Action Plan

Diabetes

June 2020

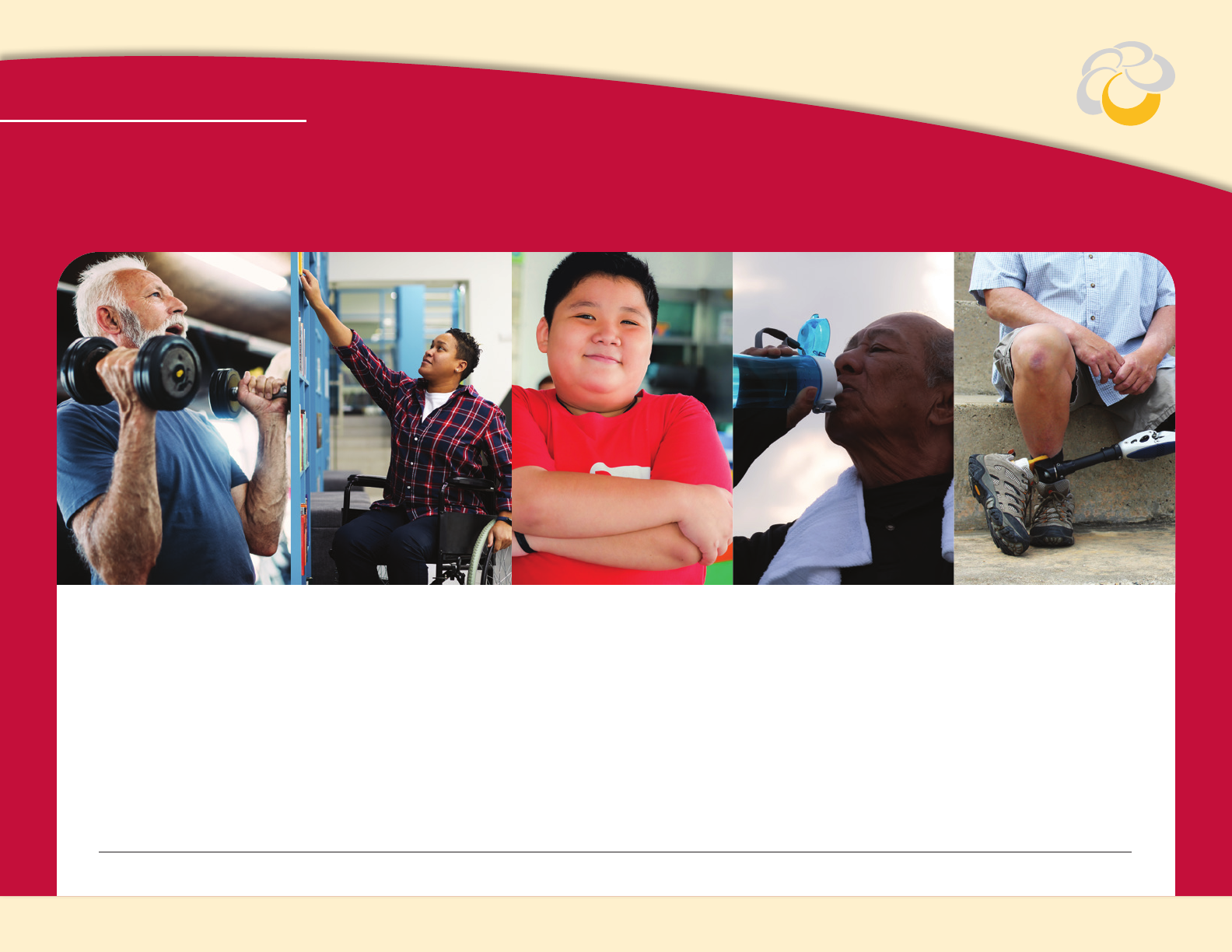

Dear Maryland Partners,

In some way, diabetes affects every Marylander. You may have

diabetes or know someone who does. You may have lost a loved one

to complications from the disease. You may be a parent seeking to

adopt healthy food and activity habits. You may be a health care or

program provider in the community treating or helping people with

diabetes. You may be an employer concerned about how diabetes

affects productivity and health insurance costs. Or you may be a

taxpayer considering how to reduce the diabetes burden to our

State’s vitality and economy. Regardless of where you live in our State,

diabetes takes a toll, but it is a disease we can prevent or mitigate.

Diabetes is the sixth leading cause of death in Maryland. According

to the federal government, the number of US adults diagnosed with

diabetes has more than doubled in the past 20 years. And in Maryland,

over a third of all adults have prediabetes, the condition that often

leads to diabetes.

There are many reasons for all Marylanders to get involved against this

preventable disease. To that end, the Maryland Department of Health

and others have created the State’s inaugural 2019-2024 Diabetes Action

Plan. The Plan provides information on the disease burden in Maryland,

and best practices for the State and its partners to implement to

prevent and manage diabetes. It will serve as the State’s guide by

which we will set specific goals and measure our successes. These

actions address all Marylanders:

• People who are at a healthy weight, to prevent the onset of

overweight and obesity;

• People who are overweight and obese, to achieve a healthy weight;

• People with prediabetes and gestational diabetes, to participate in

prevention programs to halt disease progression; and

• People with diabetes, to get the care they need to control their disease

and enjoy optimum health.

Informed by extensive input and comment from many partners,

the strategies in this Plan are far-reaching. We are grateful for the

enthusiastic support which was offered by so many as we developed

this Plan. Success in defeating diabetes requires broad and strong

collaboration between communities, organizations, businesses, local

governments and individuals across the State. We encourage you to

use the Plan to identify steps you can take to prevent and manage

diabetes. And, most importantly, let us know how you think your

group or community can get involved.

This is our shared call to action: to take steps today to build a Healthy

Maryland for ourselves and for future generations. We look forward to

working with you to improve the health of all Marylanders.

Yours in good health,

Frances B. Phillips, RN, MHA

Deputy Secretary for Public

Health Services

Robert R. Neall

Secretary

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 20201

In Maryland, over 10 percent of the adult

population has diabetes. An additional 34

percent of adults are estimated to have

prediabetes, a condition of high blood sugar

not quite high enough to be diabetes.

Diabetes is the sixth leading cause of death

in Maryland, and the fifth leading cause of

death for Black Marylanders in 2018. Diabetes

is also a major risk factor for developing

cardiovascular disease, the number one cause

of death for Marylanders. It is imperative to

launch a coordinated and meaningful initiative

to address the prevention and management

of diabetes in Maryland. The leading cause of

diabetes is overweight and obesity, the rate of

which has steadily increased to over 64 percent

of Maryland adults. Sedentary lifestyle is also a

risk; only 50 percent of Marylanders said they

participated in 150 minutes or more of physical

activity per week in 2017. Additionally, there are

disparities in how diabetes and its risk factors

affect Marylanders with racial/ethnic minorities,

those with less education, lower income, and

various disabilities disproportionately affected.

Diabetes and its complications cost the State

over $4.92 billion per year, and an additional

$2 billion in lost productivity.

The Maryland Diabetes Action Plan (the Plan)

includes details on the current burden of

diabetes and the factors impacting diabetes

risk. The Plan presents action steps that

organizations and partners can implement

to prevent and manage diabetes in Maryland.

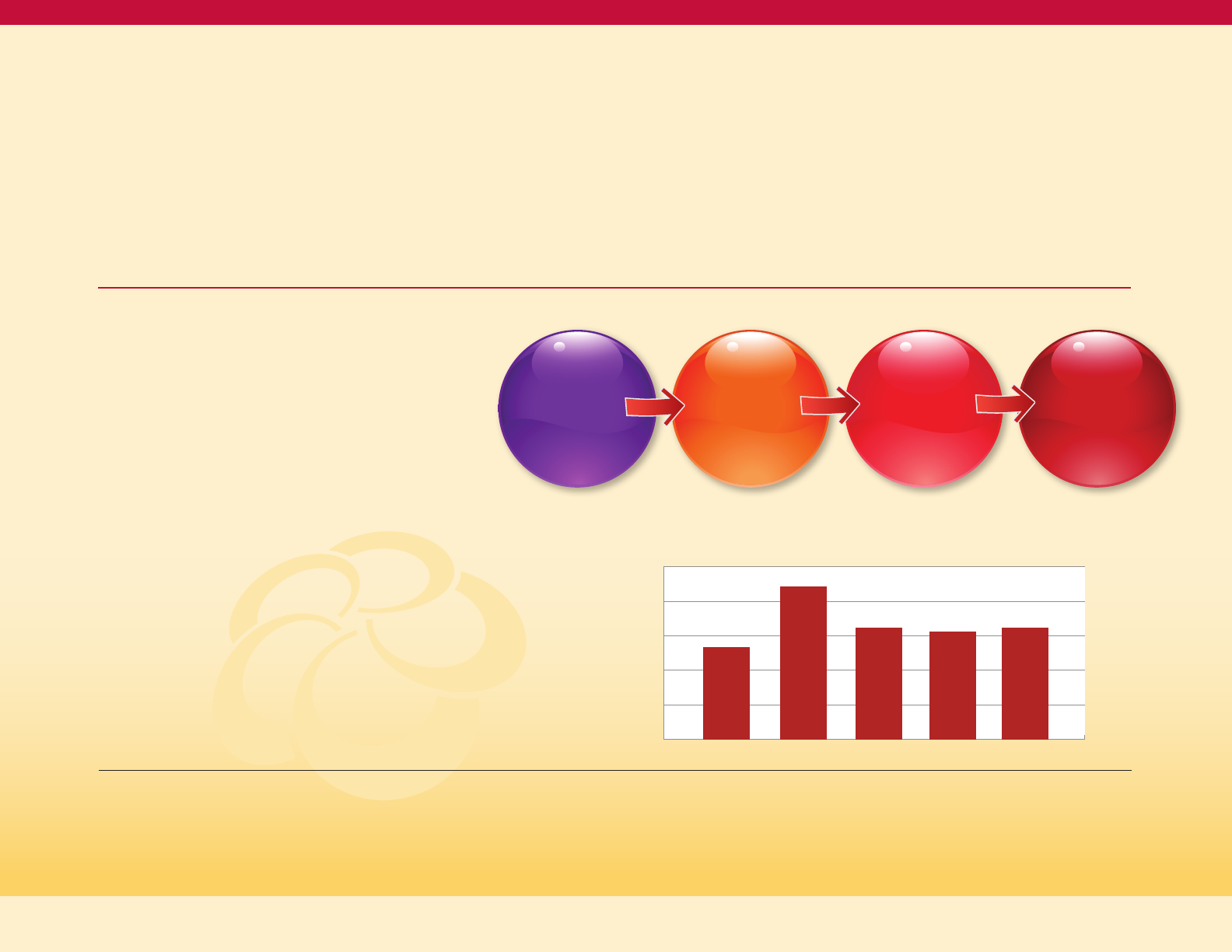

These actions steps are categorized using a

systems change model approach, working

upstream to people at a healthy weight, then

progressing as the risk increases with people

who are overweight and obese, followed by

those with prediabetes or history of gestational

diabetes, and finally includes steps to improve

outcomes in those identified with diabetes

and diabetes complications.

Our vision is that an array of all Maryland

partners, across multiple sectors, will identify

opportunities, act in their areas of influence

in ways that align efforts, resources, and

Executive Summary

Action Plan

Diabetes

funds to reduce the burden of diabetes.

The Plan includes action tables that contain

strategies and action steps targeted to

support people across the continuum

of diabetes:

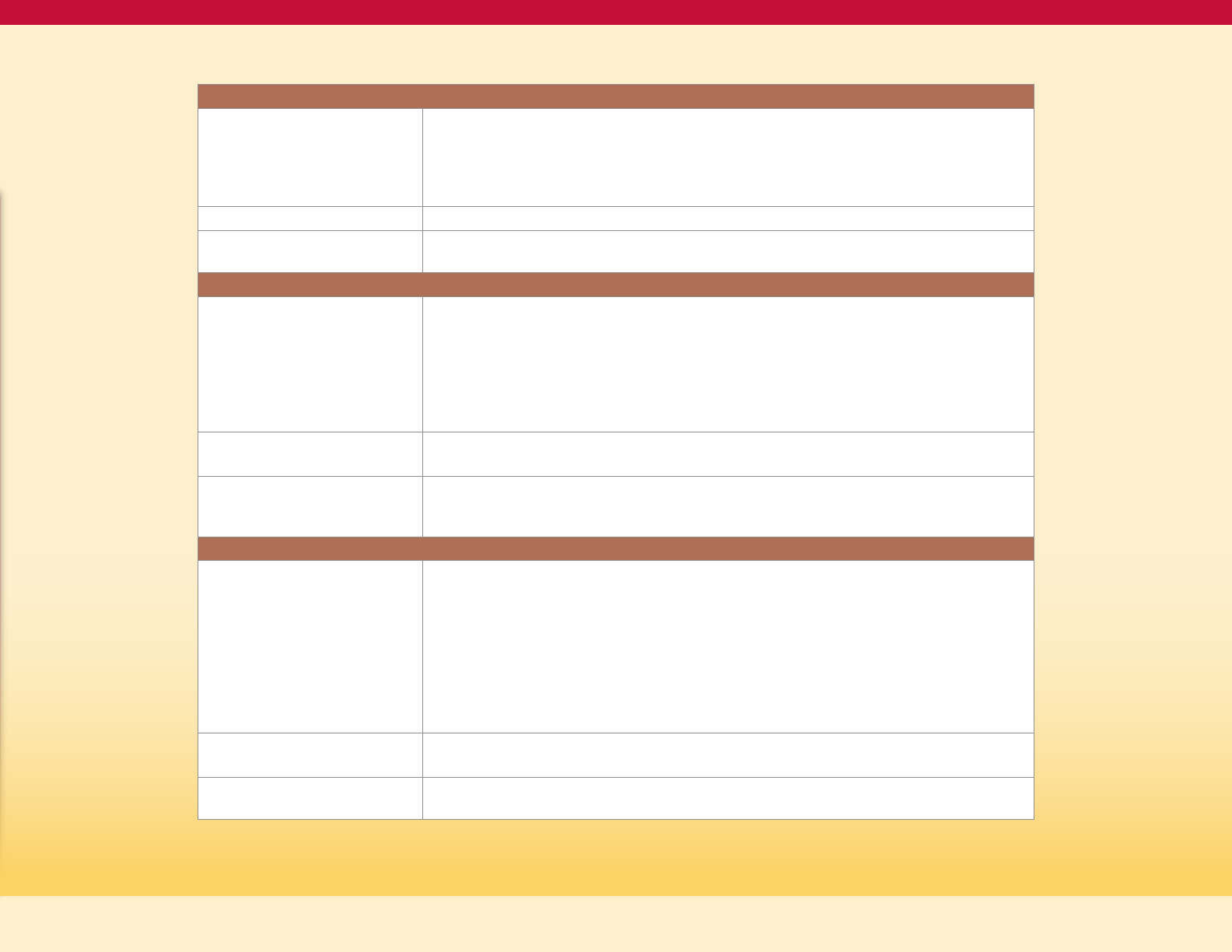

1. Keeping people at a healthy weight goal:

By 2024, 32 percent of Maryland adults will

be of healthy weight. The two objectives are

to increase access to healthy nutrition and

achieve and maintain recommended

physical activity levels for all Marylanders.

2. People who are overweight and obese goal:

By 2024, maintain the percentage of adults

with a BMI >25 at 66.5 percent; and reduce

by 10 percent the BMI >85th percentile in

high school students. The two objectives

are to improve clinical care services for

overweight and obese children and adults

and improve the availability of health lifestyle

options for overweight and obese children

and adults.

3. People with prediabetes and gestational

diabetes goal: By 2024, increase the

prevalence of Maryland adults who know

their prediabetes status by 30 percent.

The two objectives are to improve

prediabetes outcomes and reduce risk

of diabetes in women with a history of

gestational diabetes.

4. People with diabetes goal: By 2024, reduce

the age-adjusted diabetes mortality by 5

percent. The first objective is to improve the

use of standardized quality of care for people

with diabetes at all levels of the health care

system by increasing the number of

health systems statewide that utilize the

chronic care model (CCM) framework, as

recommended by the American Diabetes

Association’s 2019 Standards of Medical Care

in Diabetes. The second objective is to

reduce the number of hospitalizations and

emergency department visits each by

5 percent for people with diabetes in the

state of Maryland.

In preparation of this Diabetes ActionPlan, a

process was completed to inventory obesity,

prediabetes, and diabetes programs in

Maryland. The aim of the inventory is to assess

the availability of programs across Maryland

that address diabetes prevention, care, and

management. While the required level of

service provision across the state cannot be

determined through the inventory alone, the

Maryland Department of Health aims to use

this process to begin to identify resource gaps

and opportunities to expand efforts to address

diabetes moving forward. The scope of the

inventory is all programs serving Marylanders,

including those that serve Medicaid enrollees,

Medicare enrollees, commercial and small

business health insurance enrollees, and

the uninsured population.

