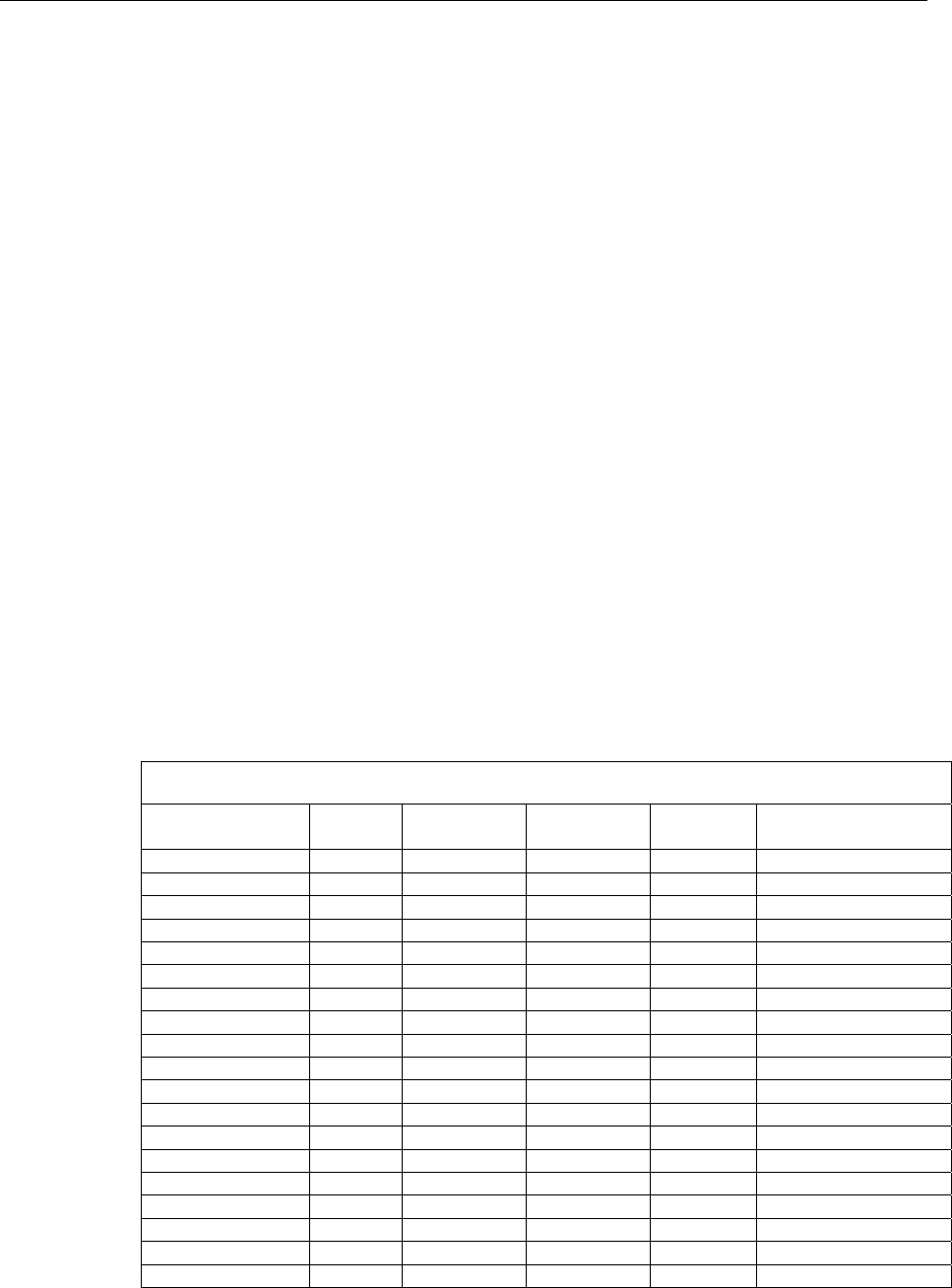

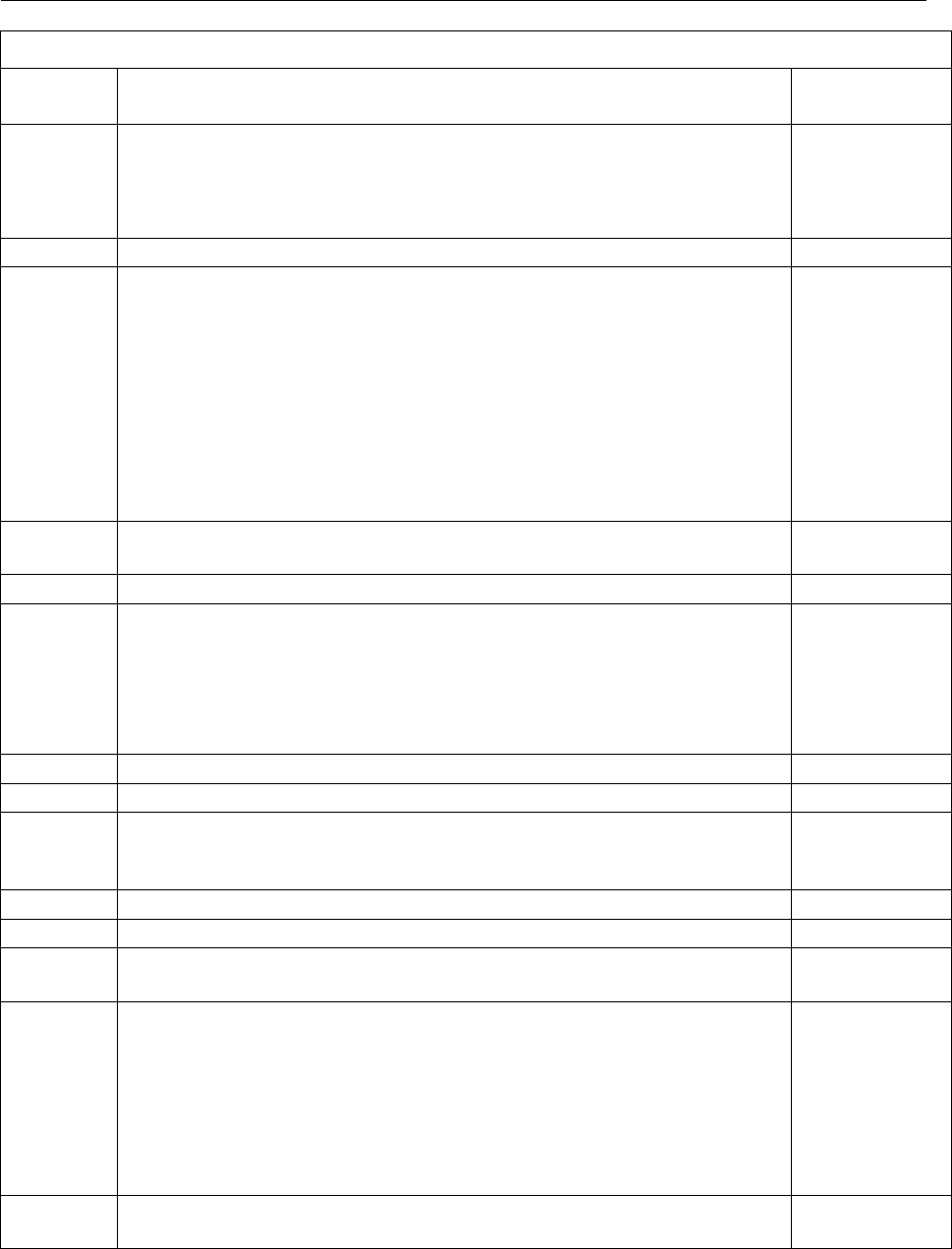

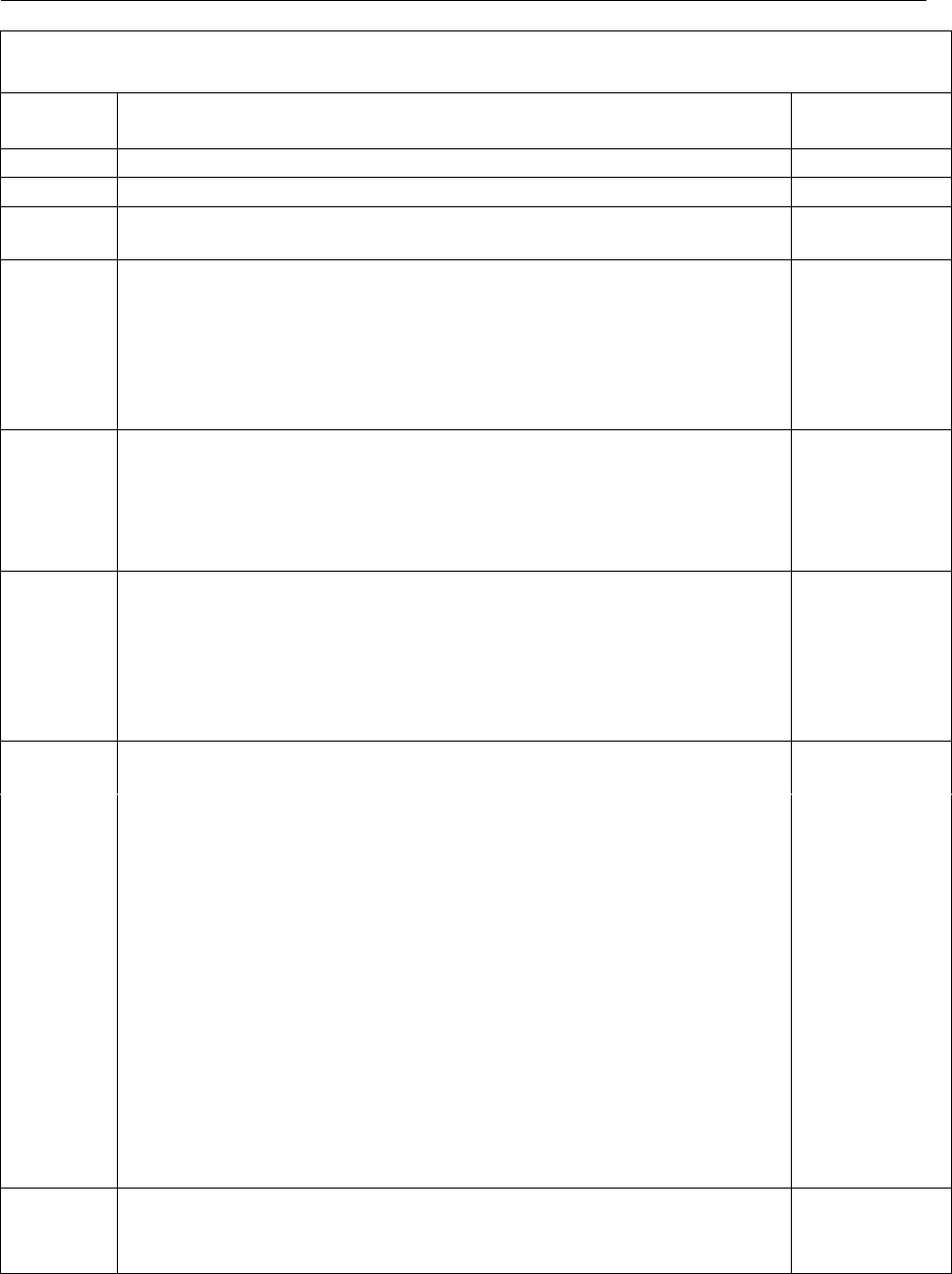

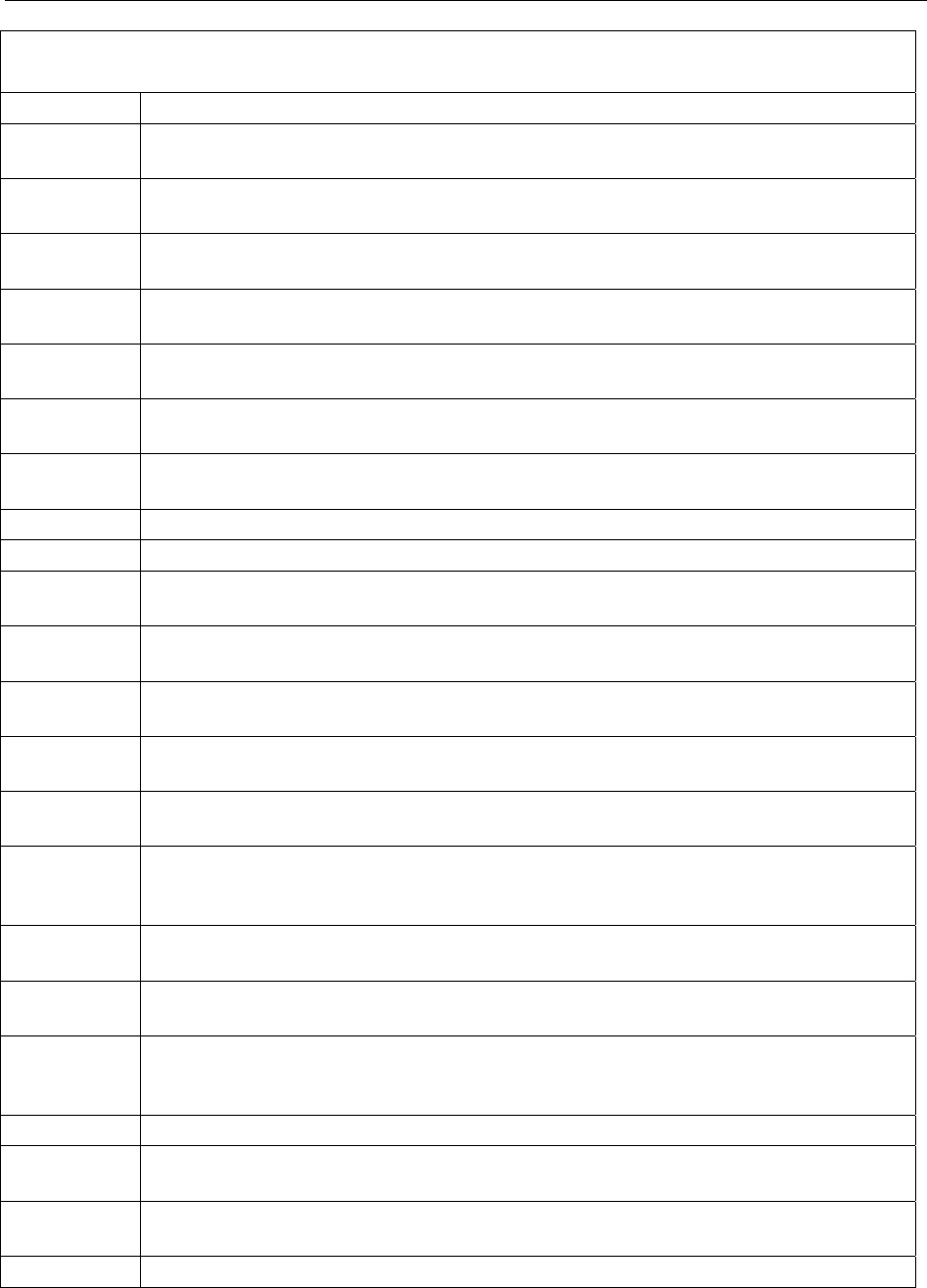

and special districts. Table 1 shows the results of a 2000 survey conducted by the

