Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other

Race-Related Findings in Published Works Derived from

the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being

by Keesha Dunbar, MBA, MSW

School of Social Work

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Richard P. Barth, PhD

School of Social Work

University of Maryland, Baltimore

CSSP is a nonprofit public policy organization that develops and promotes policies and practices that

support and strengthen families and help communities to produce equal opportunities and better futures

for all children. We work in partnership with federal, state and local government, and communities and

neighborhoods—from politicians who can craft legislation, state administrators who can set and implement

policy and practice, and networks of peers, community leaders, parents and youth to find workable

solutions to complex problems.

Casey Family Programs is the largest national foundation whose sole mission is to provide

and improve—and ultimately prevent the need for—foster care. The foundation draws on its 40 years of

experience and expert research and analysis to improve the lives of children and youth in foster care in two

important ways: by providing direct services and support to foster families and promoting improvements in

child welfare practice and policy. The Seattle-based foundation was established in 1966 by UPS founder

Jim Casey and currently has an endowment of $2 billion.

www.casey.org

The Marguerite Casey Foundation was created by Casey Family Programs in 2001

to help expand Casey’s outreach and further enhance its 37-year record of leadership in

child welfare. Based in Seattle, the Marguerite Casey Foundation is a private, independent

grant-making foundation dedicated to helping low-income families strengthen their voice and

mobilize their communities.

www.caseygrants.org

Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative was created in 2001 by Casey Family

Programs and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Based in St. Louis, the Initiative is a major national effort to

help youth in foster care make successful transitions to adulthood.

www.jimcaseyyouth.org

The Annie E. Casey Foundation is a private charitable organization dedicated to helping build

better futures for disadvantaged children in the United States. It was established in 1948 by Jim Casey,

one of the founders of United Parcel Service, and his siblings, who named the Foundation in honor of their

mother. The primary mission of the Foundation is to foster public policies, human-service reforms, and

community supports that more effectively meet the needs of today’s vulnerable children and families. In

pursuit of this goal, the Foundation makes grants that help states, cities, and neighborhoods fashion more

innovative, cost-effective responses to these needs.

www.aecf.org

Casey Family Services was established by United Parcel Service founder Jim Casey in 1976

as a source for high-quality, long-term foster care. Casey Family Services today offers a broad range

of programs for vulnerable children and families throughout the Northeast and in Baltimore, Maryland.

The direct service agency of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Services operates from

administrative headquarters in New Haven, Connecticut, and eight program divisions in Connecticut,

Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

www.caseyfamilyservices.org

Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare

318.1-3030-07

Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works casey family programs

ABOUT THE ALLIANCE

In 2004, the Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare was

established to develop and implement a national, multiyear campaign to

address racial disparities and reduce the disproportionate representation of

children from certain racial or ethnic communities in the nation’s child welfare

system.

The Alliance includes the Annie E. Casey Foundation and its direct service

agency, Casey Family Services, Casey Family Programs, the Jim Casey Youth

Opportunities Initiative, the Marguerite Casey Foundation, the Center for the

Study of Social Policy (CSSP), and parents and alumni of foster care. The

Race Matters Consortium and Black Administrators in Child Welfare (BACW)

are also partners in this work.

The efforts of the Alliance to reduce disparities and the disproportionate

number of children and youth of color in the care of child welfare agencies are

ultimately aimed at improving the outcomes for all children in care by:

• Learning what works to achieve race equity in child welfare services, in

partnership with states and local communities

• Developing and disseminating new knowledge to the field

• Promoting effective federal and state policy through education about policy

options

• Designing and implementing data collection, research, and evaluation

methods that document evidence-based practices and strategies

• Ensuring that birth parents and foster youth and alumni are leaders in

helping child welfare agencies achieve race equity in child welfare services

and programs

For more information, go to www.cssp.org/major_initiatives

/racialEquity.html.

The authors are grateful to Judith Wildfire for reviewing this document and to the

Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare for support and commentary,

and to both for suggested improvements.

© 2007 Casey Family Programs

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works i

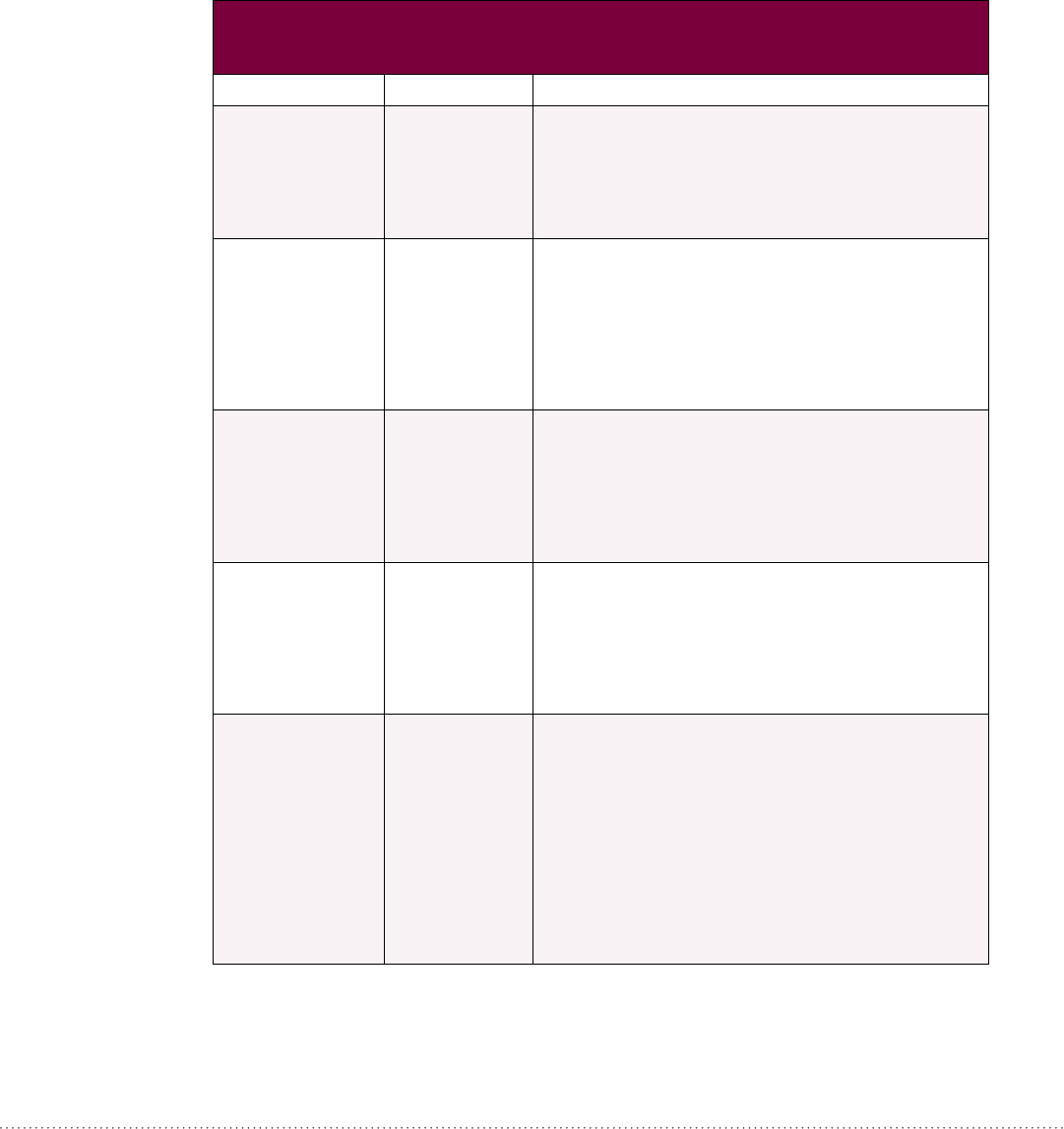

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1

INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................

5

CHILD FACTORS ............................................................................................................................

11

Early Childhood Development and Need for Early Intervention ...................................................

11

Developmental Conclusions ......................................................................................................

13

Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Need, Use, and Access ...................................

14

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Conclusions .....................................................................

22

PARENT FACTORS .........................................................................................................................

23

Parental Arrest and Child Involvement with Child Welfare Agencies ............................................

23

Parental Arrest Conclusion ........................................................................................................

25

Domestic Violence: Epidemiology and Services .........................................................................

26

Domestic Violence Conclusion ..................................................................................................

32

REUNIFICATION .............................................................................................................................

35

Reunification Conclusions ..........................................................................................................

38

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS .............................................................................................................

39

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................

43

ii

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper draws on peer-reviewed papers and chapters from data gathered during the

National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) to examine correlates

and contributors to racial disproportionality. NSCAW was commissioned in 1997 by the

Administration on Children, Youth and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, to learn about the experiences of children and families who come in contact

with child welfare agency–supervised services. The first national longitudinal study of its

kind, NSCAW is examining the characteristics, needs, experiences, and outcomes for these

children and families.

This report summarizes published and in-press articles and chapters based on the NSCAW

study in order to examine the evidence on the relationship between race/ethnicity and several

important areas related to child welfare and well-being. Topics in this review include:

(1) Child factors and related services, including (a) early childhood development and early

intervention services and (b) mental health and substance abuse treatment need and

access

(2) Parental factors and related services including (a) parental arrest and child involvement

with child welfare services agencies and (b) domestic violence—epidemiology and

services

(3) Reunification and related services

The sample size varies in these studies, as authors have endeavored to select subsamples of

NSCAW that are best suited to answer their question. The CPS sample of NSCAW was

5504

a

children who underwent child maltreatment investigations between November 1999

and April 2001. The sample for each specific analysis, however, may vary due to substantive

or methodological reasons (e.g., whether the analysis is limited to in-home, out-of-home, or

reunified cases, or whether there are missing data on variables to be included in the analysis).

The analyses in these studies were, generally, not intended to isolate the effects of race or

ethnicity on child welfare outcomes or child well-being. All of the studies did, however,

include race and ethnicity in their multivariate models—allowing for an understanding of

whether race and ethnicity was associated with outcomes of interest, above and beyond other

family and child characteristics.

Findings

Overall: Race/ethnicity was not found to be a significant predictor in the receipt of services

for children remaining at home, nor was it an indicator of whether children would be placed

a

After some initial papers and reports were written, three cases were dropped from the study because they

involved participants who were incarcerated and were judged not to have given allowable informed consent.

2

in out-of-home care. Differences were found by race, however, with respect to reunification

and services received.

CHILD FACTORS

Early Childhood Development and Early Intervention Services: What can NSCAW

studies tell us about the relationship between early childhood development needs and service

receipt? The findings show that race and ethnicity are strongly correlated with the overall

level of child welfare involvement and the receipt of services. White children are more likely

to remain at home than to be removed from their homes following the investigation of the

case. Race and ethnicity were also found to be predictive factors in service receipt: Black

children are less likely to receive developmental services than white children, and the racial

inconsistencies in services received remain even after controlling for need.

Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Need, Use, and Access: What can

NSCAW studies tell us about the relationship between race, mental health care services, and

substance abuse treatment need, use, and access? Race/ethnicity accounts for differentials in

overall mental health service use. Specifically, African American and Hispanic children were

more likely to use services than white children even though African American children did

not demonstrate elevated need as a group—that is, their mental health problems were no

greater than other children. In the 6- to 10-year-old age group, however, African American

children showed significant unmet need. They were less likely to receive mental health

services than white children in this age group when other variables were controlled.

Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use are also related to the organization of

services. African American and Hispanic children are less likely to receive specialty mental

health services than white children (while holding the county variable constant). In another

study of caregivers, Hispanic caregivers were significantly more likely to receive substance

abuse services, and black non-Hispanic caregivers were significantly less likely to receive

mental health services.

Emotional and behavioral problems for youth and need for mental health treatment were

measured using the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). Interaction

between Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) score and race/ethnicity was found

to be statistically significant: African American children used fewer services than children

of Caucasian ancestry at all values on the CBCL, which suggests lower service use at equal

levels of need. As the CBCL levels increased, the inconsistency in service use was reduced.

Nonetheless, the relative percentage of African American children receiving services was still

smaller. Race/ethnicity (African American versus White) was found to predict outpatient

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 3

mental health services use while other variables were constant. This does not suggest the

reason for the non-use of services, only the occurrence.

PA R E N T / FAMILY FA C T O R S

Domestic Violence: What do we know about the relationship between domestic violence,

race, and child welfare system participation from the NSCAW studies? Race was not found

to be a significant predictor in the underidentification of domestic violence in a home.