MDH published an online draft of the plan and

encouraged the public and partners to provide

feedback. Over 30 responses were submitted

by institutions and individuals. MDH worked to

integrate the feedback into this final version.

As Maryland seeks to prevent and better

manage diabetes, all partners are encouraged

to implement action steps, while also sharing

innovative and best practices for expansion

across the state that aligns with the Diabetes

Action Plan and improves the health of

all Marylanders.

2Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

3

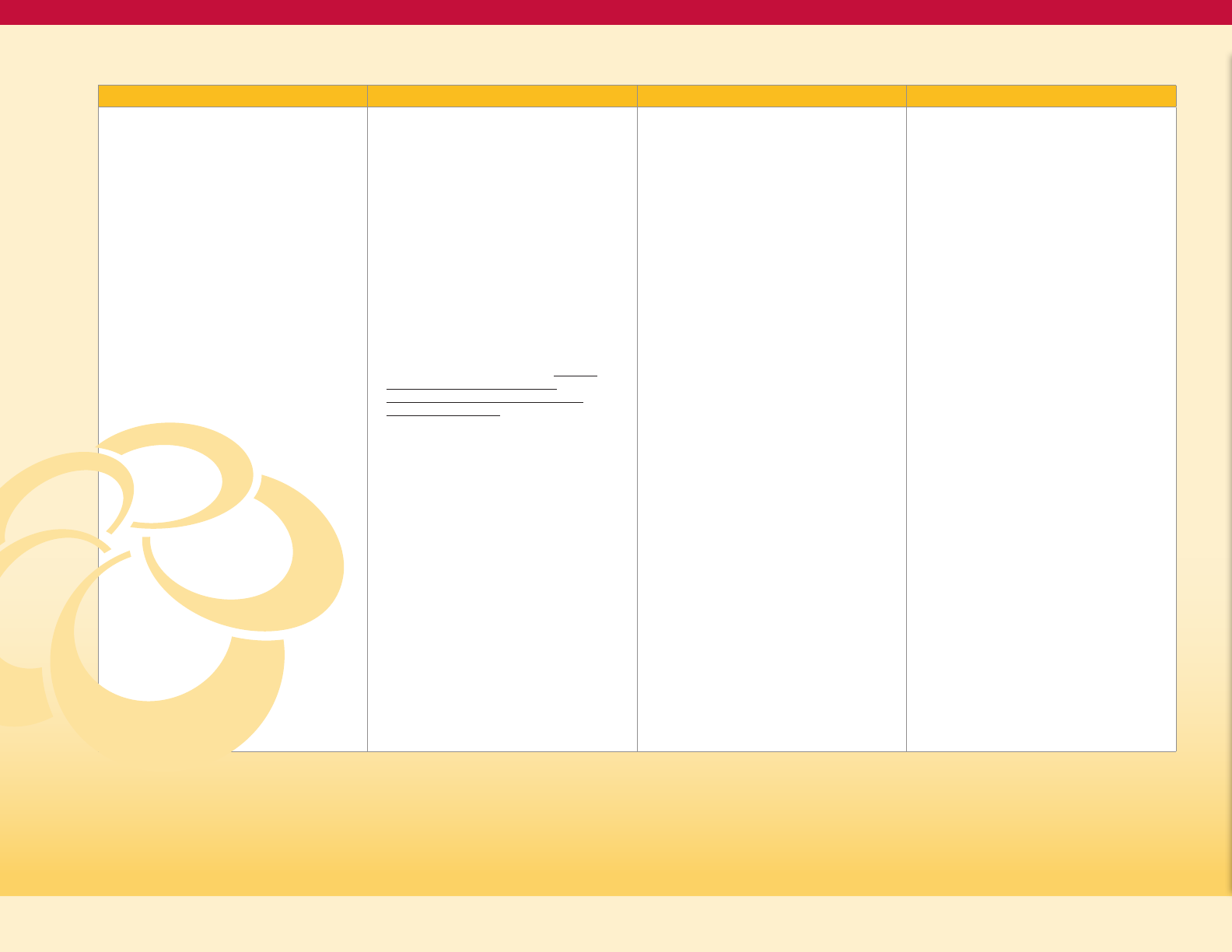

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................................................................1

I. The Burden and Consequences of Diabetes in Maryland ...................................................................................... 6

What is Diabetes? ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6

How Common is Diabetes in Maryland? .................................................................................................................................................7

Adults with Diagnosed Diabetes and Its Precursor Conditions in Maryland ............................................................7

Geographic Distribution of Diabetes in Maryland ...................................................................................................................... 8

How Serious are the Consequences of Diabetes for Maryland? ............................................................................................ 9

Diabetes as a Cause of Death .................................................................................................................................................................... 9

Complications of Diabetes ........................................................................................................................................................................ 10

Utilization Rates and Costs for Diabetes ............................................................................................................................................11

Diabetes-related hospital discharges in Maryland ..............................................................................................................11

Diabetes-related Prevention Quality Indicators (PQIs).....................................................................................................11

Diabetes Inpatient Hospital Charges ...........................................................................................................................................12

Diabetes Emergency Department Visits ..................................................................................................................................12

Utilization Differences for Medicaid Enrollees with Diabetes vs. Without Diabetes...................................13

Cost Burden of Diabetes in Maryland .........................................................................................................................................13

Medicaid Costs of Diabetes in Maryland .................................................................................................................................. 14

II. Determinants and Risk Factors for Diabetes: Opportunities for Intervention ...........................................15

Diabetes by Age and Sex ..................................................................................................................................................................................15

Diabetes and Weight ..........................................................................................................................................................................................17

Adult Prevalence of Excess Weight in Maryland .........................................................................................................................18

Overweight/Obesity in Women of Childbearing Age .............................................................................................................. 19

Excess Weight among Children .............................................................................................................................................................21

Diabetes and Physical Activity ..................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Diabetes and Tobacco .......................................................................................................................................................................................24

Diabetes and Oral Health ................................................................................................................................................................................ 25

Diabetes and Income .........................................................................................................................................................................................26

Diabetes and Level of Education ...............................................................................................................................................................27

Diabetes and Health Literacy .......................................................................................................................................................................28

Diabetes and Disability .....................................................................................................................................................................................29

Diabetes and Mental Health .........................................................................................................................................................................30

Gestational Diabetes ...........................................................................................................................................................................................31

Prediabetes ................................................................................................................................................................................................................31

Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Risk ......................................................................................................................... 32

Diabetes and Health Equity ...........................................................................................................................................................................33

Table of Contents

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

4

Figure 1: Diabetes Risk Continuum ..............................................................................................................................................................7

Figure 2: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Race/Ethnicity (R/E), ..................................

Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS) ............................................................................................................................................................................7

Figure 3: Map of Age-Adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Jurisdictions, ............................... 8

Figure 4: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Jurisdiction, ................................................... 8

Figure 5: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Race and

Jurisdiction, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS) ............................................................................................................................................. 9

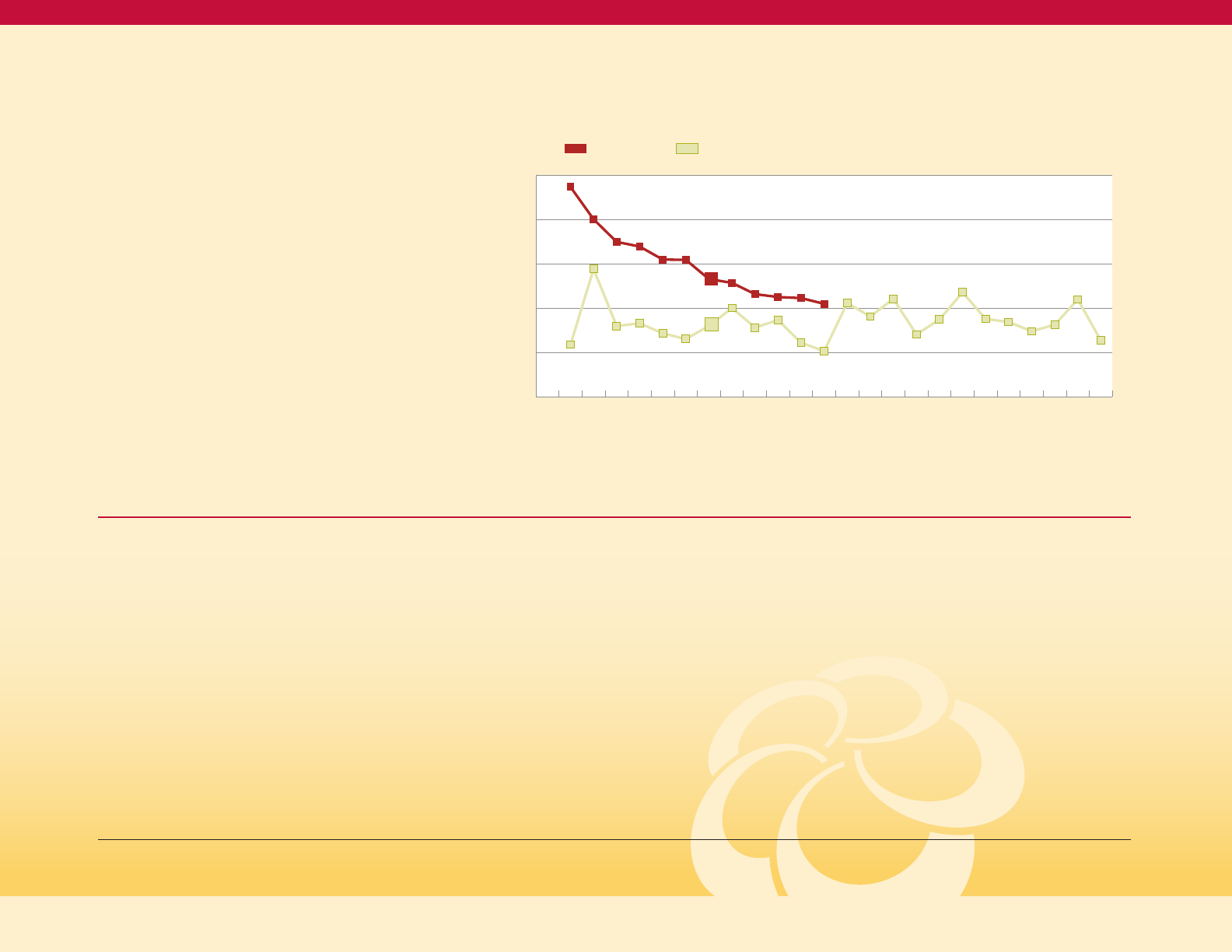

Figure 6: Age-Adjusted Death Rate for Diabetes, by Race/Ethnicity, Maryland 2009-2018 ............................... 10

Figure 7: Age-adjusted Death Rate for Diabetes, Maryland and the United States,

2009-2018 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 10

Figure 8: Diabetes Composite (PQI 93) per 100,000 Population Aged 18+ in Maryland .......................................12

Figure 9: Adult Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Diabetes, by Age and Sex, Maryland

2015-17 (BRFSS) ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 15

Figure 10: Age-adjusted Adult Incidence Rate of Diagnosed Diabetes, by Sex, U.S.,

1980 to 2017 (National Health Interview Survey)........................................................................................................................16

Figure 11: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Diabetes, by

Race/Ethnicity and Weight Status, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS) ........................................................................................17

Figure 12: Age-adjusted Adult Obesity Prevalence by Jurisdiction, Maryland

2015-17 (BRFSS) .................................................................................................................................................................................................18

Figure 13: Weight Category Distribution of Women of Childbearing Age, by Race .................................................19

III. Intervention Strategies and Actions Steps for Diabetes Prevention and Control................................. 34

Rationale Behind Four Risk Populations for Diabetes ................................................................................................................34

Interventions for the Healthy Weight Population .......................................................................................................................... 36

Interventions for the Overweight and Obese Populations ...................................................................................................... 37

Interventions for the Gestational Diabetes and Prediabetes Populations ...................................................................38

Interventions for Managing Diabetes and Diabetes Complications ................................................................................40

Managing and Controlling Diabetes ........................................................................................................................................................41

IV. Action Tables for Diabetes Prevention and Control ............................................................................................ 43

V. Inventory of Diabetes-related Resources/Appendices ....................................................................................... 54

Development of a Diabetes Program Inventory .............................................................................................................................54

Diabetes Prevention and Care .....................................................................................................................................................................55

HealthChoice Diabetes Prevention Program (HealthChoice DPP) .............................................................................55

Investing in Prevention Programs.............................................................................................................................................................55

Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................56

Contributors ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................57

Table of Figures

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

5

Figure 14: Crude Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Physical Activity

Status and Race, Maryland 2011-13 (BRFSS) .................................................................................................................................22

Figure 15: Age-adjusted Prevalence of 150 Minutes per Week of Physical Activity .................................................23

Figure 16: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes by Smoking Status ......................................24

Figure 17: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Current Smoking, by Diabetes

Status, Maryland 2017 (BRFSS) .............................................................................................................................................................24

Figure 18: Age-adjusted Prevalence of Doctor Diagnosed Diabetes, By Income and

BMI Status (Maryland BRFFS 2015-2017) ........................................................................................................................................26

Figure 19: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Doctor Diagnosed Diabetes, by Income

and Race, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS) ................................................................................................................................................26

Figure 20: Distribution of Household Income by Black or White Race ........................................................................... 27

Figure 21: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes, by Education

and Black or White Race, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS) ............................................................................................................27

Figure 22: Distribution of Education Level, for NH Black and NH White Adults,

Maryland 2011-13 (BRFSS) ..........................................................................................................................................................................28

Figure 23: Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Doctor Diagnosed Diabetes, By Presence

or Absence of Selected Disabilities (Maryland BRFSS 2015-2017) ................................................................................. 29

Figure 24: Age-Adjusted Percent of Adults Ever Diagnosed with Depression,

by Diagnosed Diabetes Status, Maryland 2017 (BRFSS) .....................................................................................................30

Figure 25: Social Determinants of Health .............................................................................................................................................32

Figure 26: Diabetes Systems Thinking Model ...................................................................................................................................35

Figure 27: Three Buckets of Prevention .................................................................................................................................................35

Table 1: Diabetes-related Hospital Discharge Count and Rate per 1,000

Adult Marylanders ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

Table 2: PQI 93 Discharge Frequency and Rate per 1,000 Adult Marylanders .............................................................. 11

Table 3: Diabetes-related ED Visit Count and Rate per 1,000 Population ....................................................................... 12

Table 4: Admission, ED Visit, and Ambulatory Visit Prevalence and Rates; and Average

Payments Comparing Medicaid Enrollees with and without Diabetes, Maryland, 2017...............................13

Table 5: Trend in Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Weight Classification (BMI groups),

Maryland 2013-2017 ........................................................................................................................................................................................18

Table 6: Pre-pregnancy BMI of Active Pregnant Women as of October 7, 2019 ........................................................20

Table 7: Prevalence of Weight Classes Among Children Participating in WIC

in Maryland (by Jurisdiction, July-December 2018; 40,935 Total Children) ............................................................ 22

Table of Tables

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

Action Plan

Diabetes

6

Section I:

The Burden and Consequences of Diabetes in Maryland

Diabetes is a chronic disease that affects the

way the body handles glucose, which is the

sugar in the blood used by the body for

energy. An inability of cells to properly absorb

glucose, due to inadequate insulin production

or a resistance of cells to the action of insulin,

or both, results in high blood glucose levels,

which is called diabetes. There are several types

of diabetes, the most common of which is type

2 diabetes. The other major types are type 1

diabetes, which usually has onset during

childhood and adolescence, and gestational

diabetes, which occurs during pregnancy.

1

Type 1 diabetes results from an autoimmune

attack against the cells in the pancreas that

produce insulin. This leads to an almost

complete lack of insulin, early severe

symptoms, and a dependence on insulin

treatment to sustain life. About 4 percent

of diabetes in the United States is type 1

diabetes.

2

The risk factors and interventions

discussed in this plan may not all apply to

type 1 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes results in most cases from a

resistance to the action of insulin on cells.

This insulin resistance is related to overweight

and obesity, particularly fat located in the

abdomen. The degree to which the insulin

resistance manifests as high blood sugar

depends on how well, and for how long,

the pancreas can overproduce insulin to

compensate for the insulin resistance in the

cells. A decline in the insulin production

capacity with older age is one reason that type

2 diabetes often emerges at older ages. Type 2

diabetes can exist without symptoms for

years, which is why approximately 24 percent

of persons with diabetes don’t know that they

have it.

3

About 95 percent of diabetes in the

United States is type 2 diabetes. The risk factors

and most interventions discussed in this plan

are designed for type 2 diabetes.

Most public health surveillance data do

not distinguish between type 1 and type 2

diabetes but refer to the two combined.

However, since type 2 diabetes is 95 percent

of the total, patterns seen in the surveillance

data are the patterns of type 2 diabetes.

4

Public health data also often only measure

persons who know that they have diabetes,

which means that true diabetes prevalence

may be approximately one quarter higher

than the estimates of diagnosed

diabetes prevalence.