International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO). The survey asked property tax

administrators what major units of government (independent taxing districts) receive

revenue directly from the property tax or from a central collector of property tax (such as a

county collector). Respondents were asked not to include government entities that receive

property taxes indirectly (from another government). The survey found that counties in 45

states, municipalities in 48 states and the District of Columbia, townships in 24 states,

school districts in 42 states and special districts in 20 states receive revenue directly from

property taxes. In two states—Connecticut and Rhode Island—municipalities receive all

property tax revenue, but in most states property tax revenue is allocated among counties,

municipalities and school districts. Generally, school districts are the most dependent on

property taxes because cities and counties often have other revenue sources such as local

option sales or income taxes.

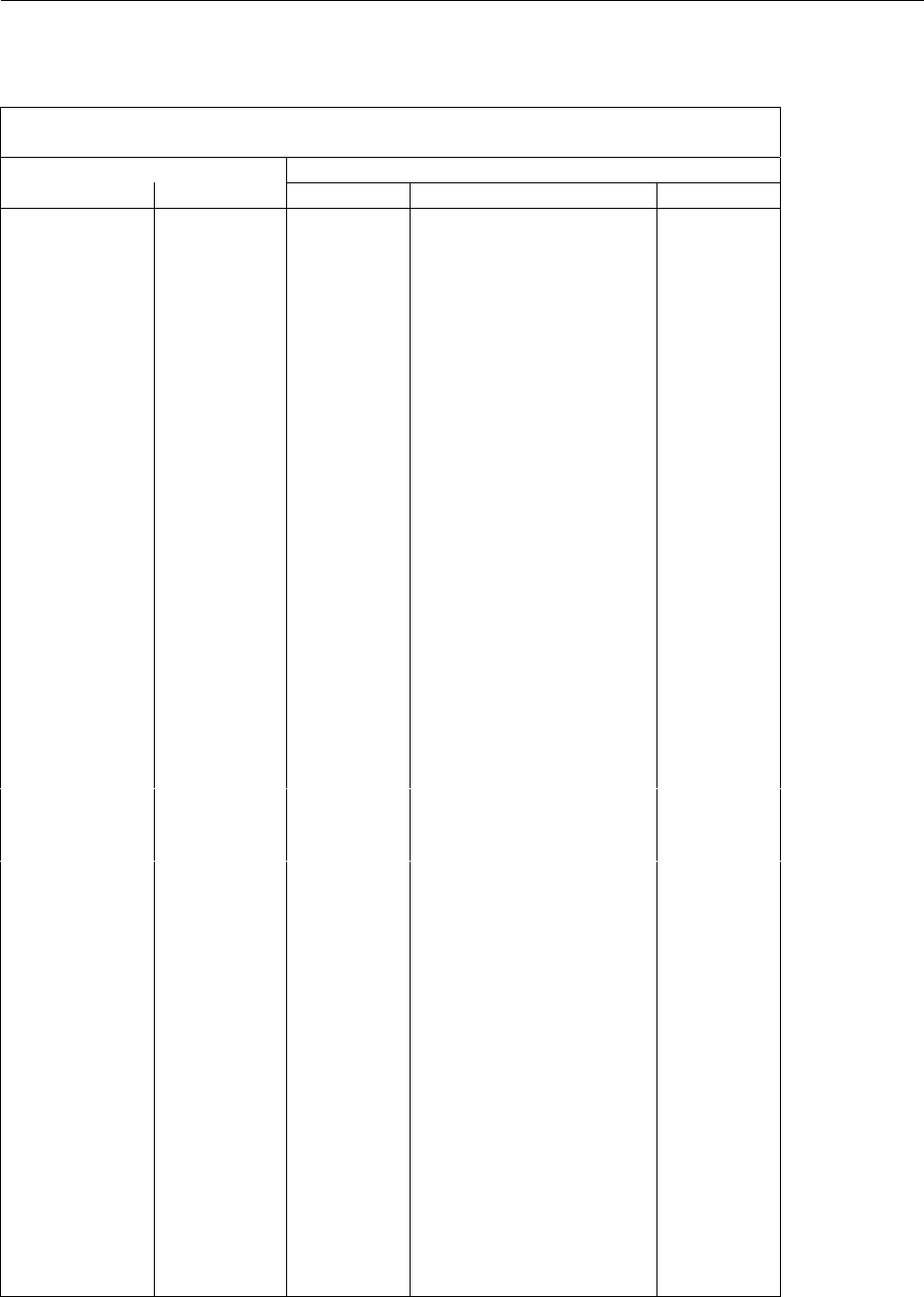

Table 1. Major Units of Local Government Receiving Property Tax

State/Jurisdiction

County

City or

Municipality

Township or

Equivalent

School

District

Special District or

Other Entity

Alabama

9 9 9

Alaska

9 9 9

Arizona

9 9 9 9

Arkansas

9 9 9

California

9 9 9

Colorado

9 9 9 9

Connecticut

9

Delaware

9 9 9

Florida

9 9 9 9

Georgia

9 9 9

Hawaii

9 9

Idaho

9 9 9 9

Illinois

9 9 9 9 9

Indiana

9 9 9 9 9

Iowa

9 9 9 9 9

Kansas

9 9 9 9 9

Kentucky

9 9 9 9

Louisiana

9 9 9 9 9

Maine

9 9

The Property Tax 5

National Conference of State Legislatures

Table 1. Major Units of Local Government Receiving Property Tax

(continued)

State/Jurisdiction

County

City or

Municipality

Township or

Equivalent

School

District

Special District or

Other Entity

Maryland

9 9

Massachusetts

9 9

Michigan

9 9 9 9

Minnesota

9 9 9 9

Mississippi

9 9 9 9

Missouri

9 9 9 9 9

Montana

9 9 9 9

Nebraska

9 9 9 9 9

Nevada

9 9 9 9 9

New Hampshire

9 9 9

New Jersey N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A

New Mexico

9 9 9

New York

9 9 9 9

North Carolina

9 9 9

North Dakota

9 9 9 9 9

Ohio

9 9 9 9 9

Oklahoma

9 9 9 9

Oregon

9 9 9 9 9

Pennsylvania

9 9

Rhode Island

9

South Carolina

9 9 9 9

South Dakota

9 9 9 9 9

Tennessee

9 9 9

Texas

9 9 9 9

Utah

9 9 9 9

Vermont

9 9 9

Virginia

9 9 9

Washington

9 9 9 9

West Virginia

9 9 9

Wisconsin

9 9 9 9

Wyoming

9 9 9 9

District of Columbia

9

Total 45 49 24 42 20

Source: International Association of Assessing Officers, Property Tax Policies and Administrative Practices

in Canada and the United States, 2000.

In addition, 15 states levy property taxes at the state level. This issue is discussed further on

page 13.

How Property Taxes Work

The way in which property taxes operate is complicated, and the general public sometimes

confuses the process of valuing property with the process of determining tax rates. Property

values and tax rates are equally important in determining how much tax is due and how

much property tax bills change from year to year.

6 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

The process of determining how much a homeowner owes has two separate steps:

• Determining the taxable value of the property.

• Determining the amount of the tax on the basis of taxable value.

Determining the taxable value. The first step is determining the taxable value of the

property. Assessors—locally elected in many states—set the value of property, based upon

standards established in state law. In setting property values, assessors typically use market

value—in which they consider the sales prices of comparable property in the same area—and

factors such as square footage, garages, decks, the number of bathrooms, and other amenities.

Assessors also consider remodeling and other improvements that increase the property’s

value.

Assessors typically employ one or more of the following methods to value real property:

• The “market data” or “comparable sales” method, under which value is determined by

analyzing recent sales of similar properties in the vicinity;

• The “cost” method, under which value is determined by analyzing the cost to construct

or replace the subject property; and

• The “income” method, under which value is determined by capitalizing the anticipated

annual income for the useful life of the subject property.

1

Regardless of the method, the assessment process is a frequent subject of complaint about the

property tax system. Even in states that have professional assessors, valuing property is not an

exact science. Property owners with similar homes in the same areas can face very different

tax bills, depending upon the time of the last assessment and other factors.

State law sets the frequency of reassessment. Intervals between reappraisals vary from one to

10 years. Longer assessment cycles can be troublesome in areas where property values are

increasing rapidly because several years of property appreciation can cause large increases in

property taxes. (However, this problem can be mitigated over time if the amount of taxable

property within a tax district grows, because the district will have a larger tax base.) In

addition, 34 states and the District of Columbia adjust property values between reappraisals

using statistical methods such as sales-ratio analysis, which compare sales prices to assessed

values.

