Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Marine Policy

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpol

Mapping the global value and distribution of coral reef tourism

Mark Spalding

a,

⁎

, Lauretta Burke

b

, Spencer A. Wood

c,d

, Joscelyne Ashpole

e,1

, James Hutchison

e,2

,

Philine zu Ermgassen

e,f,3

a

Global Ocean Team, The Nature Conservancy, Department of Physical, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Siena, Pian dei Mantellini, 44, 53100 Siena, Italy

b

World Resources Institute, 10 G Street NE Suite 800, Washington, DC 20002, USA

c

School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

d

Natural Capital Project, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

e

Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, UK

f

School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, UK

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Coral reef

Tourism and recreation

Environmental economics

Ecosystem services

Valuation

Social media

ABSTRACT

Global coral reef related tourism is one of the most significant examples of nature-based tourism from a single

ecosystem. Coral reefs attract foreign and domestic visitors and generate revenues, including foreign exchange

earnings, in over 100 countries and territories. Understanding the full value of coral reefs to tourism, and the

spatial distribution of these values, provides an important incentive for sustainable reef management. In the

current work, global data from multiple sources, including social media and crowd-sourced datasets, were used

to estimate and map two distinct components of reef value. The first component is local “reef-adjacent” value, an

overarching term used to capture a range of indirect benefits from coral reefs, including provision of sandy

beaches, sheltered water, food, and attractive views. The second component is “on-reef” value, directly

associated with in-water activities such diving and snorkelling. Tourism values were estimated as a proportion of

the total visits and spending by coastal tourists within 30 km of reefs (excluding urban areas). Reef-adjacent

values were set as a fixed proportion of 10% of this expenditure. On-reef values were based on the relative

abundance of dive-shops and underwater photos in different countries and territories. Maps of value assigned to

specific coral reef locations show considerable spatial variability across distances of just a few kilometres. Some

30% of the world's reefs are of value in the tourism sector, with a total value estimated at nearly US$36 billion,

or over 9% of all coastal tourism value in the world's coral reef countries.

1. Introduction

Coral reef related tourism is an important and still fast-growing

industry, providing employment and income to over 100 jurisdictions

world-wide, and often generating much-needed foreign earnings [1–6].

Coastal tourism in the vicinity of coral reefs is not always benign:

negative impacts can include degradation and loss of marine life

through activities such as diving and snorkelling [7–9], as well as

indirect impacts arising from poorly planned coastal development,

including dredging, building on intertidal spaces, and increases in

pollution and solid waste [10–12]. Despite these risks, tourism may be a

less significant threat than fishing, land-based run-off or coral bleaching

[13], and may even help to reduce some threats, notably over-fishing,

by offering financial or social incentives for sustainable management

[14–17]. Many visitors to coral reefs already have heightened environ-

mental awareness [18] and reef visitation can both help to fund [19]

and to encourage [20] coral reef conservation.

Much of the focus on the value and impacts of coral reef tourism has

focused on the direct use of coral reefs for in-water activities. The

indirect value of coral reefs in driving coastal tourism remains less well

quantified, but is also important. Studies have shown the considerable

importance of clear water and beach characteristics such as fine sand in

influencing tourist preferences [21–23]. There is also a sizeable

literature on the multiple ecosystem functions provided by coral reefs

which may support tourism benefits, including the generation of fine

sand beaches [24], the maintenance and building of islands [25,26],

protection from wave erosion and storm damage [27], and the

production of seafood [28]. Coral reef imagery also plays an important

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.05.014

Received 31 January 2017; Received in revised form 8 May 2017; Accepted 8 May 2017

⁎

Corresponding author.

1

Present address: Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, UK.

2

Present address: Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Monkstone House, City Road, Peterborough, PE1 1JY, UK.

3

Present address: School of GeoSciences, Grant Institute, The Kings Buildings, James Hutton Road, EH9 3FE, UK.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

0308-597X/ © 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/BY/4.0/).

MARK

role in marketing [29], while the perception of reef proximity, even for

non-reef users, may be an important draw [23,30]. Finally, the health

benefits associated with proximity to nature and to marine environ-

ments more generally are now increasingly realised [31,32], and are

also likely to be played out in coral reef settings.

Given the broad array of economic and social benefits that coral

reefs provide, there are growing attempts to build more sustainable

approaches to reef-related tourism [33–37]. In large part, however,

such efforts remain the target of individual operators, a few small island

nations or some operators in the diving sector. The wider call for

corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been slow to influence the

tourism sector in general, with biodiversity conservation remaining low

on the agenda even among those corporations who are engaging in CSR

more broadly [38]. Against this background, a clear, quantified and

reliable understanding of the value of coral reefs for tourism in specific

settings could help, by raising awareness and highlighting opportunities

for strengthening coral reef conservation, both in the public sphere and

in the tourism sector.

Previous efforts to quantify the value and to describe the spatial

distribution of reef-related tourism at large scales have been limited.

Without mapping, de Groot et al. [39] generated a mean value for coral

reef recreation of US$96,302 ha

−1

yr

−1

. This figure was derived from

29 studies, with a median value of US$1562 ha

−1

yr

−1

, but ranging

from zero to almost US$1.5 million ha

−1

yr

−1

. The large mean value

from this study was used in preference to the median value in a direct

benefit transfer approach to all coral reefs, generating a global estimate

of value of US$2.7 trillion per year, or 2.2% of all global ecosystem

service values [derived from supplementary materials in 40],afigure

that seems impossibly high given the spatially restricted nature of coral

reef tourism. Elsewhere, Brander et al. [1] had already drawn attention

to the challenges of such extrapolation: with data from 100 separate

reef recreation studies, they conducted out-of-sample value transfer

tests and estimated average transfer errors of 186%, a figure they

deemed “unlikely to be acceptable in most policy-making scenarios” (pg

215).

Given the challenges of developing value transfer approaches,

alongside the acknowledged benefits of developing an understanding

not only of global values but of the spatial distribution of such value,

this work presents a novel approach to accurately quantify global reef

values and to distribute these values to specific reefs at local scales. The

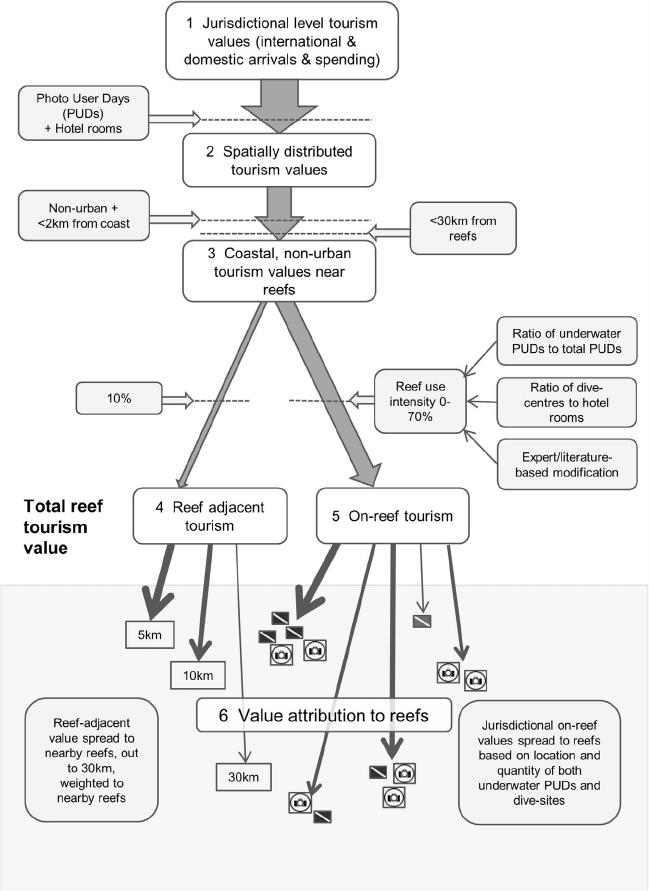

Fig. 1. A schematic representation of the methods employed to filter and spatially distribute components of national tourism statistics to coral reefs. Numbered stages are set out in

detailed text description. Photo User Days (PUDs) give a measure of the intensity of photography in specified locations, they are more fully explained below.