Race/ethnicity was, however, found to be a significant factor in the continuation of domestic

violence occurrences in a case. Caregiver

b

race or ethnicity was associated with severe physical

violence (relative to no violence) reported at 18 months, with African American women

having approximately twice the odds for reporting severe physical violence compared to

white non-Hispanic women. In addition, African American women who were referred to

child welfare agency–supervised services reported approximately three times greater risk

of experiencing more severe forms of physical violence (e.g., getting beaten up, choked,

threatened with a weapon) compared to white non-Hispanic women when age, marital

status, socioeconomic factors, and other background variables were controlled.

Parental Arrest: What is the relationship between parental arrest, race, and entry into the

child welfare system? NSCAW-related studies have found that parents of African American

children who entered out-of-home care were significantly more likely to have experienced a

recent arrest, and African American children with incarcerated parents were also found to be

overrepresented in the proportion of investigated cases. At the same time, family and child

risk factors identified by child welfare workers (e.g., serious mental illness, active domestic

violence) at the time of intake were lower among African American parents who had been

arrested than among other arrested parents. This suggests that some of the overrepresentation

of entrances into foster care is mediated by police actions in arresting African American

parents and, perhaps, by child welfare agency inaction in developing mechanisms that help

divert children from foster care during parental arrests.

Reunification: What do we know about the relationship between race, reunification,

child’s age, and receipt of services? Findings show that race and reunification have differing

relationships, depending on a child’s age. Overall, for children younger than 7 months and

children older than 10 years of age, racial differences are large; indeed, the greatest racial

variation between predictors of reunification and the outcome of reunification is evidenced

for infants and adolescents.

African American infants are less likely to experience reunification than white infants; in

addition, African American youth over 10 years of age, as well as youth of other racial and

b

The information from the study from which this information was extracted (Connelly et al., 2006) was

taken from permanent caregivers, generally biological family members.

4

ethnic groups over 10, are significantly less likely to return home than white youth. For

youth over 10 years old, the likelihood of reunification continues to be significantly smaller

for children of color compared to white children even when controlling for risk factors, child

behavior, and agency and parent actions. Offsetting the lower risk of reunification for some

age groups are parenting support (for infants) and a higher frequency of seeing mothers

during visits (for children 10 and older).

Summary

A wide array of findings was drawn from the analyses. Some findings suggest that race

and ethnicity effects are related to developmental status or to the organization of mental

health services in the agency, in addition to the potential association with parental arrest.

These findings offer more specificity about how to further understand and address racial

disproportionality. Findings related to parental arrest indicate that African American families

that experience arrest are more common than non-African American families that experience

arrest but have fewer family and child risks, suggesting that child welfare interventions for

African Americans before and after arrest should be developed to address this aspect of their

experience.

Other than this finding, there is a lack of a consistent race or ethnicity effect, suggesting a

continued need to better understand how unfair services to African American children and

families are most likely to arise, e.g., under which circumstances, which children of what age

and with what challenges, and in which families.

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 5

INTRODUCTION

Data about service receipt are often difficult to interpret. The meaning of analyses of racial

disproportionality and disparity in child welfare agency-supervised services depends, in

some measure, on the extent to which race and ethnicity seem to be the primary factors in

determining disproportionality or disparity. Alternately, these differences may be attributable

to other co-occurring factors. Both the absence of a race effect and the presence of a race

effect can, at times, be explained by other variables that obscure the true relationship

between race and the particular outcome of interest.

The first of the three most fundamental challenges to interpreting most child welfare

research is determining what “case status” means. That is, whether it is good or bad to

receive a given service (like placement into foster care) may depend on many factors. The

second fundamental problem is that the source of child welfare agency–supervised services

information is generally the child welfare worker, and there is little direct information from

the parent or child. This reliance on a single source of information is a substantial divergence

from the ideals of social science research. The third difficult area of interpretation is that of

explaining the causes of racial disproportionality and disparity. If findings offer explanations

arising from factors that are not evenly distributed among children and families of different

ethnic or racial groups, this leaves open the possible explanations that differences in

outcomes may be attributable to these factors.

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) offers new

opportunities to gain insight into these issues because the study has developmental measures

(not just case status measures) and includes parental self-reporting on parenting behavior and

other health and mental health measures. The study also has many more indicators of family

and child functioning than has ever been available in a child welfare study. In addition,

NSCAW features a national sample that was drawn to be representative of cases investigated

following a child maltreatment allegation. The overall NSCAW sample size for these analyses

is generally 5504 children undergoing child maltreatment investigations between November

1999 and April 2001. The sample for each specific analysis, however, may vary due to

substantive or methodological reasons (e.g., whether the analysis is limited to in-home, out-

of-home, or reunified cases, or whether there are missing data on variables to be included in

the analysis).

Researchers oversampled infants to ensure there would be enough cases going through to

permanency planning. In addition, researchers oversampled for sexual abuse cases (to ensure

that there would be adequate statistical power to analyze this kind of abuse alone) and cases

receiving ongoing services after investigation (to ensure adequate power to understand the

process of services) (Dowd, Kinsey, Wheeless, Suresh, & NSCAW Research Group, 2002).

6

The race/ethnic groups were determined from information provided by the child, caregiver,

or caseworker. When more than one race was reported by a respondent, the rarest race (of

five categories) was assigned based on 1990 U.S. Census data. The race order (from rarest to

most common) was: American Indian/Alaskan Native<Asian/Native Hawaiian/other Pacific

Islander<Black/African American<White<Other (Dowd et al., 2002). In addition, Research

Triangle Institute (RTI) created a derived variable to combine the two separate variables that

defined race and ethnicity. Those who were classified as Hispanic based on the ethnicity

variable (“is the child of Hispanic origin?”: yes/no) were assigned to the Hispanic category

on the combined variable as well. American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Native Hawaiian/

other Pacific Islander, and Other were assigned to the non-Hispanic Other category. The

racial/ethnic groups that will be the focus of the analyses are white, black, and Hispanic/

Latino, because the sample size was too small for Native Americans despite concerns about

racial disparity.

This report summarizes published and unpublished-but-in-press articles and chapters based

on the NSCAW study. Topics in this review include the following:

(1) Child factors and related services including (a) early childhood development and

early intervention services and (b) mental health and substance abuse treatment need

and access

(2) Parental factors and related services including (a) parental arrest and child involvement

with child welfare services agencies and (b) domestic violence—epidemiology and

services

(3) Reunification and related services

In the spring and summer of 2006, we inventoried the published and in-press papers with

these topics, conducted a preliminary reading of those papers to determine whether race and

ethnicity was included in modeling of the dependent measures of concern, and completed

our final selection of 11 articles or chapters and the baseline NSCAW report. (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2005).

CHILDREN AND CAREGIVERS WITH COMPLETED CWS INVESTIGAT I O N S

Knowledge of the demographics of children and families involved in the child welfare system

is important to understanding the implications of findings on the relationship between race/

ethnicity and service receipt. In the NSCAW sample, which represents the nation’s children

who had completed investigations for maltreatment in the late 1990s (whether or not they

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 7

were subsequently substantiated), the racial demographics of these children are as follows:

47% white/non-Hispanic, 28% African American/non-Hispanic, 18% Hispanic/Latino,

and 17% Other. “African American children are overrepresented among children who are

investigated (as compared with children in the general American population).” (NSCAW

Research Group, 2005, pp. 3– 6.) See Table 1.