2

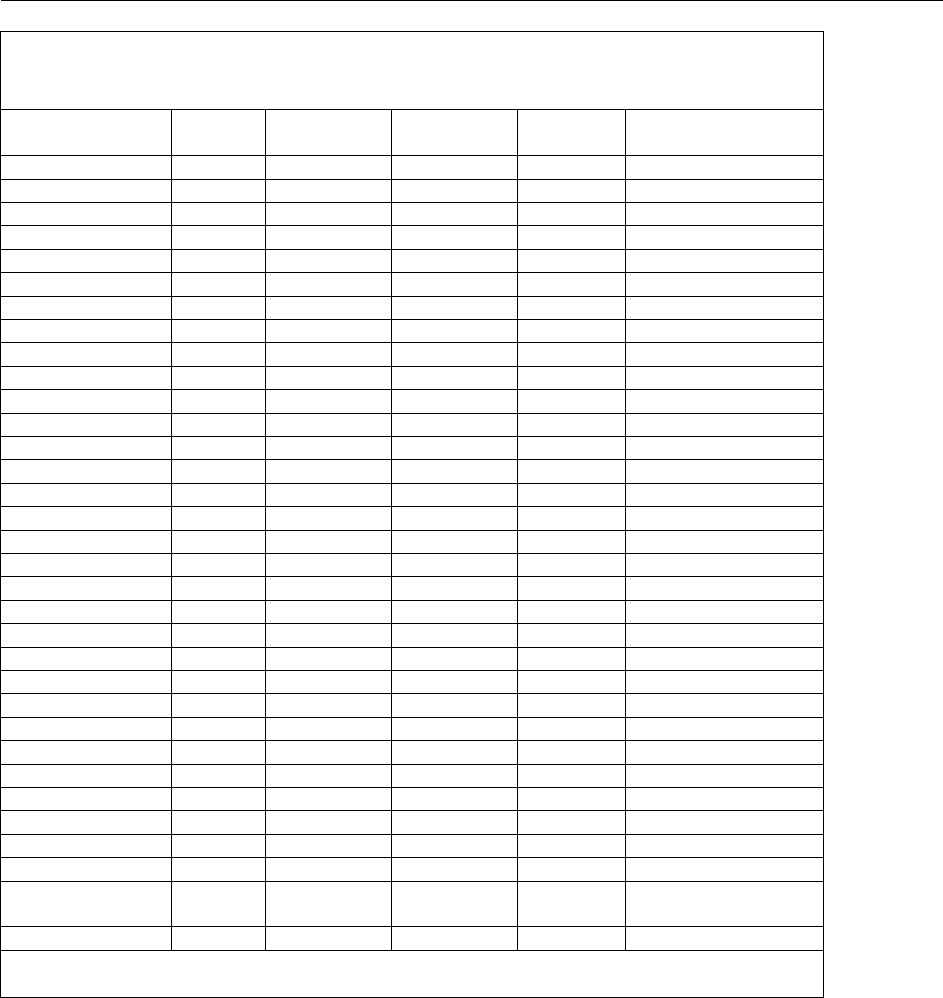

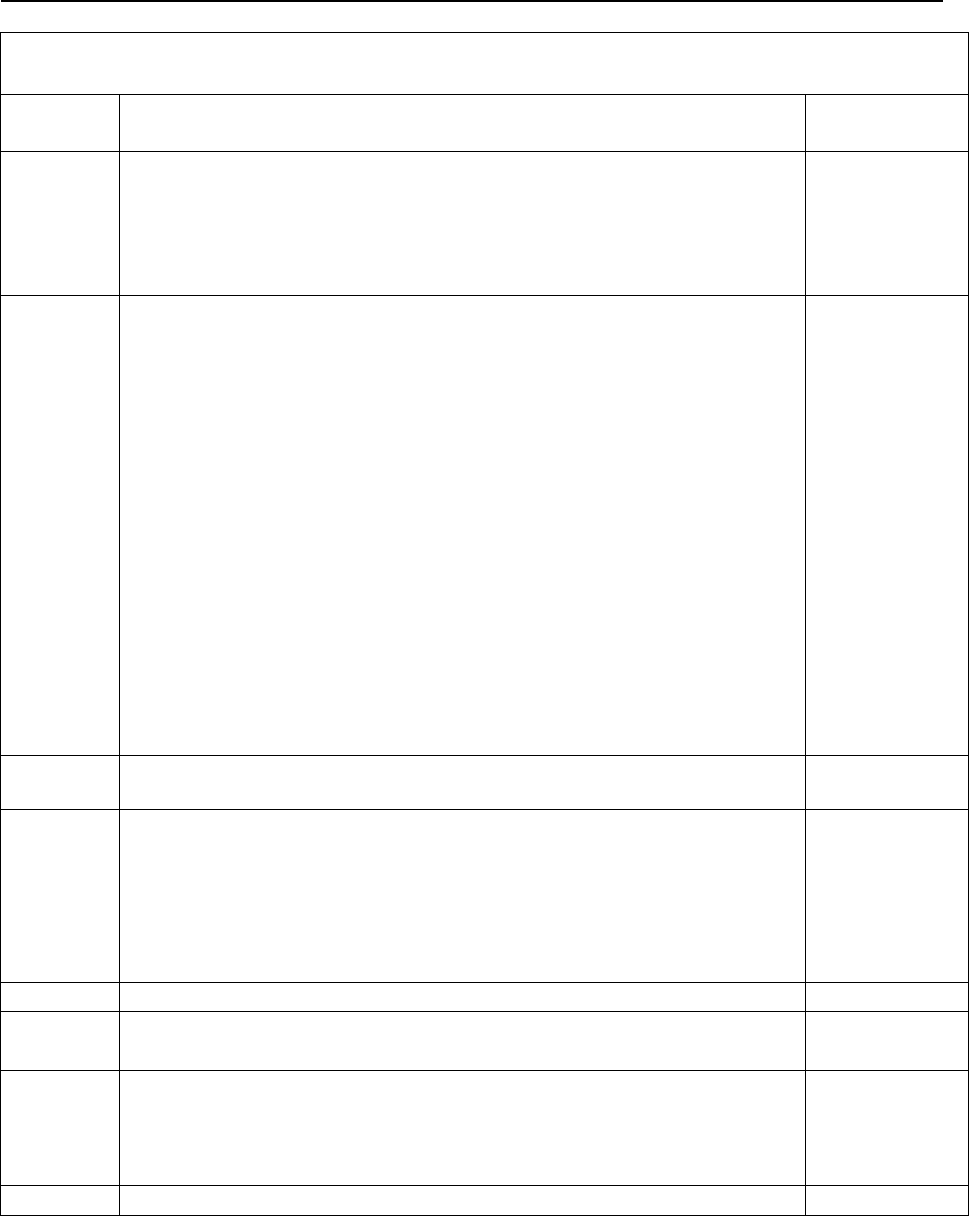

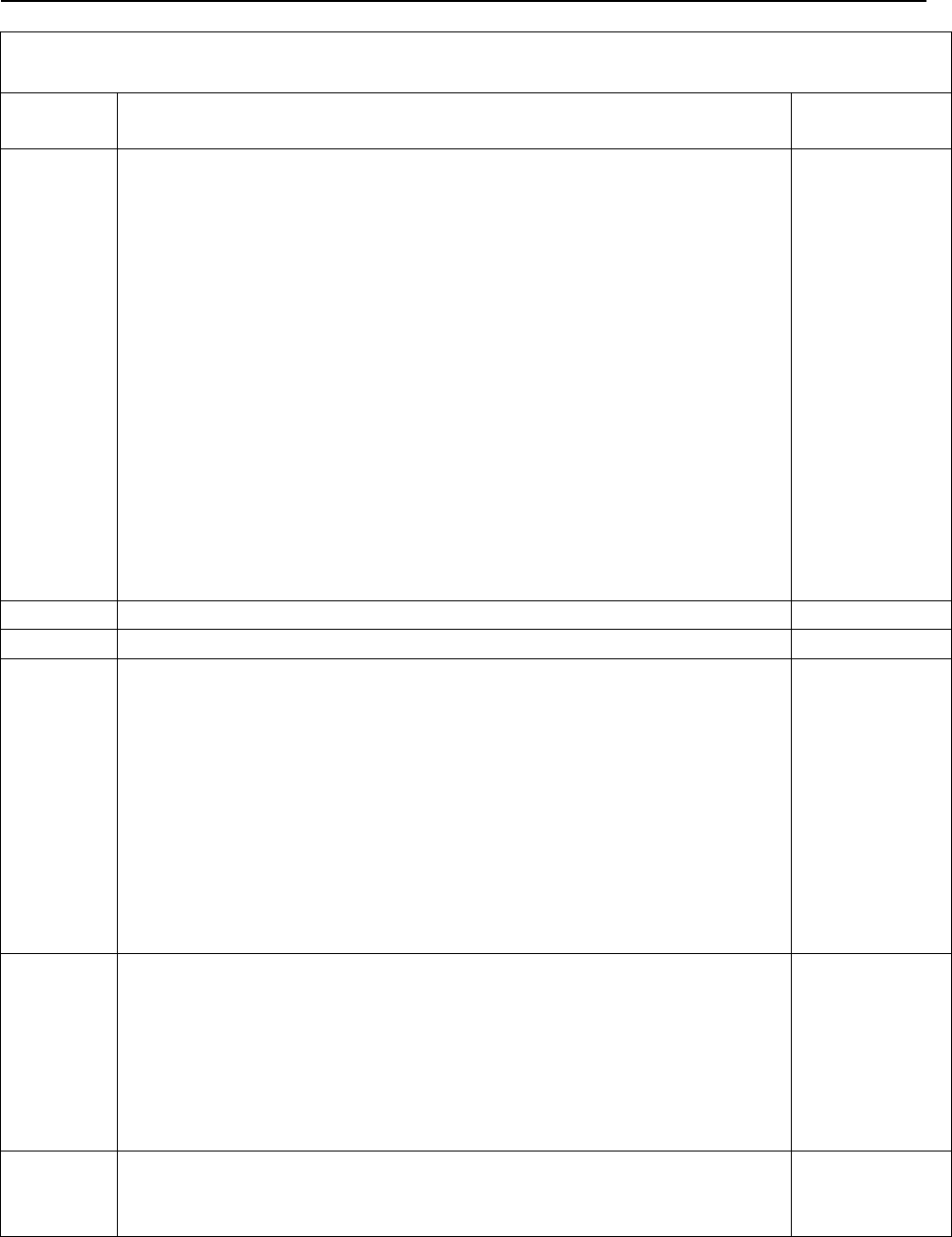

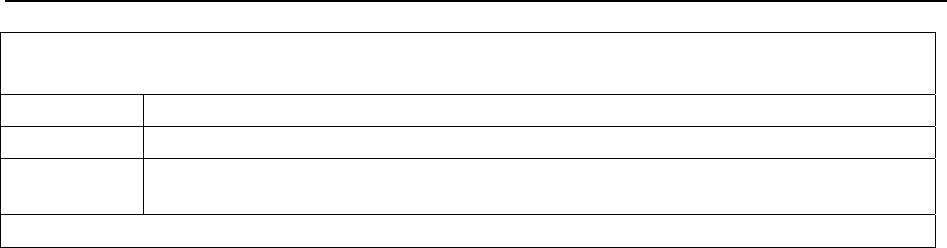

Table 2 shows real property appraisal cycles by state.

Table 2. Real Property Appraisal Cycles by State

Years in

Cycle

State/Jurisdiction Total

1 Alaska, Arizona, California, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky,

Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey,

New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon,

Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia,

Wyoming

25

2 Colorado, Iowa, Missouri, Virginia 4

3 Arkansas, District of Columbia, Maryland, Massachusetts, Texas 5

4 Alabama, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maine,

Minnesota

8

The Property Tax 7

National Conference of State Legislatures

Table 2. Real Property Appraisal Cycles by State

(continued)

Years in

Cycle

State/Jurisdiction Total

5 Idaho, Nevada, South Carolina, Utah, Wisconsin 5

6 Ohio, Tennessee 2

8 North Carolina 1

10 Rhode Island 1

Source: International Association of Assessing Officers, 2000 and Commerce Clearing

House, 2001

To complicate matters further, the responsibility for assessing property is different in each

state. In some states, the counties handle the assessing; in others, the cities do. In two

states—Maryland and Montana—all property is centrally assessed by the state. In the

majority of states, property is assessed at the county level. However, most states centrally

assess certain types of property—such as railroad and utility property—at the state level.

Table 3 shows the number of assessing units by government level in each state.

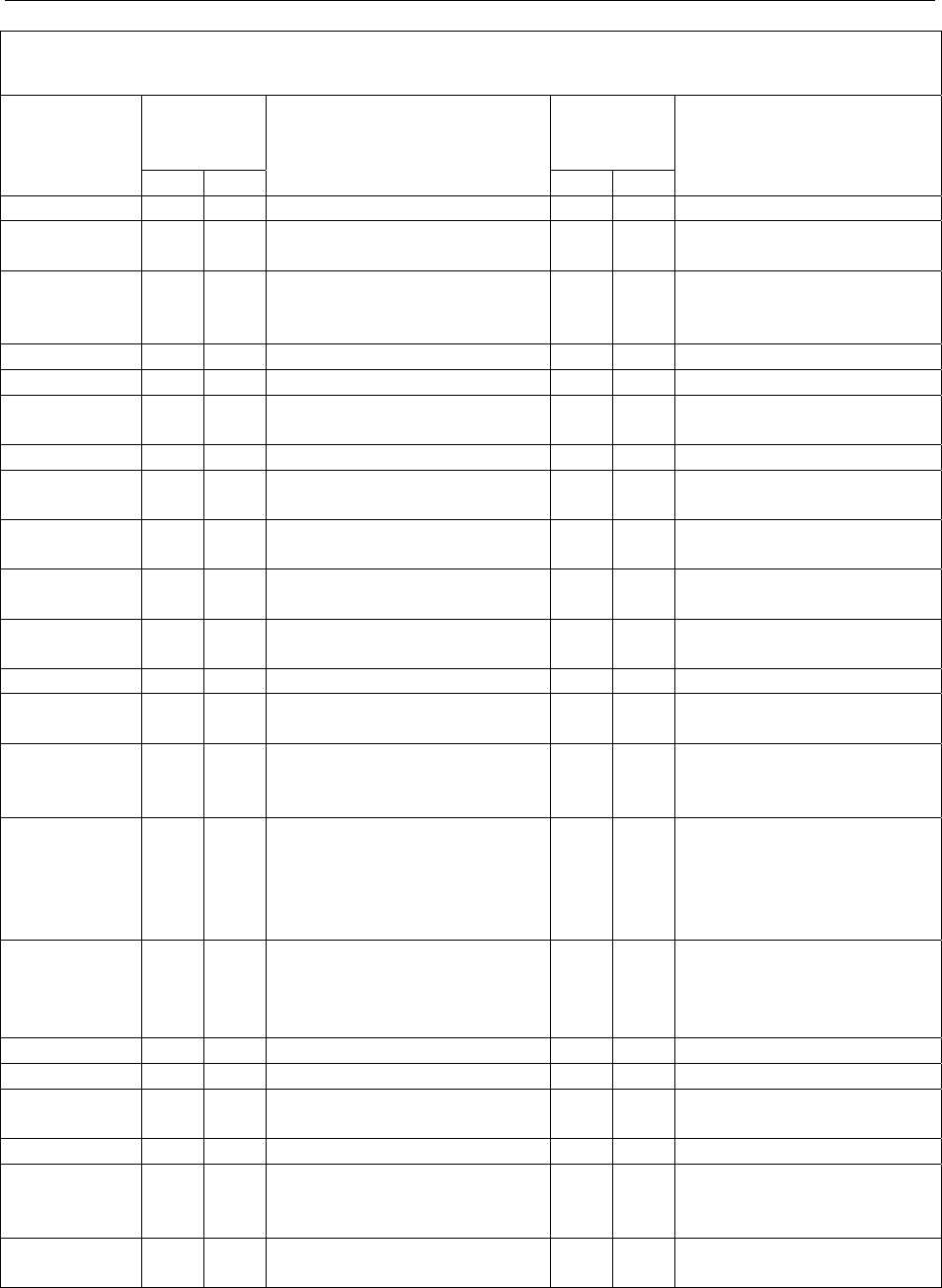

Table 3. The Number of Assessing Units by Government Level

State/Jurisdiction

County

City or

Municipality

Township or

Equivalent

State Other Total

Alabama 67 1 68

Alaska 12 13 2 27

Arizona 15 1 16

Arkansas 75 1 76

California 58 1 1 60

Colorado 63 1 64

Connecticut 19 150 169

Delaware 3 1 4

Florida 67 1 68

Georgia 159 1 160

Hawaii 4 4

Idaho 44 1 45

Illinois 102 920 1 1,023

Indiana 92 1008 1 1,101

Iowa 99 8 1 108

Kansas 105 1 106

Kentucky 120 1 121

Louisiana 70 1 71

Maine 492 492

Maryland 1 1

Massachusetts 39 312 1 352

Michigan 267 1245 1 1,527

Minnesota 87 9 1 97

Mississippi 82 301 1 384

Missouri 114 1 1 116

Montana 7 7

Nebraska 93 1 94

Nevada 17 1 18

New Hampshire 259 1 260

New Jersey 335 232 567

8 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Table 3. The Number of Assessing Units by Government Level

(continued)

State/Jurisdiction

County

City or

Municipality

Township or

Equivalent

State Other Total

New Mexico 33 101 1 135

New York 2 61 920 1 215 1,199

North Carolina 100 1 101

North Dakota 53 361 1380 1 1,795

Ohio 88 1 89

Oklahoma 77 1 78

Oregon 36 1 37

Pennsylvania 67 67

Rhode Island 8 31 39

South Carolina 46 1 47

South Dakota 65 1 66

Tennessee 95 1 1 97

Texas 253 253

Utah 29 1 30

Vermont 251 1 252

Virginia 95 40 91 2 228

Washington 39 1 40

West Virginia 55 1 56

Wisconsin 584 1255 1 6 1,897

Wyoming 23 1 24

District of Columbia 1 1

Source: International Association of Assessing Officers, Property Tax Policies and Administrative

Practices in Canada and the United States, 2000.

