’

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

(14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956)

An ideal society should be mobile, should be full of channels

for conveying a change taking place in one part to other parts.

In an ideal society there should be many interests consciously

communicated and shared. There should be varied and free

points of contact with other modes of association. In other

words there should be social endosmosis. This is fraternity,

which is only another name for democracy. Democracy is

not merely a form of Government. It is primarily a mode of

associated living, of conjoint communicated experience. It

is essentially an attitude of respect and reverence towards

fellowmen.

- Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

in ‘Annihilation of Caste’

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR

WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

VOL. 1

Compiled

by

Vasant Moon

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches

Vol. 1

First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : 14 April, 1979

Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014

ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9

Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from

Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead.

©

Secretary

Education Department

Government of Maharashtra

Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/-

Publisher:

Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001

Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589

Fax : 011-23320582

Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in

The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032

for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee

Printer

M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana

MESSAGE

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was

a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true

nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the

oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle

for social justice.

The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of

publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought

out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world.

In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee

of Dr. Ambedkar, constituted under the chairmanship of the then Prime Minister

of India, the Dr. Ambedkar Foundation (DAF) was set up for implementation of

different schemes, projects and activities for furthering the ideology and message

of Dr. Ambedkar among the masses in India as well as abroad.

The DAF took up the work of translation and publication of the Collected Works

of Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar published by the Government of Maharashtra

in English and Marathi into Hindi and other regional languages. I am extremely

thankful to the Government of Maharashtra’s consent for bringing out the works

of Dr. Ambedkar in English also by the Dr. Ambedkar Foundation.

Dr. Ambedkar’s writings are as relevant today as were at the time when these

were penned. He firmly believed that our political democracy must stand on the

base of social democracy which means a way of life which recognizes liberty,

equality and fraternity as the principles of life. He emphasized on measuring the

progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved.

According to him if we want to maintain democracy not merely in form, but also

in fact, we must hold fast to constitutional methods of achieving our social and

economic objectives. He advocated that in our political, social and economic life,

we must have the principle of one man, one vote, one value.

There is a great deal that we can learn from Dr. Ambedkar’s ideology and

philosophy which would be beneficial to our Nation building endeavor. I am glad

that the DAF is taking steps to spread Dr. Ambedkar’s ideology and philosophy

to an even wider readership.

I would be grateful for any suggestions on publication of works of Babasaheb

Dr. Ambedkar.

(Kumari Selja)

Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment

& Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Kumari Selja

Collected Works of Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar (CWBA)

Editorial Board

Kumari Selja

Minister for Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

and

Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Shri Manikrao Hodlya Gavit

Minister of State for Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

Shri P. Balram Naik

Minister of State for Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

Shri Sudhir Bhargav

Secretary

Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

Shri Sanjeev Kumar

Joint Secretary

Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India

and

Member Secretary, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Shri Viney Kumar Paul

Director

Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Shri Kumar Anupam

Manager (Co-ordination) - CWBA

Shri Jagdish Prasad ‘Bharti’

Manager (Marketing) - CWBA

Shri Sudhir Hilsayan

Editor, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material

Publication Committee, Maharashtra State

EDITORIAL BOARD

1. S

HRI KAMALKISHOR KADAM … …. … President

Minister For Education

2. S

HRI JAVED KHAN … … … Vice-President

Education Minister For State

3. S

HRI R. S. GAVAI … … … Vice-President

4. S

HRI DADASAHEB RUPAVATE … … … Executive President

5. S

HRI B. C. KAMBLE … … … Member

6. D

R. P. T. BORALE … … … Member

7. S

HRI GHANSHYAM TALVATKAR … … … Member

8. S

HRI SHANKARRAO KHARAT … … … Member

9. S

HRIMATI SHANTABAI DANI … … … Member

10. S

HRI WAMAN NIMBALKAR … … … Member

11. S

HRI PRAKASH AMBEDKAR … … … Member

12. S

HRI R. R. BHOLE … … … Member

13. S

HRI S. S. REGE … … … Member

14. D

R. BHALCHANDRA PHADKE … … … Member

15. S

HRI DAYA PAWAR … … … Member

16. S

HRI LAXMAN MANE … … … Member

17. P

ROF. N. D. PATIL … … … Member

18. P

ROF. MORESHWAR VANMALI … … … Member

19. P

ROF. JANARDAN WAGHMARE … … … Member

20. B

ARRISTER P. G. PATIL … … … Member

21. D

R. M. P. MANGUDKAR … … … Member

22. P

ROF. G. P. PRADHAN … … … Member

23. S

HRI B. M. AMBHAIKAR … … … Member

24. S

HRI N. M. KAMBLE … … … Member

25. P

ROF. J. C. CHANDURKAR … … … Member

26. Secretary, Education Department … … Member

27. Director of Education … … … Member-Secretary

28. S

HRI V. W. MOON, O.S.D. … … … Member

FOREWORD

Maharashtra is a land of saints and sages, philosophers and political

savants, social thinkers, social reformers and leaders of national

eminence, who have not only moulded and enriched all facets of

life of Maharashtra but have also made singular contribution to the

growth and development of India.

Maharashtra, an ancient land in the Deccan, has witnessed the

flowering, growth and spread of the Buddhist thought and culture

and Sanskrit Scholarship. We have saints like Namdeo, Eknath,

Chokhamela, Sawata Maharaj, Gora, Dnyaneshwar, Sena and others.

We also see the rise of Indian Nationalism in the form of Shivaji

the Great. In Mahatma Phuley, a contemporary of Karl Marx, we

have the ‘patria protestas of the Indian social revolution and the

first leader of the peasants. Lokmanya Tilak has been accredited as

the Father of Indian unrest, Ranade as the Father of Indian socio-

economic thought, Gokhale as the thinker whom no less a person

than Mahatma Gandhi acclaimed as his political Guru and Savarkar

as an ardent revolutionary. In Shahu Chhatrapati, we had a unique

king who was a relentless fighter for social equality. Maharshi Shinde

was a great social reformer who combined revolutionary fervour with

a liberal attitude. Thus, there has been a galaxy of great men in

different fields in Maharashtra. It may not be too much to say that

there was a time in pre-independent India when Maharashtra had

virtually become the centre of all activities, whether social, economic

or political. The period from Phuley to Ambedkar can, therefore, be

aptly described as the dawn of social revolution in the history not

only of Maharashtra but of the country as a whole.

VIII FOREWORD

In Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, we have not only a crusader against

the caste system, a valiant fighter for the cause of the downtrodden

in India but also an elder statesman and national leader whose

contribution in the form of the Constitution of India will be cherished

forever by posterity. In fact his fight for human rights and as an

emancipator of all those enslaved in the world gave him international

recognition as a liberator of humanity from injustice, social and

economic. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru paid a glowing tribute to

Dr. Ambedkar while moving a condolence resolution in the Parliament

as follows:

“Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar was a symbol of revolt against all oppressive features

of the Hindu Society.”

There is, therefore, a vital need to preserve the thoughts of this great

son of India as expressed by him in his writings and speeches. While

some efforts are being made in that direction by some institutions

and research scholars, there is an urgent need to bring together all

the material available and publish it in a series of volumes.

The Government of Maharashtra has, under its various schemes,

so far published the works of Mahatma Phuley, Mahatma Gandhi

and saints such as Tukaram, Dnyaneshwar, Namdeo, Eknath and

others. The Government had set up an Advisory Committee in 1976,

with the Education Minister as the Chairman and comprising political

followers of Dr. Ambedkar, scholars and noted writers, to compile the

thoughts and writings of Dr. Ambedkar and have them published.

The Committee set up the following Editorial Board :

(1) Prof. M. B. Chitnis, Chairman

(2) Prof. Anant Kanekar

(3) Dr. P. T. Borale

(4) Dr. Vinayakrao E. Moray

(5) Shri S. P. Bhagwat

(6) Shri G. M. Bomblay, Director, Stale Institute of Education,

Pune

(7) Shri Vasant Moon, Officer on Special Duty

The Government of Maharashtra desires to bring a series of

volumes comprising all the available writings and speeches of

FOREWORD IX

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. The present publication is the result of

sustained work done by the Advisory Committee and particularly

by the Editorial Board. I thank all the members of the Editorial

Board, Mrs. Savita w/o Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Mrs. Meerabai

Yeshwant Ambedkar and Shri Prakash Ambedkar, for their willing

co-operation. I am particularly glad that this long awaited commitment

is being fulfilled. I sincerely hope that people in general and the

youth in particular, in Maharashtra and all over the country, will

derive inspiration and guidance from the thoughts of Dr. Babasaheb

Ambedkar and come forward to contribute their mite for the social

reconstruction of the country.

(SHARAD PAWAR)

Chief Minister

Maharashtra State

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

It is almost ten years since the first edition of the first volume of the

Writings and Speeches of Dr. B.R. alias Babasaheb Ambedkar was published.