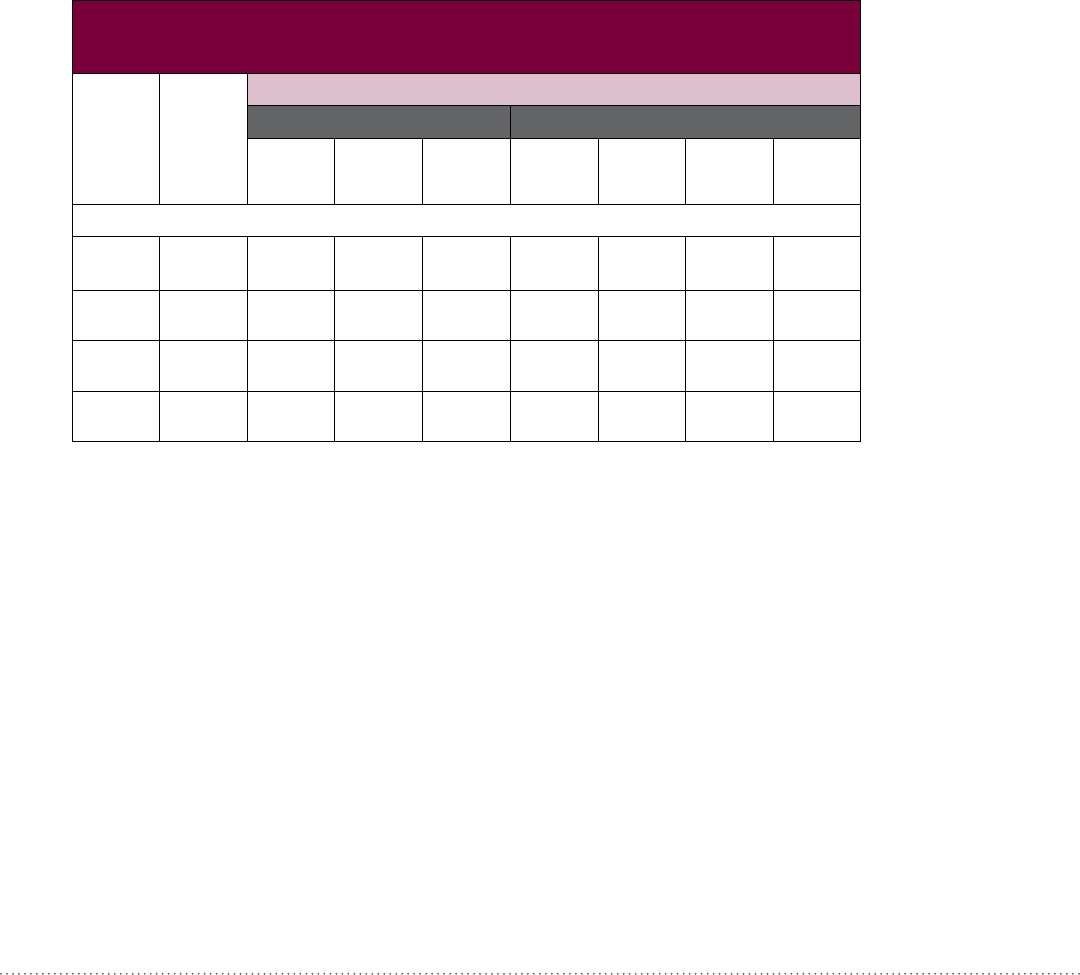

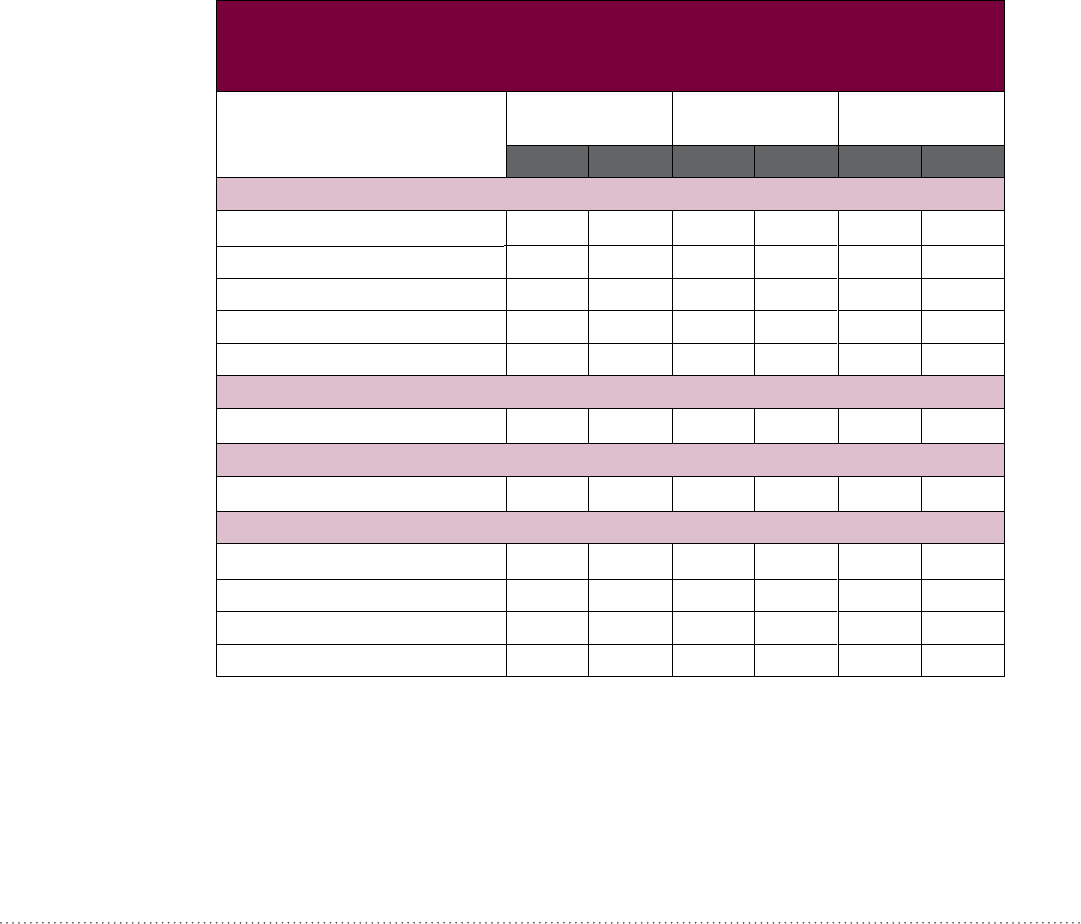

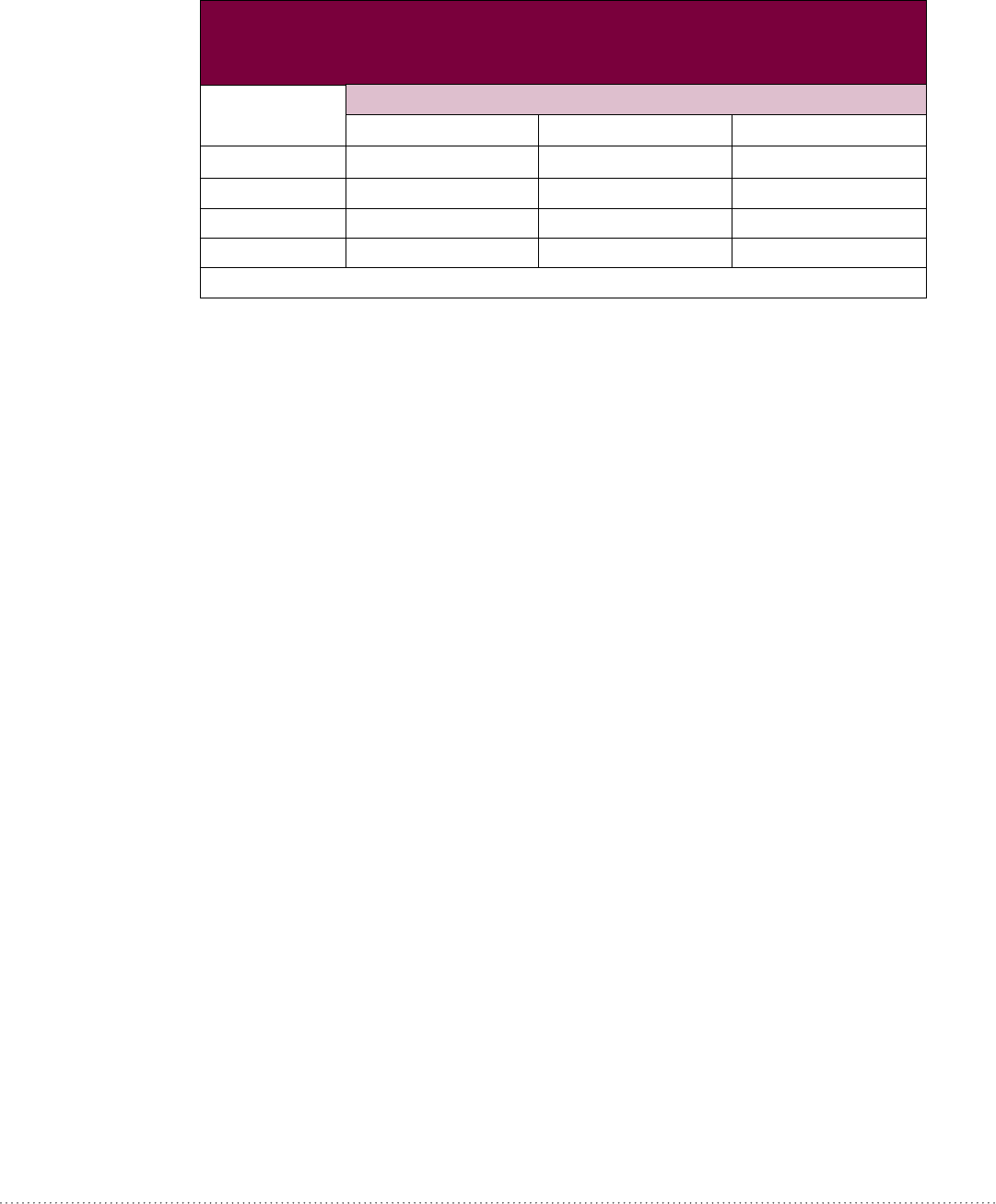

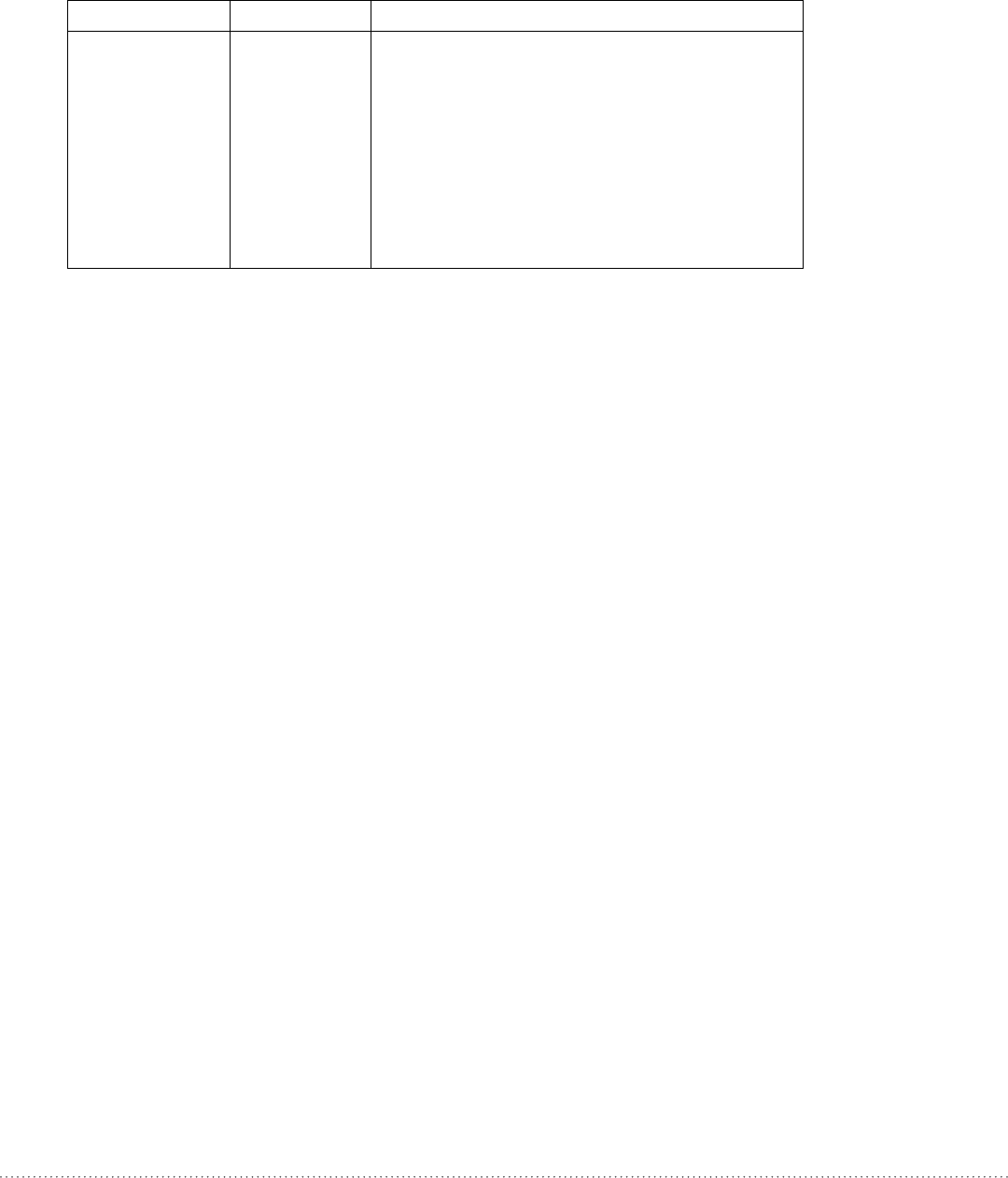

Setting

In-Home Out-of-Home

Percent/(SE)

Foster

Care

Services

No

Services

TOTAL

In-Home

Kinship

Foster

Care

Total

Race/

Ethnicity

Group

Care

TOTAL

Out-of-

Home

28.1

(2.5)

46.9

(3.7)

18.0

(2.9)

6.9

(0.8)

26.0

(2.6)

47.9

(4.1)

19.3

(3.4)

6.8

(1.0)

30.9

(3/1)

45.4

(3.8)

16.6

(3.1)

7.2

(1.3)

27.3

(2.6)

47.2

(3.7)

18.6

(3.1)

6.9

(0.8)

38.4

(5.6)

38.9

(5.6)

14.9

(4.5)

7.8

(2.2)

33.7

4.3)

47.7

(5.1)

13.1

(3.2)

5.6

(1.8)

18.0

(5.9)

61.9

(9.5)

12.0

(4.5)

8.1

(3.9)

34.6

(3.8)

44.8

(4.1)

14.0

(2.8)

6.7

(1.4)

African

American

White

Hispanic

Other

Table 1

Characteristics, Living Situations, and Maltreatment of Children Involved with the Child Welfare

System: Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Setting of Children Entering the Child Welfare System

(Weighted)

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data; standard errors are in parentheses. Source: U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, 2005, p. 62.

In addition to examining the racial breakdown of children and families involved with

child welfare agency–supervised services, it is also important to review the race/ethnic

contributions in service receipt and placement. Table 1 also depicts the simple bivariate

relationship between race/ethnicity and service receipt (those who either received no services,

those where cases were closed at intake, or those who received in-home services); and the

comparison of in-home versus out-of-home care (NSCAW Research Group, 2005). Race/

ethnicity was not found to be a significant predictor in the receipt of services for children

remaining at home, nor was it an indicator in whether children would be placed in out-of-

home care (NSCAW Research Group, 2005).

Another important factor to examine is the racial breakdown of current caregivers (in-

home and out-of-home) of the children in the study: 51% of the caregivers are white/non-

8

Hispanic; 26% are African American/non-Hispanic; 17% are Hispanic; and 7% are classified

as being of Other race/ethnicity (Table 2). The NSCAW report also included information

on the correspondence between race/ethnicity of the foster caregivers and children in their

care (NSCAW Research Group, 2005). See Table 3. Most (92%) white children were placed

with a self-identified white caregiver, whereas only two-thirds (66%) of African American

children were placed with a self-identified African American caregiver. Among the one-third

of African American children not identified as placed with an African American caregiver,

about half were placed with a caregiver identified as white. For Hispanic children, only 42%

were placed with a caregiver self-identified as Hispanic.

Note: Children in group care and other types of care were eliminated from these analyses because there were

multiple caregivers but only one was interviewed; therefore, determining a “match” between caregivers and

children was not possible. Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for

Children and Families, 2005, p. 209.