After the assessor determines the market value of the property, it is multiplied by the

assessment ratio to determine the taxable value (also known as assessed value), which may be

different than the appraised market value if the ratio is less than 100 percent. State law

determines the assessment ratio. These ratios are applied because they allow some flexibility

with tax policy and provide a way to levy more or less tax on different types of property

without using different tax rates. One reason states use assessment ratios of less than 100

percent is that it allows them to provide tax breaks to homeowners and farmers but to levy

higher taxes on businesses.

In many states, property is categorized by type, which allows policymakers to assign different

assessment ratios to different classes of property. In Alabama, for example, the residential

property classification carries a 10 percent assessment ratio, and business property falls into a

classification that has a 20 percent assessment ratio. Thus, the taxable value of a $100,000

home is $10,000 ($100,000 x .10), and the taxable value of a $100,000 business is $20,000

($100,000 x .20). At the same tax rate, businesses pay twice as much as homeowners on

property of the same market value. Residential property taxation also is more straightforward

because most residences are primary homes, not second homes, which may be taxed

differently. However, commercial property varies tremendously, ranging from apartment

buildings to factories to retail malls and, depending on the state and its classification system,

these all may be taxed differently. Therefore, how property is classified can significantly affect

how it is taxed due to different assessment ratios.

The Property Tax 9

National Conference of State Legislatures

States differ greatly in the number of separate classes of property they differentiate. At one

extreme are those that distinguish no classes; at the other are states that differentiate more

than 10 classes. Homes and farms generally receive the most favored treatment under

classification systems, while businesses, particularly utilities, tend to be treated less favorably.

Appendix B shows how state classification systems differentiate between various property

types.

Determining the tax. The second step after determining the taxable value is to determine the

amount of the tax. The taxable value is multiplied by the local tax rate to determine the total

tax due. In many states, the county, city, school district and special districts (flood control,

fire protection, library, sewer and water districts) each account for a portion of the total local

tax rate. Some states require that the voters approve tax rates, while others allow locally

elected officials (county commissioners, city

councils, or school boards) to set tax rates

without a popular vote. Some states actually

set rates in state law by establishing maximum

rates.

To determine the actual rate, the taxing

authority determines how much revenue it

needs to generate through property taxes. That

amount is divided by the total taxable value of

the property in the district to determine a tax

rate. Property tax rates are simply a function of

how much the local government has budgeted,

which explains why they vary from year to

year.

Tax rates are commonly referred to as mill

levies; a mill is one-tenth of a cent. A 1 mill

levy means that the taxpayer owes $1 for every

$1,000 in taxable property value. The rate

applied usually will represent an aggregation of

the various rates of different taxing

jurisdictions where the property is located.

Because rates vary and different assessment

ratios are applied, the best way to measure

property taxes is through the effective rate,

which is the proportion of tax dollars paid to

market value. This is really the only way to

compare the effect of property taxes across jurisdictions. To calculate the effective tax rate,

divide the property tax paid by market value of the property. For example, the effective tax

rate of a house valued at $200,000 and a property tax of $2,000 is $2,000 / $200,000 = 0.01

= 1.0 percent. The 1.0 percent effective rate then can be compared with the effective rates of

other properties in different locations.

Manufactured housing makes up an increasing proportion of

U.S single family homes. Several factors drive the growth,

including affordability, better financing, and a shift in

population toward rural areas, especially in the South and

Southwest. “Manufactured housing” refers to structures built

in a factory to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD) standards, transported to a site and

installed. The industry uses the term “mobile home” to refer

to manufactured homes produced prior to 1976, although

the Census Bureau lumps both types together.

For tax purposes, residential manufactured housing may be

classified as either real or personal property. More than half

the states use multiple measures to determine classification,

with the most significant factors being whether units are

permanently affixed, owner-occupied, or situated on the

owner’s land.

When classified as real property, manufactured homes

generally are assessed at the same rates as other houses.

However, some states provide a tax break. For example,

Arizona assesses manufactured housing at 82 percent and

other homes at 100 percent of their respective market values.

When classified as personal property—usually because a unit

is located in a mobile home park or is not permanently

affixed—valuation is frequently based on the sales price.

Subject to an ad valorem tax, manufactured houses and

mobile homes are generally treated as a depreciable asset such

as a car.

Source: L. Kenneth Hubbell, “A Comparative Study of the

Taxation of Manufactured Housing,” in State Tax Notes

(April 26, 1999).

10 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Other Valuation Methods

Historically, property taxes were based on the market value of the property. Over time,

however, exceptions to this standard have been provided as a tax benefit to specified types of

property such as agricultural land, historic property, and other special use property. These

frequently are valued on the basis of their “current actual use,” which typically is a much

lower value. Use value attempts to determine a value based upon the actual production of the

property and to remove other influences that affect the market value of real estate.

Agricultural land. Most states employ some version of use value, rather than market value,

for determining agricultural land values for property tax purposes. Even if the “use value”

standard is not specifically employed, agricultural land generally is taxed at a lower effective

rate. Michigan, for example, does not have use value for agricultural land. However,

agricultural lands are not assessed taxes for local school uses, thus accomplishing much the

same result as use valuation but eliminating the need for use value taxation procedures.

Appendix C shows how states value agricultural land.

Because agricultural land is subject to less tax, it is a desirable classification. Depending on

the state and its administrative rulings, agricultural use may be defined rather loosely to allow

some questionable inclusions. To deal with this issue, most states have established certain

threshold tests to establish whether the land in question is truly being used for agricultural

purposes. For example, Florida has a procedure for determining when agricultural use value

no longer is appropriate. When the sales price of a tract of land is greater than or equal to

three times the use value of the tract, it no longer is considered agricultural land. Montana

currently is examining how agricultural land is taxed. This is primarily due to the fact that

many acres of land are being bought for recreation and tourism purposes, yet still qualify as

agricultural land for tax purposes.

Other land. In addition to agricultural land, lawmakers often apply the use value standard to

timberland, open space and historic buildings.

Personal property. Personal property also is valued differently than real property. Usually, it

is valued on the basis of depreciation. Industry-based valuation guides commonly are used.

For example, motor vehicles are subject to property taxes in a number of states; however, the

tax due decreases each year as the vehicle depreciates (usually using “blue book” value as the

guide). In Wisconsin, personal property is valued based on its acquisition cost, with

adjustments for inflation and depreciation. Because some types of property—such as

computer and other high-tech equipment —have a short shelf life, most states have

constructed tables to reflect various depreciation cycles.

Equalization

Equalization is the process states undertake to ensure that assessments are uniform

throughout the state. Most states use a state or local review board to compare the work of

local assessors. If inconsistencies are found among jurisdictions or classes of property, the

board can require that adjustments be made. For example, the South Dakota Department of

Revenue adjusts local assessments to ensure that the median assessment within each county

represents at least 85 percent of the market value.

The Property Tax 11

National Conference of State Legislatures

For further uniformity, most states have adopted central assessment to ensure equity in the

appraisal of certain complex properties, such as utility, railroad and manufacturing.

Appeals

Each state has a formal process for appealing the assessed value of property. However, tax

rates (mill levies) are not subject to appeal. Although the process varies among states, some

elements are common. In most states, taxpayers may call the assessor’s office and provide

evidence (comparable property sales, clarify incorrect information, other factors affecting

property value) to demonstrate that the assessment is incorrect. If the taxpayer is still not

satisfied, he or she may appeal to an elected body, such as a county board, that exists

specifically to hear property valuation appeals. In most states, county board or elected body

decisions may be appealed to the courts.

Most states have specific deadlines for appealing property valuations. Once these deadlines

have passed, taxpayers’ appeals will not be heard.

3

Property Tax Limits

Property tax policy is also shaped by other factors. Throughout the country, state laws and

constitutional provisions limit property taxes in many ways, including limitations on

property assessment increases, on property tax rates and on overall local revenue growth.

Many limitations have been adopted in states that allow the initiative petition process, which

lets citizens make laws and amend state constitutions. California’s Proposition 13,

Massachusetts’ Proposition 2 1/2 and Oregon’s “Cut and Cap” are notable examples of

property tax limitation measures initiated directly by voters. However, notwithstanding the

citizen initiative process, most states have some type of constraint on property taxes. (Limits

will be discussed in more detail in the second publication of this series.)

Reliance on the Property Tax

Local government reliance on property taxes reached its peak in the 1970s; then came

taxpayer revolts and the ensuing tax limits. As a result, state and local governments reduced

reliance on the property tax in the latter part of the 20

th

century; however, it remains a major

revenue generator.

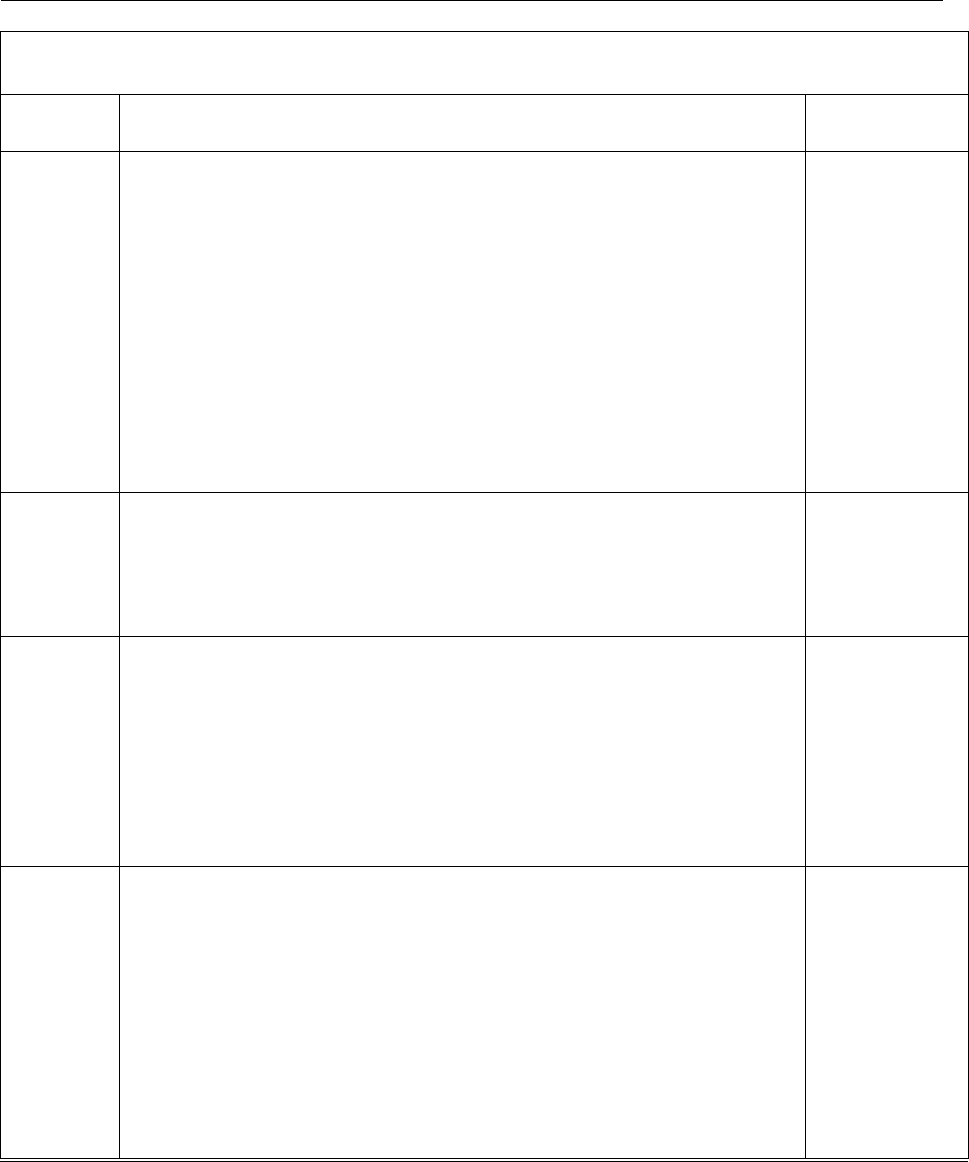

The property tax is still the primary tax source for local governments. It is responsible for

approximately 72 percent of all local tax revenue. Table 4 shows the amount of local tax

revenue derived from the property tax. (Keep in mind that the comparison here is between

property taxes and locally raised taxes only and does not include other sources of local

revenue such as state and federal aid.) Local governments in 13 states rely on property taxes

for more than 90 percent of their tax revenue. The property tax generates between 80

percent and 90 percent of local revenue in seven states. Thirty states are above the national

average of 72.3 percent. The nine states with less than 60 percent local government tax

reliance on the property tax are Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, New