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

105

work draws on a variety of data-sources including national-level visitor

and expenditure statistics, together with locally accurate data from

industry, social media and crowd-sourced datasets to support the

spatial modelling of value distribution.

2. Framework and methods

In this work, coral reef related tourism is defined as the combined

tourism and recreation activities that can be attributed to the presence

of coral reefs. The value of such tourism is explored here using metrics

of monetary value and tourist trip equivalents (a term used to account

for the fact that many of the statistics are built up from fractions of total

arrivals, acknowledging that reefs are only part of most destination

choices). Two components of coral reef tourism are distinguished: on-

reef or in situ values are derived from direct non-extractive reef uses

including diving, snorkelling and glass-bottom boat tours [41]; reef-

adjacent or ex situ values are not derived from in-water activities, but

are indirectly linked to the presence of nearby reefs. The latter may

include the role of reefs in generating clear calm waters and beach sand,

outstanding views, fresh seafood and even their widespread use in

advertising, all of which help to draw people to coral reef regions.

Recreational fishing may represent an important additional value which

we were unable to incorporate into our model, in large part due to the

highly variable nature of reef dependency: much recreational fishing in

coral reef countries targets non-reef fish in offshore waters.

Tourism was examined in the over 100 jurisdictions (countries and

territories) around the world which have coral reefs. Statistics on travel

and tourism to each jurisdiction were used as initial inputs. “Big data”

from commercial, crowd-sourced, and social-media platforms were then

used to make predictions of tourism expenditure and visitation to non-

urban areas that could reasonably be linked to coral reefs. Paired,

independent datasets were used to strengthen the robustness of the

model, and the outputs were cross-referenced to existing studies.

Finally, these tourism values were linked back and assigned to the

reefs that were considered to be generating these values. Fig. 1 gives a

schematic of this work, while details of the datasets and the methodo-

logical process are described below.

1. Jurisdictional-level tourism. Expenditure statistics were largely

taken from the World Travel and Tourism Council [42] and

represent spending for tourist and business trips, including travel

and accommodation. Jurisdictions were largely countries and

territories, although, due to the strong geographical differences,

the US states of Hawaii and Florida were considered as distinct

jurisdictions. Arrivals, largely derived from the UN World Travel

Organisation (UNTWO) [43], include recorded overnight stays by

international, cruise ship, and domestic visitors; they do not

incorporate length of stay. The decision to include all travel in this

initial step was driven by a desire to ensure a more complete and

consistent dataset. Non-relevant travel was filtered out as outlined

in the subsequent steps (below). Gaps in these data were filled from

other international or national, sources (see Appendix A). Where

possible, data were gathered for all years from 2008 to 2012. Local

currency data were converted to historic US dollar values for 30

June of the relevant year. These values were then converted to 2013

values using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) price deflator (data.

worldbank.org).

2. Distribution of national tourism. In order to develop an estimate

of the geographic distribution of national tourism and expenditures,

two independent data sources were used: the distribution of hotel

rooms, and the distribution and frequency of geo-located photo-

graphs from the popular image-sharing website Flickr. Hotel rooms

give an approximate measure of overnight visitor intensity. The

Global Accommodation Reference Database (GARD), a commercial

database, was generously made available (http://www.delta-check.

de)

for the coral reef nations of the world. This provided location

and size (number of rooms) data for 125,498 hotels in coral reef

jurisdictions. Publicly sourced photographs from Flickr include large

quantities of geo-located photographs world-wide – an estimated

40–50 million have been uploaded to www.flickr.com annually

since 2010. The geographic distribution of photos gives an indica-

tion of human activity and particularly leisure-based activities, and

the spread and density of such photos have already been developed

as a metric to quantify tourist activity [44]. Following the same

approach as that work, a consistent spatial metric of the intensity of

photography was utilised. Known as photo-user-days (PUD), these

represent the total number of days, across all users, that at least one

photograph was taken in a given area [44]. Average annual PUD per

~1 km gridded cell was computed for all coral reef nations and

territories, including offshore waters, for the years 2005–2012.

Wood et al. [44] and subsequent authors [45,46] have recognised

possibilities of biases in the spatial distribution of Flickr images,

based on who is uploading photographs and the numbers of

photographs being taken of different recreational activities. With

the hotels layer the present authors were not aware of any biases,

however reporting may be better for some locations than others.

Both layers were independently derived, but on comparison they

tracked one another relatively well (N=103 coastal states with

hotels and PUDs, Pearson's r =0.899, p < 0.001). Using each layer,

a weighted distribution map was generated, showing the national

tourism values assigned to locations based on the numbers of PUDs

and, independently at this step, hotel rooms for each country or

territory.

3. Coastal non-urban tourism near reefs. It was then necessary to

filter out the tourism values that were unlikely to be reef-related

from the national totals. Using weighted distribution maps described

above, values were removed from three broad geographic extents: a)

Non-coastal areas, defined as any areas beyond 2 km landwards and

seawards of the coastline, b) Urban areas, defined as towns and

cities of greater than 10,000 people [47], and c) Non-reef areas,

defined as areas over 30 km from reefs that are unlikely to be

benefitting in any substantial way from the presence of reefs [48].

The influence of business travel, deliberately included in the initial

input statistics (1, above), is likely to be considerably reduced in this

stage, as a large proportion will be urban and non-coastal. For the

remainder, it was considered likely that business travel to coastal

resorts near coral reefs will in part be driven by the attraction that

reefs provide, and therefore that it was important to include such

travel.

The resulting two maps of coastal non-urban PUD and hotel-rooms

were then aggregated into a single statistic for coastal non-urban

tourism within 30 km of a coral reef (hereafter termed reef-coast

tourism) for each country. While the correspondence between PUDs

and hotel rooms was reassuring, it was felt that both layers, in

different places, showed varying levels of completeness, and further

that by combining both sources of information any unseen biases, or

more local effects, could be reduced. To achieve this, the two layers

were combined with a weighting of 2:1 towards the use of PUDs,

which gave a more detailed spatial portrayal of visitor use than hotel

rooms. This layer showed that 44% of coastal tourism in coral reef

jurisdictions occurs within 30 km of reefs. If the distance was

reduced to 10 km, that

figure

only dropped to 36%, suggesting that

most tourism is in fact much closer to coral reefs than 30 km. Clearly

not all tourism in this zone is attributable to coral reefs (see

following steps), but this initial step provided a clear starting point

for understanding the proportion of coastal tourism potentially

attributable to coral reefs.

4. Reef-adjacent values. Many tourists do not take part in on-reef

activities such as diving, snorkelling and boat-trips, but coral reefs

may still play a critical role in attracting them to particular

locations. While such reef-adjacent benefits are widely agreed to

be key drivers of tourism in many locations, the authors were

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

106

unaware of any existing models which would enable the prediction

of such values across multiple jurisdictions. Many existing reef

valuation studies look only at on-reef values (reef visitation, diver

numbers, etc.), while others provide total values for “reef regions”,

with the implicit assumption that all tourism can somehow be

related to the presence of the reef. Given that the on-reef values

were disaggregated separately (below), the approach taken here for

these reef-adjacent values was to assign a simple estimate of 10% of

the value of all reef-coast tourism to coral reefs. This is likely to be

conservative: some other studies have assigned higher values, but

these could also be more easily disputed. For example, Sarkis et al.