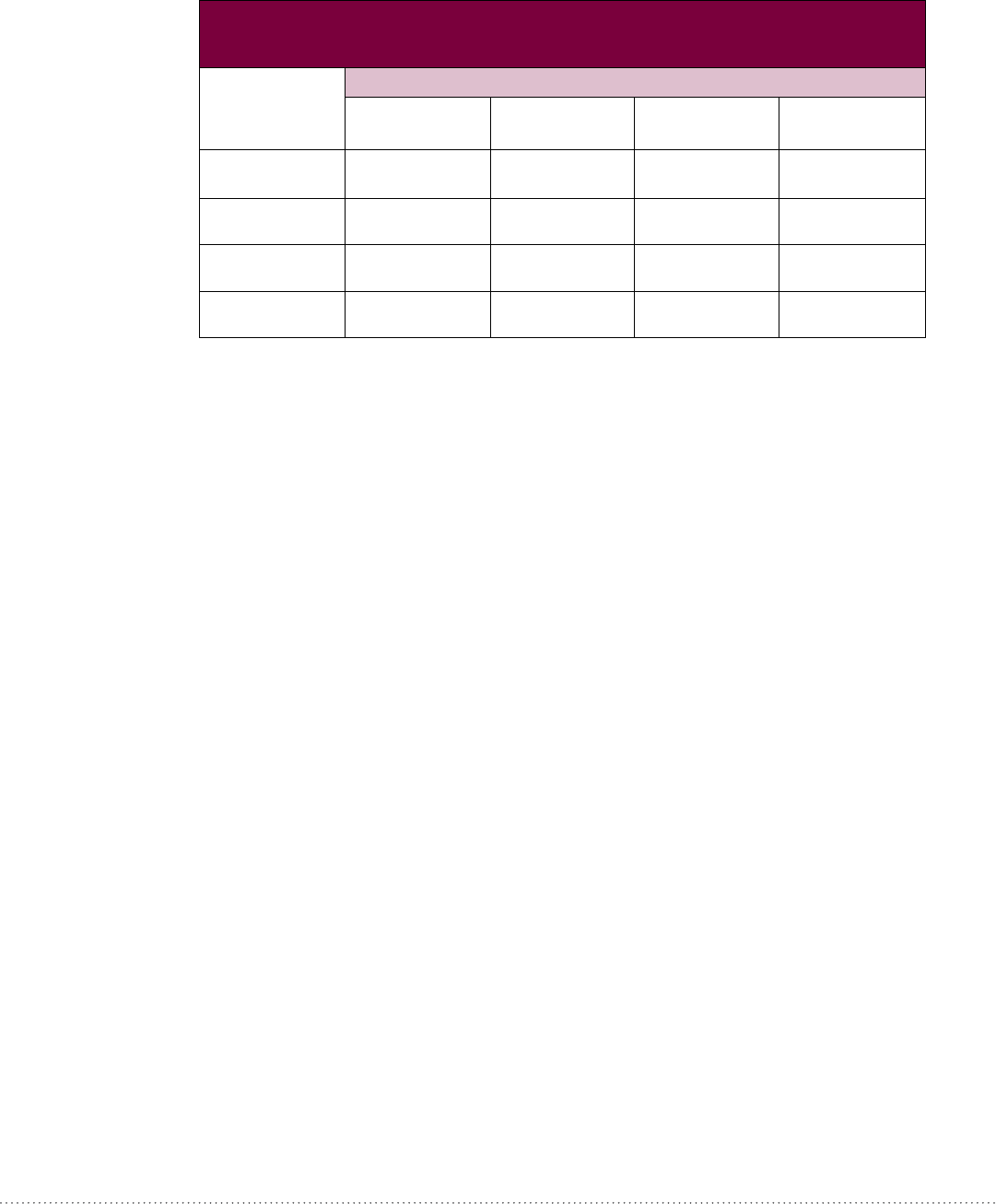

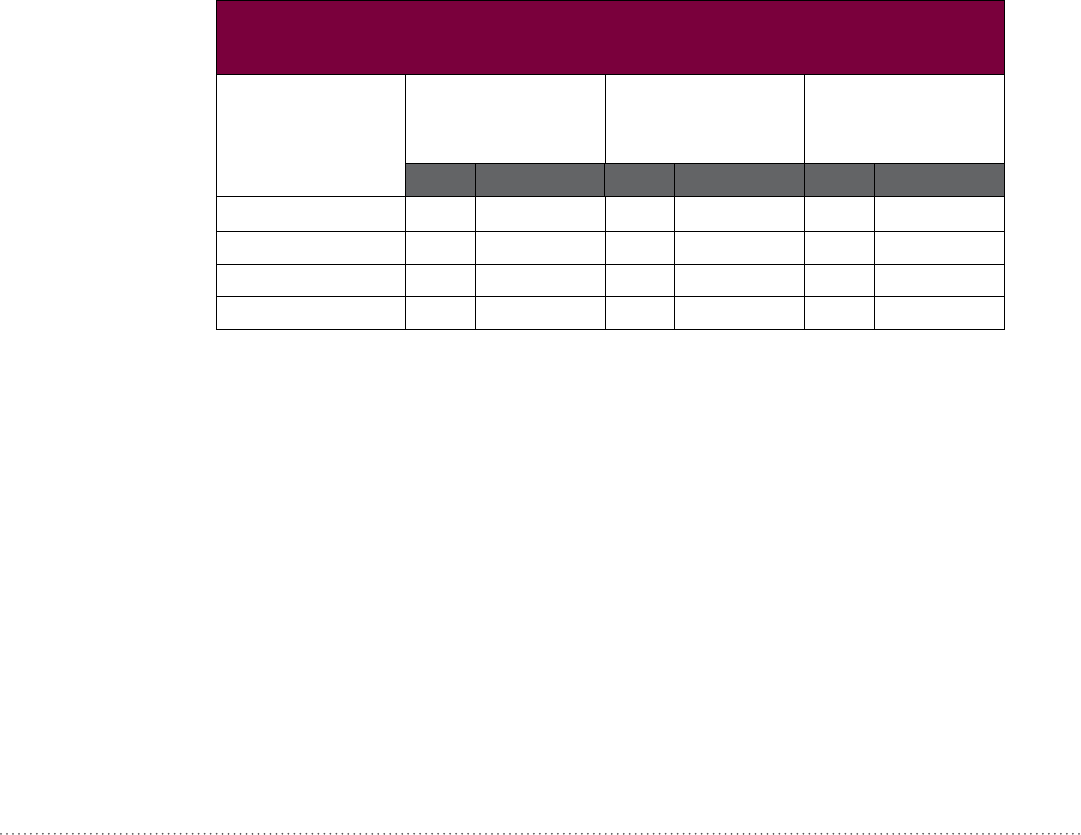

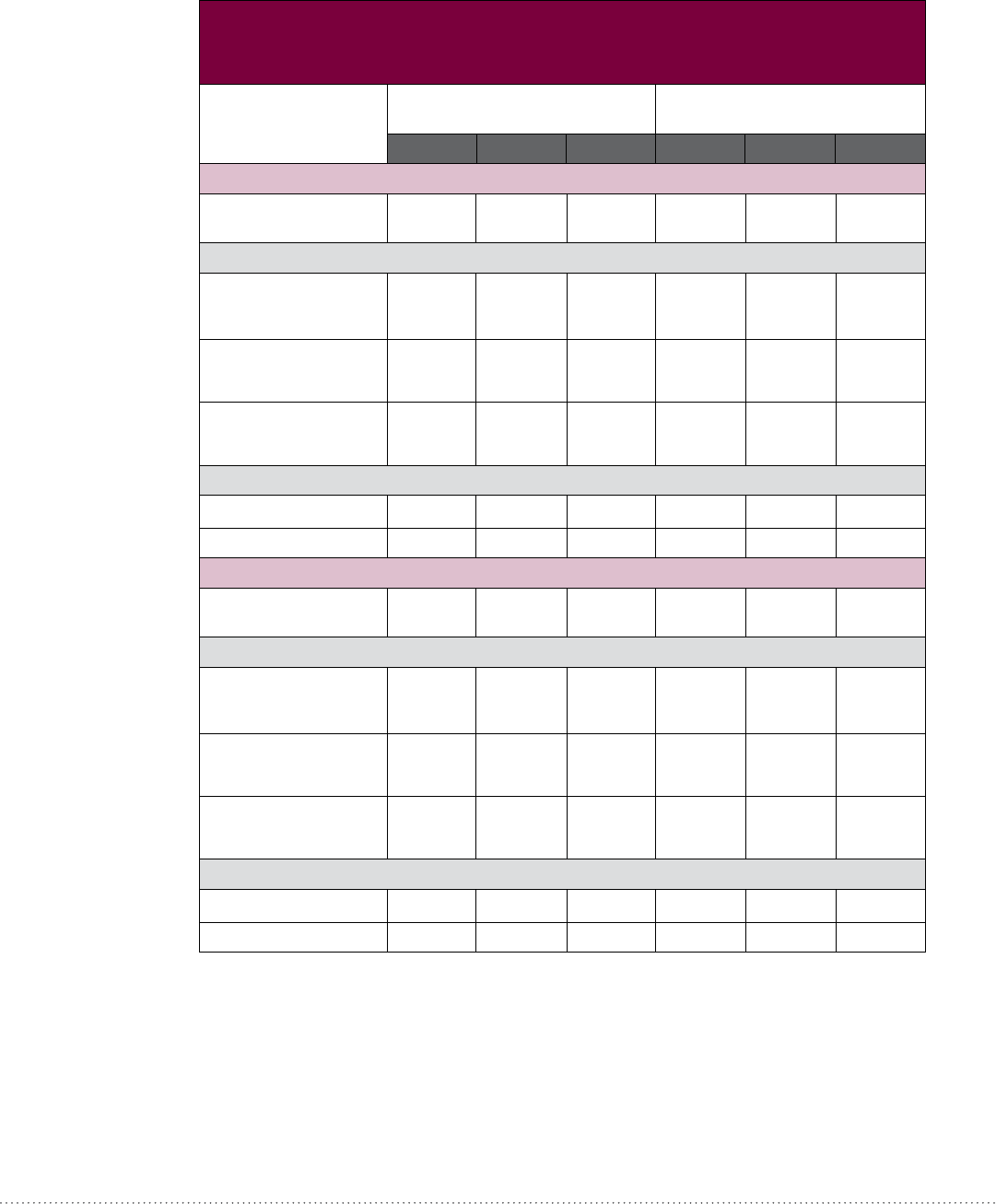

Setting

In-Home Out-of-Home

Percent/(SE)

Foster

Care

Services

No

Services

TOTAL

In-Home

Kinship

Foster

Care

Total

Race/

Ethnicity

Group

Care

TOTAL

Out-of-

Home

25.5

(2.7)

51.4

(2.7)

16.3

(3.3)

6.8

(1.0)

23.5

(2.9)

51.2

(4.3)

17.6

(4.0)

7.8

(1.3)

28.4

(2.9)

51.2

(3.8)

15.4

(3.0)

5.0

(0.8)

24.8

(3.4)

51.2

(3.8)

17.0

(3.5)

7.0

(1.1)

24.0

(2.8)

51.2

(3.8)

13.2

(7.0)

5.8

(1.6)

29.6

(4.0)

56.8

(4.7)

9.2

(2.2)

4.4

(1.1)

51.9

(12.2)

41.3

(11.4)

X

X

30.9

(3.6)

53.9

(5.2)

10.4

(3.5)

4.8

(0.9)