What is Diabetes?

Diabetes Care. January 01 2019; volume 42 issue Supplement 1.

2

ADA website https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/statistics-about-diabetes

3

Id fn 2

4

Id fn 2

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

7

Prediabetes is a condition where blood

sugar levels are higher than normal, but not

high enough to be considered diabetes.

Prediabetes is a precursor condition on the

pathway from normal glucose levels to type 2

diabetes; the development of type 1 diabetes is

usually so rapid that there is no “prediabetes”

state that precedes type 1 diabetes. A fasting

glucose level of 100 to 125 mg/dL, a hemoglobin

A1C level of 5.7 percent to 6.4 percent, or a

two-hour glucose level in an oral glucose

tolerance test of 140 to 199 mg/dL

defines prediabetes.

5

Prediabetes often goes unrecognized by both

individuals and their health care providers;

nine of 10 adults who have prediabetes do

not know they have it.

6

CDC estimates that

34 percent of U.S. adults have prediabetes.

7

Diabetes and prediabetes are serious

conditions that can lead to complications

including heart disease and stroke,

blindness, amputations, nerve damage,

and kidney disease.

A disease is important to public health

if it is both common and has serious

consequences. Diabetes is both common

and serious in Maryland.

https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/getting-tested.html

6

https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html

7

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017.

8

Maryland Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2017.

9

United States Census, 2017.

10

Diabetes Care. January 01 2019; volume 42 issue Supplement 1.

11

Based on Maryland Adult Population, sources: US 2017 Census; 2017 Maryland BRFSS; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017.

12

Based on Maryland Adult Population, sources: US 2017 Census; 2017 Maryland BRFSS; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. Categories are not equal, percentages in this figure do not equal 100.

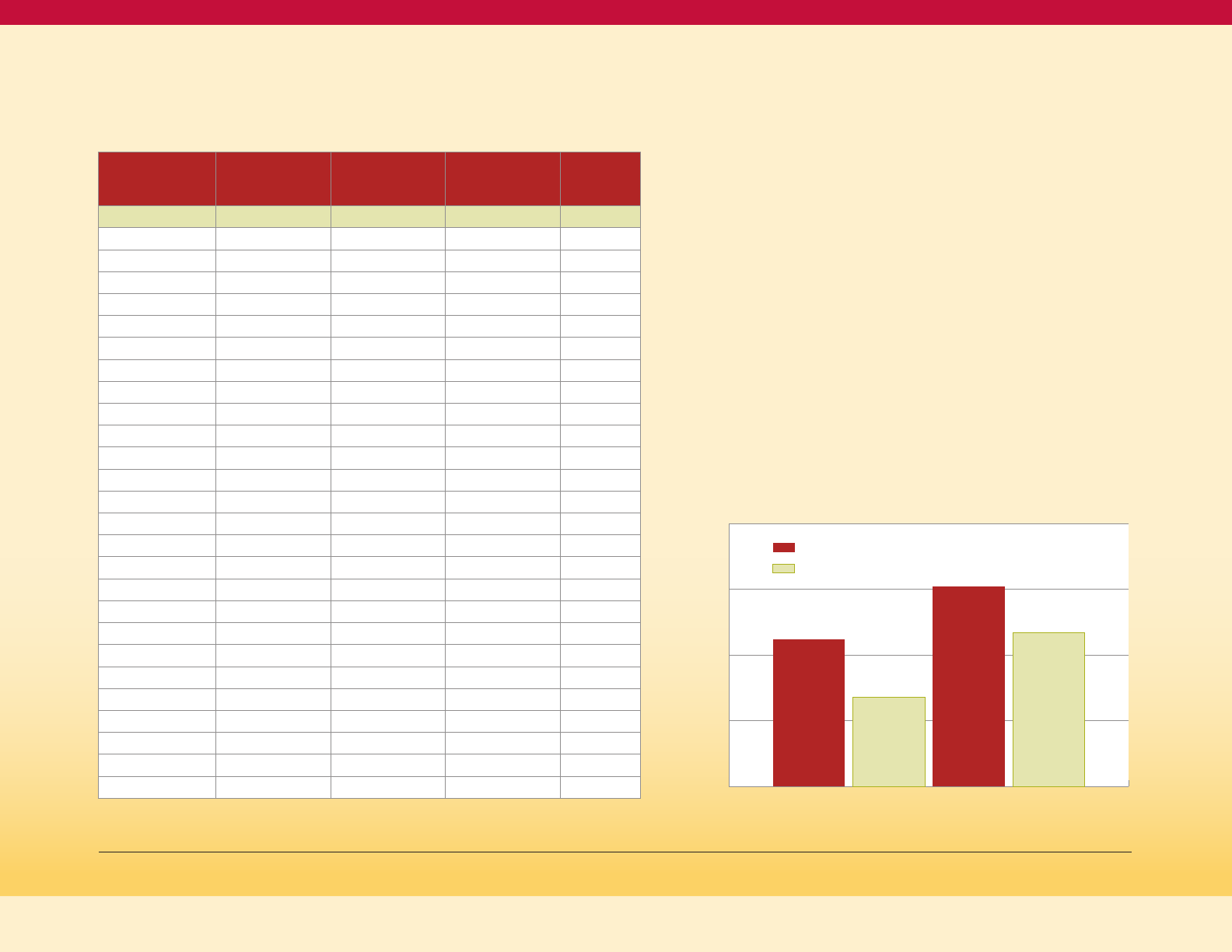

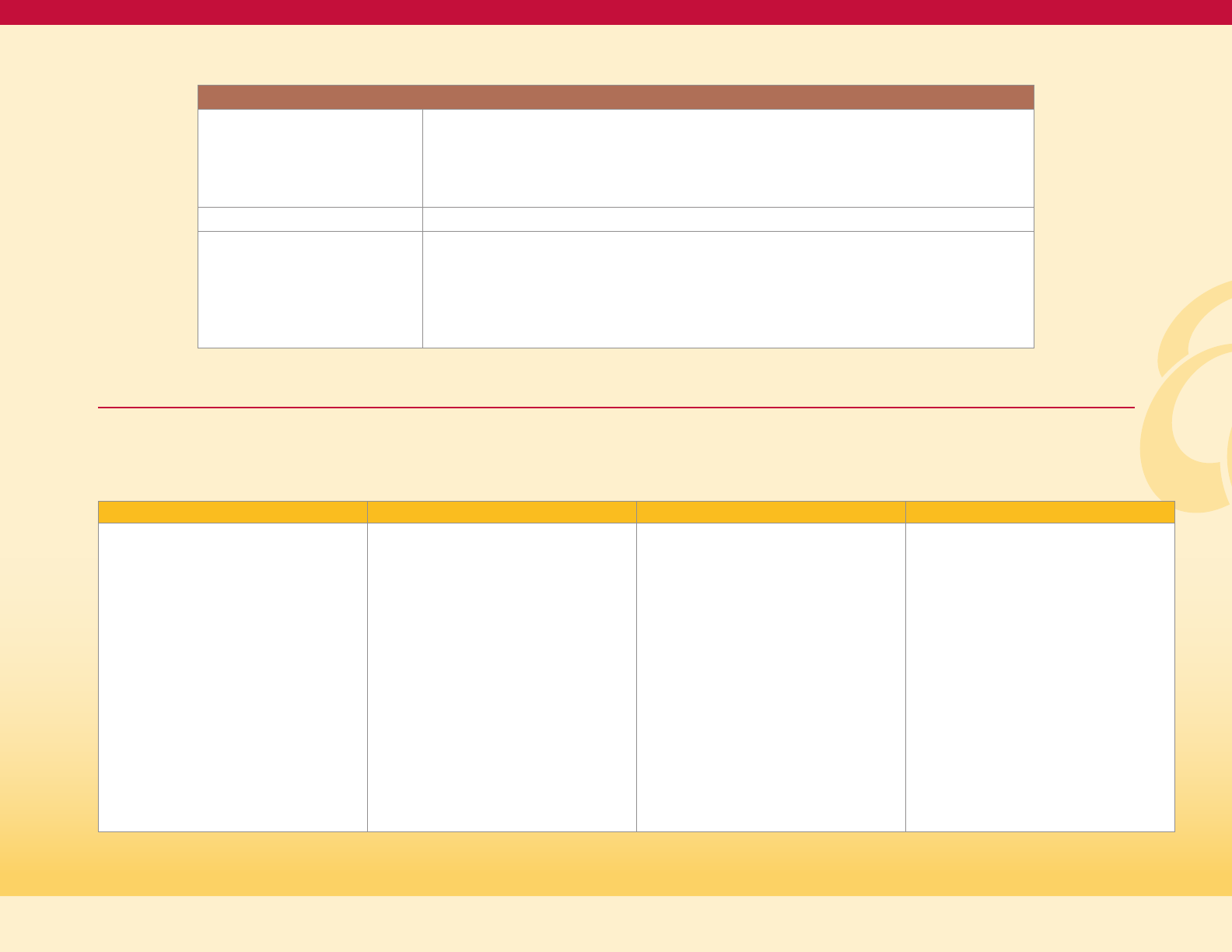

Adults with Diagnosed Diabetes and Its

Precursor Conditions in Maryland

An estimated 10.5 percent of the adult

population in Maryland, or 488,942 adults,

have diabetes.

8,9

In Maryland an estimated

1.6 million adults or 34 percent of the adult

population have prediabetes (see Figure

1 on this page).

10,11

The adult prevalence of diagnosed diabetes is

highest in Non-Hispanic (NH) Blacks, followed

by Non-Hispanic Asians and Hispanics, and

lowest in Non-Hispanic Whites, as shown in

Figure 2 on this page.

How Common is Diabetes in Maryland?

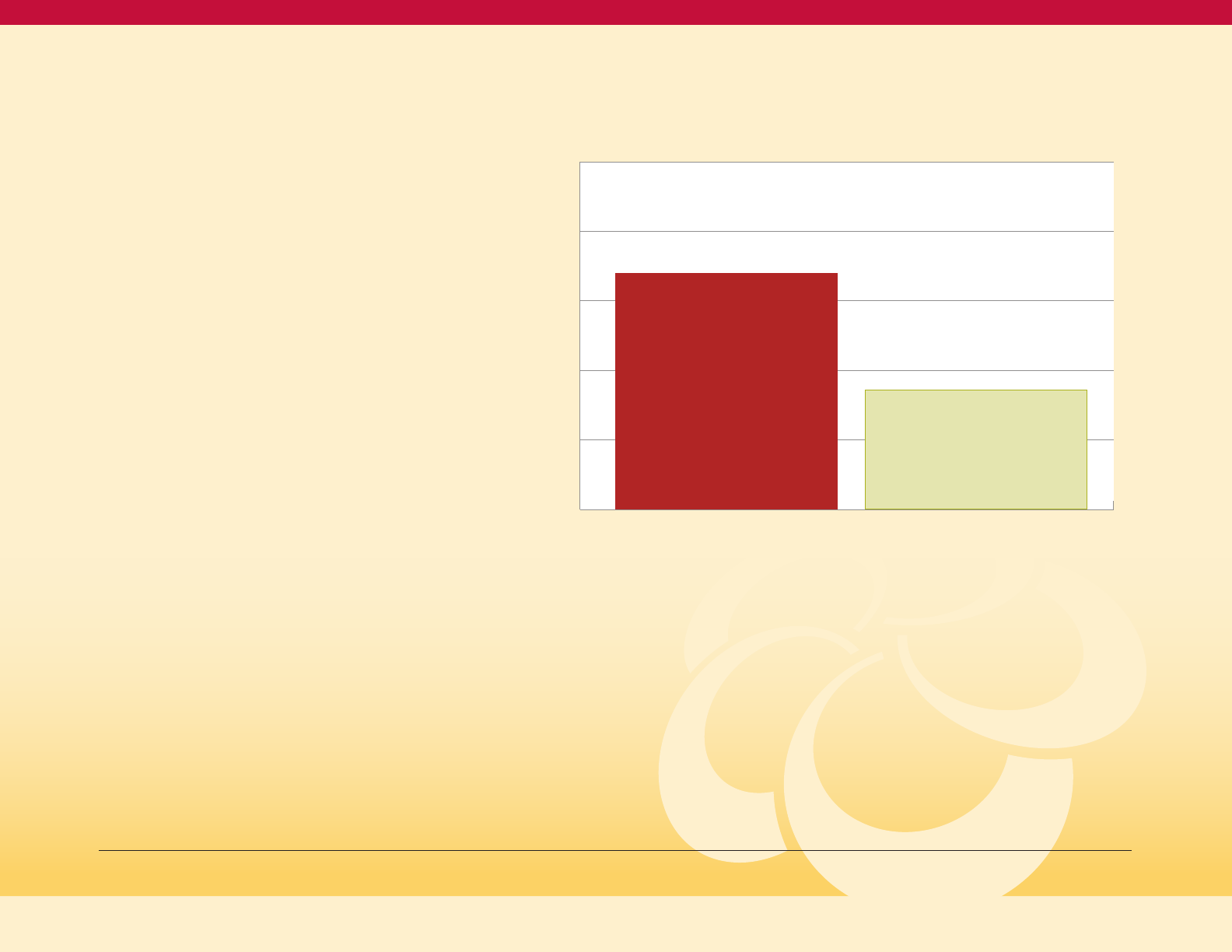

Diabetes Risk Continuum

12

Figure 1

Healthy

Population

1,351,479

(32%)

Overweight

and Obese

2,799,259

(66.2%)

Prediabetes

1,575,829

(33.9%)

Diagnosed

Diabetes and

Diabetes with

Complications

488,942

(10.5%)

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes

by Race/Ethnicity (R/E), Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Figure 2