[4] suggest that visiting the beach was a prime motivation for some

16% of visitors in Bermuda, while arguing that the beaches

themselves are formed by the reefs and thus entirely coral reef

dependent.

5. On-reef tourism values. Some of the highest tourism values from

individual reefs are linked to direct, in-water uses, notably scuba

diving, snorkelling and boat tours. The magnitude of on-reef tourism

is influenced by a suite of natural, social and economic factors

including biodiversity and reef health, ease of access to reefs,

available infrastructure, history, and culture. Existing efforts to

quantify on-reef tourism cover few jurisdictions and there is little

consistency in methods. A novel approach was therefore devised to

quantify the relative importance of on-reef tourism as a proportion

of total reef-coast tourism, with help from existing studies to help

calibrate these efforts (see Appendix A). This approach used two

proxy measures: abundance of dive shops relative to hotel rooms

and abundance of underwater photographs relative to all photo-

graphs shared on Flickr. For the first metric, data on the locations of

more than 4000 dive shops world-wide were obtained from a crowd-

sourced database, generously provided by www.diveboard.com.

These were used to generate statistics on the number of dive shops

per 1000 hotel rooms within the reef-coast region of each country.

For the second metric, the collection of geo-located photographs

shared on Flickr (see Method 2 above) were used to obtain a subset

of images that were tagged with a keyword related to underwater

recreation. Multiple search terms in eight languages were used to

maximise the reach of this subset (see Appendix A). In total, the

search identified over 14,500 PUDs according to the underwater

images within 30 km of a coral reef. The ratio of underwater PUDs

to total PUDs were then generated in the reef-coast regions of each

country.

These two ratios gave independent estimates of national on-reef use

intensity. Ignoring values where either dataset held zero data there

was a significant positive correlation between the rank-orders of

jurisdictions developed from each dataset (n=89 jurisdictions with

both datasets, Pearson's r =0.632, p < 0.001).

While the authors felt the overall approach was strong, they were

also aware of gaps or weaknesses in some of these datasets. For

example, there were four jurisdictions where the (limited) dive

tourism was not represented by any dive shops. Given these

concerns it was felt appropriate to use both datasets, alongside

some further expert intervention. Both datasets were scaled between

1 and 100 to produce relative measures. These numbers were then

compared against each other and against several external sources

(see Appendix A). Overall, underwater PUDS were the more

spatially detailed and sensitive of the two datasets, and were also

likely to represent the full range of in-water activities, including

snorkelling and glass-bottom boat tourism alongside diving. Thus, a

single on-reef use intensity statistic was generated, weighted 2:1 in

favour of underwater PUDs over the dive shop metric. Where the

two on-reef tourism metrics were well correlated, and where there

was no evidence for errors (86 of the 102 jurisdictions with tourism)

this single weighted number was used, capped at 70%, as the

preferred metric for the proportion of remaining reef-coast tourism

which could be assigned to on-reef value.

For the remaining 16 territories known to have reef tourism, but

with limited data or showing disagreement among the underwater

PUD and dive-shop metrics, an equivalent number was generated

through the following process (see Appendix A for further details).

Where data were missing or very limited from either one of the two

metrics (i.e. there were few or no underwater PUDs or dive shops), a

new score was developed that was weighted towards the other

metric, or used that metric alone (three territories). Where data

were considered poor and were clearly divergent from a recent and

comparable literature source, the numbers were replaced with that

alternative (four territories). Where there was evidence, based on

expert-knowledge and/or available references, that both metrics

were under- or over-reporting, scores were altered to the best

approximation of the authors (nine territories).

Finally, the remaining 90% of reef-coast tourism (excluding the 10%

assigned to reef-adjacent values) for each jurisdiction was multi-

plied by the estimate for on-reef tourism estimates described above

(ranging from 0% to 70%) to give an estimate of on-reef value for

each jurisdiction.

6. Value attribution to reefs. The final stage of this work was to

separately assign the reef-adjacent and the on-reef values to the

reefs that are likely to be generating those values. To ascribe reef-

adjacent tourism expenditures, the national dollar and tourist trip

equivalent values were distributed separately following PUD den-

sities and hotel rooms within 30 km of a coral reef. The two layers

were then combined with a 2:1 weighting as above, and the values

from this combined layer were then attributed to nearby reefs (up to

30 km distant), using a series of steps (see Appendix A) with a

weighting to assign the greatest proportion of these values to the

nearest reefs (within 5 km).

For on-reef values two layers were employed to assign reef use-

intensity: underwater PUDs, as described above, and a global dataset of

dive-sites provided from diveboard.com. The dive-sites dataset is a

crowd-sourced dataset, and required some cleaning to remove duplicate

sites (based on identical geographic locations). The final layer held

8938 sites for the coral reef jurisdictions used in this study.

Both dive sites and underwater PUDs were buffered to a circle of

5 km radius to allow for the possible alignment errors between these

and the coral reef layer. Similar numbers of dive sites and underwater

PUDs were found in coral reef regions and so the two were simply

combined (unweighted) to develop a map of in situ use intensity, and

this map was intersected with the global coral reef map, giving every

500 m reef cell a measure of use-intensity.

The national on-reef tourism values were then distributed based on

this use-intensity map. This was irrespective of distance from hotels or

proximity to cities as it was felt that the underwater PUDs and dive-sites

were reliable metrics and were further enabling the model to account

for the highly variable distances that are travelled in different jurisdic-

tions, as well as to capture those reefs supporting multi-day “livea-

board” reef tourism.

Reef-adjacent and on-reef tourism values were summed to arrive at

a final estimate and map of tourism value on coral reefs.

Summary statistics were generated from the various stages of this

work, enabling us to give an indication of the value of coastal tourism,

coastal tourism near reefs, and finally reef value, both combined and

separately for the two components. The maps were also used to

generate a better understanding of the patterns and to overlay national

and territorial boundaries in order to derive politically relevant

summary statistics.