African

American

White

Hispanic

Other

Table 2

Current Caregiver Demographics by Service Setting

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 9

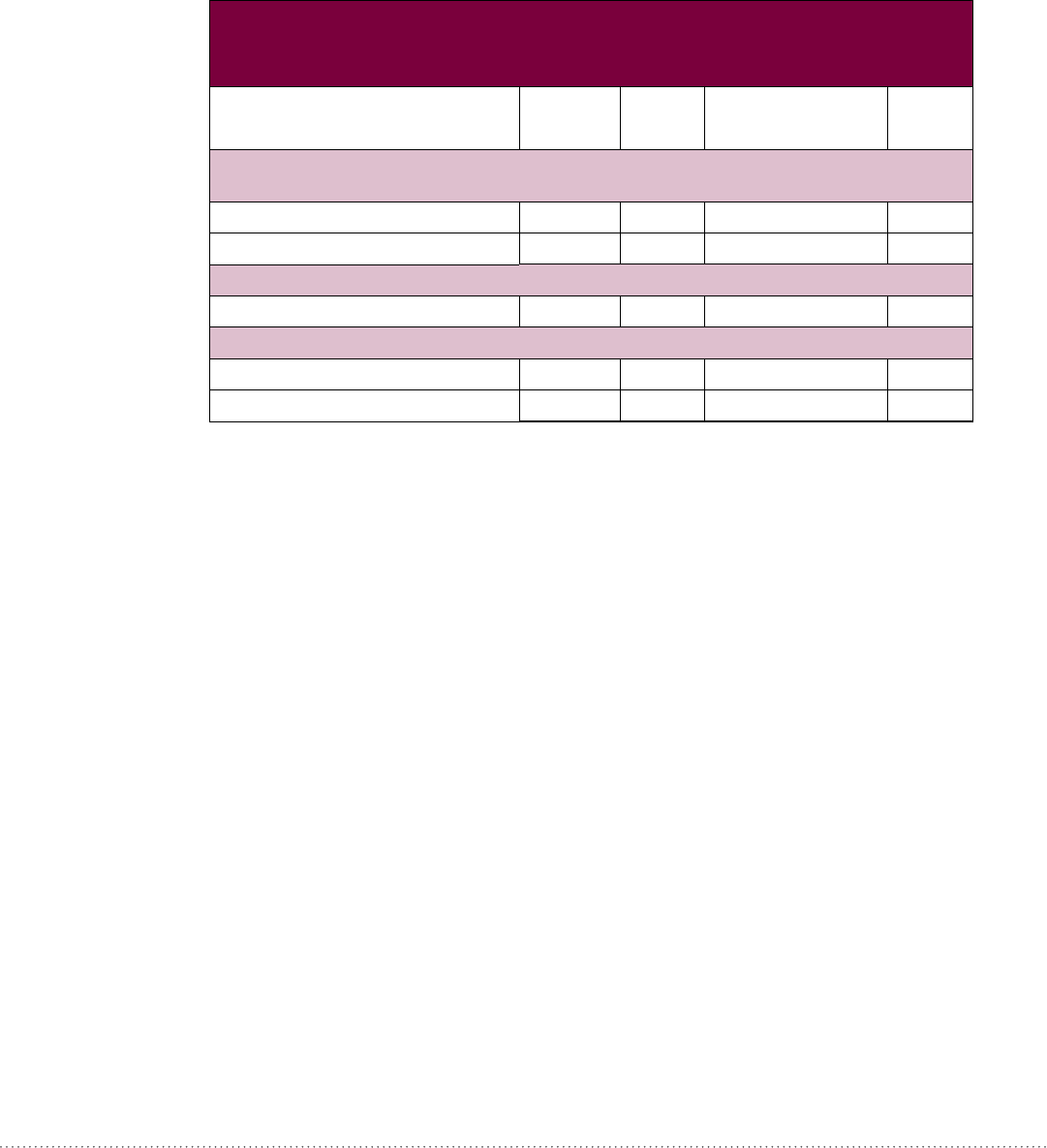

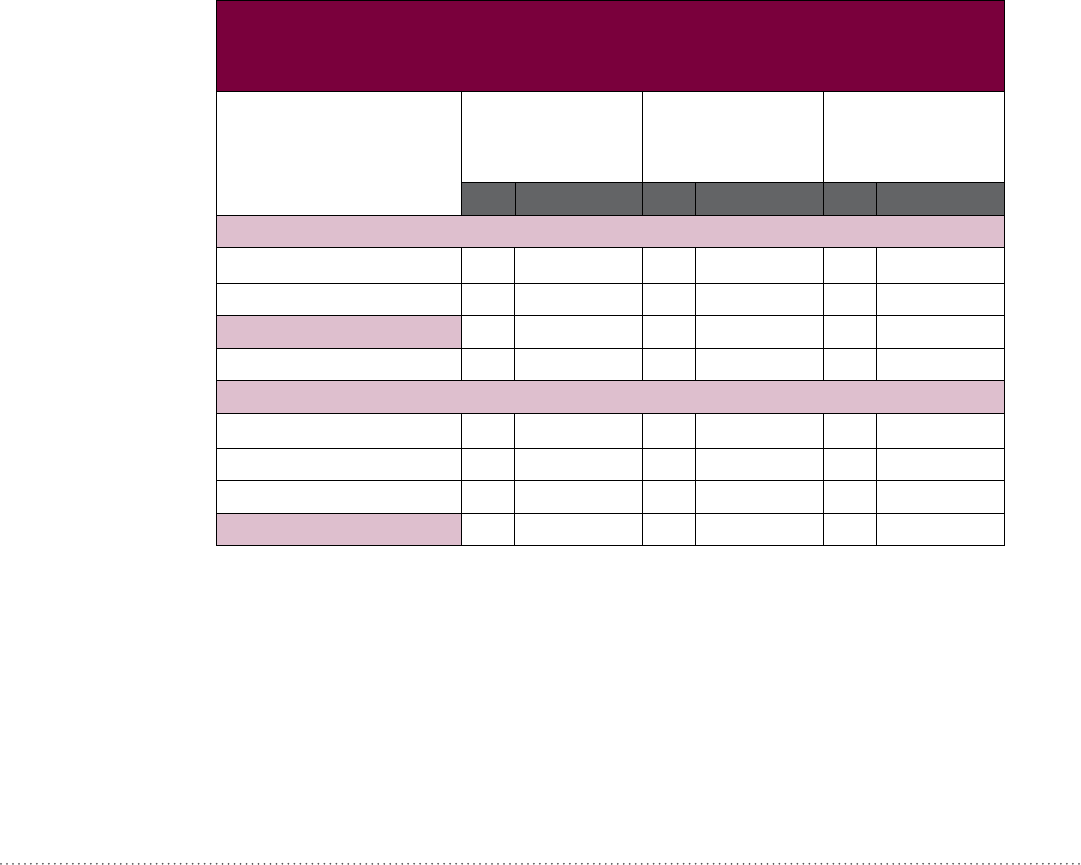

Note: Bold numbers indicate that the caregiver is the same race/ethnicity as the child. Children in group care

and other care are excluded. Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for

Children and Families, 2005, p. 210.

Race/Ethnicity of Current Caregiver

Race/

Ethnicity of Child

African American

-

Percent (SE)

Hispanic Percent

(SE)

White Percent

(SE)

Other Percent

(SE)

65.5

(6.0)

3.3

(1.2)

3.6

(1.6)

4.7

(2.2)

16.0

(4.7)

92.4

(2.0)

48.5

(20.5)

42.4

(9.4)

13.4

(7.2)

2.9

(1.3)

42.0

(21.0)

9.1

(5.5)

5.1

(2.9)

2.4

(1.1)

2.7

(2.0)

31.4

(7.9)

African

American

White

Hispanic

Other

Table 3

Non-kinship Foster Care: A Comparison of the Child to Caregiver Race/Ethnicity

10

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 11

CHILD FACTORS

Early Childhood Development and Need for Early

Intervention Services

OVERVIEW AND METHODS

Identification of early child development needs and the receipt of related early intervention

services is an important topic in the child welfare arena. Children involved in the child

welfare system often have a higher level of developmental and behavioral need than those

who are not. Minimal research exists that examines the relationship between race and

ethnicity and the need and receipt of services within the child welfare population. There is

one published NSCAW article related to early childhood development and the need for early

intervention services that includes race and ethnicity as a predictor of service use (Stahmer,

Leslie, Hurlburt, Barth, Webb, & Landsverk, et al., 2005). The purpose of that study was

to determine the level of developmental and behavioral need in young children entering

the child welfare system, to determine the level of early intervention services use, and to

observe variation in need and service use based on age and level of involvement in the child

welfare system. This article does not solely focus on the relationship between early childhood

development and the need for early intervention services and race/ethnicity, although it does

include race/ethnicity in the analysis.

Participants. The sample for that study focused specifically on 2,813 children who were

6 years of age and younger from the study sampling frame. The cohort included children

from birth to 14 years of age at the time of sampling who had contact with the child welfare

system during a 15-month period that began in October 1999. The racial/ethnic mix of

the sample was 29 percent African American, 47 percent white, 19 percent Hispanic, and 5

percent Other.

Procedure. Field representatives performed several interviews with caregivers regarding the

children in their care in order to assess the child directly. Assessments were conducted at

an average of 5.3 and 13.2 months after onset of the child welfare investigation. Children

included in that article were between 1 and 71 months of age at the time of the first

interview.

Measures. Sociodemographic information was collected regarding the child’s age, gender,

and race/ ethnicity. The level of child welfare system involvement and the history of alleged

maltreatment of children were both obtained from child welfare agency workers. Workers

were asked to identify the types of maltreatment that had been alleged by using a modified

maltreatment-classification scale. Measures were obtained in five areas to estimate the risk for

developmental and behavioral problems in young children and the need for early intervention

12

services. Comprehensive screening assessments were used to measure developmental/cognitive

status, which varied with the age of the child. The language and communication level was

assessed in order to determine the possibility of language delay, using the Preschool Language

Scales. In order to understand behavioral needs, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was

used. Social skills were measured in children 3 to 5 years of age by using the Social Skills

Rating Scale (SSRS). Adaptive behavior was measured using the Vineland Adaptive Behavior

Scale screener. Measures were categorized into five domains for analyses: developmental/

cognitive status, adaptive behavior, behavior problems, communication, and social skills.

Service use information regarding whether a child had received any services was obtained

from interviews with current caregivers.

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

In a simple bivariate comparison, race/ethnicity was found to be related to the overall level of

child welfare system involvement (p <.01). Children remaining at home were more likely to

be white than children removed from their homes.

c

This was true for in-home cases that were

opened to child welfare agency–supervised services as well as for those that were not open.

Children remaining at home with an open case were less likely to be Hispanic than children

removed from their homes (all differences were at the p < .05 level). Differences in child

welfare services received were also strongly associated with maltreatment type.

Service Use. A multivariate analysis determined the relationship between race/ethnicity and

service use in the mental health, education, or primary care sectors. Age, race/ethnicity, and

level of risk were significantly related to service use. Over all, a strong relationship was shown

between developmental risk and service receipt: Children with two areas of developmental

and behavioral risk were five times as likely to receive services (p ≤ .001). Younger children

were less (OR=.33) likely to receive services (p < .001). To summarize:

The level of child welfare system involvement was also found to predict

service use; children living at home, regardless of whether they had an

active case, were much less likely to receive services for developmental or

behavioral problems than children living in out-of-home care; children at

home without an active case were the least likely to receive services.

(Stahmer et al., 2005, p. 896.)

Race/ethnicity was also found to be associated with service use; it was determined that black

children were about half as likely to receive services as white children: OR = 0.44 (0.25, 0.79;

p < .05). Stahmer et al. (2005) also found this difference to be consistent at the various levels

c

This finding appears to run counter to the earlier finding that there was no difference in the placement by

race, suggesting that the finding stated, here, might be an age-related finding.

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 13

of risk especially when two risk factors were present. While the reasons for these differences

were not addressed in their study, the authors did find that the racial inconsistencies in

services received remained even after controlling for need. (See Table 4.)

Source: Stahmer et al., 2005, p. 897.

Developmental Conclusions

The findings show that race and ethnicity are strongly correlated with the overall level of

child welfare system involvement and the receipt of services. White children are more likely

to remain at home than to be removed from their homes when a child welfare case is opened.

Race and ethnicity were also found to be predictive factors in service receipt: Black children

are less likely to receive services than white children and the racial inconsistencies in services

received remained even after controlling for need.

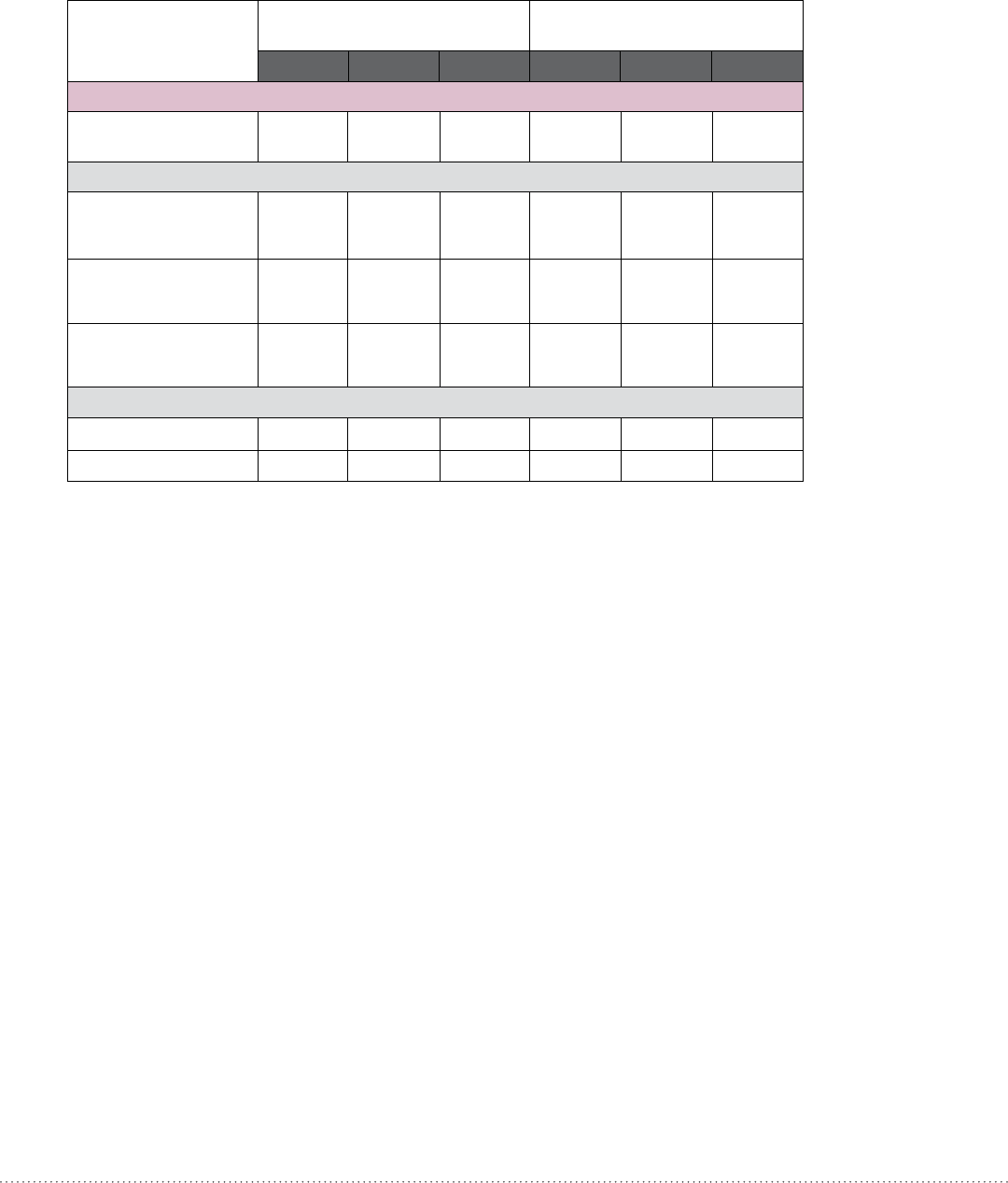

PSE

B

Coefficient

1.02

1.64

– 1.10

– 0.82

– 0.27

Odds Ratio

(95% Confidence

Interval)