15%

12%

9%

6%

3%

0%

8.0%

NH White

13.3%

NH Black

9.7%

NH Asian

9.4%

Hispanic

9.7%

All R/E

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

8

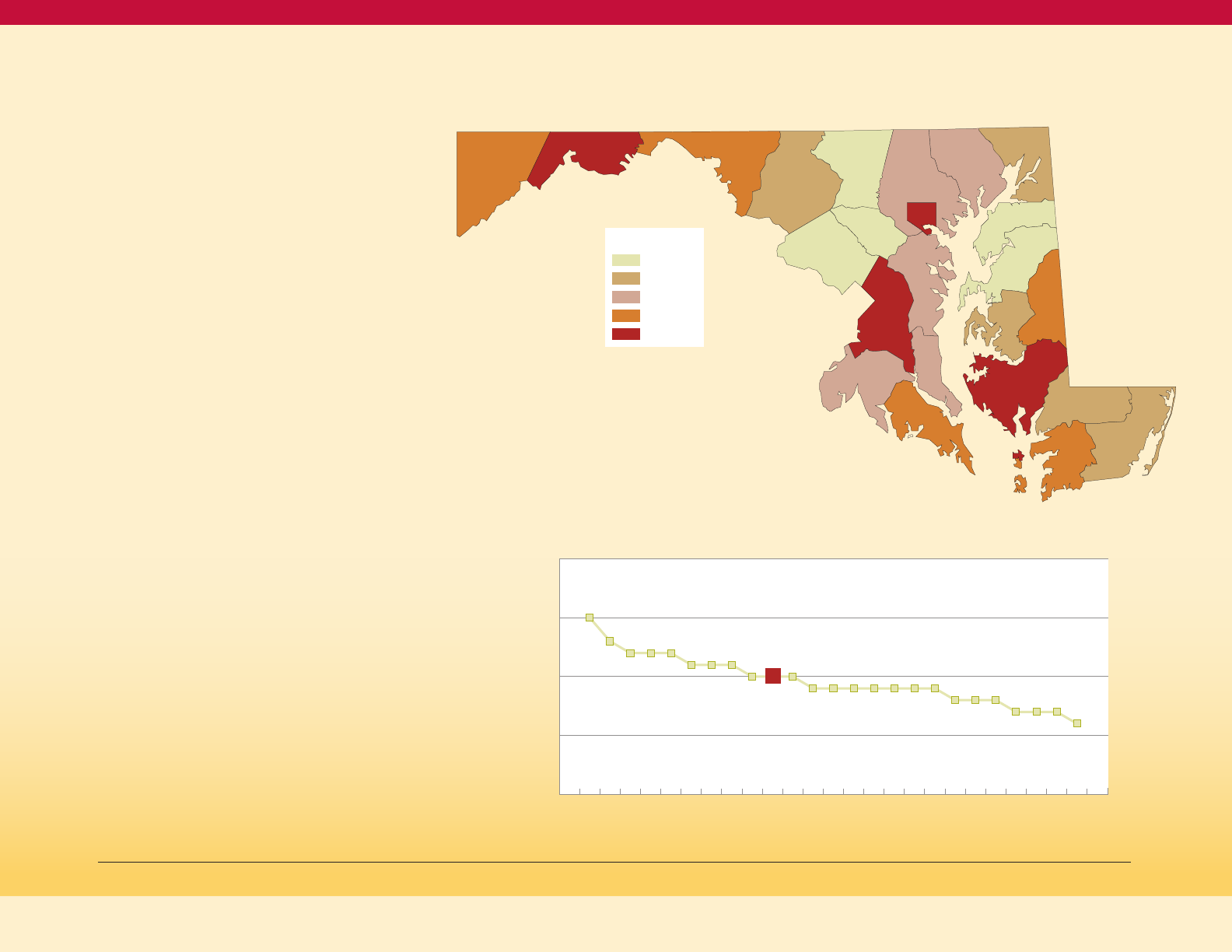

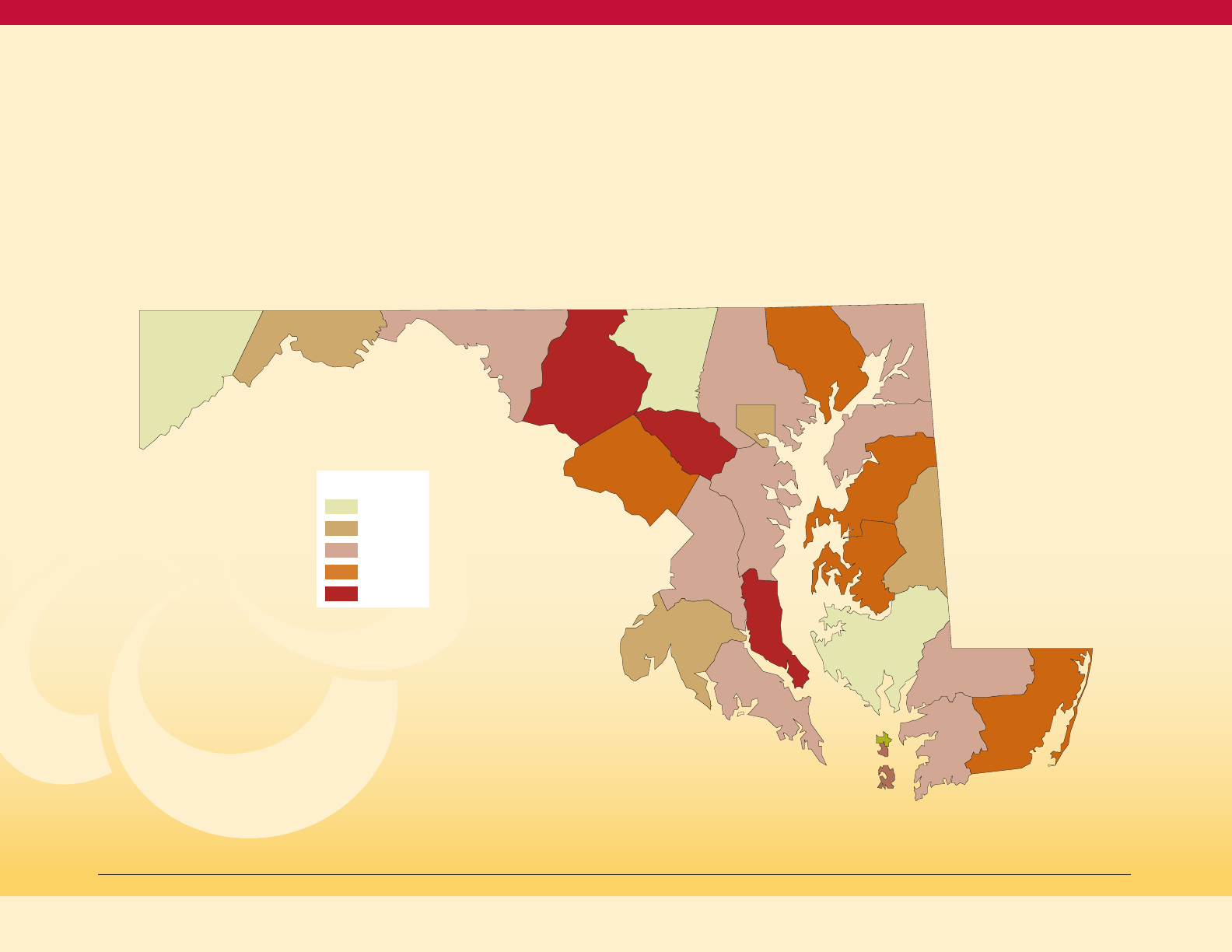

Geographic Distribution of Diabetes

in Maryland

Adult prevalence of diagnosed diabetes is

mapped in Figure 3 on this page. As shown in

Figure 4 on this page, the jurisdictions with

prevalence rates of adults with diagnosed

diabetes that exceed the Maryland Statewide

rate are Dorchester, Allegany, Prince George’s,

Garrett, Washington, Somerset, and Caroline

Counties and Baltimore City.

13

These high rates

of diabetes are seen in jurisdictions with high

minority populations (Baltimore City, Prince

George’s County) and in certain rural

jurisdictions in Western and Southern

Maryland and on the Eastern Shore. Notably,

all three jurisdictions in Western Maryland are

among the six highest prevalence rates.

There are several reasons for the high

diabetes prevalence rates in rural jurisdictions.

Many rural residents experience risk factors

for diabetes and may lack access to services

to prevent diabetes or manage their diabetes.

Rural residents, as well as the urban poor,

experience barriers to adequate physical

activity and healthy eating.

14

Additional

challenges revolve around access to health

care, including resource shortages of

physicians and providers located in rural

areas. Workforce shortages in rural areas

may decrease provider referral to National

DPP, Diabetes Self-Management Education

and Support (DSMES) programs, Chronic

Disease Self-Management programs and

nutrition programs, as well as the availability

of these programs. Other challenges include

limited access to transportation to travel to

appointments with primary care or specialty

care providers.

Map of Age-Adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed

Diabetes by Jurisdictions, Maryland, 2015-2017 (BRFSS)

Figure 3

13

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

14

O'Connor A and Wellinius G. Rural-urban disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Public Health. October 2015, vol. 126: 813-820

Garrett

Allegany

Washington

Frederick

Carroll

Montgomery

Prince

Georges

Charles

St. Mary’s

Calvert

Anne

Arundel

Harford

Cecil

Kent

Queen

Anne’s

Caroline

Talbot

Dorchester

Wicomico

Worchester

Somerset

Baltimore

County

Howard

Balt.

City

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes

by Jurisdiction, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Figure 4

% with diagnosed diabetes

Dorch

Alleg

Prince G

B City

Garrett

Wash

Somer

St. Mary

Caroline

Maryland

Anne A

Calvert

Balt Co

Charles

Harford

Worc

Wico

Cecil

Fred

Talbot

Kent

Queen A

Howard

Mont

Carroll

15%

20%

10%

5%

0%

15%

13%

12%12%12%

11% 11% 11%

10%

10%

10%

9% 9% 9% 9% 9% 9% 9%

8% 8% 8%

7% 7% 7%

6%

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

≤ 8.27%

≤ 9.13%

≤ 9.5%

≤ 11.53%

≤ 15.13%

Legend

9

The range of adult diabetes prevalence rates

becomes even greater when rates by race

and jurisdiction are examined, as shown in

Figure 5. The Non-Hispanic White rate in

Dorchester County is particularly high at 14

percent, with other Non-Hispanic White rates

ranging from 5 percent to 12 percent. The Black

rates start at a low of about 11 percent in

Howard and Montgomery counties and rise

to a high of 20 percent and 24 percent in

Dorchester and Talbot counties respectively

(among the jurisdicitons where the

Non-Hispanic Black rate is reportable).

Of note, Dorchester County has the highest

Non-Hispanic White rate, and the second

highest Non-Hispanic Black rate.

These data indicate that diagnosed diabetes is

common in Maryland, and that the burden of

diabetes prevalence varies by race and place.

The consequences of diabetes for Maryland are

presented below.

How Serious are the Consequences of Diabetes for Maryland?

Diabetes is the sixth leading cause of death

in Maryland; in 2018, 2.8 percent of all deaths

in the State were due to diabetes.

15

Diabetes

is also a risk factor for heart disease (leading

cause of death in Maryland) and stroke (third

leading cause of death in Maryland), and so

contributes to even more deaths in Maryland

than those specifically attributed to diabetes

on death certificates.

16

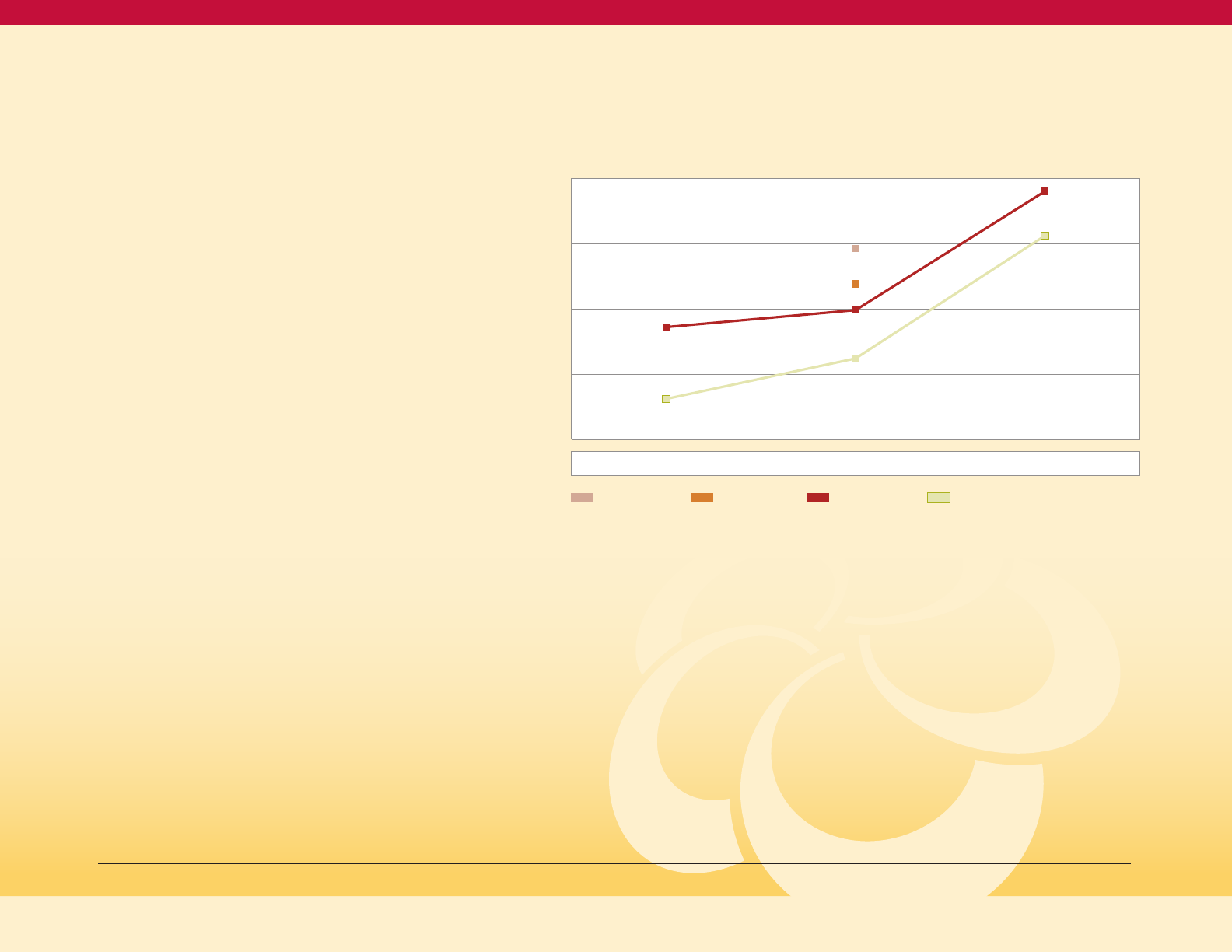

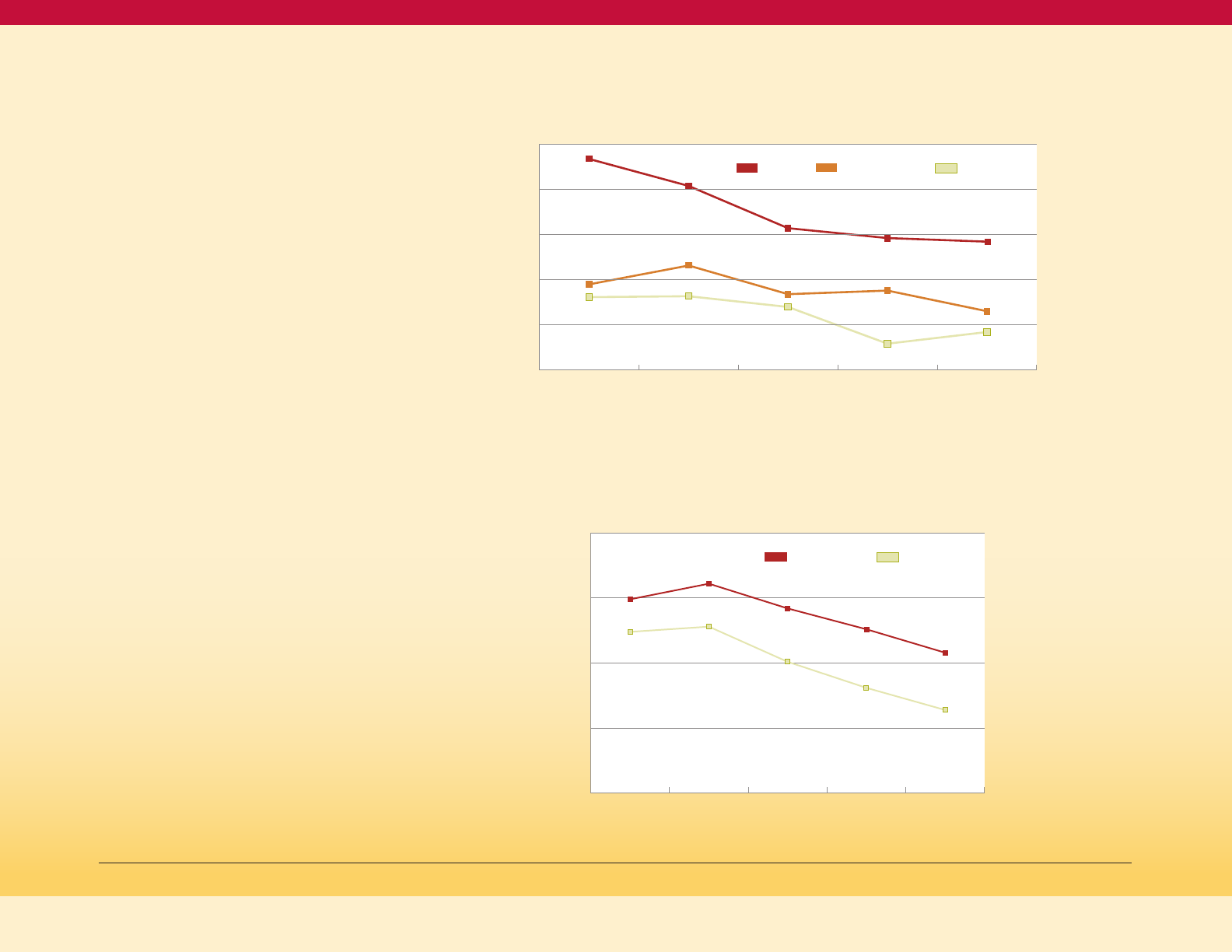

Figure 6 on the next page shows that the

age-adjusted diabetes mortality rate in

Maryland declined from 20.7 in 2009 to a

recent low of 18.3 in 2015, but then rose to 19.6

per 100,000 people in 2018. This increase from

2015 to 2018 occurred mostly in the NH Black

population and less so in the NH White

population. Consistent with the greater burden

of diabetes prevalence in the Black community,

the diabetes mortality rate for Blacks is about

twice as high as the mortality rate for Whites.

17

Comparing Maryland to the United States

(Figure 7), death rates were essentially

identical in 2009. From 2009 to 2015, Maryland

improved more rapidly than the US. However,

after 2015, the rising Black diabetes death

rate in Maryland has resulted in the overall

Maryland rate converging toward the

national rate.

18

15

Maryland Vital Statistics Annual report (2018): //health.maryland.gov/vsa/Documents/Reports%20and%20Data/Annual%20Reports/2018annual_rev3.pdf

16

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

17

Id fn 15

18

Id fn 15

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes

by Race and Jurisdiction, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Figure 5

% with diagnosed diabetes

15%

25%

10%

5%

0%

20%

Talbot

Dorch

Fred

Anne A

Wico

B City

Maryland

Prince G

Charles

Balt Co

Howard

Mont

Alleg

Calvert

Caroline

Carroll

Cecil

Garrett

Harford

Kent

Queen A

St. Mary

Wash

Worc

Diabetes as a Cause of Death

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

6%

8%

14%

8%

7%

7%

8%

10%

8%

7%

6%

5%

11%

9%

11%

7%

9%

12%

9%

8%

7%

8%

11%

6%

24%

20%

18%

17%

16%

15%

13%

13%

12%

11%

11%

11%

NH WhiteNH Black

Complications of Diabetes

Diabetes causes a variety of serious

complications related to its effects on large

and small blood vessels. Diabetes promotes

atherosclerosis, the process where

cholesterol builds up in the larger blood

vessels. This increases the risk of heart disease,

heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral vascular

disease (blocked arteries in the arms and legs).