During these ten years the Government could publish six volumes of Writings

and Speeches of Dr. Ambedkar who has emerged from these pages as a

constructive social reformer and legal philosopher who in the originality

of his analysis and profundity of his convictions and conceptions compels

comparison with the best minds of the East and the West and who still

shapes our thinking. It is not difficult to discern the reasons for the Second

Edition against this background. We have availed of this opportunity to

correct obvious printing errors in the Second Edition of the first volume

which contains Dr. Ambedkar’s contributions such as Castes in India;

Annihilation of Caste; Maharashtra as a Linguistic Province; Need for checks

and balances; Thoughts on Linguistic States; Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah;

Evidence before the Southborough Committee; Federation Vs. Freedom;

Communal Deadlock and a Way to solve it; States and Minorities; Small

Holdings in India; and Mr. Russell and the Reconstruction of Society. In all

these apparently diverse topics, it is not difficult to discern the silver strands

of fundamental reflections on the value of equality as the comer stone of

the constitutional polity in democracy. It is interesting to refer to what Dr.

Ambedkar writes apropos of Mr. Russell and the reconstruction of society

which is a review of Bertrand Russell’s ‘Principles of Social Reconstruction.’

Writes Dr. Ambedkar :

“Of the many reasons urged in support of the Indian view of life one is that

it is chiefly owing to its influence that India alone of all the oldest countries

has survived to this day. This is a statement often heard and even from persons

whose opinions cannot be too easily set aside. With the proof or disproof,

however, of this statement, I do not wish to concern myself. Granting the fact

of survival I mean to make a statement yet more important. It is this: there

are many modes of survival and not all are equally commendable. For instance,

mobility to beat timely retreat may allow weaker varieties of people to survive.

So the capacity to grovel or lie low may equally as the power of rising to the

occasion be the condition of the survival of a people.”

Dr. Ambedkar drawing copiously on his vast erudition, eloquently citing

Burke, depicts the ideal society in Annihilation of Caste. He says: “If you ask

me, my ideal would be a society based on liberty, equality and fraternity....

an ideal society should be mobile, should be full of channels for conveying a

change taking place in one part to other parts.” Dr. Ambedkar incorporated

these values of liberty, equality and fraternity in the Constitution of free

India. It is a living tribute to his juristic genius and social conscience that

over the years, the High Courts and the Supreme Court have shaped the

law to serve the social ends of Governmental efforts to improve the lot of

the poor.

XII

Dr. Ambedkar was a supreme social architect who looked upon law as

the instrument of creating a sane social order in which the development of

individual would be in harmony with the growth of society. His approach finds

a responsive chord in the writings of Roscoe Pound- an eminent American

jurist of our century. Writes Roscoe Pound:

“Law in the sense of the legal order has for its subject matter relations of

individual human beings with each other and the conduct of individual so far

as they affect other or affect the social or economic order. Law in the sense

of the body of authoritative grounds of or guides to judicial decisions and

administrative action has for its subject matter, the expectations of claims or

wants held or asserted by individual human beings or groups of human beings

which affect their relations or determine their conduct.”

Law embodies the civilisational values of the time and place. Civilisation

in this sense is the development of human faculties to their most complete

possibilities. Civilisation has two sides viz. control over external or physical

nature and control over internal or human nature. The Writings and Speeches

of Dr. Ambedkar show what values Indians should develop and how they

should modernise their social and political institutions. They provide the rich

source of the civilising influences in our society. The range of his topics, the

width of his vision, the depth of his analysis, the rationality of his outlook and

the essential humanity of his suggestions for action evoke ready responses.

Such was Dr. Ambedkar-a man whose talents, acquirements and virtues

were so extraordinary that the more his character is considered, the more

he will be regarded by the present age and by posterity with admiration

and reverence, to paraphrase the words of James Bosewell who spoke about

his mentor Dr. Johnson in his inimitable classical biography. We shall feel

rewarded in our efforts if we are compelled to bring out the third edition of

the Writings and Speeches in the centenary year of his birth, as that would

be the best way to cherish his memory and honour his precepts in practice.

(Kamalkishor Kadam)

Education Minister

Maharashtra State

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Ambedkar’s thoughts as reflected in his writings and speeches

have significant importance in tracing the history and growth of

social thought in India. In the course of time so many of his

publications are not even available in the market. In some cases the

authentic editions are getting out of print. Besides, as time passes,

many of his observations in matters social, economic and political

are coming true. Social tensions and caste conflicts are continuously

on the increase. Dr. Ambedkar’s thoughts have therefore, assumed

more relevance today. If his solutions and remedies on various socio-

economic problems are understood and followed, it may help us to

steer through the present turmoil and guide us for the future. It was

therefore very apt on the part of the Government of Maharashtra to

have appointed an Advisory Committee to compile all the material

available on Dr. Ambedkar for publishing the same in a suitable

form. All efforts are therefore being made to collect what the learned

Doctor wrote and spoke.

In the present volume, besides Castes in India. Annihilation of

Caste, his address on Justice Ranade. Federation versus Freedom

and other publications, some of his articles not easily available such

as Small Holdings in India, Review on Russell’s book etc. ; have also

been included.

The salient features of the contents of this volume are presented

below :

Castes in India

Dr. Ambedkar read this paper, before the Anthropology Seminar

of Dr. Goldenweizer during his stay at the Columbia University

XIV INTRODUCTION

for the Doctoral studies. Naturally he deals with the subject of Caste

system from the Anthropological point of view. He observes that the

population of India is mixture of Aryans, Dravidians, Mongolians and

Scythians. Ethrically all people are heterogeneous. According to him,

it is the unity of culture that binds the people of Indian Peninsula

from one end to the other. After evaluating the theories of various

authorities on Caste, Dr. Ambedkar observes that the superimposition

of endogamy over exogamy is the main cause of formation of caste

groups. Regarding endogamy, he states that the customs of ‘Sati’,

enforced widow-hood for life and child-marriage are the outcome of

endogamy. To Dr. Ambedkar, sub-division of a society is a natural

phenomenon and these groups become castes through ex-communication

and imitation.

Annihilation of Caste

This famous address invited attention of no less a person than

Mahatma Gandhi. Dr. Ambedkar observes that the reformers among

the high-caste Hindus were enlightened intellectuals who confined

their activities to abolish the enforced widow-hood, child-marriage,

etc., but they did not feel the necessity for agitating for the abolition

of castes nor did they have courage to agitate against it. According

to him, the political revolutions in India were preceded by the social

and religious reforms led by saints. But during the British rule,

issue of political independence got precedence over the social reform

and therefore social reform continued to remain neglected. Pointing

to the. Socialists, he remarked that the Socialists will have to fight

against the monster of caste either before or after the revolution. He

asserts that caste is not based on division of labour. It is a division

of labourers. As an economic organisation also, caste is a harmful

institution. He calls upon the Hindus to annihilate the caste which is

a great hindrance to social solidarity and to set up a new social order

based on the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity in consonance

with the principles of Democracy. He advocates inter-caste marriage

as one of the solutions to the problem. But he stresses that the belief

in the ‘Shastras’ is the root cause of maintaining castes. He therefore

suggests, “Make every man and woman free from the thraldom of the

INTRODUCTION XV

‘Shastras’, cleanse their minds of the pernicious notions founded on

the ‘Shastras’ and he or she will interdine and intermarry”. According

to him, the society must be bused on reason and not on atrocious

traditions of caste system.

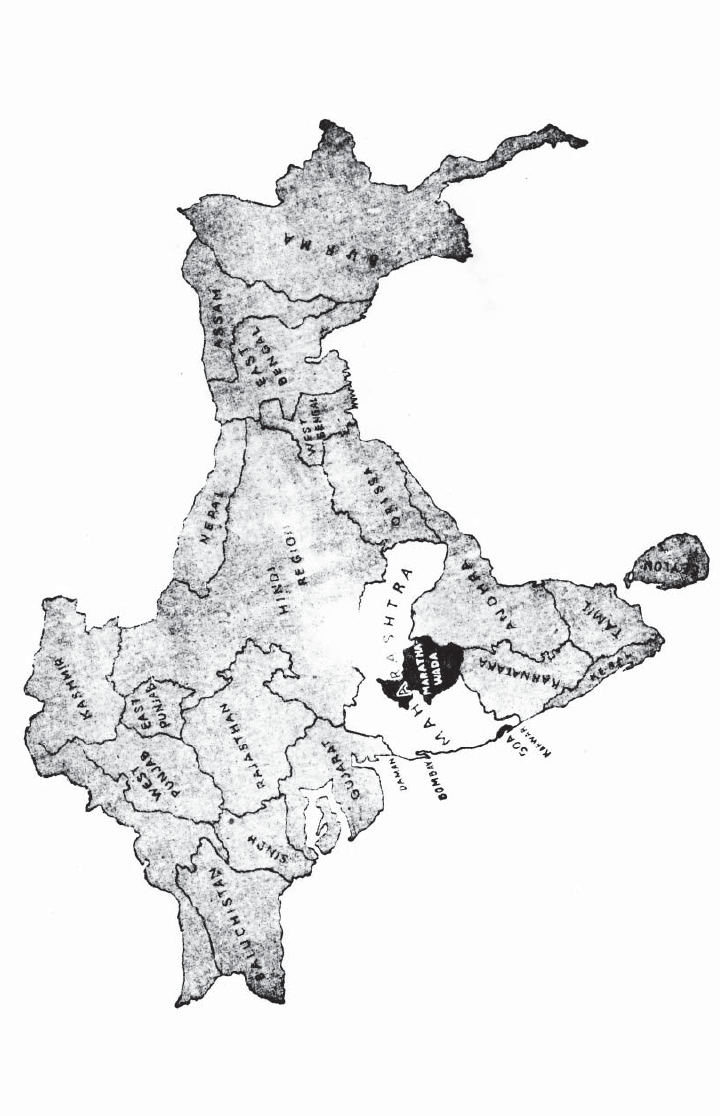

Maharashtra as a Linguistic Province

Part II includes Dr. Ambedkar’s major writings on linguistic States.