Mexico, New York, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

4

12 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

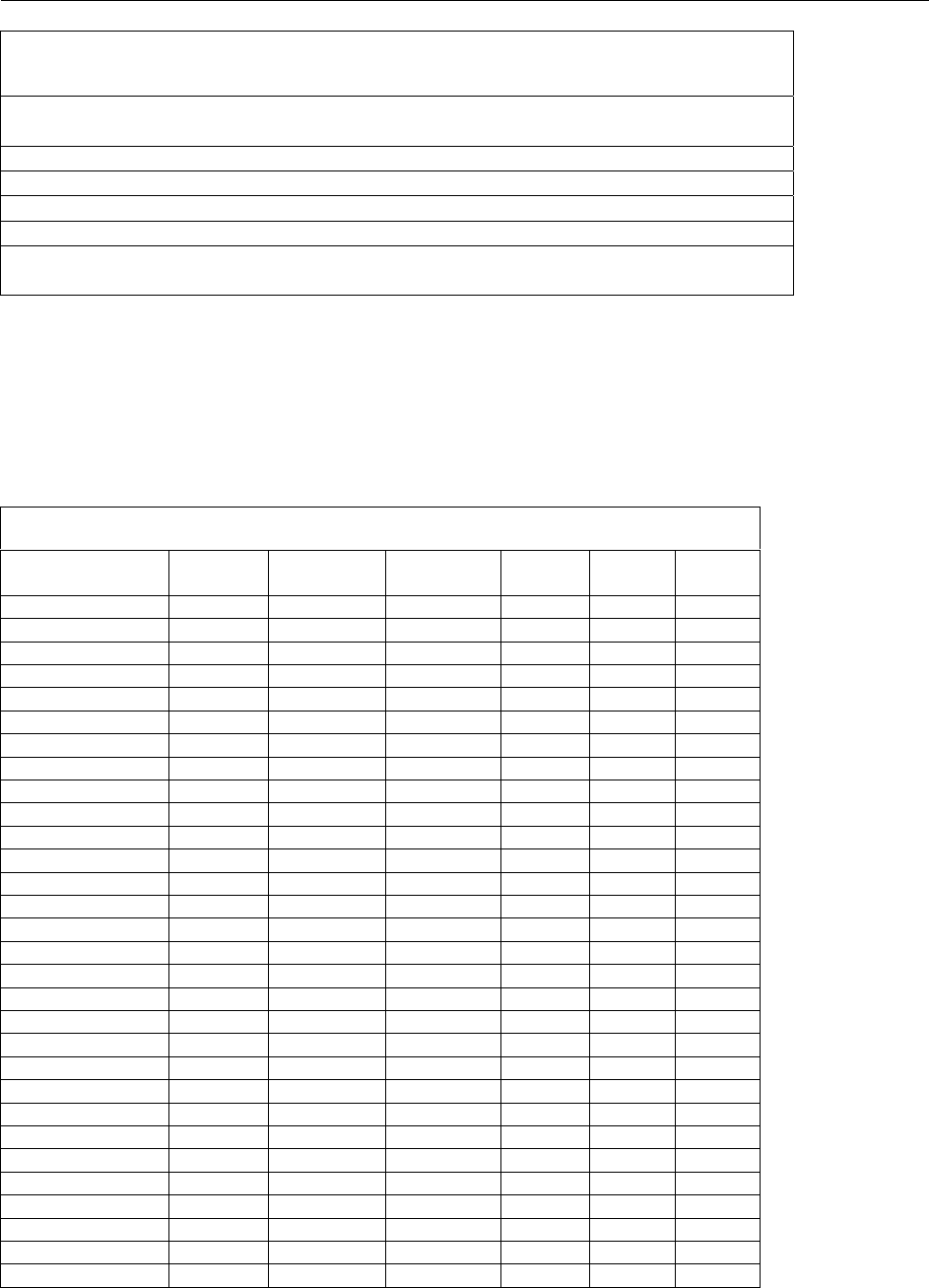

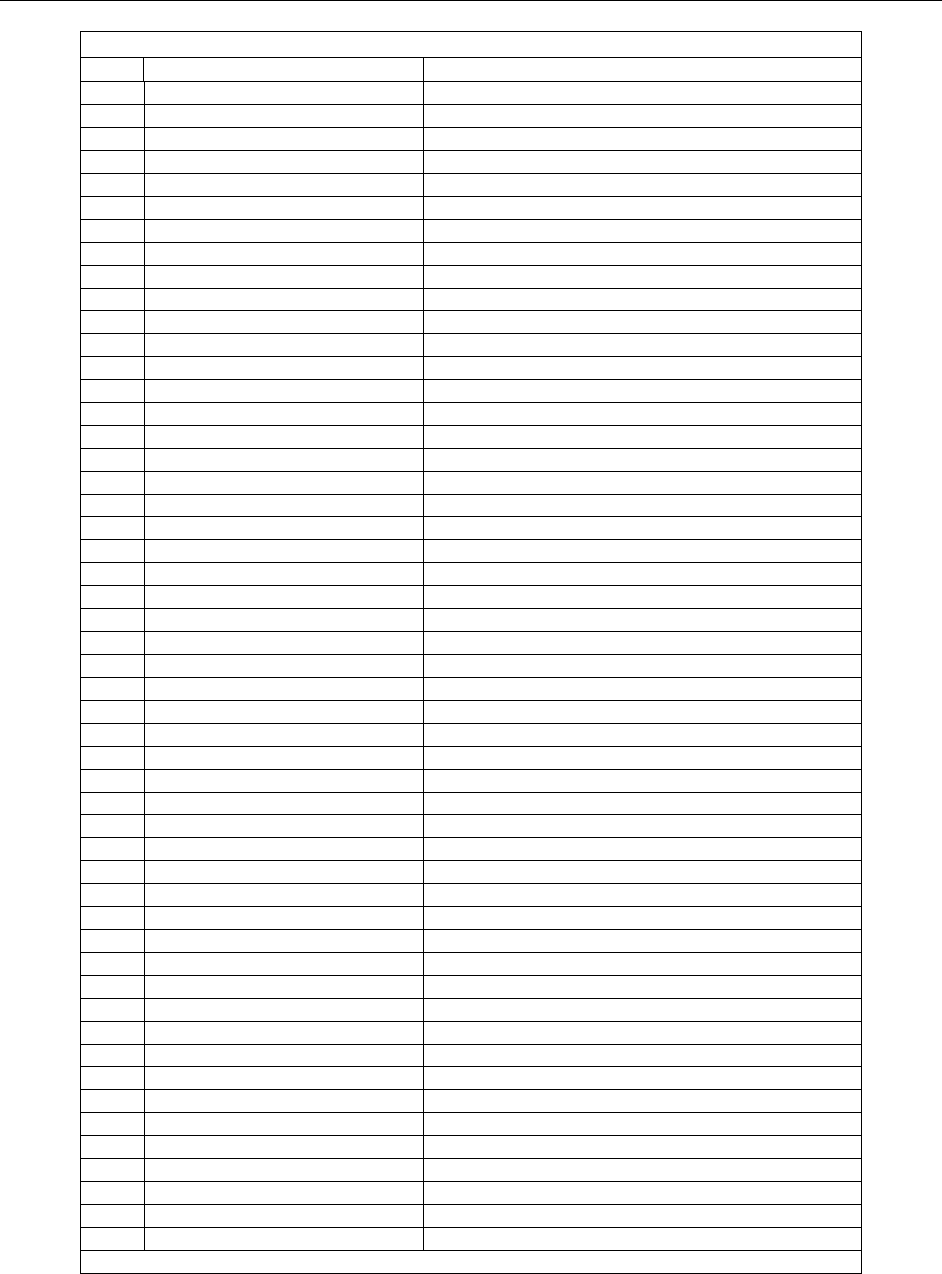

Table 4. Local Property Taxes as a Percent of Local Taxes, Fiscal Year 1999

Rank State/Jurisdiction Percent Rank State/Jurisdiction Percent

1 New Hampshire 98.8% 27 Florida 78.7%

2 Rhode Island 98.6 28 Wyoming 77.6

3 Connecticut 98.3 29 Kansas 76.5

4 New Jersey 97.9 30 North Carolina 74.6

5 Maine 97.6

United States 72.3

6 Massachusetts 96.9 31 Virginia 71.7

7 Vermont 95.8 32 Arizona 70.6

8 Montana 95.3 33 Pennsylvania 69.7

9 Minnesota 94.5 34 California 66.2

10 Wisconsin 94.0 35 Ohio 66.0

11 Idaho 93.9 36 Utah 65.7

12 Mississippi 91.8 37 Arkansas 64.6

13 Iowa 90.3 38 Nevada 63.3

14 Michigan 89.8 39 Washington 62.4

15 Indiana 88.6 40 Colorado 61.5

16 North Dakota 88.1 41 Missouri 60.2

17 South Carolina 84.9 42 Georgia 59.5

18 Illinois 82.9 43 Tennessee 59.0

19 West Virginia 82.8 44 New York 57.0

20 Oregon 80.1 45 Maryland 55.2

21 Texas 79.8 46 New Mexico 54.2

22 Nebraska 79.6 47 Kentucky 53.9

23 Hawaii 79.6 48 Oklahoma 52.7

24 Alaska 79.3 49 Louisiana 39.4

25 Delaware 79.0 50 Alabama 37.5

26 South Dakota 78.9

Source: State Policy Reports, September 2001.

The level of property tax revenue depends heavily on the degree of fiscal centralization in a

state and on the division of responsibility between state and local governments. Other factors

that influence property tax levels include local spending and the extent to which local

governments have access to other forms of revenue. Many states with property tax limits

authorize local option sales and income taxes so that local governments have other own-

source revenues in addition to state aid. On the other hand, many New England states rely

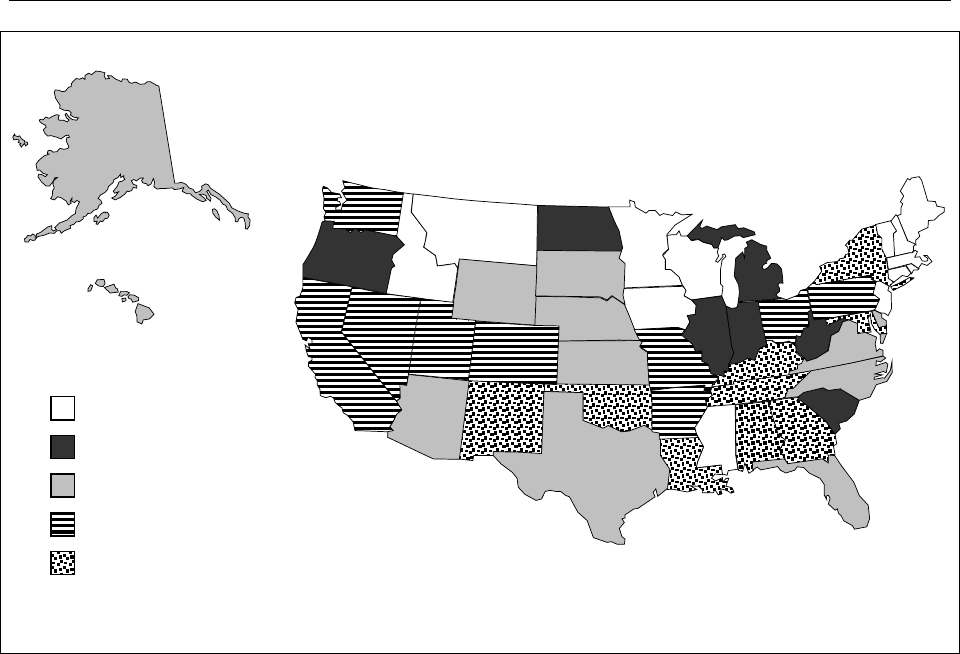

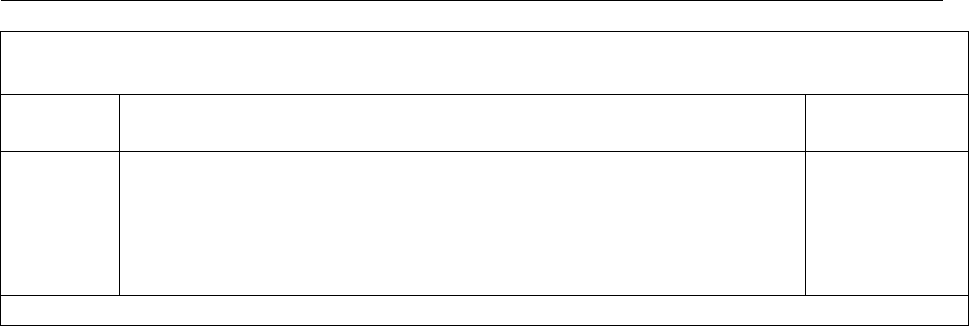

heavily on property taxes because they have few local option alternatives. Figure 1 shows

regional differences in reliance on the property tax as local tax source.