The effects of diabetes on small blood vessels

leads to eye disease, blindness, kidney disease,

end-stage kidney failure that requires

transplant or dialysis, and nerve disease.

19

The combination of nerve disease and

vascular disease in the legs results in

amputations caused by diabetes.

10

19

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

Age-Adjusted Death Rate for Diabetes, by

Race/Ethnicity, Maryland 2009-2018

Figure 6

Rate per 100,000 population

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Non-Hispanic Black

All Races

Non-Hispanic White

Hispanic

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

NH Black 34.5 35.9 34.3 31.2 32.2 33.7 28.2 31.7 33.8 32.4

All Races 20.7 19.8 20.8 19.1 19.0 19.6 18.3 19.6 20.3 19.6

NH White 17.5 15.5 17.4 16.1 15.5 16.4 16.0 16.1 16.3 16.4

Hispanic - - - 15.8 11.3 10.3 8.6 16.4 12.3 7.3

Source: Maryland Vital Statistics Annual report (2018)

Age-adjusted Death Rate for Diabetes, Maryland

and the United States, 2009-2018

Figure 7

Rate per 100,000 population

MD

US

25

20

0

15

10

5

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

US 21.0 20.8 21.6 21.2 21.2 20.9 21.3 21.0 21.5 -

MD 20.7 19.8 20.8 19.1 19.0 19.6 18.3 19.6 20.3 19.6

11

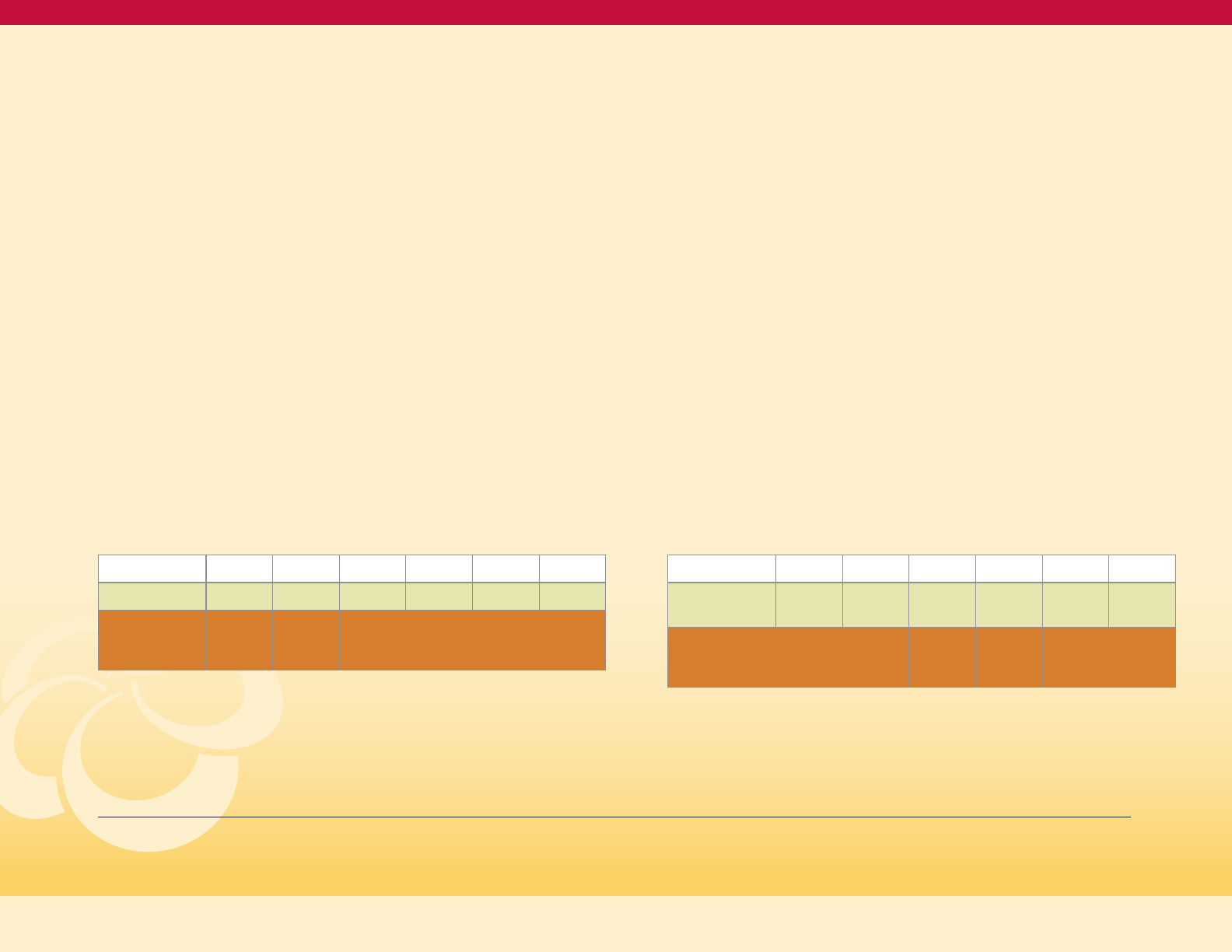

PQI 93 Discharge Frequency and Rate

per 1000 Adult Marylanders

Table 2

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

PQI 93

Discharges

10,494 10,511 10,045 9,539 10,484 11,571

Discharges

per 1000

adults

2.34 2.34 2.24 2.13 2.34 2.58

Utilization Rates and Costs for Diabetes

Diabetes-related hospital discharges

in Maryland

In 2018, a total of 11,738 hospital discharges

(inpatient and observation stays greater than

or equal to 24 hours) were reported with

diabetes as the primary diagnosis among

Maryland adults aged 18 years or older. This is

equivalent to 2.5 hospital discharges per 1,000

Maryland adults.

20,21

In Table 1, the numerator is discharges with

diabetes-related primary diagnosis code at

Maryland hospitals among adults with

valid Maryland zip codes, denominator is

adult Maryland population based on

5-year American Community Survey. 2017

denominator is used for 2018 (as 2018 data

was not available at the time of this report).

Diabetes-related Prevention Quality

Indicators (PQIs)

PQIs reflect admissions for ambulatory-

care sensitive conditions that could have

been prevented with access to high-quality

outpatient care. The Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality has specified four

individual PQIs for diabetes and

one composite:

22,23

• PQI 01 Diabetes Short-Term Complications

Admission Rate (primary diagnosis code of

diabetes with: ketoacidosis, hyperosmolarity,

or coma)

• PQI 03 Diabetes Long-Term Complications

Admission Rate (primary diagnosis code

of diabetes with: renal, eye, neurological,

circulatory, or complications not

otherwise specified)

• PQI 14 Uncontrolled Diabetes Admission

Rate (primary diagnosis code of diabetes

without mention of short-term or long-term

complications)

• PQI 16 Lower-Extremity Amputation among

Patients with Diabetes Rate (any-listed

diagnosis of diabetes and any-listed

procedure of lower-extremity amputation)

• PQI 93 Diabetes Composite (includes any of

the four above PQIs)

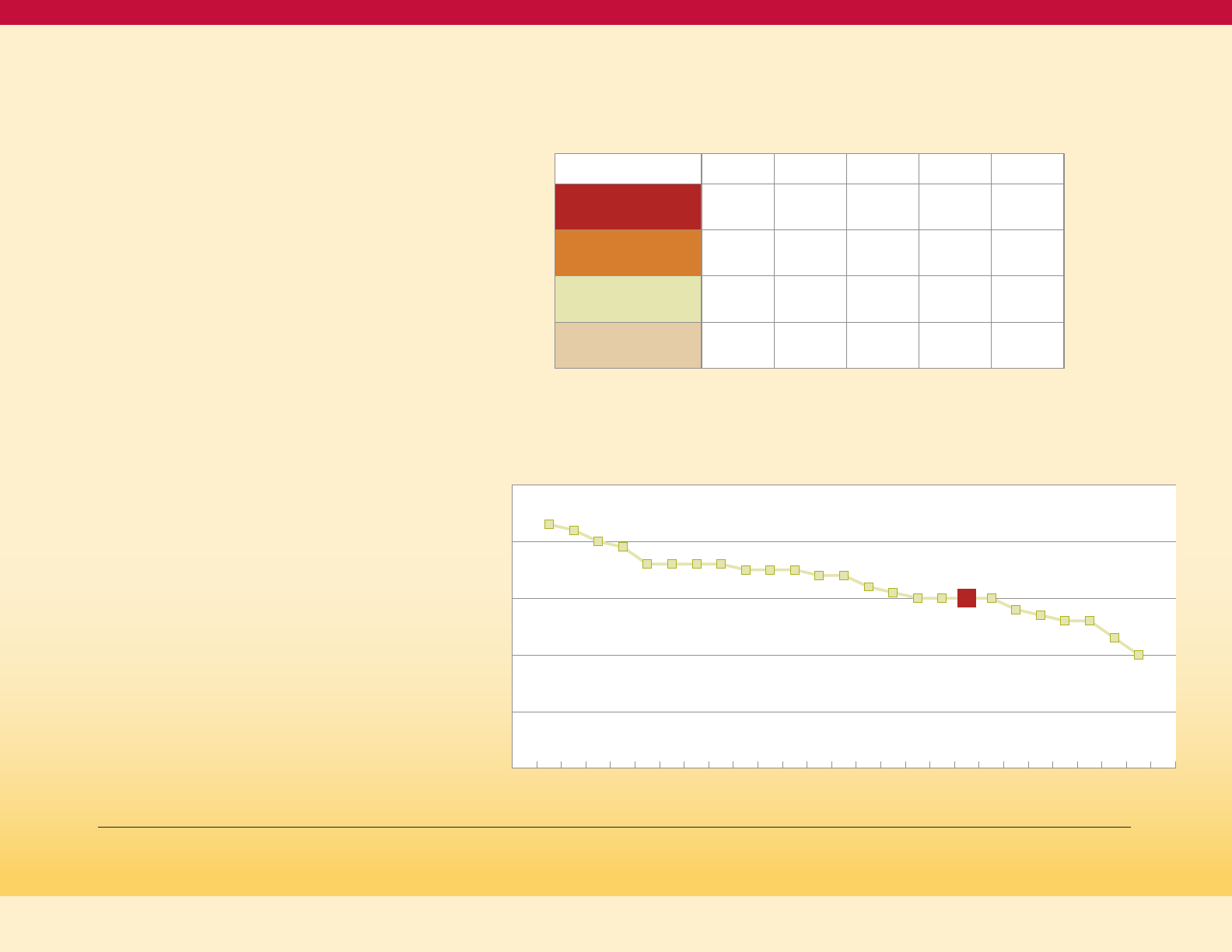

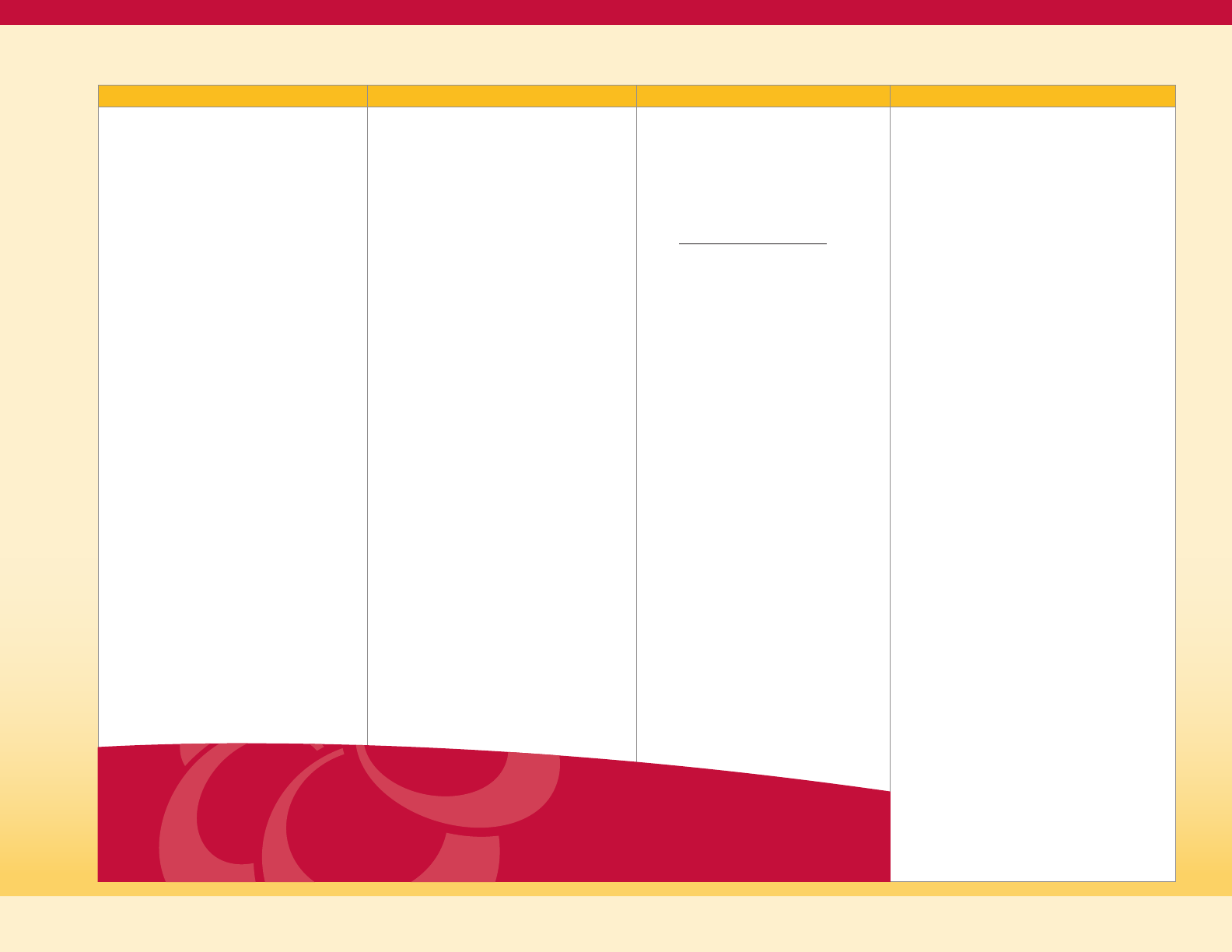

As indicated in the table below, the number

of Diabetes PQIs in Maryland and the rate

of Diabetes PQIs per 1000 adults have

fluctuated over time but have generally

increased since 2013.

24

Diabetes-related Hospital Discharge Count

and Rate per 1000 Adult Marylanders

Table 1

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Discharges

10,676 10,689 10,357 10,823 11,735 11,738

Discharges

per 1000

adults

2.38 2.35 2.26 2.35 2.52 2.53

20

Trends between the ICD9 period (2013-2015) and ICD 10 period (2016-2018) should be treated with caution due to ICD transition. For this section, diabetes refers to Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

21

MATCH, Health Service Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), Maryland Hospital Discharges and Ambulatory Care Data.

22

https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives

23

Many, but not all, discharges with a primary diagnosis of diabetes are included in the PQI counts. For example, Marylanders younger than 18 and those transferred from another institution are not

included in the PQI counts

24

MATCH, Health Service Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), Maryland Hospital Discharges and Ambulatory Care Data.

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

12

The disease burden of diabetes also reflects

a healthcare disparity by race (see Figure 8).

Black Marylanders experience a higher rate

of diabetes-related avoidable hospitalizations

compared to white Marylanders, with 434

people having diabetes-related avoidable

hospitalizations for every 100,000 Black

Marylanders (or 4.34 per 1000) compared to

170 for every 100,000 White Marylanders

(or 1.7 per 1000) in 2017.

25

This means that the

black rate is 2.6 times as high as the White

rate, and that 62 percent of Black discharges

are excess (would not occur if Black rate was

the same as White rate).

Diabetes Inpatient Hospital Charges

In 2017, Maryland hospitals charged

approximately $197 million for diabetes-related

hospital stays for Marylanders, compared to

$150 million dollars in 2013, an increase of more

than 30 percent. This estimate includes

Maryland residents of all ages with a primary

diagnosis of diabetes or a diabetes-related

complication (such as lower-extremity

amputation). The estimate excludes patients

seen in the Emergency Department (ED)

and released without an inpatient stay.

26

Diabetes Emergency Department Visits

In 2017, there were a total number of 121,301

ED visits related to Diabetes.

27

This indicates a

rate of 20.23 visits per 1,000 Marylanders.

25

Id fn 24.

26

MATCH, Health Service Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), Maryland Hospital Discharges and Ambulatory Care Data.