3. Results

Of the 117 jurisdictions in this study, 102 registered at least some

tourism value (the remainder including many uninhabited territories as

well as jurisdictions with ongoing conflicts, see Appendix A). The global

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

107

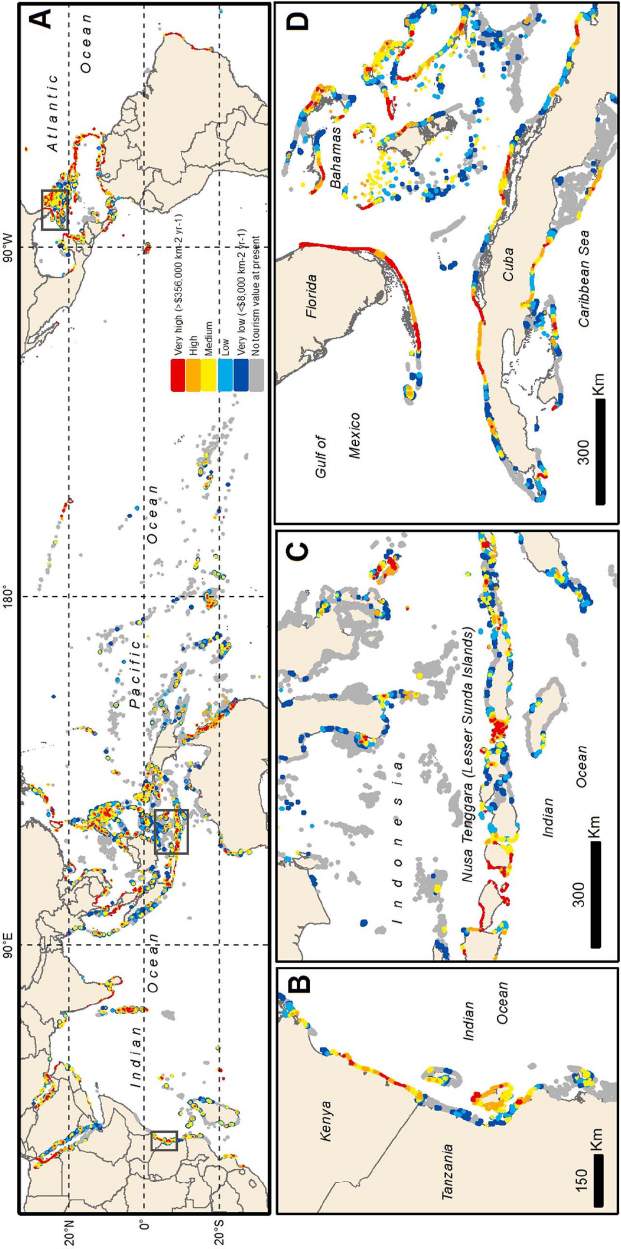

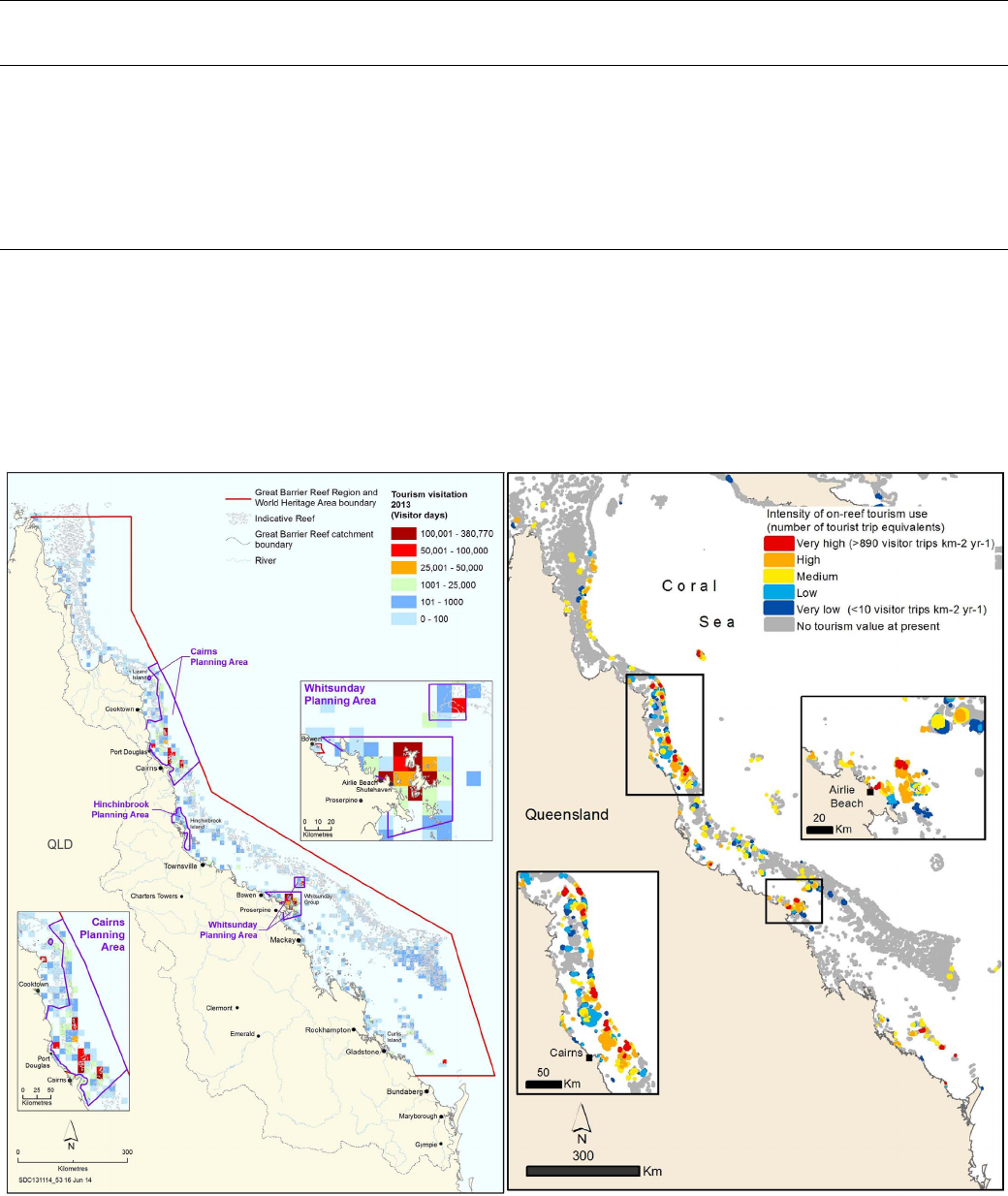

Fig. 2. Economic value of coral reefs for tourism (A). This figure summarises the combined dollar values of expenditures for on-reef and reef-adjacent tourism. Reefs without assigned tourism value are grey; all other reefs present values binned into

quintiles. Lower panels show Kenya and Tanzania (B), South-central Indonesia (C), and Northern Caribbean, with part of Florida, Cuba and the Bahamas (D). (Further maps can be seen in Appendix A and online at maps.oceanwealth.org).

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

108

spread of these values is presented in Fig. 2, while summary statistics

are presented in Table 1.

Reef tourism is calculated to be worth some US$35.8 billion dollars

globally every year, representing the total of within-country expendi-

ture by international and domestic visitors that the authors believe can

be assigned to the presence of coral reefs. This is about 1.51% of all

visitor spending (a number which includes domestic and international

visitor spending, including local travel and accommodation) in coral

reef jurisdictions. Visitor numbers equate to some 70 million tourist trip

equivalents, or 1.24% of all visitors to coral reef jurisdictions, where

visits include only overnight and multiple night stays by international,

cruise-ship, and domestic visitors (but do not account for the length of

stay). These are likely to be conservative estimates, but it should also be

noted that tourism is a very large industry in several of the countries in

the study (such as USA, Brazil, China and Australia), with coral reefs

being only a minor component. Across the world's coral reef jurisdic-

tions some 40% of coastal, non-urban tourist arrivals and 43% of

expenditures were made within 30 km of coral reefs. Well over 20% of

these values are attributed directly to the presence of coral reefs

(Table 1).

Global statistics hide the considerable variability in the value of

coral reef tourism captured in this work, as shown in the global map

(Fig. 2). In dollar terms 70.4% of reefs are recorded as having zero

tourism value, with the remainder reaching values of millions of

international dollars per square kilometre per year. This high varia-

bility, already noted by previous authors [1,39], is an important

feature: the mean value of all cells with any tourism value is US

$482,428 km

−2

yr

−1

, while the median value is only US

$48,000 km

−2

yr

−1

. The top 1% of cells are recording values greater

than US$7,248,000 km

−2

yr

−1

and their combined value makes up

some 33% of the global total values. Such high value reefs are

nonetheless broadly distributed – over 70% of jurisdictions with reef

tourism have at least some of their reef estate generating values greater

than $1,000,000 km

−2

yr

−1

. National summaries (Tables 2, 3 and

Appendix A) capture a portion of this variety, however, even within

nations there is large variation from reef to reef (Fig. 2).

While the models and data enable many di fferent approaches for

exploration (see also http://maps.oceanwealth.org), national level

summaries provide valuable information at a policy-relevant scale.