0.32

0.36

0.2

0.29

0.41

2.76 (1.47, 5.19)

5.18 (2.54, 10.58)

0.33 (0.22, 0.50)

0.44 (.025, 0.79)

0.76 (0.33,1.74)

0.001

0.000

0.0173

Developmental and behavioral need

(ref = no risk)

1 risk score

≥ 2 risk scores

Age (ref = 3–5 y)

0–2y

Race/ethnicity (ref = white/nonHispanic)

Black/non-Hispanic

Hispanic

Table 4

Logistic-Regression Analysis of Any Service Use (Educational, Mental Health, or Primary Care)

According to Model Variables (N=2813)

14

Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Need, Use,

and Access

OVERVIEW AND METHODS

Four NSCAW articles address mental health and substance abuse diagnosis, treatment, or the

access to mental health services. These four articles are cited within this review (Burns et al.,

2004; Hurlburt, et al., 2004; Leslie, Hurlburt, Landsverk, Barth, & Slymen, 2004; Libby,

Orton, Barth, & Burns, 2007). None of these articles focused their examination on the

relationship between substance abuse and treatment or the access to mental health services

on the one hand, and the race/ethnicity of children or parents on the other. Each of them

did include race/ethnicity in their analysis, however. Moreover, Burns et al. (2004) identified

factors related to the need for and use of mental health services among youth, with special

attention to differences by age groups (3–5, 6–10, and 11+), at the time of entrance into

NSCAW.

Participants. The sample was limited to children ages 2 years and above (N=3,803) to

correspond to age-related measures of mental health need. 29.6% of the sample included in

these analyses fell into the preschool group (2 to 5 years), 41.9 in the school age group (6

to 10 years), and 28.6% in the adolescent group (11 to 14 years). The racial demographics

of the sample consisted of 47.6 percent white, 28 percent African American, 17.5 percent

Hispanic , and 7 percent members of other racial/ethnic groups.

Procedure. Logistic regression was used to examine variables associated with service use.

Demographic variables were included in all models. Clinical need measures and the nature

of available services varied due to the presence of multiple informants; separate models were

estimated by age group.

Measures. Burns et al. report that:

Emotional and behavioral problems for youth and need for mental health

treatment was measured using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL); the

Youth Self Report (YSR); and the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF). Data on

the use of mental health services in the 12 months preceding the survey

interview are based on an adapted version of the Child and Adolescent

Services Assessment (CASA). A modified Maltreatment Classification Scale

(Manly et al., 1994) was used to identify the types of maltreatment alleged

in the most recent report using emotional abuse, and neglect. Youth were

categorized as being in one of four possible living situations at the time

of the investigation: (1) with their permanent primary caregiver, typically

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 15

a parent; (2) non-relative foster care; (3) kinship foster care; or (4) group

home/residential treatment center. Child welfare workers identified family

risk factors based on the information/knowledge available to them at the

time of the case investigation. (Burns et al., 2004.)

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

In order to understand disparity in mental health service receipt, logistic models were used

to examine factors related to service use across the three age groups (see Table 5). “While

controlling for other factors, children across all age groups scoring in the clinical range on

the CBCL were 2.5–3.6 times more likely to receive mental health services.” (Burns et al.,

2004, p. 965.)

*p < .01; **p < .001. Source: from Burns et al., 2004, Table 2, p. 965.

Demographic Characteristics

Table 5

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models of Past-Year Mental Health Service Use by Youth (Ages

2–15) Who Were Subjects of Investigated Reports of Maltreatment (N = 3,211)

Ages 2– 5

(N=970)

Ages 6– 10

(N=1,274)

Ages 11– 14

(N=971)

Selected Variables

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Child age (continuous)

African American (versus white)

Hispanic (versus white)

Other (versus white)

Male (versus female)

1.3

.5

.8

3.0

1.9

.9 – 1.7

.2 – 1.2

.3 – 2.3

.8 – 10.9

.9 – 4.3

1.0

.4*

.6

.3

.8

.9 – 1.2

.2 – .8

.2 – 1.8

.1 – .8

.5 – 1.4

.9

.7

1.4

1.0

1.2

.8 – 1.2

.3 – 1.4

.7 – 2.9

.2 – 4.1

.7 – 2.1

Clinical range CBCL

(64 and above versus below 64)

3.5* 1.3 – 9.5 2.9** 1.6 – 5.2 2.7* 1.5 – 5.1

Placement

In-home (versus out-of-home)

.6 .3 – 1.5 .4** .2 – .6 .4* .2 – .7

Parental Risk Factors

Parent severe mental illness

Impaired parenting skills

Parent physical impairment

Monetary problems

2.0

.6

2.8

1.2

.5 – 8.6

.3 – 1.5

.9 – 8.5

.5 – 2.8

1.6

.8

.7

1.4

.8 – 3.0

.4 – 1.5

.3 – 1.9

.7 – 2.9

2.4*

1.3

.8

1.3

1.3 – 4.3

.6 – 2.6

.4 – 1.9

.7 – 2.2

16

In summary, African American youth did not demonstrate elevated need as a group—that

is, their mental health problems were no greater than other children—but they did show

significant unmet need among the 6- to 10-year-old age group, and they were less likely

to receive mental health services than white youth in this age group when other variables

were controlled. For African American youth age 6–10, the OR = .4 (.2,.8) p <.01 and for

school-age children and adolescents living at home, the OR = .4 (.2,.6) p <.001, indicating a

significantly reduced likelihood of receiving mental health care.

The second study in this group endeavored to further understand the disparity in care for

children from ethnic communities (Hurlburt et al., 2004). Specifically, this study examined

how patterns of specialty mental health service use among children involved in the child

welfare system vary as a function of the degree of coordination between local child welfare

and mental health agencies.

Participants. This article focused specifically on children in NSCAW who were removed

from their homes or were living in a family in which a case was opened for child welfare

agency supervised services after substantiation of abuse or neglect (N=2823). The racial/

ethnic mix of the study’s participants was 33% African American, 47% white, 13%

Hispanic, and 7% members of other groups.

Procedures. This study uses data from initial interviews with child welfare workers and

initial and 12-month follow-up interviews with current caregivers. County-level data were

also collected from agency informants by trained research assistants.

Measures. Hurlburt et al. reported:

Sociodemographics and placement information were collected and classified

from study participants. The child welfare worker identified the types of

suspected maltreatment using a modified Maltreatment Classification Scale

(Manly et al., 1994). For each case in the NSCAW, caseworkers reported

the presence or absence of risk factors that resulted in the family having

contact with child welfare. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used

to estimate emotional and behavioral problems for youth and the need for

mental health treatment. Current caregivers responded to questions about

children’s mental health service use in an adapted version of the Child and

Adolescent Services Assessment. The strength of linkages existing between

child welfare and mental health agencies at the local level was assessed

through 2 different interview modules, one focusing on mental health

services available to children in the child welfare system and one focusing

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 17

on characteristics of the local mental health agency in the county. Regional

variation in specialty mental health provider supply was estimated. Variables

that describe the child population size and the level of poverty in the county

were included as control variables in multivariate models. Hurlburt et al., 2004.

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

Multivariate models were used to predict the relationship between specialty mental health

service use and each of the child- and family-level predictors (see Table 6). Hurlburt et al.

(2004) found the interactions of CBCL score with the strength of interagency linkages

(between the local child welfare and mental health service systems), in addition to the

interaction of race/ethnicity with interagency linkages to be significant. Race/ethnicity

accounted for differentials in service use; specifically, African American children were

0.61 times as likely and Hispanic children were about half as likely to use services as

white children.

Bold OR (CI) =p<.05. Source: Hurlburt et al., 2004, p. 1222.

Racial/ethnic disparities in service use are also related to the organization of services. African

American and Hispanic children are less likely to receive specialty mental health services than

white children (while holding the county variable constant).

Yet, linkages between child welfare and mental health moderated the

relationship between race/ethnicity and service use with the effect primarily

focused on service use patterns by African American children; OR = 0.15

Table 6

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models of Specialty Mental Health Service Use During One Year

Race/Ethnicity

Step 1:

Child and Family

Predictors

(N=2275)

Step 2:

County-Level Control

Variables Added

(N=2182)

Step 3:

Provider Supply and

Linkage Variables Added

(N=2099)

African American

Other

Hispanic

White

β

– 0.50

– 0.68

– 0.43

1.00

OR (CI)

.61 (.39 – .94)

.51 (.28 – .93)

.65 (.36 – 1.17)

β

– 0.49

– 0.62

– 0.36

1.00

OR (CI)

.61 (.38 – .97)

.53 (.30 – .96)

.70 (.38 – 1.29)

β

– 1.91

– 0.84

– 0.74

1.00

OR (CI)

.15 (.03 – .63)

.43(.07 – 2.52)

.48 (.13 – 1.75)

18

(0.03– 0.63); p < 04. In counties with stronger child welfare/mental health

linkages, differentials in service use between African American children and

white children diminished. As linkage levels increase, differences in rates of

service use between white and African American children diminish;

OR = 1.12 (1.01, 1.25). Hurlburt et al., 2004, p. 1223.

The authors believed that the coordination of services between child welfare and mental

health agencies, as it relates to the mental health needs of children, may be able to prevent

disparities in mental health care use among African American children.

In order to estimate the prevalence and severity of family mental health and substance

abuse problems, and the impact on children involved with child welfare systems and their

caregivers, the third study measured the co-occurrence of caregiver alcohol, drug, and mental

health (ADM) problems with children’s behavioral problems (Libby, Orton, Barth, & Burns,

2007). Understanding whether this level of co-occurrence varies by race and ethnicity could

be important to culturally and racially competent service planning.

Participants. Analyses presented were limited to children who were 2 to 14 years of age

baseline in the core NSCAW sample. Interviews were completed at baseline and at 18

months to collect data from the child, current caregiver, and the child welfare worker. In

order to keep data consistent, only children with caregivers who were constant between

baseline and 18 months were included in these analyses (N=1,876).

Procedure. Logistic regression was used to: (1) estimate relationships between baseline

child and caregiver characteristics and caregiver ADM problems, (2) estimate relationships

between child and caregiver risk factors and caregiver service receipt for substance use

problems at 18 months, and (3) estimate relationships between child and caregiver risk

factors and caregiver service receipt for mental health problems at 18 months (Libby

et al., 2007).

Measures. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF)

was used to interview caregivers at baseline in order to assess substance dependence (drug

or alcohol dependence separately) and occurrence of a major depressive episode. At the

time of investigation, child welfare workers assessed caregiver risk factors for substance

use and emotional problems; the youth were not given standardized interviews, however.

Consequently, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used to estimate emotional

and behavioral problems for youth and the need for mental health treatment. A modified

Maltreatment Classification Scale was used to identify types of maltreatment. At 12 and

18 months, the child welfare worker was asked questions regarding referrals made for each

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 19

OR

3.40

1.32

---

(95% CI)

(2.26, 5.10)**

(0.71, 2.43)

---

OR

0.98

0.40

0.30

1.00

(95% CI)

(0.39, 2.46)

(0.11, 1.42)

(0.12, 0.76)*

---

OR

3.22

0.92

0.51

1.00

(95% CI)

(1.34, 7.72)**

(0.32, 2.60)

(0.17, 1.54)

---

caregiver and services received by the caregiver since the last interview. Subsequent action was

taken depending upon the status of the referral or service receipt (Libby et al., 2007).