27

Defined based on CCS categories among all patients at Maryland hospitals.

Table 3

Diabetes-related ED Visit Count and

Rate per 1,000 Population

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Number of

ED visits

122,439 123,875 124,928 124,420 121,301

Population

5,834,299 5,887,776 5,930,538 5,959,902 5,996,079

Visit Rate

per 1,000

20.99 21.04 21.07 20.88 20.23

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

Figure 8

Diabetes Composite (PQI 93) per 100,000

Population Aged 18+ in Maryland

PQI 93 per 100k adults

500

400

300

200

100

0

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Black

466 402 424 406 434

Total

234 234 224 213 234

White

152 146 156 155 170

13

Utilization Differences for Medicaid Enrollees

with Diabetes vs. Without Diabetes

To further demonstrate the individual and

societal costs of diabetes, the data below shows

that compared to Medicaid enrollees without a

diagnosis of diabetes, those with diabetes

• Are 2.4 times as likely to have an

inpatient admission

• Have four times as many admissions

per enrollee

• Are 1.3 times as likely to have an ED visit

• Have 1.7 times as many ED visits per enrollee

• Are 1.1 times as likely to have an

ambulatory visit

• Have 2.3 times as many ambulatory visits

per enrollee

• Have 3.1 times the level of average

fee-for-service payment, and

• Have 2.5 time the level of average

MCO payment.

Cost Burden of Diabetes in Maryland

Diabetes and prediabetes cost an estimated

$7.01 billion in Maryland each year.

29

Serious

complications of diabetes include heart

disease, stroke, amputation, end-stage

kidney disease, blindness, and death.

People with diabetes have medical expenses

approximately 2.3 times higher than those who

do not have diabetes.

30

Total direct medical

expenses for diagnosed and undiagnosed

diabetes, prediabetes and gestational

diabetes in Maryland was estimated at

$4.92 billion in 2017. In addition, another $2.09

billion was spent on indirect costs from lost

productivity due to diabetes.

31,32

28

Maryland Department of Health, Health Care Financing/Medicaid, data provided September 2019.

29

Diabetes Care Volume 41, December 2018, https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/41/12/2526.full.pdf

30

Diabetes Care. January 01 2019; volume 42 issue Supplement 1.

31

Id fn 29

32

The Hilltop Institute. (2016, May 20).Briefing Report: An Examination of Service Utilization and Expenditures among Adults with Diabetes Enrolled in Maryland’s Medicaid Managed Care Program.

Baltimore, MD: UMBC. Retrieved from: https://www.medchi.org/Portals/18/files/pdfs/Hilltop%20Briefing%20Report_Medicaid%20Diabetes%20Analysis_Final_5-20-16.pdf?ver=2016-10-27-143345-240.

Admission, ED Visit, and Ambulatory Visit Prevalence and Rates;

and Average Payments Comparing Medicaid Enrollees with and

without Diabetes, Maryland, 2017

28

Table 4

Calendar Year 2017

Medicaid Enrollees

with Diabetes

Medicaid Enrollees

without Diabetes

Ratio: Diabetes

to No Diabetes

% with One or More

Inpatient Admissions

24.8% 10.3% 2.4

Average Admissions

per Enrollee

0.4 0.1 4.0

% with One or More

ED visits

42.7% 33.2% 1.3

Average ED visits

per Enrollee

1.2 0.7 1.7

% with One or More

Ambulatory Visits

93.4% 87.0% 1.1

Average Ambulatory

Visits per Enrollee

11.8 5.1 2.3

Average Fee-for-Service

Payment

$12,334 $3,961 3.1

Average MCO Payment

$9,794 $3,909 2.5

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

14

33

Id fn 32

34

The average Medicaid expenditure does not adjust for participants for the length of enrollment in Medicaid (i.e., the costs for the one cohort could be higher because the cohort is enrolled for longer

periods in Medicaid and has more opportunity to receive services). The PMPM method adjusts for length of Medicaid enrollment.

35

The Hilltop Institute (2019, August 29). Analyses of Medicaid Expenditure Data for the Diabetes Action Plan, 2013-2017. Baltimore, MD: UMBC.

36

Kick payments are supplemental funds that the Department pays to managed care organizations (MCOs) outside of their regular capitation payments to better target resources for a specific set of

services or having a certain condition. For example, MCOs currently receive kick payments for the birth event and for beneficiaries receiving Hepatitis C treatment.

Medicaid Costs of Diabetes in Maryland

People with diabetes cost the State's Medicaid

program twice as much as those without the

chronic condition, a study commissioned by

MedChi, the Maryland State Medical Society

has found.

33

No other insurance utilization data

was available at the time of plan completion.

In CY 2017, total expenditures for Medicaid

participants with diabetes amounted to nearly

$1.9 billion. Between CY 2013 and CY 2017, total

Medicaid per-member-per-month (PMPM)

expenditures for individuals with diabetes was

two to three times higher than users without

diabetes ($1,652 vs. $688 in CY 2017). Similar

to the PMPM expenditures, average Medicaid

expenditures among eligible individuals with

diabetes was two to three times higher than for

individuals without diabetes ($18,202 vs. $7,516

in CY 2017). For individuals with diabetes, the

average Medicaid PMPM expenditure reduced

from $1,746 to $1,652 among users between

CY 2013 and CY 2017. This reduction was due

to a lower average fee-for-service PMPM

expenditure among Medicaid beneficiaries

with diabetes (from $1,362 in CY 2013 to $1,119

in CY 2017) and lower average PMPM capitation

and kick payments for beneficiaries with

diabetes enrolled in the HealthChoice

managed care program (from $1,031 in CY

2013 to $926 in CY 2017).

34,35,36

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

15

Action Plan

Diabetes

Section II:

Determinants and Risk Factors for Diabetes: Opportunities for Intervention

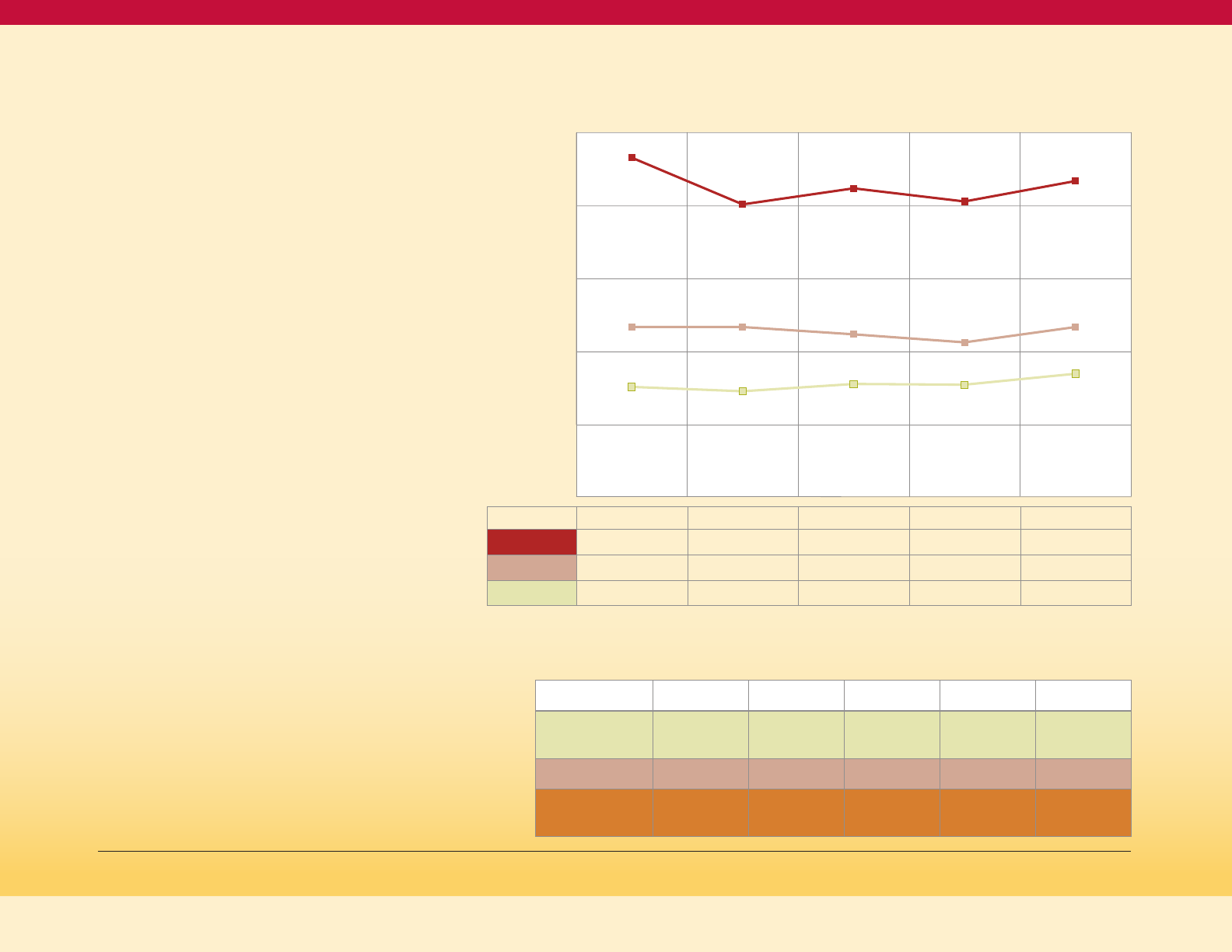

Diabetes by Age and Sex

Diabetes is more common in older adults. In

Maryland, in 2015-17 combined, about 26

percent of men and 20.2 percent of women

aged 65 and older had been diagnosed with

diabetes compared to about 5 percent of

adults aged 35-44 (Figure 9).

37

Diabetes in

older adults has been linked to a reduction

in functional status, higher mortality, and

increased risk of institutionalization.

The increasing prevalence of diabetes with

advancing age is part of the natural history

of the disease, which means that these age

differences are not an “age disparity.” Obesity

is more common at older ages, which

increases insulin resistance, and reduction

of insulin secretion also occurs at older ages.

Age is not a modifiable factor but

understanding age effects is important

to evaluating other determinants and risk

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-17.

% with diagnosed diabetes

Figure 9

Adult Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Diabetes,

by Age and Sex, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

Age Group 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

30%

Male

Female

5.5%

11.0%

19.4%

26.0%

5.1%

10.0%

15.9%

20.2%

0%

16

factors. Because of this strong age effect, the

remaining analyses will display age-adjusted

diabetes prevalence rates to disentangle the

effects of age from the effects of other

determinants and risk factors.

Gender is generally not considered to be a

risk factor for diabetes. In Figure 9, male and

female prevalence is essentially the same

below age 55. While there are somewhat

higher rates for males at ages 55 and older,

this does not mean that females should be

considered a “low risk” group.

This is confirmed by the equal incidence rates

(rate of new cases) between males and females

nationally shown inFigure 10on this page

(incidence rate data by sex is not available for

Maryland). (https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/

DiabetesAtlas.html#[DM1]).

Figure 10

Age-adjusted Adult Incidence Rate

of Diagnosed Diabetes, by Sex, U.S., 1980 to 2017

(National Health Interview Survey)

38

38

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

8

10

6

4

2

0

rate per 1000 population

Male

Female

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

17

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

NIDDK, https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-type-2-diabetes

Diabetes and Weight

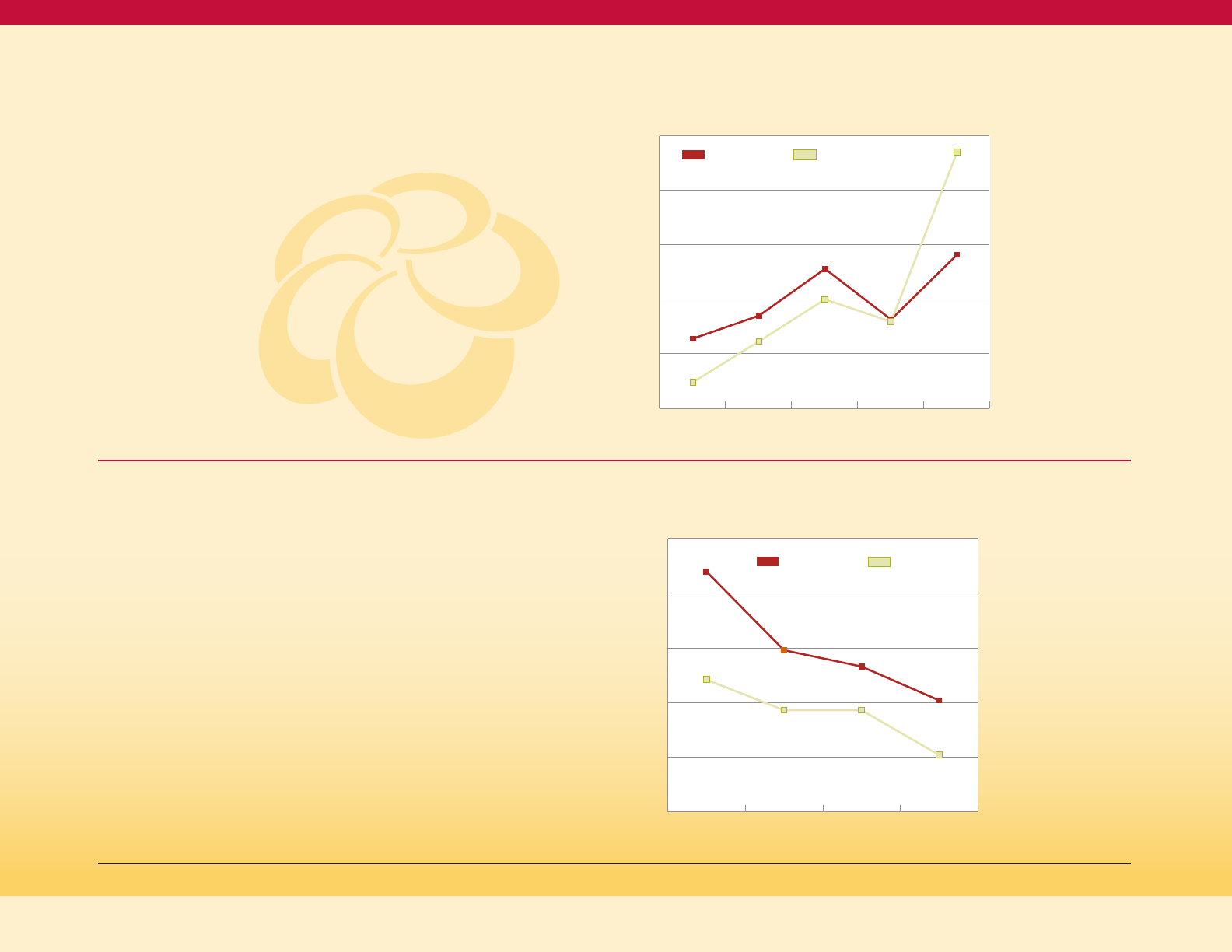

In Maryland, as in the nation, the prevalence

of diabetes increases as weight classification

moves from healthy weight, through

overweight, and to obesity. As seen in Figure

11 on this page, in Maryland there is a small

step-up in diabetes prevalence between

healthy weight and overweight, and a larger

step-up in prevalence between overweight

and obesity. This relationship of prevalence to

weight status is similar for Non-Hispanic Blacks

and Non-Hispanic Whites.

In addition, Figure 11 shows that the higher

diabetes prevalence for minorities presented

earlier (Figure 2) persists within weight

categories, with Non-Hispanic Black diabetes

prevalence higher than Non-Hispanic White

in all weight categories, and Hispanic and Asian

prevalence higher at overweight (the only

category with reportable data for those

populations in this analysis).

39

This indicates

that the racial/ethnic disparity in diabetes

prevalence is not simply an issue of more

excess weight in minority populations,

although for some groups that contributes

to the disparity.

Higher BMI correlates with greater abdominal

fat, and abdominal fat increases insulin

resistance, which can produce high levels of

blood glucose.

40

Insulin is produced by the

pancreas and is the hormone that moves the

sugar out of the blood and into the cells. When

an individual has excess body fat, the body’s

cells become resistant to insulin, which is

why overweight and obesity are risk factors

for diabetes. The body’s response to

insulin-resistant cells increases insulin

production to the point that the pancreas

begins to fail to keep up with the insulin

demand. Failure to produce and/or utilize

enough insulin results in diabetes.