Maharashtra as a Linguistic Province is his first statement on the

creation of linguistic provinces. It is a memorandum submitted in

1948 to the Linguistic Provinces Commission. While acknowledging

the danger to the Unity of India inherent in the creation of linguistic

provinces with their pride in race, language and literature developing

into mentalities of being separate nations, Dr. Ambedkar sees certain

definite political advantages in the reconstitution of provinces on

linguistic basis. With the proviso that the official language of the State

shall be the official language of the Central Government, Dr. Ambedkar

maintains that a linguistic province with a homogeneous population

is more suitable for the working of democracy than a heterogeneous

population can ever be. Since six provinces in India exist as linguistic

provinces the question of the reconstitution of Bombay, Madras and

Central Provinces as unilingual provinces cannot be postponed in view

of the new democratic constitution of free India.

Dr. Ambedkar next pleads for the creation of an unilingual

Maharashtra as a province with a single legislature and single executive

by merging with it all the contiguous Marathi-speaking districts of the

Central Province and Berar with the City of Bombay as its capital.

Dr. Ambedkar refutes on historical, geographical, demographical,

commercial, economic and other grounds with solid documentary

proof, the arguments which are advanced in support of the separation

of the city of Bombay from Maharashtra and its constitution into a

separate province. Spurning the proposal of settling the problem of

Bombay by arbitration he asserts that Maharashtra and Bombay are

not merely inter-dependent but that they are really one and integral.

Need for Checks and Balances

In this article published in the ‘Times of India’ after tracing the

history and growth of the concept of linguistic States Dr. Ambedkar

XVI INTRODUCTION

examines their viability and communal set-up. The State of Andhra,

according to him will not be viable if the other Telugu-speaking area

from the State of Hyderabad remains excluded from it. The caste set

up, he observes, within the linguistic areas like PEPSU, Andhra and

Maharashtra will be of one or two major castes large in number and

a few minor castes living in subordinate dependence on the major

castes. He questions the propriety of consolidating in one huge State

all people who speak the same language. Consolidation which creates

separate consciousness may lead to animosity between State and

State. Accepting however the fact that there is a case for linguistic

provinces he advocates that there should be checks and balances to

ensure that caste majority does not abuse its power under the garb

of linguistic State.

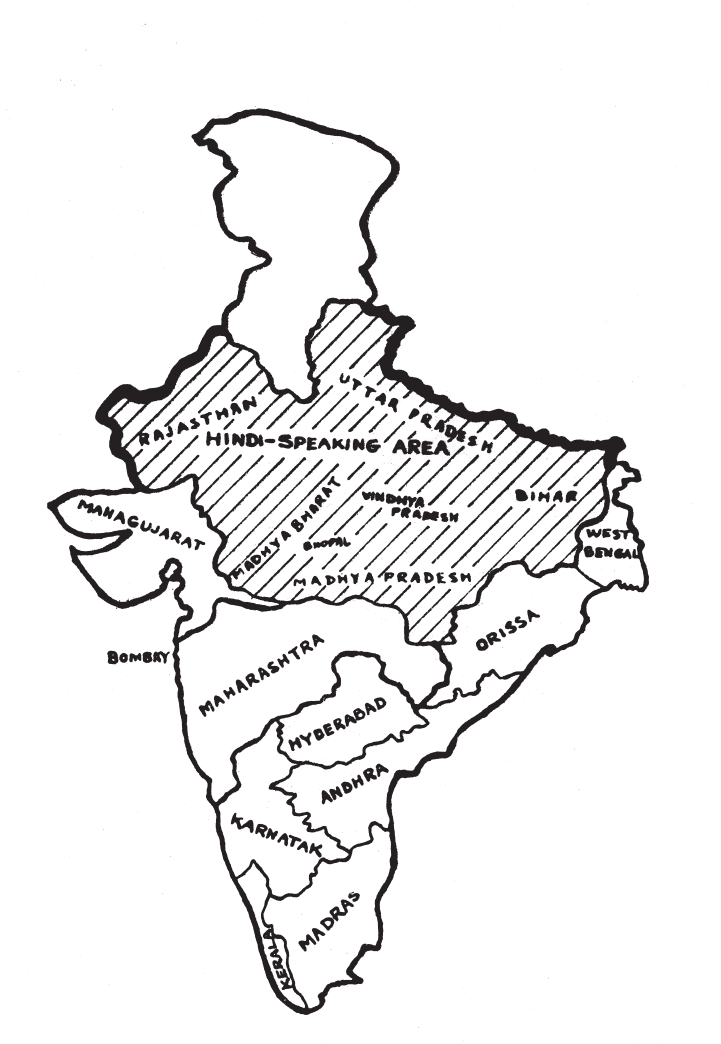

Thoughts on Linguistic States

‘Thoughts on Linguistic States’ is Dr. Ambedkar’s final statement on

the formation of linguistic States that came as a critique of the report

of the States Reorganization Commission. What the Commission has

created, according to him, is not a mere disparity between the States

by leaving U.P. and Bihar as they are, but by adding to them a

new and bigger Madhya Pradesh with Rajasthan. It creates a new

political problem of the consolidated Hindi-speaking North versus the

balkanized South. Considering the vast cultural differences between

the two sectors and the apprehensions of dominance of the North

articulated by the leaders of the South Dr. Ambedkar predicts the

danger of a conflict between the two in course of time. He observes

that the Commission should have followed the principle of “one State

one language” and not “one language one State”

He favours formation of unilingual States as against multi-

lingual States for the very sound reasons that the former fosters

the fellow-feeling which is the foundation of a stable and

democratic State, while the latter with its enforced juxtaposition

of two different linguistic groups leads to faction fights for

leadership and discrimination in administration — factors which

are incompatible with democracy. His support for unilingual

States is however qualified by the condition that its official language

INTRODUCTION XVII

shall be Hindi and until India becomes fit for this purpose, English

shall continue. He foresees the danger of a unilingual Stale developing

an independent nationality if its regional language is raised to the

status of official language.