Tables 2, 3 give the findings for the 10 jurisdictions with the highest

levels of tourism expenditure and tourist trip equivalents, presenting

both the combined values and the separated values for reef-adjacent

and on-reef contributions to these values. The dominant position of

Egypt in these statistics was likely correct at the time of the input data,

but this value has most likely since fallen sharply due to changes in

tourism caused by geopolitics and regional instability. It is interesting

to draw attention to the significant variance in the contribution of on-

reef versus reef-adjacent tourism.

From the national-scale summary data provided in Appendix A it is

possible to investigate the relative importance of coral reef tourism,

both as a proportion of all tourism, or indeed as a proportion of GDP.

Such numbers show the particular importance of reef tourism in small

island jurisdictions. In each of the Maldives, Palau, Bonaire, the Turks

and Caicos Islands, and the British Virgin Islands, coral reefs support

over one third of all tourism value and 10% or more of the entire GDP.

Although a quantitative evaluation of accuracy has not been made,

the spatial distribution and relative importance of tourism appears to

match well with both expert opinion and other datasets. For example,

Fig. 3 shows the current map alongside the map of day visits plotted by

the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Setting aside the higher

resolution of the current map, the approximate locations of reef use

correspond well with on-reef use data derived in the present work.

Given the differences in units it not possible to directly compare

numbers, but total visitor numbers also suggest a broad agreement:

the current work estimates a total of 1.45 million trip equivalents for

on-reef tourism the Great Barrier Reef. This number lies between the

estimates, based on industry reporting, of 1.1 million “people visiting

coral sites” [49] and the estimate of 1.8 million “visits” to the Great

Barrier Reef Marine Park in 2013 [50]. Separately, our maps also show

a close visual correlation with a variety of on-reef uses that were

mapped at very high resolution using aerial surveys for the Ningaloo

reef system in Australia [51], further increasing our confidence in the

reliability of our method.

In comparing the geographic distribution of on-reef values with

reef-adjacent values it is noteworthy that on-reef use is more spatially

restricted, recording values from only about 15% of the world's coral

reefs. Given that on-reef tourism counts for a little over half of the total

estimated economic values this clearly represents a much higher value

per unit area for many reefs (average US$512,650 km

−2

yr

−1

, median

US$128,000 km

−2

yr

−1

). There are very few places where on-reef

tourism occurs with no reef-adjacent values – these largely represent

remote reefs being visited by liveaboard dive vessels such as the reefs of

the Coral Sea and parts of Eastern Indonesia. Reef-adjacent tourism is

more widespread, covering 26% of the world's reefs, with typically

Table 1

Total values associated with the various steps of the methods chain.

Spending (US$

million)

Proportion of total Proportion of

coastal

Tourist trip equivalents

(thousands)

Proportion of total Proportion of

coastal

Total for all coral reef nations 2,371,967 100% 5,650,099 100%

Coastal non-urban tourism 378,737 16.0% 100% 814,406 14.4% 100%

Coastal non-urban within

30 km of coral reefs

163,213 6.9% 43.1% 323,707 5.7% 39.7%

Reef-adjacent tourism 16,321 0.7% 4.3% 32,371 0.6% 4.0%

On-reef tourism 19,459 0.8% 5.1% 37,524 0.7% 4.6%

Total adjacent and on-reef

value

35,780 1.5% 9.4% 69,895 1.2% 8.6%

Table 2

Estimated expenditures by tourists within the ten jurisdictions with the highest total

values. Note that due to the strong geographical differences, the US states of Hawaii and

Florida have been treated independently.

Proportion

of tourism

which is

coastal,

non-urban

Reef-

adjacent

tourism

value

(Million

US$ per

year)

Proportion

of reef-

coast

tourism

assigned as

on-reef

On-reef

tourism

value

(Million

US$ per

year)

Total

tourism

value

(Million

US$ per

year)

Egypt 44% 947.5 53% 4519.8 5467.3

Indonesia 29% 1106.2 20% 1991.2 3097.5

Mexico 27% 1657.4 9% 1342.5 2999.9

Thailand 34% 1331.6 9% 1078.6 2410.2

Australia 24% 473.1 40% 1703.0 2176.1

China 13% 1348.1 2% 88.1 1435.1

Philippines 30% 451.2 23% 934.0 1385.1

USA (Hawaii) 58% 680.1 9% 550.8 1230.9

Japan 10% 542.6 13% 634.9 1177.5

USA (Florida) 11% 850.6 4% 306.2 1156.8

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

109

lower values (average US$250,612 km

−2

yr

−1

, median US

$20,000 km

−2

yr

−1

). It is worth noting that some of the locations

identified as solely important for reef-adjacent benefits may not be

generating on-reef tourism, either because they are degraded, or

because they are naturally occurring in turbulent or turbid waters

and do not offer accessible, attractive features to divers and snorkelers.

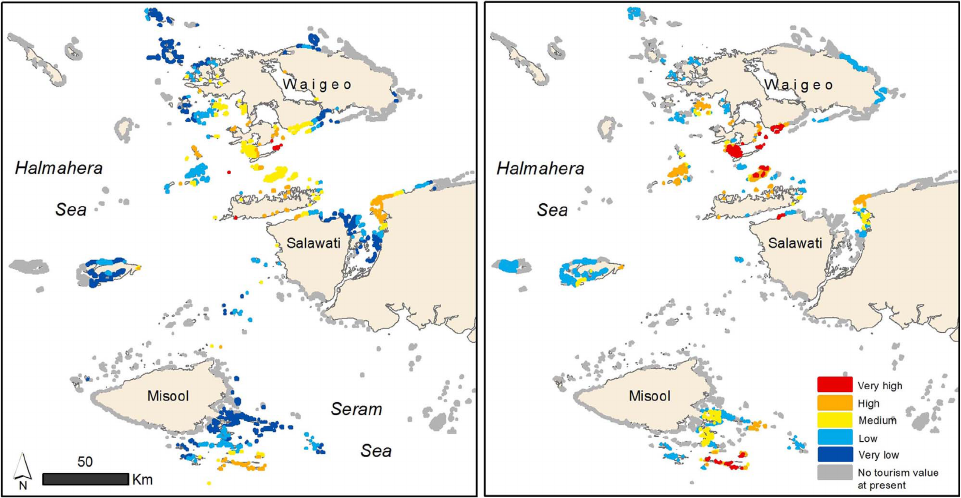

These might include many Persian Gulf reefs, and those off the

mainland coasts of India and China. In most places, however, on-reef

and reef-adjacent values are broadly co-located, with differences

expressed in different levels of value and more subtle difference in

spatial extent, as shown in Fig. 4.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The current work quantifies, for the first time, both the global value

of coral reefs for tourism and recreation, and the spatial variability of

Table 3

Estimates of visitation by tourists within the ten jurisdictions with the highest total values. Note that the numbers are “tourist trip equivalents” represent numbers of trips that could be

directly assigned to the presence of reefs, allowing for proportional inclusion of arrival statistics where the reef was only a part of the reason for the visit. Total numbers visiting or

otherwise benefiting from the coral reefs would be much higher.

Proportion of visitors that

are coastal, non-urban

Reef-adjacent tourism value

(1000 visitor trip equivalents)

Proportion of reef-coast

tourism assigned as on-

reef

On-reef tourism value (1000

visitor trip equivalents)

Total tourism value (1000

visitor trip equivalents)

Indonesia 29% 6722.3 20% 12,100.1 18,822.4

Philippines 30% 3406.5 23% 7051.4 10,457.9

China 13% 8462.6 2% 1523.3 9985.9

Egypt 44% 818.7 53% 3905.4 4719.0

USA (Florida) 11% 2377.8 4% 856.0 3233.8

Mexico 27% 1544.7 9% 1251.2 2795.9

Malaysia 19% 780.7 20% 1405.2 2185.9

Australia 24% 408.2 40% 1469.4 1877.5

Japan 10% 840.5 13% 983.4 1823.9

Cayman Islands 99% 175.7 55% 869.8 1045.6

Fig. 3. Coral reef tourism in the Great Barrier Reef. Left: day visits to the Marine Park – the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority estimates over 80% of tourism takes place in only 7%

of the region [50, p112]. Right: on-reef tourism from the current work for the same areas. The maps, derived from independent sources, appear to be well correlated with both the location

and the intensity of use.