Figure 11

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed

Diabetes, by Race/Ethnicity and Weight Status,

Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Healthy Weight Over Weight Obese

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

% with diagnosed diabetes

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

3.1%

6.2%

15.6%

8.6%

9.9%

19.0%

11.90%

14.6%

NH WhiteNH BlackNH Asian Hispanic

18

Adult Prevalence of Excess Weight

in Maryland

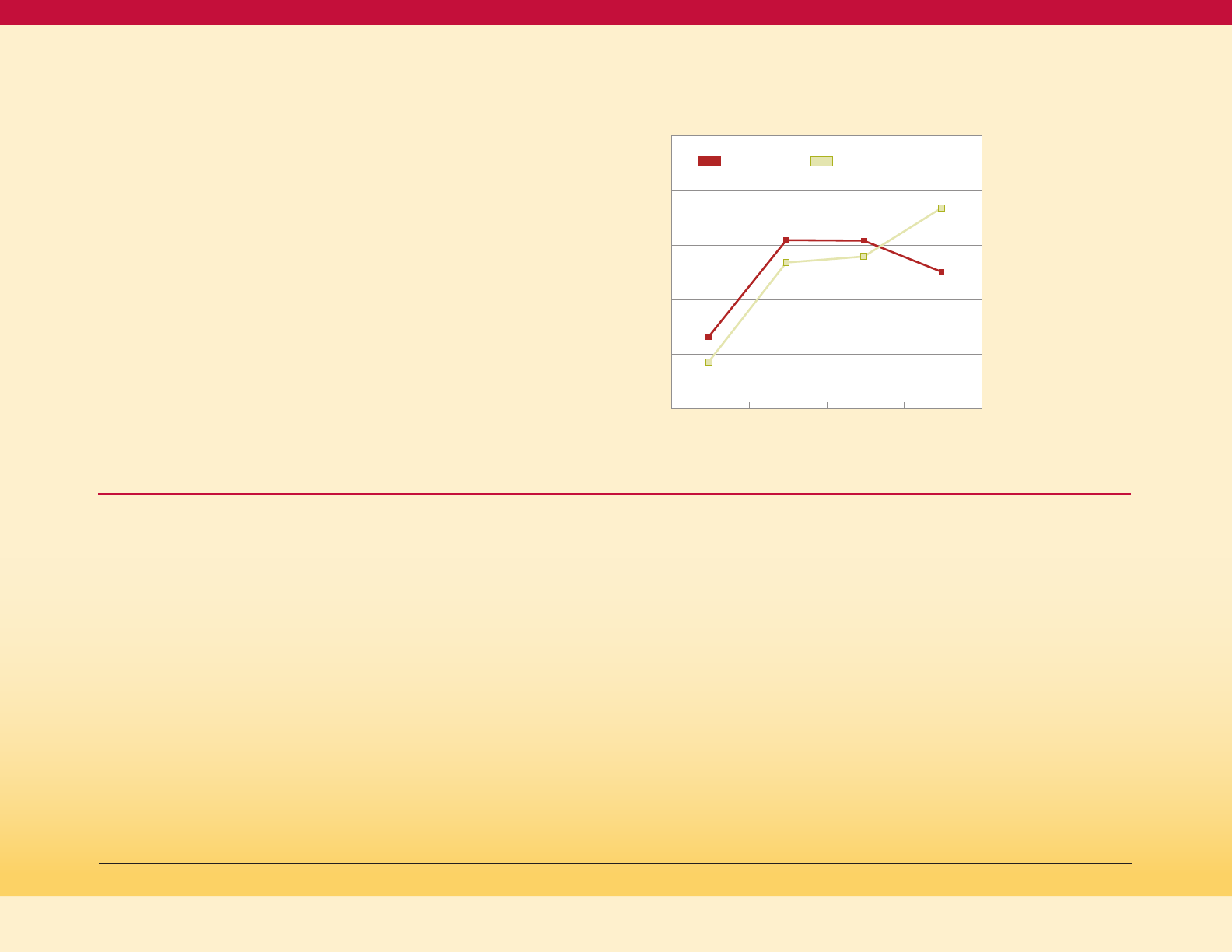

Based on data from 2017, in Maryland, 34.6

percent of the population is overweight, and

30.8 percent of the population is obese.

41

Five-year trend data shows that the proportion

of Marylanders who are obese is increasing,

and the proportion of Marylanders who are

overweight has been relatively stable. In

addition, the healthy weight population in

Maryland is decreasing from 35.1 percent in

2013 to 32.7 percent in 2017.

42

Figure 12 shows a wide range of obesity

prevalence rates by jurisdiction in Maryland,

ranging from a low of 20 percent in

Montgomery County to a high of 43 percent

in Caroline County. Several factors influence

the obesity prevalence rate in a jurisdiction,

including the racial and ethnic mix and the

socio-economic status of the population.

44

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Maryland Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2013-2017

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health. BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data.

https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/.

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Adult Weight Classification by Body Mass

Index (BMI) Age-Adjusted Prevalence and

Trend, Maryland 2013-2017

43

Table 5

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Obese

27.6% 29.0% 28.2% 29.4% 30.8%

Overweight

35.5% 34.9% 35.7% 34.1% 34.6%

Healthy Weight

35.1% 34.5% 33.7% 34.8% 32.7%

Underweight

1.9% 1.6% 2.4% 1.8% 1.9%

Age-adjusted Adult Obesity Prevalence by

Jurisdiction, Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Figure 12

30%

50%

20%

10%

0%

40%

Caroline

Somer

Wash

Dorch

Garrett

St. Mary

Wort

Prince G

Charles

Wico

B City

Carroll

Alleg

Cecil

Calvert

Balt Co

Harford

Maryland

Kent

Anne A

Fred

Queen A

Talbot

Howard

Mont

% obese

43%

42%

40%

39%

36% 36% 36% 36%

35% 35% 35%

34% 34%

32%

31%

30% 30%

30%

30%

28%

27%

26% 26%

23%

20%

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

19

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Overweight/Obesity in Women

of Childbearing Age

The prevalence of overweight and obesity

among women of childbearing age is of

particular interest since this will determine

the prevalence of pre-pregnancy diabetes

and the incidence of gestational diabetes

among pregnant women. Both conditions

increase the risk of adverse infant and

maternal outcomes.

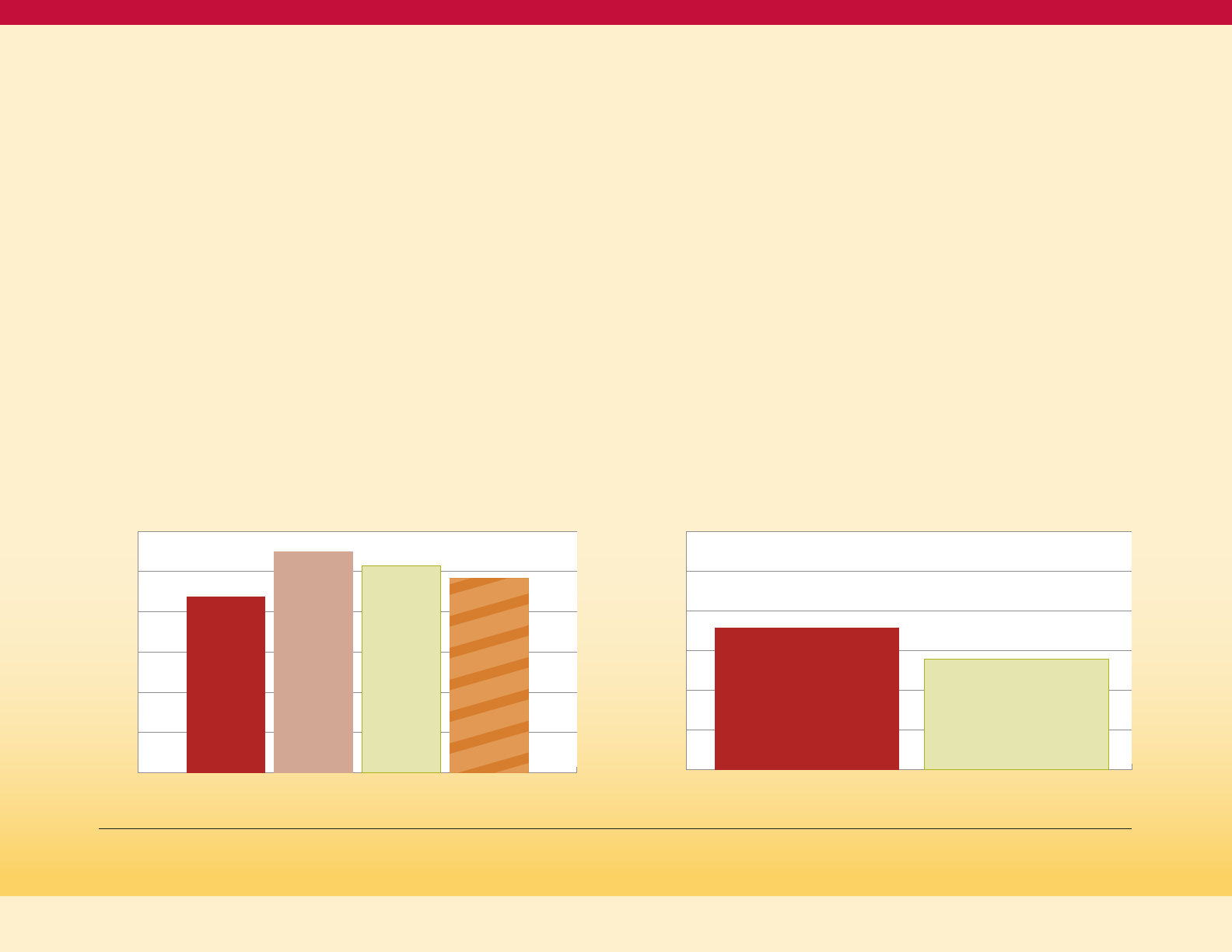

Figure 13 on this page shows the weight

category distribution of women age 18-44 for

Non-Hispanic Whites and Non-Hispanic Blacks.

For Non-Hispanic Whites, a slight majority of

the women are in the healthy weight category

(50.9 percent) while for Non-Hispanic Blacks

the most prevalent weight category is obesity

(40.8 percent). Both racial groups have similar

prevalence of overweight, but very different

prevalence in the healthy weight and

obese categories.

45

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

% in the weight category

Figure 13

Weight Category Distribution of Women

of Childbearing Age, by Race Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

Healthy Weight Over Weight Obese

50%

40%

30%

20%

60%

50.9%

32.2%

27.1%

26.1%

40.8%

23.1%

10%

0%

NH WhiteNH Black

20

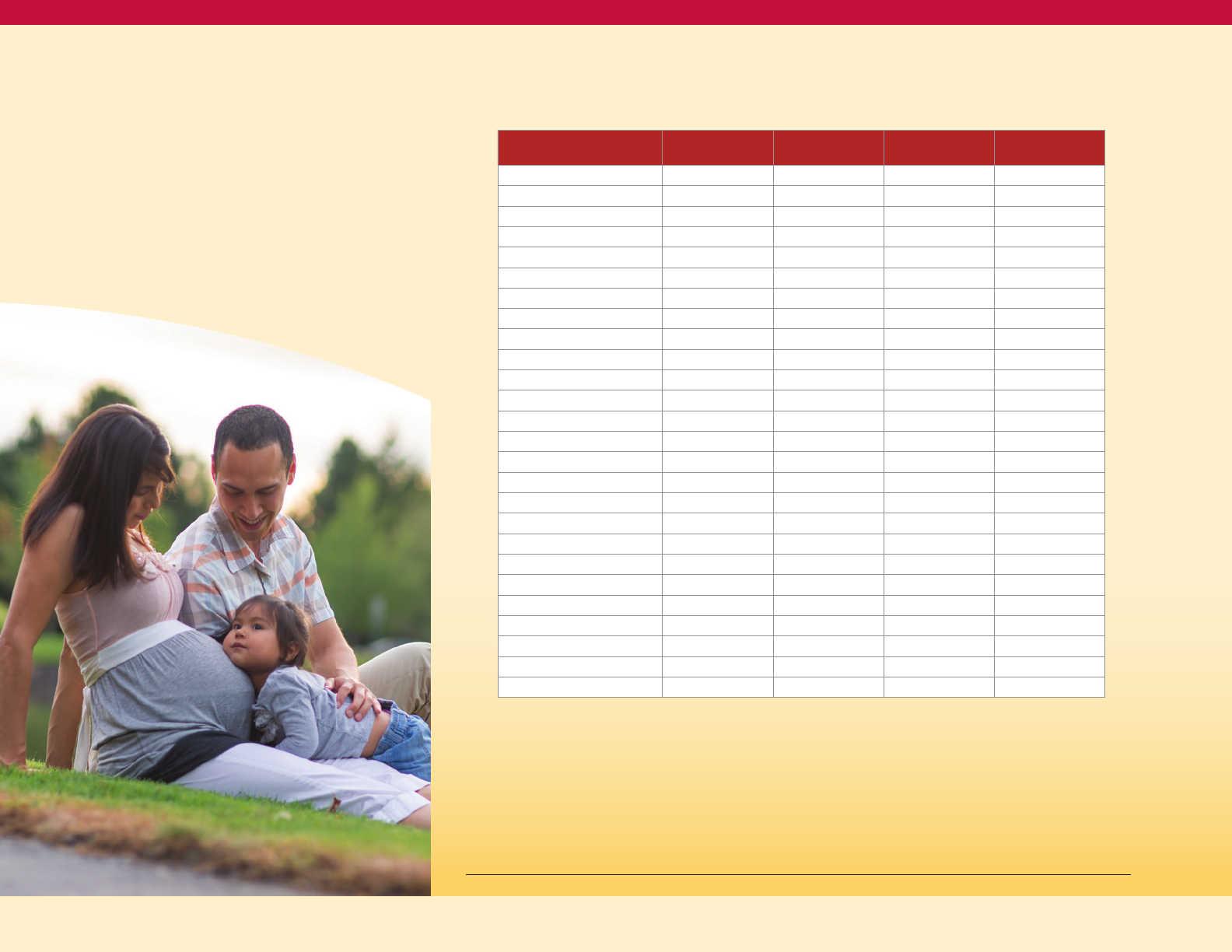

Table 6 on this page shows the pre-pregnancy

BMI classification for pregnant women active

in the Women Infants and Children (WIC)

program Statewide and by jurisdiction.

Statewide, 36 percent have an obese BMI,

with a range of 29 percent in Montgomery

and Garrett counties to 46 percent in Talbot,

48 percent in Dorchester and 61 percent in

Somerset counties.

46

Maryland Women Infant and Children Program, communicated October 7, 2019.

Pre-pregnancy BMI of Active Pregnant Women

as of October 7, 2019, Maryland WIC Program

Table 6

County

Underweight

BMI < 18.5

Normal Weight

BMI 18.5-24.9

Overweight

BMI 25.0-29.9

Obese

BMI > 30.0

Allegany 4% 43% 21% 32%

Anne Arundel 2% 35% 26% 36%

Baltimore City 4% 31% 24% 40%

Baltimore County 4% 35% 25% 36%

Calvert 4% 35% 28% 33%

Caroline 1% 35% 28% 35%

Carroll 6% 38% 24% 32%

Cecil 5% 36% 23% 35%

Charles 6% 35% 27% 33%

Dorchester 2% 29% 21% 48%

Frederick 3% 37% 30% 30%

Garrett 8% 44% 19% 29%

Harford 7% 31% 26% 36%

Howard 1% 35% 34% 30%

Kent 5% 30% 24% 41%

Montgomery 3% 34% 34% 29%

Prince George's 3% 31% 31% 35%

Queen Anne's 0% 35% 29% 36%

Somerset 7% 20% 12% 61%

St. Mary's 3% 33% 22% 42%

Talbot 6% 12% 36% 46%

Washington 4% 35% 21% 39%

Wilcomico 3% 35% 23% 40%

Worcester 5% 32% 29% 34%

State 3% 33% 28% 36%

Total Pregnant Women = 10,015

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

21

Excess Weight among Children

Maryland does not have state-level data on

diabetes in children. The SEARCH for Diabetes

in Youth study is aimed at understanding more

about diabetes among children and young

adults in the United States; the incidences of

both type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths

increased significantly in the 2002–2012 period,

particularly among youths of minority racial

and ethnic groups.

47

State level data on overweight and obesity

is available. In children and adolescents,

overweight and obesity are defined by

comparing weight for height (the Body Mass

Index or BMI) to a reference population that

precedes the recent rise in rates of childhood

obesity. Comparisons are made to the

corresponding age and sex of the child.

Underweight is falling below the 5th percentile

of that reference population, normal weight is

being 5th to below 84th percentile, overweight

but not obese is being 85th to below 95th

percentile, and obese is being 95th

percentile or above.

48

The Maryland Youth Risk Behavior Survey

(YRBS) is an on-site survey of Maryland

students in a sample of middle and high

school classrooms focusing on health-related

behaviors and tobacco-use prevalence. The

survey does not include elementary schools.

The survey is conducted every two years and is

self-reported. According to the 2016 Youth Risk

Behavior Survey, 26.4 percent of Maryland high

school students are overweight or obese.

49

The percentage of high school students

who are overweight and obese were 11.5

percentand 14.9 percent, respectively. Based

on this data, interventions and strategies to

address overweight and obesity must be

targeted to children and youth as well as

adults to prevent diabetes.