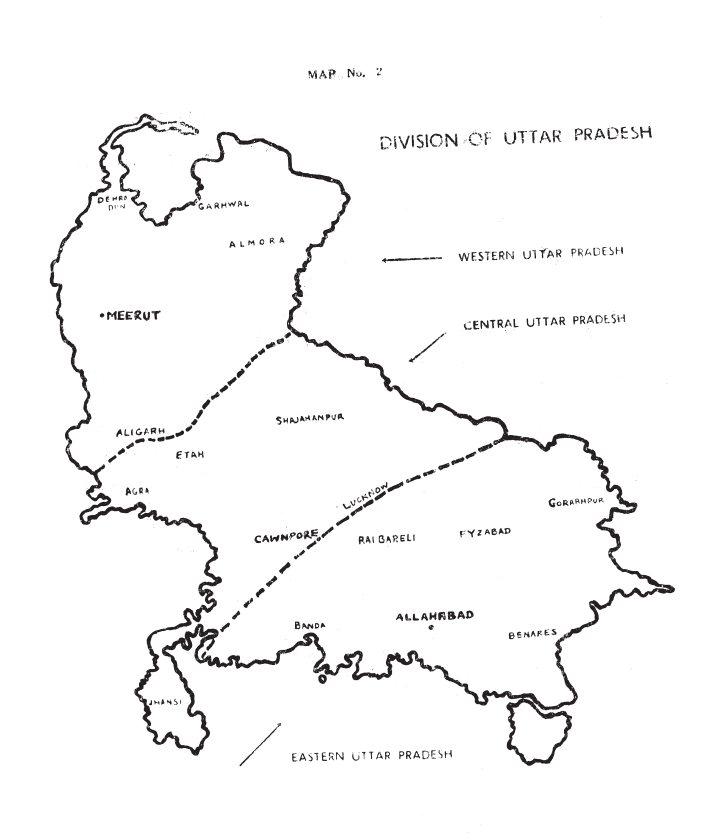

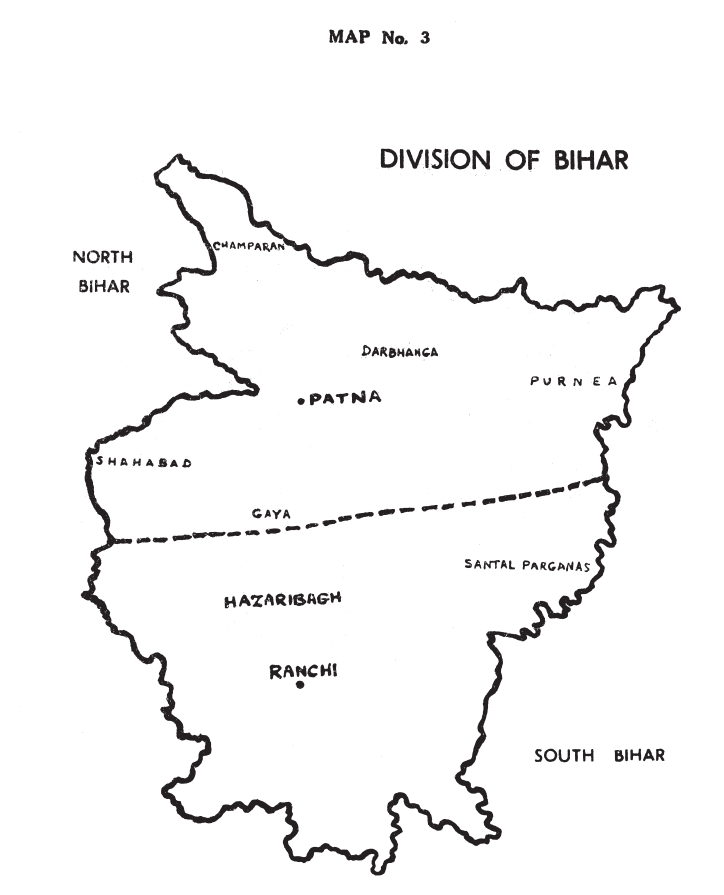

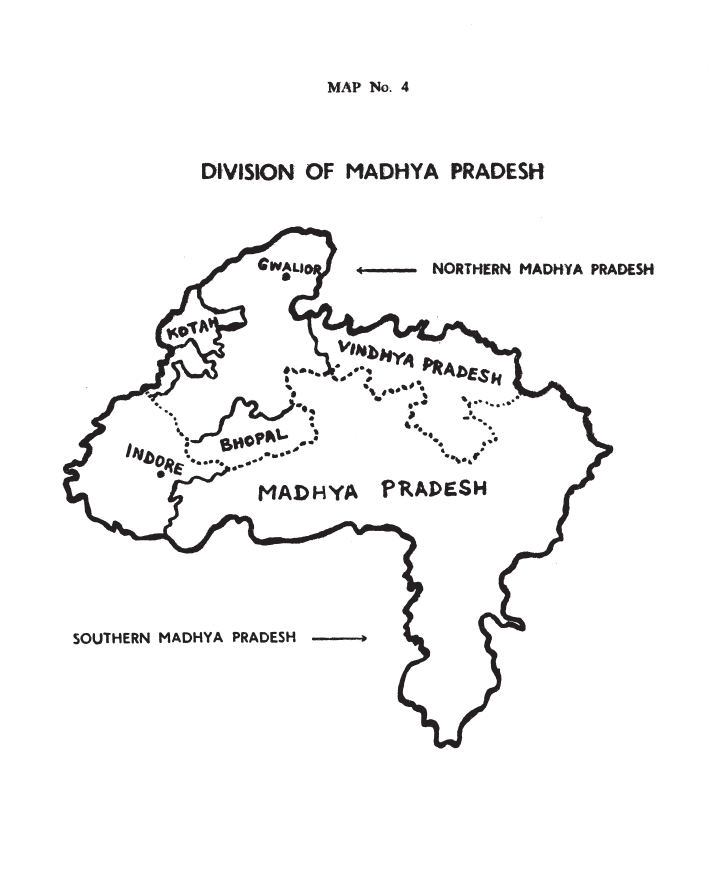

To remove the disparity between the large States of the North and

the small States of the South which has been accentuated by the

absence of the provision for equal representation of the States in the

central legislature irrespective of their areas and popula tions, Dr.

Ambedkar’s remedy is to divide the larger States into units with a

population not exceeding two crores. He suggests tentatively division

of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh into two States each and of United

Provinces into three States. Each of these States being unilingual the

division will not affect the concept of a linguistic State. His proposal

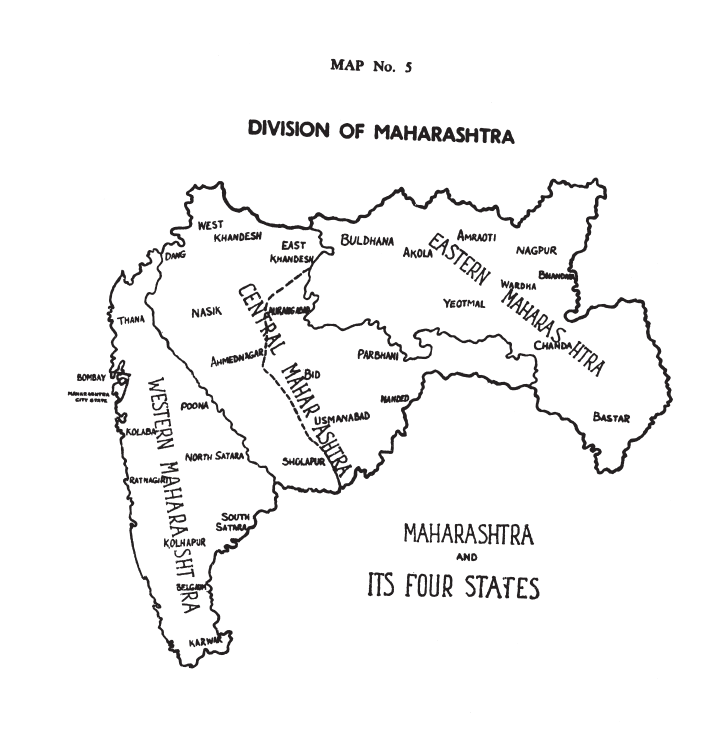

for Maharashtra is to divide it, as in ancient times, into three States

of Western, Central and Eastern Maharashtra with Bombay City as

a separate city State of Maharashtra. Such smaller States, in his

opinion, will meet the requirements of efficient administration and the

special needs of different areas. It will also satisfy their sentiments.

In a smaller State the proportion of majority to minority which

in India is not political but communal and unchangeable, decreases

and the danger of the majority practising tyranny over the minority is

also minimised. To give further protection to minorities against such

tyranny, Dr. Ambedkar suggests amendment of the constitution that

will provide a system of plural-member constituencies (two or three)

with cumulative voting.

Dr. Ambedkar advocate’s also the creation of a second capital for

India and locating it in the South preferably in the city of Hyderabad

to ease the tension and political polarization of the North and the

South.

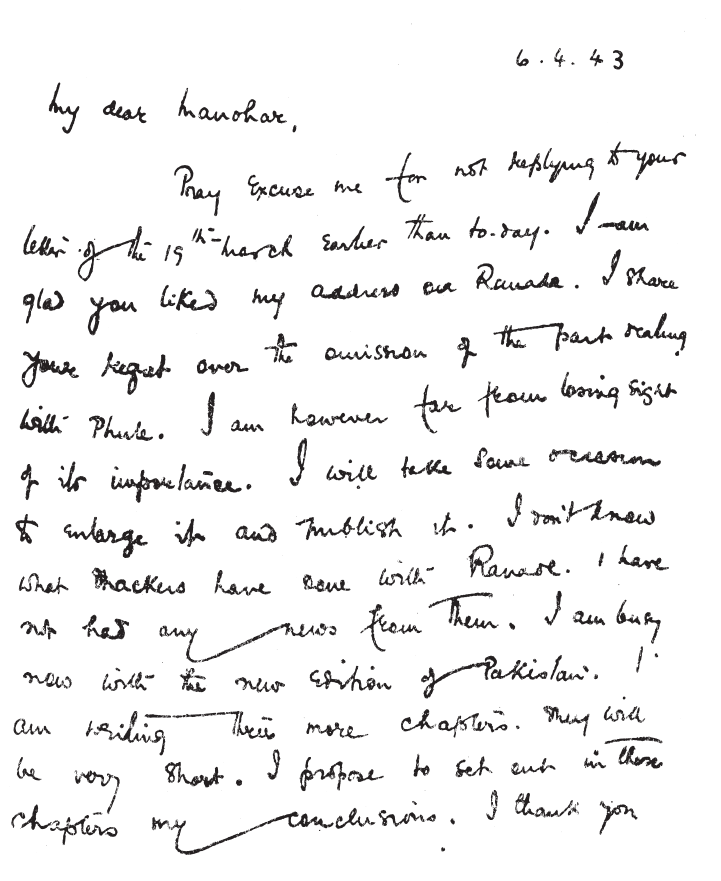

Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah

Dr. Ambedkar delivered this important address on the 101st birth

anniversary of Justice Ranade, one of India’s foremost political

and social thinkers. At the beginning of his address, Dr. Ambedkar

discusses the role of man as a maker of history. According to him,

XVIII INTRODUCTION

the theory of Buckle that the history is created by Geography and

Physics, and that of Marx that it is the result of economic forces,

both speak the half truth. They do not give any place to man.

But Dr. Ambedkar asserts that man is a factor in the making of

history and that environmental forces alone are not the makers of

history.