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

110

this value. The estimated US$35.8 billion generated annually by coral

reefs is probably conservative, but nonetheless an important sum. The

spatial distribution of this value is highly variable: seventy percent of

the world's coral reefs have no value in the current model, but even

among the remainder the range is considerable, from just a few

thousands of dollars up to several millions of dollars per square

kilometre of reef per year. The summary values from this work (mean

US$482,428 km

−2

yr

−1

, median US$48,000 km

−2

yr

−1

) are far lower

than those of de Groot et al. [39] (US$9,630,200 km

−2

yr

−1

and US

$156,200 km

−2

yr

−1

), a difference that likely reflects both the con-

servative nature of the current model and the likelihood that any

numbers generated from a synthesis of field studies like de Groot would

be biased towards higher value sites. The authors believe the current

work to provide a more accurate estimate.

In terms of visitor numbers, the estimated global total presented

here – some 70 million tourist trip equivalents – can be most

appropriately equated to visits that would not have been made to these

places without the presence of reefs. The actual numbers of persons

visiting reefs, or receiving some indirect benefits from them, would be

far higher.

While visitor numbers and dollar values are broadly aligned, they

do not follow identical patterns (Tables 2, 3, and Appendix A). By using

both dollar and visitor numbers it is possible to explore the relative

importance of tourism in different locations. Such approaches can be

further helped by contextualising the numbers – while reef dependent

tourism makes up 60% of total tourism revenues in the Maldives and

43% of GDP, the values for Australia are only 2.4% of all tourism and

less than 0.2% of GDP (See Appendix A). Within jurisdictions the maps

identify areas where coral reef tourism is particularly valuable – such

values need to be seen and utilised, particularly where there may be

pressures on coral reefs, competing uses, risks or trade-offs associated

with other activities.

Tourism is highly aggregated in space. Visitation is likely driven by

transport and infrastructure and perhaps reinforced through the selec-

tion of sites by reputation and previous use, and these undoubtedly help

to explain the concentration of tourism benefits to only 30% of reefs,

and indeed the even narrower concentration of on-reef tourism to only

15% of reefs. Given this concentration, one perhaps more surprising

observation is that the reefs generating more than US$1 million km

−2

per year (less than 3% of all reefs) are widely distributed across 71

jurisdictions, and across all continents and oceans.

While the actual numbers and maps are important, the current work

also highlights a new and important approach to the mapping of

tourism value. The use of “big data” from multiple sources including

traditionally generated maps alongside social media and crowd-sourced

datasets, offers a remarkably rich new frontier in terms of mapping and

understanding previously unmappable natural processes and human

interactions. While publicly-generated geospatial information could be

further tested, and refined, the wise use of such data already offers a

means to generate real field “observations” by non-experts at scales

sufficient to capture real-world activities or phenomena in a manner

that is currently unthinkable with expert-observation alone.

These approaches could be modified and improved in several ways

by future studies. The current work deliberately downscaled PUD data

to a 1 km grid in order to achieve more manageable processing times.

While the model could be re-run with these same layers at finer

resolutions, it is equally important to point out that the same process

could be undertaken at smaller scales and with other input layers, such

as national and sub-national level information on visitor numbers and

spending, hotels, dive centres and dive-sites. Also, in the present work,

a number of assumptions were made using expert judgement, including

the 2 km coastal boundary, the 30 km distance for reef-related tourism,

and the 10% reef-adjacent value. The authors believe that this approach

is conservative, but other users could update and repeat this work with

improved, or indeed more spatially nuanced parameterisation.

The existence of vast areas of coral reefs with zero value for tourism

needs to be viewed in a broader context. Such reefs are clearly not

value-less. They have values, both monetary and non-monetary, for

fisheries, coastal protection, genetic diversity, and more [52,53]. Coral

reefs everywhere have myriad non-use or existence values associated

with their biodiversity, cultural, spiritual and inspirational worth

[54,55]. Indeed, such values may be highest on less heavily used reefs.

In addition, the current maps do not consider option or future use

values for reef tourism, although managers and governments may still

be interested to use these findings to help to inform them on potential

tourism values of reefs in other areas.

Fig. 4. Relative economic value of coral reefs for tourism in Raja Ampat, Indonesia, separated into reef-adjacent values (left) and on-reef values (right). The lack of local infrastructure

and hotels probably explains the low values of the former, while the methods used here of linking value directly to dive-sites and underwater photographs ensures that the values of reefs

that are distant from built tourist infrastructure are still recorded in the model for on-reef values.

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

111

It is further important to note that coral reef tourism is rarely

environmentally neutral. As mentioned in the introduction, it has been

held responsible for the deterioration of many reefs, but such impacts

are not inevitable. Well-managed tourism can be highly sustainable,

and may represent a preferred option for safeguarding biodiversity in

places where local communities need income and employment from

their reefs and want to balance multiple competing objectives [35].

Nature-dependent and nature-based tourism and recreation are of

considerable social, cultural and economic importance, far beyond the

example of coral reefs. Other ecosystems attract visitors for activities

such as birdwatching, boating, recreational fishing, whale-watching,

and more. Other studies have begun to explore some of these activities

at different scales [56–61]. Beyond these nature-based activities, there

is still a paucity of research around the value of ex-situ, ecosystem-

adjacent, benefits such as views, water quality enhancement, food

supply and so forth. Work is also limited on the value-flows away from

critical ecosystems: this work maps the source of benefits (the reefs),

however understanding the geographic flow of such value is also

critically important [62]. While many benefits may remain in local

communities, coral reefs and other ecosystems also contribute to wider

tourism and tax revenues within individual jurisdictions. Reef tourism,

in particular, is highly international, and benefits extend to remote

beneficiaries via international hotel chains, airlines, tour operators and

even the manufacturers of products from dive equipment to souvenirs.

Such flows of benefits away from the locations where the coral reefs

occur can be a source of concern to the host nations. At the same time,

raising awareness of such values to reef-remote communities, for

example in the countries of northern Europe or the USA, could increase

the imperative for supporting coral reef conservation even among

nations that do not have coral reefs.

The broad distribution of very high value reefs shown in this study

should be used to highlight the widespread and critical importance of

these ecosystems to the tourism industry, and further should be used by

the same industry to ensure their facilities and activities do not have

any negative impact on reefs. In a growing array of cases, industry

players are already making advances towards reducing impacts and

contributing to reef conservation [17,63,64], but the same players, and

others, should further use this improved understanding to demand

policy and management interventions, including protected areas and

environmental improvements such as controls over land-based sources

of pollution, to ensure continued or improved reef health.

While the approaches presented here could be improved and

adapted for use in different settings, they already represent a powerful

resource with which to support such changes. Coral reef dependent

tourism goes beyond the well-known suite of in-water activities, and the

combined values of reef tourism are significant to industry players,

local communities and governments. Armed with improved informa-

tion, it is hoped that sustainable management of coral reefs will become

a higher priority in processes ranging from the management of

individual resorts to the representation of coral reef dependent tourism

in the rapid growth of marine spatial planning.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dave Fisher of the Natural Capital

Marine team in Seattle for help in the data processing. They would like

to thank Delta-Check for providing us with the Global Accommodation

Reference Database; and Diveboard for providing their database on

dive-sites and dive-shops. The World Travel and Tourism Council

provided valuable feedback on the use of their database. Kate

Longley-Wood of The Nature Conservancy provided further valuable

support on the mapping. Funding: This work was supported by the

Cambridge Conservation Initative; the Lyda Hill Foundation; and the

Moore Foundation.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the

online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.05.014.