The Women Infant and Children (WIC)

program childhood participants (children 2

to 5 years of age, July–December 2018) have

their height and weight checked during

regular WIC visits. Table 7 shows that of these

children, 17 percent were at or above 95th

percentile BMI (obese), and 16 percent were

of 85th to below 95th percentile BMI

(overweight but not obese).

50

Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. Elizabeth J. Mayer-Davis, Ph.D., Jean M. Lawrence, Sc.D., M.P.H., M.S.S.A., Dana Dabelea, M.D., Ph.D., Jasmin Divers, Ph.D., Scott

Isom, M.S., Lawrence Dolan, M.D, Giuseppina Imperatore, M.D., Ph.D., Barbara Linder, M.D., Ph.D., Santica Marcovina, Ph.D., Sc.D., David J. Pettitt, M.D., Catherine Pihoker, M.D., Sharon Saydah, Ph.D., M.H.S.,

and Lynne Wagenknecht, Dr.P.H. et al., for the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study*. https://www.searchfordiabetes.org.

https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html.

Maryland Department of Health, Youth Behavior Risk Survey, 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/ccdpc/Reports/Pages/yrbs.aspx

Id fn 46

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

22

Id fn 51

National Physical Activity Guidelines;

https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/index.html

Maryland BRFSS 2011-2013.

Prevalence of Weight Classes Among

Children Participating in WIC in Maryland

(by Jurisdiction, July-December 2018; 40,935 Total Children)

51

Table 7

County

Underweight

BMI < 5th

Percentile

Healthy WT BMI

between 5th to

< 84th percentile

Overweight BMI

between 85th to

< 94th percentile

Obese

BMI ≥ 95th

percentile

Maryland 3% 63% 16% 17%

Allegany 3% 67% 17% 13%

Anne Arundel 3% 65% 17% 14%

Baltimore City 3% 70% 15% 12%

Baltimore County 3% 62% 17% 18%

Calvert 4% 62% 15% 20%

Caroline 3% 68% 15% 14%

Carroll 3% 58% 18% 21%

Cecil 1% 69% 15% 16%

Charles 5% 63% 18% 15%

Dorchester 3% 60% 18% 19%

Frederick 3% 62% 17% 18%

Garrett 5% 68% 15% 12%

Greater Baden 5% 62% 14% 18%

Harford 4% 69% 14% 13%

Howard 3% 64% 15% 17%

Johns Hopkins 3% 65% 14% 17%

Kent 4% 66% 16% 14%

Montgomery 2% 59% 18% 21%

Prince George's 4% 62% 15% 18%

Queen Anne's 1% 64% 13% 22%

Somerset 7% 63% 13% 17%

St. Mary's 3% 67% 17% 13%

Talbot 1% 66% 15% 18%

Washington 4% 62% 18% 16%

Wicomico 4% 64% 15% 17%

Worcester 2% 67% 14% 17%

Diabetes and Physical Activity

Sedentary Lifestyle

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

encourages adults to move more and sit less.

Adults should get at least 150 minutes of

physical activity each week and children should

be active for at least 60 minutes a day (preschool

children should be moving throughout the day).

52

A sedentary lifestyle puts individuals at increased

risk for developing a variety of chronic health

conditions, including type 2 diabetes. Research

shows that an active lifestyle reduces the risk of

chronic health conditions like diabetes. The adult

prevalence of diagnosed diabetes is higher in

those who do not meet weekly physical activity

guidelines compared to those who do meet those

guidelines (Figure 14).

53

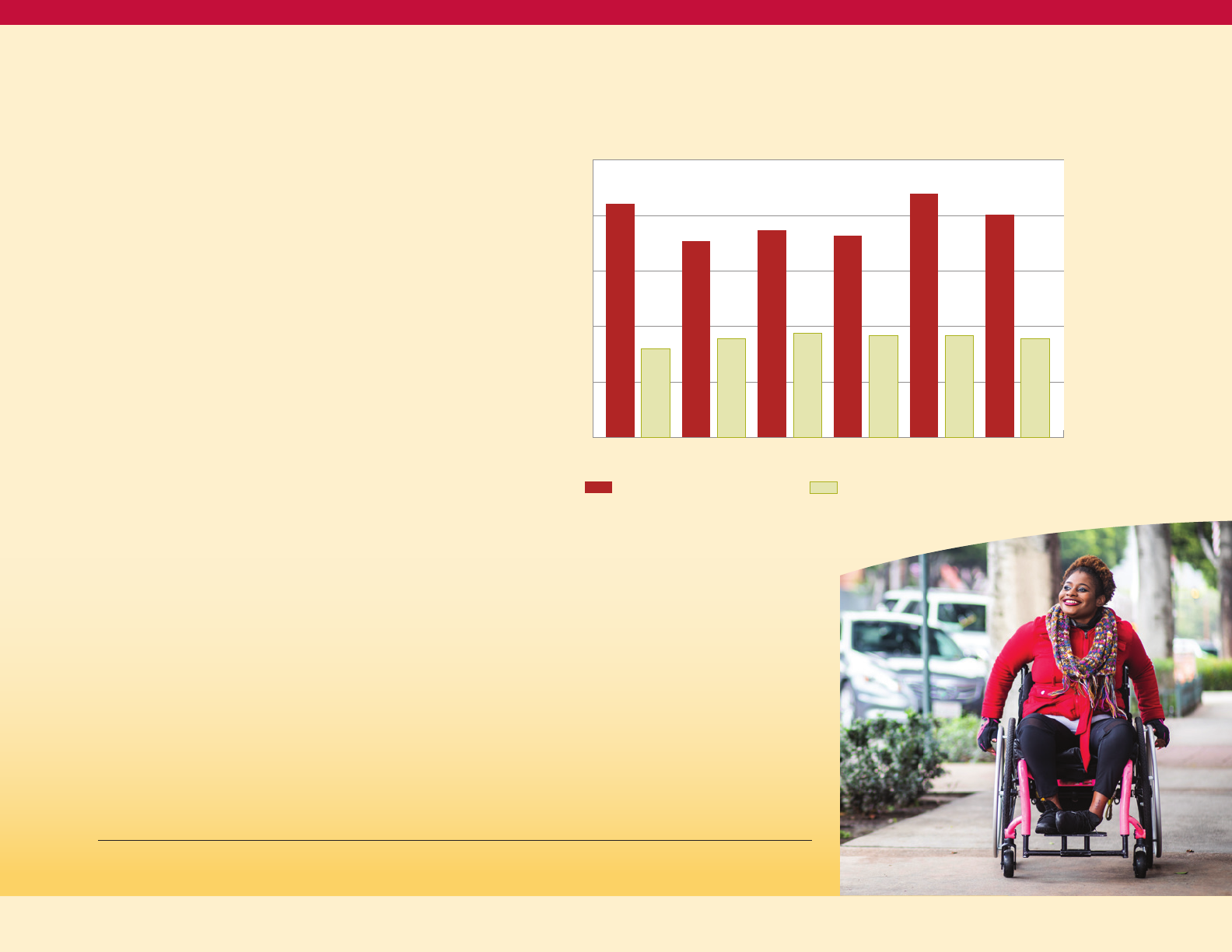

Crude Adult Prevalence of Diagnosed

Diabetes by Physical Activity Status and Race,

Maryland 2011-13 (BRFSS)

Figure 14

Met Not Met

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

% with diagnosed diabetes

11.2%

6.8%

15.2%

11.7%

NH Black

NH White

recommended weekly physical activity

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

23

The pattern of lower diabetes prevalence

in persons getting more physical activity is

seen for both Non-Hispanic Whites and

Non-Hispanic Blacks.

With physical activity being a determinant

of diabetes risk, the distribution of physical

activity participation across the State is

important to program planning. In Maryland,

adults without diabetes were more likely

to participate in at least 150 minutes of

moderate physical activity each week

(51.9 percent) versus those with diabetes

(44.2 percent). Meeting the physical activity

recommendation is more common for

Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks compared

with Hispanics.

54

The jurisdiction-specific

prevalence of meeting the 150 minute per

week physical activity recommendation is

mapped in Figure 15 below.

Maryland BRFSS 2017.

Garrett

Allegany

Washington

Frederick

Carroll

Montgomery

Prince

Georges

Charles

St. Mary’s

Calvert

Anne

Arundel

Harford

Cecil

Kent

Queen

Anne’s

Caroline

Talbot

Dorchester

Wicomico

Worchester

Somerset

Baltimore

County

Howard

Balt.

City

Age-adjusted Prevalence of 150 Minutes per Week of Physical Activity

(Maryland BRFSS 2017)

Figure 15

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

≤ 41.5%

≤ 46.8%

≤ 50.5%

≤ 53.5%

≤ 57.9%

Legend

24

https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/diseases/diabetes.html

https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/smoking-and-diabetes.html

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Maryland Quitline, FY2019, communicated October 9, 2019.

Smokers have a 30 percent to 40 percent

higher risk of developing diabetes compared

to non-smokers.

55

Studies have shown that

smoking can increase blood sugar levels and

decrease the body’s ability to use insulin.

People with diabetes who smoke need larger

doses of insulin to control their blood sugar

than those who do not smoke. Smoking

can increase the risk of certain diabetes

complications,

56

particularly the large blood

vessel effects related to atherosclerosis

(cholesterol deposits). These complications

are heart disease, heart attacks, stroke,

peripheral vascular disease, and amputations.

In Maryland, the adult prevalence of diagnosed

diabetes is higher in current and former

smokers than it is in non-smokers (Figure 17):

about 8.8 percent of non-smokers have

diagnosed diabetes, compared to 11.0 percent

and 10.3 percent of former and current

smokers, respectively.

57

Because smoking is a synergistic cause with

diabetes for large blood vessel complications

(heart attacks, strokes, leg artery blockage and

amputations), smoking is an important risk

factor to target among persons with diabetes.

In 2017, 17.9 percent of Maryland adults with

diabetes were current smokers, compared to

the 13.9 percent proportion of current smokers

among adults without diabetes (Figure 18).

58

The Maryland Department of Health manages

the MD Quitline, a free service for Maryland

residents 13 years and older to help quit

tobacco use. The MD Quitline tracks

information about smokers with diabetes.

In fiscal year 2019, approximately, 1,500 of

Quitline participants reported being told

by a provider they have prediabetes, 160

participants reported type 1 diabetes and

1,000 participants reported type 2 diabetes.

In fiscal year 2019, the Quitline was used by

a total of 8,155 phone participants and 1,340

web participants.

59

Diabetes and Tobacco

Figure 16

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of

Diagnosed Diabetes by Smoking Status,

Maryland 2015-17 (BRFSS)

12%

10%

8%

6%

4%

Never

Smoker

Former

Smoker

Current

Smoker

All

2%

0%

8.77%

11.00%

10.27%

9.67%

Figure 17

Age-adjusted Adult Prevalence of Current Smoking,

by Diabetes Status, Maryland 2017 (BRFSS)

30%

25%

0%

20%

15%

10%

5%

Doctor Diagnosed Diabetes (excl. women told only during pregnancy)

Doctor Diagnosed Diabetes No Diabetes

Percentage who are current smokers

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

17.9%

13.9%

25

“The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2012,” Diabetes Care, December 2014, vol. 37.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: National estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011.

American Dental Association, https://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/d/diabetes

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/gum-disease-dental-problems

Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia. 2012; 55(1):21–31. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2342-y.

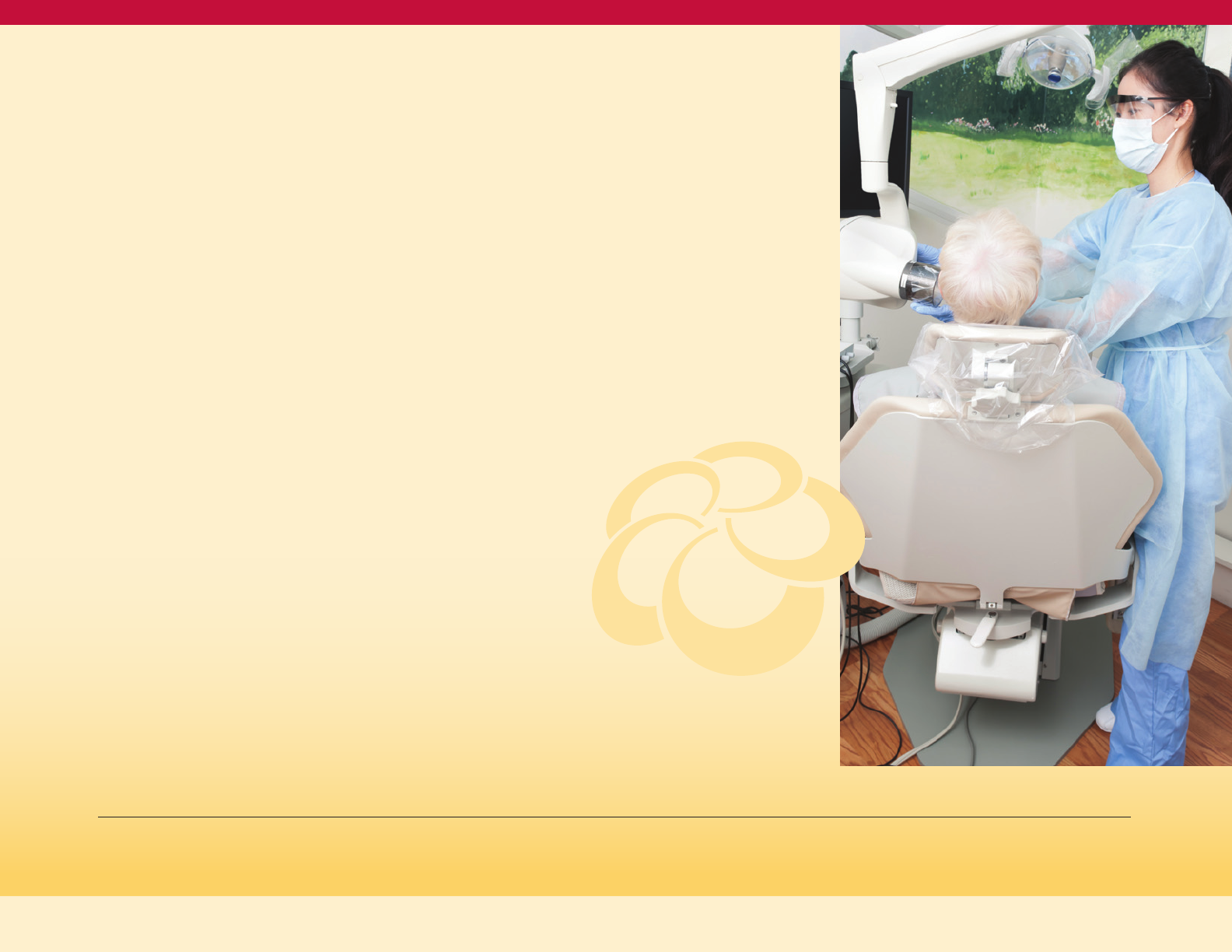

Diabetes and Oral Health

Diabetes impacts almost every part of the

body and can result in many complications,

including the increased likelihood of oral

health complications. The American Dental

Association has identified periodontal disease

as the most common dental disease affecting

those living with diabetes, affecting nearly 22

percent of those diagnosed. This is especially

true with increasing age. Poor blood sugar

control increases the risk for gum problems.

People with diabetes are twice as likely to

develop periodontitis and periodontitis can

also elevate blood sugar levels.

60

Periodontal disease is more common in people

with diabetes, so people with diabetes need

to be especially diligent about getting regular

dental examinations.

61

According to the CDC,

diabetes can increase the risk of periodontitis

for the following groups:

• Among young adults, those with diabetes

have about twice the risk of developing

periodontitis as those without diabetes.

• Adults ages 45 or older with poorly

controlled diabetes (A1C >9 percent)

are 2.9 times more likely to have severe

periodontitis than those without diabetes.

• People who smoke and have persistently

elevated glucose levels have a 4.6 times

greater risk for developing periodontitis.

62

Elevated glucose levels in the mouth can also

cause pain, infection and associated problems

in the mouth, potentially affecting the teeth,

gums, jaw, and tissues such as the tongue, the

roof and bottom of the mouth, and the inside

of the cheeks. When diabetes is not controlled,

high glucose levels in saliva help harmful

bacteria grow. These bacteria combine with

food to form plaque. Plaque can cause a variety

of oral diseases ranging from gum disease

and bad breath to bone loss, and tooth decay

or cavities. Gum disease can be more severe

and take longer to heal if you have diabetes.

In-turn, having gum disease can make your

glucose hard to control.

63

Research continues

to show that bi-directional relationship

between periodontal disease and diabetes.

People with diabetes have a higher prevalence

of periodontal disease and those with

untreated periodontal disease have challenges

with glycemic control.

64

Maryland Diabetes Action Plan 2020

26

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

Maryland BRFSS, 2015-2017.

The prevalence of diabetes is strongly

determined by income. As seen in Figure 18

and Figure 19, prevalence of diagnosed

diabetes is higher for adults with income

below $15,000 compared to adults with

income at or above $75,000.

65

This gradient of higher diabetes prevalence