Dr. Ambedkar further proceeds to discuss the tests of a great man

as propounded by Carlyle the apostle of Hero Worship, and also of

other political thinkers. After exhaustive discussion, he observes that

sincerity and intellect the combination of which are necessary to make

a man great. But these qualifications are not alone sufficient. A man

possessed of these two qualities must be motivated by the dynamics

of a social purpose and must act as a scavenger of society.

According to Dr. Ambedkar, Ranade was a great man by any

standard. He wanted to vitalize the Hindu society to create social

democracy. Ranade lived in times when social and religious customs,

however unmoral, were regarded as sacrosanct. What appeared to

Ranade to be shames and wrongs of the Hindu society, were considered

by the people to be most sacred injunctions of their religion. Ranade

wanted to vitalize the conscience of the Hindu society which became

moribund as well as morbid. Ranade aimed to create a real social

democracy. without which there could be no sure and stable politics.

Dr. Ambedkar points out that Ranade’s aim was to cleanse the old

order and improve the moral tone of the Hindu society.

Concluding his address, Dr. Ambedkar cautions against despotism.

He says, “ Despotism does not cease to be despotism because it is elective.

Nor does despotism become agreeable because the Despots belong to

our own kindred ………….. The real guarantee against despotism is

to confront it with the possibility of its dethronement ………………….

of its being superseded by a rival party.”

Evidence before the Southborough Committee

Dr. Ambedkar’s evidence before the Southborough Committee

was his first assay in political writings. The evidence comprises

of a written statement submitted to the Franchise Committee

INTRODUCTION XIX

under the Chairmanship of Rt. Hon’ble Lord Southborough and

also of the oral evidence before the same Committee on January

27, 1919.

After arguing theoretically that any scheme of franchise and

constituency that fails to bring about representation of opinions

as well as representation of persons falls short of creating a

popular Government. He shows how very relevant the two

factors are in the context of the Indian society which is ridden

into castes and religious communities. Each caste group tends to

create its own distinctive type of like-mindedness which depends

upon the extent of communication, participation or endosmosis.

Absence of this endosmosis is most pronounced between touchable and

untouchable Hindus, more than between the religious communities

such as Hindus, Muslims, Parsees etc. These communities have on

secular plane common material interests. There will be in such groups

landlords, labourers and capitalists. The untouchables are, however,

isolated by the Hindus from any kind of social participation. They

have been dehumanised by socio-religious disabilities almost to the

status of slaves. They are denied the universally accepted rights of

citizenship. Their interests are distinctively their own interests and

none else can truly voice them.

On the population basis, Dr. Ambedkar demands for the

untouchables of the Presidency of Bombay, eight to nine

representatives in the Bombay Legislative Council with franchise

pitched as low for them as to muster a sizable electorate. While

reviewing the various schemes proposed by different organiza tions he

criticises the Congress scheme which offers communal representation

only to the Muslims and leaves untouchables to seek representation

in general electorate as typical of the ideology of its leaders who are

political radicals and social tories. He does not agree with the proposals

of moderates to reserve only one or two seats for the untouchables in

plural constituencies as this does not give them effective representation.

He brushes aside the proposal of the Depressed Class Mission for

nomination by co-option by the elected members of the Council as

an attempt to dictate to the untouchables what their good shall

be, instead of an endeavour to agree with them so that they may seek

XX INTRODUCTION

to find the good of their own choice. The communal representation

with reserved seats for the most depressed community, he holds out,

will not perpetuate social divisions, but will act as a potent solvent for

dissolving them by providing opportunities for contact, co-operation and

re-socialisation of fossilised attitudes. Moreover it was the demand of

the untouchables for self-determination which the major communities

too were claiming from the British bureaucracy.

Federation versus Freedom

Dr. Ambedkar’s two addresses, “Federation vs. Freedom” and

“Communal Deadlock and a Way to solve It” were delivered

by him before the Gokhale Institute of Economics. Pune on

January 29, 1939 and at the session of the All India Scheduled Castes

Federation held in Bombay on May 6, 1945 respectively. They are in

the nature of tracts of the time. In 1939 all major political parties

of India had accepted and some were even implementing that part

of the Government of India Act, 1935 which related to provincial

autonomy. The question of accepting the Federal structure at the

Centre was however, looming large on the political horizon of India.

Dr. Ambedkar who till then had not expressed in public his views

on the subject took the opportunity to do so before the learned body

of the Gokhale Institute of Economics.

In the address he sets out briefly the outline of the scheme

of Federation and examines it in the light of accepted tests of

democratic federations in operation. The examination reveals

that the scheme granted only a limited responsibility at the centre;

it has the potentiality to evolve into a dominion status. There is

inequality of status between the two sets of federating units viz. the

Provinces and the Princely States. Federation is a natural corollary of

autonomous provinces. They join the Federation as a natural course,

while accession of the princely States is governed by the various

conditions of their historical treaties with the British crown and the

instrument of accession they would sign. Accession of the States and

not only of the autonomous provinces, is the precondition for the

implementation of the Federation. The representation of the provinces

to the two Federal Houses is by election but the State representatives

INTRODUCTION XXI

are the nominees of their autocratic rulers and owe their allegiance to

the rulers. These representatives will always be at the beck and call

of the British bureaucracy which yields paramountcy over the rulers.

Instead of fostering one all India nationalism, the Indian Princely

States being treated under the Federation as foreign territories will

encourage separatist tendencies. The scheme also does not permit

the Federal Legislature to discuss the conduct of the ruler nor the

administration of his State, though his nominees can participate in

the debate pertaining to a province and vote on the issue. As in the

matter of representation so too in that of taxation, administration,

legislation etc, there is, in the scheme discrimination in favour of

the princes. The princes thus become arbiters of the destiny of the

British India.

On these and several other counts Dr. Ambedkar rejects the Federal

structure as envisaged by the Government of India Act of 1935. His

solution of the problem of the States is, to regard it not as a political

one but as an administrative one. To tackle it legally is to pension

off princes and annexe their territories as is done under the Land

Acquisition Act which allows private rights and properties to be

acquired for political purposes.

According to Dr. Ambedkar, excepting the Princes, and the Hindu

Mahasabha which felt that the accession of the Princes was an accretion

to the Hindu strength, no major political party was happy with the

scheme of the Federation. The view of the freeman and of the poor

man of whom the Federation does not seem to take any account says

Dr. Ambedkar, will be a similar one. If the Federation comes the

autocracy of the Princes will be a menace to the freedom of a freeman

and obstacle to the poor man who wants constitution to enable him

to have old values revalued and to have vested rights devastated.

Communal Deadlock and a Way to solve It

“Communal Deadlock and a Way to solve It” is yet another

tract of the time included in this volume. It purports to be a

constructive proposal put forth on behalf of the Scheduled

Castes for the future constitution of India. This plan was one

of the many advanced by Dr. Ambedkar’s contemporaries to

explore the possibility of solving the communal problem in the

XXII INTRODUCTION

eventful year of 1945. Earlier, in 1941. Dr. Ambedkar had

advocated creation of Pakistan on the principle of self-deter mination’

and also as a historical necessity. The present tract sets out an

alternative plan which in his opinion would ensure a United India,

where with proper checks and balances interests of all minorities

would be safeguarded.

He is wholly opposed to the setting of a Constituent Assembly

before the communal problem is solved. Moreover India has already

constitutional ideas and constitutional forms ready at hand in the

Government of India Act of 1935. All that is necessary is to delete

those sections of the Act, which are inconsistent with Dominion status.

If at all there is to be a Constituent Assembly, says Dr. Ambedkar.

the communal question should not form a part of it.

After examining the two schemes for Constituent Assembly one each

by Sir Stafford Cripps and Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, Dr. Ambedkar

concludes that both the schemes leave the communal question unsolved.

In his opinion all such schemes and plans advocated so far fail because

of their wrong approach. They proceed by a method instead of by a

principle. The ultimate result is constant appeasement of ever-growing

demands of communal minorities.

The principle he enunciates is that in India majority being communal

majority and not a convertible political majority, the majority rule is

untenable in theory and unjustifiable in practice. The major community

should be content with relative majority. Even this should not be so

large as to enable it to secure an absolute majority by coalition with

a smaller minority to establish its rule. In the same way the major

minority should also not have the possibility to secure a majority by

similar combination. The combination of all minorities should however

have an absolute majority in the legislature. Dr. Ambedkar has set

out in detail how the application of these principles would reflect

community-wise in the central and provincial legislatures.

Dr. Ambedkar’s proposal is mainly for a United India; but

even if the partition of India eventuates, he expects, the Muslims

of Pakistan not to deny the benefit of these principles to

INTRODUCTION XXIII

non-Muslim residents of their country. Their co-religionists, who

otherwise would be a helpless minority in India, will have their interests

safeguarded by the acceptance of these principles. Abandonment of

the principle of majority rule in politics cannot, in the opinion of Dr.

Ambedkar, affect the Hindus in other walks of life such as social

and economic.

States and Minorities

States and minorities is a memorandum on the safeguards for the

minorities in general and the Scheduled Castes in particular drafted

by Dr. Ambedkar and submitted to the Constituent Assembly on behalf

of the All-India Scheduled Castes Federation in the year 1946. It is

in the form of draft articles of a constitution, followed by explanatory

notes and other statistics.