References

[1] L.M. Brander, P. Van Beukering, H.S.J. Cesar, The recreational value of coral reefs: a

meta-analysis, Ecol. Econ. 63 (1) (2007) 209–218.

[2] H.S. Cesar, P. Van Beukering, Economic valuation of the coral reefs of Hawai'i, Pac.

Sci. 58 (2) (2004) 231–242.

[3] K.P. Ransom, S.C. Mangi, Valuing recreational benefits of coral reefs: the Case of

Mombasa Marine National Park and Reserve, Kenya, Environ. Manag. 45 (1) (2010)

145–154.

[4] S. Sarkis, P.H. van Beukering, E. McKenzie, L. Brander, S. Hess, T. Bervoets, L.-v. der

Putten, M. Roelfsema, Total economic value of Bermuda's Coral Reefs: a summary,

in: C.R.C. Sheppard (Ed.), Coral Reefs of the United Kingdom Overseas Territories,

Springer, Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2013, pp. 201–211.

[5] G. Musa, K. Dimmock, Scuba Diving Tourism, Routledge, Abington, UK, 2013, p.

212.

[6] L.M. Brander, F.V. Eppink, P. Schägner, P.J.H. van Beukering, A. Wagtendonk, GIS-

Based Mapping of Ecosystem Services: the Case of Coral Reefs, in: R.J. Johnston,

J. Rolfe, R.S. Rosenberger, R. Brouwer (Eds.), Benefit Transfer of Environmental

and Resource Values: A Guide for Researchers and Practitioners, Springer,

Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2015, pp. 465–485.

[7] J.B. Lamb, J.D. True, S. Piromvaragorn, B.L. Willis, Scuba diving damage and

intensity of tourist activities increases coral disease prevalence, Biol. Conserv. 178

(2014) 88–96.

[8] T. Albuquerque, M. Loiola, Jd.A.C.C. Nunes, J.A. Reis-Filho, C.L.S. Sampaio,

A.O.H.C. Leduc, In situ effects of human disturbances on coral reef-fish assemblage

structure: temporary and persisting changes are reflected as a result of intensive

tourism, Mar. Freshw. Res. 66 (1) (2014) 23–32.

[9] H. Hasler, J.A. Ott, Diving down the reefs? Intensive diving tourism threatens the

reefs of the northern Red Sea, Mar. Pollut. Bull. 56 (10) (2008) 1788–1794.

[10] J. Davenport, J.L. Davenport, The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport

on coastal environments: a review, Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 67 (1–2) (2006)

280–292.

[11] P. Wongthong, N. Harvey, Integrated coastal management and sustainable tourism:

a case study of the reef-based SCUBA dive industry from Thailand, Ocean Coast.

Manag. 95 (2014) 138–146.

[12] P.-J. Liu, P.-J. Meng, L.-L. Liu, J.-T. Wang, M.-Y. Leu, Impacts of human activities on

coral reef ecosystems of southern Taiwan: a long-term study, Mar. Pollut. Bull. 64

(6) (2012) 1129–1135.

[13] V.J. Harriott, Marine tourism impacts on the Great barrier reef, Tour. Mar. Environ.

1 (1) (2004) 29–40.

[14] A. Cruz-Trinidad, R.C. Geronimo, P.M. Aliño, Development trajectories and impacts

on coral reef use in Lingayen Gulf, Philippines, Ocean Coast. Manag. 52 (3

–4)

(2009)

173–180.

[15] O. Arizpe, M. Covarrubias, Sustainable tourism planning for the only coral reef in

the Gulf of California: Cabo Pulmo national park, WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 139

(2010) 263–273.

[16] C. Cater, E. Cater, The economic impacts of marine wildlife tourism, in: J. Higham,

M. Lück (Eds.), Marine Wildlife and Tourism Management: Insights from the

Natural and Social Sciences, CAB International, Wallingford, 2007, pp. 145–162.

[17] L.M. Nordlund, U. Kloiber, E. Carter, S. Riedmiller, Chumbe Island Coral

Park—governance analysis, Mar. Policy 41 (2013) 110–117.

[18] T.F. Ong, G. Musa, SCUBA divers' underwater responsible behaviour: can environ-

mental concern and divers' attitude make a difference? Curr. Issues Tour. 15 (4)

(2012) 329–351.

[19] J.P. Hawkins, C.M. Roberts, D. Kooistra, K. Buchan, S. White, Sustainability of

scuba diving tourism on coral reefs of Saba, Coast. Manag. 33 (4) (2005) 373–387.

[20] P. Dearden, M. Bennett, R. Rollins, Perceptions of diving impacts and implications

for reef conservation, Coast. Manag. 35 (2–3) (2007) 305–317.

[21] M.C. Uyarra, I.M. Côté, J.A. Gill, R.R.T. Tinch, D. Viner, A.R. Watkinson, Island-

specific preferences of tourists for environmental features: implications of climate

change for tourism-dependent states, Environ. Conserv. 32 (1) (2005) 11–19.

[22] L. Onofri, P.A.L.D. Nunes, Beach ‘lovers' and ‘greens': a worldwide empirical

analysis of coastal tourism, Ecol. Econ. 88 (0) (2013) 49–56.

[23] N. Beharry-Borg, R. Scarpa, Valuing quality changes in Caribbean coastal waters for

heterogeneous beach visitors, Ecol. Econ. 69 (5) (2010) 1124–1139.

[24] C.T. Perry, P.S. Kench, M.J. O’Leary, K.M. Morgan, F. Januchowski-Hartley, Linking

reef ecology to island building: parrotfish identified as major producers of island-

building sediment in the Maldives, Geology 43 (6) (2015) 503–506.

[25] P.S. Kench, Developments in coral reef and reef island geomorphology,

Geomorphology 222 (0) (2014) 1–2.

[26] C.T. Perry, P.S. Kench, S.G. Smithers, B. Riegl, H. Yamano, M.J. O'Leary,

Implications of reef ecosystem change for the stability and maintenance of coral

reef islands, Glob. Change Biol. 17 (12) (2011) 3679–3696

.

[27] F. Ferrario, M.W. Beck, C.D. Storlazzi, F. Micheli, C.C. Shepard, L. Airoldi, The

effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation, Nat.

Commun. 5 (3794) (2014) 9.

[28] J.N. Kittinger, L.T. Teneva, H. Koike, K.A. Stamoulis, D.S. Kittinger, K.L.L. Oleson,

E. Conklin, M. Gomes, B. Wilcox, A.M. Friedlander, From reef to table: social and

ecological factors affecting coral reef fisheries, artisanal seafood supply chains, and

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

112

seafood security, PLoS One 10 (8) (2015) e0123856.

[29] J. Day, S. Skidmore, T. Koller, Image selection in destination positioning: a new

approach, J. Vacat. Mark. 8 (2) (2002) 177–186.

[30] A. Ghermandi, P.A.L.D. Nunes, R. Portela, R. Nalini, S.S. Teelucksingh,

Recreational, cultural and aesthetic services from estuarine and coastal ecosystems,

FEEM Working Paper, 2010.

[31] R. Russell, A.D. Guerry, P. Balvanera, R.K. Gould, X. Basurto, K.M.A. Chan, S. Klain,

J. Levine, J. Tam, Humans and nature: how knowing and experiencing nature affect

well-being, Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 38 (1) (2013) 473–502.