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

Table 7 presents results from the multivariate logistic regression model; only children whose

caregiver had a baseline ADM problem (40%) were included in these models. Libby et al.

(2007) found that there was no significant difference between the caregiver’s race/ethnicity

and the caregiver’s ADM problems at baseline. In further analysis, the study estimated the

likelihood of service receipt for substance use and mental health problems by the caregiver

between baseline and 18 months. The study found that Hispanic caregivers were significantly

more likely to receive substance abuse services (OR=10.96 (3.32, 36.17), p<0.01), and

black/non-Hispanic caregivers were significantly less likely to receive mental health services

(OR=0.23 (.72, 8.7), p <0.001).

Child had clinically significant (>= 64) CBCL at baseline

Table 7

Predicting Baseline Caregiver ADM Problems and Wave 3 Caregiver ADM Service Receipt with

Baseline Child ADM Problems and Baseline Caregiver Risk Factors

Externalizing

Internalizing

Child in-home at baseline

Out-of-home at baseline

Caregiver ADM

problem at baseline

Caregiver received

services for substance

problem at Wave 3

1

Caregiver received

services for mental

health problem

at Wave 3

1

Child’s age (years)

1.79

1.18

1.00

1.11

0.24

2.82

1.00

0.99

(1.04, 3.10)*

(0.79, 1.74)

---

(0.71, 1.77)

(0.07, 0.83)*

(0.88, 8.99)

---

(0.39, 2.56)

(0.71, 5.95)

(0.43, 2.11)

---

(0.22,0.94)*

2.06

0.95

1.00

0.45

2 – 5

6 – 10

11 – 14

Child’s gender (female)

Table 7 continued on next page.

* p < .05; ** p < 0.01

1

Only caregivers with an ADM problem at baseline were included in this model.

20

Caregiver race/ethnicity

Black/non-Hispanic

Hispanic

Other

White/non-Hispanic

1.39

0.81

0.83

1.00

2.51

10.96

2.02

1.00

(0.80, 2.40)

(0.43, 1.57)

(0.35, 1.99)

---

(0.72, 8.70)

(3.32, 36.17)**

(0.50, 8.14)

---

(0.11, 0.51)**

(0.34, 4.91)

(0.12, 2.47)

---

0.23

1.29

0.53

1.00

* p < .05; ** p < 0.01

1

Only caregivers with an ADM problem at baseline were included in this model.

Source: Libby et al., 2007, Table 6–3, p. 115

The final study on mental health service needs and use determined whether interactions

between clinical and non-clinical factors, specifically race/ethnicity and abuse type, affect

service use among children in foster care (Leslie, Hurlburt, Landsverk, Barth, & Slymen,

2004).

Participants. A group of children were specifically selected for this study to represent

children who had been in out-of-home placement for approximately 12 months at the time

of sampling, termed the “One Year in Foster Care” (OYFC) sample (N=1, 291). More than

half (56%) of this sample had caregiver interviews completed. The racial demographics

of the sample included 37% Caucasian, 39% African American, 16% Hispanic, and 8%

Other. In addition, 57% of children were placed in nonrelative foster care, followed by 33%

placements in kinship and 11% placements in group homes.

Procedure. Caregivers and children were interviewed if permission was granted. Interview

data were entered directly into computers by the field representatives. The sample of children

selected for this study had been living with their current caregiver for an average of 17.84

months. What’s more, 71.5% of the child/caregiver sample matched on reported race/

ethnicity.

Measures. Sociodemographics and placement information were collected and classified

from the study’s participants. The child welfare worker identified the types of suspected

Table 7 continued from previous page.

OR OR(95% CI) (95% CI) OR (95% CI)

Caregiver ADM

problem at baseline

Caregiver received

services for substance

problem at Wave 3

1

Caregiver received

services for mental

health problem

at Wave 3

1

N

1413 745 745

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 21

maltreatment using a modified Maltreatment Classification Scale. For each case in the

NSCAW, caseworkers reported the presence or absence of risk factors that resulted in the

family having contact with child welfare. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used

to estimate emotional and behavioral problems for youth and the need for mental health

treatment. The use of mental health services was measured using an adapted version of the

Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA). The current study included information

on the use of outpatient and residential services since the time of the investigation leading to

the current out-of-home placement (Leslie et al., 2004).

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

In the multivariate analysis examining the use of outpatient mental health service, race/

ethnicity was found not to be a significant factor related to service use; when comparing

African American children to white children, however, African-Americans were OR = .34

times as likely to access services (95% CI .14, .86).

In additional multivariate analyses, the study investigated whether the level of need

(according to CBCL score) for services differed by race/ethnicity of the child, after applying

statistical controls to account for other differences. The authors found that the interaction

between CBCL score and race/ethnicity was statistically significant using a likelihood ratio

test. In addition, African Americans used fewer services than children of white ancestry at

all values on the CBCL. The authors ran a regression analysis with an interaction term with

CBCL as a continuous variable by race/ethnicity; the African American by CBCL score

interaction term was significant at p < .01, while other racial/ethnic groups’ interactions

were found not to be significant. AfricanAmerican youths were less likely to access services

compared to whites when CBCL scores were lower. As the levels increased, the inconsistency

in service use decreased. Nonetheless, the quantity of African American children receiving

services remained smaller than the number of white children receiving services.

While all other variables in the regression model were held constant, race/ethnicity (African

American versus white) was found to predict outpatient mental health services use.

This finding may represent expanded use of services by Caucasian children

at lower CBCL scores—i.e., more preventive interventions—or constrained

use of services by African-American children. However, given that a CBCL

score of 64 or greater represents the 98th percentile with respect to need for

services, the authors anticipate that this finding reflects unmet need.

(Leslie et al., 2004, p. 708.) This paper did not assess factors that contributed to limiting

access to services for African American children.

22

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Conclusions

These studies of mental health and substance abuse treatment strengthen previous findings

that children in foster care have high rates of need and that race/ethnicity is associated with

less access to mental health services. African American children were significantly less likely

to use services than white and Hispanic children (Hurlburt et al., 2004) unless they were

in well-coordinated service systems. Although African American children did not display

elevated need as a group or diminished services as a group, African American youth age 6–10

should receive special attention as they were found to have a significantly reduced likelihood

of receiving mental health care versus other races in their age group (Burns et al., 2004).

When examining the relation of race/ethnicity to receipt of mental health services by

caregivers, Libby et al. (2007) found that black non-Hispanic caregivers were significantly

less likely to receive mental health services than other races. Leslie et al. (2004) found race/

ethnicity not to be a significant factor in outpatient mental health service receipt, however.

Leslie et al. also found that race/ethnicity (African American versus white) was a predictor of

outpatient mental health services use even while other variables were held constant. Further

analysis must be conducted in order to truly understand the racial disparities in service need

and receipt, but these studies offer some important new insights into these dynamics.

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 23

PARENT FACTORS

Parental Arrest and Child Involvement with Child Welfare

Agencies

OVERVIEW AND METHODS

Impact of parental arrest on service use has long been discussed in the literature (e.g., Pelton,

1991; Shireman, Miller, and Brown, 1981); however, there is a lack of detailed information

regarding ways that race and ethnicity may be related to the overlapping responses to

parental arrest within the child welfare population.

One NSCAW article related to parental arrest and children involved with child welfare

services agencies is that of Phillips, Barth, Burns, and Wagner, 2004 (previously cited in this

review). This study provided the first national estimate of parental arrest among children

who are the subjects of reports of maltreatment investigated by child welfare agencies. The

article also compared the relationship between arrested parents of different racial/ethnic

groups in the analysis.

Participants. The sample for this study focused specifically on children who were the

subjects of reports of maltreatment investigated by child welfare agencies. The sample of

5,504 children selected from completed case investigations/assessments forms the basis

for the present analyses.

d

Approximately half the children were white (46.1%), and about

one-quarter were African American (28.4%); smaller proportions were Hispanic children

(18.4%) or children of other racial/ethnic groups (3.8%).

Procedure. The children, from birth to age 15, were selected to take part in the NSCAW

survey between October 1999 and December 2000. Approximately 11% of the children

were in out-of-home placements. Boys and girls were equally represented.

Measures. The recent arrest of a parent was determined through two sources of information:

the child welfare worker’s and a parent’s reports. Child welfare workers were asked to

identify parent risk factors that existed at the time of the case investigation and the types

of maltreatment that had been alleged using a modified Maltreatment Classification Scale

(Manly, Cicchetti, and Barnett, 1994). Regarding the type of placement, children were

categorized as being in one of five possible living situations:

(a) with the person who was their permanent primary caregiver, typically their parent, at the

time of the investigation

d

In some research, the sample is identified as 5501, because three parents were interviewed in prison and their

data was later removed. Also, some published and in-press NSCAW papers make reference to investigations/

assessments because there were a few states that had already begun to implement an alternative response

system, and in these states, the investigation was called an assessment.

24

(b) with relatives

(c) in non-relative foster care

(d) in institutional placements (e.g., residential treatment and group homes)

(e) “other”

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000),

completed by the primary caregiver of children age 2 years and older, was used to estimate

clinically significant emotional and behavioral problems.

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y: PARENTA L A R R E S T A N D

PLACEMENT IN OUT-OF-HOME CARE

Race and ethnicity have a significant association with variation in the rates of parental

arrest, which, in turn, has a significant association with placement into foster care. African

American children with incarcerated parents were found to be overrepresented in the

proportion of investigated cases with a recent arrest. Yet the risk factors identified by child

welfare workers at the time of intake were lower among African American parents who

had been arrested than among other arrested parents. Thus, African American parents who

are arrested may have less cumulative risk than other arrested parents. This suggests that

some of the overrepresentation of entrances into foster care is mediated by police actions in

arresting African American parents and, perhaps, child welfare agency inaction in developing

mechanisms that help divert children from foster care during parental arrests.

Race and ethnicity had a significant relationship (p <.001) to the variation in the rates of

parental arrest. Approximately 12.5% of the children assessed for maltreatment by child

welfare agencies had parents who had recently been arrested. African American children with

incarcerated parents were overrepresented in this sample; only 28% of African American

children were subjects of maltreatment reports, but they constituted 43% of the children

with arrested parents (see Table 8). In contrast, Hispanic children were underrepresented;

Hispanic children comprised approximately 18% of the investigated maltreatment reports

but only represented 10% of children whose parents had experienced incarceration. Last, it

was found that the proportion of all arrests involving whites is considerably higher (69.7%)

than the proportion of arrested white parents in this study. Nearly one in every five African

American children (19.9%) in the sample had a parent who had been recently arrested—this

was double the rate for white children and about four times the rate for Hispanic children

and children from other races and ethnicities. Compared with other children who come to

the attention of child welfare agencies, those with arrested parents are significantly more

likely to be in out-of-home care.

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 25

Note. Values are weighted percentages. Source: Phillips et al., 2004, p. 178.

Parental Arrest Conclusion

Parents who were arrested had a greater number of risk factors (e.g., impaired parenting,

serious mental illness, trouble meeting basic needs, active domestic violence, and substance

abuse). Other notable factors, although not statistically significant, were that:

[T]he rate of four parental risk factors (i.e., impaired parenting, physical

impairment (at the level of a trend), trouble meeting basic needs, and

substance abuse) were lower among African American parents who had

been arrested than among other arrested parents. Arrested African American

parents also were different from non African American parents in that they

had the fewest children over age 11 (14.6%) and the highest rate of prior

reports of maltreatment (76.3%). Further, reported rates of emotional

maltreatment (9.8%) were lowest and reported rates of failure to supervise

(54.2%) and sexual maltreatment were highest among arrested African

American parents relative to other arrested parents (11.6%). (Phillips et al.,

2004, p. 181).