The memorandum sets out in specific terms fundamental rights of

citizens, safeguards of the rights of minorities and Scheduled Castes to

representation in the legislatures, local bodies, executive and services.

It also provides for special provisions for education and new settlement

of the Scheduled Castes in separate villages. The very first article is

allotted to the admission of Indian States into the Union which are

here classified as Qualified and Unqualified on admission to the

Union. The qualified State has an obligation to have an internal

government which is in consonance with the principles Underlying

the Constitution of the Union. The territory of the Unqualified states

will be treated as the territory of the Union.

The memorandum not only prescribes the rights and privileges of

the Scheduled Castes but also lays down the remedies in the event

of encroachment upon them. For this the author draws heavily from

his own memorandum submitted to the minorities of the Round

Table Conference in 1931. They are derived from the United States

statutes and amendments passed in the interest of the Negroes after

their emancipation and from the Burma Anti-boycott Act. One of the

novel features of the memorandum is the provision for the election of

the Prime Minister — Union and provincial — by the whole house

of the legislature, of the representatives of the different minorities in

XXIV INTRODUCTION

the cabinet by members of each minority in the house and of the

representatives of the majority community in the executive again by

the whole house.

Another unique feature is the provision of remedies against invasion

of the fundamental rights of citizens of freedom from economic

exploitation and from want and fear. This is sought to be accomplished

by constitutional provision enforceable within ten years of the passing of

the constitution for alteration of the economic structure of the country.

In short by adopting state socialism, it envisages state ownership and

management of all key and basic industries and insurance. Agriculture

which is included in the key industries is to be organised on collectivised

method. Owners of the nationalised industries and land are to be

compensated in the form of debentures. The debenture-holders are

entitled to receive interest at such rates as defined by the law.

Small Holdings in India

The subjects of Dr. Ambedkar’s Doctoral thesis were in the disciplines

of economics only. The present paper was one of his articles dealing

with the problem of agricultural economy of the Country. Amongst

several problems of agricultural economy dealing with agricultural

production, Dr. Ambedkar chose the subject of the size of holdings as

it affects the productivity of agriculture.

Dr. Ambedkar in his paper points out that the holdings of

land in India are not small but they are also scattered. This

feature of Indian agriculture has caused great anxiety

regarding agriculture which Dr. Ambedkar designates as an industry.

The problems of these holdings are two-fold—(1) How to con-

solidate the holdings and (2) after consolidation, how to perpe -

tuate the said consolidation. The heirs of deceased in India desire

to secure share from each survey number of the deceased rather

than distributing complete holdings amongst themselves. This

has resulted into rendering the farming most inefficient and

causing several problems. Dr. Ambedkar discusses methods

for consolidation e.g., restripping, restricted sale of the occupancy

of the fragmented land to the contagious holder and the right of

INTRODUCTION XXV

pre-emption. In this connection Dr. Ambedkar discusses the report

of the Baroda Committee and the proposals of Prof. Jevons and

Mr. Keatinge, and points out that the consolidation may obviate the

evils of scattered holdings, but it will not obviate the evils of small

holdings unless the consolidated holding becomes an economic holdings.

While discussing the terms of economic holding, Dr. Ambedkar

observes, “Mere size of land is empty of all economic connotation………….

It is the right or wrong proportion of other factors of production to

a suit of land that renders the latter economic or uneconomic”. Thus

a small farm may be economic as well as a large farm. Verifying

the statistics at length, he concludes that “the existing holdings are

uneconomic, not, however, in the sense that they are too small but

that they are too large” as against the inadequacy of other factors of

production. He therefore suggests that the remedy lies in not enlarging

the holding but in the matter of increasing capital and capital goods.

According to Dr. Ambedkar, the evil of small holding is the product

of mal-adjustment of the Indian social economy. A large part of

population of superfluous and idle labour exerts high pressure on

agriculture. He tries to analyse how to remedy the ills of agriculture

and suggests that industrialization of India is the soundest remedy

for the agricultural problems of India.

Mr. Russell and the Reconstruction of Society

While reviewing the book “Principles of Social Reconstruction”

by the Honourable Mr. Bertrand Russell, Dr. Ambedkar deals

only with the analysis of the institution of Property and the modi-

fications it is alleged to produce in human nature. Commenting

on the observations of Mr. Russell on the philosophy of war,

Dr. Ambedkar opines that Mr. Russell is against war but is not

for quieticism. Quieticism is another name of death. Activity

leads to growth. He suggests that to achieve anything we must use

force ; only we must use it constructively as energy and not destructively

as violence. The pacifist Mr. Russell, according to Dr. Ambedkar,

thinks that even war is an activity leading to the growth

XXVI INTRODUCTION

of the individual and condemns it only because it results in death and

destruction. He therefore thinks that Russell would welcome milder

forms of war.

Dr. Ambedkar further discusses the analysis of effects of property

as propounded by Mr. Russell. Regarding the mental effects of

property, he finds that Russell’s discussion on this aspect is marked

by certain misconceptions. Criticising the statement about “love of

money” as interpreted by Mr. Russell, Dr. Ambedkar points out that

there is genuine difference in the outlook of the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’.

Hence their attitude about money will be different. According to him,

Mr. Russell failed to inquire into the purpose of the love of money

which has given rise to wrong conception. Dr. Ambedkar feels that

this thesis is shaky from the production side of our life.

He further proceeds to discuss and prove how the above proposition

is also untenable from the consumption side of life. Here the learned

Doctor enters into a psychological discussion of the desires and

pleasures. We leave this interesting discussion to be read by the readers

in original without taking their much time.

The editors do not claim to have covered all the main features of

the closely reasoned arguments of the learned Doctor in the present

volume.

Members of the Editorial Board are deeply indebted to the Hon’ble

Chief Minister of Maharashtra State, Shri Sharad Pawar and Hon’ble

Minister for Education, Shri Sadanand Varde, for their valuable

help, guidance and co-operation in bringing out this volume. We are

also grateful to Shri Sapre, the Director of Government Printing and

Stationery, and his staff for having helped us in bringing out this

book in record time.

MEMBERS

EDITORIAL BOARD

CONTENTS

FOREWARD .. .. .. vii

PREFACE .. .. .. xi

INTRODUCTION .. .. .. xiii

PAGE

PART I

ON CASTE

1 C

ASTES IN INDIA .. .. .. 3

2 A

NNIHILATION OF CASTE .. .. .. 23

PART II

ON LINGUISTIC STATES

3 M

AHARASHTRA AS A LINGUISTIC PROVINCE .. 99

4 N

EED FOR CHECKS AND BALANCES .. .. 129

5 T

HOUGHTS ON LINGUISTIC STATES .. .. 137

PART III

ON HERO AND HERO-WORSHIP

6 R

ANADE, GANDHI AND JINNAH .. .. 205

PART IV

ON CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS

7 E

VIDENCE BEFORE THE SOUTHBOROUGH COMMITTEE .. 243

8 F

EDERATION VERSUS FREEDOM .. 279

9 C

OMMUNAL DEADLOCK AND A WAY TO SOLVE IT .. 355

10 S

TATES AND MINORITIES .. .. .. 381

PART V

ON ECONOMIC PROBLEMS

11 S

MALL HOLDINGS IN INDIA .. .. .. 453

12 M

R. RUSSELL AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF SOCIETY 481

INDEX .. .. .. 493

PART I

ON CASTE

CASTES IN INDIA

Their Mechanism, Genesis and

Development

Paper read before

the Anthropology Seminar

of

Dr. A. A. Goldenweizer

at

The Columbia University, New York, U.S.A.

on

9th May 1916

From : Indian Antiquary, May 1917, Vol. XLI

1

CASTES IN INDIA

Many of us, I dare say, have witnessed local, national or international

expositions of material objects that make up the sum total of human

civilization. But few can entertain the idea of there being such a thing as

an exposition of human institutions. Exhibition of human institutions is a

strange idea ; some might call it the wildest of ideas. But as students of

Ethnology I hope you will not be hard on this innovation, for it is not so,

and to you at least it should not be strange.

You all have visited, I believe, some historic place like the ruins of Pompeii,

and listened with curiosity to the history of the remains as it flowed from the

glib tongue of the guide. In my opinion a student of Ethnology, in one sense

at least, is much like the guide. Like his prototype, he holds up (perhaps

with more seriousness and desire of self-instruction) the social institutions

to view, with all the objectiveness humanly possible, and inquires into their

origin and function.

Most of our fellow students in this Seminar, which concerns itself with

primitive versus modern society, have ably acquitted themselves along

these lines by giving lucid expositions of the various institutions, modern

or primitive, in which they are interested. It is my turn now, this evening,

to entertain you, as best I can, with a paper on “Castes in India : Their

mechanism, genesis and development”

I need hardly remind you of the complexity of the subject I intend to

handle. Subtler minds and abler pens than mine have been brought to the

task of unravelling the mysteries of Caste ; but unfortunately it still remains

in the domain of the “unexplained”, not to say of the “un-understood” I am

quite alive to the complex intricacies of a hoary institution like Caste, but I

am not so pessimistic as to relegate it to the region of the unknowable, for

I believe it can be known. The caste problem is a vast one, both theoretically

and practically. Practically, it is an institution that portends tremendous

consequences. It is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief,

6

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

for “as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or

have any social intercourse with outsiders ; and if Hindus migrate to other

regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem.”