The Property Tax 13

National Conference of State Legislatures

Figure 1. Local Property Taxes as a Percent of Local Taxes, FY 1999

More than 90%, n = 13

80% to 90%, n = 7

Less than 60%, n = 9

70% to 80%, n = 12

60% to 70%, n = 9

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2001.

Appendix D shows property taxes as a percentage of state and local revenue, which provides

some perspective as to the importance of the property tax to the state revenue picture as a

whole. This appendix takes into account all state revenues, including non-tax revenues such

as user fees and federal funds.

State Property Taxes. Only a few states rely on property taxes for state revenue. Property

taxes currently comprise more than 10 percent of state revenue in just four states—Montana,

Vermont, Washington and Wyoming.

Typically, states levy taxes on specific types of property, such as motor vehicles, utility

company property, railroad property, aircraft and equipment, and oil and gas property. Only

15 states levy statewide taxes on real property.

Among the states, Minnesota and New Hampshire most recently have adopted a statewide

tax on real property. During the 2001 legislative session, as part of a larger tax relief and

reform package, Minnesota adopted a new statewide property tax on business property (and

cabins) with the revenue growth from year to year dedicated to education.

In 1999, lawmakers in New Hampshire, seeking additional revenues to fund education

because of a school finance equity suit, approved a statewide property tax of $6.60 per

$1,000 of valuation. This was reduced to $5.80 per $1,000 of valuation during the 2001

legislative session.

14 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

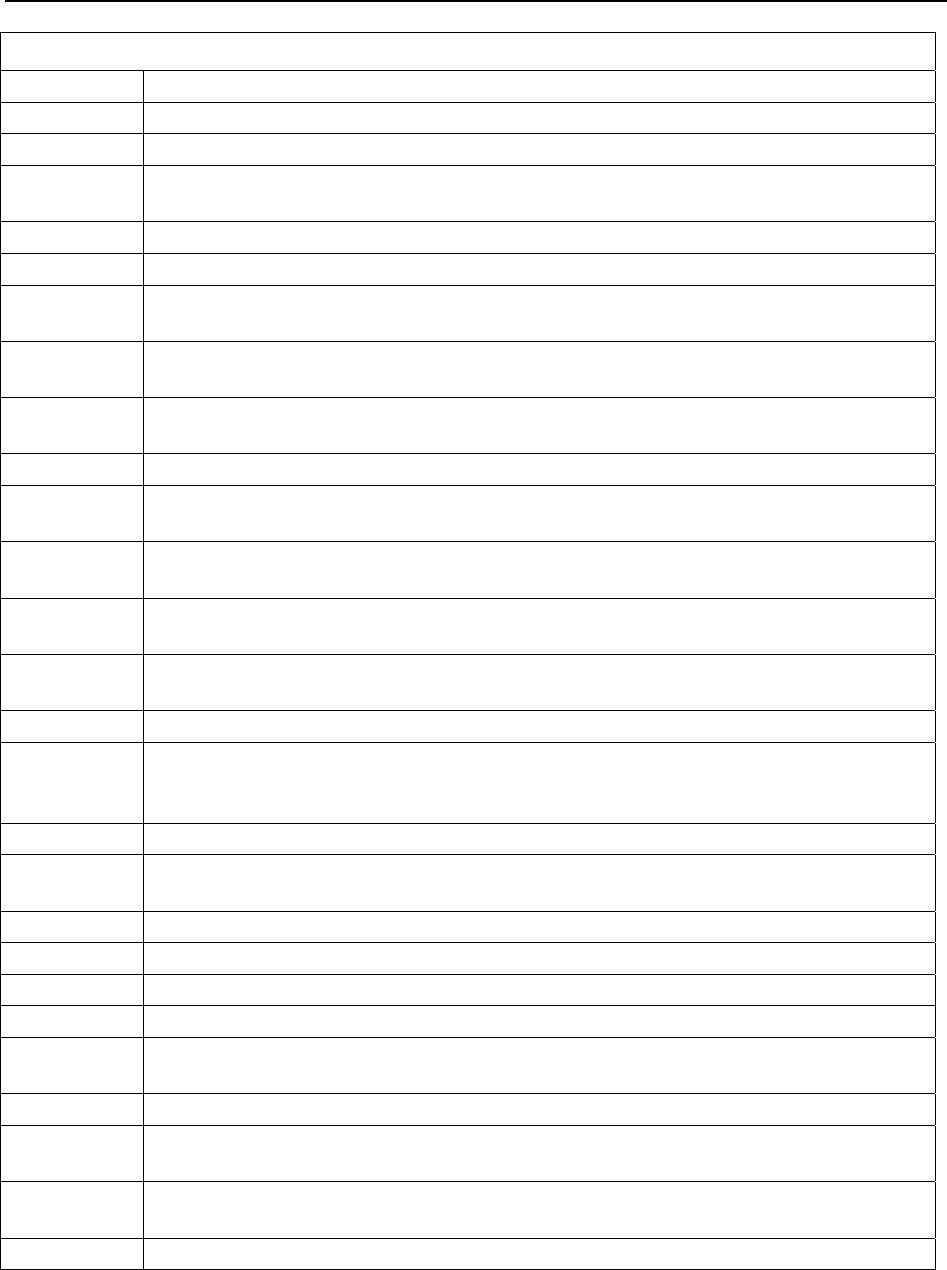

Table 5. Statewide Property Taxes

State State Property Tax Rate on Real Property

Alabama The rate of taxation for state purposes is 0.65 percent annually on the assessed value

of taxable property in the state.

Indiana The total state tax rate is limited to 1¢ (.33¢, beginning March 1, 2001) on each

$100 of valuation.

Kansas Permanent state tax levies include a 1 mill levy for state educational institutions; a

0.5 mill levy for state institutions caring for the mentally ill, retarded and visually

handicapped; and a 0.25 mill levy for state correctional institutions.

Kentucky The state tax rate on real property is 14.1 cents per $100 of valuation.

Maryland The state levy on real property is 21 cents per $100 of assessed valuation.

Michigan A state education tax is imposed on all taxable property at a rate of 6 mills.

Minnesota A statewide property tax is imposed on all business real property and cabins. The

total levy amount is set grow annually by the amount of inflation; therefore, the rate

will vary from year to year.

Montana The state levies a 95 mill statewide tax for school finance equalization, plus an

additional 6 mills for community colleges.

Nevada The state property tax of 15 cents per $100 of assessed value is used exclusively to

service debt.

New

Hampshire

A statewide property tax for education is imposed at the rate of $6.60 per $1,000 of

value. The tax is set to expire in January 2003.

Utah The state rate of tax cannot exceed 0.00048 per $1 of taxable value of taxable

property in the state.

Vermont A statewide education property tax is imposed on all nonresidential and homestead

property at a rate of $1.10 per $100 of equalized education property value.

Washington The state levies a school property tax at the rate of $0.36 per $100 of market value.

Wisconsin A state tax of 0.2 mills, imposed annually on all taxable property, is used to fund

state forestry programs.

Wyoming A state tax of 12 mills is levied annually for school support.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures and Commerce Clearing House, State Tax Guide,

March 2001.