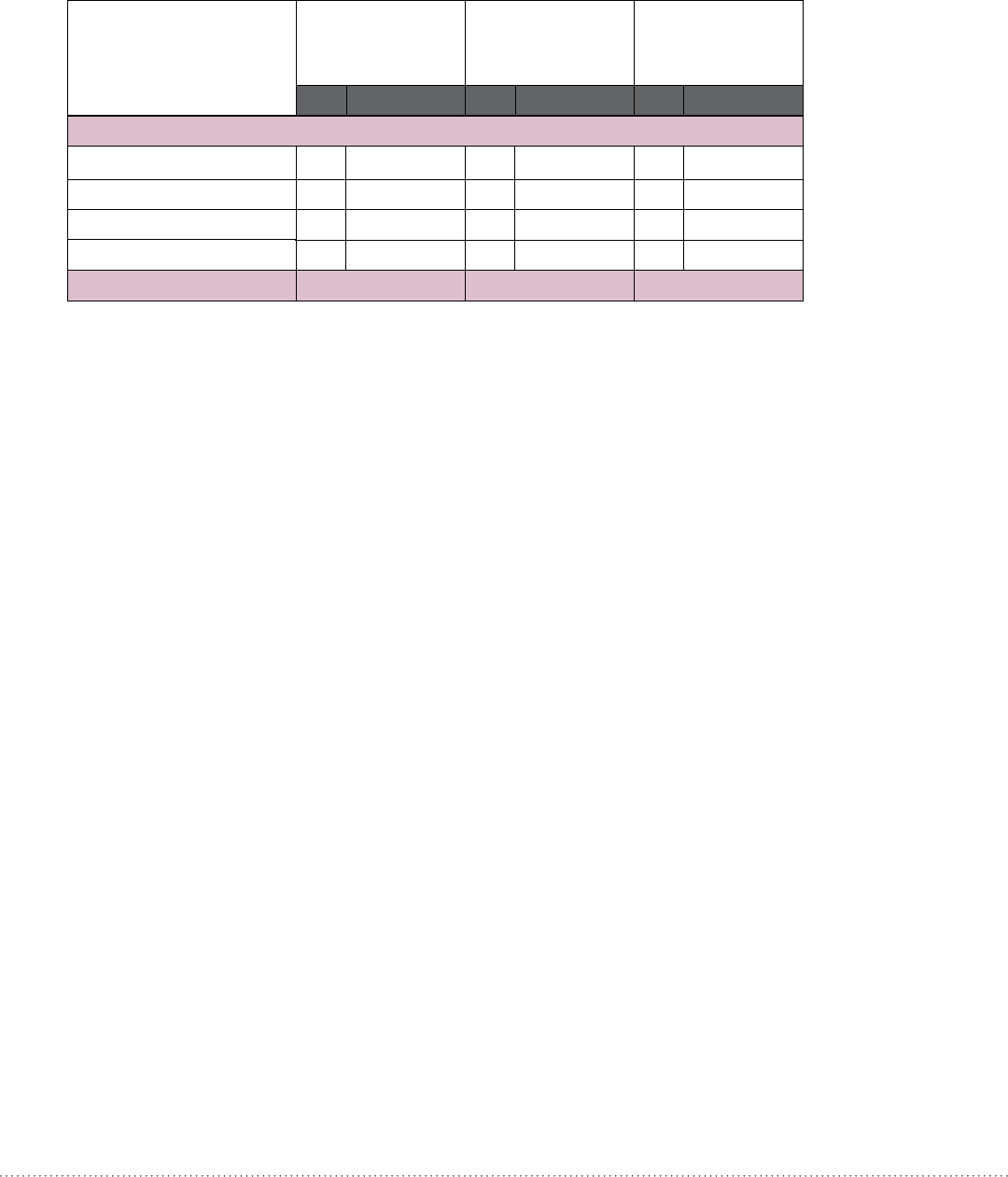

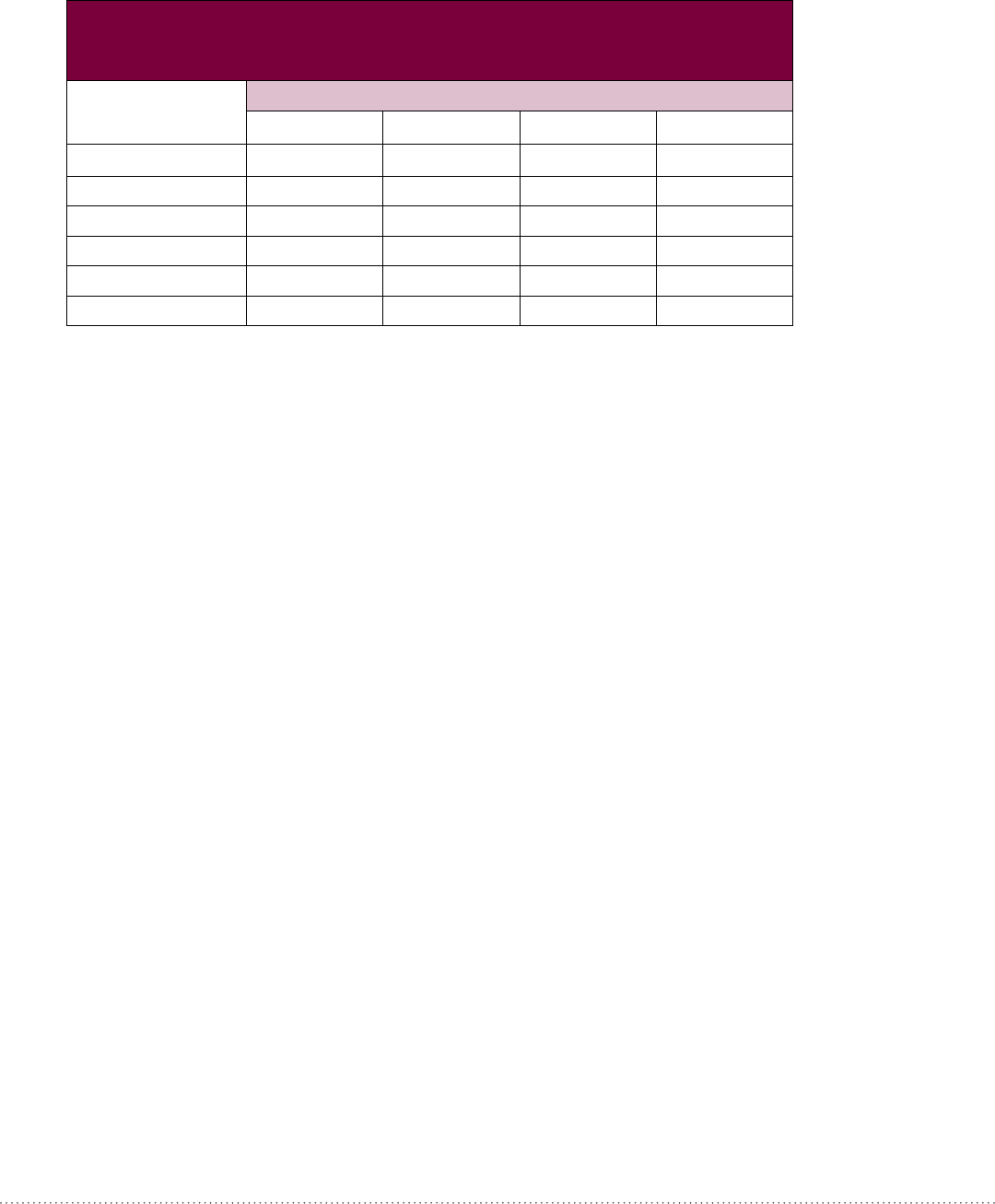

Race/

Ethnicity of Child

Yes

TOTALNo

43.1

42.6

10.5

3.8

26.1

46.7

19.8

7.5

28.4

46.1

18.4

7.1

African American

White

Hispanic

Other

Table 8

Comparison of Demographic Characteristics of Children Whose Parents Were or Were Not Arrested

(N=5,322)

Recent Parental Arrest

Significance: F(2.4, 217.4) = 10.1, p<.001

26

Domestic Violence: Epidemiology and Services

OVERVIEW AND METHODS

The overlap between domestic violence and child welfare agency-supervised services has

long been known and increasingly documented. Yet relatively little attention has been given

to ways that race and ethnicity may be related to the occurrence, and response to, domestic

violence within the child welfare population. We cite NSCAW articles related to domestic

violence in addition to information found in the ACF report: Connelly, Hazen, Coben,

Kelleher, Barth, and Landsverk, 2006; Hazen, Connelly. Kelleher, Barth, and Landverk,

2006; Hazen, Connelly, Kelleher, Landsverk, and Barth, 2004; Kohl, Barth, Hazen, and

Landsverk, 2005. None of these articles focused their examination on the relationship

between domestic violence and race/ethnicity, although each of them included race/ethnicity

in their analysis.

A pair of articles examined the underlying epidemiology of domestic violence within the

child welfare population: Hazen et al., 2004 and Hazen et al., 2006. The purpose of these

studies was to determine the prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among

female caregivers of children reported to child protective services in addition to determining

the relationship between intimate partner violence and child behavior problems.

Participants. The analyses presented in these papers are limited to the core child protective

services sample (N=5,504) of the NSCAW study. These analyses included children who

were not in out-of-home placement at the time of the baseline interview. Among these

4,037 cases, 3,612 (89.5%) had baseline interviews with a female caregiver in which data on

intimate partner violence were obtained. The samples vary slightly along racial/ethnic lines

but consist of approximately 27% African American individuals, 49% white individuals,

17% Hispanic individuals, and 7% individuals of other racial/ethnic groups.

Procedure. Information about child and caregiver mental health, service use, and family

environment information was obtained from caregiver interviews. Child welfare workers

were interviewed regarding initial case investigation and prior contact with child protective

services.

Measures. Researchers gathered demographic and background information was gathered

from caregivers on a range of demographic characteristics. The following scales were used

during assessment in this study respectively: The Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS1) was used

to assess information regarding intimate partner violence and the physical violence scale was

employed to assess caregivers’ experiences with intimate partner violence; the World Health

Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form was used to assess

Racial Disproportionality, Race Disparity, and Other Race-Related Findings in Published Works 27

mental health and substance use issues of the caregiver; the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

was used to assess child behavior problems; and the physical health scale of the Short-Form

Health Survey (SF-12) was used to assess the physical health of the caregiver. (Hazen et al.,

2004, pp. 305–306).

MAJOR FINDINGS IN RELAT I O N T O R A C E / E T H N I C I T Y

NSCAW Research Group (2005) stipulated that several characteristics (i.e., gender, types

of maltreatment, etc.) of children who were placed in out-of-home care were comparable to

those who remained at home. Hazen et al. (2004) found that

[D]espite these general findings it cannot be concluded that the children

who were in out-of-home care have families with similar incidence or

intensity of intimate partner violence as the children described in this paper.

In fact, the presence of intimate partner violence in the home may have

influenced some child protective services caseworkers to place children in

out-of-home care.” (Hazen et al. [2004], p. 304.)

Hazen et al. (2006) found that the use of corporal punishment (p <.05) and psychological

aggression (p =.05) in the presence of severe intimate partner violence were significant

moderators in child behavior problems and had some relationship to race/ethnicity. Hispanic

children were likelier to have lower externalizing scores compared with non-Hispanic white

children (B = – 2.67; p < .05). Black children had the lowest externalizing scores relating to

aggressive and delinquent behavior; race was not found to be significantly associated with the

internalizing behavior of children.

Another study provides further understanding of the intersection of domestic violence,

child welfare, and race/ethnicity. In this study, information was obtained about whether

child welfare workers recognized domestic violence in the home during the investigative

process for maltreatment (Kohl et al., 2005). This study also endeavored to determine the

factors associated with the child welfare worker’s underidentification of domestic violence

in cases; the level of domestic violence services use over the 18-month period following

the investigated maltreatment; how the caseworker’s identification of domestic violence

compared to caregiver self-report of domestic violence victimization; and the factors

associated with referral and receipt of domestic violence services.

Participants. Analyses for this study involved the permanent female caregivers (N=3135)

of children remaining in the home following allegations of maltreatment. Caregivers were

included in the study regardless of the outcome of the child maltreatment investigation. This

28

allowed for comparisons between caregivers in families who did and did not receive child

welfare services. Families receiving ongoing services had some level of follow-up contact with

the child welfare agency following the investigation, while those without services did not. In

this sample of female caregivers of children remaining at home, 27% received child welfare

services and 73% did not get those services. The sample consisted of 25% African American

individuals, 51% white individuals, 17% Hispanic individuals, and 7% individuals of other

racial/ethnic groups.

Procedures. The indicators for domestic violence used in this study came from two

sources: child welfare worker interviews and caregiver interviews. Face-to-face interviews

were conducted with the permanent caregiver of children remaining in the home, with or

without child welfare services, at baseline and at 18 months. The child welfare worker also

participated in a face-to-face interview at baseline, 12 months after, and 18 months after the

investigation.

Measures. The child welfare worker was given a risk assessment instrument to complete

for each caregiver at the time of entrance into the system to determine if active domestic

violence toward the caregiver was present and if there was a history of domestic violence

in the home. Domestic violence services data were also collected from the caregiver and the

child welfare worker. Following the questions about domestic violence victimization on

the caregiver interview, the women were asked about domestic violence services. When a

referral was made, a follow-up question inquired as to whether the referral resulted in the

receipt of services. Through the data analysis approach, descriptive statistics were calculated

on demographic characteristics of the overall sample and for caregivers who did and did

not report domestic violence victimization within the 12 months preceding the baseline

interview. Next, analyses were conducted to identify the level of agreement between caregiver

report of domestic violence and child welfare worker report of domestic violence. The rates