1

Theoretically,

it has defied a great many scholars who have taken upon themselves, as

a labour of love, to dig into its origin. Such being the case, I cannot treat

the problem in its entirety. Time, space and acumen, I am afraid, would

all fail me, if I attempted to do otherwise than limit myself to a phase of

it, namely, the genesis, mechanism and spread of the caste system. I will

strictly observe this rule, and will dwell on extraneous matters only when

it is necessary to clarify or support a point in my thesis.

To proceed with the subject. According to well-known ethnologists, the

population of India is a mixture of Aryans, Dravidians, Mongolians and

Scythians. All these stocks of people came into India from various directions

and with various cultures, centuries ago, when they were in a tribal state.

They all in turn elbowed their entry into the country by fighting with their

predecessors, and after a stomachful of it settled down as peaceful neighbours.

Through constant contact and mutual intercourse they evolved a common

culture that superseded their distinctive cultures. It may be granted that

there has not been a thorough amalgamation of the various stocks that make

up the peoples of India, and to a traveller from within the boundaries of

India the East presents a marked contrast in physique and even in colour

to the West, as does the South to the North. But amalgamation can never

be the sole criterion of homogeneity as predicated of any people. Ethnically

all people are heterogeneous. It is the unity of culture that is the basis of

homogeneity. Taking this for granted, I venture to say that there is no country

that can rival the Indian Peninsula with respect to the unity of its culture.

It has not only a geographic unity, but it has over and above all a deeper

and a much more fundamental unity—the indubitable cultural unity that

covers the land from end to end. But it is because of this homogeneity that

Caste becomes a problem so difficult to be explained. If the Hindu Society

were a mere federation of mutually exclusive units, the matter would be

simple enough. But Caste is a parcelling of an already homogeneous unit,

and the explanation of the genesis of Caste is the explanation of this process

of parcelling.

Before launching into our field of enquiry, it is better to advise ourselves

regarding the nature of a caste I will therefore draw upon a few of the best

students of caste for their definitions of it:

(1) Mr. Senart, a French authority, defines a caste as “a close corporation,

in theory at any rate rigorously hereditary : equipped with a certain

traditional and independent organisation, including a chief and a

council, meeting on occasion in assemblies of more or less plenary

1. Ketkar, Caste, p. 4.

7

CASTES IN INDIA

authority and joining together at certain festivals : bound together

by common occupations, which relate more particularly to marriage

and to food and to questions of ceremonial pollution, and ruling its

members by the exercise of jurisdiction, the extent of which varies,

but which succeeds in making the authority of the community more

felt by the sanction of certain penalties and, above all, by final

irrevocable exclusion from the group”.

(2) Mr. Nesfield defines a caste as “a class of the community which disowns

any connection with any other class and can neither intermarry nor

eat nor drink with any but persons of their own community”.

(3) According to Sir H. Risley, “a caste may be defined as a collection of

families or groups of families bearing a common name which usually

denotes or is associated with specific occupation, claiming common

descent from a mythical ancestor, human or divine, professing to

follow the same professional callings and are regarded by those who

are competent to give an opinion as forming a single homogeneous

community”.

(4) Dr. Ketkar defines caste as “a social group having two characteristics :

(i) membership is confined to those who are born of members and

includes all persons so born ; (ii) the members are forbidden by an

inexorable social law to marry outside the group”.

To review these definitions is of great importance for our purpose. It will

be noticed that taken individually the definitions of three of the writers

include too much or too little : none is complete or correct by itself and all

have missed the central point in the mechanism of the Caste system. Their

mistake lies in trying to define caste as an isolated unit by itself, and not

as a group within, and with definite relations to, the system of caste as a

whole. Yet collectively all of them are complementary to one another, each

one emphasising what has been obscured in the other. By way of criticism,

therefore, I will take only those points common to all Castes in each of the

above definitions which are regarded as peculiarities of Caste and evaluate

them as such.

To start with Mr. Senart. He draws attention to the “idea of pollution”

as a characteristic of Caste. With regard to this point it may be safely said

that it is by no means a peculiarity of Caste as such. It usually originates

in priestly ceremonialism and is a particular case of the general belief in

purity. Consequently its necessary connection with Caste may be completely

denied without damaging the working of Caste. The “idea of pollution” has

been attached to the institution of Caste, only because the Caste that enjoys

the highest rank is the priestly Caste : while we know that priest and purity

are old associates. We may therefore conclude that the “idea of pollution”

is a characteristic of Caste only in so far as Caste has a religious flavour.

8

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

Mr. Nesfield in his way dwells on the absence of messing with those outside

the Caste as one of its characteristics. In spite of the newness of the point

we must say that Mr. Nesfield has mistaken the effect for the cause. Caste,

being a self-enclosed unit naturally limits social intercourse, including

messing etc. to members within it. Consequently this absence of messing

with outsiders is not due to positive prohibition, but is a natural result of

Caste, i.e. exclusiveness. No doubt this absence of messing originally due to

exclusiveness, acquired the prohibitory character of a religious injunction,

but it may be regarded as a later growth. Sir H. Risley, makes no new point

deserving of special attention.

We now pass on to the definition of Dr. Ketkar who has done much

for the elucidation of the subject. Not only is he a native, but he has also

brought a critical acumen and an open mind to bear on his study of Caste.

His definition merits consideration, for he has defined Caste in its relation

to a system of Castes, and has concentrated his attention only on those

characteristics which are absolutely necessary for the existence of a Caste

within a system, rightly excluding all others as being secondary or derivative

in character. With respect to his definition it must, however, be said that

in it there is a slight confusion of thought, lucid and clear as otherwise it

is. He speaks of Prohibition of Intermarriage and Membership by Autogeny

as the two characteristics of Caste. I submit that these are but two aspects

of one and the same thing, and not two different things as Dr. Ketkar

supposes them to be. If you prohibit intermarriage the result is that you

limit membership to those born within the group. Thus the two are the

obverse and the reverse sides of the same medal.

This critical evaluation of the various characteristics of Caste leave no doubt

that prohibition, or rather the absence of intermarriage—endogamy, to be

concise—is the only one that can be called the essence of Caste when rightly

understood. But some may deny this on abstract anthropological grounds, for

there exist endogamous groups without giving rise to the problem of Caste. In

a general way this may be true, as endogamous societies, culturally different,

making their abode in localities more or less removed, and having little to

do with each other are a physical reality. The Negroes and the Whites and

the various tribal groups that go by name of American Indians in the United

States may be cited as more or less appropriate illustrations in support of

this view. But we must not confuse matters, for in India the situation is

different. As pointed out before, the peoples of India form a homogeneous

whole. The various races of India occupying definite territories have more or

less fused into one another and do possess cultural unity, which is the only

criterion of a homogeneous population. Given this homogeneity as a basis,

Caste becomes a problem altogether new in character and wholly absent in

the situation constituted by the mere propinquity of endogamous social or

9

CASTES IN INDIA

tribal groups. Caste in India means an artificial chopping off of the population

into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another

through the custom of endogamy. Thus the conclusion is inevitable that

Endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste, and if we

succeed in showing how endogamy is maintained, we shall practically have

proved the genesis and also the mechanism of Caste.

It may not be quite easy for you to anticipate why I regard endogamy as

a key to the mystery of the Caste system. Not to strain your imagination

too much, I will proceed to give you my reasons for it.

It may not also be out of place to emphasize at this moment that no

civilized society of today presents more survivals of primitive times than does

the Indian society. Its religion is essentially primitive and its tribal code, in

spite of the advance of time and civilization, operates in all its pristine vigour

even today. One of these primitive survivals, to which I wish particularly to

draw your attention is the Custom of Exogamy. The prevalence of exogamy

in the primitive worlds is a fact too wellknown to need any explanation.

With the growth of history, however, exogamy has lost its efficacy, and

excepting the nearest blood-kins, there is usually no social bar restricting

the field of marriage. But regarding the peoples of India the law of exogamy

is a positive injunction even today. Indian society still savours of the clan

system, even though there are no clans ; and this can be easily seen from

the law of matrimony which centres round the principle of exogamy, for it is

not that Sapindas (blood-kins) cannot marry, but a marriage even between

Sagotras (of the same class) is regarded as a sacrilege.

Nothing is therefore more important for you to remember than the fact

that endogamy is foreign to the people of India. The various Gotras of

India are and have been exogamous : so are the other groups with totemic

organization. It is no exaggeration to say that with the people of India

exogamy is a creed and none dare infringe it, so much so that, in spite of

the endogamy of the Castes within them, exogamy is strictly observed and

that there are more rigorous penalties for violating exogamy than there are

for violating endogamy. You will, therefore, readily see that with exogamy

as the rule there could be no Caste, for exogamy means fusion. But we have

castes ; consequently in the final analysis creation of Castes, so far as India

is concerned, means the superposition of endogamy on exogamy. However,

in an originally exogamous population an easy working out of endogamy

(which is equivalent to the creation of Caste) is a grave problem, and it is

in the consideration of the means utilized for the preservation of endogamy

against exogamy that we may hope to find the solution of our problem.