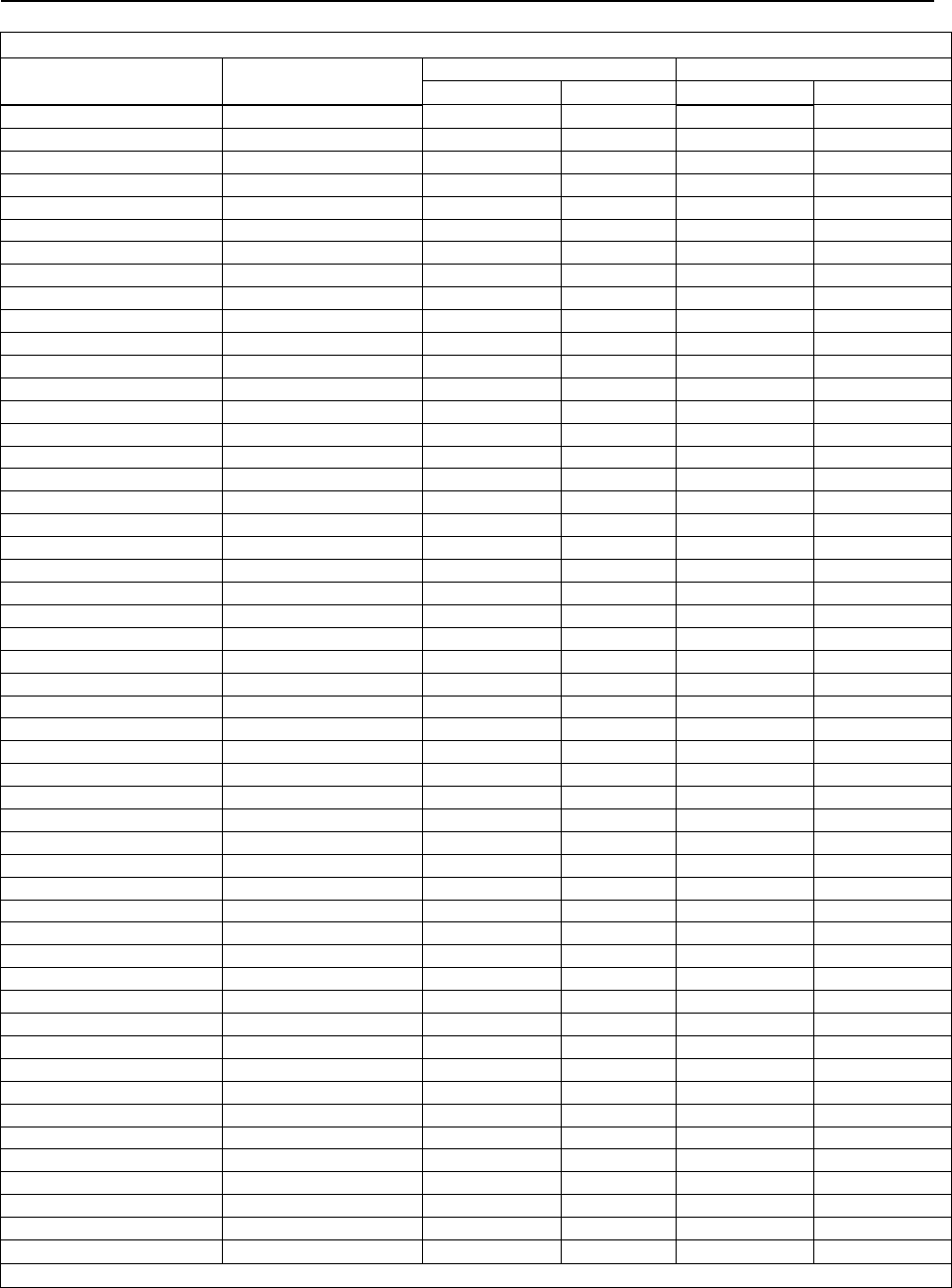

Property Tax Burdens

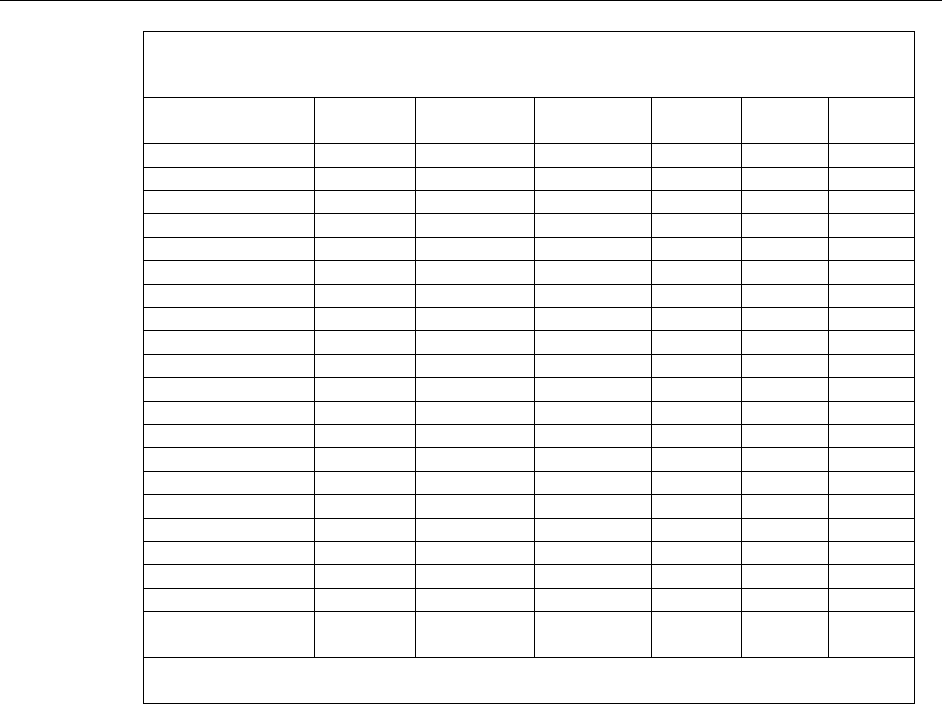

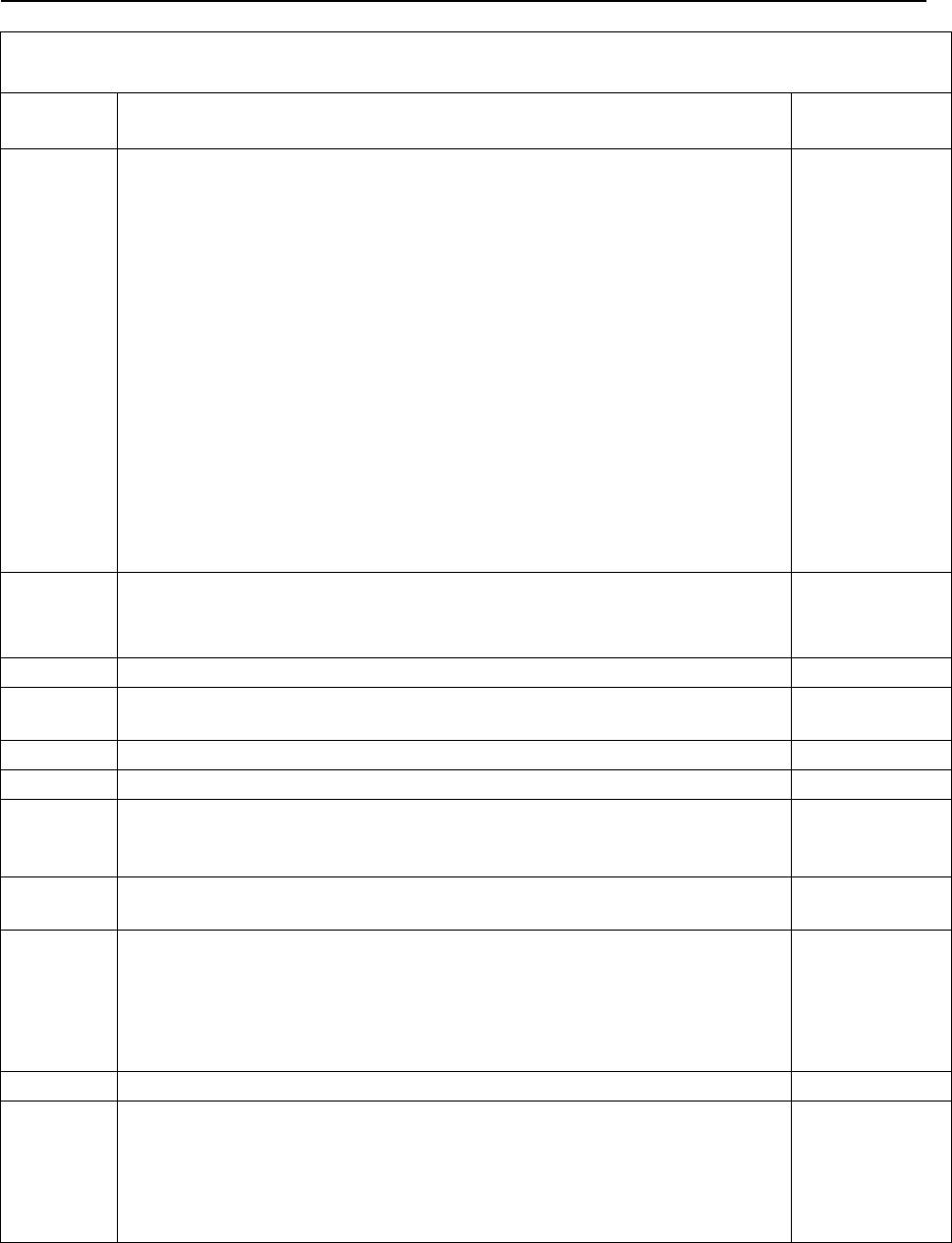

When considering property tax policies, lawmakers frequently are concerned about how

property taxes in one state compare to those in other states. Table 6 shows state and local

property taxes per capita and as a percentage of personal income. Many fiscal experts

The Property Tax 15

National Conference of State Legislatures

consider tax burdens as a percentage of personal income the best measurement because it

takes into account the overall wealth of the state and captures its residents’ ability to pay.

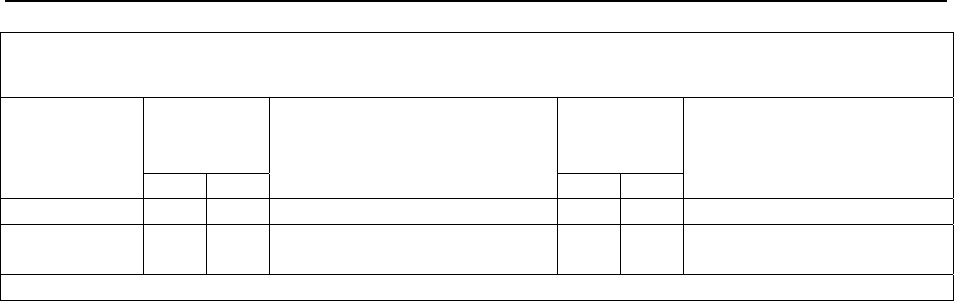

Table 6. State and Local Property Taxes Per Capita and as a Percentage of Personal

Income, FY 1999

Per Capita Per $100 Income

State

Collections

in thousands Amount Rank Amount Rank

New Hampshire $2,014,400 $1,677.3 2 5.7% 1

Maine 1,546,856 1,234.5 7 5.3 2

Vermont 765,688 1,289.0 6 5.2 3

New Jersey 14,336,025 1,760.5 1 5.2 4

Montana 891,131 1,009.2 13 4.8 5

Rhode Island 1,285,113 1,296.8 5 4.6 6

Wyoming 522,697 1,089.0 11 4.4 7

Alaska 727,813 1,173.9 9 4.2 8

New York 24,758,694 1,360.6 4 4.2 9

Connecticut 5,174,841 1,576.7 3 4.2 10

Wisconsin 5,524,611 1,052.3 12 4.0 11

Illinois 14,099,968 1,162.6 10 3.9 12

Texas 18,804,963 938.2 16 3.7 13

Nebraska 1,567,009 940.6 15 3.6 14

Iowa 2,532,735 882.8 20 3.6 15

Massachusetts 7,300,559 1,182.3 8 3.6 16

South Dakota 617,287 842.1 22 3.5 17

Washington 5,763,411 1,001.3 14 3.5 18

Indiana 5,177,129 871.1 21 3.5 19

Florida 13,900,952 919.9 18 3.5 20

North Dakota 497,220 784.3 29 3.4 21

Michigan 8,810,590 893.2 19 3.3 22

Minnesota 4,458,850 933.6 17 3.2 23

Arizona 3,584,155 750.1 32 3.2 24

Ohio 9,334,354 829.2 25 3.2 25

Kansas 2,115,021 796.9 28 3.1 26

Idaho 815,660 651.5 35 3.0 27

Oregon 2,558,189 771.5 30 3.0 28

Virginia 5,757,546 837.7 24 3.0 29

Pennsylvania 9,659,064 805.3 26 2.9 30

Colorado 3,413,607 841.6 23 2.9 31

South Carolina 2,475,954 637.1 36 2.9 32

California 25,424,960 767.1 31 2.8 33

Georgia 5,422,816 696.3 34 2.7 34

Maryland 4,144,064 801.2 27 2.6 35

Arkansas 1,401,967 549.6 40 2.6 36

Utah 1,191,691 559.5 39 2.5 37

Mississippi 1,389,918 502.0 41 2.5 38

Nevada 1,261,135 697.1 33 2.4 39

Missouri 3,305,361 604.5 37 2.4 40

North Carolina 4,350,642 568.6 38 2.3 41

West Virginia 811,771 449.2 45 2.2 42

Tennessee 2,684,026 489.4 43 2.0 43

Kentucky $1,666,329 $420.7 46 1.9 44

Hawaii 594,558 501.7 42 1.9 45

16 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Table 6. State and Local Property Taxes Per Capita and as a Percentage of Personal

Income, FY 1999

(continued)

Per Capita Per $100 Income

State

Collections

in thousands Amount Rank Amount Rank

Oklahoma 1,237,654 368.6 48 1.7% 46

Louisiana 1,620,130 370.6 47 1.7 47

New Mexico 587,849 337.8 49 1.6 48

Delaware 348,517 462.2 44 1.6 49

Alabama 1,191,792 272.7 50 1.2 50

United States $239,427,272 879.7 3.3

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2001.

Both ranking methods show enormous variation among the states. New Hampshire holds

the top spot for property taxes as a percent of income and is second for property taxes per

capita. New Jersey ranks first on a per capita basis and fourth on property taxes relative to

personal income. Alabama’s property tax burdens are about a third of the national average.

Although such tables provide some perspective about property tax burdens and how states

rank, it is important not to draw too many conclusions from them because the data alone has

many limitations. A state that relies heavily on property taxes may rank high here but low in

other taxes. For example, New Hampshire has a high property tax burden, but residents

there pay no general sales tax and no income tax on anything other than interest and

dividend income. Generally speaking, it is a low tax state and ranks 49

th

in overall tax

collections as a percentage of personal income, a fact that is not evident from these property

tax tables. Appendix E shows how states rank when all state and local taxes are considered.

In addition, some states provide property tax relief to taxpayers in ways that are not reflected

in the tables, through such mechanisms as income tax breaks or with direct payments

(rebates and refunds). (In fact, property tax relief is such a significant part of state property

tax policy that it is the subject of the next publication of the NCSL Foundation Fiscal

Partners.)

Also, there is no way to know anything about the services those property tax dollars may buy.

A municipality with high property taxes may be providing taxpayers services well above the

national average, while a government with a low tax base may be providing very little. The

data do not tell the whole story.

It is difficult to measure whether taxes or services are “too low” or “too high” from the

information contained in the tables. These political questions are decided by citizens and

lawmakers in each state. It is most important to examine the overall tax structure and

spending climate of a state before making judgments about its tax policy.

National Conference of State Legislatures 17

Appendix A. Tax Treatment of Personal and Intangible Property, by State

(continued)

Personal

Property

Taxable?

Intangible

Property

Taxable?

State/

Jurisdiction

Yes No Comments Yes No Comments

Alabama

9 9

Specific intangibles, such as

corporate shares, bonds and

hoarded money are taxable

Alaska

9 9

Arizona

9 9

Arkansas

9 9

California

9 9

Colorado

9

The first $2,500 is exempt

9

Connecticut

9 9

Delaware

9

Only property of captive

insurance companies is taxable

9

Florida

9 9

State tax on intangible

property of 1 mill

Georgia

9

The first $500 is exempt

9

Hawaii

9 9

Idaho

9 9

Illinois

9 9

Indiana

9 9

Iowa

9

Some items of personal

property are deemed to be real

property

9

Intangible tax levied only on

credit unions and loan

agencies

Kansas

9 9

Kentucky

9 9

Specified property is taxable

Louisiana

9 9

Bank stock, insurance

company credits, loan and

finance company credits, and

public service property are

excluded from the intangibles

exemption

Maine

9 9

Maryland

9

Only business property greater

than $10,000 located at an

individual’s home is taxable

9

Massachusetts

9 9

Michigan

9 9

Minnesota

9

Specified items are taxable

9

Mississippi

9 9

Specified property is taxable

Missouri

9 9

Montana

9 9

Nebraska

9

Only depreciable business

property or property used for

the production of income that

has a life span of more than one

year is taxable

9

18 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix A. Tax Treatment of Personal and Intangible Property, by State

(continued)

Personal

Property

Taxable?

Intangible

Property

Taxable?

State/

Jurisdiction

Yes No Comments Yes No Comments

Nevada

9 9

New

Hampshire

9 9

New Jersey

9

Only personal property of

certain utilities and petroleum

refineries is taxable

9

New Mexico

9

Specified items are taxable

9

New York

9 9

North

Carolina

9

Non-business property is not

taxable

9

North Dakota

9

Specified items are taxable

9

Ohio

9

Only business property in

excess of $10,000 is taxable

9

Intangibles held by an

intangibles dealer are taxable

Oklahoma

9

Counties may enact a full

exemption

9

Oregon

9

Only personal property used in

a trade or business is taxable

9

Pennsylvania

9 9

Specified intangibles are

taxable

Rhode Island

9 9

South

Carolina

9 9

South Dakota

9

Only personal property of

centrally assessed utilities is

taxable

9

Tennessee

9

Only personal property used in

a trade or business is taxable

9

Only certain intangibles of

insurance companies, loan

and investment companies

and cemetery companies are

taxable

Texas

9

Unless a locality elects

otherwise, only income –

producing personal property is

taxable

9

Only certain intangibles of

insurance companies and

savings and loan associations

are taxable

Utah

9 9

Vermont

9 9

Virginia

9

Local governments may enact

an exemption

9

Washington

9 9

West Virginia

9 9

Specified intangible property

is taxable, although the tax is

being phased out

Wisconsin

9

Only business property is

taxable

9

Appendices 19

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix A. Tax Treatment of Personal and Intangible Property, by State

(continued)

Personal

Property

Taxable?

Intangible

Property

Taxable?

State/

Jurisdiction

Yes No Comments Yes No Comments

Wyoming

9 9

District of

Columbia

9

Only property used in a trade

of business

9

Source: Commerce Clearing House, State Tax Guide, 2001.

20 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Alabama Class 1: Utility 30%

Class 2: All real and personal property not in other classes 20

Class 3: Agricultural, historic and residential 10

Class 4: Motor vehicles 15

Alaska No classifications. All property is assessed at its full and true value. 100%

Arizona Class 1: Mining, utilities, commercial and telecommunications 25%

Class 2: Agricultural and nonprofit 16

Class 3: Residential property 10

Class 4: Rented residential property 10

Class 5: Railroad and flight 5

Class 6: Special purposes 5

Class 7: Commercial historic 1

Class 8: Historic / residential 1

Class 9: Possessor interests on government property 1

Arkansas No specific classes of property—real and personal property are taxed the same

Note: Agricultural and other special valued lands are assessed at their use value.