[32] E. Papathanasopoulou, M.P. White, C. Hattam, A. Lannin, A. Harvey, A. Spencer,

Valuing the health benefits of physical activities in the marine environment and

their importance for marine spatial planning, Mar. Policy 63 (2016) 144–152.

[33] C. Townsend, Dive tourism, sustainable tourism, and social responsibility: a

growing agenda, in: B. Garrod, S. Gössling (Eds.), New Frontiers in Marine Tourism:

Diving Experiences, Sustainability, Management, Elsevier, Oxford, UK, 2008, pp.

140–152.

[34] C.M. Cameron, J.B. Gatewood, Beyond sun, sand and Sea: the emergent tourism

programme in the Turks and Caicos Islands, J. Herit. Tour. 3 (1) (2008) 55–73.

[35] K.K. Arkema, G.M. Verutes, S.A. Wood, C. Clarke-Samuels, S. Rosado, M. Canto,

A. Rosenthald, M. Ruckelshaus, G. Guannel, J. Toft, J. Fariesa, J.M. Silvera,

R. Griffina, Anne D. Guerry, Embedding ecosystem services in coastal planning

leads to better outcomes for people and nature, PNAS 112 (24) (2015) 7390–7395.

[36] A. Diedrich, The impacts of tourism on coral reef conservation awareness and

support in coastal communities in Belize, Coral Reefs 26 (4) (2007) 985–996.

[37] R. Scheyvens, E. Hughes, S. Pratt, D. Harrison, Tourism and CSR in the Pacific, in: S.

Pratt, D. Harrison (Eds.), Tourism in Pacific Islands: Current Issues and Future

Challenges, pp. 134–147, 2015.

[38] D. de Grosbois, Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel

industry: commitment, initiatives and performance, Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 31 (3)

(2012) 896–905.

[39] R. de Groot, L. Brander, S. van der Ploeg, R. Costanza, F. Bernard, L. Braat,

M. Christie, N. Crossman, A. Ghermandi, L. Hein, S. Hussain, P. Kumar, A. McVittie,

R. Portela, L.C. Rodriguez, P. ten Brink, P. van Beukering, Global estimates of the

value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units, Ecosyst. Serv. 1 (1) (2012)

50–61.

[40] R. Costanza, R. de Groot, P. Sutton, S. van der Ploeg, S.J. Anderson, I. Kubiszewski,

S. Farber, R.K. Turner, Changes in the global value of ecosystem services, Glob.

Environ. Change 26 (0) (2014) 152–158.

[41] A. Coghlan, K.R. Fox, B. Prideaux, M. Lück, Successful interpretation in Great

Barrier Reef tourism: dive in or keep out of it? Tour. Mar. Environ. 7 (3–4) (2011)

167–178.

[42] WTTC, Travel & Tourism. Economic Impact 2014: World, World Travel and Tourism

Council, London, 2014.

[43] UNWTO, Compendium of Tourism Statistics, 2013, World Tourism Organization

(UNTWO), Madrid, 2013.

[44] S.A. Wood, A.D. Guerry, J.M. Silver, M. Lacayo, Using social media to quantify

nature-based tourism and recreation, Sci. Rep. 3 (2013) 2976.

[45] B.L. Keeler, S.A. Wood, S. Polasky, C. Kling, C.T. Filstrup, J.A. Downing,

Recreational demand for clean water: evidence from geotagged photographs by

visitors to lakes, Front. Ecol. Environ. 13 (2) (2015) 76–81.

[46] C. Sessions, S.A. Wood, S. Rabotyagov, D.M. Fisher, Measuring recreational

visitation at U.S. national parks with crowd-sourced photographs, J. Environ.

Manag. 183 (3) (2016) 703–711.

[47] DeLorme Publishing Company, UrbanAreas. A Subset of DeLorme World Base Map

(DWBM), DeLorme Publishing Company, Inc., Yarmouth, Maine, USA, 2010.

[48] L. Burke, K. Reytar, M. Spalding, A.L. Perry, Reefs at Risk Revisited, World

Resources Institute, The Nature Conservancy, WorldFish Center, International Coral

Reef Action Network, UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre and Global

Coral Reef Monitoring Network, Washington, D.C, 2011.

[49] Oxford Economics, Valuing the effects of Great Barrier Reef bleaching, Great Barrier

Reef Foundation, Newstead, Australia, 2009.

[50] GBRMPA, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2014, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

Authority, Townsville, Australia, 2014.

[51] C.B. Smallwood, L.E. Beckley, S.A. Moore, H.T. Kobryn, Assessing patterns of

recreational use in large marine parks: a case study from Ningaloo Marine Park,

Australia, Ocean Coast. Manag. 54 (4) (2011) 330–340.

[52] H. Cesar, L. Burke, L. Pet-Soede, The Economics of Worldwide Coral Reef

Degradation, Cesar Environmental Economics Consulting (CEEC), Arnhem, The

Netherlands, 2003.

[53] L. Brander, Pv Beukering, The Total Economic Value of U.S. Coral Reefs: a Review

of the Literature, NOAA, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA, 2013, p. 32.

[54] R.F. Subade, H.A. Francisco, Do non-users value coral reefs?: economic valuation of

conserving Tubbataha Reefs, Philippines, Ecol. Econ. 102 (2014) 24–32.

[55] J.-B. Marre, L. Brander, O. Thebaud, J. Boncoeur, S. Pascoe, L. Coglan, N. Pascal,

Non-market use and non-use values for preserving ecosystem services over time: a

choice experiment application to coral reef ecosystems in new Caledonia, Ocean

Coast. Manag. 105 (2015) 1–14.

[56] R.C. Anderson, M.S. Adam, A.-M. Kitchen-Wheeler, G. Stevens, Extent and

Economic Value of Manta ray watching in Maldives, Tour. Mar. Environ. 7 (1)

(2011) 15–27.

[57] A.M. Cisneros-Montemayor, M. Barnes-Mauthe, D. Al-Abdulrazzak, E. Navarro-

Holm, U.R. Sumaila, Global economic value of shark ecotourism: implications for

conservation, Oryx 47 (03) (2013) 381–388.

[58] A.M. Cisneros-Montemayor, U.R. Sumaila, A global estimate of benefits from

ecosystem-based marine recreation: potential impacts and implications for man-

agement, J. Bioecon. 12 (3) (2010) 245–268.

[59] J. Herfaut, H. Levrel, O. Thébaud, G. Véron, The nationwide assessment of marine

recreational fishing: a French example, Ocean Coast. Manag. 78 (2013) 121–131.

[60] J.E.S. Higham, L. Bejder, S.J. Allen, P.J. Corkeron, D. Lusseau, Managing whale-

watching as a non-lethal consumptive activity, J. Sustain. Tour. 24 (1) (2016)

73–90.

[61] P. Prayaga, J. Rolfe, N. Stoeckl, The value of recreational

fishing

in the Great barrier

reef, Australia: a pooled revealed preference and contingent behaviour model, Mar.

Policy 34 (2) (2010) 244–251.

[62] E.G. Drakou, L. Pendleton, M. Effron, J.C. Ingram, L. Teneva, When ecosystems and

their services are not co-located: oceans and coasts, ICES J. Mar. Sci. (2017).

[63] J. de Groot, S.R. Bush, The potential for dive tourism led entrepreneurial marine

protected areas in Curacao, Mar. Policy 34 (5) (2010) 1051–1059.

[64] M.J.M. Bottema, S.R. Bush, The durability of private sector-led marine conserva-

tion: a case study of two entrepreneurial marine protected areas in Indonesia, Ocean

Coast. Manag. 61 (2012) 38–48.

M. Spalding et al.

Marine Policy 82 (2017) 104–113

113