Thus the superposition of endogamy on exogamy means the creation of caste.

But this is not an easy affair. Let us take an imaginary group that desires

to make itself into a Caste and analyse what means it will have to adopt to

10

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

make itself endogamous. If a group desires to make itself endogamous a

formal injunction against intermarriage with outside groups will be of no

avail, especially if prior to the introduction of endogamy, exogamy had been

the rule in all matrimonial relations. Again, there is a tendency in all groups

lying in close contact with one another to assimilate and amalgamate, and

thus consolidate into a homogeneous society. If this tendency is to be strongly

counteracted in the interest of Caste formation, it is absolutely necessary

to circumscribe a circle outside which people should not contract marriages.

Nevertheless, this encircling to prevent marriages from without creates

problems from within which are not very easy of solution. Roughly speaking,

in a normal group the two sexes are more or less evenly distributed, and

generally speaking there is an equality between those of the same age.

The equality is, however, never quite realized in actual societies. At the

same time to the group that is desirous of making itself into a caste the

maintenance of equality between the sexes becomes the ultimate goal, for

without it. endogamy can no longer subsist. In other words, if endogamy

is to be preserved conjugal rights from within have to be provided for,

otherwise members of the group will be driven out of the circle to take care

of themselves in any way they can. But in order that the conjugal rights be

provided for from within, it is absolutely necessary to maintain a numerical

equality between the marriageable units of the two sexes within the group

desirous of making itself into a Caste. It is only through the maintenance

of such an equality that the necessary endogamy of the group can be kept

intact, and a very large disparity is sure to break it.

The problem of Caste, then, ultimately resolves itself into one of repairing

the disparity between the marriageable units of the two sexes within it. Left

to nature, the much needed parity between the units can be realized only

when a couple dies simultaneously. But this is a rare contingency. The

husband may die before the wife and create a surplus woman, who must be

disposed of, else through intermarriage she will violate the endogamy of the

group. In like manner the husband may survive his wife and be surplus man,

whom the group, while it may sympathise with him for the sad bereavement,

has to dispose of, else he will marry outside the Caste and will break the

endogamy. Thus both the surplus man and the surplus woman constitute a

menace to the Caste if not taken care of, for not finding suitable partners

inside their prescribed circle (and left to themselves they cannot find any,

for if the matter be not regulated there can only be just enough pairs to

go round) very likely they will transgress the boundary, marry outside and

import offspring that is foreign to the Caste.

Let us see what our imaginary group is likely to do with this surplus man

and surplus woman. We will first take up the case of the surplus woman.

11

CASTES IN INDIA

She can be disposed of in two different ways so as to preserve the endogamy

of the Caste.

First: burn her on the funeral pyre of her deceased husband and get

rid of her. This, however, is rather an impracticable way of solving the

problem of sex disparity. In some cases it may work, in others it may not.

Consequently every surplus woman cannot thus be disposed of, because it

is an easy solution but a hard realization. And so the surplus woman (=

widow), if not disposed of, remains in the group : but in her very existence

lies a double danger. She may marry outside the Caste and violate endogamy,

or she may marry within the Caste and through competition encroach upon

the chances of marriage that must be reserved for the potential brides in

the Caste. She is therefore a menance in any case, and something must

be done to her if she cannot be burned along with her deceased husband.

The second remedy is to enforce widowhood on her for the rest of her life.

So far as the objective results are concerned, burning is a better solution

than enforcing widowhood. Burning the widow eliminates all the three evils

that a surplus woman is fraught with. Being dead and gone she creates no

problem of remarriage either inside or outside the Caste. But compulsory

widowhood is superior to burning because it is more practicable. Besides

being comparatively humane it also guards against the evils of remarriage

as does burning; but it fails to guard the morals of the group. No doubt

under compulsory widowhood the woman remains, and just because she is

deprived of her natural right of being a legitimate wife in future, the incentive

to immoral conduct is increased. But this is by no means an insuperable

difficulty. She can be degraded to a condition in which she is no longer a

source of allurement.

The problem of surplus man (= widower) is much more important and

much more difficult than that of the surplus woman in a group that desires

to make itself into a Caste. From time immemorial man as compared with

woman has had the upper hand. He is a dominant figure in every group

and of the two sexes has greater prestige. With this traditional superiority

of man over woman his wishes have always been consulted. Woman, on the

other hand, has been an easy prey to all kinds of iniquitous injunctions,

religious, social or economic. But man as a maker of injunctions is most

often above them all. Such being the case, you cannot accord the same kind

of treatment to a surplus man as you can to a surplus woman in a Caste.

The project of burning him with his deceased wife is hazardous in two

ways : first of all it cannot be done, simply because he is a man. Secondly,

if done, a sturdy soul is lost to the Caste. There remain then only two

solutions which can conveniently dispose of him. I say conveniently, because

he is an asset to the group.

12

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

Important as he is to the group, endogamy is still more important, and

the solution must assure both these ends. Under these circumstances he

may be forced or I should say induced, after the manner of the widow, to

remain a widower for the rest of his life. This solution is not altogether

difficult, for without any compulsion some are so disposed as to enjoy self-

imposed celibacy, or even to take a further step of their own accord and

renounce the world and its joys. But, given human nature as it is, this

solution can hardly be expected to be realized. On the other hand, as is

very likely to be the case, if the surplus man remains in the group as an

active participator in group activities, he is a danger to the morals of the

group. Looked at from a different point of view celibacy, though easy in

cases where it succeeds, is not so advantageous even then to the material

prospects of the Caste. If he observes genuine celibacy and renounces the

world, he would not be a menace to the preservation of Caste endogamy or

Caste morals as he undoubtedly would be if he remained a secular person.

But as an ascetic celibate he is as good as burned, so far as the material

well-being of his Caste is concerned. A Caste, in order that it may be large

enough to afford a vigorous communal life, must be maintained at a certain

numerical strength. But to hope for this and to proclaim celibacy is the same

as trying to cure atrophy by bleeding.

Imposing celibacy on the surplus man in the group, therefore, fails both

theoretically and practically. It is in the interest of the Caste to keep him

as a Grahastha (one who raises a family), to use a Sanskrit technical term.

But the problem is to provide him with a wife from within the Caste. At

the outset this is not possible, for the ruling ratio in a caste has to be one

man to one woman and none can have two chances of marriage, for in a

Caste thoroughly self-enclosed there are always just enough marriageable

women to go round for the marriageable men. Under these circumstances

the surplus man can be provided with a wife only by recruiting a bride

from the ranks of those not yet marriageable in order to tie him down to

the group. This is certainly the best of the possible solutions in the case

of the surplus man. By this, he is kept within the Caste. By this means

numerical depletion through constant outflow is guarded against, and by

this endogamy morals are preserved.

It will now be seen that the four means by which numerical disparity

between the two sexes is conveniently maintained are : (1) burning the widow

with her deceased husband ; (2) compulsory widowhood—a milder form of

burning ; (3) imposing celibacy on the widower and (4) wedding him to a girl

not yet marriageable. Though, as I said above, burning the widow and imposing

celibacy on the widower are of doubtful service to the group in its endeavour

to preserve its endogamy, all of them operate as means. But means, as forces,

when liberated or set in motion create an end. What then is the end that

these means create ? They create and perpetuate endogamy, while caste and

13

CASTES IN INDIA

endogamy, according to our analysis of the various definitions of caste, are

one and the same thing. Thus the existence of these means is identical with

caste and caste involves these means.

This, in my opinion, is the general mechanism of a caste in a system of

castes. Let us now turn from these high generalities to the castes in Hindu

Society and inquire into their mechanism. I need hardly premise that there

are a great many pitfalls in the path of those who try to unfold the past,

and caste in India to be sure is a very ancient institution. This is especially

true where there exist no authentic or written records or where the people,

like the Hindus, are so constituted that to them writing history is a folly,

for the world is an illusion. But institutions do live, though for a long time

they may remain unrecorded and as often as not customs and morals are

like fossils that tell their own history. If this is true, our task will be amply

rewarded if we scrutinize the solution the Hindus arrived at to meet the

problems of the surplus man and surplus woman.

Complex though it be in its general working the Hindu Society, even to

a superficial observer, presents three singular uxorial customs, namely :

(i) Sati or the burning of the widow on the funeral pyre of her deceased

husband.

(ii) Enforced widowhood by which a widow is not allowed to remarry.

(iii) Girl marriage.

In addition, one also notes a great hankering after Sannyasa (renunciation)

on the part of the widower, but this may in some cases be due purely to

psychic disposition.

So far as I know, no scientific explanation of the origin of these customs

is forthcoming even today. We have plenty of philosophy to tell us why these

customs were honoured, but nothing to tell us the causes of their origin and

existence. Sati has been honoured (Cf. A. K. Coomaraswamy, Sati: A Defence

of the Eastern Woman in the British Sociological Review, Vol. VI, 1913)

because it is a “proof of the perfect unity of body and soul” between husband

and wife and of “devotion beyond the grave”, because it embodied the ideal

of wifehood, which is well expressed by Uma when she said, “Devotion to her

Lord is woman’s honour, it is her eternal heaven : and O Maheshvara”, she