20%

California No classifications. All property is assessed at its full value. 100%

Colorado The constitution restricts the percentage of residential property assessed value

to 45 percent of total assessed property value. The assessment rate for

commercial real property is fixed at 29 percent. The legislature adjusts the

residential assessment ratio each year. For the 2001 and 2002 property tax year,

the residential assessment ratio is established at 9.15 percent of a property’s

actual value.

Varies

Connecticut No classifications. Property is assessed at 70 percent of actual value. 70%

Delaware No classifications. All property is assessed at its true value. 100%

Florida No classifications. Property (other than homesteads or property valued on use)

is assessed at its full cash value. Homesteads are assessed at just value as of Jan.

1, 1994.

100%

Georgia No classifications. Property is assessed at 40% of fair market value. 40%

Hawaii No classifications. All taxable real property is assessed at its fair market value. 100%

Idaho Property is classified as either real property, personal property or operating

property of public utilities.

100%

Illinois Class 1: Residential (counties under 200,000 inhabitants)

Residential (counties over 200,000 inhabitants)

25%

Class 2: Farm 33.3

Class 3: Commercial 33.3

Class 4: Industrial 33.3

Class 5: Railroad 33.3

Class 6: Mineral 33.3

Indiana No specific classifications. (Prior to March 1, 2001, property was assessed at

33.3 percent.)

100%

Appendices 21

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Iowa Residential 100%

Agricultural (assessed at 100% of productivity)

Commercial

Industrial

Utilities/Railroad

Kansas Real Property:

Class 1: Residential 11.5%

Class 2: Agricultural 30

Class 2: Agricultural 12

Class 3: Vacant lots 12

Class 4: Nonprofit 33

Class 5: Public utility real property 25

Class 6: Commercial and industrial real property 30

Class 7: Other real property 30

Personal Property:

Class 1: Mobile homes used for residential purposes 11.5

Class 2: Most mineral leasehold interests 30

Class 3: Most public utility tangible personal property and inventories 33

Class 4: Motor vehicles 30

Class 5: Most commercial and industrial machinery and equipment 25

Class 6: All other tangible personal property 30

Kentucky All property is assessed at its fair cash value. Classification is achieved through

differential tax rates.

100%

Louisiana Residential/land 10%

Residential improvements 10

Electric cooperative properties (excluding land) 15

Public service property (excluding land) 25

Other 15

Agricultural, marsh and timber land 10 (use)

Maine No classifications. Property is assessed at its just value. 100%

Maryland Real property 40%

Personal property 100

Class 1: Residential 100%

Class 2: Open space land 100

Class 3: Commercial 100

Massachu-

setts

Class 4: Industrial 100

Michigan No specific classifications. Property is assessed at 50% of true cash value. 50%

22 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Minnesota Property is assessed at full market value but is taxed at different rates depending

on the type and value of property, as follows:

Tax Rates 2002:

Disabled homestead up to $32,000 0.45%

Residential homestead 1.0 or 1.25

Residential non-homestead 1.0 or 1.5

Apartments 0.9 or 1.8

Commercial/industrial/public utility 1.5 or 2.0

Seasonal recreational commercial 1.0 or 1.25

Seasonal recreational residential 1.0 or 1.25

Agricultural homestead 0.55 or 1.0

Agricultural non-homestead 1.0

Miscellaneous properties 1.0 or 1.5

Class 1: Residential 10%

Class 2: All non-residential real property 15

Class 3: Personal (except motor vehicles) 15

Class 4: Public utility property 30

Mississippi

Class 5: Motor vehicles 30

Missouri Class 1a: Real residential 19%

Class 1b: Real agricultural 12

Class 1c: Real utility, industrial, commercial and railroad 32

Class 2a: Personal property 33.3

Class 2b: Grain and crops 0.5

Class 2c: Livestock 12

Class 2d: Farm machinery 5

Class 3: Intangible personal property 33.3

Montana Property is assessed at 100 percent of market value. However, taxable value is

the value upon which the tax is levied and is a percentage of market value.

2002 Taxable

Value:

Class 1: Net proceeds of mines (except coal and metal) 100%

Class 2: Gross proceeds of metal mines 3

Class 3: Agricultural land

Nonproductive mining claims

Nonagricultural land between 20 acres and 160 acres

3.46

3.46

24.220

Class 4: Residential, commercial and industrial land and improvements

Golf courses

Idle agricultural and timber processing property

Mobile homes

3.460

1.730

3.460

3.460

Appendices 23

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Class 5: Air and water pollution control equipment

Rural electrical and telephone cooperatives

Real and personal property of “new industry”

Machinery and equipment used in electrolytic reduction facilities

Real and personal property of research and development firms

Real and personal property used to produce gasohol

3

3

3

3

3

3

Class 6: Livestock

Rental or lease equipment less than $15,000

Machinery and equipment used in canola seed oil processing

1 (0 in 2003)

1 (0 in 2003)

1 (0 in 2003)

Class 7: Qualifying rural electric associations 8

Class 8: Business personal property 3

Class 9: Real and personal property of pipelines and certain electric property 12

Class 10: Forest lands 0.35

Class 11: Repealed

Class 12: Railroad and airline transportation property 4.270 (2000)

Class 13: Telecom property and electrical generation property 6

Nebraska Class 1: Residential 100%

Class 2: Personal (excluding motor vehicles) 100

Class 3: Agricultural 80

Nevada No classifications. Property is assessed at 35 percent of taxable value. 35%

New

Hampshire

No specific classifications. 100%

New Jersey No specific classifications. Taxable value is a percentage of true value. 20% - 100%

New Mexico Property is classified as either residential or nonresidential. 33.3%

New York New York state law provides that all property within a municipality be assessed

at a uniform percent of market value. The level of assessment can be 5 percent,

20 percent, 50 percent, or any other percent up to 100 percent.

Varies

North

Carolina

No specific classes. Historic property is taxed at 50 percent. 100%

Class 1: Residential 9%

Class 2: Agricultural 10

Class 3: Commercial 10

Class 4: Centrally assessed property except wind turbine generators 10

North

Dakota

Class 5: Centrally assessed wind turbine generators 3

Ohio No specific classes. Most property is assessed at 35 percent. 35%

Oklahoma For locally assessed property, the county assessor sets the ratio

Real property 11% – 13.5%

Personal property 10 - 15

Public service corporation property (centrally assessed) 22.85

Railroad and air carrier property (centrally assessed) 12.08

24 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Oregon No specific classifications 100%

Pennsylvania No specific classifications. Assessment ratios vary by county. 75% - 100%

Rhode

Island

No state classifications: cities may have own classification system. Varies

Class 1: Real and personal property of manufacturers and utilities 10.5%

Class 2: Residential 4

Class 3: Agricultural realty 4

Class 4: Real and personal property of transportation companies 9.5

Class 5: All other real property 6

South

Carolina

Class 6: All other personal property (except certain water craft) 10.5

South Dakota has four property classifications: 100%

Nonagriculture

Agriculture

Owner-occupied single-family dwellings

South

Dakota

Nonagricultural acreage

Tennessee Residential 25%

Real property of utilities 55

Real industrial and commercial property 40

Personal property 5

Personal property of utilities 55

Personal industrial and commercial property 30

Texas Texas has 14 property categories; 13 are valued at 100 percent of market value;

rural real property (category D) is valued on its productivity valuation.

100%

Category A: Single-family residences

Category B: Multi-family residences

Category C: Vacant lots

Category D: Rural real property

Category F1: Commercial real property

Category F2: Industrial real property

Category G: Oil, gas and minerals

Category J: Utilities

Category L1: Commercial personal property

Category L2: Industrial personal property

Category M: Other personal property

Category N: Intangible personal and uncertified property

Category O: Residential inventory

Category S: Special inventory

Utah Primary residential property 55%

Other locally assessed real property 100

Centrally assessed property (utilities, mines, airlines, railroads, etc.) 100

Appendices 25

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications

Assessment

Ratios

Vermont The following real property categories are assessed at full value: 100%

1. Residential property with less than 6 acres of land

2. Residential with 6 or more acres of land

3. Mobile home on land not owned by the owner of the mobile home

4. Mobile home on land owned by owner of the mobile home

5. Vacation property with less than 6 acres of land

6. Vacation property with more than 6 acres of land

7. Commercial

8. Commercial apartments

9. Industrial

10. Operating property of electric utilities

11. Operating property of other utilities

12. Farm

13. Other

14. Woodland

15. Undeveloped land that is not mostly wooded

Virginia No specific classifications. 100%

Washington No specific classifications. 100%

West

Virginia

Class 1a: Tangible personal property used for agriculture while owned by the

producer

60%

Class 1b: Agricultural products while owned by the producer

Class 1c: Intangible personal property such as notes, bonds and stocks

Class 2a: Property owned, used and occupied by the owner for residential

purposes

Class 2b: Farms occupied and cultivated by owners or bonafide tenants.

Class 3: Real and personal property situated outside of municipalities,

exclusive of classes 1 and 2

Class 4: Real and personal property situated inside of municipalities,

exclusive of classes 1 and 2

Wisconsin Class1: Residential 100%

Class 2: Commercial

Class 3: Manufacturing

Class 4: Agricultural

Class 5: Swamp or waste

Class 6: Productive forest land

Class 7: Other

Wyoming Class 1: Gross mineral and mine products 100%

Class 2: Industrial property 11.5

Class 3: All other property 9.5

26 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix B. Property Classification, by State

(continued)

State/

Jurisdiction

Types of Property Classifications Assessment

Ratios

Class 1: Residential 100%

Class 2: Non-owner occupied residential 100

Class 3: Hotels and motels 100

Class 4: Improved real property that is not class 1, 2 or 3 100

District of

Columbia

Class 5: All real property that is not any other class 100

Source: Commerce Clearing House, 2001, NCSL and International Association of Assessing Officers, 2000.

Appendices 27

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix C. Tax Treatment of Agricultural Property, by State

State Comments

Alabama Upon request of the owner, agricultural property will be appraised on current use value

Alaska Farmland is assessed on the basis of full and true value for farm use

Arizona Agricultural land, pasture land, timber land, residential and commercial land, excluding

structures, used primarily as such, must be valued upon the basis of its productivity or use.

Arkansas Agricultural land, pasture land and timberland valuation is based on soil productivity

California Land zoned exclusively for agricultural purposes may be assessed only on the basis of use.

Colorado The actual value of agricultural lands must be determined solely by consideration of the

earning or productive capacity of such lands capitalized at 13 percent.

Connecticut Special provisions are made for classification and taxation of woodlands, farmland,

forestland, open-space land, and shellfish lands.

Delaware The value of qualified land actively devoted to agricultural, horticultural or forest use is

that value which such lands have for such purposes.

Florida Agricultural land may be assessed based solely on its agricultural use.

Georgia Taxable real property used for the commercial production of agricultural products is

assessed at 75% of the value at which other real property is assessed.

Hawaii Agricultural property is valued according to its agricultural use, regardless of the value it

might have for another purpose or any neighboring land uses.

Idaho The assessed value of agricultural property is determined using the income approach rather

than the market data approach.

Illinois Land used for agricultural purposes is assessed on the basis of its economic productivity

value.

Indiana Agricultural land is valued by a formula based on the soil productivity factor.

Iowa Agricultural property is assessed at its actual value by giving exclusive consideration to its

productivity and net earning capacity, determined on the basis of its use for agricultural

purposes.

Kansas Agricultural land is appraised at the value of the land for agricultural purposes.

Kentucky Upon application, agricultural or horticultural land will be valued at its agricultural or

horticultural value.

Louisiana Agricultural, horticultural, marsh and timberlands are assessed on their use value.

Maine The value of land classified as farmland is based on its current use value as farmland.

Maryland Qualified farmland is assessed at 50 percent of its use value.

Massachusetts Qualified agricultural or horticultural land is assessed and taxed on its use value.

Michigan Agricultural lands are not assessed taxes for local school uses, which accomplishes much the

same result as use valuation but eliminates the need for use value taxation procedures.

Minnesota Qualified agricultural property is classified as such and is taxed at a lower rate.

Mississippi Agricultural land is assessed at a specified percentage of its true value, according to current

use.

Missouri The true value in money of land that is agricultural and horticultural property is that value

such land has for agricultural or horticultural use.

Montana Agricultural land is assessed at 100 percent of its productive capacity based on yield.

28 A Guide to Property Taxes: An Overview

National Conference of State Legislatures

Appendix C. Tax Treatment of Agricultural Property, by State

(continued)

State Comments

Nebraska Agricultural and horticultural land constitutes a separate and distinct class of property and

is required to be valued at 80 percent of its actual value.

Nevada Approved agricultural or open space land is assessed at 35 percent of its value as agricultural

or open space land.

New

Hampshire

Open space land is assessed at its current use value.

New Jersey Land not less than 5 acres devoted to agricultural or horticultural use may qualify for use

value assessment.

New Mexico The value of land used primarily for agricultural purposes is determined on the basis of the

land’s capacity to produce agricultural products.

New York Owners of qualified agricultural land are entitled to an agricultural assessment, the value of

which is determined annually by the state.

North

Carolina

Agricultural, horticultural and forest land that meets certain qualifications may be taxed

based on its present use.

North Dakota Agricultural property is valued at 10 percent of its true and full value.

Ohio Agricultural land is appraised at its current value for agricultural use purposes.

Oklahoma The use value of agricultural land must be determined using the income capitalization

approach to valuation.

Oregon Land within a farm use zone used exclusively for farming is, for assessment purposes,

valued at its value for farm use.

Pennsylvania Qualified farm, agricultural reserve and/or forest reserve land may, upon application of the

owner, be assessed according to its value for farm or forest use.

Rhode Island Designated farmland, forestland of not less than 10 acres, and open space land will be